It was beginning to get dark in the big nursery. Outside the wind howled and the rain beat steadily against the window-pane. Rudolf and Ann sat as close to the fire as they could get, waiting for Betsy to bring the lamp. Peter had built himself a comfortable den beneath the table and was having a quiet game of Bears with Mittens, the cat, for his cub—quiet, that is, except for an angry mew now and then from Mittens, who had not enjoyed an easy moment since the arrival of the three children that morning.

"Rudolf," Ann was saying, as she looked uneasily over her shoulder, "I almost wish we hadn't come to stay at Aunt Jane's alone without mother. I don't believe I like this room, it's so big and creepy. I don't want to go to bed. Especially"—she added, turning about and pointing into the shadows behind her—"especially I don't want to go to bed in that!"

The big bed in Aunt Jane's old nursery was the biggest and queerest the children had ever seen. It was the very opposite of the little white enameled beds they were used to sleeping in at their apartment in New York, being a great old-fashioned four-poster with a canopy almost touching the ceiling. It was hung with faded chintz, and instead of a mattress it had a billowy feather bed over which were tucked grandmother's hand-spun sheets and blankets covered by the gayest of quilts in an elaborate pattern of sprigged and spotted calico patches. The two front posts of the bed were of dark shiny wood carved in a strange design of twisted leaves and branches, and to Ann, as she looked at them by the leaping flickering firelight, it seemed as if from between these leaves and branches odd little faces peered and winked at her, vanished, and came again and yet again.

"Bother!" exclaimed Rudolf so loud that his little sister started. "It's just a bed, that's all. It'll be jolly fun getting into it. I believe I'll ask if I can't sleep there, too, instead of in the cot. I wanted to take a running jump at it when we first came this morning, but Aunt Jane wouldn't let me with my boots on. She said she made that quilt herself, when she was a little girl. We'll all climb in together to-night as soon as Betsy goes, and have a game of something—I dare say we'll feel just like raisins in a pudding!"

"All the same," said Ann, "I don't think I like it, Rudolf. I wish Betsy would bring the lamp!"

It was almost dark now, and they could not see, but only hear, Peter as he came shuffling out of his den, dragging his unhappy cub, and prowled around the darkest corners of the room. Being a bear, he was not at all afraid, but made himself very happy for a while with pouncing and growling, searching for honey, and eating imaginary travelers. Then the cub escaped, and Peter tired of his game. Rudolf and Ann heard him tugging at the door of an old-fashioned cupboard in a far corner of the room, and presently he came over to the fire, carrying a wooden box in his arms.

"Oh, Peter, you naughty boy!" cried Ann. "You've been at the cupboard, and Aunt Jane said expressly we were not to take anything out of it!"

"You are just like Bluebeard's wife," began Rudolf, but Peter—as was his way—paid no attention to either of them. He put the box down on the hearth-rug, and got on his hands and knees to open it. Then, of course, the other two thought they might as well see what there was to see, and all three heads bent over the box. After all it contained nothing very wonderful, the cover itself being the prettiest part, Ann thought, for on it was painted a bright-colored picture of a little girl in a funny, high-waisted, old-fashioned dress, making a curtsy to a little boy dressed like an old gentleman and carrying a toy ship in his hand. The box was filled with old toys, most of them chipped or broken. There was a very small tea-set with at least half of the cups missing, a wooden horse which only possessed three legs, and the remains of a regiment of battered tin soldiers.

"How funny the box smells—and the toys, too!" Ann said. "Sort of queer and yet sweet, like mother's glove case. I think she said it was sandal-wood. That set must have been a darling when it was new, but there's only just a speck of blue left and the gilt is every bit gone. These must be Aunt Jane's toys that she had when she was little."

"That was a long time ago," remarked Rudolf thoughtfully. "I don't see why Aunt Jane didn't throw 'em away, they're awful trash, I think. Those soldiers aren't bad, but—"

Just then Ann's sharp eyes caught Peter as he was about to slip away with a little parcel done up in silver paper that had lain all by itself at the very bottom of the box. By this time she and Rudolf had both forgotten that they had no more right than Peter to any of the things in the box, and both threw themselves on their little brother. Peter fought and kicked, but was at last forced to surrender the little parcel. Under the silver paper which Rudolf hurriedly tore off, was layer after layer of pink tissue infolding something which the boy, when he came to it at last, tossed on the floor in his disgust.

"Pshaw," he exclaimed, "it's nothing in the world but an old corn-cob!"

"Yes, it is, too," said Ann, picking it up. "It's a doll, the funniest old doll I ever saw!"

And a strange little doll she was, made out of nothing more or less than a withered corn-cob, her face—such a queer little face—painted on it, and her hair and dress made very cleverly out of the corn shucks. Ann burst out laughing as she looked at the old doll, and turning to her new children, Marie-Louise and Angelina-Elfrida, which her mother had given her for Christmas, she placed the two beauties on the hearth-rug, one on each side of the corn-cob, just to see the difference. This seemed to make Peter very cross. He tried his best to snatch away the old doll, but Rudolf, to tease him, held him off with one hand while with the other he seized the poor creature by her long braids and swung her slowly over the fire.

"Wouldn't it be fun, Ann," said he, "to see how quick she'd burn?"

"Oh, you mustn't, Rudolf," Ann cried, "Aunt Jane mightn't like it. I shouldn't be surprised if she'd punish you."

At that Rudolf lowered the old doll almost into the blaze, and she would most certainly have burned up, she was so very dry and crackly, if at that very moment Aunt Jane had not come into the room and snatched her out of his hand. Rudolf never remembered to have seen Aunt Jane so vexed before. Her blue eyes flashed, and her cheeks were quite pink under her silver-colored hair. He expected she would scold, but she didn't, she only said—"Oh, Rudolf!" in a rather unpleasant way, and then, after she had carefully restored the corn-cob doll to her wrappings, she knelt down and began to gather up the old toys which the children had scattered over the hearth-rug. Ann and Rudolf helped her, and Peter who, though a very mischievous little boy, was always honest, confessed that he had been the one to open the old cupboard and take out the box. He seemed to feel rather uncomfortable about it, and after the things had been put away, he climbed upon Aunt Jane's lap and hid his head upon her shoulder. "Never mind, Peter, dear," she said, holding him very tight, "I always meant to show you my old toys some day. I dare say you children think it strange that I have kept such shabby things so long, but when I was a little girl I did not have such beautiful toys as you have now, and the few I had I loved very dearly."

"Was this your nursery, Aunt Jane," Ann asked.

"Yes, dear. I slept all alone in the big bed, and I kept my toys always in the old cupboard. I spent many and many an hour curled up on that window-seat, playing with my doll. Yes, I did have others, Ann, but I think I loved the corn-cob doll best of all, perhaps because she was the least beautiful."

"Didn't you have any little boys to play with?" Rudolf asked. "Other boys beside father and Uncle Jim, I mean."

"There was one little boy who came sometimes," Aunt Jane said. "He lived in the nearest house to ours, though that was a mile away. Those were his tin soldiers you saw in the box. He gave them to me to keep for him when he went away to school, and thought himself too big to play at soldiers any more."

"And when he came back from school, did he used to come and see you?"

"Yes, he used to come every summer till he got big."

"And what did the little boy do when he got big, Aunt Jane?"

"When he got big," said Aunt Jane slowly, looking very hard into the fire, "he went away to sea."

"O-ho!" cried Rudolf. "And when he came back what did he bring you?"

"He never did come back," said Aunt Jane, and she bent her head low over Peter's so that the children should not see how shiny wet her eyes were. Ann and Rudolf did see, however, and politely forced back the dozen questions trembling on the tips of their tongues about the different ways there were of being lost at sea. Rudolf in particular would have liked to know whether it was a hurricane or sharks or pirates or a nice desert island that had been the end of that little boy, and he was about to begin his questioning in a roundabout manner by asking whether sea serpents had often been known to swallow ships whole, when the door opened, and in came Betsy, Aunt Jane's old servant. She had the lamp in one hand and the great brass warming-pan, with which she always warmed the big bed, in the other.

Her arrival disturbed the pleasant group by the nursery fire, and reminded Aunt Jane that it was the children's bedtime. She kissed them good night, heard them say their prayers, and then went quickly away, leaving Betsy to help them undress. Now this was rather unwise of Aunt Jane, for Betsy and the children did not get on. She was one of those uncomfortable persons who refuse to understand how a little conversation makes undressing so much less unpleasant. She was not inclined to give Rudolf any information on the subject of sea serpents, nor would she listen to Ann's remarks on how much more fashionable hot-water bottles were than warming-pans. She had even no sympathy for Peter when he wished to be considered a diver going down to the bottom of the sea after gold, instead of a little boy being bathed in a tin tub.

