Title: The Pilgrimage of Grace, 1536-1537, and the Exeter Conspiracy, 1538, Volume 1 (of 2)

Author: Madeleine Hope Dodds

Ruth Dodds

Release date: January 16, 2026 [eBook #77706]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Cambridge University Press, 1915

Credits: Richard Tonsing, Tim Lindell, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

The authors wish to express their most sincere gratitude to Miss Myra Curtis, Professor A. F. Pollard, Mr I. J. Bell of the British Museum, Mr H. R. Leighton, the Rev. J. Wilson, and Mr T. C. Hodgson for their kind and valuable help in the preparation of this book.

The documents transcribed by the authors from the originals have been given in the original spelling; in those which have been taken from printed copies the spelling has been modernised.

The spelling of proper names of persons and places is that used in the Index to the Letters and Papers of Henry VIII.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I | The Turning-Point | 1 |

| II | Plots and Tokens | 14 |

| III | Affinity and Confederacy | 28 |

| IV | Facts and Rumours | 63 |

| V | The Rising in Lincolnshire | 89 |

| VI | The Failure of Lincolnshire | 117 |

| VII | The Insurrection in the East Riding | 141 |

| VIII | The Pilgrims’ Advance | 168 |

| IX | The Extent of the Insurrection | 192 |

| X | The Musters at Pontefract | 227 |

| XI | The First Appointment at Doncaster | 241 |

| XII | The First Weeks of the Truce | 273 |

| XIII | The Council at York | 308 |

| XIV | The Council at Pontefract | 341 |

| MAPS | ||

| I | Map of England showing the Areas of Disaffection | To face p. 1 |

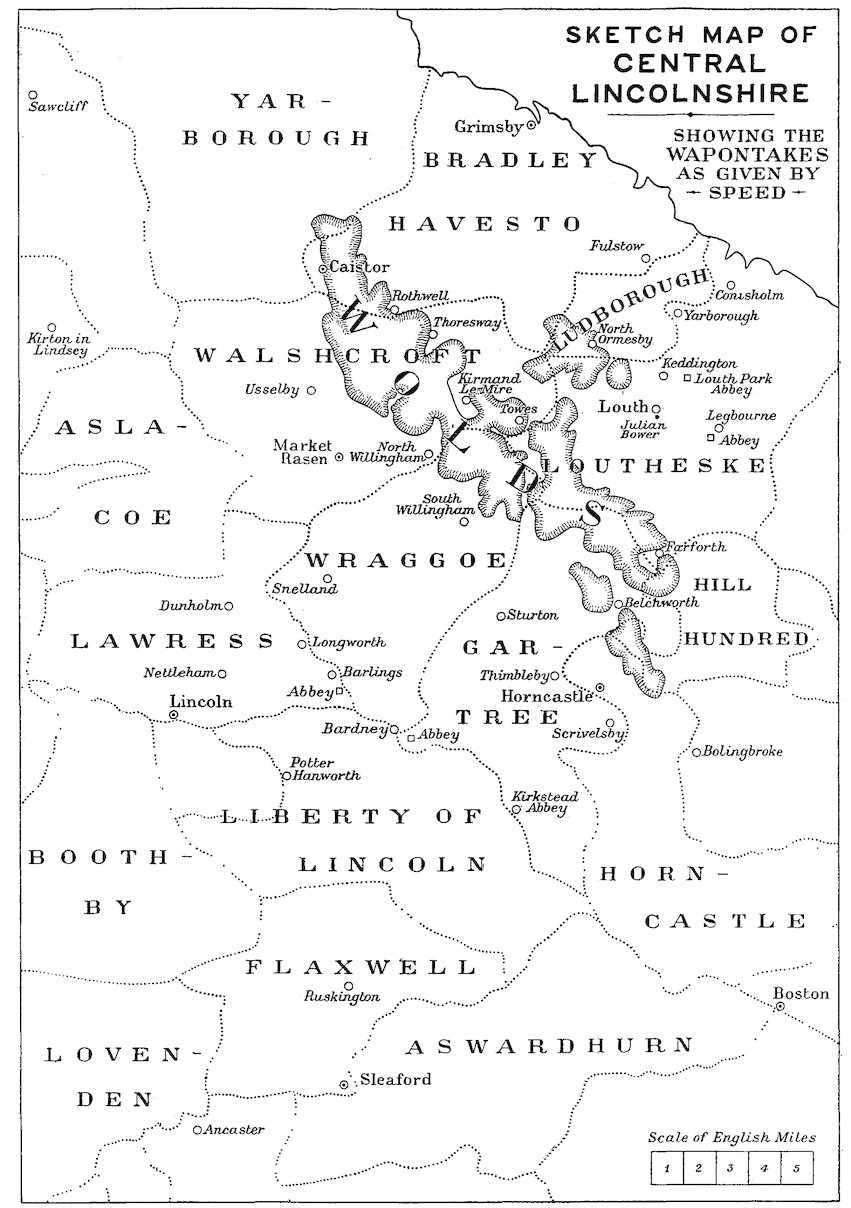

| II | Central Lincolnshire | „ „ |

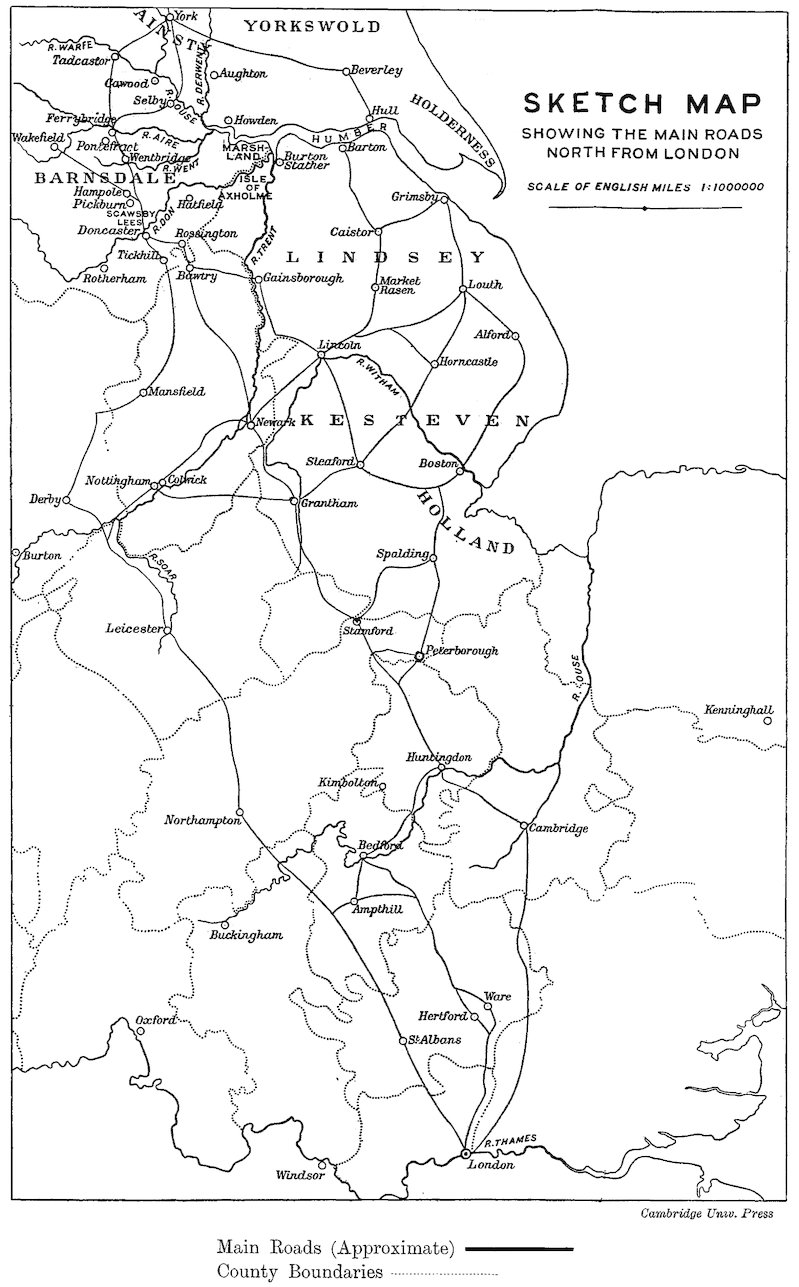

| III | The Main Roads from London to the North | „ „ |

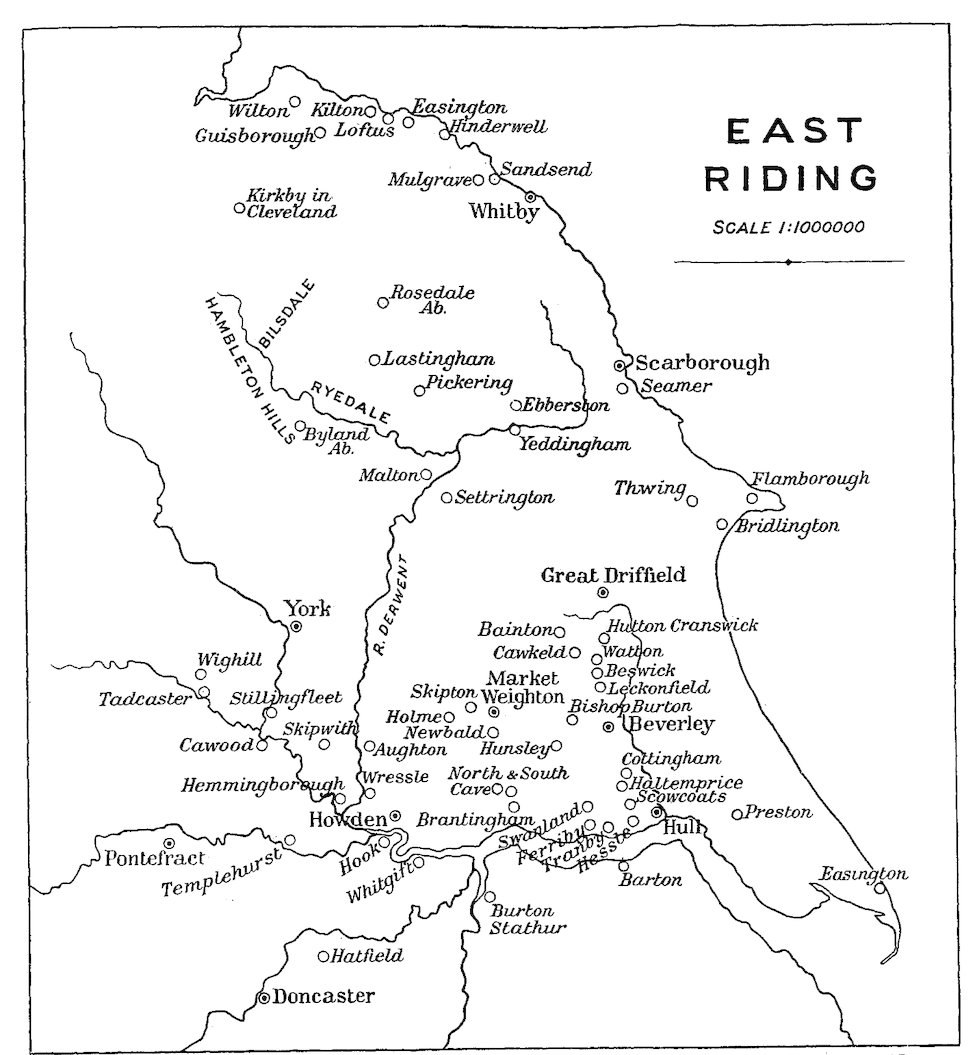

| IV | The East Riding of Yorkshire | „ „ |

| V | The Northern Counties | „ „ |

Cambridge Univ. Press

Cambridge Univ. Press

Cambridge Univ. Press

Cambridge Univ. Press

Cambridge Univ. Press

In order to see the rebellion of 1536–7 in its true perspective it is necessary to make a preliminary survey of the political position in England before the first rising took place. At the end of July 1536 Henry VIII’s domestic relations were more settled than they had been for the last ten years. The execution of Anne Boleyn on 19 May had been followed by his marriage with Jane Seymour, who was indisputably his lawful wife. The parliament which met on 8 June declared the two children of the King’s former wives, Mary and Elizabeth, illegitimate, and settled the succession to the crown upon the issue of the King’s latest marriage: that failing, the King was empowered to determine his heir himself either by will or by letters patent[1]. It was believed that the object of this statute was to bring into the succession Henry’s illegitimate son, Henry Duke of Richmond, who, however, died on 23 July[2]. After his death the situation with regard to the succession was practically the same as it had been before the divorce of Katherine of Arragon was proposed. The King was legally married, but it was considered unlikely that Queen Jane would have a child, and unless he acknowledged Mary, his heir by blood was the King of Scotland, whose claim was exceedingly unpopular in England. If the King died it was certain that Mary would be chosen by the nation as their queen, whether she was legitimate or illegitimate. Moreover the power to offer her hand in marriage might be useful to her father in foreign affairs.

A reconciliation between the King and his daughter was effected in July[3], and the greater part of England would have rejoiced if the matter had gone still further[4],—if Henry had acknowledged Mary, beheaded Cromwell, burnt Latimer and the heretic bishops, and reconciled himself with the Pope, who in return would certainly have 2been willing to recognise Queen Jane and her possible children. Apart from all other objections to this change of policy, however, there was one fatal obstacle; the King could not afford it.

The characters of the Tudor Kings have made so deep an impression on English history that it is easy to explain the events of their reigns by attributing everything to their personal traits, but Henry’s need of money was due to something that lay deeper than his own extravagance and rapacity. The whole of Europe was undergoing great economic changes, in consequence of the discovery of new trade routes and the importation of gold and silver from America, which depreciated the value of the coinage. Prices rose and the spending power of any fixed sum of money diminished. As the royal revenues were almost entirely customary and therefore fixed, it followed that the King was growing poorer while the expenses of government were constantly increasing as the nation emerged from feudal into modern life[5].

