Miss Clara H. Barton.

Engd. by John Sartain.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Woman's Work in the Civil War, by

Linus Pierpont Brockett and Mary C. Vaughan

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Woman's Work in the Civil War

A Record of Heroism, Patriotism, and Patience

Author: Linus Pierpont Brockett

Mary C. Vaughan

Commentator: Henry W. Bellows

Release Date: June 18, 2007 [EBook #21853]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WOMAN'S WORK IN THE CIVIL WAR ***

Produced by Robert Cicconetti, Cally Soukup and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was made using scans of public domain works from the

University of Michigan Digital Libraries.)

Transcriber's Note:

Illustrations originally printed in the middle of sentences have been moved to the nearest paragraph break.

Because sections of this book were written by different people, accent, spelling and hyphen usage is inconsistent. These inconsistencies have been preserved except where noted.

For a complete list, please see the end of this document.

WOMAN'S WORK IN THE CIVIL WAR

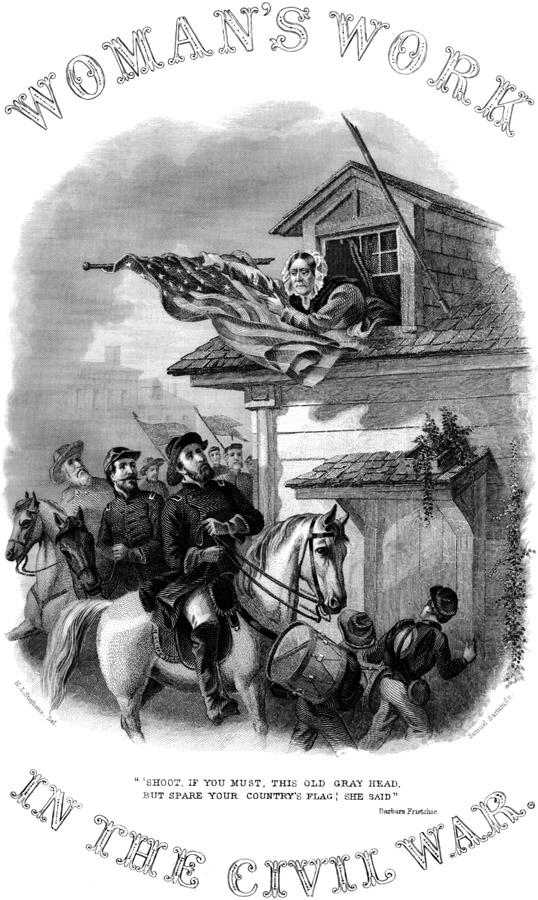

"'SHOOT, IF YOU MUST, THIS OLD GRAY HEAD.

BUT SPARE YOUR COUNTRY'S FLAG,' SHE SAID."

Barbara Frietchie.

H. L. Stephens, Del. Samuel Sartain, Sc.

The preparation of this work, or rather the collection of material for it, was commenced in the autumn of 1863. While engaged in the compilation of a little book on "The Philanthropic Results of the War" for circulation abroad, in the summer of that year, the writer became so deeply impressed with the extraordinary sacrifices and devotion of loyal women, in the national cause, that he determined to make a record of them for the honor of his country. A voluminous correspondence then commenced and continued to the present time, soon demonstrated how general were the acts of patriotic devotion, and an extensive tour, undertaken the following summer, to obtain by personal observation and intercourse with these heroic women, a more clear and comprehensive idea of what they had done and were doing, only served to increase his admiration for their zeal, patience, and self-denying effort.

Meantime the war still continued, and the collisions between Grant and Lee, in the East, and Sherman and Johnston, in the South, the fierce campaign between Thomas and Hood in Tennessee, Sheridan's annihilating defeats of Early in the valley of the Shenandoah, and Wilson's magnificent expedition in Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia, as well as the mixed naval and military victories at Mobile and Wilmington, were fruitful in wounds, sickness, and death. Never had the gentle and patient ministrations of woman been so needful as in the last year of the war; and never had they been so abundantly bestowed, and with such zeal and self-forgetfulness.

From Andersonville, and Millen, from Charleston, and Florence, from Salisbury, and Wilmington, from Belle Isle, and Libby Prison, came also, in these later months of the war, thousands of our bravest and noblest heroes, captured by the rebels, the feeble remnant of the tens of thousands imprisoned there, a majority of whom had perished of cold, nakedness, starvation, and disease, in those charnel houses, victims of the fiendish malignity of the rebel leaders. These poor fellows, starved to the last degree of emaciation, crippled and dying from frost and gangrene, many of[22] them idiotic from their sufferings, or with the fierce fever of typhus, more deadly than sword or minié bullet, raging in their veins, were brought to Annapolis and to Wilmington, and unmindful of the deadly infection, gentle and tender women ministered to them as faithfully and lovingly, as if they were their own brothers. Ever and anon, in these works of mercy, one of these fair ministrants died a martyr to her faithfulness, asking, often only, to be buried beside her "boys," but the work never ceased while there was a soldier to be nursed. Nor were these the only fields in which noble service was rendered to humanity by the women of our time. In the larger associations of our cities, day after day, and year after year, women served in summer's heat and winter's cold, at their desks, corresponding with auxiliary aid societies, taking account of goods received for sanitary supplies, re-packing and shipping them to the points where they were needed, inditing and sending out circulars appealing for aid, in work more prosaic but equally needful and patriotic with that performed in the hospitals; and throughout every village and hamlet in the country, women were toiling, contriving, submitting to privation, performing unusual and severe labors, all for the soldiers. In the general hospitals of the cities and larger towns, the labors of the special diet kitchen, and of the hospital nurse were performed steadily, faithfully, and uncomplainingly, though there also, ever and anon, some fair toiler laid down her life in the service. There were many too in still other fields of labor, who showed their love for their country; the faithful women who, in the Philadelphia Refreshment Saloons, fed the hungry soldier on his way to or from the battle-field, till in the aggregate, they had dispensed nearly eight hundred thousand meals, and had cared for thousands of sick and wounded; the matrons of the Soldiers' Homes, Lodges, and Rests; the heroic souls who devoted themselves to the noble work of raising a nation of bondmen to intelligence and freedom; those who attempted the still more hopeless task of rousing the blunted intellect and cultivating the moral nature of the degraded and abject poor whites; and those who in circumstances of the greatest peril, manifested their fearless and undying attachment to their country and its flag; all these were entitled to a place in such a record. What wonder, then, that, pursuing his self-appointed task assiduously, the writer found it growing upon him; till the question came, not, who should be inscribed in this roll, but who could be omitted, since it was evident no single volume could do justice to all.

In the autumn of 1865, Mrs. Mary C. Vaughan, a skilful and practiced writer, whose tastes and sympathies led her to take an interest in the work, became associated with the writer in its preparation, and to her zeal in collecting,[23] and skill in arranging the materials obtained, many of the interesting sketches of the volume are due. We have in the prosecution of our work been constantly embarrassed, by the reluctance of some who deserved a prominent place, to suffer anything to be communicated concerning their labors; by the promises, often repeated but never fulfilled, of others to furnish facts and incidents which they alone could supply, and by the forwardness of a few, whose services were of the least moment, in presenting their claims.

We have endeavored to exercise a wise and careful discrimination both in avoiding the introduction of any name unworthy of a place in such a record, and in giving the due meed of honor to those who have wrought most earnestly and acceptably. We cannot hope that we have been completely successful; the letters even now, daily received, render it probable that there are some, as faithful and self-sacrificing as any of those whose services we have recorded, of whom we have failed to obtain information; and that some of those who entered upon their work of mercy in the closing campaigns of the war, by their zeal and earnestness, have won the right to a place. We have not, knowingly, however, omitted the name of any faithful worker, of whom we could obtain information, and we feel assured that our record is far more full and complete, than any other which has been, or is likely to be prepared, and that the number of prominent and active laborers in the national cause who have escaped our notice is comparatively small.

We take pleasure in acknowledging our obligations to Rev. Dr. Bellows, President of the United States Sanitary Commission, for many services and much valuable information; to Honorable James E. Yeatman, the President of the Western Sanitary Commission, to Rev. J. G. Forman, late Secretary of that Commission, and now Secretary of the Unitarian Association, and his accomplished wife, both of whom were indefatigable in their efforts to obtain facts relative to western ladies; to Rev. N. M. Mann, now of Kenosha, Wisconsin, but formerly Chaplain and Agent of the Western Sanitary Commission, at Vicksburg; to Professor J. S. Newberry, now of Columbia College, but through the war the able Secretary of the Western Department of the United States Sanitary Commission; to Mrs. M. A. Livermore, of Chicago, one of the managers of the Northwestern Sanitary Commission; to Rev. G. S. F. Savage, Secretary of the Western Department of the American Tract Society, Boston; Rev. William De Loss Love, of Milwaukee, author of a work on "Wisconsin in the War," Samuel B. Fales, Esq., of Philadelphia, so long and nobly identified with the Volunteer Refreshment Saloon, Dr. A. N. Read, of Norwalk, Ohio,[24] late one of the Medical Inspectors of the Sanitary Commission, Dr. Joseph Parrish, of Philadelphia, also a Medical Inspector of the Commission, Mrs. M. M. Husband, of Philadelphia, one of the most faithful workers in field hospitals during the war, Miss Katherine P. Wormeley, of Newport, Rhode Island, the accomplished historian of the Sanitary Commission, Mrs. W. H. Holstein, of Bridgeport, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, Miss Maria M. C. Hall, of Washington, District of Columbia, and Miss Louise Titcomb, of Portland, Maine. From many of these we have received information indispensable to the completeness and success of our work; information too, often afforded at great inconvenience and labor. We commit our book, then, to the loyal women of our country, as an earnest and conscientious effort to portray some phases of a heroism which will make American women famous in all the future ages of history; and with the full conviction that thousands more only lacked the opportunity, not the will or endurance, to do, in the same spirit of self-sacrifice, what these have done.

