S. Huntingdon

Title: The life and times of Selina, Countess of Huntingdon, Vol. 1 of 2

Author: Aaron Crossley Hobart Seymour

Release date: December 21, 2025 [eBook #77517]

Language: English

Original publication: London: William Edward Painter, Strand, 1844

Credits: Brian Wilson, Karin Spence and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

THE LIFE AND TIMES

OF

SELINA, COUNTESS OF HUNTINGDON.

S. Huntingdon

BY A MEMBER OF THE HOUSES OF SHIRLEY AND HASTINGS.

SIXTH THOUSAND—WITH COPIOUS INDEX.

VOL. I.

ENTERED AT STATIONERS’ HALL.

LONDON: WILLIAM EDWARD PAINTER, STRAND;

AND JOHN SNOW, PATERNOSTER ROW.

1844.

[v]

It was the express wish of Lady Huntingdon, that, at least for some years after her decease, her memory should be suffered to rest, and her actions to make their own impression on the minds of men. In deference to this wish, all attempts at the publication of her Correspondence have been resisted by her noble relatives; and it is only at the present day that a Cadet of her illustrious family, after long years employed in the collection and examination of the documents and papers to which he alone, perhaps, was in a condition to have easy and continued access, has been induced to arrange his materials into the form of a Memoir of the Life and Times of Selina, Countess of Huntingdon.

Circumstances having prevented the author from personally superintending the publication of this work, a large share of responsibility has been thrown on those to whose hands it was committed; but the task was a labour of love, and the publication has been conducted with all possible regard to the public demand for ample information, to the feelings of the living, and the memory of the dead.

Among the illustrious characters of the eighteenth century, no one has shone more conspicuously in the religious world, or enjoyed a greater share of heartfelt esteem and love, than the[vi] venerable Countess of Huntingdon. Above all her celebrated contemporaries, she was honoured with a life of continued usefulness, protracted to the utmost period of mortal existence; with extraordinary talents, ample means, and a head and heart alike devoted to promote the “glory of God in the highest, and on earth peace and good-will towards man.”

Her body has long been committed to the earth from which it sprang, and her soul has returned to God who gave it, but she has left on earth a testimony which will outlive monuments of brass and stone—a reputation which has spread to the corners of the world—and a name which is reverenced by all whose approbation is praise.

The curiosity that has been as generally expressed as universally felt, to know more of the life and character of this, in the best sense of the word, illustrious woman, is a feeling which ought to be respected; and it has at length become a duty to make every effort in order to save from destruction those invaluable records of her heart and feeling, those delightful traits of her distinguished friends, those heart-stirring pictures of her private and every-day life, and those important records of her public services to religion and humanity, which are contained in these volumes, and which, but for the present publication, might have expired with their compiler, or have left but a vague memory of her excellence, except in those instances where the sacrifice of her fortune has raised imperishable monuments to her piety.

The object of the present work has been to afford a view of the “life and times” of this distinguished woman, so clear and ample as to render superfluous all future or collateral efforts at illustration. Every fact and incident of her long life is here recorded—every triumph of the cross under her vigorous and well-directed leading—every place of worship opened under[vii] her auspices—and every mark of divine favour and encouraging grace bestowed upon her labours.

Conscious of the purity of his motive, and having for all his incentive the desire to pay just tribute to the memory of the departed saint whose name he honours, the author has spoken truth from his heart, resolved to flatter no one—to know no fear in the discharge of his duty. He has sought, with candid zeal, to avoid every evidence of a sectarian or party spirit in his statements. Bigotry, on both sides, may censure; but the just and generous, on all sides, will approve his course. Narrow prejudices are already vanishing; and good men, of all denominations, are ready to embrace the truth and each other. The good Countess was, in this respect, before her age; and it is her Catholic and Christian spirit which appears to have inspired her kinsman in the composition of this Memoir. Read in the same spirit, it will serve to accelerate the benevolent current of true godliness, and to sweep away the narrow and contracted dispositions which would check its overflow or turn aside its course.

With this feeling, the author has drawn, without hesitation, from all accessible sources, the illustrative matter of his Memoir. The biographies of Whitefield, Wesley, Venn, and the works and letters of Fletcher, Berridge, Romaine, Watts, Hill, and other eminently pious individuals, have supplied invaluable contributions to the work; but its more valuable portion consists in the original letters and anecdotes with which it teems, and in the straightforward integrity of purpose in its author. Of himself and of his work, he says—

“To God, only wise, the Author of every good and perfect gift, my humble acknowledgments are paid. His grace rendered the subject of this Memoir what she was—His wisdom directed her pious and benevolent efforts for the extension of the Redeemer’s kingdom—and His Spirit supported her in her[viii] departing hours. To Him, therefore, and Him alone, whose influence I implore, I commit these Memoirs, such as they are, in the hope that He will vouchsafe His blessing on a work which originated in an ardent desire to promote His glory; and that He will render it an instrument to extend the knowledge and experience of the glorious Gospel of God our Saviour.”

