Title: Duval's artistic anatomy

Completely revised with additional original illustrations

Author: Mathias Duval

Editor: Andrew Melville Paterson

Release date: January 20, 2026 [eBook #77743]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1905

Credits: Tim Lindell, Karin Spence and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Completely Revised with additional Original Illustrations.

Edited and Amplified by

A. MELVILLE PATERSON, M.D.

LATE DERBY PROFESSOR OF ANATOMY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF LIVERPOOL

FUNK & WAGNALLS COMPANY

New York and London

First published September 1884

Reprinted 1885, 1888, 1890, 1891, 1892, 1894, 1896, 1898, 1899, 1901, 1903, 1904

Revised and Enlarged Edition 1905. Reprinted 1907, 1911, 1914, 1916, 1919

[v]

Few words of preface are needed here. The preface of the original edition still holds good, and sufficiently defines the aims and scope of the book. The first object aimed at is to facilitate the study of artistic anatomy by the demonstration of the meaning of the appearances presented by the various parts of the body. Incidentally it is hoped that through close study the powers of observation will be quickened. By a simple narration of the structure of the body and its mechanism, particularly in relation to surface forms, it is hoped that the student of art may correctly and intelligently appreciate the why and wherefore of the parts which he is called upon to paint or model.

One would reiterate and emphasise the necessity of two additional aids to this end. In his studies the student should have and use the opportunity of seeing and handling the separate bones and also an articulated skeleton; and where possible, he should have access to a fully equipped anatomical museum. He should further take advantage of all means of studying on the living model—on himself, on other[vi] models—and in casts, the movements, attitudes, and gestures of the body, and the resulting surface forms. By these two studies it becomes possible to correlate properly the superficial appearances with the deeper structures, such as bones, joints, and muscles, which are mainly responsible for the characteristic features presented in the living state.

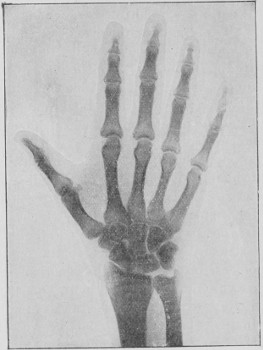

I have to express my indebtedness to my friend Dr. Thurstan Holland for the radiograph (Fig. 25, p. 80) specially prepared by him for this work; and to the publisher of Cunningham’s Text Book of Anatomy for permission to use the figure (p. 315) of the muscles of expression.

A. M. P.

Liverpool, July, 1905.

[vii]

This little work is an epitome of a course of lectures which for about ten years I had the honour of delivering at the École des Beaux-Arts. If during that time I have arrived at a right understanding of the teachings of anatomy, I owe it to the great interest taken in the subject by my listeners of all ages; and my first duty is to thank them for their free interchange of ideas with me, thus enabling me to understand their requirements and the mode of satisfying them. But if the mode of exposition I have adopted is to be rendered clear to a constantly renewed audience, I must, in publishing this work, first explain to the reader how the lectures are to be used, and the principles which guided me in their production.

This summary of anatomy is intended for those artists who, having commenced their special studies, have drawn the human form either from the antique or from the living model—who, in a word, have already what may be termed a general idea of forms, attitudes, and movements. It is intended to furnish them with a scientific notion of those forms,[viii] attitudes, and movements. Thus it is far less a description of the forms of a particular region than the anatomical explanation of those forms, and of their modifications in a state of repose or movement, that we have in view. That is why, instead of proceeding from the surface to the deeper organs and to the skeleton, we take the latter as the starting-point of our studies. In this way alone can we determine the laws which govern the movements of the adjacent segments of the limbs upon each other, and the movements of the limbs with regard to the trunk, as also the reciprocal action of these segments towards each other and in relation to the whole body.

When to these fundamental notions is added a knowledge of the muscular masses which move these bones, the artist will at once be enabled to analyse through the skin, as through a transparent veil, the action of the parts which produce the various forms with their infinite variety of character and movement.

This method of teaching, which may be said to proceed by synthesis, differs from that followed by the generality of works on this subject—books which treat by analysis. We make special allusion to the treatise of Gerdy,[1] which is about the most careful work on plastic anatomy yet published, but which[ix] errs in a somewhat too lengthy description of external form, whilst sufficient space is not devoted to explaining the anatomical reasons of those forms. On the other hand, the remaining anatomical works in the hands of the students in our art schools generally comprise a volume of text and an illustrated atlas.[2] Under these conditions, may I be allowed to remark, somewhat severely, it may be, that our young artists study the atlas by copying and re-copying the plates, but do not read the text? Thus it will be understood why, in this work, a different method has been pursued; and the fact of the plates being intermixed with the text, and in such a way that they cannot well be understood without the aid of the accompanying pages, will in all probability result in the student thoroughly and carefully perusing the text.

Passing on to the manner of using the present work, we must acknowledge that reading anatomical details is at first dry; it will always be so, unless proceeded with in a simple and systematic manner. In the oral courses, the lecturer, handling the objects, and aided by his improvised drawings on the blackboard, can make the most complex parts interesting; and by adroit repetitions and varied illustrations, fix the attention and render the subject[x] comprehensible, whereas it is quite different in a written description. In this case it is the reader who must animate the text for himself by examining and manipulating the parts needful for the elucidation of the descriptions. For this purpose a skeleton and a good plaster cast will suffice. On the cast, with the aid of the plates which accompany the text, it will be easy to follow the course of the muscles; and in this way alone will the study of them become profitable, the student being enabled to examine the model on different sides. By handling the bones, by placing the articulating surfaces in contact, the dry descriptions of the mechanism of the joints will take a tangible form, and will henceforth remain impressed on the memory. For example, notwithstanding our diagrams of the movements of pronation and supination, it is only by handling the bones of the forearm that the student will be enabled to fully appreciate the marvellous mechanism by which the rotation of the radius round the ulna is effected, allowing the hand to present alternately its palmar and dorsal surface; and the same is the case in regard to the skeleton of the foot and head, and the movements of the lower jaw, &c.

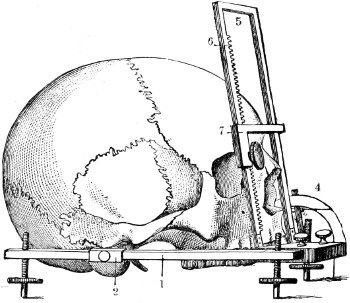

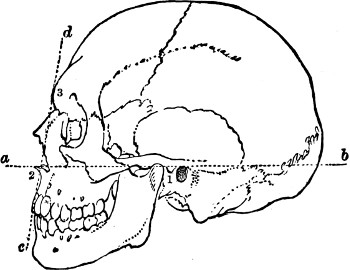

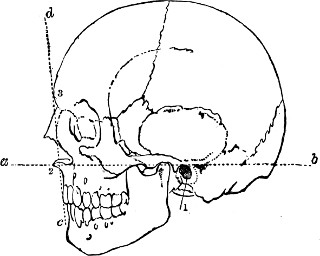

The artist will find in this book some pages devoted to the facial angle, to the forms of the head, brachycephalic and dolichocephalic heads, and[xi] to some other questions of anthropology, and will doubtless thank us for having considered here ideas which are daily becoming familiar to the general public.

Our only regret concerning these anthropological studies is that the limits of this volume did not permit us to go deeper into the teachings of the anthropological laboratory, the direction of which was confided to me after the loss of our illustrious master, Broca.

I take this opportunity of expressing my gratitude to my excellent master, Professor Sappey, who allowed me to borrow from his magnificent treatise on anatomy the figures on osteology and myology which constitute the chief merit of this work; and to my friend and colleague, E. Cuyer, whose skilful pencil reproduced the figures from the photographic atlas of Duchenne, as well as the two illustrations of the Gladiator, and the sundry diagrammatic drawings which complete the theoretical explanations of the text.

M. DUVAL.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Introduction to the Revised Edition | 1 |

| II. | Introduction.—Plastic Anatomy: Its History, Importance, and Objects—Order of these Studies—Division of Subject | 7 |

—THE SKELETON, ARTICULATIONS,

PROPORTIONS. —THE SKELETON, ARTICULATIONS,

PROPORTIONS.

|

||

| III. | Osteology and Arthrology in General—Nomenclature—Vertebral Column | 19 |

| IV. | Skeleton of the Trunk (Thorax)—Sternum—Ribs—Thorax as a Whole | 41 |

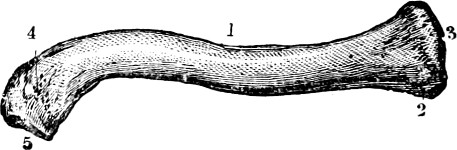

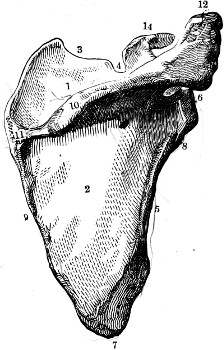

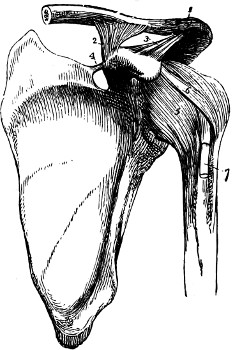

| V. | Skeleton of Shoulder—Clavicle—Scapula—Head of Humerus—Shoulder Joint | 55 |

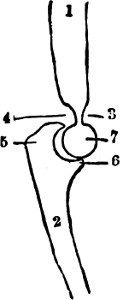

| VI. | Humerus and Elbow Joint | 67 |

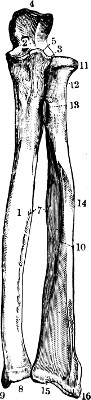

| VII. | Skeleton of Fore-Arm—Radius and Ulna—Movements of Pronation and Supination | 77 |

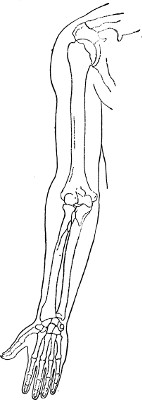

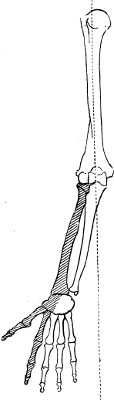

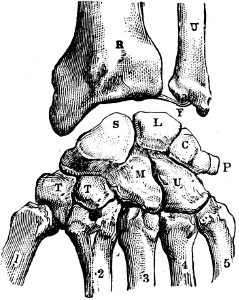

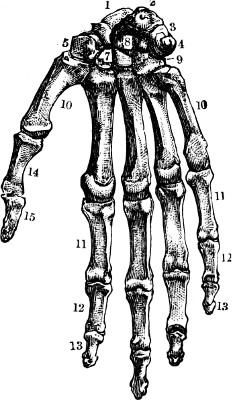

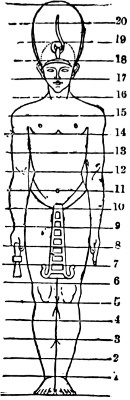

| VIII. | Skeleton of the Hand—Wrist (Carpus)—Hand and Fingers (Metacarpal Bones and Phalanges)—Proportions of the Upper Limb—Egyptian Canon—Brachial Index | 87 |

