Project Gutenberg's The Best Portraits in Engraving, by Charles Sumner This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Best Portraits in Engraving Author: Charles Sumner Release Date: September 11, 2007 [EBook #22574] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BEST PORTRAITS IN ENGRAVING *** Produced by Irma Špehar and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

BY

CHARLES SUMNER.

Fifth Edition.

FREDERICK KEPPEL & CO.

NEW YORK,

20 EAST 16th STREET.

LONDON, PARIS,

3 DUKE STREET, ADELPHI. 27 QUAI DE L'HORLOGE.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1875, by

FREDERICK KEPPEL,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress at Washington.

Engraving is one of the fine arts, and in this beautiful family has been the especial handmaiden of painting. Another sister is now coming forward to join this service, lending to it the charm of color. If, in our day, the "chromo" can do more than engraving, it cannot impair the value of the early masters. With them there is no rivalry or competition. Historically, as well as æsthetically, they will be masters always.

Everybody knows something of engraving, as of printing, with which it was associated in origin. School-books, illustrated papers, and shop windows are the ordinary opportunities open to all. But while creating a transient interest, or, perhaps, quickening the taste, they furnish little with regard to the art itself, especially in other days. And yet, looking at an engraving, like looking at a book, may be the beginning of a new pleasure and a new study.

Each person has his own story. Mine is simple. Suffering from continued prostration, disabling me from the ordinary activities of life, I turned to engravings for employment and pastime. With the invaluable assistance of that devoted connoisseur, the late Dr. Thies, I went through the Gray collection at Cambridge, enjoying it like[4] a picture-gallery. Other collections in our country were examined also. Then, in Paris, while undergoing severe medical treatment, my daily medicine for weeks was the vast cabinet of engravings, then called Imperial, now National, counted by the million, where was everything to please or instruct. Thinking of those kindly portfolios, I make this record of gratitude, as to benefactors. Perhaps some other invalid, seeking occupation without burden, may find in them the solace that I did. Happily, it is not necessary to visit Paris for the purpose. Other collections, on a smaller scale, will furnish the same remedy.

In any considerable collection, portraits occupy an important place. Their multitude may be inferred when I mention that, in one series of portfolios, in the Paris cabinet, I counted no less than forty-seven portraits of Franklin and forty-three of Lafayette, with an equal number of Washington, while all the early Presidents were numerously represented. But, in this large company, there are very few possessing artistic value. The great portraits of modern times constitute a very short list, like the great poems or histories, and it is the same with engravings as with pictures. Sir Joshua Reynolds, explaining the difference between an historical painter and a portrait-painter, remarks that the former "paints men in general, a portrait-painter a particular man, and consequently a defective model."[1] A portrait, therefore, may be an accurate presentment of its subject without æsthetic value.

But here, as in other things, genius exercises its accustomed [5]sway without limitation. Even the difficulties of a "defective model" did not prevent Raffaelle, Titian, Rembrandt, Rubens, Velasquez, or Vandyck from producing portraits precious in the history of art. It would be easy to mention heads by Raffaelle, yielding in value to only two or three of his larger masterpieces, like the Dresden Madonna. Charles the Fifth stooped to pick up the pencil of Titian, saying "it becomes Cæsar to serve Titian!" True enough; but this unprecedented compliment from the imperial successor of Charlemagne attests the glory of the portrait-painter. The female figures of Titian, so much admired under the names of Flora, La Bella, his daughter, his mistress, and even his Venus, were portraits from life. Rembrandt turned from his great triumphs in his own peculiar school to portraits of unwonted power; so also did Rubens, showing that in this department his universality of conquest was not arrested. To these must be added Velasquez and Vandyck, each of infinite genius, who won fame especially as portrait-painters. And what other title has Sir Joshua himself?

Historical pictures are often collections of portraits arranged so as to illustrate an important event. Such is the famous Peace of Münster, by Terburg, just presentedSuyderhoef. by a liberal Englishman to the National Gallery at London. Here are the plenipotentiaries of Holland, Spain, and Austria, uniting in the great treaty which constitutes an epoch in the Law of Nations. The engraving by Suyderhoef is rare and interesting. Similar in character is the Death of Chatham, by Copley, where the illustrious[6] statesman is surrounded by the peers he had been addressing—every one a portrait. To this list must be added the pictures by Trumbull in the Rotunda of the Capitol at Washington, especially the Declaration of Independence, in which Thackeray took a sincere interest. Standing before these, the author and artist said to me, "These are the best pictures in the country," and he proceeded to remark on their honesty and fidelity; but doubtless their real value is in their portraits.

