DEDICATED TO THE MEN OF THE SOUTH WHO SUFFERED EXILE. IMPRISONMENT AND DEATH FOR THE DARING SERVICE THEY RENDERED OUR COUNTRY AS CITIZENS OF THE INVISIBLE EMPIRE

This volume closes, as originally planned,

“The Leopard’s Spots”

“The Clansman”

“The Traitor”

“The Clansman” ended with the political triumph of the Klu Klux Klan, or Invisible Empire. The story of “The Traitor” opens with the order of dissolution by General Forest and is set in the atmosphere of the fierce neighborhood feuds which marked the Klan’s downfall in the Piedmont region of the South.

Thomas Dixon, Jr.

New York, 1907.

CONTENTS

LEADING CHARACTERS OF THE STORY

CHAPTER II—MR. HOYLE RECEIVES A SHOCK

CHAPTER VI—SCALAWAG AND CARPETBAGGER

CHAPTER VII—THE REIGN OF FOLLY

CHAPTER X—THE STRENGTH OF THE WEAK

CHAPTER XI—THROUGH THE SECRET PANEL

CHAPTER II—WEIGHED AND FOUND WANTING

CHAPTER IV—ACKERMAN SECURES A PLEDGE

CHAPTER VI—THE TRAIN FOR THE NORTH

CHAPTER VII—THE DAUGHTER OF EVE

CHAPTER VIII—THE TRACKS AT THE DOOR

CHAPTER XII—THE TRAP IS SPRUNG

CHAPTER XIV—THE JUDGMENT HALL OF FATE

CHAPTER II—THROUGH PRISON BARS

CHAPTER IV—THE HON. STEPHEN HOYLE

CHAPTER VI—THROUGH DEEP WATERS

CHAPTER VII—THE PRISONER AT THE BAR

CHAPTER VIII—THE MINISTRY OF ANGELS

CHAPTER IX—THE DAY OF ATONEMENT

CHAPTER X—UNDER BRIGHT SKIES—AN EPILOGUE

Scene: The Foothills of North Carolina.

Time: 1870 to 1872.

John Graham.............Ex-chief of the Klan

Major Graham............His Father

Billy...................His Brother

Alfred..................The Family Butler

Mrs. Wilson.............Their Landlady

Susie...................Her Daughter

Dan Wiley...............A Mountaineer

Steve Hoyle.............Chief of the New Klan

Judge Butler............Of the U. S. Circuit Court

Stella..................His Daughter

Aunt Julie Ann..........His Cook

Maggie..................Stella’s Maid

Suggs...................A Detective

Ackerman................Of the U. S. Secret Service

Alexander Larkin........A Carpetbagger

Isaac A. Postle.........A Sanctified Man

The Attorney General of the United States Hon. Reverdy Johnson of Maryland

Hon. Henry Stanbery.....Of Ohio

U. S. Grant.............The President

WHAS the mather with the latch!

He shook it gently.

“No mistake about it—grown solid to the fence. I’ll have to climb over.”

He touched the points of the sharp pickets, suddenly straightened himself with dignity and growled:

“I won’t climb over my own fence, and I won’t scratch under. I’ll walk straight through.”

A vicious lurch against the gate smashed the latch and he fell heavily inside.

He had scarcely touched the ground when a fair girl of eighteen, dressed in spotless white, reached the gate, running breathlessly, darted inside, seized his arm and helped him to his feet.

“Mr. John, you must come home with me,” she said eagerly.

“Grot to see old Butler, Miss Susie.”

“You’re in no condition to see Judge Butler.” She spoke with tenderness and yet with authority.

“And why not?” he argued good-naturedly. “Ain’t I dressed in my best bib and tucker?”

He brushed the dirt from his seedy frock coat and buttoned it carefully.

“You’ve been drinking,” pleaded the girl.

“Yet I’m not drunk!” he declared triumphantly.

“Then you’re giving a good imitation,” she said with an audible smile.

“Miss Susie, I deny the allegation.”

He bowed with impressive dignity.

Susie drew him firmly toward the street.

“You mustn’t go in—I ran all the way to stop you in time—you’ll quarrel with the Judge.”

“That’s what I came for.”

“Well, you musn’t do it. Mama says the Judge has the power to ruin you.”

John’s eyes shot a look of red hate toward the house and his strong jaws snapped.

“He has done it already, child!” he growled; paused, and changed his tone to a quizzical drawl. “The fact is, Miss Susie, I’ve merely imbibed a little eloquence on purpose to-night to tell this distinguished ornament of the United States Judiciary, without reservation and with due emphasis, just how many kinds of a scoundrel he really is.”

“Don’t do it.”

“It’s my patriotic duty.”

“But you’ll fight.”

“Far from it, Miss Susie. I may thrash the Judge incidentally during our talk, but there will be no fight.”

“Please don’t go in, Mr. John!” she pleaded softly.

“I must, child,” he answered, smilingly but firmly. “Old Butler to-day used his arbitrary power to disbar me from the practice of law. If that order stands, I’m a pauper. I already owe your mother for two months’ board.”

“We don’t want the money,” eagerly broke in the girl.

“Two months’ board,” he went on, ignoring her interruption, “for my dear old crazy Dad, helpless as a babe with his faithful servant Alfred who must wait on him—two months’ board for my bouncing brother Billy, an eighteen-year-old cub who never missed a meal—two months’ board for my war-tried appetite that was never known to fail. No, Miss Susie, we can’t impose on the good nature of the widow Wilson and her beautiful daughter who does the work of a slave without wages and without a murmur.”

Susie’s eyes suddenly fell.

“No, I’ve given Alfred orders to pack. We must move to-morrow.”

“You’ll do nothing of the kind,” cried the girl. “You can pay us when you are able. Your father saved us from want during the war. We owe him a debt that can’t be paid. He is no trouble, and Alfred works the garden. Mother loves Billy as if he were my brother. And we are honoured in having you in our home.”

The tender gray eyes were lowered again.

John looked at her curiously, bowed and kissed her hand.

“Thanks, Miss Susie! I appreciate, more than I can tell, your coming alone after me here to-night—a very rash and daring thing for a girl to do in these troublesome times. Such things make a fellow ashamed that he ever took a drink, make him feel that life is always worth the fight—and I’m going to make it to-night—and I’m going to win!”

“Then don’t give old Butler the chance to ruin you,” pleaded the gentle voice.

“I won’t, my little girl, I won’t—don’t worry! I’ll play my trump card—I’ve got it here.”

He fumbled in his pocket and drew out a letter which he crushed nervously in his slender but powerful hand, drawing his tall figure suddenly erect.

The girl saw that her pleadings were in vain, and said helplessly:

“You won’t come back with me?”

“No, Miss Susie, I’ve serious work just now with the present lord of this manor; my future hangs on the issue. I’ll win—and I’ll come home later in the evening without a scratch.”

Again the slender white hand rested on his arm. “Promise me to wait an hour until you are cooler and your head is clear before you see him—will you?”

“Maybe,” he said evasively.

“If you do appreciate my coming,” she urged, “at least show it by this; promise for my sake, won’t you?”

He hesitated a moment and answered with courtesy:

“Yes, I promise for your sake, Susie, my little mascot and fellow conspirator of The Invisible Empire—good-bye!” He seized her hand, and held it a moment. “My! my! but you look one of us to-night, with that sylph figure robed in white standing there ghost-like in the moonlit shadows!”

“I wish I could share your dangers. I’d go on a raid with you if you’d let me,” she cried eagerly.

“No doubt,” he laughed.

“I’ll sit up until you come,” she whispered as she turned and left him.

John Graham leaned against the picket fence and watched intently the white figure until Susie Wilson disappeared. The talk with her had more than half sobered him.

“And now for business,” he muttered, turning through the open gate toward the house. He stopped suddenly with amazement.

“Well, what the Devil! every window from cellar to attic ablaze with light. And the old scoundrel has always kept it dark as the grave.”

He seated himself on a rustic bench in the shadows to await the lapse of the hour he had promised Susie, and pondered more carefully the plan of personal vengeance against Butler which was now rapidly shaping itself in his mind. That he had the power, as chief of the dreaded Ku Klux Klan, to execute it was not to be doubted. The Invisible Empire obeyed his word without a question.

Tender memories of his childhood began to flood his soul. Beneath these trees he had spent the happiest days of life—the charmed life of the old régime. He could see now the stately form of his mother moving among its boxwood walks directing the work of her slaves.

He had not been there before since the day her body was carried from the hall five years ago and laid to rest in the family vault in the far corner of the lawn. Ah, that awful day! Could he ever forget it? The day old Butler brought his deputy marshals and evicted his father and mother from the home they loved as life itself!

The Graham house had always been a show place in the town of Independence. Built in 1840, by John’s grandfather, Robert Graham, the eccentric son of Colonel John Graham of Revolutionary fame, it was a curious mixture of Colonial and French architecture. The French touches were tributes to the Huguenot ancestry of his grandmother.

