The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Long Roll, by Mary Johnston This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Long Roll Author: Mary Johnston Release Date: July 13, 2007 [EBook #22066] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LONG ROLL *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

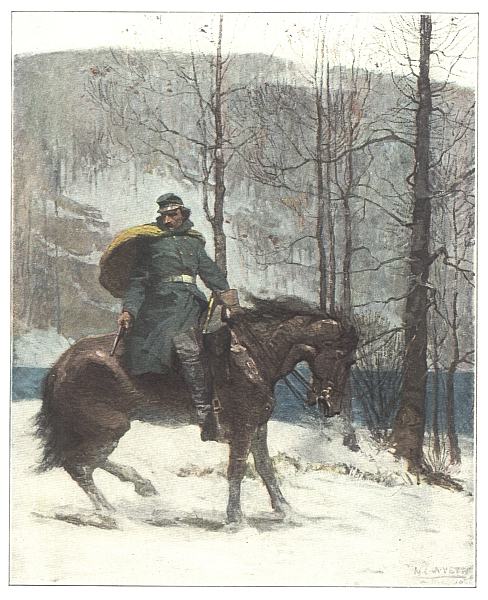

| THE LONG ROLL. The first of two books dealing with the war between the States. With Illustrations in color by N. C. Wyeth. |

| LEWIS RAND. With Illustrations in color by F. C. Yohn. |

| AUDREY. With Illustrations in color by F. C. Yohn. |

| PRISONERS OF HOPE. With Frontispiece. |

| TO HAVE AND TO HOLD. With 8 Illustrations by Howard Pyle, E. B. Thompson, A. W. Bette, and Eileen McConnell. |

| THE GODDESS OF REASON. A Drama |

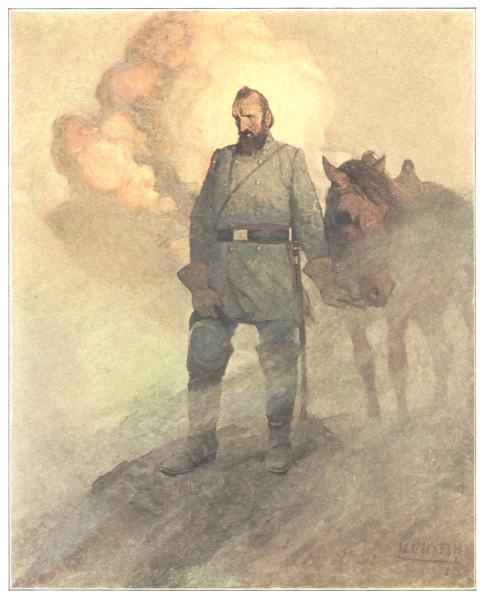

STONEWALL JACKSON

STONEWALL JACKSON

To name the historians, biographers, memoir and narrative writers, diarists, and contributors of but a vivid page or two to the magazines of Historical Societies, to whom the writer of a story dealing with this period is indebted, would be to place below a very long list. In lieu of doing so, the author of this book will say here that many incidents which she has used were actual happenings, recorded by men and women writing of that through which they lived. She has changed the manner but not the substance, and she has used them because they were "true stories" and she wished that breath of life within the book. To all recorders of these things that verily happened, she here acknowledges her indebtedness and gives her thanks.

| I. | The Botetourt Resolutions | 1 |

| II. | The Hilltop | 7 |

| III. | Three Oaks | 19 |

| IV. | Greenwood | 28 |

| V. | Thunder Run | 45 |

| VI. | By Ashby's Gap | 60 |

| VII. | The Dogs of War | 72 |

| VIII. | A Christening | 83 |

| IX. | Winchester | 100 |

| X. | Lieutenant McNeil | 112 |

| XI. | "As Joseph was a-Walking" | 121 |

| XII. | "The Bath and Romney Trip" | 135 |

| XIII. | Fool Tom Jackson | 150 |

| XIV. | The Iron-clads | 172 |

| XV. | Kernstown | 193 |

| XVI. | Rude's Hill | 207 |

| XVII. | Cleave and Judith | 217 |

| XVIII. | McDowell | 229 |

| XIX. | The Flowering Wood | 247 |

| XX. | Front Royal | 263 |

| XXI. | Steven Dagg | 277 |

| XXII. | The Valley Pike | 296 |

| XXIII. | Mother and Son | 312 |

| XXIV. | The Foot Cavalry | 331 |

| XXV. | Ashby | 343 |

| XXVI. | The Bridge at Port Republic | 354 |

| XXVII. | Judith and Stafford | 371 |

| XXVIII. | The Longest Way Round | 382 |

| XXIX. | The Nine-Mile Road | 399 |

| XXX. | At the President's | 412 |

| XXXI. | The First of the Seven Days | 434 |

| XXXII. | Gaines's Mill | 446 |

| XXXIII. | The Heel of Achilles | 465 |

| XXXIV. | The Railroad Gun | 481 |

| XXXV. | White Oak Swamp | 498 |

| XXXVI. | Malvern Hill | 516 |

| XXXVII. | A Woman | 530 |

| XXXVIII. | Cedar Run | 545 |

| XXXIX. | The Field of Manassas | 557 |

| XL. | A Gunner of Pelham's | 572 |

| XLI. | The Tollgate | 580 |

| XLII. | Special Orders, No. 191 | 589 |

| XLIII. | Sharpsburg | 602 |

| XLIV. | By the Opequon | 616 |

| XLV. | The Lone Tree Hill | 629 |

| XLVI. | Fredericksburg | 639 |

| XLVII. | The Wilderness | 655 |

| XLVIII. | The River | 670 |

| Stonewall Jackson | Frontispiece |

| The Lovers | 220 |

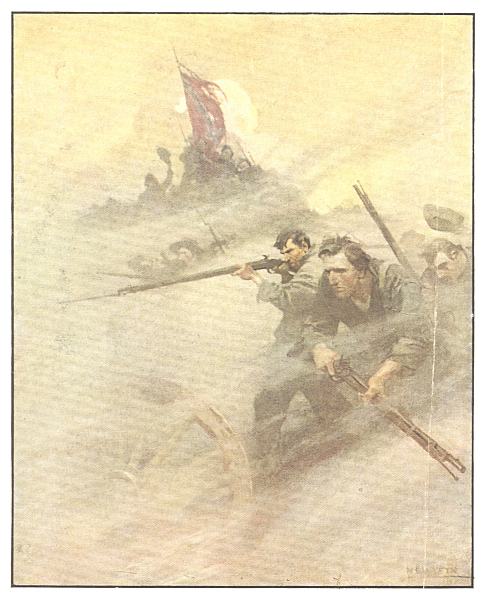

| The Battle | 456 |

| The Vedette | 642 |

On this wintry day, cold and sunny, the small town breathed hard in its excitement. It might have climbed rapidly from a lower land, so heightened now were its pulses, so light and rare the air it drank, so raised its mood, so wide, so very wide the opening prospect. Old red-brick houses, old box-planted gardens, old high, leafless trees, out it looked from its place between the mountain ranges. Its point of view, its position in space, had each its value—whether a lesser value or a greater value than other points and positions only the Judge of all can determine. The little town tried to see clearly and to act rightly. If, in this time so troubled, so obscured by mounting clouds, so tossed by winds of passion and of prejudice, it felt the proudest assurance that it was doing both, at least that self-infatuation was shared all around the compass.

The town was the county-seat. Red brick and white pillars, set on rising ground and encircled by trees, the court house rose like a guidon, planted there by English stock. Around it gathered a great crowd, breathlessly listening. It listened to the reading of the Botetourt Resolutions, offered by the President of the Supreme Court of Virginia, and now delivered in a solemn and a ringing voice. The season was December and the year, 1860.

The people of Botetourt County, in general meeting assembled, believe it to be the duty of all the citizens of the Commonwealth, in the present alarming condition of our country, to give some expression of their opinion upon the threatening aspect of public affairs....

In the controversies with the mother country, growing out of the effort[Pg 2] of the latter to tax the Colonies without their consent, it was Virginia who, by the resolution against the Stamp Act, gave the example of the first authoritative resistance by a legislative body to the British Government, and so imparted the first impulse to the Revolution.

Virginia declared her Independence before any of the Colonies, and gave the first written Constitution to mankind.

By her instructions her representatives in the General Congress introduced a resolution to declare the Colonies independent States, and the Declaration itself was written by one of her sons.

She furnished to the Confederate States the father of his country, under whose guidance Independence was achieved, and the rights and liberties of each State, it was hoped, perpetually established.

She stood undismayed through the long night of the Revolution, breasting

the storm of war and pouring out the blood of her sons like water on

every battlefield, from the ramparts of Quebec to the sands of Georgia.

A cheer broke from the throng. "That she did—that she did! 'Old

Virginia never tire.'"

