The Project Gutenberg EBook of Speed the Plough, by Thomas Morton

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Speed the Plough

A Comedy, In Five Acts; As Performed At The Theatre Royal, Covent Garden

Author: Thomas Morton

Release Date: September 29, 2006 [EBook #19407]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SPEED THE PLOUGH ***

Produced by Steven desJardins and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team

PRINTED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE MANAGERS FROM THE PROMPT BOOK.

WITH REMARKS

PRINTED FOR LONGMAN, HURST, REES, AND ORME,

PATERNOSTER ROW.

SAVAGE AND EASINGWOOD,

PRINTERS, LONDON.

This comedy excites that sensation, which is the best security for the success of a drama—curiosity. After the two first acts are over, and pleasantly over, with the excellent drawn characters of Ashfield and his wife, and the very just satire which arises from Sir Abel's propensity to modern improvements—the acts that follow excite deep interest and ardent expectation; both of which are so highly gratified at the conclusion of the play, that, from the first night of its performance, it has ranked among the best of the author's productions, and in the first class of modern comedies.

The various characters of this play are admirably designed, but not so happily finished as the author meant them to be—witness, Bob Handy, who begins a self-conceited coxcomb, and ends a tragedy confidant.

But the good intentions of an author are acceptable: execution will not always follow conception; and the last may often give as much instruction, though not equal delight with the former: as an instance, who does not see the folly of attempting to do every thing in Handy, though he is more the shadow, than the substance of a character.

Notwithstanding there are some parts, not so good as others, in this comedy, there is no one character superior to the rest, nor any one in particular, which makes a forcible impression on the memory:—this proves, (in consequence of the acknowledged merit of the play) the fable to be a good one, and that a pleasing combination has been studied and effected by the author, with infinite skill, however incompetent to his own brilliant imagination.

The plot, and serious characters of this comedy, are said to be taken from a play of Kotzebue's, called, "The Duke of Burgundy,"—if they are, Mr. Morton's ingenuity of adapting them to our stage has been equal to the merit he would have had in conceiving them; for that very play called, "The Duke of Burgundy," by some verbal translator,—was condemned or withdrawn at Covent Garden Theatre, not very long before "Speed the Plough" was received with the highest marks of admiration.

The characters of Sir Philip Blandford, his brother, and his nephew, may have been imported from Germany, but surely, all the other personages of the drama are of pure English growth.

The reception of this play, when first performed, and the high station it still holds in the public opinion, should make criticism cautious of attack—but as works of genuine art alone are held worthy of investigation, and as all examinations tend to produce a degree of censure, as well as of praise, "Speed the Plough" is not exempt from the general lot of every favourite production.

An auditor will be much better pleased with this play, than a reader; for though it is well written, and interspersed with many poetical passages, an attentive peruser will find inconsistencies in the arrangement of the plot and incidents, which an audience, absorbed in expectation of final events, and hurried away by the charm of scenic interest, cannot easily detect.

The most prominent of these blemishes are:—Miss Blandford falls in love with a plough-boy at first-sight, which she certainly would not have done, but that some preternatural agent whispered to her, he was a young man of birth. But whether this magical information came from the palpitation of her heart, or the quickness of her eye, she has not said.—A reader will, however, gladly impute the cause of her sudden passion to magic, rather than to the want of female refinement.

The daughter has not less decorum in love, than the father in murder.—That a character, grave and stern, as Sir Philip Blandford is described, should entrust any man, especially such a man as Bob Handy, with a secret, on which, not only his reputation, but his life depended, can upon no principle of reason be accounted for; unless the author took into consideration, what has sometimes been observed,—that a murderer, in contrivance to conceal his guilt, foolishly fixes on the very means, which bring him to conviction.

| Sir Philip Blandford | Mr. Pope. | |

| Morrington | Mr. Murray. | |

| Sir Abel Handy | Mr. Munden. | |

| Bob Handy | Mr. Fawcett. | |

| Henry | Mr. H. Johnston. | |

| Farmer Ashfield | Mr. Knight. | |

| Evergreen | Mr. Davenport. | |

| Gerald | Mr. Waddy. | |

| Postillion | Mr. Abbot. | |

| Young Handy's Servant | Mr. Klanert. | |

| Peter | Mr. Atkins. | |

| Miss Blandford | Mrs. H. Johnston. | |

| Lady Handy | Mrs. Dibdin. | |

| Susan Ashfield | Miss Murray. | |

| Dame Ashfield | Mrs. Davenport. |

In the fore ground a Farm House.—A view of a Castle at a distance.

Farmer Ashfield discovered at a table, with his jug and pipe.

Enter Dame Ashfield, in a riding dress, and a basket under her arm.

Ash. Well, Dame, welcome whoam. What news does thee bring vrom market?

Dame. What news, husband? What I always told you; that Farmer Grundy's wheat brought five shillings a quarter more than ours did.

Ash. All the better vor he.

Dame. Ah! the sun seems to shine on purpose for him.

Ash. Come, come, missus, as thee hast not the grace to thank God for prosperous times, dan't thee grumble when they be unkindly a bit.

Dame. And I assure you, Dame Grundy's butter was quite the crack of the market.

Ash. Be quiet, woolye? aleways ding, dinging Dame Grundy into my ears—what will Mrs. Grundy zay? What will Mrs. Grundy think—Canst thee be quiet, let ur alone, and behave thyzel pratty?

Dame.—Certainly I can—I'll tell thee, Tummas, what she said at church last Sunday.

Ash. Canst thee tell what parson zaid? Noa—Then I'll tell thee—A' zaid that envy were as foul a weed as grows, and cankers all wholesome plants that be near it—that's what a' zaid.

Dame. And do you think I envy Mrs. Grundy indeed?

Ash. Why dant thee letten her aloane then—I do verily think when thee goest to t'other world, the vurst question thee ax 'il be, if Mrs. Grundy's there—Zoa be quiet, and behave pratty, do'ye—Has thee brought whoam the Salisbury news?

Dame. No, Tummas: but I have brought a rare wadget of news with me. First and foremost I saw such a mort of coaches, servants, and waggons, all belonging to Sir Abel Handy, and all coming to the castle—and a handsome young man, dressed all in lace, pulled off his hat to me, and said—"Mrs. Ashfield, do me the honour of presenting that letter to your husband."—So there he stood without his hat—Oh, Tummas, had you seen how Mrs. Grundy looked!

Ash. Dom Mrs. Grundy—be quiet, and let I read, woolye? [Reads.] "My dear farmer" [Taking off his hat.] Thankye zur—zame to you, wi' all my heart and soul—"My dear farmer"—

Dame. Farmer—Why, you are blind, Tummas, it is—"My dear father"—Tis from our own dear Susan.

Ash. Odds dickens and daizeys! zoo it be, zure enow!—"My dear feyther, you will be surprized"—Zoo I be, he, he! What pretty writing, bean't it? all as straight as thof it were ploughed—"Surprized to hear, that in a few hours I shall embrace you—Nelly, who was formerly our servant, has fortunately married Sir Abel Handy Bart."—

Dame. Handy Bart.—Pugh! Bart. stands for Baronight, mun.

Ash. Likely, likely,—Drabbit it, only to think of the zwaps and changes of this world!

Dame. Our Nelly married to a great Baronet! I wonder, Tummas, what Mrs. Grundy will say?

Ash. Now, woolye be quiet, and let I read—"And she has proposed bringing me to see you; an offer, I hope, as acceptable to my dear feyther"—

Dame. "And mother"—

Ash. Bless her, how prettily she do write feyther, dan't she?

Dame. And mother.

Ash. Ees, but feyther first, though——"As acceptable to my dear feyther and mother, as to their affectionate daughter—Susan Ashfield."—Now bean't that a pratty letter?

Dame. And, Tummas, is not she a pretty girl?

Ash. Ees; and as good as she be pratty—Drabbit it, I do feel zoo happy, and zoo warm,—for all the world like the zun in harvest.

Dame. Oh, Tummas, I shall be so pleased to see her, I shan't know whether I stand on my head or my heels.

Ash. Stand on thy head! vor sheame o' thyzel—behave pratty, do.

Dame. Nay, I meant no harm—Eh, here comes friend Evergreen the gardener, from the castle. Bless me, what a hurry the old man is in.

Enter Evergreen.

Everg. Good day, honest Thomas.

Ash. Zame to you, measter Evergreen.

Everg. Have you heard the news?

Dame. Any thing about Mrs. Grundy?

Ash. Dame, be quiet, woolye now?

Everg. No, no—The news is, that my master, Sir Philip Blandford, after having been abroad for twenty years, returns this day to the castle; and that the reason of his coming is, to marry his only daughter to the son of Sir Abel Handy, I think they call him.

Dame. As sure as two-pence, that is Nelly's husband.

Everg. Indeed!—Well, Sir Abel and his son will be here immediately; and, Farmer, you must attend them.

Ash. Likely, likely.

Everg. And, mistress, come and lend us a hand at the castle, will you?—Ah, it is twenty long years since I have seen Sir Philip—Poor gentleman! bad, bad health—worn almost to the grave, I am told.—-What a lad do I remember him—till that dreadful—[Checking himself.] But where is Henry? I must see him—must caution him—[A gun is discharged at a distance.] That's his gun, I suppose—he is not far then—Poor Henry!

Dame. Poor Henry! I like that indeed! What though he be nobody knows who, there is not a girl in the parish that is not ready to pull caps for him—The Miss Grundys, genteel as they think themselves, would be glad to snap at him—If he were our own, we could not love him better.

Everg. And he deserves to be loved—Why, he's as handsome as a peach tree in blossom; and his mind is as free from weeds as my favourite carnation bed. But, Thomas, run to the castle, and receive Sir Abel and his son.

Ash. I wool, I wool—Zo, good day. [Bowing.] Let every man make his bow, and behave pratty—that's what I say.—Missus, do'ye show un Sue's letter, woolye? Do ye letten see how pratty she do write feyther.

[Exit.

Dame. Now Tummas is gone, I'll tell you such a story about Mrs. Grundy—But come, step in, you must needs be weary; and I am sure a mug of harvest beer, sweetened with a hearty welcome, will refresh you.

[Exeunt into the house.

