Title: Conversation

Author: J. Frank Davis

Release date: January 26, 2026 [eBook #77793]

Language: English

Original publication: Chicago, IL: The McCall Company, 1930

Credits: Prepared by volunteers at BookCove (bookcove.net)

Of all the twenty-odd legal justifications for homicide in Texas, the second most common is the epithet which is never spoken by gentlemen in the presence of ladies except on the New York stage. There were no ladies in front of the Somersworth post office when Jim Begley culminated a sharp quarrel over a horse-trade by speaking this epithet distinctly and viciously to Newt Shaw; and Newt, under all the rules and precedents, was justified in his immediate action, which was to draw a forty-five revolver, place the muzzle of it against Begley’s stomach and begin shooting. He fired three rapid shots.

This would have seriously discommoded Begley if he had not been wearing a metal breastplate beneath his vest. It bruised him somewhat even as it was, and made him stagger as he pulled his own pistol. He didn’t pull it as fast as he might have been expected to, some of the witnesses said afterward—they thought it had caught in his holster, although others gave him credit for deliberately letting Newt get so much of a start that there could be no question as to his having the right to kill Newt, which he did with one shot as soon as he got the gun out.

The coroner’s jury had no difficulty in reaching its decision. Another of the twenty-odd justifications, naturally, is self-defense, and as a juryman said succinctly during their brief deliberation: “If a man aint shooting in self-defense when another man has a pistol stuck in his ribs and it’s smoking, then there aint no meaning to the English language.”

So the jury turned Jim Begley loose; the lodge buried Newt, and the incident closed for the moment with a few mildly-spoken but admonitory remarks by the sheriff as he gave Begley back his gun.

“Newt wa'n't exactly what you could call a leading citizen,” he said. “He aint as much a loss to the community as some would be. But if ever you should happen to kill a man that was popular, in just that way— I wouldn’t do it too many times, Begley. I don’t know, if I was you, as I’d go to do it any more times—not with a breastplate on.”

“The breastplate is off—from now on,” Begley said.

“I’ll pass the word around,” the sheriff told him. “I’d be kind of hurt if you should ever make me out a liar about that.... So would you.”

“You can trust me, Sheriff,” Begley assured him.

“Yes suh. And watch you!”

That might have ended it—Somersworth being one of those Texas towns where personal criticism is soft-pedaled in the interest of public and private health—if Curly Stewart hadn’t been seriously in love with Mamie Goodale, who had black hair and blue eyes and was the junior biscuit-shooter at the Eagle House dining-room.

Curly, until Jim Begley struck town, had seemed to be sitting pretty with Mamie, but now he wasn’t sitting pretty with her; he wasn’t sitting with her at all; Begley was. Almost every night, after the dishes were washed at the hotel, and always, on Saturday nights, at the picture show. Curly had cared very little for Newt Shaw, but now he felt a distinct personal resentment over his killing. He almost succeeded in convincing himself that Newt had been a friend of his.

He touched upon the subject of Newt and Begley and the ethics of breastplates, in general conversation, to a number of people. He touched upon it to Mamie one night when he was the last man in to supper at the hotel, and his language was not tactful.

“Jim Begley coming round tonight, as usual?” he asked.

“What if he is?”

“He aint the right kind,” Curly said. “It aint that I’m jealous or anything—oh, yes, cuss it, of course I am! But there’s more than that. I don’t admire to see you running round with a feller like him. He aint the kind for you.”

“Is that so?” replied Mamie.

“He’s yellow. Any man that’ll put on a breastplate when he isn’t going to fight but one man is yellow. The whole town thinks it. The only reason they don’t say so is because they aint looking for trouble.”

“You must be,” said Mamie.

“No, I aint. I aint no gun-fighter, and you know it.”

“You’re a good talker.”

“You can’t marry him, Mamie. Now, listen—”

She interrupted him.

“I aint aimin’ to marry anybody, not at this minute. When I do, though, he’ll have to be good at something more than conversation.”

“At dirty killings, maybe,” Curly retorted. “All right, go to it and marry him. You’ll find he aint got no real sand.”

“Who aint?” growled Jim Begley, behind them.

“I aint got no gun on,” Curly told him. “Seeing as you asked, I was speaking of you.”

“And it’s safe to, when you aint,” Begley said. “But have one on the next time I see you. I’ve been hearing some of the things you’ve been saying about me. Now you’ll back ’em up, or get out of the county. This town’s got too small for both of us.”

