Project Gutenberg's The Ship of Fools, Volume 1, by Sebastian Brandt This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Ship of Fools, Volume 1 Author: Sebastian Brandt Translator: Alexander Barclay Release Date: December 23, 2006 [EBook #20179] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SHIP OF FOOLS, VOLUME 1 *** Produced by Frank van Drogen, Keith Edkins and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

| Transcriber's note: | A few typographical errors in the 1874 introduction have been corrected. They appear in the text like this, and the explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked passage. In the spirit of the 1874 edition, the text of the Ship of Fools itself has been retained exactly as it stands, even to the punctuation. |

TRANSLATED BY

VOLUME FIRST

MDCCCLXXIV.

It is necessary to explain that in the present edition of the Ship of Fools, with a view to both philological and bibliographical interests, the text, even to the punctuation, has been printed exactly as it stands in the earlier impression (Pynson's), the authenticity of which Barclay himself thus vouches for in a deprecatory apology at the end of his labours (II. 330):—

"... some wordes be in my boke amys

For though that I my selfe dyd it correct

Yet with some fautis I knowe it is infect

Part by my owne ouersyght and neglygence

And part by the prynters nat perfyte in science

And other some escaped ar and past

For that the Prynters in theyr besynes

Do all theyr workes hedelynge, and in hast"

Yet the differences of reading of the later edition (Cawood's), are surprisingly few and mostly unimportant, though great pains were evidently bestowed on the production of the book, all the misprints being carefully corrected, and the orthography duly adjusted to the fashion of the time. These differences have, in this edition, been placed in one alphabetical arrangement with the glossary, by which plan it is believed reference to them will be made more easy, and much repetition avoided.

