Title: Of the making of a book

a few technical suggestions intended to serve as aids to authors

Compiler: D. Appleton and Company

Release date: January 25, 2026 [eBook #77776]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1904

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/77776

Credits: deaurider, Terry Jeffress, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

[i]

I

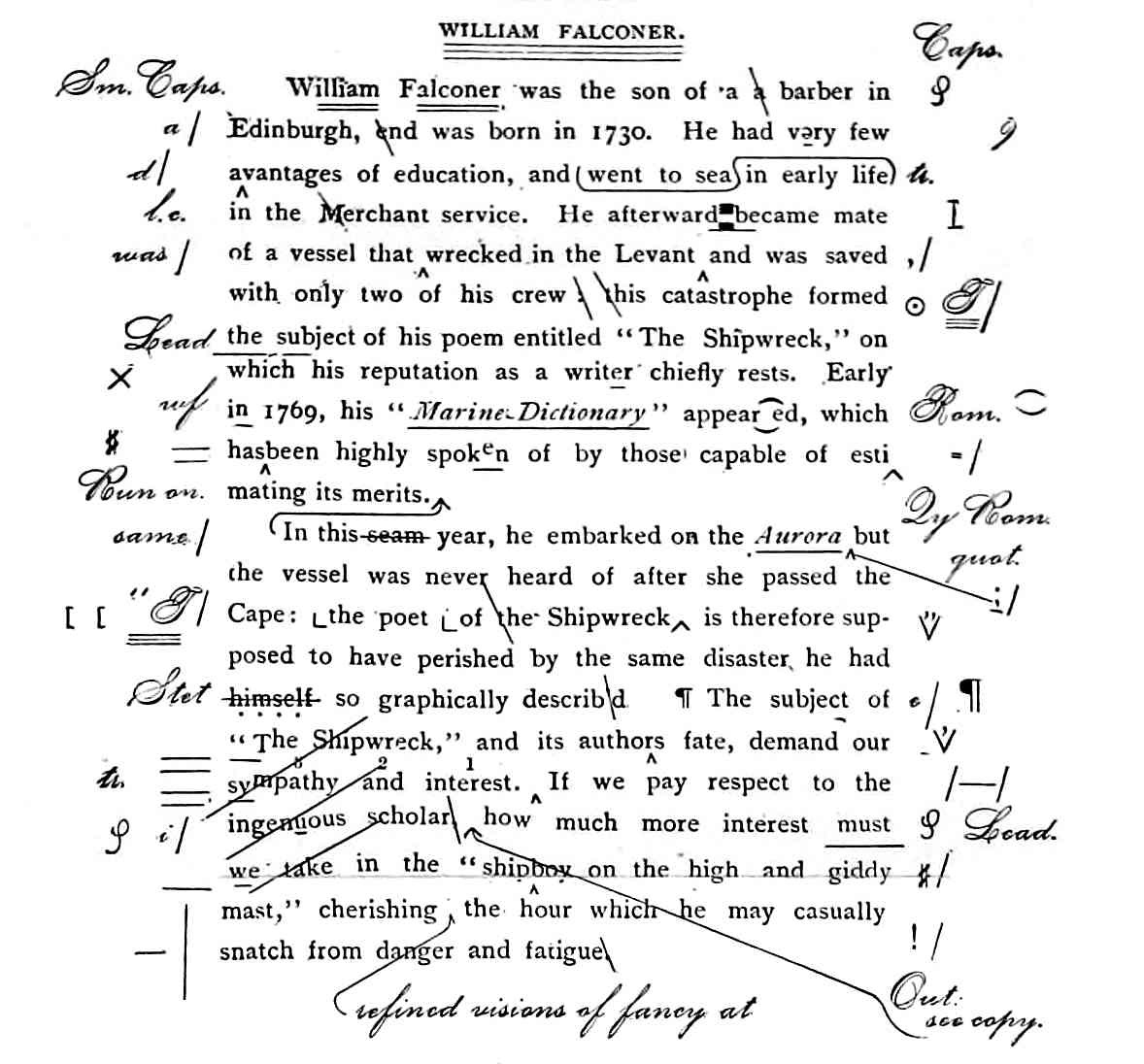

SPECIMEN PROOF SHEET

SHOWING MARKS USED IN PROOF-READING.

[v]

II

SPECIMEN PROOF SHEET

SHOWING THE SAME PAGE AS AFTERWARDS CORRECTED

IN THE TYPE.

