George Henry Borrow

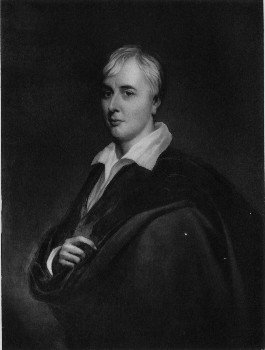

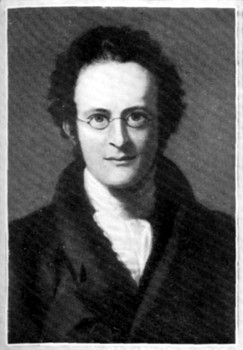

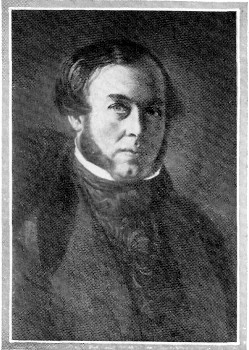

George Henry BorrowFrom a painting by Henry Wyndham Phillips

Project Gutenberg's George Borrow and His Circle, by Clement King Shorter

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: George Borrow and His Circle

Wherein May Be Found Many Hitherto Unpublished Letters Of

Borrow And His Friends

Author: Clement King Shorter

Release Date: November 12, 2006 [EBook #19767]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GEORGE BORROW AND HIS CIRCLE ***

Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net. (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/Million

Book Project).

George Henry Borrow

George Henry Borrow

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

1913

Transcriber's Notes: Minor typos have been corrected. There is Persian and Russian writing in this book, which have been marked as [Persian] or as [Russian]. In this text, full page illustrations used the same page number as the previous non illustration page, so, for example, there were two page 16. I have added an a after the illustration page number for the sake of clarity.

I have to express my indebtedness first of all to the executors of Henrietta MacOubrey, George Borrow's stepdaughter, who kindly placed Borrow's letters and manuscripts at my disposal. To the survivor of these executors, a lady who resides in an English provincial town, I would particularly wish to render fullest acknowledgment did she not desire to escape all publicity and forbid me to give her name in print. I am indebted to Sir William Robertson Nicoll without whose kindly and active intervention I should never have taken active steps to obtain the material to which this biography owes its principal value. I am under great obligations to Mr. Herbert Jenkins, the publisher, in that, although the author of a successful biography of Borrow, he has, with rare kindliness, brought me into communication with Mr. Wilfrid J. Bowring, the grandson of Sir John Bowring. To Mr. Wilfrid Bowring I am indebted in that he has handed to me the whole of Borrow's letters to his grandfather. I have to thank Mr. James Hooper of Norwich for the untiring zeal with which he has unearthed for me a valuable series of notes including[Pg vi] certain interesting letters concerning Borrow. Mr. Hooper has generously placed his collection, with which he at one time contemplated writing a biography of Borrow, in my hands. I thank Dr. Aldis Wright for reading my chapter on Edward FitzGerald; also Mr. W.H. Peet, Mr. Aleck Abrahams, and Mr. Joseph Shaylor for assistance in the little known field of Sir Richard Phillips's life. I have further to thank my friends, Edward Clodd and Thomas J. Wise, for reading my proof-sheets. To Theodore Watts-Dunton, an untiring friend of thirty years, I have also to acknowledge abundant obligations.

C. K. S.

| Preface, | v |

| Introduction, | xv |

| CHAPTER I | |

| CAPTAIN BORROW OF THE WEST NORFOLK MILITIA, | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| BORROW'S MOTHER, | 12 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| JOHN THOMAS BORROW, | 18 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| A WANDERING CHILDHOOD, | 36 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| GEORGE BORROW'S NORWICH—THE GURNEYS, | 54 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| GEORGE BORROW'S NORWICH—THE TAYLORS, | 63 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| GEORGE BORROW'S NORWICH—THE GRAMMAR SCHOOL, | 70 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| GEORGE BORROW'S NORWICH—THE LAWYER'S OFFICE, | 79 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| SIR RICHARD PHILLIPS, | 87 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| 'FAUSTUS' AND 'ROMANTIC BALLADS,' | 101 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| 'CELEBRATED TRIALS' AND JOHN THURTELL, | 112 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| BORROW AND THE FANCY, | 126 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| EIGHT YEARS OF VAGABONDAGE, | 133 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| SIR JOHN BOWRING, | 138 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| BORROW AND THE BIBLE SOCIETY, | 153 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| ST. PETERSBURG AND JOHN P. HASFELD, | 162 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

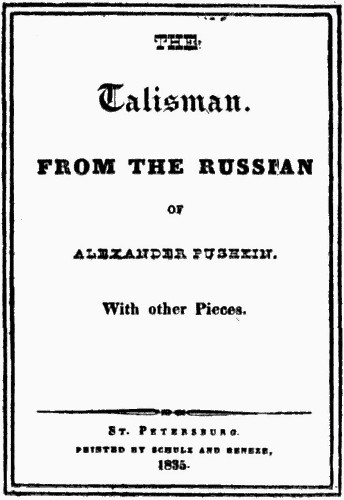

| THE MANCHU BIBLE—'TARGUM'—'THE TALISMAN,' | 169 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| THREE VISITS TO SPAIN, | 179 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| BORROW'S SPANISH CIRCLE, | 201 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| MARY BORROW, | 215 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| 'THE CHILDREN OF THE OPEN AIR,' | 226 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| 'THE BIBLE IN SPAIN,' | 237 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| RICHARD FORD, | 248 |

| CHAPTER XXIV | |

| IN EASTERN EUROPE, | 260 |

| CHAPTER XXV | |

| 'LAVENGRO,' | 275 |

| CHAPTER XXVI | |

| A VISIT TO CORNISH KINSMEN, | 289 |

| CHAPTER XXVII | |

| IN THE ISLE OF MAN, | 296 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII | |

| OULTON BROAD AND YARMOUTH, | 304 |

| CHAPTER XXIX | |

| IN SCOTLAND AND IRELAND, | 320 |

| CHAPTER XXX | |

| 'THE ROMANY RYE,' | 341 |

| CHAPTER XXXI | |

| EDWARD FITZGERALD, | 350 |

| CHAPTER XXXII | |

| 'WILD WALES,' | 364 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII | |

| LIFE IN LONDON, | 379 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV | |

| FRIENDS OF LATER YEARS, | 389 |

| CHAPTER XXXV | |

| BORROW'S UNPUBLISHED WRITINGS, | 401 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI | |

| HENRIETTA CLARKE, | 413 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII | |

| THE AFTERMATH, | 434 |

| INDEX, | 439 |

| George Borrow, | Frontispiece |

| A photogravure portrait from the painting by Henry Wyndham Phillips. | |

| PAGE | |

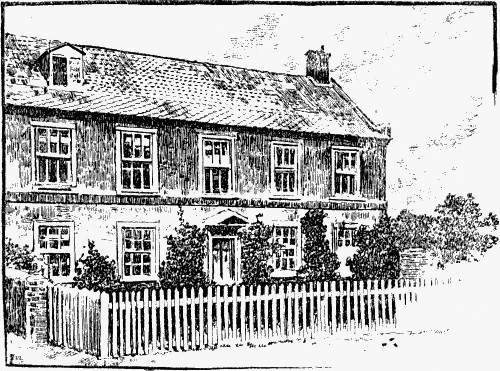

| The Borrow House, Norwich, | 16 |

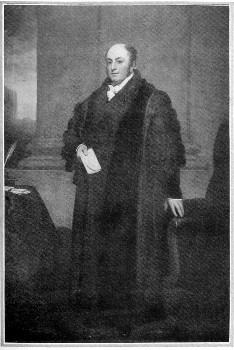

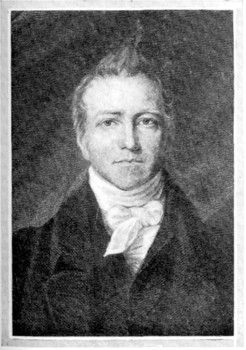

| Robert Hawkes, Mayor of Norwich in 1824, | 24 |

| From the painting by Benjamin Haydon in St. Andrew's Hall, Norwich. | |

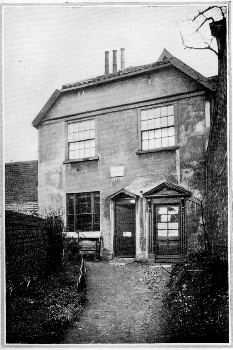

| George Borrow, | 32 |

| From a portrait by his brother, John Thomas Borrow, in the National Portrait Gallery, London. | |

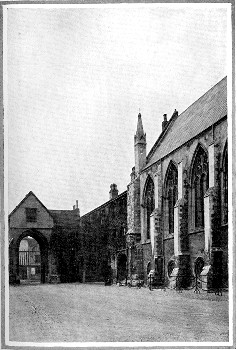

| The Erpingham Gate and the Grammar School, Norwich | 72 |

| William Simpson, | 80 |

| From a portrait by Thomas Phillips, R.A., in the Black Friars Hall, Norwich. | |

