Title: A picture of Stirling

a series of eight views

Author: Robert Chambers

Engraver: J. Gellatly

Illustrator: A. S. Masson

Release date: January 27, 2026 [eBook #77794]

Language: English

Original publication: Edinburgh: John Hewit, 1830

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/77794

Credits: Susan Skinner and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

A. S. Masson Delt. J. Gellatly Sculpt.

STIRLING.

Published by John Hewit. Bookseller.

John Anderson Junr. 55 North Bridge. William Hunter 23 South Hanover Street.

and J. Gellatly West Register Street.

EDINBURGH.

1830.

A SERIES OF

EIGHT VIEWS,

ENGRAVED BY JOHN GELLATLY,

FROM

DRAWINGS BY ANDREW S. MASSON;

WITH

Historical and Descriptive Notices,

BY ROBERT CHAMBERS,

AUTHOR OF “THE PICTURE OF SCOTLAND.”

STIRLING:

PUBLISHED BY JOHN HEWIT, BOOKSELLER;

JOHN ANDERSON, JUN., 55. NORTH BRIDGE STREET;

WILLIAM HUNTER, 23. SOUTH HANOVER STREET; AND

JOHN GELLATLY, WEST REGISTER STREET,

EDINBURGH.

M.D.CCC.XXX.

JOHNSTONE, PRINTER,

104. HIGH STREET, EDINBURGH.

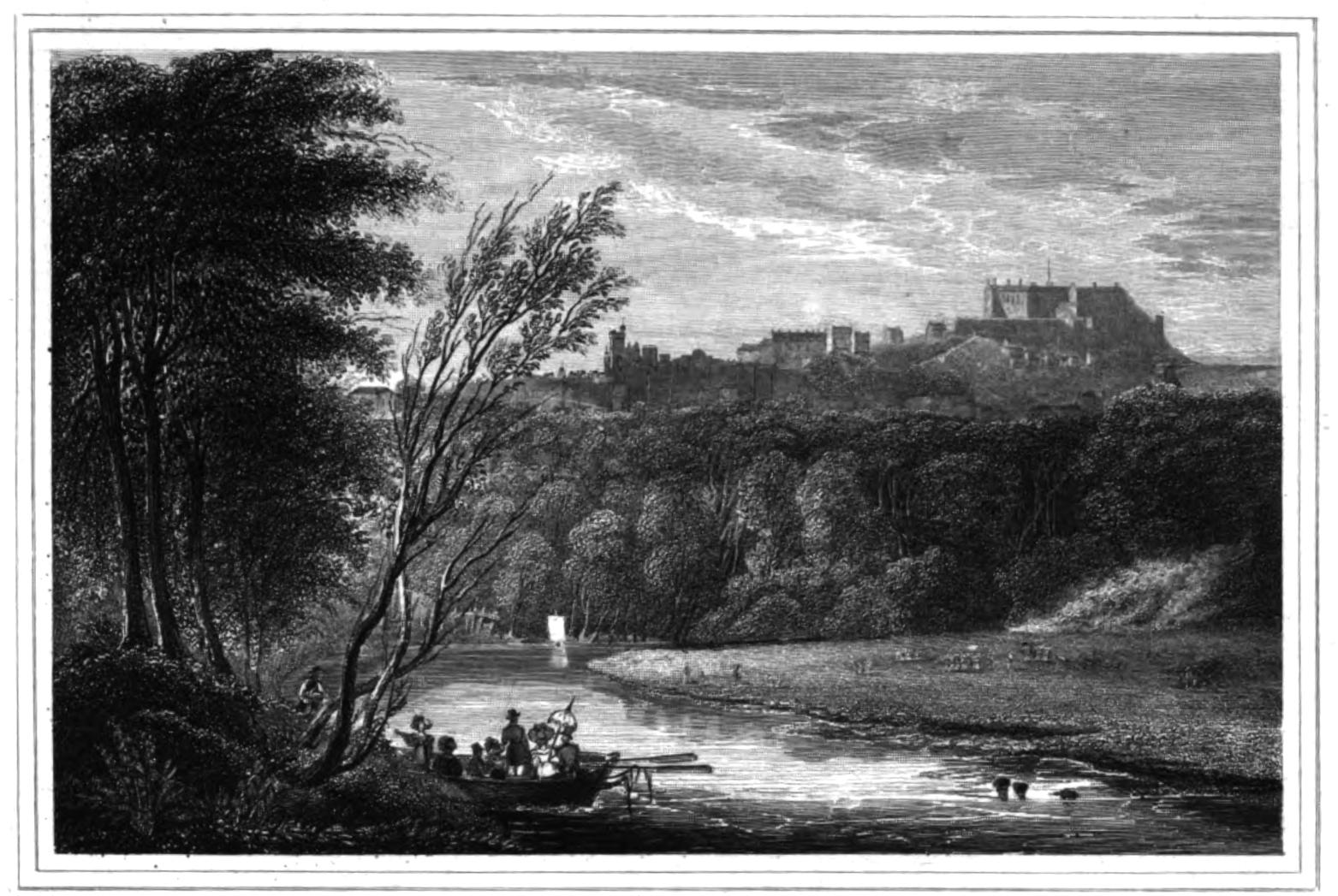

A. S. Masson Delt. J. Gellatly Sculpt.

VIEW of STIRLING

FROM the FORTH.

{1}

Stirling, the capital of the county of the same name, the seat of a presbytery, and one of the oldest royal burghs in Scotland, is a town of about nine thousand inhabitants, situated upon an eminence near the river Forth, thirty-five miles north-west of Edinburgh, and about twenty-seven north-east of Glasgow. It is in 56 degrees 12 minutes north latitude, and 3 degrees 50 minutes west longitude from London. It is a place little noted for manufacture or commerce, although not altogether destitute of these advantages, the weaving of carpets, of tartans, and of cotton goods, having long flourished in it to a considerable extent, and the Forth being navigable up to the town for vessels of small burden. It is chiefly for its antiquities and the interesting historical associations connected with them, together with the singularly delightful circumstances of its situation, that Stirling is remarkable, in the eyes of either the native of Scotland or the foreign tourist.

First, as to Situation. It occupies a central place in the southern moiety of Scotland, where the rivers Forth and Clyde contract the country into a narrow isthmus, the greater part of which is rendered impassable by a barrier of mountains, and which the Romans at one time completely fortified by a ditch and wall. Situated, with its {2}castle, on a hill overlooking the only place where the mountains and river permitted this isthmus to be traversed, Stirling was, at an early time, a place of such importance as to be dignified with the epithet of ‘the Key of the Highlands,’ implying that it could open or obstruct the passage to that region at its pleasure. For this reason, the neighbourhood of the town abounds in fields of strife; at least a dozen, some of them the most remarkable in Scottish history, being pointed out from the walls of the castle. It used to be remarked of Stirling, that it was the only place in Scotland which could be approached, in any thing like a direct line, from any other part of the country, without crossing an arm of the sea; a fact which will be made plain to the reader by a glance at a map of Scotland, where he will not fail to observe, that all the principal roads of a longitudinal direction, have a confluence at Stirling, parting off at no great distance in all other directions. But, perhaps, the importance which the town formerly derived from this circumstance, could not be better illustrated than by a reference to the events of the insurrection of 1715, the whole of which turned upon the successful defence of the bridge by the Duke of Argyll; who thus, with only about fifteen hundred men, prevented an army, supposed, at one time, to have numbered ten thousand, from descending upon the low country.

Stirling enjoys the distinction, in local antiquities (which Edinburgh does not) of having been a Roman station. It is situated about ten miles to the north of the wall which Lollius Urbicus, the lieutenant of Antoninus, built between the firths of Forth and Clyde, to restrain the remoter barbarians; and the vestiges of a road of incursion, or military causeway, which the Romans afterwards led {3}north by Ardoch, have been discovered in such a direction on both sides of the town, as to prove that the castle was upon its line. On the south side of the town, in particular, near the village of Newhouse, traces of this road were distinctly seen not many years ago, in improving a piece of marshy ground in the field called Clifford Park, immediately behind the house of the proprietor. At the conclusion of the seventeenth century, a stone near the castle bore this inscription: ‘In excu. agit. leg. ii.,’ which being extended into ‘In excubias agitantes legionis secundæ,’ means, that the soldiers of the second legion there held nightly and daily watch. (1)[A]

During the middle ages, when this country, like the Saxon heptarchy, was divided among various small parcels of people, Stirling was upon the confines of the Scottish empire on the south, and of the British on the north; that is to say, the predecessors of the present royal family of Britain were at the head of a tribe of Scots occupying the country north from this, while the three nations of provincial or Romanized Britons or Bretts, occupied various longitudinal stripes of what is now called the south of Scotland, and the north of England, having the Forth for their boundary. This fact seems to be alluded to by the insignia which figure on the obverse of the ancient seal of the corporation of Stirling—a bridge, with a crucifix in the centre of it, men armed with bows on the one side of the bridge, and men armed with spears on the other, and the legend, Hic armis Bruti et Scoti stant hac cruce tutt. While thus placed in command of a pass between the countries of two or three different savage nations, each of which was disposed to aggress upon the other, it may be supposed, notwithstanding the peaceful announcement {4}darkly insinuated by this legend, that the bridge and fields of Stirling were often drenched with native blood.

Stirling seems to have been made a royal burgh, some time after the Scottish sovereign, Malcolm the Second, pushed his empire across the Forth, in the early part of the eleventh century. In 1119, less than a hundred years after this extension of the kingdom, Alexander the First granted the town its earliest known charter as a burgh which, however, is only a confirmation of some one which had been granted before. Stirling thus ranks with Edinburgh, Berwick, and Roxburgh, in a list which Chalmers presents of the four earliest institutions of this kind in Scotland; an association, by the way, which for some centuries enjoyed a sort of superiority or jurisdiction over the other royal burghs of Scotland, in the shape of a commercial Parliament, styled the Curia Quatuor Burgorum, (the earlier form of the present Convention of Scottish Burghs.) It is a circumstance strongly characteristic of the time when Stirling procured its first known charter, that the four royal burghs of Scotland were the appendages of the four principal fortresses. This is proved by the fact that King William the Lion was, in 1175, ransomed by his subjects from the English, who had taken him prisoner, by delivering up ‘the four principal fortresses, Stirling, Edinburgh, Roxburgh, and Berwick.’ From what different sources do the wealth and dignity of towns now arise!

As it was the importance of its castle which caused Stirling to become a royal burgh, so does the town seem to have been extended in proportion to the value or use of that fortress. We have few data for ascertaining the progress which the town has made from age to age in {5}size, prosperity, or population. It must have been benefited by the establishment of the neighbouring Abbey of Cambuskenneth in 1147, and by that of the Convent of Dominican Friars in 1233. In the reign of Bruce, when the castle was so considerable a place that that sovereign fought the battle of Bannockburn, mainly that he might get it into his possession; the town could not fail to have become larger than it was at the time of its receiving burgal honours. After the accession of the house of Stuart, when the castle became a royal residence, its prosperity must have received a great impulse. There is a tradition that at one time Stirling had a keen struggle with Edinburgh, for the honour of being pronounced the capital of the kingdom, and only lost the object of contention by a sort of neck heat, the provost having unluckily ceded the head seat, at a grand public banquet, to the provost of Edinburgh, which was held decisive of the matter at issue. Of course, the tradition is a vague one, and cannot be set forward as authority; yet such an impression could only have been made upon the popular mind, in consequence of a strong conviction, long entertained, of the eminence of Stirling in the list of Scottish burghs. Throughout the successive reigns of the Jameses, as they are called, the town must have increased very considerably in wealth and trade. We can see from the books of the royal treasurers, which are preserved in the Register House at Edinburgh, that Stirling then possessed tradesmen and artists of a high order, who purveyed articles of luxury to the court, such as could not now be produced in Stirling. Without some considerable resources, the town could never have produced citizens able to found such hospitals as those of Spittal in the reign of James V. and Cowan in the reign of Charles I. Yet, it is probable that what trade it enjoyed in these reigns, was chiefly the {6}result of its being the residence of the courtiers, and of the noblemen and gentlemen of the country around. Spottiswood the historian, characterises it, in 1585, as a town, ‘little remarkable for merchandise.’ It had then a number of booths or shops, formed of the vaults on which all houses were built in those days; and what is a remarkable enough feature, all the shop-windows were defended by stauncheons, as in some places of Ireland at the present day. The border thieves, who accompanied the expedition of the banished protestant lords in the year just quoted, made but little, Spottiswood says, of the ‘booths;’ it was in the stables of the nobility that they got their best prey. It was easy to conceive, however, that at the time when the houses of the courtiers in Broad Street were comparatively new; when the houses of the Earls of Mar and Stirling were occupied by their respective proprietors in the splendid style of those days; and when the buildings of the castle and the adjacent royal gardens were in their first and best state, Stirling must have been a very handsome town, without the assistance of shops; but, in all probability, the town never possessed, throughout those times of its greatest splendour, above three thousand inhabitants. It was found, in 1755, to contain only 3951; and assuredly, when the circumstances of the country at large are considered, the number must have rather encreased than decreased, during the preceding hundred and fifty years. This is rendered the more probable by the fact that, in 1792, the population had encreased to 4698, and that it is at present supposed to be nearly double that number.