Mamie, her eyes wide, spoke not a word. “I'm leaving on the Number Eight tonight for San ’Tonio; got some business there that’ll take two days,” went on Begley. “I’ll be back Saturday mawnin’. When you and me meet, you’d better come a-smokin’, because I will.... If you’ve got any sense, you wont be here when I get back. Go get you another place to live in—if you want to live a’tall. Hear me?”

Curly’s mouth was dry. In all his twenty-two years he had never shot at a man, and he had hoped he never would have to. He ought to have known his free conversation might lead to this, yet now it came as a shock. He swallowed hard and said lamely: “I hear you.”

“For your last thought—if you see fit to stay here till I get back,” Begley sneered, “you can remember that it don’t pay to be too talkative.... Nothing else you want to say, suh?”

“No,” Curly replied. He was perfectly aware that he was making a weak showing, and he couldn’t help it. He knew Jim Begley’s ability at gunplay and he knew his own. He could shoot straight, but he couldn’t draw fast, and Begley could do both.

Yet, as he left the dining-room—and wondered just what the look in Mamie’s eyes meant—he knew he was not going to leave town.

He avoided speech with Mamie throughout Thursday and Friday. He cleaned his revolver and reloaded it carefully, though he knew he would probably never have a chance to fire it.

The sheriff came to him on Friday night.

“I hear you and Jim Begley had a few words,” he said. “I can arrest him when he gets off the train and put him under a peace bond, if you say so.”

“I'd stand great in this town after that, wouldn’t I?”

The sheriff, who liked Curly, showed relief. “Good!” he said. “He wont have any breastplate on. And I’ll be handy to see fair play.” He added: “Don’t let anything scare you. Keep your nerve. He may not keep his. I aint at all sure he’s got anywhere near as much as he wants folks to think he has. He was asking quite a number, before he left town, night before last, about your shooting—and he seemed right anxious. I gather all the boys spoke highly of you.”

“That’s good,” Curly said, wholly unable to look cheerful. “Maybe they’ll attend in a body, with flowers.”

“Son,” said the sheriff, “barring me and one other, the folks around town don’t know whether you are quick on the draw or not—and neither does Begley. And I think his gun did stick when he killed Newt Shaw, and he’ll remember that—he can’t help it. If you could bust his nerve—”

“What with? Conversation?” Curly asked bitterly.

The sheriff smiled grimly. “Well, that’s been done,” he said. “And between you and me, Mamie Goodale was saying a little while ago—to me, confidential—that she believed you could do it. You’re some talkative—but conversation aint all you’ve got.”

“Did Mamie say that?”

“She said she believed so.”

Curly grinned, naturally, for the first time in two days. “Thanks, Sheriff,” he said. “Maybe I can think up something.”

