Illustrated By Lejaren A. Hiller

INCLUDING THAT OF TRANSLATION INTO FOREIGN LANGUAGES, INCLUDING THE SCANDINAVIAN, 1909, 1910, BY JAMES HORSBURGH, JR, 1910, BY DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY PUBLISHED, OCTOBER, 1910

The geography in this novel may easily be recognized by one familiar with the country. For that reason it is necessary to state that the characters therein are in no manner to be confused with the people actually inhabiting and developing that locality. The Power Company promoted by Baker has absolutely nothing to do with any Power Company utilizing any streams: the delectable Plant never exercised his talents in Sierra North. The author must decline to acknowledge any identifications of the sort. Plant and Baker and all the rest are, however, only to a limited extent fictitious characters. What they did and what they stood for is absolutely true.

He worked desperately. The heat of the flames began to scorch his face and hands.

The men calmly withdrew the long ribbon of steel and stood to one side.

"I beg pardon," said he. The girl turned.

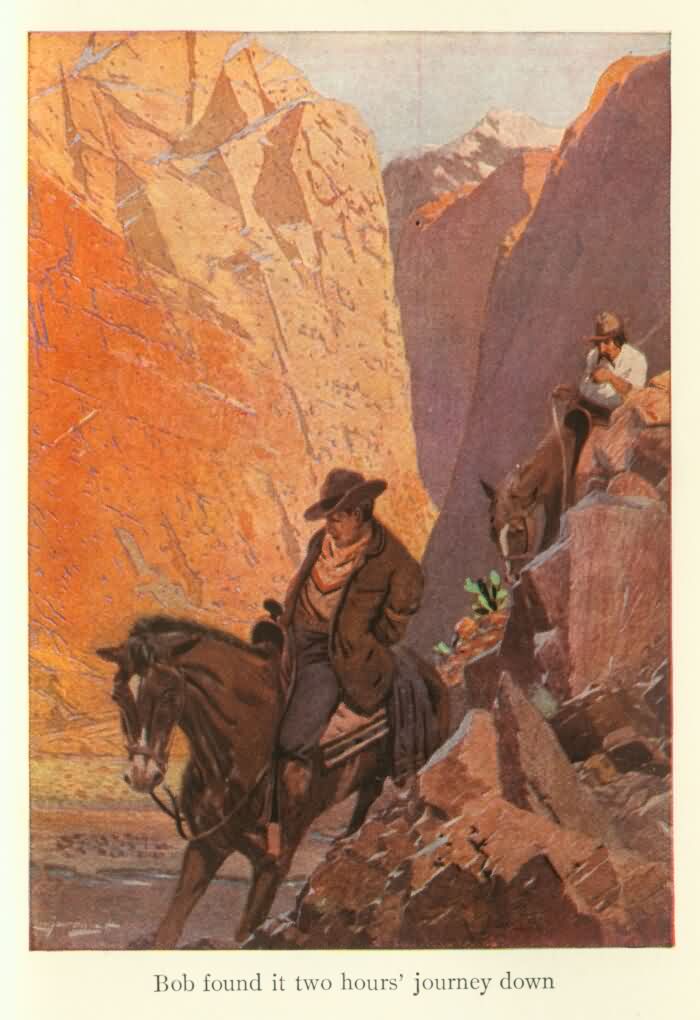

Bob found it two hours' journey down.

Late one fall afternoon, in the year 1898, a train paused for a moment before crossing a bridge over a river. From it descended a heavy-set, elderly man. The train immediately proceeded on its way.

The heavy-set man looked about him. The river and the bottom-land growths of willow and hardwood were hemmed in, as far as he could see, by low-wooded hills. Only the railroad bridge, the steep embankment of the right-of-way, and a small, painted, windowless structure next the water met his eye as the handiwork of man. The windowless structure was bleak, deserted and obviously locked by a strong padlock and hasp. Nevertheless, the man, throwing on his shoulder a canvas duffle-bag with handles, made his way down the steep railway embankment, across a plank over the ditch, and to the edge of the water. Here he dropped his bag heavily, and looked about him with an air of comical dismay.

The man was probably close to sixty years of age, but florid and vigorous. His body was heavy and round; but so were his arms and legs. An otherwise absolutely unprepossessing face was rendered most attractive by a pair of twinkling, humorous blue eyes, set far apart. Iron-gray hair, with a tendency to curl upward at the ends, escaped from under his hat. His movements were slow and large and purposeful.

He rattled the padlock on the boathouse, looked at his watch, and sat down on his duffle-bag. The wind blew strong up the river; the baring branches of the willows whipped loose their yellow leaves. A dull, leaden light stole up from the east as the afternoon sun lost its strength.

By the end of ten minutes, however, the wind carried with it the creak of rowlocks. A moment later a light, flat duck-boat shot around the bend and drew up at the float.

"Well, Orde, you confounded old scallywattamus," remarked the man on the duffle-bag, without moving, "is this your notion of meeting a train?"

The oarsman moored his frail craft and stepped to the float. He was about ten years the other's junior, big of frame, tanned of skin, clear of eye, and also purposeful of movement.

"This boathouse," he remarked incisively, "is the property of the Maple County Duck Club. Trespassers will be prosecuted. Get off this float."

Then they clasped hands and looked at each other.

"It's surely like old times to see you again, Welton," Orde broke the momentary silence. "It's been—let's see—fifteen years, hasn't it? How's Minnesota?"

"Full of ducks," stated Welton emphatically, "and if you haven't anything but mud hens and hell divers here, I'm going to sue you for getting me here under false pretences. I want ducks."

"Well, I'll get the keeper to shoot you some," replied Orde, soothingly, "or you can come out and see me kill 'em if you'll sit quiet and not rock the boat. Climb aboard. It's getting late."

Welton threw aboard his duffle-bag, and, with a dexterity marvellous in one apparently so unwieldy, stepped in astern. Orde grinned.

"Haven't forgotten how to ride a log, I reckon?" he commented.

Welton exploded.

"Look here, you little squirt!" he cried, "I'd have you know I'm riding logs yet. I don't suppose you'd know a log if you'd see one, you' soft-handed, degenerate, old riverhog, you! A golf ball's about your size!"

"No," said Orde; "a fat old hippopotamus named Welton is about my size—as I'll show you when we land at the Marsh!"

Welton grinned.

"How's Mrs. Orde and the little boy?" he inquired.

"Mrs. Orde is fine and dandy, and the 'little boy,' as you call him, graduated from college last June," Orde replied.

"You don't say!" cried Welton, genuinely astounded. "Why, of course, he must have! Can he lick his dad?"

"You bet he can—or could if his dad would give him a chance. Why, he's been captain of the football team for two years."

"And football's the only game I'd come out of the woods to see," said Welton. "I must have seen him up at Minneapolis when his team licked the stuffing out of our boys; and I remember his name. But I never thought of him as little Bobby—because—well, because I always did remember him as little Bobby."

"He's big Bobby, now, all right," said Orde, "and that's one reason I wanted to see you; why I asked you to run over from Chicago next time you came down. Of course, there are ducks, too."

"There'd better be!" said Welton grimly.

"I want Bob to go into the lumber business, same as his dad was. This congressman game is all right, and I don't see how I can very well get out of it, even if I wanted to. But, Welton, I'm a Riverman, and I always will be. It's in my bones. I want Bob to grow up in the smell of the woods—same as his dad. I've always had that ambition for him. It was the one thing that made me hesitate longest about going to Washington. I looked forward to Orde & Son."

He was resting on his oars, and the duck-boat drifted silently by the swaying brown reeds.

Welton nodded.

"I want you to take him and break him in. I'd rather have you than any one I know. You're the only one of the outsiders who stayed by the Big Jam," Orde continued. "Don't try to favour him—that's no favour. If he doesn't make good, fire him. Don't tell any of your people that he's the son of a friend. Let him stand on his own feet. If he's any good we'll work him into the old game. Just give him a job, and keep an eye on him for me, to see how well he does."

"Jack, the job's his," said Welton. "But it won't do him much good, because it won't last long. We're cleaned up in Minnesota; and have only an odd two years on some odds and ends we picked up in Wisconsin just to keep us busy."

"What are you going to do then?" asked Orde, quietly dipping his oars again.

"I'm going to retire and enjoy life."

Orde laughed quietly.

"Yes, you are!" said he. "You'd have a high old time for a calendar month. Then you'd get uneasy. You'd build you a big house, which would keep you mad for six months more. Then you'd degenerate to buying subscription books, and wheezing around a club and going by the cocktail route. You'd look sweet retiring, now, wouldn't you?"