Betsy had a horrid way of scrubbing, being none too careful about soap in people's eyes, and Peter came out dreadfully clean. Feeling that he needed comforting of some sort, he looked about for Mittens and discovered him at last, taking a much needed nap behind the sofa. Squeezing the weary cat carefully under one arm, Peter began to climb by the aid of a chair into the big bed. Betsy caught sight of him and guessed his plan. Poor little Peter's hopes were dashed.

"No you don't, Master Peter," she snapped at him. "Ye don't take no cats to bed with ye—not in this house!" And she grabbed Mittens away very roughly, set him outside the door, and shut it with a bang. After she had tucked the bedclothes firmly about the little boy, she turned her attention to Rudolf and Ann, evidently thinking Peter was settled for the night—which shows just how much Betsy knew about him. Peter waited patiently till she was in the depths of an argument with Rudolf who was trying vainly to make her understand that the dirt upon his face was merely the effect of his dark complexion. Then Peter slipped out of bed, darted out of the door, and returned in a moment or two with the unhappy Mittens once more a prisoner beneath his arm. This time he managed to conceal the cat from Betsy's sharp eyes.

At last all three children were in the big bed, Rudolf having refused to consider sleeping in the cot, and Betsy, after a gruff good night, departed, carrying the lamp with her. Now that the room was in darkness except for the flickering light of the dying fire, Ann's fears began to come back to her. She sat up in bed and peered round her into the dark corners.

"I—I wish Betsy had left the light," she said. "But it would have been no use asking her."

"Not a scrap," said Rudolf. "Not that I mind the dark," he added hastily, "I rather like it, only don't let's lie still and—and—listen for things. Let's play something."

"Shall we try who can keep their eyes shut longest," suggested Ann.

"Oh, that's a stupid game! Beside Peter would beat anyway, for he's half asleep now. Shake him up, Ann."

When shaken up Peter refused to admit that, he was even sleepy. He was very cross, and immediately began to accuse Rudolf of having taken his cat. This Rudolf—and also Ann—denied. They had seen Peter smuggle Mittens into bed the second time, but had supposed he must have escaped and followed Betsy out.

"No, he didn't neither," Peter insisted. "I had him after she went. He was 'most tamed."

"Then," said Ann, "he must be in the room and we might as well have him to play with. Rudolf, I dare you to get up and look for him!"

And Rudolf got up—just to show he was not afraid. Before stepping into those dark shadows, however, he armed himself with his tin sword, a weapon he was in the habit of taking to bed with him in case of burglars, and with this he poked bravely under the bed and in all the dark corners, calling and coaxing Mittens to come forth. At last both he and Ann felt sure the cat could not be in the room.

"He must have got out somehow," said Rudolf. "Anyway, I sha'n't bother any more looking for him." Still grasping his sword, he climbed back into the big bed between his brother and sister. Peter was still cross and grumbly. He kept insisting that Mittens might have disappeared inside the bed—which was a piece of nonsense neither of the others would listen to.

After some discussion Rudolf and Ann agreed that the very nicest thing to do would be to make a tent out of the bedclothes, and seeing Peter was again inclined to nod, they shook him awake and sternly insisted on his joining in the game. By tying the two upper corners of the covers to the posts at the head of the great bed a splendid tent was quickly made, bigger than any the children had ever played in before, so big that Rudolf, who was to lead the procession into its white depths, began to feel just the least little bit afraid,—of what he hardly knew. How high the white walls rose! Not like a snuggly bed-tent, but like—like a real white-walled cave. Being a brave boy, he quickly put these unpleasant thoughts out of his mind, and grasping his sword, crawled on his hands and knees into the dark opening. Behind him came Ann, and behind Ann, Peter.

"Are you ready?" asked Rudolf. "Then in we go!"

It was not surprising that the big bed should be different from any other bed the children had ever played in, yet it was certainly taking them a long, long time to crawl to the foot!

"It must have a foot," thought the brave captain of the band, as he plunged farther and farther into the depths of the white cave. "All beds have." Then he stopped suddenly as a loud squeal of mingled surprise and terror came from just behind him.

"Oh, Rudolf," Ann cried, "I don't want to play this game any longer—let's go back!" In the half-darkness Rudolf felt her turn round on Peter, who was close behind her. "Go back, Peter," she ordered.

"I can't," came a little voice out of the gloom.

"You must—oh, Peter, hurry!"

"I can't go back," said Peter calmly, "because there isn't any back. Put your hand behind me and feel."

It was true. Just how or when it had happened none of them could tell, but the soft drooping bedcovers had suddenly, mysteriously risen and spread into firm white walls behind and on either side, leaving only a narrow passageway open in front. It was nonsense to go on their hands and knees any longer, for even Rudolf, who was tallest, could not touch the arched white roof when he stood up and stretched his arm above his head. He could not see Ann's face clearly, but he could hear her beginning to sniff.

"Now, Ann," said he sternly, though in rather a weak voice, "don't you know what this is? This is an adventure."

"I don't care," sniffed Ann, "I don't want an adventure. I want to go back—back to Aunt Jane!" And the sniff developed into a flood of tears.

"Peter is not crying, and he is only six."

This rebuke told on Ann, for she was almost eight. "But what are we go—going to do?" she asked, her sobs decreasing into sniffs again.

"We'll just have to go on, I suppose, and see what happens."

"Well, I think—I think Aunt Jane ought to be ashamed of herself to put us in such a big bed we could get lost in it!"

"Maybe"—came the voice of Peter cheerfully from behind them—"maybe she wanted to lose us, like bad people does kittens."

"Peter, don't be silly," ordered Rudolf sternly. "There isn't really anything that can happen to us," he went on, speaking slowly and thoughtfully, "because we all know that we really are in bed. We know we didn't get out, so of course we must be in."

This was good sense, yet somehow it was not so comforting as it ought to have been, not even to Rudolf himself who now began to be troubled by a disagreeable kind of lump in his throat. Luckily he remembered, in time to save himself from the disgrace of tears, how his father had once told him that whistling was an excellent remedy for boys who did not feel quite happy in their minds. He began to whistle now, a poor, weak, little whistle at first, but growing stronger as he began to feel more cheerful. Grasping his sword, he started ahead, calling to the others to follow him.

The white passage was so narrow that the children had to walk along it one behind another in Indian file. The floor was no longer soft and yielding but firm and hard under their feet, and by stretching out their hands they could almost touch the smooth white walls on either side of them. At first the way was perfectly straight ahead, but after they had walked what seemed to them a long, long time, the passage curved sharply and widened a little. The children noticed, much to their relief, that it was growing lighter around them.

"I'm getting tired," Ann announced at last. "See, Ruddy, there is a nice flat black rock. Let's sit down and rest on it."

There was room for them all on the large flat rock, and when they were settled on it, Peter remarked: "I'm hungry!" Now this was a thing Peter was used to saying at all times and on all occasions, so it was just like him to bring it out now as cheerfully and confidently as if Betsy had been at his elbow with a plate of bread and butter.

"Oh, dear," Ann exclaimed, "what a long, long while it seems since we had our tea! I suppose it will soon be time to think about starving." And she took her little handkerchief out of the pocket of her nighty and began to wipe her eyes with it.

"Not yet," said Rudolf hastily. "I put some candy into my pajamas pocket when I went to bed, because the time I like to eat it best is just before breakfast—if people only wouldn't row so about my doing it. Let me see—it was two chocolate mice I had—I hope they didn't get squashed when we were playing! No, here they are." The chocolate mice were a little the worse for wear, in fact there were white streaks on them where the chocolate had rubbed off on the inside of Rudolf's pocket, but the children didn't mind that. They thought they had never seen anything that looked more delicious.

"I will cut them in three pieces with my sword," said Rudolf. "You may have the heads, Ann, and me the middle parts, and Peter the tails because he is the youngest."

This arrangement did not suit Peter. "I will not eat the tails," he screamed, kicking his heels angrily against the rock,—"the tails is made out of nassy old string!" And, I am sorry to say, Peter made a snatch at both chocolate mice and knocked them out of Rudolf's hand. This, of course, made it necessary for Rudolf to box Peter's ears, and a tussle quickly followed, in the middle of which something dreadful happened. The large flat rock they were sitting on gave several queer shakes and heaves and then suddenly rose right up under the three children and threw them head over heels into the air. They were not a bit hurt, but they were very, very much surprised when they scrambled to their feet and saw the rock erect on a long kind of tail it had, glaring at them out of one red angry eye.

Ann was the first to recognize it. "Oh, oh," she cried, "it's not a rock at all—it's Betsy's Warming-pan!"

