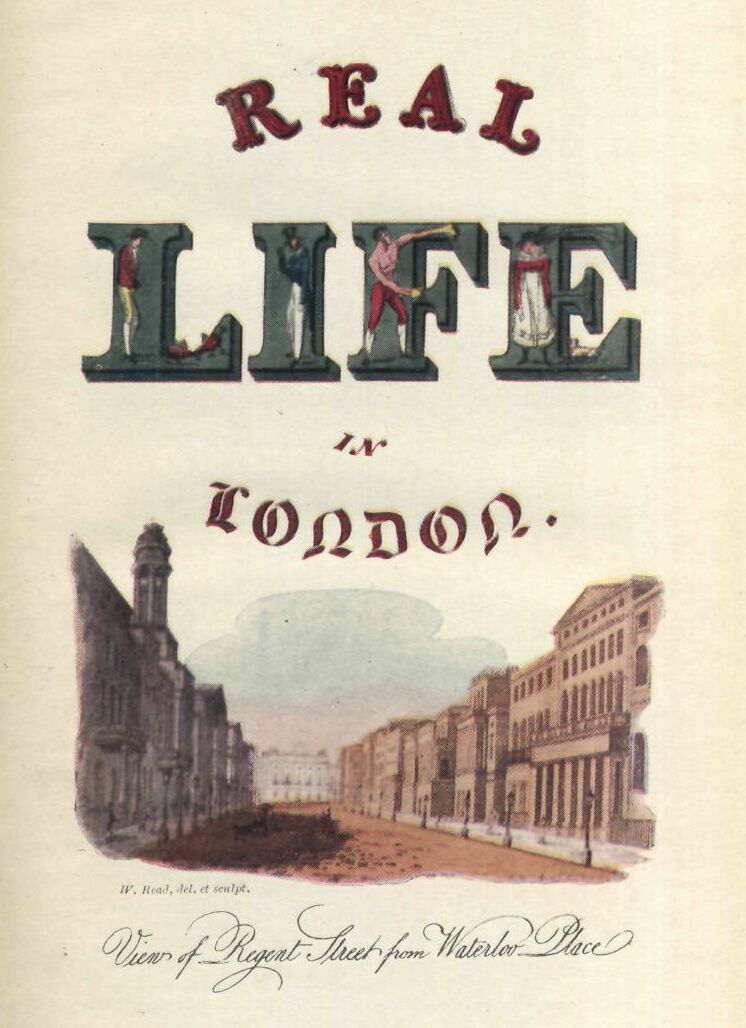

| Main Index |

| Volume I. Part 1 |

| Volume II. Part 1 |

| Volume II. Part 2 |

|

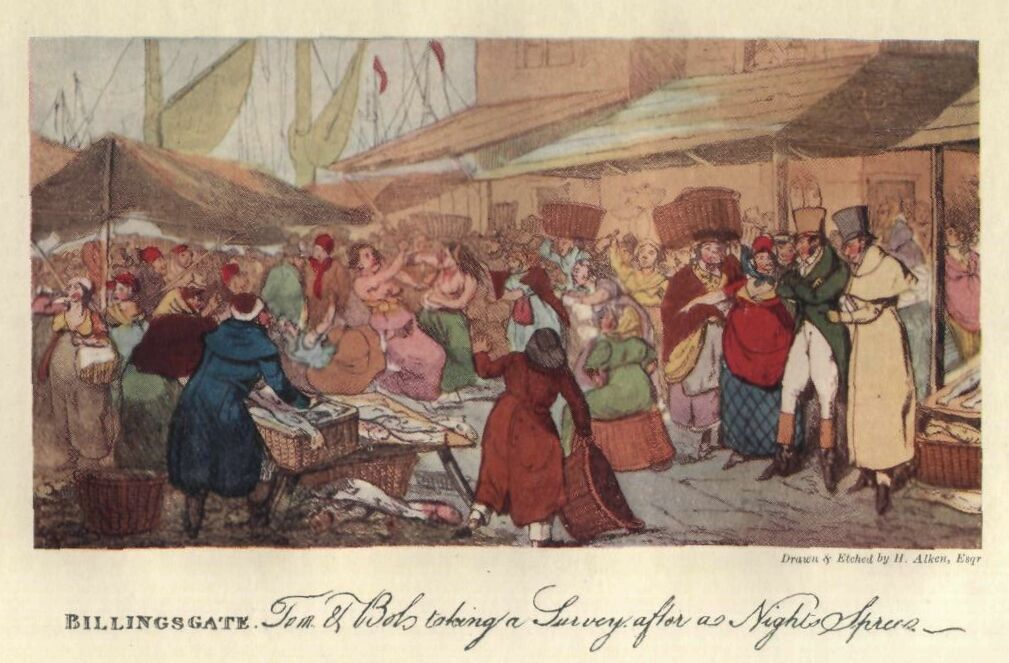

Page298 Real Life at Billingsgate |

"Here fashion and folly still go hand in hand,

With the Blades of the East, and the Bucks of the Strand;

The Bloods of the Park, and paraders so gay,

Who are lounging in Bond Street the most of the day—

Who are foremost in all that is formed for delight,

At greeking, or wenching, or drinking all night;

For London is circled with unceasing joys:

Then, East, West, North and South, let us hunt them, my boys."

[258] THE entrance to the house had attracted Tallyho's admiration as they proceeded; but the taste and elegance of the Coffee-room, fitted up with brilliant chandeliers, and presenting amidst a blaze of splendour every comfort and accommodation for its visitors, struck him with surprise; in which however he was not suffered to remain long, for Merrywell and Mortimer had laid their plans with some degree of depth and determination to carry into execution the proposed ramble of the evening, and had ordered a private room for the party; besides which, they had invited a friend to join them, who was introduced to Tom and Bob, under the title of Frank Harry. Frank Harry was a humorous sort of fellow, who could tell a tough story, sing a merry song, and was up to snuff, though he frequently got snuffy, singing,

"The bottle's the Sun of our table,

His beams are rosy wine:

We, planets never are able

Without his beams to shine.

Let mirth and glee abound,

You'll soon grow bright

With borrow'd light,

And shine as he goes round."

He was also a bit of a dabbler at Poetry, a writer of Songs, Epigrams, Epitaphs, &c.; and having been a long resident in the East, was thought to be a very useful guide on such an excursion, and proved himself a very [259] pleasant sort of companion: he had a dawning pleasantry in his countenance, eradiated by an eye of vivacity, which seemed to indicate there was nothing which gave him so much gratification as a mirth-moving jest.

"What spirits were his, what wit and what whim, Now cracking a joke, and now breaking a limb."

Give him but food for laughter, and he would almost consider himself furnished with food and raiment. There was however a pedantic manner with him at times; an affectation of the clerical in his dress, which, upon the whole, did not appear to be of the newest fashion, or improved by wearing; yet he would not barter one wakeful jest for a hundred sleepy sermons, or one laugh for a thousand sighs. If he ever sigh'd at all, it was because he had been serious where he might have laugh'd; if he had ever wept, it was because mankind had not laugh'd more and mourn'd less. He appeared almost to be made up of contrarieties, turning at times the most serious subjects into ridicule, and moralizing upon the most ludicrous occurrences of life, never failing to conclude his observations with some quaint or witty sentiment to excite risibility; seeming at the same time to say,

"How I love to laugh;

Never was a weeper;

Care's a silly calf,

Joy's my casket keeper."

During dinner time he kept the table in a roar of laughter, by declaring it was his opinion there was a kind of puppyism in pigs that they should wear tails—calling a great coat, a spencer folio edition with tail-pieces—Hercules, a man-midwife in a small way of business, because he had but twelve labours—assured them he had seen a woman that morning who had swallowed an almanac, which he explained by adding, that her features were so carbuncled, that the red lettered days were visible on her face—that Horace ran away from the battle of Philippi, merely to prove that he was no lame poet—he described Critics as the door-porters to the Temple of Fame, whose business was to see that no persons slipped in with holes in their stockings, or paste buckles for diamond ones, but was much in doubt whether they always performed their duty honestly—he called the Sun the Yellow-hair'd Laddie [260] —and the Prince of Darkness, the Black Prince—ask'd what was the difference between a sigh-heaver and a coal-heaver; but obtaining no answer, I will tell you, said he—The coal-heaver has a load at his back, which he can carry—but a sigh-heaver has one at his heart, which he can not carry. He had a whimsical knack of quoting old proverbs, and instead of saying, the Cobbler should stick to his last, he conceived it ought to be, the Cobbler should stick to his wax, because he thought that the more practicable—What is bred in the bone, said he, will not come out with the skewer; and justified his alteration by asserting it must be plain enough to the fat-headed comprehensions of those epicurean persons who have the magpie-propensity of prying into marrow-bones.

Dashall having remarked, in the course of conversation, that necessity has no law.

He declared he was sorry for it—it was surely a pity, considering the number of learned Clerks she might give employ to if she had—her Chancellor (continued he) would have no sinecure of it, I judge: hearing the petitions of her poor, broken-fortuned and bankrupt, subjects would take up all his terms, though every term were a year, and every year a term. Thus he united humour with seriousness, and seriousness with humour, to the infinite amusement of those around him.

Merrywell, who was well acquainted with, and knew his humour, took every opportunity of what is called drawing him out, and encouraging his propensity to punning, a species of wit at which he was particularly happy, for puns fell as thick from him as leaves from autumn bowers; and he further entertained them with an account of the intention he had some short time back of petitioning for the office of pun-purveyor to his late Majesty; but that before he could write the last line—"And your petitioner will ever pun" it was bestowed upon a Yeoman of the Guard. Still, however, said he, I have an idea of opening business as a pun-wright in general to his Majesty's subjects, for the sale and diffusion of all that is valuable in that small ware of wit, and intend to advertise—Puns upon all subjects, wholesale, retail, and for exportation. N B. 1. An allowance will be made to Captains and Gentlemen going to the East and West Indies—Hooks, Peakes, Pococks,{1} supplied on

1 Well-known dramatic authors.

[261] moderate terms—worn out sentiments and clap-traps will be taken in exchange. N B. 2. May be had in a large quantity, in a great deal box, price five acts of sterling comedy per packet, or in small quantities, in court-plaster sized boxes, price one melodrama and an interlude per box. N B. 3. The genuine puns are sealed with a true Munden grin—all others are counterfeits—Long live Apollo, &c. &c.

