On the death of Sir Walter Scott in 1832, his entire literary remains were placed at the disposal of his son-in-law, Mr. John Gibson Lockhart. Among these remains were two volumes of a Journal which had been kept by Sir Walter from 1825 to 1832. Mr. Lockhart made large use of this Journal in his admirable life of his father-in-law. Writing, however, so short a time after Scott's death, he could not use it so freely as he might have wished, and, according to his own statement, it was "by regard for the feelings of living persons" that he both omitted and altered; and indeed he printed no chapter of the Diary in full.

There is no longer any reason why the Journal should not be published in its entirety, and by the permission of the Hon. Mrs. Maxwell-Scott it now appears exactly as Scott left it—but for the correction of obvious slips of the pen and the omission of some details chiefly of family and domestic interest.

The original Journal consists of two small 4to volumes, 9 inches by 8, bound in vellum and furnished with strong locks. The manuscript is closely written on both sides, and towards the end shows painful evidence of the physical prostration of the writer. The Journal abruptly closes towards the middle of the second volume with the following entry—probably the last words ever penned by Scott—

In the annotations, it seemed most satisfactory to follow as closely as possible the method adopted by Mr. Lockhart. In the case of those parts of the Journal that have been already published, almost all Mr. Lockhart's notes have been reproduced, and these are distinguished by his initials. Extracts from the Life, from James Skene of Rubislaw's unpublished Reminiscences, and from unpublished letters of Scott himself and his contemporaries, have been freely used wherever they seemed to illustrate particular passages in the Journal.

With regard to Scott's quotations a certain difficulty presented itself. In his Journal he evidently quoted from memory, and he not unfrequently makes considerable variations from the originals. Occasionally, indeed, it would seem that he deliberately made free with the exact words of his author, to adapt them more pertinently to his own mood or the impulse of the moment. In any case it seemed best to let Scott's quotations appear as he wrote them. His reading lay in such curious and unfrequented quarters that to verify all the sources is a nearly impossible task. It is to be remembered, also, that he himself held very free notions on the subject of quotation.

I have to thank the Hon. Mrs. Maxwell-Scott for permitting me to retain for the last three years the precious volumes in which the Journal is contained, and for granting me access to the correspondence of Sir Walter preserved at Abbotsford, and I have likewise to acknowledge the courtesy of His Grace the Duke of Buccleuch for allowing me the use of the Scott letters at Dalkeith. To Mr. W.F. Skene, Historiographer Royal for Scotland, my thanks are warmly rendered for intrusting me with his precious heirloom, the volume which contains Sir Walter's letters to his father, and the Reminiscences that accompany them—one of many kind offices towards me during the last thirty years in our relations as author and publisher. I am also obliged to Mr. Archibald Constable for permitting me to use the interesting Memorandum by James Ballantyne.

Finally, I have to express my obligation to many other friends, who never failed cordially to respond to any call I made upon them.

D.D.

EDINBURGH, 22 DRUMMOND PLACE,

October 1, 1890.

PORTRAIT, painted by JOHN GRAHAM GILBERT, R.S.A., for the Royal Society, Edinburgh. Copied by permission of the Council of the Society, Frontispiece

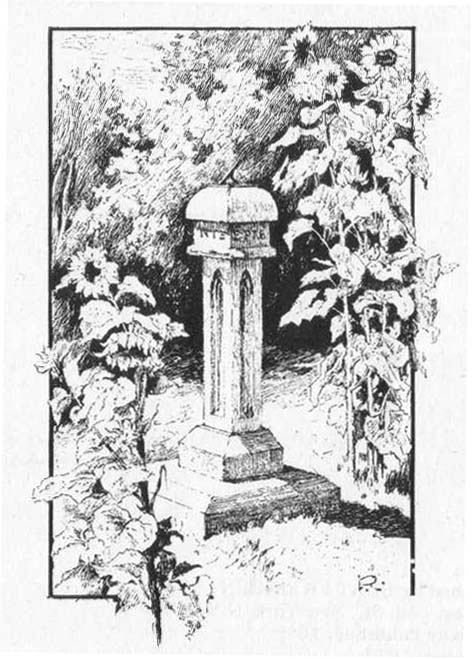

VIGNETTE on Title-page

"The Dial-Stone" in the Garden, from drawing made at Abbotsford by GEORGE REID, R.S.A.

"WORK WHILE IT IS DAY."

ΝΥΞ ΓΑΡ ΕΡΧΕΤΑΙ

"I must home to 'work while it is called day; for the night cometh when no man can work.' I put that text, many a year ago, on my dial-stone; but it often preached in vain."—SCOTT'S Life, x. 88.

MAP OF ABBOTSFORD, from the Ordnance Survey, 1858, to face p. 414.

PORTRAIT, painted by SIR FRANCIS GRANT, P.R.A., for the Baroness Ruthven, and now in the National Portrait Gallery of Scotland. Copied by permission of the Hon. The Board of Manufactures, Frontispiece

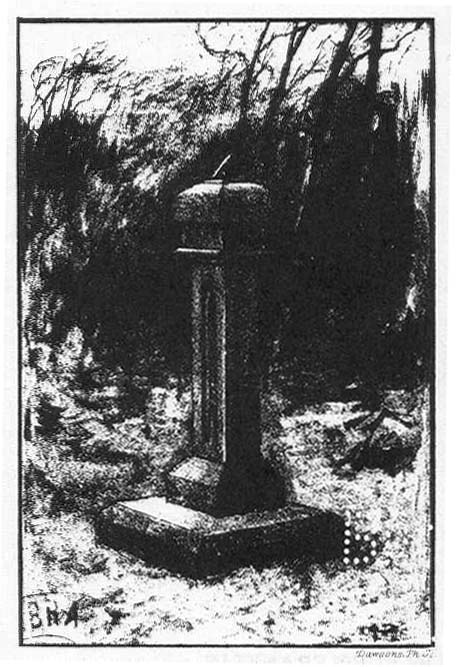

VIGNETTE on Title-page

"The Dial-Stone" in the Garden, from drawing made at Abbotsford by George Reid, R.S.A.

"THE NIGHT COMETH."

ΝΥΞ ΓΑΡ ΕΡΧΕΤΑΙ.

"I must home to work while it is called day; for the night cometh when no man can work. I put that text, many years ago, on my dial-stone; but it often preached in vain."—Scott's Life, x. 88.

Published by BURT FRANKLIN

235 East 44th St., New York, N.Y. 10017

Originally Published: 1890

Reprinted: 1970

Printed in the U.S.A.

S.B.N. 32110

Library of Congress Card Catalog No.: 73-123604

Burt Franklin: Research and Source Works Series 535

Essays in Literature and Criticism 82

"I shall have a peep at Bothwell Castle if it is only for half-an-hour. It is a place of many recollections to me, for I cannot but think how changed I am from the same Walter Scott who was so passionately ambitious of fame when I wrote the song of Young Lochinvar at Bothwell; and if I could recall the same feelings, where was I to find an audience so kind and patient, and whose applause was at the same time so well worth having, as Lady Dalkeith and Lady Douglas? When one thinks of these things, there is no silencing one's regret but by Corporal Nym's philosophy: Things must be as they may. One generation goeth and another cometh."—To LORD MONTAGU, June 28th, 1825.

PORTRAIT, painted by JOHN GRAHAM GILBERT, R.S.A., for the Royal Society, Edinburgh. Copied by permission of the Council of the Society, Frontispiece

VIGNETTE on Title-page

"The Dial-Stone" in the Garden, from drawing made at Abbotsford by GEORGE REID, R.S.A.

"WORK WHILE IT IS DAY."

ΝΥΞ ΓΑΡ ΕΡΧΕΤΑΙ

"I must home to 'work while it is called day; for the night cometh when no man can work.' I put that text, many a year ago, on my dial-stone; but it often preached in vain."—SCOTT'S Life, x. 88.

MAP OF ABBOTSFORD, from the Ordnance Survey, 1858, to face p. 414.

