This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Ting-a-ling

Author: Frank Richard Stockton

Release Date: March 16, 2007 [eBook #20836]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TING-A-LING***

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1869, By FRANK R. STOCKTON, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

Copyright, 1882,

By CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS.

Copyright, 1910, By WILLIAM S. STOCKTON.

To

THE MEMORY OF ALL GOOD GIANTS, DWARFS, AND FAIRIES

This Book

IS GRATEFULLY DEDICATED.

In a far country of the East, in a palace surrounded by orange groves, where the nightingales sang, and by silvery lakes, where the soft fountains plashed, there lived a fine old king. For many years he had governed with great comfort to himself, and to the tolerable satisfaction of his subjects. His queen being dead, his whole affection was given to his only child, the Princess Aufalia; and, whenever he happened to think of it, he paid great attention to her education. She had the best masters of embroidery and in the language of flowers, and she took lessons on the zithar three times a week.

A suitable husband, the son of a neighboring monarch, had been selected for her when she was about two hours old, thus making it unnecessary for her to go into society, and she consequently passed her youthful days in almost entire seclusion. She was now, when our story begins, a woman more beautiful than the roses of the garden, more musical than the nightingales, and far more graceful than the plashing fountains.

One balmy day in spring, when the birds were singing lively songs on the trees, and the crocuses were coaxing the jonquils almost off their very stems with their pretty ways, Aufalia went out to take a little promenade, followed by two grim slaves. Closely veiled, she walked in the secluded suburbs of the town, where she was generally required to take her lonely exercise. To-day, however, the slaves, impelled by a sweet tooth, which each of them possessed, thought it would be no harm if they went a little out of their way to procure some sugared cream-beans, which were made excellently well by a confectioner near the outskirts of the city. While they were in the shop, bargaining for the sugar-beans, a young man who was passing thereby stepped up to the Princess, and asked her if she could tell him the shortest road to the baths, and if there was a good eating-house in the neighborhood. Now as this was the first time in her life that the Princess had been addressed by a young man, it is not surprising that she was too much astonished to speak, especially as this youth was well dressed, extremely handsome, and of proud and dignified manners,—although, to be sure, a little travel-stained and tired-looking.

When she had somewhat recovered from her embarrassment, she raised her veil, (as if it was necessary to do so in speaking to a young man!) and told him that she was sure she had not the slightest idea where any place in the city was,—that she very seldom went into the city, and never thought about the way to any place when she did go,—that she wished she knew where those places were that he mentioned, for she would very much like to tell him, especially if he was hungry, which she knew was not pleasant, and no doubt he was not used to it, but that indeed she hadn't any idea about the way anywhere, but—

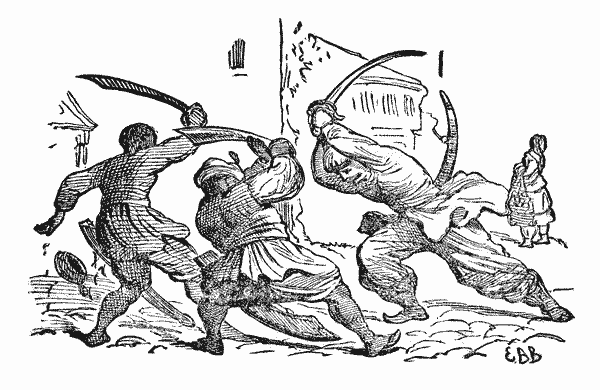

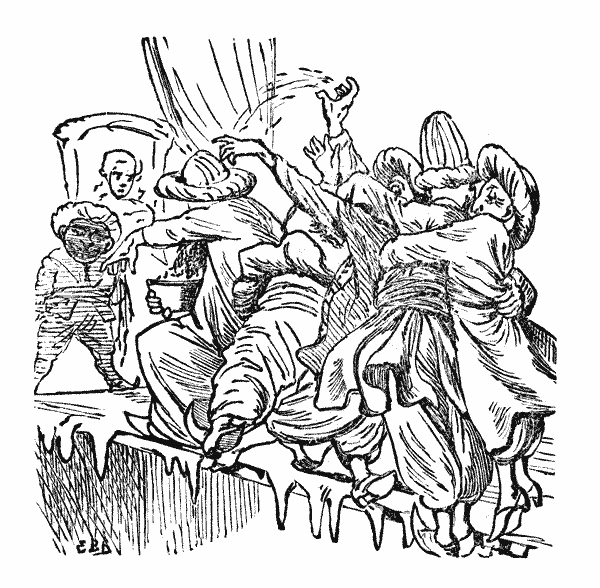

There is no knowing how long the Princess might have run on thus (and her veil up all the time) had not the two slaves at that moment emerged from the sugar-bean shop. The sight of the Princess actually talking to a young man in the broad daylight so amazed them, that they stood for a moment dumb in the door. But, recovering from their surprise, they drew their cimeters, and ran toward the Prince (for such his every action proclaimed him to be). When this high-born personage saw them coming with drawn blades, his countenance flushed, and his eyes sparkled with rage. Drawing his flashing sword, he shouted, "Crouch, varlets! Lie with the dust, ye dogs!" and sprang furiously upon them.

The impetuosity of the onslaught caused the two men to pause, and in a few minutes they fell back some yards, so fast and heavy did the long sword clash upon their upraised cimeters. This contest was soon over, for, unaccustomed to such a vigorous method of attack, the slaves turned and fled, and the Prince pursued them down a long street, and up an alley, and over a wall, and through a garden, and under an arch, and over a court-yard, and through a gate, and down another street, and up another alley, and through a house, and up a long staircase, and out upon a roof, and over several abutments, and down a trap-door, and down another pair of stairs, and through another house, into another garden, and over another wall, and down a long road, and over a field, clear out of sight.

When the Prince had performed this feat, he sat down to rest, but, suddenly bethinking himself of the maiden, he rose and went to look for her.

"I have chased away her servants," said he; "how will she ever find her way anywhere?"

If this was difficult for her, the Prince found that it was no less so for himself; and he spent much time in endeavoring to reach again the northern suburbs of the city. At last, after considerable walking, he reached the long street into which he had first chased the slaves, and, finding a line of children eagerly devouring a line of sugared cream-beans, he remembered seeing these confections dropping from the pockets of the slaves as he pursued them, and, following up the clew, soon reached the shop, and found the Princess sitting under a tree before the door. The shop-keeper, knowing her to be the Princess, had been afraid to speak to her, and was working away inside, making believe that he had not seen her, and that he knew nothing of the conflict which had taken place before his door.

Up jumped Aufalia. "O! I am so glad to see you again! I have been waiting here ever so long. But what have you done with my slaves?"

"I am your slave," said the Prince, bowing to the ground.

"But you don't know the way home," said she, "and I am dreadfully hungry."

Having ascertained from her that she was the King's daughter, and lived at the palace, the Prince reflected for a moment, and then, entering the shop, dragged forth the maker of sugared cream-beans, and ordered him to lead the way to the presence of the King. The confectioner, crouching to the earth, immediately started off, and the Prince and Princess, side by side, followed over what seemed to them a very short road to the palace. The Princess talked a great deal, but the Prince was rather quiet. He had a good many things to think about. He was the younger son of a king who lived far away to the north, and had been obliged to flee the kingdom on account of the custom of allowing only one full-grown heir to the throne to live in the country.

"Now," thought he, "this is an excellent commencement of my adventures. Here is a truly lovely Princess whom I am conducting to her anxious parent. He will be overwhelmed with gratitude, and will doubtless bestow upon me the government of a province—or—perhaps he will make me his Vizier—no, I will not accept that,—the province will suit me better." Having settled this little matter to his mind, he gladdened the heart of the Princess with the dulcet tones of his gentle voice.

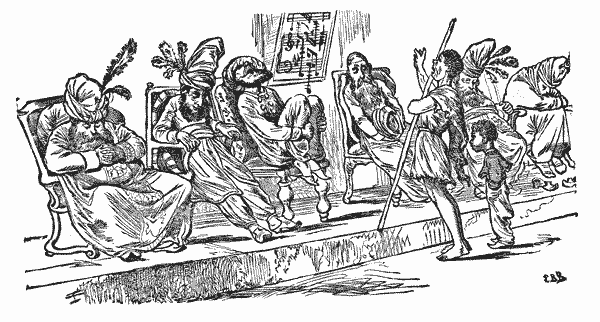

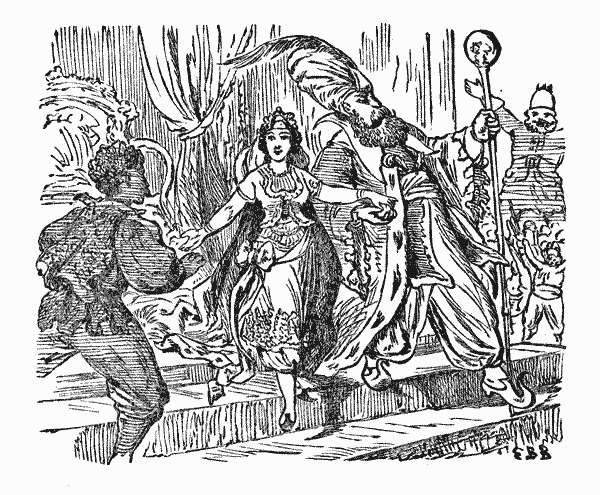

On reaching the palace, they went directly to the grand hall, where the King was giving audience. Justly astounded at perceiving his daughter (now veiled) approaching under the guidance of a crouching sugar-bean maker and a strange young man, he sat in silent amazement, until the Prince, who was used to court life, had made his manners, and related his story. When the King had heard it, he clapped his hands three times, and in rushed twenty-four eunuchs.

"Take," said the monarch, "this bird to her bower." And they surrounded the Princess, and hurried her off to the women's apartments.

