Title: Jakie's Christmas

Author: Lida B. Robertson

Release date: December 22, 2025 [eBook #77524]

Language: English

Original publication: Boston: The Christopher Publishing House, 1927

Credits: Susan E., David E. Brown, Andrew Butchers, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

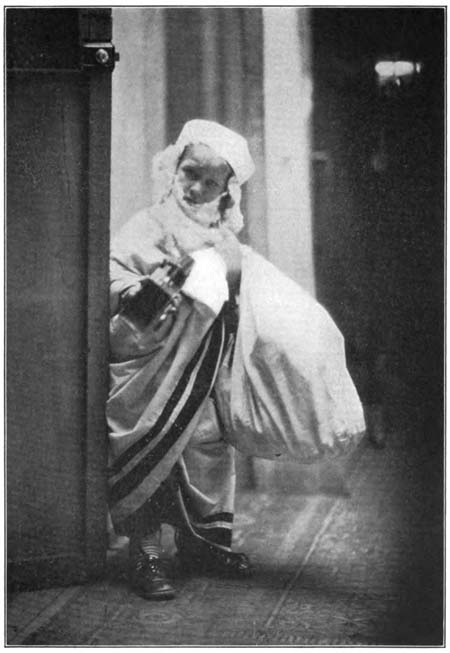

JAKIE AS FAT OLD SANTA CLAUS

JAKIE’S CHRISTMAS

BY

LIDA B. ROBERTSON

Author of the prize winning short-stories:

“How The Bad Boy Was Won”; “Women in The

Farm Home”; and “How to Rule a Husband.”

The Christopher Publishing House

Boston, U. S. A.

Copyright 1927

BY THE CHRISTOPHER PUBLISHING HOUSE

MADE IN AMERICA

TO THOSE WHO ARE KIND;

“FOR AS A LITTLE CANDLE SHINES IN THE DARKNESS

SO IS THE GOOD DEED IN A NAUGHTY WORLD”

Jakie’s Christmas

Christmas was near. Pictures of laughing, fat, jolly, old Christmas Santa Claus filled the daily papers, filled the magazines. In all of the store-windows were beautiful Christmas decorations and full of toys.

In the pictures Santa Claus’ beard hung down from his chin as white as cotton, and his long white bushy hair peeped from under his cap.

Jakie, a happy, joyous, little country boy lived miles from town in a log-cabin in the backwoods with his Mamsy, as he called his grandmother. Just the two lived together as Jakie’s father and mother were dead, and his grandfather too. They lived in the very same log house which his father built, as a pioneer; he cleared away the wild woods when Alabama was new, and settled the land and built a farm home. All of the home-folks were dead; just Mamsy and little Jakie left. Mamsy owned a cow and some pigs. She raised turkeys and chickens to sell. But the foxes had crept out of the bushes and devoured the young turkeys; hawks had caught the young chickens and carried them away to eat. Mamsy had done her very level best but she was old and she was poor. Sorrowfully she had to tell Jakie not to look for Christmas Santa Claus,—not to hang up his stocking, that they were too poor this year.

It was a clear day, sunshiny and beautiful. Jakie was out in the hickory grove in front of their cabin, kicking the brown leaves that lay on the ground like a carpet, first with one foot then with the other. Every day he had gathered the fallen nuts from under the trees, but was hoping to find some still hiding under the leaves.

[10]A country wagon came bumping and rumbling along the rough country road in front of Jakie’s house. Folks did not pass his home often. He stopped kicking the leaves to gaze at the passing wagon. A newspaper blew out of the wagon, fluttered around and around, by the wind, and fell to the ground in the middle of the road, without the farmer noticing or missing it. Jakie dashed out to the road, snatched the paper up, and raced after the farmer and his wagon, yelling as loud as his voice could, over the rattling, bumping noise of the wagon:

“Mister! Mister! Mister! Mister!”

The farmer heard him, grunted “waw” to his horse and looked backward. Jakie was following him with something in his hand. He waited until Jakie overtook him panting and out of breath and held the paper, above his head, as high as his short arm could reach, to the farmer. The farmer looked down at the paper a minute while Jakie explained, panting:

“Here’s your newspaper the wind blew out your wagon.”

The man answered:

“It’s nothing! It’s just a paper saying some store in town is giving away presents to children,—you can have it. I don’t want it.”

The farmer chuckled to his horse and drove on down the road, leaving Jakie standing still, in the middle of the road, staring at the paper in wonder. There was big, fat, jolly, old Christmas Santa Claus with a huge pack of toys on his back, with both hands beckoning to children to come to him and get a present. One outstretched hand held a toy-train, the other a very large doll. Little girls and big girls, little boys and big boys were racing, running, hurrying, scurrying to him. Nurses with babies in go-carts were running to him, and mamas with babies in their arms were running to him,—all to receive gifts. Jakie pointed his forefinger at them trying to count them but they were too many. Mamsy had told him they were too poor, not [11]to look for Christmas Santa Claus at their house way out in the backwoods.

Here was Santa Claus in town giving things away to children, giving toy-trains to boys, and big dolls to girls.

His heart fluttered faster, joy and hope flashed into his eager eyes as he continued to gaze at the picture. He would run and show the picture to Mamsy and beg her to take him to town to Christmas Santa Claus and get a present too. His feet dashed back toward the house; he held the corner of the paper, which fluttered behind him by the wind like a kite-tail to a kite.

He yelled every step “Mamsy! Mamsy! Mamsy!”

She heard his excited yells and it scared her. She rushed to the door, to meet him. He held the paper up waving it over his head. He reached the door:

“Look Mamsy! here’s Christmas Santa Claus in town giving away things to all the children—take me to him and get one!”

He held the paper wide open with both hands for Mamsy to see for herself, what he said was true. Mamsy looked at it intently then shook her head in no, saying:

“We can’t go! We got nothing to ride and it’s too far to walk.”

Mamsy was grown up. She had forgotten how, as a little child, Christmas thrilled her. She had no way to ride to town, and no money to buy Christmas things and no way to take Jakie. Jakie did not beg nor argue with Mamsy to go. When she said no she meant it. It was useless. His hope sank in very keen disappointment. The eager look of joy vanished from his face. He sat down dolefully upon the front step, holding the paper open before his eyes to gaze at happy children racing with each other to get to Christmas Santa Claus. He wished he was one of them, but he could not go. Two big tears rolled down his cheeks and fell on the paper making two wet spots.

