Title: The gateway to China

pictures of Shanghai

Author: Mary Ninde Gamewell

Release date: January 26, 2026 [eBook #77783]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1916

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/77783

Credits: Alan, deaurider and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

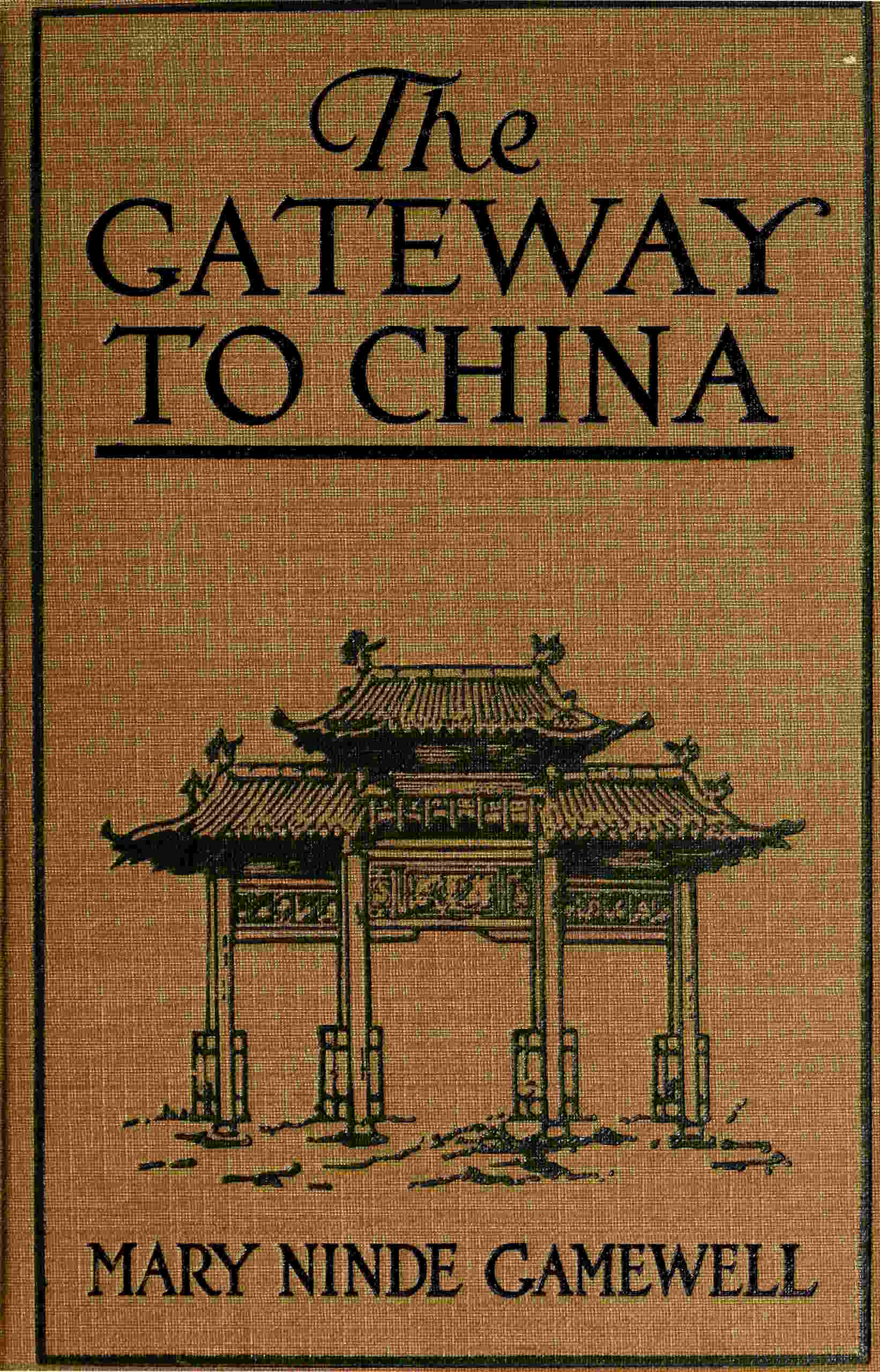

MR. BAO ON LEFT, ONE OF THE THREE FOUNDERS

OF THE COMMERCIAL PRESS, WITH OTHER

MEMBERS OF THE STAFF

(See chapter “A Wizard Publishing House”)

THE

GATEWAY TO CHINA

PICTURES OF SHANGHAI

BY

MARY NINDE GAMEWELL

Author of “We Two Alone in Europe”

ILLUSTRATED

New York Chicago Toronto

Fleming H. Revell Company

London and Edinburgh

Copyright, 1916, by

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

New York: 158 Fifth Avenue

Chicago: 17 N. Wabash Ave.

Toronto: 25 Richmond St., W.

London: 21 Paternoster Square

Edinburgh: 100 Princes Street

[Pg 7] TO MY HUSBAND

PREFACE

SHANGHAI is a little world, where all China in miniature may be studied at close range. Thither drift Chinese from every province in the country, who for the most part in the new environment follow their age-long customs and cherish their inherited traditions. But the city is also remarkable for its rapid and constant changes. A member of a local book-firm declared not long since, “We have never tried to publish a guide to Shanghai because in six months it would be out of date.” To an Occidental the chief fascination of this busy metropolis lies in the curious commingling of things old and new, practices ancient and modern, which meet one at every turn. More strikingly than any other city in the Far East, Shanghai represents the Orient in transition. To catch and portray some of these shifting scenes, the following “Pictures” have been drawn, with the hope that they may stimulate interest in China and awaken a new love and admiration for the Chinese people. It need hardly be explained that no attempt has been made at a complete study of the subjects described. This is particularly true of the last chapter, where several phases of missionary activity have been touched upon by way of illustration, while societies and organizations doing an equally valuable work have not been mentioned. The history of the Christian Literature Society, for example,[Pg 8] reads like a romance and it is a well-established fact that its books had much to do in shaping the radical policy of the late Emperor Kuang Hsü and the liberals of that period, which eventuated in the dawn of progress and a New China. To all friends, Chinese and foreign, whose suggestions and criticisms have helped make possible this little book, warmest thanks are extended.

M. N. G.

Methodist Episcopal Mission,

Shanghai, China.

[Pg 9]

CONTENTS

| I. | Evolution of a City | 13 |

| II. | Civic Features | 20 |

| III. | Street Rambles | 42 |

| IV. | The Lure of the Shops | 57 |

| V. | Housekeeping Problems | 73 |

| VI. | Something About Vehicles | 91 |

| VII. | A Peep into the Schoolroom | 106 |

| VIII. | A Wizard Publishing House | 127 |

| IX. | The Chinese City | 140 |

| X. | Customs Old and New | 155 |

| XI. | A Typical Shanghai Wedding | 172 |

| XII. | Foreign Philanthropies | 185 |

| XIII. | Chinese Successes in Social Service | 199 |

| XIV. | The Romance and Pathos of the Mills |

217 |

| XV. | A Page from the Story of Protestant Missions |

234 |

[Pg 11]

ILLUSTRATIONS

| Mr. Bao on Left, One of the Three Founders of the Commercial Press, with Other Members of the Staff |

