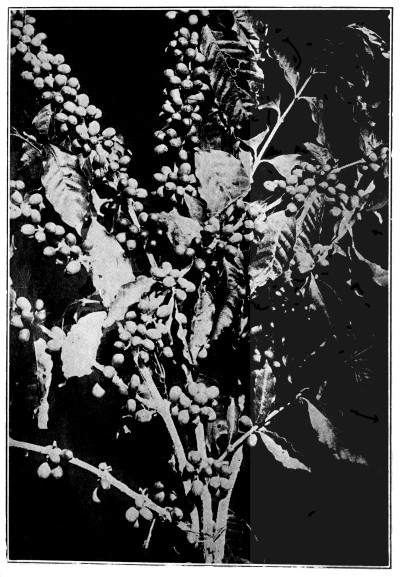

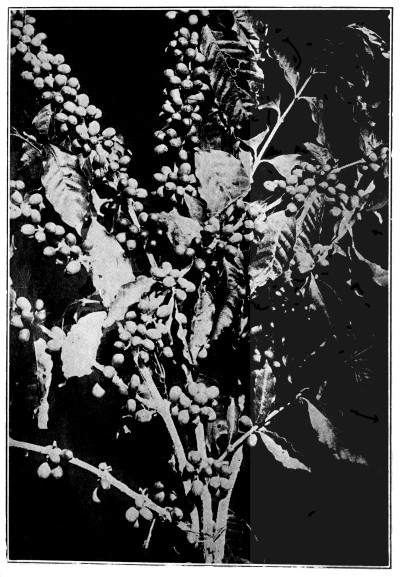

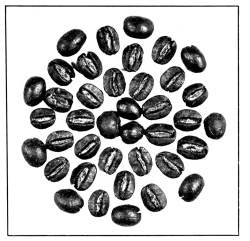

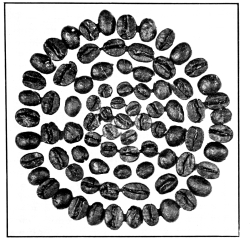

Near View of Berries of Coffea Arabica

Title: Coffee merchandising

A handbook to the coffee business giving elementary and essential facts pertaining to the history, cultivation, preparation, and making of coffee

Author: William H. Ukers

Release date: December 27, 2025 [eBook #77554]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: The Tea and coffee trade journal co, 1924

Credits: Charlene Taylor and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Near View of Berries of Coffea Arabica

A Handbook to the Coffee Business Giving Elementary

and Essential Facts Pertaining to the History,

Cultivation, Preparation, and Marketing

of Coffee

By

William H. Ukers, M.A.

Editor, The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal

Author, All About Coffee; A Trip to Brazil

NEW YORK

The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal Co.

1924

Copyright 1924

By

THE TEA AND COFFEE TRADE JOURNAL CO.

New York

International Copyright Secured

All Rights Reserved in the U. S. A. and Foreign Countries

PRINTED IN THE U. S. A.

To My Co-workers on

The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal

[Pg vii]

This work has been written in response to a demand for a handbook for the especial use of those engaged in the coffee business. To a certain extent it represents a condensation of the author’s encyclopedic work, “All About Coffee.” “Coffee Merchandising,” however, is designed primarily for beginners in the coffee business. It will be found to contain all the elementary and essential facts pertaining to the history, cultivation, preparation, and marketing of coffee.

In it the author has tried to avoid dogmatism. He has aimed to tell briefly the story of coffee, including all those things which every intelligent coffee man should know concerning the early history of the beverage, the botany of the plant, the chemistry of coffee, how coffee grows, how it is prepared for the market, how it is bought and sold in the countries of production, and how it is marketed at wholesale and at retail in the United States. In the telling of the story the author has given the reader the best thought of the trade on all controversial questions, striving to keep his own opinions in the background.

Then, too, the aim has been not only to tell the history story, but to show how successful men in the coffee trade have built up the most enduring business. For this reason the work should prove a source of inspiration, as well as a fount of knowledge, for students and salesmen.

Those who may wish to make a more thorough study of the subject, to delve deeply into the history, romance, and poetry of coffee, or its scientific aspects, are referred to “All About Coffee,” by the same author.

There are two important factors which make for success in the [Pg viii] coffee business,—faith and work,—an abiding faith in the opportunity which it offers to render a public service and which inspires the faithful student to get all the facts about coffee so as to be able to give reasons for his faith; then an intelligent application of the knowledge coupled with that diligence in business which always spells success in any trade or profession—and lo! the battle is won. It is the author’s hope that “Coffee Merchandising” will prove a lamp that will shed some helpful light on the way of all those who are pushing on to greater achievements in the coffee business.

[Pg ix]

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER I. | |

| A Short History of Coffee | |

| A brief account of the beginning of coffee in the Near East—Early | |

| legends, persecutions, first printed references—The introduction | |

| of the beverage into England, France, and Germany—Early London | |

| and Paris coffee houses—The story of the spread of coffee | |

| propagation around the coffee belt of the world—Early American | |

| coffee houses | Page 1 |

| CHAPTER II. |

|

| The Botany of Coffee | |

| Its complete classification by class, sub-class, order, family, | |

| genus, and species—How Coffea arabica grows, flowers, and | |

| bears—Other species and hybrids | Page 17 |

| CHAPTER III. |

|

| Chemistry and Pharmacology of Coffee | |

| The chief factors which enter into coffee goodness—Brief discussion | |

| of caffein and caffeol—Coffee’s place in a rational dietary | |

| —Latest scientific discoveries that establish the whole truth | |

| about coffee as a wholesome, satisfying drink for the great | |

| majority of people and cause it to be regarded as the servant, | |

| rather than the destroyer, of civilization | Page 25 |

| CHAPTER IV. |

|

| Where Coffee Grows | |

| Locating the principal coffee-growing districts in the world’s | |

| coffee belt, with a commercial coffee chart of the leading | |

| growths, giving market names and general trade characteristics | |

| Page 31 | |

| CHAPTER V. |

|

| How Coffee Is Grown | |

| Coffee cultivation in general—Soil, climate, rainfall, altitude, | |

| propagation, shade windbreaks, diseases—How the plant grows | |

| in all the principal producing countries | Page 37 |

| CHAPTER VI. |

|

| Preparing Green Coffee for Market | |

| The marvelous coffee package, one of the most ingenious in all | |

| nature—How coffee is harvested—Picking—Dry and wet methods | |

| of preparation—Pulping—Fermentation and washing—Drying— | |

| Hulling, or peeling and polishing—Sizing or grading— | |

| Preparation methods of different countries | Page 43 [Pg x] |

| CHAPTER VII. |

|

| Buying Coffee in the Producing Countries | |

| How green coffee is bought and sold in the countries of origin | |

| Page 61 | |

| CHAPTER VIII. |

|

| Buying and Selling Green Coffee at Wholesale | |

| The seven stages of transportation—Handling coffee at New York— | |

| How green coffee is graded—Spot-market trading—Buying coffee | |

| C. & F.—Futures and hedging—Buying and selling commissions— | |

| Brokers—The Exchange Clearing House—Brazil quotations—London, | |

| Havre, and Hamburg markets—Rulings | Page 69 |

| CHAPTER IX. |

|

| Green and Roasted Coffee Characteristics | |

| The trade values, bean characteristics, and cup merits of the | |

| leading coffees of commerce—Appearance, aroma, and flavor in | |

| cup testing—How experts test coffees—Typical sample-roasting | |

| and cup-testing outfit | Page 81 |

| CHAPTER X. |

|

| Coffee Blending | |

| Blending green coffees—Properly balanced blends—Low-priced and | |

| high-priced blends—Blends for restaurant and hotel trade— | |

| Doubtful value of sample blends | Page 105 |

| CHAPTER XI. |

|

| Coffee Roasting | |

| Separating, milling, and mixing—The roasting operation—Dry and | |

| wet roasts—Finishing and coating—Cost card for roasters— | |

| Cooling and stoning—Roasting equipment—Blending roasted coffee | |

| —A trip through a model coffee-roasting plant—Evolution of | |

| coffee-roasting apparatus | Page 111 |

| CHAPTER XII. |

|

| Coffee Grinding | |

| “Steel-cut” coffee—Wholesale coffee grinding—Evolution of | |

| grinding apparatus | Page 131 |

| CHAPTER XIII. |

|

| Selling Roasted Coffee at Wholesale | |

| How coffees are sold at wholesale—The wholesale salesman’s | |

| place in merchandising—Ten things every master salesman | |

| should know—Profit sharing for salesmen—Some coffee costs | |

| analyzed—Common sense in cost finding—Terms and credits— | |

| About package coffees—Coffee-selling chart—Various types | |

| of coffee containers—Labels—Coffee-packaging economies— | |

| Practical grocer helps—Coffee sampling—Premium method of | |

| sales promotion | Page 139 [Pg xi] |

| CHAPTER XIV. |

|

| Selling Coffee at Retail | |

| How coffees are sold at retail—The place of the grocer, the tea | |

| and coffee dealer, the chain store, and the wagon-route | |

| distributer in the scheme of distribution—Starting in the | |

| retail coffee business—Coffee blends for retailers—Small | |

| roasters for retail dealers—Model coffee departments—Creating | |

| a coffee trade—Meeting competition—Profits and costs— | |

| Splitting nickels—Figuring costs and profits—A credit policy | |

| for retailers—Premiums for retailers—How to build and hold a | |

| retail coffee business | Page 155 |

| CHAPTER XV. |

|

| Brewing Coffee in Hotels and Restaurants | |

| Analyzing the potential market—The supreme coffee test—Freshly | |

| roasted and freshly ground—Coffee-brewing conclusions—Coffee | |

| urns—Rules for making coffee in hotels and restaurants— | |

| General directions for improving coffee service—How to | |

| operate a successful coffee shop, with sample menus, hints | |

| on equipment and service | Page 175 |

| CHAPTER XVI. |

|

| Production and Consumption of Coffee | |

| A statistical study of world production and consumption of | |

| coffee by countries—Coffee in the United States—The trend | |

| of the trade in 1923—Brazil’s coffee valorization | Page 197 |

| CHAPTER XVII. |

|

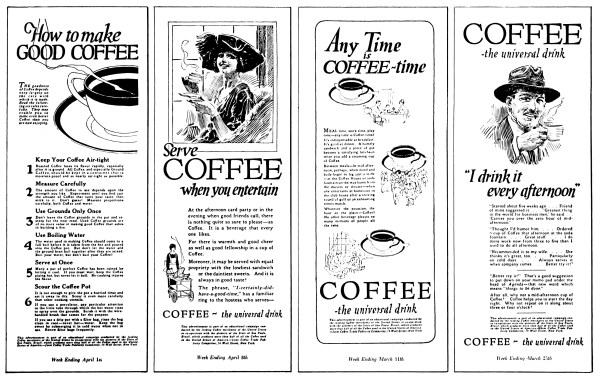

| Coffee Advertising | |

| The first coffee advertisement—Evolution of coffee advertising— | |

| Package-coffee advertising—Advertising to the trade—Advertising | |

| by various mediums—Advertising for retailers with ready-made | |

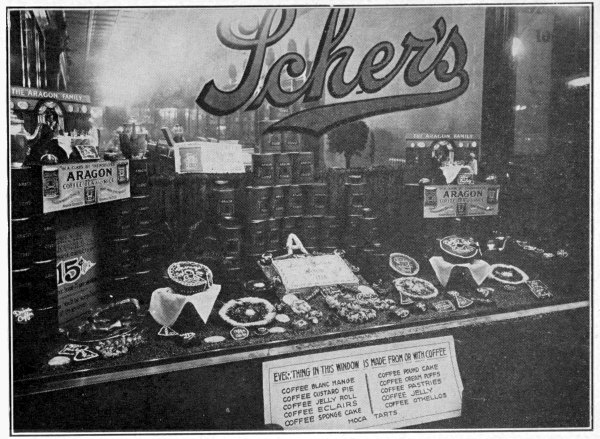

| sample copy—Advertising to the nose—Successful coffee window | |

| displays—Advertising by government propaganda—Coffee | |

| advertising efficiency | Page 219 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. |

|

| Coffee Making in the Home | |

| The importance of correct grinding and brewing—Drip or filter | |

| coffee—Boiled or steeped coffee—Percolated coffee—The | |

| perfect cup of coffee—Some coffee recipes | Page 233 |

[Pg xii]

