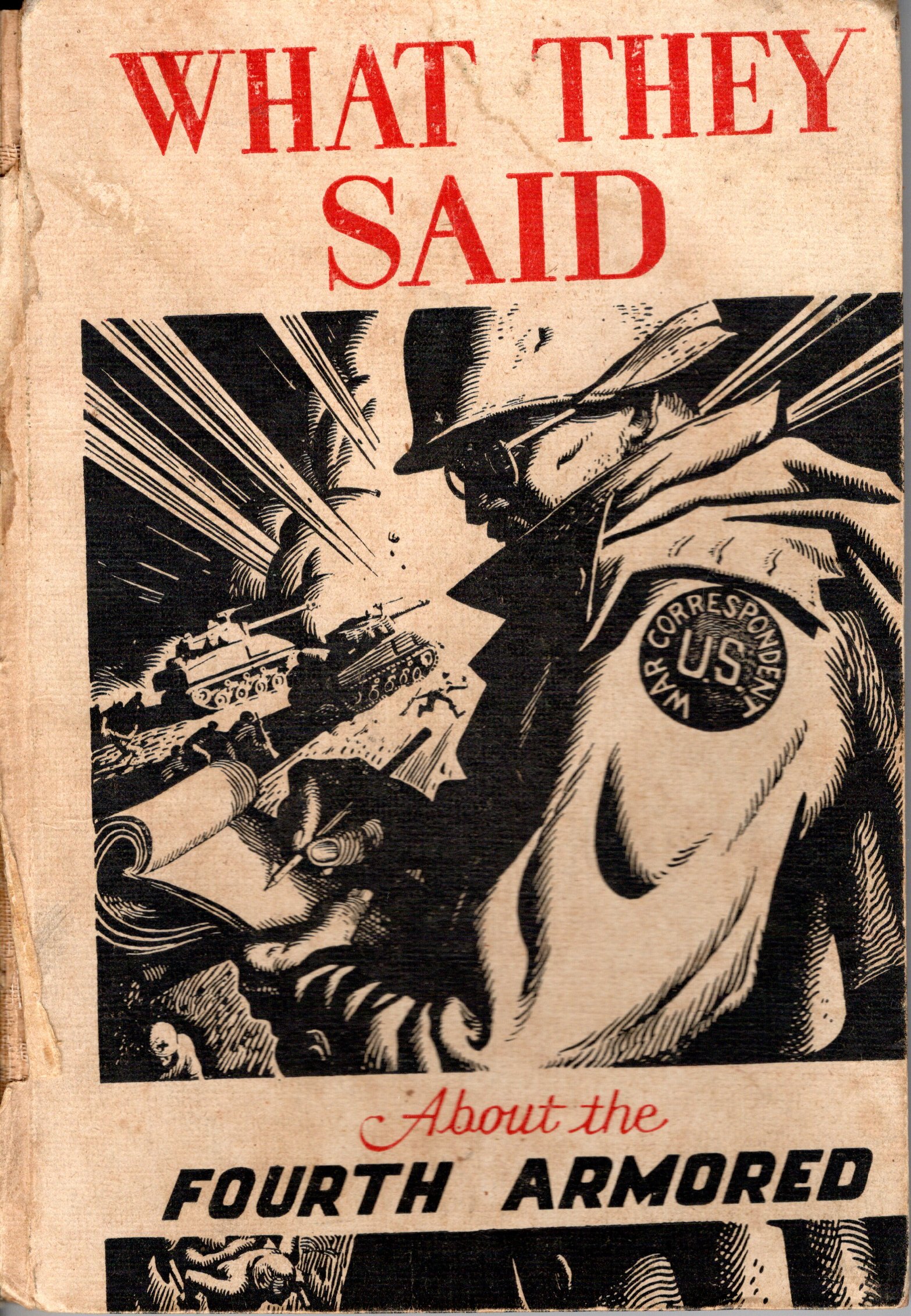

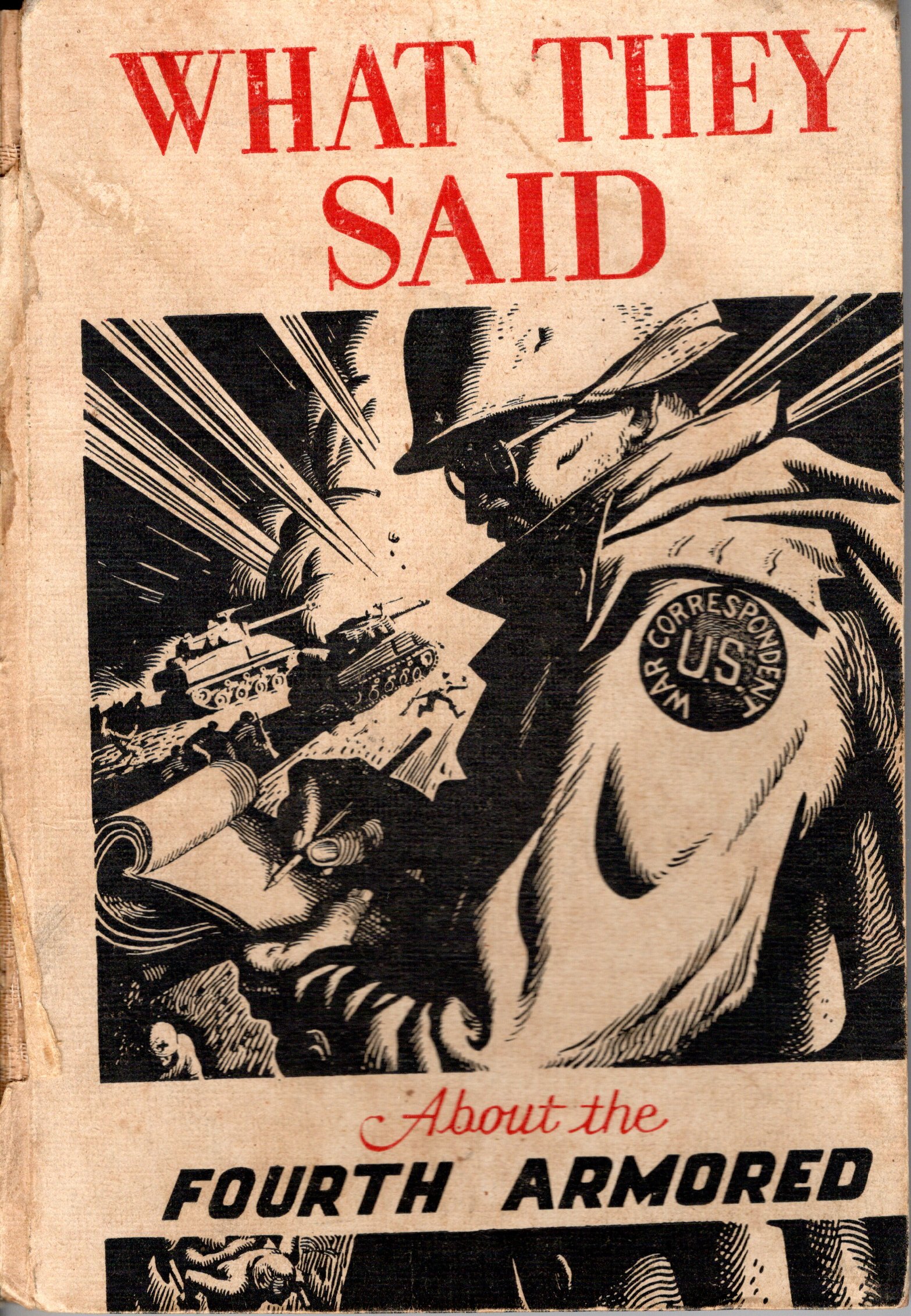

Title: What they said about the Fourth Armored Division

Author: 4th United States. Army. Armored Division

Release date: February 16, 2026 [eBook #77963]

Language: English

Original publication: Landshut: Herder-Landshut, 1945

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/77963

Credits: Fabbian G. Dufoe, III

Compiled and published by the Public Relations Section, Headquarters, Fourth Armored Division. Cover design and Bastogne page by S/Sgt. Frank Besedick. Chapter titles by Sgt. Edward R. Thomas. Photographs by 5th Detachment, 166th Signal Photo Company