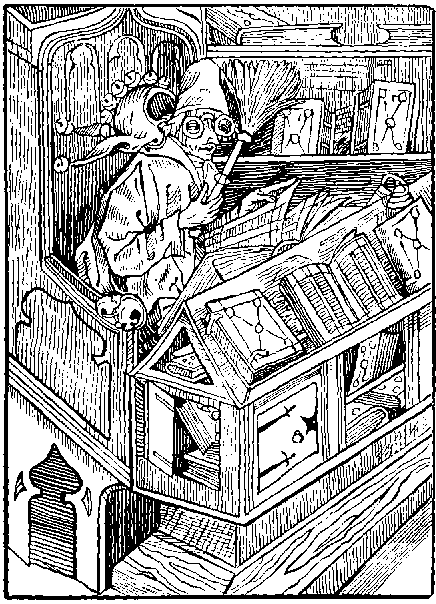

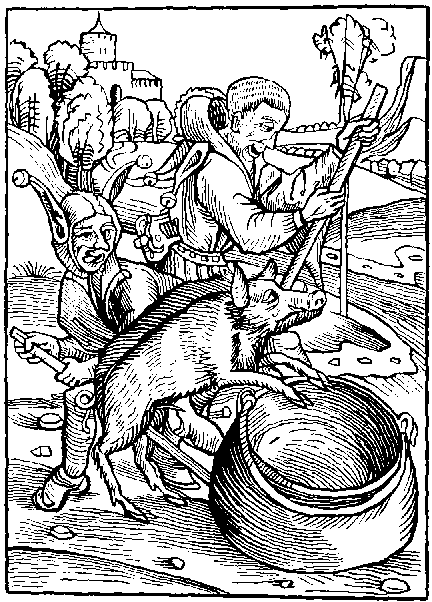

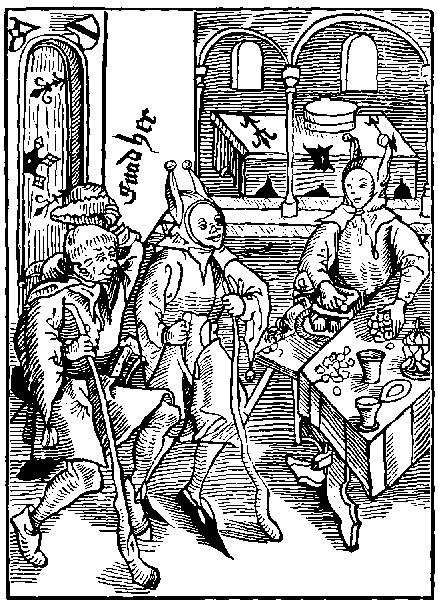

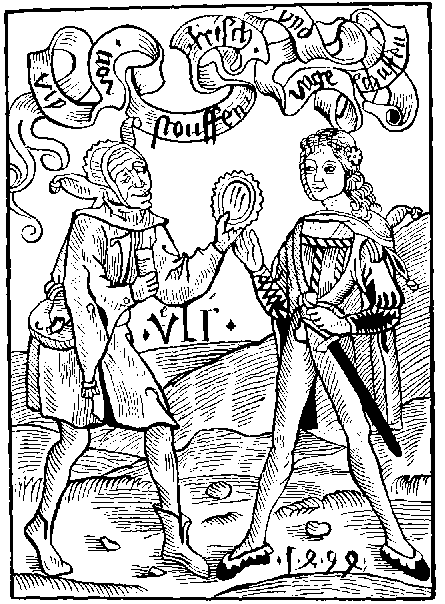

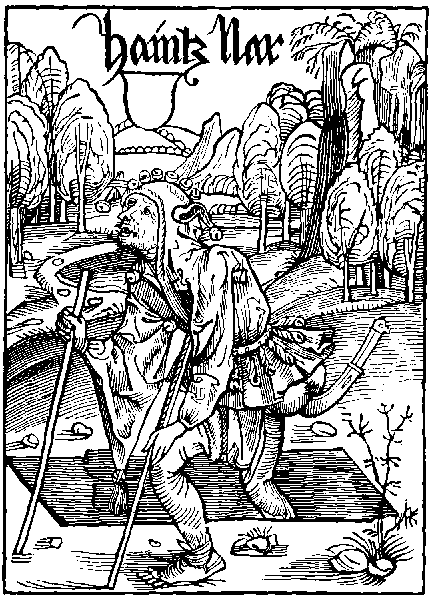

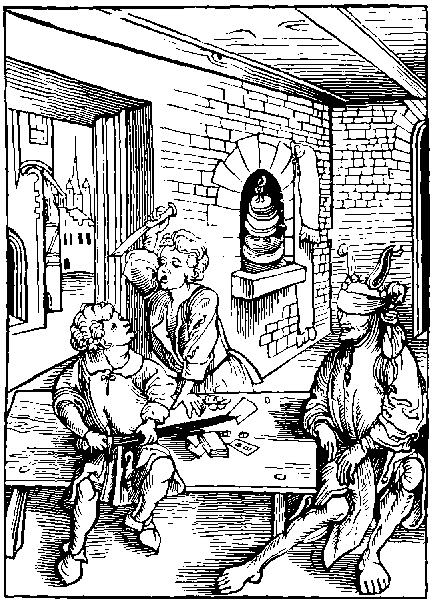

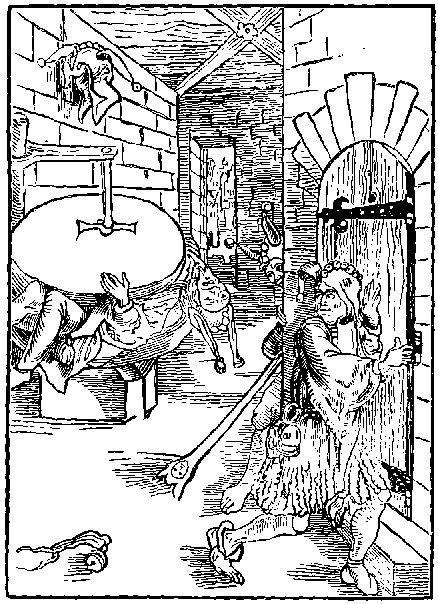

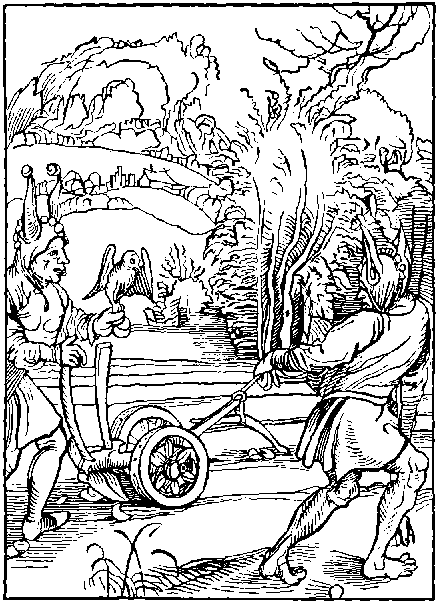

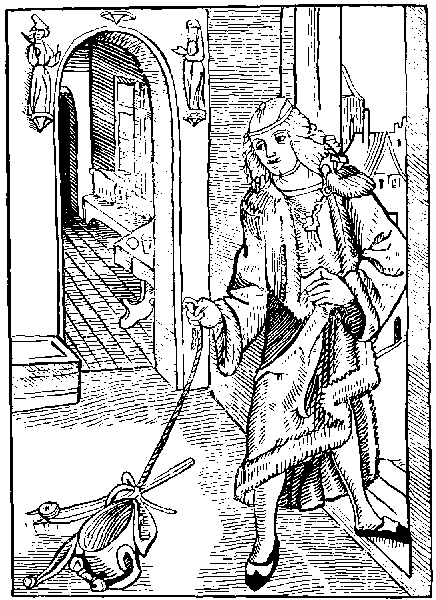

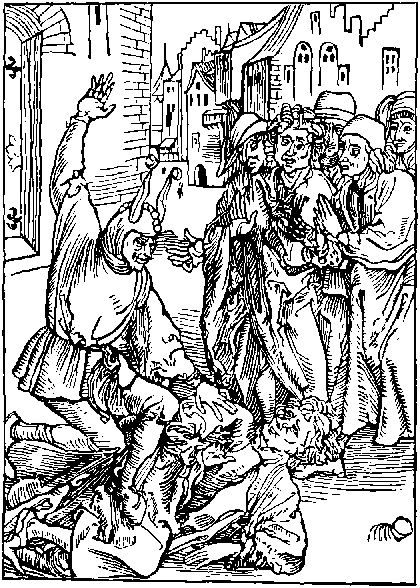

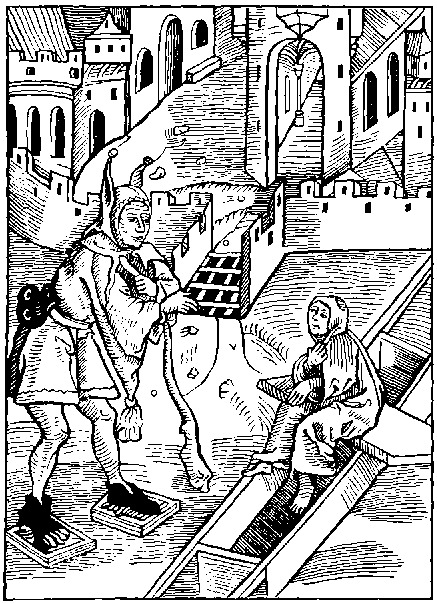

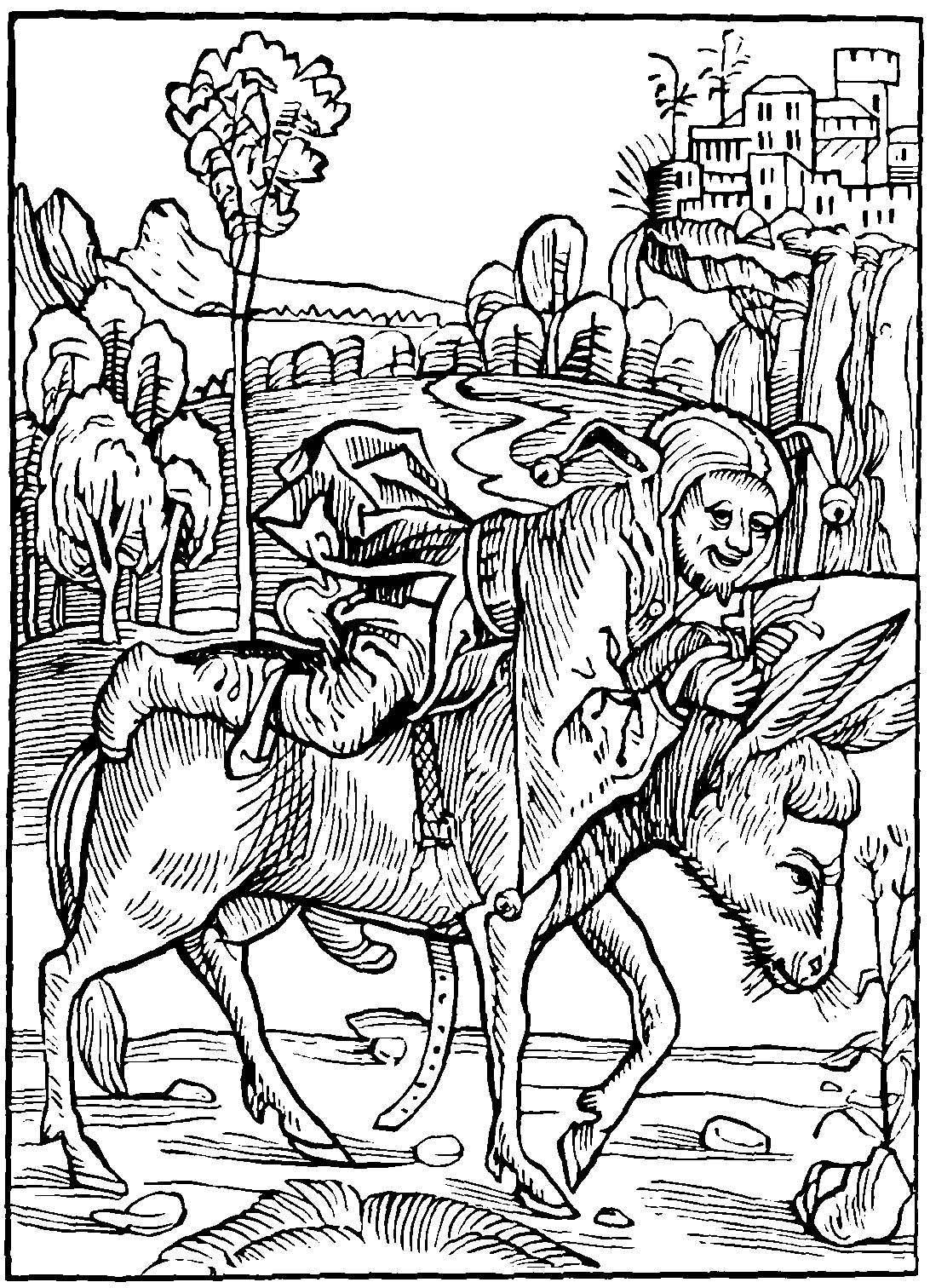

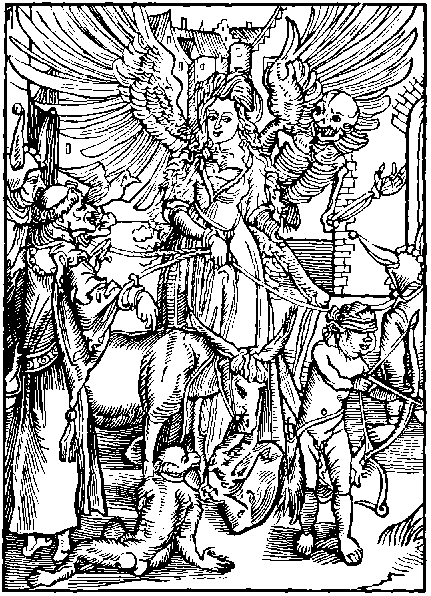

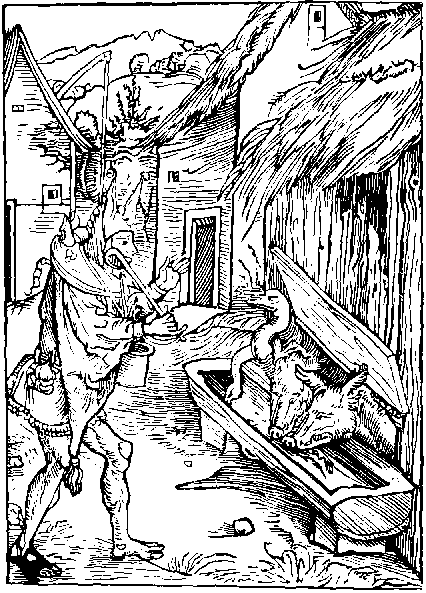

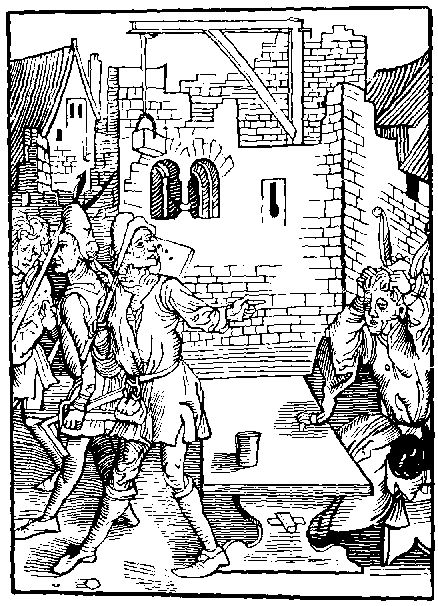

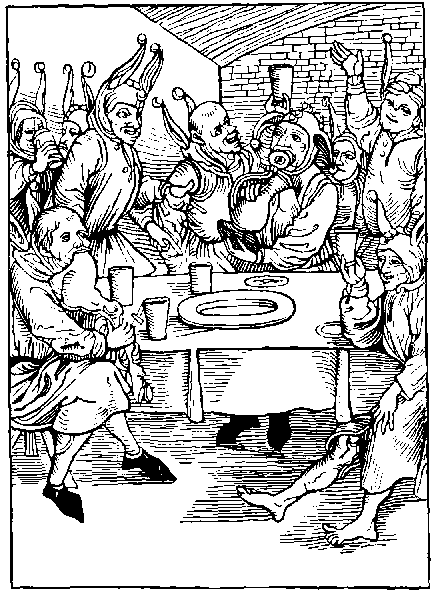

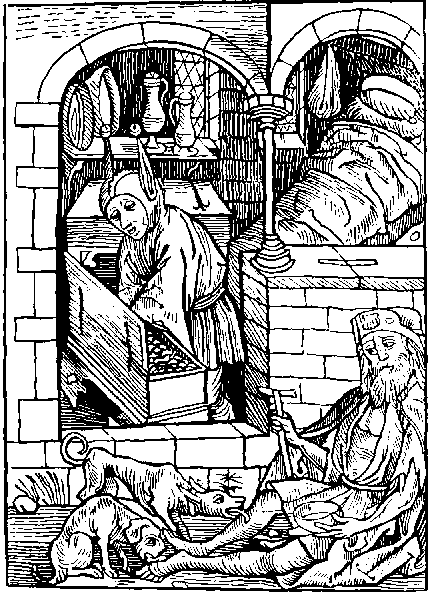

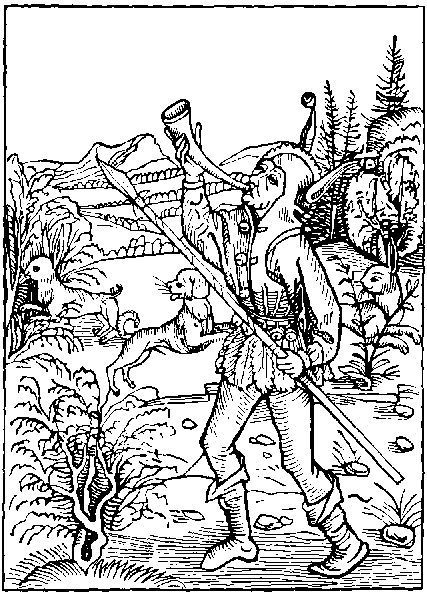

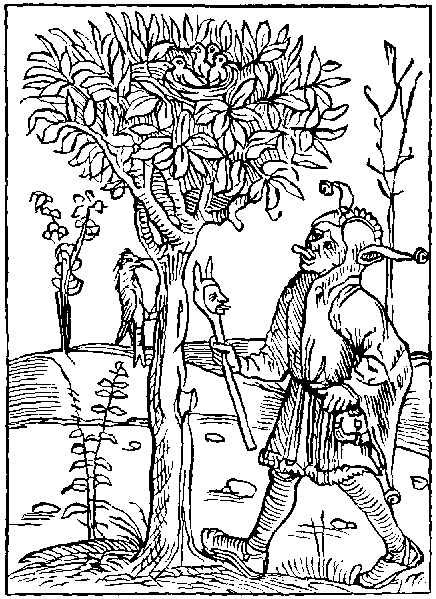

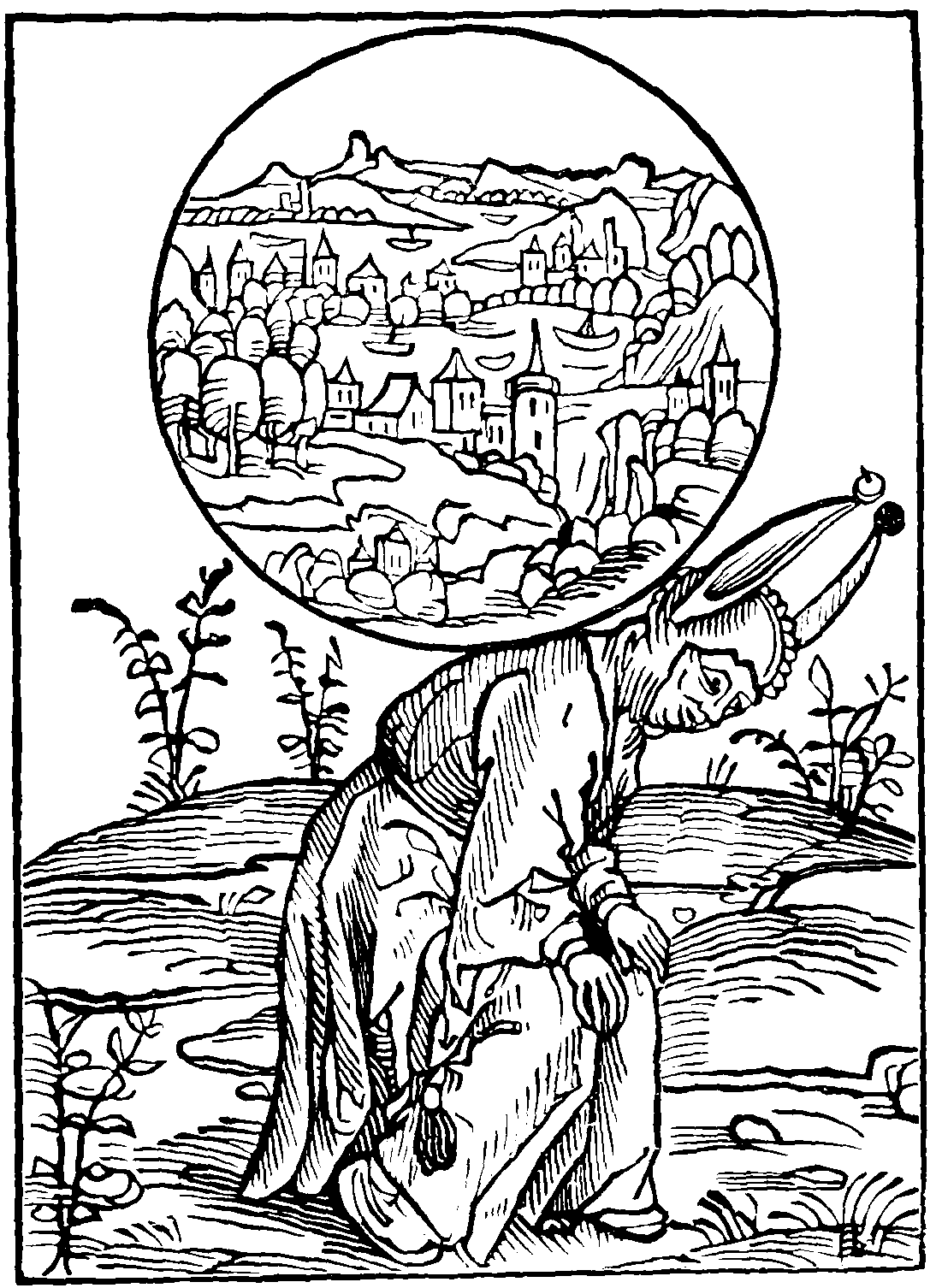

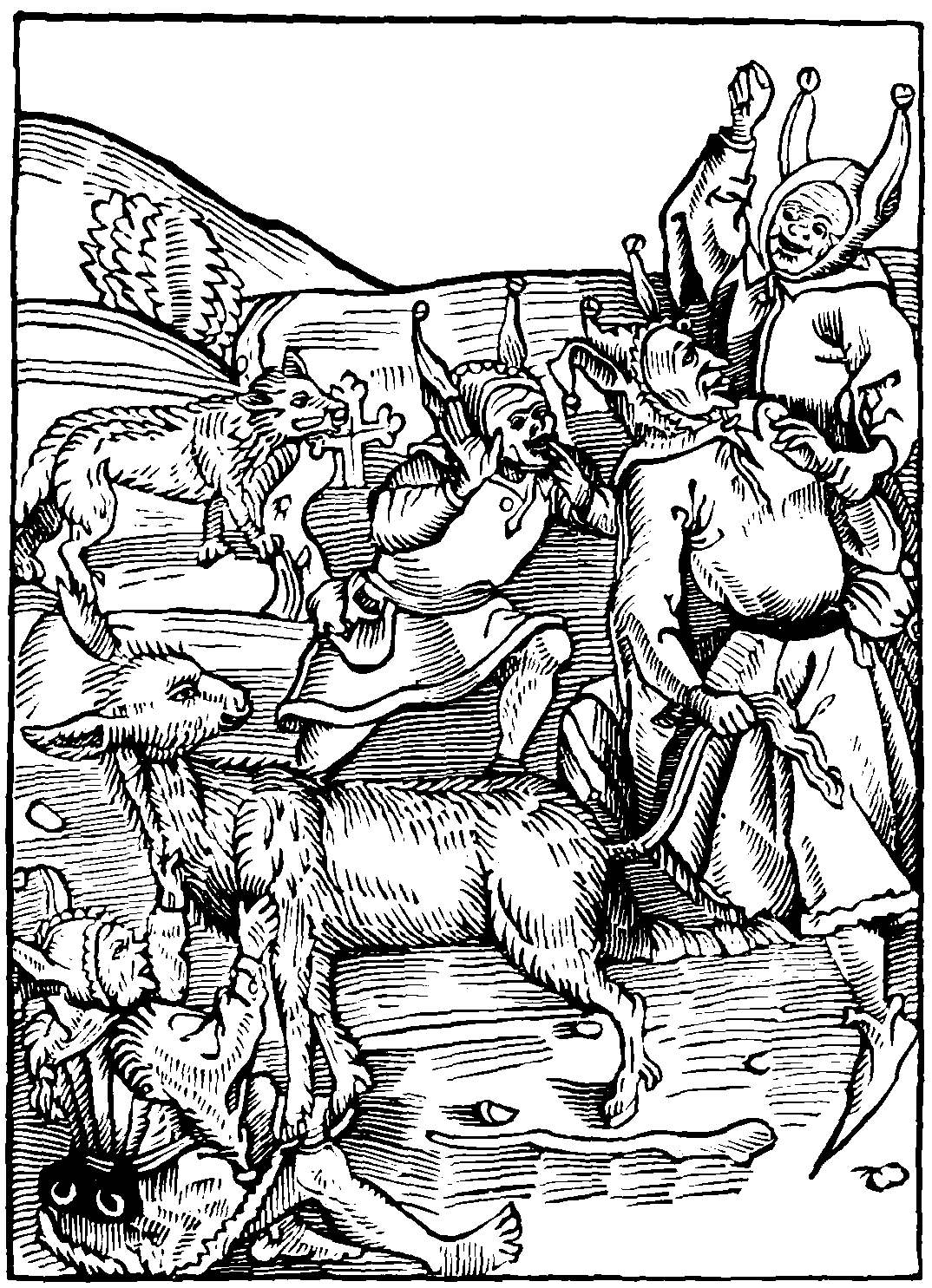

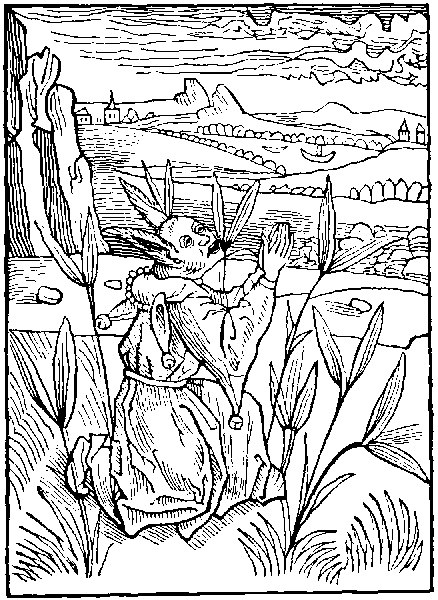

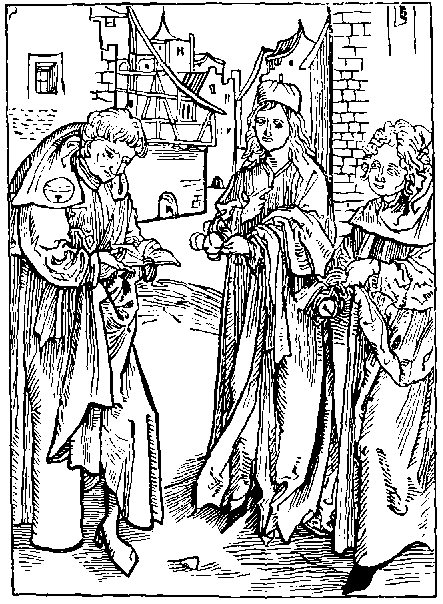

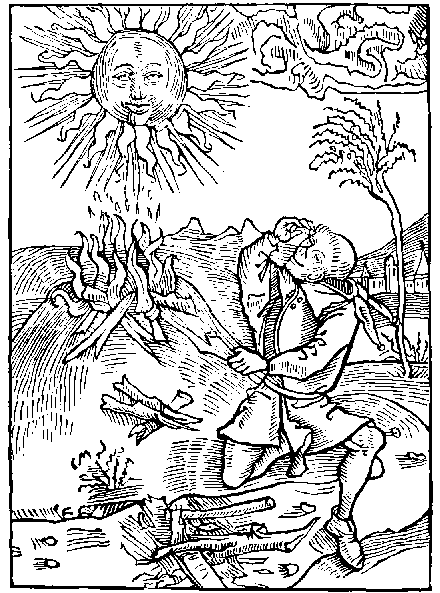

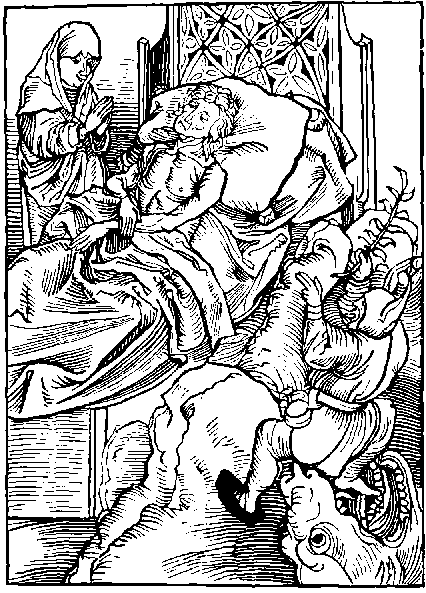

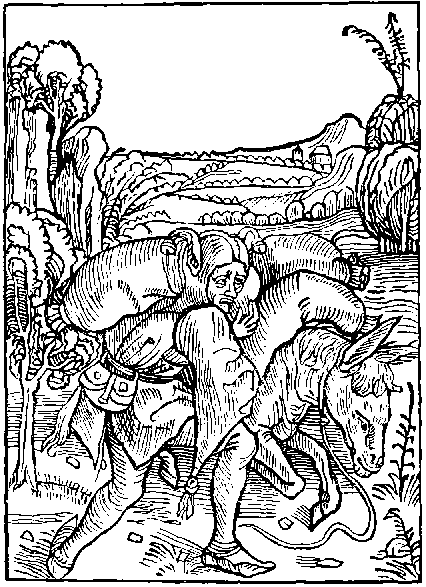

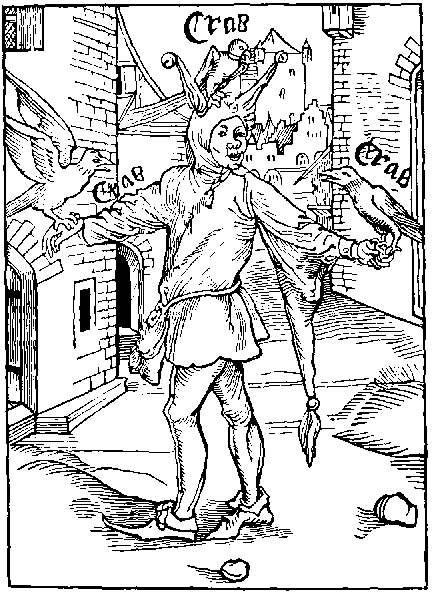

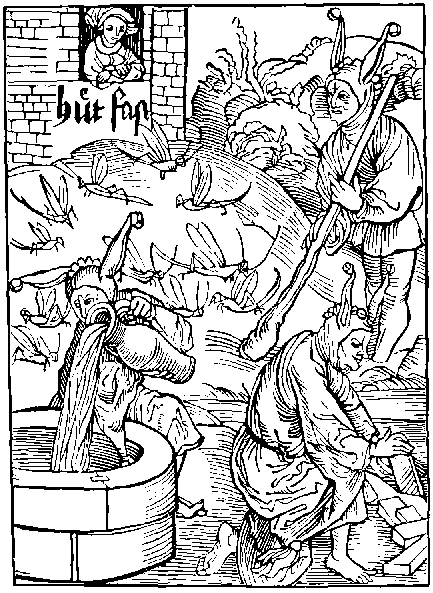

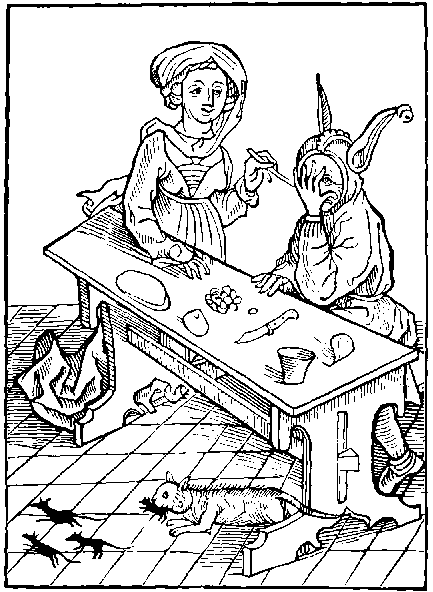

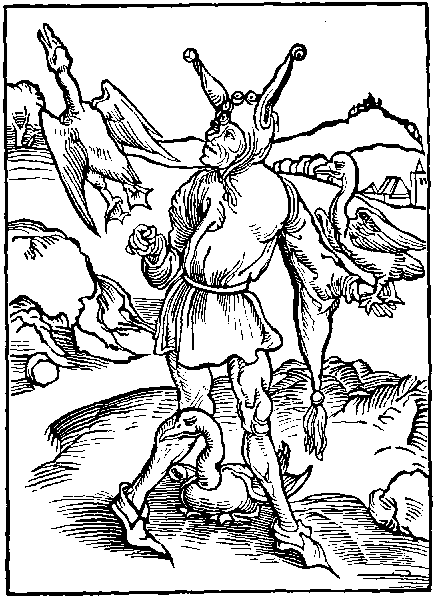

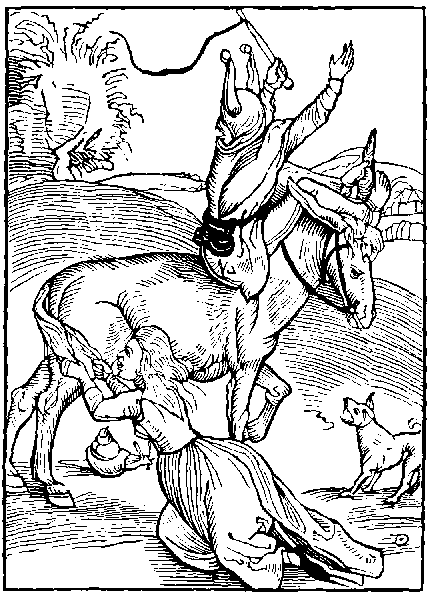

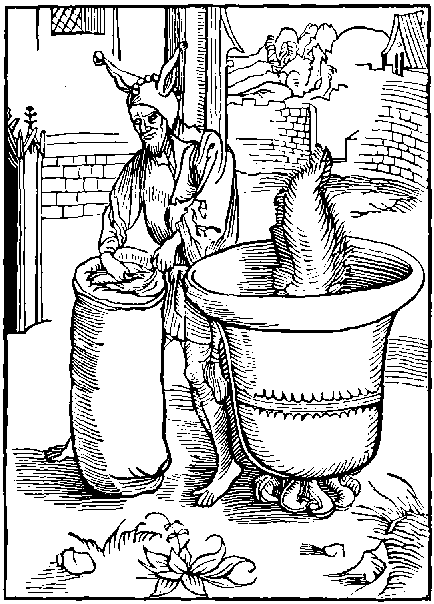

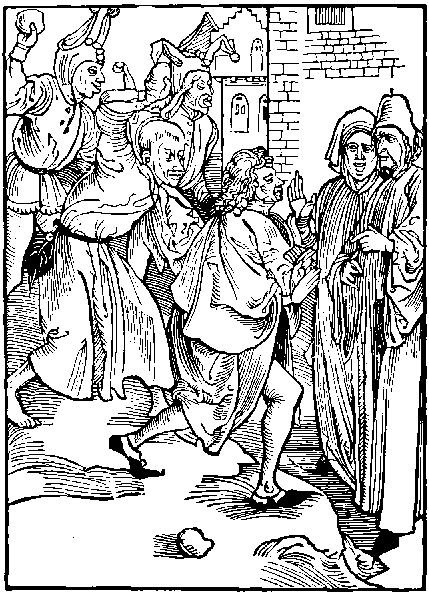

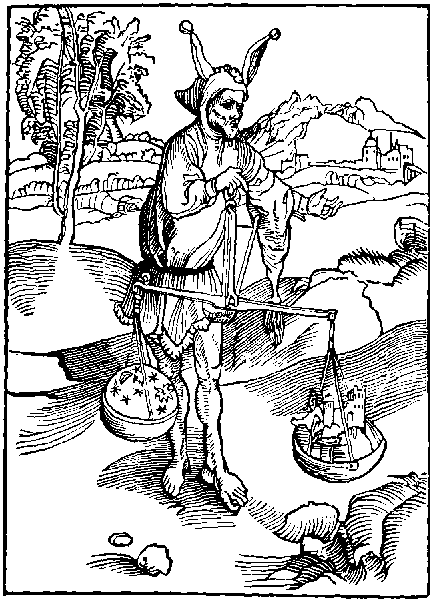

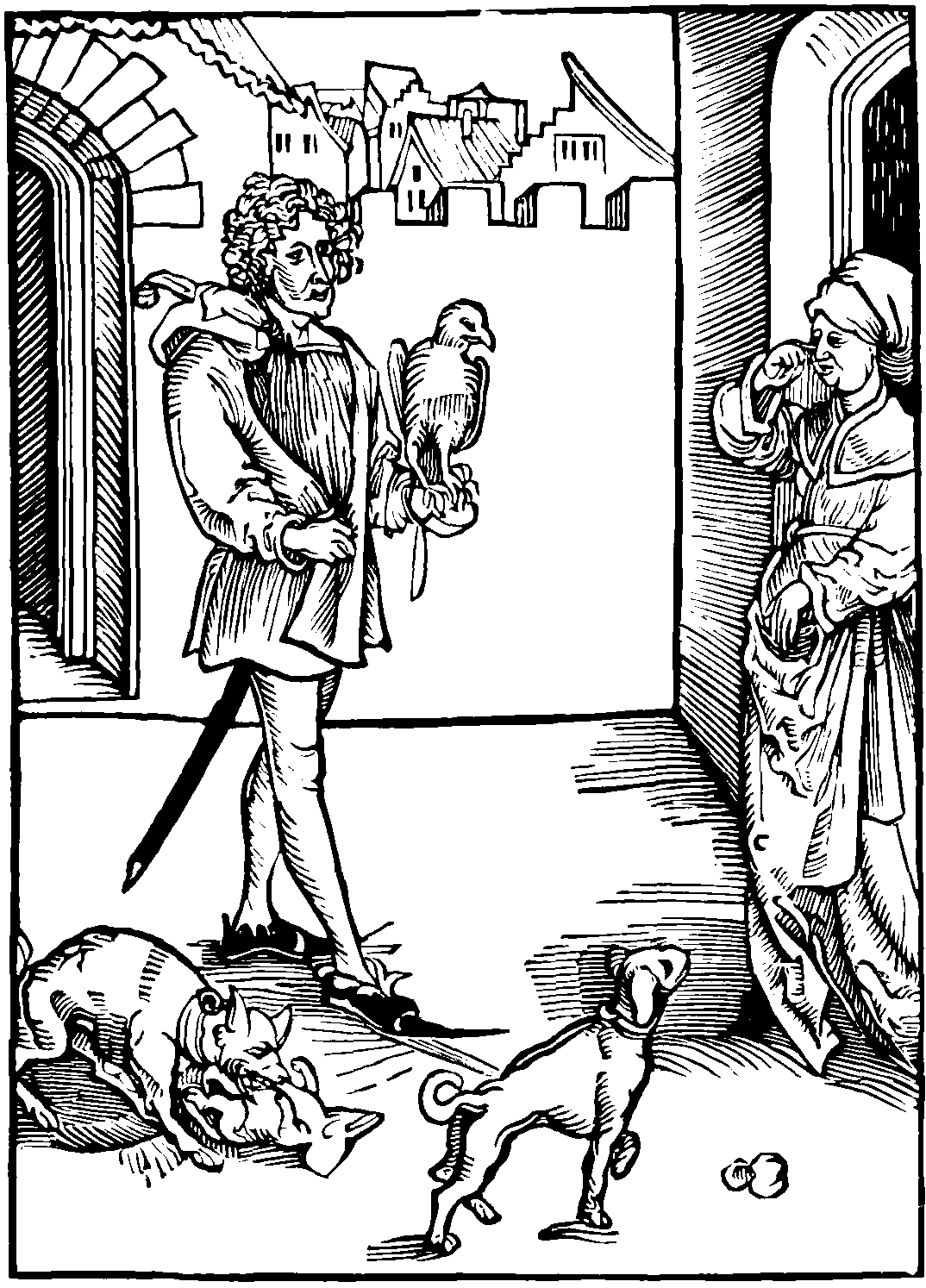