L. P. B.

Brooklyn, N. Y., February, 1867.

| Page | |

| DEDICATION. | 19 |

| PREFACE. | 21 |

| TABLE OF CONTENTS. | 25-51 |

| INTRODUCTION BY HENRY W. BELLOWS, D. D. | 55 |

| INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER. | |

| Patriotism in some form, an attribute of woman in all nations and climes—Its modes of manifestation—Pæans for victory—Lamentations for the death of a heroic leader—Personal leadership by women—The assassination of tyrants—The care of the sick and wounded of national armies—The hospitals established by the Empress Helena—The Beguines and their successors—The cantiniéres, vivandiéres, etc.—Other modes in which women manifested their patriotism—Florence Nightingale and her labors—The results—The awakening of patriotic zeal among American women at the opening of the war—The organization of philanthropic effort—Hospital nurses—Miss Dix's rejection of great numbers of applicants on account of youth—Hired nurses—Their services generally prompted by patriotism rather than pay—The State relief agents (ladies) at Washington—The hospital transport system of the Sanitary Commission—Mrs. Harris's, Miss Barton's, Mrs. Fales', Miss Gilson's, and other ladles' services at the front during the battles of 1862—Services of other ladies at Chancellorsville, at Gettysburg—The Field Relief of the Sanitary Commission, and services of ladies in the later battles—Voluntary services of women in the armies in the field at the West—Services in the hospitals of garrisons and fortified towns—Soldiers' homes and lodges, and their matrons—Homes for Refugees—Instruction of the Freedmen—Refreshment Saloons at Philadelphia—Regular visiting of hospitals in the large cities—The Soldiers' Aid Societies, and their mode of operation—The extraordinary labors of the managers of the Branch Societies—Government clothing contracts—Mrs. Springer, Miss Wormeley and Miss Gilson—The managers of the local Soldiers' Aid Societies—The sacrifices made by the poor to contribute supplies—Examples—The labors of the young and the old—Inscriptions on articles—The poor seamstress—Five hundred bushels of wheat—The five dollar gold piece—The army of martyrs—The effect of this female patriotism in stimulating the courage of the soldiers—Lack of persistence in this work among the Women of the South—Present and future—Effect of patriotism and self-sacrifice in elevating and ennobling the female character. | 65-94 |

| PART I. SUPERINTENDENT OF NURSES. | |

| MISS DOROTHEA L. DIX. | |

| Early history—Becomes interested in the condition of prison convicts—Visit to Europe—Returns in 1837, and devotes herself to improving the condition of paupers, lunatics and prisoners—Her efforts for the establishment of Insane Asylums—Second visit to Europe—Her first work in the war the nursing of Massachusetts soldiers in Baltimore—Appointment[26] as superintendent of nurses—Her selections—Difficulties in her position—Her other duties—Mrs. Livermore's account of her labors—The adjutant-general's order—Dr. Bellows' estimate of her work—Her kindness to her nurses—Her publications—Her manners and address—Labors for the insane poor since the war. | 97-108 |

| PART II. LADIES WHO MINISTERED TO THE SICK AND WOUNDED IN CAMP, FIELD, AND GENERAL HOSPITALS. | |

| CLARA HARLOWE BARTON. | |

| Early life—Teaching—The Bordentown school—Obtains a situation in the Patent Office—Her readiness to help others—Her native genius for nursing—Removed from office in 1857—Return to Washington in 1861—Nursing and providing for Massachusetts soldiers at the Capitol in April, 1861—Hospital and sanitary work in 1861—Death of her father—Washington hospitals again—Going to the front—Cedar Mountain—The second Bull Run battle—Chantilly—Heroic labors at Antietam—Soft bread—Three barrels of flour and a bag of salt—Thirty lanterns for that night of gloom—The race for Fredericksburg—Miss Barton as a general purveyor for the sick and wounded—The battle of Fredericksburg—Under fire—The rebel officer's appeal—The "confiscated" carpet—After the battle—In the department of the South—The sands of Morris Island—The horrors of the siege of Forts Wagner and Sumter—The reason why she went thither—Return to the North—Preparations for the great campaign—Her labors at Belle Plain, Fredericksburg, White House, and City Point—Return to Washington—Appointed "General correspondent for the friends of paroled prisoners"—Her residence at Annapolis—Obstacles—The Annapolis plan abandoned—She establishes at Washington a "Bureau of records of missing men in the armies of the United States"—The plan of operations of this Bureau—Her visit to Andersonville—The case of Dorrance Atwater—The Bureau of missing men an institution indispensable to the Government and to friends of the soldiers—Her sacrifices in maintaining it—The grant from Congress—Personal appearance of Miss Barton. | 111-132 |

| HELEN LOUISE GILSON. | |

| Early history—Her first work for the soldiers—Collecting supplies—The clothing contract—Providing for soldiers' wives and daughters—Application to Miss Dix for an appointment as nurse—She is rejected as too young—Associated with Hon. Frank B. Fay in the Auxiliary Relief Service—Her labors on the Hospital Transports—Her manner of working—Her extraordinary personal influence—Her work at Gettysburg—Influence over the men—Carrying a sick comrade to the hospital—Her system and self-possession—Pleading the cause of the soldier with the people—Her services in Grant's protracted campaign—The hospitals at Fredericksburg—Singing to the soldiers—Her visit to the barge of "contrabands"—Her address to the negroes—Singing to them—The hospital for colored soldiers—Miss Gilson re-organizes and re-models it, making it the best hospital at City Point—Her labors for the spiritual good of the men in her hospital—Her care for the negro washerwomen and their families—Completion of her work—Personal appearance of Miss Gilson. | 133-148 |

| MRS. JOHN HARRIS.[27] | |

| Previous history—Secretary Ladies' Aid Society—Her decision to go to the "front"—Early experiences—On the Hospital Transports—Harrison's Landing—Her garments soaked in human gore—Antietam—French's Division Hospital—Smoketown General Hospital—Return to the "front"—Fredericksburg—Falmouth—She almost despairs of the success of our arms—Chancellorsville—Gettysburg—Following the troops—Warrenton—Insolence of the rebels—Illness—Goes to the West—Chattanooga—Serious illness—Return to Nashville—Labors for the refugees—Called home to watch over a dying mother—The returned prisoners from Andersonville and Salisbury | 149-160 |

| MRS. ELIZA C. PORTER. | |

| Mrs. Porter's social position—Her patriotism—Labors in the hospitals at Cairo—She takes charge of the Northwestern Sanitary Commission Rooms at Chicago—Her determination to go, with a corps of nurses, to the front—Cairo and Paducah—Visit to Pittsburg Landing after the battle—She brings nurses and supplies for the hospitals from Chicago—At Corinth—At Memphis—Work among the freedmen at Memphis and elsewhere—Efforts for the establishment of hospitals for the sick and wounded in the Northwest—Co-operation with Mrs. Harvey and Mrs. Howe—The Harvey Hospital—At Natchez and Vicksburg—Other appeals for Northern hospitals—At Huntsville with Mrs. Bickerdyke—At Chattanooga—Experiences in a field hospital in the woods—Following Sherman's army from Chattanooga to Atlanta—"This seems like having mother about"—Constant labors—The distribution of supplies to the soldiers of Sherman's army near Washington—A patriotic family. | 161-171 |

| MRS. MARY A. BICKERDYKE. | |

| Previous history of Mrs. Bickerdyke—Her regard for the private soldiers—"Mother Bickerdyke and her boys"—Her work at Savannah after the battle of Shiloh—What she accomplished at Perryville—The Gayoso Hospital at Memphis—Colored nurses and attendants—A model hospital—The delinquent assistant-surgeon—Mrs. Bickerdyke's philippic—She procures his dismissal—His interview with General Sherman—"She ranks me"—The commanding generals appreciate her—Convalescent soldiers vs. colored nurses—The Medical Director's order—Mrs. Bickerdyke's triumph—A dairy and hennery for the hospitals—Two hundred cows and a thousand hens—Her first visit to the Milwaukee Chamber of Commerce—"Go over to Canada—This country has no place for such creatures"—At Vicksburg—In field hospitals—The dresses riddled with sparks—The box of clothing for herself—Trading for butter and eggs for the soldiers—The two lace-trimmed night-dresses—A new style of hospital clothing for wounded soldiers—A second visit to Milwaukee—Mrs. Bickerdyke's speech—"Set your standard higher yet"—In the Huntsville Hospital—At Chattanooga at the close of the battle—The only woman on the ground for four weeks—Cooking under difficulties—Her interview with General Grant—Complaints of the neglect of the men by some of the surgeons—"Go around to the hospitals and see for yourself"—Visits Huntsville, Pulaski, etc.—With Sherman from Chattanooga to Atlanta—Making dishes for the sick out of hard tack and the ordinary rations—At Nashville and Franklin—Through the Carolinas with Sherman—Distribution of supplies near Washington—"The Freedmen's Home and Refuge" at Chicago. | 172-186 |

| MARGARET ELIZABETH BRECKINRIDGE. By Mrs. J. G. Forman.[28] | |

| Sketch of her personal appearance—Her gentle, tender, winning ways—The American Florence Nightingale—What if I do die?—The Breckinridge family—Margaret's childhood and youth—Her emancipation of her slaves—Working for the soldiers early in the war—Not one of the Home Guards—Her earnest desire to labor in the hospitals—Hospital service at Baltimore—At Lexington, Kentucky—Morgan's first raid—Her visit to the wounded soldiers—"Every one of you bring a regiment with you"—Visiting the St. Louis hospitals—On the hospital boats on the Mississippi—Perils of the voyage—Severe and incessant labor—The contrabands at Helena—Touching incidents of the wounded on the hospital boats—"The service pays"—In the hospitals at St. Louis—Impaired health—She goes eastward for rest and recovery—A year of weakness and weariness—In the hospital at Philadelphia—A ministering angel—Colonel Porter her brother-in-law killed at Cold Harbor—She goes to Baltimore to meet the body—Is seized with typhoid fever and dies after five weeks illness. | 187-199 |