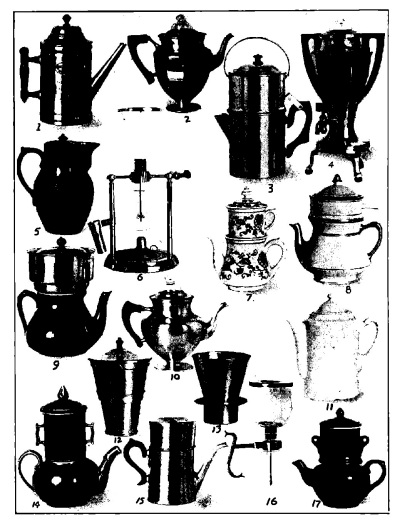

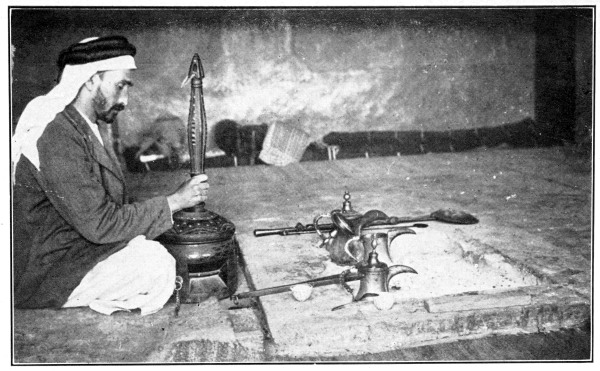

INDEX TO ILLUSTRATIONS

| Facing page | |

| Near view of berries of Coffea arabica (frontispiece) | iii |

| Legendary discovery of the coffee drink | 1 |

| First advertisement for coffee | 6 |

| A coffee house in the time of Charles II | 10 |

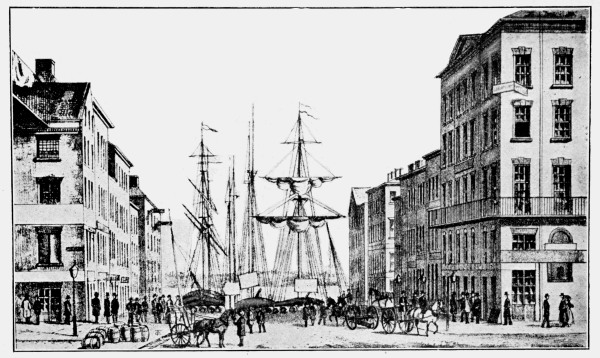

| Merchants Coffee House in New York | 14 |

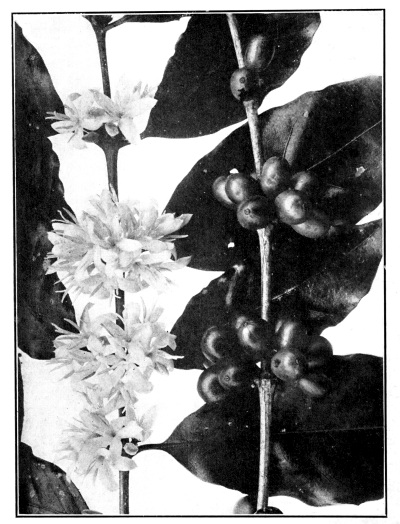

| Coffea arabica flower and fruit | 17 |

| Green and roasted Bogota coffee | 25 |

| 800,000 coffee trees in bearing | 31 |

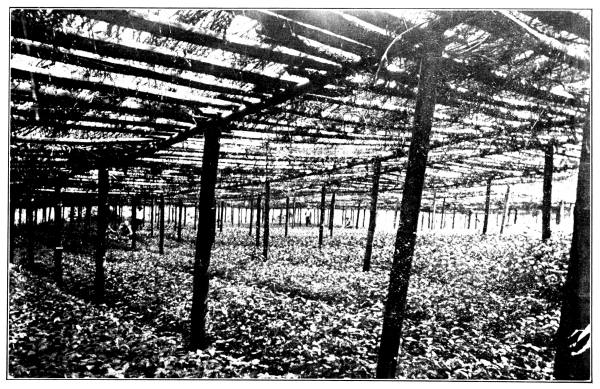

| Coffee nursery under a bamboo roof | 37 |

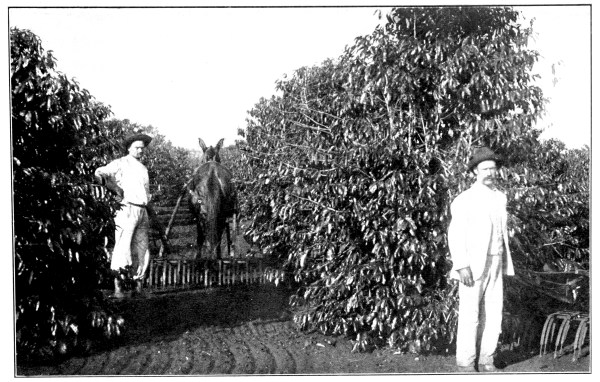

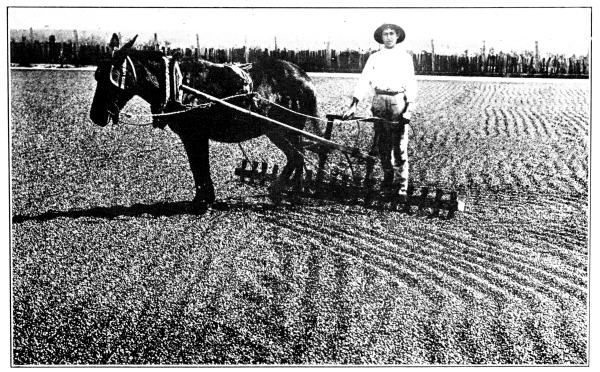

| Efficient weeding and harrowing at Ribeirao Preto | 38 |

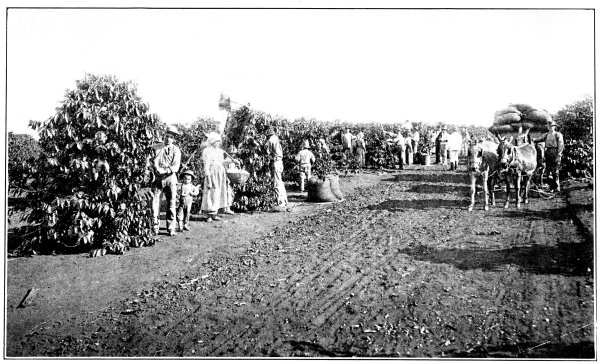

| Picking coffee on a well-kept fazenda | 43 |

| Coffee drying ground, Sao Paulo | 50 |

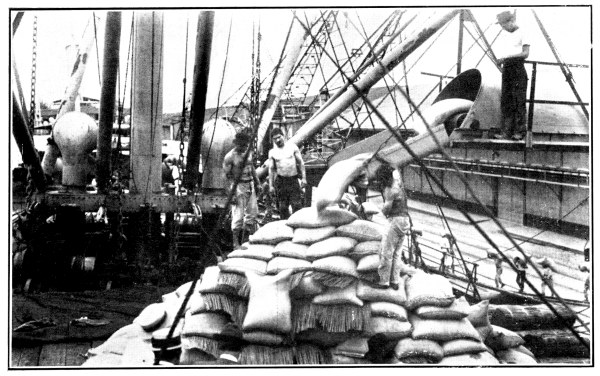

| Loading coffee aboard ship at Santos | 61 |

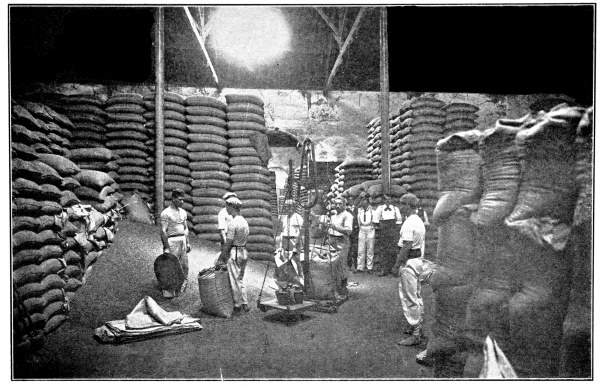

| Weighing and sacking coffee at Santos | 62 |

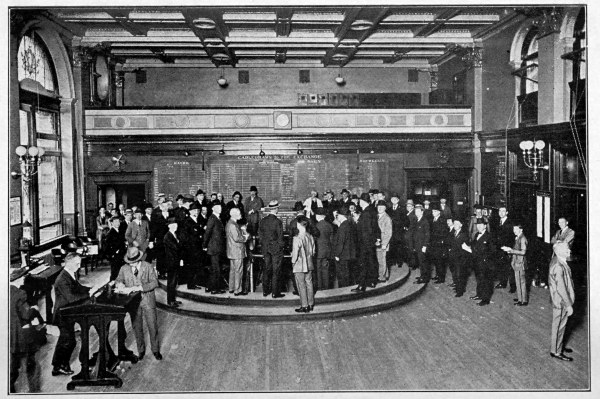

| Coffee pit in the New York Coffee & Sugar Exchange | 69 |

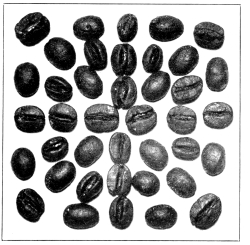

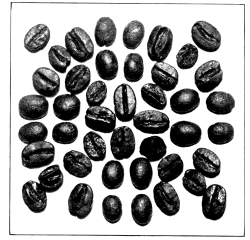

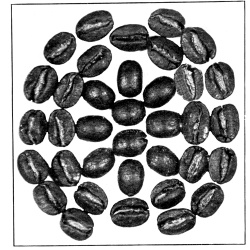

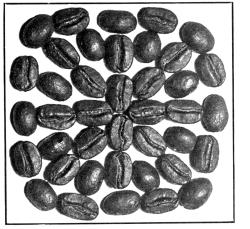

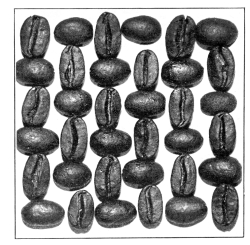

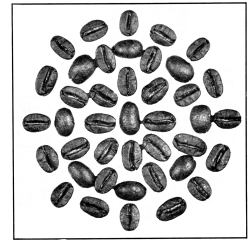

| Samples of typical roasted coffee beans | 81, 86, 90, 98 |

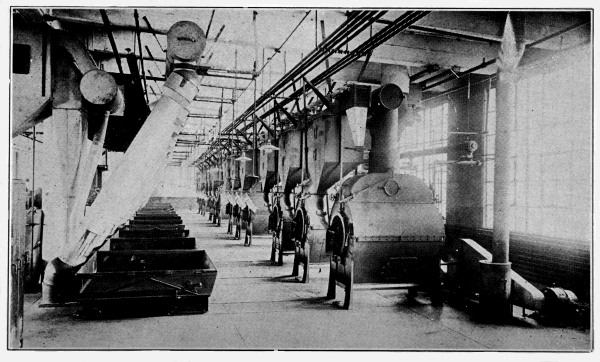

| Modern gas coffee-roasting plant | 111 |

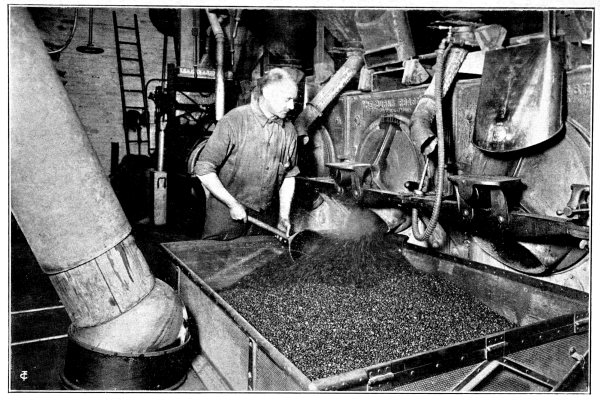

| Dumping the roast in a coal roasting plant | 118 |

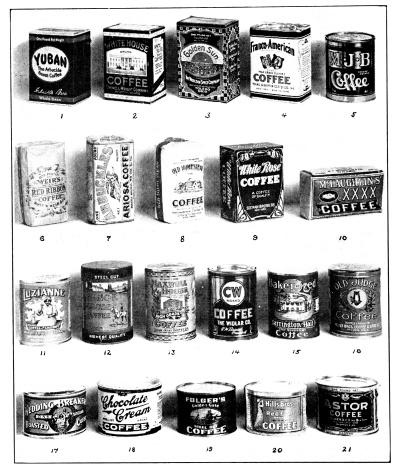

| Some leading trade-marked coffee containers | 139 |

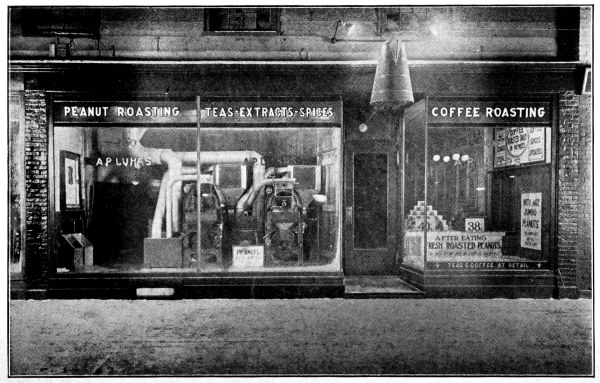

| Luhrs, of Poughkeepsie, features freshly roasted coffee | |

| in his window | 155 |

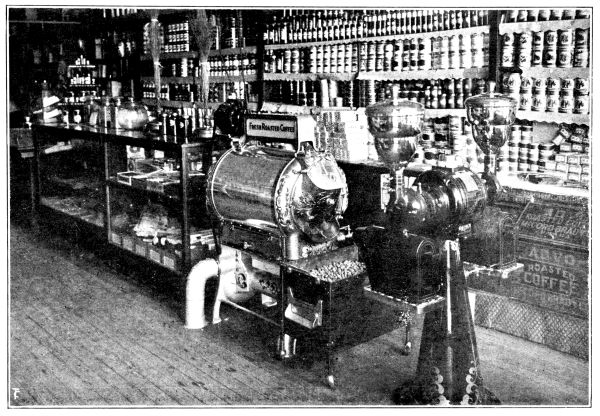

| Johnson of Red Oak roasts before the customer | 162 |

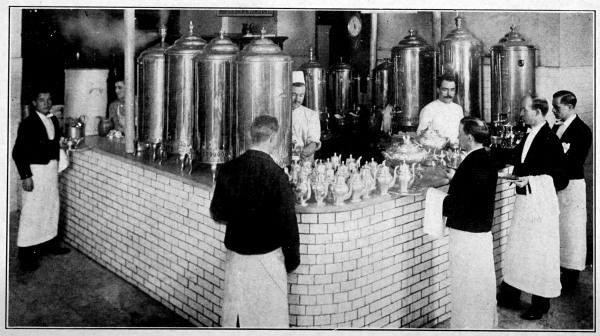

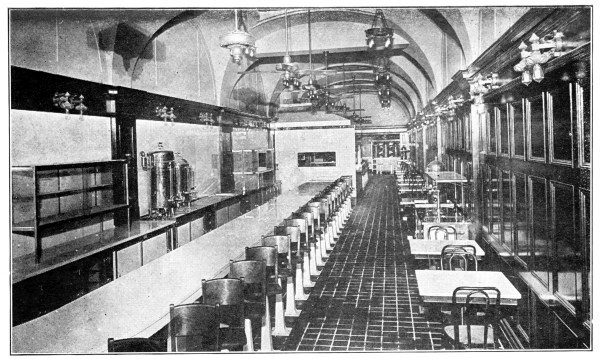

| One of the coffee kitchens of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel | 175 |

| Day and night coffee room of the Rice Hotel, Houston | 184 |

| Advertising copy of the Joint Coffee Trade Publicity | |

| Committee | 219 |

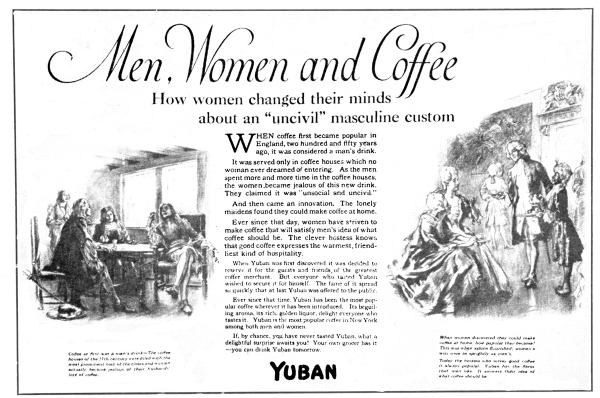

| Drawing upon history for social-intercourse atmosphere | 224 |

| A prize-winning coffee window display | 228 |

| Coffee-making devices used in United States | 233 |

| Brewing the guest’s coffee in a Mohammedan home | 236 |

| Showing how grinding breaks open the oil cells | 242 |

Legendary Discovery of the Coffee Drink:

Kaldi and His Dancing Goats

From a drawing by a modern French artist

[Pg 1]

A brief account of the beginning of coffee in the Near East—Early legends, persecutions, first printed references—The introduction of the beverage into England, France, and Germany—Early London and Paris coffee houses—The story of the spread of coffee propagation around the coffee belt of the world—Early American coffee houses.

