The Project Gutenberg eBook, 1914, by John French, Viscount of Ypres

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: 1914

Author: John French, Viscount of Ypres

Release Date: February 6, 2008 [eBook #24538]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 1914***

E-text prepared by Michael Ciesielski, Christine P. Travers,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

Transcriber's note

Obvious printer's errors have been corrected; all other

inconsistencies are as in the original. The author's

spelling has been retained.

The changes from the errata (at the end of the book)

have been included in the text.

|

1914

THIS BOOK

IS DEDICATED TO

THE RT. HON. DAVID LLOYD GEORGE, M.P.,

TO WHOSE PREVISION, ENERGY

AND TENACITY THE ARMY

AND THE EMPIRE

OWE SO MUCH.

1914

BY

FIELD-MARSHAL VISCOUNT FRENCH OF YPRES,

K.P., O.M., ETC.

WITH MAPS

LONDON

CONSTABLE AND COMPANY LTD.

1919

CONTENTS (p. vii)

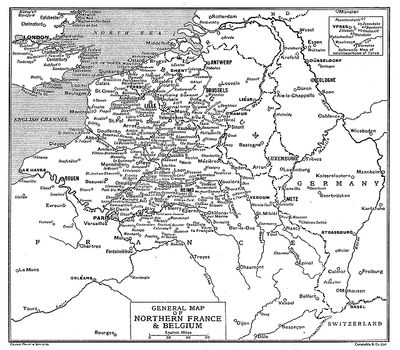

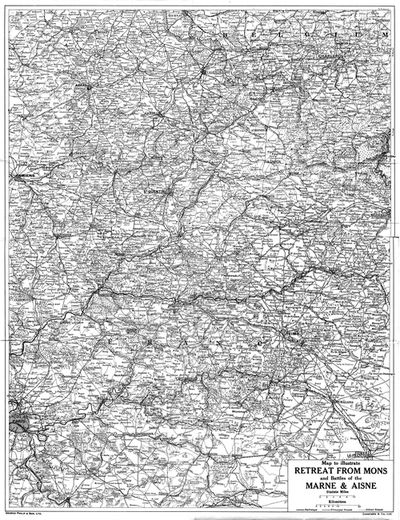

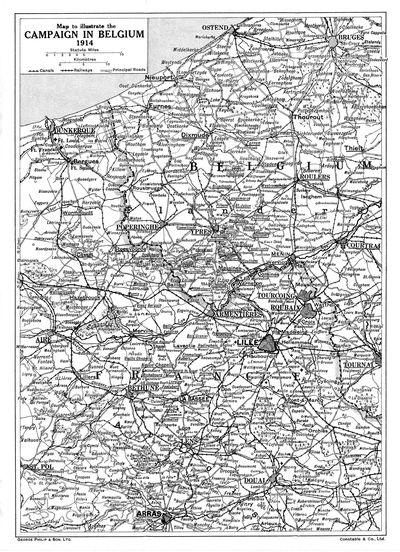

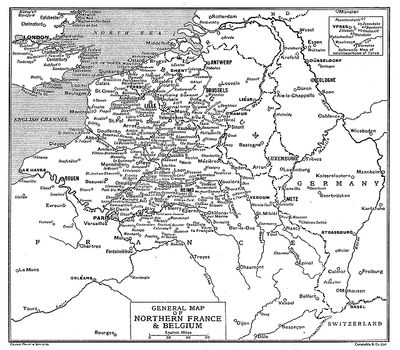

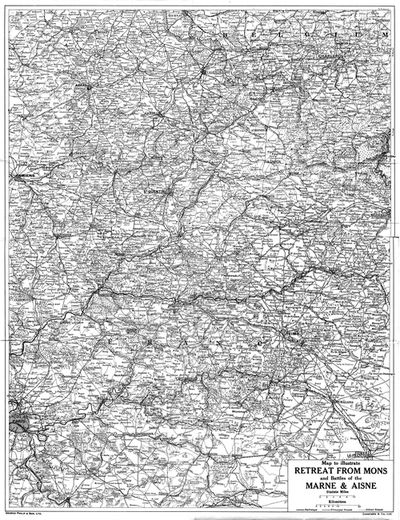

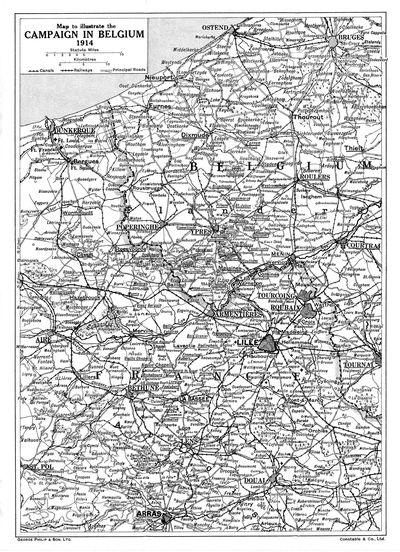

LIST OF MAPS.

PREFACE (p. xi)

Le Maréchal French commandait en Chef l'Armée Britannique au début de

la Guerre.

Comme on le sait, les allemands ont cherché en 1914 à profiter de leur

supériorité numérique et de l'écrasante puissance de leur armement,

pour mettre hors de cause les Armées Alliées d'Occident, par une

manœuvre enveloppante, aussi rapide que possible.

Après avoir cherché en vain la décision à la Marne, puis à l'Aisne et

à la Somme, ils la poursuivent successivement à Arras, sur l'Yser et à

Ypres.

À mesure que dans cette course à la mer, le terrain disponible se

restreint devant eux, les coups se précipitent et se répètent plus

violents, les réserves s'engagent, de nouveaux Corps d'Armée entrent

en ligne nombreux et intacts. La reddition d'Anvers assure d'ailleurs

à l'ennemi d'importantes disponibilités.

Mais déjà l'Armée Belge, appuyée de troupes françaises, arrête les

allemands sur l'Yser, de Nieuport à Dixmude. Après avoir pris part aux

actions de l'Aisne, l'Armée Britannique a été transportée dans le

Nord. C'est ainsi qu'elle s'engage (p. xii) progressivement de

La Bassée à Ypres, s'opposant partout à l'invasion.

Bref, les allemands, après avoir vainement développé leurs efforts de

la Mer à la Lys, dès le 15 octobre, sont dans l'obligation, à la fin

du mois, de vaincre à Ypres, ou bien leur manœuvre échoue

définitivement, leur offensive expire en Occident et la Coalition

reste debout.

Ainsi sont-ils amenés, sur ce point d'Ypres, dans une lutte acharnée,

à concentrer leurs moyens, une forte artillerie lourde largement

approvisionée, renforcée de minenwerfers, de corps d'armée nombreux et

renouvelés.

Quant aux Alliés, ils sont réduits à recevoir le choc avec des

effectifs restreints, des munitions comptées et rares, une faible

artillerie lourde. Toute relève leur est interdite par la pénurie de

troupes, quelle que soit la durée de la bataille. Pour ne citer qu'un

exemple, le premier corps britannique reste engagé du 20 octobre au 15

novembre—au milieu des plus violentes attaques et malgré de

formidables pertes.

Mais à cette dernière date la bataille était gagnée. Les Alliés

avaient infligé un retentissant échec à l'ennemi: ils avaient sauvé

les communications de la Manche et par là fixé le sort et l'avenir de

la Coalition.

Si l'union étroite du Commandement Allié et la valeur des troupes ont

permis ces glorieux résultats, c'est que le Maréchal French a déployé

la plus entière (p. xiii) droiture, la plus complète confiance, la

plus grande énergie: résolu à se faire passer sur le corps plutôt qu'à

reculer.

La Grande-Bretagne avait trouvé en lui un grand soldat. Il avait

maintenu ses troupes à la hauteur de celles de Wellington.

Avec l'émotion d'un souvenir profond et toujours vivant, je salue le

vaillant compagnon d'armes des rudes journées et les glorieux drapeaux

Britanniques de la Bataille d'Ypres.

Maréchal de France.(Back to Content)

CHAPTER I (p. 001)

PRELIMINARY

For years past I had regarded a general war in Europe as an eventual

certainty. The experience which I gained during the seven or eight

years spent as a member of the Committee of Imperial Defence, and my

three years tenure of the Office of Chief of the General Staff,

greatly strengthened this conviction.

For reasons which it is unnecessary to enter upon, I resigned my

position as Chief of the Staff in April, 1914, and from that time I

temporarily lost touch with the European situation as it was

officially represented and appreciated.