The building crowned the summit of a hill and was surrounded by twenty-five acres of trees of native growth beneath which wound labyrinths of walks hedged by boxwood. Its shape was a huge, red brick rectangle, three and a half stories in height, with mansard roof broken by quaint projecting French windows. On three sides porches had been added, their roof supported by small white Colonial columns. The front door, of pure Colonial pattern, opened directly into a great hall of baronial dimensions, at the back of which a circular stairway wound along the curved wall.

The attic story was lighted by the windows of an observatory. From the hall one could thus look up through the galleries of three floors and the slightest whisper from above was echoed with startling distinctness. The strange noises which the Negro servants had heard floating down from these upper spaces had been translated into ghost stories which had grown in volume and picturesque distinction with each succeeding generation. The house had always been “haunted.”

The family vault in the remotest corner of the lawn was built of solid masonry sunk deep into the hillside. Its iron doors, which were never locked, opened through a mass of tangled ivy and honeysuckle climbing in all directions over the cedars and holly which completely hid its existence.

Popular tradition said that Robert Graham had loved his frail Huguenot bride with passionate idolatry, and anticipating her early death, had constructed this vault, a very unusual thing in this section of the South. It was whispered, too, that he had dug a secret passage-way from the house to this tomb, that he might spend his evenings near her body without the prying eyes of the world to watch his anguish. Whether this secret way was a myth or reality only the Grahams knew. Not one of the family had ever been known to speak of the rumour, either to affirm or deny it.

A year after his wife’s death Robert Graham was found insane, wandering among the trees at the entrance of the vault. This branch of the family had always been noted for it’s men of genius and it’s touch of hereditary insanity.

On the day of his mother’s burial John Graham had found his own father sitting in the door of this tomb hopelessly insane.

But he had not accepted the theory of hereditary insanity in the case of his father. The Major was a man of quiet courteous manners, deliberate in his habits, a trained soldier, a distinguished veteran of the Mexican war, conciliatory in temper, and a diplomat by instinct. He had never had a quarrel with a neighbour or a personal feud in his life.

The longer John Graham brooded over this tragedy to-night, the fiercer grew his hatred of Butler. Something had happened in the hall the day of his mother’s death which had remained a mystery. Aunt Julie Ann, who stayed with the new master of the old house as his cook, had told John that she had heard high words between Butler and the Major, and when she was called, found her mistress dead on the floor and his father lying moaning beside her.

John had always held the theory that Butler had used rough or insulting language to his mother; his father had resented it, and the Judge, taking advantage of his weakness from a long illness of typhoid fever, had struck the Major a cowardly blow. The shock had killed his mother, and rendered his father insane. Experts had examined the Major’s head, however, and failed to discover any pressure of the skull on the brain. Yet John held this theory as firmly as if he had been present and witnessed the tragedy.

He rose from his seat, walked to the front entrance of the house and looked at his watch by the bright light which streamed through the leaded glass beside the door. He had yet ten minutes.

He retraced in part his steps, followed the narrow path to the foot of the hill and entered the vault. Feeling his way along the sides to the arched niche in the rear, he pressed his shoulder heavily against the right side of the smooth stone wall forming the back of the niche, and felt it instantly give. The rush of damp air told him that the old underground way was open.

He smiled with satisfaction. He knew that this passage led through a blind wall in the basement of the house and up into the great hall by a panel in the oak wainscoting under the stairs.

“It’s easy! My men could seize him without a struggle!” he said grimly, slowly allowing the door to settle back of its own weight into place again.

He stood for a moment in the darkness of the vault, clinched his fist at last and exclaimed:

“I’ll do it!—but I prefer the front door. I’ll try that first.”

A few minutes later he had reached the house, knocked loudly and stood waiting an answer.

Aunt Julie Ann’s black face smiled him a hearty welcome.

“Come right in, Marse John, honey, an’ make yo’ sef at home. I sho is glad ter see ye!”

John walked deliberately across the hall and sat down on the old mahogany davenport under the stairs behind which he knew the secret door opened. He reached back carelessly, played with the spring and felt it yield.

Aunt Julie Ann’s huge form waddled after him. “Fore I pass de time er day I mus’ tell ye Marse John, what de Jedge say. He give ‘structions ter all de folks dat ef any Graham put his foot ter dat do’ ter tell ‘im he don’t low you inside dis yard! I tell ye, so’s I kin tell him I tell ye—Cose, I can’t help it dat you brush right pass me an’ come in, can I, honey?”

“Of course not, Aunt Julie Ann.”

Her big figure shook with suppressed laughter. “De very idee er me keepin’ Mammy’s baby outen dis house when I carry him across dis hall in my arms de day he wuz born! An how’s all de folks, Marse John?”

“About as usual, thank you, Aunt Julie Ann. How are you?”

“Poorly, thank God, poorly.”

“Why, what’s the matter?”

She glanced furtively up into the dim moonlit gallery of the observatory and whispered:

“Dey wuz terrible times here las’ night!”

“What happened?”

“Ghosts!”

“What, again?” John laughed.

“Nasah, dem wuz new ones! We got de lights all burnin’ ter-night. De Jedge, he wuz scared outen ten years growth. He been in bed all day, des now git up ter supper. Wuz Marse William well las’ night?”

“As well as usual, yes; Alfred put him to bed early.”

“Well, sho’s you born, his livin’ ghost wuz here! He wuz clothed an’ in his right min’ too! I hear sumfin walkin’ up in de attic ’bout leben erclock, an’ I creep out in de hall an’ look up, an’ bress de Lawd, dar stood you Pa leanin’ ober de railin’ lookin’ right at me! Well, sah, I wuz scared dat bad I couldn’t holler. I look ergin an’ dar stood yo Ma, my dead Missy, right side er him.”

“Ah, Aunt Julie Ann, you were walking in your sleep.”

“Nasah! I’se jist as waked as I is now. I try my bes’ ergin ter holler, but I clean los’ my breath and couldn’t. So I crawl to the Jedge’s room, an’ tell him what I see. He wuz scared most ter death, but he follow me out in de hall an’ look up. He seed ‘em too an’ drop down side er me er foamin’ at de mouf. He’s powerful scary anyhow, de Jedge is—des like us niggers. I got him ter bed and poured er big drink er licker down ‘im, an’ when he come to, he make me promise nebber ter tell nobody, an’ I promise. Cose, hit’s des like I’se talkin’ ter myself, honey, when I tell you.”

“And this morning he gave orders to admit no one of the tribe of Graham inside the yard again?”

“Yassah!”

“Well, tell his Honour that I am here and wish to see him at once.”

“Yassah, I spec he won’t come down—but I tell ‘im, sah.”

She waddled up the stairs to the Judge’s room. John heard the quarrel between them. Aunt Julie Ann’s voice loud, shrill, defiant, insolent, above the Judge’s. She served him for his money and her love for the old house, but secretly she despised him as she did all poor white trash and in such moments made no effort to hide her feelings.

“Bully for Aunt Julie Ann!” John chuckled.

When she returned, he slipped the last piece of money he possessed into her hand and smiled.

“Keep it for good luck,” he said.

“Yassah! De Jedge say he be down as soon as he dresses—he all dress now but he des want ter keep you waitin’.”

“I understand,” said John with a laugh. “Are you sure, Aunt Julie Ann, that the ghost of the Major you saw last night wasn’t the real man himself?”

“Cose I’se sho’. Hit wuz his speret!”

“Alfred says he’s walking in his sleep of late; at least he found mud on his shoes the other morning when he got up.”

“De Lawd, Marse John, hit wuz his speret, des lak I tell ye. He didn’t look crazy no mo’n you is. He look des lak he look in de ole days when we wuz all rich an’ proud and happy. He wuz laughin’ an’ talkin’ low like to my Missy an’ she wuz laughin’ an talkin’ back at ‘im. I seed ‘em bof wid my own eyes des ez plain ez I see you now, chile.”

“You thought you did, anyway.”

“Cose I did, honey. De doors is all locked an’ bolted wid new iron bolts—nuttin but sperets kin get in dis house atter dark—de Jedge he sees ‘em too—des ez plain ez I did.”

“And this coward is set to rule a downtrodden people,” John muttered fiercely under his breath. “Yes it’s easy, he’ll do what I tell him to-night, or—I’ll—use—the—power I wield—to—execute—the judgment—of—a—just—God.”

“What you say, honey?” Aunt Julie Ann asked.

“Nothing.”

“Dar’s de Jedge commin’ now,” she whispered, hastily leaving.

John kept his seat in sullen silence until the shuffling footsteps of his enemy had descended the stairs and crossed half the space of the hall.

The younger man rose and gazed at him a moment, his eyes flashing with hatred he could no longer mask.

