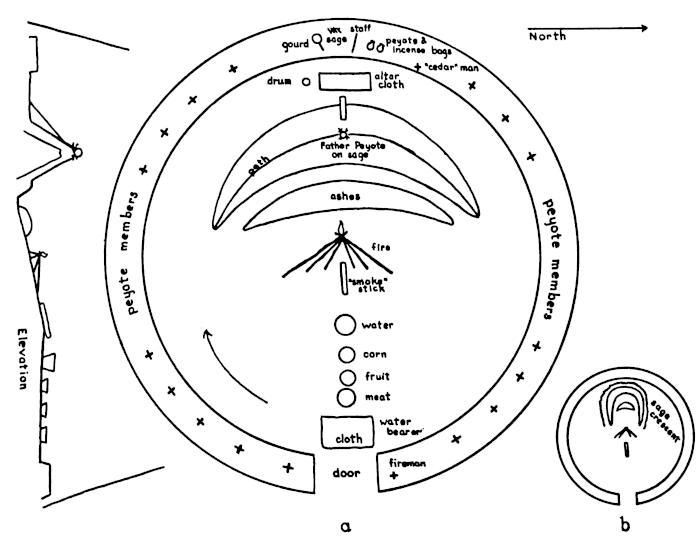

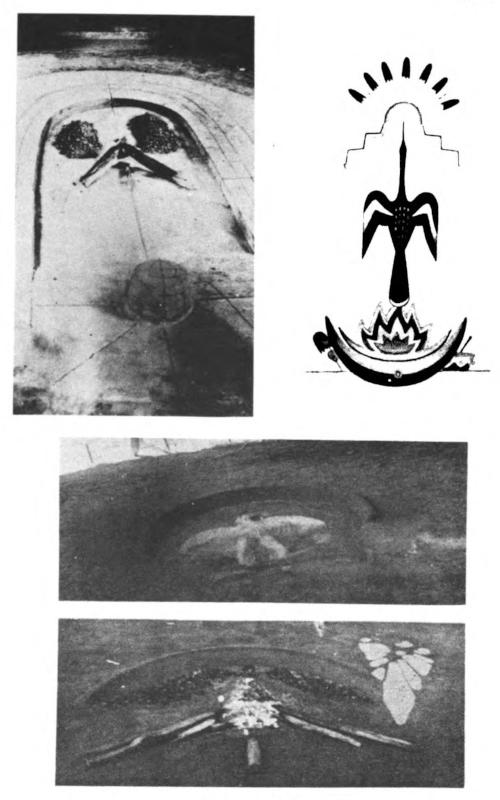

Fig. 1. Arrangement of interior of tipi for peyote meeting. a, Kiowa “standard” peyote meeting; b, Comanche horseshoe moon variant.

Title: The peyote cult

Author: Weston La Barre

Release date: January 26, 2026 [eBook #77791]

Language: English

Original publication: Hamden, CT: The Shoe String Press, 1959

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/77791

Credits: Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

[1]

Transcriber’s Note: The author’s citations of works published in languages other than English are sometimes inaccurately spelt. In addition, he uses a mixture of standard and nonstandard IPA symbols to transcribe words in the Kiowa and other Native American languages; these are preserved as originally printed.

THE PEYOTE CULT

BY

WESTON LA BARRE

Professor of Anthropology

Duke University

REPRINTED BY

THE SHOE STRING PRESS, INC.

Hamden, Connecticut

1959

[2]

© 1959, THE SHOE STRING PRESS, INC.

Originally published as

Yale University Publications

in Anthropology

Number 19

Reprinted by permission of the Department of Anthropology, Yale University

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

[3]

The field work which is a partial basis of this study was begun in the summer of 1935, when the writer was a member of the Laboratory of Anthropology at Santa Fé ethnological group which worked with the Kiowa under Dr. Alexander Lesser of Columbia University. The field work was continued alone in the summer of 1936 with funds granted by Yale University and the American Museum of Natural History. Field data were gathered with varying completeness from fifteen tribes: Kiowa, Comanche, Shawnee, Kickapoo, Osage, Quapaw, Seminole, Delaware, Pawnee, Cheyenne, Caddo, Oto, Ponca, Kiowa Apache and Wichita; in the case of the Kiowa, Oto, and Wichita two peyote meetings each were attended.

The debt to my almost constant field companion, Charles Apekaum (Kiowa), game warden, ex-Navy man, graduate of Chilocco, Haskell, and Carlisle, and my chief interpreter, is such that I may say my work could not have been carried out with such comparative facility and speed without his aid. His knowledge of people and places was invaluable to me. Special appreciation is expressed to Mr. Alfred Wilson (Cheyenne) of Thomas, Oklahoma, several times state president of the Native American Church, for lending me numerous letters and other documents from the official files of the organization, and to Jim Waldo (Kiowa) and Kiowa Charley for similar documents, including the articles of incorporation and state charter. To Jim Pettit (Oto) of Red Rock, local president of the Native American Church, and Charles Tyner (Quapaw) of Miami, the added debt of personal hospitality was incurred. The following informants were of particular help in gathering data: Cecil and Henry Murdock (Kickapoo); Sly Picard, George May and Henry Hunt (Wichita); Jim Aton, Belo Kozad and Homer Buffalo (Kiowa); Howard White Wolf (Comanche); Carl Pettit, Murray Little-crow, and Mrs. George Pipestem (Oto); Albert Stamp (Seminole); Tom and Collins Panther (Shawnee); Tennyson Berry (Kiowa Apache); Robert Little-dance and Louis MacDonald (Ponca); Mack Haag (Cheyenne); Elijah Reynolds (Delaware); and Sun Chief and James Sun-eagle (Pawnee). To Jonathan Koshiway (Oto), founder of the Church of the First-born, I wish to express appreciation for his painstaking efforts at completeness of information made on my behalf.

In a study of this scope one necessarily incurs considerable debts to colleagues for aid generously given and gratefully received. The notes of James Mooney on Kiowa, Comanche, and Tarahumari peyote, deposited in the Bureau of American Ethnology, as well as manuscripts by Frances Densmore on Winnebago, and Dr. Truman Michelson on Sauk and Fox peyote, were made available through the generosity of Dr. Matthew Stirling, to whom I express particular thanks. Mrs. Elna Smith very kindly lent further Bureau of American Ethnology material which had been in her care. Mr. D. F. Murphy of the Indian Office amplified my Osage notes, and Mr. John Collier, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, [4]has been generous with information of legal and administrative nature. To Donald Collier, student at the University of Chicago, and Ing. Luis Híjar y Haro of Mexico City, I express appreciation for bibliographic items, as well as to Dr. Ralph Beals of the University of California at Los Angeles. Richard Schultes, student at Harvard University, who was with me for an ethnobotanical study during several weeks of my second summer of work, has also been generous in giving help on bibliographic as well as botanical and pharmaceutical matters. Dr. E. A. Hoebel of New York University made available his notes on Northern Cheyenne and Comanche peyote. Dr. Ruth Benedict of Columbia University and Dr. M. E. Opler of the University of Chicago have aided with Mescalero Apache notes, and the latter has very generously lent valuable manuscript notes on Tonkawa, Carrizo and Lipan peyotism. Dr. Frank Speck of the University of Pennsylvania was fertile with suggestions during the second period of field work, and since its completion has contributed important Delaware material. Mrs. Erminie Voegelin, student at Yale University, kindly lent her voluminous notes on Shawnee peyote, as did Mrs. Anne Cooke for the Ute, and John Noon, student at the University of Pennsylvania, for the Kickapoo. Dr. A. H. Gayton kindly lent an interesting paper on datura. While the present paper was still in proof form, Dr. Leslie A. White of the University of Michigan and Dr. Fred Eggan of the University of Chicago generously lent material on Taos and Northern Cheyenne peyotism respectively.

To Dr. Edward Sapir of Yale University, to the Laboratory of Anthropology at Santa Fé, and to Dr. Clark Wissler of the American Museum of Natural History, I wish to express my thanks for making available the funds on which field work was undertaken. To Dr. Sapir and to Dr. John Dollard of the Institute of Human Relations at Yale University I owe the warm personal debt of founding a knowledge and an interest in matters of psychological import herein treated. And to Dr. Leslie Spier, my dissertation adviser, I express gratitude for his constant stimulating interest, valuable bibliographic help, and leads of considerable ethnographic significance.

Weston La Barre

In the twenty years since the original publication of this book, studies of peyotism have continued to appear, until there are at present over one thousand bibliographic items on the ethnography of peyotism and related subjects. The author has summarized recent studies in an extended review of “Twenty Years of Peyote Studies,” which is in press for appearance in an early issue of Current Anthropology. Readers interested in following two decades of developments in peyotism may wish to be referred to this publication.

[5]

| PAGE | |

| Preface | 3 |

| Introduction | 7 |

| Botanical and Physiological Aspects of Peyote | 10 |

| Botany | 10 |

| Ethnobotany | 11 |

| Names for peyote | 14 |

| Etymology of “peyotl” | 16 |

| Identification of peyote | 17 |

| Physiology of Peyote Intoxication | 17 |

| The Ethnology of Peyotism | 23 |

| Non-ritual Uses of Peyote | 23 |

| Ritual Uses of Peyotl | 29 |

| Huichol | 30 |

| Tarahumari | 33 |

| Comparison of Mexican peyote rituals | 35 |

| Mescalero Apache and transitional forms of ritual | 40 |

| Kiowa-Comanche type rite | 43 |

| Comparison of Mexican, transitional, and Plains peyotism | 54 |

| Comparative Study of Plains Peyotism | 57 |

| Psychological Aspects of Peyotism | 93 |

| Historical Interpretations | 105 |

| The Pre-peyote Mescal Bean Cult | 105 |

| History of the Diffusion of Peyotism | 109 |

| Appendix 1: Peyote in Mexico | 124 |

| Appendix 2: Peyote and the Mescal Bean | 126 |

| Appendix 3: Peyote and Teo-nanacatl | 128 |

| Appendix 4: “Plant Worship” in Mexico and the United States | 131 |

| Appendix 5: Chemistry of Peyote | 138 |

| Appendix 6: Physiology of Peyote | 139 |

| Appendix 7: John Wilson, the Revealer of Peyote | 151 |

| Appendix 8: Christian Elements in the Peyote Cult | 162 |

| Appendix 9: The Native American Church and Other Peyote Churches | 167 |

| Bibliography | 175 |

[6]

