This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Gold Hunter's Adventures

Or, Life in Australia

Author: William H. Thomes

Illustrator: Champney

Release Date: June 13, 2005 [eBook #16050]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GOLD HUNTER'S ADVENTURES***

BOSTON:

LEE AND SHEPARD, PUBLISHERS.

NEW YORK:

CHARLES T. DILLINGHAM.

| INTRODUCTION | 13 | |

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| FIRST THOUGHTS OF GOING TO AUSTRALIA.—DEPARTURE FROM CALIFORNIA.—LIFE ON BOARD SHIP.—ARRIVAL AT WILLIAMS TOWN.—DESCRIPTION OF MELBOURNE.—A CONVICT'S HUT. | 15 | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| A MORNING IN AUSTRALIA.—JOURNEY TO THE MINES OF BALLARAT.—THE CONVICT'S STORY.—BLACK DARNLEY, THE BUSHRANGER. | 20 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| TRAVELLING IN AUSTRALIA.—AN ADVENTURE WITH SNAKES.—CARRYING THE MAILS. | 29 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| EATING BROILED KANGAROO MEAT.—AUSTRALIAN SPEAKS AND AMERICAN RIFLES. | 34 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| THE SOLITARY STOCKMAN.—SHOOTING A KANGAROO. | 41 | |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| ADVENTURE WITH A DOG.—THE MURDER IN THE RAVINE.—STORY OF AN OUTRAGED WOMAN. | 47 | |

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| BLACK DARNLEY'S VILLANY.—THE CONVICT STOCKMAN. | 56 | |

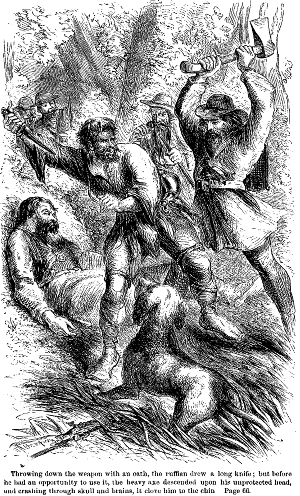

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| AN EXPEDITION.—A FIGHT WITH BUSHRANGERS.—DEATH OF BLACK DARNLEY. | 61 | |

| CHAPTER IX. | ||

| THE STOCKMAN'S DAUGHTER.—MOUNTED POLICE OF MELBOURNE. | 68 | |

| CHAPTER X. | ||

| DESPERATE DEEDS OF TWO CONVICTS.—LIEUT. MURDEN'S STORY. | 73 | |

| CHAPTER XI. | ||

| SAGACITY OF A DOG.—A NIGHT'S ADVENTURES. | 79 | |

| CHAPTER XII. | ||

| DISCOVERY OF A MASONIC RING.—FUNERAL PYRE OF BLACK DARNLEY. | 87 | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | ||

| THE STOCKMAN AND HIS PARROT.—DARING PLOT OF A ROBBER CHIEFTAIN. | 93 | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | ||

| DISCOVERY OF STOLEN TREASURES IN THE STOCKMANS'S CELLAR. | 101 | |

| CHAPTER XV. | ||

| DYING CONFESSION OF JIM GULPIN, THE ROBBER. | 107 | |

| CHAPTER XVI. | ||

| A FORCED MARCH TOWARDS MELBOURNE. | 114 | |

| CHAPTER XVII. | ||

| TRIUMPHAL ENTRY INTO MELBOURNE. | 120 | |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | ||

| LARGE FIRE IN MELBOURNE.—ENGLISH MACHINES AT FAULT. | 127 | |

| CHAPTER XIX. | ||

| PARDON OF SMITH AND THE OLD STOCKMAN.—GRAND DINNER AT THE GOVERNOR'S. | 134 | |

| CHAPTER XX. | ||

| DUEL BETWEEN FRED AND AN ENGLISH LIEUTENANT. | 142 | |

| CHAPTER XXI. | ||

| PREPARATIONS FOR THE SEARCH FOR GULPIN'S BURIED TREASURES. | 151 | |

| CHAPTER XXII. | ||

| DEPARTURE FROM MELBOURNE.—FIGHT WITH THE NATIVES. | 158 | |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | ||

| ARRIVAL AT THE OLD STOCKMAN'S HUT.—MYSTERIOUS INTERRUPTIONS DURING THE HUNT. | 164 | |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | ||

| ROBBERY OF THE CART.—CAPTURE OF STEEL SPRING. | 171 | |

| CHAPTER XXV. | ||

| STEEL SPRING'S HISTORY. | 176 | |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | ||

| FINDING OF THE TREASURE. | 181 | |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | ||

| CAPTURE OF ALL HANDS, BY THE BUSHRANGERS. | 187 | |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | ||

| OPPORTUNE ARRIVAL OF LIEUTENANT MURDEN AND HIS FORCE.—ROUT OF THE BUSHRANGERS. | 195 | |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | ||

| REVENGE OF THE BUSHRANGERS.—FIRING OF THE FOREST. | 201 | |

| CHAPTER XXX. | ||

| PERILOUS SITUATION DURING THE FIRE.—STEEL SPRING TURNS UP. | 208 | |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | ||

| CAPTURE OF THE BUSHRANGERS, AND DEATH OF NOSEY. | 213 | |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | ||

| RETURN TO THE STOCKMAN'S HUT.—SMITH IN LOVE. | 219 | |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | ||

| RECOVERY OF THE GOLD.—ARRIVAL AT BALLARAT. | 226 | |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | ||

| THE BULLY OF BALLARAT.—FRED FIGHTS A DUEL. | 234 | |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | ||

| BALLARAT CUSTOMS, AFTER A DUEL. | 242 | |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | ||

| ARRIVAL AT BALLARAT.—MR. BROWN'S STORY. | 249 | |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | ||

| FINDING OF A 110 LB. NUGGET.—CAVING IN OF A MINE. | 257 | |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | ||

| INCIDENTS IN LIFE AT BALLARAT. | 265 | |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | ||