Welton grinned back, a trifle ruefully.

"You can no more retire than I can," Orde went on. "And as for enjoying life, I'll trade jobs with you in a minute, you ungrateful old idiot."

"I know it, Jack," confessed Welton; "but what can I do? I can't pick up any more timber at any price. I tell you, the game is played out. We're old mossbacks; and our job is done."

"I have five hundred million feet of sugar pine in California. What do you say to going in with me to manufacture?"

"The hell you have!" cried Welton, his jaw dropping. "I didn't know that!"

"Neither does anybody else. I bought it twenty years ago, under a corporation name. I was the whole corporation. Called myself the Wolverine Company."

"You own the Wolverine property, do you?"

"Yes; ever hear of it?"

"I know where it is. I've been out there trying to get hold of something, but you have the heart of it."

"Thought you were going to retire," Orde pointed out.

"The property's all right, but I've some sort of notion the title is clouded."

"Why?"

"Can't seem to remember; but I must have come against some record somewhere. Didn't pay extra much attention, because I wasn't interested in that piece. Something to do with fraudulent homesteading, wasn't it?"

Orde dropped his oars across his lap to fill and light a pipe.

"That title was deliberately clouded by an enemy to prevent my raising money at the time of the Big Jam, when I was pinched," said he. "Frank Taylor straightened it out for me. You can see him. As a matter of fact, most of that land I bought outright from the original homesteaders, and the rest from a bank. I was very particular. There's one 160 I wouldn't take on that account."

"Well, that's all right," said Welton, his jolly eyes twinkling. "Why the secrecy?"

"I wanted a business for Bob when he should grow up," explained Orde; "but I didn't want any of this 'rich man's son' business. Nothing's worse for a boy than to feel that everything's cut and dried for him. He is to understand that he must go to work for somebody else, and stand strictly on his own feet, and make good on his own efforts. That's why I want you to break him in."

"All right. And about this partnership?"

"I want you to take charge. I can't leave Washington. We'll get down to details later. Bob can work for you there the same as here. By and by, we'll see whether to tell him or not."

The twilight had fallen, and the shores of the river were lost in dusk. The surface of the water itself shone with an added luminosity, reflecting the sky. In the middle distance twinkled a light, beyond which in long stretches lay the sombre marshes.

"That's the club," said Orde. "Now, if you disgrace me, you old duffer, I'll use you as a decoy!"

A few moments later the two men, opening the door of the shooting-box, plunged into a murk of blue tobacco smoke. A half-dozen men greeted them boisterously. These were just about to draw lots for choice of blinds on the morrow. A savoury smell of roasting ducks came from the tiny kitchen where Weber—punter, keeper, duck-caller and cook—exercised the last-named function. Welton drew last choice, and was commiserated on his bad fortune. No one offered to give way to the guest, however. On this point the rules of the Club were inflexible.

Luckily the weather changed. It turned cold; the wind blew a gale. Squalls of light snow swept the marshes. Men chattered and shivered, and blew on their wet fingers, but in from the great open lake came myriads of water-fowl, seeking shelter, and the sport was grand.

"Well, old stick-in-the-mud," said Orde as, at the end of two days, the men thawed out in a smoking car, "ducks enough for you?"

"Jack," said Welton solemnly, "there are no ducks in Minnesota. They've all come over here. I've had the time of my life. And about that other thing: as soon as our woods work is under way, I'll run out to California and look over the ground—see how easy it is to log that country. Then we can talk business. In the meantime, send Bob over to the Chicago office. I'll let Harvey break him in a little on the office work until I get back. When will he show up?"

Orde grinned apologetically.

"The kid has set his heart on coaching the team this fall, and he don't want to go to work until after the season," said he. "I'm just an old fool enough to tell him he could wait. I know he ought to be at it now—you and I were, long before his age; but----"

"Oh, shut up!" interrupted Welton, his big body shaking all over with mirth. "You talk like a copy-book. I'm not a constituent, and you needn't run any bluffs on me. You're tickled to death with that boy, and you are hoping that team will lick the everlasting daylights out of Chicago, Thanksgiving; and you wouldn't miss the game or have Bob out of the coaching for the whole of California; and you know it. Send him along when you get ready."

Bob Orde, armed with a card of introduction to Fox, Welton's office partner, left home directly after Thanksgiving. He had heard much of Welton & Fox in the past, both from his father and his father's associates. The firm name meant to him big things in the past history of Michigan's industries, and big things in the vague, large life of the Northwest. Therefore, he was considerably surprised, on finding the firm's Adams Street offices, to observe their comparative insignificance.

He made his way into a narrow entry, containing merely a high desk, a safe, some letter files, and two bookkeepers. Then, without challenge, he walked directly into a large apartment, furnished as simply, with another safe, a typewriter, several chairs, and a large roll-top desk. At the latter a man sprawled, reading a newspaper. Bob looked about for a further door closed on an inner private office, where the weighty business must be transacted. There was none. The tall, broad, lean young man hesitated, looking about him with a puzzled expression in his earnest young eyes. Could this be the heart and centre of those vast and far-reaching activities he had heard so much about?

After a moment the man in the revolving chair looked up shrewdly over his paper. Bob felt himself the object of an instant's searching scrutiny from a pair of elderly steel-gray eyes.

"Well?" said the man, briefly.

"I am looking for Mr. Fox," explained Bob.

"I am Fox."

The young man moved forward his great frame with the easy, loose-jointed grace of the trained athlete. Without comment he handed his card of introduction to the seated man. The latter glanced at it, then back to the young fellow before him.

"Glad to see you, Mr. Orde," he unbent slightly. "I've been expecting you. If you're as good a man as your father, you'll succeed. If you're not as good a man as your father, you may get on—well enough. But you've got to be some good on your own account. We'll see." He raised his voice slightly. "Jim!" he called.

One of the two bookkeepers appeared in the doorway.

"This is young Mr. Orde," Fox told him. "You knew his father at Monrovia and Redding."

The bookkeeper examined Bob dispassionately.

"Harvey is our head man here," went on Fox. "He'll take charge of you."

He swung his leg over the arm of his chair and resumed his newspaper. After a few moments he thrust the crumpled sheet into a huge waste basket and turned to his desk, where he speedily lost himself in a mass of letters and papers.

Harvey disappeared. Bob stood for a moment, then took a seat by the window, where he could look out over the smoky city and catch a glimpse of the wintry lake beyond. As nothing further occurred for some time, he removed his overcoat, and gazed about him with interest on the framed photographs of logging scenes and camps that covered the walls. At the end of ten minutes Harvey returned from the small outer office. Harvey was, perhaps, fifty-five years of age, exceeding methodical, very competent.

"Can you run a typewriter?" he inquired.

"A little," said Bob.

"Well, copy this, with a carbon duplicate."

Bob took the paper Harvey extended to him. He found it to be a list, including hundreds of items. The first few lines were like this:

Sec. 4 T, 6 N.R., 26 W S.W. 1/4 of N.W. 1/4

4

6 26

N.W. 1/4 of N.W. 1/4

4

6 26

S.W. 1/4 of S.W. 1/4

5

6 26

S.W. 1/4 of N.W. 1/4

5

6 26

S.E. 1/4 of N.W. 1/4

After an interminable sequence, another of the figures would change, or a single letter of the alphabet would shift. And so on, column after column. Bob had not the remotest notion of what it all meant, but he copied it and handed the result to Harvey. In a few moments Harvey returned.

"Did you verify this?" he asked.

"What?" Bob inquired.

"Verify it, check it over, compare it," snapped Harvey, impatiently.

Bob took the list, and with infinite pains which, nevertheless, could not prevent him from occasionally losing the place in the bewilderment of so many similar figures, he managed to discover that he had omitted three and miscopied two. He corrected these mistakes with ink and returned the list to Harvey. Harvey looked sourly at the ink marks, and gave the boy another list to copy.

Bob found this task, which lasted until noon, fully as exhilarating as the other. When he returned his copies he ventured an inquiry.

"What are these?" he asked.

"Descriptions," snapped Harvey.

In time he managed to reason out the fact that they were descriptions of land; that each item of the many hundreds meant a separate tract. Thus the first line of his first copy, translated, would have read as follows:

"The southwest quarter of the northwest quarter of section number four, township number six, north, range number twenty-six, west."