Title |

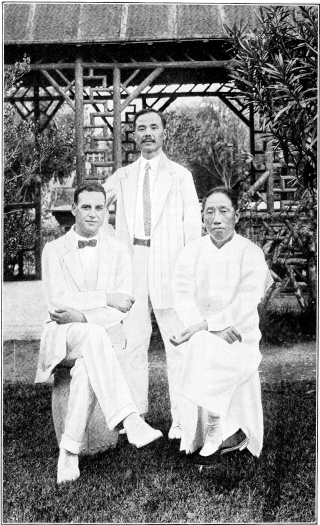

| Chinese Policemen Drawn up for Inspection | 20 |

| Some Shops on Nanking Road | 58 |

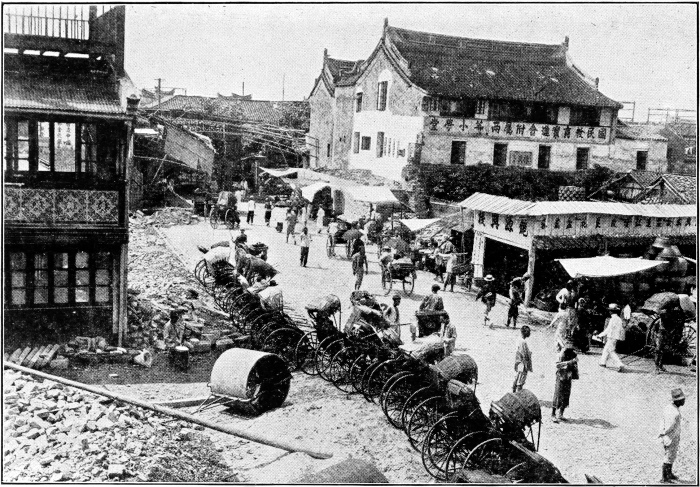

| High, Black Rickshas Outside the Foreign Settlement | 92 |

| Advertising Singer Sewing Machine Products | 106 |

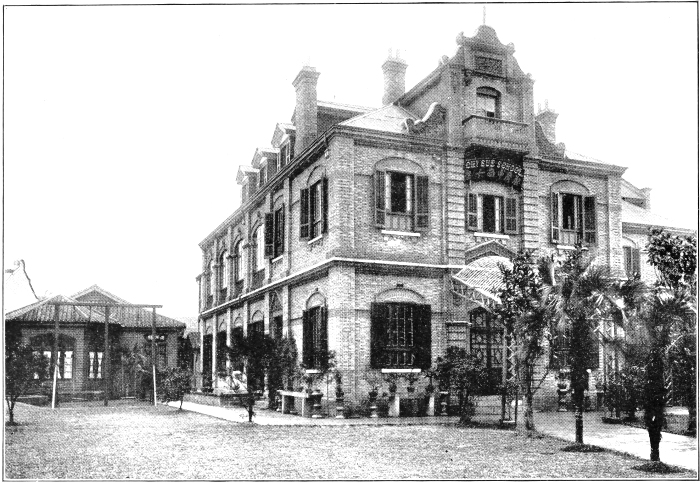

| Miss Zee’s New School Building. Kindergarten in the Rear |

120 |

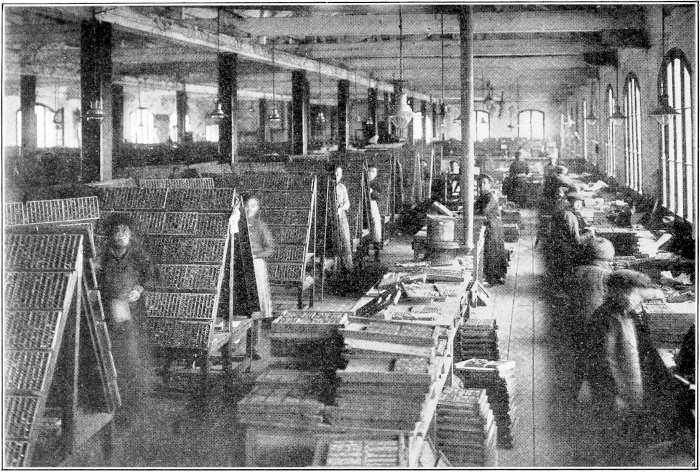

| Chinese Composing Room | 128 |

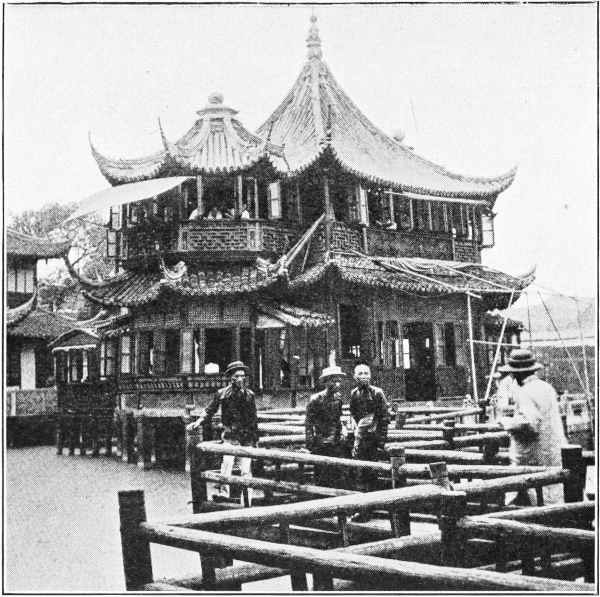

| The Original Willow Pattern Tea House | 140 |

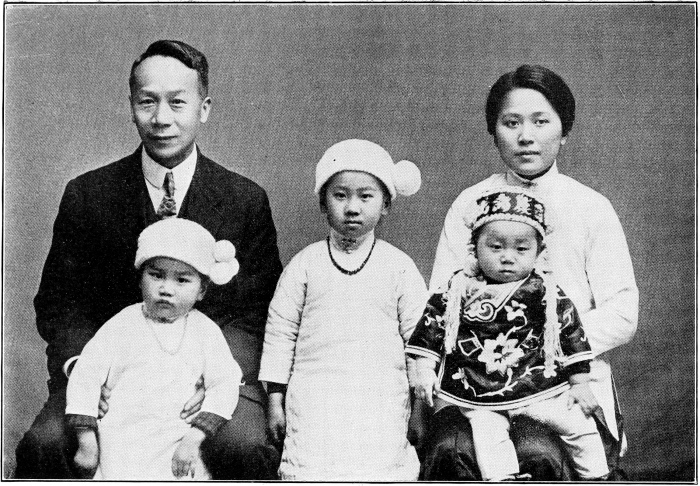

| A Modern Chevalier and His Happy Family | 156 |

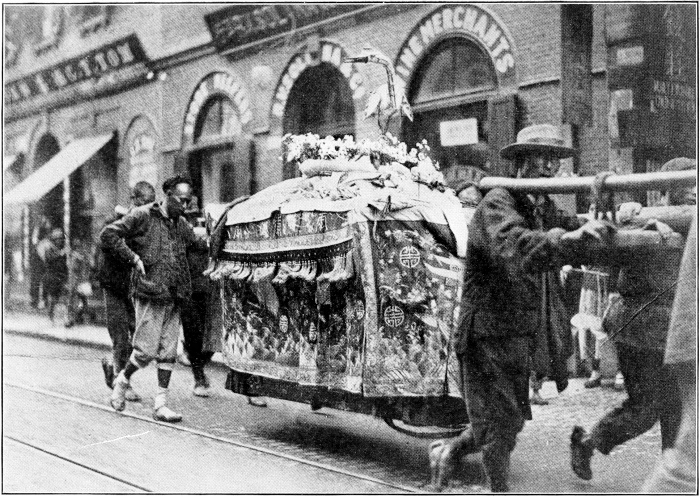

| The Coffin in a Funeral Procession | 160 |

| School Girls in Gymnasium Drill | 168 |

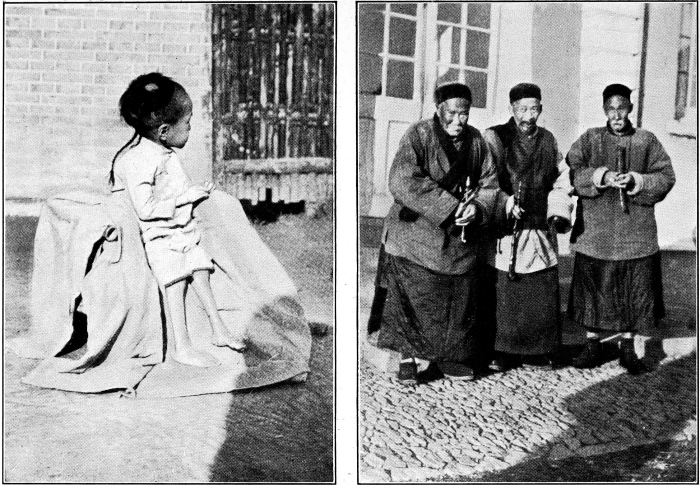

| Rescued Child Just Brought to the Children’s Refuge—Old Men at the Home of the Little Sisters of the Poor |

186 |

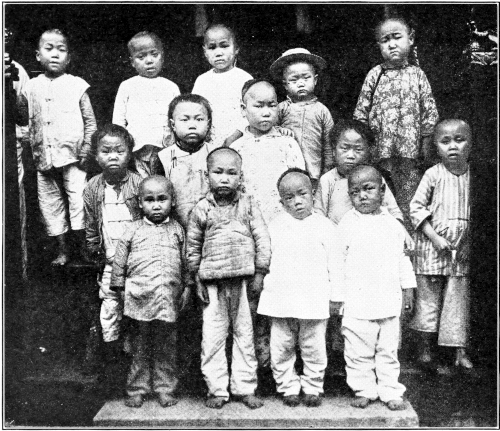

| Rescued Kidnapped Children as They Were Photographed for Advertisement in the Chinese Daily Newspapers |

200 |

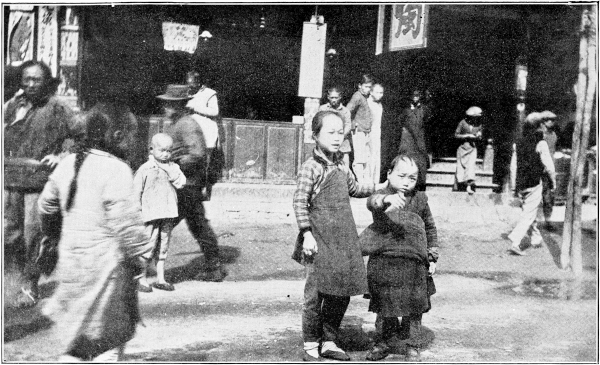

| On the Way to the Mill | 218 |

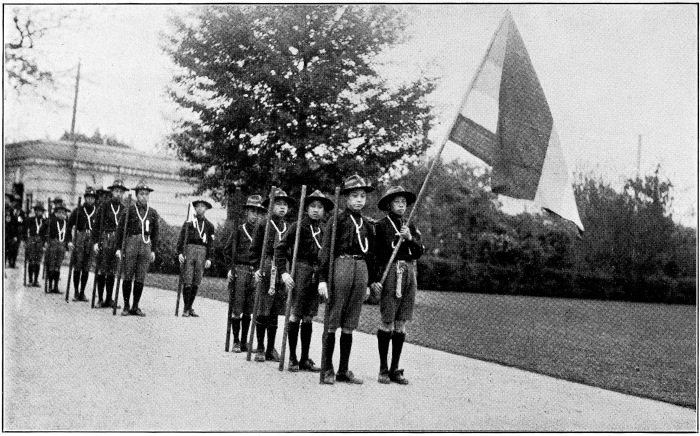

| Chinese Boy Scouts | 234 |

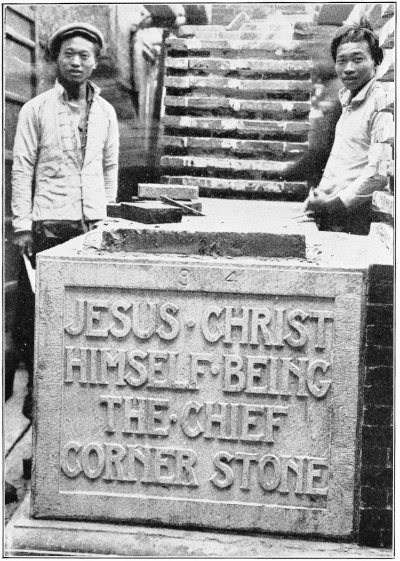

| Corner Stone of Boys’ Building, Y. M. C. A. | 244 |

[Pg 13]

EVOLUTION OF A CITY

FROM time immemorial the Yangtsekiang has deposited at its mouth quantities of silt borne downward from the far West on its mighty yellow tide. Little by little, water gave place to mud flats, and mud flats to green fields. On this alluvium a handful of fisher-folk settled a thousand or so years ago, and from their straggling village gradually evolved the Shanghai of today. Shanghai means “Mart on the Sea,” but the city is now sixty miles inland. The Whangpoo River, a branch of the Yangtse, that flows past it, has during the past fifty years narrowed one-third, and only by constant dredging is the channel kept open.