Then he clapped his hands twice, and in rushed twenty-four armed guards from another door.

"Bind me this dog!" quoth the King, pointing to the Prince. And they bound him in a twinkling.

"Is this the way you treat a stranger?" cried the Prince.

"Aye," said the King, merrily. "We will treat you royally. You are tired. To-night and to-morrow you shall be lodged and feasted daintily and the day after we will have a celebration, when you shall be beaten with sticks, and shall fight a tiger, and be tossed by a bull, and be bowstrung, and beheaded, and drawn and quartered, and we will have a nice time. Bear him away to his soft couch."

The guards then led the Prince away to be kept a prisoner until the day for the celebration. The room to which he was conducted was comfortable, and he soon had a plenteous supper laid out before him, of which he partook with great avidity. Having finished his meal, he sat down to reflect upon his condition, but feeling very sleepy, and remembering that he would have a whole day of leisure, to-morrow, for such reflections, he concluded to go to bed. Before doing so, however, he wished to make all secure for the night. Examining the door, he found there was no lock to it; and being unwilling to remain all night liable to intrusion, he pondered the matter for some minutes, and then took up a wide and very heavy stool, and, having partially opened the door, he put the stool up over it, resting it partly on the door and partly on the surrounding woodwork, so that if any one tried to come in, and pushed the door open, the stool would fall down and knock the intruder's head off. Having arranged this to his satisfaction, the Prince went to bed.

That evening the Princess Aufalia was in great grief, for she had heard of the sentence pronounced upon the Prince, and felt herself the cause of it. What other reason she had to grieve over the Prince's death, need not be told. Her handmaidens fully sympathized with her; and one of them, Nerralina, the handsomest and most energetic of them all, soon found, by proper inquiry, that the Prince was confined in the fourth story of the "Tower of Tears." So they devised a scheme for his rescue. Each one of the young ladies contributed her scarf; and when they were all tied together, the conclave decided that they made a rope plenty long enough to reach from the Prince's window to the ground.

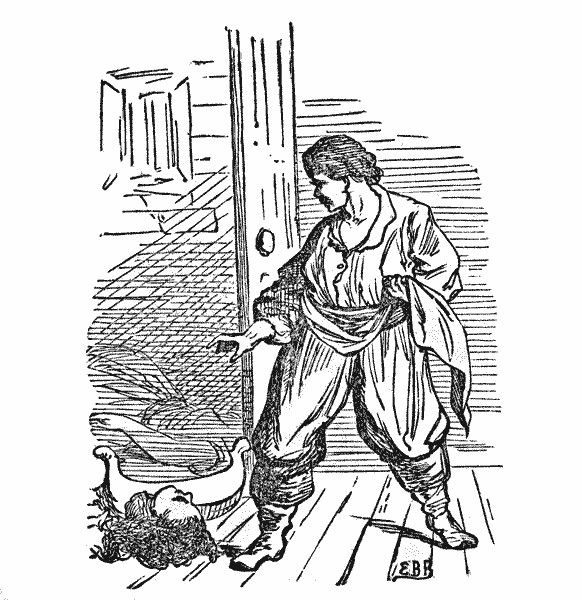

Thus much settled, it only remained to get this means of escape to the prisoner. This the lady Nerralina volunteered to do. Waiting until the dead of night, she took off her slippers, and with the scarf-rope rolled up into a ball under her arm, she silently stepped past the drowsy sentinels, and, reaching the Prince's room, pushed open the door, and the stool fell down and knocked her head off. Her body lay in the doorway, but her head rolled into the middle of the room.

Notwithstanding the noise occasioned by this accident, the Prince did not awake; but in the morning, when he was up and nearly dressed, he was astonished at seeing a lady's head in the middle of the room.

"Hallo!" said he. "Here's somebody's head."

Picking it up, he regarded it with considerable interest. Then seeing the body in the doorway, he put the head and it together, and, finding they fitted, came to the conclusion that they belonged to each other, and that the stool had done the mischief. When he saw the bundle of scarfs lying by the body, he unrolled it, and soon imagined the cause of the lady's visit.

"Poor thing!" he said; "doubtless the Princess sent her here with this, and most likely with a message also, which now I shall never hear. But these poor women! what do they know? This rope will not bear a man like me. Well! well! this poor girl is dead. I will pay respect to her."

And so he picked her up, and put her on his bed, thinking at the time that she must have fainted when she heard the stool coming, for no blood had flowed. He fitted on the head, and then he covered her up with the sheet; but, in pulling this over her head, he uncovered her feet, which he now perceived to be slipperless.

"No shoes! Ah me! Well, I will be polite to a lady, even if she is dead."

And so he drew off his own yellow boots, and put them on her feet, which was easy enough, as they were a little too big for her. He had hardly done this, and dressed himself, when he heard some one approaching; and hastily removing the fallen stool, he got behind the door just as a fat old fellow entered with a broadsword in one hand, and a pitcher of hot water and some towels in the other. Glancing at the bed, and seeing the yellow boots sticking out, the old fellow muttered: "Gone to bed with his clothes on, eh? Well, I'll let him sleep!" And so, putting down the pitcher and the towels, he walked out again. But not alone, for the Prince silently stepped after him, and by keeping close behind him, followed without being heard,—his politeness having been the fortunate cause of his being in his stocking-feet. For some distance they walked together thus, the Prince intending to slip off at the first cross passage he came to. It was quite dusky in the long hall way, there being no windows; and when the guard, at a certain place, made a very wide step, taking hold of a rod by the side of the wall as he did so, the Prince, not perceiving this, walked straight on, and popped right down an open trap-door.

Nerralina not returning, the Princess was in great grief, not knowing at first whether she had eloped with the Prince, or had met with some misfortune on the way to his room. In the morning, however, the ladies ascertained that the rope was not hanging from the Prince's window, and as the guards reported that he was comfortably sleeping in his bed, it was unanimously concluded that Nerralina had been discovered in her attempt, and had come to grief. Sorrowing bitterly, somewhat for the unknown mishap of her maid of honor, but still more for the now certain fate of him she loved, Aufalia went into the garden, and, making her way through masses of rose-trees and jasmines, to the most secluded part of the grounds, threw herself upon a violet bank and wept unrestrainedly, the tears rolling one by one from her eyes, like a continuous string of pearls.

Now it so happened that this spot was the pleasure ground of a company of fairies, who had a colony near by. These fairies were about an inch and a half high, beautifully formed, and of the most respectable class. They had not been molested for years by any one coming to this spot; but as they knew perfectly well who the Princess was, they were not at all alarmed at her appearance. In fact, the sight of her tears rolling so prettily down into the violet cups, and over the green leaves, seemed to please them much, and many of the younger ones took up a tear or two upon their shoulders to take home with them.

There was one youth, the handsomest of them all, named Ting-a-ling, who had a beautiful little sweetheart called Ling-a-ting.

Each one of these lovers, when they were about to return to their homes, picked up the prettiest tear they could find. Ting-a-ling put his tear upon his shoulder, and walked along as gracefully as an Egyptian woman with her water-jug; while little Ling-a-ting, with her treasure borne lightly over her head, skipped by her lover's side, as happy as happy could be.

"Don't walk out in the sun, my dearest," said Ting-a-ling. "Your shin-shiney will burst."

"Burst! O no, Tingy darling, no it won't. See how nice and big it is getting, and so light! Look!" cried she, throwing back her head; "I can see the sky through it; and O! what pretty colors,—blue, green, pink, and"—And the tear burst, and poor little Ling-a-ting sunk down on the grass, drenched and drowned.

Horror-stricken, Ting-a-ling dropped his tear and wept. Clasping his hands above his head, he fell on his knees beside his dear one, and raised his eyes to the blue sky in bitter anguish. But when he cast them down again, little Ling-a-ting was all soaked into the grass. Then sterner feelings filled his breast, and revenge stirred up the depths of his soul.

"This thing shall end!" he said, hissing the words between his teeth. "No more of us shall die like Ling-a-ting!"

So he ran quickly, and with his little sword cut down two violets, and of the petals he made two little soft bundles, and, tying them together with his garters, he slung them over his shoulder. Full of his terrible purpose, he then ran to the Princess, and, going behind her, clambered up her dress until he stood on her shoulder, and, getting on the top of her head, he loosened a long hair, and lowered himself down with it, until he stood upon the under lashes of her left eye. Now, his intention was evident. Those violet bundles were to "end this thing." They were to be crammed into the source of those fatal tears, to the beauty of which poor Ling-a-ting had fallen a victim.

"Now we shall see," said he, "if some things cannot be done as well as others!" and, kneeling down, he took one bundle from his shoulder, and prepared to put it in her eye. It is true, that, occupying the position he did, he, in some measure, obstructed the lady's vision; but as her eyes had been so long dimmed with tears, and her heart overshadowed with sorrow, she did not notice it.

Just as Ting-a-ling was about to execute his purpose, he happened to look before him, and saw, to his amazement, another little fairy on his knees, right in front of him. Starting back, he dropped the bundle from his hand, and the other from his shoulder. Then, upon his hands and knees, he stared steadfastly at the little man opposite to him, who immediately imitated him. And there they knelt with equal wonder in each of their countenances, bobbing at each other every time the lady winked. Then did Ting-a-ling get very red in the face, and, standing erect, he took strong hold of the Princess's upper eyelash, to steady himself, resolved upon giving that saucy fairy a good kick, when, to his dismay, the eyelash came out, he lost his balance, and at the same moment a fresh shower of tears burst from her eyes, which washed Ting-a-ling senseless into her lap.

