Front Cover

Title: Theodosia Ernest

Complete in two volumes

Author: A. C. Dayton

Release date: January 27, 2026 [eBook #77796]

Language: English

Original publication: Memphis: South-Western Publishing House, 1866

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/77796

Credits: Dustin Speckhals

Front Cover

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1866, by

R. B. Davidson,

In the District Court of the United States for the Middle District of Tennessee.

Theodosia Ernest:

Or, The Heroine of Faith.

“Mother, have I ever been baptized?” The questioner was a bright, intelligent, blue-eyed lad, some thirteen summers old. The deep seriousness of his countenance, and the earnest, wistful gaze with which he looked into his mother’s face, showed that, for the moment at least, the question seemed to him a very important one.

“Certainly, my son; both you and your sister were baptized by the Rev. Doctor Fisher, at the time when I united with the church. Your sister remembers it well, for she was six years old; but you were too young to know any thing about it. Your Aunt Jones said it was the most solemn scene she ever witnessed; and such a prayer as the good old doctor made for you, I never heard before.”

“But, mother,” rejoined the lad, “sister and I have been down to the river to see a lady baptized by the Baptist minister, who came here last month and commenced preaching in the school-house. They went down into the river, and then he plunged her under the water, and [4] quickly raised her out again; and sister says if that was baptism, then we were not baptized, because we stood on the dry floor of the church, and the preacher dipped his hand into a bowl of water, and sprinkled a few drops on our foreheads: and she says Cousin John Jones was not baptized either; for the preacher only took a little pitcher of water, and poured a little stream upon his head. Sister says she don’t see how there can be three baptisms, when the Scripture says, ‘One Lord, one faith, one baptism.’”

“Your sister is always studying about things above her reach, my son. It is better for young people like you not to trouble yourselves too much about these knotty questions in theology.”

“But, mother, this don’t seem to me to be a knotty question at all. One minister takes a person down into the water, and dips her under it; another stands on the dry floor of the church before the pulpit, and sprinkles a few drops into her face; another pours a little stream upon her head. Now, anybody can see that they do three different things; and if each of them is baptism, then there must be three baptisms. There is no theology about that, is there?”

“Yes, my child, this is a theological question, and I suppose it must be a very difficult one, since I am told that some very good and wise men disagree about it.”

“But, mother, they all agree that there is only one baptism, do they not? And if there is only one, why don’t they just look into the Testament and see what it is? If the Testament says sprinkle, then it is sprinkling; if it says pour, then it is pouring; if it says dip, then it is dipping. I mean to read the Testament, and see if I cannot decide which it is for myself.”

“Do you think, my son, that you will be able to know as much about it as your Uncle Jones, or Dr. Fisher, [5] who baptized you, or Dr. Barnes, whose notes you use in learning your Sunday-school lesson, and all the pious and learned ministers of our church, and the Methodist Church, and the Episcopal Church? They have studied the Testament through and through, and they all agree that a child who is sprinkled is properly baptized.”

“Yes, mother, but if the baptisms in the New Testament were sprinkling (and of course they were, or such wise and good men would not say so), why can’t I find it there, as well as anybody?”

“Very well, my son, you can read and see; but if you should happen to come to a different conclusion from these great and learned men, I hope you won’t set up your boyish judgment against that of the wisest theologians of the age. But here comes your sister. I wonder if she is going to become a theologian too!”

Mrs. Ernest (the mother of whom we are speaking) was born of very worthy parents, who were consistent members of the Presbyterian Church; and she had grown up as one of the “baptized children of the church.” As she “appeared to be sober and steady, and to have sufficient knowledge to discern the Lord’s body,” she was doubtless informed, according to the directions of the confession of faith, page 504, that it was “her duty and her privilege to come to the Lord’s supper.” But she had felt no inclination to do so until after the death of her husband. Then, in the day of her sorrow, she looked upward, and began to feel a new, though not an intense interest in the things of religion. She made a public profession, and requested baptism for her two children.

The little boy was then an infant and his sister was about six years old, a sprightly, interesting child, whose flowing ringlets, dimpled chin, rosy cheeks, and sparkling eyes, were the admiration of every beholder.

[6]Twelve years had passed. The lovely girl had become a beautiful and remarkably intelligent young lady. The little babe had grown into the noble looking, blue-eyed lad, with a strong, manly frame, and a face and brow which gave promise of capacity and independence of thought far above the average of his companions.

Theodosia and Edwin. How they loved each other! She, with the doting affection of an elder child and only sister, who had watched the earliest developments of his mind, and been his companion and his teacher from his infancy; he, with the confiding, reverential, yet familiar love of a kind-hearted and impulsive boy, to one who was to him the standard at once of female beauty and womanly accomplishments.

Theodosia came in, not with that elastic step and sprightly air which was habitual with her, but with a slow and solemn gait; scarcely raising her eyes to meet her mother’s inquiring gaze, she passed through to her own room, and closed the door.

The mother was struck with the deep and earnest seriousness of her face and manner. What could it mean? What could have happened to distress her child?

“Edwin, my son, what is the matter with your sister?”

“Indeed, mother, I do not know of any thing. We stood together talking at the river bank, and just before we left, Mr. Percy came up to walk home with her. It must be something that has happened by the way.”

The mother’s mind was relieved. Mr. Percy had been for many months a frequent and welcome visitor at their pretty cottage, and had made no secret of his admiration of her accomplished and beautiful daughter; though he had never, until a few weeks since, formally declared his love. Mrs. Ernest did not doubt but that some lovers’ quarrel had grown up in their walk, and this [7] had cast a shadow upon Theodosia’s sunny face. She waited somewhat impatiently for her daughter to come out and confirm her conjectures. She did not come, however, and at length the mother arose, and softly opening the door, looked into the room. Theodosia was on her knees. She did not hear the door, or become conscious of the presence of her mother. In broken, whispered sentences, mingled with sobs, she prayed: “Oh, Lord, enlighten my mind. Oh, teach me thy way. Let me not err in the understanding of thy word; and oh give me strength, I do beseech thee, to do whatever I find to be my duty. I would not go wrong. Help! oh help me to go right!”

Awe-struck and confounded, Mrs. Ernest drew back, and tremblingly awaited the explanation she so much desired to hear.

When at length the young lady came out, there was still upon her face the same serious earnestness of expression, but there seemed less of sadness, and there was also that perfect repose of the countenance, which is the result of a newly formed, but firmly settled determination of purpose.

Mrs. Ernest, as she looked at her, was more perplexed than ever. She was, however, resolved to obtain at once a solution of the mystery.

“Mr. Percy walked home with you, did he not, my daughter?”.

“Yes, mother.”

“Did you find him as interesting as usual? What was the subject of your conversation?”

“We were talking of the baptism at the river.”

“Of nothing else?”

“No, mother; this occupied all the time.”

“Did he say nothing about himself?”

[8]“Not a word, mother, except in regard to the question whether he had ever been baptized.”

“Why, what in the world has possessed you all? Your brother came running home to ask me if he had been baptized; Mr. Percy is talking about whether he has been baptized. I wonder if you are not beginning to fancy that you have never been baptized?”

“I do indeed begin to doubt it, mother; for if that was baptism which we witnessed at the river this evening, I am quite sure that I never was.”

“Well, I do believe that Baptist preacher is driving you all crazy. Pray tell me, what did he do or say, that gave you such a serious face, and put these new crotchets in your head?”

