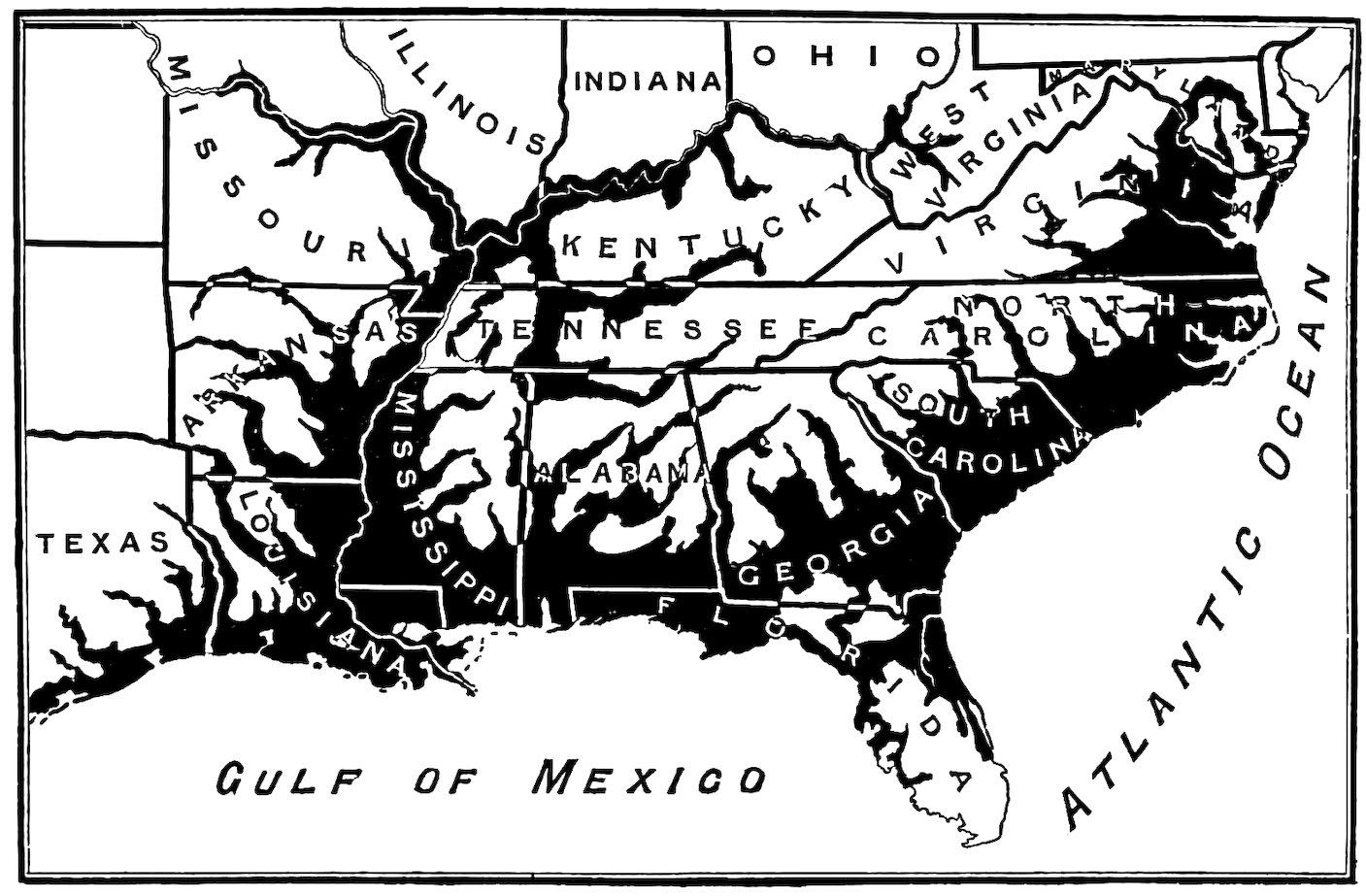

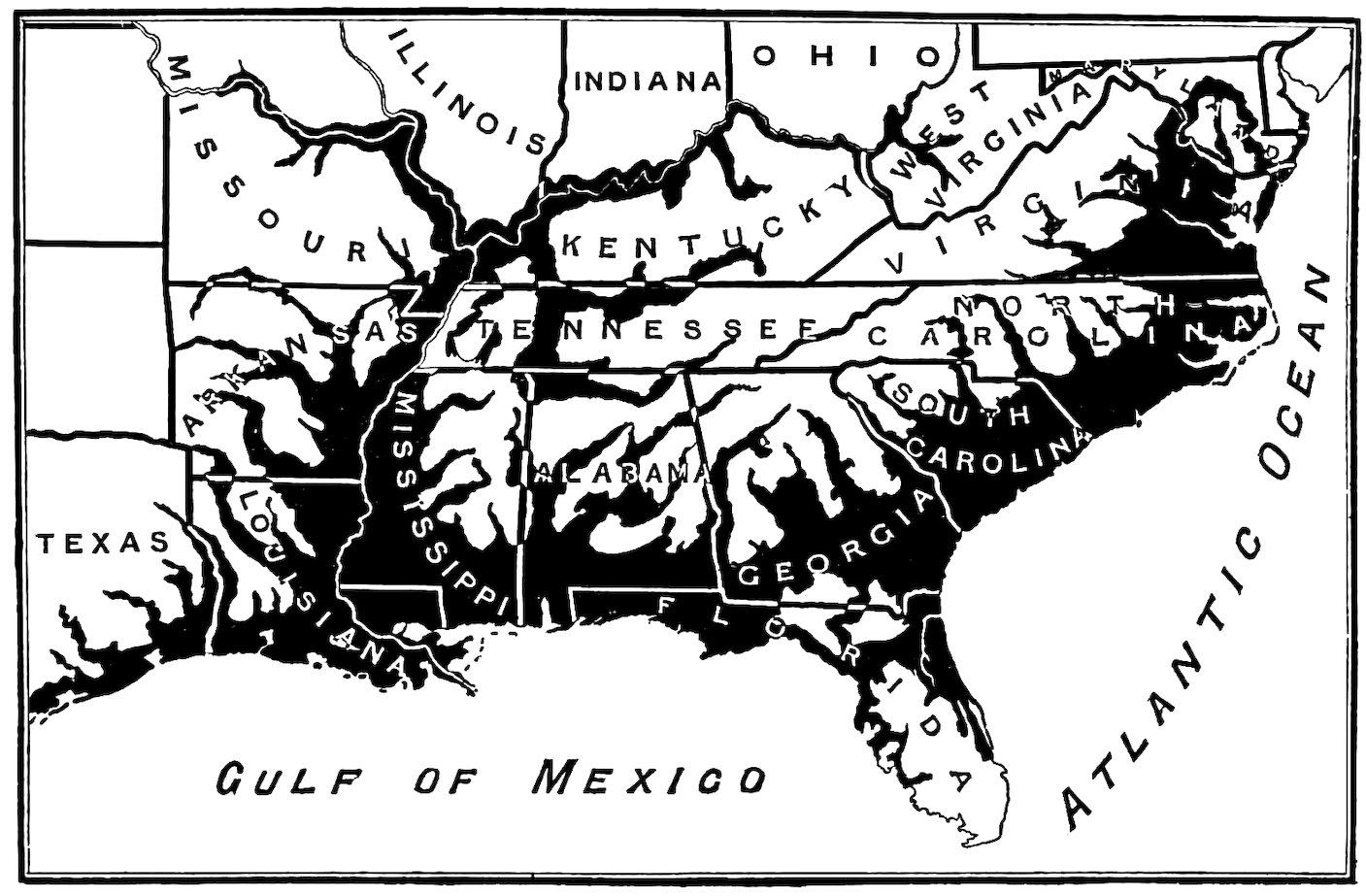

THE “BLACK BELT.”