Unquestionably the finest assemblage of portraits anywhere is that of the artists occupying two halls in the gallery at Florence, being autographs contributed by the masters themselves. Here is Raffaelle, with chestnut-brown hair, and dark eyes full of sensibility, painted when he was twenty-three, and known by the engraving of Forster—Julio Romano, in black and red chalk on paper,—Massaccio, called the father of painting, much admired—Leonardo da Vinci, beautiful and grand,—Titian, rich and splendid,—Pietro Perugino, remarkable for execution and expression,—Albert Dürer, rigid but masterly,—Gerhard Dow, finished according to his own exacting style,—and Reynolds, with fresh English face; but these are only examples of this incomparable collection, which was begun as far back as the Cardinal Leopold de Medici, and has been happily continued to the present time. Here are the lions, painted by themselves, except, perhaps, the foremost of all, Michael Angelo, whose portrait seems the work of another. The impression from this collection is confirmed by that of any group of[7] historic artists. Their portraits excel those of statesmen, soldiers, or divines, as is easily seen by engravings accessible to all. The engraved heads in Arnold Houbraken's biographies of the Dutch and Flemish painters, in three volumes, are a family of rare beauty.[2]

The relation of engraving to painting is often discussed; but nobody has treated it with more knowledge or sentiment than the consummate engraver Longhi in his interesting work, La Calcografia.[3] Dwelling on the general aid it renders to the lovers of art, he claims for it greater merit in "publishing and immortalizing the portraits of eminent men for the example of the present and future generations;" and, "better than any other art, serving as the vehicle for the most extended and remote propagation of deserved celebrity." Even great monuments in porphyry and bronze are less durable than these light and fragile impressions subject to all the chances of wind, water, and fire, but prevailing by their numbers where the mass succumbs. In other words, it is with engravings as with books; nor is this the only resemblance between them. According to Longhi, an engraving is not a copy or imitation, as is sometimes insisted, but a translation. The engraver translates into another language, where light and shade supply the place of colors. The duplication of [8]a book in the same language is a copy, and so is the duplication of a picture in the same material. Evidently an engraving is not a copy; it does not reproduce the original picture, except in drawing and expression; nor is it a mere imitation, but, as Bryant's Homer and Longfellow's Dante are presentations of the great originals in another language, so is the engraving a presentation of painting in another material which is like another language.

Thus does the engraver vindicate his art. But nobody can examine a choice print without feeling that it has a merit of its own different from any picture, and inferior only to a good picture. A work of Raffaelle, or any of the great masters, is better in an engraving of Longhi or Morghen than in any ordinary copy, and would probably cost more in the market. A good engraving is an undoubted work of art, but this cannot be said of many pictures, which, like Peter Pindar's razors, seem made to sell.

Much that belongs to the painter belongs also to the engraver, who must have the same knowledge of contours, the same power of expression, the same sense of beauty, and the same ability in drawing with sureness of sight as if, according to Michael Angelo, he had "a pair of compasses in his eyes." These qualities in a high degree make the artist, whether painter or engraver, naturally excelling in portraits. But choice portraits are less numerous in engraving than in painting, for the reason, that painting does not always find a successful translator.

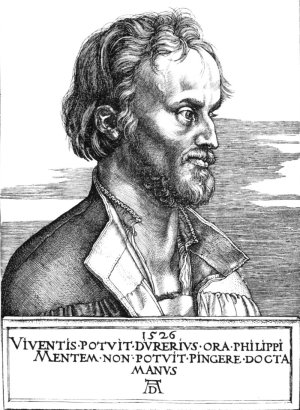

PHILIP MELANCTHON.

(Engraved by Albert Dürer from his own Design.)[9]

The earliest engraved portraits which attract attention are by Albert Dürer, who engraved his own work, translating himself. His eminence as painter was continued asDürer. engraver. Here he surpassed his predecessors, Martin Schoen in Germany, and Mantegna in Italy, so that Longhi does not hesitate to say that he was the first who carried the art from infancy in which he found it to a condition not far from flourishing adolescence. But, while recognizing his great place in the history of engraving, it is impossible not to see that he is often hard and constrained, if not unfinished. His portrait of Erasmus is justly famous, and is conspicuous among the prints exhibited in the British Museum. It is dated 1526, two years before the death of Dürer, and has helped to extend the fame of the universal scholar and approved man of letters, who in his own age filled a sphere not unlike that of Voltaire in a later century. There is another portrait of Erasmus by Holbein, often repeated, so that two great artists have contributed to his renown. That by Dürer is admired. The general fineness of touch, with the accessories of books and flowers, shows the care in its execution; but it wants expression, and the hands are far from graceful.

Another most interesting portrait by Dürer, executed in the same year with the Erasmus, is Philip Melancthon, the St. John of the Reformation, sometimes called the teacher of Germany. Luther, while speaking of himself as rough, boisterous, stormy, and altogether warlike, says, "but Master Philippus comes along softly and gently,[10] sowing and watering with joy according to the rich gifts which God has bestowed upon him." At the date of the print he was twenty-nine years of age, and the countenance shows the mild reformer.

Agostino Caracci, of the Bolognese family, memorable in art, added to considerable success as painter undoubted triumphs as engraver. His prints are numerous, and manyCaracci. are regarded with favor; but out of the long list not one is so sure of that longevity allotted to art as his portrait of Titian, which bears date 1587, eleven years after the death of the latter. Over it is the inscription, Titiani Vicellii Pictoris celeberrimi ac famosissimi vera effigies, to which is added beneath, Cujus nomen orbis continere non valet! Although founded on originals by Titian himself, it was probably designed by the remarkable engraver. It is very like, and yet unlike the familiar portrait of which we have a recent engraving by Mandel, from a repetition in the gallery of Berlin. Looking at it, we are reminded of the terms by which Vasari described the great painter, guidicioso, bello e stupendo. Such a head, with such visible power, justifies these words, or at least makes us believe them entirely applicable. It is bold, broad, strong, and instinct with life.

