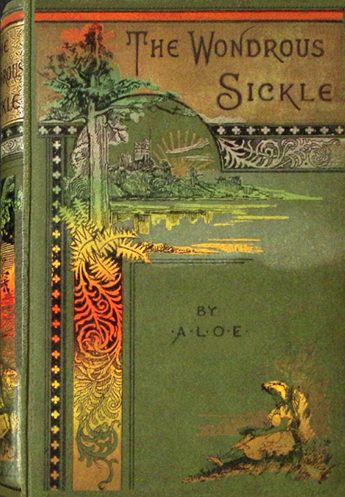

Title: The wondrous sickle, and other stories

Author: A. L. O. E.

Release date: December 30, 2025 [eBook #77569]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Gall and Inglis, 1892

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

Day by day the monarch went out to reap his corn

and bind up his sheaves.

And Other Stories

BY

A. L. O. E.

Authoress of "Ned Franks,"

"The White Bear's Dean," &c.

London

GALL AND INGLIS, 25 PATERNOSTER SQUARE;

AND EDINBURGH.

Contents.

——————

THE TWENTY-FOUR PIECES OF SILVER

THE

WONDROUS SICKLE

And Other Stories

FATH MASIH had been appointed "patwari" * in a large village. Though many Hindus and Mahomedans in that village had been annoyed at the situation being given to a Christian, and some bigoted individuals annoyed him as much as they could, the poor in general were pleased. Here was a man who dealt justly; here was a man who took no bribes; here was a man ready to listen to the appeal of the humblest, a friend of the widow and the orphan. The people thought better of Christianity, when they saw the life led by the Christian.

* The business of the patwari is to measure land, keep a map of

the district, &c. His is a small office under Government, giving

considerable opportunity for fleecing the peasantry.

Fath Masih and his wife were almost shut out from intercourse with any others of their own faith. The only Christian whom they ever saw was Ishák, who had a place in the Forest Department at a station ten miles distant, and who, about once a-month, managed to come over and see them. Ishák was a pious man, and a warm friend of Fath Masih. It might be expected that the meeting between the two Christians would be a great pleasure to both. It would, indeed, have been so, had not Ishák, every time that he came to Durhiala, found Fath Masih more and more in low health, and depressed in spirits.

"I can hardly endure this life," said the poor patwari, one day, as he sat under the shade of a banyan beside his friend. "My wife and I have no one with whom to hold Christian converse. There is no church in which, on Sundays, our souls can be refreshed by hearing the Word of God. When we are in trouble, there is no one to remind us that the Lord chasteneth those whom He loveth. If we look to the right, behold, a Hindu temple,—to the left, we see through the trees the domes of a Mahomedan mosque. It is very depressing!"

"It is so, indeed," replied Ishák, who was himself in much the same position. "But you have still the comfort of the Bible and prayer."

The face of Fath Masih grew only the sadder. He gave a deep sigh before he replied,—"The worst of all is that I am losing my pleasure in reading the Bible, and all my comfort in prayer. My soul, from want of Christian intercourse, is becoming dry, like a field that never is watered. I fear that were my Lord to send a message to me, as He did to Ephesus of old, it would be, 'I have something against thee: thou hast fallen from thy first love'" (Rev. ii. 4). The words ended with a deep sigh.

Ishák looked anxiously at his friend, whose melancholy was evidently affecting his health.

"Does your wife feel the loneliness as much as you do?" asked Ishák, after a pause.

"Perhaps not," replied Fath Masih gravely. "Many women come to visit my wife, both Mahomedan and Hindu, but their talk is mere gossip. They show their jewels, expect my wife to take pleasure in their weddings, and mourn at their funerals. But, of course, there is no religious intercourse between them."

Ishák looked almost as grave as his friend on hearing this. He had noticed that Moni's dress was less distinctively Christian than it had been in the city in which she had formerly dwelt; that she wore more gaudy ornaments, as if to look like the women around her. He fancied that Fath Masih was not quite satisfied with his wife, and felt that, in this heathen place, her love, like his own, was growing cold.

"I sometimes wonder whether I ought to stop in Durhiala," said Fath Masih.

"Your present situation was procured with much difficulty," observed his friend; "and I remember how fervently you thanked God for granting your prayers at last, and enabling you to be independent of all assistance from the Mission."

"Yes, I was thankful, and I am thankful, for this," replied Fath Masih. "I think it a mean thing, and a wrong thing, for a man who can support himself to be always coming for help, and taking from the store, which is all too small to supply the wants of such as are really unable to work. I have seen men—with a great show of religion, too—who seemed to me like the leech, with their one cry of 'Give, give!' Thank God! I am able to help the good cause a little myself, instead of sitting with folded hands, expecting others to put bread into the mouth of a sluggard." Fath Masih followed the excellent example of those who always give at least a tenth of whatever they possess to God, and find that they are never the poorer for so doing.

"Were you to leave your post here, you would be dependent again," observed Ishák.

"That is what keeps me here, and the thought that God sent me here," said Fath Masih. "But am I right in believing that He sent me here, when my soul is in danger of starving for lack of spiritual food? Its life seems to be decreasing day by day. If we remain here long, I fear that we shall be 'dead' Christians—Christians only in name!" Fath Masih turned his face aside, to hide the tears that had started into his eyes.

Ishák said nothing more at that time, and indeed had then no opportunity to continue the subject, for Moni gave notice that she had served up the evening meal.

The food was eaten almost in silence. Fath Masih felt too sad and too ill to care to eat much, and his friend was lost in thought. But when the "pilau" was succeeded by fruit, as the heap of ripe mangoes rapidly lessened, Ishák, in a cheerful tone, engaged in conversation, and even Fath Masih, swallowing the luscious golden juice, seemed to forget half his gloom. Ishák offered to tell a story, and Moni, as well as her husband, gladly listened.

"Once upon a time there was a king, good and just, and beloved by his subjects. But he had not been long seated on the throne before his health began to fail. Re cared not to go forth from his palace, and all its beautiful adornments gave him no pleasure. The feast spread before him he scarcely tasted, for all his appetite was gone. The king grew thin, his form wasted, he had no spirit either for work or amusement. At last, the courtiers whispered amongst themselves, 'Alas! Alas! Our king is gradually wasting away! He will not long remain in this world!'

"Many doctors were sent for; various were the opinions which they gave as to the cause of the king's illness, the nature of his disease. Some persons even hinted at poison. Much medicine was given to the king, but still he grew no better. He seemed at last unable to do anything but recline on cushions, taking hardly any nourishment, and finding solace in nothing but smoking his hookah. It was commonly reported in the city, 'Our good king is going to die.'

"At last, a very famous physician from a neighbouring country was sent by its friendly king. The fame of this physician had been spread far and wide, so numerous had been the cures which he had wrought. It was said, 'Our king's last chance is from this man's skill; if it fail in this case, all hope is lost!'

"The physician was admitted to the presence of the king, whom he found pale and almost lifeless, with closed eyes, extended on his soft couch. The physician felt the king's pulse, inquired into his symptoms, and then asked for twenty-four hours before deciding on his case.

"Those twenty-four hours were a time of great anxiety to many both within and without the palace, and most of all to the poor sick king.

"The next day the physician returned with something wrapped up in an embroidered cloth, and with a countenance so cheerful that the hearts of all gathered hope.

"'Have you, O physician! found out any cure for my grievous sickness?' asked the king.

"'I have found something, O Ruler of the world! which, by the favour of the All-merciful, may work a cure, if used with courage and perseverance,' said the physician.

"'I will shrink from no remedy, however painful,' cried the king, 'if only my lost health can be restored.'

"The physician slowly opened the folds of the cloth, and behold! a bright sickle, with handle of carved ivory, appeared in view. The attendants looked on in wonder, for they knew not by what magic power a sickle could work a cure.

"Then said the physician, 'Every day, O mighty Monarch! take this sickle in your royal hand, and descend into yon field in which I behold corn ripening in the sunshine. Ply the sickle with force and vigour, until the ivory handle almost cleave to the hand that grasps it, and the toil-drops stand on your Majesty's brow. Then, returning to the palace, deign to partake of the food which will then be set before your Majesty. Persevere in thus using my sickle until yon field be reaped, and if my lord's health be not improved, let his servant's head be the forfeit.'