For many years the obscure fishing-station gave no promise of its future greatness; but all things come to them that wait, and Shanghai’s prosperity began when an official in charge of shipping and customs was stationed there in 1075. Five hundred years later, the place had blossomed out into a kind of Oriental Athens, celebrated for its musicians, poets, prose writers, and statesmen. It gave birth, also, to women of repute, praised far and wide as models of virtue and filial piety. The city, like human beings, had its vicissitudes. Again and again, it was infested by[Pg 14] Chinese and Japanese pirates, swept by typhoons, inundated by torrential rains. Although in the latitude of Savannah, Georgia, one piercingly cold winter it was almost buried under snow, the river covered with ice, and men and animals frozen to death.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century Shanghai’s population was estimated at over half a million, and her star was in the ascendant. A forest of masts from a thousand quaint junks, each gaily painted to represent a fish, with staring eyes—for how, say Chinese mariners, can a ship see where to go without eyes?—thronged the anchorage. Shanghai was the busy seaport for the central provinces reached by the Yangtse and for points up and down the coast. Long before ever a foreigner settled within her borders her commercial possibilities had been largely realized and her position as “Queen of the Sea” assured.

In 1842 occurred the great epoch in her history, when with four other cities she was forced by Great Britain to throw open her gates as a treaty port. The first Occidentals to reside within the city were the British Consul and his suite. The most pressing business that confronted the resident British was to secure land for a permanent foreign settlement. They soon discovered that it was one thing to select the site but quite another to get it. The territory chosen lay to the north and west of the Chinese City and for the most part consisted of cultivated fields, dotted here and yonder with a village, and always and everywhere graves, rising in pyramidal grass-grown mounds. As usual, the chief difficulty was over the graves, which[Pg 15] the purchasers agreed should remain undisturbed. When finally the British were in complete possession of the land, they decided the struggle had been even more severe and nerve-racking than the capture of the City. The French followed close on the heels of the British, demanding from the Chinese a concession of their own, something that the Americans a little later, with less friction and noise, simply quietly appropriated.

In 1848, five years after the opening of the Settlement, it is recorded that the foreign population numbered over one hundred, including a few women. How imagination takes wings to itself and pictures the conditions under which the community lived at that time! There were no hill resorts to flee to for a refreshing breeze in summer, no electric fans to temper the heat, no ice-cooled drinks, no screens to shut out the flies and mosquitoes. A stroll on the street was robbed of its pleasure by lack of sanitation, and a ramble even in the near suburbs almost unendurable because of the excrement used on the fields as a fertilizer. Cholera, plague, and other Oriental diseases waxed rampant, and in the first foreign cemetery many a tiny mound watered with tears wrung from aching hearts, told an eloquent story of young lives sacrificed to make possible the Shanghai of to-day.

An outstanding event in the history of Shanghai was the investment of the city in the early 60’s by the T’aiping rebels, those fanatical hordes that for fourteen years kept the country in a ferment, and well-nigh overthrew the Manchu dynasty. As the excited[Pg 16] rebels advanced from the west the populace around fled before them to Shanghai. In the original Land Regulations drawn up by the foreigners Chinese were forbidden to reside in the Settlement. The panic-stricken refugees, however, could not be restrained. They camped first on the outskirts, but soon afterward pushed in and overran the Settlement without let or hindrance. Shacks were built to house them. They went up by the hundreds, like mushrooms, in a night, and real estate speculators reaped a rich harvest, for often the refugees were people of wealth and paid handsome rentals. Many of these same speculators, who, carried away by their good fortune, continued to build at a mad rate, suffered heavy losses, and some even bankruptcy, when at the close of the Rebellion the crowds began emptying out as fast as they had poured in. One reason for the wholesale exodus of the Chinese was their dislike of the sanitary regulations at that time in force in the Settlement, and they were in great fear lest the foreigners might gain sufficient control over the Chinese officials to put the same hated rules into operation in the interior cities. Though so many refugees returned to their homes just as soon as it was safe to do so, large numbers remained, enjoying the protection offered them in the Settlement. Efforts were made from time to time to eject them, but without avail, while others gradually drifted into this desirable haven. Thus began what Shanghai has ever since continued to be, an asylum for the lawless from all parts of China. The class of respectable unfortunates is also numerous. A Chinese “Who’s Who” for Shanghai,[Pg 17] if accurately compiled, would astonish the reader with its list of half-forgotten, erstwhile famous personages, deposed officials, bankrupt aristocrats, antiquated scholars, men who figured prominently in the affairs of the world, but, having lost “face,” favor, and fortune, find the cosmopolitan metropolis a safe retreat in which to end their days.

“First things” always possess a peculiar interest, and of these Shanghai can lay claim to her full share. The first railroad ever laid in China ran between Shanghai and the forts at Woosung, twelve miles distant, where the Whangpoo River joins the Yangtse. The two men sent out to survey the line had a hard time of it and one of them was nearly killed by the infuriated people, who declared he should not desecrate the graves of their ancestors that lay in the path of the proposed road. This line was completed in 1876, but it was destined to a short existence. The stealing of window-glass and the blue silk window curtains by Chinese passengers, unable to comprehend their utility except as a means to fill their pockets with coveted cash, was a small matter. The road roused the deep-seated resentment of all classes, and from the first was doomed. The grand finalé came when a group of Shanghai officials perfunctorily inspected the entire line from their sedan-chairs, scorning to stoop to the indignity of riding on the train, and gravely pronounced it a menace. Soon after this the rails were tom up and it was long before others were laid in their places. But the world moved even under the reign of the Manchus, and before their sun had set the shriek of the locomotive was heard[Pg 18] many times every day between Shanghai and Woosung, while in the “most pro-foreign city in the world” sedan-chairs are almost as great a novelty as trains were formerly.

It seems strange that it should have been during the stressful period of the T’aiping Rebellion that one of the greatest boons China ever fell heir to was conferred on the distracted nation. That was the inauguration in Shanghai of the Imperial Maritime Customs, called by one writer “the most telling Western leaven ever introduced into China.” The story of the Customs service under the Chinese is one long, tiresome record of failure, graft, and loss, and it was not till 1854, when the management was assumed by foreigners, whose probity became at once the wonder and delight of the natives, that a change was effected. Guided through half a century by the master hand of Sir Robert Hart, to whom must also be given much of the credit of the National Chinese Postal System established during his incumbency, the work has gone on growing steadily and yielding an increasing revenue. It is eminently fitting that a statue of Sir Robert in characteristic pose, should recently have been unveiled in the Bund Park close by the Custom House.

Shanghai has not yet reached the zenith of her prosperity. The Customs receipts last year were larger than ever before. Twenty and more vessels bound for as many different ports often leave her docks in a single day. Never was there as much building in progress, especially of Chinese houses. The Western traveller who looks out upon the wide Bund, flanked by handsome[Pg 19] foreign buildings, with automobiles and carriages speeding to and fro, almost wonders whether he is not arriving at a European capital instead of a city in China. The native population has grown to over a million. Of the twenty-one thousand resident foreigners, including Japanese and East Indians, about five thousand are British and fifteen hundred Americans. The city is a political theatre where plots are hatched and reforms initiated. It is the national headquarters of missionary work, the chief seat of commerce, the home of progress, in short the nerve-centre of China whose influence reaches out to the remotest corners of the land. Shanghai faces problems and dangers peculiar to the Orient, but her future is bright with the promise of boundless development.

[Pg 20]

CIVIC FEATURES

“THE quaintest little republic in the world” is what Shanghai is often called. Certainly there is no city like it in China. Within its present limits are peoples from many countries, eighteen having consular representation, and all living, in the main, amicably together under a polyglot governing body whose members are elected by popular vote. The working out of the present system of autonomy was a difficult task. The city fathers long ago fought their way through more than one bitter controversy, for there were many minds as well as many nationalities. The Land and Municipal Regulations now in use are practically the same as those adopted back in 1869. Ten years after Shanghai became a treaty port the French withdrew from the union and set up a government of their own. The others formed themselves into the “International Settlement,” latterly known as the “Model Settlement.” Truth compels the admission, however, that it is not in all respects as worthy a “model” as its wellwishers would like to see it. Still it has admirable features, and as self-respecting a metropolis as Hongkong was urged by one of her citizens [Pg 21]in a recent appeal to wake up and emulate the example of stirring, progressive Shanghai.

CHINESE POLICEMEN DRAWN UP FOR INSPECTION

The centre around which everything political revolves is the Municipal Council. The consuls of the International Settlement each spring call a meeting of the rate-payers or electors. Any foreigner who owns or rents property of a fixed value possesses the right of franchise. The rate-payers elect the members of the Municipal Council, and that done they retire from the public gaze till the following year, unless convened for special business. The Council holds weekly sessions. Its nine members are unsalaried business men. Chinese are not eligible to membership, but Japanese are, though as a matter of fact there never had been a Japanese member, greatly to this people’s displeasure, until a year ago, when one succeeded in getting elected. Judicial authority is vested in the consuls. Each consul arbitrates for his own nationals except in the cases of the three countries having fully organized law courts with resident judges. These are England, America, and Germany. The English court was established years ago; the American held its first session in 1907. The Chinese are extremely sore on the subject of extraterritoriality. That it does not exist in Japan only adds to their grief and mortification. Since the New Law Codes have been framed the nation is more insistent than ever that this thorn in its flesh shall be removed and foreign courts abolished. But the new laws are not widely operative, and until the old methods of bribery and torture are forever relegated to the past the Treaty Powers will continue to claim exclusive[Pg 22] rights over their subjects, and the subjects to demand protection.