[Edinburgh,] November 20, 1825.—I have all my life regretted that I did not keep a regular Journal. I have myself lost recollection of much that was interesting, and I have deprived my family and the public of some curious information, by not carrying this resolution into effect. I have bethought me, on seeing lately some volumes of Byron's notes, that he probably had hit upon the right way of keeping such a memorandum-book, by throwing aside all pretence to regularity and order, and marking down events just as they occurred to recollection. I will try this plan; and behold I have a handsome locked volume, such as might serve for a lady's album. Nota bene, John Lockhart, and Anne, and I are to raise a Society for the suppression of Albums. It is a most troublesome shape of mendicity. Sir, your autograph—a line of poetry—or a prose sentence!—Among all the sprawling sonnets, and blotted trumpery that dishonours these miscellanies, a man must have a good stomach that can swallow this botheration as a compliment.

I was in Ireland last summer, and had a most delightful tour. It cost me upwards of £500, including £100 left with Walter and Jane, for we travelled a large party and in style. There is much less exaggerated about the Irish than is to be expected. Their poverty is not exaggerated; it is on the extreme verge of human misery; their cottages would scarce serve for pig-styes, even in Scotland, and their rags seem the very refuse of a rag-shop, and are disposed on their bodies with such ingenious variety of wretchedness that you would think nothing but some sort of perverted taste could have assembled so many shreds together. You are constantly fearful that some knot or loop will give, and place the individual before you in all the primitive simplicity of Paradise. Then for their food, they have only potatoes, and too few of them. Yet the men look stout and healthy, the women buxom and well-coloured.

Dined with us, being Sunday, Will. Clerk and Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe. W.C. is the second son of the celebrated author of Naval Tactics.[1] I have known him intimately since our college days; and, to my thinking, never met a man of greater powers, or more complete information on all desirable subjects. In youth he had strongly the Edinburgh pruritus disputandi; but habits of society have greatly mellowed it, and though still anxious to gain your suffrage to his views, he endeavours rather to conciliate your opinion than conquer it by force. Still there is enough of tenacity of sentiment to prevent, in London society, where all must go slack and easy, W.C. from rising to the very top of the tree as a conversation man, who must not only wind the thread of his argument gracefully, but also know when to let go. But I like the Scotch taste better; there is more matter, more information, above all, more spirit in it. Clerk will, I am afraid, leave the world little more than the report of his fame. He is too indolent to finish any considerable work.[2] Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe is another very remarkable man. He was bred a clergyman, but did not take orders, owing I believe to a peculiar effeminacy of voice which must have been unpleasant in reading prayers. Some family quarrels occasioned his being indifferently provided for by a small annuity from his elder brother, extorted by an arbitral decree. He has infinite wit and a great turn for antiquarian lore, as the publications of Kirkton,[3] etc., bear witness. His drawings are the most fanciful and droll imaginable—a mixture between Hogarth and some of those foreign masters who painted temptations of St. Anthony, and such grotesque subjects. As a poet he has not a very strong touch. Strange that his finger-ends can describe so well what he cannot bring out clearly and firmly in words. If he were to make drawing a resource, it might raise him a large income. But though a lover of antiquities, and therefore of expensive trifles, C.K.S. is too aristocratic to use his art to assist his revenue. He is a very complete genealogist, and has made many detections in Douglas and other books on pedigree, which our nobles would do well to suppress if they had an opportunity. Strange that a man should be curious after scandal of centuries old! Not but Charles loves it fresh and fresh also, for, being very much a fashionable man, he is always master of the reigning report, and he tells the anecdote with such gusto that there is no helping sympathising with him—the peculiarity of voice adding not a little to the general effect. My idea is that C.K.S., with his oddities, tastes, satire, and high aristocratic feelings, resembles Horace Walpole—perhaps in his person also, in a general way.—See Miss Hawkins' Anecdotes[4] for a description of the author of The Castle of Otranto.

No other company at dinner except my cheerful and good-humoured friend Missie Macdonald,[5] so called in fondness. One bottle of champagne with the ladies' assistance, two of claret. I observe that both these great connoisseurs were very nearly, if not quite, agreed, that there are no absolutely undoubted originals of Queen Mary. But how then should we be so very distinctly informed as to her features? What has become of all the originals which suggested these innumerable copies? Surely Mary must have been as unfortunate in this as in other particulars of her life.[6]

November 21.—I am enamoured of my journal. I wish the zeal may but last. Once more of Ireland. I said their poverty was not exaggerated; neither is their wit—nor their good-humour—nor their whimsical absurdity—nor their courage.

Wit.—I gave a fellow a shilling on some occasion when sixpence was the fee. "Remember you owe me sixpence, Pat." "May your honour live till I pay you!" There was courtesy as well as wit in this, and all the clothes on Pat's back would have been dearly bought by the sum in question.

Good-humour.—There is perpetual kindness in the Irish cabin; butter-milk, potatoes, a stool is offered, or a stone is rolled that your honour may sit down and be out of the smoke, and those who beg everywhere else seem desirous to exercise free hospitality in their own houses. Their natural disposition is turned to gaiety and happiness; while a Scotchman is thinking about the term-day, or, if easy on that subject, about hell in the next world—while an Englishman is making a little hell of his own in the present, because his muffin is not well roasted—Pat's mind is always turned to fun and ridicule. They are terribly excitable, to be sure, and will murther you on slight suspicion, and find out next day that it was all a mistake, and that it was not yourself they meant to kill at all at all.

Absurdity.—They were widening the road near Lord Claremont's seat as we passed. A number of cars were drawn up together at a particular point, where we also halted, as we understood they were blowing a rock, and the shot was expected presently to go off. After waiting two minutes or so, a fellow called out something, and our carriage as a planet, and the cars for satellites, started all forward at once, the Irishmen whooping and crying, and the horses galloping. Unable to learn the meaning of this, I was only left to suppose that they had delayed firing the intended shot till we should pass, and that we were passing quickly to make the delay as short as possible. No such thing. By dint of making great haste, we got within ten yards of the rock when the blast took place, throwing dust and gravel on our carriage, and had our postillion brought us a little nearer (it was not for want of hallooing and flogging that he did not), we should have had a still more serious share of the explosion. The explanation I received from the drivers was, that they had been told by the overseer that as the mine had been so long in going off, he dared say we would have time to pass it—so we just waited long enough to make the danger imminent. I have only to add that two or three people got behind the carriage, just for nothing but to see how our honours got past.

Went to the Oil Gas Committee[7] this morning, of which concern I am president, or chairman. It has amused me much by bringing me into company with a body of active, business-loving, money-making citizens of Edinburgh, chiefly Whigs by the way, whose sentiments and proceedings amuse me. The stock is rather low in the market, 35s. premium instead of £5. It must rise, however, for the advantages of the light are undeniable, and folks will soon become accustomed to idle apprehensions or misapprehensions. From £20 to £25 should light a house capitally, supposing you leave town in the vacation. The three last quarters cost me £10, 10s., and the first, £8, was greatly overcharged. We will see what this, the worst and darkest quarter, costs.

Dined with Sir Robert Dundas,[8] where we met Lord and Lady Melville. My little nieces (ex officio) gave us some pretty music. I do not know and cannot utter a note of music; and complicated harmonies seem to me a babble of confused though pleasing sounds. Yet songs and simple melodies, especially if connected with words and ideas, have as much effect on me as on most people. But then I hate to hear a young person sing without feeling and expression suited to the song. I cannot bear a voice that has no more life in it than a pianoforte or a bugle-horn. There is something about all the fine arts, of soul and spirit, which, like the vital principle in man, defies the research of the most critical anatomist. You feel where it is not, yet you cannot describe what it is you want. Sir Joshua, or some other great painter, was looking at a picture on which much pains had been bestowed—"Why, yes," he said, in a hesitating manner, "it is very clever—very well done—can't find fault; but it wants something; it wants—it wants, damn me—it wants THAT"—throwing his hand over his head and snapping his fingers. Tom Moore's is the most exquisite warbling I ever heard. Next to him, David Macculloch[9] for Scots songs. The last, when a boy at Dumfries, was much admired by Burns, who used to get him to try over the words which he composed to new melodies. He is brother of Macculloch of Ardwell.