The cloth being removed, the wine was introduced, and

"As wine whets the wit, improves its native force,

And gives a pleasant flavour to discourse,"

Frank Harry became more lively at each glass—"Egad!" said he, "my intention of petitioning to be the king's punster, puts me in mind of a story."

"Can't you sing it?" enquired Merrywell.

"The pipes want clearing out first," was the reply, "and that is a sign I can't sing at present; but signal as it may appear, and I see some telegraphic motions are exchanging, my intention is to shew to you all the doubtful interpretation of signs in general."

"Let's have it then," said Tom; "but, Mr. Chairman, I remember an old Song which concludes with this sentiment—

"Tis hell upon earth to be wanting of wine."

"The bottle is out, we must replenish."

The hint was no sooner given, than the defect was remedied; and after another glass,

"King James VI. on his arrival in London, (said he) was waited on by a Spanish Ambassador, a man of some erudition, but who had strangely incorporated with his learning, a whimsical notion, that every country ought to have a school, in which a certain order of men should be taught to interpret signs; and that the most expert in this department ought to be dignified with the title of Professor of Signs. If this plan were adopted, he contended, that most of the difficulties arising from the ambiguity of language, and the imperfect acquaintance which people of one nation had with the tongue of another, would be done away. Signs, he argued, arose from the dictates of nature; and, as they were the same in every country, there could be no danger of their being misunderstood. Full of this project, the Ambassador was [262] lamenting one day before the King, that the nations of Europe were wholly destitute of this grand desideratum; and he strongly recommended the establishment of a college founded upon the simple principles he had suggested. The king, either to humour this Quixotic foible, or to gratify his own ambition at the expense of truth, observed, in reply, 'Why, Sir, I have a Professor of Signs in one of the northernmost colleges in my dominions; but the distance is, perhaps, six hundred miles, so that it will be impracticable for you to have an interview with him.' Pleased with this unexpected information, the Ambassador exclaimed—'If it had been six hundred leagues, I would go to see him; and I am determined to set out in the course of three or four days.' The King, who now perceived that he had committed himself, endeavoured to divert him from his purpose; but, finding this impossible, he immediately caused letters to be written to the college, stating the case as it really stood, and desired the Professors to get rid of the Ambassador in the best manner they were able, without exposing their Sovereign. Disconcerted at this strange and unexpected message, the Professors scarcely knew how to proceed. They, however, at length, thought to put off their august visitant, by saying, that the Professor of Signs was not at home, and that his return would be very uncertain. Having thus fabricated the story, they made preparations to receive the illustrious stranger, who, keeping his word, in due time reached their abode. On his arrival, being introduced with becoming solemnity, he began to enquire, who among them had the honour of being Professor of Signs? He was told in reply, that neither of them had that exalted honour; but the learned gentleman, after whom he enquired, was gone into the Highlands, that they conceived his stay would be considerable; but that no one among them could even conjecture the period of his return. 'I will wait his coming,' replied the Ambassador, 'if it be twelve months.'

"Finding him thus determined, and fearing, from the journey he had already undertaken that he might be as good as his word, the learned Professors had recourse to another stratagem. To this they found themselves driven, by the apprehension that they must entertain him as long as he chose to tarry; and in case he should unfortunately weary out their patience, the whole affair must terminate [263] in a discovery of the fraud. They knew a Butcher, who had been in the habit of serving the colleges occasionally with meat. This man, they thought, with a little instruction might serve their purpose; he was, however, blind with one eye, but he had much drollery and impudence about him, and very well knew how to conduct any farce to which his abilities were competent.

"On sending for Geordy, (for that was the butcher's name) they communicated to him the tale, and instructing him in the part he was to act, he readily undertook to become Professor of Signs, especially as he was not to speak one word in the Ambassador's presence, on any pretence whatever. Having made these arrangements, it was formally announced to the Ambassador, that the Professor would be in town in the course of a few days, when he might expect a silent interview. Pleased with this information, the learned foreigner thought that he would put his abilities at once to the test, by introducing into his dumb language some subject that should be at once difficult, interesting, and important. When the day of interview arrived, Geordy was cleaned up, decorated with a large bushy wig, and covered over with a singular gown, in every respect becoming his station. He was then seated in a chair of state, in one of their large rooms, while the Ambassador and the trembling Professors waited in an adjoining apartment.

"It was at length announced, that the learned Professor of Signs was ready to receive his Excellency, who, on entering the room, was struck with astonishment at his venerable and dignified appearance. As none of the Professors would presume to enter, to witness the interview, under a pretence of delicacy, (but, in reality, for fear that their presence might have some effect upon the risible muscles of Geordy's countenance) they waited with inconceivable anxiety, the result of this strange adventure, upon which depended their own credit, that of the King, and, in some degree, the honour of the nation.

"As this was an interview of signs, the Ambassador began with Geordy, by holding up one of his fingers; Geordy replied, by holding up two. The Ambassador then held up three; Geordy answered, by clenching his fist, and looking sternly. The Ambassador then took an orange from his pocket, and held it up; Geordy returned the compliment, by taking from his pocket a [264] piece of a barley cake, which he exhibited in a similar manner. The ambassador, satisfied with the vast attainments of the learned Professor, then bowed before him with profound reverence, and retired. On rejoining the agitated Professors, they fearfully began to enquire what his Excellency thought of their learned brother? 'He is a perfect miracle,' replied the Ambassador, 'his worth is not to be purchased by the wealth of half the Indies.' 'May we presume to descend to particulars?' returned the Professors, who now began to think themselves somewhat out of danger. 'Gentlemen,' said the Ambassador, 'when I first entered into his presence, I held up one finger, to denote that there is one God. He then held up two, signifying that the Father should not be divided from the Son. I then held up three, intimating, that I believed in Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. He then clenched his fist, and, looking sternly at me, signified, that these three are one; and that he would defy me, either to separate them, or to make additions. I then took out an orange from my pocket, and held it up, to show the goodness of God, and to signify that he gives to his creatures not only the necessaries, but even the luxuries of life. Then, to my utter astonishment, this wonderful man took from his pocket a piece of bread, thus assuring me, that this was the staff of life, and was to be preferred to all the luxuries in the world. Being thus satisfied with his proficiency and great attainments in this science, I silently withdrew, to reflect upon what I had witnessed.' "Diverted with the success of their stratagem, the Professors continued to entertain their visitor, until he thought prudent to withdraw. No sooner had he retired, than the opportunity was seized to learn from Geordy, in what manner he had proceeded to give the Ambassador such wonderful satisfaction; they being at a loss to conceive how he could have caught his ideas with so much promptitude, and have replied to them with proportionable readiness. But, that one story might not borrow any features from the other, they concealed from Geordy all they had learned from the Ambassador; and desiring him to begin with his relation, he proceeded in the following manner:—'When the rascal came into the room, after gazing at me a little, what do you think, gentlemen, that he did? He held up one finger, as much as to say, you have only one eye. I then held up two, to [265] let him know that my one eye was as good as both of his. He then held up three, as much as to say, we have only three eyes between us. This was so provoking, that I bent my fist at the scoundrel, and had it not been for your sakes, I should certainly have risen from the chair, pulled off my wig and gown, and taught him how to insult a man, because he had the misfortune to lose one eye. The impudence of the fellow, however, did not stop here; for he then pulled out an orange from his pocket, and held it up, as much as to say, Your poor beggarly country cannot produce this. I then pulled out a piece of good cake, and held it up, giving him to understand, that I did not care a farthing for his trash. Neither do I; and I only regret, that I did not thrash the scoundrel's hide, that he might remember how he insulted me, and abused my country.' We may learn from hence, that if there are not two ways of telling a story, there are at least two ways of understanding Signs, and also of interpreting them."

This story, which was told with considerable effect by their merry companion, alternately called forth loud bursts of laughter, induced profound silence, and particularly interested and delighted young Mortimer and Tallyho; while Merrywell kept the glass in circulation, insisting on no day-light{1} nor heel-taps,{2} and the lads began to feel themselves all in high feather. Time was passing in fearless enjoyment, and Frank Harry being called on by Merrywell for a song, declared he had no objection to tip 'em a rum chant, provided it was agreed that it should go round.

This proposal was instantly acceded to, a promise made that he should not be at a loss for a good coal-box;{3} and after a little more rosin, without which, he said, he could not pitch the key-note, he sung the following[266]

SONG.

Oh, London! dear London! magnanimous City,

Say where is thy likeness again to be found?

Here pleasures abundant, delightful and pretty,

All whisk us and frisk us in magical round;

1 No day-light—That is to leave no space in the glass; or,

in other words, to take a bumper.

2 Heel-taps—To leave no wine at the bottom.

3 Coal-box—A very common corruption of chorus.

Here we have all that in life can merry be,

Looking and laughing with friends Hob and Nob,

More frolic and fun than there's bloom on the cherry-tree,

While we can muster a Sovereign Bob.

(Spoken)—Yes, yes, London is the large world in a small compass: it contains all the comforts and pleasures of human life—"Aye aye, (says a Bumpkin to his more accomplished Kinsman) Ye mun brag o' yer Lunnun fare; if smoak, smother, mud, and makeshift be the comforts and pleasures, gie me free air, health and a cottage."—Ha, ha, ha, Hark at the just-catch'd Johnny Rata, (says a bang-up Lad in a lily-shallow and upper toggery) where the devil did you come from? who let you loose upon society? d———e, you ought to be coop'd up at Exeter 'Change among the wild beasts, the Kangaroos and Catabaws, and shewn as the eighth wonder of the world! Shew 'em in! Shew 'em in! stir him up with a long pole; the like never seen before; here's the head of an owl with the tail of an ass—all alive, alive O! D———me how the fellow stares; what a marvellous piece of a mop-stick without thrums.—"By gum (says the Bumpkin) you looks more like an ape, and Ise a great mind to gie thee a douse o' the chops."—You'd soon find yourself chop-fallen there, my nabs, (replies his antagonist)—you are not up to the gammon—you must go to College and learn to sing

Oh, London! dear London! &c.

