This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Oscar

The Boy Who Had His Own Way

Author: Walter Aimwell

Release Date: April 11, 2006 [eBook #18153]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OSCAR***

In the story of OSCAR is portrayed the career of a bright but somewhat headstrong boy, who was over-indulged by his parents, and who usually managed to "have his own way," by hook or by crook. The book is designed to exhibit some of the bad consequences of acquiring a wayward and lawless spirit, and of falling into indolent, untruthful, and disobedient habits. These are its main lessons, intermingled with which are a variety of others, of scarcely less importance to the young.

Winchester, Mass.

"THE AIMWELL STORIES" are designed to portray some of the leading phases of juvenile character, and to point out their tendencies to future good and evil. This they undertake to do by describing the quiet, natural scenes and incidents of everyday life, in city and country, at home and abroad, at school and upon the play-ground, rather than by resorting to romantic adventures and startling effects. While their main object is to persuade the young to lay well the foundations of their characters, to win them to the ways of virtue, and to incite them to good deeds and noble aims, the attempt is also made to mingle amusing, curious, and useful information with the moral lessons conveyed. It is hoped that the volumes will thus be made attractive and agreeable, as well as instructive, to the youthful reader.

Each volume of the "Aimwell Stories" will be complete and independent of itself, although a connecting thread will run through the whole series. The order of the volumes, so far as completed, is as follows:—

I. OSCAR; OR, THE BOY WHO HAD HIS OWN WAY.

II. CLINTON; OR, BOY-LIFE IN THE COUNTRY.

III. ELLA; OR, TURNING OVER A NEW LEAF.

IV. WHISTLER; OR, THE MANLY BOY.

V. MARCUS; OR, THE BOY-TAMER.

VI. JESSIE; OR, TRYING TO BE SOMEBODY.

Bridget and her little realm—A troop of rude intruders—An imperious demand—A flat refusal—Prying investigations—Biddy's displeasure aroused—Why Oscar could not find the pie—Another squabble, and its consequences—Studying under difficulties—Shooting peas—Ralph and George provoked—A piece of Bridget's mind—Mrs. Preston—George's complaint—Oscar rebuked—A tell-tale—Oscar's brothers and sisters—His father and mother.

Oscar's school—The divisions and classes—Lively and pleasant sights—Playing schoolmaster—Carrying the joke too far to be agreeable—Oscar's indolence in school—Gazing at the blackboard—A release from study, and an unexpected privilege—Whiling away an hour—Doing nothing harder work than studying—A half-learned lesson—A habit of Oscar's—A ridiculous blunder—Absurd mistakes of the British government about the great lakes—Oscar less pardonable than they—Another blunder—Difference between guessing and knowing—Oscar detained after school—His recitation—Good advice—Remembering the blackboard—Willie Davenport—A pounding promised.

Whistler—Why Ralph liked him—Why Oscar disliked him—A caution—A sudden attack—An unexpected rescue—The stranger's advice—A brave and manly answer—Whistler refuses to expose Oscar's name—The boys separate—George's report of the scene, and Ralph's explanation—Oscar's return—His sister's rebuke—His mother's inquiries—Misrepresentations—Willie exonerated—Forgiving enemies—An unpleasant promise called to mind—Mr. Preston's action in the matter—Oscar refuses to punish himself—The chamber—A surprise—Falsehood—Exposure—The account settled—Silence—Late rising and a cold breakfast—What Mrs. Preston said—Its effect upon Oscar—Concealed emotion—Mistaken notions of manliness—Good impressions made—George's narrow escape.

Alfred Walton—His home—Hotel acquaintances—Coarse stories and jokes—Andy—His peculiarities—Tobacco—A spelling lesson—The disappointment—Anger—Bright and her family—Fun and mischief—The owner of the pups—A promise—A ride to the depôt—A walk about the building—Examining wheels—The tracks—An arrival—A swarm of passengers—Two young travellers taken in tow—Their story—Arrival at the hotel—A walk—Purchase of deadly weapons—A heavy bill—Gifts to Alfred and Oscar—A brave speech for a little fellow—Going home.

The Sabbath—Uneasiness—Monday morning—A pressing invitation to play truant—Hesitation—The decision—Oscar's misgivings—Manners of the two travellers—A small theft—Flight—A narrow escape—A costly cake of sugar—The bridge to Charlestown—The monument—The navy yard—Objects of interest—Incidents of Joseph's life—A slight test of his courage—Oscar's plans—Going to dinner—A grand "take in"—Alfred's disclosures—Real character of the young travellers—Their tough stories—A mutual difficulty—Confessing what cannot be concealed—Good advice and mild reproof—The teacher's leniency explained.

A command—Passing it along—Reluctant obedience—A poor excuse—A bad habit—Employment for vacation—Oscar's opposition to the plan—Frank the errand-boy—Thanksgiving week—A busy time—Oscar's experience as store-boy—Learning to sweep—Doing work well—A tempting invitation—Its acceptance—A ride—Driving horses—The errand—The return—Oscar at the store—Sent off "with a flea in his ear"—The matter brought up again—Oscar's excuse unsatisfactory—Ralph's services rewarded—Difference between the two boys.

Grandmother's arrival—Surprises—Presents—Oscar at a shooting-match—Bad company—Cruel sport—Home again—Prevarication—A remonstrance—Impudence, and a silent rebuke—The dinner—A stormy afternoon—A disappointment—Evening in the parlor—A call for stories—How the Indians punished bad boys—What Oscar thought of it—An Indian story—The hostile party—The alarm—The stratagem—The onset—The retreat—The victory—Laplot River—Widow Storey's retreat—Misfortunes of her husband—Her enterprise and industry—Fleeing from the British—The subterranean abode—Precautions to prevent discovery—Uncle James—The fellow who was caught in his own trap—Old Zigzag—His oddities—His tragic end—How the town of Barre, Vt., got its name—A well-spent evening.

One of her habits—Ella's complaint—Alice's reproof—Ella's rude reply to her grandmother—A mild rebuke—A sterner reproof—Shame and repentance—Popping corn—George's selfishness—A fruitless search for the corn-bag—Bad Temper—An ineffectual reproof—George's obstinacy—How he became selfish—Difficulty of breaking up a bad habit—What he lost by his selfishness—Oscar's dog—He is named "Tiger"—His portrait—His roguishness—Oscar's trick upon his grandmother—Unfortunate ending—Tiger's destructiveness—A mystery, and its probable solution—Oscar's falsehood—Tiger's banishment decreed, but not carried out—Grandmother Lee's remonstrance with Oscar—Bridget's onset—Oscar's excuse—Moral principle wanting—Mrs. Lee's departure.

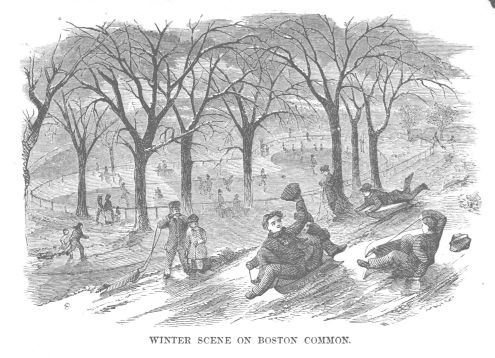

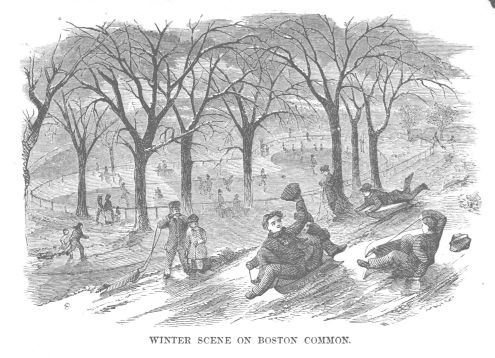

Coasting—Oscar's sled—Borrowing and lending—A merry scene on the Common—Various sleds and characters—A collision—Damage to Ralph and the "Clipper"—Not accidental—The guilty parties called to account—No satisfaction obtained—Ralph's trouble—Oscar's anger—His revenge—A fight—His termination—Skating—Tiger on the ice—His plunge into an air-hole—His alarm and escape—Going home—Unfounded fears awakened—Tiger's shame—A talk about air-holes—What they are for, and how they are made—Skaters should be cautious—A change in Tiger's habits—A great snow-storm—Appearance of the streets—Fun for the boys—A job for Oscar—He is wiser than his father—Nullification of a command—The command repeated—Icy sidewalks—Laziness and its excuses—A wise suggestion—Duty neglected—Oscar called to account—His excuses—Unpleasant consequences of his negligence—The command repeated, with a "snapper" at the end—The dreaded task completed.