Outside and gate of the Castle—Servants cross the stage, laden with different packages.

Enter Ashfield.

Ash. Drabbit it, the wold castle 'ul be hardly big enow to hold all thic lumber.

Sir Abel Handy. [Without.] Gently there! mind how you go, Robin.

[A crash.

Ash. Who do come here? A do zeem a comical zoart ov a man—Oh, Abel Handy, I suppoze.

Enter Sir Abel Handy.—Servant following.

Sir Abel. Zounds and fury! you have killed the whole county, you dog! for you have broke the patent medicine chest, that was to keep them all alive!—Richard, gently!—take care of the grand Archimedian corkscrews!—Bless my soul! so much to think of! Such wonderful inventions in conception, in concoction, and in completion!

Enter Peter.

Well, Peter, is the carriage much broke?

Peter. Smashed all to pieces. I thought as how, sir, that your infallible axletree would give way.

Sir Abel. Confound it, it has compelled me to walk so far in the wet, that I declare my water-proof shoes are completely soaked through. [Exit Peter.] Now to take a view with my new invented glass!

[Pulls out his glass.

Ash. [Loud and bluntly.] Zarvent, zur! Zarvent!

Sir Abel. [Starting.] What's that? Oh, good day.—Devil take the fellow?

[Aside.

Ash. Thankye, zur; zame to you with all my heart and zoul.

Sir Abel. Pray, friend, could you contrive gently to inform me, where I can find one Farmer Ashfield.

Ash. Ha, ha, ha! [Laughing loudly.] Excuse my tittering a bit—but your axing mysel vor I be so domm'd zilly [Bowing and laughing.]—Ah! you stare at I beceas I be bashful and daunted.

Sir Abel. You are very bashful, to be sure. I declare I'm quite weary.

Ash. If you'll walk into the castle, you may zit down, I dare zay.

Sir Abel. May I indeed? you are a fellow of extraordinary civility.

Ash. There's no denying it, zur.

Sir Abel. No, I'll sit here.

Ash. What! on the ground! Why you'll wring your ould withers—

Sir Abel. On the ground—no, I always carry my seat with me [Spreads a small camp chair.]—Here I'll sit and examine the surveyor's account of the castle.

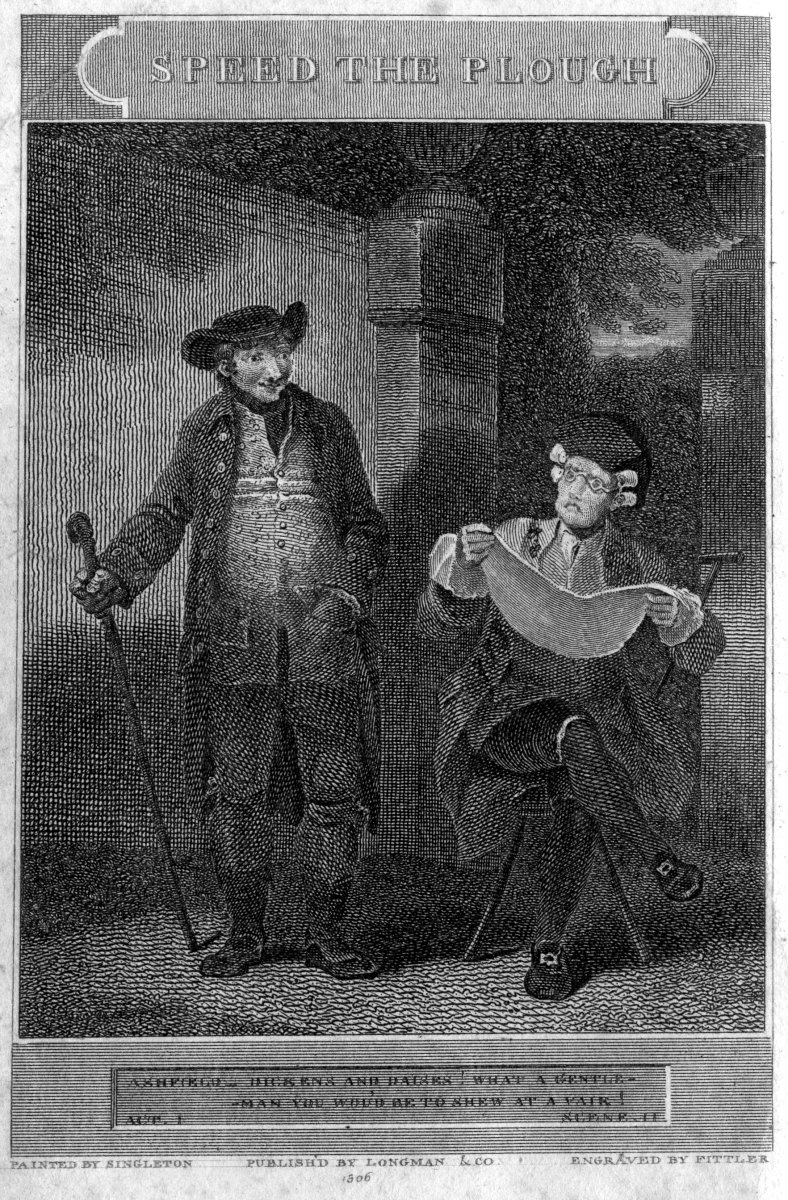

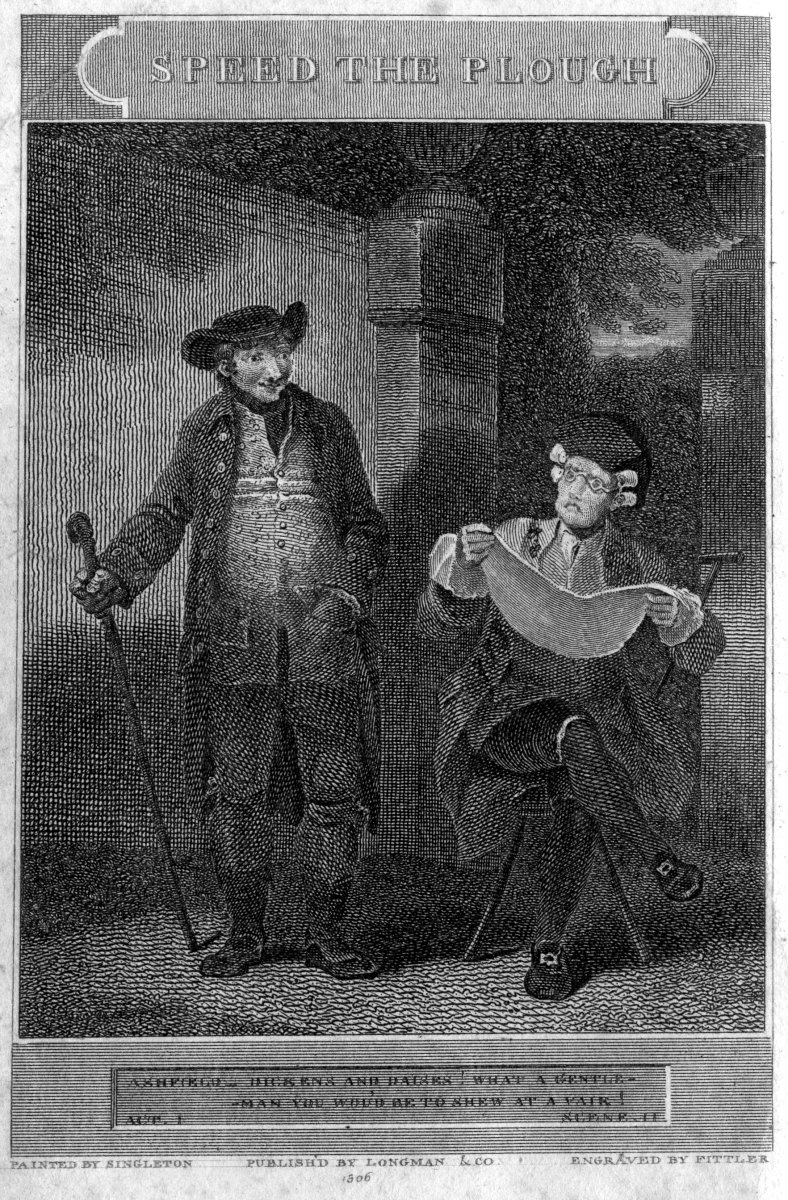

Ash. Dickens and daizeys! what a gentleman you wou'd be to shew at a vair!

Sir Abel. Silence fellow, and attend—"An account of the castle and domain of Sir Philip Blandford, intended to be settled as a marriage portion on his daughter, and the son of Sir Abel Handy,—by Frank Flourish, surveyor.—Imprimis—The premises command an exquisite view of the Isle of Wight."—Charming! delightful! I don't see it though [Rising.]—I'll try with my new glass—my own invention—[He looks through the glass.] Yes, there I caught it—Ah! now I see it plainly—Eh! no—I don't see it, do you?

Ash. Noa, zur, I doant—but little zweepy do tell I he can zee a bit out from the top of the chimbley—zoa, an you've a mind to crawl up you may zee un too, he, he!

Sir Abel. Thank you—but damn your titter. [Reads.]—"Fish ponds well stocked"—That's a good thing, Farmer.

Ash. Likely, likely—but I doant think the vishes do thrive much in theas ponds.

Sir Abel. No! why?

Ash. Why, the ponds be always dry i'the zummer; and I be tould that bean't wholesome vor the little vishes.

Sir Abel. Not very, I believe—Well said surveyor! "A cool summer house."

Ash. Ees, zur, quite cool—by reason the roof be tumbled in.

Sir Abel. Better and better—"the whole capable of the greatest improvement."—Come, that seems true however—I shall have plenty to do, that's one comfort—I have such contrivances! I'll have a canal run through my kitchen.—I must give this rustic some idea of my consequence. [Aside.] You must know, Farmer, you have the honour of conversing with a man, who has obtained patents for tweezers, tooth-picks, and tinder boxes—to a philosopher, who has been consulted on the Wapping docks and the Gravesend tunnel; and who has now in hand two inventions which will render him immortal—the one is, converting saw dust into deal boards, and the other is, a plan of cleaning rooms by a steam engine—and, Farmer, I mean to give prizes for industry—I'll have a ploughing match.