| PLATES | |

| Explanation of plates | AT END |

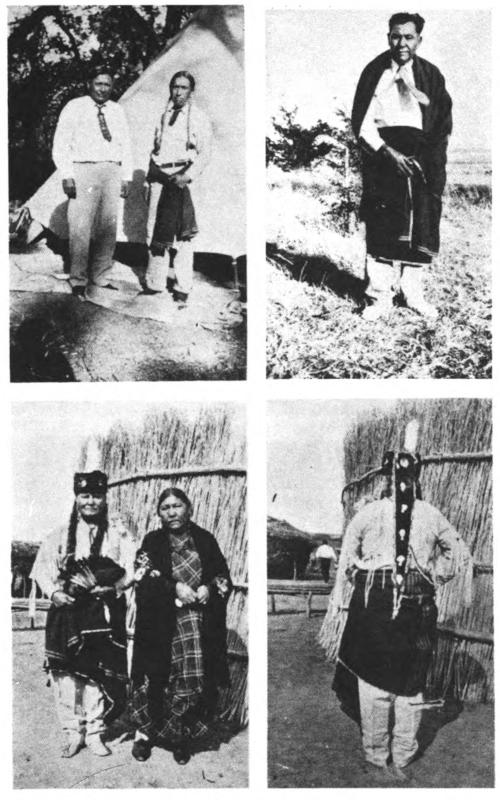

| 1. Peyote leaders | |

| 2. Altar and ash birds | |

| TEXT FIGURES | |

| PAGE | |

| 1. Arrangement of tipi for peyote meeting (Kiowa) | 44 |

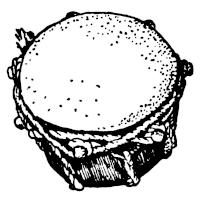

| 2. Peyote paraphernalia | 47 |

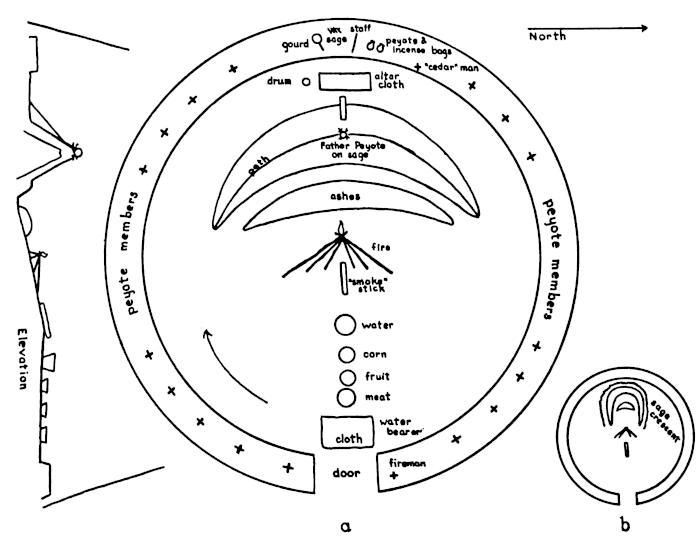

| 3. Peyote drum | 49 |

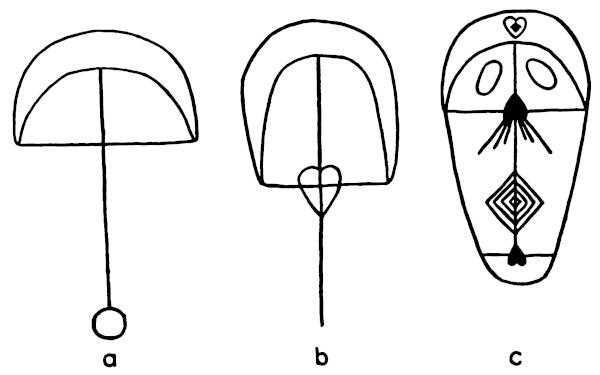

| 4. Peyote altars or moons | 75 |

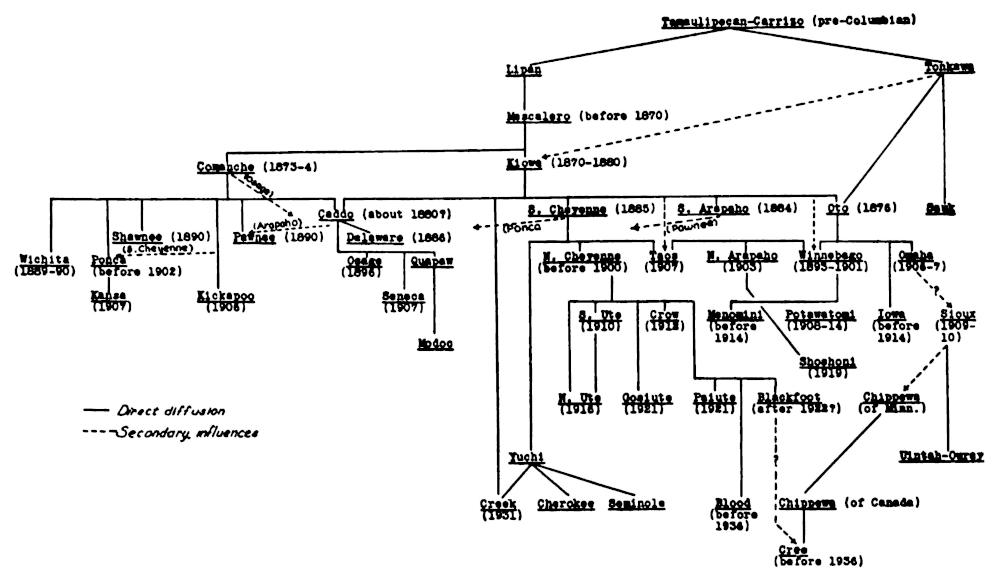

| 5. The diffusion of peyotism | 122 |

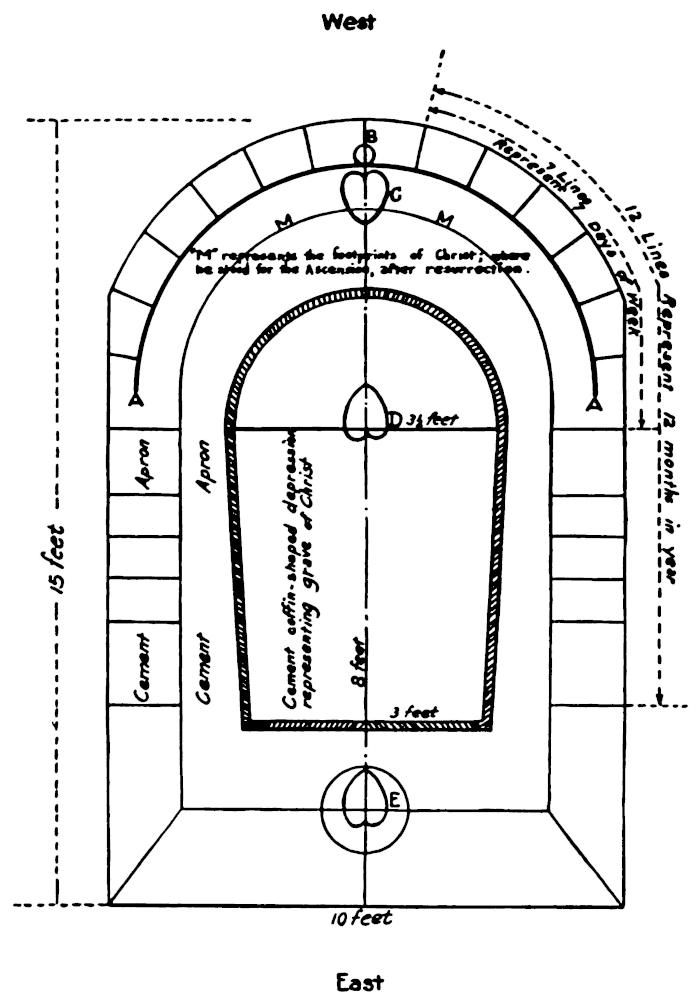

| 6. Cement altar of the Big Moon rite (Osage) | 154 |

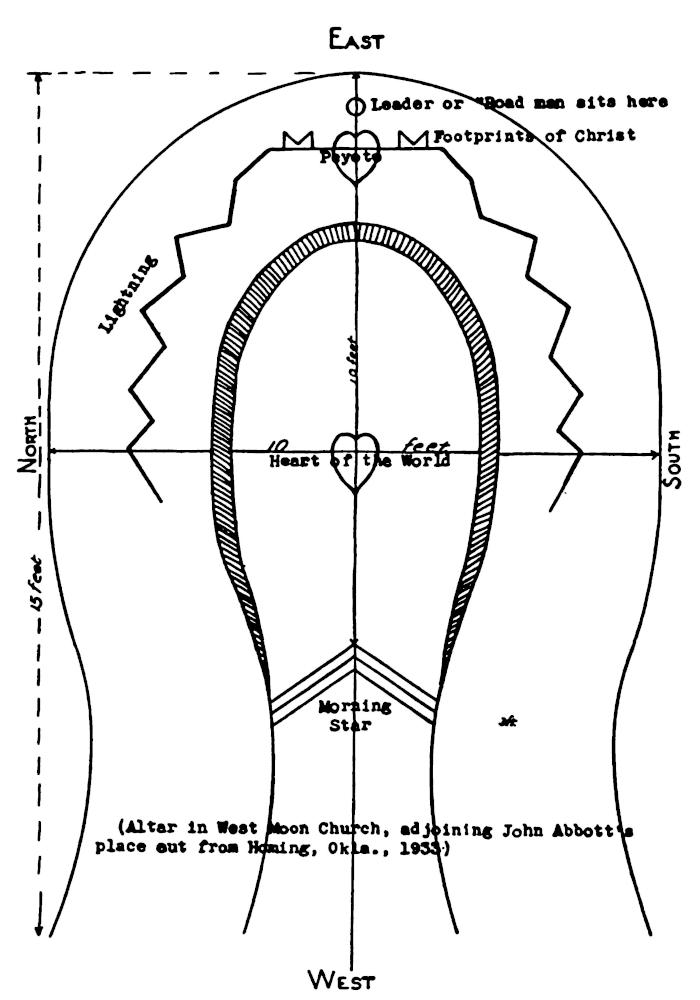

| 7. Altar in West Moon Church (Osage) | 155 |

[7]

Peyote (Nahuatl, peyotl) or Lophophora williamsii Lemaire, is a small, spineless, carrot-shaped cactus growing in the Rio Grande Valley and southward. It contains nine narcotic alkaloids of the isoquiniline series, some of them strychnine-like in physiological action, the rest morphine-like. In pre-Columbian times the Aztec, Huichol, and other Mexican Indians ate the plant ceremonially either in the dried or green state. This produces profound sensory and psychic derangements lasting twenty-four hours, a property which led the natives to value and use it religiously. Peyote is not, however, the same as teo-nanacatl, as Safford believed; the latter is a narcotic mushroom which likewise had a Mexican distribution. The term “peyotl” is also used in Mexico to designate other cacti and non-cacti, some of which, like peyote, are reputed to have aphrodisiac and other properties.