This print, like the Erasmus of Dürer, is among those selected for exhibition at the British Museum, and it deserves the honor. Though only paper with black lines, it is, by the genius of the artist, as good as a picture. In all engraving nothing is better.

Contemporary with Caracci was Hendrik Goltzius, at[11] Harlem, excellent as painter, but, like the Italian, pre-eminent as engraver. His prints show mastery of the art,Goltzius. making something like an epoch in its history. His unwearied skill in the use of the burin appears in a tradition gathered by Longhi from Wille, that, having commenced a line, he carried it to the end without once stopping, while the long and bright threads of copper turned up were brushed aside by his flowing beard, which at the end of a day's labor so shone in the light of a candle that his companions nicknamed him "the man with the golden beard." There are prints by him which shine more than his beard. Among his masterpieces is the portrait of his instructor, Theodore Coernhert, engraver, poet, musician, and vindicator of his country, and author of the national air, "William of Orange," whose passion for liberty did not prevent him from giving to the world translations of Cicero's Offices and Seneca's Treatise on Beneficence. But that of the ENGRAVER HIMSELF, as large as life, is one of the most important in the art. Among the numerous prints by Goltzius, these two will always be conspicuous.

JAN LUTMA.

(Etched by Rembrandt from his own Design.)

In Holland Goltzius had eminent successors. Among these were Paul Pontius, designer and engraver, whose portrait of Rubens is of great life and beauty, and Rembrandt,Pontius. who was not less masterly in engraving than in painting, as appears sufficiently in his portraits of the Burgomaster Six, the two Coppenols, the Advocate Tolling,Rembrandt. the goldsmith Lutma, all showing singular facility and originality. Contemporary with Rembrandt was Cornelis[12] Visscher, also designer and engraver, whose portraits wereVisscher. unsurpassed in boldness and picturesque effect. At least one authority has accorded to this artist the palm of engraving, hailing him as Corypheus of the art. Among his successful portraits is that of a Cat; but all yield to what are known as the Great Beards, being the portraits of William de Ryck, an ophthalmist at Amsterdam, and of Gellius de Bouma, the Zutphen ecclesiastic. The latter is especially famous. In harmony with the beard is the heavy face, seventy-seven years old, showing the fulness of long-continued potation, and hands like the face, original and powerful, if not beautiful.

THE SLEEPING CAT.

(Engraved by Cornelis Visscher from his own Design.)

In contrast with Visscher was his companion Vandyck, who painted portraits with constant beauty and carried into etching the same Virgilian taste and skill. His aquafortisVandyck. was not less gentle than his pencil. Among his etched portraits I would select that of Snyders, the animal painter, as extremely beautiful. M. Renouvier, in his learned and elaborate work, Des Types et des Maniéres des Maîtres Graveurs, though usually moderate in praise, speaks of these sketches as "possessing a boldness and delicacy which charm, being taken, at the height of his genius, by the painter who knew the best how to idealize the painting of portraits."

Such are illustrative instances from Germany, Italy, and Holland. As yet, power rather than beauty presided, unless in the etchings of Vandyck. But the reign of Louis XIV. was beginning to assert a supremacy in engraving as in literature. The great school of French engravers[13] which appeared at this time brought the art to a splendid perfection, which many think has not been equalled since, so that Masson, Nanteuil, Edelinck, and Drevet may claim fellowship in genius with their immortal contemporaries, Corneille, Racine, La Fontaine, and Molière.

THE SUDARIUM OF ST. VERONICA.

(Engraved by Claude Mellan from his own Design.)

The school was opened by Claude Mellan, more known as engraver than painter, and also author of most of the designs he engraved. His life, beginning with the sixteenthMellan. century, was protracted beyond ninety years, not without signal honor, for his name appears among the "Illustrious Men" of France, in the beautiful volumes of Perrault, which is also a homage to the art he practiced. One of his works, for a long time much admired, was described by this author:

"It is a Christ's head, designed and shaded, with his crown of thorns and the blood that gushes forth from all parts, by one single stroke, which, beginning at the tip of the nose, and so still circling on, forms most exactly everything that is represented in this plate, only by the different thickness of the stroke, which, according as it is more or less swelling, makes the eyes, nose, mouth, cheeks, hair, blood, and thorns; the whole so well represented and with such expressions of pain and affliction, that nothing is more dolorous or touching."[4]

This print is known as the Sudarium of St. Veronica. Longhi records that it was thought at the time "inimitable," and was praised "to the skies;" but people think differently now. At best it is a curiosity among portraits. A [14]traveler reported some time ago that it was the sole print on the walls of the room occupied by the director of the Imperial Cabinet of Engravings at St. Petersburgh.