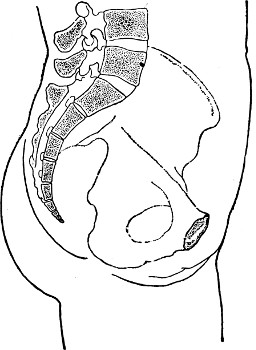

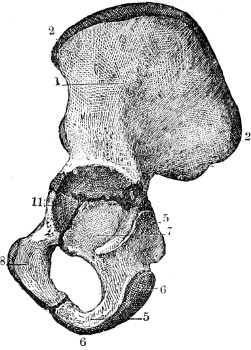

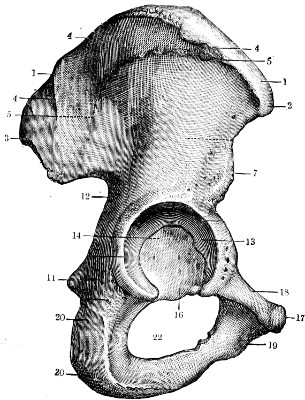

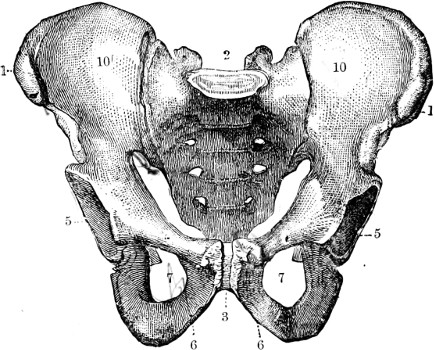

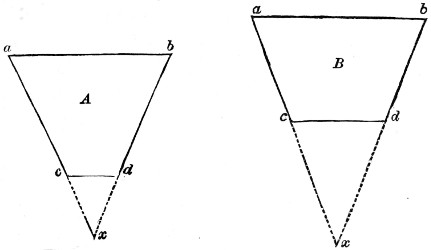

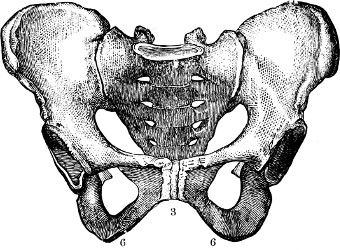

| IX. | Skeleton of the Hips—Pelvis (Iliac Bones and Sacrum)—The Pelvis according to Sex | 103 |

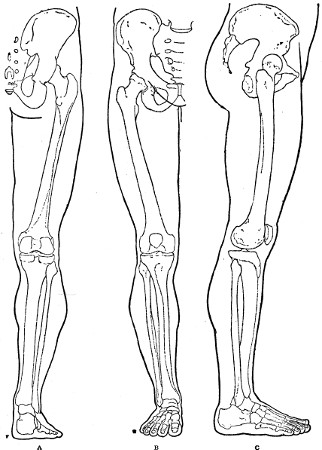

| X. | The Femur and the Articulations of the Hips—Proportions of the Hips and Shoulders | 116 |

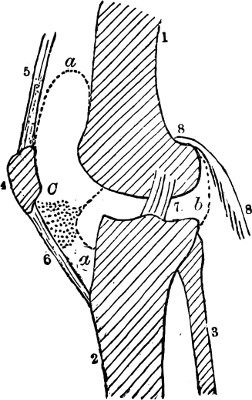

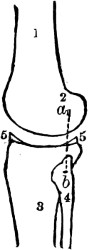

| XI. | The Femur and the Articulation of the Knee Joint; the Shape of the Region of the Knee | 131 |

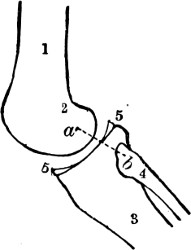

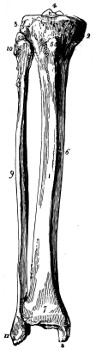

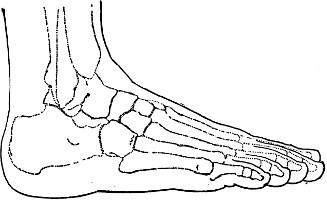

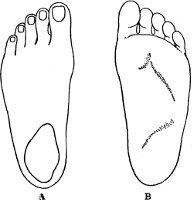

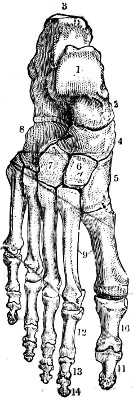

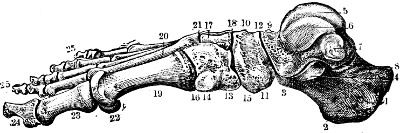

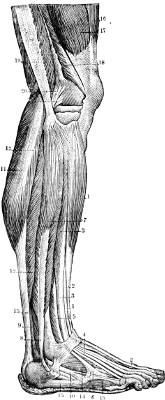

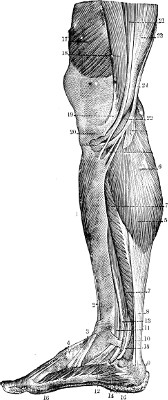

| XII. | Skeleton of the Leg: Tibia and Fibula, the Malleoli or Ankles—General View of the Skeleton of the Foot; Tibio-Tarsal Articulation | 146 |

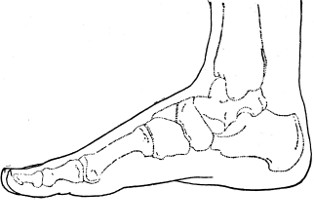

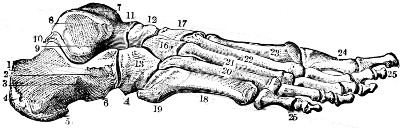

| XIII. | Skeleton of the Foot; Tarsus; Metatarsus; Toes and Fingers—Proportions of the Lower Limb—The Foot as a Common Measure | 155 |

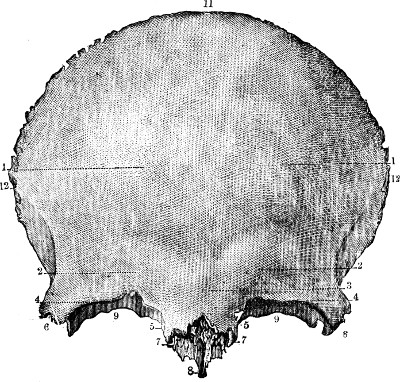

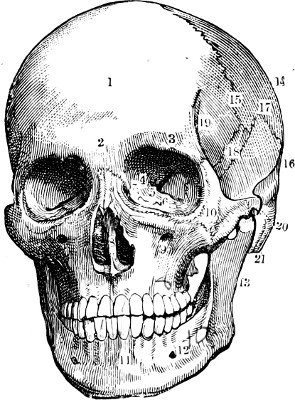

| XIV. | Skeleton of the Head: Skull (Occipital, Parietal, Frontal, Temporal Bones); Shapes of the Skull (Dolicocephalic and Brachycephalic Heads) | 164 |

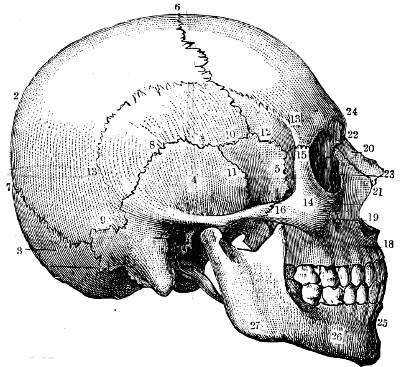

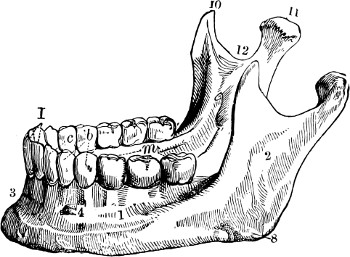

| XV. | Skeleton of the Face: The Orbital Cavities; Lower Jaw; Teeth; Facial Angle of Camper | 173 |

—MYOLOGY. —MYOLOGY.

|

||

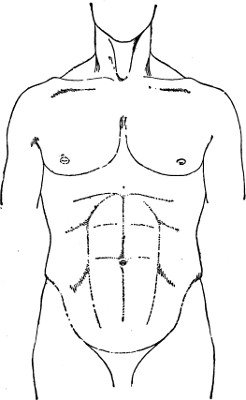

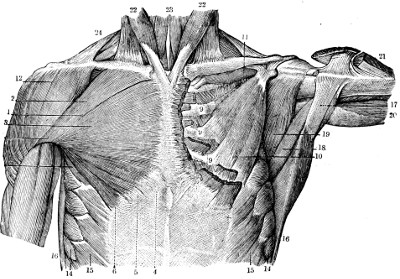

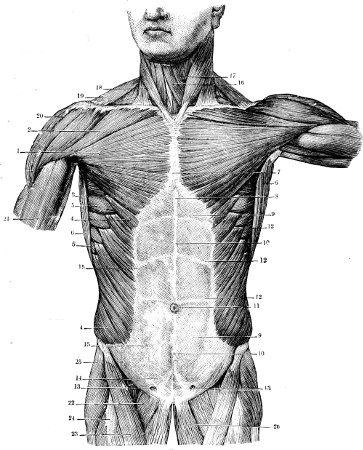

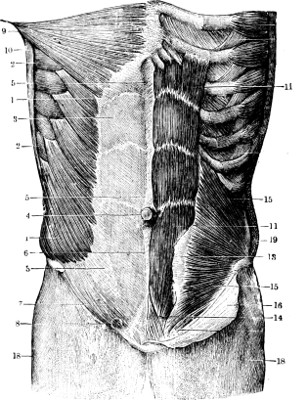

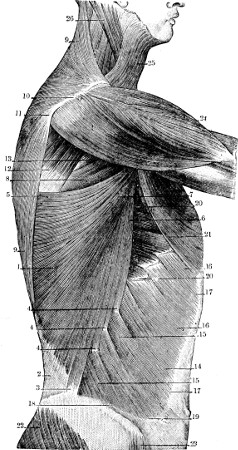

| XVI. | Of the Muscles in General—Muscles of the Trunk: Anterior Region (Pectoralis Major; the Oblique and Recti Muscles of the Abdomen) | 189 |

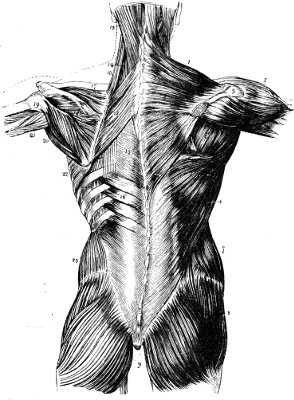

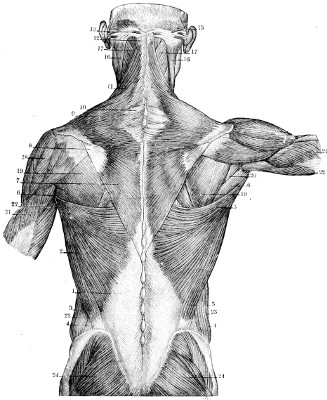

| XVII. | Muscles of the Back: Trapezius, Latissimus Dorsi, and Teres Major Muscles | 205 |

| XVIII. | Muscles of the Shoulder: Deltoid: Serratus Magnus; The Hollow and Shape of the Arm-pit | 215 |