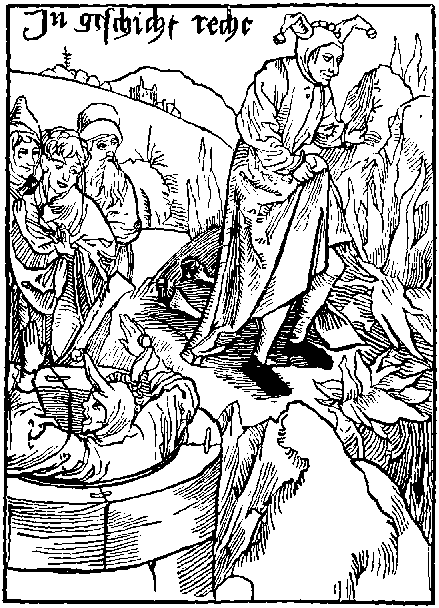

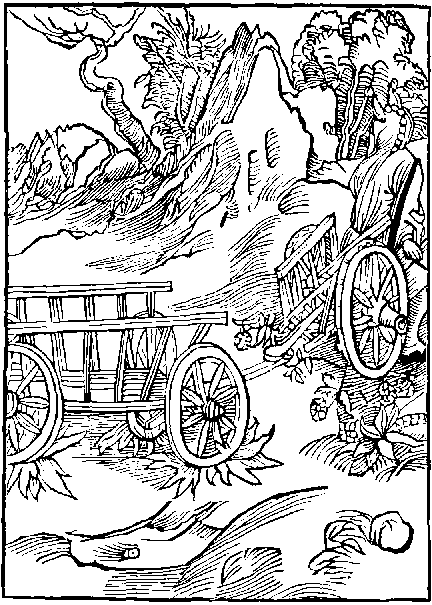

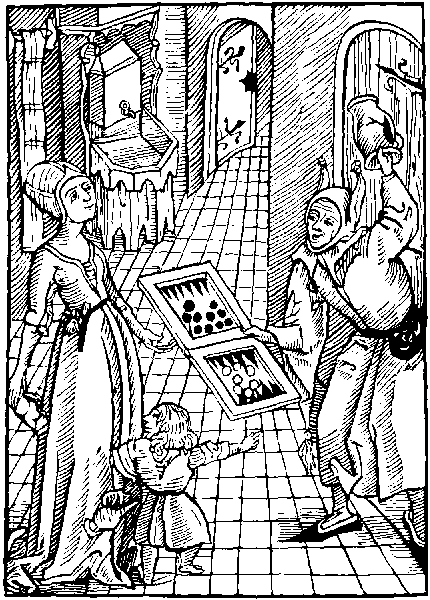

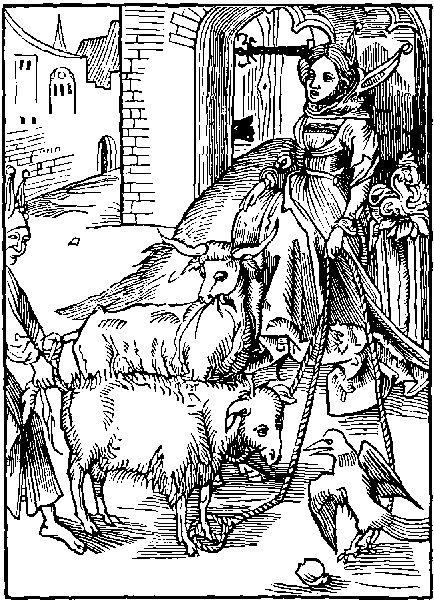

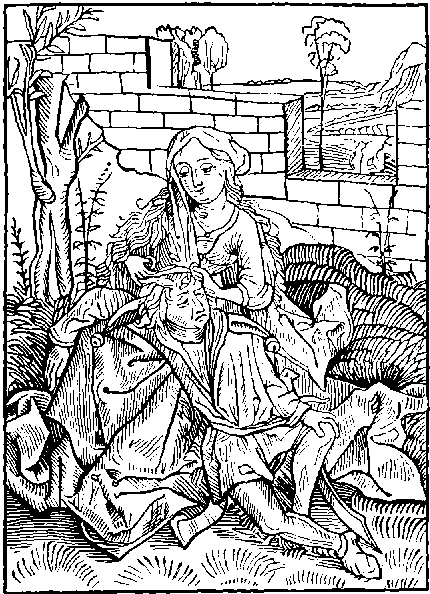

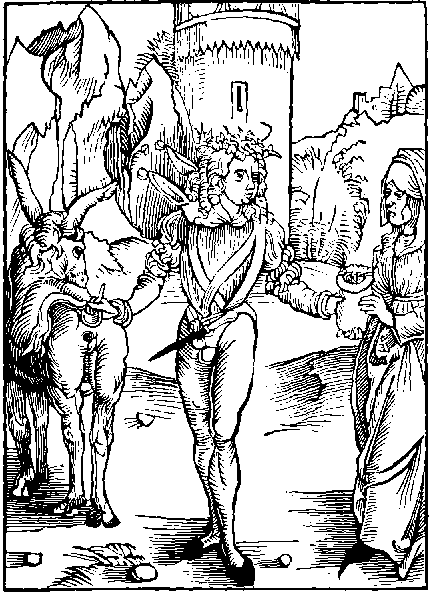

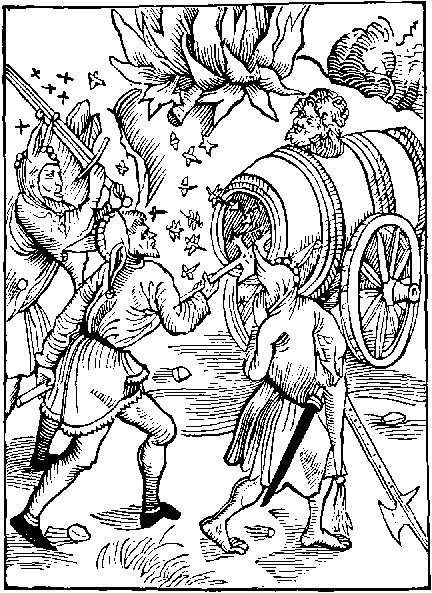

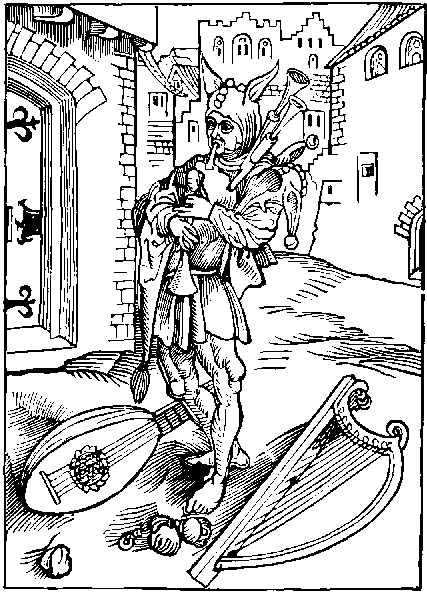

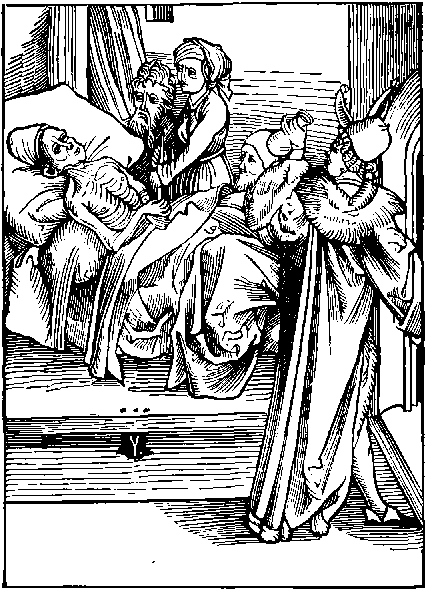

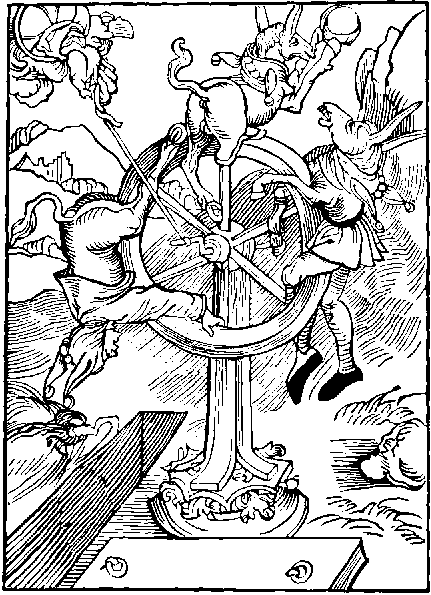

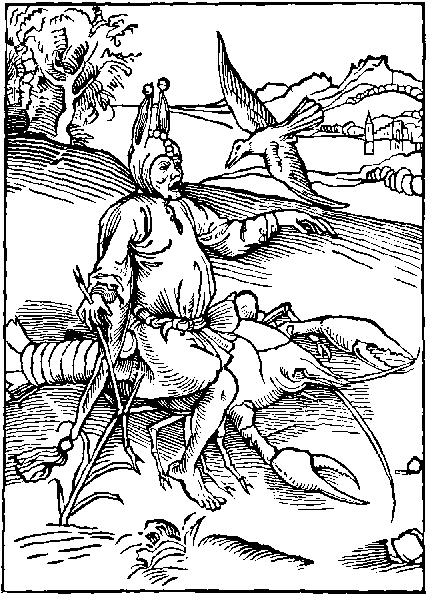

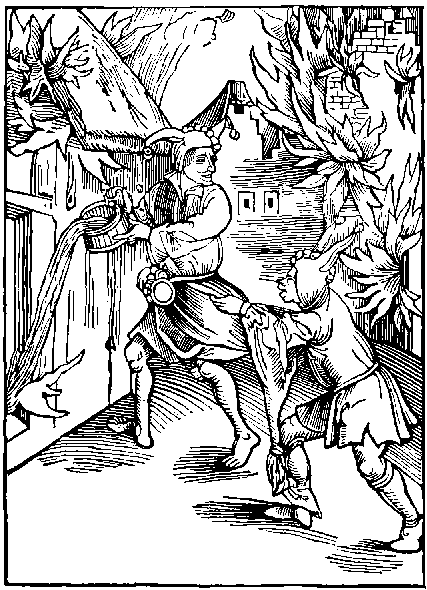

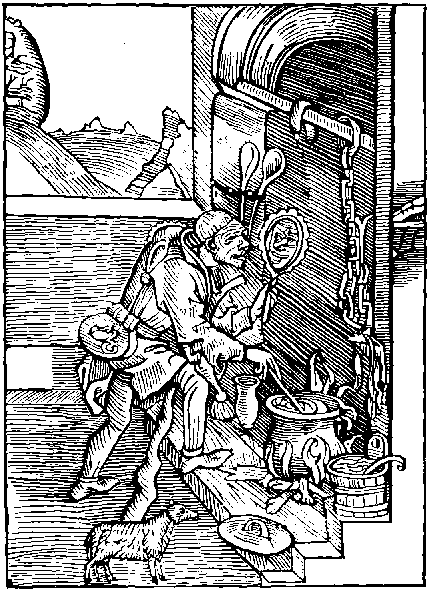

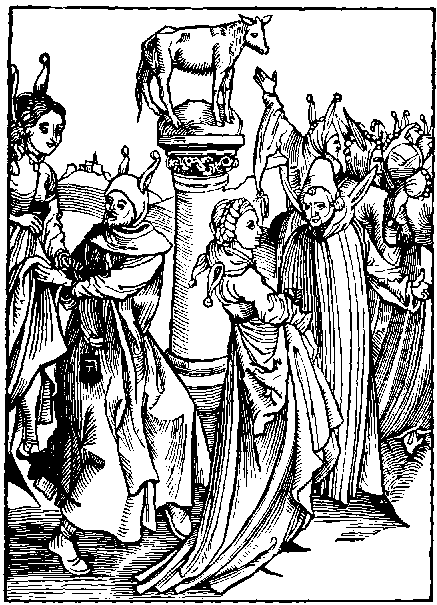

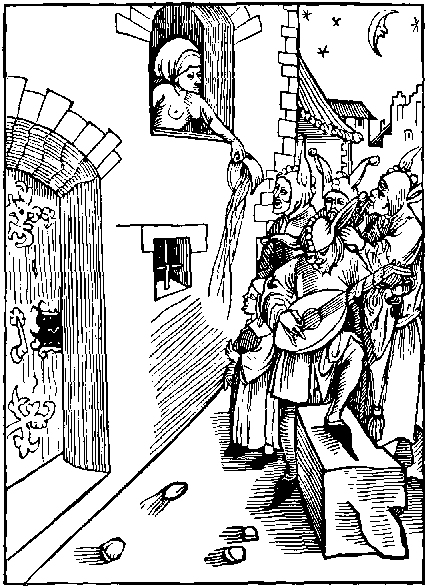

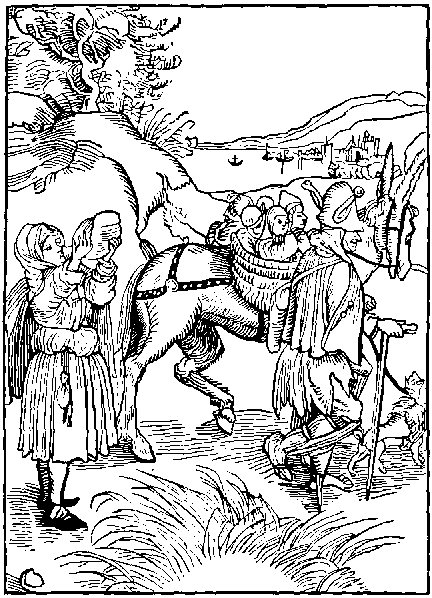

The woodcuts, no less valuable for their artistic merit than they are interesting as pictures of contemporary manners, have been facsimiled for the present edition from the originals as they appear in the Basle edition of the Latin, "denuo seduloque reuisa," issued under Brandt's own superintendence in 1497. This work has been done by Mr J. T. Reid, to whom it is due to say that he has executed it with the most painstaking and scrupulous fidelity.

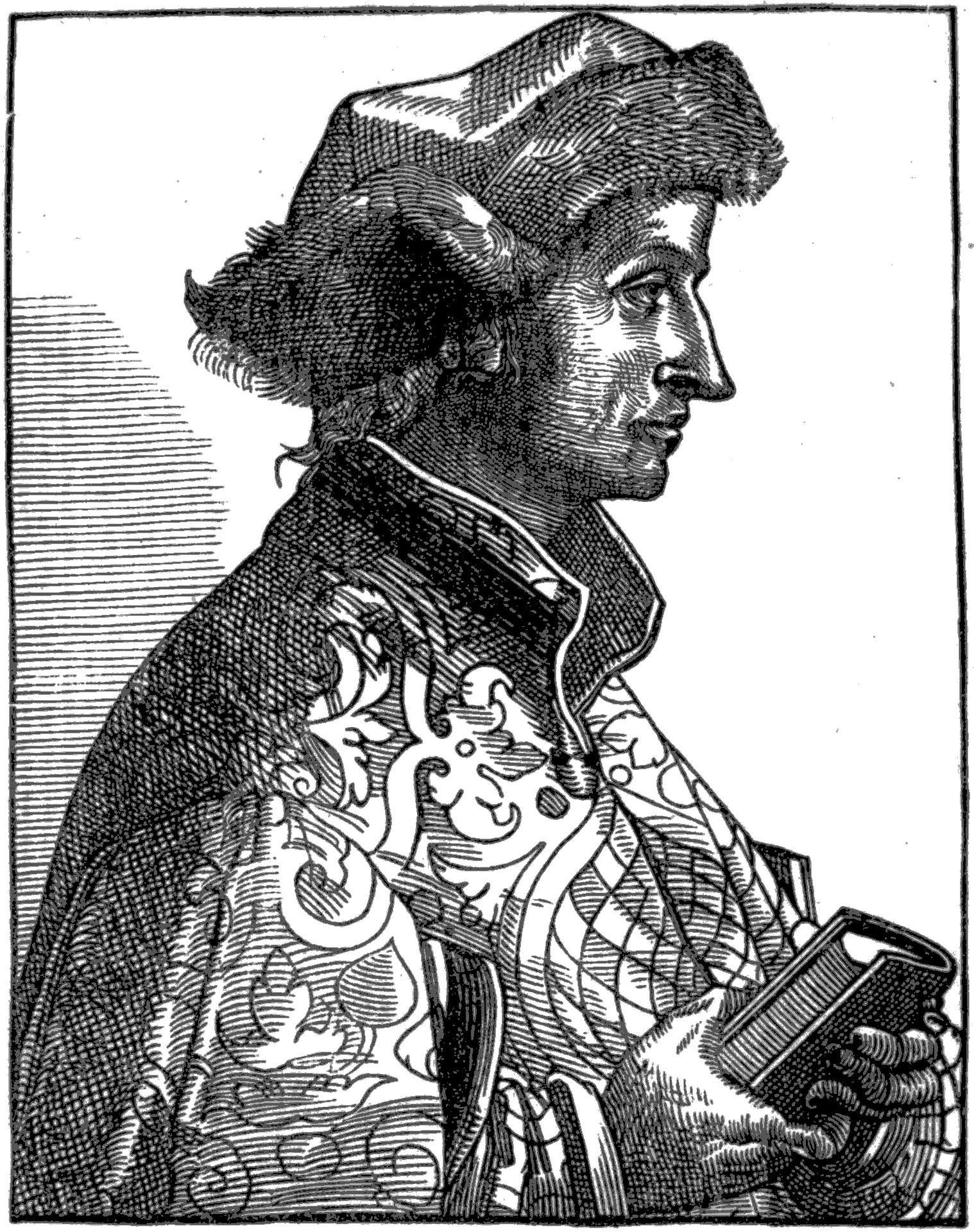

The portrait of Brandt, which forms the frontispiece to this volume, is taken from Zarncke's edition of the Narrenschiff; that of Barclay presenting one of his books to his patron, prefixed to the Notice of his life, appears with a little more detail in the Mirror of Good Manners and the Pynson editions of the Sallust; it is, however, of no authority, being used for a similar purpose in various other publications.

For the copy of the extremely rare original edition from which the text of the present has been printed, I am indebted to the private collection and the well known liberality of Mr David Laing of the Signet Library, to whom I beg here to return my best thanks, for this as well as many other valuable favours in connection with the present work.

In prosecuting enquiries regarding the life of an author of whom so little is known as of Barclay, one must be indebted for aid, more or less, to the kindness of friends. In this way I have to acknowledge my obligations to Mr Æneas Mackay, Advocate, and Mr Ralph Thomas, ("Olphar Hamst"), for searches made in the British Museum and elsewhere.

For collations of Barclay's Works, other than the Ship of Fools, all of which are of the utmost degree of rarity, and consequent inaccessibility, I am indebted to the kindness of Henry Huth, Esq., 30 Princes' Gate, Kensington; the Rev. W. D. Macray, of the Bodleian Library, Oxford; W. B. Rye, Esq., of the British Museum; Henry Bradshaw, Esq., of the University Library, Cambridge; and Professor Skeat, Cambridge.

For my brief notice of Brandt and his Work, it is also proper to acknowledge my obligations to Zarncke's critical edition of the Narrenschiff (Leipzig, 1854) which is a perfect encyclopædia of everything Brandtian.

Advocates' Library,

Edinburgh, December 1873.