I remember spending a week in June of that year in Paris, and when

passing through Dover on my return, my old friend, Jimmie Watson

(Colonel Watson, late of the 60th Rifles, A.D.C. to the Khedive of

Egypt), looked into my carriage window and told me of the murder of

the Archduke Francis Ferdinand and his Consort. I cannot say that I

actually regarded this tragedy as being the prelude which should lead

ultimately to a great European convulsion, but in my own mind, and in

view of my past experience, it created a feeling of unrest within me

and an (p. 002) instinctive foreboding of evil. Then came a few weeks

of the calm which heralded the storm—a calm under cover of which

Germany was vigorously preparing for "the day."

One afternoon, late in July, I was the guest at lunch of the German

Ambassador, Prince Lichnowski. It was a small party, comprising, to

the best of my recollection, only Princess Henry of Pless, Lady

Cunard, Lord Kitchener, His Excellency and myself. The first idea I

got of the storm which was brewing came from a short conversation

which I had with the Ambassador in a corner of the room after lunch.

He was very unhappy and perturbed, and he plainly told me that he

feared all Europe would be in a blaze before we were a fortnight

older. His feeling was prophetic. His surprising candour foreshadowed

the moral courage with which Prince Lichnowski subsequently issued his

famous apologia.

On July 28th Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. The military

preparations of the Dual Monarchy inevitably led to a partial

mobilisation by Russia against Austria, whereupon the German Emperor

proclaimed the "Kriegsgefahrszustand" on July 31st, following this up

by declaring war against Russia on August 1st. On August 2nd German

troops entered Luxemburg and, without declaration of war, violated

French territory. Great Britain declared war against Germany on August

4th and against Austria on August 12th, France having broken off

relations with Austria two days earlier.

On Thursday, July 30th, I was sent for by the Chief of the Imperial

General Staff, and was given private intimation that, if an

expeditionary force were sent to France, I was to command it. On

leaving the room I (p. 003) found some well-known newspaper

correspondents in the passage. I talked a little with them and found

that great doubt existed in their minds as to whether this country

would support France by force of arms. This doubt was certainly shared

by many.

I remember well that on the morning of Saturday, August 1st, the day

upon which Germany declared war on Russia, and it was known that the

breaking out of hostilities between Germany and France was only a

question of hours, I received a visit from the Vicomte de la Panouse,

the French Military Attaché in London. He told me that the Ambassador

was much disheartened in mind by these doubts and fears. We talked

matters over, and he came to dinner with me that night. Personally, I

felt perfectly sure that so long as Mr. Asquith remained Prime

Minister, and Lord Haldane, Sir Edward Grey and Mr. Winston Churchill

continued to be members of the Cabinet, their voices would guide the

destinies of the British Empire, and that we should remain true to our

friendly understanding with the Entente Powers. As the result of the

long conversation I had with the Vicomte de la Panouse, I think I was

successful in causing this conviction to prevail at the French

Embassy.

England declared war on Germany on Tuesday, August 4th, and on the 5th

the mobilisation of Regulars, Special Reserve and Territorials was

ordered. On Wednesday, August 5th, a Council of War was held at 10,

Downing Street, under the Presidency of the Prime Minister. Nearly all

the members of the Cabinet were present, whilst Lord Roberts, Lord

Kitchener, Sir Charles Douglas, Sir Douglas Haig, the late Sir James

Grierson, General (now Sir Henry) Wilson and myself were directed to

(p. 004) attend. To the best of my recollection the two main subjects

discussed were:—

- The composition of the Expeditionary Force.

- The point of concentration for the British Forces on

their arrival in France.

As regards 1.

It was generally felt that we were under some obligation to France to

send as strong an army as we could, and there was an idea that one

Cavalry Division and six Divisions of all arms had been promised. As

to the exact number, it did not appear that we were under any definite

obligation, but it was unanimously agreed that we should do all we

could. The question to be decided was how many troops it was necessary

to keep in this country adequately to guard our shores against

attempted invasion and, if need be, to maintain internal order.

Mr. Churchill briefly described the actual situation of the Navy. He

pointed out that the threat of war had come upon us at a most

opportune moment as regards his own Department, because, only two or

three weeks before, the Fleet had been partially mobilised, and large

reserves called up for the great Naval Review by His Majesty at

Spithead and the extensive naval manœuvres which followed it. So

far as the Navy was concerned, he considered Home Defence reasonably

secure; but this consideration did not suffice to absolve us from the

necessity of keeping a certain number of troops at home. After this

discussion it was decided that two Divisions must for the moment

remain behind, and that one Cavalry Division and four Divisions of all

arms should be sent out as speedily as possible. This meant a force of

approximately 100,000 men.

As (p. 005) regards 2.

The British and French General Staffs had for some years been in close

secret consultation with one another on this subject. The German

menace necessitated some preliminary understanding in the event of a

sudden attack. The area of concentration for the British Forces had

been fixed on the left flank of the French, and the actual detraining

stations of the various units were all laid down in terrain lying

between Maubeuge and Le Cateau. The Headquarters of the Army were

fixed at the latter place.

This understanding being purely provisional and conditional upon an

unprovoked attack by Germany, the discussion then took the turn of

overhauling and reviewing these decisions, and of making arrangements

in view of the actual conditions under which war had broken out. Many

and various opinions were expressed; but on this day no final

decisions were arrived at. It was thought absolutely necessary to ask

the French authorities to send over a superior officer who should be

in full possession of the views and intentions of the French General

Staff. It was agreed that no satisfactory decision could be arrived at

until after full discussion with a duly accredited French Officer. I

think this is the gist of the really important points dealt with at

the Council.

During the week the Headquarters of the Expeditionary Force were

established in London at the Hotel Metropole, and the Staff was

constituted as follows:—

- Chief of Staff

Gen. Sir Archibald Murray.

- Sub-Chief

Brig.-Gen. H. H. Wilson.

- Adjutant-General

Major-Gen. Neville Macready.

- Quartermaster-General

Major-Gen. Sir William Robertson.

- Director of Intelligence

Brig.-Gen. Macdonogh.

- (p. 006) C.R.A.

Major-Gen. Lindsay.

- C.R.E.

Brig.-Gen. Fowke.

- Military Secretary

Col. the Hon. W. Lambton.

- Principal Medical Officer

Surg.-Gen. T. P. Woodhouse.

- Principal Veterinary Officer

Brig.-Gen. J. Moore.

It was about Thursday the 7th, or Friday the 8th, August, that Lord

Kitchener was appointed Secretary of State for War, and on Monday, the

10th, the Mission sent by the French Government arrived. It was headed

by Colonel Huguet, a well-known French Artillery Officer who had

recently been for several years French Military Attaché in London.

As before mentioned, one of the most important matters remaining for

discussion and decision was finally to determine whether the original

plan as regards the area of concentration for the British Forces in

France was to be adhered to, or whether the actual situation demanded

some change or modification. There was an exhaustive exchange of views

between soldiers and Ministers, and many conflicting opinions were

expressed. The soldiers themselves were not agreed. Lord Kitchener

thought that our position on the left of the French line at Maubeuge

would be too exposed, and rather favoured a concentration farther back

in the neighbourhood of Amiens. Sir Douglas Haig suggested postponing

any landing till the campaign had actively opened and we should be

able to judge in which direction our co-operation would be most

effective.

Personally, I was opposed to these ideas, and most anxious to adhere

to our original plans. Any alteration in carrying out our

concentration, particularly if this meant delay, would have upset the

French plan of campaign (p. 007) and created much distrust in the

minds of our Allies. Delay or hanging back would not only have looked

like hesitation, but might easily have entailed disastrous

consequences by permanently separating our already inferior forces.

Having regard to what we subsequently knew of the German plans and

preparations, there can be no doubt that any such delayed landing

might well have been actively opposed. As will be seen hereafter, we

were at first hopeful of carrying out a successful offensive, and, had

those hopes been justified, any change or delay in our original plans

would have either prevented or entirely paralysed it. The vital

element of the problem was speed in mobilisation and concentration,

change of plans meant inevitable and possibly fatal delay.

Murray, Wilson, Grierson and Huguet concurred in my views, and it was

so settled.

The date of the embarkment of the Headquarters Staff was fixed for

Friday, August 14th.

During the fateful days which intervened, daily and almost hourly

reports reached us as to the progress of mobilisation both of our

Allies and our Enemies. From the first it became quite evident that

the German system of mobilisation was quicker than the French. There

was reason to believe that Germany had partly mobilised some classes

of her reserves before formal mobilisation. The splendid stand made by

the Belgians in defence of their frontier fortresses is well known,

and the course of the preliminary operations on the Belgian and

Luxemburg frontiers, as well as those in the neighbourhood of Nancy,

gave us hope that the wonderful army of which we had heard so much,

was not altogether the absolutely invincible war machine we had been

led to expect and believe. (p. 008) During this most critical time,

my mind was occupied day and night with anxious thought. I will try to

recall those days of the first half of August, 1914, and crystallise

the result of my meditations. This will serve to show the doubts,

fears, hopes and aspirations, in short the mental atmosphere in which

I awaited the opening of the campaign.