Physiologically, the salient characteristic of peyote is its production of visual hallucinations or color visions, as well as kinaesthetic, olfactory and auditory derangements. Psychiatrists have used it (experimentally) with unsatisfactory results in producing temporary psychosis, and therapeutically its use has been similarly disappointing because of the uncertainty of action of the antagonistic alkaloids of pan-peyotl. First, exhilaration is produced by the strychnine-like alkaloids, followed by profound depression, nausea and wakefulness, and finally, under the influence of the morphine-like alkaloids, brilliant color visions are produced, which last for several hours. There are no ill after-effects, and peyote is not known to be habit-forming. These properties have led to a number of non-ritual uses by natives for prophesying, clairvoyance, finding lost objects and the like, as well as empirically for the cure of all manner of illnesses.

In Mexico peyote was used seasonally in an agricultural-hunting religious festival, preceded by a ritual pilgrimage for the plant. Participants danced all night around a fire to the rasp-music of the shaman, as they ate the drug in this tribal celebration. Since about 1870 the cult has spread to the United States, particularly in the Plains, where nearly all groups use it. In the Southwest transitional region peyote became deeply involved in shamanistic rivalries and witchcraft, and in the Plains with war. A pre-peyote narcotic, the “mescal bean” (Sophora secundiflora) had there prepared the way for its introduction. The Plains cult is like the warriors’ societies of earlier times in some respects. The Kiowa, Comanche and Caddo were the chief agents of the spread of the cult throughout the entire Plains region to southern Canada and parts of the Great Basin. The standard ritual is an all-night meeting in a tipi around a crescent-shaped earthen mound and a ceremonially-built fire; here a special drum, gourd rattle and carved staff are passed around after smoking and purifying ceremonies, as each person sings four “peyote songs.” Various water-bringing [8]ceremonies occur at midnight and dawn, when there is a “baptism” or curing rite, followed by a special ritual breakfast of parched com, fruit, and boneless meat.

The Caddo-Delaware John Wilson had peyote visions that led him to modify the altar and ceremony; this new form has spread to the Caddo, Delaware, Quapaw, Osage and others. Wilson was one of a long line of Indian prophet-messiahs, and his “moon” has been somewhat exploited economically. The Oto teacher, Jonathan Koshiway, founded a Christianized version of peyotism which spread to the Omaha, Winnebago and others. An organization of confederated tribes known as “The Native American Church” grew out of Koshiway’s “Church of the First-born” (which latter spread to Negro groups also). The cult has had considerable legal difficulties.

Praying and doctoring in meetings, and occasionally public confession of sins, are the major means for the liquidation of life-anxieties of this profoundly functional cult’s many present-day communicants. In the following pages we shall attempt to delineate the history of the study of the cult, the various botanical questions surrounding peyote, its physiological action and the various ethnological, psychological and historical questions involved in its diffusion.

First of modern students to describe the peyote rite was James Mooney, who visited the Kiowa, Comanche, Tarahumari, and “a number of other tribes, among them the Mexican tribes of the Sierra Madre, and as far south as the City of Mexico.”[1] But at his death he had published no further study of peyote; ethnographers of the period were in general concerned with preserving complete records of older native cultures, and ignored or paid scant attention to the modern cult of peyote. Mooney himself gave little notice to the rite in his monographs on the Cheyenne and the Kiowa,[2] although at the time he was undoubtedly the authority on the subject.

Wissler, for example, barely mentions the peyote cult.[3] Indeed, in its role of modern destroyer or supplanter of older native religions, peyote was even a matter of concern[4] and annoyance to some ethnographers. Lumholtz, with wonted thoroughness, published considerable data on Huichol and Tarahumari peyote in 1898 and later, and Kroeber in 1902 wrote a chapter on Arapaho peyote which has remained a model for later investigators.[5]

It remained for Paul Radin, however, in his studies of Winnebago peyote,[6] to point out to ethnographers an engrossingly interesting, but widely ignored, religious cult which was growing and spreading before their very eyes. Since the appearance of his papers in [9]the years following 1914, the ethnographic literature on peyote has grown considerably, due importantly to the impetus Radin gave such studies. Lowie devoted a chapter partly to peyote in his book Primitive Religion; Rouhier paid some attention to ethnographic questions in his pharmacological monograph on peyote; and Wagner wrote a short comparative paper based largely on the Comanche and Huichol cults. Petrullo’s Diabolic Root was devoted entirely to Delaware peyotism.[7]

No comparative treatment of the peyote cult of the order of Mooney’s on the Ghost Dance, Lowie’s on Plains societies, or Spier’s on the Sun Dance had ever been made when Dr. Maurice Smith of the University of Oklahoma began his studies. The unfortunate death of this investigator, however, prevented the finishing of his work, of which only a short paper[8] has seen publication. But studies of the peyote cult in individual tribes, both published and in manuscript, have multiplied to such an extent since the time of Kroeber’s and Radin’s studies that the time appears ripe to attempt an integrated comparative treatment of the religion.

[1] Mooney, A Kiowa Mescal Rattle, 64-65; Mescal Plant and Ceremony (from which dates the medical and pharmaceutical interest in peyote); statement in Peyote, as Used in Religious Worship, 58.

[2] The Cheyenne, 418; Calendar History, 237-39.

[3] The American Indian, 376.

[4] Skinner, Material Culture, 42-43; Societies of the Iowa, 693-94, 724.

[5] Lumholtz, Tarahumari Dances; Huichol Indians; Explorations en Mexique; Symbolism of the Huichol; Unknown Mexico; Kroeber, The Arapaho, 398-410.

[6] Radin, Sketch of the Peyote Cult; The Winnebago Tribe, 388-426; Crashing Thunder.

[7] Lowie, Primitive Religion, 200-204; Rouhier, Monographie du Peyotl; Wagner, Entwicklung und Verbreitung; Petrullo, The Diabolic Root.

[8] Smith, Mrs. Maurice G., A Negro Peyote Cult.

[10]

Numerous errors involved in the study of peyote, many of them still widely current, make it advisable to identify our subject-matter clearly at the very outset of our study. The plant peyote was first described by Sahagún in 1560 as a narcotic cactus used ritually by the Chichimeca, the root peiotl.[1] Jacinto de la Serna[2] in 1626 mentioned peyote, which he distinguished from other intoxicants. The first properly botanical description was made in 1638 by Hernandez,[3] the naturalist of Philip II of Spain, under the rubric De Peyotl Zacatensi, seu radice molli et lanuginosa. Ortega,[4] again, in 1754, mentioned peyote as used in a Cora dance.

Since 1845 peyote has had numerous modern botanical classifications, being listed variously as Echinocactus williamsii Lem., Anhalonium williamsii Lem., Mammillaria williamsii Coulter, Echinocactus lewinii Hennings, Mammillaria lewinii Karsten, Lophophora lewinii Thompson, etc. The commonest designation in the older ethnological literature is Anhalonium lewinii or A. williamsii. For a considerable period it was thought that these last were two species—a point argued both on botanical and ethnographic grounds—but the present classification of peyote is as a single species, the unique member of its genus, Lophophora williamsii.[5]

[11]

The peyote plant is a curious and unique little cactus. It has no spines whatsoever, and ranges from the carrot-like to the turnip-like in shape and size, without, however, any branches or leaves. The rounded top surface, which alone appears above the soil (and which, cut off and dried, becomes the peyote “button”), is divided radially by straight, or slightly spiral, or sinuous furrows that in some specimens become so complex as to lose the appearance of ribs altogether. These ribs bear little tufts or pencils of matted grayish-white hair, not unlike artists’ fine camel’s-hair brushes. It is from these that the cactus takes both its modern botanical designation, Lophophora (“I bear crests”) and its Aztec name peyotl (from the resemblance to cocoon-silk). In the center of the top there is a little spot of closely matted fuzz, from which the ribs derive and grow; the flower, borne on a stalk, grows from here too, the pinkish-whitish blossom growing into a rapidly maturing club-shaped pinkish-reddish fruit.[6]

Several matters regarding the botany of peyote should be discussed, for their having given rise to legends about the plant. After discussing the nefarious uses to which the Chichimeca put peyote, Hernandez writes that

on this account the root scarcely issues forth, but conceals itself in the ground, as if it did not wish to harm those who discover and eat it.[7]

Dr. Parsons[8] recounts a Taos origin legend in which peyote acts even more spectacularly. A warrior on the war-path heard a singing, and when he approached,

the plant would go open and shut like this [the narrator moves his finger-tips close together and then opens them].... Then the plant told the Indian to come inside. But the opening was so small. Then it got bigger; it got to be a big hole in the ground, a square hole. The Indian went down the hole. There was a big hollow place down there in the ground, round like a kiva.

And the story continues, telling of how the Indian learned the peyote rite from the man in the kiva. On scrutiny this appears to be the Kiowa origin legend for peyote, modified by the addition of familiar Pueblo folk-tale motifs. The Kiowa themselves say,

you must look closely at peyote, because it is like a mole when it comes on top of the ground—if you don’t look closely it is gone again.

