The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Letters of Queen Victoria, Volume 1 (of

3), 1837-1843), by Queen Victoria

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Letters of Queen Victoria, Volume 1 (of 3), 1837-1843)

A Selection from Her Majesty's Correspondence Between the

Years 1837 and 1861

Author: Queen Victoria

Editor: Arthur Christopher Benson and Viscount Esher

Release Date: December 5, 2006 [EBook #20023]

Most recently updated: May 3, 2009

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LETTERS QUEEN VICTORIA ***

Produced by Paul Murray, Lesley Halamek and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

|

This is the first volume of three. The index of this three-volume work is in Volume III, with links to all three volumes; and some footnotes are linked between volumes. These links are designed to work when the book is read on line. For information on the downloading of all three interlinked volumes so that the links work on your own computer, see the Transcriber's Note at the end of this book. |

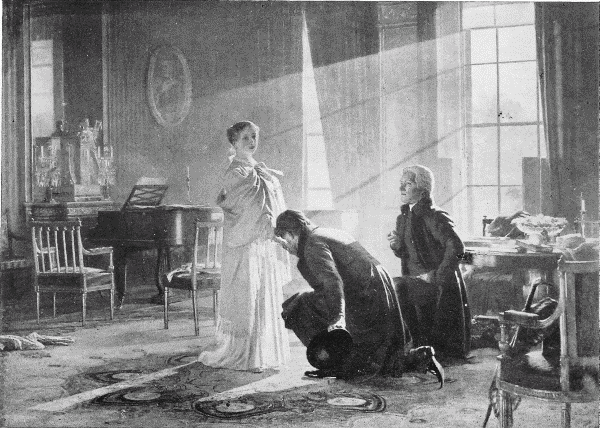

QUEEN VICTORIA RECEIVING THE NEWS OF HER ACCESSION TO THE THRONE, JUNE 20, 1837

From the picture by H. T. Wells, R.A., at Buckingham Palace

Entrusted by His Majesty the King with the duty of making a selection from Queen Victoria's correspondence, we think it well to describe briefly the nature of the documents which we have been privileged to examine, as well as to indicate the principles which have guided us throughout. It has been a task of no ordinary difficulty. Her Majesty Queen Victoria dealt with her papers, from the first, in a most methodical manner; she formed the habit in early days of preserving her private letters, and after her accession to the Throne all her official papers were similarly treated, and bound in volumes. The Prince Consort instituted an elaborate system of classification, annotating and even indexing many of the documents with his own hand. The result is that the collected papers form what is probably the most extraordinary series of State documents in the world. The papers which deal with the Queen's life up to the year 1861 have been bound in chronological order, and comprise between five and six hundred volumes. They consist, in great part, of letters from Ministers detailing the proceedings of Parliament, and of various political memoranda dealing with home, foreign, and colonial policy; among these are a few drafts of Her Majesty's replies. There are volumes concerned with the affairs of almost every European country; with the history of India, the British Army, the Civil List, the Royal Estates, and all the complicated machinery of the Monarchy and the Constitution. There are letters from monarchs and royal personages, and there is further a whole series of volumes dealing with matters in which the Prince Consort took a special interest. Some of them are arranged chronologically, some by subjects. Among the most interesting volumes are those containing the letters written by Her Majesty to her uncle Leopold, King of the Belgians, and his replies.1 The collection of letters from and to Lord Melbourne forms another hardly less interesting series. In many places Queen Victoria caused extracts, copied from her own private Diaries, dealing with important political events or describing momentous interviews, to be inserted in the volumes, with the evident intention of illustrating and completing the record.

Footnote 1: A set of volumes containing the Queen's letters to Lord John Russell came into our hands too late to be made use of for the present publication.

It became obvious at once that it was impossible to deal with [page iv] these papers exhaustively. They would provide material for a historical series extending to several hundred volumes. Moreover, on the other hand, there are many gaps, as a great deal of the business of State was transacted by interviews of which no official record is preserved.

His Majesty the King having decided that no attempt should be made to publish these papers in extenso, it was necessary to determine upon some definite principle of selection. It became clear that the only satisfactory plan was to publish specimens of such documents as would serve to bring out the development of the Queen's character and disposition, and to give typical instances of her methods in dealing with political and social matters—to produce, in fact, a book for British citizens and British subjects, rather than a book for students of political history. That the inner working of the unwritten constitution of the country; that some of the unrealised checks and balances; that the delicate equipoise of the component parts of our executive machinery, should stand revealed, was inevitable. We have thought it best, throughout, to abstain from unnecessary comment and illustration. The period is so recent, and has been so often traversed by historians and biographers, that it appeared to us a waste of valuable space to attempt to reconstruct the history of the years from which this correspondence has been selected, especially as Sir Theodore Martin, under the auspices of the Queen herself, has dealt so minutely and exhaustively with the relations of the Queen's innermost circle to the political and social life of the time. It is tempting, of course, to add illustrative anecdotes from the abundant Biographies and Memoirs of the period; but our aim has been to infringe as little as possible upon the space available for the documents themselves, and to provide just sufficient comment to enable an ordinary reader, without special knowledge of the period, to follow the course of events, and to realise the circumstances under which the Queen's childhood was passed, the position of affairs at the time of her accession, and the personalities of those who had influenced her in early years, or by whom she was surrounded.

The development of the Queen's character is clearly indicated in the papers, and it possesses an extraordinary interest. We see one of highly vigorous and active temperament, of strong affections, and with a deep sense of responsibility, placed at an early age, and after a quiet girlhood, in a position the greatness of which it is impossible to exaggerate. We see her character expand and deepen, schooled by mighty experience into patience and sagacity and wisdom, and yet never losing a particle of the strength, the decision, and the devotion with [page v] which she had been originally endowed. Up to the year 1861 the Queen's career was one of unexampled prosperity. She was happy in her temperament, in her health, in her education, in her wedded life, in her children. She saw a great Empire grow through troubled times in liberty and power and greatness; yet this prosperity brought with it no shadow of complacency, because the Queen felt with an increasing depth the anxieties and responsibilities inseparable from her great position. Her happiness, instead of making her self-absorbed, only quickened her beneficence and her womanly desire that her subjects should be enabled to enjoy a similar happiness based upon the same simple virtues. Nothing comes out more strongly in these documents than the laborious patience with which the Queen kept herself informed of the minutest details of political and social movements both in her own and other countries.

It is a deeply inspiring spectacle to see one surrounded by every temptation which worldly greatness can present, living from day to day so simple, vivid, and laborious a life; and it is impossible to conceive a more fruitful example of duty and affection and energy, displayed on so august a scale, and in the midst of such magnificent surroundings. We would venture to believe that nothing could so deepen the personal devotion of the Empire to the memory of that great Queen who ruled it so wisely and so long, and its deeply-rooted attachment to the principle of constitutional monarchy, as the gracious act of His Majesty the King in allowing the inner side of that noble life and career to be more clearly revealed to a nation whose devotion to their ancient liberties is inseparably connected with their loyalty to the Throne.

Our special thanks, for aid in the preparation of these volumes, are due to Viscount Morley of Blackburn, who has read and criticised the book in its final form; to Mr J. W. Headlam, of the Board of Education, and formerly Fellow of King's College, Cambridge, for much valuable assistance in preparing the prefatory historical memoranda; to Mr W. F. Reddaway, Fellow of King's College, Cambridge, for revision and advice throughout, in connection with the introductions and annotations; to Lord Knollys, for criticism of selected materials; to Lord Stanmore, for the loan of valuable documents; to Dr Eugene Oswald, for assistance in translation; to Mr C. C. Perry and M. G. Hua, for verification of French and German documents; to Miss Bertha Williams, for unremitting care and diligence in preparing the volumes for press; to Mr John Murray, our publisher, for his unfailing patience and helpfulness; and especially to Mr Hugh Childers, for his ungrudging help in the preparation of the Introductory annual summaries, and in the political and historical annotation, as well as for his invaluable co-operation at every stage of the work.