WILLIAM FALCONER.

William Falconer was the son of a barber in Edinburgh, and was born in 1730. He had very few advantages of education, and in early life went to sea in the merchant service. He afterward became mate of a vessel that was wrecked in the Levant, and was saved with only two of his crew. This catastrophe formed the subject of his poem entitled “The Shipwreck,” on which his reputation as a writer chiefly rests. Early in 1769, his “Marine Dictionary” appeared, which has been highly spoken of by those capable of estimating its merits. In this same year, he embarked on the “Aurora”; but the vessel was never heard of after she passed the Cape: the poet of “The Shipwreck” is therefore supposed to have perished by the same disaster he had himself so graphically described.

The subject of “The Shipwreck,” and its author’s fate, demand our interest and sympathy.—If we pay respect to the ingenious scholar who compiled the “Marine Dictionary,” how much more interest must we take in the “ship boy on the high and giddy mast,” cherishing refined visions of fancy at the hour which he may casually snatch from danger and fatigue!

[vi]

OF THE

MAKING OF A BOOK

A FEW TECHNICAL SUGGESTIONS

INTENDED TO SERVE AS

AIDS TO AUTHORS

Julius Cæsar, Act IV, Scene iii.

COMPILED BY THE LITERARY DEPARTMENT OF

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

436 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK

1904

[vii]

Copyright, 1904, by

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

[viii]

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| I. | Apologia | 1 |

| II. | Of the Manuscript | 7 |

| III. | Of Composition and the Proofs | 19 |

| IV. | Of the Proof-Reading | 27 |

| V. | Of the Illustrations | 37 |

| VI. | Of Publicity | 47 |

| Index | 53 |

These suggestions were undertaken in the hope that they would not prove to be a work of supererogation. In some instances these anticipations, in the nature of things, will be disappointed. There are authors whose care and precision, in the preparation of their manuscripts, and the reading of their proofs, may put to shame the work of editors and printers. As help to such as these, the book is not intended. It is merely hoped that it may interest them, and that they, perhaps, will see how it might have been made better.

The art of printing is so largely a mechanical art, with fixed restrictions as to what can and what can not be [4]done within a given space of type, that even the experienced writer will sometimes find himself confronted with results that had not occurred to him as possible. Perhaps there never yet was made a book in which authors’ errors did not exist, as, indeed, it is probable that there never existed one which was absolutely correct as to its type. Eternal vigilance is as clearly the price of correct book-making as of liberty. For these reasons the experienced author may be able to appreciate the motives which have prompted these hints.

To authors who are strangers to the details of type-setting and “make-up,” perhaps no apology for the intrusion will be necessary. It comes constantly within the experience of publishers to be asked for information about these matters, and while it is a pleasure always to give it, a brief conversation or a few letters often fail, [5]on the one hand to make the point clear, and on the other to cover the necessary ground.

Within these pages an attempt has been made to set forth the essential points briefly and yet with some comprehensiveness. The experience of many years and of many persons has been drawn upon and recognized authorities have been consulted. Those who have had a share in the compilation understand how important these points are—how common it is for the experienced author to neglect them, and how they themselves are seldom wholly guiltless of infractions of the rules.

F. W. H.

Manuscripts should be submitted either in typewriting or in handwriting that is perfectly legible. Black ink should be used. The paper should be white, of medium weight, and uniform in size. The number of words written on each page should be approximately the same. Small sheets are to be preferred, 8 ✕ 10 being the best size. There should be half an inch of space between the lines, whether the manuscript be written by hand or on a typewriter, and the writing should be on one side of the sheet only. Liberal margins should be left both at the top and at the left-hand side. Typewritten manuscripts are always best. Probably [10] three-fourths of the manuscripts now submitted to publishers are typewritten.

The pages should be numbered consecutively to the end of the book, not separately by chapters. Inserted pages, following for example page 25, should be numbered as 25a, 25b, 25c, etc. Pages that have been taken out should likewise be accounted for. If pages 25, 26, 27, and 28 have been eliminated, sheet 24 should be numbered “24–28.” Additions at special places on the original pages, intended as insertions, should be written on separate sheets, placed with the pages in which they are to be inserted, and the place of insertion indicated thus: “Here insert A,” or “Here insert B,” the new pages being marked “A matter,” or “B matter.”