The Judge halted, moved his feet nervously and fumbled at the big gold watch-chain he wore across his ponderous waist. His shifting bead eyes sought the floor, and then he suddenly lifted his drooping head like a turtle, approached John in a fawning, creeping, half-walk, half-shuffle, and extended his hand.

“I bid you welcome, young man, to the old home of your ancestors. In fact, I’m delighted to see you. I heard to-day that you would probably call this evening, and had the servants illuminate every room in your honour.”

“Indeed!” John sneered.

“Yes, I’ve wished for some time that I might have such an opportunity to talk things over with you.”

John had turned from the proffered hand and seated himself with deliberate insolence.

“Thanks for the illuminations in honour of my family!”

The sneer with which he spoke was not lost on the Judge. His patronising judicial air, so newly acquired, wavered before the cold threat of the younger man’s manner. Yet he recovered himself sufficiently to say:

“My boy, I like your high spirit, but I must give you a little fatherly advice.”

“Seeing that my own father at present cannot do so.”

The Judge ignored the interruption and seated himself with an attempt at dignity.

“Mr. Graham, you must recognise the authority of the United States Government.”

“Which means you?”

“I was compelled to make an example of disloyalty.”

“You disbarred me from personal malice.”

“For your treasonable utterances.”

“I have the right to criticise your degradation of the judiciary in using it to further your political ambitions.”

“I disbarred you for treason and contempt of court.”

John rose and stood glaring at the judge whose shifting eyes avoided him.

“Well, you’re on solid ground there, your Honour! Were I the master of every language of earth, past master of all the dead tongues of the ages, a genius in the use of every epithet the rage of man ever spoke, still words would have no power to express my contempt for you!”

The Judge shuffled his big feet as if to rise.

“Sit still!” John growled. “I’ve come here to-night to demand of you two things.”

“You’re in no position to demand anything of me!” spluttered Butler, running his hand nervously through his heavy black hair.

“Two things,” John went on evenly: “First revoke your order and restore me to my law practice to-morrow morning.”

“Not until you apologise for your criticism.”

“That’s what I’m doing now. I profoundly regret the incident. I should have kicked you across the street—criticism was an error of judgment.”

Butler shambled to his feet, trembling with rage, pulled nervously at his beard again and gasped:

“How dare you insult me in my house!”

“It’s my house!” flashed the angry answer.

“Your house?” the Judge stammered, again tugging at his beard.

“Yes, sit down.”

The astonished jurist dropped into his chair, his shifting basilisk eyes dancing with a new excitement.

“Your house, your house—why, what—what!”

“Yes and you’re going to vacate it within two weeks.”

“What do you mean, sir?” demanded the Judge, plucking up his courage for a moment.

“I mean that the distinguished jurist, Hugh Butler, who had the honour of presiding over the trial of Jefferson Davis, and now aspires to the leadership of his party in the South, was living in a stolen house when he delivered his famous charge concerning traitors to the grand jury, that morning in Richmond. It is with peculiar personal pleasure that I now brand you to your face—coward, liar, perjurer, thief!”

John paused a moment to watch the effects of his words on his enemy. The cold sweat began to appear in the bald spot above the Judge’s forehead, and his answer came with gasping feeble emphasis:

“I bought this house and paid for it!”

“Exactly!” sneered the younger man. “But I never knew until I got this letter”—he drew the letter from his pocket—“just how you came to buy a house which cost $50,000 for so trifling a sum of money.”

“Who wrote that letter?” interrupted the Judge eagerly.

“Evidently a friend of yours, once high in your councils, who has grown of late to love you as passionately as I do. And I think he could put a knife into your ribs with as much pleasure.”

The Judge winced and glanced nervously into the galleries.

“Don’t worry, your Honour. If you take the medicine I prescribe, amputation will not be necessary. Let me read the letter. It’s brief but to the point:”

To John Graham, Esq.

Dear Sir: The secret of Butler’s possession of your estate is simple. Under his authority as United States Judge, he ordered its confiscation, forced his wife to buy it for $2,800, at a fake sale, which had not been advertised, and later had it reconveyed to him. His wife refused to live in the house, sent her daughter to school in Washington, and died two years later from the conscious dishonour she had been obliged at least in secret to share. A suit brought before the United States Supreme Court will restore your property, hurl a scoundrel from the bench, and cover him with everlasting infamy.

A Former Pal of His Honour.

“An anonymous slanderer!” snorted the judge.

“Yet he expresses himself with vigour and accuracy, and his words are backed by circumstantial evidence.”

Butler sprang to his feet livid with rage crying:

“John Graham, you’re drunk!”

“Just drunk enough to talk entertainingly to you, Judge.”

“Will you leave my house? or must I call an officer to eject you, sir?” he thundered.

“A process of law is slow and expensive, Judge,” said John with a drawl. “I haven’t the money at present to waste on a suit, May I ask when you will vacate this estate?”

“When ordered to do so by the last court of appeal, sir!”

John looked the Judge squarely in the eye and slowly said:

“You are before the last court of appeal now, and it’s judgment day.”

“I understand your threat, sir, but I want to tell you that your Ku Klux Klan has had its day. The President is aroused—Congress has acted. I’ll order a regiment of troops to this town tomorrow! Dare to lift the weight of your little finger against my authority and I’ll send your crazy old father to the county poorhouse and you to the gallows—to the gallows! I warn you!” John took a step closer to his enemy, towering over his slouchy figure menacingly, and said, “When will you vacate this house?”

Butler grasped the back of his chair, trembling with fury.

“The possession of this estate is the fulfillment of one of the proudest ambitions of my life.”

“When will you get out?”

“And my daughter has just returned to-day from Washington, a beautiful accomplished woman, to preside over it.”

“When—will—you—get—out?”

“When ordered by the Supreme Court of the United States—or when I’m carried out—feet—foremost—through—that—door!”

The Judge choked with anger.

“Then, until we meet again!”

John bowed with mock courtesy, walked across the hall to the alcove and took his hat from the rack where Aunt Julie Ann had hung it, just as Stella Butler sprang through the rear entrance with a joyous shout, reached at a bound the Judge’s side and threw her arms around his neck.

“Oh! Papa, what a glorious night! Steve and I had such a ride!” The Judge placed his hand on her lips and whispered:

“My dear, there’s someone here.”

Stella glanced over her shoulder and saw John fumbling his hat in embarrassment.

“Why it’s the famous Mr. John Graham—introduce me, quick!”

“Not to-night, dear; I do not wish you to know him.”

Stella released herself and, with a ripple of girlish laughter, walked boldly over to John, her face wreathed in friendly smiles.

“Mr. Graham, permit me to introduce myself, Stella Butler. My father has just forbidden it. I care nothing for your old politics—shall we not be friends?”

She extended a dainty little hand and John took it stammering incoherently. Never had he touched a hand so warm, and tender and so full of vital magnetism. It thrilled him with strange confusion.

Never had he seen a vision of such bewildering loveliness. An exquisite oval face with lines like a delicate cameo, cheeks of ripe-peach red, a crown of unruly raven-black hair, and big brown eyes shaded by heavy lashes. Her dress showed the perfection of good taste and careful study—a yellow satin, trimmed in old lace that fitted her rounded little figure without a wrinkle, dainty feet in snow-white stockings and bow-tipped slippers that peeped in and out mischievously as she walked, and with it all a magnetic personality which riveted and held the attention.

He stared at her a moment dumb with wonder. Could it be possible that a girl of such extraordinary beauty, of such remarkable character, of such appealing manners could have been born of such a father!

“As the new mistress of your old home let me bid you a hearty welcome, Mr. Graham,” she said softly. “You must come often and tell me all its legends and ghost stories?”

The Judge shuffled uneasily and cleared his throat with nervous anger.

“Now keep still, Papa! I’m going to make this old house ring with joy and laughter. I won’t have any of your political quarrels. I’m going to be friends with everybody, as my mother was—they say she was a famous belle in her day, Mr. Graham?”

“So I have often heard,” John answered with increasing confusion, as he retreated toward the door.

“You will come again?”

“I hope to soon,” he gravely answered as he bowed himself out the door.

STEVE HOYLE had called early at the Judge’s to see Stella the morning after John’s encounter in the hall. As he paced restlessly back and forth waiting the return of Stella’s maid, he was evidently in an ugly humour.

When he heard the story at the hotel late the night before, that his hated rival in politics and society had dared to venture into Judge Butler’s home, he could not believe it. And the idea that Stella should receive him had cut his vanity to the quick.

The richest young man in the county, he aspired to be the most popular, and he had long enjoyed the distinction in the estimation of his friends of being the handsomest man in his section of the state. In his own estimation there had never been any question about this. And beyond a doubt he was a magnificent animal. Six feet tall, a superb figure, somewhat coarse and heavy in the neck, with smooth, regular features. He was slightly given to fat, but his complexion was red and clean as a boy’s, and he might well be pardoned his vanity when one remembered his money.