[12]

These curious legends, however, are not without some histological[9] and ecological reality. In this semi-desert region the subterranean funnel-formed tap-root of the plant is covered with woody scales which form a rigid shell. Rouhier writes:[10]

All this chlorophyll-region [the portion above the ground] is tumid, plump and fleshy, firm and elastic to the touch, when, after the season of heavy rains, the plant is replete and vigorous. During the hot season it droops and shrivels, becomes soft, and has a dull rumpled look. It retracts then into the rigid cylinder formed by the desiccated corky desquammated part of the stem; the plant literally gives the impression of pulling its head into its neck. (M. Diguet has told us that the plant, at this time, buries itself in the soil, as though drawn, by a powerful force of traction of its adventive radicles, at the base of the funnel which its tap-root has bored.)

Another matter of ethnobotanical interest concerns the supposed existence of two varieties of peyote.[11] In discussing Peyotl Zacatensis Hernandez[12] writes that “they say they are male and female.” The Huichol likewise distinguish two kinds of Peyote, one, the more active and bitter in taste and presenting smaller and more numerous mammillations on the surface, called Tzinouritehua-hicouri, “Peyotl of the Gods,” the other, whose physiological effect is less pronounced, called Rhaïtoumuanitarihua-hicouri, “Peyotl of the Goddesses.” In the opinion of Rouhier,[13] “The Peyotl of the Goddesses ... is the young form of Echinocactus williamsii [= Lophophora williamsii], and the Peyotl of the Gods is its adult form.”

Nor is this the end of the matter. It is well known that sex is attributed to plants in the Plains, but there is also a well-defined pattern regarding the sex[14] specifically of peyote [13]throughout Mexico and the Plains. The Huichol have a tutelary goddess for peyote called Hatzimouika; the peyote deity of the Tarahumari, on the other hand, is male, and great reverence is paid by them to the hikuli walúla sälíami, or “hikuli great authority,” literally, who is surrounded by smaller plants, his “servants,” and who, not satisfied with mere sheep and goats, demands the sacrifice of oxen.

Being persons, peyote plants naturally talk and sing on occasion. Lumholtz[15] writes of the Tarahumari belief that

in the fields in which it grows, it sings beautifully, that the Tarahumare may find it. It says, “I want to go to your country, that you may sing your songs to me.” ... It also sings in the bag while it is being carried home. One man, who wanted to use his bag as a pillow, could not sleep, he said, because the plants made so much noise.

Bennett and Zingg[16] mention the Tarahumari belief that the singing one hears as the bakánawa moves about in the night near the sleeper may be made clearer by chewing a bit of the plant. Indeed, Mooney[17] says the Tarahumari find the peyote by hearing its song, Híkurówa, which it sings day and night. Peyote speaks to the Tarahumari shaman during the night of dancing and curing, and encourages him with words and by singing to him. The fetish-plant in the ceremony proper is placed on the altar under a half-gourd resonator; the rasping of the shaman, thus amplified, is very pleasing to peyote, who manifests his strength by the amount of noise produced with his aid.

In the Plains, however, when pleased with the singing, the peyote goddess actually joins in with it.[18] The Kiowa call her sęⁱmąyi, literally, “Peyote Woman.” Mooney describes a Kiowa peyote rattle on which she is represented, and at her feet the Morning Star, which heralds her approach. A Taos origin legend for peyote tells of a warrior abandoned [14]by his companions, who heard a singing and rattling near where he lay, and finally discovered it coming from the blossom in the center of the top of the plant.

The Shawnee[19] say that if you listen carefully you can “catch songs” from Peyote Woman. The Kickapoo likewise have the concept of the peyote “goddess” who sometimes sings in meetings when pleased; one informant further said that “the spirit of a woman who had been faithful to peyote sings after she has passed away. Sometimes we put pieces of food near the fire for spirits of a dead man or woman or child. Sometimes you hear a man’s voice too.” The Lipan say they hear “Changing Woman’s” voice in peyote meetings. The Wichita believe it is kicu·ídie, “the woman who stays in the water,” and her little son, wi·ḱιdiwιdá, “the boy who rolls along the banks of the water,” who are mentioned in prayer, and who give power in meetings. The “peyote-woman” belief is attenuated elsewhere in the Plains.[20]

Native terms for peyote differ somewhat in denotation and connotation. For clarity sake we shall list only those terms referring specifically to Lophophora williamsii. Native classifications of cacti, as well as extensions of the term “peyotl,” will be discussed in an appendix, as involving special problems.

The Huichol of Jalisco call peyote hícuri, hicori, xicori or hicouri (in the notation of speakers of different European languages); sometimes they refer to it metaphorically as foutouri, “flower.” The Cora of the Tepic mountains term peyote huatari, houtari or watara; the Tepehuane of Durango, kamaba. The Tarahumari of Chihuahua call it hikuli or hikori, sometimes adding, according to Lumholtz, the epithet wanamé (or houanamé), “superior,” to designate the peyote par excellence; the same meaning appears to be indicated in the reduplication híkurí-íkuríwa.[21]

The Opata[22] call it pejori, the Otomi beyo. The Pima of the Gila River region use the name peyori. The Comecrudo or Carrizo of Tamaulipas call peyote kóp, and Gatschet recorded the term kúampamát for “bailar el peyote” (“many are dancing [the peyote dance]”). The Lipan name is xʷucdjiyahi, “pricker one eats.” The Tonkawa of southern [15]Texas call peyote nonč-gáⁱɛn; the Taos name is walena, the generic term for “medicine.” Mescalero Apache call it ho or hos; the Wichita nesac’. The Comanche wokwi or wokowi is said by Mooney to be the generic name for cacti.[23] The Arapaho call peyote hahaayāⁿx. Most of the Oklahoma tribes have their own version of the term peyotl, such as the Kickapoo pi·yot, or, like them, they may use some older native term for “medicine” such as natáⁱnoni. John Wilson (Caddo-Delaware), curiously, called peyote “sugar” or “bee-sugar”; and some Anadarko Delaware call peyote-eating “ear-eating.”

Whites have used numerous confusing and erroneous non-botanical terms for Lophophora williamsii. Of these usages the commonest, “mescal,” “mescal beans” or “mescal buttons” are the most confusing. Mescal (from the Nahuatl mexcalli, “metl [maguey] liquor”) in northern Mexico, properly refers to the Agave americana or Agave spp. baked in earth ovens and widely eaten in the Southwest, and from which the Mescalero Apache take their name. By extension the term is applied to the intoxicant distilled from the native beer, pulque, also made from Agave spp. A more precise designation of this native brandy (as opposed to the native beer) is tesvino and its variants, from the Nahuatl tehuinti or teyuinti, “intoxicating.”[24]

“Mescal bean” as used to designate Lophophora williamsii is quite indefensible, being wrong on two counts: the “mescal” bean proper is Sophora secundiflora (= Broussonetia secundiflora) or, incorrectly, Erythrina flabelliformis. The former is a red bean which was used in a pre-peyote narcotic cult of the southern Plains, to be discussed later. The adjectival use of “mescal” in the designations “mescal beans” or “mescal buttons” no doubt comes from the known intoxicating properties of the distilled liquor mescal, as extended in meaning to other unfamiliar new intoxicants, Sophora secundiflora (bean), and Lophophora williamsii (cactus); the term “dry whisky” bears this out. Lumholtz,[25] indeed, wrote that the Texas Rangers, during the Civil War, when taken prisoner and deprived of all other stimulating drinks, soaked peyote (which they called “white mule”) in water and became intoxicated on the liquid. Further confusion of peyote with mescal has arisen from the north Mexican habit of mixing the two in a drink. Dealers call peyote the “turnip [16]cactus” or “dumpling cactus” from its shape, to which also refers the local Mexican term biznagas, “carrot.” A local name in Starr County, Texas, where the plant grows abundantly, is challote, but the usual dealers’ name is “peyote buttons,” from their flat shape when dried.

A precise understanding of the meaning of this term is essential, for it gives a linguistic clue of primary importance in botanical identification. Molina[26] in 1571 recorded the Nahuatl term peyutl, whose elastic and imprecise sense designates something white, shining, silky or woolly, and which applies to the moth-cocoon, a spider-web, a fine tissue, or, indeed, from its appearance (familiar enough to the Aztecs) even to the pericardium or covering of the heart. Rémi Siméon, in his Nahuatl dictionary of 1885, lists “Peyotl or Peyutl—A plant whose root served to make a drink that took the place of wine (Sahagún); silkworm cocoon; pericardium, envelope of the heart.”[27]

This etymology, the oldest as well as the most authoritative, is accepted by Rouhier.[28] The present writer, having been informed of its linguistic impeccability, further finds it explanatory of otherwise curious extensions of the term “peyotl” in Hernandez,[29] as well as later Mexican usages. Various plants in Mexico besides Lophophora williamsii, some of them not even belonging to the Cactus Family, have been called “peyote.” In each case, however, there has been some part of the plant to which the meanings of flocculence or cocoon-like woolly pubescence descriptively can legitimately apply. An appendix is devoted to the clearing up of this terminological confusion.

[17]

We have now touched upon the etymological connotation of “peyotl,” and its extended denotation in Mexican usage. But one further matter remains to be pointed out, viz., incorrect identification and misusages involving peyote. Safford[30] in 1915 adequately indicated the identity of the modern peyote of the Plains with the peiotl of Sahagún and other earlier Spanish writers. Not content, however, with proving this somewhat obvious point, he went beyond and even contrary to his evidence and attempted to prove the identity of peyote with a further narcotic mentioned in Spanish sources, a yellow thin-stemmed mushroom, called teo-nanacatl by the Aztec. This confusing and wholly erroneous identification is discussed at length in an appendix, inasmuch as it has unfortunately won wide acceptance.

A more widespread error is the application of the terms “mescal,” “mescal bean” or “mescal button” to the cactus Lophophora williamsii or peyote. These misusages are common in the literature on peyote, and arise from confusion with a pre-peyote narcotic of the southern Plains and Texas, the red bean of Sophora secundiflora, a true member of the Bean Family. The word “mescal” as applied either to the cactus or the bean is erroneous and misleading, and should properly be applied only to the “Indian cabbage” (Agave spp.) of the Southwest, or the brandy distilled from Agave-beer or pulque.[31] The true “mescal bean” is discussed elsewhere.