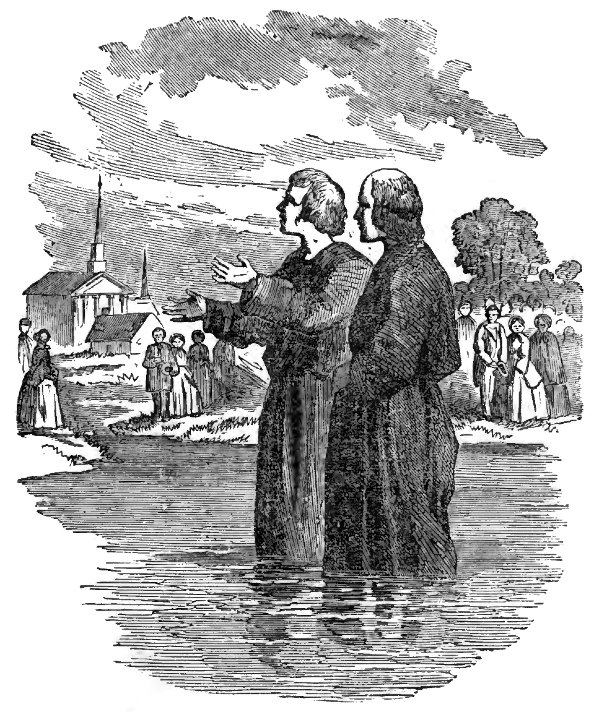

“Nothing at all, mother, He simply read from the New Testament the account of the baptism of Jesus and of the Eunuch. Then he took the candidate, and they went down both of them into the water, and he baptized her, and then they came up out of the water. I could not help seeing that this is just what is recorded of Jesus and the Eunuch. If so, then it is the baptism of the Scriptures; and it is certainly a very different thing from that which was done to me, when Dr. Fisher sprinkled a few drops of water in my face.”

“Of course, my dear, it was different; but I don’t think the quantity of water employed affects the validity of the baptism. There is no virtue in the water, and a few drops are just as good as all the floods of Jordan.”

“But, mother, it is not in the quantity of water that the difference consists; it is in the act performed. One sprinkles a little water in the face; another pours a little water on the head; another buries the whole body under the water and raises it out again. Two apply the water to the person, the other plunges the person into the water. They are surely very different acts: [9] [10] [11] and if what I saw this evening was scriptural baptism, then it is certain that I have never been baptized.”

“Well, my child, we won’t dispute about it now; but I hope you are not thinking about leaving your own church; the church in which your grandfather and your grandmother lived and died: and in which so many of the most talented and influential families in the country are proud to rank themselves, to unite with this little company of ignorant, ill- mannered mechanics and common people, who have all at once started up here from nothing.”

“You know, my mother, that it is about a year since I made a profession of religion. I trust that before I did so, I had given myself up to do the will of my Heavenly Father. Since then I have felt that I am not my own. I am bought with a price. It is my pleasure, as well as my duty, to obey my Saviour I ask, as Paul did, Lord, what wilt thou have me to do? You taught me this lesson of obedience yourself; and I am sure you would not have me on any account neglect or refuse to obey my Saviour. If He commands me to be baptized, and the command has never been obeyed, I shall be obliged to do it. And I trust my mother will encourage me in my obedience to that precious Redeemer she taught me to love.”

One who looked into the mother’s face, at that moment, might have read there “a tablet of unutterable thoughts.” She did not try to speak them. We will not try to write them. She sat silent for a moment, drew her breath deeply and heavily, then rising hastily, went to look for something in her daughter’s room.

Theodosia was not only grieved but surprised at the evident distress which she had given her mother. While on her knees in prayer to God after her return from the river, she had determined to do her duty, and obey the [12] commandment of Jesus Christ, her blessed Saviour, whatever she might find it to be. But she had not determined to be immersed. That river baptism, connected with the reading of those passages of Scripture, had only filled her mind with doubts; these doubts had yet to become convictions. The investigation was yet to be made. The question, Have I ever been baptized? had been prayerfully asked. It was yet to be conscientiously answered. But if the very doubt was so distressing to her mother, and so ridiculous to Mr. Percy (as it had seemed to be from some remarks he made on the way home from the river), how would the final decision affect them, if it should be made in favor of immersion! Yet, aided by power from on high, she felt her resolution grow still stronger to please God rather than those whom she loved better than all else on earth. And she had peace verging almost on joy.

When her mother came back, Theodosia saw that she had been weeping; but no further allusion was made to the subject of Baptism, until Mr. Percy came in after supper.

This young man was a lawyer. He had united with the Presbyterian Society, to which Mrs. Ernest and her daughter belonged, during an extensive revival of religion, while he was yet a mere boy. Since he had come to years of maturity, he had constantly doubted whether he was really a converted man, and often seriously regretted the obligation that bound him to a public recognition of the claims of personal religion. He often made it convenient to be absent when the Sacrament of the Supper was to be celebrated, from an inward consciousness that he was an unfit communicant; yet his external deportment was unexceptionable, and his brethren regarded him as a most excellent member, and one whose intellectual capacity and acquirements [13] would, one day, place him in a condition to reflect great honor on the denomination to which he belonged.

He had already taken a high position in the ranks of his profession; and had come to the sage conclusion, that the possession of the heart and hand of the charming Theodosia was all that was required to complete his arrangements for worldly happiness; and having overheard her remark to her brother, that if what they had just witnessed was baptism, they had never been baptized, he hastened to her side, and on their way home exerted all his powers of raillery to drive this new conception from her mind.

As for himself, he had never had a serious thought upon the question. He had been told that he was baptized in his infancy, and took it for granted that all was right. He had very serious doubts about his ever having been converted, but never the shadow of a doubt whether he had been baptized. When he listened to the religious conversation of some of his friends, and especially of the young lady of whom we are speaking, he heard many expressions, which, to him, were meaningless, and seemed almost fanatical. They talked of sorrows which he had never felt; of joys, the source of which he could not understand; and strangest of all, to him, appeared that habitual subjection to the Master’s will, which led them to ask so constantly, and so earnestly, not what was desirable to themselves or agreeable to those about them, but what was required by the command of Christ.

That one should do this, or that, under the conviction that to refuse or neglect to do so would endanger their soul’s salvation, he could easily understand; but how any one could attach much importance to any act not absolutely essential to obtain eternal life, was to his mind an unfathomable mystery, He had himself determined to secure his own soul’s salvation at any cost, and if he [14] had believed that immersion would insure salvation, he would have been immersed a hundred times, had so much been required. But thinking it as easy to get to heaven without, as with it, the whole business of baptism seemed to him as of the slightest imaginable consequence.

“What difference does it make to you, Miss Ernest,” said he, “whether you have been baptized or not? Baptism is not essential to salvation.”

“True,” she replied; “but if my Saviour commanded me to be baptized, and I have never done it, I have not obeyed him. I must, so far as I can, keep all his commandments.”

“But who of us ever does this? I am sure I have not kept them all. I am not certain that I know what they all are. If our salvation depended on perfect obedience to all his commandments, I doubt if any body would be saved but you. You are the only person I ever knew who had no faults.”

“Oh! Mr. Percy, do not trifle with such a subject. It is not a matter of jesting. I do not perfectly obey. I wish I could. I am grieved at heart day after day to see how far I fall short of his requirements. Oh, no. I do not hope or seek for salvation by my obedience. If I am ever saved, it will be by boundless mercy freely forgiving me. But then, if I love my Saviour, how can I wilfully refuse obedience to his requirements? I do not obey to secure heaven by my obedience, but to please him who died to make it possible for a poor lost sinner like me ever to enter heaven. I think I would endeavor to do his will, even if there were no heaven and no hell.”

Mr. Percy did not understand this. If he had been convinced that there was no heaven and no hell, he felt quite sure that all the rites, and rules, and ceremonies of religion would give him very little trouble. It was only in order to save his soul that he meddled with religion at all; and all that could be dispensed with, without endangering his own final salvation, he regarded as of very little consequence. He read some portion of the Scriptures almost every day (when business was not too pressing). He said over a form of prayer; and sometimes went to the communion table, because he regarded these as religious duties, in the performance of which, and by leading a moral life, he had some indistinct conception that he was working out for himself eternal salvation. Take away this one object, and he had no further use for religion, or religious ordinances.

“I know,” said he, “that you are a more devoted Christian than I ever hope to be, but you surely cannot regard baptism as any part of religion. It is a mere form. A simple ceremony. Only an outward act of the body not affecting the heart or the mind. Why even the Baptists themselves, though they talk so much about it, and attach so much importance to it, admit that true believers can be saved without it.”

“That is not the question in my mind, Mr. Percy. I do not ask whether it is essential to salvation, but whether it is commanded in the Word of God. I do not feel at liberty to sin as much as I can, without abandoning the hope that God will finally forgive me. I cannot think of following my Saviour as far off as I can, without resigning my hopes of heaven. Why should I venture as near the verge of hell as I can go without falling in? My Saviour died upon the cross for my salvation. I trust in Him to save me. But he says, ‘If ye love me, keep my commandments’—not this one or that one, but all his commandments. How can I pretend to love, if I do not obey him? If he commands me to be baptized, and I have not done it, I must do it yet. And if that which we saw at the river was baptism, then I have never been baptized.”

