Title: The Captive Singer

Author: Marie Bjelke Petersen

Release date: February 22, 2026 [eBook #78003]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1917

Credits: David E. Brown and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

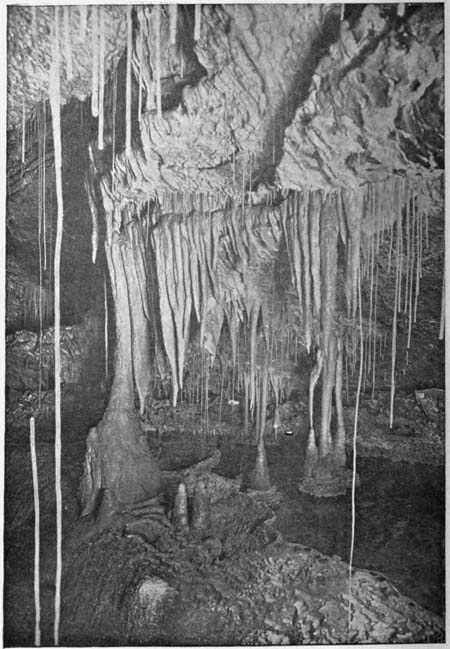

Photo. Spurling & Son, Launceston.

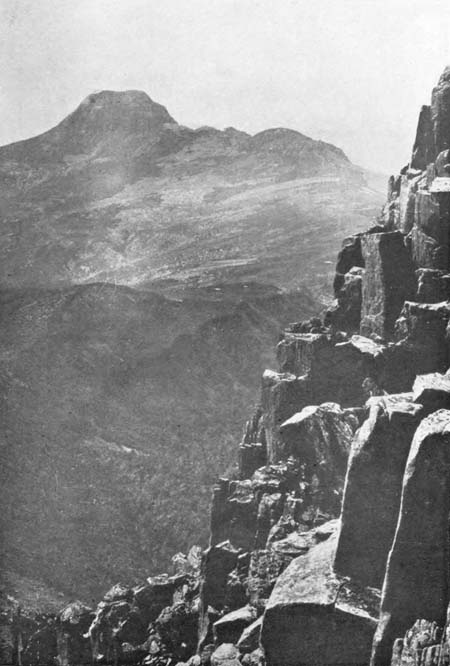

THE LIMESTONE CAVES.

THE CAPTIVE SINGER

BY

MARIE BJELKE PETERSEN

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

LONDONNEW YORK TORONTO

Printed in Great Britain by

Richard Clay & Sons, Limited,

BRUNSWICK ST., STAMFORD ST., S.E.,

AND BUNGAY, SUFFOLK.

TO

THE PURE WHITE ANGEL

WHOSE LOVE HAS LIFTED ME,

WHOSE WINGS HAVE SHELTERED ME,

WHOSE COMPANIONSHIP HAS INSPIRED ME,

I MOST LOVINGLY AND REVERENTLY

PRESENT THIS BOOK

I’LL SING THEE SONGS OF ARABY

| CHAP. | PART I | PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| I. | THE HOT-HOUSE | 1 |

| II. | IN THE WILDS | 14 |

| III. | THE VOICE IN THE CAVE | 25 |

| IV. | THE EXPLANATION | 43 |

| V. | THE BLACK HORSE AND HIS RIDER | 52 |

| VI. | IN THE DUSK | 68 |

| VII. | BY THE MARBLE CLIFFS | 76 |

| VIII. | FATE | 89 |

| IX. | APPROACHING THE RAPIDS | 102 |

| X. | THE GIRL IN THE YELLOW GOWN | 113 |

| XI. | AT THE SHRINE | 120 |

| XII. | THE CONFESSION | 133 |

| PART II | ||

| I. | THE INTRUDER | 144 |

| II. | IRIS AND RALPH | 157 |

| III. | JUSTIN GOES AWAY | 168 |

| IV. | THE BAR OF DESTINY | 177 |

| V. | REMORSE | 185 |

| VI. | HER RESOLVE | 190 |

| VII. | CONSOLED | 195 |

| VIII. | CAPTAIN BARTON’S PLAN | 201[viii] |

| IX. | TO THE RESCUE | 206 |

| X. | THE SUMMIT | 218 |

| XI. | WHAT THE FIELD-GLASSES REVEALED | 237 |

| XII. | HER OFFER | 251 |

| XIII. | THE GOLDEN ROAD | 262 |

| XIV. | “HOPE” | 270 |

| PART III | ||

| I. | THE EARL’S VISIT | 275 |

| II. | THE CABLES | 285 |

| III. | THEIR GOAL | 298 |

“Imagine any one brought up like Iris Dearn actually preferring Australia to London—it is as bad as liking briar-roses better than orchids!” And the speaker allowed her large dark eyes, now cold with scorn, to wander round the crowded reception rooms, decorated with the rare flowers she had just named.

“Yes, it is rather peculiar, Lady Maud,” replied the thin, elderly man she had addressed, moving one of his wrinkled, well-manicured hands. “Still, Australia is a very fascinating country. It is the baby-nation, of course; but the baby is able to toddle now and it has most charming—though perhaps a little wilful and wayward—baby ways. I believe it also shows signs of great intelligence; it is going to make a deep imprint in history—I should not be in the least surprised if Australia turned out to be the genius in the World’s family!”

Lady Maud Townsville made a slight movement with her scantily covered shoulders. “Infant prodigies rarely grow up anything but bores,” she said disdainfully.

“I did not mean to imply that Australia was an [2]infant prodigy—it is far from that! In fact at present it is merely a delightful, healthy child, a little spoilt by rather excessive petting from Providence, but vigorous and lively, with most engaging ways and full of promise for future development!”

Just then all conversation was suddenly hushed into silence, for a famous soprano had made her way to the piano and the accompanist was striking the opening chords of her song.

Her voice was clear, rich and full. She trilled like a bird, and words dropped from her lips like smooth round pearls of sound.

She sang about love, blue skies and purling streams. Her music brought summer with it: soft breezes from the sea, and the lap of drowsy sun-kissed waves. It suggested drifting white clouds, swaying corn, scarlet poppies, new-mown grass and buttercups. It made the swelling tones of exuberant larks tremble into the warm orchid-scented air of the luxurious drawing-rooms. The guests filling them were suddenly carried back to long sunlit days spent in magnificent country places, roaming in green mysterious woods, wandering by silvery lakes, and driving under long avenues of beech, oak, or stately fir trees.

“Her singing has atmosphere,” remarked Sir Edwin Graves when the song was over. “She brought back summer to us in this chilly, foggy November night. Her music has power to do that. But it could not set the air stirring with passion.”

Lady Maud permitted her costly fan to drop to her pale blue silk knees. “Who wants passion [3]in these modern times?—it is out of date. We have outgrown it—with all other savagery.”

“Do you really place love, with its servant, passion, under the category of savagery?” inquired Sir Edwin, turning to his companion with a look in his watery blue eyes as if he were regarding a specimen in a museum which rather interested him.

“Love of what?” asked the woman beside him, with a touch of mockery in her cool voice; “of rank—position—fabulous wealth?” And her fine eyes swept the moving, stirring rooms with their artistic splendour and soft languorous elegance.

He met her derision composedly. “No, I meant love of one human being for another—the kind of love which would lay down life itself for the object of its devotion.”

“Hopelessly ancient sentiments, my dear Sir Edwin! That kind of affection died with Romeo. In these days we flirt with the good-looking men, but we marry the rich ones.” Lady Maud lifted her well-poised head with a touch of defiance. She was marrying one of England’s richest men, whose reputation was as notorious as his wealth.

A little lower down the room sat a beautiful woman with coppery hair, dreamy eyes and a complexion like white and pink rose petals. A tall, dark man, with a well-formed, mask-like face stood beside her. He had just asked her a question and she raised her great limpid eyes to his as if she were merely replying to some casual remark, but her tones were low as she said, “I wish you would not ask me these questions here.”

[4]“May I ask them somewhere else—may I come and see you alone to-morrow afternoon?” He bent over her a little and a curious expression struggled into his mask-like features.

“My husband insists on my motoring down with him to-morrow to look at a new shooting-box he is rather keen on getting; we shall not be back till late,” she replied evenly.

“But will you let me come some other time?”

“I shall be at home on Sunday afternoon at five o’clock.”

“May I come then and—ask?”

“Yes, but remember I have not promised to answer you.” And her smooth tones held a soft challenge in their careless banter.

A plain woman, with large, protruding teeth, watched them from the other side of the room. “Lady Langton is going too far in this flirtation,” she commented to herself with a snarling smile; “she will end in the divorce court one of these days, and then—” a gleam of malicious anticipation shot for a moment into her long narrow eyes—“then we shall have some spicy revelations!”

On a rose-coloured settee sat the hostess, Lady Dearn, talking to an elderly Duchess.

Lady Dearn was rather short, but she had a well-proportioned figure and held herself with youthful straightness. Her face was not beautiful, but it pleased. Her rather small china-blue eyes had just the right amount of animation; they looked expressive without betraying the least feeling; they held refined vivacity which never bordered on vulgar excitement.