"The sick monarch agreed to try the virtue of the wonderful sickle, which, when not actually used, was, by his command, to be kept locked up in a sandal-wood chest. No one was to touch one ear of corn in the little field except the king, who hoped to gather health from its reaping.

"He went forth alone on the following morning with the wonderful sickle, nor returned till his hand almost clave to the ivory, and the toil-drops stood on his brow.

"Bring me food—and quickly!' cried the king, 'I am half dead with fatigue!' And he threw himself back on his cushions.

"Food was served in silver vessels. The courtiers looked on wondering as the king proceeded to eat it.

"'Yesterday,' whispered one, 'the dishes went away almost as full as when they were brought. To-day the king has almost finished the pilau, and now he is busy with the curry and rice!'

"After a plentiful meal, the king, who was usually sleepless, fell into a long, deep slumber. When he awoke, he observed with a smile, 'I have not had such a sleep for many months. There must be magic virtue in the sickle.'

"Day by day the monarch went out to reap his corn, and bind up his sheaves, which were always given to the poor. Day by day he returned weary, and very hungry. His step grew firmer, his eye brighter, he was far more cheerful and hopeful. Soon the king gave audience to ambassadors, then felt able again to judge the cause of the poor in person. All the dwellers in the city rejoiced to see his returning health, all praised the gifted physician, and sick grandees offered the latter thousands of rupees for magic sickles like that used by the king.

"When all the corn in the little field had been reaped by the royal hand, the monarch sent for the physician. He loaded the doctor with praises and costly gifts, and permitted him to return to his own land. The wonderful sickle was preserved amongst the choicest treasures of the king."

"Was there really magic virtue in the sickle?" asked Fath Masih, when Ishák had finished his story.

Ishák's only reply was a smile.

"I suspect that the real medicine in it was the work which it made the king do, and the cure was the effect of that work on the monarch's health and spirits," observed Moni, who was a very intelligent woman.

"True," was Ishák's reply, "and it was not without a purpose that I have told you this story, which I read in a book long ago. Fath Masih! Your soul is faint, you are almost weary of life; you think that you are placed in a spiritual desert; I see in it a field, yea, a promising field of corn. You are surrounded by enemies of your faith; there is not one amongst them that is not a possible convert to that faith. To the Hindu temple and Mahomedan mosque throng beings with immortal souls, souls that our Lord died to save, souls that may be won for Him. Take the sharp weapon of God's Word in your hand; grasp it by the ivory handle of prayer. Why hath God brought you to this dark place but that your light may shine to His glory! There is little danger of love dying out when it is actively, prayerfully engaged in work for the good of souls."

Fath Masih made no reply, his eyes were fixed on the ground. A painful consciousness had come upon him that his conduct had been that of the man who buried his talent in the earth. He was becoming less and less "fervent in spirit," because not "serving the Lord."

No more was said in conversation on the subject, but when Ishák that evening led the family devotions, he earnestly prayed that the Holy Spirit of God might be shed into the heart of each present, that not one might stand idle when the Lord saith, 'Go work in my vineyard;' but that all might inherit the blessing promised to those who, turning 'many to righteousness, shall shine as the stars for ever and ever.' (Daniel xii. 3).

"We are all weakness!" he cried. "But Thou, O Lord, art our strength! Thou canst put treasure into earthen vessels; Thou canst touch the dumb lips with living fire; Thou canst give power to the feeblest reaper; and from Thee alone we look for the harvest, the precious harvest of souls!"

Ishák departed on the following morning, and a longer time than usual elapsed before he was again able to revisit his friend. The weather being exceedingly hot, Ishák started on his long walk to Durhiala whilst the stars were yet shining in the sky, and arrived about two hours after sunrise.

As Ishák approached the village, he met ten or twelve little children, some of whom had primers in their hands, and who were smilingly repeating to each other some simple rhyme which they had just been learning.

"What! Is there a school in Durhiala?" asked Ishák of the eldest child of the party.

"No, there never was a school," said the child; "but the patwari's bibi lets us come to her of a morning, and teaches us 'bhajans' * and our letters, and when we learn well, she sometimes gives us fruit."

* A wild kind of song, much admired by Hindus.

"And she tells us such nice stories!" cried a smiling, bright-eyed little girl.

"What kind of stories?" asked Ishák.

Then half-a-dozen eager voices answered at once—

"Oh! About the Holy Baby that was put in a manger."

"About the Lord who loves little children."

"About the song of the angels."

"About the lost sheep and the Good Shepherd!"

Ishák smiled on the eager little pupils, and passed on, with a silent thanksgiving to God that Moni had laid her hand to the sickle.

One lame little girl came limping after the rest.

Ishák stopped to speak to her also. "Have you too been to the patwari's bibi?" he asked.

The child looked up timidly into his face, and reading kindness there she replied, "She has been putting something on my bad boils to make them well."

"Is the bibi clever at making people well?" inquired Ishák.

The girl looked rather doubtful. "She could not make little brother well, though she tried," was the child's reply. "She sat beside him all night long, but he died in the morning, and poor mother sobbed and wailed, for he was her only boy."

"Did the bibi not try to comfort her?" asked Ishák gently, stooping down to listen to the scarcely audible reply.

"The bibi told mother that she had lost her own—her only little baby; but she said that God had comforted her in her trouble, for she knew that her baby had gone to be with the Lord Jesus, who carries little lambs in His bosom."

Again a silent thanksgiving arose from the heart of Ishák. "My friend's wife is like the woman who hid leaven in three measures of meal," he said to himself. "Oh! May God make this once childless woman the spiritual mother of many!"

Ishák had now come in view of the patwari's house. He saw Fath Masih, who was engaged in such earnest conversation with an intelligent-looking young man, that he did not notice the approach of his friend.

Tired as he was, Ishák would not interrupt the conversation, for, from the earnest manner of the speakers, and the few words which reached his ears, it was evident that it was on the subject of religion. Ishák saw Fath Masih place a little book in the young man's hand, and heard his parting words, "You promise to read it—and with prayer!"

The reply Ishák could not hear, but he read it in the thoughtful countenance of the young man as he turned and departed with a copy of the Gospel in his hand.

Then Fath Masih caught sight of Ishák, and hastened to welcome him, with a countenance beaming with joy. As he grasped his friend's hand, he exclaimed, "O Ishák, I thank God for bringing me here! I think that there are three real inquirers in this place!"

"You too have laid your hand to the sickle," said Ishák; "and, to judge from your face, you do not find the work irksome."

"It is a blessed, blessed work!" exclaimed Fath Masih. "God forgive me for leaving it so long undone! I feel now that not only missionaries, but every Christian in India should pass on the glad tidings to others. I used to content myself with praying, 'Lord! The harvest is great; send forth more labourers into Thy harvest.' Now I myself have heard His call, and venture humbly to say, 'Here am I, send me!'"

"But do not your efforts raise up much opposition?" asked Ishák. "Do you not bring yourself into trouble?"

"I have sometimes a little of that trouble which is coupled with a blessing," replied Fath Masih cheerfully. "But I never now feel that weariness, that deadness of spirit which oppressed me when last you were here. My experience has been something like that of the king in your story," he added, smiling; "I find that health, and vigour, and joy come from the use of the wonderful sickle!"

THE sun had set; the red glow had just died away in the sky, but the moon had risen. A railway official, named Karim, stood on the platform of the small station of Banda, watching for an expected train. A zamindar (peasant) * named Matrá, came up to him, and asked him respectfully when the train from Calcutta would arrive.

* In parts of India, a farmer.

"I expect it in ten minutes," answered Karim.

The zamindar sat down on the ground, like one who is very weary. As Karim looked at him, pity arose in the official's heart. Matrá was quite young, scarcely eighteen years of age, but lines of care were already on his features. His blanket was little better than a rag. His limbs, naturally strong and graceful, were thin as if from lack of food. As he sat on the ground, a deep sigh came from the poor zamindar.

"You seem tired," observed Karim kindly.

"I was up before the sun, and have been driving the plough all the day," said Matrá; "and now I have just walked seven miles to this station."

"Are you going a long journey?" asked Karim, who noticed that the zamindar had no bundle with him, not even a hookah or brass lota.

