The Project Gutenberg eBook of English Caricature and Satire on Napoleon I. Volume II (of 2), by John Ashton

Release Date: October 12, 2015 [eBook #50185]

[Most recently updated: November 25, 2022]

Language: English

Produced by: Chris Curnow, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s note: Cover created by Transcriber and placed in the Public Domain.

VOL. II.

WORKS BY JOHN ASHTON.

A HISTORY OF THE CHAP-BOOKS OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY. With nearly 400 Illustrations, engraved in facsimile of the originals. Crown 8vo. cloth extra, 7s. 6d.

SOCIAL LIFE IN THE REIGN OF QUEEN ANNE. From Original Sources. With nearly 100 Illustrations. Crown 8vo. cloth extra, 7s. 6d.

HUMOUR, WIT, AND SATIRE OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY. With nearly 100 Illustrations. Crown 8vo. cloth extra, 7s. 6d.

London: CHATTO & WINDUS, Piccadilly.

ENGLISH

CARICATURE AND SATIRE

ON

NAPOLEON I.

BY

JOHN ASHTON

AUTHOR OF ‘SOCIAL LIFE IN THE REIGN OF QUEEN ANNE’ ETC.

WITH 115 ILLUSTRATIONS BY THE AUTHOR

IN TWO VOLUMES—VOL. II.

London

CHATTO & WINDUS, PICCADILLY

1884

All rights reserved

LONDON: PRINTED BY

SPOTTISWOODE AND CO., NEW-STREET SQUARE

AND PARLIAMENT STREET

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| PAGE | |

| INVASION SQUIBS—CADOUDAL’S CONSPIRACY—EXECUTION OF THE DUC D’ENGHIEN—CAPTAIN WRIGHT | 1 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

| NAPOLEON PROCLAIMED EMPEROR—THE FLOTILLA—INVASION SQUIBS | 12 |

| CHAPTER XL. | |

| NAPOLEON’S CORONATION | 23 |

| CHAPTER XLI. | |

| NAPOLEON’S LETTER TO GEORGE THE THIRD—NAVAL VICTORIES—CROWNED KING OF ITALY—ALLIANCE OF EUROPE—WITHDRAWAL OF THE ‘ARMY OF ENGLAND’ | 35 |

| CHAPTER XLII. | |

| SURRENDER OF ULM—BATTLE OF TRAFALGAR—PROPOSALS FOR PEACE—DANIEL LAMBERT | 45 |

| CHAPTER XLIII. | |

| NEGOTIATIONS FOR PEACE—DEATH OF FOX—NAPOLEON’S VICTORIOUS CAREER—HIS PROCLAMATION OF A BLOCKADE OF ENGLAND | 57 |

| CHAPTER XLIV.vi | |

| NAPOLEON’S POLISH CAMPAIGN—BATTLE OF EYLAU—MEETING OF THE EMPERORS AT TILSIT—CAPTURE OF THE DANISH FLEET | 65 |

| CHAPTER XLV. | |

| FRENCH ENTRY INTO PORTUGAL—BLOCKADE OF ENGLAND—FLIGHT OF THE PORTUGUESE ROYAL FAMILY—THE PENINSULAR WAR—FLIGHT OF KING JOSEPH | 75 |

| CHAPTER XLVI. | |

| PENINSULAR WAR, continued—MEETING AT ERFURT | 87 |

| CHAPTER XLVII. | |

| RETREAT TO CORUNNA—THE BROKEN BRIDGE OVER THE DANUBE—WAGRAM—JOSEPHINE’S DIVORCE | 96 |

| CHAPTER XLVIII. | |

| FAILURE OF EXPEDITIONS TO SPAIN, PORTUGAL, AND HOLLAND—NAPOLEON’S WOOING OF, AND MARRIAGE WITH, MARIA LOUISA—BIRTH OF THE KING OF ROME—NAPOLEON IN THE NURSERY | 110 |

| CHAPTER XLIX. | |

| A NAVAL ENGAGEMENT—NAPOLEON’S TOUR IN GERMANY—DECLARATION OF WAR WITH RUSSIA—ENTRY INTO WILNA—SMOLENSKO—BORODINO—ENTRY INTO MOSCOW—BURNING OF THE CITY—NAPOLEON’S RETREAT | 123 |

| CHAPTER L. | |

| REJOICINGS IN ENGLAND OVER THE RESULT OF NAPOLEON’S RUSSIAN CAMPAIGN—THE EMPEROR’S RETURN TO FRANCE | 138 |

| CHAPTER LI. | |

| THE ARMISTICE—BATTLE OF VITTORIA—DEFEAT AT LEIPSIC—THE BRIDGE BLOWN UP | 150 |

| CHAPTER LII.vii | |

| NAPOLEON’S RETURN TO PARIS—HIS RECEPTION | 164 |

| CHAPTER LIII. | |

| L’HOMME ROUGE—NAPOLEON’S SUPERSTITION | 172 |

| CHAPTER LIV. | |

| NAPOLEON AGAIN TAKES THE FIELD—HIS DEFEATS—THE ALLIES AT PARIS—NAPOLEON ABDICATES—HIS ATTEMPT TO POISON HIMSELF | 181 |

| CHAPTER LV. | |

| NAPOLEON LEAVES FOR ELBA—HIS RECEPTION THERE | 194 |

| CHAPTER LVI. | |

| NAPOLEON AT ELBA—HIS OCCUPATIONS WHILST THERE—FAITH BROKEN WITH HIM—THE VIOLET—GENERAL REJOICINGS AT HIS EXILE | 203 |

| CHAPTER LVII. | |

| NAPOLEON’S ESCAPE FROM ELBA—UNIVERSAL CONSTERNATION—FLIGHT OF THE BRITISH FROM FRANCE—CARICATURES ON HIS RETURN | 214 |

| CHAPTER LVIII. | |

| PREPARATIONS FOR WAR—THE SHORT CAMPAIGN—WATERLOO—NAPOLEON’S ABDICATION | 225 |

| CHAPTER LIX. | |

| NAPOLEON A PRISONER—SENT TO THE ISLE OF AIX—NEGOTIATIONS FOR SURRENDER—GOES ON BOARD THE ‘BELLEROPHON’ | 233 |

| CHAPTER LX. | |

| NAPOLEON ON BOARD THE ‘BELLEROPHON’—ARRIVAL AT TORBAY—CURIOSITY OF THE PEOPLE—THE ENGLISH GOVERNMENT DETERMINE TO SEND HIM TO ST. HELENA | 239 |

| CHAPTER LXI.viii | |

| NAPOLEON IS SENT ON BOARD THE ‘NORTHUMBERLAND’—HE PROTESTS AGAINST HIS EXILE—PUBLIC OPINION AS TO HIS TREATMENT | 250 |

| CHAPTER LXII. | |

| VOYAGE TO ST. HELENA—CESSATION OF CARICATURES | 259 |

| INDEX | 269 |

The Volunteer movement was well shown in a print by A. M., November 1803: ‘Boney attacking the English Hives, or the Corsican caught at last in the Island.’ There are many hives, the chief of which has a royal crown on its top, and is labelled ‘Royal London Hive. Threadneedle Street Honey’—which Napoleon is attacking, sword in hand. George the Third, as Bee Master, stands behind the hives, and says, ‘What! what! you plundering little Corsican Villain, have you come to rob my industrious Bees of their Honey? I won’t trust to your oath. Sting, Sting the Viper to the heart my good Bees, let Buz, Buz be the Word in the Island.’ The bees duly obey their master’s request, and come in clouds over Napoleon, who has to succumb, and pray, kneeling, 2‘Curse those Bees they sting like Scorpions. I did not think this Nation of Shopkeepers could sting so sharp. Pray good Master of the Bees, do call them off, and I will swear by all the three creeds which I profess, Mahometan, Infidel, and Christian, that I will never disturb your Bees again.’

‘Selling the Skin before the Bear is caught, or cutting up the Bull before he is killed,’ is by I. Cruikshank (December 21, 1803), and represents a Bull reposing calmly on the English shore, whilst on the opposite or French coast is Bonaparte, Talleyrand, and several Generals. Bonaparte, pointing to the Bull, says: ‘I shall take the Middle part, because it contains the Heart and Vitals—Talley, you may take the head, because you have been accustomed to take the Bull by the horns.’ Britannia stands, fully armed, behind the Bull, by an ‘alarm post,’ on which hangs a bell, ‘British Valor,’ which she is preparing to ring: ‘When these Mounseers have settled their plan, I will just rouse the Bull, and then see who will be cut up first.’

‘New Bellman’s Verses for Christmas 1803!’ is an extremely inartistic work of an unknown man (December 1803); the only thing worth quoting about it are these verses:—

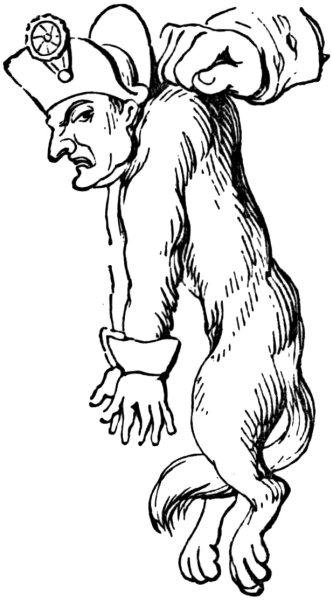

‘More than expected, or too many for Boney’ (artist unknown, December 1803), shows him as an Ass, on whose3 back is John Bull, Russia, Prussia, and Germany. Says Russia, ‘We all depend upon you Mr. Bull—give him a little more spurring, and we’ll soon make him feel the Rowels.’ John mildly expostulates with his quadruped: ‘Come—come, don’t be sulky—if you won’t go in a snaffle, you must be forced to go in a curb.’

Dean Swift’s immortal book did yeoman’s service to the caricaturists, and we find it again employed in a print by West, December 1803: ‘The Brobdingnag Watchman preventing Gulliver’s landing.’ It is very feeble, and merely consists of George the Third as a watchman turning the light of the ‘Constitutional Lanthorn’ upon Bonaparte and his companions, who are attempting a landing.

Another print, by West (December 1803), shows ‘Mr. and Mrs. Bull giving Buonaparte a Christmas Treat!’ The latter is bound to a post in sight of, but beyond reach of, the national fare of this festival. John Bull says, holding up a piece of beef, in derision, ‘Yes, yes—the Beef is very good, so is the pudding too—but the deuce a morsel do you get of either, Master Boney.’ Mrs. Bull too, who is drinking from a frothing tankard, says: ‘Your health Master Boney, wishing you a merry Christmas,’ but offers him none.