| ATTEMPT OF THE HOUSEBREAKER.—ATTACK BY THE SNAKE. | 272 | |

| CHAPTER XL. | ||

| DEATH OF THE BURGLAR BY THE SNAKE. | 278 | |

| CHAPTER XLI. | ||

| VISIT TO SNAKES' PARADISE. | 284 | |

| CHAPTER XLII. | ||

| FLIGHT FROM THE SNAKES.—ATTACKED BY THE BUSHRANGERS. | 291 | |

| CHAPTER XLIII. | ||

| TRIUMPHANT ENTRY INTO BALLARAT, WITH THE BUSHRANGERS. | 299 | |

| CHAPTER XLIV. | ||

| THRASHING A BULLY. | 305 | |

| CHAPTER XLV. | ||

| A YOUNG GIRL'S ADVENTURES IN SEARCH OF HER LOVER. | 312 | |

| CHAPTER XLVI. | ||

| A MARRIAGE, AND AN ELOPEMENT. | 318 | |

| CHAPTER XLVII. | ||

| COLLECTING TAXES OF THE MINERS. | 326 | |

| CHAPTER XLVIII. | ||

| MURDEN AND STEEL SPRING ARRIVE FROM MELBOURNE. | 333 | |

| CHAPTER XLIX. | ||

| CATCHING A TARL AS WELL AS A CASSIOWARY. | 340 | |

| CHAPTER L. | ||

| ARRIVAL OF SMITH.—ATTEMPT TO BURN THE STORE. | 346 | |

| CHAPTER LI. | ||

| ATTEMPT TO BURN THE STORE. | 353 | |

| CHAPTER LII. | ||

| THE ATTEMPT TO MURDER MR. CRITCHET. | 359 | |

| CHAPTER LIII. | ||

| OPPORTUNE ARRIVAL OF MR. BROWN.—THEY SEND FOR STEEL SPRING. | 366 | |

| CHAPTER LIV. | ||

| THE WAY THE COLONISTS OBTAIN WIVES IN AUSTRALIA. | 372 | |

| CHAPTER LV. | ||

| ADVENTURES AT DAN BRIAN'S DRINKING-HOUSE. | 378 | |

| CHAPTER LVI. | ||

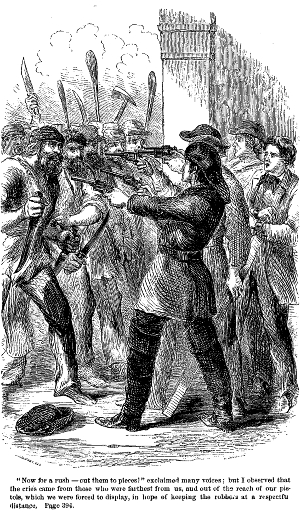

| ADVENTURES CONTINUED. | 383 | |

| CHAPTER LVII. | ||

| MORE OF THE SAME SORT. | 390 | |

| CHAPTER LVIII. | ||

| CONVALESCENCE OF MR. CRITCHET, AND OUR DISCHARGE FROM THE CRIMINAL DOCKET. | 398 | |

| CHAPTER LIX. | ||

| OUR TEAMSTER BARNEY, AND HIS WIFE. | 403 | |

| CHAPTER LX. | ||

| MIKE FINDS THE LARGE "NUGGET." | 410 | |

| CHAPTER LXI. | ||

| THE RESULT OF GROWING RICH TOO RAPIDLY. | 414 | |

| CHAPTER LXII. | ||

| THE FLOUR SPECULATION.—MR. CRITCHET'S STORY. | 419 | |

| CHAPTER LXIII. | ||

| THE SAME, CONTINUED. | 427 | |

| CHAPTER LXIV. | ||

| MR. BROWN'S DISCHARGE FROM THE POLICE FORCE.—BILL SWINTON'S CONFESSION. | 434 | |

| CHAPTER LXV. | ||

| THE EXPEDITION AFTER BILL SWINTON'S BURIED TREASURES. | 439 | |

| CHAPTER LXVI. | ||

| JOURNEY AFTER THE BURIED TREASURE. | 445 | |

| CHAPTER LXVII. | ||

| THE HUNT FOR THE BURIED TREASURE. | 451 | |

| CHAPTER LXVIII. | ||

| THE ISLAND GHOST.—NARROW ESCAPE OF MR. BROWN. | 456 | |

| CHAPTER LXIX. | ||

| CAPTURE OF THE GHOST. | 461 | |

| CHAPTER LXX. | ||

| THE GHOST AND THE BUSHRANGERS. | 468 | |

| CHAPTER LXXI. | ||

| SAM TYRELL AND THE GHOST. | 474 | |

| CHAPTER LXXII. | ||

| FINDING THE BURIED TREASURE. | 484 | |

| CHAPTER LXXIII. | ||

| THE ESCAPE FROM THE FIRE. | 490 | |

| CHAPTER LXXIV. | ||

| ARRIVAL AT MR. WRIGHT'S STATION. | 496 | |

| CHAPTER LXXV. | ||

| SUPPER.—RETURN OF MR. WRIGHT'S SCOUTS. | 501 | |

| CHAPTER LXXVI. | ||

| MIKE TUMBLES INTO THE RIVER.—ARRIVAL OF THE BUSHRANGERS. | 511 | |

| CHAPTER LXXVII. | ||

| CAPTURE OF THE BUSHRANGERS. | 517 | |

| CHAPTER LXXVIII. | ||

| PUNISHING THE BULLY. | 524 | |

| CHAPTER LXXIX. | ||

| MR. WRIGHT'S FARM.—DEATH OF KELLY. | 529 | |

| CHAPTER LXXX. | ||

| JOURNEY BACK TO BALLARAT. | 536 | |

| CHAPTER LXXXI. | ||

| STEEL SPRING IN THE FIELD.—ATTEMPT OF THE COMMISSIONER TO CONFISCATE OUR HORSES. | 542 | |

| CHAPTER LXXXII. | ||

| SAME CONTINUED.—DEATH OF ROSS. | 549 | |

| CHAPTER LXXXIII. | ||

| ARREST OF FRED.—TRIP TO MELBOURNE, AND ITS RESULTS. | 555 |

Since my return from Australia, I have been solicited by a number of friends to give them a history of my adventures in that land of gold, where kangaroos are supposed to be as plenty as natives, and jump ten times as far, and where natives are imagined to be continually lying in ambush for the purpose of making a hearty meal upon the bodies of those unfortunate travellers who venture far into the interior of the country—where bushrangers are continually hanging about camp fires, ready to cut the weasands of those who close their eyes for a moment—and lastly, where every other man that you meet is expected to be a convict, transported from the mother country for such petty crimes as forgery, house-breaking, and manslaughter in the second degree.

My friends have all desired to hear me relate these particulars, and have honored me with a large attendance at my rooms, and sat late at night, and drank my wine and water, and smoked my cigars, with a relish that did me great credit, as it showed that I am something of a connoisseur in the choice of such luxuries. And then they laughed so loudly at my jokes, no matter how poor they were, that, for a few days after my arrival home, I really thought the air of Australia had improved and sharpened my wit.

I should, no doubt, have continued feasting those who listened so patiently to my yarns, had not a sudden idea entered my head, one night, when the company were the most boisterous. I was in the act of raising a glass of wine to my mouth, when it occurred to me that before I left this country for Australia, via California, scarcely one of those present had assembled on the dock to bid me farewell.

I placed the untasted wine upon the table again, lighted a cigar, and was soon buried in smoke and reflection. I thought of the time when I had not money enough to pay my passage to the Golden State—of the exertions I had made to raise the amount necessary, and the many refusals that I had met with at the hands of those who now professed to be my friends.

I blew aside the smoke that enveloped my head, and fixed my eyes upon one red-faced cousin, who owned bank shares, and bought stocks when low, and sold them when a rise had taken place. He had laughed at me for my impertinence in supposing that he could loan me money, and now he was seated at my table, chuckling at my jokes, and swearing, while he helped himself to liquor, that I was the best fellow alive, and that there was nothing but what he would do for me.

Could it be possible that the possession of fifty or sixty thousand dollars had wrought such a change? I was forced to believe it, and I grew sad at the thought, and no more jokes escaped my lips that night; but the company remained as late as usual, and declared by a unanimous vote that they would meet again at the same place the next evening, and hear further particulars.

Before sunset the next day I had changed my apartments, and taken private lodgings with a friend who had visited me but once since my return, and had then refused to accept of the hospitalities that I was disposed to offer him. He had lent me money without security—he had declined taking interest for the same—he had welcomed me on my arrival as warmly as I expected—he did not ask me how much dust I had brought back and he never said a word about his wish to be repaid the few hundred dollars that he had advanced me when I left home to seek my fortune. When I did offer him the money, and thrust a diamond ring upon his finger as a token of my esteem, he blushed like a young school girl, and declared that he didn't deserve it.

At his house, then, I took up my abode; and while his family treat me with respect, they possess none of the fawning which characterizes my other friends. As the latter have frequently expressed their sorrow for my sudden removal, and their anxiety to know what events befell me in the mines of Australia, I have come to the conclusion that I would put them in print; and now those who used to drink my liquor and feast at my table will learn how I acquired my fortune, and then, if so disposed, they can follow in my footsteps and gain a competence for themselves.

This much I have told the reader in confidence, and with the hope that it will not be repeated, as my red-faced cousin, who every day is to be seen on 'Change, might be seriously angry if he was suspected of mercenary motives. With this introduction I will commence my narrative.

It was as hot an afternoon on the banks of the American Fork as ever poor mortals could be subjected to and still retain sufficient vitality to draw their breath. Under a small tent, stretched upon their backs, with shirt collars unbuttoned, boots off, and a most languid expression upon their faces, were two men—both of them of good size, with a fair display of muscle, broad-chested, hands hard and blackened with toil, yet not badly formed; for had they been but covered with neat fitting gloves, and at an opera, ladies might have thought they were small.

These two men, one of whom was reading a newspaper, while the other was trying to take a siesta, were Frederick Button, and his faithful companion, the writer of these adventures, whom we will distinguish by the name of Jack, as it is both familiar and common, and has the merit of being short.

As I was reading the paper, the contents of which interested me, I paid but little attention to my friend, until I suddenly laid it down, and said,—

"Fred, let's go to Australia."

"Go to the d——l," he replied, turning on his side, his back towards me, and uttering a long w-h-e-w, as though he had found it difficult to catch his breath, it was so hot.

"We should find it hotter in the regions of his Satanic Majesty than here; but that is something that concerns you alone, as no doubt you are fully aware."

Fred uttered a grunt—he was too warm to laugh, and I again returned to the charge.

"Gold mines have been discovered in Australia, and ships are up at San Francisco for Melbourne. A party of twenty left there last week, and more are to follow."

There was no reply, and I continued:—

"It is stated in this paper that a man took out a lump of gold weighing one hundred and twenty pounds, and that he had been but ten days in the mines when he found it."

"What?" cried Fred, suddenly sitting up, and wiping the perspiration from his brow.

I repeated the statement.

"It's a d——d lie," cried Fred.

