Emile Verhaeren

Emile Verhaeren

Emile Verhaeren

Emile Verhaeren

INDEX

INTRODUCTORY NOTE

From "LES VILLAGES ILLUSOIRES"

RAIN

THE FERRYMAN

THE SILENCE

THE BELL-RINGER

THE SNOW

THE GRAVE-DIGGER

THE WIND

THE FISHERMEN

THE ROPE-MAKER

From "LES HEURES CLAIRES"

I.

VIII.

XVII.

XXI.

From "LES APPARUS DANS MES CHEMINS"

ST. GEORGE

THE GARDENS

SHE OF THE GARDEN

From "LA MULTIPLE SPLENDEUR"

THE GLORY OF THE HEAVENS

LIFE

JOY

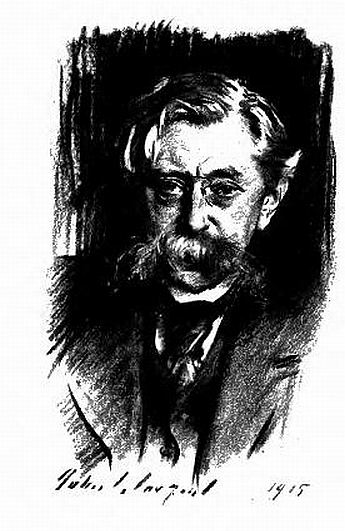

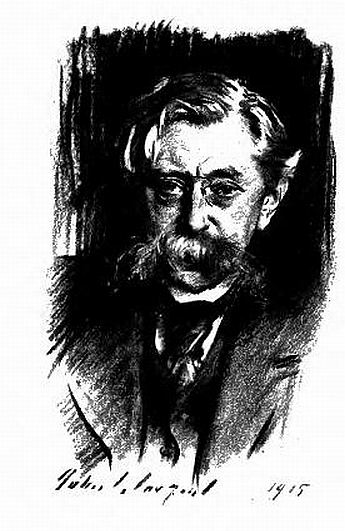

Emile Verhaeren, remarkable among of the brilliant group of writers representing "Young Belgium," and one who has been recognized by the literary world of France as holding a foremost place among the lyric poets of the day was born at St. Amand, near Antwerp, in 1855. His childhood was passed on the banks of the Scheldt, in the midst of the wide-spreading Flemish plains, a country of mist and flood, of dykes and marshes, and the impressions he received from the mysterious, melancholy character of these surroundings, have produced a marked and lasting influence upon his work. Yet the other characteristics with which it is stamped—the wealth of imagination, the gloomy force, the wonderful descriptive power and sense of colour, which set the landscape before one as a picture, suggest rather the possibility of Spanish blood in the poet's veins—and again, his somewhat morbid subjectivity and tendency to self-analysis mark him as the child of the latter end of our nineteenth century.

Verhaeren entered early in life upon the literary career. After some time spent at a college in Ghent, he became a student at the University of Louvain, and here he founded and edited a journal called "La Semaine," in which work he was assisted by the singer Van Dyck, and by his friend and present publisher, Edmond Deman. He also formed, about this time, a close friendship with Maeterlinck. In 1881, Verhaeren was called to the Bar at Brussels, but soon gave up his legal career to devote himself entirely to literature. In 1883 he published his first volume of poems, and shortly afterwards became one of the editors of "L'Art Moderne," to which, as well as to other contemporary periodicals, he was for many years a contributor. In 1892 he founded, with the help of two other friends, the "Section of Art" in the "House of the People," a popular institution in Brussels, where performances of the best music, as well as lectures upon literary and artistic subjects, were given. In spite, however, of the work which all this entailed, and of the many interests created by his ardent appreciation of the various branches of art and literature, Verhaeren continued to labour unceasingly at his poetical work, and between 1883 and 1897 brought out successively eleven small volumes: Les Flamandes, Les Moines, Les Soirs, Les Débâcles, Les Flambeaux Noirs, Les Apparus dans mes chemins, Les Campagnes Hallucinées, Les Villages Illusoires, Les Villes Tentaculaires, Les Heures Claires, and Les Aubes.

Throughout this entire series the intellectual and spiritual development of the poet may be closely traced—from the materialism which pervades Les Flamandes, and the despairing pessimism and lurid emotion—the throes of a self-centred soul in revolt against fate—which are so powerfully portrayed in Les Débâcles and Les Flambeaux Noirs, and are apparent even in the opening pages of Les Apparus dans mes chemins—to the tender, hopeful mysticism which marks the latter poems in that volume, and the wonderful sympathy with Nature, even in her saddest aspects—the subtle power of endowing those aspects with a profound and ennobling symbolism, which characterise the most beautiful of the poems in Les Villages Illusoires. Les Heures Claires is the name given to a volume of love-songs, an exquisite record of golden hours spent in a garden at spring-time—spring-time in a double sense.

The task of making an adequate and typical selection from a poet's work is always difficult, and in this case it has been decided to limit the field of selection, at least for the present, to the three last-named volumes, which embody what may, I think, be considered as Verhaeren's highest achievement in the realm of lyrical poetry.

In style, Verhaeren is essentially the apostle of the "Vers libre"; and his handling of rhyme and rhythm, his coining of words where he finds the French vocabulary insufficient, have called down upon him some criticism from those of his French contemporaries who are sticklers for the older rules and more conventional forms of versification. But however this may be, it remains an undeniable fact that Verhaeren has at his command a rare and powerful poetic eloquence—a wealth of imagery, a depth of thought and a subtlety of expression which perhaps are not to be imprisoned behind the bars of a too rigid convention. English readers have already been accustomed by their own poets to the "vers libre," and it is not so much, therefore, for my adherence to this form, as for my failure adequately to render Verhaeren's peculiar and striking beauty of language, that I beg their indulgence for the following translations.

From "LES VILLAGES ILLUSOIRES"

RAIN

Long as unending threads, the long-drawn rain

Interminably, with its nails of grey,

Athwart the dull grey day,

Rakes the green window-pane—

So infinitely, endlessly, the rain,

The long, long rain.

The rain.

Since yesternight it keeps unravelling

Down from the frayed and flaccid rags that cling

About the sullen sky.