One of the most deeply-rooted feudal theories was that “the King should live of his own,” that is, that the ordinary revenues derived from the crown lands, the customs and feudal dues, should serve for the ordinary needs of the government, and that taxes should be levied only in time of war, or to meet extraordinary need. This theory had seldom corresponded to facts, and it was now quite untenable, but the tax-payer naturally cherished it. Henry’s taxation had already aroused great discontent, but the need for a sufficient revenue did not grow less, and the King could not afford to give up the money which, as supreme head of the Church of England, he diverted from the Pope, or the still more considerable sum that he hoped to derive from the suppression of the monasteries. But while the great mass of the nation desired nothing so much as the remission of all taxes, the educated classes were beginning to realise that this would not be such a very desirable state of affairs. The idea was just beginning to emerge that if the King did not need money he would never call a parliament, and that the liberties of the nation depended on its control of taxation. When the King declared that if only the wealth of the monasteries were in his hands he would never ask his people for money again, there were a few who saw that the King’s wealth was a much more serious danger than the King’s poverty[6].

The state of affairs on the continent permitted Henry to do as he pleased, for Francis I had again attacked Charles V, and the Pope 3could do nothing while his two champions were cutting each other’s throats. Henry therefore continued to carry out the policy expressed in the acts of his two last parliaments, the long parliament which met in December 1529 and was dissolved in March 1536, and its brief successor which met in June and was dissolved in July 1536.

A word must be said about the composition of these parliaments. A Tudor House of Commons was not, of course, representative in the modern sense of the word, for it consisted exclusively of country gentlemen and wealthy merchants, who were in most cases appointed by a small close body rather than popularly elected. The influence of the crown, exercised through the sheriff or through some local magnate, was paramount at the nomination of members, and it does not seem to have been resented, so long as the chosen candidate was a well-known man in the district for which he was appointed. The electors were willing that the King should choose the man most pleasing to himself among perhaps a dozen equally eligible persons, but gentlemen and burgesses alike resented the “carpet-bagger,” the stranger sent down from the court, who knew nothing of the place and despised the provincials whom he nominally represented[7]. They also objected to members who held government posts, and, curiously enough, bye-elections were considered an abuse, as it was maintained that when a member died his seat ought to remain vacant until the next general election[8].

The parliament of 1529–36 violated even these elementary conditions of representation; Cromwell, who came into power during these seven years, gradually developed the art of managing the House of Commons to an extent which had never been known before, and the electors were powerless in his hands, because they could not understand what was happening[9]. It must also be noticed that the electors in 1529 had very little means of knowing what measures would be brought before the parliament. They knew of course that the King would want money, and they knew also that the question of the divorce would be dealt with, but even the best-informed can hardly have foreseen the act for the dissolution of the smaller monasteries. It must, therefore, be borne in mind that the acts of this parliament were not passed with the consent, or even with the knowledge, of the nation. Their true originator was believed to be Thomas Cromwell. Whether his rise had been slow or rapid, this remarkable man was now (1536) at the height of his 4power[10], and the greater number of this parliament’s acts were stages in the progress of his policy. By birth Cromwell came of the English lower middle class, but part of his early manhood was spent in Italy[11], and his character was an illustration of the proverb “An Englishman Italianate is a devil incarnate.” He belonged to the new school of political thought which had for its exponents Philip de Commines and Machiavelli, and for its heroes Louis XI and Caesar Borgia. Thomas Cromwell, clothier, solicitor and moneylender, seems genuinely to have believed that it was the duty of any man who by birth, luck or skill became a prince, to make himself absolute, and to guard against any breath of opposition at home as carefully as he did against any hint of attack from abroad. He was really convinced that an absolute autocracy was the best form of government for any country, and that it was the duty of a good subject to do everything in his power to strengthen the hand of the King. Religion meant nothing at all to him. He conformed to the existing usages, whatever they might be, but distinctions between creeds only interested him in so far as they might be used politically. Honour, mercy, conscience, were simply the prevailing weaknesses of mankind, which might be employed for his advantage, just as he might take advantage of drunkenness or stupidity. It was not so much that he disregarded as that he never felt them. With all this moral insensibility he was a singularly efficient administrator. Instead of fearing and slighting the houses of parliament, he manipulated them for his own ends, while his spy system was unrivalled. But this was the darker side of his labours; it was also part of his policy to promote trade, to put the kingdom in a state of defence, to repress crime and violence as well as rebellion. His faults as a statesman were rapacity and a too great desire to interfere in every department of life. It was now six years since his celebrated promise “to make Henry the richest king that ever was in England”[12]; at last the treasures of the monasteries were within his grasp, and his promise seemed on the point of fulfilment.