The present section of our study proposes to deal with the physiology of peyote intoxication only insofar as it may be supposed to have influenced the form of native culture-patterns and rites surrounding its use. The efficacy of native doctoring with peyote, however, must be decided on the basis of properly controlled medical experiments, of a sort discussed in Appendix 6, and is not at issue here.

So far as the brute effect of the drugs is concerned, the first stage is one of physical and mental exhilaration. To this physiological fact no doubt is due the Mexican use of peyote in foot-races, in war and for allaying hunger and thirst when on fasting pilgrimages for the plant. Expression of this exhilaration by dancing is common in Mexico, and is found likewise among the Tonkawa, the Lipan and sporadically in the Plains.[32]

[18]

Gross attitudinal behavior may be exhibited in extreme cases. Lumholtz[33] says of the Huichol that

in a few cases a man may consume so much that he is attacked with a fit of madness, rushing backward and forward, trying to kill people, and tearing his clothes to pieces. People then seize upon him, and tie him hand and foot, leaving him thus until he regains his senses. Such occasions are thought to be due to infringements of the law of abstinence imposed upon them before and during the feast.

This semi-psychotic state is no doubt as much conditioned culturally as the Malay “running amok”; in Mexico early Spanish writers repeatedly describe native visions as sometimes horribly frightening as well as sometimes laughable. Indeed, in Mexico, among the Mescalero, and the early Plains users, aggressions welling up under peyote intoxication commonly took the form of witchcraft fear and counter-witchcraft. Typically in the Plains, however, the attitude repeatedly emphasized is that of intertribal brotherhood and an individual feeling of friendliness and well-being. Nevertheless some fifty native visions collected indicate great variability in the psychic state. A Taos instance records euphoria to the point of laughter,[34] but Crashing Thunder (Winnebago)[35] experienced a state of deep depression and intense fear:

The next morning [he writes] I tried to sleep. I suffered a great deal. I lay down in a very comfortable position. After a while a fear arose in me. I could not remain in that place, so I went out into the prairie, but here again I was seized with this fear. Finally I returned to a lodge near the one in which the peyote meeting was being held, and there I lay down alone. I feared that I might do something foolish to myself if I remained there alone, and I hoped that someone would come and talk to me. Then someone did come and talk to me, but I did not feel any better. I went inside the lodge where the meeting was taking place. “I am going inside,” I told him. I went in and sat down. It was very hot and I felt as though I was going to die. I was very thirsty, but I feared to ask for water. I thought that I was surely going to die. I began to totter over. I died and my body was moved by another life. I began to move about and make signs. It was not myself doing it and I could not see it. At last it stood up. The eagle feathers and the gourds, these it said, were holy. They also had a large book there. What was contained in the book my body saw. It was the Bible.... Not I, but my body standing there, had done the talking [this schizoid quality of consciousness in peyote intoxication has been frequently noted by white observers]. After a while I returned to my normal condition. Some of the people present had been frightened thinking I had gone crazy. Others, on the other hand, liked it. It was discussed a great deal; they called it the “shaking state.”

The vision experiences of John Wilson (Caddo-Delaware) and Enoch Hoag (Caddo) are typical results of physiologically-induced hallucinations in individuals whose culture-background highly values vision-experiences.[36] The Enoch Hoag “moon” had its origin [19]apparently in a (tetanic?) trance, wherein he saw himself as dead, with many people around him weeping and his arms composed on his chest as with a corpse. His companions tried to give him water with a spoon, but his jaws were stiff—a common symptom of strychnine poisoning.[37]

The stimulating effect of peyote may partly account for the holding of meetings at night, for there is no desire or ability to sleep for ten or twelve hours after eating peyote; however, all-night meetings for various purposes are not unknown in the Plains, and the older culture pattern merely exploits the physiological fact as a limiting condition probably. Some observers report that, although there is heightened reflex-activity (including those of the skin), peyote induces a partial skin anaesthesis. A Zacatecas ceremony reported by Arlegui,[38] on the occasion of the birth of the first male child, appears to utilize this virtue of the plant:

The relatives gather and invite other Indians to a horrible ceremony of which the father is the object. They give him to drink a brew concocted of a root called peyot and which not only has the property of intoxicating him who drinks it, but also renders him insensible and drugs the flesh and paralyzes the whole body. This drink is administered to the patient after twenty-four hours of fasting. Then he is seated on a staghorn in a place specially chosen for this. The Indians come with sharpened bones and teeth of different animals. Then with different ridiculous ceremonies, they approach the unfortunate victim one by one; each one makes a wound on him, without pity, making a great deal of blood flow out; and as those present are numerous, the wounds are many and the unfortunate person is so maltreated that, from head to foot, he offers a lamentable spectacle.... According to how the miserable victim has borne this, they augur the valor which the son of a father who has suffered so much will possess.

The stages of peyote intoxication have been noted by natives. Writing of the Kiowa and Comanche, Mooney[39] maintained that “in the peyote ceremonies, the songs of those [20]present are more vigorous after midnight,” and informants frequently indicate their awareness of this.[40] Kroeber says of this period late in the intoxication that[41]

the physiological discomforts have usually worn off, and the pleasurable effects are now at their height. It appears that new songs, inspired perhaps by the visions of the night, are often composed during this day.

Many well known songs composed by such leaders as Quanah Parker (Comanche), Enoch Hoag (Caddo) and John Wilson (Caddo-Delaware, called Nĭshkûntŭ or “Moonhead”) are said to have arisen from the auditory hallucinations of peyote intoxication. The popular song “Heyowiniho” came to John Wilson in a synaesthetic auditory hallucination in which he heard the sound of the sun’s rising. Crashing Thunder[42] said of the beating of a drum that “the sound almost raised me in the air so pleasurably loud did it sound to me.” Other kinaesthetic derangements have been reported in visions.

The dilation of the pupils of the eyes possibly explains the Huichol[43] belief that the squirrel- and skunk-fetishes of their ceremony can see better than ordinary people, guiding and guarding the hikuli-seekers on their way. Visual phenomena, indeed, are perhaps the most conspicuous effects of peyote eating. The colors red and yellow, usually with reference to birds and feathers, are common in both Mexican and Plains peyote symbolism.[44] The widespread Plains belief that peyote makes one see better may derive from pupil-dilation; white observers have reported acuter vision in peyote intoxication from this cause. Indians frequently manifest a marked “photophobia” even in the mild morning sunlight after meetings, and many younger men affect colored glasses at this time.

The peyote alkaloids cause increased salivation, and there is a constant noise in meetings of spitting as the users eat peyote; in some meetings attended individual tin-can spittoons were provided. The increased flow of saliva probably accounts for the thirst-allaying effect of the plant encountered in the origin legends and elsewhere, but this and the diuretic[45] action of the drugs cause thirst to reappear more strongly later. A regular feature, [21]therefore, of the typical Plains ritual is the bringing in of water at midnight and in the morning, which is passed around clockwise.[46] The widespread taboo on the use of salt in connection with peyote may have some reference to this action of the plant.[47] On the other hand, the use of sweet[48] foods is a necessary part of the ritual; these are stereotyped both in the Plains and Mexico to include parched corn in sugar-water, sweet fruit, and sweetened meat either dried and powdered or cut into chunks, and candy is a regular feature in some meetings. Sugar may in effect relieve the stage of depression in peyote intoxication somewhat.[49]

The classification of plants into male and female on the basis of their physiological action has, as we have seen, a botanical basis. We are convinced on the other hand, however, that peyote has no effect whatsoever in the curbing of an appetite for liquor. Both native and white apologists[50] for peyote advance this argument in extenuation and defence. Natives are perfectly sincere in their belief that the antagonism of peyote and alcohol is physiological (even in the face of conspicuous contrary evidence),[51] and Plains Indians are annoyed and hurt at the widespread association of drinking and peyote-eating through the confusion of the term “mescal.” Yet the stubborn ethnographic fact remains that in Mexico peyote is commonly drunk with tesvino or mescal.

Various other physiological effects noted by whites find native parallels. Many of the visions recorded for natives deal with synaesthesias of sight and hearing and smell, and [22]there occur cases of taste- and smell-hallucinations as well as the more common auditory and visual ones. Kinaesthetic derangements are also not unknown.[52]

One final question is less of physiological than psychological and ethnographic import. Along with teo-nanacatl, marihuana (Cannabis spp.) and the Peyotl Xochimilcensis (Cacalia cordifolia), peyote has been said to have an aphrodisiac action. This association suggests that a matter of Spanish-White or Mexican-Indian ethnography is involved.[53] But love-magic was not unknown either in Mexico or the Plains, and it is conceivable that this new medicine (particularly since it was used for “witching”) because of its other spectacular effects, might have been valued for this purpose also.

We have now discussed the bearing of physiological reactions on the peyote ritual and other native behavior: the exhilarating first effect of the drug (in the allaying of hunger and thirst on the march, to give courage in war, and strength in dancing and racing) and the second stage of depression and visions (“running amok,” witchcraft-suspicion, psychic fear-states, euphoria and feeling of brotherhood, partial anaesthesia, the “suffering to learn something” characteristic of the Plains vision quest, synaesthesias, auditory hallucinations, and “catching songs,” visual hallucinations, and “learning” of painting- and bead-designs, symbolical birds and feathers, etc.).

We found, too, behavior definitely related to the pupil-dilating power of peyote as well as its sialogogue and diuretic action; the injunction against salt and the use of sweet foods, however, may involve culture-historical matters. We have been skeptical of the alleged anti-alcoholic virtue of peyote, and have likewise doubted that physiologically peyote is either aphrodisiac or anaphrodisiac, despite heated claims on both sides. The efficacy of native doctoring with peyote is a special problem treated elsewhere along with the therapeutic and psychiatric experiments of Whites.

The following ethnographic part of our study deals first with the non-ritual uses of peyote, arising from its special properties, and secondly with the ritualization of its use.

[1] “They [the Chichimeca] have a considerable knowledge of plants and roots, their qualities and their virtues. They were the first to discover and use the root called peiotl, which enters among their comestibles in the place of wine” (Sahagún, Histoire générale, 10:661-62). Again, “There is another herb, like tunas of the earth [tunas is the Spanish name for the fruit of the prickly pear, Opuntia opuntia]; it is called peiotl; it is white; it is produced in the north country; those who eat or drink it see visions either frightful or laughable; this intoxication lasts two or three days and then ceases” (Sahagún, Historia general, 3:241; in Safford, An Aztec Narcotic, 294-95).