An unknown artist gives an undated picture of ‘a Cock and Bull Story.’ Napoleon, as the Gallic Cock, on his side of the Channel, sings

John Bull, who is peacefully reposing in his pastures rejoins:—

In 1803 was published an amusing squib, in which the names of various plays are very ingeniously made into a patriotic address:—

THE GREEN ROOM OPINION

OF THE

Threatened Invasion.Should the Modern Tamerlane revive the tragedy of England Invaded, and, in the progress of his Wild goose Chace, escape the Tempest, he will find that, with us, it is Humours of the Age to be Volunteers. He will prove that we have many a Plain Dealer, who will tear off the Mask, under which the Hypocrite, this Fool of Fortune, this Choleric man, has abused a credulous world. Should he, to a Wonder, attempt a Trip to Scarborough, to set them all alive at Portsmouth, or to get on both sides of the gutter, he will assuredly meet a Chapter of Accidents on his Road to Ruin; for Britannia and the Gods are in Council, to make him a Castle Spectre: he will, too late, discover the Secret of Who’s the Dupe; and that it is the Custom of the Country of John Bull, to shew the Devil to pay to any Busybody, who seeks to enforce on us Reformation.

This Double Dealer, who has excited dismay Abroad and at Home, and gained Notoriety by the magnitude of the mischiefs he has achieved, still presumes, by the Wheel of Fortune, like another Pizarro, to satiate his Revenge, and to learn How to grow Rich, by renewing the distressing scenes of the Siege of Damascus; until amongst the desolated ruins of our City, he should establish himself like a London Hermit. That he Would if he Could, is past all doubt; but if he will take a Word to the Wise, from a Man of the World, he will believe He’s much to blame, and All in the Wrong; for the Doctor and the Apothecary are in the Committee; and by good Management, are forward in the Rehearsal of the5 lively Comedy of the Way to keep Him under Lock and Key. They may not be able to produce for him a Cure for the Heartache, or for the Vapourish Man, but they will shew him at least Cheap Living, and prove that he has sown his Wild Oats, in a Comedy of Errors.

The Poor Soldier, whose generous heart expands to render Love for Love, is like the gallant and gay Lothario, armed for either field, and prepared to give Measure for Measure; and to convert the Agreeable Surprize, which the Acre Runaway anticipates in the Camp, from the Beaux Stratagem into a Tale of Mystery. Appearances are against him, as well as the Chances; but he is a desperate Gamester; and although his schemes of Conquest will end in Much ado about Nothing, like a Midsummer’s night’s Dream, or a Winter’s Tale, yet he is Heir at Law to our hate; and Every one has his Fault, if he does not unite to revive the splendid scenes of Edward the Black Prince, and Henry the Fifth, when France trembled beneath our arms at Cressy and Agincourt; and give to this unprincipled Bajazet an exit corresponding with his crimes.

A NEW SONG OF OLD SAYINGS.

The year 1804 was a most eventful one for Napoleon. With all his hatred of England, and his wish for her invasion, he was powerless in that matter, and had plenty to employ him at home. The English had got used to their bugbear the flotilla, and the caricaturist had a rest. Napoleon had his hands full. First and foremost was that conspiracy against his life and government, in which Georges Cadoudal, Moreau, and Pichegru figure so prominently, and which entailed the execution of the Duc d’Enghien.

Whatever may have been Napoleon’s conduct in this affair, these two last lines are undoubtedly false. The duke had been residing at Ettenheim, in the duchy of Baden, and was thought to be there in readiness to head the Royalists in case of need, that his hunting was but a pretext to cover flying visits to Paris, and that he was the person whom Georges Cadoudal and his fellow conspirators always received bareheaded. He was seized, brought to Paris, and lodged in the Château de Vincennes. A few hours’ rest, and he was roused at midnight to go before his judges. It was in vain he pleaded the innocence of his occupations, and begged to have an interview with the First Consul; yet he declared he had borne arms against France, and his wish to serve in the war on the English side against8 France; and owned that he received a pension of one hundred and fifty guineas a month from England. He was found guilty and condemned to death, and two hours afterwards was led out into the ditch of the fortress, and there shot, a priest being refused him. O’Meara, describing a conversation with Napoleon on this subject, says: ‘I now asked if it were true that Talleyrand had retained a letter written by the Duc d’Enghien to him until two days after the duke’s execution? Napoleon’s reply was, “It is true; the duke had written a letter offering his services, and asking a command in the Army from me, which that scelerato, Talleyrand, did not make known until two days after his execution.” I observed that Talleyrand, by his culpable concealment of the letter, was virtually guilty of the death of the duke. “Talleyrand,” replied Napoleon, “is a briccone, capable of any crime. I,” continued he, “caused the Duc d’Enghien to be arrested in consequence of the Bourbons having landed assassins in France to murder me. I was resolved to let them see that the blood of one of their princes should pay for their attempts, and he was accordingly tried for having borne arms against the republic, found guilty, and shot, according to the existing laws against such a crime.”’

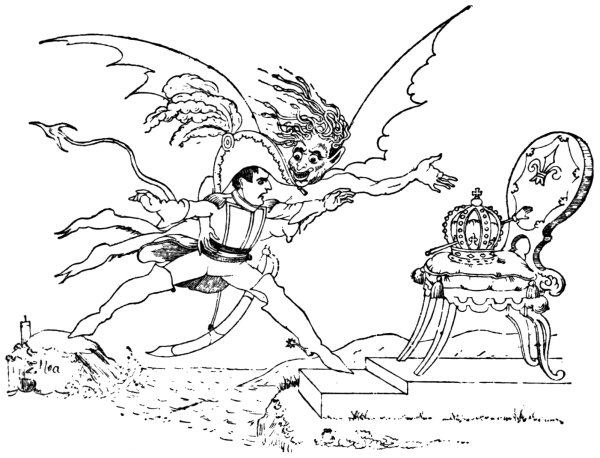

Ansell (June 2, 1804) gives us ‘The Cold Blooded Murderer, or the Assassination of the Duc d’Enghien,’ in which the duke is represented as being bound to a tree, a soldier on either side holding a torch, whilst Napoleon is running his sword into his heart. D’Enghien bravely cries out, ‘Assassin! your Banditti need not cover my Eyes, I fear not Death, tho’ perhaps a guiltless countenance may appall your bloodthirsty soul.’ Napoleon, whilst stabbing his victim, says: 9‘Now de whole World shall know de courage of de first grand Consul, dat I can kill my enemies in de Dark, as well as de light, by Night as well as by Day,—dare—and dare I had him—hark, vat noise was dat? ah! ’tis only de Wind—dare again, and dare—Now I shall certainly be made Emperor of de Gulls.’1 Devils are rejoicing over the deed, and are bearing a crown. They say: ‘This glorious deed does well deserve a Crown, thus let us feed his wild ambition, untill some bold avenging hand shall make him all our own.’

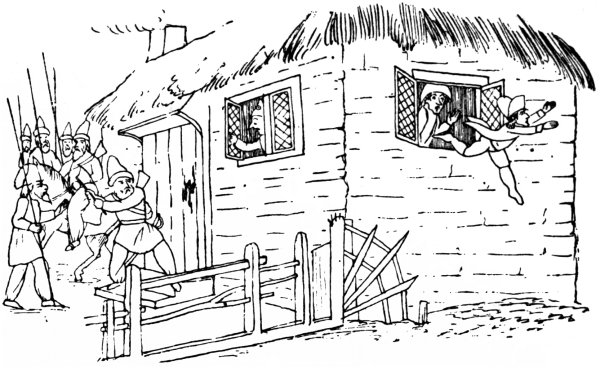

A Captain Wright figures in this plot; and, as he was an Englishman, and his name is frequent both in the caricature and satire of the day, some notice of him must be given. He was a lieutenant in the Royal Navy, and somehow got mixed up with this conspiracy. He took Georges Cadoudal and others on board either at Deal or Hastings, and crossed over to Beville, where there was a smuggler’s rope let down from an otherwise inaccessible cliff. By means of this they were drawn up, and went secretly to Paris. The plot failed, and they were thrown into prison, Wright being afterwards captured at sea. Cadoudal went to the scaffold, Pichegru was found strangled in his cell; and Wright, the English said, after being tortured in prison, to compel him to give evidence against his companions, was assassinated by order of Napoleon.

The latter, however, always indignantly denied it, saying that Captain Wright committed suicide. In O’Meara’s book he denies it several times, and an extract or two will be worth noting. ‘In different nights of August, September, and December 1803 and January 1804, Wright landed Georges, Pichegru, Rivière, Costa, St. Victor, La Haye, St. Hilaire, and others at Beville. The four last named had been accomplices in the former attempt to assassinate me by means of the infernal machine, and most of the rest were well known to be chiefs of the Chouans,’ &c. ‘There was something glorious in Wright’s death. He preferred10 taking away his own life, to compromising his government.’ ‘Napoleon in very good spirits. Asked many questions about the horses that had won at the races, and the manner in which we trained them; how much I had won or lost; and about the ladies, &c. “You had a large party yesterday,” continued he. “How many bottles of wine? Drink, your eyes look like drink,” which he expressed in English. “Who dined with you?” I mentioned Captain Wallis amongst others. “What! is that the lieutenant who was with Wright?” I replied in the affirmative. “What does he say about Wright’s death?” I said, “He states his belief that Wright was murdered by orders of Fouché, for the purpose of ingratiating himself with you. That six or seven weeks previous, Wright had told him that he expected to be murdered like Pichegru, and begged of him never to believe that he would commit suicide; that he had received a letter from Wright, about four or five weeks before his death, in which he stated that he was better treated, allowed to subscribe to a library, and to receive newspapers.” Napoleon replied, “I will never allow that Wright was put to death by Fouché’s orders. If he was put to death privately, it must have been by my orders, and not by those of Fouché. Fouché knew me too well. He was aware that I would have had him hanged directly, if he attempted it. By this officer’s own words, Wright was not au secret, as he says he saw him some weeks before his death, and that he was allowed books and newspapers. Now, if it had been in contemplation to make away with him, he would have been put au secret for months before, in order that people might not be accustomed to see him for some time previous, as I thought this * * * intended to do in November last. Why not examine the gaolers and turnkeys? The Bourbons have every opportunity of proving it, if such really took place. But your ministers11 themselves do not believe it. The idea I have of what was my opinion at that time about Wright, is faint; but, as well as I can recollect, it was that he ought to have been brought before a military commission, for having landed spies and assassins, and the sentence executed within forty-eight hours. What dissuaded me from doing so, I cannot clearly recollect. Were I in France at this moment, and a similar occurrence took place, the above would be my opinion, and I would write to the English Government: ‘Such an officer of yours has been tried for landing brigands and assassins on my territories. I have caused him to be tried by a military commission. He has been condemned to death. The sentence has been carried into execution. If any of my officers in your prisons have been guilty of the same, try, and execute them. You have my full permission and acquiescence. Or, if you find, hereafter, any of my officers landing assassins on your shores, shoot them instantly.’”’