In external appearance, Stirling bears a striking resemblance, though a miniature one, to Edinburgh; each town being built on the ridge and sides of a hill which rises gradually {7}from the east, and presents an abrupt crag towards the west; and each having a principal street on the surface of the ridge, the upper end of which opens upon the castle. The truth is, the hills on which Edinburgh and Stirling are situated, are evidently the peculiar result of some strange convulsion of nature, which has suddenly projected them above a level surface. Of the same order of hills are Arthur’s Seat, Salisbury Crags, and the Calton Hill, near Edinburgh, and the hill of Craigforth, and the Abbey Crag near Stirling; the whole of which present a precipice to the west, and decline gently towards a low plain on the east. The interior and more ancient streets of Stirling, present rather a mean appearance, being generally long, narrow, and containing many old fashioned and decayed houses. The High Street, however, or Broad Street, as it is now less happily called, has long furnished an exception to this remark, its appearance being spacious and imposing, and its houses lofty, though, in various instances, antique. Since the commencement of the present century, several of the other streets, such as Baker Street, King Street, and Port Street, have been much improved, and filled with shops, which formerly were scarcely to be seen out of the limits of Broad Street; a very striking proof, if any were wanting, of the prosperity of the neighbouring agricultural district, on which Stirling, in these times, mainly depends. Every road, too, which leads out of the town, is now lined with neat modern villas, which speak towards the wealth and comfort of the inhabitants; many of these are occupied by persons of fortune, or annuitants, who have retired, after an adventurous life, to spend the conclusion of their days in their native town. The stranger is apt to exclaim against the pavement of the streets of Stirling, which is very uneasy and irregular; but at the more open parts of the town, there is a flag {8}pavement for foot passengers. The town has been lighted of late years with a very brilliant gas. One circumstance in its environs is much to be admired, the prevalence of gardens and orchards, which serves to give an inexpressibly pleasing air of comfort to the tout ensemble, as seen from any point. The stranger, moreover, will scarcely fail to envy the citizen of Stirling, for the delightful walks which are laid out for his convenience, along the south-west side of the town, and around what are called the Gowlan Hills. These I can safely pronounce, so far as prospect is concerned, to be matchless in Scotland.

Stirling has its affairs administered by a town-council, consisting of fourteen merchants or guild brethren, and seven trades councillors or deacons, who are all annually chosen. The office-bearers in the council are, a provost, four bailies, a dean-of-guild, treasurer, and convener. The present set, or burgal constitution, was granted by his late Majesty, with advice of his privy council, on the 23d of May 1781. It is characterised as one of the most liberal in Scotland; but, in the opinion of the intelligent and respectable men of all parties in the burgh, few if any beneficial consequences have resulted from it, and it still calls loudly for amendment.

The provost and bailies have a very extensive civil and criminal jurisdiction, in virtue of a charter granted to the town by King James IV., which erected the burgh into a separate sheriffship: they had previously gratified the hereditary sheriff of the county, for the cession of this part of his right. The jurisdiction of the dean-of-guild has latterly been much circumscribed. His being called, along with the bailie of the quarter, and the convener of the trades, to inspect and report, in disputes between {9}conterminous proprietors, relative to their properties, is almost the only remnant of his former authority. Anciently, the provost wore a black gown and bands; now, his only mark of distinction is a gold chain, which is only of modern date (2). The dean-of-guild, when installed into office in the guild-hall, has a ribbon thrown round his neck, at which is suspended a very ancient gold ring, set in precious stones, with the inscription, ‘Yis for ye Deine of ye Geild of Stirling.’ Of late years, the guildry have presented him with a splendid gold chain, to which is attached a medal, bearing the more modern arms of the town. The costume of the town-officers or sergeants, who are four in number, is evidently very ancient. It consists of a cocked hat, turned up with broad silver lace; a long scarlet coat, richly decorated, and having a white button, on which are engraved the town’s arms; scarlet breeches, buckled at the knee; white stockings; a basket-hilted sword, and the ancient Scottish halbard (3).

Besides its burgh court, Stirling is the seat of a sheriff, a commissary, and a justice of peace court. The circuit court of justiciary meets in it twice a-year; and the jury court occasionally. It contains two churches of the establishment, one episcopalian chapel, and five other places of worship for different orders of Christians. Stirling is remarked by the inhabitants of neighbouring towns, to be a place of extraordinary sanctitude. The principal sect which has parted from the church of Scotland, since its establishment at the revolution, began here about eighty years ago, under the auspices of the Reverend Ebenezer Erskine, who was originally minister of what was called the third charge of the parish of Stirling. The place of worship occupied by this divine, after his {10}secession from the church, continued in use till lately, when a new one was erected behind it. It is now proposed to erect a monument to Erskine on its site, exactly at the spot where he was buried. The parish of Stirling comprehends the burgh, properly so called, and all its extensive burgal domains, with the exception of Spittal and Causewayhead (4).

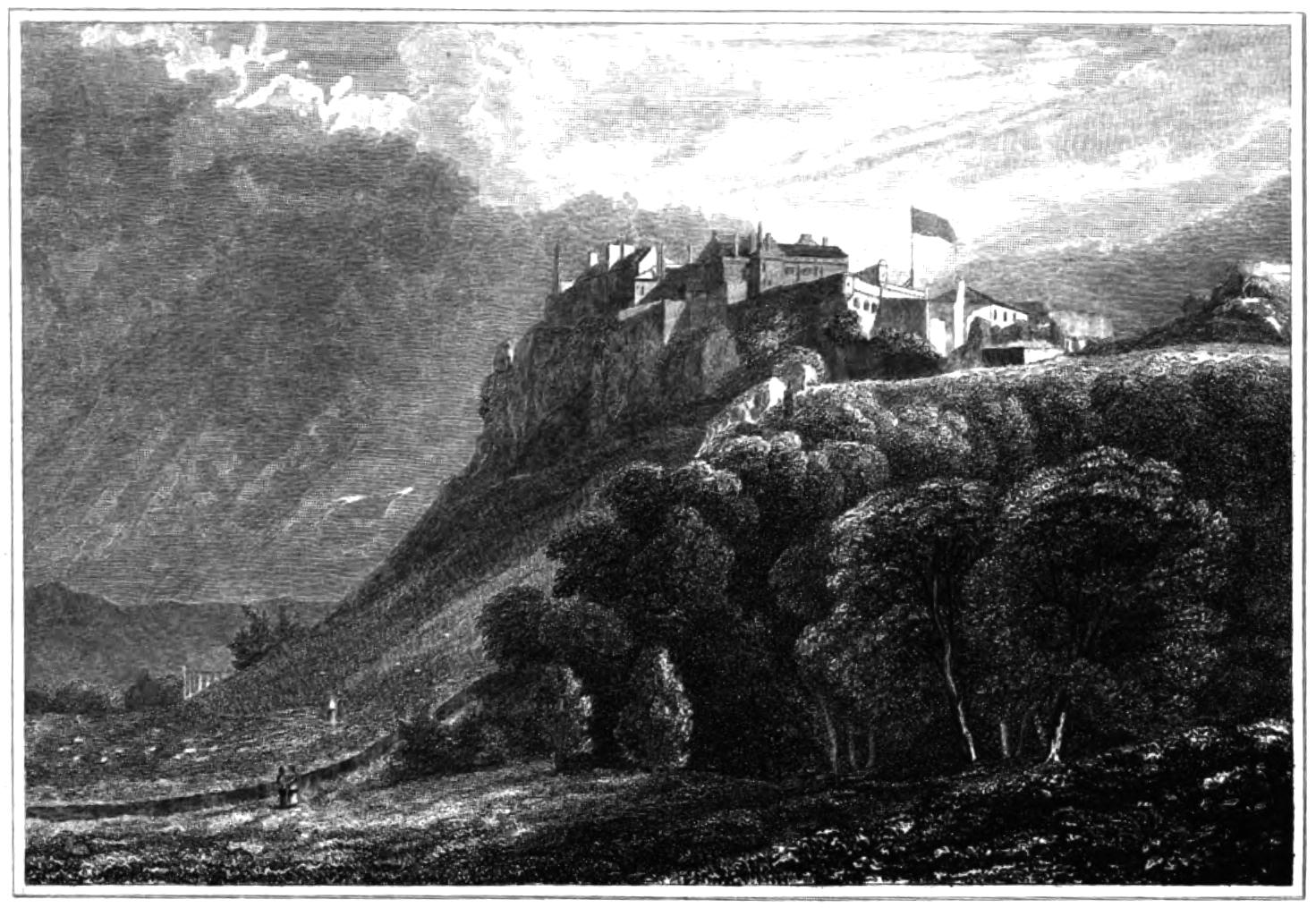

The Castle, to which, as already mentioned, Stirling owed its first existence and its early prosperity, and which is still decidedly the most important feature of the town, naturally assumes the second place in this series of sketches. The view here presented is from the low ground by the south-west shoulder of the town, formerly the royal gardens; and it represents that part of the fortress, where the rock is most precipitous and picturesque, and the buildings most interesting. The history of this stronghold can be traced back to the early times when the Romans here surveyed, perhaps from the bare rock, the boundless forests which then stretched away to the north. We also find Stirling Castle to have been a frequent object of contention among the various minor nations which, under separate sovereignties, occupied the central part of the British Isle, during the first ages succeeding the retirement of the Romans from Britain. It is unnecessary, however, to present a detail of transactions which are at once obscure and not generally interesting. The only circumstance which seems worthy of notice in regard to this part {11}of the history of Stirling Castle, is, that it seems to have then been a mere tower, like an ordinary baronial fortalice, such being the appearance it bears on the more ancient seal of the burgh.

A. S. Masson delt. J. Gellatly Sculpt.

STIRLING CASTLE.

From The Kings Park.