A unique institution peculiar to Shanghai, indeed, as some one has called it, “the most unique institution ever dedicated to justice,” is the Mixed Court. In the early days, when Chinese were made prisoners in the International Settlement, they were turned over to the Chinese City officials for trial and punishment, but justice was rare, and cruel or unduly lenient treatment the rule. To protect the Chinese, and insure fair dealing in those cases in which foreigners were involved, as well as to try the cases of foreigners having no consular representation, the Mixed Court was established in 1865. It has not proved a wholly satisfactory solution of the difficulty, for the law in force is the Chinese law, and the foreign assessor, an Englishman, American, or German, according to the day of the week, who occupies a seat on the judicial bench beside the Chinese judge, ranks as little more than a figurehead, acting merely in an advisory capacity. Practically though, it must be said, and this is particularly true since 1911, he is coming to be the real power behind the throne, and to exercise pretty much of a controlling influence. At the time of the revolution the management of the Mixed Court passed from the hands of the Chinese to the control of the Municipal Council. The change was effected quietly, so that while the Chinese were well aware of what was going on they could appear not to know, and thus save their “face.” If only “face” can be preserved facts are of small moment.

A morning spent in visiting the Mixed Court[Pg 23] is to most people an experience of absorbing interest, as it throws innumerable side-lights on Chinese life and character. At half-past nine each morning, the hour of opening court, the foreign assessor and the Chinese judge walk in and take their seats, each flanked by his interpreters and clerks of solemn mein. The witnesses, Chinese and foreign, assemble on opposite sides of the room, the prisoners, most of them poor forlorn specimens of humanity, file into the docket closely guarded by Sikh and Chinese policemen, with an English sergeant-at-arms on duty near by, while in the hall, around the door and pressing as far inside as they dare, gathers the curious, motley crowd of onlookers, many of them relatives and friends of the prisoners, but stolidly immobile during all the proceedings. Is there another place in the world where such a variety of cases is heard as at the Shanghai Mixed Court, cases civil and criminal, tragic, pathetic and comic? Some are intricate enough to tax the wisdom of a Solomon, and some are simple as a child’s play. An old couple appeared one morning to petition for a divorce. Their faces wore such a kindly expression, they seemed so at peace with mankind in general and each other in particular, that the judge was puzzled. “Have you quarreled?” he asked. “Oh, no.” “Don’t you live happily together?” “We are most happy and that is why we are here,” hastily explained the old woman. Then the whole story was poured out. An evil omen had convinced them that in the future they would quarrel frightfully, separate, and die apart of broken[Pg 24] hearts, so in order to avert such a calamity they had determined to take time by the forelock and part company while they were still good friends. A few words of advice and assurance set matters all right, and it was not long before the aged lovers, for that is what they really were, passed smilingly out of the courtroom, hand in hand, to return to their humble home. No executions take place in the Settlement. Prisoners sentenced to capital punishment are handed over to the Chinese authorities, and here again “face” is considered, for while the death sentence has actually been passed the court in the Chinese City is allowed to assume that it has not, and proceed as if the prisoner was condemned on its own initiative.

The building occupied by the Mixed Court is bounded on the right by the Woman’s Prison and on the left by the Debtor’s Prison. Under the Chinese regime discipline was practically nil and affairs were left largely to run themselves. Inmates of the Debtor’s Prison might smoke opium and gamble to their heart’s content, provided they could get the money, while dancing-girls furnished them entertainment. In the woman’s prison conditions were even worse. The top floor was set apart as a rendezvous for the young children of the prisoners, wretched, neglected little ones, exposed to every kind of evil influence. Their mothers in the cells below did pretty much as they liked. One of their tricks was to thrust their hands between the iron rods at the windows, and tear away by main force the corrugated iron screen so that they could chatter noisily with the people in the street[Pg 25] below, and by letting down a string draw up food or anything else their friends were minded to tie on the end. The wardresses (the only man about the place is the gatekeeper) were deceitful, faithless, open to bribes, in fact little better than the women behind the bars.

But marked changes have taken place during the past few years. As soon as the foreign municipality assumed control, a prerogative by the way likely any time to revert to the Chinese, who are considerably nettled over their loss of authority, the young children were removed from their pernicious environment and placed in a Home under the care of a Christian woman. The Municipal Council supports this Home. The whole staff of wardresses was dismissed and their places filled by others who were strictly watched till their faithfulness was proved. The filthy building underwent a thorough cleaning, repainting, and calcimining. Baths, laundries, and doctors’ examining rooms were added to the plant and the prisoners required to exercise an hour daily in the sunny, cement-paved court, which has resulted in a marked improvement in the health record. The chief lack now is industrial work for the women, who have absolutely no employment except scrubbing the corridors and washing their own clothes. The sole break in the dull monotony of their lives comes when the gentle, sweet-faced missionary from the Door of Hope visits the prison with her Chinese Bible woman, going from cell to cell to sing, read, and pray. Four women are confined in a cell, which is fairly well lighted and sufficiently large. The Chinese[Pg 26] beds are entirely devoid of bedding even in the coldest weather, the padded garments of the prisoners being expected to suffice. Nursing babies up to four or five months old are allowed to stay with their mothers. Most of the women are convicted for kidnapping, and the sentences do not extend at the longest beyond eight or ten years.

The Debtor’s Prison is officially known as the “House of Detention.” Its prisoners are not chained, may walk about freely, smoke, play games provided they are not games of chance, and at certain hours each day are allowed to see their friends in a small room at one side. On a winter’s day, when the windows and door of this room are shut, the contracted space packed with people, and the air heavy enough with tobacco smoke to cut with a knife, it is almost as much as a foreigner’s life is worth to take even a hasty peep inside. The prisoners provide their own bedding and food, with the exception of rice, and on the whole appear to enjoy themselves and to be in no hurry for their release, though some have hidden away quite enough money to pay their debt if they cared to, and others have relatives or friends who could easily pay it for them. Recently two men were set at liberty by the court on the presumption that they were really unable to meet their obligation, one after seven years’ imprisonment and the other five. The Municipal jail for men is several miles away, in a more open part of the city. Its massive, gray brick walls shut in between eleven and twelve hundred prisoners, all of them Chinese, for foreign prisoners are lodged temporarily in small prisons connected[Pg 27] with their consulates, or, when the consulate has no prison, in the British jail. The discipline and upkeep of the jail are about perfect. The superintendent is a Christian who arranges for regular Sunday services for the prisoners, the Young Men’s Christian Association having general charge.

Industrial work of various kinds, including tailoring, mat weaving, and carpentering, is carried forward on a large scale, and a considerable amount of the city’s road-paving and repairing is done by the prisoners. Short terms in jail are rather welcomed than otherwise by many of the men, for they mean to them shelter, good food, warm blankets, and a chance to learn a trade under the most favourable conditions. Indeed, it has come to pass that many habitual offenders are in the habit of flocking to Shanghai as soon as the cold weather sets in with the express purpose of putting up at the jail for the winter. A specific instance occurred a while ago when a Chinese walked into one of the police stations and cheerfully announced that he wanted to be arrested. “My belong velly bad man,” he said, “velly bad man.” Not being able to give any special reason why he should be arrested at that particular time, he was told to go about his business. But he insisted. He was “velly bad,” and wanted to be arrested, and it was with a look of pained surprise that he made his way out of the station. As he walked down the street, thinking with dismay of the cold weather ahead, a happy inspiration struck him. He went in search of a policeman, and having found one, proceeded to beat him. He did his work thoroughly,[Pg 28] was quickly arrested by another policeman, and taken to the nearest police station, beaming with satisfaction. The problem of his winter’s lodging had been solved. A moot question for some time past has been the advisability of reviving the practice of flogging with the bamboo. Many officials, Chinese as well as foreign, contend that this punishment as formerly administered by the Mixed Court, was thoroughly humane, and that as it has real terror for the Chinese nothing begins to be so effective in preventing crime, which has of late been greatly on the increase.

Formerly there was no Reformatory, and young boys convicted of no worse crime than petty stealing were often confined in the same cell with hardened criminals. It was the present superintendent who agitated the need of a separate building for the boys under sixteen, and finally a great three-story warehouse was purchased and fitted up for this purpose by the Municipal Council. Some of the lads are as young as nine. “The longer I live in China and the more I see of its poverty-stricken multitudes the less I blame any one for stealing,” exclaimed a Y.M.C.A. visitor at the Reformatory. The boys do industrial work in the morning and in the afternoon study, drill, and play. The fire drill is fine, but the military drill is the boys’ delight. Those best trained take turns in acting as drill-master. They give the orders in English and the company responds with a vim. Insubordination is punished by obliging the offender to scrub the wooden floors with sand, sometimes for a whole day. They are kept beautifully white. “You should see the kitchen!” said a frequent[Pg 29] caller to a new comer. “It is so clean you could eat off the floor!” Several Christian Chinese business men in Shanghai have an understanding with the superintendent that they will receive a limited number of boys sent out from the reformatory, give them employment and a chance to begin life anew.

One of the first things that impressed itself on the early foreign settlers in Shanghai was the need of an adequate police force. In the beginning it was limited to a handful of Chinese watchmen under the joint jurisdiction of the Chinese and foreigners. An amusing story of those days is that the police were in the habit of lining up for inspection in their own nondescript garments, but wearing foreign military caps and carrying in place of rifles closed Chinese umbrellas of oiled paper! Now the city is well guarded by 230 English policemen, 450 Sikh Indians, and over a thousand Chinese. The picturesque red turbans of the Sikhs are conspicuous everywhere. These men are harsh but efficient preservers of the peace. The Chinese are afraid of them. There is one especially tall Sikh of whom his foreign superior says, “He is the only man that I am absolutely certain will carry out my orders in my absence as if I were present.” One of his duties is to punish Chinese police delinquents by putting them through a severe physical drill half an hour long in summer and an hour in winter. “It looks easy enough,” a foreign lady remarked, as she watched the men, “Why, I exercise harder than that when I play tennis.” “Oh no, you don’t bring into action every muscle in this way,” smiled the head officer.[Pg 30] “These men are glad enough to lie down and rest after their stunt is finished. I had one man that fainted, but he was abnormal.” What makes this punishment especially objectionable to the Chinese is that it is administered by a Sikh. If an English officer were over them it would not hurt half so much. The work of a policeman attracts the Chinese and there is never any lack of recruits. The course of training lasts three months. Scientific wrestling appeals to the novice strongly and he soon acquires real skill. The officers have a unique method of putting a stop to fighting among the men. The combatants are given boxing gloves, forbidden to bite or kick, two favorite forms of attack with them, and then made to fight until they are thoroughly tired out. One such experience usually works a cure for all time.