“How is Iris?” asked the stately Duchess.

[5]Lady Dearn lifted her eyebrows slightly. “She is always happy in Australia. I cannot understand how it is the child has taken such a fancy to that wild place. I am sure it is most extraordinary she should care for that sort of life!”

“There is no talk of her coming home, then?” Iris was a great favourite with the magnificent old lady.

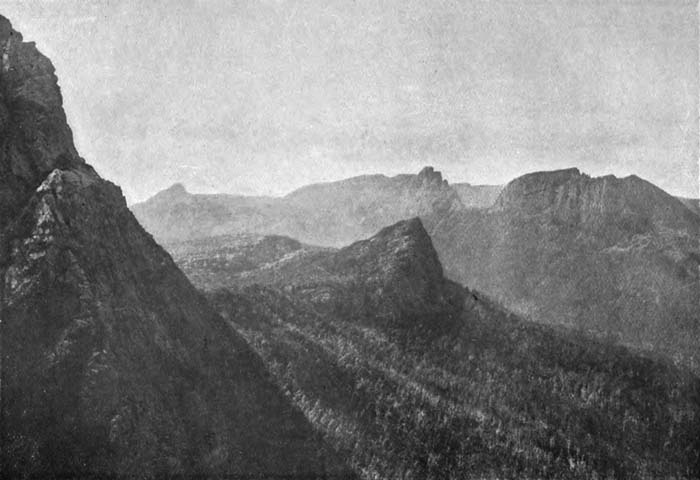

“Not the slightest. She and her cousin are going to spend the summer in Tasmania, at some terrible out-of-the-way place amongst great lonely mountains, where there are lots of horrid caves and all that kind of thing.” Lady Dearn shuddered a little. “Think of my daughter preferring that to this!” And she glanced round her superb home with a puzzled expression on her serene, unlined face.

“But you will surely not allow Iris to stay out there too long? It is perfectly appalling for such a beautiful and charming girl as that to waste her loveliness on gum-trees and kangaroos.”

“It is certainly shocking—but how can I prevent it? When children grow up they please themselves.” She made a pretty little deprecating gesture of helplessness.

“Of course the young must live their own lives, and they have a right to please themselves, if their tastes run along—well——” she hesitated slightly.

“Civilised lines,” suggested the aggrieved parent, “but when they do not, you think mothers should interfere; quite so, I agree with you. But I am powerless; Iris is deaf to reason and persuasion; she is of age, and, as you know, has her own money—what can I do? It is late to restrain her now; [6]I should never have allowed her to go for that first trip with her father—that did the damage; she was never happy in London afterwards.”

As she talked to the Duchess, she caught sight of her second daughter, Helen, standing by a large console mirror, speaking to a dignitary of the Church. She sighed a little. Helen was so plain, and she pined for admiration and attention, while her beautiful sister was so indifferent to these things that, after two seasons of continual social triumph, she had chosen to hide her loveliness in the untamed solitudes of the Australian bush! It was exasperating! And how would it all end? She was losing all her chances of a brilliant marriage, and no girl had better chances than Iris. Her remarkable beauty and delightful personality had taken London by storm.

When she made her début the society papers had been full of her praises. Her photo had appeared in all the magazines. Every one with two eyes agreed about her perfect features, her dazzling colouring, superb figure and elegant bearing. Every one had enthused about the wonderful blue of her eyes, their bewildering expression, the phenomenal length of her black lashes and her enchanting smile! Iris could have married nobility of highest rank, and now—a wave of annoyance flushed Lady Dearn’s smooth face. Why was Iris so different from Helen? Why had she no ambition, no appreciation of the enormous advantages circumstances had placed at her disposal? How could the vast plains of Australia, the rugged mountains of Tasmania, prove a stronger attraction than all London was prepared to shower on this [7]imperious young beauty, who stood aloof and unmoved by all its homage and adulation? Lady Dearn’s vexation increased as she thought of her daughter’s inexplicable choice.

But the Hon. Iris Dearn was being discussed by more people than her mother and her ducal friend that night. In another room, close to a large marble Venus, a small lavender-tinted lady talked in low eager tones about her to a young officer who had just returned from India on furlough. He had evidently expected to see the girl at her mother’s reception, and the woman beside him was pouring very annoying information into his attentive ear. “You know Iris was only eighteen when her father was ordered a long sea voyage,” she was saying, “and dear Lady Dearn was so busy, the winter season just commencing, so of course she could not take him herself, and the dear child begged so hard to be allowed to go—she just adored her father; so eventually her mother yielded, though she did not approve of her going at all, as she was to come out that season.

“They went to South Australia and stayed for some months with a niece of Lord Dearn’s, who had married a squatter there. When Lord Dearn returned to England,” continued the colourless voice, “his health gave way completely, and he died soon afterwards. Poor Lady Dearn was so upset—it was dreadful to lose such a devoted husband, and having to postpone Iris’s coming out, again; for of course she could not be presented while they were in mourning. So dear Iris was nearly twenty when she made her début. She only had two seasons in London, and then, as ill-fate [8]would have it, the cousin they stayed with in Australia lost her husband, came to England for a short trip, and persuaded Iris to go back with her—not that she needed much persuasion; I think she would have gone sooner or later in any case, for she was perfectly in love with the place—such a pity, people simply raved about her here! But—” a sentimental look crept into her small, sharp-featured face, “she doesn’t seem to have any heart for men at all, only an odd infatuation for that far-away, strange land.”

The handsome bronzed face of the young officer relaxed a little.

“I can’t understand it at all,” went on the talkative little woman in lavender; “of course there can’t be any of her own class out there for her to mix with, except her cousin, and she has probably deteriorated by this time, having lived there for years. It is most curious! And Iris was so fastidious, too—no one in London was good enough for her. I believe she had rather a rupture with her mother over some Earl she wanted her to marry, and the girl absolutely refused, because he had once—well, you know what men are—though this was rather an ugly piece of gossip. But Iris would have nothing to do with him on that account, and yet she has gone out to stay for an indefinite time in a country where England sends her—well—the dregs of her families! They used to be sent to America—these unfortunates—but now they send them to Australia instead; so much safer—America was much too close, and the banished ones had a way of returning unexpectedly.”

The speaker sighed becomingly. “You remember [9]young Strathfell—the second son? Terrible about him, wasn’t it? His father has never got over it. Ah, perhaps you were in India when it happened. He must have had a wild strain in him, poor boy, for he actually quarrelled with his father because he wanted to become a professional singer, and of course the old man would not give his consent to such a thing. But he really had a marvellous voice, quite the most touching I have ever heard; and he was so handsome and delightful! Still, it was really too foolish to quarrel with his father, be disinherited, and never be allowed to visit his home again—all for the sake of singing! His father made him promise never to use his own name either. He had the decency not to appear in public in England, but he created a perfect furore on the Continent and in America! However it all came to a sad end; he nearly drank himself to death, and finally went to Australia, and has not been heard of since. Then there was General Foulsham’s son——”

But her listener was not interested any longer, and, making some excuse of wishing to speak to their hostess, he left her.

After his departure, a lady sitting on her right in a smart black gown, with a huge scarlet poppy fastened at the point where gauzy shoulder-straps met in front of her low-cut bodice, said to Miss Marshall, “I heard you telling Captain Barton all about Iris. I don’t wonder you are mystified; it is really tragic! And she had such brilliant offers! But goodness knows what will happen to her now. I suppose she will end by marrying some bushranger!” prophesied the Hon. Mrs. [10]St. Hill Cresden, turning her rather well-shaped head to watch an American multi-millionaire who had just passed.

“A bushranger?” repeated her companion questioningly, “There are no bushrangers in Australia nowadays.”

“Oh, dear Miss Marshall, don’t take me so literally; I didn’t mean a bushranger, of course, but a bushman, or whatever you call them; they are really all the same, you know—Iris will end by marrying one of them. I shall write and warn her.”

“How dreadful! But after she has been mixed up with the people there I shall not be surprised at anything she does. It must be most demoralising never meeting any one of her own class, except the failures we send out. I wonder if Iris will come across young Foulsham. He was so clever and had his share of good looks too; but they say his debts were terrible! No wonder, for his fancy for actresses was on a large scale too, I believe; debts and actresses generally go together, don’t you think? He had to be sent out; it is just as well Australia was discovered! I wonder what they are all doing now? Minding sheep, I suppose—such a nice, healthy occupation for prodigals; all the men seem to do that out there;—what an alarming number of sheep there must be when it takes everybody in the country to look after them!”

The famous soprano began to sing again.

Her guitar-like tones pulsated through the sumptuous rooms. They floated into the hot brilliant spaces as soft moonbeams float into night. They brought dream-like radiance; the liquid [11]splendour of silent lakes caressed by silver rays from a rising moon; the faint echo of boatmen lilting softly as shiny oars glided over the limpid deep.

“She has been to Italy,” said a young diplomatist to Lady Maud, when the singer had withdrawn.

They were standing in a small alcove sheltered by a profusion of palms and ferns.

