THE APPRECIATION OF MUSIC

VOL. I.

THE APPRECIATION OF MUSIC CLOTH $1.50

By Thomas Whitney Surette and Daniel Gregory Mason

SUPPLEMENTARY VOLUME OF MUSICAL ILLUSTRATIONS $1.00

VOL. II.

GREAT MODERN COMPOSERS CLOTH $1.50

By Daniel Gregory Mason

VOL. III.

SHORT STUDIES IN GREAT MASTERPIECES

By Daniel Gregory Mason

OTHER WORKS

BY

DANIEL GREGORY MASON

A GUIDE TO MUSIC. A BOOK FOR BEGINNERS CLOTH $1.25

ORCHESTRAL INSTRUMENTS AND WHAT THEY DO,

WITH TWENTY-SEVEN ILLUSTRATIONS AND

ORCHESTRAL CHART CLOTH $1.25

VOLUME I

BY

THOMAS WHITNEY SURETTE

AND

DANIEL GREGORY MASON

NINTH EDITION

Supplementary Volume of Musical Illustrations

Price $1.00

NEW YORK

THE H. W. GRAY CO.

SOLE AGENTS FOR

NOVELLO & CO., LTD.

COPYRIGHT, 1907, BY

THE H. W. GRAY COMPANY

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

PREFATORY NOTE.

This book has been prepared in order to provide readers who wish to listen to music intelligently, yet without going into technicalities, with a simple and practical guide to musical appreciation written from the listener's rather than from the professional musician's standpoint.

The authors believe that there is at the present moment a genuine need for such a book. Teachers in schools, colleges, and universities, educators in all parts of the country, and the music-loving public generally, are every day realizing more vividly the importance of applying to music the kind of study which has long been fruitfully pursued in the other arts; and with the adoption, in 1906, by the College Entrance Examination Board, of musical appreciation as a subject which may be offered for entrance to college, this mode of studying music has established itself firmly in our educational system. Yet its progress is still hampered by the lack of suitable text-books. The existing books are for the most part either too technical to be easily followed by the general reader, or so rhapsodical and impressionistic as to be of no use to him.

In the following pages an effort has been made, first, to present to the reader in clear and untechnical language [iv] an account of the evolution of musical art from the primitive folk-song up to the symphony of Beethoven; second, to illustrate all the steps of this evolution by carefully chosen musical examples, in the form of short quotations in the text and of complete pieces printed in a supplement; third, to facilitate the study of these examples by means of detailed analysis, measure by measure, in many cases put into the shape of tabular views; and fourth, to mark out the lines of further study by suggesting collateral reading.

Too much stress cannot be laid on the fact that the music itself is the central point of the scheme of study, to which the reader must return over and over again. Carefully attentive, concentrated listening to the typical pieces presented in the supplement is the essence of the work, to which the reading of the text is to be considered merely as an aid. These pieces are for the most part not beyond the reach of a pianist of moderate ability.

At the same time, the authors have realized that some readers who might profit much by such study will not be able to play, or have played for them, even these pieces. For them, however, the music will still be accessible through mechanical instruments.

In view of the fact that one of the chief difficulties in the study of musical appreciation is the unfamiliarity of classical music to the ordinary student, the use of an instrument by the students themselves should form an important part of the work in classes where this book is used as a [v] text-book. It is hoped that with such practical laboratory work by all members of the class, and with the help of collateral reading done outside the class under the direction of the teacher, and tested by written papers on assigned topics, the course of study outlined here will be found well-suited to the needs of schools and colleges, as well as of general readers.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| PAGE | ||

| ELEMENTS OF MUSICAL FORM. | 1 | |

| I. | INTRODUCTORY | 1 |

| II. | WHAT TO NOTICE FIRST | 3 |

| III. | MUSICAL MOTIVES | 4 |

| IV. | WHAT THE COMPOSER DOES WITH HIS MOTIVES | 6 |

| V. | THE FIRST STEPS AS REVEALED BY HISTORY | 10 |

| VI. | A SPANISH FOLK-SONG | 12 |

| VII. | BALANCE OF PHRASES | 13 |

| VIII. | SUMMARY | 14 |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| FOLK-SONGS. | 16 | |

| I. | FOLK-SONGS AND ART SONGS | 17 |

| II. | AN ENGLISH FOLK-SONG | 20 |

| III. | KEY AND MODULATION | 21 |

| IV. | BARBARA ALLEN | 22 |

| V. | NATIONAL CHARACTERISTICS IN FOLK-SONGS | 25 |

| VI. | AN IRISH FOLK-SONG | 26 |

| VII. | A GERMAN FOLK-SONG | 28 |

| VIII. | SUMMARY | 30 |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| THE POLYPHONIC MUSIC OF BACH. | 31 | |

| I. | WHAT IS POLYPHONY | 32 |

| II. | AN INVENTION BY BACH | 33 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 1. | ||

| Bach: Two-voice, Invention. No, VIII, in F-major | 34 | |

| III. | A FUGUE BY BACH | 37 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 2. | ||

| |

Bach: Fugue No. 2, in C-minor, in three voices. "Well-tempered Clavichord," Book I |

38 |

| IV. | GENERAL QUALITIES OF BACH'S WORK | 43 |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| THE DANCE AND ITS DEVELOPMENT. | 48 | |

| I. | MUSICAL CHARACTER OF DANCES | 48 |

| II. | PRIMITIVE DANCES | 52 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 3. | ||

| Corelli: Gavotte in F-major | 56 | |

| III. | A BACH GAVOTTE | 57 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 4. | ||

| Bach: Gavotte in D-minor, from the Sixth English Suite | 57 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| THE SUITE. | 62 | |

| I. | DERIVATION OF THE SUITE | 62 |

| II. | THE SUITES OF BACH | 65 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 5. | ||

| Bach: Prelude to English Suite, No. 3, in G-minor | 65 | |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 6. | ||

| Bach: Sarabande in A-minor, from English Suite, No. 2 | 68 | |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 7. | ||

| Bach: Gigue, from French Suite, No. 4, in E-flat | 71 | |

| III. | THE HISTORIC IMPORTANCE OF THE SUITE | 72 |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| THE RONDO. | 74 | |

| I. | DERIVATION OF THE RONDO | 75 |

| II. | A RONDO BY COUPERIN | 79 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 8. | ||

| Couperin: "Les Moissonneurs" ("The Harvesters") | 80 | |

| III. | FROM COUPERIN TO MOZART | 83 |

| IV. | A RONDO BY MOZART | 86 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 9. | ||

| Mozart: Rondo from Piano Sonata in B-flat major | 87 | |

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| THE VARIATION FORM—THE MINUET. | 93 | |

| I. | VARIATIONS BY JOHN BULL | 94 |

| II. | A GAVOTTE AND VARIATIONS BY RAMEAU | 97 |

| III. | HANDEL'S "HARMONIOUS BLACKSMITH" | 100 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 10. | ||

| Handel: "The Harmonious Blacksmith," from the Fifth Suite for Clavichord | 101 | |

| IV. | HAYDN'S ANDANTE WITH VARIATIONS, IN F-MINOR | 103 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 11. | ||

| Haydn: Andante with Variations, in F-minor | 104 | |

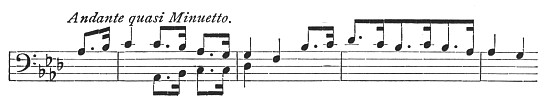

| V. | THE MINUET | 108 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| SONATA-FORM, I. | 110 | |

| I. | COMPOSITE NATURE OF THE SONATA | 110 |

| II. | ESSENTIALS OF SONATA-FORM | 111 |

| III. | A SONATA BY PHILIP EMANUEL BACH | 114 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 12. | ||

| Philip Emanuel Bach: Piano Sonata in F-minor, first movement | 115 | |

| IV. | HARMONY AS A PART OF DESIGN | 125 |

| V. | SUMMARY | 126 |

| CHAPTER IX. | ||

| SONATA-FORM, II. | 128 | |

| I. | HAYDN AND THE SONATA-FORM | 128 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 13. | ||

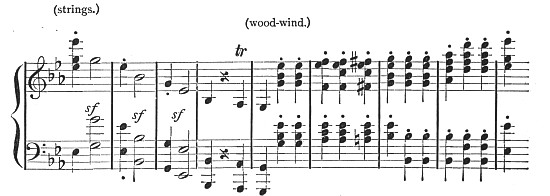

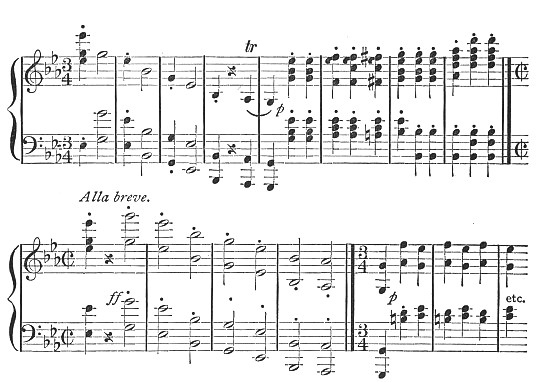

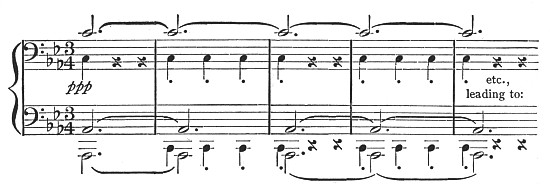

| Haydn: "Surprise Symphony," first movement | 131 | |

| II. | MOZART AND THE SONATA-FORM | 134 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 14. | ||

| Mozart: Symphony in G-minor, first movement | 136 | |

| III. | MOZART'S ARTISTIC SKILL | 138 |

| CHAPTER X. | ||

| THE SLOW MOVEMENT. | 143 | |

| I. | VARIETIES OF FORM | 143 |

| II. | SLOW MOVEMENTS OF PIANO SONATAS | 145 |

| III. | THE STRING QUARTET | 148 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 15. | ||

| |

Haydn: Adagio in E-flat major, from the String Quartet in G-major, op. 77, No. 1 |