Printed in Landshut, Germany, September 1945

Printed and bound by Herder-Landshuk

| Shiniest Helmet In ETO | Page | 1 |

| Tiger Jack’s Spearheads | ” | 4 |

| The Furrow | ” | 15 |

| Bastogne | ” | 25 |

| Rat Chase to the Rhine | ” | 36 |

| The Victory of the Rhine | ” | 51 |

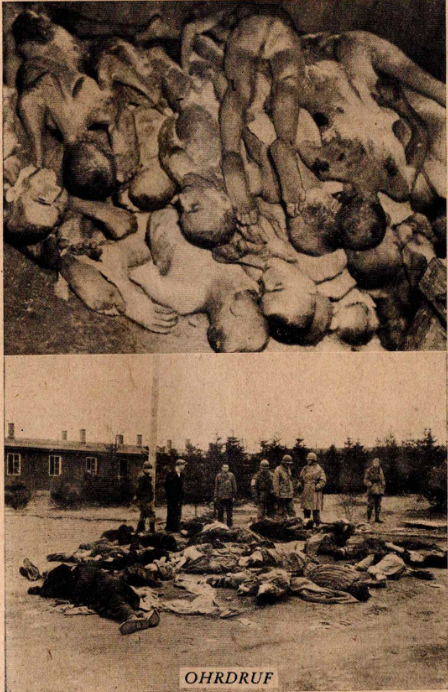

| Ohrdruf | ” | 54 |

| Death and Apple Blossoms | ” | 59 |

| “Colonel Abe” | ” | 64 |

| Three Division Heroes | ” | 75 |

| Hello BBC | ” | 84 |

| Men and Medals | ” | 88 |

| They Called Us | ” | 92 |

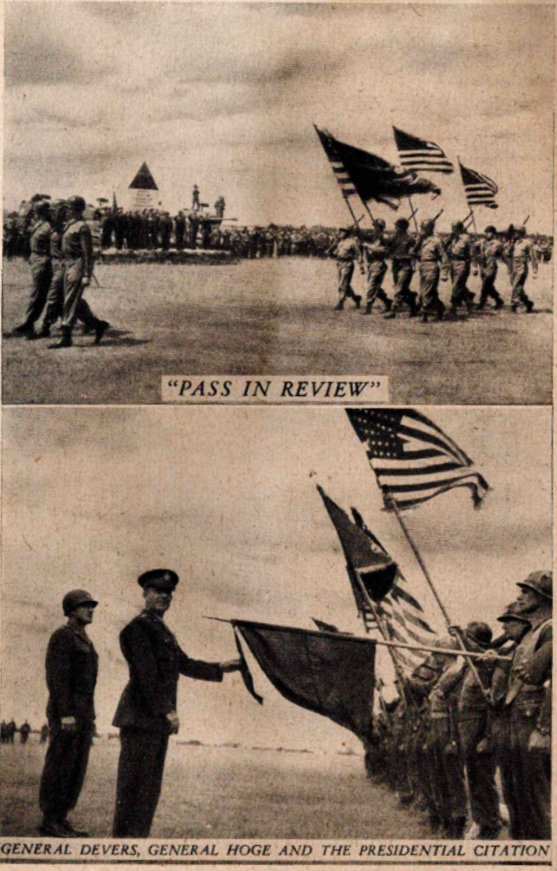

| The Presidential Citation | ” | 96 |

| Collier’s Excerpts | ” | 101 |

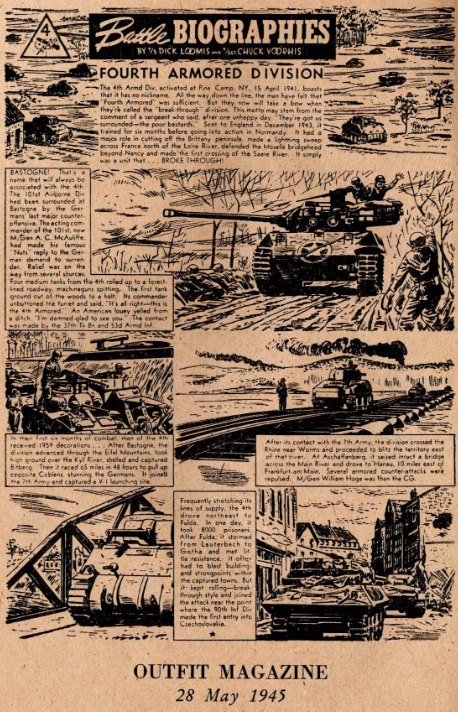

“What They Said,” is a book compiling various magazine articles and newspaper stories that have been written about the Fourth Armored Division since it entered combat.

To print everything that has been written about the division would require several volumes. Therefore, we have tried to make a representative selection that will give you a general idea of what “They”, the war correspondents, the home town newspapers, and the radios all over the country thought and said about the Fourth Armored Division.

Some of these stories you may have already read. Others you may be reading for the first time. Although you might have already read everything that lies between the covers of this little book, it will still be prized in years to come—years when you can lean back with the satisfaction of knowing that you shared in a great victory, and be reminded of “What They Said”

For those who are new to the division, this book will help you

understand what it means to be a member of the Fourth Armored.

Something of what the Fourth Armored is and has done is related in

this book by impartial people outside the division whose job it was to

report the news as they saw it.

(Public Relations Section.)

SHAEF, March 28—The War Department, by direction of the President, has cited the entire 4th Armored Division for “extraordinary tactical accomplishment during the period from December 22 to March 27, inclusive,” it was announced here today.

This made the 4th Armored the second complete U. S. Army division in history to be so cited. The 101st Airborne was presented with a Presidential Citation by General Eisenhower on March 15.

Referred to by the Nazis as “America’s elite 4th Panzer Division,” the infantry and tank teams of the 4th spearheaded the 3d Army’s race across France.

The 4th has been commanded by Major General John S. Wood and Major General Hugh J. Gaffey, and is now operating under Major General William M. Hoge, of Lexington, Mo.

The 4th Armored’s most recent accomplishments include its move from Sarreguemines to Arlon; its great drive to relieve the 101st Airborne at Bastogne; the history-making 60-mile dash to the Rhine River; the move to Mainz, and the current drive on into Germany.

Stars and Stripes, March 29, 1945

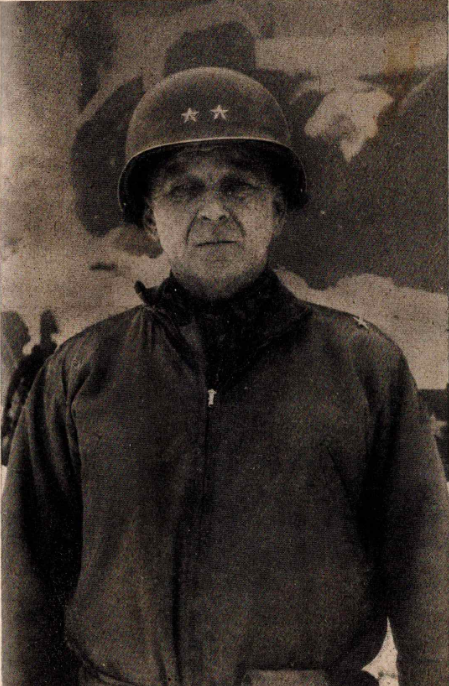

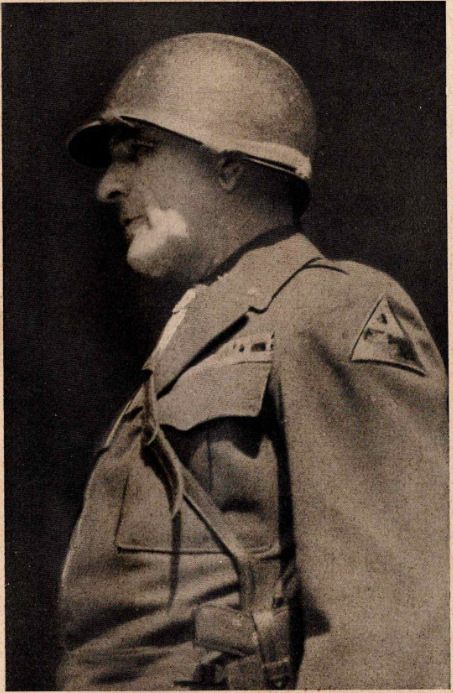

Major General John S. Wood

Division Commander

18 June 1942-3 December 1944

Brigadier General Bruce C. Clarke

Division Commander, 20 June 1945-5 July 1945

CCA Commander, 1 Nov. 1943-1 Nov. 1944

By Roelif Loveland

(Cleveland Plain Dealer)

When Patton came to Third Army briefings his boots were shining

And his helmet was shining, and campaign bars were thick.

Somebody said: “The Germans will see them, general.”

“Hell,” replied Patton, “I want the Germans to see ’em

“And send word back that Patton is on the job.”

That was in Normandy, and a lot has happened since Normandy.

The American Third Army has taken its place in history.

The American Third Army, tanks and tank destroyers and bloody

infantry—

The American Third Army, which swept across France, and kept going.

It has gone a long way since that apple orchard in Normandy.

Where Patton gave his first press conference

And talked about his chances of getting to Paris first,

Before any of the other American generals,

Told of a little bet he had made, but that’s his business.

They let the French enter Paris, for obvious reasons,

And Patton and his army kept on fighting.

Third Army correspondents went to Paris en masse; that

was the story,

But the Old Man with the burnished helmet kept on fighting—

Patton and his boys.

They kept going until gasoline and ammunition ran out.

It had been told.

And they sat by the Moselle for nervous weeks.

And when they got the stuff to go with, they went.

And they brought the war home to the German people,

Who had always fought past wars in other people’s back

yards.

And the Germans didn’t like it, damn them!

They could dish it out, but they couldn’t take it—

At least not the way other people had taken it for weary

years and years.

I can remember the Fourth Armored Division.

The last time I saw them they were sitting in a field of mud,

And the wind was cold and the rain drenching,

“They dropped some in this morning,” a captain said,

“but hit nothing.”

By one of the tanks the lads had constructed a sort of

lean-to.

They were sitting there, on boxes which had contained

rations.

The colonel of the outfit, guests being present, broke

out cigars.

“German cigars,” he said. “Not too bad, either.”

They weren’t too bad, and they weren’t too good.

There was always one nice thing about an armored outfit—

They got there first, and they corralled most of the wet goods.

They were generous lads, these boys who rode in the

stinking tanks.

It was always nice to go and see an armored outfit.

Yesterday the paper said: “The Third Army’s Fourth Armored

Division,

“Plunging 19 miles eastward, raced into the outskirts

of Gotha,

“Reaching a point three-fourths the way across the Reich

from Czechoslovakia

“And 140 miles from Berlin.”

A lot of the tanks which were in the rain-soaked October mud,

And a lot of the men who were sitting on boxes by the tanks,

And a lot of the infantrymen who were slogging in wet shoes

Very probably never got to Germany at all.

Some of them went to hospitals, and some of them died,

For of such is the institution of war.

But I cannot help feeling proud when I read of Third Army.

I cannot help but feel proud when I think of Third Army.

I cannot forget Patton, with the shiniest helmet in the E. T. O.

Who wanted the Germans to know he was there,

And who, by God, made ’em regret it.

By Wes Gallagher

“GENERAL PATTON’S armored spearheads ripped...” Week after week last summer that phrase dotted the news stories of the American Third Army’s unprecedented race across France. The lifting of security wraps now makes it possible to introduce you to Lieutenant General George Patton’s prize “armored spearheads.”

That is, if you can catch up with one. At the height of the summer campaign it was worth your life to do so—particularly with Major General John S. “Tiger Jack” Wood’s crack Fourth Armored Division.

From July 28, when the Fourth jumped off from Cherbourg peninsula, until late September, when it breached the German line on the Moselle River, it operated virtually continuously behind the German lines. And when the Germans launched their big counteroffensive in December, tanks of the 4th rumbled to the relief of the American forces holding the besieged communications center of Bastogne.

During the summer campaign, the Fourth at times was as far as seventy-five miles ahead of the bulk of the Third Army moving in its wake. Supplies had to be brought up in tank-guarded convoys.

Correspondents could catch up with the Fourth’s combat commands with one of these convoys or could take their chances in sixty-mile-an-hour jeep dashes through German-sprinkled territory.

The roads behind Tiger Jack’s clanking hard-boiled armored family were usually considered unsafe for “thin-skinned” vehicles, which means anything less armored than a light tank. And the Lord knows nothing is more thin-skinned than a jeep, unless it’s a correspondent.

Most of Wood’s thousands of soldiers from American farms and fields act as though they themselves were armor-plated—especially Wood. When mine fields halted his tank columns just outside of Coutances in the dash down the Cherbourg peninsula toward Brittany, Wood suddenly appeared at the head of his columns clad immaculately, as always, in polished boots, riding pants, a trim jacket, and sun glasses, which he wears rain or shine.