[16]“And so you think that all the learned world are wrong, and this shoemaker, turned preacher, is right; that our parents are no better than heathens, and a young lady of eighteen is bound to teach them their duty, and set them a good example. Really it will be a feast to the poor Baptists to know what a triumph they have gained. It will be considered quite respectable to be immersed after Miss Theodosia Ernest has gone into the water.”

“Oh, Mr. Percy,” said the young lady (and her eyes were filled with tears), “how can you talk thus lightly of an ordinance of Jesus Christ? Was it not respectable to be immersed after the glorious Son of God had gone into the water? If my dear Redeemer was immersed, and requires it of me, I am sure I need not hesitate to associate with those who follow his example and obey his commandments, even though they should be poor, and ignorant, and ungenteel.”

“Forgive me, Miss Ernest, I did not intend to offend you; but really the idea did appear exceedingly ridiculous to me, that a young lady who had never spent a single month in the exclusive study of theology, should set herself up so suddenly as a teacher of Doctors of Divinity. If sprinkling were not baptism, we surely have talent, and piety, and learning enough in our church to have discovered the error and abandoned the practice long ago. But pardon me. I will not say one word to dissuade you from an investigation of the subject. And I am very sure, when you have studied it carefully, you will be more thoroughly convinced than ever before of the truth of our doctrines, and the correctness of our practice. If you will permit, I will assist you in the examination; for I wish to look into the subject a little to fortify my own mind with some arguments against these new comers, as I understand there [17] are several others of our members who are almost as nearly convinced that they have never been baptized as you are, and I expect to be obliged to have an occasional discussion, in a quiet way.”

“Oh, yes. I shall be so happy to have your assistance. You are so much more capable of eliciting the truth than I am. When shall we begin?”

“To-night, if you please. I will call in after supper, and we will read over the testimony.”

They parted at her mother’s door. He went to his office, revolving in his mind the arguments that would be most likely to satisfy her doubts. She retired to her closet and poured out her heart to God in earnest prayer for wisdom to know, and strength to do all her Heavenly Master’s will, whatever it might be; and before she rose from her knees, had been enabled to resolve, with full determination of purpose, to obey the commandment, even though it caused the loss of all things for Christ. The only question in her heart was now, “Lord, what wilt thou have me to do?”

True to his promise, Mr. Percy came in soon after supper, anticipating an easy victory over the doubts and difficulties which had so suddenly suggested themselves to the mind of his intended bride. He could not help admiring her more, and loving her better, for that independence of thought and conscientious regard for right, which made the discussion necessary; and it gratified his vanity to think how fine a field he should have to display those powers of argument which he had sedulously cultivated for the advantage of his professional pursuits.

How he succeeded will be seen in the next chapter.

[18] [19]The book of testimony.

The question stated.

Meaning of the word baptize as settled by Christ himself.

Value of Lexicons.

A mother’s arguments.

The daughter’s answer.

First Night’s Study.

“Now, Miss Theodosia,” said he, “let us begin by examining the witnesses. When we have collected all the testimony, we shall be able to sum up on the case, and you shall bring in the verdict.”

“That is right,” said she, with a smile the first that had illumined her face since she stood by the water. “‘To the law and to the testimony; if they speak not according to this word, it is because there is no light in them.’ Here (may it please the court) is the record,” handing him a well-worn copy of the New Testament.

“Well, how are we to get at the point about which we are at issue? It is agreed, I believe, that Jesus Christ commanded his disciples in all ages, to be baptized.”

“Yes, sir, I so understand it.”

“Then it would seem that our question is a very simple one. It is, whether you and I, and others who, like us, have been sprinkled in their infancy, have ever been baptized? In other words, Is the sprinkling of infants, in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, the baptism which is required in this book?”

“That is the question,” she replied. “I merely want to know if I was ever baptized. I was sprinkled in the church. That lady, to-day, was immersed into the river. If she was baptized, I was not. That is the point. There is but one baptism. Which is it? the sprinkling or the dipping?”

[22]“Oh, if that is all, we can soon settle the question. Sprinkling and pouring and dipping are all baptism. Baptism is the application of water as a religious ordinance. It don’t matter as to the mode of application. It may be done one way or another, so that it is done with the right design. I see from what your difficulty has arisen. You have misapprehended the nature of the word baptize. You have considered it a specific, rather than a generic term.”

“I don’t know, Mr. Percy, whether I quite comprehend you. My difficulty arose from a conviction that the baptism, which we witnessed to-day, was just such a one as is described in the Scriptures, where they went down into the water and came up out of the water— whereas my baptism had nothing about it that at all resembled the scriptural pattern. Please don’t try to mystify the subject but let us see which was the real baptism.”

“I did not design to mystify the subject, but to bring it into a clearer light. The meaning expressed by some words, is rather a result than an act. If I say to my servant, go down to the office, he may run there, or walk there, or ride there, and he obeys me, equally, whichever he does—so that he gets there, it is all I require of him. Go, then, is a generic or general word, including a possible variety of acts. If I say to him, run down to the office, he does not obey unless he goes in this specified manner. So we call run a specific term. That is very plain, is it not?”

“Certainly, Mr. Percy; I comprehend that.”

“Well, then, I say that baptize is a generic term. Jesus Christ said, baptize all nations. He does not say whether you shall do it by sprinkling, or pouring, or dipping; so that you attain the end proposed, you may do it as you please. If he had said, sprinkle all nations; [23] that is specific, and his ministers must have sprinkled. If he had said pour upon them with water, that is a specific act, and they must all have poured. If he had said, dip them in water, then they must all have dipped. The word would have required it. But he used the general term baptize, which signifies any application of water as a religious ordinance, and of course it does not matter as to the mode. You may take your choice.”

“But I should, even in that case,” said she, “feel inclined to choose the same mode that He did, and which the early disciples did. There must have been some reason for his preference. But how do you determine that the word baptize is a generic term, as you call it— having three or four different meanings?”

“Simply by reference to the dictionary. Look at Webster. He is good authority; is he not. He defines baptism to be the application of water as a religious ordinance. What more do you want?”

“But, Mr. Percy,” said Edwin, who had been a silent, but very attentive listener, “the Baptist preacher told Mr. Anxious, the other day, that baptize and baptism were not English words at all, but the Greek words baptizo and baptismos, transferred into the English Bible and not translated. He said that King James would not permit the translators to translate all the words, for fear of disturbing the faith and practice of the church of England, and so they just kept the Greek word—but if they had translated it at all, it must have read dip or immerse instead of baptize.”

“Very well, Edwin, but it is not likely that the Baptist preacher is much wiser than Presbyterian preachers, or Methodist preachers, or Episcopal preachers. If dip had been the necessary, or even the common meaning of the word, it is very improbable that it would have remained for this unlearned and obscure sect to have [24] discovered it. Such statements may do very well to delude their simple followers, but they cannot be expected to impose upon the educated world.”

“But, Mr. Percy, I have looked up the words in my Greek Lexicon, and I find it is just as he said—Baptizo does mean to immerse. Baptismos does mean immersion.

“Oh, as to that, I suppose you got hold of a Baptist Lexicon.”

“Well, here it is; Donegon’s Greek Lexicon You can look for yourself.”

Mr. Percy (who, if he was not a thorough Greek scholar, yet knew enough of the language to read it readily,) glanced at the word where Edwin had marked it, and ran his eye along the cognate words.

“Baptizo—To immerse repeatedly into a liquid, to submerge, to soak thoroughly, to saturate.

“Baptisis or Baptismos, immersion; Baptisma, an object immersed; Baptistes, one who immerses; Baptos, immersed, dyed Bapto to dip, to plunge into water, etc.”

He was astonished. The thought had never occurred to him before, that baptize was not an English, but a Greek word; and that he should look in the Greek Lexicon, rather than Webster’s Dictionary, to ascertain its real meaning, as it occurred in the New Testament. He turned to the title page and preface for some evidence that this was a Baptist Lexicon, but learned that it was published under the supervision of some of the Faculty of the Presbyterian Theological Seminary at Princeton, N. J.; the very headquarters of orthodox Presbyterianism.