In the twelfth century, as already stated, Stirling Castle had reached the distinction of being one of the four principal fortresses in the kingdom. Such it continued to be during the celebrated wars which Edward I. of England carried on for the subjugation of Scotland, when it was frequently taken and retaken, after protracted sieges, and under circumstances which go to prove its great strength at that period. It was the last part of the kingdom which Bruce reduced to his obedience; a feat which he only performed by gaining the victory of Bannockburn. It first became a favourite royal residence about the reign of James I., whose son, James II., was born in it, and also kept for some time during his minority. James III. was extremely partial to Stirling Castle; he increased the buildings by a palace, part of which is supposed to be still extant, and by founding a Chapel-royal within the walls. James IV. gave Stirling and Edinburgh Castles to his queen, Margaret of England, (daughter of Henry VII.) as her jointure houses; on which occasion, she was infeoffed in her property by the ceremony of the Scotch and English soldiers marching in and out of the two castles alternately—perhaps as a token of that mutual wish of peace on the part of the two countries, from which the marriage had sprung. James IV. frequently resided here during lent, in attendance upon the neighbouring church of the Franciscans, where he was in the habit of fasting and doing penance on his bare knees, for his concern in the death of his father. The poet Dunbar writes a poem in allusion to this circumstance, which is entitled, ‘his {12}Dirige to the King bydand oure lang in Stirling,’ and is to be found in Sibbald’s Chronicle of Scottish Poetry. James V., who was born and crowned in Stirling Castle, further adorned it by the erection of the present Palace. It was also occupied by the widow of this prince, Mary of Guise, queen regent, who erected the battery towards the east, called the French Battery from having been built by her French auxiliaries (5). Mary, daughter of this princess, here celebrated the baptism of her son, afterwards James VI.; on which occasion there was a prodigious display of courtly hospitality. James, whose baptism took place in December 1566, was removed in February 1566–7 to Edinburgh, but was soon after sent back to Stirling, where he spent the years of his childhood till he was thirteen years of age. The apartments which he occupied, with his preceptor, George Buchanan, and where that learned man, in 1577–8, wrote his History of Scotland, are still shewn in the Palace, though now degraded into the character of a joiner’s work-shop. James did not make Stirling the jointure-house of his queen; that honour was reserved for Dunfermline. Here, however, he baptised his eldest son, Prince Henry, for which purpose he built a new chapel on the site of the old one. The fortress continued afterwards in considerable strength. In 1651, when employed by the Scottish Estates, in the honourable service of keeping the national registers, it was besieged and taken by General Monk. In 1681, James, Duke of York, afterwards James II., visited Stirling, with his family, including the Princess, afterwards Queen Anne. A scheme was formed, in 1689, by Lord Dundee, and other friends of this monarch, for rescuing the Castle for his service from the revolutionists, but in vain. In the reign of Queen Anne, its fortifications were considerably extended, and it was declared to be one of the four fortresses {13}in Scotland, which were to be ever after kept in repair, in terms of the Treaty of Union with England. Since then, it has experienced little change in external aspect, except its being gradually rendered more and more a barrack for the accommodation of modern soldiers. It formed a capital point d’appui, as already mentioned, for the Duke of Argyll in 1715, when he encamped his little army in the park, and resolutely defended the passage of the Forth against the insurgent forces under the Earl of Mar. In 1745, Prince Charles led his Highland army across the Forth by the fords of Frew, about six miles above Stirling; but he made no attempt upon the castle till the succeeding year, when, in returning from England, he laid siege to it in proper form, but was obliged to retire to the Highlands, without being able to make any impression upon it.

Such being the chief general memorabilia connected with Stirling Castle, I shall proceed to point out the various particular objects which successively occur to a stranger in visiting it, together with the various historical facts connected with them individually.

The visiter first passes under two archways, which give access through two several walls of defence, the external fortifications of the castle. These were erected at the expence of Queen Anne, who at the same time caused a deep fosse to be dug in front of each. The outer fosse is passed by a draw bridge. We learn from Slezer’s view of the castle, taken in the reign of King William, that the external fortifications of the castle formerly consisted of two large block-houses, or double towers, like the north-west angle of Holyroodhouse, or the western part of Falkland Palace. These are taken away, except the {14}lower part of one, through which a double-doored gate-way yet gives access to the interior court-yard. That the strength of the castle was improved by the demolition of these block-houses, and the erection of the two exterior walls, cannot reasonably be doubted; but the writer of the additions to Slezer’s descriptions in the second edition of the Theatrum Scotiæ, 1718, informs us that the Jacobites believed Queen Anne to have secretly entertained a design of weakening the castle by these operations, in order that it might the more easily become a prey to her brother when he should make his expedition into Britain for the recovery of his crown.

Immediately after passing the last gate-way, which was formerly defended by a port-cullis, a battery, called the Over, or Upper Port Battery, is found to extend to the right hand, overlooking the beautiful plain through which the river takes its winding course, as also the distant Highlands, and a multiplicity of other objects. The ground on this side of the castle is not precipitous, but gradually descends, in a series of rocky eminences called the Gowlan or Gowan hills, towards the bridge. On the ridge of the nearest hillock, the remains of a low rampart are still to be seen, extending in a line exactly parallel with the battery. These are the vestigia of the works which Prince Charles caused to be erected against the castle, in 1746. The situation, as may be easily conceived by the spectator, was very unfortunate. The castle, as we are informed in a print of the time, overlooked the besiegers so completely, that the garrison could see them down to the very buckles of their shoes. Accordingly, they were able to kill a great number of their Celtic assailants. The Prince made no impression whatever on the fortress.

{15}

Between the castle walls and the Highland battery, a road may be seen leading down the hill towards the village of Raploch. This is called the Ballangeigh road, from two words, signifying the windy pass. At the same time, a low browed archway, passing out of the court-yard, near the Parliament House, and which formerly was connected with a large gateway through the exterior wall, is called the Ballangeigh Entry. According to many distinct traditionary stories, (6) it was the custom of King James Fifth to travel in disguise among his subjects, under the title of the Gudeman of Ballangeigh, assuming a name from this minute part of his property, upon the same fashion, I presume, with that which still makes the Earl of Morton popularly known as the Gudeman of Aberdour, and the Duke of Gordon as Gudeman of the Bog. At the bottom of the Ballangeigh road, adjacent to the village of Raploch, there is a house (lately rebuilt) and a small triangular park (now partly intersected by the road leading from the village to the bridge), which James V. gave by letters under his signet, to one John Adamson and his wife, for the service of ‘keeping the washers’ tubs, and setting furms, binks, and other plautery for the washers, and drying of their clothes;’ in other words, for the service, of taking care of the tubs, and providing all necessary articles for the washers of the King, while washing and dressing his Majesty’s clothes at the Raploch Burn. Mary of Guise, the widow of James, confirmed this grant by a charter, granted by her to the descendents of Adamson and his wife, at her Castle of Stirling in 1550, for the additional service of ‘the daily prayers to be said by them for umquhill our deceist spouse, the Kingis grace, and us.’ James VI. again confirmed it by a charter, granted by him, at his Castle of Stirling in 1594. Both these charters are still extant.

{16}

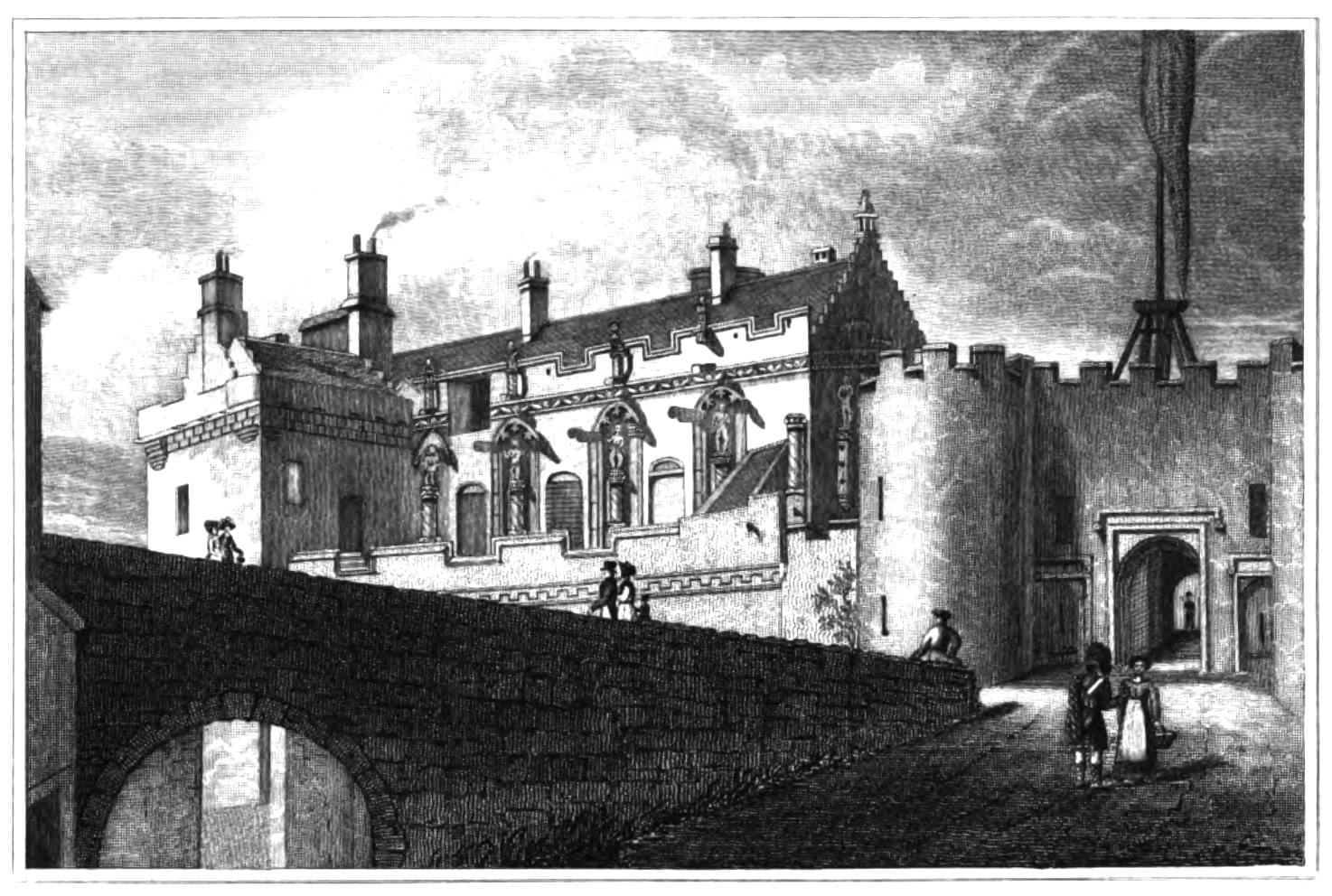

The Palace of James V. has its eastern aspect towards this court-yard. It is a quadrangular building, having three ornamented sides presented to the view of the spectator, and a small square in the centre. The accompanying view (Plate III.) represents its southern side, being taken from the gateway under the block-house, through which the court-yard is entered. On each of the ornamented sides of this building, there are five or six slight recesses, in each of which a pillar rises close to the wall, having a statue on the top. These images are now much defaced, but enough yet remains to shew that they had been originally, like every other part of the palace, in a very extraordinary taste. Most of those on the eastern side are mythological figures—apparently Omphale, Queen of Lydia, Perseus, Diana, Venus, and so forth. On the northern side of the palace, opposite to the chapel-royal, they are more of a this-world order. The first from the eastern angle is unquestionably one of the royal founder, whom it represents as a short man, dressed in a hat and frock-coat, with a bushy beard. Above the head of this figure, an allegorical being extends a crown with a scroll, on which are the letter I. and the figure 5, for James V., (which are also seen above various windows of the building,) and the Scottish lion crouches beneath his feet. Next to the king is the statue of a young beardless man, holding a cup in his hand, who is supposed to be the king’s cup-bearer. Besides the principal figures, there are others springing from the wall near them; one of which is evidently Cleopatra with the asp on her breast. The visiter may derive a very good hour’s amusement from the inspection of these curious relics, some of which are valuable as commemorating costumes.

A. S. Masson Delt. J. Gellatly Sculpt.

PALACE

STIRLING CASTLE.

{17}

The small square within the Palace is called the Lions’ Den, from its having been the place, according to tradition, where the king kept his lions. It presents nothing remarkable in appearance.

The apartments of the Palace were formerly noble alike in their dimensions and decorations. Part of the lower flat of the northern side was occupied by a hall or chamber of presence, the walls and ceiling of which, previously to 1777, were adorned by a multitude of figures, carved on oak, in low relief, and supposed, with much probability, to represent the persons of the king, his family, and his courtiers. The walls were stripped of these most beautiful and most interesting ornaments in 1777, in consequence of one having fallen down and struck a castle soldier, who was passing at the time. Fortunately, at the very juncture when they were about to be condemned for fire-wood, an individual of taste observed a little girl going along the castle-hill with one in her hand, which she was carrying towards the town. Having secured possession of it for a trifle, the individual mentioned, immediately busied himself to collect and preserve as many of the rest as yet remained. Strange to say, this person was no other than the keeper of the jail of Stirling; and it was to that house of care that he carried the beautiful carvings which he had rescued. They were kept there for upwards of forty years, when, having attracted the attention of the lady of General Graham, deputy-governor of the castle, drawings, not only of these, but of others, which had found their way into the possession of Henry Cockburn, Esq., advocate, and other individuals, were made by her and an artist of the name of Blore, and then given to the {18}world, in a series of masterly engravings, published by Mr Blackwood of Edinburgh, in an elegant volume, entitled, Lacunar Strevilinense. Those which were in the jail of Stirling have now been transferred to the justiciary court-room, adjacent to it; but they have been much disfigured by the paint with which the civic taste has covered them. The lofty hall which they formerly adorned is now, alas! a mere barrack for private soldiers; but it is yet designated by the title of The King’s Room.