Coffee is at least 1,000 years old. It was first mentioned in literature by Rhazes, a famous Arabian physician, about the year 900; only Rhazes called it bunchum. The early Arabians called the bean and the tree that bore it bunn; the drink, bunchum.

Our word “coffee” comes from the Arabic qahwah, through the Turkish kahveh, being originally one of the names employed for wine in Arabic. The word has no connection with the town of Kaffa in Abyssinia, as many writers have supposed. Its final form in French became café; in German, kaffee. The North American Indians knew it as kaufee.

Coffee was first a food, then a wine, a medicine, and lastly a beverage. Its use as a popular beverage dates back 700 years.

Coffee Was First a Food Ration

In the beginning, the whole ripe berries, beans, and hulls were crushed and molded into food balls held in shape with fat. This was about 800 A. D. The Galla, a wandering African tribe, still make use of these food balls. One of them, of the size of a billiard ball, constitutes a day’s ration, and sustains them on long marches. The inhabitants of the island of Groix, off the coast of Brittany, also thrive on a diet that [Pg 2] includes roasted coffee beans. But, however nourishing these isolated groups may find coffee taken in this way, so far they have no imitators, and the rest of the world wisely prefers to use it in the liquid form.

Following its use as a food ration, a kind of aromatic wine was made in Africa from the fermented juice of the hulls and pulp of the ripe berries. Next a medicine was made by boiling the dried berries in water. About 1200, the practice began of making a drink from the dried hulls alone and boiling in water. Toasting the hulls followed, and about 1300 it was the custom to roast the dried beans after hulling and to boil them whole. Grinding in mortars was a later development.

Same Early Legends

Sheik Omar, a doctor-priest and a disciple of Sheik Schadheli, the patron saint and legendary founder of Mocha, quite by chance discovered coffee as a beverage at Ousab in Arabia in 1258. Omar was in exile and facing starvation. He was forced to eat certain berries which he found growing on wild bushes in his Ousab retreat. In this way he discovered that they were possessed of stimulating—or, as he called it, magical—properties. Later he tried roasting them and boiling them in water. He got even better results. Next he prescribed the drink for those of his former patients who came to visit him, and these carried back such stories of benefits received that Omar was invited to return in triumph to Mocha, where a monastery was built in his honor and he himself was made a saint.

There are several versions of this legend. One ascribes the discovery of the drink to an Arabian herdsman in upper Egypt, or Abyssinia, who complained to the abbot of a neighboring monastery that the goats confined to his care became strangely frolicsome after eating the berries of wild shrubs found near their feeding grounds. The abbot tried the berries on himself, and, being astonished at their exhilarating effects, experimented by boiling them in water and ordering [Pg 3] the decoction served to his monks, who too often fell asleep over their nightly religious ceremonies. Thereafter the monks found no difficulty in keeping awake.

