The Project Gutenberg eBook, Romantic Ballads, by George Borrow

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

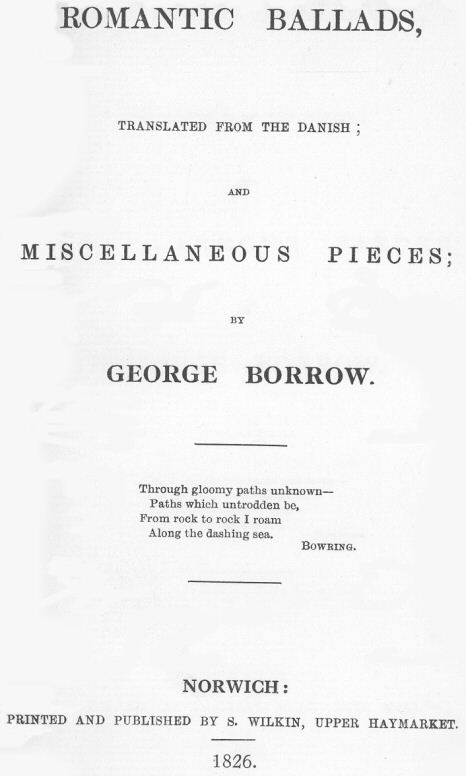

Title: Romantic Ballads

translated from the Danish; and Miscellaneous Pieces

Author: George Borrow

Release Date: August 31, 2006 [eBook #2430]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII)

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ROMANTIC BALLADS***

Transcribed from the 1913 Jarrold and Sons edition by David Price, email ccx074@pglaf.org

by

GEORGE BORROW.

* * * * *

Through gloomy paths unknown—

Paths which untrodden be,

From rock to rock I roam

Along the dashing sea.BOWRING.

* * * * *

NORWICH:

printed and published by jarrold and

sons.

1913

Contents.

Preface

Lines from Allan Cunningham to George Borrow

The Death-raven. From the Danish of Oehlenslæger

Fridleif and Helga. From the Danish of Oehlenslæger

Sir Middel. From the Old Danish

Elvir-shades. From the Danish of Oehlenslæger

The Heddybee-spectre. From the Old Danish

Sir John. From the Old Danish

May Asda. From the Danish of Oehlenslæger

Aager and Eliza. From the Old Danish

Saint Oluf. From the Old Danish

The Heroes of Dovrefeld. From the Old Danish

Svend Vonved. From the Old Danish

The Tournament. From the Old Danish

Vidrik Verlandson. From the Old Danish

Elvir Hill. From the Old Danish

Waldemar’s Chase

The Merman. From the Old Danish

The Deceived Merman. From the Old Danish

Miscellanies.

Cantata

The Hail-storm. From the Norse

The Elder-witch

Ode. From the Gælic

Bear song. From the Danish of Evald

National song. From the Danish of Evald

The Old Oak

Lines to Six-foot Three

Nature’s Temperaments. From the Danish of Oehlenslæger

The Violet-gatherer. From the Danish of Oehlenslæger

Ode to a Mountain-torrent. From the German of Stolberg

Runic Verses

Thoughts on Death. From the Swedish of C. Lohman

Birds of Passage. From the Swedish

The Broken Harp

Scenes

The Suicide’s Grave. From the German

The ballads in this volume are translated from the Works of Oehlenslæger, (a poet who is yet living, and who stands high in the estimation of his countrymen,) and from the Kiæmpé Viser, a collection of old songs, celebrating the actions of the ancient heroes of Scandinavia.

The old Danish poets were, for the most part, extremely rude in their versification. Their stanzas of four or two lines have not the full rhyme of vowel and consonant, but merely what the Spaniards call the “assonante,” or vowel rhyme, and attention seldom seems to have been paid to the number of feet on which the lines moved along. But, however defective their poetry may be in point of harmony of numbers, it describes, in vivid and barbaric language, scenes of barbaric grandeur, which in these days are never witnessed; and, which, though the modern muse may imagine, she generally fails in attempting to pourtray, from the violent desire to be smooth and tuneful, forgetting that smoothness and tunefulness are nearly synonymous with tameness and unmeaningness.

I expect shortly to lay before the public a complete translation of the Kiæmpé Viser, made by me some years ago; and of which, I hope, the specimens here produced will not give an unfavourable idea.

It was originally my intention to publish, among the “Miscellaneous Pieces,” several translations from the Gælic, formerly the language of the western world; the noble tongue

“A labhair Padric’ nninse Fail na Riogh.

‘San faighe caomhsin Colum náomhta’ n I.”Which Patrick spoke in Innisfail, to heathen chiefs of old

Which Columb, the mild prophet-saint, spoke in his island-hold—

but I have retained them, with one exception, till I possess a sufficient quantity to form an entire volume.

On his proposing to translate the ‘Kiæpé Viser.’

Sing, sing, my friend; breathe life again

Through Norway’s song and Denmark’s strain:

On flowing Thames and Forth, in flood,

Pour Haco’s war-song, fierce and rude.

O’er England’s strength, through Scotland’s

cold,

His warrior minstrels marched of old—

Called on the wolf and bird of prey

To feast on Ireland’s shore and bay;

And France, thy forward knights and bold,

Rough Rollo’s ravens croaked them cold.

Sing, sing of earth and ocean’s lords,

Their songs as conquering as their swords;

Strains, steeped in many a strange belief,

Now stern as steel, now soft as grief—

Wild, witching, warlike, brief, sublime,

Stamped with the image of their time;

When chafed—the call is sharp and high

For carnage, as the eagles cry;

When pleased—the mood is meek, and mild,

And gentle, as an unweaned child.

Sing, sing of haunted shores and shelves,

St. Oluf and his spiteful elves,

Of that wise dame, in true love need,

Who of the clear stream formed the steed—

How youthful Svend, in sorrow sharp,

The inspired strings rent from his harp;

And Sivard, in his cloak of felt,

Danced with the green oak at his belt—

Or sing the Sorceress of the wood,

The amorous Merman of the flood—

Or elves that, o’er the unfathomed stream,

Sport thick as motes in morning beam—

Or bid me sail from Iceland Isle,

With Rosmer and fair Ellenlyle,

What time the blood-crow’s flight was south,

Bearing a man’s leg in its mouth.

Though rough and rude, those strains are rife

Of things kin to immortal life,

Which touch the heart and tinge the cheek,

As deeply as divinest Greek.

In simple words and unsought rhyme,

Give me the songs of olden time.

The silken sail, which caught the summer breeze,

Drove the light vessel through the azure seas;

Upon the lofty deck, Dame Sigrid lay,

And watch’d the setting of the orb of day:

Then, all at once, the smiling sky grew dark,

The breakers rav’d, and sinking seem’d the bark;

The wild Death-raven, perch’d upon the mast,

Scream’d ’mid the tumult, and awoke the blast.

Dame Sigrid saw the demon bird on high,

And tear-drops started in her beauteous eye;

Her cheeks, which late like blushing roses bloom’d,

Had now the pallid hue of fear assum’d:

“O wild death-raven, calm thy frightful rage,

Nor war with one who warfare cannot wage.

Tame yonder billows, make them cease to roar,

And I will give thee pounds of golden ore.”

“With gold thou must not hope to pay the brave,

For gold I will not calm a single wave,

For gold I will not hush the stormy air,

And yet my heart is mov’d by thy despair;

Give me the treasure hid beneath thy belt,

And straight yon clouds in harmless rain shall melt,

And down I’ll thunder, with my claws of steel.

Upon the merman clinging to your keel.”

“What I conceal’d beneath my girdle bear,

Is thine—irrevocably thine—I swear.

Thou hast refus’d a great and noble prey,

To get possession of my closet key.

Lo! here it is, and, when within thy maw,

May’st thou much comfort from the morsel draw!”

The polish’d steel upon the deck she cast,

And off the raven flutter’d from the mast.

Then down at once he plung’d amid the main,

And clove the merman’s frightful head in twain;

The foam-clad billows to repose he brought,

And tam’d the tempest with the speed of thought;

Then, with a thrice-repeated demon cry,

He soar’d aloft and vanish’d in the sky:

A soft wind blew the ship towards the land,

And soon Dame Sigrid reach’d the wish’d-for

strand.

Once, late at eve, she play’d upon her harp,

Close by the lake where slowly swam the carp;

And, as the moon-beam down upon her shone,

She thought of Norway, and its pine-woods lone.

