A soldier of the Disciplinary Corps hadn't

cracked up in all the years of Captain Morrow's

service. Bronson was the first ... Bronson

who reckoned he was one of the rare beings

who had heard THE CALL from Mars.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories January 1952.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The small cargo rocket was halfway to Venus when Bronson decided it was time to take it over. He took care of Orlan first. While Orlan slept in his bunk, Bronson hit him behind the ear with an alloy bar and killed him instantly. He then dragged him down to the cargo bins. The robot was down there, waiting to be sent out into the highly radioactive areas of Venus where the valuable stuff was, but where no human could go. He dumped Orlan in there. It might be construed as an accident, but it probably wouldn't matter to Bronson one way or the other.

Bronson then went up the narrow ladder to the control room where Captain Morrow sat with his broad back to Bronson, bent over the charts. He felt slightly nervous now, looking at Morrow's back. He brushed the black hair out of his eyes. His long, rather hard face tightened a little.

He eased the neurogun free and said softly, "Morrow, get up and turn around slowly. I'm taking this ship to Mars instead of Venus."

Morrow did what he was told. The Disciplinary Corps were conditioned to be amoral and fairly unemotional. But Morrow's gray eyebrows raised. His smooth tanned face twisted. "How unexpected can anything be, Bronson?"

"Get over there," Bronson said. He had figured out the new course already, and it took him only a minute to change the present one.

"A Corpsman hasn't cracked up as long as I've been in the Service and that's a long time, Bronson. What hit you?"

"I don't know. I'm going to Mars, that's all."

"Why?"

"Because there's a death penalty for going there. Maybe because something's there no one's supposed to know about. I found out something very interesting, Morrow. The Call comes from there!"

Morrow's eyes widened a little more. But he didn't ask any more questions. Bronson tied him in his bunk with plastic cord so he wouldn't interfere for a while. He rather liked Morrow, said sentiment being unusual for a Corpsman. But that was another of Bronson's deviant characteristics that had perplexed him for some time.

By the time the rocket approached Deimos, Morrow expressed something that had seemingly been bothering him. He called Bronson in there and it wasn't an act. He was interested. He wasn't mad, or particularly disturbed. Just curious and interested.

"What are your plans, Bronson?"

"Land on Deimos and take the auxiliary sled to Mars. I'll have something in reserve and can approach Mars with less chance of being spotted. If there's anything there to spot me. I'll find out."

Morrow nodded. "That's the way I'd have done it. Will you see me again before you finish this unbelievable incident?"

"Sure. I'll have to. I wouldn't want to come back to Deimos and find you'd taken the rocket. Loneliness doesn't appeal to me. I'll be back to kill you. Maybe not the way I did Orlan. Probably in an easier way."

"Thanks," Morrow said.

Bronson felt nothing about having killed Orlan. Why should he? Such feeling was reserved for the illiterate masses. And yet, somehow he felt differently. Orlan had served in the Elimination details and had been responsible for the killing of a few thousand people. Orlan couldn't have any kick coming even if he could kick.

Bronson got the rocket down and looked out over the airless cold of the rock called Deimos, at the stark contrast of shadows dark as death and splashes of light brilliant as flame. But no movement. Nothing but an eternal lifeless cold.

He went in for his last scene with Morrow. Bronson's stomach went hollow as he stared at Morrow's empty bunk. He started to twist suddenly, grabbing for the neurogun. His arm froze.

Morrow was over in the corner, a gun in his hand. "That plastic is stronger than any alloy cable," he said, gesturing toward the bunk. "It's odd though—but a flame, say from one's cigarette lighter, will burn this particular kind of plastic like paper. You know why I waited?"

"No," Bronson whispered hoarsely.

"I was waiting for you to bring the rocket down. I had a lighter worked to the point where a pull in the right direction would slide it into my hand. Sit down, Bronson, and talk to me. Throw that gun into the corner."

Bronson threw the gun, then sat down stiffly, clenched his big hands together, feeling the sweat slippery between them.

"Tell me about it, Bronson. I'm a little curious. So curious I might do something rather unexpected myself."