The buildings on the western side of the square, adjoining to the palace of James V., are of a much plainer and more antique character. It is supposed that they are of a date antecedent to the reign of James II.; a room being still shown, where that monarch is said to have stabbed the Earl of Douglas. James II. was exceedingly annoyed, through the whole of his reign, by this too powerful family of nobles, which at one time had so nearly unsettled him from his throne, that, in a fit of disgust, he formed the resolution of retiring to the continent. William, Earl of Douglas, having entered into a league with the Earls of Crawford and Ross against their sovereign, James invited him to Stirling Castle, and endeavoured to prevail upon him to break the treasonous contract. Tradition says, that the King led him out of his audience-chamber (now the drawing-room of the deputy-governor of the castle,) into a small closet close beside it, (now thrown into the drawing-room,) and there proceeded to entreat that he would break the league. Douglas peremptorily refusing, James at last exclaimed in rage, ‘Then, if you will not, I shall,’ and instantly plunged his dagger into the body of the obstinate noble. According to tradition, his body was thrown over the {19}window of the closet into a retired court-yard behind, and there buried; in confirmation of which, the skeleton of an armed man was found in the ground, at that place, some years ago. Some of the less credible chronicles of these early events affirm, that Douglas came to Stirling upon a safe-conduct under the King’s hand, and that his followers nailed the paper upon a large board, which they dragged at a horse’s tail, through the streets of Stirling, threatening at the same time to burn the town. The King’s closet, or Douglas’ Room—for it is known by both names—is a small apartment, very elaborately decorated in an old taste. In the centre of the ceiling is a large star having radii of iron; and around the cornices are two inscriptions. The upper one is as follows, ‘JHS (7) Maria salvet rem pie pia’—which may be thus extended, constructed, and translated, ‘Pie Jesus, hominum salvator, pia Maria, salvete regem’—Holy Jesus, the saviour of men, and holy Mary, save the King. The lower inscription is ‘Jacobus Scotor Rex’—James, King of Scots.

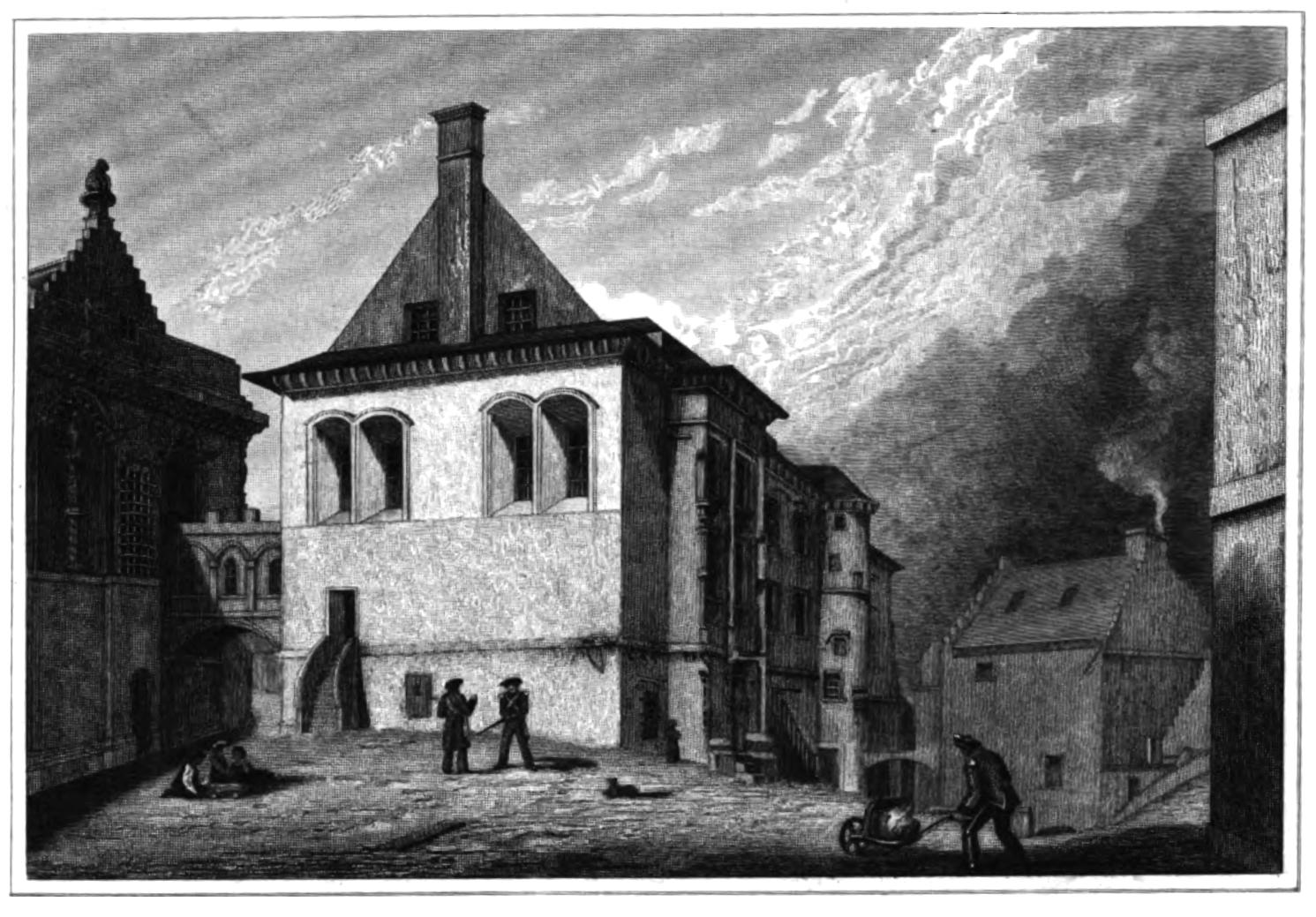

A. S. Masson Delt. J. Gellatly Sculpt.

PARLIAMENT HOUSE.

STIRLING CASTLE.

The eastern side of the square, opposite to this range of ancient buildings, is the Parliament House, (Plate IV.) a structure erected by James III. in the Saxon style of architecture, and which formerly had a noble appearance, though now rendered plain by the alterations necessary for converting it into a barrack. The hall within this building was a hundred and twenty feet long, and had a magnificent oaken roof. Parliaments were frequently assembled in it. It is a somewhat remarkable circumstance, that Linlithgow and Stirling, two of the Scottish King’s private palaces, had each a parliament-hall connected with it. James III. also erected within the castle a chapel-royal or college of secular priests, consisting of a dean or provost, an archdean, a treasurer and subdean, {20}a chanter, a subchanter, and various other officers. This chapel he endowed most liberally. The original register of it is still preserved in the Advocates’ Library, along with the chartulary of the Abbey of Cambuskenneth.

The northern side of the square is occupied by the new chapel, which James VI., as already mentioned, erected, in 1594, for the scene of the baptism of his son Prince Henry. The ceremonial which distinguished this affair, was one of extraordinary magnificence and cost, being such as to be suitable in the eyes of the father, for the heir-presumptive of three great monarchies. A very full account of it is yet extant; and a more splendid piece of pageantry was never seen in Scotland, till the visit of his present Majesty in 1822. There existed, till lately, in the chapel, the hull of a boat, eighteen feet in length, and eight across the deck, which had been drawn on four wheels into the banquet-hall, with confections and other dainties for the company assembled. The chapel is now converted into an armoury; but less damage has been done to its exterior than to that of the other buildings in the castle, by the ruthless hands which have been at work upon them for a series of years. Previously to its being made an armoury, the roof was a species of pannelling without much ornament; but, from the centre, there hung, in one piece of wood, figures of the castles of Edinburgh, Stirling, Dunbarton, and Blackness, surmounted by a crown, which is still preserved in the building.

Such are the objects usually pointed out to strangers as most worthy of notice in Stirling Castle. It is now necessary to attend to those objects of interest in the neighbourhood, which are historically or locally connected with it.

{21}

The King’s Gardens merit the first notice. They lie immediately to the south-west of the Castle-hill, and to the south of the Castle. Their present condition is that of a marshy piece of pasture-ground; and it cannot be said of them, as of the gardens of the deserted village,

This interesting monument of the taste of our national sovereigns is completely desolated, so far as shrubs and flowers are concerned. The utmost exertion of the memory of the present generation, can only recollect an old cherry-tree, which stood at the corner of one of the parterres, and which was burnt down by the wadding of a shot, which some thoughtless sportsman fired into its decayed trunk, as he happened to pass it on his way home from the fields (8).

It is yet possible, however, to trace on this desolate spot, the peculiar form into which the ground had been thrown by its royal proprietors. In the centre, a series of concentric mounds, of a polygonal, but perfectly regular shape, and rising above one another towards the middle, is yet most distinctly visible. An octagonal mound in the centre, is called the King’s Knote, and is said, by tradition, to have been the scene of some forgotten play or recreation, which the King used to enjoy on that spot with his court. In an earlier age, this strange object seems to have been called ‘the Round Table;’ and, in all probability, it was the scene of the out-of-door’s game of that name, founded upon the history of King Arthur, and of which the courtly personages of former times are known to have been so fond. Barbour, in his heroic poem of ‘the Bruce,’ which he wrote at the conclusion of the fourteenth century, thus alludes to it:

{22}

Lyndsay, in his Complaynt of the Papingo, written in 1530, thus also alludes to it:

To give further countenance to this supposition, we have the ascertained fact that James IV., with whom Stirling was a favourite and frequent residence, was excessively fond of the game of the Round Table, which probably appealed, in a peculiar manner, to his courtly and chivalric imagination.

It is a circumstance not to be omitted, that a piece of ground to the west, not so distinctly marked as this, but within the limits of the gardens, is called the Queen’s Knote. It should also be observed, that ‘King Villyamis Note,’ is the name of a song or ballad, quoted in ‘The Complaynt of Scotland,’ as popular in 1549, and which was probably descriptive of some game played here.

A canal is still visible at the east end of the gardens. It flowed on the north by the wall, marching with the ground now belonging to the Earl of Mar, and discharged itself into another canal or reservoir, which is still very perceptible at the west end, adjoining the King’s Park.

The King’s Park lies beyond the gardens, towards the {23}south and south-west. It is about three miles in circumference, is surrounded by a wall of great antiquity, (9.) but is now almost entirely divested of wood, being chiefly pasture and cultivated ground. Here the king hunted the deer when disposed to enjoy the pleasures of the chace. A small oblong enclosure, which lies between the Castle and this territory, is called the Butt Park, having been the place where the court formerly enjoyed the sport of shooting at the butts. It is a somewhat remarkable circumstance, that the king and his attendants were in the habit of reaching these parks, not by the gradual descent of Ballangeigh, as might be supposed, but by a steep zig-zag path, which was led down the south-west face of the Castle-bank, (from a postern now built up, but still visible,) and immediately within the park wall, which there ascends the hill to the external fortifications of the Nether-bailiary of the Castle. This path is hardly to be now discerned.