The most important event of the year to Napoleon himself, was his being made Emperor. Although First Consul for life, with power to appoint his successor, it did not satisfy his ambition. He would fain be Emperor, and that strong will, which brooked no thwarting, took measures to promote that result. In the Senate M. Curée moved, ‘that the First Consul be invested with the hereditary power, under the title of Emperor,’ and this motion was but feebly fought against by a few members, so that at last an address was drawn up, beseeching Napoleon to yield to the wishes of the nation. A plébiscite was taken on the subject, with the result that over three millions and a half people voted for it, and only about two thousand against it. On May 18, Cambacérès, at the head of the Senate, waited upon Napoleon, at St. Cloud, with an address detailing the feelings and wishes of the nation. It is needless to say that Napoleon ‘accepted the Empire, in order that he might labour for the happiness of the French.’

The flotilla, on the other side of the Channel, was still looked upon with uneasiness, and watched with jealous care. Still, we find that it was only at the commencement of the year that it was caricatured, Napoleon’s being made Emperor proving a more favourite subject; and, besides, a feeling sprung up that there was not much mischief in it.

One of the most singular caricatures, in connection with the projected invasion, that I have met with is by Ansell, January 6, 1804. ‘The Coffin Expedition, or Boney’s Invincible Armada Half seas over.’ The flotilla is here represented as gunboats, in the shape of coffins: all the crews, naval and military, wearing shrouds; whilst at the masthead of each vessel is a skull with bonnet rouge. It is needless to say they are represented as all foundering, one man exclaiming, ‘Oh de Corsican Bougre was make dese Gun boats on purpose for our Funeral.’ Some British vessels are in the mid distance, and two tars converse thus: ‘I say Messmate, if we dont bear up quickly, there will be nothing left for us to do.’ ‘Right, Tom, and I take them there things at the Masthead to be Boney’s Crest, a skull without brains.’

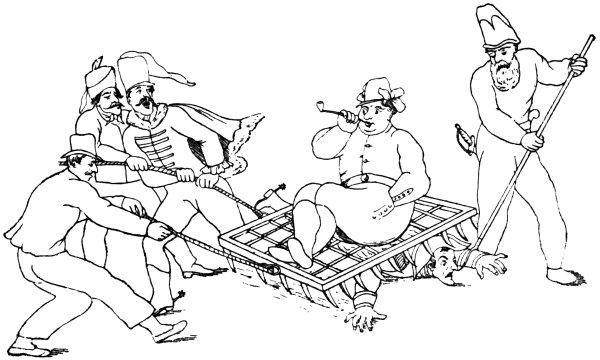

‘Dutch Embarkation; or Needs must when the Devil drives!!’ (artist unknown, January 1804) represents Bonaparte, with drawn sword, driving fat, solid Dutchmen each into a gun-boat about as big as a walnut-shell. One remonstrates: ‘D—n such Liberty, and D—n such a Flotilla!! I tell you we might as well embark in Walnut Shells.’ But Bonaparte replies: 15‘Come, come, Sir, no grumbling, I insist on your embarking and destroying the modern Carthage—don’t you consider the liberty you enjoy—and the grand flotilla that is to carry you over!’

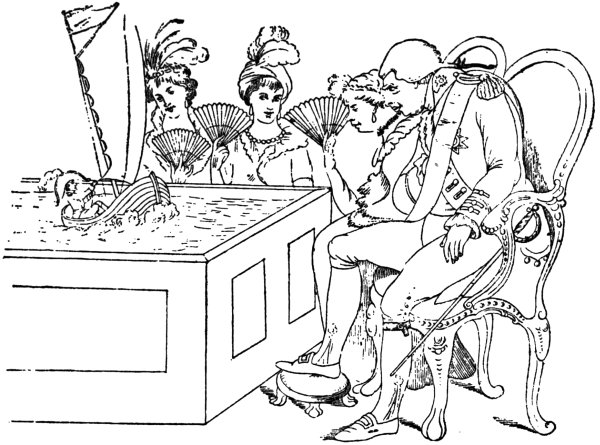

As good a one as any of Gillray’s caricatures is the King of Brobdingnag and Gulliver, February 10, 1804—scene, ‘Gulliver manœuvring with his little boat in the cistern.’ The king and queen (excellent likenesses) and two princesses are looking on at Bonaparte sailing, whilst the young princes are blowing, to make a wind for him. Lord Salisbury stands behind the royal chair, and beefeaters and ladies of the court complete the scene. This, however, is specially described as ‘designed by an amateur, etched by Gillray.’

‘A French Alarmist, or John Bull looking out for the Grand Flotilla!!’ (West, March 1804.) He is on the coast, accompanied by his bull-dog, and armed with a sword, looking through a telescope. Behind him is a Frenchman, who is saying, 16‘Ah! Ah! Monsieur Bull,—dere you see our Grande flotilla—de grande gon boats—ma foi—dere you see em sailing for de grand attack on your nation—dere you see de Bombs and de Cannons—Dere you see de Grande Consul himself at de head of his Legions. Dere you see——’ But John Bull replies, ‘Mounseer, all this I cannot see—because ’tis not in sight.’

We now come to the caricatures relating to the Empire.

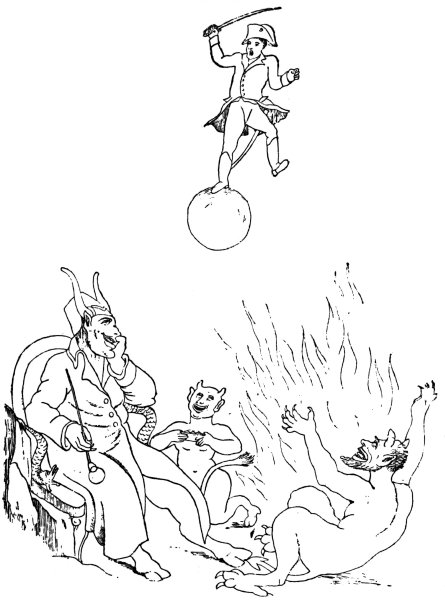

A print, attributed to Rowlandson (May 1804?), shows ‘A Great Man on his Hobby Horse, a design for an Intended Statue on the Place la Liberté at Paris.’ Napoleon is riding the high horse ‘Power,’ which prances on a Globe.

‘A new French Phantasmagoria’ is by an unknown artist (May 1804). John Bull cannot realise the fact of Napoleon being Emperor, but stares at him through an enormous pair of spectacles. ‘Bless me, what comes here—its time to put on my large spectacles, and tuck up my trowsers. Why, surely, it can’t be—it is Bonny too, for all that. Why what game be’st thee at now? acting a play mayhap. What hast thee got on thy head there? always at some new freak or other.’ Bonaparte, in imperial robes, and with crown and sceptre, holds out his hand, and says: ‘What! my old Friend, Mr. Bull, don’t you know me?’

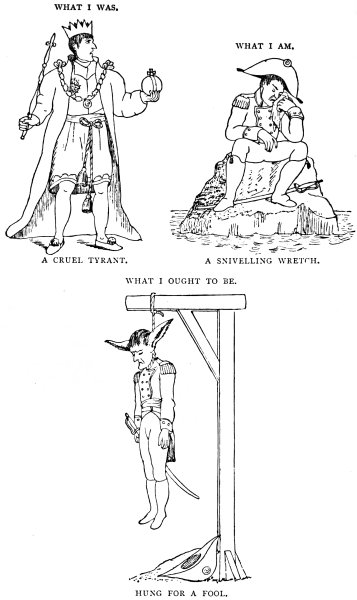

Ansell gives us (May 28, 1804) ‘The Frog and the Ox, or The Emperor of the Gulls in his stolen gear.’ Napoleon, very small, is depicted as capering about in imperial robes, with an enormous crown made of coins, daggers, and a cup of poison; his sceptre has for its top a guillotine. George the Third is regarding him through his glass. Napoleon says, ‘There Brother! there! I shall soon be as Big as you, it’s a real Crown, but it’s cursed heavy, my Head begins to ache already. I say Can’t we have a grand meeting like Henry the 8th and Francis the 1st?’ King George cannot quite make out the mannikin. 17‘What have we got here, eh? A fellow that has stolen some Dollars, and made a Crown of them, eh? and then wants to pass them off for Sterling; it won’t go, it won’t pass Fellow.’ Beside the King is a bull, and behind Napoleon is a frog, who is trying to swell to the bull’s proportions, whilst John Bull laughingly remarks, ‘Dang it, why a looks as tho a’d burst: a’l nerr be zo big as one of our Oxen tho.’

‘Injecting blood Royal, or Phlebotomy at St. Cloud,’ shews Napoleon, in his new phase of power, having the blood of a Royal Tiger infused into his veins. He says, ‘It’s a delightful operation! I feel the Citizenship oozing out at my fingers’ ends.—let all the family be plentifully supplied! Carry up a Bucket full to the Empress immediately!!!’

In June 1804 I. Cruikshank drew a picture called ‘the Right Owner.’ Louis the Eighteenth appears to Napoleon, and, pointing to his crown, says, ‘That’s Mine.’ Napoleon, who is seated on his throne, armed with sword, pistols, and dagger, shrinks back in violent alarm, exclaiming, ‘Angels and Ministers of Grace defend me.’

‘A Proposal from the New Emperor’ is a caricature by Ansell (July 9, 1804). He comes, cap, or rather crown, in hand, to John Bull, saying, ‘My Dear Cousin Bull—I have a request to make you—the good people whom I govern, have been so lavish of their favors towards me—that they have exhausted every title in the Empire—therefore, in addition, I wish you to make me a Knight of Malta.’ John Bull replies, ‘I’ll see you d—d first!! You know I told you so before.’

‘The Imperial Coronation’ is a very inartistic sketch by an unknown artist (July 31, 1804). Napoleon is being crowned by the Pope, who says, ‘In a little time you shall see him, and in a little time you shall not see him,’ and then lets down the crown, with cruel force, by a rope and18 pulley from the gibbet from which it has been suspended. Its weight crushes him through the platform on which he has been sitting, and he exclaims, ‘My dear Talleyrand, save me; My throne is giving way. I am afraid the foundation is rotten, and wants a deal of mending.’ Talleyrand sympathisingly answers, ‘Oh, Master, Master, the Crown is too heavy for you.’