Wood marched into the town on foot under fire, captured a German soldier and found a patch through the mine fields. He picked his way through the town on foot, sending back a message for his tanks to follow him. The columns never stopped again until they ran out of gasoline six weeks later at the Moselle. The general was later awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his bravery at Coutances.

Burly and as athletic at fifty-six as he was when he played end for the University of Arkansas and the Military Academy just before the last war, Wood is one general who looks the part. Eternally restless, he paces ceaselessly back and forth, even finding it difficult to sit still long enough to eat his meals. When he does stand still it is with feet wide apart, hands on hips, in an attitude that dares anyone to start something.

Wood is a long-time crony of the rough, tough Third Army’s pistol-packing commander, and is one of the few subordinate generals who are not intimidated by Patton’s roars of disapproval. When Patton roars, Wood roars right back at him. The pacing and roaring prompted one of the division’s Cub observation pilots to pin the nickname “Tiger Jack” on him last summer and it shows signs of sticking. Wood lives in the field with his division and refuses to move out of his tent—and the mud—until his men can do likewise. That means he will be in a tent for the rest of the war. His restlessness and tremendous pride in the division send him on daylight-to-dark visits to every unit, and every man in the division feels Tiger Jack knows him personally.

The best description of Wood comes from an officer in the division who, for the sake of his personal safety, must remain nameless. “The general is a sort of Army edition of Clarence Day’s father in Life with Father,” he says.

In peacetime Wood used to work out his surplus energy on the tennis and squash courts, running his officers ragged, until he got the Palm Springs, California, tennis professional, Lieutenant Lewis Wetherell, as his aide. Wetherell can beat him at tennis, but Wood is tops in squash.

In battle, the Fourth’s commander either flies over the area in a Cub plane as a passenger for a personal look, or grabs his field radio and indulges in a play-by-play direction of the fighting with his field commanders.

No order in the Fourth Armored Division is ever written. Wood gives orders to his field commanders verbally and in person, to make sure they are understood. His commanders do likewise.

The 800-mile drive through the heart of France conducted by the Fourth Armored Division, a masterpiece of strategy, was conducted on such a verbal and personal basis. Wood trained his division to work as a family. He mixed units until every commander was able to recognize another’s voice over the field radio. That did away with confusing code names.

To understand the magnitude of the task of operating such an armored force, visualize a fair-sized small American town suddenly put in steel houses and trucks and zigzagged from New York to Chicago over strange highways so as to cover 1,900 miles—the mileage rolled up by some of the Fourth Armored’s tanks in the fighting from July to September.

Visualize the problem of bringing up some thousands of tons of supplies weekly to feed and maintain this traveling steel village, not to mention the vast amounts of gasoline necessary to keep it rolling. In one day’s advance last summer, the steel monsters consumed 700 gallons of fuel for each mile gained.

Then visualize traveling hospitals, repair shops, kitchens, and a complete telephone and radio system linking all the various units into a co-ordinated whole.

An armored division does not travel as one strung-out column. Usually it is broken into combat commands known as CCA, CCB, etc. The composition of the combat commands changes from task to task. One day CCA might be composed of a battalion of tanks and motorized infantry backed by other attached units, such as combat engineers to build bridges, its own antiaircraft units, tank destroyers, artillery, and its own scouting force of Cub planes and reconnaissance squadrons of armored cars and jeeps. The next day it might be changed to double the number of tanks, half the infantry, and half the attached units, depending on the objective.

The combat commands usually advance in parallel columns, with the tanks in the middle and the infantry on the sides, or vice versa, until opposition is met. Radio and Cub planes link the commands with Wood’s headquarters, which is usually close behind the most advanced command. Each command is self-sustaining for limited periods. At times the commands of the Fourth have been engaged on separate tasks hundreds of miles apart, but usually they are fairly close together so as to be self-supporting.

After you have started this vast mass of material moving on a strange road system, so co-ordinated as to arrive at a given spot at a given time, you have the task of maintaining its complicated mechanism day after day against a hostile force seeking to smash and disrupt it.

That, very roughly, is the problem of fighting the Fourth Armored Division, or any American armored division, for that matter. It is a problem which Tiger Jack’s division solved with a perfection that has been unsurpassed in any battle during this war. No German Panzer division that smashed through Poland in 1939 or France in 1940 or Russia in 1941 accomplished as much in so short a period.

An armored division does not have the room or facilities to take prisoners. Its mission is to cut up the enemy forces and destroy their communications, leaving isolated pockets behind to be mopped up by the infantry division. But the Fourth Armored in two months’ fighting across France, from the last of July to October captured more than 15,000 prisoners, killed 5,000 more Germans, destroyed 317 tanks, 150 large artillery pieces, and 1,500 other German vehicles. During this period the Fourth met and defeated elements of eighteen German divisions and brigades.

An armored division is designed to destroy the fighting power of an enemy and not particularly to capture territory. But consider what the Fourth did in accomplishing its mission. It swept down the Cherbourg peninsula on the right flank of the Third Army, captured Coutances, and raced down the coast to Avranches, where it took vital bridges and dams in an area where the Germans could have held up the American advance for many days if they had had time to blow them. From Avranches, the Fourth drove straight across Brittany, cutting off this great peninsula with its vital harbors by capturing Nantes and Vannes. As a by-product, the division contained the German U-boat base of Lorient.

Then it turned north in a great right hook while still on the right flank of the Third Army. It had the dual job of smashing the enemy before it and at the same time protecting the Army’s exposed flank in central France. This was one of the most difficult assignments of the war.

Orleans, Sens, Troyes, St. Dizier, and Commercy fell in rapid succession to the division’s highly-developed shock attacks. The Fourth pushed on to cross the Moselle River and encircle Nancy, forcing the Germans to withdraw from the city which for centuries has been the key to northern France. During the advance, crossings were forced on the Loire, Seine, Marne, Meuse, and Meurthe Rivers.

Once halted north of Nancy, and only by lack of supplies Tiger Jack’s ironclad family proved it could fight as well on the defensive as on the offensive when it repelled the heaviest German tank counterattacks of the campaign, destroying more than 200 German tanks in fifteen days of fighting from September into October.

So much for the cold statistics on Patton’s number one “spearhead.”

The Fourth’s energetic commander is not the only individualist in the division. It is full of happy extroverts, and all seem obsessed with the idea that the war must be fought twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, at top speed.

For example, there is the general’s personal reconnaissance Cub pilot, Major Charles Carpenter, a former Praying Colonel football player from Centre College and more recently a history teacher in Moline, Illinois, high school. A history teacher does not seem the type to earn the nickname of “Bazooka Charlie,” but Carpenter is a legend in an outfit where reckless bravery is commonplace.

If there is a fight within a hundred miles, he is in it or over it. His nickname stems from the six bazookas tied to the muslin-and-wood wings of his tiny Cub plane and fired from a trigger in the cockpit. Cubs were made to fly behind the Allied lines, not over the enemy. A good-sized rock in the right place would knock one of them down. But Carpenter tied on his bazookas and started flying over the German lines looking for tanks to shoot at. He has at least five of them to his credit.

More often than not Carpenter has landed in the middle of a busy battlefield to take a personal look, and he has taken an uncounted number of loose Germans as prisoners.

The legend started last summer when Carpenter was commanding the Cub unit attached to the division and was out in a jeep scouting for an advanced landing ground. He came upon a group of infantry pinned down in a ditch by sporadic 88 fire. There was also an American Sherman tank which was not advancing.

Carpenter jumped on top of the tank, grabbed the 50-caliber machine gun and fired a burst over the infantry’s head, with the advice that the next burst would be lower unless they attacked. Then, riding on top of the tank without a helmet and firing the 50-caliber, he led an attack that broke up the stalemate and took the immediate objective.

But he drove on. The German tanks in the vicinity were fighting a rear-guard action, and every time Carpenter came to a corner he would yell down into the turret, “Let ’em have it!” and the tank’s 75-mm. would bang away. This worked fine for five corners, but on the sixth he yelled, the 75 fired—and some distance away the bulldozer on another Sherman flew high in the air. No one was injured, but since both tanks involved belonged to another division, Carpenter was arrested. The irate commander was all for shooting the hard-working history teacher on the spot. Wood, hearing of the incident, rushed over and rescued his Cub commander and made him his personal pilot.

Carpenter weighs over 200, as does Wood, and with both of them flying in a flimsy Cub, the plane waddles around in the air like a bloated duck. However, weight or no weight, the bazookas are always loaded when it takes off.

Carpenter is quite outspoken in his ideas on how to fight a war. Briefly they are, “Attack, attack, and then attack again.” The whole division, from the enlisted men to the commanding general, echoes his sentiments.

There is Sergeant Edward A. Rejrat, a former steelworker from Scranton, Pennsylvania. He’s a tank commander. Rejrat’s thirty-ton Sherman turned a corner in a narrow street in Avranches to come face to face with a fifty-six-ton German Tiger tank sixty yards away. Rejrat ordered the tank driver to put on full speed and ram the Tiger before it could bring its gun to bear. One shot, and the Sherman would have been a tangled mass of wreckage.

The two steel monsters crashed with a metallic roar. The long-barreled 88 was too big to swing around at close quarters and engage the American tank. Rejrat brought his shorter 75 up against the turret of the Tiger and cut loose with four quick thunderous shots which rattled the American tank crew around like peas in a pod. The concussion from the last shell, a high explosive, overturned the Sherman, but Rejrat and his crew scampered out and away from the burning Tiger.

You couldn’t spend any time around the Fourth without hearing a dozen men say, “The guy you want to see is Clarke of the CCA.”

They were referring to General Bruce C. Clarke of Syracuse, New York, then a colonel commanding the CCA of the Fourth. In eight weeks of violent fighting he won the reputation of being one of the most brilliant young armored-force strategists in either the First or Third American armies, and certainly the most unorthodox and daring. Later Clarke was promoted to brigadier general and put in command of a combat team of the Seventh Armored Division. It was Clarke who delayed the Germans’ December breakthrough in Belgium by holding the key road junction of St. Vith against overwhelming odds, not for two days —as he had been ordered to—but for five.

Clarke served as an enlisted man in the Coast Artillery in the last war and later was graduated from West Point. He also holds degrees in engineering from Cornell and a bachelor of laws degree from La Salle University. In one tour of duty he taught military science at the University of Tennessee and served as wrestling coach there.