The low black sky;

Since yesternight, so slowly, patiently.

Unravelling its threads upon the roads.

Upon the roads and lanes, with even fall

Continual.

Along the miles

That 'twixt the meadows and the suburbs lie,

By roads interminably bent, the files

Of waggons, with their awnings arched and tall.

Struggling in sweat and steam, toil slowly by

With outline vague as of a funeral.

Into the ruts, unbroken, regular,

Stretching out parallel so far

That when night comes they seem to join the sky.

For hours the water drips;

And every tree and every dwelling weeps.

Drenched as they are with it.

With the long rain, tenaciously, with rain

Indefinite.

The rivers, through each rotten dyke that yields.

Discharge their swollen wave upon the fields.

Where coils of drownèd hay

Float far away;

And the wild breeze

Buffets the alders and the walnut-trees;

Knee-deep in water great black oxen stand,

Lifting their bellowings sinister on high

To the distorted sky;

As now the night creeps onward, all the land,

Thicket and plain,

Grows cumbered with her clinging shades immense.

And still there is the rain,

The long, long rain.

Like soot, so fine and dense.

The long, long rain.

Rain—and its threads identical,

And its nails systematical,

Weaving the garment, mesh by mesh amain,

Of destitution for each house and wall,

And fences that enfold

The villages, neglected, grey, and old:

Chaplets of rags and linen shreds that fall

In frayed-out wisps from upright poles and tall.

Blue pigeon-houses glued against the thatch,

And windows with a patch

Of dingy paper on each lowering pane,

Houses with straight-set gutters, side by side

Across the broad stone gambles crucified,

Mills, uniform, forlorn.

Each rising from its hillock like a horn,

Steeples afar and chapels round about,

The rain, the long, long rain,

Through all the winter wears and wears them out.

Rain, with its many wrinkles, the long rain

With its grey nails, and with its watery mane;

The long rain of these lands of long ago,

The rain, eternal in its torpid flow!

THE FERRYMAN

The ferryman, a green reed 'twixt his teeth,

With hand on oar, against the current strong

Had rowed and rowed so long.

But she, alas! whose voice was hailing him

Across the far waves dim.

Still further o'er the far waves seemed to float,

Still further backwards, 'mid the mists, remote.

The casements with their eyes.

The dial-faces of the towers that rise

Upon the shore,

Watched, as he strove and laboured more and more.

With frantic bending of the back in two,

And start of savage muscles strained anew.

One oar was suddenly riven,

And by the current driven,

With lash of heavy breakers, out to sea.

But she, whose voice that hailed him he could hear

There 'mid the mist and wind, she seemed to wring

Her hands with gestures yet more maddening

Toward him who drew not near.

The ferryman with his surviving oar

Fell harder yet to work, and more and more

He strove, till every joint did crack and start,

And fevered terror shook his very heart.

The rudder broke

Beneath one sharp, rude stroke;

That, too, the current drove relentlessly,

A dreary shred of wreckage, out to sea.

The casements by the pier,

Like eyes immense and feverish open wide,

The dials of the towers—those widows drear

Upstanding straight from mile to mile beside

The banks of rivers—obstinately gaze

Upon this madman, in his headstrong craze

Prolonging his mad voyage 'gainst the tide.

But she, who yonder in the mist-clouds hailed

Him still so desperately, she wailed and wailed,

With head outstretched in fearful, straining haste

Toward the unknown of the outstretched waste.

Steady as one that had in bronze been cast,

Amid the blenched, grey tempest and the blast.

The ferryman his single oar yet plied.

And, spite of all, still lashed and bit the tide.

His old eyes, with hallucinated gaze,

Saw that far distance—an illumined haze—

Whence the voice sounded, coming toward him still.

Beneath the cold skies, lamentable, shrill.

The last oar broke—

And this the current hurried at one stroke,

Like a frail straw, towards the distant sea.

The ferryman, with arms dropped helplessly

Sank on his bench, forlorn.

His loins with vain efforts broken, torn.

Drifting, his barque struck somewhere, as by chance,

He turned a glance

Towards the bank behind him then—and saw

He had not left the shore.

The casements and the dials, one by one.

Their huge eyes gazing in a foolish stare.

Witnessed the ruin of his ardour there;

But still the old, tenacious ferryman

Firm in his teeth—for God knows when, indeed—

Held the green reed.

THE SILENCE

Ever since ending of the summer weather.

When last the thunder and the lightning broke,

Shatt'ring themselves upon it at one stroke,

The Silence has not stirred, there in the heather.

All round about stand steeples straight as stakes,

And each its bell between its fingers shakes;

All round about, with their three-storied loads,

The teams prowl down the roads;

All round about, where'er the pine woods end,

The wheel creaks on along its rutty bed,

But not a sound is strong enough to rend

That space intense and dead.

Since summer, thunder-laden, last was heard.

The Silence has not stirred;

And the broad heath-land, where the nights sink down

Beyond the sand-hills brown.

Beyond the endless thickets closely set,

To the far borders of the far-away.

Prolongs It yet.

Even the winds disturb not as they go

The boughs of those long larches, bending low

Where the marsh-water lies,

In which Its vacant eyes

Gaze at themselves unceasing, stubbornly.

Only sometimes, as on their way they move,

The noiseless shadows of the clouds above.

Or of some great bird's hov'ring flight on high,

Brush It in passing by.

Since the last bolt that scored the earth aslant,

Nothing has pierced the Silence dominant.

Of those who cross Its vast immensity,

Whether at twilight or at dawn it be,

There is not one but feels

The dread of the Unknown that It instils;

An ample force supreme, It holds Its sway

Uninterruptedly the same for aye.

Dark walls of blackest fir-trees bar from sight

The outlook towards the paths of hope and light;

Huge, pensive junipers

Affright from far the passing travellers;

Long, narrow paths stretch their straight lines unbent.

Till they fork off in curves malevolent;

And the sun, ever shifting, ceaseless lends

Fresh aspects to the mirage whither tends

Bewilderment

Since the last bolt was forged amid the storm,

The polar Silence at the corners four

Of the wide heather-land has stirred no more.

Old shepherds, whom their hundred years have worn

To things all dislocate and out of gear,

And their old dogs, ragged, tired-out, and torn.