About 1300, it is recorded that the coffee drink was a popular decoction among the churchmen. It was made from the roasted berries, crushed with a mortar and pestle, the powder being placed in boiling water and the drink taken down, grounds and all.

About 1454, Sheik Gemalledin, mufti of Aden, having discovered the virtues of the coffee berry on a journey to Abyssinia, sanctioned the secular use of coffee in Arabia Felix. It quickly reached Mecca and Medina. About 1500, the propagation of the plant had spread from Abyssinia through Arabia and into Ceylon.

Early Coffee Persecutions

In 1511, soon after the drink had reached Cairo, and the coffee house had become a favorite resort, Kair Bey, governor of Mecca, being outraged by the extent to which the new drink was being consumed by clergy and laymen, called a consultation of lawyers, physicians, and leading citizens, and succeeded in browbeating a majority into issuing an indictment of the beverage, while he issued an edict prohibiting its use. His master, the sultan of Cairo, ordered it revoked shortly thereafter, and Kair Bey subsequently came to an inglorious end, being first exposed as “an extortioner and a public robber” and then slowly “tortured to death.”

In 1524, the kadi of Mecca tried his hand at closing the coffee houses, because of disorders, but permitted coffee drinking in private. By 1532, the coffee house had taken root in Damascus and Aleppo. In 1534, a religious fanatic denounced coffee in Cairo, and led a mob against the coffee houses, many of which were wrecked. The city was divided into two parties,—for and against coffee. To put an end to the [Pg 4] agitation, the chief judge invited the leading physicians to a conference, and at the end not only served coffee to all present, but drank some himself.

In 1554, the first coffee houses were opened in Constantinople by Shemsi of Damascus and Hekem of Aleppo. Here, too, religious zealots soon became jealous of their popular appeal, and about 1570 they put forth the argument that roasted coffee was a kind of charcoal, and, as the Koran forbade the use of charcoal among the other unsanitary foods, the use of coffee was against the law of the Koran. The mufti was so impressed by this that he ruled that coffee was forbidden by the law of the Prophet.

The prohibition was more honored in the breach than in the observance. Coffee drinking continued in secret, instead of in the open; and when Amurath III, about 1580, at the further solicitation of the churchmen, declared that coffee should be classed as a wine, also forbidden by Mohammed, and ordered all coffee houses suppressed, the people only smiled and persisted in their disobedience. The civil officers, finding it useless to try to destroy the custom, winked at violations of the law, and, for a consideration, permitted the sale of coffee privately; so that many Ottoman “speakeasies” sprang up,—places where coffee might be had behind shut doors, shops where it was sold in back rooms.

This was enough to reestablish the coffee houses by degrees. The prohibition was repealed de facto, if not de jure. Then came a mufti less scrupulous or more knowing than his predecessor, who declared that coffee was not to be looked upon as coal, and that the drink made from it was not forbidden by the law. There was a general renewal of coffee drinking; religious devotees, preachers, lawyers, and the mufti himself indulging in it, their example being followed by the whole court and the city.

First Printed References

The first printed reference to coffee appeared as chaube in Rauwolf’s Travels, published in German at Frankfort and Lauingen [Pg 5] in 1582. Rauwolf was a German physician and botanist, who made a journey to the Levant in 1573.

The first authentic account of the origin of coffee was written by the sheik Abd-al-Kadir, in an Arabian manuscript still preserved in the Bibliotheque Nationale at Paris.

The first printed reference to coffee in English appeared as chaoua in a note of Paludanus in Linschoten’s Travels, translated from the Dutch and published in London in 1598.

About 1600, coffee cultivation was introduced into southern India by a Moslem pilgrim, Baba Budan.

The first printed reference to coffee in English, employing the modern form of the word, appeared in W. Parry’s book, Sherley’s Travels, as coffe, in 1601. In 1610, Sir George Sandys in his Travels recorded, “The Turks sip a drink called coffa (of the berry that it is made of) in little china dishes, as hot as they can suffer it.” Francis Bacon also wrote in 1627, “They have in Turkey a drink called coffa made of a berry of the same name, as black as soot, and of a strong scent. This drink comforteth the brain and heart and helpeth digestion.” In 1632, Burton, in his Anatomy of Melancholy, wrote, “The Turks have a drink called coffa, so named from a berry black as soot and as bitter.”

Coffee Baptized by the Pope

The news of coffee caused early dissensions in Italy. Because coffee drinking originated in Mohammedan lands, many churchmen in the 16th century were concerned about the propriety of permitting its use in Christendom, denouncing it as an invention of Satan. Discussion arose, and the disputants appealed to Pope Clement VIII for a decision. The pope wisely decided to drink some before committing himself.

After imbibing a steaming beaker, according to the much quoted legend, [Pg 6] the pope exclaimed, “Why, this Satan’s drink is so delicious that it would be a pity to let the infidels have exclusive use of it! We shall fool Satan by baptizing it, and making it a truly Christian beverage.” This he did, and added the Church’s seal of approval to the waxing popularity of the harmless and invigorating decoction. Coffee was introduced into Venice in 1615.

The drink was brought to England by Canopios, a Cretan student at Oxford, in 1637. A Dutch merchant offered beans from Mocha at public sale in Amsterdam in 1640, although the drink was introduced into Holland as early as 1616. Coffee came to France in 1644. In 1645, the first coffee house was opened in Venice.

A Jew named Jacobs opened the first coffee house in England, at Oxford, in 1650. The first coffee house in London was opened by Pasqua Rosee, a Greek youth, body servant to Daniel Edwards, a London merchant who brought the boy back from Smyrna with him. When in the Levant, Mr. Edwards had acquired the coffee habit. In London, Pasqua was wont to prepare the beverage for his master daily. The novelty of the drink caused the Edwards house to be overrun with company, and Edwards, in self-defense, set the youth up in a shed or tent in St. Michaels Alley, Cornhill, opposite the church. Here, in the same year, Pasqua Rosee issued the first advertisement for coffee in English. It was in the form of a handbill acclaiming “The Vertue of the Coffee Drink.” After leaving England, Pasqua Rosee went to Holland and opened a coffee house there.

First Newspaper Advertisement for Coffee

The first newspaper advertisement for coffee appeared in the Publick Adviser, London, May 19, 1657. It was as follows:

The Vertue of the COFFEE Drink.

First publiquely made and sold in England, by Pasqua Rosee.

The Grain or Berry called Coffee,

groweth upon little Trees, only in the

Deserts of Arabia.

It is brought from thence, and drunk generally throughout

all the Grand Seigniors

Dominions.

It is a simple innocent thing, composed into a Drink, by being dryed in an Oven, and ground to Powder, and boiled up with Spring water, and about half a pint of it to be drunk, fasting an hour before, and not Eating an hour after, and to be taken as hot as possibly can be endured; the which will never fetch the skin off the mouth, or raise any Blisters, by reason of that Heat.

The Turks drink at meals and other times, is usually Water, and their Dyet consist; much of Fruit; the Crudities whereof are very much corrected by this Drink.

The quality of this Drink is cold and Dry, and though it be a Dryer, yet it neither heats, nor inflames more then hot Posset.

It so closeth the Orifice of the Stomack, and fortifies the heat with; it’s very good to help digestion, and therefore of great use to be bout 3 or 4 a Clock afternoon, as well as in the morning.

It quickens the Spirits, and makes the Heart Lightsome. is good against sore Eys, and the better if you hold your Head o’er it, and take in the Steem that way.

It suppresseth Fumes exceedingly, and therefore good against the Head-ach, and will very much stop any Defluxion of Rheums, that distil from the Head upon the Stomack, and so prevent and help Consumptions; and the Cough of the Lungs.

It is excellent to prevent and cure the Dropsy, Gout, and Scurvey.

It is known by experience to be better then any other Drying Drink for People in years, or Children that have any running humors upon them, as the Kings Evil. &c.

It is very good to prevent Mis-carryings in Child-bearing Women.

It is a most excellent Remedy against the Spleen, Hypocondriack Winds, or the like.

It will prevent Drowsiness, and make one fit for busines, if one have occasion to Watch, and therefore you are not to Drink of it after Supper, unless you intend to be watchful, for it will hinder sleep for 3 or 4 hours.

It is observed that in Turkey, where this is generally drunk, that they are not trobled with the Stone, Gout, Dropsie, or Scurvey, and that their Skins are exceeding cleer and white.

It is neither Laxative nor Restringent.

Made and Sold in St. Michaels Alley in Cornhill; by Pasqua Rosee, at the Signe of his own Head.

First Advertisement for Coffee (1652)

Handbill used by Pasqua, who opened the first coffee house

in London. (Reproduced from the original in the British Museum.)

[Pg 7]

In Bartholomew Lane on the back side of the Old Exchange, the drink called Coffee (which is a very wholesome and Physical drink, having many excellent vertues), closes the Orifice of the Stomach, fortifies the heat within, helpeth Digestion, quickneth the Spirits, maketh the heart lightsom, is good against Eye-sores, Coughs, or Colds, Rhumes, Consumptions, Head-ach, Dropsie, Gout, Scurvey, Kings Evil, and many others is to be sold both in the morning and at three of the clock in the afternoon.

Meanwhile, in 1656, coffee was subjected to further persecution in Constantinople, where the grand vizier Kuprili, for political reasons, suppressed the coffee houses and prohibited the use of coffee. For the first violation the punishment inflicted was cudgeling; for the second offense the offender was sewed in a leather bag and thrown into the Bosporous.

Despite the severe penalties staring them in the face, violations of the law were plentiful among the people of Constantinople. Venders of the beverage appeared in the market places with “large copper vessels with fire under them; and those who had a mind to drink were invited to step into any neighboring shop where every one was welcome on such an account.”

Later, Kuprili, having assured himself that the coffee houses were no longer a menace to his policies, permitted the free use of the beverage that he had previously forbidden.

At this time to refuse or to neglect to give coffee to their wives was a legitimate cause for divorce among the Turks. The men made promise when marrying never to let their wives be without coffee. “That,” says Fulbert de Monteith, “is perhaps more prudent than to swear fidelity.”

In 1657, coffee appeared in Paris, but it was not served publicly until introduced by Soliman Aga, the Turkish ambassador, in 1669. He made it in Turkish style, had it served by black slaves, “on bended knees, in tiny cups of egg-shell porcelain, and poured out in saucers of gold and silver, placed on embroidered silk doylies, fringed with gold bullion.” Naturally, his sumptuous coffee functions became the rage of Paris. [Pg 8]

The coffee drink came to North America in 1668. It was first sold in Boston in 1670.

Opposition to London Coffee Houses

Coffee and the coffee houses were fiercely attacked by publicans and ale-house keepers in London between the Restoration and 1675. A series of broadsides and tracts were launched against them. They bore such titles as, “A cup of coffee: or coffee in its colours,” “A Broadside against coffee, or the marriage of the Turk,” and “The Women’s petition against coffee,” the latter presenting the argument that coffee made men as “unfruitful as the deserts whence that unhappy berry is said to be brought.”