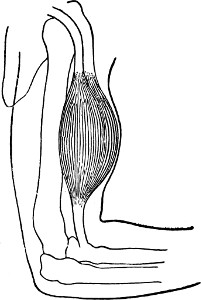

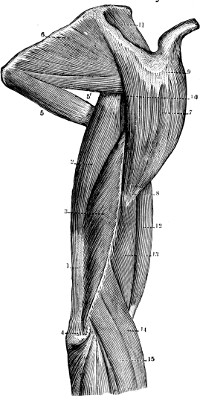

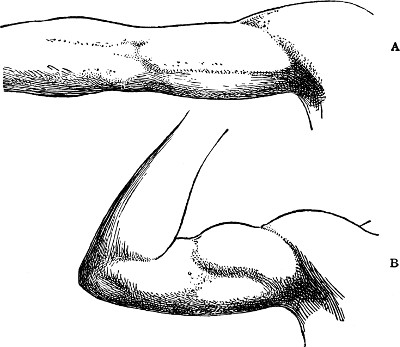

| XIX. | Muscles of the Arm: Biceps; Coraco-Brachialis: Brachialis Anticus; Triceps; Shape of the Arm | 224 |

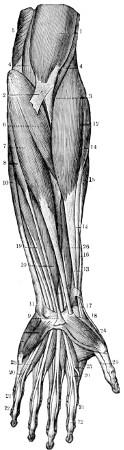

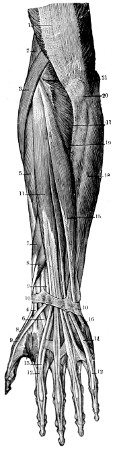

| XX. | Muscles of the Fore-Arm and Hand: The Anterior, External, and Posterior Superficial Muscles | 232 |

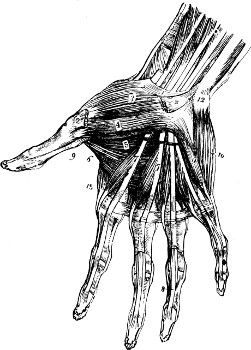

| XXI. | Muscles of the Fore-Arm and Hand (continued): The Deep Posterior Muscles of the Fore-Arm (Anatomical Snuff-Box); Muscles of the Hand | 244 |

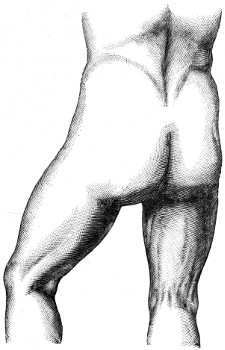

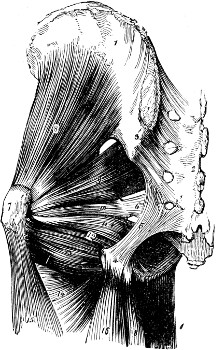

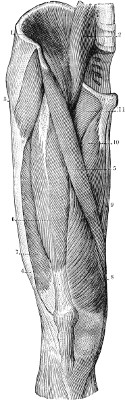

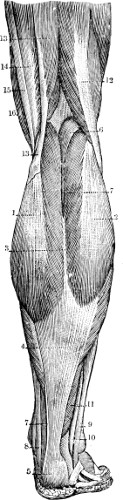

| XXII. | Muscles of the Pelvis; the Gluteal Muscles; Fascia Lata; Muscles of the Thigh; Sartorius, Quadriceps, Adductors, &c. | 252 |

| XXIII. | Muscles of the Leg; Tendo Achillis; Muscles of the Foot | 268 |

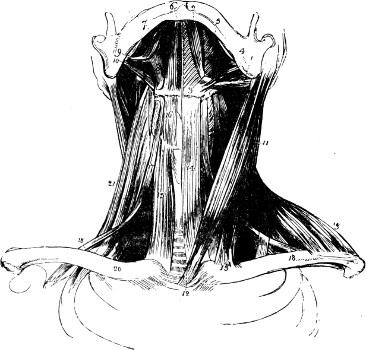

| XXIV. | Muscles of the Neck: Sterno-Cleido-Mastoid, Infra-Hyoid, and Supra-Hyoid Muscles | 281 |

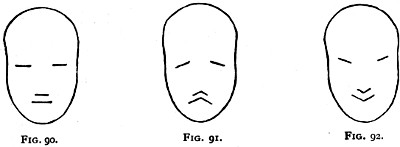

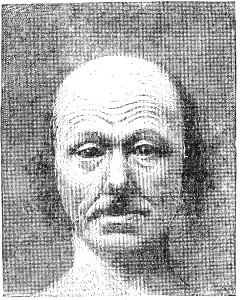

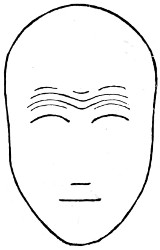

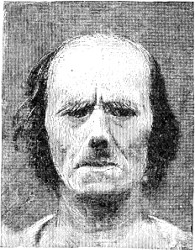

| XXV. | Muscles of the Head; Muscles of Mastication; Muscles of Expression: History (Leonardo da Vinci; Humbert de Superville; Duchenne of Boulogne, and Darwin) | 291 |

| XXVI. | Muscles of Expression; Possible and Impossible Combinations of Certain Contractions of the Muscles of the Face | 310 |

DUVAL’S

ARTISTIC ANATOMY

[1]

Artistic Anatomy

In offering instruction in anatomy to artists, one feels compelled at the outset to attempt an answer to the question: Of what use is anatomy, scientifically considered, in the training of the artist?

The artist requires to know his technique, just as an architect or an engineer needs to start with a knowledge of his materials.

Looking backward, we see that science and art have ever progressed side by side. The history of Egypt, of Greece, of the Renaissance, shows glorious traditions of art, along with a full development of learning and philosophy. The advancement of science and of art has always occurred simultaneously, and there never has been a time when they have been divorced from one another.

This is par excellence the age of technical education. There is no questioning the importance of science, or the aid the arts have received from it. We see it in architecture, in the influence of terra-cotta and steel frames; and in art, in the introduction of aniline colours.

Painting and sculpture are the earliest of the arts, and have produced some of the most cherished[2] monuments of history; and originally the chief object portrayed was the human form, in action or repose.

Let us for a moment consider to what extent art has been indebted to anatomy in the production of the masterpieces of the past.

1. Egypt.—Egypt presents the first great School of Art, as of letters and philosophy, and from Egypt knowledge and culture flowed to Greece and Italy.

The vestiges of Egyptian art extant to-day comprise for the most part statues—some of them portraits—coins, sculpture (in low relief), and flat, painted outlines. As a rule, the representations of the human form pretend to no exact representation of detail of form or expression, and for the most part are executed in a formal and stereotyped fashion.

The amount of anatomical knowledge demanded by the art of Egypt could obviously be acquired by direct observation of the nude or semi-nude figures of the living. The history of Egypt, profoundly interesting from all points of view, is of special interest to the anatomist, and centres round the mode of treatment of the dead.

Ascribed usually to a belief in the immortality of the soul, the ceremonial treatment of the body after death was elaborate, and essentially religious. The body was regarded as sacred, and the process of embalming was a religious rite, entrusted to a band of the priesthood—Charhebs or Paraschistes—and no greater detail of anatomical examination was permitted than was deemed necessary for the proper[3] preservation of the body. This band of the priesthood was moreover shunned and outcast, and yet with all these disadvantages some knowledge of anatomical structure must have been obtained.

It was only later, when Greek influence became felt, that a study of anatomy arose in the Medical School of Alexandria. Egypt was the nursing mother of medical teaching, and Alexandria was the first great medical school. Erasistratus (B.C. 285) was the first great anatomist, and he utilised condemned criminals for dissection. Herophilus, a Jew, is said to have dissected 600 bodies.

2. Greece and Rome.—The historical importance of Egyptian art and the Alexandrine School of Anatomy lies in the influence which they exerted upon the culture of Greece and Italy.

Science and art were introduced directly into Greece and Italy from Egypt. Anatomical knowledge in Greece begins with Hippocrates (B.C. 400), who studied in Egypt under Democritus of Abdara. Galen, later (A.D. 131), the great Roman physician, was a Greek by birth, and was taught his anatomy by Heraclianus at Alexandria.

Art in those days had ideals. Its aims were the perpetuation of the godlike, the heroic, the representation of perfect beauty and manly strength. Every reproduction was required to be, if possible, more beautiful than the original—virtually, as Lessing says, a law against caricature. “By no people,” says Winckelmann, “was beauty so highly esteemed as by the Greeks.”

Moreover, the Greek artist was surrounded by a crowd of witnesses, in the masterpieces of[4] sculpture, and in the living active forms of perfect manhood and womanhood. In the games there were ample opportunities for the study of the nude; and every evanescent, subtle movement could be noticed of the lithe and supple frame of the athlete.

Marked attention was given to physical culture; clothing was light, movements free, so that the environment was perfect for the purposes of the sculptor or figure-painter. Prizes were given for beauty, and the artists were the judges.

The work of the artistic anatomist of those days was superficial in a double sense. Cremation was the usual mode of burial, the anatomist dissected apes, and beyond an occasional opportunity of handling human bones, little exact anatomical knowledge was available. But from the artist’s point of view all the anatomy they needed was before their eyes. The best models procurable were before them; and an art that in some respects is perfect owes nothing to the science of anatomy.

3. The Art of the Renaissance.—Egyptian art shows knowledge of form; Greco-Roman art, knowledge of form and proportion; the art of the Renaissance reaches a higher platform, in its portrayal of movement and the expression of emotion.

Three factors combined to give the impetus to art at the time of the revival of learning. In 1315 Mondino di Luzzi made the first public demonstration of the anatomy of the human body. In 1400–1420 the process of wood-engraving, and subsequently the art of printing, were invented. Linked with these two facts, and with the general advance[5] of learning, science, and art, was the great religious revival of that period. The religious sentiment gave the keynote to the artistic pre-eminence of the old masters. Their themes were great, and the result was a grandeur and a power that no merely decorative or realistic school can ever attain.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, artists and anatomists are constantly found in association as fellow-workers and as personal friends. The great work of Andreas Vesalius on Anatomy was illustrated in an exact and artistic manner by Jan van Calcker, Titian’s favourite pupil. Leonardo da Vinci and Della Torre; Michael Angelo and Colombo; Benvenuto Cellini and Da Carpi; and other names might be cited to show the close relations of the artists and anatomists of those days.

There is little doubt that the old masters seized every opportunity of becoming acquainted with anatomical structure. Vasari used to advise his pupils to study “the antique, the nude, and dissections from nature.” Michael Angelo was in the habit of first sketching his figures in the nude condition, and afterwards clothing them with the necessary drapery. Leonardo da Vinci has left few complete pictures; but there are numerous sketches in existence (notably at Milan) in which he has drawn with precision, dissections—e.g., of the knee joint, with bones, ligaments, and muscles in proper position. Ruskin says of him: “We have in this great master a proof of the manner in which genius submits to labour in order to attain perfection.”