Morin was a contemporary of Mellan, and less famous at the time. His style of engraving was peculiar, being a mixture of strokes and dots, but so harmonized as to produceMorin. a pleasing effect. One of the best engraved portraits in the history of the art is his Cardinal Bentivoglio; but here he translated Vandyck, whose picture is among his best. A fine impression of this print is a choice possession.

CARDINAL BENTIVOGLIO.

(Painted by Anthony Van Dyck, and Engraved by Jean Morin.)

Among French masters Antoine Masson is conspicuous for brilliant hardihood of style, which, though failing in taste, is powerful in effect. Metal, armor, velvet, feather,Masson. seem as if painted. He is also most successful in the treatment of hair. His immense skill made him welcome difficulties, as if to show his ability in overcoming them. His print of Henri de Lorraine, Comte d'Harcourt, known as Cadet à la Perle, from the pearl in the ear, with the date 1667, is often placed at the head of engraved portraits, although not particularly pleasing or interesting. The vigorous countenance is aided by the gleam and sheen of the various substances entering into the costume. Less powerful, but having a charm of its own, is that of Brisacier, known as the Gray-haired Man, executed in 1664. The remarkable representation of hair in this print has been a model for artists, especially for Longhi, who recounts that he copied it in his head of Washington. Somewhat similar is the head of Charrier, the criminal judge at Lyons. Though inferior in hair, it surpasses the other in expression.[15]

Nanteuil was an artist of different character, being to Masson as Vandyck to Visscher, with less of vigor than beauty. His original genius was refined by classical studies,Nanteuil. and quickened by diligence. Though dying at the age of forty-eight, he had executed as many as two hundred and eighty plates, nearly all portraits. The favor he enjoyed during life was not diminished with time. His works illustrate the reign of Louis XIV., and are still admired. Among these are portraits of the King, Annie of Austria, John Baptiste van Steenberghen, the Advocate-General of Holland, a heavy Dutchman, François de la Motte Le Vayer, a fine and delicate work, Turenne, Colbert, Lamoignon, the poet Loret, Maridat de Serrière, Louise-Marie de Gonzague, Louis Hesselin, Christine of Sweden—all masterpieces; but above these is the Pompone de Bellièvre, foremost among his masterpieces, and a chief masterpiece of art, being, in the judgment of more than one connoisseur, the most beautiful engraved portrait that exists. That excellent authority, Dr. Thies, who knew engraving more thoroughly and sympathetically than any person I remember in our country, said in a letter to myself, as long ago as March, 1858:

"When I call Nanteuil's Pompone the handsomest engraved portrait, I express a conviction to which I came when I studied all the remarkable engraved portraits at the royal cabinet of engravings at Dresden, and at the large and exquisite collection there of the late King of Saxony, and in which I was confirmed or perhaps, to which I was led, by the director of the two establishments, the late Professor Frenzel."

And after describing this head, the learned connoisseur proceeds:[16]—

"There is an air of refinement, vornehmheit, round the mouth and nose as in no other engraving. Color and life shine through the skin, and the lips appear red."

It is bold, perhaps, thus to exalt a single portrait, giving to it the palm of Venus; nor do I know that it is entirely proper to classify portraits according to beauty. In disputing about beauty, we are too often lost in the variety of individual tastes, and yet each person knows when he is touched. In proportion as multitudes are touched, there must be merit. As in music a simple heart-melody is often more effective than any triumph over difficulties, or bravura of manner, so in engraving the sense of the beautiful may prevail over all else, and this is the case with the Pompone, although there are portraits by others showing higher art.

No doubt there have been as handsome men, whose portraits were engraved, but not so well. I know not if Pompone was what would be called a handsome man, although his air is noble and his countenance bright. But among portraits more boldly, delicately, or elaborately engraved, there are very few to contest the palm of beauty.

POMPONE DE BELLIÈVRE.

(Painted by Charles Le Brun, and Engraved by Robert Nanteuil.)

And who is this handsome man to whom the engraver has given a lease of fame? Son, nephew, and grandson of eminent magistrates, high in the nobility of the robe, with two grandfathers chancellors of France, himself at the head of the magistry of France, first President of Parliament according to inscription on the engraving, Senatus Franciæ Princeps, ambassador to Italy, Holland, and England, charged in the latter country by Cardinal Mazarin[17] with the impossible duty of making peace between the Long Parliament and Charles the First, and at his death, great benefactor of the General Hospital of Paris, bestowing upon it riches and the very bed on which he died. Such is the simple catalogue, and yet it is all forgotten.