Here the streets are so gay, and the features so smiling,

With uproar and noise, bustle, bother, and gig;

The lasses (dear creatures! ) each sorrow beguiling,

The Duke and the Dustman, the Peer and the Prig;

Here is his Lordship from gay Piccadilly,

There an ould Clothesman from Rosemary Lane;

Here is a Dandy in search of a filly,

And there is a Blood, ripe for milling a pane.

(Spoken)—All higgledy-piggledy, pigs in the straw—Lawyers, Lapidaries, Lamplighters, and Lap-dogs—Men-milliners, Money-lenders, and Fancy Millers, Mouse-trap Mongers, and Matchmen, in one eternal round of variety! Paradise is a pail of cold water in comparison with its unparalleled pleasures—and the wishing cap of Fortunatus could not produce a greater abundance of delight—Cat's Meat—Dog's Meat—Here they are all four a penny, hot hot hot, smoking hot, piping hot hot Chelsea Buns—Clothes sale, clothes—Sweep, sweep—while a poor bare-footed Ballad Singer with a hoarse discordant voice at intervals chimes in with

"They led me like a pilgrim thro' the labyrinth of care,

You may know me by my sign and the robe that I wear;"

[267] so that the concatenation of sounds mingling all at once into one undistinguished concert of harmony, induces me to add mine to the number, by singing—

Oh, London! dear London! &c.

The Butcher, whose tray meets the dough of the Baker,

And bundles his bread-basket out of his hand;

The Exquisite Lad, and the dingy Flue Faker,{1}

And coaches to go that are all on the stand:

Here you may see the lean sons of Parnassus,

The puffing Perfumer, so spruce and so neat;

While Ladies, who flock to the fam'd Bonassus,

Are boning our hearts as we walk thro' the street.

(Spoken)—"In gude truth," says a brawney Scotchman, "I'se ne'er see'd sic bonny work in a' my liefe—there's nae walking up the streets without being knock'd doon, and nae walking doon the streets without being tripp'd up."—"Blood-an-oons, (says an Irishman) don't be after blowing away your breath in blarney, my dear, when you'll want it presently to cool your barley broth."—"By a leaf," cries a Porter with a chest of drawers on his knot, and, passing between them, capsizes both at once, then makes the best of his way on a jog-trot, humming to himself, Ally Croaker, or Hey diddle Ho diddle de; and leaving the fallen heroes to console themselves with broken heads, while some officious friends are carefully placing them on their legs, and genteelly easing their pockets of the possibles; after which they toddle off at leisure, to sing

Oh, London! dear London! &c.

Then for buildings so various, ah, who would conceive it,

Unless up to London they'd certainly been?

'Tis a truth, I aver, tho' you'd scarcely believe it,

That at the Court end not a Court's to be seen;

Then for grandeur or style, pray where is the nation

For fashion or folly can equal our own?

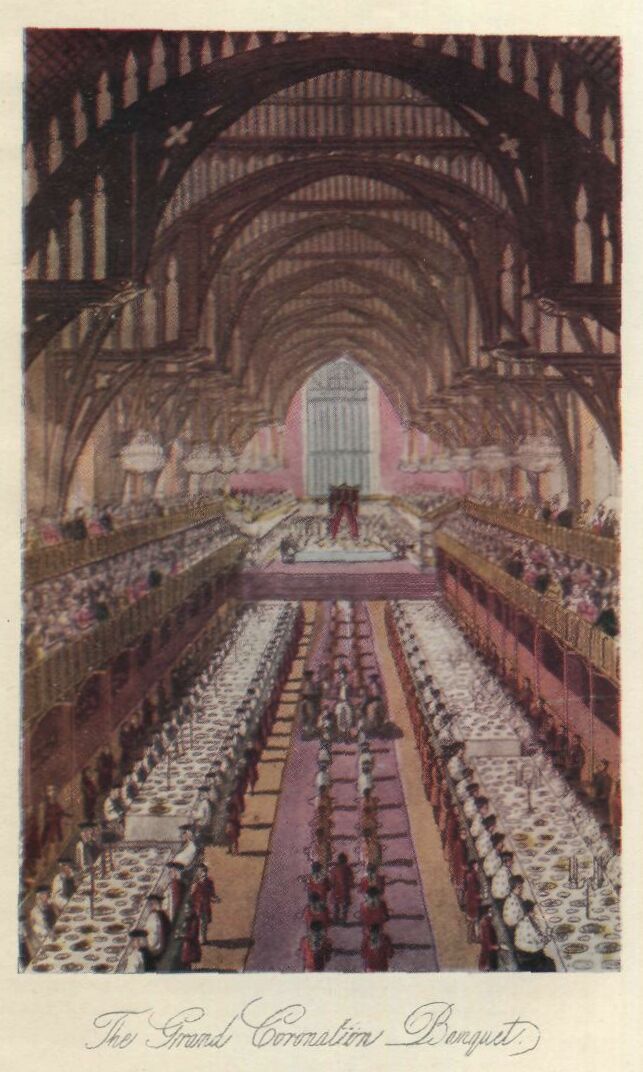

Or fit out a fête like the grand Coronation?

I defy the whole world, there is certainly none.

(Spoken)—Talk of sights and sounds—is not there the Parliament House, the King's Palace, and the Regent's Bomb—The Horse-guards, the Body-guards, and the Black-guards—The Black-legs, and the Bluestockings—The Horn-blower, and the Flying Pie-man—The Indian Juggler—Punch and Judy—(imitating the well-known Show-man)—The young and the old, the grave and the gay—The modest Maid and the willing Cyprian—The Theatres—The Fives Court and the Court of Chancery—[268]

1 Flue Faker—A cant term for Chimney-sweep.

The Giants in Guildhall, to be seen by great and small, and,

what's more than all, the Coronation Ball—

Mirth, fun, frolic, and frivolity,

To please the folks of quality:

For all that can please the eye, the ear, the taste, the touch,

the smell,

Whether bang-up in life, unfriended or undone,

No place has such charms as the gay town of London.

Oh, Loudon! dear London! &c.

The quaint peculiarities of the Singer gave indescribable interest to this song, as he altered his voice to give effect to the various cries of the inhabitants, and it was knock'd down with three times three rounds of applause; when Merrywell, being named for the next, sung, accompanied with Dashall and Frank Harry, the following

GLEE.

"Wine, bring me wine—come fill the sparkling glass,

Brisk let the bottle circulate;

Name, quickly name each one his fav'rite lass,

Drive from your brows the clouds of fate:

Fill the sparkling bumper high,

Let us drain the bottom dry.

Come, thou grape-encircled Boy!

From thy blissful seats above,

Crown the present hours with joy,

Bring me wine and bring me love:

Fill the sparkling bumper high,

Let us drain the bottom dry.

Bacchus, o'er my yielding lip

Spread the produce of thy vine;

Love, thy arrows gently dip,

Temp'ring them with generous wine:

Fill the sparkling bumper high,

Let us drain the bottom dry."

In the mean time, the enemy of life was making rapid strides upon them unheeded, till Dashall reminded Merrywell of their intended visit to the East; and that as he expected a large portion of amusement in that quarter, he proposed a move.

They were by this time all well primed—ripe for a rumpus—bang-up for a lark or spree, any where, any how, or with any body; they therefore took leave of their present scene of gaiety.[269]

"Wand'ring with listless gait and spirits gay,

They Eastward next pursued their jocund way;

With story, joke, smart repartee and pun,

Their business pleasure, and their object fun."

IT was a fine moonlight evening, and upon leaving the Globe, they again found themselves in the hurry, bustle, and noise of the world. The glare of the gas-lights, and the rattling of coaches, carts and vehicles of various-descriptions, mingled with

"The busy hum of men,"

attracted the attention of their eyes and ears, while the exhilarating juice of the bottle had given a circulation to the blood which enlivened imagination and invigorated fancy. Bob conceived himself in Elysium, and Frank Harry was as frisky as a kitten. The first object that arrested their progress was the house of Mr. Hone, whose political Parodies, and whose trials on their account, have given him so much celebrity. His window at the moment exhibited his recent satirical publication entitled a Slap at Slop and the Bridge Street Gang.{1}

1 The great wit and humour displayed in this publication

have deservedly entitled it to rank high among the jeu

desprit productions of this lively age—to describe it were

impossible—to enjoy it must be to possess it; but for the

information of such of our readers as are remote from the

Metropolis, it may perhaps be necessary to give something

like a key of explanation to its title. A certain learned

Gentleman, formerly the Editor of the Times, said now to be

the Conductor of the New Times, who has by his writings

rendered himself obnoxious to a numerous class of readers,

has been long known by the title of Dr. Slop; in his

publication, denominated the mock Times, and the Slop Pail,

he has been strenuous in his endeavours to support and

uphold a Society said to mis-call themselves The

Constitutional Society, but now denominated The Bridge

Street Gang; and the publication alluded to, contains

humorous and satirical parodies, and sketches of the usual

contents of his Slop Pail; with a Life of the learned

Doctor, and an account of the origin of the Gang.

[270] "Here," said Tom, "we are introduced at once into a fine field of observation. The inhabitant of this house defended himself in three different trials for the publication of alleged impious, profane, and scandalous libels on the Catechism, the Litany, and the Creed of St. Athanasius, with a boldness, intrepidity, and perseverance, almost unparalleled, as they followed in immediate succession, without even an allowance of time for bodily rest or mental refreshment."

"Yes," continued Frank Harry, "and gained a verdict on each occasion, notwithstanding the combined efforts of men in power, and those whose constant practice in our Courts of Law, with learning and information at their fingers ends, rendered his enemies fearful antagonists."

"It was a noble struggle," said Tallyho; "I remember we had accounts of it in the country, and we did not fail to express our opinions by subscriptions to remunerate the dauntless defender of the rights and privileges of the British subject."