Ash. Will you, zur?

Sir Abel. Yes; for I consider a healthy young man, between the handles of a plough, as one of the noblest illustrations of the prosperity of Britain.

Ash. Faith and troth! there be some tightish hands in theas parts, I promize ye.

Sir Abel. And, Farmer, it shall precede the hymeneal festivities—

Ash. Nan!

Sir Abel. Blockhead! The ploughing match shall take place as soon as Sir Philip Blandford and his daughter arrive.

Ash. Oh, likely, likely.

Enter Servant.

Serv. Sir Abel, I beg to say, my master will be here immediately.

Sir Abel. And, sir, I beg to ask who possesses the happiness of being your master?

Serv. Your son, sir, Mr. Robert Handy.

Sir Abel. Indeed! and where is Bob?

Serv. I left him, sir, in the belfrey of the church.

Sir Abel. Where?

Serv. In the belfrey of the church.

Sir Abel. In the belfrey of the church! What was he doing there?

Serv. Why, Sir, the natives were ringing a peal in honour of our arrival—when my master finding they knew nothing of the matter, went up to the steeple to instruct them, and ordered me to proceed to the Castle—Give me leave, Sir Abel, to take this out of your way. [Takes the camp chair.] Sir, I have the honour—

[Bows and Exit.

Sir Abel. Wonderful! My Bob, you must know, is an astonishing fellow!—you have heard of the admirable Crichton, may be? Bob's of the same kidney! I contrive, he executes—Sir Abel invenit, Bob fecit. He can do everything—everything!

Ash. All the better vor he. I zay, zur, as he can turn his head to everything, pray, in what way med he earn his livelihood?

Sir Abel. Earn his livelihood!

Ash. Ees, zur;—How do he gain his bread!

Sir Abel. Bread! Oh, he can't earn his bread, bless you! he's a genius.

Ash. Genius! Drabbit it, I have got a horze o' thic name, but dom' un, he'll never work—never.

Sir Abel. Egad; here comes my boy Bob!—Eh! no—it is not! no.

Enter POSTBOY, with a round hat and cane.

Why, who the devil are you?

Postb. I am the postboy, your honour, but the gem'man said I did not know how to drive, so he mounted my horse, and made me get inside—Here he is.

Enter Handy, jun. with a postboy's cap and whip.

Handy, jun. Ah, my old Dad, is that you?

Sir Abel. Certainly! the only doubt is, if that be you?

Handy, jun. Oh, I was teaching this fellow to drive—Nothing is so horrible as people pretending to do what they are unequal to—Give me my hat—That's the way to use a whip.

Postb. Sir, you know you have broke the horses' knees all to pieces.

Handy, jun. Hush, there's a guinea.

[Apart.

Sir Abel. [To Ashfield.] You see, Bob can do everything. But, sir, when you knew I had arrived from Germany, why did you not pay your duty to me in London?

Handy, jun. Sir, I heard you were but four days married, and I would not interrupt your honeymoon.

Sir Abel. Four days! oh, you might have come.

[Sighing.

Handy, jun. I hear you have taken to your arms a simple rustic, unsophisticated by fashionable follies—a full blown blossom of nature.

Sir Abel. Yes!

Handy, jun. How does it answer?

Sir Abel. So, so!

Handy, jun. Any thorns?

Sir Abel. A few.

Handy, jun. I must be introduced—where is she?

Sir Abel. Not within thirty miles; for I don't hear her.

Ash. Ha, ha, ha!

Handy, jun. Who is that?

Sir Abel. Oh, a pretty behaved tittering friend of mine.

Ash. Zarvent, zur—No offence, I do hope—Could not help tittering a bit at Nelly—when she were zarvent maid wi' I, she had a tightish prattle wi' her, that's vor zartain.

Handy, jun. Oh! so then my honoured mamma was the servant of this tittering gentleman—I say, father, perhaps she has not lost the tightish prattle he speaks of.

Sir Abel. My dear boy, come here—Prattle! I say did you ever live next door to a pewterer's?—that's all—you understand me—did you ever hear a dozen fire-engines full gallop?—were you ever at Billingsgate in the sprat season?—or——

Handy, jun. Ha, ha!

Sir Abel. Nay, don't laugh, Bob.

Handy, jun. Indeed, sir, you think of it too seriously. The storm, I dare say, soon blows over.

Sir Abel. Soon! you know what a trade wind is, don't you, Bob? why, she thinks no more of the latter end of her speech, than she does of the latter end of her life—

Handy, jun. Ha! ha!

Sir Abel. But I won't be laugh'd at—I'll knock any man down that laughs! Bob, if you can say any thing pleasant, I'll trouble you; if not, do what my wife can't—hold your tongue.

Handy, jun. I'll shew you what I can do—I'll amuse you with this native.

[Apart.

Sir Abel. Do—do—quiz him—at him, Bob.

Handy, jun. I say, Farmer, you are a set of jolly fellows here, an't you?

Ash. Ees, zur, deadly jolly—excepting when we be otherwise, and then we bean't.

Handy, jun. Play at cricket, don't you?

Ash. Ees, zur; we Hampshire lads conceat we can bowl a bit or thereabouts.

Handy, jun. And cudgel too, I suppose?

Sir Abel. At him, Bob.

Ash. Ees, zur, we sometimes break oon another's heads, by way of being agreeable, and the like o'that.

Handy, jun. Understand all the guards? [Putting himself in an attitude of cudgelling.]

Ash. Can't zay I do, zur.

Handy, jun. What! hit in this way, eh? [Makes a hit at Ashfield, which he parries, and hits young Handy violently.]

Ash. Noa, zur, we do hit thic way.

Handy, jun. Zounds and fury!

Sir Abel. Why, Bob, he has broke your head.

Handy, jun. Yes; he rather hit me—he somehow——

Sir Abel. He did indeed, Bob.

Handy, jun. Damn him—The fact is, I am out of practice.

Ash. You need not be, zur; I'll gi' ye a belly full any day, wi' all my heart and soul.

Handy, jun. No, no, thank you—Farmer, what's your name?

Ash. My name be Tummas Ashfield—any thing to say against my name?

[Threatening.

Handy, jun. No, no—Ashfield! shou'd he be the father of my pretty Susan—Pray have you a daughter?

Ash. Ees, I have—any thing to zay against she?

Handy, jun. No, no; I think her a charming creature.

Ash. Do ye, faith and troth—Come, that be deadly kind o'ye however—Do you zee, I were frightful she were not agreeable.

Handy, jun. Oh, she's extremely agreeable to me, I assure you.

Ash. I vow, it be quite pratty in you to take notice of Sue. I do hope, zur, breaking your head will break noa squares—She be a coming down to theas parts wi' lady our maid Nelly, as wur—your spouse, zur.

Handy, jun. The devil she is! that's awkward!

Ash. I do hope you'll be kind to Sue when she do come, woolye, zur?

Handy, jun. You may depend on it.

Sir Abel. I dare say you may. Come, Farmer, attend us.

Ash. Ees, zur; wi' all respect—Gentlemen, pray walk thic way, and I'll walk before you.

[Exit.

Sir Abel. Now, that's what he calls behaving pretty. Damn his pretty behaviour.

[Exeunt.

A Grove.

[Morrington comes down the stage, wrapped in a great coat—He looks about—then at his watch, and whistles—which is answered.]

Enter Gerald.

Mor. Here, Gerald! Well, my trusty fellow, is Sir Philip arrived?

Ger. No, sir; but hourly expected.

Mor. Tell me, how does the castle look?

Ger. Sadly decayed, sir.

Mor. I hope, Gerald, you were not observed.

Ger. I fear otherwise, sir; on the skirts of the domain I encountered a stripling with his gun; but I darted into that thicket, and so avoided him.

[Henry appears in the back ground, in a shooting dress, attentively observing them.]

Mor. Have you gained any intelligence?

Ger. None: the report that reached us was false—The infant certainly died with its mother—Hush! conceal yourself—we are observed—this way.

[They retreat—Henry advances.

Henry. Hold! as a friend, one word!

[They exeunt, he follows them, and returns.

Again they have escaped me—"The infant died with its mother"—This agony of doubt is insupportable.

Enter Evergreen.

Everg. Henry, well met.

Henry. Have you seen strangers?

Everg. No!

Henry. Two but now have left this place—They spoke of a lost child—My busy fancy led me to think I was the object of their search—I pressed forward, but they avoided me.

Everg. No, no; it could not be you; for no one on earth knows but myself, and——

Henry. Who? Sir Philip Blandford?

Everg. I am sworn, you know, my dear boy; I am solemnly sworn to silence.

Henry. True, my good old friend; and if the knowledge of who I am can only be obtained at the price of thy perjury, let me for ever remain ignorant—let the corroding thought still haunt my pillow, cross me at every turn, and render me insensible to the blessings of health and liberty—yet, in vain do I suppress the thought—who am I? why thus abandoned? perhaps the despised offspring of guilt—Ah! is it so?

[Seizing him violently.

Everg. Henry, do I deserve this?

Henry. Pardon me, good old man! I'll act more reasonably—I'll deem thy silence mercy.

Everg. That's wisely said.

Henry. Yet it is hard to think, that the most detested reptile that nature forms, or man pursues, has, when he gains his den, a parent's pitying breast to shelter in; but I——

Everg. Come, come, no more of this.

Henry. Well!—--I visited to-day that young man who was so grievously bruised by the breaking of his team.

Everg. That was kindly done, Henry.

Henry. I found him suffering under extreme torture, yet a ray of joy shot from his languid eye—for his medicine was administered by a father's hand—it was a mother's precious tear that dropped upon his wound—Oh, how I envied him!

Everg. Still on the same subject—I tell thee, if thou art not acknowledged by thy race, why, then become the noble founder of a new one.—Come with me to the castle, for the last time.

Henry. The last time!

Everg. Aye, boy; for, when Sir Philip arrives, you must avoid him.

Henry. Not see him! where exists the power that shall prevent me?

Everg. Henry, if you value your own peace of mind—if you value an old man's comfort, avoid the castle.

Henry. [Aside.] I must dissemble with this honest creature—Well, I am content.