149 |

| IV. | GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS | 151 |

| V. | FORM OF HAYDN'S ADAGIO | 152 |

| VI. | MOZART AND THE CLASSIC STYLE | 153 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 16. | ||

| Mozart: Andante from String Quartet in C-major | 156 | |

| VII. | FORM OF MOZART'S ANDANTE | 159 |

| CHAPTER XI. | ||

| BEETHOVEN—I. | 161 | |

| I. | GENERAL CHARACTER OF BEETHOVEN'S WORK | 161 |

| II. | ANALYSIS OF A BEETHOVEN SONATA | 166 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 17. | ||

| Beethoven: Path?ique Sonata, first movement | 166 | |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 18. | ||

| Beethoven: Path?ique Sonata, second movement | 170 | |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 19. | ||

| Beethoven: Path?ique Sonata, third movement | 171 | |

| III. | SUMMARY | 174 |

| CHAPTER XII. | ||

| BEETHOVEN—II. | 176 | |

| I. | FORM AND CONTENT | 176 |

| II. | BEETHOVEN'S STYLE | 178 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 20. | ||

| Beethoven: The Fifth Symphony, first movement | 181 | |

| III. | THE DRAMATIC ELEMENT IN BEETHOVEN'S MUSIC | 185 |

| IV. | THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE FIRST MOVEMENT OF THE FIFTH SYMPHONY | 187 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | ||

| BEETHOVEN—III. | 191 | |

| I. THE SLOW MOVEMENT BEFORE BEETHOVEN | 191 | |

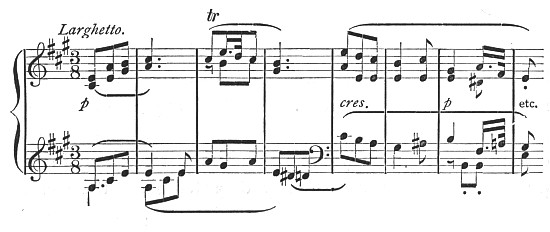

| II. | THE SLOW MOVEMENTS OF BEETHOVEN'S EARLY SYMPHONIES | 192 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 21. | ||

| Beethoven: The Fifth Symphony. Slow movement | 195 | |

| III. | INDIVIDUALITY OF THE ANDANTE OF THE FIFTH SYMPHONY | 198 |

| IV. | THE HARMONIC PLAN | 201 |

| V. | THE UNIVERSALITY OF BEETHOVEN'S GENIUS | 203 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | ||

| BEETHOVEN—IV. | 205 | |

| I. | BEETHOVEN'S HUMOR | 205 |

| II. | SCHERZOS FROM BEETHOVEN'S SONATAS | 209 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 22. | ||

| Beethoven: Scherzo from the Twelfth Sonata | 209 | |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 23. | ||

| Beethoven: Scherzo from the Fifteenth Sonata | 210 | |

| III. | THE SCHERZOS OF BEETHOVEN'S SYMPHONIES | 211 |

| EXAMPLE FOR ANALYSIS, No. 24. | ||

| Beethoven: Scherzo from the Fifth Symphony | 218 | |

| IV. | GENERAL SUMMARY | 221 |

THE APPRECIATION OF MUSIC

Of the thousands of people who consider themselves lovers of music, it is surprising how few have any real appreciation of it. It is safe to say that out of any score of persons gathered to hear music, whether it be hymn, song, oratorio, opera, or symphony, ten are not listening at all, but are looking at the others, or at the performers, or at the scenery or programme, or are lost in their own thoughts. Five more are basking in the sound as a dog basks in the sun—enjoying it in a sleepy, languid way, but not actively following it at all. For them music is, as a noted critic has said, "a drowsy reverie, relieved by nervous thrills." Then there are one or two to whom the music is bringing pictures or stories: visions of trees, cascades, mountains, and rivers fill their minds, or they dream of princesses in old castles, set free from magic slumber by brave heroes from afar. Perhaps also there is one who takes a merely scientific interest in the music: he is so busy analysing themes and labelling motives that he forgets to enjoy. Only two out of the twenty are left, then, who are actively following the melodies, living over again the thoughts of the composer, really appreciating, by vigorous and delightful attention, the beauties of the music itself.

Can we not, you and I, join the ranks of these true lovers of music? Can we not learn to free our minds of all side issues as we listen—to forget audience, performers, and scene, to forget princesses and heroes, to forget everything except this unique experience that is unfolding itself before our ears? Can we not, arousing ourselves from our drowsy reverie, follow with active co-operation and vivid pleasure each tone and phrase of the music, for itself alone?

One thing is sure: Unless we can do so, we shall miss the keenest enjoyment that music has to offer. For this enjoyment is not passive, but active. It is not enough to place ourselves in a room where music is going on; we must by concentrated attention; absorb and mentally digest it. Without the help of the alert mind, the ear can no more hear than the eye can see. Sir Isaac Newton, asked how he had made his wonderful discoveries, answered, "By intending my mind." In no other way can the lover of music penetrate its mysteries.

Knowledge of musical technicalities, on the other hand, is not necessary to appreciation, any more than knowledge of the nature of pigments or the laws of perspective is necessary to the appreciation of a picture. Such technical knowledge we may dispense with, if only we are willing to work for our musical pleasure by giving active attention, and if we have some guidance as to what to listen for among so many and such at first confusing impressions. Such guidance to awakened attention, such untechnical direction what to listen for, it is the object of this book to give.

It is no wonder, when one stops to think of it, that music, in spite of its deeply stirring effect upon us, often defeats our best efforts to understand what it is all about, and leaves us after it is over with the uncomfortable sense that we have had only a momentary pleasure, and can take nothing definite away with us. It is as if we had been present at some important event, without having the least idea why it was important, or what was its real meaning. All of us, at one time or another, must have had this experience. And, indeed, how could it be otherwise? Music gives us nothing that we can see with our eyes or touch with our hands. It does not even give our ears definite words that we can follow and understand. It offers us only sounds, soft or loud, long or short, high or low, that flow on inexorably, and that too often come to an end without leaving any tangible impressions behind them. No wonder we are often bewildered by an experience so peculiar and so fleeting.

Yet these sounds, subtle as they are, have a sense, a logic, an order of their own; and if we can only learn how to approach them, we can get at this inner orderliness that makes them into "music." The process of perception which we have to learn here is somewhat akin to certain more familiar processes. For example, what comes to our eyes from the outer world is simply a mass of impressions of differently colored and shaped spots of light; only gradually, as we grow out of infancy, do we learn that one group of these spots of light shows us "a house," another "a tree," [4] and so on. Similarly words, as we easily realize in the case of a foreign language, are to the untrained ear mere isolated sounds of one kind or another; only with practice do we learn to connect groups of them into intelligible sentences. So it is with music. The sounds are at first mere sounds, separate, fragmentary, unrelated. Only after we have learned to group them into definite melodies, as we group spots of lights into houses or trees, and words into sentences, do they become music for us. To approach sounds in such a way as to "make sense" of them—that is the art of listening to music.

The first step in making sense of any unfamiliar thing is to get quite clearly in mind its central subject or subjects, as, for example, the fundamental idea of a poem, the main contention of an essay, the characters of a novel, the text of a sermon. All music worthy of the name has its own kind of subjects; and if we can learn to take note of, remember, and recognize them, we shall be well on the road to understanding what at first seems so intangible and bewildering.

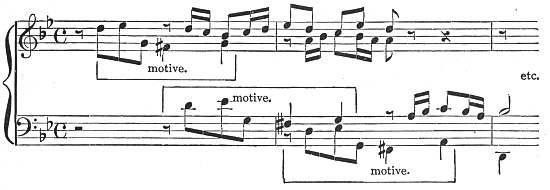

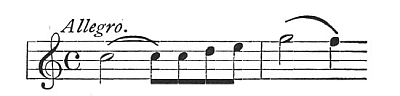

A possible confusion, due to the use of terms, must here be guarded against. The word "subject" is used in a special sense, in music, to mean an entire theme or melody, of many measures' duration—thus we speak of "the first subject of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony," meaning the entire contents of measures 6-21. Now this is obviously a different meaning of the word "subject" from the general one we use when we speak of the subject of a poem or a [5] picture, as the fundamental idea about which it all centers. This long musical "subject" all centers about a little idea of four notes, announced in the first two measures of the symphony:

But as we are already using the word "subject" to mean something else, we must have another name for this brief characteristic bit out of which so much is made, and for this the word "motive" is used. Here again there is a difference of usage which must be noted. When we speak of a "motive" or "leading motive" of Wagner, we mean not a short group of this kind, but an entire melody associated with some special character or idea; e. g., "the Siegfried motive." Let us here, however, keep the word "motive" to mean a short characteristic group of tones or "figure," and the word "subject" to mean a complete melody or theme built up out of one or more motives.

The smallest elements into which we can analyze the subject-matter of music are "motives"—that is, bits of tune, groups of from two to a dozen tones, which have an individuality of their own, so that one of them cannot possibly be confused with another.

"Yankee Doodle," for instance, begins with a motive of seven notes, which is quite individual, and wholly different from the motive of six notes at the beginning of "God Save the King," or the motive of five notes at the beginning of the "Blue Danube" waltz. The three motives are so different that nobody of ordinary musical intelligence would confound [6] them one with another, any more than he would confound the subject of Longfellow's "Psalm of Life" with that of Browning's "Incident of the French Camp," or the characters in "Dombey and Son" with those in "Tom Jones." The whole musical individuality of each of the three tunes grows out of the individuality of its special motive.

Here, evidently, is a matter of primary importance to the would-be intelligent music lover. If he can learn to distinguish with certainty whatever "motives" he hears, half the battle is already gained.

Four points will be noticeable in any motive he may hear. Its notes will vary as to (1) length, (2) accent, (3) meter or grouping into regular measures of two, three, or four notes, and (4) pitch. If he can once form the habit of noticing them, he will have no further difficulty in recognizing the themes of any music, and, what is even more important, following the various evolutions through which they pass as the composer works out his ideas. The importance of such active participation in the composer's thought cannot be exaggerated. Without it there cannot be any true appreciation of music; through it alone does the listener emerge from "drowsy reverie, relieved by nervous thrills" into the clear daylight of genuine artistic enjoyment.

Let us put ourselves now in the place of a composer who has thought of certain motives, and who wishes to make them into a complete piece of music. What shall we [7] do next with these scraps of melody, attractive but fragmentary? Now, one thing we can see at once from our knowledge of arts other than music. We must somehow or other keep repeating our central ideas, or our piece will wander off into mazes and fail to have any unity or intelligibility; yet we must also vary these repetitions, or they will become monotonous, and the finished piece will have no variety or sustained interest. The poet must keep harking back to the main theme of his poem, or it will degenerate into an incoherent rhapsody; but he must present new phases of the root idea, or he will simply repeat himself and bore his readers. The architect, having chosen a certain kind of column, say, for his building, must not place next to it another style of column, from a different country and period, or his building will become a mess, a medley, a nightmare; but neither must he make his entire building one long colonnade of exactly similar columns, for then it would be hopelessly dull. In short, every artist has to solve in his own way the problem of combining unity of general impression with variety of detail. Without either one of these essentials, no art can be beautiful.

Here we are, then, with our motive and with the problem before us of repeating it with modifications sufficient to lend it a new interest, but not radical enough to hide its identity.

