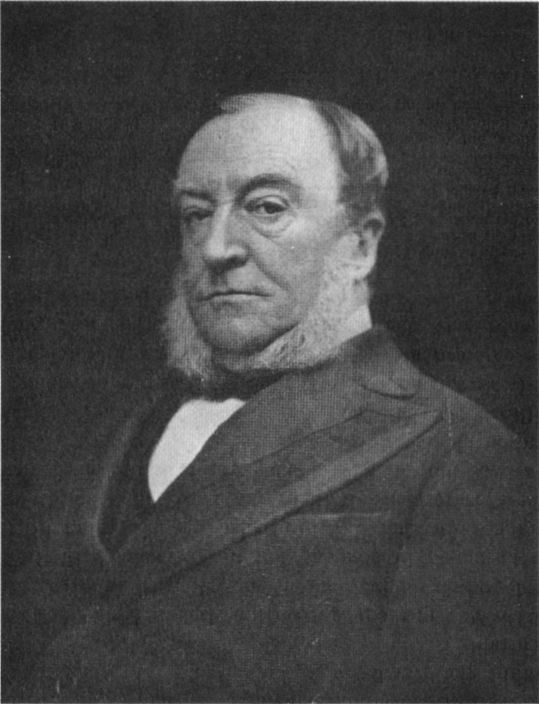

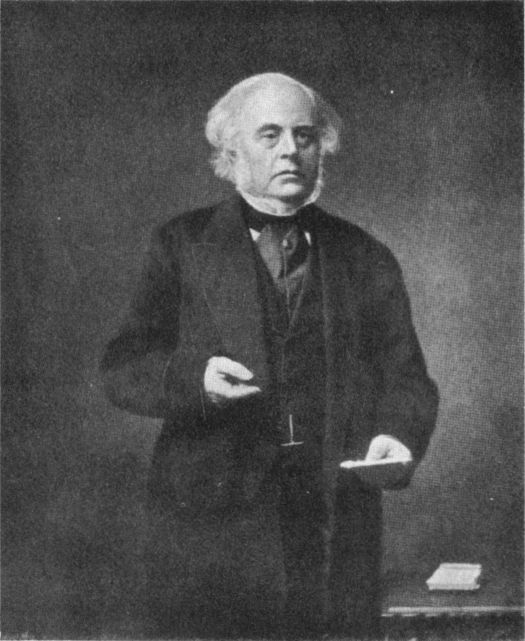

LORD JOHN RUSSELL

(From Trevelyan's "Garibaldi and the Making of Italy")

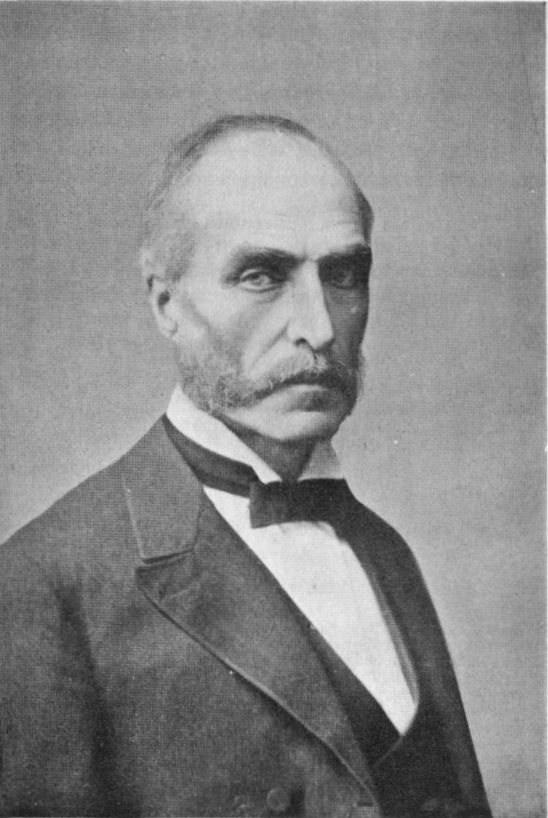

LORD JOHN RUSSELL

(From Trevelyan's "Garibaldi and the Making of Italy")

This work was begun many years ago. In 1908 I read in the British Museum many newspapers and journals for the years 1860-1865, and then planned a survey of English public opinion on the American Civil War. In the succeeding years as a teacher at Stanford University, California, the published diplomatic correspondence of Great Britain and of the United States were studied in connection with instruction given in the field of British-American relations. Several of my students prepared excellent theses on special topics and these have been acknowledged where used in this work. Many distractions and other writing prevented the completion of my original plan; and fortunately, for when in 1913 I had at last begun this work and had prepared three chapters, a letter was received from the late Charles Francis Adams inviting me to collaborate with him in preparing a "Life" of his father, the Charles Francis Adams who was American Minister to Great Britain during the Civil War. Mr. Adams had recently returned from England where he had given at Oxford University a series of lectures on the Civil War and had been so fortunate as to obtain copies, made under the scholarly supervision of Mr. Worthington C. Ford, of a great mass of correspondence from the Foreign Office files in the Public Record Office and from the private papers in the possession of various families.

The first half of the year 1914 was spent with Mr. Adams at Washington and at South Lincoln, in preparing the "Life." Two volumes were completed, the first by Mr. [V1:pg vi] Adams carrying the story to 1848, the second by myself for the period 1848 to 1860. For the third volume I analysed and organized the new materials obtained in England and we were about to begin actual collaboration on the most vital period of the "Life" when Mr. Adams died, and the work was indefinitely suspended, probably wisely, since any completion of the "Life" by me would have lacked that individual charm in historical writing so markedly characteristic of all that Mr. Adams did. The half-year spent with Mr. Adams was an inspiration and constitutes a precious memory.

The Great War interrupted my own historical work, but in 1920 I returned to the original plan of a work on "Great Britain and the American Civil War" in the hope that the English materials obtained by Mr. Adams might be made available to me. When copies were secured by Mr. Adams in 1913 a restriction had been imposed by the Foreign Office to the effect that while studied for information, citations and quotations were not permissible since the general diplomatic archives were not yet open to students beyond the year 1859. Through my friend Sir Charles Lucas, the whole matter was again presented to the Foreign Office, with an exact statement that the new request was in no way related to the proposed "Life" of Charles Francis Adams, but was for my own use of the materials. Lord Curzon, then Foreign Secretary, graciously approved the request but with the usual condition that my manuscript be submitted before publication to the Foreign Office. This has now been done, and no single citation censored. Before this work will have appeared the limitation hitherto imposed on diplomatic correspondence will have been removed, and the date for open research have been advanced beyond 1865, the end of the Civil War.

Similar explanations of my purpose and proposed work were made through my friend Mr. Francis W. Hirst to the [V1:pg vii] owners of various private papers, and prompt approval given. In 1924 I came to England for further study of some of these private papers. The Russell Papers, transmitted to the Public Record Office in 1914 and there preserved, were used through the courtesy of the Executors of the late Hon. Rollo Russell, and with the hearty goodwill of Lady Agatha Russell, daughter of the late Earl Russell, the only living representative of her father, Mr. Rollo Russell, his son, having died in 1914. The Lyons Papers, preserved in the Muniment Room at Old Norfolk House, were used through the courtesy of the Duchess of Norfolk, who now represents her son who is a minor. The Gladstone Papers, preserved at Hawarden Castle, were used through the courtesy of the Gladstone Trustees. The few citations from the Palmerston Papers, preserved at Broadlands, were approved by Lieut.-Colonel Wilfred Ashley, M.P.

The opportunity to study these private papers has been invaluable for my work. Shortly after returning from England in 1913 Mr. Worthington Ford well said: "The inside history of diplomatic relations between the United States and Great Britain may be surmised from the official archives; the tinting and shading needed to complete the picture must be sought elsewhere." (Mass. Hist. Soc. Proceedings, XLVI, p. 478.) Mr. C.F. Adams declared (ibid., XLVII, p. 54) that without these papers "... the character of English diplomacy at that time (1860-1865) cannot be understood.... It would appear that the commonly entertained impressions as to certain phases of international relations, and the proceedings and utterances of English public men during the progress of the War of Secession, must be to some extent revised."