Two more big tears rolled down his cheeks and he [12]wiped them off with his sleeve. The sun went down. The twilight grew too dim for him to see the picture. He arose and went inside. Mamsy was cooking their supper in the oven of the open fire-place. Out of Mamsy’s way to the left of the popping, blazing, cheery wood fire-light he spread his paper wide open on the floor. He stretched himself full length on the floor beside the open paper; his elbows on the floor and his chin resting in his uplifted open palms. The bright fire-light shone upon his face, a very, sober, wistful little face gazing at the children scampering, racing and running toward Christmas Santa Claus—wishing he was one of them. Mamsy called him to supper, he arose folded the paper like a boy folds one, cranksided, and laid it in his mother’s trunk, that was his own now, and in which he kept his “keeps.” He ate his bread and milk, and slipped off to bed, with his clothes on, without Mamsy’s noticing it. He shut his eyes very tight, but he did not fall asleep. He was arguing to himself in the darkness, for Mamsy had come to bed and was asleep, “Mamsy is got old feets, but my feets is new. She can’t walk to town, but I can! I is big enough to go by my own self and get me and Mamsy a present from Christmas Santa Claus.” His eyes closed; he fell asleep dreaming of going to see Santa Claus.

Next morning the room was dark, but the roosters were flapping their wings and crowing for the day break; crowing to folks to awaken them, and tell them the day was coming to get up and work, get up and be smart. Jakie’s eyes flew wide open. Instead of seeing Santa Claus, as in his happy dream, the room was dark,—and Mamsy was snoring. He was disappointed. In his sleep Santa Claus had given him a present, given him a toy-train, and he was the happiest little boy in the world, he thought. His disappointment made him argue again:

“I’m big enough to go to Christmas Santa Claus by my own self, and get me and Mamsy a present.” He could stand it no longer.

[13-14]

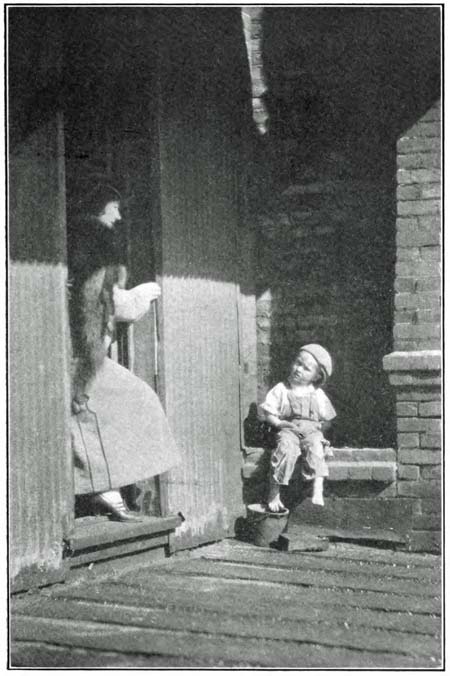

JAKIE TRUDGING ALONG ALONE, AFOOT

[15]Slowly he thrust one bare-foot from under the cover, then the other foot, lowering them to the floor. He let himself downward upon his “all-fours” to the floor and crawled as softly as a cat to the back door of the cabin home. One hinge was off of the door and it sagged at the bottom, just a wide enough hole, for him to squeeze through, without awakening Mamsy. He cautiously eased himself through to the out-of-doors. He halted on the step. He bent his listening ear down to the gap; Mamsy was still snoring. He crawled down the steps, to the ground. He sneaked away, his heart beating very fast lest a broken twig and rustling leaves tell on him, and awaken Mamsy and she call him back. Joy urged him onward, unafraid, in the dark through the grove of hickory trees to the rough country road. The stars twinkled down upon a lonely little boy, bravely, trudging along the rough country road, ragged, bare-foot, alone, and afoot! His bare-feet trod on rough places and pebbles, but onward he hurried not seeming to mind them. He was too happy to know that he was hungry. This joyous, little, Christmas-tramp was bent on finding Christmas Santa Claus, to obtain a Christmas gift for himself and for Mamsy, and had slipped off without eating any breakfast. The dim light in the east told him the sun was coming up soon, so he could see better how to travel. He sat down on the side of the road to rest, a moment, hoping somebody might come along and let him ride, “give him a lift,” they call it in the country. He knew not how far he had come nor how far he had to go to get to Santa Claus; he was too happy to know or care! He arose and walked manfully on. He heard a faint-rumbling noise through the woods afar down the road behind him. He stopped. He listened! It was a wagon coming down the road toward him. He stood on the side of the road and waited for it. When it reached him he looked up timidly into the kind farmer’s face, driving the wagon and team, asking:

“Mister can I ride on your wood to town?”

[16]The farmer was hauling oak wood to town to sell. He looked at Jakie, such a little fellow alone and wondered. He called out “climb in!”

Jakie eagerly stuck one bare-foot on a spoke of the wheel, then poked the other bare-foot upon a higher up spoke and scrambled and clutched at the wheel tire, to climb up into the wagon body. The man watched Jakie’s nimble pluck and bent downward holding his hand down to him to assist him. He invited him to sit beside him on the spring seat instead of riding on the sticks of rough wood.

“Where are you going little fellow?” the man asked Jakie after he twisted and fidgeted himself comfortably in his seat with his dirty bare-feet dangling downward, too short to reach the bottom of the wagon.

“I is going to town to find Christmas Santa Claus,” Jakie answered proudly, looking up into the kind man’s face for him to agree with him that he was big enough. But the man said:

“You are a very little boy to be going to town all by yourself.”

“I is big enouf!” Jakie insisted, bravely. Then he explained: “Mamsy’s feets is old, she can’t walk so far and we is got nothin’ to ride in.” His eyes glistered joyously!

“Christmas Santa Claus is in town giving way things to children. Mamsy say we is too poor for him to come to us house. I is going to hunt him and get me and Mamsy a present.”

The kind man looked at the holes in Jakie’s clothes, looked at his happy face, looked at his soiled bare-feet, without shoes, in winter-time, and he did not wonder that he wanted a Christmas present for himself and for Mamsy. He ran his hand down into his breeches pocket and drew out some change. With a merry twinkle in his eyes he said:

“Hold up your hands!”

Up went both of Jakie’s hands, held close together like children play thimble. The man dropped five [17]nickels, one by one into Jakie’s hands, making him count them one by one. Jakie stared at his hands full of money. He felt very rich. He had had once in a while one nickel, all his own, to buy things at the cross-roads country store, to buy an apple, an orange, or candy. But never before had a handful of nickels all his own. The man asked him:

“What are you going to buy with your money?”

“Bananas!” exclaimed Jakie, his beaming smile radiantly happy that he could buy, “heaps of em,” he said.

Happiness showed in the man’s smiling face at making a child so happy, he said:

“I got ahead of your Christmas Santa Claus. I gave you a present first.”

Jakie clutched his money very tight, two nickles in one fist and three in the other.

“Thanky Mister, you is a good man—what’s you name?”

“My name is Sam Foster,” the man told him, then said, “Now tell me your name and where you live.”

“I is named Jakie Barnett, Mamsy and me lives to Clear Creek way back yonder.”