Cromwell’s low birth exposed him to the scorn of his contemporaries, and has been brought up against him even by modern historians; nevertheless if it were necessary to make a choice between his moral character and that of his high-born opponent, Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, it could scarcely be denied that Norfolk was the greater scoundrel of the two. He was simply a courtier and 5politician, with not a tenth of Cromwell’s ability. By inclination he was conservative and favoured the Old Learning, but if he could advance himself by denying his politics or his faith he was quite ready to abandon either. Cromwell at least had a political end in view; Norfolk merely wished to aggrandise himself and had no other object.

It goes without saying that the two regarded each other with the bitterest hatred. After the fall of Anne Boleyn Cromwell managed to procure Norfolk’s banishment from the court, but they were in constant correspondence with each other. Among all the records of misery, crime and brutality in the Letters and Papers of the time there is perhaps nothing more horrible than Norfolk’s letters to Cromwell; the sickly expressions of goodwill, the filthy jokes, the grimaces of thankfulness, make them vile reading. But not many letters were written in the summer of 1536, for Norfolk had just been worsted, and Cromwell was completely master of the situation.

The general course of Cromwell’s systematic attack on the Church is so well known that it is necessary only to recapitulate those features which chiefly aroused popular indignation.

In 1529, the first year of Henry’s long parliament, a very sweeping measure was passed to regulate the clergy. They were prohibited from holding any land by lease. All leases held by ecclesiastics must be transferred to laymen before the next Michaelmas. Spiritual persons were prohibited from trading, except in the case of monasteries selling the produce of their own lands for their own needs. No priest was henceforth to hold more than one benefice of value above £8 yearly, but existing pluralists might retain four; members of the King’s Council, chaplains of the royal family or of peers, and brothers of peers and knights, were permitted to hold three, and Doctors of Divinity might hold two. Every priest was required to reside on one of his benefices, but exceptions were made in favour of pilgrims, persons on the King’s service, scholars at universities, and royal chaplains. Spiritual persons were prohibited from keeping breweries and tan-yards[13]. The chief object of this statute was probably to facilitate the transference of ecclesiastical property to laymen[14]. It must have caused great indignation among the clergy. They may have hoped at first that it would not be strictly enforced, but in 1536 it was re-enacted with still more stringent residentiary clauses[15].

6In 1530 the clergy of England were called upon to face the overwhelming charge that they had all offended against the Statute of Praemunire by acknowledging Wolsey’s legatine authority. In order to buy their pardon from the King they were compelled to pay a heavy fine. In addition to this the King demanded that they should acknowledge him “the only Protector and Supreme Head of the Church and clergy of England,” and that cure of souls was committed to him, “curæ animarum ejus majestati commissæ et populo sibi commisso debite inservire possimus.” He made other demands, but these were the most important points. The clergy would only accept the title qualified by the phrase “quantum per Christi leges licet,” “as far as the laws of Christ will allow.”[16] They applied the same qualifications to the phrase about the cure of souls “ut et curæ animarum populi ejus majestati commissi dehinc servire possimus,” “and so far (as the laws of Christ will allow) we are able to agree that the cure of the souls of his people has been committed to his Majesty.” This acknowledgment was made, as far as can be discovered, only by the southern convocation. The questions were not put to the northern convocation, and it seems that at least three of the northern bishops, Tunstall being one, protested against the new title, even with the modification[17]. However the King was satisfied for the moment by the compromise, and the clergy were solemnly pardoned[18].

It is not necessary to go into the complicated questions of the Petition of the Commons, the Answer of the Ordinaries, and the Submission of the Clergy in 1532, as they were not understood by the people at large[19]. Passing over the anti-papal legislation of the following years, those acts which were protested against by the rebels are the only ones which need be mentioned. The first of these was the Act which conditionally restrained the payment of Annates or First Fruits to Rome in 1532[20], a prohibition which was made absolute in 1534[21]. The fault found with this statute was not that the payments were no longer made to Rome, but that they were still levied by the King.

In 1534 Henry attacked the Church of Rome at a vital point. On 31 March of that year the question was put to the Convocation of Canterbury, “Whether the Roman pontiff has any greater 7jurisdiction bestowed on him by God in the Holy Scripture in this realm of England than any other foreign bishop?” Only four of those present voted for the Pope’s authority, and it was consequently resolved by a large majority that he had no such power[22]. On 5 May the same resolution was passed by the Convocation of York without a dissenting vote[23]. Following on this, Henry caused the Supremacy Act to be passed in November 1534. This measure conferred upon the King and his heirs for ever the title of “Only supreme head on earth of the Church of England.” The saving clause “quantum per Christi leges licet” was quietly ignored[24].

It must always be remembered that behind this brief summary the great drama of the rival queens, Katherine of Arragon and Anne Boleyn, had been running its course. The anti-papal acts so far had been diplomatic moves. In the more remote country districts they were probably hardly known and not at all understood. But at this point Henry resolved to make the whole nation realise their altered relation to Rome.

In April 1535 Henry issued a mandate which declared that “sundry persons both religious and secular, priests and curates, daily set forth and extol the jurisdiction and authority of the Bishop of Rome, otherwise called Pope, sowing their pestilential and false doctrine, praying for him in the pulpit, making him a god, illuding and seducing our subjects, and bringing them into great errors, sedition and evil opinions, more preserving the power, laws and jurisdiction of the said bishop than the most holy laws and precepts of Almighty God.” Any person offending in this way was to be apprehended at once and committed to prison without bail until the King’s pleasure in his case was known[25]. Royal letters were sent out on 1 June 1535 to all the bishops to command them to declare the King’s new title in their sermons every Sunday, and to cause their clergy to do the same. The name of the Bishop of Rome was to be erased from all services and mass books. This was followed on the 3rd by an “Order for preaching and bidding of the beads in all sermons to be made within the realm.” The Pope and the Cardinals of Rome were no longer to be named in the bidding of the beads. The prayers were to be “for the whole Catholic Church and for the Catholic Church of the realm; for the King, only Supreme Head of the Catholic Church of England, for Queen Anne and the Lady Elizabeth, for the whole clergy and temporality, and especially for 8such as the preacher might name of devotion; for the souls of the dead, and specially of such as it might please the preacher to name.” Every preacher was ordered to preach against the usurped power of the Bishop of Rome, and they were to abstain for one year from any reference to purgatory, honouring of saints, marriage of priests, pilgrimages, miracles[26]. The shock which this measure gave to the nation will be to some extent illustrated in the following chapters. It struck at the very foundations of the existing creed. The papal authority was not always popular in England,—men grumbled at the Pope, sneered at him, criticised him,—but that he was the only supreme head of Christianity was as firmly believed and as confidently accepted as that the sun rose in the east. When simple country priests were called upon to deny weekly a proposition which they had never before dreamed of questioning, they and their congregations might well think that the foundations of society were giving way, and their worst fears seemed to be realised by the Act for the Suppression of the Smaller Monasteries, passed in the following year[27]. It is not necessary to repeat the well-known story of Henry’s dealings with the monasteries, and the whole of the following work is a commentary on it.

In the same year the privileges of the palatinate of Durham and other exempted districts were abolished[28].

In the short parliament of June-July 1536 two Acts were passed of considerable importance. By one all bulls, breves, dispensations and faculties from the Pope now within the realm were declared void[29]. In 1534 the clergy had been prohibited from obtaining dispensations, etc. from Rome[30], but those obtained before 12 March 1533 had been expressly declared valid. Now, however, they were required to surrender their papal licences, etc. to the Archbishop of Canterbury before Michaelmas 1537[31]. The Imperial ambassador, Chapuys, reported that this was the statute which the parliament was most reluctant to pass, as it involved serious questions of legitimacy, “but in the end everything must go as the King wishes.”[32] The other statute dealt with the question of sanctuary and benefit of clergy. Already several statutes had been passed limiting this much abused privilege[33]. In this statute benefit of clergy was denied to any ecclesiastic who committed the crimes 9specified in former statutes as those for which no layman might claim benefit. The offending priest was to be punished like a layman, without degradation from his holy orders[34].