A Funeral Panegyric pronounced at his death, now before me in the original pamphlet of the time,[5] testifies to more than family or office. In himself he was much, and not of those who, according to the saying of St. Bernard, give out smoke rather than light. Pure glory and innocent riches were his, which were more precious in the sight of good men, and he showed himself incorruptible, and not to be bought at any price. It were easy for him to have turned a deluge of wealth into his house; but he knew that gifts insensibly corrupt,—that the specious pretext of gratitude is the snare in which the greatest souls allow themselves to be caught,—that a man covered with favors has difficulty in setting himself against injustice in all its forms, and that a magistrate divided between a sense of obligations received and the care of the public interest, which he ought always to promote, is a paralytic magistrate, a magistrate deprived of a moiety of himself. So spoke the preacher, while he portrayed a charity tender and prompt for the wretched, a vehemence just and inflexible to the dishonest and wicked, with a sweetness noble [18]and beneficent for all; dwelling also on his countenance, which had not that severe and sour austerity that renders justice to the good only with regret, and to the guilty only with anger; then on his pleasant and gracious address, his intellectual and charming conversation, his ready and judicious replies, his agreeable and intelligent silence, his refusals, which were well received and obliging; while, amidst all the pomp and splendor accompanying him, there shone in his eyes a certain air of humanity and majesty, which secured for him, and for justice itself, love as well as respect. His benefactions were constant. Not content with giving only his own, he gave with a beautiful manner still more rare. He could not abide beauty of intelligence without goodness of soul, and he preferred always the poor, having for them not only compassion but a sort of reverence. He knew that the way to take the poison from riches was to make them tasted by those who had them not. The sentiment of Christian charity for the poor, who were to him in the place of children, was his last thought, as witness especially the General Hospital endowed by him, and presented by the preacher as the greatest and most illustrious work ever undertaken by charity the most heroic.

Thus lived and died the splendid Pompone de Bellièvre, with no other children than his works. Celebrated at the time by a Funeral Panegyric now forgotten, and placed among the Illustrious Men of France in a work remembered only for its engraved portraits, his famous life shrinks, in the voluminous Biographie Universelle of[19] Michaud, to the seventh part of a single page, and in the later Biographie Généralle of Didot disappears entirely. History forgets to mention him. But the lofty magistrate, ambassador, and benefactor, founder of a great hospital, cannot be entirely lost from sight so long as his portrait by Nanteuil holds a place in art.

Younger than Nanteuil by ten years, Gérard Edelinck excelled him in genuine mastery. Born at Antwerp, he became French by adoption, occupying apartments in theEdelinck. Gobelins, and enjoying a pension from Louis XIV. Longhi says that he is the engraver whose works, not only according to his own judgment, but that of the most intelligent, deserve the first place among exemplars, and he attributes to him all perfections in highest degree, design, chiaro-oscuro, ærial perspective, local tints, softness, lightness, variety, in short everything which can enter into the most exact representation of the true and beautiful without the aid of color. Others may have surpassed him in particular things, but, according to the Italian teacher, he remains by common consent "the prince of engraving." Another critic calls him "king."

It requires no remarkable knowledge to recognize his great merits. Evidently he is a master, exercising sway with absolute art, and without attempts to bribe the eye by special effects of light, as on metal or satin. Among his conspicuous productions is the Tent of Darius, a large engraving on two sheets, after Le Brun, where the family of the Persian monarch prostrate themselves before Alexander, who approaches with Hephæstion. There is also[20] a Holy Family, after Raffaelle, and the Battle of the Standard, after Leonardo da Vinci; but these are less interesting than his numerous portraits, among which that of Philippe de Champaigne is the chief masterpiece; but there are others of signal merit, including especially that of Madame Heliot, or La Belle Religieuse, a beautiful French coquette praying before a crucifix; Martin van der Bogaert, a sculptor; Frederic Léonard, printer to the king; Mouton, the Lute-player; Martinus Dilgerus, with a venerable beard white with age; Jules Hardouin Mansart, the architect; also a portrait of Pompone de Bellièvre which will be found among the prints of Perrault's Illustrious Men.

The Philippe de Champaigne is the head of that eminent French artist after a painting by himself, and it contests the palm with the Pompone. Mr. Marsh, who is an authority, prefers it. Dr. Thies, who places the latter first in beauty, is constrained to allow that the other is "superior as a work of the graver," being executed with all the resources of the art in its chastest form. The enthusiasm of Longhi finds expression in unusual praise:

"The work which goes the most to my blood, and with regard to which Edelinck, with good reason, congratulated himself, is the portrait of Champaigne. I shall die before I cease to contemplate it with wonder always new. Here is seen how he was equally great as designer and engraver."[6]

MARTIN VAN DER BOGAERT.

(Painted by Hyacinthe Rigaud, and Engraved by Gérard Edelinck.)

And he then dwells on various details; the skin, the flesh, the eyes living and seeing, the moistened lips, the chin covered with a beard unshaven for a few days, and the hair in all its forms.

Between the rival portraits by Nanteuil and Edelinck it is unnecessary to decide. Each is beautiful. In looking at them we recognize anew the transient honors of public service. The present fame of Champaigne surpasses that of Pompone. The artist outlives the magistrate. But does not the poet tell us that "the artist never dies?"

As Edelinck passed from the scene, the family of Drevet appeared, especially the son, Pierre Imbert Drevet, born in 1697, who developed a rare excellence, improvingDrevet. even upon the technics of his predecessor, and gilding his refined gold. The son was born engraver, for at the age of thirteen he produced an engraving of exceeding merit. He manifested a singular skill in rendering different substances, like Masson, by the effect of light, and at the same time gave to flesh a softness and transparency which remain unsurpassed. To these he added great richness in picturing costumes and drapery, especially in lace.