I. Cruikshank drew ‘Harlequin’s last Skip’ (August 23, 1804). Bonaparte is represented in a harlequin’s suit, enormous cocked hat, boots, and a blackened face. His sword is broken, and, with upraised hands, in a supplicating attitude, he exclaims, ‘O Sacre Dieu! John Bull is de very Devil.’ John Bull, with upraised cudgel, says: ‘Mr. Boney Party, you have changed Characters pretty often and famously well, and skipped about at a precious rate. But this Invasion hop is your last—we have got you snug—the devil a trap to get through here—Your conjuration sword has lost its Power; you have lied till you are black in the face, and there is no believing a word you say—so now you shall carry John Bull’s mark about with you, as every swaggerer should.’

‘British men of war towing in the Invader’s Fleet,’ artist unknown (September 25, 1804), shows a number of English sailors seated on the necks of French and Dutch men, whom they are guiding over the sea to England. One sailor, evidently a Scotchman, is pulling his opponent’s ears; the poor Frenchman cries out, ‘Oh Morbleu! de salt water make me sick; O mine pauvre Ears!’ but his ruthless conqueror has no pity, ‘Deil tak your soul, ye lubberly Loon, gin ye dinna mak aw sail, I’ll twist off your lugs.’ An English sailor rides the redoubtable Boney, and pulls his nose: 19‘Steady Master Emperor, if you regard your Imperial Nose. Remember a British Tar has you in tow—No more of this wonderful, this great and mighty nation who frighten all the world with their buggabo invasion.’ But Boney pleads, ‘Oh! mercy, take me back, me will make you all Emperors; it will be Boney here, Boney there, and Boney everywhere, and me wish to my heart me was dead.’ An Irish sailor on a Dutchman yells out, ‘By Jasus, my Jewel, these bum boats are quizzical toys and sure—heave ahead, you bog trotting spalpeen, or I shall be after keel hauling you. Huzza, Huzza, Huzza, my boys, Huzza! ’Tis Britannia boys, Britannia rules the waves.’ Another Dutchman complains, ‘O Mynheer Jan English you vill break my back.’ But the relentless sailor who bestrides him takes out his tobacco-box, and says, ‘Now for a quid of comfort! pretty gig for Jack Tars. Good bye to your bombast, we’re going to Dover, Was ever poor Boney, so fairly done over.’

A most remarkable caricature by Ansell (October 25, 1804) shows to what length party spirit will lead men—making truth entirely subservient to party purposes. It probably paid to vilify Napoleon, and consequently this picture was produced. It is called ‘Boney’s Inquisition. Another Specimen of his Humanity on the person of Madame Toussaint.’ Whatever may be our opinion of his treatment of Toussaint l’Ouverture, the only record we have in history (and I have expended much time and trouble in trying to find out the truth of the matter) is that his family, who were brought to France at the same time as himself, took up their residence at Agen, where his wife died in 1816. His eldest son, Isaac, died at Bordeaux in 1850. Now to describe the picture. Madame l’Ouverture is depicted as being bound to a stretcher nearly naked, whilst three Frenchmen are tearing her breasts with red-hot pincers. Another is pulling out her finger-nails with a similar instrument. She exclaims: 20‘Oh Justice! Oh Humanity, Oh Deceitfull Villain, in vain you try to blot the Character of the English: ’tis their magnanimity which harrasses your dastard soul.’ One of the torturers says: ‘Eh! Diable! Why you no confess noting?’ Napoleon is seated on his throne, watching the scene with evident delight, chuckling to himself, ‘This is Luxury. Jaffa, Acre, Toulon and D’Enghien was nothing to it. Slave, those pincers are not half hot, save those nails for my Cabinet, and if she dies, we can make a confession for her.’

‘The Genius of France nursing her darling’ is by a new hand, T. B. d——lle (November 26, 1804). 21‘France, whilst dandling her darling, and amusing him with a rattle, sings—

An unknown artist (December 11, 1804) gives us ‘The death of Madame Republique.’ Madame lies a corpse on her bed. Sieyès, as nurse, dandles the new emperor. John Bull, spectacles on nose, inquires, ‘Pray Mr. Abbé Sayes—what was the cause of the poor lady’s Death? She seem’d at one time in a tolerable thriving way.’ Sieyès replies, ‘She died in Child bed, Mr. Bull, after giving birth to this little Emperor.’

‘The Loyalist’s Alphabet, an Original Effusion,’ by James Bisset (September 3, 1804), consists of twenty-four small engravings, each in a lozenge.

‘A, stands for Albion’s Isle,’—Britannia seated.

‘B, for brave Britons renown’d.’—A soldier and sailor shaking hands.

‘C, for a Corsican tyrant,’—Napoleon, with a skull, the guillotine, &c., in the background.

‘D, his dread downfall must sound.’—Being hurled from his throne by lightning.

‘E, for embattl’d we stand,’—A troop of soldiers.

‘F, ’gainst the French our proud Foes,’—shews England guarded by her ships,’ and the flotilla coming over.

‘G, for our glorious Gunners,’—Three artillerymen, and a cannon.

‘H, for Heroical blows,’—shews a ship being blown up.

‘I, for Invasion once stood,’—Some soldiers carousing. The English flag above the tricolour.

22 ‘J, proves ’twas all a mere Joke.’—A soldier laughing heartily, and holding his sides.

‘K, for a favorite King, to deal against Knaves a great stroke.—Medallion of George the Third.

‘L, stands for Liberties’ laws,’—A cap of liberty, mitre, pastoral staff, crown, and open book.

‘M, Magna Charta’s strong chain.’—A soldier, sailor, Highlander, and civilian, joining hands.

‘N, Noble Nelson, whom Neptune, near Nile crown’d the Lord of the Main,’—is a portrait of the Hero.

‘O, stands for Britain’s fam’d Oak,’—which is duly portrayed.

‘P, for each brave British Prince.’—The three feathers show the Prince of Wales, in volunteer uniform.

‘Q, never once made a Question, Respecting the Deeds they’d evince,’—is an officer drawing his sword.

‘If R, for our Rights takes the field,’—is a yeomanry volunteer.

‘Or S, should a signal display,’—The British Standard.

‘They’d each call with T for the Trumpet. To Horse my brave boys and away.’—A mounted Trumpeter.

‘U, for United, we stand, V for our bold Volunteers,’—represents one of the latter.

‘Whom W welcomes in War, and joins loyal X in three Cheers.’—A soldier and sailor, with hands clasped, cheering.

‘With Y all our Youths sally forth, the standards of Freedom advance,’—is a cannon between two standards.

‘With Z proving Englishmen’s Zeal, to humble the Zany of France,’—shews Napoleon with a fool’s cap on, chained to the wall in a cell.

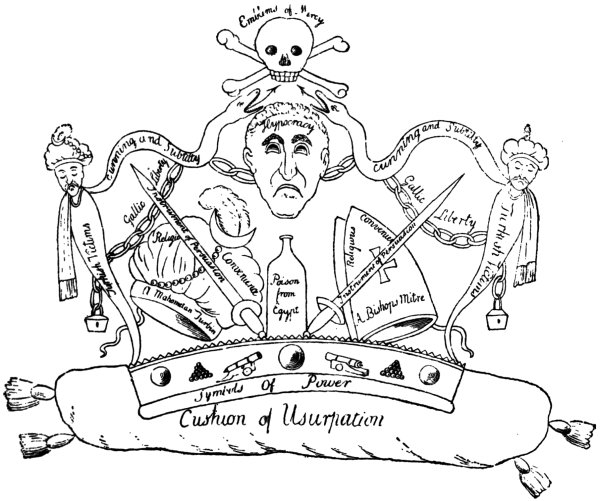

Napoleon’s coronation was the great event of the year; but some time before it was consummated the English caricaturist took advantage of it, and J. B. (West), in September 1804, produced a ‘Design for an Imperial Crown to be used at the Coronation of the New Emperor.’ A perusal of the foregoing pages will render any explanation unnecessary.

Napoleon omitted no ceremony which could enhance the pageant of his coronation. The Pope must be present:24 no meaner ecclesiastic should hallow this rite, and he was gently invited to come to Paris for this purpose. Poor Pius VII. had very little option in the matter. His master wanted him, and he must needs go; but Napoleon gilded the chain which drew him. During the whole of his journey he was received with the greatest reverence, and could hardly have failed to have been impressed with the great care and attention paid to him. For instance, the dangerous places in the passage of the Alps were protected by parapets, so that his Holiness should incur no danger. On his arrival at Paris he was lodged in the Tuileries, and a very delicate attention was paid him—his bedchamber was fitted as a counterpart of his own in the palace of Monte-Cavallo, at Rome.

The eventful 2nd of December came at last; but, before we note the ceremony itself, we must pause awhile to see how the English caricaturist treated the procession.

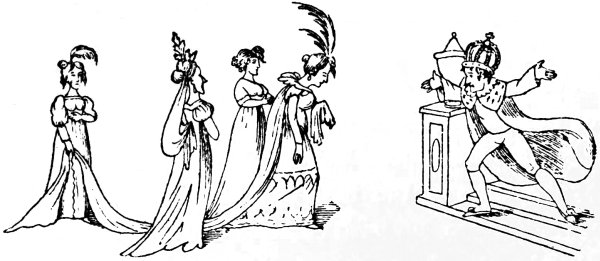

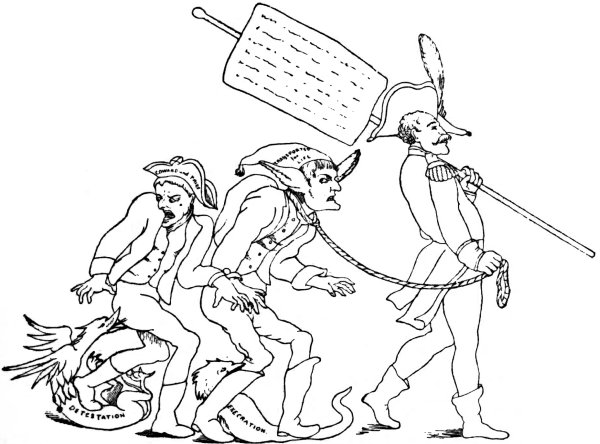

Hardly any one of Gillray’s caricatures (January 1, 1805) is as effective as ‘The Grand Coronation Procession of Napoleone the 1st, Emperor of France, from the Church of Notre Dame, Dec. 2nd, 1804. Redeunt Satania regna, Iam nova progenies cœlo demittitur alto!’ Huge bodies of troops form the background, whose different banners are—a comet setting the world ablaze; an Imperial crown and the letters SPQN; un Dieu, un Napoleon; a serpent biting its tail, surrounding a crowned N. and a Sun, ‘Napoleone ye 1st le Soleil de la Constitution.’