By the time that this mass of legislation was completed there were very few people in England who knew what they were really intended by the government to believe. In order that the new state of things might be understood, the King as Supreme Head of the Church of England, with the advice and assent of Convocation, published Ten Articles about Religion. They were issued in June 1536, when the year’s prohibition of controversy about purgatory, pilgrimages, etc. was at an end[35]. The first five articles stated those points in belief which were necessary to salvation. They were the grounds of faith, as set forth in the Bible, the Creeds as interpreted by the patristic traditions not contrary to Scripture, and by the Acts of the Four Councils; Justification; Baptism; Penance, which included confession and good works; and the Sacrament of the Altar. Thus only three of the seven sacraments were named as essential. The other five Articles dealt with such points “as have been of a long continuance for a decent order and honest policy, prudently instituted and used in the churches of our realm, and be for that same purpose and end to be observed and kept accordingly, although they be not expressly commanded of God, nor necessary to our salvation.” These were paying honour to saints, placing their images in churches and praying to them; the rites and ceremonies of the Church; and the belief in purgatory, which involved prayers for the dead[36].

The Ten Articles received the assent of the southern, but not of the northern convocation, although they were signed by the Archbishop of York and the Bishop of Durham[37]. They were supplemented in July by an order of the Supreme Head and Convocation that no holy days should be observed in harvest time, 1 July–29 September, except the feasts of the Apostles, the Virgin Mary, and St George; or in the law terms, except Ascension Day, the Nativity of St John the Baptist, All Hallows and Candlemas; all feasts of the Dedication should be observed on the first Sunday in October, and no “church holidays,” which were the feasts of the patron saints of churches, should be observed unless they fell on an authorised holy day[38].

10In the same month these new regulations were enforced by the first Royal Injunctions of Henry VIII[39]. The publication of these injunctions “was the first act of pure supremacy done by the King, for in all that had gone before he had acted with the concurrence of Convocation.”[40] The Ten Articles were a compromise between the Old and the New Learning, but the Injunctions, which were issued in Cromwell’s name, went further in the way of innovations. The clergy were ordered to preach every Sunday for the next quarter, and afterwards twice a quarter, on the subject of the King’s Supremacy, setting forth the abolition of the Bishop of Rome’s pretended authority. They were also to expound and enforce the Ten Articles and to declare the new order for holy days. They were to discourage superstitious ceremonies, and to exhort all men to “apply themselves to the keeping of God’s commandments and fulfilling of His works of charity, rather than to make pilgrimages or bestow money on saints and relics.” In this the Injunctions went further than the Articles, in which pilgrimages were not mentioned. Another innovation was the order that all servants and young people must be taught the Lord’s Prayer, the Creed and the Ten Commandments in English. The remaining injunctions directed the clergy to study, give alms, lead sober lives, etc.

In addition to these measures, any one of which was sufficient to arm all the forces of tradition and religious conservatism against the King, several important political Acts had been passed, which were scarcely more likely to be popular. Among these the three Succession Acts were the most important. The first declared the Princess Mary illegitimate and entailed the succession on the heirs male of the King and Anne Boleyn, or failing heirs male, on the Princess Elizabeth. All were to swear to maintain this act, under penalty of high treason[41]. The second Succession Act confirmed the first and supplied a form of oath to be taken[42], but this was superseded by the third, which has been described above. The Treason Act gave a new definition of high treason. It was declared to be high treason “if any person ... do maliciously wish, will or desire by words or writing, or by craft imagine, invent, practise, or attempt any bodily harm to be done or committed to the King’s most royal person, the queen’s or their heir’s apparent, or to deprive them of their dignity, title or name of their royal estates, or slanderously and maliciously 11publish and pronounce, by express wri. ting or words, that the King our sovereign lord should be heretic, schismatic, tyrant, infidel or usurper of the crown.”[43] This act was passed only after prolonged debate in the House of Commons, and the King was forced to permit the word “maliciously” to be inserted; this was done in the hope of saving those who could not conscientiously call the King Supreme Head of the Church, but did and said nothing to prevent others from giving him the title[44].

It was for offences against these statutes, the second Succession Act and the Treason Act, that Sir Thomas More and Cardinal Fisher were put to death in July 1535. Pope Paul III, roused at last by this deliberate defiance of his authority, prepared a bull of interdict and deposition against Henry in the autumn of the same year[45]. But he had not sufficient faith in his own curses to launch them at Henry without adequate secular support. If he had had the courage of a medieval pope, he would have published the bull with perfect confidence that it would accomplish its own work, without earthly aid; what is more, it would very likely have been effective, as will be shown hereafter. Paul III, however, endeavoured to back up his supernatural threats by physical force, and failed. Francis I protested vigorously against the publication of the bull, as he was Henry’s ally, while Charles V was not in a position to lend his aid, and the Pope suspended it for the time[46].

Returning to the unpopular statutes of the long parliament, the financial situation must be briefly considered. Henry’s money troubles have already been mentioned. The usual levies by direct taxation, the Fifteenth and the Tenth, had originally been the actual fraction of the tax-payer’s possessions, but since 1334 they had become fixed payments levied from each county without reassessment, and therefore did not represent the wealth of the nation[47]. In addition to the usual Fifteenth and Tenth, the long parliament granted to the King a general subsidy of 1d. in the £ on incomes above £20 a year, levied by commissioners who were sent into every shire to discover through the constables the amount which each person ought to pay[48]. In Henry’s reign at any rate a real 12assessment was made, and the measure was consequently exceedingly unpopular.

Another act which was designed to increase the revenue was the Statute of Uses[49]. The object of this statute was to preserve intact to the King the feudal dues from estates which were held directly from him in chief. Such estates might not be given by will, but their holders usually provided for their families by leaving a rent charge on the estate to the use of their younger children or other dependents. The statute abolished such uses entirely, and thus deprived the whole family, except the eldest son, of any income from an estate held in chief from the King.

These statutes were all passed at the direct instance of the King, and chiefly for his profit, but statutes of a more disinterested character were not more popular. Tudor statesmen were firmly convinced that it was their duty to regulate the trade of the nation in every possible way. Their constant interference in minute points must have been most exasperating to tradesmen, and although their object was always the common good, such unwise meddling produced bad results more often than good ones, and therefore was detested not only by the sellers, but also by the buyers, whose interests it was supposed to protect. Moreover the common people had no confidence in the government, and were always ready to believe rumours that these acts would turn out to be new forms of taxation.

A statute which aroused great indignation in the eastern counties was passed in 1535. Clothiers were ordered to weave into their cloth their respective trade marks, and to specify the length of each piece of cloth on a seal attached to it. Until this was done the aulnager was not permitted to seal the goods. At the same time the legal breadth of various kinds of cloth, which had been regulated by previous statutes, was increased, except in the case of Suffolk set cloths. The provisions of the statute did not apply to the county of Worcester[50].

In order, to check the evils of enclosures, which were increasing rapidly[51], it was enacted that no grazier might keep a flock of more than 2,000 sheep[52], and by another statute landowners who had abandoned husbandry for sheep-farming since 1515, were ordered to re-erect or repair the houses of husbandry on their lands under 13penalty of forfeiting half the land to the crown[53]. These two statutes were intended to check the depopulation caused by sheep-farming enclosures, and were therefore popular in intention, but they were naturally resented by the landowners, and rumours spread that both cattle and sheep were to be taxed or confiscated.

Other measures with an equally good object had equally unfortunate results. Ever since 1529 the government had been endeavouring to keep down the price of meat. As all prices were rising rapidly during this period, owing to causes beyond the control of legislation, these efforts had exasperated the butchers, while they left the purchasers in a rather worse case than before[54]. In 1534 by one of several statutes dealing with the subject the Lords of the Council were empowered to issue proclamations “from time to time as the case shall require to set and tax reasonable prices of all such kinds of victuals” as “cheese, butter, capons, hens, chickens,” etc.[55] It seems possible that this statute, together with the ineffective regulations which accompanied it, gave rise to the rumour that all poor men were to be prohibited from eating “white meat” unless they paid a tax to the King on every chicken, capon or such-like[56]. But whether the rumour may be traced to this statute or not, it will be seen in what follows that the butchers sought their revenge on the King by taking an active part in the insurrection.

From this brief review it is obvious that the government had been pursuing a remarkably daring policy in all departments of national life. In the following chapters an attempt will be made to show how the different classes were affected by this varied mass of legislation, and what their feelings were towards its originators, the King and Thomas Cromwell.

Before the Act dissolving the Lesser Monasteries was passed, in March 1536, the opposition to Henry’s policy was too much broken up by class distinctions to be very formidable; nor did the chief of the conservative nobles ever encourage the popular movement. Henry was able to crush his opponents separately, when a united attack might have shaken even his weight from the throne.

In the first place he was opposed by the party of the Old Nobility. By this we do not mean Norfolk and other time-servers of his opinion, but another and weaker faction, the remaining members of the Yorkist nobility, who had survived the Wars of the Roses. The religious problems of Henry’s reign somewhat obscure its connection with the history of the century before it. The days of Cranmer and Pole seem so far removed from those of Warwick the Kingmaker and Richard Crookback that it requires an effort to realise that Henry had to deal with a legacy of trouble from the earlier period, as well as with his own share of the difficulties of the new age. The previous storm had not yet passed away when the new cloud appeared on the horizon and the two broke in full fury upon the unfortunate house of Pole.