| Friends of Borrow's Early Years— | |

| Sir John Bowring in 1826, | 96 |

| John P. Hasfeld in 1835, | 96 |

| William Taylor, | 96 |

| Sir Richard Phillips, | 96 |

| The Family of Jasper Petulengro, | 128 |

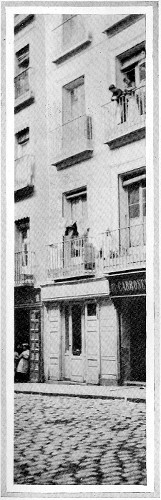

| Where Borrow Lived in Madrid, | 192 |

| The Calle del Principe, Madrid, | 192 |

| A hitherto Unpublished Portrait of George Borrow, | 304 |

| Taken in the garden of Mrs. Simms Reeve of Norwich in 1848. | |

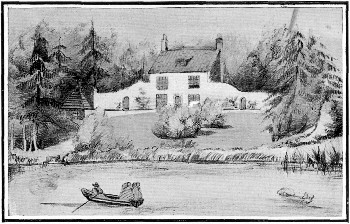

| Oulton Cottage from the Broad, | 352 |

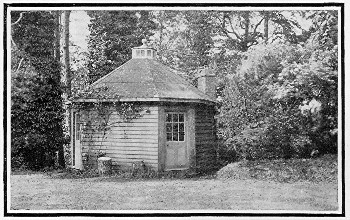

| The Summer-House, Oulton, as it is to-day, | 352 |

| George Borrow's Birthplace at Dumpling Green, | 35 |

| From a Drawing by Fortunino Matania. | |

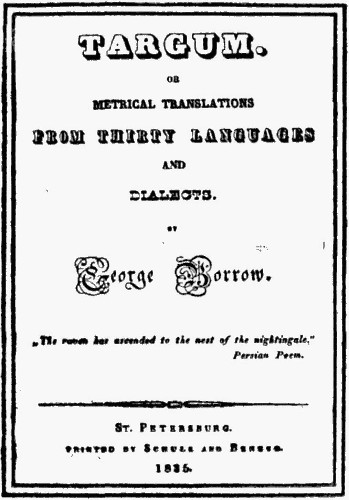

| Title-Pages of 'Targum' and 'The Talisman,' | 178 |

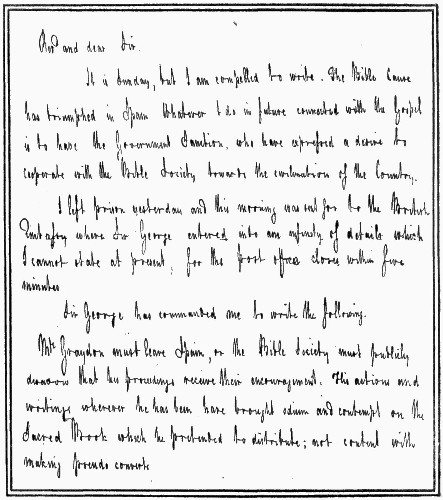

| Portion of a Letter From George Borrow To the Rev. Samuel Brandram, | 187 |

| Written From Madrid, 13th May 1838. | |

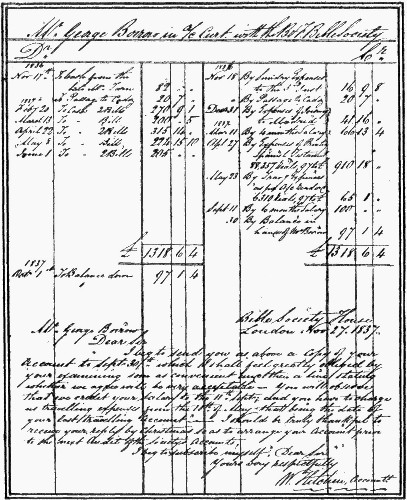

| Facsimile of an Account of George Borrow's Expenses in Spain made out by the Bible Society, | 190 |

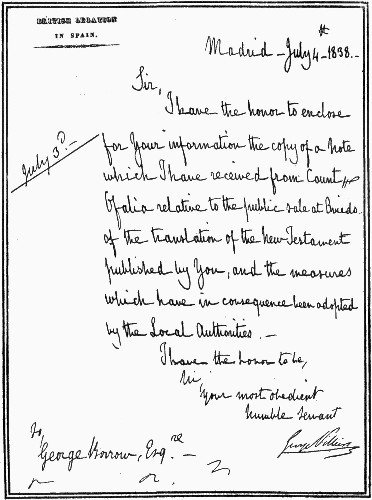

| A Letter from Sir George Villiers, afterwards Earl of Clarendon, British Minister to Spain, to George Borrow, | 211 |

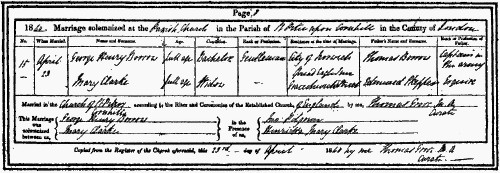

| Mrs. Borrow's Copy of her Marriage Certificate, | 222 |

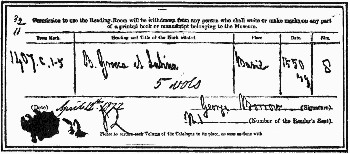

| An Application for a Book in the British Museum, with Borrow's Signature, | 230 |

| A Shekel, | 244 |

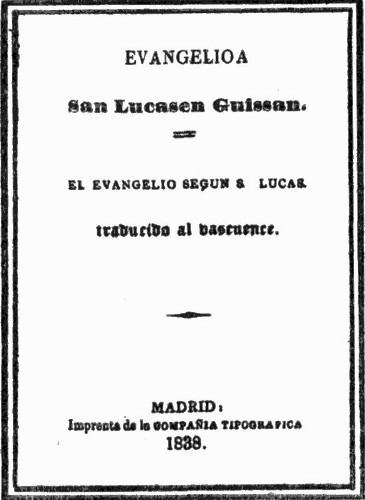

| Title-Page of Basque Translation by Oteiza of the Gospel of St. Luke, | 247 |

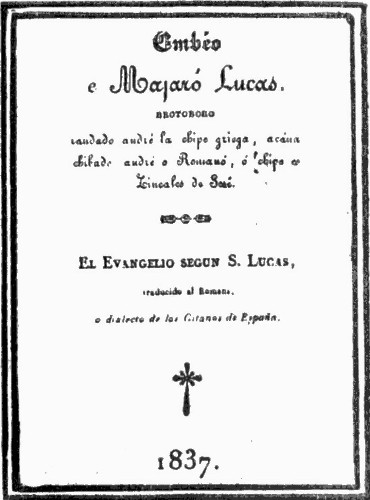

| Title-Page of First Edition of Romany Translation of the Gospel of St. Luke, | 247 |

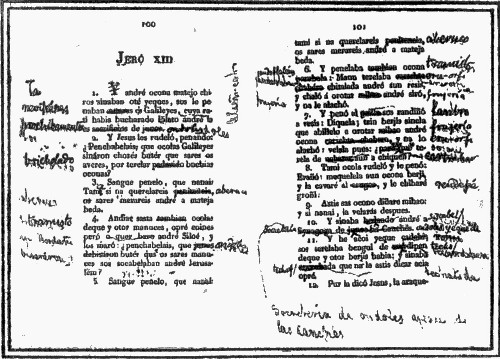

| Two Pages From Borrow's Corrected Proof Sheets of Romany Translation of the Gospel of St. Luke, | 247 |

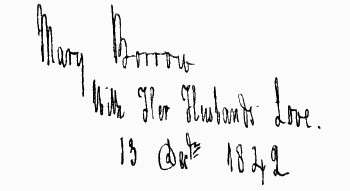

| Inscriptions in Borrow's Handwriting on his Wife's Copies Of 'The Bible in Spain' and 'Lavengro,' | 275 |

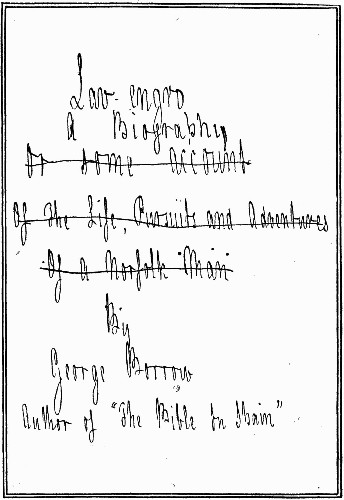

| The Original Title-Page of 'Lavengro,' | 280 |

| From the Manuscript in the possession of the Author of 'George Borrow and his Circle.' | |

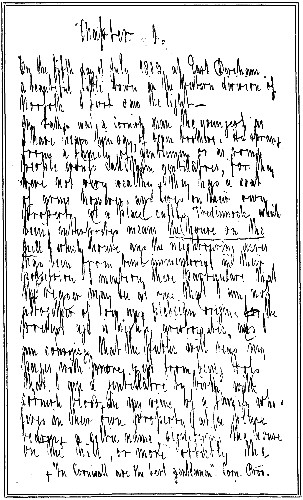

| Facsimile of the First Page of 'Lavengro,' | 282 |

| From the Manuscript in the possession of the Author of 'George Borrow and his Circle.' | |

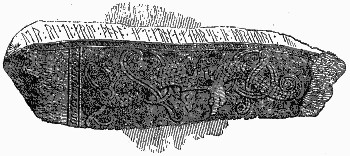

| Runic Stone From the Isle of Man, | 302 |

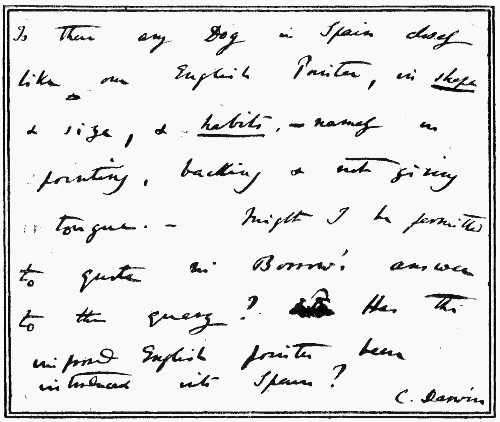

| Facsimile of a Communication from Charles Darwin to George Borrow, | 318 |

| Facsimile of a Page of the Manuscript of 'The Romany Rye,' | 346 |

| From the Borrow Papers in the possession of the Author of 'George Borrow and his Circle.' | |