Title: Black America

A study of the ex-slave and his late master

Author: Sir W. Laird Clowes

Release date: December 27, 2025 [eBook #77558]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Cassell and Co, 1891

Credits: Richard Tonsing, Tim Lindell, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

THE “BLACK BELT.”

| Introduction | vii | |

| The Black Belt | 1 | |

| The Ex-Slave as Master | 19 | |

| The Ex-Slave as he is | 67 | |

| The Position of the Southern White | 127 | |

| Some Suggested Solutions | 151 | |

| The Ideal Solution | 181 | |

| Appendix:— | ||

| A. The Population of the South | 216 | |

| B. Colour Caste | 217 | |

| C. Slavery in the North | 224 | |

| D. The Growth of the Coloured Race | 232 | |

| Index | 233 | |

In the autumn of 1890 I was commissioned by The Times to go to the southern part of the United States in order to study upon the spot the conditions of the very extraordinary social problem which has gradually arisen there during the past two hundred years, and which has assumed new and peculiar importance since the manumission of the negroes and “coloured” people, and the nominal extension to them of all the privileges of American citizenship. For this study I was in some degree prepared, not only by a long-indulged fondness for the subject, but also by a previous residence in the United States. The result of my inquiries took the form of a series of ten letters, which appeared in The Times in November and December, 1890, and in January viiiof the present year. These letters, with considerable additions, and with such corrections as fuller knowledge and the kind assistance of numerous correspondents have suggested, are now reprinted. They embrace, I think, a fair and comprehensive view of the problem in all its most significant aspects. I have conversed, without prejudice, with whites and with blacks, with Republicans and with Democrats, with men who are in office, and with men who are anxious to find themselves there; and I have not consciously closed my ears to any argument from any quarter. This volume, therefore, may, I trust, be accepted as containing a true account of a state of affairs which is without parallel in the history of modern civilisation, and which is, no doubt, destined to exercise a momentous, and possibly a terrible, influence upon the future of America.

Briefly summarised, the situation in the South is as follows. The inhabitants, black and white, have all been given equal rights by the amended Constitution of the Union. Each man of full age is as much a citizen as his fellow. That is the ixview of the law, from Maine to California. But in the South there are several millions of people whose veins contain more or less negro blood. A generation ago these people, or their parents, were, almost without exception, slaves in the hands of the Southern whites. A great revolution was effected. The black suddenly ceased to be a slave; and, within a few years, he was presented not only with his freedom, but also, in theory at least, with all the privileges that were previously the sole possession of the white. This raising of the black from the depths of slavery to the heights of citizenship was the work of outside forces. It was not done by the Southern white, nor, save as regards mere manumission, was it done with his approval or consent. He was not in a position to resist the will of the victorious North. Indeed, the North imperiously forced its will upon him, and even used as its agents the very blacks who had but just been liberated from bondage. This policy created bad blood between whites and blacks. From the moment of its full enforcement harmonious working between blacks xand whites in the field of politics, and in most other spheres, became impossible. The Southern white assumed a sullenly rebellious attitude. He determined that he would render a dead letter the grant of citizenship to the black; and to a very large extent he has done so. But, in the meantime, the black, in certain districts, has been increasing more rapidly than the white; and to-day, in some of those districts, he actually outnumbers him, while in others he equals him, and will outnumber him in the early future. Still, nevertheless—even where he is in a conclusive minority—the Southern white persists in his dogged resolution not to allow the black to meddle with the machinery of government, not to permit him for an instant to wear the full robe of citizenship that has been presented to him by the North. This is the bare kernel of the situation. Hitherto the black has, upon the whole, meekly submitted to this illegal deprivation of his rights. Can he be expected to submit for ever? Or will he some day attempt by force to seize that to which he is by law entitled? Should he ever do xithis, either alone or backed by all the resources of the North, there will be a scene of horror such as the South never witnessed in the darkest days of the Civil War. So much is absolutely certain.

What follows aspires to be an impartial review not only of the present aspects but also of the past history of the complex problem which has thus been created. It includes, also, a humble suggestion for the permanent solution of that problem. I have attempted to show, firstly, where the problem exists in its most pressing and dangerous form; secondly, the reasons which impel the South to refuse to constitutionally solve the problem by allowing the majority to rule; thirdly, the intolerable position of the Southern black; and, fourthly, the intolerable position of the Southern white. The position of all parties concerned naturally demands that some way out of the difficulty should be invented. I have, therefore, gone on to show, fifthly, what solutions have been advocated, and why they must all be ineffective; and, sixthly, what appears to me to xiibe the best, the most just, and the only radical solution.

This solution is one which, I admit, I almost despair of seeing carried out. The peaceable removal of the negroes from the United States, and their establishment across the ocean in a country and in circumstances that would be propitious not only to their own development but also to the development of their barbarous kindred, are measures which would involve very great expense. But it is not, I believe, on the score of expense that the average American is likely to reject the scheme. His great inheritance provides him with wealth more than sufficient to enable him to pay all his debts, including those huge ones which he owes to the black. He is much more likely to adopt a characteristic attitude such as he has adopted in the past towards many other threatening questions. One of the most distinguished of living American statesmen said to me in November last: “If my country should ever come to frightful disaster, it will be, I am convinced, because it is the xiiiincurable habit of my countrymen to cherish the belief that they are so much the special care of Providence that it would be superfluous, on their part, to take even simple and ordinary precautions for their own protection.”

The total population of the United States, exclusive of Alaska and of the Indian Territory, was, according to the official returns of the Tenth Census, 50,155,783. This Census was taken as long ago as 1880; but it is, and will for some time continue to be, the latest enumeration concerning which full statistical details are in possession of the world. An Eleventh Census was taken in June, 1890. This, so far as has as yet been ascertained, fixes the population of the great Republic at 62,622,250.[1] The details of it are, however, still unknown. We are altogether in the dark as to how many of the people are males and how many females, how many white and how many coloured; and months, if not years, may be expected to elapse before the hard-working Census Bureau at Washington shall find itself in a position to enlighten us upon these and other particular points of interest. But there is no reason 2to suppose that the full details of the Eleventh Census will, when they are published, greatly surprise the statistical experts who have made a special study of the increase of American population in the past and of its probable increase in the future; nor are there any signs that the results of the Eleventh Census will, upon one point of special significance, be much more reassuring than were those of the Tenth. That point of special significance is the rate of increase of the coloured people in certain extensive sections of the old slave-holding States of the South. This rate of increase has hitherto been vastly superior to that of the white people in the same districts, and is a thing of no new growth. The four States, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, were numbered for the first time in 1790. Their white and coloured populations in that year and in the year 1880, and the rates of increase per cent. during the ninety intermediate years, are shown in the following tables:—

1. Note.—See Appendix.

| 3 | |||

| WHITE POPULATION. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790. | 1880. | Increase per Cent. | |

| Virginia | 442,117 | 880,858 | 99·2 |

| North Carolina | 288,204 | 867,242 | 200·9 |

| South Carolina | 140,178 | 391,105 | 179·0 |

| Georgia | 52,886 | 816,906 | 1,442·9 |

| COLOURED POPULATION. | |||

| Virginia | 305,493 | 631,616 | 106·7 |

| North Carolina | 105,547 | 531,277 | 402·4 |

| South Carolina | 108,895 | 604,332 | 454·9 |

| Georgia | 29,662 | 725,133 | 2,344·6 |

While, therefore, in the ninety years the white population of the four States has grown from 923,385 to only 2,956,111, the coloured population has grown from 549,597 to 2,492,358. In other words, while the whites have increased only 220·1 per cent., the blacks have increased 353·4 per cent., and the latter have been continuing to increase with superior speed in face of the facts that now for more than a generation black immigration has practically ceased, and that the black race is considerably shorter-lived than the white. It is remarkable, too, that in each of the four States the rate of increase has been greater among the blacks than among the whites.

In only the above-mentioned four of the eight old Slave States of the South was there a Census in 1790. The first census of Mississippi was taken in 1800, of Louisiana in 1810, of Alabama in 1820, and of Florida in 1830. The first enumerations of the eight States showed a total white population of 1,066,711; the Census of 41880 showed the white population to be 4,695,253, an increase of 340·2 per cent. On the other hand, the first enumerations of the eight States showed a coloured population of but 654,308, while the Census of 1880 showed a coloured population of no less than 4,353,097, or an increase of 563·7 per cent. Whereas, therefore, at the earliest enumerations the blacks formed only about 38 per cent. of the population, they formed in 1880 about 48 per cent. In short, in these States, and in the period under review, the blacks steadily drew ever nearer and nearer to the attainment of a numerical majority. In 1860 they were still nearly half a million behind the whites. To-day, in the eight old Slave States of the South the whites and the blacks are practically equal in numbers, and in several individual States the blacks have a formidable and growing majority.