With these glowing words of the pious author, the conductors commit his work to the candid judgment of the enlightened reader; remarking merely, as they are in justice bound to do, that the religious institution now known as “The Connexion of the late Countess of Huntingdon” does not incur the slightest responsibility with regard to this work; and that the reverend author of the Introduction to the present volume has undertaken to resume his pen for a similar introductory paper to the second volume of these Memoirs.

[ix]

PART I.

Man, amidst an almost infinite variety of circumstances, and modified, both in body and mind, by a thousand accidental influences, is, in every age and country, essentially the same. The os sublime and the mens alta alike distinguish him from the other inhabitants of the earth, and show, whatever may be his complexion and mental training, that God has made him to have dominion over the works of his hands—has put all things in subjection under him. Nor is there less of identity in man’s moral propensities than in his corporeal and instinctive powers. Bent from his original rectitude, he stoops towards earth and the things of earth, and gives sad proof of having lost affection for the Source of his existence, and of being inclined to worship the creature more than the Creator. The rude savage, the superstitious devotee, and the intellectual sceptic do not like to retain God in their knowledge—that God who is “glorious in holiness,” who is partially made known to his creatures by the works of his hands, and more fully revealed, and in a more encouraging light, by the words of his mouth.

This Atheistic spirit laboured with a giant’s strength to deface the character of Deity impressed on the world before the flood; had cursed the earth with abominable idolatry, or with heartless[x] superstition, before the coming of our Lord in the flesh; and, not satisfied with the mischief effected under dispensations of mercy less intelligible and distinct, has, to a most awful extent, corrupted a Church, professedly Christian, as it had polluted both the Jewish temple and the Patriarchal tent. To educe good out of evil is the province of the Supreme Good; to pervert the good, and, so far as it relates to his own perceptions and conduct, to abuse and prostitute it to the worst of purposes, is, alas! the work of man.

Nothing can more affectingly evince the truth of this remark than the contrast of the Church of Rome with the Church of the Apostles; than the pomp and mummery, the dogmatism and tyranny, the secularity, the superstition, and the heathenism of Popery, with the simplicity, the spirituality, and the divinity of that religion which the writers of the New Testament advocated, for which they all suffered, and for which most of them died. The vapour which, rising from the twofold shores of Corinth and the province of Galatia, annoyed St. Paul, continued to spread itself and to increase in density, till the true Church of Jesus Christ became scarcely perceptible, and ultimately was totally obscured by the thick and dark cloud. Let the mind proceed from the apostles to Eusebius, thence to Augustine, and the next advance is to settled darkness, rendered visible by a few solitary rays of piety—real, though faint and sickly—and the transient scintillations of scholastic wit and learning. The page of ecclesiastical history, though inscribed by persons less evangelical than the Milners, will show that even superstition was only one shade in the dark ages; that vital godliness, as if in disgust, had fled from the Church, as she was pleased to call herself, to deserts, and mountains, and dens, and caves of the earth; that justification before God, by faith alone in Jesus Christ, the “Articulus stantis aut cadentis Ecclesiæ,” as Luther termed it, was buried beneath the records of Councils and the volumes of Fathers; and that men, having renounced the Lord as their RIGHTEOUSNESS, were without him as their STRENGTH. Like Samson, the Church was shorn of her energy and deprived of sight—the sport of the Philistines.

[xi]

It was the glory of the Reformation that it struck at the root of the evil. The Church of Rome, not satisfied with seeking righteousness by the works of the law, must needs arrogate to herself a property in works of supererogation, and impudently bring it into the market; but for this daring imposition on common sense, the fire of Luther might have been employed rather in consuming the drapery of the Man of Sin than in the destruction of his person. The sale of indulgences, however, was such an outrage on the principle of the Gospel, that it roused his powerful mind, even when only partially enlightened, to bring all its united force against the blighting and unholy doctrine of human merit. Thus, in the process of resuscitation, the Holy Spirit, by the agency of the Reformers, instead of restoring vital heat by friction at the extremities, breathed into the dead Church the breath of life, and restored to her a living soul. Animation diffused itself through a vast range of nominal Christians, converting them into living members of the body of Christ; and the life, which was felt to be redeemed, was consecrated to Him “who loved his Church, and gave himself for it.”

The number of truly converted persons was, no doubt, very considerable in the days of the Reformers, and the hallowed work progressed under their survivors, both on the continent of Europe and in Great Britain. It would, however, be false charity to conclude that all Protestants, even during the warmth and freshness of the Reformation, were true Christians: an acquaintance with the history of the times and with human nature, as well as with the subsequent condition of Protestant Christendom, will compel us to say, “that all were not Israel who were of Israel;” that multitudes, from political and secular motives, and from the force of custom, or from a conviction of the truth rather as an intellectual than as a moral proposition, protested more against the errors of the Man of Sin than against his iniquities, and were more anxious for emancipation from the thraldom of superstition, than from the bondage of corruption. The easy transition, indeed, of the majority from one state to another, under Henry the Eighth and the youthful Edward; their coming back again to Popery under Mary; and their[xii] ready return to Protestantism under her sister, proves that, however many loved the truth, even unto the death, more were indifferent to its divine claims, and accommodated themselves to the times. The Vicar of Bray was only one of many who ebbed and flowed with the ocean, and of those who will always show that a national religious improvement may be effected where the renewal of the mind in the great body of society does not take place. Worldly men will preserve the element of their character amidst great external modifications—an element as decidedly opposed to the holy and humbling truths of the Gospel in the Protestant as in the Papist, though exhibited under different forms.