It seemed to Jakie that he had come miles and miles, but it was only two miles he had come. It was a long way to his small feet that he had walked and he was so glad now to be riding. He told the man he had a billy goat that he hitched to the wooden wheels for a wagon; told about his hickory nuts, and about their cow, as they rode along together to town. The man drove many streets out of his way to the business street of stores, which sold toys, and christmas trees, everything to make children happy! He told Jakie to keep straight on and on and he would see the stores. Jakie nimbly jumped down off the wagon. The man held his money for him, until he leaped to the ground and held his faded cap with both hands for the man to drop his money into it. He crammed the money [18]into his breeches pocket, waved good-bye to Mr. Foster, who carefully instructed him to wait at the store that had a picture horse in the window,—after Christmas Santa Claus gave him his present, and he would take him back home. The man drove away in another direction to deliver his wood, and Jakie ran down the street toward the stores. He was afraid to wait, Christmas Santa Claus might give away all those presents to those children running to him, before he got there. He passed a fruit-stand. A big bunch of bananas dangled over-head. He halted. He bought half-dozen. The man let him sit on an empty-fruit-basket turned bottom upwards! Jakie clambered on it and crossed one foot on his knee to make “a lap” to hold his bananas. He peeled two, holding one in each hand and stuffed his mouth entirely too full for digestion. But he was hungry; he had left home without any breakfast, and he was in a hurry! He ran onward and saw crowds and crowds of people on both sides of the street. He stared at the folks he saw expecting to find big, fat, jolly old, Christmas Santa Claus, somewhere in the crowds on the side-walk. The picture showed him on the street and the children rushing to him. On and on he walked looking eagerly this way and that way. He would recognize him in a minute, from his picture. He stopped before shop-windows to stare at the wonderful toys, trains, flying machines, bicycles, everything for boys,—and he wished he had every one of them. He was growing tired, he was weary, his little heart was feeling down cast. He stopped and asked some boys “Where’s Christmas Santa Claus?” They laughed at him, and winked at each other saying: “Go ahead he’s down the street!”

Jakie resolutely trudged on down the street. He spied some small Santa Clauses in the show windows, but no live Santa Claus. He felt too shy to ask again where to find him,—boys had laughed at him!

[19-20]

JAKIE WITH A BANANA IN EACH HAND

The wind began to blow quite cold. He heard people [21]on the street say “A norther,” a blizzard, was coming. He never heard of a blizzard, that it was a bitter-cold north wind which froze everything. He was getting very tired, and very unhappy. He had walked and walked such a long time, and could not find Christmas Santa Claus. He wondered if he were too late and Santa Claus had given away all of his presents, he had in his pack, to the children and had gone home.

The cold wind was blowing against his bare-feet, and bare arms and hands, and through the holes in his breeches legs. He thrust his hands into his pockets to warm them, but his bare-feet were just as cold. He began to shiver.

His teeth began to chatter. He was very tired, but he ran along, as fast as he could in a crowded street, to get warm. He was very, very tired and was getting colder instead of warmer. His toes smarted, his hands hurt, his ears tingled, he ached all over. He was very hungry, he was very lonely, he was very miserable, he was very cold, and had not yet found Christmas Santa Claus on the street. Two big tears dropped upon his cheeks; he wiped them off with his banana-stained hands. He was shivering violently, he was lost, he was freezing and did not know it. He spied an open door leading to an upstairs. He went in, to get behind the door out of the cold wind, to wait and get warmer. But the wind blew louder and colder and whistled around the door upon him, crouched close up in the corner.

He began to sob, he was lost and alone in a city. He did not know where he was. He knew not where the store was with the pretty picture of a horse, so he could go there and let Mr. Foster take him home to Mamsy. He could not walk home. He sobbed louder, but none of the hurrying people passing by heard him. But the eyes of Him who is upon the sparrow was upon little Jakie behind that door, and sent a beautiful friend to him. A lovely girl in a long warm cloak, with a purse full of Christmas money to buy love-gifts [22]for her home-folks and friends, came tripping down the street right by the door where poor, cold, miserable little Jakie was behind the door. She heard a child’s sobs and stopped to locate them. They came from behind the open door. She stepped inside and peeped behind it, and found Jakie crying and freezing.

“You poor little boy!” she exclaimed. “What are you doing here?” Jakie heard her kind voice and stared at her through his tears, and sobbed, “I is huntin’ for Santa Claus, and can’t—can’t find him nowhere!” The fair young girl’s face beamed upon him tenderly and her eyes twinkled merrily as she asked him:

“Won’t I do just as well as Santa Claus?” Jakie looked up into her lovely face and wondered if she was an angel sent to him like Mamsy said came to the shepherds one night. Again the fair young girl asked: “Won’t I do just as well as Santa Claus?” She held out her hand to him. He explained, “Santa Claus was in a paper and children was running to him to git presents and I wanted him to give me one. Does you know him? Does you know where he is? I come by myself to find him. I is hunted everywhere for him. I is Mamsy’s little Jakie. She can’t walk so far, we got nothing to ride in. I come my own self to hunt him.”

Frances Bestor asked Jakie again, extending her gloved hand toward him: “Won’t I do as well as Santa Claus? Come with me and you shall have a present.”

[23-24]

JAKIE CRYING AND FREEZING

[25]Jakie placed his soiled hand into her dainty gloved hand. She felt the cold of his little hand through her glove. She led him through the crowded street as fast as they could push their way. People stared at a richly dressed, elegant girl, hurrying along the street leading by the hand a ragged, bare-foot child. But Frances’ heart was dancing over the real Christmas fun she was going to have with Jakie. She pulled him in front of her in the partition of a revolving door of a big department store. Jakie was astonished and dumb. He had never seen a revolving door. He stared as if in a bewildered dream at the beautiful store inside. He had never seen anything so beautiful. The victrola was playing Christmas-carols. Gay Christmas bells hung everywhere in the store. Red and green tissue-paper ribbons hung over-head like beautiful tangled spider-webs. It seemed to Jakie that he had suddenly stepped into heaven. He stared about, dazed, as Frances led him through the store to the boy’s clothing department. She stopped by a radiator to get him warm. She stood him close to it, holding his shivering little hands, in hers, to the pipes to warm them. When he stopped shivering she left him standing there to get thoroughly warm. She whispered to the clerk to take him to the dressing room and dress him up in all the things a little boy needs. She picked out a suit of clothes and everything for a little boy’s outfit. She came back to him and taking his hand in hers said as he looked up into her face:

“Go with this young man and he will dress you up so you won’t be so cold.” Jakie followed the clerk to the dressing room. Frances walked away toward the front of the store to wait for him.

“Mister is dis heaven where my dead mama went to?” he asked.

“Not exactly; this is a store dressed up for Christmas to sell things to people, for little boys.”

A sober, troubled look came into Jakie’s face and he timidly explained:

“Mister, I is got no money to buy things. I is got two nickels to take to my Mamsy.”

“You are not buying them,” laughed the clerk. “That pretty young lady who brought you in here is your Santa Claus.”