Translations from the Spanish have been made with the aid of Mr. H. W. Tessen of the Yale Graduate School.

[2] “Teo-nanacatl [has] ... the same properties as ololiuhqui or peyote, since when eaten or drunk, they intoxicate those who partake of them, depriving them of their senses, and making them believe a thousand absurdities” (Manual de Ministros; in Safford, An Aztec Narcotic, 309-10).

[3] “Peyote of Zacatecas, or soft and lanuginous root. The root is of nearly medium size, sending forth no branches nor leaves above ground, but with a certain wooliness adhering to it, on which account it could not be aptly figured by me” (De Historia Plantarum, 3:70; in Safford, An Aztec Narcotic, 295. See also Rouhier, Monographie du Peyotl, 43-44).

[4] “Nearby [the leader] was placed a tray filled with peyote, which is a diabolical root [raiz diabolica] that is ground up and drunk by them so that they may not become weakened by the exhausting efforts of so long a function” (Ortega, Historia del Nayarit; in Safford, An Aztec Narcotic, 295).

[5] Those interested in the taxonomic problem should consult the numerous botanical references in the bibliography. Britton and Rose, in their four volume work on the Cactaceae classify peyote as Lophophora williamsii, which will be followed in the present study.

[6] The most succinct and complete description of the plant is found in Britton and Rose, The Cactaceae, 83-84.

Peyote’s range is comprehended within an irregularly-shaped lozenge from Deming, New Mexico, to Corpus Christi, Texas, to Puebla, Sombrerete, Zacatecas, and back to Deming. That is, the valley of the Rio Grande (north), Tamaulipecan Mountains (east), the watershed of the affluents of the right bank of the Rio Grande de Santiago and Rio de Mezquital (south), and the foothills of the Sierra Madre, the Sierra de Durango and the Sierra del Nayarit (west). It prefers the calcareous and argillaceous soils of the Cretaceous formation in the north of this region.

[7] In Safford, Aztec Narcotic, 295; see also Narcotic Plants, 401.

[8] Parsons, Taos Pueblo, 63.

[9] The best histological account is in Rouhier, Monographie, 34-42; the work of Dr. Helia Bravo, Nota acerca de la Histología, is more recent. Richard Schultes at Harvard has also pursued histological studies. It is noteworthy that the Indians ordinarily take only the upper portion of the plant, which contains a larger proportion of the alkaloids according to Rouhier.

[10] Rouhier, op. cit., 25. I am persuaded that many such insights would be afforded us in ethnography if we had a less cavalier attitude toward native science and history: for after all even our own science grows from criticism of traditional notions.

[11] From the middle of the last century there has raged an acrimonious debate as to whether there are two varieties of peyote corresponding to Anhalonium williamsii and A. lewinii. The former, it was contended, had seven or eight straight ribs and lacked most of the alkaloids of the latter, which had more numerous (twelve or more) sinuous ribs. This long, somewhat nationalistic debate may be regarded as ended since Rouhier (Monographie, 67) in 1926 figured a bicephalous plant on the same root, one head being a true williamsii, the other a perfect lewinii. It is apparent that the lewinii “variety” is merely an older plant, which often takes the williamsii aspect in its younger stages of growth; the more numerous alkaloids of the former more mature plant is likewise purely a growth-phenomenon, as are the rib-configurations and mammillations, though environmental and seasonal conditions may be involved as well.

[12] Hernandez, De Historia Plantarum, 204, “Se dice que hay macho y hembra.” Inaccurately translated by Safford, Aztec Narcotic, 295, and Rouhier, Monographie, 43. The simplest and most obvious translation is the most satisfactory. According to the Lipan (Opler, Use of Peyote, 279) male peyotes bloom red, female peyotes white.

[13] Diguet, Le Peyote, 25; Rouhier, Monographie, 133.

[14] Handbook of the American Indians. 1:604b. Spier informs me this is also Navaho and perhaps Pueblo as well. As indicated elsewhere, peyote, teo-nanacatl and associated plants have repeatedly been thought to be aphrodisiacs. The supposed sex of the plants may have some reference to this belief; cf. the Huichol belief that “Maize is a little girl whom one sometimes can hear weeping in the fields; she is afraid of the wild beasts, the coyote and others that eat corn” (Lumholtz, Unknown Mexico, 2:279). Different colors of corn belong to different deities also; it is interesting to note that the Huichol attribute different colors symbolically to peyote which have no effective reality (Rouhier, op. cit., 133). In 1935, in a non-peyote context, Apekaum told me that cotton plants in a field we were passing were male and female; some trees were male, too, and others female, he thought. No botanical realities were involved in any of these cases. The Jivaro also attribute sex to plants (Karsten, Civilization, 301, 304-06, 314-15, 323) as do the Aymará and others.

[15] Lumholtz, Unknown Mexico, 1:362.

[16] Bennett and Zingg, The Tarahumara, 295.

[17] Mooney, Tarumari-Guayachic; Lumholtz, Unknown Mexico, 1:365; Bennett and Zingg, The Tarahumara, 293.

[18] This auditory hallucination of hearing voices in peyote intoxication is most striking. Several explanations may be offered: the cultural (the belief is common in Mexico and the Plains that peyote talks and sings), the physiological (white observers, many in obvious ignorance of the ethnographic facts, have reported aural hallucinations), or the physical (the peculiarly resonant vibrations of the water-drum echoing from the taut, cone-shaped canvas of the tipi). A physiological constant for Indians and whites (culturally modified) seems indicated. See Mooney, A Kiowa Mescal Rattle, 65; Parsons, Taos Pueblo, 63.

[19] Statements without references are understood to be made from my own field work.

[20] The Cora peyote goddess appears to be “Mother Hūrimoa” (Preuss, Die Nayarit-Expedition, 103). Tarahumari dancers sometimes imitate hikuli’s talk with a sound which reminded Lumholtz of the crow of a cock (Tarahumari Dances, 455). The Lipan information is from Opler (The Use of Peyote).

[21] Diguet, Le peyote et son usage, 21, 25; Rouhier, Monographie, 4; Safford, An Aztec Narcotic, 297; Lumholtz, Unknown Mexico, 1:357, 2: passim; Preuss, Die Nayarit-Expedition, 103; Bennett and Zingg, Tarahumara, 135; Mooney, Tarumari-Guayachic.

[22] Rudo Ensayo (1760) in Mooney, Tarumari-Guayachic. A note by F. W. H[odge] indicates a purely medicinal use of peyote for the Opata. Otomi: León, fide Mooney; Mooney doubts this, somewhat unwarrantedly I think. Pima: Alegre, in Mooney, Tarumari-Guayachic. Comecrudo: Handbook of the American Indians, 1:209a; Mooney, Tarumari-Guayachic, whose source is probably Gatschet. Lipan: Opler, The Use of Peyote. Tonkawa: Mooney, op. cit. Taos: Parsons, Taos Pueblo, 114, note 115. Mescalero Apache: Rouhier, Monographie, 4 (Opler records this as xuc); Safford, An Aztec Narcotic, 297; Mooney, op. cit. Comanche: Mooney, Miscellaneous Notes; the present writer recorded wↄ´kweᵖⁱ and pua´kιt (= “medicine”).

[23] Mooney (Peyote Notebook, 21) likewise says the Kiowa term for peyote sęⁱ means “prickly” or “prickly fruit” and is generic for all cacti. But peyote, it will be remembered, is conspicuous for its lack of spines; perhaps this was an older term for the prickly pear, Opuntia opuntia, transferred to the more recently known plant. In any case it occurs nowadays in many compounds: sęⁱmąyi, “peyote woman,” sęⁱpiⁱ, “peyote meeting,” etc., and in the phrase behábe sęⁱᴅɔki, “smoke, peyote power.” (Compare the Comanche hos mäbä´mho’i.) See also Mooney, Calendar History, 239; Rouhier, Monographie, 4; Kroeber, The Arapaho, 399; Speck, Notes on the Life of John Wilson, 552.

[24] See Handbook of the American Indians, 2:845, 846 (the Yuma, Mohave, Ute, Apache, etc., use it). The Mescalero Apache do not derive their name from the use of the peyote, “mescal,” as Mooney stated, being so designated long before they knew or used peyote. In the second etymology see Siméon, Dictionnaire, 436; also Safford, An Aztec Narcotic, 293. See also La Barre, Native American Beers, 225.

[25] Lumholtz, Unknown Mexico, 1:358. For “dry whiskey” see the New Century Dictionary, Supplement: “Mescal Buttons.” For the other names see Rouhier, op. cit., 4; Britton and Rose, The Cactaceae, 3:84 (the spelling pellote of Velasco, from Mooney, is a Castillianization of the Nahuatl); Peyotes, datos para su estudia, 209. The spelling pezote in Alarcón, Tratato de las Supersticiones, 131, is obviously a copyist’s error.

[26] de Molina, Vocabulario, 80, “Peyutl—capullo de feda, o de gufano.” The Spanish o and u constitute a single phoneme in Nahuatl, according to Mr. Benjamin Whorf, so the vowel is purely a matter of recording. On the other hand, Reko’s etymology in Was bedeutet das Wort Teo-Nanacatl? (lent through the courtesy of R. E. Schultes) is inadmissable. He writes: “Pe-yotl, Old-Aztec Pi-yautli, is quite clear in its etymology: Pi is the significative (or affix) for ‘little.’ ... Yau-tli is always something narcotic or strong narcotic-smelling substance. Yau- is the root, -tli the post-positive article (substantive significative).... A pi-yautli (pe-yotl) is therefore the mildly intoxicating poison, in contrast with Hua-yautli (today Guayule, sap of the Gum-tree, which smells very strong) which means extremely intoxicating.” This is an ad hoc forcing of an etymology on a word, according to Whorf: in the first instance “old Aztec” pi-yautli appears to be an assumed rather than a quoted form; but even so, -yautli should not give -yotl or -iotl of Sahagún’s recording, but an unchanged -yautli. If the rules for Nahuatl sound-change are to be observed, peyotl must come from an uncontracted stem of two syllables, plus the absolutive suffix, this stem being pe-yo; -yautli, on the other hand, must come from a contracted stem, originally of two syllables, ya-wi (the -i standing for a variable or unknown vowel), plus the absolutive suffix, having the form -tl when preceded by a vowel, -tli when preceded by a consonant, i.e., a contracted stem. As for the first syllable, pi- and pe- are absolutely distinct phonemically in Aztec. The etymology, therefore, is neither phonetically nor phonemically correct, and assumes random and unexplained sound changes. The writer is grateful to Mr. Whorf for the preceding information. P. Augustin Hunt y Cortes (in Rouhier, 7) derives peyotl from the active verb pepeyoni, pepeyon, “to move, to stir, to set into motion, to excite, to activate.” Other offerings are “child” and a derivation from peyonanic, “stimulate, goad, prick, incite.” These are untenable for the same reasons that Reko’s is.

