Title: Snow-flakes

A chapter from the book of nature

Author: Israel P. Warren

Release date: February 15, 2026 [eBook #77946]

Language: English

Original publication: Boston: American Tract Society, 1863

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/77946

Credits: Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

A CHAPTER FROM THE

BOOK OF NATURE.

PUBLISHED BY THE

AMERICAN TRACT SOCIETY,

No. 28 CORNHILL, BOSTON.

Entered according to Act of Congress,

in the year 1863, by

THE AMERICAN TRACT SOCIETY,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court

for the District of Massachusetts.

GEO. C. RAND & AVERY,

STEREOTYPERS AND PRINTERS.

[Pg 5]

A brief article on Snow-flakes, in one of the periodicals published by the American Tract Society in the winter of 1862-3, accompanied by a cut exhibiting some of their forms, elicited from its readers many expressions of interest, and suggested the preparation of a book on this curious but generally little-known subject.

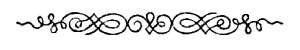

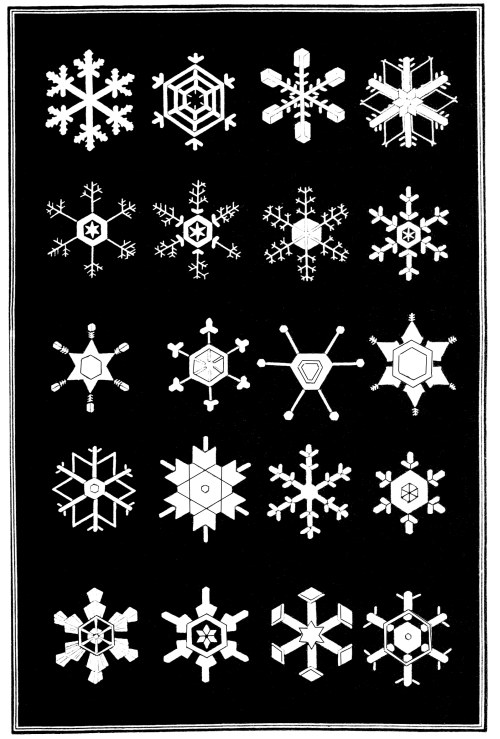

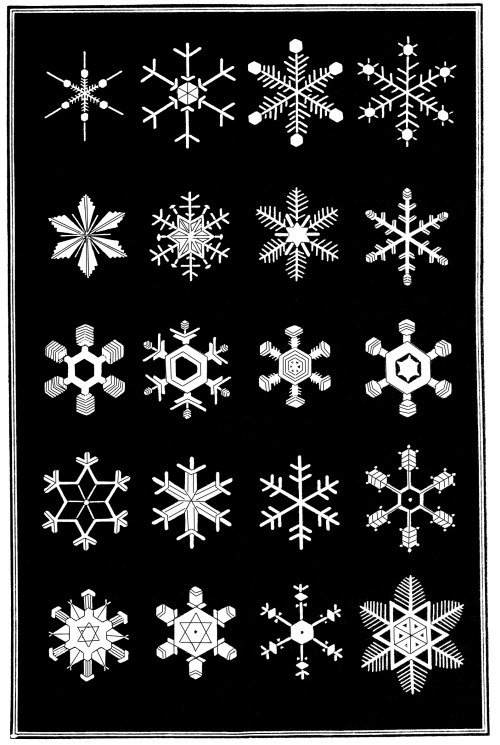

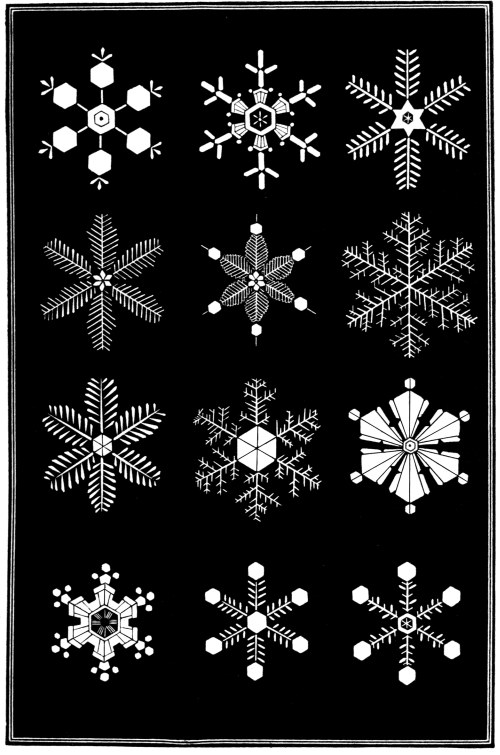

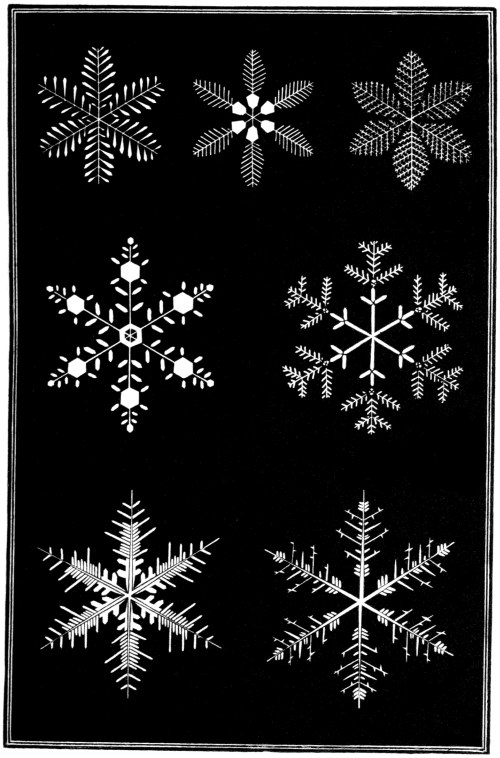

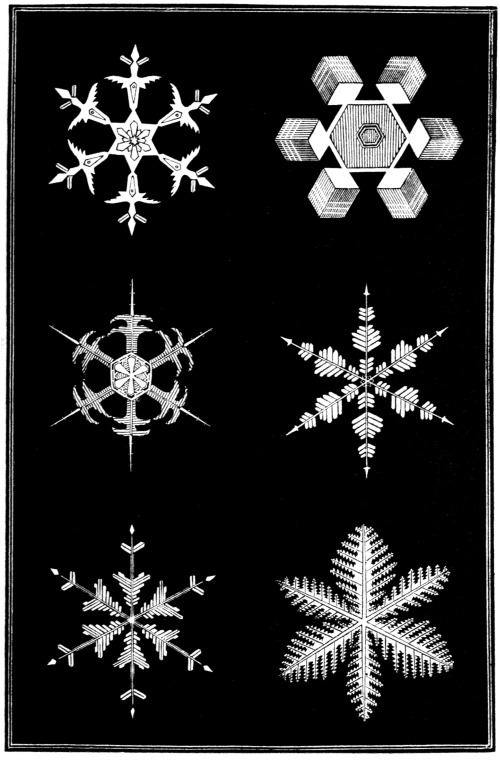

The beautiful forms of many of the snow-crystals were observed and sketched more than a century ago. The Transactions of the Royal Society of London, for 1755, contain representations of ninety-one varieties, with descriptions by Dr. Nettis. Captain William Scoresby, the eminent English navigator, has given, in his Arctic Regions, drawings of ninety-six varieties. More recently, numerous specimens, [Pg 6] with accompanying descriptions, have been given to the public by James Glaisher, Esq., of Lewisham, England. It is from these sources, chiefly, that the figures here exhibited have been derived.