By her unaided efforts the Northwestern Territory was conquered, whereby the Mississippi, instead of the Ohio River, was recognized as the boundary of the United States by the treaty of peace.

To secure harmony, and as an evidence of her estimate of the value of the Union of the States, she ceded to all for their common benefit this magnificent region—an empire in itself.

When the Articles of Confederation were shown to be inadequate to secure peace and tranquillity at home and respect abroad, Virginia first moved to bring about a more perfect Union.

At her instance the first assemblage of commissioners took place at Annapolis, which ultimately led to a meeting of the Convention which formed the present Constitution.

The instrument itself was in a great measure the production of one of her sons, who has been justly styled the Father of the Constitution.

The government created by it was put into operation, with her

Washington, the father of his country, at its head; her Jefferson, the

author of the Declaration of Independence, in his cabinet; her Madison,

the great advocate of the Constitution, in the legislative hall.

"And each of the three," cried a voice, "left on record his judgment [Pg 3]as

to the integral rights of the federating States."

Under the leading of Virginia statesmen the Revolution of 1798 was brought about, Louisiana was acquired, and the second war of independence was waged.

Throughout the whole progress of the Republic she has never infringed on the rights of any State, or asked or received an exclusive benefit.

On the contrary, she has been the first to vindicate the equality of all the States, the smallest as well as the greatest.

But, claiming no exclusive benefit for her efforts and sacrifices in the common cause, she had a right to look for feelings of fraternity and kindness for her citizens from the citizens of other States.... And that the common government, to the promotion of which she contributed so largely, for the purpose of establishing justice and ensuring domestic tranquillity, would not, whilst the forms of the Constitution were observed, be so perverted in spirit as to inflict wrong and injustice and produce universal insecurity.

These reasonable expectations have been grievously disappointed—

There arose a roar of assent. "That's the truth!—that's the plain

truth! North and South, we're leagues asunder!—We don't think alike, we

don't feel alike, and we don't interpret the Constitution alike! I'll

tell you how the North interprets it!—Government by the North, for the

North, and over the South! Go on, Judge Allen, go on!"

In view of this state of things, we are not inclined to rebuke or

censure the people of any of our sister States in the South, suffering

from injury, goaded by insults, and threatened with such outrages and

wrongs, for their bold determination to relieve themselves from such

injustice and oppression by resorting to their ultimate and sovereign

right to dissolve the compact which they had formed and to provide new

guards for their future security.

"South Carolina!—Georgia, too, will be out in January.—Alabama as

well, Mississippi and Louisiana.—Go on!"

Nor have we any doubt of the right of any State, there being no common umpire between coequal sovereign States, to judge for itself on its own responsibility, as to the mode and manner of redress.

The States, each for itself, exercised this sovereign power when they dissolved their connection with the British Empire.

They exercised the same power when nine of the States seceded from the Confederation and adopted the present Constitution, though two States at first rejected it.

The Articles of Confederation stipulated that those articles should be inviolably observed by every State, and that the Union should be perpetual, and that no alteration should be made unless agreed to by Congress and confirmed by every State.

Notwithstanding this solemn compact, a portion of the States did,

without the consent of the others, form a new compact; and there is

nothing to show, or by which it can be shown, that this right has been,

or can be, diminished so long as the States continue sovereign.

"The right's the right of self-government—and it's inherent and

inalienable!—We fought for it—when didn't we fight for it? When we

cease to fight for it, then chaos and night!—Go on, go on!"

The Confederation was assented to by the Legislature for each State; the Constitution by the people of each State, for such State alone. One is as binding as the other, and no more so.

The Constitution, it is true, established a government, and it operates directly on the individual; the Confederation was a league operating primarily on the States. But each was adopted by the State for itself; in the one case by the Legislature acting for the State; in the other by the people, not as individuals composing one nation, but as composing the distinct and independent States to which they respectively belong.

The foundation, therefore, on which it was established, was federal, and the State, in the exercise of the same sovereign authority by which she ratified for herself, may for herself abrogate and annul.

The operation of its powers, whilst the State remains in the Confederacy, is national; and consequently a State remaining in the Confederacy and enjoying its benefits cannot, by any mode of procedure, withdraw its citizens from the obligation to obey the Constitution and the laws passed in pursuance thereof.

But when a State does secede, the Constitution and laws of the United States cease to operate therein. No power is conferred on Congress to enforce them. Such authority was denied to the Congress in the convention which framed the Constitution, because it would be an act of war of nation against nation—not the exercise of the legitimate power of a government to enforce its laws on those subject to its jurisdiction.

The assumption of such a power would be the assertion of a prerogative

claimed by the British Government to legislate for the Colonies in[Pg 5]all

cases whatever; it would constitute of itself a dangerous attack on the

rights of the States, and should be promptly repelled.

There was a great thunder of assent. "That is our doctrine—bred in the

bone—dyed in the weaving! Jefferson, Madison, Marshall, Washington,

Henry—further back yet, further back—back to Magna Charta!"

These principles, resulting from the nature of our system of confederate States, cannot admit of question in Virginia.

In 1788 our people in convention, by their act of ratification, declared and made known that the powers granted under the Constitution, being derived from the people of the United States, may be resumed by them whenever they shall be perverted to their injury and oppression.

From what people were these powers derived? Confessedly from the people of each State, acting for themselves. By whom were they to be resumed or taken back? By the people of the State who were then granting them away. Who were to determine whether the powers granted had been perverted to their injury or oppression? Not the whole people of the United States, for there could be no oppression of the whole with their own consent; and it could not have entered into the conception of the Convention that the powers granted could not be resumed until the oppressor himself united in such resumption.

They asserted the right to resume in order to guard the people of Virginia, for whom alone the Convention could act, against the oppression of an irresponsible and sectional majority, the worst form of oppression with which an angry Providence has ever afflicted humanity.

Whilst therefore we regret that any State should, in a matter of common grievance, have determined to act for herself without consulting with her sister States equally aggrieved, we are nevertheless constrained to say that the occasion justifies and loudly calls for action of some kind....

In view therefore of the present condition of our country, and the causes of it, we declare almost in the words of our fathers, contained in an address of the freeholders of Botetourt, in February, 1775, to the delegates from Virginia to the Continental Congress, "That we desire no change in our government whilst left to the free enjoyment of our equal privileges secured by the constitution; but that should a tyrannical sectional majority, under the sanction of the forms of the constitution, persist in acts of injustice and violence toward us, they only must be answerable for the consequences."[Pg 6]

That liberty is so strongly impressed upon our hearts that we cannot think of parting with it but with our lives; that our duty to God, our country, ourselves and our posterity forbid it; we stand, therefore, prepared for every contingency.

Resolved therefore, That in view of the facts set out in the foregoing

preamble, it is the opinion of this meeting that a convention of the

people should be called forthwith; that the State in its sovereign

character should consult with the other Southern States, and agree upon

such guarantees as in their opinion will secure their equality,

tranquillity and rightswithin the Union.

The applause shook the air. "Yes, yes! within the Union! They're not

quite mad—not even the black Republicans! We'll save the Union!—We

made it, and we'll save it!—Unless the North takes leave of its

senses.—Go on!"

And in the event of a failure to obtain such guarantees, to adopt in

concert with the other Southern States, or alone, such measures as may

seem most expedient to protect the rights and ensure the safety of the

people of Virginia.

The reader made an end, and stood with dignity. Silence, then a beginning of sound, like the beginning of wind in the forest. It grew, it became deep and surrounding as the atmosphere, it increased into the general voice of the county, and the voice passed the Botetourt Resolutions.