It is in these last States most particularly that what is known as the Negro Problem constitutes the most serious and complex social question of the hour. For most of the other States of the Union the problem possesses as yet only a secondary interest. The total number of negroes and coloured people in the whole of the United States in 1880 was 6,580,793. Of these, 4,353,097 lived, as has been seen, in the eight old Slave States of the South, and there formed 5practically one-half of the population; 1,660,674 lived in the seven border States, Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, Arkansas, Texas, and Tennessee, with 7,132,457 white fellow-citizens around them; and the remaining 567,022 were all but lost among the 31,575,260 whites—not to mention the Chinese and Indians—in the rest of the Union. So sparse, indeed, is the negro population, save in the fifteen States that have been named, that it need not be considered as a factor of any weight whatever; but in those fifteen States it is an ever-present force that demands recognition by all political parties. The fifteen States may be thus grouped:—

| Population, 1880. | Percentage of Coloured. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White. | Coloured. | |||

| A | Missouri | 2,022,826 | 145,350 | 6·7 |

| Kentucky | 1,377,179 | 271,451 | 16·4 | |

| Delaware | 120,160 | 26,442 | 18·1 | |

| Maryland | 724,693 | 210,230 | 22·4 | |

| Texas | 1,197,237 | 393,384 | 24·7 | |

| Tennessee | 1,138,831 | 403,151 | 26·1 | |

| Arkansas | 591,531 | 210,666 | 26·2 | |

| B | North Carolina | 867,242 | 531,277 | 37·9 |

| Virginia | 880,858 | 631,616 | 41·7 | |

| Georgia | 816,906 | 725,133 | 47·0 | |

| Florida | 142,605 | 126,690 | 47·1 | |

| Alabama | 662,185 | 600,103 | 47·5 | |

| C | Louisiana | 454,954 | 483,655 | 51·4 |

| Mississippi | 479,398 | 650,291 | 57·5 | |

| South Carolina | 391,105 | 604,332 | 60·6 | |

6In the States grouped under A, or, at least, in portions of them, the negro question occasionally assumes importance, though it is normally dormant. That it is not more often to the fore appears to result mainly from the political apathy or stupidity of the coloured population, which is frequently in a position, acting with organisation and method, to affect the balance of parties. In the States grouped under B the power of the negro is, theoretically, considerably greater. He has a vote in North Carolina if he be an actual citizen and not a convict; in Virginia if he be an actual citizen and not a lunatic, idiot, convict, duellist, or soldier; in Georgia if he be an actual taxpaying citizen and not a lunatic, idiot, or criminal; in Florida if he be a United States citizen, or have declared an intention of becoming one, and if he be not a lunatic, idiot, criminal, duellist, or bettor on elections; and in Alabama if he be a citizen, or have declared an intention of becoming one, and if he be not an idiot, an Indian, or a person convicted of crime. In none of these States is it definitely required that the negro voter shall be able to read or write; in only one is it required that he shall be even a taxpayer. The general requisites are merely manhood, a certain length of residence, and registration. Finally, in the States grouped 7under C, the negro is, if only he cared, and were permitted, to exercise his franchise, all-powerful. In Louisiana the qualification for the suffrage at present excludes no male citizen who, being of age, is not an idiot, lunatic, or criminal. In Mississippi the law is equally generous. In South Carolina the male citizen who is of age may vote unless he be a lunatic, an inmate of an asylum, almshouse, or prison, a duellist, or a soldier. There is no property or taxpaying qualification. The fifteenth amendment to the Constitution of the United States declares that “the right of the citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State on account of race, colour, or previous condition of servitude;” and the spirit of that amendment is, in theory, most fully honoured by all the Commonwealths. So completely is this the case that in 1880 the voting populations of the three States (C) were officially returned as:—

| White. | Coloured. | |

|---|---|---|

| Louisiana | 108,810 | 107,977 |

| Mississippi | 108,254 | 130,278 |

| South Carolina | 86,900 | 118,889 |

The slight coloured voting inferiority in Louisiana in 1880 is attributable to the high rate 8of infant and child mortality among the negroes as compared with the whites. It probably exists no longer. There is now, almost beyond question, a very considerable coloured voting majority in all these States, and probably a slight one in Alabama as well. The American Constitution recognises the right of the majority to rule. The impartial observer, therefore, might expect to find the government of Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina, and possibly also of Alabama, almost, if not entirely, in the hands of the negro and coloured majority; but upon his arrival in the South he finds no trace of anything of the kind. He finds, on the contrary, that the white man rules as supremely as he did in the days of slavery. The black man is permitted to have little or nothing to say upon the point; he is simply thrust on one side. At every political crisis the cry of the minority is, “This is a white man’s question,” and the cry is generally uttered in such a tone as to effectually warn off the black man from meddling with the matter.

I purpose later to show by what methods the white man attains his object when the usual cry fails to produce the whole of the expected result. I purpose also to show some of the reasons that are advanced by the Southern white man for his consistent refusal to countenance any negro 9interference in the affairs of State. For the present I confine myself to indicating the situation as it is and as it will be, and to suggesting that the existing white supremacy, whether it be for good or for evil, cannot continue indefinitely, and must eventually give place, either by free concession or as a tribute to brute force, to a new order of things.

Not only in Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina, as wholes, is there a negro majority among the population, a similar majority exists in nearly all the low-lying portions of the Southern States, from the Chesapeake to Florida and from Florida to the borders of Mexico, and especially in those low-lying districts that are removed from the great towns.[2] The face of the country consists, speaking broadly, of hill-tracts, and of cities, where the whites are in a majority, and of lowlands, where the blacks are numerically supreme; and there are obvious natural reasons at the bottom of this division of the races. Heat is irksome to the Anglo-Saxon and correspondingly grateful to the negro. Trade, mining, and manufactures attract the white man; agriculture and tillage are preferred by the black. In the undrained lowlands the negro constitution defies fevers and other ills that often weaken if they 10do not actually prove fatal to the white man’s health. And so, apart from questions of births and deaths, some parts of the Southern States tend to every year become blacker, while others as steadily become whiter.

2. Note.—See Map.

And the process which is initiated by geographical and climatic considerations is regularly aided by economical ones. The white man cannot compete as a labourer, or even as an artisan, upon equal terms with the black. He needs higher pay and better food. In black centres, therefore, the poor white man finds himself daily becoming more and more out of his element. Ordinary petty village trades, such as cobbling, tailoring, smithery, and carpentry, are thus, throughout the South, falling very much into the hands of the negroes; while the poor white men, who once had a monopoly of such humble pursuits, are going elsewhere in search of employment. They go, not to the uplands and cities of the South, but to the North, and, above all, to the new West, where every working man with strong arms, a good head, and an honest heart, has to-day the most brilliant of prospects.

The blacks, on the other hand, move about very little. They appreciate such little comforts as they have been able to gather around them 11since their manumission, and neither the cold North nor the half-settled West has any charms for them. They have at present no strong ambitions and very few wants. In the estimation of ninety-nine out of a hundred of them a cabin in sunny South Carolina is a much more desirable thing than a five-storeyed house in New York or Chicago, and immeasurably preferable to a store in Nebraska or a hut in Wyoming. Moreover, the black likes to be among his black kinsmen. A white man may occasionally persuade himself to regard a negro as his brother, in theory at least. The black man cares little for theory, and bluntly recognises the white man as a person of alien and, upon the whole, objectionable character from surface to core. And even the most sympathetic white man prefers, in practice, to be surrounded by a white majority rather than by a black, especially when he is at home in the bosom of his family.

These considerations, almost as much as the superior fecundity and fewer wants of the negro, are leading the Black Belt of the South to become blacker than ever. White immigration has almost ceased; white emigration is growing. In 1880, as has been shown, there were 391,105 whites and 604,332 blacks in South Carolina. Of these only 7,686, or ·7 per cent., were of foreign birth. 12Twenty years before, the number of foreign-born people in the State had been 9,986, and in 1870 it had been 8,074. In the eight old Slave States of the South (B and C) there were, in 1860, 148,662 foreign-born residents, in 1870 but 123,931, and in 1880 only 119,686; while of persons born out of the States, but within the United States, there were 1,813 less in 1880 than in 1870. These are facts which, even if taken alone, are of deep significance. Still more striking, however, are some estimates which have been drawn up for me by a distinguished statistical expert at Washington, and which show the probable numerical aspect of the race question in the eight old Slave States in the near future. Several years ago Professor E. W. Gilliam published a forecast of the developments of the present situation. His estimate of the rate of increase of the Southern whites and negroes was somewhat more alarmist than that which I am now able to give. The new estimate is based upon the general, though not upon the detailed, results of the Census of 1890; and as it also makes allowance for the often alleged imperfections of the Census of 1870, I think that it may be accepted as, upon the whole, a better one than that of Mr. Gilliam, or, indeed, than any that has yet been attempted. I feel bound to mention Mr. Gilliam’s name in connection 13with this matter, for his tables have been very widely quoted, and have been made the foundation of much discussion and speculation. I only reject them because I have others which are the results of fuller and later knowledge. Mr. Gilliam’s views on some unfortunately less changeable aspects of the race question remain to-day as true and as valuable as when they were committed to paper seven years ago, and I hope to quote them when, after having completed the dry statistical survey of the whole subject, I proceed to deal with the difficulties and dangers of the Southern problem. Here, in the meantime, is my informant’s estimate of the white and coloured populations of the Black Belt States in the years 1900 and 1910 respectively:—