| MRS. STEPHEN BARKER. | |

| Family of Mrs. Barker—Her husband Chaplain of First Massachusetts Heavy Artillery—She accompanies him to Washington—Devotes herself to the work of visiting the hospitals—Thanksgiving dinner in the hospital—She removes to Fort Albany and takes charge as Matron of the Regimental Hospital—Pleasant experiences—Reading to the soldiers—Two years of labor—Return to Washington in January, 1864—She becomes one of the hospital visitors of the Sanitary Commission—Ten hospitals a week—Remitting the soldiers' money and valuables to their families—The service of Mr. and Mrs. Barker as lecturers and missionaries of the Sanitary Commission to the Aid Societies in the smaller cities and villages—The distribution of supplies to the disbanding armies—Her report. | 200-211 |

| AMY M. BRADLEY. | |

| Childhood of Miss Bradley—Her experiences as a teacher—Residence in Charleston, South Carolina—Two years of illness—Goes to Costa Rica—Three years of teaching in Central America—Return to the United States—Becomes corresponding clerk and translator in a large glass manufactory—Beginning of the war—She determines to go as a nurse—Writes to Dr. Palmer—His quaint reply—Her first experience as nurse in a regimental hospital—Skill and tact in managing it—Promoted by General Slocum to the charge of the Brigade Hospital—Hospital Transport Service—Over-exertion and need of rest—The organization of the Soldiers' Home at Washington—Visiting hospitals at her leisure—Camp Misery—Wretched condition of the men—The rendezvous of distribution—Miss Bradley goes thither as Sanitary Commission Agent—Her zealous and multifarious labors—Bringing in the discharged men for their papers—Procuring the correction of their papers, and the reinstatement of the men—"The Soldiers' Journal"—Miss Bradley's object in its establishment—Its success—Presents to Miss Bradley—Personal appearance. | 212-224 |

| MRS. ARABELLA GRIFFITH BARLOW. | |

| Birth and education of Mrs. Griffith—Her marriage at the beginning of the war—She accompanies her husband to the camp, and wherever it is possible ministers to the wounded or sick soldiers—Joins the Sanitary Commission in July, 1862, and labors among the sick and wounded at Harrison's Landing till late in August—Colonel Barlow severely wounded at Antietam—Mrs. Barlow nurses him with great tenderness, and at the same time ministers to the wounded of Sedgwick Hospital—At[29] Chancellorsville and Gettysburg—General Barlow again wounded, and in the enemy's lines—She removes him and succors the wounded in the intervals of her care of him—In May, 1864, she was actively engaged at Belle Plain, Fredericksburg, Port Royal, White House, and City Point—Her incessant labor brought on fever and caused her death July 27, 1864—Tribute of the Sanitary Commission Bulletin, Dr. Lieber and others, to her memory. | 225-233 |

| MRS. NELLIE MARIA TAYLOR. | |

| Parentage and early history—Removal to New Orleans—Her son urged to enlist in the rebel army—He is sent North—The rebels persecute Mrs. Taylor—Her dismissal from her position as principal of one of the city schools—Her house mobbed—"I am for the Union, tear my house down if you choose!"—Her house searched seven times for the flag—The Judge's son—"A piece of Southern chivalry"—Her son enlists in the rebel army to save her from molestation—New Orleans occupied by the Union forces—Mrs. Taylor reinstated as teacher—She nurses the soldiers in the hospitals, during her vacations and in all the leisure hours from her school duties, her daughter filling up the intermediate time with her services—She expends her entire salary upon the sick and wounded—Writes eleven hundred and seventy-four letters for them in one year—Distributes the supplies received from the Cincinnati Branch of Sanitary Commission in 1864, and during the summer takes the management of the special diet of the University Hospital—Testimony of the soldiers to her labors—Patriotism and zeal of her children—Terms on which Miss Alice Taylor would present a confederate flag to a company. | 234-240 |

| MRS. ADALINE TYLER. | |

| Residence in Boston—Removal to Baltimore—Becomes Superintendent of a Protestant Sisterhood in that city—Duties of the Sisterhood—The "Church Home"—Other duties of "Sister" Tyler—The opening of the war—The Baltimore mob—Wounding and killing members of the Sixth Massachusetts regiment—Mrs. Tyler hears that Massachusetts men are wounded and seeks admission to them—Is refused—She persists, and threatening an appeal to Governor Andrew is finally admitted—She takes those most severely wounded to the "Church Home," procures surgical attendance for them, and nurses them till their recovery—Other Union wounded nursed by her—Receives the thanks of the Massachusetts Legislature and Governor—Is appointed Superintendent of the Camden Street Hospital, Baltimore—Resigns at the end of a year, and visits New York—The surgeon-general urges her to take charge of the large hospital at Chester, Pennsylvania—She remains at Chester till the hospital is broken up, when she is transferred to the First Division General Hospital, Naval Academy, Annapolis—The returned prisoners—Their terrible condition—Mrs. Tyler procures photographs of them—Impaired health—Resignation—She visits Europe, and spends eighteen months there, advocating as she has opportunity the National cause—The fiendish rebel spirit—Incident relative to President Lincoln's assassination. | 241-250 |

| MRS. WILLIAM H. HOLSTEIN. | |

| Social position of Mr. and Mrs. Holstein—Early labors for the soldiers at home—The battle of Antietam—She goes with her husband to care for the wounded—Her first emotions at the sight of the wounded—Three years' devotion to the service—Mr. and Mrs. Holstein devote themselves mainly to field hospitals—Labors at Fredericksburg, in the Second Corps Hospital—Services after the battle of Chancellorsville—The march toward Pennsylvania in June, 1863—The Field Hospital of the Second[30] Corps after Gettysburg—Incidents—"Wouldn't be buried by the side of that raw recruit"—Mrs. Holstein Matron of the Second Corps Hospital—Tour among the Aid Societies—The campaign of 1864-5—Constant labors in the field hospitals at Fredericksburg, City Point, and elsewhere, till November—Another tour among the Aid Societies—Labors among the returned prisoners at Annapolis. | 251-259 |

| MRS. CORDELIA A. P. HARVEY. By Rev. N. M. Mann. | |

| The death of her husband, Governor Louis P. Harvey—Her intense grief—She resolves to devote herself to the care of the sick and wounded soldiers—She visits St. Louis as Agent for the State of Wisconsin—Work in the St. Louis hospitals in the autumn of 1862—Heroic labors at Cape Girardeau—Visiting hospitals along the Mississippi—The soldiers' ideas of her influence and power—Young's Point in 1863—Illness of Mrs. Harvey—She determines to secure the establishment of a General Hospital at Madison, Wisconsin, where from the fine climate the chances of recovery of the sick and wounded will be increased—Her resolution and energy—The Harvey Hospital—The removal of the patients at Fort Pickering to it—Repeated journeys down the Mississippi—Presented with an elegant watch by the Second Wisconsin Cavalry—Her influence over the soldiers—The Soldiers' Orphan Asylum at Madison. | 260-268 |

| MRS. SARAH R. JOHNSTON. | |

| Loyal Southern women—Mrs. Johnston's birth and social position—Her interest in the Union prisoners—"A Yankee sympathizer"—The young soldier—Her tender care of him, living and dead—Work for the prisoners—Her persecution by the rebels—"Why don't you pin me to the earth as you threatened"—"Sergeant, you can't make anything on that woman"—Copying the inscriptions on Union graves, and statistics of Union prisoners—Her visit to the North. | 269-272 |

| EMILY E. PARSONS. By Rev. J. G. Forman. | |

| Her birth and education—Her preparation for service in the hospitals—Receives instruction in the care of the sick, dressing wounds, preparation of diet, etc.—Service at Fort Schuyler Hospital—Mrs. General Fremont secures her services for St. Louis—Condition of St. Louis and the other river cities at this time—First assigned to the Lawson Hospital—Next to Hospital steamer "City of Alton"—The voyage from Vicksburg to Memphis—Return to St. Louis—Illness—Appointed Superintendent of Nurses to the large Benton Barracks Hospital—Her duties—The admirable management of the hospital—Visit to the East—Return to her work—Illness and return to the East—Collects and forwards supplies to Western Sanitary Commission and Northwestern Sanitary Commission—The Chicago Fair—The Charity Hospital at Cambridge established by her—Her cheerfulness and skill in her hospital work. | 273-278 |

| MRS. ALMIRA FALES. | |

| The first woman to work for the soldiers—She commenced in December, 1860—Her continuous service—Amount of stores distributed by her—Variety and severity of her work—Hospital Transport Service—Harrison's Landing—Her work in Pope's campaign—Death of her son—Her sorrowful toil at Fredericksburg and Falmouth—Her peculiarities and humor. | 279-283 |

| CORNELIA HANCOCK.[31] | |

| Early labors for the soldiers—Mr. Vassar's testimony—Gettysburg—The campaign of 1864—Fredericksburg and City Point. | 284-286 |