"Tip us your flipper"{1} said Harry—-"then I see you are a true bit of the bull breed—one of us, as I may say. Well, now you see the spot of earth he inhabits—zounds, man, in his shop you will find amusement for a month—see here is The House that Jack Built—there is the Queen's Matrimonial Ladder, do you mark?—What think you of these qualifications for a Gentleman?

"In love, and in liquor, and o'ertoppled with debt, With women, with wine, and with duns on the fret."

There you have the Nondescript—

"A something, a nothing—what none understand,

Be-mitred, be-crowned, but without heart or hand;

There's Jack in the Green too, and Noodles, alas!

"Who doodle John Bull of gold, silver, and brass.

"Come," said Dashall, "you must cut your story short; I know if you begin to preach, we shall have a sermon as long as from here to South America, so allons;" and with this impelling his Cousin forward, they

1 Tip us your Flipper—your mawley—your daddle, or your

thieving hook; are terms made use of as occasions may suit

the company in which they are introduced, to signify a desire

to shake hands.

[271] approached towards Saint Paul's, chiefly occupied in conversation on the great merit displayed in the excellent designs of Mr. Cruikshank, which embellish the work they had just been viewing; nor did they discover any thing further worthy of notice, till Bob's ears were suddenly attracted by a noise somewhat like that of a rattle, and turning sharply round to discover from whence it came, was amused with the sight of several small busts of great men, apparently dancing to the music of a weaver's shuttle.{1}

"What the devil do you call this?" said he—"is it an exhibition of wax-work, or a model academy?"

"Neither," replied Dashall; "this is no other than the shop of a well-known dealer in stockings and nightcaps, who takes this ingenious mode of making himself popular, and informing the passengers that

"Here you may be served with all patterns and sizes,

From the foot to the head, at moderate prices;"

with woolens for winter, and cottons for summer—Let us move on, for there generally is a crowd at the door, and there is little doubt but he profits by those who are induced to gaze, as most people do in London, if they can but entrap attention. Romanis is one of those gentlemen who has contrived to make some noise in the world by puffing advertisements, and the circulation of poetical handbills. He formerly kept a very small shop for the sale of hosiery nearly opposite the East-India House, where he supplied the Sailors after receiving their pay for a long voyage, as well as their Doxies, with the articles in which he deals, by obtaining permission to style himself "Hosier to the Rt. Hon. East India Company." Since which, finding his trade increase and his purse extended, he has extended his patriotic views of clothing the whole population of London by opening shops in various parts, and has at almost all times two or three depositories for

1 Romanis, the eccentric Hosier, generally places a loom near the door of his shops decorated with small busts; some of which being attached to the upper movements of the machinery, and grotesquely attired in patchwork and feathers, bend backwards and forwards with the motion of the works, apparently to salute the spectators, and present to the idea persons dancing; while every passing of the shuttle produces a noise which may be assimilated to that of the Rattlesnake, accompanied with sounds something like those of a dancing-master beating time to his scholars. [272] his stock. At this moment, besides what we have just seen, there is one in Gracechurch Street, and another in Shoreditch, where the passengers are constantly assailed by a little boy, who stands at the door with some bills in his hand, vociferating—Cheap, cheap."

"Then," said Bob, "wherever he resides I suppose may really be called Cheapside?"

"With quite as much propriety," continued Ton, "as the place we are now in; for, as the Irishman says in his song,

"At a place called Cheapside they sell every thing dear."

During this conversation, Mortimer, Merrywell, and Harry were amusing themselves by occasionally addressing the numerous Ladies who were passing, and taking a peep at the shops—giggling with girls, or admiring the taste and elegance displayed in the sale of fashionable and useful articles—justled and impeded every now and then by the throng. Approaching Bow Church, they made a dead stop for a moment.

"What a beautiful steeple!" exclaimed Bob; "I should, though no architect, prefer this to any I have yet seen in London."

"Your remark," replied Dashall, "does credit to your taste; it is considered the finest in the Metropolis. St. Paul's displays the grand effort of Sir Christopher Wren; but there are many other fine specimens of his genius to be seen in the City. His Latin Epitaph in St. Paul's may be translated thus: 'If you seek his monument, look around you;' and we may say of this steeple, 'If you wish a pillar to his fame, look up.' The interior of the little church, Walbrook,{1} (St. Stephen's) is likewise considered a

1 This church is perhaps unrivalled, for the beauty of the

architecture of its interior. For harmony of proportion,

grace, airiness, variety, and elegance, it is not to be

surpassed. It is a small church, built in the form of a

cross. The roof is supported by Corinthian columns, so

disposed as to raise an idea of grandeur, which the

dimensions of the structure do not seem to promise. Over the

centre, at which the principal aisles cross, is a dome

divided into compartments, the roof being partitioned in a

similar manner, and the whole finely decorated. The effect

of this build-ing is inexpressibly delightful; the eye at

one glance embracing a plan full and distinct, and

afterwards are seen a greater number of parts than the

spectator was prepared to expect. It is known and admired on

the Continent, as a master-piece of art. Over the altar is a

fine painting of the martyrdom of St. Stephen, by West.

[273] chef d'ouvre of the same artist, and serves to display the versatility of his genius."

Instead however of looking up, Bob was looking over the way, where a number of people, collected round a bookseller's window, had attracted his attention.

"Apropos," cried Dashall,—"The Temple of Apollo—we should have overlook'd a fine subject, but for your remark—yonder is Tegg's Evening Book Auction, let us cross and see what's going on. He is a fellow of 'infinite mirth and good humour,' and many an evening have I passed at his Auction, better amused than by a farce at the Theatre."

They now attempted to cross, but the intervening crowd of carriages, three or four deep, and in a line as far as the eye could reach, for the present opposed an obstacle.

"If I could think of it," said Sparkle, "I'd give you the Ode on his Birth-day, which I once saw in MS.—it is the jeu d'esprit of a very clever young Poet, and who perhaps one of these days may be better known; but poets, like anatomical subjects, are worth but little till dead."

"And for this reason, I suppose," says Tom, "their friends and patrons are anxious they should rather be starved than die a natural death."

"Oh! now I have it—let us remain in the Church-yard a few minutes, while the carriages pass, and you shall hear it."[274]

"Ye hackney-coaches, and ye carts,

That oft so well perform your parts

For those who choose to ride,

Now louder let your music grow—

Your heated axles fiery glow—

Whether you travel quick or slow-

In Cheapside.

For know, "ye ragged rascals all,"

(As H——- would in his pulpit bawl

With cheeks extended wide)

Know, as you pass the crowded way,

This is the happy natal day

Of Him whose books demand your stay

In Cheapside.

'Twas on the bright propitious morn

When the facetious Tegcy was born,

Of mirth and fun the pride,

That Nature said "good Fortune follow,

Bear him thro' life o'er hill and hollow,

Give him the Temple of Apollo

In Cheapside."

Then, O ye sons of Literature!

Shew your regard for Mother Nature,

Nor let her be denied:

Hail! hail the man whose happy birth

May tell the world of mental worth;

They'll find the best books on the earth

In Cheapside.

"Good!" exclaimed Bob; "but we will now endeavour to make our way across, and take a peep at the subject of the Ode."

Finding the auction had not yet commenced, Sparkle proposed adjourning to the Burton Coffee House in the adjacent passage, taking a nip of ale by way of refreshment and exhilaration, and returning in half an hour. This proposition was cordially agreed to by all, except Tallyho, whose attention was engrossed by a large collection of Caricatures which lay exposed in a portfolio on the table beneath the rostrum. The irresistible broad humour of the subjects had taken fast hold of his risible muscles, and in turning them over one after the other, he found it difficult to part with such a rich fund of humour, and still more so to stifle the violent emotion it excited. At length, clapping his hands to his sides, he gave full vent to the impulse in a horse-laugh from a pair of truly Stentorian lungs, and was by main force dragged out by his companions.

While seated in the comfortable enjoyment of their nips of ale, Sparkle, with his usual vivacity, began an elucidation of the subjects they had just left. "The collection of Caricatures," said he, "which is considered the largest in London, are mostly from the pencil of that self-taught artist, the late George Woodward, and display not only a genuine and original style of humour in the design, but a corresponding and appropriate character in the dialogue, or speeches connected with the figures. Like his contemporary in another branch of the art, George Morland, he possessed all the eccentricity and thoughtless improvidence so common and frequently so fatal to genius; and had not his good fortune led him towards Bow Church, he must have suffered severe privations, and perhaps eventually have perished of want. Here, he always found a ready market, and a liberal price for his productions, however rude or hasty the sketch, or whatever might be the subject of them."