It has been no part of our design, in this work, to enter into any scientific statements concerning the snow-flakes, or the laws of their formation. A brief general description of them is all that has been attempted. Yet the reader should not, from this, infer that there is any question respecting the truthfulness of the sketches. The drawings were originally made with scientific precision, and have been carefully copied. A few simple figures at the top of page 11 are designed to show the primary geometrical forms under which the snow-vapor crystallizes. With that exception, they are all representations of individual crystals, actually observed and sketched with the aid of the microscope.

It is proper to add, however, that these representations are highly magnified, especially those on the last two or three plates. The real size of the crystals observed by Scoresby varied from one thirty-fifth to one-third of an inch in diameter. Dr. Nettis remarks: “The natural size of most of the shining, quadrangular particles, and of the little [Pg 7] stars of snow, as well the simple as the more compound ones, does not exceed the twentieth part of an inch.” The dimensions as well as form of the crystals seem to depend upon the amount of vapor in the atmosphere, the temperature, and other circumstances not easy to specify.

We may be permitted to express the hope that many of our readers will examine for themselves these beautiful productions of nature. In our own climate, the “treasures of the snow” are open to all who choose to explore them; and there can scarcely be an amusement more entertaining, and at the same time instructive, than that of observing and sketching these delicate crystals. No expensive or complicated apparatus is needed for this purpose. A good microscope is the chief requisite; besides which, a pair of dividers and a rule will be sufficient. We subjoin a statement from Mr. Glaisher of his own mode of making his examinations.

“For the information of those who would carefully observe snow-crystals, I may remark that my own plan of procedure is to expose a thick surface of plate-glass on the outer side of the window, resting on the ledge. Seated within the room, I am enabled, with comparative comfort, and at my leisure, to make my drawings and record my observations, the accuracy of which I am able to verify to my [Pg 8] satisfaction, as the crystal received upon the cold surface of the glass, itself several degrees below freezing, remains a sufficient length of time for the requirements of the observer. In many cases, it becomes frozen to the glass, and is thus secured from the influence of the wind, which not unfrequently snatches away some most intricate form from the desiring eye of the observer.”

If this work shall be the means of introducing any of our readers to the knowledge of this interesting department of the Creator’s works, and eliciting those sentiments of admiration and reverence which his wonder-working power should inspire in every beholder, it will not have been issued in vain.

Boston, 1863.

[Pg 9]

| 1. | SNOW STRUCTURE, | 13 |

| 2. | UNITY IN DIVERSITY, | 23 |

| 3. | PERFECTION, | 31 |

| 4. | PURITY, | 41 |

| 5. | GRACE, | 51 |

| 6. | BEAUTY, | 63 [Pg 10] |

| 7. | WEAKNESS, | 75 |

| 8. | POWER, | 89 |

| 9. | GLADNESS, | 101 |

| 10. | GLOOM, | 115 |

| 11. | BENEFICENCE, | 125 |

| 12. | INSTRUCTION, | 139 |

[Pg 11]

He saith to the Snow, Be thou on the face of the Earth.—Job 37:6.

When the watery vapors in the atmosphere are in sufficient quantities to be precipitated to the earth, and at the same time their temperature is at or below the freezing point, their particles unite, but not as fluid drops. In approaching each other they arrange themselves in regular figures, called crystals. The various forms of these may be grouped into three general classes.

1. Prismatic, having three or six sides, usually the latter (page 11, figs. 2, 4). Scoresby compares the finest specimens of these to “white hairs cut into lengths not exceeding a quarter of an inch.” [Pg 14]

2. Pyramidal, either triangular or hexagonal (figs. 5, 6). They are exceedingly small, being only one-thirtieth of an inch in hight.

3. Lamellar, consisting of thin and flat plates, some of them stelliform, having six points radiating from a center (fig. 11), and some hexagonal (page 21, fig. 1). Both these species are in infinite abundance, and of all sizes, from the smallest speck to one-third of an inch in diameter.

These three leading forms are endlessly combined, and give rise to innumerable varieties, from the simplest to the most complex. Pyramids are mounted on prisms, at one or both ends (page 11, figs. 7, 8); prisms are united in one star-like figure, like spokes of a wheel (fig. 10), and both are joined with plates in all conceivable forms of beauty and diversity. The specimens shown throughout our series of engravings illustrate these. The plates themselves are complex, showing within their outer boundaries white lines, which divide them into triangles, stars, hexagons, and other regular figures. Some plates are transparent, others opaque (page 21, fig. 13).

When the prisms are combined with plates, it is generally in the same plane, but sometimes the former are set perpendicularly to the surfaces [Pg 15] of the latter (page 29, figs. 18, 19, 20, 21). These singular figures resemble a wheel with its axle. Scoresby says that on one occasion, snow of this kind fell upon the deck of his ship to the depth of three or four inches!

In some instances the central plate has little prisms or spines projecting from it like hairs, on one or both sides, at an angle of sixty degrees. Sometimes, instead of a plate, the central part is a little rough mass like a hailstone, bristling with spines, somewhat resembling a chestnut-bur.

Much attention has been given to the meteorological conditions of the atmosphere during the fall of snow, to ascertain in what circumstances the different varieties of crystals are produced. Nothing very definite, however, is discoverable in this respect. The general facts are thus summed up by Mr. Scoresby: “When the temperature of the air is within a degree or two of the freezing point, and much snow falls, it frequently consists of large, irregular flakes, such as are common in Britain. Sometimes it exhibits small granular, or large rough, white concretions; at others it consists of white spiculæ, or flakes composed of coarse spiculæ, or rude, stellated crystals formed of visible [Pg 16] grains. But in severe frosts, though the sky appears perfectly clear, lamellar flakes of snow of the most regular and beautiful forms are always seen floating in the air and sparkling in the sunbeams; and the snow which falls in general is of the most elegant texture and appearance.”

Of the hidden causes which originate these beautiful productions, nothing whatever is known. Some have imagined that they are to be found in the forms of the primal atoms of water, which are assumed to be triangles or hexagons, and which, therefore, uniting by their similar sides or edges, must give rise to crystals of regular forms. Others find the solution in magnetic or electrical affinities, which are supposed to require the particles to unite by some law of polar attraction. But even if these theories were demonstrated, they would explain nothing. Why the particles must unite in these particular methods, or what is the nature of attraction itself, no man knows. It is sufficient to say, with the learned and devout navigator who has done most to make us acquainted with these beautiful objects, “Some of the general varieties in the figures of the crystals may be referred to the temperature of the air; but the particular and endless [Pg 17] modifications of similar classes of crystals can only be referred to the will and pleasure of the great First Cause, whose works, even the most minute and evanescent, and in regions the most remote from human observation, are altogether admirable.”