Margaret, Countess of Salisbury, the only living child of George, Duke of Clarence, was chief among the old aristocracy, who were now sometimes called the party of the White Rose. Katherine of Arragon had been warmly attached to the Countess and her family. The tender-hearted queen believed that Margaret’s brother was sacrificed in order to bring about her marriage with Prince Arthur. The Countess’ eldest son, Henry, Lord Montague, married Jane Neville, daughter to Lord Abergavenny, while her daughter Ursula became the wife of Lord Stafford, the Duke of Buckingham’s son. It was even whispered that higher honours awaited the Poles. The Countess became governess to the Princess Mary, and Queen Katherine 15would gladly have seen a marriage between her daughter and her friend’s son Reginald, who was a promising lad of sixteen when Mary was born in 1516. The family was closely connected by blood and friendship with Edward Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter, and his wife Gertrude. The Marquis was the son of Katherine, the youngest daughter of Edward IV, and therefore heir to the throne, after the Tudors: a very dangerous position[57].

Henry had learnt his lesson from his father too well to allow this state of things to continue. For the last hundred years the nobles had kept the kingdom in a turmoil. Northumberland, Warwick, the second Duke of Buckingham, had in turn made and unmade kings at their pleasure; now the day of reckoning had come. The two Henrys performed in England the work that Richelieu was to achieve in France a century later; they made the nobles realise at the cost of much bloodshed, that there was to be one king in the country, not half-a-dozen. No one can deny that they triumphed only by means of cruelty and injustice, and that their motives were selfish. But when it is considered how greatly the nation benefited, and when the fate of countries like Poland where the work was never carried out is remembered, it seems ungrateful to abuse the kings who did so much for their country at the cost of their reputation.

Buckingham was executed in 1521 and his son was ruined[58]; Montague and Abergavenny were thrown into prison[59] and made to pay heavy fines. The reason was simply that they were powerful enough to be dangerous, and Henry was powerful enough to crush them.

So far the King had acted from the old motives and guarded against the old dangers; with the divorce of Katherine new factors came into play. The Pole family was devoted to the Queen, and would in any case have opposed the divorce. In addition to this motive the Countess was a very devout woman and had brought up her sons to be pillars of the Church[60]. In 1532 Reginald Pole with some difficulty obtained leave to go abroad, to escape acquiescence in the divorce.

Reginald Pole was a man of quiet, amiable and studious disposition. He had been educated at the King’s expense, and was genuinely fond of his patron. There seems to be little doubt that if 16he had been left alone he would have been content to live peacefully in Italy with his friends and his studies. There he could have deplored the misfortunes of his country without attempting to remedy them by any more dangerous means than the vague, ineffectual plots at which legitimists always excel. But he was shaken out of his tranquillity by Henry himself. Early in 1535 Starkey, the King’s chaplain, who was a friend of Pole’s, sent him a royal command to state in writing his opinion on the royal title of Supreme Head of the Church of England. Henry wished to force Pole to take up a definite position. If he was friendly he might be useful; if hostile, he was dangerous, and the King was determined to know how to regard him. Pole was at first reluctant to undertake the task, but once he embarked on it he worked hard, and indulged to the full in the dangerous satisfaction of giving the King a piece of his mind. The book “De Unitate Ecclesiastica” was finished by the end of the year, but it was not despatched until Pole received the news of Anne Boleyn’s fall. Then, imagining, that the King might now be induced to change his policy, he sent it to England, at the end of May 1536, by the hands of his trusted servant Michael Throgmorton. It was, as its name implies, a vigorous defence of the one and indivisible Catholic Church under one supreme head, the Pope. The language of the book does not exceed the bounds of controversy as then observed; though, considering the King’s figure, the comparison between Henry and an unclean barrel was rather tactless. But Pole stated with perfect frankness his very strong disapproval of the King’s proceedings. From that time forth there was no hope that Henry would ever be reconciled to his kinsman[61].

The interest of the book to a modern reader lies in its revelation of Pole’s point of view. He had an essentially medieval mind; throughout his writings he assumes the political ideal of the middle ages, which pictured the Pope and the Emperor as the spiritual and secular heads of Europe. If any lesser king withdrew his allegiance from the Pope it was the Emperor’s duty to make him return to the fold. Hence it was the obvious duty of Charles V to reduce Henry to obedience. It never seems to have occurred to Pole that any life which there might once have been in this theory was now extinguished, and that the condition of affairs in medieval Europe had passed away for ever. After Katherine’s death Charles had no more justification for invading England simply because he disapproved of the English government than England had for invading France 17because she disapproved of Napoleon. Besides, what with Francis I, the Turks and the German Reformers, Charles had so many embarrassments that it was in the highest degree improbable he would ever be free to attempt the subjugation of England. But Pole was blind to all this, and he and his English friends continued to put their trust in foreign princes with disastrous consequences to themselves.

Pole had written his book at the King’s express request, stating his opinions quite honestly; he believed his country was going to perdition, and that a patriot’s only hope lay in force. From the point of view of the English government the book was certainly treasonable. It clearly and expressly urged all Englishmen to take up arms against the King, and exhorted two foreign princes to invade the country and help the rebels. Pole, however, was very careful that the manuscript should not be copied or printed, and its contents were only known to three or four of his friends[62]. It is unnecessary to describe the King’s anger on receiving the book, or the letters of remonstrance which he forced the Countess of Salisbury and Lord Montague to write to the offending author. He himself dissembled his anger, and summoned Pole to return home and there confer with wise men on the subject, about which he was misinformed. Pole was too prudent to accept this royal invitation[63].

The policy of the White Rose party is embodied in “De Unitate.” The plan at the root of all their scheming was that Charles V should invade England, marry Mary to Reginald Pole[64], force Henry to acknowledge Katherine, and establish a sort of regency, leaving Henry only the title of King. There were two serious flaws in this scheme. First, the conspirators overlooked the fact that an invasion was sure to cause a violent reaction in favour of Henry, who was at least an Englishman: they were, indeed, hopelessly out of touch with the feeling of the nation at large. Secondly, nothing was more unlikely than that Charles would consent to a marriage between Mary and Pole, for he regarded her as his property and would be sure, if he had the opportunity, to bestow her hand on some dependant of his own. Ruling, as he did, over so many different countries, he could not realise how strong national feeling was in such an isolated kingdom as England, and how desirable therefore an English husband would be for Mary, if she was ever to become Queen.

18Thus the White Rose party was following quite the wrong path, intent on will-o’-the-wisp hopes of the Emperor’s help when they should have turned to the mass of the nation for assistance. After Katherine’s death the prospect that Charles would interfere in English politics was very distant. King Henry did not “wear yellow for mourning” for nothing[65]. But Exeter and the Poles looked only to the Emperor, and while they did this Henry had little to fear from them. Other members of the party saw their mistake after a while. First among these was Lord Darcy.

Thomas, Lord Darcy, was the son of Sir William Darcy by his wife Euphemia, daughter to Sir John Langton[66]. On his father’s death (1488) he came into the lands in Lincolnshire which had belonged to the Darcys since Doomsday Book was compiled, and also those lands in Yorkshire, including the family seat of Templehurst, which had come to the family by marriage in the reign of Edward III. He was already over twenty-one and had probably married Dousabella[67], daughter to Sir Richard Tempest of the Dale, who was the mother of his four sons, George, Richard, William and Arthur. Darcy was raised to the peerage in 1505. In the same year he was made steward of the lands of the young Earl of Westmorland. This young man became Earl in 1523. The Earl’s character has left few traces upon history. Norfolk described him as “of such heat and hastiness of nature as to be unmeet” to hold the office of Warden of the Marches[68]. He was connected with the White Rose party by his marriage with Katherine, daughter to the unfortunate Duke of Buckingham. His mother was Edith, sister to William, Lord Sandes.

Darcy’s great influence in the north was in part owing to this connection with the Nevilles which was strengthened by his second marriage, to Lady Neville, the young Earl’s mother. Darcy held various offices of trust on the Borders during the reign of Henry VII. The King kept a watchful eye on his powerful servant, and in 1496 he was indicted at Quarter Sessions in the West Riding for giving various people his badge, “a token or livery called the Buck’s Head.” However, Henry by his well-known system of compensation created him Deputy Warden of the East and Middle Marches (16 Dec., 1498) and later Warden of the East Marches 19(1 Sept., 1505). On the accession of Henry VIII his offices were confirmed to him[69].