Chinese barracks are clean and severely plain. “We carry on a constant warfare against bedbugs,” says the foreign sergeant. “I do not allow a hook or nail in the walls, except the bracket back of each bed for holding the rifle, and that I wouldn’t permit up again, for vermin hide in the corners.” Every Saturday the planks on which the men sleep are scrubbed with sand and water. The sand soon works into the pores of the wood where bugs are apt to lodge, so it acts both as a cleanser and an insect preventive. When a man goes home to spend a day, as he is sometimes allowed to do, the barracks on his return must undergo a special cleaning, for he is sure to bring back a fresh relay of bugs. The past year an innovation has been introduced in furnishing the[Pg 31] Chinese police with rifles, a convincing proof of their general faithfulness and the trust reposed in them. They are not permitted to take the rifles to their homes, but when going off duty leave them at the police stations.

The Sikh recruiting station is on the same grounds with the Chinese but in a separate yard. The chief embarrassment in connection with the Sikhs is their food. They are East Indians and can not eat what the Chinese do. Caste rules are inflexible and time must be given them to prepare food in their own way no matter how greatly the staff is inconvenienced. The Sikhs are stern disciplinarians, but in character no more dependable than most of the Chinese, nor in some cases as much so. A Sikh watchman patrolling an outlying district rang one evening the doorbell of a foreigner’s house. “It is raining,” he remarked blandly. “Can I have a chair and sit on your veranda?” It was observed afterward that he frequently camped on the veranda when it was not raining. The Sikhs are not required to learn Chinese, but they are encouraged to do so by being promoted and given higher salaries when they can speak it. Chinese is demanded of European policemen. They of course constitute the backbone of the staff. The Municipal Department supports a hospital, one of the cleanest and best in the city, for Chinese policemen; it is also used for prisoners from the Municipal Jail. Women prisoners when sick are sent to a woman’s mission hospital.

In case of riot or other emergency Shanghai would not need to rely wholly on the police force, for it has a dependable Volunteer Corps, at present 1,300 strong.[Pg 32] As long ago as 1853 the Volunteer Corps was organized, and ever since the T’aiping Rebellion, when the members rendered such valiant service, there has been occasion time and again to turn to them for help. Their most recent laurels were won during the Rebellion in the summer of 1913, when Shanghai was the centre of the war zone. To watch the Corps at drill or on parade, so many sturdy young men among the older ones in the ranks, gives foreign residents an exhilarating sense of security, and warms their hearts with a glow of honest pride in their defenders. Among the many nationalities represented in the Volunteer Corps is a strong Chinese contingent, and it causes a still further quickening of the pulse to learn from the commanding officer that whenever the Chinese Volunteers have been called into action their efficiency and loyalty have been in the highest degree commendable. During the past year a Volunteer Motor Car Company was added to the force. It started with eighteen private cars and men to run them, but in case of need practically all the private as well as public cars in the city would be placed at the disposal of the Volunteers.

The Shanghai Fire Department dates back to 1866. The three chief officers are employees of the Municipal Council, but all the members of the four companies are volunteers. There are three fire stations and three watch towers, besides a one-thousand-gallon fire float moored at one of the jetties on the Bund. Three motor vehicles are in use and the purpose is to abolish horses as rapidly as possible. In a cosmopolitan city like[Pg 33] Shanghai, where all sorts of buildings crowd upon one another in the densely populated districts, fires are constantly breaking out, but the Fire Brigade handles them so well that destructive ones are rare.

“Why is it your letters always come to me with a two-cent United States stamp on them?” wrote a bright American club woman to a friend in Shanghai. Her perplexity is not surprising, since even certain government departments in Washington have been known to send to Shanghai franked envelopes bearing five-cent stamps. The independence of the “Little Republic,” albeit on Chinese soil, is emphasized by its having six foreign postoffices—British, American, German, French, Russian, and Japanese. Three countries—Great Britain, America, and Germany—have legalized the domestic rate of postage to and from Shanghai. But home letters forwarded from Shanghai to interior points require the usual foreign postage of five cents, and parcels from abroad sent inland must be rewrapped, restamped, and go through the Chinese postoffice.[1]

[1] As these pages go to press arrangements are being made for an International Parcel Post.

It is a pity that China failed to improve her flood-tide of opportunity in 1878, when she was formally invited to join the International Postal Union, in the hope that it would encourage her to establish a national postoffice. But with a short-sighted policy she declined to do so, and it was not till September 1st, 1914, that this privilege was finally embraced. Though for years a national postoffice was urged upon the people and often seemed about[Pg 34] to materialize through the efforts of progressive statesmen like Li Hung Chang, yet it did not really make its appearance till 1896. Up to that time mail was distributed from local stations under local control, and as means of rapid transit were very few, much of it was delivered by couriers. There are still many courier routes in the interior where railroads and steamers do not penetrate, but the couriers, often on foot, sometimes on mule or horseback, waste no time in getting over the ground, not infrequently travelling between eighty and ninety miles a day, and this in spite of unspeakably bad roads, to say nothing of brigands, floods, and a few other minor difficulties! Shanghai is the largest distributing centre in China, and in the substantial red brick Chinese postoffice, just across the road from the British postoffice, an enormous business is carried on. All heads of departments are foreigners. Periodically the Chinese voice a protest, declaring that as the Chinese staff has now received sufficient training, it is prepared to fill unaided the most responsible positions. But sagacious Chinese politicians are loth to release the foreigners, realizing that a change at the present time would inevitably entail a grave risk. It is rather interesting that the newest and handsomest postoffice building in Shanghai is the Japanese. There are no foreign postmen except Japanese. Chinese postmen in neat green livery cover their route on bicycles. There are six deliveries a day in the business districts and three and four in the residential. One family was so disturbed by the postman bringing mail at ten o’clock or later at night, and insistently ringing the door-bell[Pg 35] until it was answered, that they requested him to defer delivering the late mail until morning, but he continued to call whenever he had letters, evidently impressed that the postoffice rules were inflexible and must no more be broken than the laws of the Medes and Persians.

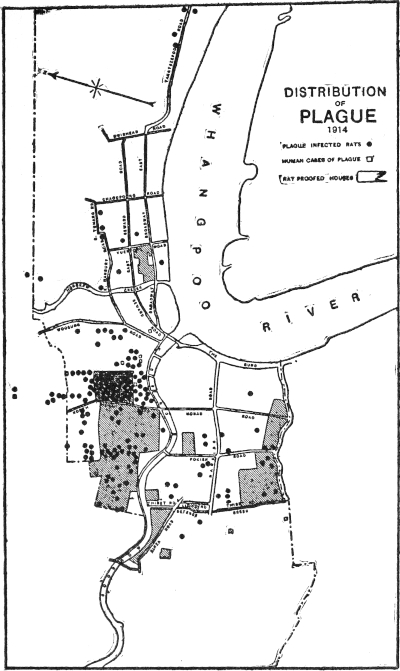

Probably the most interesting of any branch of the foreign Municipal government is the Health Department. Eighteen years ago when the doctor in charge settled in Shanghai and started a campaign against disease, he was not building on another man’s foundation, for nothing like it had ever been attempted. A member of the staff has aptly called the Municipal laboratory “the brain of the department.” It is certainly kept busy in a thousand ways. People from all over China, for one thing, turn to it for the Pasteur treatment. But its chief work centres about plague prevention. Plague is the bane of the Orient, and plague, it was discovered in 1908, is transmitted to human beings through fleas that carry the poison from infected rats. Then to prevent plague, rats must be exterminated, no easy matter in a city like Shanghai. The campaign began in this way. The city was divided into districts, the districts into sub-districts and sub-districts into blocks, and a map made of the whole. A raid on rats followed. Every one caught, dead or alive, was taken to the laboratory and an examination made. A black-headed pin was stuck in the map over the spot where each plague-infected rat was found. A red headed pin on the map indicated a human death from plague. In this way it was soon learned what parts of the city were specially invaded by the pests. To[Pg 36] kill the rats, however, amounted to little, for others soon appeared to take their places. Something more radical needed to be done. After the Municipal Council had passed rules calling for the rat-proofing of houses, a more difficult task confronted the officers of the Health Department in getting the rules enforced. They were needed badly enough for foreign houses, but were drawn up especially for Chinese dwellings where often four and five families are crowded like sardines into one small building. At first the Chinese strenuously opposed and ridiculed the rules but later came to regard them more favorably. The people are terrorized at the outbreak of plague, and when a few years ago Shanghai was threatened with a bad epidemic, they were ready for the time being to submit to anything that promised to stamp it out and prevent another visitation. The rules demand that there shall be no open space underneath the ground floor, and by laying three inches of tar chips on six inches of concrete, it is impossible for rats to enter the house from below. The health officers also urge upon householders, although not included in the rules, that walls be made solid and the upper story left without a ceiling, showing simply the bare rafters. Many old houses as well as new ones are treated in this way. Sometimes a whole block of old houses is rat-proofed at one time. While the work goes on the people turn out of their homes and camp in the street in front of them, cooking their meals over little charcoal fires, and squatting patiently about till they can go back. But education is a slow process and opposition still continues. The ideal worked toward[Pg 38] is the one already reached in Manila and held up as an example, “No hollow spaces whatever accessible to rats.” With the most careful economy it costs the Health Department two cents to catch each rat, yet whenever notified by a foreign or Chinese tenant it is prepared to send its employees with traps to rid the premises. Stationary garbage receptacles of concrete, with spring lids, that are fire and rat proof, have been placed in large numbers all over the city. Several times a day they are emptied through an opening below and the contents carried off in municipal carts. The receptacles are liked by the Chinese, who seldom now throw their garbage on the ground.