Oft watch It, on the soundless lowlands near,

Or downs of gold beflecked with shadows' flight,

Sit down immensely there beside the night.

Then, at the curves and corners of the mere.

The waters creep with fear;

The heather veils itself, grows wan and white;

All the leaves listen upon all the bushes,

And the incendiary sunset hushes

Before Its face his cries of brandished light.

And in the hamlets that about It lie.

Beneath the thatches of their hovels small

The terror dwells of feeling It is nigh.

And, though It stirs not, dominating all.

Broken with dull despair and helplessness,

Beneath Its presence they crouch motionless,

As though upon the watch—and dread to see.

Through rifts of vapour, open suddenly

At evening, in the moon, the argent eyes

Of Its mute mysteries.

THE BELL-RINGER

Yon, in the depths of the evening's track,

Like a herd of blind bullocks that seek their fellows,

Wild, as in terror, the tempest bellows.

And suddenly, there, o'er the gables black

That the church, in the twilight, around it raises

All scored with lightnings the steeple blazes.

See the old bell-ringer, frenzied with fear.

Mouth gaping, yet speechless, draw hastening near.

And the knell of alarm that with strokes of lead

He rings, heaves forth in a tempest of dread

The frantic despair that throbs in his head.

With the cross at the height

Of its summit brandished, the lofty steeple

Spreads the crimson mane

Of the fire o'er the plain

Toward the dream-like horizons that bound the night;

The city nocturnal is filled with light;

The face of the swift-gathered crowds doth people

With fears and with clamours both street and lane;

On walls turned suddenly dazzling bright

The dusky panes drink the crimson flood

Like draughts of blood.

Yet, knell upon knell, the old ringer doth cast

His frenzy and fear o'er the country vast.

The steeple, it seems to be growing higher

Against the horizon that shifts and quivers,

And to be flying in gleams of fire

Far o'er the lakes and the swampy rivers.

Its slates, like wings

Of sparks and spangles, afar it flings.

They fly toward the forests across the night:

And in their passage the fires exhume

The hovels and huts from their folds of gloom,

Setting them suddenly all alight.

In the crashing fall of the steeple's crown

The cross to the brazier's depth drops down,

Where, twisted and torn in the fiery fray,

Its Christian arms are crushed like prey.

With might and main

The bell-ringer sounds his knell abroad.

As though the flames would burn his God.

The fire

Funnel-like hollows its way yet higher,

'Twixt walls of stone, up the steeple's height;

Gaining the archway and lofty stage

Where, swinging in light, the bell bounds with rage.

The daws and the owls, with wild, long cry

Pass screeching by;

On the fast-closed casements their heads they smite,

Burn in the smoke-drifts their pinions light,

Then, broken with terror and bruised with flight.

Suddenly, 'mid the surging crowd.

Fall dead outright.

The old man sees toward his brandished bells

The climbing fire

With hands of boiling gold stretch nigher.

The steeple

Looks like a thicket of crimson bushes,

With here a branch of flame that rushes

Darting the belfry boards between;

Convulsed and savage flames, they cling,

With curves that plant-like curl and lean.

Round every joist, round every pulley,

And monumental beams, whence ring

The bells, that voice forth frenzied folly.

His fear and anguish spent, the ringer

Sounds his own knell

On his ruined bell.

A final crash,

All dust and plaster in one grey flash,

Cleaves the whole steeple's height in pieces;

And like some great cry slain, it ceases

All on a sudden, the knell's dull rage.

The ancient tower

Seems sudden to lean and darkly lower;

While with heavy thuds, as from stage to stage

They headlong bound.

The bells are heard

Plunging and crashing towards the ground.

But yet the old ringer has never stirred.

And, scooping the moist earth out, the bell

Was thus his coffin, and grave as well.

THE SNOW

Uninterruptedly falls the snow,

Like meagre, long wool-strands, scant and slow,

O'er the meagre, long plain disconsolate.

Cold with lovelessness, warm with hate.

Infinite, infinite falls the snow.

Like a moment's time.

Monotonously, in a moment's time;

On the houses it falls and drops, the snow.

Monotonous, whitening them o'er with rime;

It falls on the sheds and their palings below.

And myriad-wise, it falls and lies

In ridgèd waves

In the churchyard hollows between the graves.

The apron of all inclement weather

Is roughly unfastened, there on high;

The apron of woes and misery

Is shaken by wind-gusts violently

Down on the hamlets that crouch together

Beneath the dull horizon-sky.

The frost creeps down to the very bones,

And want creeps in through the walls and stones;

Yea, snow and want round the souls creep close,

—The heavy snow diaphanous—

Round the stone-cold hearths and the flameless souls

That wither away in their huts and holes.

The hamlets bare

White, white as Death lie yonder, where

The crookèd roadways cross and halt;

Like branching traceries of salt

The trees, all crystallized with frost,

Stretch forth their boughs, entwined and crost.

Along the ways, as on they go

In far procession o'er the snow.

Then here and there, some ancient mill,

Where light, pale mosses aggregate,

Appears on a sudden, standing straight

Like a snare upon its lonely hill.

The roofs and sheds, down there below.

Since November dawned, have been wrestling still,

In contrary blasts, with the hurricane;

While, thick and full, yet falls amain

The infinite snow, with its weary weight,

O'er the meagre, long plain disconsolate.

Thus journeys the snow afar so fleet.

Into every cranny, on every trail;

Always the snow and its winding-sheet,

The mortuary snow so pale.

The snow, unfruitful and so pale.

In wild and vagabond tatters hurled

Through the limitless winter of the world.

THE GRAVE-DIGGER

In the garden yonder of yews and death,

There sojourneth

A man who toils, and has toiled for aye.

Digging the dried-up ground all day.

Some willows, surviving their own dead selves.

Weep there around him as he delves.

And a few poor flowers, disconsolate

Because the tempest and wind and wet

Vex them with ceaseless scourge and fret.

The ground is nothing but pits and cones,

Deep graves in every corner yawn;

The frost in the winter cracks the stones,

And when the summer in June is born

One hears, 'mid the silence that pants for breath,

The germinating and life of Death

Below, among the lifeless bones.