When one piece of a page is to be joined to another, pins should not be used, but mucilage. Pieces of paper [11]pinned together are in danger of being separated, and thus may easily be lost or may get hopelessly disarranged.

The manuscript should never have the sheets fastened to one another at the top or side, except by means of clips, which are easily removable. If they are sewn together, or fastened with eyelets, the printers in separating the sheets will mutilate them and often injure them seriously. This point will be understood by those who know that each printer puts into type only a part of the manuscript, and sometimes only a few pages.

Paragraphs should be carefully indicated by indenting the first line about one-half inch, or by a ¶ mark; otherwise it will be difficult for the printers to determine satisfactorily the intentions of the author in regard to them. Should the printer’s arrangement, as shown when the [12]proofs arrive, be found unsatisfactory, an alteration must be charged as the author’s. Paragraphs should occur frequently. Ordinarily not more than 200, or at most 300, words should appear in one paragraph.

Punctuation marks should also be carefully made; failures to indicate them systematically are constant sources of error.

A book containing 80,000 words should have at least ten chapters. Fifteen would seldom be too many. The number might even be twenty. In a history or biography, or in any work of a serious kind, these subdivisions help materially to open up the text, showing the reader on a hasty examination something of the contents.

Each chapter should be provided with a title of its own. This applies to fiction as well as to other books. When the volume is printed, the chapter [13]titles will appear reproduced at the top of each right-hand page, with the title of the book at the top of each left-hand page. This will materially assist the reader in examining the book. Historical and biographical works should have date-lines accompanying each chapter title.

Quotation marks should always be carefully indicated, showing where the quoted passage begins and where it ends.

Foot-notes should be clearly designated. A systematic method should be employed to distinguish them from the text. Some authors separate text and notes by heavy lines across the page, which is a good method. The word “foot-note” should be written on this matter, and it should be supplied with an asterisk (*), a corresponding asterisk (*) appearing in the text, or with a figure 1. In a new book foot-notes should be used sparingly. [14]Whenever possible the information should be incorporated in the text. When the information consists of citations or references, however, it often can not go anywhere else than in foot-notes.

The utmost care should be taken to write proper names, figures, foreign words and phrases plainly and in full. Abbreviations and signs, such as MS., etc., Fig., and the like, should not be used in a purely literary work, but are admissible in text-books, cyclopedias, and other condensed and utilitarian writings.

Until reminded of delay authors sometimes fail to supply essential portions of their manuscripts, such as title-pages, prefaces, tables of contents, lists of illustrations, and indexes when necessary. These items are important parts of a book, and all, except the index, should be delivered with the manuscript.

[15]

The index of a book should not be furnished on cards or slips, but on sheets of the same size as the paper used for the manuscript of the text. The cards, or slips, used in making the index can, however, be pasted on sheets, and delivered in that form. Technical books should be indexed as fully as possible, and cross-references should be made. For example, in a medical book “abscess of the cornea” should appear both under “Abscess, of the cornea” and under “Corneal abscess.”

The index is usually made from the page-proofs. It is desirable to have the manuscript of the index ready for the printers at the earliest moment, so that the printing may not be delayed. But in case serious corrections have been made on the page-proofs, resulting in any change in the page numbers, the index should, without fail, be verified later from [16]the foundry-proofs which show the pages as they will appear when printed.

Whenever the plan of a book calls for two kinds of type, a larger kind for the main text, and a smaller for quoted passages (or for other matter less important than the main text), the manuscript should have the two kinds clearly distinguished from one another. This is best done by drawing a vertical line alongside the quoted passages with the words “smaller type” written on the line.

Technical books, which require many heads and subheads, should have the character of the heads indicated: main heads, by three lines underneath them; subheads, by a double line, and side-heads (composed of the first words of a paragraph) by a wavy line.

In indicating capital, small capital, and italic words, one line underscored [17]means italics; two lines mean small capitals, and three lines capitals.

In submitting a manuscript to a publishing house, with a view to an opinion as to its availability, an author should send a brief but precise summary of its scope and purposes. This will facilitate an examination of the manuscript by the publishers’ “readers,” and thus hasten the decision for which the author waits.

Let it be urged that the manuscript be delivered in final and complete form just as the author wishes it printed. To correct manuscript requires merely the stroke of a pen; while to correct type is laborious and expensive. The cost of authors’ corrections in the proofs could be avoided entirely if the original manuscript were made absolutely correct. It should be gone over with great care before it is forwarded to the publishers. Especially should typewriters’ errors as to punctuation [18]and the use of capitals be corrected.