"I am not going on any journey," replied the zamindar. "I have come to meet the train, because I hope that it may bring my father."

"You must be very anxious to see him that you come so far after a long day's work," observed Karim, seating himself beside the zamindar on an empty box which chanced to be on the platform.

It was pleasant to the zamindar to have some one to converse with, some one who spoke in a friendly tone, and who was willing to listen. Matrá was soon telling his simple story.

"My father is a sepoy," he said, "and it is ten or twelve years since he left our village to march away with his regiment. I can remember that day very well; how grand I thought it to see the sepoys marching, and hear the music playing. But we have never had anything but trouble since that unlucky day. First came my marriage."

"Was that a trouble?" asked Karim, smiling.

"It did not seem so at the time. We had fine clothes, and feasting, and drum-beating, and fireworks let off in our village. It was a grand 'tamasha!' The girl's family were Chhatries, so, of course, my grandfather would have all done in good style, and many rupees were given both to the father of the bride and the Brahmins, and there were jewels to buy besides. Then first my grandfather fell into debt, and in debt we have been ever since. It is easier to get into a bog than out of it."

Karim nodded his head in assent.

"You must be very anxious to see him that you come so

far after a long day's work," observed Karim.

"Before the girl came to live with us," continued the young zamindar, "as she was playing with her little companions on the top of the house, she fell over, broke her neck, and was taken up dead!"

Matrá could not be expected to mourn much for a child-wife whom he had hardly seen. Karim rightly guessed that the zamindar's evident regret was chiefly on account of the debt incurred by the expense of such a profitless marriage. "And what were your other troubles?" he asked.

"My grandfather fell sick not long after this, and sick he continued for years. He had no son but my father, and my father was far away with the army. Mere boy as I was, I did what I could, looked after the buffaloes, and worked in the fields, but I could not do the work of a man. And there was always the debt a-growing, like the gourds in the rains."

"Did your father do nothing to help you?" inquired Karim.

"He sent several times five-rupee notes," said the zamindar, "but it was like throwing stones into a bog, which swallows them up and you see no more of them. The money-lenders could never have enough. My mother fretted and went on pilgrimage, and bathed at holy ghauts, and did pujá at many shrines. But she took the smallpox and died, though she had made many offerings to the goddess of smallpox." Matrá sighed very deeply; the loss of his mother lay much more heavily on his heart than that of his little wife.

"You have indeed had troubles," observed Karim.

"You have not heard the end of them," said the poor young zamindar. "My grandfather died at last. I paid all the respect I could to his body. I feasted for days a hundred neighbours who came to its burning, gave a cow and many rupees to the Máhá-Brahmin, and myself carried the ashes to the Ganges, though it was just the season when the corn was ripe for reaping. If I had been in the bog of debt before, I was now up to my eyes! It's heartless work watering one's fields in the dry season, and seeing the corn springing up so green, when one knows that the money-lender may sweep down any day like the locusts, and eat up all the fruit of one's toil!"

"Is not running into debt at all the cause of the mischief?" observed Karim.

"What is to be done?" said the zamindar sadly. "Wedding and funeral ceremonies are the ruin of the poor, and bad seasons which come now and then, when there's drought, and the heat dries up all the crop."

"Have you no relations to help you?" asked Karim.

"Not one on earth but my poor old grandmother, who is now scarcely able even to spin or card cotton; and my father, who has been so long away. But he is coming back at last!" said the zamindar, and a look of joy beamed on his careworn face. "I had a letter from him some weeks ago (I've learned to read a little in a village school), and I made out that he would be here before the rabi * harvest is ripe; the corn is green enough yet, but I thought that after work, I would come over here to meet him. Maybe my father will arrive sooner than he said; any-ways, I would not miss my chance of the first sight of him, if I had to walk twenty miles."

* The spring harvest. Let it be borne in mind that there are two annual

harvests at least in some parts of India, so that the zamindar may

often be seen ploughing in one field, while a rich crop covers the next

one.

"Would you remember the face of the father whom you have not seen since you were a child?" asked Karim.

"I know that he was tall—taller than any other peasant in our village—and that he used to seat me on his shoulder, and then I could pluck mangoes from the high boughs," replied Matrá, brightening at the recollection of the happy time which he had had with his father. "I can't just bring his face to my mind—I wish that I could—but surely I should know him if he arrived. How long the train is of coming!" he said suddenly, looking down the long, dark line of railway.

"The whistle has not yet sounded," said the official; "we shall have notice when the train is drawing near."

"I TOO have had many troubles," said Karim, after a little pause, "perhaps even greater troubles than you. But my Father has helped me out of them all."

"It is a great thing to have a father near at hand," said the young zamindar. "Probably you live with yours, and see him every day."

"I have never seen Him yet," replied Karim.

"Never seen him yet!" repeated Matrá. "Then you are worse off than I am. But you say that he helps you in all your troubles."

"There is not a thing that happens to grieve me that I do not tell Him of," said Karim, "and my Father sets everything right. There never was another so kind and so wise, or so powerful either."

"Then I wonder that he keeps you here looking after the trains," observed Matrá. "He might find some better situation for you; or, if he be rich, give you all that you want, without need of your working at all."

"My Father thinks it better for me to earn my bread by honest labour," observed the official. "But after awhile, He will call me to His own beautiful dwelling-place, and put splendid robes upon me, and give me freely all that my heart can desire."

"I wish that my father could do so," said Matrá; "but I doubt that he will ever have enough to pay off our debt. Does your father live very far off, that he never sees you at all?"

"He sees me always," said Karim, looking upwards; "night and day, in darkness and light, He is ever close beside me. God is my Heavenly Father, I have now no parent beside Him."

"Are you a Christian?" asked the zamindar. There was a little scorn in his tone as he uttered the word.

"I am a Christian," was Karim's reply. "A year ago, I had father, mother, brother, sisters, friends, and as many rupees as I chose to spend; now I am cast off by every one except that Heavenly Father, whose love makes up for all."

The zamindar did not understand why a man should give up home and everything for the sake of changing his religion. "I suppose that you were a Mahomedan," he said.

"I was, and a bigoted one," replied Karim.

"I think that the Mahomedan religion is good for the Mahomedans, and the Christian for the English, and the Hindu for us Hindus," said Matrá. "I believe what my fathers believed, and do what my fathers did. They always performed pujá to the gods."

"And what benefit did they receive from so doing?" asked Karim.

It was a difficult question to answer; Matrá did not attempt to reply.

"You do pujá to many gods; we pray but to One Supreme Being," said Karim; "He is the Maker of everything that we behold, the bright sun, yon moon, earth, sea, and the myriads of creatures that live therein. As to a man there can be but one father, so can there be but one God, and that God is Love. This is what we are taught in our holy Book."

"I know that you Christians believe not in Krishan, Vishnu, or Mahedeo," said Matrá, slowly rising to his feet, as if inclined to end the conversation.

"Listen to me, brother," said Karim, also rising to a standing position. "You are expecting your father by the coming train, a father whom you love, though you do not remember his face. Suppose that, when the train stops, a Brahmin should get out of a carriage, and carry with him some dozens of images, one with the head of an elephant, another with a hundred arms, another with no shape at all, and should say to you, 'Rejoice, O zamindar! "These" are the fathers whom you have been expecting so long! Would you take the figures of brass or stone to your bosom, and cry, 'Now am I satisfied!' Would you receive the lifeless things, and acknowledge them to be your parent indeed?"

The zamindar shook his head. He was expecting a living father, a loving father; he could not receive as such any image of stone or brass.

"And if it would be an insult to your parent to let an image for one moment take his place, think you that the one great Father, the Eternal, the Invisible, is not offended when His creatures liken Him to such monstrous forms as you do pujá to in your temples?"

"No one ever spake such things to me before," said Matrá, his common sense striving against the force of old habits, and his fear of the anger of those whom he had been taught to look on as gods.

"Listen but a minute longer," said Karim earnestly. "If in your village you heard any one saying that your father had committed theft, murder, and done other things that it is shameful even to mention, would you listen with a pleased countenance, and reward the speaker at the end?"

"I would break the liar's head with my goad!" muttered the young zamindar.