4. Modern Art.—For many reasons modern art is more dependent than ever upon anatomical[6] knowledge. Not to dwell upon the ennobling power of religious feeling—notably absent from modern art—the artist of the present day suffers from the plutocratic conditions of modern life, the inartistic fashions of modern dress, and the difficulty of obtaining accurate and well-formed human models; and is compelled to depend more and more upon a scientific knowledge of anatomy.

Among the old masters there is often an excessive exhibition of anatomical structure, and this is liable to occur even more in some of the work of modern artists. A little knowledge is a dangerous thing; and it is of supreme importance that the anatomical knowledge used by the painter or sculptor should be properly applied, so that form, proportion, contour, and expression may all have equal value.

It is too common, unfortunately, for present-day models to be disproportionate in form and deficient in muscular development, and the mistakes of nature are too often reproduced, in the form of defects or exaggerations, in modern sculpture and pictures. The student should seize every opportunity of studying the well-developed living nude form in action in order to obtain an adequate idea of the pattern which he desires to copy.

[7]

Anatomy in general; the anatomy of the external forms of man; physiology of the same.—Origin of the knowledge of the Greek artists of the anatomy of external forms; the influence of gymnastics upon Greek art.—The Renaissance and anatomical study: Mondino di Luzzi (1316).—The anatomical studies of Leonardo da Vinci, Michael Angelo, and Raphael.—Titian and Andreas Vesalius.—The anatomical course of the School of Painting (1648).—What the artist requires in the study of anatomy: proportions, forms (or contours), attitudes, movements.—The order of these studies; divisions of the subject.

Anatomy, as the derivation of the word indicates (from ἀνὰ, across, and τομὴ, section), is the study of the parts composing the body—muscles, bones, tendons, ligaments, various viscera, &c.—parts which we separate one from the other by dissection, in order to examine their shapes and their relations and connections.

This study may be accomplished in various ways: (1) from a philosophical and comparative point of view, by seeking the analogies and differences that the organs present in animals of different species—which is called Comparative Anatomy; (2) from a practical point of view, by seeking out the arrangement of organs, the knowledge of which is indispensable to the physician and surgeon—this is called Surgical or Topographical Anatomy; (3) by examining the nature and arrangement of the organs which determine the external forms of the body—this is Plastic Anatomy, called also the[8] Anatomy of External Forms, the Anatomy of Artists. It is the anatomy of external forms that we shall study here; but the artist ought to know not only the form of the body in repose, or in the dead subject, but also the principal changes of form in the body when in a state of activity, of movement, and of function, and should understand the causes which determine these changes. Plastic anatomy ought to be supplemented by a certain amount of knowledge of the functions of the organs, e.g., muscles and articulations; so that under the title of anatomy of the external forms of man we shall study at the same time the anatomy and the physiology of the organs which determine these forms. We should be contending for what has been long since conceded, were we to endeavour to show to what an extent the studies of anatomy and physiology are indispensable to the artist, who seeks to represent the human form under many and various types of action. Nevertheless, it may be useful to explain how the chefs-d’œuvre of ancient art have been produced with admirable anatomical exactness by men who certainly had not gone through any anatomical studies, and to show what special conditions aided them to acquire, by constant practice, the knowledge that we are obliged to seek day by day in the study of anatomy.

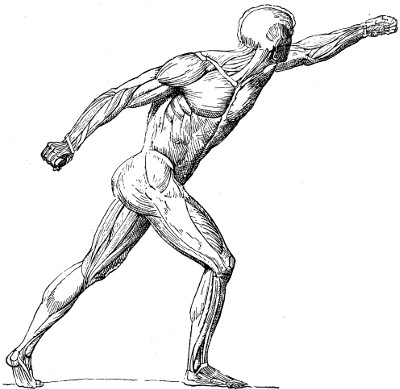

The Greek sculptors have reproduced the human form with marvellous anatomical exactness; in fact, the works of Phidias (the Theseus and the Ilissus), those of Myron (the Discobolus), those of Lysippus and of Praxiteles (the Sleeping Fawn), those of Agasias (the Fighting Gladiator), and other masterpieces[9] given as models in all the schools of art, are such that it is impossible to find fault with them, or to discover in them the least inexactitude, either from an anatomical or a physiological point of view;[3] in fact, not only are the muscles, for example, prominent exactly in their places, but, more than that, these prominences are differently accentuated in corresponding muscles on the different sides, according to the nature of the movement; one side will present the muscles swelled up in a state of contraction, or the muscles may be in repose—that is, relaxed and relatively flattened. At the time when these works of art were produced, the study of anatomy, or even the dissection of the human body, had not yet been attempted; the respect in which the dead body was held was such that the physicians themselves, who should have been able to justify their motives for this study, had never as yet dissected a human body. In order to supply this want of direct knowledge Hippocrates had dissected animals, and had arrived at certain conclusions by the analogy that exists between the organs of quadrupeds and those in man. Galen himself dissected monkeys only, seeking to confine his examination to animals whose anatomical construction might be considered as most closely resembling that of man. Galen never possessed a human skeleton, for in a passage in his anatomical works he states the pleasure that he[10] found in studying at last some human bones that had been deposited in a marshy place by a river which had overflowed its banks. We seem, then, to have a singular contradiction between these two facts, as we know on the one hand that the Greek artists have shown in their works a most rigorous anatomical exactitude, whilst on the other hand neither they nor their contemporary physicians and surgeons had made a study of the anatomy of man by the practice of dissection.

But this contradiction disappears altogether when we examine the conditions which permitted those artists to have constantly before their eyes the nude human body, living and in motion, and so set them to work to analyse the forms, and thus to acquire, by the observation of the mechanism of active muscular changes, a knowledge almost as precise as that which is now obtained by the accurate study of anatomy and physiology. It is sufficient, in fact, to recall to mind the extreme care the ancients gave to the development of strength, and of physical beauty, by gymnastic exercises. In Homer we see the heroes exercising themselves in racing, in quoit-throwing, and in wrestling; later we come to the exercise of the athletes who trained themselves to carry off the palm in the Olympic games; and it is evident, in spite of the ideas that we hold now respecting wrestlers and acrobats, that the profession of an athlete was considered a glorious one, as being one which not only produced a condition of physical beauty and high character, but constituted in itself a true nobility. Thus the life of the gymnast came to exercise a decisive influence[11] on Greek art. The prize of the conqueror in the Olympic games was a palm, a crown of leaves, an artistic vase; but the chief glory of all was that the statue of the victor was sculptured by the most celebrated artist of the time. Thus Phidias produced the handsome form of Pantarces, and these athletic statues form almost the only archives of the Olympiads, upon which Emeric David was able to reconstruct his Greek Chronology. From these works, which became ideals of strength and beauty, the artist had long been able to study his model, which he saw naked every day, not only before his exercises, whilst rubbing himself over with oil, but during the race, or the leaping match, which showed the muscles of the inferior extremities, or during the throwing of the quoit, which made the contractions of the muscular masses of the arm and the shoulder prominent; and during the wrestling matches, which from the infinite varieties of effort, successively brought all the muscular powers into play. Was it then surprising that the images of the gods, destitute of movement and of life, which had so long satisfied the religious sentiment of the people, were succeeded by artistic representations of man in action in statues such as could embody the idea of strength and beauty, studies of the living statues of the gymnasium? Further, we shall see the decline of art proceed side by side with the abandonment of the exercises of the gymnasium. Much later, in the Middle Ages, art awoke and embodied ideas in figures without strength and life indeed, but which nevertheless express in a marvellous manner the mysterious aspirations of the[12] period; but these have not anything in common with the realistic representation of the human form, well developed and active, as seen in Greek art. At the time of the Renaissance, artists not having any longer a living source of study in athletic sports, recognised the necessity of seeking for more precise knowledge in the anatomical study of the human body, in addition to the inspiration drawn from the study of the antique, and thus we see that the revival of the plastic arts occurred simultaneously with the introduction of the practice of dissection. This was not brought about without some difficulty.

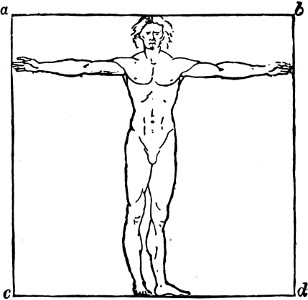

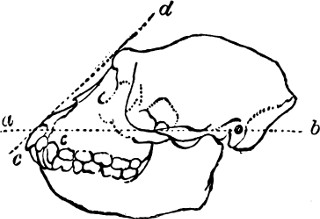

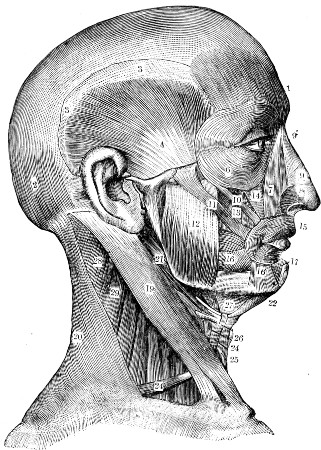

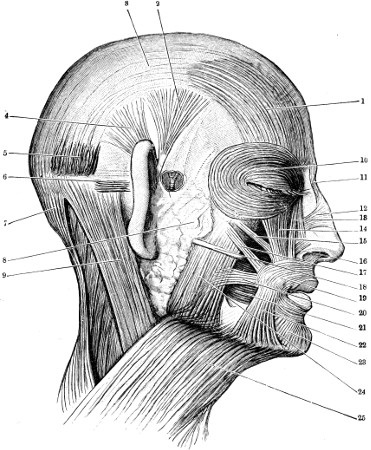

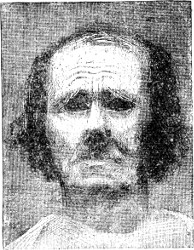

Fig. 1.

Reproduction of a drawing of an anatomical study by Leonardo da Vinci. (Choulant’s work, page 8.) This design represents the minute dissection of the muscles of the lateral region of the neck and trunk.]

In the year 1230, Frederic II., Emperor of Germany, and King of the Two Sicilies, passed a law prohibiting the practice of medicine without the practitioners having first studied the anatomy of the human body. In spite of two papal excommunications hurled against the author of this edict, dissections were henceforth regularly pursued in Italy; and one century later—in the year 1316—Mondino di Luzzi was able to write the first treatise on human anatomy, containing descriptions made from studies of the dead body. This treatise was printed in 1478. Artists rivalled physicians in the ardour with which they pursued their anatomical studies; and it may be said that all the painters and sculptors in the fifteenth century gave most careful attention to dissection, or at least studied demonstrations made upon the dead body, for all have left, amongst their drawings, studies that leave no doubt on this head. Among the great masters it may be noted that Leonardo da Vinci (14521519)[13] left thirteen portfolios of various drawings and studies, among which are numerous anatomical studies of remarkable fidelity. The greater number of these were taken from Milan by the French in 1796, and afterwards they were in part restored to Italy; some of them, however, went to enrich the British Museum in London, and were published by[14] Chamberlain.[4] In Fig. 1 is reproduced one of these anatomical drawings. It shows with what care—perhaps with over-scrupulous care—the illustrious master endeavoured to separate by dissection the various fasciculi of pectoral muscle, deltoid, and sterno-cleido-mastoid. It may be noted also that in his Treatise on Painting, Leonardo da Vinci devotes numerous chapters to the description of the muscles of the body, the joints of the limbs and of the “cords and small tendons which meet together when the muscles contract to produce its action,” &c.; and finally, in this same Treatise on Painting, he makes allusion at different times to a Treatise on Anatomy, which he intended to publish, and for which he had gathered together numerous notes. These are fortunately preserved in the Royal Library at Windsor.