When he recovered, he was still sticking to the Princess's silk apron, all unobserved, as she sat in her own room talking to one of her maids, who had just returned from a long visit into the country. Slipping down to the floor, Ting-a-ling ran all shivering to the window, to the seat of which he climbed, and getting upon a chrysanthemum that was growing in a flower-pot in the sunshine, he took off his shoes and stockings, and, hanging them on a branch to dry, laid down in the warm blossom; and while he was drying, listened to the mournful tale that Aufalia was telling her maid, about the poor Prince that was to die to-morrow. The more he heard, the more was his tender heart touched with pity, and, forgetting all his resentment against the Princess, he felt only the deepest sympathy for her misfortunes, and those of her lover. When she had finished, Ting-a-ling had resolved to assist them, or die in the attempt!

But, as he could not do much himself, he intended instantly to lay their case before a Giant of his acquaintance, whose good-humor and benevolence were proverbial. So he put on his shoes and stockings, which were not quite dry, and hastily descended to the garden by means of a vine which grew upon the wall. The distance to the Giant's castle was too great for him to think of walking; and he hurried around to a friend of his who kept a livery-stable. When he reached this place, he found his friend sitting in his stable-door, and behind him Ting-a-ling could see the long rows of stalls, with all the butterflies on one side, and the grasshoppers on the other.

"How do you do?" said Ting-a-ling, seating himself upon a horse-block, and wiping his face. "It is a hot day, isn't it?"

"Yes, sir," said the livery-stable man, who was rounder and shorter than Ting-a-ling. "Yes, it is very warm. I haven't been out to-day."

"Well, I shouldn't advise you to go," said Ting-a-ling. "But I must to business, for I'm in a great hurry. Have you a fast butterfly that you can let me have right away?"

"O yes, two or three of them, for that matter."

"Have you that one," asked Ting-a-ling, "that I used to take out last summer?"

"That animal," said the livery-stable man, rising and clasping his hands under his coat-tail, "I am sorry to say, you can't have. He's foundered."

"That's bad," said Ting-a-ling, "for I always liked him."

"I can let you have one just as fast," said the stable-keeper. "By the way, how would you like a real good grasshopper?"

"Too hot a day for the saddle," said Ting-a-ling; "and now please harness up, for I'm in a dreadful hurry."

"Yes, sir, right away. But I don't know exactly what wagon to give you. I have two first-rate new pea-pods; but they are both out. However, I can let you have a nice easy Johnny-jump-up, if you say so."

"Any thing will do," said Ting-a-ling, "only get it out quick."

In a very short time a butterfly was brought out, and harnessed to a first-class Johnny-jump-up. The vehicles used by these fairies were generally a cup-like blossom, or something of that nature, furnished, instead of wheels, with little bags filled with a gas resembling that used to inflate balloons. Thus the vehicle was sustained in the air, while the steed drew it rapidly along.

As soon as Ting-a-ling heard the sound of the approaching equipage, he stood upon the horse-block, and when the wagon was brought up to it, he quickly jumped in and took the reins from the hostler. "Get up!" said he, and away they went.

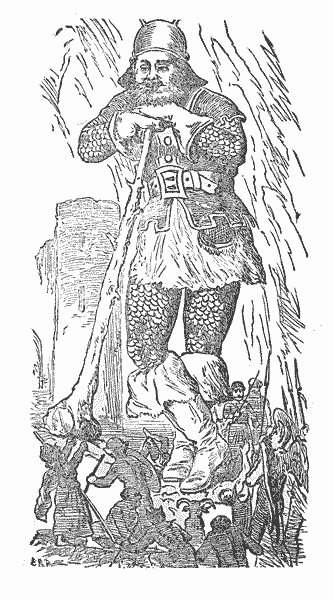

It was a long drive, and it was at least three in the afternoon when Ting-a-ling reached the Giant's castle. Drawing up before the great gates, he tied his animal to a hinge, and walked in himself under the gate. Going boldly into the hall, he went up-stairs, or rather he ran up the top rail of the banisters, for it would have been hard work for him to have clambered up each separate step. As he expected, he found the Giant (whose name I forgot to say was Tur-il-i-ra) in his dining-room. He had just finished his dinner, and was sitting in his arm-chair by the table, fast asleep. This Giant was about as large as two mammoths. It was useless for Ting-a-ling to stand on the floor, and endeavor to make himself heard above the roaring of the snoring, which sounded louder than the thunders of a cataract. So, climbing upon one of the Giant's boots, he ran up his leg, and hurried over the waistcoat so fast, that, slipping on one of the brass buttons, he came down upon his knees with great force.

"Whew!" said he, "that must have hurt him! after dinner too!"

Jumping up quickly, he ran easily over the bosom, and getting on his shoulder, clambered up into his ear. Standing up in the opening of this immense cavity, he took hold of one side with his outstretched arms, and shouted with all his might,—

"Tur-il-i! Tur-il-i! Tur-il-i-RA!"

Startled at the noise, the Giant clapped his hand to his ear with such force, that had not Ting-a-ling held on very tightly, he would have been shot up against the tympanum of this mighty man.

"Don't do that again!" cried the little fellow. "Don't do that again! It's only me—Ting-a-ling. Hold your finger."

Recognizing the voice of his young friend, the Giant held out his forefinger, and Ting-a-ling, mounting it, was carried round before the Giant's face, where he proceeded to relate the misfortunes of the two lovers, in his most polished and affecting style.

The Giant listened with much attention, and when he had done, said, "Ting-a-ling, I feel a great interest in all young people, and will do what I can for this truly unfortunate couple. But I must finish my nap first, otherwise I could not do anything. Please jump down on the table and eat something, while I go to sleep for a little while."

So saying, he put Ting-a-ling gently down upon the table. But this young gentleman, having a dainty appetite, did not see much that he thought he would like; but, cutting a grain of rice in two, he ate the half of it, and then laid down on a napkin and went to sleep.

When Tur-il-i-ra awoke, he remembered that it was time to be off, and, waking Ting-a-ling, he took out his great purse, and placed the little fairy in it, where he had very comfortable quarters, as there was no money there to hurt him.

"Don't forget my wagon when you get to the gate," said Ting-a-ling, sleepily, rolling himself up for a fresh nap, as the Giant closed the purse with a snap. Tur-il-i-ra, having put on his hat, went down-stairs, and crossed the court-yard in a very few steps. When he had closed the great gates after him, he bethought himself of Ting-a-ling's turn-out, which the fairy had mentioned as being tied to the hinge. Not being able to see anything so minute at the distance of his eyes from the ground, he put on his spectacles, and getting upon his hands and knees, peered closely about the hinges.

"O! here you are," said he, and, picking up the butterfly and wagon, he put them in his vest pocket—that is, all excepting the butterfly's head. That remained fast to the hinge, as the Giant forgot he was tied. Then our lofty friend set off at a smart pace for the King's castle; but notwithstanding his haste, it was dark when he reached it.

"Come now, young man," said he, opening his purse, "wake up, and let us get to work. Where is that Prince you were talking about?"

"Well, I'm sure I don't know," said Ting-a-ling, rubbing his eyes. "But just put me up to that window which has the vine growing beneath it. That is the Princess's room, and she can tell us all about it."

So the giant took him on his finger, and put him in the window. There, in the lighted room, Ting-a-ling beheld a sight which greatly moved him. Although she had slept but little the night before, the Princess was still up, and was sitting in an easy-chair, weeping profusely. Near her stood a maid-of-honor, who continually handed her fresh handkerchiefs from a great basketful by her side. As fast as the Princess was done with one, she threw it behind her, and the great pile there showed that she must have been weeping nearly all day. Getting down upon the floor, Ting-a-ling clambered up the Princess's dress, and reaching, at last, her ear, shouted into it,—

"Princess! Princess! Stop crying, for I'm come!"

The Princess was very much startled; but she did not, like the Giant, clap her hand to her ear, for if she had, she would have ruined the beautiful curls which stood out so nicely on each side. Ting-a-ling implored her to be quiet, and told her that the Giant had come to assist her, and that they wanted to know where the Prince was confined.

"I will tell you! I will show you!" cried the Princess quickly, and, jumping up, she ran to the window with Ting-a-ling still at her ear. "O you good giant," she cried, "are you there? If you will take me, I will show you the tower, the cruel tower, where my Prince is confined."

"Fear not!" said the good Giant. "Fear not I soon will release him. Let me take you in my hands, and do you show me where to go."

"Are you sure you can hold me?" said the Princess, standing timidly upon the edge of the window.

"I guess so," said the Giant. "Just get into my hands."

And, taking her down gently, he set her on his arm, and then he took Ting-a-ling from her hair, and placed him on the tip of his thumb. Thus they proceeded to the Tower of Tears.

"Here is the place," said the Princess. "Here is the horrid tower where my beloved is. Please put me down a minute, and let me cry."

"No, no," said the Giant; "you have done enough of that, my dear, and we have no time to spare. So, if this is your Prince's tower, just get in at the window, and tell him to come out quickly, and I will take you both away without making any fuss."

"That is the window—the fourth-story one. Lift me up," said the Princess.

But though the Giant was very large, he was not quite tall enough for this feat, for they built their towers very high in those days. So, putting Ting-a-ling and the Princess into his pocket, he looked around for something to stand on. Seeing a barn near by, he picked it up, and placed it underneath the window. He put his foot on it to try if it would bear him, and, finding it would (for in those times barns were very strong), he stood upon it, and looked in the fourth-story window. Taking his little friends out of his pocket, he put them on the window-sill, where Ting-a-ling remained to see what would happen, but the Princess jumped right down on the floor. As there was a lighted candle on the table, she saw that there was some one covered up in the bed.

"O, there he is!" said she. "Now I will wake him up, and hurry him away." But just at that moment, as she was going to give the sleeper a gentle shake, she happened to perceive the yellow boots sticking out from under the sheet.

"O dear!" said she in a low voice, "if he hasn't gone to bed with his boots on! And if I wake him, he will jump right down on the floor, and make a great noise, and we shall be found out."