On the court house portico sat the prominent men of the county, lawyers and planters, men of name and place, moulders of thought and leaders in action. Out of these came the speakers. One by one, they stepped into the clear space between the pillars. Such a man was cool and weighty, such a man was impassioned and persuasive. Now the tense crowd listened, hardly breathing, now it broke into wild applause. The speakers dealt with an approaching tempest, and with a gesture they checked off the storm clouds. "Protection for the manufacturing North at the expense of the agricultural South—an old storm centre! Territorial Rights—once a speck in the west, not so large as a man's hand, and now beneath it, the wrangling and darkened land! The Bondage of the African Race—a heavy cloud! Our English fathers raised it; our northern brethren dwelled with it; the currents of the air fixed it in the South. At no far day we will pass from under it. In the mean time we would not have it burst. In that case underneath it would lie ruined fields and wrecked homes, and out of its elements would come a fearful pestilence! The Triumph of the Republican Party—no slight darkening of the air is that, no drifting mist of the morning! It is the triumph of that party which proclaims the Constitution a covenant with death and an agreement with hell!—of that party which tolled the bells, and fired the minute guns, and draped its churches with black, and all-hailed as saint and martyr the instigator of a bloody and servile insurrection in a sister State, the felon and murderer, John Brown! The Radical, the Black Republican, faction, sectional rule, fanaticism, violation of the Constitution, aggression, tyranny, and wrong—all these are in the bosom of that cloud!—The Sovereignty of the State. Where is the tempest which threatens here? Not here, Virginians! but in the pleasing assertion of the North, 'There is no sovereignty of the State!' 'A State is merely to the Union what a county is to a State.' O shades of John Randolph of Roanoke, of Patrick Henry, of Mason and Madison, of Washington and Jefferson! O shade of John Marshall even, whom we used to think too Federal! The Union! We thought of the Union as a golden thread—at the most we thought of it as a strong servant we had made between us, we thirteen artificers—a beautiful Talus to walk our coasts and cry 'All's well!' We thought so—by the gods, we think so yet! That is our Union—the golden thread, the faithful servant; not the monster that Frankenstein made, not this Minotaur swallowing States! The Sovereignty of the State! Virginia fought seven years for the sovereignty of Virginia, wrung it, eighty years ago, from Great Britain, and has not since resigned it! Being different in most things, possibly the North is different also in this. It may be that those States have renounced the liberty they fought for. Possibly Massachusetts—the years 1803, 1811, and 1844 to the contrary—does regard herself as a county. Possibly[Pg 8] Connecticut—for all that there was a Hartford Convention!—sees herself in the same light. Possibly. 'Brutus saith 't is so, and Brutus is an honourable man!' But Virginia has not renounced! Eighty years ago she wrote a certain motto on her shield. To-day the letters burn bright! Unterrified then she entered this league from which we hoped so much. Unterrified to-morrow, should a slurring hand be laid upon that shield, will she leave it!"

Allan Gold, from the schoolhouse on Thunder Run, listened with a swelling heart, then, amid the applause which followed the last speaker, edged his way along the crowded old brick pavement to where, not far from the portico, he made out the broad shoulders, the waving dark hair, and the slouch hat of a young man with whom he was used to discuss these questions. Hairston Breckinridge glanced down at the pressure upon his arm, recognized the hand, and pursued, half aloud, the current of his thought. "I don't believe I'll go back to the university. I don't believe any of us will go back to the university.—Hello, Allan!"

"I'm for the preservation of the Union," said Allan. "I can't help it. We made it, and we've loved it."

"I'm for it, too," answered the other, "in reason. I'm not for it out of reason. In these affairs out of reason is out of honour. There's nothing sacred in the word Union that men should bow down and worship it! It's the thing behind the word that counts—and whoever says that Massachusetts and Virginia, and Illinois and Texas are united just now is a fool or a liar!—Who's this Colonel Anderson is bringing forward? Ah, we'll have the Union now!"

"Who is it?"

"Albemarle man, staying at Lauderdale.—Major in the army, home on furlough.—Old-line Whig. I've been at his brother's place, near Charlottesville—"

From the portico came a voice. "I am sure that few in Botetourt need an introduction here. We, no more than others, are free from vanity, and we think we know a hero by intuition. Men of Botetourt, we have the honour to listen to Major Fauquier Cary, who carried the flag up Chapultepec!"[Pg 9]

Amid applause a man of perhaps forty years, spare, bronzed, and soldierly, entered the clear space between the pillars, threw out his arm with an authoritative gesture, and began to speak in an odd, dry, attractive voice. "You are too good!" he said clearly. "I'm afraid you don't know Fauquier Cary very well, after all. He's no hero—worse luck! He's only a Virginian, trying to do the right as he sees it, out yonder on the plains with the Apaches and the Comanches and the sage brush and the desert—"

There was an interruption. "How about Chapultepec?"—"And the Rio Grande?"—"Didn't we hear something about a fight in Texas?"

The speaker laughed. "A fight in Texas? Folk, folk, if you knew how many fights there are in Texas—and how meritorious it is to keep out of them! No; I'm only a Virginian out there." He regarded the throng with his magnetic smile, his slight and fine air of gaiety in storm. "As you know, I am by no means the only Virginian, and they are heroes, the others, if you like!—real, old-line heroes, brave as the warriors in Homer, and a long sight better men! I am happy to report to his kinsmen here that General Joseph E. Johnston is in health—still loving astronomy, still reading du Guesclin, still studying the Art of War. He's a soldier's soldier, and that, in its way, is as fine a thing as a poet's poet! I see men before me who are of the blood of the Lees. Out there by the Rio Grande is a Colonel Robert E. Lee, of whom Virginia may well be proud! There are few heights in those western deserts, but he carries his height with him. He's marked for greatness. And there are 'Beauty' Stuart, and Dabney Maury, the best of fellows, and Edward Dillon, and Walker and George Thomas, and many another good man and true. First and last, there's a deal of old Virginia following Mars, out yonder! We've got Hardee, too, from Georgia, and Van Dorn from Mississippi, and Albert Sidney Johnston from Kentucky—no better men in Homer, no better men! And there are others as soldierly—McClellan with whom I graduated at West Point, Fitz-John Porter, Hancock, Sedgwick, Sykes, and Averell. McClellan and Hancock are from Pennsylvania, Fitz-John Porter is from New Hampshire, Sedgwick from Connecticut, Sykes from Delaware, and Averell from New York. And away, away out yonder, in the midst of sage brush and Apaches, when any of us chance to meet around a camp-fire, there we sit, while coyotes are yelling off in the dark, there we sit and tell stories of home, of Virginia[Pg 10] and Pennsylvania, of Georgia and New Hampshire!"

He paused, drew himself up, looked out over the throng to the mountains, studied for a moment their long, clean line, then dropped his glance and spoke in a changed tone, with a fiery suddenness, a lunge as of a tried rapier, quick and startling.

"Men of Botetourt! I speak for my fellow soldiers of the Army of the United States when I say that, out yonder, we are blithe to fight with marauding Comanches, with wolves and with grizzlies, but that we are not—oh, we are not—ready to fight with each other! Brother against brother—comrade against comrade—friend against friend—to quarrel in the same tongue and to slay the man with whom you've faced a thousand dangers—no, we are not ready for that!

"Virginians! I will not believe that the permanent dissolution of this great Union is come! I will not believe that we stand to-day in danger of internecine war! Men of Botetourt, go slow—go slow! The Right of the State—I grant it! I was bred in that doctrine, as were you all. Albemarle no whit behind Botetourt in that! The Botetourt Resolutions—amen to much, to very much in the Botetourt Resolutions! South Carolina! Let South Carolina go in peace! It is her right! Remembering old comradeship, old battlefields, old defeats, old victories, we shall still be friends. If the Gulf States go, still it is their right, immemorial, incontrovertible!—The right of self-government. We are of one blood and the country is wide. God-speed both to Lot and to Abraham! On some sunny future day may their children draw together and take hands again! So much for the seceding States. But Virginia,—but Virginia made possible the Union,—let her stand fast in it in this day of storm! in this Convention let her voice be heard—as I know it will be heard—for wisdom, for moderation, for patience! So, or soon or late, she will mediate between the States, she will once again make the ring complete, she will be the saviour of this great historic Confederation which our fathers made!"

A minute or two more and he ended his speech. As he moved from between the pillars, there was loud applause. The county was largely Whig, honestly longing—having put on record what it thought of the present mischief and the makers of it—for a peacefu[Pg 11]l solution of all troubles. As for the army, county and State were proud of the army, and proud of the Virginians within it. It was amid cheering that Fauquier Cary left the portico. At the head of the steps, however, there came a question. "One moment, Major Cary! What if the North declines to evacuate Fort Sumter? What if she attempts to reinforce it? What if she declares for a compulsory Union?"

Cary paused a moment. "She will not, she will not! There are politicians in the North whom I'll not defend! But the people—the people—the people are neither fools nor knaves! They were born North and we were born South and that is the chief difference between us! A Compulsory Union! That is a contradiction in terms. Individuals and States, harmoniously minded, unite for the sweetness of Union and for the furtherance of common interests. When the minds are discordant, and the interests opposed, one may be bound to another by Conquest—not otherwise! What said Hamilton? To coerce a State would be one of the maddest projects ever devised!" He descended the court house steps to the grassy, crowded yard. Here acquaintances claimed him, and here, at last, the surge of the crowd brought him within a yard of Allan Gold and his companion. The latter spoke. "Major Cary, you don't remember me. I'm Hairston Breckinridge, sir, and I've been once or twice to Greenwood with Edward. I was there Christmas before last, when you came home wounded—"

The older man put out a ready hand. "Yes, yes, I do remember! We had a merry Christmas! I am glad to meet you again, Mr. Breckinridge. Is this your brother?"

"No, sir. It's Allan Gold, from Thunder Run."

"I am pleased to meet you, sir," said Allan. "You have been saying what I should like to have been able to say myself."

"I am pleased that you are pleased. Are you, too, from the university?"

"No, sir. I couldn't go. I teach the school on Thunder Run."[Pg 12]

"Allan knows more," said Hairston Breckinridge, "than many of us who are at the university. But we mustn't keep you, sir."