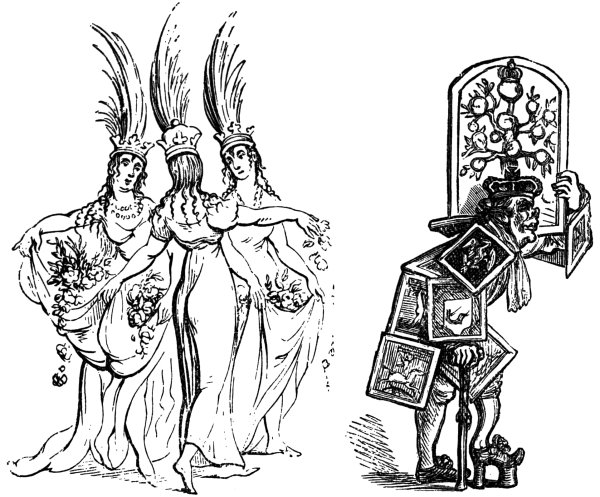

The procession is headed by ‘His Imperial Highness Prince Louis Buonaparte Marbœuf’ (a delicate hint as to his paternity), ‘High Constable of the Empire,’ who, theatrically dressed, struts, carrying a drum-major’s staff fashioned like a sceptre. Behind him come 25‘The Three Imperial Graces, viz. their Imp. High. Princess Borghese, Princess Louis (cher amie of ye Emperor) & Princess Joseph Bonaparte.’ These ladies are clad in a most diaphanous costume, which leaves little of their forms to the imagination, and they occupy themselves by scattering flowers as they pass along.

After them comes ‘Madame Talleyrand (ci-devant Mrs. Halhead the Prophetess),’ a stout, Jewish-looking woman, who is ‘Conducting the Heir Apparent in ye Path of Glory’—and a most precocious little imp it looks. After them hobbles ‘Talleyrand Perigord, Prime Minister and King at Arms, bearing the Emperor’s Genealogy,’ which begins with ‘Buone Butcher,’ goes on with ‘Bonny Cuckold,’ till it reaches the apex of ‘Boney Emperor.’ Pope Pius VII. follows, and under his cope is the devil disguised as an acolyte, bearing a candle; Cardinal Fesch is by, and acts as thurifer. The incense is in clouds: 26‘Les Addresses des Municipalités de Paris—Les Adorations des Badauds—Les Hommages des Canailles—Les Admirations des Fous—Les Congratulations des Grenouilles—Les Humilités des Poltrons.’

Then comes the central figures of the pageant, ‘His Imperial Majesty Napoleone ye 1st and the Empress Josephine,’ the former scowling ferociously, the latter looking blowsy, and fearfully stout. Three harridans, ‘ci-devant Poissardes,’ support her train, whilst that of Napoleon is borne by a Spanish don, an Austrian hussar, and a Dutchman, whose tattered breeches testify to his poverty. These are styled ‘Puissant Continental Powers—Train Bearers to the Emperor.’ Following them come ‘Berthier, Bernadotte, Angerou, and all the brave Train of Republican Generals;’ but they are handcuffed, and their faces display, unmistakably, the scorn in which they hold their old comrade. Behind them poses a short corpulent figure, ‘Senator Fouché, Intendant General of ye Police, bearing the Sword of Justice.’ But Fouché is not content with this weapon.27 His other hand grasps an assassin’s dagger, and both it, and the sword, are well imbrued in blood. The rear of the procession is made up of a ‘Garde d’Honneur,’ which consists of a gaoler with the keys of the Temple and a set of fetters; a mouchard with his report, ‘Espionnage de Paris;’ Monsieur de Paris, the executioner, bears a coil of rope with a noose, and a banner with a representation of the guillotine—and a prisoner, holding aloft two bottles respectively labelled Arsenic and Opium. More banners and more soldiers fill up the background.

What a sight that must have been on the morning of the 2nd of December! Visitors from all parts of France were there; and the cathedral of Notre-Dame must have presented a gorgeous coup d’œil, with its splendid ecclesiastical vestments, its magnificent uniforms, and the beautiful dresses and jewels of the ladies. It can hardly be imagined, so had better be described in the words of an eyewitness, Madame Junot.3

‘Who that saw Notre-Dame on that memorable day, can ever forget it? I have witnessed in that venerable pile the celebration of sumptuous and solemn festivals; but never did I see anything at all approximating in splendour to the coup d’œil exhibited at Napoleon’s Coronation. The vaulted roof re-echoed the sacred chanting of the priests, who invoked the blessing of the Almighty on the ceremony about to be celebrated, while they awaited the arrival of the Vicar of Christ, whose throne was prepared near the altar. Along the ancient walls of tapestry were ranged, according to their rank, the different bodies of the State, the deputies from every City; in short, the representatives of all France assembled to implore the benediction of Heaven on the sovereign of the people’s choice. The waving plumes which adorned the hats of the28 Senators, Counsellors of State, and Tribunes; the splendid uniforms of the military; the clergy in all their ecclesiastical pomp; and the multitude of young and beautiful women, glittering in jewels, and arrayed in that style of grace and elegance which is only seen in Paris;—altogether presented a picture which has, perhaps, rarely been equalled, and certainly never excelled.

‘The Pope arrived first; and at the moment of his entering the Cathedral, the anthem Tu es Petrus was commenced. His Holiness advanced from the door with an air at once majestic and humble. Ere long, the firing of cannon announced the departure of the procession from the Tuileries. From an early hour in the morning the weather had been exceedingly unfavourable. It was cold and rainy, and appearances seemed to indicate that the procession would be anything but agreeable to those who joined it. But, as if by the especial favour of Providence, of which so many instances are observable in the career of Napoleon, the clouds suddenly dispersed, the sky brightened up, and the multitudes who lined the streets from the Tuileries to the Cathedral, enjoyed the sight of the procession, without being, as they had anticipated, drenched by a December rain. Napoleon, as he passed along, was greeted by heartfelt expressions of enthusiastic love and attachment.

‘On his arrival at Notre-Dame, Napoleon ascended the throne, which was erected in front of the grand altar. Josephine took her place beside him, surrounded by the assembled sovereigns of Europe. Napoleon appeared singularly calm. I watched him narrowly, with the view of discovering whether his heart beat more highly beneath the imperial trappings, than under the uniform of the guards; but I could observe no difference, and yet I was at the distance of only ten paces from him. The length of29 the ceremony, however, seemed to weary him; and I saw him several times check a yawn. Nevertheless, he did everything he was required to do, and did it with propriety. When the Pope anointed him with the triple unction on his head and both hands, I fancied, from the direction of his eyes, that he was thinking of wiping off the oil rather than of anything else; and I was so perfectly acquainted with the workings of his countenance, that I have no hesitation in saying that was really the thought that crossed his mind at that moment. During the ceremony of anointing, the Holy Father delivered that impressive prayer which concluded with these words:—“Diffuse, O Lord, by my hands, the treasures of your grace and benediction on your servant, Napoleon, whom, in spite of our personal unworthiness, we this day anoint Emperor, in your name.” Napoleon listened to this prayer with an air of pious devotion; but just as the Pope was about to take the crown, called the Crown of Charlemagne, from the altar, Napoleon seized it, and placed it on his own head. At that moment he was really handsome, and his countenance was lighted up with an expression, of which no words can convey an idea. He had removed the wreath of laurel which he wore on entering the church, and which encircles his brow in the fine picture of Gérard. The crown was, perhaps, in itself, less becoming to him; but the expression excited by the act of putting it on, rendered him perfectly handsome.

‘When the moment arrived for Josephine to take an active part in the grand drama, she descended from the throne and advanced towards the altar, where the Emperor awaited her, followed by her retinue of Court ladies, and having her train borne by the Princesses Caroline, Julie, Eliza, and Louis. One of the chief beauties of the Empress Josephine was not merely her fine figure, but the elegant30 turn of her neck, and the way in which she carried her head; indeed, her deportment, altogether, was conspicuous for dignity and grace. I have had the honour of being presented to many real princesses, to use the phrase of the Faubourg St.-Germain, but I never saw one who, to my eyes, presented so perfect a personification of elegance and majesty. In Napoleon’s countenance, I could read the conviction of all I have just said. He looked with an air of complacency at the Empress as she advanced towards him; and when she knelt down—when the tears, which she could not repress, fell upon her clasped hands, as they were raised to Heaven, or rather to Napoleon—both then appeared to enjoy one of those fleeting moments of pure felicity, which are unique in a lifetime, and serve to fill up a lustrum of years. The Emperor performed, with peculiar grace, every action required of him during the ceremony; but his manner of crowning Josephine was most remarkable: after receiving the small crown, surmounted by the Cross, he had first to place it on his own head, and then to transfer it to that of the Empress. When the moment arrived for placing the crown on the head of the woman, whom popular superstition regarded as his good genius, his manner was almost playful. He took great pains to arrange this little crown, which was placed over Josephine’s tiara of diamonds; he put it on, then took it off, and finally put it on again, as if to promise her she should wear it gracefully and lightly.’

It is almost painful, after reading this vivid and soul-stirring description, to have to descend to the level of the caricaturist descanting on the same subject; it is a kind of moral douche bath, giving all one’s nerves a shock.

Authentic news of the coronation did not reach England for nearly a fortnight, and it was not till December 15 that the ‘Times’ was able to give its readers a full account of the ceremony. ‘The Thunderer’ waxed very wroth about it, as may be seen by the following extract from its leader of that date:—

‘The “Moniteur” merely insinuates that the sun miraculously penetrated through a thick fog, to be present at it: a compliment which is a little diminished by a subsequent assertion, that the lamps were afterwards able to supply his place by giving a noon-day brilliancy to the night. Then follows a disgusting hypocritical panegyric upon the union of civil and religious acts and ceremonies, the sublime representation of all that human and divine affairs could assemble to strike the mind—the venerable Apostolic virtues of the poor Pope, and the most astonishing genius of Buonaparte crowned by the most astonishing destiny!

‘The public will find these details, under their proper head, in this paper. To us, we confess, all that appears worthy of remark or memory in that opprobrious day is, that amongst all the Royalists and Republicans of France, it was able to produce neither a Brutus nor a Chœreas!

‘The day subsequent to the coronation, the people of Paris were entertained upon the bridges, boulevards, and public places, with popular sports, dancing, and other pastimes and diversions.