So she went to the foot of the bed, and pulled off the boots very gently.

"White stockings!" said she. "What does this mean? I know the Prince wore green stockings, for I took particular notice how well they looked with his yellow boots. There must be something wrong, I declare! Let me run to the other end of the bed, and see how it is there. O my! O my!" cried she, turning down the sheet. "A woman's head! Wrong both ways! O what shall I do?"

Letting the sheet drop, she accidentally touched the head, which immediately rolled off on to the floor.

"Loose! Loose!! Loose!!!" she screamed in bitter agony, clasping her hands above her head. "What shall I ever do? O misery! misery me! Some demon has changed him, all but his boots. O Despair! Despair!"

And, without knowing what she did, she rushed frantically out of the room, and along the dark passage, and popped right down through the open trap.

"What's up?" said the Giant, putting his face to the window. "What's all this noise about?"

"O I don't know," said Ting-a-ling, almost crying, "but somebody's head is off; and it's a lady—all but the boots—and the Princess has run away! O dear! O dear!"

"Come now!" said Tur-il-i-ra, "Ting-a-ling, get into my pocket. I must see into this myself, for I can't be waiting here all night, you know."

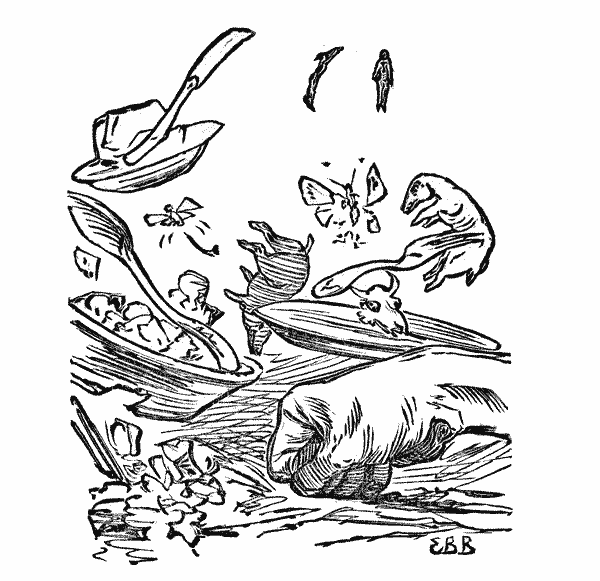

So the Giant, still standing on the barn, lifted off the roof of the tower, and threw it to some distance. He then, by the moonlight, examined the upper story, but, finding no Prince or Princess, brushed down the walls until he came to the floor, and, taking it up, he looked carefully over the next story. This he continued, until he had torn down the whole tower, and found no one but servants and guards, who ran away in all directions, like ants when you destroy their hills. He then kicked down all those walls which connected the tower with the rest of the palace, and, when it was all level with the ground, he happened to notice, almost at his feet, a circular opening like an entrance to a vault, from which arose a very pleasant smell as of something good to eat. Stooping down to see what it was that caused this agreeable perfume, he perceived that at the distance of a few yards the aperture terminated in a huge yellow substance, in which, upon a closer inspection, he saw four feet sticking up—two with slippers, and two with green stockings.

"Why, this is strange!" said he, and, stooping down, he felt the substance, and found it was quite soft and yielding. He then loosened it by passing his hand around it, and directly lifted it out almost entire.

"By the beard of the Prophet!" he cried, "but this is a cheese!" and, turning it over, he saw on the other side two heads, one with short black hair, and the other covered with beautiful brown curls.

"Why, here they are! As I'm a living Giant! these must be the Prince and Princess, stowed away in a cheese!" And he laughed until the very hills cracked.

When he got a little over his merriment, he asked the imprisoned couple how they got there, and if they felt comfortable. They replied that they had fallen down a trap, and had gone nearly through this cheese, where they had stuck fast, and that was all they had known about it; and if the blood did not run down into their heads so, they would be pretty comfortable, thank him—which last remark the Giant accounted for by the fact, that, when lovers are near each other, they do not generally pay much attention to surrounding circumstances.

"This, then," said he, rising, "is where the King hardens his cheeses, is it? Well, well, it's a jolly go!" And he laughed some more.

"O Tur-il-i-ra," cried Ting-a-ling, looking out from the vest-pocket, "I'm so glad you've found them."

"Well, so am I," said the Giant.

Then Tur-il-i-ra, still holding the cheese, walked away for a little distance, and sat down on a high bank, intending to wait there until morning, when he would call on the King, and confer with him in relation to his new-found treasure. Leaning against a great rock, the Giant put the cheese upon his knees in such a manner as not to injure the heads and feet of the lovers, and dropped into a very comfortable sleep.

"Don't I wish I could get my arms out!" whispered the Prince.

"O my!" whispered the Princess.

Ting-a-ling, having now nothing to occupy his mind, and desiring to stretch his legs, got out of the vest-pocket where he had remained so safely during all the disturbance, and descended to the ground to take a little walk. He had not gone far before he met a young friend, who was running along as fast as he could.

"Hallo! Ting-a-ling," cried the other. "Is that you? Come with me, and I will show you the funniest thing you ever saw in your life."

"Is it far?" said Ting-a-ling, "for I must be back here by daylight."

"O no! come on. It won't take you long, and I tell you, it's fun!"

So away they ran, merrily vaulting over the hickory-nuts, or acorns, that happened to be in their way, in mere playfulness, as if they were nothing. They soon came to a large, open space, so brightly lighted by the moon, that every object was as visible as if it were daylight. Scattered over the smooth green were thousands of fairies of Ting-a-ling's nation, the most of whom were standing gazing intently at a very wonderful sight.

Seated on a stone, under a great tree that stood all alone in the centre of this plain, was a woman without any head. She moved her hands rapidly about over her shoulders, as if in search of the missing portion of herself, and, encountering nothing but mere air, she got very angry, and stamped her feet, and shrugged her shoulders, which amused the fairies very much, and they all set up a great laugh, and seemed to be enjoying the fun amazingly. On one side, down by a little brook, was a busy crowd of fairies, who appeared to be washing something therein. Scattered all around were portions of the Tower of Tears, much of which had fallen hereabouts.

Ting-a-ling and his friend had not gazed long upon this scene before the sound of music was heard, and in a few moments there appeared from out the woods a gorgeous procession. First came a large band of music, ringing blue-bells and blowing honeysuckles. Then came an array of courtiers, magnificently dressed; and, after them, the Queen of the fairies, riding in a beautiful water-lily, drawn by six royal purple butterflies, and surrounded by a brilliant body of lords and ladies.

This procession halted at a short distance in front of the lady-minus-a-head, and formed itself into a semicircle, with the Queen in the centre. Then the crowd at the brook were seen approaching, and on the shoulders of the multitude was borne a head. They hurried as fast as their heavy load would permit, until they came to the tree under which sat the headless Nerralina, who, bed and all, had fallen here, when the Giant tore down the tower. Then quickly attaching a long rope (that they had put over a branch directly above the lady) to the hair of the head, they all took hold of the other end, and, pulling with a will, soon hoisted the head up until it hung at some distance above the neck to which it had previously belonged. Now they began to lower it slowly, and the Queen stood up with her wand raised ready to utter the magic word which should unite the parts when they touched. A deep silence spread over the plain, and even the lady seemed conscious that something was about to happen, for she stood up and remained perfectly still.

There was but one person there who did not feel pleasure at the approaching event, and that was a dwarf about a foot high, very ugly and wicked, who, by some means or other, had got into this goodly company, and who was now seated in a crotch of the tree, very close to the rope by which the crowd was lowering the lady's head. No one perceived him, for he was very much the color of the tree, and there he sat alone, quivering with spite and malice.

At the moment the head touched the ivory neck, the Queen, uttering the magic word, dropped the end of the wand, and immediately the head adhered as firmly as of old.

But a wild shout of horror rang through all the plain! For, at the critical moment, the dwarf had reached out his hand, and twisted the rope, so that when the head was joined, it was wrong side foremost—face back!

Just then the little villain stuck his head out from behind the branch, and, giving a loud and mocking laugh of triumph, dropped from the tree. With a yell of anger the whole crowd, Queen, courtiers, common people, and all, set off in a mad chase after the dwarf, who fled like a stag before the hounds.

All were gone but little Ting-a-ling, and when he saw the dreadful distress of poor Nerralina, who jumped up, and twisted around, and ran backward both ways, screaming for help, he stopped not a minute, but ran to where he had left the Giant, and told him, as fast as his breathing would allow, the sad story.

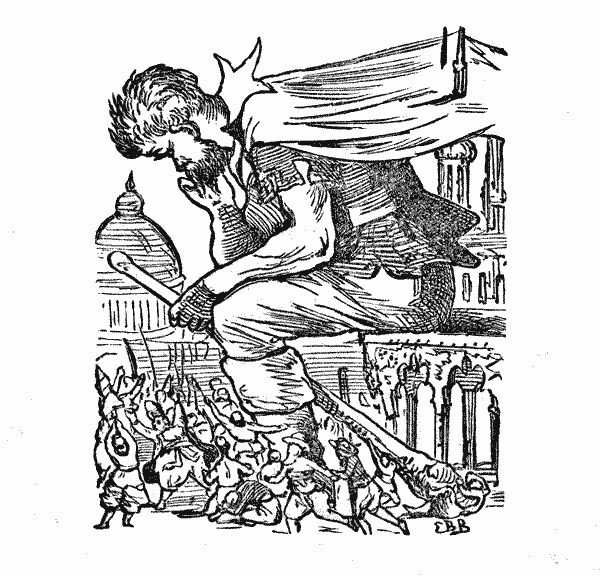

Rubbing his eyes, Tur-il-i-ra perceived that it was nearly day, and concluded to commence operations. He placed Ting-a-ling on his shirt-frill, where he could see what was going on, and, taking about eleven strides, he came to where poor Nerralina was jumping about, and, picking her up, put her carefully into his coat-tail pocket. Then, with the cheese in his hand, he walked slowly toward the palace.