| 1900. | 1910. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White. | Coloured. | White. | Coloured. | |

| North Carolina | 1,010,000 | 865,000 | 1,100,000 | 1,020,000 |

| Virginia | 985,000 | 835,000 | 1,050,000 | 965,000 |

| Georgia | 1,060,000 | 1,090,000 | 1,190,000 | 1,310,000 |

| Florida | 295,000 | 245,000 | 380,000 | 340,000 |

| Alabama | 870,000 | 935,000 | 1,000,000 | 1,125,000 |

| Louisiana | 582,000 | 755,000 | 655,000 | 915,000 |

| Mississippi | 645,000 | 840,000 | 750,000 | 965,000 |

| South Carolina | 465,000 | 875,000 | 510,000 | 1,055,000 |

| 5,912,000 | 6,440,000 | 6,635,000 | 7,695,000 | |

| 12,352,000 | 14,330,000 | |||

14As illustrating the moderation of this estimate, it is worth while adding that Professor Gilliam, writing in 1883, was of opinion that, from 1880 onwards, the whites in the South might be expected to increase at the rate of 2 per cent. per annum, and to double their numbers in thirty-five years, and that the blacks in the South might be expected to increase at the rate of 3½ per cent. per annum and to double their numbers in twenty years. These formulæ would give to the eight old Slave States about 9,390,000 whites in 1915, and about 17,400,000 blacks in 1920. The actual rate of increase is, however, a comparatively unimportant matter. The significant fact of the situation is that in three or four of the eight States the coloured population already outnumbers the white, and that in every one of the remaining four or five States the existing white majority has been for years growing smaller and smaller, and bids fair within a very short period to disappear entirely, and to make place for an overwhelming and ever-growing black majority.

At present, even in South Carolina, which is the “blackest” State in the Union, the white, and the white alone, rules. He seized power, in self-defence it is true, by fraud and violence, and he retains it by deception and intimidation; yet, strange to say, even the most respected and (in 15ordinary dealings) upright white people of the South excuse and defend this course of procedure; and, stranger still, very many honourable citizens of the North, Republicans as well as Democrats, do not hesitate to declare, “If I were a Southern white man I should act as the Southern white men do.” The cardinal principle of the political creed of 99 per cent. of the Southern whites is that the white man must rule at all costs and at all hazards. In comparison with this principle every other article of political faith dwindles into ridiculous insignificance. White domination is a living question that dwarfs tariff reform, protection, free trade, and the very pales of party. The white who does not believe in it above all else is regarded as a traitor and an outcast. The race question is, in the South, the sole question of burning interest. If you be sound on that question you are one of the elect; if you be unsound, you take rank as a pariah or as a lunatic.

After the War of Secession the North complacently folded its hands and announced that the race problem had been for ever disposed of. It soon learned that such had not been precisely the case. Then, after making an ill-advised and spasmodic effort at settlement, it declared that the race problem was no longer its affair, and that it might be left to solve itself. But since 16then years have elapsed, and the question still remains unsettled, paralysing the South, menacing the whole Union, and liable at any moment to involve hundreds of thousands of miles of territory and millions of human lives in a catastrophe scarcely inferior to that of the great Civil War. Is it not time, then, for something to be done towards freeing the South from the incubus of the situation, and the North from the danger that lurks still along the line which, less than a generation ago, saw Federal and Confederate striving in vain to settle this very question?

It may be asked: Why cannot the South submit itself to the operation of those principles by which the North is governed? Why not allow the majority—no matter what may be its hue—to rule?

The answer is that the experiment has been to some extent tried, and has utterly failed. The history of the attempt and of the failure is given in the following chapter. The outlines of that history must be studied by every one who aspires to understand the nature and difficulties of the Southern problem as it exists to-day. I do not, therefore, apologise for setting forth at some length the gloomy narrative of one of the most extraordinary episodes in the modern history of any civilised country. If I needed further excuse, 17I might find it in the fact that my story, though it deals with events of comparatively recent occurrence and of a very terrible character, is unknown to the majority of Englishmen. Even in the North it is now well-nigh forgotten; and only in the long-suffering South are the hideous lessons of it still fully remembered.

The Civil War ended in 1865, and the Confederacy lay crushed and dead. With it died slavery in the United States. The Slavery Question was, of course, the fons et origo of the war, but it was by no means the sole, or even the ostensible, point at issue between North and South. Nor was anything beyond the mere manumission of the slave ever involved in the slavery question. The North did not fight that the manumitted slave might be placed on terms of perfect equality with the white man, or even that he might obtain the franchise. It fought, so far as slavery was concerned, for manumission, and for nothing else; and it gained its point. The point is expressed in the Amendment XIII. to the Constitution, which declares that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

20And it may be said at once that there is now nowhere in the United States any party which regrets that slavery has been abolished, or which would restore it to-morrow, even if it were able to do so by a stroke of the pen. Yet there is, and always has been, not merely in the South, but also in the North and West, a very powerful party which is of opinion that the manumitted slave and the uneducated negro and coloured man ought not to be placed on terms of perfect equality with the white man, and ought not to be permitted to exercise the franchise. Indeed, the slave’s emancipation, as well as his citizenship, was effected as a tribute to military and political, rather than to moral, exigencies. Writing to W. S. Speer, on October 23rd, 1860, Mr. Lincoln said:—

“I appreciate your motive when you suggest the propriety of my writing for the public something disclaiming all intention to interfere with slaves or slavery in the States; but in my judgment it would do no good. I have already done this many, many times, and it is in print and open to all who will read.”

And, writing to Mr. Lincoln on December 26th following, Mr. Seward said:—

“I met on Monday my Republican associates on the Committee of Thirteen, and afterwards the whole Committee. With the unanimous consent of our section, I offered three 21propositions which seemed to me to cover the ground of the suggestion made by you through Mr. Weed, as I understood it. First, that the Constitution should never be altered so as to authorise Congress to abolish or interfere with slavery in the States. This was accepted.”

This attitude of the Republican leaders changed as the war went on; but even then the giving to the negro of full political rights and perfect equality was not contemplated. Amendment XIII. says nothing on that head, and Mr. Lincoln, in his last days, expressed himself as opposed to such a wholesale measure. But, the South having been conquered, means had to be devised for keeping it for a time under political subjection, and no means were more obvious or ready to hand than, firstly, a military occupation, with all that such occupation entails; and, secondly, the extension of the suffrage and of the full rights of citizenship to the people who, up to the time of the war, had been slaves. These people, not two or three per cent. of whom possessed the simplest rudiments of education, naturally looked upon the North as a Heavensent deliverer, and were in consequence anxious, when they obtained the suffrage, to support their Northern friends. Thus they were Republicans almost to a man. The Southern whites were, and still are, with nearly equal unanimity, 22Democrats. In the North, so far as my observation enables me to judge, the Republican party enfolds the majority of the brains and ability of the population. In the South, beyond all doubt, the Democratic party is the party of knowledge and mental power. And in the South, moreover, so far as educated white men are concerned, it is practically the only party. There are Southern Republicans; but they are, almost without exception, negroes, coloured people, or the lowest and most ignorant class of whites.

At first, the process of “reconstructing” the ex-Confederate States was not made to involve the employment of the liberated slave as an agent for the subjection of his former master; but as time went on the black man’s obvious utility was perceived. The following sketch will show how the eight old Slave States in which there was, and still is, the largest negro and coloured element, passed from the condition in which they found themselves at the end of the war to the condition in which they are at the present moment. The particulars concerning Alabama are mainly summarised from a paper by Mr. Hilary A. Herbert, member of Congress for that State; those concerning North Carolina from a paper by Mr. Zebulon B. Vance, United States Senator for that State; those concerning South Carolina from a 23paper by Mr. John J. Hemphill, member of Congress for that State; those concerning Georgia from a paper by Mr. Henry G. Turner, member of Congress for that State; those concerning Florida from a paper by Mr. Samuel Pasco, United States Senator for that State; those concerning Virginia from a paper by Mr. Robert Stiles, a distinguished Virginian; those concerning Mississippi from a paper by Mr. Ethelbert Barksdale, ex-member of Congress for that State; and those concerning Louisiana from a paper by Mr. B. J. Sage. These papers, with others, were collected and published during the past year by Mr. Hilary A. Herbert at Baltimore, under the general title of “Why the Solid South?”[3] and they form, I think, the most instructive key that has yet been fitted to the great question, “Why are the United States practically two nations?” I have had the honour of meeting several of the writers, and I believe them to be all men of uprightness and fairness. I have added numerous illustrative details which have been supplied to me from other trustworthy sources, which, however, I need not here catalogue.