Michael Angelo also (1475–1564) made at Florence many laborious studies of dissection, and left among his drawings beautiful illustrations of anatomy, of which several have been published in Choulant’s work, and by Seroux d’Agincourt.[5] Finally, we have numerous drawings by Raphael himself, as proof of his anatomical researches, among which we ought to mention, as particularly remarkable, a study of the skeleton intended to give him the exact indication of the direction of the limbs and the position of the joints for a figure of the swooning[15] Virgin in his painting of the Entombment (Choulant, p. 15). We cannot end this short enumeration without quoting further the names of Titian and Andreas Vesalius, in order to show into what intimate relations artists and anatomists were brought by their common studies. Titian, in fact, is considered the real author of the admirable figures which illustrate the work—“De Humani Corporis Fabrica”—of the immortal anatomist, Andreas Vesalius, justly styled the restorer of anatomy. It is necessary, however, to add that though some of the drawings are by Titian, the greater number were executed by his pupil, Jan van Calcker, as is pointed out in the preface to the edition of the work published at Basle in 1543.

The renaissance of the plastic arts and that of anatomy were therefore simultaneous, and closely bound up one with the other; ever since that time it has been generally recognised that it is necessary to get by anatomical study that knowledge of form which the Greeks found themselves able to embody in consequence of the opportunities they had of studying the human figure in the incessant exercises of the gymnasium. Again, in 1648, when Louis XIV. founded at Paris the Académie de Peinture et de Sculpture, which later on took the title of the École des Beaux-Arts, two sections of study were instituted side by side with the studios properly so called, for imparting to the pupils instruction considered as fundamental, and indispensable to the practice of art. These were the sections of perspective and anatomy.

It is not our place to plead, otherwise than by[16] the preceding historical considerations, the cause of anatomy in its relation to painting and sculpture; but we ought at least to examine what method is likely to prove the most useful for its study. If each anatomical detail does not correspond to an artistic need we are liable in following any treatise written with other than an artistic aim to be entangled in superfluous names and useless descriptions; while at the same time we might neglect details which are to the artist of great importance, although considered of secondary value by authors who have written especially for students in medicine.

We ought, then, to ask ourselves, in the first place, what are the ideas that the artist should seek for in his study of anatomy? To this question all will reply that the ideas of proportion, of form, of attitudes and movements are those in which anatomy is relied upon to furnish precise rules; and as the expression of the emotions, either in painting or sculpture, cannot be reproduced except by various changes in the general attitude of the body, and in the special mechanism of the physiognomy moved by the muscles, we must conclude that our study should deal not only with proportions, form, attitudes and movements, but also with the expression of the emotions and passions. This, then, is the object to be attained. Suppose we try to accomplish it by examining in a first series of studies all that belongs to proportions; afterwards, in a second series, all that has relation to form; in a third, attitudes, &c. Such an order of proceeding, logical though it be, will have the disadvantage[17] of causing numerous repetitions, and the more serious inconvenience of artificially separating parts which in the structure of the body are intimately connected. Thus, form is determined sometimes by osseous prominences, sometimes by the soft parts, which may be muscular or tendinous. Attitudes are determined by the muscles; but these are subject to laws which result from the position and action of the joints; so with movements in the expression of which it is necessary to consider, at the same time, what the conformation of the osseous levers (the direction of the bones and their articulation) allows, as well as that which the muscles accomplish, also the direction of the muscles and the differences of shape produced by their swelling and tension in action, as well as when the antagonistic muscles are relaxed. Proportions themselves cannot be defined without an exact knowledge of the skeleton, for it is the bones alone which furnish us with the landmarks from which to take measurements. A knowledge of the bones and of their articular mechanism is indispensable to us, that we may guard ourselves against being deceived in certain apparent changes of length in the limbs when certain movements take place.

We see, then, that all the ideas previously enumerated as to proportion, form, attitude, movement, depend on the study of the skeleton and muscles. It will thus be easiest and most advantageous to proceed in the following manner:—We will first of all study the skeleton, which will teach us the direction of the axis of each part of the limbs, the[18] relative lengths and proportions of these portions, and the osseous parts which remain uncovered by the muscles, and show beneath the skin the shape and the mechanism of the articulations in their relation to movements and attitudes. We shall then study the muscles, and endeavour to know their shapes, at the same time that, we complete the knowledge we shall have acquired of attitudes and movements. In the third place, we will attempt the analysis of the expression of the passions and emotions; and the study of the muscles of the face, of which the mechanism in the movements of the physiognomy is so special that it would be inconvenient to attempt to treat it with that of the muscles of the trunk and limbs.

[19]

THE SKELETON, ARTICULATIONS, PROPORTIONS.

Osteology and Arthrology.—Anatomical nomenclature: median line; lateral parts; the meaning of terms.—Of the bones in general: long bones (shafts and extremities); flat bones (surfaces, borders); short bones.—Prominences (processes, spines); cavities and depressions of bone (fossæ, grooves).—Bone and cartilage.—The axial skeleton: the vertebral column.—The vertebræ (bodies, transverse processes, spinous processes, &c.).—Cervical, Dorsal, Lumbar vertebræ.—Articulations of the vertebræ.—Movements of the spine.—Movements of the head (atlas and axis).—The curves of the vertebral column.—Relation of the vertebral column to the surface.—Proportions of the parts of the spine.

It is not necessary to emphasise further the importance of a study of the skeleton. By its means we obtain a knowledge of form and proportions; by a study of the several articulations we become acquainted with the complex mechanism by which the whole is knit together, and by which the movements of the various parts of the body occur. Further, the relations of the skeleton to the surface forms of different parts of the body are of fundamental importance. The science of Osteology is the study of bones (ὀστέον, bone; λόγος, description); Arthrology is the study of joints (ἅρθρον, a joint):[22] Myology is the study of muscles (μυς; λογος). The bones are the levers of movement: the articulations represent the fixed points or fulcra of these levers; while the powers which produce motion are represented by the muscles.

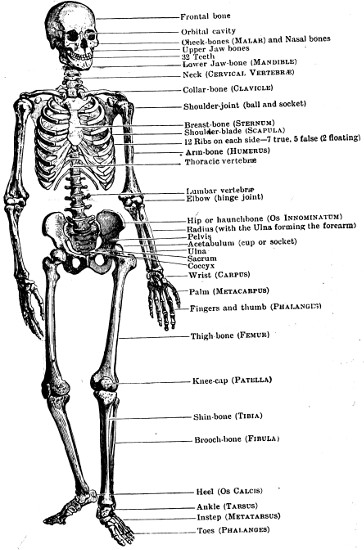

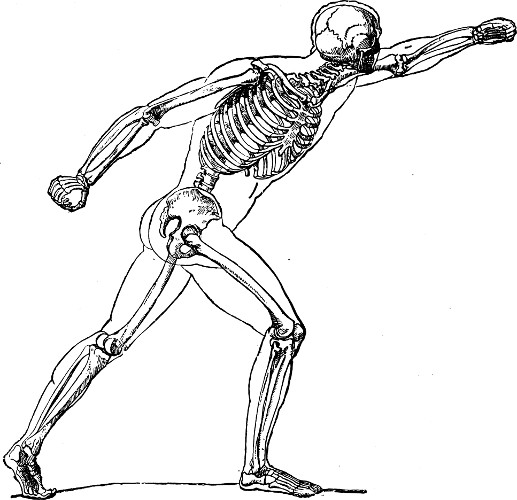

Fig. 2.

Front View of the Skeleton.

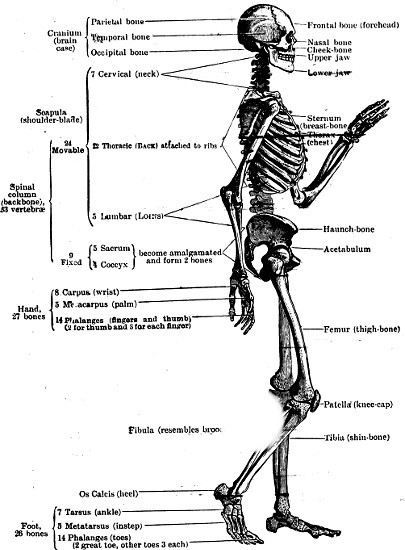

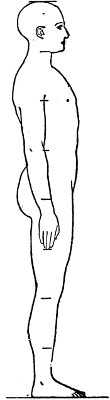

Fig. 3.

Side View of the Skeleton.

Before describing in detail the different parts of the skeleton, it is necessary to consider the method of nomenclature, so that by the employment of proper terms the subsequent descriptions may be more intelligible.

Nomenclature.—In the description of the bones, as of other organs, we have to consider the relation of the portion under consideration to the rest of the body. The figure is always regarded as occupying the erect position, with the face, the palms of the hands, and the toes directed forward. Thus each bone, as well as the other organs or parts, will be found under one or other of two different conditions: either it is median in position, and a vertical plane passing through the longitudinal axis of the body divides it into two similar segments; or else it is lateral in position, and situated outside this median plane. As a type of the first class, we will take the sternum, or breast-bone (see Fig. 11, p. 42). This is a central single bone; it has no fellow, and is composed of two symmetrical portions, one part on the right and one part on the left. As a type of the second class, we will take the humerus (Fig. 18, p. 60), which is a bone situated at the side and one of a pair, inasmuch as there are two, one on the right and one on the left of the median plane. From these two examples it is easy to understand that for the description of each single[23] and symmetrical bone it will be necessary to speak of anterior parts or surfaces directed towards the front of the body, of posterior parts (directed backwards), of lateral portions (right and left), and finally, of parts superior and inferior, looking upwards and downwards (in the case of the sternum a superior and inferior extremity): on the other hand, in the description of a paired and non-symmetrical bone, we shall also have to speak as heretofore of parts superior and inferior, anterior and posterior; but instead of two similar symmetrical portions, one on each side of an imaginary line, it has two dissimilar halves, of which the one looking towards the median plane—towards the axis of the body—is called the internal part, and the other, looking to the outer side (as away from the axis), is called the external part. It is necessary, for brevity and accuracy, to clearly comprehend the meaning of these terms in descriptive anatomy (anterior and posterior, internal and external, superior and inferior) which serve to show the relation of the parts to the skeleton as a whole.

After this first division of bones into single and median, and into double and lateral, if we glance at the skeleton (Figs. 2, 3), it seems at first sight that the various bones present an infinite variety of shape, and defy classification or nomenclature; careful attention, however, will show us that they may be all included in one of the following three classes—viz., long bones, flat or broad bones, and short bones.