In effect they could do so no longer. Major Cary was swept away by acquaintances and connections. The day was declining, the final speaker drawing to an end, the throng beginning to shiver in the deepening cold. The speaker gave his final sentence; the town band crashed in determinedly with "Home, Sweet Home." To its closing strains the county people, afoot, on horseback, in old, roomy, high-swung carriages, took this road and that. The townsfolk, still excited, still discussing, lingered awhile round the court house or on the verandah of the old hotel, but at last these groups dissolved also. The units betook themselves home to fireside and supper, and the sun set behind the Alleghenies.

Allan Gold, striding over the hills toward Thunder Run, caught up with the miller from Mill Creek, and the two walked side by side until their roads diverged. The miller was a slow man, but to-day there was a red in his cheek and a light in his eye. "Just so," he said shortly. "They must keep out of my mill race or they'll get caught in the wheel."

"Mr. Green," said Allan, "how much of all this trouble do you suppose is really about the negro? I was brought up to wish that Virginia had never held a slave."

"So were most of us. You don't hold any."

"No."

"No more I don't. No more does Tom Watts. Nor Anderson West. Nor the Taylors. Nor five sixths of the farming folk about here. Nor seven eighths of the townspeople. We don't own a negro, and I don't know that we ever did own one. Not long ago I asked Colonel Anderson a lot of questions about the matter. He says the census this year gives Virginia one million and fifty thousand white people, and of these the fifty thousand hold slaves and the one million don't. The fifty thousand's mostly in the tide-water counties, too,—mighty little of it on this side the Blue Ridge! Ain't anybody ever accused Virginians of not being good to servants! and it don't take more'n half an eye to see that the servants love their white people. For slavery itself, I ain't quarrelling for it, and neither was Colonel Anderson. He said it was abhorrent in the sight of God and man. He said the old House of Burgesses used to try to stop the bringing in of negroes, and that the Colony was always appealing to the king against the traffic. He said that in 1778, two years after Virginia declared her Independence, she passed the statute prohibiting the slave trade. He said that she was the first country in the civilized world to stop the trade—passed her statute thirty years before England! He said that all our great Revolutionary men[Pg 13] hated slavery and worked for the emancipation of the negroes who were here; that men worked openly and hard for it until 1832. Then came the Nat Turner Insurrection, when they killed all those women and children, and then rose the hell-fire-for-all, bitter-'n-gall Abolition people stirring gunpowder with a lighted stick, holding on like grim death and in perfect safety fifteen hundred miles from where the explosion was due! And as they denounce without thinking, so a lot of men have risen with us to advocate without thinking. And underneath all the clamour, there goes on, all the time, quiet and steady, a freeing of negroes by deed and will, a settling them in communities in free States, a belonging to and supporting Colonization Societies. There are now forty thousand free negroes in Virginia, and Heaven knows how many have been freed and established elsewhere! It is our best people who make these wills, freeing their slaves, and in Virginia, at least, everybody, sooner or later, follows the best people. 'Gradual manumission, Mr. Green,' that's what Colonel Anderson said, 'with colonization in Africa if possible. The difficulties are enough to turn a man's hair grey, but,' said he, 'slavery's knell has struck, and we'll put an end to it in Virginia peacefully and with some approach to wisdom—if only they'll stop stirring the gunpowder!'"

The miller raised his large head, with its effect of white powder from the mill, and regarded the landscape. "'We're all mighty blind, poor creatures,' as the preacher says, but I reckon one day we'll find the right way, both for us and for that half million poor, dark-skinned, lovable, never-knew-any-better, pretty-happy-on-the-whole, way-behind-the-world people that King James and King Charles and King George saddled us with, not much to their betterment and to our certain hurt. I reckon we'll find it. But I'm damned if I'm going to take the North's word for it that she has the way! Her old way was to sell her negroes South."

"I've thought and thought," said Allan. "People mean well, and yet there's such a dreadful lot of tragedy in the world!"

"I agree with you there," quoth the miller. "And I certainly don't deny that slavery's responsible for a lot of bitter tal[Pg 14]k and a lot of red-hot feeling; for some suffering to some negroes, too, and for a deal of harm to almost all whites. And I, for one, will be powerful glad when every negro, man and woman, is free. They can never really grow until they are free—I'll acknowledge that. And if they want to go back to their own country I'd pay my mite to help them along. I think I owe it to them—even though as far as I know I haven't a forbear that ever did them wrong. Trouble is, don't any of them want to go back! You couldn't scare them worse than to tell them you were going to help them back to their fatherland! The Lauderdale negroes, for instance—never see one that he isn't laughing! And Tullius at Three Oaks,—he'd say he couldn't possibly think of going—must stay at Three Oaks and look after Miss Margaret and the children! No, it isn't an easy subject, look at it any way you will. But as between us and the North, it ain't the main subject of quarrel—not by a long shot it ain't! The quarrel's that a man wants to take all the grist, mine as well as his, and grind it in his mill! Well, I won't let him—that's all. And here's your road to Thunder Run."

Allan strode on alone over the frozen hills. Before him sprang the rampart of the mountains, magnificently drawn against the eastern sky. To either hand lay the fallow fields, rolled the brown hills, rose the shadowy bulk of forest trees, showed the green of winter wheat. The evening was cold, but without wind and soundless. The birds had flown south, the cattle were stalled, the sheep folded. There was only the earth, field and hill and mountain, the up and down of a narrow road, and the glimmer of a distant stream. The sunset had been red, and it left a colour that flared to the zenith.

The young man, tall, blond, with grey-blue eyes and short, fair beard, covered with long strides the frozen road. It led him over a lofty hill whose summit commanded a wide prospect. Allan, reaching this height, hesitated a moment, then crossed to a grey zigzag of rail fence, and, leaning his arms upon it, looked forth over hill and vale, forest and stream. The afterglow was upon the land. He looked at the mountains, the great mountains, long and clean of line as the marching rollers of a giant sea, not split or jagged, but even, unbroken, and old, old, the oldest almost in the world. Now the ancient forest clothed them, while they were given, by some constant trick of the light, the distant, dreamy blue from which they took their name. The Blue Ridge—the Blue Ridge—and then the[Pg 15] hills and the valleys, and all the rushing creeks, and the grandeur of the trees, and to the east, steel clear between the sycamores and the willows, the river—the upper reaches of the river James.

The glow deepened. From a farmhouse in the valley came the sound of a bell. Allan straightened himself, lifting his arms from the grey old rails. He spoke aloud.

| Breathes there the man with soul so dead,— |

The bell rang again, the rose suffused the sky to the zenith. The young man drew a long breath, and, turning, began to descend the hill.

Before him, at a turn of the road and overhanging a precipitous hollow, in the spring carpeted with bloodroot, but now thick with dead leaves, lay a giant oak, long ago struck down by lightning. The branches had been cut away, but the blackened trunk remained, and from it as vantage point one received another great view of the rolling mountains and the valleys between. Allan Gold, coming down the hill, became aware, first of a horse fastened to a wayside sapling, then of a man seated upon the fallen oak, his back to the road, his face to the darkening prospect. Below him the winter wind made a rustling in the dead leaves. Evidently another had paused to admire the view, or to collect and mould between the hands of the soul the crowding impressions of a decisive day. It was, apparently, the latter purpose; for as Allan approached the ravine there came to him out of the dusk, in a controlled but vibrant voice, the following statement, repeated three times: "We are going to have war.—We are going to have war.—We are going to have war."

Allan sent his own voice before him. "I trust in God that's not true!—It's Richard Cleave, there, isn't it?"

The figure on the oak, swinging itself around, sat outlined against the violet sky. "Yes, Richard Cleave. It's a night to make one think, Allan—to make one think—to make one think!" Laying his hand on the trunk beside him, he sprang lightly down to the roadside, where he proceeded to brush dead leaf and bark from his clothing with an old gauntlet. When he spoke it was still in the same moved, vibrating voice. "War's my métier. That's a curious thing to be said by a country lawyer in peaceful old Virginia in this year[Pg 16] of grace! But like many another curious thing, it's true! I was never on a field of battle, but I know all about a field of battle."

He shook his head, lifted his hand, and flung it out toward the mountains. "I don't want war, mind you, Allan! That is, the great stream at the bottom doesn't want it. War is a word that means agony to many and a set-back to all. Reason tells me that, and my heart wishes the world neither agony nor set-back, and I give my word for peace. Only—only—before this life I must have fought all along the line!"

His eyes lightened. Against the paling sky, in the wintry air, his powerful frame, not tall, but deep-chested, broad-shouldered, looked larger than life. "I don't talk this way often—as you'll grant!" he said, and laughed. "But I suppose to-day loosed all our tongues, lifted every man out of himself!"

"If war came," said Allan, "it couldn't be a long war, could it? After the first battle we'd come to an understanding."

"Would we?" answered the other. "Would we?—God knows! In the past it has been that the more equal the tinge of blood, the fiercer was the war."