DISTRIBUTION OF PLAGUE 1914

The danger from contagious diseases is not so easily controlled. There is no law requiring small-pox, cholera, or even plague patients to go to the Chinese Isolation Hospital. Moral suasion is the only influence that can be brought to bear on them, and it is not always sufficiently powerful. But a vigorous campaign in the interest of the prevention of disease is continually in progress. Every month, and every day of the month, printed circulars are scattered broadcast. They are written in both English and Chinese, and relate to sanitation, hygiene, the danger of promiscuous spitting, of flies and mosquitoes, the need of removing stagnant water and rat-proofing houses. In the autumn and winter notices are posted on electric light and telephone poles calling the attention of passers-by to free vaccination for Chinese at any one of the sixteen branch offices of the health department. Health lectures are given weekly at the health offices, and not only that but heed is paid to the[Pg 39] old proverb: “If the hill will not come to Mahomet, Mahomet will go to the hill.” Although the lectures, which are of a popular character, usually draw a large, attentive crowd, trained Chinese employees lecture in schools, tea-shops, and other places where the people are wont to gather. They carry around a dinner bell which they ring to attract an audience, and they soon have it. When the lectures first began the people did not understand their intent, and they aroused almost fierce opposition. But the Chief of the Department, a physician of great tact and urbanity, sent invitations to some of the leading business men and officials to meet him at a specified time and place when he addressed them in person explaining the character of his campaign. After that there was no further trouble. A large force of coolies is employed to fight mosquitoes. They work in pairs in districts assigned to them. Their duty is to gather up old tins, bottles, and broken crockery, warn residents against leaving about their premises tubs, empty flower-pots, and other vessels capable of holding rain-water, obliterating shallow pools and slushy places by means of scratch drains or filling them up with house ashes, and sprinkling kerosene oil on stagnant water that can not be drawn off. The coolies are inspired to faithfulness by frequent and unannounced inspection of their work.

Among the many business houses regularly inspected by the Health Department are dairies, laundries, tea, fruit, and meat shops, restaurants and bakeries. Licenses prohibit in tea-shops the hawking of fresh food stuffs on the premises; dairies, bakeries, and laundries[Pg 40] must be calcimined twice a year, no one shall sleep or eat in them, nor may they be attached to a dwelling-house. In bakeries the spraying of fluid from the mouth on the products of the bakery is prohibited, and in laundries the same rule applies to the sprinkling of clothes. In dairies workers are required to keep their clothes clean and wash their hands before milking. Always and everywhere spitting is forbidden and also the employment of persons with communicable diseases. To suppose that these rules are carried out to the letter, would be altogether too much to expect of human nature. That they act as a powerful deterrent is certainly true. The foreign dairies are the best, but one Chinese dairy enjoys the enviable reputation of never having been either fined or cautioned. The Municipal Slaughter House is kept strictly sanitary and cattle and carcasses are examined daily. Good meat is stamped with the words “Killed Municipal Slaughter House.” Inferior meat but free from disease is marked “2nd Quality.” No meat for foreign consumption is allowed to be brought into the Settlement unless it bears the Municipal stamp.

Tuberculosis is the Chinaman’s Nemesis, and too often pursues him from the cradle to the grave. It is also frightfully common among the poor Eurasians who herd together under lamentable conditions. The only remedy for this prevailing malady seems to be to educate, educate, educate, and that is being done as thoroughly and effectively as possible. The Society of King’s Daughters recently did a fine thing. They planned a Tuberculosis Exhibit, which was held for a week or more in an empty down town store. Much[Pg 41] of the exhibit was loaned and set up by the Young Men’s Christian Association that is itself carrying on a telling campaign against China’s “White Scourge.” Maps, charts, pictures, devices of all kinds for arresting the attention and teaching a lesson, were arranged attractively, but two things in particular produced a profound impression. One was a bell that every thirty-seven seconds clanged ominously. Over it hung a placard announcing in Chinese and English that every time the bell tolled some poor victim in China died of tuberculosis. The other design was more conspicuously placed in one of the large show windows and always attracted a crowd of absorbed, silent Chinese. The sight that held them spell-bound was a perfect model of a Chinese house, out of which stepped a Chinaman, who, after walking a few steps, fell into a Chinese coffin that instantly disappeared in the earth. This happened every eight seconds and each drop of the coffin represented a death from tuberculosis somewhere in the world.

Before 1898 there was practically no Health Department and no health campaign. If progress at times seems slow, one has only to look back to realize what a marvellous change for the better has been wrought in a decade and a half. Perhaps more to the Health Department than to any other branch of the Municipal Government Shanghai owes its right to be called “The Model Settlement.” The group of Central Municipal Buildings covering an entire square in the heart of the city forms one of the finest plants of the kind to be found in the Far East.

[Pg 42]

STREET RAMBLES

“I HAVE lived in China nearly twenty-five years, yet I never go on the street without seeing something new and interesting,” exclaimed a vivacious little missionary doctor to a group of fresh arrivals. Her remark was made about Peking, but the outdoor life in Shanghai has its own unique charm.

To begin with, in the International Settlement there are no “streets” at all, so called; only roads. Some of the byways, to be sure, too narrow and short to be dignified as roads, go by the name of “lane,” and the city boasts a “Broadway,” or, to be exact, “Broadway Road.” It is unnecessary to explain that this lies in the district originally ceded to the Americans. The Shanghai Broadway makes no pretense of emulating in appearance or importance its western prototype, though quite a brisk trade is carried on in the modest shops near its lower end.

The first permanent foreign settlement was along the Bund, beginning with the site occupied by the British consular offices and residence. The splendid Bund, bounded on one side by sightly bank and club, steamboat and insurance buildings, and on the other by the Whangpoo River, is the city’s pride and glory. It[Pg 43] is hard to realize that this wide, white road, humming with life and swept by costly automobiles, was once nothing but a well-trodden tow-path bordering a marsh. Away to the south, across what until recently was an ill-smelling creek but is now being rapidly metamorphosed into a handsome boulevard, begins the French Bund, with its wharves and warehouses, and where it ends the Chinese Bund starts.

The characteristic feature of the Chinese Bund is its boat population. For more than half a mile little boats called sampans, protected by a low arched covering of bamboo mats, line the shore and extend well out into the river. Each tiny sampan swarms with life as if it were an ant-hill. The occupants are permanent householders and their habitations are anchored. Many of them were originally famine refugees from the north. Most of the men earn a living as wharf coolies. The wives add a little to the income by gathering rags to make into shoe soles and by patching and darning old garments for coolies without families who pay a few cash in return. Planks set on stakes serve as footpaths to connect the boats with the shore, and little toddlers run about on the narrowest of them at will, yet rarely tumble into the water or soft mud below. Births, marriages, and funerals lend variety to the life of the boat people. Two or three empty coffins usually stand about on the wharf ready for an emergency, and are meanwhile useful as benches, especially for the women when they sew.

The International Bund on its water side is unobstructed with buildings, except at the Customs jetty,[Pg 44] and is laid out in grass plots which gradually widen near the Garden Bridge into the Public Gardens. This charming little park in the heart of the city, with its lawns, flowers, shade trees, and a band-stand where the celebrated Municipal Band plays in summer, is a favorite resting place for weary pedestrians and a rendezvous for parents and nurses with young children. Chinese are not admitted to the Gardens, except nurses with foreign children, unless dressed in foreign clothes or accompanied by a foreigner. This is to keep the grounds from being overrun by the coolie class. The Customs jetty has witnessed many a stirring scene. Trim launches carry outgoing passengers twelve miles down the river to the anchored ocean liners beyond the “bar” and bring them up the river on arrival. Its sheltering roof has caught the echo of sobs and laughter, tremulous good-byes and joyous welcomes.

The river at this point is half a mile wide and presents an animated picture. Every variety of craft floats on its waters, from the busy sampan to the light-draught coasting vessel or man-of-war. Whether seen beneath the radiance of the noonday sun, or under a starlit sky, reflecting myriads of twinkling lights, it is a never-failing delight to resident and visitor alike.

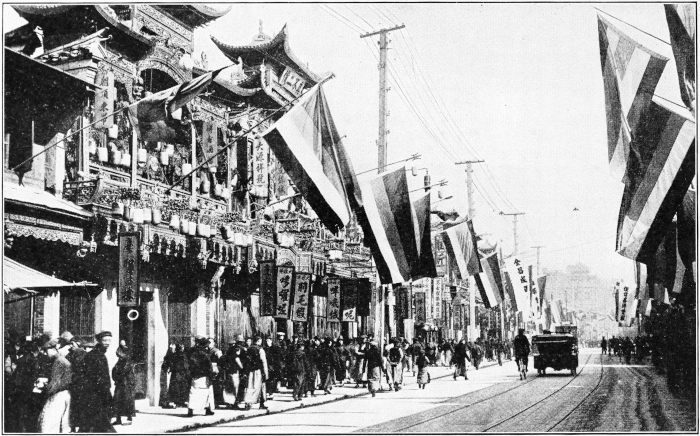

The most picturesque, as well as the leading business street in Shanghai is Nanking Road, or as the Chinese call it, “The Great Horse Road.” “Great,” however qualifies “Road” and not “Horse,” for while numerous horses travel over it, most of them are the small swift-footed Mongolian ponies, whose clattering little hoofs are heard early and late. Indeed the name[Pg 45] “Great Horse Road” strikes one as rather out of date in these days of the ever-present automobile, of which there are already more than eight hundred in Shanghai. Nanking Road starts at the Bund with the Palace Hotel, and following the windings of a former creek, ends at the race course. For a short distance west of the Bund it is given up mainly to foreign stores, the largest and finest in the city. Then the street widens and becomes an avenue of high grade Chinese shops, many of them with the national flag afloat and all displaying aloft the characteristic vertical signboard in black and gold. The vista in either direction on a bright day is quite dazzling, and especially at night when the avenue from end to end is ablaze with electric lights. Then crowds of Chinese going to and from the theatres and tea-houses, or simply out for a stroll, jostle each other on the sidewalks and pour over into the road, where they narrowly escape being knocked down by rapidly moving vehicles. Conspicuous everywhere are the Chinese “Women of the Street,” or rather the girls and children, for nearly all are pitifully young. Bedecked and bejeweled, they stand sometimes in the bright glare, but oftener within the shadow of a closed doorway, or at the entrance to a lane, usually in groups under the care of an older woman who acts as “business agent.” A notable hour on Nanking Road is between five and six on Saturday afternoon, when it seems as if the whole city turns out to loaf or saunter in quest of pleasure. A babel of shrill voices rings in the ear, mingled with the shouts of ricsha coolies and the tooting of motor cars. It is a gay,[Pg 46] panoramic scene, such as could hardly be duplicated anywhere else in China.