Snow is formed in the higher regions of our atmosphere. It is the wild, raging water of the ocean, the gentle rill of the mountains, the beautiful lake, and the vilest pond on earth, all taxed and made to contribute at the bidding of their Lord to this department of his treasure-house. They send up their tribute in the finest particles of moisture; the steady contribution coming up from all parts of the globe indiscriminately. No matter what king claims the fields and rivers and mountains to minister to his wants, our God makes them all fill his treasury. The vapor comes up like gold, in grains and nuggets. It must be cast into the King’s furnace and formed into his coin, before he can use it. Now tell me how he makes snow out of vapor. You can answer it in one sentence,—by diminishing the heat. Easily said; but who can do [Pg 18] it? A profound philosopher, in remarking on the magnificent glacial phenomenon of January, 1845, when for eight days there was one of the most wonderful displays of the effects of cold perhaps ever witnessed in our latitude, when the earth and every twig seemed covered with diamonds, says of it, “Job speaks of the balancing of the clouds as among the mysteries of ancient philosophy. But how much nicer the balancing and counter-balancing of the complicated agencies of the atmosphere, in order to bring out this glacial miracle in full perfection! What wisdom and power short of infinite could have brought it about?” It is equally appropriate to ask, What but infinite power could produce all the agencies and instruments needed in creating one flake of snow? The tiny creature says, as you examine it,—

“The hand that made me is divine!”

[Pg 19]

The First Snow.

Peboan.

[Pg 21]

Obedience to law is apparent in all the works of the Creator. However varied or complicated their structure, however intricate their motions, however multiform their aspects, there is an all-wise design pervading them, a clue running through all diversities, and reducing all to unity and harmony in the grand scheme of the universe. The Lord hath his way in them all; and that is the single line of righteousness and beneficence.

Amid the endless varieties of the snow-crystals a singular law of unity is apparent. It is the angle of sixty degrees, or some multiple of it. This is one-sixth of the complete circle; hence the hexiform or [Pg 24] six-sided configuration of its prisms and plates. It is curious to glance over the patterns which we exhibit, and trace the operations of this law. Let the congealing vapor assume what fantastic shapes it will, let it riot in the profusion of its beautiful efflorations, yet it can never escape the control of that central attraction which binds them all in one. Hence their name, flakes, i. e., flocks; the fleecy crystals, though spreading abroad each in its utmost individual liberty, being still retained within one ownership and belonging to one fold.

Like this law of unity in nature is God’s great law of love in his moral realm. It is the principle of order and harmony throughout his intelligent universe. God’s own nature is love, and it reigns among all the shining ranks of heaven. And in the numberless worlds which fill immensity, and through the utmost variety of capacities and grades of beings, it needs but the fulfillment of this law to secure universal joy. Love is the one principle which binds all individuals and provinces of his rational kingdom to each other, and each to his throne.

One great law of crystallization controls the whole snow world. Every [Pg 25] flake has a skeleton as distinct as the human skeleton, and yet the individual flake is as different from its neighbor as man is from his. The fundamental law of the snow is to crystallize in three, or some multiple of three. All its angles must be sixty, or one hundred and twenty. All its prisms and pyramids must be triangular or hexagonal; whether spicular, or pyramidal, or lamellar, it ever conforms to its own great law of order, and thus conveys delight to the eye, and most delight to him who, having pleasure in the works of God, searches them out.

Some men reproach the Protestant Church for its various sects. But let such men examine God’s works. Unity in variety is the law of the snow. There is a Trinity in it. Every snow-flake imitates its Creator by being three in one. It has a stern basis of fundamental doctrine; and it would excommunicate any snow-flake that tried to stand on any other. But around that fundamental unity is the free play of individual peculiarities. All snow-flakes are alike essentially, while probably no two are identical in details.

[Pg 26]

The Snow-Shower.

[Pg 27]

To a Snow-Flake.

A STRIKING characteristic of the snow-crystal is its perfection of form. Whatever be the type of its structure, that type is completed with the utmost regularity and nicety. Every angle is of the prescribed size,—not a degree more or less. The number of parts is uniform. You will never see a star with five rays, nor seven. With a precision which art would strive in vain to excel, the pattern is carried out in detail with the most exact symmetry, and in the most nicely-adjusted proportions.

It is so in every snow-crystal, unless broken or otherwise [Pg 32] injured. God has no show specimens in his cabinets, elaborately finished, while the mass of them are left imperfect. There are no obscure corners, no back apartments, where the half-formed, ill-shapen, abortive portions of his work are gathered, out of sight. The tiniest speck that is lost in the countless multitudes that robe the earth is as perfect as if the skill of the Creator had been expended upon this alone. The flake that falls in the vast polar solitudes, where no eye of man will ever see it, or that plunges to instant death in the ocean, is wrought with as much care and fidelity as if it were to sparkle in a regal crown.

If there be apparent exceptions to this general statement, they are only apparent, and even these confirm the fact. In ordinary storms, large portions of the flakes are broken, sometimes reduced almost to shapeless dust. Often the flakes, coming in contact with each other, adhere, and constitute masses which are very irregular. Sometimes, however, this union gives rise to regular forms, as twelve-pointed stars, which are believed to be two hexagons, the one of them overlapping the other. (Page 11, fig. 22, 23.) A few cases have been observed where a ray or point of a star has become the germinating center of a twin or parasitic star, forming [Pg 33] together a structure anomalous as a whole, though regular in each of its individual parts. (Page 99, fig. 2.)

This universal perfection of figure results from the constancy and uniformity of the laws which govern the process of crystallization. But it is not too much to go beyond these, and behold a Divine mind which loves beauty for its own sake, and delights to sow it broadcast throughout creation. Though there be no human eye to behold and to admire, they will not therefore be unbeheld. It is not true that

The universe is full of conscious intelligence, from him who is the “Father of lights,” downward through endless ranks of being, and the hymn of admiring praise perpetually ascends to him for the perfection and glory of his works.

Obey God. His laws to the snow-flake are designed to make it beautiful and useful. So are his laws to you. He tells the flake to put on such a form and go to such a place, and it goes without murmuring or reluctance. Obey God, and you will put on the beauty of holiness and bless the world.

[Pg 34]

The Snow-Flake.

Mabel’s Wonder.

It Snows!

PURITY

is one of the most striking characteristics of the new-fallen

snow. “It is,” says Sturm, “a result of the congregated reflections

of light from the innumerable small faces of the crystals. The same

effect is produced when ice is crushed to fragments. It is extremely

light and thin, consequently full of pores, and these contain air; it

is farther composed of parts more or less compact, and such a substance

does not admit the sun’s rays to pass, neither does it absorb them; on

the contrary, it reflects them very powerfully, and this gives it the

dazzling white appearance we see in it.”

[Pg 42]

You shall look out upon a gray, frozen earth, and a gray, chilling sky. The trees stretch forth naked branches imploringly. The air pinches and pierces you; a homesick desolation clasps around your shivering, shrinking frame, and then God works a miracle. The windows of heaven are opened, and there comes forth a blessing. The gray sky unlocks her treasures, and softness and whiteness and warmth and beauty float gently down upon the evil and the good. Through all the long night, while you sleep, the work goes noiselessly on. Earth puts off her earthliness; and when the morning comes, she stands before you in the white robes of a saint. The sun hallows her with baptismal touch, and she is glorified. There is no longer on her pure brow any thing common or unclean. The Lord God hath wrapped her about with light as with a garment. His divine charity hath covered the multitude of her sins, and there is no scar or stain, no “mark of her shame,” or “seal of her sorrow.” The far-off hills swell their white purity against the pure blue of the heaven. The sheeted splendor of the fields sparkles back a thousand suns for one. The trees lose their nakedness and misery and [Pg 43] desolation, and every slenderest twig is clothed upon with glory.