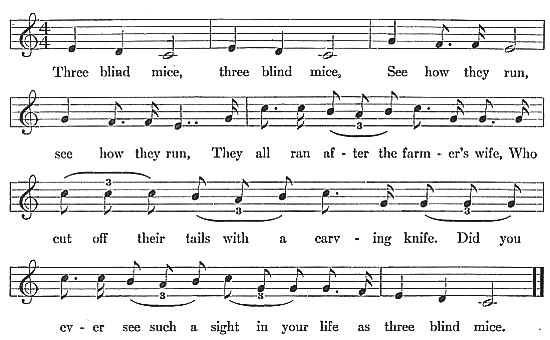

If we are making our music for several voices or instruments, or for several parts all played on one instrument like the organ or the piano, we can let these different voices or parts sound the motive in succession. If, while [8] the new voice takes the motive, the voice previously brought in goes on with something new, then we shall have a very agreeable mingling of unity and variety. This is the method used in all canons, fugues, inventions, and so on, and in vocal rounds. For an example, take the round called "Three Blind Mice" (see Figure I).

FIGURE I. "THREE BLIND MICE."

Three blind mice, three blind mice, See how they run,

see how they run, They all ran af - ter the farm - er's wife, Who

cut off their tails with a carv - ing knife. Did you

ev - er see such a sight in your life as three blind mice.

One person, A, begins this melody alone, and sings it through. When he has reached the third measure, B strikes in at the beginning. When B in his turn has reached the third measure (A being now at the fifth), C comes in in the same way. In a word, the three people sing the same tune in rotation (whence the name, "round"). And the tune, of course, is so contrived that all its different sections, sounded simultaneously by the various voices, [9] merge in harmony. This kind of literal repetition by one part of what another has just done is called "imitation," and is a fundamental principle of all that great department of music known as the "polyphonic," or many-voiced.

But now, notice another kind of repetition in this little tune. Measures 3 and 4 practically repeat, though at a different place in the scale, the three-note motive of measures 1 and 2. (In order to conform to the words, the second note is now divided into two, but this is an unimportant alteration.) The naturalness of this kind of repetition is obvious. Having begun with our motive in one place, it easily occurs to us to go on by repeating it, in the same voice, but higher or lower in pitch than at first. The mere fact that it is higher or lower gives it the agreeable novelty we desire, yet it remains perfectly recognizable. We may call this sort of repetition, which, like "imitation," is of the greatest utility to the composer, "transposition," to indicate that the motive is shifted to a new place or pitch.

But suppose we do not wish either to imitate or to transpose our motive, is there any other way in which we can effectively repeat it? Yes:—we can follow its first appearance with something else, entirely different, and after this interval of contrast, come back again and restate our motive just as it was at first. Looking at "Three Blind Mice" again, we see that this device, as well as the other two, is used there. After the fifth, sixth, and seventh measures, which contain the contrast, the eighth measure returns literally to the original motive of three notes, thus rounding [10] out and completing the tune. This third kind of repetition, which may be called "restatement after contrast," or simply "restatement," is also widely in use in all kinds of music. A most familiar instance occurs in "Way Down upon the Suwanee River."

Let us keep distinctly in mind, in all our study, these three modes of repetition, which are of radical importance to musical design: 1st, the imitation of a motive in a different "voice" or "part"; 2d, the transposition of a motive, in the same voice, to a higher or lower place in the scale; 3d, the restatement of a motive already once stated, after an intervening contrast. We shall constantly see these kinds of repetition—imitation, transposition, and restatement—used by the great composers to give their music that unity in variety, that variety in unity, without which music can be neither intelligible nor beautiful.

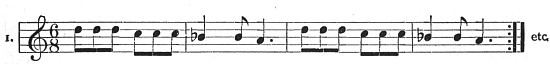

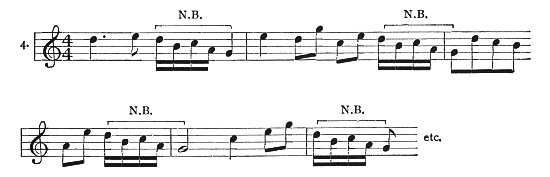

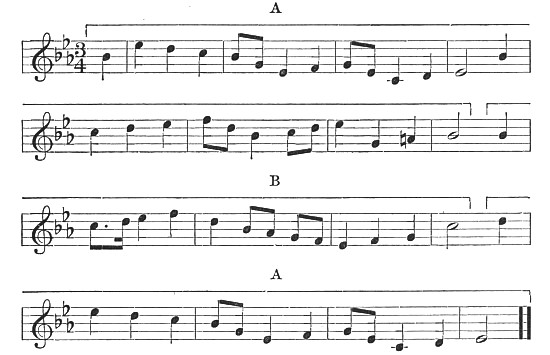

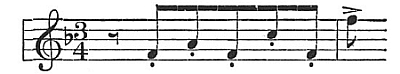

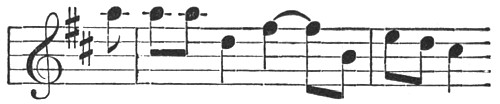

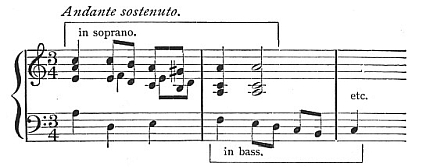

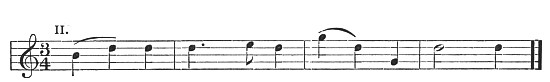

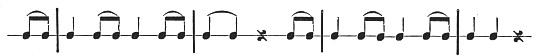

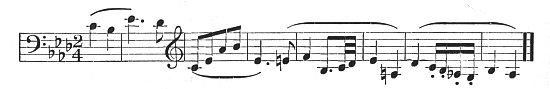

It must not be thought that these ways of varying musical motives without destroying their identity were quickly found out by musicians. On the contrary, it took centuries, literally centuries, to discover these devices that seem to us so simple. All savage races are musically like children; they cannot keep more than one or two short bits of tune in mind at the same time, and these they simply repeat monotonously. The first two examples in Figure II, taken from Sir Hubert Parry's "The Evolution of the Art of Music," give an idea of the first stage of the savage musician.

1.

2.

3.

4.

FIGURE II. TUNES OF PRIMITIVE SAVAGES.

The first is from Australia, the second from Tongataboo. Both are made of a single motive endlessly repeated without relief.

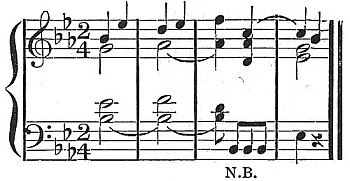

In a slightly higher stage, two motives are used, but with little more skill. Number 3, in Figure II, is an example. Then come tunes in which one or more motives, repeated literally, are still the main feature of the design, but in which a certain amount of variety is introduced between the repetitions (see Number 4, in Figure II, a Russian tune). Here the little characteristic figure of four short notes and a long, marked N.B., is agreeably relieved by other material.

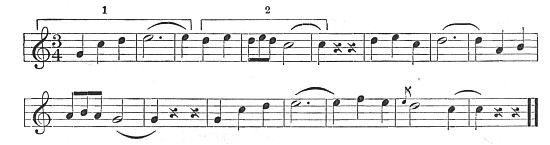

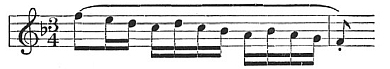

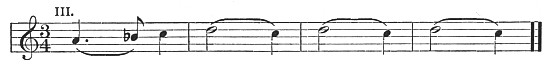

From such primitive music as this to the beautiful "folk-song" of the modern nations is a long step indeed. Even in the simplest real folk-songs, the means of varied repetition of ideas that we have been discussing are used with an ingenuity which places them on an infinitely higher level than these primitive efforts of savages. It is true that in folk-songs, which were sung by a single voice instead of a group of voices, the device of "imitation" was used hardly at all:—that is available only where there are several different voices to imitate one another. But in order to see what good use was made of "transposition" and "restatement" we need take only a single example, from Galicia in Spain (see Figure III). Let us examine this tune in some detail, as a preparation for a further study of folk-songs in a later article.

From Galicia in Spain.

FIGURE III. FOLK-SONG.

The tune, in spite of its impression of considerable variety, is founded entirely on two motives—

In the sixth and seventh measures, (1) is so altered and transposed that it ends on D instead of on C, and in the eighth, ninth, and tenth measures (2) is transposed so as to end on G instead of on C. By these transpositions the important element of contrast is introduced, and when therefore we have, at the end, the two motives given again almost exactly as to first, we get, by this restatement after contrast, a delightful sense of unity and completeness. The means here are wonderfully simple, but the effect is truly artistic.

An important principle of musical design is introduced to our notice by this little melody. It will be observed that it divides itself into three equal parts: the statement, measures 1-5; the contrast, measures 6-10; and the restatement, measures 11-15. (We may represent these by the letters A, B, and A.) Now these three parts, being of equal length and similar material, balance each other just as lines in poetry do. One makes us expect another, which, when it comes, fulfills our expectation. Thus we get the impression of regularity, order, symmetry. This element of symmetry, or the balancing of one phrase of melody by another, like the balancing of one line of poetry by another, as in the verses

"The lowing herd winds slowly o'er the lea,

And leaves the world to darkness and to me."

is a most important one, as we shall soon see, in all modern music.

This balance of one large section of a melody by another is often referred to by the term "rhythm," owing to its analogy with "rhythm" in architecture (in the symmetry, for example, of two halves of a building). But it is simpler to keep the word rhythm, in music, to mean rather a characteristic combination of tones, as regards their relative length and accent, as, "the rhythm of the first motive in Beethoven's Fifth Symphony" (see motive quoted on page 5). In the present articles the word will be used in this latter sense.

In this chapter we have seen how music, in spite of its subtle, intangible nature, has certain definite features called "motives," which we can learn to recognize and follow by noticing the length, accent, metrical arrangement, and movement "up" or "down," of the tones of which they are composed.

We have seen that these primary motives are worked up into complete pieces of music by being repeated with such alterations as serve to vary them pleasantly without disguising them beyond recognition. The chief kinds of modified repetition we have noticed are "imitation," "transposition," and "restatement after contrast." All of these we have seen illustrated in "Three Blind Mice."

We have remarked how very gradually musicians got away from monotonous harping on their ideas by using these [15] devices. In connection with the Spanish folk-song, we have noted that, although imitation was not available, transposition and restatement were most effectively used.

Finally, we have seen that music, like poetry, has its larger balance of phrases, by which whole parts of a melody are set off against one another and made to balance, just as lines do in verse.

In succeeding chapters we shall trace out all these principles in more detail.

SUGGESTIONS FOR COLLATERAL READING.

Parry: "The Evolution of the Art of Music," Chapters I and II; Dickinson: "The Study of the History of Music," Chapter I; Grove: "Dictionary of Music and Musicians," article "Form."

In the first chapter we have traced the evolution of the formal element in music, the element through which it gradually attained coherence. We have seen that this element is an expression of that common sense which rules in all things; that the various expedients adopted in music as means of keeping the central idea before the listener, and, at the same time, providing him with sufficient variety to retain his interest, are dictated by that sense of fitness that operates everywhere in life. And these simple formal principles, so conceived, will be found to underlie the larger musical forms that will engage our attention in succeeding chapters.