Jakie stared, astonished. He had been hunting for a big, fat, old man with long white beard and long white hair, and the clerk called that beautiful girl Santa Claus. He was deeply bothered. He asked eagerly “Is dis Santa Claus’ store?”

[26]The man laughed and shook his head, saying, “No, but she is your Santa Claus giving you all these fine clothes, I am going to put on you....” Jakie then argued to himself:

“Christmas Santa Claus must wear dresses in daytime to keep from scaring children.”

The clerk helped him to remove his ragged clothes, wash his face, wash his hands and wash his feet. He helped Jakie pull on a warm white union suit first. Jakie stared in the mirror at himself all in white. He did not recognize himself. He asked bewildered:

“Is dis me, Mister?”

The clerk smiled at Jakie’s change in looks even from his ragged breeches to white unions and was greatly amused at his asking “is it me.” He answered, “Yes, it is you. Don’t you know yourself?”

“I is never had no store-clothes in all my life,” Jakie explained, admiring himself in the mirror. He started off to go back to Frances with only his white unions on.

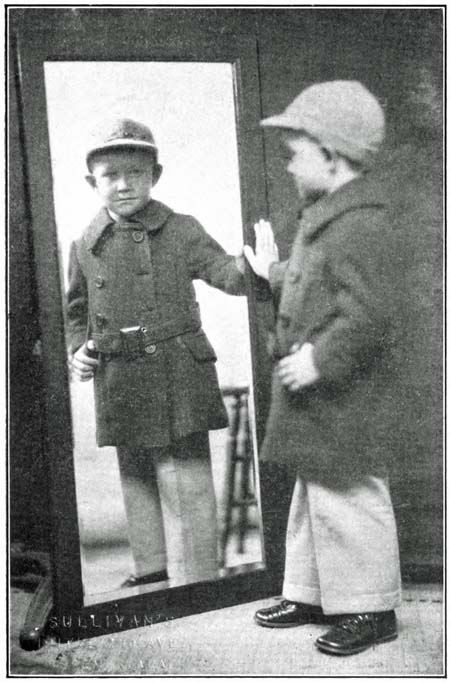

“Hold on!” exclaimed the clerk, “that is your underwear! Here is your fine suit, she picked out for you,” holding up a boy’s pretty grey suit, and cap to match.

Jakie’s eyes opened wider than ever in astonishment. The clerk helped him to dress, helped him to put on the new suit, draw on pretty grey socks on his bare-feet, lace up new shoes, comb his hair, and fit a cap to his head. Now Jakie looked like a full-fledged city boy, handsome and up-to-date. He twisted and turned before the looking glass. The clerk watched him. Jakie said:

“Don’t look-y like me—Don’t seem like me! Is it me, sure ’nouf?”

The clerk burst into a merry laugh, assuring him:

“It’s you sure enough. Now go thank your Christmas Santa Claus. She gave you all these nice things.”

Jakie hesitated a moment then said:

“Mister, it don’t seem like me. I just wears what folks give me, and what Mamsy makes.”

[27-28]

“DON’T LOOK LIKE ME.”

[29]“It’s sure enough you,” the clerk re-assured him, and handed him a bundle tied up neatly, which contained his old clothes, saying again:

“Now go thank your Christmas Santa Claus.”

Jakie marched toward Frances feeling like a king in his new clothes. She did not know him. She thought he was a city boy. He stopped in front of her, taking off his cap as a little gentleman. His clean, handsome face, and happy beaming eyes looked straight at her. He asked shyly.

“Is you Christmas Santa Claus?” She recognized him and laughed:

“Oh no! Santa Claus is a man, old, big and fat.”

“That man say you is!” insisted Jakie pointing back toward the clerk. “Is you Miss Christmas Santa Claus?”

“No indeed! little man,” answered Frances, laying her hand on his shoulder and patting him affectionately. “I am no Santa Claus at all. I love Christmas, and I love little boys like you. You came to town hunting for Santa Claus you saw in a picture. You could not find him. You said I would do. Christmas is Jesus’ birthday and He sent me to act Santa Claus to you. You needed a big friend when you were lonely, cold, and lost behind that door. Jesus sent me to find you. He sent me to be your big friend, and sent you to be my little friend.”

He grabbed her hand and kissed it. Then asked:

“If you isn’t Christmas Santa Claus is you an angel what Mamsy say came to find the shepherds in the dark?”

Frances blushed. Jakie’s compliment flushed her cheeks, a rosy pink. The clerk came to hand her the bill for the suit and outfit, and heard Jakie’s inquiry about an angel.

“Yes, she is your angel, my boy. Watch her pay for all the nice clothes you have on, out of her purse.”

Jakie watched her open her purse and handed several bills of paper money to the clerk. She closed her purse and asked him:

[30]“Little man where do you live?”

“I lives to Clear Creek, it’s a long, long, way. I walked some and rided some.”

“How will you get home in the cold?”

“I is going back in a wagon I comed in, take me to where a picture horse is in a window.”

Frances led him to the toy-counter to select a toy; she knew his boy-heart wanted some happy plaything. How his eyes stared at a whole counter of Christmas toys!

“Pick out what you want,” she said.

Jakie timidly hesitated.

“Pick out what you want,” she urged him.

Shyly he raised his hand, his heart fluttering in wildest joy, and touched a toy-auto.

Frances caught it up and handed it to the clerk to wrap it up, but she spied the wistful look in his face to carry it just as it was, in his own hands. She reached and took the toy from the clerk and placed it in his hands. He looked up into her face, hugging the auto tight, and said:

“Yes, you is a angel.”

Frances thought he was happy over his new clothes but the auto-toy, all his own, was what his little heart wanted! His eyes danced, his mouth broke into a radiant, joyous, laugh. Again he watched her open her purse and take out her money and pay for his toy. She caught his hand, the other hand hugged his auto-toy, and led him out of the store. They passed through the revolving door into the crowded street. Jakie jerked his hand away suddenly from hers and darted away in the crowd. She stood still utterly astonished. He seemed so sweet and truthful it amazed her for him to wildly snatch his hand out of hers, and dart away from her. She watched him shove himself along in the crowd. She saw him grab the dress-skirt in the back of an old country woman wearing a faded, gingham dress, and a country sun-bonnet, with a faded shawl pinned close up around her [31]neck and shoulders. The woman wheeled around astonished, at a little city boy rudely snatching her by her dress-skirt, and holding a new toy in his hand. She did not recognize her little Jakie.

“It’s me!” he exclaimed, laughing at her not knowing him in his new clothes.

Then she grew very pale, almost fainted when she saw her little boy in all the new clothes. She was hunting for a bare-foot, ragged child on the streets. She had borrowed a neighbor’s horse and wagon to come to town to hunt for him. She could think of nothing else but that her little grandson had helped himself to the new toy and to all the new things he wore. But Jakie was too happy, and too innocent, holding to Mamsy’s dress-skirt pulling her along back to Frances, through the crowd, to notice how scared and pale Mamsy was, and called out to Frances:

“Here’s my Mamsy!”