In the ten years previous to the War, I had constantly envisaged the

probable course of events leading up to the outbreak of this

world-war, as well as the manner of the outbreak itself. In

imagination I had seen the spark suddenly emitted in some obscure

corner of Europe, followed by the blowing-up of one huge magazine,

such as the declaration of war between Russia and Austria would prove

to be, then the conflagration spreading with lightning speed, and I

had seemed to have a foretaste amid it all of the anxious hesitation

which would precede our entry into the war.

I have been a member of the Committee of Imperial Defence since 1906,

and have assisted at the innumerable deliberations of that Aulic

Council. It was somewhere about 1908 that the certainty of a war was

forced upon my mind. Lord Haldane was then Secretary of State for War

and I was Inspector-General of the Forces. Lord Haldane was himself

alive to the possibility of war; but, while he hoped to ward it off by

diplomacy and negotiation, he fully acquiesced in the desirability of

making every preparation which could be carried out in complete

secrecy. He told me that were he in power, if and when the event

occurred, he would designate me to command the Expeditionary Force,

and requested me to study the problem carefully and do all I could to

be ready. It thus fell out that in August, 1914, the many

possibilities and (p. 009) alternatives of action were quite familiar

to my mind.

It is now within the knowledge of all that the General Staffs of Great

Britain and France had, for a long time, held conferences, and that a

complete mutual understanding as to combined action in certain

eventualities existed.

Belgium, however, remained a "dark horse" up to the last, and it is

most unfortunate that she could never be persuaded to decide upon her

attitude in the event of a general war. All we ever had in our mind

was defence against attack by Germany. We had guaranteed the

neutrality of Belgium, and all reports pointed to an intention by

Germany to violate that neutrality. What we desired above all things

was that Belgium should realise the danger which subsequently laid her

waste. We were anxious that she should assist and co-operate in her

own defence. The idea of attacking Germany through Belgium or in any

other direction never entered our heads.

Pre-war arrangements like these were bound in such circumstances to be

very imperfect, though infinitely better than none at all.

It will be of interest at this point to narrate a conversation I had

with the Emperor William in August, 1911. When His Majesty visited

this country in the spring of that year to unveil the statue of Queen

Victoria, he invited me to be his guest at the grand cavalry

manœuvres to be held that summer in the neighbourhood of Berlin.

It was an experience I shall never forget, and it impressed me

enormously with the efficiency and power of the German cavalry. It was

on about the third day of (p. 010) the manœuvres that the Emperor

arrived by train at five in the morning to find the troops drawn up on

the plain close by to receive him. I have never seen a more

magnificent military spectacle than they presented on that brilliant

August morning, numbering some 15,000 horsemen with a large force of

horse artillery, jäger and machine guns.

When His Majesty had finished the inspection of the line, and the

troops had moved to take up their points for manœuvre, the Emperor

sent for me. He was very pleasant and courteous, asked me if I was

made comfortable, and if I had got a good horse. He then went on to

say that he knew all our sympathies in Great Britain were with France

and against Germany. He said he wished me to see everything that could

be seen, but told me he trusted to my honour to reveal nothing if I

visited France.

After the manœuvres of the day were completed, at about 11 or 12

o'clock, I was placed next to His Majesty at luncheon and we had

another conversation. He asked me what I thought of what I had seen in

the morning and told me that the German cavalry was the most perfect

in the world; but he added: "It is not only the Cavalry; the

Artillery, the Infantry, all the arms of the Service are equally

efficient. The sword of Germany is sharp; and if you oppose Germany

you will find how sharp it is."

Before I left, His Majesty was kind enough to present me with his

photograph beautifully framed. Pointing to it, he remarked,

semi-jocularly: "There is your archenemy! There is your disturber of

the peace of Europe!"

Reverting to my story. Personally, I had always thought that Germany

would violate Belgian neutrality, and (p. 011) in no such half

measure as by a march through the Ardennes, which was what our joint

plans mainly contemplated. I felt convinced that if ever she took this

drastic step, she would make the utmost use of it to pour over the

whole country and outflank the Allies.

The principal source of the terrible anxiety I felt took its root in

the thought that we were too much mentally committed to meet an attack

from the east, instead of one which was to come as it actually did. It

reassured me, however, to know that our actual dispositions did not

preclude the possibility of stemming the first outburst of the storm

so effectively as to ward off any imminent danger which might threaten

Northern France and the Channel Ports.

To turn from the province of strategy to the sphere of tactics, a

life-long experience of military study and thought had taught me that

the principle of the tactical employment of troops must be

instinctive. I knew that in putting the science of war into practice,

it was necessary that its main tenets should form, so to speak, part

of one's flesh and blood. In war there is little time to think, and

the right thing to do must come like a flash—it must present itself

to the mind as perfectly obvious.

No previous experience, no conclusion I had been able to draw from

campaigns in which I had taken part, or from a close study of the new

conditions in which the war of to-day is waged, had led me to

anticipate a war of positions. All my thoughts, all my prospective

plans, all my possible alternatives of action, were concentrated upon

a war of movement and manœuvre. I knew perfectly well that modern

up-to-date inventions would materially influence and modify our

previous conceptions as to the employment (p. 012) of the three arms

respectively; but I had not realised that this process would work in

so drastic a manner as to render all our preconceived ideas of the

method of tactical field operations comparatively ineffective and

useless. Judged by the course of events in the first three weeks of

the War, neither French nor German generals were prepared for the

complete transformation of all military ideas which the development of

the operations inevitably demonstrated to be imperative for waging war

in present conditions.

It is easy to be "wise after the event"; but I cannot help wondering

why none of us realised what the most modern rifle, the machine gun,

motor traction, the aeroplane and wireless telegraphy would bring

about. It seems so simple when judged by actual results. The modern

rifle and machine gun add tenfold to the relative power of the defence

as against the attack. This precludes the use of the old methods of

attack, and has driven the attack to seek covered entrenchments after

every forward rush of at most a few hundred yards.

It has thus become a practical operation to place the heaviest

artillery in position close behind the infantry fighting line, not

only owing to the mobility afforded by motor traction but also because

the old dread of losing the guns before they could be got away no

longer exists. The crucial necessity for the effective employment of

heavy artillery is observation, and this is provided by the balloon

and the aeroplane, which, by means of wireless telegraphy, can keep

the batteries instantly informed of the accuracy of their fire.

I feel sure in my own mind that had we realised the true effect of

modern appliances of war in August, 1914, there would have been no

retreat from Mons, and that if, in (p. 013) September, the Germans

had learnt their lesson, the Allies would never have driven them back

to the Aisne. It was in the fighting on that river that the eyes of

all of us began to be opened.

New characteristics of offensive and defensive war began vaguely to be

appreciated; but it required the successive attempts of Maunoury, de

Castelnau, Foch and myself to turn the German flanks in the north in

the old approved style, and the practical failure of these attempts,

to bring home to our minds the true nature of war as it is to-day.

About the middle of November, 1914—after three and a half months of

war—we were fairly settled down to the war of positions.

It was, therefore, in a somewhat troubled frame of mind that I began

to play my humble part in this tremendous episode in the history of

the world. The new lessons had to be learned in a hard school and

through a bitter experience. However, for good or for evil, I have

always been possessed of a sanguine temperament. No one, I felt, had

really been able to gauge the respective fighting values of the French

and German Armies. I hoped for the best and rather believed in it; and

in this confident spirit, although anxious and watchful, I landed at

Boulogne at 5 p.m. on August 14th, 1914.

It will be a fitting close to this chapter if I add the instructions

which I received from His Majesty's Government before leaving.

"Owing to the infringement of the neutrality of Belgium by Germany,

and in furtherance of the Entente which exists between this country

and France, His Majesty's Government has decided, at the request of

the French (p. 014) Government, to send an Expeditionary Force to

France and to entrust the command of the troops to yourself.

"The special motive of the Force under your control is to support and

co-operate with the French Army against our common enemies. The

peculiar task laid upon you is to assist the French Government in

preventing or repelling the invasion by Germany of French and Belgian

territory and eventually to restore the neutrality of Belgium, on

behalf of which, as guaranteed by treaty, Belgium has appealed to the

French and to ourselves.

"These are the reasons which have induced His Majesty's Government to

declare war, and these reasons constitute the primary objective you

have before you.