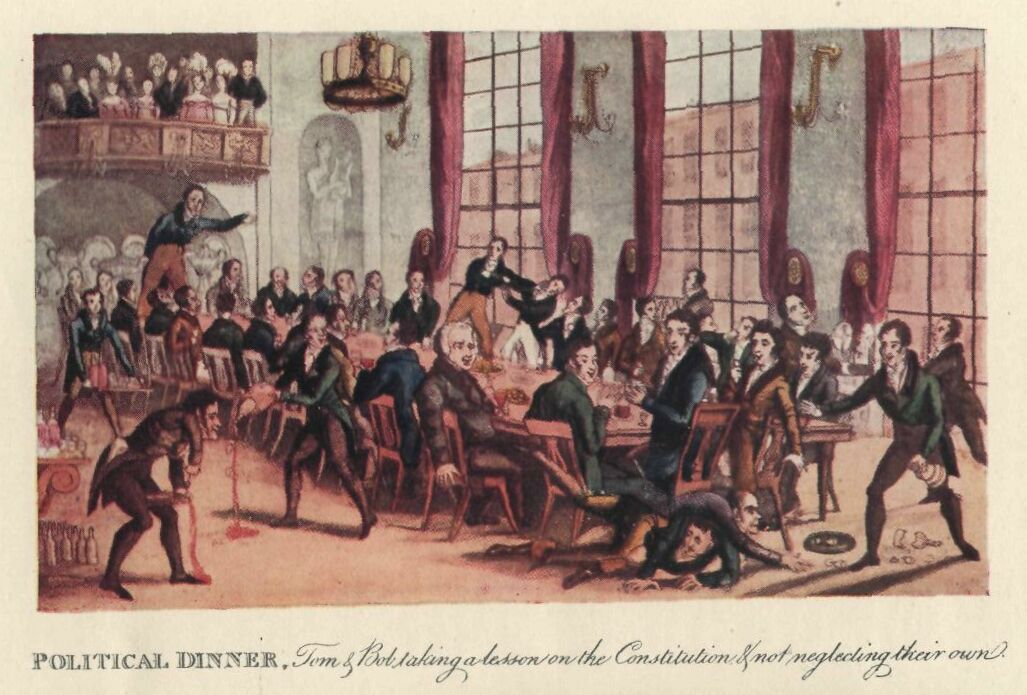

[275] "As to books," continued he, "all ages, classes, and appetites, may be here suited. The superficial dabbler in, and pretender to every thing, will find collections, selections, beauties, flowers, gems, &c. The man of real knowledge may here purchase the elements, theory, and practice of every art and science, in all the various forms and dimensions, from a single volume, to the Encyclopedia at large. The dandy may meet with plenty of pretty little foolscap volumes, delightfully hot-pressed, and exquisitely embellished; the contents of which will neither fatigue by the quantity, nor require the laborious effort of thought to comprehend. The jolly bon-vivant and Bacchanal will find abundance of the latest songs, toasts, and sentiments; and the Would-be-Wit will meet with Joe Miller in such an endless variety of new dresses, shapes, and sizes, that he may fancy he possesses all the collected wit of ages brought down to the present moment. The young Clerical will find sermons adapted to every local circumstance, every rank and situation in society, and may furnish himself with a complete stock in trade of sound orthodox divinity; while the City Epicure may store himself with a complete library on the arts of confectionary, cookery, &c, from Apicius, to the "Glutton's Almanack." The Demagogue may furnish himself with flaming patriotic speeches, ready cut and dried, which he has only to learn by heart against the next Political Dinner, and if he should not 'let the cat out,' by omitting to substitute the name of Londonderry for Cæsar, he may pass off for a second Brutus, and establish an equal claim to oratory with Burke, Pitt, and Fox. The——"

"Auction will be over," interrupted Bob, "before you get half through your descriptive Catalogue of the Books, so finish your nip, and let us be off."

They entered, and found the Orator hard at it, knocking down with all the energy of a Crib, and the sprightly wit of a Sheridan. Puns, bon mots, and repartees, flew about like crackers.

"The next lot, Gentlemen, is the Picture of London,—impossible to possess a more useful book—impossible to say what trouble and expence may be avoided by the possession of this little volume. When your Country Cousins pay you a visit, what a bore, what an expence, to be day after day leading them about—taking them up the Monument—down the Adelphi—round St. Paul's—across the [276] Parks, through the new Streets—along the Strand, or over the Docks, the whole of which may be avoided at the expence of a few shillings. You have only to clap into their pocket in the morning this invaluable little article, turn them out for the day, and, if by good luck they should not fall into the hands of sharpers and swindlers, your dear Coz will return safe home at night, with his head full of wonders, and his pockets empty of cash!"

"The d——l," whispered Bob, "he seems to know me, and what scent we are upon."

"Aye," replied his Cousin, "he not only knows you, but he knows that some of your cash will soon be in his pockets, and has therefore made a dead set at you."

"Next lot, Gentlemen, is a work to which my last observation bore some allusion; should your friends, as I then observed, fortunately escape the snares and dangers laid by sharpers and swindlers to entrap the unwary, you may, perchance, see them safe after their day's ramble; but should—aye, Gentlemen, there's the rub—should they be caught by the numerous traps and snares laid for the Johnny Raw and Greenhorn in this great and wicked metropolis, God knows what may become of them. Now, Gentlemen, we have a remedy for every disease—here is the London Spy or Stranger's Guide through the Metropolis; here all the arts, frauds, delusions, &c. are exposed, and—Tom, give that Gentleman change for his half crown, and deliver Lot 3.—As I was before observing, Gentlemen—Turn out that young rascal who is making such a noise, cracking nuts, that I can't hear the bidding.—Gentlemen, as I before observed, if you will do me the favour of bidding me—"

"Good night, Sir," cried a younker, who had just exploded a detonating cracker, and was making his escape through the crowd.

"The next lot, gentlemen, is the Young Man's best Companion, and as your humble Servant is the author, he begs to decline any panegyric—modesty forbids it—but leaves it entirely with you to appreciate its merits—two shillings—two and six—three shillings—three and six—four, going for four—for you, Sir, at four."

"Me, Sir! Lord bless you, I never opened my mouth!"

"Perfectly aware of that, Sir, it was quite unnecessary—I could read your intention in your eye—and observed the muscle of the mouth, call'd by anatomists the

[277] zygomaticus major, in the act of moving. I should have been dull not to have noticed it—and rude not to have saved you the trouble of speaking: Tom, deliver the Gentleman the lot, and take four shillings."

"Well, Sir, I certainly feel flattered with your acute and polite attention, and can do no less than profit by it—so hand up the lot—cheap enough, God knows."

"And pray," said Dashall to his Cousin as they quitted, "what do you intend doing with all your purchases? why it will require a waggon to remove them."

"O, I shall send the whole down to Belville Hall: our friends there will be furnished with a rare stock of entertainment during the long winter evenings, and no present I could offer would be half so acceptable."

"Well," remarked Mortimer, "you bid away bravely, and frequently in your eagerness advanced on yourself: at some sales you would have paid dearly for this; but here no advantage was taken, the mistake was explained, and the bidding declined in the most fair and honourable manner. I have often made considerable purchases, and never yet had reason to repent, which is saying much; for if I inadvertently bid for, and had a lot knocked down to me, which I afterwards disliked, I always found an acquaintance glad to take it off my hands at the cost, and in several instances have sold or exchanged to considerable advantage. One thing I am sorry we overlooked: a paper entitled, "Seven Reasons," is generally distributed during the Sale, and more cogent reasons I assure you could not be assigned, both for purchasing and reading in general, had the seven wise men of Greece drawn them up. You may at any time procure a copy, and it will furnish you with an apology for the manner in which you have spent your time and money, for at least one hour, during your abode in London."

Please, Sir, to buy a ha'porth of matches, said a poor, squalid little child without a shoe to her foot, who was running by the side of Bob—it's the last ha'porth, Sir, and I must sell them before I go home.

This address was uttered in so piteous a tone, that it could not well be passed unheeded.

"Why," said Tallyho, "as well as Bibles and Schools for all, London seems to have a match for every body."

"Forty a penny, Spring-radishes," said a lusty bawling [278] fellow as he passed, in a voice so loud and strong, as to form a complete contrast to the little ragged Petitioner, 'who held out her handful of matches continuing her solicitations. Bob put his hand in his pocket, and gave her sixpence.

"We shall never get on at this rate," said Tom; "and I find I must again advise you not to believe all you hear and see. These little ragged run-abouts are taught by their Parents a species of imposition or deception of which you are not aware, and while perhaps you congratulate yourself with 'the thought of having done a good act, you are only contributing to the idleness and dissipation of a set of hardened beings, who are laughing at your credulity; and I suspect this is a case in point—do you see that woman on the opposite side of the way, and the child giving her the money?"

"I do," said Tallyho; "that, I suppose, is her mother?"

"Probably," continued Dashall—"now mark what will follow."

They stopped a short time, and observed that the Child very soon disposed of her last bunch of matches, as she had termed them, gave the money to the woman, who supplied her in return with another last bunch, to be disposed of in a similar way.

"Is it possible?" said Bob.

"Not only possible, but you see it is actual; it is not however the only species of deceit practised with success in London in a similar way; indeed the trade of match-making has latterly been a good one among those who have been willing to engage in it. Many persons of decent appearance, representing themselves to be tradesmen and mechanics out of employ, have placed themselves at the corners of our streets, and canvassed the outskirts of the town, with green bags, carrying matches, which, by telling a pityful tale, they induce housekeepers and others, who commiserate their situation, to purchase; and, in the evening, are able to figure away in silk stockings with the produce of their labours. There is one man, well known in town, who makes a very good livelihood by bawling in a stentorian voice,

"Whow whow, will you buy my good matches,

Whow whow, will you buy my good matches,

Buy my good matches, come buy'em of me."

[279] He is usually dressed in something like an old military great coat, wears spectacles, and walks with a stick."

"And is a match for any body, match him who can,", cried Frank Harry; "But, bless your heart, that's nothing to another set of gentry, who have infested our streets in clean apparel, with a broom in their hands, holding at the same time a hat to receive the contributions of the passengers, whose benevolent donations are drawn forth without inquiry by the appearance of the applicant."

"It must," said Tallyho, "arise from the distresses of the times."

"There may be something in that," said Tom; "but in many instances it has arisen from the depravity of the times—to work upon the well-known benevolent feelings of John Bull; for those who ambulate the public streets of this overgrown and still increasing Metropolis and its principal avenues, are continually pestered with impudent impostors, of both sexes, soliciting charity—men and women, young and old, who get more by their pretended distresses in one day than many industrious and painstaking tradesmen or mechanics do in a week. All the miseries, all the pains of life, with tears that ought to be their honest and invariable signals, can be and are counterfeited—limbs, which enjoy the fair proportion of nature, are distorted, to work upon humanity—fits are feigned and wounds manufactured—rags, and other appearances of the most squalid and abject poverty, are assumed, as the best engines of deceit, to procure riches to the idle and debaucheries to the infamous. Ideal objects of commiseration are undoubtedly to be met with, though rarely to be found. It requires a being hackneyed in the ways of men, or having at least some knowledge of the town, to be able to discriminate the party deserving of benevolence; but

"A begging they will go will go,

And a begging they will go."

The chief cause assigned by some for the innumerable classes of mendicants that infest our streets, is a sort of innate principle of independence and love of liberty. However, it must be apparent that they do not like to work, and to beg they are not ashamed; they are, with very few exceptions, lazy and impudent. And then what [280] is collected from the humane but deluded passengers is of course expended at their festivals in Broad Street, St. Giles's, or some other equally elegant and appropriate part of the town, to which we shall at an early period pay a visit. Their impudence is intolerable; for, if refused a contribution, they frequently follow up the denial with the vilest execrations.