A compulsory ride—Merited retribution—A sad plight for a proud boy—Laughter and ridicule—Oscar's neatness and love of dress—The patched jacket—Oscar's objections to it—Benny Wright, the boy of many patches—His character—The jacket question peremptorily settled—A significant shake of the head—A watch wanted—Why boys carry watches—Punctuality—Oscar's tardiness at school—The real cause of it—Thinking too much of outside appearances—Character of more consequence than cloth—An offer—The conditions—A hard question—How to accomplish an object—Oscar's waywardness—Boarding-school discipline—The High School—An anticipated novelty.

Oscar's shrewdness—His reputation for integrity—A new want—Perplexity—A chance for speculation—A dishonest device—Its success—Secrecy—The fraud discovered—Oscar's defence—Restitution refused—Indignation—The Monday morning lesson in morals—Dishonesty—Rectifying mistakes—The principle unfolded—Restoring lost articles—A case for Oscar to decide—His reluctant decision—Taking advantage of another's ignorance—Duty of restitution—Other forms of dishonesty—Better to be cheated than to cheat—Effect of the lesson upon Oscar.

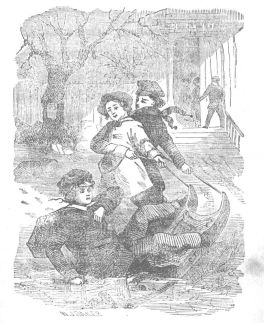

Wet feet—A command disobeyed—Dabbling in the water—Playing on the ice—An unexpected adventure—Afloat on an ice-cake—A consultation—Danger and alarm—Spectators—A call for help—A critical situation—The rescue—Effects of the adventure—Feverish dreams—Strange feelings—The doctor's visit—Lung fever—The Latin prescription—Oscar's removal—He grows worse—Peevishness—Passing the crisis—Improved behavior—Getting better—General rejoicings—Further improvement—Return of a bad habit—Fretfulness and impatience—A dispute—First attempt to sit up—Its failure—First day in an easy chair—The sweets of convalescence—Danger of a relapse.

Hunger—An evil suggestion—First visit down stairs—Midnight supper—Weakness and exhaustion—An ill turn—The doctor's visit—The mystery explained—Contents of a sick boy's stomach—The doctor's abrupt farewell—His recall—Promise of obedience—Punishment for imprudence—Directions—Effects of the relapse—Slow recovery—The menagerie procession—A wet morning—Disobedience—Exposure, and its consequences—Reading—The borrowed book—The curious letter—Puzzles, with illustrations—Guessing riddles—Oscar's treatment of Benjamin—His present feelings towards him—Ella's copy of the letter—Oscar's growing impatience—An arrival—Uncle John—The loggers—Cousins never seen—A journey decided upon—Solution of riddles, conundrums, &c.

Setting out—A long and wearisome ride—Portland—The hotel—Going to bed—The queer little lamp—Lonesomeness—The evening prayer—Morning—Breakfast—The railroad depôt—Oscar's partiality for stage-coaches and good horses—Eighty miles by steam—Dinner—The stage-coach—An outside seat—The team and the roads—Villages—Mail bags—Forests and rivers—End of the stage ride—Jerry—An Introduction—A ride in a wagon—Bashfulness—An invisible village—The journey's end—Mrs. Preston—More shy cousins—Supper—Evening employments—Attempting to "scrape acquaintance"—Mary tells Oscar his name—More questions—The tables turned—Getting acquainted in bed.

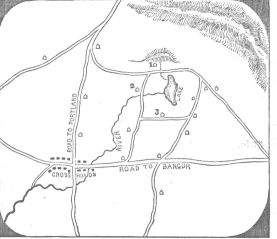

A dull morning—New acquaintances—Inquiries about Jerry's school-time—A long vacation—Work—Playmates—Rain—A fine sunrise—The distant pond—A call to breakfast—Preliminary operations—Jerry's uncombed head—Oscar's neatness—Jerry sent from the table—Bad manners—Bathing in the pond—An anticipated pleasure interdicted—The river—A walk—The pond—Map of Brookdale—Going to ride—The Cross-Roads—Billy's speed discussed—The variety store—All sorts of things—Oscar's purchase—Returning home—Short evenings—A nap—A queer dream—Oscar's smartness at dreaming—Making fun of a country store—Mary's question—Crying babies—Teasing—Walking backwards—A trip and a fall—A real crying baby—Mary comforted—Jerry cuffed—Mortification.

Forgotten medicine and renewed health—An excursion planned—A gun wanted, but denied—Setting out on a long tramp—Swamps—Upland—Brooks—How Brookdale got its name—Cutting canes—Birch and beech—How to crook the handle of a cane—The philosophy of it explained—The cigars—Fine groves—Stopping to rest—The forest described—Birds and guns—Other game—Jim Oakley's strange animal—Moose—The man who met a bear—A race—Mysterious disappearance of the bear—The probable cause of his visit—The boy who killed two bears—Oscar's courage—Prospect Rock—A fine view—The rabbit—The woodchuck's hole—Crossing a swamp—Mosquitoes—The pond—The hermit's hut—Some account of "Old Staples"—Buried treasures—Making a fire—Baking potatoes and toasting cheese—Drinking pond water—Dinner—Hunting for the hermit's money—What they meant to do with it—A bath proposed—Smoothing over the matter—Going Into water—Drying their hair—Going home—Lost In the woods—Arrival home—One kind of punishment for wrong-doing.

The missing cap—Splitting wood—Jerry and Emily—A quarrel begun—The cap found—A drink of buttermilk—Oscar's opinion of it—Jerry's love for it—Another delay—Feeding the fowls—A mysterious letter—The Shanghae rooster's complaint—Curiosity excited—The suspected author—Clinton's education—Keeping dark about the letter—Who Clinton was—Where he lived—Killing caterpillars—How caterpillars breed—The young turkeys—The brood of chickens—The hen-coop—Clinton's management of the poultry—His profits—Success the result of effort, not of luck—The "rooster's letter" not alluded to—The piggery—The barn—"The horse's prayer"—A new-comer—Her name—A discovery—Relationship of Clinton to Whistler—Mrs. Davenport—Oscar conceals his dislike of Whistler—The shop—Specimens of Clinton's work—Going home.

A forgotten duty called to mind—Letter writing—A mysterious allusion—The private room—No backing out—Making a beginning—Getting stuck—Idling away time—Prying into letters—A commotion among the swallows—Teaching the young ones how to fly—A good lesson lost—Mary and her book—Her talk about the pictures—A pretty picture—A wasted hour—Making another attempt—His success—Effects of being in earnest—A copy of Oscar's letter—Emily's inquisitiveness—A rebuke—The message she wanted to send—The meadow lot—Mulching for trees—Going to the old wood lot—Cutting birch twigs-Forgetting to be lazy—The load—A ride to the Cross-Roads—Mailing the letter—Paying the postage in advance.

Hankerings after a gun—A plan—Jim Oakley's gun—A dispute—An open rupture—The broken gun—Going home mad—A call from Clinton—The toiler—Summons home—Disappointment—Bad feeling between Oscar and Jerry—How they slept—Remarks about their appearance at the breakfast table—Borrowing trouble—Another visit proposed—Jerry's explosion of anger—His imprudence—Confinement down cellar—An unhappy day—"Making up" at night—A duty neglected—Inquiries about the gun—Starting for home—A pleasant drive—The stage-coach—The cars—Luncheon—Half an hour in Portland—The Boston train—A spark in the eye—Pain and inflammation—Boston—Ralph's surprise—Welcome home—The eye-stone—The intruder removed.

Oscar's dread of going to school—Unsuccessful pleas—Oscar at school—His indifference to his studies—A "talent for missing"—A reproof—Kicking a cap—Whistler's generosity—Benny Wright—Oscar's bad conduct—Regarded as incorrigible—The tobacco spittle—Oscar's denial—Betrayed by his breath—A successful search—The teacher's rebuke—The new copy—Its effect—A note for Oscar's father—What it led to—Concealment of real feelings—Bridget's complaint—The puddle on the kitchen floor—Oscar's story—Conflicting reports—A new flare-up—The truth of the matter—Bridget's departure—Examination day—The medals—The certificate for the High School—A refusal—Bitter fruits of misconduct.