This was the case in the reign of Elizabeth. We hail, indeed, with feelings kindred with those of Milton when he escaped “the Stygian Pool,” the settling of a better order of ecclesiastical affairs, the liberty of prophesying given to the ministers of Christ, and the eminent piety, learning, and zeal of many of the clergy. Her reign is as illustrious for men devoted to the kingdom of our Lord Jesus Christ as it is for patriots and politicians: the preaching and the writings of those men, some of whom were the survivors of the martyrs, and of whom others seemed to grow out of their ashes, tended much to instruct the people in the great principles of the Gospel. These labourers, however, were few, compared with the extent and population of their spheres of action, and they could not fail to leave the mass of the people without the knowledge of true religion, and, consequently, unrenewed by its power. Nay, the majority of those who professed to guide the blind were themselves, it is to be feared, destitute of the wisdom that cometh from above, and thus unqualified to show to others the way of salvation; for we are informed that, “by the Report of the visitors to the Queen, it was found that comparatively very few of the Popish Bishops, Clergy, and Heads of Colleges, resigned their preferments on account of the new order of things; and it was remembered that the greatest part of them went with the tide in Edward’s reign, and veered about as readily with the wind on the accession of Mary.” (Custance’s Reformation). It would have been ex fumo dare lucem, indeed, if such men had done[xiii] much towards the evangelizing of the nation. The Queen, herself a genuine Tudor, aiming at absolute sovereignty, wished to encircle her throne with clouds of darkness, admitting only so much light as might show that she, and not the Bishop of Rome, was seated on it. She chose, and with reason, men of powerful minds to assist her in working the State machine; but she by no means wished that society at large should be enlightened with principles which, raising the intellectual as well as the moral character, and cherishing a consciousness of this elevation, would probably lead her subjects to question, where it was more convenient to her that they should obey. “One preacher is enough for a county,” was the recorded expression of her sentiment on this most important subject.

We must, therefore, conclude, that under this extraordinary ruler—for one does not like to contemplate her as a woman—the nation, as a whole, with all its improvements, was dark, or, at best, only relieved with a dim religious light. Under James, the Bible was re-translated, copies of it were multiplied, and ministers sincerely Protestant greatly increased in number; but there was a re-action in theological sentiments, which tended to lower the tone of piety in those even who were truly religious. Calvinism, as it is called, had, before this reign, in numerous instances, assumed an appearance of harshness, in the employment of supralapsarian terms, though so generally and ably supported by men of the most holy character and kindly hearts; but now the influence of Arminius was experienced. A large part of the clergy went over from scholastic terms and metaphysical notions, more speculative than practical, to doctrines which, as they reject the grace by which we are saved, necessarily leave the soul, amidst all its moral boastings, in the bonds of iniquity. This obscuration of the glorious Gospel of the blessed God by low, self-righteous instructors, more than by any affectation of godliness, in the time of the Protector, prepared the nation for that laxity, both of morals and of creed—that licentiousness and infidelity, which stamp infamy on the reign of the second Charles. The ribaldry of Rochester, the[xiv] wit of Butler, and the buffoonery of South, all had a baneful influence on the court and the nation, and obscured the holy light which had appeared to radiate from the stake of the martyrs.

Morals and religious principles have perhaps never been at a lower ebb in our nation, since the Reformation, than during this period—a period, the true character of which it is one of the most difficult studies in English history to determine. Even the best men of the age, in their joy for a restored monarchy, and bewilderment at the splendour and politeness of the Court, were led to give a false colour to their records of these times, and to merge the all-important considerations of morals and truth in the theoretic speculations of a civil and religious establishment. Whatever may be said on the question of equity, there can, we imagine, be no doubt in an unprejudiced Christian, that the ejecting of the Nonconformists, and the patronizing of a very different class of men, taken as a whole, both ecclesiastic and secular, was a heavy blow inflicted on true piety, and introduced a style of preaching which operates as a soporific on the moral sense, and as a cloud on the moral vision. Most victories are costly, and the triumph of monarchical principle, however desirable, by overlaying the living and evangelical spirit with a uniform machinery, in too many instances worked by careless hands, was gained at an expense which it is not easy to calculate, but which must qualify the pleasure suggested to a loyal heart by the return of the twenty-ninth of May.

England may well be proud of the science and literature of the subsequent age, and call it Augustan. Newton and Locke, in the worlds of matter and of mind; Dryden, Pope, and Thomson, in that of the imagination; and Addison, with a host of prose writers, on subjects of taste and morals—have given it claims to distinction, and illuminated its pages in intellectual history. These writers obtained great influence over the nation, and whatever good they effected, by giving currency to thought, they directed it in channels leading from evangelical piety, to sentiment, and ethics, and taste, or to physical knowledge. The waters were indeed clear and beautiful, but they were unhealthy, and, in some respects, the opposite of the prophetic[xv] stream, of which it is predicated, “Everything shall live whither the river cometh.” The most chaste and moral of these popular works, though recognizing Christianity, are unvivified by its spirit; and while they advocate the claims of virtue, found not their argument on the principles of the Gospel, and teach, often not otherwise than as a heathen would have taught, social duties and graces, rather than “the obedience of faith.” The founder of Methodism was not far from the truth when he said that few things were more unfriendly to the progress of the Gospel than the national fondness for Addison’s Spectator.