"Then let's go and prove it so."

"How's the climate in that part of the world—hot or cold?"

"About the same as here."

Fred meditated for a few minutes, lighted his pipe, and smoked on in silence; and as there was nothing better to do. I joined him.

"We are not making a fortune here in California, and if we don't do any thing in Australia, we shall see the country, and that will be worth something," I said.

"Then let's go," cried Fred, refilling his pipe; and that very evening we commenced selling our stock of superfluous articles to our numerous neighbors, saving nothing but tent, revolvers, rifles, and a few other articles that would stand us in need when we reached Australia.

A week from the day that we made up our mind to try what luck there was in store for us in Australia, we were on board of a clipper ship, and with some two dozen other steerage passengers (for Fred and myself were determined to be economical) we were passing through the Golden Gate on our way to a strange land, where we did not possess a friend or acquaintance that we knew of.

"Well," said Fred, as he stood on deck at the close of the day, and saw the mountains of California recede from view, "it's precious little fun I've seen in that country; and if our new home is not more exciting, I shall be like the Irishman who pined away because he couldn't get up a fight."

"Don't give yourself any uneasiness on that score," replied the mate, who chanced to overhear the remark. "I'll warrant that you'll see as many musses as you'll care to mix in."

"Then, Australia, thou art my home," cried Fred, with a theatrical wave of his hand, as though bidding adieu to the Golden State forever.

Fred was one of the most peaceable men in the world, and never commenced a quarrel; but when once engaged in a conflict, he was like a lion, and would as soon think of yielding as the royal beast.

For nearly fifty days did we roll on the Pacific, amusing ourselves by playing at "all fours," speculating on the chances of our arrival, and making small wagers on the day that we should drop anchor; and after we had all lost and won about an equal amount, we were one morning overjoyed by the sight of land. Standing boldly in towards a low coast, with no signs of a harbor, it was not until we were within half a mile of the shore that we discovered a narrow entrance that opened into Hobson's Bay; when we dropped anchor opposite to a town consisting of a dozen or twenty houses, and over one of them floated the flag of England.

"Well, Mr. Mate," asked Fred, as the men went aloft to furl sails, "do you call that densely-populated city Melbourne?"

"That!" replied the mate, with a look of contempt at the scattered houses. "That be d——d. That's Williams Town. Melbourne is a fine city, seven miles from here, and where all the luxuries of life can be obtained; but tobacco is the dearest one—so be careful of your weed."

As the officers of the custom house were even then coming on board, we thanked him for the hint, and put ours out of their reach.

Williams Town is situated at the mouth of the River Zarra, on Hobson's Bay, and at one time actually threatened to become a place of considerable importance; but the water for domestic use was too bad to be tolerated, and most of those who had settled there were glad to retrace their steps to Melbourne, where a better sort of article exists.

"How are the mines? Do they still hold out?" I inquired of one of the crew of the custom house boat, who was leaning against the rail in a languid manner, as though he had been overworked for the past six months.

"Yes, I s'pose so," he answered; and he spoke as though each word cost him an immense amount of labor.

"Then, Fred, we are in luck," I cried, turning to my partner who stood near at hand.

"Intend going to the mines?" the man asked, with a sudden show of interest.

"Such is our intention," I replied.

"'Mericans, I suppose," he inquired.

"Yes."

"Then don't go if you want to keep the number of your mess," the boatman said.

"Why not?" Fred ventured to inquire.

"'Cos they kill Yankees at the mines. Jim," he continued, turning to a comrade, "how many 'Mericans were killed week afore last at Ballarat?"

"O, I don't know," replied the individual referred to. "A dozen or twenty, I believe. Might have been more or less. I'm not 'ticular within a man or two."

"Thank you for your information," cried Fred. "And now one question more. Can you tell me how many Englishmen were killed by those same Americans, before they died?"

This question appeared to astonish the men; for they looked at each other, and then examined Fred with scrutinizing glances.

"I guess he'll do," they said, at length; and finding that we were not to be frightened, they turned their attention to passengers more credulous, and actually made some of them believe what they said was true.

The next morning we hired a boat to take our luggage to the wharf, where the steamers, which ply between Sydney, Geelong, and Melbourne, stop. Our traps did not amount to much, as we had no money to spare for freighting, and when we first stepped upon the soil of Australia, our worldly possessions consisted of four shirts, do. pants, two pairs of boots, blankets, tents, &c., the whole weighing just one hundred and fifty pounds—not a large amount, but sufficient for two men, whose wants were easily supplied.

There were a dozen rough, loaferish looking men, whiling away their time upon the wharf; but as they confined themselves to simply asking a few questions as to what part of the world we came from, and received satisfactory answers, they soon lost all interest in us, and began to speculate what time the steamer would arrive.

She did not reach the dock until noon; and as we had seen enough of Williams Town, we readily embarked, and in an hour's time were at Melbourne, gazing with interest at every thing that met our view.

The city was full of life and business: heaps of goods were exposed ready for transportation to the mines, and large, lumbering carts of English build were crawling slowly through the streets, drawn by five and six yoke of oxen, while the drivers, armed with whips, the lashes of which were of immense length, though the stock or handle was barely two and a-half feet long, whirled them over the frightened animals' heads, and whenever they struck the poor brutes, a small, circular piece of skin was taken out, leaving the quivering flesh exposed to the sun, and a prey for the numerous insects that hovered in the air.

We carried our stuff on shore, and then considered what was necessary to get to the mines; and while we rested upon our bundles, and ate a portion of the salt junk and biscuit that the cook of the ship had insisted upon our taking with us, we took a calm survey of Melbourne—its advantages and disadvantages. The city occupies two sides of a valley, called East Hill and West Hill, and is well laid out.

The streets are broad, unpaved, and formed so that during the heavy rains the water will centre into the gutters, which are flagged with a substantial kind of stone to prevent the sidewalks from washing away during the rainy season, when the gutters resemble small mountain torrents, and enough head is obtained to carry half a dozen sawmills.

At the place where we landed there is barely sufficient room for the steamer to turn round for the bay, or arm, of the River Zarra is small, and the water shoal. Every available place near the landing was crowded, however, with crafts of all descriptions, from the light-draughted schooner to huge launches, with loads of goods which they had received from ships lying in Hobson's Bay. Altogether, the scene reminded one very much of San Francisco; and so our spirits rose as we contemplated the bustle going on.

"Well, my men, are you in want of work?" asked a well-dressed elderly gentleman, who had arrived in a carriage driven by a coachman in livery, and a footman, dressed in the same garb. He appeared to own every thing that he looked at; for we had seen half a dozen men take his orders, and then proceed to obey them with alacrity.

"We thought we'd try the mines first," I replied, in answer to his question.

"Hard work—hard work," he said, with a smile. "Americans, I see—smart men in that country. Hope you'll do well here. Afraid not if you go to the mines. Want men to help get these goods under shelter. Like to employ you;" and off he bustled.

"A pretty good sort of man, I guess," remarked Fred.

"I say, stranger," I asked, turning to a person with a cartman's frock on, who was seated on a box smoking a pipe, "can you tell me who that gentleman is?"

"I didn't see any gentleman," he answered, without even taking his pipe from his mouth.

"Why, I mean the one who just spoke to us—the man with the white vest and gold buttons."

"Him—he's a ticket-of-leave man, and has more money than half of the merchants in Melbourne," replied the cartman.

"What, that man a convict?" I asked, with surprise.

"Just so—transported for fourteen years for house-breaking. Behaved himself, and so got liberty to enter into business; and now he is at the top of the heap. In two years his time will be out, and then he can stay or go where he pleases."

After this piece of news the convict became an object of curiosity to us, and we watched him until he entered his carriage and drove off, his coachman treating him with as much respect as he would the governor general.

"I say," asked Fred of our new acquaintance, "do all convicts get rich? Because if they do I want to become one as soon as possible."

"Not all," replied the man; "but some blunder into luck, and others are shrewd and look after the chances. I don't suppose I shall ever be rich, although I am doing pretty well."

"And are you a—"

I didn't like to say convict, and so I hesitated.

"O, yes; I was sentenced to ten years' transportation for writing another man's name instead of my own on a piece of paper."

"That is forgery."

The convict smiled, as much as to say, you have hit it, and continued to smoke his pipe with infinite satisfaction.

"I should like to know if the company we are likely to meet in the mines are of the same class?" muttered Fred.

"Most of them," replied the man, who appeared to be a man of education; "and you'll find them more honest than those never sentenced, because they know that their freedom depends upon their reputation."