Early in the new reign occurred the strangest adventure of Darcy’s life—his expedition to Spain. Ferdinand had asked his son-in-law for the aid of 1500 English archers in his war against the Moors. Darcy at his own request was appointed leader of this force. The troops were mustered on 29 March, 1511. The expedition, consisting of five companies of 250 men each, sailed from Plymouth in May and arrived at Cadiz on 1 June. There was in Darcy something of the spirit of his crusading ancestors; but the time for a crusade had passed. The English were unruly and quarrelled with the Spaniards so much that Ferdinand was only too glad to seize the excuse of a truce with the Moors to pack them off home again. They were in Spain little more than a fortnight, and on 17 June reembarked without having loosed a shaft against the enemy. Darcy was bitterly disappointed and to add to his troubles the voyage home was long and stormy: on 3 August they had only reached St Vincent and he was obliged to spend large sums on victualling the ships and paying his men. His life-long friend, Sir Robert Constable, was one of the five captains under him who shared the humiliation and expense of it all. Such an experience might have made him shun all further dealings with Spain, but on his return to England the Spanish ambassador dealt liberally with him in the matter of money and overcame his resentment. The archers who went out to fight for a Christian prince against the Moors wore as their badge a curious device called the “Five Wounds of Christ.”[70]

Darcy took no part in the war with Scotland in 1513. He was not on the glorious field of Flodden, where the future Duke of Norfolk, then Lord Admiral, won such fame that for long years he was beloved through all the north. Darcy had gone with the King to France, where at the siege of Terouanne some accident caused the rupture from which he suffered for the rest of his life. He returned to the strenuous work of governing the Borders, of which more will be said hereafter. During the period of Cardinal Wolsey’s power, Darcy was on good terms with him; but in July 1529 he drew up an indictment of the falling favourite. This, in the form of articles, was signed by the Peers in Parliament, on 1 Dec. of the same year. Exactly how much discredit attaches to him for thus acting against a man for whom he had long professed friendship, must be decided by others. The case against Darcy is made rather worse by the fact 20that he was at first ready to forward the divorce of Katherine of Arragon. He signed the Memorial of the Lords to Clement VII, and even appeared as a witness at the Queen’s trial, although he had no evidence of any importance to give. On the other hand, he must have disapproved of Wolsey’s policy for some time, and the tie between the two men never seems to have been very close. Like others he was slow to realise the lengths to which Henry was prepared to go in order to get what he wanted. He did not foresee that Wolsey’s policy might lead to a policy of still more daring innovation. But when the situation was plain to him he fully declared himself. In January 1532 Norfolk made an appeal to a private meeting of persons of importance to defend the Royal Prerogative against foreign interference, with the suggestion that matrimonial causes, i.e. the divorce of Katherine, ought to be considered a matter of temporal jurisdiction. Darcy answered. In his speech he maintained that such causes were undoubtedly spiritual, and therefore the Pope was the supreme judge in them. He further insinuated that the King’s Council were trying to escape the responsibility of deciding on a course of action by dragging others into the matter[71]. He also addressed the Lords on the fitness of parliament to deal with matters touching the Faith, but the date and purport of this declaration are uncertain[72]. The result of his boldness was that he was informed that his presence was not required at the succeeding sessions[73] of the parliament.

Nevertheless he was not allowed to return to the north, but was kept in London, much against his will, from the winter of 1529[74] till at least as late as July 1535. The King would have been well advised to remember the proverb about idle hands. Darcy, the statesman and warrior, was kept some five years with nothing to do but brood over the changes which were taking place around him, and over the violation of his deepest and most honourable feelings. Cromwell and the King might have foreseen the result. Darcy had a strong sentiment of personal loyalty to the King; he could not bear it to be thought that “Old Tom had one traitor’s tooth in his head.” But as an honest man and a good Christian he felt he could not stand by and see the Queen and her daughter dishonoured, the Church destroyed, and the land brought under an absolute despotism, without making an effort to save them. The doctrine of the responsibility of the minister salved his conscience; it was easy to 21believe that if only Cromwell could be removed, Henry would turn back from the strange and dangerous road along which he was being led.

Darcy was on intimate terms with Lord Hussey, a member of one of the new official families which sprang up so plentifully under the Tudors. Sir William Hussey, father to John, Lord Hussey, was Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench in 17 Edward IV[75]; his parents are unknown. John Hussey assisted in putting down Lovell’s Rebellion in 1486, and obtained a footing at Court. He was partner to the exactions of Empson and Dudley, and on the accession of Henry VIII was obliged to obtain a pardon, but he did not lose favour with the King. He received large grants of land in Lincolnshire, where his seat was at Sleaford[76]; there he was unpopular with his neighbours, who accused him of arrogance and ostentation[77]. He served in France in 1513, and was employed on diplomatic missions until in 1529 he was summoned to the House of Lords as Baron Hussey of Sleaford. Through the whole of his career he had been a loyal and unquestioning supporter of the government as it was. His promotion was probably due to the King’s desire to strengthen his party in the House of Lords. He did what was required of him; he signed the document requesting the Pope to sanction the divorce of Katherine, and gave evidence for the King at the Queen’s trial. But Darcy, who was really opposed to the divorce, had done as much as this. There is no doubt, however, that Henry believed Hussey to be a man whom he could safely trust, for in 1533 he was appointed chamberlain to the King’s daughter Mary, who had just been declared illegitimate[78]. It was to his tender care she was confided for the time of insult and desolation her father had in store for her. Unfortunately for Hussey a warm friendship sprang up between Mary and his wife Lady Anne, the daughter of George Grey, Earl of Kent[79]. Hussey himself, though fairly hard-hearted, seems to have been touched by the sufferings of his helpless charge. It must have been this sympathy which drew him into communication with the White Rose party.

About midsummer 1534 Darcy dined with Hussey at his London house, and his old friend Sir Robert Constable was there as well. 22They talked of a sermon preached by Sir Francis Bigod’s priest; Bigod was a young man of great lands in the north, who inclined to the New Learning; his father had been among Darcy’s friends. In the sermon under discussion the chaplain had “likened our Lady to a pudding when the meat was out.” Not unnaturally shocked by such an expression, they all declared they would be “none heretics” but die Christian men. There by Hussey’s account the matter ended; but in September of the same year he was in communication with the Imperial ambassador[80].

Hitherto one of the King’s most unfaltering supporters, Hussey at this time unquestionably indulged in treasonable practices. All the disaffected nobles carried on secret correspondence with Chapuys, and Hussey among the rest begged him to urge the Emperor to invade England[81], where everyone was ready to welcome him. Chapuys’ correspondence reveals the fact that the nobles, at least, were at that time thoroughly out of sympathy with the King’s policy. Sir Geoffrey Pole, the younger brother of Lord Montague and Reginald, was anxious to leave England, and offered to enter the Emperor’s service in Spain. He gave up the plan when Chapuys pointed out that he would leave his friends in the greatest danger; they were already regarded with enough suspicion[82].

Meanwhile Darcy was making every effort to obtain permission to quit the Court and go home[83]. But this was steadily refused. In July (1534) he was upon the jury of peers which acquitted Lord Dacre from a charge of high treason[84].

In September he was the most considerable of all the peers who were secretly urging on Charles V an invasion of England[85]. This is the most indefensible part of Darcy’s conduct. To attempt to change the policy of the government, even by force if no other way is possible, may be justifiable. But it was very different to invite a foreign prince to invade England, and it was a pity that Darcy was so much swayed by the prevailing policy of the White Rose party as to consent to the scheme. Doubtless the excuse he would have offered was the position of Katherine and Mary. They were helpless in the King’s hands. They were inconvenient to him, and people who inconvenienced Henry seldom lived long. A national rising would only add to the danger of their situation; but if Charles joined the rebels the Princesses would at 23worst be held as hostages while a sudden raid might snatch them from Henry’s grasp[86]. With this object Darcy requested Charles to send a small force to the mouth of the Thames, for Mary was at Greenwich. Katherine at Kimbolton was so much further from the Court that the rebels might hope to rescue her themselves. For the rest, the old lord only asked the Emperor to come to some understanding with the King of Scots, and to send to the North some money, which was very scarce there, and a small number of arquebus men[87]. Both he and Hussey believed the discontent to be so widespread that a national rising would soon effect all that was required without any further assistance from abroad. But Charles was too busy to send even this slight aid. He instructed his ambassador to hold out vague hopes to the White Rose party and to do nothing[88].

For some time this policy succeeded. There was much passing up and down of messages and tokens, and nothing at all was done. Darcy gave Chapuys “a gold pansy, well enamelled” during the autumn. The pansy was the badge of the Poles and was to prove a sign of doom to that unhappy house. At Christmas he presented him with a handsome sword, which Chapuys supposed to indicate indirectly that the times were ripe “pour jouer des couteaulx.” His brother-in-law, the brave Lord Sandes, sent expressions of sympathy; and even the Earl of Northumberland, who was believed to be the most loyal of the nobles, sent his physician to Chapuys to assure him that the King was on the brink of ruin[89]. But time wore on; winter drew to spring and spring to summer—the bloody spring and summer of the executions under the Supremacy Act[90]. The Carthusians fell, Sir Thomas More and the gentle Fisher. Still Darcy was detained in London. Nor was he suspected without good reason, for he had long since told Chapuys that once back in the north he would secretly prepare for a general rising. In May he sent an elderly relative of his[91] to the Imperial ambassador, whom the latter described quaintly as “of more virtue and zeal than appears externally.” This man proposed to go in person to the Emperor to discover whether he really meant to send help, for if he was only deluding the English they were determined to act for themselves. Chapuys warned him that he would bring Darcy into danger, but he replied that once his master was in the north he would not care a button for any suspicions[92].