Everg. That's right—that's right,—Henry—Be but thou resigned and virtuous, and He, who clothes the lily of the field, will be a parent to thee.

[Exeunt.

A Lodge belonging to the Castle.

Dame Ashfield discovered making lace.

Enter Handy, jun.

Handy, jun. A singular situation this my old dad has placed me in; brought me here to marry a woman of fashion and beauty, while I have been professing, and I've a notion feeling, the most ardent love for the pretty Susan Ashfield—Propriety says, take Miss Blandford—Love says, take Susan—Fashion says, take both—but would Susan consent to such an arrangement?—and if she refused, would I consent to part with her?—Oh, time enough to put that question, when the previous one is disposed of—[Seeing Dame.] How do you do? How do you do?—Making lace, I perceive—Is it a common employment, here?

Dame. Oh, no, sir? nobody can make it in these parts but myself!—Mrs. Grundy, indeed, pretends—but, poor woman! she knows no more of it than you do.

Handy, jun. Than I do! that's vastly well;—My dear madam, I passed two months at Mechlin for the express purpose.

Dame. Indeed!

Handy, jun. You don't do it right—now I can do it much better than that. Give me leave, and I'll shew you the true Mechlin method [Turns the cushion round, kneels down, and begins working.] First you see, so—then, so—

Enter Sir Abel, and Miss Blandford.

Sir Abel. I vow, Miss Blandford, fair as I ever thought you, the air of your native land has given additional lustre to your charms!—[Aside.] If my wife looked so—Ah! but where can Bob be?—You must know, miss, my son is a very clever fellow! you won't find him wasting his time in boyish frivolity!—no; you will find him—

[Sees him.

Miss B. Is that your son, sir?

Sir Abel. [Abashed.] Yes, that's Bob!

Miss B. Pray, sir, is he making lace, or is he making love?

Sir Abel. Curse me if I can tell. [Hits him with his stick.] Get up, you dog! don't you see Miss Blandford?

Handy, jun. [Starting up.] Zounds! how unlucky! Ma'am, your most obedient servant. [Endeavours to hide the work.] Curse the cushion!

[Throws it off.

Dame. Oh! he has spoiled my lace!

Handy, jun. Hush! I'll make you a thousand yards another time—You see, ma'am, I was explaining to this good woman—what—what need not be explained again—Admirably handsome, by Heaven!

[Aside.

Sir Abel. Is not she, Bob?

Handy, jun. [To Miss B.] In your journey from the coast, I conclude you took London in your way? Hush!

[To Dame.

Miss B. Oh no, sir, I could not so soon venture into the beau monde; a stranger just arrived from Germany—

Handy, jun. The very reason—the most fashionable introduction possible! but I perceive, sir, you have here imitated other German importations, and only restored to us our native excellence.

Miss B. I assure you, sir, I am eager to seize my birthright, the pure and envied immunities of an English woman!

Handy, jun. Then I trust, madam, you will be patriot enough to agree with me, that as a nation is poor, whose only wealth is importation—that therefore the humble native artist may ever hope to obtain from his countrymen those fostering smiles, without which genius must sicken and industry decay. But it requires no valet de place to conduct you through the purlieus of fashion, for now the way of the world is, for every one to pursue their own way; and following the fashion is differing as much as possible from the rest of your acquaintance.

Miss B. But, surely sir, there is some distinguishing feature, by which the votaries of fashion are known?

Handy, jun. Yes; but that varies extremely—sometimes fashionable celebrity depends on a high waist—sometimes on a low carriage—sometimes on high play, and sometimes on low breeding—last winter it rested solely on green peas!

Miss B. Green peas!

Handy, jun. Green peas—That lady was the most enchanting, who could bring the greatest quantity of green peas to her table at Christmas! the struggle was tremendous! Mrs. Rowley Powley had the best of it by five pecks and a half, but it having been unfortunately proved, that at her ball there was room to dance and eat conveniently—that no lady received a black eye, and no coachman was killed, the thing was voted decent and comfortable, and scouted accordingly.

Miss B. Is comfort then incompatible with fashion?

Handy, jun. Certainly!—Comfort in high life would be as preposterous as a lawyer's bag crammed with truth, or his wig decorated with coquelicot ribbons! No—it is not comfort and selection that is sought, but numbers and confusion! So that a fashionable party resembles Smithfield market,—only a good one when plentifully stocked—and ladies are reckoned by the score, like sheep, and their husbands by droves, like horned cattle!

Miss B. Ha, ha! and the conversation—

Handy, jun. Oh! like the assembly—confused, vapid, and abundant; as "How do, ma'am!—no accident at the door?—he, he!"—"Only my carriage broke to pieces!"—"I hope you had not your pocket picked!"—"Won't you sit down to faro?"—"Have you many to-night?"—"A few, about six hundred!"—"Were you at Lady Overall's?"—"Oh yes; a delicious crowd, and plenty of peas, he, he!"—and thus runs the fashionable race.

Sir Abel. Yes; and a precious run it is—full gallop all the way: first they run on—then their fortune is run through—then bills are run up—then they are run hard—then they've a run of luck—then they run out, and then they run away!—But I'll forgive fashion all its follies in consideration of one of its blessed laws.

Handy, jun. What may that be!

Sir Abel. That husband and wife must never be seen together.

Enter Servant.

Serv. Miss Blandford, your father expects you.

Miss B. I hope I shall find him more composed.

Handy, jun. Is Sir Philip ill?

Miss B. His spirits are extremely depressed, and since we arrived here this morning his dejection has dreadfully increased.

Handy, jun. But I hope we shall be able to laugh away despondency.

Miss B. Sir, if you are pleased to consider my esteem as an object worth your possession, I know no way of obtaining it so certain as by your shewing every attention to my dear father.

[As they are going,

Enter Ashfield.

Ash. Dame! Dame! she be come!

Dame. Who? Susan! our dear Susan?

Ash. Ees—zo—come along—Oh, Sir Abel! Lady Nelly, your spouse, do order you to go to her directly!

Handy, jun. Order! you mistake—

Sir Abel. No, he don't—she generally prefers that word.

Miss B. Adieu! Sir Abel.

[Exeunt Miss Blandford and Handy, jun.

Sir Abel. Oh! if my wife had such a pretty way with her mouth.

Dame. And how does Susan look?

Ash. That's what I do want to know, zoa come along—Woo ye though—Missus, let's behave pratty—Zur if you pleaze, Dame and I will let you walk along wi' us.

Sir Abel. How condescending! Oh, you are a pretty behaved fellow!

[Exeunt.

Farmer Ashfield's Kitchen.

Enter Lady Handy and Susan.

Susan. My dear home, thrice welcome!—What gratitude I feel to your ladyship for this indulgence!

Lady H. That's right, child!

Susan. And I am sure you partake my pleasure in again visiting a place, where you received every protection and kindness my parents could shew you, for, I remember, while you lived with my father—

Lady H. Child! don't put your memory to any fatigue on my account—you may transfer the remembrance of who I was, to aid your more perfect recollection of who I am.

Susan. Lady Handy!

Lady H. That's right, child!—I am not angry.

Susan. [Looking out.] Ah! I see my dear father and mother coming through the garden.

Lady H. Oh! now I shall be caressed to death; but I must endure the shock of their attentions.

Enter Farmer and Dame, with Sir Abel.

Ash. My dear Susan!

[They run to Susan.

Dame. My sweet child! give me a kiss.

Ash. Hald thee! Feyther first though—Well, I be as mortal glad to zee thee as never war—and how be'st thee? and how do thee like Lunnun town? it be a deadly lively place I be tuold.

Dame. Is not she a sweet girl?

Sir Abel. That she is.

Lady H. [With affected dignity.] Does it occur to any one present, that Lady Handy is in the room?

Sir Abel. Oh, Lud! I'm sure, my dear wife, I never forget, that you are in the room.

Ash. Drabbitit! I overlooked Lady Nelly, sure enow; but consider, there be zome difference between thee and our own Susan! I be deadly glad to zee thee, however.

Dame. So am I, Lady Handy.

Ash. Don't ye take it unkind I han't a buss'd thee yet—meant no slight indeed.

[Kisses her.

Lady H. Oh! shocking!

[Aside.

Ash. No harm I do hope, zur.

Sir Abel. None at all.

Ash. But dash it, Lady Nelly, what do make thee paint thy vace all over we rud ochre zoo? Be it vor thy spouse to knaw thee?—that be the way I do knaw my sheep.

Sir Abel. The flocks of fashion are all marked so, Farmer.

Ash. Likely! Drabbit it! thee do make a tightish kind of a ladyship zure enow.

Dame. That you do, my lady! you remember the old house?

Ash. Aye; and all about it, doant ye? Nelly! my lady!

Lady H. Oh! I'm quite shock'd—Susan, child! prepare a room where I may dress before I proceed to the castle.

[Exit Susan.

Enter Handy, jun.

Handy, jun. I don't see Susan—I say, Dad, is that my mamma?

Sir Abel. Yes—speak to her.

Handy, jun. [Chucking her under the chin] A fine girl, upon my soul!

Lady H. Fine girl, indeed! Is this behaviour!

Handy, jun. Oh! beg pardon, most honoured parent. [She curtsies.]—-that's a damned bad curtsey, I can teach you to make a much better curtsey than that!

Lady H. You teach me, that am old enough to—hem!

Handy, jun. Oh! that toss of the head was very bad indeed—Look at me!—That's the thing!

Lady H. Am I to be insulted? Sir Abel, you know I seldom condescend to talk.

Sir Abel. Don't say so, my lady, you wrong yourself.

Lady H. But, when I do begin, you know not where it will end.

Sir Abel. Indeed I do not.

[Aside.

Lady H. I insist on receiving all possible respect from your son.

Handy, jun. And you shall have it, my dear girl!—Madam, I mean.

Lady H. I vow, I am agitated to that degree—Sir Abel! my fan.

Sir Abel. Yes, my dear—Bob, look here, a little contrivance of my own. While others carry swords and such like dreadful weapons in their canes, I more gallantly carry a fan. [Removes the head of his cane, and draws out a fan.] A pretty thought, isn't it? [Presents it to his lady.]

Ash. Some difference between thic stick and mine, beant there, zur?

[To Handy, jun.