November 22.—MOORE. I saw Moore (for the first time, I may say) this season. We had indeed met in public twenty years ago. There is a manly frankness, and perfect ease and good breeding about him which is delightful. Not the least touch of the poet or the pedant. A little—very little man. Less, I think, than Lewis, and somewhat like him in person; God knows, not in conversation, for Matt, though a clever fellow, was a bore of the first description. Moreover, he looked always like a schoolboy. I remember a picture of him being handed about at Dalkeith House. It was a miniature I think by Sanders,[10] who had contrived to muffle Lewis's person in a cloak, and placed some poignard or dark lanthorn appurtenance (I think) in his hand, so as to give the picture the cast of a bravo. "That like Mat Lewis?" said Duke Henry, to whom it had passed in turn; "why, that is like a MAN!" Imagine the effect! Lewis was at his elbow.[11] Now Moore has none of this insignificance; to be sure his person is much stouter than that of M.G.L., his countenance is decidedly plain, but the expression is so very animated, especially in speaking or singing, that it is far more interesting than the finest features could have rendered it.

I was aware that Byron had often spoken, both in private society and in his Journal, of Moore and myself in the same breath, and with the same sort of regard; so I was curious to see what there could be in common betwixt us, Moore having lived so much in the gay world, I in the country, and with people of business, and sometimes with politicians; Moore a scholar, I none; he a musician and artist, I without knowledge of a note; he a democrat, I an aristocrat—with many other points of difference; besides his being an Irishman, I a Scotchman, and both tolerably national. Yet there is a point of resemblance, and a strong one. We are both good-humoured fellows, who rather seek to enjoy what is going forward than to maintain our dignity as lions; and we have both seen the world too widely and too well not to contemn in our souls the imaginary consequence of literary people, who walk with their noses in the air, and remind me always of the fellow whom Johnson met in an alehouse, and who called himself "the great Twalmley—inventor of the floodgate iron for smoothing linen." He also enjoys the mot pour rire, and so do I.

Moore has, I think, been ill-treated about Byron's Memoirs; he surrendered them to the family (Lord Byron's executors) and thus lost £2000 which he had raised upon them at a most distressing moment of his life. It is true they offered and pressed the money on him afterwards, but they ought to have settled it with the booksellers and not put poor Tom's spirit in arms against his interest.[12] I think at least it might have been so managed. At any rate there must be an authentic life of Byron by somebody. Why should they not give the benefit of their materials to Tom Moore, whom Byron had made the depositary of his own Memoirs?—but T.M. thinks that Cam Hobhouse has the purpose of writing Byron's life himself. He and Moore were at sharp words during the negotiation, and there was some explanation necessary before the affair ended. It was a pity that nothing save the total destruction of Byron's Memoirs would satisfy his executors.[13] But there was a reason—Premat nox alta.

It would be a delightful addition to life, if T.M. had a cottage within two miles of one. We went to the theatre together, and the house, being luckily a good one, received T.M. with rapture. I could have hugged them, for it paid back the debt of the kind reception I met with in Ireland.[14]

Here is a matter for a May morning, but much fitter for a November one. The general distress in the city has affected H. and R.,[15] Constable's great agents. Should they go, it is not likely that Constable can stand, and such an event would lead to great distress and perplexity on the part of J.B. and myself. Thank God, I have enough at least to pay forty shillings in the pound, taking matters at the very worst. But much distress and inconvenience must be the consequence. I had a lesson in 1814 which should have done good upon me, but success and abundance erased it from my mind. But this is no time for journalising or moralising either. Necessity is like a sour-faced cook-maid, and I a turn-spit whom she has flogged ere now, till he mounted his wheel. If W-st-k[16] can be out by 25th January it will do much, and it is possible.

------'s son has saved his comrade on shipboard by throwing himself overboard and keeping the other afloat—a very gallant thing. But the Gran giag' Asso[17] asks me to write a poem on the civic crown, of which he sends me a description quoted from Adam's Antiquities, which mellifluous performance is to persuade the Admiralty to give the young conservator promotion. Oh! he is a rare head-piece, an admirable Merron. I do not believe there is in nature such a full-acorned Boar.[18]

Could not write to purpose for thick-coming fancies; the wheel would not turn easily, and cannot be forced.

Went to dine at the L[ord] J[ustice]-C[lerk's][20] as I thought by invitation, but it was for Tuesday se'nnight. Returned very well pleased, not being exactly in the humour for company, and had a beef-steak. My appetite is surely, excepting in quantity, that of a farmer; for, eating moderately of anything, my Epicurean pleasure is in the most simple diet. Wine I seldom taste when alone, and use instead a little spirits and water. I have of late diminished the quantity, for fear of a weakness inductive to a diabetes—a disease which broke up my father's health, though one of the most temperate men who ever lived. I smoke a couple of cigars instead, which operates equally as a sedative—

I smoked a good deal about twenty years ago when at Ashestiel; but, coming down one morning to the parlour, I found, as the room was small and confined, that the smell was unpleasant, and laid aside the use of the Nicotian weed for many years; but was again led to use it by the example of my son, a hussar officer, and my son-in-law, an Oxford student. I could lay it aside to-morrow; I laugh at the dominion of custom in this and many things.

November 23.—On comparing notes with Moore, I was confirmed in one or two points which I had always laid down in considering poor Byron. One was, that like Rousseau he was apt to be very suspicious, and a plain downright steadiness of manner was the true mode to maintain his good opinion. Will Rose told me that once, while sitting with Byron, he fixed insensibly his eyes on his feet, one of which, it must be remembered, was deformed. Looking up suddenly, he saw Byron regarding him with a look of concentrated and deep displeasure, which wore off when he observed no consciousness or embarrassment in the countenance of Rose. Murray afterwards explained this, by telling Rose that Lord Byron was very jealous of having this personal imperfection noticed or attended to. In another point, Moore confirmed my previous opinion, namely, that Byron loved mischief-making. Moore had written to him cautioning him against the project of establishing the paper called the Liberal, in communion with such men as P.B. Shelley and Hunt,[21] on whom he said the world had set its mark. Byron showed this to the parties. Shelley wrote a modest and rather affecting expostulation to Moore.[22] These two peculiarities of extreme suspicion and love of mischief are both shades of the malady which certainly tinctured some part of the character of this mighty genius; and, without some tendency towards which, genius—I mean that kind which depends on the imaginative power—perhaps cannot exist to great extent. The wheels of a machine, to play rapidly, must not fit with the utmost exactness, else the attrition diminishes the impetus.

Another of Byron's peculiarities was the love of mystifying; which indeed may be referred to that of mischief. There was no knowing how much or how little to believe of his narratives. Instance:—Mr. Bankes[23] expostulating with him upon a dedication which he had written in extravagant terms of praise to Cam Hobhouse, Byron told him that Cam had teased him into the dedication till he had said, "Well; it shall be so,—providing you will write the dedication yourself"; and affirmed that Cam Hobhouse did write the high-coloured dedication accordingly. I mentioned this to Murray, having the report from Will Rose, to whom Bankes had mentioned it. Murray, in reply, assured me that the dedication was written by Lord Byron himself, and showed it me in his own hand. I wrote to Rose to mention the thing to Bankes, as it might have made mischief had the story got into the circle. Byron was disposed to think all men of imagination were addicted to mix fiction (or poetry) with their prose. He used to say he dared believe the celebrated courtezan of Venice, about whom Rousseau makes so piquante a story, was, if one could see her, a draggle-tailed wench enough. I believe that he embellished his own amours considerably, and that he was, in many respects, le fanfaron de vices qu'il n'avoit pas. He loved to be thought awful, mysterious, and gloomy, and sometimes hinted at strange causes. I believe the whole to have been the creation and sport of a wild and powerful fancy. In the same manner he crammed people, as it is termed, about duels, etc., which never existed, or were much exaggerated.

Constable has been here as lame as a duck upon his legs, but his heart and courage as firm as a cock. He has convinced me we will do well to support the London House. He has sent them about £5000, and proposes we should borrow on our joint security £5000 for their accommodation. J.B. and R. Cadell present. I must be guided by them, and hope for the best. Certainly to part company would be to incur an awful risk.

What I liked about Byron, besides his boundless genius, was his generosity of spirit as well as purse, and his utter contempt of all the affectations of literature, from the school-magisterial style to the lackadaisical. Byron's example has formed a sort of upper house of poetry. There is Lord Leveson Gower, a very clever young man.[24] Lord Porchester too,[25] nephew to Mrs. Scott of Harden, a young man who lies on the carpet and looks poetical and dandyish—fine lad too, but—

Talking of Abbotsford, it begins to be haunted by too much company of every kind, but especially foreigners. I do not like them. I hate fine waistcoats and breast-pins upon dirty shirts. I detest the impudence that pays a stranger compliments, and harangues about his works in the author's house, which is usually ill-breeding. Moreover, they are seldom long of making it evident that they know nothing about what they are talking of, except having seen the Lady of the Lake at the Opera.