Fig. 4.

The Complete Skeleton (in the attitude of “The Fighting Gladiator” of Agasias).

The long bones, which usually act as the axes of the limbs (e.g., the humerus, femur, tibia, &c.),[24] are composed of a central portion, cylindrical or prismatic in shape, called the body, shaft, or diaphysis (διαφύω, to be between), and of two extremities or epiphyses (ἐπιφύω, to be at the end), usually marked by protuberances and articular surfaces. The flat bones (e.g., the shoulder-blade and the hip bone) are formed of osseous plates, on which are various surfaces, borders, and angles.[25] Finally, the small bones, which are found in the vertebral column and in the extremities of the limbs, the hand and foot (carpus and tarsus), present a diversity of form in which cylindrical, cubical, and wedge-like shapes can be made out.

Whether the bone be long, flat, or short, it presents prominences and depressions. The projecting portions of bone are called by various names—tuberosities, protuberances, processes, apophyses, crests, spines, tubercles. To some of these names is added an adjective, which shows, more or less exactly, the form of the process or projection. Thus we speak of a spinous process, mastoid process (μαστὸς, a nipple; εἶδος, form), styloid process, &c. The depressions upon the bones are called by various names—fossa, groove, foramen, sinus, canal, notch, cavity, &c. To these also are added names which indicate their shape, as the digital fossa, from its resemblance to the imprint of a finger; the glenoid cavity (γλήνη, cavity), the cotyloid cavity (χοτύλη, a basin); but more frequently still, the added adjective bears allusion to a connection of the cavity with certain organs, as the bicipital groove, that which contains the tendon of the biceps, or the canine fossa, in relation to the root of the canine tooth.

Structure of Bone.—Bone is characterised by its density, toughness and elasticity. If a long bone, such as the femur, is sawn in two lengthwise, its extremities are found to be composed of a delicate network of cancellous, or spongy bone, in the interstices of which marrow and blood are contained during life; the shaft of the bone is composed,[26] for the most part, of a cylindrical tube of dense, ivory-like compact bone, which encloses the hollow medullary canal of the bone, also filled with marrow during life. The dense bone of the shaft is continuous with a thin sheet of hard bone, which covers over the spongy bone of the extremities.

In the case of the flat and short bones, the structure is like that of the extremities of the long bones. The mass of the bone is composed of cancellous tissue, with a surrounding thinner envelope of compact bone.

If a bone is burnt, it loses one-third in weight, becomes brittle, and loses its organic constituents, retaining its inorganic materials—chiefly calcium phosphate and calcium carbonate. If it is subjected to prolonged soaking in an acid such as hydrochloric acid, its inorganic salts are removed, it becomes soft and pliable, it loses two-thirds of its weight and retains only its organic materials—connective tissues. These in boiling produce glue.

In certain situations bone is found in conjunction with a substance which differs from it in its elasticity, its want of rigidity (it is soft enough to be divided by the scalpel), and in its translucent colour. This substance is known by the name of cartilage. Thus the curved bones termed ribs are prolonged at their anterior extremities by a portion called the costal cartilage, which presents the same form as the ribs properly so called. The bones forming the freely movable joints (like the shoulder, hip and knee joints) are capped by thin layers of hyaline articular cartilage, which forms a pliant elastic cushion in relation to the articulation.

[27]

Most of the bones, at the commencement of their formation, are constructed solely of cartilage, which is gradually transformed into bone as the animal grows by the deposition in it of lime salts; and this transformation of primitive cartilage into bone may be more or less complete according to the species or age of the animal. With advancing age the bones tend to become more and more calcified. Thus we find that in the skeletons of old people the costal and other cartilages may be more or less ossified.

The Subdivisions of the Skeleton.—The human skeleton is characterised by peculiarities due to the assumption of the erect position, the high development of the brain, and the possession of extraordinary manual dexterity. All these factors leave their impress on the bones of the skeleton, as may be seen by comparing the human skeleton with that of such a quadruped as the dog.

The skeleton is subdivided into axial and appendicular parts. The axial skeleton includes the vertebral column, ribs and sternum, and the bones of the cranium and face. The appendicular skeleton comprises the bones of the limbs. In the following pages, for convenience of description, an account will be given of the vertebral column, sternum, and ribs first; of the limbs second; reserving to the last the account of the skeleton of the cranium and face.

The Vertebral Column.—The vertebral column (Figs. 5, 8) is composed of a number of bones named vertebræ, superimposed on one another, and partially separated from one another by a series of intervertebral[28] discs. The column is subdivided into groups of vertebræ, by reason of its connections with other parts of the axial skeleton, or with the skeleton of the limbs.

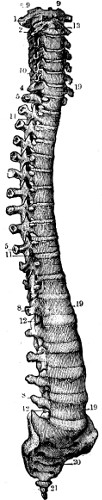

Fig. 5.

The Vertebral Column (antero-lateral aspect).—1, the first cervical vertebra (atlas);—9, 9, its occipital articulating surfaces;—2, the second cervical vertebra, or axis;—13, its body;—4, seventh cervical;—5, 5, transverse processes of the ten first thoracic vertebræ;—8, 8, transverse processes of the lumbar vertebræ;—10, 11, 12, articular processes;—19, 19, bodies of the lumbar vertebræ;—20, the sacrum;—21, the coccyx.

The head is poised on the upper end of the column, and causes the peculiarities, to be described later, in the first two vertebræ (atlas and axis). The attachment of the ribs to the sides of the vertebral column causes the separation of three regions: (1) cervical, belonging to the neck, and comprising seven vertebræ; (2) thoracic (or dorsal), belonging to the thorax, or chest, and comprising twelve vertebræ; and (3) lumbar, belonging to the loin, and comprising five vertebræ. The attachment of the hip bones to the sides of the succeeding vertebræ leads to the fusion of the next five vertebræ together, under the name of the os sacrum, which will be described along with the hip bone and pelvis. Finally, below the sacrum are four small, rudimentary vertebræ, known as the coccyx, forming the attenuated remains of a caudal appendage.

[29]

There are thus, altogether, normally thirty-three vertebræ: seven cervical, twelve thoracic, five lumbar (constituting together twenty-four movable vertebræ); five sacral, and four coccygeal vertebræ (constituting nine fixed vertebræ, which help to form the pelvic basin).

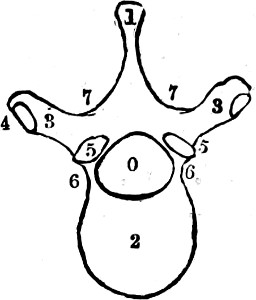

Fig. 6.

Outline of a Vertebra (upper surface).—0, vertebral foramen;—1, spinous process;—2, body of vertebra;—3, 3, transverse process with articulating facets (4, 4) for the tuberosity of the rib (see p. 30);—5, 5, superior articular processes;—6, 6, the parts which connect the body with the base of the transverse and articular processes;—7, 7, vertebral laminæ.

The vertebral column is intended not only to form an axis for the rest of the skeleton, but also to serve as an attachment, direct or indirect, for all the other bony structures; it also forms a bony canal, within which the spinal marrow is contained. It is for this reason that each of the pieces which compose it, called a vertebra, is a sort of bony ring (Fig. 6). The anterior portion of the ring is very thick, representing the segment of a cylinder, and is called the body of the vertebra (2, Fig. 6); and the vertebral column, considered as the median column of support, is essentially constituted by the superposition of these vertebral bodies upon one another, separated by the intervertebral discs. Behind each vertebral body is an arch, the neural arch, which encloses the neural ring. The spinal or neural canal is formed by the combination and connection together of the neural rings. Each neural arch is comparatively slender, but it gives origin to certain projections or processes, three in[30] number, on each side, of which one directed transversely outwards is called the transverse process (3, Fig. 6). In the thoracic region these give partial attachment to the ribs. The other two—directed more or less vertically, one above, the other below—are called the articular processes, superior and inferior. These serve for uniting together the arches of adjoining vertebræ (5, 5, Fig. 6). Finally, the posterior portion of the neural arch is prolonged backwards as a protuberance, more or less pointed, called the spinous process (1, Fig. 6).

Such are the most important parts which we find in each vertebra, but they present particular characters according to the region to which each vertebra belongs. The description of the sacrum and the coccyx, which are formed of vertebræ welded together, and articulating with the hip bones, will be given with that of the pelvis.

The more important features of the movable vertebræ which contribute to give to the whole column its general form are: (1) the size, particularly of the bodies, of the vertebræ; and (2) the characters of the transverse processes. The bodies of the vertebræ are smallest in the upper thoracic region, and increase in size upwards and downwards from the fourth thoracic vertebra. The bodies are largest and most prominent in the loin; in the neck the vertebræ are broad in the transverse diameter, but their antero-posterior diameters are less. The vertebral column is weakest in the upper thoracic and upper lumbar regions, and most mobile in the neck and thorax. Rotary power in the loin[32] is practically prevented by the shape of the lumbar articular processes, which interlock the vertebral arches in this region.

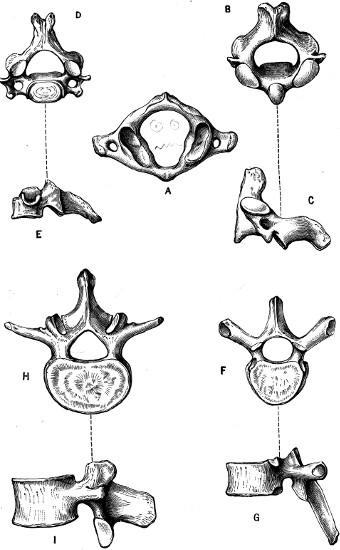

Fig. 7.

The Movable Vertebræ.—A, atlas (upper surface); B C, axis; D E, cervical vertebra; F G, thoracic vertebra; H I, lumbar vertebra.

The spinous processes of the vertebræ, which project more or less obviously in the middle line beneath the skin in different regions, in the cervical region are short and bifid; in the thoracic region they are long, sloped downwards, and “bayonet-shaped”; in the lumbar region they are directed straight backwards, and are “hatchet-shaped.”

Besides these general characters in each region there are certain vertebræ which demand special mention owing to the peculiarities of their shape. These are the first two and the last cervical.

The first cervical vertebra (Fig. 7, A), called the Atlas, because as directly supporting the head, it has been compared to the giant Atlas, supposed by the ancients to support the heavens, is a bony ring with only transverse processes, and on the upper and lower aspects of its lateral portion, two pairs of articular surfaces; the superior articular surfaces are hollow oval surfaces which articulate with the convex condyles of the occipital bone; and by the occipito-atlantoid joints provide for flexion and extension of the head on the spinal column. The inferior articular surfaces are flat and directed downwards to articulate with the axis and form the atlanto-axial joint, which is responsible for the movement from side to side of the head upon the trunk. The axis, or second vertebra (Fig. 7, B C), is so called from the presence on the upper surface of its body of a tooth-like process, the odontoid process (ὀδοὺς, tooth; ἔιδος, form), which projects upwards in an osseofibrous[33] ring formed by a transverse ligament in the anterior part of the ring of the atlas. Ligaments extend from this process to the occipital bone, and it forms a pivot round which the head and the atlas move in the lateral movements of the head upon the spinal column.