Frances quickly held her hand out to Mamsy. She saw Mamsy was about to faint. She hastily explained to her:

“I found your little Jakie, cold, lost and crying behind a door, on the street. He was hunting for Santa Claus, and could not find him. So I played Santa Claus to him, and gave him all he wears, and gave him the toy-auto too.”

The color came back into Mamsy’s face, Frances handed to her the bundle of Jakie’s old garments. Mamsy’s fears fled; joy and gratitude beamed in her care-worn, wrinkled, face.

“God bless you! God bless you child!” holding Frances’ hand tight in hers, she lifted it and bent over and touched her lips upon it in gratitude. Then she explained:

“I’m old and we are poor but I loves him and keeps him. We got nothing much way out in the backwoods. He wanted some Christmas so bad he come off to hunt a Santa Claus he saw in a picture. I got nothin’ to ride in, and it’s too far to walk. I borrowed a [32]neighbor’s wagon and horse to come hunt him. God took care of him and sent you to him.” Mamsy’s eyes filled with tears.

Jakie was listening and watching them. He broke in:

“Mamsy she say Jesus sent her to me, did He?”

“He sure did!” Mamsy answered. “You would a been frozen by now in this cold wind. Jesus sure did send her to you, for your Christmas Santa Claus!”

Mamsy was shivering, and Frances noticed how thin her shawl and her dress were. Jakie’s upturned face was gazing at Frances. She leaned over and whispered to him:

“Bring your Mamsy into the store and let us make her happy too. I want to be her Christmas Santa Claus too.”

Jakie seized Mamsy’s dress-skirt again and began pulling toward the revolving door, saying:

“Come on Mamsy! come on! She say she wants to be your Christmas Santa Claus too.”

Dazed and reluctant, Mamsy allowed Jakie to pull her on. She was afraid of the revolving door and held back. Frances stepped close beside her, and placing her hand on her back gently shoved her forward, hurrying through.

The beautiful decorations everywhere in the store, for Christmas, made Mamsy feel it looked like heaven. She and Jakie followed Frances to the elevator. They had never seen a box going up and down in the wall, as Mamsy called it. It frightened them both. They clung to each other afraid.

Frances led the way out to the cloak department. Frances picked out a dark-blue, long, warm cloak for Mamsy. She insisted on Mamsy trying it on. But Mamsy protested declaring:

“Honey, I’m nothing but an old country woman. Never worn a city cloak. I always wears shawls.”

But Frances persuaded her to try it on. She stood before one mirror looking at herself in the long pretty [33]cloak. Jakie stood before another mirror admiring himself, twisting and turning. He called out to Mamsy:

“You don’t look like you, and me don’t look like me.”

Mamsy accepted the cloak, and Frances slipped to one side and paid the clerk for it, happy that Mamsy had it to ride the long way back home in the bitter cold.

Mamsy looked as changed as Jakie when they came down the elevator. Frances knew they must be hungry, as it was long past their dinner time. They came out of the store. Frances invited them to go to a lunch counter and get a hot lunch. Mamsy said she must first see if the horse was where she tied him. Frances went with them around the corner to the side street where the horse stood tied to the hitching post, humped and drawn up from the cold. Frances observed very carefully the horse and wagon; she was planning some Christmas fun with it. They went to the lunch counter farther down the street. Their happy faces wore a greater change than they looked in their new clothes.

She saw them seated at the counter, and went to the cash-clerk, paid for their lunch. She bade them good-bye, after she wrote on her card their address.

“You is an angel,” Jakie insisted. He waved his hand to her until she closed the door behind her.

She walked very fast, almost running in such a hurry to get back to the wagon. She entered a grocery store close by. She picked out oranges, apples, cakes, candies, pecans, raisins and bananas, for Jakie’s Christmas. The clerk tied them in separate bags, then put all the bags into a coarse crocker-sack, and tied it.

Frances spied a picture in the store of the same big, fat, old Santa Claus. She begged for it, and wrote in big letters “Jakie which Santa Claus do you like best?” The clerk pasted it on the bag, swung the sack over his shoulder, and hurried out to the wagon; [34]Frances saying, “Hurry quick! hurry before they come back to the wagon.”

She paid for the things in the sack. She stood, then to examine her pocket-book, to count what money she had left. Her purse was empty,—just a few pennies left to buy Christmas love-gifts for her home-folks and friends. Instead, all of her money had been spent on a dear, ragged little orphan boy, hunting for Santa Claus. And upon a dear old country woman to keep her warm.

Her face beamed, for her heart whispered to her that her money went where it gave the greatest joys at Christmas time.

Yes, her purse was really empty,—no money left in it! But unspeakable happiness whispered to her: Jesus’ own words:

“In as much as ye did it unto the least of these ye did it unto me!”

And his birthday is “love-day” of one toward another, all over the world, and among all people and children where the Bible is loved.

Jakie’s home in the backwoods, was close to Mr. Cripple Jim’s home. Mr. Cripple Jim was a dear old man seventy years old, who looked for, listened for, watched for, happy little Jakie’s bare-feet to come tripping up the steps, knock on his door bringing the milk which Mamsy sent to him every day.

Just before Christmas, Mr. Cripple Jim listened for, and watched for, Jakie all day long—but Jakie never came! He never missed coming. Mr. Cripple Jim really felt lonesome, for Jakie was full of fun. The sun was getting low in the west. Night was coming on,—and yet no Jakie came.

He heard noisy, stamping shoes coming up the steps—not Jakie’s nimble bare-feet. But the knock was Jakie’s funny bim! bim! bim! on the door.

“Come in!” the dear old man called out.

The door pushed open. Jakie came in closing the door behind him to shut off the cold winter wind. He stood still mischievously staring at him. Mr. Cripple Jim did not recognize him. Jakie burst into a merry laugh bouncing up and down.

“It’s me!”

“Sure didn’t know you!” exclaimed Mr. Cripple Jim, chuckling.

“You look like a city chap. Where you get such fine clothes?”

Jakie put the bucket of milk on the table, laughing gleefully, “Mr. Cripple Jim you didn’t know me!” Jakie stood by his chair telling him:

“My billy goat was scared of me, he run off, he didn’t know me! The chickens cackled and run from me,—they didn’t know me—nuthin knows me!”

It was a great joke to Jakie to be turned into a city boy in store-bought clothes, so nothing knew him. Mr. Cripple Jim laughed too. He loved Jakie and Jakie [36]loved him. He was constantly whittling with his pen-knife, as he sat alone before his fire, some sort of toy a boy likes. Jakie’s tongue rattled on like a victrola-record telling Mr. Cripple Jim about all the wonderful things he saw in town and about the beautiful girl who spent all of her Christmas money on him. He bent over nearer to Mr. Cripple Jim’s chair with a great secret, whispering into his ear:

“Mamsy say I kin hang up my stocking now, cause my Big Friend give me all dese clothes.”