Let us always keep in mind that, while the psychological effect of music remains a considerable mystery, and the appreciation of great music must be a personal and individual act involving a certain receptivity and sensitiveness to musical impressions, yet the perception of the logic or sense in a piece of music is a long step towards understanding it, and one of the best means of cultivating that receptivity and sensitiveness.

Folk-songs have been described by an eminent writer[1] as "the first essays made by man in distributing his notes [17] so as to express his feelings in terms of design." We shall shortly examine some typical folk-songs in order to see how this design gradually became larger and more various, and how, through this process, the foundations were laid for the masterpieces of modern instrumental music. We shall see that this advance has accompanied an advance in civilization; that as men's lives have become better ordered, as higher standards of living and thinking have appeared, the sense of beauty has grown until, finally, this steady progress has resulted in the creation of certain permanent types. It must be kept in mind, however, that these primitive types are largely the result of instinctive effort, and not of conscious musical knowledge. The science of music, as we know it, did not exist when these songs were written.

In order to distinguish between Folk-songs and songs like those of Schubert and Schumann, musicians call the latter "Art" songs. The folk-song is a na?e product, springing almost unconsciously from the hearts of simple people, and not intended to convey any such definite expression of the meaning of the words as is conveyed in modern songs. While there are specimens[2] of the art song that closely approach the simplicity and beauty of the folk-song, the art song in general is not only of wider range and of wider application to men's thoughts and feelings, but it also has, as an integral part of it, an accompaniment of which the folk-song, in its pure state, is entirely devoid.

A further distinguishing characteristic of the folk-song is that it is often composed in one of the old ecclesiastical "modes."

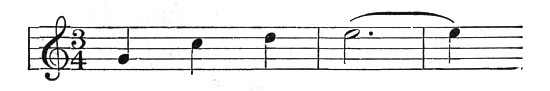

These modes were old forms of the scale that existed before our modern harmonic system came into use. The following English folk-song, called "Salisbury Plain," is in the "Aeolian" mode.

FIGURE IV.

This song is written in the scale represented by the white keys of a pianoforte beginning on A, and the peculiarly quaint effect of it is due to the unusual intervals of that scale as compared with our common scale forms. There are various modes[3] called "Phrygian," "Dorian," etc., each having its own peculiar quality. This quaintness and characteristic quality to be observed in modal folk-songs almost entirely disappears when an accompaniment of modern harmony is added, as is often done.

Folk-songs occupied a much more important place in the lives of the people who used them than is commonly supposed. When we consider that at the time the earliest of them were written few people could read or write, that books were printed in Latin, and that there were no newspapers, railways, or telegraphs, we can understand how large a part these old songs played in the scheme of life. The strolling singer was the newspaper of the time. Furthermore, the general illiteracy of the people made of the folk-song a natural vent for their feelings. With a limited vocabulary at their disposal, it was natural that they should use the song as a medium of expression for their joys and sorrows. Gesture was also part of their language, and in a modified way, as a means of expression, may be said to have performed something of the function of song. Many of the oldest melodies existed as an adjunct to dancing and religious ceremonials, and were, therefore, to some extent utilitarian. But so intimate was their relation to the ideas and feelings of the people who used them that, in spite of the crudeness and simplicity of the medium employed, the songs of the various nations are entirely distinct from each other, and to a remarkable degree express the characteristics of the people who produced them.

The songs used with this chapter are chosen chiefly to illustrate the various methods (already described) of attaining variety and unity in music. If little space is devoted here to other considerations, the reader must bear in mind that our purpose is to lead him finally to as complete an appreciation as possible of the masterpieces of instrumental [20] music, and that this appreciation must begin with a perception of the relationships between the various parts of a primitive piece of music.

In Figure V is shown the old English song "Polly Oliver."[4]

FIGURE V.

This is a traditional song handed down without any record of its origin, from generation to generation. Its unknown composer has managed very deftly to make it hang together. A good deal is made, in particular, of the characteristic little motive of three notes which first occurs at the beginning of the third measure.[5] In the very next measure, the fourth, this is "transposed" to a lower position. Going on, we find it coming in again, most effectively, [21] in measure 7, this time transposed upwards; and it occurs again twice at the end of the melody. Thus a certain unity is given to the entire tune. Again, the device of repetition after contrast is well used. After measures 1-9, which state the main idea of the melody, measures 9-13 come in with a pronounced contrast; but this is immediately followed up, in measures 13-17, by a literal repetition of the first four measures, which serves to round out and satisfactorily complete the whole. We thus see illustrated once more the scheme of form which, in the last chapter, we denoted by the letters A-B-A.

This song presents a further element of form by means of which much variety is imparted to music.

It will be noticed that the first phrase of "Polly Oliver" (measures 1-5) moves about the tone E-flat and ends upon it with the effect of coming to rest, and that the second phrase (measures 5-9) similarly moves about and comes to rest on the tone B-flat. The last phrase (13-17), like the first, moves about E-flat. This moving about a certain tone, which is, so to speak, the center of gravity of the whole phrase, is called by musicians "being in the key of" that tone; and when the center of gravity changes, musicians say that the piece "modulates" from one key to another. Thus, this first phrase is in the key of E-flat, the second modulates to the key of B-flat, and the song later modulates back again to the key of E-flat. Here we have another very important principle in modern music, the principle [22] of "key" or "tonality,"—important because it makes possible a great deal of variety that still does not interfere with unity. By putting the first part of a piece in one key, the second part in another, and finally the last part in the original key, we can get much diversity of effect, and at the same time end with the same impression with which we began. We shall only gradually appreciate the immense value to the musician of this arrangement of keys.

A further element of form is found in "Polly Oliver," namely, the balance of phrases. This balance of phrases one against another is derived ultimately from the timed motions of the body in dancing, or from the meter of the four line verse to which the music was sung. And this balance of phrases, derived from these elemental sources, still dominates in the melodies of the great masters, although it is managed with constantly increasing freedom and elasticity, so that we find in modern music little of that sing-song mechanical regularity which we may note in most folk-songs and dances.

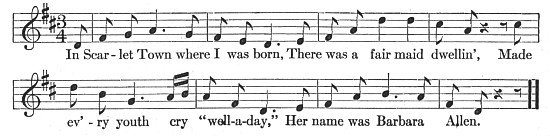

Let us now examine another old English song, "Barbara Allen."

FIGURE VI.

This also is a traditional song. The words celebrate the emotion of unrequited love, a favorite subject with the old ballad writers. In the music, we shall find a further illustration of the use of the devices already referred to.

We note first of all that there is throughout the melody a constant use of one rhythmic motive. This figure appears in the first four notes of the song, and is found at the beginning of every other measure save the fifth and the last. While these transpositions are not so literal as is that at the beginning of "Polly Oliver," they are nevertheless sufficiently close to serve the purpose of preserving unity while still providing variety. The tune is held together by this insistence on the motive; there is considerable variety in the melody [24] of the various phrases, but through it all runs this persistent rhythm.

Although "Barbara Allen" does not, strictly speaking, contain a modulation, since there is in the melody no note foreign to the key in which the song is written, yet the first and last phrases center round D, the key-note, while the second phrase (to the words "There was a fair maid dwellin'") centers round and comes to rest on A, thus producing the effect of a half pause, as if punctuated with a semicolon.

A very important point should be noted in reference to these half pauses or modulations in a melody, namely, that they usually occur on the fifth note of the scale of the original key, called by musicians the "dominant." In the three songs we have considered thus far the second phrase has so ended. This modulation to the dominant is the most common one in music, and we shall often have occasion to refer to it in later chapters.

Finally, a comparison of the third phrase of the music—"there was a fair maid dwellin'"—with the last—"her name was Barbara Allen"—will reveal a considerable similarity in both rhythm and melodic contour or curve. By means of this similarity, and by the return, in the last phrase, to the original key, our sense of proportion is satisfied and a certain logic is imparted to the tune. It should also be noticed that the melody is a perfect example of that balance of phrases already referred to, the two halves (1-5 and 5-9) being of precisely the same length.

"Barbara Allen" is like many other English tunes in being straightforward, positive, and, in a measure, unromantic. It lacks the soft, undulating, and poetic element to be observed in the Spanish folk-song (see Chapter I), but has a vigor and somewhat matter-of-fact quality characteristic of the race that produced it. The story was evidently popular in the olden time, as many versions of it with different music have been found all over England. All the important events of the times were celebrated in song. There were, for example, many songs about Napoleon and the danger of an invasion of England, such as "Boney's Lamentation." Songs were written about political affairs and about religion, and there were many dealing with popular characters such as Robin Hood. Celebrated criminals became the subjects of songs, while poaching and other lawless acts committed by the peasants—which in those days were punished with the greatest severity—were frequently used as the basis for the strolling singers' ballads. Such titles as "Here's adieu to all Judges and Juries," "The Gallant Poachers," and "Botany Bay" are frequently to be found.

From a perusal of a large number of the old songs one gathers a quite comprehensive idea of the ways of life and the thoughts and feelings of the people of "Merrie England." A kind of rude philosophy seems to have evolved itself out of the mass of common sentiment. And the verses, rude as they are, have a characteristic directness and vigor that gives them a value of their own.

Plain, definite narrative characterizes most of the English songs. The name of the hero and heroine are usually given with the greatest accuracy, as are all the other details of the story. One old English song, for example, begins as follows:

while another is entitled:

Still another begins:

This quality is in marked contrast to the more romantic and poetic element to be found in the songs of many European nations. This energetic and straightforward quality in old English melodies does not prevent them from being beautiful; they are true to human nature and unspoiled by sophistry.

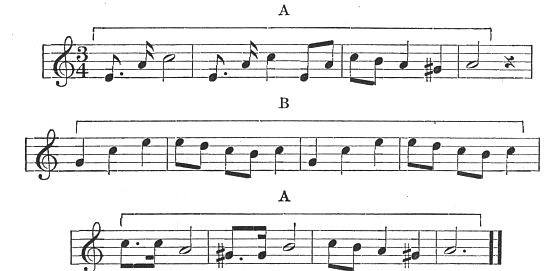

Our next illustration is an Irish song called "The Flight of the Earls," one of the most beautiful of melodies. (See Figure VII.)

In this illustration the curved lines represent the phrases and correspond to the lines of the poem, while the brackets show the larger formal structure of the melody, A being the statement, or clause of assertion, B the clause of contrast, and A the restatement. A mere glance at this music will show how certain phrases are used [27] throughout to hold the melody together. The first and second measures,[6] for example, contain a phrase of which one part or the other will be found in almost every measure of the song. The first half of the song ends at 9 with a modulation to the fifth above, or dominant, while the "restatement after contrast" (beginning on the last note of measure 13) is quite clear.

FIGURE VII.