"The place of your assembly, according to present arrangements, is

Amiens, and during the assembly of your troops you will have every

opportunity for discussing with the Commander-in-Chief of the French

Army, the military position in general and the special part which your

Force is able and adapted to play. It must be recognised from the

outset that the numerical strength of the British Force and its

contingent reinforcement is strictly limited, and with this

consideration kept steadily in view it will be obvious that the

greatest care must be exercised towards a minimum of losses and

wastage.

"Therefore, while every effort must be made to coincide most

sympathetically with the plans and wishes of our Ally, the gravest

consideration will devolve upon you as to participation in forward

movements where large bodies of French troops are not engaged and

where your Force may be unduly exposed to attack. Should a contingency

of this sort be contemplated, I look to you to inform me fully and

give me time to communicate to you (p. 015) any decision to which His

Majesty's Government may come in the matter. In this connection I wish

you distinctly to understand that your command is an entirely

independent one, and that you will in no case come in any sense under

the orders of any Allied General.

"In minor operations you should be careful that your subordinates

understand that risk of serious losses should only be taken where such

risk is authoritatively considered to be commensurate with the object

in view.

"The high courage and discipline of your troops should, and certainly

will, have fair and full opportunity of display during the campaign,

but officers may well be reminded that in this, their first experience

of European warfare, a greater measure of caution must be employed

than under former conditions of hostilities against an untrained

adversary.

"You will kindly keep up constant communication with the War Office,

and you will be good enough to inform me as to all movements of the

enemy reported to you as well as to those of the French Army.

"I am sure you fully realise that you can rely with the utmost

confidence on the wholehearted and unswerving support of the

Government, of myself, and of your compatriots, in carrying out the

high duty which the King has entrusted to you and in maintaining the

great tradition of His Majesty's Army.

"(Signed) KITCHENER,

"Secretary of State"(Back to Content)

CHAPTER II (p. 016)

THE BRITISH EXPEDITIONARY FORCE

I have thought fit to interrupt my narrative here to devote some pages

to the composition of the original Expeditionary Force. The First

Expeditionary Force consisted of the First Army Corps (1st and 2nd

Divisions) under Lieut.-Gen. Sir Douglas Haig; the Second Army Corps

(3rd and 5th Divisions) under Lieut.-Gen. Sir James Grierson (who died

shortly after landing in France and was succeeded by Gen. Sir Horace

Smith-Dorrien), and the Cavalry Division under Major-Gen. E. H. H.

Allenby. To these must be added the 19th Infantry Brigade, which, at

the opening of our operations in France, was employed on our Lines of

Communication. The original Expeditionary Force was subsequently

augmented by the 4th Division, which detrained at Le Cateau on August

25th. The 4th Division and the 19th Infantry Brigade were, on the

arrival of Gen. Pulteney in France, on August 30th, formed into the

Third Army Corps, to which the 6th Division was subsequently added.

For the purpose of convenient reference, I have included in this

chapter the composition of the 6th Division, which joined us on the

Aisne, and of the 7th Division and the 3rd Cavalry Division, which

came into line with the original Expeditionary Force in Belgium in the

opening stages of the First Battle of Ypres; as also of the Lahore

Division of the Indian Corps, which likewise took part in the Battle

of Ypres.

(p. 017)

THE FIRST EXPEDITIONARY FORCE.

General Officer Commanding-in-Chief:

Field-Marshal Sir J. D. P. French.

Chief of the General Staff:

Lieut.-Gen. Sir A. J. Murray.

Adjutant-General:

Major-Gen. Sir C. F. N. Macready.

Quartermaster-General:

Major-Gen. Sir W. R. Robertson.

First Army Corps:

Lieut.-Gen. Sir Douglas Haig.

1st Division:

Major-Gen. S. H. Lomax,

wounded October 31st, replaced by Brig.-Gen. Landon (temp.),

then by Brig.-Gen. Sir D. Henderson.

1st Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. F. I. Maxse,

succeeded by Brig.-Gen. FitzClarence, V.C. (killed, November

11th). Col. McEwen then took command. Later on, Col.

Lowther was appointed to command the Brigade.

1st Batt. Coldstream Guards.

1st Batt. Scots Guards.

London Scottish (joined Brigade in November).

1st Batt. Royal Highlanders (the Black Watch).

2nd Batt. Royal Munster Fusiliers (cut to pieces at Etreux,

August 29th, replaced by 1st Batt. Cameron Highlanders).

(p. 018)

2nd Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. E. S. Bulfin,

wounded November 1st, succeeded by Col. Cunliffe-Owen (temp.).

Brig.-Gen. Westmacott took command November 23rd.

2nd Batt. Royal Sussex Regt.

1st Batt. Northampton Regt.

1st Batt. N. Lancs Regt.

2nd Batt. K.R.R.

3rd Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. H. J. S. Landon,

appointed to command the Division after October 31st, Col.

Lovett taking command of Brigade. Brig.-Gen. R. H. K.

Butler was appointed to command the Brigade November

13th.

1st Batt. The Queen's Royal West Surrey Regt. (cut up

October 31st, replaced by 2nd Royal Munster Fusiliers).

1st Batt. S. Wales Borderers.

1st Batt. Gloucester Regt.

2nd Batt. Welsh Regt.

Divisional Cavalry:

"C" Squadron 15th Hussars.

1st Cyclist Co.

Royal Engineers:

23rd & 26th Field Cos.

1st Signal Co.

Royal Artillery:

R.F.A. Batteries—

XXV. Brigade—113, 114, 115.

XXVI. Brigade—116, 117, 118.

XXIX. Brigade—46, 51, 54.

XLIII. Brigade (Howitzer)—30, 40, 57.

Heavy Battery R.G.A.—26.

1st Divisional Train.

R.A.M.C.: 1st, 2nd, & 3rd Field Ambulances.

(p. 019)

2nd Division:

Major-Gen. C. C. Monro.

4th (Guards) Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. R. Scott-Kerr,

wounded September 1st and succeeded by Brig.-Gen. the Earl

of Cavan (arrived September 18th).

2nd Batt. Grenadier Guards.

3rd Batt. Coldstream Guards.

2nd Batt. Coldstream Guards.

1st Batt. Irish Guards.

1st Herts (T.F.)

(joined Brigade about November 10th).

5th Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. R. C. B. Haking,

wounded on September 16th; succeeded by Lieut.-Col.

Westmacott until Haking returned on November 20th.

2nd Batt. Worcester Regt.

2nd Batt. Highland L.I.

2nd Batt. Oxf. & Bucks L.I.

2nd Batt. Connaught Rangers.

(2nd Connaughts were amalgamated with their 1st Batt. at the end of November

and replaced in the Brigade by 9th H.L.I. (Glasgow Highlanders).)

6th Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. R. H. Davies,

invalided in September; succeeded by Brig.-Gen. Fanshawe,

September 13th.

1st Batt. The King's (Liverpool) Regt.

1st Batt. Royal Berks Regt.

2nd Batt. S. Staffs Regt.

1st Batt. K.R.R.

(p. 020)

Divisional Cavalry:

"B" Squadron 15th Hussars.

2nd Cyclist Co.

Royal Engineers:

5th & 11th Field Cos.

2nd Signal Co.

Royal Artillery:

R.F.A. Batteries—

XXIV XXXIV. Brigade—25, 50, 70.

XXXVI. Brigade—15, 48, 71.

XLI. Brigade—9, 16, 17.

XLIV. Brigade (Howitzer)—47, 56, 60.

Heavy Battery R.G.A.—35.

2nd Divisional Train.

R.A.M.C.: 4th, 5th & 6th Field Ambulances.

Second Army Corps:

Lieut.-Gen. Sir James Grierson,

died August 17th; succeeded by Gen. Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien.

3rd Division:

Major-Gen. Hubert I. W. Hamilton,

killed October 14th; Major-Gen. Mackenzie in command till

end of October; then Major-Gen. Wing till November 6th;

then Major-Gen. Haldane.

(p. 021)

7th Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. F. W. N. McCracken,

3rd Batt. Worcester Regt.

1st Batt. Wilts Regt.

2nd Batt. S. Lancs Regt.

2nd Batt. Royal Irish Rifles.

8th Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. B. J. C. Doran,

invalided October 23rd; Brig.-Gen. Bowes took over command.

2nd Batt. Royal Scots.

2nd Batt. Royal Irish Regt. (Battalion cut up at Le Pilly,

October 20th; became G.H.Q. troops, replaced by 2nd

Suffolks.)

4th Batt. Middlesex Regt.

1st Batt. Gordon Highlanders. (Employed as G.H.Q. troops

during September, being replaced by 1st Devons, but rejoined

Brigade at beginning of October.)

9th Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. F. C. Shaw,

wounded November 12th; succeeded by Lieut.-Col. Douglas

Smith, Royal Scots Fusiliers.