Bronson felt numb and sick. And then he started talking and as he talked he forgot about Morrow, and the last few months on Earth were vivid during re-call.

He remembered mostly the long agonizing nights in his dark apartment alone in Central City, suffering the intense agony of increasing anxiety and fear.

He had thought from the start that it was only a matter of time until someone found out that he had gotten THE CALL.

Incredible that a Corpsman should get THE CALL. To the illiterate masses, sure. But that didn't matter. They didn't know what THE CALL was, nor what happened when they got it.

But Bronson knew, only too well, what happened. It wasn't what they thought. To them it was the culmination of an intensely religious experience, an ecstasy of realization. THE CALL entitled them to leave their routine, mindless work and play, and follow THE CALL to some Earthly paradise or other. None of them had seen it, or rather no one had ever returned to tell of it.

Bronson had seen it. A little white room. A chair in the middle. You sat there. You were strapped down. A little gas pellet dropped from the ceiling. You didn't know what hit you, but you never worried anymore. From there a conveyor belt carried you into an incinerator.

They didn't know what hit them, so it didn't matter. But Bronson knew! That made all the difference. He had been lucky to have gotten THE CALL alone in his apartment. When he had looked at Mars, that's when it had hit him. An indescribable experience bordering on dope dreaming, but not the same. An odd tingling, a feeling of marvelous detachment from anything Earthly, and after a while it seemed there were voices in his mind, and the touch of an alien thought pattern, perhaps. He didn't know.

The association of THE CALL with Mars grew until there was nothing else, except his fear of discovery. He didn't want to die. Living wasn't so bad for a Corpsman. One lived pretty high above the menial masses with their happy, idiot faces. There were many privileges, and though a Corpsman couldn't marry, one was allowed to develop interesting friendships with the women Corps members.

That was another thing. Marie Thurston. What if, as a result of long intimacy, she should suspect?

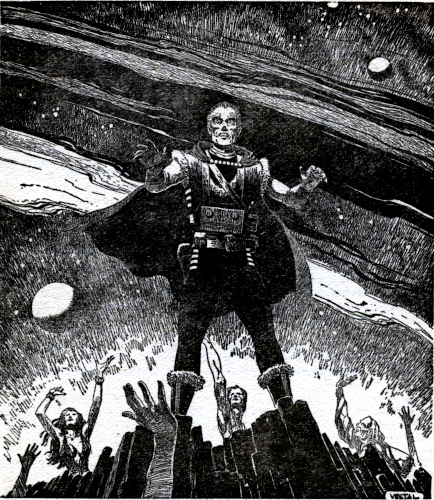

He paced in his apartment, perspiration streaming down his throat, his muscles tense. He didn't want the little white room. Sometime THE CALL would strike him out there where people were, and he'd act like any of the others. Raise his arms. Raise them to sky, walk blindly, oblivious to anything else, his head raised, his mouth gaping, his eyes closed, feet slogging, stumbling. Mumbling—

But it seemed that Bronson was wrong about that. The masses wanted it and they didn't know what THE CALL was, so no inhibitory factors. But Bronson knew, and as a result, he found he didn't get THE CALL unless he asked for it.

He could look at Mars from his darkened quarters at night alone, and get THE CALL, and no one knew. And what surprised Bronson was that he did ask for it. THE CALL became an obsession, with even the Pleasure Marts, and Marie, sliding into unimportance.

He had to deal with an enigma. He had two choices. Assume he was insane, the most logical, perhaps. Or that he wasn't insane, in which case THE CALL was a phenomenon with some material basis in fact outside of himself.

He decided on the latter as a working hypothesis. He tried to find out what might really be back of THE CALL. There were the files in the Corps headquarters at Central City. He questioned some sources subtly. Studied people who got THE CALL. He even managed to talk with Jacson, one of the higher echelon Psychologists. The Psychologists had taken over, established the New System, above them was a small Elite Ruling class no one ever contacted. They lived apart with very very special privileges. The Psychologists kept things as they were. They were the Pavlovians, the reflex boys. Something to do with dogs and ringing bells.