Wheat-fields, corn-fields, and meadow-lands are all alike wrapped by its dazzling mantle. Here and there some straggling weeds refuse to be hidden, and stand up in unsightly contrast with the pure white surface around them. The stone walls, entirely concealed, only look like a low ridge; but the snow can not contrive to cover up the rail-fences, but only heap up a bank by their side. The woods, with their bare trunks and intermingling branches, cast a shadow, notwithstanding the absence of leaves, and we are glad again to come into the warm sunshine. Evergreens do not brighten a winter landscape. They seem as if they were mourning in sympathy with their spoiled brethren of the forest; and look dusky and almost black, like somber sentinels along the road. The snow sparkles with its crystals. What purity! “Whiter than snow!” The longing of the soul for purity, the faith in the cleansing power that is able thus to purify, are breathed in the prayer, “Wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow!”

The deep, deep snow offers no temptations to wander in the fields, or [Pg 44] step away from the beaten track. One well-defined road, from which the driver reluctantly turns aside on meeting another sleigh, has alone broken the crust on its surface, and determines its depth. Foot-passengers step out into the deep snow, and wait till the sleigh passes, but are glad at once to step back again. How well would it be if Christians thus dreaded to step aside from the narrow way that leadeth unto life, and were as ready to return to its secure footing,—the path beaten by blessed foot-prints!

What comes from heaven is pure; but the tendency is to soil it, and that which keeps nearest heaven most escapes the pollution of earth. At the foot of the Alps you find the roaring, muddy stream, the clay-stained snow. But on the summit of Mt. Blanc is a pure robe of celestial white, never stained, only sometimes covered with a roseate gauze to salute the setting sun.

The snow is very beautiful when it has first fallen. Many of our poets have had recourse to the snow-flake for some of their finest poetical [Pg 45] images; nor do I know a fitter emblem of innocence and purity than a falling flake, ere it receives the stain of earth. There are but few things with which we can compare snow for purity. The Psalmist says, “He giveth the snow like wool; he scattereth the hoar frost like ashes.” “Wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow.” Milton has made beautiful allusion to it in his hymn on the Nativity, where he says,—

[Pg 46]

The Snow-Wreath.

[Pg 47]

The First Snow.

OLD

and dreary as winter is, it is not devoid of interest to the man

of taste and Christian sentiment. Look at the delicate snow-flake.

With what grace of motion has God endowed it! How childlike, gently,

peacefully, confidingly the little creature comes down into our

turbulent earth! It is not difficult to conceive that it comes as an

attendant on some angel, whose movements it imitates.

We have sat and watched the fall of snow until our head grew dizzy, for it is a bewitching sight to persons speculatively inclined. There is an aimless way of riding down, a simple, careless, thoughtless motion, that [Pg 52] leads you to think that nothing can be more nonchalant than snow. And then it rests upon a leaf or alights upon the ground, with such a dainty step, so softly, so quietly, that you almost pity its virgin helplessness. If you reach out your hand to help it, your very touch destroys it. It dies in your palm, and departs as a tear.

Nowhere is snow so beautiful as when one sojourns in a good old-fashioned mansion in the country, bright and warm, full of home joy and quiet. You look out through large windows and see one of those flights of snow in a still, calm day, that make the air seem as if it were full of white millers or butterflies, fluttering down from heaven. There is something extremely beautiful in the motion of these large flakes of snow. They do not make haste, nor plump straight down with a dead fall, like a whistling rain-drop. They seem to be at leisure; and descend with that quiet, wavering, sideway motion which birds sometimes use when about to alight. You think you are reading; and so you are, but it is not in the book that lies open before you. The silent, dreamy hour passes away, and you have not felt it pass. The trees are dressed with snow. The long arms of evergreens bend with its weight; the rails [Pg 53] are doubled, and every post wears a starry crown. The well-sweep, the bucket, the well-curb are fleeced over. And still the silent, quivering air is full of trooping flakes, thousands following to take the place of all that fall. The ground is heaped, the paths are gone, the road is hidden, the fields are leveled, the eaves of buildings jut over, and, as the day moves on, the fences grow shorter, and gradually sink from sight. All night the heavens rain crystal flakes. Yet, that roof, on which the smallest rain pattered audible music, gives no sound. There is no echo in the stroke of snow, until it waxes to an avalanche and slips from the mountains. Then it fills the air like thunderbolts.

Falling snow is beautiful in a forest. It comes wavering down among the trees without a whisper, and takes to the ground without the sound of a footfall. Evergreen trees grow intense in contrasts of dark-green ruffled with radiant white. Bush and tree are powdered and banked up. Not the slightest sound is made in all the work which fills the woods [Pg 54] with winter soil many feet deep. When the morning comes, then comes the sun also. The storm has gone back to its northern nest to shed its feathers there. The air is still, cold, bright. But what a glory rests upon the too brilliant earth! Are these the January leaves?—is this the winter efflorescence of shrub and tree? You can scarcely look for the exceeding brightness. Trees stand up against the clear, gray sky, brown and white in contrast, as if each trunk and bough and branch and twig had been coated with ermine, or with white moss. There is an exquisite airiness and lightness in the masses of snow on trees and fences, when seen just as the storm left them. The wind or sun soon disenchants the magic scene.

[Pg 55]

The Snow-Storm.

The Spirit of the Snow.

[Pg 61]

NOW

is the adornment of winter. Its beauty is a compensation for the

loss of the flowers and foliage of the milder seasons. When Nature has

put off her green robes, when the fields have become bare, the streams

and lakes ice-bound, and the hum of the bees and the songs of the birds

are no longer heard, then God opens his treasure-house and brings forth

jewels for the coronation of the year. He throws over the earth a robe

of purest white, he festoons each shrub and tree with diamonds and

pearls, and bids every beholder rejoice in these manifestations of his

[Pg 64]

skill. For all the beauty of the earth is but the outward expression

of the beauty which dwells eternal in the Divine Mind. Each six-leaved

blossom of winter had its pattern in his thought before it was created;

and all the diversities of its forms show the wealth of his resources

even in the smallest things. So God has not left himself “without

witness” for a single season. Each has its message from heaven,

unfolding his glories, and bidding man behold and adore.

All the roofs are blanketed with snow; all the fences are bordered. Every gate-post is statuesque; every wood-pile is a marble quarry. Harshest outlines are softened. Instead of angles and ruggedness and squalor, there are billowy, fleecy undulations. Nothing so rough, so common, so ugly, but it has been transfigured into newness of life. Every where the earth has received beauty for ashes, the oil of joy for mourning, the garment of praise for the spirit of heaviness. Without sound of hammer or ax, without the grating of saw or the click of chisel, prose has been sculptured into poetry. The actual has put on the silver vail of the ideal.

[Pg 65] It is almost impossible to paint the glory of the northern winter forests. Every tree, laden with the purest snow, resembled a Gothic fountain of bronze, covered with frozen spray, through which only suggestive glimpses of its delicate tracery could be obtained. From every side we looked over thousands of such mimic fountains, shooting low or high, from their pavements of ivory and alabaster. It was an enchanted wilderness,—white, silent, gleaming, and filled with inexhaustible forms of beauty. To what shall I liken those glimpses under the boughs, into the depths of the forest, where the snow destroyed all perspective, and brought the remotest fairy nooks and coverts, too lovely and fragile to seem cold, into the glittering foreground? “Wonderful!” “Glorious!” I could only exclaim in breathless admiration.