In addition to the new English materials I have been fortunate in the generosity of my colleague at Stanford University, Professor Frank A. Golder, who has given to me transcripts, obtained at St. Petersburg in 1914, of all [V1:pg viii] Russian diplomatic correspondence on the Civil War. Many friends have aided, by suggestion or by permitting the use of notes and manuscripts, in the preparation of this work. I have sought to make due acknowledgment for such aid in my foot-notes. But in addition to those already named, I should here particularly note the courtesy of the late Mr. Gaillard Hunt for facilities given in the State Department at Washington, of Mr. Herbert Putnam, Librarian of Congress, for the transcript of the Correspondence of Mason and Slidell, Confederate Commissioners in Europe, and of Mr. Charles Moore, Chief of Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress, for the use of the Schurz Papers containing copies of the despatches of Schleiden, Minister of the Republic of Bremen at Washington during the Civil War. Especially thanks are due to my friend, Mr. Herbert Hoover, for his early interest in this work and for his generous aid in the making of transcripts which would otherwise have been beyond my means. And, finally, I owe much to the skill and care of my wife who made the entire typescript for the Press, and whose criticisms were invaluable.

It is no purpose of a Preface to indicate results, but it is my hope that with, I trust, a "calm comparison of the evidence," now for the first time available to the historian, a fairly true estimate may be made of what the American Civil War meant to Great Britain; how she regarded it and how she reacted to it. In brief, my work is primarily a study in British history in the belief that the American drama had a world significance, and peculiarly a British one.

EPHRAIM DOUGLASS ADAMS.

November 25, 1924

| LORD JOHN RUSSELL | Frontispiece |

| From Trevelyan's "Garibaldi and the Making of Italy" | |

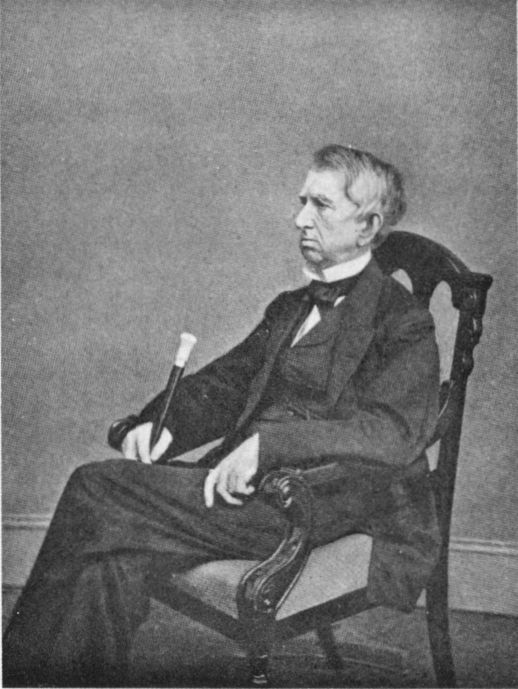

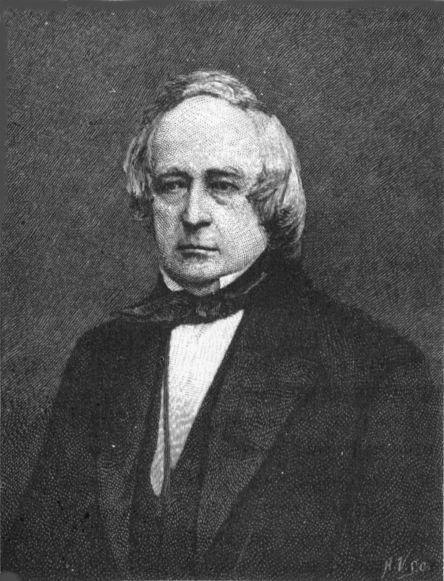

| LORD LYONS (1860) | Facing p. 42 |

| From Lord Newton's "Life of Lord Lyons" (Edward Arnold & Co.) | |

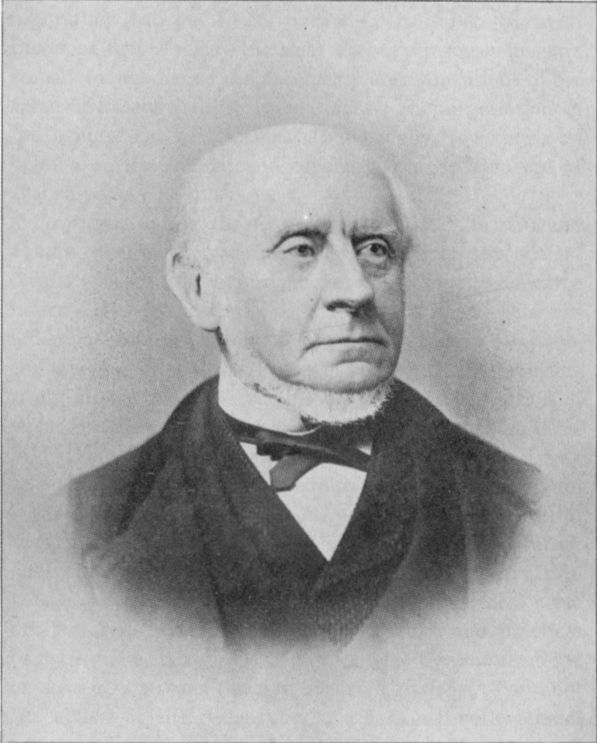

| SIR WILLIAM GREGORY, K.C.M.G. | 90 |

| From Lady Gregory's "Sir William Gregory, K.C.M.G.: An Autobiography" (John Murray) | |

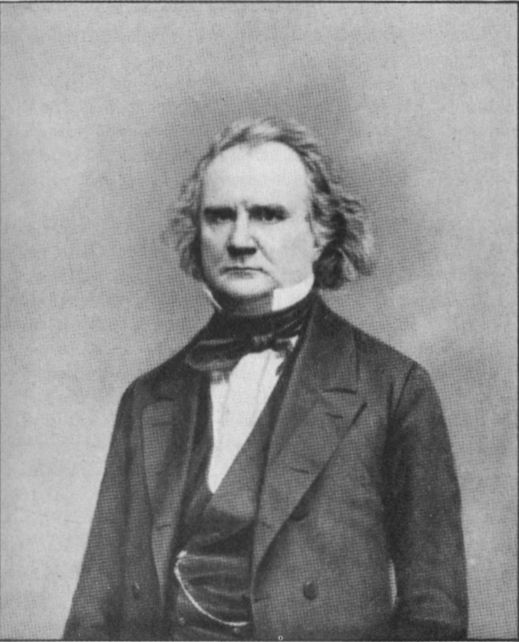

| WILLIAM HENRY SEWARD | 114 |

| From Lord Newton's "Life of Lord Lyons" (Edward Arnold & Co.) | |

| C.F. ADAMS | 138 |

| From a photograph in the United States Embassy, London | |

| JAMES M. MASON | 206 |

| From a photograph by L.C. Handy, Washington | |

| "KING COTTON BOUND" | 262 |

| Reproduced by permission of the Proprietors of "Punch" |

In 1862, less than a year after he had assumed his post in London, the American Minister, Charles Francis Adams, at a time of depression and bitterness wrote to Secretary of State Seward: "That Great Britain did, in the most terrible moment of our domestic trial in struggling with a monstrous social evil she had earnestly professed to abhor, coldly and at once assume our inability to master it, and then become the only foreign nation steadily contributing in every indirect way possible to verify its judgment, will probably be the verdict made against her by posterity, on calm comparison of the evidence[1]." Very different were the views of Englishmen. The historian, George Grote, could write: "The perfect neutrality [of Great Britain] in this destructive war appears to me almost a phenomenon in political history. No such forbearance has been shown during the political history of the last two centuries. It is the single case in which the English Government and public--generally so meddlesome--have displayed most prudent and commendable forbearance in spite of great temptations to the contrary[2]." And Sir William Harcourt, in September, 1863, declared: "Among all Lord Russell's many titles to fame and to public gratitude, the manner in which he has steered the vessel of State through the Scylla and Charybdis of the American War will, I think, always stand conspicuous[3]."

[V1:pg 2]Minister Adams, in the later years of the Civil War, saw reason somewhat to modify his earlier judgment, but his indictment of Great Britain was long prevalent in America, as, indeed, it was also among the historians and writers of Continental Europe--notably those of France and Russia. To what extent was this dictum justified? Did Great Britain in spite of her long years of championship of personal freedom and of leadership in the cause of anti-slavery seize upon the opportunity offered in the disruption of the American Union, and forgetting humanitarian idealisms, react only to selfish motives of commercial advantage and national power? In brief, how is the American Civil War to be depicted by historians of Great Britain, recording her attitude and action in both foreign and domestic policy, and revealing the principles of her statesmen, or the inspirations of her people?