[page vi]CHAPTER I | PAGES |

| Ancestry of Queen Victoria—Houses of Brunswick, Hanover, and Coburg—Family connections—The English Royal Family—The Royal Dukes—Duke of Cumberland—Family of George III.—Political position of the Queen | 1-7 |

CHAPTER IIQueen Victoria's early years—Duke and Duchess of Kent—Parliamentary grant to Duchess of Kent—The Queen of Würtemberg—George IV. and the Princess—Visits to Windsor—Duchess of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld—Education of the Princess—The Duchess of Kent's letter to the Bishops—Religious instruction—Result of examination—Speech by Duchess of Kent—The Princess's reminiscences of Claremont—William IV. and the Princess—The accession—Queen Victoria's character and temperament—Her sympathy with the middle classes |

8-21 |

CHAPTER IIIQueen Victoria's relations and friends—King Leopold's influence—Queen Adelaide—Baroness Lehzen—Baron Stockmar |

22-26 |

CHAPTER IV1821-1835Observations on the correspondence with King Leopold and others—First letter received by Queen Victoria—Her first letter to Prince Leopold—Birthday letters—King Leopold's description of his Queen—His valuable advice—The Princess's visit to Hever Castle—King Leopold's advice as to reading, and the Princess's reply—New Year greeting—On autographs—The Princess's confirmation—King Leopold's advice as to honesty and sincerity |

27-42 |

CHAPTER V1836Visit of Prince Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg—Invitation to the Prince of Orange—Arrival of Princes Ernest and Albert—The Princess's appreciation of Prince Albert—King Leopold's advice as to conversation—Crisis in Spain—Farewell letter—The Princess and the Church—Death of Charles X.—Abuse of King Leopold—Revolution at Lisbon—The Princess's name—Newspaper attacks on King Leopold |

43-55 |

CHAPTER VI1837Spain and Portugal—Music with Princes Ernest and Albert—Parliamentary language and political passion—The throne of Greece—Queen of the Belgians' dowry—The English Press—The Princess's establishment—Young Belgian cousins—Irish Municipal Bill—Whig Ministers—Birthday rejoicings—King Leopold's advice and encouragement—Accession imminent—Condition of the King—Reliance on Lord Melbourne—The Princess and the Church—The Accession—The Queen's journal—Interview with Lord Melbourne—The Queen's first Council—Letter from the King of the French—Congratulations from King Leopold—Nationality of the Queen—The Queen and her Ministers—Reflection advised—Baron Stockmar—Important subjects for study—Sister Queens—Letter from Queen Adelaide—Buckingham Palace—Madame de Lieven—Parliament prorogued—England and Russia—Discretion advised—Singing lessons—The elections—Prevalence of bribery—End of King Leopold's visit—Reception at Brighton—Security of letters—England and France—France and the Peninsula—Count Molé—The French in Africa—Close of the session—Prince Albert's education—Canada—Army estimates—Secretaries of State |

56-101 |

CHAPTER VII1838Lord Melbourne—Canada—Influence of the Crown—Daniel O'Connell—Position of Ministers of State in England and abroad—New Poor Law—Pressure of business—Prince Albert's education—Favourite [page viii] horses—Deaths of old servants—The Coronation—Address from Bishops—Ball at Buckingham Palace—Independence and progress of Belgium—Anglo-Belgian relations—Foreign policy—Holland and Belgium—Coronation Day—Westminster Abbey—The enthronement—Receiving homage—Popular enthusiasm—Coronation incidents—Pages of honour—Extra holidays for schools—Review in Hyde Park—Lord Durham and Canada—Government of Canada—Ireland and O'Connell—Death of Lady John Russell—The Queen's sympathy with Lord John Russell—Belgium and English Government—Belgium and Holland—Canada—Resignation of the Earl of Durham—English Church for Malta—Disappointment of Duke of Sussex—Brighton |

102-140 |

CHAPTER VIII1839Murder of Lord Norbury—Holland and Belgium—Dissension in the Cabinet—The Duke of Lucca—Portugal—Ireland and the Government—England and Belgium—Prince Albert's tour in Italy—Jamaica—Change of Ministry imminent—The Queen's distress—Interviews with the Duke of Wellington and Sir Robert Peel—Lord Melbourne on Sir Robert Peel—The Household—Proposed new Cabinet—Interview with Lord Melbourne—The Ladies of the Household and Sir Robert Peel—Reply to Sir Robert Peel—Resignation of Sir Robert Peel—The Queen's journal—Cabinet minute—Whigs resume office—Ball at Buckingham Palace—Lord John Russell and Sir Robert Peel—The Queen on the crisis—King Leopold's approval—The penny postage—The Queen and Prince Albert—Syria—England and the Sultan—Proposed visit of King Louis Philippe—Preparing the Queen's speech—King Leopold's feeling for the Queen—Coming visit of Prince Albert—Arrival of Princes Ernest and Albert—The Queen's engagement to Prince Albert—Lord Melbourne's congratulations—King Leopold's satisfaction—Austria and the Porte—The Queen's happiness—Queen Louise's congratulations—The Queen's letters to the Royal Family—The Prince's religion—Announcement to the Council—Marriage treaty—Question of a peerage—English susceptibilities—Letter from Donna Maria—Household appointments—Mayor of Newport knighted—The word "Protestant"—The Prince's coat-of-arms—The Prince and Mr Anson—Appointment of Treasurer—The Prince and Lord Melbourne |

141-208 |

CHAPTER IX1840Letters to Prince Albert—Opening of Parliament—The Prince's grant—The Prince at Brussels—Marriage of the Queen and Prince—Public enthusiasm—Plays in Lent—Debate on the Corn Laws—England and China—Disturbance at the Opera—Murder of Lord William Russell—Mrs Norton—Character of Princess Charlotte—English manners—Oxford's attempt on the Queen's life—Egypt and the Four Powers—Prince Louis Napoleon—King Leopold at Wiesbaden—A threatened crisis—France and the East—A difficult question—Serious measures—Palmerston and France—Views of King Louis Philippe—Propositions for settlement—Attitude of France—Pacific instructions—The Porte and Mehemet Ali—Bombardment of Beyrout—Guizot and Thiers—Differing views—The Queen's influence—An anxious time—Attempt on life of King Louis Philippe—Negotiation with France advised—Thiers more moderate—Death of Lord Holland—Change of Ministry in France—Importance of conciliation—The Prince's name in the Prayer-book—King Leopold on Lord Palmerston—Birth of the Princess Royal—Settlement of Eastern Question |

209-252 |

CHAPTER X1841Letter to King Leopold—The Prince and literature—The speech from the throne—Domestic happiness—Duke of Wellington's illness—England and the United States—Operations in China—Lord Cardigan—Army discipline—The Nottingham election—The Budget—Irish Registration Bill—Sugar duties—Ministerial crisis—Lord Melbourne's advice—Dissolution or resignation—The Household question—Sir Robert Peel—Mr Anson's intervention—Interview with Lord Melbourne—King Leopold's sympathy—The Corn Laws—The Queen's journal—The Prince's support—Further interviews—Resignation postponed—The Queen and the Church—King Leopold's advice—The Queen's impartiality—Difficulties removed—Vote of want of confidence—The country quiet—King Leopold's views—Fiscal Policy—Marriage of Lord John Russell—Visit to Nuneham—Archbishop Harcourt—The Prince visits Oxford—Letter from Lord Brougham—Visit to Woburn Abbey—Lord Melbourne and the Garter—A dreaded moment—Debate on the Speech—Overwhelming majority—Resignation—New arrangements—Parting [page x] with Lord Melbourne—The Prince in a new position—The Queen and Sir Robert Peel—Lord Melbourne's opinion of the Prince—The Household question—New Cabinet—Lord Melbourne's official farewell—Sir Robert Peel's reception—New appointments—Council at Claremont—The Lord Chamberlain's department—The French ambassador—Confidential communications—The diplomatic corps—Governor-General of Canada—India and Afghanistan—Lord Ellenborough—Russia and Central Asia—Indian finances—The Spanish mission—Correspondence with Lord Melbourne—Fine Arts Commission—Peers and audiences—Lord Radnor's claim—The Chinese campaign—English and foreign artists—Lord Melbourne and the Court—The Queen and her Government—Baron Stockmar's opinion—Lord Melbourne's influence—Baron Stockmar and Sir Robert Peel—Professor Whewell—Queen Christina—Queen Isabella—French influence in Spain—Holland and Belgium—Dispute with United States—Portugal—The English Constitution—The "Prime Minister"—The "Secretaries of State"—Baron Stockmar expostulates with Lord Melbourne—Birth of Heir-apparent—Created Prince of Wales—The Royal children |