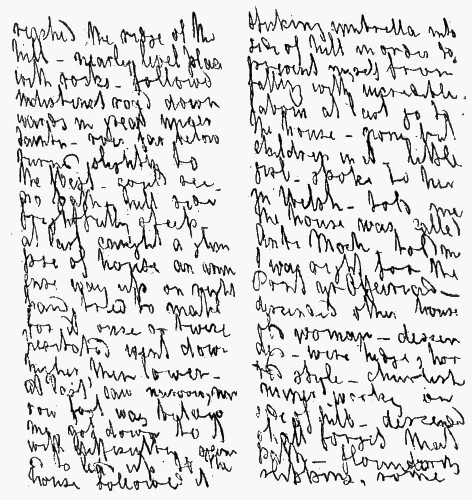

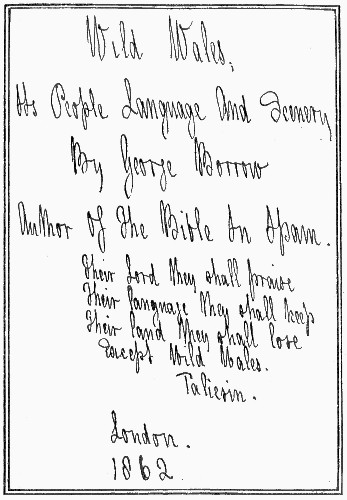

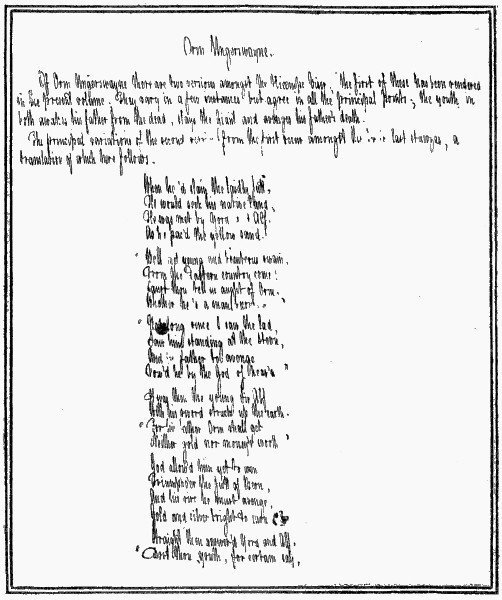

| 'Wild Wales' in its Beginnings, | 365 |

| Two pages from one of George Borrow's Pocket-books with pencilled notes made on his journey through Wales. | |

| Facsimile of the Title-Page of 'Wild Wales,' | 368 |

| From the original Manuscript in the possession of the Author of 'George Borrow and his Circle.' | |

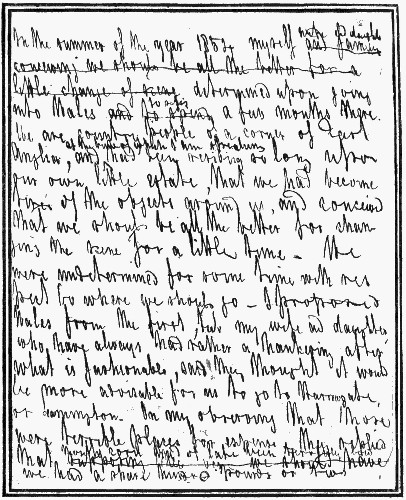

| Facsimile of the First Page of 'Wild Wales,' | 370 |

| From the original Manuscript in the possession of the Author of 'George Borrow and his Circle.' | |

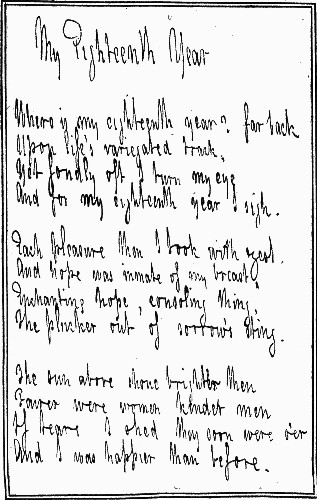

| Facsimile of a Poem from 'Targum,' | 403 |

| A Translation from the French by George Borrow. | |

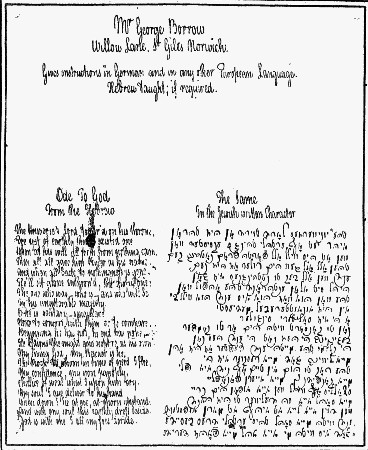

| Borrow as a Professor of Languages—an Advertisement, | 409 |

| A Page of the Manuscript of Borrow's 'Songs of Scandinavia'—an unpublished work, | 411 |

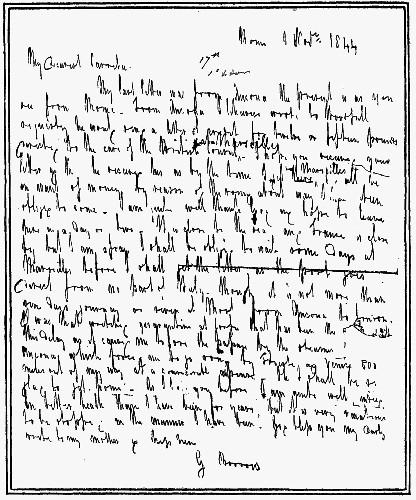

| A Letter from Borrow to his Wife written from Rome in his Continental Journey of 1844, | 418 |

It is now exactly seventeen years ago since I published a volume not dissimilar in form to this under the title of Charlotte Brontë and her Circle. The title had then an element of novelty, Dante Gabriel Rossetti's Dante and his Circle, at the time the only book of this particular character, having quite another aim. There are now some twenty or more biographies based upon a similar plan.[1] The method has its convenience where there are earlier lives of a given writer, as one can in this way differentiate the book from previous efforts by making one's hero stand out among his friends. Some such apology, I feel, is necessary, because, in these days of the multiplication of books, every book, at least other than a work of imagination, requires ample apology. In Charlotte Brontë and her Circle I was able to claim that, even though following in the footsteps of Mrs. Gaskell, I had added some four hundred new letters by Charlotte Brontë to the world's knowledge of that interesting woman, and still more considerably enlarged our knowledge of her sister Emily. This achievement has been generously acknowledged, and I am most proud of the testimony of the most accomplished of living biographers, Sir George Otto Trevelyan, who once rendered me the following quite spontaneous tribute:[Pg xvi]

We have lately read aloud for the second time your Brontë book; let alone private readings. It is unique in plan and excellence, and I am greatly obliged to you for it. Apart from the pleasure of the book, the form of it has always interested me as a professional biographer. It certainly is novel; and in this case I am pretty sure that it is right.

With such a testimony before me I cannot hesitate to present my second biography in similar form. In the case of George Borrow, however, I am not in a position to supplement one transcendent biography, as in the case of Charlotte Brontë and Mrs. Gaskell. I have before me no less than four biographies of Borrow, every one of them of distinctive merit. These are:

Life, Writings, and Correspondence of George Borrow. Derived from Official and other Authentic Sources. By William I. Knapp, Ph.D., LL.D. 2 vols. John Murray, 1899.

George Borrow: The Man and his Work. By R. A. J. Walling. Cassell, 1908.

The Life of George Borrow. Compiled from Unpublished Official Documents. His Works, Correspondence, etc. By Herbert Jenkins. John Murray, 1912.

George Borrow: The Man and his Books. By Edward Thomas. Chapman and Hall, 1912.

All of these books have contributed something of value and importance to the subject. Dr. Knapp's work it is easiest to praise because he is dead.[2] His biography of Borrow was the effort of a lifetime. A scholar with great linguistic qualifications for writing the biography of an author whose knowledge of languages was one of[Pg xvii] his titles to fame, Dr. Knapp spared neither time nor money to achieve his purpose. Starting with an article in The Chautauquan Magazine in 1887, which was reprinted in pamphlet form, Dr. Knapp came to England—to Norwich—and there settled down to write a Life of Borrow, which promised at one time to develop into several volumes. As well it might, for Dr. Knapp reached Norfolk at a happy moment for his purpose. Mrs. MacOubrey, Borrow's stepdaughter, was in the humour to sell her father's manuscripts and books. They were offered to the city of Norwich; there was some talk of Mr. Jeremiah Coleman, M.P., whose influence and wealth were overpowering in Norwich at the time, buying them. Finally, a very considerable portion of the collection came into the hands of Mr. Webber, a bookseller of Ipswich, who later became associated with the firm of Jarrold of Norwich. From Webber Dr. Knapp purchased the larger portion, and, as his bibliography indicates (Life, vol. ii. pp. 355-88), he became possessed of sundry notebooks which furnish a record of certain of Borrow's holiday tours, about a hundred letters from and to Borrow, and a considerable number of other documents. The result, as I have indicated, was a book that abounded in new facts and is rich in new material. It was not, however, a book for popular reading. You must love the subject before you turn to this book with any zest. It is a book for your true Borrovian, who is thankful for any information about the word-master, not for the casual reader, who might indeed be alienated from the subject by this copious memoir. The result was somewhat discouraging. There were not enough of true Borrovians in those years, and the book was not received too generously. The two volumes have gone out of[Pg xviii] print and have not reached a second edition. Time however, will do them justice. As it is, your good Borrow lover has always appreciated their merits. Take Lionel Johnson for example, a good critic and a master of style. After saying that these 'lengthy and rich volumes are a monument of love's labour, but not of literary art or biographical skill,' he adds: 'Of his over eight hundred pages there is not one for which I am not grateful' and every new biographer of Borrow is bound to re-echo that sentiment. Dr. Knapp did the spade work and other biographers have but entered into his inheritance. Dr. Knapp's fine collection of Borrow books and manuscripts was handed over by his widow to the American nation—to the Hispanic Society of New York. Dr. Knapp's biography was followed nine years later by a small volume by Mr. R. A. J. Walling, whose little book adds considerably to our knowledge of Borrow's Cornish relatives, and is in every way a valuable monograph on the author of Lavengro. Mr. Herbert Jenkins's book is more ambitious. Within four hundred closely printed pages he has compressed every incident in Borrow's career, and we would not quarrel with him nor his publisher for calling his life a 'definitive biography' if one did not know that there is not and cannot be anything 'definitive' about a biography except in the case of a Master. Boswell, Lockhart, Mrs. Gaskell are authors who had the advantage of knowing personally the subjects of their biographies. Any biographer who has not met his hero face to face and is dependent solely on documents is crippled in his undertaking. Moreover, such a biographer is always liable to be in a manner superseded or at least supplemented by the appearance of still more documents. However, Mr. Jenkins's excellent biography has the[Pg xix] advantage of many new documents from Mr. John Murray's archives and from the Record Office Manuscripts. His work was the first to make use of the letters of George Borrow to the Bible Society, which the Rev. T. H. Darlow has published as a book under that title, a book to which I owe him an acknowledgment for such use of it as I have made, as also for permission to reproduce the title-page of Borrow's Basque version of St. Luke's gospel. There only remains for me to say a word in praise of Mr. Edward Thomas's fine critical study of Borrow which was published under the title of George Borrow: The Man and his Books. Mr. Thomas makes no claim to the possession of new documents. This brings me to such excuse as I can make for perpetrating a fifth biography. When Mrs. MacOubrey, Borrow's stepdaughter, the 'Hen.' of Wild Wales and the affectionate companion of his later years, sold her father's books and manuscripts—and she always to her dying day declared that she had no intention of parting with the manuscripts, which were, she said, taken away under a misapprehension—she did not, of course, part with any of his more private documents. All the more intimate letters of Borrow were retained. At her death these passed to her executors, from whom I have purchased all legal rights in the publication of Borrow's hitherto unpublished manuscripts and letters. I trust that even to those who may disapprove of the discursive method with which—solely for my own pleasure—I have written this book, will at least find a certain biographical value in the many new letters by and to George Borrow that are to be found in its pages. The book has taken me ten years to write, and has been a labour of love.