Here was a new phase of the subject. He could only promise to look into this point more particularly the next day; when, he said, he would procure several different [25] Lexicons, by different authors, and compare them with each other.

“In the meantime,” said Theodosia, “there is an idea that strikes my mind very forcibly; and that is, that the Saviour himself has fixed, by his own act, the meaning of the word as he employed it.”

“How so, Miss Theodosia?”

“Just in this way; suppose we admit that it had a dozen meanings before he used it, and that in other books it has a dozen meanings still, yet it is certain that he was baptized. Now, in his baptism a certain act was performed. It may have been sprinkling, pouring, or dipping; but whatever it was, that act was what He meant by baptism. That act was what He commanded. His disciples must so have understood it. He gave (if I may speak so) a Divine sanction to that meaning. And when the word was afterward used in reference to his ordinance, it could never have any other. If he was immersed, then the question is decided; baptism is immersion. If he was sprinkled, baptism is sprinkling. If he was poured upon, baptism is pouring. So we need not trouble ourselves about the Lexicons, but can get all our information from the Testament itself.”

“There is a great deal of force in that suggestion, Miss Theodosia. It is a pity you could not be a lawyer. (And he thought what a partner for a lawyer she would be, and how happy it was for him that he had been able to persuade her to promise to become Mrs. Percy.) But while it is true that we may find all the testimony that we need within the record, yet it is important that we get at the real meaning of the record. And as that was written in Greek, I see no reason why we should not seek in the Greek for its true sense. If baptizo means to dip, and baptismos means a dipping, an immersion, we shall be obliged to rest our cause upon some other [26] ground. There must, however, be some mistake about this. I will look into it to-morrow.”

“I do not care what the Lexicons say,” rejoined Theodosia, “I want to get my instructions entirely out of the word of God. I don’t wish to go out of the ‘record,’ as you lawyers say.”

“You are right in that; but how are we to learn the meaning of the record? If any document is brought into court, it is a rule of law, founded on common sense, that the words which it contains are to be understood in their most common, every-day sense, according to the usage of the language in which they are written. Now this document, the New Testament, it seems, was written in Greek, and we are in doubt about the meaning of one of the words. We go to the Lexicon, not for any testimony as to the facts of the case, but only to learn the meaning of a very important word used by the witnesses. Matthew and several other witnesses depose that Jesus and others were baptized. If they were present in court, we would ask them what they mean by that word, baptize. We would require them to describe, in other language, the act which was performed —to tell us whether it was a sprinkling, a pouring, or a dipping. But as we cannot bring them personally into court, we must ascertain what they meant in the best way we can; and that is by a careful examination of the words which they used, and the meaning that would have been attached to them at the time they used them, by the people to whom they were addressed. Now as the documents were written in Greek, of course they used words in the common Greek sense. And we must ascertain their meaning just as we would any other Greek word in any other Greek author; and that is by reference to the lexicons or dictionaries of the Greek language.”

[27]“Very well, Mr. Percy; you talk like a judge. But what if you find all the lexicons agree with this? What if they all say that the word means dip, plunge, immerse?”’

“Why then, we must either admit that those who are said to have been baptized, were plunged, dipped, immersed, or deny the correctness of the Lexicons.”

“But if you deny the correctness of the Lexicons in regard to this word, what confidence can we have in them in regard to other words? Brother Edwin is studying Greek, and as often as he comes to a word which he has not met with before, he finds it in the Lexicon, and so learns its meaning; but if the Lexicons are wrong in this word, they may be wrong in all. Is there no appeal from the authority of the Lexicons?”

“Certainly, we may do in Greek as we do every day in English studies; we appeal from Johnson to Webster, and from Webster to Walker, and from Walker to Worcester. If one does not suit us we may go to another.”

“One more question. Are any of these Lexicons Baptist books, made for the purpose of teaching Baptist sentiments? If so, you know they might be doubtful testimony.”

“On the contrary, the Lexicons are made by classical scholars, for the sole purpose of aiding students in the acquisition of the Greek language. I do not suppose any one of them was made with any reference to theological questions, and probably no one of them by a person connected with the Baptist denomination. It is certain most of them were not, and if they all agree in regard to this word, it must be conceded that they did not give it a meaning to suit their personal theological views. There are a number of them in the College library, and I will examine them all to-morrow, and tell you the result.”

[28]Mr. Percy went back to his office studying the new phase of the question presented in the meaning of the word. “If baptizo in the Greek means to dip, in its primary, common, every-day use, then Jesus Christ was dipped. Then every time the record says a person was baptized, it expressly says he was dipped. I wonder if it can possibly be so. If so, why have our wise and talented preachers never discovered it? or, knowing it, can it be possible that they have systematically concealed it?”

Theodosia retired to her chamber, where she spent a few moments in prayer to God for the guidance of the Holy Spirit, and then took her Testament and read how they were baptized of John in the river of Jordan. How Jesus, after he was baptized, came up out of the water. How they went down both into the water, both Philip and the eunuch, and he baptized him, and when they were come up out of the water, the Spirit of the Lord caught away Philip. She compared these statements with what she had seen at the river, and did not need any testimony from the Lexicons to satisfy her that John’s baptism and Philip’s baptism was immersion. Why else did they go into the water? Why else was it done in the river? Ministers don’t go into the river to sprinkle their subjects now-a-days. There was no reason for doing it then. Must I then unite with this obscure sect and be immersed? Must I break away from the communion that I love so dearly—from all my friends and relatives? Must I part from my dear old pastor, who was, under God, the means of my conversion —who has so often counselled me, prayed with me and for me, wept over me, and cherished me as though I had been his own child? The very thought was terrible. She threw herself on her bed and wept aloud. Her crying brought her mother to her side. She [29] kneeled beside the bed, took the poor girl’s hand in both of hers, and bade her try to banish this distressing subject from her thoughts. It was not worth while, she said, for a young girl like her to set up her own opinions, or even to entertain doubts in opposition to her minister and others who had spent their lives in the study of this very thing. As for herself, if her pastor, Mr. Johnson, said any thing was in the Bible, she always took it for granted it was there. He had more time to look into these things than she had. It was his business to do it; and he was better qualified to do it than any of his people. And of course, if sprinkling was not true baptism, he would never have practiced it.

“But, mother,” sobbed the weeping girl, “I must answer to God, and not to pastor Johnson. Much as I love him, I trust I love my Saviour better; and if my pastor says one thing, and Jesus Christ another, Mr. Johnson himself has often told us to obey God rather than man. I have no choice; I must obey my Saviour.”

“Of course you must, my child; but Mr. Johnson knows better what the Saviour commands than you do. He understands all about these questions. And he will assure you that you have been properly baptized. I know that he agrees exactly with Dr. Fisher, who baptized you, as you yourself well remember.”

“I remember that he sprinkled a little water in my face, mother; but if that was baptism which I witnessed to-day, he certainly did not baptize me.”

“Well, my dear, try and compose yourself, and go to sleep; and I will send for our pastor to come and see you to-morrow. It will soon satisfy your mind.”

“I hope he may; and I will try to sleep. Good-night, mother.”

[30] [31]In which Theodosia is assisted

by Mr. Percy, the pastor, and the

schoolmaster.

Presbyterian Authorities:

Mr. Barnes;

or, explaining scripture by

scripture.

Theodosia’s opinion of theological writers.

More authorities:

Dr. McKnight, Dr. Chalmers, John Calvin,

Prof.

Stewart, John Wesley, &c.

Second Night’s Study.

Punctual to his promise, Mr. Percy came in soon after supper on the next evening, and found the Rev. Mr. Johnson, the pastor of the church, already there. He had called early to take a social cup of tea, having learned that Theodosia was “like to go crazy about these new-fangled Baptist notions.”

He did not think she looked much like a maniac, however, though there was a deep saddened seriousness about her face. Nor did she act like a maniac, for never before had she seemed so respectfully affectionate to him and to her mother.

He had not said a word upon the subject of dispute, and seemed reluctant to approach it; but when Mr. Percy came in, it could no longer be postponed.

“I am very glad to meet you here, Mr. Johnson,” said the young man. “Miss Theodosia and I had quite a discussion yesterday evening on the subject of baptism. She has taken a fancy that she has never been baptized; and I believe that I nearly exhausted my logic in trying to convince her that she had. I hope your arguments will be more effectual than mine.”