Nor was the political feeling without its baneful influence on the religious character of the people. As the fashion of the Court, under the profligate Charles, had raised up many wits, like Butler, to caricature true piety, by confounding it with hypocrisy, so the repeated efforts made to restore the Stuarts filled Protestants with a dread of change, and induced the High Church party, most unjustly, to consider all Dissenters, however attached to the House of Brunswick, and however excelling in all the virtues of true religion, as confederate with the Scottish Nonjurors and Jacobites; and thus, by an easy though fallacious transition, to identify evangelical doctrine with revolutionary propensities.

This, as the following work will show, was a reason assigned by the local magistrates of the day for their leaving the Methodist preachers unprotected to the mal-treatment of the mob, in opposition to royal pleasure directly expressed; and this, too, was the pretext under which the magistrates themselves avowedly and ostensibly excited the ignorant to violence and outrage. Let us not be deemed illiberal if we notice, as one cause of the general apathy, the great popularity of Tillotson. It would, indeed, be uncandid and unjust not to recognize his numerous excellences, both as a man and as a writer, and his merit of giving a more popular character to pulpit addresses in the Established Church; but whatever other good his sermons may have effected, there was little in them to send the people home imbued with the great principles of the Gospel, and sympathizing with St. Paul, when he exclaims, “But God forbid[xvi] that I should glory, save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by whom the world is crucified unto me, and I unto the world.”

An almost total absence of evangelical doctrine—the blood of sprinkling—and an evident carelessness about the great object of the Christian ministry, even where there may not be gaiety and immorality of conduct, are so palpably inconsistent and reprehensible in a professed minister of the Gospel, that the evil, in a great degree, neutralizes itself; but when moral excellence combines with truth indeed, animated with zeal and affection, yet lacking that prominence of the all-important doctrines of revelation which the Holy Ghost has in all ages been pleased to bless to the glorifying of Christ, a sort of quietus is ministered to the conscience, and decorum and formality take the place of “repentance towards God, and faith towards our Lord Jesus Christ.” Such writers as Tillotson, and his older friend, Barrow, will be studied with advantage by men spiritually minded, because such readers will give an evangelical cast to the strong reasoning and beautiful illustrations of these writers; but where the tone of feeling is to be received from the authors themselves, we cannot but think that it will be cold. English literature, from Steele to Johnson, though its period has become an era in the history of morals, has had the same tendency. Amusement and instruction, taste and decorum, were circulated among a people now denominated “a reading nation;” but who ever heard of a sinner being brought to true repentance, and to rejoice in Christ Jesus, having no confidence in the flesh, by a paper of the Spectator or of the Rambler? All these movements, indeed, had a beneficial influence on society, in preparing the way for a revival in religion, by exciting the attention and teaching the mind how to think; but the direct effect, in most cases, of such instruction, was either to lull the moral sense altogether, or to awaken it to a class of feelings of a self-righteous character, and, as such, opposed to the Gospel—the righteousness which is of God by faith.

Thus the slumbering embers of the martyr-flame had died out, and a degeneracy of doctrine and profligacy of manners had spread a chilling and destructive influence over a partially enlightened[xvii] community; and infidelity, political convulsions, and even literature itself, had each contributed its quota to form a national soporific. Happily, there were a few in the national pulpits who had not drank of this cup, and among the Dissenters some holy men, such as Watts and Doddridge, well represented those who had suffered for conscience sake after the Restoration. Theological writings, too, had accumulated, which will continue to instruct and bless the Church of Christ till she shall know even as she is known: but there was a heaviness in those folios, and too much of evenness in the public ministrations of the word, for an age which needed a moral disturbance to prevent its sleeping the sleep of death. Arguments against infidelity, and ethics cold though beautiful, were the usual themes of the parochial desk; and the withering influence of Arianism, or of a heartless orthodoxy, produced death in many of the Dissenting congregations. England and Wales, therefore, in an improved condition of politics and literature, and perhaps also of morals, was generally benumbed by the torpedo of formality; and the vital feeling and zealous activity of Christianity were known to the few only, and these rather mourned over the state of things in secret, than exerted themselves in public to effect an alteration.