The forests were indescribable in their silence, whiteness, and wonderful variety of snowy adornment. The weeping birches leaned over the road and formed white-fringed arches; the firs wore mantles of ermine, and muffs and tippets of the softest swan’s down. Snow, wind, [Pg 66] and frost had wrought the most marvelous transformations. Here were kneeling nuns with their arms hanging listlessly by their sides, and the white cowls falling over their faces. There lay a warrior’s helmet; lace curtains, torn and ragged, hung from the points of little Gothic spires. Caverns, lined with sparry incrustations, silver palm-leaves, doors, loop-holes, arches, and cascades were thrown together in fantastic confusion, and mingled with the more decided forms of the larger trees, which were trees but in form, so completely were they wrapped in their dazzling disguise. It was an enchanted land, where you scarcely dared breathe, lest a breath might break the spell.

The new snow had fallen on the mountains, and the vast basin of the Monte Rosa chain lay before us, clothed in flowing robes of the most pure and spotless white; while every little nook and ledge, and inequality of rock on which the snow could rest, was covered with the same virgin luster, so that it looked as if the sides of the craggy mountains were flecked and dashed with spray, and as if myriads of foaming torrents were coursing down the precipices, streaking their [Pg 67] surface with their white tracks in every direction. After we turned to the right and began the ascent, the light became stronger, and the outline sharper, and our view of the vast glacier basin more uninterrupted and clear. The valley of Macregnaga goes very far into the heart of the mountain, so that all the snowy part of Monte Rosa rises in one great mass directly above it. The sun came up, and for two or three minutes, not more, all the upper part of this vast region of snow was dyed of the deepest crimson,—not pink, as an evening view of the Alps often is; then, for much longer, it was of the most brilliant gold,—just the color of a new sovereign; and then, as the sun overtopped the lower mountains, and their shadows were no longer thrown upward, this gorgeous coloring gave place to a dazzling glare. Miles off, as we were, we could hardly look at the snowy basin without blinking.

There is in us a want of taste to appreciate the exquisite beauty of the snow-flakes that we tread under foot. There is a narrow selfishness which does not even inquire what are the moral or æsthetic uses of the snow; but is contented or sad to see it come upon the earth, according [Pg 68] as it affects our arrangements and wishes. Our education has this radical defect, that it does not teach us to make the senses the instruments of our higher faculties; to study nature, to revere every thing that God makes; that it fails to form us to the highest exercises of which we are capable, and leaves us ignorant of some of the most interesting and important objects of knowledge: God,—his word, his works and ourselves.

Beauty.

[Pg 69]

The Beautiful Snow.

[Pg 73]

Lightness and weakness are symbolized by the snow. You can not draw near one of these delicate crystals without danger of destroying it. Your breath will melt it; nay, even the radiation of warmth from your person will, ere you are aware, crumble down the whole fairy structure so elaborately wrought. It floats down, the sport of every breath of air. It can not ruffle the feather of a bird by its falling. It perishes if the sun looks at it. Yet God takes care of it,—numbers it among his treasures. It is not overlooked by him amid all its fellows. When it dies in a tear, God bottles that tear and keeps it still in his [Pg 76] treasure-house. Fear not, ye of little faith; ye are of more value than mountains of snow-flakes. Does the Almighty create and delight in it, preserve and guide this little creature, and will he not take care of you, and delight to make you beautiful in holiness, and serviceable in his kingdom? Look up when it storms. The sun is on the other side. God guides the cloud, the wind, the rain, and the snow, and numbers the hairs of your head.

Do a little good at a time, and all the time. The Himalaya is ordered to put on a new robe. How is it to be done? Will a mighty vestment drop from heaven and encircle the mighty ranges of her peaks? No; millions of little maids of honor will come down, and each one contribute some little thread to weave the splendid robe. And by every one doing the little committed to it, the giant mountain stands robed in its celestial garment. You organize a Sunday school among neglected children, and go every Sunday, like a little snow-flake, to add present labor to past. Keep on; that is the way the Himalaya gets its robe.

No good is lost. Stop not to count your converts, to weigh the results [Pg 77] of your labors, but keep on like the gentle snow, flake after flake, without noise or parade. Parent, teacher, preacher, patriot, work on!

We see the instability of snow, and the rapidity with which it disappears when played upon by the sunbeams, or exposed to the effects of a humid, mild air, and frequent showers. Frequently the whole aspect of nature, in a few hours, assumes a new appearance, and scarcely a trace of snow is left behind. By these sudden changes we may justly be reminded of the inconstancy and vanity of all human affairs. Fleeting as the snow beneath the sunbeams are all the enjoyments and gratifications which do not arise from the influence of religion, the exercise of the mind, and the feelings of the heart; if we cultivate these, we shall be enabled to enjoy a portion of that felicity which endureth for ever,—the sure reward of virtue and a well-spent life.

Soon another silent force will come forth, and a noiseless battle will ensue, in which this now innumerable army of snow-flakes shall be [Pg 78] itself vanquished. A rain-drop is stronger than a snow-flake. One by one, the armed drops will dissolve the crystals and let forth the spirit imprisoned in them. Descending quickly into the earth, the drops shall search the roots, and give their breasts to myriad mouths. The bud shall open its eye, the leaf shall lift up its head, the grass shall wave its spear, and the forests hang out their banners! How significant is this silent, gradual, but irresistible power of rain and snow of moral truth in this world! “For, as the rain cometh down, and the snow from heaven, and returneth not thither, but watereth the earth, and maketh it bring forth and bud that it may give seed to the sower and bread to the eater; so shall my word be that goeth forth out of my mouth; it shall not return unto me void, but it shall accomplish that which I please, and it shall prosper in the thing whereto I sent it.”

[Pg 79]

Nothing Lost.

[Pg 81]

Snow-Flakes.

[Pg 83]

The Snow-Shower.

Questions and Answers.

[Pg 87]

I F any one should ask what is the most harmless and innocent thing on earth, he might be answered, a snow-flake. And yet, in its own way of exerting itself, it stands among the foremost powers on earth. When it fills the air, the sun can not shine, the eye becomes powerless; neither hunter, nor pilot, guide nor watchman, is any better than a blind man. The eagle and the mole are on a level of vision. All the kings of the earth could not send forth an edict to mankind, saying, “Let labor cease.” But this white-plumed light infantry clears out the fields, drives men home from the highway, and puts half a continent [Pg 90] under ban. It is a despiser of old landmarks, and very quietly unites all properties, covering up fences, hiding paths and roads, and doing in one day a work which the engineers and laborers of the whole earth could not do in years!

But let the wind arise, and how is this peaceful seeming of snow-flakes changed! In an instant the air raves. There is fury and spite in the atmosphere. It pelts you and searches you out in every fold and seam of your garments. It comes without search-warrant into each crack and crevice of your house. It pours over the hills, and lurks down in valleys, or roads, or cuts, until in a night it has entrenched itself formidably against the most expert human strength; for now, lying in drifts huge and wide, it bids defiance to engine and engineer. Before it this wonderful engine is as tame as a wounded bird; all its spirit is gone. No blow is struck. The snow puts forth no power. It simply lies still. That is enough. The laboring engine groans and pushes; backs out and plunges in again; retreats and rushes again. It becomes entangled. The snow is every where. It is before it and behind it. It penetrates the whole engine, is sucked up in the draft, whirls in [Pg 91] sheets into the engine-room; torments the cumbered wheels, clogs the joints, and, packing down under the drivers, it fairly lifts the ponderous engine from its feet, and strands it across the track! Well done, snow! That was a notable victory!