The Gowlan Hills, which lie between the Castle and the Bridge, form another of the objects, in the immediate neighbourhood, most deserving of notice. The most northernly eminence of these hills, is called the Mote-hill, which implies that, like various other eminences of the same appearance throughout Scotland, as at Scone in Perthshire, Dalmellington in Ayrshire, Carnwath and Biggar in Clydesdale, Minniegaff in Galloway, &c. &c. it was used at an early time as a place for the administration of justice—mote signifying law,—hence the phrase moot point, expressing a case at issue in law. The Mote-hill of Stirling is still observably marked at top with the benches of earth on which the jurors sat: in the centre there is a mound somewhat like the King’s Knote. In later times, this hill was used as a place of execution. In 1424, {24}James I. here caused to be beheaded, his cousin, Murdoch Duke of Albany, together with Walter and Alexander, the sons of that prince, and the Earl of Lennox, his aged father-in-law, all in the course of two days, in retribution, it is supposed, for the exertions which they had made to get him kept prisoner in England, while they enjoyed the management of his kingdom. The author of the Lady of the Lake thus apostrophises the Mote-hill:

At a later period still, the early part of the sixteenth century, this mount was used by James V., in his minority, for a much more agreeable purpose, to wit, that of amusing himself by sliding down its steep sides on the bone of a cow’s head. On this account, probably, it was called the Hurly Hawky, (hawky being a familiar word for cow in Scotland,) a name which is still sometimes applied to it. Lyndsay, in his ‘Complaynt,’ written anno 1529, stating what he had himself done for James in his childhood, to amuse and instruct him, and bewailing the efforts made by the less grave companions of his boyhood, to mislead his mind, says:

At present, the Mote-hill forms a delightful part of the public walks, already mentioned with such high praise.

{25}

The only other objects, connected with Stirling Castle, which fall to be noticed at this place, are the Valley, and the Ladies’ Hill. The Valley is an enclosed and somewhat hollow piece of waste ground, now belonging to the burgh, lying a little below the south side of the esplanade formed in front of the Castle. It is about a hundred yards in extent, either way; but is said to have been much larger before the erection of the Earl of Mar’s house in 1570, when the garden attached to that edifice was taken off its length. The use of the Valley in former times was that of a tournament ground; while the Ladies’ Hill, (which was formerly considerably broader,) rising by one of its sides, was a sort of theatre for the female spectators, whose bright eyes, in the words of Milton, here

A remarkable conflict took place in the Valley during the reign of James II., who revived the sanguinary species of the tournament, which his father had suppressed. Two noble Burgundians, named Lelani, one of whom, Jacques, was as celebrated a knight as Europe could boast of, together with one squire Meriadet, challenged three Scottish knights to fight with lance, battle-axe, sword, and dagger. Having been all solemnly knighted by the king, they engaged in the Valley. Of the three Scotsmen, two were Douglasses, and the third belonged to the honourable family of Halket. Soon throwing away their lances, they had recourse to the axe, when, one of the Douglasses being killed, the king threw down his baton, to put a stop to a combat which had then become too unequal to furnish proper amusement. Before this, the remaining Douglas and one of the Lelanis, had had such a tough {26}encounter, that of all their weapons none remained save a dagger in the hand of Douglas, which, however, he could not use, as the Burgundian held his wrists together, and whirled him in the struggle round the lists. The other Lelani had fought well; but, being comparatively unskilled in the use of the battle-axe, he had his vizor, weapons, and armour, beat almost to pieces. The Douglas who was killed, fell by the battle-axe of Meriadet the squire.

Among the festivities which attended the baptism of Prince Henry in 1594, were tournaments and running at the ring in the Valley. On that occasion, it was surrounded by guards finely apparelled, to prevent the crowd from breaking in, and a scaffold was erected on one side for the queen, her ladies, and the foreign ambassadors; to which illustrious group the performers uniformly made a low obeisance on entering. This, however, was but the silver age of chivalry, and no blood was shed in these amusements.

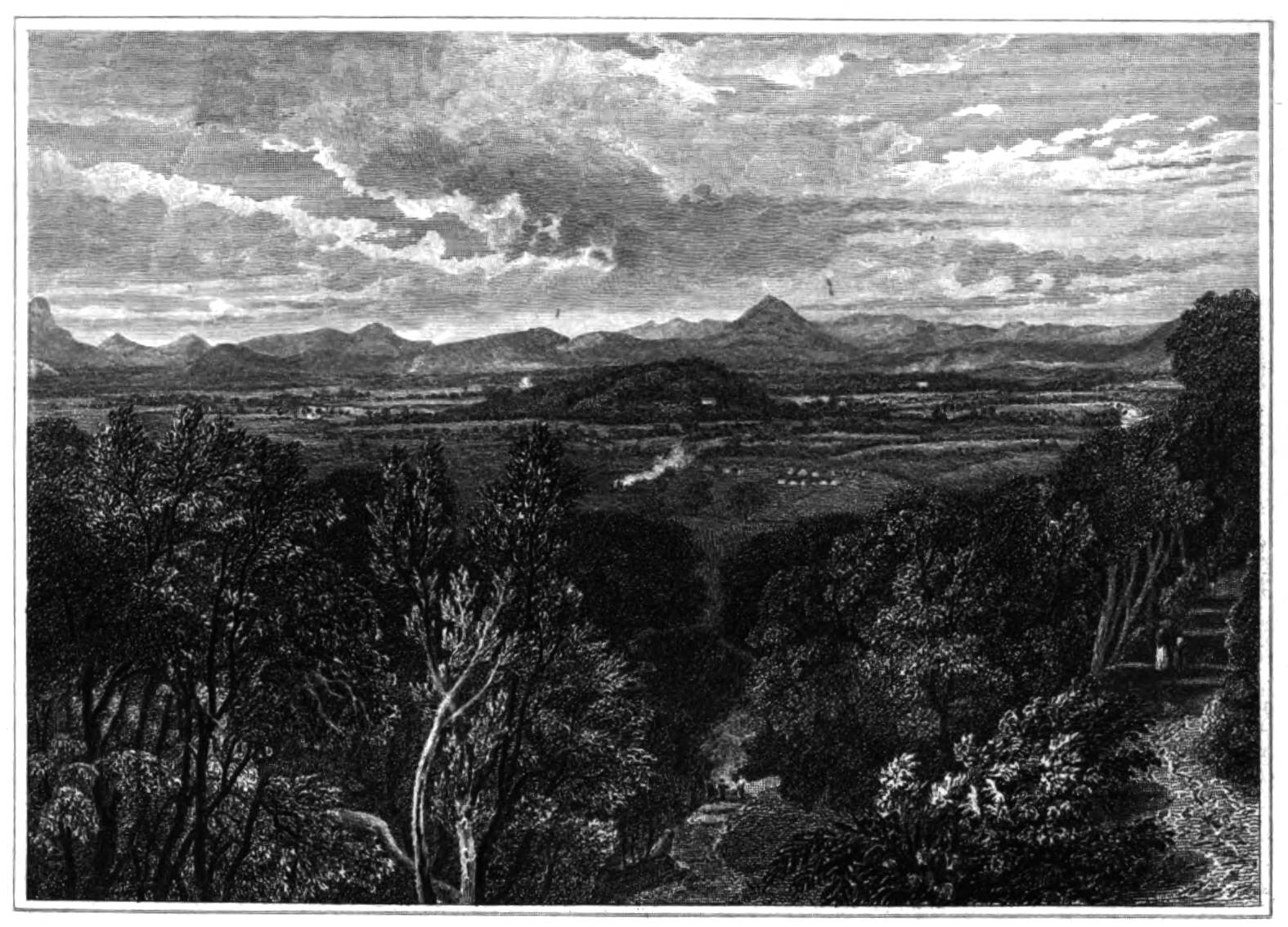

A. S. Masson Delt. J. Gellatly Sc

VIEW FROM THE CASTLE WALKS, STIRLING.

Ben Ledi & Ben Lomond in the Distance.

Some attention yet remains to be paid to the delightful walks which pervade these most interesting localities. The public walks in Stirling are quite matchless in Scotland. The oldest of them is one which was begun in 1723, along the top of the rock which skirts the town to the south-west, and immediately under the wall which formerly fortified the town in that quarter. It was a Mr Edmonstoun, of Cambus-Wallace, who had the taste and public spirit to commence this work, which the magistrates completed about the end of the century. Since then, the walk has been extended round the back of the castle rock, and along the skirts of the Gowlan Hills, so as to make them a sort of inverted amphitheatre for seeing {27}all the objects around Stirling. It is thus possible to see an amazing multiplicity of interesting objects within the space of about a mile of walk. Beginning at the old walk under the town-wall, the spectator sees, first, Bannockburn and Gillies Hill, the scenery of Bruce’s famous victory, and the field of Sauchie, which terminated the reign of the unfortunate James III.; near at hand, the steeple of Ninian’s church, deprived of its attendant place of worship, in 1746, by Prince Charles’ Highlanders, who blew it up after using it as a powder magazine; farther to the west, Touch House, still the seat of a branch of the Seton family, who were the King’s armour-bearers; then Craigforth, a beautifully wooded hill, rising abruptly from the plain, and having a bold precipice presented to the west (Plate V.); then the Teith, the Allan, and the Links of the Forth in all their windings. In the remoter parts of the scene, the spectator sees Benlomond, and his grand fraternity of lesser brothers, including Benledi, and Benvoirlich, which give an inconceivably magnificent air to the picture. Here it is curious to consider, that, from the castle above you, you can see, on one hand, the towers of academic, polished, intellectual Edinburgh, a place where civilization may be said to be carried to a pitch of exquisite perfection, while, on the other, you gaze on an alpine region where the people yet wear part of the dress, and mostly speak the language which obtained in Europe, before even the early ages of Grecian and Roman refinement. It is strange, thus to link together the extremes of human society,—thus to associate the nineteenth century before Christ, and the nineteenth century after him, for no less remote from each other, in reality, are the ideas arising from a view of Edinburgh and of the Highlands. But, it is not alone the objects at a distance from Stirling, that constitute the pleasure of a promenade over its walks. The objects {28}more nearly at hand, come in for an immense share of this pleasure. ‘Who can look,’ says a citizen of Stirling, in an eloquent letter upon this very subject, ‘who can look upon our castle, and its palace, and noble park, upon the Royal Gardens and their celebrated Table, upon the Ladies’ Hill and the Valley below it, and upon our fine old Franciscan tower, so remarkable for its simple majesty, without being carried back in his imagination to the splendid scenes of other times;—to the reigns of the gallant and accomplished Jameses, to the days of tilt and tournament, and courtly pomp, to the feats of a brave and knightly nobility, to the chivalry and romance, in short, of Scottish history. No man of taste, or lover of his country, ever traversed our walks without pleasure, or left them without regret.’