“Really, my children, I don’t know,” said the old man, “what I may be able to do; I have never studied these controversies much; I think it is better to live in peace and let every one enjoy his own conscientious opinion. These discussions are apt to run into disputes and quarrels, and often occasion a great deal of ill [34] feeling. I have known them to divide churches, and even families. It is better to avoid them.”

“But what are we to do with such lovely heretics as this?” said the young man, with a smile and a sly glance toward her mother. “She must be satisfied that she has been baptized, or you will have her running to the school-house next Sunday to hear that uneducated Baptist preacher, and ten to one, she will ask him to go down into the water and baptize her according to the New Testament model. She says she wants to be baptized as Jesus Christ was, and that was in the river, you know.”

“Oh, as to that,” rejoined the pastor, “there is no evidence that Jesus Christ was immersed in the river at all. It has been satisfactorily proved that he was sprinkled or poured upon; and it is very certain that sprinkling was practiced by the apostles and early Christians.”

“Oh, I am so glad to hear you say that,” replied the young lady. “You don’t know what a load it has taken off my mind. Do tell me how it is ascertained that Christ did not go into the river, and what evidence there is that he was sprinkled, and it was sprinkling which he commanded. You can’t imagine how anxious I am to know.”

“Well, I don’t know that I can call up all the evidence just at this time, and we would not have time to go over it, if I could; but you may be assured that there is such evidence, and that of the most satisfactory character, or else all the learned and talented theological scholars of the various Pedobaptist churches would not have continued for so many ages, to teach and practice it.”

“Certainly, I have no doubt the evidence exists, since you say so; but can’t you tell me what it is, or show me [35] where to find it? I shall never be able to rest in peace till I am convinced that I have been baptized. And if that which I witnessed at the river yesterday was baptism, I am sure I never was.”

“Oh, don’t be so confident, my daughter. There are more modes of baptism than one. That was, perhaps, one mode (though of that I have some doubt). You were baptized by another mode. That may have been baptism. Yours certainly was.”

“Well, do please prove it to me some way, Mr. Johnson. What you say is something like what Mr. Percy said yesterday. He told me that baptize was a generic term, expressing rather a certain result than any specific act. I think that was the idea, was it not, Mr. Percy?”

“Exactly; and if so, I leave it to Mr. Johnson if the manner of reaching the result is not a matter of indifference.”

“Certainly,” said the pastor; “‘baptism is the application of water as a religious ordinance.’ It does not matter about the quantity of water or the mode of applying it.”

“Yes; that is what mother said yesterday. And we looked in Webster, and found that such was, indeed, the present English use of the word baptize. But brother says baptize is a Greek word slightly modified, and transferred from the Greek Testament to the English. It is the New Testament meaning in the time of Christ, and among the people for whom the Gospels were first written, that we want, not the meaning that it has acquired in the English since its transfer to our language.”

“You see, pastor, she is going to be hard to satisfy. She pleads her cause like a lawyer.”

“No, no, Mr. Percy, I will not be hard to satisfy. I desire, I long, I pray to be satisfied. I can never rest [36] till I am satisfied. I only ask for the evidence. You said yesterday that baptizo was a generic term meaning to sprinkle; to pour, or to dip; but we found it in the Lexicon, and it proved to be a specific term meaning only to dip. Not a word was there about sprinkling or pouring. It was simply and only dipping. To-day, Mr. Johnson tells me about several modes—but they are not modes of dipping. And yet if the Greek word baptismos, baptism, means dipping, then they must, in order to be modes of baptism, be modes of dipping. But, Mr. Percy, you have not yet told us the result of your examination of other Lexicons.”

“We can make nothing out of them. I am sorry to say they all agree substantially with the one you have in the house. If we trust to them we must grant that the word means primarily and ordinarily to dip, to plunge, to immerse. Of this there is no doubt.”

“Then I am more perplexed than ever. You said yesterday that in order to know what the act was which the disciples performed and Christ commanded, we must ascertain the precise meaning of baptize, as they employed it in the Greek language. You have examined all the Lexicons (the highest authorities) and find they all agree in saying it was dip, plunge, immerse. You admitted yesterday that if they should agree in this, the question was settled. If they said baptize meant to dip, and baptismos a dipping or immersion, then every time we read that one was baptized, we must understand that he was immersed. I thought that was a plain, straightforward case. I felt that I could understand it. Well, now you say you have examined carefully the other Lexicons, and they all agree with this. No one says sprinkle, no was says pour—all say dip, and consequently the Gospel says that Jesus was dipped of John in the river of Jordan. But then our pastor says that [37] he has evidence that Jesus did not enter the river at all, and that he was sprinkled, and not dipped. Of course he would not say it, unless it was so, but I really don’t understand how it could be so.”

“I have some curiosity on that point myself,” said Mr. Percy, evidently relived to find he could (for the moment at least), take the other side of the question. “I find myself in a very close place. These Lexicons have killed me. I don’t know what to say. I suppose, of course, there is some way to get around the difficulty; but I must leave it to our pastor to point it out. For my part, I submit the case.”

“Really,” said Mr. Johnson, “the question never presented itself to me in just this light before. You must give me a little time to consider about it. And in the meantime let me beg of you both that you will examine some of the standard writers upon the subject. I do not think you have done this yet. What have you in the house?”

“Not a book upon the subject, except it be the Bible, and I don’t much care to read any other till we have examined that. If sprinkling is there, it ought to be so plainly taught that I can see it for myself. If I can’t find it, I will always doubt if it is there,” rejoined the young lady.

“True, my child,” said the pastor; “but we often fail to see things at first glance, which are very evident when they have once been pointed out, and our attention fixed upon them. This is the advantage of using proper helps to understand the Scriptures. Those not familiar with the language in which they were written, and with the customs and manners of the people to whom they were originally addressed, will derive great assistance from judicious criticisms. I like, myself, always to read [38] a commentary on every chapter that I attempt to understand.”

“Oh, as to commentaries, we have Barnes’ Notes on the Gospels, and on some of the Epistles. And we have McKnight’s exposition and new translation of the Epistles. Uncle Jones admires these old volumes of McKnight’s very much, but they always seemed very dry to me. I love Mr. Barnes, and have studied his notes in Sunday-school and Bible class all my life.”

“Mr. Barnes is a very learned and eminent divine,” replied the pastor. “His notes have attained a wide circulation, and won for him an enduring reputation. You cannot follow a safer guide. Have you examined him upon the subject?”

“I suppose,” said she, “that I have read it a dozen times, but I never thought any thing particularly about it, and don’t recollect a word.”

“Suppose, then, you get his Notes, and let us look at them a moment before I leave. I can stay but a few minutes longer.”

Edwin had found the volume while they were talking of it, and now handed it to the pastor.

“I suppose we shall find it here, Matthew iii. 6, as this is the place where the word baptize first occurs. Mr. Percy, will you have the kindness to read it aloud for our common benefit?”

Mr. Percy read: “And were baptized of him in Jordan, confessing their sins.” “The word baptize signifies, originally, to tinge, to dye, to stain, as those who dye clothes. It here means to cleanse or wash any thing by the application of water. (See note, Mark vii. 4.)

“Washing or ablution was much in use among the Jews, as one of the rites of their religion. It was not customary, however, to baptize those who were converted [39] to the Jewish religion until after the Babylonish captivity.

“At the time of John, and for some time previous, they had been accustomed to administer a rite of baptism or washing to those who became proselytes to their religion, that is, who were converted from being Gentiles.” … “John found this custom in use, and as he was calling the Jews to a new dispensation, to a change in the form of their religion, he administered this rite of baptism or washing to signify the cleansing from their sins, and adopting the new dispensation, or the fitness for the pure reign of the Messiah. They applied an old ordinance to a new purpose; as it was used by John it was a significant rite or ceremony, intended to denote the putting away of impurity, and a purpose to be pure in heart and life.”

Mr. Percy stopped reading, and looking up at Mr. Johnson, said, “Pardon me, pastor, but if Mr. Barnes were present here as a witness in this case, I would like to ask him a single question by way of a cross- examination. He says that ‘Washing or ablution was much in use among the Jews as one of the rites of their religion,’ and yet he tells us that baptism was not in use till after the captivity. Must not baptism then have been something new and different from the washing or ablution?”