1st Batt. Northumberland Fusiliers.

4th Batt. Royal Fusiliers.

1st Batt. Lincolnshire Regt.

1st Batt. Royal Scots Fusiliers.

Divisional Cavalry:

"A" Squadron 15th Hussars.

3rd Cyclist Co.

Royal Engineers:

56th & 57th Field Cos.

3rd Signal Co.

(p. 022)

Royal Artillery:

R.F.A. Batteries—

XXIII. Brigade—107, 108, 109.

XL. Brigade—6, 23, 49.

XLII. Brigade—29, 41, 45.

XXX. Brigade (Howitzer)—128, 129, 130.

Heavy Battery R.G.A.—48.

3rd Divisional Train.

R.A.M.C.: 7th, 8th, & 9th Field Ambulances.

5th Division:

Major-Gen. Sir Charles Fergusson,

invalided October 22nd; succeeded by Major-Gen. Morland.

13th Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. G. J. Cuthbert,

invalided about the end of September; succeeded by Brig.-Gen.

Hickie, who went sick October 13th, Col. Martyn getting

command (temp.).

2nd Batt. K.O. Scottish Borderers.

2nd Batt. (Duke of Wellington's) West Riding Regt.

1st Batt. Royal West Kent Regt.

2nd Batt. K.O. Yorkshire L.I.

14th Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. S. P. Rolt,

invalided October 29th;

succeeded by Brig.-Gen. F. S. Maude.

2nd Batt. Suffolk Regt. (replaced by 1st Devons at the

beginning of October, and became G.H.Q. troops).

1st Batt. East Surrey Regt.

1st Batt. Duke of Cornwall's L.I.

2nd Batt. Manchester Regt.

(p. 023)

15th Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. Count A. E. W. Gleichen.

1st Batt. Norfolk Regt.

1st Batt. Cheshire Regt.

1st Batt. Bedford Regt.

1st Batt. Dorset Regt.

Divisional Cavalry:

"A" Squadron 19th Hussars.

Royal Engineers:

17th & 59th Field Cos.

5th Cyclist Co.

Royal Artillery:

R.F.A. Batteries—

XV. Brigade—11, 52, 80.

XXVII. Brigade—119, 120, 121.

XXVIII. Brigade—122, 123, 124.

VIII. Brigade (Howitzer)—37, 61, 65.

Heavy Battery R.G.A.—108.

5th Divisional Train.

R.A.M.C.: 13th, 14th, & 15th Field Ambulances.

19th Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. L. G. Drummond,

succeeded early in September by Brig.-Gen. F. Gordon.

[Note.—This Brigade was formed from units on Lines of

Communication, and was attached successively to the Cavalry

Division, Second Corps and Fourth Division during the retreat

from Mons and advance to the Aisne. In the Flanders fighting

of October-November, 1914, it worked with the Sixth Division.]

2nd Batt. Royal Welsh Fusiliers.

1st Batt. Scottish Rifles.

1st Batt. Middlesex Regt.

2nd Batt. Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders.

19th Field Ambulance.

(p. 024)

Cavalry Division:

Major-Gen. E. H. H. Allenby,

took command of the Cavalry Corps on its formation in October,

Brig.-Gen. De Lisle taking command of the 1st Cavalry

Division.

1st Cavalry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. C. J. Briggs.

2nd Dragoon Guards.

5th Dragoon Guards.

11th Hussars.

2nd Cavalry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. H. De B. De Lisle,

transferred to command 1st Cavalry Division in October

and succeeded by Brig.-Gen. Mullins.

4th Dragoon Guards.

9th Lancers.

18th Hussars (Queen Mary's Own).

3rd Cavalry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. Hubert De La Poer Gough.

4th Hussars.

5th Lancers.

16th Lancers.

4th Cavalry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. Hon. C. E. Bingham.

Household Cavalry (Composite Regt.).

6th Dragoon Guards.

3rd Hussars.

(p. 025)

5th Cavalry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. Sir Philip P. W. Chetwode.

12th Lancers.

20th Hussars.

2nd Dragoons (Scots Greys).

Royal Horse Artillery:

Batteries—"D," "E," "I," "J," "L" ("L" Battery went

home to refit after Néry (September 1st), and was replaced

by "H," R.H.A., which arrived about the middle of

September).

Royal Engineers:

1st Field Squadron.

1st Signal Squadron.

[Note.—In September the 2nd Cavalry Division was formed,

consisting at first of the 3rd and 5th Cavalry Brigades under

Major-Gen. Gough, Brig.-Gen. Vaughan taking command of the

3rd Cavalry Brigade. With these brigades were "D" and "E"

Batteries, R.H.A. In October the 4th Cavalry Brigade was

transferred to the 2nd Cavalry Division, as was also "J"

Battery, R.H.A. The 2nd Cavalry Division had the 2nd Field

Squadron R.E. and 2nd Signal Squadron.]

R.A.M.C.: corresponding Cavalry Field Ambulances.

Royal Flying Corps:

Brig.-Gen. Sir David Henderson.

Aeroplane Squadrons Nos. 2, 3, 4, and 5.

4th Division:

Major-Gen. T. D. O. Snow,

invalided September; succeeded by Major-Gen. Sir H. Rawlinson,

who was transferred to 4th Army Corps early in

October and replaced by Major-Gen. H. F. M. Wilson.

(p. 026)

10th Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. J. A. L. Haldane,

appointed to command 3rd Division, November 6th; succeeded

by Brig.-Gen. Hull.

1st Batt. Royal Warwickshire Regt.

2nd Batt. Seaforth Highlanders.

1st Batt. Royal Irish Fusiliers.

2nd Batt. Royal Dublin Fusiliers.

11th Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. A. G. Hunter-Weston.

1st Batt. Somersetshire L.I.

1st Batt. Hampshire Regt.

1st Batt. E. Lancs Regt.

1st Batt. Rifle Brigade.

12th Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. H. F. M. Wilson,

in command of the 4th Division in October, and on promotion

succeeded by Col. F. G. Anley.

1st Batt. K.O. (R. Lancaster) Regt.

2nd Batt. Lancashire Fusiliers.

2nd Batt. Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers.

2nd Batt. Essex Regt.

Divisional Cavalry:

"B" Squadron 19th Hussars.

4th Cyclist Co.

Royal Engineers:

7th & 9th Field Cos.

4th Signal Co.

(p. 027)

Royal Artillery:

R.F.A. Batteries—

XIV. Brigade—39, 68, 88.

XXIX. Brigade—125, 126, 127.

XXXII. Brigade—27, 134, 135.

XXXVII. Brigade—31, 35, 55.

Heavy Battery, R.G.A.—31.

R.A.M.C.: 10th, 11th, & 12th Field Ambulances.

Lines of Communication and Army Troops:

1st Batt. Devonshire Regt. (transferred to 8th Brigade about

middle of September, later to 14th Brigade).

1st Batt. Cameron Highlanders (replaced 2nd Munsters in 1st

Brigade about September 6th).

[Note.—The 28th London (Artists' Rifles), 14th London

(London Scottish), 6th Welsh and 5th Border Regt. were all in

France before the end of the First Battle of Ypres, as was also

the Honourable Artillery Company. These battalions were all

at first on Lines of Communication.]

6th Division:

Major-Gen. J. L. Keir.

16th Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. C. Ingouville-Williams.

1st Batt. East Kent Regt. (The Buffs).

1st Batt. Leicestershire Regt.

1st Batt. Shropshire L.I.

2nd Batt. York and Lancaster Regt.

(p. 028)

17th Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. W. R. B. Doran.

1st Batt. Royal Fusiliers.

2nd Batt. Leinster Regt.

1st Batt. N. Staffs Regt.

3rd Batt. Rifle Brigade.

18th Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. W. N. Congreve, V.C.

1st Batt. West Yorks Regt.

2nd Batt. Notts and Derby Regt.

1st Batt. East Yorks Regt.

(the Sherwood Foresters).

2nd Batt. Durham. L.I.

Divisional Cavalry:

"C" Squadron 19th Hussars.

6th Cyclist Co.

Royal Engineers:

12th & 38th Field Cos.

6th Signal Co.

Royal Artillery:

R.F.A. Batteries—

II. Brigade—21, 42, 53.

XXIV. Brigade—110, 111, 112.

XXXVIII. Brigade—24, 34, 72.

XII. Brigade (Howitzer)—43, 86, 87.

Heavy Battery R.G.A.—24.

6th Divisional Train.

R.A.M.C.: 16th, 17th & 18th Field Ambulances.

7th Infantry Division:

Major-Gen. T. Capper.

20th Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. H. G. Ruggles-Brise.

1st Batt. Grenadier Guards.

2nd Batt. Border Regt.