“Yet love I Denmark,” said she, “and the

Danes,

For o’er them Alf, my mighty husband, reigns.”

Then ’neath her girdle something mov’d and

yearn’d,

And into terror all her bliss was turn’d.

“Ah! now I know thy meaning, cruel bird . . . ”

Long sat she, then, and neither spoke nor stirr’d.

Faint, through the mist which rob’d the sky in gray,

The pale stars glimmer’d from the milky way.

“Ah! now I know thy meaning, cruel bird . . . ”

She strove in vain to breathe another word.

Above her head, its leaf the aspen shook—

Moist as her cheek, and pallid as her look.

Full five months pass’d, ere she, ’mid night and

gloom,

Brought forth with pain an infant from her womb:

They baptiz’d it, at midnight’s murky hour,

Lest it should fall within the demon’s power.

It was a boy, more lovely than the morn,

Yet Sigrid’s heart with bitter care was torn.

Deep in a grot, through which a brook did flow,

With crystal drops they sprinkled Harrald’s brow.

He grew and grew, till upon Danish ground

No youth to match the stripling could be found;

He was at once so graceful and so strong—

His look was fire, and his speech was song.

When yet a child, he tam’d the battle steed,

And only thought of war and daring deed;

But yet Queen Sigrid nurs’d prophetic fears,

And when she view’d him, always swam in tears.

One evening late, she lay upon her bed,

(King Alf, her noble spouse, was long since dead)

She felt so languid, and her aching breast

With more than usual sorrow was oppress’d.

Ah, then she heard a sudden sound that thrill’d

Her every nerve, and life’s warm current

chill’d:—

The bird of death had through the casement flown,

And thus he scream’d to her, in frightful tone:

“The wealthy bird came towering,

Came scowering,

O’er hill and stream.

‘Look here, look here, thou needy bird,

How gay my feathers gleam.’

“The needy bird came fluttering,

Came muttering,

And sadly sang,

‘Look here, look here, thou wealthy bird,

How loose my feathers hang.’

“Remember, Queen, the stormy day,

When cast away

Thou wast so nigh:—

Thou wast the needy bird that day,

And unto me didst cry.

“Death-raven now comes towering,

Comes scowering,

O’er hill and stream;

But when wilt thou, Dame Sigrid fair,

Thy plighted word redeem.”

A hollow moan from Sigrid’s bosom came,

While he survey’d her with his eye of flame:

“Fly,” said she; “demon monster, get thee

hence!

My humble pray’r shall be my son’s defence.”

She cross’d herself, and then the fiend flew out;

But first, contemptuously he danc’d about,

And sang, “No pray’r shall save him from my rage;

In Christian blood my thirst I will assuage.”

Young Harrald seiz’d his scarlet cap, and cried,

“I’ll probe the grief my mother fain would

hide;”

Then, rushing into her apartment fair,

“O mother,” said he, “wherefore sitt’st

thou there,

Far from thy family at dead of night,

With lips so mute, and cheeks so ghastly white?

Tell me what lies so heavy at thy heart;

Grief, when confided, loses half its smart.”

“O Harrald,” sigh’d she, yielding to his

pray’r,

“Creatures are swarming in the earth and air,

Who, wild with wickedness, and hot with wrath,

Wage war on those who follow virtue’s path.

One of those fiends is on the watch for thee,

Arm’d with a promise wrung by him from me:

His blood-shot eyes in narrow sockets roll,

And every night he leaves his mirksome hole.

“He was a kind of God, in former days;

Kings worshipp’d him, and minstrels sang his praise;

But when Christ’s doctrine through the dark North

flam’d,

His, and all evil spirits’ might was tam’d.

He now is but a raven; yet is still

Full strong enough to work on thee his will:

Lost is the wretch who in his power falls—

Vainly he shrieks, in vain for mercy calls.”

She whisper’d to him then, with bloodless lip,

What had befallen her on board the ship;

But youthful Harrald listen’d undismay’d,

And merely gripp’d the handle of his blade.

“My son,” she murmur’d, when her tale was

told,

“Fear withers me, but thou look’st blythe and

bold.”

The youth uplifted then his sparkling eye,

And said, whilst gazing on the moon-lit sky,

“Once, my dear mother, at the close of day,

Among tall flowers in the grove I lay,

Soft sang the linnets from a thousand trees,

And, sweetly lull’d, I slumber’d by degrees.

Then, heaven’s curtain was, methought, undrawn,

And, clad in hues that deck the brow of morn,

An angel slowly sank towards the earth,

Which seem’d to hail him with a smile of mirth.

“He rais’d his hand, and bade me fix my eye

Upon a chain which, hanging from the sky,

Embrac’d the world; and, stretching high and low,

Clink’d, as it mov’d, the notes of joy and wo:

The links that came in sight were purpled o’er

Full frequently with what seem’d human gore;

Of various metals made, it clasp’d the mould,—

Steel clung to silver, iron clung to gold.

“Then said the angel, with majestic air,—

‘The chain of destiny thou seest there.

Accept whate’er it gives, and murmur not;

For hard necessity has cast each lot.’

He vanish’d—I awoke with sudden start,

But that strange dream was graven on my heart.

I go wherever fate shall please to call,—

Without God’s leave, no fly to earth can fall.”

It thunders—and from midnight’s mirky cloud,

Comes peal on peal reverberating loud:

The froth-clad breakers cast, with sullen roar,

A Scottish bark upon the whiten’d shore.

Straight to the royal palace hasten then

A lovely maid and thirty sea-worn men.

Minona, Scotland’s princess, Scotland’s boast,

The storm has driven to the Danish coast.

Oft, while the train hew timber in the groves,

Minona, arm in arm, with Harrald roves.

Warm from his lip the words of passion flow;

Pure in her eyes the flames of passion glow.

One summer eve, upon a mossy bank,

Mouth join’d to mouth, and breast to breast, they sank:

The moon arose in haste to see their love,

And wild birds carroll’d from the boughs above.

But now the ship, which seem’d of late a wreck,

Floats with a mast set proudly on her deck.

Minona kisses Harrald’s blooming face,

Whilst he attends her to the parting place.

His bold young heart beats high against his side—

She sail’d away—and, like one petrified,

Full long he stood upon the shore, to view

The smooth keel slipping through the waters blue.

Months pass, and Sigrid’s sorrow disappears;

The wild death-raven’s might no more she fears;

A gentle red bedecks her cheek again,

And briny drops her eye no longer stain.

“My Harrald stalks in manly size and strength;

Swart bird of darkness, I rejoice at length;

If thy curst claw could hurt my gallant son,

Long, long, ere this, the deed would have been done.”

But Harrald look’d so moody and forlorn,

And thus his mother he address’d one morn:

“Minona’s face is equall’d by her mind;

Methinks she calls me from her hills of wind?

Give me a ship with men and gold at need,

And let me to her father’s kingdom speed;

I’ll soon return, and back across the tide

Bring thee a daughter, and myself a bride.”

Dame Sigrid promis’d him an answer soon,

And went that night, when risen was the moon,

Deep through the black recesses of the wood,

To where old Bruno’s shelter’d cabin stood.

She enter’d—there he sat behind his board,

His woollen vestment girded by a cord;

The little lamp, which hung from overhead,

Gleam’d on the Bible-leaves before him spread.

“Hail to thee, Father!—man of hoary age,

Thy Queen demands from thee thy counsel sage.

Young Harrald to a distant land will go,

And I his destiny would gladly know:

Thou read’st the stars,—O do the stars portend

That he shall come to an untimely end?

Take from his mother’s heart this one last care,

And she will always name thee in her pray’r.”

The hermit, rising from his lonely nook,

With naked head, and coldly placid look,

Went out and gaz’d intently on the sky,

Whose lights were letters to his ancient eye.

“The stars,” said he, “in friendly order

stand,

One only, flashes like an angry brand:—

Thy Harrald, gentle Queen, will not be slain

Upon the Earth, nor yet upon the Main.”

While thus the seer prophetically spoke,

A flush of joy o’er Sigrid’s features broke:

“He’ll not be slain on ocean or on land,”

She said, and kiss’d the hermit’s wrinkled hand;

“Why then, I’m happy, and my son is free

To mount his bark, and gallop through the sea:

Upon the grey stone he will sit as king,

When, in the grave, my bones are mouldering.”

The painted galley floats now in the creek—

Flags at her mast, and garlands at her beak;

High on the yard-arm hoisted is the sail,

Half spread it flutters in the evening gale.