“And I,” said Theodosia, “would like to ask a question too; perhaps pastor Johnson can answer it as well as Mr. Barnes. He says, when they received a convert from the Gentiles, they baptized him; John found this rite in use, and merely applied an old ordinance to a new purpose. Now, I want to know how this ordinance was administered. What was the act which they performed upon the proselyte? Did they sprinkle him, or pour upon him, or was he immersed? If this can be ascertained, it will of course determine what it was that [40] John did when he baptized. Can you tell us, Mr. Johnson, which it was?”

“Yes, my child; it was universally conceded that the Jewish proselyte baptism was immersion. I do not know that this has ever been denied by any writer on either side of the controversy. It is distinctly stated to have been immersion by Dr. Lightfoot, Dr. Adam Clarke, Prof. Stuart, and others who have espoused our cause.”

“How then do you get rid of the difficulty? If, as Mr. Barnes says, ‘John applied an old ordinance to a new purpose,’ and that old ordinance was immersion, it is absolutely certain that John was immersed. There is not room for even the shadow of a doubt.”

“It would seem to be so indeed,” said the pastor. “I never thought of it just in that light before. But though it is admitted by all that the proselyte baptism was immersion, it is doubted by many whether it existed at all before the time of John. Some think it originated about the time of Christ, and that the Jews practiced it in imitation of John’s baptism.”

“I do not see,” rejoined Mr. Percy, “how it can make the slightest difference in the result of the argument, whether it was in use before the time of John, or was borrowed from him. If they immersed before the time of John, and he borrowed his rite from them, of course it was immersion that he borrowed. If they immersed after the time of John, and borrowed their rite from him, of course John immersed, or they could not have borrowed immersion from him.”

“But if John immersed,” said Theodosia, “then Jesus was immersed by John. This immersion was called his baptism. The disciples saw it, and spake of it as such; and ever afterward, whenever baptism was mentioned, their minds would revert to this act; and so, when Jesus said [41] to them, ‘Go and baptize,’ they must have understood him to mean, that they should go and repeat on others the rite which they had seen performed on him. And not only so,” added the young lady, “but Christ’s disciples had themselves been accustomed to practice the same baptism under his own eye. If John immersed, they had not only witnessed his immersion of Jesus, but they had themselves immersed hundreds, if not thousands, under the personal direction of Jesus himself.”

“That would certainly settle the question. But where did you make that discovery?” asked Mr. Percy, incredulously.

“Oh, it is in the record,” she replied. “Here is the testimony, John iii. 22, 23: ‘After these things, came Jesus and his disciples into the land of Judea, and there he tarried with them, and baptized. And John also was baptizing in Ænon, near to Salim, because there was much water there; and they came, and were baptized.’ And in the next chapter it says that the ‘Pharisees heard that Jesus made and baptized more disciples than John.’ Now John baptized and Jesus baptized. They both did the same thing; that is as plain as words can make it: as plain as though it said Jesus walked, and John also walked; or Jesus talked, and John also talked. Whatever it was that John did, Jesus was doing the same thing. “If John’s baptism was immersion, then Jesus and his disciples were immersing, and they immersed more than John.”

“That is really,” said Mr. Percy, “a complete demonstration. Don’t you think so, Mr. Johnson?”

“Well, I must confess it looks so at the first glance. We must look into this matter another time. Let us, for the present, see what Mr. Barnes says further. [42] Please read on, Mr. Percy; I have not much more time to spare this evening.”

Mr. Percy read on:

“The Hebrew word (tabal) which is rendered by the [Greek] word baptize, occurs in the Old Testament in the following places:—Lev. iv. 6; xiv. 6, 51; Num. xix. 18; Ruth ii. 14; Ex. xii. 22; Deut. xxxiii. 24; Ezk. xxiii. 15; Job ix. 31; Lev. ix. 9; 1 Sam. ix. 27; 2 Kings v. 14; viii. 15; Gen. xxxvii. 31; Joshua iii. 15. It occurs in no other places; and from a careful examination of these passages, its meaning among the Jews is to be derived.”

“Oh,” said the young lady, “that is what I like; I like to find the meaning in the Scriptures, then I know I can rely upon it. Just wait a minute, Mr. Percy, if you please, till I can get my Bible and hunt out those place, and see how it reads. If it reads sprinkle, then it is all right—sprinkling is baptism; if it reads pour, then pouring is baptism; if it reads dip, then dipping is baptism. We will soon see.”

“Let me read a little further, Miss Theodosia, and perhaps you may not think it necessary to examine the texts.”

She had, however, got her Bible, and was getting ready to turn to each text in order, when he resumed as follows:

“From these passages, it will be seen that its radical meaning is not to sprinkle or to immerse. It is to dip. Commonly for the purpose of sprinkling or for some other purpose.”

“What? Do let me see that. Pardon me, pastor, but what does the good man mean? It is not to sprinkle; it is not to immerse; it is to dip! Edwin, please get Webster’s Dictionary, and tell us the difference between the meaning of dip and immerse.”

[43]“Here it is. Immerse is to plunge into a fluid. Dip is to plunge any thing into a fluid, and instantly take it out again.”

“Why, Mr. Percy, that just describes the act of baptism which we saw at the river. It was not an immersion, strictly speaking, but a dipping, a plunging beneath the water, and a raising out again. ‘It is not to sprinkle or to immerse; it is to dip! Commonly for the purpose of sprinkling, or for some other purpose.’”

“What are you laughing at, brother Edwin?”

“I was only thinking how a preacher would look, dipping a man ‘for the purpose of sprinkling’ him. But see! there goes my teacher, and I believe he is a Baptist. At any rate he goes to all their meetings. Let me call him in; he can tell us something more about these things.”

And before any one could interfere, he had run to the door and hailed Mr. Courtney.

Seeing this, the Rev. Mr. Johnson arose, and reminding the company that he had an engagement at that hour, promised to call again and talk over the matter more, at another day, and took his leave, passing out just as the teacher was coming in.

“Mr. Courtney,” said Mr. Percy, “perhaps you can help us a little. We were just looking at Barnes on Baptism.”

“I did not know he had ever written on the subject, except some very singular remarks he made in his Notes on the third chapter of Matthew.”

“It was those we were examining, and I infer that you do not think very favorably of his argument.”

“I think he makes a very strong argument for the Baptists.”

“How so?”

“Simply thus: It is an axiom in logic as well as in [44] mathematics, ‘that things which are equal to the same thing, are equal to one another.’ Now he states a very remarkable and exceedingly significant fact, when he says that the Hebrew word tabal is rendered by the word baptize. It occurs, he says, fifteen times in the Hebrew Bible. Now when the Jews translated their Scriptures into Greek, whenever they came to this word, they rendered it baptize; and when our translators came to this same word, they rendered it by the English word dip. It follows, therefore, since dip in English and baptize in Greek are both equivalent to tabal in Hebrew, they must be equivalent to each other.

“Mr. Barnes says further, that the true way to ascertain the meaning of this word among the Jews, is to examine carefully the fifteen places where it occurs in the Old Testament. I see, Miss Ernest, that you have the Bible in your hand; suppose you turn to those places, and let us see how they read. It will not take more than a few minutes of our time.”

“I had gotten the book for that very purpose, sir. I like this way of study, comparing Scripture with Scripture. I always feel better satisfied with my conclusions when I have drawn them for myself directly from the Bible.”

“Well, here is the first place, Leviticus iv. 6: ‘And the priest shall dip his finger in the blood.’

“The second, Leviticus xiv. 6: ‘And shall dip them into the blood of the bird that was killed over running water.’

“The third, Leviticus xiv. 51: ‘And dip them in the blood of the slain bird and in the running water.’

“The fourth, Numbers xix. 18: ‘And a clean person shall take hyssop, and dip it into the water.’

“The fifth, Ruth ii. 14: ‘And Boaz said unto her at [45] [46] [47] meal time, come thou hither, and eat of the bread, and dip thy morsel in the vinegar.’

“The sixth, Exodus xii. 22: ‘And ye shall take a bunch of hyssop, and dip it in the blood.’

“The seventh, Deuteronomy xxxiii. 24: ‘And let him dip his foot in oil.’

“The eighth, Ezekiel xxiii. 15: ‘Exceeding in dyed attire.’