Handy, jun. [Moving away.] Yes, there is.—[To Lady H.] Do you call that fanning yourself? [Taking the fan.] My dear ma'am, this is the way to manœuvre a fan.

Lady H. Sir, you shall find [To Handy, jun.] I have power enough to make you repent this behaviour, severely repent it—Susan!

[Exit followed by Dame.

Handy, jun. Bravo! passion becomes her; she does that vastly well.

Sir Abel. Yes, practice makes perfect.

Enter Susan.

Susan. Did your ladyship call?—Heavens! Mr. Handy!

Handy, jun. Hush! my angel! be composed! that letter will explain. [Giving a letter, noticed by Ashfield.] Lady Handy wishes to see you.

Susan. Oh, Robert!

Handy, jun. At present, my love, no more.

[Exit Susan, followed by Ashfield.

Sir Abel. What were you saying, sir, to that young woman?

Handy, jun. Nothing particular, sir. Where is Lady Handy going?

Sir Abel. To dress.

Handy, jun. I suppose she has found out the use of money.

Sir Abel. Yes; I'll do her the justice to say she encourages trade.—Why, do you know, Bob, my best coal pit won't find her in white muslins—round her neck hangs an hundred acres at least; my noblest oaks have made wigs for her; my fat oxen have dwindled into Dutch pugs, and white mice; my India bonds are transmuted into shawls and otto of roses; and a magnificent mansion has shrunk into a diamond snuff-box.

Enter Countryman.

Coun. Gentlemen, the folks be all got together, and the ploughs be ready—and——

Sir Abel. We are coming.

[Exit Servant.

Handy, jun. Ploughs?

Sir Abel. Yes, Bob, we are going to have a grand agricultural meeting.

Handy, jun. Indeed!

Sir Abel. If I could but find a man able to manage my new-invented curricle plough, none of them would have a chance.

Handy, jun. My dear sir, if there be any thing on earth I can do, it is that.

Sir Abel. What!

Handy. I rather fancy I can plough better than any man in England.

Sir Abel. You don't say so! What a clever fellow he is! I say, Bob, if you would—

Handy, jun. No! I can't condescend.

Sir Abel. Condescend! why not?—much more creditable, let me tell you, than gallopping a maggot for a thousand, or eating a live cat, or any other fashionable achievement.

Handy, jun. So it is—Egad! I will—I'll carry off the prize of industry.

Sir Abel. But should you lose, Bob.

Handy, jun. I lose! that's vastly well!

Sir Abel. True, with my curricle plough you could hardly fail.

Handy, jun. With my superior skill, Dad—Then, I say, how the newspapers will teem with the account.

Sir Abel. Yes.

Handy, jun. That universal genius, Handy, junior, with a plough——

Sir Abel. Stop—invented by that ingenious machinist, Handy, senior.

Handy, jun. Gained the prize against the first husbandmen in Hampshire—Let our Bond-street butterflies emulate the example of Handy, junior.—

Sir Abel. And let old city grubs cultivate the field of science, like Handy, senior—Ecod! I am so happy!

Lady H. [Without.] Sir Abel!

Sir Abel. Ah! there comes a damper.

Handy, jun. Courage! you have many resources of happiness.

Sir Abel. Have I? I should be very glad to know them.

Handy, jun. In the first place you possess an excellent temper.

Sir Abel. So much the worse; for if I had a bad one, I should be the better able to conquer hers.

Handy, jun. You enjoy good health—

Sir Abel. So much the worse; for if I were ill, she wouldn't come near me.

Handy, jun. Then you are rich—

Sir Abel. So much the worse; for had I been poor, she would not have married me. But I, say, Bob, if you gain the prize, I'll have a patent for my plough.

Lady H. [Without.] Sir Abel! I say—

Handy, jun. Father, could not you get a patent for stopping that sort of noise?

Sir Abel. If I could, what a sale it would have!—No, Bob, a patent has been obtained for the only thing that will silence her—

Handy, jun. Aye—What's that?

Sir Abel. [In a whisper.] A coffin! hush!—I'm coming, my dear.

Handy, jun. Ha, ha, ha!

[Exeunt.

A Parlour in Ashfield's House.

Enter Ashfield and Wife.

Ash. I tell ye, I zee'd un gi' Susan a letter, an I dan't like it a bit.

Dame. Nor I: if shame should come to the poor child—I say, Tummas, what would Mrs. Grundy say then?

Ash. Dom Mrs. Grundy; what would my poor wold heart zay? but I be bound it be all innocence.

Enter Henry.

Dame. Ah, Henry! we have not seen thee at home all day.

Ash. And I do zomehow fanzie things dan't go zo clever when thee'rt away from farm.

Henry. My mind has been greatly agitated.

Ash. Well, won't thee go and zee the ploughing match?

Henry. Tell me, will not those who obtain prizes be introduced to the Castle?

Ash. Ees, and feasted in the great hall.

Henry. My good friend, I wish to become a candidate.

Dame. You, Henry!

Henry. It is time I exerted the faculties Heaven has bestowed on me; and though my heavy fate crushes the proud hopes this heart conceives, still let me prove myself worthy of the place Providence has assigned me.—[Aside.] Should I succeed, it will bring me to the presence of that man, who (I know not why) seems the dictator of my fate.—[To them.] Will you furnish me with the means?

Ash. Will I!—Thou shalt ha' the best plough in the parish—I wish it were all gould for thy zake—and better cattle there can't be noowhere.

Henry. Thanks, my good friend—my benefactor—I have little time for preparation—So receive my gratitude, and farewell.

[Exit.

Dame. A blessing go with thee!

Ash. I zay, Henry, take Jolly, and Smiler, and Captain, but dan't ye take thic lazy beast Genius—I'll be shot if having vive load an acre on my wheat land could please me more.

Dame. Tummas, here comes Susan reading the letter.

Ash. How pale she do look! dan't she?

Dame. Ah! poor thing!—If——

Ash. Hauld thy tongue, woolye?

[They retire.

Enter Susan, reading the letter.

Susan. Is it possible! Can the man to whom I've given my heart write thus!—"I am compelled to marry Miss Blandford; but my love for my Susan is unalterable—I hope she will not, for an act of necessity, cease to think with tenderness on her faithful Robert."——Oh man! ungrateful man! it is from our bosoms alone you derive your power; how cruel then to use it, in fixing in those bosoms endless sorrow and despair!—--"Still think with tenderness"—Base, dishonourable insinuation—He might have allowed me to esteem him. [Locks up the letter in a box on the table, and exit weeping.]

[Ashfield and Dame come forward.]

Ash. Poor thing!—What can be the matter—She locked up the letter in thic box, and then burst into tears.

[Looks at the box.

Dame. Yes, Tummas; she locked it in that box sure enough.

[Shakes a bunch of keys that hangs at her side.

Ash. What be doing, Dame? what be doing?

Dame. [With affected indifference.] Nothing; I was only touching these keys.

[They look at the box and keys significantly.

Ash. A good tightish bunch!

Dame. Yes; they are of all sizes.

[They look as before.

Ash. Indeed!—Well—Eh!—Dame, why dan't ye speak? thou canst chatter fast enow zometimes.

Dame. Nay, Tummas—I dare say—if—you know best—but I think I could find——

Ash. Well, Eh!—you can just try you knaw [Greatly agitated.] You can try, just vor the vun on't: but mind, dan't ye make a noise. [She opens it.] Why, thee hasn't opened it?

Dame. Nay, Tummas! you told me!

Ash. Did I?

Dame. There's the letter!

Ash. Well, why do ye gi't to I?—I dan't want it, I'm sure. [Taking it—he turns it over—she eyes it eagerly—he is about to open it.]—She's coming! she's coming! [He conceals the letter, they tremble violently.] No, she's gone into t'other room. [They hang their heads dejectedly, then look at each other.] What mun that feyther an mother be doing, that do blush and tremble at their own dater's coming. [Weeps.] Dang it, has she desarv'd it of us—Did she ever deceive us?—Were she not always the most open hearted, dutifullest, kindest—and thee to goa like a dom'd spy, and open her box, poor thing!

Dame. Nay, Tummas——

Ash. You did—I zaw you do it myzel!—you look like a thief, now—you doe—Hush!—no—Dame—here be the letter—I won't reead a word on't; put it where thee vound it, and as thee vound it.

Dame. With all my heart.

[She returns the letter to the box.

Ash. [Embraces her.] Now I can wi' pleasure hug my wold wife, and look my child in the vace again—I'll call her, and ax her about it; and if she dan't speak without disguisement, I'll be bound to be shot—Dame, be the colour of sheame off my face yet?—I never zeed thee look ugly before——Susan, my dear Sue, come here a bit, woollye?

Enter Susan.

Susan. Yes, my dear father.

Ash. Sue, we do wish to give thee a bit of admonishing and parent-like conzultation.

Susan. I hope I have ever attended to your admonitions.

Ash. Ees, bless thee, I do believe thee hast, lamb; but we all want our memories jogg'd a bit, or why else do parson preach us all to sleep every Zunday—Zo thic be the topic—Dame and I, Sue, did zee a letter gi'd to thee, and thee—bursted into tears, and lock'd un up in thic box—and then Dame and I—we—that's all.

Susan. My dear father, if I concealed the contents of that letter from your knowledge, it was because I did not wish your heart to share in the pain mine feels.

Ash. Dang it, didn't I tell thee zoo?

[To his wife.

Dame. Nay, Tummas, did I say otherwise?

Susan. Believe me, my dear parents, my heart never gave birth to a thought my tongue feared to utter.

Ash. There, the very words I zaid?

Susan. If you wish to see the letter, I will shew it to you.

[She searches for the key.

Dame. Here's a key will open it.

Ash. Drabbit it, hold thy tongue, thou wold fool? [Aside.] No, Susan. I'll not zee it—I'll believe my child.

Susan. You shall not find your confidence ill-placed—it is true the gentleman declared he loved me; it is equally true that declaration was not unpleasing to me—Alas! it is also true, that his letter contains sentiments disgraceful to himself, and insulting to me.

Ash. Drabbit it, if I'd knaw'd that, when we were cudgelling a bit, I wou'd ha' lapt my stick about his ribs pratty tightish, I wou'd.