In nodding the head the movement occurs primarily at the occipito-atlantoid joint; in shaking the head, the chief movement is between the atlas and axis. These functions, of no moment in the production of surface forms, are of too great an importance in respect of the articulations of the head and trunk to be omitted here.

Fig. 8.

Vertebral Column (lateral view).—1 to 7, bodies of cervical vertebræ;—8 to 19, bodies of thoracic vertebræ;—20 to 24, bodies of lumbar vertebræ;—A, A, spinous processes;—B, B, articular surfaces of transverse processes for the tuberosities of the ribs;—C, auricular surface of sacrum.

The seventh cervical vertebra, or vertebra prominens, is so called because of the extraordinary length of its spinous process, which, except in very stout people, forms a projection easily visible beneath the skin; and this projection is also[34] more conspicuous as it corresponds to that part of the neck where the trapezius muscle, represented only by a fibrous layer—not fleshy—forms a flat surface at the back of the neck. In the centre of this surface the projection of the seventh cervical spine appears on the level of a transverse line passing through the superior border of the shoulder (see Fig. 3). It may be observed that when the model bends the head forward the spinous process of the seventh cervical becomes very prominent. It should also be noted that in the majority of cases the spinous processes of the sixth cervical and first thoracic vertebræ also give rise to superficial projections above and below that produced by the vertebra prominens.

We have been disconnecting the vertebræ in order to account for the construction of the vertebral column; we must next see how the different vertebræ are placed one upon the other—how they articulate in such a manner as to form a column, not rigid, but elastic and curved. The vertebræ are placed one on each other so that the inferior articular processes of one fit exactly on to the superior articular processes of the next beneath, and thus throughout the series we see (Fig. 8) that the bodies of the vertebræ are not in contact one with the other, the space which separates them being filled in the living subject by elastic fibrous discs. These intervertebral discs are very thick in the lumbar region, and become thinner in proportion as we ascend to the superior dorsal and cervical regions. They are thicker in the cervical and lumbar regions than in the thorax; and taken[35] together they form one-seventh of the length of the spinal column. Being compressible and elastic, these fibrous discs give to the column, formed by the placing one on another of the bodies of the vertebræ, a certain degree of flexibility, whereas a column formed of bone alone would have been quite rigid.

In addition to the intervertebral discs, a series of ligaments which join together the posterior portions of the neural arches (laminæ) is of great importance. Composed of yellow elastic tissue to a large extent, they are known as the ligamenta subflava. They consist of two short bands placed on each side of the root of the spinous process, uniting the inferior border of the lamina of one vertebra with the superior border of the lamina situated next below it.

The yellow or elastic tissue which composes these ligaments is similar to a piece of india-rubber; it is elastic—that is to say, it is able to stretch, and to return again by its own reaction to its original size when the cause which extended it has ceased to act: so that each movement of flexion of the column in front results in moving the vertebræ on one another, at the same time stretching these elastic ligaments. When the anterior muscles of the trunk which accomplish this flexion cease to contract, it is not necessary, in order to straighten the column, that the posterior muscles of the back should come into play; the elasticity of the ligamenta subflava suffices for this, as they return to their original dimensions and draw together the vertebral laminæ. We may say, then, that there is at the posterior[36] portion of the column within each vertebra a pair of small springs which keeps the column erect, so that the erect attitude of the trunk is maintained simply by the presence of the elastic ligaments; although more is required when a man supports upon his back any extra weight or burden.

The Ligamentum Nuchæ (paxwax) is a large and powerful ligament composed of yellow elastic tissue. It is highly developed in quadrupeds, and is attached between the spinous processes of the cervical vertebræ and the occipital crest, a vertical ridge on the back of the skull. In man it is a rudimentary structure (as the head is poised on top of the vertebral column) and forms a membranous partition separating and giving partial attachment to the muscles of either side at the back of the neck.

Curves of the Vertebral Column.—The vertebral column is subject to a slight lateral curvature, generally towards the right side. Its chief curves, however, are antero-posterior, and are four in number (Fig. 8): two, the thoracic and sacral curves, concave forwards, are primitive embryonic curves; two, cervical and lumbar, convex forwards, are secondary in their origin. The convexity forwards of the cervical region is to be connected with the raising upwards of the head on the trunk; the convex lumbar curve is due to the straightening of the lower limb, which in the course of development is brought into line with the vertebral axis.

These curves (except the pelvic or sacral curve) are to be associated with a difference in the thickness in front and behind of the vertebral bodies,[37] and of the intervertebral discs in the different regions of the spine.

In most animals the vertebral column has but two curves, one the cervical curve, which is convex inferiorly, the other the dorso-lumbar, which is concave inferiorly.

We have now to examine the influence that the vertebral column has in moulding the external form of the body, and to see if the length of the column can be made use of for a system of proportion.

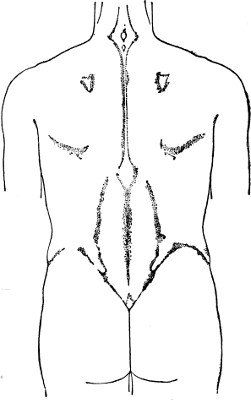

It is evident, in the first place, that the posterior portions of the vertebræ only can affect the outline of the body, the anterior portions, the bodies of the vertebræ, being deeply hidden in the cavity of the thorax and abdomen. Therefore, in the skeleton the posterior surface of the vertebral column (Fig. 9) presents itself under the aspect of a median crest, formed by a series of spinous processes, the spinal crest, on each side of which is a groove bounded laterally by the series of transverse processes (the vertebral furrow). In the living subject these grooves are filled up by powerful and thick muscles, which project in such a manner that in the erect position the back presents a furrow in the median line bounded on each side by these muscles, at the bottom of which furrow the bony structure of the vertebral column is shown only by a series of projections placed one beneath the other, like the beads of a necklace, each one being formed by the summit or free extremity of a spinous process. These projections are well seen in the thoracic region, in which the curvature of the column is convex backwards, and they show themselves still[38] more clearly when the subject bends forward, and thereby increases this curvature. They are not visible in the cervical region, where the ligamentum nuchæ projects to the surface, and a bed of powerful muscles covers them; but we have seen that the seventh cervical, or vertebra prominens—along with the sixth also in many cases—is remarkable for the projection which its spinous process makes. Finally, in the lumbar region these projections are but little marked, the spinous processes here being short and terminated not by points, but by straight borders (Fig. 8).

Fig. 9.

Vertebral Column (posterior view).—1, 1, cervical transverse processes;—2, 2, thoracic transverse processes;—3, 3, lumbar transverse processes;—7, 8, 9, 10, spinous processes;—11, 11, articular surfaces for occipital bone of skull;—12, odontoid process of the axis;—13, 14, sacrum and coccyx.

The measurements of the vertebral column are useful, on the one hand, as absolute measurements of length and height, and, on the other hand, in giving the ratio of its length to the stature of the subject. The height of the vertebral column in the average adult man is from twenty-three to twenty-four inches, being five for the cervical region, eleven for the thoracic, and seven inches for the lumbar region. But as the length of the vertebral column does not serve as a common[39] measure for the total height of the body or for its different parts, it cannot be used as the basis of a system of proportion. A German zoologist, Carus, has advanced the idea that the length of the column forms one third of the height; but this proposition is not exact. On the other hand, it is not easy to measure the column from the atlas as far as the last lumbar vertebra,[40] without taking account of the sacrum and coccyx. It will be more frequently found that the length of the trunk, from the superior limit of the thorax to the inferior limit of the pelvis, gives a measurement more easy to take, and more useful for comparing the general proportions of the body.

Fig. 10.

Outline of the Back and Shoulders.

It is enough to say here that the proportion of the vertebral column to the height varies according to age and sex, and according as the stature of the individual is very great or very little; the vertebral column is, in fact, in comparison with the height, longer in the infant and in the female than in the adult male; it is also much longer in proportion to the height in subjects of short stature than in tall people. The cause of difference of stature between men and women, infants and adults, long people and short, is principally due to the length of the lower extremities—a question which will be dealt with in a subsequent chapter.

[41]

The Sternum: its three portions—manubrium, gladiolus, xiphoid appendage; position and direction of the sternum; its dimensions, absolute and relative.—The ribs; the true ribs, the false and floating ribs; the obliquity and curvature of the ribs.—Of the thorax in general; its posterior aspect, anterior aspect, and base.

We have already seen that that portion of the vertebral column which is formed by the seven cervical vertebræ is free, and forms of itself the bony structure of the neck. It is the same in the lumbar region, where the five vertebræ alone form the bony structure of the abdomen. The twelve thoracic vertebræ, however, corresponding to the upper two-thirds of the trunk, are in connection with the ribs and sternum, and constitute with these bones the osseous frame-work of the thorax.

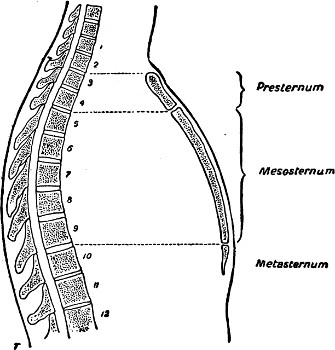

The Sternum.—In the front part of the thorax is the sternum, a bone in the middle line, single and symmetrical (Fig. 11). This bone is, in quadrupeds, formed of a considerable number of separate bones jointed together in a linear series. In the human subject it consists of three separate parts, one superior, one in the middle, and one inferior, known respectively as the pre-sternum, meso-sternum, and meta-sternum. The whole bone has been compared in shape to a short Roman sword, of which the pre-sternum represents the handle,[42] or manubrium; the meso-sternum, the longest piece, is the body, or gladiolus; and the meta-sternum, the pointed extremity of the sword, and usually tipped with cartilage, is the ensiform or xiphoid cartilage. Thus constituted, the sternum presents for our consideration an anterior surface, a posterior surface, two lateral borders, an upper and a lower extremity.

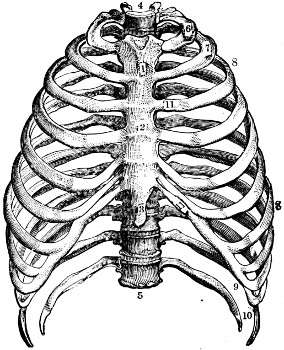

Fig. 11.

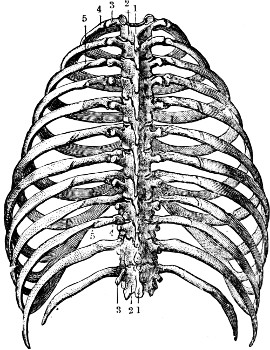

Thorax (anterior view).—1, pre-sternum, or manubrium of sternum;—2, meso-sternum, or body;—3, meta-sternum, or xiphoid appendage;—4, body of first thoracic vertebra;—5, twelfth thoracic vertebra;—6 and 7, first and second ribs;—8, 8, the true or sternal ribs;—9, 10, the floating ribs;—11, costal cartilages.