| MRS. MARY MORRIS HUSBAND. | |

| Her ancestry—Patriotic instincts of the family—Service in Philadelphia hospitals—Harrison's Landing—Nursing a sick son—Ministers to others there—Dr. Markland's testimony—At Camden Street Hospital, Baltimore—Antietam—Smoketown Hospital—Associated with Miss M. M. C. Hall—Her admirable services as nurse there—Her personal appearance—The wonderful apron with its pockets—The battle-flag—Her heroism in contagious disease—Attachment of the soldiers for her—Her energy and activity—Her adventures after the battle of Chancellorsville—The Field Hospital near United States Ford—The forgetful surgeon—Matron of Third Division, Third Corps Hospital, Gettysburg—Camp Letterman—Illness of Mrs. Husband—Stationed at Camp Parole, Annapolis—Hospital at Brandy Station—The battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania—Overwhelming labor at Fredericksburg, Port Royal, White House, and City Point—Second Corps Hospital at City Point—Marching through Richmond—"Hurrah for mother Husband"—The visit to her "boys" at Bailey's Cross Roads—Distribution of supplies—Mrs. Husband's labors for the pardon or commutation of the sentence of soldiers condemned by court-martial—Her museum and its treasures. | 287-298 |

| THE HOSPITAL TRANSPORT SERVICE. | |

| The organization of this service by the United States Sanitary Commission—Difficulties encountered—Steamers and sailing vessels employed—The corps of ladies employed in the service—The headquarters' staff—Ladies plying on the Transports to Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, and elsewhere—Work on the Daniel Webster—The Ocean Queen—Difficulties in providing as rapidly as was desired for the numerous patients—Duties of the ladies who belonged to the headquarters' staff—Description of scenes in the work by Miss Wormeley and Miss G. Woolsey—Taking on patients—"Butter on soft bread"—"Guess I can stand h'isting better'n him"—"Spare the darning needles"—"Slippers only fit for pontoon bridges"—Visiting Government Transports—Scrambling eggs in a wash-basin—Subduing the captain of a tug—The battle of Fair Oaks—Bad management on Government Transports—Sufferings of the wounded—Sanitary Commission relief tent at the wharf—Relief tents at White House depot at Savage's Station—The departure from White House—Arrival at Harrison's Landing—Running past the rebel batteries at City Point—"I'll take those mattresses you spoke of"—The wounded of the seven days' battles—"You are so kind, I—am so weak"—Exchanging prisoners under flag of truce. | 299-315 |

| OTHER LABORS OF SOME OF THE MEMBERS OF THE HOSPITAL TRANSPORT CORPS. | |

| Miss Bradley, Miss Gilson, Mrs. Husband, Miss Charlotte Bradford, Mrs. W. P. Griffin, Miss H. D. Whetten. | 316, 317 |

| KATHERINE PRESCOTT WORMELEY. | |

| Birth and parentage—Commencement of her labors for the soldiers—The Woman's Union Aid Society of Newport—She takes a contract for army clothing to furnish employment for soldiers' families—Forwarding[32] sanitary goods—The hundred and fifty bed sacks—Miss Wormeley's connection with the Hospital Transport Service—Her extraordinary labors—Illness—Is appointed Lady Superintendent of the Lovell General Hospital at Portsmouth Grove, Rhode Island—Her duties—Resigns in October, 1863—Her volume—"The United States Sanitary Commission"—Other labors for the soldiers. | 318-323 |

| THE MISSES WOOLSEY. | |

| Social position of the Woolsey sisters—Mrs. Joseph Howland and her labors on the Hospital Transport—Her tender and skilful nursing of the sick and wounded of her husband's regiment—Poem addressed to her by a soldier—Her encouragement and assistance to the women nurses appointed by Miss Dix—Mrs. Robert S. Howland—Her labors in the hospitals and at the Metropolitan Sanitary Fair—Her early death from over-exertion in connection with the fair—Her poetical contributions to the National cause—"In the hospital"—Miss Georgiana M. Woolsey—Labors on Hospital Transports—At Portsmouth Grove Hospital—After Chancellorsville—Her work at Gettysburg with her mother—"Three weeks at Gettysburg"—The approach to the battle-field—The Sanitary Commission's Lodge near the railroad depot—The supply tent—Crutches—Supplying rebels and Union men alike—Dressing wounds—"On dress parade"—"Bread with butter on it and jelly on the butter"—"Worth a penny a sniff"—The Gettysburg women—The Gettysburg farmers—"Had never seen a rebel"—"A feller might'er got hit"—"I couldn't leave my bread"—The dying soldiers—"Tell her I love her"—The young rebel lieutenant—The colored freedmen—Praying for "Massa Lincoln"—The purple and blue and yellow handkerchiefs—"Only a blue one"—"The man who screamed so"—The German mother—The Oregon lieutenant—"Soup"—"Put some meat in a little water and stirred it round"—Miss Woolsey's rare capacities for her work—Estimate a lady friend—Miss Jane Stuart Woolsey—Labors in hospitals—Her charge of the Freedmen at Richmond—Miss Sarah C. Woolsey, at Portsmouth Grove Hospital. | 324-342 |

| ANNA MARIA ROSS. | |

| Her parentage and family—Early devotion to works of charity and benevolence—Praying for success in soliciting aid for the unfortunate—The "black small-pox"—The conductor's wife—The Cooper Shop Hospital—Her incessant labors and tender care of her patients—Her thoughtfulness for them when discharged—Her unselfish devotion to the good of others—Sending a soldier to his friends—"He must go or die"—The attachment of the soldiers to her—The home for discharged soldiers—Her efforts to provide the funds for it—Her success—The walk to South Street—Her sudden attack of paralysis and death—The monument and its inscription. | 343-351 |

| MRS. G. T. M. DAVIS. | |

| Mrs. Davis a native of Pittsfield, Massachusetts—A patriotic family—General Bartlett—She becomes Secretary of the Park Barracks Ladies' Association—The Bedloe's Island Hospital—The controversy—Discharge of the surgeon—Withdrawal from the Association—The hospital at David's Island—Mrs. Davis's labors there—The Soldiers' Rest on Howard Street—She becomes the Secretary of the Ladies' Association connected with it—Visits to other hospitals—Gratitude of the men to whom she has ministered—Appeals to the women of Berkshire—Her encomiums on their abundant labors. | 352-356 |

| MARY J. SAFFORD.[33] | |

| Miss Safford a native of Vermont, but a resident of Cairo—Her thorough and extensive mental culture—She organizes temporary hospitals among the regiments stationed at Cairo—Visiting the wounded on the field after the battle of Belmont—Her extemporized flag of truce—Her remarkable and excessive labors after the battle of Shiloh—On the Hospital steamers—Among the hospitals at Cairo—"A merry Christmas" for the soldiers stationed at Cairo—Illness induced by her over-exertion—Her tour in Europe—Her labors there, while in feeble health—Mrs. Livermore's sketch of Miss Safford—Her personal appearance and petite figure—"An angel at Cairo"—"That little gal that used to come in every day to see us—I tell you what she's an angel if there is any". 357-361 | |

| MRS. LYDIA G. PARRISH. | |

| Previous history—Early consecration to the work of beneficence in the army—Visiting Georgetown Seminary Hospital—Seeks aid from the Sanitary Commission—Visits to camps around Washington—Return to Philadelphia to enlist the sympathies of her friends in the work of the Commission—Return to Seminary Hospital—The surly soldier—He melts at last—Visits in other hospitals—Broad and Cherry Street Hospital, Philadelphia—Assists in organizing a Ladies' Aid Society at Chester, and in forming a corps of volunteer nurses—At Falmouth, Virginia, in January, 1863, with Mrs. Harris—On a tour of inspection in Virginia and North Carolina with her husband—The exchange of prisoners—Touching scenes—The Continental Fair—Mrs. Parrish's labors in connection with it—The tour of inspection at the Annapolis hospitals—Letters to the Sanitary Commission—Condition of the returned prisoners—Their hunger—The St. John's College Hospital—Admirable arrangement—Camp Parole Hospital—The Naval Academy Hospital—The landing of the prisoners—Their frightful sufferings—She compiles "The Soldiers' Friend" of which more than a hundred thousand copies were circulated—Her efforts for the freedmen. | 362-372 |

| MRS. ANNIE WITTENMEYER. | |

| Early efforts for the soldiers—She urges the organization of Aid Societies, and these become auxiliary at first to the Keokuk Aid Society, which she was active in establishing—The Iowa State Sanitary Commission—Mrs. Wittenmeyer becomes its agent—Her active efforts for the soldiers—She disburses one hundred and thirty-six thousand dollars worth of goods and supplies in about two years and a-half—She aids in the establishment of the Iowa Soldiers' Orphans' Home—Her plan of special diet kitchens—The Christian Commission appoint her their agent for carrying out this plan—Her labors in their establishment in connection with large hospitals—Special order of the War Department—The estimate of her services by the Christian Commission. | 373-378 |

| MELCENIA ELLIOTT. By Rev. J. G. Forman. | |

| Previous pursuits—In the hospitals in Tennessee in the summer and autumn of 1862—A remarkably skilful nurse—Services at Memphis—The Iowa soldier—She scales the fence to watch over him and minister to his needs, and at his death conveys his body to his friends, overcoming all difficulties to do so—In the Benton Barracks Hospital—Volunteers to nurse the patients in the erysipelas ward—Matron of the Refugee Home at St. Louis—"The poor white trash"—Matron of Soldiers' Orphans' Home at Farmington, Iowa. | 379-383 |

| MARY DWIGHT PETTES. By Rev. J. G. Forman.[34] | |

| A native of Boston—Came to St. Louis in 1861, and entered upon hospital work in January, 1862—Her faithful earnest work—Labors for the spiritual as well as physical welfare of the soldiers, reading the Scriptures to them, singing to them, etc.—Attachment of the soldiers to her—She is seized with typhoid fever contracted in her care for her patients, and dies after five weeks' illness—Dr. Eliot's impressions of her character. | 384-388 |