His father, the elder Hoyle, who had avoided service in the war by hiring a substitute, had emerged from the tragedy far wealthier than when he entered it. Some people hinted that if the Treasury Agents, who had stolen the cotton of the country under the absurd and infamous Confiscation Act of Congress, would speak, they might explain this fortune. They had never spoken. The old fox had been too clever and his tracks were all covered.

Steve had recently met Stella at one of her school receptions in Washington while on business for his father, yielded instantly to her spell, and they were engaged. He felt that he had condescended to honour the Judge by marrying into his family.

Butler never had been a slave owner, and in spite of his fawning ambitions as a turncoat politician and social aspirant, he was still poor—so poor in fact that he could scarcely keep up appearances in the Graham mansion. Steve planned to live there after his marriage in a style befitting his wealth and social position. He noted the faded covering on the old mahogany furniture and determined to make it shine with new plush on his advent as master.

He walked over to the hall mirror and adjusted his tie. He was getting nervous. Stella was keeping him waiting longer than usual. She was doing this to tease him, but he would have his revenge when they were married.

Steve had quickly come to a perfect understanding with the Judge. The Piedmont Congressional District, which included several mountain counties, was overwhelmingly Democratic. The Judge, as the Republican leader, had promised Steve to put up no candidate, but to support him as an independent if the approaching Democratic Convention nominated John Graham for Congress.

Steve as a man of capital proclaimed that the money interests of the North should be cultivated and that a deal with the enemy was always better than a fight.

Sure of his success, he had already promised Stella with boastful certainty a brilliant social season in Washington as his wife. In spite of his immense vanity, he knew that this promise had gone far to win her favour. She too was vain of her beauty, and her social ambitions were boundless. He had received her mild professions of love with a grain of salt. She was yet too young and beautiful to take life seriously. His fortune and his good looks had been the magnets that drew her. But he was content. He would make her love him in due time. He was sure of it. Yet on two occasions he had observed that she had shown a disposition to flirt skilfully and daringly with every handsome fellow who came her way—and it had distressed him not a little.

He was angry and uneasy this morning, and made up his mind to assert his rights with dignity—and yet with a firmness that would leave no question as to who was going to be master in his house. He decided to nip Stella’s acquaintance with John Graham in the bud on the spot. That he had called for any other reason than to see her, never occurred to him.

When Maggie, Stella’s little coal black maid, at length reappeared, she was grinning with more than usual cunning.

“Miss Stella say she be down in a minute,” she said with a giggle.

“You’ve been gone a half hour,” Steve answered frowning.

“I spec I is,” observed Maggie, continuing to giggle and glance furtively at Steve.

“What’s the matter with you?” he asked suspiciously.

“Nuttin.”

He held up a quarter and beckoned. She hastened to his side.

“I want us to be good friends.”

She took the money, grinned again and said: “Yassah!”

“Now, what have you been giggling about?”

“Mr. John Graham wuz here last night!”

“So I hear. Did he see Miss Stella?”

“Deed he did! Dat’s what dey all come fur. She so purty dey can’t hep it.”

“How long did he stay?”

“Till atter midnight!”

“Indeed!”

“Yassah!” Maggie went on, walling her eyes with tragic earnestness. “She play de pianer fur ’im long time in de parlour, an’ he sing fur her an’ den she sing fur ’im.”

Steve cleared his throat angrily.

“Yassah! an’ atter dey git froo singin’ she take him out fur er stroll on de lawn an’ dey go way down in de fur corner an’ set in one er dem rustics fur ’bout er hour. Den dey come in an’ bof un ’em set in de moonlight in de hammock right close side an’ side, and he talk low an’ sof, an’ she laugh, an’ laugh, an’ hit ’im wid er fan—jesso! Yassah. Sh! She comin’ now!”

The girl darted out of sight as Stella’s dress rustled in the hall above.

Steve pulled himself together with an effort, and met her at the foot of the stairs.

She made an entrancing picture as she slowly descended the steps, serenely conscious of her beauty and its power over the man below whose eyes were now devouring her. The flowing train of her cream-coloured morning gown made her look a half foot taller than she was. She had always fretted at her diminutive stature, and wore her dresses the extreme length to give her added height.

With a gracious smile she welcomed Steve and he attempted to kiss her. She repulsed him firmly and allowed him to kiss her hand.

“Stella dear,” he began petulantly, with an accent of offended dignity, “you must quit this foolishness! We have been engaged three weeks and I’ve never touched your lips.”

She laughed and tossed her pretty head.

“And we’re engaged!”

“Not yet married,” she observed, lifting her arched brows.

“I have honoured you with my fortune and my life.”

“Thanks,” she interrupted smiling.

Steve flushed and went on rapidly.

“Really, Stella, the time has come for a serious talk between us.”

She seated herself at the piano and ran her fingers lightly over the keys. Steve followed, a frown clouding his smooth handsome forehead.

“Will you hear me?” he asked.

“Certainly!” she answered, turning on him her big brown eyes. In their depths he might have seen a sudden dangerous light, had he been less absorbed in himself. As it was he only saw a smile lurking about the corners of her lips which irritated him the more.

“I understand that John Graham called on you last night?”

“Indeed, I hadn’t heard it,” she answered lightly.

“And stayed until after midnight.”

Stella sprang to her feet, looked steadily at Steve, frowned, walked to the door and called:

“Maggie!”

The black face appeared instantly.

“Yassum!” she answered, with eager innocence.

“Have you said anything about Mr. Graham’s visit last night?”

Maggie walled her eyes in amazement at such an outrageous suspicion.

“No, M’am! I aint open my mouf—has I Mister Steve?”

“Certainly not,” Steve answered curtly.

“I thought I heard your voice in the hall,” Stella continued, looking sternly at Maggie.

“Nobum! Twan’t me. I nebber stop er second. I pass right straight on froo de hall—nebber even look t’ward Mr. Steve.”

“You can go,” was the stern command. “Yassum!” Maggie half whispered, backing out the door, her eyes travelling quickly from Steve to her mistress.

“As my affianced bride,” he went on firmly, “I cannot afford to have you receive the man who is my bitterest enemy.”

With a smile, Stella quickly but quietly removed the ring from her hand and gave it to Steve, who stood for a moment paralysed with astonishment. “Stella!” he gasped.

“The burden of your affianced bride is too heavy for my young shoulders.”

“Forgive me dear!” he pleaded.

“I prefer to receive whom I please, when and where I please, without consulting you. When I need a master to order my daily conduct, I’ll let you know.

“But, Stella, dear!”

“Miss Butler—if you please!”

“I—I only meant to tell you that I love you desperately, that I’m jealous and ask you not to torture me—you cannot mean this, dear?”

“How dare you address me in that manner again!” she cried, flaming with anger, the tense little figure drawn to its full height.

Steve attempted to take her hand, but the fierce light in her eyes stopped him without a word.

“Leave this house instantly!” she said, with quiet emphasis.

With deep muttered curses in his soul against John Graham, Steve turned and left.

As he passed through the doorway, a black face peeped from the alcove and giggled.

TRUE to his word Butler called for a regiment of United States troops.

On the second day after his interview with the Judge, John Graham watched from his office window the blue coats march through the streets of Independence to their camp.

He turned to his chair beside a quaint old mahogany desk and wrote an official order to each of the eight district chiefs of the Invisible Empire who were under his command in the state.

When he had finished his task he sat for an hour in silence staring out of his window and seeing nothing save the big brown eyes of a beautiful girl—eyes of extraordinary size and brilliance that seemed to be searching the depths of his soul. It was a new and startling experience in his life. He had made love harmlessly after the gallant fashion of his race to many girls; yet none of them had found the man within.

He was angry with himself now for his inability to shake off the impression Stella Butler had made. He hated her very name. The idea of his ever seeking the hand of a Butler in marriage made him shiver. To even meet her socially with such a father was unthinkable. And yet he kept thinking.

Two things especially about her haunted him with persistence and had thrown a spell over his imagination—the strange appealing tenderness of her eyes and the marvellous low notes of her voice, a voice at once musical, and warm with slumbering passion. Her voice seemed the echo of ravishing music he had heard somewhere, or dreamed or caught in another world he fancied sometimes his soul had inhabited before reaching this. Never had he heard a voice so full of feeling, so soft, so seductive, so full of tender appeal. Its every accent seemed to caress.

He cursed himself for brooding over her and then came back to his brooding with the certainty of fate. Yet it should make no difference in his fight with old Butler. He would kick that fawning, creeping scoundrel out of his house if it was the last and only thing he ever accomplished on earth. The only question he still debated was the time and method of the execution of his plan.

One thing became more and more clear—he was going to need the full use of every faculty with which God had endowed him and he must set his house in order.