"To make the wretched blest,

Private charity is best."

"The common beggar spurns at your laws; indeed many of their arts are so difficult of detection, that they are enabled to escape the vigilance of the police, and with impunity insult those who do not comply with their wishes, seeming almost to say,

"While I am a beggar I will rail,

And say there is no sin but to be rich;

And being rich, my virtue then shall be,

To say there is no vice but beggary."

"Begging has become so much a sort of trade, that parents have been known to give their daughters or sons the begging of certain streets in the metropolis as marriage portions; and some years ago some scoundrels were in the practice of visiting the outskirts of the town in sailors' dresses, pretending to be dumb, and producing written papers stating that their tongues had been cut out by the Algerines, by which means they excited compassion, and were enabled to live well."

"No doubt it is a good trade," said Merry well, "and I expected we should have been made better acquainted with its real advantages by Capt. Barclay, of walking and sporting celebrity, who, it was said, had laid a wager of 1000L. that he would walk from London to Edinburgh in the assumed character of a beggar, pay all his expences of living well on the road, and save out of his gains fifty pounds."

"True," said Tom, "but according to the best account that can be obtained, that report is without foundation. The establishment, however, of the Mendicity Society{1}

1 The frauds and impositions practised upon the public are

so numerous, that volumes might be filled by detailing the

arts that have been and are resorted to by mendicants; and

the records of the Society alluded to would furnish

instances that might almost stagger the belief of the most

credulous. The life of the infamous Vaux exhibits numerous

instances in which he obtained money under genteel

professions, by going about with a petition soliciting the

aid and assistance of the charitable and humane; and

therefore are continually cheats who go from door to door

collecting money for distressed families, or for charitable

purposes. It is, however, a subject so abundant, and

increasing by every day's observation, that we shall for the

present dismiss it, as there will be other opportunities in

the course of the work for going more copiously into it.

[281] is calculated to discover much on this subject, and has already brought to light many instances of depravity and deception, well deserving the serious consideration of the public."

As they approached the end of the Poultry,—"This," said Dashall, "is the heart of the first commercial city in the known world. On the right is the Mansion House, the residence of the Lord Mayor for the time being."

The moon had by this time almost withdrawn her cheering beams, and there was every appearance, from the gathering clouds, of a shower of rain.

"It is rather a heavy looking building, from what I can see at present," replied Tallyho.

"Egad!" said Tom, "the appearance of every thing at this moment is gloomy, let us cross."

With this, they crossed the road to Debatt's the Pastry Cook's Shop.

"Zounds!" said Tom, casting his eye upon the clock, "it is after ten; I begin to suspect we must alter our course, and defer a view of the east to a more favourable opportunity, and particularly as we are likely to have an accompaniment of water."

"Never mind," said Merrywell, "we can very soon be in very comfortable quarters; besides, a rattler is always to be had or a comfortable lodging to be procured with an obliging bed-fellow—don't you begin to croak before there is any occasion for it—what has time to do with us?"

"Aye aye," said Frank Harry, "don't be after damping us before we get wet; this is the land of plenty, and there is no fear of being lost—come along."

"On the opposite side," said Tom, addressing his Cousin, "is the Bank of England; it is a building of large extent and immense business; you can now only discern its exterior by the light of the lamps; it is however a place [282] to which we must pay a visit, and take a complete survey upon some future occasion. In the front is the Royal Exchange, the daily resort of the Merchants and Traders of the Metropolis, to transact their various business."

"Come," said Merry well, "I find we are all upon the right scent—Frank Harry has promised to introduce us to a house of well known resort in this neighbourhood—we will shelter ourselves under the staple commodity of the country—for the Woolsack and the Woolpack, I apprehend, are synonimous."

"Well thought of, indeed," said Dashall; "it is a house where you may at all times be certain of good accommodation and respectable society—besides, I have some acquaintance there of long standing, and may probably meet with them; so have with you, my boys. The Woolpack in Cornhill," continued he, addressing himself more particularly to Tallyho, "is a house that has been long established, and deservedly celebrated for its general accommodations, partaking as it does of the triple qualifications of tavern, chop-house, and public-house. Below stairs is a commodious room for smoking parties, and is the constant resort of foreigners,{1}

1 There is an anecdote related, which strongly induces a

belief that Christian VII. while in London, visited this

house in company with his dissipated companion, Count

Holcke, which, as it led to the dismissal of Holcke, and the

promotion of the afterwards unfortunate Struensée, and is

perhaps not very generally known, we shall give here.

One day while in London, Count Holcke and Christian vir.

went to a well-known public-house not far from the Bank,

which was much frequented by Dutch and Swedish Captains:

Here they listened to the conversation of the company,

which, as might be expected, was full of expressions of

admiration and astonishment at the splendid festivities

daily given in honour of Christian VII. Count Holcke, who

spoke German in its purity, asked an old Captain what he

thought of his King, and if he were not proud of the honours

paid to him by the English?—"I think (said the old man

dryly) that with such counsellors as Count Holcke, if he

escapes destruction it will be a miracle."—' Do you know

Count Holcke, my friend, (said the disguised courtier) as

you speak of him thus familiarly?'—"Only by report (replied

the Dane); but every person in Copenhagen pities the young

Queen, attributing the coolness which the King shewed

towards her, ere he set out on his voyage, to the malicious

advice of Holcke." The confusion of this minion may be

easier conceived than described; whilst the King, giving the

Skipper a handful of ducats, bade him speak the truth and

shame the devil. As soon, however, as the King spoke in

Danish, the Skipper knew him, and looking at him with love

and reverence, said in a low, subdued tone of voice—"

Forgive me, Sire, but I cannot forbear my tears to see you

exposed to the temptations of this extensive and wicked

Metropolis, under the pilotage of the most dissolute

nobleman of Denmark." Upon which he retired, bowing

profoundly to his Sovereign, and casting at Count Holcke a

look full of defiance and reproach. Holcke's embarrassment

was considerably increased by this, and he was visibly hurt,

seeing the King in a manner countenanced the rudeness of the

Skipper.

This King, who it should seem determined to see Real Life

in London, mingled in all societies, participating in their

gaieties and follies, and by practices alike injurious to

body and soul, abandoned himself to destructive habits,

whose rapid progress within a couple of years left nothing

but a shattered and debilitated hulk afflicted in the

morning of life with all the imbecility of body and mind

incidental to extreme old age.

[283] who are particularly partial to the brown stout, which they can obtain there in higher perfection than in any other house in London. Brokers and others, whose business calls them to the Royal Exchange, are also pretty constant visitors, to meet captains and traders—dispose of different articles of merchandise—engage shipping and bind bargains—it is a sort of under Exchange, where business and refreshment go hand in hand with the news of the day, and the clamour of the moment; beside which, the respectable tradesmen of the neighbourhood meet in an evening to drive dull care away, and converse on promiscuous subjects; it is generally a mixed company, but, being intimately connected with our object of seeing Real Life in London, deserves a visit. On the first floor is a good room for dining, where sometimes eighty persons in a day are provided with that necessary meal in a genteel style, and at a moderate price—besides other rooms for private parties. Above these is perhaps one of the handsomest rooms in London, of its size, capable of dining from eighty to a hundred persons. But you will now partake of its accommodations, and mingle with some of its company."

By this time they had passed the Royal Exchange, and Tom was enlarging upon the new erections lately completed; when all at once,

"Hallo," said Bob, "what is become of our party?" "All right," replied his Cousin; "they have given us the slip without slipping from us—I know their movements to a moment, we shall very soon be with them—this way—this way," said he, drawing Bob into the narrow passage which leads to the back of St. Peter's Church, Cornhill—"this is the track we must follow."

Tallyho followed in silence till they entered the house, and were greeted by the Landlord at the bar with a bow of welcome; passing quickly to the right, they were saluted with immoderate volumes of smoke, conveying to their olfactory nerves the refreshing fumes of tobacco, and almost taking from them the power of sight, except to observe a bright flame burning in the middle of the room. Tom darted forward, and knowing his way well, was quickly seated by the side of Merrywell, Mortimer, and Harry; while Tallyho was seen by those who were invisible to him', groping his way in the same direction, amidst the laughter of the company, occasionally interlarded with scraps which caught his ear from a gentleman who was at the moment reading some of the comments from the columns of the Courier, in which he made frequent pauses and observations.

[284] "Why, you can't see yourself for smoke," said one; "D———n it how hard you tread," said another. And then a line from the Reader came as follows—"The worthy Alderman fought his battles o'er again—Ha, ha, ha—Who comes here 1 upon my word, Sir, I thought you had lost your way, and tumbled into the Woolpack instead of the Skin-market.—' It is a friend of mine, Sir.'—That's a good joke, upon my soul; not arrived yet, why St. Martin's bells have been ringing all day; perhaps he is only half-seas over—Don't tell me, I know better than that—D———n that paper, it ought to be burnt by—The fish are all poison'd by the Gas-light Company—Six weeks imprisonment for stealing two dogs!—Hides and bark—How's sugars to-day?—Stocks down indeed—Yes, Sir, and bread up—Presto, be gone—What d'ye think of that now, eh?—Gammon, nothing but gammon—On table at four o'clock ready dressed and—Well done, my boy, that's prime."

These sentences were uttered from different parts of the room in almost as great a variety of voices as there must have been subjects of conversation; but as they fell upon the ear of Tallyho without connection, he almost fancied himself transported to the tower of Babel amidst the confusion of tongues.

"Beg pardon," said Tallyho, who by this time had gained a seat by his Cousin, and was gasping like a turtle for air—"I am not used to this travelling in the dark; but I shall be able to see presently."

"See," said Frank Harry, "who the devil wants to see more than their friends around them? and here we are at home to a peg."

[285] "I shall have finished in two minutes, Gentlemen," said the Reader,{1} cocking up a red nose, that shone with resplendent lustre between his spectacles, and then continuing to read on, only listened to by a few of those around him, while a sort of general buz of conversation was indistinctly heard from all quarters.

They were quickly supplied with grog and segars, and Bob, finding himself a little better able to make use of his eyes, was throwing his glances to every part of the room, in order to take a view of the company: and while Tom was congratulated by those who knew him at the Round Table—Merrywell and Harry were in close conversation with Mortimer.