As he spoke he moved across to the sapling where was fastened his horse, loosed him, and sprang into the saddle. The horse, a magnificent bay, took the road, and the three began the long descent. It was very cold and still, a crescent moon in the sky, and lights beginning to shine from the farmhouses in the valley.

"Though I teach school," said Allan, "I like the open. I like to do things with my hands, and I like to go in and out of the woods. Perhaps, all the way behind us, I was a hunter, with a taste for books! My grandfather was a scout in the Revolution, and his father was a ranger.... God knows, I don't want war! But if it comes I'll go. We'll all go, I reckon."

"Yes, we'll all go," said Cleave. "We'll need to go."

The one rode, the other walked in silence for a time; then said the first, "I shall ride to Lauderdale after supper and talk to Fauquier Cary."

"You and he are cousins, aren't you?"

"Third cousins. His mother was a Dandridge—Unity Dandridge."[Pg 17]

"I like him. It's like old wine and blue steel and a cavalier poet—that type."

"Yes, it is old and fine, in men and in women."

"He does not want war."

"No."

"Hairston Breckinridge says that he won't discuss the possibility at all—he'll only say what he said to-day, that every one should work for peace, and that war between brothers is horrible."

"It is. No. He wears a uniform. He cannot talk."

They went on in silence for a time, over the winter road, through the crystal air. Between the branches of the trees the sky showed intense and cold, the crescent moon, above a black mass of mountains, golden and sharp, the lights in the valley near enough to be gathered.

"If there should be war," asked Allan, "what will they do, all the Virginians in the army—Lee and Johnston and Stuart, Maury and Thomas and the rest?"

"They'll come home."

"Resigning their commissions?"

"Resigning their commissions."

Allan sighed. "That would be a hard thing to have to do."

"They'll do it. Wouldn't you?"

The teacher from Thunder Run looked from the dim valley and the household lamps up to the marching stars. "Yes. If my State called, I would do it."

"This is what will happen," said Cleave. "There are times when a man sees clearly, and I see clearly to-day. The North does not intend to evacuate Fort Sumter. Instead, sooner or later, she'll try to reinforce it. That will be the beginning of the end. South Carolina will reduce the fort. The North will preach a holy war. War there will be—whether holy or not remains to be seen. Virginia will be called upon to furnish her quota of troops with which to coerce South Carolina and the Gulf States back into the Union. Well—do you think she will give them?"

Allan gave a short laugh. "No!"

"That is what will happen. And then—and then a greater State than any will be forced into secession! And then the Virginians in the army will come home."[Pg 18]

The wood gave way to open country, softly swelling fields, willow copses, and clear running streams. In the crystal air the mountain walls seemed near at hand, above shone Orion, icily brilliant. The lawyer from a dim old house in a grove of oaks and the school-teacher from Thunder Run went on in silence for a time; then the latter spoke.

"Hairston Breckinridge says that Major Cary's niece is with him at Lauderdale."

"Yes. Judith Cary."

"That's the beautiful one, isn't it?"

"They are all said to be beautiful—the three Greenwood Carys. But—Yes, that is the beautiful one."

He began to hum a song, and as he did so he lifted his wide soft hat and rode bareheaded.

"It's strange to me," said Allan presently, "that any one should be gay to-day."

As he spoke he glanced up at the face of the man riding beside him on the great bay. There was yet upon the road a faint after-light—enough light to reveal that there were tears on Cleave's cheek. Involuntarily Allan uttered an exclamation.

The other, breaking off his chant, quite simply put up a gauntleted hand and wiped the moisture away. "Gay!" he repeated. "I'm not gay. What gave you such an idea? I tell you that though I've never been in a war, I know all about war!"

Having left behind him Allan Gold and the road to Thunder Run, Richard Cleave came, a little later, to his own house, old and not large, crowning a grassy slope above a running stream. He left the highway, opened a five-barred gate, and passed between fallow fields to a second gate, opened this and, skirting a knoll upon which were set three gigantic oaks, rode up a short and grass-grown drive. It led him to the back of the house, and afar off his dogs began to give him welcome. When he had dismounted before the porch, a negro boy with a lantern took his horse. "Hit's tuhnin' powerful cold, Marse Dick!"

"It is that, Jim. Give Dundee his supper at once and bring him around again. Down, Bugle! Down, Moira! Down, Baron!"

The hall was cold and in semi-darkness, but through the half-opened door of his mother's chamber came a gush of firelight warm and bright. Her voice reached him—"Richard!" He entered. She was sitting in a great old chair by the fire, idle for a wonder, her hands, fine and slender, clasped over her knees. The light struck up against her fair, brooding face. "It is late!" she said. "Late and cold! Come to the fire. Ailsy will have supper ready in a minute."

He came and knelt beside her on the braided rug. "It is always warm in here. Where are the children?"

"Down at Tullius's cabin.—Tell me all about it. Who spoke?"

Cleave drew before the fire the chair that had been his father's, sank into it, and taking the ash stick from the corner, stirred the glowing logs. "Judge Allen's Resolutions were read and carried. Fauquier Cary spoke—many others."

"Did not you?"

"No. They asked me to, but with so many there was no need. People were much moved—"

He broke off, sitting stirring the fire. His mother watched the deep hollows with him. Closely resembling as he did his long dead father, the inner tie, strong and fine, was rather between him and the woman who had given him birth. Wedded ere she was seventeen, a mother at eighteen, she sat now beside her first-born, still beautiful, and crowned by a lovely life. She had kept her youth, and he had come early to a man's responsibilities. For years now they had walked together, caring for the farm, which was not large, for the handful of servants, for the two younger children, Will and Miriam. The eighteen years between them was cancelled by their common interests, his maturity of thought, her quality of the summer time. She broke the silence. "What did Fauquier Cary say?"

"He spoke strongly for patience, moderation, peace—I am going to Lauderdale after supper."

"To see Judith?"[Pg 20]

"No. To talk to Fauquier.... Maury Stafford is at Silver Hill." He straightened himself, put down the ash stick, and rose to his feet. "The bell will ring directly. I'll go upstairs for a moment."

Margaret Cleave put out a detaining hand. "One moment—Richard, are you quite, quite sure that she likes Maury Stafford so well?"

"Why should she not like him? He's a likable fellow."

"So are many people. So are you."

Cleave gave a short and wintry laugh. "I? I am only her cousin—rather a dull cousin, too, who does nothing much in the law, and is not even a very good farmer! Am I sure? Yes, I am sure enough!" His hand closed on the back of her chair; the wood shook under the sombre energy of his grasp. "Did I not see how it was last summer that week I spent at Greenwood? Was he not always with her?—supple and keen, easy and strong, with his face like a picture, with all the advantages I did not have—education, travel, wealth!—Why, Edward told me—and could I not see for myself? It was in the air of the place—not a servant but knew he had come a-wooing!"

"But there was no engagement then. Had there been we should have known it."

"No engagement then, perhaps, but certainly no discouragement! He was there again in the autumn. He was with her to-day." The chair shook again. "And this morning Fauquier Cary, talking to me, laughed and said that Albemarle had set their wedding day!"

His mother sighed. "Oh, I am sorry—sorry!"

"I should never have gone to Greenwood last summer—never have spent there that unhappy week! Before that it was just a fancy—and then I must go and let it bite into heart and brain and life—" He dropped his hand abruptly and turned to the door. "Well, I've got to try now to think only of the country! God knows, things have come to that pass that her sons should think only of her! It is winter time, Mother; the birds aren't mating now—save those two—save those two!"

Upstairs, in his bare, high-ceiled room, his hasty toilet made, he stood upon the hearth, beside the leaping fire, and looked about him. Of late—since the summer—everything was clarifying. There was at work some great solvent making into naught the dross of custom and habitude. The glass had turne[Pg 21]d; outlines were clearer than they had been, the light was strong, and striking from a changed angle. To-day both the sight of a face and the thought of an endangered State had worked to make the light intenser. His old, familiar room looked strange to him to-night. A tall bookcase faced him. He went across and stood before it, staring through the diamond panes at the backs of the books. Here were his Coke and Blackstone, Vattel, Henning, Kent, and Tucker, and here were other books of which he was fonder than of those, and here were a few volumes of the poets. Of them all, only the poets managed to keep to-night a familiar look. He took out a volume, old, tawny-backed, gold-lettered, and opened it at random—

| Her face so faire, as flesh it seemed not, But hevenly pourtraict of bright angels hew, Cleare as the sky, withouten blame or blot— |

A bell rang below. Youthful and gay, shattering the quiet of the house, a burst of voices proclaimed "the children's" return from Tullius's cabin. When, in another moment, Cleave came downstairs, it was to find them both in wait at the foot, illumined by the light from the dining-room door. Miriam laid hold of him. "Richard, Richard! tell me quick! Which was the greatest, Achilles or Hector?"