He opened the door of the little cupboard above his desk and took from it a decanter of moonshine whiskey Dan Wiley, one of his mountain men, had always kept filled for him. From the drawer he took two packs of cards and a case of poker chips. The cards and chips he rolled in a newspaper, placed in his stove and set them on fire. He smiled as he stood and listened to the roar of the sudden blaze. He raised his window and hurled the red-eyed decanter across the vacant lot in the rear of his office and saw it break into a hundred fragments on a pile of stones.

“Wonder what Dan will say to that when he comes this morning?” he exclaimed, looking at his watch and resuming his seat.

He heard a stealthy footfall at the door, turned and saw the tall lanky form of the mountaineer smiling at him.

“Well, Chief, you sent for me?”

“Yes, come in Dan!”

Dan Wiley tipped in and stood pulling his long moustache thoughtfully, before taking a chair.

“What’s on your mind?” asked John.

“I heered somethin’.”

“About me?”

“Yes, and it pestered me.”

“Well?”

“They say you got drunk night ’fore last.”

“And you’re going to preach me a sermon on temperance, you confounded old moonshining distilling sinner!”

“Ye mustn’t git drunk,” observed Dan seriously.

“But, didn’t you bring me the whiskey?”

“Not to git drunk on. I brought it as a compliment. My whiskey’s pure mountain dew, life restorer—it’s medicine.”

“It’s good whiskey, I’ll say that,” said John. “Even if you don’t pay taxes on it. You brought the men?”

“Yes, but Chief, I’m oneasy.”

“What about?”

“Don’t like the looks er them dam Yankees. I’m a member er the church an’ a law abidin’ citizen.”

“Yet I hear that a revenue officer passed away in your township last fall.”

“Rattlesnakes and Revenue officers don’t count—they ain’t human.”

“I see!” laughed John.

“Say,” Dan whispered, “you ain’t calculatin’ ter make a raid ternight with them thousand blue-coats paradin’ round this town, are ye?”

“That’s my business, Dan,” was John’s smiling answer. “It’s your business as a faithful night-hawk of the Empire to obey orders. Are you ready?”

“Well, Chief, I followed you four years in the war, an’ I’ve never showed the white feather yet, but these is ticklish times. There’s a powerful lot er damfools gettin’ ermongst us, an’ I want ter ax ye one question?”

“What?”

“Are ye goin’ ter git drunk ter-night?”

John walked to Dan’s side and placed his hand on his shoulder, and said slowly:

“I’ll never touch another drop of liquor as long as I live. Does that satisfy you?”

“I never knowd a Graham ter break his word.” John pressed the mountaineer’s hand.

“Thanks Dan.”

“I’m with you—and I’ll charge the mouth of the pit with my bare hands if you give the order.”

“Good. Meet me at the spring in the woods behind the old cemetery at eleven o’clock to-night with forty picked men.”

“Forty!—better make it an even thousand, man for man with the Yanks.”

“Just forty men, mark you—picked men, not a boy or a fool among them.”

“I understand,” said Dan, turning on his heel toward the door.

“And see to it”—called John—“I want them mounted on the best horses in the county and every man armed to the teeth.”

Dan nodded and disappeared.

By eight o’clock the town was in a ferment of excitement and the streets were crowded with feverish groups discussing a rumour which late in the afternoon had spread like wild-fire. From some mysterious source had come the announcement that a great Ku Klux parade was to take place in Independence at midnight for the purpose of overawing if not attacking the regiment of soldiers, which had just been quartered in the town.

By eleven o’clock the entire white population, men, women and children, were crowding the sidewalks of the main street.

Billy Graham passed John’s office with Susie Wilson leaning on his arm. Billy was in high feather and Susie silent and depressed.

“Great Scott, Miss Susie, what’s the matter? This isn’t a funeral. It’s a triumphant demonstration of power to our oppressors.”

“I wish they wouldn’t do it with all these troops in town,” answered the girl, anxiously glancing at the dark window of John’s office.

“Bah! The Ku Klux have been getting pusillanimous of late—haven’t been on a raid in six months. They need a leader. Give me a hundred of those white mounted men and I’d be the master of this county in ten days!”

“It’s a dangerous job, Billy.”

“That’s the only kind of a job that interests me. A dozen wholesome raids would put these scalawags and carpetbaggers out of business. There ought to be five thousand men in line tonight. I’ll bet they don’t muster a thousand. It wouldn’t surprise me if they backed out altogether.”

“I wish they would,” sighed Susie.

“Of course you do, little girl,” said Billy with sudden patronising tenderness. “I know what you need.”

Susie smiled and asked demurely:

“What?”

Billy seized both her hands and drew her under the shadow of a tree.

“A strong manly breast on which to lean—Susie, my Darling, I love you! Will you be my wife?”

Susie burst into a fit of laughter and Billy dropped her hands in rage.

“You treat the offer of my heart as a senseless joke, young woman?”

“No, Billy dear, I don’t. I appreciate it more than words can express. You have paid me the highest tribute a girl can receive, but the idea of marrying a boy of your age is ridiculous!”

“Ridiculous! Ridiculous! How dare you insult me? I’m as old as you are!” thundered Billy.

“Yes, we are each eighteen.”

“And your mother married at sixteen.”

“And she’s still only sixteen,” said the girl with a sigh.

“Wait a few days and I’ll show you whether I’m a man or not,” said Billy, with insulted dignity. “Come, your mother is waiting for us at the corner.”

Mrs. Wilson stood among a group of boys chatting and joking. She belonged to the type of widows, fair, fat and frivolous. Time had dealt gently with her. She was still handsome in spite of her weight, and intensely jealous lest her serious daughter supplant her in the affections of the youth of Independence.

She greeted Billy with just the words to heal his wounded vanity.

“My! Billy, but you look serious and manly! I’d kiss you if the other boys were not here. You ought to be at the head of that line of white raiders to-night”—she dropped her voice to a whisper—“I’ll be making your disguise before long.”

Billy turned from Susie and devoted himself with dignity to her mother.

The widow lifted her hand in sudden warning.

“Sh! Billy, the enemy! There goes Stella Butler with that fat little detective whom the Judge has imported with the troops.”

“Captain” Suggs of the Secret Service was more than duly impressed with his importance as he forced his pudgy figure through the throng on the sidewalk, ostentatiously protecting Stella from the touch of the crowd.

“It’s arrant nonsense, Miss Stella,” he was saying, as they passed. “These Southern people are savages, I know——”

“Why, Captain, I’m a Southerner too,” said the girl archly.

“I mean the disloyal traitors of the South—not the broad-minded patriots like your father,” Suggs hastened to explain. “I say it’s arrant nonsense this talk of such a parade by these traitors. I credit them with too much cunning to dare to flaunt their treason in the streets here to-night with a regiment of troops and the head of the Secret Service on the spot.”

The little fellow expanded his chest and puffed his cheeks.

Billy doubled his fist, and made a dash for him. With a suppressed scream, Mrs. Wilson caught him.

“Billy! for heaven’s sake, are you crazy!” They passed on down the street toward the Judge’s house.

“I’m not so sure they will not parade, Mr. Suggs,” Stella replied.

“Don’t be alarmed, Miss Stella!” he urged soothingly. “I’ve taken ample means to protect you and your father from any attack of these assassins and desperadoes if they dare enter the town.”

“I’m not afraid of them, Captain, she answered lightly.

“Of course not—we’re here and ready for them. The very audacity of their manner is an insult to the Government.”

“I like audacity. It stirs your blood,” Stella cried, her brown eyes twinkling.

Suggs leaned nearer and said in his deepest voice:

“Let them dare this insult to authority to-night and you’ll see audacity come to sudden grief in front of your father’s house.”

“Have you prepared an ambush?” Stella asked eagerly.

“Better. We’ve an extra hundred loyal policemen on the spot. Each of them is sworn to capture dead or alive any Ku Klux raider who shows his head. I hope they’ll come—but it’s too good to be true. With a dozen prisoners safe in jail, before to-morrow dawns I’ll have the secrets of the Klan in my pocket. I’ll make things hum in Washington. Watch me. It’s the big opportunity of life I’ve been waiting for—my only fear is I’ll miss it.”

“I think you’ll get it, Mr. Suggs,” was the laughing answer.

She had scarcely spoken, when a tow-headed boy rushed into the middle of the street and yelled, “Gee bucks! Look out! They’re a comin’!”

Men, women and children rushed into the street.

Suggs stood irresolute and tightened his grip on Stella’s arm.

Down the street cheers burst forth and as they died away the clatter of horses’ hoofs rang clear, distinct, defiant. They were riding slowly as in dress parade.

Another cheer was heard and Suggs stepped into the street and reconnoitred.

His face wore a puzzled look as he returned to Stella’s side.

“They’ve actually ridden past the regimental camp. I can’t understand why the Colonel did not attack them.”

“Gee Whilikens, there’s a million of ’em!” cried a boy nearby.

“Perhaps the Colonel thought discretion the better part of valour, Mr. Suggs,” suggested Stella smilingly.