253-369 |

CHAPTER XI1842Letter from Queen Adelaide—Disasters in Afghanistan—The Oxford movement—Church matters—The Duke of Wellington and the christening—Lord Melbourne ill—A favourite dog—The King of Prussia—Marriage of Prince Ernest—Christening of the Prince of Wales—The Corn Laws—Marine excursion—Fall of Cabul—Candidates for the Garter—The Earl of Munster—The Queen and Income Tax—Lambeth Palace—Sale at Strawberry Hill—Selection of a governess—Party politics—A brilliant ball—The Prince and the Army—Lady Lyttelton's appointment—Goethe and Schiller—Edwin Landseer—The Mensdorff family—Attack on the Queen by Francis—Letters from Queen Adelaide and Lord Melbourne—Successes in Afghanistan—Sir R. Sale and General Pollock—Debate on Income Tax—The Queen's first railway journey—Conviction of Francis—Presents for the Queen—Another attack on the Queen by Bean—Death of Duke of Orleans—Grief of the Queen—Letters from the King and Queen of the French—Leigh Hunt—Lord Melbourne on marriages—Resignation of Lord Hill—Appointment of Duke of Wellington—Manchester riots—Military assistance—Parliament prorogued—Causes of discontent—Mob in [page xi] Lincoln's Inn Fields—Trouble at the Cape—Tour in Scotland—Visit to Lord Breadalbane—Return to Windsor—Royal visitors—A steam yacht for the Queen—Future of Queen Isabella—The Princess Lichtenstein—Historical works—Walmer Castle—Lord Melbourne's illness—The Crown jewels—Provision for Princess Augusta—Success in China—A treaty signed—Victories in Afghanistan—Honours for the army—The gates of Somnauth—France and Spain—Major Malcolm—The Scottish Church—A serious crisis—Letter from Lord Melbourne—Esteem for Baron Stockmar |

370-449 |

CHAPTER XII1843Recollections of Claremont—Historical writers—Governor-Generalship of Canada—Mr Drummond shot—Mistaken for Sir Robert Peel—Death of Mr Drummond—Demeanour of MacNaghten—Letter from Lord Melbourne—Preparations for the trial—The Royal Family and politics—King Leopold and Sir Robert Peel—The American treaty—Position of the Prince of Wales—Good wishes from Queen Adelaide—Proposed exchange of visits—Mr Cobden's speech—The new chapel—Fanny Burney's diary—MacNaghten acquitted—Question of criminal insanity—Princess Mary of Baden—The Prince and the Levées—Sir Robert Peel's suggestions—Police arrangements—Looking for the comet—Flowers from Lord Melbourne—The Royal children—The toast of the Prince—King of Hanover's proposed visit—Gates of Somnauth restored—Death of Duke of Sussex—Birth and christening of Princess Alice—Irish agitation—Rebecca riots—Duchess of Norfolk's resignation—Duelling in the Army—Outpensioners of Chelsea—Crown jewels—Obstruction of business—Lord Melbourne on matrimonial affairs—Visit to Château d'Eu—Increased troubles in Wales—Royal visitors—England and Spain—Arrest of O'Connell—Duc de Bordeaux not received at Court—Duc de Nemours expected—Visit to Cambridge—Duc d'Aumale's engagement—Indian affairs—Loyalty at Cambridge—Proposed visit to Drayton Manor—Travelling arrangements—Duchesse de Nemours—Birmingham—Canadian seat of government—Chatsworth—American view of monarchy—Prince Metternich and Spain |

450-512 |

| Queen Victoria receiving the News of her Accession

to the Throne, 20th June 1837. From the picture by H. T. Wells, R.A., at Buckingham Palace |

Frontispiece |

| T.R.H. The Duchess of Kent and the Princess

Victoria. From the miniature by H. Bone, after Sir W. Beechey, at Windsor Castle |

Facing p. 8 |

| H.R.H. The Princess Victoria, 1827. By Plant, after Stewart. From the miniature at Buckingham, Palace |

Facing p. 16 |

| H.M. King William IV. From a miniature at Windsor Castle |

Facing p. 72 |

| H.R.H. The Prince Consort, 1840. From the portrait by John Partridge at Buckingham Palace |

Facing p. 176 |

| H.M. Queen Victoria, 1841. From the drawing by E. F. T., after H. E. Dawe, at Buckingham Palace |

Facing p. 272 |

Queen Victoria, on her father's side, belonged to the House of Brunswick, which was undoubtedly one of the oldest, and claimed to be actually the oldest, of German princely families. At the time of her birth, it existed in two branches, of which, the one ruled over what was called the Duchy of Brunswick, the other over the Electorate (since 1815 the Kingdom) of Hanover, and had since 1714 occupied the throne of England. There had been frequent intermarriages between the two branches. The Dukes of Brunswick were now, however, represented only by two young princes, who were the sons of the celebrated Duke who fell at Quatre-Bras. Between them and the English Court there was little intercourse. The elder, Charles, had quarrelled with his uncle and guardian, George IV., and had in 1830 been expelled from his dominions. The obvious faults of his character made it impossible for the other German princes to insist on his being restored, and he had been succeeded by his younger brother William, who ruled till his death in 1884. Both died unmarried, and with them the Ducal family came to an end. One Princess of Brunswick had been the wife of George IV., and another, Augusta, was the first wife of Frederick I., King of Würtemberg, who, after her death, married a daughter of George III. The King of Würtemberg was also, by his descent from Frederick Prince of Wales, first cousin once removed of the Queen. We need only notice, in passing, the distant connection with the royal families of Prussia, the Netherlands, and Denmark. The Prince of Orange, who was one of the possible suitors for the young Queen's hand, was her third cousin once removed.

THE HOUSE OF SAXE-COBURG-GOTHAThe House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, to which the Queen belonged on her mother's side, and with which she was to be even more intimately connected by her marriage, was one of the numerous branches into which the ancient and celebrated House of Wettin had broken up. Since the 11th century they [page 2] had ruled over Meissen and the adjoining districts. To these had been added Upper Saxony and Thuringia. In the 15th century the whole possessions of the House had been divided between the two great branches which still exist. The Albertine branch retained Meissen and the Saxon possessions. They held the title of Elector, which in 1806 was exchanged for the title of King. Though the Saxon House had been the chief protectors of the Reformation, Frederick Augustus I. had, on being elected to the throne of Poland, become a Roman Catholic; and thereby the connection between the two branches of the House had to a great extent ceased. The second line, that of the Ernestines, ruled over Thuringia, but, according to the common German custom, had again broken up into numerous branches, among which the Duchies of Thuringia were parcelled out. At the time of the Queen's birth there were five of these, viz., Gotha-Altenburg, Coburg-Saalfeld, Weimar-Eisenach, Meiningen, and Hildburghausen. On the extinction of the Gotha line, in 1825, there was a rearrangement of the family property, by which the Duke of Hildburghausen received Altenburg, Gotha was given to the Duke of Coburg, and Saalfeld with Hildburghausen added to Meiningen. These four lines still exist.

The Ernestine princes had, by this constant division and sub-division, deprived themselves of the opportunity of exercising any predominant influence, or pursuing any independent policy in German affairs; and though they had the good fortune to emerge from the revolution with their possessions unimpaired, their real power was not increased. Like all the other princes, they had, however, at the Congress of Vienna, received the recognition of their full status as sovereign princes of the Germanic Confederation. Together they sent a single representative to the Diet of Frankfort, the total population of the five principalities being only about 300,000 inhabitants.

It was owing to this territorial sub-division and lack of cohesion that these princes could not attach to their independence the same political importance that fell to the share of the larger principalities, such as Hanover and Bavaria, and they were consequently more ready than the other German princes to welcome proposals which would lead to a unification of Germany.

It is notable that the line has produced many of the most enlightened of the German princes; and nowhere in the whole of Germany were the advantages of the division into numerous small States so clearly seen, and the disadvantages so little felt, as at Weimar, Meiningen, Gotha, and Coburg.

[page 3] THE HOUSE OF COBURGThe House of Coburg had gained a highly conspicuous and influential position, owing, partly, to the high reputation for sagacity and character which the princes of that House had won, and partly to the marriage connections which were entered into about this time by members of the Coburg House with the leading Royal families of Europe. Within ten years, Princes of Coburg were established, one upon the throne of Belgium, and two others next to the throne in Portugal and England, as Consorts of their respective Queens.