Will, slight and fair, home for the holidays from Lexington and, by virtue of his cadetship in the Virginia Military Institute, an authority on most things, had a movement of impatience. "Girls are so stupid! Tell her it was Hector, and let's go to supper! She'll believe you."

Within the dining-room, at the round table, before the few pieces of tall, beaded silver and the gilt-banded china, while Mehalah the waitress brought the cakes from the kitchen and the fire burned softly on the hearth below the Saint Memin of a general and law-giver, talk fell at once upon the event of the day, the meeting that had passed the Botetourt Resolutions. Miriam, with her wide, sensitive mouth, her tip-tilted nose, her hazel eyes, her air of some quaint, bright garden flower swaying on its stem, was for war and music, and both her brothers to become generals. "Or Richard can be the general, and you be a cavalryman like Cousin Fauquier! Richard can fight like Napoleon and you may fight like Ney!"

The cadet stiffened. "Thank you for nothing, Missy! Anyhow, I shan't sulk in my tents like your precious Achilles—just for a girl! Richard! 'Old Jack' says—"

"I wish, Will," murmured his mother, "that you'd say 'Major Jackson.'"

The boy laughed. "'Old Jack' is what we call him, ma'am! The other wouldn't be respectful. He's never 'Major Jackson' except when he's trying to teach natural philosophy. On the drill ground he's 'Old Jack.' Richard, he says—Old Jack says—that not a man since Napoleon has understood the use of cavalry."

Cleave, sitting with his eyes upon the portrait of his grandfather, answered dreamily: "Old Jack is probably in the right of it, Will. Cavalry is a great arm, but I shall choose the artillery."

His mother set down her coffee cup with a little noise, Miriam shook her hair out of her eyes and came back from her own dream of the story she was reading, and Will turned as sharply as if he were on the parade ground at Lexington.

"You don't think, then, that it is just all talk, Richard! You are sure that we're going to fight!"

"You fight!" cried Miriam. "Why, you aren't sixteen!"

Will flared up. "Plenty of soldiers have died at sixteen, Missy! 'Old Jack' knows, if you don't—"

"Children, children!" said Margaret Cleave, in a quivering voice. "It is enough to know that not a man of this family but would fight now for Virginia, just as they fought eighty odd years ago! Yes, and we women did our part then, and we would do it now! But I pray God, night and day—and Miriam, you should pray too—that this storm will not burst! As for you two who've always been sheltered and fed, who've never had a blow struck you, who've grown like tended plants in a garden—you don't know what war is! It's a great and deep Cup of Trembling! It's a scourge that reaches the backs of all! It's universal destruction—and the gift that the world should pray for is to build in peace! That is true, isn't it, Richard?"

"Yes, it is true," said Richard. "Don't, Will," as the boy began to speak. "Don't let's talk any more about it to-night. After all, a deal of storms go by—and it's a wise man who can read Time's order-book." He rose from the table. "It's like the fable. The King may die, the Ass may die, the Philosopher may die—and[Pg 23] next Christmas maybe the peacefullest on record! I'm going to ride to Lauderdale for a little while, and, if you like, I'll ask about that shotgun for you."

A few minutes later and he was out on the starlit road to Lauderdale. As he rode he thought, not of the Botetourt Resolutions, nor of Fauquier Cary, nor of Allan Gold, nor of the supper table at Three Oaks, nor of a case which he must fight through at the court house three days hence, but of Judith Cary. Dundee's hoofs beat it out on the frosty ground. Judith Cary—Judith Cary—Judith Cary! He thought of Greenwood, of the garden there, of a week last summer, of Maury Stafford—Stafford whom at first meeting he had thought most likable! He did not think him so to-night, there at Silver Hill, ready to go to Lauderdale to-morrow!—Judith Cary—Judith Cary—Judith Cary. He saw Stafford beside her—Stafford beside her—Stafford beside her—

"If she love him," said Cleave, half aloud, "he must be worthy. I will not be so petty nor so bitter! I wish her happiness.—Judith Cary—Judith Cary. If she love him—"

To the left a little stream brawled through frosty meadows; to the right rose a low hill black with cedars. Along the southern horizon stretched the Blue Ridge, a wall of the Titans, a rampart in the night. The line was long and clean; behind it was an effect of light, a steel-like gleaming. Above blazed the winter stars. "If she love him—if she love him—" He determined that to-night at Lauderdale he would try to see her alone for a minute. He would find out—he must find out—if there were any doubt he would resolve it.

The air was very still and clear. He heard a carriage before him on the road. It was coming toward him—a horseman, too, evidently riding beside it. Just ahead the road crossed a bridge—not a good place for passing in the night-time. Cleave drew a little aside, reining in Dundee. With a hollow rumbling the carriage passed the streams. It proved to be an old-fashioned coach with lamps, drawn by strong, slow grey horses. Cleave recognized the Silver Hill equipage. Silver Hill must have been supping with Lauderdale. Immediately he divined who was the horseman. The carriage drew alongside, the lamps making a small ring of light. "Good-evening, Mr. Stafford!" said Cleave. The other raised his hat. "Mr. Cleave, is it not? Good-evening, sir!" A voice spoke within the coach. "[Pg 24]It's Richard Cleave now! Stop, Ephraim!"

The slow grey horses came to a stand. Cleave dismounted, and came, hat in hand, to the coach window. The mistress of Silver Hill, a young married woman, frank and sweet, put out a hand. "Good-evening, Mr. Cleave! You are on your way to Lauderdale? My sister and Maury Stafford and I are carrying Judith off to Silver Hill for the night.—She wants to give you a message—"

She moved aside and Judith took her place—Judith in fur cap and cloak, her beautiful face just lit by the coach lamp. "It's not a message, Richard. I—I did not know that you were coming to Lauderdale to-night. Had I known it, I—Give my love, my dear love, to Cousin Margaret. I would have come to Three Oaks, only—"

"You are going home to-morrow?"

"Yes. Fauquier wishes to get back to Albemarle—"

"Will you start from Lauderdale?"

"No, from Silver Hill. He will come by for me. But had I known," said Judith clearly, "had I known that you would ride to Lauderdale to-night—"

"You would dutifully have stayed to see a cousin," thought Cleave in savage pain. He spoke quietly, in the controlled but vibrant voice he had used on the hilltop. "I am sorry that I will not see you to-night. I will ride on, however, and talk to Fauquier. You will give my love, will you not, to all my cousins at Greenwood? I do not forget how good all were to me last summer!—Good-bye, Judith."

She gave him her hand. It trembled a little in her glove. "Come again to Greenwood! Winter or summer, it will be glad to see you!—Good-bye, Richard."

Fur cap, cloak, beautiful face, drew back. "Go on, Ephraim!" said the mistress of Silver Hill.

The slow grey horses put themselves into motion, the coach passed on. Maury Stafford waited until Cleave had remounted. "It has been an exciting day!" he said. "I think that we are at the parting of the ways."[Pg 25]

"I think so. You will be at Silver Hill throughout the week?"

"No, I think that I, too, will ride toward Albemarle to-morrow. It is worth something to be with Fauquier Cary a little longer."

"That is quite true," said Cleave slowly. "I do not ride to Albemarle to-morrow, and so I will pursue my road to Lauderdale and make the most of him to-night!" He turned his horse, lifted his hat. Stafford did likewise. They parted, and Cleave presently heard the rapid hoofbeat overtake the Silver Hill coach and at once change to a slower rhythm. "Now he is speaking with her through the window!" The sound of wheel and hoof died away. Cleave shook Dundee's reins and went on toward Lauderdale. Judith Cary—Judith Cary—There are other things in life than love—other things than love—other things than love.... Judith Cary—Judith Cary....

At Three Oaks Margaret Cleave rested upon her couch by the fire. Miriam was curled on the rug with a book, an apple, and Tabitha the cat. Will mended a skate-strap and discoursed of "Old Jack." "It's a fact, ma'am! Wilson worked the problem, gave the solution, and got from Old Jack a regular withering up! They'll all tell you, ma'am, that he excels in withering up! 'You are wrong, Mr. Wilson,' says he, in that tone of his—dry as tinder, and makes you stop like a musket-shot! 'You are always wrong. Go to your seat, sir.' Well, old Wilson went, of course, and sat there so angry he was shivering. You see he was right, and he knew it. Well, the day went on about as usual. It set in to snow, and by night there was what a western man we've got calls a 'blizzard.' Barracks like an ice house, and snowing so you couldn't see across the Campus! 'T was so deadly cold and the lights so dismal that we rather looked forward to taps. Up comes an orderly. 'Mr. Wilson to the Commandant's office!'—Well, old Wilson looked startled, for he hadn't done anything; but off he marches, the rest of us predicting hanging. Well, whom d' ye reckon he found in the Commandant's office?"

"Old Jack?"