“Red tape,” the detective explained with disgust—“he has no order. Just wait until the assassins walk into the trap I’ve laid for them. Come, we will hurry to your gate. I want you to see what happens.”

They crossed the street and hurried to the Judge’s place.

Suggs summoned the commander of his force of “metropolitan” police and in short sharp tones gave his orders.

“Are your men all ready, officer?”

“Yessir!”

“Fully armed?”

“You bet.”

“Handcuffs ready?”

“All ready.”

“Good. Throw your line, double column, across the street, stop the parade and arrest them one at a time.”

Suggs squared his round shoulders as best he could; the officer saluted and returned to his place to execute the order.

When the cordon formed across the street the boys yelled and the news flashed from lip to lip far down the line. A great crowd quickly gathered surging back and forth in waves of excitement as the raiders approached.

The white ghostlike figures could now be seen, the draped horse and rider appearing of gigantic size in the shimmering moonlight.

“Now we’ll have some fun,” exclaimed Suggs with a triumphant smile.

Stella trembled with excitement, two bright red spots appearing on her dimpled cheeks, her eyes sparkling.

Amid constant cheers from the crowds the line of white figures slowly approached the cordon of police without apparently noticing their existence.

“Now for the climax of the drama!” cried Suggs, watching with eager interest the rapidly closing space between the Clansmen and his police.

The officer in command, noting an uneasy tension along his lines, crossed the street in front of his men exhorting them.

“Stand your ground, boys!” he said firmly.

“Better save your hides, you scalawag skunks!” yelled an urchin from the crowd.

The leader of the Klan was now but ten feet away, towering tall, white and terrible, with an apparently interminable procession of mounted ghosts behind him.

The line of police swayed in the centre.

The Clansman leader lifted his hand, and the shrill scream of his whistle rang three times, and each white figure answered with a long piercing cry.

The police cordon broke into scurrying fragments and melted into the throngs on the sidewalks, while the procession of white and scarlet horsemen, without a pause, passed slowly on amid shouts of laughter from the people who had witnessed the fiasco.

“Well, I’ll be d———! excuse me, Miss Stella!”

Suggs cried in a stupor of blank amazement, his round little figure suddenly collapsing like a punctured balloon.

“You can’t help admiring such men, Captain!” the girl laughed.

Suggs who had lost the power of speech wandered among the crowd in search of his commanding officer.

As the parade passed the Judge’s gate, Stella stood wide-eyed, tense with excitement, watching the tall horseman with two scarlet crosses on his breast who led the procession.

“The spirit of some daring knight of the middle ages come back to earth again!” she cried. “Superb! Superb! I could surrender to such a man!”

A lace handkerchief fluttered from her bosom and waved a moment above her head. The tall figure turned in astonishment, bowed, tipped his spiked helmet, and without realising it suddenly reined his horse to a stand—and the whole line halted.

The leader whispered to a tall figure by his side, apparently his orderly, who turned to the line behind and shouted.

“Boys! three cheers for the little gal at the gate! She’s all right! The purtiest little gal in the countee—oh!”

A rousing cheer rose from the ranks.

A ripple of sweet girlish laughter broke the silence which followed, the lace handkerchief fluttered again and the line moved slowly on.

Stella counted them.

“Only forty men. And they dared a regiment!” With another laugh, she deserted Suggs and disappeared in the flowers and shrubbery toward the house as the last echoes of the raiders died away in the distance.

The Clansmen descended a hill, turned sharply to the right toward the river and broke into a quick gallop. Within thirty minutes they entered a forest on the river bank, and down its dim aisles, lit by moonbeams, slowly wound their way to their old rendezvous.

The signal was given to dismount and disrobe the horses. Within a minute the white figures gathered about a newly opened grave.

The men began to whisper excitedly to one another.

“What’s this?”

“What’s the matter?”

“Who’s dead?”

“You’re too many for me!”

“What’s up, Steve Hoyle?” asked one of the raiders.

“It’s beyond me, sonny. The Grand Dragon of the State honours us with his presence to-night and is in command—he will no doubt explain. Have a drink.” He handed the group a flask of whiskey, and passed on.

When the men had assembled beside the shallow grave, the chaplain led in prayer.

The tall figure with the double scarlet cross on his breast removed his helmet and faced the men.

“Boys,” began John Graham, “you have assembled here to-night for the last time as members of the Invisible Empire!”

“Hell!”

“What’s that?”

The exclamations, half incredulous, half angry, came from every direction with suddenness and unanimity which showed the men to be utterly unprepared for such an announcement.

“Yes,” the even voice went on, “I hold in my hand an official order of the Grand Wizard of the Empire, dissolving its existence for all time. Our Commander-in-chief has given the word. As loyal members of the order, we accept his message.”

“Then our parade to-night was not a defiance of these soldiers who have marched into town?” sneered a voice.

“No, Steve Hoyle, it was not. Our parade to-night was in accordance with this order of dissolution. It was our last formal appearance. Our work is done——”

Steve saw in a flash his opportunity to defeat his enemy and make himself not only the master of his Congressional District but of the state itself.

“Not by a damn sight!” snapped the big square jaw.

“You refuse as the commander of this district to obey the order of the Grand Wizard?” asked the tall quiet figure.

“I refuse, John Graham, to accept your word as the edict of God!” was the quick retort. “Our men can vote on this and decide for themselves.”

“Yes, vote on it!”

“We’ll decide for ourselves!”

The quick responses which came from all sides showed the temper of the men. John Graham stepped in front of the big leader of the district.

“Look here, Steve Hoyle, I want no trouble with you to-night, nor in the future—but I’m going to carry this order into execution here and now.”

“Let’s see you do it!” was the defiant answer.

“I will,” he continued. “Boys!”

There was the ring of conscious authority in his tones and the men responded with sharp attention.

“You have each sworn to obey your superior officer on the penalty of your life?”

“Yes!”

“You are men of your word. As the Grand Dragon of the State I command you to deliver to me immediately your helmets and robes.”

With the precision of soldiers they deposited them in the open grave. Steve Hoyle surrendered his last.

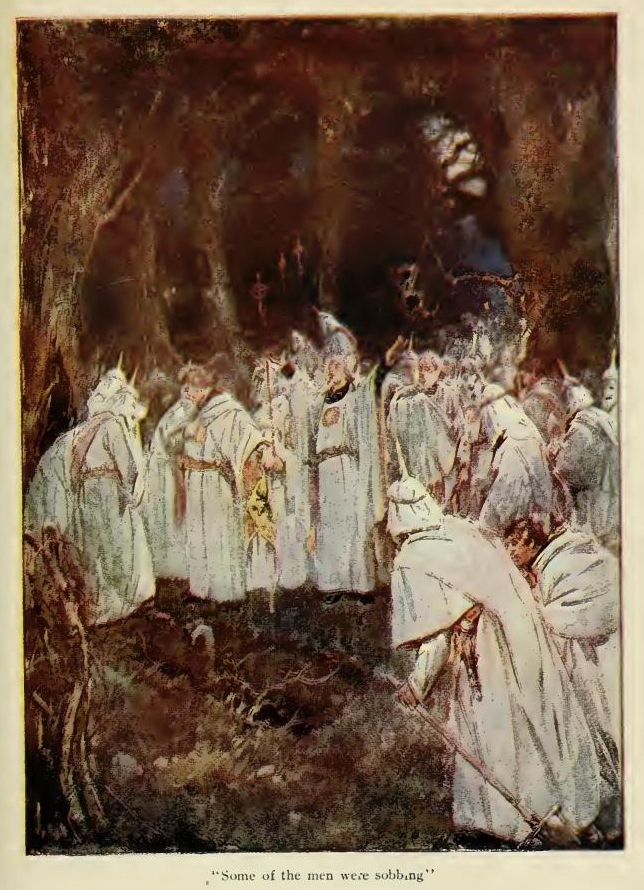

When all had been placed in the grave, John Graham removed his own, reverently placed it with the others, tied two pieces of pine into the form of the fiery cross, lighted its ends, drew the ritual of the Klan from his pocket, set it on fire and held it over the grave while the ashes slowly fell on the folds of the white and scarlet regalia which he also ignited. Some of the men were sobbing. While the regalia rapidly burned he turned and said:

“Boys, I thank you. You have helped me do a painful thing. But it is best. Our work is done. We have rescued our state from Negro rule. We dissolve this powerful secret order in time to save you from persecution, exile, imprisonment and death. The National Government is getting ready to strike. When the blow falls it will be on the vanished shadow of a ghost. There’s a time to fight, and a time to retreat. We retreat from a field of victory.

“I should have dissolved the Klan a month ago. I confess to you a secret. I waited because I meant to strike with it a blow at a personal enemy. I realise now that I stood as your leader on the brink of the precipice of social anarchy. Forgive me for the wrong I might have done, had you followed me. As Grand Dragon of the Empire I declare this order dissolved forever in the state of North Carolina!”