By the first marriage of the Duchess of Kent, the Queen was also connected with a third class of German princes—the Mediatised, as those were called who during the revolution had lost their sovereign power. Many of these were of as ancient lineage and had possessed as large estates as some of the regnant princes, who, though not always more deserving, had been fortunate enough to retain their privileges, and had emerged from the revolution ranking among the ruling Houses of Europe. The mediatised princes, though they had ceased to rule, still held important privileges, which were guaranteed at the Congress of Vienna. First, and most important, they were reckoned as "ebenburtig," which means that they could contract equal marriages with the Royal Houses, and these marriages were recognised as valid for the transmission of rights of inheritance. Many of them had vast private estates, and though they were subjected to the sovereignty of the princes in whose dominions these lay, they enjoyed very important privileges, such as exemption from military service, and from many forms of taxation; they also could exercise minor forms of jurisdiction. They formed, therefore, an intermediate class. Since Germany, as a whole, afforded them no proper sphere of political activity, the more ambitious did not disdain to take service with Austria or Prussia, and, to a less extent, even with the smaller States. It was possible, therefore, for the Queen's mother, a Princess of Saxe-Coburg, to marry the Prince of Leiningen without losing caste. Her daughter, the Princess Feodore, the Queen's half-sister, married Ernest, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, and thus established an interesting connection with perhaps the most widely-spread and most distinguished of all these families. The House of Hohenlohe would probably still have been a reigning family, had not the Prince of Hohenlohe preferred to fight in the Prussian army against Napoleon, rather than receive gifts from him. His lands were consequently confiscated and passed to other princes who were less scrupulous. The family has given two Ministers President to Prussia, a General in chief command of the Prussian army, a Chancellor to the German Empire, and [page 4] one of the most distinguished of modern military writers. They held, besides their extensive possessions in Würtemberg and Bavaria, the County of Gleichen in Saxe-Coburg.

FAMILY CONNECTIONSIt will be seen therefore that the Queen was intimately connected with all classes that are to be found among the ruling families of Germany, though naturally with the Catholic families, which looked to Austria and Bavaria for guidance, she had no close ties. But it must be borne in mind that her connection with Germany always remained a personal and family matter, and not a political one; this was the fortunate result of the predominance of the Coburg influence. Had that of the House of Hanover been supreme, it could hardly have been possible for the Queen not to have been drawn into the opposition to the unification of Germany by Prussia, in which the House of Hanover was bound to take a leading part, in virtue of its position, wealth, and dignity.

It will be as well here to mention the principal reigning families of Europe to which Queen Victoria was closely allied through her mother.

The Duchess of Kent's eldest brother, Ernest, Duke of Saxe-Coburg, was the father of Albert, Prince Consort. Her sister was the wife of Alexander, Duke of Würtemberg. The Duchess of Kent's nephew, Ferdinand (son of Ferdinand, the Duchess's brother), married Maria da Gloria, Queen of Portugal, and was father of Pedro V. and Luis, both subsequently Kings of Portugal.

The Duchess's third brother, Leopold (afterwards King of the Belgians), married first the Princess Charlotte, daughter of George IV., and afterwards the Princess Louise Marie, eldest daughter of King Louis Philippe. Prince Augustus (son of Ferdinand, the Duchess of Kent's brother) married another daughter of Louis Philippe, the Princess Clémentine, while Prince Augustus's sister, Victoria, married the Duc de Nemours, a son of Louis Philippe. Another nephew, Duke Friedrich Wilhelm Alexander, son of the Duchess of Würtemberg, married the Princess Marie, another daughter of Louis Philippe.

Thus Queen Victoria was closely allied with the royal families of France, Portugal, Belgium, Saxe-Coburg, and Würtemberg.

THE ENGLISH ROYAL FAMILYOn turning to the immediate Royal Family of England, it will be seen that the male line at the time of the Queen's accession was limited to the sons, both named George, of two of the younger brothers of George IV., the Dukes of Cumberland and Cambridge. The sons of George III. played their part in the national life, shared the strong interest in military matters, and showed the great personal courage which was a tradition of the family.

[page 5]It must be borne in mind that abstention from active political life had been in no sense required, or even thought desirable, in members of the Royal House. George III. himself had waged a lifelong struggle with the Whig party, that powerful oligarchy that since the accession of the House of Hanover had virtually ruled the country; but he did not carry on the conflict so much by encouraging the opponents of the Whigs, as by placing himself at the head of a monarchical faction. He was in fact the leader of a third party in the State. George IV. was at first a strong Whig, and lived on terms of the greatest intimacy with Charles James Fox; but by the time that he was thirty, he had severed the connection with his former political friends, which had indeed originally arisen more out of his personal opposition to his father than from any political convictions. After this date he became, with intervals of vacillation, an advanced Tory of an illiberal type. William IV. had lived so much aloof from politics before his accession, that he had had then no very pronounced opinions, though he was believed to be in favour of the Reform Bill; during his reign his Tory sympathies became more pronounced, and the position of the Whig Ministry was almost an intolerable one. His other THE ROYAL DUKES brothers were men of decided views, and for the most part of high social gifts. They not only attended debates in the House of Peers, but spoke with emotion and vigour; they held political interviews with leading statesmen, and considered themselves entitled, not to over-rule political movements, but to take the part in them to which their strong convictions prompted them. They were particularly prominent in the debates on the Catholic question, and did not hesitate to express their views with an energy that was often embarrassing. The Duke of York and the Duke of Cumberland had used all their influence to encourage the King in his opposition to Catholic Emancipation, while the Duke of Cambridge had supported that policy, and the Duke of Sussex had spoken in the House of Lords in favour of it. The Duke of York, a kindly, generous man, had held important commands in the earlier part of the Revolutionary war; he had not shown tactical nor strategical ability, but he was for many years Commander-in-Chief of the Army, and did good administrative work in initiating and carrying out much-needed military reforms. He had married a Prussian princess, but left no issue, and his death, in 1827, left the succession open to his younger brother, the Duke of Clarence, afterwards King William IV., and after him to the Princess Victoria.

The Duke of Kent was, as we shall have occasion to show, a strong Whig with philanthropic views. But the ablest of the [page 6] princes, though also the most unpopular, was the Duke of Cumberland, who, until the birth of the Queen's first child, was heir presumptive to the Throne. He had been one of the most active members of the ultra-Tory party, who had opposed to the last the Emancipation of the Catholics and the Reform Bill. He had married a sister-in-law of the King of Prussia, and lived much in Berlin, where he was intimate with the leaders of the military party, who were the centre of reactionary influences in that country, chief among them being his brother-in-law, Prince Charles of Mecklenburg.

In private life the Duke was bluff and soldier-like, of rather a bullying turn, and extraordinarily indifferent to the feelings of others. "Ernest is not a bad fellow," his brother William IV. said of him, "but if anyone has a corn, he will be sure to tread on it." He was very unpopular in England.

On the death of William IV. he succeeded to the throne of Hanover, and from that time seldom visited England. His first act on reaching his kingdom was to declare invalid the Constitution which had been granted in 1833 by William IV. His justification for this was that his consent, as heir presumptive, which was necessary for its validity, had not at the time been asked. The act caused great odium to be attached to his name by all Liberals, both English and Continental, and it was disapproved of even by his old Tory associates. None the less he soon won great popularity in his own dominions by his zeal, good-humour, and energy, and in 1840 he came to terms with the Estates. A new Constitution was drawn up which preserved more of the Royal prerogatives than the instrument of 1833. Few German princes suffered so little in the revolution of 1848. The King died in 1851, at the age of eighty, and left one son, George, who had been blind from his boyhood. He was the last King of Hanover, being expelled by the Prussians in 1866. On the failure of the Ducal line of Brunswick, the grandson of Ernest Augustus became heir to their dominions, he and his sons being now the sole male representatives of all the branches of the House of Brunswick, which a few generations ago was one of the most numerous and widely-spread ruling Houses in Germany.1

Footnote 1: Of the daughters of George III., Princess Amelia had died in 1810, and the Queen of Würtemberg in 1828; two married daughters survived—Elizabeth, wife of the Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg, and Mary, who had married her cousin, the Duke of Gloucester, and lived in England. There were also two unmarried daughters, the Princesses Augusta and Sophia, living in England.