“The ninth, Job ix. 31: ‘Yet shalt thou plunge me in the ditch.’

“The tenth, Leviticus ix. 9: ‘And he dipped his finger in the blood.’

“The eleventh, 1 Samuel xiv. 27: ‘And he (Jonathan) put forth the end of the rod that was in his hand, and dipped it in the honey comb.’

“The twelfth, 2 Kings viii. 16: ‘And he (Hazael) took a thick cloth, and dipped it in the water, and spread it on his face.’

“The thirteenth, Joshua iii. 15: ‘The feet of the priests that bare the ark were dipped in the brim of Jordan.’

“The fourteenth, 2 Kings v. 14: ‘And he went down and dipped himself seven times in Jordan.’

“The fifteenth, Genesis xxxvii. 31: ‘And they took Joseph’s coat, and killed a kid, and dipped the coat in the blood.’

“The passage in the 2 Kings v. 14, is very remarkable, since it corresponds precisely in the Septuagint to the text in Matthew. The Septuagint says of Naaman, Ebaptizato en to Jordane. Matthew says of the people baptized by John, Ebaptisonto en to Jordane. Nobody has ever questioned the correctness of the translation in Kings. He dipped himself in Jordan; and had Matthew been translated by the same rule, it must have read, they were dipped by John in Jordan.

[48]“But I fear this subject may be disagreeable to you. Mr. Barnes, I know, is a most eminent minister of your own denomination, and I ought probably to have avoided speaking thus in your presence.”

“Oh, no, sir,” said the young lady; “I want to learn the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, on this subject. I am glad to learn it from any source, and in any way. Perhaps you can assist us further; but let us see what further Mr. Barnes has to say.”

Mr. Percy read again:

“In none of these cases can it be shown that the meaning of the word is to immerse entirely. But in nearly all the cases the notion of applying the water to a part only of the person or object, though it was by dipping, is necessarily supposed.… It cannot be proved, from an examination of the passages in the Old and New Testaments, that the idea of a complete immersion ever was connected with the word, or that it ever in any case occurred.”

“Stop, Mr. Percy,” said the young lady. “Pray stop, and let me think a moment. Can it be possible that a good man, a pious minister of Jesus Christ, could dare to trifle thus with the holy Word of God? Oh, it is wonderful! I cannot understand it! He said just now, that the meaning of the word ‘was to dip for the purpose of sprinkling, or for some other purpose.’ To dip means to plunge any thing into a fluid, and immediately take it out again. To immerse means merely to plunge the object in the fluid. Whatever is dipped, therefore, is of necessity immersed, to the same extent that it is dipped; and yet he says these things which the Word says were dipped, were none of them entirely immersed.”

“Do not think too hardly of him,” said Mr. Percy. “An advocate who has a bad cause to sustain (I know [49] from experience), is sometimes obliged to resort to just such a jumble, to cover the weak points of his argument.”

“Perhaps,” said Theodosia, “it might be excusable in a lawyer, though even of that I am doubtful; but that a minister of the holy Word of Jesus should thus stoop to ‘darken counsel with words without knowledge,’ is something I never conceived of till now.”

“When you have become more familiar with the influence which passion and prejudice, and especially early education and church attachments, exert upon the minds of even the wisest and best of men,” said Mr. Courtney, “these things will not appear so strange to you. Mr. Barnes doubtless believes that sprinkling is baptism. He was taught so in early life, and has for many years taught others so. To convince him of the contrary, would now be almost or quite impossible, and when any text of Scripture comes in opposition to this opinion, he can hardly help perverting or misunderstanding it. You desired to know the true meaning of the word baptize, as it was used in our Saviour’s time among the Jews; and you applied to him for information. He told you very properly that you must go to those places where it occurs in the original of their own Scriptures, and pointed out to you the fifteen places, which he assures you are the only places in which it occurs. He has thus given the matter into your own hands. You turn to the places, one by one, and find that in fourteen out of the fifteen it clearly means to dip. That such is the case, he does not deny. He is obliged to grant that ‘its radical meaning is to dip.’ This, now, he has proved from the Scriptures themselves. But this overthrows his sprinkling, so he must get rid of its force. This he undertakes to do—1. By intimating that there is some important difference between dipping and immersion. ‘It is not sprinkling nor immersion,’ he says; ‘it is [50] dipping.’ And then he tries to confuse the matter by mixing in the object, ‘for the purpose of sprinkling, or for some other purpose,’ as though the purpose modified the act performed. The baptism mentioned in these fourteen places was equally dipping, whether it was performed for the purpose of sprinkling, as when the priest dipped the hyssop; or for the purpose of smearing, as when the priest dipped the tip of his finger in oil; or for the purpose of cleansing, as when Naaman dipped himself in Jordan; or for the purpose of pollution, as when Job was plunged in the ditch; or merely for the purpose of wetting, as when Ruth dipped her morsel, or Hazael his thick cloth. The wetting, the defiling, the cleansing, the smearing, were not the baptism; they were not the dipping, but a consequence of it. The sprinkling was not the baptism, the dipping, but a subsequent and altogether a different act. Then to make ‘confusion worse confounded,’ he intimates some vast distinction between entire immersion and dipping. These things, said to be baptized in these fourteen places, he can’t deny were dipped; but ‘none of them,’ he says, ‘were entirely immersed.’ But the extent of the immersion does not affect the meaning of the word. The word immersed expressed only the act of plunging the object into the fluid. The word dip expressed this act, and the additional one of taking it out again; and this, he said and proved, was the Scriptural meaning of baptize. As far, then, as they were baptized, they were dipped; and as far as they were dipped, they were immersed. We learn the extent of the dipping from other words, not from this one. If Naaman is said to have dipped himself, or Hazael the cloth, there is not the slightest reason to doubt that the whole person and the whole cloth were immersed. If Jonathan dipped the end of his staff, why the end only was immersed. It was [51] immersed, however, just as much as it was dipped or baptized.”

“But,” said Mr. Percy, “what will you do with the hyssop, and the living bird, etc., that were to be baptized into the blood of the slain bird, and where Mr. Barnes says it is clearly impossible that they all should be immersed in the blood of the single bird.”

“I simply say that they could be immersed in it as easily as they could be dipped in it. If you will turn to Leviticus xiv. 6, you will see that the blood of the slain bird was to be caught over running water; and as it rested on, or mixed with the water, these things could all be entirely immersed, if need be. You will remember, however, that in common language the whole of a thing is often mentioned when a part is only meant. I say, for instance, that I dipped my pen in ink, and wrote a line; you do not understand that I dipped more than the point—enough to take up the ink to write. If I tell you that I dipped my hair brush in water, and smoothed my hair, you do not understand that I dipped it in, handle and all, but only the bristles. So only enough of the cedar wood, and hyssop, and scarlet, etc., may have been dipped to take up enough to sprinkle with; but as much as they were baptized, so much were they dipped; and so far as they were dipped, just so far were they immersed. But it does not make any difference to Mr. Barnes or his sprinkling brethren, whether the dipping was partial or complete; for they do not dip their subjects of baptism at all, in whole or in part, for the purpose of sprinkling, or for any other purpose; and, therefore, if the Scriptural meaning of the word baptize is to dip, as Mr. Barnes has so clearly proved by Scripture itself, then they do not baptize at all.”

“Oh, yes, I see now how it was,” said Theodosia, “when Dr. Fisher performed this ceremony upon me. [52] He baptized his own hand; for he dipped that in the bowl, but he only sprinkled me; and therefore, according to the showing of Mr. Barnes himself, I have never been baptized.”

“Do not put down the book yet,” said Mr. Courtney. “Just turn to Matthew xx. 22, and you will find that Mr. Barnes has no more difficulty than the greatest Baptist in the land, in understanding the word baptism to signify not only immersion, but complete immersion, whenever it does not refer to the ordinance.

“The baptism that I am baptized with.” On this Mr. B. remarks as follows: ‘Are ye able to suffer with me the trials and pains which shall come upon you in endeavoring to build up my kingdom? Are ye able to be plunged deep in afflictions? to have sorrows cover you like water, and to be sunk beneath calamities as floods, in the work of religion? Afflictions are often expressed by being sunk in the floods and plunged in the deep waters.’ (Ps. lix. 2; Isa. xliii. 2; Ps. cxxiv. 4, 5; Sam. iii. 54.)