He rubbed his hands proudly over his clothes, “an she give us a big, big, Santa Claus pack in a wagon. Mamsy say she won’t have to buy nuthin for me in a l-o-n-g time. Mamsy say Jesus sent my Big Friend to peep behind de door and find me a freezing.”

Then he laughed out loud telling of the picture of fat old Santa Claus, that fooled him, pinned on top of the sack. “Us is rich now Mr. Cripple Jim!”

Mr. Cripple Jim listened; his eyes fixed on Jakie’s happy, beaming face. His mind and memory flew back over the years when his own happy little children, his own boys and girls, hung up their stockings Christmas Night around his fire-side. He could see their fun and frolic diving their hands down into the mystery stockings Christmas morning. Now he was an infirm, old man living all alone, using crutches to get about. “All gone, singing the songs of heaven now, and he was just waitin’ to go too,” he would say. He sat before the fire in a chair; one crutch lying on the floor beside his chair, and the other crutch lying on the floor on the other side of the chair.

Tears trickled down the old man’s wrinkled face. No one left to live with him; none left to love him; none left for him to love. He was dependent upon very kind neighbors to look after him. The men chopped his wood for his fire. The women kindly cooked his food and brought to him. Jakie was his cheer and his sunbeam. Jakie saw his tears, his tender heart felt sorry for the lonely old man. He [37]wanted to console him. So he asked him what was uppermost in his own happy heart:

“Does you hang up your stocking?”

The dear old man shook his head, sadly:

“No little man. I’m too old now, and I got no little children to hang up stockings to make fun and a noisy Christmas Morning.”

“No you ain’t too old to hang up your stocking. You ain’t old as fat old Santa Claus, what fills up children’s stockings.”

Mr. Cripple Jim stared into the fire, without answering him, tears still wet his cheeks. Jakie still pleaded:

“Jesus will send a big friend to you like he sent Her to me.” He ran to the head of Mr. Cripple Jim’s bedstead. Laying his hand upon the bed post at the head, said:

“Hang it up right here. Won’t you hang up your stocking Mr. Cripple Jim like me, right here?” and he patted his hand on the post.

Mr. Cripple Jim brushed his tears off with his hand. He smiled back to little Jakie whose kind heart was trying to make him forget, trying to cheer a lonely crippled old man.

“All right,” he nodded, “I’ll hang up my stocking right there to please you.”

“Won’t us have fun!” Jakie exclaimed coming back to the fire. “Suppose Santa Claus forgets me. He ain’t a been coming here in a long time,” Mr. Cripple Jim said to tease Jakie.

“Jesus won’t forgit you. I knows. He didn’t forgit me ’hind de door freezing. He sent me all I got on.” And again he rubbed his hands proudly over his new clothes.

Jakie was satisfied. He hurried out of the door. He looked back at Mr. Cripple Jim to remind him before he shut it.

“Don’t you forgit it!”

Mr. Cripple Jim chuckled, “That child thinks I’m [38]the age of him. To please him I’ll hang up my stocking right now,—to keep from forgitin’ it,—cause old folks is powerful forgitful. I got no stocking to hang up, no women here to wear em. My socks will do just the same.” He lifted up his crutches, raised himself up on them. He hobbled to his trunk. He rummaged inside until he found the new pair of socks Mamsy had knitted for him. He hunted for a pin, he could not find a pin. He hobbled back to his chair. He broke off a splinter from the wood, piled beside his hearth. He sharpened it with his pocket knife and stuck it through the upper edges of the socks, pinning them together. He hobbled to the bed post. He straddled the socks across the bedboard like a boy’s legs straddle a pony’s back.

“There!” he said, “I won’t forgit it now. God bless that child he is made me forgit my troubles!”

Through the wind, Jakie raced back home. He rushed into the house, panting:

“Mr. Cripple Jim say he will hang up his stocking like me!”

Mamsy was sitting by the fire very tired, waiting for Jakie. Jakie pulled off his store-clothes for his old clothes. He drew his little stool before the fire. He sat very still staring into the fire. Mamsy sat very still staring into the fire too. The winter wind moaned and whistled outside. Suddenly Jakie looked up into Mamsy’s face, his eyes twinkling. Eagerly he exclaimed, “Mamsy me wants to give my billy goat to my Big Friend cause she give us heaps of things.”

Mamsy felt inclined to laugh outright at the very idea of sending a country-billy-goat to a city girl as a Christmas gift. Jakie was in eager earnest. She kept her face straight lest she hurt his feelings. She said, kindly:

“City folks got no where’s to keep a billy goat in town.”

[39-40]

GOD BLESS MY BIG FRIEND

[41]Jakie’s billy goat was the only thing of his very own which he possessed. He loved billy. Billy was his only playmate. He was willing to part with billy to his Big Friend who called him her Little Friend, as a Christmas love-gift. He sighed keenly disappointed. Mamsy proposed:

“Send her one of my turkeys. I saved it to buy some shoes for you. She done give the shoes.”

“But Mamsy,” Jakie objected, “I wants to send her what’s mine.”

They both sat very still again. Jakie watching the bright little fire-sparks fly up the chimney.

He called them fire-bugs because they resembled fire flies. He reached over to the pile of wood by the hearth to fling a fresh stick of fat pine into the fire, and make it blaze brightly.

“Oh Mamsy!” he exclaimed, seizing hold of another stick, “I ken send her some fat, lightwood splinters to start her fire. Mr. Lane hauls it to town to sell to folks. They pays him heaps of money for it.”

Mamsy was pleased. Quickly she agreed:

“You send the splinters and I send the turkey.” Jakie was satisfied. He wanted to rush out in the dark to the woodpile to hunt for a fat stick. Mamsy persuaded him to wait until to-morrow. He was sleepy and shed off his everyday clothes for his “nightie” and knelt down at Mamsy’s knee to say his evening prayers. He folded his hands together and bowed his head. His sweet voice said aloud: “God bless my Mamsy, God bless me and make me a good little boy, so I will go to my Mama in heaven. God bless my Big Friend, for Jesus’ sake amen.”

He raised his head. He stared up at Mamsy astonished. Tears were trickling down her cheeks. He could not understand! He was so happy and Mamsy was crying. Mamsy saw the troubled look in his face. She laid her hand upon his head and explained:

“The Lord is been good to us today. This morning we was so po, you run off to town a-huntin’ for Santa Claus to give you a present, cause we was too po fur you to hang up your stocking. The foxes eat up my [42]young turkeys; the hawks caught my little chickens. I had nuthin to sell to git money to buy us things. The Lord is changed it all. He sent that fine, good, city girl when you was lost to find you, like He sent Angels outen the heavens to sing to the shepherds that night, feeding their sheep; that a wee baby had come named Jesus, to show us how to love each other. He come po like us, cause so many po-folks is in the world. He knows how po-folks lives and po-folks feels without money, to buy clothes and nice things.