‘Upon the Place de Concorde, still stained with the blood of the lawful sovereign of France, were erected saloons and pavilions for dancing waltzes. Medals were given away to the populace; illuminations, artificial fireworks, pantomimes, and buffoons, musicians, temporary theatres, everything was represented and administered that could intoxicate and divert this vain and wicked people from contemplating34 the crime they were committing. To the profanation of the preceding day, it seems that all the orgies of wantonness and corruption succeeded in the most curious and careful rotation, and that all the skill and science of the Davids and Cheniers has been exhausted to keep them for four and twenty hours from thinking upon what they had done.’

But not only in leaders did the ‘Times’ pour forth its wrath; it published little jokelets occasionally, which were meant to be very stinging, as, for instance: Monsieur Napoleon has distributed his Eagles by thousands. What his talents might be doubtful of accomplishing, he expects from his talons.’

The ‘Daily Advertiser’, too, of December 15 contains some pretty sentiments on the coronation, such as, 35‘If Modern Europe will, after such fair notice, and a notice so often repeated, by the French Government, still remain in sluggish inaction, in stupid astonishment, at the success of that Ruffian, who now wields the sceptre of Charlemagne, and has dragooned the Pope to his Coronation, it is evident that nations so besotted are only fit to be enslaved.’

NAPOLEON’S LETTER TO GEORGE THE THIRD—NAVAL VICTORIES—CROWNED KING OF ITALY—ALLIANCE OF EUROPE—WITHDRAWAL OF THE ‘ARMY OF ENGLAND.’

Very shortly after his coronation, and with the commencement of the year 1805, Napoleon wrote a letter to George the Third, intimating how beneficial peace would be to both countries.

The text of this letter, and its answer, are as follow:—

Sire, my brother,—Called to the throne by Providence, and the suffrages of the Senate, the people, and the army, my first feeling was the desire for peace. France and England abuse their prosperity: they may continue their strife for ages; but will their governments, in so doing, fulfil the most sacred of the duties which they owe to their people? And how will they answer to their consciences for so much blood uselessly shed, and without the prospect of any good whatever to their subjects? I am not ashamed to make the first advances. I have, I flatter myself, sufficiently proved to the world that I fear none of the chances of war. It presents nothing which I have occasion to fear. Peace is the wish of my heart; but war has never been adverse to my glory. I conjure your Majesty, therefore, not to refuse yourself the satisfaction of giving peace to the world. Never was an occasion more favourable for calming the passions, and giving ear only to the sentiments of humanity and reason. If that opportunity be lost, what limit can be assigned to a war which all my efforts have been unable to terminate? Your Majesty has gained more during the last ten years than the whole extent of Europe in riches and36 territory: your subjects are in the very highest state of prosperity: what can you expect from a war? To form a Coalition of the Continental powers? Be assured the Coalition will remain at peace. A coalition will only increase the strength and preponderance of the French Empire. To renew our intestine divisions? The times are no longer the same. To destroy our finances? Finances founded on a flourishing agriculture can never be destroyed. To wrest from France her Colonies? They are to her only a secondary consideration; and your Majesty has already enough and to spare of these possessions. Upon reflection, you must, I am persuaded, yourself arrive at the conclusion, that the war is maintained without an object; and what a melancholy prospect, for two great nations to combat merely for the sake of fighting! The world is surely large enough for both to live in; and reason has still sufficient power to find the means of reconciliation, if the inclination only is not wanting. I have now, at least, discharged a duty dear to my heart. May your Majesty trust to the sincerity of the sentiments which I have now expressed, and the reality of my desire to give the most convincing proofs of it.

George the Third could not, constitutionally, personally reply to this letter, so Lord Mulgrave answered it, under date of January 14, and addressed it to Talleyrand. It ran thus:

His Britannic Majesty has received the letter addressed to him by the Chief of the French Government There is nothing which his Majesty has more at heart, than to seize the first opportunity of restoring to his subjects the blessings of peace, provided it is founded upon a basis not incompatible with the permanent interests, and security, of his dominions. His Majesty is persuaded that that object cannot be attained but by arrangements, which may at the same time provide for the future peace, and security, of Europe, and prevent a renewal of the dangers, and misfortunes, by which it is now overwhelmed. In conformity with these sentiments, his Majesty feels that he cannot give a more specific answer to the overture which he has received until he has had time to communicate with the Continental powers to whom he37 is united in the most confidential manner, and particularly the Emperor of Russia, who has given the strongest proofs of the wisdom, and elevation, of the sentiments by which he is animated, and of the lively interest which he takes in the security and independence of Europe.

Apropos of this pacific overture, there is a very badly drawn picture by Woodward (February 1, 1805), ‘A New Phantasmagoria for John Bull.’ Napoleon is seated on the French coast, directing his magic lantern towards John Bull, exclaiming, ‘Begar de brave Galanté shew for Jonny Bull.’ The magic lantern slide shows Napoleon coming over on a visit, with a tricoloured flag in one hand, the other leading the Empress Josephine, whose dress is semée with bees. ‘Here we come Johnny—A flag of Truce Johnny—something like a Piece! all decked out in Bees, and stars, and a crown on her head; not such a patched up piece as the last.’ The Russian bear is on one rock, John Bull on another—the latter having his sword drawn. He says: ‘You may be d—d, and your piece too! I suppose you thought I was off the watch—I tell you, I’ll say nothing to you till I have consulted Brother Bruin, and I hear him growling terribly in the offing.’

So we see that there was no hope of peace, as yet, and the war goes on. I can hardly localise the following caricature:—

Argus (January 24, 1805) drew ‘The glorious Pursuit of Ten against Seventeen.

The French and Spaniards are in full flight, calling out, ‘By Gar dare be dat tam Nelson dat Salamander dat do love to live in de fire, by Gar we make haste out of his way, or he blow us all up.’ Nelson leads on nine old sea38 dogs, encouraging them thus: ‘The Enemy are flying before you my brave fellows, Seventeen against Ten of us. Crowd all the Sail you can, and then for George, Old England—Death or Victory!!!’ His followers utter such sentences as the following: ‘My Noble Commander, we’ll follow you the world over, and shiver my Timbers but we shall soon bring up our lee way, and then, as sure as my name is Tom Grog, we’ll give them another touch of the Battle of the Nile’—‘May I never hope to see Poll again, if I would not give a whole month’s flip if these lubberly Parly vous would but just stop one half watch,’ &c. &c.

The style in which our sailors worked is very aptly illustrated in a letter from an officer on board the Fisgard, off Cape St. Vincent, dated November 28, 1804.5 We must remember that war was not officially declared against Spain until January 11, 1805; but this gentleman writes: ‘We cannot desire a better station; we heard of hostilities with Spain on October the 15th, and on that very day we captured two Ships. Lord Nelson received from us the first intelligence—we have already taken twelve ships and entertain hopes of as many more. Yesterday we fell in with the Donegal, Capt. Sir R. Strachan, who has taken a large Spanish Frigate, the Amphitrite, after a chase of 46 hours, and 15 minutes’ action, in which the Spanish Captain was killed; the prize was from Cadiz, with despatches for Teneriffe and the Havana, laden with stores. The Amphitrite Frigate, of 42 Guns, was one of the finest Frigates in the Spanish Navy. The Donegal chased the Amphitrite for several hours, sometimes gaining upon her, and sometimes losing; at length the Amphitrite carried away her mizen top mast, which enabled the Donegal to come up with her. A Boat was then despatched by Sir Richard for the purpose of bringing the Spanish Captain39 on board. Some difficulty arose from neither party understanding the language of the other; at length Sir Richard acquainted the Spanish Captain, that in compliance with the Orders he had received from his Admiral, he was under the necessity of conducting the Amphitrite back again to Cadiz, and he allowed the Spanish Captain three minutes to determine whether he would comply without compelling him to have recourse to force. After waiting six minutes in vain for a favourable answer, the Donegal fired into the Amphitrite, which was immediately answered with a broadside. An engagement then ensued, which lasted about eight minutes, when the Amphitrite struck her colours. During this short engagement the Spanish Captain was unfortunately killed by a musket ball. The Donegal has also captured another Spanish ship, supposed the richest that ever sailed from Cadiz, her cargo reported worth 200,000l.’

Another letter, dated November 29, adds, ‘We have this day taken a large Ship from the River de la Plata.’

They had captured the following ships previous to December 3:—

| Nostra Signora del Rosario | value | £10,000 |

| Il Fortuna | ” | 8,000 |

| St. Joseph | ” | 12,000 |

| La Virgine Assumpto | ” | 6,000 |

| Apollo | ” | 15,000 |

| Signora del Purificatione | ” | 40,000 |

| Fawket | ” | 1,100 |

| Gustavus Adolphus | ” | 1,000 |

| A Settee | ” | 600 |

| A Ship with Naval Stores | ” | 40,000 |

On February 26, 1805, Gillray published ‘The Plumb Pudding in danger; or State Epicures taking un Petit Souper—’ the great globe itself, and all which it inherits,40 ‘is too small to satisfy such insatiable appetites.’ Napoleon is taking all Europe, whilst Pitt is calmly appropriating all the ocean to himself.

There is now almost a total cessation of caricature until the autumn; and it probably was in this wise. Napoleon did not actively bother this country; his thoughts were, for the time, elsewhere. On March 17 a deputation from the Italian Republic waited upon him, stating that it was the desire of their countrymen that he should be their monarch, and accordingly on April 2 he and Josephine left Paris for Milan.

An amateur drew, and Gillray etched (August 2, 1805), ‘St. George and the Dragon, a Design for an Equestrian Statue from the Original in Windsor Castle.’ Napoleon (a most ferocious dragon) has seized upon poor Britannia, who, dropping her spear and shield, her hair dishevelled, and her dress disordered, with upraised arm, attempts to avert her fate; but St. George (George the Third) on horseback, comes to the rescue, and, smiting that dragon, cleaves his crown.

As a practical illustration of the servile adulation with which he was treated, take the following etching by Woodward (September 15, 1805): ‘Napoleon’s Apotheosis Anticipated, or the Wise Men of Leipsic sending Boney to Heaven before his time!!! At the German University of Leipsic, it was decreed that the Constellation called Orion’s Belt should hereafter be named Napoleon in Honor of that Hero.—Query—Did the Wise men of Leipsic mean it as an honor, or a reflection on the turbulent spirit of Boney, as the rising of Orion is generally accompanied with Storms and Tempests, for which reason he has the Sword in his hand.’ Orion has his belt round Napoleon’s neck, and is hoisting him up to heaven thereby; Napoleon is kicking and struggling, and exclaims, ‘What are you about—I tell you I would rather stay where I was.’ The German savants are watching him through their telescopes, saying, ‘He mounts finely’—43‘I think we have now made ourselves immortal’—‘It was a sublime idea’—‘Orion seems to receive him better than I expected.’ This is confirmed in ‘Scot’s Magazine,’ 18078: ‘The University of Leipzig has resolved henceforth to call by the name of Napoleon that group of stars which lies between the girdle and the sword of Orion; and a numerous deputation of the University was appointed to present the “Conqueror” with a map of the group so named!’