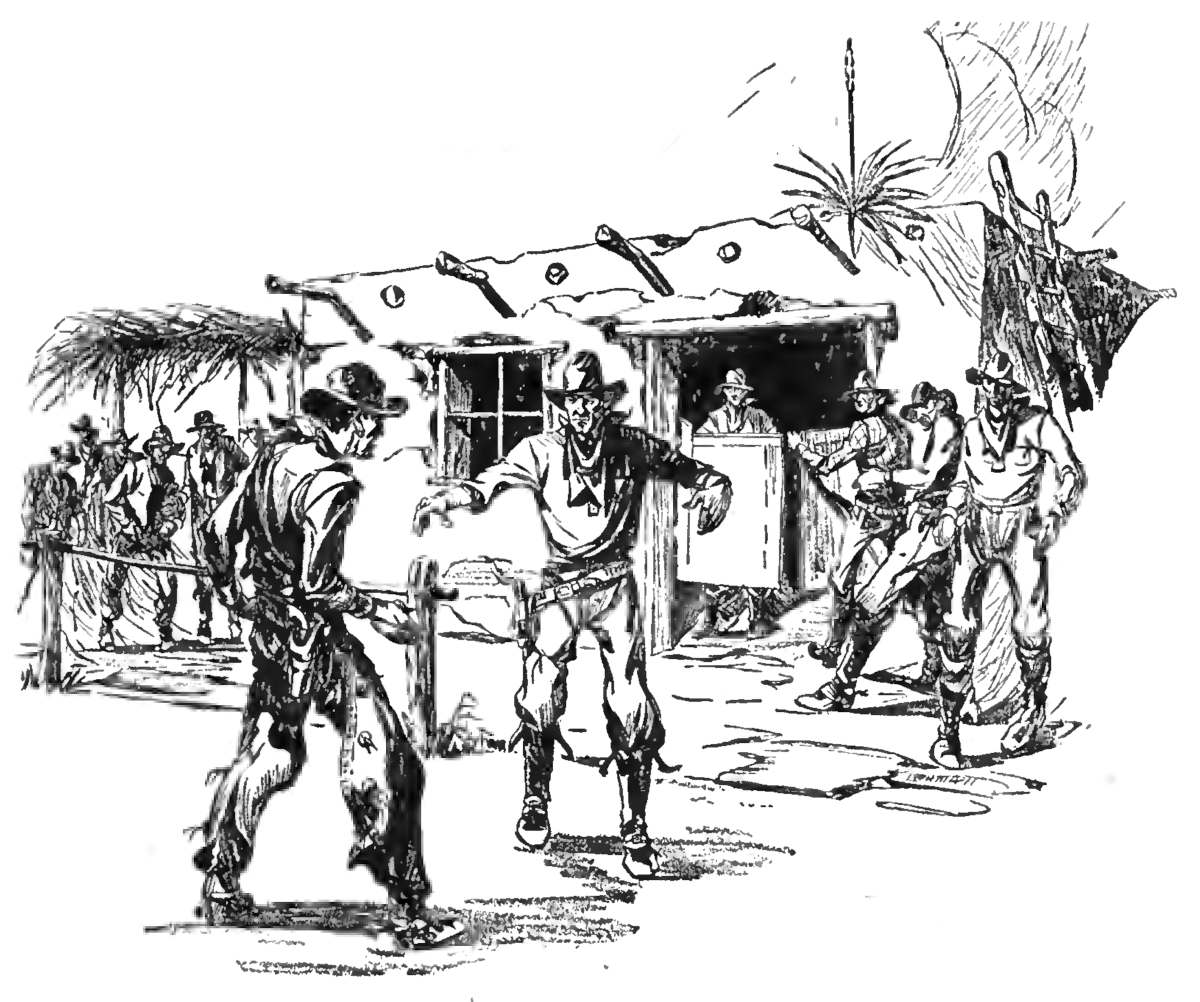

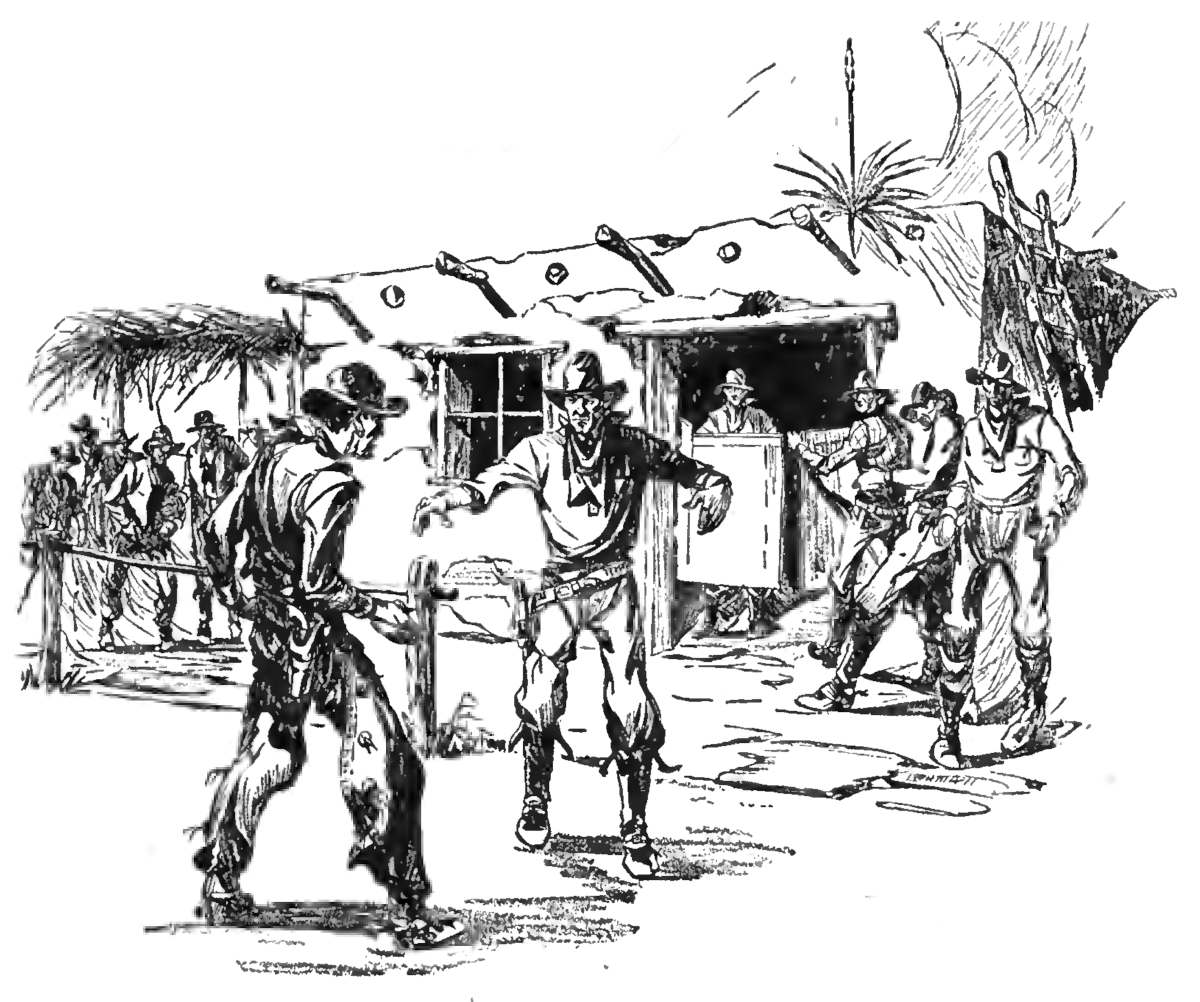

They met at noon, Curly and Jim Begley, in the little plaza in front of the post office, both coatless, both with holstered pistols at their thighs, well forward, within easy reach of swinging right arms. And to the surprise of all the well-out-of-range spectators and the horror of Curly’s friends, he spread his hands and lifted them, and thus in a position which forbade Begley’s shooting unless he wanted to face a charge of Murder, walked swiftly toward him. Begley stopped and waited, tense.

His hands still raised, Curly began to talk when he was yet thirty feet from his enemy. His voice was clear and carrying, and untremulous.

“Say, I’m tired of packing this gun,” he said. “I aint in the habit of doing it, and it’s heavy, and I don’t like it, hot weather like this. Maybe there’s a misunderstanding. Maybe when you heard I said things about you, you didn’t hear it straight. I want to tell you just what I said. Maybe when I’m through, you wont figure it’s necessary for us to have any trouble at all.”

Apologizing! Quitting! Jim Begley’s pose relaxed. His face, somehow, registered intense relief.

“Go ahead. I’ll listen,” he said tolerantly, almost smiling.

“You can’t draw while my hands are up,” Curly reminded him. “When I get through talking, you can go after your pistol if you still want to,”—he was four feet away now, and he stopped, his eyes on Begley’s,—“an’ be deader’n hell before you get