3. “Why the Solid South? or, Reconstruction and its Results.” Baltimore: R. H. Woodward and Co. 1899.

After the close of the war, each of the vanquished States received from the President a 24provisional governor, who had authority to call a convention to frame a constitution of government. The States soon recognised the new situation. Under the new order of things the suffrage was still confined to white men, and senators and representatives were duly elected, and awaited permission to act. They were almost all Democrats. This fact had its effect upon the Republicans, and when the Thirty-ninth Congress opened in December, 1865, Mr. Thad. Stevens, who thenceforth took the lead in the matter, said:—“According to my judgment, they” (the insurrectionary States) “ought never to be recognised as capable of acting in the Union, or of being counted as valid States, until the Constitution shall have been so amended as to make it what its makers intended, and so as to secure perpetual ascendency to the party of the Union.”

Mr. Stevens’ plans were two—to reduce the representation to which the late slave-holding States were entitled under the Constitution, and to enfranchise blacks and disenfranchise whites. But even so late as 1865–6 the North was not prepared to grant negro suffrage. Pennsylvania, Ohio, Connecticut, and other States, would have none of it. It was agreed, however, in February, 1866, that neither House should admit any member 25from the late Insurrectionary States until the report of a joint committee which had been appointed to consider the question of reconstruction should be received.

This was a declaration of war upon President Johnson’s plan of pacification, but President Johnson did not give way. He vetoed a Bill to confer many rights—not including suffrage—upon the freedmen, because, in his opinion, it was unconstitutional. Then followed the struggle over the proposed Amendment XIV. to the Constitution, an amendment which apportioned representatives in Congress upon the basis of the voting population, and which provided that no person should hold office under the United States who, having taken an oath as a Federal or State officer to support the Constitution, had subsequently engaged in war against the Union. This struggle led to much bad blood, in spite of the fact that the amendment in its original form did not pass.

Still worse feeling was stirred up by the action of the Freedmen’s Bureau agents in the South. The Freedmen’s Bureau had been established in 1865 to act as the guardian of freedmen, with power to make their contracts, settle their disputes with employers, and care for them generally. Many of the agents of this Bureau 26traded upon their position, and, with a view to furthering their own political aspirations, deliberately fomented race hatreds. They widely disseminated among the freedmen a belief that the lands of their former owners were, at least to some extent, to be divided among the ex-slaves; and, said General Grant, “the effect of the belief in the division of lands is idleness and accumulation in camps, towns, and cities.” A more salutary lesson would have been that in the sweat of his face must a man earn his bread; but this the agents, as a mass, did not teach. On the contrary, they demoralised the labour situation in the South, and, later, nearly all of them took advantage of, and reaped profit from, the demoralisation which they had created. Their ranks supplied an enormous number of candidates for office.

In the meanwhile the joint committee on reconstruction was at work. It consisted of twelve Republicans and only three Democrats; and on the sub-committee, which collected evidence respecting the condition of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Arkansas, there was no Democrat at all.

The situation in those and the other Southern States was confessedly not good. The ex-Confederate soldiers had returned home demoralised 27by defeat, and found four millions of slaves demoralised by sudden manumission and by the action of the Freedmen’s Bureau agents; and, naturally, there was much friction between the races. But the committee’s report of the nature and amount of that friction was greatly exaggerated. As to the State of Alabama, only five witnesses were examined, all of them being Republican politicians of notoriously partisan character. These witnesses had everything to gain and nothing to lose by “reconstruction”; and, as a matter of fact, when “reconstruction” followed, one of them became Governor of his State, a second a Senator in Congress, a third a permanent official at Washington, a fourth a Circuit Judge in Alabama, and the fifth a Judge of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia. It may not have been propter hoc, but it was certainly post hoc, and the coincidence is suspicious.

Upon the strength of the report the ex-Confederate States were held to be out of the Union. Their exact status remained to be determined by the voice of the North, as expressed at the polls. The elections were held in due course; and on the first Monday in December, 1866, the Republicans came back to the last session of the Thirty-ninth Congress flushed with victory. They had 28a majority of thirty-one in the Senate and of ninety-four in the House.

But President Johnson, with his vetoes, still stood firm; and “for the purpose of securing the fruits of the victories gained” the impeachment of the President was determined upon. I need not go into the circumstances of that impeachment, the ultimate excuse for which was the dismissal of Mr. Stanton from the Secretaryship of War. Suffice it to say that Congress took steps for “the extension of the suffrage to the coloured race in the district of Columbia, both as a right and as an example.”

Mr. Buckalew, of Pennsylvania, discussing the Bill, said, fairly enough, “Our ancestors placed suffrage on the broad common-sense principle that it should be lodged in, and exercised by, those who could use it most wisely, and most safely, and most efficiently to serve the ends for which Government was instituted,” and “not upon any abstract or transcendental notion of human rights which ignored the existing facts of social life. I shall not vote to degrade suffrage. I shall not vote to pollute and corrupt the foundations of political power, either in my own State or in any other.” On the other hand, Senator Sumner declared, “Now, to my mind, nothing is clearer than the absolute necessity of suffrage for 29all coloured persons in the disorganised States.” (This was in reference to an informal understanding that the late Confederate States were to share the fate of the district of Columbia.) “It will not,” he continued, “be enough if you give it to those who read and write. You will not in this way acquire the voting force which you need there for the protection of Unionists, whether white or black. You will not secure the new allies who are essential to the national cause.”

The Bill, thus cynically supported, passed; but on January 7th, 1867, was vetoed by the President. The Republican majority, however, was not to be balked. In spite of the facts that all resistance to Federal authority in the South had long since ceased, and that, according to a decision of Mr. Justice Nelson, of the Supreme Court, States in which the civil government had been restored under the pacific Presidential plan were entitled to all the rights of States in the Union—in spite of these facts Congress solemnly decided that the war was not over; and in March, 1867, it passed the celebrated Reconstruction Acts, in face of the President’s veto. These Acts annulled the State Governments then in operation; divided the States into military districts, and placed them under martial law; enfranchised the negroes; disenfranchised all, whether pardoned 30or not, who had participated in the war against the Union, if they had previously held any executive, legislative, or judicial office under the State or general Government; and provided for the calling of conventions, the framing and adopting of State constitutions, and the election of State officials. In the interim the military commanders were given absolute power, death sentences only being subject to the approval of the President.

This action of the Republicans was far from being in accordance with the just and statesmanlike principles of Lincoln, who, writing in 1862 to Governor Shepley, in Louisiana, said that only respectable citizens of Louisiana, voted for by other respectable citizens, were wanted as representatives in Washington. “To send,” he continued, “a parcel of Northern men here, elected, as would be understood, and perhaps justly so, at the point of the bayonet, would be disgraceful and outrageous.” In less than five years party spirit had blinded even great Republicans to these dictates of generosity and far-seeing patriotism. Garfield so far forgot his usually chivalrous character as to say exultingly, “This Bill sets out by laying its hands on the rebel governments and taking the very breath of life out of them; in the next place it puts the bayonet at the breast of every rebel in the South; in the 31next place it leaves in the hands of Congress, utterly and absolutely, the work of reconstruction.”

Now, indeed, the ex-Confederate States were about to pay dearly for their faults in the past. They had fought, and had poured forth blood and treasure; they had been beaten, and they had submitted, but they were not forgiven. They had enslaved the black. Henceforth, for a season, the black, ignorant, unscrupulous, dissolute, and corrupt, was to enslave them.

What I have written so far applies equally to all the Southern States. The miserable fortunes of each individual State from the time of the passing of the Reconstruction Acts have next to be followed. I will endeavour to be brief, but no study of the negro question in the United States can, as has been said, be perfect, or even comprehensible, without some allusion to the terrible penalty that was exacted from a brave but vanquished people in and after 1867. The States were one and all Democratic. By June, 1868, eight out of the eleven were represented in both branches of Congress. Of the representatives, all but two were Republicans; of the Senators, not one was a Democrat; and one-half of the whole were Northerners, who had been elected by means such as Mr. Lincoln, in 321862, had declared to be disgraceful and outrageous. In 1871, when all the States had been reconstructed, the South was represented at Washington by seventy Republicans and only fifteen Democrats.

RECONSTRUCTION IN ALABAMA.