Vacation—Associates—Edward Mixer—His character—Loitering around railroad depôts—An excursion into the country—The railroad bridge—Fruit—A fine garden—Getting over the fence—Looking for birds' nests—Disappearance of Edward and Alfred—A chase—Escape of the boys—Hailing each other—Edward's account of the adventure—A grand speculation—Pluck—Secrecy—Curiosity not gratified—Arrival of Oscar's uncle—The officer's interview with Mr. Preston—The real character and history of Ned—Timely warning—Oscar's astonishment—What he knew concerning Ned—A hint about forming new acquaintances—Oscar's removal from city temptations decided on—A caution and precaution—Departure—Ned's arrest and sentence—The "grand speculation" never divulged.

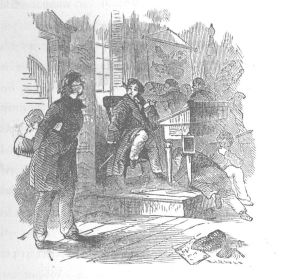

Bridget, the Irish servant girl, had finished the house-work for the day, and sat down to do a little mending with her needle. The fire in the range, which for hours had sent forth such scorching blasts, was now burning dim; for it was early in October, and the weather was mild and pleasant. The floor was swept, and the various articles belonging in the room were arranged in their proper places, for the night. The mistress of the kitchen,—for Bridget claimed this as her rank, if not her title,—was humming a queer medley of tunes known only to herself, as her clumsy fingers were trying to coax the needle to perform some dextrous feat that it did not seem inclined to do in her hands. What she was thinking about, is none of our business; but whatever it was, her revery was suddenly disturbed, and the good nature that beamed from her face dispelled, by the noisy clattering of more than one pair of little boots on the stairs. In a moment, the door opened with a jerk and a push, and in bounded three boys, with as little display of manners or propriety as so many savages might exhibit. The oldest directed his steps to the closet, singing, as he peered round among the eatables:

"Eggs, cheese, butter, bread,--

Stick, stock, stone-dead."

"Biddy," he continued, "I 'm hungry—give me something to eat, quick."

Bridget paid no attention to this demand, but only twitched her needle with a little more energy.

"I say, Biddy," continued the boy, "what did you have for supper? Come, give me some, I 'm half starved."

"And why did n't ye come when the supper was ready, if ye wanted any?" said Bridget. "If ye won't ate with the rest, it's not me that will wait upon ye, Master Oscar."

"Well," continued Oscar, "if you won't help me, I guess I can help myself. Ralph, what did you have for supper?"

The boy addressed named over several articles, among which were cake and mince-pie, neither of which could Oscar find in the closet.

"Where did you put the pie, Biddy?" he inquired.

"It 's where ye won't find it," replied Bridget, "that's jist where it is."

"I bet I will find it, come now," said Oscar, with a determined air; and he commenced the search in earnest, prying into every covered dish, opening every drawer and bucket, and overhauling and disarranging every part of the closet. Bridget was just then in too irritable a mood to bear this provoking invasion of her realm with patience. In an angry tone, she ordered the intruder to leave the closet, but he took no notice of the command. She repeated the order, making it more emphatic by calling him a "plague" and a "torment," but he did not heed it. Then she threatened to tell his parents of his misconduct, but this had no effect. Oscar continued his search for some minutes, but without success; and he finally concluded to make his supper of bread and butter, since he could find nothing more tempting to his appetite.

The fact was, Oscar was getting in the habit of being absent from his meals, and calling for food at unseasonable hours, much to the annoyance of Bridget. She had complained of this to his mother several times, without effect; and now she thought she would try a little expedient of her own. So, when she cleared away the supper-table that evening, before Oscar came home, she hid away the cake and pies with which the others had been served, and left only bread and butter in the closet. She gained her end, but the boy, in rummaging for the hidden articles, had made her half an hour's extra work, in putting things to rights again.

As Oscar stepped out of the closet, after his solitary supper, he moved towards the youngest of the other boys, saying:

"Here, George, open your mouth and shut your eyes, and I 'll give you something to make you wise."

George declined the gift, but Oscar insisted, and tried to force it upon him. A struggle ensued, and both rolled upon the floor, the one crying and screaming with anger, and the other laughing as though he considered it good fun. George shut his teeth firmly together, but Oscar succeeded in rubbing enough of the mysterious article upon his lips to enable him to tell what it was. It proved to be a piece of pepper, a plate of which Oscar had found in the closet.

This little experiment, however, did not leave George in a very pleasant frame of mind. It was some time before he got over his blubbering and pouting. Oscar called him a "cry-baby," for making such a fuss about a little bit of pepper, which epithet did not aid him much in forgetting the injury he had received.

After awhile, quiet and harmony were in a measure restored. Ralph and George got their school-books, and began to look over the lessons they were to recite in the morning; but Oscar not only remained idle, himself, but seemed to try to interrupt them as much as possible, by his remarks. By-and-bye, finding they did not take much notice of his observations, he took from his jacket pocket a small tin tube, and commenced blowing peas through it, aiming them at his brothers, at Bridget, and at the lamp. Ralph, after two or three had taken effect on his face, got up in a pet, and took his book up stairs to the sitting-room. George scowled and scolded, as the annoying pellets flew around his head, but he did not mean to be driven away by such small shot. Bridget, too, soon lost her patience, as the peas rattled upon the newly-swept floor.

"Git away with yer pays, Oscar," said she; "don't ye be clutterin' up the clane floor with 'em, that's a good b'y."

"They aint 'pays,' they are peas," replied Oscar; "can't you say peas, Biddy?"

"I don't care what ye call 'em," said Bridget; "only kape the things in yer pocket, and don't bother me with 'em."

"Who 's bothering you?" said Oscar; "me 'pays' don't make any dirt—they 're just as clean as your floor."

"Ye 're a sassy b'y, that's jist what ye are."

"Well, what are you going to do about it?"

"Faith, if it was me that had the doin' of it, I bet I 'd larn ye better manners, ye great, impudent good-for-nothin', if I had to bate yer tin times a day."

"You would n't, though, would you?" said Oscar; and he continued the shower of peas until he had exhausted his stock, and then picked most of them up again, to serve for some future occasion. He had hardly finished this last operation, when his mother, who had been out, returned home. As soon as she entered the kitchen, George began to pour out his complaints to her.

"Mother," he said, "Oscar 's been plaguing us like everything, all the evening. He got me down on the floor, and rubbed a hot pepper on my mouth, and tried to make me eat it. And he's been rummaging all round the kitchen, trying to find some pie. And then he went to shooting peas at us, and he got Bridget real mad, and Ralph had to clear out, to study his lesson. I told him—"

"There, there, George, that will do," replied his mother; "I am sick of hearing these complaints. Oscar, why is it that I can't stir out of the house, when you are at home, without your making trouble with Bridget or the children? I do wish you would try to behave yourself properly. You are getting the ill-will of everybody in the house, by your bad conduct. I really believe your brothers and sisters will begin to hate you, before long, if you keep on in this way. For your own sake, if for nothing more, I should think you would try to do better. If I were in your place, I would try to keep on good terms with my brothers and sisters, if I quarrelled with everybody else."

Oscar made no reply to this, and the subject was soon dropped. His mother was too much accustomed to such complaints of his misconduct, to think very seriously of them; and he was himself so used to such mild rebukes as the foregoing, that they made little impression upon his mind. The boys, who all slept in one chamber, soon retired for the night; but Oscar took no further notice of the occurrences of the evening, except to apply the nickname of "mammy's little tell-tale" to George—a title of contempt by which he often addressed his little brother.

I am afraid that the title of "tell-tale" was not wholly undeserved by George. True, he often had just cause of complaint; but he was too ready to bring whining accusations against his brothers and sisters, for every trifling thing. He complained so much that his mother could not always tell when censure was deserved. It had become a habit with him, and a dozen times a day he would go to her, with the complaint that Oscar had been plaguing him, or Ella had got something that belonged to him, or Ralph would not do this or that.

George, who was the youngest of the children, was at this time seven years old; Ralph was two years and half older, and Oscar, who was the oldest son, was about half way between thirteen and fourteen. They had two sisters. Alice, the oldest, was fifteen years of age, and Eleanor, or Ella, as she was commonly called, was about eleven.