"And yet you are willing that Brahmins should tell you of deities committing crimes, which, if committed by a man, would drive him from society and bring him to prison, or to the gallows! Look at yon clear sky with its pure moon, and the stars just beginning to shine above us, can you believe it to be peopled with beings revelling in blood, delighting in suffering, pleased with the shrieks of helpless babes flung into the Ganges, or the groans of victims crushed under Juggernath's car? Does not Nature, beautiful, bounteous, pure, tell of a Maker all perfect and holy—repeat, as it were, the words of our Book, that there is one God, the Heavenly Father of all, and that He is Love?"

There was no time for reply, for as Karim uttered the last word, the whistle was heard which announced the coming train. Soon, snorting and puffing, like some mighty monster, its one red eye gleaming through the gloom, the train rushed up. It slackened its pace, and then stopped as it reached the side of the platform. Karim was ready at his post. With lamp in his hand, he passed from carriage to carriage, giving the name of the station in case any traveller should wish to alight.

Eagerly Matrá ran along the platform, passing the carriages occupied by Europeans with scarcely a glance at the faces within, but anxiously peering into every one filled with natives. The station was a small one, and but few passengers alighted. There was a sahib whose "sais" (groom) was waiting with his horse, a bunniah and his family, and that was all. There was not a trace of a sepoy.

It was with a heavy heart as well as weary limbs that poor Matrá left the station. He knew too well the face of the bunniah, for he owed him a debt, and had found in him one of the hardest of his creditors. The poor man slunk away, as debtors will, with mingled fear and shame. Matrá murmured to himself as he left the station, "I have had my weary walk for nothing."

HAD Matrá indeed had his walk for nothing? Any one who could have read his heart as he went on his homeward way would hardly have said so. A seed of truth, a living seed had been dropped there, and had found good soil to grow in. As Matrá walked on, with the soft pure moonlight around him, he almost forgot his weariness, he almost forgot his burden of debt, so constantly were Karim's words coming back to his mind—"There is but one God, and that God is Love."

"The one God of the English seems to do more for them than our millions of gods do for us," thought Matrá. "The English press onward like that engine which I saw rushing into the station, with a long line of carriages behind it. What speed, what straight course, what power! We go on like one of our country waggons, creaking along in the old ruts, and sometimes a wheel comes off or an ox drops down, and there we are left on the road. What makes the difference between us? The engine goes faster and better, pushed on by something which we cannot see, than does the cart with the oxen which we always are goading. The God of the Christians must be a very strong God, and the man at the station says that He is a very kind one; but it's likely enough that He would have nothing to do with poor Hindu zamindars such as we."

Matrá found his old grandmother Sibbi still awake, and preparing for him some chapatties. The poor old woman, with her shrunken fleshless limbs, looked almost like a living skeleton as she crouched by her little oven. There was not much appearance of life about her except in the wistful black eyes deep sunken under the brows whitened by age.

Sibbi was a strange old woman, not like the others in the village, and no great favourite with them. She could actually think of something besides marriage and funeral ceremonies, pilgrimages and pujás. Even before she became a widow, Sibbi's whole heart had not been set on her ornaments, and she had sold all of any value to help to pay her husband's debts, taking even the ring out of her nose. Sibbi had drawn upon herself the anger of the Máhá-Brahmin, by suggesting to her grandson that on account of their exceeding poverty, the gift to him of a very old and almost useless cow might be sufficient. It was indeed the only one which the family possessed, but another was procured to satisfy the covetousness of the Brahmin.

It was supposed, and probably with reason, that the difference which existed between old Sibbi and her neighbours was caused by her having, when eleven years old, passed six weeks in the house of an English lady. The parents of Sibbi had lost her at one of the great melás at which tens of thousands of Hindus assemble, melás which occasion a fearful amount of confusion, disease, and misery. An English magistrate found the poor girl, frightened and almost famished, crying by the side of the road. In compassion, he took her home to his wife. Sibbi received in that English home kindness which she never forgot. She was clothed, fed, and allowed to attend on the Mem Sahiba's sweet little girl.

In that house Sibbi had, as it were, a glimpse of paradise; and though a loving daughter, she was hardly glad when her parents found her at last. The parents took her away back to their village, though the lady offered to keep her. From that day, the usual occupations of zamindars' girls were those of Sibbi. She cooked, she carded cotton and spun it, she worked in the fields; married early, was a servant to her husband, and a slave to her husband's mother; but she often recalled the past, and asked herself if the six weeks, so unlike all that preceded or followed them, had not been a beautiful dream! One persuasion remained on her mind, that there were other places in the world besides her mud-built village, and that people existed more clever, and at least as holy as Brahmins.

Matrá sat down hungry to his insufficient meal, having first washed his hands, feet, and face. He could have eaten twice as much as was prepared, but took care to leave something for his poor old grandmother. Matrá took his meal in silence, but then told Sibbi all that had passed between himself and the man at the station.

"One God,—and that God is Love!" repeated Sibbi to herself, looking like one trying to recall something that has almost escaped memory, as she put her wasted hand to her wrinkled forehead. "Missy Baba learned to say that, little Missy Baba—the pretty one—who died. I almost cried my eyes out when they took her away to bury her!"

Tears came into the old woman's eyes as she remembered the sorrow which nearly fifty years had not effaced from her loving heart. "Missy Baba could not speak many words even in her own language, but the Mem taught her to say, 'Our Father' and 'God is Love,' that she might repeat them to me. She said them both the very day that she died. And when I was crying and moaning over the little form that looked so peaceful where it lay still and cold on the bed with a rose on its breast, the Mem said to me, quite quiet and calm-like, 'She has gone to the God who is Love.' I never shall forget that night! I wondered why the Mem did not moan and beat her breast as we do, she loved the little darling so dearly."

"Perhaps," thought Matrá, "the same great Father who helps that Christian in all his troubles was comforting the poor mother too." Then Matrá observed aloud, "How could the Mem Sahib be sure that her child had been taken to her God—how could she know that her soul had not passed, by a new birth, into some unclean dog or ass?"

"I am sure that it never did!" said Sibbi quickly. "Missy Baba's soul could never have gone into anything unclean. I often think that she's somewhere up above, like one of those; stars, safe with the Heavenly Father!" And as she spoke, the old Hindu pointed with her trembling fingers to a brilliant star in the east.

Another seed of truth had been dropped into the mind of Matrá, a thought of One who could not only support in life, but receive after death. But it was as yet as a seed wrapt up in its husk, that needs warmth and moisture to make it rise up to life, and burst forth to beauty.

"I WONDER whether that poor half-starved fellow will come over again this evening on the chance of meeting his father," said Karim to himself, as on the following evening he again took his station on the platform to watch for the train. "Here come some to meet the train, but I take it that they are very different sort of folk from my zamindar."

A prisoner, in clanking irons, led by two policemen, stood now on the platform. He was going to be tried on a charge of murder, and if a man's character could be read in his face, this one might have been deemed guilty of any crime. Fierce wolf-like eyes glared under a mass of shaggy hair, and as he squatted on the ground, just under the yellow gleam of the lamp, he looked somewhat like a wild beast crouching in the act to spring.

As Karim gazed at this wretched man with mingled pity and disgust, he was saluted by Matrá, the zamindar. Karim courteously returned the salám, and then walked to the other end of the platform, that conversation might not be overheard by policemen or prisoner, if, as he thought probable, the zamindar should talk to him again.

As he expected, Matrá followed his steps.

"Have you been thinking over what I said to you last night?" asked Karim, when both men had reached the end of the platform.

"I've thought of little else," said the peasant. "As I watered my buffaloes, and drove my plough, I was always turning over in my mind what you told me of the one God, who lives up yonder, the God of Love."

"And you believe that I spake truth?" asked the railway official.

"How can I believe it?" cried the zamindar bitterly. "If God be a God of love, why is the world so full of misery? Why are the poor oppressed and trodden down like the dust under foot? Why is there crime and wickedness?" Matrá pointed as he spake towards the prisoner. "The sun, the dew, the rain, and the green crops seem to tell us that there is a great God who made them, and who wishes man to be happy; but thorns and briars, locusts and blight, plague and pestilence, poverty and famine, they tell quite a different tale. If God be good, and powerful too, how came misery into the world?"