Look at the gentle flake coming down so silently, and then turn to contemplate its prodigious effects. Parent of a thousand of the streams and rivers that water and fertilize our globe, the snow-flake is equally the parent of the thundering avalanche that at St. Bernard overwhelms the unhappy traveler before he reaches the hospitable convent. In the afternoon, you find yourself suddenly caught in a storm. What is it that eclipses the sun, hours before his setting, that hides every landmark from the sight of the anxious guide, that turns day into sudden night? It is the snow-flake; for in the little thing is the hiding of God’s power.

And is there not wealth as well as power in the enormous quantity of this one form of treasure lavished on the earth in one year? In one night you have found the earth covered with a carpet two feet in thickness. But if it requires millions of flakes for one cubic foot, [Pg 92] what must it require to cover half the breadth of a continent on a meridian line of one thousand miles? And if that is repeated several months in each year, the mind staggers in the attempt at computation. “He giveth his snow like wool!” He scatters his pearls and diamonds by innumerable millions upon the earth. What prodigality of bounty our King displays!

The sovereign God gives the snow. It comes when he pleases, and falls where it pleases him to have it, on your house and your land; and you have no title that can prevent or bar his right. Napoleon may be the dread of kings, the mightiest monarch and warrior of the earth. He may be stronger than Russia, and may penetrate as far as Moscow. But Jehovah will there put a bridle in his mouth and a hook in his nostrils, and turn him backward, baffled, broken, disgraced. And he wanted for an instrument to accomplish his purposes the army of snow-flakes. He laid the deep covering of snow upon the earth; and the mighty army found themselves conquered by this little, gentle, silent instrument of God’s power. God could have sent one warm storm of rain, and set the French army free. But he did not. He ruleth in the armies of heaven and doeth his pleasure among the inhabitants of the earth.

[Pg 93]

Scene in a Vermont Winter.

The Pass of the Sierra.

[Pg 99]

HOW delightful is the face of nature when the morning light first dawns upon a country embosomed in snow! The thick mist which obscured the earth and concealed every object from our view at once vanishes. How beautiful are the tops of the trees, hoary with frost! The hills and valleys, reflecting the sunbeams, assume various tints; all nature is animated by the genial influence of the brightness, and, robed in white, delights the traveler with her novel and delicate appearance. How beautiful to see the white hills, the [Pg 102] forests, and the groves all sparkling! What a delightful combination these objects present! Observe the brilliancy of the hedges! See the lofty trees bending beneath their dazzling burden! The surface of the earth appears one vast plain mantled in white and splendid array.

Already snow-birds are fluttering for a foothold, and showering down the frosty dust from the twigs. The hens and their uplifted lords are beginning to wade with dainty steps through the chilly wool. Boys are aglee with sleds; men are out with shovels, and dames with brooms. Bells begin to ring along the highway, and heavy oxen with craunching sleds are wending toward the woods for the winter’s supply of fuel. The school-house is open, and a roasting fire rages in the box-stove. Little boys are crying with chilblains, and little girls are comforting them with the assurance that it will “stop aching pretty soon,” and the boys seem unwilling to stop crying until then. Big boys are shaking their coats, and stamping off the snow, which peels easily from sleek, black-balled boots, or shoes burnished with tallow. Out of doors, the snowballs are flying, and every body laughs but the one that’s hit. Down go the wrestlers. The big ones “rub” the little ones; the little [Pg 103] ones in turn “rub” the smaller ones. The passers-by are pelted; and many a lazy horse has motives of speed applied to his lank sides. Even the schoolmaster is but mortal, and must take his lot; for many an “accidental” snowball plumps into his breast and upon his back before the rogues will believe that it is the schoolmaster.

But days go by. The snow drifts,—fences are banked up ten feet high. Hills are broken into a “coast” for boys’ sleds. They slide and pull up again, and toil on in their slippery pleasure. They tumble over and turn over; they break down, or smash up; they run into each other, or run races, in all the moods and experiences of rugged frolic. Then comes the digging of chambers in the deep drifts, room upon room, the water dashed on overnight freezing the snow-walls into solid ice. Forts are also built, and huge balls of snow rolled up, till the little hands can roll the mass no longer.

For two days it had been storming. The air was murky and cross. The snow was descending, not peacefully and dreamily, but whirled and made [Pg 104] wild by fierce winds. The forests were laden with snow, and their interior looked murky and dreadful as a witch’s den. Through such scenes I began my ride upon the plow-shoving engine. The engineers and firemen were coated with snow from head to foot, and looked like millers who had not brushed their coats for ten years. The floor on which we stood was ice and snow half melted. The wood was coated with snow. The locomotive was frosted all over with snow,—wheels, connecting-rods, axles, and every thing but the boiler and smoke-stack. The side and front windows were glazed with crusts of ice, and only through one little spot in the window over the boiler could I peer out to get a sight of the plow. The track was indistinguishable. There was nothing to the eye to guide the engine in one way more than another. It seemed as if we were going across fields and plunging through forests at random. And this gave no mean excitement to the scene, when two ponderous engines were apparently driving us in such an outlandish excursion. But their feet were sure, and unerringly felt their way along the iron road, so that we were held in our courses.

Nothing can exceed the beauty of snow in its own organization, in the gracefulness with which it falls, in the molding of its drift-lines, [Pg 105] and in the curves which it makes when streaming off on either side from the plow. It was never long the same. If the snow was thin and light, the plow seemed to play tenderly with it, like an artist doing curious things for sport, throwing it in exquisite curves that rose and fell, quivered and trembled as they ran. Then suddenly striking a rift that had piled across the track, the snow sprang out, as if driven by an explosion, twenty and thirty feet, in jets and bolts; or like long-stemmed sheaves of snow,—outspread, fan-like. Instantly, when the drift was passed, the snow seemed by an instinct of its own to retract, and played again in exquisite curves, that rose and fell about our prow. “Now you’ll get it,” says the engineer, “in that deep cut.” We only saw the first dash, as if the plow had struck the banks of snow before it could put on its graces, and shot it distracted and headlong up and down on either side, like spray or flying ashes. It was but a second. For the fine snow rose up around the engine, and covered it in like a mist, and, sucking round, poured in upon us in sheets and clouds, mingled with the vapor of steam, and the smoke which, from impeded draft, poured out, filled the engine-room and darkened it so [Pg 106] that we could not see each other a foot distant, except as very filmy specters glowering at each other. Our engineers had on buffalo coats whose natural hirsuteness was made more shaggy by tags of snow melted into icicles. To see such substantial forms changing back and forth into a spectral lightness, as if they went back and forth between body and spirit, was not a little exciting to the imagination.

When we struck deep bodies of snow, the engine plowed through them laboriously, quivering and groaning with the load, but shot forth again, nimble as a bird, the moment the snow grew light and thin.

Nothing seemed wilder than to be in one of these whirling storms of smoke, vapor, and snow, you on one ponderous monster, and another roaring close behind, both engines like fiery dragons harnessed and fastened together, and looming up when the snow and mists opened a little, black and terrible. It seemed as if you were in a battle. There was such energetic action, such irresistible power, such darkness and light alternating, and such fitful half-lights, which are more exciting to the imagination than light or darkness. Thus, whirled on in the bosom of a storm, you sped across the open fields, full of wild-driving [Pg 107] snow; you ran up to the opening of the black pine and hemlock woods, and plunged into their somber mouth as if into a cave of darkness, and wrestled your way along through their dreary recesses, emerging to the cleared field again, with whistles screaming and answering each other back and forth from engine to engine.