The Duke of Sussex was in sympathy with many Liberal movements, and supported the removal of religious disabilities, the abolition of the Corn Laws, and Parliamentary Reform.

The Duke of Cambridge was a moderate Tory, and the most [page 7] conciliatory of all the princes. But for more than twenty years he took little part in English politics, as he was occupied with his duties as Regent of Hanover, where he did much by prudent reforms to retain the allegiance of the Hanoverians. On his return to England he resumed the position of a peacemaker, supporting philanthropic movements, and being a generous patron of art and letters. He was recognised as "emphatically the connecting link between the Crown and the people." Another member of the Royal Family was the Duke of Gloucester, nephew and son-in-law of George III.; he was more interested in philanthropic movements than in politics, but was a moderate Conservative, who favoured Catholic Emancipation but was opposed to Parliamentary Reform.

Thus we have the spectacle of seven Royal princes, of whom two succeeded to the Throne, all or nearly all avowed politicians of decided convictions, throwing the weight of their influence and social position for the most part on the side of the Tory party, and believing it to be rather their duty to hold and express strong political opinions than to adopt the moderating and conciliatory attitude in matters of government that is now understood to be the true function of the Royal House.

INDEPENDENCE OF THE QUEENThe Queen, after her accession, always showed great respect and affection for her uncles, but they were not able to exercise any influence over her character or opinions.

This was partly due to the fact that from an early age she had imbibed a respect for liberal views from her uncle Leopold, King of the Belgians, to whom she was devoted from her earliest childhood, and for whom she entertained feelings of the deepest admiration, affection, and confidence; but still more was it due to the fact that, from the very first, the Queen instinctively formed an independent judgment on any question that concerned her; and though she was undoubtedly influenced in her decisions by her affectionate reliance on her chosen advisers, yet those advisers were always deliberately and shrewdly selected, and their opinions were in no case allowed to do more than modify her own penetrating and clear-sighted judgment.

T.R.H. The Duchess of Kent and the Princess Victoria.

From the miniature by H. Bone, after Sir W. Beechey, at Windsor Castle

Alexandrina Victoria, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland and Empress of India, was born on Monday, 24th May 1819, at Kensington Palace.

THE DUKE AND DUCHESS OF KENTHer father, Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn (1767-1820), the fourth son of George III., was a man of decided character, kindly, pious, punctual, with a strict sense of duty and enlightened ideas. He was a devoted soldier, and, as Queen Victoria once said, "was proud of his profession, and I was always taught to consider myself a soldier's child." He had a wide military experience, having served at Gibraltar, in Canada, and in the West Indies. He had been mentioned in despatches, but was said to be over-strict in matters of unimportant detail. His active career was brought to an end in 1802, when he had been sent to Gibraltar to restore order in a mutinous garrison. Order had been restored, but the Duke was recalled under allegations of having exercised undue severity, and the investigation which he demanded was refused him, though he was afterwards made a Field-Marshal.

He was a man of advanced Liberal ideas. He had spoken in the House of Lords in favour of Catholic Emancipation, and had shown himself interested in the abolition of slavery and in popular education. His tastes were literary, and towards the end of his life he had even manifested a strong sympathy for socialistic theories.

At the time of the death of the Princess Charlotte, 6th November 1817, the married sons of King George III. were without legitimate children, and the surviving daughters were either unmarried or childless. Alliances were accordingly arranged for the three unmarried Royal Dukes, and in the course of the year 1818 the Dukes of Cambridge, Kent, and Clarence led their brides to the altar.

The Duchess of Kent (1786-1861), Victoria Mary Louisa, was a daughter of Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. She [page 9] was the widow of Emich Charles, Prince of Leiningen,1 whom she had married in 1803, and who had died in 1814, leaving a son and a daughter by her.

Footnote 1: Leiningen, a mediatised princely House of Germany, dating back to 1096. In 1779 the head of one of the branches into which it had become divided, the Count of Leiningen-Dachsburg-Hardenburg, was raised to the rank of a prince of the Empire, but the Peace of Lunéville (1801) deprived him of his ancient possessions, extending about 232 miles on the left bank of the Rhine. Though no longer an independent Prince, the head of the House retains his rank and wealth, and owns extensive estates in Bavaria and Hesse.

The Duke of Kent died prematurely—though he had always been a conspicuously healthy man—at Sidmouth, on the 23rd of January 1820, only a week before his father.

A paper preserved in the Windsor archives gives a touching account of the Duke's last hours. The Regent, on the 22nd of January, sent to him a message of solicitude and affection, expressing an anxious wish for his recovery. The Duke roused himself to enquire how the Prince was in health, and said, "If I could now shake hands with him, I should die in peace." A few hours before the end, one who stood by the curtain of his bed heard the Duke say with deep emotion, "May the Almighty protect my wife and child, and forgive all the sins I have committed." His last words—addressed to his wife—were, "Do not forget me."

The Duchess of Kent was an affectionate, impulsive woman, with more emotional sympathy than practical wisdom in worldly matters. But her claim on the gratitude of the British nation is that she brought up her illustrious daughter in habits of simplicity, self-sacrifice, and obedience.

As a testimony to the sincere appreciation entertained by the politicians of the time for the way in which the Duchess of Kent had appreciated her responsibilities with regard to the education of a probable heir to the Crown of England, we may quote a few sentences from two speeches made in the House of Commons, in the debate which took place (27th May 1825) on the question of increasing the Parliamentary annuity paid to the Duchess, in order to provide duly for the education of the young Princess.

The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Mr Robinson, afterwards Lord Ripon, said:

"The position in which this Princess stood with respect to the throne of the country could not fail to make her an object of general interest to the nation. He had not himself the honour of being acquainted with the Duchess of Kent, but he believed that she had taken the greatest pains with her daughter's education. She had been brought up in principles of piety and morality, and to feel a proper sense, he meant by [page 10] that an humble sense, of her own dignity, and the rank which probably awaited her. Perhaps it might have been fit to have brought this matter before Parliament at an earlier period."

Mr Canning said:

"All parties agreed in the propriety of the Grant, and if Government had anything to answer for on this point, it was for having so long delayed bringing it before the House. There could not be a greater compliment to Her Royal Highness than to state the quiet unobtrusive tenor of her life, and that she had never made herself the object of public gaze, but had devoted herself to the education of her child, whom the House was now called upon to adopt."

EARLY REMINISCENCESIn the year 1872 Queen Victoria wrote down with her own hand some reminiscences of her early childhood, the manuscript of which is preserved at Windsor, and which may be quoted here.

"My earliest recollections are connected with Kensington Palace, where I can remember crawling on a yellow carpet spread out for that purpose—and being told that if I cried and was naughty my 'Uncle Sussex' would hear me and punish me, for which reason I always screamed when I saw him! I had a great horror of Bishops on account of their wigs and aprons, but recollect this being partially got over in the case of the then Bishop of Salisbury (Dr Fisher, great-uncle to Mr Fisher, Private Secretary to the Prince of Wales), by his kneeling down and letting me play with his badge of Chancellor of the Order of the Garter. With another Bishop, however, the persuasion of showing him my 'pretty shoes' was of no use. Claremont remains as the brightest epoch of my otherwise rather melancholy childhood—where to be under the roof of that beloved Uncle—to listen to some music in the Hall when there were dinner-parties—and to go and see dear old Louis!—the former faithful and devoted Dresser and friend of Princess Charlotte—beloved and respected by all who knew her—and who doted on the little Princess who was too much an idol in the House. This dear old lady was visited by every one—and was the only really devoted Attendant of the poor Princess, whose governesses paid little real attention to her—and who never left her, and was with her when she died. I used to ride a donkey given me by my Uncle, the Duke of York, who was very kind to me. I remember him well—tall, rather large, very kind but extremely shy. He always gave me beautiful presents. The last time I saw him was at Mr Greenwood's [page 11] house, where D. Carlos lived at one time,—when he was already very ill,—and he had Punch and Judy in the garden for me.

"To Ramsgate we used to go frequently in the summer, and I remember living at Townley House (near the town), and going there by steamer. Mamma was very unwell. Dear Uncle Leopold went with us.

"To Tunbridge Wells we also went, living at a house called Mt. Pleasant, now an Hotel. Many pleasant days were spent here, and the return to Kensington in October or November was generally a day of tears.