The Pan, giving a deep throaty kind of growl, began to shuffle toward them. "I'd like to have the warming of you three," he snarled. "I'll teach you to come sitting on top of me playing your tricks on my rheumatic bones—waking me out of the first good nap I've had in weeks!--I'll fix you—"

"We're really very sorry," Ann began. "We didn't mean to sit on you, we thought—"

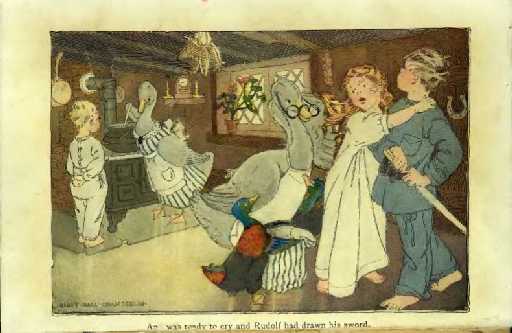

But the Warming-pan did not want to hear what Ann thought. He turned round on her fiercely. "You're the young person," he snapped, "who made the polite remarks about my figure this evening? Eh, didn't you? Can you deny it? Called me old-fashioned and 'country'—said nobody ever used me any more!--I'll teach you to talk about hot-water bottles when I'm through with you!" As he spoke he came closer and closer to Ann, snorting and puffing and glaring at her out of his one terrible eye. Although he was so round and waddled so clumsily, dragging his long tail behind him, his appearance was quite dreadful. He reminded Rudolf of the dragon in Peter's picture-book, and he hastily tried to imagine how Saint George must have felt when defending his princess. Clutching his sword, he thrust himself in front of Ann and bravely faced the Warming-pan. "Run!" he called to the others, "Fly!--and I will fight this monster to the death."

Ann, dragging Peter by the hand, made off as fast as she could go, and the Pan tried his best to dodge Rudolf and rush after her. Again and again Rudolf's sword struck him, but it only rattled on his brassiness, and making a horrible face, he popped three live coals out of his mouth which rolled on the ground unpleasantly close to Rudolf's bare toes. Then they had it hot and heavy until at last the knight managed to get his blade entangled with the dragon's long tail, and tripped the creature up. Then, without waiting for his enemy to get himself together again and heartily tired of playing Saint George, Rudolf turned and ran after Ann and Peter. Long before he caught up to them, however, he heard the Pan behind him, snorting and scolding. Luckily it did not seem able to stop talking, so that it lost what little breath it had and was soon obliged to halt. For some time Rudolf caught snatches of its unpleasant remarks, such as—"Children nowadays—wish he had 'em—he'd show 'em—bread and water—good thick stick!--" Rudolf was obliged to run with his fingers in his ears before that disagreeable voice died away in the distance.

At last he saw Peter and Ann waiting for him at a turn in the passage just ahead, and in another moment he flung himself panting on the ground beside them. "What a beast he was!" Rudolf exclaimed.

"Dreadful!" said Ann. "I shall tell Aunt Jane never, never to let Betsy put him in our bed again." And then, after she had thanked Rudolf very prettily for saving her life, and that hero had recovered his breath and rested a little after the excitement of the battle, they all felt ready to start on their way again.

No sooner had they turned the corner ahead of them than they found themselves in broad daylight. The passage was now so wide that all three could walk abreast, holding hands; a moment more and they stood at the mouth of the long white cave or tunnel they had been walking through. There was open country beyond them, and just opposite to where the children stood was the queerest little house that they had ever seen. It was long and very low, hardly more than one story high, and was painted blue and white in stripes running lengthwise. In the middle was a little front door with a window on either side of it and three square blue and white striped steps leading up to it. From the chimney a trail of thick white smoke poured out. As the three children stood staring at the house, Peter cried out: "It's snowing!"

Sure enough the air was full of thick white flakes.

"Oh, dear, oh, dear!" Ann wailed, "what shall we do now? We can't go back in the cave because the Warming-pan might catch us, and if we stay here Peter will catch his death of cold out in the snow in his night drawers—and so will we all. Oh, what would mother say!"

"But we are not out in the snow, Ann," began Rudolf in his arguing voice. "We are in in the snow."

"And it is not wet," added Peter who was trying to roll a snowball out of the white flakes that were piling themselves on the ground with amazing quickness.

"I don't care," said Ann. "I know mother wouldn't like us to be in in it or out in it. I'm going to knock at the door of that house this minute and ask if they won't let us stay there till the storm's over."

"All right," said Rudolf, "only I hope the people who live there don't happen to be any relation of the Warming-pan."

It was a dreadful thought. The three children looked at the house and hesitated. Then Rudolf laughed, drew his precious sword, which he had fastened into the belt of his pajamas, and mounted the steps, the others following behind him.

"You be all ready to run," he whispered, "if you don't like the looks of the person who comes. Now!" And he knocked long and loud upon the blue and white striped door.

The door flew open almost before Rudolf had stopped knocking, but there was nothing very alarming about the person who stood on the threshold. Ann said afterward she had thought at first it was a Miss Spriggins who came sometimes to sew for her mother, but it was not; it was only a very large gray goose neatly dressed in blue and white bed-ticking, with a large white apron tied round her waist and wearing big spectacles with black rims to them.

"Nothing to-day, thank you," said the Goose.

"But please—" began Rudolf.

"No soap, no baking powder, no lightning rods, no hearth-brooms, no cake tins, no life insurance—" rattled the Goose so rapidly that the children could hardly understand her—"nothing at all to-day, thank you!"

"But we want something," Ann cried, "we want to come in!"

"I never let in peddlers," said the Goose, and she slammed the door in their faces. As she slammed it one of her broad apron-strings caught in the crack, and Rudolf seized the end of it. When the Goose opened the door an inch or so to free herself he held on firmly and said:

"Tell us, please, are you the Warming-pan's aunt?"

The Gray Goose looked immensely pleased, but shook her head.

"Nothing so simple," said she, "nor, so to speak, commonplace, since the relationship or connection if you will have it, is, though perfectly to be distinguished, not always, as it were, entirely clear, through his great-grandfather who, as I hope you are aware, was a Dutch-Oven, having run away with a cousin of my mother's uncle's stepfather, who was three times married, numbers one, two and three all having children but none of 'em resembling one another in the slightest, which, as you may have perceived, is only the beginning of the story, but if you will now come in, not forgetting to wipe your feet, and try to follow me very carefully, I'll be delighted to explain all particulars."

The children were glad to follow the Lady Goose into the house, though they thought she had been quite particular enough. They found it impossible to wipe their feet upon the mat because it was thick with snow, and when the door was closed behind them, they were surprised to feel that it was snowing even harder inside the house than it was out. For a moment they stood half blinded by the storm, unable to see clearly what kind of room they were in or to tell whose were the voices they heard so plainly. A great fluttering, cackling, and complaining was going on close to them, and a hoarse voice cried out:

"One hundred and seventeen and three-quarters feathers to be multiplied by two-sevenths of a pound. That's a sweet one! Do that if you can, Squealer."

"You can't do it yourself," a whining voice replied. "I've tried the back and the corners and the edges—there's no more room—"

Then came the sound of a sudden smack, as if some one's ears had been boxed when he least expected it, and this was followed by a loud angry squawk. Now the flakes, which had been gradually thinning, died away entirely, and the children suddenly discovered that they had not been snowflakes at all but only a cloud of white feathers sent whirling through the house, out of the windows, and up the chimney by some disturbance in the midst of a great heap in one corner of the room as high as a haystack. From the middle of this heap of feathers stuck up two very thin yellow legs with shabby boots that gave one last despairing kick and then were still. Near by at a counter a Gentleman Goose in a long apron was weighing feathers on a very small pair of scales, and at his elbow stood a little duck apprentice with the tears running down his cheeks. He was doing sums in a greasy sort of butcher's book that seemed quite full already of funny scratchy figures.

"That must be Squealer, the one who got his ears boxed," whispered Ann to Rudolf, "but what do you suppose is the matter with the other duck, the one in the heap? He will be smothered, I know he will!"

Rudolf thought so, too, yet it didn't seem polite to mention it. The Lady Goose had been busily helping the children to brush off the feathers that were sticking to them, and patting Peter on the back with her bill because he said he was sure he had swallowed at least a pound. She now brought forward chairs for them all. As the children looked around more closely they saw that the room they were in was a very cozy sort of place, long and low and neatly furnished with a white deal table, a shiny black cook-stove, a great many bright copper saucepans, and a red geranium in the window. A large iron pot was boiling merrily on the stove and from time to time the Gray Goose stirred its contents with a wooden spoon. It smelled rather good, and Peter, sniffing, began to put on his hungry expression.

"No, not even a family resemblance," went on the Gray Goose, waving her spoon, "although, as is generally known, a Roman nose is characteristic in our family, having developed in fact at the time of that little affair when we repelled the Gauls in the year—"

But Rudolf felt he could not stand much more of this. "I beg your pardon," he interrupted, "but would you mind if we helped the little one out of the heap, the—the—duck who is getting so thoroughly smothered?"

"Not at all, if you care about it," said the Gray Goose kindly. "Squawker'll be good now, won't he, Father?"