Clarke developed the CCA’s shattering shock assaults which captured German strongholds before the Nazi commanders knew what happened. At Troyes, where it looked like suicide to make a frontal assault, he spread his command out in old desert style and rushed the city at top speed, overrunning German gun positions before they could fire and hurdling antitank ditches. He forced his way into Troyes and took the garrison town in a matter of hours when it might well have taken days.

The rule book says that tanks should not try to fight in cities, but Clarke sent his medium tanks racing into Orleans so fast that they caught German officers walking in the streets with packages under their arms and shot them down in their tracks. In the ensuing all-night fight Clarke’s tanks fought up one street and down another and cleared Orleans without losing a single tank.

While preparing to attack Commercy, of World War I fame, Clarke heard that the Germans were about to blow the bridge. He quickly gathered up every available vehicle and tank and charged down into the city, firing every gun in a typical high-speed shock assault which makes use of the tremendous fire power of an armored division’s automatic weapons. So frightened were the Germans that they fled without blowing a single bridge, and the Nazi commander escaped in a staff car without his shirt.

Clarke led some of these attacks in his own tank. In others, he flew in a Cub over the attacking columns, directing the battles verbally by radio.

He has done just about everything with tanks that supposedly could not be done. Tanks, for example, are not supposed to be a match for Germany’s famed 88 gun, but Clarke’s Shermans have attacked and overrun dozens of German guns and shut the crews before they could fire a round. He has that rare faculty of being able to pick the enemy’s weak spot almost at a glance, and has so inspired the confidence of his men that they believe any attack he plans is certain of success.

I first met Clarke on the side of a hill north of Nancy. A tank battle was under way near by. He had rolled up in a dust-covered jeep for a quick conference with General Wood and Major General Manton Eddy, commander of the Twelfth Corps in the Third Army.

The enlisted men sitting around in foxholes and armored cars had taken the arrival of the generals with the usual indifference of front-line soldiers, but when the dusty jeep arrived with the husky tanned colonel, necks craned and there were murmurs, “Here comes Clarke.”

A strict disciplinarian and rather coldly reserved, Clarke did not enjoy the friendly place in the hearts of the men of the division that Wood commands, but there was no doubting the respect of officers and men for his ability.

While a stray German gun, which had been overrun but whose crew apparently was unaware it was surrounded by portions of an armored division, banged away so close that the concussion moved your shirt, Clarke spread a map on the ground and the two generals knelt down on each side and discussed the situation as though they were in their own homes.

None of the three looked up as infantry probed the side of the hill for the hidden gun. After getting his instructions, Clarke jumped up and was gone in a matter of seconds back toward his combat command.

A few days later, when rain bogged down the tanks, I was able to corner Clarke in a muddy straw-strewn tent and record some of his ideas on tank warfare.

“Warfare is mental, not physical,” Clarke began. “When you upset the enemy you have him licked, particularly the German. He is big and slow to react, and if you cut his communications and lines of contact he will just take to the woods. But if you give him time to sit down and get out the rule book, he is tough as Hell.”

Clarke himself has little respect for rule books, although he knows and reads them all. “We received the other day a battle-experience note in which some joker wrote that the American Sherman with its 75 is no match for the German forty-five-ton Panther tank with its heavy armor,” he explained. “That would have scared hell out of us if we hadn’t just knocked out more than a hundred Panthers with our Shermans and tank destroyers in a three-day battle.”

The American tanks were more maneuverable than the heavy German models, he explained, and could race in and fire before the Germans could bring their slower turrets to bear.

“Most people and too many officers think a tank was made to fire its big gun,” Clarke continued, striking his fist in his hand. “It wasn’t. It was made to carry a machine gun into close quarters with the enemy. The tank machine gun is the greatest weapon of this war and we should have more of them on our tanks. The big gun is for defense against other tanks.”

Clarke believes that the desert battles in Libya in which large forces of tanks stood off and slugged one another have warped the true conception of armored fighting. Tanks must keep on the move and close in on the enemy to get at the soft spots, such as supply columns, headquarters, and gun crews, he said.

“Tanks are weapons of terror. They have a definite mental effect on the enemy when they come charging in, firing their machine guns. From Normandy to the Moselle River most of my tanks never fired their basic loads for their big guns.

“In fact,” concluded Clarke, “the safest place to be in this war is behind the enemy lines. They don’t know what the hell to do when you get there, and they just run.”

Clarke had the statistics to prove his point. The whole division had suffered fewer casualties in eight weeks of offensive warfare behind the German lines than it did in two weeks of defensive warfare north of the Moselle. Small wonder that the Fourth Armored Division’s battle cry is “Attack, attack, and then attack again!” (Liberty Magazine, Feb. 10, 1945)

By Sgt. Saul Levitt

YANK Staff Correspondent

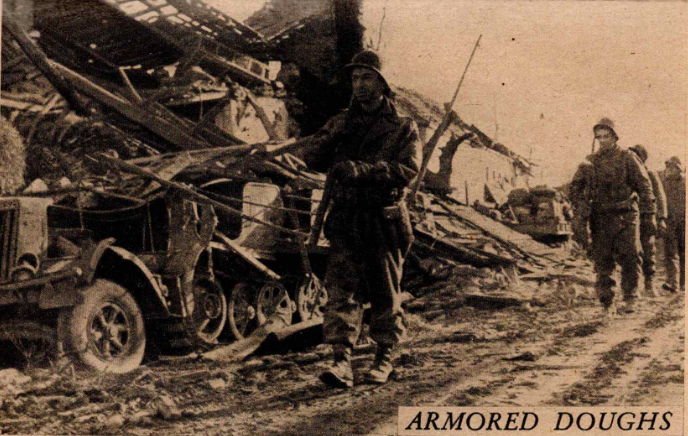

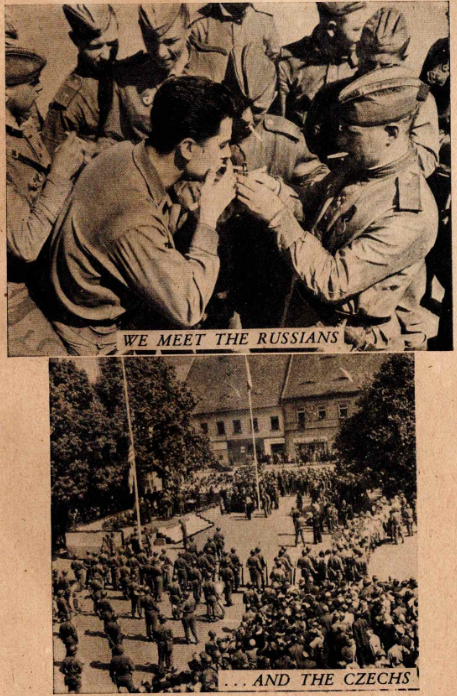

WITH THE 4TH ARMORED DIVISION IN GERMANY—The iron tread of the 4th Armored Division is moving across Germany and nothing can hold it. Everywhere along the way the earth-shaking power of its big tanks is visible. The crowds of people streaming along the roads—French, Russian and Czech—are freed peoples beginning to march home through the furrow plowed by the armor. That armor is still ahead of us, it doesn’t stop. What is more, even the CPs behind it don’t know exactly where it is.

“Get to the next town and keep going,” they say. “You’ll find it.”

We are on its track all right, for we’re moving through towns where the ruins still smolder and smoke. “The 4th Armored was here two days ago,” someone says. Elsewhere, a great furrow in the fields shows where the tanks bedded down and rested for a few hours.

Our jeep follows the armor’s tracks. There are fires on the horizon. Around us lie the hostile fields, the stretches of woods where no one moves. Someone is probably watching from there, though, for it is off the track of the armor. The following Infantry will have to clean this hostile country up.

We came to a town which Combat Command “B” of the 4th Armored plastered a day ago. It is still smoking. The effect of the roaring tanks and of the long, black gun-muzzles that stick out ahead of them shows in the faces of the German civilians of this community.

“They’re around here somewhere,” says somebody. “Get on the autobahn, pick up a 4th Armored supply truck and keep following.”

There is a low sky overhead. We find the armor’s deep furrow in the muddy hills, and climb and reach the autobahn, a great German highway, where traffic is meager and fast. A 4th Armored truck is ahead and we are catching up. Some planes make their turn and we get out of the jeep and, by God, they are Me-109s beating up the road toward us.

There is nothing faster than a plane and nothing slower than a man at a time like this. We scramble down an embankment and into a culvert and all hell is breaking out above us. The 50 calibers on the ground and the 20mm cannonfire of the planes are both going at once and the ground above is being rapped with the sound of giant hailstones. Then silence.

Again they come. The Germans don’t want us on their favorite highway. Three times more we hear the thunder of their engines, the whistling of their wings, and the rapping of the 20 mm. hailstones. Then it’s quiet again. We climb up the embankment and into the jeep and get going.

We wish we could find that armor somewhere and 25 miles farther on we finally overtake its tail-end. Down below the highway rest the tanks, the half-tracks, the jeeps and the big guns spread out in a pasture like resting cattle, right in the middle of Germany as if to say: “What are you going to do about it?”

There are fires on many parts of the horizon. The biggest is to the south, where a whole train is burning as one car after another explodes. “We were trying to get a couple of Panther tanks on the other side of the tracks,” says someone. “So we got the train which was in our way.”

The nose of the 4th. Armored is still farther up, past Creuzberg. We are some 25 miles west of Gotha and more than 75 miles from Frankfurt, which was yesterday’s news. German women who pass in the village of Nesselroden move about with their faces averted. In the house we stop at there is a place marked for everything and everything is in its proper place. A place is marked for the table towel, another for the glass towel, a third for the blessing of God on the house, a fourth for the picture of the son in the Nazi uniform. Signs and slogans are everywhere. All night long a clock in the house rings out the hours and half hours, adding another touch of order to this too-perfectly-ordered home and providing assurance that even in his sleep a good German will know what’s what.

The next day we move up the long train of armor toward Combat Command “B”. It is a winding trail that avoids the autobahn and the big town of Eisenach, which has not yet been taken. On we go, over back-country roads, past civilians with beaten faces. The Werra River isn’t wide here, but there was a tough fight for it yesterday. The 4th Armored’s 24th Armored Engineer Battalion bridged it under enemy fire, saw their bridge knocked out, and put it in again. A small river and small bridge, but a big operation.

We get past Creuzberg, which resisted yesterday and paid for it, for there is no patience in the 4th Armored. The 4th wrecked Creuzberg because Creuzberg wouldn’t surrender, and now people are shoveling through the still-smoking ashes, looking for things.