“Very likely,” replied Lady Maud, beginning to move her fan languidly to and fro.

“Why don’t you come to Italy for Christmas? The climate is most delightful in the winter,” said the man in the foreign service, turning to his companion questioningly.

Lady Maud stopped the swaying movement of her fan and regarded the toes of her pale blue silk slippered feet with a speculative air. “I had thought of going to Rome for the winter; but after all I think I had better reserve Italy for my honeymoon.” She glanced up at him now.

She was not disappointed, for she saw him wince.

“Maud,” he began, a dark look coming into his bright eyes, “you can’t possibly—you don’t mean to say that you really will——”

“My dear Cecil, of course I will—nothing is surer.”

“It’s preposterous!” he replied with some heat.

“What is preposterous—his fortune?” she asked with gracious derision.

He looked between her lashes. “I was thinking of his—reputation.”

Lady Maud’s eyelids flickered a little; then she answered with defiant composure: “You don’t suppose notorious wealth can exist without [12]correspondingly notorious other things, do you? I am afraid your experience of the world is too limited to permit you to rise high in the diplomatic service.”

The man bent over her suddenly. “Maud, for heaven’s sake throw him over—and—marry for—”

“How stiflingly hot it is here.” She stepped out from the sheltering palms and stood in full view of the crowded rooms. “Please take me to my aunt, I believe she wants to go home early. Ah, there she is coming towards us. It has been so nice to see you again, Cecil—I hope to meet you in Rome—some day—good-night.” She made a little gracious movement towards him with her fan and joined an old lady in black velvet, wearing a magnificent diamond tiara.

“What a confounded nuisance that Iris is away just now,” muttered Captain Barton to himself, as he sat frowningly in a corner of a taxi on his way to his club. “I shall call on Lady Dearn to-morrow and get her permission to go out and persuade the girl to come back—it is outrageous for her to be out there! I believe I shall just be able to do it in the time.”

Then he glanced out on the crowded streets. It was a dreary looking night. The pavements glittered dully with moisture and mud. The noise of the traffic was muffled by a chilly fog. Yet he loved the place. To one coming from the glare of India the thick cold atmosphere was exhilarating. It was really hard luck having to leave London so soon. But some months ago he had seen his old playmate’s photograph in her court dress in a [13]magazine, and the lovely picture had sent the blood tingling through his veins and made him determined to marry her. Of course others had been determined about the same thing, and failed; but then—Ralph Barton straightened his tall, well-knit figure—girls could never resist him: he was a great favourite in India; so, if he really meant business, and made Iris aware of it, of course it would be all right—of course—of course.

“He looks like a gentleman,” said Iris Dearn, drawing patterns in the fine white dust with the point of her elegant parasol.

“He not only looks like a gentleman, I am sure he is one,” replied her cousin, with slight emphasis, as she threw back the long streamers of her silver-grey veil which a light breeze had blown teasingly before her face.

“Then I wonder how he comes to be in this position,” mused the girl, ceasing to make patterns in the dust and looking dreamily up the straight bush road by which they were sitting.

Mrs. Henderson shrugged her massive shoulders. “Now, my dear, you have touched on a mystery that we shall never solve. All that we shall ever know is, that Mr. Rees is a gentleman and that he is a driver and guide at this very out-of-the-way place. How he came to occupy this position we shall never be told.”

Iris Dearn made no comment at the moment. Her deep blue eyes, shadowed by very black luxuriant lashes, were still gazing in gentle abstraction up the sunlit track. “It would be interesting to know a little about his past, don’t you think? He talks so well and I am sure he has had a splendid [15]education; he really ought to be doing very different work from this.”

“Yes, he does talk well; and there is no doubt about his education. As you say, it would be rather interesting to know how he came to take up his present work. But we shall not be told anything about that. Though we have been out with him so much, and had so many talks, he has never once referred to his past; in fact, have you noticed that he never talks about himself at all, and if by any chance any one makes the slightest personal reference, he shrinks into unapproachable aloofness at once? Miss Smith was telling me yesterday, that he has been with them for nearly three years, but that he had never told them anything of his former life, and he is not the kind of man they care to ask questions about his private affairs: for though he is so awfully good to every one and has that air of deferential courtesy, he has an impenetrable reserve as well, which keeps even the most curious people at bay.”

“Yes,” acquiesced Miss Dearn, following the movements of a terra-cotta tinted butterfly flickering among some flowering bushes. “He is not the sort of man to satisfy idle curiosity. He will not stand being patronised either. That vulgar little woman with all the diamonds, in the tourist party last week, tried to patronise him when they first went out, but she soon gave it up! I never saw anything better done than the neat, courteous way he put her in her place, and without in the least appearing to do so; it was masterly!”

“Yes, that was really clever—I felt inclined to clap and say ‘Bravo!’”

[16]“So did I. That really was an odious little woman—the way she first spoke to him made me want to shake her.”

Mrs. Henderson’s small plump hands were again occupied putting the streamers of her veil away from her face; when this was accomplished she said, turning her round, kind face to her cousin, “By the way, Iris, that soft new shade of blue you wore last night suited you to perfection—it just matched your eyes.”

But her cousin was not interested in clothes just then. “He is very brave,” she said irrelevantly, turning the soft oval of her face once more towards the long stretch of glistening road. “Wasn’t it splendid the way he caught that runaway horse the other day and saved that poor old drunkard’s life!”

“Yes, it was most heroic; and he was nearly killed himself over it. My heart just stood still when the horse dragged him all that distance—still he managed to pull it up in the end. But it was a reckless thing to do, and the old fellow in the cart wasn’t worth the risk! Miss Smith says Mr. Rees is always doing things like that; he doesn’t mind what dangers he runs into as long as he helps somebody. The whole district comes to him for help. If their cows or horses are ill they always send for him, and he often sits up all night with people, too. Miss Green’s father, at the shop, has awful heart attacks, and whenever they come on they always send for Mr. Rees, and he frequently has to stay with the invalid till early morning.”

Miss Dearn’s delicately gloved hand began to stroke the moss-covered log on which they were sitting. “I have never met any one so kind and [17]thoughtful. He seems to think of everything for every one’s comfort, and does it all in such a quiet unobtrusive manner that one hardly realises he is doing anything at all. I wonder if he is happy,” she pondered with cool, detached interest.

“Happy!” repeated her cousin, “how could any man be happy with eyes like that? Haven’t you noticed the deep melancholy in them when he is not talking? It is really there all the time, even when he smiles; but, when he is silent and thinks himself unobserved, the sadness in his face makes my heart positively ache!”

Her companion brushed away a little green beetle which had lighted on her dainty gown. “Grey eyes always look sad, don’t you think? They are so much sadder than blue or brown ones—like grey skies, always looking a little wistful.”

Mrs. Henderson suddenly glanced at her small, gold wrist-watch. “We really must go back,” she said rising slowly. “We ought to be in good time for dinner to-night; generally we are so late with all these long outings. By the way, Mr. Rees asked me, just before we came out, if we would care to have another look at the big caves; a large party is arriving to-night and wants to see them to-morrow. I believe he wants us to go, and said he would save us the front seats in the brake if we decided to visit the caves again. It is so nice of him always to keep the best seats for us. I was so amused the other day when I was standing on the verandah waiting for you: one of the ladies tried her best to secure the seat next to him, and coaxed in the most arch and fascinating way to get it; but he was relentless and the front seats [18]were rigidly reserved for us. I think he likes to have us there.”

“That is only because we have been here so long and been out with him so often,” said Miss Dearn, opening her long ivory-handled parasol.

“Perhaps so; yet, even in his aloof way, he may like some visitors better than others I suppose—he certainly talks more to us than to any of the other people.”

Iris made no reply as she walked beside her cousin, tall, erect, slender—all in white, from her slim shoes to her slanting parasol; her exquisite profile with its bewildering contours of chin and throat softly outlined against the bronze-green bush, her deep blue eyes, shadowed almost to blackness by their long drooping lashes, looking straight before her.

Mrs. Henderson glanced at her and exclaimed involuntarily: “Iris, you ought to be closely veiled. It is really not fair to men, having a girl looking like you walking about—it is not! I don’t wonder so many of them have gone absolutely mad over you—I should myself if I were a man! I wonder no one has ever come at night and run away with you—I shouldn’t blame them if they did!”

Iris smiled a soft, indulgent smile. She had been accustomed to such admiration all her life. “No one ever feels as badly as that—they all get over it in time. Anyhow up here there is not the slightest danger, as we never see any men except those awful tourists who stare, and stare, and then—go away.”

Neither the girl nor her cousin thought of the driver just then.

[19]By this time they had left the bush track and were now walking on the open main road leading to the small township where they were staying. The great chain of mountains surrounding the district had come into view. A soft haze and the pale blue smoke of bush fires made the towering ridges look strangely remote and out of reach. It seemed as if they had shrunk back into some impenetrable reserve, which would never lift again and reveal their austere savage beauty.

“Here comes Mr. Rees,” said Mrs. Henderson suddenly, interrupting herself in the middle of a remark about the English letters she had received that morning.