[1] As for example, Garrick and his Circle; Johnson and his Circle; Reynolds and his Circle; and even The Empress Eugénie and her Circle.

[2] William Ireland Knapp died in Paris in June 1908, aged seventy-four. He was an American, and had held for many years the Chair of Modern Languages at Vassar College. After eleven years in Spain he returned to occupy the Chair of Modern Languages at Yale, and later held a Professorship at Chicago. After his Life of Borrow was published he resided in Paris until his death.

George Henry Borrow was born at Dumpling Green near East Dereham, Norfolk, on the 5th of July 1803. It pleased him to state on many an occasion that he was born at East Dereham.

On an evening of July, in the year 18—, at East D——, a beautiful little town in a certain district of East Anglia, I first saw the light,

he writes in the opening lines of Lavengro, using almost the identical phraseology that we find in the opening lines of Goethe's Wahrheit und Dichtung. Here is a later memory of Dereham from Lavengro:

What it is at present I know not, for thirty years and more have elapsed since I last trod its streets. It will scarcely have improved, for how could it be better than it was? I love to think on thee, pretty, quiet D——, thou pattern of an English country town, with thy clean but narrow streets branching out from thy modest market-place, with their old-fashioned houses, with here and there a roof of venerable thatch, with thy one half-aristocratic mansion, where resided the Lady Bountiful—she, the generous and kind, who loved to visit the sick, leaning on her golden-headed cane, while the sleek old footman walked at a respectful distance behind. Pretty, quiet D——, with thy venerable church, in which moulder the mortal remains of England's sweetest and most pious bard.

Then follows an exquisite eulogy of the poet Cowper, which readers of Lavengro know full well. Three years before Borrow was born William Cowper died in this very town, leaving behind him so rich a legacy of poetry and of prose, and moreover so fragrant a memory of a life in which humour and pathos played an equal part. It was no small thing for a youth who aspired to any kind of renown to be born in the neighbourhood of the last resting-place of the author of The Task.

Yet Borrow was not actually born in East Dereham, but a mile and a half away, at the little hamlet of Dumpling Green, in what was then a glorious wilderness of common and furze bush, but is now a quiet landscape of fields and hedges. You will find the home in which the author of Lavengro first saw the light without much difficulty. It is a fair-sized farm-house, with a long low frontage separated from the road by a considerable strip of garden. It suggests a prosperous yeoman class, and I have known farm-houses in East Anglia not one whit larger dignified by the name of 'hall.' Nearly opposite is a pond. The trim hedges are a delight to us to-day, but you must cast your mind back to a century ago when they were entirely absent. The house belonged to George Borrow's maternal grandfather, Samuel Perfrement, who farmed the adjacent land at this time. Samuel and Mary Perfrement had eight children, the third of whom, Ann, was born in 1772.

In February 1793 Ann Perfrement, aged twenty-one, married Thomas Borrow, aged thirty-five, in the Parish Church of East Dereham, and of the two children that were born to them George Henry Borrow was the younger. Thomas Borrow was the son of one John Borrow of St. Cleer in Cornwall, who[Pg 3] died before this child was born, and is described by his grandson[3] as the scion 'of an ancient but reduced Cornish family,[Pg 4] tracing descent from the de Burghs, and entitled to carry their arms.' This claim, of which I am thoroughly sceptical, is endorsed by Dr. Knapp,[4] who, however, could find no trace of the family earlier than [Pg 5]1678, the old parish registers having been destroyed. When Thomas Borrow was born the family were in any case nothing more than small farmers, and Thomas Borrow and his brothers were working on the land in the intervals of attending the parish school. At the age of eighteen Thomas was apprenticed to a maltster at Liskeard, and about this time he joined the local Militia. Tradition has it that his career as a maltster was cut short by his knocking his master down in a scrimmage. The victor fled from the scene of his prowess, and enlisted as a private soldier in the Coldstream Guards. This was in 1783, and in 1792 he was transferred to the West Norfolk Militia; hence his appearance at East Dereham, where, now a serjeant, his occupations for many a year were recruiting and drilling.[5] It is recorded that at a theatrical performance at East Dereham he first saw, presumably on the stage of the county-hall, his future wife—Ann Perfrement. She was, it seems, engaged in a minor part in a travelling company, not, we may assume, altogether with the sanction of her father, who, in spite of his inheritance of French blood, doubtless shared the then very strong English prejudice against the stage. However, Ann was[Pg 6] one of eight children, and had, as we shall find in after years, no inconsiderable strength of character, and so may well at twenty years of age have decided upon a career for herself. In any case we need not press too hard the Cornish and French origin of George Borrow to explain his wandering tendencies, nor need we wonder at the suggestion of Nathaniel Hawthorne, that he was 'supposed to be of gypsy descent by the mother's side.' You have only to think of the father, whose work carried him from time to time to every corner of England, Scotland, and Ireland, and of the mother with her reminiscence of life in a travelling theatrical company, to explain in no small measure the glorious vagabondage of George Borrow.

Behold then Thomas Borrow and Ann Perfrement as man and wife, he being thirty-five years of age, she twenty-one. A roving, restless life was in front of the pair for many a day, the West Norfolk Militia being stationed in some eight or nine separate towns within the interval of ten years between Thomas Borrow's marriage and his second son's birth. The first child, John Thomas Borrow, was born on the 15th April 1801.[6] The second son, George Henry Borrow, the subject of this memoir, was born in his grandfather's house at Dumpling Green, East Dereham, his mother having found a natural refuge with her father while her husband was busily recruiting in Norfolk. The two children passed with their parents from place to place, and in 1809 we find them once again in East[Pg 7] Dereham. From his son's two books, Lavengro and Wild Wales, we can trace the father's later wanderings until his final retirement to Norwich on a pension. In 1810 the family were at Norman Cross in Huntingdonshire, when Captain Borrow had to assist in guarding the French prisoners of war; for it was the stirring epoch of the Napoleonic conflict, and within the temporary prison 'six thousand French and other foreigners, followers of the Grand Corsican, were now immured.'

What a strange appearance had those mighty casernes, with their blank blind walls, without windows or grating, and their slanting roofs, out of which, through orifices where the tiles had been removed, would be protruded dozens of grim heads, feasting their prison-sick eyes on the wide expanse of country unfolded from that airy height. Ah! there was much misery in those casernes; and from those roofs, doubtless, many a wistful look was turned in the direction of lovely France. Much had the poor inmates to endure, and much to complain of, to the disgrace of England be it said—of England, in general so kind and bountiful. Rations of carrion meat, and bread from which I have seen the very hounds occasionally turn away, were unworthy entertainment even for the most ruffian enemy, when helpless and a captive; and such, alas! was the fare in those casernes.

But here we have only to do with Thomas Borrow, of whom we get many a quaint glimpse in Lavengro, our first and our last being concerned with him in the one quality that his son seems to have inherited, as the associate of a prize-fighter—Big Ben Brain. Borrow records in his opening chapter that Ben Brain and his father met in Hyde Park probably in 1790, and that after an hour's conflict 'the champions shook hands and retired, each having experienced quite enough of the other's prowess.' Borrow further relates that four months afterwards Brain 'died in the arms of my father, who read to him the Bible in his last[Pg 8] moments.' Dr. Knapp finds Borrow in one of his many inaccuracies or rather 'imaginings' here, as Brain did not die until 1794. More than once in his after years the old soldier seems to have had a shy pride in that early conflict, although the piety which seems to have come to him with the responsibilities of wife and children led him to count any recalling of the episode as a 'temptation.' When Borrow was about thirteen years of age, he overheard his father and mother discussing their two boys, the elder being the father's favourite and George the mother's:

'I will hear nothing against my first-born,' said my father, 'even in the way of insinuation: he is my joy and pride; the very image of myself in my youthful days, long before I fought Big Ben, though perhaps not quite so tall or strong built. As for the other, God bless the child! I love him, I'm sure; but I must be blind not to see the difference between him and his brother. Why, he has neither my hair nor my eyes; and then his countenance! why, 'tis absolutely swarthy, God forgive me! I had almost said like that of a gypsy, but I have nothing to say against that; the boy is not to be blamed for the colour of his face, nor for his hair and eyes; but, then, his ways and manners!—I confess I do not like them, and that they give me no little uneasiness.'[7]

Borrow throughout his narrative refers to his father as 'a man of excellent common sense,' and he quotes the opinion of William Taylor, who had rather a bad reputation as a 'freethinker' with all the church-going citizens of Norwich, with no little pride. Borrow is of course the 'young man' of the dialogue. He was then eighteen years of age:

'Not so, not so,' said the young man eagerly; 'before I knew you I knew nothing, and am still very ignorant; but of late my[Pg 9] father's health has been very much broken, and he requires attention; his spirits also have become low, which, to tell you the truth, he attributes to my misconduct. He says that I have imbibed all kinds of strange notions and doctrines, which will, in all probability, prove my ruin, both here and hereafter; which—which——'

'Ah! I understand,' said the elder, with another calm whiff. 'I have always had a kind of respect for your father, for there is something remarkable in his appearance, something heroic, and I would fain have cultivated his acquaintance; the feeling, however, has not been reciprocated. I met him the other day, up the road, with his cane and dog, and saluted him; he did not return my salutation.'

'He has certain opinions of his own,' said the youth, 'which are widely different from those which he has heard that you profess.'