When he arrived there, he found the people running about, and crowding around the ruins of the Tower of Tears. He passed on, however, to the great Audience Chamber, and, looking in, saw the King sitting upon his throne behind a velvet-covered table, holding an early morning council, and receiving the reports of his officers concerning the damage. As this Hall, and the doors thereof, were of great size, the Giant walked in, stooping a little as he entered.

He marched right up to the King, and held the cheese down before him.

"Here, your Majesty, is your daughter, and the young Prince, her lover. Does your Majesty recognize them?"

"Well, I declare!" cried the King. "If that isn't my great cheese, that I had put in the vault-flue to harden! And my daughter and that young man in it! What does this mean? What have you been doing, Giant?"

Then Tur-il-i-ra related the substance of the whole affair in a very brief manner, and concluded by saying that he hoped to see them made man and wife, as he considered them under his protection, and intended to see them safely through this affair. And he held them up so that all the people who thronged into the Hall could see.

The people all laughed, but the King cried "Silence!" and said to the Giant, "If the young man is of as good blood as my daughter, I have no desire to separate them. In fact, I don't think I am separating them. I think it's the cheese!"

"Come! come!" said the Giant, turning very red in the face, "none of your trifling, or I'll knock your house down over your eyes!"

And, putting the cheese down close to the table, he broke it in half, letting the lovers drop out on the velvet covering, when they immediately rushed into each other's arms, and remained thus clasped for a length of time.

They then slowly relinquished their hold upon each other, and were exchanging looks of supreme tenderness, when the Prince, happening to glance at his feet, sprang back so that he almost fell off the long table, and shouted,—

"Blood! Fire! Thunder! Where's my boots? Boots! Slaves! Hounds! Get me my boots! boots!! boots!!!"

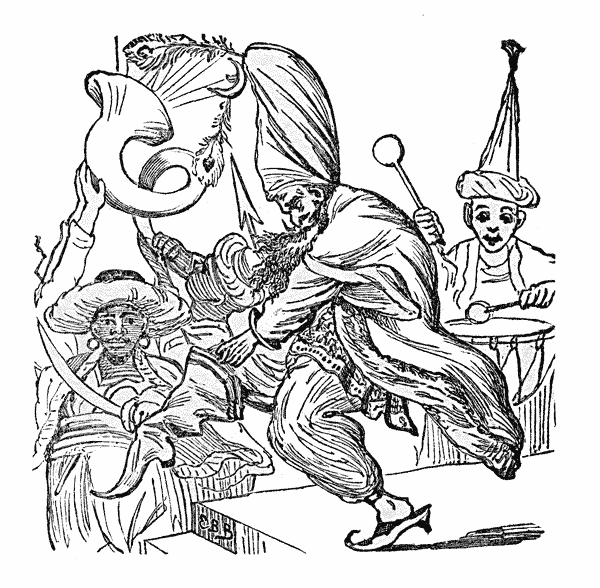

"O! he's a Prince!" cried the King, jumping up. "I want no further proof. He's a Prince. Give him boots. And blow, horners, blow! Beat your drums, drummers! Join hands all! Clear the floor for a dance!"

And in a trice the floor was cleared, and about five thousand couples stood ready for the first note from the band.

"Hold up!" cried the Giant. "Hold up! here is one I forgot," and he commenced feeling in his pockets. "I know I have got her somewhere. O yes, here she is!" and taking the Lady Nerralina from his coat-tail pocket, he put her carefully upon the table.

Every face in the room was in an instant the picture of horror,—all but that of the little girl whose duty it was to fasten Nerralina's dress every morning,—who got behind the door, and jumping up, and clapping her hands and heels, exclaimed, "Good! good! Now she can see to fasten her own frock behind!"

The Prince was the first to move, and, with tears in his eyes, he approached the luckless lady, who was sobbing piteously.

"Poor thing!" said he, and, putting his arm around her, he kissed her. What joy thrilled through Nerralina! She had never been kissed by a man before, and it did for her what such things have done for many a young lady since—it turned her head!

"Blow, horners, blow!" shouted the King. "Join hands all!"

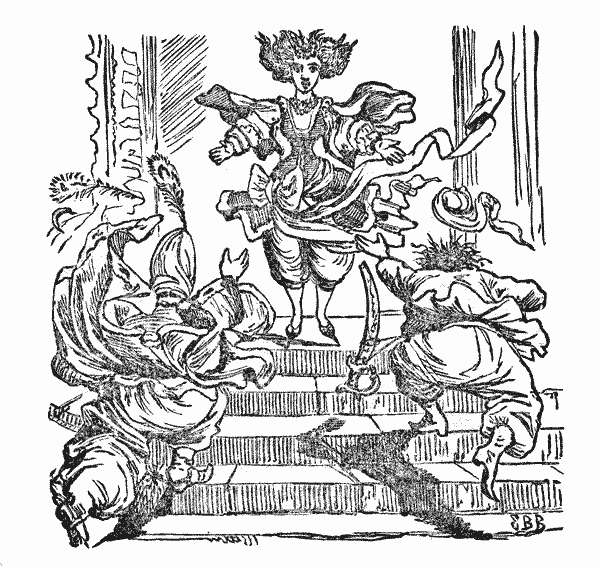

Seizing Nerralina's hand, and followed by the Prince and Princess, who sprang from the table, he led off the five thousand couples in a grand gallopade.

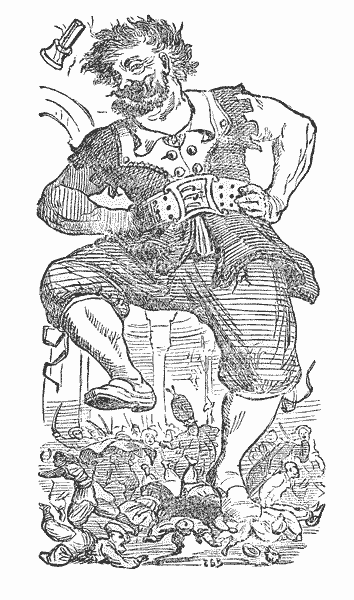

The Giant stood, and laughed heartily, until, at last, being no longer able to restrain himself, he sprang into the midst of them, and danced away royally, trampling about twenty couples under foot at every jump.

"Dance away, old fellow!" shouted the King, from the other end of the room. "Dance away, my boy, and never mind the people."

And the music blew louder, and round they all went faster and faster, until the building shook and trembled from the cellar to the roof.

At length, perfectly exhausted, they all stopped, and Ting-a-ling, slipping down from the Giant's frill, went out of the door.

"O!" said he, wiping the tears of laughter from his eyes, "it was all so funny, and every body was so happy—that—that I almost forgot my bereavement."

Ting-a-ling, for some weeks after the death of his young companion, Ling-a-ting, seemed quite sad and dejected. He spent nearly all his time lying in a half-opened rose-bud, and thinking of the dear little creature who was gone. But one morning, the bud having become a full-blown rose, its petals fell apart, and dropped little Ting-a-ling out on the grass. The sudden fall did not hurt him, but it roused him to exertion, and he said, "O ho! This will never do. I will go up to the palace, and see if there is anything going on." So off he went to the great palace; and sure enough something was going on. He had scarcely reached the court-yard, when the bells began to ring, the horns to blow, the drums to beat, and crowds of people to shout and run in every direction, and there was never such a noise and hubbub before.

Ting-a-ling slipped along close to the wall, so that he would not be stepped on by anybody; and having reached the palace, he climbed up a long trailing vine, into one of the lower windows. There he saw the vast audience-chamber filled with people, shouting, and calling, and talking, all at once. The grand vizier was on the wide platform of the throne, making a speech, but the uproar was so great that not one word of it could Ting-a-ling hear. The King himself was by his throne, putting on the bulky boots, which he only wore when he went to battle, and which made him look so terrible that a person could hardly see him without trembling. The last time that he had worn those boots, as Ting-a-ling very well knew, he had made war on a neighboring country, and had defeated all the armies, killed all the people, torn down all the towns and cities, and every house and cottage, and ploughed up the whole country, and sowed it with thistles, so that it could never be used as a country any more. So Ting-a-ling thought that as the King was putting on his war boots, something very great was surely about to happen. Hearing a fizzing noise behind him, he turned around, and there was the Prince in the court-yard, grinding his sword on a grindstone, which was turned by two slaves, who were working away so hard and fast that they were nearly ready to drop. Then he knew that wonderful things were surely coming to pass, for in ordinary times the Prince never lifted his finger to do anything for himself.