[27] Siméon, Dictionnaire 412, 436.

[28] Rouhier, Monographie 7.

[29] De Historia Plantarum, 3:70 (Peyotl Xochimilcensi). Peyote, because of its abundance in certain localities, figures frequently in place names.

[30] Safford, An Aztec Narcotic; see also other items by this author in the bibliography.

[31] See the New Century Dictionary, “Pulque,” 4841, a word conjectured to be of Carib (Haiti or Cuba) or Spanish origin. Agave and maguey are the American aloe, sometimes called “century plant” (cf. “maguey,” 3578, “agave,” 108). “Mescal” proper, therefore, = Agave americana = maguey = American aloe = “century plant.”

[32] White Wolf (Comanche) tells of Kuaheta, at the time acting as fireman in Comanche Jack’s meeting, that he once failed to return after having asked to leave the tipi. Commissioned to investigate, White Wolf found him outside “jumping like a deer” from deep peyote intoxication. Hoebel relates a similar experience in a Northern Cheyenne meeting. Tonakat, the well-known Kiowa “witch,” once forced a man to get up and dance in a meeting (Autobiography of a Kiowa Indian, recorded by the writer, 1936). Jonathan Koshiway (Oto) laughingly told me of a meeting in Kansas where the singer’s jaw became locked; the whole meeting was upset while they shook and fanned him with cedar incense until his jaw “came back.” This may have been an effect of the strychnine-like alkaloids in peyote, as in the case of Tom Panther (Shawnee) who became unable to talk or sing once in George Fry’s meeting: “it took me four or five minutes to say the word ‘study’,” he said.

[33] Lumholtz, Huichol Indians, 9.

[34] Parsons, Taos Pueblo, 63.

[35] Radin, Crashing Thunder, 198-99.

[36] Fernberger (Further Observations, 368), citing Petrullo, writes: “The best reporters of this group of Indians [Delaware] insist that visions may occur under peyote intoxication but that it has become socially admirable to suppress these visions and that, after some practice, this may be successfully accomplished.” But after establishing ordinarily friendly relations with informants I found no such reticence about visions; these, indeed, were publicly discussed in the Sunday forenoons after meetings (usually spent lounging under “shades” quietly exchanging peyote experiences). Many, like Spotted Horse (Kiowa), Tom Panther (Shawnee) and Sly Picard (Wichita) distinguished the ordinary effects of peyote from full-blown “visions”; and some corrective modesty is occasionally exhibited for the familiar Plains assertiveness and individualism, for, in fact, through peyote visions individuals push themselves to positions of leadership and influence. Fernberger continues: “The informants also state that they are able to control visions when they occur, that is, to change the vision to that of any particular known object or to hold a vision that occurs in consciousness for a considerable time. Both of these statements are totally at variance with the descriptions of all previous observers of the visual manifestations.” We disagree with this dictum; many informants would paraphrase the statement of Tom Panther (Shawnee) that in peyote intoxication, “I wasn’t boss of myself.” White observers too have remarked on the dualism of consciousness exhibited by Crashing Thunder. One might even go so far as to say that this is a reason natives think of peyote as an external “power” working its influence on them.

[37] Is the peculiar mode of wearing a blanket in meetings due to the necessity of supporting the back in strychnine-opisthotonos (from lophophorine and anhalonine)?

[38] Arlegui, Crónica, 144; Rouhier, Monographie, 331.

[39] Mooney, in Rouhier, op. cit., 344.

[40] “We’re pulling for daylight now—that’s the time those boys sang a little faster” (Voegelin, Shawnee Field Notes). “I wish you could see Quanah’s songs—they just like beautiful race horses—go fast” (Mooney, Peyote Notebook, 12).

[41] Kroeber, The Arapaho, 404-405. Maillefert (La Marihuana, 6) says that marihuana habitués in Mexico have special songs that they sing together; a marked feature of the Mexican use of drugs, of which this may be a case, is the pattern of group-narcosis.

[42] Radin, Crashing Thunder, 178.

[43] Lumholtz, Unknown Mexico, 2:272.

[44] This is obviously heavily culture-conditioned, but Klüver (Mescal, 41) records the predominance of red and green early in peyote intoxication, and yellow and blue in later stages, with possible reference to the Ladd-Franklin phylogenetic theory of color vision.

[45] Maillefert (loc. cit.) says marihuana habitués believe water decreases the effect of the drug, and therefore they do not use it when smoking. Although the peyote leader must otherwise be present all through the meeting (to prevent rival witching among the Apache), a fixed part of the Plains ritual is his exit alone at midnight to whistle at the four points of the compass, an opportunity which is no doubt exploited. Again, spitholes are a part of Tarahumari altars (Lumholtz, Unknown Mexico, 1:365).

[46] The Caddo, however, make a point of not drinking water at night, as though looking upon the meeting as a vision-ordeal; this aberrance is given point by the fact that they do no doctoring in peyote meetings either, and must make four rounds of the drum before quitting, no matter if it takes until noon of the next day.

[47] The Comanche exclude the eating of pork also, but whether this is because pork is commonly a salt meat or because it is oily like the flesh of another tabooed food animal, the bear, I do not know.

[48] Maillefert (op. cit., 6-7) says marihuana smokers believe that sugar augments the effect of the “grifos” (“reefers” in Harlem parlance), so they eat sweets while smoking them. Compare the consuming of honey with teo-nanacatl in Mexico.

[49] The Arapaho (Kroeber, 407) use a more magical means to this end: they tie four bunches of yellow-hammer or other feathers at the northeast, southeast, southwest and northwest poles of the tipi to brush the bodies of worshippers who become tired.

[50] E.g., Skinner, Societies of the Iowa, 694.

[51] For mescal (the agave-drink distilled from pulque) and peyote are mixed and used together in northern Mexico. Yet Mooney often and at length produced this argument with regard to alcohol; Skinner said it destroyed the desire of tobacco as well (see appendix on the Native American Church). But peyote, physiologically and culturally, is only one more means of achieving the culturally valued state of psychic derangement, and such fundamentally deep-rooted patterns as this one is in native America do not change over-night. Even so, is the cure any better than the disease? The writer was a little startled when a Kiowa friend, an ardent peyote user, suggested that we go to a neighboring town one mid-week to drink. When I sought to discover his attitude on this he soon made it clear that it was no matter of moral sentimentality but purely one of physiology: there wasn’t another peyote meeting until Saturday, so what was the harm? One can eat lobsters one day and ice-cream the next, but one ought not eat them the same day. This informant conceived of the antagonism as a fight between liquor- and peyote-power, a matter-of-fact attitude probably not universal, and by no means as cynical as it seems.

[52] Rouhier (Monographie, 320) however suggests that the illusions of phonation (the distance, strangeness and hollowness of the voice) may not be entirely sensory, i.e. auditory, but may also be a matter of voice-production; he cites Ellis, Putt, and Eshner.

[53] Note the ritual necessity that a woman bring the morning water into a meeting formerly restricted to men, and the mythological significance of the “Peyote Woman.” Opler (The Influence of Aboriginal Pattern) says that Mescalero saw women in visions and wanted them, believing that if one began with visions of women they would stay with him. Crashing Thunder (Radin, 177) confessed that at one time he attended meetings chiefly to find “a woman whom I cared to marry permanently. Before long,” he says, “that was the only thing that I would think of when I attended the meetings.” We have on the other hand, however, the healthy skepticism of an Oto who said, “You can see dead people in meetings, but peyote won’t get you a woman you desire though. She makes up her mind.” But may not other explanations than the physiologically-aphrodisiac be involved? Might there not be an association with promiscuity of the ritual mingling of the sexes (for in the older Sun Dance just this was implied when the main lodge-pole was brought in) in a region where sexual segregation ritually was usual? Compare the injunction of one Ghost Dance prophet to the people not to think of women, but to join hands with them on either side and dance the Ghost Dance. Would he have made the explicit statement if it had not been implicitly considered reasonable to expect natural sexual arousement or preoccupation in a rite in which men and women are not separated? Indeed, there is evidence among the Shawnee at least that sexual opportunities afforded through the Ghost Dance were not left unexploited.

[23]

An Oto in all seriousness informed the writer that “peyote doesn’t work outside meetings, because I have tried it”—a belief understandable in a group whose sole acquaintance with the plant is through a recent ritual.[1] Nevertheless, owing to its marked physiological properties peyote is widely used both in Mexico and the Plains non-ritually, a fact which forms an interesting ethnological background to the rite proper.

One of the most important and striking of these uses is in prophecy and divination. We find the Spanish missionaries in Mexico early protesting against this abomination. The confessional of Padre Nicolás de León[2] contains the following questions for the priest to ask the penitent:

Art thou a sooth-sayer? Dost thou foretell events by reading omens, interpreting dreams, or by tracing circles and figures on water? Dost thou garnish with flower garlands the places where idols are kept? Dost thou suck the blood of others? Dost thou wander about at night, calling upon demons to help thee? Hast thou drunk peyotl, or given it to others to drink, in order to discover secrets, or to discover where stolen or lost articles were?

This last was no idle matter, as appears from other evidence; Hernandez[3] says that

[the Peyotl Zacatensis] causes those [Chichimeca] devouring it to be able to foresee and to predict things; such, for instance, as whether on the following day the enemy will make an attack upon them; or whether the weather will continue favorable; or to discern who has stolen from them some utensil or anything else; and other things of like nature which the Chichimeca really believe they have found out.