"Oh, I'm sure he'll be good," Ann cried, and she ran ahead of Rudolf to catch hold of one of the thin yellow legs and give it a mighty pull.

"He'll be good," said the Gentleman Goose gravely, speaking for the first time, "when he's roasted. Very good indeed'll Squawker be—with apple sauce!" And he smacked his lips and winked at Peter who was standing close beside him, looking up earnestly into his face.

Peter thought a moment. Then he said: "I likes currant jelly on my duck. I eats apple sauce on goose."

The Gentleman Goose appeared suddenly uncomfortable. He began nervously stuffing little parcels of the feathers he had been weighing into small blue and white striped bags, which he threw one after the other to Squealer, who never by any chance caught them as he turned his back at every throw. "I suppose," said the Gentleman Goose to Peter in a hesitating, anxious sort of voice, "you believe along with all the rest, what's sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander, don't you? I suppose there's nothing sauce-y about yourself now, is there?" And apparently comforted by his miserable little joke he went on with his weighing.

By this time the other little duck had been hauled out of the heap of feathers by Ann and Rudolf, and stood coughing and sneezing and gasping in the middle of the floor. As soon as he had breath enough he began calling pitifully for some one to brush the down off his Sunday trousers. The Gray Goose came good-naturedly to his assistance, but as she brushed him all the wrong way, the children couldn't see that she improved him very much. Squawker seemed quite pleased, however, and turned himself round and round for their approval.

"What kind of birds are these new ones?" he asked the Lady Goose when she had finished with him.

"Why just three more of us, Squawker, dear," she answered.

This remark made all three children open their eyes very wide.

"Nonsense," began Rudolf angrily, "we aren't geese!"

From the other end of the room came the voice of the Gentleman Goose, who spoke without turning round. "What makes you think that?" he asked.

"Because we aren't—we—"

—"You're molting pretty badly, of course, now you mention it," interrupted the Lady Goose, "you and the little one. But this one's feathers seem in nice condition." As she spoke she laid a long claw lovingly on Ann's head. "How much would you say a pound, father?"

"Can't say till I get 'em in the scales, of course," and, smoothing down his apron, the Gentleman Goose advanced toward Ann in a businesslike fashion. The two little apprentices, carrying bags, followed at his heels.

Ann clung to Rudolf. "I haven't any feathers," she screamed. "They're curls. I'm not a nasty bird—I'm a little girl with hair!"

"She doesn't want to be plucked!" exclaimed the Gray Goose who had returned to the stove to stir the contents of the iron pot. "Well, now, did you ever! Maybe it goes in her family. I had a great-aunt once on my father's side who—"

"They're feathers, all right," chuckled Squawker. "You're a perfect little duck, that's what I think."

"Me, too," chimed in Squealer.

The Gentleman Goose reached over the Lady Goose's shoulder, snatched the spectacles off her nose without so much as by your leave, set them crookedly on his own, and looked over them long and earnestly at Ann. "So you want to call 'em hair, do you?" he snapped. "I suppose you think you belong in a hair mattress!"

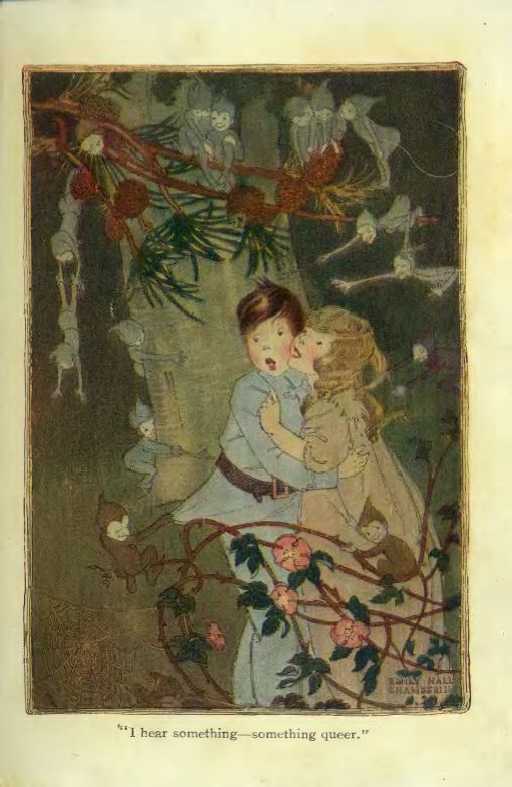

Ann was ready to cry, and Rudolf had drawn his sword with the intention of doing his best to protect her, when at that moment a new voice was heard. Looking in at the little window over the top of the red geranium the children saw a good-humored furry face with long bristly whiskers and bright twinkly eyes.

"Anybody mention my name?" said the voice, and a large Belgian Hare leaped lightly into the room. He was handsomely dressed in a light overcoat and checked trousers, and wore gaiters over his patent-leather boots. He had a thick gold watch-chain, gold studs and cuff buttons besides other jewelry, and in one hand he carried a high hat, in the other a small dress-suit case and a tightly rolled umbrella.

"What's the matter here?" he inquired cheerfully.

"Why, this bird," explained the Gentleman Goose, pointing his claw disdainfully at Ann, "says it has no feathers, which you can see for yourself is not the case. It has feathers, therefore it is a bird. Birds of a feather flock together. That settles it, I think! Come along, boys. To work!"

At his command the two duck apprentices, who were standing one on either side of Ann, made feeble dashes at the two long curls nearest them. Rudolf stepped forward but the Hare was before him. He only needed to stare at the two ducks through a single eye-glass he had screwed into one of his eyes to make them turn pale and drop their claws to their sides.

"Now once more," said the Hare to Ann. "What did you say you call those unpleasantly long whiskers of yours?"

"Hair," Ann answered meekly, for she was too frightened to be offended.

"Hair!" echoed Rudolf and Peter loudly.

"Bless me," said their new friend, "that's not at all my business, is it? Not at all in my line—oh, no!" He gathered up his hat, dress-suit case, and little umbrella from the floor where he had dropped them. "Be sure you don't follow me," he said, nodding pleasantly and winking at the children. Then he stepped to the door without so much as a look at the Gentleman Goose who called out angrily:

"Stop, stop! Catch 'em, Squealer—at 'em, Squawker—hold 'em, boys!"

It was too late. The boys were too much afraid of the Hare to do more than flutter and squawk a little, and as the Gentleman Goose did not seem inclined to make an attack single-handed, the Hare, with the children behind him, got to the door in safety. Peter, however, had to be dragged along by Ann and Rudolf, for the Lady Goose had just removed the great pot from the stove in time to prevent its contents from boiling over, and the little boy was sniffing hungrily at the steam. Now she came after the children carrying a large spoonful of the bubbling stuff. "All done, all done," she cried. "Don't go without a taste, dears."

"What's done?" asked Peter, eagerly turning back to her.

"Worms, dear; red ones and brown ones," answered the Lady Goose,—"boiled in vinegar, you know—just like mother used to make—with a wee bit of a grasshopper here and there for flavoring. Mother had the recipe handed down in her family—her side—you know, from my great-great-grandmother's half-sister who was a De l'Oie but married a Mr. Gans and was potted in the year—"

They got Peter through the door by main force, Ann and Rudolf pushing behind and the Hare pulling in front. Even then, I am ashamed to say, Peter kept calling out that he would like "just a taste", and he didn't see why the Goose's worms wouldn't be just as good as the white kind cook sent up with cheese on the top!

As they hurried away from the Goose's house, the children cast one last look behind them. There at the window was the Lady Goose waving in farewell the spoon she had stirred the hot worms with. Suddenly a whirl of white feathers flew out of the chimney, the window and the door, which the children in their haste had left open behind them, and hid her completely from their sight. At the same instant two feeble shrieks came from within the house.

"Squealer and Squawker both went into the heap that time, I guess," said Rudolf.

"I'm glad of it!" Ann cried. "I'd never help either of the horrid little things out again. Would you, sir?" she asked, turning politely to the Hare.

"I dare say not," he answered, yawning. "That is, of course, unless I had particularly promised not to. In that case I suppose I'd have to."

All three children looked very much puzzled.

"Would you mind telling us," asked Ann timidly, "what you meant when you said this"—and she touched her hair—"was not your business?"

"Not at all," said the Hare cheerfully. "I meant that it was."

"But you said—"

"Oh, what I said was, of course, untrue."

"Do you mean you tell stories?" Ann looked very much shocked, and so did the others.

"Certainly," said the Hare, "that's my business, I'm a False Hare, you know. Oh, dear, yes, I tell heaps and heaps of stories, as many as I possibly can, only sometimes I forget and then something true will slip out of me. Oh, it's a hard life, it is, to be thoroughly untruthful every single day from the time you get up in the morning till the time you go to bed at night—round and round the clock, you know! No eight-hour day for me. Ah, it's a sad, sad life!" He sighed very mournfully, at the same time winking at Rudolf in such a funny way that the boy burst out laughing. "Take warning by me, young man," he continued solemnly, "and inquire very, very carefully concerning whatever business you go into. If I had known what the life of a False Hare really was, I doubt if I should have ever—But, dear me, this will never do—you're getting me into mischief! I've hardly done so much as a fib since we met."