"It is a sad story, and a somewhat long one," said Karim, "but if you wish, you shall hear the account given in our Scriptures."

"I wish to hear it," said Matrá.

"The good God when He had made this world, created one man and one woman, from whom all the people that ever lived are descended."

"What!" exclaimed Matrá in surprise. "English, Hindus, Brahmins, Mehtars,—all descended from one pair! This is not what our Vedas tell us."

"No indeed," replied Karim; "your Gorus tell you that Brahmins came from Brahma's mouth, and low caste folk from his feet; being Brahmins themselves, they have their own reasons for telling you this," he added, with a smile. "But listen to the true account given in the Holy Scriptures. This first pair, named Adam and Eve, God placed in a beautiful garden, where they lived in love, innocence, and joy. They had abundance of fruits to eat; only as regarded one tree, the Maker of all gave command, 'Thou shalt not eat of its fruit; if thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die."

"Such a command was easily obeyed," observed Matrá.

"There was an evil spirit, called Satan, who envied the peace and happiness in which dwelt Adam and Eve. He had, however, no power to harm them, unless he could tempt them into sin. Alas! He succeeded too well! It was as if the husband and wife had had a choice placed before them, 'Will you believe God or Satan? Will you choose God or Satan to be your master?' A fatal choice was made. The woman ate of the forbidden fruit and gave it to her husband, and from that hour both fell under the power of cruel Satan. Misery, pain, sin, and death came into the world!"

"An evil hour for the first pair," said Matrá, "as it was for my grandfather when he first got into the clutches of the money-lenders, and mortgaged our land. But was it not rather hard that all the race born of this man and woman should suffer as well as themselves?"

"Let us take your simile," said Karim. "Your grandfather, by his act, laid a heavy debt upon you, his grandson, but you yourself, by your own account, have added to the debt. So not only were Adam and Eve sinners, but Satan once getting power in the world, has tempted and drawn into sin every man and woman in it, and one terrible sentence, that of death for the body, and death for the soul (which is eternal separation from God) hangs over all."

"Could not God forgive us all the debt, as He is, as you tell me, Love?" inquired the zamindar.

"If your creditor took you before the judge, and that judge were the kindest man in the world, he might pity you, indeed, but justice would compel him to give a sentence against you. The judge might be powerful, wise and good, but still you would be ruined."

Poor Matrá looked very sad; he knew that this was indeed too true. A just and kind judge could not save him from the consequences of incurring a debt which he could not pay.

"I don't think that there is any comfort at all in your religion," said the zamindar with a sigh. "If it only tells us that we are in the power of a wicked spirit, and that we are separated for ever from God, and have a great debt like a heavy stone hung round our necks to drown us, it makes us out to be in a miser able state indeed."

"But from that state God has found a way to save us," cried Karim cheerfully. "If you were to be told how all your debt could be cleared off at once, and that you should be restored to your father, and live all the rest of your life in plenty and peace, would not your heart be glad?"

"I should feel as if I were in heaven!" cried Matrá. But he sighed after he had uttered the words, for he felt that he could no more hope for such joy than he could build a house on a rainbow.

"God 'has' found a way of saving us, of freeing us from Satan, of paying our debt, of—" here Karim was suddenly interrupted by the shrill railway whistle.

Matrá had been so much interested in the conversation that he had almost forgotten for the moment why he had come to the station. But now the sound of the whistle gave him joy, for it might be the signal that his father was near.

The same sound made a groan burst from the wretched prisoner, for it told him that he was soon to be hurried off to the place of his trial, probably the place of his execution. It is with such different feelings that God's children and His enemies hear that death draws nigh. To the first it brings hopes of a blissful meeting, to the latter the terror of coming judgment

AGAIN, on the train's arrival, Matrá ran anxiously along the line of carriages, in search of his father. There was the usual hum of many speaking, and the hissing noise of the steam let out from the boiler, but no sound of greeting from a once familiar voice! The prisoner was hurried by his keepers into a third-class carriage, and Matrá saw him no more.

Once again the zamindar sorrowfully retraced his steps homewards. He had not the same peaceful feeling which had soothed him on the preceding night. It was not so much a God of Love that had been presented to his mind, as the terrible condition of those born and living in sin.

"Satan was cruel indeed to make the man and woman so miserable," thought Matrá, "when they were so peaceful and happy. Why did they listen to his evil counsel? But I might as well ask, why did we go into debt? We knew well enough that a money-lender's heart is as hard as a buffalo's hide. The crackers at my wedding were soon let off, the fireworks died into darkness, the sweetmeats were eaten, the fun was over, and then came the debt to crush us! We've had to pay dear for the honour of the thing. Why, all that we have borrowed for wedding, burning, and everything else hardly came to 500 rupees, and I'm sure that, little by little, 'we've paid the whole sum three times over,' * yet the debt remains large as ever!

"Our land is mortgaged, every inch of it; my creditors only leave the fields to me now, because they enable me to work, and as long as I can work, they can squeeze something out of me still, ay, if it were my very life-blood! Were I to fall sick—and ill-fed as I am, I am likely enough to do so—they would be down on me at once. My poor old grandmother and I might just lie down by the side of the road and perish of hunger. That station-man did but mock my misery when he asked how I should feel if I heard that my debt could be cleared off at once, and I be restored to my father, with peace and plenty before me. That never, never will be!"

* I fear that this is no exaggeration. The simple peasants are

grievously cheated, and pay enormous interest.

Matrá walked fast, as if he wished to walk away from his own bitter thoughts, but they followed him like his black shadow. When he had almost reached his mud hut, which was at the nearer end of the village, the zamindar heard a low murmuring behind some bushes, in a voice which he recognised as that of his grandmother.

Noiselessly Matrá approached the spot, near enough to catch the meaning of the words uttered. The old woman, with her hands pressed together, and her forehead almost touching the ground was in the attitude of one performing pujá, but there was no temple or idol in that place, only the quiet jungle before her, and the dark blue sky above her. These were the words which the zamindar heard, broken by a few low sobs—

"I have done pujá at many shrines, but the gods do not hear me; I am poor and old, and getting blind, and if my son does not come back soon, I shall die without seeing his face. O God of Love! Hear me! We are very needy and wretched, and sorely want Thy help. Perhaps up in the bright place Thou canst look down on us poor ignorant folk, who do not even know how to pray. Wilt Thou be angry if I too say, 'Our Father,' and beg Thee very, very hard to send back my only son!"

A slight rustling in the bush made by Matrá, startled the poor old woman. She raised herself trembling lest she should have drawn upon herself a storm of wrath by such a strange and terrible act as that of addressing the God of the Christians. It had been some remembrance of olden days that had made the poor creature attempt to do what she had seen done by the English lady and Missy Baba.

Matrá looked on Sibbi quietly for some time without uttering a word. In the faint moonlight, and with her dimmed eyes she could not tell from his face whether her grandson were angry or not. Still less could Sibbi read the strange thoughts that were rising in the soul of Matrá. Without knowing it, the old Hindu had dropped another seed of life into the zamindar's heart. He saw devotion in a form to him perfectly new. It was no shouting of "Rám! Rám!" or "Hari! Hari!" No wild loud singing and drum-beating before a painted idol; no Brahmin's purchased prayers! It was addressing an unseen Being as if He could listen, and answer, and help. It was like a child's cry of pain, which a parent at least understands.

Matrá turned silently away.

Sibbi said to herself, "He despises me; he thinks I have done an evil thing. If I were not his grandmother, Matrá would spurn me with his foot, and get the Brahmins to curse me."

But Matrá's silence was not that of contempt, it was that of perplexity and doubt. As he lay down to rest that night on his charpai, wrapped in his ragged blanket, Matrá, caught himself repeating some of his grandmother's words of prayer.

When in the morning Matrá looked towards the rising sun, he thought of what the Christian had told him about the God who made it, and wondered whether there were in truth such a Being, to whom the sorrowful might go in their troubles, to find in Him a Father indeed. Then Matrá remembered what the Christian had been saying when the conversation had been suddenly interrupted, of God's having found a way to save poor sinners.