—And that it represented forty acres of timber land. The stupendous nature of such holdings made him gasp, and he gasped again when he realized that each of his mistakes meant the misplacement on the map of enough for a good-sized farm. Nevertheless, as day succeeded day, and the lists had no end, the mistakes became more difficult to avoid. The S, W, E, and N keys on the typewriter bothered him, hypnotized him, forced him to strike fantastic combinations of their own. Once Harvey entered to point out to him an impossible N.S.

Over his lists Harvey, the second bookkeeper, and Fox held long consultations. Then Bob leaned back in his office chair to examine for the hundredth time the framed photographs of logging crews, winter scenes in the forest, record loads of logs; and to speculate again on the maps, deer heads, and hunting trophies. At first they had appealed to his imagination. Now they had become too familiar. Out the window were the palls of smoke, gigantic buildings, crevasse-like streets, and swirling winds of Chicago.

Occasionally men would drift in, inquiring for the heads of the firm. Then Fox would hang one leg over the arm of his swinging chair, light a cigar, and enter into desultory conversation. To Bob a great deal of time seemed thus to be wasted. He did not know that big deals were decided in apparently casual references to business.

Other lists varied the monotony. After he had finished the tax lists he had to copy over every description a second time, with additional statistics opposite each, like this:

S.W. 1/4 of N.W. 1/4, T. 4 N.R., 17, W. Sec. 32,

W.P.

68, N. 16, H. 5.

The last characters translated into: "White pine, 68,000 feet; Norway pine, 16,000 feet; hemlock, 5,000 feet," and that inventoried the standing timber on the special forty acres.

And occasionally he tabulated for reference long statistics on how Camp 14 fed its men for 32 cents a day apiece, while Camp 32 got it down to 27 cents.

That was all, absolutely all, except that occasionally they sent him out to do an errand, or let him copy a wordy contract with a great many whereases and wherefores.

Bob little realized that nine-tenths of this timber—all that wherein S P (sugar pine) took the place of W P—was in California, belonged to his own father, and would one day be his. For just at this time the principal labour of the office was in checking over the estimates on the Western tract.

Bob did his best because he was a true sportsman, and he had entered the game, but he did not like it, and the slow, sleepy monotony of the office, with its trivial tasks which he did not understand, filled him with an immense and cloying languor. The firm seemed to be dying of the sleeping sickness. Nothing ever happened. They filed their interminable statistics, and consulted their interminable books, and marked squares off their interminable maps, and droned along their monotonous, unimportant life in the same manner day after day. Bob was used to out-of-doors, used to exercise, used to the animation of free human intercourse. He watched the clock in spite of himself. He made mistakes out of sheer weariness of spirit, and in the footing of the long columns of figures he could not summon to his assistance the slow, painstaking enthusiasm for accuracy which is the sole salvation of those who would get the answer. He was not that sort of chap.

But he was not a quitter, either. This was life. He tried conscientiously to do his best in it. Other men did; so could he.

The winter moved on somnolently. He knew he was not making a success. Harvey was inscrutable, taciturn, not to be approached. Fox seemed to have forgotten his official existence, although he was hearty enough in his morning greetings to the young man. The young bookkeeper, Archie, was more friendly, but even he was a being apart, alien, one of the strangely accurate machines for the putting down and docketing of these innumerable and unimportant figures. He would have liked to know and understand Bob, just as the latter would have liked to know and understand him, but they were separated by a wide gulf in which whirled the nothingnesses of training and temperament. However, Archie often pointed out mistakes to Bob before the sardonic Harvey discovered them. Harvey never said anything. He merely made a blue pencil mark in the margin, and handed the document back. But the weariness of his smile!

One day Bob was sent to the bank. His business there was that of an errand boy. Discovering it to be sleeting, he returned for his overcoat. Harvey was standing rigid in the door of the inner office, talking to Fox.

"He has an ingrained inaccuracy. He will never do for business," Bob caught.

Archie looked at him pityingly.

The winter wore away. Bob dragged himself out of bed every morning at half-past six, hurried through a breakfast, caught a car—and hoped that the bridge would be closed. Otherwise he would be late at the office, which would earn him Harvey's marked disapproval. Bob could not see that it mattered much whether he was late or not. Generally he had nothing whatever to do for an hour or so. At noon he ate disconsolately at a cheap saloon restaurant. At five he was free to go out among his own kind—with always the thought before him of the alarm clock the following morning.

One day he sat by the window, his clean, square chin in his hand, his eyes lost in abstraction. As he looked, the winter murk parted noiselessly, as though the effect were prearranged; a blue sky shone through on a glint of bluer water; and, wonder of wonders, there through the grimy dirty roar of Adams Street a single, joyful robin note flew up to him.

At once a great homesickness overpowered him. He could see plainly the half-sodden grass of the campus, the budding trees, the red "gym" building, and the crowd knocking up flies. In a little while the shot putters and jumpers would be out in their sweaters. Out at Regents' Field the runners were getting into shape. Bob could almost hear the creak of the rollers smoothing out the tennis courts; he could almost recognize the voices of the fellows perching about, smell the fragrant reek of their pipes, savour the sweet spring breeze. The library clock boomed four times, then clanged the hour. A rush of feet from all the recitation rooms followed as a sequence, the opening of doors, the murmur of voices, occasionally a shout. Over it sounded the sharp, half-petulant advice of the coaches and the little trainer to the athletes. It was getting dusk. The campus was emptying. Through the trees shone lights. And Bob looked up, as he had so often done before, to see the wonder of the great dome against the afterglow of sunset.

Harvey was examining him with some curiosity.

"Copied those camp reports?" he inquired.

Bob glanced hastily at the clock. He had been dreaming over an hour.

A little later Fox came in; and a little after that Harvey returned bringing in his hand the copies of the camp reports, but instead of taking them directly to Bob for correction, as had been his habit, he laid them before Fox. The latter picked them up and examined them. In a moment he dropped them on his desk.

"Do you mean to tell me," he demanded of Harvey, "that seventeen only ran ten thousand? Why, it's preposterous! Saw it myself. It has a half-million on it, if there's a stick. Let's see Parsons's letter."

While Harvey was gone, Fox read further in the copy.

"See here, Harvey," he cried, "something's dead wrong. We never cut all this hemlock. Why, hemlock's 'way down."

Harvey laid the original on the desk. After a second Fox's face cleared.

"Why, this is all right. There were 480,000 on seventeen. And that hemlock seems to have got in the wrong column. You want to be a little more careful, Jim. Never knew that to happen before. Weren't out with the boys last night, were you?"

But Harvey refused to respond to frivolity.

"It's never happened before because I never let it happen before," he replied stiffly. "There have been mistakes like that, and worse, in almost every report we've filed. I've cut them out. Now, Mr. Fox, I don't have much to say, but I'd rather do a thing myself than do it over after somebody else. We've got a good deal to keep track of in this office, as you know, without having to go over everybody else's work too."

"H'm," said Fox, thoughtfully. Then after a moment, "I'll see about it."

Harvey went back to the outer office, and Fox turned at once to Bob.

"Well, how is it?" he asked. "How did it happen?"

"I don't know," replied Bob. "I'm trying, Mr. Fox. Don't think it isn't that. But it's new to me, and I can't seem to get the hang of it right away."

"I see. How long you been here?"

"A little over four months."

Fox swung back in his chair leisurely.

"You must see you're not fair to Harvey," he announced. "That man carries the details of four businesses in his head, he practically does the clerical work for them all, and he never seems to hurry. Also, he can put his hand without hesitation on any one of these documents," he waved his hand about the room. "I can't."

He stopped to light the stub of a long-extinct cigar.

"I can't make it hard for that sort of man. So I guess we'll have to take you out of the office. Still, I promised Welton to give you a good try-out. Then, too, I'm not satisfied in my own mind. I can see you are trying. Either you're a damn fool or this college education racket has had the same effect on you as on most other young cubs. If you're the son of your father, you can't be entirely a damn fool. If it's the college education, that will probably wear off in time. Anyhow, I think I'll take you up to the mill. You can try the office there. Collins is easy to get on with, and of course there isn't the same responsibility there."

In the buffeting of humiliation Bob could not avoid a fleeting inner smile over this last remark. Responsibility! In this sleepy, quiet backwater of a tenth-floor office, full of infinite little statistics that led nowhere, that came to no conclusion except to be engulfed in dark files with hundreds of their own kind, aimless, useless, annoying as so many gadflies! Then he set his face for the further remarks.

"Navigation will open this week," Fox's incisive tones went on, "and our hold-overs will be moved now. It will be busy there. We shall take the eight o'clock train to-night." He glanced sharply at Bob's lean, set face. "I assume you'll go?"