Certain details may be pointed out for the benefit of the student. The first phrase, ending on the note D (5), gives a sense of being poised for a moment before proceeding to the next note, D not being a point of rest such as is supplied by the C with which the second phrase ends—at 9. The same device is used at the end of the third phrase (13). The clause of contrast (9-13), while based on the rhythm [28] of the motive of three notes at the beginning of the song, is distinguished from either of the other two parts by the absence of the characteristic sixteenth-note figure of measure two.

This song justifies all that we have said about the poetic beauty of folk-songs. Within its short compass are contained elements of perfection that may well astonish those who look on folk-songs as immaterial to the development of the art of music. For this melody is as complete and perfect an expression of that natural idealism that seems to have animated human beings from the earliest times as is the present day music of our own ideals.

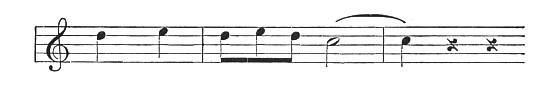

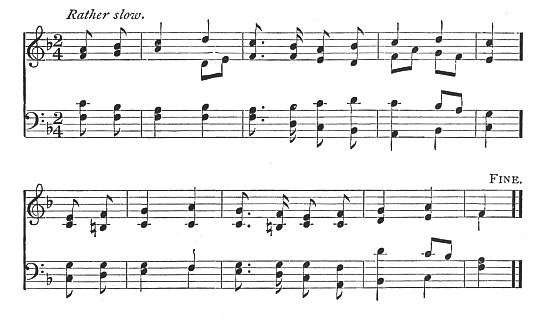

The next illustration is a well known German folk-song called "Sister Fair."

FIGURE VIII.

This melody is one of great beauty and tenderness. Like many other German folk-songs, it is full of quiet sentiment, not over-strained, but sweet and wholesome. [29] It contains certain formal elements with which we are already familiar: (1) "Repetition," between the first motive in measures 1 and 2, between measures 5-6 and 7-8, and between measures 3-4 and 11-12; (2) "transposition," where the motive in measure 9 is inverted in measure 10 (this is an imitation of rhythm but not of melody); (3) "restatement after contrast," the last four measures being, in effect, a repetition of the first four with the first motive from measure 9 inverted; (4) "modulation," the first phrase being in A-minor, the second in C-major, and the last in A-minor again. This is a particularly clear example of a modulation, as the three phrases distinctly centre round their respective key-notes, or tonal centres. It should be noted that the modulation is not to the fifth above the key-note, as in most of the other examples, but to the third above. This is common in songs in the minor key.

Quite a distinct charm is imparted to the first phrase of this melody by the use at the end of measure 2 of the little rhythmic figure that has already appeared at the beginning of the first and second measures. There is an unexpected charm in this shifting of a motive from one part of a measure to another. We shall see this device of musical construction in many of the larger works that are dealt with in later chapters.

There are a great many beautiful German folk-songs which would be well worth study here did space permit. The student is referred to such collections as Reimann's "Das Deutsche Lied," where the best of them will be found.

In this brief study of folk-songs we have noted that the stream of pure native melody was independent of the art-song and followed its own natural channel, but that, in spite of its limitation, presents to us some well developed formal types.

We have seen how important a part modulation plays in the plan of a piece of music, and how, by means of a change of key, a new kind of variety may be imparted to a melody.

We have observed how closely the old songs reflect the characteristics of the people who produced them, and how intimate was the connection between the songs—with the verses to which they were set—and the thoughts and feelings of those who used them.

In studying the German folk-song we have observed a subtle element of form, namely, the shifting of a motive from one part of a measure to another.

In the next chapter we shall take up the study of simple polyphonic pieces, such as have already been referred to in dealing with the round, "Three Blind Mice."

SUGGESTIONS FOR COLLATERAL READING.

Parry: "The Evolution of the Art of Music," Chapter III; Grove's "Dictionary of Music and Musicians," articles "Song" and "Form."

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Sir Hubert Parry in "The Evolution of the Art of Music."

[2] Such as Schubert's "Haiden-R?slein."

[3] The reader will find an account of these modes in Grove's Dictionary of Music under "Modes, Ecclesiastical."

[4] In Hadow's "Songs of the British Islands" (Curwen & Co., London).

[5] The first partial measure is counted as one.

[6] The partial measure at the beginning is counted as one.

We have seen in the last chapter some typical examples of folk-songs, which have served to give us an impression of folk-music in general, since it always conforms, in all essentials, to the type they illustrate. Folk-music is generally simple and unsophisticated in expression; it is generally cast in short and obvious forms; and it generally consists of a single melody, either sung alone or accompanied, on some primitive instrument, by a few of the commonest chords.

The prominence given to a single melody by music of this type, however, makes it unsuitable for groups of different voices, such as a vocal quartet or a chorus; and therefore when musicians began to pay attention to music intended for church use they had to work out a different style, in which several parts, sung by the various voices, could be strongly individualized. This led to what is called the "polyphonic," or "many-voiced" style. Another reason why the ecclesiastical style always remained unlike the secular was that the learned church musicians disdained any use of those methods which grew up in connection with folk-songs and dances, considering them profane or vulgar. Had they been willing to study them, they might have added much vitality to church music; but they maintained an attitude of aloofness and of contempt for the popular music.

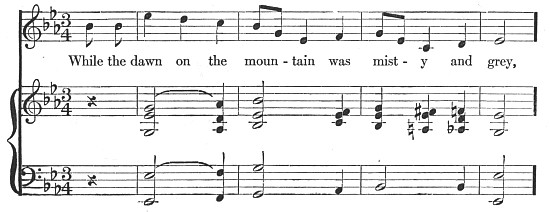

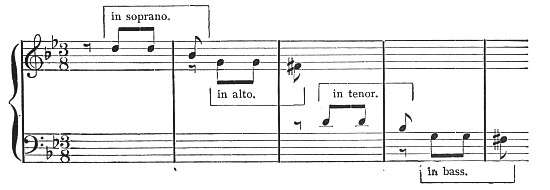

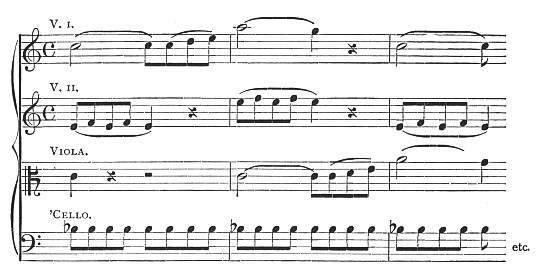

The peculiarity of the polyphonic style is that that portion of the music which accompanies the chief melody is no longer a series of chords as in folk-music, but a tissue of secondary melodies, like the chief one, and hardly less important. (This arises, as we have just suggested, from the necessity of giving each of the four voices or groups of voices,—soprano, alto, tenor, and bass,—something individual and interesting to do.) The difference between the two styles is apparent even to the eye, on the printed page. A folk-song, or any other piece in "homophonic" or "one-voiced" style, has the characteristic appearance of a line of notes on top (the melody), with groups of other notes hanging down from it here and there, like clothes from a clothes line (the accompaniment). A Bach fugue, in print, presents the appearance of four (or more) interlacing lines of notes. (See Figure IX.)

(a) Beginning of "Polly Oliver."

While the dawn on the mountain was mist-y and grey,

(b) Passage from Bach Fugue in G-minor

"Well-Tempered Clavichord," Book I.

FIGURE IX. DIFFERENCE BETWEEN "HOMOPHONIC" AND "POLYPHONIC" STYLE.

Historically speaking, the first great culmination of the polyphonic style is found in the ecclesiastical choruses of Palestrina (1528-1594); but it was not until somewhat later that this style was applied to instrumental music. In the inventions, canons, preludes, toccatas, and fugues of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750), we get the first great examples of polyphony as applied, not to merely ecclesiastical music, but to music which by its secular character and its variety of emotional expression is universal in scope.

Such is the ingenuity and the perfection of detail in Bach's works in the polyphonic style that a life-time might be spent in studying them. They have that delicacy of inner adjustment more usually found in the works of nature than in those of man; their melodies grow out of their motive germs as plants put forth leaves and flowers; their separate voices fit into one another like the crystals in a bit of quartz; and the whole fabric of the music stands on its elemental harmonies as solidly as the mountains on their granite bases. [34] We can hope to see as little of this august country of Bach's mind by analyzing a few pieces as a man may see of the hills and moors in a day's excursion—but, nevertheless, a beginning must be made.

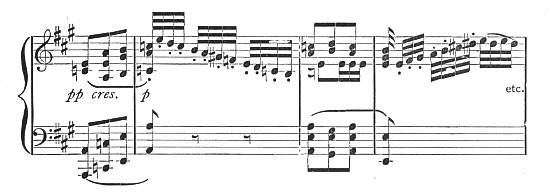

The essential features of this music may be seen in even so simple a piece as the Invention in F-major, number 7, in the two-voiced inventions, though it is written for only two voices and is but thirty-four measures long.

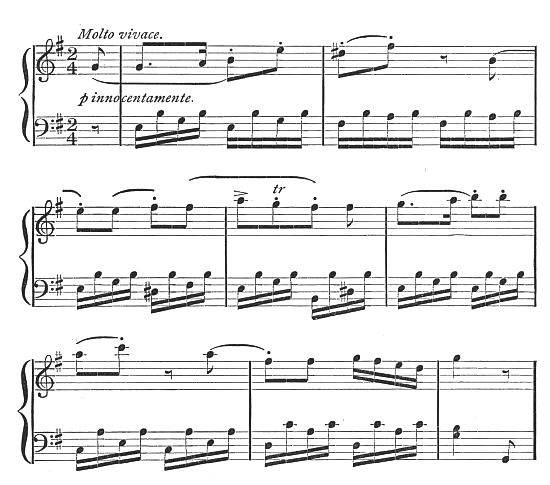

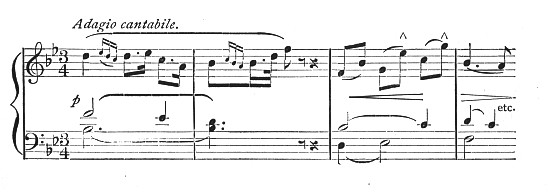

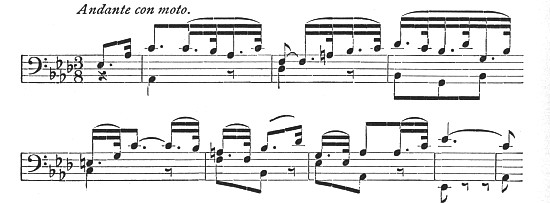

Bach: Two-voice Invention No. VIII., in F-Major.

The subject or theme of this invention is a melody of two measures' length, first given out by the soprano, and consists of two motives or characteristic figures, one in eighth-notes, staccato, making a series of leaps, thus:

and one a graceful descending run in sixteenth-notes, thus

Notice how charmingly the staccato and the legato are contrasted in these motives.