Napoleon hardly reckoned on Austria taking up arms against him without a formal declaration of war, and was rather put to it to find men to oppose the Allies, whose forces were reckoned at 250,000 men; whilst France, though with 275,000 men at her disposal, had 180,000 of them locked up in the so-called ‘Army of England.’ We can imagine his chagrin in having to forego his cherished plan of invasion, and being compelled to withdraw his troops from the French shores.

The ‘Times’ (how different a paper it was in those days to what it is now!) is jubilant thereupon.9 ‘The Scene that now opens upon the soldiers of France, by being obliged to leave the coast and march eastwards, is sadly different from that Land of Promise, which, for two years, has been held out to them, in all sorts of gay delusions. After all the efforts of the Imperial Boat-Builder, instead of sailing over the Channel, they will have to cross the Rhine. The bleak forests of Suabia will make but a sorry exchange for the promised spoils of our Docks and Warehouses. They will not find any equivalent for the plunder of the Bank in another bloody passage through “the Valley of Hell”; but they seem to have forgotten the magnificent promise of the Milliard.’

The French papers affected to make light of this death-blow to their hopes; one of them, quoted in the44 ‘Times’ of September 13, says: ‘Whilst the German Papers, with much noise, make more troops march than all the Powers together possess, France, which needs not to augment her forces in order to display them in an imposing manner, detaches a few thousand troops from the Army of England to cover her frontiers, which are menaced by the imprudent conduct of Austria.’

The caricaturist, of course, made capital out of it, and Rowlandson (October 1, 1805) designed ‘The departure from the Coast or the End of the Farce of Invasion.’ Napoleon, seated on a sorry ass, is sadly returning, inland, homeward, to the intense delight of some French monkeys. His Iron Crown is tottering off his head, and his steed is loaded with the Boulogne Encampment, the Army of England, and Excuses for non-performance. The British Lion on the English cliffs lifts his leg and gives Boney a parting salute. The latter exclaims, ‘Bless me, what a shower! I shall be wet through before I reach the Rhine.’

The action of the Allies is shown by the caricature, ‘Tom Thumb at Bay, or the Sovereigns of the Forest roused at last,’ by Ansell (October 1805), which shows the Lilliputian Emperor, who has thrown away his crown and sceptre, being fiercely pursued by a double-headed eagle, a bear, and a boar, and is rushing into the open jaws of a ferocious lion. ‘Which way shall I escape? If I fly from the Bear and the Eagle, I fall into the jaws of the Lion!!’ Holland, Spain, and Italy, all have yokes round their necks—but, seeing Bonaparte’s condition, Holland takes his off and lays it on the ground. The Spaniard, surprised, exclaims, ‘Why! Mynheer, you have got your yoke off!’ And the Italian, who is preparing to remove his, says, ‘I think Mynheer’s right, and now’s the time, Don, to get ours off.’ An army of rats is labelled, 45‘Co-Estates ready to assist.’

Meantime the Austrians were in a very awkward position. General Mack was, from October 13, closely invested in Ulm, and Napoleon had almost need to restrain his troops, who were flushed with victory and eager for the assault. The carnage on both sides would, in such a case, have been awful; but Napoleon clearly pointed out to Mack his position: how that, in eight days, he would be forced to capitulate for want of food: that the Russians were yet far off, having scarcely reached Bohemia; that no other aid was nigh:—and on October 20, the gates of Ulm were opened, and 36,000 Austrian troops slowly defiled therefrom. Sixteen generals surrendered with Mack, and Napoleon treated them generously. All the officers were allowed to go home, their parole, not to fight against France until there had been a general exchange of prisoners, only being required; and Napoleon sent 50,000 prisoners into France, distributing them throughout the agricultural districts.

Gillray drew (November 6, 1805) ‘The Surrender of Ulm, or Buonaparte and Genl Mack coming to a right understanding—Intended as a Specimen of French Victories—i.e. Conquering without Bloodshed!!!’ It shows a little Napoleon, seated on a drum, whilst Mack and some other generals are grovelling on all fours, delivering up their46 swords, banners, and the keys of Ulm, to the conqueror. Napoleon, pointing to three large sacks of money, borne by as many soldiers, exclaims: ‘There’s your Price! There’s Ten Millions—Twenty!! It is not in my Army alone that my resources of Conquering consists!! I hate victory obtain’d by effusion of blood.’ ‘And so do I,’ says the crawling Mack; ‘What signifies Fighting when we can settle it in a safer way.’ On the ground is a scroll of ‘Articles to be deliver’d up. 1 Field Marshal. 8 Generals in Chief. 7 Lieutenant Generals. 36 Thousand Soldiers. 80 pieces of Cannon. 50 Stand of Colours. 100,000 Pounds of Powder. 4,000 Cannon Balls.’

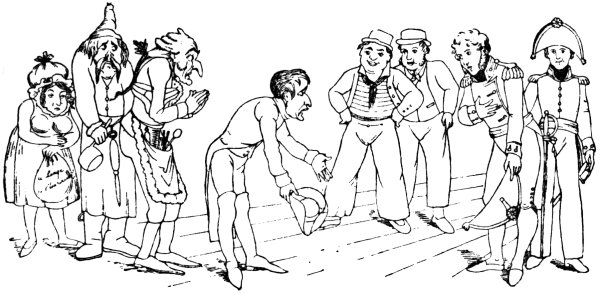

This subject also attracted the pencil of I. Cruikshank (November 19, 1805): ‘Boney beating Mack—and Nelson giving him a Whack!! or the British Tars giving Boney his Hearts desire, Ships, Colonies and Commerce.’ Mack is kneeling in a suppliant manner before Bonaparte, who stamps upon his captive’s sword, addressing him: ‘I want not your Forts, your Cities, nor your territories! Sir, I only want Ships, Colonies and Commerce’—a very slight variation from the real text of his address to the vanquished Austrian officers: ‘I desire nothing further upon the Continent. I want ships, colonies, and commerce; and it is as much your interest, as mine, that I should have them.’ During this peroration military messengers are arriving. One calls out, ‘May it please your King’s Majesty’s Emperor. That Dam Nelson take all your ships. Twenty at a time. Begar, if you no come back directly they vill not leave you vone boat to go over in.’ Another runs along crying, ‘Run, ma foi, anoder Dam Nelson take ever so many more ships.’ This is an allusion to the battle of Trafalgar (October 21, 1805),10 where Nelson paid for his47 victory with his life. This is further illustrated in another portion of the engraving, by Nelson, who is towing the captured vessels, kneeling at Britannia’s feet, saying: ‘At thy feet, O Goddess of the seas, I resign my life in the service of my country.’ Britannia replies: ‘My Son, thy Name shall be recorded in the page of History on tablets of the brightest Gold.’

Rowlandson (November 13, 1805) further alludes to the surrender of Ulm and the battle of Trafalgar: ‘Nap Buonaparte in a fever on receiving the Extraordinary Gazette of Nelson’s Victory over the combined Fleets.’ Boney is very sick and miserable, the combined effects of the news which he has read in the paper which falls from his trembling hands—the ‘Extraordinary Gazette. 19 Sail of the line taken by Lord Nelson.’ He appeals to four doctors, who are in consultation on his case: ‘My dear Doctors! those Sacré Anglois have play’d the Devil vid my Constitution. Pray tell me what is the matter with me. I felt the first symptoms when I told Genl Mack I wanted Ships, Colonies and Commerce. Oh dear! oh dear! I shall want more ships now—this is a cursed sensation—Oh I am very qualmish.’ One doctor opines it is ‘a desperate case,’ another that he is ‘Irrecoverable.’ One recommends bleeding; but one has thoroughly investigated the case, and found out the cause: ‘Begar, me have found it out, your heart be in your breeches!’

48 There were no caricatures of the battle of Trafalgar—the victory was purchased at too great a cost; but Gillray executed a serious etching in memory of Nelson, published on December 29, 1805, the funeral of the hero taking place on the subsequent 9th of January.

The following caricature shows the quality of news supplied to our forefathers:—

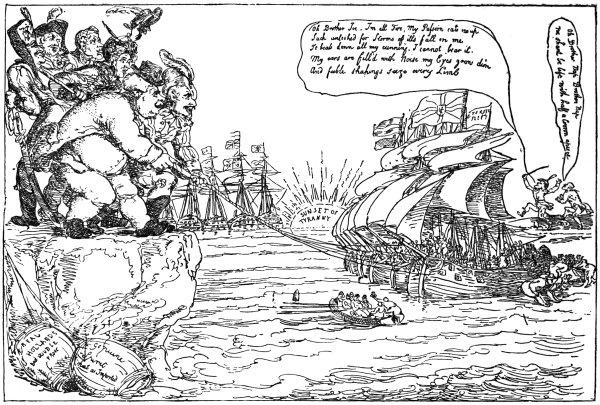

‘John Bull exchanging News with the Continent’ is by Woodward, December 11, 1805, and represents Napoleon and a French newsboy on a rock called Falsehood, disseminating news the reverse of true. The ‘Journal de l’Empire’ says that Archduke Charles is dead with fatigue; the ‘Journal de Spectacle’ that England is invaded. The ‘Gazette de France’ informs us that the English fleet is dispersed, and the ‘Publicité’ follows it with the news that the combined fleets are sent in pursuit. False bulletins are being scattered broadcast. These, however, have but little effect on John Bull, who, attired as a newsboy, stands on the rock of Truth, flourishing a paper, ‘Trafalgar London Gazette extraordinary,’ and bellowing through his horn, ‘Total defeat of the Combin’d Fleets of France and Spain,’ which is vividly depicted in the background.

‘Tiddy doll, the great French Gingerbread Baker, drawing out a new Batch of Kings—his man Hopping Talley mixing up the Dough,’ is a somewhat elaborate etching by Gillray (January 23, 1806). The celebrated gingerbread maker has, on a ‘peel,’ three kings, duly gilt—Bavaria, Wurtemberg, and Baden—which he is just introducing into the ‘New French Oven for Imperial Gingerbread.’ On a chest of three drawers, relatively labelled Kings and Queens, Crowns and Sceptres, and Suns and Moons, are a quantity of ‘Little Dough Viceroys, intended for the next batch.’ Under the oven is an 49‘Ash hole for broken Gingerbread,’ and a broom—‘the Corsican Besom of Destruction’—has swept therein La République Française, Italy, Austria, Spain, Netherlands, Switzerland, Holland, and Venice. On the ground is a fool’s cap and bells, which acts as a cornucopia (labelled ‘Hot Spiced Gingerbread, all hot; Come, who dips in my lucky bag’), which disgorges stars and orders, principalities, dukedoms, crowns, sceptres, cardinals’ hats, and bishops’ mitres; and a baker’s basket is full of ‘True Corsican Kinglings for Home Consumption and Exportation.’