"Oh, you mustn't mind us," said Rudolf, trying hard not to laugh, as he and Ann and Peter marched along beside the False Hare. "You mustn't let us interfere with your—your business, you know. We sha'n't mind, at least we'll try not to. Whatever you say we'll believe just the opposite. It'll be as if he were a kind of game," he added to Ann who was still looking very doubtful. She looked happier at once, for Ann was quick at games and knew it.

"I think," said she to the False Hare, "that I heard something about you the other day—at least I suppose it must have been you. It was at a tea-party given by a friend of mine,"—here Ann put on her most grown-up manner and made her voice sound as much like her mother's as possible—"a Mrs. Mackenzie who lives in the city. One lady said to another lady, 'How fashionable false hair is getting!'"

The False Hare stroked his whiskers to hide a pleased smile. "Bless me," said he, "I should think so! Keeps a fellow on the jump, I can tell you—this social whirl. And then, when bedtime comes along and a chap ought to get a bit of rest after a day's hard fibbing, why then—there's the dream business. I can't neglect that."

The children did not understand and said so.

"Well," said the False Hare, "I'll just explain, and then I really must get back to business. Now then, suppose a hound dreams about a hare? It's a dream hare, isn't it?"

"Yes, of course," they cried.

"And a dream hare is not a real hare, is it? And a hare that's not a real hare is a false hare, isn't it? So there I am. That's where I come in. Simple, isn't it?"

"You make it sound simple," said Rudolf politely. "We're much obliged. And now would you mind telling us where we are coming to, and what is beyond this steep hill just ahead of us?"

The Hare screwed his glass into his eye and looked thoughtfully at the country round about. "I can tell you, of course," he said, "but it won't be the truth. I really must get back to business."

"Oh, never mind telling us at all, then," said Rudolf, who was becoming rather vexed, "I see there's no use asking you any questions."

During their conversation with the False Hare, the children had been hurrying along over a stretch of open level country. Now the ground began to slope gradually upward and soon they were climbing a very steep hill. It was hard traveling, for the hill was covered with thick, fuzzy, whitish-yellow grass which tangled itself round their feet, and gave them more than one fall. Ann and Rudolf had to stop often to pick up Peter, for he was rather fat and his legs were too short to carry him along as fast as theirs did. The False Hare hurried ahead by leaps and bounds that would soon have carried him out of sight of his companions if he had not stopped now and then to wait for them. When the children caught up to him, they would find him sitting on his little dress-suit case, smoking a chocolate cigarette, and laughing at them.

"Oh, don't mention it," he would say when they apologized for keeping him waiting. "I don't mind. I like waiting for slow-pokes! It's nothing to me if I miss a dozen appointments and get driven out of the dream business by that old what's-his-name—Welsh Rabbit!"

This sort of talk was rather annoying, and after a while the children decided not to heed it any longer. Indeed they were all three tired with their climb, and were glad to sink down on the soft fuzzy grass and rest a while. The False Hare bounded ahead, calling back to them "Not to hurry", but when he found he could not tease them into following, he sauntered back to meet them, looking as cool and fresh and neat as when he started. Peter had been rather in the dumps ever since he had been refused a taste of the Lady Goose's dinner, and now he looked thoughtfully at the Hare's suit case.

"Has you got anything to eat in there?" he asked, his little face brightening.

"Gracious, yes," said the False Hare lightly. "Lemme see! What do little boys like best? Cinnamon buns an' chocolate cake an' butterscotch an' lemon pie an' soda-water an' gingerbread an' jujubes an' hokey-pokey an 'popcorn balls an'—" He might have gone on forever, but Ann and Rudolf would not stand any more of it. They rose angrily and dragging Peter after them, continued their climb. Just as they had almost reached the top of the hill, the False Hare bounded past them with a laughing salute and a wave of his paw, and dropped out of sight over the brink of the ridge. A moment more and they all stood on the edge of a cliff so steep that they were in danger of tumbling over. From beneath the Hare's voice called up to them, "Nobody ever thought of a sheet of water—oh, no!"

Before their eyes lay the last thing the children had expected to see, a large piece of water quite calm and smooth, without a sign of a sail on it, nor were there any bathers or children playing on the narrow strip of beach directly beneath them. At first it seemed as if it would be impossible for them to climb down the face of that steep cliff to the water, but the False Hare had done it, and they determined that they must manage it somehow. After looking about carefully, they found a set of rude steps cut in the side of the cliff. They were very far apart, to be sure, for climbers whose legs were not of the longest, but Rudolf helped Ann and Ann helped Peter and at last they were all safely down and standing beside the False Hare, who was strolling along the edge of the water.

"Hullo," said he, sticking his glass in his eye and looking at Ann. "What makes the whiskerless one so cheerful?"

Rudolf and Peter were not surprised when they turned to look at Ann to see that she was ready to cry.

"What's the matter, Ann?" they asked.

"Oh, dear, dear!" sighed Ann. "Whatever will become of us now? We can't go back. Even if we could climb up the cliff, I'd never pass that dreadful Goose's house again, no, not for anything! But how are we going to get any farther without a boat?"

The False Hare pretended to wipe away a tear with the back of his paw. "No boat," he groaned. "Oh, dear, dear, dear—no boat!"

The faces of the three children brightened immediately, for they were beginning to understand his ways. "Hurrah!" cried Rudolf, waving his sword.

Sure enough, coming round a bend in the shore where the bushes had hidden it from their sight, was a small boat rowed by two white candy mice.

After neatly and carefully turning up the bottoms of his trousers so that they should not get wet, the False Hare bounded on a rock that rose out of the water a few feet from shore, and stood ready to direct the landing of the boat. There was some sense in this, for certainly neither of the two mice was what could be called good oarsmen. One of them had just unshipped the little sail, and—not seeming to know what else to do with it—had cut it loose from the oar that served as a mast and wrapped it round and round his body, tying himself tightly with a piece of string.

Rudolf thought he had never in his life seen people in a boat do so many queer and unnecessary things in so short a time as those two mice did. They would stop rowing every few minutes and begin sweeping out the floor of their boat with a small broom, dusting seats, cushions, and oar-locks with a little feather duster tied with a pink ribbon. Then, after a few, rapid, nervous strokes at the oars, one or the other of them would pull his blade out of the water and polish it anxiously with his handkerchief, as if the important thing was to keep it dry. They would probably never have reached land that day if this had depended on their own efforts, but luckily the breeze was blowing them in the right direction.

All this time the False Hare had been waiting on the rock, and now as the boat was almost within reach, he began leaping up and down, clapping his paws and calling out in the heartiest tones: "Go it, my dear old Salts! Hurrah, my fine Jack Tars! You're a pair of swell old sea-dogs, you are. Only don't hurt yourselves, you know. We wouldn't like to see you work!"

It seemed as if the white mice knew the False Hare and the value of his remarks, for they made no attempt to answer him, but only looked more and more frightened and uncomfortable. When their boat was at last beached, they jumped out of it, turned their backs to the rest of the party, and standing as close together as they could get, gazed anxiously out over the water. Seen close by there was something familiar about the look of these mice to the three children, yes, even though they had grown a great deal, and had disguised themselves by the simple method of licking the chocolate off each other! Rudolf and Ann hoped Peter would not notice it, but nothing of the sort ever escaped him. He walked around in front of the two mice, who tried vainly not to meet his eye, looked at them long and earnestly, and said:

"I say, Mr. Mouses, was you always white?"

The mice turned a pale greenish color in their embarrassment and looked nervously at each other, but answered never a word.

"I thought," continued Peter, staring steadily at them, "that last time I saw you you was choc'late. Did you wash it off—on purpose?" he added sternly.

"Excuse me, sir, we don't believe in washing," muttered one of the poor things hastily.

Ann shook her head at Peter. "Hush!" she whispered. "You mustn't be rude to them when they are going to lend us their boat so kindly." Then she asked in a loud voice, hoping to change the subject: "Who is going to row? Will you, Mr. False Hare?"

"Why certainly, dearie, I adore rowing," said the False Hare sweetly.

"Then you will have to, Rudolf, and I will look after Peter. 'He is always so apt to fall out of a boat. I dare say the mice will be glad of a rest."