The entire invention is made out of this subject by means of those methods of varied repetition discussed in Chapter I., especially "imitation" and "transposition." For example, [35] the lower voice, which we will call the bass, "imitates," almost exactly, through the first eleven measures, what the soprano says a measure before it. On the other hand, in measure 12 the bass starts the ball a-rolling by giving the subject (this time in the key of C), and the soprano takes its turn at imitating. Then, from measure 29 to the end, it is again the soprano which leads and the bass which imitates. The student should trace out these imitations in detail, admiring the skill with which they are made always harmonious.

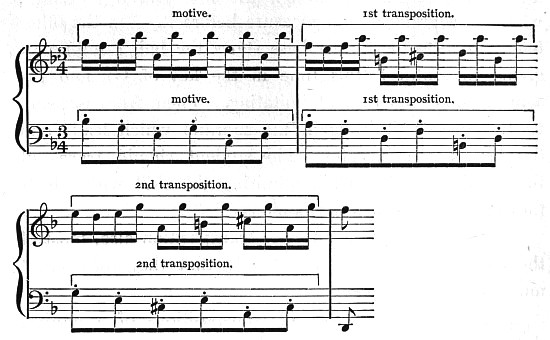

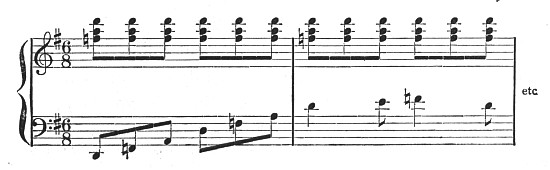

There are many instances of transposition also, most of them carried out so systematically that they form what musicians call "sequences."

A sequence is a series of transpositions of a motive, shifting it in pitch either upward or downward, and carried out systematically through several repetitions. Examples: measures 4, 5, and 6, transposition of the motive in soprano, three repetitions; measures 21, 22, 23, transposition of motives of both voices, three repetitions; measures 24, 25, transposition of motives of both voices, two repetitions. The second of these sequences is shown in Figure X.

It will be noted what a strong sense of regular, orderly progress these sequences impart to the melodies.

It is interesting to see that the same general scheme of keys is embodied in this invention that we have observed in folk-songs: i. e., the modulation to the "dominant" in the middle (measure 12), and the return at the end to the original key. This divides the piece into two unequal halves, the first making an excursion away from the home [36] key, the second returning home—much as the King of France, with twenty thousand men, marched up the hill and then marched down again. Such a two-part structure is observable in thousands of short pieces, and is called by musicians "binary form."

FIGURE X. "Sequence" from Bach's Invention in F-Major.

The difference in texture between this piece and any folk-song or dance will best be appreciated by playing over the bass part alone, when it will be seen that, far from being mere "filling" or accompaniment, it is a delightful melody in itself, almost as interesting as its more prominent companion. Indeed, in the whole invention there are only two tones (the C and the A in the final chord) which are not melodically necessary. Such is the splendid economy and clearness of Bach's musical thinking.

Before going further, the reader should examine for himself [37] several typical inventions, as, for example, No. I, in C-major; No. II, in C-minor; No. X, in G-major, and No. XIII, in A-minor, in this set by Bach, noting in each case: (1) the individuality of the motives used, (2) the imitations from voice to voice, (3) the sequences, (4) the modulations, (5) the polyphonic character, as evidenced by the self-sufficiency and melodic interest of the bass, and (6) the structural division of the entire invention into more or less distinct sections.

The same general method of composing that is exemplified in the inventions we see applied on a larger scale in the fugues of Bach.

The definition of a fugue given by some wag—"a piece of music in which one voice after another comes in, and one listener after another goes out"—is true only when the listeners are uneducated. For a trained ear there is no keener pleasure than following the windings of a well written fugue. It is, at the same time, true that a fugue presents especial difficulties to the ear, because of its intricately interwoven melodies. In a folk-song there is not only but one melody, with nothing to distract the attention from it, but it is composed in definite phrases of equal length, like the lines in poetry, with a pause at the end of each, in which the mind of the listener can take breath, so to speak, and rest a moment before renewing attention. Not so in the fugue, where the bits of tune occur all through the whole range of the music, are of varying lengths and character, and overlap [38] in such a way that there are few if any moments of complete rest for the attention. Perhaps this is the chief reason why fugues have the reputation of being "dry."

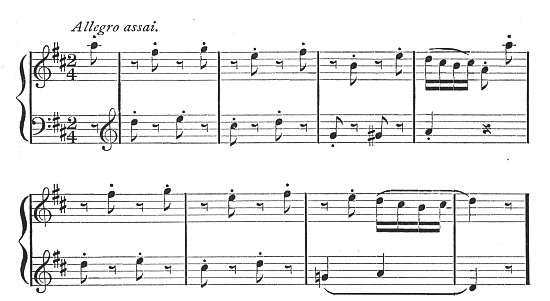

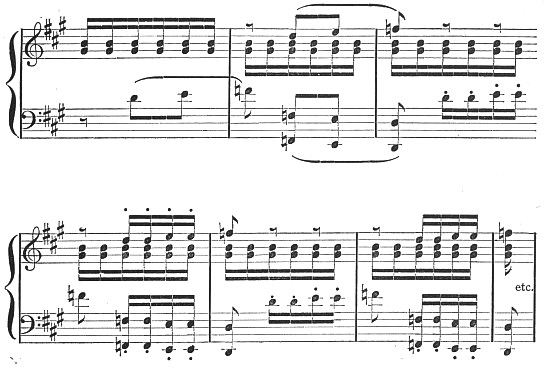

As is suggested by the derivation of the word "fugue," from the Latin "fuga," a flight, the characteristic peculiarity of the form is the entrance, one after another, of the several voices, which thus seem to pursue or chase one another, to go through a sort of musical game of "tag," in which first one and then another is "It." First one voice begins with the "subject" of the fugue, in the "tonic" key (key in which the piece is written). Next enters a second voice, "imitating" the first, but presenting the subject not in the "tonic," but in the "dominant" key. Then a third, once more in the tonic, and finally the fourth, again in the dominant. After these entrances all four voices proceed to play with the subject, transposing it in all sorts of ingenious ways, and straying off at times into episodes, generally in "sequence" form, but finally coming back, towards the end of the fugue, with renewed energy to the subject itself. All this may be seen in such an example as the Fugue in C-minor in Bach's "Well-Tempered Clavichord."

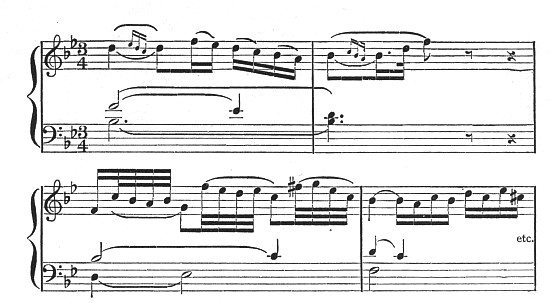

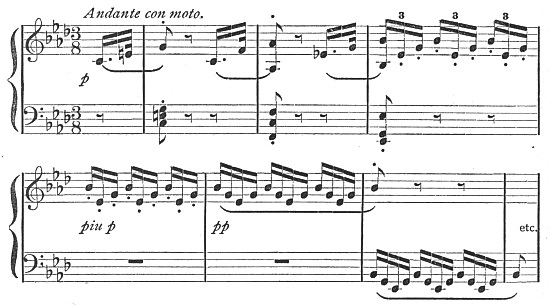

Bach: Fugue No. 2, C-minor, in three voices. "Well-Tempered Clavichord." Book 1. [7]

Like all the fugues in Bach's "Well-Tempered Clavichord," this fugue is preceded by a prelude, in free style, like a series of embroideries on chords, intended to prepare [39] the nearer for the more active musical enjoyment of the fugue to come. Parry, in the "Oxford History of Music," says of the Prelude of Bach and Handel: "It might be a simple series of harmonies such as a player might extemporize before beginning the Suite or the Fugue, [such is the case in the present prelude]; or, its theme might be treated in a continuous consistently homogeneous movement unrestricted as to length, but never losing sight of the subject" ... etc.

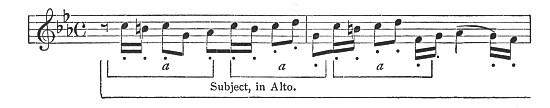

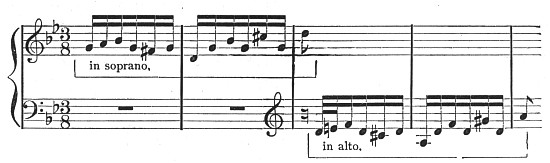

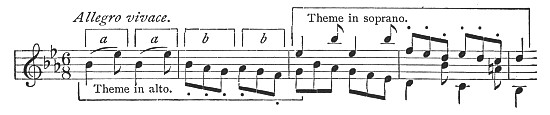

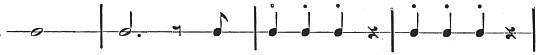

A fugal subject is usually longer and more pretentious than an invention subject, and more nearly approaches what we should call a complete melody. It may contain several motives. Moreover, while the second voice is "answering" the subject, the first voice continues with further melody, and if this is of definite, individual character it may easily assume almost as great importance as the subject itself, in which case we may give it the name of "counter-subject." In Figure XI the subject and counter-subject of this fugue are shown. The long brackets show subject and counter-subject; the short brackets show the three chief motives, marked a, b, and c. The simplicity of the melodic material is noticeable. Motive a, which, with its three repetitions, forms most of the subject, consists of five tones, in a charming and unforgettable rhythm of two shorts and three longs. Motive b is simply a descending scale, in equal short notes. Motive c is four equal long notes. Play the subject and counter-subject through separately, several times, and get them well "by heart" before going farther.

This fugue is a wonderful example of what a master-composer can make out of simple materials; the whole piece is built from these three motives. Our analysis may conveniently be made in tabular form, the student being expected to trace out the development for himself, measure by measure.