The night before he goes, young Harrald stray’d

Into the wood where first he saw his maid:

Burning impatience fever’d all his blood,

He wish’d for wings to bear him o’er the flood.

Then sigh’d the wind among the bushy grounds,

Far in the distance rose the yell of hounds:

The flame-wisps, starting from the sedge and grass,

Hung, ’mid the vapours, over the morass.

Up to him came a beldame, wildly drest,

Bearing a closely-folded feather-vest:

She smil’d upon him with her cheeks so wan,

Gave him the robe, and was already gone.

Young Harrald, though astonish’d, has no fears;

The mighty garment in his hand he rears:

Of wond’rous lovely feathers it was made,

Which once the roc and ostrich had array’d.

He wishes much to veil in it his form,

And speed as rapidly as speeds the storm:

He puts it on, then seeks the open plain,—

Takes a short flight, and flutters back again.

“Courage!” he cried, “I will no longer

stay;

Scotland shall see me, ere the break of day.”

Then like a dragon in the air he soars,

Startled from slumber, in his wake it roars.

His wings across the ocean take their flight;

Groves, cities, hills, have vanish’d from his

sight,—

See! there he goes, lone rider of the sky,

Miles underneath him, black the billows lie.

He hears a clapping on the midnight wind:

Speed, Harrald, speed! the raven is behind.

Flames from his swarthy-rolling eye are cast:—

“Ha! Harrald,” scream’d he, “have we met

at last?”

For the first time, the youth felt terror’s force;

Pale grew his cheek, as that of clammy corse,

Chill was his blood, his nervous arm was faint,

While thus he stammer’d forth his lowly plaint:

“I see it is in vain to strive with fate;

Thank God, my soul is far above thy hate;

But, ere my mortal part thou dost destroy,

Let me one moment of sweet bliss enjoy:

The fair unmatch’d Minona is my love,

For her I travell’d, fool-like, here above:

Let me fly to her with my last farewell,

And I am thine, ere morning decks the fell.”

Firmly the raven holding him in air,

Survey’d his prize with fiercely-rabid glare:

“Now is the time to wreak on thee my lust;

Yet thou shalt own that I am good and just.”

Then from its socket, Harrald’s eye he tore,

And drank a full half of the hero’s gore:—

“Since I have mark’d thee, thou art free to go;

But loiter not when thou art there below.”

Young Harrald sinks with many a sob and tear,

Down from the sky to nature’s lower sphere:

He rested long beneath the poplar tall,

Which grew up, under the red church’s wall.

Then, rising slow, he feebly stagger’d on,

Till his Minona’s bower he had won.

Trembling and sad he stood beside the door—

Pale as a spectre, and besprent with gore!

“Minona, come, ere Harrald’s youthful heart

Is burst by love and complicated smart.

Soon will his figure disappear from earth,

Yet we shall meet in heaven’s halls of mirth:

Minona, come and give me one embrace,

That I may instantly my path retrace.”

Thus warbles he in passion’s wildest note,

While death each moment rattles in his throat.

Minona came: “Almighty God!” she cried,

“My Harrald’s ghost has wander’d o’er the

tide;

Red clots of blood his yellow tresses streak,

Drops of the same are running down his cheek.”

“Minona, love, survey me yet more near,

It is no shadow which accosts thee here;

Place thy warm hand upon my heart, and feel

Whether it beats for thee with slacken’d zeal.”

At once the current of her tears she stopp’d,

His arm upheld her, or the maid had dropp’d;

The roses faded from her face away,

And on her head the raven locks grew gray.

All he had borne, and what he yet must bear,

He murmurs to her whilst she trembles there:

The hero then with dying ardour press’d,

For the last time, his bosom to her breast.

“Farewell! Minona, all my fears are flown,

And if I grieve, it is for thee alone:

Give me a kiss, and give me too a smile,

And let not tears that parting look defile.

Now will I drink the bitter draught of death,

And yield courageously my forfeit breath:—

Farewell! may heaven take thee in its care,”

He said, and mounted swiftly in the air.

She gaz’d; but he had vanish’d from her view;

She stood forsaken in the damp and dew,

Then dark emotion quiver’d in her eye,

And thus she pray’d, with hands uplifted high:

“Thou who wert vainly tempted in the wild,

Thou who wert always charitably mild,

Thou who mad’st Peter walk on billows blue,

Enable me my Harrald to pursue.”

Sunken already was the morning star,

The song of nightingales was heard afar,

The red sun peep’d above the mountain’s brow,

And flowers scented all the vale below.

There came a youthful maiden, gaily drest,

Bearing upon her back a feather-vest;

Fondly she kiss’d Minona’s features wan,

Gave her the robe, and then at once was gone.

And straight Minona clothes in it her limbs,

And soaring upward through the ether swims:

To moan and sob, her madden’d breast disdains,

Too big for such low comfort are its pains.

The fowls that meet her in yon airy fields,

She clips in pieces with an axe she wields;

Each clanging pinion ceaselessly she plies,

But cannot meet the raven or his prize.

She hears a faint shriek in the air below,

And, swift as eagle pounces on his foe,

Down, down, she dropp’d, and lighted on the shore,

Which far and wide was wet with Harrald’s gore.

She smil’d so ruefully, but still was mute—

His good right hand was lying at her foot:

That pledge of truth, in love’s unclouded day,

Was the sole remnant of the demon’s prey.

Deep in her breast she hid the bloody hand,

And bade adieu, for ever, to the land:

Again she scower’d through the airy path,

Her eyeballs terrible with madden’d wrath:

The raven-sorcerer at length she spied,

And soon her steel was with his hot blood dyed:

The huge black body, piecemeal, found a grave

Amid the bosom of the briny wave.

The ocean billows fret and foam no more,

But softly rush towards the pebbled shore,

On which the lindens stand, in many a group,

With leafy boughs that o’er the waters droop.

There floats one single cloudlet in the blue,

Close where the pale moon shows her face anew:

It is Minona dying there that flies,—

She sinks not!—no—she mounts unto the skies.

The woods were in leaf, and they cast a sweet shade;

Among them walk’d Helga, the beautiful maid.

The water is dashing o’er yon little stones;

She sat down beside it, and rested her bones.

She sat down, and soon, from a bush that was near,

Sir Fridleif approach’d her with sword and with spear:

“Ah, pity me, Helga, and fly me not now,

I live, only live, on the smile of thy brow:

“In thy father’s whole garden is found not a

rose,

Which bright as thyself, and as beautiful grows.”

“Sir Fridleif, thy words are but meant to deceive,

Yet tell me what brings thee so late here at eve.”

“I cannot find rest, and I cannot find ease,

Though sweet sing the linnets among the wild trees;

“If thou wilt but promise, one day to be mine,

No more shall I sorrow, no more shall I pine.”

She sank in his arms, and her cheeks were as red

As the sun when he sinks in his watery bed;

But soon she arose from his loving embrace;

He walk’d by her side, through the wood, for a space.

“Now listen, young Fridleif, the gallant and bold,

Take off from my finger this ring of red gold,

Take off from my finger this ring of red gold,

And part with it not, till in death thou art cold.”

Sir Fridleif stood there in a sorrowful plight,

Salt tears wet his eyeballs, and blinded his sight.

“Go home, and I’ll come to thy father with

speed,

And claim thee from him, on my mighty grey steed.”

Sir Fridleif, at night, through the thick forest rode,

He fain would arrive at his lov’d one’s abode;

His harness was clanking, his helm glitter’d sheen,

His horse was so swift, and himself was so keen:

He reach’d the proud castle, and jump’d on the

ground,

His horse to the branch of a linden he bound;

He shoulder’d his mantle of grey otter skin,

And through the wide door, to Sir Erik went in.

“Here sitt’st thou, Sir Erik, in scarlet

array’d;

I’ve wedded thy daughter, the beautiful maid.”

“And who art thou, Rider? what feat hast thou done?

No nidering coward shall e’er be my son.”

“O far have I wander’d, renown’d is my

name,

The heroes I conquer’d wherever I came:

“Han Elland, ’t is true, long disputed the

ground,

But yet he receiv’d from my hand his

death-wound.”

Sir Erik then alter’d his countenance quite,

And out hurried he, in the gloom of the night.

“Fill high, little Kirstin, my best drinking cup,

And be the brown liquor with poison mixt up.”

She gave him the draught, and returning with speed,

“Young gallant,” said he, “thou must taste my

old mead.”

Sir Fridleif unbuckled his helmet and drank;

Sweat sprung from his forehead—his features grew blank.