These were ably answered by coffee’s defenders, and the drink continued to find favor in spite of its detractors.

The beverage was introduced into Germany in 1670, and the next year the first coffee house in France was opened in Marseilles. Pascal, an Armenian, opened the first coffee house in Paris, at the Fair of St. Germain, in 1672. The progenitor of the real French café was the Procope, opened in Paris in 1689 by Francois Procope, a lemonade vender of Florence.

The coffee house spread rapidly in France. In the reign of Louis XV, there were over 600 cafés in Paris. These became famous: Tour d’Argent, the Royal Drummer, Café Foy, Régence, Momus, Café de Paris, Voisins, Café de la Paix, and Tortoni. At the close of the 18th century there were over 800 cafés in Paris; in 1843, there were over 3,000. They played an important part in the French Revolution, in the development of French literature and of the stage. Among the notables that frequented them were Voltaire, Rousseau, Fontenelle, Beaumarchais, Diderot, Desmoulins, Napoleon, Marie Antoinette, de Musset, Victor Hugo, Gautier, Talleyrand, Marat, Robespierre, Danton, and Rossini. [Pg 9]

While it is recorded that coffee made slow progress with the court of Louis XIV, the next king, Louis XV, to please his mistress du Barry, gave it a tremendous vogue. It is related that he spent $15,000 a year for coffee for his daughters.

Coffee Houses Suppressed

In 1675, Charles II of England issued a proclamation to close all London coffee houses as places of sedition. By that time there were hundreds of them, and they were known as penny universities. The king’s proclamation was so unpopular in nearly all quarters that it stands today as one of the worst political blunders in history. Upon petition of the coffee traders, the order was revoked eleven days after issue.

Some Famous Coffee Houses

The London coffee houses of the 17th and 18th centuries were centers of wit and learning. They were referred to as the “penny universities” because they were great schools of conversation, and the entrance fee was only a penny. Twopence was the usual price of a dish of coffee or tea, this charge also covering newspapers and lights. Quoting a poem of the period:

By 1715, there were 2,000 coffee houses in London. Every profession, trade, class, and party had its coffee house. Men had their coffee houses as now they have their clubs; sometimes contented with one, sometimes belonging to three or four. Johnson, for instance, was connected with St. James’s, the Turk’s Head, the Bedford, Peele’s, besides the taverns which he frequented. Addison and Steele used Button’s; Swift, Button’s, the Smyrna, and St. James’s; Dryden, Will’s; Pope, Will’s and Button’s; Goldsmith, the St. James’s and the Chapter; [Pg 10] Fielding, the Bedford; Hogarth, the Bedford and Slaughter’s; Sheridan, the Piazza; Thurlow, Nando’s.

Among the famous English coffee houses of the 17th-18th century period were St. James’s, Will’s, Garraway’s, White’s, Slaughter’s, the Grecian, Button’s, Lloyd’s, Tom’s, and Don Saltero’s.

St. James’s was a Whig house frequented by members of Parliament, with a fair sprinkling of literary stars. Garraway’s catered to the gentry of the period, many of whom naturally had Tory proclivities.

One of the notable coffee houses of Queen Anne’s reign was Button’s. Here Addison could be found almost every afternoon and evening, along with Steele, Davenant, Carey, Philips, and other kindred minds. Pope was a member of the same coffee house club for a year, but his inborn irascibility eventually led him to drop out of it.

At Button’s, a lion’s head, designed by Hogarth after the Lion of Venice, “a proper emblem of knowledge and action, being all head and paws,” was set up to receive letters and papers for the Guardian. The Tatler and the Spectator were born in the coffee house, and probably English prose would never have received the impetus given it by the essays of Addison and Steele had it not been for coffee-house associations.

Pope’s famous Rape of the Lock grew out of coffee-house gossip. The poem itself contains one charming passage on coffee:

A Coffee House in the Time of Charles II

From a woodcut of 1674

[Pg 11] Another frequenter of the coffee houses of London, when he had the money to do so, was Daniel Defoe, whose Robinson Crusoe was the precursor of the English novel. Henry Fielding, one of the greatest of all English novelists, loved the life of the more bohemian coffee houses, and was, in fact, induced to write his first great novel, Joseph Andrews, through coffee-house criticisms of Richardson’s Pamela.

Other frequenters of the coffee houses of the period were Thomas Gray and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Garrick was often to be seen at Tom’s in Birchin Lane, where also Chatterton might have been found on many an evening before his untimely death.

The second half of the 18th century was covered by the reigns of the Georges. The coffee houses were still an important factor in London life, but were influenced somewhat by the development of gardens in which were served tea, chocolate, and other drinks, as well as coffee. At the coffee houses themselves, while coffee remained the favorite beverage, the proprietors, in the hope of increasing their patronage, began to serve wine, ale, and other liquors. This seems to have been the first step toward the decay of the coffee house.

The coffee houses, however, continued to be the centers of intellectual life. When Samuel Johnson and David Garrick came together to London, literature was temporarily in a bad way, and the hack writers dwelt in Grub Street.

It was not until after Johnson had met with some success, and had established the first of his coffee-house clubs at the Turk’s Head, that literature again became a fashionable profession. [Pg 12]

This really famous literary club met at the Turk’s Head from 1763 to 1783. Among the most notable members were Johnson, the arbiter of English prose; Oliver Goldsmith; Boswell, the biographer; Burke, the orator; Garrick, the actor; and Sir Joshua Reynolds, the painter. Among the later members were Gibbon, the historian, and Adam Smith, the political economist.

Certain it is that during the sway of the English coffee house, and at least partly through its influence, England produced a better prose literature, as embodied alike in her essays, literary criticisms, and novels, than she ever had produced before.

The advent of the pleasure garden brought coffee out into the open in England; and one of the reasons why gardens, such as Ranelagh and Vauxhall, began to be more frequented than the coffee houses was that they were popular resorts for women as well as for men. All kinds of beverages were served in them, and soon the women began to favor tea as an afternoon drink. At least, the great development in the use of tea dates from this period, and many of these resorts called themselves tea gardens.

After the Turks failed in their attack on Vienna in 1683, Kolschitzky, a hero of the siege, was given the supplies of green coffee which they left in their flight, and with them he opened the first coffee house in Vienna.

Early Coffee Propagation

In 1696 and again in 1699, the Dutch introduced the propagation of coffee into Java. The same year the first coffee house (the King’s Arms) was opened in New York.

“Java” coffee seeds were received at the Amsterdam Botanical Gardens in 1706, and in 1714 a plant raised from them was presented to Louis XIV and by him nurtured in the Jardin des Plantes at Paris. It was a seedling of this plant that Captain Gabriel De Clieu carried to Martinique in 1723, sharing his drinking water with it on a long voyage. [Pg 13]

In 1715, coffee cultivation was first introduced into Haiti and Santo Domingo. Later came hardier plants from Martinique. In 1715-17, the French Company of the Indies introduced the cultivation of the plant into the isle of Bourbon (now Réunion) by a ship captain named Dufougeret-Grenier from St. Malo. It did so well that nine years later the island began to export coffee.

The Dutch brought the cultivation of coffee to Surinam in 1718. The first coffee plantation in Brazil was started at Pará in 1723 with plants brought from French Guiana, but it was not a success. The English brought the plant to Jamaica in 1730. In 1740, Spanish missionaries introduced coffee cultivation into the Philippines from Java. In 1748, Don José Antonio Gelabert introduced coffee into Cuba, bringing the seed from Santo Domingo. In 1750, the Dutch extended the cultivation of the plant to the Celebes. Coffee was introduced into Guatemala about 1750-60. The intensive cultivation in Brazil dates from the efforts begun in the Portuguese colonies in Pará and Amazonas in 1752. Porto Rico began the cultivation of coffee about 1755. In 1760, João Alberto Castello Branco brought to Rio de Janeiro a coffee tree from Goa, Portuguese India. The news spread that the soil and climate of Brazil were particularly adapted to the cultivation of coffee. Molke, a Belgian monk, presented some seeds to the Capuchin monastery at Rio in 1774. Later, the bishop of Rio, Joachim Bruno, became a patron of the plant and encouraged its propagation in Rio, Minas, Espirito Santo, and São Paulo. The Spanish voyager, Don Francisco Xavier Navarro, is credited with the introduction of coffee into Costa Rica from Cuba in 1779. In Venezuela, the industry was started near Caracas by a priest, José Antonio Mohedano, with seed brought from Martinique in 1784.

Coffee cultivation in Mexico began in 1790, the seed being brought from the West Indies. In 1817, Don Juan Antonio Gomez instituted intensive [Pg 14] cultivation in the state of Vera Cruz. In 1825 the cultivation of the plant was begun in the Hawaiian Islands with seeds from Rio de Janeiro. The English began to cultivate coffee in India in 1840. In 1852, coffee cultivation was begun in Salvador with plants brought from Cuba. In 1878, the English began the propagation of coffee in British Central Africa, but it was not until 1901 that coffee cultivation was introduced into British East Africa from Réunion. In 1887, the French introduced the plant into Tonkin, Indo-China.

Frederick, the Great Beer Drinker

Germany also had its attempts at coffee suppression. Frederick the Great, of Prussia, had a violent scorn for any beverage so innocuous as coffee—until he found in its increasing popularity, despite his tirades and ukases against it, a comfortable source of revenue to the crown.

Following is the text of Frederick’s celebrated Coffee and Beer Manifesto issued September 13, 1777, a curiosity:

It is disgusting to notice the increase in the quantity of coffee used by my subjects and the amount of money that goes out of the country in consequence. Everybody is using coffee. If possible, this must be prevented. My people must drink beer. His Majesty was brought up on beer, and so were his ancestors and his officers. Many battles have been fought and won by soldiers nourished on beer; and the king does not believe that coffee-drinking soldiers can be depended upon to endure hardship or to beat his enemies in case of the occurrence of another war.

Later, in 1781, Frederick established state coffee-roasting plants and made the coffee business a government monopoly. The common people were forbidden to roast their own coffee. “Coffee smellers” were employed to seek out violations of the law. In 1784, Maximilian Frederick, elector of Cologne, prohibited the use of coffee except by the well-to-do. The decree failed of its purpose.

Holland early adopted the coffee house, and the Dutch were the pioneer coffee traders. History records no intolerance of coffee in Holland.

Merchants Coffee House in New York (at the Right)

as It Appeared 1772-1804

The original coffee house of this name was opened on the northwest corner of Wall and Water Streets about 1737, and was moved to the southeast corner in 1772.

[Pg 15] If Vienna helped make coffee famous, London and Paris gave us the last word in coffee houses. The two most picturesque chapters in the history of coffee have to do with the period of the old London and Paris coffee houses of the 17th and 18th centuries. Much of the poetry and romance of coffee centers around this time. The London coffee house was, however, a male institution; indeed, out of it came the solid British club. The Parisian coffee house, on the other hand, was, like everything French, distinctly Gallic. Women were welcome, and it is not to be wondered that the French adaptation of the oriental coffee house became in time a much more esthetic and artistic institution,—the unique French café.