He seized a shovel and covered with earth and leaves the ashes of the burned regalia.

Steve Hoyle stepped quickly in front of his rival. The veins on his massive neck stood out like cords and his eyes shone ominously in the moonlight. The slender figure of John Graham instinctively stiffened at the threat of his movement as the two men faced each other.

“The Klan is now a thing of the past?” asked Steve.

“Yes.”

“As though it had never been?”

“As though it had never existed.”

“Then your authority is at an end?”

“As an officer of the Klan, yes. As a leader of men, no.”

“The officer only interests me—Boys!” Steve’s angry voice rang with defiance.

The men gathered closer.

“The Invisible Empire is no more. Its officers are as dead as the ashes of its ritual. Meet me here to-morrow night at eleven o’clock to organise a new order of patriots! Will you come?”

“Yes!”

“You bet your life!”

The answers seemed to leap from every throat at the same moment.

John Graham’s face went white for a moment and his fist closed.

“Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel, Steve Hoyle,” he said with slow emphasis.

“And traitors pose as moral leaders,” was the retort.

“Time will show which of us is a traitor. Will you dare thus to defy me and reorganise this Klan?”

“Wait and see!”

John Graham stepped close to his rival, and, in a low voice unheard save by the man to whom he spoke, said:

“Take back that order and tell those men to go home and stay there.”

“I’ll see you in hell first!” came the answer in a growl.

Scarcely had the words passed his lips when John Graham’s fist shot into his rival’s face.

The blow was delivered so quickly Steve’s heavy form struck the ground before the astonished men could interfere.

In a moment a dozen men sprang between them and John said with quiet emphasis, glaring at his enemy:

“I’ll be in my office at ten o’clock to-morrow morning, to receive any communication you may wish to make—you understand!”

And deliberately mounting his horse, he rode away into the night alone.

JOHN GRAHAM walked briskly to his office the next morning at a quarter to ten, and found Dan Wiley standing at the door.

The lank mountaineer merely nodded, followed the young lawyer into the office, and stood in silence watching him as he opened a case of duelling pistols which had been handed down through four generations of his family.

“Don’t do it,” said Dan abruptly.

“I’ve got to.”

“Ain’t no sense in it.”

“It’s the only way, Dan, and I’m going to ask you to be my second.”

Dan placed his big rough hand on the younger man’s shoulders.

“Lemme be fust, not second.”

“It’s not my way!”

“That’s why I’m axin ye. You’re the biggest man in the state! I seed it last night as ye stood there makin’ that speech to the boys. You’ll be the Governor if ye don’t do some fool thing like this. If ye fight ’im, an’ he kills ye, your’e a goner. If you kill him, you’re ruined—what’s the use?”

“It can’t be helped,” was the quiet answer.

“Are ye goin’ ter kill ’im?”

“Yes. The Klan was the only way to save our civilisation. I’ve sowed the wind and now I begin to see that somebody must reap the whirlwind. I realised it all in a flash last night when that scoundrel called the men to reorganise.”

“They won’t follow him.”

“The fools will, and there are thousands outside clamouring to get in. I’ve kept the young and reckless out as far as possible. Steve Hoyle knows that he can beat me for Congress with this new wildcat Klan at his back. He hasn’t sense enough to see that the spell of authority once broken, he wields a power no human hand can control. It will be faction against faction, neighbour against neighbour, man against man—the end martial law, prison bars and the shadow of the gallows. I can save the lives of thousands of men, and my state from crime and disgrace by killing this fool as I’d kill a mad dog, and I’m going to do it!”

“Hit’ll ruin ye, boy!”

“I know it.”

“Look here, John Graham, do me a special favour. Leave Steve to me. My wife’s dead and I aint got a chick or a child—you’ve defended me without a cent and you’re the best friend I’ve got in the world. It’s my turn now. Nobody would miss me.”

“I’d miss you, Dan!” said John slowly.

The two men silently clasped hands and looked into each other’s faces.

“You’re a fool to do this, boy”—the mountaineer’s voice broke.

“Of course, Dan, many of our old-fashioned ways are foolish but at least they hold the honour of man, and the virtue of woman dearer than human life!”

A boy suddenly opened the door without knocking and handed John a note.

He read it aloud with a scowl:

My friends have decided that I shall not play into your hands by an absurd appeal to the Code of the Dark Ages. I’ll fight you in my own way at a time and place of my own choosing and with weapons that will be effective.

Steve Hoyle.

“Now, by gum, you’ll have to leave ’im to me,” laughed the mountaineer.

John tore the note into bits and turned to the boy:

“No answer, you can go.”

“He’ll pick you off some night from behind a tree,” warned Dan.

“Sneak and coward!” muttered John.

“Ye won’t let me help ye?”

“No, go home and disband your men.”

“May they keep the rig?”

“If you won’t go on a raid.”

“I’ll not, unless you need me, John Graham,” cried the mountaineer grasping again his young leader’s hand.

“All right. I can trust you. Keep their costumes in your house under lock and key until I call for them.”

As Dan turned slowly through the door he drawled over his shoulder: “You’ll ’em purty quick!”

WHEN Dan Wiley closed the door John turned to his desk and drew from a pigeon hole the mass of legal papers containing the evidence he had gathered of Butler’s theft of his estate.

The dissolution of the Klan had left him only the process of the law by which to recover it. Yet it was only a question of time when the decision of the Supreme Court would hurl the Judge from the Graham home and arraign him for impeachment.

Now that he was ready to file the suit, his mind was in a tumult of hesitation. The soft invisible hand of a girl was holding his hand. He gazed steadily at the documents and saw nothing that was within. The ink lines slowly resolved themselves into the raven glossy hair of Stella piled in curling confusion above her white forehead, and he was trying in vain to find the depths of her wonderful eyes.

Something in the expression of those eyes held his memory in a perpetual spell—their remarkable size and their dilation when she spoke. They seemed to enfold him in a soft mantle of light.

He suddenly bundled the papers, replaced them, and took up his pen.

“I’ve got to see her—that’s all!” he exclaimed. “Who knows? Perhaps I’m answering the great summons of life. I’ll put it to the test. At least I’ll not throw my chance away for a house, some trees and a few acres of dirt. When Love calls life’s too short for revenge.”

On a sheet of delicate old note paper with a crest of yellow and black at the top, he wrote:

My Dear Miss Butler:

You were gracious enough to ask me to call again. I cannot believe your words were mere conventional phrases. Their accent was too genuine and sincere. So I beg the privilege of calling to-day while your father, my valiant political enemy, is busy down town with the delegates to his convention which meets to-morrow. I anxiously await your answer.

Sincerely,

John Graham.

“Unless I’ve mistaken her character, she’ll see me!” he mused as he sealed the note.

He went at once to Mrs. Wilson’s, found Alfred, and gave him the missive.

“Take that to the Judge’s and give it to Miss Stella.”

Alfred stared.

“Down to de ole place!”

“Yes, of course.”

Alfred sat down and laughed.

“Well, fore de Lawd, doan dat beat ye!”

“Shut up, and hurry back—I’ll wait for you at the office.”

“Yassah, right away, sah!”

“And Alfred, not a word to a living soul of this.”

“No, sah, cose not Marse John—I know how tis ’my sef’—de course er true love ain’t run smooth wid me nuther.”

“Quick, now, don’t you lose a minute.”

John returned to his office to await with impatience the word that would mean the beginning of a new chapter in his life.

Alfred placed the note carefully under his hat and hastened to the Judge’s, laughing and chuckling to himself.

For reasons best known to himself he entered by the carriage way.

At the wide double gate still stood the old lodge-keeper’s cottage, a relic of the slave regime. In the cottage Aunt Julie Ann lived with Uncle Isaac, her latest husband. Alfred had once been honoured with that relationship before the war, but Isaac had whipped him and taken Aunt Julie Ann by force of arms.

Alfred was much the larger man of the two, tall, awkward and slow of movement, while Isaac was small and active as a cat. The agility of his movements had swept Aunt Julie Ann’s imagination by storm. The contrast to her own three hundred pounds had no doubt been the secret charm.

She had loudly professed her love for Alfred until she saw Isaac thrash him, and without a word she surrendered to the new lord and refused to recognise her former husband.

This happened two years before the war and Alfred had watched and waited the day of his revenge to dawn. Many a night he had prowled around her cottage spying and listening at the keyhole for her cry of help. He had heard at last that Isaac was beating her unmercifully and he chuckled with grim satisfaction. Every opportunity he got he hung around the cottage and listened for the long expected cry. As he approached the gates this morning in a peculiarly romantic frame of mind, remembering the mission he was on, he heard Uncle Isaac’s voice in sharp accents within, hectoring it over his former spouse.

He crept to the door and listened breathlessly.

“Dar now, I’se jes’ in time ter sabe my lady love!”