FIGURE XI. SUBJECT AND COUNTER-SUBJECT OF BACH'S FUGUE IN C-MINOR

(WELL-TEMPERED CLAVICHORD)

TABLE OF THEMATIC TREATMENT OF FUGUE IN C-MINOR

| Measures. | |

| 1-2 | Subject in Alto. |

| 3-4 | Subject "answered" in Soprano ("imitation"), counter-subject in Alto. |

| 5-6 | Episode 1: Motive a prominent in Soprano. |

| 7-8 | Subject in Bass, counter-subject in Soprano, fragments of motive c in Alto. |

| 9-10 | Episode 2: Motive a tossed between Soprano and Alto, motive b in Bass. |

| 11-12 | Subject, in key of E-flat major, in Soprano, counter-subject in Bass. |

| 13-14 | Episode 3: Motive b in Soprano, motive c in other two voices. |

| 15-16 | Subject in Alto, counter-subject in Soprano, motive c in Bass. |

| 17-19 | Episode 4: Motives a and b variously distributed between all three voices. |

| 20-21 | Subject in Soprano, in tonic key again, counter-subject in Alto, motive c in Bass, |

| 22-25 | Episode 5: Motives a and b in all voices. |

| 26-28 | Climax: Subject in Bass, motives b and c in other voices. |

| 29-31 | Coda: Subject in Soprano. |

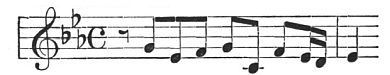

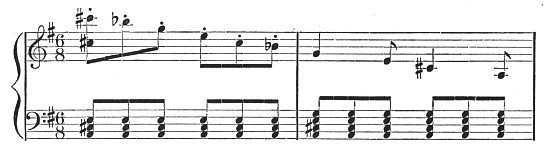

Note that all the episodes take the form of sequences, as, for example, in the following instance (measures 9-10):

FIGURE XIa. A SEQUENCE FROM BACH'S FUGUE IN C-MINOR.

The general form of this fugue illustrates the same principles of modulation, and of restatement of subject after contrast, that we noticed in the folk-songs and in the invention. This may be tabulated thus:

TABLE SHOWING STRUCTURE OF FUGUE IN C-MINOR.

| A. | B. | A. |

| STATEMENT. | CONTRAST. | RESTATEMENT. |

| Measures 1-10 in key of | Measures 11-19 in various keys, | Measures 20-31 in |

| C-minor. | beginning with E-flat. | C-minor. |

The modulation in this case, however, is not to the "dominant" key, but to what is called the "relative major" key, as is usual in pieces written in minor keys, [42] (see the folk-song, "Sister Fair," in Chapter II), the reason being that the relative major affords the most natural contrast to a minor key, just as the dominant affords the most natural contrast to a major key.

The conclusion is emphasized by the finely rugged statement of the subject in Bass at measure 26.

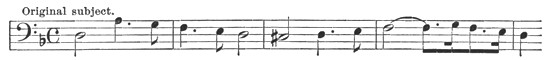

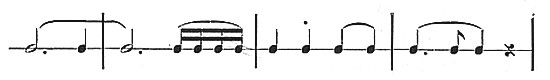

The treatment of this fugue, for all its consummate skill, is comparatively simple. It does not employ the more subtle devices often employed in fugues, of which may be mentioned the following:

1. "Inversion:" The subject turned upside down, while retaining its identity by means of its rhythm.

Original Subject.

Inversion.

FIGURE XII. THE DEVICE OF "INVERSION."

Original Subject.

Augmentation.

Original Subject.

Diminution.

FIGURE XIII. THE DEVICES OF "AUGMENTATION" AND "DIMINUTION."

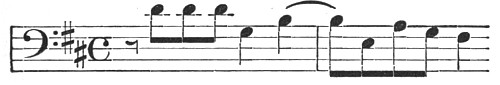

2. "Augmentation and Diminution:" The length of the notes doubled or halved, while their relative length, or rhythm, is carefully maintained. (Figure XIII.)

3. "Shifted rhythm:"[8] The subject shifted as regards its position in the measure, so that all the accents fall differently.

Original Subject.

Shifted.

FIGURE XIV. DEVICE OF "SHIFTED RHYTHM."

4. "Stretto:" The imitation of the subject by a second voice occurring prematurely, before the first voice has completed the subject, frequently with highly dramatic effect. (b) in Figure IX is an example of stretto.

These devices are mentioned here not only because they occur in many fugues, but because they are used in the symphonic music of Mozart and Beethoven, as we shall later have occasion to see.

Perhaps the most exacting of all tests applicable to music is the test of economy. Are there superfluous tones that do not enrich the harmony? Are there unnecessary subjects not needed to fill the scheme of design? If so, no matter how beautiful the music, it is defective as art. Bach bears this test victoriously. There is not a note of his writing which one would willingly sacrifice. There is not [44] a melody that is not needed. Each subject is not merely introduced and dismissed, but is developed to the utmost, so that all that was implicit in its germ becomes explicit in its final form. There is no confusion of the outline, no overcrowding of the canvas, no blotchiness in the color. As Giotto proved his supremacy among draughtsmen by the apparently simple but really enormously difficult feat of drawing a complete, perfect circle with one stroke of the pencil, so Bach constantly proves his supremacy among musicians by making two voices satisfy the ear like an orchestra. And this purity of texture is quite compatible with the utmost richness. Indeed, Bach's polyphonic scores are inimitably rich, since each voice sings its own melody, and the melodies all interplay harmoniously like the lines of a well-composed picture. Those who call Bach's fugues dry make an astonishing confession of their own insensibility or crudity of taste. Bach's melodies are not, to be sure, like "Annie Laurie" or "Home, Sweet Home." But neither is daylight like candle light; yet we do not call it darkness because it is diffused through all the atmosphere instead of concentrated in a single visible ray.

Bach's daring has been the subject of the endless admiration of students. Especially in the matter of harmony he did things in the eighteenth century, and entirely on his own responsibility, that whole schools of composers band together with a sense of revolutionary courage to do in the twentieth. He is truly one of the most modern of composers, and will always remain so. Composers who [45] might have been his grandsons are now antiquated, while he is always contemporary with the best musical thought. Brahms, irritated at Rubinstein's persistent patronizing of "Papa Haydn" in his book, "A Conversation on Music," remarked in his dry way: "Rubinstein will soon be Great-grandfather Rubinstein, but Haydn will then be still Papa Haydn." The same might be said even more truly of Bach, who will always be the father of musicians.

Another way in which Bach is modern is in the variety of his musical expression. It is not only that his range of different species of works is so great, reaching from the ecstatically tender and exalted religious choral compositions, such as cantatas, motets, oratorios, and passions, through the grand and monumental organ toccatas and fugues, to the intimate, colloquial suites and sonatas for orchestra and for clavichord; it is even more wonderful that in a single work, such as the "Well-Tempered Clavichord," he knows how to sound the whole gamut of human feeling, from the deep and sombre passions of the soul to the homely gaiety or bantering humor of an idle moment.[9] Bach might have boasted, had it been in his nature to boast, that in this work he had not only written in every key known to musicians, but in every mood known to men. It is the musical "Com?ie Humaine."

Bach lived quietly and in almost complete obscurity; for the last quarter-century of his life he held a post as teacher of music and church-music director in Leipsic.

He travelled little, sought no worldly fame, took no pains to secure performances of his works, and, above all, made no compromise with the popular taste of his day. He produced his great compositions, one after another, in the regular day's work, for performance in his church or by local orchestras and players. He never pined for a recognition that in the nature of things he could not have; he wrote the music that seemed good to him, and thought that his responsibility ended there, and that his reward lay there. The cynic who said "Every man has his price" was evidently not acquainted with the life of Bach. Steadily ignoring those temptations to prostitute his genius for the public's pleasure, which so materially affected the life course of his great contemporary Handel, he followed his own ideals with an undivided mind. As always happens in such cases, since it takes decades for the world to comprehend a sincere individual, or even centuries if his individuality is deep and unique, he was not appreciated in his life-time, nor for many years after his death.

Indeed, he is not appreciated now, for a man can be appreciated only by his equals. But we have at last got an inkling of the treasure that still lies hidden away in Bach; and while Handel and the other idols of the age sound daily more thin and archaic, Bach grows ever richer as the understanding we bring to him increases, and still holds out his promise of novel and perennial artistic delights.

SUGGESTIONS FOR COLLATERAL READING.

W. R. Spalding: "Tonal Counterpoint." Edward Dickinson: "Study of the History of Music," Chapter XX. C. H. H. Parry: "Evolution of the Art of Music," Chapter VIII.

FOOTNOTES:

[7] Number the measures, and call the voices soprano, alto, and bass.

[8] The reader should examine the example of shifted rhythm given in the second chapter in dealing with the German song, "Sister Fair."

[9] In Book I, for example, Fugue II is as light and delicate as XII is serious and earnest; XVI is pathetic, XVII vigorous and rugged, XVIII thoughtful and mystical, etc.

In the last chapter we studied the most important applications of the "polyphonic" style, which originated in music for voices, to the music of instruments. We saw how in such music the attention of the composer was divided among several equally important voices or parts, and how much he made of the principle of imitation; and in connection with the fugue we remarked that the very complex interweaving of the different voices in such music, one beginning before another leaves off, and all together making an intricate web, presented certain difficulties to the listener accustomed to the more modern style, in which a single voice has the melody, and stops short at regular intervals, giving the hearer a chance to draw breath, as it were, and renew attention for what is coming next. Listening to modern music is like reading a series of short sentences, each clearly and definitely ended by its own full stop. Listening to the old polyphony is more like reading one of those long and involved sentences of De Quincey or Walter Pater, in which the clauses are intricately interwoven and mutually dependent, so that we can get the sense only by a long-sustained effort of attention.

This more involved style, suitable to voices, but less [49] natural to instruments, had historically a very long life. Much of the instrumental music of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries was in fact nothing but a transference to instruments of music really conceived for voices. Thus, for example, in the sixteenth century, when madrigals and canzonas, which were compositions for voices in the polyphonic style but of a more secular character than church music, were exceedingly popular, the composers for stringed instruments and for the then very fashionable lutes, "when they wanted something of a superior order, ... simply played madrigals, or wrote music in imitation of any of the varieties of choral music, not realizing that without the human tones ... which gave expression to the rising and falling of the melodic material, the effect was pointless and flat."[10] Even Bach and Handel, in the eighteenth century, were, by their deeply-rooted habit of thinking vocally, in some degree hampered in the search for a purely instrumental style. Instrumental music, having to get along without words, must find some principle of coherence, some kind of definite design, which will make it intelligible without the help of words, and enable it to stand on its own feet.

And here comes in the importance of folk-song, and of the folk-dance which grew up beside it, to our modern instrumental music. For both song and dance pointed the way to such a principle of independent intelligibility, through definite balance of phrases (see Chapter I), and through contrasts and resemblances of key in the various phrases and [50] sections of a composition. Music intended to accompany songs or dances had to consist of balanced phrases of equal length—in the case of songs, because it had to reproduce the verse structure of the words, which of course were composed in regular stanzas of equal lines, and in the case of dances, because it had to afford a basis for symmetrical movements of the body. And when once it was thus divided up into equal phrases, it took musicians but a short time to find that these phrases could be effectively contrasted, and made the parts of larger musical organisms, by being put into different keys (as we have seen in the instances of modulation cited in Chapters II and III). How vital these principles of structure in balanced phrases and sections, and of contrast of keys, are to the entire modern development of music, we shall realize fully only as we proceed.