It was to answer this question that the present work was originally undertaken; but as investigation proceeded it became progressively more clear that the great crisis in America was almost equally a crisis in the domestic history of Great Britain itself and that unless this were fully appreciated no just estimate was possible of British policy toward America. Still more it became evident that the American Civil War, as seen through British spectacles, could not be understood if regarded as an isolated and unique situation, but that the conditions preceding that situation--some of them lying far back in the relations of the two nations--had a vital bearing on British policy and opinion when the crisis arose. No expanded examination of these preceding conditions is here possible, but it is to a summary analysis of them that this first chapter is devoted.

On the American War for separation from the Mother Country it is unnecessary to dilate, though it should always [V1:pg 3] be remembered that both during the war and afterwards there existed a minority in Great Britain strongly sympathetic with the political ideals proclaimed in America--regarding those ideals, indeed, as something to be striven for in Britain itself and the conflict with America as, in a measure, a conflict in home politics. But independence once acknowledged by the Treaty of Peace of 1783, the relations between the Mother Country and the newly-created United States of America rapidly tended to adjust themselves to lines of contact customary between Great Britain and any other Sovereign State. Such contacts, fixing national attitude and policy, ordinarily occur on three main lines: governmental, determined by officials in authority in either State whose duty it is to secure the greatest advantage in power and prosperity for the State; commercial, resulting, primarily, from the interchange of goods and the business opportunities of either nation in the other's territory, or from their rivalry in foreign trade; idealistic, the result of comparative development especially in those ideals of political structure which determine the nature of the State and the form of its government. The more obvious of these contacts is the governmental, since the attitude of a people is judged by the formal action of its Government, and, indeed, in all three lines of contact the government of a State is directly concerned and frequently active. But it may be of service to a clearer appreciation of British attitude and policy before 1860, if the intermingling of elements required by a strict chronological account of relations is here replaced by a separate review of each of the three main lines of contact.

Once independence had been yielded to the American Colonies, the interest of the British Government rapidly waned in affairs American. True, there still remained the valued establishments in the West Indies, and the less considered British possessions on the continent to the [V1:pg 4] north of the United States. Meanwhile, there were occasional frictions with America arising from uncertain claims drawn from the former colonial privileges of the new state, or from boundary contentions not settled in the treaty of peace. Thus the use of the Newfoundland fisheries furnished ground for an acrimonious controversy lasting even into the twentieth century, and occasionally rising to the danger point. Boundary disputes dragged along through official argument, survey commissions, arbitration, to final settlement, as in the case of the northern limits of the State of Maine fixed at last by the Treaty of Washington of 1842, and then on lines fair to both sides at any time in the forty years of legal bickering. Very early, in 1817, an agreement creditable to the wisdom and pacific intentions of both countries, was reached establishing small and equal naval armaments on the Great Lakes. The British fear of an American attack on Canada proved groundless as time went on and was definitely set at rest by the strict curb placed by the American Government upon the restless activities of such of its citizens as sympathized with the followers of McKenzie and Papineau in the Canadian rebellion of 1837[4].

None of these governmental contacts affected greatly the British policy toward America. But the "War of 1812," as it is termed in the United States, "Mr. Madison's War," as it was derisively named by Tory contemporaries in Great Britain, arose from serious policies in which the respective governments were in definite opposition. Briefly, this was a clash between belligerent and neutral interests. Britain, fighting at first for the preservation of Europe against the spread of French revolutionary influence, later against the Napoleonic plan of Empire, held the seas in her grasp and exercised with vigour all the accustomed rights of a naval [V1:pg 5] belligerent. Of necessity, from her point of view, and as always in the case of the dominant naval belligerent, she stretched principles of international law to their utmost interpretation to secure her victory in war. America, soon the only maritime neutral of importance, and profiting greatly by her neutrality, contested point by point the issue of exceeded belligerent right as established in international law. America did more; she advanced new rules and theories of belligerent and neutral right respectively, and demanded that the belligerents accede to them. Dispute arose over blockades, contraband, the British "rule of 1756" which would have forbidden American trade with French colonies in war time, since such trade was prohibited by France herself in time of peace. But first and foremost as touching the personal sensibilities and patriotism of both countries was the British exercise of a right of search and seizure to recover British sailors.

Moreover this asserted right brought into clear view definitely opposed theories as to citizenship. Great Britain claimed that a man once born a British subject could never cease to be a subject--could never "alienate his duty." It was her practice to fill up her navy, in part at least, by the "impressment" of her sailor folk, taking them whenever needed, and wherever found--in her own coast towns, or from the decks of her own mercantile marine. But many British sailors sought security from such impressment by desertion in American ports or were tempted to desert to American merchant ships by the high pay obtainable in the rapidly-expanding United States merchant marine. Many became by naturalization citizens of the United States, and it was the duty of America to defend them as such in their lives and business. America ultimately came to hold, in short, that expatriation was accomplished from Great Britain when American citizenship was conferred. On shore they were safe, for Britain did not attempt [V1:pg 6] to reclaim her subjects from the soil of another nation. But she denied that the American flag on merchant vessels at sea gave like security and she asserted a naval right to search such vessels in time of peace, professing her complete acquiescence in a like right to the American navy over British merchant vessels--a concession refused by America, and of no practical value since no American citizen sought service in the British merchant marine.

This "right of search" controversy involved then, two basic points of opposition between the two governments. First America contested the British theory of "once a citizen always a citizen[5]"; second, America denied any right whatever to a foreign naval vessel in time of peace to stop and search a vessel lawfully flying the American flag. The right of search in time of war, that is, a belligerent right of search, America never denied, but there was both then and later much public confusion in both countries as to the question at issue since, once at war, Great Britain frequently exercised a legal belligerent right of search and followed it up by the seizure of sailors alleged to be British subjects. Nor were British naval captains especially careful to make sure that no American-born sailors were included in their impressment seizures, and as the accounts spread of victim after victim, the American irritation steadily increased. True, France was also an offender, but as the weaker naval power her offence was lost sight of in view of the, literally, thousands of bona fide Americans seized by Great Britain. Here, then, was a third cause of irritation connected with impressment, though not a point of governmental dispute as to right, for Great Britain professed her earnest desire to restore promptly any American-born sailors whom her naval officers had seized through error. In fact many such sailors were soon liberated, but a large number either continued to serve [V1:pg 7] on British ships or to languish in British prisons until the end of the Napoleonic Wars[6].

There were other, possibly greater, causes of the War of 1812, most of them arising out of the conflicting interests of the chief maritime neutral and the chief naval belligerent. The pacific presidential administration of Jefferson sought by trade restrictions, using embargo and non-intercourse acts, to bring pressure on both England and France, hoping to force a better treatment of neutrals. The United States, divided in sympathy between the belligerents, came near to disorder and disruption at home, over the question of foreign policy. But through all American factions there ran the feeling of growing animosity to Great Britain because of impressment. At last, war was declared by America in 1812 and though at the moment bitterly opposed by one section, New England, that war later came to be regarded as of great national value as one of the factors which welded the discordant states into a national unity. Naturally also, the war once ended, its commercial causes were quickly forgotten, whereas the individual, personal offence involved in impressment and right of search, with its insult to national pride, became a patriotic theme for politicians and for the press. To deny, in fact, a British "right of search" became a national point of honour, upon which no American statesman would have dared to yield to British overtures.

In American eyes the War of 1812 appears as a "second war of Independence" and also as of international importance in contesting an unjust use by Britain of her control of the seas. Also, it is to be remembered that no other war of importance was fought by America until the Mexican War of 1846, and militant patriotism was thus centred on the two wars fought against Great Britain. [V1:pg 8] The contemporary British view was that of a nation involved in a life and death struggle with a great European enemy, irritated by what seemed captious claims, developed to war, by a minor power[7]. To be sure there were a few obstinate Tories in Britain who saw in the war the opportunity of smashing at one blow Napoleon's dream of empire, and the American "democratic system." The London Times urged the government to "finish with Mr. Bonaparte and then deal with Mr. Madison and democracy," arguing that it should be England's object to subvert "the whole system of the Jeffersonian school." But this was not the purpose of the British Government, nor would such a purpose have been tolerated by the small but vigorous Whig minority in Parliament.