Farther on we move, through a woods, and get one of those shocks of a kid moving through a toy chamber of horrors at Coney Island. There are dead German tanks in the woods, facing the road and hidden until you come right up on them. Then it’s as if the tanks were alive and had got you right there. But the tanks are dead. This was a German tank-maintenance and repair area. Live American armor has already caught this crippled German armor, lighting charges under it and throwing white phosphorus stuff at it. Now the German tanks smoke and burn, and one is just a pink stove, silently burning in the woods.

This is evidence of how the Germans have been driven to cover. They have had to hide tank-repair areas in the woods because nothing that shows in Germany is safe from our air these days. We have driven them to the woods and to the caves, and now we are pushing them east, out of their own country.

We get out of the woods in a hurry because it is eerie there and maybe Germans are watching us go by. More fires are burning on the horizon. The deep track of the tanks is still ahead of us. We reach a town which is only a few miles from the big city of Gotha. The German air comes up again and the sky is filled with smoke and the sounds of anti-aircraft and cannon. We climb a hill to another woods, where Me-109s are tucked in among the trees. The Germans had smashed these planes themselves as the armor ran them down. These deadly little planes have knocked out may Forts and Libs, and here they are broken and burnt by the Germans in a woods.

The 4th Armored is moving out of Metebach now, and we get in behind a half-track and follow down the road. The tanks wheel in their iron treads, the machineguns point at the sky, and Aspach shows up, five miles from Gotha. From within the houses, the civilians watch, but if you look at one of them steadily he turns away. The power of the armor is shadowed in these German faces. They stick their heads out of their windows and watch blankly, absolutely neutral.

And now the tanks and half-tracks move up to a crossroads outside of Aspach. They cover the roads out of town in long powerful lines as the evening comes down. More fires blaze on the horizon. The German air comes over again, the Me-109s moving across the sky as the .50-caliber fire goes after them. The planes twist, turn and plunge through the sky after a Cub plane, like a hawk after a sparrow. The Cub comes down low over the fields with an Me dropping after it and the guns of the armor drive the Me off just in time. The German air comes in again as the sun goes down—two, three, four times more—and one at last grabs a vehicle in the long line on the road and the vehicle begins to burn. Another Me comes across, no more than 10 feet above the column, turning on one wing, almost striking the ground, but keeping going. No planes are knocked down here tonight, but the report is that more than 34 were brought down yesterday and we have been able to count at least six wrecked ones during this movement toward Gotha.

The 4th should be in Gotha by tomorrow morning, and now it rests outside the city. Rain begins to fall, but the fires sowed by the big guns still burn on the horizon and so does our column’s vehicle which the Me hit on the road. The 4th will move through fires into the city of Gotha tomorrow morning.

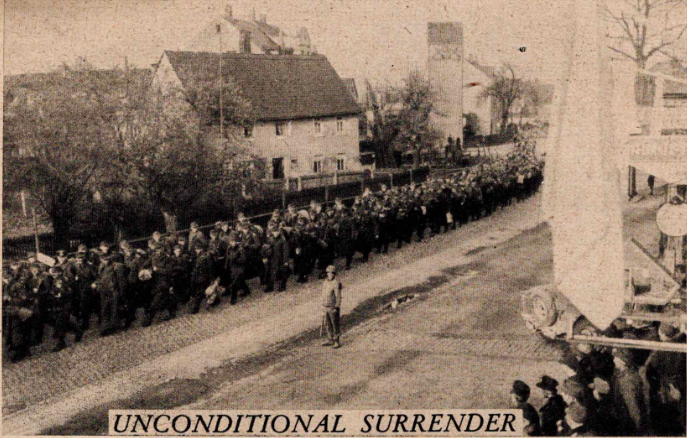

In the morning there is a brief moment of indecision. Gotha has been asked to surrender, and if it will not, then the big guns will go to work. The 4th isn’t going to wait very long. Finally, it appears that Gotha will surrender. The surrender has been demanded by the Division and at last the answer comes through the armored infantry battalion, which is up front at the edge of the city. Minutes from now another German city will fall and within 10 days and 200 miles of movement we will have taken Darmstadt, llanau, Aschaffenburg, Hersfeld and Gotha.

The German air comes up over the road and we get into a patch of woods. Under the roar of the guns and the enemy engines overhead, the infantrymen had a word or two to say about this ebbing war. Pfc. Joseph Tegge of Anderson, Ind., a. rifleman, wanted to know what the hell the Germans are fighting for at this stage of the game.

“A stubborn bastard,” he says. “He knows he’s done for, but he keeps on fighting anyway.”

The men are exasperated; it doesn’t make sense anymore. Yesterday, 16 of our infantrymen had been killed while protecting a tank.

We leave the woods and move on, and then the enemy air goes to work again and we get into a barn where T/5 Wilson E. Kendall of Ogdensburg, N. Y., who has been with the 4th Armored since Pine Camp, comes up with that one about going home.

Then the air is clear once more, like after a rain squall, and we get into the jeep and move slowly down a hill into Gotha, past German dead in ditches, past a burnt-out American tank, past a hospital for German soldiers where a guy at a window thumbs his nose at us and then disappears. If he tries that on our tankers, they’ll surely go up after him.

We get down into the square and are at the City Hall, where pieces of broken glass lie all over the streets.

We are again in the midst of one of those starting-from-scratch moments. In the City Hall are the temporary German officials of the city of Gotha together with Lt. Robert Townsend of San Antonio, Tex., aide to the 4th Armored commander, Major General William M. Hoge.

“You will first of all bring in all arms, cameras and ammunition,” says Townsend. He sits down in the old council chamber of the City Hall, surrounded by murals of the ancient city. A Hollander, a young fellow from Rotterdam who speaks both English and German, acts as interpreter. He has been in Germany for several years, another one of the millions of dragooned “auslanders,” or foreign laborers, in the Reich.

The Germans around the table look shrewd and they talk with the tact of losers. Order begins to appear. The men of the 89th Infantry Division show in the town, moving from house to house, and you can see them in the square from the windows of the City Hall.

A Polish woman with a small child stands outside the door and the assistant Division commander, coming into the council chamber, pauses for a moment in the doorway and tells the woman that things will be better for them soon.

We leave Gotha that afternoon, grabbing the tail of the 4th Armored as it goes through, and now the columns curve south, driving 15 miles to Ohrdruf and Mühlberg, and coming to rest more than 200 miles from the Rhine.

On the very edge of Mühlberg the column comes across what must be the last German train going east. The Division’s artillery simply wheels a 155mm. howitzer around and knocks out the train. It is Sgt. Roy Mercurio’s gun crew which does this. Mercurio is from Toledo, Ohio, and his gunners are Cpl. Cleo Smith of Los Gates, Calif., Pfc. Homer Garrison of Shelbyville, Mo., and Pfc. Joe Valenti of St. Louis, Mo.

When we reach Mühlberg, a soldier asks: “How far are we from Texas?” We draw a map on the ground, using a stick for a pencil, drawing the outline of the eastern coast of the United States, as we remember it, and the outline of the western coast of Europe, and then France and Germany as far as Gotha. We figure over that map for a while and finally somebody says: “Nearly 5,000 miles to Texas, maybe.” And the soldier from Texas sighs and walks off.

Heading back, we can follow the long furrow which the 4th Armored has plowed since it broke through at a point above Frankfurt. This country behind the 4th Armored, which was deadly three days ago, has been cleared. Now the liberated, thousands of them, are going home through the furrow. French and English soldiers of 1940, Czechs, Poles and Russians are on the road. We can go back now along one of the world’s finest roads, which Hitler built for war and not for civilians, and which the Americans are now using for war. Our traffic, our supplies and infantry, is pouring through, pouring east, as thick as Fourth of July traffic on the Lincoln Highway.

It is one of the great sights of our time and on the faces of the Germans along the way there is still the look of numb amazement that an enemy from thousands of miles away actually rides through Germany now.

And tomorrow morning the 4th Armored will cut its tread deeper into the German earth again, moving eastward.

* * *

German soldiers facing the 4th Armored were told (according to a captured document): each American had qualified for the Division by proving that (1) he had been born a bastard, (2) he had murdered his mother—TIME, March 19, 1945.

* * *

By Joseph Driscoll

New York Herald-Tribune, January 1945

Cobra King is the name of a shell-scarred, stout, armored forty-ton Sherman tank. With a first lieutenant from Texas in the turret the Cobra sliced through the German circle about Bastogne the afternoon of December 26, 1944. Other men and tanks of the Fourth Armored fought as hard to relieve Bastogne, but the Cobra got there first—at 4:45 p. m. the day after Christmas.

The tank commander was Lieutenant Charles P. Boggess, Jr., who played high school football at Greenville, Ill., before moving to Austin, Texas.

At the tank’s 75-millimeter gun was Corporal Milton B. Dickerman, of Newark, who made bomb racks in a Kearny, N. J., factory before he became a tanker three years ago.

The loader, Private James G. Murphy, hails from a small farm near Bryan, Texas, and was attending Sam Houston State Teachers College at Huntsville, Texas, until he got in the Army two years ago.

The bow gunner was Private Harold Hafner, of Arlington, Wash., who was graduated from Arlington High School in 1943 right into the Army.

A Georgia tractor farmer, Private Hubert J. J. Smith, of Cartersville, drove the tank. His initials stand for James Jackson, but he has no idea why he has two middle names.

By noon of December 26 Cobra King squatted on a ridge south of the Belgian hamlet of Clochimont. Its heavy-barreled snout pointed north-east toward Bastogne three miles away.

One of the great tank fighters of this war, Colonel Creighton W. Abrams, of West Newton, Mass., commander of the 37th Tank Battalion of the 4th Armored, swept his arm forward in the signal to advance. Cobra King snorted into the attack at the head of a column of tanks and armored infantry halftracks. The armored vehicles charged up the snow-covered road like a gray file of trumpeting elephants.

Incidentally, we saw a real elephant on this road one day, passing tanks going the other way and making an odd contrast, but it was a circus elephant entertaining children.

Lieutenant Boggess, commanding nine mediums in the tank push that relieved Bastogne, had warned his men that it wasn’t going to be a picnic. The men haven’t been on a picnic since the Fourth Armored left the States a year ago, so that was all right with them.

A veteran of thirty-three years, Lieutenant Boggess described the situation:

“The Germans had these two little towns of Clochimont and Assenois on this secondary road we were using to get to Bastogne. Beyond Assenois the road ran up a ridge through heavy woods. There were lots of Germans there too.”