He was eminently a portrait engraver, which I must insist is the highest form of the art, as the human face is the most important object for its exercise. Less clear and simple than Nanteuil, and less severe than Edelinck, he gave to the face individuality of character, and made his works conspicuous in art. If there was excess in the accessories, it was before the age of Sartor Resartus, and he only followed the prevailing style in the popular paintings of Hyacinthe Rigaud. Art in all its forms had become florid, if not meretricious, and Drevet was a representative of his age.

Among his works are important masterpieces. I name[22] only Bossuet, the famed eagle of Meaux; Samuel Bernard, the rich Councillor of State; Fénelon, the persuasive teacher and writer; Cardinal Dubois, the unprincipled minister, and the favorite of the Regent of France; and Adrienne Le Couvreur, the beautiful and unfortunate actress, linked in love with the Marshal Saxe. The portrait of Bossuet has everything to attract and charm. There stands the powerful defender of the Catholic Church, master of French style, and most renowned pulpit orator of France, in episcopal robes, with abundant lace, which is the perpetual envy of the fair who look at this transcendent effort. The ermine of Dubois is exquisite, but the general effect of this portrait does not compare with the Bossuet, next to which, in fascination, I put the Adrienne. At her death the actress could not be buried in consecrated ground; but through art she has the perpetual companionship of the greatest bishop of France.

JACQUES BÉNIGNE BOSSUET, BISHOP OF MEAUX.

(Painted by Hyacinthe Rigaud, and Engraved by Pierre Imbert Drevet.)

With the younger Drevet closed the classical period of portraits in engraving, as just before had closed the Augustan age of French literature. Louis XIV. decreedBalechou. engraving a fine art, and established an academy for its cultivation. Pride and ostentation in the king and theBeauvarlet. great aristocracy created a demand which the genius of the age supplied. The heights that had been reached could not be maintained. There were eminent engravers still; but the zenith had been passed. Balechou, who belonged to the reign of Louis XV., and Beauvarlet, whose life was protracted beyond the reign of terror, both produced portraits of merit. The former is noted for a certain clearness[23] and brilliancy, but with a hardness, as of brass or marble, and without entire accuracy of design; the latter has much softness of manner. They were the best artists of France at the time; but none of their portraits are famous. To these may be added another contemporary artist, without predecessor or successor, Stephen Ficquet, unduly disparagedFicquet. in one of the dictionaries as "a reputable French engraver," but undoubtedly remarkable for small portraits, not unlike miniatures, of exquisite finish. Among these the rarest and most admired are La Fontaine, Madame de Maintenon, Rubens and Vandyck.

Two other engravers belong to this intermediate period, though not French in origin: Georg F. Schmidt, born at Berlin, 1712, and Johann Georg Wille, born in the smallSchmidt. town of Königsberg, in the Grand Duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt, 1717, but attracted to Paris, they became the greatest engravers of the time. Their work is French, andWille. they are the natural development of that classical school.

Schmidt was the son of a poor weaver, and lost six precious years as a soldier in the artillery at Berlin. Owing to the smallness of his size he was at length dismissed,Schmidt. when he surrendered to a natural talent for engraving. Arriving at Strasburg, on his way to Paris, he fell in with Wille, a wandering gunsmith, who joined him in his journey, and eventually, in his studies. The productions of Schmidt show ability, originality, and variety, rather than taste. His numerous portraits are excellent, being free and life-like, while the accessories of embroidery and drapery are rendered with effect. As an etcher he ranks[24] next after Rembrandt. Of his portraits executed with the graver, that of the Empress Elizabeth of Russia is usually called the most important, perhaps on account of the imperial theme, and next those of Count Rassamowsky, Count Esterhazy, and De Mounsey, which he engraved while in St. Petersburgh, where he was called by the Empress, founding there the Academy of Engraving. But his real masterpieces are unquestionably Pierre Mignard and Latour, French painters, the latter represented laughing.

L'INSTRUCTION PATERNELLE, (THE "SATIN GOWN.")

(Painted by Gerard Terburg, and Engraved by Johann Georg Wille.)

Wille lived to old age, not dying till 1808. During this long life he was active in the art to which he inclined naturally. His mastership of the graver was perfect,Wille. lending itself especially to the representation of satin and metal, although less happy with flesh. His Satin Gown, or L'Instruction Paternelle, after Terburg, and Les Musiciens Ambulans, after Dietrich, are always admired. Nothing of the kind in engraving is finer. His style was adapted to pictures of the Dutch school, and to portraits with rich surroundings. Of the latter the principal are Comte de Saint-Florentin, Poisson Marquis de Marigny, John de Boullongne, and the Cardinal de Tencin.

Especially eminent was Wille as a teacher. Under his

influence the art assumed a new life, so that he became

father of the modern school. His scholars spread everywhere,Bervic.

and among them are acknowledged masters. He

was teacher of Bervic, whose portrait of Louis XVI. in hisToschi.

coronation robes is of a high order, himself teacher of the

Italian Toschi, who, after an eminent career, died as late

as 1858; also teacher of Tardieu, himself teacher of the[25]

brilliant Desnoyers, whose portrait of the Emperor Napoleon

in his Coronation Robes is the fit complement toDesnoyers.

that of Louis XVI.; also teacher of the German, J. G.

von Müller, himself father and teacher of J. Frederick vonMüller.