The peace of 1814, signed at Ghent, merely declared an end of the war, quietly ignoring all the alleged causes of the conflict. Impressment was not mentioned, but it was never again resorted to by Great Britain upon American ships. But the principle of right of search in time of peace, though for another object than impressment, was soon again asserted by Great Britain and for forty years was a cause of constant irritation and a source of danger in the relations of the two countries. Stirred by philanthropic emotion Great Britain entered upon a world crusade for the suppression of the African Slave Trade. All nations in principle repudiated that trade and Britain made treaties with various maritime powers giving mutual right of search to the naval vessels of each upon the others' merchant vessels. The African Slave Trade was in fact outlawed for the flags of all nations. But America, smarting under the memory of impressment injuries, and maintaining in any case the doctrine that in time of peace the national flag protected a vessel from interference [V1:pg 9] or search by the naval vessels of any other power, refused to sign mutual right of search treaties and denied, absolutely, such a right for any cause whatever to Great Britain or to any other nation. Being refused a treaty, Britain merely renewed her assertion of the right and continued to exercise it.

Thus the right of search in time of peace controversy was not ended with the war of 1812 but remained a constant sore in national relations, for Britain alone used her navy with energy to suppress the slave trade, and the slave traders of all nations sought refuge, when approached by a British naval vessel, under the protection of the American flag. If Britain respected the flag, and sheered off from search, how could she stop the trade? If she ignored the flag and on boarding found an innocent American vessel engaged in legal trade, there resulted claims for damages by detention of voyage, and demands by the American Government for apology and reparation. The real slave trader, seized under the American flag, never protested to the United States, nor claimed American citizenship, for his punishment in American law for engaging in the slave trade was death, while under the law of any other nation it did not exceed imprisonment, fine and loss of his vessel.

Summed up in terms of governmental attitude the British contention was that here was a great international humanitarian object frustrated by an absurd American sensitiveness on a point of honour about the flag. After fifteen years of dispute Great Britain offered to abandon any claim to a right of search, contenting herself with a right of visit, merely to verify a vessel's right to fly the American flag. America asserted this to be mere pretence, involving no renunciation of a practice whose legality she denied. In 1842, in the treaty settling the Maine boundary controversy, the eighth article sought a method of escape. Joint cruising squadrons were provided for the coast of [V1:pg 10] Africa, the British to search all suspected vessels except those flying the American flag, and these to be searched by the American squadron. At once President Tyler notified Congress that Great Britain had renounced the right of search. Immediately in Parliament a clamour was raised against the Government for the "sacrifice" of a British right at sea, and Lord Aberdeen promptly made official disclaimer of such surrender.

Thus, heritage of the War of 1812 right of search in time of peace was a steady irritant. America doubted somewhat the honesty of Great Britain, appreciating in part the humanitarian purpose, but suspicious of an ulterior "will to rule the seas." After 1830 no American political leader would have dared to yield the right of search. Great Britain for her part, viewing the expansion of domestic slavery in the United States, came gradually to attribute the American contention, not to patriotic pride, but to the selfish business interests of the slave-holding states. In the end, in 1858, with a waning British enthusiasm for the cause of slave trade suppression, and with recognition that America had become a great world power, Britain yielded her claim to right of search or visit, save when established by Treaty. Four years later, in 1862, it may well have seemed to British statesmen that American slavery had indeed been the basic cause of America's attitude, for in that year a treaty was signed by the two nations giving mutual right of search for the suppression of the African Slave Trade. In fact, however, this was but an effort by Seward, Secretary of State for the North, to influence British and European opinion against the seceding slave states of the South.

The right of search controversy was, in truth, ended when American power reached a point where the British Government must take it seriously into account as a factor in general world policy. That power had been steadily and rapidly advancing since 1814. From almost the first moment [V1:pg 11] of established independence American statesmen visualized the separation of the interests of the western continent from those of Europe, and planned for American leadership in this new world. Washington, the first President, emphasized in his farewell address the danger of entangling alliances with Europe. For long the nations of Europe, immersed in Continental wars, put aside their rivalries in this new world. Britain, for a time, neglected colonial expansion westward, but in 1823, in an emergency of European origin when France, commissioned by the great powers of continental Europe, intervened in Spain to restore the deposed Bourbon monarchy and seemed about to intervene in Spanish America to restore to Spain her revolted colonies, there developed in Great Britain a policy, seemingly about to draw America and England into closer co-operation. Canning, for Britain, proposed to America a joint declaration against French intervention in the Americas. His argument was against the principle of intervention; his immediate motive was a fear of French colonial expansion; but his ultimate object was inheritance by Britain of Spain's dying influence and position in the new world.

Canning's overture was earnestly considered in America. The ex-Presidents, Jefferson and Madison, recommended its acceptance, but the Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams, opposed this, favouring rather a separate declaration by the United States, and of this opinion was also President Monroe. Thus arose the Monroe Doctrine announcing American opposition to the principle of "intervention," and declaring that the American continents were no longer to be regarded as open to further colonization by European nations. The British emergency situation with France, though already quieted, caused Monroe's Message to be greeted in England with high approval. But Canning did not so approve it for he saw clearly that the Monroe Doctrine was a challenge [V1:pg 12] not merely to continental Europe, but to England as well and he set himself to thwart this threatening American policy. Had Canning's policy been followed by later British statesmen there would have resulted a serious clash with the United States[8].

In fact the Monroe Doctrine, imposing on Europe a self-denying policy of non-colonial expansion toward the west, provided for the United States the medium, if she wished to use it, for her own expansion in territory and in influence. But for a time there was no need of additional territory for that already hers stretched from the Atlantic to the Rocky Mountains, two-thirds of the way from ocean to ocean. Her population was growing fast. But four millions at the time of the Revolution, there were thirteen millions in 1830, and of these nearly a third were already across the Appalachian range and were constantly pressing on towards new lands in the South and West. The Monroe Doctrine was the first definite notice given to Europe of America's preconceived "destiny," but the earlier realization of that destiny took place on lines of expansion within her own boundaries. To this there could be no governmental objection, whether by Great Britain or any other nation.

But when in the decade 1840 to 1850, the United States, to the view of British statesmen, suddenly startled the world by entering upon a policy of further territorial expansion, forsaking her peaceful progress and turning toward war, there was a quick determination on a line of British policy as regards the American advance. The first intimation of the new American policy came in relation to the State of Texas which had revolted from Mexico in 1836, and whose independence had been generally recognized by 1842. To this new state Britain sent diplomatic and consular agents and these reported two factions among the people--one [V1:pg 13] seeking admission to the American Union, one desiring the maintenance of independence.

In 1841 Aberdeen had sent Lord Ashburton to America with instructions to secure, if possible, a settlement of all matters in dispute. Here was a genuine British effort to escape from national irritations. But before the Treaty of 1842 was signed, even while it was in the earlier stages of negotiation, the British Government saw, with alarm, quite new questions arising, preventing, to its view, that harmonious relation with the United States the desire for which had led to the Ashburton mission. This new development was the appearance of an American fever for territorial expansion, turning first toward Texas, but soon voiced as a "manifest destiny" which should carry American power and institutions to the Pacific and even into Central America. Among these institutions was that of slavery, detested by the public of Great Britain, yet a delicate matter for governmental consideration since the great cotton manufacturing interests drew the bulk of their supplies of raw cotton from the slave-holding states of America. If Texas, herself a cotton state, should join the United States, dependence upon slave-grown cotton would be intensified. Also, Texas, once acquired, what was there to prevent further American exploitation, followed by slave expansion, into Mexico, where for long British influence had been dominant?

On the fate of Texas, therefore, centred for a time the whole British policy toward America. Pakenham, the British minister to Mexico, urged a British pressure on Mexico to forgo her plans of reconquering Texas, and strong British efforts to encourage Texas in maintaining her independence. His theory foreshadowed a powerful buffer Anglo-Saxon state, prohibiting American advance to the south-west, releasing Britain from dependence on American cotton, and ultimately, he hoped, leading Texas to abolish [V1:pg 14] slavery, not yet so rooted as to be ineradicable. This policy was approved by the British Government, Pakenham was sent to Washington to watch events, a chargé, Elliot, was despatched to Texas, and from London lines were cast to draw France into the plan and to force the acquiescence of Mexico.

In this brief account of main lines of governmental contacts, it is unnecessary to recite the details of the diplomatic conflict, for such it became, with sharp antagonisms manifested on both sides. The basic fact was that America was bent upon territorial expansion, and that Great Britain set herself to thwart this ambition. But not to the point of war. Aberdeen was so incautious at one moment as to propose to France and Mexico a triple guarantee of the independence of Texas, if that state would acquiesce, but when Pakenham notified him that in this case, Britain must clearly understand that war with America was not merely possible, but probable, Aberdeen hastened to withdraw the plan of guarantee, fortunately not yet approved by Mexico[9].