The type-setter works “by the piece”; his wages depend upon the amount of work he can perform, and this amount depends directly upon the legibility and systematic arrangement of the manuscript.

Manuscripts should never be rolled or folded, but placed flat, in a box or between boards. They should be sent by express. The charge is usually less than if sent by mail, and the package can be more easily traced in case it is lost in transit.

After the author has read his galley-proofs, he should in all cases return his manuscript to the printer, so that the proof-reader may be able to refer to it in deciding any question in dispute in the final reading.

[19]

When the composition (which means type-setting, whether by hand or by machine) has been begun, the lines of type are laid by the printer in a long, narrow, shallow receptacle of metal known as a galley. Type enough to make three or four pages of a book can be placed on one of these galleys. The first proof is taken from this type, and hence is known as a galley-proof. After several galleys have been filled with type (usually ten or twenty), proofs of the matter are taken and read by proof-readers, and the type-setters’ errors corrected; then new galley-proofs, with the manuscript, are sent to the [22]author, who is expected to read, correct, and return these proofs with the manuscript. Meanwhile, the composition is continued by the printers, proofs are again read and corrected, and another set of ten or more galley-proofs is sent to the author.

On receipt by the printers of the galley-proofs from the author, with his corrections marked on them (these proofs now taking the name of “foul proofs”), the corrections are made in the type, still standing in the galley, and new proofs are then taken. The new proofs are known as “revised proofs,” or “revises,” to distinguish them from the first galley-proofs. The “revises” are not sent to the author unless especially requested. But the proof-readers go carefully over them to see that all changes have been accurately made in the type.

The type is now ready to be made up into pages. A given number of [23]type-lines on the galley are measured off, lifted out, and placed on a table. The page-heading is then set and added at the top, with a figure at the end, or at the bottom of the page, to denote the page number. These pages of type are tied together with twine to hold them fast and proofs are taken. These are known as “page-proofs,” and are supposed to contain no errors. Lest there should have been some slip by the author in his first reading, or by the compositor in making the author’s changes, the page-proofs are sent to the author, together with the foul proofs, in order that the author may see if his corrections and changes have all been properly made.

The type-pages are then ready for casting at the foundry. An electrotype plate for each page is made, this plate being a solid piece of metal. Meanwhile the type is sent back to [24]the composing-room and distributed in its original cases, or melted up, because the book is to be printed from the plates and not from the type. Proofs, however, had been taken from the type-pages just before the plates were made. These are known as “plate-proofs,” or “foundry-proofs,” and a set of them is usually sent to the author. In technical books a careful reading of these final proofs should take place. Any errors should be reported without delay, as the book is usually printed as soon as these plates are ready. An author can not be too prompt at this point.

Foundry-proofs are distinguished from others by a heavy, black rule around the page made by ink from the pieces of metal, known as “guards,” which are placed about the type to hold it fast while the cast is taken, these pieces of metal having taken the place of the twine.

[25]

Nearly all proofs are taken on wet paper from a hand-press, which prevents the letters from looking clean and sharp. The same is true of the proofs of illustrations taken by the printers. But if the proofs of illustrations be engravers’ proofs, they show the illustrations about as they will appear in the book.

When the proofs first reach the author, they are supposed to conform accurately to the manuscript as the author has furnished it. The compositor has completed his part of the work up to that point. Proofs, both galley and page, are sent to the author in duplicate, the galley-proofs being accompanied by the manuscript. The author should make all his corrections on the set having a memorandum stamped in red, and return them, with the manuscript, to the publisher. The duplicate set of proofs should be retained by him for purposes of reference, or for use in case the originals should be lost. The author ought to transfer to his duplicate set the changes he has made [30]on the set he sends back to the printers. All proofs stamped in red must go back to the printers—galley, page, and foundry proofs.

A clause in the contract between the author and the publishers provides that the publishers shall pay only a fixed percentage of the cost of the author’s proof corrections, this percentage being reckoned on the original cost of the composition and electrotype plates. For example, in a book of 400 pages, which costs for composition and plates $400, there would be an allowance to the author of $40 for corrections, if the percentage were 10 per cent, or $60 in case the percentage were 15 per cent. When authors get their first royalty statements, they often fail to understand why this sum was exceeded, especially if they are not acquainted with the details of type-setting and electrotyping.