It is not for us to hazard even a conjecture respecting the number of persons who truly loved our Lord Jesus in this country at the earlier part of the last century. Piety is essentially a quiet and secret thing, and, though it labours to do good at all times, is greatly dependent on circumstances for the platform on which it acts—that may be the domestic hearth, or it may be “a spectacle to the world.” At this period, as if wearied with political distractions and disgusted with the impertinence of infidelity, the pious of all denominations very much sought retirement. We may hope, therefore, that the number of those who loved the Gospel was much greater than at first, and by comparison with the present age, it seems to have been; and perhaps no documents furnished greater proofs of this delightful fact than the early correspondence of the Countess of Huntingdon. This gives the most satisfactory evidence that “honourable women not a few,” and some men also in the highest walks, were quietly[xviii] exercising the Christian graces, and waiting and longing for better days, before the Methodists had obtained publicity. Christians in the lower ranks of the community, though less conspicuous, were not likely to be far behind the rich and the noble in true religion; from which we infer that a goodly number, even in those seasons of visible lifelessness, was reserved by himself for the God of all grace, especially to hail and to aid the new era which was about to rise on the Church. Extending charity, however, to the utmost point which correct judgment will allow, we must look back on that period with feelings far from pleasurable. The Church is not likely to be in a healthy state when she is without exercise, and when she makes little or no aggressions on the world; nor can she richly enjoy those blessings herself which she is not anxious to distribute to others. But there are speculations which may not become us: “the day shall declare it.”

Happy was it for the world that this slumbering did not continue—that men arose, who, instead of enquiring about the number who should be saved, themselves strove to enter in at the strait gate, and zealously endeavoured to excite others to follow their example. The rise of Methodism now took place, in a band of brothers who studied at Oxford. Mr. John Wesley, in point of time as well as of talent, may be considered the first, though it is evident that He, who brings the blind by a way they know not, was simultaneously preparing the hearts of many for a most efficient co-operation in the blessed work about to be performed. Such were Whitefield, Charles Wesley, Ingham, and Hervey. The piety of these great men was deep and energetic, and it clothed them with so much boldness, that, although their pretensions were humble, and they were in a great degree the creatures of circumstances, as well as of divine grace, yet they were distinguished from their contemporaries—even from the best of them—and appeared the representatives of the ancient prophets and apostles. Men felt that they were the servants of the Most High, and earnest in declaring unto them the way of salvation. Like the ministry of John the Baptist, theirs was a voice in the wilderness, and while it proclaimed the kingdom of heaven, it was heard with no ordinary attention.

[xix]

The reader who, piously curious, desires to trace the movements of the Holy Spirit on the heart, will find no common gratification in the following records: he will behold, in so many parts of the great deep, numerous symptoms of life, and will conclude that they are not to be attributed to any artificial or partial heat, but to divine power. “The Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.” There is, perhaps, no error to which we are more exposed than that of supposing that the originators of a series of movements, à priori, saw the whole process from the beginning, and acted from plan rather than from circumstances. We see the connexion which an event has with its antecedent, and therefore imagine the agent was well acquainted with the tendency of the one to effect the other. Universal experience, however, contradicts this inference: even in the history of men of this world, whose plans are often sagaciously formed, and whose object is more definite, we see that the ultimate success is more owing to a skilful and prompt use of accidents than to the guidance of an original design. No philosophy, independently of experience, could foresee the branching and stately oak in the acorn.

To assert, therefore, that the founders of Methodism began their career by chalking out their future operations, is to pay a compliment to their foresight at the expense of truth, and of the continued superintendence of that Being who apportions to his servants their daily work, as much as he does their daily bread. God has a plan, but he does not expose it to the workmen of the temple: it is enough that each knows what he has to do, and how to perform it, at the present moment.

The following history will abundantly verify these sentiments. Can a sober man, however systematized, imagine that anything like the impression which was made would have been effected, both in our own country and in America, if the leaders of the cause—all of whom were attached to the Established Church—had maintained what is called regularity, and a tame canonical obedience to men who had no spirit of enterprise in their character? Would the highways and hedges have been visited? Would the various branches of orthodox Dissenters have been[xx] roused to co-operation? Would lay agency have been made available to the furtherance of the cause? Would the more regular clergy themselves have been so active and useful within the pale of their own community, if there had been no pressure and provocation from without?

Now, nothing is more evident than that this irregularity was unintended. Zeal, indeed, was enkindled, but it would have continued to warm the churches had it not been dislodged by ecclesiastical power. The fire, however, was inextinguishable; and being forbidden to burn on the usual altar, it sought every avenue of escape, and visited and blessed other places. Field-preaching succeeded rejection from the churches; and the Countess of Huntingdon, who thought only of chaplains for her preachers, and of Episcopal ordination for her students, was at length compelled, very much against her will, to violate ecclesiastical order, and shelter herself and her companions in zeal under the Act of Toleration. This growth in the cause of the Gospel, and extension of their original design, characterize these “workers together with God,” and secure all the glory of the plan, as it does that of the execution, to Him: while this view of the economy meets a thousand objections urged by the enemies of vital godliness against this labour of mercy.

If, turning from the more general to the more particular instance, we contemplate the chief subject of the following biography, we shall recognize the same characteristic of divine guidance. How steadily and beautifully does grace advance in the Countess! We follow her, in the present history, from the girl of nine years of age, impressed with solemn thought and purposes on witnessing a funeral, through a series of changes, till we mark an elevation of spirit truly and sublimely Christian, which rises above the splendour of a court—which dares to allow zeal to act, first in visiting the poor—then in opening the drawing-room for noble hearers of the Gospel—then in the employment of laymen and in providing chapels for the accommodation of the multitude, even although those chapels were to be denominated conventicles! The CHILD becomes a MOTHER in Israel indeed, and theologians of the first-rate powers feel it a privilege to[xxi] learn the way of God more perfectly from the lips and the pen of this saintly woman.