2nd Batt. Scots Guards.

2nd Batt. Gordon Highlanders.

(p. 029)

21st Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. H. E. Watts.

2nd Batt. Bedfordshire Regt.

2nd Batt. Royal Scots Fusiliers.

2nd Batt. Yorkshire Regt.

2nd Batt. Wiltshire Regt.

22nd Infantry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. S. T. B. Lawford.

2nd Batt. The Queen's Royal West Surrey Regt.

2nd Batt. Royal Warwickshire Regt.

1st Batt. Royal Welsh Fusiliers.

1st Batt. S. Staffs Regt.

Divisional Cavalry:

Northumberland Yeomanry (Hussars).

7th Cyclist Co.

Royal Engineers:

54th & 55th Field Cos.

7th Signal Co.

Royal Artillery:

R.H.A. Batteries—"F" and "T."

R.F.A. Batteries—

XXII. Brigade—104, 105, 106.

XXV. Brigade—12, 35, 58.

Heavy Batteries R.G.A.—111, 112.

R.A.M.C.: 21st, 22nd and 23rd Field Ambulances.

3rd Cavalry Division:

Major-Gen. The Hon. Julian Byng.

6th Cavalry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. E. Makins.

3rd Dragoon Guards (joined the Division early in November).

North Somerset Yeomanry (attached to the Brigade before the

end of First Battle of Ypres).

1st Dragoons (The Royals).

10th Hussars.

(p. 030)

7th Cavalry Brigade:

Brig.-Gen. C. T. McM. Kavanagh.

1st Life Guards.

2nd Life Guards.

Royal Horse Guards (the Blues).

Royal Horse Artillery:

Batteries "C" and "K."

Royal Engineers:

3rd Field Squadron.

R.A.M.C.: 6th, 7th and 8th Cavalry Field Ambulances.(Back to Content)

CHAPTER III (p. 031)

THE SAILING OF THE EXPEDITIONARY FORCE

I left Charing Cross by special train at 2 p.m. on Friday, August

14th, and embarked at Dover in His Majesty's cruiser "Sentinel." Sir

Maurice FitzGerald and a few other friends were at the station to see

me off, and I was accompanied by Murray, Wilson, Robertson, Lambton,

Wake, Huguet and Brinsley FitzGerald (my private secretary). The day

was dark, dull and gloomy, and rather chilly for August. Dover had

ceased to be the cheery seaside resort of peace days, and had assumed

the appearance of a fortress expecting momentary attack. Very few

people were about, and the place was prepared for immediate action.

The fine harbour was crowded with destroyers, submarines, and a few

cruisers; booms barred all the entrances and mines were laid down.

It was the first time since war had been declared that I witnessed the

outward and visible signs of the great struggle for which we were

girding our loins. Not the least evidence of this was the appearance

of the officers and men of the "Sentinel." All showed in their faces

that strained, eager, watchful look which told of the severe and

continual daily and nightly vigil. This was very marked, and much

impressed me.

We sailed a little before 4 and landed at Boulogne about 5.30 in the

evening. I was met by the Governor, the Commandant, and the port

officials, and we had a very hearty reception. There were several rest

camps at Boulogne, (p. 032) and I was able to visit them. Officers

and men looked fit and well, and were full of enthusiasm and cheer.

Boulogne was only a secondary port of embarkation, but I can vividly

recall the scene. Everyone knows the curious and interesting old town,

with its picturesque citadel, situated on a lofty hill. On all sides

were evidences of great activity and excitement. Soldiers and sailors,

both British and French, were everywhere. All were being warmly

welcomed and cheered by the townspeople.

The declining August sun lit up sinuous columns of infantry ascending

the high ground to their rest camps on the plateau to the sound of

military bands. From the heights above the town, the quays and

wharves, where the landing of troops and stores was unceasingly going

forward, looked like human beehives. Looking out to sea, one could

distinguish approaching transports here and there between the ever

wary and watchful scout, destroyer and submarine, which were jealously

guarding the route.

Over all towered the monument to the greatest world-soldier—the

warrior Emperor who, more than a hundred years before, had from that

spot contemplated the invasion of England. Could he have now revisited

"the glimpses of the moon," would he not have rejoiced at this

friendly invasion of France by England's "good yeomen," who were now

offering their lives to save France from possible destruction as a

Power of the first class? It was a wonderful and never to be forgotten

scene in the setting sun; and, as I walked round camps and bivouacs, I

could not but think of the many fine fellows around me who had said

good-bye to Old England for ever.

We left Boulogne at 7.20 the same evening, and reached Amiens at 9.

There I was met by General Robert (Military Governor) and his staff,

the Prefect and officials. Amiens was (p. 033) the Headquarters of

General Robb, the Commander of our Line of Communications, and it was

also the first point of concentration for our aircraft, which David

Henderson commanded, with Sykes as his chief assistant. Whilst at

Amiens I was able to hold important discussions with Robb and

Henderson as to their respective commands.

I left Amiens for Paris on the morning of the 15th and we reached the

Nord Terminus at 12.45 p.m., where I was met by the British Ambassador

(now Lord Bertie) and the Military Governor of Paris. Large crowds had

assembled in the streets on the way to the Embassy, and we were

received with tremendous greetings by the people. Their welcome was

cordial in the extreme. The day is particularly memorable to me,

because my previous acquaintance with Lord Bertie ripened from that

time into an intimate friendship to which I attach the greatest value.

I trust that, when the real history of this war is written, the

splendid part played by this great Ambassador may be thoroughly

understood and appreciated by his countrymen. Throughout the year and

a half that I commanded in France, his help and counsel were

invaluable to me.

We drove to the Embassy and lunched there. In the afternoon,

accompanied by the Ambassador, I visited M. Poincaré. The President

was attended by M. Viviani, Prime Minister, and M. Messimy, Minister

for War. The situation was fully discussed, and I was much impressed

by the optimistic spirit of the President. I am sure he had formed

great hopes of a victorious advance by the Allies from the line they

had taken up, and he discoursed playfully with me on the possibility

of another battle being fought by the British on the old field of

Waterloo. He said the attitude of the French nation was admirable,

that they were very calm and determined.

After (p. 034) leaving the President I went to the War Office. Maps

were produced; the whole situation was again discussed, and

arrangements were made for me to meet General Joffre at his

Headquarters the next day.

In the evening I dined quietly with Brinsley FitzGerald at the Ritz,

and here it was curious to observe how Paris, like Dover, had put on a

sombre garb of war. The buoyant, optimistic nature of the French

people was apparent in the few we met; but there was no bombastic,

over-confident tone in the conversation around us; only a quiet, but

grim, determination which fully appreciated the tremendous

difficulties and gigantic issues at stake. The false optimism of "À

Berlin" associated with 1870 was conspicuously absent. In its place, a

silent determination to fight to the last franc and to the last man.

We left Paris by motor early on the 16th, and arrived at Joffre's

Headquarters at Vitry-le-François at noon. A few minutes before our

arrival a captured German flag (the first visible trophy of war I had

seen) had been brought in, and the impression of General Joffre which

was left on my mind was that he possessed a fund of human

understanding and sympathy.

I had heard of the French Commander-in-Chief for years, but had never

before seen him. He struck me at once as a man of strong will and

determination, very courteous and considerate, but firm and steadfast

of mind and purpose, and not easily turned or persuaded. He appeared

to me to be capable of exercising a powerful influence over the troops

he commanded and as likely to enjoy their confidence.

These were all "first impressions"; but I may say here that everything

I then thought of General Joffre was far more than confirmed

throughout the year and a half of fierce (p. 035) struggle during

which I was associated with him. His steadfastness and determination,

his courage and patience, were tried to the utmost and never found

wanting. History will rank him as one of the supremely great leaders.

The immediate task before him was stupendous, and nobly did he arise

to it.

I was quite favourably impressed by General Berthelot (Joffre's Chief

of Staff) and all the Staff Officers I met, and was much struck by

their attitude and bearing. There was a complete absence of fuss, and

a calm, deliberate confidence was manifest everywhere. I had a long

conversation with the Commander-in-Chief, at which General Berthelot

was present. He certainly never gave me the slightest reason to

suppose that any idea of "retirement" was in his mind. He discussed

possible alternatives of action depending upon the information

received of the enemy's plans and dispositions; but his main intention

was always to attack.

There were two special points in this conversation which recur to my

mind.

As the British Army was posted on the left, or exposed flank, I asked

Joffre to place the French Cavalry Division, and two Reserve Divisions

which were echeloned in reserve behind, directly under my orders. This

the Commander-in-Chief found himself unable to concede.