| LOUISA MAERTZ. By Rev. J. G. Forman. | |

| Her birth and parentage—Her residence in Germany and Switzerland—Her fondness for study—Her extraordinary sympathy and benevolence—She commences visiting the hospitals in her native city, Quincy, Illinois, in the autumn of 1861—She takes some of the wounded home to her father's house and ministers to them there—She goes to St. Louis—Is commissioned as a nurse—Sent to Helena, then full of wounded from the battles in Arkansas—Her severe labors here—Almost the only woman nurse in the hospitals there—"God bless you, dear lady"—The Arkansas Union soldier—The half-blind widow—Miss Maertz at Vicksburg—At New Orleans. | 390-394 |

| MRS. HARRIET R. COLFAX. | |

| Early life—A widow and fatherless—Her first labors in the hospitals in St. Louis—Her sympathies never blunted—The sudden death of a soldier—Her religious labors among the patients—Dr. Paddock's testimony—The wounded from Fort Donelson—On the hospital boat—In the battle at Island No. Ten—Bringing back the wounded—Mrs. Colfax's care of them—Trips to Pittsburg Landing, before and after the battle of Shiloh—Heavy and protracted labor for the nurses—Return to St. Louis—At the Fifth Street Hospital—At Jefferson Barracks—Her associates—Obliged to retire from the service on account of her health in 1864. | 395-399 |

| CLARA DAVIS. | |

| Miss Davis not a native of this country—Her services at the Broad and Cherry Street Hospital, Philadelphia—One of the Hospital Transport corps—The steamer "John Brooks"—Mile Creek Hospital—Mrs. Husband's account of her—At Frederick City, Harper's Ferry, and Antietam—Agent of the Sanitary Commission at Camp Parole, Annapolis, Maryland—Is seized with typhoid fever here—When partially recovered, she resumes her labors, but is again attacked and compelled to withdraw from her work—Her other labors for the soldiers, both sick and well—Obtaining furloughs—Sending home the bodies of dead soldiers—Providing head-boards for the soldiers' graves. | 400-403 |

| MRS. R. H. SPENCER. | |

| Her home in Oswego, New York—Teaching—An anti-war Democrat is convinced of his duty to become a soldier, though too old for the draft—Husband and wife go together—At the Soldiers' Rest in Washington—Her first work—Matron of the hospital—At Wind-Mill Point—Matron in the First Corps Hospital—Foraging for the sick and wounded—The march toward Gettysburg—A heavily laden horse—Giving up her last blanket—Chivalric instincts of American soldiers—Labors during the battle of Gettysburg—Under fire—Field Hospital of the Eleventh Corps—The hospital at White Church—Incessant labors—Saving a soldier's life—"Can you go without food for a week?"—The basin of broth—Mrs. Spencer appointed agent of the State of New York for the[35] care of the sick and wounded soldiers in the field—At Brandy Station—At Rappahannock Station and Belle Plain after the battle of the Wilderness—Virginia mud—Working alone—Heavy rain and no shelter—Working on at Belle Plain—"Nothing to wear"—Port Royal—White House—Feeding the wounded—Arrives at City Point—The hospitals and the Government kitchen—At the front—Carrying supplies to the men in the rifle pits—Fired at by a sharpshooter—Shelled by the enemy—The great explosion at City Point—Her narrow escape—Remains at City Point till the hospitals are broken up—The gifts received from grateful soldiers. | 404-415 |

| MRS. HARRIET FOOTE HAWLEY. By Mrs. H. B. Stowe. | |

| Mrs. Hawley accompanies her husband, Colonel Hawley, to South Carolina—Teaching the freedmen—Visiting the hospitals at Beaufort, Fernandina and St. Augustine—After Olustee—At the Armory Square Hospital, Washington—The surgical operations performed in the ward—"Reaching the hospital only in time to die"—At Wilmington—Frightful condition of Union prisoners—Typhus fever raging—The dangers greater than those of the battle-field—Four thousand sick—Mrs. Hawley's heroism, and incessant labors—At Richmond—Injured by the upsetting of an ambulance—Labors among the freedmen—Colonel Higginson's speech. | 416-419 |

| ELLEN E. MITCHELL. | |

| Her family—Motives in entering on the work of ministering to the soldiers—Receives instructions at Bellevue Hospital—Receives a nurse's pay and gives it to the suffering soldiers—At Elmore Hospital, Georgetown—Gratitude of the soldiers—Trials—St. Elizabeth's Hospital, Washington—A dying nurse—Her own serious illness—Care and attention of Miss Jessie Home—Death of her mother—At Point Lookout—Discomforts and suffering—Ware House Hospital, Georgetown—Transfer of patients and nurse to Union Hotel Hospital—Her duties arduous but pleasant—Transfer to Knight General Hospital, New Haven—Resigns and accepts a situation in the Treasury Department, but longing for her old work returns to it—At Fredericksburg after battle of the Wilderness—At Judiciary Square Hospital, Washington—Abundant labor, but equally abundant happiness—Her feelings in the review of her work. | 420-426 |

| JESSIE HOME. | |

| A Scotch maiden, but devotedly attached to the Union—Abandons a pleasant and lucrative pursuit to become a hospital nurse—Her earnestness and zeal—Her incessant labors—Sickness and death—Cared for by Miss Bergen of Brooklyn, New York. | 427, 428 |

| MISS VANCE AND MISS BLACKMAR. By Mrs. M. M. Husband. | |

| Miss Vance a missionary teacher before the war—Appointed by Miss Dix to a Baltimore hospital—At Washington, at Alexandria, and at Gettysburg—At Fredericksburg after the battle of the Wilderness—At City Point in the Second Corps Hospital—Served through the whole war with but three weeks' furlough—Miss Blackmar from Michigan—A skilful and efficient nurse—The almost fatal hemorrhage—The boy saved by her skill—Carrying a hot brick to bed. | 429, 430 |

| H. A. DADA AND S. E. HALL.[36] | |

| Missionary teachers before the war—Attending lectures to prepare for nursing—After the first battle of Bull Run—At Alexandria—The wounded from the battle-field—Incessant work—Ordered to Winchester, Virginia—The Court-House Hospital—At Strasburg—General Banks' retreat—Remaining among the enemy to care for the wounded—At Armory Square Hospital—The second Bull Run—Rapid but skilful care of the wounded—Painful cases—Harper's Ferry—Twelfth Army Corps Hospital—The mother in search of her son—After Chancellorsville—The battle of Gettysburg—Labors in the First and Twelfth Corps Hospitals—Sent to Murfreesboro', Tennessee—Rudeness of the Medical Director—Discomfort of their situation—Discourtesy of the Medical Director and some of the surgeons—"We have no ladies here—There are some women here, who are cooks!"—Removal to Chattanooga—Are courteously and kindly received—Wounded of Sherman's campaign—"You are the God-blessedest woman I ever saw"—Service to the close of the war and beyond—Lookout Mountain. | 431-439 |

| MRS. SARAH P. EDSON. | |

| Early life—Literary pursuits—In Columbia College Hospital—At Camp California—Quaker guns—Winchester, Virginia—Prevalence of gangrene—Union Hotel Hospital—On the Peninsula—In hospital of Sumner's Corps—Her son wounded—Transferred to Yorktown—Sufferings of the men—At White House and the front—Beef soup and coffee for starving wounded men—Is permitted to go to Harrison's Landing—Abundant labor and care—Chaplain Fuller—At Hygeia Hospital—At Alexandria—Pope's campaign—Attempts to go to Antietam, but is detained by sickness—Goes to Warrenton, and accompanies the army thence to Acquia Creek—Return to Washington—Forms a society to establish a home and training school for nurses, and becomes its Secretary—Visits hospitals—State Relief Societies approve the plan—Sanitary Commission do not approve of it as a whole—Surgeon-General opposes—Visits New York city—The masons become interested—"Army Nurses' Association" formed in New York—Nurses in great numbers sent on after the battles of Wilderness, Spottsylvania, etc.—The experiment a success—Its eventual failure through the mismanagement in New York—Mrs. Edson continues her labors in the army to the close of the war—Enthusiastic reception by the soldiers. 440-447 | |

| MARIA M. C. HALL. | |

| A native of Washington city—Desire to serve the sick and wounded—Receives a sick soldier into her father's house—Too young to answer the conditions required by Miss Dix—Application to Mrs. Fales—Attempts to dissuade her—"Well girls here they are, with everything to be done for them"—The Indiana Hospital—Difficulties and discouragements—A year of hard and unsatisfactory work—Hospital Transport Service—The Daniel Webster—At Harrison's Landing with Mrs. Fales—Condition of the poor fellows—Mrs. Harris calls her to Antietam—French's Division and Smoketown Hospitals—Abundant work but performed with great satisfaction—The French soldier's letter—The evening or family prayers—Successful efforts for the religious improvement of the men—Dr. Vanderkieft—The Naval Academy Hospital at Annapolis—In charge of Section five—Succeeds Mrs. Tyler as Lady Superintendent of the hospital—The humble condition of the returned prisoners from Andersonville and elsewhere—Prevalence of typhus fever—Death of her assistants—Four thousand patients—Writes for "The Crutch"—Her joy in the success of her work. | 448-454 |

| THE HOSPITAL CORPS AT THE NAVAL ACADEMY HOSPITAL, ANNAPOLIS.[37] | |

| The cruelties which had been practiced on the Union men in rebel prisons—Duties of the nurses under Miss Hall—Names and homes of these ladies—Death of Miss Adeline Walker—Miss Hall's tribute to her memory—Miss Titcomb's eulogy on her—Death of Miss M. A. B. Young—Sketch of her history—"Let me be buried here among my boys"—Miss Rose M. Billing—Her faithfulness as a nurse in the Indiana Hospital, (Patent Office,) at Falls Church, and at Annapolis—She like the others falls a victim to the typhus generated in Southern prisons—Tribute to her memory. | 455-460 |