Jacson gave the usual answer. "Regression. But only a few get THE CALL each year. It can never cause social disorganization or dissociation. The last symptom of the old escape drive away from unpleasant reality, inherent in the germ cells no doubt. But now there's no escape. Everybody has fun. No troubles. No conflicts. Someday there'll be no one getting THE CALL."

Who was he kidding, Bronson thought? More got the call each year. That was hush-hush. Jacson said other things, too. He talked a little about the pre-New System era. It was schizophrenic, reality and fantasy all mixed up, and everyone wanting to escape. But the Pavlovians fixed that. There were bells everywhere in the world. And everyone was happy, and having fun all the time. Why should I be skeptical, Bronson thought?

He found out a few bits of information in the files, but nothing that meant anything to him. The stuff about Mars, and the penalty for going there. No reasons. It was Marie who gave him the idea, a solid course of action. They were taking a small private monorail car to the ocean for an under-sea trip. Bronson admired Marie's beauty for a while, but then he began thinking about THE CALL. Marie had a good build where it counted. The big brown eyes and the face a little on the pert side, and always so sweet and smiling. And always full of fun. One seldom saw a face that wasn't full of fun.

But he didn't react much to her beauty tonight. He stared down through the falling dusk at the ruins of old cities like bones piled in the moonlight. Monoliths, leaning and cracked, to a former age no one remembered. And about which all records had been destroyed.

Bronson said softly, "Sure, there was a big war. Because everybody was crazy, it's said. But what happened? Who fought who for what and why and how? The New System is supposed to be sane. But if we don't really know what the other was like, what's the basis for comparison?"

"You think too much," Marie said, and grinned and kissed the lobe of his ear. "The idea is to have fun. What's really troubling you, darling? You can tell me."

If I want to go into the little white room, I can.

"And anyway," she said, "what better proof of insanity do you need than the fact that they almost blew themselves and the whole world into an asteroid belt?"

"They?" he whispered. "Who were they? Everybody didn't do it. I know all the stock answers. They weren't sane, socialized, didn't know how to live together. Big weapons ahead of social science. Imbalance blew up the world. The war came off in 2037. Economic problems were solved. Production-consumption balance figured out. Industry producing more than enough for all, no wants. Who fought who, for what?"

She frowned. He irritated her these days. He interfered with her love of living and that was a Number One Sin. Having fun was a twenty-four hour a day job. And unless you thought about proscribed subjects, even thinking wasn't considered fun.

"Darling," she said. "If you don't snap out of it, we'll have to find other companions. Life's too short to bother with questions that have no important answers."

He shrugged. Until the situation between himself and THE CALL cleared up, there wouldn't be any room for any other problems, Marie included. He said, "I wonder what's really behind those poor devils who get THE CALL?"

She gasped. "Why should you be bothered about—oh, well, they regress that's all. The psychologists let them believe they're having visions of paradise and that makes it easier for them. But it's regressive aberration and they have to be eliminated to prevent social disorganization." She sounded like a parrot, he thought. "What's so mysterious about it?"

"I don't know," Bronson said. "But the past's dead, buried, the tomb markings burned. The psychologists are the only ones who're really supposed to know. They're not talking. We're the disciplinary boys who keep things turning their way. But I'd sure like to know some things."

"You'd better snap out of it. I'd hate to think of you getting that pellet in your lap."

Bronson laughed. "I wonder if it would make any difference to you at all? The sea is full of fish, all about the same general shape and efficiency as I am. I have curiosity. An interest in what no one seems to know. A dissatisfaction, and those are my only unique qualities—those you reject me for. Otherwise I'd be like everyone else. Drop me for those few unique qualities, and you'd find millions of others equally satisfying to your basic demands for male companionship."

She frowned harder. The moonlight streaming through the duralex windows into the lonely, hurtling car gave her blonde hair an eery shine. "Darling, I've liked you because you're a 'man'. I didn't know you were secretly the un-fun type. Here it is then, straight. Either climb down to my level and act like a Good Joe, or I'll be selecting one of those other few million."

Bronson didn't care much now. He didn't say it to her especially. He murmured it to—the stars maybe—but he was afraid to look up there. This would be a very bad time to get THE CALL!

"All those who get THE CALL," he said, "are always looking at the Stars."