We sat staring at our informant for some time; but after a while he knocked the ashes from his pipe, and arose as though going.

"If you want your traps taken to the mines at a reasonable rate, I'll do it for you, as I start to-morrow with a load of goods for Ballarat," he said, after a moment's hesitation.

"Is that mine productive?" we asked.

"It's as rich as any of them. You may sink a shaft and strike a vein, and you may get nothing. It's all a lottery."

We consulted together for a few minutes, and concluded to try our fortunes at Ballarat, and so signified to our acquaintance.

"Then shoulder your traps, and I'll show you my shanty. You can sleep there to-night, and, let me tell you, it's a favor that I wouldn't grant to half of my countrymen."

As we considered pride out of place in that country, we readily accepted his offer, and in a few minutes were walking through the streets of Melbourne with a convicted felon.

We found his hut to be built of rough boards, with but one room; and the furniture consisted of a stove, wooden benches, a pine table, and a curiosity in the shape of a bedstead.

That night we learned more of the customs of the Australians from our host, who gave the name of Smith as the one which he was to be called by, than we should have found out by a six months' residence.

Over a bottle of whiskey, which was made in Yankeeland, we spent our first night in Australia.

"Come," said Smith, about ten o'clock, "it's time we were asleep, for we start early in the morning, and before to-morrow night you'll not feel as fresh as you do at present."

As he spoke he removed the whiskey, and in half an hour deep snoring was the only sound of life in the convict's hut.

"Hallo!" cried a gruff voice, accompanied by a gentle shake, which was sufficient to arouse Fred and myself from a deep sleep, that was probably caused by the whiskey.

The time had passed so swiftly that it did not seem an hour since we had first stretched ourselves upon our blankets on the floor.

We rubbed our eyes and sat up, looking around the Australian's hut, almost fancying that we were still dreaming. A spluttering tallow candle was dimly burning, stuck in the neck of a porter bottle, and a fire was lighted in the old broken stove, on which was hissing a spider filled with small bits of beef and pieces of potatoes. A sauce pan was doing duty for a coffee-pot, and the fragrant berry was agreeable to the nostrils of hungry men. Our host, the convict Smith, after he had aroused us, seated himself upon a three-legged stool, and was busily employed stirring up the savory mess, and trying to make a wheezy pipe draw; and as the tobacco which he was smoking was damp, and the meat was liable to burn, his time was fully occupied.

"Come, rouse up." Smith said, when he saw that we were awake; and while he spoke, he was trying to coax a coal into the pipe, but it obstinately refused to go.

"We'll be off in an hour's time; so I'm getting a little bit of breakfast ready before we start. Get up, and help me set the table."

We rolled up our blankets, and in a few minutes had drawn the rough table to the middle of the room, and placed thereupon our tin plates and quart pots.

As breakfast was not quite ready, I strolled out of doors, and found that the first streaks of daylight were just visible, and the stars looked white and silverish. There were no clouds to obscure the sight, and for a short time I stood watching the gradual changes that were taking place as the sun edged its way towards the horizon. First long streaks of a bright golden color were extended like huge arms, and then they changed to a subdued pink tint that defied the art of a painter to transfer to canvas. Glorious are the views to be obtained in Australia at sunrise, and if those of Italy excel them, it must indeed be a land for poets and painters.

A heavy dew had fallen during the night, and refreshed the aromatic plants that sprouted beneath my feet; and as they were crushed by my heavy tread, they yielded up their life with a perfumed breath that filled the air with fragrance, and made me regret that I had no other means of locomotion beside my feet.

The heavy rumbling of carts over the dry streets was heard, and an occasional crack of the dreadful whip and the fierce shout of the driver proved that there were others stirring as early as ourselves.

"Breakfast is ready," shouted Fred from the door of the hut; and I retraced my steps to the home of the convict, whom I found still sucking his pipe and pouring out the coffee.

Our meal was soon over, for the delicacy of civilized life was not particularly observed, and our long seclusion from the society of females had rendered us little better than savages, as far as manners were concerned.

"Now, then, pack up your traps, and he ready for a start. I'll be along here with my team in half an hour, as my freight is already loaded."

"Rut we shall need provisions for the route," I said.

"Of course you will; but as I have to take some for myself, I'll get a quantity for you also, and charge just what I pay. At Ballarat you'll find enough to eat, and men to trust you if short of money."

Smith left to get his cattle, and while absent we washed the tin pans and got all ready for a start. Our rifles were reloaded, and revolvers examined, and after we had indulged in the luxury of a smoke, we heard the voice of the convict shouting in no gentle tones to his oxen, as they stopped in front of the hut.

"All ready?" asked Smith, coiling up his long whip, at the sight of which the cattle fairly trembled, and pricked up their ears as though ready for a stampede.

"All ready," we answered, bringing out our traps and lashing them on the team.

The coffee pot and skillet were not forgotten, as we calculated if we met any game they would both be of service. A keg of water, a bottle of whiskey, a bag of ship bread, a large piece of pork, a few potatoes, coffee, a bag of flour, and a bag of sugar, were the articles needed for our long journey to the mines of Ballarat.

Smith locked the door of his hut, hung the key about his neck attached to a thick cord, and then, uncoiling his dreadful whip, he sounded the signal for an advance.

The cattle strained at their yokes, and the huge, clumsy, English-built team creaked over the road, and groaned as though offering strong remonstrance against the journey.

There were five yoke of oxen attached to the cart, and as they were in fair condition and had not been worked for a few days, they took the load along the level road at a brisk walk; and it was not until we had got beyond the city's limits and left Melbourne in the distance, that the animals fell into their accustomed steady walk.

"I suppose that there is but little use in our carrying our rifles in our hands?" I asked of Smith, as he walked by the side of the cattle.

"I have been waiting for you to ask the question ever since we left Melbourne," Smith replied; "I thought I wouldn't say any thing until you got tired of carrying them. There is but little fear of our meeting with bushrangers so near the city; and as for game, we may see some, but not within rifle range. Put your guns in the cart, and don't touch them until we camp to-night."

We gladly followed his advice, for the sun had risen, and began scorching us with its rays, although, when we started, the air was quite cool, and a jacket was not uncomfortable.

"How far is Geelong from Melbourne?" I asked, after we had relieved ourselves of the rifles.

"Between fifty and sixty miles."

"Do we pass near the town?"

"No, we branch off near Mount Macedonskirt, the range of mountains by that name, and which you can see in the distance; cross a barren tract of country, where no water but sink-holes is to be found for forty miles; strike the mines of Victoria; and then we are near the gold fields of Ballarat."

"Where I hope we shall make a fortune and return to Melbourne in less than six months," Fred cried.

"Amen," ejaculated Smith; but he smiled as he thought what a slight chance there was of our prayers being answered.

We met some half a dozen teams on their way back to Melbourne from the mines, and we surveyed the drivers as we would rare animals, for they were covered with a thick coating of white dust that had filled their hair and whiskers, and looked as though a bushel of corn meal had been scattered over their heads.

Each cart contained two or more invalids, who appeared, by their dejected air, to have taken farewell of the world, and didn't think it worth while attempting to live any longer; and when a question was asked them, it was with great reluctance that they returned an answer, and if they did speak, it was in tones so faint that with difficulty they could be understood.

Three times did the convict stop his cart to supply some little luxury to the invalids; and while he declined payment for his refreshments, it did not prevent him from requesting the sick men to say, when they reached Melbourne, that they had been befriended by himself. We were struck by this peculiarity, and as soon as the team's moved on, we resolved to inquire the reason.

"Why are you so particular that those men should mention your name for the charities that you perform?" asked Fred.

Smith smiled, but it was of the melancholy sort of mirth, and did not come from his heart. He hesitated, as though considering whether he should make a full expression or reserve his confidence. At length he said,—

"I told you that I was sentenced to transportation for ten years. Five of them have passed, and I am at liberty to trade on my own account, yet liable at any moment to be remanded back to my old station, and work worse than a slave on the docks, or at any menial employment. I have so far managed very well. I have saved money, and own shares in the Royal Bank of Melbourne, besides two good houses that are paying me a large percentage. The property is mine, and government cannot touch a penny of it; yet I would willingly give all that I possess to be at liberty to call myself a free man, and to know that I am no longer watched by those in power. When I received my sentence I determined upon the course I would adopt. I never murmured at my work, no matter how disagreeable it was—I was respectful and obedient, and after a year's hardship I was favorably reported at head quarters, and was then allowed to live with a man who kept cattle, and had made a fortune as a drover. I served him faithfully for two years, and upon his report I was allowed a ticket of leave, and commenced business for myself. I am comparatively a free man; but if any unfavorable report should be heard concerning me, farewell to my present liberty. For five long years I should be used like a brute, and before my term expired I should be in a felon's grave; for a man must possess a constitution of iron to endure the tasks that are inflicted upon a convict remanded back to the tender mercies of overseers whose hearts are harder than the ball and chain which many of their prisoners wear."