The solution of this diplomatic contest thus rested with Texas. Did she wish annexation to the United States, or did she prefer independence? Elliot, in Texas, hoped to the last moment that Texas would choose independence and British favour. But the people of the new state were largely emigrants from the United States, and a majority of them wished to re-enter the Union, a step finally accomplished in 1846, after ten years of separate existence as a Republic. The part played by the British Government in this whole episode was not a fortunate one. It is the duty of Governments to watch over the interests of their subjects, and to [V1:pg 15] guard the prestige and power of the state. Great Britain had a perfect right to take whatever steps she chose to take in regard to Texas, but the steps taken appeared to Americans to be based upon a policy antagonistic to the American expansion policy of the moment. The Government of Great Britain appeared, indeed, to have adopted a policy of preventing the development of the power of the United States. Then, fronted with war, she had meekly withdrawn. The basic British public feeling, fixing the limits of governmental policy, of never again being drawn into war with America, not because of fear, but because of important trade relations and also because of essential liking and admiration, in spite of surface antagonisms, was not appreciated in America. Lord Aberdeen indeed, and others in governmental circles, pleaded that the support of Texan independence was in reality perfectly in harmony with the best interests of the United States, since it would have tended toward the limitation of American slavery. And in the matter of national power, they consoled themselves with prophecies that the American Union, now so swollen in size, must inevitably split into two, perhaps three, rival empires, a slave-holding one in the South, free nations in North and West.

The fate of Texas sealed, Britain soon definitely abandoned all opposition to American expansion unless it were to be attempted northwards, though prophesying evil for the American madness. Mexico, relying on past favours, and because of a sharp controversy between the United States and Great Britain over the Oregon territory, expected British aid in her war of 1846 against America. But she was sharply warned that such aid would not be given, and the Oregon dispute was settled in the Anglo-Saxon fashion of vigorous legal argument, followed by a fair compromise. The Mexican war resulted in the acquisition of California by the United States. British agents in this province of [V1:pg 16] Mexico, and British admirals on the Pacific were cautioned to take no active steps in opposition.

Thus British policy, after Texan annexation, offered no barrier to American expansion, and much to British relief the fear of the extension of the American plans to Mexico and Central America was not realized. The United States was soon plunged, as British statesmen had prophesied, into internal conflict over the question whether the newly-acquired territories should be slave or free.

The acquisition of California brought up a new problem of quick transit between Atlantic and Pacific, and a canal was planned across Central America. Here Britain and America acted together, at first in amity, though the convention signed in 1850 later developed discord as to the British claim of a protectorate over the Atlantic end of the proposed canal at San Juan del Nicaragua. But Britain was again at war in Europe in the middle 'fifties, and America was deep in quarrel over slavery at home. On both sides in spite of much diplomatic intrigue and of manifestations of national pride there was governmental desire to avoid difficulties. At the end of the ten-year period Britain ceded to Nicaragua her protectorate in the canal zone, and all causes of friction, so reported President Buchanan to Congress in 1860, were happily removed. Britain definitely altered her policy of opposition to the growth of American power.

In 1860, then, the causes of governmental antagonisms were seemingly all at an end. Impressment was not used after 1814. The differing theories of the two Governments on British expatriation still remained, but Britain attempted no practical application of her view. The right of search in time of peace controversy, first eased by the plan of joint cruising, had been definitely settled by the British renunciation of 1858. Opposition to American territorial advance but briefly manifested by Britain, had ended with [V1:pg 17] the annexation of Texas, and the fever of expansion had waned in America. Minor disputes in Central America, related to the proposed canal, were amicably adjusted.

But differences between nations, varying view-points of peoples, frequently have deeper currents than the more obvious frictions in governmental act or policy, nor can governments themselves fail to react to such less evident causes. It is necessary to review the commercial relations of the two nations--later to examine their political ideals.

In 1783 America won her independence in government from a colonial status. But commercially she remained a British colony--yet with a difference. She had formed a part of the British colonial system. All her normal trade was with the mother country or with other British colonies. Now her privileges in such trade were at an end, and she must seek as a favour that which had formerly been hers as a member of the British Empire. The direct trade between England and America was easily and quickly resumed, for the commercial classes of both nations desired it and profited by it. But the British colonial system prohibited trade between a foreign state and British colonies and there was one channel of trade, to and from the British West Indies, long very profitable to both sides, during colonial times, but now legally hampered by American independence. The New England States had lumber, fish, and farm products desired by the West Indian planters, and these in turn offered needed sugar, molasses, and rum. Both parties desired to restore the trade, and in spite of the legal restrictions of the colonial system, the trade was in fact resumed in part and either permitted or winked at by the British Government, but never to the advantageous exchange of former times.

The acute stage of controversy over West Indian trade was not reached until some thirty years after American Independence, but the uncertainty of such trade during a [V1:pg 18] long period in which a portion of it consisted in unauthorized and unregulated exchange was a constant irritant to all parties concerned. Meanwhile there came the War of 1812 with its preliminary check upon direct trade to and from Great Britain, and its final total prohibition of intercourse during the war itself. In 1800 the bulk of American importation of manufactures still came from Great Britain. In the contest over neutral rights and theories, Jefferson attempted to bring pressure on the belligerents, and especially on England, by restriction of imports. First came a non-importation Act, 1806, followed by an embargo on exports, 1807, but these were so unpopular in the commercial states of New England that they were withdrawn in 1810, yet for a short time only, for Napoleon tricked the United States into believing that France had yielded to American contentions on neutral rights, and in 1811 non-intercourse was proclaimed again with England alone. On June 18, 1812, America finally declared war and trade stopped save in a few New England ports where rebellious citizens continued to sell provisions to a blockading British naval squadron.

For eight years after 1806, then, trade with Great Britain had steadily decreased, finally almost to extinction during the war. But America required certain articles customarily imported and necessity now forced her to develop her own manufactures. New England had been the centre of American foreign commerce, but now there began a trend toward manufacturing enterprise. Even in 1814, however, at the end of the war, it was still thought in the United States that under normal conditions manufactured goods would again be imported and the general cry of "protection for home industries" was as yet unvoiced. Nevertheless, a group of infant industries had in fact been started and clamoured for defence now that peace was restored. This situation was not unnoticed in Great Britain [V1:pg 19] where merchants, piling up goods in anticipation of peace on the continent of Europe and a restored market, suddenly discovered that the poverty of Europe denied them that market. Looking with apprehension toward the new industries of America, British merchants, following the advice of Lord Brougham in a parliamentary speech, dumped great quantities of their surplus goods on the American market, selling them far below cost, or even on extravagant credit terms. One object was to smash the budding American manufactures.

This action of British merchants naturally stirred some angry patriotic emotions in the circles where American business suffered and a demand began to be heard for protection. But the Government of the United States was still representative of agriculture, in the main, and while a Tariff Bill was enacted in 1816 that Bill was regarded as a temporary measure required by the necessity of paying the costs of the recent war. Just at this juncture, however, British policy, now looking again toward a great colonial empire, sought advantages for the hitherto neglected maritime provinces of British North America, and thought that it had found them by encouragement of their trade with the British West Indies. The legal status of American trade with the West Indies was now enforced and for a time intercourse was practically suspended.

This British policy brought to the front the issue of protection in America. It not only worked against a return by New England from manufacturing to commerce, but it soon brought into the ranks of protectionists a northern and western agricultural element that had been accustomed to sell surplus products to West Indian planters seeking cheap food-stuffs for their slaves. This new protectionist element was as yet not crystallized into a clamour for "home markets" for agriculture, but the pressure of opinion was beginning to be felt, and by 1820 the question [V1:pg 20] of West Indian trade became one of constant agitation and demanded political action. That action was taken on lines of retaliation. Congress in 1818 passed a law excluding from American ports any British vessel coming from a port access to which was denied to an American vessel, and placing under bond in American ports British vessels with prohibition of their proceeding to a British port to which American vessels could not go. This act affected not merely direct trade with the West Indies, but stopped the general custom of British ships of taking part cargoes to Jamaica while en route to and from the United States. The result was, first, compromise, later, under Huskisson's administration at the British Board of Trade, complete abandonment by Britain of the exclusive trade basis of her whole colonial system.

The "retaliatory system" which J.Q. Adams regarded as "a new declaration of independence," was, in fact, quickly taken up by other non-colonial nations, and these, with America, compelled Great Britain to take stock of her interests. Huskisson, rightly foreseeing British prosperity as dependent upon her manufactures and upon the carrying trade, stated in Parliament that American "retaliation" had forced the issue. Freedom of trade in British ports was offered in 1826 to all non-colonial nations that would open their ports within one year on terms of equality to British ships. J.Q. Adams, now President of the United States, delayed acceptance of this offer, preferring a treaty negotiation, and was rebuffed by Canning, so that actual resumption of West Indian trade did not take place until 1830, after the close of Adams' administration. That trade never recovered its former prosperity.