Since ages longer than he can know,

The grave-digger brings his human woe,

That never wears out, and lays its head

Slowly down in that earthy bed.

By all the surrounding roads, each day

They come towards him, the coffins white,

They come in processions infinite;

They come from the distances far away.

From corners obscure and out-of-the-way.

From the heart of the towns—and the wide-spreading

plain.

The limitless plain, swallows up their track;

They come with their escort of people in black.

At every hour, till the day doth wane;

And at early dawn the long trains forlorn

Begin again.

The grave-digger hears far off the knell,

Beneath weary skies, of the passing bell,

Since ages longer than he can tell.

Some grief of his each coffin carrieth—

His wild desires toward evenings dark with death

Are here: his mournings for he knows not what:

Here are his tears, for ever on this spot

Motionless in their shrouds: his memories.

With gaze worn-out from travelling through the years

So far, to bid him call to mind the fears

Of which their souls are dying—and with these

Lies side by side

The shattered body of his broken pride.

His heroism, to which nought replied,

Is here all unavailing;

His courage, 'neath its heavy armour failing.

And his poor valour, gashed upon the brow.

Silent, and crumbling in corruption now.

The grave-digger watches them come into sight,

The long, slow roads.

Marching towards him, with all their loads

Of coffins white.

Here are his keenest thoughts, that one by one

His lukewarm soul hath tainted and undone;

And his white loves of simple days of yore,

in lewd and tempting mirrors sullied o'er;

The proud, mute vows that to himself he made

Are here—for he hath scored and cancelled them,

As one may cut and notch a diadem;

And here, inert and prone, his will is laid,

Whose gestures flashed like lightning keen before.

But that he now can raise in strength no more.

The grave-digger digs to the sound of the knell

'Mid the yews and the deaths in yonder dell.

Since ages longer than he can tell.

Here is his dream—born in the radiant glow.

Of joy and young oblivion, long ago—

That in black fields of science he let go,

That he hath clothed with flame and embers bright,

—Red wings plucked off from Folly in her flight—

That he hath launched toward inaccessible

Spaces afar, toward the distance there,

The golden conquest of the Impossible,

And that the limitless, refractory sky,

Sends back to him again, or it has ere

So much as touched the immobile mystery.

The grave-digger turneth it round and round—

With arms by toil so weary made,

With arms so thin, and strokes of spade—

Since what long times?—the dried-up ground.

Here, for his anguish and remorse, there throng

Pardons denied to creatures in the wrong;

And here, the tears, the prayers, the silent cries,

He would not list to in his brothers' eyes.

The insults to the gentle, and the jeer

What time the humble bent their knees, are here;

Gloomy denials, and a bitter store

Of arid sarcasms, oft poured out before

Devotedness that in the shadow stands

With outstretched hands.

The grave-digger, weary, yet eager as well.

Hiding his pain to the sound of the knell,

With strokes of the spade turns round and round

The weary sods of the dried-up ground.

Then—fear-struck dallyings with suicide;

Delays, that conquer hours that would decide:

Again—the terrors of dark crime and sin

Furtively felt with frenzied fingers thin:

The fierce craze and the fervent rage to be

The man who lives of the extremity

Of his own fear:

And then, too, doubt immense and wild affright.

And madness, with its eyes of marble white,

These all are here.

His head a prey to the dull knell's sound,

In terror the grave-digger turns the ground

With strokes of the spade, and doth ceaseless cast

The dried-up earth upon his past.

The slain days, and the present, he doth see,

Quelling each quivering thrill of life to be.

And drop by drop, through fists whose fingers start.

Pressing the future blood of his red heart;

Chewing with teeth that grind and crush, each part

Of that his future's body, limb by limb,

Till there is but a carcase left to him;

And shewing him, in coffins prisoned,

Or ever they be born, his longings dead.

The grave-digger yonder doth hear the knell,

More heavy yet, of the passing bell.

That up through the mourning horizons doth swell

What if the bells, with their haunting swing,

Would stop on a day that heart-breaking ring!

And the endless procession of corse after corse.

Choke the highways no more of his long remorse

But the biers, with the prayers and the tears,

Immensely yet follow the biers;

They halt by crucifix now, and by shrine,

Then take up once more their mournful line;

On the backs of men, upon trestles borne.

They follow their uniform march forlorn;

Skirting each field and each garden-wall.

Passing beneath the sign-posts tall,

Skirting along by the vast Unknown,

Where terror points horns from the corner-stone.

The old man, broken and propless quite.

Watches them still from the infinite

Coming towards him—and hath beside

Nothing to do, but in earth to hide

His multiple death, thus bit by bit,

And, with fingers irresolute, plant on it

Crosses so hastily, day by day,

Since what long times—he cannot say.

THE WIND

Crossing the infinite length of the moorland,

Here comes the wind,

The wind with his trumpet that Heralds November;

Endless and infinite, crossing the downs,

Here comes the wind

That teareth himself and doth fiercely dismember;

Which heavy breaths turbulent smiting the towns,

The savage wind comes, the fierce wind of November!

Each bucket of iron at the wells of the farmyards,

Each bucket and pulley, it creaks and it wails;

By cisterns of farmyards, the pulleys and pails

They creak and they cry,

The whole of sad death in their melancholy.

The wind, it sends scudding dead leaves from the birches

Along o'er the water, the wind of November,

The savage, fierce wind;

The boughs of the trees for the birds' nests it searches,

To bite them and grind.

The wind, as though rasping down iron, grates past,

And, furious and fast, from afar combs the cold

And white avalanches of winter the old.

The savage wind combs them so furious and fast.

The wind of November.

From each miserable shed

The patched garret-windows wave wild overhead

Their foolish, poor tatters of paper and glass.

As the savage, fierce wind of November doth pass!

And there on its hill

Of dingy and dun-coloured turf, the black mill,

Swift up from below, through the empty air slashing,

Swift down from above, like a lightning-stroke flashing,

The black mill so sinister moweth the wind.

The savage, fierce wind of November!

The old, ragged thatches that squat round their steeple,

Are raised on their roof-poles, and fall with a clap,

In the wind the old thatches and pent-houses flap,

In the wind of November, so savage and hard.