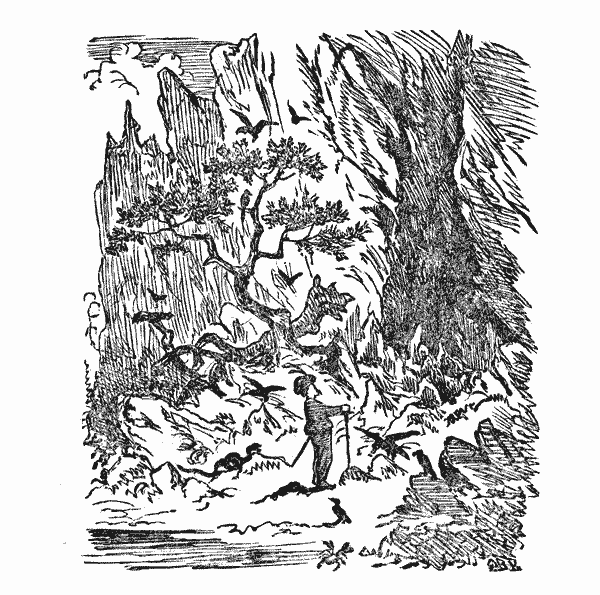

Just then, a little page, who had been sent for the King's spurs, and couldn't find them, and who was therefore afraid to go back, stopped to rest himself for a minute against the window where Ting-a-ling was standing. As his head just reached a little above the window-seat, Ting-a-ling went close to his ear and shouted to him, to please tell him what was the matter. The page started at first, but, seeing it was only a little fairy, he told him that the Princess was lost, and that the whole army was going out to find her. Before he could say anything more, the King was heard to roar for his spurs, and away ran the little page, whether to look again for the spurs, or to hide himself, is not known at the present day. Ting-a-ling now became very much excited. The Princess Aufalia, who had been married to the Prince but a month ago, was very dear to him, and he felt that he must do something for her. But while he was thinking what this something might possibly be, he heard the clear and distinct sound of a tiny bell, which, however, no one but a fairy could possibly have heard above all that noise. He knew it was the bell of the fairy Queen, summoning her subjects to her presence; and in a moment he slid down the vine, and scampered away to the gardens. There, although the sun was shining brightly, and the fairies seldom assembled but by night, there were great crowds of them, all listening to the Queen, and keeping much better order than the people in the King's palace. The Queen addressed them in soul-stirring strains, and urged every one to do their best to find the missing Princess. In the night she had been taken away, while the Prince and everybody were asleep. "And now," said the Queen, untying her scarf, and holding it up, "away with you, every one! Search every house, garden, mountain, and plain, in the land, and the first one who comes to me with news of the Princess Aufalia, shall wear my scarf!" And, as this was a mark of high distinction, and conveyed privileges of which there is no time now to tell, the fairies gave a great cheer (which would have sounded to you, had you heard it, like a puff of wind through a thicket of reeds), and they all rushed away in every direction. Now, though the fairies of this tribe could go almost anywhere, through small cracks and key-holes, under doors, and into places where no one else could possibly penetrate, they did not fly, or float in the air, or anything of that sort. When they wished to travel fast or far, they would mount on butterflies and all sorts of insects; but they seldom needed such assistance, as they were not in the habit of going far from their homes in the palace gardens. Ting-a-ling ran, as fast as he could, to where a friend of his, whom we have mentioned before kept grasshoppers and butterflies to hire; but he found he was too late,—every one of them was taken by the fairies who had got there before him. "Never mind," said Ting-a-ling to himself, "I'll catch a wild one;" and, borrowing a bridle, he went out into the meadows, to catch a grasshopper for himself. He soon perceived one, quietly feeding under a clover-blossom. Ting-a-ling slipped up softly behind him; but the grasshopper heard him, and rolled his big eyes backward, drawing in his hind-legs in the way which all boys know so well. "What's the good of his seeing all around him?" thought Ting-a-ling; but there is no doubt that the grasshopper thought there was a great deal of good in it, for, just as Ting-a-ling made a rush at him, he let fly with one of his hind-legs, and kicked our little friend so high into the air, that he thought he was never coming down again. He landed, however, harmlessly on the grass on the other side of a fence. Nothing discouraged, he jumped up, with his bridle still in his hand, and looked around for the grasshopper. There he was, with his eyes still rolled back, and his leg ready for another kick, should Ting-a-ling approach him again. But the little fellow had had enough of those strong legs, and so he slipped along the fence, and, getting through it, stole around in front of the grasshopper; and, while he was still looking backward with all his eyes, Ting-a-ling stepped quietly up before him, and slipped the bridle over his head! It was of no use for the grasshopper to struggle and pull back, for Ting-a-ling was astraddle of him in a moment, kicking him with his heels, and shouting "Hi! Hi!"

Away sprang the grasshopper like a bird, and he sped on and on, faster than he had ever gone before in his life, and Ting-a-ling waved his little sword over his head, and shouted "Hi! Hi!"

So on they went for a long time; and in the afternoon the grasshopper began to get very tired, and did not make anything like such long jumps as he had done at first. They were going down a grassy hill, and had just reached the bottom, when Ting-a-ling heard some one calling him. Looking around him in astonishment, he saw that it was a little fairy of his acquaintance, younger than himself, named Parsley, who was sitting in the shade of a wide-spreading dandelion.

"Hello, Parsley!" cried Ting-a-ling, reining up. "What are you doing there?"

"Why you see, Ting-a-ling," said the other, "I came out to look for the Princess."—

"You!" cried Ting-a-ling; "a little fellow like you!"

"Yes, I!" said Parsley; "and Sourgrass and I rode the same butterfly; but by the time we had come this far, we got too heavy, and Sourgrass made me get off."

"And what are you going to do now?" said Ting-a-ling.

"O, I'm all right!" replied Parsley. "I shall have a butterfly of my own soon."

"How's that?" asked Ting-a-ling, quite curious to know.

"Come here!" said Parsley; and so Ting-a-ling got off his grasshopper, and led it up close to his friend. "See what I've found!" said Parsley, showing a cocoon that lay beside him. "I'm going to wait till this butterfly's hatched, and I shall have him the minute he comes out."

The idea of waiting for the butterfly to be hatched, seemed so funny to Ting-a-ling, that he burst out laughing, and Parsley laughed too, and so did the grasshopper, for he took this opportunity to slip his head out of the bridle, and away he went!

Ting-a-ling turned and gazed in amazement at the grasshopper skipping up the hill; and Parsley, when he had done laughing, advised him to hunt around for another cocoon, and follow his example.

Ting-a-ling did not reply to this advice, but throwing his bridle to Parsley, said, "There, you would better take that. You may want it when your butterfly's hatched. I shall push on."

"What! walk?" cried Parsley.

"Yes, walk," said Ting-a-ling. "Good-by."

So Ting-a-ling travelled on by himself for the rest of the day, and it was nearly evening when he came to a wide brook with beautiful green banks, and overhanging trees. Here he sat down to rest himself; and while he was wondering if it would be a good thing for him to try to get across, he amused himself by watching the sports and antics of various insects and fishes that were enjoying themselves that fine summer evening. Plenty of butterflies and dragon-flies were there, but Ting-a-ling knew that he could never catch one of them, for they were nearly all the time over the surface of the water; and many a big fish was watching them from below, hoping that in their giddy flights, some of them would come near enough to be snapped down for supper. There were spiders, who shot over the surface of the brook as if they had been skating; and all sorts of beautiful bugs and flies were there,—green, yellow, emerald, gold, and black. At a short distance, Ting-a-ling saw a crowd of little minnows, who had caught a young tadpole, and, having tied a bluebell to his tail, were now chasing the affrighted creature about. But after a while the tadpole's mother came out, and then the minnows caught it!

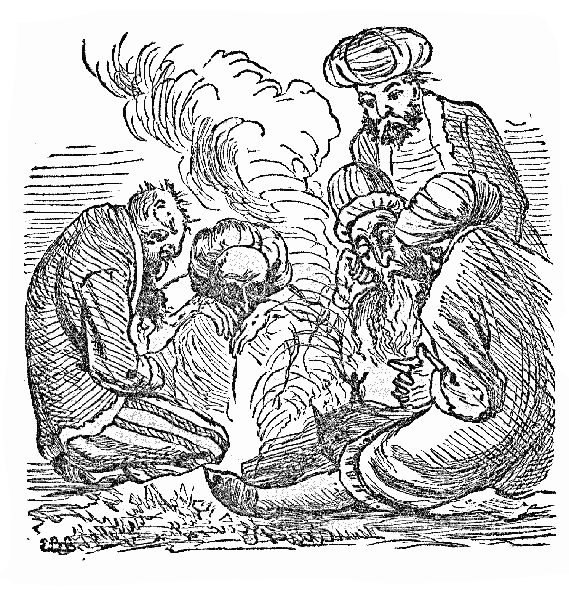

While watching all these lively creatures, Ting-a-ling fell asleep, and when he awoke, it was dark night. He jumped up, and looked about him. The butterflies and dragon-flies had all gone to bed, and now the great night-bugs and buzzing beetles were out; the katydids were chirping in the trees, and the frogs were croaking among the long reeds. Not far off, on the same side of the brook, Ting-a-ling saw the light of a fire, and so he walked over to see what it meant. On his way, he came across some wild honeysuckles, and, pulling one of the blossoms, he sucked out the sweet juice for his supper, as he walked along. When he reached the fire, he saw sitting around it five men, with turbans and great black beards. Ting-a-ling instantly perceived that they were magicians, and, putting the honeysuckle to his lips, he blew a little tune upon it, which the magicians hearing, they said to one another, "There is a fairy near us." Then Ting-a-ling came into the midst of them, and, climbing up on a pile of cloaks and shawls, conversed with them; and he soon heard that they knew, by means of their magical arts, that the Princess had been stolen the night before, by the slaves of a wicked dwarf, and that she was now locked up in his castle, which was on top of a high mountain, not far from where they then were.

"I shall go there right off," said Ting-a-ling.

"And what will you do when you get there?" said the youngest magician, whose name was Zamcar. "This dwarf is a terrible little fellow, and the same one who twisted poor Nerralina's head, which circumstance of course you remember. He has numbers of fierce slaves, and a great castle. You are a good little fellow, but I don't think you could do much for the Princess, if you did go to her."

Ting-a-ling reflected a moment, and then said that he would go to his friend, the Giant Tur-il-i-ra; but Zamcar told him that that tremendous individual had gone to the uttermost limits of China, to launch a ship. It was such a big one, and so heavy, that it had sunk down into the earth as tight as if it had grown there, and all the men and horses in the country could not move it. So there was nothing to do but to send for Tur-il-i-ra. When Ting-a-ling heard this, he was disheartened, and hung his little head. "The best thing to do," remarked Alcahazar, the oldest of the magicians, "would be to inform the King and his army of the place where the Princess is confined, and let them go and take her out."