Bob was remembering certain trying afternoons on the field when as captain, and later as coach, he had told some very high-spirited boys what he considered some wholesome truths. He was remembering the various ways in which they had taken his remarks.

"Yes, sir," he replied.

"Well, you can go home now and pack up," said Fox. "Jim!" he shot out in his penetrating voice; then to Harvey, "Make out Orde's check."

Bob closed his desk, and went into the outer office to receive his check. Harvey handed it to him without comment, and at once turned back to his books. Bob stood irresolute a moment, then turned away without farewell.

But Archie followed him into the hall.

"I'm mighty sorry, old man," he whispered, furtively. "Did you get the G.B.?"

"I'm going up to the mill office," replied Bob.

"Oh!" the other commiserated him. Then with an effort to see the best side, "Still you could hardly expect to jump right into the head office at first. I didn't much think you could hold down a job here. You see there's too much doing here. Well, good-bye. Good luck to you, old man."

There it was again, the insistence on the responsibility, the activity, the importance of that sleepy, stuffy little office with its two men at work, its leisure, its aimlessness. On his way to the car-line Bob stopped to look in at an open door. A dozen men were jumping truck loads of boxes here and there. Another man in a peaked cap and a silesia coat, with a pencil behind his ear and a manifold book sticking out of his pocket shouted orders, consulted a long list, marked boxes and scribbled in a shipping book. Dim in the background huge freight elevators rose and fell, burdened with the mass of indeterminate things. Truck horses, great as elephants, magnificently harnessed with brass ornaments, drew drays, big enough to carry a small house, to the loading platform where they were quickly laden and sent away. From an opened upper window came the busy click of many typewriters. Order in apparent confusion, immense activity at a white heat, great movement, the clanging of the wheels of commerce, the apparition and embodiment of restless industry—these appeared and vanished, darted in and out, were plain to be seen and were vague through the murk and gloom. Bob glanced up at the emblazoned sign. He read the firm's name of well-known wholesale grocers. As he crossed the bridge and proceeded out Lincoln Park Boulevard two figures rose to him and stood side by side. One was the shipping clerk in his peaked cap and silesia coat, hurried, busy, commanding, full of responsibility; the other was Harvey, with his round, black skull cap, his great, gold-bowed spectacles, entering minutely, painstakingly, deliberately, his neat little figures in a neat, large book.

The train stopped about noon at a small board town. Fox and Bob descended. The latter drew his lungs full of the sparkling clear air and felt inclined to shout. The thing that claimed his attention most strongly was the dull green band of the forest, thick and impenetrable to the south, fringing into ragged tamaracks on the east, opening into a charming vista of a narrowing bay to the west. Northward the land ran down to sandpits and beyond them tossed the vivid white and blue of the Lake. Then when his interest had detached itself from the predominant note of the imminent wilderness, predominant less from its physical size—for it lay in remote perspective—than from a certain indefinable and psychological right of priority, Bob's eye was at once drawn to the huge red-painted sawmill, with its very tall smokestacks, its row of water barrels along the ridge, its uncouth and separate conical sawdust burner, and its long lines of elevated tramways leading out into the lumber yard where was piled the white pine held over from the season before. As Bob looked, a great, black horse appeared on one of these aerial tramways, silhouetted against the sky. The beast moved accurately, his head held low against his chest, his feet lifted and planted with care. Behind him rumbled a whole train of little cars each laden with planks. On the foremost sat a man, his shoulders bowed, driving the horse. They proceeded slowly, leisurely, without haste, against the brightness of the sky. The spider supports below them seemed strangely inadequate to their mass, so that they appeared in an occult manner to maintain their elevation by some buoyancy of their own, some quality that sustained them not only in their distance above the earth but in a curious, decorative, extra-human world of their own. After a moment they disappeared behind the tall piles of lumber.

Against the sky, now, the place of the elephantine black horse and the little tram cars and the man was taken by the masts of ships lying beyond. They rose straight and tall, their cordage like spider webs, in a succession of regular spaces until they were lost behind the mill. From the exhaust of the mill's engine a jet of white steam shot up sparkling. Close on its apparition sounded the exultant, high-keyed shriek of the saw. It ceased abruptly. Then Bob became conscious of a heavy rud, thud of mill machinery.

All this time he and Fox were walking along a narrow board walk, elevated two or three feet above the sawdust-strewn street. They passed the mill and entered the cool shade of the big lumber piles. Along their base lay half-melted snow. Soggy pools soaked the ground in the exposed places. Bob breathed deep of the clear air, keenly conscious of the freshness of it after the murky city. A sweet and delicate odour was abroad, an odour elusive yet pungent, an aroma of the open. The young man sniffed it eagerly, this essence of fresh sawdust, of new-cut pine, of sawlogs dripping from the water, of faint old reminiscence of cured lumber standing in the piles of the year before, and more fancifully of the balsam and spruce, the hemlock and pine of the distant forest.

"Great!" he cried aloud, "I never knew anything like it! What a country to train in!"

"All this lumber here is going to be sold within the next two months," said Fox with the first approach to enthusiasm Bob had ever observed in him. "All of it. It's got to be carried down to the docks, and tallied there, and loaded in those vessels. The mill isn't much—too old-fashioned. We saw with 'circulars' instead of band-saws. Not like our Minnesota mills. We bought the plant as it stands. Still we turn out a pretty good cut every day, and it has to be run out and piled."

They stepped abruptly, without transition, into the town. A double row of unpainted board shanties led straight to the water's edge. This row was punctuated by four buildings different from the rest—a huge rambling structure with a wide porch over which was suspended a large bell; a neatly painted smaller building labelled "Office"; a trim house surrounded by what would later be a garden; and a square-fronted store. The street between was soft and springy with sawdust and finely broken shingles. Various side streets started out bravely enough, but soon petered out into stump land. Along one of them were extensive stables.

Bob followed his conductor in silence. After an interval they mounted short steps and entered the office.

Here Bob found himself at once in a small entry railed off from the main room by a breast-high line of pickets strong enough to resist a battering-ram. A man he had seen walking across from the mill was talking rapidly through a tiny wicket, emphasizing some point on a soiled memorandum by the indication of a stubby forefinger. He was a short, active, blue-eyed man, very tanned. Bob looked at him with interest, for there was something about him the young man did not recognize, something he liked—a certain independent carriage of the head, a certain self-reliance in the set of his shoulders, a certain purposeful directness of his whole personality. When he caught sight of Fox he turned briskly, extending his hand.

"How are you, Mr. Fox?" he greeted. "Just in?"

"Hullo, Johnny," replied Fox, "how are things? I see you're busy."

"Yes, we're busy," replied the man, "and we'll keep busy."

"Everything going all right?"

"Pretty good. Poor lot of men this year. A good many of the old men haven't showed up this year—some sort of pull-out to Oregon and California. I'm having a little trouble with them off and on."

"I'll bet on you to stay on top," replied Fox easily. "I'll be over to see you pretty soon."

The man nodded to the bookkeeper with whom he had been talking, and turned to go out. As he passed Bob, that young man was conscious of a keen, gimlet scrutiny from the blue eyes, a scrutiny instantaneous, but which seemed to penetrate his very flesh to the soul of him. He experienced a distinct physical shock as at the encountering of an elemental force.

He came to himself to hear Fox saying:

"That's Johnny Mason, our mill foreman. He has charge of all the sawing, and is a mighty good man. You'll see more of him."

The speaker opened a gate in the picket railing and stepped inside.

A long shelf desk, at which were high stools, backed up against the pickets; a big round stove occupied the centre; a safe crowded one corner. Blue print maps decorated the walls. Coarse rope matting edged with tin strips protected the floor. A single step down through a door led into a painted private office where could be seen a flat table desk. In the air hung a mingled odour of fresh pine, stale tobacco, and the closeness of books.

Fox turned at once sharply to the left and entered into earnest conversation with a pale, hatchet-faced man of thirty-five, whom he addressed as "Collins." In a moment he turned, beckoning Bob forward.

"Here's a youngster for you, Collins," said he, evidently continuing former remarks. "Young Mr. Orde. He's been in our home office awhile, but I brought him up to help you out. He can get busy on your tally sheets and time checks and tally boards, and sort of ease up the strain a little."

"I can use him, right now," said Collins, nervously smoothing back a strand of his pale hair. "Glad to meet you, Mr. Orde. These 'jumpers' ... and that confounded mixed stuff from seventeen ..." he trailed off, his eye glazing in the abstraction of some inner calculation, his long, nervous fingers reaching unconsciously toward the soiled memoranda left by Mason.