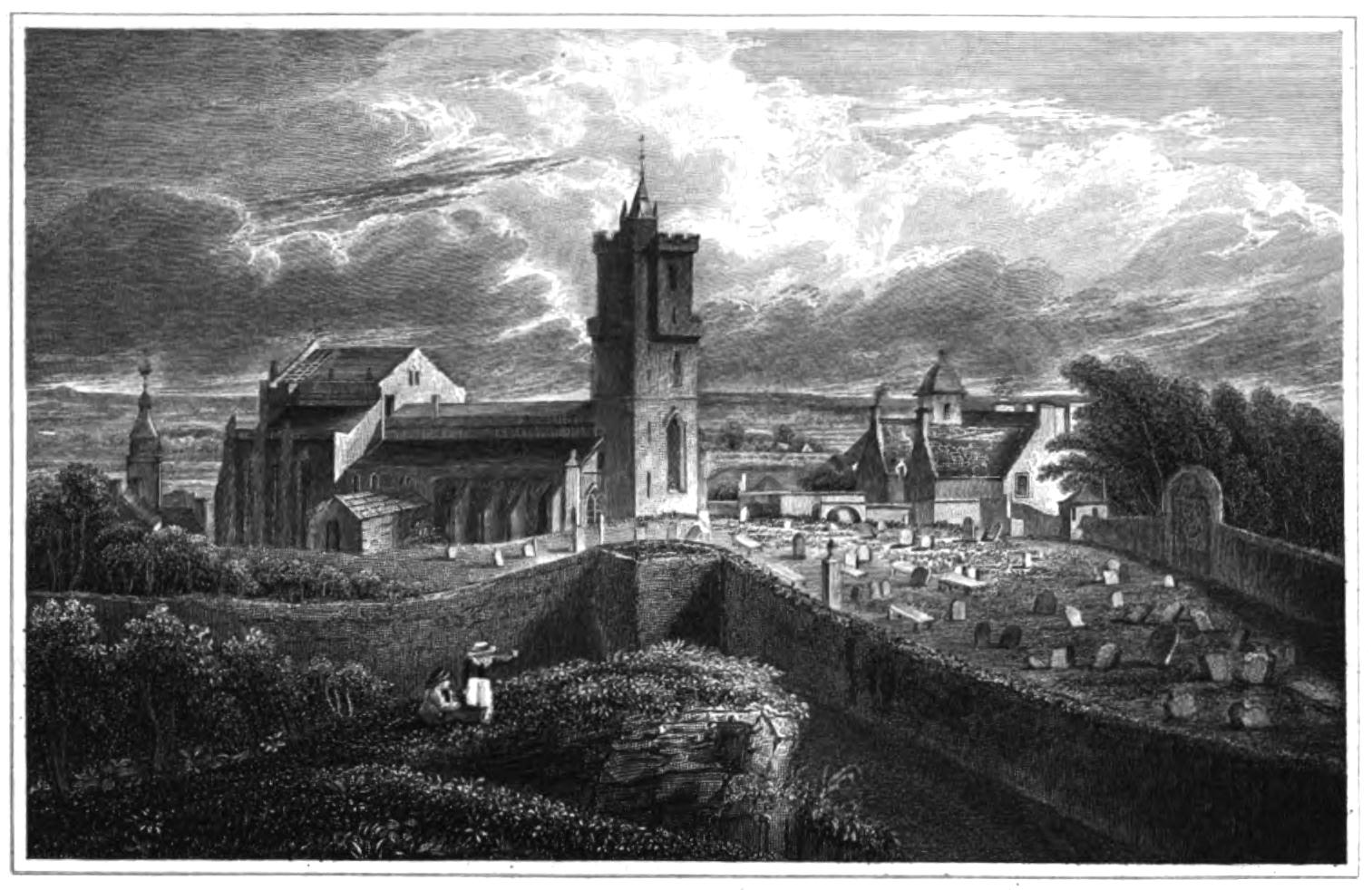

The East and West Churches are here represented as seen from a spot behind the Ladies’ Hill, the spectator being supposed to look in a south-east direction.

These Churches, though anciently one, are now separate places of worship; but, being attached to each other in the way represented, they are only distinguished in modern times by the epithets here applied to them. The division took place in 1656.

A. S. Masson Delt. J. Gellatly Sc

East & West Churches Stirling.

From the Ladies Hill

{29}

The West Church was originally the place of worship connected with the Franciscan or Grey Friars’ Monastery, which was founded in Stirling by James IV., in 1494. It cannot, therefore, be of an older date. It appears to have had a projecting square building at each corner. One of these at the north-west corner was, according to tradition, the chapel of Margaret, daughter of Henry the Seventh, James the Fourth’s queen. The interior was of beautiful architecture; and on the arch (now converted into a window) which formed the entrance to it, may still be seen, from the outside of the church, the rose of England and thistle of Scotland. Another of these projections at the north-east corner, is now an aisle belonging to the family of Moir of Leckie. Another at the south-east corner, on the left hand of the present entrance to the church, became the burying-place of the Earls of Stirling; Sir William Alexander, the first Earl, having been brought from London and buried in it. The remaining projection, situated at the south-west corner, was at one time an entrance to the church. All these excrescences, with the exception of that now belonging to the family of Moir of Leckie, were lately taken away, when the West Church was repaired. On that occasion the church was very tastefully fitted up. In the West Church are the monuments of Lieutenant-Colonel Blackadder, of the Cameronian Regiment; and Dr David Doig, Rector of the Grammar School of Stirling. Blackadder was Deputy-Governor of the Castle in 1715, and wrote memoirs of himself, which possess considerable interest. Doig was one of the first scholars of his day, and wrote the articles, Philology and Mysteries, in the Encyclopædia Britannica, and some very learned letters on the savage state, addressed to Lord Kames.

{30}

The East Church, at least the chancel, was built by Cardinal Beatoun; but, though a later, and in external appearance a more magnificent structure, it is not, in reality, of such elegant architecture as its more aged neighbour. Its east window is tall and handsome, the mullions fortunately being still preserved. Around the exterior of the building are eleven buttresses, each having a vacant niche, which are supposed to have been filled, before the Reformation, with statues of the apostles, Judas of course excepted. In the chancel of the East Church was a tomb-stone bearing this inscription, in Latin:—‘In memory of Margaret Steuart, grand-daughter of James V., King of Scots; daughter to the Earl of Murray, regent, and Anne Keith, a lady of quality; wife to the Earl of Arrol. She died of a distemper upon Sabbath, the 2d April, in the year of our Lord 1586, in the 16th year of her age. The Lord, who alone united us, has parted us by death.’

The church of Stirling is remarkable in Scottish history, as the place where the regent Earl of Arran, in 1543, abjured the Catholic faith, and avowed the Protestant doctrines; which, however, he afterwards renounced. Here, also, on the 29th of July 1567, James VI. was crowned, at the age of thirteen months and ten days, John Knox preaching the coronation sermon, and Lords Lindsay and Ruthven, who extorted the resignation of the crown from the unfortunate Mary, being among the nobles who assisted at the ceremony. In 1651, Monk took possession of the tower, or steeple, from which he proceeded to batter the castle. The Highlanders, in 1746, assumed the same station, for the purpose of celebrating their victory at Falkirk, which they did by ringing of bells, and discharging fire-arms from the battlements. On both of these occasions, the steeple suffered from the shot of the {31}castle; and hollows are still pointed out on its sides, which are said to have been occasioned by the bullets. The steeple is distinguished by a majestic simplicity, which, without elaborate ornament of any kind, renders it an object of no inconsiderable interest to the spectator.

The building seen to the right of the churches, in the annexed view, is Cowan’s Hospital, built in 1639. John Cowan, a merchant in Stirling, between the years 1633 and 1637, left forty thousand merks, to endow an hospital, or alms-house, for twelve decayed brethren of the guild or mercantile corporation of Stirling. The money was invested in the purchase of lands, which now yield a revenue of upwards of £3400 sterling per annum. From this fund about a hundred and forty persons, at present, receive relief. The front of the house exhibits a full-length statue of the founder, which will be looked upon with interest as a memorial of the costume of the better order of Scottish burghers, in the reign of Charles I.

A. S. Masson Delt. J. Gellatly Sculpt.

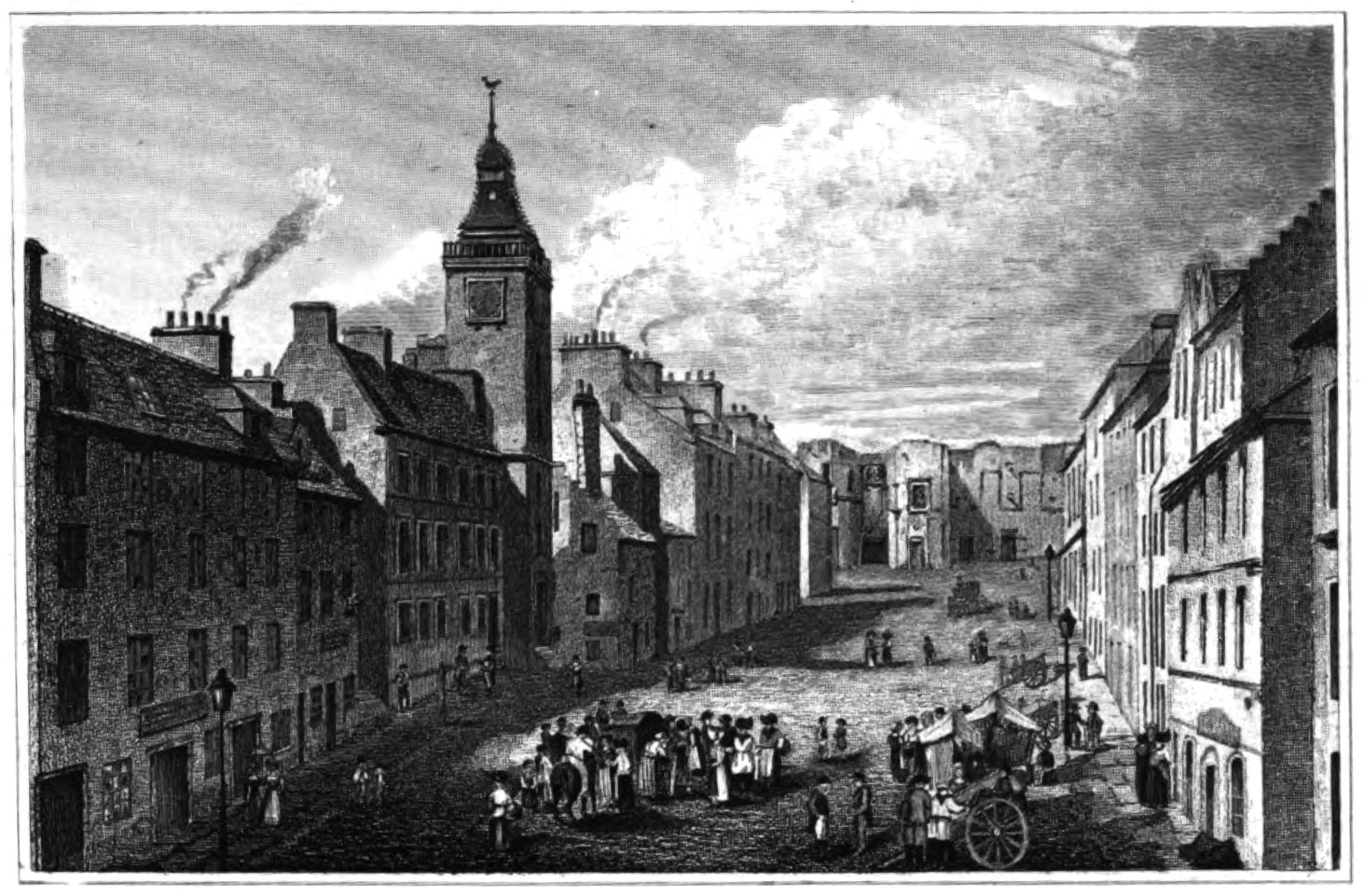

BROAD STREET.

STIRLING.

The High Street, or Broad Street, as it is now commonly called, is the principal street in Stirling. It lies, in the shape of a parallelogram, on the upper part of the hill whereon the town is built; and, what with the height of the houses, their substantial, and, in various instances, {32}antique architecture, the steeple of the town-house, and other favourable circumstances, it makes a very respectable appearance. The present draught represents it as seen from the bottom, looking upwards to the castle, the view at the top being closed by the ruins of the house of the regent Earl of Mar.

In the centre of this street, opposite the town-house, once stood a market-cross, of beautiful workmanship. It was a lofty stone pillar, to the base of which there was an ascent on all sides, by flights of steps. On the top of this pillar sat a figure of the Scottish unicorn, extending the shield of the royal arms of Scotland, surmounted by the crown. This cross was barbarously pulled down about thirty-five years ago. The unicorn, however, was preserved, and is, at present, to be seen in front of the building in Spittal Street, containing the fire-engine.

At the time when Stirling was an abode of the court, Broad Street appears to have been chiefly occupied by noblemen. The situations of the houses occupied by the Earls of Morton, Glencairn, Lennox, and other bold figurants in the history of Mary and James, are all here pointed out; as also, a house at the bottom, now the office of a branch of the Bank of Scotland, which is said to have been the residence, successively, of Darnley, and of the young Prince Henry, his grandson, when at nurse. On the site of the present weigh-house, was the house of the family of Lennox.