Susan. Pray, father, don't you resent his conduct to me.

Ash. What! mayn't I lather un a bit?

Susan. Oh, no! I've the strongest reasons to the contrary!

Ash. Well, Sue, I won't—I'll behave as pratty as I always do—but it be time to go to the green, and zee the fine zights—How I do hate the noise of thic dom'd bunch of keys—But bless thee, my child—dan't forget that vartue to a young woman be vor all the world like—like—Dang it, I ha' gotten it all in my head; but zomehow—I can't talk it—but vartue be to a young woman what corn be to a blade o'wheat, do you zee; for while the corn be there it be glorious to the eye, and it be called the staff of life; but take that treasure away, and what do remain? why nought but thic worthless straw that man and beast do tread upon.

[Exeunt.

An extensive view of a cultivated country—A ploughed field in the centre, in which are seen six different ploughs and horses—At one side a handsome tent—A number of country people assembled.

Enter Ashfield and Dame.

Ash. Make way, make way for the gentry! and, do ye hear, behave pratty as I do—Dang thee, stond back, or I'll knack thee down, I wool.

Enter Sir Abel, and Miss Blandford, with Servants.

Sir Abel. It is very kind of you to honour our rustic festivities with your presence.

Miss B. Pray, Sir Abel, where is your son?

Sir Abel. What! Bob? Oh, you'll see him presently—[Nodding significantly.]—Here are the prize medals; and if you will condescend to present them, I'm sure they'll be worn with additional pleasure.—I say, you'll see Bob presently.—Well, Farmer, is it all over?

Ash. Ees, zur; the acres be plough'd and the ground judg'd; and the young lads be coming down to receive their reward—Heartily welcome, miss, to your native land; hope you be as pleased to zee we as we be to zee you, and the like o'that.—Mortal beautizome to be sure—I declare, miss, it do make I quite warm zomehow to look at ye. [A shout without.] They be coming—Now, Henry!

Sir Abel. Now you'll see Bob!—now my dear boy, Bob!—here he comes.

[Huzza.

Enter Henry and two young Husbandmen.

Ash. 'Tis he, he has don't—Dang you all, why dan't ye shout? Huzza!

Sir Abel. Why, zounds, where's Bob?—I don't see Bob—Bless me, what has become of Bob and my plough?

[Retires and takes out his glass.

Ash. Well, Henry, there be the prize, and there be the fine lady that will gi' it thee.

Henry. Tell me who is that lovely creature?

Ash. The dater of Sir Philip Blandford.

Henry. What exquisite sweetness! Ah! should the father but resemble her, I shall have but little to fear from his severity.

Ash. Miss, thic be the young man that ha got'n the goulden prize.

Miss B. This! I always thought ploughmen were coarse, vulgar creatures, but he seems handsome and diffident.

Ash. Ees, quite pratty behaved—it were I that teach'd un.

Miss B. What's your name?

Henry. Henry.

Miss B. And your family?

[Henry, in agony of grief, turns away, strikes his forehead, and leans on the shoulder of Ashfield.]

Dame. [Apart to Miss B.] Madam, I beg pardon, but nobody knows about his parentage; and when it is mentioned, poor boy! he takes on sadly—He has lived at our house ever since we had the farm, and we have had an allowance for him—small enough to be sure—but, good lad! he was always welcome to share what we had.

Miss B. I am shock'd at my imprudence—[To Henry.] Pray pardon me; I would not insult an enemy, much less one I am inclined to admire—[Giving her hand, then withdraws it.]—to esteem—you shall go to the Castle—my father shall protect you.

Henry. Generous creature! to merit his esteem is the fondest wish of my heart—to be your slave, the proudest aim of my ambition.

Miss B. Receive your merited reward. [He kneels—she places the medal round his neck—the same to the others.]

Sir Abel. [Advances.] I can't see Bob: pray, sir, do you happen to know what is become of my Bob?

Henry. Sir?

Sir Abel. Did not you see a remarkable clever plough, and a young man——

Henry. At the beginning of the contest I observed a gentleman; his horses, I believe, were unruly; but my attention was too much occupied to allow me to notice more.

[Laughing without.

Handy, jun. [Without.] How dare you laugh?

Sir Abel. That's Bob's voice!

[Laughing again.

Enter Handy, jun. in a smock frock, cocked hat, and a piece of a plough in his hand.

Handy, jun. Dare to laugh again, and I'll knock you down with this!—Ugh! how infernally hot!

[Walks about.

Sir Abel. Why, Bob, where have you been?

Handy, jun. I don't know where I've been.

Sir Abel. And what have you got in your hand?

Handy, jun. What! All I could keep of your nonsensical ricketty plough.

[Walks about, Sir Abel following.

Sir Abel. Come, none of that, sir.—Don't abuse my plough, to cover your ignorance, sir? where is it, sir? and where are my famous Leicestershire horses, sir?

Handy, jun. Where? ha, ha, ha! I'll tell you as nearly as I can, ha, ha! What's the name of the next county?

Ash. It be called Wiltshire, zur.

Handy, jun. Then, dad, upon the nicest calculation I am able to make, they are at this moment engaged in the very patriotic act of ploughing Salisbury plain, ha ha! I saw them fairly over that hill, full gallop, with the curricle plough at their heels.

Ash. Ha, ha! a good one, ha ha!

Handy, jun. But never mind, father, you must again set your invention to work, and I my toilet:—rather a deranged figure to appear before a lady in. [Fiddles.] Hey day! What! are you going to dance?

Ash. Ees, zur; I suppose you can sheake a leg a bit?

Handy, jun. I fancy I can dance every possible step, from the pas ruse to the war-dance of the Catawbaws.

Ash. Likely.—I do hope, miss, you'll join your honest neighbours; they'll be deadly hurt an' you won't gig it a bit wi' un.

Miss B. With all my heart.

Sir Abel. Bob's an excellent dancer.

Miss B. I dare say he is, sir? but on this occasion, I think I ought to dance with the young man, who gained the prize—I think it would be most pleasant—most proper, I mean; and I am glad you agree with me.—So, sir, if you'll accept my hand—

[Henry takes it.

Sir Abel. Very pleasantly settled, upon my soul!—Bob, won't you dance?

Handy, jun. I dance!—no, I'll look at them—I'll quietly look on.

Sir Abel. Egad now, as my wife's away, I'll try to find a pretty girl, and make one among them.

Ash. That's hearty!—Come, Dame, hang the rheumatics!—Now, lads and lasses, behave pratty, and strike up.

[A dance.

[Handy, jun. looks on a little, and then begins to move his legs—then dashes into the midst of the dance, and endeavours to imitate every one opposite to him; then being exhausted, he leaves the dance, seizes the fiddle, and plays 'till the curtain drops.]

An Apartment in the Castle.

Sir Philip Blandford discovered on a couch, reading, Servants attending.

Sir Philip. Is not my daughter yet returned?

Serv. No, Sir Philip.

Sir Philip. Dispatch a servant to her.

[Exit Servant.

Re-enter Servant.

Serv. Sir, the old gardener is below, and asks to see you.

Sir Philip. [Rises and throws away the book.] Admit him instantly, and leave me.— [Exit Servant.

Enter Evergreen, who bows, then looking at Sir Philip, clasps his hands together, and weeps.

Does this desolation affect the old man?—Come near me—Time has laid a lenient hand on thee.

Everg. Oh, my dear master! can twenty years have wrought the change I see?

Sir Philip. No; [Striking his breast.] 'tis the canker here that hath withered up my trunk;—but are we secure from observation?

Everg. Yes.

Sir Philip. Then tell me, does the boy live?

Everg. He does, and is as fine a youth—

Sir Philip. No comments.

Everg. We named him—

Sir Philip. Be dumb! let me not hear his name. Has care been taken he may not blast me with his presence?

Everg. It has, and he cheerfully complied.

Sir Philip. Enough! never speak of him more. Have you removed every dreadful vestige from the fatal chamber? [Evergreen hesitates.]—O speak!

Everg. My dear master! I confess my want of duty. Alas! I had not courage to go there.

Sir Philip. Ah!

Everg. Nay, forgive me! wiser than I have felt such terrors.—The apartments have been carefully locked up; the keys not a moment from my possession:—here they are.

Sir Philip. Then the task remains with me. Dreadful thought! I can well pardon thy fears, old man.—O! could I wipe from my memory that hour, when—

Everg. Hush! your daughter.

Sir Philip. Leave me—we'll speak anon.

[Exit Evergreen.

Enter Miss Blandford.

Miss B. Dear father! I came the moment I heard you wished to see me.

Sir Philip. My good child, thou art the sole support that props my feeble life. I fear my wish for thy company deprives thee of much pleasure.

Miss B. Oh no! what pleasure can be equal to that of giving you happiness? Am I not rewarded in seeing your eyes beam with pleasure on me?

Sir Philip. 'Tis the pale reflection of the lustre I see sparkling there.—But, tell me, did your lover gain the prize?

Miss B. Yes, papa.

Sir Philip. Few men of his rank—

Miss B. Oh! you mean Mr. Handy?

Sir Philip. Yes.

Miss B. No; he did not.

Sir Philip. Then, whom did you mean?

Miss B. Did you say lover? I—I mistook.—No—a young man called Henry obtained the prize.

Sir Philip. And how did Mr. Handy succeed?

Miss B. Oh! It was so ridiculous!—I will tell you, papa, what happened to him.

Sir Philip. To Mr. Handy?

Miss B. Yes; as soon as the contest was over Henry presented himself. I was surprised at seeing a young man so handsome and elegant as Henry is.—Then I placed the medal round Henry's neck, and was told, that poor Henry—

Sir Philip. Henry!—So, my love, this is your account of Mr. Robert Handy!

Miss B. Yes, papa—no, papa—he came afterwards, dressed so ridiculously, that even Henry could not help smiling.

Sir Philip. Henry again!

Miss B. Then we had a dance.

Sir Philip. Of course you danced with your lover?

Miss B. Yes, papa.

Sir Philip. How does Mr. Handy dance?

Miss B. Oh! he did not dance till—

Sir Philip. You danced with your lover?

Miss B. Yes—no papa!—Somebody said (I don't know who) that I ought to dance with Henry, because—

Sir Philip. Still Henry! Oh! some rustic boy. My dear child, you talk as if you loved this Henry.