The crosses—and they are the arms of dead people—

The crosses that stand in the narrow churchyard

Fall prone on the sod

Like some great flight of black, in the acre of God.

The wind of November!

Have you met him, the savage wind, do you remember?

Did he pass you so fleet,

—Where, yon at the cross, the three hundred roads meet—

With distressfulness panting, and wailing with cold?

Yea, he who breeds fears and puts all things to flight,

Did you see him, that night

When the moon he o'erthrew—when the villages, old

In their rot and decay, past endurance and spent,

Cried, wailing like beasts, 'neath the hurricane bent?

Here comes the wind howling, that heralds dark weather,

The wind blowing infinite over the heather.

The wind with his trumpet that heralds November!

THE FISHERMEN

The spot is flaked with mist, that fills,

Thickening into rolls more dank,

The thresholds and the window-sills,

And smokes on every bank.

The river stagnates, pestilent

With carrion by the current sent

This way and that—and yonder lies

The moon, just like a woman dead,

That they have smothered overhead,

Deep in the skies.

In a few boats alone there gleam

Lamps that light up and magnify

The backs, bent over stubbornly,

Of the old fishers of the stream,

Who since last evening, steadily,

—For God knows what night-fishery—

Have let their black nets downward slow

Into the silent water go.

The noisome water there below.

Down in the river's deeps, ill-fate

And black mischances breed and hatch.

Unseen of them, and lie in wait

As for their prey. And these they catch

With weary toil—believing still

That simple, honest work is best—

At night, beneath the shifting mist

Unkind and chill.

So hard and harsh, yon clock-towers tell.

With muffled hammers, like a knell,

The midnight hour.

From tower to tower

So hard and harsh the midnights chime.

The midnights harsh of autumn time,

The weary midnights' bell.

The crew

Of fishers black have on their back

Nought save a nameless rag or two;

And their old hats distil withal,

And drop by drop let crumbling fall

Into their necks, the mist-flakes all.

The hamlets and their wretched huts

Are numb and drowsy, and all round

The willows too, and walnut trees,

'Gainst which the Easterly fierce breeze

Has waged its feud.

No bayings from the forest sound,

No cry the empty midnight cuts—

The midnight space that grows imbrued

With damp breaths from the ashy ground.

The fishers hail each other not—

Nor help—in their fraternal lot;

Doing but that which must be done.

Each fishes for himself alone.

And this one gathers in his net,

Drawing it tighter yet,

His freight of petty misery;

And that one drags up recklessly

Diseases from their slimy bed;

While others still their meshes spread

Out to the sorrows that drift by

Threateningly nigh;

And the last hauls aboard with force

The wreckage dark of his remorse.

The river, round its corners bending,

And with the dyke-heads intertwined.

Goes hence—since what times out of mind?—

Toward the far horizon wending

Of weariness unending.

Upon the banks, the skins of wet

Black ooze-heaps nightly poison sweat.

And the mists are their fleeces light

That curl up to the houses' height.

In their dark boats, where nothing stirs,

Not even the red-flamed torch that blurs

With halos huge, as if of blood.

The thick felt of the mist's white hood,

Death with his silence seals the sere

Old fishermen of madness here.

The isolated, they abide

Deep in the mist—still side by side.

But seeing one another never;

Weary are both their arms—and yet

Their work their ruin doth beget.

Each for himself works desperately,

He knows not why—no dreams has he;

Long have they worked, for long, long years,

While every instant brings its fears;

Nor have they ever

Quitted the borders of their river,

Where 'mid the moonlit mists they strain

To fish misfortune up amain.

If but in this their night they hailed each other

And brothers' voices might console a brother!

But numb and sullen, on they go,

With heavy brows and backs bent low,

While their small lights beside them gleam,

Flickering feebly on the stream.

Like blocks of shadow they are there.

Nor ever do their eyes divine

That far away beyond the mists

Acrid and spongy—there exists

A firmament where 'mid the night.

Attractive as a loadstone, bright

Prodigious planets shine.

The fishers black of that black plague,

They are the lost immeasurably,

Among the knells, the distance vague,

The yonder of those endless plains

That stretch more far than eye can see:

And the damp autumn midnight rains

Into their souls' monotony.

THE ROPE-MAKER

In his village grey

At foot of the dykes, that encompass him

With weary weaving of curves and lines

Toward the sea outstretching dim,

The rope-maker, visionary white.

Stepping backwards along the way,

Prudently 'twixt his hands combines

The distant threads, in their twisting play.

That come to him from the infinite.

When day is gone.

Through ardent, weary evenings, yon

The whirr of a wheel can yet be heard;

Something by unseen hands is stirred.

And parallel o'er the rakes, that trace

An even space

From point to point along all the way,

The flaxen hemp still plaits its chain

Ceaseless, for days and weeks amain.

With his poor, tired fingers, nimble still.

Fearing to break for want of skill

The fragments of gold that the gliding light

Threads through his toil so scantily—

Passing the walls and the houses by

The rope-maker, visionary white,

From depths of the evening's whirlpool dim,

Draws the horizons in to him.

Horizons that stretch back afar.

Where strife, regrets, hates, furies are:

Tears of the silence, and the tears

That find a voice: serenest years,

Or years convulsed with pang and throe:

Horizons of the long ago,

These gestures of the Past they shew.

Of old—as one in sleep, life, errant, strayed

Its wondrous morns and fabled evenings through;

When God's right hand toward far Canaan's blue

Traced golden paths, deep in the twilight shade.

Of old, 'twas life exasperate, huge and tense,

Swung savage at some stallion's mane—life, fleet.

With mighty lightnings flashing 'neath her feet,

Upreared immensely over space immense.

Of old, 'twas life evoking ardent will;

And hell's red cross and Heaven's cross of white

Each marched, with gleam of steely armours' light.

Through streams of blood, to heavens of victory still.

Of old—life, livid, foaming, came and went

'Mid strokes of tocsin and assassin's knife;

Proscribers, murderers, each with each at strife,

While, mad and splendid. Death above them bent.

'Twixt fields of flax and of osiers red.

On the road where nothing doth move or tread,

By houses and walls to left and right

The rope-maker, visionary white,

From depths of evening's treasury dim

Draws the horizons in to him.

Horizons that stretch yonder far.