If popularity be taken as the measure of success in literary effort, Sebastian Brandt's "Ship of Fools" must be considered one of the most successful books recorded in the whole history of literature. Published in edition after edition (the first dated 1494), at a time, but shortly after the invention of printing, when books were expensive, and their circulation limited; translated into the leading languages of Europe at a time when translations of new works were only the result of the most signal merits, its success was then quite unparalleled. It may be said, in modern phrase, to have been the rage of the reading world at the end of the fifteenth and throughout the sixteenth centuries. It was translated into Latin by one Professor (Locher, 1497), and imitated in the same language and under the same title, by another (Badius Ascensius, 1507); it appeared in Dutch and Low German, and was twice translated into English, and three times into French; imitations competed with the original in French and German, as well as Latin, and greatest and most unprecedented distinction of all, it was preached, but, we should opine, only certain parts of it, from the pulpit by the best preachers of the time as a new gospel. The Germans proudly award it the epithet, "epoch-making," and its long-continued popularity affords good, if not quite sufficient, ground for the extravagant eulogies they lavish upon it. Trithemius calls it "Divina Satira," and doubts whether anything could have been written more suited to the spirit of the age; Locher compares Brandt with Dante, and Hutten styles him the new law-giver of German poetry.

A more recent and impartial critic (Müller, "Chips from a German Workshop," Vol. III.), thus suggestively sets forth the varied grounds of Brandt's wonderful popularity:—"His satires, it is true, are not very powerful, nor pungent, nor original. But his style is free and easy. Brant is not a ponderous poet. He writes in short chapters, and mixes his fools in such a manner that we always meet with a variety of new faces. It is true that all this would hardly be sufficient to secure a decided success for a work like his at the present day. But then we must remember the time in which he wrote.... There was room at that time for a work like the 'Ship of Fools.' It was the first printed book that treated of contemporaneous events and living persons, instead of old German battles and French knights. People are always fond of reading the history of their own times. If the good qualities of their age are brought out, they think of themselves or their friends; if the dark features of their contemporaries are exhibited, they think of their neighbours and enemies. Now the 'Ship of Fools' is just such a satire which ordinary people would read, and read with pleasure. They might feel a slight twinge now and then, but they would put down the book at the end, and thank God that they were not like other men. There is a chapter on Misers—and who would not gladly give a penny to a beggar? There is a chapter on Gluttony—and who was ever more than a little exhilarated after dinner?

There is a chapter on Church-goers—and who ever went to church for respectability's sake, or to show off a gaudy dress, or a fine dog, or a new hawk? There is a chapter on Dancing—and who ever danced except for the sake of exercise? There is a chapter on Adultery—and who ever did more than flirt with his neighbour's wife? We sometimes wish that Brant's satire had been a little more searching, and that, instead of his many allusions to classical fools (for his book is full of scholarship), he had given us a little more of the chronique scandaleuse of his own time. But he was too good a man to do this, and his contemporaries were no doubt grateful to him for his forbearance."

Brandt's satire is a satire for all time. Embodied in the language of the fifteenth century, coloured with the habits and fashions of the times, executed after the manner of working of the period, and motived by the eager questioning spirit and the discontent with "abusions" and "folyes" which resulted in the Reformation, this satire in its morals or lessons is almost as applicable to the year of grace 1873 as to the year of gracelessness 1497. It never can grow old; in the mirror in which the men of his time saw themselves reflected, the men of all times can recognise themselves; a crew of "able-bodied" is never wanting to man this old, weather-beaten, but ever seaworthy vessel. The thoughtful, penetrating, conscious spirit of the Basle professor passing by, for the most part, local, temporary or indifferent points, seized upon the never-dying follies of human nature and impaled them on the printed page for the amusement, the edification, and the warning of contemporaries and posterity alike. No petty writer of laborious vers de societe to raise a laugh for a week, a month, or a year, and to be buried in utter oblivion for ever after, was he, but a divine seer who saw the weakness and wickedness of the hearts of men, and warned them to amend their ways and flee from the wrath to come. Though but a retired student, and teacher of the canon law, a humble-minded man of letters, and a diffident imperial Counsellor, yet is he to be numbered among the greatest Evangelists and Reformers of mediæval Europe whose trumpet-toned tongue penetrated into regions where the names of Luther or Erasmus were but an empty sound, if even that. And yet, though helping much the cause of the Reformation by the freedom of his social and clerical criticism, by his unsparing exposure of every form of corruption and injustice, and, not least, by his use of the vernacular for political and religious purposes, he can scarcely be classed in the great army of the Protestant Reformers. He was a reformer from within, a biting, unsparing exposer of every priestly abuse, but a loyal son of the Church, who rebuked the faults of his brethren, but visited with the pains of Hell those of "fals herytikes," and wept over the "ruyne, inclynacion, and decay of the holy fayth Catholyke, and dymynucion of the Empyre."

So while he was yet a reformer in the true sense of the word, he was too much of the scholar to be anything but a true conservative. To his scholarly habit of working, as well as to the manner of the time which hardly trusted in the value of its own ideas but loved to lean them upon classical authority, is no doubt owing the classical mould in which his satire is cast. The description of every folly is strengthened by notice of its classical or biblical prototypes, and in the margin of the Latin edition of Locher, Brandt himself supplied the citations of the books and passages which formed the basis of his text, which greatly added to the popularity of the work. Brandt, indeed, with the modesty of genius, professes that it is really no more than a collection and translation of quotations from biblical and classical authors, "Gesamlet durch Sebastianu Brant." But even admitting the work to be a Mosaic, to adopt the reply of its latest German editor to the assertion that it is but a compilation testifying to the most painstaking industry and the consumption of midnight oil, "even so one learns that a Mosaic is a work of art when executed with artistic skill." That he caused the classical and biblical passages flitting before his eyes to be cited in the margin proves chiefly only the excellence of his memory. They are also before our eyes and yet we are not always able to answer the question: where, e.g., does this occur? ... Where, e.g., occur the following appropriate words of Goethe: "Who can think anything foolish, who can think anything wise, that antiquity has not already thought of."

Of the Greek authors, Plutarch only is used, and he evidently by means of a Latin translation. But from the Latin large draughts of inspiration are taken, direct from the fountainhead. Ovid, Juvenal, Persius, Catullus, and Seneca, are largely drawn from, while, strangely enough, Cicero, Boethius, and Virgil are quoted but seldom, the latter, indeed, only twice, though his commentators, especially Servetus, are frequently employed. The Bible, of course, is a never-failing source of illustration, and, as was to be expected, the Old Testament much more frequently than the New, most use being made of the Proverbs of Solomon, while Ecclesiastes, Ecclesiasticus, and the Sapientia follow at no great distance.

The quotations are made apparently direct from the Vulgate, in only a few cases there being a qualification of the idea by the interpretation of the Corpus Juris Canonici. But through this medium only, as was to be expected of the professor of canon law, is the light of the fathers of the Church allowed to shine upon us, and according to Zarncke (Introduction to his edition of the Narrenschiff, 1854), use of it has certainly been made far oftener than the commentary shows, the sources of information of which are of the most unsatisfactory character. On such solid and tried foundations did Brandt construct his great work, and the judgment of contemporaries and posterity alike has declared the superstructure to be worthy of its supports.

The following admirable notice from Ersch and Grüber (Encyclopädie) sums up so skilfully the history, nature, and qualities of the book that we quote at length:—"The Ship of Fools was received with almost unexampled applause by high and low, learned and unlearned, in Germany, Switzerland, and France, and was made the common property of the greatest part of literary Europe, through Latin, French, English, and Dutch translations. For upwards of a century it was in Germany a book of the people in the noblest and widest sense of the word, alike appreciated by an Erasmus and a Reuchlin, and by the mechanics of Strassburg, Basel, and Augsburg; and it was assumed to be so familiar to all classes, that even during Brandt's lifetime, the German preacher Gailer von Kaiserberg went so far as to deliver public lectures from the pulpit on his friend's poem as if it had been a scriptural text. As to the poetical and humorous character of Brandt's poem, its whole conception does not display any extraordinary power of imagination, nor does it present in its details any very striking sallies of wit and humour, even when compared with older German works of a similar kind, such as that of Renner. The fundamental idea of the poem consists in the shipping off of several shiploads of fools of all kinds for their native country, which, however, is visible at a distance only; and one would have expected the poet to have given poetical consistency to his work by fully carrying out this idea of a ship's crew, and sailing to the 'Land of Fools.' It is, however, at intervals only that Brandt reminds us of the allegory; the fools who are carefully divided into classes and introduced to us in succession, instead of being ridiculed or derided, are reproved in a liberal spirit, with noble earnestness, true moral feeling, and practical common sense. It was the straightforward, the bold and liberal spirit of the poet which so powerfully addressed his contemporaries from the Ship of the Fools; and to us it is valuable as a product of the piety and morality of the century which paved the way for the Reformation. Brandt's fools are represented as contemptible and loathsome rather than foolish, and what he calls follies might be more correctly described as sins and vices.

"The 'Ship of Fools' is written in the dialect of Swabia, and consists of vigorous, resonant, and rhyming iambic quadrameters. It is divided into 113 sections, each of which, with the exception of a short introduction and two concluding pieces, treats independently of a certain class of fools or vicious persons; and we are only occasionally reminded of the fundamental idea by an allusion to the ship. No folly of the century is left uncensured. The poet attacks with noble zeal the failings and extravagances of his age, and applies his lash unsparingly even to the dreaded Hydra of popery and monasticism, to combat which the Hercules of Wittenberg had not yet kindled his firebrands. But the poet's object was not merely to reprove and to animadvert; he instructs also, and shows the fools the way to the land of wisdom; and so far is he from assuming the arrogant air of the commonplace moralist, that he reckons himself among the number of fools. The style of the poem is lively, bold, and simple, and often remarkably terse, especially in his moral sayings, and renders it apparent that the author was a classical scholar, without however losing anything of his German character."

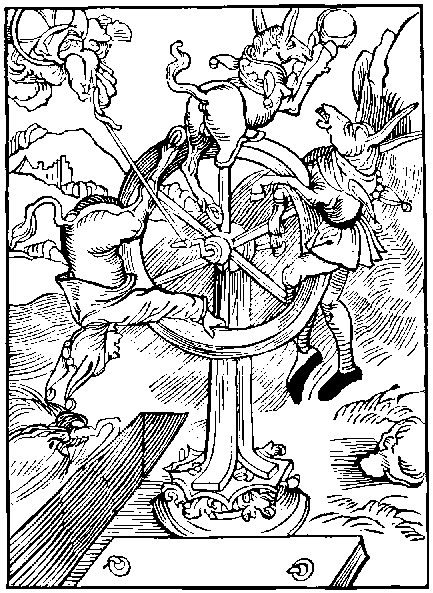

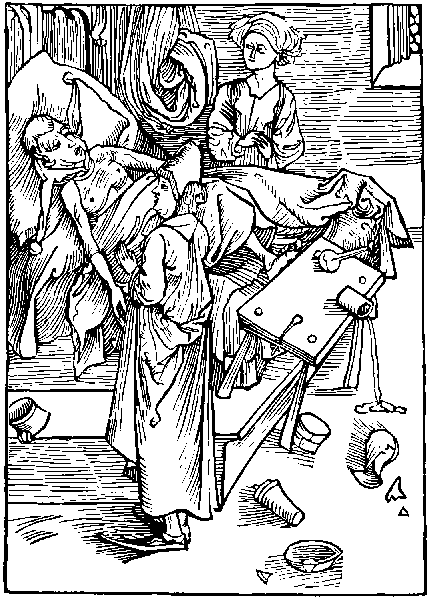

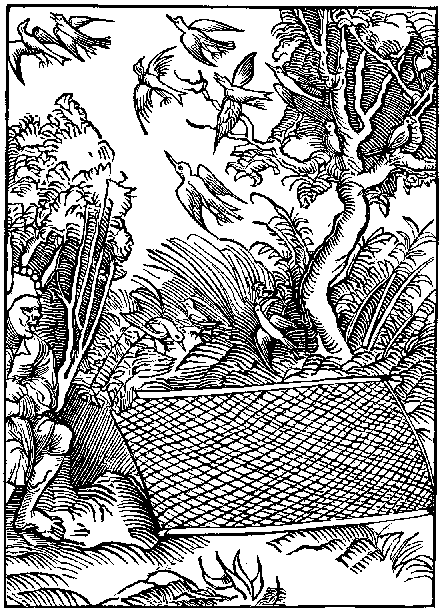

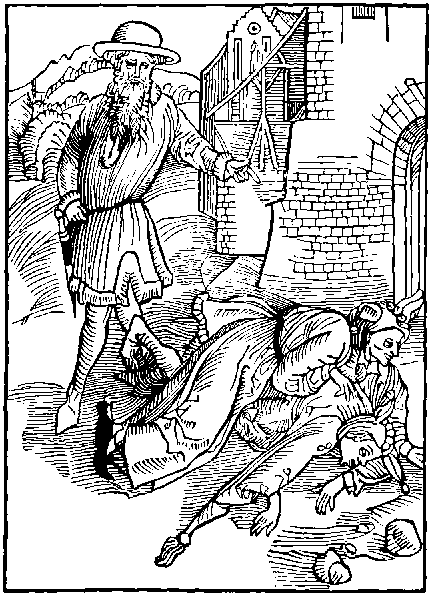

Brandt's humour, which either his earnestness or his manner banished from the text, took refuge in the illustrations and there disported itself with a wild zest and vigour. Indeed to their popularity several critics have ascribed the success of the book, but for this there is no sufficient authority or probability. Clever as they are, it is more probable that they ran, in popularity, but an equal race with the text. The precise amount of Brandt's workmanship in them has not been ascertained, but it is agreed that "most of them, if not actually drawn, were at least suggested by him." Zarncke remarks regarding their artistic worth, "not all of the cuts are of equal value. One can easily distinguish five different workers, and more practised eyes would probably be able to increase the number. In some one can see how the outlines, heads, hands, and other principal parts are cut with the fine stroke of the master, and the details and shading left to the scholars. The woodcuts of the most superior master, which can be recognized at once, and are about a third of the whole, belong to the finest, if they are not, indeed, the finest, which were executed in the fifteenth century, a worthy school of Holbein. According to the opinion of Herr Rudolph Weigel, they might possibly be the work of Martin Schön of Colmar.... The composition in the better ones is genuinely Hogarth-like, and the longer one looks at these little pictures, the more is one astonished at the fulness of the humour, the fineness of the characterisation and the almost dramatic talent of the grouping." Green, in his recent work on emblems, characterizes them as marking an epoch in that kind of literature. And Dibdin, the Macaulay of bibliography, loses his head in admiration of the "entertaining volume," extolling the figures without stint for "merit in conception and execution," "bold and free pencilling," "spirit and point," "delicacy, truth, and force," "spirit of drollery," &c., &c.; summarising thus, "few books are more pleasing to the eye, and more gratifying to the fancy than the early editions of the 'Stultifera Navis.' It presents a combination of entertainment to which the curious can never be indifferent."

Whether it were the racy cleverness of the pictures or the unprecedented boldness of the text, the book stirred Europe of the fifteenth century in a way and with a rapidity it had never been stirred before. In the German actual acquaintance with it could then be but limited, though it ran through seventeen editions within a century; the Latin version brought it to the knowledge of the educated class throughout Europe; but, expressing, as it did mainly, the feelings of the common people, to have it in the learned language was not enough. Translations into various vernaculars were immediately called for, and the Latin edition having lightened the translator's labours, they were speedily supplied. England, however, was all but last in the field but when she did appear, it was in force, with a version in each hand, the one in prose and the other in verse.