"I was brought up very simply—never had a room to myself till I was nearly grown up—always slept in my Mother's room till I came to the Throne. At Claremont, and in the small houses at the bathing-places, I sat and took my lessons in my Governess's bedroom. I was not fond of learning as a little child—and baffled every attempt to teach me my letters up to 5 years old—when I consented to learn them by their being written down before me.

GEORGE IV."I remember going to Carlton House, when George IV. lived there, as quite a little child before a dinner the King gave. The Duchess of Cambridge and my 2 cousins, George and Augusta, were there. My Aunt, the Queen of Würtemberg (Princess Royal), came over, in the year '26, I think, and I recollect perfectly well seeing her drive through the Park in the King's carriage with red liveries and 4 horses, in a Cap and evening dress,—my Aunt, her sister Princess Augusta, sitting opposite to her, also in evening attire, having dined early with the Duke of Sussex at Kensington. She had adopted all the German fashions and spoke broken English—and had not been in England for many many years. She was very kind and good-humoured but very large and unwieldy. She lived at St James's and had a number of Germans with her. In the year '26 (I think) George IV. asked my Mother, my Sister and me down to Windsor for the first time; he had been on bad terms with my poor father when he died,—and took hardly any notice of the poor widow and little fatherless girl, who were so poor at the time of his (the Duke of Kent's) death, that they could not have travelled back to Kensington Palace had it not been for the kind assistance of my dear Uncle, Prince Leopold. We went to Cumberland Lodge, the King living at the Royal Lodge. Aunt Gloucester was there at the same time. When we arrived at the Royal Lodge the King took me by the hand, saying: 'Give me your little paw.' He was large and gouty but with a wonderful dignity and charm of manner. He wore the wig which was so much worn in those days. Then he said [page 12] he would give me something for me to wear, and that was his picture set in diamonds, which was worn by the Princesses as an order to a blue ribbon on the left shoulder. I was very proud of this,—and Lady Conyngham pinned it on my shoulder. Her husband, the late Marquis of Conyngham, was the Lord Chamberlain and constantly there, as well as Lord Mt. Charles (as Vice-Chamberlain), the present Lord Conyngham.

"None of the Royal Family or general visitors lived at the Royal Lodge, but only the Conyngham family; all the rest at Cumberland Lodge. Lady Maria Conyngham (now dead, first wife to Lord Athlumney, daughter of Lord Conyngham), then quite young, and Lord Graves (brother-in-law to Lord Anglesey and who afterwards shot himself on account of his wife's conduct, who was a Lady of the Bedchamber), were desired to take me a drive to amuse me. I went with them, and Baroness (then Miss) Lehzen (my governess) in a pony carriage and 4, with 4 grey ponies (like my own), and was driven about the Park and taken to Sandpit Gate where the King had a Menagerie—with wapitis, gazelles, chamois, etc., etc. Then we went (I think the next day) to Virginia Water, and met the King in his phaeton in which he was driving the Duchess of Gloucester,—and he said 'Pop her in,' and I was lifted in and placed between him and Aunt Gloucester, who held me round the waist. (Mamma was much frightened.) I was greatly pleased, and remember that I looked with great respect at the scarlet liveries, etc. (the Royal Family had crimson and green liveries and only the King scarlet and blue in those days). We drove round the nicest part of Virginia Water and stopped at the Fishing Temple. Here there was a large barge and every one went on board and fished, while a band played in another! There were numbers of great people there, amongst whom was the last Duke of Dorset, then Master of the Horse. The King paid great attention to my Sister,2 and some people fancied he might marry her!! She was very lovely then—about 18—and had charming manners, about which the King was extremely particular. I afterwards went with Baroness Lehzen and Lady Maria C. to the Page Whiting's cottage. Whiting had been at one time in my father's service. He lived where Mr Walsh now does (and where he died years ago), in the small cottage close by; and here I had some fruit and amused myself by cramming one of Whiting's children, a little girl, with peaches. I came after dinner to hear the band play in the Conservatory, which is still standing, and which was lit up by [page 13] coloured lamps—the King, Royal Family, etc., sitting in a corner of the large saloon, which still stands.

Footnote 2: The Princess Feodore of Leiningen, afterwards Princess of Hohenlohe, Queen Victoria's half-sister.

"On the second visit (I think) the following year, also in summer, there was a great encampment of tents (the same which were used at the Camp at Chobham in '53, and some single ones at the Breakfasts at Buckingham Palace in '68-9), and which were quite like a house, made into different compartments. It rained dreadfully on this occasion, I well remember. The King and party dined there, Prince and Princess Lieven, the Russian Ambassador and Ambassadress were there.

"I also remember going to see Aunt Augusta at Frogmore, where she lived always in the summer.

"We lived in a very simple, plain manner; breakfast was at half-past eight, luncheon at half-past one, dinner at seven—to which I came generally (when it was no regular large dinner party)—eating my bread and milk out of a small silver basin. Tea was only allowed as a great treat in later years.

DUCHESS OF SAXE-COBURG-SAALFELD"In 1826 (I think) my dear Grandmother, the Dowager Duchess of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, came to Claremont, in the summer. Mamma and my sister went on part of the way to meet her, and Uncle Leopold I think had been to fetch her as far as Dover. I recollect the excitement and anxiety I was in, at this event,—going down the great flight of steps to meet her when she got out of the carriage, and hearing her say, when she sat down in her room, and fixed her fine clear blue eyes on her little grand-daughter whom she called in her letters 'the flower of May,' 'Ein schönes Kind'—'a fine child.' She was very clever and adored by her children but especially by her sons. She was a good deal bent and walked with a stick, and frequently with her hands on her back. She took long drives in an open carriage and I was frequently sent out with her, which I am sorry to confess I did not like, as, like most children of that age, I preferred running about. She was excessively kind to children, but could not bear naughty ones—and I shall never forget her coming into the room when I had been crying and naughty at my lessons—from the next room but one, where she had been with Mamma—and scolding me severely, which had a very salutary effect. She dined early in the afternoon and Uncle Leopold asked many of the neighbours and others to dinner to meet her. My brother Prince Leiningen came over with her, and was at that time paying his court to one of her ladies, Countess Klebelsberg, whom he afterwards married—against the wish of his grandmother and mother—but which was afterwards quite made up. In November (I think, or it may have been at the end of October) she left, taking my sister with her back to Coburg. I was very ill at [page 14] that time, of dysentery, which illness increased to an alarming degree; many children died of it in the village of Esher. The Doctor lost his head, having lost his own child from it, and almost every doctor in London was away. Mr Blagden came down and showed much energy on the occasion. I recovered, and remember well being very cross and screaming dreadfully at having to wear, for a time, flannel next my skin. Up to my 5th year I had been very much indulged by every one, and set pretty well all at defiance. Old Baroness de Späth, the devoted Lady of my Mother, my Nurse Mrs Brock, dear old Mrs Louis—all worshipped the poor little fatherless child whose future then was still very uncertain; my Uncle the Duke of Clarence's poor little child being alive, and the Duchess of Clarence had one or two others later. At 5 years old, Miss Lehzen was placed about me, and though she was most kind, she was very firm and I had a proper respect for her. I was naturally very passionate, but always most contrite afterwards. I was taught from the first to beg my maid's pardon for any naughtiness or rudeness towards her; a feeling I have ever retained, and think every one should own their fault in a kind way to any one, be he or she the lowest—if one has been rude to or injured them by word or deed, especially those below you. People will readily forget an insult or an injury when others own their fault, and express sorrow or regret at what they have done."

THE EDUCATION OF THE PRINCESSIn 1830 the Duchess of Kent wished to be satisfied that the system of education then being pursued with the Princess was based on the right lines, and that due moral and intellectual progress was being made. A memorandum, carefully preserved among the archives, gives an interesting account of the steps which she took to this end.

LETTER TO THE BISHOPSThe Duchess therefore brought the matter under the consideration of those whom, from their eminent piety, great learning, and high station, she considered best calculated to afford her valuable advice upon so important a subject. She stated to the Bishops of London and Lincoln3 the particular course which had been followed in the Princess's education, and requested their Lordships to test the result by personal examination. The nature and objects of Her Royal Highness's appeal to these eminent prelates will be best shown by the following extracts from her letter to the Bishops:—

"'The Princess will be eleven years of age in May; by the death of her revered father when she was but eight months old, [page 15] her sole care and charge devolved to me. Stranger as I then was, I became deeply impressed with the absolute necessity of bringing her up entirely in this country, that every feeling should be that of Her native land, and proving thereby my devotion to duty by rejecting all those feelings of home and kindred that divided my heart.