Miss Dearn followed the direction of her cousin’s gaze. “Are you sure that is he?” she asked a little absently. She was thinking just then of her mother’s urgent appeal to come home immediately.

“Why, of course! Who else in this place walks like that? If nothing else gives him away, his walk does. No one but a gentleman could walk that way; there is a suggestion of Eton or Harrow about it.”

They watched the man in the paddock making his way to the road. He was rather tall, straight, well-made, and he moved with an ease and careless grace which made it a pleasure to look at him. As he came nearer they could distinguish his finely chiselled features, which bore their usual expression of preoccupation and quiet gravity.

He had reached the fence now and vaulted over it with the lightness of a deer, then he greeted the ladies waiting for him in the shade of a large wattle.

“Good afternoon,” he said in an exceedingly [20]pleasant voice, lifting his cap and baring a very shapely head, covered with thick black short-cut hair.

He wore a loose brown Norfolk jacket, a little the worse for wear, but of good material and cut, and his pink-striped shirt was spotless. There was an air of neatness about him—not the punctilious, fussy kind, but the unstudied correctness which comes naturally to those who have good taste in clothes, and know how to put them on without wasting much time over their toilet.

“Are you coming home too, Mr. Rees?” said Mrs. Henderson, with the friendly graciousness she would bestow on an equal.

“Yes—may I walk along with you?”

“Of course, we shall be glad to have a chat with you—we haven’t had a talk for two or three days.”

Miss Dearn awoke from the contemplation of her mother’s letter. “Have you been on another errand of mercy?” she inquired turning a dazzling impersonal smile on the driver.

“Do you call going to a farm to return a borrowed horse by such an exalted name?” queried Rees, a momentary light coming into his sad grey eyes.

“I wonder what makes you do all these kind things,” the girl mused, ignoring his reply. “We have been talking about you this afternoon and saying how wonderful it is of you to help the whole neighbourhood the way you do. We watched you stop that runaway horse the other day—that was really heroic!” she concluded with a fine sweep of her head and a glowing splendour in her eyes.

Iris Dearn had a magnificent way of bestowing praise. She did it in such a regal, generous way, [21]like a beneficent goddess distributing large bounty, yet without the faintest tinge of patronage in her manner.

A slight flush crept under the tan of the guide’s face. “You exaggerate my usefulness, Miss Dearn. As for the bolting horse, any one would have tried to stop it, and I just happened to be on the spot,” he answered a little hastily, but without awkward embarrassment.

Her blue eyes looked steadily into his. “Mr. Rees, we have never met any one so ready to help others as you; it has been quite a revelation to see the way you bear the burdens of the whole district; I didn’t know there were people like you in the world!”

It was the first opportunity she had had of letting him know how much they admired his bravery in rescuing the poor old drunkard two days before.

A buggy was just passing and the rumbling of the wheels made conversation impossible.

When the noise of the vehicle had died away Mrs. Henderson said: “Miss Smith told me this morning about some Australian writer who visits here.”

“What is his name?” asked her cousin with keen interest.

“Brian Shadwell.”

“I have never read any of his books—I suppose they are Australian?” questioned Miss Dearn turning to the driver.

“No, they are not Australian. His scenes are generally laid in England.”

“How disappointing! I should think it would [22]be far more interesting to describe the life out here. If I were a writer I should revel in putting the atmosphere of this place on paper and sending it broadcast over the world;—it would be like bottling up sunshine and mountain breezes, and distributing them everywhere! But are his books good?”

“I have only seen two of them. They did not appeal to me,” said Rees a little diffidently. “He writes about a very undesirable type of woman,” he added, expanding a little.

“What are they like?” interrogated Mrs. Henderson.

“Shallow, pale-faced, exotic; the kind of women who become engaged to a man for the sake of excitement and sensation only.”

“I wonder what type of woman you really admire,” said Mrs. Henderson, making a bold attempt to draw him out.

Rees stooped, picked up some broken glass lying on the road, and threw it away. When he was erect again, he replied: “That is a subject I have not thought much about—a driver can’t afford to, you know.” And then he led the conversation into quite different channels.

A little while afterwards they turned a corner of the road and the insignificant, self-conscious little township came into view. It consisted of a few scattered cottages, one small shop, two churches, a home-made-looking post office and a large, imposing boarding-house facing the great western mountains.

“Isn’t this the quaintest place you ever saw!” exclaimed Miss Dearn, her blue eyes luminous [23]with animation. “Except for the boarding-house it looks like a garment which has been put away in a drawer and forgotten for many years, but eventually found and put out to air.”

“It is so strange there is no hotel here; I am sure one would pay well,” observed Mrs. Henderson, looking towards the big stone boarding-house.

The driver glanced suddenly at a small garden they were passing and did not reply for a moment. Then he said in slow, measured tones: “We have local option here you know, and the people won’t have a licensed house.”

While Iris was changing her gown for dinner that evening Mrs. Henderson came into her room. “I am sure Mr. Rees is not married,” she remarked, with the air of one whose harmless curiosity on some small matter has been satisfied. “I don’t think he will ever marry either; he evidently doesn’t think he can afford the luxury of a wife. He spoke as if he had settled the question finally.”

“I don’t think he cares for women; though he is so delightfully chivalrous to them they do not seem to interest him in the least. He is so much occupied with other things that he has no time for sentiment. If he has ever been in love, he has got over it long ago.”

“I wish you were a little more interested in love, Iris,” commented her cousin.

Iris glanced composedly at her own beautiful reflection in the mirror. “I am interested in an abstract way, of course—every one is. But I don’t want to have any personal experience of [24]it. I am awfully interested in the South Pole Exploration, but haven’t the least desire to go tumbling about among the icebergs myself.”

“Your mother would not be at all surprised if you joined the next Shackleton expedition, I am sure; after the awful shock you have already given her by coming out here she would be prepared for anything.”

Iris turned, put her lovely arms round her cousin’s neck and kissed her fondly. “If it were not for you I am afraid I should not be here now. But poor dear mother does get so perplexed over what she calls my uncivilised tendencies. She cannot understand how this wild flower happened to come into her highly cultivated garden. I have often wondered how I came to be there myself.”

“My dear, you get the strain from your father’s side, of course—from your Italian grandmother.”

“Doesn’t Miss Dearn look a perfect vision in evening dress!” remarked Miss Smith to Rees as she brought him some mountain trout at dinner that night, glancing over to the small table at the other side of the room, where Mrs. Henderson and her cousin were sitting. “I have never seen any one look quite so dazzling—have you? Her skin is so soft and white, and that wonderful colour in her cheeks makes me think of the shade on the breast of a robin; and her hair—is it brown or golden? Just look at her eyes, they seem like great blue shimmering stars!—she is lovely!”

“That’s right!” replied Rees, laconically, addressing his attention to the mountain trout before him.

“My lamp has gone out—where is the guide?” cried a girlish voice excitedly, as she clutched at the wire rope acting as a protecting fence to prevent visitors slipping into the chasm below.

“Take my lamp,” said an elderly man, who had come up behind her, “mine is all right,” and he held out the lantern to her as he spoke.

“No! No! I will not take yours,” she expostulated; “it would not be fair; but if you will be so good as to call the guide, I shall be much obliged to you—I will stand here on this firm rock till he comes.”

The elderly man disappeared into the confusion of weird shadows and flickering blotches of light cast by numerous small lamps, revealing walls of stalactitic formation, clammy boulders, and the constant moving of blurred figures, climbing steadily upwards towards an inky darkness.

Presently a form appeared making his way downwards, and a lanky youth came into view, looking distortedly raw-boned and uncouth in the partly lit gloom.

“Take this lamp, miss,” he said, passing her his lantern, “I’ll help you up,” and he extended a hard rough hand with large protruding knuckles.

[26]But the lady did not take the proffered help. “I want the guide,” she said insistently. “Will you be kind enough to ask him to come to me? I have already sent one messenger for him.”

“I’m the guide,” replied the gruff voice good-naturedly. “These caves belong to us, and we always take people through them ourselves.”

“Ah, it is the driver I should have asked for then—isn’t he here? I saw him come in.”

“Yes, he did come in, but I don’t know where he is now.”

Very reluctantly the lady took the lamp, but ignored the outstretched hand.

Presently, however, she found the climbing so steep that she was glad of assistance. She hurried on as fast as the slippery stones would permit, and was finally rewarded by hearing the hollow echo of distant voices; and, as she bravely made faster progress, a crowd of fantastic figures came into view. They were standing under a huge alabaster-like archway, looking at the beautiful roof, lined with long limestone icicles which had dropped into many wonderful shapes. In one corner was a large harp-like formation, where stalactites spanned from ceiling to floor into delicate strings, which produced sweet reluctant sounds, as some of the men tapped them gently with their sticks.