The early history of coffee in the United States centers around the coffee houses of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. These were patterned largely after the English prototype. Gradually they became taverns, and not infrequently evolved into hotels. In Colonial days, Americans were also large consumers of tea, and, indeed, were in a fair way to become a nation of tea drinkers, when King George III perpetrated that fatal blunder known as the Stamp Act. The Boston Tea Party of 1773 cast the die for coffee. It became a patriotic duty to drink something else, and coffee didn’t have to come from England. Thus was started a national habit which made coffee our national drink. So, when the coffee house disappeared, the coffee drink was found to be strongly intrenched in the homes of the people, and it has stayed there ever since,—“King of the American breakfast table.”

In Boston, the London, Crown, and the Gutteridge were the best known early coffee houses. Later came the King’s Head, Indian Queen, and Green Dragon. The Exchange Coffee House, erected in 1808, was a seven-story skyscraper, and was probably the largest and most costly [Pg 16] commercial coffee house ever built. It was a center of marine intelligence, like Lloyd’s of London.

The burghers of New Amsterdam began to substitute coffee for “must,” or beer, in 1668. In 1683, the year following William Penn’s settlement on the Delaware, we find him buying supplies of coffee in the New York market, and paying for them at the rate of 18 shillings and 9 pence (about $4.68) a pound.

The King’s Arms (1696) was the first coffee house in New York. It was followed by the historic Merchants Coffee house (sometimes called “the birthplace of our Union”), the Exchange, Whitehall, Burns, and Tontine houses.

The coffee houses of early Philadelphia loom large in the history of the city and the republic. Picturesque in themselves, with their distinctive colonial architecture, their associations were also romantic. Many a civic, sociological, and industrial reform came into existence in the low-ceilinged, sanded-floor main rooms of the city’s early coffee houses. One of those reforms was the ultimate abandonment of the public slave auctions which were held regularly on a platform in the street before the second London coffee house, kept by William Bradford, the printer.

There is this to be remarked in closing this brief sketch of the early history of coffee: In Europe and in America the houses where the coffee drink was first served became forums of democracy and temples of free speech. Wherever introduced, coffee has spelled revolution. It ushered in the Commonwealth in England, it was first aid to the French Revolution, and it undoubtedly helped make the American republic.

Coffea Arabica (Costa Rica)

Flower and Fruit

[Pg 17]

Its complete classification by class, sub-class, order, family, genus, and species—How Coffea arabica grows, flowers, and bears—Other species and hybrids.

The coffee tree, scientifically known as Coffea arabica, belongs to the two-leaved class of a large sub-kingdom of vegetable plants known as the Angiospermæ. Because it bears a flower arranged with its corolla all in one piece, forming a tube-shaped arrangement, it is further classified as Sympetalæ or Metachlamydeæ, which means that its petals are united.

Pursuing its classification still further, botanists place it in the order Rubiales and in the family Rubiaceæ or madder family, which also includes various herbs, and a few American plants, like the familiar bluets or Quaker ladies, and partridge berries. Quinine and ipecac are also members of this family.

Botany divides all families into smaller sections known as genera, and the coffee plant belongs to the genus Coffea. Under this genus are several sub-genera, and to the sub-genus Eucoffea belongs the common coffee, which the trade and the general public know best, Coffea arabica.

Coffea arabica is the original species indigenous to Abyssinia and Arabia, and for many years it was known as “Java” when it came from Java and “Mocha” when it came from Arabia. The Arabica seed transplanted to different soils and climates takes on local characteristics, and this gives us Bourbon, Mexican, Coban, Blue Mountain, Bogota, Bourbon Santos, etc., as the case may be.

There are many other species of coffee besides Arabica. They [Pg 18] haven’t been described frequently, because, with one or two exceptions, they are commercially unimportant. Indeed, all botanists do not agree in their classification of the species and varieties of the Coffea genus. The systematic division of this interesting genus is far from finished; in fact, it may be said hardly to be begun.

Coffea arabica we know best because of the important role it plays in commerce.

| Kingdom | Vegetable |

| Sub-kingdom | Angiospermæ |

| Class | Dicotyledoneae |

| Sub-class | Sympetalæ or Metachlamydeæ |

| Order | Rubiales |

| Family | Rubiaceæ |

| Genus | Coffea |

| Sub-genus | Eucoffea |

| Species | C. arabica |

The coffee plant most cultivated for its berries is, as already stated, Coffea arabica, which is found in tropical regions, although it can grow in temperate climates. Unlike most plants that grow best in the Tropics, it can stand low temperatures. It requires shade when it grows in hot, low-lying districts; but, when it grows on elevated land, it thrives without such protection. There are about eight recognized species of Coffea.

Coffea arabica is a shrub with evergreen leaves, and reaches a height of fourteen to twenty feet when fully grown. The shrub produces branches of two forms, known as uprights and laterals. When young, the plants have a main stem, the upright; which, however, eventually sends out side shoots, the laterals. The laterals may send out other laterals, known as secondary laterals, but no lateral can ever produce an upright. The laterals are produced in pairs and are opposite, the pairs being borne in whorls around the stem. The laterals are produced only when the joint of the upright, to which they are attached, is young; and, if they are broken off at that point, the upright has no [Pg 19] power to reproduce them. The upright can produce new uprights also; but, if an upright is cut off, the laterals at that position tend to thicken up. This is very desirable, as the laterals produce the flowers, which seldom appear on the uprights. This fact is utilized in pruning the coffee tree, the uprights being cut back, the laterals then becoming more productive. Planters generally keep their trees pruned down to six to twelve feet.

The leaves are lanceolate, or lance-shaped, being borne in pairs opposite each other. They are three to six inches in length, thin, but of firm texture. They are very dark green on the upper surface, but much lighter underneath. The margin of the leaf is entire and wavy. In some tropical countries, the natives brew a coffee tea from the leaves of the coffee tree.

The coffee flowers are small, white, and very fragrant, having a delicate characteristic odor. They are borne in the axils of the leaves in clusters, and several crops are produced in one season, depending on the conditions of heat and moisture that prevail in the particular season. The different blossomings are classed as main blossoming and smaller blossomings. In semi-dry, high districts, as in Costa Rica or Guatemala, there is one blossoming season, about March, and flowers and fruit are not found together, as a rule, on the trees; but in lowland plantations, where rain is perennial, blooming and fruiting continue practically all the year, and ripe fruits, green fruits, open flowers, and flower buds are to be found at the same time on the same branchlet, not mixed together, but in the order indicated.

The flowers are tubular, the tube of the corolla dividing into five white segments. The number of petals is not at all constant, not even for flowers of the same tree.

While the usual color of the coffee flower is white, the fresh stamens and pistils may have a greenish tinge, and in some cultivated species the corolla is pale pink. [Pg 20]

The size and condition of the flowers are entirely dependent on the weather. The flowers are sometimes very small, very fragrant, and very numerous; while at other times, when the weather is not hot and dry, they are very large, but not so numerous. Both these kinds “set fruit,” as it is called; but at times, especially in a very dry season, the trees bear flowers that are few in number, small, and imperfectly formed, the petals frequently being green instead of white. These flowers do not set fruit. The flowers that open on a dry sunny day show a greater yield of fruit than those which open on a wet day, as the first mentioned have a better chance of being pollinated by the insects and the wind.

After the flowers droop, there appear what are commercially known as coffee berries. Botanically speaking, “berry” is a misnomer. These little fruits are not berries, such as are well represented by the grape; but are drupes, which are better exemplified by the cherry and the peach. In the course of six or seven months, these coffee drupes develop into little red balls about the size of an ordinary cherry; but, instead of being round, they are somewhat ellipsoidal, having at the outer end a small umbilicus. The drupe of the coffee usually has two locules, each containing a little “stone” (the seed and its parchment covering), from which the coffee bean (seed) is obtained. Actually, then, the coffee berry is not a berry but a “drupe”; also, the coffee bean is not a “bean” but a seed.

Some few drupes contain three beans, while others, at the outer ends of the branches, contain only one round bean, known as the peaberry. The number of pickings corresponds to the different blossomings in the same season; and one tree of the species Arabica may yield from one to twelve pounds a year.

In countries like India and Africa, the birds and monkeys eat the ripe coffee berries. The so-called “monkey coffee” of India, according to [Pg 21] Arnold, is the undigested coffee beans that passed through the alimentary canal of the animal.

The outer fleshy part or pulp surrounding the coffee beans is at present of no commercial importance. From the human standpoint, the pulp, or pericarp, as it is scientifically called, is rather an annoyance, as it must be removed in order to procure the beans. This is done in one of two ways. The first is known as the dry method, in which the entire fruit is allowed to dry, and is then cracked open. The second is called the wet method; the pericarp is removed by machine, and two wet, slimy seed packets are obtained. These packets, which look for all the world like seeds, are allowed to dry in such a way that fermentation takes place. This rids them of all the slime; and, after they are thoroughly dry, the endocarp, the so-called parchment covering, is easily cracked open and removed. At the same time that the parchment is removed, a thin silvery membrane, known scientifically as the spermoderm (which means seed skin), referred to in the trade as the silver skin, beneath the parchment, comes off too. There are always small fragments of this silver skin to be found in the groove of the coffee bean contained within the parchment packet.

We have said that the coffee tree yields from one to twelve pounds a year, but of course this varies with the individual tree and also with the region. In some countries the whole year’s yield is less than 200 pounds an acre, while there is on record a patch in Brazil which yields about seventeen pounds a tree, bringing the acre yield much higher.

The beans do not retain their vitality for planting for any considerable time; and, if they are thoroughly dried, or are kept for longer than three or four months, they are useless for that purpose. It takes the seed about six weeks to germinate and to appear above ground. Trees raised from seed begin to blossom in about three years, but a good crop cannot be expected of them for the first five or six years. Their usefulness, save in exceptional cases, is ended in about thirty years. [Pg 22]

The coffee tree can be propagated other than by seeds. The upright branches may be used as slips, which, after taking root, will produce seed-bearing laterals. The laterals themselves cannot be used as slips. In Central America, the natives sometimes use coffee uprights for fences, and it is no uncommon sight to see the fence posts “growing.”

Thus far there are 12 recognized varieties of Arabica, as follows: Laurina, Murta, Menosperma, Mokka, Purpurescens, Variegata, Amarella, Bullata, Angustifolia, Erecta, Maragogipe, and Columnaris.

Two other species of coffee that have become better known in the trade are Liberica and Robusta. Liberica is a much larger and sturdier tree than Arabica, and sometimes reaches a height of thirty feet. Its leaves are twice as long, and the flowers are larger and borne in dense clusters. At any time during the season, the same tree may bear flowers, white or pinkish, and fragrant, or even green, together with fruits, some green, some ripe and of a brilliant red. The corolla has been known to have seven segments, though as a rule it has five. The fruits are large, round, and dull red; the pulps are not juicy, and are somewhat bitter. Unlike Coffea arabica, the ripened berries do not fall from the trees, and so the picking may be delayed at the planter’s convenience. The Liberica bean produces a drink which is classed as inferior to Arabica by trade experts.