Miss B. Oh! no, papa—and I am certain he don't love me.

Sir Philip. Indeed!

Miss B. Yes, papa; for, when he touched my hand, he trembled as if I terrified him; and instead of looking at me as you do, who I am sure love me, when our eyes met, he withdrew his and cast them on the ground.

Sir Philip. And these are the reasons, which make you conclude he does not love you?

Miss B. Yes, papa.

Sir Philip. And probably you could adduce proof equally convincing that you don't love him?

Miss B. Oh, yes—quite; for in the dance he sometimes paid attention to other young women, and I was so angry with him! Now, you know, papa, I love you—and I am sure I should not have been angry with you had you done so.

Sir Philip. But one question more—Do you think Mr. Handy loves you?

Miss B. I have never thought about it, papa.

Sir Philip. I am satisfied.

Miss B. Yes, I knew I should convince you.

Sir Philip. Oh, love; malign and subtle tyrant, how falsely art thou painted blind! 'tis thy votaries are so; for what but blindness can prevent their seeing thy poisoned shaft, which is for ever doomed to rankle in the victim's heart.

Miss B. Oh! now I am certain I am not in love; for I feel no rankling at my heart. I feel the softest, sweetest sensation I ever experienced. But, papa, you must come to the lawn. I don't know why, but to-day nature seems enchanting; the birds sing more sweetly, and the flowers give more perfume.

Sir Philip. [Aside.] Such was the day my youthful fancy pictured!—How did it close!

Miss B. I promised Henry your protection.

Sir Philip. Indeed! that was much. Well I will see your rustic here. This infant passion must be crushed. Poor wench! some artless boy has caught thy youthful fancy.—Thy arm, my child.

[Exeunt.

A Lawn before the Castle.

Enter Henry and Ashfield.

Ash. Well! here thee'rt going to make thy bow to Sir Philip. I zay, if he should take a fancy to thee, thou'lt come to farm, and zee us zometimes, wo'tn't, Henry?

Henry. [Shaking his hand.] Tell me, is that Sir Philip Blandford, who leans on that lady's arm?

Ash. I don't know, by reason, d'ye zee, I never zeed'un. Well, good bye! I declare thee doz look quite grand with thic golden prize about thy neck, vor all the world like the lords in their stars, that do come to theas pearts to pickle their skins in the zalt zea ocean! Good b'ye, Henry!

[Exit.

Henry. He approaches! why this agitation? I wish, yet dread, to meet him.

Enter Sir Philip and Miss Blandford, attended.

Miss B. The joy your tenantry display at seeing you again must be truly grateful to you.

Sir Philip. No, my child; for I feel I do not merit it. Alas! I can see no orphans clothed with my beneficence, no anguish assuaged by my care.

Miss B. Then I am sure my dear father wishes to show his kind intentions. So I will begin by placing one under his protection [Goes up the stage, and leads down Henry. Sir Philip, on seeing him, starts, then becomes greatly agitated.]

Sir Philip. Ah! do my eyes deceive me! No, it must be him! Such was the face his father wore.

Henry. Spake you of my father?

Sir Philip. His presence brings back recollections, which drive me to madness!—How came he here?—Who have I to curse for this?

Miss B. [Falling on his neck.] Your daughter.

Henry. Oh sir! tell me—on my knees I ask it! do my parents live! Bless me with my father's name, and my days shall pass in active gratitude—my nights in prayers for you. [Sir Philip views him with severe contempt.] Do not mock my misery! Have you a heart?

Sir Philip. Yes; of marble. Cold and obdurate to the world—ponderous and painful to myself—Quit my sight for ever!

Miss B. Go, Henry, and save me from my father's curse.

Henry. I obey: cruel as the command is, I obey it—I shall often look at this, [Touching the medal.] and think on the blissful moment, when your hand placed it there.

Sir Philip. Ah! tear it from his breast.

[Servant advances.

Henry. Sooner take my life! It is the first honour I have earned, and it is no mean one; for it assigns me the first rank among the sons of industry! This is my claim to the sweet rewards of honest labour! This will give me competence, nay more, enable me to despise your tyranny!

Sir Philip. Rash boy, mark! Avoid me, and be secure.—Repeat this intrusion, and my vengeance shall pursue thee.

Henry. I defy its power!—You are in England, sir, where the man, who bears about him an upright heart, bears a charm too potent for tyranny to humble. Can your frown wither up my youthful vigour? No!—Can your malediction disturb the slumbers of a quiet conscience? No! Can your breath stifle in my heart the adoration it feels for that pitying angel? Oh, no!

Sir Philip. Wretch! you shall be taught the difference between us!

Henry. I feel it now! proudly feel it!—You hate the man, that never wronged you—I could love the man, that injures me—You meanly triumph o'er a worm—I make a giant tremble.

Sir Philip. Take him from my sight! Why am I not obeyed?

Miss B. Henry, if you wish my hate should not accompany my father's, instantly begone.

Henry. Oh, pity me!

[Exit.

[Miss Blandford looks after him—Sir Philip, exhausted, leans on his servants.

Sir Philip. Supported by my servants! I thought I had a daughter!

Miss B. [Running to him.] O you have, my father! one that loves you better than her life!

Sir Philip. [To Servant.] Leave us. [Exit Servant. Emma, if you feel, as I fear you do, love for that youth—mark my words! When the dove wooes for its mate the ravenous kite; when nature's fixed antipathies mingle in sweet concord, then, and not till then, hope to be united.

Miss B. O Heaven!

Sir Philip. Have you not promised me the disposal of your hand?

Miss B. Alas! my father! I didn't then know the difficulty of obedience!

Sir Philip. Hear, then, the reasons why I demand compliance. You think I hold these rich estates—Alas, the shadow only, not the substance.

Miss B. Explain, my father!

Sir Philip. When I left my native country, I left it with a heart lacerated by every wound, that the falsehood of others, or my own conscience, could inflict. Hateful to myself, I became the victim of dissipation—I rushed to the gaming table, and soon became the dupe of villains.—My ample fortune was lost; I detected one in the act of fraud, and having brought him to my feet, he confessed a plan had been laid for my ruin; that he was but an humble instrument; for that the man, who, by his superior genius, stood possessed of all the mortgages and securities I had given, was one Morrington.

Miss B. I have heard you name him before. Did you not know this Morrington?

Sir Philip. No; he, like his deeds, avoided the light—Ever dark, subtle, and mysterious. Collecting the scattered remnant of my fortune, I wandered, wretched and desolate, till, in a peaceful village, I first beheld thy mother, humble in birth, but exalted in virtue. The morning after our marriage she received a packet, containing these words: "The reward of virtuous love, presented by a repentant villain;" and which also contained bills and notes to the high amount of ten thousand pounds.

Miss B. And no name?

Sir Philip. None; nor could I ever guess at the generous donor. I need not tell thee what my heart suffered, when death deprived me of her. Thus circumstanced, this good man, Sir Abel Handy, proposed to unite our families by marriage; and in consideration of what he termed the honour of our alliance, agreed to pay off every incumbrance on my estates, and settle them as a portion on you and his son. Yet still another wonder remains.—When I arrive, I find no claim whatever has been made, either by Morrington or his agents. What am I to think? Can Morrington have perished, and with him his large claims to my property? Or, does he withhold the blow, to make it fall more heavily?

Miss B. 'Tis very strange! very mysterious! But my father has not told me what misfortune led him to leave his native country.

Sir Philip. [Greatly agitated.] Ha!

Miss B. May I not know it?

Sir Philip. Oh, never, never, never!

Miss B. I will not ask it—Be composed—Let me wipe away those drops of anguish from your brow.—How cold your cheek is! My father, the evening damps will harm you—Come in—I will be all you wish—indeed I will.

[Exeunt.

An Apartment in the Castle.

Enter Evergreen.

Everg. Was ever any thing so unlucky! Henry to come to the Castle and meet Sir Philip! He should have consulted me; I shall be blamed—but, thank Heaven, I am innocent.

[Sir Abel and Lady Handy without.]

Lady H. I will be treated with respect.

Sir Abel. You shall, my dear.

[They enter.

Lady H. But how! but how, Sir Abel? I repeat it—

Sir Philip. [Aside.] For the fiftieth time.

Lady H. Your son conducts himself with an insolence I won't endure; but you are ruled by him, you have no will of your own.

Sir Abel. I have not, indeed.

Lady H. How contemptible!

Sir Abel. Why, my dear, this is the case—I am like the ass in the fable; and if I am doomed to carry a packsaddle, it is not much matter who drives me.

Lady H. To yield your power to those the law allows you to govern!—

Sir Abel. Is very weak, indeed.

Everg. Lady Handy, your very humble servant; I heartily congratulate you, madam, on your marriage with this worthy gentleman—Sir, I give you joy.

Sir Abel. [Aside.] Not before 'tis wanted.

Everg. Aye, my lady, this match makes up for the imprudence of your first.

Lady H. Hem!

Sir Abel. Eh! What!—what's that—Eh! what do you mean?

Everg. I mean, sir—that Lady Handy's former husband—

Sir Abel. Former husband!—Why, my dear, I never knew—Eh!

Lady H. A mumbling old blockhead!—Didn't you, Sir Abel? Yes; I was rather married many years ago; but my husband went abroad and died.

Sir Abel. Died, did he?

Everg. Yes, sir, he was a servant in the Castle.

Sir Abel. Indeed! So he died—poor fellow!

Lady H. Yes.

Sir Abel. What, you are sure he died, are you?

Lady H. Don't you hear?

Sir Abel. Poor fellow! neglected perhaps—had I known it, he should have had the best advice money could have got.

Lady H. You seem sorry.

Sir Abel. Why, you would not have me pleased at the death of your husband, would you?—a good kind of man?

Everg. Yes; a faithful fellow—rather ruled his wife too severely.

Sir Abel. Did he! [Apart to Evergreen.] Pray do you happen to recollect his manner!—Could you just give a hint of the way he had?

Lady H. Do you want to tyrannize over my poor tender heart?—'Tis too much!

Everg. Bless me! Lady Handy is ill—Salts! salts!