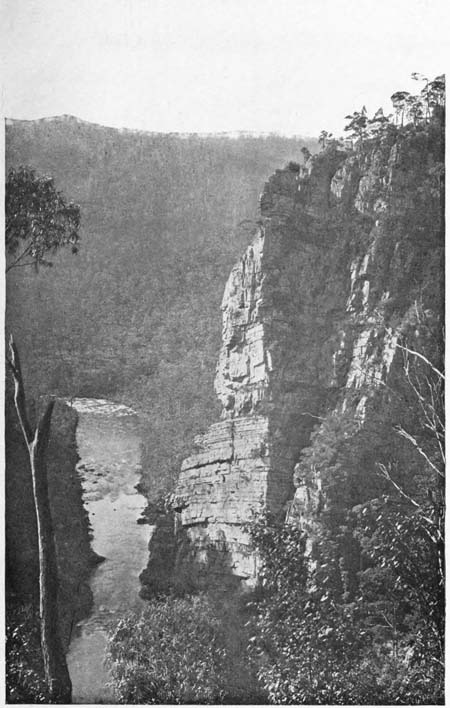

From the archway the caves led into a long tunnel, paved halfway across with large boulders, leaving a terrible chasm on the other side of the stones, from which rose the dull roar of invisible water, leaping in ferocious strength somewhere far below in the blackness.

“I don’t think I shall go any farther to-day,” [27]said Iris Dearn to her cousin, placing her raincoat on a big flat rock and sitting down. “I have seen it all before, you know, and I have a fancy to stay here in all this weirdness by myself—it will give me such strange feelings, feelings I should never have under any other circumstances——”

“But surely you will be too frightened to be here all alone—it would be horrible,” interrupted her cousin, looking after the rest of the party, who were a little ahead.

“No, I shall not be afraid—I am sure I shall enjoy it.”

“Are you certain?” asked Mrs. Henderson, with misgiving in her tones.

“Yes, quite sure.”

“Then I will go with the others, for I should not like to be left here, even if there were two of us—— Ugh!” she shuddered. “This is like Hades, this hollow hill. Isn’t it strange, so many of the hills in this locality seem to be hollow. Well, if you want to stay, I’m going to hurry on to catch the others—I suppose it will be quite two hours before we come back, so there will be plenty of time for the new sensations you are pining for.”

Iris watched her making her way after the vanishing lights and soon they had all turned a corner and disappeared in the darkness.

The girl placed her lamp on one of the low stony ledges, its bright rays illumining the boulder-strewn track, but leaving the stalactitic ceiling in gloomy dimness. Then she sat down again and looked about the cave with curious wonder. Moist rocks bleared at her across the abyss. She heard the drip of water she could not see, filtering through [28]slimy dark places. Beyond the rays of her lantern the blackness brooded all round her as a thick, impenetrable mass, which stood waiting to swallow the timid glow from her lamp; suddenly Iris shuddered. She was not easily frightened, but something cold and clammy seemed to reach out black, stealthy hands towards her. Mrs. Henderson’s words came back to her. Was this hollow hill a Hades? Was she sitting now in the ante-room of some Underworld—a terrible Underworld, piled with gloom and forbidding shapes; an Underworld of gaping chasms, of treacherous streams bounding in unfathomable depths; a world of eerie sounds, menacing objects, slippery footholds, of slimy water creeping insidiously from rock to rock?

Was there really such a Hades? And who were the occupants of such a place? Was it the abode of departed beings, who had now been dragged down by the shadow of their deeds to this abode of gloom?

Iris shivered. Were these spirits round her now? She fancied she could hear soft, wailing notes blending with the drip of the water around her.

And suppose her lamp should go out!

She started violently.

The thick darkness would spring upon her. She felt that. It was crouching to spring. It was only waiting for the feeble lantern to go out and its power would be complete. It could assert itself, exercise its forces. She would be utterly at its mercy then. And those wailing spirits would gather round her—she could hear their faint whine now. And if the light failed they would crowd in [29]upon her, drag her down—down—down into those awful, bottomless chasms!

She shut her eyes and felt her cheeks blanch with horrible coldness.

If only she had gone with the others!

Then suddenly a voice rose from the black vacuum below. It wound its way a little uncertainly towards her. She listened in surprise. Who could be singing down there? Surely no human being could be so far below in that awful ravine? Was it some spirit chained in the bottomless cavern—some spirit cast into the darkness to endure æons of misery in the cruel, merciless gloom? A soul who longed for light, for freedom, whose whole being quivered for sunlit air, blue skies, and the sight of purple hills?—who yearned passionately for gladness, the song of birds, the soft murmurs of the sea, and yet was doomed to an endless existence amid the horrors of this clammy night? What was it? Had her imagination beguiled her senses? Listen!

The sweet notes seemed to hold memories of days lived in the sunlight, in freedom, in gladness! In them burned pain, anguish, hopelessness. The soul was in despair. It would never be free again, never climb out of its horrible prison.

It was a man’s voice, soft, rich, full of sad sweetness, gentle remorse smouldering in every note.

Iris listened intently. She had forgotten her own fears. In her heart surged a deep pity for the being who sang so sorrowfully far below her in the fearful desolation. A strange longing began to stir in her to grope her way down into the gaping [30]fissure, till she reached the captive singer. She half dreamed he might be a spirit who had lived a sordid earth-life, committed evil deeds; but he was repentant now; his tones trembled with sadness; he had endured age-long imprisonment in the icy gloom, till his whole soul was one quivering, sobbing remorse! Surely there should be some consolation for him now? She wanted to go and comfort him. There was no one else to do so. All other feet had hurried on. She alone had halted and heard the song-sobs from the cleft. The quest must be hers. Some great Fate had willed it so. She had heard the cry of anguish and she must respond. She shook off the dream, but it returned.

What would the spirit be like? Would it be some shrivelled up old being who had lived many years in the sunshine-world, before being cast into the under-one? The voice was so mellow, yet throbbing with repressed youth; it pulsated with unfulfilled hopes, a manhood broken, bound with fetters intolerable! No, the spirit who sang could not be old; buoyant youth still surged in his veins, blending with the ripe, full powers of maturity.

The girl had risen. She leant over the big rocks barring the way to the singer’s haunt. All at once the song ceased. The ugly stillness came back, a silence relieved only by the far-away rush of water and the constant dripping from the wet stones.

She leant farther over the boulders and peered into the huge black gulf. But she could see nothing in the murky expanse. And yet somewhere deep down in the clammy loneliness sat an imprisoned soul. She must reach him. She could not leave [31]him entombed in that black solitude. She must make him sing again till she could find her way to him.

“Please sing again,” she called, leaning over the rocks and sending her voice down through the pitchy gloom.

There was a moment’s pause, then a well-known voice replied, “Is that you, Miss Dearn?”

“Yes,” she answered, with slight bewilderment in her tones. To find that the being about whom she had woven these strange fancies was Rees, the driver, had a curious effect on her. It partly brought her back to solid reality, and yet she was unable to dismiss all her conjectures at once; they clung to him and made him appear in a new light. The sympathy which had welled up within her for the unknown singer in the cave still went out to the man who called to her through the dark spaces.

“Miss Dearn, where are you—are you all alone?”

She sat down and uttered a sigh of relief as she heard the hollow echo of footsteps making their way towards her. Sometimes they were loud and distinct, at others they died away in the darkness as if they would never reach her. Then the echoes grew louder and a faint glimmer of light appeared at the other end of the tunnel. Shortly afterwards she could distinguish a form climbing rapidly up the stony pathway towards her, and a few moments later the driver was beside her.

She watched him with strange interest. He was always pleasant to look at. His form was so perfectly proportioned, and, though slight, there was a suggestion of steely strength about it. His large, [32]sombre eyes met hers in the dimness, and it seemed to her there was a new, deep sadness in them.

“Miss Dearn, how did you come to be left here all by yourself?” he almost demanded.

“I wished it. I wanted to be here alone for awhile to see what it was like,” she replied, smiling reassuringly into his anxious face.

“They should not have allowed you to do it—it is not safe. Suppose your lamp had gone out and I had not been here, and you had tried to grope your way back in the darkness—think of it, if you had slipped, or taken one false step——” He stopped abruptly.

She looked up at him quickly. His handsome lean face was very grave and pale. Her fancies about the pain-stricken entombed spirit came back to her.

“Won’t you sit down?” she said, with a little sigh. “No, don’t sit on those wet rocks; have half of my coat.” And she moved a little to make room for him on the stone beside her.

“Where have you been?” she asked very quietly.

“Down in a deep ravine.”

“Don’t you ever take visitors there?”

“No. It is too dangerous, and there is such a lot of water, quite a big stream.”

“A stream deep enough to drown in?”

“Yes.”

The girl shuddered slightly. The caves were really terrible; they over-awed her with their weird black heights, their narrow burrow-like passages, the invisible tumultuous streams and blood-curdling, yawning depths. In the sunlight the imperious young Englishwoman walked with assured [33]confidence, unafraid, but here, surrounded by these mysterious wonders, her courage failed her and she felt baffled and subdued. “And you go down into those caverns without a lantern—I saw you carrying a torch.”

“With a big party there are not enough lamps to spare one for me. But I lit a small dry branch I had brought with me, and it just kept alight till I was within the rays of your lantern. It was odd: it took only one match to light it, but, in lighting that one match, I dropped my box and it fell into the stream.”