In Alabama, as elsewhere, a working and fairly satisfactory Government had been summarily overthrown by the Reconstruction Acts. It now made way for a Republican Government dominated by negroes, most of whom could neither read nor express an intelligent opinion on any current topic. The negroes almost to a man were Republican, and so violent was unreasoning party feeling among them that a few blacks who were Democrats were expelled from their churches. There was a negro majority in the Convention which was elected in 1867 to frame a new Constitution; and, although it was required that for the ratification of the Constitution a majority of the registered electors of the State should vote, the new Constitution was ratified by Congress, in defiance of the fact that the necessary majority had not voted. Under the new Constitution began an era of Republican control of an avowedly Democratic State, with 33twenty-six negroes in the House and one in the Senate. During this period legislators, as one of their number is reported to have said, “sold their votes for prices that would have disgraced a negro in the time of slavery.” Money was obtained for public works, but never legitimately expended, and the only people to profit were the Northern “carpet-baggers” and the Southern negroes, many of whom were not even taxpayers. A state of strife and ill-feeling was sedulously kept up between the races, and jobbery and corruption were universal and unveiled. After the elections of 1872, so outrageous were the frauds on the part of the managers that both Democrats and Republicans claimed the victory, and for a season there were rival Legislatures in existence. The Democrats, however, submitted, in presence of United States’ troops.

All kinds of most incompetent men were appointed to judicial positions. For example, the first judge of the criminal court at Selma was one Corbin, an old Virginian, who had never practised law. Its first clerk was Roderick Thomas, a coloured man, who until after his manumission was wholly without education. When Corbin left the Bench, Thomas succeeded him, and another coloured man, as ignorant as Thomas, succeeded to the position of clerk. 34Here is an extract, illustrative of the character of Corbin, from that eccentric judge’s charge to the grand jury on July 27th, 1874:—

“Time was, and not very distantly, gentlemen, when this charge was done up and delivered in grand old style: when grand old judges, robed in costly black silk gowns and coiffured with huge old periwigs, swelling out their august personages, were escorted into the Court-rooms by obsequious sheriffs, bearing high before them and with stately step their blazoned insignia of offices.... Fair ladies and courtly old dames of pinguid proportions, in rich and rustling silk brocades, flocked to grace the Court-room with their enchanting presence and to hear the august, gowned, and periwigged old judges ventilate their classic literature and their cultivated oratory in the grandiloquent old charge.”

Corbin quarrelled with his party, which got rid of him. His characteristic comment was that the Republicans were “a parcel of pigs; as soon as one got an ear of corn the others took after him to get it away.”

Such appointments as his were some of the fruits of ignorant negro dominion in Alabama. They exasperated the Democrats, who, in spite of much that is not creditable to them, are, and ever since the war have been, the most respectable party in the State. In less than seven years this negro domination rendered the State bankrupt and the population furious. The elections of 1874 were, in consequence, attended by much 35regretable fraud and violence, and, by some means, a Democratic majority was obtained. It has kept itself in office ever since; it has remodelled the Constitution; it has brought back economy and, I believe, honesty in the administration of the public funds; it has largely reduced the State indebtedness, and it has wholly restored the public credit. It may have gained and preserved its object by discreditable means, but it has not abused its power, and to-day, save for the black shadow of the Race Question, Alabama flourishes.

RECONSTRUCTION IN NORTH CAROLINA.

North Carolina fared much as did Alabama. Under the Reconstruction Acts and Amendment XIV. her most intelligent voters were proscribed, and power fell into the hands of plunderers and adventurers. The result of the voting for the Constitutional Convention in 1867 was that one hundred and ten Republicans and only ten Democrats were returned by a notoriously Democratic State; and the new Constitution of 1868 introduced an era of despotism and fraud. The negroes were permitted to vote before they were legally entitled to the suffrage, and in the new Senate there were thirty-eight Republicans and 36twelve Democrats, while in the House there were eighty Republicans and forty Democrats. Several of the negro members of the Legislature were unable to read. At every opportunity these men robbed the State and trifled with its credit. There was open corruption and universal bribery. There was formed a political “ring,” which demanded, and generally received, 10 per cent. on all appropriations passed by the Legislature. Lavish entertainments were given and paid for out of public money. “A regular bar was established in the Capitol, and it was said that, with somewhat less publicity, some of its rooms were devoted to the purposes of prostitution. Decency fled abashed; the spectacle of coarse, ignorant negroes sitting at table, drinking champagne and smoking Havannah cigars, was not uncommon.

“I cannot refrain,” continues Mr. Vance, “from telling a story which I have heard of one, old ‘Cuffy,’ who was a member of that body, and a shining light in the movement of progress—one who, in the language of Mr. Hoar, had his ‘face turned towards the morning light.’ A friend, going to see him one night at his rooms, found him sitting at a table, by the dim light of a tallow dip, laboriously counting a pile of money, and chuckling to himself. ‘Why,’ said his visitor, ‘what amuses you so, Uncle Cuffy?’ ‘Well, 37boss,’ he replied, grinning from ear to ear, ‘I’se been sold in my life ’leven times, an’, fo’ de Lord, dis is de fust time I eber got de money.’”

The boldness of the robbers of the State was extraordinary. On one occasion they obtained authority for an issue of bonds to the amount of nearly £3,000,000 sterling, for the construction of a railway. These bonds were all issued, but not so much as a single yard of the line was ever laid down. Yet the people submitted patiently, until what was known as the Schoffner Act was passed. This, under the pretence of suppressing internal disorders, authorised the Governor, at his discretion, to declare any county in a state of insurrection, to proclaim martial law, and to try accused persons by drumhead court-martial. It also authorised the raising of two regiments of troops, one of which was composed of negroes, and the other of which was made up of white desperadoes, under the command of the infamous Kirk. The proceedings under this Act were of such a terrorising nature that the whole country took alarm. Many Republicans, black and white, joined the Democrats; at the elections of 1870, after a shorter reconstruction period than fell to the lot of many other States, the Democrats successfully reasserted themselves, and North Carolina was redeemed. She has not 38since recovered her financial position, but she bids fair to do so.

RECONSTRUCTION IN SOUTH CAROLINA.

So cruelly did South Carolina suffer during the era of reconstruction, and so completely was she abased, that before the period of her sufferings ended she became known as the “Prostrate State.” Her best white citizens being disfranchised, she could not make her real voice heard, and, in 1867, the election of delegates to the Convention for the framing of a new constitution for her resulted in the return of sixty-three negroes or coloured people and but thirty-four whites. The latter were, almost without exception, either Northern adventurers or Southern renegades; the former were, as a body, as ignorant as it is possible to conceive. In 1868 the constitution which had been drawn up by this strange Convention was adopted, chiefly upon the strength of the votes of the negroes who were not then legally enfranchised, but who, nevertheless, were encouraged by the Republican managers to go to the polls.

Under the new constitution a General Assembly was elected. It included seventy-two whites and eighty-five coloured men or negroes, and of 39the total number one hundred and thirty-six were Republicans and only twenty-one Democrats. All this happened in spite of the fact that Amendment XV. to the United States Constitution, the amendment which conferred the franchise upon the negro, was not ratified until March 30, 1870. General R. K. Scott, of Ohio, an ex-officer of the Freedmen’s Bureau, was chosen Governor, and, almost immediately, the black majority, assisted by the white Republican carpet-baggers, began to tyrannise over the white Democrats, and to exploit the State in their own private interests.

An Act passed in 1869 abolished the long-established rule of evidence that all men shall be considered innocent until proved guilty, and expressly directed that if the person whose rights under the Act were alleged to have been denied happened to be coloured, then the burden of proof would be on the defendant; so that any person or corporation named in the Act, if simply accused by a person of colour, was thereby to be presumed to be guilty, and was liable to be subjected to heavy penalties upon this mere accusation, without a particle of proof by the plaintiff or any other witness.

As for the extravagance of the new rulers, it was unlimited. When they first met in legislative 40assembly, in 1868, they used the same building which the whites had occupied before them, and they furnished it inexpensively. But as soon as they realised their power, they exhibited their luxurious tastes, and furnished anew the legislative halls in the State House. For clocks that had cost 8s. 6d. they substituted clocks that cost £120; for spittoons that had cost 1s. 8d. they substituted spittoons that cost £1 14s.; for benches that had cost 16s. 6d. they substituted crimson sofas that cost £40; for chairs that had cost 4s. 2d. they substituted crimson plush gothic chairs that cost £12; for desks that had cost £2 they substituted desks that cost £35; and for looking-glasses that had cost 16s. 6d. they substituted mirrors that cost £120. The furnishing of the hall of the House of Representatives of this impoverished State cost £19,000. The same hall has recently been very nicely refurnished for £612. At least forty bed-rooms were furnished at the public expense, some of them three times over. A restaurant was also maintained in one of the committee rooms of the Capitol at Columbia, and there officials and their friends and relatives helped themselves, without stint, to food, liquors, and cigars, at the cost of the taxpayer. For six years this restaurant was kept open every day from eight o’clock on one morning until 41three o’clock on the next. In a single session the restaurant swallowed up £25,000.