The Robusta plant is larger than either Arabica or Liberica. The leaves of Robusta are much thinner than those of Liberica, though not so thin as those of Arabica. The tree, as a whole, is a very hardy variety, and bears blossoms even when it is less than a year old. It blossoms throughout the entire year, the flowers having six-parted corollas. The berries are smaller than those of Liberica, but are much thinner skinned; so that the coffee bean is actually not any smaller. They mature in ten months. Although the plants bear as early as the first year, the yield for the first two years is of no account, but by the [Pg 23] fourth year the crop is large. Recently cup tests have established high merits in certain strains of Robusta. A variety of Robusta called Canephora has flowers tinged with red, its unripe berries are purple, and the bean narrower and more oblong than Robusta. It grows well in high altitudes. Among the allied Robusta species are Ugandæ and Quillou.

Experiments in coffee culture are constantly being made by well-known botanists, and some interesting hybrids have been produced, the most popular belonging to a crossing of Liberica and Arabica. Excelsa, an allied Liberica species, has also given much promise.

A species of coffee growing wild in the Comoro Islands and Madagascar has been found practically caffein-free. Certain Porto Rico coffees are also very low in caffein content.

[Pg 24]

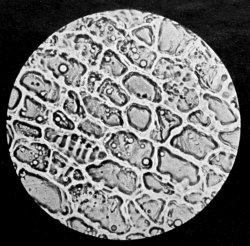

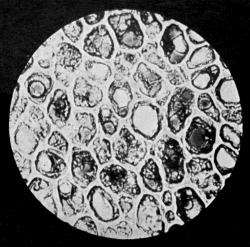

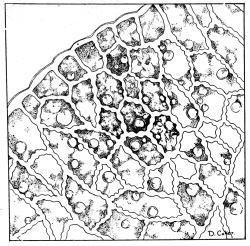

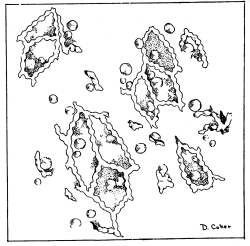

Green (Longitudinal Cross Section).

Roasted (Tangential).

Green and Roasted Bogota Coffee

(Magnified 200 Diameters)

[Pg 25]

The chief factors which enter into coffee goodness—Brief discussion of caffein and caffeol—Coffee’s place in a rational dietary—Latest scientific discoveries which establish the whole truth about coffee as a wholesome, satisfying drink for the great majority of people and cause it to be regarded as the servant, rather than the destroyer, of civilization.

Generally speaking, the trade and the consumer are concerned chiefly with those factors which enter into coffee goodness. These are the caffein content and the caffeol. Caffein supplies the principal stimulant. It increases the capacity for muscular and mental work without harmful reaction. The caffeol supplies the flavor and the aroma,—that indescribable oriental fragrance that woos us through the nostrils, forming one of the principal elements that make up the lure of coffee. There are several other constituents, including certain innocuous so-called caffetannic acids, which, in combination with the caffeol, give the beverage its rare gustatory appeal.

In the roasting of green coffee, part of the original caffein content is lost by sublimation (vaporizing), and caffeol is formed. Chemists recognize two groups of constituents which are formed during roasting and are soluble in water,—heavy extractives and light aromatic materials.

The heavy extractives include caffein, mineral matter, proteins, caramel, and sugars, “caffetannic acid,” and various organic materials. Some fat will also be found in the average coffee brew, melted from the bean by the heated water and carried along with the solution. The light extractives are collectively known as caffeol. [Pg 26]

Caffein has a slightly bitter taste, but, because of the small percentage present in a cup of coffee, it contributes little to its cup value. Nevertheless, it furnishes the stimulation for which coffee is generally consumed. The caffein content of Coffea arabica, green, is 1.5 percent.

The mineral matter, together with certain decomposition and hydrolysis products of crude fiber and chlorogenic acid, contribute toward the astringency or bitterness of the cup. The proteins are present in such small quantity that their only role is to raise somewhat the almost negligible food value of a coffee infusion. The body, or what might be called the licorice-like character, of coffee is due to the presence of bodies of a glucosidic nature and to caramel. The degree to which a coffee is sweet-tasting or not is, of course, dependent upon its other characteristics, but probably varies directly with the reducing sugar content.

The term “caffetannic acid” is a misnomer, for the substances called by this name are in all probability mainly coffalic and chlorogenic acids, neither of which is a true tannin, nor do they evince but few of the characteristic reactions of tannic acid. Some neutral coffees will show as high a “caffetannic acid” content as other acid-charactered ones. Careful chemical analysis has shown that the actual acidities of some East Indian coffees vary from 0.013 to 0.033 percent. These figures my be taken as reliable examples of the true acid content of coffee, and, though they seem very low, it is not at all incomprehensible that the acids they indicate produce the acidity in a cup of coffee. They probably are mainly volatile organic acids together with other acidic-natured products of roasting.

We know that very small quantities of acid are readily detected in fruit juices and beer, and that variation in their percentages is quickly noticed, while the neutralization of this small amount of acidity leaves an insipid drink. Hence it seems quite likely that this small acid content gives to the coffee brew its essential acidity. A few minor experiments on neutralization have proved the production of a [Pg 27] very flat beverage by thus treating a coffee infusion. Acidity of certain coffees most apparently should be attributed to such compounds rather than to the miscalled “caffetannic acid.” For personal proving of this statement, put a small pinch of the weakly alkalin baking soda (NaHCO₃) into a cup of coffee and note the difference that it makes.

The light aromatic materials and other substances that are steam-distillable (i. e., which are driven off when coffee is concentrated by boiling) are important factors in determining the individuality of coffees. These compounds (caffeol) vary greatly in the percentages present in different coffees, and thus are largely responsible for our ability to distinguish coffees in the cup. It is these compounds that supply the pleasingly aromatic and appetizing odor to coffee.[1]

Like all good things in life, the drinking of coffee may be abused. Indeed, those having an idiosyncratic susceptibility to alkaloids should be temperate in the use of tea, coffee, or cocoa. In every high-tensioned country, there is likely to be a small number of people who, because of certain individual characteristics, cannot drink coffee at all. These belong to the abnormal minority of the human family. Some people cannot eat strawberries, but that would not be a valid reason for a general condemnation of strawberries. One may be poisoned, says Thomas A. Edison, from too much food. Horace Fletcher was certain that overfeeding caused all our ills. Overindulgence in meat is likely to spell trouble for the strongest of us. Coffee is, perhaps, less often abused than wrongly accused. It all depends. A little more tolerance!

Trading upon the credulity of the hypochondriac and the caffein sensitive, in recent years there has appeared in America and abroad a curious collection of so-called coffee substitutes. They are “neither fish, nor flesh, nor good red herring.” Most of them have been shown by official government analyses to be sadly deficient in food [Pg 28] value, their only alleged virtue. One of our contemporary attackers of the national beverage bewails the fact that no palatable hot drink has been found to take the place of coffee. The reason is not hard to find. There can be no substitute for coffee. Dr. Harvey W. Wiley has ably summed up the matter by saying, “A substitute should be able to perform the functions of its principal. A substitute in a war must be able to fight. A bounty jumper is not a substitute.”

A brief summarization of available information on the pharmacology of coffee indicates that it should be used in moderation, particularly by children, the permissible quantity for adults varying with the individual, his constitution, mode of living, etc., and ascertainable only through personal observation.

Recent scientific research has destroyed many bugaboos manufactured by the traducers of our national beverage; for one, the alleged harmful effects of the caffein content. We now know that the small amount of caffein in the coffee cup is distinctly beneficial to the majority and that it is a pure stimulant having no harmful reaction.

Then there was the notion that cream in coffee made the beverage indigestible. The statement was made that milk or cream caused the coffee liquid to become coagulated when it came into contact with the acids of the stomach. This is true, but it does not carry with it the inference that indigestibility accompanies this coagulation. Milk and cream, upon reaching the stomach, are coagulated by the gastric juice, but the casein product formed is not indigestible. These liquids, when added to coffee, are partly acted upon by the small acid content of the brew, so that the gastric juice action is not so pronounced, for the coagulation was started before ingestion, and the coagulable constituent, casein, is more dilute in the cup as consumed than it is in milk. Accordingly, the particles formed by it in the stomach will be relatively smaller and more quickly and easily digested than milk per se. [Pg 29]

Used in moderation, coffee has invariably proved a valuable stimulant, increasing personal efficiency in mental and physical labor. Its action in the alimentary regime is that of an adjuvant food, aiding digestion, favoring increased flow of the digestive juices, promoting intestinal peristalsis, and not tanning any part of the digestive organs. It reacts on the kidneys as a diuretic, and increases the excretion of uric acid; which, however, is not to be taken as evidence that it is harmful in gout. Coffee has been indicated as a specific for various diseases, its functions therein being the raising and sustaining of low vitalities. Its effect upon longevity is virtually nil. A small proportion of humans who are very nervous may find coffee undesirable, but sensible consumption of coffee by the average, normal, non-neurasthenic person will not prove harmful but beneficial.

Until the campaign of education recently conducted by coffee men in the United States, many neurotics received with gladness the tales of the harmfulness of coffee. They eagerly welcomed the doubtful substitutes, coffee minus the caffein, or some nauseating cereal preparation. They were convinced that by avoiding coffee they could cure their nervous condition.

Commenting upon the campaign of enlightenment, the New York Medical Journal & Medical Record said:

This whole question has been exaggerated. Coffee in moderation does not produce nervous ailments. Removal of coffee from the diet does not cure them. Coffee with cream and sugar is a source of food and energy. In many cardiac and nephritic conditions there is no better or simpler preparation than well prepared coffee.

It is amusing to see chocolate, cocoa, and even tea substituted for coffee in various nervous or other conditions, when as a matter of fact the amount of stimulus cup for cup is the same or even greater. What foundation there is for giving children and old persons various chocolate preparations in place of coffee is difficult to determine.

It would be well to look at the coffee question squarely and not cover the situation by inane avoidances. Coffee is one of the mainstays [Pg 30] of our rapid civilization. Those adults who wish to live and enjoy life, let them drink their coffee in peace. Those who wish to ascribe illness or nervousness to magical causes, let them abandon it.

This is an able summing up of the question of the alleged harmfulness of coffee. Those who may wish to examine the evidence pro and con will find it detailed in the chapter on the pharmacology of coffee in All About Coffee. Opinions, names, and full references are given there.

For more than three years the Massachusetts Institute of Technology made an exhaustive investigation of coffee. This investigation was made at the invitation of the coffee trade of the United States to determine by scientific research the whole truth about coffee and coffee making. It involved a total cost of $40,000 and was one of the most thorough investigations ever made of any food product.