“I never have drain’d, since the day I was

born,

A bitterer draught, from a costlier horn:

“My course is completed, my life is summ’d up,

For treason I smell in the dregs of the cup.”

Sir Erik then said, while he stamp’d on the ground,

“Young knight, ’t is thy fortune to die like a

hound.

“My best belov’d friend thou didst boast to have

slain,

And I have aveng’d him by giving thee bane:

“Not Helga, but Hela, [1] shall now be thy

bride;

Dark blue are her cheeks, and she looks stony-eyed.”

“Sir Erik, thy words are both witty and wise,

And hell, when it has thee, will have a rich prize!

“Convey unto Helga her gold ring so red;

Be sure to inform her when Fridleif is dead;

“But flame shall give water, and marble shall bleed,

Before thou shalt win by this treacherous deed:

“And I will not die like a hound, in the straw,

But go, like a hero, to Odin and Thor.”

He cut himself thrice, with his keen-cutting glaive,

And went to Valhalla, [2] the way of the

brave.

The knight bade his daughter come into the room:

“Look here, my sweet child, on thy merry

bridegroom.”

She look’d on the body, and gave a wild start;

“O father, why hadst thou so cruel a heart?”

She moan’d and lamented, she rav’d and she

curst;

She look’d on her love, till her very eyes burst.

At midnight, Sir Erik was standing there mute,

With two pallid corses beside his cold foot:

He stood stiff and still; and when morning-light came,

He stood, like a post, without life in his frame.

The youth and the maid were together interr’d,

Sir Erik could not from his posture be stirr’d:

He stood there, as stiffly, for thirty long days,

And look’d on the earth with a petrified gaze.

’T is said, on the night of the thirtieth long day,

To dust and to ashes he moulder’d away.

So tightly was Swanelil lacing her vest,

That forth spouted milk, from each lily-white breast;

That saw the Queen-mother, and thus she begun:

“What maketh the milk from thy bosom to run?”

“O this is not milk, my dear mother, I vow;

It is but the mead I was drinking just now.”

“Ha! out on thee minion! these eyes have their sight;

Would’st tell me that mead, in its colour, is

white?”

“Well, well, since the proofs are so glaring and strong,

I own that Sir Middel has done me a wrong.”

“And was he the miscreant? dear shall he pay,

For the cloud he has cast on our honour’s bright ray;

I’ll hang him up; yes, I will hang him with scorn,

And burn thee to ashes, at breaking of morn.”

The maiden departed in anguish and wo,

And straight to Sir Middel it lists her to go;

Arriv’d at the portal, she sounded the bell,

“Now wake thee, love, if thou art living and

well.”

Sir Middel he heard her, and sprang from his bed;

Not knowing her voice, in confusion he said,

“Away: for I have neither candle nor light,

And I swear that no mortal shall enter this night!”

“Now busk ye, Sir Middel, in Christ’s holy name;

I fly from my mother, who knows of my shame;

She’ll hang thee up; yes, she will hang thee with scorn,

And burn me to ashes, at breaking of morn.”

“Ha! laugh at her threat’nings, so empty and wild;

She neither shall hang me, nor burn thee, my child:

Collect what is precious, in jewels and garb,

And I’ll to the stable and saddle my barb.”

He gave her the cloak, that he us’d at his need,

And he lifted her up, on the broad-bosom’d steed.

The forest is gain’d, and the city is past,

When her eyes to the heaven she wistfully cast.

“What ails thee, dear maid? we had better now stay,

For thou art fatigu’d by the length of the way.”

“I am not fatigu’d by the length of the way;

But my seat is uneasy, in truth, I must say.”

He spread, on the cold earth, his mantle so wide;

“Now rest thee, my love, and I’ll watch by thy

side.”

“O Jesus, that one of my maidens were near!

The pains of a mother are on me, I fear.”

“Thy maidens are now at a distance from thee,

And thou art alone in the forest with me.”

“’Twere better to perish, again and again,

Than thou should’st stand by me, and gaze on my

pain.”

“Then take off thy kerchief, and cover my head,

And perhaps I may stand in the wise-woman’s

stead.”

“O Christ, that I had but a draught of the wave!

To quench my death-thirst, and my temples to lave.”

Sir Middel was to her so tender and true,

And he fetch’d her the drink in her gold-spangled shoe.

The fountain was distant, and when he drew near,

Two nightingales sat there and sang in his ear:

“Thy love, she is dead, and for ever at rest,

With two little babes that lie cold on her breast.”

Such was their song; but he heeded them not,

And trac’d his way back to the desolate spot;

But oh, what a spectacle burst on his view!

For all they had told him was fatally true.

He dug a deep grave by the side of a tree,

And buried therein the unfortunate three.

As he clamp’d the mould down with his iron-heel’d

boot

He thought that the babies scream’d under his foot:

Then placing his weapon against a grey stone,

He cast himself on it, and died with a groan.

Ye maidens of Norway, henceforward beware!

For love, when unbridled, will end in despair.

A sultry eve pursu’d a sultry day;

Dark streaks of purple in the sky were seen,

And shadows half conceal’d the lonely way;

I spurr’d my courser, and more swiftly rode,

In moody silence, through the forests green,

Where doves and linnets had their lone abode:

It was my fate to reach a brook, at last,

Which, by sweet-scented bushes fenc’d around,

Defiance bade to heat and nipping blast.

Inclin’d to rest, and hear the wild birds’

song,

I stretch’d myself upon that brook’s soft bound,

And there I fell asleep and slumber’d long;

And only woke, O wonder, to perceive

A gold-hair’d maiden, as a snowdrop pale,

Her slender form from out the ground upheave:

Then fear o’ercame me, and this daring heart

Beat three times audibly against my mail;

I wish’d to speak, but could no sound impart.

And see! another maid rose up and took

Some drops of water from the foaming rill,

And gaz’d upon me with a wistful look.

Said she, “What brings thee to this lonely place?

But do not fear, for thou shalt meet no ill;

Thou steel-clad warrior, full of youth and grace.”

“No;” sang the other, in delightful tone,

“But thou shalt gaze on prodigies which ne’er

To man’s unhallow’d eye have yet been

shown.”

The brook which lately brawl’d among the trees

Stood still, the murmur of that song to hear;

No green leaf stirr’d, and fetter’d seem’d the

breeze.

The thrush, upstarting in the distant dell,

Shook its brown wing, with golden streaks array’d,

And ap’d the witch-notes, as they rose and fell.

Bright gleam’d the lake’s broad sheet of liquid

blue,

Where, with the rabid pike, the troutling play’d;

The rose unlock’d its folded leaves anew,

And blush’d, besprinkled with the night’s cold

tear.

Once more the lily rais’d its head and smil’d,

All ghastly white, as when it decks the bier.

Though sweet she sang, my fears were not the less,

For in her accents there was something wild,

Which I can feel, ’t is true, but not express.

“Come with us,” sang she, “deep below the

earth,

Where sun ne’er burns, and storm-winds never rave;

Come with us to our halls of princely mirth,

“There thou shalt learn from us the Runic lay;

But dip thee, first, in yonder crystal wave,

Which binds thee to the Elfin race for aye:

“Though painted flowers on earth’s breast

abound,

Yet we have far more lovely ones below;

Like grass the chrysolites there strew the ground.”

“O come,” the other syren did exclaim,

“For rubies there more red than roses grow—

The sapphir’s blue the violet puts to shame.”

I rais’d my eyes to heaven’s starry dome,

And gripp’d my faulchion with convulsive might,

Resolv’d no witchcraft should my mind o’ercome.

My lengthen’d silence vex’d the maidens sore:

“Wilt thou detain us here the live-long night,

Or must we, stripling, proffer something more?

“Taught by us, thou shalt bind the rugged

bear,—

Seize on the mighty dragon’s heap of gold,—

And slay the cockatrice while in her lair!

“But from thy breast the blood we will suck out,

Unless thou follow us beneath the mould!

Decide, decide, nor longer pause in doubt!”

Cold sweat I shed, and as, with trembling hand,

I strove to whirl my beaming faulchion round,

It sank, enthrall’d by magic’s potent band.

Each witch drew nigh, with dagger high uprear’d;

Just then a cock, beyond the wild wood’s bound,

Crew loud—and in the earth they disappear’d.

I flung myself upon my frighten’d barb,

Just as the shades began to grow less murk,

And sun-beams clad the sky in gayer garb.