Dined at St. Catherine's[26] with Lord Advocate, Lord and Lady Melville, Lord Justice-Clerk,[27] Sir Archibald Campbell of Succoth, all class companions and acquainted well for more than forty years. All except Lord J.C. were at Fraser's class, High School.[28] Boyle joined us at college. There are, besides, Sir Adam Ferguson, Colin Mackenzie, James Hope, Dr. James Buchan, Claud Russell, and perhaps two or three more of and about the same period—but

"Apparent rari nantes in gurgite vasto."[29]

November 24.—Talking of strangers, London held, some four or five years since, one of those animals who are lions at first, but by transmutation of two seasons become in regular course Boars!—Ugo Foscolo by name, a haunter of Murray's shop and of literary parties. Ugly as a baboon, and intolerably conceited, he spluttered, blustered, and disputed, without even knowing the principles upon which men of sense render a reason, and screamed all the while like a pig when they cut its throat. Another such Animaluccio is a brute of a Sicilian Marquis de —— who wrote something about Byron. He inflicted two days on us at Abbotsford. They never know what to make of themselves in the forenoon, but sit tormenting the women to play at proverbs and such trash.

Foreigner of a different cast,—Count Olonym (Olonyne—that's it), son of the President of the Royal Society and a captain in the Imperial Guards. He is mean-looking and sickly, but has much sense, candour, and general information. There was at Abbotsford, and is here, for education just now, a young Count Davidoff, with a tutor Mr. Collyer. He is a nephew of the famous Orloffs. It is quite surprising how much sense and sound thinking this youth has at the early age of sixteen, without the least self-conceit or forwardness. On the contrary, he seems kind, modest, and ingenuous.[30] To questions which I asked about the state of Russia he answered with the precision and accuracy of twice his years. I should be sorry the saying were verified in him—

Saw also at Abbotsford two Frenchmen whom I liked, friends of Miss Dumergue. One, called Le Noir, is the author of a tragedy which he had the grace never to quote, and which I, though poked by some malicious persons, had not the grace even to hint at. They were disposed at first to be complimentary, but I convinced them it was not the custom here, and they took it well, and were agreeable.

A little bilious this morning, for the first time these six months. It cannot be the London matters which stick on my stomach, for that is mending, and may have good effects on myself and others.

Dined with Robert Cockburn. Company, Lord Melville and family; Sir John and Lady Hope; Lord and Lady R. Kerr, and so forth. Combination of colliers general, and coals up to double price; the men will not work, although, or rather because, they can make from thirty to forty shillings per week. Lord R.K. told us that he had a letter from Lord Forbes (son of Earl Granard, Ireland), that he was asleep in his house at Castle Forbes, when awakened by a sense of suffocation which deprived him of the power of stirring a limb, yet left him the consciousness that the house was on fire. At this moment, and while his apartment was in flames, his large dog jumped on the bed, seized his shirt, and dragged him to the staircase, where the fresh air restored his powers of exertion and of escape. This is very different from most cases of preservation of life by the canine race, when the animal generally jumps into the water, in which [element] he has force and skill. That of fire is as hostile to him as to mankind.

November 25.—Read Jeffrey's neat and well-intended address[32] to the mechanics upon their combinations. Will it do good? Umph. It takes only the hand of a Lilliputian to light a fire, but would require the diuretic powers of Gulliver to extinguish it. The Whigs will live and die in the heresy that the world is ruled by little pamphlets and speeches, and that if you can sufficiently demonstrate that a line of conduct is most consistent with men's interest, you have therefore and thereby demonstrated that they will at length, after a few speeches on the subject, adopt it of course. In this case we would have [no] need of laws or churches, for I am sure there is no difficulty in proving that moral, regular, and steady habits conduce to men's best interest, and that vice is not sin merely, but folly. But of these men each has passions and prejudices, the gratification of which he prefers, not only to the general weal, but to that of himself as an individual. Under the action of these wayward impulses a man drinks to-day though he is sure of starving to-morrow. He murders to-morrow though he is sure to be hanged on Wednesday; and people are so slow to believe that which makes against their own predominant passions, that mechanics will combine to raise the price for one week, though they destroy the manufacture for ever. The best remedy seems to be the probable supply of labourers from other trades. Jeffrey proposes each mechanic shall learn some other trade than his own, and so have two strings to his bow. He does not consider the length of a double apprenticeship. To make a man a good weaver and a good tailor would require as much time as the patriarch served for his two wives, and after all, he would be but a poor workman at either craft. Each mechanic has, indeed, a second trade, for he can dig and do rustic work. Perhaps the best reason for breaking up the association will prove to be the expenditure of the money which they have been simple enough to levy from the industrious for the support of the idle. How much provision for the sick and the aged, the widow and the orphan, has been expended in the attempt to get wages which the manufacturer cannot afford them, with any profitable chance of selling his commodity?

I had a bad fall last night coming home. There were unfinished houses at the east end of Atholl Place,[33] and as I was on foot, I crossed the street to avoid the material which lay about; but, deceived by the moonlight, I stepped ankle-deep in a sea of mud (honest earth and water, thank God), and fell on my hands. Never was there such a representative of Wall in Pyramus and Thisbe—I was absolutely rough-cast. Luckily Lady S. had retired when I came home; so I enjoyed my tub of water without either remonstrance or condolences. Cockburn's hospitality will get the benefit and renown of my downfall, and yet has no claim to it. In future though, I must take a coach at night—a control on one's freedom, but it must be submitted to. I found a letter from [R.] C[adell], giving a cheering account of things in London. Their correspondent is getting into his strength. Three days ago I would have been contented to buy this consola, as Judy says,[34] dearer than by a dozen falls in the mud. For had the great Constable fallen, O my countrymen, what a fall were there!

Mrs. Coutts, with the Duke of St. Albans and Lady Charlotte Beauclerk, called to take leave of us. When at Abbotsford his suit throve but coldly. She made me, I believe, her confidant in sincerity.[35] She had refused him twice, and decidedly. He was merely on the footing of friendship. I urged it was akin to love. She allowed she might marry the Duke, only she had at present not the least intention that way. Is this frank admission more favourable for the Duke than an absolute protestation against the possibility of such a marriage? I think not. It is the fashion to attend Mrs. Coutts' parties and to abuse her. I have always found her a kind, friendly woman, without either affectation or insolence in the display of her wealth, and most willing to do good if the means be shown to her. She can be very entertaining too, as she speaks without scruple of her stage life. So much wealth can hardly be enjoyed without some ostentation. But what then? If the Duke marries her, he ensures an immense fortune; if she marries him, she has the first rank. If he marries a woman older than himself by twenty years, she marries a man younger in wit by twenty degrees. I do not think he will dilapidate her fortune—he seems quiet and gentle. I do not think that she will abuse his softness—of disposition, shall I say, or of heart? The disparity of ages concerns no one but themselves; so they have my consent to marry, if they can get each other's. Just as this is written, enter my Lord of St. Albans and Lady Charlotte, to beg I would recommend a book of sermons to Mrs. Coutts. Much obliged for her good opinion: recommended Logan's[36]—one poet should always speak for another. The mission, I suppose, was a little display on the part of good Mrs. Coutts of authority over her high aristocratic suitor. I do not suspect her of turning dévote, and retract my consent given as above, unless she remains "lively, brisk, and jolly."[37]

Dined quiet with wife and daughter. R[obert] Cadell looked in in the evening on business.

I here register my purpose to practise economics. I have little temptation to do otherwise. Abbotsford is all that I can make it, and too large for the property; so I resolve—

No more building;

No purchases of land till times are quite safe;

No buying books or expensive trifles—I mean to any extent; and

Clearing off encumbrances, with the returns of this year's labour;—

Which resolutions, with health and my habits of industry, will make me "sleep in spite of thunder."

After all, it is hard that the vagabond stock-jobbing Jews should, for their own purposes, make such a shake of credit as now exists in London, and menace the credit of men trading on sure funds like H[urst] and R[obinson]. It is just like a set of pickpockets, who raise a mob, in which honest folks are knocked down and plundered, that they may pillage safely in the midst of the confusion they have excited.