The father of these boys and girls was a shop-keeper in Boston. His business required so much of his attention, that he was seldom with his family, except at meal-times and nights. Even in the evening he was usually at the shop; but when it so happened that he could remain at home after tea, it was his delight to settle himself comfortably down in the big rocking chair, in the well-lighted sitting-room, and to muse and doze, while Alice sang, and played upon the piano-forte. He had so many other cares, that he did not like to be troubled with bad reports of his children's conduct, This was so well understood by all the family, that even George seldom ventured to go to him with a complaint. The management of domestic affairs was thus left almost entirely with Mrs. Preston, and she consulted her husband in regard to these matters only when grave troubles arose.

I have thus briefly introduced to my readers the family, one of whose members is to form the principal subject of the following pages.

The school which Oscar attended was held in a large and lofty brick building, a short distance from the street on which he lived. His brothers attended the same school, but his sisters did not, it being only for boys. The pupils numbered four or five hundred—a good many boys to be together in one building. But though belonging to one school, and under the control of one head master, they did not often meet together in one assembly. They were divided into eight or ten branches, of about fifty scholars each, and each branch had its own separate room and teacher. There were however, only four classes in the whole school; and a this time Oscar was a member of the first, or highest class. There was a large hall in the upper story of the building, in which the entire school assembled on exhibition days, and when they met for the practice of singing or declamation.

There were lively and merry times in the vicinity of the school-house, I can assure you, for half an hour before the opening of school, and for about the same length of time after the exercises closed. Four hundred boys cannot well be brought together, without making some stir. Every morning and afternoon, as the pupils went to and from school, the streets in the neighborhood would for a few minutes seem to swarm with boys, of every imaginable size, shape, manners, dress, and appearance. Usually, they went back and forth in little knots; and with their books and slates under their arms, their bright, happy faces, their joyous laugh, and their animated movements, they presented a most pleasing sight,—"a sight for sore eyes," as a Scotchman might say. If anybody disputes this, he must be a sour and crabbed fellow.

Oscar, although not the most prompt and punctual of scholars, used occasionally to go to school in season to have a little fun with his mates, before the exercises commenced. One day, entering the school-room a little before the time, he put on an old coat which his teacher wore in-doors, stuck a quill behind his ear, and made a pair of spectacles from some pasteboard, which he perched upon his nose. Arranged, in this fantastical manner, he seated himself with great dignity in the teacher's chair, and began to "play school-master," to the amusement of several other boys. It so happened that the teacher arrived earlier than usual that day, and he was not a little amused, as he suddenly entered the room, and witnessed the farce that was going on. Oscar jumped from his seat, but the master made him take it again, and remain in it just as he caught him, with his great-coat, pasteboard spectacles and quill, until all the scholars had assembled, and it was time to commence the studies of the day. This afforded fine sport to the other boys, but Oscar did not much relish the fun, and he never attempted to amuse himself in that way again.

I am sorry that this harmless piece of roguery is not the most serious charge that candor obliges me to bring against Oscar. But to tell the truth, he was not noted either for his studious habits or his correct deportment; and there was very little prospect that he would be considered a candidate for the "Franklin medals," which were to be distributed to the most deserving members of his class, when they graduated, the ensuing July. And yet Oscar was naturally a bright and intelligent boy. He was quick to learn, when he applied himself; but he was indolent, and did not like to take the trouble of studying his lessons. Whenever he could be made to take hold of a lesson in earnest, he soon mastered it; but the consciousness of this power often led him to put off his lessons to the last minute, and then perhaps something would happen to prevent his preparing himself at all.

A day or two after the "kitchen scene" described in the preceding chapter, Oscar was sitting at his desk in the school-room, with an open book before him, but with his eyes idly staring at a blackboard affixed to one of the walls. The teacher watched him a moment, and then spoke to him.

"Oscar," he said, "what do you find so very fascinating about that blackboard? You have been looking at it very intently for several minutes—what do you see that interests you so!"

Oscar hung his head, but made no reply.

"Are you ready to recite your geography lesson?" continued the master.

"No, sir."

"Why do you not study it, then'"

"I don't feel like studying," replied Oscar.

"Very well," said the teacher, quite pleasantly; "if you don't feel like it, you need n't study. You may come here."

Oscar stepped out to the platform on which the teacher's desk was placed.

"There," continued the master, pointing to a blackboard facing the school, "you may stand there and look at that board just as long as you please. But you must not look at anything else, and I would advise you not to let me catch your eyes turning either to the right or the left. Now mind and keep your eyes on the board, and when you feel like studying let me know."

Oscar took the position pointed out to him, with his back towards the boys, and with his face so near the blackboard, that he could see nothing else without turning his head—an operation that would be sure to attract the attention of the master. At first he thought it would be good fun to stand there, and for awhile the novelty of the thing did amuse him a little. When he began to grow weary, he contrived to interest himself by tracing out the faint chalk-marks of long-forgotten problems, that had not been entirely obliterated from the blackboard. This afforded employment for his mind for a time; but by-and-bye he began to grow tired and uneasy. His eyes longed to see something else, and his legs were weary of standing so long in one position. He wondered, too, whether the boys were looking at him, and whether they smiled at his strange employment. At last, after doing penance about an hour, his exhaustion got the better of his stubbornness, and on informing the master that he thought ho could study now, he was permitted to take his seat.

After returning to his desk, Oscar had but little time to finish learning his geography lesson, before the class was called out to recite. As was too often the case, he was but half prepared. The subject of the lesson was New York State. Several of the questions put to Oscar were answered wrong, either wholly or in part. When asked what great lakes bordered on New York, he replied:

"Lake Erie and Lake Superior."

When the question was given to another, and correctly answered, Oscar exclaimed:

"That's what I meant—Erie and Ontario; but I was n't thinking what I said."

This was somewhat of a habit with Oscar. When he "missed" a question, he was very apt to say, after the next boy had answered it, "I knew, only I could n't think," or, "I was just going to say so."

Another question put to him was, whether the water of the great New York lakes was fresh or salt. Oscar replied that it was salt. It is but justice to add, how ever, that nothing was said in the lesson of the day, on this point, although the question had occurred in a previous lesson. Noticing that several of the boys laughed at Oscar's blunder, the teacher remarked:

"That was a very foolish answer, Oscar, but you are not the first nor the wisest person that has made the same mistake. When the British went to war with us, in 1812, it is said that all their war vessels intended to navigate the lakes, were furnished with tanks and casks for carrying a full supply of freshwater; and I have been told that an apparatus is still in existence in one of the Canadian navy yards, which the English government sent over, some years ago, for distilling fresh water from Lake Erie. But an American school-boy of your age ought to know better than this, if an English lord of the admiralty does not. These great lakes are among the remarkable features of our own country, and every American child should know something about them. I should suppose," continued the teacher, "that a boy who could afford to look steadily at nothing for an hour, might take a little pains to inform himself about so common a matter as this, so as not to appear so ridiculous, when a simple question is asked him."

Before the lesson was concluded, Oscar made still another mistake. There was an allusion in the lesson to the great fire of 1885, by which an immense amount of property in New York city was destroyed. When the teacher asked him how many buildings were said to have been consumed, he replied:

"Three hundred and fifty—five hundred and thirty—no, three hundred and fifty."

"Which number do you mean?" inquired the master.

"I aint sure which it is," replied Oscar, after a moment's hesitation; "it's one or the other, I don't know which."

"You are about as definite," said the teacher, "as the Irish recruit, who said his height was five feet ten or ten feet five, he was n't certain which. But are you sure that the number of buildings burnt was either three hundred and fifty, or five hundred and thirty?"

"Why—yes—I—believe—it was one or the other," replied Oscar, hesitatingly.

"You believe it was, do you? Well, I believe you know just nothing about the lesson. You may go to your seat, and study it until you can answer every question; and after school I will hear you recite it, and remember, you will not go home until you can recite it."

The class continued their recitation, and Oscar returned to his seat, and commenced studying the lesson anew. It was already late in the afternoon, and as he did not like the idea of stopping after school, he gave pretty close attention to his book during the rest of the session. About fifteen minutes after the school was dismissed, he told the teacher he was prepared to recite, and he succeeded in getting through the lesson with tolerable accuracy. When he had finished, the teacher talked with him very plainly about his indolent habits in school, and the consequences that would hereafter result from them.