Let each young warrior from such places fly:

Disease and death beneath the flowers lurk;

And elves would suck the warm blood from his eye.

I clomb in haste my dappled steed,

And gallop’d far o’er mount and mead;

And when the day drew nigh its close,

I laid me down to take repose.

I laid me down to take repose,

And slumbers sweet fell o’er my brows:

And then, methought, as there I slept,

From out the ground the dead man leapt.

Said he, “If thou art valiant, Knight,

My murder soon will see the light;

For thou wilt ride to Heddybee,

Where live my youthful brothers three:

“And there, too, thou wilt surely find

My father dear and mother kind;

And there sits Kate, my much-loved wife,

Who with her women took my life.

“They chok’d me, as in bed I lay,

Then wrapp’d me in a truss of hay;

And bore me out at dead of night,

And laid me in this lonely height.

“The Groom, who lately clean’d my stall,

Now struts and vapours through my hall,—

Eats gaily with my silver knife,

And sleeps with Kate, my much-lov’d wife.

“His place is highest at the board;

But what is most to be deplor’d,

He gives my babes so little bread,

And mocks them now their sire is dead.

“Clad in my clothes he proudly stalks

Along the shady forest-walks;

And, arm’d with bow and hunting spear,

He shoots my birds and stabs my deer.

“Were I alive, to meet him now,

All underneath the linden bough,

With no one nigh, my wrath to check,

I’d wring his head from off his neck!

“But hie thee hence to Heddybee,

Where live my youthful brothers three;

First tell them all—then stab the groom—

Allow my wife a milder doom.”

Sir Lavé to the island stray’d;

He wedded there a lovely maid:

“I’ll have her yet,” said John.

He brought her home across the main,

With knights and ladies in the train:

“I’m close behind,” said John.

They plac’d her on the bridal seat;

Sir Lavé bade them drink and eat:

“Aye: that we will,” said John.

The servants led her then to bed,

But could not loose her girdle red!

“I can, perhaps,” said John.

He shut the door with all his might;

He lock’d it fast, and quench’d the light:

“I shall sleep here,” said John.

A servant to Sir Lavé hied;—

“Sir John is sleeping with the bride:”

“Aye, that I am,” said John.

Sir Lavé to the chamber flew:

“Arise, and straight the door undo!”

“A likely thing!” said John.

He struck with shield, he struck with spear—

“Come out, thou Dog, and fight me here!”

“Another time,” said John.

“And since thou with my bride hast lain,

To our good king I will complain.”

“That thou canst do,” said John.

As soon as e’er the morning shone,

Sir Lavé sought our monarch’s throne;

“I’ll go there too,” said John.

“O King, chastise this wicked wight,

For with my wife he slept last night.”

“’T is very true,” said John.

“Since ye two love one pretty face,

Your lances must decide the case.”

“With all my heart,” said John.

The sun on high was shining bright,

And thousands came to see the fight:

“Lo! here I am:” said John.

The first course that they ran so free,

Sir John’s horse fell upon his knee:

“Now help me God!” said John.

The next course that they ran, in ire,

Sir Lavé fell among the mire.

“He’s dead enough!” said John.

The victor to the castle hied,

And there in tears he found the bride:

“Thou art my own,” said John.

That night, forgetting all alarms,

Again she blest him in her arms.

“I have her now!” said John.

May Asda is gone to the merry green wood;

Like flax was each tress on her temples that stood;

Her cheek like the rose-leaf that perfumes the air;

Her form, like the lily-stalk, graceful and fair:

She mourn’d for her lover, Sir Frovin the brave,

For he had embark’d on the boisterous wave;

And, burning to gather the laurels of war,

Had sail’d with King Humble to Orkney afar:

At feast and at revel, wherever she went,

Her thoughts on his perils and dangers were bent;

No joy has the heart that loves fondly and dear—

No pleasure save when the lov’d object is near!

May Asda walk’d out in the bonny noon-tide,

And roam’d where the beeches grew up in their pride;

She sat herself down on the green sloping hill,

Where liv’d the Erl-people, [4] and where they live

still:

Then trembled the turf, as she sat in repose,

And straight from the mountain three maidens arose;

And with them a loom, and upon it a woof,

As white as the snow when it falls on the roof.

Of red shining gold was the fairy-loom made;

They sang and they danc’d, and their swift shuttles

play’d;

Their song was of death, and their song was of life,

It sounded like billows in tumult and strife.

They gave her the woof, with a sorrowful look,

And vanish’d like bubbles that burst on the brook;

But deep in the mountain was heard a sweet strain,

As the lady went home to her bower again.

The web was unfinish’d; she wove and she spun,

Nor rested a moment, until it was done;

And there was enough, when the work was complete,

To form for a dead man a shirt or a sheet.

The heroes return’d from the well-foughten field,

And bore home Sir Frovin’s corse, laid on a shield;

Sad sight for the maid! but she still was alert,

And sew’d round the body the funeral shirt:

And when she had come to the very last stitch,

Her feelings, so long suppress’d, rose to a pitch,

The cold clammy sweat from her features outbroke;

Death struck her, and meekly she bow’d to the stroke.

She rests with her lover now deep in the grave,

And o’er them the beeches their mossy boughs wave;

There sing the Erl-maidens their ditties aloud,

And dance while the merry moon peeps from the cloud.

Have ye heard of bold Sir Aager,

How he rode to yonder isle;

There he saw the sweet Eliza,

Who upon him deign’d to smile.

There he married sweet Eliza,

With her lands and ruddy gold—

Wo is me! the Monday after,

Dead he lay beneath the mould!

In her bower sat Eliza;

Rent the air with shriek and groan;

All which heard the good Sir Aager,

Underneath the granite stone.

Up his mighty limbs he gather’d,

Took the coffin on his back;

And to fair Eliza’s bower

Hasten’d, by the well-known track.

On her chamber’s lowly portal,

With his fingers long and thin,

Thrice he tapp’d, and bade Eliza

Straightway let her bridegroom in!

Straightway answer’d fair Eliza,

“I will not undo my door

Till I hear thee name sweet Jesus,

As thou oft hast done before.”

“Rise, O rise, my own Eliza,

And undo thy chamber door;

I can name the name of Jesus,

As I once could do before.”

Up then rose the sweet Eliza,—

Up she rose, and twirl’d the pin.

Straight the chamber door flew open,

And the dead man glided in.

With her comb she comb’d his ringlets,

For she felt but little fear:

On each lock that she adjusted

Fell a hot and briny tear.

“Listen, now, my good Sir Aager,

Dearest bridegroom, all I crave

Is to know how it goes with thee,

In that lonely place, the grave?”

“Every time that thou rejoicest,

And thy breast with pleasure heaves,

Then that moment is my coffin

Lin’d with rose and laurel leaves.

“Every time that thou art shedding

From thine eyes the briny flood,

Then that moment is my coffin

Fill’d with black and loathsome blood.

“Heard I not the red cock crowing,

Distant far upon the wind?

Down to dust the dead are going,

And I may not stop behind.

“Heaven’s ruddy portals open,—

Daylight bursts upon my view;

Though the word be hard to utter,

I must bid thee, love, adieu!”

Up his mighty limbs he gather’d,

Took the coffin on his back,

To the church-yard straight he hasten’d

By the well-known, beaten, track.

Up then rose the sweet Eliza;

Tear-drops on her features stood,

While her lover she attended

Through the dark and dreary wood.

When they reach’d the lone enclosure,

(Last, sad, refuge of the dead)—

From the cheeks of good Sir Aager

All the lovely colour fled:

“Listen, now, my sweet Eliza,

If my peace be dear to thee:

Never, then, from this time forward,

Shed a single tear for me.

“Turn thy lovely eyes to heaven,

Where the stars are beaming pale;

Thou canst tell me, then, for certain,

If the night begins to fail.”

When she turn’d her eyes to heaven,

All with stars besprinkled o’er,

In the earth the dead man glided,

And she never saw him more.

Homeward went the sweet Eliza;

Oh, her heart was chill and cold:—

Wo is me! the Monday after,

Dead she lay beneath the mould!

St. Oluf was a mighty king,

Who rul’d the Northern land;

The holy Christian faith he preach’d,

And taught it, sword in hand.

St. Oluf built a lofty ship,

With sails of silk so fair;

“To Hornelummer I must go,

And see what’s passing there.”

“O do not go,” the seamen said,

“To yonder fatal ground,

Where savage Jutts, [5] and wicked elves,

And demon sprites, abound.”