He peeped cautiously through the keyhole and saw Aunt Julie Ann’s huge form busy at the ironing board, while Isaac sat majestically in a rocker delivering to her an eloquent discourse on Sanctification in general and his own sinless perfection in particular. Isaac had changed his name several times after the war, following the example of many Negroes who were afraid the use of their old master’s name might some day serve as the badge of slavery. He had lately become a Northern Methodist exhorter of great fame and went from church to church holding revivals, particularly among the sisters of the church, calling them to the life of stainless purity of those who had not merely “salvation,” as the ordinary Methodist or Baptist understood it, but “sanctification” as only those of the inner circle of the Lord knew it.

Isaac had long ago been “sanctified,” and had declared not only his sinless nature but had boldy proclaimed himself a prophet of the new dispensation and had finally fixed his name as “Isaac the Apostle,” which had been simplified by busy clerks in written form to Isaac A. Postle.

Aunt Julie Ann had heard of his wonderful success in his sanctification meetings with misgivings, as the large majority of his converts were invariably among the sisters. She had finally dared to question the authenticity of his apostolic call. Her scepticism had aroused Isaac to a frenzy of religious enthusiasm. That the wife of his bosom should be the only voice to question his divine mission was proof positive that she had in some mysterious way become possessed of the devil—perhaps seven devils.

He determined to cast them out—by moral suasion if possible—if not, by the main strength of his good right arm. He must set his own house in order lest the very source of his inspiration be poisoned by lack of faith. He was devoting this morning to the task when Alfred arrived.

He had just finished a long and fervid explanation of the mystery of Sanctification.

“Fur de las’ time I axes ye, ’oman, what sez ye ter de word er de Lawd?”

Aunt Julie Ann banged the board with the iron and merely grunted:

“Huh!”

Isaac rose and repeated his question with rising wrath:

“What sez ye ter de word er de Lawd?”

“I ain’ heared de Lawd say nuttin yit!”

“An’ why ain’t ye?”

“Case you keep so much fuss I can’t hear nuttin’, Isaac Graham!”

“Doan you call me dat name, you brazen sinner dat sets in de seat er de scornful! Is ye ready ter repent an’ sin no mo?”

Isaac approached her threateningly and Alfred, watching with bulging eyes, clutched the stick he had picked up.

“Tech me if ye dare—I bus’ yo head open wid dis flat-iron!”

Isaac knew his duty now and determined to perform it without further ceremony. The anointed of the Lord had been threatened by the ungodly. He drew a seasoned hickory withe from a crack where he had hidden it and approached his sceptical spouse.

Aunt Julie Ann began to whimper.

“Put down dat flat-iron!” he sternly commanded.

Alfred peering through the keyhole gasped in amazement as he saw her drop the iron heavily on the floor.

Isaac raised his switch and began to whip her. Around and around she flew screaming, begging, pleading for mercy. But Isaac continued to lay on steadily.

Alfred tried to rise and rush to the rescue but somehow he couldn’t move. To his own surprise the performance fascinated him. He sat peering with satisfaction.

“Dat’s paying her back now fur leavin’ me fer dat low live rascal. Give it to her, old man! Give it to her! She sho’ deserves it!”

At length Isaac paused, and eyed her steadily while he shook his switch with unction.

“I axes ye now, does ye believe in de Sanctification er de Saints?”

“Yes, Lawd, I sees it now!” she cried with fervour.

“An’ thanks me fer showin’ ye de error er yo’ way?”

“Yes, honey! I’m gwine ter seek dat Sanctification myself!”

“Glory! We’se er comin’ on!”

Aunt Julie Ann picked up the flat-iron. Isaac eyed her with suspicion but he was too much elated with his victory to notice anything unusual in her manner.

“Ye b’lieves now in de Sanctification er de Lawd’s messenger Isaac A. Postle?”

With a sudden flash of her eye Aunt Julie Ann hurled the flat-iron straight at the head of the Lord’s messenger saying:

“No, I ain’t sed dat yit!”

But Isaac was quick. He dodged in time. The corner of the flat-iron merely tipped his ear and smashed through the window.

He grabbed his ear with sudden pain and gripped his switch with renewed zeal.

“I see I’se des begun—one debble out, but dey’s six mo’ ter come!”

Again he whipped her around the room, threw her down, held her hair and banged her head against the floor.

“Fur de las’ time I axes ye, is de Lawd’s messenger, Isaac A. Postle, a sanctified one?”

Bang! Bang! Bang! went her head against the planks.

“Yes honey, I sees it now!” she cried with enthusiasm.

“Dat’s de way!”

“Does ye lub me fur showin’ ye de light?”

Bang! Bang! went her head.

“Yes, Lawd, I lub ye.”

“Say it strong.”

Bang! Bang! went her head.

“I lubs ye, my honey, yes I do!” shouted Aunt Julie Ann.

“An’ I’se de only man dat ye ebber lub?”

A moment’s pause, and again bang! bang! went her head.

Alfred couldn’t wait for the answer; he gripped his stick, sprang through the door, knocked the Apostle flat on his back, and jumped on him.

Aunt Julie Ann was more astonished than Isaac at her sudden deliverance.

She scrambled to her feet and gazed for a moment in amazement at Alfred as he pummelled Isaac’s head against the floor with one hand and pounded him with the other.

At every thump of his head Isaac yelled:

“God sabe me! de debble done got me! Help, Lawd, help! Save me Lawd—save me now!” Alfred pounded steadily away.

Aunt Julie Ann, when she caught her breath, grasped Alfred’s arm and yelled:

“What yer doin’ here, nigger!”

He wrenched his arm loose from her grasp and hit Isaac a smashing blow in the mouth as he cried again for help.

“Git often my ole man. I tell ye!” screamed Aunt Julie Ann, gripping Alfred by the throat.

“Name er God, ’oman, what yer doin’ when I comes here ter save ye!” cried Alfred, wrenching himself from her grip and returning to his work on Isaac.

“Git often ’im, I tell ye, fo’ I bus’ yer open!” she panted, towering above the writhing pair. She began to pound Alfred over the head with her fists, but he worked steadily away on Isaac without noticing the interruptions.

Suddenly Aunt Julie Ann threw both arms around his neck, bent his lank figure double across Isaac’s prostrate form, and hurled her three hundred pounds squarely across the two writhing men. There was dead silence for a moment and then Isaac groaned:

“God save me now! we’se bof gone! De house done fall on us!”

“Na! honey, it’s me!” cried Aunt Julie Ann, “an’ I got ’im in de gills!”

She rolled over and pulled Alfred with her—both hands gripped to his throat.

In a moment Isaac was on his feet.

“De Lawd hear my cry!” he exclaimed with unction, pouncing on Alfred and pounding him unmercifully while his faithful spouse held him fast. Alfred found his voice at last, and began to yell murder.

Steve Hoyle, who was pacing the walk in front of the Judge’s anxiously waiting an answer to a pleading letter he had sent to Stella asking for an interview, heard the cries and rushed to Alfred’s rescue.

He pulled Isaac and Aunt Julie Ann off in time to save his hat and portions of his clothes.

As he entered the cottage, he had seen instantly the note in John Graham’s handwriting which Alfred had dropped on the floor. He picked it up hastily and put it in his pocket.

When Alfred got out the door, he did not stand on the order of his going. He struck a bee line for John Graham’s office and ran every step of the way without looking back.

John was pacing the floor, his heart beating out the interminable minutes.

Alfred burst into the room, his nose bleeding, a gash across his forehead, his clothes torn and spotted with the blood from his nose. He was still wild with the fear of death which had clutched his soul as the light of day faded under Aunt Julie Ann’s awful grip on his throat.

He dropped, panting and speechless, on the floor. “For God’s sake, Alfred, what’s happened!” John cried, seizing a glass of water and pressing it to his lips.

“Dey kill me, Marse John!”

“Who did it?—what for?”

“De folks at de Judge’s.”

“Where’s my note?”

“Dunno sah!”

“Didn’t you deliver it?”

“Dunno sah!”

“Did you go to the house?”

“Dunno sah!”

“Where did this happen?”

“At de gate, sah, dey wuz layin’ fer me—De Judge mus’ er tole ’em ter kill me.”

“Who did it?”

“Ole Isaac and Julie Ann jump on me fust, but tow’d de last dey wuz er dozen. Six un ’em wuz er beatin’ me on de head at de same time, three er four wuz er settin’ on top er me, two had me by the throat an’ de res’ un ’em wuz er steady kickin’ me in de stummick. Dey’d er had me sho’ by dis time ef I hadn’t kotch my breaf an’ holler’d.”

“And who helped you?”

“Mr. Steve Hoyle wuz dar ter see Miss Stella an’ he run in an’ pulled ’em off. When I lit out for home I wuz er sight sho nuff. I hear Miss Stella come up ter Mr. Steve an’ bust out laffin’ fit ter kill herself.”

“And you don’t know what became of the note?”