At a distant part of the room, one could perceive boxes containing small parties of convivials, smoking and drinking, every one seeming to have some business of importance to claim occasional attention, or engaged in,

"The loud laugh that speaks the vacant mind." In one corner was a stout swarthy-looking man, with large whiskers and of ferocious appearance, amusing those around him with conjuring tricks, to their great satisfaction and delight; nearly opposite the Reader of the Courier, sat an elderly Gentleman{2} with grey hair, who heard

1 To those who are in the habit of visiting this room in an

evening, the character alluded to here will immediately be

familiar. He is a gentleman well known in the neighbourhood

as an Auctioneer, and he has a peculiar manner of reading

with strong emphasis certain passages, at the end of which

he makes long pauses, laughs with inward satisfaction, and

not infrequently infuses a degree of pleasantry in others.

The Courier is his favourite paper, and if drawn into an

argument, he is not to be easily subdued.

"At arguing too each person own'd his skill,

For e'en tho' vanquish'd, he can argue still."

2 This gentleman, who is also well known in the room, where

he generally smokes his pipe of an evening, is plain and

blunt, but affable and communicative in his manners—bold in

his assertions, and has proved himself courageous in

defending them—asthmatic, and by some termed phlegmatic;

but an intelligent and agreeable companion, unless thwarted

in his argument—a stanch friend to the late Queen and the

constitution of his country, with a desire to have the

Constitution, the whole Constitution, and nothing but the

Constitution.

[286] what was passing, but said nothing; he however puffed away large quantities of smoke at every pause of the Reader, and occasionally grinn'd at the contents of the paper, from which. Tallyho readily concluded that he was in direct political opposition to its sentiments.

The acquisition of new company was not lost upon to those who were seated at the round table, and it was not long before the Hon. Tom Dashall was informed that they hoped to have the honour of his Cousin's name as a member; nor were they backward in conveying a similar hint to Frank Harry, who immediately proposed his two friends, Mortimer and Merry well; an example which was followed by Tom's proposing his Cousin.

Such respectable introductions could not fail to meet the approbation of the Gentlemen present,—consequently they were unanimously elected Knights of the Round Table, which was almost as quickly supplied by the Waiter with a capacious bowl of punch, and the healths of the newmade Members drank with three times three; when their attention was suddenly drawn to a distant part of the room, where a sprightly Stripling, who was seated by the swarthy Conjuror before mentioned, was singing the following Song:

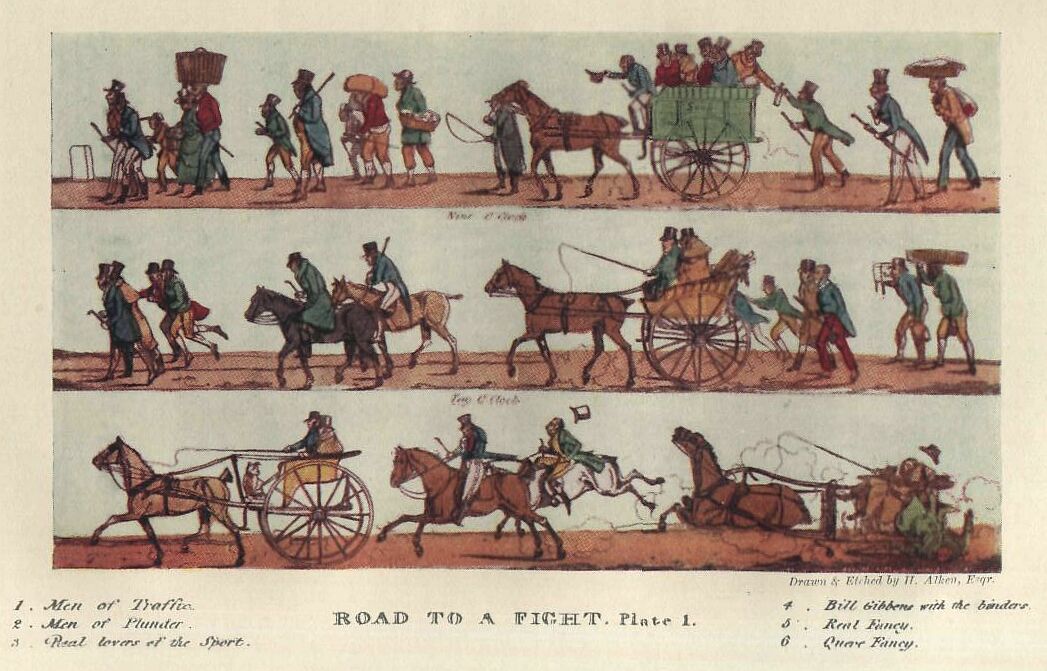

THE JOYS OF A MILL,

OR

A TODDLE TO A FIGHT.

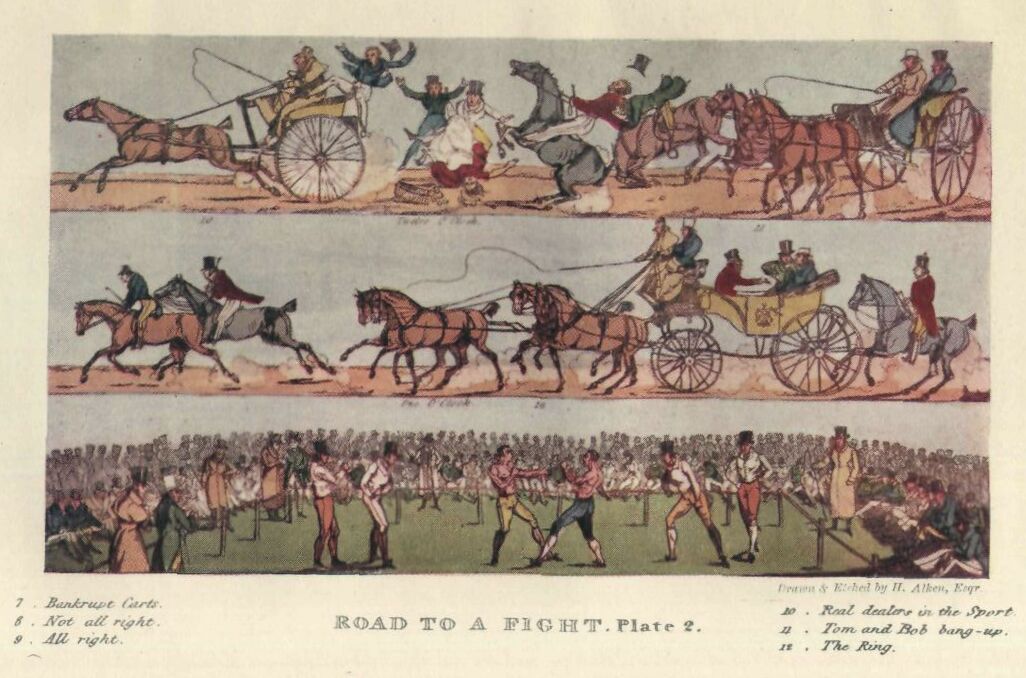

"Now's the time for milling, boys, since all the world's agog

for it,

Away to Copthorne, Moulsey Hurst, or Slipperton they go;

Or grave or gay, they post away, nay pawn their very togs

for it,

And determined to be up to all, go down to see the show:

Giddy pated, hearts elated, cash and courage all to view it,

Ev'ry one to learn a bit, and tell his neighbours how to do it;

E'en little Sprites in lily whites, are fibbing it and rushing it,

Your dashing Swells from Bagnigge Wells, are flooring it and

flushing it:

Oh! 'tis a sight so gay and so uproarious,

That all the world is up in arms, and ready for a fight.

The roads are so clogg'd, that they beggar all description now,

With lads and lasses, prim'd and grogg'd for bang-up fun and

glee;

Here's carts and gigs, and knowing prigs all ready to kick up a row,

And ev'ry one is anxious to obtain a place to see;

Here's a noted sprig of life, who sports his tits and clumner too,

And there is Cribb and Gully, Belcher, Oliver, and H armer too,

With Shelton, Bitton, Turner, Hales, and all the lads to go it well,

Who now and then, to please the Fancy, make opponents know it

well:

Oh! 'tis a sight, &c.

But now the fight's begun, and the Combatants are setting to,

Silence is aloud proclaim'd by voices base and shrill;

Facing, stopping—-fibbing, dropping—claret tapping—betting too—

Reeling, rapping—physic napping, all to grace the mill;

Losing, winning—horse-laugh, grinning—mind you do not glance

away,

Or somebody may mill your mug, and of your nob in Chancery;

For nobs and bobs, and empty fobs, the like no tongue could ever

tell—

See, here's the heavy-handed Gas, and there's the mighty Non-

pareil:

Oh! 'tis a sight, &c.