| OTHER LABORS OF SOME OF THE MEMBERS OF THE ANNAPOLIS HOSPITAL CORPS. | |

| The Maine stay of the Annapolis Hospital—Miss Titcomb—Miss Newhall—Miss Usher—Other ladies from Maine—The Maine camp and Hospital Association—Mrs. Eaton—Mrs. Fogg—Mrs. Mayhew—Miss Mary A. Dupee and her labors—Miss Abbie J. Howe—Her labors for the spiritual as well as physical good of the men—Her great influence over them—Her joy in her work. | 461-466 |

| MRS. A. H. AND MISS S. H. GIBBONS. | |

| Mrs. Gibbons a daughter of Isaac T. Hopper—Her zeal in the cause of reform—Work of herself and daughter in the Patent Office Hospital in 1861—Visit to Falls Church and its hospital—Sad condition of the patients—"If you do not come and take care of me I shall die"—Return to this hospital—Its condition greatly improved—Winchester and the Seminary Hospital—Severe labors here—Banks' retreat—The nurses held as prisoners—Losses of Mrs. and Miss Gibbons at this time—At Point Lookout—Exchanged prisoners from Belle Isle—A scarcity of garments—Trowsers a luxury—Fifteen months of hospital service—Conflicts with the authorities in regard to the freedmen—The July riots in New York in 1863—Mrs. Gibbons' house sacked by the rioters—Destruction of everything valuable—Return to Point Lookout—The campaign of 1864-5—Mrs. and Miss Gibbons at Fredericksburg—An improvised hospital—Mrs. Gibbons takes charge—The gift of roses—The roses withered and dyed in the soldiers' blood—Riding with the wounded in box cars—At White House—Labors at Beverly Hospital, New Jersey—Mrs. Gibbons' return home—Her daughter remains till the close of the war. | 467-475 |

| MRS. E. J. RUSSELL. | |

| Government nurses—Their trials and hardships—Mrs. Russell a teacher before the war—Her patriotism—First connected with the Regimental Hospital of Twentieth New York Militia (National Guards)—Assigned to Columbia College Hospital, Washington—After three years' service resigns from impaired health, but recovering enters the service again in Baltimore—Nursing rebels—Her attention to the religious condition of the men—Four years of service—Returns to teaching after the war. | 477-479 |

| MRS. MARY W. LEE. | |

| Mrs. Lee of foreign birth, but American in feeling—Services in the Volunteer Refreshment Saloon—A noble institution—At Harrison's Landing, with Mrs. Harris—Wretched condition of the men—Improvement under the efforts of the ladies—The Hospital of the Epiphany at Washington—At Antietam during the battle—The two water tubs—The[38] enterprising sutler—"Take this bread and give it to that woman"—The Sedgwick Hospital—Ordering a guard—Hoffman's Farm Hospital—Smoketown Hospital—Potomac Creek—Chancellorsville—Under fire from the batteries on Fredericksburg Heights—Marching with the army—Gettysburg—The Second Corps Hospital—Camp Letterman—The Refreshment Saloon again—Brandy Station—A stove half a yard square—The battles of the Wilderness—At Fredericksburg—A diet kitchen without furniture—Over the river after a stove—Baking, boiling, stewing, and frying simultaneously—Keeping the old stove hot—At City Point—In charge of a hospital—The last days of the Refreshment Saloon. | 480-488 |

| CORNELIA M. TOMPKINS. By Rev. J. G. Forman. | |

| A scion of an eminent family—At Benton Barracks Hospital—At Memphis—Return to St. Louis—At Jefferson Barracks. | 489, 490 |

| MRS. ANNA C. McMEENS. By Mrs. E. S. Mendenhall. | |

| A native of Maryland—The wife of a surgeon in the army—At Camp Dennison—One of the first women in Ohio to minister to the soldiers in a military hospital—At Nashville in hospital—The battle of Perryville—Death of Dr. McMeens—At home—Laboring for the Sanitary Commission—In the hospitals at Washington—Missionary work among the sailors on Lake Erie. | 491, 492 |

| MRS. JERUSHA R. SMALL. By Mrs. E. S. Mendenhall. | |

| A native of Iowa—Accompanies her husband to the war—Ministers to the wounded from Belmont, Donelson, and Shiloh—Her husband wounded at Shiloh—Under fire in ministering to the wounded—Uses all her spare clothing for them—As her husband recovers her own health fails—The galloping consumption—The female secessionist—Going home to die—Buried with the flag wrapped around her. | 493, 494 |

| MRS. S. A. MARTHA CANFIELD. By Mrs. E. S. Mendenhall. | |

| Wife of Colonel H. Canfield—Her husband killed at Shiloh—Burying her sorrows in her heart—She returns to labor for the wounded in the Sixteenth Army Corps, in the hospitals at Memphis—Labors among the freedmen—Establishes the Colored Orphan Asylum at Memphis. | 495 |

| MRS. THOMAS AND MISS MORRIS. | |

| Faithful laborers in the hospitals at Cincinnati till the close of the war. | 496 |

| MRS. SHEPARD WELLS. By Rev. J. G. Forman. | |

| Driven from East Tennessee by the rebels—Becomes a member of the Ladies' Union Aid Society at St. Louis, and one of its Secretaries—Superintends the special diet kitchen at Benton Barracks—An enthusiastic and earnest worker—Labor for the refugees. | 497, 498 |

| MRS. E. C. WITHERELL. By Rev. J. G. Forman. | |

| A lady from Louisville—Her service in the Fourth Street Hospital, St. Louis—"Shining Shore"—The soldier boy—On the "Empress" hospital steamer nursing the wounded—A faithful and untiring nurse—Is attacked with fever, and dies July, 1862—Resolutions of Western Sanitary Commission. | 499-501 |

| PHEBE ALLEN. By Rev. J. G. Forman.[39] | |

| A teacher in Iowa—Volunteered as a nurse in Benton Barracks hospital—Very efficient—Died of malarious fever in 1864, at the hospital. | 502 |

| MRS. EDWIN GREBLE. | |

| Of Quaker stock—Intensely patriotic—Her eldest son, Lieutenant John Greble, killed at Great Bethel in 1861—A second son served through the war—A son-in-law a prisoner in the rebel prisons—Mrs. Greble a most assiduous worker in the hospitals of Philadelphia, and a constant and liberal giver. | 503, 504 |

| MRS. ISABELLA FOGG. | |

| A resident of Calais, Maine—Her only son volunteers, and she devotes herself to the service of ministering to the wounded and sick—Goes to Annapolis with one of the Maine regiments—The spotted fever in the Annapolis Hospital—Mrs. Fogg and Mrs. Mayhew volunteer as nurses—The Hospital Transport Service—At the front after Fair Oaks—Savage's Station—Over land to Harrison's Landing with the army—Under fire—On the hospital ship—Home—In the hospitals around Washington, after Antietam—The Maine Camp Hospital Association—Mrs. J. S. Eaton—After Chancellorsville—In the field hospitals for nearly a week, working day and night, and under fire—At Gettysburg the day after the battle—On the Rapidan—At Mine Run—At Belle Plain and Fredericksburg after the battle of the Wilderness—At City Point—Home again—A wounded son—Severe illness of Mrs. Fogg—Recovery—Sent by Christian Commission to Louisville to take charge of a special diet kitchen—Injured by a fall—An invalid for life—Happy in the work accomplished. | 505-510 |

| MRS. E. E. GEORGE. | |

| Services of aged women in the war—Military agency of Indiana—Mrs. George's appointment—Her services at Memphis—At Pulaski—At Chattanooga—Following Sherman to Atlanta—Matron of Fifteenth Army Corps Hospital—At Nashville—Starts for Savannah, but is persuaded by Miss Dix to go to Wilmington—Excessive labors there—Dies of typhus. | 511-513 |

| MRS. CHARLOTTE E. McKAY. | |

| A native of Massachusetts—Enters the service as nurse at Frederick city—Rebel occupation of the city—Chancellorsville—The assault on Marye's Heights—Death of her brother—Gettysburg—Services in Third Division Third Corps Hospital—At Warrenton—Mine Run—Brandy Station—Grant's campaign—From Belle Plain to City Point—The Cavalry Corps Hospital—Testimonials presented to her. | 514-516 |

| MRS. FANNY L. RICKETTS. | |

| Of English parentage—Wife of Major-General Ricketts—Resides on the frontier for three years—Her husband wounded at Bull Run—Her heroism in going through the rebel lines to be with him—Dangers and privations at Richmond—Ministrations to Union soldiers—He is selected as a hostage for the privateersmen, but released at her urgent solicitation—Wounded again at Antietam, and again tenderly nursed—Wounded at Middletown, Virginia, October, 1864, and for four months in great danger—The end of the war. | 517-519 |

| MRS. JOHN S. PHELPS.[40] | |

| Early history—Residence in the Southwest—Rescues General Lyon's body—Her heroism and benevolence at Pea Ridge and elsewhere. | 520, 521 |

| MRS. JANE R. MUNSELL. | |

| Maryland women in the war—Barbara Frietchie—Effie Titlow—Mrs. Munsell's labors in the hospitals after Antietam and Gettysburg—Her death from over-exertion. | 522, 523 |

| PART III. LADIES WHO ORGANIZED AID SOCIETIES, RECEIVED AND FORWARDED SUPPLIES TO THE HOSPITALS, DEVOTING THEIR WHOLE TIME TO THE WORK, ETC. | |