November 26.—The court met late, and sat till one; detained from that hour till four o'clock, being engaged in the perplexed affairs of Mr. James Stewart of Brugh. This young gentleman is heir to a property of better than £1000 a year in Orkney. His mother married very young, and was wife, mother, and widow in the course of the first year. Being unfortunately under the direction of a careless agent, she was unlucky enough to embarrass her own affairs by many transactions with this person. I was asked to accept the situation of one of the son's curators; and trust to clear out his affairs and hers—at least I will not fail for want of application. I have lent her £300 on a second (and therefore doubtful) security over her house in Newington, bought for £1000, and on which £600 is already secured. I have no connection with the family except that of compassion, and may not be rewarded even by thanks when the young man comes of age. I have known my father often so treated by those whom he had laboured to serve. But if we do not run some hazard in our attempts to do good, where is the merit of them? So I will bring through my Orkney laird if I can. Dined at home quiet with Lady S. and Anne.

November 27.—Some time since John Murray entered into a contract with my son-in-law, John G. Lockhart, giving him on certain ample conditions the management and editorship of the Quarterly Review, for which they could certainly scarcely find a fitter person, both from talents and character. It seems that Barrow[38] and one or two stagers have taken alarm at Lockhart's character as a satirist, and his supposed accession to some of the freaks in Blackwood's Magazine, and down comes young D'Israeli[39] to Scotland imploring Lockhart to make interest with my friends in London to remove objections, and so forth. I have no idea of telling all and sundry that my son-in-law is not a slanderer, or a silly thoughtless lad, although he was six or seven years ago engaged in some light satires. I only wrote to Heber and to Southey—the first upon the subject of the reports which had startled Murray, (the most timorous, as Byron called him, of all God's booksellers), and such a letter as he may show Barrow if he judges proper. To Southey I wrote more generally, acquainting him of my son's appointment to the Editorship, and mentioning his qualifications, touching, at the same time, on his very slight connection with Blackwood's Magazine, and his innocence as to those gambades which may have given offence, and which, I fear, they may ascribe too truly to an eccentric neighbour of their own. I also mentioned that I had heard nothing of the affair until the month of October. I am concerned that Southey should know this; for, having been at the Lakes in September, I would not have him suppose that I had been using interest with Canning or Ellis to supersede young Mr. Coleridge,[40] their editor, and place my son-in-law in the situation; indeed I was never more surprised than when this proposal came upon us. I suppose it had come from Canning originally, as he was sounding Anne when at Colonel Bolton's[41] about Lockhart's views, etc. To me he never hinted anything on the subject. Other views are held out to Lockhart which may turn to great advantage. Only one person (John Cay[42] of Charlton) knows their object, and truly I wish it had not been confided to any one. Yesterday I had a letter from Murray in answer to one I had written in something a determined style, for I had no idea of permitting him to start from the course after my son giving up his situation and profession, merely because a contributor or two chose to suppose gratuitously that Lockhart was too imprudent for the situation. My physic has wrought well, for it brought a letter from Murray saying all was right, that D'Israeli was sent to me, not to Lockhart, and that I was only invited to write two confidential letters, and other incoherencies—which intimate his fright has got into another quarter. It is interlined and franked by Barrow, which shows that all is well, and that John's induction into his office will be easy and pleasant. I have not the least fear of his success; his talents want only a worthy sphere of exertion. He must learn, however, to despise petty adversaries. No good sportsman ought to shoot at crows unless for some special purpose. To take notice of such men as Hazlitt and Hunt in the Quarterly would be to introduce them into a world which is scarce conscious of their existence. It is odd enough that many years since I had the principal share in erecting this Review which has been since so prosperous, and now it is placed under the management of my son-in-law upon the most honourable principle of detur digniori. Yet there are sad drawbacks so far as family comfort is concerned. To-day is Sunday, when they always dined with us, and generally met a family friend or two, but we are no longer to expect them. In the country, where their little cottage was within a mile or two of Abbotsford, we shall miss their society still more, for Chiefswood was the perpetual object of our walks, rides, and drives. Lockhart is such an excellent family man, so fond of his wife and child, that I hope all will go well. A letter from Lockhart in the evening. All safe as to his unanimous reception in London; his predecessor, young [Coleridge], handsomely, and like a gentleman, offers his assistance as a contributor, etc.

November 28.—I have the less dread, or rather the less anxiety, about the consequences of this migration, that I repose much confidence in Sophia's tact and good sense. Her manners are good, and have the appearance of being perfectly natural. She is quite conscious of the limited range of her musical talents, and never makes them common or produces them out of place,—a rare virtue; moreover she is proud enough, and will not be easily netted and patronised by any of that class of ladies who may be called Lion-providers for town and country. She is domestic besides, and will not be disposed to gad about. Then she seems an economist, and on £3000,[43] living quietly, there should be something to save. Lockhart must be liked where his good qualities are known, and where his fund of information has room to be displayed. But, notwithstanding a handsome exterior and face, I am not sure he will succeed in London Society; he sometimes reverses the proverb, and gives the volte strette e pensiere sciolti, withdraws his attention from the company, or attaches himself to some individual, gets into a corner, and seems to be quizzing the rest. This is the want of early habits of being in society, and a life led much at college. Nothing is, however, so popular, and so deservedly so, as to take an interest in whatever is going forward in society. A wise man always finds his account in it, and will receive information and fresh views of life even in the society of fools. Abstain from society altogether when you are not able to play some part in it. This reserve, and a sort of Hidalgo air joined to his character as a satirist, have done the best-humoured fellow in the world some injury in the opinion of Edinburgh folks. In London it is of less consequence whether he please in general society or not, since if he can establish himself as a genius it will only be called "Pretty Fanny's Way."

People make me the oddest requests. It is not unusual for an Oxonian or Cantab, who has outrun his allowance, and of whom I know nothing, to apply to me for the loan of £20, £50, or £100. A captain of the Danish naval service writes to me, that being in distress for a sum of money by which he might transport himself to Columbia, to offer his services in assisting to free that province, he had dreamed I generously made him a present of it. I can tell him his dream by contraries. I begin to find, like Joseph Surface, that too good a character is inconvenient. I don't know what I have done to gain so much credit for generosity, but I suspect I owe it to being supposed, as Puff[44] says, one of those "whom Heaven has blessed with affluence." Not too much of that neither, my dear petitioners, though I may thank myself that your ideas are not correct.

Dined at Melville Castle, whither I went through a snow-storm. I was glad to find myself once more in a place connected with many happy days. Met Sir R. Dundas and my old friend George, now Lord Abercromby,[45] with his lady, and a beautiful girl, his daughter. He is what he always was—the best-humoured man living; and our meetings, now more rare than usual, are seasoned with a recollection of old frolics and old friends. I am entertained to see him just the same he has always been, never yielding up his own opinion in fact, and yet in words acquiescing in all that could be said against it. George was always like a willow—he never offered resistance to the breath of argument, but never moved from his rooted opinion, blow as it listed. Exaggeration might make these peculiarities highly dramatic: Conceive a man who always seems to be acquiescing in your sentiments, yet never changes his own, and this with a sort of bonhomie which shows there is not a particle of deceit intended. He is only desirous to spare you the trouble of contradiction.