Nor was this by any means all. In 1873 Mr. J. S. Pike, late United States Minister to Holland, a Republican, and originally a staunch Abolitionist, wrote a little book[4] on the situation in South Carolina. His testimony cannot be challenged. He, at least, was no Southern Democrat, full of hatred to “niggers,” and to all the works of the North; and the picture that he painted is one which shows corruption, extravagance, and legislative wickedness such as never prevailed even in Hayti in its worst days. Describing “A Black Parliament,” he says:—

4. “The Prostrate State.”

“Here, then, is the outcome, the ripe, perfected fruit of the boasted civilisation of the South after 200 years of experience. A white community that had gradually risen from small beginnings till it grew into wealth, culture, and refinement, and became accomplished in all the arts of civilisation; that successfully asserted its resistance to a foreign tyranny by deeds of conspicuous valour; that achieved liberty and independence through the fire and tempest of civil war, and illustrated itself in the councils of the nation by orators and statesmen worthy of any age or nation—such a community is then reduced to this. It lies prostrate in the dust, ruled over by this strange conglomerate, gathered from the ranks of its own servile population.... In the place of this old aristocratic society stands the rude form of the most ignorant 42democracy that mankind ever saw invested with the functions of government. It is the dregs of the population habited in the robes of their intelligent predecessors, and asserting over them the rule of ignorance and corruption through the inexorable machinery of a majority of numbers. It is barbarism overwhelming civilisation by physical force.... We will enter the House of Representatives. Here sit 124 members; of these twenty-three are white men, representing the remains of the old civilisation.... These twenty-three white men are but the observers, the enforced auditors, of the dull and clumsy imitation of a deliberative body, whose appearance in their present capacity is at once a wonder and a shame to modern civilisation.... The Speaker is black, the clerk is black, the door-keepers are black, the little pages are black, the Chairman of the Ways and Means is black, and the chaplain is coal-black. At some of the desks sit coloured men whose types it would be hard to find outside of Congo; whose costumes, visages, attitudes, and expressions only befit the forecastle of a buccaneer.”

Such were the rulers of a State that then contained over 300,000 white men and women.

In 1869 an exclusively coloured militia was organised, and, by the end of 1870, 96,000 men were enrolled in it. To fourteen regiments of these men arms and ammunition were issued before the re-election of General Scott in 1870; they officially attended political meetings and were paid for their services there, and they were confessedly enrolled and used for political purposes. An armed constabulary was maintained for the 43same objects. On June 25, 1870, J. W. Anderson, a deputy-constable, reported to his chief:— “We can carry the county (York) if we get constables enough, by encouraging the militia, and frightening the poor white men. I am going into the campaign for Scott.” And on July 8, 1870, Joseph Crews, a deputy-constable, reported from Laurens county:—“We are going to have a hard campaign up here, and we must have more constables. I will carry the election here with the militia if the constables will work with me. I am giving out ammunition all the time. Tell Scott he is all right here now.” Again, testifying before a legislative committee in 1877, J. B. Hubbard, the Chief Constable, said:—

“It was understood that by arming the coloured militia and keeping some of the most influential officers under pay, a full vote would be brought out for the Republicans, and the Democracy, or many of the weak-kneed Democrats, intimidated. At the time the militia was organised, there was, comparatively speaking, but little lawlessness. The militia, being organised and armed, caused an increase of crime and bloodshed in most of the counties, in proportion to their numbers and the number of arms and amount of ammunition furnished them.”

Governor Scott spent £75,000 of public money in the advancement of his candidature, and his majority of 30,000 votes was due entirely to terrorism and bribery. In 1871 it 44was discovered that the Financial Board had illegally issued several millions of State bonds, and there was a movement for the impeachment of Scott, who was a member of the Board. To save himself Scott issued three warrants upon the Armed Force Fund, leaving the amounts blank, and gave them to two of his political associates. The warrants were afterwards filled up for £9,729, and the money was used to bribe members of the Legislature, the result being that the Governor escaped. In the meantime, so outrageous was the waste of public money, and so unabashed the general corruption, that several outbreaks occurred. These were suppressed by a suspension in certain counties of the writ of habeas corpus; but there is no doubt that they represented chiefly the efforts of honest citizens to protect themselves when they found that the Government did not protect them.

Mr. Franklin J. Moses, jun., succeeded General Scott as Governor, in 1872; and under him corruption grew more rampant than ever. Writing soon after that person had assumed office, Mr. J. S. Pike said:—

“The whole of the late Administration ... was a morass of rottenness, and the present Administration was born of the corruptions of that.... There seems to be no hope, therefore, that the villainies of the past will be 45speedily uncovered. The present Governor was Speaker of the last House, and he is credited with having issued during his term of office over $400,000 (£80,000) of pay certificates, which are still unredeemed and for which there is no appropriation, but which must be saddled on the taxpayers sooner or later.... Taxation is not in the least diminished; and nearly $2,000,000 per annum are raised for State expenses where $400,000 formerly sufficed.... The new Governor has the reputation of spending $30,000 to $40,000 a year on a salary of $3,500; but his financial operations are taken as a matter of course, and only referred to with a slight shrug of the shoulders.... The total amount of the stationery bill of the House for the twenty years preceding 1861 averaged $400 (£80) per annum. Last year it was $16,000 (£3,200).... It is bad enough to have the decency and intelligence and property of the State subjected to the domination of its ignorant black pauper multitude, but it becomes unendurable when to that ignorance the worst vices are superadded.”

Moses’s rule was far worse than Scott’s. There was more waste, more corruption, and more lawlessness. In 1874 a committee was appointed to represent the state of affairs to the President; but Moses and his fellows learnt betimes of this intention, and, having misappropriated £500 of public money for the purpose, were able to checkmate the move. It is impossible here to go into details of the various legislative and political scandals of the period. So venal was Moses, and so notoriously did he sell his power, that, more than once, judges 46announced from the bench their unwillingness to put the people to the expense and trouble of convicting criminals for the Governor to pardon.

Governor D. H. Chamberlain, a well-meaning and honest Republican, succeeded this miscreant in 1874; yet he proved too weak to control his party. Owing to the action of a remnant of Scott’s negro militia, a bloody riot occurred in Edgefield county in January, 1875; and in his treatment of this event, as well as in his attempts to lessen the public expenditure, Mr. Chamberlain showed that he was animated by the best desires; but in 1875 his efforts to ensure the purity and integrity of the Bench were circumvented by a conspiracy among his followers; and among the judges then chosen was the infamous ex-Governor Moses. Mr. Chamberlain refused to commission him, and the man never served. The circumstances of his choice, however, aroused the country, and determined the people to oust the Republicans. At the elections of 1876 they chose as their Governor General Wade Hampton, and put Democrats and white men into all official and representative positions. In this election there were fraud and violence on both sides; but, while the Democrats were fighting for their liberty, and almost for their lives, the Republicans were fighting mainly for office alone. And 47the victors have not, upon the whole, abused their victory. They have introduced administrative economy; they have restored the credit of their State; they have cared for education and general progress; and they have brought back a fair measure of peace and a large one of prosperity.

And here I should add one word more concerning Moses. After his fall from power he became a criminal of the vulgarest character. In 1881 he was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment for fraud to the amount of $25; in 1884 he was sentenced to three months’ imprisonment for swindling; in 1885 he was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment for fraud to the amount of $34; and in the same year he was sent to prison for three years for five other fraudulent transactions. After his release he was arrested for stealing overcoats from the hall of a New York house. He was apparently an incorrigible scoundrel first and last.

In 1877 a committee was appointed by the Legislature of South Carolina to inquire into and report upon the scandals of the period from 1867 to 1876. I cannot resist the temptation of making a few extracts from the report:—

“If the simple statement was made that Senators and Members of the House were furnished with everything they 48desired, from swaddling clothes and cradle to the coffin of the undertaker, from brogans to chignons, from finest extracts to best wines and liquors, and that all was paid for by the State, it would create a smile of doubt and derision; but when we make the statement, and prove it by several witnesses and by vouchers found in the offices of the Clerks of the Senate and House, all must, with sorrow, admit the truthfulness of the report.

“A. O. Jones, Clerk of the House, testifies that supplies were furnished under the head of ‘legislative expenses,’ ‘sundries,’ and ‘stationery,’ and included refreshments for committee rooms, groceries, clocks, horses, carriages, dry goods, furniture of every description, and miscellaneous articles of merchandise for the personal use of the members.

“It is shown that on March 4, 1872, Solomon furnished the Senate with $1,631 worth of wines and liquors, and on the 7th day of the same month with $1,852 75c. worth.