| WOMAN'S CENTRAL ASSOCIATION OF RELIEF. By Mrs. Julia B. Curtis. | |

| Organization and officers of the Association—It becomes a branch of the United States Sanitary Commission—Its Registration Committee and their duties—The Selection and Preparation of Nurses for the Army—The Finance and Executive Committee—The unwillingness of the Government to admit any deficiency—The arrival of the first boxes for the Association—The sacrifices made by the women in the country towns and hamlets—The Committee of Correspondence—Twenty-five thousand letters—The receiving book, the day-book and the ledger—The alphabet repeated seven hundred and twenty-seven times on the boxes—Mrs. Fellows and Mrs. Colby solicitors of donations—The call for nurses on board the Hospital Transports—Mrs. W. P. Griffin and Mrs. David Lane volunteer, and subsequently other members of the Association—Mrs. D'Orémieulx's departure for Europe—Mr. S. W. Bridgham's faithful labors—Creeping into the Association rooms of a Sunday, to gather up and forward supplies needed for sudden emergencies—The First Council of Representatives from the principal Aid Societies at Washington—Monthly boxes—The Federal principle—Antietam and Fredericksburg exhaust the supplies—Miss Louisa Lee Schuyler's able letter of inquiry to the Secretaries of Auxiliaries—The plan of "Associate Managers"—Miss Schuyler's incessant labors in connection with this—The set of boxes devised by Miss Schuyler to aid the work of the Committee on Correspondence—The employment of Lecturers—The Association publish Mr. George T. Strong's pamphlet, "How can we best help our Camps and Hospitals"—The Hospital Directory opened—The lack of supplies of clothing and edibles, resulting from the changed condition of the country—Activity and zeal of the members of the Woman's Central Association—Miss Ellen Collins' incessant labors—Her elaborate tables of supplies and their disbursement—The Association offers to purchase for the Auxiliaries at wholesale prices—Miss Schuyler's admirable Plan of Organization for Country Societies—Alert Clubs founded—Large contributions to the stations at Beaufort and Morris Island—Miss Collins and Mrs. W. P. Griffin in charge of the office through the New York Riots in July, 1863—Mrs. Griffin, is chairman of Special Relief Committee, and makes personal visits to the sick—The Second Council at Washington—Miss Schuyler and Miss Collins delegates—Miss Schuyler's efforts—The whirlwind of Fairs—Aiding the feeble auxiliaries by donating an additional sum in goods equal to what they raised, to be manufactured by them—Five thousand dollars a month thus expended—A Soldiers' Aid Society Council—Help to Military Hospitals near the city, and the Navy, by the Association—Death of its President, Dr. Mott—The news of peace—Miss Collins' Congratulatory Letter—The Association continues its work to July 7—Two hundred and ninety-one thousand four hundred and seventy-five shirts distributed—Purchases made for Auxiliaries, seventy-nine thousand three hundred and ninety dollars and fifty-seven cents—Other expenditures of money for the purposes of the Association,[41] sixty-one thousand three hundred and eighty-six dollars and fifty-seven cents—The zeal of the Associated Managers—The Brooklyn Relief Association—Miss Schuyler's labors as a writer—Her reports—Articles in the Sanitary Bulletin, "The Soldiers' Friend," "Nelly's Hospital," &c. &c.—The patient and continuous labors of the Committees on Correspondence and on Supplies—Territory occupied by the Woman's Central Association—Resolutions at the Final Meeting. | 527-539 |

| SOLDIERS' AID SOCIETY OF NORTHERN OHIO. | |

| Its organization—At first a Local Society—No Written Constitution or By-laws—Becomes a branch of the United States Sanitary Commission in October, 1861—Its territory small and not remarkable for wealth—Five hundred and twenty auxiliaries—Its disbursement of one million one hundred and thirty-three thousand dollars in money and supplies—The Northern Ohio Sanitary Fair—The supplies mostly forwarded to the Western Depôt of the United States Sanitary Commission at Louisville—"The Soldiers' Home" built under the direction of the Ladies who managed the affairs of the Society, and supplied and conducted under their Supervision—The Hospital Directory, Employment Agency, War Claim Agency—The entire time of the Officers of the Society for five and a half years voluntarily and freely given to its work from eight in the morning till six or later in the evening—The President, Mrs. B. Rouse, and her labors in organizing Aid Societies and attending to the home work—The labors of the Secretary and Treasurer—Editorial work—The Society's printing press—Setting up and printing Bulletins—The Sanitary Fair originated and carried on by the Aid Society—The Ohio State Soldiers' Home aided by them—Sketch of Mrs. Rouse—Sketch of Miss Mary Clark Brayton, Secretary of the Society—Sketch of Miss Ellen F. Terry, Treasurer of the Society—Miss Brayton's "On a Hospital Train," "Riding on a Rail"—Visit to the Army—The first sight of a hospital train—The wounded soldiers on board—"Trickling a little sympathy on the Wounded"—"The Hospital Train a jolly thing"—The dying soldier—Arrangement of the Hospital Train—The arduous duties of the Surgeon. | 540-552 |

| NEW ENGLAND WOMEN'S AUXILIARY ASSOCIATION. | |

| Its organization and territory—One million five hundred and fifteen thousand dollars collected in money and supplies by this Association—Its Sanitary Fair and its results—The chairman of the Executive Committee Miss Abby W. May—Her retiring and modest disposition—Her rare executive powers—Sketch of Miss May—Her early zeal in the Anti-slavery movement—Her remarkable practical talent, and admirable management of affairs—Her eloquent appeals to the auxiliaries—Her entire self-abnegation—Extract from one of her letters—Extract from her Final Report—The Boston Sewing Circle and its officers—The Ladies' Industrial Aid Association of Boston—Nearly three hundred and forty-seven thousand garments for the soldiers made by the employés of the Association, most of whom were from soldiers' families—Additional wages beyond the contract prices paid to the workwomen, to the amount of over twenty thousand dollars—The lessons learned by the ladies engaged in this work. | 553-559 |

| THE NORTHWESTERN SANITARY COMMISSION. | |

| The origin of the Commission—Its early labors—Mrs. Porter's connection with it—Her determination to go to the army—The appointment of Mrs. Hoge and Mrs. Livermore as Managers—The extent and variety of their labors—The two Sanitary Fairs—Estimate of the amount raised by the Commission. | 560-561 |

| MRS. A. H. HOGE.[42] | |

| Her birth and early education—Her marriage—Her family—She identifies herself from the beginning with the National cause—Her first visit to the hospitals of Cairo, Mound City and St. Louis—The Mound City Hospital—The wounded boy—Turned over for the first time—"They had to take the Fort"—Rebel cruelties at Donelson—The poor French boy—The mother who had lost seven sons in the Army—"He had turned his face to the wall to die"—Mrs. Hoge at the Woman's Council at Washington in 1862—Labors of Mrs. Hoge and Mrs. Livermore—Correspondence—Circulars—Addresses—Mrs. Hoge's eloquence and pathos—The ample contributions elicited by her appeals—Visit to the Camp of General Grant at Young's Point, in the winter of 1862-3—Return with a cargo of wounded—Second visit to the vicinity of Vicksburg—Prevalence of scurvy—The onion and potato circulars—Third visit to Vicksburg in June, 1863—Incidents of this visit—The rifle-pits—Singing Hymns under fire—"Did you drop from heaven into these rifle-pits?"—Mrs. Hoge's talk to the men—"Promise me you'll visit my regiment to-morrow"—The flag of the Board of Trade Regiment—"How about the blood?"—"Sing, Rally round the Flag Boys"—The death of R—"Take her picture from under my pillow"—Mrs. Hoge at Washington again—Her views of the value of the Press in benevolent operations—In the Sanitary Fairs at Chicago—Her address at Brooklyn, in March, 1865—Gifts presented her as a testimony to the value of her labors. | 562-576 |

| MRS. MARY A. LIVERMORE. | |

| Mrs. Livermore's childhood and education—She becomes a teacher—Her marriage—She is associated with her husband as Editor of The New Covenant—Her scholarship and ability as a writer and speaker—The vigor and eloquence of her appeals—"Women and the War"—The beginnings of the Northwestern Sanitary Commission—The appointment of Mrs. Livermore and Mrs. Hoge as its managers—The contributions of Mrs. Livermore to the press, on subjects connected with her work—"The backward movement of General McClellan"—The Hutchinsons prohibited from singing Whittier's Song in the Army of the Potomac—Mrs. Livermore's visit to Washington—Her description of "Camp Misery"—She makes a tour to the Military Posts on the Mississippi—The female nurses—The scurvy in the Camp—The Northwestern Sanitary Fair—Mrs. Livermore's address to the Women of the Northwest—Her tact in selecting the right persons to carry out her plans at the Fair—Her extensive journeyings—Her visit to Washington in the Spring of 1865—Her invitation to the President to be present at the opening of the Fair—Her description of Mr. Lincoln—His death and the funeral solemnities with which his remains were received at Chicago—The final fair—Mrs. Livermore's testimonials of regard and appreciation from friends and, especially from the soldiers. | 577-589 |

| GENERAL AID SOCIETY FOR THE ARMY, BUFFALO. | |

| Organization of the Society—Its first President, Mrs. Follett—Its second President, Mrs. Horatio Seymour—Her efficient Aids, Miss Babcock and Miss Bird—The friendly rivalry with the Cleveland Society—Mrs. Seymour's rare ability and system—Her encomiums on the labors of the patriot workers in country homes—The workers in the cities equally faithful and praiseworthy. | 590-592 |

| MICHIGAN SOLDIERS' AID SOCIETY. | |

| The Patriotic women of Michigan—Annie Etheridge, Mrs. Russell and others—"The Soldiers' Relief Committee" and "The Soldiers' Aid Society" of Detroit—Their Consolidation—The officers of the New Society—Miss Valeria Campbell the soul of the organization—Her multifarious labors—The[43] Military Hospitals in Detroit—The "Soldiers' Home" in Detroit—Michigan in the two Chicago Fairs—Amount of money and supplies raised by the Michigan Branch. | 593-595 |