“You is little and Mamsy is old. He will always take care of you. He will make you a good little boy and make folks love you like he did today.” She pointed to her Bible, lying on the pine-table, which she read every day saying; “It’s all in there—when you gets bigger you will read it for yourself.”

Jakie stood up and ran and jumped into bed, in the very place he had sneaked from under the cover that morning when the roosters were crowing for the dawn of the day. He lay still as he was very tired and fell asleep.

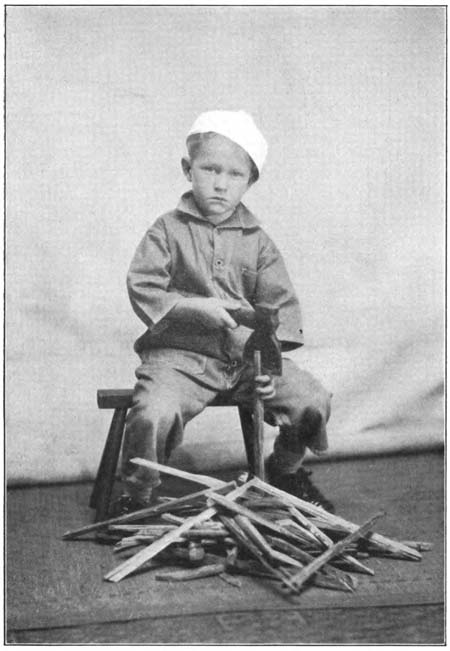

Early next morning he hopped out of bed. He stuck his feet into his overalls in a great hurry, and clapped his cap on his head. He ran eagerly out to the woodpile to hunt for the fattest lightwood stick he could find. He grabbed hold of the stick; fattest he could find. He dragged it on the ground, pulling it, puffing and grunting, panting and blowing to the steps. He called Mamsy to help him get it up the steps. She came to help him. She brought her ax and chopped the big stick into smaller sticks. Jakie gathered them up in his arms and carried them inside, by the fire. He placed his little stool close to the fire-place. Mamsy lent her hatchet to him. He sat on the stool and split the sticks into fine splinters.

[43-44]

HE SPLIT THE STICKS INTO FINE SPLINTERS

[45]Mamsy tied them in small bundles. Then tied a stout string around the small bundles into one large bundle. Together he and Mamsy caught the fat turkey and bagged it, with its head peeping out, in the same coarse sack they found full of Christmas gifts. Frances had tucked her card into the sack bearing her street, her name, and her number. “My po writin’ might git it lost!” said Mamsy, so she sewed the card on the sack “to make sure,” their Christmas gift would get to the beautiful, loving, kind city girl who had scattered such happy joys, into their hearts.

A kind neighbor hauling chickens and turkeys to town to sell, carried them into the City to leave on the front porch; Christmas gifts of love—the only thing they had to give. Jakie watched the neighbor’s wagon roll away toward town, wondering what his Big Friend would say when she got their Christmas gifts. He was so happy he wanted to make other people happy.

He ran into the house to Mamsy begging her:

“Mamsy Mr. Cripple Jim is so lonesome he cried! Let me go fill his stocking. Dress me up like fat old Santa Claus. You go with me, and I ken sneak into the house and put things in his stocking, and he will think I is sure ’nough old Santa Claus. Fix me so he won’t know me.” Mamsy promised.

The chickens had gone to roost. Billy was in his pen. The cow and calf in their shed for the night. Jakie was wildly excited, he said:

“Mamsy, dress me up now like fat old Santa Claus. Make me stick out jess like him. Put long white hair on me; put long white beard on me too. I want to fool Mr. Cripple Jim.”

Mamsy got her shawl and with a needle and thread tacked the shawl all around him until he looked like “a rolly-polly,” or a brownie. She stirred flour and water together into paste. She smeared the paste on his chin and cheeks and stuck snowy white cotton to it for his beard. She pinned cotton in his cap, for white hair. He was ready to go. He got a switch to stick in Mr. Cripple Jim’s stocking, because Mamsy stuck a switch in his stocking once to make him laugh. He wanted to make Mr. Cripple Jim laugh. He coiled the switch and stuck it into the meal sack Mamsy gave him for a pack on his back. She dropped oranges, apples, candy and raisins in the pack. Also put into it a cake of fresh butter, a can of coffee, and a new pair of woolen socks, she knitted to give to him. Jakie danced up and down, watching her.

Mamsy baked a pan of nice corn bread and buttered it hot; and drew a pot of hot coffee to take Mr. Cripple Jim a hot supper. While he ate it Jakie could slip in and fill his stocking. She put the supper in a split basket. She lifted the sack upon her own shoulder to carry to Mr. Cripple Jim’s door for Jakie; it was too heavy for him. The basket of supper she carried on her arm. Jakie was so bundled up he waddled in the path behind Mamsy like a fat baby. They reached the house. Mamsy lifted Jakie’s pack off of her shoulder, and put it on Jakie’s back. She knocked on the door.

[47-48]

CAUTIOUSLY JAKIE PUSHED OPEN THE DOOR

[49]“Come in,” the lonely old man called out.

Mamsy went in. Jakie hid in the dark outside listening and peeping through a crack in the door.

Mr. Cripple Jim looked expecting Jakie to come in behind Mamsy. He was disappointed. Jakie heard him ask Mamsy:

“Where’s the boy!”

Jakie’s heart beat faster, breathless he waited for Mamsy’s answer. She always told the truth. He wondered if she would tell on him and spoil all of his fun. But she said evasively:

“He’s about somewheres, up to a boy’s capers.”

Quickly she set the coffee-pot on the hot coals of the fire to heat it. She placed the buttered bread on the table beside him. Jakie eagerly watched her hurry and get a cup and pour the coffee into the cup and set it on the table. Mr. Cripple Jim edged himself around to eat the hot supper—with his back to the door. This was what Mamsy wanted, so he would not see Jakie when he sneaked in. Jakie started inside and jumped back. Mr. Cripple Jim turned his face around toward the bed, pointing his finger toward his stocking: “See I hung up my stocking to please the boy.”

He turned back to eat. He insisted upon Mamsy’s sitting down in a chair. She refused. She stood exactly between him and the door. He was busy eating. Mamsy stuck her hand behind her and beckoned Jakie to sneak in. She talked loud and fast to the aged man so he could not hear Jakie slip in.

Very slowly and cautiously Jakie pushed open the door, and slipped inside, closing the door behind him. He tiptoed to the head of the bed as softly as a little mouse. He nearly burst into a laugh, aloud, when he saw Mr. Cripple Jim’s socks astride the head-board. He set his pack down on the floor. He rummaged in his pack and got an apple and squeezed it into the sock; he squeezed an orange into the other sock. He put candy, and raisins into the socks; he stuck the [50]switch straight up in a sock, and giggled over how it would make Mr. Cripple Jim laugh.