"'When the Princess approached her fifth year I considered it the proper time to begin in a moderate way her education—an education that was to fit Her to be either the Sovereign of these realms, or to fill a junior station in the Royal Family, until the Will of Providence should shew at a later period what Her destiny was to be.

"'A revision of the papers I send you herewith will best shew your Lordships the system pursued, the progress made, etc. I attend almost always myself every lesson, or a part; and as the Lady about the Princess is a competent person, she assists Her in preparing Her lessons for the various masters, as I resolved to act in that manner so as to be Her Governess myself. I naturally hope that I have pursued that course most beneficial to all the great interests at stake. At the present moment no concern can be more momentous, or in which the consequences, the interests of the Country, can be more at stake, than the education of its future Sovereign.

"'I feel the time to be now come that what has been done should be put to some test, that if anything has been done in error of judgment it may be corrected, and that the plan for the future should be open to consideration and revision. I do not presume to have an over-confidence in what I have done; on the contrary, as a female, as a stranger (but only in birth, as I feel that this is my country by the duties I fulfil, and the support I receive), I naturally desire to have a candid opinion from authorities competent to give one. In that view I address your Lordships; I would propose to you that you advert to all I have stated, to the papers I lay before you, and that then you should personally examine the Princess with a view of telling me—

"'Mr Davys4 will explain to you the nature of the Princess's [page 16] religious education, which I have confided to him, that she should be brought up in the Church of England as by Law established. When she was at a proper age she commenced attending Divine Service regularly with me, and I have every feeling, that she has religion at Her heart, that she is morally impressed with it to that degree, that she is less liable to error by its application to Her feelings as a Child capable of reflection. The general bent of Her character is strength of intellect, capable of receiving with ease, information, and with a peculiar readiness in coming to a very just and benignant decision on any point Her opinion is asked on. Her adherence to truth is of so marked a character that I feel no apprehension of that Bulwark being broken down by any circumstance.

"'I must conclude by observing that as yet the Princess is not aware of the station that she is likely to fill. She is aware of its duties, and that a Sovereign should live for others; so that when Her innocent mind receives the impression of Her future fate, she receives it with a mind formed to be sensible of what is to be expected from Her, and it is to be hoped, she will be too well grounded in Her principles to be dazzled with the station she is to look to.'"

Footnote 3: Charles James Blomfield, Bishop of London, 1828-1853, and John Kaye, Bishop of Lincoln, 1827-1853.

Footnote 4: The Rev. George Davys, the Princess's instructor, afterwards successively Dean of Chester and Bishop of Peterborough.

The examination was undertaken by the Bishops, with highly satisfactory results. Their report says:

"The result of the examination has been such as in our opinion amply to justify the plan of instruction which has been adopted. In answering a great variety of questions proposed to her, the Princess displayed an accurate knowledge of the most important features of Scripture History, and of the leading truths and precepts of the Christian Religion as taught by the Church of England, as well as an acquaintance with the Chronology and principal facts of English History remarkable in so young a person. To questions in Geography, the use of the Globes, Arithmetic, and Latin Grammar, the answers which the Princess returned were equally satisfactory.

"Upon the whole, we feel no hesitation in stating our opinion that the Princess should continue, for some time to come, to pursue her studies upon the same plan which has been hitherto followed, and under the same superintendence. Nor do we apprehend that any other alterations in the plan will be required than those which will be gradually made by the judicious director of Her Highness's studies, as the mind expands, and her faculties are strengthened."

RESULT OF EXAMINATIONThe Duchess of Kent referred all this correspondence to the [page 17] Archbishop of Canterbury.5 His memorandum is preserved; it states he has considered the Report, and further, has himself personally examined the Princess. He continues:

"I feel it my duty to say that in my judgment the plan of Her Highness's studies, as detailed in the papers transmitted to me by command of your Royal Highness, is very judicious, and particularly suitable to Her Highness's exalted station; and that from the proficiency exhibited by the Princess in the examination at which I was present, and the general correctness and pertinency of her answers, I am perfectly satisfied that Her Highness's education in regard to cultivation of intellect, improvement of talent, and religious and moral principle, is conducted with so much care and success as to render any alteration of the system undesirable."

Footnote 5: Dr William Howley.

The Princess was gradually and watchfully introduced to public life, and was never allowed to lose sight of the fact that her exalted position carried with it definite and obvious duties. The following speech, delivered at Plymouth in 1832, in answer to a complimentary deputation, may stand as an instance of the view which the Duchess of Kent took of her own and her daughter's responsibilities:—

"It is very agreeable to the Princess and myself to hear the sentiments you convey to us. It is also gratifying to us to be assured that we owe all these kind feelings to the attachment you bear the King, as well as to his Predecessors of the House of Brunswick, from recollections of their paternal sway. The object of my life is to render the Princess worthy of the affectionate solicitude she inspires, and if it be the Will of Providence she should fill a higher station (I trust most fervently at a very distant day), I shall be fully repaid for my anxious care, if she is found competent to discharge the sacred trust; for communicating as the Princess does with all classes of Society, she cannot but perceive that the greater the diffusion of Religion, Knowledge, and the love of freedom in a country, the more orderly, industrious, and wealthy is its population, and that with the desire to preserve the constitutional Prerogatives of the Crown ought to be co-ordinate the protection of the liberties of the people."

CLAREMONTThe strictness of the régime under which the Princess was brought up is remarkable; and it is possible that her later zest for simple social pleasures is partly to be accounted for by the [page 18] austere routine of her early days. In an interesting letter of 1843 to the Queen, recalling the days of their childhood, Princess Feodore, the Queen's half-sister, wrote—

"Many, many thanks, dearest Victoria, for your kind letter of the 7th from dear Claremont. Oh I understand how you like being there. Claremont is a dear quiet place; to me also the recollection of the few pleasant days I spent during my youth. I always left Claremont with tears for Kensington Palace. When I look back upon those years, which ought to have been the happiest in my life, from fourteen to twenty, I cannot help pitying myself. Not to have enjoyed the pleasures of youth is nothing, but to have been deprived of all intercourse, and not one cheerful thought in that dismal existence of ours, was very hard. My only happy time was going or driving out with you and Lehzen; then I could speak and look as I liked. I escaped some years of imprisonment, which you, my poor darling sister, had to endure after I was married. But God Almighty has changed both our destinies most mercifully, and has made us so happy in our homes—which is the only real happiness in this life; and those years of trial were, I am sure, very useful to us both, though certainly not pleasant. Thank God they are over!... I was much amused in your last letter at your tracing the quickness of our tempers in the female line up to Grandmamma,6 but I must own that you are quite right!"

Footnote 6: Augusta Caroline Sophia, Dowager-Duchess of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, a Princess of Reuss Ebersdorf (1757-1831).

But if there was little amusement, there was, on the other hand, great devotion; the Princess, as a child, had that peculiar combination of self-will and warm-heartedness which is apt to win for a child a special love from its elders. The Princess Feodore wrote to the Queen, in 1843—

"... Späth7 wished me to thank you for the coronation print, as she could not write to you or Albert now, she says! why, I don't see. There certainly never was such devotedness as hers, to all our family, although it sometimes shows itself rather foolishly—with you it always was a sort of idolatry, when she used to go upon her knees before you, when you were a child. She and poor old Louis did all they could to spoil you, if Lehzen had not prevented and scolded them nicely sometimes; it was quite amusing."

Footnote 7: Baroness Späth, Lady-in-Waiting to the Duchess of Kent.

[page 19]The Princess was brought up with exemplary simplicity at Kensington Palace, where her mother had a set of apartments. She was often at Claremont, which belonged to her uncle Leopold, King of the Belgians; holidays were spent at Ramsgate, Tunbridge Wells, Broadstairs, and elsewhere.