They all got into the boat, Rudolf took the oars, Ann sat in the bow with Peter beside her, and the False Hare settled himself comfortably in the stern with a mouse squeezed on either side of him. He wanted to pet them a little, so he said, but from the strained expressions on their faces and the startled squeaks they gave from time to time, it seemed as if they were hardly enjoying his attentions. The children loved being on the water better than anything else, and they would have been perfectly happy now, if the False Hare had not had quite so many nice compliments to make to Rudolf on his rowing, and if the white mice had not complained so bitterly of them all for "sitting all over the boat cushions," and "wetting the nice dry oars!" They were enjoying themselves very much, in spite of this, when suddenly Ann, who had very sharp eyes, called out:

"Sail ahead!"

At first Rudolf thought she had said this just because it sounded well, but on turning his head he saw for himself a small boat heading toward them as fast as it could come. A moment more and the children could see the black flag floating at its masthead.

"Oh, oh!" screamed Ann, "that's a skull and cross-bones. It's a pirate ship!"

"Hurrah!" Rudolf shouted. "How awfully jolly! Just like a book."

"Dee-lightful!" the False Hare exclaimed, shuddering all over to the tips of his whiskers. "If there's one thing I do dote on it is pirates—dear old things!"

As for the two white mice, after one glance at the ship, they gave two little shrieks and hid their faces in their paws.

Rudolf shipped his oars while he loosened his sword. "I shall be prepared to fight," said he, "though I am afraid we must make up our minds to being captured. Our enemy's boat is not so large—it's not much more than a catboat—but there are only four of us, as the mice don't count, and I suppose there must be at least a dozen of the pirates."

The False Hare smiled a sickly sort of smile. "And such nice ones," he murmured. "Such gentle, well-behaved, well-brought-up, polite pirates! Just the sort your dear parents would like to have you meet. Those fellows don't know anything about shooting, stabbing, mast-heading or plank-walking; oh, no! They don't do such things."

Ann turned pale at the False Hare's words, but Rudolf only laughed. "What luck!" he exclaimed. "I'm nine years old and I've never seen a real live pirate, and goodness knows when I ever will again—I wouldn't miss this for anything." Then, as he saw how really worried his little sister looked, he added cheerfully. "They may sail right past without speaking to us, you know."

But this was not to be the case. Nearer and nearer came the pirate craft until at last the children could see, painted in black letters on her side, her name, The Merry Mouser. A group of pirates was gathered at the rail, staring at the rowboat through their glasses. There was no mistake about these fellows being pirates—that was easy enough to see from their queer bright-colored clothes and the number of weapons they carried, even if the ugly black flag had not been floating over their heads. At the bow stood he who was evidently the Pirate Chief. He was dressed in some kind of tight gray and white striped suit with a red sash tied round his waist stuck full of shiny-barreled pistols and long bright-bladed knives. A red turban decorated his head and under it his brows met in the fiercest kind of frown. His arms were folded on his breast. As Rudolf looked at this fellow, he began to have the queerest feeling that somewhere—somehow—under very different conditions—he had seen the Pirate Chief before!

Just at that instant he heard the sound of a struggle behind him, and turning round he saw that Peter had become terribly excited. "Mittens! Mittens!" he screamed, and breaking loose from Ann's hold, he stood up and leaned so far over the side of the boat that he lost his balance and fell into the water. Ann screamed, the False Hare—I am ashamed to say—merely yawned and kept his paws in his pockets. Rudolf had kicked off his shoes and was ready to jump in after Peter, when he saw that quick as a flash, on an order from their Chief, the pirates had lowered a long rope with something bobbing at the end of it. Peter when he came to the surface, seized this rope and was rapidly hauled on board the pirate ship.

Ann came near falling overboard herself in her excitement. "Oh, Ruddy, Ruddy!" she begged, "let's surrender right away quick. We can't leave poor darling Peter to be carried off by those terrible cats."

"Cats?" said Rudolf, staring stupidly at the pirates. "Why so they are cats, Ann! Somehow I hadn't noticed that before. But, look, they are sending a boat to us now."

In a small boat which had been towed behind the catboat, a couple of pirates—big, rough-looking fellows—were sculling rapidly toward the children. Cats indeed they were, but such cats as Ann and Rudolf had never seen before, so big and black and bold were they, their teeth so sharp and white, their eyes so round and yellow! One had a red sash and one a green, and each carried knives and pistols enough to set up a shop.

"Surrender!" they cried in a businesslike kind of way as they laid hold of the bow of the rowboat, "or have your throats cut—just as you like, you know."

Of course the children didn't like, and then, as Ann said, they had to remember Peter. Much against his will, Rudolf was now forced to surrender his beloved sword. The False Hare handed over all his belongings—his jewelry, his suit case, and his little umbrella—without the slightest hesitation, humming a tune as he did so, but his voice cracked, and Ann and Rudolf noticed that the tip of his nose had turned quite pale. The prisoners were quickly transferred to the other boat, and the pirate with the green sash took the oars. Just as all was ready for the start the cat in red cried:

"Hold on a minute, Growler! I'll just jump back into their old tub to see if we've left any vallybles behind!"

"All right, Prowler."

It was then and only then that Rudolf and Ann remembered the two white mice! The last time they had noticed them was at the moment of Peter's ducking when in their excitement, the foolish creatures had hidden their faces on each other's shoulders, rolled themselves into a kind of ball, and stowed themselves under a seat. Prowler leaped into the little boat which the pirates had fastened by a tow-rope to their own, and during his search he kept his back turned to his companions. He was gone but a moment, and when he returned his whiskers were very shiny, and he was looking extremely jolly as he hummed a snatch of a pirate song.

"Find anything?" asked Growler, eying him suspiciously. "If you did, and don't fork it out before the Chief, you'll catch it. 'Twill be as much as your nine lives are worth!"

"Oh, 'twas nothing—nothing of any importance," answered Prowler airily.

Rudolf and Ann looked at each other, but neither of them spoke. Both the pirate cats now settled to the oars and the boat skimmed along the water in the direction of the Merry Mouser. As they drew alongside, Growler muttered in a not unfriendly whisper:

"Look here, youngsters, here's a word of advice that may save you your skins. Don't show any cheek—not to me or Prowler, we're the mates—and above all, not to the Chief!"

"What is your Chief's name, Mr. Growler, dear sir?" asked Ann timidly.

Growler flashed his white teeth at her. Then he looked at Prowler and both mates repeated together as if they were saying a lesson: "The name of our illustrious Chief is Captain Mittens—Mittens, the Pitiless Pirate—Mittens, the Monster of the Main!"

"Why—why—my Aunt Jane had a tiger cat once with white paws—" Ann began, but then she stopped suddenly, for Rudolf had given her a sharp pinch. A terrible frown had spread over the faces of both Growler and Prowler. "Above all," whispered the mate in low and earnest tones, "none of that! If you don't want to be keel-hauled, don't recall his shameful past!"

When Rudolf and Ann and the False Hare, under guard of Growler and Prowler, reached the deck of the Merry Mouser, they found Peter, dressed in a dry suit of pirate clothing and looking none the worse for his wetting. He was being closely watched by a big Maltese pirate whose strong paw with its sharp claws outspread rested on his shoulder, but as Rudolf and Ann were led past him, he managed to whisper, "Look out! Mittens is awful cross at us!"

Foolish Ann paid no attention to this warning. She was so glad to see her Aunt Jane's pet again that she snatched her hand out of Prowler's paw, and ran toward the Pirate Chief. "Kitty, Kitty, don't you know me?" she cried. "Oh, Puss, Puss!"

For a moment Captain Mittens stood perfectly silent, bristling to the very points of his whiskers with passion. Then he ordered in a hoarse kind of growl: "Bring the bags."

Instantly two ugly black and white spotted cats dived into the little cabin and brought out an armful of neat, black, cloth bags with drawing strings in them. "One moment," commanded Mittens in a very stern voice, "any plunder?"

Growler, the mate, bowed low before his chief. "'Ere's a werry 'andsome weapon, sir," said he, handing over Rudolf's sword. "Nothing else on the little ones, sir, but this 'ere gentleman"—pointing to the False Hare—"was loaded down with jools."

Hearty cheers sprang from the furry throats of the crew, while broad grins spread over their whiskered faces as they listened to this pleasing news.

"Silence," snarled Mittens—and every cat was still. "Now then," he commanded Growler, "hand 'em over."

Very much against his will, Growler emptied his pockets of the False Hare's jewelry and handed it over to his Chief. Mittens took the gold watch and chain, the flashing pin and studs, the beautiful diamond ring and put them all on, glaring defiantly at his crew as he did so. So fierce was that scowl of his, so sharp and white the teeth he flashed at them, so round and terrible his gleaming yellow eyes that not a cat dared object, though the faces of all plainly showed their anger and disappointment at this unfair division of the spoils.

"Now, what's in there," demanded Mittens, as he gave a contemptuous kick to the False Hare's dress-suit case. Growler opened it and took out a dozen paper collars, a little pair of pink paper pajamas, and a small black bottle labeled "Hare Restorer."