"And you really think that the relief you afford to those returned miners will be heard of, and that it will mitigate your sentence?"

"Certainly. The poor fellows will go to the hospital, and while there I shall be held in grateful remembrance. The physician will hear of my name, and one of these days I hope to receive a full pardon. But whether I do or not, I shall be conscious that I have done my duty, and in some measure atoned for the crime that I committed."

Smith cracked his long whip to let the oxen know that he was not asleep, and the cattle, rousing from their snail pace at the sound of the scourge, accelerated their steps, and strained at their yokes as though they would tear them from their necks.

We remained silent while getting over a mile of the dusty road; but, as the oxen fell into their slow pace again, we renewed the conversation.

"You think that the system of letting convicts have leave tickets is a good one, then?" we asked.

"In some cases I think that it works well; but all men are not alike, and while some play the hypocrite and profess good conduct, others are never allowed their liberty because they brood over their past life so much that they never smile. They are marked as sullen and discontented, and are worked until their spirits are broken, and they no longer hope for freedom. The energy and enterprise of liberated felons have increased the trade of Australia until she is no longer a burden to the mother country, and I hope, before I die, to see this island conducted as an independent government. It would be better for England, and I need not tell you how much better it would be for us."

"Are the bushrangers, that we hear so much about, really dangerous fellows to meet?" we asked.

"They are the very scum of the great cities of England—desperate men who are usually sentenced for life, and therefore have no hope of mercy; and many of them desire none. As soon as they can effect an escape they do so, and fleeing to the wilds of the island, either join a band of ruffians like themselves, or else, fearful of trusting to men that are as treacherous as wolves, will roam without companions for many days, living upon sheep, which are easily obtained from herds without the knowledge of the shepherds, and very often with their consent, to be at last betrayed and shot by the very man who was trusted most. There are hundreds of them upon the very route that we must take, and every day there are murders and robberies committed, and all the vigilance of the guard, who escort gold dust from the mines to Melbourne, is necessary to insure its protection.

"Teams like our own, however, are most attended to, and if we should wake up in the night, and by the light of the camp fire see half a dozen ferocious-looking fellows standing over us, it would be better to let them take what they want, and go their way in peace, than to trust to an appeal to arms or oppose them. Once rouse them to anger, and our lives would not be worth a sixpence; for they think no more of shedding the blood of a man than they would that of a sheep."

"I think it would be better to give them a trial than be robbed, especially when we possess weapons like these," cried Fred, touching his revolver, which he carried in a belt around his waist.

Smith looked at my companion for a moment in silence, as though trying to satisfy himself whether Fred was in earnest, or only talking because danger was remote.

"I've carried many men to the mines," he said at length, "and been robbed some half a dozen times; but I always found that while my passengers were firm for resistance at the beginning of the journey, yet at night a different opinion was formed, and the boldest has consented to give up a shirt or pair of boots without a murmur."

Fred laughed good naturedly, and spoke jestingly in reply.

"That was because you never freighted Americans. Englishmen may consent to have their boots pulled off, but Yankees would be apt to remonstrate."

"I hope that we shall have no occasion to test your courage," said Smith; "but if we meet Black Darnley, I shall not blame you for keeping quiet."

"And who is Black Darnley?" we asked.

"An escaped convict, who has been at large for three years; and, in spite of the two hundred pounds reward, no one has ventured to attempt his capture. He swears that he will never be taken alive, and he will keep his word. He has no fear of two or even three ordinary men, for he possesses the strength of a Hercules and the desperation of a wounded tiger. Of all the bushrangers on the island, he is the worst; and yet he always treats me well, and lets me pass without levying toll, for he and I are old acquaintances, and often have a social chat together about times gone by."

"Tell us where you first met him," we said, crowding nearer the convict to hear his story.

"Wait until we halt for a rest and feed the cattle. Half a mile from here is a small stream of water, and under the shade of some trees near at hand, we'll boil our coffee, and then I'll tell you about my first meeting with Black Darnley."

As it was about noon, and we had travelled near twelve miles, the proposed halt was any thing but disagreeable. Besides, the sun was nearly overhead, burning and scorching us with its intense rays, and causing the oxen to protrude their tongues and drag their weary feet along as though they hardly possessed life enough to reach the water spoken of.

A sharp crack of Smith's whip and the cattle started into life again; and as he continued to flourish the dreaded lash over their heads, they kept up their speed until we reached the stream, which slowly trickled through dry plains, with scorched grass and withered shrubs; but, near the banks of the river, which during the rainy season became a mighty torrent, green trees and rank grass afforded an agreeable shade from the burning sun.

The cattle were unyoked, and allowed to wander where they pleased, Smith being confident of finding them near the water when he got ready to start.

"Black Darnley, as he is called, owing to his swarthy complexion," began Smith, after a fire was made, and water for the coffee started to boiling, "was transported in the same ship as myself; but our conduct during the passage to Australia was widely different, he was rebellious, and I docile. He was half the time wearing irons, and when free from fetters endeavoring to create a mutiny. I never meditated any such project, and threatened one time to disclose his plans if he did not give them up.

"He swore vengeance against me, and after that I always avoided him. Six different times during the passage he was severely flogged, and when that was found to have no effect, he was starved into a respectful demeanor; but as soon as he had recruited his exhausted strength, he would again commence his old career of insolence, and once more be punished. He is a strong man, and stands nearly six feet six, with shoulders broad and arms covered with muscle, while not a pound of surplus flesh is on his body. Before he committed the crime for which he was transported, he was a prize-fighter; but having lost a battle, he turned his attention to house-breaking, as an agreeable diversion from his former course of life. He was betrayed by a comrade, and sentenced for fourteen years. He will never live to see his sentence expire; for, cunning as he is, his day of capture will not long be delayed.

"Upon our arrival at Sydney, he was branded with a black mark against his name, and the most laborious work was his daily task, besides the privilege of dragging a chain and ball after him. He managed to secrete a knife about his person one day, and when the guard the next morning ordered him to perform some heavy work, he struck the man to the heart with his weapon, broke his chain, and fled.

"A horse standing near the dock where he was employed, he mounted, and escaping the shower of balls that flew after him, and defying all opposition, he reached the wilds of Australia.

"It was a bold strike for liberty, and only one time in a thousand could it be achieved.

"Before he effected his escape I had been taken into the service of a man who owned large herds of sheep, and on one of his immense tracts of land was I stationed to look after a flock of nearly ten thousand. I in fact became a stockman, and lived a solitary life, with no one to speak to unless it was to those who brought me a few necessary articles once a month, and then departed to supply other stations.

"I was not discontented with my lot, and yet at times I longed to see a human face and hear a voice speak in my native tongue. I used to receive visits occasionally from the miserable natives, who hang around a sheep station; but as I never encouraged their intrusions, and watched their doings with a sharp eye, they generally avoided me. Twice they tried to murder me, but I was wary and escaped.

"The hut in which I lived was built of logs, plastered on the outside with clay to keep out the rain, and contained one room, with a fireplace, a bed made of sheep skins, a table and two stools. The door was a stout one, made expressly to resist a siege in case the natives grew vicious, and was secured on the inside by a large bar.

"I have been thus particular in my description of my habitation, because one night, when the rain was pouring down in torrents, and the wind beat against the hut as though it would take it from its foundation, I was startled by hearing a loud knock at the door.

"I had been sitting before the fire for a long time, trying to picture out my future life, for my past was already too well known, when the summons disturbed me. I started to my feet, and sought the door, where my dog was already snuffing and uttering angry growls, as though suspicious that the person on the outside was not exactly such a guest as his master would wish for in that lonely habitation. While I was uncertain what to do, another knock, louder than the first, startled the dog into a howl; but I hushed his noise, and taking down my gun, that hung over my bed, I asked what was wanted.

"'In the name of God give me shelter,' cried a voice that I thought I recognized, although I could not call to mind where I had heard it.

"'Who are you?' I asked.

"'A stranger who has been to various stations for the purpose of buying cattle, and has lost his way. Give me shelter for the night, and God will reward you.'