WILLIAM IV.In June 1830 George IV. died, and William IV. succeeded to the Throne. He had no legitimate offspring living; and it consequently became practically certain that if the Princess outlived her uncle she would succeed him on the Throne. The Duchess of Kent's Parliamentary Grant was increased, and she took advantage of her improved resources to familiarise the Princess with the social life of the nation. They paid visits to historic houses and important towns, and received addresses. This was a wise and prudent course, but the King spoke with ill-humour of his niece's "royal progresses." The chief cause of offence was that the Princess was not allowed by the Duchess of Kent to make her public appearances under his own auspices, as he not unnaturally desired. He also began to suspect that the Princess was deliberately kept away from Court; a painful controversy arose, and the Duchess became gradually estranged from her brother-in-law, in spite of the affectionate attempts of Queen Adelaide to smooth matters over. His resentment culminated in a painful scene, in 1836, when the King, at a State banquet at Windsor, made a speech of a preposterous character; speaking of the Duchess, who sat next him, as "that person," hinting that she was surrounded with evil advisers, and adding that he should insist on the Princess being more at Court. The Princess burst into tears; the Duchess sate in silence: when the banquet was over, the Duchess ordered her carriage, and was with difficulty prevailed upon to remain at Windsor for the night. The King went so far in May 1837 as to offer the Princess an independent income, and the acceptance of this by the Princess caused the Duchess considerable vexation; but the project dropped. The King died in the following month, soon after the Princess had attained her legal majority; he had always hoped that the Duchess would not be Regent, and his wish was thus fulfilled.

It is no exaggeration to say that the accession of the Princess Victoria reinstated the English monarchy in the affections of the people. George IV. had made the Throne unpopular; William IV. had restored its popularity, but not its dignity. Both of these kings were men of decided ability, but of unbalanced temperament. In politics both kings had followed a somewhat similar course. George IV. had begun life as a strong Whig, and had been a close friend of Fox. Later in life his political position resolved itself into a strong dislike of [page 20] Roman Catholic Relief. William IV. had begun his reign favourably inclined to Parliamentary Reform; but though gratified by the personal popularity which his attitude brought him in the country, he became alarmed at the national temper displayed. It illustrates the tension of the King's mind on the subject that, when he was told that if the Reform Bill did not pass it would bring about a rebellion, he replied that if it did bring about a rebellion he did not care: he should defend London and raise the Royal Standard at Weedon (where there was a military depôt); and that the Duchess of Kent and the Princess Victoria might come in if they could.

The reign of William IV. had witnessed the zenith of Whig efficiency. It had seen the establishment of Parliamentary and Municipal Reform, the Abolition of Slavery, the new Poor Law, and other important measures. But, towards the end of the reign, the Whig party began steadily to lose ground, and the Tories to consolidate themselves. Lord Melbourne had succeeded Lord Grey at the head of the Whigs, and the difference of administration was becoming every month more and more apparent. The King indeed went so far as abruptly to dismiss his Ministers, but Parliament was too strong for him. Lord Melbourne's principles were fully as liberal as Lord Grey's, but he lacked practical initiative, with the result that the Whigs gradually forfeited popular estimation and became discredited. The new reign, however, brought them a decided increase of strength. The Princess had been brought up with strong Whig leanings, and, as is clear from her letters, with an equally strong mistrust of Tory principles and politicians.

CHARACTER AND TEMPERAMENTA word may here be given to the Princess's own character and temperament. She was high-spirited and wilful, but devotedly affectionate, and almost typically feminine. She had a strong sense of duty and dignity, and strong personal prejudices. Confident, in a sense, as she was, she had the feminine instinct strongly developed of dependence upon some manly adviser. She was full of high spirits, and enjoyed excitement and life to the full. She liked the stir of London, was fond of dancing, of concerts, plays, and operas, and devoted to open-air exercise. Another important trait in her character must be noted. She had strong monarchical views and dynastic sympathies, but she had no aristocratic preferences; at the same time she had no democratic principles, but believed firmly in the due subordination of classes. The result of the parliamentary and municipal reforms of William IV.'s reign had been to give the middle classes a share in the government of the country, and it was supremely fortunate that the Queen, by a providential gift of temperament, thoroughly understood the [page 21] middle-class point of view. The two qualities that are mostSYMPATHY WITH MIDDLE CLASSES characteristic of British middle-class life are common sense and family affection; and on these particular virtues the Queen's character was based; so that by a happy intuition she was able to interpret and express the spirit and temper of that class which, throughout her reign, was destined to hold the balance of political power in its hands. Behind lay a deep sense of religion, the religion which centres in the belief in the Fatherhood of God, and is impatient of dogmatic distinctions and subtleties.

H.R.H. The Princess Victoria, 1827.

By Plant, after Stewart. From the miniature at Buckingham, Palace

It may be held to have been one of the chief blessings of Queen THE KING OF THE BELGIANS Victoria's girlhood that she was brought closely under the influence of an enlightened and large-minded Prince, Leopold, her maternal uncle, afterwards King of the Belgians. He was born in 1790, being the youngest son of Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, and his youth was spent in the Russian military service. He had shown talent and courage in the field, and had commanded a battalion at Lützen and Leipsic. He had married, in 1816, the Princess Charlotte, only child of George IV. For many years his home was at Claremont, where the Princess Charlotte had died; there the Princess Victoria spent many happy holidays, and grew to regard her uncle with the most devoted affection, almost, indeed, in the light of a father. It is said that Prince Leopold had hoped to be named Regent, if a Regency should be necessary.1 He was offered, and accepted, the throne of Greece in 1830, but shrank from the difficulties of the position, and withdrew his acceptance upon the plea that Lord Aberdeen, who was then Foreign Secretary, was not prepared to make such financial arrangements as he considered satisfactory.2

Footnote 1: A practical proof of his interest in his niece may be found in the fact that for years he contributed between three and four thousand a year to the expenses of her education, and for necessary holidays by the sea, at a time when the Duchess of Kent's Parliamentary Grant was unequal to the increasing expenses of her household.

Footnote 2: Greece after having obtained autonomy was in a practically bankrupt condition, and the Powers had guaranteed the financial credit of the country until it was able to develop its own resources.

It is interesting to observe from the correspondence that King Leopold seems for many years to have continued to regret his decision; it was not that he did not devote himself, heart and soul, to the country of his adoption, but there seems to have been a romantic element in his composition, which did not find its full satisfaction in presiding over the destinies of a peaceful commercial nation.

In 1831, when Louis Philippe, under pressure from Lord Palmerston, declined the throne of Belgium for his son the Duc [page 23] de Nemours, Prince Leopold received and accepted an offer of the Crown. A Dutch invasion followed, and the new King showed great courage and gallantry in an engagement near Louvain, in which his army was hopelessly outnumbered. But, though a sensitive man, the King's high courage and hopefulness never deserted him. He ruled his country with diligence, ability, and wisdom, and devoted himself to encouraging manufactures and commerce. The result of his firm and liberal rule was manifested in 1848, when, on his offering to resign the Crown if it was thought to be for the best interests of the country, he was entreated, with universal acclamation, to retain the sovereignty. Belgium passed through the troubled years of revolution in comparative tranquillity. King Leopold was a model ruler; his deportment was grave and serious; he was conspicuous for honesty and integrity; he was laborious and upright, and at the same time conciliatory and tactful.

He kept up a close correspondence with Queen Victoria, and paid her several visits in England, where he was on intimate terms with many leading Englishmen. It would be difficult to over-estimate the importance of his close relations with the Queen; by example and precept he inspired her with a high sense of duty, and from the first instilled into her mind the necessity of acquainting herself closely with the details of political administration. His wisdom, good sense, and tenderness, as well as the close tie of blood that existed between him and the Queen, placed him in a unique position with regard to her, and it is plain that he was fully aware of the high responsibility thus imposed upon him, which he accepted with a noble generosity. It is true that there were occasions when, as the correspondence reveals, the Queen was disposed to think that King Leopold endeavoured to exercise too minute a control over her in matters of detail, and even to attempt to modify the foreign policy of England rather for the benefit of Belgium than in the best interests of Great Britain; but the Queen was equal to these emergencies; she expressed her dissent from the King's suggestions in considerate and affectionate terms, with her gratitude for his advice, but made no pretence of following it.

QUEEN ADELAIDEFor her aunt, Queen Adelaide, the Princess Victoria had always felt a strong affection; and though it can hardly be said that this gentle and benevolent lady exercised any great influence over her more vigorous and impetuous niece, yet the letters will testify to the closeness of the tie which united them.

Queen Adelaide was the eldest child of George, Duke of Saxe-Meiningen; her mother was a princess of Hohenlohe-Langenburg.