The anterior surface is smooth, but the union of the manubrium with the body of the sternum is marked by a prominent transverse ridge (sternal angle), due to the difference in direction of the[43] two pieces at their junction. This projecting angle is very remarkable in some subjects, and gives a clearly marked convex shape to the superior portion of the anterior surface of the thorax. The posterior surface of the bone, which it is not necessary for artists to study, is generally flat, and presents a returning angle corresponding to the projecting angle of the anterior surface.

The superior extremity of the sternum, forming the broader portion of the bone, is marked by three notches, or depressions: two lateral, one on each side, articulating with the inner end of the clavicle, and one in the middle called the suprasternal, or episternal, notch. This notch, which is easily discerned on the living model, forms the inferior border of the deep depression situated at the lower part of the front of the neck. Its depth is still further increased by the inner ends of the clavicles and by the sterno-cleido-mastoid muscles on either side.

The inferior extremity of the sternum is formed by the meta-sternum, or xiphoid appendage, which remains very frequently in the cartilaginous state, in the form of a plate, thin and tapering. In shape and direction it is very variable, being sometimes pointed, rounded, or bifurcated. It may be situated in a plane corresponding to that of the body of the sternum, or it may be placed obliquely or project forwards or backwards. In a case where it projects in front it may cause a slight elevation of the skin of the region of the pit of the stomach, or epigastrium; but it is a detail of form so irregular that it is not worth reproducing, except in the[44] representation of violent muscular exertion or extreme attenuation.

The lateral borders of the sternum are not vertical, but concave. The sternum is narrowest at the manubrio-sternal junction, the manubrium increasing in size towards its upper end, and the gladiolus, or body of the bone, enlarging towards its inferior part. Each lateral border is marked by seven small notches, or depressions, for the reception of the anterior extremity of each of the cartilages of the first seven ribs. The highest of these depressions is situated on the border of the manubrium just below the clavicular articular surface; the second depression is situated opposite the manubrio-sternal junction, partly on the pre-sternum, partly on the meso-sternum; those following are situated on the edge of the body of the bone, or meso-sternum, and the spaces between the depressions become smaller as they approach its lower extremity, so that the last depressions for the sixth and seventh costal cartilages are almost fused into one. The seventh costal cartilage is usually attached opposite the sterno-xiphoid junction, and is thus connected with both meso-sternum and meta-sternum.

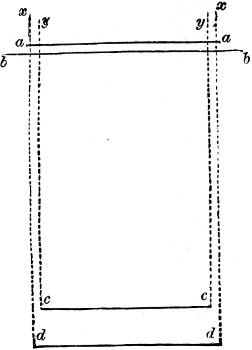

It is necessary also to determine the exact position and direction of the sternum in relation to the other parts of the thorax, in the complete skeleton. The direction of the sternum is not vertical, but very oblique; it forms an angle of fifteen to twenty degrees, with a vertical line passing through the inferior extremity (Fig. 12), and an angle of severity to seventy-five[45] degrees, with a horizontal line passing through the same extremity (Fig. 12). The manubrium is more oblique than the body of the sternum, and the body of the sternum than the xiphoid cartilage. Such is the direction of the sternum in the male; in the female it is less oblique, and approaches the vertical—a disposition which artists are prone to exaggerate by giving a more rounded form to the superior portion of the thorax in the female.

Fig. 12.

Relations of the Sternum to the Vertebral Column.

To compare the relations of the sternum with the rest of the thorax, it is necessary further to determine the level of the parts corresponding to the two extremities in relation to the vertebral column. The upper end of the sternum does not correspond to the first thoracic vertebra, but rather to the disc which separates the second and third, so that the horizontal plane passing through the superior extremity of the sternum strikes the second thoracic vertebra at its lower part (Fig. 12). The horizontal plane passing through the lower end of[46] the sternum strikes the tenth thoracic vertebra; so that, viewing the thorax in profile, the sternum is seen to project between the second and eleventh vertebræ. The exact level of the bone varies with the movements of the chest wall in respiration.

The average length of the sternum in the adult man is eight inches. The pre-sternum, or manubrium, is usually about half as long as the meso-sternum, or body of the bone.

The most important measurement, however, is the length of the sternum without the xiphoid appendage. A measurement equivalent to the length of the sternum is found in various parts of the skeleton, which for the most part are adjacent to the sternum, and the sternal length may be taken as a common measure for constructing a correctly proportioned torso.

As a fact, this measure of the length of the manubrium and body of the sternum is equal to (1) the clavicle, to (2) the vertebral border of the shoulder-blade, and to (3) the distance which separates the two shoulder-blades in the figure when the arms are hanging by the side; further, the length of the sternum is equal to (4) the length of the hand without the third phalanx of the middle finger.

The Ribs.—The thoracic part of the vertebral column and the sternum being known, it is easy to understand the arrangement of the parts which complete the thorax. These parts are the ribs and costal cartilages, arranged somewhat like the hoops of a cask, proceeding from the vertebral column to the sides of the sternum; the ribs articulate posteriorly with the vertebral column, and are connected[47] anteriorly to the sternum or to one another by the costal cartilages. The ribs are twelve in number on each side. They are known as first, second, and third ribs, etc., counting from above downwards; the first seven are the true ribs, or sternal ribs, which have their costal cartilages directly joined to the sternum; the next three (eighth, ninth, and tenth) ribs are the vertebro-costal ribs, as the costal cartilage of each articulates with the cartilage of the preceding rib; the last two, the eleventh and twelfth, are the false, floating or vertebral ribs: they are remarkable for their shortness; they are provided at their extremities with only rudimentary cartilages, which are pointed, and project by free extremities among the muscles of the walls of the abdomen.

In a general sense the ribs are long bones, presenting an external surface and an internal surface, a superior border and an inferior border. They are not horizontal, but oblique, from above downwards and from behind forwards: so that the anterior extremity of a rib is always placed on a lower level than its posterior extremity.

A typical rib possesses three curves. It is bent from behind forwards in a downward direction; it is bent like the hoop of a cask in order to surround the thorax, and presents, therefore, a curve similar to that of a scroll, of which the convexity is turned outwards and the concavity inwards; and, again, it is twisted upon itself as if the anterior extremity had been forcibly carried inwards by a movement of rotation upon its own axis. This curvature of torsion makes the surface, which is really external[48] in the central portion of the rib, become a superior surface in the anterior portion. In order to have a good idea of the torsion of the ribs it is necessary to take a single rib and place it on a horizontal surface, such as a table; it will be then seen that, instead of its being in contact through its entire extent with the flat surface, it touches it only at two points, as if it formed a half-hoop of a cask to which a slight spiral twist had been given.

The ribs vary much in length, in order to correspond to the ovoid shape of the thorax; their length increases from the first to the eighth, which is the longest, and corresponds to the largest part of the thorax; and it gradually diminishes from the eighth to the twelfth.

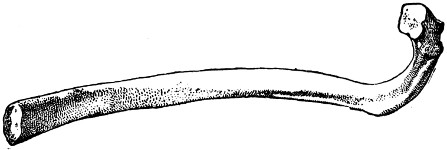

A typical rib (Fig. 13) consists of the following portions, an indication of which is useful for the study of the shape of the thorax. The posterior extremity is slightly raised, and constitutes the head of the rib. It is shaped like a wedge, and articulates with the bodies of two vertebræ as a rule, and it is received, precisely like a wedge, into the space which separates the bodies of these vertebræ; so that it is in contact by the summit of the wedge with the intervertebral disc, and by the surfaces of the wedge with the vertebra which is situated above and that which is situated below the disc. Beyond the head, the rib presents a portion thin and compressed from before backwards, called the neck of the rib, which is placed in front of the transverse process of the vertebra corresponding to it.

At the external extremity of the neck is a slight enlargement called the tubercle, which corresponds[49] to the level of the external extremity of the transverse process of the vertebra, and which articulates with the corresponding transverse process (Fig. 7, F G). By means of the connections of the head with the bodies of the vertebræ, and of the tubercle of the rib with the transverse process of the thoracic vertebra which corresponds to it, the posterior end of the rib moves on these joints as on a fulcrum, in the act of respiration; the chest cavity being enlarged by the uplifting of the shaft of the rib and by the eversion of the rib simultaneously.

Fig. 13.—A Typical Rib.

Passing on from the tubercle, the shaft of the rib is formed of a bar of bone, which at first is directed outwards and backwards (Fig. 13); then, after travelling some distance, it bends abruptly, so as to be directed forward, describing the characteristic curve of the rib. We give to this bend the name of the angle of the rib. The series of the angles of the ribs shows, upon the posterior aspect of the thorax, a line plainly visible, curved, with its convexity outwards, and having its summit at the level of the eighth rib, which is the longest, and upon which a relatively[50] greater distance separates the angle from the tubercle.

Fig. 14.

Thorax (posterior view).—1, 1, spinous processes of the thoracic vertebræ;—2, 2, vertebral laminæ;—3, 3, series of transverse processes;—4, 4, the parts of the ribs included between the tuberosities and the angles of the ribs;—5, 5, angles of the ribs, becoming more distant from the vertebral column as the rib becomes more inferior.

Such are the characters of ribs in general. For the peculiar characters of the several ribs, after we have spoken of the last two ribs, it will suffice to note the shortness of the upper ribs, and principally of the first, which is flattened from above downward. In other words, it is curved along the borders, and not along the surfaces, and it does not present any twist. The last two ribs, besides being the shortest as a rule (excepting the first rib), are peculiar in their straightness and in the rudimentary nature of[51] the angles; they further have no articulation with the transverse processes of the corresponding vertebræ.

The costal cartilages are attached to the extremities of the ribs in front: these cartilages, in proceeding to join the sternum, follow a course more or less oblique, so that the cartilage of the first rib is oblique from above downwards, and from without inwards; and those following present the same obliquity (Fig. 11), which becomes more accentuated in the cartilages lower down. The spaces which separate these cartilages are wide above, especially between the cartilages of the three first ribs, and become narrower towards the lower part of the chest.

The Thorax as a Whole.—The thorax, the constituent parts of which we have just examined, forms a kind of truncated cone, with its base below and its apex above; but, from an artist’s point of view as to form, it is not necessary to take this into account, as the shape of the summit of the thorax is completely changed by the addition of the osseous girdle constituted by the clavicle and shoulder-blade.

We limit ourselves, then, to a rapid view of the posterior surface, the anterior surface, and the base of the thorax.

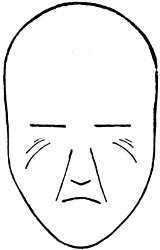

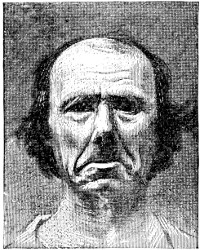

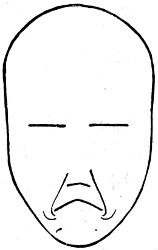

The posterior surface (Fig. 14) presents upon the skeleton, in the median line, the series of spinous processes, and on each side, first a row of transverse processes and then the angles of the ribs. As already explained (p. 37), respecting these several details, the summits of the spinous processes, although just[52] under the skin, are scarcely visible, especially in a very muscular subject.