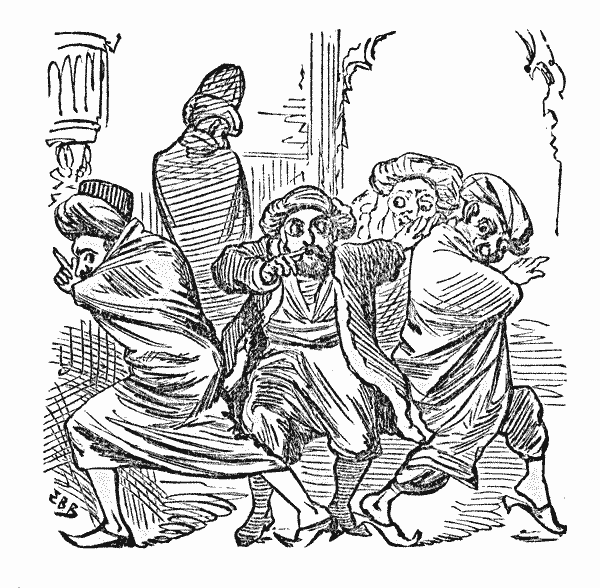

"O no!" cried Ting-a-ling, who, if his body was no larger than a very small pea-pod, had a soul as big as a water-melon. "If the King knows it, up he will come with all his drums and horns, and the dwarf will hear him a mile off and either kill the Princess, or hide her away. If we were all to go to the castle, I should think we could do something ourselves." This was the longest speech that Ting-a-ling had ever made; and when he was through, the youngest magician said to the others that he thought it was growing cooler, and the others agreed that it was. After some conversation among themselves in an exceedingly foreign tongue, these kind magicians agreed to go up to the castle, and see what they could do. So Zamcar put Ting-a-ling in the folds of his turban, and the whole party started off for the dwarf's castle. They looked like a company of travelling merchants, each one having a package on his back and a great staff in his hand. When they reached the outer gate of the castle, Alcahazar, the oldest, knocked at it with his stick, and it was opened at once by a shiny black slave, who, coming out, shut it behind him, and inquired what the travellers wanted.

"Is your master within?" asked Alcahazar.

"I don't know," said the slave.

"Can't you find out?" asked the magician.

"Well, good merchant, perhaps I might; but I don't particularly want to know," said the slave, as he leaned back against the gate, leisurely striking with his long sword at the night-bugs and beetles that were buzzing about.

"My friend," said Alcahazar, "don't you think that is rather a careless way of using a sword? You might cut somebody."

"That's true," said the slave. "I didn't think of it before;" but he kept on striking away, all the same.

"Then stop it!" said Alcahazar, the oldest magician, striking the sword from his hand with one blow of his staff. Upon this, up stepped Ormanduz, the next oldest, and whacked the slave over his head; and then Mahallah, the next oldest, struck him over the shoulders; and Akbeck, the next oldest, cracked him on the shins; and Zamcar, the youngest, punched him in the stomach; and the slave sat down, and begged the noble merchants to please stop. So they stopped, and he humbly informed them that his master was in.

"We would see him," said Alcahazar.

"But, sirs," said the slave, "he is having a grand feast."

"Well," said the magician, "we're invited."

"O noble merchants!" cried the slave, "why did you not tell me that before?" and he opened wide the gate, and let them in. After they had passed the outer gate, which was of wood, they went through another of iron, and another of brass, and another of copper, and then walked through the court-yard, filled with armed slaves, and up the great castle steps; at the top of which stood the butler, dressed in gorgeous array.

"Whom have you here, base slave?" cried the gorgeous butler.

"Five noble merchants, invited to my lord's feast," said the slave, bowing to the ground.

"But they cannot enter the banqueting hall in such garbs," said the butler. "They cannot be noble merchants, if they come not nobly dressed to my lord's feast."

"O sir!" said Alcahazar, "may your delicate and far-reaching understanding be written in books, and taught to youth in foreign lands, and may your profound judgment ever overawe your country! But allow us now to tell you that we have gorgeous dresses in these our packs. Would we soil them with the dust of travel, ere we entered the halls of my lord the dwarf?"

The butler bowed low at this address, and caused the five magicians to be conducted to five magnificent chambers, where were slaves, and lights, and baths, and soap, and towels, and wash-rags, and tooth-brushes; and each magician took a gorgeous dress from his pack, and put it on, and then they were all conducted (with Ting-a-ling still in Zamcar's turban) to the grand hall, where the feast was being held. Here they found the dwarf and his guests, numbering a hundred, having a truly jolly time. The dwarf, who was dressed in white (to make him look larger), was seated on a high red velvet cushion at the end of the hall, and the company sat cross-legged on rugs, in a great circle before him. He was drinking out of a huge bottle nearly as big as himself, and eating little birds; and judging by the bones that were left, he must have eaten nearly a whole flock of them. When he saw the five magicians entering, he stopped eating, and opened his eyes in amazement, and then shouted to his servants to tell him who these people were, who came without permission to his feast; but as no one knew, nobody answered. The guests, seeing the stately demeanor and magnificent dresses of the visitors, thought that they were at least five great monarchs.

"My lord the dwarf," said Alcahazar, advancing toward him, "I am the king of a far country; and passing your castle, and hearing of your feast, I have made bold to come and offer you some of the sweet-tasting birds of my kingdom." So saying, he lifted up his richly embroidered cloak, and took from under it a great silver dish containing about two hundred dozen hot, smoking, delicately cooked, fat little birds. Under the dish were fastened lamps of perfumed oil, all lighted, and keeping the savory food nice and hot. Making a low bow, the magician placed the dish before the dwarf, who tasted one of the birds, and immediately clapped his hands with joy. "Great King!" he cried, "welcome to my feast! Slaves, quick! make room for the great king!" As there was no vacant place, the slaves took hold of one of the guests, and gave him what the boys would call a "hist," right through the window, and Alcahazar took his place. Then stepped forward Ormanduz, and said, "My lord the dwarf, I am also the king of a far country, and I have made bold to offer you some of the wine of my kingdom." So saying, he lifted his gold-lined cloak, and took from beneath it a crystal decanter, covered with gold and ruby ornaments, with one hundred and one beautifully carved silver goblets hanging from its neck, and which contained about eleven gallons of the most delicious wine. He placed it before the dwarf, who, having tasted the wine, gave a great cheer, and shouted to his slaves to make room for this mighty king. So the slaves took another guest by the neck and heels, and sent him, slam-bang, through the window, and Ormanduz took his place. Then stepped forward Mahallah, and said, "My lord the dwarf, I am also the king of a far country, and I bring you a sample of the venison of my kingdom." So saying, he raised his velvet cloak, trimmed with diamonds, and took from under it a whole deer, already cooked, and stuffed with oysters, anchovies, buttered toast, olives, tamarind seeds, sweet-marjoram, sage, and many other herbs and spices, and all piping hot, and smelling deliciously. This he put down before the dwarf, who, when he had tasted it, waved his goblet over his head, and cried out to the slaves to make room for this mighty king. So the slaves seized another guest, and out of the window, like a shot, he went, and Mahallah took his place. Then Akbeck stepped up, and said, "My lord the dwarf, I am also the king of a far country, and I bring you some of the confections of my dominions." So saying, he took from under his cloak of gold cloth, a great basket of silver filagree work, in which were cream-chocolates, and burnt almonds, and sponge-cake, and lady's fingers, and mixtures, and gingernuts, and hoar-hound candy, and gum-drops, and fruit-cake, and cream candy, and mintstick, and pound-cake, and rock candy, and butter taffy, and many other confections, amounting in all to about two hundred and twenty pounds. He placed the basket before the dwarf, who tasted some of these good things, and found them so delicious, that he lay on his back and kicked up his heels in delight, shouting to his slaves to make room for this great king. As the next guest was a big, fat man, too heavy to throw far, he was seized by four slaves, who walked him Spanish right out of the door, and Akbeck took his place. Then Zamcar stepped forward and said, "My lord the dwarf, I also am king of a far country, and I bring you some of the fruit of my dominions." And so saying, he took from beneath his gold and purple cloak, a great basket filled with currants as big as grapes, and grapes as big as plums, and plums as big as peaches, and peaches as big as cantaloupes, and cantaloupes as big as water-melons, and water-melons as big as barrels. There were about nineteen bushels of them altogether, and he put them before the dwarf, who, having tasted some of them, clapped his hands, and shouted to his slaves to make room for this mighty king; but as the next guest had very sensibly got up and gone out, Zamcar took his seat without any delay. Then Ting-a-ling, who was very much excited by all these wonderful performances, slipped down out of Zamcar's turban, and, running up towards the dwarf, cried out, "My lord the dwarf, I am also the king of a far country, and I bring you"—and he lifted up his little cloak; but as there was nothing there, he said no more, but clambered up into Zamcar's turban again. As nobody noticed or heard him, so great was the bustle and noise of the festivity, his speech made no difference one way or the other. After everybody had eaten and drunk until they could eat and drink no more, the dwarf jumped up and called to the chief butler, to know how many beds were prepared for the guests; to which the butler answered that there were thirty beds prepared. "Then," said the dwarf, "give these five noble kings each one of the best rooms, with a down bed, and a silken comfortable; and give the other beds to the twenty-five biggest guests. As to the rest, turn them out!" So the dwarf went to bed, and each of the magicians had a splendid room, and twenty-five of the biggest guests had beds, and the rest were all turned out. As it was pouring down rain, and freezing, and cold, and wet, and slippery (for the weather was very unsettled on this mountain), and all these guests, who now found themselves outside of the castle gates, lived many miles away, and as none of them had any hats, or knew the way home, they were very miserable indeed.