Again, both song and dance have proved supremely important to the development of the homophonic style (one melody, with accompaniment not itself melodic). In the case of song the reason is obvious. A song rendered by a solo voice, with instrumental accompaniment, naturally takes the homophonic style, since it would be highly artificial to make the subordinate element in the combination as prominent as the chief one. Dance is less inevitably homophonic than song; indeed many dances, as we shall see, are to a greater or less degree polyphonic; but nevertheless the tendency toward homophony is always apparent. In the first place, the interweaving of many melodies would tend to obscure the division into definite phrases, since an inner melody might sometimes fill up the pause in the main one, [51] as we saw it constantly doing in the fugue. Secondly, the mode of performing dances tends to give prominence to a single melody. The old dances were generally played by one melodic instrument, such as a violin or hautboy, accompanied by chords on an instrument of the lute or guitar [52] family, and frequently by a drum to strengthen the accents. Such a combination affords but one prominent "voice," and does not lend itself naturally to polyphonic writing.

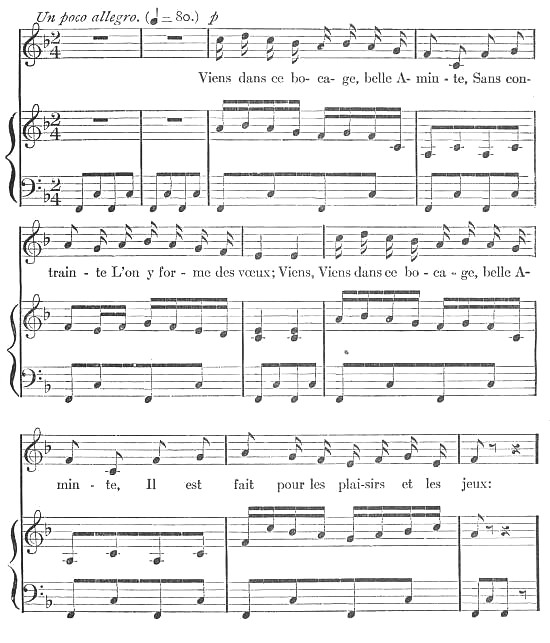

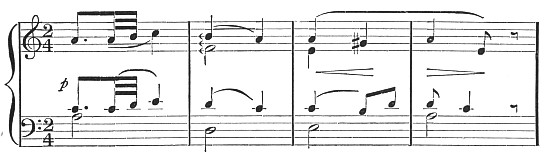

FIGURE XV.

Viens dans ce bo- ca- ge, belle A- min - te,

Sans contrain - te L'on y for - me des vœux; Viens,

Viens dans ce bo - ca - ge, belle A- min - te,

Il est fait pour les plai-sirs et les jeux:

The "Tambourin," for instance, an old French dance of Provence, was played by one performer, the melody with one hand on the "galoubet," a kind of pipe or flageolet, and the accompanying rhythm with the other on a small drum. The quotation in Figure XV, taken from Wekerlin's collection, "Echos du Temps Pass?" (Vol. III), is a good example of this ancient dance. In this arrangement for piano, the left hand imitates the drum, and the right hand the "galoubet" or pipe. This quotation illustrates the common use of dance melodies in songs. Many primitive airs were so used in the olden times.

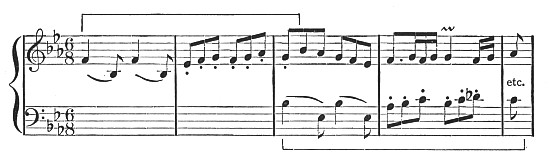

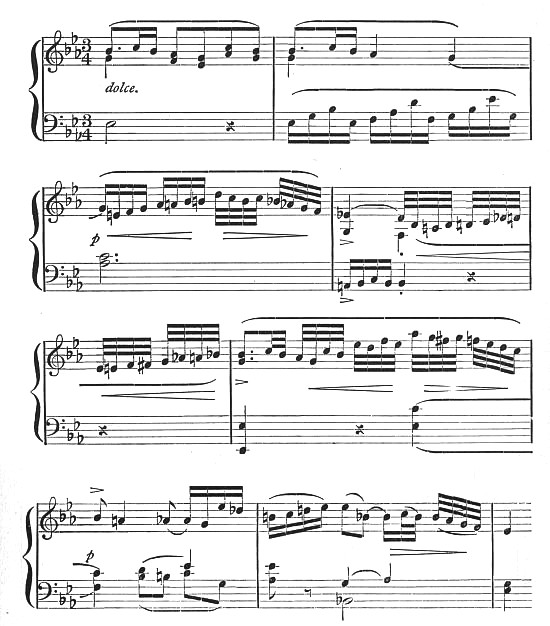

The rude dances which spring up spontaneously in all communities, savage as well as civilized, and of which we in America have examples in the war-dances of Indians and the cake-walks of negroes, are thus seen to be pregnant of influence on developed musical art, no less than the folk-songs which we discussed in the second chapter, and the more academic music in the polyphonic style which we treated in the third. Both songs and dances, indeed, sometimes enter into artistic music even in their crude form, but in most cases composers treat them with a certain freedom, and in various ways enhance their effectiveness, as Haydn, for instance, treats the Croatian folk-tune "Jur Postaje," in [53] the Andante of his "Paukenwirbel" Symphony. In Figure XVI the reader will see both the crude form of the tune and the shape into which Haydn moulds it for his purposes.

"Jur Postaje."

HAYDN'S Version.

FIGURE XVI.

In the long process of development which songs and dances thus undergo at the hands of composers, they of course lose to some extent their contrasting characters, until in modern music the dance and the song elements are as inextricably interwoven as the warp and the woof of a well-made fabric.

As imitation is only slightly available in homophonic music, the unity so vital to all art is attained in dances chiefly by transpositions of motives, often in systematic "sequences," by more or less exact balance of phrases, and by restatement after contrast. In crude examples these means are crudely used; in the work of masters they are treated with more subtlety and elasticity; but always a careful analysis will discover them. It will now prove enlightening to compare, from this point of view, three dance tunes of very different degrees of merit.

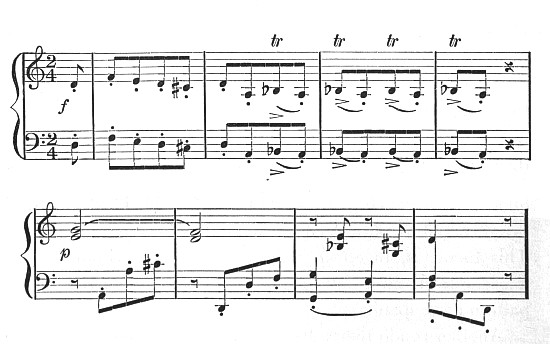

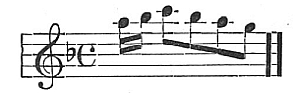

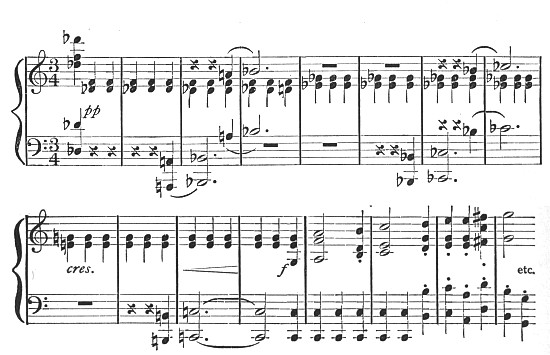

FIGURE XVII.

A "Branle" or "Brawl" from Arbeau's Orchesographie, (1545).

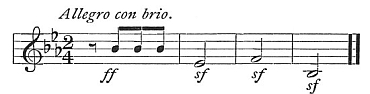

Figure XVII shows an ancient "Branle" or "Brawl" of the sixteenth century, taken from Arbeau's "Orchesographie," published in 1545.

The strong meter, causing a distinct accent on the first note of each measure, will at once be noted, especially if it be contrasted with the more moderate accentuation of the folk-songs of Chapter II. Such strong meter is naturally characteristic of all dance tunes, intended as they are to guide and stimulate the regular steps of the dancer.

The phrase balance, though marked, is not absolutely regular, but the two two-measure phrases at the beginning and the single one at the end suffice to give an impression of pronounced symmetry. The six-measure phrase after the double-bar is generated by the sequential treatment of the little motive of measure 5.

This sequence (measures 5, 6, 7, 8, 9) is worthy of note because of the excessive length to which it is carried. Five repetitions are too many, and grow monotonous. A more skilful composer would have secured his unity without so great a sacrifice of variety—in a word, he would have treated a device good in itself with less crudity.

The exact repetition of measures 3-4 at the end is an effective use of restatement after contrast. Although the whole of the original theme is not given, there is enough of it to give the sense of orderliness in design.

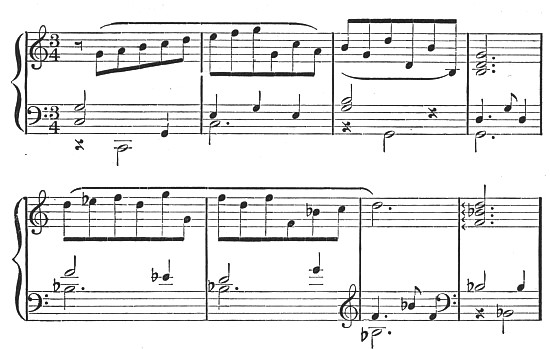

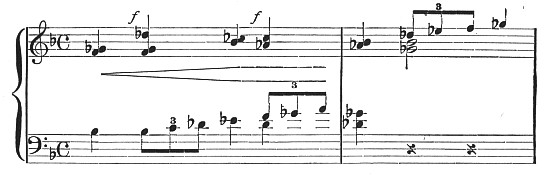

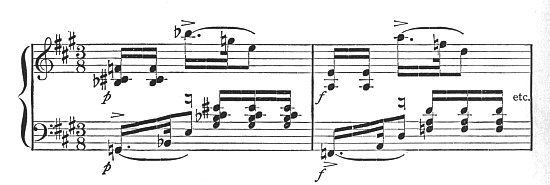

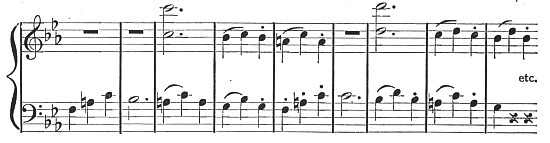

A Gavotte in F-major by Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713), the famous violin virtuoso of the seventeenth century, printed in Augener's edition of Pieces by Corelli, will illustrate a distinctly higher stage in the treatment of a dance form. This is well worth a brief analysis.

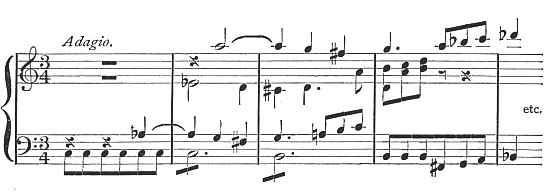

Corelli: Gavotte in F-Major.