[31]

To add a single word in the proofs, if the word be of different length from the excluded word, may involve the resetting of several lines; while, to add a single word after the plate has been made, may sometimes cost as much as the original composition and plate of an entire page. In type set by machine, the changing of a single letter or punctuation mark requires the resetting of the entire line.

To insure the least cost, all author’s corrections should be made on the first galley-proofs. Corrections in galley-proofs can be minimized with a little care. When confined to the occasional substitution of one word or of several words of about the same length, the cost is usually small. But the cancellation or addition of half a line will require an overrunning of type from that point to the end of the paragraph, which may mean the space of a page, or even more if the [32]paragraph is a long one. If several other changes should be made in the same paragraph, it would be found easier to reset the entire paragraph, doubling the cost. A galley-proof sometimes contains so many corrections that the entire galley must be reset.

An author should never make alterations on a page-proof, if he can avoid doing so. In the galleys there is flexibility for additions and subtractions, but in the pages the mass of type is fixed accurately to the line. When an author makes a change in a page-proof, it should be remembered that if several words or a sentence are added, it may be necessary for the printers practically to reset every line on that page, and possibly to overrun all pages to the end of the chapter. Should the pages contain cuts, this difficulty will become still greater, so that it might be less costly [33]to reset the entire page, or even more. Corrections in page-proofs, therefore, when made at all, should, if possible, be limited to the space of the page, the matter taken out and the new matter put in containing the same number of letters.

When the author’s page-proofs and foul proofs have been returned to the printers, any new corrections indicated by the author are made in the type. A proof-reader again reads the pages over, to make it certain that the first proof-reader and the author have not overlooked any errors. This is called foundry-reading. Should the foundry-reader detect any errors due to the author’s oversight in going over his proofs, he either corrects the error or returns the page on which it occurs for the author to answer the query or approve of the correction.

On all proofs the abbreviation [34]“Qy.” for “query,” or a question mark (?), should always be answered. Such memoranda indicate that a question has arisen with the printers, as to a statement made or an apparent inconsistency, and the author alone can answer it.

After the plates have been cast, corrections are sometimes asked for which might have been made in the galley-proofs or in the original manuscript. Corrections in plates are very difficult and always costly. Only the simplest changes can be made without resetting and recasting.

Letters about corrections should not be sent direct to the publishers unless it should have been found impossible to make the corrections on the proofs themselves. The publishers’ office and the printers’ place of work are usually in different parts of a town, if not in different towns, or different States.

[35]

If corrections are to be made for a new edition of a book, the author should ask the publisher to send a set of sheets on which to mark the corrections. By this means accuracy will be best secured.

Let it be repeated that all proofs should be returned promptly. The holding back of proofs delays publication. Pages can not be made up until the return of galley-proofs in consecutive order. If there are serious delays, the publishers may not be able to issue the book at the proper season, or at the propitious time. The loss thus incurred will fall on the author as well as the publisher.

Authors unfamiliar with the technical marks used in correcting proofs are referred to the frontispiece of this book, where is given a specimen of a corrected proof-sheet, showing the markings most commonly used. Along with it may be seen the same [36]page of matter printed from type as corrected according to the markings.

The author sometimes asks if all the changes marked on his proofs are made at his expense. The answer is that only the corrections which he himself makes, or authorizes to be made, are charged to him.

When two or more persons read the proofs, one set only—that having the printers’ red stamp on it—embodying all the corrections, should be returned to the publishers.

[37]

Material and instructions for the illustrations should be furnished to the publishers apart from the manuscript, as the former, known as “engraver’s copy,” is used by the engraver, while the latter, “printer’s copy,” is used only by the printers. If the two kinds of copy are furnished in one mass, they must be separated by the publishers. It is not necessary that the places for the illustrations be indicated on the margins of the manuscript. The place for such instructions is on the margin of the galley-proofs.

Drawings, prints, and unmounted photographs should not be folded or rolled, but furnished flat. Valuable [40]books, from which cuts are to be copied, should be covered with Manila paper, in order to avoid soiling them by handling in the various departments of an engraving establishment. Cuts to be reproduced from books should be described in written lists, not indicated by slips of paper inserted between leaves. Such slips, if dropped out by accident, can not always be properly replaced.

Relief cuts, whether engraved in line or in stipple, can be printed on ordinary book paper, but those made by the half-tone process require a coated paper, which, being less flexible in the binding and more expensive, is not used except for books containing a large number of half-tone plates of varying sizes—some full page, some set into the text.