"The latter part of the solicitation sounded as though uttered in a hypocritical tone, and I was undecided whether to comply with the request, or send him to the next station, about ten miles distant. A fresh gust of wind influenced me; I slipped off the bar and opened the door; but next moment I would have given all the sheep under my charge to have had my guest where he was five minutes previous, with the oak bar across the door; for by the flickering fire that blazed upon the hearth I saw that my visitor was Black Darnley.

"He was greatly altered since I had seen him last. His clothes hung in tatters about his body, while his large feet were shoeless and bleeding profusely: but the fire of his black eyes was unquenched, and the bony form, still upright in spite of the hard labor to which he had been subjected, gave assurance, to my dismay, that he still possessed his giant strength.

"The instant he entered the hut he closely scrutinized my face, and then cast hurried glances around the room to see if I were alone. Satisfied that I was, he strode to the fire, and seated himself near its cheerful blaze.

"'I have seen your face somewhere,' he said, looking at me keenly.

"'I should think you would remember it,' I replied, 'for we were both passengers in the same ship.'

"He started up with a fearful oath, and would have rushed upon me; but I brought my gun to my shoulder, and kept him at bay.

"'I remember you now,' he said, and seemed inclined to dash at me in spite of the weapon which I held in my hand. 'You are the one that threatened to betray me when I wished to take the ship. I swore to have your life for your cowardice; but I retract the oath, and now let us be friends. Give me shelter, and something to eat, and to-morrow I will leave you for a distant station.'

"'You are deceiving me,' I said, still retaining my hold of the gun, and looking at him suspiciously.

"'No, by ——, I'm not,' Darnley cried, with a look of sincerity: 'here, let me prove it. Ten days ago I murdered one of the guards, and fought my way to this part of the country in hopes of joining a gang of bushrangers. Since that time I have been pursued and hunted like a wild beast; but they haven't captured Black Darnley yet.'

"He laughed triumphantly as he spoke, and thought of the long chase that he had given the police of Sydney.

"'You are a strong man, much stronger than myself, and if I am upon an equal footing with you, could crush me as easily as an eggshell.'

"I still retained my hold of the gun, but I no longer covered his huge body with its barrel.

"'Look at me!' he said, baring his arms, which were shrunken, and holding them up for my inspection. 'For three days I've not tasted food, or closed my eyes in sleep. I've run and skulked from tree to tree during that time, and heard the tramping of horses as the policemen strove to follow my trail. I am weak, exhausted, and a child could overcome me now.'

"'But after your strength is recruited, you may act the part of a serpent, and sting the one that warmed you into life,' I answered, half resolved to trust him.

"'I don't blame you for your suspicions,' he cried, moodily, seating himself by the fire again, and holding his hands towards the blaze to dry his ragged shirt. 'I am defenceless, and you hold a loaded gun. Discharge its contents into my body, and then go and obtain a full pardon from government for the murder of Black Darnley.'

"He bowed his head and sat scowling at the fire, as though he cared not what became of him, and was rather anxious, than otherwise, that I should end his career of crime.

"'I'll trust you,' I said, replacing my gun over the bed and taking a seat beside him, and I did so with perfect confidence.

"'Your clothes are wet and ragged,' I remarked, after a few moments' silence, during which he did not remove his eyes from the fire.

"'A starving man cares but little about his dress,' he answered, glancing over his ragged suit, and stooping to wipe the gravel from his bloody feet.

"'You shall have all that you want to eat,' I answered; and I hastily put a kettle of water upon the fire to make him a cup of tea, and then laid upon the table nearly the whole carcass of a lamb which I had roasted that day. He still sat by the fire and gazed at the flames as though he read his past life amid the coals that glowed upon the hearth, and was trying to read the future. I went to my small stock of clothing and took out a flannel shirt and pair of trousers, much the worse for wear, but still warm and dry.

"'Strip off your wet garments," I said, 'and accept of these.'

"He started, and looked me full in the face, as though reading my thoughts.

"'I have wronged you,' he cried, while doing as I directed. 'I thought when I proposed to take the ship, that you were a coward, because you refused to join me. You are a braver man than myself.'

"'It was because I knew that certain death not only awaited you and I, but half of those who were not aware of the plot. The innocent and guilty would have been massacred without mercy by our taskmasters.'

"'But we could have slain half a dozen of them before dying ourselves,' he exclaimed, with a touch of his old fierceness, and a wave of his long arms, as though, even then, weak as he was, he would like to strangle his oppressors. I made no reply, but assisted him to dress; and after he had squeezed his body into my clothes, which were two sizes too small for him, the water on the fire boiled, and I made a strong cup of tea, and then bade him eat to repletion. He needed no second invitation, but fell to work like a wild animal, and craunched bones and flesh between his strong teeth in such a ravenous manner that I had expectations of his choking himself; and I don't know that I should have been sorry if he had. The lamb rapidly disappeared, but not until every bone was picked, and half-eaten, did he evince that he was satisfied, and again drew towards the fire, into which he continued to gaze until he began to nod with weariness.

"'You are sleepy,' I said. 'Occupy my bed to-night, and I'll sit by the fire.'

"'The floor will do for me. Give me a sheep-skin and let me stretch myself before the fire.'

"Finding that he was resolved not to deprive me of the bed, I spread half a dozen skins upon the hearth, and giving him a pipe well filled with tobacco, retired to my couch, and lay watching his huge form by the faint flicker of the fire, which had begun to grow dim.

"In a few minutes Darnley's head, which he had supported upon his hand, sank upon his pillow; 'the pipe dropped from his mouth, and by his heavy breathing I knew that he slept. Wicked thoughts then crowded upon my mind. Within my reach was a gun, well charged with slugs, and there, lying upon the hearth, was an escaped convict, whose life was forfeited by the laws of Australia, and pardon and official patronage granted to any man that shed his blood. Nay, more, I had the moans of purchasing my freedom by exhibiting proofs that I had taken his life, and I thought of the many years that must elapse before my term would expire.

"I reached towards the gun, and considered that I should but do my duty in slaying him as he lay; but other thoughts succeeded, and I now thank God that my hands are not stained with the blood of a man who trusted to my goodness of heart. I fell asleep during my meditations, and when I awoke, Darnley was still sleeping in front of the cold fireplace.

"I moved about the room as gently as possible, and tried to avoid awakening him; but while I was endeavoring to kindle a fire, he suddenly started up, his countenance inflamed with passion, and his deep-set eyes glaring like those of a tiger.

"'I'll never be taken alive,' he shouted, throwing his huge form upon mine, and crushing me to the ground with his weight, while his hand sought my throat which was compressed in his grasp until my eyes started nearly from their sockets.

"In his half-awakened madness I should have been strangled, had it not been for my dog, that flew at his leg, and inflicted a savage bite that caused Darnley to relinquish his hold and turn upon the brute; but by the time that he had staggered to his feet, he awakened to his situation, and became calm and penitent, and asked my pardon a dozen times for his mistake. I forgave him, but resolved to keep at a respectful distance the next time he slept.

"I gave him a hearty breakfast, and when he got ready to leave placed a pair of sheep-skin shoes upon his feet; but all my arguments did not induce him to accept of the garments that belonged to me, as he feared that in case he was taken they would be traced and involve me in trouble. It was considerate in him certainly, but from that day to this he has baffled all attempts at capture; but how much longer he will be permitted to go at large is only known to God."

"And did he ever pay you another visit at the hut?" I asked, as Smith paused.

"Quite frequently; but he always came alone, and would not allow one of the gang whom he gathered about him to molest my flocks. I saw him on my last trip to the mines, and he tried to bribe me to purchase him a pair of revolvers; but I refused, and he left me without a word of reproach."

It was nearly four o'clock when Smith finished his account of the bushranger; and as the heat was not so oppressive as at noon, we decided to travel eight or ten miles farther that evening, before we camped for the night.

The oxen were found, driven towards the cart, and yoked; and, with many a sharp crack of the stockman's whip, we crossed the stream, and once more pursued our way towards Ballarat.

During the rainy season in Australia, the roads leading to the mines are almost impassable, as the soil is light and the water easily penetrates to a great depth. Teams, with half a dozen yoke of cattle, can scarcely draw a heavy cart, as the brutes sink to their knees in mud at every step, and the wheels of the vehicle are buried to the axletree most of the time. Five or ten miles per day is as great a distance as animals can travel; and even at that rate it is quite common for the oxen to give out, and be left by the roadside, a prey for dogs and other wild animals.

The natives of the island,—for the race bears no resemblance to that class of people to whom we are wont to ascribe an elastic step, a noble bearing, and undaunted courage—have been known to follow a team for twenty-four hours, expressly for the purpose of picking the bones of an ox which they imagined would soon give out; and when the poor brute is left to die, they crowd upon him like vultures, and hack off huge strips of quivering fresh before his breath has departed.