The second point I recall is the high esteem in which the General

Commanding the 5th French Army, General Lanrezac, which was posted on

my immediate right, was held by Joffre and his Staff. He was

represented to me as the best Commander in the French Army, on whose

complete support and skilful co-operation I could thoroughly rely.

Before leaving, the Commander-in-Chief handed me a written (p. 036)

memorandum setting forth his views as he had stated them to me,

accompanied by a short appreciation of the situation made by the Chief

of the General Staff.

We motored to Rheims, where we slept that night. Throughout this long

motor journey we passed through great areas of cultivated country. All

work, it seemed, had ceased; the crops were half cut, and stooks of

corn were lying about everywhere. It was difficult to imagine how the

harvest would be saved; but one of my most extraordinary experiences

in France was to watch the farming and agriculture going on as if by

magic. When, how, or by whom it was done, has always been an enigma to

me. There can be no doubt that the women and children proved an

enormous help to their country in these directions. Their share of the

victory should never be forgotten. It has been distilled from their

sweat and tears.

On the morning of the 17th I went to Rethel, which was the

Headquarters of the General Commanding the 5th French Army. Having

heard such eulogies of him at French G.H.Q., my first impressions of

General Lanrezac were probably coloured and modified in his favour;

but, looking back, I remember that his personality did not convey to

me the idea of a great leader. He was a big man with a loud voice, and

his manner did not strike me as being very courteous.

When he was discussing the situation, his attitude might have made a

casual observer credit him with practical powers of command and

determination of character; but, for my own part, I seemed to detect,

from the first time my eyes fell upon him, a certain over-confidence

which appeared to ignore the necessity for any consideration of

alternatives. Although we arrived at a mutual understanding which

included no idea or thought of "retreat," I (p. 037) left General

Lanrezac's Headquarters believing that the Commander-in-Chief had

over-rated his ability; and I was therefore not surprised when he

afterwards turned out to be the most complete example, amongst the

many this War has afforded, of the Staff College "pedant," whose

"superior education" had given him little idea of how to conduct war.

On leaving Rethel, I motored to Vervins, where I interviewed the

Commanders of the French Reserve Divisions in my immediate

neighbourhood, and reached my Headquarters at Le Cateau late in the

afternoon.

The first news I got was of the sudden death of my dear old friend and

comrade, Jimmie Grierson (General Sir James Grierson, Commanding the

2nd Army Corps). He was taken ill quite suddenly in the train on his

way to his own Corps Headquarters, and died in a few minutes. I had

known him for many years, but since 1906 had been quite closely

associated with him; for he had taken a leading part in the

preparation of the Army for war throughout that time. He possessed a

wonderful personality, and was justly beloved by officers and men

alike. He was able to get the best work out of them, and they would

follow him anywhere. He had been British Military Attaché in Berlin

for some years, and had thus acquired an intimate knowledge of the

German Army. An excellent linguist, he spoke French with ease and

fluency, and he used to astonish French soldiers by his intimate

knowledge of the history of their regiments, which was often far in

excess of what they knew themselves. His military acquirements were

brilliant, and in every respect thoroughly up-to-date. Apart from the

real affection I always felt for him, I regarded his loss as a great

calamity in the conduct of the campaign.

His (p. 038) place was taken by Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, although I

asked that Sir Herbert Plumer might be sent out to me to succeed

Grierson in command of the 2nd Corps. As a matter of fact, the

question of Sir James Grierson's successor was not referred to me at

all. The appointment was made at home. Although I knew Sir Horace to

be a soldier who had done good service and possessed a fine record, I

had asked for Sir Herbert Plumer because I felt he was the right man

for this command.

Lord Kitchener had asked me to send him a statement of the French

dispositions west of the Meuse. I sent him this in the following

letter:—

"Headquarters,

"Le Cateau,

"August 17th, 1914.

"My Dear Lord K.

"With reference to your wire asking for information as to the position

of French troops west of the line Givet—Dinant—Namur—Brussels, I

have already replied by wire in general terms. I now send full

details.

"A Corps of Cavalry (three divisions less one brigade), supported by

some Infantry, is north of the River Sambre between Charleroi and

Namur. This is the nearest French force to the Belgian Army, and I do

not know if and where they have established communication with them,

nor do the French.

"One French Corps, with an added Infantry Brigade and a Cavalry

Brigade, is guarding the River Meuse from Givet to Namur. The bridges

are mined and ready to be blown up.

"In rear of this corps, two more corps are moving—one on

Philippeville, the other on Beaumont. Each of these two corps is

composed of three divisions. In rear of (p. 039) them a fourth corps

assembles to-morrow west of Beaumont. Three Reserve divisions are

already in waiting between Vervins and Hirson. Another Reserve

division is guarding the almost impassable country between Givet and

Mézières.

"Finally, other Reserve formations are guarding the frontier between

Maubeuge and Lille.

"I left Paris on Sunday morning (16th) by motor, and reached the

Headquarters of General Joffre (French Commander-in-Chief) at 12. They

are at Vitry-le-François. He quite realises the importance and value

of adopting a waiting attitude. In the event of a forward movement by

the German Corps in the Ardennes and Luxemburg, he is anxious that I

should act in echelon on the left of the 5th French Army, whose

present disposition I have stated above. The French Cavalry Corps now

north of the Sambre will operate on my left front and keep touch with

the Belgians.

"I spent the night at Rheims and motored this morning to Rethel, the

Headquarters of General Lanrezac, Commander 5th French Army. I had a

long talk with him and arranged for co-operation in all alternative

circumstances.

"I then came on to my Headquarters at this place where I found

everything proceeding satisfactorily and up to time. I was much

shocked to hear of Grierson's sudden death near Amiens when I arrived

here. I had already wired asking you to appoint Plumer in his place,

when your wire reached me and also that of Ian Hamilton, forwarded—as

I understand—by you. I very much hope you will send me Plumer;

Hamilton is too senior to command an Army Corps and is already engaged

in an important command at home.

"Please (p. 040) do as I ask you in this matter? I needn't assure you

there was no 'promise' of any kind.

"Yours sincerely,

"(Signed)J. D. P. French.

"P.S.—I am much impressed by all I have seen of the French General

Staff. They are very deliberate, calm, and confident. There was a

total absence of fuss and confusion, and a determination to give only

a just and proper value to any reported successes. So far there has

been no conflict of first-rate importance, but there has been enough

fighting to justify a hope that the French artillery is superior to

the German."

It was on Tuesday, August 18th, that I was first able to assemble the

Corps Commanders and their Staffs. Their reports as to the transport

of their troops from their mobilising stations to France were highly

satisfactory.

The nation owes a deep debt of gratitude to the Naval Transport

Service and to all concerned in the embarking and disembarking of the

Expeditionary Force. Every move was carried out exactly to time, and

the concentration of the British Army on the left of the French was

effected in such a manner as to enable every unit to obtain the

requisite time to familiarise troops with active service conditions,

before it became necessary to make severe demands upon their strength

and endurance.

My discussion with the Corps Commanders was based upon the following

brief appreciation of the situation on that day. This was as

follows:—

"Between Tirlemont (to the east of Louvain) and Metz, the enemy has

some 13 to 15 Army Corps and seven Cavalry Divisions. A certain number

of reserve troops are (p. 041) said to be engaged in the offensive of

Liége, the forts of which place are believed to be still intact,

although some of the enemy's troops hold the town.

"These German Corps are in two main groups, seven to eight Corps and

four Cavalry Divisions being between Tirlemont and Givet. Six to seven

Corps and three Cavalry Divisions are in Belgian Luxemburg.

"Of the northern group, it is believed that the greater part—perhaps

five Corps—are either north and west of the Meuse, or being pushed

across by bridges at Huy and elsewhere.

"The general direction of the German advance is by Waremme on

Tirlemont. Two German Cavalry Divisions which crossed the Meuse some

days ago have reached Gembloux, but have been driven back to Mont

Arden by French cavalry supported by a mixed Belgian brigade.

"The German plans are still rather uncertain, but it is confidently

believed that at least five Army Corps and two or three Cavalry

Divisions will move against the French frontiers south-west, on a

great line between Brussels and Givet.

"The 1st French Corps is now at Dinant, one Infantry and one Cavalry

Brigade opposing the group of German Corps south of the Meuse.

"The 10th and 3rd Corps are on the line Rethel—Thuin, south of the

Sambre. The 18th Corps are moving up on the left of the 10th and 3rd.

"Six or seven Reserve French Divisions are entrenched on a line

reaching from Dunkirk, on the coast, through Cambrai and La Capelle,

to Hirson.

"The Belgian Army is entrenched on a line running north-east and

south-west through Louvain."