“We were going through fast, all guns firing, straight up that road to bust through before they had time to get set. I thought of a lot of things as we took off. I thought of whether the road would be mined; whether the bridge in Assenois would be blown, whether they would be ready at their anti-tank guns.”

“Then we charged, and I didn’t have any time to wonder.”

Spraying machine-gun and cannon fire, the tanks charged with throttles open.

“I used the 75 like a machine-gun,” Gunner Dickerman said. “Murphy was plenty busy throwing in the shells. We shot twenty-one rounds in a few minutes and I don’t know how much machine-gun stuff.”

“As we got to Assenois an anti-tank gun in a halftrack fired at us. The shell hit the road in front of the tank and threw dirt all over. I got the halftrack in my sights and hit it with high explosive. It blew up.”

Dirt from the enemy shell burst had smeared the driver’s periscope.

“I made out okay, although I couldn’t see very good,” Driver Smith drawled. “I sorta guessed at the road. Had a little trouble when my left brake locked and the tank turned up a road we didn’t want to go. So I just stopped her, backed her up and went on again.”

Unlucky Assenois was blowing to bits under artillery barrages laid down by American guns. Through the smoke, dust, flying debris and shell splinters the armor drove on. Our artillery kept the enemy down and cut short his defensive fire.

“Bastogne was the next town down the road, but we still had those woods to go through,” Lieutenant Boggess recalled.

Kafner kept his bow machine gun playing around the fir trees and the road ahead. Dark enemy figures ran and fell in the dusk. In the forest darkness a square concrete blockhouse painted green loomed ahead. Dickerman sent three shells smashing into it. Later the infantry found twelve Germans there.

Lieutenant Boggess pulled the galloping Cobra down to a canter. Colored parachutes clotting the countryside; some of them caught in the tall trees, indicated where ammo, food and penicillin had been dropped to the American paratroops and tankers besieged in Bastogne and its defense perimeter. The question now was whether the Cobra King was among friend or foe.

“I spotted some foxholes filled with men in G. I. uniforms,” Boggess continued. “I yelled for them to come out, because we thought the Germans might have men in our uniforms around Bastogne ready to knock us off. Nobody moved, so I called again.

“After they heard me say that it was okay and we were the 4th Armored, a lieutenant from the engineers climbed out of his hole and said he was glad to see us. They had me covered, too, I found out.”

“You know,” commented New Jersey’s Dickerman, “We never really got to see that town of Bastogne after all. Wasn’t the M. P.’s fault, either—no off limits business. Soon as we got to the perimeter defenses we turned right around to guard the road on the edge of town.”

Sgt. Joe McCarthy, YANK Staff Correspondent, reporting the seemingly impossible swing of Third Army units toward Bastogne at the height of Von Rundstedt’s breakthrough, in the January 21, 1945 issue of YANK, included the following:

The most spectacular role in the move was that played by the Fourth Armored Division which dashed to the aid of the besieged 101st Airborne Division at Bastogne. The story of what happened during the same time to the 26th Division, which moved up on the Fourth Armored’s right flank and tackled the tough job of crossing the Sure River to the east of Bastogne without getting much of a play in the newspapers, is less dramatic but more typical. It gives you some idea of what it was like for the average infantry outfit that was in on this deal during the joyous Christmas season of 1944.

Nobody in the 26th Division can get over the way their part of the Third Army made its move north from Metz. Probably no military movement of such a large scale was ever carried out with more speed and less red tape. The book was thrown out of the window and all the OCS rules about road discipline were forgotten. Each outfit simply tried to get its vehicles on the road as soon as possible and, after they were on the road, to keep moving.

“And them roads were jammed,” one of the truck drivers said. “Us and the Fourth Armored and God only knows how many other divisions. We were bumper to bumper all the way. Good thing it was a cloudy day. If the Germans ever had air out, they would have slaughtered us.”

By SAUL LEVITT

Since December 27 it has been possible to come up from the south into Bastogne through the corridor originally established by elements of the Fourth Armored Division. The corridor is still so narrow that you can see and hear the battle on both sides of the main Arlon-Bastogne highway, but since the 26th there is no longer any Bastogne pocket. Now the fight takes place three quarters of the way around Bastogne, but the evidence of the desperate eight days of fighting until the Fourth Armored Division broke through has not entirely disappeared.

* * *

Meanwhile, to the south, elements of the Fourth Armored Division commanded by Colonel Creighton W. Abrams and its attached unit of infantry from the 80th Division, the 318th Regiment, were fighting north in a series of savage encounters, trying to force some kind of passage to Bastogne.

Farther away, at the 12th Evacuation Hospital, volunteer doctors and medics prepared to take off by plane and drop down by glider into the Bastogne pocket. The next day five doctors and four sergeant medics took off.

Some of them had never been in a plane before. The doctors thought it was going to be a parachute jump at first but were ready anyway. They took off on Dec. 26, landed near Bastogne in the snow, and set up their hospital. There could be no question of taking their wounded out, not until the lifeline from the south could reach Bastogne.

The lifeline was being made down below Bastogne. It was being forged by tanks through teller mine fields on the roads.

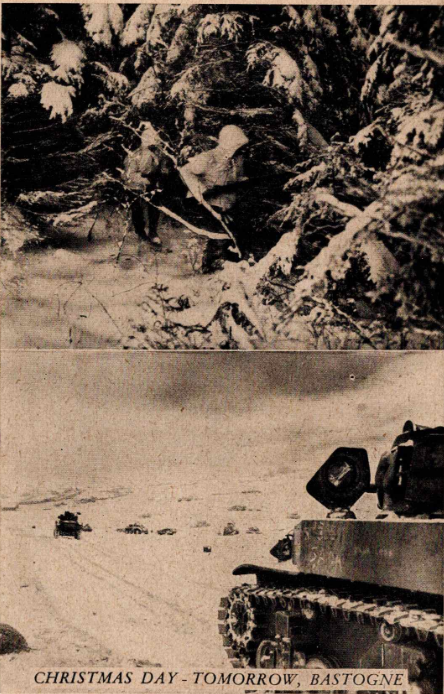

The Fourth Armored was going north. Stopped cold at noon of the 26th by heavy resistance and with further movement possible only at the heaviest cost, they decided to force through at once. They knew it would have to be a very fast and continuous movement. The armor took off, playing machine-gun fire on the woods and surrounding hills. In that drive through to Bastogne, lasting more than four days, they killed, captured, and took prisoner more than 2,000 Germans. But they did not come through easily. The straight rush through the German ring cost lives.

In the woods north of Assenois, Lt. Charles Boggess Jr., lifted his head out of a turret and spoke to the first American soldiers on the inside of the pocket. They were engineers of the 326th Airborne who had maintained the southernmost salient of the perimeter. As Lt. Boggess lifted his head out of the turret nobody said anything to him. He said, “Come on out, it’s all right. It’s the Fourth Armored.” Nobody moved or answered. It was late afternoon under the dark green firs. Boggess yelled again, and again nobody answered.

Finally a young officer crawled out of a hole, but the two men kept each other covered. The engineer officer said at last, “I’m Lt. Webster.” They shook hands. Later Gen. McAuliffe rode out in a jeep and shook hands with some of the men. And as dusk started to come down Col. Abrams rode through—a short stocky man with sharp features—already a legendary figure in this war.

The Fourth Armored seems to span the history of this war. In France, you met the division as it made its first big play in the hot summer days, going through Coutances in our big breakthrough after St. Lo. Again you ran across the outfit in the fall as its big tanks lumbered through the mud of Vollerdingen, near the German border, with the tanks out of contact across the mine-covered hills where neither man nor jeep could follow them.

And now they showed in Bastogne, lumbering through the snow with the men of the 80th Division, against the blooming green of the pine trees and into the town itself ...

The battle of the Bastogne pocket ended at 1545 on December 26, 1944.

By Jack Bell

Columbus, Ohio, Citizen, January 6, 1945

WITH THE U. S. FOURTH ARMORED DIVISION, Belgium—The road to Bastogne is paved with bad intentions—enemy and friendly tanks which slugged it out during the dramatic drive up from the south to relieve the 101st Airborne Division and its complement of tanks.

Other battles are in progress as generals feint and parry with armies across the frozen wastes. But the soldiers have their pets, and every man of the Fourth Armored Division has the battle of Bastogne heading the “Hit Parade.”

Bastogne caught the public fancy. We shot 20,000 troops in to save it. Every soldier overseas knew of the encirclement which shut them off, the days of fog which shut off air power for four days. The entire Allied Expeditionary Force had one question: “What about Bastogne.”

I was with the powerful and confident “Fourth Armored” the day its tanks and armored infantry rolled off the line of departure toward Bastogne. Snow fell gently. Mud was deep, but day after day they forded and bridged streams, mopping up the steadily stiffening German opposition. Each night they paused, then fought on.

“For if we get only 2,000 yards we’re that much nearer the men in Bastogne,” was the expression of Lt. Col. Delk Oden, Elgin, Tex., tank battalion commander.

At last they met in pitched battle. South of Bastogne in the villages of Chaumont and Assenois, dozens of tanks along the streets and in the field are mute evidence of the mighty struggle that preceded the entry into Bastogne, leaving both armies weaker when it was over.

Then one evening at 4 o’clock, Lt. Charles Boggess, Jr., Greenville, Ill., up in the hatch of a tank, said: “You all know we’ve got to get to those men in the town. All you’ve got to do is keep em rollin’ and follow me. It won’t be any picnic but we’ll make it.”

He buttoned down the hatch, roared away and the others followed. They rumbled through wrecks of tanks in Assenois, through a terrific barrage from American guns, a daring maneuver that paid fat dividends for the artillery kept the Germans in holes and 400 prisoners were taken by the infantry which followed.

Up the road Lt. Boggess and the tanks rolled. The smoke in Assenois caused a slight break in the column after four had rounded a turn. The others stopped to check the route. The pause gave the Jerries time to toss Teller mines onto the road. A halftrack hit one. Captain Bill Dwight, Grand Forks, Michigan, leaped from a tank and threw the mines off the road and the rescue party rolled on.

They went full speed, with every machine gun spraying the roadside and the woods every foot of the way, turning the quiet dusk into mad warfare. Germans were running everywhere, usually away from the blazing guns.

Lt. Boggess met outposts of besieged Americans outside of the city, but the men were not quite convinced that his tanks were friendly. It had been a long time since they had seen friendly troops. Nor was the lieutenant sure that he had met friends, or Germans in American uniforms, which they have been wearing wholesale since taking American prisoners.

But both soon were convinced, and the siege ended.

That is, it ended after a fashion. The infantry followed the tanks, mopping up both sides of the road. Trucks of food and shells and ambulances dashed into town.