“Whilst fraud, bribery, and corruption were rife in every department of the State Government, nothing equalled the infamy attending the management of public printing.... From 1868 to 1876 the sums paid for public printing amounted to $1,326,589 (£265,318)—a sum largely in excess of the cost of public printing from the establishment of the State Government up to 1868.... The public printing in this State cost $450,000 (£90,000) in one year, and exceeded the cost of like work in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Maryland, and New York by $122,932 (£24,588).”

The Committee gives a list of the names of twenty-two Senators and Representatives who received sums varying from £10 to £1,000 under what was called the “division and silence arrangement,” and it also gives a list of those 49who were bribed to vote for these enormous appropriations. Governor Moses received £4,000, Mr. Cardozo (treasurer) received £2,500, and so on. It is not surprising that under so iniquitous a system the State printing bill, which, during the seventy-eight years ending 1868 had been but £121,800, mounted up in the eight years (1868–76) to £265,318. During the negro-Republican era of reconstruction South Carolina’s monthly printing bill averaged £11,133; during General Wade Hampton’s administration it averaged £103.

RECONSTRUCTION IN GEORGIA.

In Georgia the reconstruction period was likewise full of fraud and corruption. In one short session the pay and mileage allowances of members and officers of the General Assembly amounted to $979,055, or £195,811, and there were no fewer than one hundred and four clerks, or nearly one clerk to every two members. Between 1868 and 1870 the State debt increased from $5,827,000 to $18,183,000, and the State bonds became almost unmarketable, while all public works either fell to ruin or were “run” by, and mainly for the benefit of, unscrupulous adventurers of the worst type. During 50his term of three years Governor Bullock, the Reconstruction Governor, pardoned three hundred and forty-six offenders against the law, some of whom actually received pardon before trial. Indeed, seven pardons before trial were granted to one man, who pleaded them to seven separate indictments. The elections of December, 1870, put an end to this. The Democratic victory was overwhelming, and, before the Deputies of the people could confront him, Bullock had resigned office and fled the State. Since that moment prosperity has revived.

RECONSTRUCTION IN FLORIDA.

In Florida, the first Reconstruction Governor, Harrison Reed, very nearly doubled the State expenditure during his four years of office. Railway and legislative scandals were common. From Governor downwards every official seemed to be equally corrupt and equally devoid of patriotism. On one occasion an Act of the Legislature was forged; and, armed with it, the Governor claimed, but failed to obtain, some agricultural land scrip that was in the hands of the Treasury at Washington. The ballot-boxes were tampered with, and the election returns falsified. In the meantime the State Treasury was often so empty that even 51telegraph charges could not be paid. The second Reconstruction Governor, O. B. Hart, who assumed office in 1873, realised the deplorable condition of affairs, but proved powerless to effect reforms. People were kidnapped, really that they might be unable to vote, but professedly in order that they might appear as witnesses in distant courts of justice. A similar process was, on at least one occasion, applied to members of the State Senate, two of whom were arrested and carried to Jacksonville, in order that they might not imperil by their votes the nefarious schemes of their Republican colleagues. The elections of 1876 placed the Democrats in power and introduced a new and more reputable era.

RECONSTRUCTION IN VIRGINIA.

During the reconstruction period Virginia’s sufferings were less painful and considerably briefer than were those of most of the other old slave States with which I am dealing. Such misfortunes as she experienced were attributable, nevertheless, to causes exactly the same as those which brought South Carolina to the lowest depths of misery and degradation. In Virginia, as elsewhere, the reconstruction laws disfranchised the majority of the best native whites and 52handed over the country to the tender mercies of ignorant blacks, prompted by unscrupulous carpet-baggers. Yet in Virginia the process known as reconstruction seems to have been singularly uncalled for save as a purely party measure. It was not needed for the protection of the negroes. Professor Alexander Johnston, in the “Cyclopædia of Political Science,” calls attention to the conspicuous equity of the Virginia statute, made after the war but before reconstruction, for the regulation of contracts between blacks and whites. Reconstruction was needed only for the preservation of Republican power. It ended in 1870, but while it lasted it had a very bad effect upon all the institutions of the State, and especially upon the judiciary. Says Mr. Robert Stiles:—“The writer has appeared in a circuit court of Virginia before a bench upon which sat a so-called Judge, who had the day before been a clerk in a village grocery store, and who was not better fitted for the dignity and duty devolved upon him than the average grocery clerk would be.”

RECONSTRUCTION IN MISSISSIPPI.

In Mississippi the period was much longer and much more severe and stormy. It was Mr. John Q. Adams, of Massachusetts, who, describing 53the treatment during this time of the vanquished and resigned Southerners, said that the Northerners scorned the protests of the ex-Confederates, “repelled their aid, insulted their misery, and inflicted on them an abasement which they felt to be intolerable in posting over them their slaves of yesterday to secure their pledge of submission to the Constitution of the United States.” The South, therefore, was by no means alone in feeling that she was aggrieved.

In Mississippi, as in other States, a Convention met after the passing of the Reconstruction Acts to draw up a new State Constitution. The Convention was of the usual “black and tan” complexion, and in the qualities of ignorance, corruption, and depravity was almost all that the imagination can conceive. “It was,” says Mr. Ethelbert Barksdale, “a fool’s paradise for the negroes, who undertook to perform what they were incapable of doing; and, as to their mercenary white leaders, the stream of purpose which ran through all their actions was plunder and revenge. Not one of the authors and abettors of the plan was actuated by a higher motive than party success. Not one of them believed that it would promote the restoration of the Union to substitute the rule of knaves and negroes for the State Governments which they had overthrown. 54They knew the depravity of the white renegades whom they had commissioned to do this work, and they knew, to employ the language of a Northern statesman and Union soldier, that ‘in the whole historic period of the world the negro race had never established or maintained a Government for themselves.’”

The Convention was very deliberate in its action. Its members lived in a state of luxury unknown to their previous habits. They voted themselves $10 (£2) a day, and paid their innumerable hangers-on correspondingly high wages; and, although the body cost about £100,000 sterling while it sat, it would have cost far more but for the inexorable attitude of the commanding general, who, in the interregnum, was practically dictator.

The Constitution which the Convention drew up was promptly rejected at the polls, and was only ratified in a modified form upon the holding of a second election in 1869. As originally devised it would have excluded half the intelligent white population from all offices, and would even have actually and permanently disfranchised anyone who during the war had charitably contributed to the relief of sick and suffering Confederate soldiers.

The first election under the Amended Constitution 55returned a Legislature four-fifths composed of negroes and carpet-baggers, and the negroes had a majority. The immediate consequences were that corruption began to regulate every public and legislative transaction, and that the State started on a career which led it with daily accelerating speed in the direction of ruin. Within six years 6,400,000 acres of land were adjudged forfeited for non-payment of the taxes which were necessary to support the extravagance and folly of the ruling clique. Thenceforward, until, at least, these lands were redeemed, taxation fell with correspondingly increased weight upon the rest of the unfortunate State. And so matters went from bad to worse until, after years of tyranny, waste, and extravagance on the part of their governors, the whites could submit no longer.

From a taxpayers’ petition addressed to the Legislature on January 4th, 1875, I extract the following:—

“To show the extraordinary and rapid increase of taxation imposed on this impoverished people, these particulars are cited:—In 1869 the State levy was 10 cents on the hundred dollars of assessed value of lands. For the year 1871 it was four times as great. For 1872 it was four times as great. For the year 1873 it was eight and a half times as great. For the year 1874 it was fourteen times as great.... In 56many counties the increase in the county levies has been still greater.”

At this crisis Mr. George E. Harris, a Republican ex-Attorney-General and member of Congress, wrote:—“The people are in a state of exasperation, and in their poverty and desperation they are in arms against the burden of taxes levied and collected on their property.” But the petition was laughed at by those who were profiting by the misery of the citizens. The people, therefore, roused themselves, and, partially, it may be, by violence and fraud, but wholly in self-defence, rescued the State at the elections of 1875 from its abasement. Since then there has been no important break in the steady financial, agricultural, educational, and industrial improvement of Mississippi.

RECONSTRUCTION IN LOUISIANA.

Louisiana, alas, fared much worse than Mississippi—worse, in fact, than any of the old slave States; for even in South Carolina the agony was not so bloody.

The Constitutional Convention of 1867 was elected on a registration list which had been so manipulated as to show only 45,218 white voters to 84,436 black ones; and at the legislative 57elections of 1868 the successful candidates were chiefly negroes. Indeed, in the Senate there were but about half a dozen whites.

To the summit of this mass of ignorance and corruption a creature named Henry C. Warmoth at once climbed. By arts which can best be compared with those of the political schemer in a burlesque, he had already ingratiated himself with the negroes; and he had little difficulty in inducing his protégés to make him the first Reconstruction Governor of Louisiana.