There was a short silence, then Miss Dearn said, with soft ardour: “What a wonderful voice you have! Why is it you have never let us hear it before?”

“I very rarely sing,” he replied, with courteous reserve.

All at once there was a bright flash, the flame in the lantern had made a quick flickering leap and then sunk into tired dimness.

“Great Cæsar! I believe that lamp is going out!” exclaimed Rees, as he sprang up hastily.

By the time he was on his feet, there had been another flicker, followed by sudden darkness.

“And we have no matches!” cried Miss Dearn in dismay.

“No; that is the worst of it. The lanterns have not been properly looked after lately; owing to the number of visitors they have been used so constantly, and I have been fearing some experience like this; the boys are pretty careless. I wanted them to let me look after the lamps for them, but they wouldn’t hear of it.”

[34]“Whatever shall we do?” whispered Miss Dearn fearfully.

“We can do nothing except wait till the others come back.”

“But they will be over an hour yet; it is not more than half-an-hour since they left me. Don’t you think you could take me out?” she suggested, with a touch of entreaty in her voice.

“Of course, I could find the way out in the dark, but it would be most dangerous to take you. You see we have to climb down those slippery boulders nearly all the way and you might easily slip, even with my help, and sprain your ankle or worse. The only way I would dare to take you is to—carry you.”

“Oh no!” protested the girl. “I could not possibly let you do such a thing—I am far too heavy.”

“I can carry heavy weights, and you are light.”

“No! I could not let you attempt it,” she said with finality.

“Well, then, we must wait for the others.”

He sat down again.

Neither of them spoke now.

The oppressive gloom was awful. It settled down all around them, brooded over them, crept closer and closer. Iris felt its moist, icy breath on her cheek. It struck chill. She felt cold all over. She shut her eyes, but even then she could feel the stealthy darkness pressing in upon her. It held a gruesome weight. It seemed as if the great hill above them was crushing down on them—if the rocky ceiling should give way!—she caught her [35]breath with fear! They would be entombed then—buried alive! She almost cried out in her anguish. And there was that turbulent water rushing headlong in the black spaces—the mighty torrent she could not see. But if it should rise—young Gill, the guide, had told her it had risen once and flooded the lower part of the caves. If it should rise now!—the distant roar seemed to grow louder; was it swelling already? She knew that streams and rivers in the district often rose with a rush; if this stream should do so now, it would flood the lower passages, so that they could not get out. Her heart beat in wild fear.

“Oh, isn’t it awful?” she gasped.

“What is awful?” asked the man at her side calmly, but with a gentle touch of sympathy.

“The darkness and—everything; aren’t you afraid?”

“No, of course not.”

She breathed a deep sigh: half of relief because of the strength his calmness brought her, and half from new terror as she listened to the hidden water splashing more loudly in the stillness.

She moved instinctively nearer to her companion.

He felt her tremble.

“Miss Dearn, are you really frightened?”

There was deep concern in his voice now.

“I am,” she faltered. “I know it is dreadfully foolish of me—but I can’t help it.”

“What are you afraid of?” he asked gently.

“The blackness—everything. It is so terrible to be right down here in this unearthly place—the top of the tunnel might give way and all that fearful hill fall on us.”

[36]“The ceiling will not give way—it is strong, solid rock,” he soothed her.

“Mr. Gill told me there had been landslips here which completely buried part of the caves.”

“But not where these firm rocks are overhead.”

There was another awful silence.

Then he felt her tremble violently again.

“Miss Dearn, don’t be afraid—there is really nothing to fear.” She felt the strong sympathy in his tones.

But it did not set her terror at rest. “Can’t you hear that water?—oh, how I hate it! You can’t see it and—I believe it is rising.”

“It will not rise.”

“It does sometimes. Mr. Gill told me it has risen and destroyed that lovely fern corner near the entrance. Oh, if only you could take me out—I don’t know how to stay here all that time!”

She was shaking from head to foot now.

The driver grew alarmed. “Miss Dearn, I will take you out if you will allow me to carry you. I can easily do it. I promise to bring you out in safety. Will you?”

“No! No! I could not let you do it.” Her tones were again final.

“But I can’t bear you to suffer like this.” There was a tremor in his words.

“Oh, I know I am absolutely absurd, but this is—Hades——”

He felt her swaying slightly against him. He caught her in his arms quickly.

“Are you faint, Miss Dearn?” he ejaculated under his breath.

There was no answer.

[37]“My God, she has fainted!” he muttered.

He drew her closer towards him so that her head rested comfortably against his shoulder, then he dipped his handkerchief in one of the pools between the rocks and began to bathe her forehead gently.

She was unconscious for only a few minutes before she began to stir restlessly. She lifted her head slightly, then let it sink back wearily.

“Miss Dearn, are you feeling better?” he asked anxiously.

“Where—where am I?” she murmured vaguely.

“You are here in the cave—with me,” involuntarily his arms tightened round her.

“Yes, yes,” she answered drowsily; “I remember the darkness was just going to choke me—it is coming back again,” she added, fear returning to her voice.

“No, no, it is not coming back—nothing shall harm you, I am holding you—just rest quietly till you feel better.”

She drew a deep sigh and lay back more calmly. Presently she moved again. “I am better now,” she whispered and made an effort to sit up.

“Please don’t exert yourself, just stay where you are; you were frozen and you are just getting warm now.”

“How kind you are to me!” she breathed. “It was ridiculous of me to faint. I have never done such a thing before. I suppose it was the want of air and being so terribly—frightened.”

“You are not afraid now, are you?” he asked, bending over her.

“No,” she faltered; “but—I—mustn’t stay here.”

[38]“Of course you must. I am not going to run any risk of your fainting again,” he said, with tender concern.

She did not stir for some time. There was wonderful comfort in the sheltering clasp of his arms, it brought her a strange sense of security, a delicious calm crept over her. All at once she understood why every one trusted this man, why all sought his help, why weak things came to him for protection. She felt the strength emanating from him. Within his arms was a rest which was wonderful. “I am so thankful you are here,” she said under her breath, “if I had been all alone now I should just have gone mad with terror.”

“I am more glad than I can say to be here, but you know you should never have been left by yourself—it is too much for any one who is not accustomed to it, especially as the lamp went out and you have more than your share of imagination.”

Another silence fell between them and in the silence a sense of horror returned. She could hear the water clamouring to reach her. It really seemed to be rising—she was sure it was coming nearer.

“Oh, do talk,” she cried in fear; “don’t let me hear that horrible water—it seems——” She stopped and instinctively nestled closer to him.

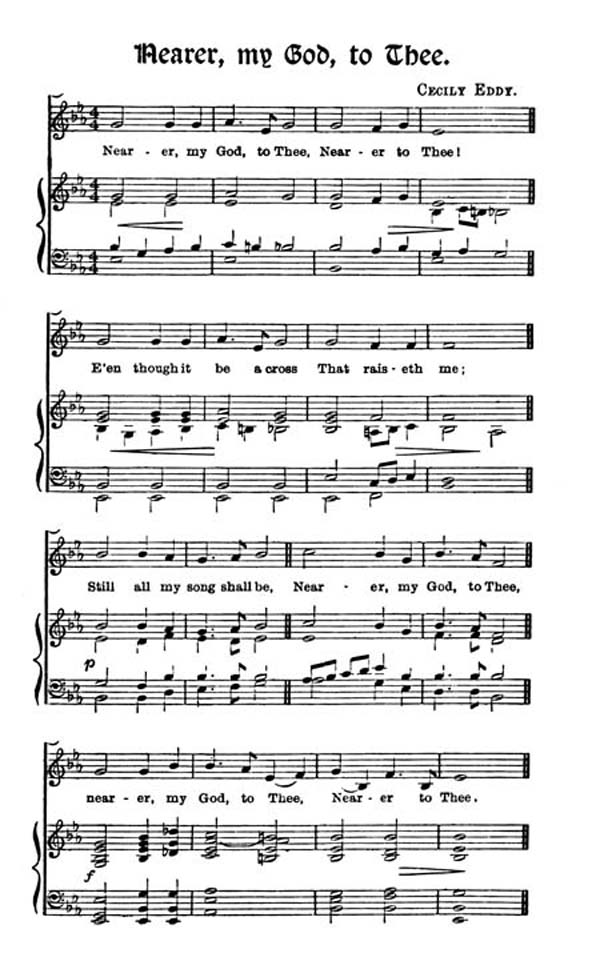

“Would you like me to sing to you?”

“Please do.”

He paused a moment as if considering what he should sing, and then he began in soothing exquisite tones—

“I’ll sing thee songs of Araby.”

The water receded. The awful darkness drew [39]back. She forgot everything but the delightful sound of his voice. It was a true tenor, deliciously soft on the high notes and containing an ethereal purity throughout its entire range. He sang with the perception and feelings of a born artist, and with the perfection of a highly trained one. Every note quivered with beauty and tender sympathy, and when he reached the climax—

his voice held a melting, an almost unbearable, sweetness.