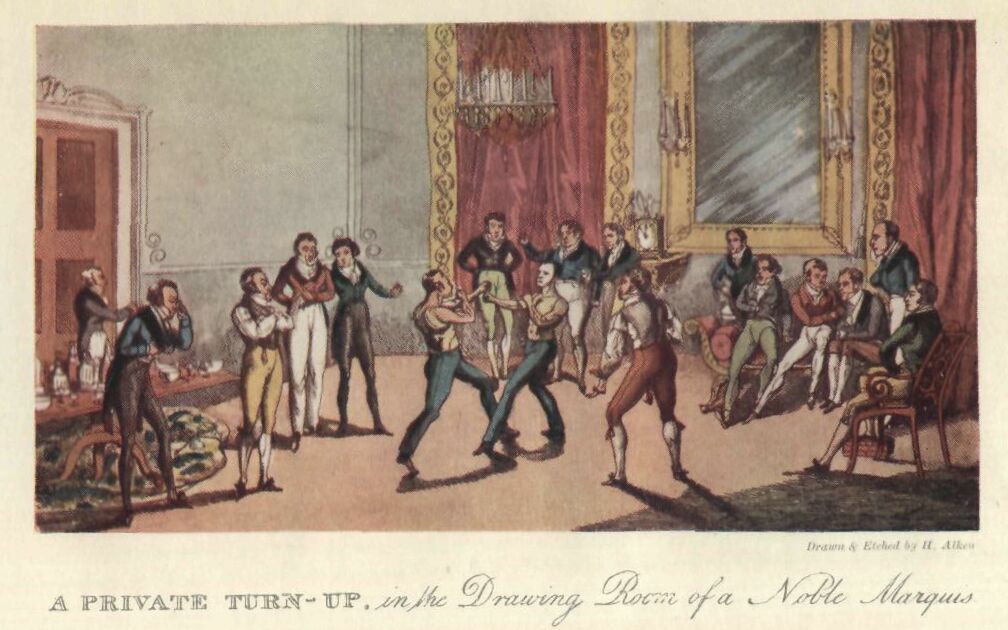

Thus milling is the fashion grown, and ev'ry one a closer is;

With lessons from the lads of fist to turn out quite the thing;

True science may be learn'd where'er the fam'd Mendoza is,

And gallantry and bottom too from Scroggins, Martin, Spring;

For sparring now is all the rage in town, and country places

too,

And collar-bones and claret-mugs are often seen at races too;

While counter-hits, and give and take, as long as strength can

hold her seat,

Afford the best amusement in a bit of pugilistic treat:

Oh! 'tis a sight, &c.

While this song was singing, universal silence prevailed, but an uproar of approbation followed, which lasted for some minutes, with a general call of encore, which however soon subsided, and the company was again restored to their former state of conversation; each party appearing distinct, indulged in such observations and remarks as were most suitable or agreeable to themselves.

Bob was highly pleased with this description of a milling match; and as the Singer was sitting near the person who had excited a considerable portion of his attention at intervals in watching his tricks, in some of which great ingenuity was displayed, he asked his Cousin if he knew him.

"Know him," replied Tom, "to be sure I do; that is no other than Bitton, a well-known pugilist, who frequently exhibits at the Fives-Court; he is a Jew, and employs his time in giving lessons."

"Zounds!" said Mortimer, "he seems to have studied the art of Legerdemain as well as the science of Milling."

"He is an old customer here," said a little Gentleman at the opposite side of the table, drawing from his pocket a box of segars{1}—"Now, Sir," continued he, "if you wish for a treat," addressing himself to Tallyho, "allow me to select you one—there, Sir, is asgar like a nosegay—I had it from a friend of mine who only arrived yesterday—you don't often meet with such, I assure you."

Bob accepted the offer, and was in the act of lighting it, when Bitton approached toward their end of the room with some cards in his hand, from which Bob began to anticipate he would shew some tricks upon them.

As soon as he came near the table, he had his eye upon the Hon. Tom Dashall, to whom he introduced 'himself by the presentation of a card, which announced his benefit for the next week at the Fives-Court, when all the prime lads of the ring had promised to exhibit.

"Egad!" said Dashall, "it will be an excellent opportunity—what, will you take a trip that way and see the mighty men of fist?"

"With all my heart," said Tallyho.

"And mine too," exclaimed Mortimer.

It was therefore quickly determined, and each of the party being supplied with a ticket, Bitton canvassed the room for other customers, after which he again retired to his seat.

"Come," said a smartly dressed Gentleman in a white hat, "we have heard a song from the other end of the room, I hope we shall be able to muster one here."

1 This gentleman, whose dress and appearance indicate

something of the Dandy, is a resident in Mark Lane, and

usually spends his evening at the Round Table, where he

appears to pride himself upon producing the finest segars

that can be procured, and generally affords some of his

friends an opportunity of proving them deserving the

recommendations with which he never fails to present them.

This proposition was received with applause, and, upon Tom's giving a hint, Frank Harry was called upon—the glasses were filled, a toast was given, and the bowl was dispatched for a replenish; he then sung the following Song, accompanied with voice, manner, and action, well calculated to rivet attention and obtain applause:

PIGGISH PROPENSITIES,

THE BUMPKIN IN TOWN.

"A Bumpkin to London one morning in Spring,

Hey derry, ho derry, fal de rai la,

Took a fat pig to market, his leg in a string,

Hey derry, ho derry, fal de rai la;

The clown drove him forward, while piggy, good lack!

Lik'd his old home so well, he still tried to run back—

(Spoken)—Coome, coome (said the Bumpkin to himself,) Lunnun is the grand mart for every thing; there they have their Auction Marts, their Coffee Marts, and their Linen Marts: and as they are fond of a tid-bit of country pork, I see no reason why they should not have" a Pork and Bacon Mart—so get on (pig grunts,) I am glad to hear you have a voice on the subject, though it seems not quite in tune with my

Hey derry, ho derry, fal de ral la.

It chanc'd on the road they'd a dreadful disaster,

Hey derry, ho derry, fal de rai la;

The grunter ran back 'twixt the legs of his master,

Hey derry, ho derry, fal de rai la;

The Bumpkin he came to the ground in a crack,

And the pig, getting loose, he ran all the way back!

(Spoken)—Hallo, (said the clown, scrambling up again, and scratching his broken head,) to be sure I have heard of sleight-of-hand, hocus-pocus and sich like; but by gum this here be a new manouvre called sleight of legs; however as no boanes be broken between us, I'll endeavour to make use on 'em once more in following the game in view: so here goes, with a

Hey derry, ho derry, &c.

He set off again with his pig in a rope,

Hey derry, ho derry, fal de rai la,

Reach'd London, and now for good sale 'gan to hope

Hey derry, ho derry, fal de rai la;

But the pig, being beat 'till his bones were quite sore.

Turning restive, rush'd in at a brandy-shop door.

(Spoken)—The genteeler and politer part of the world might feel a little inclined to call this piggish behaviour; but certainly after a long and fatiguing journey, nothing can be more refreshing than a drap of the cratur; and deeming this the regular mart for the good stuff, in he bolts, leaving his master to sing as long as he pleased—Hey derry, he deny, &c.

Here three snuffy Tabbies he put to the rout,

Hey derry, ho derry, fal de rai lft,

With three drams to the quartern, that moment serv'd

out,

Hey derry, ho derry, fal de rai la;

The pig gave a grunt, and the clown gave a roar,

When the whole of the party lay flat on the floor!

(Spoken)—Yes, there they lay all of a lump; and a precious group there was of them: The old women, well prun'd with snuff and twopenny, and bang-up with gin and bitters—the fair ones squalled; the clown growled like a bear with a broken head; the landlord, seeing all that could be seen as they roll'd over each other, stared, like a stuck pig! while this grand chorus of soft and sweet voices from the swinish multitude was accompanied by the pig with his usual grunt, and a

Hey derry, ho derry, &o.

The pig soon arose, and the door open flew,

Hey derry, ho derry, fal de ral la,

When this scrambling group was expos'd to my view,

Hey deny, ho derry, fal de ral la;

He set off again, without waiting for Jack,

And not liking London, ran all the way back!

(Spoken)—The devil take the pig! (said the Bumpkin) he is more trouble than enough. "The devil take you (said Miss Sukey Snuffle) for you are the greatest hog of the two; I dare say, if the truth was known, you are brothers."—"I declare I never was so exposed in all my life (said Miss Delia Doldrum.) There's my beautiful bloom petticoat, that never was rumpled before in all my life—I'm quite shock'd!"—"Never mind, (said the landlord) nobody cares about it; tho' I confess it was a shocking affair."—'I wish he and his pigs were in the horse-pond (continued she, endeavouring to hide her blushes with her hand)—Oh my—oh my!'—"What?" (said Boniface)—'Oh, my elbow! (squall'd out Miss Emilia Mumble) I am sure I shall never get over it.'—"Oh yes you will (continued he) rise again, cheer your spirits with another drop of old Tom, and you'll soon be able to sing

Hey derry, ho derry, &c.

By mutual consent the old women all swore,

Hey derry, ho derry, fal de rai la,

That the clown was a brute, and his pig was a boar,

Hey derry, ho derry, fal de rai la;

He paid for their liquor, but grumbled, good lack,

Without money or pig to gang all the way back.

(Spoken)—By gum (said he to himself, as he turn'd from the door) if the Lunneners likes country pork, country pork doant seem to like they; and if this be the success I'm to expect in this mighty great town in search of the Grand Mart, I'll come no more, for I thinks as how its all a flax; therefore I'll make myself contented to set at home in my own chimney corner in the country, and sing

Hey derry, ho derry, &c.

This song had attracted the attention of almost every one in the room; there was a spirit and vivacity in the singer, combined with a power of abruptly changing his voice, to give effect to the different passages, and a knowledge of music as well as of character, which gave it an irresistible charm; and the company, who had assembled round him, at the close signified their approbation by a universal shout of applause.

All went on well—songs, toasts and sentiments—punch, puns and witticisms, were handed about in abundance; in the mean time, the room began to wear an appearance of thinness, many of the boxes were completely deserted, and the Knights of the Bound Table were no longer surrounded by their Esquires—still the joys of the bowl were exhilarating, and the conversation agreeable, though at times a little more in a strain of vociferation than had been manifested at the entrance of our party. It was no time to ask questions as to the names and occupations of the persons by whom he was surrounded; and Bob, plainly perceiving Frank Harry was getting into Queer Street, very prudently declined all interrogatories for the present, making, however, a determination within himself to know more of the house and the company.

Mortimer also discovered symptoms of lush-logic, for though he had an inclination to keep up the chaff, his dictionary appeared to be new modelled, and his lingo abridged by repeated clips at his mother tongue, by which he afforded considerable food for laughter.

Perceiving this, Tallyho thought it prudent to give his Cousin a hint, which was immediately taken, and the party broke up.[292]

"O there are swilling wights in London town

Term'd jolly dogs—choice spirits—alias swine,

Who pour, in midnight revel, bumpers down,

Making their throats a thoroughfare for wine.

These spendthrifts, who life's pleasures thus outrun,

Dosing with head-aches till the afternoon,

Lose half men's regular estate of Sun,

By borrowing too largely of the Moon:

And being Bacchi plenus—full of wine—

Although they have a tolerable notion

Of aiming at progressive motion,

Tis not direct, 'tis rather serpentine."