She didn't say anything.

He said, "I wonder if there's something connecting THE CALL with the stars? Something out of Space. Maybe there's something real about THE CALL."

She jumped up, leaned over him. Her eyes seemed hard now and distant. "Darling. Why the devil don't you go up there among the Stars and find out for yourself?"

He sat there staring at her, scarcely seeing her. At the moment, he didn't think about it logically. But the suggestion hit him hard and deep and he knew then, though he didn't think about it anymore that night, that that was exactly what he would try to do.

He didn't see Marie again, but once. At that time she was hanging on the crooked elbow of one of the other few million. It didn't really matter who. A big blond lad with a constant glittering smile. A Good Joe who would always be having a good time, and who never never would ask any questions.

There was a slight tinge of jealousy for a moment, and when that passed he didn't seem to care much at all. It was the System that made everybody seem so much like everyone else so that it became so difficult to see anything special in a lover. Everything was for convenience, strictly, and any irritation was an unnecessary unpleasantness that seldom occurred.

Curiosity was irritating in the New System. A person who got THE CALL was so irritating he was eliminated. They would find out sooner or later about him, and then they would kill him. So he volunteered for duty on an Earth-Venus cargo three-man rocket.

He had nothing to lose but his life in attempting to grab the rocket and take it to Mars. And almost any other imaginable way of losing it would be preferable to being taken into the little white room—knowing what to expect instead of Paradise.

Bronson stopped talking. Morrow leaned forward. "What do you expect to find on Mars?"

"What? But—you mean you'll let me—?"

Morrow nodded slowly. "Maybe. I've been curious too at times. We have that much in common. Maybe the new blood has been conditioned more thoroughly than I have, but I've been in a long time, and I get bored with routine. Now here's a situation that is stimulating, and I say to myself, why not exploit it? However, I've never gotten THE CALL, and that puts up a wall between us. Otherwise, I feel a certain rapport."

"Well, are you making a deal or something?"

"Yes, you might say, a kind of deal. Curious, this idea of yours that THE CALL comes from Mars, added to the fact that it's forbidden to go to Mars. In the period immediately following the beginning of the New System, I understand a few rockets went to Mars. None of them ever came back. No one ever heard of them again."

Morrow sat there, apparently thinking. "So I'm curious, Bronson. You've already flaunted the law by taking this ship, killing Orlan. You've admitted you have THE CALL. Certainly you'd be no worse off if you went to Mars. You might find out something interesting. So there could be a chance for you. Go on to Mars if you like. I'll wait here five days. I'll fix the log and the reports, and arrange it so it will appear that there was an accident on Venus. If you're not back in five days, I'll stop off at Venus, load a cargo, return to Earth."

Bronson stared, then said, "And if I do come back, what then?"

"I'll rig up a story about Orlan. Too much radiation on Venus. That's happened a few times before. Officially you'll not be responsible for Orlan's death. And if you get away from Mars, you can do as you like. Stay if you want to. Or return to Earth with the rocket, and take a chance on it being discovered that you have THE CALL, or being able to conceal it. That's your business. All I ask of you, Bronson, is your word that you'll come back here in five days if you can. And satisfy my curiosity."

Later Morrow said, "Good luck, Bronson. Whatever good luck will mean to you."

Bronson thought about that as he dropped the small grav-sled toward Mars' surface. Anticipation became anxiety, fear mixed with excitement, as the sled circled the planet a number of times for purposes of observation.

What will good luck mean to me?

The memory of his experience during THE CALL came back after he spotted the big metal dome in the deep valley and landed behind a low rise of red hills. He lay there bottled up inside the narrow, gun-like barrel of the sled, his helmeted head tight up against the instrument panel.

A metal dome, like the monstrous bald head of a giant buried to the eyebrows. He had seen no other sign of habitation, no structures of anything, only barren sea-bottoms and high naked crags. The dome might be all that was left of what the traders had built here before the Blowup.

Funny, he didn't feel anything like THE CALL now. He felt nothing but fear.

Red dust sprayed up around as he crawled out of the sled. He readjusted his oxygen mask, threw the electronic rifle over his shoulder, and finally reached the top of the ridge and looked down at the dome. It had a gray quiet quality. His throat was tense and his chest ached as he got down on his stomach to watch.