Alcahazar did not go to bed, but sat in his room and reflected. He saw that the dwarf had given this feast on account of his joy at having captured the Princess, and thus caused grief to the King and Prince, and all the people; but it was also evident that he was very sly, and had not mentioned the matter to any of the company. The other magicians did not go to bed either, but sat in their rooms, and thought the same thing; and Ting-a-ling, in Zamcar's turban, was of exactly the same opinion. So, in about an hour, when all was still, the magicians got up, and went softly over the castle. One went down into the lower rooms, and there were all the slaves, fast asleep; and another into one wing of the castle, and there were half the guests, fast asleep; and another into the other wing, and there were the rest of the guests, fast asleep; and Alcahazar went into the dwarf's room, in the centre of the castle, and there was he, fast asleep, with one of his fists shut tight. The magician touched his fist with his magic staff, and it immediately opened, and there was a key! So Alcahazar took the key, and shut up the dwarf's hand again. Zamcar went up to the floor, near the top of the house, and entered a large room, which was empty, but the walls were hung with curtains made of snakes' skins, beautifully woven together. Ting-a-ling slipped down to the floor, and, peeping behind these curtains, saw the hinge of a door; and without saying a word, he got behind the curtain; and, sure enough, there was a door! and there was a key-hole! and in a minute, there was Ting-a-ling right through it! and there was the Princess in a chair in the middle of a great room, crying as if her heart would break! By the light of the moon, which had now broken through the clouds, Ting-a-ling saw that she was tied fast to the chair. So he climbed up on her shoulder, and called her by name; and when the Princess heard him and knew him, she took him into her lovely hands, and kissed him, and cried over him, and laughed over him so much, that her joy had like to have been the death of him. When she got over her excitement, she told him how she had been stolen away; how she had heard her favorite cat squeak in the middle of the night, and how she had got up quickly to go to it, supposing it had been squeezed in some door, and how the wicked dwarf, who had been imitating the cat, was just outside the door with his slaves; and how they had seized her, and bound her, and carried her off to this castle, without waking up any of the King's household. Then Ting-a-ling told her that his five friends were there, and that they were going to see what they could do; and the Princess was very glad to hear that, you may be sure. Then Ting-a-ling slipped down to the floor, and through the key-hole; and as he entered the room where he had left Zamcar, in came Alcahazar with the key and the other magicians with news that everybody was asleep. When Ting-a-ling had told about the Princess, Alcahazar pushed aside the curtains, unlocked the door with the key, and they all entered the next room.

There, sure enough, was the Princess Aufalia; but, right in front of her, on the floor, squatted the dwarf, who had missed his key, and had slipped up by a back way! The magicians started back on seeing him; the Princess was crying bitterly, and Ting-a-ling ran past the dwarf (who was laughing too horribly to notice him), and climbing upon the Princess's shoulder, sat there among her curls, and did his best to comfort her.

"Anyway," said he, "I shall not leave you again," and he drew his little sword, and felt as big as a house. The magicians now advanced towards the dwarf; but he, it seems, was a bit of a magician himself, for he waved a little wand, and instantly a strong partition of iron wire rose up out of the floor, and, reaching from one wall to the other, separated him completely from the five men. The magicians no sooner saw this, than they cried out, "O ho! Mr. Dwarf, is that your game?"

"Yes," said the little wretch, chuckling; "can you play at it?"

"A little," said they; and each one pulled from under his cloak a long file; and filing the partition from the wall on each side, which only needed a few strokes from their sharp files, they pulled it entirely down. But before the magicians could reach him, the dwarf again waved his wand, and a great chasm opened in the floor before them, which was too wide to jump over, and so deep that the bottom could not be seen.

"O ho!" cried the magicians; "another game, eh!"

"Yes indeed," cried the dwarf. "Just let me see you play at that."

Each of the magicians then took from under his magic cloak a long board, and, putting them over the chasm, they began to walk across them. But the dwarf jumped up and waved his wand, and water commenced to fall on the boards, where it immediately froze; and they were so slippery, that the magicians could hardly keep their feet, and could not make one step forward. Even standing still, they came very near falling off into the chasm below. "I suppose you can play at that," said the dwarf; and the magicians replied.

"O yes!" and each one took from under his cloak a pan of ashes, and sprinkled the boards, and walked right over. But before they reached the other edge, the dwarf pushed the chair, which was on rollers, up against the wall behind him, which opened; and instantly the Princess, Ting-a-ling, and the dwarf disappeared, and the wall closed up. Without saying a word, the magicians each drew from beneath his cloak a pickaxe, and they cut a hole in the wall in a few minutes. There was a large room on the other side, but it was entirely empty. So they sat down, and got out their magical calculators, and soon discovered that the Princess was in the lowest part of the castle; but the magical calculators being a little out of order, they could not show exactly her place of confinement. Then the five hurried down-stairs, where they found the slaves still asleep; but one poor little boy, whose business it was to get up early every morning and split kindling wood, having had none of the feast, was not very sleepy, and woke up when he heard footsteps near him. The magicians asked him if he could show them to the lowest part of the castle. "All right," said he; "this way;" and he led them to where there was a great black hole, with a windlass over it. "Get in the bucket," said he, "and I will lower you down."

"Bucket!" cried Alcahazar. "Is that a well?"

"To be sure it is," said the boy, who had nothing on but the baby-clothes he had worn ever since he was born; and which, as he was now about ten years old, had split a good deal in the back and arms, but in length they were very suitable.

"But there can be no one down there," said the magician. "I see deep water."

"Of course there is nobody there," replied the boy. "Were you told to go down there to meet anybody? Because, if you were, you had better take some tubs down with you, to sit in. But all I know about it is, that it's the lowest part of this old hole of a castle."

"Boy," said Alcahazar, "there is a young lady shut up down here somewhere. Do you know where she is?"

"How old is she?" asked the boy.

"About seventeen," said the magician.

"O then! if she is no older than that, I should think she'd be in the preserve-closet, if she knew where it was," and the boy pointed to a great door, barred and locked, where the dwarf, who had a very sweet tooth, kept all his preserves locked up tight and fast. Zamcar stooped and looked through the key-hole of this door, and there, sure enough, was the Princess! So the boy proved to be smarter than all the magicians. Each of our five friends now took from under his cloak a crowbar, and in a minute they had forced open the great door. But they had scarcely entered, when the dwarf, springing on the arm of the chair to which the Princess was still tied, drew his sword, and clapped it to her throat, crying out, that if the magicians came one step nearer, he would slice her head off.

"O ho!" cried they, "is that your game?"

"Yes indeed," said the chuckling dwarf; "can you play at it?"

The magicians did not appear to think that they could; but Ting-a-ling, who was still on the Princess's shoulder, though unseen by the dwarf, suddenly shouted, "I can play!" and in an instant he had driven his little sword into the dwarf's eye, who immediately sprang from the chair with a howl of anguish. While he was yelling and skipping about, with his hands to his eyes, the poor boy, who hated him worse than pills, clapped a great jar of preserves over him, and sat down on the bottom of the jar! The magicians then untied the Princess; and as she looked weak and faint, Zamcar, the youngest, took from under his cloak a little table, set with everything hot and nice for supper; and when the Princess had eaten something and taken a cup of tea, she felt a great deal better. Alcahazar lifted up the jar from the dwarf, and there was the little rascal, so covered up with sticky jam, that he could not speak and could hardly move. So, taking an oil-cloth bag from under his cloak, Alcahazar dropped the dwarf into it, and tied it up, and hung it to his girdle. The two youngest magicians made a sort of chair out of a shawl, and they carried the Princess on it between them, very comfortably; and as Ting-a-ling still remained on her shoulder, she began to feel that things were beginning to look brighter. They then asked the poor boy what he would like best as a reward for what he had done; and he said that if they would shut him up in that room, and lock the door tight, and lose the key, he would be happy all the days of his life. So they left the boy (who knew what was good, and was already sucking away at a jar of preserved green-gages) in the room, and they shut the door and locked it tight, and lost the key; and he lived there for ninety-one years, eating preserves; and when they were all gone, he died. All that time he never had any clothes but his baby-clothes, and they got pretty sticky before his death. Then our party left the castle; and as they passed the slaves still fast asleep, the three oldest magicians took from under their cloaks watering-pots, filled with water that makes men sleep, and they watered the slaves with it, until they were wet enough to sleep a week. When they went through the gates of copper, brass, iron, and wood, they left them all open behind them. They had not gone far before they saw seventy-five men, all sitting in a row at the side of the road, and looking woefully indeed. They had been wet to the skin, and were now frozen stiff, not one of them being able to move anything but his eyelids, and they were all crying as if their hearts would break. So the magicians stopped, and the three oldest each took from under his cloak a pair of bellows, and they blew hot air on the poor creatures until they were all thawed. Then Alcahazar told them to go up to the castle, and take it for their own, and live there all the rest of their lives. He informed them that the dwarf was his prisoner, and that the slaves would sleep for a week.

When the seventy-five guests (for those who had been taken from the feast, had joined their comrades) heard this, they all started up, and ran like deer for the castle; and when they reached it, they woke up their comrades, and took possession, and lived there all their lives. The man who had been first thrown through the window, and who had broken the way through the glass for the others, was elected their chief, because he had suffered the most; and excepting the trouble of doing their own work for a week, until the slaves awoke, these people were very happy ever afterwards.

It was just daylight when our party left the dwarf's castle, and by the next evening they had reached the palace. The army had not got back, and there was no one there but the ladies of the Princess. When these saw their dear mistress, there was never before such a kissing, and hugging, and crying, and laughing. Ting-a-ling came in for a good share of praise and caressing; and if he had not slipped away to tell his tale to the fairy Queen, there is no knowing what would have become of him. The magicians sat down outside of the Princess's apartments, to guard her until the army should return; and the ladies would have kissed and hugged them, in their gratitude and joy, if they had not been such dignified and grave personages.