It is not only that the snow makes fair what was good before, but it is a messenger of love from heaven, bearing glad tidings of great joy. Hope for the future comes down to the earth in every tiny snow-flake. Underneath, as they span the hillside, and lie lightly piled in the valleys, the earth-spirits and fairies are ceaselessly working out their multifold plans. The grasses hold high carnival safe under their crystal roof. The roses and lilies keep holiday. The snow-drops and hyacinths, and the pink-lipped May-flower, wait as they that watch for the morning. The life that stirs beneath thrills to the life that stirs above. The spring sun will mount higher and higher in the heavens; the sweet snow will sink down into the arms of the violets, and, at the word of the Lord, the Earth shall come up once more as a bride adorned for her husband.

[Pg 108]

The Time of Snow.

A Winter Sketch.

[Pg 113]

Hast thou seen the treasures of the hail, which I have

reserved against the time of trouble?—Job 38:22.

NOT in his splendors, only, nor his beneficence, does God manifest himself to men. “The Lord Most High is terrible.” His holiness is for ever arrayed in frowns and rebuke against wrong. It is pleasant to dwell on his love, to speak of him as the Father of all his creatures, full of pity and condescension for the most erring. The heart that responds to his with reciprocal affection, penitent for sins committed, trustful in his promises of pardon through a Redeemer, and constrained by filial devotion to grateful service and worship, may rest in the sweet contemplation of his goodness. But let [Pg 116] it not be forgotten at the same time that he is holy as well as good, “merciful and gracious, long-suffering, and abundant in goodness and truth, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin, and that he will by no means clear the guilty.”

It is fitting that this part, also, of the Divine character should be illustrated in his works. Therefore, he hath appointed the earthquake, the lightning, and the tempest, to be, with the sunshine and the gentle breezes, representatives of himself. Even the snow, so soft and beautiful, he makes a messenger of gloom. The dark, fierce winter storm sweeps over the earth as the very spirit of desolation. The tiny flakes, charged with the mission which he gives them, fly forth in numbers infinite to buffet, to bewilder, to overwhelm whatever is exposed to them. Who can resist these “treasures” of the storm when let loose in their strength? “Who can stand before his cold?”

Winter is a fitting image of decay and death; and the cold, white, winding-sheet that shrouds the blighted flowers, of the robe that is spread over the still form of our heart’s crushed and faded blossoms. True, the flowers shall spring again, and our treasures will be [Pg 118] restored to us in the land of eternal summer. Nevertheless, the dreary hour of separation is not joyous, but grievous. Our hopes are withered, our hearts are chilled; disappointment, absence, present loss, distress and torture us. All is gloom, desolation, and anguish. The sun may shine, but his beams are cold and glassy. No pleasures spring about our path. Our life is buried with our darlings in the icy bosom of nature. O Winter, bleak, dismal, wasting, inexorable Winter! Hasten thy footsteps, and bring us to the bright expectant Spring!

Winter.

[Pg 120]

The Path through

the Snow.

December Snow.

[Pg 123]

The Rain cometh down and the Snow from heaven, and watereth the earth, and maketh it bring forth and bud, that it may give seed to the sower and bread to the eater.—Isaiah 55:10.

THE great design of the snow is benevolent. It is appointed to water the earth, but not like the rain. That comes down and produces its effects and passes away, and is absent just when the heat is at its hight, and evaporation most rapid. But the snow comes down in the winter, and lies upon the high mountain ranges all through the hottest weather, gradually supplying the streams and rivers on which human life depends. The great Father of Waters, our grand Mississippi, is a child of the snow; and often his waters swell [Pg 126] when other streams are drying up. The very heat which is drinking up their waters is melting the snows on the Rocky Mountains, and replenishing his wasted bulk. The Nile is the child of snow; and its annual rise, on which the life of Egypt depends, is occasioned by its melting. The sun, approaching the summer solstice, finds the snows of the winter all treasured up for his magic touch to transform to water.

The snow tempers the heat of the atmosphere. And in this it has two opposite powers and offices. It heats and it cools. By being a non-conductor of heat, and at the same time translucent, it enables the Esquimaux to build his winter house entirely of its solid blocks; being the warmest substance for this purpose, in nature, so far as waste of heat is concerned, and at the same time serving the purpose of windows by transmitting the light in a broad mass into his humble dwelling. Animals live under its shelter in the severest cold. And the very earth is protected by it. Tender roots lie sheltered from the frosts by its thick covering. The winds that visit the south of India, our latitude, and Southern Europe, in summer, come across over the great snow tracts of the Himalaya, or the Alps, or the Rocky Mountains, charged with refreshing coolness.

[Pg 127]

And while its pure whiteness makes an agreeable change from the verdure of summer, it is admirably adapted to the various latitudes of the earth in modifying the light. The farther the sun withdraws from any part of the earth, the less light he emits there. And the snow follows him at respectful distance, increasing its bounty, as his rays diminish. The consequence is, our long winter nights are cheered by this brilliant covering that gathers and reflects all the scattered beams the sun has left. The long polar nights are not only illuminated, but also beautified by its wonderful phenomena.

Snow furnishes the most splendid material for road making. To it we owe the cheerful movement of the sleigh; and the lumbermen of our forests can do nothing until it has come to enable them to bring their timber to the streams.

But few of us at home can realize the protecting power of this warm coverlet of snow. No eider-down in the cradle of an infant is tucked in more kindly than the sleeping dress of Winter about this feeble flower-life. The first warm snows, falling on a thickly-pleached carpet [Pg 128] of grasses, heaths, and willows, enshrine the flowery growths which nestle round them in a non-conducting air-chamber; and, as each successive snow increases the thickness of the cover, we have, before the intense cold of winter sets in, a light, cellular bed covered by drift, six, eight or ten feet deep, in which the plants retain their vitality.

The early spring and late fall and summer snows are more cellular and less condensed than the nearly impalpable powder of winter. The drifts, therefore, that accumulate during nine months of the year, are dispersed in well-defined layers of different density. We have first the warm cellular snows which surround the plant; next, the fine, impacted snow-dust of winter; and above these, the later, humid deposits of the spring.

It is interesting to observe the effects of this disposition of layers upon the safety of the vegetable growths below them. These, at least in the earliest summer, occupy the inclined slopes that face the sun, and the several strata of snow take, of course, the same inclination. The consequence is, that as the upper snow is dissipated by the early thawings, and sinks upon the more compact layer below, it is, to a great extent, arrested, and runs off like rain from a slope of clay. [Pg 129] The plant reposes thus in its cellular bed, guarded from the rush of waters, and protected too from the nightly frosts by the icy roof above it.

There is a pretty, curious old town in Germany. The streets are narrow and the houses very quaint, with their pointed, gable-ends toward the street. One house stands somewhat isolated from the rest. It is at an angle where two streets meet, and is built with so many projections and jutting windows and carved friezes that it is quite a study.

One cold, cold afternoon in midwinter, when the silent frost was penetrating every where, and men moved quickly, muffled up in furs,—a time for people to close their doors, and gather round their firesides,—all the quiet inhabitants were astir. There was a bustle of preparation in parlor and kitchen; and young and old, wrapping their garments about them, were ready to go out in the cold. There were dismay and confusion in all the streets. Why?