Broad Street was the scene of an incident very remarkable in Scottish history, which occurred in 1571. The party which espoused the falling interest of Queen Mary, was then in possession of Edinburgh, while the Protestant {33}faction, which supported her infant son against her, had Stirling for its head-quarters. The whole of the leading men of the king’s party were assembled at Stirling, early in September 1571, to attend a parliament, when the queen’s men at Edinburgh projected a daring enterprise against them. In the dead of night, a band, several hundred strong, consisting chiefly of borderers, was led off from the capital towards Stirling, under the command of Lord Claud Hamilton, and the Lairds of Buccleugh and Fernieherst, being guided to their destination by a man of the name of Bell, who was a native of Stirling. They entered the open, defenceless, unwatched town, long before day-break, and immediately planting a guard at the door of each slumbering noble, soon had the whole in their power. The Earl of Lennox, regent for James, surrendered at discretion, and, with many of his friends, was placed on the back of a horse behind a sturdy borderer, to be carried off prisoner to Edinburgh. Unfortunately for them, the Earl of Morton repelled their assault for such a length of time as gave occasion to a counter-surprise. The noise having disturbed the Earl of Mar in the Castle, he brought down sixteen harquebusiers into his lodging at the head of the street, (then in the process of building,) and, having planted them securely, he commanded a volley to be fired down the street at the enterprisers, who, without stopping any time to ascertain the force of this contemptible enemy, at once took to their heels, crowded through the narrow pass at the bottom, where many were trodden to death, and instantly left the town. Many of the queen’s men, on this occasion, yielded themselves prisoners to the very men who had been seated behind them in that capacity a few minutes before. The Earl of Lennox, however, did {34}not thus recover his freedom. He was cut down, by an invidious enemy, at the village of Newhouse, about half-a-mile from the South Port, on the way to Edinburgh. This was altogether an affair very characteristic of the time when it happened,—a time when the bravest exploits were sometimes rendered naught by the want of a little discipline, and surprise was almost sure to be attended by success.

The house of the Earl of Mar is almost the only one of the private palaces of that age, now surviving in any shape. It faces down Broad Street, from any part of which it must have had, when entire, a fine appearance. It was, originally, a quadrangular building, with a small court in the centre. We are now only left the ruins of the front of the square. In the centre of this front are the royal arms of Scotland, and, on the two projecting towers on each side, those of the regent and his countess, all in a state of fine preservation; but a number of figures jutting out from the rest of the wall, are in a most mutilated state, and only remain to give us some idea of the costumes of the age when the house was built. The date on the building is 1570, the year before the Earl of Mar became regent. He procured the greater part of the stones from the ruins of Cambuskenneth Abbey, of which he had got a grant. John Knox exclaimed against this as sacrilege, and prophesied the consequent ruin of his family, not remembering, apparently, what share he himself had had in the demolition of these fine buildings. The Earl, either to disarm the criticism which might be directed against the curious taste in which his house was built, or to deprecate the charge of sacrilege, put the three following inscriptions over various door-ways giving entrance to the building:

{35}

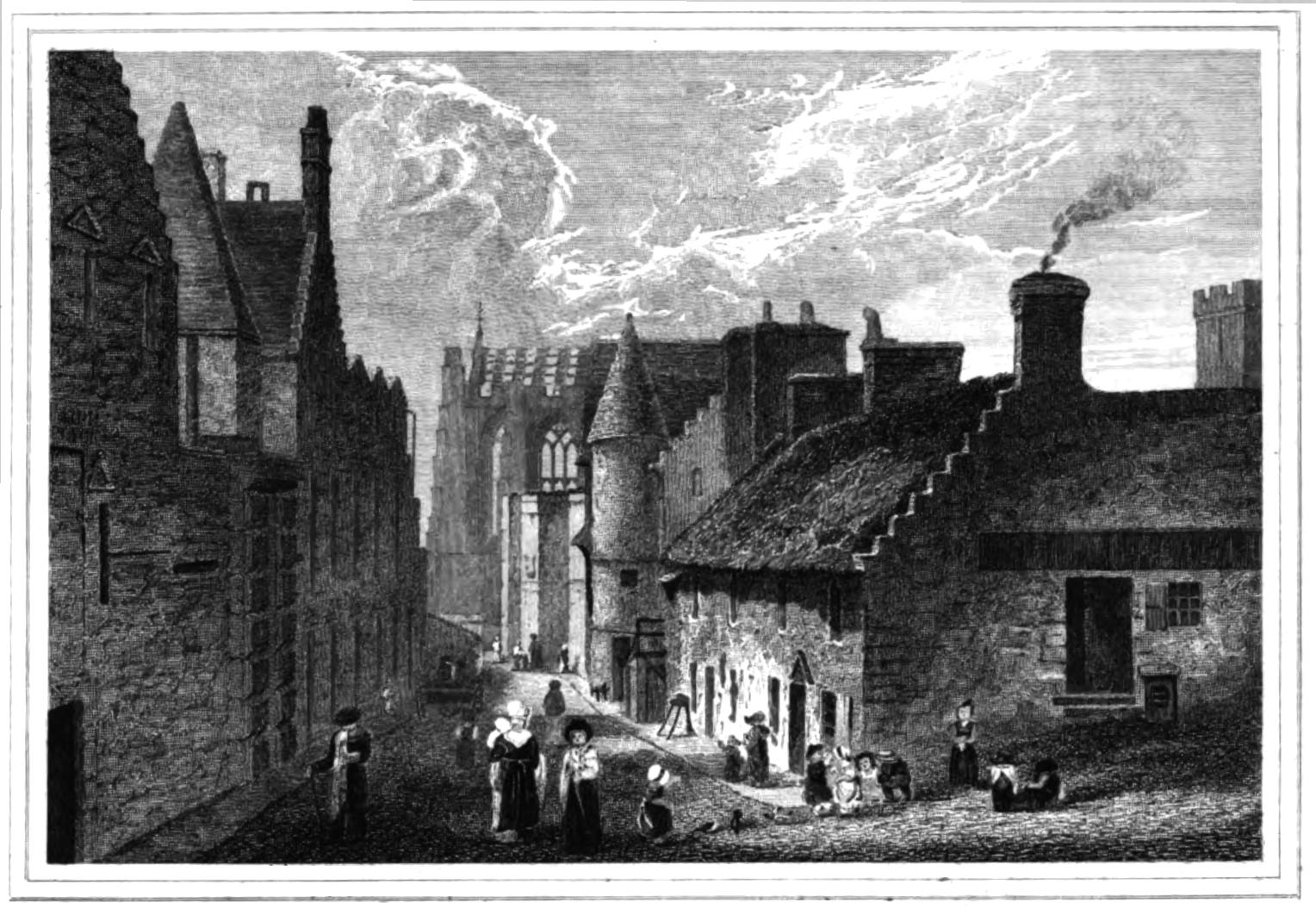

A. S. Masson Delt. J. Gellatly Sculpt.

CASTLE WYND

STIRLING.

A narrow street leads off from the upper end of Broad Street towards the Castle, and is called the Castle Wynd. It has been thought proper to give a sketch of this alley, both on account of the interesting character of the historical objects which it contains, and their strikingly picturesque effect, when fore-shortened by a view from the upper end. The nearest object, on the left side of the plate, is the front of Argyll’s Lodging; the house, with the projecting stair-case, is a very ancient one, which has a coat-of-arms on the front of the wall, now nearly obliterated. Farther on, is Mar’s Work; and, in the extremity of the view, is the north side of the chancel of the East Church. Such a picture of antiquity, we believe, is nowhere now to be seen in Scotland; but, a few years ago, it was even more striking than it is at present, another curiously antique house having then stood on the east side of the street, between Mar’s Work and the Church.

Argyll’s Lodging is a large quadrangular house, built in the lordly style which prevailed during the reigns of James, and the first Charles. It was erected at the expense of Sir William Alexander, a personage who rose, in consequence of his genius and courtly qualities, from the condition of being Laird of Menstrie, (a small estate to the north-east of Stirling,) to immense {36}wealth, and high title. Prince Henry, who was baptised in the castle, honoured him with his particular notice, and introduced him at the Court of England, where James the Sixth knighted him, and made him master of requests. He addressed a Parœnesis to the Prince, which is said to be his master-piece, and wrote an elegy on his death, in 1612, in strains nowise inferior to those of Drummond of Hawthornden, who bewailed that mournful event in an ‘elegy on the death of Mœliades,’ a name by which the Prince was known. King James appointed him preceptor to Henry’s brother, Charles; and Charles, coming to the throne in 1625, gave him a right of appointing the hundred baronets of Nova Scotia, from each of whom he received £200 sterling; raised him to various high offices of state in succession; and, finally, on the occasion of his coronation at Holyroodhouse, in 1633, created him Earl of Stirling, Viscount Canada, and Lord Alexander of Tullibody. Nova Scotia, and Canada, he is said to have discovered and colonised; and he had other extensive possessions in America. James the Sixth used to call him his philosophical poet; Ben Johnson, who travelled to Scotland to visit Hawthornden, corresponded with him; and Addison said of his whole works, which are not a few in number, that ‘he had read them with the greatest satisfaction.’ His prosperity not being continued to his offspring, this splendid house, which must have been the wonder of its day, fell into the hands of the Argyll family. Here the unfortunate Earl of Argyll received and entertained the Duke of York and his family, in 1680, when they came to visit Stirling Castle. Only five years after, he suffered death at the instance of his royal guest, who had then become James II. By another singular vicissitude of fortune, John, Duke of Argyll, in 1715, here held his counsel of war, when employed to {37}break the interest of the son of the same James. Sir William Alexander built the centre and northern wing in 1633; and over the principal door of the centre, leading by an oaken staircase to the grand hall, is his full coat-of-arms, with the motto ‘per mare per terras,’ still perfectly entire. Over the windows of these parts of the building too, may still be seen the initials of William, Earl Stirling, and Jane, Countess Stirling, surmounted by a coronet.

From the Argyll family, the building passed successively into the hands of other individuals. In 1799, the crown purchased it, and converted it into a military hospital, and apartments for the barrack-master and his serjeant. No other damage, however, has been done, than that of removing a balcony above the outer gate, or entrance from the Castle Wynd, which added considerably to the effect of the building. The roof being somewhat in a state of disrepair, it is now proposed, we understand, to modernize it. May such a piece of sacrilege be averted! May the baronial taste of Sir William Alexander, one of the most accomplished men of his age, and the favourite of Princes, be respected! The southern wing appears to have been added by some of the Argyll family, as one of the doors of entrance to it from the court-yard, is dated 1674, and the crest of the Campbells (a boar’s head), is observable, in ludicrous multiplication, over the windows of all that part of the building.

The Castle Wynd was, on the 17th of March 1578, the scene of the death of John, Lord Glammis, a sagacious nobleman, who held the office of Chancellor of Scotland. He had a ‘deidly feid,’ as it was called, with David, Earl of Crawford. The two happened to pass each other in {38}the Castle Wynd, very nearly opposite to the Earl of Mar’s house. No collision took place between themselves; but, unfortunately, two fellows who went in their respective retinues quarrelled and began to fight; on which a pistol was fired, the ball of which went through Lord Glammis’ head. He immediately expired.