"All of 'em worth about two cents retail," snorted Mittens with a bitter look at the False Hare. "And that umbrella, I see, is not made to go up! Huh! Drowning's too good for you!"

"I feel so myself, sir," said the False Hare humbly. "You see," he added, wiping away a tear with the back of his paw, "I'm so fond of the water!"

Mittens thought a moment, keeping his eye firmly fastened on the Hare. "I'll fix you," he cried, "I'll tie you up in one of those bags!"

The False Hare put his paw behind his ear. "Bags?" said he. "Excuse me, sir, but did you say bags?"

"Yes, I did," roared the Pirate Chief. "Bags! Bags! Bags!"

"Oh, thank you!" cried the False Hare cheerily. "Just my favorite resting-place—a nice snug bag. Mind you have them draw the string tight, won't you?"

Mittens flew into a terrible passion. "I have it," he roared, "I'll send you adrift! Here, boys, get that boat ready!"

Then the Hare began to cry, to sob, to beg for mercy, till the children felt actually ashamed of him. "Look here, Mittens," Rudolf began.

"Captain Mittens," corrected the pirate coldly.

It was hard for Rudolf, but he dared not anger the pirate cat any further. "Don't hurt him, please, Captain Mittens," he begged. "He's only a—" Then he stopped, for the False Hare was making a terrible face at him behind the handkerchief with which he was pretending to wipe his eyes.

"Tie his paws!" commanded Mittens, without so much as a look at Rudolf. "There—that's a nice bit of string hanging out of his pocket—take that. Now—chuck him in the boat!"

In a trice the black and white spotted cats, who seemed to be common sailors, had tied the False Hare's paws behind him with his own string, lowered him into the mice's little boat from which they had already removed the oars, gave it a push, and sent him cruelly adrift!

"Oh, Rudolf," cried tender-hearted Ann, "what will become of him? Poor old Hare!"

"Po-o-o-r old Hare," came back a dismal echo from the little boat already some distance away. Then they saw that the False Hare had freed his paws—that string must have been made of paper like his clothes and his umbrella—and was standing up in his boat waving a gay farewell to all aboard the Merry Mouser.

"Good-by, kidlets!" he called in mocking tones. "Hope you have a good time with the tabbies!" And then to Mittens, "Good-by, old Whiskers!"

At this insult to their Chief all the pirate cats began firing their revolvers, but their aim must have been very poor indeed, as none of their shots came anywhere near the Hare's boat. Indeed, a great many of the cats had forgotten to load their weapons, though they kept snapping away at their triggers as if that did not matter in the slightest. The False Hare merely bowed, kissed his paw to Captain Mittens, and then began using his silk hat as a paddle so skilfully that in a few moments he was far beyond their range.

Growler edged up to Prowler. "I say, old chap," he chuckled, "I s'pose that's what they mean by a hare-breadth escape?"

Prowler grinned. "It's one on the Chief, anyway," said he joyfully. "Not a breath of wind, ye know, not so much as a cats-paw—no chance of a chase."

"What's that?" Captain Mittens had crept up behind the two mates and bawled in Prowler's ear. "What's that? No wind? Why not, I'd like to know? What d'ye mean by running out o' wind? Head her for Catnip Island this instant, or I'll have ye skinned!"

"Yes, sir, I'll do my best, sir," answered Prowler meekly. "But you see, sir, the breeze havin' died, sir, it'll be a tough job to get the Merry Mouser—"

"Prowler!" The chief, who had been standing close beside the unlucky mate while he spoke, now came closer yet and fixed his terrible eye on Prowler's shining whiskers. "How long," he asked, speaking very slowly and distinctly, "is—it—since—you—have—tasted mouse?"

Prowler trembled all over. "A—a—week, sir," he mumbled, "that is, I couldn't swear to the date, sir, but 'twas at my aunt's and she never has us to tea on a Monday, for that's wash-day, nor on a Tuesday, for that's missionary, so it must 'a' been—"

"No use, 't won't work, Prowler." The Chief grinned and waved a paw to one of the spotted sailors. "Here, you, bring along the Cat-O'-Nine-Tails!"

At this the children were immediately very much interested, for they had never in their lives seen a cat with more than one tail.

"It would take nine times as much pulling—" Rudolf was whispering to Peter, when he noticed a new commotion among the sailors. The black and white sea-cat had turned to carry out the Chief's order when suddenly some one called out "A breeze, a breeze!" and in the excitement of getting the Merry Mouser under way, the captain's attention was turned, and Prowler and his crime were forgotten.

All this time Ann and Rudolf and Peter had been standing a little apart from the rest under guard of the Maltese pirate at whose feet lay the dreadful black bags all ready for use. In the confusion Rudolf turned to Ann and whispered, "Do you suppose we could possibly stir up a mutiny? Prowler must be pretty sore against the Chief! If we could only get him and Growler on our side and make them help us seize Mittens and drop him overboard."

But Ann shook her head, and as for Peter he doubled up his little fists and cried out loud: "Nobody sha'n't touch my Mittens! I don't care if he is a pirate cat. I'm going to ask my Aunt Jane if I can't take him home with me to Thirty-fourth Street!"

"Sh—sh!" Ann whispered, putting her hand over his mouth, but it was too late! Mittens had crept stealthily up behind Peter and now he popped one of the black bags over his head. At the same instant, Ann, kicking and struggling, vanished into another held open by two of the spotted cats, and before Rudolf could rush to her rescue a third bag descended over his own head. It was no use struggling, yet struggle they did, till Mittens sent three of the spotted sailors to sit on them, and then they soon quieted down. There were one or two small breathing holes in each bag, or else the children would surely have suffocated, so stout and heavy were those spotted cats. After what seemed to them a very long time a cry of "Land ho!" was raised, and the cats got up and rushed away to join in the general fuss and confusion of getting the Merry Mouser ready for her landing.

Rudolf had been working his hardest at one of the holes in his bag and soon he was able to get a good view of his immediate surroundings.

"Cheer up!" he called to Ann and Peter. "We're coming close to the island."

"Has it got coral reefs and palm-trees and cocoanuts and savages, friendly ones, I mean?" came in muffled tones from Ann's bag.

"Has it got monkeys and serpents an' turtles an'—an'—shell-fish?" demanded Peter from his.

"N-no," said Rudolf, "I don't see any of those things yet. There are a great many trees, some of 'em coming most down to the edge of the water, but they're not palm-trees, they're willows, the kind you pick the little furry gray things off in early spring—"

"Pussy-willows, of course, stupid!" interrupted Ann.

"Yes, and back of that there are fields with tall reeds or grasses with brown tips to them."

"Cattails!" giggled Ann.

"And there's a big high cliff, too, with a little stream of water running down, and—" But here Rudolf stopped, for Growler and Prowler rushed up, cut the strings of the three bags, and released the children from their imprisonment. Hardly did they have time to stretch themselves before the Merry Mouser brought up alongside her landing-place, and in a moment more the children were being led ashore, each under guard of a cat pirate to prevent escape.

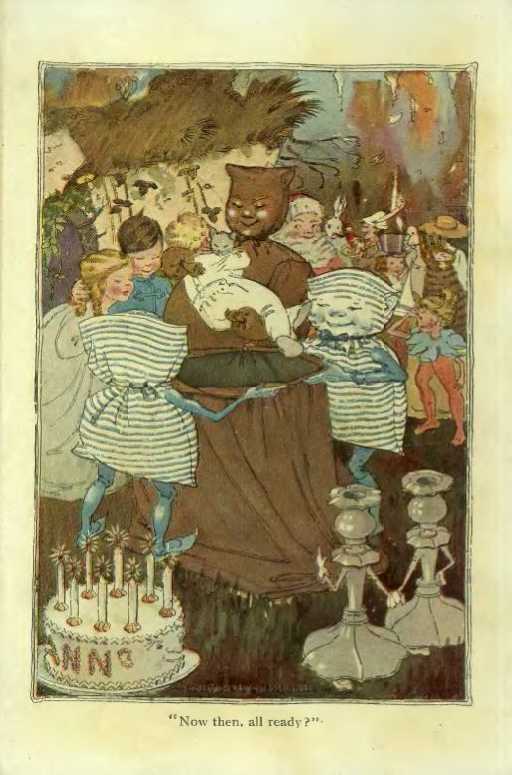

Little cats, big cats, black, white, gray, yellow, striped, spotted, Maltese, tortoise-shell, calico, and tiger cats! Cats of all sizes and all kinds, cats of all ages, from tiny furry babies wheeled in perambulators by their mamas to gray old grandpas hobbling along by the aid of canes or crutches—all the cats of Catnip Island had trooped down to the shore to watch the landing of the Merry Mouser. Captain Mittens, decked out in the False Hare's jewelry, was the first to leave the pirate ship. He stepped along jauntily, nose in the air and the haughtiest kind of expression on his whiskered face. After him came Growler leading Rudolf, then Prowler with Ann, then the Maltese pirate with Peter by the hand. The spotted sailors brought up the rear, all but two who had been left to guard the ship. As soon as the shore cats saw that their Chief had brought home three prisoners from his cruise, they set up a great yowl of joy, and began to dance, prancing and bounding in the air and whirling round and round upon their hind legs.