Meanwhile the long period of controversy, from 1806 to 1830, had resulted in a complete change in the American situation. It is not a sufficient explanation of the American belief in, and practice of, the theory of protection to attribute [V1:pg 21] this alone to British checks placed upon free commercial rivalry. Nevertheless the progress of America toward an established system, reaching its highest mark for years in the Tariff Bill of 1828, is distinctly related to the events just narrated. After American independence, the partially illegal status of West Indian trade hampered commercial progress and slightly encouraged American manufactures by the mere seeking of capital for investment; the neutral troubles of 1806 and the American prohibitions on intercourse increased the transfer of interest; the war of 1812 gave a complete protection to infant industries; the dumping of British goods in 1815 stirred patriotic American feeling; British renewal of colonial system restrictions, and the twelve-year quarrel over "retaliation" gave time for the definite establishment of protectionist ideas in the United States. But Britain was soon proclaiming for herself and for the world the common advantage and the justice of a great theory of free trade. America was apparently now committed to an opposing economic theory, the first great nation definitely to establish it, and thus there resulted a clear-cut opposition of principle and a clash of interests. From 1846, when free trade ideas triumphed in England, the devoted British free trader regarded America as the chief obstacle to a world-wide acceptance of his theory.

The one bright spot in America, as regarded by the British free trader, was in the Southern States, where cotton interests, desiring no advantage from protection, since their market was in Europe, attacked American protection and sought to escape from it. Also slave supplies, without protection, could have been purchased more cheaply from England than from the manufacturing North. In 1833 indeed the South had forced a reaction against protection, but it proceeded slowly. In 1854 it was Southern opinion that carried through Congress the reciprocity treaty with the British American Provinces, partly brought about, no [V1:pg 22] doubt, by a Southern fear that Canada, bitter over the loss of special advantages in British markets by the British free trade of 1846, might join the United States and thus swell the Northern and free states of the Union. Cotton interests and trade became the dominant British commercial tie with the United States, and the one great hope, to the British minds, of a break in the false American system of protection. Thus both in economic theory and in trade, spite of British dislike of slavery, the export trading interests of Great Britain became more and more directed toward the Southern States of America. Adding powerfully to this was the dependence of British cotton manufactures upon the American supply. The British trade attitude, arising largely outside of direct governmental contacts, was bound to have, nevertheless, a constant and important influence on governmental action.

Governmental policy, seeking national power, conflicting trade and industrial interests, are the favourite themes of those historians who regard nations as determined in their relations solely by economic causes--by what is called "enlightened self-interest." But governments, no matter how arbitrary, and still more if in a measure resting on representation, react both consciously and unconsciously to a public opinion not obviously based upon either national or commercial rivalry. Sometimes, indeed, governmental attitude runs absolutely counter to popular attitude in international affairs. In such a case, the historical estimate, if based solely on evidences of governmental action, is a false one and may do great injustice to the essential friendliness of a people.

How then, did the British people, of all classes, regard America before 1860, and in what manner did that regard affect the British Government? Here, it is necessary to seek British opinion on, and its reaction to, American institutions, ideals, and practices. Such public opinion can [V1:pg 23] be found in quantity sufficient to base an estimate only in travellers' books, in reviews, and in newspapers of the period. When all these are brought together it is found that while there was an almost universal British criticism of American social customs and habits of life, due to that insularity of mental attitude characteristic of every nation, making it prefer its own customs and criticize those of its neighbours, summed up in the phrase "dislike of foreigners"--it is found that British opinion was centred upon two main threads; first America as a place for emigration and, second, American political ideals and institutions[10].

British emigration to America, a governmentally favoured colonization process before the American revolution, lost that favour after 1783, though not at first definitely opposed. But emigration still continued and at no time, save during the war of 1812, was it absolutely stopped. Its exact amount is unascertainable, for neither Government kept adequate statistics before 1820. With the end of the Napoleonic wars there came great distress in England from which the man of energy sought escape. He turned naturally to America, being familiar, by hearsay at least, with stories of the ease of gaining a livelihood there, and influenced by the knowledge that in the United States he would find people of his own blood and speech. The bulk of this earlier emigration to America resulted from economic causes. When, in 1825, one energetic Member of Parliament, Wilmot Horton, induced the Government to appoint a committee to investigate the whole subject, the result was a mass of testimony, secured from returned emigrants or from their letters home, in which there constantly appeared one main argument influencing the labourer type of emigrant; he [V1:pg 24] got good wages, and he was supplied, as a farm hand, with good food. Repeatedly he testifies that he had "three meat meals a day," whereas in England he had ordinarily received but one such meal a week.

Mere good living was the chief inducement for the labourer type of emigrant, and the knowledge of such living created for this type remaining in England a sort of halo of industrial prosperity surrounding America. But there was a second testimony brought out by Horton's Committee, less general, yet to be picked up here and there as evidence of another argument for emigration to America. The labourer did not dilate upon political equality, nor boast of a share in government, indeed generally had no such share, but he did boast to his fellows at home of the social equality, though not thus expressing it, which was all about him. He was a common farm hand, yet he "sat down to meals" with his employer and family, and worked in the fields side by side with his "master." This, too, was an astounding difference to the mind of the British labourer. Probably for him it created a clearer, if not altogether universal and true picture of the meaning of American democracy than would have volumes of writing upon political institutions. Gradually there was established in the lower orders of British society a visualization of America as a haven of physical well-being and personal social happiness.

This British labouring class had for long, however, no medium of expression in print. Here existed, then, an unexpressed public opinion of America, of much latent influence, but for the moment largely negligible as affecting other classes or the Government. A more important emigrating class in its influence on opinion at home, though not a large class, was composed about equally of small farmers and small merchants facing ruin in the agricultural and trading crises that followed the end of the European war. The [V1:pg 25] British travellers' books from 1810 to 1820 are generally written by men of this class, or by agents sent out from co-operative groups planning emigration. Generally they were discontented with political conditions at home, commonly opposed to a petrified social order, and attracted to the United States by its lure of prosperity and content. The books are, in brief, a superior type of emigrant guide for a superior type of emigrant, examining and emphasizing industrial opportunity.

Almost universally, however, they sound the note of superior political institutions and conditions. One wrote "A republican finds here A Republic, and the only Republic on the face of the earth that ever deserved the name: where all are under the protection of equal laws; of laws made by Themselves[11]." Another, who established an English colony in the Western States of Illinois, wrote of England that he objected to "being ruled and taxed by people who had no more right to rule and tax us than consisted in the power to do it." And of his adopted country he concludes: "I love the Government; and thus a novel sensation is excited; it is like the development of a new faculty. I am become a patriot in my old age[12]." Still another detailed the points of his content, "I am here, lord and master of myself and of 100 acres of land--an improvable farm, little trouble to me, good society and a good market, and, I think, a fine climate, only a little too hot and dry in summer; the parson gets nothing from me; my state and road taxes and poor rates amount to §25.00 per annum. I can carry a gun if I choose; I leave my door unlocked at night; and I can get snuff for one cent an ounce or a little more[13]."

From the first days of the American colonial movement [V1:pg 26] toward independence there had been, indeed, a British interest in American political principles. Many Whigs sympathized with these principles for reasons of home political controversy. Their sympathy continued after American independence and by its insistent expression brought out equally insistent opposition from Tory circles. The British home movement toward a more representative Government had been temporarily checked by the extremes into which French Liberalism plunged in 1791, causing reaction in England. By 1820 pressure was again being exerted by British Liberals of intelligence, and they found arguments in such reports as those just quoted. From that date onward, and especially just before the passing of the Reform Bill of 1832, yet always a factor, the example of a prosperous American democracy was an element in British home politics, lauded or derided as the man in England desired or not an expansion of the British franchise. In the earlier period, however, it is to be remembered that applause of American institutions did not mean acceptance of democracy to the extent of manhood franchise, for no such franchise at first existed in America itself. The debate in England was simply whether the step forward in American democracy, was an argument for a similar step in Great Britain.

Books, reviews and newspapers in Great Britain as the political quarrel there grew in force, depicted America favourably or otherwise according to political sympathies at home. Both before and after the Reform Bill of 1832 this type of effort to mould opinion, by citation of America, was widespread. Hence there is in such writing, not so much the expression of public opinion, as of propaganda to affect that opinion. Book upon book, review upon review, might be quoted to illustrate this, but a few notable examples will suffice.