"I will tie up the buffaloes a little earlier than usual," said Matrá to himself, "that I may have a longer talk with the Christian. He at least finds comfort in his religion, and I have none in mine. I will hear of the way of being saved of which he told me; there is no harm in knowing what other men believe. That Christian must have found something in his faith very precious to be ready to give up for its sake father, mother, all that he had in the world. Did he not say that the love of his God made up for the loss of all?"

"I WANT to hear the end of your account of what you Christians think about man and his miseries," said the zamindar, as again he stood on the railway platform beside his new friend.

"I would rather tell you of the way of escape which God has made for man out of his miseries," replied the Christian. "I know the way, for I am in it; I wish you to know it also, for it is open to you."

The two men seated themselves, the one to speak, and the other to listen.

"God pitied lost man," continued Karim, "yet Divine justice and truth required that by man punishment should be borne. No mere human being could help his brother, because every one was himself under the same condemnation. You, for instance, could not pay a brother's debt, because you are in the same strait as he."

"I could certainly help no one out of a bog in which I am sinking myself," sighed Matrá.

"So God sent His own Son into the world to become a man, that He might suffer as man, and for man," said Karim.

"Stop! You told me that there is but one God, and now you speak of His Son!" exclaimed Matrá. "Do you Christians worship two Gods?"

"There is but one God," replied Karim with reverence, "and yet we find from our Scriptures that in this One there are three Persons, the Father, the Son, and the Spirit, so closely joined that they are One, and yet each in Himself a distinct object of devotion."

"I do not understand," said Matrá.

"Man cannot understand the deep things of God, but what is revealed we must believe. A simile makes it more simple to my own mind," continued Karim, "and it may make it more simple to yours. Is the sun in the sky one object or two?"

"Certainly there is but one sun," replied Matrá.

"When we speak of the sun, we mean the sun and his beams also, for the sun and his beams are as one. Yet, seen through a mist, the sun appears shorn of his beams, and sometimes, on the other hand, we see the rays when the sun himself is hidden. In one sense, therefore, they are distinct, while in another they form but one glorious sun."

"It is a mystery," said the zamindar thoughtfully, "but I think that all religions have mysteries."

"The great God," continued Karim, "sent His Son into the world to save sinners by the sacrifice of Himself. Christ came as the sunbeams come down, to enlighten, warm, and bless. As a body was needed for sacrifice, the Saviour assumed a mortal body. He was born of a pure virgin. Thus the Lord Jesus Christ was Man that He might suffer, whilst ever continuing to be God that He might save."

"A deity putting on a mortal form—that is an avatar," said Matrá. "I did not know that Christians, like Hindus, believe in avatars."

"Your Brahmins," said Karim, "tell you that one of your deities nine times became incarnate, and that while inhabiting a body—as a fish, a tortoise, a boar—he performed wonders, or committed crimes. We Christians believe but in one sinless avatar; that God's Son appeared as a mortal, that He might conquer Satan, give an example of perfect holiness, and then die as a sacrifice for sin. The Lord Jesus, before His avatar, knew perfectly well what His life on earth would be, and what its terrible close. He knew that He would be despised and rejected, poor and afflicted, He knew that He would be put to a death of torture, nailed hands and feet to a cross. His death was the punishment of sin, but of sin 'not His own;' He stood in our place, bore the shame of our guilt, and paid our debt with His blood."

"Do you indeed believe this?" exclaimed the astonished Hindu.

"As firmly as I believe in my own existence; so firmly that I would lay down my life as a witness to its truth, as thousands of Christians have laid down their lives."

"The Son of God slain as a sacrifice for sin! It sounds so strange, so wonderful!" cried Matrá.

"It is love passing knowledge," said Karim. "Love in the Father to send His Son; love in the Son to be willing to die for man. The idea of sacrifice is no new thing to Hindus. Do not your books tell of the wondrous merit of the sacrifice of a thousand horses? But what is the value of the blood of a crore of horses, weighed against one drop of the blood of an Incarnate God!"

"And what do you think that you gain by this great sacrifice?" inquired Matrá.

"Everything!" exclaimed the Christian with animation, his whole face radiant with joy. "First, there is the debt of sin wiped out as if it had never been, full and free forgiveness. Then there is peace with God—adoption into His family, and an inheritance of endless glory and joy in the kingdom of heaven. No mere absorption, no loss of individuality, which is the highest hope of the Hindu, but conscious happiness, unutterable bliss in the society of blessed saints and angels dwelling together in perfect love in the presence of the Heavenly Father of all."

THE words were still on Karim's lips, when he interrupted himself by the sudden exclamation, "See yonder!"

"There is a man running along the line!" said Matrá, looking in the same direction.

"The madman!" cried Karim. "He will be crushed by the coming train!" And loudly he shouted, again and again, to warn the man off the dangerous line.

The runner appeared not to heed or to hear. The speed at which he was advancing left him no breath to call out, but he threw up his arms wildly as if to excite attention.

"There may have been some accident to the train!" exclaimed Karim.

The words went like a knife to the heart of Matrá. He could hardly forbear rushing forwards to meet the runner, but Karim laid a hand on his arm. The men had not long to wait. In two minutes the panting messenger reached the platform.

"Train ran off the line!" he gasped forth. "Carriages smashed—people killed!"

Karim instantly hurried away to the telegraph office, and as rapidly as he could sent off a message to the nearest station, then went in search of some one to despatch with the tidings to the magistrate of the neighbouring town. He would have sent Matrá, but Matrá was not on the platform.

The zamindar was rushing along the line to the place where the accident had occurred. In his overwhelming anxiety, his former fatigue was forgotten; only Matrá felt as if weights were attached to his feet, for his speed could not keep pace with his will.

The scene of the accident was reached. The engine, a huge black object, loomed before Matrá, half encircled by a mass of broken carriages. A number of passengers were standing about, some shouting for help, some moaning with pain, some, especially women, crying with terror.

"Is any one killed?" gasped forth Matrá; he could hardly utter the question.

"A good many are hurt, only one killed," replied a railway guard, whose face bore the mark of severe bruises. "A sepoy lies yonder, poor fellow! His head was crushed under a wheel!" As he spoke, he pointed to a spot a few yards distant, where, in a little pool of blood, a fearful object to behold, lay the corpse of a tall sepoy.

In a moment, poor Matrá was on his knees beside the body, beating his breast, and sobbing forth, "My father! It is my father!"

It was to him a terrible moment. For years the young zamindar's hopes had clung to a meeting with his parent, the thought of seeing Bhola Náth had been the one bright spot in Matrá's prospect, the one sweet drop in his cup. And now as he looked on that poor mangled disfigured corpse, and saw in it the wreck of all his hopes, the strength and courage of Matrá completely gave way, he wept and sobbed like a child.

And if such was the grief of the son, what was the anguish of the poor old mother, when, on the following day, the sepoy's body was carried to her wretched hovel! Then indeed did Sibbi bewail the day of her birth; she tore the grey hairs from her head, and uttered bitter wailings, the wailings of those who mourn without hope.

By this time, poor Matrá had regained some calmness, but it was the calmness of despair. He had to make preparations for burning the corpse that night, and so miserably poor was he, that he had the bitter task of collecting most of the materials himself. The Brahmins, knowing that Matrá had no more power even to borrow, took very little interest in the funeral rites; one even reproached poor Sibbi, saying that the terrible misfortune which had come upon her was doubtless due to the wrath of the gods whom she had offended. It mattered little now to Sibbi whether they reproached her or not. Does the agitated ocean show more disturbance because of the pelting of a shower?

Nearly two hours after sunset the sad preparations were completed. The sepoy's corpse was laid on the funeral pile, the head to the north, the feet to the south. A man with shaven head set fire to the pile, and soon red flames were crackling and curling around the body, and a mass of smoke was obscuring the light of the full moon. Meta, in silent anguish, stood by, watching the fire do its terrible work.

"My son! What dost thou here?" exclaimed a voice behind him.

Matrá started, as if he had been spoken to by the dead. Turning round, he uttered a cry of joyful surprise, and then threw himself into the arms of his father!

Yes, it was indeed Bhola Náth who had arrived at Banda by that evening's train, and had come in time to see his mother and son, in bitter woe, paying the last honours to the corpse of one in no way related to them, whilst he whom they mourned as dead stood in life and vigour beside them. Sibbi rushed forward with extended arms, shrieking forth, "My son! My son!"