Padre Arlegui,[4] after mentioning the therapeutic uses to which the Zacatecans put peyote, complains that

this would not be so bad if they did not abuse its virtues, for, in order to have a knowledge of the future and find out how their battles will turn out, they drink it brewed in water, and, as it is very strong, it intoxicates them with a paroxysm of madness, and all the fantastic hallucinations that come over them with this horrible drink they seize upon as omens of the future, imagining that the root has revealed to them their future.

[24]

Prieto[5] says of a Tamaulipecan group that

often in these orgies was wont to impose silence, at the height of their drunkenness, the voice of some ancient, who, assuming a magisterial tone, prognosticated to them future events, usually depicting them as sad and unhappy, and in spite of the lugubriousness of his predictions, he usually ended his harangue by exhorting them to enjoy in the dance the interval between the present and the next unhappiness.

Alarcón[6] adds other functions and relates of other drinks similarly used:[7]

If the consultation is about a lost or stolen article or concerning a woman who has absented herself from her husband, or some similar thing, here enters the gift of false prophecy, and the divining that has been pointed out in the preceding treatises; the divination is made in one of two ways, either by means of a trance or by drinking peyote or ololiuhqui or tobacco to attain this end, or commanding that another drink it, and ordering him to remain under its spell; and in all this goes implicitly hand in hand the pact with the devil who by means of said drinks appears to them and speaks to them, giving them to understand that he who speaks to them is the ololiuhqui or the peyote or whatever beverage that they had drunk for the said end; and the sorry part of it is that many put faith in [the drink] as in the very lying cheats themselves, [indeed] even more than in the evangelical predicators.

As we move farther north in Mexico the use of peyote in prophesying becomes valuable in warning of the approach of the enemy.[8] For the Tarahumari Lumholtz[9] says that the [25]various kinds of hikori were particularly good “to drive off wizards, robbers, and Apaches, and to ward off disease.” Of Anhalonium fissuratum he says “robbers are powerless against it, for Sunami calls soldiers to its aid,” while the variety Rosapara “is particularly effective in frightening off Apaches and robbers.”

In the Comanche version of the usual Plains origin tale of peyote, the leader of a group on the war-path goes up alone to an Apache camp where a peyote ceremony is in progress. Though an enemy, he is invited in, the leader telling him that peyote had predicted his coming in a vision.[10] One Comanche informant said eating peyote enables one to hear an enemy coming, though still far away; peyote likewise predicted the success of one of the last Comanche horse-raids, and aided in its prosecution.

From these uses of peyote in war it is no jump to its fetishistic use as a protector in war[11] and in ordinary witchcraft. Sahagún[12] writes that peyote

[26]

is a common food of the Chichimecas, for it stimulates them and gives them sufficient spirit to fight and have neither fear, thirst, nor hunger, and they say it guards them from all danger.

De la Serna[13] said that ololiuhqui and peyote were carried by persons “forsaken of God” as charms against all injuries, and Arlegui deplored the custom of parents to “hang little bags on their children, and inside of them in place of the four Evangels that they place around the necks of children in Spain, [to] place peyot or some other herb.” Arias described a surreptitious worship of the fetish: the natives hung the herb in the choirs “as a special creation of the malignant spirit which they designate with the name of Naycuric,” and they communicated with the numen by drinking an infusion of peyote instead of wine.[14]

Peyote is also a powerful protection against witchcraft in ritual foot-races. Rivals are liable to throw bones and herbs on the track and cause the Tarahumari runner to be bewitched and lose the race, which is run at night. For this contingency, however, “hikuli and the dried head of an eagle or a crow may be worn under the girdle as a protection.”[15] Peyote is a great protection too when traveling, both in war and on peyote-pilgrimages.[16]

The Comanche commonly wore peyotes in buckskin bags attached to beaded bandoliers, recalling the mescal bean bandolier which the Kiowa and others commonly wore in battle. Indeed, peyote was even a part of the Θawikila and Kispoko war bundles of the Shawnee, long before they knew the generalized peyote ritual—a custom similar to the Iowa use of mescal beans in their war bundles.[17]

[27]

But in Mexico and the Southwest war and witching are closely connected ideologically. As a matter of fact, peyote itself as well as the peyote shaman’s rasp, is employed in Tarahumari witchcraft.[18] Among the Mescalero Apache,[19] however, witching within the tribe by rival peyote shamans was an ever-present anxiety, their feuds being conceived in terms of battles and war, with the “shooting” of arrows and struggles to see who had the more powerful and compelling songs. The Mescalero peyote leader was merely a shaman primus inter pares, whose major function was to prevent witching in meetings. The purpose of the Tonkawa peyote songs, it is said, was to ward off the enemies’ witching. Witching with peyote is less in evidence in the Plains, save among the Kiowa, Comanche, and Cheyenne who early received it, but as late as the time when the Caddo-Delaware messiah John Wilson took peyote and the Ghost Dance to the Quapaw there was witching by “shooting” objects. The Northern Cheyenne feared the “trickiness” of peyote itself; and the Lipan fireman was chosen for his braveness because “he has to go out at night to get wood and it is a frightening job sometimes, especially when one is under the influence of peyote; peyote is sure a joker!”

Besides this fetishistic use in war, peyote was also used somewhat more “technologically” to cure wounds. Alegre writes that the Sonoran

manner of curing the wounds is with peyote, that they call peyori after it has been made into a [28]powder, with which they fill the cut, cleaning it and renewing it three times every two days, or with a species of balm composed of [maguey].

Prieto says that, in Tamaulipecan war, among the provisions carried by the women in the rear were

gourds full of peyote and water ... and in addition to all these provisions they carry some plants, which, chosen and prepared beforehand serve to stop hemorrhages from the wounds, and to aid in their curing.

The Opata used pejori for arrow-wounds, cleaning them out with cotton squills on sticks dipped in the powder; the Lipan put peyote on wounds of all kinds.[20]

The other therapeutic uses of peyote are various. At Taos it was used for snake-bite. The Caxcanes of Teo-caltiche employed peyote for cramps and fainting spells, the Chichimeca for relieving painful joints. The Tarahumari apply peyote externally for bruises, snake-bites and rheumatism. The Huichol use few remedies except hikuli, unlike the Tepecano who use many, but it is good for anything from a minor ache to a major wound. Medicinal uses are also recorded for the Tepecano, Yaqui, Opata, Pima, Papago, Cora and Lipan.[21]

In the Plains a Wichita case of blindness of fifteen years’ standing was cured by the sole application of peyote-infusion.[22] Radin cites a similar Winnebago case. The Kiowa use peyote as a panacea: uses are recorded for tooth-ache, hemorrhages, headache, consumption, fever, breast pains, skin disease, hiccough, rheumatism, childbirth, diabetes, colds and pulmonary diseases in general. Mooney records the further use as a “tonic aperitif.” The Shawnee chew peyote into poultices for sores and snake-bites and eat it for colds, pneumonia, rheumatism, aches and pains.[23]

The remaining non-ritual uses of peyote are quite varied. The Acaxee employed it in some manner in their ball games, probably eating it in small doses, according to Beals. In Tlaxcala peyote was used by “the auxiliary forces of the conquistadores, in order not to feel fatigue on their marches”—a widespread use in Mexico; in the Plains the typical [29]origin legend tells of peyote aiding a seriously wounded warrior or a woman and child left behind by their companions without food or drink. The legend is not unlike the common Plains stories of receiving power from animals in a stress-situation; Old Man Horse (Kiowa) said “peyote is the only plant from which one can get power,” obviously thinking in terms of the old vision quest. Peyote in fact gave power to perform shamanistic tricks in the old days.[24]

The Tarahumari, among other things, left a hikuli plant with the corpse, the motive for which is unstated.[25] A Wichita, captured in war and imprisoned, was aided in escaping unseen from the enemy camp by his fetish-plant; the lobbying power of peyote in influencing Federal bonus legislation has already been mentioned. Indeed, peyote has had a record of unbroken success in preventing Federal anti-peyote legislation.[26]

Despite the unsatisfactory state of the literature, it is clear that the ceremonial use of peyote in Mexico differs widely from that in the Plains. First we shall characterize the Mexican type by summarizing the Huichol and Tarahumari rites, and later adding comparative Mexican data.

[30]

Though the most important of their fiestas, Huichol peyotism is a seasonal matter, the hikuli seldom being eaten outside the ceremonial period in January. In October a preliminary trip lasting fifteen days each way is made to Real Catorce (San Luis Potosí) to obtain the plants. The eight or twelve pilgrims bathe and sleep in the temple with their wives the night before leaving, not washing again until the feast some four months later. After receiving new names for the trip, the next morning they pray around a fire, wearing squirrel tails tied to their hats, and sacrifice five tortillas[27] to the fire. Then, after sprinkling their heads with a deer-tail dipped in water steeped with certain herbs, all weep as each man puts his right hand on his wife’s left shoulder and bids her farewell.[28]

Their route is full of religious associations, since formerly the gods went out to seek peyote and now are met with in the shape of mountains, stones and springs; their dreams en route are also important in deciding religious arrangements for the coming year (who is to sacrifice cattle for rain, who is to be fire-maker, etc.). The pilgrims carry sacred hour-glass shaped gourds and the leader also carries the yákwai, a ball of native-grown tobacco called macuchi, which is solemnly distributed after they pass Puerta de Cerda. In the afternoon they place ceremonial arrows toward the four corners of the world, and sit around a fire until midnight. Tobacco belongs to the personified fire; after much praying the leader touches the tobacco-ball with his plumes and wraps small portions in corn husks[29] “so that they look like diminutive tamales,” and each man puts one in a special tobacco-gourd tied to his quiver. This act symbolizes the birth of tobacco and henceforth they must preserve ritual order on the march, and only cease to be the “prisoner” of Grandfather Fire when the sacred bundles are given back to him, i.e., burned.

On the fourth afternoon the women at home gather to confess their sins to Grandfather Fire; they knot palm-leaves lest they forget the name of even a single lover and the men consequently find no hikuli. After this public confession each woman throws her leaf into the fire and becomes ritually clean. The men make a similar confession “to the five winds” a little beyond Zacatecas and burn their tallies in the fire. The hikuli-seekers are henceforth gods and the leaders fast (save for eating stray plants) until they reach the peyote country.[30]