St. Oluf climb’d the vessel’s side;

His courage nought could tame!

“Heave up, heave up the anchor straight;

Let’s go in Jesu’s name.

“The cross shall be my faulchion now—

The book of God my shield;

And, arm’d with them, I hope and trust

To make the demons yield.”

And swift, as eagle cleaves the sky,

The gallant vessel flew;

Direct for Hornelummer’s rock,

Through ocean’s wavy blue.

’T was early in the morning tide

When she cast anchor there;

And, lo! the Jutt stood on the cliff,

To breathe the morning air:

His eyes were like the burning beal—

His mouth was all awry;

The truth I tell, and say he stood

Full twenty cubits high:

His beard was like a horse’s mane,

And down his bosom roll’d;

The claws that fenc’d his finger ends

Were frightful to behold.

“I never yet have seen,” he cried,

“A ship come near my strand,

That here to shore I could not drag,

By putting out my hand.”

The good St. Oluf smil’d thereat,

And thus address’d his crew:

“Now hold your tongues, and well observe

What I’m about to do.”

The giant stretch’d his mighty arm;

The ship was nigh his own;

But when St. Oluf rais’d the cross,

He sank knee-deep in stone.

“Here am I, sunk knee-deep in stone!

My legs I cannot move;

But, since my back and fists are free,

My might thou yet shalt prove.”

“Be still, be still, thou noisy guest—

Be still for evermore;

Become a rock and beetle there,

Above the billows hoar.”

Up started then, from out the hill,

The demon’s hoary wife;

She curs’d the king a thousand times,

And brandish’d high her knife.

Sore wonder’d then the little elves,

Who sat within the hill,

To see their mother, all at once,

Stand likewise stiff and still:

“’T is done,” they cried, “by yonder

wight,

Who rides upon the waves;

Let’s wade out to him, through the surf,

And beat him with our staves.”

At Hornelummer happen’d then,

What happen’d ne’er before;

The elfins wish’d to leave the hill,

And could not find a door:

They ran their heads against the wall,

And tried to break it through;

They could not break the solid rock,

But broke their necks in lieu.

Now, thanks to God, and Jesus Christ,

And good St. Oluf’s arm,

To Hornelummer we can sail

Without mishap or harm.

On Dovrefeld, [6] in Norway,

Were once together seen

The twelve heroic brothers

Of Ingeborg, the queen:

And they were all magicians,

Possest of mighty art,

Who freely read the Runic,

And knew the rhyme by heart. [7]

The first could turn the lightning,

And quench its ruddy gleam:

The second, with a whisper,

Could still the running stream:

The third beneath the water

Could dive like any fish:

The fourth could get provision

By striking on his dish:

The fifth upon the gold harp

So pleasantly could play,

That all the men who heard him

Began to dance away:

The sixth, he had a bugle,

And when he blew a blast,

The stoutest of his foemen

Would fly before him fast:

The seventh, unimpeded,

Through solid hills could roam:

The eighth could walk the ocean,

When billows were in foam:

The ninth could draw, by magic,

The fishes from the deep:

The tenth was never weary,

Nor overcome by sleep:

The eleventh bound the dragon

Which crept among the grass;

And all he wish’d to happen

Was sure to come to pass:

The twelfth, who was reputed

The wisest of the band,

Knew what was going forward

In every foreign land.

And now, forsooth, I tell ye,

Who listen to my strain,

That such a set of brothers

Will ne’er be seen again.

Grimm, in the preface to his German translation of the Kiæmpé Viser, characterizes this Ballad in the following magnificent words:—

“Seltsam ist das Lied von dem Held Vonved. Unter dem Empfang des Zauberseegens und mit räthselhaften Worten, dass er nie wiederkehre oder dann den Tod seines Vaters rächen müsse, reitet er aus. Lange sieht er keine Stadt und keinen Menschen, dann, wer sich ihm entgegen stelit, den wirft er nieder, den Hirten legt er seine Räthsel vor über das edelste und abscheuungswürdigste, übar den Gang der Sonne und die Ruhe des Todten: wer sie nicht Iöst, den erschlägt er; trotzig sitzt er unter den Helden, ihre Anerbietungen gefallen ihm nicht, er reitet heim, erschlägt zwölf Zauberweiber, die ihm entgegen kommen, dann seine Mutter, endlich zernichtet er auch sein Saitenspiel, damit kein Wohllaut mehr den wilden Sinn besänftige. Es scheint dieses Lied vor allen in einer eigenen Bedeutung gedichtet, und den Mismuth eines zerstörten herumirrenden Gemüths anzuzeigen, das seine Räthsel will gelöst haben: es ist die Angst eines Menschen darin ausgedrückt, der die Flügel, die er fühlt, nicht frei bewegen kann, und der, wenn ihn diese Angst peinigt, gegen alles, auch gegen sein Liebstes, wüthen muss. Dieser Charakter scheint dem Norden gantz eigenthümlich; in dem seltsamen Leben Königs Sigurd des Jerusalemfahrers, auch in Shakspeare’s Hamlet ist etwas ähnliches.”

“Singular is the song of the hero Vonved. After having received the magic blessing, he rides out, darkly hinting that he must never return, or have avenged the death of his father. For a long time he sees no city and no man; he then overthrows whomsoever opposes him; he lays his enigmas before the herdsmen, concerning that which is most grand, and that which is most horrible; concerning the course of the sun and the repose of the dead; he who cannot explain them is slaughtered. Haughtily he sits among the heroes—their invitations do not please him—he rides home—slays twelve sorceresses who come against him—then his mother, and at last he demolishes his harp, so that no sweet sound shall in future soften his wild humour. This song, more than any of the rest, seems to be composed with a meaning of its own; and shows the melancholy of a ruined, wandering mind, which will have its enigmas cleared up! The anguish of a man is expressed therein, who cannot move freely the wings which he feels; and, who, when this anguish torments him, is forced to deal out destruction against all—even against his best-beloved. Such a character seems to be quite the property of the North. In the strange life of King Sigurd, the wanderer to Jerusalem, and likewise in Shakspeare’s Hamlet, there is something similar.”

Svend Vonved sits in his lonely bower;

He strikes his harp with a hand of power;

His harp return’d a responsive din;

Then came his mother hurrying in:

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

In came his mother Adeline,

And who was she, but a queen, so fine:

“Now hark, Svend Vonved! out must thou ride,

And wage stout battle with knights of pride.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Avenge thy father’s untimely end;

To me, or another, thy gold harp lend;

This moment boune [8] thee, and straight begone!

I rede [9] thee, do it, my own dear son.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

Svend Vonved binds his sword to his side;

He fain will battle with knights of pride.

“When may I look for thee once more here?

When roast the heifer, and spice the beer?”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“When stones shall take, of themselves, a flight,

And ravens’ feathers are woxen [10] white,

Then may’st thou expect Svend Vonved home:

In all my days, I will never come.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

His mother took that in evil part:

“I hear, young gallant, that mad thou art;

Wherever thou goest, on land or sea,

Disgrace and shame shall attend on thee.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

He kiss’d her thrice, with his lips of fire:

“Appease, O mother, appease thine ire;

Ne’er wish me any mischance to know,

For thou canst not tell how far I may go.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Then I will bless thee, this very day;

Thou never shalt perish in any fray;

Success shall be in thy courser tall;

Success in thyself, which is best of all.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Success in thy hand, success in thy foot,

In struggle with man, in battle with brute;

The holy God and Saint Drotten [11] dear

Shall guide and watch thee through thy career.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“They both shall take thee beneath their care,

Then surely thou never shalt evily fare:

See yonder sword of steel so white,

No helm nor shield shall resist its bite.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

Svend Vonved took up the word again—

“I’ll range the mountain, and rove the plain,

Peasant and noble I’ll wound and slay;

All, all, for my father’s wrong shall pay.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

Svend Vonved bound his sword to his side,

He fain will battle with knights of pride;

So fierce and strange was his whole array,

No mortal ventur’d to cross his way.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

His helm was blinking against the sun,

His spurs were clinking his heels upon, . . .