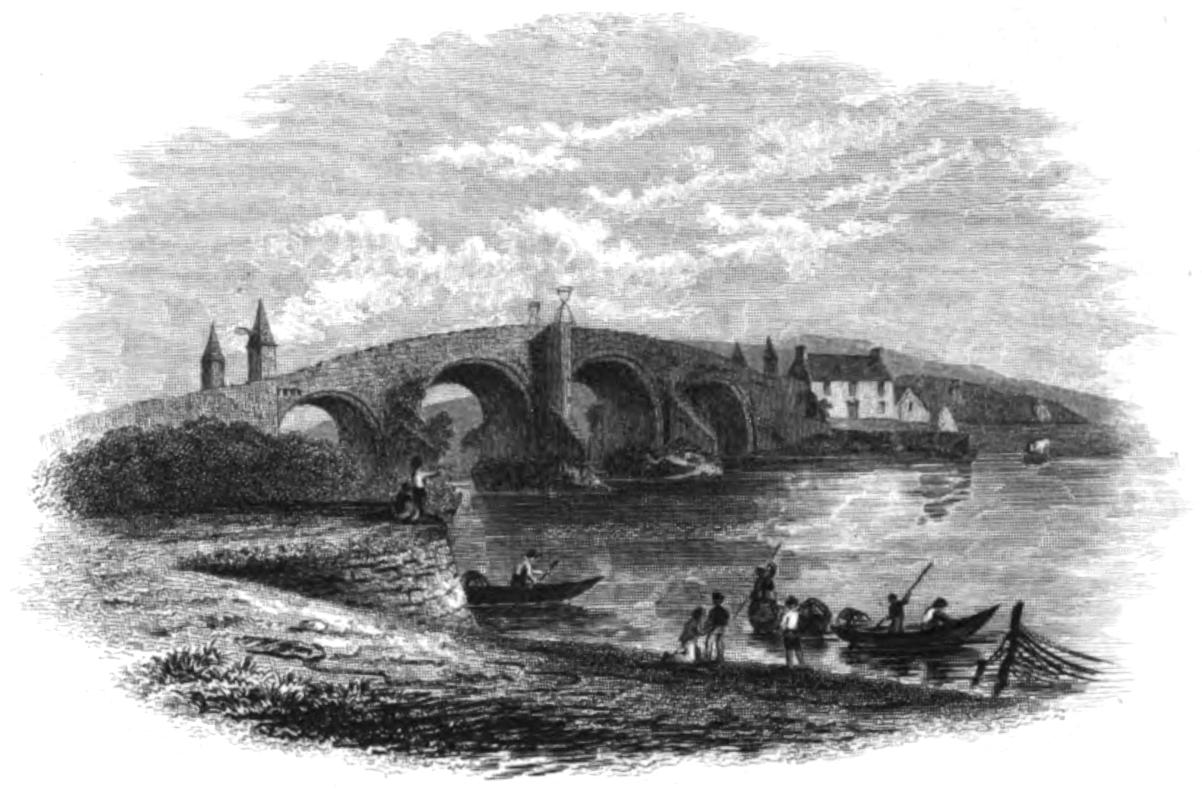

The Bridge over the Forth at Stirling, is by far the most noted structure of the kind in Scotland. Being the first convenience of the sort, which occurs on the Forth for fifty miles upwards from the mouth of its estuary, and having been, till lately, almost the only access for wheeled carriages into the northern department of Scotland; there can be little wonder that it is so. Furthermore, it is old; furthermore, it is conspicuous in the history of the country. Altogether, it is one of the most notable public objects in the kingdom.

At a very early period, there was a wooden bridge across the Forth, about a mile above the present stone structure; probably it was at first the work of the Romans. It is this bridge which figures on the obverse side of the ancient seal of the town. It was, on the 13th of September 1297, the cause of a decisive victory gained by Sir William Wallace, over the English, under Cressingham {39}and De Warenne. By permitting half of the southern army to cross over, the Scottish hero and his companions destroyed them with great ease. It is said, by tradition, that he gave a blast on his horn, as a signal for the onset, from the top of the Abbey Craig, and that, by causing a man to saw through the bridge below the feet of his enemies, he greatly increased the slaughter. The remains of this bridge are visible at low water, and the place is still a ford. Montrose led his army through the water at this point, when on his march to fight the battle of Kilsyth, in 1645. It is near the mill of Kildean.

The age of the stone bridge is unknown; but it must be at least as old as 1571, when Archbishop Hamilton was hanged upon it, by the King’s faction, under the Regent Lennox. It is of very antique structure, being narrow, high in the centre, and composed of arches. Formerly, it had a gate leading through two small flanking towers, near the south end, and another gate leading through two similar towers, near the north end: there were also two low ones in the centre. A painting over the door of one of the rooms of the Town House, represents the bridge in this state. General Blakeney, the governor of the castle in 1745, caused the south arch to be destroyed, in order to intercept the Highlanders, both in their march south, in parties, to reinforce Prince Charles, and in their retreat northwards on desertion. On this account, when the royal army came to follow Charles to the north, in February 1746, the Duke of Cumberland was obliged to supply the place of the deficient arch, by logs and boards of wood; which was one of the reasons why he never overtook, or came near his enemy, till the battle of Culloden.

{40}

For some time, it has been proposed, to substitute a new structure for this venerable one, at some place in the immediate neighbourhood. How many ages must elapse, before it shall acquire the same quality of interesting associations, which our memories connect with the subject of this plate!

{41}

This stone is near the highest point of the western brow of the Gowlan Hills, facing the farm-house of Raploch, and of course, to the north of the old gate which entered the Nether Bailiary of the castle, from the Ballangeigh Road. The inscription may be said to be now wholly obliterated; but the fact rests on the authority of Sir Robert Sibbald, Timothy Pont, and other antiquaries.

The magistracy of Stirling have, at various periods, exerted themselves to receive, with befitting honour, the descendants of those royal personages, who formerly rendered their castle the scene of a permanent court.

James VI., of whose boyhood it was the well-remembered scene, visited the town, in the course of the tour which he performed through his native kingdom, in 1617, after he had been fourteen years absent in England. The Council Register yet bears witness to the exertions of the civic dignitaries on this occasion. On the 12th of May, they ordained ‘the treasurer to buy some leaves of gold to gilt his Majesties armes on the croce,’ and statuted that ‘the Burrow Yett’ (that is, the gate of the town, at what is called the South Port) and also the bridge, should be repaired, preparatory to his Majesty’s arrival. On the 26th of May, they appointed ‘Mr Robert Murray, (commissary of Stirling,) to mak and deliver the speech to the Kingis Majistie, at his first entry in the towne, conform to the direction of the counsell.’ On the 15th of July, they authorised the Treasurer ‘to borrow £100 for the townes use, agains the tyme of his Majesties cumyn;’ they soon after borrowed five hundred merks, besides, to be a propine, or present to the king.

Charles I. was the next royal personage who honoured Stirling with a visit. On the 13th of May, 1633, ‘the Provest, Baillies, and Counsall, {42}being convenit, concludis and agreis for a propine aganis his Majesties cuming to yis town, viz., a silver cup, to be maid in gude fassioun, sett with a cover overgilt with gold, at the sicht of the magistratis, on ye townis chairges, to be payit out be thair Thesaurer, quhilk sall be allowit to him in his comptis.’ On the ensuing 4th and 8th of July, it is observable, from the Register, that the whole of his Majesty’s household were admitted burgesses gratis. Among the number, which is not a small one, were William, Lord Bishop of London, (the famous Laud,) William, Lord Bishop Elect of Hereford, and John, Bishop of Ross.

It is perhaps a more interesting fact than any of the above, that Stirling gave a welcome to Charles II., when he visited it in the course of his unhappy pilgrimage in Scotland, in 1650–1, for the recovery of the kingdoms lost by his father. There are many things in the council records to denote, that the magistracy, at that trying period, and even during the dominancy of the commonwealth, retained a strong feeling of loyalty for the descendant of their ancient kings. Stirling was one of the Scottish burghs which Cromwell disfranchised, for not consenting to the union he desired to effect betwixt Scotland and England. A somewhat amusing anecdote is handed down by tradition, in reference to Charles the Second’s residence at Stirling. It seems that he thought proper to pay a personal visit to the Reverend Mr Guthrie, the puritan minister of the town; nothing at that period being practicable without the good will and influence of the clergy. When Charles entered the manse, Mrs Guthrie bustled about, with the officious kindness of a housewife, to get a chair for the king. ‘Never mind, gudewife,’ said the cynic; ‘the king’s a young man, and can tak a chair for himsel.’ We can scarcely suppose that Charles would be much offended at this singular piece of rudeness, which must have been too characteristic to fail in tickling a mind like his. Yet it might make him less anxious to save Guthrie from the death to which he was doomed, for his distinguished disloyalty, after the Restoration.

Stirling appears to have lent a good deal of money to this sovereign, during his misfortunes, besides performing other acts of service in behalf of himself and his friends. It is a pleasure to add, that he retained a grateful sense of the kindness of the citizens of Stirling, and, on arriving at his period of power, extended and confirmed their former privileges.

The town was honoured in 1681, by the visit of James, Duke of York and Albany, (afterwards James II.,) who then resided in Scotland, in a sort of honourable banishment, to escape the hostility of the Monmouth and {43}Shaftesbury party, who were endeavouring to procure his exclusion from the throne. The magistrates and council, under date, October 21, 1680, ‘recommendis to the dean-of-guild and conveiner, to speik to thair respective incorporations, anent the provyding of partizans agane his Royal Highnes reception, and to report thair opinions to the magistrats, Saturday nixt.’ On the 4th of February 1681, the magistrates and council, in full convention, received and admitted to the honours and privileges of their burgh, ‘James, Duke of York and Albanie;’ besides a great number of his attendants, among whom is conspicuous, ‘Collonel John Churchill, attending on his Royall Highness.’ This person, at the time in question, was page to the Duke; but, in after times, reached the pinnacle of greatness and fame as Duke of Marlborough. It would appear that the magistracy presented the freedom of the town to his Royal Highness, in an expensive gold box, as the following entry occurs in the register, under date, March 14, 1681: ‘Ordains the thesaurer to pay William Law, goldsmith, thrie hundreth eightin pundis, fiftein shilling, for the gold-box he furnished to his Royall Highnes burges ticket.’ [This Law must have been the father of the celebrated projector of the Mississippi Scheme.]

As a farther testimony of the loyalty of the town at this period, the following entry may be quoted: ‘The seavint day of October 1681, admittis and receaves Captain John Graham of Claverhouse, Sir Andro Bruce of Earlshall, Mr David Grahame, brother to Claverhouse, James Montgomerie, ane of the corporalls of Claverhouse troupe, Alexander Scott, writer in Edinburgh, William Dickison, son to ________ Dickison, proveist of Forfar, David Buchanan, servant to Claverhouse, John Cuming and Adam Galloway, Claverhouse trumpetters, burgesses and guild brethren of the said brugh gratis; and they present made faith, as use is. And also admittis and receaves David Neve, Robert Kerr, William Sluthers, and John Purveis, servitors to Claverhouse, John Simpson and Alexander Watson, servitors to Earleshall, John Wallace and Alexander Luggat, servitors to William Grahame, cornet of Claverhouse troupe, and John Watson, servitor to Robert Murray, ane of the said troupe, neighbours and burgesses of the said brugh, and that gratis; and ilk ane made faith, as use is.’

No other royal personage visited Stirling till Prince Charles Stuart, grandson to the ill-starred prince who was received with so much gratulation as above, forced his entrance into the town, with his army of Highlanders, on the 8th of January 1746. The town was, on that occasion, held out with considerable spirit, for two days; but was forced at last to capitulate. The letter which Charles sent to summon the magistrates to surrender, is yet extant in the town-clerk’s office.

{44}

By an act of the Scottish Parliament, in 1437, various burghs in the Lowlands were appointed to keep the various standard measures for liquid and dry goods, from which all others throughout the country were to be taken. To Edinburgh was appointed the honour of keeping the standard Ell—to Perth the Reel—to Lanark the Pound—to Linlithgow the Firlot—and to Stirling the Pint. This was a judicious arrangement, both as it was calculated to prevent any attempt at an extensive or general scheme of fraud, and as the commodities, to which the different standards referred, were supplied in the greatest abundance by the districts and towns, to whose care they were committed; Edinburgh being then the principal market for cloth, Perth for yarn, Lanark for wool, Linlithgow for grain, and Stirling for distilled and fermented liquors.

The Pint Measure, popularly called the Stirling Jug, is still kept with great care in the town where it was first deposited four hundred years ago. It is made of brass, in the shape of a hollow cone truncated; and it weighs 14 lb. 10 oz. 1 dr. 18 grs. Scottish Troy. The mean diameter of the mouth is 4.17 inches English—of the bottom 5.25 inches,—and the mean depth 6 inches. On the front, near the mouth, in relief, there is a shield bearing a lion rampant, the Scottish national arms; and near the bottom is another shield, bearing an ape passant gardant, with the letter S. below, supposed to be the armorial bearing of the foreign artist who probably was employed to fabricate the vessel. The handle is fixed with two brass nails; and the whole has an appearance of rudeness, quite proper to the early age when it was first instituted by the Scottish Estates, as the standard of liquid measure for this ancient bacchanalian kingdom.