Fifteen years elapsed from the appearance of the first German edition, before the English metrical version "translated out of Laten, French, and Doche ... in the colege of Saynt Mary Otery, by me, Alexander Barclay," was issued from the press of Pynson in 1509. A translation, however, it is not. Properly speaking, it is an adaptation, an English ship, formed and fashioned after the Ship of Fools of the World. "But concernynge the translacion of this boke; I exhort ye reders to take no displesour for yt, it is nat translated word by worde acordinge to ye verses of my actour. For I haue but only drawen into our moder tunge, in rude langage the sentences of the verses as nere as the parcyte of my wyt wyl suffer me, some tyme addynge, somtyme detractinge and takinge away suche thinges as semeth me necessary and superflue. Wherfore I desyre of you reders pardon of my presumptuous audacite, trustynge that ye shall holde me excused if ye consyder ye scarsnes of my wyt and my vnexpert youthe. I haue in many places ouerpassed dyuers poetical digressions and obscurenes of fables and haue concluded my worke in rude langage as shal apere in my translacion."

"Wylling to redres the errours and vyces of this oure royalme of England ... I haue taken upon me ... the translacion of this present boke ... onely for the holsome instruccion commodyte and doctryne of wysdome, and to clense the vanyte and madness of folysshe people of whom ouer great nombre is in the Royalme of Englonde."

Actuated by these patriotic motives, Barclay has, while preserving all the valuable characteristics of his original, painted for posterity perhaps the most graphic and comprehensive picture now preserved of the folly, injustice, and iniquity which demoralized England, city and country alike, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, and rendered it ripe for any change political or religious.

"Knowledge of trouth, prudence, and iust symplicite

Hath vs clene left; For we set of them no store.

Our Fayth is defyled loue, goodnes, and Pyte:

Honest maners nowe ar reputed of: no more.

Lawyers ar lordes; but Justice is rent and tore.

Or closed lyke a Monster within dores thre.

For without mede: or money no man can hyr se.

Al is disordered: Vertue hath no rewarde.

Alas, compassion; and mercy bothe ar slayne.

Alas, the stony hartys of pepyl ar so harde

That nought can constrayne theyr folyes to refrayne."

His ships are full laden but carry not all who should be on board.

"We are full lade and yet forsoth I thynke

A thousand are behynde, whom we may not receyue

For if we do, our nauy clene shall synke

He oft all lesys that coueytes all to haue

From London Rockes Almyghty God vs saue

For if we there anker, outher bote or barge

There be so many that they vs wyll ouercharge."

The national tone and aim of the English "Ship" are maintained throughout with the greatest emphasis, exhibiting an independence of spirit which few ecclesiastics of the time would have dared to own. Barclay seems to have been first an Englishman, then an ecclesiastic. Everywhere throughout his great work the voice of the people is heard to rise and ring through the long exposure of abuse and injustice, and had the authorship been unknown it would most certainly have been ascribed to a Langlande of the period. Everywhere he takes what we would call the popular side, the side of the people as against those in office. Everywhere he stands up boldly in behalf of the oppressed, and spares not the oppressor, even if he be of his own class. He applies the cudgel as vigorously to the priest's pate as to the Lolardes back. But he disliked modern innovation as much as ancient abuse, in this also faithfully reflecting the mind of the people, and he is as emphatic in his censure of the one as in his condemnation of the other.

Barclay's "Ship of Fools," however, is not only important as a picture of the English life and popular feeling of his time, it is, both in style and vocabulary, a most valuable and remarkable monument of the English language. Written midway between Chaucer and Spenser, it is infinitely more easy to read than either. Page after page, even in the antique spelling of Pynson's edition, may be read by the ordinary reader of to-day without reference to a dictionary, and when reference is required it will be found in nine cases out of ten that the archaism is Saxon, not Latin. This is all the more remarkable, that it occurs in the case of a priest translating mainly from the Latin and French, and can only be explained with reference to his standpoint as a social reformer of the broadest type, and to his evident intention that his book should be an appeal to all classes, but especially to the mass of the people, for amendment of their follies. In evidence of this it may be noticed that in the didactic passages, and especially in the L'envois, which are additions of his own, wherever, in fact, he appears in his own character of "preacher," his language is most simple, and his vocabulary of the most Saxon description.

In his prologue "excusynge the rudenes of his translacion," he professes to have purposely used the most "comon speche":—

"My speche is rude my termes comon and rural

And I for rude peple moche more conuenient

Than for estates, lerned men, or eloquent."

He afterwards humorously supplements this in "the prologe," by:—

"But if I halt in meter or erre in eloquence

Or be to large in langage I pray you blame not me

For my mater is so bad it wyll none other be."

So much the better for all who are interested in studying the development of our language and literature. For thus we have a volume, confessedly written in the commonest language of the common people, from which the philologist may at once see the stage at which they had arrived in the development of a simple English speech, and how far, in this respect, the spoken language had advanced a-head of the written; and from which also he can judge to what extent the popularity of a book depends, when the language is in a state of transition, upon the unusual simplicity of its style both in structure and vocabulary, and how far it may, by reason of its popularity, be influential in modifying and improving the language in both these respects. In the long barren tract between Chaucer and Spenser, the Ship of Fools stands all but alone as a popular poem, and the continuance of this popularity for a century and more is no doubt to be attributed as much to the use of the language of the "coming time" as to the popularity of the subject.

In more recent times however, Barclay has, probably in part, from accidental circumstances, come to be relegated to a position among the English classics, those authors whom every one speaks of but few read. That modern editions of at least his principal performance have not appeared, can only be accounted for by the great expense attendant upon the reproduction of so uniquely illustrated a work, an interesting proof of which, given in the evidence before the Select Committee of the House of Commons on the Copyright act in 1818, is worth quoting. Amongst new editions of standard but costly works, of which the tax then imposed by the act upon publishers of giving eleven copies of all their publications free to certain libraries prevented the publication, is mentioned, Barclay's "Ship of Fools;" regarding which Harding, the well known bookseller, is reported to have said, "We have declined republishing the 'Ship of Fools,' a folio volume of great rarity and high price. Our probable demand would not have been more than for a hundred copies, at the price of 12 guineas each. The delivery of eleven copies to the public libraries decided us against entering into the speculation."

A wider and more eager interest is now being manifested in our early literature, and especially in our early popular poetry, to the satisfaction of which, it is believed, a new edition of this book will be regarded as a most valuable contribution. Indeed, as a graphic and comprehensive picture of the social condition of pre-Reformation England; as an important influence in the formation of our modern English tongue; and as a rich and unique exhibition of early art, to all of which subjects special attention is being at present directed, this mediæval picture-poem is of unrivalled interest.

OF THE

Whether this distinguished poet was an Englishman or a Scotchman has long been a quæstio vexata affording the literary antiquary a suitable field for the display of his characteristic amenity. Bale, the oldest authority, simply says that some contend he was a Scot, others an Englishman, (Script. Illust. Majoris Britt. Catalogus, 1559). Pits (De Illust. Angliæ Script.,) asserts that though to some he appears to have been a Scot, he was really an Englishman, and probably a native of Devonshire, ("nam ibi ad S. Mariam de Otery, Presbyter primum fuit"). Wood again, (Athen. Oxon.), by the reasoning which finds a likeness between Macedon and Monmouth, because there is a river in each, arrives at "Alexander de Barklay, seems to have been born at or near a town so called in Somersetshire;" upon which Ritson pertinently observes, "there is no such place in Somersetshire, the onely Berkeley known is in Gloucestershire." Warton, coming to the question double-shotted, observes that "he was most probably of Devonshire or Gloucestershire," in the one case following Pits, and in the other anticipating Ritson's observation.

On the other hand Bale, in an earlier work than the Catalogus, the Summarium Ill. Maj. Britt. Script., published in 1548, during Barclay's life time, adorns him with the epithets "Scotus, rhetor ac poeta insignis." Dempster (Hist. ecclesiastica), styles him "Scotus, ut retulit ipse Joannes Pitsæus." Holinshed also styles him "Scot"! Sibbald gives him a place in his (MS.) Catalogues of Scottish poets, as does also Wodrow in his Catalogues of Scots writers. Mackenzie (Lives of the Scots writers) begins, "The Barklies, from whom this gentleman is descended, are of a very ancient standing in Scotland." Ritson (Bib. Poetica), after a caustic review of the controversy, observes "both his name of baptism and the orthography of his surname seem to prove that he was of Scottish extraction." Bliss (Additions to Wood) is of opinion that he "undoubtedly was not a native of England," and Dr Irving (Hist. of Scot. Poetry) adheres to the opinion of Ritson.

Such contention, whatever may be the weight of the evidence on either side, is at any rate a sufficient proof of the eminence of the individual who is the subject of it; to be his birthplace being considered an honour of so much value to the country able to prove its claim to the distinction as to occasion a literary warfare of several centuries' duration.

We cannot profess to have brought such reinforcements to either side as to obtain for it a complete and decisive victory, but their number and character are such as will probably induce one of the combatants quietly to retire from the field. In the first place, a more explicit and unimpeachable piece of evidence than any contained in the authors mentioned above has been found, strangely enough, in a medical treatise, published about twenty years after Barclay's death, by a physician and botanist of great eminence in the middle of the sixteenth century, who was a native of the isle of Ely, at the Monastery of which Barclay was for some time a monk.

It is entitled "A dialogue both pleasaunt and pietifull, wherein is a godlie regiment against the Fever Pestilence, with a consolation and comforte against death.—Newlie corrected by William Bullein, the author thereof.—Imprinted at London by Ihon Kingston. Julij, 1573." [8vo., B.L., 111 leaves.] "There was an earlier impression of this work in 1564, but the edition of 1573 was 'corrected by the author,' the last work on which he probably was engaged, as he died in 1576. It is of no value at this time of day as a medical treatise, though the author was very eminent; but we advert to it because Bullein, for the sake of variety and amusement, introduces notices of Chaucer, Gower, Lidgate, Skelton, and Barclay, which, coming from a man who was contemporary with two of them, may be accepted as generally accurate representations.... Alexander Barclay, Dr Bullein calls Bartlet, in the irregular spelling of those times; and, asserting that he was 'born beyond the cold river of Tweed,' we see no sufficient reason for disbelieving that he was a native of Scotland. Barclay, after writing his pastorals, &c., did not die until 1552, so that Bullein was his contemporary, and most likely knew him and the fact. He observes:—'Then Bartlet, with an hoopyng russet long coate, with a pretie hoode in his necke, and five knottes upon his girdle, after Francis tricks. He was borne beyonde the cold river of Twede. He lodged upon a swete bed of chamomill, under the sinamum tree; about hym many shepherdes and shepe, with pleasaunte pipes; greatly abhorring the life of Courtiers, Citizens, Usurers, and Banckruptes, &c., whose olde daies are miserable. And the estate of shepherdes and countrie people he accoumpted moste happie and sure." (Collier's "Bibliographical Account of Early English Literature," Vol. 1., P. 97).

"The certainty with which Bulleyn here speaks of Barclay, as born beyond the Tweed, is not a little strengthened by the accuracy with which even in allegory he delineates his peculiar characteristics. 'He lodged upon a bed of sweet camomile.' What figure could have been more descriptive of that agreeable bitterness, that pleasant irony, which distinguishes the author of the 'Ship of Fools?' 'About him many shepherds and sheep with pleasant pipes, greatly abhorring the life of courtiers.' What could have been a plainer paraphrase of the title of Barclay's 'Eclogues,' or 'Miseries of Courtiers and Courtes, and of all Princes in General.' As a minor feature, 'the five knots upon his girdle after Francis's tricks' may also be noticed. Hitherto, the fact of Barclay having been a member of the Franciscan order has been always repeated as a matter of some doubt; 'he was a monk of the order of St Benedict, and afterwards, as some say, a Franciscan. Bulleyn knows, and mentions, with certainty, what others only speak of as the merest conjecture. In short, everything tends to shew a degree of familiar acquaintance with the man, his habits, and his productions, which entitles the testimony of Bulleyn to the highest credit.'" (Lives of the Scottish Poets, Vol. I., pt. ii., p. 77).

But there are other proofs pointing as decidedly to the determination of this long-continued controversy in favour of Scotland, as the soil from which this vagrant child of the muses sprung. No evidence seems to have been hitherto sought from the most obvious source, his writings. The writer of the memoir in the Biographia Brittanica, (who certainly dealt a well-aimed, though by no means decisive, blow, in observing, "It is pretty extraordinary that Barclay himself, in his several addresses to his patrons should never take notice of his being a stranger, which would have made their kindness to him the more remarkable [it was very customary for the writers of that age to make mention in their works of the countries to which they belonged, especially if they wrote out of their own];[1] whereas the reader will quickly see, that in his address to the young gentlemen of England in the 'Mirror of Good Manners,' he treats them as his countrymen,") has remarked, "It seems a little strange that in those days a Scot should obtain so great reputation in England, especially if it be considered from whence our author's rose, viz., from his enriching and improving the English tongue. Had he written in Latin or on the sciences, the thing had been probable enough, but in the light in which it now stands, I think it very far from likely." From which it is evident that the biographer understood not the versatile nature of the Scot and his ability, especially when caught young, in "doing in Rome as the Romans do." Barclay's English education and foreign travel, together extending over the most impressionable years of his youth, could not have failed to rub off any obvious national peculiarities of speech acquired in early boyhood, had the difference between the English and Scottish speech then been wider than it was. But the language of Barbour and Chaucer was really one and the same. It will then not be wondered at that but few Scotch words are found in Barclay's writings. Still, these few are not without their importance in strengthening the argument as to nationality. The following from "The Ship of Fools," indicate at once the clime to which they are native, "gree," "kest," "rawky," "ryue," "yate," "bokest," "bydeth," "thekt," and "or," in its peculiar Scottish use.[2] That any Englishman, especially a South or West of England Englishman, should use words such as those, particularly at a time of hostility and of little intercourse between the nations, will surely be admitted to be a far more unlikely thing than that a Scotchman born, though not bred, should become, after the effects of an English education and residence had efficiently done their work upon him, a great improver and enricher of the English tongue.

But perhaps the strongest and most decisive argument of all in this much-vexed controversy is to be found in the panegyric of James the Fourth contained in the "Ship of Fools," an eulogy so highly pitched and extravagant that no Englishman of that time would ever have dreamed of it or dared to pen it. Nothing could well be more conclusive. Barclay precedes it by a long and high-flown tribute to Henry, but when he comes to "Jamys of Scotlonde," he, so to speak, out-Herods Herod. Ordinary verse suffices not for the greatness of his subject, which he must needs honour with an acrostic,—

" I n prudence pereles is this moste comely kynge

A nd as for his strength and magnanymyte

C oncernynge his noble dedes in euery thynge

O ne founde or grounde lyke to hym can not be

B y byrth borne to boldnes and audacyte

V nder the bolde planet of Mars the champyon

S urely to subdue his ennemyes echone."

There, we are convinced, speaks not the prejudiced, Scot-hating English critic, but the heart beating true to its fatherland and loyal to its native Sovereign.

That "he was born beyonde the cold river of Twede," about the year 1476, as shall be shown anon, is however all the length we can go. His training was without doubt mainly, if not entirely English. He must have crossed the border very early in life, probably for the purpose of pursuing his education at one of the Universities, or, even earlier than the period of his University career, with parents or guardians to reside in the neighbourhood of Croydon, to which he frequently refers. Croydon is mentioned in the following passages in Eclogue I.:

"While I in youth in Croidon towne did dwell."

"He hath no felowe betwene this and Croidon,

Save the proude plowman Gnatho of Chorlington."

"And as in Croidon I heard the Collier preache"

"Such maner riches the Collier tell thee can"

"As the riche Shepheard that woned in Mortlake."

It seems to have become a second home to him, for there, we find, in 1552, he died and was buried.

At which University he studied, whether Oxford or Cambridge, is also a matter of doubt and controversy. Wood claims him for Oxford and Oriel, apparently on no other ground than that he dedicates the "Ship of Fools" to Thomas Cornish, the Suffragan bishop of Tyne, in the Diocese of Bath and Wells, who was provost of Oriel College from 1493 to 1507. That the Bishop was the first to give him an appointment in the Church is certainly a circumstance of considerable weight in favour of the claim of Oxford to be his alma mater, and of Cornish to be his intellectual father; and if the appointment proceeded from the Provost's good opinion of the young Scotchman, then it says much for the ability and talents displayed by him during his College career. Oxford however appears to be nowhere mentioned in his various writings, while Cambridge is introduced thus in Eclogue I.:—

"And once in Cambridge I heard a scoller say."