"Good marksmanship! It was Old Jack—snow all over, snow on his coat, on his big boots, on his beard, on his cap. He lives most a mile from the Institute, and the weather was bad, sure enough! Well, old Wilson didn't know what to expect—most likely hot shot, grape and canister with musketry fire thrown in—but he saluted and stood fast. 'Mr. Wilson,' says Old Jack, 'upon returning home and going over with closed eyes after supper as is my c[Pg 26]ustom the day's work, I discovered that you were right this morning and I was wrong. Your solution was correct. I felt it to be your due that I should tell you of my mistake as soon as I discovered it. I apologise for the statement that you were always wrong. You may go, sir.' Well, old Wilson never could tell what he said, but anyhow he accepted the apology, and saluted, and got out of the room somehow and back to barracks, and we breathed on the window and made a place through which we watched Old Jack over the Campus, ploughing back to Mrs. Jack through the blizzard! So you see, ma'am, things like that make us lenient to Old Jack sometimes—though he is awfully dull and has very peculiar notions."

Margaret Cleave sat up. "Is that you, Richard?" Miriam put down Tabitha and rose to her knees. "Did you see Cousin Judith? Is she as beautiful as ever?" Will hospitably gave up the big chair. "You must have galloped Dundee both ways! Did you ask about the shotgun?"

Cleave took his seat at the foot of his mother's couch. "Yes, Will, you may have it.—Fauquier sent his love to you, Mother, and to Miriam. They leave for Greenwood to-morrow."

"And Cousin Judith," persisted Miriam. "What did she have on? Did she sing to you?"

Cleave picked up her fallen book and smoothed the leaves. "She was not there. The Silver Hill people had taken her for the night. I passed them on the road.... There'll be thick ice, Will, if this weather lasts."

Later, when good-night had been said and he was alone in his bare, high-ceiled room, he looked, not at his law books nor at the poet's words, left lying on the table, but he drew a chair before the fireplace, and from its depths he raised his eyes to his grandfather's sword slung above the mantel-shelf. He sat there, long, with the sword before him; then he rose, took a book from the case, trimmed the candles, and for an hour read of the campaigns of Fabius and Hannibal.

The April sunshine, streaming in at the long windows, filled the Greenwood drawing-room with dreamy gold. It lit the ancient wall-paper where the shepherds and shepherdesses wooed between garlands of roses, and it aided the tone of time among the portraits. The boughs of peach and cherry blossoms in the old potpourri jars made it welcome, and the dark, waxed floor let it lie in faded pools. Miss Lucy Cary was glad to see it as she sat by the fire knitting fine white wool into a sacque for a baby. There was a fire of hickory, but it burned low, as though it knew the winter was over. The knitter's needles glinted in the sunshine. She was forty-eight and unmarried, and it was her delight to make beautiful, soft little sacques and shoes and coverlets for every actual or prospective baby in all the wide circle of her kindred and friends.

A tap at the door, and the old Greenwood butler entered with the mail-bag. Miss Lucy, laying down her knitting, took it from him with eager fingers. Place à la poste—in eighteen hundred and sixty-one! She untied the string, emptied letters and papers upon the table beside her, and began to sort them. Julius, a spare and venerable piece of grey-headed ebony, an autocrat of exquisite manners and great family pride, stood back a little and waited for directions.

Miss Lucy, taking up one after another the contents of the bag, made her comments half aloud. "Newspapers, newspapers! Nothing but the twelfth and Fort Sumter! The Whig.—'South Carolina is too hot-headed!—but when all's said, the North remains the aggressor.' The Examiner.—'Seward's promises are not worth the paper they are written upon.' 'Faith as to Sumter fully kept—wait and see.' That which was seen was a fleet of eleven vessels, with two hundred and eighty-five guns and twenty-four hundred men—'carrying provisions to a starving garrison!' Have done with cant, and welcome open war! The Enquirer.—'Virginia will still succeed in mediating. Virginia from her curule chair, tranquil and fast in the Union, will persuade, will reconcile these differences!' Amen to that!" said Miss Lucy, and took up another bundle. "The Staunton Gazette—The Farmer's Magazine—The Literary Messenger—My Blackwood—Julius!"

"Yaas, Miss Lucy."

"Julius, the Reverend Mr. Corbin Wood will be here for supper and to spend the night. Let Car'line know."

"Yaas, Miss Lucy. Easter's Jim hab obsarved to me dat Marse Edward am conducin' home a gent'man from Kentucky."

"Very well," said Miss Lucy, still sorting. "The Winchester Times—The Baltimore Sun.—The mint's best, Julius, in t[Pg 29]he lower bed. I walked by there this morning.—Letters for my brother! I'll readdress these, and Easter's Jim must take them to town in time for the Richmond train."

"Yaas, Miss Lucy. Easter's Jim hab imported dat Marse Berkeley Cyarter done recompense him on de road dis mahnin' ter know when Marster's comin' home."

"Just as soon," said Miss Lucy, "as the Convention brings everybody to their senses.—Three letters for Edward—one in young Beaufort Porcher's writing. Now we'll hear the Charleston version—probably he fired the first shot!—A note for me.—Julius, the Palo Alto ladies will stop by for dinner to-morrow. Tell Car'line."

"Yaas, Miss Lucy."

Miss Lucy took up a thick, bluish envelope. "From Fauquier at last—from the Red River." She opened the letter, ran rapidly over the half-dozen sheets, then laid them aside for a more leisurely perusal. "It's one of his swift, light, amusing letters! He hasn't heard about Sumter.—There'll be a message for you, Julius. There always is."

Julius's smile was as bland as sunshine. "Yaas, Miss Lucy. I 'spects dar'll be some excommunication fer me. Marse Fauquier sho' do favour Old Marster in dat.—He don' never forgit! 'Pears ter me he'd better come home—all dis heah congratulatin' backwards an' forwards wid gunpowder over de kintry! Gunpowder gwine burn ef folk git reckless!"

Miss Lucy sighed. "It will that, Julius,—it's burning now. Edward from Sally Hampton. More Charleston news!—One for Molly, three for Unity, five for Judith—"

"Miss Judith jes' sont er 'lumination by one of de chillern at de gate. She an' Marse Maury Stafford'll be back by five. Dey ain' gwine ride furder'n Monticello."

"Very well. Mr. Stafford will be here to supper, then. Hairston Breckinridge, too, I imagine. Tell Car'line."

Miss Lucy readdressed the letters for her brother, a year older than herself, and the master of Greenwood, a strong Whig influence in his section of the State, and now in Richmond, in the Convention there, speaking earnestly for amity, a better understanding between Sovereign States, and a happily restored Union. His wife, upon whom he had lavished an intense and chivalric devotion, was long dead, and for years his sister had taken t[Pg 30]he head of his table and cared like a mother for his children.

She sat now, at work, beneath the portrait of her own mother. As good as gold, as true as steel, warm-hearted and large-natured, active, capable, and of a sunny humour, she kept her place in the hearts of all who knew her. Not a great beauty as had been her mother, she was yet a handsome woman, clear brunette with bright, dark eyes and a most likable mouth. Miss Lucy never undertook to explain why she had not married, but her brothers thought they knew. She finished the letters and gave them to Julius. "Let Easter's Jim take them right away, in time for the evening train.—Have you seen Miss Unity?"

"Yaas, ma'am. Miss Unity am in de flower gyarden wid Marse Hairston Breckinridge. Dey're training roses."

"Where is Miss Molly?"

"Miss Molly am in er reverence over er big book in de library."

The youngest Miss Cary's voice floated in from the hall. "No, I'm not, Uncle Julius. Open the door wider, please!" Julius obeyed, and she entered the drawing-room with a great atlas outspread upon her arms. "Aunt Lucy, where are all these places? I can't find them. The Island and Fort Moultrie and Fort Sumter and Fort Pickens, and the rest of them! I wish when bombardments and surrenders and exciting things happen they'd happen nearer home!"

"Child, child!" cried Miss Lucy, "don't you ever say such a thing as that again! The way you young people talk is enough to bring down a judgment upon us! It's like Sir Walter crying 'Bonny bonny!' to the jagged lightnings. You are eighty years away from a great war, and you don't know what you are talking about, and may you never be any nearer!—Yes, Julius, that's all. Tell Easter's Jim to go right away.—Now, Molly, this is the island, and here is Fort Moultrie and here Fort Sumter. I used to know Charleston, when I was a girl. I can see now the Battery, and the blue sky, and the roses,—and the roses."

She took up her knitting and made a few stitches mechanically, then laid it down and applied herself to Fauquier Cary's letter. Molly, ensconced in a window, was already busy with her own. Presently she spoke. "Miriam Cleave says that Will passed his examination higher than any one."

"That is good!" said Miss Lucy. "They all have fine minds—the Cleaves. What else does she say?"[Pg 31]

"She says that Richard has given her a silk dress for her birthday, and she's going to have it made with angel sleeves, and wear a hoop with it. She's sixteen—just like me."