No contemplative mind will peruse The Life and Times of the Countess of Huntingdon without noticing the power and the beauty of divine grace, when brought in contact with a vigorous mind, elevated in society by nobility and fortune. That energy which, unsanctified, gives obstinacy to prejudice and pride to vanity, when under the control of “the meekness of wisdom” leads to boldness of investigation, the avowal of Evangelical truth, and to humility, which, in the sight of God, is of great price.

It will be difficult, indeed, to find an instance of the power of God unto salvation brighter than that here exhibited. A woman, a noble personage, a favourite at Court, the wife of a nobleman who only tolerated and aided her zeal as he was won over by her chaste conversation; a widow, and at times much afflicted in her children—living, too, in an age when the gaiety and superstition of the nation were scarcely disturbed by the sober and reasonable voice of truth—every disadvantage overcome, and a meek yet firm profession made of love to our Lord Jesus Christ.

Nor is the providence less conspicuous than the grace of God in the Life of the Countess, as related to her Times. There was needed a hallowed work in progress among the poor and middle classes in society, but the means of reaching these, which the necessity of the case directed, such as preaching in fields and in barns, were not likely to command the attention of the rich and the noble. There needed, therefore, an instrument to bring the Gospel into friendly contact with the highest ranks. This instrument was the Countess. There was an attraction and an influence about her which were felt by many of the great in an extraordinary degree; and not only the courtly Chesterfield, the political Duchess of Marlborough, the gay and frivolous Nash, but the infidel Bolingbroke paid her marked and sincere homage, and listened to the preachers whom she patronized and commended. Many will, doubtless, be astonished, on reading the following pages, to find so large a number of distinguished personages brought by this[xxii] zealous woman to hear the word of truth, as well in the despised conventicle as in her own habitation. It was thus, by applying the discharging-rod to the two extremes, that a shock was given, and that circulation and sensibility were effected in the social body. Many of the rich and more of the poor met together, and their place of meeting was the foot of the cross. How wisely God adapts his agents to his work!

The personal character of the Countess of Huntingdon will be best seen in the general history of her Life and Times: she stands, indeed, so connected with almost all which was good in the last century, that the character of the age, so far as religion is concerned, was in some measure her own. It is not insinuated that she alone impressed that character on the Church, but that she entirely sympathized with it, and was not a whit behind the foremost in affection for souls and zeal for God—in spirituality of mind and fervour of devotion—in contrivance and energy for the extension of the Gospel—in a large and disinterested soul. If she did not appear as the public advocate of the cause, it was because a woman is forbidden to speak in the Church; and if she did not more excel in literary productions, it was because she knew her proper talent—that she was rather fitted to think with vigour and comprehensiveness, than to marshal words to please a critical review. She never, indeed, seems to have thought of the manner and structure of her sentences, but only of giving utterance to the sentiments—always pious, frequently burning—which filled her breast. Those who may be inclined to blame her letters, as deficient in smoothness and perspicuity, will do well to remember that they were not intended for the public eye; they will also admit that some minds of a high order and especially endowed with a power over others, are remarkable for an abruptness of expression which sometimes involves confusion: of this Cromwell was a striking instance. The mental powers of Lady Huntingdon were anything but feeble. No lady, however pious and exalted by rank, could have commanded such respect as she did, unless in the possession of intellectual superiority. The sincerity of her piety and the ardour of her zeal were felt by the first personages of the land, as they were combined[xxiii] with the force of her understanding; and it is believed that the recognition of this fact, in the following work, will, by all impartial readers, be considered a sufficient refutation of Dr. Southey’s poetic imaginings of her mental weakness, and, indeed, insanity!

It will, likewise, be seen that the vigour of the Countess’s mind and the boldness of her zeal were in perfect keeping with the feminine graces. She was not an Elizabeth. The lady, the friend of the poor, the wife, the mother, the sister, the widow—all private and domestic relations—were adorned by her elegance and affection, her meekness of wisdom and boundless kindness, her chaste and winning conversation. The reader will find it difficult to judge whether she appears to the greater advantage when co-operating with the spirits which were effecting a change throughout the moral world, or when quietly moving in domestic and social life.