your hand halfway to it! And your face’ll look as scared as Newt Shaw’s did when you got him. Remember how he looked? Remember how he must have felt? That’s how you’ll look. That’s how you’ll feel—if you ever start your hand after your gun. All I said about you around this town was that you were a dirty, lyin’, double-crossin’, breastplate-wearin’, cowardly low-down whelp. If you heard I said anything worse than that, you was misinformed.”

Begley’s mind adjusted itself to the changed situation slowly and painfully. He looked into Curly’s eyes. They were hard, unflinching, boring. He looked at Curly’s right hand. It was well out and shoulder high, but its fingers were bent, ready to clutch as it came down to the gun. It had two feet farther to go than Begley’s hand. If Begley started first—and if his gun didn’t catch in the holster— The odds were all against Curly, but he looked as though he was satisfied with that. Worse, he sounded so.

“Well!” Curly snapped. “What are you waiting for? Let’s go!”

Slowly, Jim Begley’s hands went out from his sides, shaking, and he muttered: “I don’t want no trouble.”

Trying successfully to keep his own hand from trembling, Curly took Begley’s pistol from its holster.

“I’ll turn this over to the sheriff,” he said. “He’ll give it to you when you take the next train out of town. Which way—east or west?”

“Why—why, the—the Number Four east, I reckon,” Begley stammered. “I—I got some business that’s—going to take me permanent to San ’Tonio, anyway.”