Talleyrand—with a mitre on his head, and beads and cross round his waist, to show his ecclesiastical status; with a pen in his mouth, and ink-pot slung to his side, to denote his diplomatic functions—is hard at work at the ‘Political Kneading Trough,’ mixing up Hungary, Poland, Turkey, &c., whilst an eagle (Prussia) is pecking at a piece of dough (Hanover).

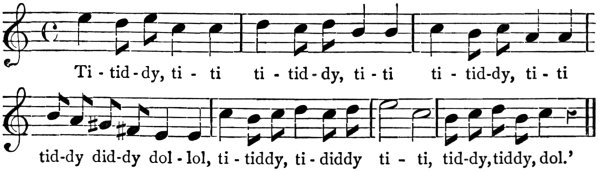

To thoroughly understand this caricature, we must first of all know something about Tiddy Doll. He was a seller50 of gingerbread, and was as famous in his time as was Colly Molly Puff in the time of Steele and Addison. He had a refrain, all his own, like a man well known to dwellers in Brighton and the West End of London—‘Brandy balls.’ Hone11 gives the best account of him that I know. Discoursing on May fair, he says: ‘Here, too, was Tiddy-doll; this celebrated vendor of gingerbread, from his eccentricity of character and extensive dealings in his way, was always hailed as the king of itinerant tradesmen.12 In his person he was tall, well made, and his features handsome. He affected to dress like a person of rank: white, gold-laced, suit of clothes, laced ruffled shirt, laced hat and feather, white silk stockings, with the addition of a fine white apron. Among his harangues to gain customers, take this as a specimen: “Mary, Mary, where are you now, Mary? I live, when at home, at the second house in little Ball Street, two steps under ground, with a wiscum, riscum, and a why not. Walk in ladies and gentlemen; my shop is on the second floor backwards, with a brass knocker at the door. Here is your nice gingerbread, your spice gingerbread; it will melt in your mouth like a redhot brickbat, and rumble in your inside like Punch and his wheelbarrow.” He always finished his address by singing this fag end of some popular ballad.

Pitt died on January 23, 1806, and Fox succeeded him.51 It is probable that Napoleon reckoned somewhat on Fox’s friendship, and hence the following caricature:—

‘Boney and the Great Secretary’ (Argus, February 1806) gives a good portrait of Fox. Napoleon wishes to be friendly: ‘How do you do, Master Charley, why you are so fine, I scarcely knew ye—don’t you remember me, why I am little Boney the Corsican—him that you came to see at Paris, and very civil I was to you, I’m sure. If you come my way I shall be glad to see you, so will my wife and family. They are a little changed in their dress, as well as you. We shall be very happy to take a little peace soup with you, whenever you are inclined, Master Charley.’ But Fox shakes his fist at him: 52‘Why, you little Corsican Reptile! how dare you come so near the person of the Right Honble C—— J—— F—— one of his M—— principal Secretaries of State, Member of the P.C. &c., &c., &c., &c., &c., &c., &c., &c.—go to see You!!! Arrogant little Man, Mr. Boney—if you do not instantly vanish from my sight—I’le break every bone in your body—learn to behave yourself in a peaceable manner, nor dare to set your foot on this happy land without My leave.’

Of ‘Pacific Overtures, or a Flight from St. Cloud, “over the Water to Charley,” a new Dramatic Peace now rehearsing’ (Gillray, April 5, 1806), only a portion is given in the accompanying illustration, but quite sufficient to explain the negotiations for peace then in progress.

This caricature is far too elaborate to reproduce the whole, and the allusions therein are extremely intricate and, nowadays, uninteresting. A theatrical stage is represented, with Napoleon descending in clouds, pointing to Terms of Peace, which are being displayed by Talleyrand, and saying, ‘There’s my terms.’ These are as follow: 53‘Acknowledge me as Emperor; dismantle your fleet; reduce your army; abandon Malta and Gibraltar; renounce all Continental connexion; your Colonies I will take at a valuation; engage to pay to the Great Nation, for seven years annually, £1,000,000; and place in my hands as hostages, the Princess Charlotte of Wales, with ten of the late administration, whom I shall name.’

King George has stepped from his box on to the stage, and is surveying this vision through his glass, exclaiming: ‘Very amusing terms indeed, and might do vastly well with some of the new made little gingerbread kings13; but we are not in the habit of giving up either “ships, or commerce, or colonies” merely because little Boney is in a pet to have them!!!’

Ansell (April 1806) drew ‘Roast Beef and French Soup. The English Lamb * * * and the French Tiger,’ and it seems merely designed for the purpose of introducing Daniel Lambert, who was then on exhibition—‘Daniel Lambert who at the age of 36 weighed above 50 Stone, 14 Pounds to the Stone, measured 3 yards 4 inches round the Body, and 1 yard 1 inch round the leg. 5 feet 11 inches high.’ It shows the redoubtable fat man seated on a couch, carving a round of beef, which is accompanied by a large mustard-pot, a huge loaf, and a foaming pot of stout. Napoleon, seated on a similar couch, on the opposite side of the table, is taking soup—then an unaccustomed article of food with Englishmen—and looks with horror at the other’s size and manner of feeding.

Daniel Lambert was like Mr. Dick in ‘David Copperfield,’ who would persist in putting King Charles the First’s head into his Memorial; he could hardly be kept out of the caricatures. Ansell produced one (May 1806)—54‘Two Wonders of the World, or a Specimen of a new troop of Leicestershire Light Horse.—Mr. Daniel Lambert, who at the age of 36 weighed above 50 Stone, 14 Pounds to the Stone, measured 3 yards 4 inches round the body and 1 yard 1 inch round the leg, 5 feet 11 inches high. The famous horse Monarch, the largest in the World is upwards of 21 hands high, (above 7 foot)14 and only 6 Years old.’ Lambert is mounted on this extraordinary quadruped, and, sword in hand, is riding at poor little Boney, who exclaims in horror, ‘Parbleu! if dis be de specimen of de English light Horse, vat vill de Heavy Horse be? Oh, by Gar, I vill put off de Invasion for anoder time.’

Yet once more are these two brought into juxtaposition, in an engraving by Knight (April 15, 1806), ‘Bone and Flesh, or John Bull in moderate Condition.’ Napoleon is looking at this prodigy, and saying, ‘I contemplate this Wonder of the World, and regret that all my Conquered Domains cannot match this Man. Pray, Sir, are you not a descendant from the great Joss of China?’ Lambert replies, ‘No Sir, I am a true born Englishman, from the County of Leicester. A quiet mind, and good Constitution, nourished by the free Air of Great Britain, makes every Englishman thrive.’

Another of Gillray’s caricatures into which Napoleon is introduced, but in which he plays a secondary part, is called ‘Comforts of a Bed of Roses; vide Charley’s elucidation of Lord C—stl—r—gh’s speech! Nightly Scene near Cleveland row.’ This is founded on a speech of Lord Castlereagh’s, in which he congratulated the Ministry as having ‘a bed of roses.’ But Fox, in reply, recounted his difficulties and miseries, and said: ‘Really, it is insulting to tell me I am on a bed of roses, when I feel myself torn, and stung, by brambles, and nettles, whichever way I turn.’

Fox and Mrs. Fox are shown as sleeping on a bed of roses, some of which peep out from underneath the rose-coloured counterpane, but which display far more of thorns than of roses. There is the India rose, the Emancipation55 rose, the French rose, the Coalition rose, and the Volunteer rose. Fox’s slumbers are terribly disturbed; his bonnet rouge, which he wears as night-cap, has tumbled off; his night-shirt is seized at the neck, on one side by the ghost of Pitt, who exclaims: ‘Awake, arise, or be for ever fall’n!’ The other side is fiercely clutched by Napoleon, who, drawn sword in hand, has just stepped on to the bed from a cannon labelled ‘Pour subjuguer le monde.’ Amidst a background of smoke appear spears, and a banner entitled ‘Horrors of Invasion.’ The Prussian eagle is preparing to swoop down upon him, and, from under the bed, crawls out a skeleton holding an hour-glass, whilst round its fleshless arm is entwined a serpent ‘Intemperance, Dropsy, Dissolution.’ John Bull, as a bull-dog, is trying to seize Napoleon.

‘John Bull threatened by Insects from all Quarters’ is by an unknown artist (April 1806). John Bull is on ‘The tight little Island,’ and seated on a cask of grog. With one hand he flourishes a cutlass, and the other grasps a pistol, of which weapon two more lie on the ground. With these he defies the insects, which come in swarms. There are Westphalian mites, American hornets, Dutch bluebottles, Italian butterflies, Turkish wasps, Danish gnats, and, worst of all, a French dragon-fly, in the shape of Napoleon. John Bull is saying: ‘Come on my Lads—give me but good sea room, and I don’t care for any of you—Why all your attacks is no more than a gnat stinging an Elephant, or a flea devouring Mr. Lambert of Leicester.’

A very clever caricature is by Knight (June 26, 1806) of ‘Jupiter Bouney granting unto the Dutch Frogs a King. The Frogs sent their deputies to petition Jupiter again for a King. He sent them a Stork, who eat them up, vide Æsop’s fables.’ The discontented Dutch spurn their King Log, and pray, 56‘We present ourselves before the throne of your Majesty. We pray that you will grant us, as the supreme Chief of our Republic, Prince Louis.’ Napoleon, as Jupiter, seated on an eagle (which is made to look as much like a devil as possible), says: ‘I agree to the request. I proclaim Prince Louis, King of Holland. You Prince! reign over this People.’ And the stork is duly despatched on its mission. Talleyrand, as Ganymede, supplies Jupiter with a cup of comfort for the discontented.

Apropos of the negotiations for peace, there is a picture of Woodward’s (July 1806), in which Fox is just closing the door behind a messenger laden with despatches. John Bull, whose pockets are stuffed with Omnium and Speculation on Peace, entreats him with clasped hands: ‘Now do Charley, my dear good boy, open the door a little bit farther, just to enable me to take in a few of my friends at the Stock Exchange.’ But Fox remonstrates: ‘Really, Mr. Bull, you are too inquisitive—don’t you see the door for Negotiation is opened? don’t you see the back of a Messenger? don’t you see he has got dispatches under his arm? what would you desire more?’