'I respect a man for entertaining an opinion of his own,' said the elderly individual. 'I hold certain opinions; but I should not respect an individual the more for adopting them. All I wish for is tolerance, which I myself endeavour to practise. I have always loved the truth, and sought it; if I have not found it, the greater my misfortune.'[8]

When Borrow is twenty years of age we have another glimpse of father and son, the father in his last illness, the son eager as usual to draw out his parent upon the one subject that appeals to his adventurous spirit, 'I should like to know something about Big Ben,' he says:

'You are a strange lad,' said my father; 'and though of late I have begun to entertain a more favourable opinion than heretofore, there is still much about you that I do not understand. Why do you bring up that name? Don't you know that it is one of my temptations? You wish to know something about him? Well, I will oblige you this once, and then farewell to such vanities—something about him. I will tell you—his—skin when he flung off his clothes—and he had a particular knack in doing[Pg 10] so—his skin, when he bared his mighty chest and back for combat; and when he fought he stood, so—if I remember right—his skin, I say, was brown and dusky as that of a toad. Oh me! I wish my elder son was here!'

Concerning the career of Borrow's father there seem to be no documents other than one contained in Lavengro, yet no Life of Borrow can possibly he complete that does not draw boldly upon the son's priceless tributes. And so we come now to the last scene in the career of the elder Borrow—his death-bed—which is also the last page of the first volume of Lavengro. George Borrow's brother has arrived from abroad. The little house in Willow Lane, Norwich, contained the mother and her two sons sorrowfully awaiting the end, which came on 28th February 1824.

At the dead hour of night—it might be about two—I was awakened from sleep by a cry which sounded from the room immediately below that in which I slept. I knew the cry—it was the cry of my mother; and I also knew its import, yet I made no effort to rise, for I was for the moment paralysed. Again the cry sounded, yet still I lay motionless—the stupidity of horror was upon me. A third time, and it was then that, by a violent effort, bursting the spell which appeared to bind me, I sprang from the bed and rushed downstairs. My mother was running wildly about the room; she had awoke and found my father senseless in the bed by her side. I essayed to raise him, and after a few efforts supported him in the bed in a sitting posture. My brother now rushed in, and, snatching up a light that was burning, he held it to my father's face. 'The surgeon! the surgeon!' he cried; then, dropping the light, he ran out of the room, followed by my mother; I remained alone, supporting the senseless form of my father; the light had been extinguished by the fall, and an almost total darkness reigned in the room. The form pressed heavily against my bosom; at last methought it moved. Yes, I was right; there was a heaving of the breast, and then a gasping. Were those words which I heard? Yes, they were words, low and[Pg 11] indistinct at first, and then audible. The mind of the dying man was reverting to former scenes. I heard him mention names which I had often heard him mention before. It was an awful moment; I felt stupefied, but I still contrived to support my dying father. There was a pause; again my father spoke: I heard him speak of Minden, and of Meredith, the old Minden Serjeant, and then he uttered another name, which at one period of his life was much on his lips, the name of ——; but this is a solemn moment! There was a deep gasp: I shook, and thought all was over; but I was mistaken—my father moved, and revived for a moment; he supported himself in bed without my assistance. I make no doubt that for a moment he was perfectly sensible, and it was then that, clasping his hands, he uttered another name clearly, distinctly—it was the name of Christ. With that name upon his lips the brave old soldier sank back upon my bosom, and, with his hands still clasped, yielded up his soul.

Did Borrow's father ever really fight Big Ben Brain or Bryan in Hyde Park, or is it all a fantasy of the artist's imagining? We shall never know. Borrow called his Lavengro 'An Autobiography' at one stage of its inception, although he wished to repudiate the autobiographical nature of his story at another. Dr. Knapp in his anxiety to prove that Borrow wrote his own memoirs in Lavengro and Romany Rye tells us that he had no creative faculty—an absurd proposition. But I think we may accept the contest between Ben Brain and Thomas Borrow, and what a revelation of heredity that impressive death-bed scene may be counted. Borrow on one occasion in later life declared that his favourite hooks were the Bible and the Newgate Calendar. We know that he specialised on the Bible and Prize-Fighting in no ordinary fashion—and here we see his father on his death-bed struggling between the religious sentiments of his maturity and the one great worldly escapade of his early manhood.

[3] In the year 1870 Borrow was asked for material for a biography by the editor of Men of the Time, a publication which many years later was incorporated in the present Who's Who. He drew up two drafts in his own handwriting, which are so interesting, and yet vary so much in certain particulars, that we are tempted to print both here, or at least that part of the second draft that differs from the first. The concluding passages of both drafts are alike. The biography as it stands in the 1871 edition of Men of the Time appears to have been compiled from the earlier of these drafts. It must have been another copy of Draft No. 1 that was forwarded to the editor:

Draft I.—George Henry Borrow, born at East Dereham in the county of Norfolk in the early part of the present century. His father was a military officer, with whom he travelled about most parts of the United Kingdom. He was at some of the best schools in England, and also for about two years at the High School at Edinburgh. In 1818 he was articled to an eminent solicitor at Norwich, with whom he continued five years. He did not, however, devote himself much to his profession, his mind being much engrossed by philology, for which at a very early period he had shown a decided inclination, having when in Ireland acquired the Irish language. At the age of twenty he knew little of the law, but was well versed in languages, being not only a good classical scholar but acquainted with French, Italian, Spanish, all the Celtic and Gothic dialects, and also with the peculiar language of the English Romany Chals or Gypsies. This speech, which, though broken and scanty, exhibits evident signs of high antiquity, he had picked up amongst the wandering tribes with whom he had formed acquaintance on a wild heath near Norwich, where they were in the habit of encamping. At the expiration of his clerkship, which occurred shortly after the death of his father, he betook himself to London, and endeavoured to get a livelihood by literature. For some time he was a hack author. His health failing he left London, and for a considerable time lived a life of roving adventure. In the year 1833 he entered the service of he British and Foreign Bible Society, and being sent to Russia edited at Saint Petersburg the New Testament in the Manchu or Chinese Tartar. Whilst at Saint Petersburg he published a book called Targum, consisting of metrical translations from thirty languages. He was subsequently for some years agent of the Bible Society in Spain, where he was twice imprisoned for endeavouring to circulate the Gospel. In Spain he mingled much with the Calóre or Zincali, called by the Spaniards Gitanos or Gypsies, whose language he found to be much the same as that of the English Romany. At Madrid he edited the New Testament in Spanish, and translated the Gospel of Saint Luke into the language of the Zincali. Leaving the service of the Bible Society he returned to England in 1839, and shortly afterwards married a Suffolk lady. In 1841 he published The Zincali, or an account of the Gypsies of Spain, with a vocabulary of their language, which he proved to be closely connected with the Sanskrit. This work obtained almost immediately a European celebrity, and was the cause of many learned works being published on the continent on the subject of the Gypsies. In 1842 he gave to the world The Bible in Spain, or an account of an attempt to circulate the Gospel in the peninsula, a work which received a warm and eloquent eulogium from Sir Robert Peel in the House of Commons. In 1844 he was wandering amongst the Gypsies of Hungary, Walachia, and Turkey, gathering up the words of their respective dialects of the Romany, and making a collection of their songs. In 1851 he published Lavengro, in which he gives an account of his early life, and in 1857 The Romany Rye, a sequel to the same. His latest publication is Wild Wales. He has written many other works, some of which are not yet published. He has an estate in Suffolk, but spends the greater part of his time in wandering on foot through various countries.

* * * *

Draft II.—George Henry Borrow was born at East Dereham in the county of Norfolk on the 5th July 1803. His father, Thomas Borrow, who died captain and adjutant of the West Norfolk Militia, was of an ancient but reduced Cornish family, tracing descent from the de Burghs, and entitled to carry their arms. His mother, Ann Perfrement, was a native of Norfolk, and descended from a family of French Protestants banished from France on the revocation of the edict of Nantes. He was the youngest of two sons. His brother, John Thomas, who was endowed with various and very remarkable talents, died at an early age in Mexico. Both the brothers had the advantage of being at some of the first schools in Britain. The last at which they were placed was the Grammar School at Norwich, to which town their father came to reside at the termination of the French war. In the year 1818 George Borrow was articled to an eminent solicitor in Norwich, with whom he continued five years. He did not devote himself much to his profession, his mind being engrossed by another and very different subject—namely philology, for which at a very early period he had shown a decided inclination, having when in Ireland with his father acquired the Irish language. At the expiration of his clerkship he knew little of the law, but was well versed in languages, being not only a good Greek and Latin scholar, but acquainted with French, Italian, and Spanish, all the Celtic and Gothic dialects, and likewise with the peculiar language of the English Romany Chals or Gypsies. This speech or jargon, amounting to about eleven hundred and twenty-seven words, he had picked up amongst the wandering tribes with whom he had formed acquaintance on Mousehold, a wild heath near Norwich, where they were in the habit of encamping. By the time his clerkship was expired his father was dead, and he had little to depend upon but the exercise of his abilities such as they were. In 1823 he betook himself to London, and endeavoured to obtain a livelihood by literature. For some time he was a hack author, doing common work for booksellers. For one in particular he prepared an edition of the Newgate Calendar, from the careful study of which he has often been heard to say that he first learned to write genuine English. His health failed, he left London, and for a considerable time he lived a life of roving adventure.

[4] Knapp's Life of Borrow, vol. i. p. 6.

[5] The writer recalls at his own school at Downham Market in Norfolk an old Crimean Veteran—Serjeant Canham—drilling the boys each week, thus supplementing his income precisely in the same manner as did Serjeant Borrow.

[6] The date has always hitherto been wrongly given. I find it in one of Ann Borrow's notebooks, but although every vicar of every parish in Chelmsford and Colchester has searched the registers for me, with agreeable courtesy, I cannot discover a record of John's birthplace, and am compelled to the belief that Dr. Knapp was wrong in suggesting one or other of these towns.

[7] Lavengro, ch. xiv.

[8] Lavengro, ch. xxiii.