"Well, I'll set you to work," he roused himself, when he perceived that the two were about to leave him. And almost before they had time to turn away he was busy at the papers, his pencil, beautifully pointed, running like lightning down the long columns, pausing at certain places as though by instinct, hovering the brief instant necessary to calculation, then racing on as though in pursuit of something elusive.

As they turned away a slow, cool voice addressed them from behind the stove.

"Hullo, bub!" it drawled.

Fox's face lighted and he extended both hands.

"Well, Tally!" he cried. "You old snoozer!"

The man was upward of sixty years of age, but straight and active. His features were tanned a deep mahogany, and carved by the years and exposure into lines of capability and good humour. In contrast to this brown his sweeping white moustache and bushy eyebrows, blenched flaxen by the sun, showed strongly. His little blue eyes twinkled, and fine wrinkles at their corners helped the twinkles. His long figure was so heavily clothed as to be concealed from any surmise, except that it was gaunt and wiry. Hands gnarled, twisted, veined, brown, seemed less like flesh than like some skilful Japanese carving. On his head he wore a visored cap with an extraordinary high crown; on his back a rather dingy coat cut from a Mackinaw blanket; on his legs trousers that had been "stagged" off just below the knees, heavy German socks, and shoes nailed with sharp spikes at least three-quarters of an inch in length.

"Thought you were up in the woods!" Fox was exclaiming. "Where's Fagan?"

"He's walkin' white water," replied the old man.

"Things going well?"

"Damn poor," admitted Tally frankly. "That is to say, the Whitefish branch is off. There's trouble with the men. They're a mixed lot. Then there's old Meadows. He's assertin' his heaven-born rights some more. It's all right. We're on their backs. Other branches just about down."

There followed a rapid exchange of which Bob could make little—talk of flood water, of "plugging" and "pulling," of "winging out," of "white water." It made no sense, and yet somehow it thrilled him, as at times the mere roll of Greek names used to arouse in his breast vague emotions of grandeur and the struggle of mighty forces.

Still talking, the two men began slowly to move toward the inner office. Suddenly Fox seemed to remember his companion's existence.

"By the way, Jim," he said, "I want you to know one of our new men, young Mr. Orde. You've worked for his father. This is Jim Tally, and he's one of the best rivermen, the best woodsman, the best boss of men old Michigan ever turned out. He walked logs before I was born."

"Glad to know you, Mr. Orde," said Tally, quite unmoved.

The two left Bob to his own devices. The old riverman and the astonishingly thawed and rejuvenated Mr. Fox disappeared in the private office. Bob proffered a question to the busy Collins, discovered himself free until afternoon, and so went out through the office and into the clear open air.

He headed at once across the wide sawdust area toward the mill and the lake. A great curiosity, a great interest filled him. After a moment he found himself walking between tall, leaning stacks of lumber, piled crosswise in such a manner that the sweet currents of air eddied through the interstices between the boards and in the narrow, alley-like spaces between the square and separate stacks. A coolness filled these streets, a coolness born of the shade in which they were cast, the freshness of still unmelted snow lying in patches, the quality of pine with its faint aromatic pitch smell and its suggestion of the forest. Bob wandered on slowly, his hands in his pockets. For the time being his more active interest was in abeyance, lulled by the subtle, elusive phantom of grandeur suggested in the aloofness of this narrow street fronted by its square, skeleton, windowless houses through which the wind rattled. After a little he glimpsed blue through the alleys between. Then a side street offered, full of sun. He turned down it a few feet, and found himself standing over an inlet of the lake.

Then for the first time he realized that he had been walking on "made ground." The water chugged restlessly against the uneven ends of the lath-like slabs, thousands of them laid, side by side, down to and below the water's surface. They formed a substructure on which the sawdust had been heaped. Deep shadows darted from their shelter and withdrew, following the play of the little waves. The lower slabs were black with the wet, and from them, too, crept a spicy odour set free by the moisture. On a pile head sat an urchin fishing, with a long bamboo pole many sizes too large for him. As Bob watched, he jerked forth diminutive flat sunfish.

"Good work!" called Bob in congratulation.

The urchin looked up at the large, good-humoured man and grinned.

Bob retraced his steps to the street on which he had started out. There he discovered a steep stairway, and by it mounted to the tramway above. Along this he wandered for what seemed to him an interminable distance, lost as in a maze among the streets and byways of this tenantless city. Once he stepped aside to give passage to the great horse, or one like him, and his train of little cars. The man driving nodded to him. Again he happened on two men unloading similar cars, and passing the boards down to other men below, who piled them skilfully, two end planks one way, and then the next tier the other, in regular alternation. They wore thick leather aprons, and square leather pieces strapped across the insides of their hands as a protection against splinters. These, like all other especial accoutrements, seemed to Bob somehow romantic, to be desired, infinitely picturesque. He passed on with the clear, yellow-white of the pine boards lingering back of his retina.

But now suddenly his sauntering brought him to the water front. The tramway ended in a long platform running parallel to the edge of the docks below. There were many little cars, both in the process of unloading and awaiting their turn. The place swarmed with men, all busily engaged in handing the boards from one to another as buckets are passed at a fire. At each point where an unending stream of them passed over the side of each ship, stood a young man with a long, flexible rule. This he laid rapidly along the width of each board, and then as rapidly entered a mark in a note-book. The boards seemed to move fairly of their own volition, like a scutellate monster of many joints, crawling from the cars, across the dock, over the side of the ship and into the black hold where presumably it coiled. There were six ships; six, many-jointed monsters creeping to their appointed places under the urging of these their masters; six young men absorbed and busy at the tallying; six crews panoplied in leather guiding the monsters to their lairs. Here, too, the sun-warmed air arose sluggish with the aroma of pitch, of lumber, of tar from the ships' cordage, of the wetness of unpainted wood. Aloft in the rigging, clear against the sky, were sailors in contrast of peaceful, leisurely industry to those who toiled and hurried below. The masts swayed gently, describing an arc against the heavens. The sailors swung easily to the motion. From below came the quick dull sounds of planks thrown down, the grind of car wheels, the movement of feet, the varied, complex sound of men working together, the clapping of waters against the structure. It was confusing, confusing as the noise of many hammers. Yet two things seemed to steady it, to confine it, keep it in the bounds of order, to prevent it from usurping more than its meet and proper proportion. One was the tingling lake breeze singing through the rigging of the ship; the other was the idle and intermittent whistling of one of the sailors aloft. And suddenly, as though it had but just commenced, Bob again became aware of the saw shrieking in ecstasy as it plunged into a pine log.

The sound came from the left, where at once he perceived the tall stacks showing above the lumber piles, and the plume of white steam glittering in the sun. In a moment the steam fell, and the shriek of the saw fell with it. He turned to follow the tramway, and in so doing almost bumped into Mason, the mill foreman.

"They're hustling it in," said the latter. "That's right. Can't give me yard room any too soon. The drive'll be down next month. Plenty doing then. Damn those Dutchmen!"

He spoke abstractedly, as though voicing his inner thoughts to himself, unconscious of his companion. Then he roused himself.

"Going to the mill?" he asked. "Come on."

They walked along the high, narrow platform overlooking the water front and the lading of the ships. Soon the trestles widened, the tracks diverging like the fingers of a hand on the broad front to the second story of the mill. Mason said something about seeing the whole of it, and led the way along a narrow, railed outside passage to the other end of the structure.

There Bob's attention was at once caught by a great water enclosure of logs, lying still and sluggish in the manner of beasts resting. Rank after rank, tier after tier, in strange patterns they lay, brown and round, with the little strips of blue water showing between like a fantastic pattern. While Bob looked, a man ran out over them. He was dressed in short trousers, heavy socks, and spiked boots, and a faded blue shirt. The young man watched with interest, old memories of his early boyhood thronging back on him, before his people had moved from Monrovia and the "booms." The man ran erratically, but with an accurate purpose. Behind him the big logs bent in dignified reminiscence of his tread, and slowly rolled over; the little logs bobbed frantically in a turmoil of white water, disappearing and reappearing again and again, sleek and wet as seals. To these the man paid no attention, but leaped easily on, pausing on the timbers heavy enough to support him, barely spurning those too small to sustain his weight. In a moment he stopped abruptly without the transitorial balancing Bob would have believed necessary, and went calmly to pushing mightily with a long pike-pole. The log on which he stood rolled under the pressure; the man quite mechanically kept pace with its rolling, treading it in correspondence now one way, now the other. In a few moments thus he had forced the mass of logs before him toward an inclined plane leading to the second story of the mill.