“You see Mr. Barnes has no more difficulty than the translators of the Old Testament, in giving the word its true meaning—to dip, to plunge, to sink beneath the waters, etc., when it does not refer to the ordinance; but when it does, all is confusion and mystery.”

“I begin to think,” said Theodosia, “that theological writers are not to be relied upon at all. And I feel more than ever inclined to trust to the Bible alone, and study it for myself. When such a man as Mr. Barnes can be so far blinded by education and prejudice as to come so near the truth and not see it—to point out the way toward it so plainly, and yet refuse to walk in it, and endeavor to hide it from others by such a strange medley of words, I have no further use for any book on the subject but the word of God. I will study that; and [53] it shall be my only guide. If I find that Jesus was sprinkled in Jordan, I will be content. If I find that he was poured upon, I must be poured upon. If I find that he was dipped, then I must be dipped.”

“Oh, no, Miss Theodosia; you are decidedly too hasty. I have often found in court, that a witness whom I expected to testify in my favor, and who evidently desired and intended to do so, has nevertheless, on a cross- examination, given such testimony as was altogether favorable to the opposite party. But I did not abandon my client, and give up my suit. I sought for other witnesses. Our information on this subject is, as yet, very limited. There are other sources of evidence; let us examine them. Something may yet turn up to change your opinion of theological writers. Did you not say you had McKnight on the Epistles in the house?”

“Yes; and uncle Jones, who you know is one of the Elders in our church, says it is one of the best, if not the very best of commentaries.”

“Well, let us see what he says. How will we find the place?”

“Take a concordance,” suggested Edwin, “and look at every place where the word baptize occurs.”

“That is a first-rate idea. Well, here is the first place. Romans vi. 4. Buried with Christ by baptism. In the note he says: ‘Christ’s baptism was not the baptism of repentance, for he never committed any sin. But he submitted to be baptized—that is, to be buried under the water by John, and to be raised out again— as an emblem of his future death and resurrection. In like manner, the baptism of believers is emblematical of their own death, burial, and resurrection; perhaps, also, it is a commemoration of Christ’s baptism.’”

[54]“Stop, Mr. Percy, are you sure you are not reading falsely?”

“Yes, I am perfectly certain. Here is the book, you can see for yourself.”

“No; but I thought you must be playing some trick on me. At any rate, McKnight must have been a Baptist. No one who believed in, and practiced sprinkling, could have written in that way.”

“Perhaps he was a Baptist. Let us look at the title page and preface, and see who and what he was. It appears from this, that James McKnight, D.D., was born Sept. 17, 1721. Licensed to preach by the Presbytery of Irwine of the Scotch Presbyterian church. Ordained at Maybole in 1753. Chosen Moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian church in 1769, which position he held for more than twenty years. This brief history of his life, prefixed to the first volume of his Notes, informs us further, that he spent near thirty years of his life in preparing these Notes, and ‘that the whole manuscript was written over and over, by his own hand, no less than five times.’ They were therefore the deliberate and carefully expressed opinions of a most eminent and very learned Presbyterian Doctor of Divinity, and presiding officer of the Presbyterian church in the country where he lived. Of course he cannot be suspected of any bias toward the obscure and despised sect called the Baptists.”

“Well, read on then. Theologians are mysterious men.”

“That is all he says on this verse. But here is verse 5th. ‘Planted together,’ etc.

“‘The burying of Christ and of believers, first in the water of baptism, and afterward in the earth, is fitly enough compared to the planting of seeds in the earth, [55] because the effect in both cases is a reviviscence to a state of greater perfection.’”

“Surely, he must consider baptism to be a burial in water. But perhaps he thinks there were several baptisms, and that dipping was one form or mode, while sprinkling was another.”

“No, for here is his note on Ephesians iv. 5. One Lord, one Faith, one Baptism.

“‘Ye all,’ says he, ‘serve one Lord, and all have the same object of faith, and have all professed that faith by the same form of baptism.’”

“Has he any thing else on the subject?”

“Yes, here, on 1 Cor. x. 2, ‘And were all baptized unto Moses in the cloud and in the sea.’

“‘Because the Israelites, by being hidden from the Egyptians under the cloud, and by passing through the Red Sea, were made to declare their belief in the Lord and his servant Moses, the Apostle very properly represents them as baptized unto Moses in the cloud and in the sea.’

“And here again—1 Cor. xv. 29—‘Else what shall they do who are baptized for the dead.’

“‘Otherwise what shall they do to repair their loss who are immersed in sufferings for the resurrection of the dead.’

“And here again—Heb. ix. 10—‘Divers washings (Baptismos).’

“‘With nothing but meats, and drinks, and divers immersions, and ordinances respecting the body.’

“One more place, and we have all that he says upon the subject.

“1 Peter iii. 21, ‘The like figure whereunto baptism doth now save us, etc.’

“The water of baptism is here called the anti-type [56] of the water of the flood, because the flood was a type or emblem of baptism in three particulars:

“1. ‘As by building an ark and entering into it, Noah showed strong faith in the promise of God, concerning his preservation, by the very water which was to destroy the Antediluvians for their sins. So by giving ourselves to be buried in the water of baptism, we show a like faith in God’s promise, that though we die and are buried, he will save us from death and the punishment of sin, by raising us up from the dead at the last day.’

“2. ‘As the preserving of Noah alive during the nine months of the flood, is an emblem of the preservation of the souls of believers while in the state of the dead, so the preserving believers alive while buried in the water of baptism, is a prefiguration of the same event.’

“3. ‘As the water of the deluge destroyed the wicked, but preserved Noah by bearing up the ark, in which he was shut up, till the waters were assuaged, and he went out to live again upon the earth; so baptism may be said to destroy [or represent the destruction of] the wicked, and to save the righteous, as it prefigures both these events. The death of the wicked it prefigures by the burial of the baptized person in the water, and the salvation of the righteous by the raising of the baptized person out of the water.’”

“Well, Mr. Percy,” said Theodosia, “what do you make of this witness? Do you wish to cross-examine him, or ask him any further questions?”

“Yes, I would like to ask the Rev. Dr. McKnight if he practiced sprinkling for baptism; and if he did, upon what grounds he could sustain a practice so different from his own exposition of the teachings of the Scripture.”

“As Dr. McKnight has not answered in his writings, and is not present in person, it may be satisfactory,” [57] suggested Mr. Courtney, “to inquire of some other representative of the same church establishment. If you have Dr. Chalmers’ Lectures on Romans, you will find the question answered.”

“Yes, sister, don’t you know mother bought Chalmers’ Lectures only the other day? I will go and get the book,” said Edwin.

“Ah, here it is—page 152; Romans vi. 4–7. ‘The original meaning of the word baptism, is immersion; and, though we regard it as a point of indifferency whether the ordinance so named be performed in this way or by sprinkling, yet we doubt not that the prevalent style of the administration, in the apostle’s days, was by the actual submerging of the whole body under water. We advert to this for the purpose of throwing light on the analogy which is instituted in these verses. Jesus Christ, by death, underwent this sort of baptism, even immersion under the surface of the ground, whence he soon emerged again by his resurrection. We, by being baptized into his death, are conceived to have made a similar translation—in the act of descending under the water of baptism, to have resigned an old life; and in the act of ascending, to emerge into a second or new life.’ Here we have a distinct avowal of the well- established fact that the meaning of the word baptism is immersion, and that the practice of the Apostolic church was conformable to this truth. But in the very face of it we have the candid declaration ‘that we (Presbyterians) regard it as a matter of indifferency whether the ordinance so named be performed in this way or by sprinkling.’”

“But, Mr. Courtney, how can it be a matter of ‘indifferency?’ If the word means immersion, then immersion was what Christ commanded—then the ‘ordinance so-called’ is ‘immersion.’ How can immersion be [58] performed by sprinkling? Really, these theologians are a strange, mysterious people. I cannot comprehend them. Christ commands me to be baptized—baptism means immersion—then, of course, if he meant any thing, he meant immersion. But these great and good men tell me it is a matter of ‘indifferency’ whether I do what he commanded, or something else altogether different from it.”

“Pardon me, Miss Theodosia; it is only when the theologians are in error, and blinded by their educational prejudices, or attachment to their church forms and dogmas, that they are so unreasonable and so mysterious.”