For a book containing no half-tones, one class of paper, never coated or calendered, is used throughout. [41]But in a book to be illustrated with half-tones in addition to the line cuts, two kinds must be used—the ordinary and the coated. In such cases it is desirable that the number of half-tones shall be limited to 4 or 8 or to multiples of 4 or 8. They must each be made of the uniform size of a full page of the book, so that they can be separately printed on the coated paper. Such illustrations are pasted in by the bookbinder and are called insets. Insets add materially to the expense of binding. If the half-tones are very numerous, it may be found best, as a matter of economy, to print the entire book on a coated paper. Coated paper, however, makes a heavy book and is not flexible.

Illustrations in colors are usually given as full-page insets; a separate printing being required for each color.

[42]

When the number of illustrations, their size and style of treatment, have been decided upon, the photographs, or drawings, are put into the engraver’s hands. When the plates have been made, proofs are sent to the author in duplicate, as are galley and page proofs of the text. One set is for the author’s use in attaching them at the proper places in the galley-proofs, the other is to be kept by him. A proof of each cut should be carefully pasted on the margin of the galley-proof, showing where it is to be inserted. Its title should be given, and if the cuts are to be numbered as “figures,” the number should be accurately written at the bottom of the cut. The printer will then place the cut at the place in the page most convenient to the one indicated by the author. The author should carefully examine the cuts and titles on receipt of the page-proof.

[43]

It is not sufficient to write on the galley-proof the words “insert cut” or “insert portrait” or “cuts already made,” etc. As stated before, a proof of the cut itself must be placed there. Among hundreds of cuts constantly on hand for “make-up” at the office of the publishers, there are frequently many which are similar in their general appearance but quite different in the purposes for which they are intended. For example, there may be several pictures of the same object, but each different from the other in size and style of engraving. The printer, it should be remembered, has no certain means of identifying the cut, except by its proof, as furnished by the author.

Galley-proofs requiring the insertion of cuts for which engraver’s proofs have not reached the author, should be held until the cuts arrive. A notification to the publishers that a [44]certain galley is ready to be returned, but requires the proof of a certain cut, will hasten the matter. If galleys requiring cuts are inadvertently returned without proofs of the cuts, the make-up of pages may go forward beyond the point where the cut should have been inserted. The cost of insertion afterward will in consequence be largely increased and may even be prohibitory. When such an omission is discovered, the make-up may be stopped in time if prompt notification reaches the publishers.

In the case of insets, however, such an omission would make no difference, these directions applying only to such cuts as are printed with the text.

The cost of authors’ alterations in a book in which there are cuts in the text is generally greater than in one without them, as the changes in the pages frequently cause resetting in [45]order that the lines may be rearranged about the cuts.

When an illustration has been taken from another book, credit should be given, in a line printed just under the illustration itself at the right-hand side, permission being first secured from the author and the publishers of the book from which it is taken. In the list of illustrations printed in the front of the book, it is not necessary to repeat the credit.

After the manuscript of a book has been accepted, the author should send to the publishers a description of the book, comprising two or three hundred words. This should outline its scope and contents. The author may also send a brief sketch of his life and work and his portrait in photograph. The photograph should be a “silver print,” not a soft-toned carbon or platinum print, from which good half-tones can not be made. A negative, however, is even better, because from it as many prints may be made as are wanted.

The selection of the size of the book, the style of the type page, the kind of paper and style of binding, [50]is usually left to the publishers, who in these matters are guided by the tastes of book-buyers and by the cost. The form of the book is a part of the publishers’ contribution to its salability. Suggestions from authors, however, are of great assistance, particularly as to illustrations and cover design.

The author can often point out to the publisher legitimate ways by which the interests of the book may be advanced. He can make suggestions as to sending out copies to reviewers by giving the names of those from whom the book is likely to secure attention. The names of teachers who might be interested in educational works would also be of value. Lists of various organizations, such as clubs and societies, whose members ought to know that the book has been published, might be supplied. These efforts should aim to place in the hands of [51]all such persons the information which they might desire to have in connection with their work or which might relate to their personal interests. Accurate and definite information alone should be given, laudation being carefully avoided.

The publishers are always ready to co-operate with the author in these matters. The two have virtually entered into a partnership in a book, and the interests of the one should be the interests of the other.