A Britisher in Shanghai once made the remark, “There are two things an Englishman must have, a king and a race-course.” The Shanghai race-course, with the Public Recreation Grounds adjoining, covers about sixty-six acres in a part of the city where property is valued the highest. The land was bought up years ago. So much open space in that locality could scarcely be secured to-day at any price.

Bubbling Well Road is a synonym for the patrician quarter of Shanghai. It is a continuation of Nanking Road and takes its name from the effervescent pool enclosed by a low cement wall at its terminus. Near by Bubbling Well is the foreign cemetery, a shady, restful spot. Every thirtieth of May the Americans gather within its gates for a national memorial service. They represent all creeds and callings, merchant and missionary, tourist and adventurer, aliens on a distant shore, drawn together by a common love for a common flag. The American corps of the Shanghai Volunteers and the “Regulars” from the American cruisers anchored in the river, march up from the Bund with bugle and fife and salute in front of the flower-strewn mounds. A few of these graves date back more than sixty years.

Some of the handsomest residences on Bubbling Well Road are owned by wealthy Chinese. Pleasant afternoons and evenings automobiles by the score flash up and down this wide, smoothly-paved road and on to the delightful suburbs beyond, many of them crowded[Pg 47] to overflowing with merry-making Chinese, women as well as men.

In the French Concession, the avenue formerly called “Paul Brunat,” after the first French Consul, but since the outbreak of the war changed to Avenue Joffre, vies with Bubbling Well Road in the elegance of its residences, which some prefer because of their more varied style of architecture. Being a newer thoroughfare, this avenue lacks in a measure the abundant shade trees and fine old gardens which are among the chief attractions of Bubbling Well Road. It is frequently pointed out to strangers as one of the few long roads in Shanghai which is also a straight one, running most of its entire length of between two and three miles with scarcely a jog.

The “tenderloin” district centres about Nanking and Foochow Roads. The latter is a narrow street with nothing at first sight to arrest the attention, but men shake their heads at the mention of it and women avoid it if possible. Its mark of distinction is the number and character of its tea-houses. They are entered directly from the street. A wide staircase leads to the restaurant which occupies the second story, the ground floor being used for business. Along the front of the building and on the side as well, if it happens to be on a corner, runs a narrow veranda, a much-sought-for gathering place in mild weather, where idlers can chat and sip their tea or wine while enjoying a view of all that is going on in the street below. The tea-houses, often richly furnished with carved black-wood from the south, are practically deserted till the latter[Pg 48] part of the afternoon, when a few loungers make their appearance. But it is at night that the crowds pour in. Then the tables fill up, Chinese musicians rend the air with what to foreign ears seems a riot of discord and by nine or ten o’clock everything is in full swing. In and out among the square tables, filling the brilliantly lighted rooms, trail slowly little processions of young girls. Nearly all are pretty and very young. Clad in silk or satin, adorned with jewelry, their faces unnatural with paint and powder, they follow the lead of the woman in charge of each group. She stops often to draw attention ingratiatingly to her charges and expatiate on their good points. When one is chosen she leaves her to her fate and passes on to dispose of others. Multitudes of victims, innocent of any voluntary wrong, having been sold into this slavery when too young to resist and not uncommonly in babyhood, are kept up hour after hour in the close atmosphere of the tea-room awaiting the pleasure of their prospective seducers. Out on the street, by ricsha and on foot, women continue to hurry to the tea-houses with their living merchandise, and still they keep arriving till the night is far advanced and business at a stand-still.

Opposite the Public Gardens, where Soochow Creek empties into the river, stand three consulates in close proximity, with their nation’s flag floating in the breeze from the flagpole. They represent Japan, America, and Germany, other Consulates occupying roomy mansions on Bubbling Well Road. The new Russian Consulate that is being built next to the German will soon be completed and add considerably to the sightliness[Pg 49] of the river front. Across the street on the corner of Broadway stands the Astor House, the oldest hostelry in Shanghai. This district, once a part of the American Concession and now known as “Hongkew,” does not bear a very fair reputation, though some of the best families still reside within its boundaries. But nothing can be said in disparagement of Hongkew Market, by far the largest and best in the city. Housekeepers on Bubbling Well Road, miles distant, have been known on occasion to send their cooks to the Hongkew market and bewail the fact that they could not go every day. What Covent Garden Market is to London this market is to Shanghai. The saying, that one of the quickest ways of getting acquainted with a city is to visit its markets, is singularly applicable here. An hour or two spent in the early morning walking, or edging one’s way through the noisy square where all nationalities congregate, is worth an entire guide-book of ordinary information. The market covers a whole block, has cement floors and wooden pillars holding up the tiled roof, running water for keeping fresh the fish and vegetables, clean stalls, and very decent people in charge of them. The women are not as numerous as the men but they manage to make their presence felt, and discuss prices and provender in shrill voices that rise above the din and tumult of the multitudes. Vendors without stalls line the sidewalks, squatting close by their baskets, and between sales sip tea or gulp down hot rice and bean curd with well-worn chop-sticks. The money-changers’ tables, protected by a strong net-work of wire, dot the place here and there, for “small[Pg 50] money” is always a necessity, the big heavy coppers and “cash” being most in evidence.

Yangtsepoo Road, meaning Poplar-Tree-Shore Road, is a continuation of Broadway, and as it is chiefly a street of mills, stands rather low in the social scale. It runs parallel with the river and should have been a residential avenue, the most beautiful in Shanghai, but somehow the mills got there first and then there was no help for it, although the fresh breezes and fine outlook are lost on the tired mill hands shut up behind brick walls from dawn to dawn.

One of the best known streets in the city and one of the longest, although it lays claim to no other distinction, is Szechuen Road. It starts at the Chinese city, changing at Soochow Creek to North Szechuen Road, then to North Szechuen Road Extension, and pursues its devious way northward far beyond Hongkew Public Park, which by the way is not in Hongkew at all. This park of forty-five acres is the largest in Shanghai, and a genuine godsend to foreigners remaining in the city during the summer. Those living in the neighbourhood seek it in the early morning and late afternoon for golf and tennis, securing the exercise so necessary to health in this Eastern climate, and from far and near people resort there in the evening to rest and listen to the band play. Along its northern end, outside the limits of the International Settlement, Szechuen Road winds back and forth like a corkscrew. Some say it follows an old buffalo path, but most agree that the road’s meanderings are due to the unwillingness of the original Chinese property owners to sell their land, since to do[Pg 51] so might affect their “good luck.” Perhaps some old graves blocked the way, and albeit no one living cherished any sentiment regarding them, still they must not be removed for fear of offending the spirits of the dead. Or possibly the terrible dragon inhabiting the nether regions in this vicinity would resent an innovation like a paved road above his domains, and naturally it would never do to arouse his ire. Hence the road-builders were obliged to let the street follow the line it could and not the one of their preference. Apropos of the superstitious fear aroused in the minds of the common people by the building operations of foreigners, the case of the Methodist chapel in the French Concession is a good illustration. When this mission church was erected many years ago, the Chinese in the neighbourhood were thrown into a state of great consternation. What would their outraged tutelary deities say and do now? How could they escape the afflictions that unquestionably would be visited upon them by the evil spirits hovering about the foreign worship house? But necessity is the mother of invention, and the terrified residents at last hit upon a happy ruse to deceive the inimical spirits which seemed to be efficacious. Any one visiting that corner to-day may see on the roof of the house just across the road from the chapel two bottles with long necks pointing toward it. The bottles represent cannon which, as the most stupid spirit may guess, are likely to belch forth fire and destruction the moment that so much as a threatening glance is cast that way!

Many of the most travelled thoroughfares in Shanghai[Pg 52] are inconveniently narrow, and in addition have scarcely any sidewalk, so that it is necessary for pedestrians to use the road. Yet the early settlers who laid out the Foreign Settlement almost quarrelled among themselves over what seemed to some an altogether unnecessary width of twenty-five feet allowed for the streets. As for sidewalks they were apparently not taken into consideration at all. The Municipal Council has now decreed that whenever a building that abuts on the street is torn down, the new one, at whatever sacrifice, must be put back several feet. This law, which is strictly enforced, is gradually working a vast improvement in the appearance and comfort of the city. All the Shanghai streets inside the foreign settlements are paved. A large number of them are macadamized, though it has been found that in the purely Chinese districts, chip paving on a bed of concrete and tar is more suitable and economical. Road repairing is constantly going on, for as the soil is alluvial, the innumerable heavy wheelbarrows and trucks cause rapid deterioration. Several of the streets, notably the Bund and Nanking Road, have received what promises to be a permanent paving, consisting of wood and lithofelt blocks on a foundation of concrete. If the public funds were sufficient to treat all the streets in the same way it would be a boon to the city and a matter of rejoicing to the populace.