The sudden appearance of Bhola Náth beside what all supposed to be his funeral pile, roused the superstitious fears of some ignorant peasants. They believed him to be no man but an evil spirit. Some actually caught up stones, and Bhola Náth was in danger of being mercilessly pelted by his neighbours, but Sibbi threw her arms around her new-found son.

"He is no ghost!" she cried. "Behold his feet are not turned backwards! His voice is the voice of a living man! It is he whom I nursed as a babe in my arms! It is indeed my son, the light of mine eyes! Now shall I die happy!" *

* This strange kind of reception of Bhola Náth by his neighbours was

suggested to me by my accomplished native critic, who knew what,

under such circumstances, would probably occur. To have "feet turned

backwards," and "to speak through the nose," are supposed by the Hindus

to be the characteristics of ghosts!

It was some time before Bhola Náth was left alone with his mother and son. There was too much to say, too much to think of, for any of the three to retire to rest. Day broke as they still sat together outside their little hut. Sibbi and Matrá looked very happy; their minds were too full of the unexpected joy of Bhola Náth's return, to have at that time any room for care or regret. But it was otherwise with Bhola Náth himself. He looked thoughtful and grave.

"Perhaps my father is thinking of the wife and parent whom he misses from our home," reflected Matrá; "those whose faces he never more can behold."

AT last, after a pause of silence, Bhola Náth thus spake:—"O mother and son! Two things are on my mind; of two things I have to tell you; one will cause you joy, the other will cause you grief. Of which shall I speak first?"

Then replied Matrá, "Father, this is a time of rejoicing, because we behold you again. Let your words, then, be of joy."

"Thou knowest, my son, that the debt which has pressed on thee has lain also as a weight on my heart. When, on leaving the service, I found myself entitled to a pension, I reasoned thus in my mind—'I am still a strong man; I can earn my living; what need is there to me of a pension? If I could change it for a sum large enough to pay off our debt at once, then would we be as free men, the mortgage would be off our land, and no money-lender could devour its produce year by year."

Sibbi and Matrá listened with intense interest.

"After turning over this matter much in my mind, I resolved to ask the advice of my colonel, and find from him if such a thing could be. The Colonel Bahadar * had shown me much favour since I had had the good fortune to save him from an enemy's sword. I went to his quarters, and made my salám, and told him of all our trouble."

* A title of respect.

"What said the Sahib Bahadar?" asked Matrá.

"He muttered to himself, 'Debt, debt; it is always the same story. Debt is the cancer that eats into the very life of this people.' Then said the sahib to me, 'How much does your family owe?'

"I replied, 'O my lord! The debt altogether is 500 rupees. It has been paid over and over again, but we could never clear off all at once; and where interest is fifty per cent.—'

"'Fifty per cent.!' exclaimed the sahib, looking more angry than I had ever seen him look before. 'This India is full of rogues, and their senseless victims, the zamindars!'

"So he strode several times up and down the room, as is the colonel's way when he is thinking. Then, after a while, he stopped straight before me.

"'Bhola Náth,' said he, 'you are a brave fellow and an honest man, and have done me a great service. I am loth that you should be all your life like a man with a halter round his neck. I will myself pay off your debt at once, but upon one condition.'"

Sibbi uttered a cry of delight, and Matrá eagerly said, "What was that one condition?" He feared that some very difficult thing, some lifelong task would be named.

"The one condition was, that neither I nor my son should ever go to a money-lender again."

"I would as lief go into the den of a hungry tiger!" exclaimed Matrá with vehemence. "Never, never again will I plunge into the bog of debt!"

The news just given by Bhola Náth caused great delight to his hearers. Matrá, remembered the words of Karim, which had seemed to him at the time like a mocking of his hopeless trouble—"How would you feel if you knew that your debt would be cleared off at once, and you be restored to your father, with peace and plenty before you?"

"And now perhaps it is better that I should tell you at once of what you will deem my evil tidings," said Bhola Náth.

"There can be no evil tidings for us now!" exclaimed the rejoicing Matrá.

"You are just reunited to a long-lost father. Would it be no sorrow to you to be separated from him again, and perhaps for ever?"

"Nothing shall separate us!" exclaimed Matrá.

"Nothing—but death," murmured old Sibbi.

"What if all the world should despise me, and abuse me, and cast me off?"

"Father! I would stand by you against all the world!" exclaimed the young zamindar.

"Then hear the truth at once," said Bhola Náth. "After three years of thinking, reading, praying, I have resolved to be baptised as a Christian!"

He looked as a brave man might do tied to a gun, when the match is brought to blow him to pieces. But there was not the loud explosion of grief and anger which he expected. Matrá looked on his father in mute surprise.

Sibbi muttered to herself, "Then I can keep my vow."

"What vow? What do you mean?" asked her son.

"When I prayed to the Christian's God to bring you back, I vowed that if He heard me, I would—" she dropped her voice to a faint whisper—"that I would throw our idol into the river!"

"Well done, brave mother!" exclaimed Bhola Náth, with an unutterable sense of relief, for he had dreaded more than anything else the grief and opposition of his parent. "And you, my son," he continued, turning towards Matrá, "will you despise me for changing a false religion for the only true one?"

"Father," replied the young zamindar, "I as yet know nothing of the Christian religion but a little which I have heard from a man at the station, who was a Mahomedan once. But you will teach me more. If I once saw my way to getting clear of the debt of sin as we are getting clear of the mortgage, let the Brahmins say what they may, I will never again worship any god but the God who has redeemed me from evil."

WE will not follow closely the events of the following days, weeks, and months. Bhola Náth sought out the native pastor of Banda, and had many interviews with him, as well as with his son's Christian friend, Karim. It was principally from the latter that Matrá received instruction, and from reading the New Testament with his father, when the work was done.

When it became known in the village that the sepoy had come back with new strange notions, that he no longer did pujá to the gods, nor feasted Brahmins, nor shouted "Rám! Rám!" bitter opposition was raised against him. Matrá and Sibbi came in for their full share of persecution. Their neighbours would not eat nor barter with them; the family were driven from the well; they were even pelted and beaten.

But blows and insults were not arguments, and the more Matrá contrasted the spirit of Hinduism with that of Christianity, the more he felt convinced that Karim and his father had found the true way of salvation. After the lapse of some months, the whole family—aged grandmother, brave father, and stalwart son—were baptised in a tank. Crowds of Hindus assembled to witness the baptism; some mocked, some abused the new converts, but in the hearts of many arose the thought, "Perhaps these honest Hindus have some good reason for changing their religion. Perhaps there is some truth in the Bible."

The family of Matrá were not long to be the only Christians in their village. As one torch lights another, so by their means gradually spread the knowledge of the Gospel.

Sibbi did not long survive her baptism. Receiving the Gospel simply, as a little child might do, she dropped peacefully asleep as her Missy Baba had done, feeling that she had a Heavenly Father, and that she was going to Him. The aged woman's body was not burned, but buried; it was laid like a seed in the ground, to rise again, even as the seed which the husbandman lays in the soil.

Matrá said, what he had never said when standing by a heathen's funeral pile, "We shall see her again in glory. Thanks to Him who died for sinners, we shall meet once more, never to be parted, in the presence of the God who is Love!"

ACHHRUMAL, the bunniah, came from Kashi (Benares) to visit his kinsman, Nand Lál, who dwelt in a little village about twenty kos distant. The home of Nand Lál was close by a jungle, and in a lonely part of the country. Achhru had never visited the place before, and, with some contempt, contrasted the mud-built village with the tall buildings, the grand pagodas, the wide "ghats" (bathing-places) of his own large and beautiful city.

On the first morning after Achhru's arrival, Nand Lál asked him how he had slept during the night.

"How could I sleep, O brother!" cried Achhru. "The horrid noises which I heard so distracted me that I could scarcely close my eyes!"

"What noises?" inquired his cousin.

"First there was such a croaking of frogs from yon pond, that one might have thought that all the frogs in Bengal had come on pilgrimage to a sacred tank, and were crying 'Rám! Rám!' together. Then, as I was beginning to drop asleep, wild wailing yells came from the jungle, as if the place were haunted by demons!"