24Hussey, who was still trusted by the government, was at his house in Sleaford about midsummer 1535. A Yorkshire gentleman, Thomas Rycard, came to visit him. He found Hussey walking in his garden, and they talked about the spread of heresy in Yorkshire. Rycard said that as yet there was little of it, “except a few particular persons who carried in their bosoms certain books.” He prayed that the nobles might “put the King’s Grace in rememberance for reformation thereof.” Hussey answered that there was no hope of their suppression unless the two counties, Yorkshire and Lincolnshire acted together, and he himself thought it would be necessary to fight for the Faith[93].

In July (1535) Chapuys reported that he had seen Darcy’s cousin again, and that “the good old lord” (his by-name among the Imperialist party) was about to go home at last[94]. It appears from a letter to Cromwell, dated at Templehurst, that he was at home by 13 Nov. The year date is not given but it must have been 1535[95].

It is not necessary to describe the character of “Old Tom” at length, for it stands out from the records so vividly that more than any of his contemporaries he seems a living man; we learn to know his out-spokenness, his grim humour, his high sense of honour at a time when the very meaning of honour was almost forgotten. It was a very cruel fate which placed him in an age when it was impossible to live according to his motto, “One God, One King, One Faith.” From the day on which Darcy rode north there was something stirring in the land far more serious than any court intrigue, or any wild scheme of the Emperor’s interference.

To do the White Rose party justice they were less concerned with hopes of their own advancement than with anxiety for Katherine and Mary. On 6 Nov. 1535, Chapuys wrote to the Emperor: “The Marchioness of Exeter has sent to inform me that the King has lately said to some of his most confidential councillors that he would not longer remain in the trouble, fear and suspense he had so long endured on account of the Queen and the Princess, and that they should see at the coming Parliament, to get him released therefrom, swearing most obstinately that he would wait no longer. The Marchioness declares that this is as true as the Gospel, and begs me to inform your Majesty and pray you to have pity upon the ladies.”[96] A few days later he related the sequel: “The personage who informed me of what I wrote to your Majesty on the 6th about the Queen and 25Princess[97]—came yesterday to this city (London) in disguise to confirm what she had sent to me to say, and conjure me to warn your Majesty, and beg you most urgently to see a remedy. She added that the King, seeing some of those to whom he used this language shed tears, said that tears and wry faces were of no avail, because even if he lost his crown he would not forbear to carry his purpose into effect.”[98]

It is evident that Henry had purposely alarmed and distressed some of Katherine’s friends by threats of an outrage which even he could scarcely have ventured to commit. Was the Marquis of Exeter himself one of the councillors who wept? Someone must have told the Marchioness about the King’s threats of getting rid of the Queen and Princess, either her husband or another of the confidential councillors. And she herself, if not her informant, was deliberately communicating the “secrets of the realm of England” to a foreign power. If the King knew this he was quite justified in regarding the Courtenays with suspicion and expelling the Marquis from the Council. The Marchioness acted treasonably, though she did only what any good woman would have done under the circumstances. But Henry could not be expected to see that. Katherine soon gave her friends no more care, for she died in January 1536. In the same month Henry’s long parliament met for its last session, that in which the Act for the Suppression of the Lesser Monasteries was to be passed.

Lord Hussey begged to be excused attendance, pleading ill-health, but really, in all probability, because he knew it would be expected to pass acts against the Church. He came joyfully to the new parliament in June, assembled on the fall of Anne Boleyn. Mary was now safe and would probably be restored to the succession; and, on the fall of the late queen, it was universally hoped that a reaction would take place in ecclesiastical matters. Here Hussey’s inclination to treason seems to have ended, and his after connection with the rebellion appears to have been sheer bad luck. Or perhaps his wife, an ardent rebel, is to be blamed. She came up with him to London, and at Whitsuntide went to visit her former mistress, the Lady Mary, with whom she had exchanged tokens from time to time since they parted. While she was with the disowned princess on Whit Monday (5 June) she was overheard to call for a drink for “the Princess,” and on Tuesday she said “the Princess” had gone walking[99]. 26As Mary’s only legal title was “the Lady Mary,” Lady Hussey was arrested and sent to the Tower[100]. The charge must have been that “the Princess” meant the Princess of Wales; Mary never was created Princess of Wales, but the title was sometimes informally given to her before 1529. In England the daughters of Kings were not called “princesses” until later times. Chapuys, writing on the first of July, said that the real reason of her imprisonment was the King’s suspicion that she had encouraged Mary in her refusal to acknowledge the Acts of Supremacy and the Succession. When he heard that Mary had refused “he made the most strict inquiries, and the Chancellor and Cromwell visited certain ladies at their houses, who, with others, were called before the Council and compelled to swear to the statutes; one of them, the wife of her chamberlain (Lady Hussey), a lady of great house, and one of the most virtuous in England, was taken to the Tower, where she is at present.”[101]

The question naturally arises, how much did Lady Hussey know of all that was brewing in the North, and what did she tell Mary? But it can never be answered, though it is certain that whatever her husband’s views Lady Hussey was strongly in sympathy with the rebels. Mary’s refusal to subscribe to the Acts caused an immense sensation at Court. The King was furious and swore in a passion that she should suffer the extreme penalty. Exeter and Fitzwilliam were excluded from the Council, because they were suspected of sympathy for her. Even Cromwell was not safe, for since Anne’s fall he had been bidding for Mary’s goodwill, in anticipation of her return to Henry’s favour. Chapuys assured Mary that she was in immediate danger[102], and that any oath she took under the circumstances would not be binding. Much against her will she yielded to his entreaties, and signed the form her father sent her, without reading it. The result was an almost immediate return to her father’s favour and she consented to dissemble in future, whenever it was necessary[103]. Lady Hussey remained in the Tower throughout July, and her health suffered from the confinement[104]. On 3 August she was examined[105], and by the beginning of October she had been released and had gone home to Sleaford[106].

Note A. Although Pole was created a Cardinal in 1536, he was not ordained until 1556, after Mary’s marriage with Philip of Spain.

Note B. The Dictionary of National Biography makes Edith his first wife and Dousabella his second, but see Letters and Papers XII (2) Index under Darcy, Dousabella and Edith.

Note C. He was possibly Dr Marmaduke Walby, a prebendary of Carlisle, who was closely connected with Sir Robert Constable. After the rebellion had broken out, Darcy proposed to send Walby to the Netherlands for help, because he knew the Imperial ambassador[107]. From this it seems probable that Walby had communicated with the ambassador on the present occasion.

Note D. The cautious language is characteristic of the Chapuys correspondence. The ambassador never mentioned a name when a substitute was to be had. “He of whom I told you” is a very common phrase; Darcy is almost invariably “the good old lord.” This may show that Chapuys feared his letters might fall into the wrong hands, or it may be merely a diplomatic habit. Letters of such vital importance must have been sent by the most reliable messengers, but there was always a risk of miscarriage. Yet if they were discovered it does not seem likely that the thin veil of anonymity could have saved those who were compromised.

Between the nobles of the Court and the husbandmen in the fields stood that great and influential class “the gentlemen.” On it the Tudor government in the main depended. The gentlemen had no more sympathy with the out-of-date dynastic dreams of the White Rose party than with the economic grievances of the commons, but they had their own grudges against the government. They were hard-worked, and gained little thanks, as Henry went on the truly royal principle that it was honour enough to be allowed to serve him. They were worried by clumsy legislation, such as the Statute of Uses; they were angry at the interference with the House of Commons; and their better nature was outraged by the suppression of the monasteries founded by their ancestors, of which they were themselves the pupils and patrons. But the guiding principle of the country gentlemen was their devotion to landed property. They hated rebellion, because, sooner or later, it was followed by confiscation of property. They feared a rising of the lower classes because it endangered their property, even when it was not originally directed against themselves. The German peasants in 1524–5 had risen against the monasteries and the Church; but out of that movement had developed a bloody civil war between the rich and the poor. If fear of loss deterred the English gentlemen from opposing the government, no less did hope of gain. When they realised that the dissolution of the monasteries meant a general scramble for more property, most of them forgot their religious scruples; but this realisation did not come all at once.

So much can safely be said, but there is very little evidence as to the discontent among the gentlemen. It is possible to discover the attitude of the discontented nobles from the letters of Chapuys, which often give us a delightful feeling of eavesdropping across four centuries. Nor is there any doubt as to the feelings of the commons—scores 29of informers bear witness to their disaffection. But there is no key to the confidence of the gentlemen. They were more cautious than the labourers, less easily watched than the nobles. Their private opinions were known only to their friends, who would not, of course, inform against them. In the few cases (all after the rising) when gentleman did inform against gentleman, there was generally a feud of some standing between them. We are reduced to arguing backward, as Henry did. The gentlemen, especially in Yorkshire, were the leaders of the Pilgrimage of Grace. We cannot really accept their own subsequent explanation that they acted against their will in fear of their own tenants. There is abundant evidence that risings of the commons alone were very easily put down.

In this chapter we attempt to sketch the histories of half-a-dozen northern families of gentle or noble blood, in order to give some idea of the state of the north at the time and to outline the lives and antecedents of the leaders of the rebellion.