Where work, strifes, ardours, science are;

Horizons that change—they pass and glide,

And on their way

They shew in mirrors of eventide

The mourning image of dark To-day.

Here—writhing fires that never rest nor end.

Where, in one giant effort all employed,

Sages cast down the Gods, to change the void

Whither the flights of human science tend.

Here—'tis a room where thought, assertive, saith

That there are weights exact to gauge her by,

That inane ether, only, rounds the sky.

And that in phials of glass men breed up death.

Here—'tis a workship, where, all fiery bright,

Matter intense vibrates with fierce turmoil

In vaults where wonders new, 'mid stress and toil,

Are forged, that can absorb space, time and night.

—A palace—of an architecture grown

Effete, and weary 'neath its hundred years.

Whence voices vast invoke, instinct with fears,

The thunder in its flights toward the Unknown.

On the silent, even road—his eyes

Still fixed towards the waning light

That skirts the houses and walls as it dies—

The rope-maker, visionary white,

From depths of the evening's halo dim

Draws the horizons in to him.

Horizons that are there afar

Where light, hope, wakenings, strivings are;

Horizons that he sees defined

As hope for some future, far and kind.

Beyond those distant shores and faint

That evening on the clouds doth paint.

Yon—'mid that distance calm and musical

Twin stairs of gold suspend their steps of blue,

The sage doth climb them, and the seer too,

Starting from sides opposed toward one goal.

Yon—contradiction's lightning-shocks lose power.

Doubt's sullen hand unclenches to the light,

The eye sees in their essence laws unite

Rays scattered once 'mid doctrines of an hour.

Yon—keenest spirits pierce beyond the land

Of seeming and of death. The heart hath ease,

And one would say that Mildness held the keys

Of the colossal silence in her hand.

Up yon—the God each soul is, once again

Creates, expands, gives, finds himself in all;

And rises higher, the lowlier he doth fall

Before meek tenderness and sacred pain.

And there is ardent, living peace—its urns

Of even bliss ranged 'mid these twilights, where

—Embers of hope upon the ashen air—

Each great nocturnal planet steadfast burns.

In his village at foot of the dykes, that bend,

Sinuous, weary, about him and wend

Toward that distance of eddying light,

The rope-maker, visionary white.

Along by each house and each garden wall.

Absorbs in himself the horizons all.

From "LES HEURES CLAIRES"

I

Oh, splendour of our joy and our delight,

Woven of gold amid the silken air!

See the dear house among its gables light,

And the green garden, and the orchard there!

Here is the bench with apple-trees o'er head

Whence the light spring is shed.

With touch of petals falling slow and soft;

Here branches luminous take flight aloft,

Hovering, like some bounteous presage, high

Against this landscape's clear and tender sky.

Here lie, like kisses from the lips dropt down

Of yon frail azur upon earth below,

Two simple, pure, blue pools, and like a crown

About their edge, chance flowers artless grow.

O splendour of our joy and of our ourselves!

Whose life doth feed, within this garden bright,

Upon the emblems of our own delight.

What are those forms that yonder slowly pass?

Our two glad souls are they,

That pastime take, and stray

Along the terraces and woodland grass?

Are these thy breasts, are these thine eyes, these two

Golden-bright flowers of harmonious hue?

These grasses, hanging like some plumage rare.

Bathed in the stream they ruffle by their touch.

Are they the strands of thy smooth, glossy hair?

No shelter e'er could match yon orchard white.

Or yonder house amid its gables light,

And garden, that so blest a sky controls,

Weaving the climate dear to both our souls.

VIII

As in the guileless, golden age, my heart

I gave thee, even like an ample flower

That opens in the dew's bright morning hour;

My lips have rested where the frail leaves part.

I plucked the flower—it came

From meadows whereon grow the flowers of flame:

Speak to it not—'tis best that we control

Words, since they needs are trivial 'twixt us two;

All words are hazardous, for it is through

The eyes that soul doth hearken unto soul.

That flower that is my heart, and where secure

My heart's avowal hides.

Simply confides

Unto thy lips that she is clear and pure.

Loyal and good—and that one's trust toward

A virgin love is like a child's in God.

Let wit and wisdom flower upon the height,

Along capricious paths of vanity;

And give we welcome to sincerity,

That holds between her fingers crystal-bright

Our two clear hearts: for what so beautiful

As a confession made from soul to soul.

When eve returns

And the white flame of countless diamonds burns.

Like myriads of silent eyes intent,

Th' unfathomed silence of the firmament.

XVII

That we may love each other through our eyes

Let us our glances lave, and make them clear,

Of all the thousand glances that they here

Have met, in this base world of servile lies.

The dawn is dressed in blossom and in dew,

And chequered too

With very tender light—it looks as though

Frail plumes of sun and silver, through the mist,

Glided across the garden to and fro,

And with a soft caress the mosses kissed.

Our wondrous ponds of blue

Tremble and wake with golden shimmerings;

Swift emerald flights beneath the trees dart through.

And now the light from hedge and path anew

Sweeps the damp dust, where yet the twilight clings.

XXI

In hours like these, when through our dream of bliss

So far from all things not ourselves we move,

What lustral blood, what baptism is this

That bathes our hearts, straining toward perfect love?

Our hands are clasped, and yet there is no prayer,

Our arms outstretched, and yet no cry is there;

Adoring something, what, we cannot say.

More pure than we are and more far away,

With spirit fervent and most guileless grown,

How we are mingled and dissolved in one;

Ah, how we live each other, in the unknown!

Oh, how absorbed and wholly lost before

The presence of those hours supreme one lies!

And how the soul would fain find other skies

To seek therein new gods it might adore;

Oh, marvellous and agonizing joy,

Audacious hope whereon the spirit hangs,

Of being one day

Once more the prey,

Beyond even death, of these deep, silent pangs.

From "LES APPARUS DANS MES CHEMINS"

ST. GEORGE

Opening the mists on a sudden through,

An Avenue!

Then, all one ferment of varied gold,

With foam of plumes where the chamfrom bends

Round his horse's head, that no bit doth hold,

St. George descends!

The diamond-rayed caparison,

Makes of his flight one declining path

From Heaven's pity down upon

Our waiting earth.