No movement. No sound. A kind of panic hit him, and impulsively, he started to twist around, not wanting to return to the sled particularly, but just wanting to see it, feel a comfort with it.

The sled was gone.

Sweat ran down his face. It loosened a nervous flush along his back which prickled painfully. No sled. He blinked several times, still no sled. There hadn't been any sound. He would have heard it take off.

He jerked himself back toward the dome. He felt the thought fingers, then, like tendrils of outside force subtly probing. Something, something greater than before, stirred incredibly through his body. The old feeling of change, of unutterable newness, of an unguessed sense, opened within him like nothing before. Then ... nothing.

He crawled down. The dome was still. No openings in it. The red dust drifting was the only movement anywhere except his own. He glanced back, hoping to see the sled. He didn't and then when he turned back toward the—

The dome wasn't there.

His fingers dug into the red dust at his sides. Sweat turned it to reddish mud on his fingers. He felt as though an immense cyst of suppuration and purulence had burst inside him. All the water in his body seemed to rush to the surface. Sweat dripped steadily, automatically from the top of his nose, over his mask. His heart pounded like a fist beating against a wall.

Just dust down there. No dome. He dropped his forehead on his arms, closed his eyes. Surely he was being influenced by outside force. Negative hallucination.

He raised his head, opened his eyes. Around him was a small island of red dust, a small oasis large enough to support him. Nothing more. Nothing else at all.

The painful tension in his chest grew until he could scarcely breathe. His jowls darkened, his mouth pressed thin by the powerful clamp of his jaw.

No—not nothing at all. Grayness, though no form, or sound or movement. Meaninglessness within nothingness surrounded by a terrible infinitude of quiet. He felt a kind of final helplessness, an utter isolation.

He glanced down then at himself as the small red oasis around him drifted as though to merge with grayness. He was going too. Even I, I, I, am going too. His feet, his legs. He brought his arms around before his face and as he did that his arms went away. He didn't feel anything.

He closed his eyes as he began, seemingly, to fall. Sensations washed through him, through fibers of seeming delirium. A vortex of nausea then, resolving in his stomach.

Somewhere, somehow, there seemed to be the promise of some kind of solidity. Of being. Bright light from within, the bright splinters of brain light lancing outward through the tender flesh of his eyeballs, dancing back and around the base of his brain in reddened choleric circles. He had a brain, a mind, yet, somewhere.

Desperately he felt his mind scurrying about inside his body. Or perhaps a retentive memory of that body, like a rodent in a maze, concentrating frantically on first the nothingness that had been a limb, then on the tingling aftermath of where his fingers had once moved.

He fought. He fought to grasp something, to see, to feel, to comprehend. He fought wildly against nothing so that it all circled around and round and exploded inside, bursting, bathing him with fire as though he were inside an air-tight container boiling himself in his own accumulating heat.

He gave up. He gave in to an overpowering drawing force. Immediately there was no fear. It was as though he had stopped struggling against a strong current in a vast ocean, and was now floating serenely away, buoyed without effort, drifting forever.

He seemed to glimpse the cloudy, shapeless motion of shadows, like storm clouds boiling and driven before a gale. Familiarity grew, impressions, inchoate mental patterns. Shadows and shapes appeared in the cloudy whiteness, ghostly and strange, and wavering outlines darkened and altered.

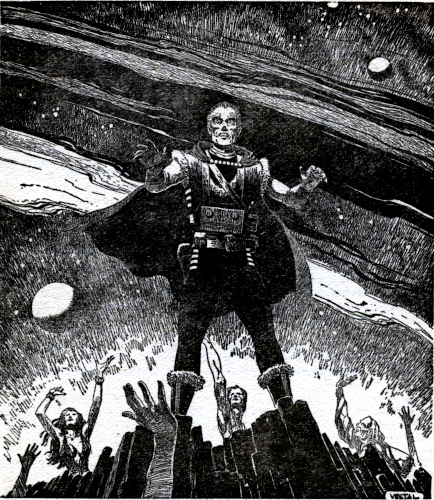

And then he became a part of IT, of something else. And he knew. He had been tested, and there had been the madness of shock as he was being investigated, and finally accepted and absorbed. None of it was incredible to Bronson after he had been taken in. The truth came through then—clear and bright.