| WOMEN'S PENNSYLVANIA BRANCH OF UNITED STATES SANITARY COMMISSION. | |

| The loyal women of Philadelphia—Their numerous organizations for the relief of the Soldier—The organization of the Women's Pennsylvania Branch—Its officers—Sketch of Mrs. Grier—Her parentage—Her residence in Wilmington, N. C.—Persecution for loyalty—Escape—She enters immediately upon Hospital Work—Her appointment to the Presidency of the Women's Branch—Her remarkable tact and skill—Her extraordinary executive talent—Mrs. Clara J. Moore—Sketch of her labors—Other ladies of the Association—Testimonials to Mrs. Grier's ability and admirable management from officers of the Sanitary Commission and others—The final report of this Branch—The condition of the state and country at its inception—The Associate Managers—The work accomplished—Peace at last—The details of Expenses of the Supply Department—The work of the Relief Committee—Eight hundred and thirty women employed—Widows of Soldiers aided—Total expenditures of Relief Committee. | 596-606 |

| THE WISCONSIN SOLDIERS' AID SOCIETY. By Rev. J. G. Forman. | |

| The Milwaukie Ladies Soldiers' Aid Society—Labors of Mrs. Jackson, Mrs. Delafield and others—Enlargement and re-organization as the Wisconsin Soldiers' Aid Society—Mrs. Henrietta L. Colt, chosen Corresponding Secretary—Her visits to the front, and her subsequent labors among the Aid Societies of the State—Efficiency of the Society—The Wisconsin Soldiers' Home—Its extent and what it accomplished—It forms the Nucleus of one of the National Soldiers' Homes—Sketch of Mrs. Colt—Death of her husband—Her deep and overwhelming grief—She enters upon the Sanitary Work, to relieve herself from the crushing weight of her great sorrow—Her labors on a Hospital Steamer—Her frequent subsequent visits to the front—Her own account of these visits—"The beardless boys, all heroes"—Sketch of Mrs. Governor Salomon—Her labors in behalf of the German and other soldiers of Wisconsin. | 607-614 |

| PITTSBURG BRANCH UNITED STATES SANITARY COMMISSION. | |

| The Pittsburg Sanitary Committee and Pittsburg Subsistence Committee—Organization of the Branch—Its Corresponding Secretary, Miss Rachael W. McFadden—Her executive ability zeal and patriotism—Her colleagues in her labors—The Pittsburg Sanitary Fair—Its remarkable success—Miss Murdock's labors at Nashville. | 615, 616 |

| MRS. ELIZABETH S. MENDENHALL. | |

| Mrs. Mendenhall's childhood and youth passed in Richmond, Va.—Her relatives Members of the Society of Friends—Her early Hospital labors—President of the Women's Soldiers' Aid Society of Cincinnati—Her appeal to the citizens of Cincinnati to organize a Sanitary Fair—Her efforts to make the Fair a success—The magnificent result—Subsequent labors in the Sanitary Cause—Fair for Soldiers' Families in December, 1864—Labors for the Freedmen and Refugees—In behalf of fallen women. | 617-620 |

| DEPARTMENT OF THE SOUTH.[44] | |

| Dr. M. M. Marsh appointed Medical Inspector of Department of the South—Early in 1863 he proceeded thither with his wife—Mrs. Marsh finds abundant work in the receipt and distribution of Sanitary Stores, in the visiting of Hospitals—Spirit of the wounded men—The exchange of prisoners—Sufferings of our men in Rebel prisons—Their self-sacrificing spirit—Supplies sent to the prisoners, and letters received from them—The sudden suspension of this benevolent work by order from General Halleck—The sick from Sherman's Army—Dr. Marsh ordered to Newbern, N. C., but detained by sickness—Return to New York—The "Lincoln Home"—Dr. and Mrs. Marsh's labors there—Close of the Lincoln Home. | 621-629 |

| ST. LOUIS LADIES' UNION AID SOCIETY. | |

| Organization of the Society—Its officers—Was the principal Auxiliary of Western Sanitary Commission—Visits of its members to the fourteen hospitals in the vicinity of St. Louis—The hospital basket and its contents—The Society's delegates on the battle-fields—Employs the wives and daughters of soldiers in bandage rolling, and subsequently on contracts for hospital and other clothing for soldiers—Its committees cutting, fitting and examining the work—Undertakes the special diet kitchen of the Benton Barracks Hospital—Establishes a branch at Nashville—Special Diet Kitchen there—Its work for the Freedmen and Refugees—Sketches of its leading officers and managers—Mrs. Anna L. Clapp, a native of Washington County, N. Y.—Resides in Brooklyn, N. Y., and subsequently in St. Louis—Elected President of Ladies' Union Aid Society at the beginning of the war, and retains her position till its close—Her arduous labors and great tact and skill—She organizes a Refugee Home and House of Industry—Aids the Freedmen, and assists in the proper regulation of the Soldiers' Home—Miss H. A. Adams, (now Mrs. Morris Collins)—Born and educated in New Hampshire—At the outbreak of the war, a teacher in St. Louis—Devoted herself to the Sanitary work throughout the war—Was secretary of the society till the close of 1864, and a part of the time at Nashville, where she established a special diet kitchen—Death of her brother in the army—Her influence in procuring the admission of female nurses in the Nashville hospitals—Mrs. C. R. Springer, a native of Maine, one of the directors of the Society, and the superintendent of its employment department, for furnishing work to soldiers' families—Her unremitting and faithful labors—Mrs. Mary E. Palmer—A native of New Jersey—An earnest worker, visiting and aiding soldiers' families and dispensing the charities of the Society among them and the destitute families of refugees—Her labors were greater than her strength—Her death occasioned by a decline, the result of over exertion in her philanthropic work. 630-642 | |

| LADIES' AID SOCIETY OF PHILADELPHIA, &c. | |

| Organization of the Society—Its officers—Mrs. Joel Jones, Mrs. John Harris, Mrs. Stephen Caldwell—Mrs. Harris mostly engaged at the front—The Society organized with a view to the spiritual as well as physical benefit of the soldiers—Its great efficiency with moderate means—The ladies who distributed its supplies at the front—Extract from one of its reports—Its labors among the Refugees—The self-sacrifice of one of its members—Its expenditures. THE PENN RELIEF ASSOCIATION—An organization originating with the Friends, but afterward embracing all denominations—Its officers—Its efficiency—Amount of supplies distributed by it through well-known ladies. THE SOLDIERS' AID SOCIETY—Another of the efficient Pennsylvania Organizations for the relief of the soldiers—Its President, Mrs. Mary A. Brady—Her labors in the Satterlee Hospital—At "Camp Misery"—At the front—After[45] Gettysburg, and at Mine Run—Her health injured by her exposure and excessive labors—She dies of heart-disease in May, 1864. | 643-649 |

| WOMEN'S RELIEF ASSOCIATION OF BROOKLYN AND LONG ISLAND. | |

| Brooklyn early in the war—Numerous channels for distribution of the Supplies contributed—Importance of a Single Comprehensive Organization—The Relief Association formed—Mrs. Stranahan chosen President—Sketch of Mrs. Stranahan—Her social position—First directress of the Graham Institute—Her rare tact and efficiency as a presiding officer and in the dispatch of business—The Long Island Sanitary Fair—Her excessive labors there, and the perfect harmony and good feeling which prevailed—Rev. Dr. Spear's statement of her worth—The resolutions of the Relief Association—Rev. Dr. Bellows' Testimony—Her death—Rev. Dr. Farley's letter concerning her—Rev. Dr. Budington's tribute to her memory. | 650-658 |

| MRS. ELIZABETH M. STREETER. | |

| Loyal Southern Women—Mrs. Streeter's activity in promoting associations of loyal women for the relief of the soldiers—Her New England parentage and education—The Ladies' Union Relief Association of Baltimore—Mrs. Streeter at Antietam—As a Hospital Visitor—The Eutaw Street Hospital—The Union Refugees in Baltimore—Mrs. Streeter organizes the Ladies' Union Aid Society for the Relief of Soldiers' families—Testimony of the Maryland Committee of the Christian Commission to the value of her labors—Death of her husband—Her return to Massachusetts. | 659-664 |

| MRS. CURTIS T. FENN. | |

| The loyal record of the men and women of Berkshire County—Mrs. Fenn's history and position before the war—Her skill and tenderness in the care of the sick—Her readiness to enter upon the work of relief—She becomes the embodiment of a Relief Association—Liberal contributions made and much work performed by others but no organization—Mrs. Fenn's incessant and extraordinary labors for the soldiers—Her packing and shipping of the supplies to the hospitals in and about New York and to more distant cities—Refreshments for Soldiers who passed through Pittsfield—Her personal distribution of supplies at the soldiers' Thanksgiving dinner at Bedloe's Island in 1862, and at David's Island in 1864—"The gentleman from Africa and his vote"—Her efforts for the disabled soldiers and their families—The soldiers' monument. | 665-675 |

| MRS. JAMES HARLAN. | |

| Women in high stations devoting themselves to the relief of the Soldiers—Instances—Mrs. Harlan's early interest in the soldier—At Shiloh—Cutting red-tape—Wounded soldiers removed northward after the battle—Death of her daughter—Her labors for the religious benefit of the soldier—Her health impaired by her labors. | 676-678 |

| NEW ENGLAND SOLDIERS' RELIEF ASSOCIATION. | |

| History of the organization—Its Matron, Mrs. E. A. Russell—The Women's Auxiliary Committee—The Night Watchers' Association—The Hospital Choir—The SOLDIERS' DEPOT in Howard Street, N. Y.—The Ladies' Association connected with it. | 679, 680 |

| PART IV. LADIES DISTINGUISHED FOR SERVICES AMONG THE FREEDMEN AND REFUGEES. | |

| MRS. FRANCES DANA GAGE.[46] | |