Hero and Lord

Of the joyous, helpful virtues all.

Sonorous, pure and crystalline!

Let his radiance fall

On my heart nocturnal and make it shine

In the wheeling aureole of his sword!

Let the wind's soft silvern whispers sound

And ring his coat of mail around,

His battle-spurs amid the fight!

—He—the St. George—who shines so bright

And comes, 'mid the wailings of my desire.

To seize and lift my poor hands higher

Toward his dauntless valour's fire!

Like a cry great with faith, to God

His lance St. George upraised doth hold;

Crossing athwart my glance he trod.

As 'twere one tumult of haggard gold.

The chrism's glow on his forehead shone,

The great St. George of duty high!

Beautiful by his heart, and by

Himself alone!

Ring, all my voices of hope, ring on!

Ring forth in me

Beneath fresh boughs of greenery,

Down radiant pathways, full of sun;

Ye glints of silvery mica, be

Bright joy amid my stones—and ye

White pebbles that the waters strew.

Open your eyes in my brooklets, through

The watery lids that cover you;

Landscape of gushing springs and sun,

With gold that quivers on misty blue,

Landscape that dwells in me, hold thou

The mirror now

To the fiery flights, that flaming roll,

Of the great St. George toward my soul!

'Gainst the black Dragon's teeth and claws,

Against the armour of leprous sores,

The miracle and sword is he;

On his breast-plate burneth Charity,

And his gentleness sends hurtling back.

In dire defeat, the Instinct black.

Fires flecked with gold, that flashing turn,

Whirlwinds of stars, those glories meet,

About his galloping horse's feet.

Deep into my remembrance burn

Their lightnings fleet!

He comes, a fair ambassador,

From white lands built with marble o'er.

Where grows, in glades beside the sea,

Upon the tree

Of goodness, fragrant gentleness.

That haven, too, he knows no less

Where wondrous ships rock, calm and still.

That freights of sleeping angels fill;

And those vast evenings, when below

Upon the water, 'mid the skies'

Reflected eyes.

Islands flash sudden forth and glow.

That kingdom fair

Whereof the Virgin ariseth Queen,

Its lowly, ardent joy is he;

And his flaming sword in the ambient air

Vibrates like an ostensory—

The suddenly flashing St. George! behold,

He strikes through my soul like a fire of gold!

He knows from what far wanderings

I come: what mists obscure my brain;

What dagger marks have deeply scarred

My thought, and with black crosses marred:

With what spent force, what anger vain.

What petty scorn of better things,

—Yea, and with what a mask I came,

Folly upon the lees of shame!

A coward was I; the world I fled

To hide my head

Within a huge and futile Me;

I builded, beneath domes of Night,

The blocks of marble, gold be-starred,

Of a hostile science, endlessly

Towards a height

By oracles of blackness barred.

For Death alone is Queen of night.

And human effort is brightest born

Only at dawn.

With opening flowers would prayer fain bloom,

And their sweet lips hold the same perfume.

The sunbeams shimmering white that fall

On pearly water, are for all

Like a caress

Upon our life: the dawn unfolds

A counsel fair of trustfulness;

And whoso hearkens thereto is saved

From his slough, where never a sin was laved.

St. George in radiant armour came

Speeding along in leaps of flame

'Mid the sweet morning, through my soul.

Young, beautiful by faith was he;

He leaned the lower down toward me

Even as I the lowlier knelt;

Like some pure, golden cordial

In secret felt.

He filled me with his soaring strength,

And with sweet fear most tenderly.

Before that vision's dignity,

Into his pale, proud hand at length

I cast the blood my pain had spent.

Then, laying upon me as he went

A charge of valour, and the sign

Of the cross on my brow from his lance divine,

He sped upon his shining road

Straight, with my heart, towards his God.

THE GARDENS

The landscape now reveals a change;

A stair—that twinèd elm-boughs hold

Enclosed 'mid hedges mystic, strange—

Inaugurates a green and gold

Vision of gardens, range on range.

Each step's a hope, that doth ascend

Stairwise to expectation's height;

A weary way it is to wend

While noonday suns are burning bright.

But rest waits at the evening's end.

Streams, that wash white from sin, flow deep,

And round about the fresh lawns twine;

While there, beneath the green banks steep,

Beside his cross, the Lamb Divine

Lies tranquilly in peaceful sleep.

The daisied grass is glad, and gay

With crystal butterflies the hedge.

Where globes of fruit shine blue; here stray

Peacocks beside the box-trees' edge:

A shining lion bars the way.

Flowers, upright as the ecstasies

And ardours of white spirits pure,

With branches springing fountain-wise,

Burst upward, and by impulse sure

To their own soaring splendour rise.

Gently and very slowly swayed.

The wind a wordless rhapsody

Sings—and the shimm'ring air doth braid

An aureole of filigree

Round every disk with emerald laid.

Even the shade is but a flight

Toward flickering radiances, that slip

From space to space; and now the light

Sleeps, with calmed rays, upon the lip

Of lilac-blossoms golden-white.

SHE OF THE GARDEN

In such a spot, with radiant flowers for halo,

I saw the Guardian Angel sit her down;

Vine-branches fashioned a green shrine above her

And sun-flowers rose behind her like a crown.

Her fingers, their white slenderness encircled

With humble, fragile rings of coral round.

Held, ranged in couples, sprays of faithful roses.

Sealed with a clasp, with threads of woollen bound.

A shimmering air the golden calm was weaving,

All filigree'd with dawn, that like a braid

Surmounted her pure brow, which still was hidden

Half in the shade.

Woven of linen were her veil and sandals.

But, twined 'mid boughs of foliage, on their hem

The theologic Virtues Three were painted;

Hearts set about with gold encompassed them.

Her silken hair, slow rippling, from her shoulder

Down to the mosses of the sward did reach;

The childhood of her eyes disclosed a silence

More sweet than speech.

My arms outstretched, and all my soul upstraining.

Then did I rise,

With haggard yearning, toward the soul suspended

There in her eyes.

Those eyes, they shone so vivid with remembrance,

That they confessed days lived alike with me:

Oh, in the grave inviolate can it change, then,

The Long Ago, and live in the To Be?

Sure, she was one who, being dead, yet brought me.