"I would advise you," he said, "to do one of two things,—either commit your lessons perfectly, hereafter, or else give up study entirely, and ask your father to take you from school and put you to some business. You can learn as fast as any boy in school, if you will only give your attention to it; but I despise this half-way system that you have fallen into. It is only wasting time to half learn a thing, as you did your geography lesson this afternoon. You studied it just enough to get a few indistinct impressions, and what little you did learn you were not sure of. It would be better for you to master but one single question a day, and then know that you know it, than to fill your head with a thousand half-learned, indefinite, and uncertain ideas. I have told you all this before, but you do not seem to pay any attention to it. I am sorry that it is so, for you might easily stand at the head of the school, if you would try."

Oscar had received such advice before, but, as his teacher intimated, he had not profited much by it. If anything, he had grown more indolent and negligent, within a few months. On going home that night, Ralph accosted him with the inquiry:

"What did you think of the blackboard, Oscar? Do you suppose you should know it again, if you should happen to see it?"

"What do you mean?" he inquired, feigning ignorance.

"O, you 've forgotten it a'ready, have you?" continued Ralph. "You don't remember seeing anything of a blackboard this afternoon, do you?"

"But who told you about it?" inquired Oscar; for though both attended the same school, their places were in different rooms.

"O, I know what's going on," said Ralph; "you need n't try to be so secret about it."

"Well, I know who told you about it—'t was Bill Davenport, was n't it?" inquired Oscar.

Willie and Ralph were such great cronies, that Oscar's supposition was a very natural one. Indeed, Ralph could not deny it without telling a falsehood, and so he made no reply. Oscar, perceiving he had guessed right, added, in a contemptuous tone:

"The little, sneaking tell-tale—I 'll give him a good pounding for that, the first time I catch him."

"You 're too bad, Oscar," interposed his brother; "Willie did n't suppose you cared anything about standing before the blackboard—he only spoke of it because he thought it was something queer."

Seeing Oscar was in so unamiable a mood, Ralph said nothing more about the subject, at that time.

The morning after the events just related, as Ralph was on his way to school, he fell in with Willie Davenport, or "Whistler," as he was often sportively called, by his playmates, in allusion to his fondness for a species of music to which most boys are more or less addicted. And I may as well say here, that he was a very good whistler, and came honestly by the title by which he was distinguished among his fellows. His quick ear caught all the new and popular melodies of the day, before they became threadbare, which gave his whistling an air of freshness and novelty that few could rival. It was to this circumstance—the quality of his whistling, rather than the quantity—that he was chiefly indebted for the name of Whistler. Nor was he ashamed of his nickname, as he certainly had no need to be; for it was not applied to him in derision, but playfully and good-naturedly.

Whistler and Ralph were good friends. There was a difference of between two and three years in their ages, Whistler being about twelve years old; but their dispositions harmonized together well, and quite a strong friendship had grown up between them. A very different feeling, however, had for some time existed between Oscar and Whistler. They were in the same class at school; but Whistler studied hard, and thus, though much younger than Oscar, he stood far before him as a scholar. This awakened some feeling of resentment in Oscar, and he never let slip any opportunity for annoying or mortifying his more industrious and successful class-mate.

On their way to school, on the morning in question, Ralph told Whistler of Oscar's threat, and advised him to avoid his brother as much as possible, for a day or two, until the affair of the blackboard should pass from his mind. Whistler heeded this caution, and was careful not to put himself in the way of his enemy. He succeeded in eluding him through the day, and was on his way home from school in the afternoon, when Oscar, who he thought had gone off in another direction, suddenly appeared at his side.

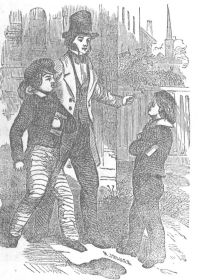

"You little tell-tale, you," cried Oscar, "what did you tell Ralph about the blackboard for! I 'll learn you to mind your own business, next time, you mean, sneaking meddler. Take that—and that," he continued, giving Whistler several hard blows with his fist. The latter attempted to dodge the blows, but did not return them, for this he knew would only increase the anger of Oscar, who was so much his superior in size and strength, as well as in the art of fisticuffs, that he could do just about as he pleased with him. The affray, however, was soon brought to an unexpected end, by a gentleman who happened to witness it. Seizing Oscar by the collar of his jacket, he exclaimed:

"Here, here, sir! what are you doing to that little fellow? Don't you know enough, you great lubber, to take a boy of your own size, if you want to fight? Now run, my little man, and get out of his way," continued the stranger, turning to Whistler, and still holding Oscar by the collar.

Whistler hesitated for a moment between the contending impulses of obedience and manliness; and then, drawing himself up to his full stature, he said, with a respectful but decided air:

"No, sir, I have n't injured him, and I won't run away from him."

"Well said, well said—you are a brave little fellow," continued the gentleman, somewhat surprised at the turn the affair was taking. "What is your name, sir?"

"William Davenport."

"And what is this boy's name?"

"Oscar," replied Willie, and there he stopped, as if unwilling to expose further the name of his abuser.

"Well you may go now, Oscar," said the gentleman, relinquishing his hold; "but if you lay your hands on William again, I shall complain of you."

The two boys walked off in opposite directions, the gentleman keeping an eye upon Oscar until Whistler was out of his reach.

A little knot of boys was drawn together by the circumstance just related, among whom was George, Oscar's youngest brother. He witnessed the attack, but knew nothing of its cause. As he went directly home, while Oscar did not, he had an opportunity to report to his mother and Ralph the scene he had just beheld. Ralph now related to his mother the incident of the preceding day, which led to the assault; for, seeing Oscar's unwillingness to have anything said about it, he had not mentioned the matter to any one at home. Ralph was a generous-hearted boy, and in this case was actuated by a regard for Oscar's feelings, rather than by fear.

Oscar did not come home that night until after dark. As he entered the sitting-room, Alice, who was seated at the piano-forte, broke short off the piece she was playing, and said, looking at him as sternly as she could,

"You great ugly boy!"

"Why, what's the matter now?" inquired Oscar, who hardly knew whether this rough salutation was designed to be in fun or in earnest; "don't I look as well as usual?"

"You looked well beating little Willie Davenport, don't you think you did?" continued his sister, with the same stern look. "I 'm perfectly ashamed of you—I declare, I did n't know you could do such a mean thing as that."

"I don't care," replied Oscar, "I 'll lick him again, if he does n't mind his own business."

As Oscar did not know that George witnessed the assault, he was at a loss to know how Alice heard of it. She refused to tell him, and he finally concluded that Whistler or his mother must have called there, to enter a complaint against him. Pretty soon Mrs. Preston entered the room, and sat down, to await the arrival of Oscar's father to tea. She at once introduced the topic which was uppermost in her mind, by the inquiry:

"Oscar, what is the trouble between you and Willie Davenport?"

"Why," replied Oscar, "he 's been telling stories about me."

"Do you mean false stories?"

"Yes—no—not exactly false, but it was n't true, neither."

"It must have been a singular story, to have been either false nor true. And as it appears there was but one story, I should like to know what it was."

"He told Ralph I had to stand up and look at a blackboard an hour."

"Was that false?"

"Yes," said Oscar, for in replying to his mother, of late, he had usually omitted the "ma'am" (madam) which no well-bred boy will fail to place after the yes or no addressed to a mother; "yes, it was a lie, for I need n't have stood there five minutes, if I had n't wanted to."

"Did you stand before the blackboard because you wanted to, or was it intended as a punishment for not attending to your lesson!"

"Why, I suppose it was meant for a punishment, but the master told me I might go to my seat, whenever I wanted to study."

"Then," said Mrs. Preston, "after all your quibbling, I don't see that Willie told any falsehood. And, in fact, I don't believe he had any idea of injuring you, when he told Ralph of the affair. He only spoke of it as a little matter of news. But even if he had told a lie about you, or had related the occurrence out of ill-will towards you, would that be any excuse for your conduct, in beating him as you did this afternoon! Do you remember the subject of your last Sabbath-school lesson?"

Oscar could not recall it, and shook his head in the negative.

"I have not forgotten it," continued his mother; "it was on forgiving our enemies, and it is a lesson that you very much need to learn. 'If ye forgive not men their trespasses, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses,'—that was one of the verses of the lesson. It is noble to forgive, but it is mean to retaliate. You must learn to conquer your resentful spirit, or you will be in trouble all the time. I shall report this matter to your father when he comes. I suppose you remember what he promised you, when you had your fight with Sam Oliver?"

Oscar remembered it very distinctly. On that occasion, his father reprimanded him with much severity, and assured him that any repetition of the fault would not go unpunished.