In the summer season, when no rain falls to lay the dust or irrigate the earth, the streams, which, during the winter, are like mountain torrents, and sweep every thing opposed to them towards the ocean, become puny little rivulets, and as the summer advances, disappear altogether from sight, and nothing but deep gulches mark the spot where but a few months before a large body of water flowed.

Then the roads become hard and dry, and the light earth, pulverized by the numerous wheels which are continually passing over it, is taken up by the hot winds and whirled along the vast, plains, obscuring the sight as effectually as though there was a deep eclipse. The eyes and nostrils of the traveller become irritated by the fine particles, and the dust is sifted into his ears and mouth. The latter gets coated with dust, and all moisture is denied the palate. Vainly the tongue is rolled from side to side to check the burning thirst, until at last the member gets so swollen that it becomes incapable of motion, and then, unless relief is soon afforded, death ensues. Water, slimy, stagnant water, is drank with as much eagerness as a glass of iced Cochituate in summer.

The various sink holes with which the prairies abound are drained of their contents, and if the traveller is unacquainted with a miner's life, he does not wait until the liquid is strained and boiled, and thus relieved of many of its bad properties, but swallows a large quantity of the nauseous filth, and for many days after repents of his folly. He that drinks at a sink hole, and suffers long and repeated attacks of fever and ague, or dysentery, in consequence, learns to avoid it in future.

As Fred and myself were old miners, and had tramped over a large portion of California, and knew the dangers of such indulgence, we were not likely to be caught; although we had a good guide with us in the person of the convict, who really appeared to take an interest in our welfare, and gave us much friendly advice.

The sun did not set for three hours after we started, on the afternoon that we crossed the gulch; and while we found the heat growing less oppressive, we certainly did not feel much refreshed by its disappearance, as our legs, unaccustomed for many days to long walks, began to grow stiff, while blisters formed upon our feet and galled us extremely.

We would have given a small sum to have been enabled to halt for the night; but pride prevented us from asking Smith to do so. We were fearful that he would laugh at us, and we had our reputation as Americans at heart too much to let him think that we were failing even on the first day from Melbourne. But as mile after mile of ground was got over, we could keep silent no longer.

"How much farther do you intend going before camping for the night?" I asked of the convict in a careless sort of way, although I could hardly prevent limping.

"Feel tired?" he inquired, with a grin.

"O, no," I answered, with an indifferent air.

"Well, as you are not tired, and night is the best time to travel, suppose we keep on until daylight?"

"I'll be —— if I do," broke in Fred. "I've got a great blister now, on my great toe, bigger than a silver dollar, and my boot seems inclined to raise others. I'll tell you what it is, Smith, for the last two months we've been on shipboard, and not walked five miles during that time, and if you think we can compete with you as a pedestrian, you are mistaken."

Fred jerked out his words as though each step he took cost him an immense amount of pain, and I've no doubt it did. The convict laughed silently, and relieved his feelings by cracking his long whip, bringing the end of the lash to bear with great precision upon the flanks of the leading yoke of cattle, which testified their appreciation of his attention by kicking at the heads of those following; and as such playful amusement was calculated to inspire vitality in the animals, they started off with renewed speed, and Fred and myself, with many groans, limped after.

"I can't stand this," cried my companion, after a few minutes' brisk walk. "My feet are raw, and getting worse every moment. I'll try an experiment."

He sat down in the middle of the road, and while the team rolled on, jerked off his boots and stockings, and declared, as we hastened to overtake Smith, that he felt he could walk all night, and that hereafter he would go barefooted.

"Well," cried Smith, as we reached the team, "how do you feel now?"

"Fresh as a daisy," returned Fred, clapping his boots together as though they were a pair of cymbals.

"What have you got in your hands?" asked Smith; for, it being already dark, it was hard to distinguish objects at a short distance.

"My boots," cried Fred, triumphantly.

"Are you barefooted?" asked the convict in surprise.

"Yes."

"Then if you value your life, put on your boots again, and keep them on as long as you are in the mines. You are liable at any moment to step upon a poisonous snake; and if bitten, no power on earth can save you. The natives pretend to cure bites, but I have some doubts on the subject."

Smith spoke seriously, and as there might be much truth in what he said, Fred willingly complied, although he groaned with pain as he drew on his boots, and once more hobbled along beside the team.

"About three months ago, I was freighting a party up to the mines," said Smith, "and a youngster became foot-sore. He took off his boots, although I told him there was danger of treading upon snakes in the dark. He laughed at me; but before his mirth had ceased, he uttered a yell, and sprang wildly towards the team, which I had suffered to get a little in advance.

"When he started, I suspected the cause, and groping carefully about in the dust with my whip, soon discovered a small snake, not larger in circumference than my lash, but which I readily recognized as one of the most poisonous in the country. The natives call them capi-ni-els, or what signifies little devils. As the impudent scamp was hissing and darting out his tongue at me, I gave him a blow on the head, ground him into powder with the heel of my boot, and then passed on to overtake the team.

"It had got some distance from me; but before I reached it, my young passenger could no longer walk, and by the time I had checked the oxen, he had swollen to twice his usual size, and was lying panting by the side of the road, incapable of moving or speaking. I got a large quantity of brandy down his throat; but it had no effect, and in twenty minutes' time he was a dead man. We buried him where he fell, and I'll show you his grave when we reach it."

"I for one shall take good care to keep my boots on," I replied, after the convict had finished his story.

"Why do they frequent a road in preference to other parts?" asked Fred, who seemed to have almost forgotten his lameness, while listening to Smith's yarn.

"Because the light dust over which we are passing retains the heat of the sun longer than the soil by the road. Snakes are fond of dragging their forms over it, as it is soft, and keeps them warm during the night. I have known teams to be stopped, and obliged to seek a route on the prairie, simply because a large number of snakes were not disposed to yield the right of way.

"The first load that I ever carried to the mines, and when I was anxious to make as much money as possible in a very short space of time, I was stopped in this same way. I was jogging along one night, all alone, and urging my oxen to their utmost speed, when all at once the leaders shied out from the road, and then stopped. I cracked my whip, and roared at them frantically, but it was of no use.

"Forward they would not budge, and at last they fairly turned, and were making very good time towards Melbourne; but I soon stopped that game, and once more got them headed the way I wanted them to go. When they arrived at the spot at which they had balked a few minutes before, they went through with the same antics, and then I thought it best to see what was the matter. Walking forward, I was saluted with a hissing sound, that greatly resembled the noise which an enraged gander emits when a stranger trespasses upon his brood.

"I paused for a moment, and tried to discover, through the darkness, what occasioned the noise, but could not, although I thought I saw something moving not far from me. I retreated, quieted my cattle, took my lantern and gun, and walked back to the spot. By the light of the candle I saw about half a bushel of snakes, coiled up in a heap, and all alive with rage at being disturbed. I hardly knew what to do. There they were, and gave no indications of leaving the road; and I no longer wondered at the reluctance of the oxen in refusing to pass over them. Had they done so, it is very probable I should have lost every one of the animals, for they could not have escaped being bitten; and then they would have died in a few hours, and I should have suffered a great pecuniary loss.

"I had a quantity of fine shot in my wagon-box, which I used for small birds. I drew the charge I had in the gun, and instead of a bullet, put in about a handful of the shot, and then setting my lantern as near the mass of snakes as I dared venture, I retreated a few paces, and taking deliberate aim, fired at them.

"The charge made dreadful havoc, and dozens of them were killed and cast out of the heap by those unharmed; but instead of causing them to escape to the prairie, they only seemed more determined to dispute the right of way, and hissed and ran out their thin, forked tongues as though defying me to do my worst. Their eyes sparkled like precious stones, and by the light of the lantern I could see them change, as they moved their position to face me, and assume a hundred different hues. It was a terrible and fascinating sight, and for a few minutes I stood and watched them twist and writhe themselves into a thousand different shapes. Seeing that I should have to make a regular business at slaughtering them, I went to work after a while, and poured volley after volley into the mass, until not more than half a dozen escaped alive.

"Even after they were dead I could not get my cattle along the road until I had first taken a shovel and thrown the bodies a considerable distance from the spot. I never saw such a large collection of serpents before, and I have often wondered why they were gathered in such a mass."

"Have you ever arrived at any conclusion?" I asked.

"I have thought that they expected an attack from some enemy of the serpent tribe, and so formed themselves into that shape for resistance."