"Richard's a good brother."

"She says that Richard has gone to Richmond—something about arms for his Company of Volunteers. Aunt Lucy—"

"Yes, dear."

"I think that Richard loves Judith."

"Molly, Molly, stop romancing!"

"I am not romancing. I don't believe in it. That week last summer he used to watch her and Mr. Stafford—and there was a look in his eyes like the knight's in the 'Arcadia'—"

"Molly! Molly!"

"And everybody knew that Mr. Stafford was a suitor. I knew it—Easter told me. And everybody thought that Judith was going to make him happy, only she doesn't seem to have done so—at least, not yet. And there was the big tournament, and Richard and Dundee took all the rings, though I know that Mr. Stafford had expected to, and Judith let Richard crown her queen, but she looked just as pale and still! and Richard had a line between his brows, and I think he thought she would rather have had the Maid of Honour's crown that Mr. Stafford won and gave to just a little girl—"

"Molly, I am going to lock up every poetry book in the house—"

"And that was one day, and the next morning Richard looked stern and fine, and rode away. He isn't really handsome—not like Edward, that is—only he has a way of looking so. And Judith—"

"Molly, you're uncanny—"

"I'm not uncanny. I can't help seeing. And the night after the tournament I slept in Judith's room, and I woke up three times, and each time there was Judith still sitting in the window, in the moonlight, and the roses Richard had crowned her with beside her in grandmother's Lowestoft bowl. And each time I asked her, 'Why don't you come to bed, Judith?' and each time she said, 'I'm not sleepy.' Then in the morning Richard rode away, and the next day was Sunday, and Judith went to church both morning and evening, and that night she took so long to say her prayers she must have been praying for the whole world—"[Pg 32]

Miss Lucy rose with energy. "Stop, Molly! I shouldn't have let you ever begin. It's not kind to watch people like that."

"I wasn't watching Judith," said Molly. "I'd scorn to do such a thing! I was just seeing. And I never said a word about her and Richard until this instant when the sunshine came in somehow and started it. And I don't know that she likes Richard any more. I think she's trying hard to like Mr. Stafford—he wants her to so much!"

"Stop talking, honey, and don't have so many fancies, and don't read so much poetry!—Who is it coming up the drive?"

"It's Mr. Wood on his old grey horse—like a nice, quiet knight out of the 'Faery Queen.' Didn't you ever notice, Aunt Lucy, how everybody really belongs in a book?"

On the old, broad, pillared porch the two found the second Miss Cary and young Hairston Breckinridge. Apparently in training the roses they had discovered a thorn. They sat in silence—at opposite sides of the steps—nursing the recollection. Breckinridge regarded the toe of his boot, Unity the distant Blue Ridge, until, Mr. Corbin Wood and his grey horse coming into view between the oaks, they regarded him.

"The air," said Miss Lucy, from the doorway, "is turning cold. What did you fall out about?"

"South Carolina," answered Unity, with serenity. "It's not unlikely that our grandchildren will be falling out about South Carolina. Mr. Breckinridge is a Democrat and a fire-eater. Anyhow, Virginia is not going to secede just because he wants her to!"

The angry young disciple of Calhoun opposite was moved to reply, but at that moment Mr. Corbin Wood arriving before the steps, he must perforce run down to greet him and help him dismount. A negro had hardly taken the grey, and Mr. Wood was yet speaking to the ladies upon the porch, when two other horsemen appeared, mounted on much more fiery steeds, and coming at a gait that approached the ancient "planter's pace." "Edward and Hilary Preston," said Miss Lucy, "and away down the road, I see Judith and Mr. Stafford."

The two in advance riding up the drive beneath the mighty oaks and dismounting, the gravel space before the white-pillared porch became a scene of animation, with beautiful, spirited horses, leaping dogs, negro servants, and gay horsemen. Edward Cary sprang up[Pg 33] the steps. "Aunt Lucy, you remember Hilary Preston!—and this is my sister Unity, Preston,—the Quakeress we call her! and this is Molly, the little one!—Mr. Wood, I am very glad to see you, sir! Aunt Lucy! Virginia Page, the two Masons, and Nancy Carter are coming over after supper with Cousin William, and I fancy that Peyton and Dabney and Rives and Lee will arrive about the same time. We might have a little dance, eh? Here's Stafford with Judith, now!"

In the Greenwood drawing-room, after candle-light, they had the little dance. Negro fiddlers, two of them, born musicians, came from the quarter. They were dressed in an elaborate best, they were as suavely happy as tropical children, and beamingly eager for the credit in the dance, as in all things else, of "de fambly." Down came the bow upon the strings, out upon the April night floated "Money Musk!" All the furniture was pushed aside, the polished floor gave back the lights. From the walls men and women of the past smiled upon a stage they no longer trod, and between garlands of roses the shepherds and shepherdesses pursued their long, long courtship. The night was mild, the windows partly open, the young girls dancing in gowns of summery stuff. Their very wide skirts were printed over with pale flowers, their bodices were cut low, with a fall of lace against the white bosom. The hair was worn smooth and drawn over the ear, with on either side a bright cluster of blossoms. The fiddlers played "Malbrook s'en va-t-en guerre." Laughter, quick and gay, or low and ripplingly sweet, flowed through the old room. The dances were all square, for there existed in the country a prejudice against round dancing. Once Edward Cary pushed a friend down on the piano stool, and whirled with Nancy Carter into the middle of the room in a waltz. But Miss Lucy shook her head at her nephew, and Cousin William gazed sternly at Nancy, and the fiddlers looked scandalized. Scipio, the old, old one, who could remember the Lafayette ball, held his bow awfully poised.

Judith Cary, dressed in a soft, strange, dull blue, and wearing a little crown of rosy flowers, danced along like the lady of Saint Agnes Eve. Maury Stafford marked how absent was her gaze, and he hoped that she was dreaming of their ride that afternoon, of the clear green woods and the dogwood stars, and of some words that he had said. In these days he was hoping against hope. Well off and well-bred, good to look at, pleasant of speech, at times indolent,[Pg 34] at times ardent, a little silent on the whole, and never failing to match the occasion with just the right shade of intelligence, a certain grip and essence in this man made itself felt like the firm bed of a river beneath the flowing water. He was not of Albemarle; he was of a tide-water county, but he came to Albemarle and stayed with kindred, and no one doubted that he strove for an Albemarle bride. It was the opinion of the county people that he would win her. It was hard to see why he should not. He was desperately in love, and far too determined to take the first "No" for an answer. Until the last eight months it had been his own conclusion that he would win.

The old clock in the hall struck ten; in an interval between the dances Judith slipped away. Stafford wished to follow her, but Cousin William held him like the Ancient Mariner and talked of the long past on the Eastern Shore. Judith, entering the library, came upon the Reverend Mr. Corbin Wood, deep in a great chair and a calf-bound volume. "Come in, come in, Judith my dear, and tell me about the dance."

"It is a pretty dance," said Judith. "Do you think it would be very wrong of you to watch it?"

Mr. Wood, the long thin fingers of one hand lightly touching the long thin fingers of the other hand, considered the matter. "Why, no," he said in a mellow and genial voice. "Why, no—it is always hard for me to think that anything beautiful is wrong. It is this way. I go into the drawing-room and watch you. It is, as you say, a very pretty sight! But if I find it so and still keep a long face, I am to myself something of a hypocrite. And if I testify my delight, if I am absorbed in your evolutions, and think only of springtime and growing things, and show my thought, then to every one of you, and indeed to myself too, my dear, I am something out of my character! So it seems better to sit here and read Jeremy Taylor."

"You have the book upside down," said Judith softly. Her old friend put on his glasses, gravely looked, and reversed the volume. He laughed, and then he sighed. "I was thinking of the country, Judith. It's the only book that is interesting now—and the recital's tragic, my dear; the recital's tragic!"

From the hall came Edward Cary's voice, "Judith, Judith, we want you for the reel!"[Pg 35]

In the drawing-room the music quickened. Scipio played with all his soul, his eyes uprolled, his lips parted, his woolly head nodding, his vast foot beating time; young Eli, black and shining, seconded him ably; without the doors and windows gathered the house servants, absorbed, admiring, laughing without noise. The April wind, fragrant of greening forests, ploughed land, and fruit trees, blew in and out the long, thin curtains. Faster went the bow upon the fiddle, the room became more brilliant and more dreamy. The flowers in the old, old blue jars grew pinker, mistier, the lights had halos, the portraits smiled forthright; but from greater distances, the loud ticking of the clock without the door changed to a great rhythm, as though Time were using a violin string. The laughter swelled, waves of brightness went through the ancient room. They danced the "Virginia Reel."

Miss Lucy, sitting beside Cousin William on the sofa, raised her head. "Horses are coming up the drive!"

"That's not unusual," said Cousin William, with a smile. "Why do you look so startled?"