IT was far greater than Bronson, but he was part of IT, and IT was part of him. And he knew.

Morrow was waiting for him. As Bronson came into the control room, Morrow's face paled and he slowly licked his lips then plunged his hand toward the neurogun. His hand froze, then crept back guiltily. He tried to speak, but his lips moved wordlessly. Sweat began pocking his face.

Bronson sat down facing Morrow. He could see Morrow now for what he was. A disease. Rather a symptom of long forgotten sickness. Maybe he could be cured.

Bronson said, "You were curious, but you would never have gotten THE CALL. You were curious and you helped me and the world, Morrow, so I'm going to explain it to you. You want to hear about it?"

"What?" Morrow said hoarsely. His eyes were sharp with fear. "Three hours—back in three hours. You look—different, so different—your eyes and—"

"I found out things, Morrow. About the War, about the Plan. Some scientists calling themselves Freedom Unlimited, bio-chemists, physicists and geneticists, organized and said they were going to bring about the realization of man's unlimited potentialities. Create a Paradise on Earth. An old dream. Those who get THE CALL haven't been so far wrong, basically. But the Psychologists reconditioned them so the real nature of THE CALL was distorted."

Morrow shook his head.

"No, and you probably won't understand after I tell you," Bronson said. "But so what? I promised to tell you. Freedom Unlimited took hold, wiped out national barriers, started to sweep the world. They had found the secret of the human mind and nervous system, adopting the methods of atomic physicists. X-rays tear an electron from an atom. They did the same thing with genes, with the cells of the nervous system. Genes and cells, the roots of life. The rock-bottom of life. The problem of the gene and that of the atom were the same. Anyway, they learned the secret of the human brain, that it was a perfect calculating machine."

Morrow was struggling with himself, not moving.

Bronson went on. "I'm controlling you some now, Morrow. You can't move. We're in a hurry so I'll make it brief; there's a job to do. A perfect calculating machine, maybe the most perfect one in the Universe, limitless, inexhaustible. Secretly, Freedom Unlimited started releasing people, clearing them of aberrations, clearing their nervous systems of sludge, fusing emotion with analytical power, so the perfect calculating machine could operate. The movement spread so fast, it threatened various governments, including those in power. The status quo would rather maintain power and be ignorant and blind than to give up their power to the final step of progress. There was a pogrom. The real reason couldn't be revealed of course, so the big powers cooked up a war to cover up the purge. It got out of hand. The result was that civilization was about wiped out. The world burned. Freedom Unlimited had learned the power of the human brain, but they were too few, and the Psychologists managed to fight them long enough to carry through the war. Freedom Unlimited fled to Mars. They couldn't engage in wholesale slaughter. But they had to survive."

It was so clear now in Bronson's mind, as though he were experiencing it.

"Many of the scientists had been killed, only a few reached Mars. But they had launched a Plan. They planted basic undying commands, responses, in the reactive primitive cells of individuals whom they knew would reproduce in kind. They knew how to treat genes like chemical formulae. They knew the genes and cells would carry these commands from generation to generation. The commands led to THE CALL. A call to come to Mars, that's all. Once they got to Mars, they would be free."

Bronson leaned forward. "But Freedom Unlimited didn't anticipate the utter nihilism, the complete inhuman attitude of those who had defeated them. There were variables. Freedom Unlimited couldn't anticipate the utter power and suppression put into effect by the Psychologists, the reflex boys. That they would condition every bit of imaginative, creative, original thought and action out of everyone but a small elite who, because of their own destructive nihilistic attitudes, were never human in the first place, but only aberrated monsters. And all the rest of humanity became little more than robots, zombies, mechanicals, their analytical power chopped off, short-circuited completely. They can only have fun like well-trained moronic children. With bells ringing everywhere, the Pavlovians turned humans into dogs."

Morrow didn't say anything. His face was pinched and afraid, confused and helpless.