Throughout his whole life George Borrow adored his mother, who seems to have developed into a woman of great strength of character far remote from the pretty play-actor who won the heart of a young soldier at East Dereham in the last years of the eighteenth century. We would gladly know something of the early years of Ann Perfrement. Her father was a farmer, whose farm at Dumpling Green we have already described. He did not, however, 'farm his own little estate' as Borrow declared. The grandfather—a French Protestant—came, if we are to believe Borrow, from Caen in Normandy after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, but there is no documentary evidence to support the contention. However, the story of the Huguenot immigration into England is clearly bound up with Norwich and the adjacent district. And so we may well take the name of 'Perfrement' as conclusive evidence of a French origin, and reject as utterly untenable the not unnatural suggestion of Nathaniel Hawthorne, that Borrow's mother was 'of gypsy descent.'[9] She was one of the eight children of Samuel[Pg 13] and Mary Perfrement, all of whom seem to have devoted their lives to East Anglia.[10] We owe to Dr. Knapp's edition of Lavengro one exquisite glimpse of Ann's girlhood that is not in any other issue of the book. Ann's elder sister, curious to know if she was ever to be married, falls in with the current superstition that she must wash her linen and 'watch' it drying before the fire between eleven and twelve at night. Ann Perfrement was ten years old at the time. The two girls walked over to East Dereham, purchased the necessary garment, washed it in the pool near the house that may still be seen, and watched and watched. Suddenly when the clock struck twelve they heard, or thought they heard, a footstep on the path, the wind howled, and the elder sister sprang to the door, locked and bolted it, and then fell in convulsions on the floor. The superstition, which Borrow seems to have told his mother had a Danish origin, is common enough in Ireland and in Celtic lands. It could scarcely have been thus rehearsed by two Norfolk children had they not had the blood of a more imaginative race in their veins. In addition to this we find more than one effective glimpse of Borrow's mother in Lavengro. We have already noted the episode in which she takes the side of her younger boy against her husband, with whom John was the favourite. We meet her again in the following dialogue, with its pathetic allusions to Dante and to the complaint—a kind of nervous exhaustion which he called 'the horrors'—that was to trouble Borrow all his days:[Pg 14]

'What ails you, my child?' said a mother to her son, as he lay on a couch under the influence of the dreadful one; 'what ails you? you seem afraid!'

Boy. And so I am; a dreadful fear is upon me.

Mother. But of what? there is no one can harm you; of what are you apprehensive?

Boy. Of nothing that I can express. I know not what I am afraid of, but afraid I am.

Mother. Perhaps you see sights and visions. I knew a lady once who was continually thinking that she saw an armed man threaten her, but it was only an imagination, a phantom of the brain.

Boy. No armed man threatens me; and 'tis not a thing like that would cause me any fear. Did an armed man threaten me I would get up and fight him; weak as I am, I would wish for nothing better, for then, perhaps, I should lose this fear; mine is a dread of I know not what, and there the horror lies.

Mother. Your forehead is cool, and your speech collected. Do you know where you are?

Boy. I know where I am, and I see things just as they are; you are beside me, and upon the table there is a book which was written by a Florentine; all this I see, and that there is no ground for being afraid. I am, moreover, quite cool, and feel no pain—but, but——

And then there was a burst of 'gemiti, sospiri ed alti guai.' Alas, alas, poor child of clay! as the sparks fly upward, so wast thou born to sorrow—Onward![11]

Our next glimpse of Mrs. Borrow is when after his father's death George had shouldered his knapsack and made his way to London to seek his fortune by literature. His elder brother had remained at home, determined upon being a painter, but joined George in[Pg 15] London, leaving the widowed mother momentarily alone in Norwich.

'And how are things going on at home?' said I to my brother, after we had kissed and embraced. 'How is my mother, and how is the dog?'

'My mother, thank God, is tolerably well,' said my brother, 'but very much given to fits of crying. As for the dog, he is not so well; but we will talk more of these matters anon,' said my brother, again glancing at the breakfast things. 'I am very hungry, as you may suppose, after having travelled all night.'

Thereupon I exerted myself to the best of my ability to perform the duties of hospitality, and I made my brother welcome—I may say more than welcome; and when the rage of my brother's hunger was somewhat abated, we recommenced talking about the matters of our little family, and my brother told me much about my mother; he spoke of her fits of crying, but said that of late the said fits of crying had much diminished, and she appeared to be taking comfort; and, if I am not much mistaken, my brother told me that my mother had of late the prayer-book frequently in her hand, and yet oftener the Bible.[12]

Ann Borrow lived in Willow Lane, Norwich, for thirty-three years. That Borrow was a devoted husband these pages will show. He was also a devoted son. When he had made a prosperous marriage he tried hard to persuade his mother to live with him at Oulton, but all in vain. She had the wisdom to see that such an arrangement is rarely conducive to a son's domestic happiness. She continued to live in the little cottage made sacred by many associations until almost the end of her days. Here she had lived in earlier years with her husband and her two ambitious boys, and in Norwich, doubtless, she had made her own friendships, although of these no record remains. The cottage still stands in its modest court, but is[Pg 16] at the moment untenanted. There is a letter extant from Cecilia Lucy Brightwell, who wrote The Life of Mrs. Opie, to Mary Borrow at Oulton, when Mrs. Borrow the elder had gone to live there, which records the fact that in 1851, two years after Mrs. Borrow had left the cottage in Willow Lane, it had already changed its appearance. Mrs. Brightwell writes:

Give my kind love to dear mother. Tell her I went past her house to-day and looked up the court. It is quite changed: all the trees and the ivy taken away.

The house was the property of Thomas King, a carpenter. You enter from Willow Lane through a covered passage into what was then known as King's Court. Here the little house faces you, and you meet it with a peculiarly agreeable sensation, recalling more than one incident in Lavengro that transpired there. In 1897 the then mayor made the one attempt of his city of a whole half century to honour Borrow by calling this court Borrow's Court—thereby conferring a ridiculously small distinction upon Borrow,[13] and removing a landmark connected with one of its own worthy citizens. For Thomas King, the carpenter, was in direct descent in the maternal line from the family of Parker, which gave to Norwich one of its most distinguished sons in the famous Archbishop of Queen Elizabeth's day. He extended his business as carpenter sufficiently to die a prosperous builder. Of his two sons one, also named Thomas, became physician to Prince Talleyrand, and married a sister of John Stuart Mill.[14] All this by the way, but there is little more to record of Borrow's mother apart from the letters addressed to her by her son, which occur in their due place in these records. Yet one little memorandum among my papers which bears Mrs. Borrow's signature may well find place here:

THE BORROW HOUSE, NORWICH

THE BORROW HOUSE, NORWICHIn the year 1797 I was at Canterbury. One night at about one o'clock Sir Robert Laurie and Captain Treve came to our lodgings and tapped at our bedroom door, and told my husband to get up, and get the men under arms without beat of drum as soon as possible, for that there was a mutiny at the Nore. My husband did so, and in less than two hours they had marched out of town towards Sheerness without making any noise. They had to break open the store-house in order to get provender, because the Quartermaster, Serjeant Rowe, was out of the way. The Dragoon Guards at that time at Canterbury were in a state of mutiny.

Ann Borrow.

[9] 24th May 1856. Dining at Mr. Rathbone's one evening last week (21st May), it was mentioned that Borrow, author of The Bible in Spain, is supposed to be of gypsy descent by the mother's side. Hereupon Mr. Martineau mentioned that he had been a schoolfellow of Borrow, and though he had never heard of his gypsy blood, he thought it probable, from Borrow's traits of character. He said that Borrow had once run away from school, and carried with him a party of other boys, meaning to lead a wandering life (The English Notebooks of Nathaniel Hawthorne, vol. ii. 1858).

[10] Samuel and Maria Perfrement were married in 1766, the latter to John Burcham. Two of her brothers survived Ann Borrow, Samuel Perfrement dying in 1864 and Philip in 1867.

[11] Lavengro, ch. xviii.

[12] Lavengro, ch. xxxvii.

[13] In May 1913 the Lord Mayor of Norwich (Mr. A. M. Samuel) purchased the Borrow house in Willow Lane for £375, and gave it to the city for the purpose of a Borrow Museum.

[14] This Thomas King was a cousin of my mother; his father built the Borrow House in Norwich in 1812. The only allusion to him I have ever seen in print is contained in a letter on Lavengro contributed by Thomas Burcham to The Britannia newspaper of June 26, 1851:—'With your criticism on Lavengro I cordially agree, and if you were disappointed in the long promised work, what must I have been? A schoolfellow of Borrow, who, in the autobiography, expected to find much interesting matter, not only relating to himself, but also to schoolfellows and friends—the associates of his youth, who, in after-life, gained no slight notoriety—amongst them may be named Sir James Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak; poor Stoddard, who was murdered at Bokhara, and who, as a boy, displayed that noble bearing and high sensitiveness of honour which partly induced that fatal result; and Thomas King, one of Borrow's early friends, who, the son of a carpenter at Norwich, the landlord of Lavengro's father, after working in his father's shop till nearly sixteen, went to Paris, entered himself as a student at one of the hospitals, and through his energy and intellect became internal surgeon of L'Hôtel Dieu and private physician to Prince Talleyrand.' Thomas Borrow Burcham was Magistrate of Southwark Police Court from 1856 till his death in 1869. He was the son of Maria Perfrement, Borrow's aunt.

John Thomas Borrow was born two years before his younger brother, that is, on the 15th April 1801. His father, then Serjeant Borrow, was wandering from town to town, and it is not known where his elder son first saw the light. John Borrow's nature was cast in a somewhat different mould from that of his brother. He was his father's pride. Serjeant Borrow could not understand George with his extraordinary taste for the society of queer people—the wild Irish and the ragged Romanies. John had far more of the normal in his being. Borrow gives us in Lavengro our earliest glimpse of his brother:

He was a beautiful child; one of those occasionally seen in England, and in England alone; a rosy, angelic face, blue eyes, and light chestnut hair; it was not exactly an Anglo-Saxon countenance, in which, by the by, there is generally a cast of loutishness and stupidity; it partook, to a certain extent, of the Celtic character, particularly in the fire and vivacity which illumined it; his face was the mirror of his mind; perhaps no disposition more amiable was ever found amongst the children of Adam, united, however, with no inconsiderable portion of high and dauntless spirit. So great was his beauty in infancy, that people, especially those of the poorer classes, would follow the nurse who carried him about in order to look at and bless his lovely face. At the age of three months an attempt was made to snatch him from his mother's arms in the streets of London, at[Pg 19] the moment she was about to enter a coach; indeed, his appearance seemed to operate so powerfully upon every person who beheld him, that my parents were under continual apprehension of losing him; his beauty, however, was perhaps surpassed by the quickness of his parts. He mastered his letters in a few hours, and in a day or two could decipher the names of people on the doors of houses and over the shop-windows.