The result of this scientific research, as announced by Professor Samuel C. Prescott, director of the institute’s Department of Biology & Public Health, shows that coffee is a wholesome, helpful, satisfying drink for the great majority of people.

The report covers many hundreds of pages, for every aspect of coffee and coffee making was studied, but in just one paragraph of 92 words Professor Prescott swept aside all the old prejudices and superstitions, and gave coffee the cleanest bill of health that could be wished. He said:

It may be stated that, after weighing the evidence, a dispassionate evaluation of the data so comprehensively surveyed has led to no alarming conclusions that coffee is an injurious beverage for the great mass of human beings, but on the contrary that the history of human experience, as well as the results of scientific experimentation, point to the fact that coffee is a beverage which, properly prepared and rightly used, gives comfort and inspiration, augments mental and physical activity, and may be regarded as the servant rather than the destroyer of civilization.

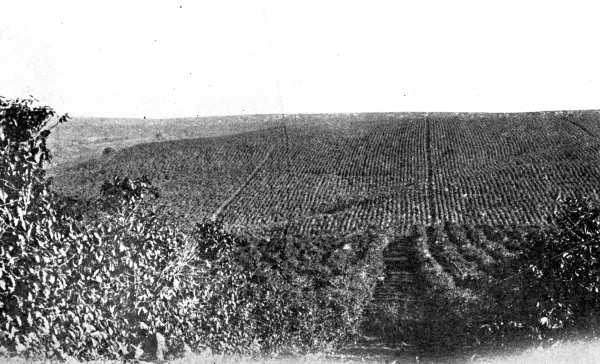

800,000 Coffee Trees in Bearing at Guatapara, Brazil

[Pg 31]

Locating the principal coffee-growing districts in the world’s coffee belt—With a commercial coffee chart of the leading growths, giving market names and general trade characteristics.

The coffee belt of the world lies between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. The coffee tree, while native to Abyssinia and Ethiopia, grows well in Java, Sumatra, and other islands of the Dutch East Indies; in India, Arabia, equatorial Africa, the Pacific islands, Mexico, Central and South America, and the West Indies.

The leading growths that find favor in the world’s markets are listed in the Commercial Coffee Chart on page 36, reproduced from All About Coffee, where they are described in greater detail. Their general trade uses are, however, discussed farther along in this work in the chapter entitled, “Green and Roasted Coffee Characteristics.”

Mexico is the principal producing country in the northern part of the western continent, and Brazil in the southern part. In Africa, the eastern coast furnishes the greater part of the supply; while, in Asia, the Netherlands Indies, British India, and Arabia lead.

Within the last two decades there has been an expansion of the production areas in South America, Africa, and in southeastern Asia, and a contraction in British India and the Netherlands Indies.

In Mexico, although coffee growing is widely distributed in most of the more southern states, the principal coffee territory is Vera Cruz, where lie the districts of Cordoba, Orizaba, Huatusco, and Coatepec. In the same region are the Jalapa district and the mountains of Puebla, where considerable coffee is grown. Farther south are the Oaxaca [Pg 32] districts on the mountain slopes of the Pacific Coast, and still farther south the districts in the state of Chiapas. The youngest district is Soconusco. On the Gulf slope of Oaxaca are many plantations; also in the western regions of the table lands of Colima and Michoacan.

In Guatemala, coffee is grown on the table lands of three great mountain ranges. The principal districts are Costa Cuca, Costa Grande, Barberena, Tumbador, Coban, Costa de Cucho, Chicacao, Xolhuitz, Pochuta, Malacatan, San Marcos, Chuva, Panan, Turgo, Escuintla, San Vincente, Pacaya, Antigua, Moran, Amatitlan, Sumatan, Palmar, Zunil, and Montagua.

In Salvador, the berry is grown in all districts that have altitudes of 1,500 to 4,000 feet. The most productive plantations are in the departments of La Paz, Santa Ana, Sonsonate, San Salvador, San Vincente, San Miguel, Santa Tecla, and Ahuachapam.

In Costa Rica, the coffee-growing districts are principally on the Pacific slope and in the central plateaus of the interior. Plantations are in the provinces of Cartago, Tres Rios, San José, Heredia, and Alajuela.

The principal plantations in Honduras are in the departments of Santa Barbara, Copan, Cortez, La Paz, Choluteca, and El Paraiso. British Honduras doesn’t raise enough coffee for domestic consumption. In Nicaragua, the most extensive plantings are in the departments of Managua, Carazo, Matagalpa, Chontales, and Jinotega. The best district for coffee growing in Panama is Bugaba, where great suitable areas exist, but the Boquete district in the province of Chiriqui produces the bulk of Panama’s coffee.

On the island of Haiti, coffee grows well in the republic of Haiti and in the Dominican Republic. The principal plantations are in the vicinity of the town of Moca in the eastern or Santo Domingo section of the island, and in the districts of Santiago, Bani, and Barahona. [Pg 33]

In Jamaica four parishes lead in coffee producing,—Manchester, St. Thomas, Clarendon, and St. Andrew. A few estates in the Blue Mountains produce the famed Blue Mountain variety.

In Porto Rico, the coffee belt extends through the western half of the island beginning in the hills along the south coast around Ponce and extending north through the center of the island almost to Arecibo, near the western end of the north coast. Some coffee is grown in 64 of the 68 municipalities. The largest plantations are in Utuado, Adjuntas, Lares, Las Marias, Yauco, Maricao, San Sebastian, Mayaguez, Ciales, and Ponce.

Coffee can be grown in practically every island of the West Indies, and is grown in a small way in many of them. Little is produced for international trade except in the islands already mentioned. Cuba was formerly a heavy producer, but now only a small quantity is grown there, and she has been forced to import from Porto Rico to supply her own needs. Guadeloupe grows coffee, some of which is shipped to Martinique and exported as the product of that country; no longer the coffee producer it was in the 18th century after De Clieu introduced the plant there. Small amounts of coffee are grown on Trinidad and Tobago.

Colombian coffees are grown in nearly all departments where the elevations range from 3,500 to 6,500 feet. Chief among them are Antioquia (capital, Medellin); Caldas (capital, Manizales); Magdalena (capital, Santa Marta); Santander (capital, Bucaramanga); Tolima (capital, Ibague); and the Federal District (capital, Bogotá). The department of Cundinamarca produces a coffee that is counted one of the best of Colombian grades. The finest grades are grown in the foothills of the Andes, in altitudes 3,500 to 4,500 feet above sea level.

In Venezuela, there are no great coffee belts as in Mexico and Central America. Many districts are days rides apart. The chain of the Maritime Andes, reaching eastward across Colombia and Venezuela, [Pg 34] approaches the Caribbean coast in the latter country. Along the slopes and foothills of these mountains are produced some of the finest grades of South American coffee. Here the best coffee grows in the tierra templada and in the lower part of the tierra fria, and is known as the café de tierra fria, or coffee of the cold, or high, land. In these regions the equable climate, the constant and adequate moisture, the rich and well-drained soil, and the protecting forest shade afford the conditions under which the plant grows and thrives best. On the fertile lowland valleys nearer the coast grows the café de tierra caliente, or coffee of the hot land.

The Guianas (British, Dutch, and French) grow coffee, but little more than is needed for home consumption.

Brazil’s commercial coffee-growing region has an estimated area of 1,158,000 square miles, and extends from the river Amazon to the southern border of the state of São Paulo, and from the Atlantic Coast to the western boundary of the state of Matto Grosso. This area is larger than that section of the United States lying east of the Mississippi River, with Texas added. In every state of the republic, from Ceará in the north to Santa Catharina in the south, the coffee tree can be cultivated profitably, and is, in fact, more or less grown in every state, if only for domestic use. However, little attention is given to coffee growing in the north, except in Pernambuco, which has only about 1,500,000 trees, as compared with the 764,000,000 trees of São Paulo in 1922.

The chief coffee-growing plantations in Brazil are on plateaus seldom less than 1,800 feet above sea level, and ranging up to 4,000 feet. The principal coffee-growing districts are in the states of São Paulo, Rio, Minas Geraes, Bahia, and Espirito Santo.

Coffee is grown in a small way in Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay, and Argentina. Ecuador gives the greatest promise. Cayo is the leading district.

In Arabia, coffee growing is confined to the mountains in the vilayet [Pg 35] of Yemen, a district along the southwestern coast, back from the Red Sea. Coffee can be grown almost anywhere in Yemen, but it is cultivated entirely in small gardens in a few scattered districts, and the total acreage is not large.

In India, half of the coffee-producing area is in Mysore; other plantations are to be found in Kurg (Coorg), the Madras districts of Malabar, and in the Nilgiri hills.

In the East India Islands, Java and Sumatra lead. Coffee is produced commercially in nearly every political district in Java, but the bulk of the yield is obtained from East Java. The names best known to the trade are those of the regencies of Besoeki and Pasoeroean, because their coffees make up 87 percent of Java’s production. Some of the better known districts are Preanger, Cheribon, Kadoe, Samarang, Soerabaya, and Tegal. Practically all the coffee districts in Sumatra are on the west coast, with Padang as headquarters. The best known are Angola, Siboga, Ayer Bangies, Mandheling, Palembang, Padang, and Benkoelen. The east coast has recently gone in for heavy plantings of Robusta. Coffee is also grown in several other islands of Dutch East Indies, chiefly Celebes, Bali, Lombok, the Moluccas, and Timor. In the Malay States, Liberica is mostly grown.

In Africa, Abyssinia supplies two coffees known as Harar and Abyssinian. The former is grown in the province of Harar and mostly around the city of Harar. The latter is the fruit of wild Arabica trees that grow mainly in the provinces of Sidamo, Kaffa, and Guma. Coffee also grows in Angola, where there are large areas of wild trees; in Liberia, Uganda, Nyasaland, and Kenya Colony.

The Kona side of the island of Hawaii produces the best known Hawaiian coffee. Other districts are Hamakua, Puna, and Olaa.

The Philippines produce a negligible amount of coffee, as does also the Queensland district of Australia. The industry is being developed in French Indo-China, however, where Robusta has been found to do very well. Some coffee is still grown in Ceylon, but it is commercially unimportant. [Pg 36]

COMMERCIAL COFFEE CHART

World’s Leading Growths, with Market Names

and General Trade Characteristics

| Grand Division |

Country | Principal Shipping Ports |

Best Known Market Names |

Trade Characteristics |

| North America |

Mexico | Vera Cruz | Coatepec Huatusco Orizaba |

Greenish to yellow bean; mild flavor. |

| Central America |

Guatemala | Puerto Barrios |

Coban Antigua |

Waxy, bluish bean; mellow flavor. |

| Salvador | La Libertad | Santa Ana Santa Tecla |

Smooth, green bean, neutral flavor. |

|

| Nicaragua | Corinto | Matagalpa | Large blue washed, fancy roast; acid cup. |

|

| Costa Rica | Puerto Limon |

Costa Ricas | Blue-greenish bean; mild flavor. |

|

| West Indies |

Haiti | Cape Haitien |