From which it seems equally, if not more, probable that he was a student at that university. "There is reason to believe that both the universities were frequented by Scotish students; many particular names are to be traced in their annals; nor is it altogether irrelevant to mention that Chaucer's young clerks of Cambridge who played such tricks to the miller of Trompington, are described as coming from the north, and as speaking the Scotish language:—

'John highte that on, and Alein highte that other,

Of o toun were they born that highte Strother,

Fer in the North, I cannot tellen where.'

"It may be considered as highly probable that Barclay completed his studies in one of those universities, and that the connections which he thus had an opportunity of forming, induced him to fix his residence in the South; and when we suppose him to have enjoyed the benefit of an English education it need not appear peculiarly 'strange, that in those days, a Scot should obtain so great reputation in England.'" (Irving, Hist. of Scot. Poetry).

In the "Ship" there is a chapter "Of unprofytable Stody" in which he makes allusion to his student life in such a way as to imply that it had not been a model of regularity and propriety:

"The great foly, the pryde, and the enormyte

Of our studentis, and theyr obstynate errour

Causeth me to wryte two sentences or thre

More than I fynde wrytyn in myne actoure

The tyme hath ben whan I was conductoure

Of moche foly, whiche nowe my mynde doth greue

Wherfor of this shyp syns I am gouernoure

I dare be bolde myne owne vyce to repreue."

If these lines are meant to be accepted literally, which such confessions seldom are, it may be that he was advised to put a year or two's foreign travel between his University career, and his entrance into the Church. At any rate, for whatever reason, on leaving the University, where, as is indicated by the title of "Syr" prefixed to his name in his translation of Sallust, he had obtained the degree of Bachelor of Arts, he travelled abroad, whether at his own charges, or in the company of a son of one of his patrons is not recorded, principally in Germany, Italy, and France, where he applied himself, with an unusual assiduity and success, to the acquirement of the languages spoken in those countries and to the study of their best authors. In the chapter "Of unprofytable Stody," above mentioned, which contains proof how well he at least had profited by study, he cites certain continental seats of university learning at each of which, there is indeed no improbability in supposing he may have remained for some time, as was the custom in those days:

"One rennyth to Almayne another vnto France

To Parys, Padway, Lumbardy or Spayne

Another to Bonony, Rome, or Orleanse

To Cayne, to Tolows, Athenys, or Colayne."

Another reference to his travels and mode of travelling is found in the Eclogues. Whether he made himself acquainted with the English towns he enumerates before or after his continental travels it is impossible to determine:

CORNIX.

"As if diuers wayes laye vnto Islington,

To Stow on the Wold, Quaueneth or Trompington,

To Douer, Durham, to Barwike or Exeter,

To Grantham, Totnes, Bristow or good Manchester,

To Roan, Paris, to Lions or Floraunce.

CORIDON.

(What ho man abide, what already in Fraunce,

Lo, a fayre iourney and shortly ended to,

With all these townes what thing haue we to do?

CORNIX.

By Gad man knowe thou that I haue had to do

In all these townes and yet in many mo,

To see the worlde in youth me thought was best,

And after in age to geue my selfe to rest.

CORIDON.

Thou might haue brought one and set by our village.

CORNIX.

What man I might not for lacke of cariage.

To cary mine owne selfe was all that euer I might,

And sometime for ease my sachell made I light."

ECLOGUE I.

Returning to England, after some years of residence abroad, with his mind broadened and strengthened by foreign travel, and by the study of the best authors, modern as well as ancient, Barclay entered the church, the only career then open to a man of his training. With intellect, accomplishments, and energy possessed by few, his progress to distinction and power ought to have been easy and rapid, but it turned out quite otherwise. The road to eminence lay by the "backstairs," the atmosphere of which he could not endure. The ways of courtiers—falsehood, flattery, and fawning—he detested, and worse, he said so, wherefore his learning, wit and eloquence found but small reward. To his freedom of speech, his unsparing exposure and denunciation of corruption and vice in the Court and the Church, as well as among the people generally, must undoubtedly be attributed the failure to obtain that high promotion his talents deserved, and would otherwise have met with. The policy, not always a successful one in the end, of ignoring an inconvenient display of talent, appears to have been fully carried out in the instance of Barclay.

His first preferment appears to have been in the shape of a chaplainship in the sanctuary for piety and learning founded at Saint Mary Otery in the County of Devon, by Grandison, Bishop of Exeter; and to have come from Thomas Cornish, Suffragan Bishop of Bath and Wells under the title of the Bishop of Tyne, "meorum primitias laborum qui in lucem eruperunt," to whom, doubtless out of gratitude for his first appointment, he dedicated "The Ship of Fools." Cornish, amongst the many other good things he enjoyed, held, according to Dugdale, from 1490 to 1511, the post of warden of the College of S. Mary Otery, where Barclay no doubt had formed that regard and respect for him which is so strongly expressed in the dedication.

A very eulogistic notice of "My Mayster Kyrkham," in the chapter "Of the extorcion of Knyghtis," (Ship of Fools,) has misled biographers, who were ignorant of Cornish's connection with S. Mary Otery, to imagine that Barclay's use of "Capellanus humilimus" in his dedication was merely a polite expression, and that Kyrkham, of whom he styles himself, "His true seruytour his chaplayne and bedeman" was his actual ecclesiastical superior. The following is the whole passage:—

"Good offycers ar good and commendable

And manly knyghtes that lyue in rightwysenes

But they that do nat ar worthy of a bable

Syns by theyr pryde pore people they oppres

My mayster Kyrkhan for his perfyte mekenes

And supportacion of men in pouertye

Out of my shyp shall worthely be fre

I flater nat I am his true seruytour

His chaplayne and his bede man whyle my lyfe shall endure

Requyrynge God to exalt hym to honour

And of his Prynces fauour to be sure

For as I haue sayd I knowe no creature

More manly rightwyse wyse discrete and sad

But thoughe he be good, yet other ar als bad."

That this Kyrkham was a knight and not an ecclesiastic is so plainly apparent as to need no argument. An investigation into Devonshire history affords the interesting information that among the ancient families of that county there was one of this name, of great antiquity and repute, now no longer existent, of which the most eminent member was a certain Sir John Kirkham, whose popularity is evinced by his having been twice created High Sheriff of the County, in the years 1507 and 1523. (Prince, Worthies of Devon; Izacke, Antiquities of Exeter.)

That this was the Kirkham above alluded to, there can be no reasonable doubt, and in view of the expression "My mayster Kyrkham," it may be surmised that Barclay had the honour of being appointed by this worthy gentleman to the office of Sheriff's or private Chaplain or to some similar position of confidence, by which he gained the poet's respect and gratitude. The whole allusion, however, might, without straining be regarded as a merely complimentary one. The tone of the passage affords at any rate a very pleasing glimpse of the mutual regard entertained by the poet and his Devonshire neighbours.

After the eulogy of Kyrkham ending with "Yet other ar als bad," the poet goes on immediately to give the picture of a character of the opposite description, making the only severe personal reference in his whole writings, for with all his unsparing exposure of wrong-doing, he carefully, wisely, honourably avoided personality. A certain Mansell of Otery is gibbeted as a terror to evil doers in a way which would form a sufficient ground for an action for libel in these degenerate days.—Ship, II. 82.

"Mansell of Otery for powlynge of the pore

Were nat his great wombe, here sholde haue an ore

But for his body is so great and corporate

And so many burdens his brode backe doth charge

If his great burthen cause hym to come to late

Yet shall the knaue be Captayne of a barge

Where as ar bawdes and so sayle out at large

About our shyp to spye about for prayes

For therupon hath he lyued all his dayes."

It ought however to be mentioned that no such name as Mansell appears in the Devonshire histories, and it may therefore be fictitious.

The ignorance and reckless living of the clergy, one of the chief objects of his animadversion, receive also local illustration:

"For if one can flater, and beare a Hauke on his fist,

He shalbe made parson of Honington or Clist."

A good humoured reference to the Secondaries of the College is the only other streak of local colouring we have detected in the Ship, except the passage in praise of his friend and colleague Bishop, quoted at p. liii.

"Softe, fooles, softe, a little slacke your pace,

Till I haue space you to order by degree,

I haue eyght neyghbours, that first shall haue a place

Within this my ship, for they most worthy be,

They may their learning receyue costles and free,

Their walles abutting and ioyning to the scholes;

Nothing they can, yet nought will they learne nor see,

Therfore shall they guide this our ship of fooles."

In the comfort, quiet, and seclusion of the pleasant Devonshire retreat, the "Ship" was translated in the year 1508, when he would be about thirty-two, "by Alexander Barclay Preste; and at that tyme chaplen in the sayde College," whence it may be inferred that he left Devon, either in that year or the year following, when the "Ship" was published, probably proceeding to London for the purpose of seeing it through the press. Whether he returned to Devonshire we do not know; probably not, for his patron and friend Cornish resigned the wardenship of St Mary Otery in 1511, and in two years after died, so that Barclay's ties and hopes in the West were at an end. At any rate we next hear of him in monastic orders, a monk of the order of S. Benedict, in the famous monastery of Ely, where, as is evident from internal proof, the Eclogues were written and where likewise, as appears from the title, was translated "The mirrour of good maners," at the desire of Syr Giles Alington, Knight.

It is about this period of his life, probably the period of the full bloom of his popularity, that the quiet life of the poet and priest was interrupted by the recognition of his eminence in the highest quarters, and by a request for his aid in maintaining the honour of the country on an occasion to which the eyes of all Europe were then directed. In a letter of Sir Nicholas Vaux, busied with the preparations for the meeting of Henry VIII., and Francis I., called the Field of the Cloth of Gold, to Wolsey, of date 10th April 1520, he begs the cardinal to "send to them ... Maistre Barkleye, the Black Monke and Poete, to devise histoires and convenient raisons to florisshe the buildings and banquet house withal" (Rolls Calendars of Letters and Papers, Henry VIII., iii. pt. 1.). No doubt it was also thought that this would be an excellent opportunity for the eulogist of the Defender of the Faith to again take up the lyre to sing the glories of his royal master, but no effort of his muse on the subject of this great chivalric pageant has descended to us if any were ever penned.

Probably after this employment he did not return to Ely; with his position or surroundings there he does not seem to have been altogether satisfied ("there many a thing is wrong," see p. lxix.); and afterwards, though in the matter of date we are somewhat puzzled by the allusion of Bulleyn, an Ely man, to his Franciscan habit, he assumed the habit of the Franciscans at Canterbury, ('Bale MS. Sloan, f. 68,') to which change we may owe, if it be really Barclay's, "The life of St Thomas of Canterbury."

Autumn had now come to the poet, but fruit had failed him. The advance of age and his failure to obtain a suitable position in the Church began gradually to weigh upon his spirits. The bright hopes with which he had started in the flush of youth, the position he was to obtain, the influence he was to wield, and the work he was to do personally, and by his writings, in the field of moral and social reformation were all in sad contrast with the actualities around. He had never risen from the ranks, the army was in a state of disorganisation, almost of mutiny, and the enemy was more bold, unscrupulous, and numerous than ever. It is scarcely to be wondered at that, though not past fifty, he felt prematurely aged, that his youthful enthusiasm which had carried him on bravely in many an attempt to instruct and benefit his fellows at length forsook him and left him a prey to that weakness of body, and that hopelessness of spirit to which he so pathetically alludes in the Prologue to the Mirror of good Manners. All his best work, all the work which has survived to our day, was executed before this date. But the pen was too familiar to his hand to be allowed to drop. His biographers tell us "that when years came on he spent his time mostly in pious matters, and in reading and writing histories of the Saints." A goodly picture of a well-spent old age. The harness of youth he had no longer the spirit and strength to don, the garments of age he gathered resignedly and gracefully about him.

On the violent dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539, when their inmates, the good and bad, the men of wisdom and the "fools," were alike cast adrift upon a rock-bound and stormy coast, the value of the patronage which his literary and personal popularity had brought him, was put to the test, and in the end successfully, though after considerable, but perhaps not to be wondered at, delay. His great patrons, the Duke of Norfolk, the Earl of Kent, Bishop Cornish, and probably also Sir Giles Alington, were all dead, and he had to rely on newer and necessarily weaker ties. But after waiting, till probably somewhat dispirited, fortune smiled at last. Two handsome livings were presented to him in the same year, both of which he apparently held at the same time, the vicarage of Much Badew in Essex, by the presentation of Mr John Pascal, to which he was instituted on February 7th, 1546, holding it (according to the Lansdowne MS. (980 f. 101), in the British Museum) till his death; and the vicarage of S. Mathew at Wokey, in Somerset, on March 30th of the same year. Wood dignifies him with the degree of doctor of divinity at the time of his presentation to these preferments.

That he seems to have accepted quietly the gradual progress of the reformed religion during the reign of Edward VI., has been a cause of wonder to some. It would certainly have been astonishing had one who was so unsparing in his exposure of the flagrant abuses of the Romish Church done otherwise. Though personally disinclined to radical changes his writings amply show his deep dissatisfaction with things as they were. This renders the more improbable the honours assigned him by Wadding (Scriptores Ordinis Minorum, 1806, p. 5), who promotes him to be Suffragan Bishop of Bath and Wells, and Bale, who, in a slanderous anecdote, the locale of which is also Wells, speaks of him as a chaplain of Queen Mary's, though Mary did not ascend the throne till the year after his death. As these statements are nowhere confirmed, it is not improbable that their authors have fallen into error by confounding the poet Barclay, with a Gilbert Berkeley, who became Bishop of Bath and Wells in 1559. One more undoubted, but tardy, piece of preferment was awarded him which may be regarded as an honour of some significance. On the 30th April 1552, the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury, London, presented him to the Rectory of All Hallows, Lombard Street, but the well-deserved promotion came too late to be enjoyed. A few weeks after, and before the 10th June, at which date his will was proved, he died, as his biographers say, "at a very advanced age;" at the good old age of seventy-six, as shall be shown presently, at Croydon where he had passed his youth, and there in the Church he was buried. "June 10th 1552, Alexander Barkley sepult," (Extract from the Parish Register, in Lyson's Environs of London).

A copy of his will, an extremely interesting and instructive document, has been obtained from Doctors' Commons, and will be found appended. It bears in all its details those traits of character which, from all that we otherwise know, we are led to associate with him. In it we see the earnest, conscientious minister whose first thought is of the poor, the loyal churchman liberal in his support of the house of God, the kind relative in his numerous and considerate bequests to his kith and kin, the amiable, much loved man in the gifts of remembrance to his many friends, and the pious Christian in his wishes for the prayers of his survivors "to Almightie God for remission of my synnes, and mercy upon my soule."

Barclay's career and character, both as a churchman and a man of letters, deserve attention and respect from every student of our early history and literature. In the former capacity he showed himself diligent, honest, and anxious, at a time when these qualities seemed to have been so entirely lost to the church as to form only a subject for clerical ridicule. In the latter, the same qualities are also prominent, diligence, honesty, bold outspokenness, an ardent desire for the pure, the true, and the natural, and an undisguised enmity to everything false, self-seeking, and vile. Everything he did was done in a pure way, and to a worthy end.