November 29.—A letter from Southey, malcontent about Murray having accomplished the change in the Quarterly without speaking to him, and quoting the twaddle of some old woman, male or female, about Lockhart's earlier jeux d'esprit, but concluding most kindly that in regard to my daughter and me he did not mean to withdraw. That he has done yeoman's service to the Review is certain, with his genius, his universal reading, his powers of regular industry, and at the outset a name which, though less generally popular than it deserves, is still too respectable to be withdrawn without injury. I could not in reply point out to him what is the truth, that his rigid Toryism and High Church prejudices rendered him an unsafe counsellor in a matter where the spirit of the age must be consulted; but I pointed out to him what I am sure is true, that Murray, apprehensive of his displeasure, had not ventured to write to him out of mere timidity and not from any [intention to offend]. I treated [lightly] his old woman's apprehensions and cautions, and all that gossip about friends and enemies, to which a splendid number or two will be a sufficient answer, and I accepted with due acknowledgment his proposal of continued support. I cannot say I was afraid of his withdrawing. Lockhart will have hard words with him, for, great as Southey's powers are, he has not the art to make them work popularly; he is often diffuse, and frequently sets much value on minute and unimportant facts, and useless pieces of abstruse knowledge. Living too exclusively in a circle where he is idolised both for his genius and the excellence of his disposition, he has acquired strong prejudices, though all of an upright and honourable cast. He rides his High Church hobby too hard, and it will not do to run a tilt upon it against all the world. Gifford used to crop his articles considerably, and they bear mark of it, being sometimes décousues. Southey said that Gifford cut out his middle joints. When John comes to use the carving-knife I fear Dr. Southey will not be so tractable. Nous verrons. I will not show Southey's letter to Lockhart, for there is to him personally no friendly tone, and it would startle the Hidalgo's pride. It is to be wished they may draw kindly together. Southey says most truly that even those who most undervalue his reputation would, were he to withdraw from the Review, exaggerate the loss it would thereby sustain. The bottom of all these feuds, though not named, is Blackwood's Magazine; all the squibs of which, which have sometimes exploded among the Lakers, Lockhart is rendered accountable for. He must now exert himself at once with spirit and prudence.[46] He has good backing—Canning, Bishop Blomfield, Gifford, Wright, Croker, Will Rose,—and is there not besides the Douglas?[47] An excellent plot, excellent friends, and full of preparations? It was no plot of my making, I am sure, yet men will say and believe that [it was], though I never heard a word of the matter till first a hint from Wright, and then the formal proposal of Murray to Lockhart announced. I believe Canning and Charles Ellis were the prime movers. I'll puzzle my brains no more about it.

Dined at Justice-Clerk's—the President—Captain Smollett, etc.,—our new Commander-in-chief, Hon. Sir Robert O'Callaghan, brother to Earl of Lismore, a fine soldierly-looking man, with orders and badges;—his brother, an agreeable man, whom I met at Lowther Castle this season. He composes his own music and sings his own poetry—has much humour, enhanced by a strong touch of national dialect, which is always a rich sauce to an Irishman's good things. Dandyish, but not offensively, and seems to have a warm feeling for the credit of his country—rather inconsistent with the trifling and selfish quietude of a mere man of society.

November 30.—I am come to the time when those who look out of the windows shall be darkened. I must now wear spectacles constantly in reading and writing, though till this winter I have made a shift by using only their occasional assistance. Although my health cannot be better, I feel my lameness becomes sometimes painful, and often inconvenient. Walking on the pavement or causeway gives me trouble, and I am glad when I have accomplished my return on foot from the Parliament House to Castle Street, though I can (taking a competent time, as old Braxie[48] said on another occasion) walk five or six miles in the country with pleasure. Well—such things must come, and be received with cheerful submission. My early lameness considered, it was impossible for a man labouring under a bodily impediment to have been stronger or more active than I have been, and that for twenty or thirty years. Seams will slit, and elbows will out, quoth the tailor; and as I was fifty-four on 15th August last, my mortal vestments are none of the newest. Then Walter, Charles, and Lockhart are as active and handsome young fellows as you can see; and while they enjoy strength and activity I can hardly be said to want it. I have perhaps all my life set an undue value on these gifts. Yet it does appear to me that high and independent feelings are naturally, though not uniformly or inseparably, connected with bodily advantages. Strong men are usually good-humoured, and active men often display the same elasticity of mind as of body. These are superiorities, however, that are often misused. But even for these things God shall call us to judgment.

Some months since I joined with other literary folks in subscribing a petition for a pension to Mrs. G. of L.,[49] which we thought was a tribute merited by her works as an authoress, and, in my opinion, much more by the firmness and elasticity of mind with which she had borne a succession of great domestic calamities. Unhappily there was only about £100 open on the pension list, and this the minister assigned in equal portions to Mrs. G—— and a distressed lady, grand-daughter of a forfeited Scottish nobleman. Mrs. G——, proud as a Highland-woman, vain as a poetess, and absurd as a bluestocking, has taken this partition in malam partem, and written to Lord Melville about her merits, and that her friends do not consider her claims as being fairly canvassed, with something like a demand that her petition be submitted to the King. This is not the way to make her plack a bawbee, and Lord M., a little miffed in turn, sends the whole correspondence to me to know whether Mrs. G——will accept the £50 or not. Now, hating to deal with ladies when they are in an unreasonable humour, I have got the good-humoured "Man of Feeling" to find out the lady's mind, and I take on myself the task of making her peace with Lord M. There is no great doubt how it will end, for your scornful dog will always eat your dirty pudding.[50] After all, the poor lady is greatly to be pitied;—her sole remaining daughter, deep and far gone in a decline, has been seized with alienation of mind.

Dined with my cousin, R[obert] R[utherford], being the first invitation since my uncle's death, and our cousin Lieutenant-Colonel Russell[51] of Ashestiel, with his sister Anne—the former newly returned from India—a fine gallant fellow, and distinguished as a cavalry officer. He came overland from India and has observed a good deal. General L—— of L——, in Logan's orthography a fowl, Sir William Hamilton, Miss Peggie Swinton, William Keith, and others. Knight Marischal not well, so unable to attend the convocation of kith and kin.

December 1st.—Colonel R[ussell] told me that the European Government had discovered an ingenious mode of diminishing the number of burnings of widows. It seems the Shaster positively enjoins that the pile shall be so constructed that, if the victim should repent even at the moment when it is set on fire, she may still have the means of saving herself. The Brahmins soon found it was necessary to assist the resolution of the sufferers, by means of a little pit into which they contrive to let the poor widow sink, so as to prevent her reaping any benefit from a late repentance. But the Government has brought them back to the regard of their law, and only permit the burning to go on when the pile is constructed with full opportunity of a locus penitentiæ. Yet the widow is so degraded if she dare to survive, that the number of burnings is still great. The quantity of female children destroyed by the Rajput tribes Colonel R. describes as very great indeed. They are strangled by the mother. The principle is the aristocratic pride of these high castes, who breed up no more daughters than they can reasonably hope to find matches for in their own tribe. Singular how artificial systems of feeling can be made to overcome that love of offspring which seems instinctive in the females, not of the human race only, but of the lower animals. This is the reverse of our system of increasing game by shooting the old cock-birds. It is a system would aid Malthus rarely.

Nota bene, the day before yesterday I signed the bond for £5000, with Constable, for relief of Robinson's house.[52] I am to be secured by good bills.

I think this journal will suit me well. If I can coax myself into an idea that it is purely voluntary, it may go on—Nulla dies sine lineâ. But never a being, from my infancy upwards, hated task-work as I hate it; and yet I have done a great deal in my day. It is not that I am idle in my nature neither. But propose to me to do one thing, and it is inconceivable the desire I have to do something else—not that it is more easy or more pleasant, but just because it is escaping from an imposed task. I cannot trace this love of contradiction to any distinct source, but it has haunted me all my life. I could almost suppose it was mechanical, and that the imposition of a piece of duty-labour operated on me like the mace of a bad billiard-player, which gives an impulse to the ball indeed, but sends it off at a tangent different from the course designed by the player. Now, if I expend such eccentric movements on this journal, it will be turning this wretched propensity to some tolerable account. If I had thus employed the hours and half-hours which I have whiled away in putting off something that must needs be done at last, "My Conscience!" I should have had a journal with a witness. Sophia and Lockhart came to Edinburgh to-day and dined with us, meeting Hector Macdonald Buchanan, his lady, and Missie, James Skene and his lady, Lockhart's friend Cay, etc. They are lucky to be able to assemble so many real friends, whose good wishes, I am sure, will follow them in their new undertaking.

December 2.—Rather a blank day for the Gurnal. Correcting proofs in the morning. Court from half-past ten till two; poor dear Colin Mackenzie, one of the wisest, kindest, and best men of his time, in the country,—I fear with very indifferent health. From two till three transacting business with J.B.; all seems to go smoothly. Sophia dined with us alone, Lockhart being gone to the west to bid farewell to his father and brothers. Evening spent in talking with Sophia on their future prospects. God bless her, poor girl! she never gave me a moment's reason to complain of her. But, O my God! that poor delicate child, so clever, so animated, yet holding by this earth with so fearfully slight a tenure. Never out of his mother's thoughts, almost never out of his father's arms when he has but a single moment to give to anything. Deus providebit.