Up this ran an endless chain armed with teeth. The man pushed one of the logs against the chain; the teeth bit; at once, shaking itself free of the water, without apparent effort, without haste, calmly and leisurely as befitted the dignity of its bulk, the great timber arose. The water dripped from it, the surface streamed, a cheerful patter, patter of the falling drops made itself heard beneath the mill noises. In a moment the log disappeared beneath projecting eaves. Another was just behind it, and behind that yet another, and another, like great patient beasts rising from the coolness of a stream to follow a leader through the narrowness, of pasture bars. And in the booms, up the river, as far as the eye could see, were other logs awaiting their turn. And beyond them the forest trees, straight and tall and green, dreaming of the time when they should follow their brothers to the ships and go out into the world.

Mason was looking up the river.

"I've seen the time when she was piled thirty feet high there, and the freshet behind her. That was ten year back."

"What?" asked Bob.

"A jam!" explained Mason.

He ducked his head below his shoulders and disappeared beneath the eaves of the mill. Bob followed.

First it was dusky; then he saw the strip of bright yellow sunlight and the blue bay in the opening below the eaves; then he caught the glitter and whirr of the two huge saws, moving silently but with the deadly menace of great speed on their axes. Against the light in irregular succession, alternately blotting and clearing the foreground at the end of the mill, appeared the ends of the logs coming up the incline. For a moment they poised on the slant, then fell to the level, and glided forward to a broad platform where they were ravished from the chain and rolled into line.

Bob's eyes were becoming accustomed to the gloom. He made out pulleys, belts, machinery, men. While he watched a black, crooked arm shot vigorously up from the floor, hurried a log to the embrace of two clamps, rolled it a little this way, a little that, hovered over it as though in doubt as to whether it was satisfactorily placed, then plunged to unknown depths as swiftly and silently as it had come. So abrupt and purposeful were its movements, so detached did it seem from control, that, just as when he was a youngster, Bob could not rid his mind of the notion that it was possessed of volition, that it led a mysterious life of its own down there in the shadows, that it was in the nature of an intelligent and agile beast trained to apply its powers independently.

Bob remembered it as the "nigger," and looked about for the man standing by a lever.

A momentary delay seemed to have occurred, owing to some obscure difficulty. The man at the lever straightened his back. Suddenly all that part of the floor seemed to start forward with extraordinary swiftness. The log rushed down on the circular saw. Instantly the wild, exultant shriek arose. The car went on, burying the saw, all but the very top, from which a stream of sawdust flew up and back. A long, clean slab fell to a succession of revolving rollers which carried it, passing it from one to the other, far into the body of the mill. The car shot back to its original position in front of the saw. The saw hummed an undersong of strong vibration. Again it ploughed its way the length of the timber. This time a plank with bark edges dropped on the rollers. And when the car had flown back to its starting point the "nigger" rose from obscurity to turn the log half way around.

They picked their way gingerly on. Bob looked back. Against the light the two graceful, erect figures, immobile, but carried back and forth over thirty feet with lightning rapidity; the brute masses of the logs; the swift decisive forays of the "nigger," the unobtrusive figures of the other men handling the logs far in the background; and the bright, smooth, glittering, dangerous saws, clear-cut in outline by their very speed, humming in anticipation, or shrieking like demons as they bit—these seemed to him to swell in the dim light to the proportions of something gigantic, primeval—to become forces beyond the experience of to-day, typical of the tremendous power that must be invoked to subdue the equally tremendous power of the wilderness.

He and Mason together examined the industriously working gang-saws, long steel blades with the up-and-down motion of cutting cord-wood. They passed the small trimming saws, where men push the boards between little round saws to trim their edges. Bob noticed how the sawdust was carried away automatically, and where the waste slabs went. They turned through a small side room, strangely silent by contrast to the rest, where the filer did his minute work. He was an old man, the filer, with steel-rimmed, round spectacles, and he held Bob some time explaining how important his position was.

They emerged finally to the broad, open platform with the radiating tram-car tracks. Here Bob saw the finished boards trundled out on the moving rollers to be transferred to the cars.

Mason left him. He made his way slowly back toward the office, noticing on the way the curious pairs of huge wheels beneath which were slung the heavy timbers or piles of boards for transportation at the level of the ground.

At the edge of the lumber piles Bob looked back. The noises of industry were in his ears; the blur of industry before his eyes; the clean, sweet smell of pine in his nostrils. He saw clearly the row of ships and the many-jointed serpent of boards making its way to the hold, the sailors swinging aloft; the miles of ruminating brown logs, and the alert little man zigzagging across them; the shadow of the mill darkening the water, and the brown leviathan timbers rising dripping in regular succession from them; the whirr of the deadly circular saws, and the calm, erect men dominating the cars that darted back and forth; and finally the sparkling white steam spraying suddenly against the intense blue of the sky. Here was activity, business, industry, the clash of forces. He admired the quick, compact alertness of Johnny Mason; he joyed in the absorbed, interested activity of the brown young men with the scaler's rules; he envied a trifle the muscle-stretching, physical labour of the men with the leather aprons and hand-guards, piling the lumber. It was good to draw in deep breaths of this air, to smell deeply of he aromatic odours of the north.

Suddenly the mill whistle began to blow. Beneath the noise he could hear the machinery beginning to run down. From all directions men came. They converged in the central alley, hundreds of them. In a moment Bob was caught up in their stream, and borne with them toward the weather-stained shanty town.

Bob followed this streaming multitude to the large structure that had earlier been pointed out to him as the boarding house. It was a commodious affair with a narrow verandah to which led steps picked out by the sharp caulks of the rivermen's boots. A round stove held the place of honour in the first room. Benches flanked the walls. At one end was a table-sink, and tin wash-basins, and roller towels. The men were splashing and blowing in the plunge-in-all-over fashion of their class. They emerged slicked down and fresh, their hair plastered wet to their foreheads. After a moment a fat and motherly woman made an announcement from a rear room. All trooped out.

The dining room was precisely like those Bob remembered from recollections of the river camps of his childhood. There were the same long tables covered with red oilcloth, the same pine benches worn smooth and shiny, the same thick crockery, and the same huge receptacles steaming with hearty—and well-cooked—food. Nowhere does the man who labours with his hands fare better than in the average lumber camp. Forest operations have a largeness in conception and execution that leads away from the habit of the mean, small and foolish economics. At one side, and near the windows, stood a smaller table. The covering of this was turkey-red cloth with white pattern; it boasted a white-metal "caster"; and possessed real chairs. Here Bob took his seat, in company with Fox, Collins, Mason, Tally and the half-dozen active young fellows he had seen handling the scaling rules near the ships.

At the men's tables the meal was consumed in a silence which Bob learned later came nearer being obligatory than a matter of choice. Conversation was discouraged by the good-natured fat woman, Mrs. Hallowell. Talk delayed; and when one had dishes to wash----

The "boss's table" was more leisurely. Bob was introduced to the sealers. They proved to be, with one exception, young fellows of twenty-one or two, keen-eyed, brown-faced, alert and active. They impressed Bob as belonging to the clerk class, with something added by the outdoor, varied life. Indeed, later he discovered them to be sons of carpenters, mechanics and other higher-class, intelligent workingmen; boys who had gone through high school, and perhaps a little way into the business college; ambitious youngsters, each with a different idea in the back of his head. They had in common an air of capability, of complete adequacy for the task in life they had selected. The sixth sealer was much older and of the riverman type. He had evidently come up from the ranks.

There was no general conversation. Talk confined itself strictly to shop. Bob, his imagination already stirred by the incidents of his stroll, listened eagerly. Fox was getting in touch with the whole situation.

"The main drive is down," Tally told him, "but the Cedar Branch hasn't got to the river yet. What in blazes did you want to buy that little strip this late in the day for?"

"Had to take it—on a deal," said Fox briefly. "Why? Is it hard driving? I've never been up there. Welton saw to all that."

"It's hell. The pine's way up at the headwaters. You have to drive her the whole length of the stream, through a mixed hardwood and farm country. Lots of patridges and mossbacks, but no improvements. Not a dam the whole length of her. Case of hit the freshet water or get hung."

"Well, we've done that kind of a job before."