John received his early education at the Norwich Grammar School, while the younger brother was kept under the paternal wing. Father and mother, with their younger boy George, were always on the move, passing from county to county and from country to country, as Serjeant Borrow, soon to be Captain, attended to his duties of drilling and recruiting, now in England, now in Scotland, now in Ireland. We are given a fascinating glimpse of John Borrow in Lavengro by way of a conversation between Mr. and Mrs. Borrow over the education of their children. It was agreed that while the family were in Edinburgh the boys should be sent to the High School, and so at the historic school that Sir Walter Scott had attended a generation before the two boys were placed, John being removed from the Norwich Grammar School for the purpose. Among his many prejudices of after years Borrow's dislike of Scott was perhaps the most regrettable, otherwise he would have gloried in the fact that their childhood had had one remarkable point in common. Each boy took part in the feuds between the Old Town and the New Town. Exactly as Scott records his prowess at 'the manning of the Cowgate Port,' and the combats maintained with great vigour, 'with stones, and sticks, and fisticuffs,' as set forth in the first volume of Lockhart, so we have not dissimilar feats set down in Lavengro. Side[Pg 20] by side also with the story of 'Green-Breeks,' which stands out in Scott's narrative of his school combats, we have the more lurid account by Borrow of David Haggart. Literary biography is made more interesting by such episodes of likeness and of contrast.

We next find John Borrow in Ireland with his father, mother, and brother. George is still a child, but he is precocious enough to be learning the language, and thus laying the foundation of his interest in little-known tongues. John is now an ensign in his father's regiment. 'Ah! he was a sweet being, that boy soldier, a plant of early promise, bidding fair to become in after time all that is great, good, and admirable.' Ensign John tells his little brother how pleased he is to find himself, although not yet sixteen years old, 'a person in authority with many Englishmen under me. Oh! these last six weeks have passed like hours in heaven.' That was in 1816, and we do not meet John again until five years later, when we hear of him rushing into the water to save a drowning man, while twenty others were bathing who might have rendered assistance. Borrow records once again his father's satisfaction:

'My boy, my own boy, you are the very image of myself, the day I took off my coat in the park to fight Big Ben,' said my father, on meeting his son, wet and dripping, immediately after his bold feat. And who cannot excuse the honest pride of the old man—the stout old man?

In the interval the war had ended, and Napoleon had departed for St. Helena. Peace had led to the pensioning of militia officers, or reducing to half-pay of the juniors. The elder Borrow had settled in Norwich. George was set to study at the Grammar School there,[Pg 21] while his brother worked in Old Crome's studio, for here was a moment when Norwich had its interesting Renaissance, and John Borrow was bent on being an artist. He had worked with Crome once before—during the brief interval that Napoleon was at Elba—but now he set to in real earnest, and we have evidence of a score of pictures by him that were catalogued In the exhibitions of the Norwich Society of Artists between the years 1817 and 1824. They include one portrait of the artist's father, and two of his brother George.[15] Old Crome died in 1821, and then John went to London to study under Haydon. Borrow declares that his brother had real taste for painting, and that 'if circumstances had not eventually diverted his mind from the pursuit, he would have attained excellence, and left behind him some enduring monument of his powers,' 'He lacked, however,' he tells us, 'one thing, the want of which is but too often fatal to the sons of genius, and without which genius is little more than a splendid toy in the hands of the possessor—perseverance, dogged perseverance.' It is when he is thus commenting on his brother's characteristics that Borrow gives his own fine if narrow eulogy of Old Crome. John Borrow seems to have continued his studies in London under Haydon for a year, and then to have gone to Paris to copy pictures at the[Pg 22] Louvre. He mentions a particular copy that he made of a celebrated picture by one of the Italian masters, for which a Hungarian nobleman paid him well. His three years' absence was brought to an abrupt termination by news of his father's illness. He returned to Norwich in time to stand by that father's bedside when he died. The elder Borrow died, as we have seen, in February 1824. The little home in King's Court was kept on for the mother, and as John was making money by his pictures it was understood that he should stay with her. On the 1st April, however, George started for London, carrying the manuscript of Romantic Ballads from the Danish to Sir Richard Phillips, the publisher. On the 29th of the same month he was joined by his brother John. John had come to London at his own expense, but in the interests of the Norwich Town Council. The council wanted a portrait of one of its mayors for St. Andrew's Hall—that Valhalla of Norwich municipal worthies which still strikes the stranger as well-nigh unique in the city life of England. The municipality would fain have encouraged a fellow-citizen, and John Borrow had been invited to paint the portrait. 'Why,' it was asked, 'should the money go into a stranger's pocket and be spent in London?' John, however, felt diffident of his ability and declined, and this in spite of the fact that the £100 offered for the portrait must have been very tempting. 'What a pity it was,' he said, 'that Crome was dead.' 'Crome,' said the orator of the deputation that had called on John Borrow,

'Crome; yes, he was a clever man, a very clever man, in his way; he was good at painting landscapes and farm-houses, but he would not do in the present instance, were he alive. He had no conception of the heroic, sir. We want some person capable of[Pg 23] representing our mayor standing under the Norman arch of the cathedral.'[16]

At the mention of the heroic John bethought himself of Haydon, and suggested his name; hence his visit to London, and his proposed interview with Haydon. The two brothers went together to call upon the 'painter of the heroic' at his studio in Connaught Terrace, Hyde Park. There was some difficulty about their admission, and it turned out afterwards that Haydon thought they might be duns, as he was very hard up at the time. His eyes glistened at the mention of the £100. 'I am not very fond of painting portraits,' he said, 'but a mayor is a mayor, and there is something grand in that idea of the Norman arch.' And thus Mayor Hawkes came to be painted by Benjamin Haydon, and his portrait may be found, not without diligent search, among the many municipal worthies that figure on the walls of that most picturesque old Hall in Norwich. Here is Borrow's description of the painting:

The original mayor was a mighty, portly man, with a bull's head, black hair, body like that of a dray horse, and legs and thighs corresponding; a man six foot high at the least. To his bull's head, black hair, and body the painter had done justice; there was one point, however, in which the portrait did not correspond with the original—the legs were disproportionably short, the painter having substituted his own legs for those of the mayor.

John Borrow described Robert Hawkes to his brother as a person of many qualifications:

—big and portly, with a voice like Boanerges; a religious man, the possessor of an immense pew; loyal, so much so that I once heard him say that he would at any time go three miles to hear any one sing 'God save the King'; moreover, a giver of excellent[Pg 24] dinners. Such is our present mayor, who, owing to his loyalty, his religion, and a little, perhaps, to his dinners, is a mighty favourite.

Haydon, who makes no mention of the Borrows in his Correspondence or Autobiography, although there is one letter of George Borrow's to him in the latter work, had been in jail for debt three years prior to the visit of the Borrows. He was then at work on his greatest success in 'the heroic'—The Raising of Lazarus, a canvas nineteen feet long by fifteen high. The debt was one to house decorators, for the artist had ever large ideas. The bailiff, he tells us,[17] was so agitated at the sight of the painting of Lazarus in the studio that he cried out, 'Oh, my God! Sir, I won't arrest you. Give me your word to meet me at twelve at the attorney's, and I'll take it.' In 1821 Haydon married, and a little later we find him again 'without a single shilling in the world—with a large picture before me not half done.' In April 1822 he is arrested at the instance of his colourman, 'with whom I had dealt for fifteen years,' and in November of the same year he is arrested again at the instance of 'a miserable apothecary.' In April 1823 we find him in the King's Bench Prison, from which he was released in July. The Raising of Lazarus meanwhile had gone to pay his upholsterer £300, and his Christ's Entry into Jerusalem had been sold for £240, although it had brought him £3000 in receipts at exhibitions. Clearly heroic pictures did not pay, and Haydon here took up 'the torment of portrait-painting' as he called it.

ROBERT HAWKES, MAYOR OF NORWICH in 1824.

ROBERT HAWKES, MAYOR OF NORWICH in 1824.'Can you wonder,' he wrote in July 1825, 'that I nauseate portraits, except portraits of clever people. I feel quite convinced that every portrait-painter, if there be purgatory, will leap at once to heaven, without this previous purification.'

Perhaps it was Mayor Hawkes who helped to inspire this feeling.[18] Yet the hundred pounds that John Borrow was able to procure must have been a godsend, for shortly before this we find him writing in his diary of the desperation that caused him to sell his books. 'Books that had cost me £20 I got only £3 for. But it was better than starvation.' Indeed it was in April of this year that the very baker was 'insolent,' and so in May 1824, as we learn from Tom Taylor's Life, he produced 'a full-length portrait of Mr. Hawkes, a late Mayor of Norwich, painted for St. Andrew's Hall in that city.' But I must leave Haydon's troubled career, which closes so far as the two brothers are concerned with a letter from George to Haydon written the following year from 26 Bryanston Street, Portman Square:

Dear Sir,—I should feel extremely obliged if you would allow me to sit to you as soon as possible. I am going to the south of France in little better than a fortnight, and I would sooner lose a thousand pounds than not have the honour of appearing in the picture.—Yours sincerely,

As Borrow was at the time in a most impoverished condition, it is not easy to believe that he would have wished to be taken at his word. He certainly had not a thousand pounds to lose. But he did undoubtedly, as we shall see, take that journey on foot through the south of France, after the manner of an earlier vagabond of literature—Oliver Goldsmith. Haydon was to be far too much taken up with his own troubles during the coming months to think any more about the Borrows when he had once completed the portrait of the mayor, which he had done by July of this year. Borrow's letter to him is, however, an obvious outcome of a remark dropped by the painter on the occasion of his one visit to his studio when the following conversation took place:

'I'll stick to the heroic,' said the painter; 'I now and then dabble in the comic, but what I do gives me no pleasure, the comic is so low; there is nothing like the heroic. I am engaged here on a heroic picture,' said he, pointing to the canvas; 'the subject is "Pharaoh dismissing Moses from Egypt," after the last plague—the death of the first-born,—it is not far advanced—that finished figure is Moses': they both looked at the canvas, and I, standing behind, took a modest peep. The picture, as the painter said, was not far advanced, the Pharaoh was merely in outline; my eye was, of course, attracted by the finished figure, or rather what the painter had called the finished figure; but, as I gazed upon it, it appeared to me that there was something defective—something unsatisfactory in the figure. I concluded, however, that the painter, notwithstanding what he had said, had omitted to give it the finishing touch. 'I intend this to be my best picture,' said the painter; 'what I want now is a face for Pharaoh; I have long been meditating on a face for Pharaoh.' Here, chancing to cast his eye upon my countenance, of whom he had scarcely taken any manner of notice, he remained with his mouth open for some time, 'Who is this?' said he at last. 'Oh, this is my brother, I forgot to introduce him——.'