"Oh, my eye!" exclaimed Rudolf, quite forgetting where he was and standing still to watch their antics. "Don't I wish I had my slingshot!"

"Hush! Silence—'nless ye want to be skinned!" It was the voice of Prowler just behind him.

"If you think I'm afraid of a lot of silly cats—" began Rudolf, but his voice was drowned by the angry yowls that burst from a hundred furry throats as the islanders pressed closer and closer.

"Oh, Rudolf, do be quiet!" Ann begged, and Rudolf, remembering that he was not only a long way from his sling shot, but that even his sword had been taken away from him, was obliged to submit. By this time the pirates had cleared a way through the crowd and the procession left the beach and entered the pussy-willow grove which Rudolf had described from the deck of the Merry Mouser. Half hidden among the trees were a number of pretty little houses, each with a neat door yard and a high back fence. Each had its name, too, on a small door plate, and it amused Ann and Peter to spell out as they went along—"Furryfield," "Mousetail Manor," "Kitten-cote," etc.

"Oh, look," Ann whispered, "see the darling, little, front doors, Peter! Just like the cat-hole in Aunt Jane's big door. The chimneys are shaped something like ears and the roofs are all covered with fur!"

"Yes," answered Peter, "and they've got little gardens to 'em, Ann. I guess that must be the catnip we smell so strong. I don't see any flowers, though, only big tall weeds, rows and rows of 'em—milkweed—that's what it is! What do you suppose they planted that for?"

Prowler, who was walking just ahead of Peter, overheard this last remark, and turning, fixed his large, round, yellow eyes on the little boy. "Don't you like milk, young man?" he asked.

"Why, yes," said Peter, very puzzled, "but not that kind, you know."

"Well, milk's milk these hard times," said Prowler, wagging his head. "It don't do to be too particerler. You like mice, don't you?" he continued.

"Why, I like candy mice," said Peter grinning, "but I never knew before that cats did!"

"Sh-sh!" Poor Prowler began to tremble all over and look anxiously about him. "Not a word of that," he murmured, "or I'm a dead cat! You keep mum about that little affair, young'un, and I'll do you a good turn yet, see if I don't!"

"All right; don't you forget!" whispered Peter.

The procession was now approaching a house considerably larger than any of the others and which had "The Pirattery" written in large letters over its door. Mittens led the way inside, the mates with the children and all the other pirates followed, together with as many of the island cats as could squeeze themselves in. The Pirattery, so the children were informed by Growler and Prowler, was an assembly hall or general meeting-place for the pirates when on shore. Its floor and the little platform at one end were strewn with rat-skin rugs of the finest quality, and its walls were adorned with handsomely stuffed and mounted mouse and fish heads, snake skins, and other trophies of the chase.

Mittens now took up his position on the platform and began a long and eloquent speech in which he related the story of the capture of his prisoners, making the most absurd boasts of the terrible risks he had run, and dwelling most particularly on the awful fate of the False Hare—while quite forgetting to mention his escape. This speech was interrupted by tremendous cheers from the island cats which were only faintly joined in by the pirates. Mittens finished by saying that a concert in celebration of the victory would now be given, after which there would be refreshments—Peter pricked up his ears at the word! —and then the plunder taken from the prisoners would be distributed among the officers and crew of the Merry Mouser. This last announcement was greeted by a volley of shrill and joyful yowls from the younger cat pirates, but Growler, frowning, whispered in Rudolf's ear:

"Don't you believe a word of that, about whacking up on the treasure! He'll never give up so much as a single shirt stud, he won't."

"I would 'a' liked them pink pajamas, I would," sighed Prowler. "They'd just suit my dark complexion."

"I can't understand," said Ann, "what it is that has made such a change in Mittens! Why, just yesterday when we got to Aunt Jane's he was asleep before the fire with a little red bow on his collar—just as soft and nice as anything, and he let us all take turns holding him!"

"He never scratched really deep all day," said Peter mournfully, "only when we dressed him up in the doll's clothes—he didn't seem to 'preciate that—an'—an' when I pulled his tail—he didn't like that, neither."

"He's a bad old thief, that's what he is!" exclaimed Rudolf, forgetting in his excitement to lower his voice. "And if we ever get back to Aunt Jane's and he's there, I'll fix him—"

A general warning hiss went up from the pirate cats who stood nearest to the children. "Be quiet," muttered Growler, "unless you want your ears bitten off? Don't you see the Chief is going to sing?"

Mittens had stepped to the front of the platform and was fixing an angry scowl upon the three children who stood between Growler and Prowler directly beneath him. When all was so quiet in the hall you could have heard a pin drop, the Chief cleared his throat and nodded to the Maltese pirate who stood ready to accompany him upon the tambourine. In the background a semicircle of other singers clutched their music and shuffled their feet rather nervously as they waited to come in at the chorus.

Mittens sang in a high plaintive voice:

You may be sure that Rudolf and Ann did not join in the burst of applause which greeted the end of Captain Mittens' song. Peter would have been glad to, for he was too young and foolish to understand how really impertinent Mittens had been, but his brother and sister quickly stopped that. As for Growler and Prowler, they merely yawned, as if they had heard this song more than once before, only faintly clapping their paws together in order not to attract the tyrant's attention to themselves. The next piece on the program, so Mittens announced, would be a duet between himself and Miss Tabitha Tortoise, entitled Moonbeams on the Back Fence. This selection proved so very noisy, so full of quavers, trills, and loud and piercing yowls, that the children decided it would be safe to attempt a little conversation.

"Oh, Rudolf," whispered Ann, "how shall we ever get away from here?"

"Don't want to get away," grumbled Peter. "We're going to have refreshments; Mittens said so."

"Nonsense; you'll have to go if we do," answered Rudolf. "But listen, what are the mates saying?"

The two black cat pirates were conversing excitedly under cover of the music, and presently the children heard what Prowler was whispering to Growler: "Look here, Matey, where's the rest of the swag, the suit case and his sword, you know?"

"On board ship, stowed away in Cap'n's cabin," answered Growler. "You don't mean to—"

"Yes, I do—I'm no 'fraid-cat—I mean to have them pink pajamas, or—"

"And where do I come in, eh?" exclaimed Growler indignantly.

"Oh, you can have the shirts and collars, Matey. Share and share alike, you know. We'll just slip off to the ship, and—"

"And take us with you," broke in Rudolf. "Do!"

"You know you promised to do us a good turn," whispered Ann. "And if you don't take us we'll tell, and we'll tell about what happened to the white mice, too—"

"And while you're about it," went on Rudolf, "you'd better take possession of the vessel. Between us we can easily manage those old spotties that were left on board. Then, don't you see, when you fellows are masters of the Merry Mouser, you'll have Mittens in your power and you can make him whack up on all the treasure!"

At this brilliant suggestion the two mates gave a smothered cheer, gazing at each other with their round yellow eyes full of joy and their whiskered mouths grinning so widely that the children could see their little red tongues and all their sharp white teeth.

"But how shall we get away without being seen?" Ann asked.

"Oh, that'll be all right," said Prowler, looking about him nervously. "Just wait till you hear 'em announce the refreshments—that always means a rush, you know. Then slip through the crowd and out by that door behind the curtain, and hustle down to the ship just as fast as ever you can lay your paws to the ground!"

Prowler had hardly finished speaking before, with a final long-drawn piercing yowl, the duet of the Pirate Chief and Miss Tabitha Tortoise came to an end, and an intermission of ten minutes for refreshments was announced. From an inner room at the back of the hall a dozen or so white cats in caps and aprons trotted forth bearing large trays loaded with very curious-looking cat-eatables.

Rudolf and Ann had now their usual trouble with Peter who at first absolutely refused to budge until he had tasted at least "one of each". When at last he was made to understand that the trays around which the cats were so greedily thronging contained nothing more inviting than roasted rats and pickled fish fins, and that these delicacies would probably not be offered to prisoners anyway, he regretfully allowed himself to be pushed through a door at the side of the hall and hurried off in the direction of the shore. Although the children, followed closely by the two mates, had managed to slip away almost unnoticed in the general excitement, yet they knew their escape must soon be discovered and they ran as fast as ever they could go.

At last they reached the wharf and scrambled up the side of the Merry Mouser, expecting each instant to receive some kind of challenge from the two spotted cats on guard. Much to their surprise they received none. This was soon explained, for the two common sailors were found in the cabin, curled up in the Captain's bunk, fast asleep.

"A nice mess they'd be in if the Chief caught 'em!" cried Growler.