Mr. Preston soon came in, and as the family sat at the tea-table, he was informed of Oscar's misconduct. After scolding the culprit with much sharpness, for his attack upon Willie, he concluded by ordering him immediately to bed. Although it yet lacked two hours of his usual bed-time, Oscar did not consider his punishment very severe, but retired to his chamber, feeling delighted that he had got off so much easier than he anticipated. Indeed, so little did he think of his father's command, that he felt in no hurry to obey it. Instead of going to bed, he sat awhile at the window, listening to the music of a flute which some one in the neighborhood was playing upon. Presently Ralph and George, who slept in the same chamber with him, came up to keep him company. They amused themselves together for some time, and Oscar quite forgot that he had been sent to bed, until the door suddenly opened, and his father, whose attention had been attracted by the noise, stood before him.

"Did n't I tell you to go to bed an hour ago, Oscar?" he inquired.

"Yes, sir."

"Why have n't you obeyed me, then?"

"Because," said Oscar, "I 've got a lesson to get to-night, and I have n't studied it yet."

"If you 've got a lesson to learn, where is your book?" inquired his father.

"It 's down stairs; I was afraid to go after it, and so I was trying to coax Ralph to get it for me."

"O, what a story!" cried George; "why, father, he has n't said one word about his book."

This was true. Oscar, in his extremity, had hastily framed a falsehood, trusting that his assurance would enable him to carry it through. And he would probably have succeeded but for George; as Ralph, in his well-meant but very mistaken kindness for Oscar, would not have been very likely to expose him. But the lie was nailed, and Oscar's bold and wicked push had only placed him in a far worse position than he occupied before. His father, for a moment, could scarcely believe his ears; but this feeling of astonishment soon gave way to a frown, before which Oscar cowered like a sheep before a lion. Mr. Preston was a man of strong passions, but of few words. Having set forth briefly but in vivid colors the aggravated nature of Oscar's three-fold offence,—his attack upon Willie, his disobedience when ordered to bed, and the falsehood with which he attempted to cover up his disobedience,—he proceeded to inflict summary and severe chastisement upon the offender. It was very rarely that he resorted to this means of discipline, but this he deemed a case where it was imperatively demanded.

Silence reigned in the boys' chamber the rest of the night. Oscar was too sullen to speak; Ralph silently pitied his brother, not less for the sins into which he had fallen than for the pain he had suffered; and George was too much taken up with thinking about the probable after-clap of this storm, to notice anything else.

Oscar was fond of his bed, and was usually the last one of the family to rise, especially in cool weather. On the morning after the occurrences above related, he laid abed later than usual even with him. His father had gone to the store, and the children were out-doors at play, before he made his appearance at the breakfast-table. He sat down to the deserted table, and was helping himself to the cold remnants of the meal, when his mother entered the room. Oscar noticed that she looked unusually sad and dejected. After sitting in silence a few moments, she remarked:

"You see how I look, this morning, Oscar. I did not sleep half an hour last night, and now I am not fit to be up from my bed—and all on your account. I am afraid your misconduct will be the death of me, yet. I used to love to think how much comfort I should take in you, when you should grow up into a tall, manly youth; but I have been sadly disappointed, so far. The older you grow, the worse you behave, and the more trouble you make me. Do you intend always to go on in this way?"

Oscar nervously spread the slice of bread before him, but made no reply. His mother continued her reproofs, in the same sad but affectionate tone. She appealed to his sense of right, to his gratitude, and to his hopes of future success and respectability in life. She described the sad end to which these beginnings of wrong-doing would inevitably lead him, and earnestly besought him to try to do better, before his bad habits should become confirmed. Her earnest manner, and her pale, haggard cheeks, down which tears were slowly stealing, touched the feelings of Oscar. Moisture began to gather in his eyes, in spite of himself. He tried to appear very much interested in the food he was eating, and to look as though he was indifferent to what his mother was saying. And, in a measure, he did succeed in choking down those good feelings which were beginning to stir in his heart, and which, mistaken boy! he thought it would be unmanly to betray.

Yes, he was mistaken—sadly mistaken. Unmanly to be touched by a mother's grief, and to be moved by a mother's tender entreaties! Unmanly to acknowledge that we have done wrong, or to express sorrow for the wrong act! Unmanly to resolve to resist temptation in the future! Where is this monstrous law of manliness to be found? If anywhere, it must be only in the code of pirates and desperadoes, who have renounced all human laws and ties.

The school hour was at hand, and Oscar was obliged to start as soon as he had finished his breakfast. Had he not stifled the better promptings of his heart, and thus done violence to his nature, he would not have left his mother without assuring her that he felt sorry for his misconduct; for he did feel some degree of regret, although he was too proud to acknowledge it. His mother, however, saw some tokens of feeling which he could not wholly conceal, and she left him with a sad heart, but with the hope that at least some faint impression had been made upon him.

And, indeed, some impression was made upon Oscar's heart. The feeling of sullenness with which he awoke, had subsided into something resembling "low spirits." Nor was this all the effect his mother's conversation had upon him. As he lay awake in the morning, he had planned the secret destruction of a beautiful sled which had been given to George, the winter previous, and which was very precious in the eyes of the owner; but now he relinquished this mean and revengeful design. Little George thus escaped the dreaded "after-clap," but he never knew what a blow it would have been, nor how near he came to feeling its full force.

One of Oscar's most intimate companions was a boy of about his own age, named Alfred Walton, who attended the same school with him. Alfred's father was dead; but he had a step-father, whom he called father, and with whom he lived. His home was to Oscar a very attractive one; for it was a public house, and had large stables and a stage-office attached, and was usually full of company. Alfred's step-father was the landlord of the hotel, and of course he and his young friends were privileged characters about the premises. Oscar and Alfred were together a great deal of the time, when out of school, and quite a warm friendship existed between them. On Wednesday and Saturday afternoons, and during the other play hours of the week, Oscar might generally be found about the hotel premises, or riding on the coaches with Alfred. He only regretted that he could not stay there altogether; for he thought it must be a fine thing to live in such a place, where he could do pretty much as he pleased, without anybody's interference. Such, at least, seemed to be the privilege of Alfred; for everybody, from his step-father down to the humblest servants, appeared to have too much other business on their hands to give much attention to his boyish movements.

Oscar made many acquaintances at the hotel, not a few of which were anything but desirable for a boy of his age and character. He was on chatty terms with all the stage-drivers, hostlers, and servants about the premises, and also got acquainted with many strangers who stopped there for a season. He was very fond of listening to the stories of the drivers and other frequenters of the stage-office, and he would sit by the hour, inhaling the smoke of their cigars, admiring their long yarns, and laughing at the jokes they cracked. Much of this conversation was coarse and even vulgar, such as a pure mind could not listen to without suffering contamination, or at least a blunting of its delicate sensibilities. It is a serious misfortune for a youth to be exposed to such influences, but Oscar did not know it, or did not believe it.

Among the hangers about the stable, was a queer fellow who went by the name of Andy. His real name was Anderson. He was weak-minded and childish, his lack of intellect taking the form of silliness rather than of stupidity. Indeed, he was bright and quick in his way, but it was a very foolish and nonsensical way. He was famous among all the boys of the neighborhood, for using strange and amusing words, and especially for a system of spelling on which he prided himself, and which is not laid down in any of the dictionaries. He afforded much sport to the boys, who would gather around him, and give him words by the dozen to spell. The readiness and ingenuity with which he would mis-spell the most simple words, was quite amusing to them. He never hesitated, nor stopped to think, but always spelt the given word in his peculiar way, just as promptly as though he did it according to a rule which he perfectly understood.

One Saturday afternoon, as Oscar and Alfred were looking about the stable, Andy suddenly made his appearance, and asked them for a bit of tobacco. Both of the boys, by the way, wished to be considered tobacco-chewers, and usually carried a good-sized piece of the vile weed in their pockets, though it must be confessed that the little they consumed was rather for appearance sake, than because they liked it. They also smoked occasionally, for the same reason.

"You must spell us a word or two, first," said Alfred, in reply to Andy's request.

"No, I can't stop—got important business to negotiate," replied Andy.

"Yes, you must," continued Alfred; "spell fun."

"P-h-u-g-n," said Andy.

"Spell hotel," continued Alfred.

"H-o-e-t-e-l-l-e."

"Spell calculate," said Oscar.

"K-a-l-k-e-w-l-a-i-g-h-t—there, that 'll do," continued Andy.