The most widely read and reviewed book on the United [V1:pg 27] States before 1840, except the humorous and flippant characterization of America by Mrs. Trollope, was Captain Basil Hall's three-volume work, published in 1829[14]. Claiming an open mind, he expected for his adverse findings a readier credence. For adverse to American political institutions these findings are in all their larger applications. In every line Hall betrays himself as an old Tory of the 'twenties, fixed in his belief, and convinced of the perfection and unalterableness of the British Constitution. Captain Hamilton, who wrote in 1833, was more frank in avowal of a purpose[15]. He states in his preface:

"... When I found the institutions and experiences of the United States deliberately quoted in the reformed parliament, as affording safe precedent for British legislation, and learned that the drivellers who uttered such nonsense, instead of encountering merited derision, were listened to with patience and approbation by men as ignorant as themselves, I certainly did feel that another work on America was yet wanted, and at once determined to undertake a task which inferior considerations would probably have induced me to decline."

Harriet Martineau, ardent advocate of political reform at home, found in the United States proofs for her faith in democracy[16]. Captain Marryat belittled Miss Martineau, but in his six volumes proved himself less a critic of America than an enemy of democracy. Answering a review of his earlier volumes, published separately, he wrote in his concluding volume: "I candidly acknowledge that the reviewer is right in his supposition; my great object has been to do serious injury to the cause of democracy[17]."

[V1:pg 28]The fact was that British governing and intellectual classes were suffering a recoil from the enthusiasms leading up to the step toward democracy in the Reform of 1832. The electoral franchise was still limited to a small minority of the population. Britain was still ruled by her "wise men" of wealth and position. Meanwhile, however, just at the moment when dominant Whig influence in England carried through that step forward toward democratic institutions which Whigs had long lauded in America, the latter country had progressed to manhood suffrage, or as nearly all leading Englishmen, whether Whig or Tory, regarded it, had plunged into the rule of the mob. The result was a rapid lessening in Whig ruling-class expression of admiration for America, even before long to the complete cessation of such admiration, and to assertions in Great Britain that the Reform of 1832 was "final," the last step toward democracy which Britain could safely take. It is not strange that the books and reviews of the period from 1830 to 1840, heavily stress the dangers and crudity of American democracy. They were written for what was now a nearly unanimous British reading public, fearful lest Radical pressure for still further electoral reform should preach the example of the United States.

Thus after 1832 the previous sympathy for America of one section of the British governing class disappears. More--it is replaced by a critical, if not openly hostile attitude. Soon, with the rapid development of the power and wealth of the United States, governing-class England, of all factions save the Radical, came to view America just as it would have viewed any other rising nation, that is, as a problem to be studied for its influence on British prosperity and power. Again, expressions in print reflect the changes of British view--nowhere more clearly than in travellers' books. After 1840, for nearly a decade, these are devoted, not to American political institutions, but to [V1:pg 29] studies, many of them very careful ones, of American industry and governmental policy.

Buckingham, one-time member of Parliament, wrote nine volumes of such description. His work is a storehouse of fact, useful to this day to the American historical student[18]. George Combe, philosopher and phrenologist, studied especially social institutions[19]. Joseph Sturge, philanthropist and abolitionist, made a tour, under the guidance of the poet Whittier, through the Northern and Eastern States[20]. Featherstonaugh, a scientist and civil engineer, described the Southern slave states, in terms completely at variance with those of Sturge[21]. Kennedy, traveller in Texas, and later British consul at Galveston, and Warburton, a traveller who came to the United States by way of Canada, an unusual approach, were both frankly startled, the latter professedly alarmed, at the evidences of power in America[22]. Amazed at the energy, growth and prosperity of the country and alarmed at the anti-British feeling he found in New York City, Warburton wrote that "they [Americans] only wait for matured power to apply the incendiary torch of Republicanism to the nations of Europe[23]." Soon after this was written there began, in 1848, that great tide of Irish emigration to America which heavily reinforced the anti-British attitude of the City of New York, and largely changed its character.

Did books dilating upon the expanding power of America reflect British public opinion, or did they create it? It is [V1:pg 30] difficult to estimate such matters. Certainly it is not uninteresting that these books coincided in point of time with a British governmental attitude of opposition, though on peaceful lines, to the development of American power, and to the adoption to the point of faith, by British commercial classes, of free trade as opposed to the American protective system. But governing classes were not the British public, and to the great unenfranchised mass, finding voice through the writings of a few leaders, the prosperity of America made a powerful appeal. Radical democracy was again beginning to make its plea in Britain. In 1849 there was published a study of the United States, more careful and exact than any previous to Bryce's great work, and lauding American political institutions. This was Mackay's "Western World," and that there was a public eager for such estimate is evidenced by the fact that the book went through four British editions in 1850[24]. At the end of the decade, then, there appeared once more a vigorous champion of the cause of British democracy, comparing the results of "government by the wise" with alleged mob rule. Mackay wrote:

"Society in America started from the point to which society in Europe is only yet finding. The equality of men is, to this moment, its corner-stone ... that which develops itself as the sympathy of class, becomes in America the general sentiment of society.... We present an imposing front to the world; but let us tear the picture and look at the canvas. One out of every seven of us is a pauper. Every six Englishmen have, in addition to their other enormous burdens, to support a seventh between them, whose life is spent in consuming, but in adding nothing to the source of their common subsistence."

British governing classes then, forgoing after 1850 opposition to the advance of American power, found themselves [V1:pg 31] involved again, as before 1832, in the problem of the possible influence of a prosperous American democracy upon an unenfranchised public opinion at home. Also, for all Englishmen, of whatever class, in spite of rivalry in power, of opposing theories of trade, of divergent political institutions, there existed a vague, though influential, pride in the advance of a people of similar race, sprung from British loins[25]. And there remained for all Englishmen also one puzzling and discreditable American institution, slavery--held up to scorn by the critics of the United States, difficult of excuse among her friends.

Agitation conducted by the great philanthropist, Wilberforce, had early committed British Government and people to a crusade against the African slave trade. This British policy was clearly announced to the world in the negotiations at Vienna in 1814-15. But Britain herself still supported the institution of slavery in her West Indian colonies and it was not until British humanitarian sentiment had forced emancipation upon the unwilling sugar planters, in 1833, that the nation was morally free to criticize American domestic slavery. Meanwhile great emancipation societies, with many branches, all virile and active, had grown up in England and in Scotland. These now turned to an attack on slavery the world over, and especially on American slavery. The great American abolitionist, Garrison, found more support in England than in his own country; his weekly paper, The Liberator, is full of messages of cheer from British friends and societies, and of quotations from a sympathetic, though generally provincial, British press.

From 1830 to 1850 British anti-slavery sentiment was at its height. It watched with anxiety the evidence of a developing struggle over slavery in the United States, [V1:pg 32] hopeful, as each crisis arose, that the free Northern States would impose their will upon the Southern Slave States. But as each crisis turned to compromise, seemingly enhancing the power of the South, and committing America to a retention of slavery, the hopes of British abolitionists waned. The North did indeed, to British opinion, become identified with opposition to the expansion of slavery, but after the "great compromise of 1850," where the elder American statesmen of both North and South proclaimed the "finality" of that measure, British sympathy for the North rapidly lessened. Moreover, after 1850, there was in Britain itself a decay of general humanitarian sentiment as regards slavery. The crusade had begun to seem hopeless and the earlier vigorous agitators were dead. The British Government still maintained its naval squadron for the suppression of the African slave trade, but the British official mind no longer keenly interested itself either in this effort or in the general question of slavery.

Nevertheless American slavery and slave conditions were still, after 1850, favourite matters for discussion, almost universally critical, by English writers. Each renewal of the conflict in America, even though local, not national in character, drew out a flood of comment. In the public press this blot upon American civilization was a steady subject for attack, and that attack was naturally directed against the South. The London Times, in particular, lost no opportunity of presenting the matter to its readers. In 1856, a Mr. Thomas Gladstone visited Kansas during the height of the border struggles there, and reported his observations in letters to the Times. The writer was wholly on the side of the Northern settlers in Kansas, though not hopeful that the Kansas struggle would expand to a national conflict. He constantly depicted the superior civilization, industry, and social excellence of the North as compared with the South[26].