It is surprising how muddy and disagreeable the streets become after only a few hours’ rain, while actual floods in the low-lying sections accompany a downpour, and this in spite of the excellent sewers. It is equally[Pg 53] interesting to note how quickly the streets dry. Almost as soon as the rain stops the water-sprinkler is out laying the dust. The Municipal street sweepers are always busy. They wear for uniform a bright red cotton jacket showing below it their faded blue trousers, and a wide-brimmed straw hat with a broad red cotton band, both band and jacket stamped with three large letters, S.M.C. (Shanghai Municipal Council). Each one is furnished with a bamboo dustpan and a small reed broom with which he ploddingly sweeps up the detritus. This débris is not wasted. Indeed in China scarcely anything is thrown away, and besides, there is no place to throw it, since all the ground is sown with crops. The Foreign Municipality utilizes the street sweepings either for fertilization or in raising low land. And right here the creeks which intersect Shanghai prove their usefulness, for the refuse is dumped from zinc-lined carts onto native boats and poled along at little expense to the place where it is needed. Shanghai could hardly do without its tidal creeks, offensive as they often are when the tide is out.

Shanghai is nothing if not a city of contrasts. Right among the elegant homes, club-houses, and private hotels on exclusive Bubbling Well Road squat the insignificant shops of “the butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker.” In front of its fashionable gardens pass fantastic idol processions, displaying as one of their prominent devices mammoth paper dragons, of variegated colours, whose opening and closing jaws and writhing scaly bodies, manipulated with cunning art by men carrying them, are gruesomely realistic. In the busiest[Pg 54] section of Nanking Road an inconspicuous passageway leads a few yards back to a grimy Buddhist temple that seems as far apart from the hurrying crowds and bustle of street traffic outside as if it were on another planet. An occasional worshiper slips in to bow before the blackened altar, where red wax candles drip grease and incense wafers are forever smouldering. In a side room, gloomy as the entrance to Dante’s Inferno, are seated tiers of black idols streaked with gilding and paint. They are a repulsive sight and one turns with relief to the living shaven-headed priests in dull grey gowns lolling about the court.

The most modernized Shanghai thoroughfares sometimes witness quaint scenes. The following was described by an eye-witness: An old Chinese woman, with all her winter padding on, tried to cross a down-town street through the maze of traffic. Ten yards or so from the pavement an electric tram car caught her full in the chest and propelled her neatly on to the further track, where another car caught her in the back. The second car pushed her staggering under the feet of a ricsha coolie drawing a Chinese cook home from market with a load of vegetables, a ham and two live ducks. By the time the old lady had disentangled a flapping duck from her elaborate headdress and the coolie had wiped the ham clean with his dirty sleeve, all the traffic of motor-cars, wheelbarrows, and broughams had been held up, and it took some minutes more of hard work to get the innocent cause of the trouble safely back to the spot from which she started.

There is a law prohibiting beggars from invading[Pg 55] the Foreign Settlement, but the law is lax and beggars—the maimed, the halt, and the blind—are all too numerous. Parents often mutilate their young children or twist their little bodies out of shape by confining them in a deep earthen vessel, intended to hold water, in order to make them successful beggars. Yet the blind eyes can many times see, and the poverty-stricken frequently have stowed away snug little sums of money, quite sufficient to keep them in comfort the rest of their lives. Begging in Shanghai is a profession, like any other, and there are beggars’ guilds and beggars’ camps where the tribes congregate. To watch them about five or six at night, trooping home to their mat sheds, with the day’s earnings securely stowed away on their dirty persons, is something to be remembered. Formerly there was a Beggar King, a regal sort of personage in spite of his rags, who with a band of associates made laws, adjudged cases, etc., but of late years the organization has been less complete. Foreigners as a rule do not make a practice of dispensing charity on the street. A certain benevolently minded individual, however, on arriving in Shanghai decided that it was his duty never to refuse to give alms. It soon fell out in consequence that he scarcely dared venture away from his own dooryard, and life became a burden until he had wrought a complete change in his habits.

The majority of the Chinese people in the Foreign Settlement live in lanes that lead off at right angles from the highways. Only fifteen or twenty feet wide, they are not open to vehicle traffic, being paved with cement, and are squalid or measurably clean according[Pg 56] to the locality and the community inhabiting them. The houses are almost precisely alike, except that some have two living rooms, one above the other, and some have four, with several very small ones at the back. In front is a tiny open court shut in by a cement wall reaching to the second story. Through a wide double door in this wall, which wall, while it protects, also keeps out light and air, the house is entered. The long line of connecting tiled roofs terminates at each end in the graceful, upturned gables the Chinese love so well. Crude handpainting and handcarved woodwork usually decorate the poorest of Chinese houses. The rental averages about fifteen dollars a month. Looking down one of these long alley-ways, that resemble good-sized cracks in the main thoroughfares, the effect is decidedly sombre, for the grey outside walls conceal the house fronts and the little courts, often made homelike and attractive with palms and flowering plants. It is the human element that saves from utter ugliness these populous alleys, which throb with life, but generally such a restless, high-pitched, uncontrolled life, that the better class of Chinese complain of the noise, and most foreigners would find them impossible places of residence.

[Pg 57]

THE LURE OF THE SHOPS

ONCE upon a time an American missionary came to China with ten pairs of boots, enough to last till the period of furlough. As he was going into the interior it was doubtless a wise provision, although leather deteriorates rapidly during the “rainy season.” Until quite recently, foreigners living away from the coast depended for goods of foreign manufacture altogether on the home market. Now they are more and more sending to Shanghai for supplies, and people in Shanghai seldom send abroad for anything. A lover of London once remarked enthusiastically, “It is a storehouse of treasures, for what it does not possess in the original it has in casts.” So one may say of Shanghai, “What it doesn’t import it copies.” And the Chinese are wonderful adepts at copying. Take a woman’s tailor, for instance. Show him a picture in a fashion book (many of them subscribe themselves for fashion books), and he will evolve something, which if not an exact reproduction, comes incredibly near it. Shanghai has four foreign department stores, all on Nanking Road, and all under English management. They are especially popular with the women. Then there are numerous lesser lights, of[Pg 58] various nationalities, most of them located on or near Nanking Road, though Broadway has its share. An Anglo-American Walkover shoe store is a boon, especially to resident Yankees. Several Parisian shops display behind plate glass, the latest designs in gowns, hats and fine lingerie. A German drug store enjoys the reputation of being the only place in town where Parke, Davis & Co.’s drugs can be bought, while an English chemist’s shop is much frequented in summer for its ice-cream sodas, a recent innovation in Shanghai. Bianchi’s ice-cream is famous, and so are Sullivan’s home-made candies. At many a counter may be purchased Huyler’s and Cadbury’s chocolates, so carefully packed that they are not a whit the worse for their journey across the briny deep. Two piano stores do a lucrative business keeping pianos in tune, and selling, besides Steinways, Chickerings, and other makes, instruments made in their factories with special reference to withstanding the climate of China. The East Indian and Japanese shops always attract, except when the Japanese are boycotted by the Chinese because of strained relations. Some Japanese began recently to fold their tents, like the Arab, and prepare to creep quietly away, when confidence was partially restored and trade revived.

SOME SHOPS ON NANKING ROAD

Living in Shanghai is proverbially high, yet it is chiefly so in comparison with other parts of China. The market is good the year around; many competent judges assert it is the best in the world. Chinese mutton and beef sell for eight or nine cents a pound. Pork and veal are a trifle more. Game is plentiful. Eggs [Pg 59]rarely go above ten cents a dozen. They are considerably smaller though than hen’s eggs at home. Fish, as might be expected, is abundant. A small variety of oyster, that makes excellent stew, is sold in bulk, and a large oyster in the shell, measuring often several inches across and weighing over a pound, brings ten or twelve coppers apiece, about six cents. Nearly every variety of fruit and vegetable known to the Western market, and many kinds peculiar to the Orient, are found here. Bamboo sprouts and water chestnuts are favorites with most foreigners as well as the Chinese. Grapefruit is imported from San Francisco, but is generally not so well liked as the native pumelo, which it resembles. Mangoes are shipped from the Philippines, and from Japan, Australia, and America come apples, much superior to those grown in China. On the other hand Chinese oranges, and particularly the loose-skinned, Mandarin oranges, are delicious. The fruit most common in the autumn is the golden-red persimmon. Cheap and luscious, without a suggestion of pucker except when under-ripe, the tempting piles, that seem to have caught and held the sunshine, are without a rival during their season. All canned and bottled goods—vegetables, fruits, pickles, olives, syrups, extracts—being imported, are expensive, but as they are more or less in the line of luxuries most of them may be dispensed with if necessary.

There is a canning factory in Shanghai, opened in 1907 by a Cantonese company. One would expect it to be Cantonese, for the southerners are the most wide-awake people in China. Besides making a variety of[Pg 60] crackers, the factory turns out quantities of tinned foods. Among them are bamboo sprouts, shrimps’ eggs, spiced roast pork, chicken with chestnuts, frogs’ legs, native and foreign fruits, soups, and what appeals particularly to the palate of foreigners, the delicious candied ginger, for which Canton has a world-wide reputation.

Drugs are costly, and constantly needed articles, such as picture wire, and hooks, are for some reason absurdly highpriced.

“Sam Joe” on Broadway claims to be the leading Chinese grocer in the city. He is certainly one of the best known. Like other grocers he keeps no fresh vegetables and no fresh fruits except apples and lemons. His place is clean and inviting, and presided over by numerous clerks of low and high degree. Any one of these middle-aged men, of dignified mien and scholarly cast of countenance, will kindly deign to take an order, discuss the merit of goods, and even point them out if within sight. But when a piece of cheese is to be wrapped up, or a bottle taken down from the shelf, he waves his long-finger-nailed hand in a lordly manner to an underling, who hastens to perform the menial service. Sam Joe used to own an automobile, with “Sam Joe, Shanghai’s leading grocer,” prominent in large gilt letters on its back. It was a familiar object for some time on the streets, but its upkeep proved too great an expense, so the firm has reverted to the ordinary delivery wagon and horse. Still, a horse-drawn wagon is extraordinary enough in this city of man labor, and Sam Joe’s outfit is in advance of most Chinese grocers,[Pg 61] who content themselves with box carts propelled by tricycles.