His horse was springing, with bridle ringing,

While sat the warrior wildly singing.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

He rode a day, he rode for three,

No town nor city he yet could see;

“Ha!” said the youth, “by my father’s

hand,

There is no city in all this land.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

He rode and lilted, he rode and sang,

Then met he by chance Sir Thulé Vang;

Sir Thulé Vang, with his twelve sons bold,

All cas’d in iron, the bright and cold.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

Svend Vonved took his sword from his side,

He fain would battle with knights so tried;

The proud Sir Thulé he first ran through,

And then, in succession, his sons he slew.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

Svend Vonved binds his sword to his side,

It lists him farther to ride, to ride;

He rode along by the grené shaw; [12]

The Brute-carl [13] there with surprise he saw.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

A wild swine sat on his shoulders broad,

Upon his bosom a black bear snor’d;

And about his fingers, with hair o’erhung,

The squirrel sported, and weasel clung.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Now, Brute-carl, yield thy booty to me,

Or I will take it by force from thee.

Say, wilt thou quickly thy beasts forego,

Or venture with me to bandy a blow?

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Much rather, much rather, I’ll fight with

thee,

Than thou my booty should’st get from me;

I never was bidden the like to do,

Since good King Esmer in fight I slew.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“And did’st thou slay King Esmer fine?

Why, then thou slewest dear father mine;

And soon, full soon, shalt thou pay for him,

With the flesh hackt off from thy every limb!”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

They drew a circle upon the sward;

They both were dour, as the rocks are hard;

Forsooth, I tell you, their hearts were steel’d,—

The one to the other no jot would yield.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

They fought for a day,—they fought for two,—

And so on the third they were fain to do;

But ere the fourth day reach’d the night,

The Brute-carl fell, and was slain outright.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

Svend Vonved binds his sword to his side,

Farther and farther he lists to ride:

He rode at the foot of a hill so steep,

There saw he a herd as he drove the sheep.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Now tell me, Herd, and tell me fair,

Whose are the sheep thou art driving there?

And what is rounder than a wheel?

And where do they eat the holiest meal?”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Where does the fish stand up in the flood?

And where is the bird that’s redder than blood?

Where do they mingle the best, best, wine?

And where with his knights does Vidrik dine?”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

There sat the herd, he sat in thought;

To ne’er a question he answer’d aught.

Svend gave him a stroke, a stroke so sore,

That his lung and his liver came out before.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

On, on went he, till more sheep he spied;

The herd sat, too, by a deep pit’s side.

“Now tell me, Herd, and tell me fair,

Whose are the sheep thou art tending there?”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“See yonder house, with turret and tower,

There feasting serves to beguile the hour;

There dwells a man, Tyggé Nold by name,

With his twelve fair sons, who are knights of fame.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Enough, Sir Herd; now lend an ear—

Go, tell Tyggé Nold to come out here.”

From his breast Svend Vonved a gold ring drew;

At the foot of the herd the gold ring he threw.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

And as Svend Vonved approach’d the spot,

His booty among them they ’gan to allot.

Some would have his polish’d glaive,

Others, his harness, or courser brave.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

Svend Vonved stops, in reflection deep;

He thought it best he his horse should keep:

His hauberk and faulchion he will not lose,

Much rather to fight the youth will choose.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Had’st thou twelve sons to the twelve thou

hast,

And cam’st in the midst of them charging me fast,

Sooner should’st thou wring water from steel,

Than thou in such fashion with me should’st deal.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

He prick’d with his spur his courser tall,

Which sprang, at once, over the gate and wall.

Tyggé Nold there he has stretch’d in blood,

And his twelve sons too, that beside him stood.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

Then turn’d he his steed, in haste, about,—

Svend Vonved, the knight, so youthful and stout;

Forward he went o’er mountain and moor,

No mortal he met, which vex’d him sore.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

He came, at length, to another flock,

Where a herd sat combing his yellow lock:

“Now listen, Herd, with the fleecy care;

Listen, and give me answers fair.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“What is rounder than a wheel?

Where do they eat the holiest meal?

Where does the sun go down to his seat?

And where do they lay the dead man’s feet?”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“What fills the valleys one and all?

What is cloth’d best in the monarch’s hall?

What cries more loud than cranes can cry?

And what can in whiteness the swan outvie?

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Who on his back his beard does wear?

Who ’neath his chin his nose does bear?

What’s more black than the blackest sloe?

And what is swifter than a roe?

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Where is the bridge that is most broad?

What is, by man, the most abhorr’d?

Where leads, where leads, the highest road up?

And say, where the hottest of drink they sup.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“The sun is rounder than a wheel.

They eat at the altar the holiest meal.

The sun in the West goes down to his seat:

And they lay to the East the dead man’s feet.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Snow fills the valleys, one and all.

Man is cloth’d best in the monarch’s hall.

Thunder cries louder than cranes can cry.

Angels in whiteness the swan outvie.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“His beard on his back the lapwing wears.

His nose ’neath his chin the elfin bears. [14]

More black is sin than the blackest sloe:

And thought is swifter than any roe.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Ice is, of bridges, the bridge most broad.

The toad is, of all things, the most abhorr’d.

To paradise leads the highest road up:

And in hell the hottest of drink they sup.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Now hast thou given me answers fair,

To each and all of my questions rare;

And now, I pray thee, be my guide,

To the nearest spot where warriors bide.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“To Sonderborg I’ll show thee straight,

Where drink the heroes early and late:

There thou wilt find of knights a crew,

Haughty of heart, and hard to subdue.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

With a bright gold ring was his arm array’d,

Full fifteen pounds that gold ring weigh’d,

That has he given the herd, for a meed,

Because he will show him the knights with speed.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

Svend Vonved enter’d the castle yard;

There Randulph, wrapt in his skins, [15] kept guard:

“Ho! Caitiff, ho! with shield and brand,

What art thou doing in this my land?”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“I will, I will, with my single hand,

Take from thee, Knave, the whole of thy land:

I will, I will, with my single toe,

Lay thee and each of thy castles low.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Thou shalt not, with thy single hand,

Take from me, Hound, an inch of my land;

And far, far less, shalt thou, with thy toe,

Lay me or one of my castles low.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Thou shalt not e’er, with finger of thine,

Strike asunder one limb of mine; [16]

I am for thee too woxen and stark,

As thou, to thy cost, shalt quickly mark.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

Svend Vonved unsheath’d his faulchion bright,

With haughty Randulph he fain will fight;

Randulph he there has slain in his might,

And Strandulph too, with full good right.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

The rest against him came out pell-mell,

Then slew he Carl Egé, the fierce and fell:—

He slew the great, he slew the small;

He slew till his foes were slaughter’d all.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

Svend Vonved binds his sword to his side,

It lists him farther to ride, to ride;

He found upon the desolate wold

A burly [17] knight, of aspect bold.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Now tell me, Rider, noble and good,

Where does the fish stand up in the flood?

Where do they mingle the best, best wine?

And where with his knights does Vidrik dine?”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“The fish in the East stands up in the flood.

They drink in the North the wine so good.

In Halland’s hall does Vidrik dine,

With his swains around, and his warriors fine.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

From his breast Svend Vonved a gold ring drew;

At the foot of the knight the gold ring he threw:

“Go! say thou wert the very last man

Who gold from the hand of Svend Vonved wan.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

Svend Vonved came where the castle rose;

He bade the watchmen the gate unclose:

As none of the watchmen obey’d his cry,

He sprang at once over the ramparts high.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

He tied his steed to a ring in the wall,

Then in he went to the wide stone hall;

Down he sat at the head of the board,

To no one present he utter’d a word.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

He drank and he ate, he ate and he drank,

He ask’d no leave, and return’d no thank;

“Ne’er have I been on Christian ground

Where so many curst tongues were clanging round.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

King Vidrik spoke to good knights three:

“Go, bind that lowering swain for me;

Should ye not bind the stranger guest,

Ye will not serve me as ye can best.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Should’st thou send three, and twenty times

three,

And come thyself to lay hold of me;

The son of a dog thou wilt still remain,

And yet to bind me have tried in vain.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Esmer, my father, who lies on his bier,

And proud Adeline, my mother so dear,

Oft and strictly have caution’d me

To waste no breath upon hounds like thee.”

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“And was King Esmer thy father’s name,

And Adeline that of his virtuous Dame?

Thou art Svend Vonved, the stripling wild,

My own dear sister’s only child.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Svend Vonved, wilt thou bide with me here?