Iris stirred in his arms. His singing moved her as she had never been moved before. It seemed to reach some unknown depth in her. It brought enchantment; but it also brought a strange fear. It held her. It enthralled her; but with it she was conscious of a curious uneasiness. It seemed as if the music laid soft chains about her, and involuntarily she shrank a little from this sweet captivity, yet some hidden part of her revelled in the magic thraldom.

Rees sang on—

Did he feel her thrill to his music? She did not stop to consider, she was only aware that her whole being responded to every note of his song. Then the last liquid sound faded into the darkness.

“Oh, sing it again,” she pleaded tremulously. “I can’t bear you to stop!”

Without comment he began the song once more.

The first time he had sung it with the natural [40]sweetness and beauty his voice possessed. He had sung to please and soothe her, to brighten the darkness. She felt that he had sung it to her as to a tired frightened child he wished to calm and rest. But as she heard the words the second time, Iris was conscious of another element, a new indefinable something which was not in his tones when he sang at first.

What had caused this subtle change?

But she could not stop to answer her stirring wonders. She was listening passionately as she had never listened to anything before. His voice floated round her, pressed close to her, caressed her with its irresistible charm. The words came to her as if they had been whispered from his soul, conveying a special message to her own and she felt something within her respond fiercely to his song.

All her fear of the cave and the horrible darkness had gone. She was only aware of this sublime singing. It rested her. It bore her into a world of rapture! Yet, mingling with the exultant gladness, was a mysterious sadness, which filled her with an odd sense of foreboding.

The song ceased.

A great wave of emotion surged up in her. She did not understand the turmoil within. She only knew it was there. She was conscious of a tumultuous peace, a delicious pain, a rapture, an anguish which was sweet! She lay in his arms mute, overcome, crushed into silence by the beauty of his music.

She felt her heart throb, her bosom sink and swell quickly, and at last the turmoil within found vent in a long, sobbing sigh. His arms about her [41]tightened, and there was the same new element in his touch there had been in his tones when he repeated the song. His enfolding still held tenderest sympathy; deep, solicitous shelter; but they held more—a new strength, or was it a new softness—and with it mingled a yearning sadness.

“Have I sung you sad too?” he breathed, his lips brushing her hair.

“I don’t know—I don’t know,” she whispered faintly; “only it was too wonderful—too amazing—I have never heard anything so heavenly!”

She felt a great sigh pass through his frame. But he said nothing, only there was an almost imperceptible pressure of his arms again.

Iris made a desperate attempt to get her feelings under control; but her effort was fruitless. She lay back in his clasp dumb, trembling, her heart throbbing wildly against his.

At last there was the sound of distant voices and a faint glimmer of light at the upper end of the tunnel. Iris started. “They are coming,” she gasped, but there was no gladness in her voice now. “Please take me out before they reach us—we can easily find our way by the sheen of their lamps. I could not bear to meet them just yet.” She had drawn gently away from him and had risen to her feet.

He sighed again. “Yes,” he replied tonelessly. “I think that will be light enough,” and he began to help her down the slimy stones.

It was difficult by the rays from the distant lamps to find foothold, but Rees guided her skilfully along the dangerous track.

They walked in absolute silence till they were [42]near the entrance, and the sunlight began to filter slowly into the gloom; then Iris said, still looking down on the slippery rocks: “You won’t tell the others about the—fainting, will you?”

“Certainly not, if you don’t wish it.”

“I don’t want them to know—I will just tell Amy quietly later on.”

They had now reached the mouth of the cave and stood quite still a moment, blinded by the glare of sunlight pouring through the wide opening.

“I hope this has not been too dreadful an experience for you,” said the driver, as he helped her over a small trickling stream.

She shaded her smarting eyes with her hand. “I don’t know—I don’t know,” she said, as one not wholly awake from a strange, vivid dream.

The rest of the party had caught up to them now. Explanations followed. Mrs. Henderson had been anxious when they did not find her cousin where she had left her.

Rees answered all questions. He seemed bent on drawing attention from Miss Dearn to himself, and Iris felt grateful to him.

She sat beside him on the way home, but tactfully he did not look at her. Mrs. Henderson was on the box-seat, too, and kept up a continuous flow of conversation, so the time passed without embarrassment.

But when they reached the township, the driver helped Miss Dearn out of the brake, and, as their hands touched, a tremor passed through the girl and a deep flush mounted to her face. She felt his clasp tighten, as if to convey his unspoken sympathy. But she did not dare raise her eyes to his.

During the following days Miss Dearn and Rees did not meet. Somehow the girl managed that she and her cousin had their meals either before the driver came into the dining-room or after he had left it, and they did not join any of the parties going for excursions.

Mrs. Henderson was rather surprised that Iris all at once seemed tired of driving and preferred walking about in the bush instead. However, she was easy-going, and quite content either to go sightseeing in the neighbourhood or stroll about in the country surrounding the township.

But Miss Dearn was most unhappy. She was torn asunder by mortification and shame. Almost as soon as she had returned to the house after her experience in the cave, a terrible realisation of what had taken place sprang upon her. She saw her own behaviour in the glaring merciless light of reason, with every particle of weakness bared before her horrified gaze.

So she, the Hon. Iris Dearn, the proud London beauty, who had held men at bay as easily as great towering cliffs hold back the sea, supremely calm, loftily ignoring the loud advances and passionate appeals of the ocean—had fallen so low that after [44]her faint she had actually remained in the driver’s arms—yes, a driver’s arms—long after her indisposition had made it necessary to do so! It was absolutely—— But she could find no word strong enough to express her unutterable scorn and amazement at her conduct! Of course, she had felt very weak after the faint, and at first, when she had attempted to sit up, it had been impossible to do so. But afterwards she had gained strength, and it was unpardonable not to have exerted it. She did not spare herself. She did not try to put the unpalatable facts away, but faced them. Even the horror of the hideous darkness in the caves supplied no extenuating excuses to her.

She had paced her room at night in hot, impetuous rage. She had clenched her hands in agony. Her tall young form had stood heaving by the window while her splendid eyes, gleaming with angry tears, had looked out into the summer darkness. So, after all, she who had thought herself so strong, who had walked through life fearless, with clear courage, undaunted gaze, head held high, had now suddenly sunk to—this!

Her moral strength had ebbed out with her physical force. She had stayed in the driver’s arms from sheer cowardice, because she had been afraid of the night and all it held. His enfolding brought comfort, support, peace, and she had yielded to the subtle consolation of his touch. Some wonderful strength had emanated from him and held her.

And there had been his song!

A tremor still passed through her as she thought of that. His singing was marvellous—the most [45]tender, exquisite thing that had ever come to her. The memory of it brought a hard aching to her throat. She had not told Amy about it, it was too sacred even to discuss with her cousin. His voice was not only delightful because of its musical beauty, but it touched deeply because it laid bare the great loftiness, the passionate warmth throbbing in the man who sang. The real man was revealed to her now. But—what must he think of her? This scorching question brought her the deepest mortification. She could never face him again—oh, the shame of it, the fierce humiliation!

She ought, of course, to pack her trunks and go away, and it rather astonished her that she did not do so. Why did she linger in a place which ought to be abhorrent to her now? She could not explain this; but she could not go away. Something held her. She was no longer quite free. Some invisible chain had been slipped round some invisible part of her and bound her to the place. She felt the soft cord, yet she did not attempt by one determined effort to break it.

Mrs. Henderson did not notice any change in her cousin, except the apparent disinclination to join the excursions she had revelled in before. The girl was a little quieter also, and at times she seemed a little paler, but that was no doubt the lassitude frequently left behind by a faint. Otherwise there was no difference. She took long strolls in the bush, smiled her bewitching, dazzling smile; laughed her rippling, silvery laughter, walked in her tall, graceful, imperious way; and yet, if Mrs. Henderson had been more keenly observant, she would have noticed that the fine colour in her cheeks [46]was often merely a flush, and the lustre in her eyes frequently the brilliance of pain.

However, though Miss Dearn kept out of the driver’s way and had managed to evade him at meals, it was impossible to remain in the township for any length of time without meeting him. So it happened that one evening as she was returning from the post office she suddenly came face to face with him. He came out of a small cottage at the side of the store just as she was passing, so there was no chance of escape.

“Good evening, Mr. Rees,” she said, with an effort at outward composure, but perplexed at the sudden leap of her heart; “are you on your way home, too?”

He answered in the affirmative, and said he had been to see Mr. Green, who had not been well all day, and then went on to speak of other indifferent things. His manner and tone were gentle and courteous, but rather distant. He seemed anxious to show her that he remembered the gulf between them, that the episode in the cave would not make the slightest difference to their relationship, and that he would never assume any tone of intimacy on that account. It seemed to Iris, as they walked along the road, that he went out of his way to make this clear.

Then all at once it occurred to her that he must have misunderstood her motive for avoiding him. He evidently thought she shunned him because she did not wish to give him an opportunity of taking advantage of a situation many men would have regarded as a legitimate stepping-stone to familiarity. How horrible and contemptible he must [47]have thought her conduct after all his kindness and tender concern!