[V1:pg 33]Mrs. Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin excited greater interest in England than in America itself. The first London edition appeared in May, 1852, and by the end of the year over one million copies had been sold, as opposed to one hundred and fifty thousand in the United States. But if one distinguished writer is to be believed, this great British interest in the book was due more to English antipathy to America than to antipathy to slavery[27]. This writer was Nassau W. Senior, who, in 1857, published a reprint of his article on "American Slavery" in the 206th number of the Edinburgh Review, reintroducing in his book extreme language denunciatory of slavery that had been cut out by the editor of the Review[28]. Senior had been stirred to write by the brutal attack upon Charles Sumner in the United States Senate after his speech of May 19-20, 1856, evidence, again, that each incident of the slavery quarrel in America excited British attention.

Senior, like Thomas Gladstone, painted the North as all anti-slavery, the South as all pro-slavery. Similar impressions of British understanding (or misunderstanding) are received from the citations of the British provincial press, so favoured by Garrison in his Liberator[29]. Yet for intellectual Britain, at least--that Britain which was vocal and whose opinion can be ascertained in spite of this constant interest in American slavery, there was generally a fixed belief that slavery in the United States was so firmly [V1:pg 34] established that it could not be overthrown. Of what use, then, the further expenditure of British sympathy or effort in a lost cause? Senior himself, at the conclusion of his fierce attack on the Southern States, expressed the pessimism of British abolitionists. He wrote, "We do not venture to hope that we, or our sons, or our grandsons, will see American slavery extirpated, or even materially mitigated[30]."

FOOTNOTES:

[1] State Department, Eng., Vol. LXXIX, No. 135, March 27, 1862.

[2] Walpole, Russell, Vol. II, p. 367.

[3] Life of Lady John Russell, p. 197.

[4] There was a revival of this fear at the end of the American Civil War. This will be commented on later.

[5] This was the position of President and Congress: yet the United States had not acknowledged the right of an American citizen to expatriate himself.

[6] Between 1797 and 1801, of the sailors taken from American ships, 102 were retained, 1,042 were discharged, and 805 were held for further proof. (Updyke, The Diplomacy of the War of 1812, p. 21.)

[7] The people of the British North American Provinces regarded the war as an attempt made by America, taking advantage of the European wars, at forcible annexation. In result the fervour of the United Empire Loyalists was renewed, especially in Upper Canada. Thus the same two wars which fostered militant patriotism in America against England had the same result in Canadian sentiment against America.

[8] Temperley, "Later American Policy of George Canning" in Am. Hist. Rev., XI, 783. Also Cambridge History of British Foreign Policy, Vol. II, ch. 2.

[9] Much has recently been published on British policy in Texas. See my book, British Interests and Activities in Texas, 1838-1846, Johns Hopkins Press, Balt., 1910. Also Adams, Editor, British Diplomatic Correspondence concerning the Republic of Texas, The Texas State Historical Association, Austin, Texas, 1918.

[10] In my studies on British-American relations, I have read the leading British reviews and newspapers, and some four hundred volumes by British travellers. For a summary of the British travellers before 1860 see my article "The Point of View of the British Traveller in America," in the Political Science Quarterly, Vol. XXIX, No. 2, June, 1914.

[11] John Melish, Travels, Vol. I, p. 148.

[12] Morris Birkbeck, Letters from Illinois, London, 1818, p. 29.

[13] Letter in Edinburgh Scotsman, March, 1823. Cited by Niles Register, Vol. XXV, p. 39.

[14] Travels in North America, 1827-28, London, 1829.

[15] Captain Thomas Hamilton, Men and Manners in America, Edinburgh and London, 1833. 2 vols.

[16] Society in America, London, 1837. 3 vols. Retrospect of Western Travel, London, 1838. 2 vols.

[17] Captain Frederick Marryat, A Diary in America, with Remarks on Its Institutions, Vol. VI, p. 293.

[18] James Silk Buckingham, America, Historical, Statistic and Descriptive, London, 1841-43. 9 vols.

[19] Notes on the United States of North America during a phrenological visit, 1838-9-40, Edinburgh, 1841. 3 vols.

[20] A Visit to the United States in 1841, London, 1842.

[21] George William Featherstonaugh, Excursion through the Slave States, London, 1844. 2 vols.

[22] William Kennedy, Texas: The Rise, Progress and Prospects of the Republic of Texas, London, 1841. 2 vols. George Warburton, Hochelaga: or, England in the New World, London, 1845. 2 vols.

[23] Warburton, Hochelaga, 5th Edition, Vol. II, pp. 363-4.

[24] Alexander Mackay, The Western World: or, Travels through the United States in 1846-47, London, 1849.

[25] This is clearly indicated in Parliament itself, in the debate on the dismissal by the United States in 1856 of Crampton, the British Minister at Washington, for enlistment activities during the Crimean War.--Hansard, 3rd. Ser., CXLIII, 14-109 and 120-203.

[26] Gladstone's letters were later published in book form, under the title The Englishman in Kansas, London, 1857.

[27] "The evil passions which 'Uncle Tom' gratified in England were not hatred or vengeance [of slavery], but national jealousy and national vanity. We have long been smarting under the conceit of America--we are tired of hearing her boast that she is the freest and the most enlightened country that the world has ever seen. Our clergy hate her voluntary system--our Tories hate her democrats--our Whigs hate her parvenus--our Radicals hate her litigiousness, her insolence, and her ambition. All parties hailed Mrs. Stowe as a revolter from the enemy." Senior, American Slavery, p. 38.

[28] The reprint is without date, but the context shows the year to be 1857.

[29] For example the many British expressions quoted in reference to John Brown's raid, in The Liberator for February 10, 1860, and in succeeding issues.

[30] Senior, American Slavery, p. 68.

It has been remarked by the American historian, Schouler, that immediately before the outbreak of the Civil War, diplomatic controversies between England and America had largely been settled, and that England, pressed from point to point, had "sullenly" yielded under American demands. This generalization, as applied to what were, after all, minor controversies, is in great measure true. In larger questions of policy, as regards spheres of influence or developing power, or principles of trade, there was difference, but no longer any essential opposition or declared rivalry[31]. In theories of government there was sharp divergence, clearly appreciated, however, only in governing-class Britain. This sense of divergence, even of a certain threat from America to British political institutions, united with an established opinion that slavery was permanently fixed in the United States to reinforce governmental indifference, sometimes even hostility, to America. The British public, also, was largely hopeless of any change in the institution of slavery, and its own active humanitarian interest was waning, though still dormant--not dead. Yet the two nations, to a degree not true of any other two world-powers, were of the same race, had similar basic laws, read the same books, and were held in close touch at many points by the steady flow of British emigration to the United States.

[V1:pg 36]When, after the election of Lincoln to the Presidency, in November, 1860, the storm-clouds of civil strife rapidly gathered, the situation took both British Government and people by surprise. There was not any clear understanding either of American political conditions, or of the intensity of feeling now aroused over the question of the extension of slave territory. The most recent descriptions of America had agreed in assertion that at some future time there would take place, in all probability, a dissolution of the Union, on lines of diverging economic interests, but also stated that there was nothing in the American situation to indicate immediate progress in this direction. Grattan, a long-time resident in America as British Consul at Boston, wrote:

"The day must no doubt come when clashing objects will break the ties of common interest which now preserve the Union. But no man may foretell the period of dissolution.... The many restraining causes are out of sight of foreign observation. The Lilliputian threads binding the man mountain are invisible; and it seems wondrous that each limb does not act for itself independently of its fellows. A closer examination shows the nature of the network which keeps the members of this association so tightly bound. Any attempt to untangle the ties, more firmly fastens them. When any one State talks of separation, the others become spontaneously knotted together. When a section blusters about its particular rights, the rest feel each of theirs to be common to all. If a foreign nation hint at hostility, the whole Union becomes in reality united. And thus in every contingency from which there can be danger, there is also found the element of safety." Yet, he added, "All attempts to strengthen this federal government at the expense of the States' governments must be futile.... The federal government exists on sufferance only. Any State may at any time constitutionally withdraw from the Union, and thus virtually dissolve it[32]."[V1:pg 37]

Even more emphatically, though with less authority, wrote one Charles Mackay, styled by the American press as a "distinguished British poet," who made the usual rapid tour of the principal cities of America in 1857-58, and as rapidly penned his impressions:

"Many persons in the United States talk of a dissolution of the Union, but few believe in it.... All this is mere bravado and empty talk. It means nothing. The Union is dear to all Americans, whatever they may say to the contrary.... There is no present danger to the Union, and the violent expressions to which over-ardent politicians of the North and South sometimes give vent have no real meaning. The 'Great West,' as it is fondly called, is in the position even now to arbitrate between North and South, should the quarrel stretch beyond words, or should anti-slavery or any other question succeed in throwing any difference between them which it would take revolvers and rifles rather than speeches and votes to put an end to[33]."