My (p. 042) general instructions were then communicated to Corps

Commanders as follows:—

"When our concentration is complete, it is intended that we should

operate on the left of the French 5th Army, the 18th Corps being on

our right. The French Cavalry Corps of three divisions will be on our

left and in touch with the Belgians.

"As a preliminary to this, we shall take up an area north of the

Sambre, and on Monday the heads of the Allied columns should be on the

line Mons—Givet, with the cavalry on the outer flank.

"Should the German attack develop in the manner expected, we shall

advance on the general line Mons—Dinant to meet it."

During these first days, whilst our concentration was in course of

completion, I rode about a great deal amongst the troops, which were

generally on the move to take up their billets or doing practice route

marches. I had an excellent opportunity of observing the physique and

general appearance of the men. Many of the reservists at first bore

traces of the civilian life which they had just left, and presented an

anxious, tired appearance; but it was wonderful to observe the almost

hourly improvement which took place amongst them. I knew that, under

the supervision and influence of the magnificent body of officers and

non-commissioned officers which belonged to the 1st Expeditionary

Force, all the reservists, even those who had been for years away from

the colours, would, before going under fire, regain to the full the

splendid military vigour, determination, and spirit which has at all

times been so marked a characteristic of British soldiers in the

field.

I received a pressing request from the King of the Belgians (p. 043)

to visit His Majesty at his Headquarters at Louvain; but the immediate

course of the operations prevented me from doing so.

The opening phases of the Battle of Mons did not commence until the

morning of Saturday, August 22nd. Up to that time, so far as the

British forces were concerned, the forwarding of offensive operations

had complete possession of our minds. During the days which

intervened, I had frequent meetings and discussions with the Corps and

Cavalry Commanders. The Intelligence Reports which constantly arrived,

and the results of cavalry and aircraft reconnaissances, only

confirmed the previous appreciation of the situation, and left no

doubt as to the direction of the German advance; but nothing came to

hand which led us to foresee the crushing superiority of strength

which actually confronted us on Sunday, August 23rd.

This was our first practical experience in the use of aircraft for

reconnaissance purposes. It cannot be said that in these early days of

the fighting the cavalry entirely abandoned that rôle. On the

contrary, they furnished me with much useful information.

The number of our aeroplanes was then limited, and their powers of

observation were not so developed or so accurate as they afterwards

became. Nevertheless, they kept close touch with the enemy, and their

reports proved of the greatest value.

Whilst at this time, as I have said, aircraft did not altogether

replace cavalry as regards the gaining and collection of information,

yet, by working together as they did, the two arms gained much more

accurate and voluminous knowledge of the situation. It was, indeed,

the timely warning they gave which chiefly enabled me to make speedy

dispositions to avert danger and disaster.

There (p. 044) can be no doubt indeed that, even then, the presence

and co-operation of aircraft saved the very frequent use of small

cavalry patrols and detached supports. This enabled the latter arm to

save horseflesh and concentrate their power more on actual combat and

fighting, and to this is greatly due the marked success which attended

the operations of the cavalry during the Battle of Mons and the

subsequent retreat.

At the time I am writing, however, it would appear that the duty of

collecting information and maintaining touch with an enemy in the

field will in future fall entirely upon the air service, which will

set the cavalry free for different but equally important work.

I had daily consultations with Sir William Robertson, the

Quartermaster-General. He expressed himself as well satisfied with the

condition of the transport, both horse and mechanical, although he

said the civilian drivers were giving a little trouble at first.

Munitions and supplies were well provided for, and there were at least

1,000 rounds per gun and 800 rounds per rifle. We also discussed the

arrangements for the evacuation of wounded.

The immediate despatch from home of the 4th Division was now decided

upon and had commenced, and I received sanction to form a 19th Brigade

of Infantry from the Line of Communication battalions.

At this time I received some interesting reports as to the work of the

French cavalry in Belgium. Their morale was high and they were very

efficient. They were opposed by two divisions of German cavalry whose

patrols, they said, showed great want of dash and initiative, and were

not well supported. They formed the opinion that the German horse did

not care about trying conclusions mounted, (p. 045) but endeavoured

to draw the French under the fire of artillery and jäger battalions,

the last-named always accompanying a German Cavalry Division.

At 5.30 a.m. on the 21st I received a visit from General de

Morionville, Chief of the Staff to His Majesty the King of the

Belgians, who, with a small staff, was proceeding to Joffre's

Headquarters. The General showed signs of the terrible ordeal through

which he and his gallant army had passed since the enemy had so

grossly violated Belgian territory. He confirmed all the reports we

had received concerning the situation generally, and added that the

unsupported condition of the Belgian Army rendered their position very

precarious, and that the King had, therefore, determined to effect a

retirement on Antwerp, where they would be prepared to attack the

flank of the enemy's columns as they advanced. He told me he hoped to

arrive at a complete understanding with the French Commander-in-Chief.

On this day, August 21st, the Belgians evacuated Brussels and were

retiring on Antwerp, and I received the following message from the

Government:—

"The Belgian Government desire to assure the British and French

Governments of the unreserved support of the Belgian Army on the left

flank of the Allied Armies with the whole of its troops and all

available resources, wherever their line of communications with the

base at Antwerp, where all their ammunition and food supplies are

kept, is not in danger of being severed by large hostile forces.

"Within the above-mentioned limits the Allied Armies may continue to

rely on the co-operation of the Belgian troops.

"Since the commencement of hostilities the Field Army has been holding

the line Tirlemont—Jodoigne—Hammemille—Louvain, where, (p. 046) up

to the 18th August, it has been standing by, hoping for the active

co-operation of the Allied Army.

"On August 18th it was decided that the Belgian Army, consisting of

50,000 Infantry rifles, 276 guns, and 4,100 Cavalry should retreat on

the Dyle. This step was taken owing to the fact that the support of

the Allies had not yet been effective, and, moreover, that the Belgian

forces were menaced by three Army Corps and three Cavalry Divisions

(the greater part of the First Army of the Meuse), who threatened to

cut their communications with their base.

"The rearguard of the 1st Division of the Army having been forced to

retire after a fierce engagement lasting five or six hours on August

18th, and the Commander of the Division having stated that his troops

were not in a fit state to withstand a long engagement owing to the

loss of officers and the weariness of the men; and, moreover, as the

Commander of the 3rd Division of the Army, which was so sorely tried

at Liége, had similarly come to the conclusion, on August 19th, that

the defence of the Dyle was becoming very dangerous, more especially

in view of the turning movement of the 2nd Army Corps and 2nd Cavalry

Division, it was definitely decided to retreat under the protection of

the forts at Antwerp.

"The general idea is now that the Field Army, in part or as a whole,

should issue from Antwerp as soon as circumstances seem to favour such

a movement.

"In this event, the Army will try to co-operate in its movements with

the Allies as circumstances may dictate."

Exhaustive reconnaissances and intelligence reports admitted of no

doubt that the enemy was taking the fullest advantage of his violation

of Belgian territory, and (p. 047) that he was protected to the right

of his advance, at least as far west as Soignies and Nivelles, whence

he was moving direct upon the British and 5th French Armies.

In further proof that, at this time, no idea of retreat was in the

minds of the leaders of the Allied Armies, I received late on Friday,

the 21st, General Lanrezac's orders to his troops. All his corps were

in position south of the Sambre, and he was only waiting the

development of a move by the 3rd and 4th French Armies from the line

Mézières—Longwy to begin his own advance.

As regards our own troops, on the evening of the 21st, the cavalry,

under Allenby, were holding the line of the Condé Canal with four

brigades. Two brigades of horse artillery were in reserve at

Harmignies. The 5th Cavalry Brigade, under Chetwode, composed of the

Scots Greys, 12th Lancers, and 20th Hussars, were at Binche, in touch

with the French.

Reconnoitring squadrons and patrols were pushed out towards Soignies

and Nivelles.

I visited Allenby's Headquarters in the afternoon of the 21st, and

discussed the situation with him. I told him on no account to commit

the cavalry to any engagement of importance, but to draw off towards

our left flank when pressed by the enemy's columns, and there remain

in readiness for action and reconnoitring well to the left.

The 1st Army Corps, under Sir Douglas Haig, was in cantonments to the

north of Maubeuge, between that place and Givry. The 2nd Corps, under

Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, was to the north-west of Maubeuge, between

that place and Sars-la-Bruyère. The 19th Infantry Brigade was

concentrating at Valenciennes.

Turning to our Ally, the 6th and 7th French Reserve Divisions

(p. 048) were entrenching themselves on a line running from Dunkirk,

through Cambrai and La Capelle, to Hirson. The 5th French Army was on

our right, the 18th French Corps being in immediate touch with the

British Army. Three Divisions of French cavalry under General Sordet,

which had been operating in support of the Belgians, were falling back