The world was joyous, excepting Germany and Japan that the Fourth had fought through and everybody said, “Bastogne is saved; thank God.”

At which time the “Fourth Armored” men dug in for what they knew would be a grim battle to keep the breach open. But, they’re old hands at this business of war and went to work. Hardly had they had time to set up their defenses before giant Tiger tanks rolled down from north of Bastogne. Our pilots came through the clouds to bomb the Tigers. We 30 lost tank destroyers, but wrecked the Tigers. A flock of light tanks shot 30,000 rounds into the woods in five minutes, and the Jerries lay dead by the hundreds. Infantrymen crawled through the snow to hit the tanks, and—

Yes, the Germans swarmed into them so furiously at times that they had to withdraw. But they never ran. Day and night they fought on, unheeded because the world which had been so concerned and had heard that Bastogne had been saved—and forgot it.

They’re having birthday celebrations just now, with fingers on triggers—just one year overseas and six months in combat. They were in the Normandy breakthrough and cut off the Brittany peninsula. One combat team liberated Nantes, and Orleans. They drove to the Seine and took the bridgehead at Troyes. They crossed the Marne three times, forced the withdrawal of the Germans from Nancy on the Moselle, and went on across the Saar. And when the Bastogne situation grew desperate, the Fourth Armored was rushed up to spearhead the corps drive to save it.

It is one of our Army’s good, tough outfits, the type that has made General George S. Patton, Jr., famous. Its skipper (then) Major General Hugh Gaffey, was Patton’s chief of staff until he came here. What a swath they have cut in Jerry’s army: thousands of prisoners, thousands killed and wounded, 450 tanks, 250 artillery pieces and 1,600 other vehicles since their landing in France.

And as this is written they await further attacks by the increasing German power, in the war’s biggest winter battle.

By Collie Small

GERMANY, BY WIRELESS. It had been a fitful night filled with the thunder of big guns and the rumble of German traffic moving along the river road, but now the noise had died away. The tankers sat waiting for the fog to lift, so they could move across the last 1,000 yards to where the Rhine swept around the big bend from Coblenz.

Then the explosions came—dull, muffled booms that rolled up from the river and shouldered their way through the filmy mists hanging over the orchards and gently rolling fields. Hidden in the fog, the slender Crown Prince Wilhelm Bridge disintegrated with a roar as the center span collapsed into the river. German soldiers and vehicles catapulted from the bridge in a tangled shower of horses, carts and men. A machine pistol spoke sharply in short sentences, then stopped. The tanks moved.

Major General Hugh J. Gaffey

Division Commander

3 December 1944-21 March 1945

At the river front, they swung right and crunched over the broken bodies and smashed vehicles strewn along the tree-lined highway. They lumbered into Urmitz, moved through streets still heavy with the pungent smell of battle smoke, than followed the road out to where the ragged stump of the bridge stood in a maze of twisted railroad tracks and girders hanging down into the river. There the column halted and the fabulous colonel who commanded the tanks turned to the equally fabulous major who commanded the armored infantry, and said, “Hell, this is the Rhine, and we’re just sitting here looking at it. Let’s go spit in it.”

They had come a long way. July, 1944, was hot and the dust swirled across the beach in stifling clouds when the fledgling 4th Armored Division’s shiny new white-starred tanks rolled up through the surf and started down the road to Ste. Mere Eglise on the shattered Normandy coast.

That was the first mile. The first prisoner was a gangling, bedraggled SS deserter who shuffled across a marsh to give himself up to the curious tankers. At Coutances, burly Maj. Gen. John S. Wood, who then commanded the division, strode into the town during a heavy artillery barrage and personally captured a German soldier.

Avranches was next. Pvt. “Red” Whitson, of Indianapolis, sat at a curve in the road, playing his machine gun like a garden hose until two dozen vehicles were burning fiercely and four dozen German bodies sprawled in the road where a plunging mass of maddened horses tried to wrench free from their traces. They left Whitson in Avranches, slumped over his smoking gun.

Then the division broke through the German defenses with a tremendous rush and sealed off the Brittany Peninsula. The mass of armor wheeled east on the right flank of Patton’s 3rd Army and started a sweeping right hook that carried clear across the face of France. In five days, three German infantry divisions and four regiments from other divisions were swept under the avalanche of clattering tanks. The swift spearheads smashed fifty-four miles to Rennes, Breton capital, hacking away at vital enemy communication lines. They sped seventy miles to Vannes. One combat command struck toward Lorient on the Brittany coast. Another drove eighty miles to the cathedral city of Nantes. There has never been anything like it.

The 4th Armored Division became a shifting island of armor in a sea of milling German troops. The tanks moved so fast that fuel and ammunition had to be flown to them from England. They ran off their maps and had to have new ones rushed from England by plane and dropped to the columns on the road. On August fourteenth, they raced 153 miles to St. Calais, refueled and within six hours were rolling again, toward the city of Orleans on the Loire. Combat Command A attacked Orleans early the next morning, took it by two-fifteen in the afternoon and turned it over to the 35th Infantry Division. On the same day, Combat Command B left the Lorient sector and sprinted eastward 264 miles in thirty-four hours, finally halting at Prunay.

In a little more than seven weeks, the 4th Armored spearhead hurtled from Normandy to the Moselle River, rolling up some 1,500 speedometer miles. They threw a pincers around beautiful Nancy and in a roaring fifteen-day battle knocked out 281 German tanks. It was on the Moselle that Sgt. Constant Klinga, of Brooklyn, made his classic observation, “They got us surrounded again, the poor devils.”

It was near Nancy that Captain James H. Fields, of Fort Worth, Texas, an armored infantry platoon leader, took fifty-five men up the bloodiest hill in Lorraine. Enemy tanks crawled up the other side of the hill and rolled down at the doughboys in their foxholes. The German tanks loomed over the desperate infantrymen and fired point-blank into the foxholes with their big 88’s. The doughboys fought wildly, but, one by one, the foxholes went silent. Shrapnel ripped into Field’s face and filled his mouth with jagged steel splinters and bone fragments from his shattered jaw. The young captain jammed a compress into his mouth, held another over his gaping cheek, and continued to fire with his left hand. He directed the shrinking platoon with hand signals and penciled notes passed from one foxhole to another. When he staggered down the hill twenty-four hours later with thirteen dazed survivors, they carried him away to a field hospital and awarded him the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Then the division plunged into the Saar. A cavalry troop stormed Gosselming and captured, intact, the bridge across the Saar River, after which they mopped up the village and took, among other prisoners, the German demolition crew charged with blowing up the bridge. They were sitting quietly in a local beer parlor when the cavalry jeeps burst into the town.

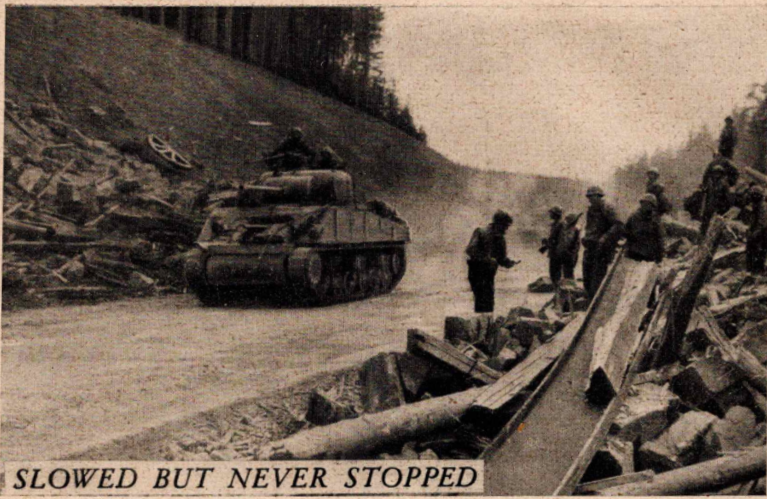

At Domfessel, the enemy road blocks were strong and well defended. So the leading Sherman charged out of an orchard and bulled its way between two houses, tearing down the walls on both sides of the narrow opening. The other tanks churned over the rubble in single file and then fanned out into the town to complete the capture.

They were still slugging away in the Saar against bitter German resistance when Patton called for Gaffey. The 4th Armored swung away from the enemy and raced north over the black-topped roads on the famous “Fire-Call Run” to besieged Bastogne under stern, aloof Maj. Gen. Hugh J. Gaffey, of Austin, Texas, successor in December to General Wood, and since promoted to corps commander. The tanks rammed their way into Bastogne and left the battered 5th German Paratroop Division reeling helplessly in its wake, 65 per cent of its strength smashed. The siege was lifted.

The tanks drove on through Bastogne. Lt. Robert Pearson, of Highland Park, Michigan, peered down from the cockpit of his tiny Cub artillery-observation plane and spotted tank movements on the edge of a woods. Pearson and his flimsy puddle jumper came down through a storm of small-arms fire to seventy-five feet to make sure the tanks were German. Then he swept away, marked the spot on a map and dropped it to the American tankers on the ground.

Under Lt. John Kingsley, of Dunkirk, New York, six Shermans slipped into ambush, only the tops of their round turrets showing above the thick foliage. The Panthers poked their long-nosed 88’s into the open and started moving across an open field. The big guns on the Shermans roared. The first German tank burst into flames, but the rest kept coming until eleven had strayed out to their death. Kingsley leaned on his turret and gazed wonderingly across the field at the eleven smoking tanks. “If the German who commands that tank company isn’t dead,” he said, “I hope they promote him to battalion commander. We could use more like him.”

The tanks were still attacking when orders came to disengage. In one of its most ticklish operations, the entire division eased away from the enemy at night, blacked out all its markings and quietly moved southward into position east of Luxembourg, where German armor was massing for an expected counterattack. The 4th Armored waited patiently, but in vain. The counterattack never came.

Patton, ringmaster for this most potent collection of armor, long had dreamed of fighting on the Rhine. At a press conference when the 3rd Army was still grinding slowly ahead against subborn opposition in Eastern France, the “Old Man” suddenly rose from his chair, strode stiff-leggedly across the room and drew the curtains back from his map while newspapermen crowded around. He waited until the room was quiet. Then he pointed to the thin blue line that marked the storied river and nodded his head slowly, as if in anticipation of some great and deep satisfaction yet to come. “That will be the day, gentlemen,” he said. “That will be the day.”