December 3.—R.P.G.[53] came to call last night to excuse himself from dining with Lockhart's friends to-day. I really fear he is near an actual standstill. He has been extremely improvident. When I first knew him he had an excellent estate, and now he is deprived, I fear, of the whole reversion of the price, and this from no vice or extreme, except a wasteful mode of buying pictures and other costly trifles at high prices, and selling them again for nothing, besides an extravagant housekeeping and profuse hospitality. An excellent disposition, with a considerable fund of acquired knowledge, would have rendered him an agreeable companion, had he not affected singularity, and rendered himself accordingly singularly affected. He was very near being a poet—but a miss is as good as a mile, and he always fell short of the mark. I knew him first, many years ago, when he was desirous of my acquaintance; but he was too poetical for me, or I was not poetical enough for him, so that we continued only ordinary acquaintance, with goodwill on either side, which R.P.G. really deserves, as a more friendly, generous creature never lived. Lockhart hopes to get something done for him, being sincerely attached to him, but says he has no hopes till he is utterly ruined. That point, I fear, is not far distant; but what Lockhart can do for him then I cannot guess. His last effort failed, owing to a curious reason. He had made some translations from the German, which he does extremely [well]—for give him ideas and he never wants choice of good words—and Lockhart had got Constable to offer some sort of terms for them. R.P.G. has always, though possessing a beautiful power of handwriting, had some whim or other about imitating that of some other person, and has written for months in the imitation of one or other of his friends. At present he has renounced this amusement, and chooses to write with a brush upon large cartridge paper, somewhat in the Chinese fashion,—so when his work, which was only to extend to one or two volumes, arrived on the shoulders of two porters, in immense bales, our jolly bibliopolist backed out of the treaty, and would have nothing more to do with R.P.[54] He is a creature that is, or would be thought, of imagination all compact, and is influenced by strange whims. But he is a kind, harmless, friendly soul, and I fear has been cruelly plundered of money, which he now wants sadly.

Dined with Lockhart's friends, about fifty in number, who gave him a parting entertainment. John Hope, Solicitor-General, in the chair, and Robert Dundas [of Arniston], croupier. The company most highly respectable, and any man might be proud of such an indication of the interest they take in his progress in life. Tory principles rather too violently upheld by some speakers. I came home about ten; the party sat late.

December 4.—Lockhart and Sophia, with his brother William, dined with us, and talked over our separation, and the mode of their settling in London, and other family topics.

December 5.—This morning Lockhart and Sophia left us early, and without leave-taking; when I rose at eight o'clock they were gone. This was very right. I hate red eyes and blowing of noses. Agere et pati Romanum est. Of all schools commend me to the Stoics. We cannot indeed overcome our affections, nor ought we if we could, but we may repress them within due bounds, and avoid coaxing them to make fools of those who should be their masters. I have lost some of the comforts to which I chiefly looked for enjoyment. Well, I must make the more of such as remain—God bless them. And so "I will unto my holy work again,"[55] which at present is the description of that heilige Kleeblatt, that worshipful triumvirate, Danton, Robespierre, and Marat.

I cannot conceive what possesses me, over every person besides, to mislay papers. I received a letter Saturday at e'en, enclosing a bill for £750; no deaf nuts. Well, I read it, and note the contents; and this day, as if it had been a wind-bill in the literal sense of the words, I search everywhere, and lose three hours of my morning—turn over all my confusion in the writing-desk—break open one or two letters, lest I should have enclosed the sweet and quickly convertible document in them,—send for a joiner, and disorganise my scrutoire, lest it should have fallen aside by mistake. I find it at last—the place where is of little consequence; but this trick must be amended.

Dined at the Royal Society Club, where, as usual, was a pleasant meeting of from twenty to twenty-five. It is a very good institution; we pay two guineas only for six dinners in the year, present or absent. Dine at five, or rather half-past five, at the Royal Hotel, where we have an excellent dinner, with soups, fish, etc., and all in good order; port and sherry till half-past seven, then coffee, and we go to the Society. This has great influence in keeping up the attendance, it being found that this preface of a good dinner, to be paid for whether you partake or not, brings out many a philosopher who might not otherwise have attended the Society. Harry Mackenzie, now in his eighty-second or third year, read part of an Essay on Dreams. Supped at Dr. Russell's usual party,[56] which shall serve for one while.

December 6.—A rare thing this literature, or love of fame or notoriety which accompanies it. Here is Mr. H[enry] M[ackenzie] on the very brink of human dissolution, as actively anxious about it as if the curtain must not soon be closed on that and everything else.[57] He calls me his literary confessor; and I am sure I am glad to return the kindnesses which he showed me long since in George Square. No man is less known from his writings. We would suppose a retired, modest, somewhat affected man, with a white handkerchief, and a sigh ready for every sentiment. No such thing: H.M. is alert as a contracting tailor's needle in every sort of business—a politician and a sportsman—shoots and fishes in a sort even to this day—and is the life of the company with anecdote and fun. Sometimes, his daughter tells me, he is in low spirits at home, but really I never see anything of it in society.

There is a maxim almost universal in Scotland, which I should like much to see controlled. Every youth, of every temper and almost every description of character, is sent either to study for the bar, or to a writer's office as an apprentice. The Scottish seem to conceive Themis the most powerful of goddesses. Is a lad stupid, the law will sharpen him;—is he too mercurial, the law will make him sedate;—has he an estate, he may get a sheriffdom;—is he poor, the richest lawyers have emerged from poverty;—is he a Tory, he may become a depute-advocate;—is he a Whig, he may with far better hope expect to become, in reputation at least, that rising counsel Mr.——, when in fact he only rises at tavern dinners. Upon some such wild views lawyers and writers multiply till there is no life for them, and men give up the chase, hopeless and exhausted, and go into the army at five-and-twenty, instead of eighteen, with a turn for expense perhaps—almost certainly for profligacy, and with a heart embittered against the loving parents or friends who compelled them to lose six or seven years in dusting the rails of the stair with their black gowns, or scribbling nonsense for twopence a page all day, and laying out twice their earnings at night in whisky-punch. Here is R.L. now. Four or five years ago, from certain indications, I assured his friends he would never be a writer. Good-natured lad, too, when Bacchus is out of the question; but at other times so pugnacious, that it was wished he could only be properly placed where fighting was to be a part of his duty, regulated by time and place, and paid for accordingly. Well, time, money, and instruction have been thrown away, and now, after fighting two regular boxing matches and a duel with pistols in the course of one week, he tells them roundly he will be no writer, which common-sense might have told them before. He has now perhaps acquired habits of insubordination, unfitting him for the army, where he might have been tamed at an earlier period. He is too old for the navy, and so he must go to India, a guinea-pig on board a Chinaman, with what hope or view it is melancholy to guess. His elder brother did all man could to get his friends to consent to his going into the army in time. The lad has good-humour, courage, and most gentlemanlike feelings, but he is incurably dissipated, I hear; so goes to die in youth in a foreign land. Thank God, I let Walter take his own way; and I trust he will be a useful, honoured soldier, being, for his time, high in the service; whereas at home he would probably have been a wine-bibbing, moorfowl-shooting, fox-hunting Fife squire—living at Lochore without either aim or end—and well if he were no worse. Dined at home with Lady S. and Anne. Wrote in the evening.

December 7.—Teind day;[58]—at home of course. Wrote answers to one or two letters which have been lying on my desk like snakes, hissing at me for my dilatoriness. Bespoke a tun of palm-oil for Sir John Forbes. Received a letter from Sir W. Knighton, mentioning that the King acquiesced in my proposal that Constable's Miscellany should be dedicated to him. Enjoined, however, not to make this public, till the draft of dedication shall be approved. This letter tarried so long, I thought some one had insinuated the proposal was infra dig. I don't think so. The purpose is to bring all the standard works, both in sciences and the liberal arts, within the reach of the lower classes, and enable them thus to use with advantage the education which is given them at every hand. To make boys learn to read, and then place no good books within their reach, is to give men an appetite, and leave nothing in the pantry save unwholesome and poisonous food, which, depend upon it, they will eat rather than starve. Sir William, it seems, has been in Germany.