While Smith was speaking, we heard a team behind us that appeared to be tearing along at a rapid rate; and even before we could discover its outlines, we distinguished the cracking of a whip as though the driver was anxious to see how many times he could snap it in a minute.

"I hear you," muttered Smith, driving his oxen to one side of the road, and stopping them. "There is no occasion for you to make so much noise to let people know that you are coming."

Even while Smith was grumbling, a light-bodied cart, with lamps on each side, drawn by a span of horses, and driven by a man who wore a sort of uniform, whizzed past us, and by the side of the team rode two soldiers, dressed in the livery of England. They were out of sight in a moment, but they threw a jest at us as they passed, and before Smith could reply, the soldiers were lost to view.

"A hard time you have of it," cried Smith, as he started his team again.

"Who are they?" we asked.

"That is a government team, and carries the mail between Melbourne and Ballarat. Day and night they are upon the move, and only stop long enough to change horses and escort. To-morrow at this time the miners will be in possession of their letters and papers, and I need not tell you how anxiously news is looked for from home."

"But are we to keep on day and night until we reach Ballarat?" asked Fred.

"No," replied Smith, touching up his cattle. "Do you see yonder light far ahead?" he cried, pointing with his whip.

"Yes."

"Well, at that light we'll prepare a cup of coffee, and sleep until morning. Cheer up; it's only a mile distant, and there is where you will get your first view of the natives of Australia."

The natives of Australia are remarkable for the slight quantity of clothing which they wear, and the thinness of their limbs. Their dress consists of a dirty piece of cloth, or skin of kangaroo, tied about their waists, leaving the upper and lower parts of their bodies naked. Their color is a dingy black, although what exact shade they would represent were they washed quite clean is a matter of conjecture. A more filthy race of beings I never saw; and if we adopt the hypothetical theory of eminent medical gentlemen, that when the pores of the skin are closed, and perspiration ceases to flow, the patient dies, then the natives in Australia should, according to that reasoning, have all been under ground years ago; for I am confident that during my residence on the island, I never saw one guilty of ablution, or manifest the slightest anxiety to mingle a little water with their dirt.

With grease upon their faces, filling their long black hair, shining upon their hands, and smeared upon their bodies, they are as disgusting a race as can be found upon the globe; and after a brief survey of their huts and habits, men of a cleanly nature never desire to see them more. Their limbs bear about as great a proportion to their bodies as the stem of a pipe to the bowl; and to see them walking, is apt to suggest an idea that their legs were never intended to carry their frames. The latter part of their bodies presents a protuberance, even in the youngsters, caused by their inordinate gluttonous nature, which prompts them, when fortunate enough to have killed game, to gorge themselves to repletion, as though they never expected to eat again, and were determined to fill their stomachs even if they burst.

We soon saw a party of natives of this description seated around a fire, black with dirt, and gorged with the flesh of a kangaroo. The stockman, Smith, was busy with his team, and had declined our assistance, as he saw that we were tired and nearly exhausted with travel. Telling us to go to the fire and see how we liked the looks of the natives, we followed his advice, and walked towards them. There were ten or twelve of them huddled together in a circle, squatted upon their haunches, each with a piece of raw flesh lying upon the ground, while other junks were broiling on the coals, to be transferred from thence to the fingers of those claiming them.

They manifested no surprise or curiosity when Fred and myself halted within a few feet of them, and regarded their feeding operations with considerable disgust. Their minds appeared to be too much occupied to pay the least attention to outward objects, and as they poked their burning food among the ashes, and licked their fingers, and grunted with satisfaction, they certainly did not seem better than so many swine. At least they were not half so clean.

"Well, of all the eating I ever saw, this is the worst," cried Fred, after a few moments' contemplation.

"Even the Indians of California would be ashamed to look so dirty," I remarked.

"Hullo," cried Smith, advancing with the sauce pan filled with water, which he had obtained somewhere in the vicinity, although we could not in the dark see any evidence of a stream. "Hullo," he cried; "what is the matter? Why don't you sit down and join the gentlemen? Well, old Bulger, how are you getting along?" addressing a native that looked older than the others, and consequently more dirty.

The brute grunted, and paid no farther attention to the address; but Smith was not to be bluffed that way.

"Let me have a chance at your fire," he said, holding the sauce pan towards him; but the native gave no attention except to his burning meat, which he turned over in the ashes with a stick, and apparently had a great desire to eat raw.

"I know of a way to start him," muttered Smith. "Stand by and watch the fun," he continued, addressing Fred and myself.

He canted the sauce pan a little one side, and allowed the water to run over the rim, and strike upon the native's naked shoulder. The fellow uttered a howl as though seared with a hot iron, and scrabbling away from the fire, left the convict free access.

"There is nothing like water to start them," cried Smith, laughing, as he put his dish upon the coals, while those who still kept their places watched his motions with their little glittering eyes, as though fearful they should also be subjected to a bath.

The native whom the convict called "Bulger" lingered around the fire for a short time, as though he had not entirely relinquished all hope of again joining the circle; but when he found that Smith showed no indication of yielding his place, he grunted his displeasure, got one of his companions to rake from the ashes his lump of flesh, and placing the burning mass upon leaves, walked towards some rude huts which were built of branches of trees and leaves of the giro.

"Good night, Bulgy," shouted Smith, as this latter toddled off; but the native paid no attention, and soon disappeared within the pile of leaves.

"You have met these poor devils before—haven't you?" I inquired of the convict.

"For the last three months they have been camped on this spot, and as water is convenient here, I generally manage to reach them in the course of the night. Besides, I make them useful in case my cattle stray away; and for a piece of tobacco not larger than my thumb they are willing to run all day."

"Bah," grunted half a dozen voices in chorus, apparently roused to animation by some word that Smith had spoken.

They extended their small hands, not larger than the paws of an orang-outang, and greatly resembling them in formation and looks.

"What do they want?" Fred asked.

"They heard me mention tobacco, and now they are begging for some. They love the needful as well as I do;" and Smith proceeded to fill his pipe, and then coolly replaced the tobacco in his pocket, much to the disappointment of the natives, who had followed his motions with anxious eyes.

"Give them a piece," I said, quick to trace disappointment in their expressionless faces.

"Not I," returned Smith. "If I want them to-morrow to run after my cattle, I shall have to give them more, for they would not recollect that I had supplied them to-night without compensation."

"Then I'll stand treat," cried Fred, handing a small piece of the needful to the nearest native, who grunted, but whether as an expression of thanks, or disappointment that it was not larger, is unknown.

The glittering eyes of the gorged natives were instantly fastened upon the fortunate possessor of the tobacco, greatly to the injury of their broiling meat. But the native upon whom the present was bestowed showed no signs of making a dividend. He carefully concealed the tobacco in a small pouch at his girdle, and after sitting a few minutes in silence, staggered to his feet, and waddled off.

"'It is get all you can and keep what you get,' with them," said Smith, as he watched the native enter his hut.

The water in the sauce pan at this moment gave indications of boiling, and as we all felt hungry, we determined to have supper before stretching our forms under the shelter of the cart. Our stock of coffee was produced, the pork and bread unpacked, and while the convict busied himself frying slices of the former, we soaked cakes of the latter in a pan of water, and sliced a few potatoes to add a relish to our meal.

At length our supper was cooked; when seated within the light of the blazing fire, we prepared to enjoy ourselves and perhaps emulate the natives in their feasts.

"How do you like your coffee?" asked Smith, as I raised my tin pot to my mouth.

Before I could reply, my attention was directed to a blaze that suddenly enveloped one of the huts, and which threatened to extend to the others. As the materials of which it was built were light and dry, but few minutes' time would be necessary to consume it; so I started up, intending to assist in extinguishing the flames.

"Let it burn," exclaimed Smith, leisurely sipping his coffee, and watching the progress of the fire; and even the natives kept their places, and appeared unmoved at the sight.

"There may be somebody in the hut," cried Fred, rising.

"Then let them get out the best way they can," answered Smith. "If these dirty scamps can't assist a comrade, I don't see why we should bother our heads."

We waited to hear no more, but rushed towards the flames; and our steps were quickened by hearing what we thought was the cry of a child.

We seized the dry branches, of which the hut was built, and tore them from their fastenings, scattering the leaves that formed the roof, and, regardless of the heat, continued to work; the flames were too powerful for us, and we were obliged to beat a retreat.

We were about to return to our supper, when we heard a shrill cry issue from the hut—not aloud, prolonged sound, such as a man would utter when in agony, but a sharp, short yell, like the wail of an infant.