A wet snow was falling at seven-thirty in the morning when the first light tank of Combat Command B clattered across the bridge over the Kyll River near Metterich, under diminutive, bespectacled Brig. Gen. (now Major General) Holmes E. Dager, of Union, New Jersey. The objective was the Rhine, sixty-six miles away through the rugged Schnee Eifel and across the undulating middle-Rhine plain. The night before, Colonel Creighton Abrams, of Agawam, Mass., deceptively pink-cheeked commander of the 37th Tank Battalion and a living legend among tankers, told his men, “The board of directors has met. We jump off at seven-thirty, and it’s ’Katy, bar the door.”

Fortified with a week’s rations, in case they outran their food-supply trains, Combat Command B moved up through the bridgehead which was established on the east bank of the Kyll by the veteran 5th Infantry Division. Combat Command A was to parallel Combat Command B to the north. The orders were simple; “Get to the Rhine.” Abrams didn’t even bother to ask what lay between his tanks and the objective. “If I plotted German divisions on my map,” he said, I’d be too frightened to move.”

Five hundred yards out of its bridgehead, Combat Command A bogged down hopelessly in the mud. Its route was hastily altered and Combat Command A was ordered to fall in behind Combat Command B. They tried to break Combat Command A away again, but the mud was too heavy on the alternate roads available. So the 4th Armored Division, Combat Command B leading, rolled along one narrow road, strung out along a sector sixty-six miles long and twenty-five feet wide.

The spearhead slashed into the surprised Germans from the south instead of from the west, the direction from which the enemy expected the attack. For the first nine miles the tanks moved parallel to the German lines, drawing fire from both the West and the east, but rolling up the enemy flank as they went. Then they turned east and the rat chase was on.

Nimble light tanks and heavy assault guns led the way over the narrow, twisting roads through the pine-clad hills of the Schnee Eifel. Halftracks and other vehicles became mired and the tanks had to tow them a part of the way. The snow turned to rain at Badem and the enemy attacked with tanks. Four of them were knocked out in a brisk duel on the road and Combat Command B pushed on past the burning hulks.

Abrams raced up and down the column in his jeep or jumped into the turret of his Sherman, pleading with his men, swearing at them, encouraging them. It was he who kept them going when it looked as though they might bog down. Once the irrepressible young colonel knocked General Dager’s helmet off with a blast from his big gun when the general got too close to the muzzle. The cherub-faced demon was never still. He ran the gamut of vocal expression from stevedore to senator and back. He often used an obscene battle cry that crackled out of radios the length of the column like the snap of a whip. At other times he just said quietly, when things were sticky, “All right, boys. Let’s get a helpin’.”

When the tanks couldn’t do it, the armored infantrymen climbed down off the tanks and did it. Major Harold Cohen, a hearty shirt maker from Spartanburg, South Carolina—whose postwar plans are whimsical enough to include shirts with pockets in their tails—commanded the 10th Armored Infantry Battalion attached to Combat Command B. With complete faith that the particular tank crew with whom they rode was the greatest tank crew in the world, the doughboys rode outside the same tanks every day, clinging to the slippery Shermans by means of special handles the tankers had welded on for them. Nothing short of death could make a doughhoy change tanks. When Cohen told Abrams how proud his men were of the tankers, Abrams said, “Cohen, my boys are fine. But they never forget they’re fighting with a nice thick wall of armor plate wrapped around them. The OD shirts on your boys don’t quite match it.”

It was like that all the way. Even the light tanks did more than they were supposed to do. Once they knocked out two massive German Tigers by slipping around to the rear of the enemy tanks while assault guns laid down a thick white phosphorous smoke screen. The little tanks darted in through the smoke and, like blow darts, shot 37-mm. shells into the unprotected engine boxes in the Tigers’ sterns.

Casualties were astonishingly light, but some never saw the river. A youthful jeep driver died in Abrams’ arms at a crossroad after driving his jeep, at sixty miles an hour, back from an enemy village two miles away. His jeep rolled to a stop and Abrams gently lifted him out, his throat streaming blood from a half-dozen machinegun bullet holes. A young platoon leader in a light tank company had his hand torn off by a bazooka shell that went through the turret in which he was standing. He looked incredulously at his hand lying on the floor of the turret. Then he leaped from the tank and with his one remaining hand he killed the German kneeling by the side of the road. The tankers said, “He didn’t have to do that, you know.”

The long armored snake wound through the steep-sided canyons, through the neat German villages where bed sheets and pillowcases fluttered from the upper stories in token of surrender, while poker-faced men and women watched the procession from behind lace curtains. The white flags drooped from slender white spear-tipped rods. Those were the rods the Nazis had distributed for the party flags that flapped in the streets in better days.

The tanks stopped that night. They counted 1,200 prisoners streaming hack toward the rear in ragged gray columns. While they waited for the supply trains to come up, the tankers brewed coffee on little stoves inside the tanks and passed hot cups out to the doughboys on the wet ground. It was snowing again in the morning when the tanks moved out. They gathered speed and raced through Daun, Darscheit and Ulmen, faster than the Germans could warn the towns. In Ulmen, a tank rolled up to the railroad station to cut the telegraph wires. A fat fraulein was waiting on the platform for her train, and almost fainted with fright when she saw the Americans. Inside the station, the telegraph key chattered: “Such and such train has just left Coblenz.” A tanker listened amusedly, then smashed the key with a rifle butt and cut the wires.

Near Putzborn, the tanks had already gone through when a supply train was ambushed. The column halted and engaged in a brisk skirmish with the Germans in the hills. After the battle, while the tanks were still parked on the road, a German staff car suddenly appeared, speeding straight toward the column. The driver had told the German general that the tanks were American, but the general, out inspecting his “forward positions,” had said, “They can’t be. They must be ours.” He was fifteen yards away when he discovered his mistake and the car ground to a stop.

Hawk-faced Lt. Gen. Ernst George Edwin Graf von Rothkirch und Trach, Prussian commander of the 53rd German Corps, looked around dazedly at the Americans and the muzzles of their guns pointed at his stomach. Lt. Bernard Liese, tank-company commander from Pittsburgh, nonchalantly leaned up against his Sherman and waited while the general walked over to him.

“Where do you think you are going?” Liege asked.

The Teuton looked around again. Then, with a rueful smile, he said, “It looks like I’m going to the American rear.”

“That’s a good guess,” Liese said.

They took the general away in a jeep. Near Weidenbach, a tire went flat. While the driver and escorting Lt. Alfred Maul, of Milwaukee, worked over the tire, artillery fire began falling near by.

Maul and the driver moved into a ditch for protection, and Maul said to Von Rothkirch, “That’s yours, isn‘t it?”

The German smiled sadly, “Don’t worry, son,” he said. “There isn’t much left.”

The column thrust deeper. Startled enemy artillery units, accustomed to being far behind the lines, were overrun before their brand-new guns had time to fire their first shot in combat. Bewildered prisoners came walking in from every conceivable type of unit, including the 226th Snow-shovel Company and the 40th Woodchopping Command. Two sailors from the merchant marine were amazed to discover themselves prisoners of an American armored division. A German officer was taken as he leisurely strolled around a town arranging billets for his men, who had come to defend the place.

At Mulheim, however, the aged Burgemeister stood defiantly on the steps of the town hall and challenged the tanks with a pistol. He fired until the gun was empty, than turned and ran into the building. Infantrymen chased him through the building. The spry old gentleman dodged nimbly from room to room, finally skipping out the back door. The doughboys finally caught the winded Burgemeister two back yards away. Puffing mightily, he surrendered.

At Kehrig, an antiaircraft regiment opened fire on the column with 20-mm. flak guns. Abrams ordered the hatches buttoned up, and the armored mass rolled forward, crushing men and guns alike. On the outskirts of the town, one tank was hit by an antitank gun and another by a bazooka as they nosed over the brow of a hill. Abrams sent out a distress call for “The Mad Russian,” a division character.

Alexis Sommaripa rolled up to the head of the column in his light tank with a special loud-speaker. For weeks, the Millwood, Virginia, evangelist had practiced a speech designed to induce Germans to surrender peacefully. He also had spent considerable time practicing in a tank, driving it through people’s back yards and testing the various guns on assorted haystacks and manure piles.

Abrams had asked him, “Why all the practice with a tank? I thought you used psychology.”

Sommaripa looked a little guilty. “Well, to tell you the truth, colonel, sometimes this baloney doesn’t work.”

Actually Sommaripa’s spiel had proved highly successful. At Kehrig, however, he didn’t quite make it. Sommaripa cleared his throat and edged his little tank up to the outskirts of the town, where a fanatical German lieutenant and fifty infantrymen were making a determined effort to block the tanks. “Come on out!” Sommaripa boomed out of the loudspeaker. “Civilians, stay in your houses! The Fourth Armored Division is prepared to destroy your town if you do not surrender! Do not expect to fire your last shell and then surrender! Surrender now—or else!”

The tanks waited for five minutes. Then, when there was no answer, they backed off and division artillery moved into position. They drenched the town with incendiaries and high-explosive shells until it was blazing. Then the tanks swept over the hill in a wave of armor and plunged into the burning town. The German lieutenant, who had fired his last shell in defiance of the warning, stepped out to surrender. Unfortunately, he met with a serious accident.

The tanks moved on. Now the traffic on the narrow road was slowing their progress. Once division headquarters told the tankers either to get everything except combat vehicles off the roads or else to get staff officers out to direct traffic. More German equipment was being destroyed every day on the dash to the Rhine than any single day during the sweep across France, and at night the tanks and bulldozers had to push the smashed enemy equipment off the road to permit the jeeps and trucks to get through the tangle.

They had nearly reached the river when a Cub plane hovering over the road reported that a German column was moving along a road near Coblenz. “The column is two thousand yards from your rear tank,” the pilot called.

Abrams switched on his radio and called to Lieutenant Liese. “There’s a column of Jerry vehicles two thousand yards up the road,” Abrams said.

“Shall I ambush them?” Liese asked.

“Hell, no!” Abrams shouted. “They’re going the same direction you are! Catch ’em!”

Liese’s Shermans lumbered out ahead of the main column at full speed. The Cub pilot, watching from the air, called down a play-by-play account.

“They’re only fifteen hundred yards from you now,” he radioed. “Go faster. Faster... Now they’re only a thousand yards from you.” He was silent for a moment while the tanks raced ahead after their quarry. Then he called again. “They’re around the next curve. Go get ’em.”

There was another moment of silence while the straining Shermans hammered down the road. Then Liese broke in excitedly, “I see ’em! I see ’em! What’ll I do?”

Abrams jumped up and down in his turret. He screamed into his transmitter, “Slaughter ’em! Slaughter the so-and-so’s!”