Her cheeks flamed suddenly in the twilight—such a thought was intolerable!

She must undeceive him at once. It was unbearable that he should think her so base and ungrateful! But how was she to do it? It would be difficult, especially to begin.

However, as they came within sight of the house, and would not have many more minutes together, she made a courageous plunge.

“Mr. Rees, there is something I want to say to you. I have wanted to say it ever since—since—that afternoon.” She ceased abruptly as if words failed her.

He waited a moment for her to continue, but, as she did not do so, he broke the silence by saying: “I was under the impression you would rather not speak to me at all.”

So he had misunderstood! The hot colour surged into her face again.

“Oh, I am so sorry,” she said in troubled tones, forgetting her own embarrassment in her eagerness to explain what he must have regarded as a cruel slight. She must be very frank with him, nothing but a full confession would be adequate now; so she continued: “I only avoided you—because—because—— Oh, Mr. Rees,” she faltered with deep agitation, “can’t you understand how I should feel after—behaving so—so—unpardonably—can’t you imagine how ashamed I should feel—how afraid to meet you? Oh, after all your kindness the other day—a kindness I shall never forget—it is dreadful to think that you misunderstand [48]me! I will be perfectly open with you—I owe you that; I have only kept out of your way because I—felt too horribly ashamed—too mortified to face you—and—I have been so miserable, I have hardly been able to sleep for the awful shame of it.”

They had reached the house now.

“Miss Dearn, would you mind coming down this lane for a few minutes—we can’t talk here near the house.” There was a perceptible unsteadiness in his voice.

Silently they turned down the narrow track fenced on both sides by great hawthorn hedges.

When they were a little distance from the main road Rees said: “You don’t know how grateful I feel because you have explained this to me. It was indeed good of you, especially when it was so difficult.” His tones showed he was deeply moved, though he spoke very quietly. “Let me thank you, Miss Dearn. But,” he came a little closer to her, “why are you ashamed? There is absolutely nothing for you to be ashamed about.”

“But I behaved most disgracefully.”

They had stopped walking. She stood before him contrite, ashamed, as superb, as beautiful in her humiliation as she had been in her graciousness and her fine appreciation of his bravery.

“Don’t say that, Miss Dearn,” and there was entreaty in his manner. “You were only frightened; and every other human being who was not used to those caves would have been terrified at being left alone so far underground in the dark.”

“Yes, but I was not alone, I had you—there was no excuse for me,” she reminded him dejectedly.

[49]“Still there were only two of us, and that is not like being with a big party. Anyhow, most people would have been dreadfully nervous, even if there had been many others with them.”

She shook her head sadly. “You make most generous allowances for me; still, of course, you must know that none of them is sufficient to excuse such conduct. I had no right to be so terrified and, even if I were afraid, I should not have showed it and—fainted and—placed you in such—an—awkward position.” She finished heroically but with downcast eyes, her long velvet lashes quivering on her flushed cheeks.

“Please don’t look at it in that way,” he pleaded; “to me it was the highest honour and most sacred privilege to be there to help you. So don’t distress yourself about it—it hurts me more than I can say to see you so troubled because of—of—what I did.”

“No, no, not because of what you did,” she interrupted him hastily. “You were only kind, so exquisitely good to me—” her voice grew low on the last words—“I am only so grieved that I should have made it necessary.”

Just then they heard running footsteps behind them, and, as they turned, they saw a little girl making her way pantingly towards them.

“Mr. Rees,” she called when she was still a few paces away, “Miss Green sent me to fetch you—her father has had another attack. Some boys at the corner said you had gone up here with a lady,” she finished breathlessly as she reached them.

“I am afraid I must go,” said the driver reluctantly: “there is no doctor here. Miss Green is [50]all alone and her father is such a heavy man she can’t manage him by herself.”

As he spoke they began to walk back to the main road. When they reached the corner Miss Dearn held out her hand to Rees, and, as he held it for a moment, he said, “I am so sorry to have to go. Please promise me that you will not distress yourself over that matter again. Believe me there is not the slightest need; will you promise?”

“I will try.”

“And will you let things be just as they were before, and let me take you for drives whenever you want to go, and—talk to me—sometimes—as you used to do?”

“Yes, of course,” she responded eagerly; “I can promise it shall not make any difference in that way.”

“I am asking you not to let it make a difference in any way.”

“Are you sure it will not make a difference to you either?” asked Miss Dearn a little shyly, but meeting his eyes bravely.

“No—not in the least,” he began reassuringly, then his tones changed suddenly, “that is—I—I shall——”

“Miss Green told me to ask you to hurry,” interrupted the child.

“I must go, then. Good-night, Miss Dearn; please do what I asked.”

“I will try; good-night.”

He hastened towards the little shop a short distance along the road, while Iris turned slowly into the house. She looked once more at his well-built, [51]retreating form as it grew blurred in the soft, violet-tinted twilight.

“That afternoon in the cave has evidently made some difference to him too,” she thought to herself; “I wonder in what way—if only he had finished that sentence I might have known.”

“Wake up, dear,” said Mrs. Henderson the following morning, stooping and gently kissing her cousin’s white arm as it nestled against the coverlet, the dainty sleeve of muslin and cobweb-lace having slipped over the delicately curved elbow.

Iris opened her deep blue eyes and looked with troubled wonder at her companion.

Mrs. Henderson explained. “You must get dressed at once, dearie; Miss Smith has just called me. Mr. Rees sent her up to ask if we would care to go with him to a place—I forget the name—but there are to be sports in aid of some charity; I was too sleepy to take in the details—only Miss Smith said it would be such a lovely drive through a part of the country we have never seen, and you said last night you would like some more trips. Mr. Rees has to go, they are to have jumping, and he has been asked at the last minute to ride one of the horses; the owner is not well enough, or, as Miss Smith put it, he has ‘funked’ it, and wants Mr. Rees to take his place. It appears they are all anxious to get him as he is such an excellent rider. But we have to start early; the place is twenty miles away and the sports commence at twelve o’clock; there are some other people from [53]the township going too, so Mr. Rees is taking the wagonette. I suppose we shall have the front seats as usual.”

An hour afterwards they were on their way.

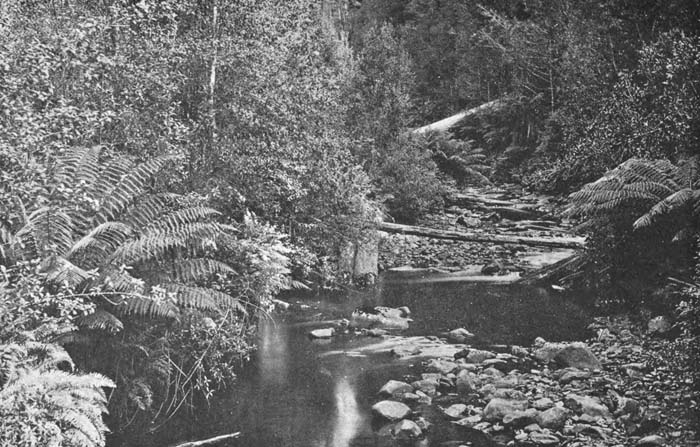

It was a lovely morning. The cloudless sky was the clear blue of baby eyes. The hills lay wrapped in dreamy gossamer haze. The air throbbed with warmth and golden sunlight. Flocks of chattering parrots flew in and out of the silver wattle trees and honey-eaters twittered merrily in bottle-brushes.

The horses danced along the road. They were very fresh and enjoyed being allowed to gallop up the numerous hills. The wagonette was filled with people gaily attired for the holiday. Mrs. Henderson and Miss Dearn were in their usual places, and Iris arranged that her cousin should sit next to the driver, for, in spite of her promise the night before, she still felt distinctly uncomfortable in his presence. She was not only ashamed of her conduct, but there was another curious emotion blending with her mortification which made her still more uneasy when she was near him. It was a strange feeling, making her want to avoid him and at the same time feel restless if she kept out of his way. That morning when he greeted her she felt her pulses beat unaccountably fast, and it was this inexplicable embarrassment which made her choose the seat farthest away from him.

Mrs. Henderson was always bright and talkative, and kept up a constant conversation with the driver. She asked a great many questions and he answered them all more extensively than usual. After they had been driving for an hour [54]it dawned on Mrs. Henderson that her cousin had said very little that morning and she at once remarked on it. “Iris,” she said suddenly, “what is the matter with you? You have hardly said a word all the way, and, now I come to think of it, you have been rather quiet the last few days—whatever is wrong?”

“Have I been quiet?” Miss Dearn replied with light composure, opening her parasol; but, before she could proceed, Rees had begun to tell Mrs. Henderson a thrilling story of bushranging days, which held her attention for the rest of the journey.

When they arrived at the sports ground it was already swarming with people; the adjacent paddocks were dotted with vehicles and horses tied to fences and shady trees. Other buggies and carts were constantly arriving. Whole families stowed away in traps were suddenly released from their tight imprisonment. Babies cried, children laughed. Men shouted country witticisms to each other. Women chattered.