Mighty dark this morning; it is past ten, and I am using my lamp. The vast number of houses built beneath us to the north certainly render our street darker during the days when frost or haze prevents the smoke from rising. After all, it may be my older eyes. I remember two years ago, when Lord H. began to fail somewhat in his limbs, he observed that Lord S.[59] came to Court at a more early hour than usual, whereas it was he himself who took longer time to walk the usual distance betwixt his house and the Parliament Square. I suspect old gentlemen often make such mistakes. A letter from Southey in a very pleasant strain as to Lockhart and myself. Of Murray he has perhaps ground to complain as well for consulting him late in the business, as for the manner in which he intimated to young Coleridge, who had no reason to think himself handsomely treated, though he has acquiesced in the arrangement in a very gentlemanlike tone. With these matters we, of course, have nothing to do; having no doubt that the situation was vacant when M. offered it as such. Southey says, in alteration of Byron's phrase, that M. is the most timorous, not of God's, but of the devil's, booksellers. The truth I take to be that Murray was pushed in the change of Editor (which was really become necessary) probably by Gifford, Canning, Ellis, etc.; and when he had fixed with Lockhart by their advice his constitutional nervousness made him delay entering upon a full explanation with Coleridge. But it is all settled now—I hope Lockhart will be able to mitigate their High Church bigotry. It is not for the present day, savouring too much of jure divino.

Dined quiet with Lady S. and Anne. Anne is practising Scots songs, which I take as a kind compliment to my own taste, as hers leads her chiefly to foreign music. I think the good girl sees that I want and must miss her sister's peculiar talent in singing the airs of our native country, which, imperfect as my musical ear is, make, and always have made, the most pleasing impression on me. And so if she puts a constraint on herself for my sake, I can only say, in requital, God bless her.

I have much to comfort me in the present aspect of my family. My eldest son, independent in fortune, united to an affectionate wife—and of good hopes in his profession; my second, with a good deal of talent, and in the way, I trust, of cultivating it to good purpose; Anne, an honest, downright, good Scots lass, in whom I would only wish to correct a spirit of satire; and Lockhart is Lockhart, to whom I can most willingly confide the happiness of the daughter who chose him, and whom he has chosen. My dear wife, the partner of early cares and successes, is, I fear, frail in health—though I trust and pray she may see me out. Indeed, if this troublesome complaint goes on—it bodes no long existence. My brother was affected with the same weakness, which, before he was fifty, brought on mortal symptoms. The poor Major had been rather a free liver. But my father, the most abstemious of men, save when the duties of hospitality required him to be very moderately free with his bottle, and that was very seldom, had the same weakness which now annoys me, and he, I think, was not above seventy when cut off. Square the odds, and good-night Sir Walter about sixty. I care not, if I leave my name unstained, and my family properly settled. Sat est vixisse.

December 8.—Talking of the vixisse, it may not be impertinent to notice that Knox, a young poet of considerable talent, died here a week or two since. His father was a respectable yeoman, and he himself, succeeding to good farms under the Duke of Buccleuch, became too soon his own master, and plunged into dissipation and ruin. His poetical talent, a very fine one, then showed itself in a fine strain of pensive poetry, called, I think, The Lonely Hearth, far superior to those of Michael Bruce, whose consumption, by the way, has been the life of his verses. But poetry, nay, good poetry, is a drug in the present day. I am a wretched patron. I cannot go with a subscription-paper, like a pocket-pistol about me, and draw unawares on some honest country-gentleman, who has as much alarm as if I had used the phrase "stand and deliver," and parts with his money with a grimace, indicating some suspicion that the crown-piece thus levied goes ultimately into the collector's own pocket. This I see daily done; and I have seen such collectors, when they have exhausted Papa and Mamma, continue their trade among the misses, and conjure out of their pockets those little funds which should carry them to a play or an assembly. It is well people will go through this—it does some good, I suppose, and they have great merit who can sacrifice their pride so far as to attempt it in this way. For my part I am a bad promoter of subscriptions; but I wished to do what I could for this lad, whose talent I really admired; and I am not addicted to admire heaven-born poets, or poetry that is reckoned very good considering. I had him, Knox,[60] at Abbotsford, about ten years ago, but found him unfit for that sort of society. I tried to help him, but there were temptations he could never resist. He scrambled on, writing for the booksellers and magazines, and living like the Otways, and Savages, and Chattertons of former days, though I do not know that he was in actual want. His connection with me terminated in begging a subscription or a guinea now and then. His last works were spiritual hymns, and which he wrote very well. In his own line of society he was said to exhibit infinite humour; but all his works are grave and pensive, a style perhaps, like Master Stephen's melancholy,[61] affected for the nonce.

Mrs. G[rant] of L. intimates that she will take her pudding—her pension, I mean (see 30th November), and is contrite, as H[enry] M[ackenzie] vouches. I am glad the stout old girl is not foreclosed; faith, cabbing a pension in these times is like hunting a pig with a soap'd tail, monstrous apt to slip through your fingers.[62] Dined at home with Lady S. and Anne.

December 9.—Yesterday I read and wrote the whole day and evening. To-day I shall not be so happy. Having Gas-Light Company to attend at two, I must be brief in journalising.

The gay world has been kept in hot water lately by the impudent publication of the celebrated Harriet Wilson, —— from earliest possibility, I suppose, who lived with half the gay world at hack and manger, and now obliges such as will not pay hush-money with a history of whatever she knows or can invent about them. She must have been assisted in the style, spelling, and diction, though the attempt at wit is very poor, that at pathos sickening. But there is some good retailing of conversations, in which the style of the speakers, so far as known to me, is exactly imitated, and some things told, as said by individuals of each other, which will sound unpleasantly in each other's ears. I admire the address of Lord A——y, himself very severely handled from time to time. Some one asked him if H.W. had been pretty correct on the whole. "Why, faith," he replied, "I believe so"—when, raising his eyes, he saw Quentin Dick, whom the little jilt had treated atrociously—"what concerns the present company always excepted, you know," added Lord A——y, with infinite presence of mind. As he was in pari casu with Q.D. no more could be said. After all, H.W. beats Con Philips, Anne Bellamy, and all former demireps out and out. I think I supped once in her company, more than twenty years since, at Mat Lewis's in Argyle Street, where the company, as the Duke says to Lucio, chanced to be "fairer than honest."[63] She was far from beautiful, if it be the same chiffonne, but a smart saucy girl, with good eyes and dark hair, and the manners of a wild schoolboy. I am glad this accidental meeting has escaped her memory—or, perhaps, is not accurately recorded in mine—for, being a sort of French falconer, who hawk at all they see, I might have had a distinction which I am far from desiring.

Dined at Sir John Hay's—a large party; Skenes there, the Newenhams and others, strangers. In the morning a meeting of Oil Gas Committee. The concern lingers a little;

December 10.—A stormy and rainy day. Walked from the Court through the rain. I don't dislike this. Egad, I rather like it; for no man that ever stepped on heather has less dread than I of catch-cold; and I seem to regain, in buffeting with the wind, a little of the high spirit with which, in younger days, I used to enjoy a Tam-o'-Shanter ride through darkness, wind, and rain,—the boughs groaning and cracking over my head, the good horse free to the road and impatient for home, and feeling the weather as little as I did.

Answered two letters—one, answer to a schoolboy, who writes himself Captain of Giggleswick School (a most imposing title), entreating the youngster not to commence editor of a magazine to be entitled the "Yorkshire Muffin," I think, at seventeen years old; second, to a soldier of the 79th, showing why I cannot oblige him by getting his discharge, and exhorting him rather to bear with the wickedness and profanity of the service, than take the very precarious step of desertion. This is the old receipt of Durandarte—Patience, cousin, and shuffle the cards;[65] and I suppose the correspondents will think I have been too busy in offering my counsel where I was asked for assistance.

A third rogue writes to tell me—rather of the latest, if the matter was of consequence—that he approves of the first three volumes of the H[eart] of Midlothian, but totally condemns the fourth. Doubtless he thinks his opinion worth the sevenpence sterling which his letter costs. However, authors should be reasonably well pleased when three-fourths of their work are acceptable to the reader. The knave demands of me in a postscript, to get back the sword of Sir W[illiam] Wallace from England, where it was carried from Dumbarton Castle. I am not Master-General of the Ordnance, that I know. It was wrong, however, to take away that and Mons Meg. If I go to town this spring, I will renew my negotiation with the Great Duke for recovery of Mons Meg.