Müller, engraver of the Sistine Madonna, in a plate whose

great fame is not above its merit; also teacher of the ItalianVangelisti.

Vangelisti, himself teacher of the unsurpassed Longhi,

in whose school were Anderloni and Jesi. Thus not onlyAnderloni

and Jesi.

by his works, but by his famous scholars, did the humble

gunsmith gain sway in art.

NAPOLEON I.

(Painted by François Gérard, and Engraved by Auguste Boucher Desnoyers.)

Among portraits by this school deserving especial mention is that of King Jerome of Westphalia, brother of Napoleon, by the two Müllers, where the genius of the artist is most conspicuous, although the subject contributes little. As in the case of the Palace of the Sun, described by Ovid, Materiam superabat opus. This work is a beautiful example of skill in representation of fur and lace, not yielding even to Drevet.

Longhi was a universal master, and his portraits are only parts of his work. That of Washington, which is rare, is evidently founded on Stuart's painting, but afterLonghi. a design of his own, which is now in the possession of the Swiss Consul at Venice. The artist felicitated himself on the hair, which is modelled after the French masters.[7] The portraits of Michael Angelo, and of Dandolo, the venerable Doge of Venice, are admired; so also is the Napoleon, as King of Italy, with the iron crown and finest lace. But his chief portrait is that of Eugene [26]Beauharnais, Viceroy of Italy, full length, remarkable for plume in the cap, which is finished with surpassing skill.

Contemporary with Longhi was another Italian engraver of widely extended fame, who was not the product of the French school, Raffaelle Morghen, born at FlorenceMorghen. in 1758. His works have enjoyed a popularity beyond those of other masters, partly from the interest of their subjects, and partly from their soft and captivating style, although they do not possess the graceful power of Nanteuil and Edelinck, and are without variety. He was scholar and son-in-law of Volpato, of Rome; himself scholar of Wagner, of Venice, whose homely round faces were not high models in art. The Aurora, of Guido, and the Last Supper, of Leonardo da Vinci, stand high in engraving, especially the latter, which occupied Morghen three years. Of his two hundred and one works, no less than seventy-three are portraits, among which are the Italian poets Dante, Petrarch, Ariosto, Tasso, also Boccaccio, and a head called Raffaelle, but supposed to be that of Bendo Altoviti, the great painter's friend, and especially the Duke of Mencada on horseback, after Vandyck, which has received warm praise. But none of his portraits is calculated to give greater pleasure than that of Leonardo da Vinci, which may vie in beauty even with the famous Pompone. Here is the beauty of years and of serene intelligence. Looking at that tranquil countenance, it is easy to imagine the large and various capacities which made him not only painter, but sculptor, architect, musician,[27] poet, discoverer, philosopher, even predecessor of Galileo and Bacon. Such a character deserves the immortality of art. Happily an old Venetian engraving reproduced in our day,[8] enables us to see this same countenance at an earlier period of life, with sparkle in the eye.

GIOVANNI BOCCACCIO

Firenze presso Luigi Bardi e C'Borgo degli Albizzi No 460

Raffaelle Morghen left no scholars who have followed him in portraits; but his own works are still regarded, and a monument in Santa Croce, the Westminster Abbey of Florence, places him among the mighty dead of Italy.

Thus far nothing has been said of English engravers. Here, as in art generally, England seems removed from the rest of the world; Et penitus toto divisos orbe Britannos. But though beyond the sphere of Continental art, the island of Shakespeare was not inhospitable to some of its representatives. Vandyck, Rubens, Sir Peter Lely, and Sir Godfrey Kneller, all Dutch artists, painted the portraits of Englishmen, and engraving was first illustrated by foreigners. Jacob Houbraken, another Dutch artist, born in 1698, was employed to execute portraits for Birch's "Heads of Illustrious Persons of Great Britain," publishedHoubraken at London in 1743, and in these works may be seen the æsthetic taste inherited from his father, author of the biography of Dutch artists, and improved by study of the French masters. Although without great force or originality of manner, many of these have positive beauty. I [28]would name especially the Sir Walter Raleigh and John Dryden.

MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS.

(Painted by Federigo Zuccaro, and Engraved by Francesco Bartolozzi.)

Different in style was Bartolozzi, the Italian, who made his home in England for forty years, ending in 1807, when he removed to Lisbon. The considerable genius which heBartolozzi. possessed was spoilt by haste in execution, superseding that care which is an essential condition of art. Hence sameness in his work and indifference to the picture he copied. Longhi speaks of him as "most unfaithful to his archetypes," and, "whatever the originals, being always Bartolozzi." Among his portraits of especial interest are several old "wigs," as Mansfield and Thurlow; also the Death of Chatham, after the picture of Copley in the Vernon Gallery. But his prettiest piece undoubtedly is Mary Queen of Scots, with her little son James I., after what Mrs. Jameson calls "the lovely picture of Zuccaro at Chiswick." In the same style are his vignettes, which are of acknowledged beauty.