They had heard that the French regiment, called the Pitiless, on its retreat from Moscow, was only three leagues off, and was to quarter in their village that night. There was every thing to fear from the revelry [Pg 130] and excesses of soldiers, who acknowledged no right but that of the strongest.

In the queer old house of which we have spoken, there was no bustle of preparation. By the fire, in a large old room, sat an aged woman and her two grandchildren. Unable from her lameness to leave home, her grandchildren would not forsake her. Her faith in God enabled her to feel that they might be safer there than when fleeing from danger.

These, the last notes of their evening hymn, died away amid the rafters of the shadowy room.

“Alas!” said the boy, mournfully, “we have no wall about us to-night to protect us from enemies.”

“He will be our Wall himself,” said the aged woman, reverently. “Think you his arm is shortened?”

“No, grandmother; but the thing is impossible without a miracle.”

“Take care, my boy; nothing is impossible with God. Hath he not said he will be a wall of fire unto his people? We must trust him and he will be our wall of defense.” [Pg 131]

They sat quietly by the fireside. The wind moaned down the large open chimney, and the snow fell softly against the window-pane. Steadily it fell all night, and the wind drifted it in high banks, covering the shed, streets, walls, and paths of the silent and deserted town. And yet there was peace by that quiet fireside, the peace that can only be felt by the mind that is stayed on God. Few words were spoken. They held one another’s hands, and looked into the fire, and listened, in the pauses of the storm, to catch the blast of the French trumpets. At nine o’clock the sound was faintly borne to them on the breeze; a few hurried blasts swept past them, intermingled with sounds of trampling feet and loud voices, and all was still.

Their hearts beat almost audibly; and they drew closer together, as they felt that they were now in the midst of their enemies. Helpless age and defenseless youth! What armor had they wherein to trust? The shield of faith! and safely they rested beneath its shadow!

Every house was a scene of revelry. Great fires were kindled. Altars were ransacked. The soldiers, with their songs and wine-cups, their oaths and blasphemy, made the streets ring, striving to drown the [Pg 132] remembrance of intense cold and terrible privation in those hours of drunken merriment.

Still the little group in the quaint old house sat peacefully through the long, long hours of the night, till morning dawned and showed them the wall of defense which God had built round about them. Exposed as was their house, from its position, to the eddies and currents of the wind, the snow had so drifted about them that the doors and windows were completely blocked up; and the French soldiers had not found it. With the daylight they had left the town.

Wind and storm had fulfilled God’s word, and encircled those who put their trust in him with a wall that protected them from their enemies,—a wall, not of fire, but of snow.

Under the Snow.

Wild-Flowers.

The Alpine Violet.

[Pg 137]

Whoso is wise and will observe these things, even they shall

shall understand the loving-kindness of the Lord.—Psalm 107: 43.

JANUARY! Darkness and light reign alike. Snow is on the frozen ground. Cold is in the air. The winter is blossoming in frost-flowers. Why is the ground hidden? Why is the earth white? So hath God wiped out the past: so hath he spread the earth, like an unwritten page, for a new year! Old sounds are silent in the forest and in the air. Insects are dead, birds are gone, leaves have perished, and all the foundations of soil remain. Upon this lies, white and tranquil, the emblem of newness and purity, the virgin robes of the yet unstained year! [Pg 140]

April! The singing month. Many voices of many birds call for resurrection over the graves of flowers, and they come forth. Go, see what they have lost. What have ice and snow and storm done unto them? How did they fall into the earth stripped and bare? How do they come forth opening and glorified? Is it then so fearful a thing to lie in the grave?

In its wild career, shaking and scourged of storms through its orbit, the earth has scattered away no treasures. The hand that governs in April governed in January. You have not lost what God has only hidden. You lose nothing in struggle, in trial, in bitter distress. If called to shed thy joys as trees shed their leaves; if the affections be driven back into the heart, as the life of flowers to their roots, yet be patient. Thou shalt lift up thy leaf-covered boughs again. Thou shalt shoot forth from thy roots new flowers. Be patient! Wait!

The sun had gone down before we entered the valley of Chamouni; the sky behind the mountain was clear, and it seemed for a few moments as if darkness was rapidly coming on. On our right hand were black, jagged, [Pg 141] furrowed walls of mountain, and on our left Mont Blanc, with his fields of glaciers and worlds of snow; they seemed to hem us in and almost press us down. But in a few moments commenced a scene of transfiguration, more glorious than any thing I had witnessed yet. The cold, white, dismal fields gradually changed into hues of the most beautiful rose-color. A bank of white clouds, which rested above the mountains, kindled and glowed, as if some spirit of light had entered into them. You did not lose your idea of the dazzling, spiritual whiteness of the snow, yet you seemed to see it through a rosy vail. The sharp edges of the glaciers and the hollows between the peaks reflected wavering tints of lilac and purple. The effect was solemn and spiritual beyond any thing I had ever seen. These words, which had often been in my mind during the day, and which occurred to me more often than any others while I was traveling through the Alps, came into my mind with a pomp and magnificence of meaning unknown before:—“For by Him were all things created that are in heaven and that are in earth, visible and invisible, whether they be thrones, or dominions, or principalities, or powers; all things were created by him and for him; and he is before all things, and by him all things consist.” [Pg 142]

In this dazzling revelation I saw not that cold, distant, unfeeling fate, or that crushing regularity of wisdom and power, which was all the ancient Greek or modern deist can behold in God; but I beheld, as it were, crowned and glorified, one who had loved with our loves, and suffered with our sufferings. Those shining snows were as his garments on the Mount of Transfiguration, and that serene and ineffable atmosphere of tenderness and beauty, which seemed to change these dreary deserts into worlds of heavenly light, was to me an image of the light shed by his eternal love on the sins and sorrows of time, and the dread abyss of eternity.

It is painful to think how our youth are coming to maturity without looking into these Treasure Houses of the King. The Bible and nature are mutually illustrative. And he has not a full Christian nature, who can not profoundly read and intensely enjoy both. As one has said of the book of nature,—and it might equally have been said of the Book of grace;—“The casual and general observer of nature soon ceases to be interested, because he looks only at the surface, and soon exhausts all [Pg 143] the novelties. He merely stands on the outside of the temple, and, after gazing for a time at its noble proportions and splendid columns, his interest subsides. But he who really studies the works of God because he loves them is admitted into the penetralia, and there ten thousand new objects reward his search, opening continually before him, until he reaches the very Holy of Holies, and becomes a consecrated Priest.” Education, then, consists in forming rather than in informing. Its two chief instruments are, not the wisdom of men, nor classical literature, but God’s works and God’s Book. Science without Revelation is of doubtful value. Revelation without Science is not seen in its fullness.

Let the snow-flake preach Sinai and Calvary, Eden and Gethsemane, the first and the second Adam. In its purity and beauty, its freshness and its bounty, it shows what a world this was when God made it. But when we see it rushing in the turbid stream, rolling in the dreadful avalanche, to bury the homes and possessions of men with their owners,—when we see it sullied and stained,—let us learn that man is fallen, that a curse is upon the earth and its lord, that “the whole creation groaneth and travaileth in pain together.”

[Pg 144]

God in Nature.

Teachings of Nature.

Transcriber’s Notes:

Deprecated spellings or ancient words were not corrected.

The illustrations have been moved so that they do not break up paragraphs and so that they are next to the text they illustrate.

Typographical and punctuation errors have been silently corrected.