"No, spell one more word—spell tobacco, and you shall have it," added Alfred.

"T-o-e-b-a-c-k-k-o-u-g-h—now hand over the 'baccy.'"

"I have n't got any—have you, Oscar?" said Alfred

Oscar fumbled in his pockets, but there was none to be found.

"You mean, contemptible scalliwags!" exclaimed Andy, "why did n't you tell me that before? You catch me in that trap again, if you can!" and he walked off in a passion, amid the laughter of Oscar and Alfred.

"Let's go and see the pups, Alf," said Oscar, after they had got done laughing over the joke they had played upon Andy.

Alfred's step-father had a fine dog of the hound species, with a litter of cunning little pups. A bed had been made for her and the little ones in a corner of the yard, adjoining the stable, with a rough covering to shelter them from wind and storms. The pups were now several weeks old. There were five of them, and a fat and frolicksome set they were too. As the boys approached them, they were frisking and capering as usual; tumbling and rolling over one another, climbing upon the back of their mother, and pulling and barking at the straw. Their mother, whose name was Bright, sat watching their gambols with a very affectionate but sedate look. Perhaps she was wondering whether she was ever so mischievous and frisky as these little fellows were. When the pups looked up and saw the boys, they stopped their fun for a time, for they were not yet much accustomed to company. Bright, however, knew both Alfred and Oscar; and as she was a dog of good education and accomplished manners, she did not allow herself to be disconcerted in the least by their presence.

"You did n't know father had given all the pups but one to me, did you, Oscar?" inquired Alfred.

"No,—has he, though?" asked Oscar.

"Yes, he has. I knew I could make him say yes, and so I teased him till he did. He 's going to pick out one, to keep, and I 'm to have all the rest."

"That's first-rate," said Oscar; "and you 'll give me one, won't you?"

"Yes, you may have one," replied Alfred; "but don't tell the boys I gave it to you, for I mean to sell the others."

"Then I 'll pay you for mine," continued Oscar; "I can get the money out of father, I guess."

"No, you shan't pay for it, for I meant you should have one of them, if you wanted it," replied Alfred.

"Thank you," said Oscar, "I should like one very much."

After looking at the dogs awhile, and canvassing their respective merits, they happened to notice that one of the drivers was about starting off with his coach.

"Halloo, Mack!" cried Alfred, "where are you going!"

"To the depôt," replied the driver.

"Let's go, Oscar," said Alfred; and both boys ran for the coach, the driver stopping until they had climbed up to his seat.

A ride of five minutes brought them to the depôt, where the driver reined up, to await the arrival of a train, which was nearly due. Many other carriages, of various kinds, were standing around the depôt, for the same purpose. Oscar and Alfred rambled about the building and adjoining grounds, watching the operations that were going on; for though they had witnessed the same operations many times before, there is something quite attractive about such scenes, even to older heads than theirs. On one track, within the depôt, were six or eight cars, beneath which a man was crawling along, carefully examining the running gear, and giving each wheel two or three smart raps with a hammer, to see if it had a clear and natural ring. These cars had lately arrived from a distant city, and must undergo a careful scrutiny before they are again used. If any break or flaw is discovered, the car is sent out to the repair-shop. On another track, the men were making up the next outward train. The particular baggage and passenger cars that were to be used, had to be separated from the others, and arranged in their proper order. Another track was kept clear, for the train that was soon to arrive. Two or three locomotives, outside of the depôt, were fizzing and hissing, occasionally moving back or forward, with a loud coughing noise, or changing from one track to another.

The bell of the looked-for train was at length heard. The engine, as it approached, was switched upon a side-track, but the cars, from which it had been detached, kept on their course until the brakes brought them to a stand in the depôt. The passengers now swarmed forth by hundreds—a curious and motley crowd of men, women, and children; good-looking people, and ill-looking ones; the fine lady in silk, and the rough backwoods-man in homespun; the middle-aged woman in black, with three trunks and four bandboxes, and the smooth-faced dandy, whose sole baggage was a slender cane.

The cars were at length emptied of their living freight, and most of the passengers had secured their baggage. Those who wished to ride, had mostly engaged seats in the various hacks and coaches, whose drivers accosted every passenger, as he got out of the cars, with their invitations to "ride up." Alfred and Oscar now started to look after the stage-coach in which they rode to the depôt. They found it loaded with passengers and baggage, and the driver was talking with two small lads, of from twelve to thirteen years of age.

"Here, Alf," said the driver, "you are just the fellow I want, but I thought you had gone. These boys want to go to the hotel, but I have n't room to take them. They say they had just as lief walk, and if you 'll let them go with you, I 'll take their trunk along."

This was readily agreed to. The driver made room for the trunk on the top of the coach, and the young strangers started for the hotel, in company with Alfred and Oscar. As they walked along, they grew quite sociable. The two new-comers,—who, by the way, were quite respectable in their appearance,—stated that they belonged in one of the cities of Maine, and had never been in Boston before. They were brothers; and both their parents being dead, they said they were on their way to the west, where they had an uncle, who had sent for them to come and live with him. They had a good many questions to ask about Boston, and said they meant to look around the city some the next day, as they must resume their journey on Monday. Alfred said he would go with them, and show them the principal sights; and Oscar, too, would have gladly volunteered, were it not that his father required him to go to church and the Sabbath-school on that day, and to stay in the house when not thus engaged.

The boys had now reached the hotel, where the trunk had already arrived. A room was appropriated to the young guests, and Alfred and Oscar conducted them to it, and remained awhile in conversation with them. By-and-bye, the oldest of the strangers asked Alfred if he would go and show them where they could buy some good pistols. Alfred readily agreed to this, and the four boys started off towards the shops where such articles are sold. On their way through the crowded streets, the new-comers found much to attract their attention. They seemed inclined to stop at every shop window, to admire some object, and it was nearly dark when they reached the place where they were to make their purchase. Here, amid the variety of pistols that were exhibited to them, they were for a time unable to decide which to choose. At length, however, aided by the advice of Alfred and Oscar, they picked out two that they concluded to buy. They also purchased a quantity of powder and balls, and then desired to look at some dirks, two of which they decided to take. Some fine pocket-knives next arrested their attention, which were examined, and greatly admired by all the boys. The oldest of the strangers, who did all the business, concluded to take four of these, and then settled for all the articles purchased. The bill was not very small, but his pocket-book was evidently well supplied, and he paid it with out any difficulty.

After they had left the store, the oldest boy gave Oscar and Alfred, each, one of the pocket-knives, to pay them for their trouble, as he expressed it. They were much pleased with their present, and felt very well satisfied with their afternoon's adventure. They were a little surprised, however, that their new friends should think it necessary to invest so largely in weapons of defence; and on their hinting this surprise, the boy who purchased the articles said, with a careless, business-like air:

"O, we 've got to travel a good many hundred miles, and there 's no knowing what rough fellows we may fall in with. But give me a good revolver and dirk, and I bet I will take care of myself, anywhere."

The seriousness with which this brave language was uttered by a boy scarcely yet in his teens, would have made even Alfred and Oscar smile, but for the consciousness of the new knives in their pockets.

It was now quite dark, and on coming to a street which led more directly towards his home, Oscar left the other boys, with the promise of seeing them again Monday morning.

The Sabbath came, and a fine autumnal day it was. Oscar's thoughts were with Alfred, and the boys whose acquaintance he had made the afternoon previous; but there was little chance for him to join them in their walks on that day. He could not absent himself from church or the Sunday-school, without his parents' knowledge; and Mr. Preston had always decidedly objected to letting the children stroll about the streets on the Sabbath. Oscar felt so uneasy, however, that in the afternoon, a little while before meeting-time, he left the house slyly, while his father was upstairs, and walked around to Alfred's. But he saw nothing of the boys, and was in his accustomed seat in the church when the afternoon services commenced.

The next morning, Oscar rose earlier than usual, and as soon as he could despatch his breakfast, he hurried over to the hotel. The travellers had concluded to defer their journey one day longer, that they might have a better opportunity to see Boston; and when Oscar approached them, they were trying to persuade Alfred to stay away from school, and accompany them in their rambles. They immediately extended the same invitation to Oscar. Both he and Alfred felt very much inclined to accede to their proposition, but they were pretty sure that it would be useless to ask their parents' consent to absent themselves from school for such a purpose. The point to be settled was, whether it would be safe to play truant for the day. Seeing that they hesitated, the oldest boy, whose name was Joseph, began to urge the matter still more earnestly.