We wish that the acquaintance had extended further, but this was not to be. Borrow was soon to commence the wanderings which were to give him much unsatisfactory fame, and the pair never met again. Let us, however, return to John Borrow, who accompanied Haydon to Norwich, leaving his brother for some time longer to the tender mercies of Sir Richard Phillips. John, we judge, seems to have had plenty of shrewdness, and was not without a sense of his own limitations. A chance came to him of commercial success in a distant land, and he seized that chance. A Norwich friend, Allday Kerrison, had gone out to Mexico, and writing from Zacatecas in 1825 asked John to join him. John accepted. His salary in the service of the Real del Monte Company was to be £300 per annum. He sailed for Mexico in 1826, having obtained from his Colonel, Lord Orford, leave of absence for a year, it being understood that renewals of that leave of absence might be granted. He was entitled to half-pay as a Lieutenant of the West Norfolk Militia, and this he settled upon his mother during his absence. His career in Mexico was a failure. There are many of his letters to his mother and brother extant which tell of the difficulties of his situation. He was in three Mexican companies in succession, and was about to be sent to Columbia to take charge of a mine when he was stricken with a fever, and died at Guanajuato on 22nd November 1838. He had far exceeded any leave that his Colonel could in fairness grant, and before his death his name had been taken off the army rolls. The question of his pay produced a long correspondence, which can be found in the archives of the Rolls Office. I have the original drafts of these letters in Borrow's handwriting.[Pg 28] The first letter by Borrow is dated 8th September 1831; it is better to give the correspondence in its order.[20] The letters speak for themselves, and require no comment.

Willow Lane, Norwich, September 8, 1831.

Sir,—I take the liberty of troubling you with these lines for the purpose of enquiring whether there is any objection to the issuing of the disembodied allowance of my brother Lieut. John Borrow of the Welsh Norfolk Militia, who is at present abroad. I do this by the advice of the Army Pay Office, a power of Attorney having been granted to me by Lieut. Borrow to receive the said allowance for him. I beg leave to add that my brother was present at the last training of his regiment, that he went abroad with the leave of his Commanding Officer, which leave of absence has never been recalled, that he has sent home the necessary affidavits, and that there is no clause in the Pay and Clothing Act to authorize the stoppage of his allowance. I have the honor to remain, Sir, your most obedient, humble servant,

George Borrow.

Willow Lane, Norwich, 17th Septr. 1831.

Sir,—I have to acknowledge the receipt of No. 33,063, dated 16th inst., from the War Office, in which I am informed that the Office does not feel authorized to give instructions for the issue of the arrears of disembodied allowance claimed by my brother Lieut. Borrow of the West Norfolk, until he attend the next training of his regiment, and I now beg leave to ask the following[Pg 29] question, and to request that I may receive an answer with all convenient speed. What farther right to his present arrears of disembodied allowance will Lieut. Borrow's appearance at the next training of his regiment confer upon him, and provided there is no authority at present for ordering the payment of those arrears, by what authority will the War Office issue instructions for the payment of the same, after his arrival in this country and attendance at the training? Sir, provided Lieut. Borrow is not entitled to his arrears of disembodied allowance at the present moment, he will be entitled to them at no future period, and I was to the last degree surprised at the receipt of an answer which tends to involve the office in an inextricable dilemma, for it is in fact a full acknowledgment of the justice of Lieutenant Borrow's claims, and a refusal to satisfy them until a certain time, which instantly brings on the question, 'By what authority does the War Office seek to detain the disembodied allowance of an officer, to which he is entitled by Act of Parliament, a moment after it has become due and is legally demanded?' If it be objected that it is not legally demanded, I reply that the affidavits filled up in the required form are in the possession of the Pay Office, and also a power of Attorney in the Spanish language, together with a Notarial translation, which power of Attorney has been declared by the Solicitor of the Treasury to be legal and sufficient. To that part of the Official letter relating to my brother's appearance at the next training I have to reply, that I believe he is at present lying sick in the Mountains above Vera Cruz, the pest-house of the New World, and that the last time I heard from him I was informed that it would be certain death for him to descend into the level country, even were he capable of the exertion, for the fever was then raging there. Full six months have elapsed since he prepared to return to his native country, having received information that there was a probability that his regiment would be embodied, (but) the hand of God overtook him on his route. He is the son, Sir, of an Officer who served his King abroad and at home for upwards of half a century; he had intended his disembodied allowance for the use of his widowed and infirm mother, but it must now be transmitted to him for his own support until he can arrive in England. But, Sir, I do not wish to excite compassion in his behalf, all I request is that he may[Pg 30] have justice done him, and if it be, I shall be informed in the next letter, that the necessary order has been given to the Pay Office for the issue of his arrears. I have the honor to remain, Sir, your most obedient, humble servant,

George Borrow.

Norwich, Novr. 24, 1831.

Sir,—Not having been favoured with an answer to the letter which I last addressed to you concerning the arrears of disembodied allowance due to Lieut. John Borrow of the West Norfolk Militia, I again take the liberty of submitting this matter to your consideration. More than six months have elapsed since by virtue of a power of attorney granted to me by Lieut. Borrow, I made demand at the army Pay Office for a portion of those arrears, being the amount of two affidavits which were produced, but owing to the much unnecessary demur which ensued, chiefly with respect to the power of Attorney, since declared to be valid, that demand has not hitherto been satisfied. I therefore am compelled to beg that an order may be issued to the Pay Office for the payment to me of the sums specified in the said affidavits, that the amount may be remitted to Lieut. Borrow, he being at present in great need thereof. If it be answered that Lieut. Borrow was absent at the last training of his regiment, and that he is not entitled to any arrears of pay, I must beg leave to observe that the demand was legally made many months previous to the said training, and cannot now be set aside by his non-appearance, which arose from unavoidable necessity; he having for the last year been lying sick in one of the provinces of New Spain. And now, Sir, I will make bold to inquire whether Lieut. Borrow, the son of an Officer, who served his country abroad and at home, for upwards of fifty years, is to lose his commission for being incapable, from a natural visitation, of attending at the training; if it be replied in the affirmative, I have only to add that his case will be a cruelly hard one. But I hope and trust, Sir, that taking all[Pg 31] these circumstances into consideration you will not yet cause his name to be stricken off the list, and that you will permit him to retain his commission in the event of his arriving in England with all the speed which his health of body will permit, and that to enable him so to do his arrears[21] you will forthwith give an order for the payment of his arrears. I have the honor to be, Sir, your very humble servant,

George Borrow.

Norwich, Decr. 13, 1831.

Sir,—I have just received a letter from my brother Lieutenant J. Borrow, from which it appears he has had leave of absence from his Colonel, the Earl of Orford, up to the present year. He says 'in a letter dated Wolterton, 21st June 1828, Lord Orford writes: "should you want a further leave I will not object to it." 20th May 1829 says: "I am much obliged to you for a letter of the 18th March, and shall be glad to allow you leave of absence for a twelvemonth." I enclose his last letter from Brussels, August 6, 1829. At the end it gives very evident proof that my remaining in Mexico was not only by his Lordship's permission, but even by his advice. Sir, if you should require it I will transmit this last letter of the Earl of Orford's, which my brother has sent to me, but beg leave to observe that no blame can be attached to his Lordship in this case, he having from a multiplicity of important business doubtless forgotten these minor matters. I hope now, Sir, that you will have no further objection to issue an order for the payment of that portion of my brother's arrears specified in the two affidavits in the possession of the Paymaster General. By the unnecessary obstacles which have been flung in my brother's way in obtaining his arrears he has been subjected to great inconvenience and distress. An early answer on this point will much oblige, Sir, your most obedient, humble servant,

George Borrow.

Willow Lane, Norwich, May 24, 1833.

Sir,—I take the liberty of addressing you for the purpose of requesting that an order be given to the Paymaster General for the issue of the arrears of pay of my brother Lieutenant John Borrow of the West Norfolk Militia, whose agent I am by virtue of certain powers of Attorney, and also for the continuance of the payment of his disembodied allowance. Lieutenant Borrow was not present at the last training of his Regiment, being in Mexico at the time, and knowing nothing of the matter. I beg leave to observe that no official nor other letter was dispatched to him by the adjutant to give him notice of the event, nor was I, his agent, informed of it, he therefore cannot have forfeited his arrears and disembodied allowance. He was moreover for twelve months previous to the training, and still is, so much indisposed from the effects of an attack of the yellow fever, that his return would be attended with great danger, which can be proved by the certificate of a Medical Gentleman practising in Norwich, who was consulted from Mexico. Lieutenants Harper and Williams, of the same Regiment, have recovered their pay and arrears, although absent at the last training, therefore it is clear and manifest that no objection can be made to Lieut. Borrow's claim, who went abroad with his Commanding Officer's permission, which those Gentlemen did not. In conclusion I have to add that I have stated nothing which I cannot substantiate, and that I court the most minute scrutiny into the matter. I have the honor to be, Sir, your most obedient and most humble servant,

George Borrow.

GEORGE BORROW

GEORGE BORROWThe last of these letters is in another handwriting than that of Borrow, who by this time had started for St. Petersburg for the Bible Society. The officials were adamant. To one letter the War Office replied that they could not consider any claims until Lieutenant Borrow of the West Norfolk Militia should have arrived in England to attend the training of his regiment. These five letters are, as we have said, in the Rolls Office, although the indefatigable Professor Knapp seems to have dropped across only two of them there. Their chief interest is in that they are the earliest in order of date of the hitherto known letters of Borrow. There is one further letter on the subject written somewhat later by old Mrs. Borrow. She also appeals to the War Office for her son's allowance.[22] It would seem clear that the arrears were never paid.

Willow Lane, Norwich, 26 May 1834.