The circumstances, too, in which she was placed, were favourable to the development of her character. Light enough shone on the professing Church to render the darkness visible; the efforts of the Oxford band, with those of other pious ministers of various denominations, both in England and in Scotland, had brought the deadness of merely formal Christianity into juxtaposition with the living truth of the Gospel, and the Countess saw the contrast, and her eye affected her heart. She wept, she vowed, she acted. She determined to throw all the weight of her influence into the scale of the Gospel; and while considerations of sex, of the disposition and views of her beloved lord, of the rank she held, and which she was so well qualified to support, would have restrained an ordinary mind of common piety from public interference, these very circumstances to her appeared to be talents of great worth, and she was excited to employ them to the greatest advantage. She beheld the rude and cruel treatment which holy men endured, as well from the educated and wealthy as from the ignorant and poor—from magistrates and ecclesiastics as much as from private individuals; and for what? For promulgating the truth—truth which she felt was essential to human salvation—and she generously stepped[xxiv] forward to their defence and encouragement. She had magnanimity enough to break the ranks of her order, and attraction enough to induce many to follow her example. She was as persevering as she was courageous; and you see her, having passed the rubicon, steadily advancing to the capitol. She remembered Lot’s wife; and no opposition—no unforeseen difficulty—no associations necessary to the furtherance of her work, however plebeian, could induce her to look backward. When, therefore, it was necessary to remove out of the drawing-room into the chapel, she did remove; and when she could no longer conduct the services with an ecclesiastical regularity, to which she was attached to the utmost reasonable extent, she braved the reproach of the conventicle; and as the demand for help increased, while clerical labourers were few, she went before even Wesley in taking advantage of lay agency. She followed where, in her judgment, God was pleased to direct; and, secluded from her former elegant associations, she ultimately gave up herself entirely to the direction of her college and of her more immediate Connexion, and to the most really Catholic co-operation with all who loved the Lord Jesus in sincerity.

The world has, perhaps, never seen a finer instance of the power of divine grace, in enabling the mind to rise above all the unchristian restraints of State etiquette, the prejudice of early ecclesiastical associations, and the spirit of party and sectarianism. The last triumph will be viewed by some who understand human nature as the greatest of the three; for it is easier to shake off the trammels of rank and of education, than to merge the individuality of selfishness in the general cause of souls and of Christ. In this fine characteristic, to the glory of her age let it be recorded, the Countess met with much sympathy. Her Life and Times will prove how grand, how sublime, were the views of most of the distinguished agents in the work of God at that stirring period. With the exception of the leader of the great section of Methodism—whose intention to organize a distinct body we do not blame—all seemed to be so intent on the general good of the Church, that they overlooked the advantage of their own particular denominations, and were too eager to[xxv] pluck men as brands from the burning, to spend time and energy in discussing questions of comparative non-importance. It was, indeed, to be expected that a time of greater leisure and calmness would follow, and that then an opportunity would be furnished of investigating the merits of the respective modes of worship and forms of government. We blame not this exercise when kept in a subordinate station; but who, possessed of a shred of the Countess’s mantle, does not weep over the state of truly Evangelical parties in the present day of strife? So far from combining their powers to oppose and overturn infidelity and idolatry, they more than waste a large portion of them in direct contention with each other. This is an unholy warfare indeed—a species of fratricide. What, indeed, is Churchmanship or Dissent compared with the salvation of the soul? The spirits of the noble group encircling the truly Catholic Selina return an answer—“What indeed!”

Should the perusal of the following pages enkindle no breast into zeal for Christ, they will certainly fail of their reward; for we can scarcely conceive of anything, next to the history of our blessed Lord and his apostles, more likely, under the divine blessing, to set the heart on fire than the facts here recorded. Zeal, glowing, active, untiring zeal, animates all the story, and forms the living soul of the entire body: and while, on the one hand, we behold how God honours zeal in his servants, in making it tell so powerfully on the world; on the other hand, we see the proper workings of the doctrines of the cross, and how they consecrate the affections and form the true philanthropist. Let the world be brought under the action of the same principles, and what a scene of brotherly kindness and charity, of mutual zeal, of millennial happiness, will it exhibit!

The publication of the Life and Times of the Countess of Huntingdon will appear to many very opportune, as a spirit of missionary enterprize has been conferred on the Churches, and success has attended, in an extraordinary degree, the efforts which have been made in the South Sea Islands,[1] so dear to the heart of this zealous and almost prophetic woman;[xxvi] and as the Lord has put it into the hearts of many to seek, with growing earnestness, the revival of this work at home. Those who look upon meetings of Christians for especial prayer for the Holy Ghost, or upon public exertions in endeavouring to impress the conscience and win over the heart to Christ, with surprise, as though some new thing had happened, will stand corrected as they find how the present movements were anticipated by those holy personages whose lives are here recorded. Had their successors in the great work been warmed with their zeal, and secured the aid of the Almighty with prayer, united and continuous as theirs, the Church would have presented a different appearance. We only, therefore, seem to be returning to the piety and fervour of the days of old, when we become most anxious to work out our principles and to win souls to our divine Redeemer. The rise and success of Methodism, in all its sections, are the models of revival meetings, and an encouragement to engage in them.