"Only the jackals," observed Nand Lál; "we so often hear the noise that we hardly heed it."

"That was not all," continued his cousin. "As I lay awake, listening to the yells of the jackals, I heard another horrible sound, which made my heart almost stand still. It was between a howl and a laugh!"

"A hyena has been prowling about," said Nand Lál. "Three kids were taken by it last week."

"When that horrible sound ceased," cried Achhru, "and the jackals had stopped their yelling, I was more troubled than ever, for my ear caught a sound which was, I am sure, the hissing of a serpent."

"There are many hereabouts," observed Nand Lál; "our people are often bitten by snakes when they go out in the jungle."

"I shall certainly not stay long in this dreadful place," thought the timid-hearted Achhru. And he suddenly remembered that there was to be a festival in honour of the goddess Lachmi, in Kashi, which he must certainly attend. He would therefore go back on that very day to the city.

Poor Nand Lál looked mortified and disappointed. "Why, brother!" he cried. "Thou hast had no time to take rest. Thou hast scarcely partaken of food in my house. After an absence of years, I had looked for a long visit, I had hoped that we should have passed weeks together!"

"We shall pass weeks, and months, too, if you will," cried Achhru, "but not in this noisy village. Come back with me to Kashi. You have never yet seen the holy city, or visited its thousands of shrines. Come and bathe in the sacred Ganges, and delight thy soul with such sights as have never met thine eyes before."

Nand Lál did not need much pressing, for he had often felt curiosity to visit Kashi, and bathe in the Ganges. His preparations were few, and speedily made. Nand Lál fastened up his cooking vessels in a little bundle, wrapped his blanket about him, put some "annas" into his hamarband, and told his wife to expect him back in a fortnight. Then he departed with his cousin.

Before the fortnight was over, however, Nand Lál found his way back to his secluded village beside the jungle. His wife welcomed him with gladness, for he was a good and gentle husband, and had never been known to beat her. Quickly she prepared the evening meal, and brought the hookah to refresh the weary traveller.

Neighbours, impelled by curiosity, came to visit Nand Lál; his wife asked him why he had returned before the appointed time.

"I could not stand the noises," replied Nand Lál, with a smile; "like my cousin Achhru, I did not like the croaking of frogs, the yelling of jackals, the howling of hyenas, the hissing of snakes."

"Why, surely Kashi is not like our jungle!" cried one of his friends.

"Not like our jungle, but a thousand times worse!" exclaimed Nand Lál.

"Explain your meaning," said his friend.

"O Nattu! The sounds of a large city are worse than any made by wild beasts," replied Nand Lál. "I have heard murmurs and complaining, the groanings of the poor, the grumbles of the rich that they are not richer. The voices of discontent are to me as the croaking of myriads of frogs."

"And your jackals, what are they?" asked Nattu, who began to see the meaning of his companion.

"I witnessed quarrelling and heard disputes. There were sellers and buyers in the bazaars abusing each other for a matter of a few pice, or even cowries, reviling each other's mothers, wives, and daughters, pouring out curses and threats; and I said to myself, 'The city has its jackals and hyenas as well as the jungle, to yell over their carrion prey.'"

"And your hissing serpents?" asked his friend. "Did you find them too in the city?"

"In the city—here—everywhere—for is there a spot in all Hindostan where the liar is not to be found? Speak not our children lies almost as soon as they can utter the name of father? But I had deemed that in a holy city I might find some who would speak the truth. Alas! The very air seemed filled with the hissing of falsehood. The bunniah lies, the beggar lies, the courtier lies, and the priest at the shrine tells the greatest lies of all. My heart grew sad, and I said to myself, 'If I could but hear of one man who keeps his lips pure from murmuring, abuse, and lying, I would go a hundred kos to prostrate myself before him, and put his foot on my head."

"Was there ever such a man?" said Nattu.

"Such was my thought," continued Nand Lál. "When passing through the bazaar one day I saw a crowd gathered together, and went up to the place in hope of seeing some 'tamasha' (show). In the midst of that crowd stood an earnest-looking man, with a book in his hand, who was addressing the people. I stood with the rest to listen, and I heard the preacher tell of One who 'did no sin, neither was guile found in His mouth, who when He was reviled, reviled not again, when He suffered, He threatened not' (1 Pet. ii. 22, 23). I exclaimed to myself, 'Here must have been a perfect man He who thus governed His lips, He who was free from all guile, must have been a saint indeed! Such a one would I choose for my Goru!'"

"But perhaps the preacher was himself telling lies when he described such a Goru," observed one of the peasants.

"He spoke as one who believes what he teaches," was the reply of Nand Lál, "and I had occasion to see that, in one thing at least, he followed the example of his Master. Some of the crowd abused the preacher; some even pelted him with dust; but he spake not an angry word. Then I said to myself, 'As is Goru, so is disciple.' Since he is like the Holy One whom he preaches, in having on his tongue the law of kindness, so also he must surely be like Him in having lips free from guile."

"Perhaps the man was a 'Karáni'" (Christian), observed Nattu.

"He certainly is a follower of Him whom he called the Lord Jesus Christ," said Nand Lál. "He spake so much of his Master's purity, goodness, and gentleness, that my heart was melted within me. I desired to hear some of the gracious words which, as the preacher said, came from the Holy One's lips. I had my desire gratified. The man with the book, looking earnestly round at the crowd, repeated to them the invitation given, as he said, by his Master,—'Come to me, all ye that are weary and heavy laden, and I will give you rest' (Matt. xi. 28). O brothers! These words were to me as the note of the 'bul-bul' (nightingale) after the howling and cries and wild yells of the jungle! Discord seemed changed to music, tumult to peace. I listened as if I could listen for ever!"

"I would that I too had heard the preacher," said Nattu.

"Close to him was a lad selling books," continued Nand Lál. "After the preacher had finished his discourse, he advised the hearers to buy the Holy Gospels, which would tell them about the Heavenly Goru. The books cost but an 'anna' each [less than 1 ½ d.]. Even I was able to buy one, and I have it here in my bosom."

"Thou art something of a scholar, Nattu; thou wilt read it to us after the day's work is done," said one of his companions.

And so the first ray of light fell on the little mud-built village beside the jungle. The Gospel was read and re-read, till the pages of the little book would hardly hold together. A whole Testament was afterwards with some difficulty procured, through a peasant going to Kashi. What had been mocked at in the city was listened to with gladness by simple zamindars. And one of the first effects of receiving the Gospel of salvation was to be noticed in the conversation of those who had learned something of Him who had no guile in His mouth. Still round the village were the noises which had so disturbed Achhru Mal: the frogs croaked from the pond, the jackals yelled in the jungle, the serpents hissed in the long rank grass; but the tongues of peasants, and even the lips of their children, now spake the truth, and had learned, as it were, a new song, words of prayer and praise to God, words of kindness and love to man.

MANY hundred years ago, a king built a palace which was a miracle of beauty. The treasures stored up within were greater than man could count. The interior of the building was inlaid with jewels, and beside it the glories of the Taj Mahal would grow pale. The king did not wish so to shroud himself in his grandeur that his subjects should not have free access to him. He gave command that a door of his palace should be left constantly open, so that all, whether rich or poor, might be able to enter his presence. There was no bell placed on that door, no bar placed across, and no guard of sepoys denied admittance: a single porter waited within. But the door was exceedingly small, its height was as that of a child but seven years old.

But to that door came a noble of high rank, who proudly traced back his lineage to kings of old. He came mounted on an elephant in a howdah of carved sandal-wood, and the gilded trappings of the elephant glittered in the sunshine.

"I will not descend from my elephant, and put myself on

a level with the low and the mean!" cried the noble.

"How shall I enter the king's palace?" he said to one of his attendants. From his lofty height he had not even noticed the little door.

Then answered the porter from within, "This is the way, O descendant of monarchs! Your honour must descend from your howdah, and even, as doth the son of the humblest peasant, enter in by this door."

"I will not descend from my elephant, and put myself on a level with the low and the mean!" cried the noble. "There should be a loftier, more worthy door for those in whose veins runs the blood of princes!"

So, full of the pride of rank, he departed, never to enter the palace, or behold the glories within.