"Yes, before!" Tally retorted. "If I had a half-crew of good, old-fashioned white-water birlers, I'd rest easy. But we don't have no crews like we used to. The old bully boys have all moved out west—or died."

"Getting old—like us," bantered Fox. "Why haven't you died off too, Jim?"

"I'm never going to die," stated the old man, "I'm going to live to turn into a grindstone and wear out. But it's a fact. There's plenty left can ride a log all right, but they're a tough lot. It's too close here to Marion."

"That is too bad," condoled Fox, "especially as I remember so well what a soft-spoken, lamb-like little tin angel you used to be, Jim."

Fox, who had quite dropped his old office self, winked at Bob. The latter felt encouraged to say:

"I had a course in college on archaeology. Don't remember much about it, but one thing. When they managed to decipher the oldest known piece of hieroglyphics on an Assyrian brick, what do you suppose it turned out to be?"

"Give it up, Brudder Bones," said Tally, dryly, "what was it?"

Bob flushed at the old riverman's tone, but went on.

"It was a letter from a man to his son away at school. In it he lamented the good old times when he was young, and gave it as his opinion that the world was going to the dogs."

Tally grinned slowly; and the others burst into a shout of laughter.

"All right, bub," said the riverman good-humouredly. "But that doesn't get me a new foreman." He turned to Fox. "Smith broke his leg; and I can't find a man to take charge. I can't go. The main drive's got to be sorted."

"There ought to be plenty of good men," said Fox.

"There are, but they're at work."

"Dicky Darrell is over at Marion," spoke up one of the scalers.

"Roaring Dick," said Tally sarcastically, "—but there's no denying he's a good man in the woods. But if he's at Marion, he's drunk; and if he's drunk, you can't do nothing with him."

"I heard it three days ago," said the scaler.

Tally ruminated. "Well," he concluded, "maybe he's about over with his bust. I'll run over this afternoon and see what I can do with him. If Tom Welton would only tear himself apart from California, we'd get on all right."

A scraping back of benches and a tramp of feet announced the nearly simultaneous finishing of feeding at the men's tables. At the boss's table everyone seized an unabashed toothpick. Collins addressed Bob.

"Mr. Fox and I have so much to go over this afternoon," said he, "that I don't believe I'll have time to show you. Just look around a little."

On the porch outside Bob paused. After a moment he became aware of a figure at his elbow. He turned to see old Jim Tally bent over to light his pipe behind the mahogany of his curved hand.

"Want to take in Marion, bub?" he enquired.

"Sure!" cried Bob heartily, surprised at this mark of favour.

"Come on then," said the old riverman, "the lightning express is gettin' anxious for us."

They tramped to the station and boarded the single passenger car of the accommodation. There they selected a forward seat and waited patiently for the freight-handling to finish and for the leisurely puffing little engine to move on. An hour later they descended at Marion. The journey had been made in an almost absolute silence. Tally stared straight ahead, and sucked at his little pipe. To him, apparently, the journey was merely something to be endured; and he relapsed into that patient absent-mindedness developed among those who have to wait on forces that will not be hurried. Bob's remarks he answered in monosyllables. When the train pulled into the station, Tally immediately arose, as though released by a spring.

Bob's impressions of Marion were of great mills and sawdust-burners along a wide river; of broad, sawdust-covered streets; of a single block of good, brick stores on a main thoroughfare which almost immediately petered out into the vilest and most ramshackle frame "joints"; of wide side streets flanked by small, painted houses in yards, some very neat indeed. Tally walked rapidly by the respectable business blocks, but pushed into the first of the unkempt frame saloons beyond. Bob followed close at his heels. He found himself in a cheap bar-room, its paint and varnish scarred and marred, its floor sawdust-covered, its centre occupied by a huge stove, its walls decorated by several pictures of the nude.

Four men were playing cards at an old round table, hacked and bruised and blackened by time. One of them was the barkeeper, a burly individual with black hair plastered in a "lick" across his forehead. He pushed back his chair and ducked behind the bar, whence he greeted the newcomers. Tally proffered a question. The barkeeper relaxed from his professional attitude, and leaned both elbows on the bar. The two conversed for a moment; then Tally nodded briefly and went out. Bob followed.

This performance was repeated down the length of the street. The stage-settings varied little; same oblong, painted rooms; same varnished bars down one side; same mirrors and bottles behind them; same sawdust-strewn floors; same pictures on the walls; same obscure, back rooms; same sleepy card games by the same burly but sodden type of men. This was the off season. Profits were now as slight as later they would be heavy. Tim talked with the barkeepers low-voiced, nodded and went out. Only when he had systematically worked both sides of the street did he say anything to his companion.

"He's in town," said Tally; "but they don't know where."

"Whither away?" asked Bob.

"Across the river."

They walked together down a side street to a long wooden bridge. This rested on wooden piers shaped upstream like the prow of a ram in order to withstand the battering of the logs. It was a very long bridge. Beneath it the swift current of the river slipped smoothly. The breadth of the stream was divided into many channels and pockets by means of brown poles. Some of these were partially filled with logs. A clear channel had been preserved up the middle. Men armed with long pike-poles were moving here and there over the booms and the logs themselves, pushing, pulling, shoving a big log into this pocket, another into that, gradually segregating the different brands belonging to the different owners of the mills below. From the quite considerable height of the bridge all this lay spread out mapwise up and down the perspective of the stream. The smooth, oily current of the river, leaden-hued and cold in the light of the early spring, hurried by on its way to the lake, swiftly, yet without the turmoil and fuss of lesser power. Downstream, as far as Bob could see, were the huge mills' with their flanking lumber yards, the masts of their lading ships, their black sawdust-burners, and above all the pure-white, triumphant banners of steam that shot straight up against the gray of the sky.

Tally followed the direction of his gaze.

"Modern work," he commented. "Band saws. No circulars there. Two hundred thousand a day"; with which cryptic utterance he resumed his walk.

The opposite side of the river proved to be a smaller edition of the other. Into the first saloon Tally pushed.

It resembled the others, except that no card game was in progress. The barkeeper, his feet elevated, read a pink paper behind the bar. A figure slept at the round table, its head in its arms. Tally walked over to shake this man by the shoulder.

In a moment the sleeper raised his head. Bob saw a little, middle-aged man, not over five feet six in height, slenderly built, yet with broad, hanging shoulders. His head was an almost exact inverted pyramid, the base formed by a mop of red-brown hair, and the apex represented by a very pointed chin. Two level, oblong patches of hair made eyebrows. His face was white and nervous. A strong, hooked nose separated a pair of red-brown eyes, small and twinkling, like a chipmunk's. Just now they were bloodshot and vague.

"Hullo, Dicky Darrell," said Tally.

The man struggled to his feet, knocking over the chair, and laid both hands effusively on Tally's shoulders.

"Jim!" he cried thickly. "Good ole Jim! Glad to see you! Hav' drink!"

Tally nodded, and, to Bob's surprise, took his place at the bar.

"Hav' 'nother!" cried Darrell. "God! I'm glad to see you! Nobody in town."

"All right," agreed Tally pacifically; "but let's go across the river to Dugan's and get it."

To this Darrell readily agreed. They left the saloon. Bob, following, noticed the peculiar truculence imparted to Darrell's appearance by the fact that in walking he always held his hands open and palms to the front. Suddenly Darrell became for the first time aware of his presence. The riverman whirled on him, and Bob became conscious of something as distinct as a physical shock as he met the impact of an electrical nervous energy. It passed, and he found himself half smiling down on this little, white-faced man with the matted hair and the bloodshot, chipmunk eyes.

"Who'n hell's this!" demanded Darrell savagely.

"Friend of mine," said Tally. "Come on."

Darrell stared a moment longer. "All right," he said at last.

All the way across the bridge Tally argued with his companion.

"We've got to have a foreman on the Cedar Branch, Dick," he began, "and you're the fellow."

To this Darrell offered a profane, emphatic and contemptuous negative. With consummate diplomacy Tally led his mind from sullen obstinacy to mere reluctance. At the corner of Main Street the three stopped.

"But I don't want to go yet, Jim," pleaded Darrell, almost tearfully. "I ain't had all my 'time' yet."

"Well," said Tally, "you've been polishing up the flames of hell for four days pretty steady. What more do you want?"

"I ain't smashed no rig yet," objected Darrell.

Tally looked puzzled.

"Well, go ahead and smash your rig and get done with it," he said.

"A' right," said Darrell cheerfully.

He started off briskly, the others following. Down a side street his rather uncertain gait led them, to the wide-open door of a frame livery stable. The usual loungers in the usual tipped-back chairs greeted him.