Meanwhile a Scotchman honorable in art comes upon the scene—Sir Robert Strange, born in the distant Orkneys in 1721, who abandoned the law for engraving.Strange. As a youthful Jacobite he joined the Pretender in 1745, sharing the disaster of Culloden, and owing his safety from pursuers to a young lady dressed in the ample costume of the period, whom he afterwards married in gratitude, and they were both happy. He has a style of his own, rich, soft, and especially charming in the tints of flesh, making him a natural translator of Titian. His most celebrated engravings are doubtless the Venus and[29] the Danaë after the great Venetian colorist, but the Cleopatra, though less famous, is not inferior in merit. His acknowledged masterpiece is the Madonna of St. Jerome called The Day, after the picture by Correggio, in the gallery of Parma, but his portraits after Vandyck are not less fine, while they are more interesting—as Charles First, with a large hat, by the side of his horse, which the Marquis of Hamilton is holding, and that of the same Monarch standing in his ermine robes; also the Three Royal Children with two King Charles spaniels at their feet, also Henrietta Maria, the Queen of Charles. That with the ermine robes is supposed to have been studied by Raffaelle Morghen, called sometimes an imitator of Strange.[9] To these I would add the rare autograph Portrait of the Engraver, being a small head after Greuze, which is simple and beautiful.

JOHN HUNTER

(Painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds, and Engraved by William Sharp.)

One other name will close this catalogue. It is that of William Sharp, who was born at London in 1746, and died there in 1824. Though last in order, this engraverSharp. may claim kindred with the best. His first essays were the embellishment of pewter pots, from which he ascended to the heights of art, showing a power rarely equalled. Without any instance of peculiar beauty, his works are constant in character and expression, with every possible excellence of execution; face, form, drapery—all are as in nature. His splendid qualities appear in the Doctors of the Church, which has taken its place as the first of English engravings. It is after the picture of Guido, [30]once belonging to the Houghton gallery, which in an evil hour for English taste was allowed to enrich the collection of the Hermitage at St. Petersburgh; and I remember well that this engraving by Sharp was one of the few ornaments in the drawing-room of Macaulay when I last saw him, shortly before his lamented death. Next to the Doctors of the Church is his Lear in the Storm, after the picture by West, now in the Boston Athenæum, and his Sortie from Gibraltar, after the picture by Trumbull, also in the Boston Athenæum. Thus, through at least two of his masterpieces whose originals are among us, is our country associated with this great artist.

It is of portraits especially that I write, and here Sharp is truly eminent. All that he did was well done; but two were models; that of Mr. Boulton, a strong, well-developed country gentleman, admirably executed, and of John Hunter, the eminent surgeon, after the painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds, in the London College of Surgeons, unquestionably the foremost portrait in English art, and the coequal companion of the great portraits in the past; but here the engraver united his rare gifts with those of the painter.

In closing these sketches I would have it observed that this is no attempt to treat of engraving generally, or of prints in their mass or types. The present subject isMandel. simply of portraits, and I stop now just as we arrive at contemporary examples, abroad and at home, with the gentle genius of Mandel beginning to ascend the sky, and our[31] own engravers appearing on the horizon. There is also a new and kindred art, infinite in value, where the sun himself becomes artist, with works which mark an epoch.

CHARLES SUMNER.

Washington, 11th Dec., 1871.

[1] Discourses before the Royal Academy, No. IV.

[2] De Groote Schonburgh der Nederlantsche Konctschilders en Schilderessen.

[3] This rare volume is in the Congressional Library, among the books which belonged originally to Hon. George P. Marsh, our excellent and most scholarly minister in Italy. I asked for it in vain at the Paris Cabinet of Engravings, and also at the Imperial Library. Never translated into French or English; there is a German translation of it by Carl Barth.

[4] Les Hommes Illustres, par Perrault, Tome ii., p. 97. The excellent copy of this work in the Congressional Library belonged to Mr. Marsh. The prints are early impressions.

[5] Panégyrique Funébre de Messire Pompone de Bellièvre, Premier Président au Parlement, pronouncé á l'Hostel-Dieu de Paris, le 17 Avril, 1657, par un Chanoine régulier de la Congrégation de France. The dedication shows this to have been the work of F. Lallemant of St. Geneviève.

[6] La Calcografia, p. 176.

[7] La Calcografia, pp. 165, 418.

[8] Les Arts au Moyen Age et à l'Epoque de la Renaissance, par Paul Lacroix, p. 198.

[9] Longhi, La Calcografia, p. 199.

End of Project Gutenberg's The Best Portraits in Engraving, by Charles Sumner

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BEST PORTRAITS IN ENGRAVING ***

***** This file should be named 22574-h.htm or 22574-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

https://www.gutenberg.org/2/2/5/7/22574/

Produced by Irma Špehar and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

https://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, is critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at https://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

https://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at https://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit https://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including including checks, online payments and credit card

donations. To donate, please visit: https://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

https://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.