Local government in Henry VIII’s reign depended to a great extent on the peers. Each nobleman was responsible for the behaviour of his own district or “country” as it was called; under his supervision the gentlemen kept order, each on his own lands. The lord’s private friendships, feuds and marriages had a widespread influence on the lives of all whom he ruled. North of Trent the gentlemen naturally grouped themselves into three clans round the three great houses of Clifford, Percy, and Neville, the heads of which were respectively the earls of Cumberland, Northumberland, and Westmorland. It is necessary to know something of genealogy in order to understand the history of a period when marriages were arranged to suit family politics rather than the inclination of the parties, and consequently a man was born to an hereditary friendship with one family, a feud with another, and perhaps depended on a third for all hope of advancement.

All the noblemen of the northern counties took part in the strenuous task of governing the Borders. The border counties, Northumberland, Cumberland, Westmorland and the Bishopric of Durham, formed a district totally different from the rest of England. Scotland was a troublesome neighbour, and the men of these counties were a hardy race, famed for their soldier-like qualities and especially for their skill as scouts and skirmishers. Then again these counties were exempted from taxation on account of the Scots’ ravages and their own special burdens of defence. Finally a state of lawlessness 30frequently prevailed, which in peaceful times never even threatened the south. The Wardens of the Marches were usually noblemen such as Lord Darcy, Lord Dacre, and the Earl of Northumberland. The power entrusted to them was regarded with much suspicion by the King, while it was quite insufficient to maintain order. As early as 1522 a secret council, under the presidency of a royal lieutenant, was organised on the Borders. In 1525 it was re-organised and placed under the presidency of Henry’s natural son the Duke of Richmond[108]. The powers of the Council naturally roused much opposition in the north. Among Lord Darcy’s papers there is a draft of a petition complaining of its authority. The petitioners protested their loyalty, and declared their willingness to prove it against any insinuations. Seeing that they were so loyal, and that the country was quiet, with no rufflings as in the days of King Henry and King Edward, “but both the titles and all lovings to God (joined) in your Grace,” the petitioners begged they might be left under the ordinary jurisdiction of the Westminster Courts, which extended all over the kingdom except in the county palatine of Durham, instead of being at the mercy of the members of the Council, who might call any man before them on the slightest pretext. They complained that so long as things went well the Council alone was praised, and if affairs went badly, wheresoever the fault might be, the whole blame was laid on the gentlemen. Moreover, the petition continued, the Council was composed of spiritual men, who were not fit to judge murders and felonies, suppress sedition, or see to the defence of the realm, “and as great clerks report, there is no manner of state within this your realm that hath more need of reformation, nor to be put under good government, than the spiritual men.” If this were true, it was not meet that they should rule under the commission they now possessed “for surely they and other spiritual men be sore moved against all temporal men.” The petition ends with protestations of loyalty, after which Darcy wrote in a note that the like commission had been tried by “my Lady the King’s grandam,” and proved greatly to the King’s disadvantage in stopping the lawful processes at Westminster Hall. From this petition it appears that Darcy, and probably other northern gentlemen, was ready to make use of the King’s anti-clerical policy for his own ends, arguing, perhaps, that though he was as loyal a son of the Church as any man, yet priests ought not to meddle in secular matters[109]. This draft was drawn up in the year 1529, 31before any of the acts aimed at the clergy had been passed, and before Darcy himself had chosen his side in the struggle between King and Pope. It was probably never presented.

Some such body as the Council of the North was absolutely necessary if any approach to law and order was to be maintained on the Borders. In proof of this it is only necessary to describe one case out of a dozen. Humphry Lisle, whose father Sir William Lisle of Felton, had led a brief but crowded career as a freebooter in 1527–8, was run down and condemned to death with his father and most of their band in 1528, when he was only thirteen. He subsequently confessed that he had assisted in an attack on Newcastle gaol, by which nine persons were liberated; that he had taken part in four cattle raids, the burning and spoiling of five farms and villages, and four highway robberies; that he had helped to capture a number of prisoners to be held to ransom, and had been present at the murder of a priest[110]. His life was spared by the Earl of Northumberland, who had captured and hanged his father, but Humphry was sent to the Tower. In 1532 he was back on the Borders and a knight, but almost immediately afterwards he was outlawed and fled to Scotland[111].

Careers of this sort being rather the rule than the exception on the Borders, the office of Warden of the Marches called for a strong man. But one could seldom be found, and the quarrels of the northern nobles among themselves embroiled matters still further. The divisions of the house of Percy, for instance, caused infinite trouble. The fifth Earl of Northumberland, surnamed the Magnificent, died in 1527, leaving numerous large debts. He had three sons by his wife Katherine, daughter and heiress of Sir Robert Spencer[112]. The heir, Henry, born about 1503, was feeble in body and, like all such men in that hurrying age, was constantly the creature of those in power. From his earliest years he was either led or bullied, first by his father and Cardinal Wolsey, in whose household he was educated, later by Cromwell and Cromwell’s dependent, Sir Reynold Carnaby. When Henry Percy was a page in the Cardinal’s service the incident occurred by which he is best known, his poor little love affair with Anne Boleyn. He seems to have offered to marry her; but the King had already shown the maid of honour favour. The Earl of Northumberland forbade his son to 32foster so dangerous a passion and hastened on his marriage with the Lady Mary Talbot, daughter to the Earl of Shrewsbury[113].

In 1527 Henry Percy became Earl of Northumberland, and on the fall of Cardinal Wolsey he was freed from the man who had exercised most influence over him. It is characteristic of Cromwell’s methods that he worked the Earl as he wished by means of the young nobleman’s own favourite, Sir Reynold Carnaby[114]. While this man retained his position the King could rely on Northumberland, who was reputed to be one of the most loyal of the peers. He was at one time in secret communication with Chapuys, but this was probably a mere freak. Darcy described him as “very light and hasty” and not to be trusted[115]. His loyalty seems to have sprung from abject fear of Henry, and he probably would have been glad enough of the King’s overthrow, though he would rather die than venture to assist in it.

The Percy estates were rich, though burdened with debt, and the castles were very strong. With them in his hands the King could keep the north in subjection and even hope to abate the confusion on the Borders. But if they were used against him by some capable commander, such as the Earl’s brother, Sir Thomas Percy, the results were sure to be serious; if foreign help were sent to the rebels, perhaps fatal. Cromwell, with Sir Reynold Carnaby to forward his plans, saw the chance of enriching the crown by the whole of the Percy lands. The Earl’s life was uncertain; his marriage turned out unhappily and there was no prospect of an heir; he was on bad terms with his brother Sir Thomas, and Carnaby took care that he should not forget the quarrel[116]. It was not surprising that the brothers should disagree, for Sir Thomas had all the conspicuous vices and virtues of his race, which were completely absent in the invalid Earl. An instance of their constant disputes occurred in 1532, when the Earl appointed Lord Ogle Deputy Warden of the Marches. Ogle was allied to Carnaby, and Sir Thomas together with his younger brother, Sir Ingram Percy, refused to recognise his authority and forbade their tenants to do so. Sir Thomas issued proclamations declaring that he was the true Warden, and Lord Ogle postponed his first Warden’s court for fear that the brothers would break it up[117].

33Sir Thomas on his side complained that the Earl had not given him the lands left to him in his father’s will until he was on the eve of marriage[118]. His wife was Eleanor, daughter and co-heiress to Harbottle of Beamish; by her he had two sons, Thomas and Henry, and a daughter. Their home was generally at Prudhoe Castle on the Tyne[119].

It does not appear that the breach between the brothers was irreparable until about 1535, in which year the King gave the childless Earl licence to appoint any one of the Percy name and blood heir to all his lands[120]. But when Sir Thomas, his natural successor, was proposed, the King raised objections[121]. The result was that in February 1535 the Earl made the King his sole heir, and an Act of Parliament was passed “concerning the assurance of the possessions of the Earl of Northumberland to the King’s Highness and his heirs[122].” Nothing could have made the Earl more unpopular, and it was probably this alienation of the family property rather than his personal extravagance and inherited debts that earned him his surname “the Unthrifty.”[123] Sir Thomas was provided for in the Act, but he could hardly be grateful for a pension when he felt himself heir by right to an earldom and the broadest lands in the north[124]. No appeal was possible when the King gained by his loss. A petition which he sent to Cromwell in July 1535 shows his helplessness. In this he related how the lands at Corbridge so tardily allowed him, which he “with great labour” had defended from the Scots, had now been granted by his brother to Sir Reynold Carnaby. Sir Thomas naturally refused to give them up, and went to remonstrate with his brother in person. But he was not allowed even to see the Earl and was rudely turned from his house. He concluded by begging that Carnaby might be removed from the Earl’s service, as he was the cause of his master’s quarrels with his wife, brothers and nearest relatives[125]. Cromwell was not likely to remove Carnaby from the place where he had been of so much use; and it was Cromwell and Carnaby whom Sir Thomas secretly denounced as the authors of his wrongs when he, with Sir Ingram, swore to be revenged on the Earl’s favourite as “the destruction of all our blood.”