Miraculous, a strength that comforteth,

And the Viaticum of her survival

Guiding me from the further side of Death.

From "LA MULTIPLE SPLENDEUR"

THE GLORY OF THE HEAVENS

Shining in dim transparence, the whole of infinity lies

Behind the veil that the finger of radiant winter weaves

And down on us falls the foliage of stars in glittering sheaves;

From out the depths of the forest, the forest obscure of the skies,

The wingèd sea with her shadowy floods as of dappled silk

Speeds, 'neath the golden fires, her pale immensity o'er;

And diamond-rayed, the moonlight, shining along the shore,

Bathes the brow of the headlands in radiance as soft as milk.

Yonder there flow, untwining and twining their loops anew!

The mighty, silvery rivers, through the translucent night;

And a glint as of wondrous acids sparkles with magic light

the cup that the lake outstretches towards the mountains blue.

Everywhere light seems breaking forth into flower and star,

Whether on shore in stillness, or wavering on the deep.

The islands are nests where silence inviolate doth deep;

An ardent nimbus hovers o'er yon horizons far.

See, from Nadir to Zenith one aureole doth reach!

Of yore, the souls exalted by faith's high mysteries

Saw, in the domination of those star-clouded skies,

Jehovah's hand resplendent and heard His silent speech.

But now the eyes that scan them no longer may there aspire

To we some god self-banished—not so, but the intricate

Tangle of marvellous problems, the messengers that wait

On Measureless Force, and veil her, there on her couch of fire.

O cauldrons of life, where matter, adown the eternal day,

Pours herself fruitful, seething through paths of scattering flame!

O flux of worlds and reflux to other worlds the same!

Unending oscillation betwixt newer and for aye!

Tumults consumed in whirlpools of speed and sound and light—

Violence we nought may reck of!—and yet there falls from thence

The vast, unbroken silence, mysterious and intense

That makes the peace, the calmness and beauty of the night!

O spheres of flame and golden, always more far and high;

Abyss to abyss still floating, onward from shade to shade!

So far, so high, all reck'ning the wisdom of man has made,

Before those giddy numbers must shrink in his hands and die!

Shining in dim transparence, the whole of infinity lies

Behind the veils that the finger of radiant winter weaves;

And down on us falls the foliage of star in glittering sheaves,

From out the depths of the forest, the forest obscure of the skies.

LIFE

To see beauty in all, is to lift our own Soul

Up to loftier heights than do chose who aspire

Through culpable suffering, vanquished desire.

Harsh Reality, dread and ineffable Whole,

Distils her red draught, enough tonic and stern

To intoxicate heads and to make the heart burn.

O clean and pure grain, whence are purged all the tares!

Clear torch, chosen out amid many whose flame;

Though ancient in splendour, is false to its name!

It is good to keep step, though beset with hard cares,

With the life that is real, to the far distant goal,

With no arm save the lucid, white pride of one's soul!

To march, thus intrepid in confidence, straight

On the obstacle, holding the stubborn hope

Of conquering, thanks to firm blows of the will,

Of intelligence prompt, or of patience to wait;

And to feel growing stronger within us the sense,

Day by day, of a power superb and intense!

To love ourselves keenly those others within

Who share a like strife with us, soar without fear

Toward that one future, whose footsteps we hear;

To love them, heart, brain, and because we are kin

Because in some dark, maddened day they have known

One anguish, one mourning, one string with our own!

To be drunk with the great human battle of wills—

—Pale, fleeting reflex of the monstrous assaults,

Golden movements of planets in heaven's high vaults—

Till one lives in all that which acts, struggles, and thrills,

And avidly opens one's heart to the law

That rules, dread and stern, the whole universe o'er!

JOY

O splendid, spacious day, irradiate

With flaming dawns, when earth shows yet more fair

Her ardent beauty, proud, without alloy;

And wakening life breathes out her perfume rare

So potently, that, all intoxicate,

Our ravished being rushes upon joy!

Be thanked, mine eyes, that now

Ye still shine clear beneath my furrowed brow

To see afar, the light vibrating there;

And you my hands, that in the sun yet thrill,

And you, my fingers, that glow golden still

Among the golden fruit upon the wall

Where hollyhocks stand tall.

Be thanked, my body, that thyself dost bear

Yet firm and swift, and quivering to the touch

Of the quick breezes or of winds profound;

And you, straight frame, and lungs outbreathing wide,

Along the shore or on the mountain-side,

The sharp and radiant air

That bathes and grips the mighty worlds around!

O festal mornings, calm in loveliness,

Rose whose pure face the dewdrops all caress,

Birds flying toward us, like some presage white,

Gardens of sombre shade or frailest light!

What time the ample summer warms the glade,

I love you, roads, by which came hither late

She who held hidden in her hands my fate.

I love you, distant marshes, woods austere,

And to its depths, I love the earth, where here

Beneath my feet, my dead to rest are laid.

So I exist in all that doth surround

And penetrate me:—all this grassy ground,

These hidden paths, and many a copse of beech:

Clear water, that no clouding shadows reach:

You have become to me

Myself, because you are my memory.

In you my life prolonged for ever seems,

I shape, I am, all that hath filled my dreams;

In that horizon vast that dazzles me,

Trees shimmering with gold, my pride are ye;

And like the knots upon your trunk, my will

Strengthens my power to sane, stanch labour still.

Rose of the pearl-hued gardens, when you kiss

My brow, a touch of living flame it is;

To me all seems

One thrill of ardour, beauty, wild caress;

And I, in this world-drunkenness,

So multiply myself in all that gleams

On dazzled eyes,

That my heart, fainting, vents itself in cries.

O leaps of fervour, strong, profound, and sweet,

As though some great wing swept thee off thy feet!

If thou hast felt them upward hearing thee

Toward infinity,

Complain not, man, even in the evil day;

Whate'er disaster takes thee for her prey

Thou to thyself shalt say

That once, for one short instant all supreme

Which time may not destroy,

Thou yet hast tasted, with quick-beating heart,

Sweet, formidable joy;

And that thy soul, beguiling thee to set

As in a dream,

Hath fused thy very being's inmost part

With the unanimous great founts of power

And that that day supreme, that single hour,

Hath made a god of thee.