Honour awaits thee, and costly cheer;

Whenever it lists thee abroad to wend,

Upon thee shall knights and swains attend.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

“Silver and gold thou never shalt lack,

Or helm to thy head, or mail to thy back;”

But to this and the like he would lend no ear,

And home to his mother he now will steer.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

Svend Vonved gallop’d along the way;

To fancies dark was his mind a prey:

Riding he enter’d the castle yard

Where stood twelve witches wrinkled and scarr’d:

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

There stood they all, with spindle and rok, [18]—

Each over the shinbone gave him a knock:

Svend turn’d his steed, in fury, round;

The witches he there has hew’d to the ground.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

He hew’d the witches limb from limb,

So little mercy they got from him;

His mother came out, and was serv’d the same,

Into fifteen pieces he hackt her frame.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

Then in he went to his lonely bower,

There drank he the wine, the wine of power:

His much-lov’d harp he play’d upon

Till the strings were broken, every one.

Look out, look out, Svend Vonved.

This is one of those Ballads which, from the days of Arild, have been much sung in Denmark: we find in it the names and bearings of most of those renowned heroes, who are mentioned separately in other poems. It divides itself into two parts;—the first, which treats of the warrior’s bearings, has a great resemblance to the 178th chapter of the Vilkina Saga, as likewise has the last part, wherein the Duel is described, to the 180th and 181st chapters of the same.

I cannot here forbear quoting and translating what Anders Sorensen Vedel, the good old Editor of the first Edition of the Kiæmpé Viser, which appeared in 1591, says concerning the apparently superhuman performances of the heroes therein celebrated.

“Hvad ellers Kiæmpernes Storlemhed Styrke og anden Vilkaar berörer, som overgaaer de Menneskers der nu leve deres Væxt og Kraft, det Stykke kan ikke her noksom nu forhandles, men skal i den Danske Krönikes tredie Bog videligere omtales. Thi det jo i Sandhed befindes og bevises af adskillige Documenter og Kundskab, at disse gamle Hellede, som de kaldes, have levet fast længer, og været mandeligere större stærkere og höiere end den gemene Mand er, som nu lever paa denne Dag.”

“That part which relates to these Warriors’ size, strength, or other qualities, so far surpassing the stature and powers of the men who now exist, cannot be here sufficiently treated upon, but shall be further discussed in the third Book of the Danish Chronicles: for, in truth, it is discovered and proved from various documents and sources, that these old heroes, as they are called, lived much longer, and were manlier, stouter, stronger, and taller, than man at the present day.”

Six score there were, six score and ten,

From Hald that rode that day;

And when they came to Brattingsborg

They pitch’d their pavilion gay.

King Nilaus stood on the turret’s top,

Had all around in sight:

“Why hold those heroes their lives so cheap,

That it lists them here to fight?

“Now, hear me, Sivard Snaresvend;

Far hast thou rov’d, and wide,

Those warriors’ weapons thou shalt prove,

To their tent thou must straightway ride.”

It was Sivard Snaresvend,

To the broad tent speeded he then:

“I greet ye fair, in my master’s name,

All, all, ye Dane king’s men.

“Now, be not wroth that here I come;

I come as a warrior, free:

The battle together we soon will prove;

Let me your bearings see.”

There stands upon the first good shield

A lion, so fierce and stark,

With a crown on his head, of the ruddy gold,

That is King Diderik’s mark.

There shine upon the second shield

A hammer and pincers bright;

Them carries Vidrik Verlandson,

Ne’er gives he quarter in fight.

There shines upon the third good shield

A falcon, blazing with gold;

And that by Helled Hogan is borne;

No knight, than he, more bold.

There shines upon the fourth good shield

An eagle, and that is red;

Is borne by none but Olger, the Dane;

He strikes his foemen dead.

There shines upon the fifth good shield

A couchant hawk, on a wall;

That’s borne by Master Hildebrand;

He tries, with heroes, a fall.

And now comes forth the sixth good shield

A linden is thereupon;

And that by young Sir Humble is borne,

King Abelon’s eldest son.

There shines upon the seventh good shield

A spur, of a fashion so free;

And that is borne by Hogan, the less,

Because he will foremost be.

There shines upon the eighth good shield

A gray wolf, meagre and gaunt;

Is borne by youthful Ulf van Jern;

Beware how him you taunt!

There shine upon the ninth good shield

Three arrows, and white are they;

Are borne by Vidrik Stageson,

And trust that gallant you may.

There shines upon the tenth good shield

A fiddle, and ’neath it a bow;

That’s borne by Folker Spillemand;

For drink he will sleep forego.

There shines upon the eleventh shield

A dragon that looks so dire;

Is carried by Orm, the youthful swain;

He trembles at no man’s ire.

And, now, behold the twelfth good shield,

And upon it a burning brand;

Is borne by stout Sir Vifferlin

Through many a prince’s land.

There stands upon the thirteenth shield

A sprig of the mournful yew;

That’s borne by Harrald Griskeson;

And he’s a comrade true.

There stand upon the fourteenth shield

A cloak, and a mighty staff;

And them bore Alsing, the stalwart monk,

When he beat his foes to chaff.

And now comes forth the fifteenth shield,

And upon it three naked blades

Are borne by good King Esmer’s sons,

In their wars and furious raids.

There stands upon the sixteenth shield,

With coal-black pinion, a crow;

That’s borne by rich Count Raadengaard;

The dark Runes well can he throw. [19]

There shines upon the seventeenth shield

A horse, so stately and high,

Is borne by Count Sir Guncelin;

“Slay! slay! bide not,” is his cry.

There shine upon the eighteenth shield

A man, and a fierce wild boar,

Are borne by the Count of Lidebierg;

His blows fall heavy and sore.

There shines upon the nineteenth shield

A hound, at the stretch of his speed;

Is borne by Oisten Kiæmpe, bold;

He risks his neck without heed.

There shines upon the twentieth shield,

Among branches, a rose, so gay;

Wherever Sir Nordman comes in war,

He bears bright honour away.

There shines on the one-and-twentieth shield

A vase, and of copper ’t is made;

That’s borne by Mogan Sir Olgerson;

He wins broad lands with his blade.

And now comes forth the next good shield,

With a sun dispelling the mirk;

And that by Asbiorn Mildé is borne;

He sets the knights’ backs at work. [20]

There shines on the three-and-twentieth shield

An arm, in a manacle bound;

And that by Alvor Sir Langé is borne,

To the heroes he hands mead round.

Now comes the four-and-twentieth shield,

And a bright sword there you see;

And that by Humble Sir Jerfing is borne;

Full worthy of that is he.

There shines upon the next good shield

A goss-hawk, striking his game;

That’s borne by a knight, the best of all—

Sir Iver Blaa is his name.

Now comes the six-and-twentieth shield,

A jav’lin there you spy;

Is borne by little Mimring Tan;

From no one will he fly.

Such knights and bearings as were there,

And who can them all relate;

It was Sivard, the Snaresvend;

No longer he deign’d to wait.

“If there be one of the Dane king’s men,

Who at Dyst [21] is willing to

ride,

Let him, I pray, without pause or delay,

Meet me by the wild wood’s side.

“The man among you, ye Danish court men,

Who at Dyst has won most meeds;

Him I am ready to fight, this day,

For both of our noble steeds.”

The heroes cast the die on the board;

The die it roll’d so wide:

“Since, young Sir Humble, it stops by thee,

’Gainst Sivard thou must ride.”

Sir Humble struck his hand on the board;

No longer he lists to play:

I tell you, forsooth, that the rosy hue

From his cheek fast faded away.

“Now, hear me, Vidrik Verlandson;

Thou art so free a man;

Do lend me Skimming, thy horse, this day;

I’ll pledge for him what I can:

“Eight good castles, in Birting’s land,

As pledges for him I’ll set;

My sister too, the lily-cheek’d maid,

A fairer thou ne’er hast met:

“Eight good castles, and eight good knights;

I’d scorn to offer thee less:

If Skimming should meet any hurt this day,

My sister thou shalt caress.”

“If yonder mountains all were gold,

And yonder streams were wine;

The whole for Skimming I would not take;

I bless God he is mine.

“Sivard is a purblind swain;

Sees not to his faulchion’s end:

If Skimming were hurt thou couldst not pay me

With the help of thy every friend.

“The sword it whirls in Sivard’s hand,

As whirl the sails of the mill;

If thou take Skimming ’gainst that wild fool,

’T is sorely against my will.”

Humble, he sat him on Skimming’s back,

So gallantly can he ride;

But Skimming thought it passing strange

That a spur was clapt to his side.

The first course that together they rode,

So strong were the knightly two,

Asunder went Humble’s saddle-ring,

And a furlong his good shield flew.

“Methinks thou art a fair young swain,

And well thy horse canst ride;

Dismount thee, straight, and gird up thy steed;

I am willing for thee to bide.”

The second course that together they rode

Was worthy of knights renown’d;