He set a toy dump-wagon on top of the socks. He hung his pack on the bed post. He crept noiselessly back to the door, slipped through, and jumped off the step into the dark. Mamsy glanced sideways. She saw the switch. Jakie had slipped out. She must hurry away. He was outside waiting in the dark, in the cold. She wished the lonely man a happy Christmas. He looked up at her, his face very happy. He had not been forgotten Christmas eve. Jakie had told him Jesus would not forget him. He gazed into the fire-light until it went out. He hobbled to his bed by the dim glow of the coals. He forgot about his stocking wondering where Jakie was, and dropped to sleep.

Silently Jakie and Mamsy stole away from the house. Jakie trudged close behind Mamsy in the foot-path homeward, the stars over-head lighting their steps. Jakie gazed upward at the vast number of twinkling stars in the sky. He asked Mamsy: “Is de stars little holes up yonder what heaven shines through and my papa and my mama can peep through down at me?”

“No,” answered Mamsy, “stars is to tell us about God. You know about the Star which showed the wise men where Jesus was. The stars is to show us every night where He is now. The wise men came a long way from the east to bring gifts to the po baby what come out of Heaven to teach us love,—teach us the sort of love that pretty girl in town showed you and me. She spent her own money to make us happy Christmas. She said He sent her to find you. He whispers to our hearts, inside, to ‘be ye kind one to another.’”

“Did He tell me to send my Big Friend a Christmas gift? an’ tell you to send de turkey?”

“Yes,” answered Mamsy, “so we won’t be gettin’ everything from folks—and give nuthin’.”

They reached their home steps. Jakie blustered up the steps ahead of Mamsy. He shoved open the door. [51]He ran to the fire-place to warm. Mamsy had piled hot ashes over the wood to smother the blaze. Jakie snatched the cotton beard from his chin, while Mamsy stirred up the fire. Jakie snapped the threads tacking the shawl and it fell to the floor. He jumped up and down clapping his hands, saying:

“I got head of fat old Santa Claus! I filled up Mr. Cripple Jim’s stocking my own self—and he didn’t know it.”

Mamsy gave him one of her new stockings to hang up. He chose the nail by the fire-place closest to his side of the bed, so he could see it the very first thing in the morning. He said his prayers and jumped into bed. He tucked his head under the cover,—and fell asleep Christmas eve as all happy children do, wishing to wake up soon Christmas morning; with stockings full, or Christmas trees!

Church bells ring out their glad-tidings over the world that Jesus came as a little child with His love-gift of Himself to all the earth. To teach us how to love and how to live; how to love and how to give! Wise men of the east followed the Star of Bethlehem to find Him. They brought rich gifts unto Him.

Christmas bells ring out their chimes glory to God in the Highest, peace on earth good will to men. Christmas trees glitter in twinkling lights, hanging full of love-gifts to rich and to poor. Children jump out of bed to dive their hands into Christmas stockings. Fire-works shoot upward. Love-gifts are exchanged all over the world for He teaches us the greatest thing in all the world is love! His love makes us sweet and makes us glad; makes us happy and makes us kind.

The dawn of the day shed its gloaming in the east. Jakie’s eyes opened. The room was dark. He pulled himself slowly from under the cover—not to awaken Mamsy. He edged himself from the bed until his feet touched the bare floor. He stretched his hands out before him and felt his way to his stocking. His hands touched his stocking. He eagerly felt it up and down, it stuck out stuffed full as a sausage. The stocking-toe touched something big and curious. He felt it with both hands. It had wheels. His heart beat faster. It had a tongue. It was a boy’s express wagon. He was astonished. He had wanted one all of his life. He felt inside of it. Something mysterious was inside. He lifted it up. A dim light came through the window, he examined the something; it was a new harness for his billy goat. His heart leaped for joy. He stepped to the other side of the hearth to see what Santa Claus brought to Mamsy. No stocking was hanging up. There was nothing! “Not a thing for Mamsy!” he [53]said to himself, “That old Santa Claus is fooled Mamsy same as he fooled me!” A happy idea came to him. He would play Santa Claus to Mamsy too. He crept to the bed on his all-fours and stole one of Mamsy’s stockings out of her shoe. He crept back to the fire-place. He hung the stocking up on a nail across the hearth from his own. Cautiously he lifted his stocking down from the nail, and went back to Mamsy’s stocking. He pulled things out of his own stocking. He dropped them into Mamsy’s stocking until it had as much in it as he had left in his stocking. He carried his stocking back and hung it on the nail. He was cold and shivering. He crept back to bed. He crawled into bed, and snuggled up to Mamsy to get warm. But he could not wait! He put his mouth close to Mamsy’s ear. He whispered:

“Mamsy! Mamsy! Santa Claus is come—sure ’nouf.”

Mamsy opened her eyes.

“Christmas gift!” he blurted out. Mamsy thrust her hand down from the edge of the bed to feel for her shoes and stockings. She always stuffed each stocking into each shoe by her bedside ready to wear next morning.

Jakie lay watching her. She said, “I sure am getting old and forgitful. I was sure I stuffed my stocking in my shoe; now I can’t find it.”

Jakie stuck his head under the cover, to giggle. She got out of bed. She felt along the floor. The stocking was not there. She hopped on the cold floor, one shoe on and one foot bare, to the fire-place, to stir up the fire. She saw her missing stocking hanging on a nail, half-full.

She saw Jakie’s stocking half empty. Jakie was peeping at her from under the cover.

He saw Mamsy take it down and press it against her cheek. He ducked his head back under the cover-lid, grinning, saying: “Mamsy don’t know I is her Santa Claus too.”

Over at Mr. Cripple Jim’s house he was laughing [54]aloud. He awoke and saw the long switch sticking up over his head. “Hah,” he said, “Old Santa has brought me a switch to warn me to be good! How did he come right over my head without my knowing it!” He raised up in bed. He pulled the socks down beside him. He reached for the pack hanging on his bed post. He poured out all the contents on his bed. He looked at the pile of good things. He wagged his head. His face was radiantly happy. He said: “A happy child made me, an old cripple man, hang up my stocking. He said Jesus won’t forgit me—he told the truth. Jesus didn’t forgit me!”

He heard such noisy, jolting, bumping, in his yard. He seized his crutches leaning against the foot of his bed. He hobbled to the door. He opened the door. He peeped out. It was Jakie sitting in his Christmas wagon driving billy harnessed up in the new harness. He yelled out to Jakie “Christmas gift.”

Jakie waved his cap. “I come to cetch you first—and you is cetched me first.” The happy little boy tied billy to the hitching post. He ran into the house to see the happy old man.

Frances had emptied her purse of all of her Christmas money,—but she had wafted Christmas joys to the dear country folk in the backwoods. And a beautiful note came through the mail from her to Jakie and to Mamsy for their love-gifts to her “of lightwood and a turkey.”

The End

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES:

Perceived typographical errors have been corrected.

Inconsistencies in hyphenation have been standardized.

Archaic or variant spelling has been retained.