"The Psychologists suspected the basis of the Plan. They converted it by conditioning into a kind of religion. Then it wasn't dangerous anymore. Meanwhile, they had also learned they could never reach Mars. There's a final step to releasing the pure analytical power of the human mind. Synthesis. Similarization. There's a dome down there shaped like the skull of a giant. Inside that metal skull is a synthesis of human intellect and machinery, pure analytical power. The brain, at its optimum, is a perfect thinking machine. No five perfect thinking machines would solve a problem differently. The result is synthesis. With synthesis came an ultimate thinking machine because it gives off energy, electrical let us say for convenience, in the form of thought.

"And that master brain down there has the will to radiate and control this great energy. It's a kind of final perfection of the unguessed power of the brain. It goes beyond the human, for them at least. They can send out beams, or rather it, sends out beams of sheer power, solid thought, by dipping into nine million brain cells plus a hundred. That brain can stop any enemy's approach to Mars, but it couldn't reach Earth. Yet.

"You follow me, Morrow?"

Morrow nodded slowly. He slumped a little. His face was shabby now and old. "Some of it," he whispered. "I don't understand. But I believe. I have to believe. You—power—"

"I have a lot of power," Bronson said. "I'll have more of it. You see, the Plan really did work in a sense. Variables work both ways. Over a period of time, circumstances meshed in such a way that a Disciplinary Corpsman named Bronson got THE CALL. The sight of the planet Mars was the key-in stimulant. I happened to be alone in my apartment so that no one knew I'd been hit. I happened to be a Corpsman which meant I knew what happened to those who got THE CALL. I couldn't accept that, so I had to look for other reasons. I also happened to never have undergone brain surgery, any prefrontal lobotomies, for example. Those things destroy the analytical mind so even Freedom Unlimited is not certain of a cure. I couldn't doubt my own sanity. So I came to Mars, I answered THE CALL. It happened to me by accident, but I had the command in my cells ready for re-stimulation."

"What now?" Morrow said. "What do you do now? What about me—and—"

"I'll go back to Earth, and start to work. With each clearing of a human being from his Pavlovian prison, I'll gain greater strength, allies. No one will know. This time there'll be no disaster because the destructive elements of war aren't there. The Psychologists are too sure of themselves. We'll win the world and free men's minds."

"And what about me?"

Bronson looked at Morrow's face. A thoroughly conditioned face really. Hardly human at all if one knew what a human face could really express. Strange, that spark of curiosity in a man whose brain had obviously undergone deadly probing with steel picks under the eyeballs, tearing apart the cells of the greatest thinking device ever developed.

"You're going to Mars," Bronson said softly. "Maybe they can clear you. I had THE CALL planted in an ancestor. You didn't. It missed you, Morrow. With the command carried forward always in the cells went also resistance to conditioning. You didn't have it, Morrow. It may be too bad and it may not. They've learned a lot in a hundred years."

Bronson got up and put a hand gently on Morrow's shoulder. "I don't know," he said. "I'm sorry. Maybe you'll be with me later. If you're not back here in a short time, that'll mean good-bye. I'll wait for you...."

Morrow got up. He nodded once to Bronson, and went out. Bronson heard the sled blast out of the rocket.

Morrow didn't come back.

Bronson took the rocket up, headed toward Venus. He would pick up the cargo; the story Morrow had arranged about an accident on Venus could work just as well to explain Bronson's single return as Morrow's.

He had some advantage in his command of the human mind. But it wasn't omnipotent by any means. He would be operating alone against murderers who had turned human beings into cattle. He would have to play it slow and with the utmost care.

And though he might fail, there would be others. He could forget about Morrow and Orlan. So much of them had been destroyed by surgery that in a comparative sense, they hadn't been really human anymore.

He wasn't troubled by the tremendous challenge ahead of him. It exalted him.

Some day, we'll win, he thought. Freedom Unlimited. The freedom of the free human mind. He might fail. But THE CALL would go on. There would always be deviants from the norm. He could fail. The Plan could not.

Bronson smiled at the twilight expanse before the rocket, wide and frosty and marvelously clear.

As long as there were people, there would always be a few who would get THE CALL.