"What are you afraid of?" he said; "come along, it's no killing affair to stay away from school just for one day. You can manage so that nobody will know it; and if they should find it out, it won't make any difference a hundred years hence. Come, now, I 'll tell you what I 'll do; if you two will go around with us to-day, I 'll give you a quarter of a dollar apiece."

Oscar and Alfred, after some little hesitation, yielded to their request, and the four boys started on their tramp. It was not without many misgivings, however, that Oscar decided to accompany them. With him, the chances of detection were much greater than with Alfred. No brothers of the latter attended school, to notice and report his absence. With Oscar, the case was different, and he did not see exactly how his truancy was to be concealed from his parents and teachers. But as Alfred was going with the boys, he finally concluded that he, too, would run the risk for at least half a day, and trust to luck to escape punishment.

It was decided to go over to the neighboring city of Charlestown, first, and visit the Monument and Navy-Yard, both of which the young strangers were quite anxious to see. Joseph, the oldest and most forward, began to be on quite intimate terms with Oscar and Alfred. He threw off every restraint, and laughed and talked with them just as if they were old acquaintances. One thing very noticeable about him, was his profanity. Neither Alfred nor Oscar, I am sorry to say, was entirely free from this wicked and disgusting habit; but they had made so little advance in this vice, compared with their new friend, that even they were slightly shocked by the frequent and often startling oaths of Joseph.

The younger lad, whose name was Stephen, appeared to be quite unlike his brother. Though sociable, he was less gay and more reserved than Joseph, but he seemed to be much interested in the novel sights that met his eye at every step.

On their way, the boys came to a cellar which was occupied by a dealer in fruits and other refreshments. Around the entrance were arranged numerous boxes of oranges, apples, nuts, candy, and similar articles, to tempt the passer-by to stop and purchase. The owner was not in sight, and Joseph, as he passed along, boldly helped himself from one of the boxes, taking a good hand-full of walnuts. On looking around, a moment after, he saw a man running up the cellar steps, and concluded that he, too, had better quicken his pace. He accordingly started on a brisk run, the other boys joining in his flight. The man, who happened to witness the theft from the back part of the cellar, soon saw that pursuit would be useless, and contented himself with shaking his fist, and uttering some anathemas which were inaudible to those for whom they were intended.

"That was a pretty narrow escape, was n't it?" said Joseph, after they had got a safe distance from the man.

"It was so," replied Alfred; "and it was lucky for you that he did n't catch you."

"Why, what do you suppose he would have done?"

"He would have taken you up for stealing, I guess, for he looked mad enough to do anything," said Alfred.

"Stealing? Pooh, a man must be a fool to make such a fuss about a cent's-worth of nuts," replied Joseph.

"I knew a boy," said Oscar, "who stole a cake of maple sugar from one of these stands, and his father had to pay two or three dollars to get him out of the scrape."

"I would n't have done it," said Joseph; "I 'd have gone to jail first—that 's just my pluck."

"But the boy did n't do it—it was his father that paid the money," added Oscar.

"O, then, I suppose the boy was n't to blame," said Joseph, with all seriousness; as though he really believed that somebody was to blame, not for stealing the maple sugar, but for satisfying the man who had been injured by the theft.

They were now upon one of the bridges which cross Charles River, and connect the cities of Boston and Charlestown. After passing half-way over, they stopped a few minutes to gaze at the scene spread out around them. Oscar and Alfred pointed out to the strangers the various objects of interest, and they then continued their walk without interruption until they reached the Monument grounds, on Bunker Hill. After examining the noble granite shaft which commemorates the first great battle of the American Revolution, they threw themselves down upon the grass, to contemplate at their leisure the fine panorama which this hill affords on a clear day.

After lingering half an hour around the Monument, they turned their steps towards the Navy-Yard. On reaching it, they found a soldier slowly pacing back and forth, in front of the gate-way; but he made no objection to their entering. Joseph and Stephen, who had never before visited an establishment of this kind, were first struck by the extent of the yard, and the air of order and neatness which seemed everywhere to prevail. They gazed with curiosity upon the long rows of iron cannons interspersed with pyramids of cannon-balls, piled up in exact order, which were spread out upon the parks. Then their wonder was excited by the dry-dock, with its smooth granite walls, its massive gates, and its capacious area, sufficient to float the largest frigate. The lofty ship-houses in which vessels are constructed, and the long stone rope-walk, with its curious machinery, also attracted their attention. So interested were they in these things, that nearly two hours elapsed before they started for home.

On their way back to the hotel, Joseph entertained Alfred and Oscar with some incidents of his life. His mother, he said, died when he was quite young. His father went to sea as the captain of a ship, two years before, and had never been heard from. He had rich relatives, who wanted him to go to West Point and be a cadet, but he did not like to study, and had persuaded them to let him and Stephen go and live with their uncle at the west, who had no boys of his own, and wanted somebody to help him to manage his immense farm. Such, in brief, was Joseph's story.

On their return route, the boys were careful to avoid passing by the cellar from which Joseph had stolen the nuts. With all his pluck and bravery, he did not care about meeting the man whose displeasure he had excited a few hours before.

It was twelve o'clock before the boys reached the hotel. Oscar, during the latter part of the walk, had been unusually silent. He was thinking how he should manage to conceal his truancy, but he could not hit upon any satisfactory plan. The more he reflected upon the matter, the more he was troubled and perplexed about it. He might possibly hide his mis-spent forenoon from his parents, but how should he explain his absence to his teachers? He could not tell. He decided, however, to see his brothers before they should get home from school, and, if they had noticed his absence, to prevail upon them to say nothing about it.

"You 'll be back again after dinner, Oscar?" said Alfred, as his friend started for home.

"Yes," replied Oscar, with some hesitation; "I 'll see you before school-time."

"School-time? You don't intend to go to school this afternoon, do you?" inquired Alfred.

Oscar did not reply, but hastened homeward. He soon found Ralph and George, but as neither of them spoke of his absence from school, he concluded that they were ignorant of it, and he therefore made no allusion to the subject.

After dinner, Oscar had about half an hour to spend with Alfred; for he felt so uneasy in his mind, that he had decided not to absent himself from school in the afternoon. He had gone but a short distance when he met his comrade, who had started in pursuit of him.

"Well," said Alfred, "we 've been taken in nicely, that's a fact."

"Taken in—what do you mean?" inquired Oscar.

"Why, by those young scamps that we 've been showing around town."

"I thought they told great stories," said Oscar; "but what have you found out about them?"

"I 've found out that they are the greatest liars I ever came across—or at least that the oldest fellow is," replied Alfred; and he then went on to relate what transpired immediately after Oscar left them, on their return from Charlestown. The landlord, it seems, requested the two strange boys to step into one of the parlors; and Alfred, not understanding the order, accompanied them. They found two men seated there, the sight of whom seemed anything but pleasant to Joseph and Stephen. These men were their fathers—for the boys were not brothers, and Joseph's account of their past life and future prospects was entirely false. They had run away from home, and the money which they had so profusely spent, Joseph stole from his father. The men, who had been put to much trouble in hunting up their wayward sons, did not greet them very cordially. They looked stern and offended, but said little. Joseph was obliged to deliver up his money to his father, and they immediately made preparations for returning home by the afternoon train.

"Well," said Oscar, when Alfred had concluded his story, "I did n't believe all that boy said, at the time, but I thought I would n't say so."

"Nor I, neither," said Alfred. "I guess he did n't expect his father's ship would arrive so suddenly, when he tried to stuff us up so."

"Did your father know you went off with them in the forenoon?" inquired Oscar.

"Yes, but he did n't care much about it. He told me I must go to school this afternoon, and not stay away again without leave."

The rules of the school required a written note of excuse from the parents, in case of absence. Neither of the boys was furnished with such an excuse, and after a little consultation, they concluded that their chances of escaping punishment would be greatest, if they should frankly confess how they had been duped and led astray by the young rogues whose acquaintance they had so suddenly and imprudently formed. They supposed that the peculiar circumstances of the case, coupled with a voluntary confession, might excite some degree of sympathy, rather than displeasure, towards them. To make the matter doubly sure, it was arranged that Alfred should speak to the master about the matter before school commenced.

When the boys reached the school-room, they found the master already at his desk. He listened with interest to Alfred's story of the runaways, and was evidently pleased that he had so frankly confessed his fault. As the hour for commencing the afternoon session had arrived, he told Alfred and Oscar they might stop after school, and he would take their case into consideration.