Bale stands alone in casting aspersions upon his moral character, asserting, as Ritson puts it, "in his bigoted and foul-mouthed way," that "he continued a hater of truth, and under the disguise of celibacy a filthy adulterer to the last;" and in his Declaration of Bonner's articles (1561, fol. 81), he condescends to an instance to the effect that "Doctoure Barkleye hadde greate harme ones of suche a visitacion, at Wellys, before he was Quene Maryes Chaplayne. For the woman whome he so religiouslye visited did light him of all that he had, sauinge his workinge tolas. For the whiche acte he had her in prison, and yet coulde nothing recouer againe." Whether this story be true of any one is perhaps doubtful, and, if true of a Barclay, we are convinced that he is not our author. It may have arisen as we have seen from a mistake as to identity. But apart from the question of identity, we have nothing in support of the slander but Bale's "foul-mouthed" assertion, while against it we have the whole tenor and aim of Barclay's published writings. Everywhere he inculcates the highest and purest morality, and where even for that purpose he might be led into descriptions of vice, his disgust carries him past what most others would have felt themselves justified in dealing with. For example, in the chapter of "Disgysyd folys" he expressly passes over as lightly as possible what might to others have proved a tempting subject:

"They disceyue myndes chaste and innocent

With dyuers wayes whiche I wyll nat expres

Lyst that whyle I labour this cursyd gyse to stynt

I myght to them mynyster example of lewdnes

And therfore in this part I shall say les

Than doth my actour."

Elsewhere he declares:

"for my boke certaynly

I haue compyled: for vertue and goodnes

And to reuyle foule synne and vyciousnes"

But citation is needless; there is not a page of his writings which will not supply similar evidence, and our great early moralist may, we think, be dismissed from Court without a stain on his character.

Indeed to his high pitched morality, he doubtless owed in some degree the great and extended popularity of his poetical writings in former times and their neglect in later. Sermons and "good" books were not yet in the sixteenth century an extensive branch of literature, and "good" people could without remorse of conscience vary their limited theological reading by frowning over the improprieties and sins of their neighbours as depicted in the "Ship," and joining, with a serious headshaking heartiness, in the admonitions of the translator to amendment, or they might feel "strengthened" by a glance into the "Mirrour of good Maners," or edified by hearing of the "Miseryes of Courtiers and Courtes of all princes in generall," as told in the "Eclogues."

Certain it is that these writings owed little of their acceptance to touches of humour or satire, to the gifts of a poetical imagination, or the grace of a polished diction. The indignation of the honest man and the earnestness of the moralist waited not for gifts and graces. Everything went down, hard, rough, even uncouth as it stood, of course gaining in truth and in graphic power what it wants in elegance. Still, with no refinement, polish or elaboration, there are many picturesque passages scattered throughout these works which no amount of polishing could have improved. How could a man in a rage be better touched off than thus ("Ship" I. 182, 15).

"This man malycious whiche troubled is with wrath

Nought els soundeth but the hoorse letter R."

The passion of love is so graphically described that it is difficult to imagine our priestly moralist a total stranger to its power, (I. 81).

"For he that loueth is voyde of all reason

Wandrynge in the worlde without lawe or mesure

In thought and fere sore vexed eche season

And greuous dolours in loue he must endure

No creature hym selfe, may well assure

From loues soft dartis: I say none on the grounde

But mad and folysshe bydes he whiche hath the wounde

Aye rennynge as franatyke no reason in his mynde

He hath no constaunce nor ease within his herte

His iyen ar blynde, his wyll alwaye inclyned

To louys preceptes yet can nat he departe

The Net is stronge, the sole caught can nat starte

The darte is sharpe, who euer is in the chayne

Can nat his sorowe in vysage hyde nor fayne"

For expressive, happy simile, the two following examples are capital:—

"Yet sometimes riches is geuen by some chance

To such as of good haue greatest aboundaunce.

Likewise as streames unto the sea do glide.

But on bare hills no water will abide.

· · · · · ·

So smallest persons haue small rewarde alway

But men of worship set in authoritie

Must haue rewardes great after their degree."—Eclogue I.

"And so such thinges which princes to thee geue

To thee be as sure as water in a siue

· · · · · · ·

So princes are wont with riches some to fede

As we do our swine when we of larde haue nede

We fede our hogges them after to deuour

When they be fatted by costes and labour."—Eclogue I.

The everlasting conceit of musical humanity is very truthfully hit off.

"This is of singers the very propertie

Alway they coueyt desired for to be

And when their frendes would heare of their cunning

Then are they neuer disposed for to sing,

But if they begin desired of no man

Then shewe they all and more then they can

And neuer leaue they till men of them be wery,

So in their conceyt their cunning they set by."—Eclogue II.

Pithy sayings are numerous. Comparing citizens with countrymen, the countryman says:—

"Fortune to them is like a mother dere

As a stepmother she doth to us appeare."

Of money:

"Coyne more than cunning exalteth every man."

Of clothing:

"It is not clothing can make a man be good

Better is in ragges pure liuing innocent

Than a soule defiled in sumptuous garment."

It is as the graphic delineator of the life and condition of the country in his period that the chief interest of Barclay's writings, and especially of the "Ship of Fools," now lies. Nowhere so accessibly, so fully, and so truthfully will be found the state of Henry the Eighth's England set forth. Every line bears the character of truthfulness, written as it evidently is, in all the soberness of sadness, by one who had no occasion to exaggerate, whose only object and desire was, by massing together and describing faithfully the follies and abuses which were evident to all, to shame every class into some degree of moral reformation, and, in particular, to effect some amelioration of circumstances to the suffering poor.

And a sad picture it is which we thus obtain of merrie England in the good old times of bluff King Hal, wanting altogether in the couleur de rose with which it is tinted by its latest historian Mr Froude, who is ably taken to task on this subject by a recent writer in the Westminster Review, whose conclusions, formed upon other evidence than Barclay's, express so fairly the impression left by a perusal of the "Ship of Fools," and the Eclogues, that we quote them here. "Mr Froude remarks: 'Looking therefore, at the state of England as a whole, I cannot doubt that under Henry the body of the people were prosperous, well-fed, loyal, and contented. In all points of material comfort, they were as well off as ever they had been before; better off than they have ever been in later times.' In this estimate we cannot agree. Rather we should say that during, and for long after, this reign, the people were in the most deplorable condition of poverty and misery of every kind. That they were ill-fed, that loyalty was at its lowest ebb, that discontent was rife throughout the land. 'In all points of material comfort,' we think they were worse off than they had ever been before, and infinitely worse off than they have ever been since the close of the sixteenth century,—a century in which the cup of England's woes was surely fuller than it has ever been since, or will, we trust, ever be again. It was the century in which this country and its people passed through a baptism of blood as well as 'a baptism of fire,' and out of which they came holier and better. The epitaph which should be inscribed over the century is contained in a sentence written by the famous Acham in 1547:—'Nam vita, quæ nunc vivitur a plurimis, non vita sed miseria est.'" So, Bradford (Sermon on Repentance, 1533) sums up contemporary opinion in a single weighty sentence: "All men may see if they will that the whoredom pride, unmercifulness, and tyranny of England far surpasses any age that ever was before." Every page of Barclay corroborates these accounts of tyranny, injustice, immorality, wretchedness, poverty, and general discontent.

Not only in fact and feeling are Barclay's Ship of Fools and Eclogues thoroughly expressive of the unhappy, discontented, poverty-stricken, priest-ridden, and court-ridden condition and life, the bitter sorrows and the humble wishes of the people, their very texture, as Barclay himself tells us, consists of the commonest language of the day, and in it are interwoven many of the current popular proverbs and expressions. Almost all of these are still "household words" though few ever imagine the garb of their "daily wisdom" to be of such venerable antiquity. Every page of the "Eclogues" abounds with them; in the "Ship" they are less common, but still by no means infrequent. We have for instance:—

"Better is a frende in courte than a peny in purse"—(I. 70.)

"Whan the stede is stolyn to shyt the stable dore"—(I. 76.)

"It goeth through as water through a syue."—(I. 245.)

"And he that alway thretenyth for to fyght

Oft at the prose is skantly worth a hen

For greattest crakers ar nat ay boldest men."—(I. 198.)

"I fynde foure thynges whiche by no meanes can

Be kept close, in secrete, or longe in preuetee

The firste is the counsell of a wytles man

The seconde is a cyte whiche byldyd is a hye

Upon a montayne the thyrde we often se

That to hyde his dedes a louer hath no skyll

The fourth is strawe or fethers on a wyndy hyll."—(I. 199.)

"A crowe to pull."—(II. 8.)

"For it is a prouerbe, and an olde sayd sawe

That in euery place lyke to lyke wyll drawe."—(II. 35.)

"Better haue one birde sure within thy wall

Or fast in a cage than twenty score without"—(II. 74)

"Gapynge as it were dogges for a bone."—(II. 93.)

"Pryde sholde haue a fall."—(II. 161).

"For wyse men sayth ...

One myshap fortuneth neuer alone."

"Clawe where it itchyth."—(II. 256.) [The use of this, it occurs again in the Eclogues, might be regarded by some of our Southern friends, as itself a sufficient proof of the author's Northern origin.]

The following are selected from the Eclogues as the most remarkable:

"Each man for himself, and the fende for us all."

"They robbe Saint Peter therwith to clothe Saint Powle."

"For might of water will not our leasure bide."

"Once out of sight and shortly out of minde."

"For children brent still after drede the fire."

"Together they cleave more fast than do burres."

"Tho' thy teeth water."

"I aske of the foxe no farther than the skin."

"To touche soft pitche and not his fingers file."

"From post unto piller tost shall thou be."

"Over head and eares."

"Go to the ant."

"A man may contende, God geueth victory."

"Of two evils chose the least."

These are but the more striking specimens. An examination of the "Ship," and especially of the "Eclogues," for the purpose of extracting their whole proverbial lore, would be well worth the while, if it be not the duty, of the next collector in this branch of popular literature. These writings introduce many of our common sayings for the first time to English literature, no writer prior to Barclay having thought it dignified or worth while to profit by the popular wisdom to any perceptible extent. The first collection of proverbs, Heywood's, did not appear until 1546, so that in Barclay we possess the earliest known English form of such proverbs as he introduces. It need scarcely be said that that form is, in the majority of instances, more full of meaning and point than its modern representatives.

Barclay's adoption of the language of the people naturally elevated him in popular estimation to a position far above that of his contemporaries in the matter of style, so much so that he has been traditionally recorded as one of the greatest improvers of the language, that is, one of those who helped greatly to bring the written language to be more nearly in accordance with the spoken. Both a scholar and a man of the world, his phraseology bears token of the greater cultivation and wider knowledge he possessed over his contemporaries. He certainly aimed at clearness of expression, and simplicity of vocabulary, and in these respects was so far in advance of his time that his works can even now be read with ease, without the help of dictionary or glossary. In spite of his church training and his residence abroad, his works are surprisingly free from Latin or French forms of speech; on the contrary, they are, in the main, characterised by a strong Saxon directness of expression which must have tended greatly to the continuance of their popularity, and have exercised a strong and advantageous influence both in regulating the use of the common spoken language, and in leading the way which it was necessary for the literary language to follow. Philologists and dictionary makers appear, however, to have hitherto overlooked Barclay's works, doubtless owing to their rarity, but their intrinsic value as well as their position in relation to the history of the language demand specific recognition at their hands.

Barclay evidently delighted in his pen. From the time of his return from the Continent, it was seldom out of his hand. Idleness was distasteful to him. He petitions his critics if they be "wyse men and cunnynge," that:—

"They shall my youth pardone, and vnchraftynes

Whiche onely translate, to eschewe ydelnes."

Assuredly a much more laudable way of employing leisure then than now, unless the translator prudently stop short of print. The modesty and singleness of aim of the man are strikingly illustrated by his thus devoting his time and talents, not to original work as he was well able to have done had he been desirous only of glorifying his own name, but to the translation and adaptation or, better, "Englishing" of such foreign authors as he deemed would exercise a wholesome and profitable influence upon his countrymen. Such work, however, moulded in his skilful hands, became all but original, little being left of his author but the idea. Neither the Ship of Fools, nor the Eclogues retain perceptible traces of a foreign source, and were it not that they honestly bear their authorship on their fore-front, they might be regarded as thoroughly, even characteristically, English productions.

The first known work from Barclay's pen[3] appeared from the press of De Worde, so early as 1506, probably immediately on his return from abroad, and was no doubt the fruit of continental leisure. It is a translation, in seven line stanzas, of the popular French poet Pierre Gringore's Le Chateau de labour (1499)—the most ancient work of Gringore with date, and perhaps his best—under the title of "The Castell of laboure wherein is richesse, vertu, and honour;" in which in a fanciful allegory of some length, a somewhat wearisome Lady Reason overcomes despair, poverty and other such evils attendant upon the fortunes of a poor man lately married, the moral being to show:—

"That idleness, mother of all adversity,

Her subjects bringeth to extreme poverty."

The general appreciation of this first essay is evidenced by the issue of a second edition from the press of Pynson a few years after the appearance of the first.

Encouraged by the favourable reception accorded to the first effort of his muse, Barclay, on his retirement to the ease and leisure of the College of St Mary Otery, set to work on the "Ship of Fools," acquaintance with which Europe-famous satire he must have made when abroad. This, his magnum opus, has been described at some length in the Introduction, but two interesting personal notices relative to the composition of the work may here be added. In the execution of the great task, he expresses himself, (II. 278), as under the greatest obligations to his colleague, friend, and literary adviser, Bishop:—

"Whiche was the first ouersear of this warke

And vnto his frende gaue his aduysement

It nat to suffer to slepe styll in the darke

But to be publysshyd abrode: and put to prent

To thy monycion my bysshop I assent

Besechynge god that I that day may se

That thy honour may prospere and augment

So that thy name and offyce may agre

· · · · · ·

In this short balade I can nat comprehende

All my full purpose that I wolde to the wryte

But fayne I wolde that thou sholde sone assende

To heuenly worshyp and celestyall delyte

Than shoulde I after my pore wyt and respyt,

Display thy name, and great kyndnes to me

But at this tyme no farther I indyte

But pray that thy name and worshyp may agre."

Pynson, in his capacity of judicious publisher, fearing lest the book should exceed suitable dimensions, also receives due notice at p. 108 of Vol. I., where he speaks of

"the charge Pynson hathe on me layde

With many folys our Nauy not to charge."

The concluding stanza, or colophon, is also devoted to immortalising the great bibliopole in terms, it must be admitted, not dissimilar to those of a modern draper's poet laureate:—

Our Shyp here leuyth the sees brode

By helpe of God almyght and quyetly

At Anker we lye within the rode

But who that lysteth of them to bye

In Flete strete shall them fynde truly

At the George: in Richarde Pynsonnes place

Prynter vnto the Kynges noble grace.

Deo gratias.

Contemporary allusions to the Ship of Fools there could not fail to be, but the only one we have met with occurs in Bulleyn's Dialogue quoted above, p. xxvii. It runs as follows:—Uxor.—What ship is that with so many owers, and straunge tacle; it is a greate vessell. Ciuis.—This is the ship of fooles, wherin saileth bothe spirituall and temporall, of euery callyng some: there are kynges, queenes, popes, archbishoppes, prelates, lordes, ladies, knightes, gentlemen, phisicions, lawiers, marchauntes, housbandemen, beggers, theeues, hores, knaues, &c. This ship wanteth a good pilot: the storme, the rocke, and the wrecke at hande, all will come to naught in this hulke for want of good gouernement.

The Eclogues, as appears from their Prologue, had originally been the work of our author's youth, "the essays of a prentice in the art of poesie," but they were wisely laid past to be adorned by the wisdom of a wider experience, and were, strangely enough, lost for years until, at the age of thirty-eight, the author again lighted, unexpectedly, upon his lost treasures, and straightway finished them off for the public eye.

The following autobiographical passage reminds one forcibly of Scott's throwing aside Waverley, stumbling across it after the lapse of years, and thereupon deciding at once to finish and publish it. After enumerating the most famous eclogue writers, he proceeds:—

"Nowe to my purpose, their workes worthy fame,

Did in my yonge age my heart greatly inflame,

Dull slouth eschewing my selfe to exercise,

In such small matters, or I durst enterprise,

To hyer matter, like as these children do,

Which first vse to creepe, and afterwarde to go.

· · · · · · · ·