Sir Abel. [Producing an essence box.] Here are salts, or aromatic vinegar, or essence of—

Everg. Any—any.

Sir Abel. Bless me, I can't find the key!

Everg. Pick the lock.

Sir Abel. It can't be picked, it is a patent lock.

Everg. Then break it open, sir.

Sir Abel. It can't be broke open—it is a contrivance of my own—you see, here comes a horizontal bolt, which acts upon a spring, therefore—

Lady H. I may die, while you are describing a horizontal bolt. Do you think you shall close your eyes for a week for this?

Enter Sir Philip Blandford.

Sir Philip. What has occasioned this disturbance?

Lady H. Ask that gentleman.

Sir Abel. Sir, I am accused—

Lady H. Convicted! convicted!

Sir Abel. Well, I will not argue with you about words—because I must bow to your superior practice—But, Sir—

Sir Philip. Pshaw! [Apart.] Lady Handy, some of your people were inquiring for you.

Lady H. Thank you, sir. Come, Sir Abel.

[Exit.

Sir Abel. Yes, my lady—I say [To Evergreen.] cou'dn't you give me a hint of the way he had—

Lady H. [Without.] Sir Abel!

Sir Abel. Coming, my soul!

[Exit.

Sir Philip. So! you have well obeyed my orders in keeping this Henry from my presence.

Everg. I was not to blame, master.

Sir Philip. Has Farmer Ashfield left the Castle?

Everg. No, sir.

Sir Philip. Send him hither. [Exit Evergreen.] That boy must be driven far, far from my sight—but where?—no matter! the world is large enough.

Enter Ashfield.

—Come hither. I believe you hold a farm of mine.

Ash. Ees, zur, I do, at your zarvice.

Sir Philip. I hope a profitable one?

Ash. Zometimes it be, zur. But thic year it be all t'other way as 'twur—but I do hope, as our landlords have a tightish big lump of the good, they'll be zo kind hearted as to take a little bit of the bad.

Sir Philip. It is but reasonable—I conclude then you are in my debt.

Ash. Ees, zur, I be—at your zarvice.

Sir Philip. How much?

Ash. I do owe ye a hundred and fifty pounds—at your zarvice.

Sir Philip. Which you can't pay?

Ash. Not a varthing, zur—at your zarvice.

Sir Philip. Well, I am willing to give you every indulgence.

Ash. Be you, zur? that be deadly kind. Dear heart! it will make my auld dame quite young again, and I don't think helping a poor man will do your honour's health any harm—I don't indeed, zur—I had a thought of speaking to your worship about it—but then, thinks I, the gentleman, mayhap, be one of those that do like to do a good turn, and not have a word zaid about it—zo, zur, if you had not mentioned what I owed you, I am zure I never should—should not, indeed, zur.

Sir Philip. Nay, I will wholly acquit you of the debt, on condition—

Ash. Ees, zur.

Sir Philip. On condition, I say, you instantly turn out that boy—that Henry.

Ash. Turn out Henry!—Ha, ha, ha! Excuse my tittering, zur; but you bees making your vun of I, zure.

Sir Philip. I am not apt to trifle—send him instantly from you, or take the consequences.

Ash. Turn out Henry! I do vow I shou'dn't knaw how to zet about it—I should not, indeed, zur.

Sir Philip. You hear my determination. If you disobey, you know what will follow—I'll leave you to reflect on it.

[Exit.

Ash. Well, zur, I'll argufy the topic, and then you may wait upon me, and I'll tell ye. [Makes the motion of turning out.]—I shou'd be deadly awkward at it, vor zartain—however, I'll put the case—Well! I goes whiztling whoam—noa, drabbit it! I shou'dn't be able to whiztle a bit, I'm zure. Well! I goas whoam, and I zees Henry zitting by my wife, mixing up someit to comfort the wold zoul, and take away the pain of her rheumatics—Very well! Then Henry places a chair vor I by the vire zide, and says—-"Varmer, the horses be fed, the sheep be folded, and you have nothing to do but to zit down, smoke your pipe, and be happy!" Very well! [Becomes affected.] Then I zays—"Henry, you be poor and friendless, zo you must turn out of my houze directly." Very well! then my wife stares at I—reaches her hand towards the vire place, and throws the poker at my head. Very well! then Henry gives a kind of aguish shake, and getting up, sighs from the bottom of his heart—then holding up his head like a king, zays—"Varmer, I have too long been a burden to you—Heaven protect you, as you have me—Farewell! I go." Then I says, "If thee doez I'll be domn'd!" [With great energy.] Hollo! you Mister Sir Philip! you may come in.—

Enter Sir Philip Blandford.

Zur, I have argufied the topic, and it wou'dn't be pratty—zo I can't.

Sir Philip. Can't! absurd!

Ash. Well, zur, there is but another word—I wont.

Sir Philip. Indeed!

Ash. No, zur, I won't—I'd zee myself hang'd first, and you too, zur—I wou'd indeed.

[Bowing.

Sir Philip. You refuse then to obey.

Ash. I do, zur—at your zarvice.

[Bowing.

Sir Philip. Then the law must take its course.

Ash. I be zorry for that too—I be, indeed, zur, but if corn wou'dn't grow I cou'dn't help it; it wer'n't poison'd by the hand that zow'd it. Thic hand, zur, be as free from guilt as your own.

Sir Philip. Oh!

[Sighing deeply.

Ash. It were never held out to clinch a hard bargain, nor will it turn a good lad out into the wide wicked world, because he be poorish a bit. I be zorry you be offended, zur, quite—but come what wool, I'll never hit thic hand against here, but when I be zure that zumeit at inside will jump against it with pleasure. [Bowing.] I do hope you'll repent of all your zins—I do, indeed, zur; and if you shou'd, I'll come and zee you again as friendly as ever—I wool, indeed, zur.

Sir Philip. Your repentance will come too late.

[Exit.

Ash. Thank ye, zur—Good morning to you—I do hope I have made myzel agreeable—and so I'll go whoam.

[Exit.

A room in Ashfield's House.

Dame Ashfield discovered at work with her needle, Henry sitting by her.

Dame. Come, come, Henry, you'll fret yourself ill, child. If Sir Philip will not be kind to you, you are but where you were.

Henry. [Rising.] My peace of mind is gone for ever. Sir Philip may have cause for hate;—spite of his unkindness to me, my heart seeks to find excuses for him—oh! that heart doats on his lovely daughter.

Dame. [Looking out.] Here comes Tummas home at last. Heyday what's the matter with the man! He doesn't seem to know the way into his own house.

Enter Ashfield, musing, he stumbles against a chair.

Tummas, my dear Tummas, what's the matter?

Ash. [Not attending.] It be lucky vor he I be's zoo pratty behaved, or dom if I—

[Doubling his fist.

Dame. Who—what?

Ash. Nothing at all; where's Henry?

Henry. Here, farmer.

Ash. Thee woultn't leave us, Henry, wou't?

Henry. Leave you! What, leave you now, when by my exertion I can pay off part of the debt of gratitude I owe you? oh, no!

Ash. Nay, it were not vor that I axed, I promise thee; come, gi'us thy hand on't then. [Shaking hands.] Now, I'll tell ye. Zur Philip did send vor I about the money I do owe 'un; and said as how he'd make all straight between us——

Dame. That was kind.

Ash. Ees, deadly kind. Make all straight on condition I did turn Henry out o'my doors.

Dame. What!

Henry. Where will his hatred cease?

Dame. And what did you say, Tummas?

Ash. Why I zivelly tould un, if it were agreeable to he to behave like a brute, it were agreeable to I to behave like a man.

Dame. That was right. I wou'd have told him a great deal more.

Ash. Ah! likely. Then a' zaid I shou'd ha' a bit a laa vor my pains.

Henry. And do you imagine I will see you suffer on my account? No—I will remove this hated form—— [Going.]

Ash. No, but thee shat'un—thee shat'un—I tell thee. Thee have givun me thy hand on't, and dom'me if thee sha't budge one step out of this house. Drabbit it! what can he do? he can't send us to jail. Why, I have corn will zell for half the money I do owe'un—and han't I cattle and sheep? deadly lean to be zure—and han't I a thumping zilver watch, almost as big as thy head? and Dame here a got——How many silk gowns have thee got, dame!

Dame. Three, Tummas—and sell them all—and I'll go to church in a stuff one—and let Mrs. Grundy turn up her nose as much as she pleases.

Henry. Oh, my friends, my heart is full. Yet a day will come, when this heart will prove its gratitude.

Dame. That day, Henry, is every day.

Ash. Dang it! never be down hearted. I do know as well as can be, zome good luck will turn up. All the way I comed whoam I looked to vind a purse in the path. But I didn't though. [A knocking at the door.]

Dame. Ah! here they are, coming to sell I suppose—

Ash. Lettun—lettun zeize and zell; we ha gotten here [Striking his breast.] what we won't zell, and they can't zell. [Knocking again.] Come in—dang it, don't ye be shy.

Enter Morrington and Gerald.

Henry. Ah! the strangers I saw this morning. These are not officers of law.

Ash. Noa!—Walk in, gemmen. Glad to zee ye wi' all my heart and zoul. Come, dame, spread a cloth, bring out cold meat, and a mug of beer.

Gerald. [To Morrington.] That is the boy. [Morrington nods.]

Ash. Take a chair, zur.

Mor. I thank, and admire your hospitality. Don't trouble yourself, good woman.—I am not inclined to eat.

Ash. That be the case here. To-day none o'we be auver hungry: misfortin be apt to stay the stomach confoundedly—

Mor. Has misfortune reached this humble dwelling?

Ash. Ees, zur. I do think vor my part it do work its way in every where.

Mor. Well, never despair.

Ash. I never do, zur. It is not my way. When the sun do shine I never think of voul weather, not I; and when it do begin to rain, I always think that's a zure zign it will give auver.

Mor. Is that young man your son?

Ash. No, zur—I do wish he were wi' all my heart and zoul.

Gerald. [To Morrington.] Sir, remember.

Mor. Doubt not my prudence. Young man, your appearance interests me;—how can I serve you?

Henry. By informing me who are my parents.

Mor. That I cannot do.

Henry. Then, by removing from me the hatred of Sir Philip Blandford.

Mor. Does Sir Philip hate you?