"Want m' rig," he demanded.

A large and leisurely man in shirt sleeves lounged out from the office and looked him over dispassionately.

"You've been drunk four days," said he, "have you the price?"

"Bet y'," said Dick, cheerfully. He seated himself on the ground and pulled off his boot from which he extracted a pulpy mass of greenbacks. "Can't fool me!" he said cunningly. "Always save 'nuff for my rig!"

He shoved the bills into the liveryman's hands. The latter straightened them out, counted them, thrust a portion into his pocket, and handed the rest back to Darrell.

"There you are," said he. He shouted an order into the darkness of the stable.

An interval ensued. The stableman and Tally waited imperturbably, without the faintest expression of interest in anything evident on their immobile countenances. Dicky Darrell rocked back and forth on his heels, a pleased smile on his face.

After a few moments the stable boy led out a horse hitched to the most ramshackle and patched-up old side-bar buggy Bob had ever beheld. Darrell, after several vain attempts, managed to clamber aboard. He gathered up the reins, and, with exaggerated care, drove into the middle of the street.

Then suddenly he rose to his feet, uttered an ear-piercing exultant yell, hurled the reins at the horse's head and began to beat the animal with his whip. The horse, startled, bounded forward. The buggy jerked. Darrell sat down violently, but was at once on his feet, plying the whip. The crazed man and the crazed horse disappeared up the street, the buggy careening from side to side, Darrell yelling at the top of his lungs. The stableman watched him out of sight.

"Roaring Dick of the Woods!" said he thoughtfully at last. He thrust his hand in his pocket and took out the wad of greenbacks, contemplated them for a moment, and thrust them back. He caught Tally's eye. "Funny what different ideas men have of a time," said he.

"Do this regular?" inquired Tally dryly.

"Every year."

Bob got his breath at last.

"Why!" he cried. "What'll happen to him! He'll be killed sure!"

"Not him!" stated the stableman emphatically. "Not Dicky Darrell! He'll smash up good, and will crawl out of the wreck, and he'll limp back here in just about one half-hour."

"How about the horse and buggy?"

"Oh, we'll catch the horse in a day or two—it's a spoiled colt, anyway—and we'll patch up the buggy if she's patchable. If not, we'll leave it. Usual programme."

The stableman and Tally lit their pipes. Nobody seemed much interested now that the amusement was over. Bob owned a boyish desire to follow the wake of the cyclone, but in the presence of this imperturbability, he repressed his inclination.

"Some day the damn fool will bust his head open," said the liveryman, after a ruminative pause.

"I shouldn't think you'd rent him a horse," said Bob.

"He pays," yawned the other.

At the end of the half-hour the liveryman dove into his office for a coat, which he put on. This indicated that he contemplated exercising in the sun instead of sitting still in the shade.

"Well, let's look him up," said he. "This may be the time he busts his fool head."

"Hope not," was Tally's comment; "can't afford to lose a foreman."

But near the outskirts of town they met Roaring Dick limping painfully down the middle of the road. His hat was gone and he was liberally plastered with the soft mud of early spring.

Not one word would he vouchsafe, but looked at them all malevolently. His intoxication seemed to have evaporated with his good spirits. As answer to the liveryman's question as to the whereabouts of the smashed rig, he waved a comprehensive hand toward the suburbs. At insistence, he snapped back like an ugly dog.

"Out there somewhere," he snarled. "Go find it! What the hell do I care where it is? It's mine, isn't it? I paid you for it, didn't I? Well, go find it! You can have it!"

He tramped vigorously back toward the main street, a grotesque figure with his red-brown hair tumbled over his white, nervous countenance of the pointed chin, with his hooked nose, and his twinkling chipmunk eyes.

"He'll hit the first saloon, if you don't watch out," Bob managed to whisper to Tally.

But the latter shook his head. From long experience he knew the type.

His reasoning was correct. Roaring Dick tramped doggedly down the length of the street to the little frame depot. There he slumped into one of the hard seats in the waiting-room, where he promptly slept. Tally sat down beside him and withdrew into himself. The twilight fell. After an apparently interminable interval a train rumbled in. Tally shook his companion. The latter awakened just long enough to stumble aboard the smoking car, where, his knees propped up, his chin on his breast, he relapsed into deep slumber.

They arrived at the boarding house late in the evening. Mrs. Hallowell set out a cold supper, to which Bob was ready to do full justice. Ten minutes later he found himself in a tiny box of a bedroom, furnished barely. He pushed open the window and propped it up with a piece of kindling. The earth had fallen into a very narrow silhouette, and the star-filled heavens usurped all space, crowding the world down. Against the sky the outlines stood significant in what they suggested and concealed—slumbering roof-tops, the satiated mill glowing vaguely somewhere from her banked fires, the blackness and mass of silent lumber yards, the mysterious, hushing fingers of the ships' masts, and then low and vague, like a narrow strip of velvet dividing these men's affairs from the star-strewn infinite, the wilderness. As Bob leaned from the window the bigness of these things rushed into his office-starved spirit as air into a vacuum. The cold of the lake breeze entered his lungs. He drew a deep breath of it. For the first time in his short business experience he looked forward eagerly to the morrow.

Bob was awakened before daylight by the unholy shriek of a great whistle. He then realized that for some time he had been vaguely aware of kindling and stove sounds. The bare little room had become bitterly cold. A gray-blackness represented the world outside. He lighted his glass lamp and took a hasty, shivering sponge bath in the crockery basin. Then he felt better in the answering glow of his healthy, straight young body; and a few moments later was prepared to enjoy a fragrant, new-lit, somewhat smoky fire in the big stove outside his door. The bell rang. Men knocked ashes from their pipes and arose; other men stamped in from outside. The dining room was filled.

Bob took his seat, nodding to the men. A slightly grumpy silence reigned. Collins and Fox had not yet appeared. Bob saw Roaring Dick at the other table, rather whiter than the day before, but carrying himself boldly in spite of his poor head. As he looked, Roaring Dick caught his eye. The riverman evidently did not recognize having seen the young stranger the day before; but Bob was again conscious of the quick impact of the man's personality, quite out of proportion to his diminutive height and slender build. At the end of ten minutes the men trooped out noisily. Shortly a second whistle blew. At the signal the mill awoke. The clang of machinery, beginning slowly, increased in tempo. The exultant shriek of the saws rose to heaven. Bob, peering forth into the young daylight, caught the silhouette of the elephantine tram horse, high in the air, bending his great shoulders to the starting of his little train of cars.

Not knowing what else to do, Bob sauntered to the office. It was locked and dark. He returned to the boarding house, and sat down in the main room. The lamps became dimmer. Finally the chore boy put them out. Then at last Collins appeared, followed closely by Fox.

"You didn't get up to eat with the men?" the bookkeeper asked Bob a trifle curiously. "You don't need to do that. We eat with Mrs. Hallowell at seven."

At eight o'clock the little bookkeeper opened the office door and ushered Bob in to the scene of his duties.

"You're to help me," said Collins concisely. "I have the books. Our other duties are to make out time checks for the men, to answer the correspondence in our province, to keep track of camp supplies, and to keep tab on shipments and the stock on hand and sawed each day. There's your desk. You'll find time blanks and everything there. The copying press is in the corner. Over here is the tally board," He led the way to a pine bulletin, perhaps four feet square, into which were screwed a hundred or more small brass screw hooks. From each depended a small pine tablet or tag inscribed with many figures. "Do you understand a tally board?" Collins asked.

"No," replied Bob.

"Well, these screw hooks are arranged just like a map of the lumber yards. Each hook represents one of the lumber piles—or rather the location of a lumber pile. The tags hanging from them represent the lumber piles themselves; see?"

"Sure," said Bob. Now that he understood he could follow out on this strange map the blocks, streets and alleys of that silent, tenantless city.

"On these tags," pursued Collins, "are figures. These figures show how much lumber is in each pile, and what kind it is, and of what quality. In that way we know just what we have and where it is. The sealers report to us every day just what has been shipped out, and what has been piled from the mill. From their reports we change the figures on the tags. I'm going to let you take care of that."

Bob bestowed his long figure at the desk assigned him, and went to work. He was interested, for it was all new to him. Men were constantly in and out on all sorts of errands. Fox came to shake hands and wish him well; he was off on the ten o'clock train. Bob checked over a long invoice of camp supplies; manipulated the copying press; and, under Collins's instructions, made out time checks against the next pay day. The insistence of details kept him at the stretch until noon surprised him.