Those persons who may look on the gracious principle of the Gospel with fear or disapprobation will remember, that if the sacred band to which these pages refer did, in their zeal for the Gospel of the grace of God, ride over the forms of dull and lifeless ethics, which had been so generally adopted, and if they did offend the vicious and the self-righteous, their object was as pure as it was benevolent. They carried with them “letters of commendation” in the holiness of their own conduct, and personified the apostolic sentiment, that “grace reigns through righteousness.” Let any man of impartial mind read the following biography, and then say that the tendency of a gratuitous salvation is licentious. Nor could such a leader, however attached to one of the great sections of Methodism, with any fairness, charge the followers of the other leader, as a body, either with an undermining of moral requirements, or with a rejection of the righteousness which is of God by faith. Let facts, and not à priori reasoning, guide the judgment, and it will decide that the doctrines of faith are doctrines which purify the heart; and that the essential, plain, scriptural statements and belief of those doctrines, and not scholastic and metaphysical[xxvii] refinements, are the great instruments, in the economy of our salvation, of transforming the mind and of adorning the character with the Christian graces. The day is gone by, we trust, or at least it ought to have passed away, when either party shall condemn the other for deductions which are not admitted; when the Calvinist shall charge the Wesleyan with denying a sinner’s justification in the sight of God by faith alone in Jesus Christ; and when the Wesleyan shall teach his hearers to identify the Calvinistic scheme, as it is generally received, with the monstrous practical error of Antinomianism. “My little children, love one another.” Perhaps few, since the days of the catholic and amiable Apostle John, have repeated these words with more sincerity and emphasis than Selina, Countess of Huntingdon. She chose her side of the controversy—and, we think, with reason; but however strongly those writers might have expressed themselves, whom, on the whole, she approved, and whatever transient alienations may have taken place, they were clouds passing before the sun: the habit of her mind was Christian affection, and her prayer was for grace to be with all them that love our Lord Jesus Christ in sincerity.

A rigid examiner and critic of the following papers may, perhaps, be able to detect some variations, at different periods of her life, in the minuter parts of the Countess’s creed, as well as in her attachments—a temporary leaning towards mysticism, or towards legality, or towards hyper-Calvinism; but these aberrations were kept within bounds, and mutually corrected each other. He will, however, never find a want of true Catholicity, or the temperament of piety low and frigid. The fervour of her Christian affections would not allow her to be indifferent and heartless; her strong sense and reverence for the holy Scriptures preserved her from the practical errors of the mystics; and her views of the Saviour were too enlarged to admit of self-righteous pride; while her concern for the glory of God and the salvation of mankind was too abiding and active to suffer her to be otherwise than “zealous of good works.” She practically as well as theoretically confessed her imperfection and[xxviii] sinfulness, whilst she rejoiced in the all-sufficiency of God her Saviour; and of no one perhaps whose name adorns the history of the Church of Christ can it be said with greater propriety than of this extraordinary Lady—“Many daughters have done virtuously, but thou excellest them all. Favour is deceitful, and beauty is vain; but a woman that feareth the Lord, she shall be praised. Give her of the fruit of her hands; and let her own works praise her in the gates.”

J. K. FOSTER.

Cheshunt College,

April 15th, 1839.

Antiquity of the Shirley Family. Saxon Origin. Norman Dignities. Royal Alliances. Foreign Crowns. British Coronets. The Clanricardes. Battle of Aghrim. The Parkers. The Lord High Chancellor found guilty. The Levinges. Irish Alliances. Birth of Lady Selina. Her Early Character. First Religious Impressions. The Grave of Youth. Piety. Private Prayer. Fashionable Life. Marriage. The Huntingdon Family. Its Ancestry. Tho Earl of Huntingdon. His Character. “Tears of the Muses.” Self-righteousness. The Methodists. Lady Margaret Hastings. The Light of Religious Truth. Force of Example. Conversion.

Lord Huntingdon. The Bishop of Gloucester. Mr. Whitefield’s Preaching. Its effects. Dr. Southey. Dr. Hurd. Archbishop Seeker. First Methodist Society. Lady Anne Frankland. Lord Scarborough. Dr. Young. Lady Fanny Shirley. Mrs. Temple. Lady Mary Wortley Montague. Lady Townshend. Mr. Pope. Mr. Ingham. Mr. Charles Wesley. Miss Robinson. Lord Lisburne. The House of Lords. Hammond the Poet. Somerville the Poet. Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough. Anecdotes. Duchess of Buckingham. Anecdotes. Duchess of Queensbury. Lord Orford. Lady Hinchinbroke.

Early Methodists. Lay Preaching. Mr. Bowers. Mr. Cennick. Itinerants. Ordination. Mr. Maxfield. Mr. Wesley’s Opinion of his Call. Mr. Wesley’s Sanction. Bishop of Derry. Fetter-lane Society. Conduct of the Bishops. Opposition without. Bickerings. Shaw. The Moravians. Separation in Fetter-lane. First Division. The Society in Moorfields. Enthusiasm. Pluralities. Bishop Burnet. Mrs. Mitchell. Anecdote. Mr. Charles Wesley and the Moravians. David Taylor. General Baptists. Mr. Bennett. Grace Murray. John Nelson.

The Clergy. Mr. Simpson. Mr. Wesley’s Opinion of him. The One Wrong Principle. Mr. Graves. His Recantation. His Explanatory Declaration. Lady Huntingdon’s Schools. Lord Huntingdon’s Character. Miss Cooper: her Death. Letters. The Poor. Death of Mr. Jones. The Poor Penitent’s Death-bed. Mr. Wesley’s preaching on his Father’s Tomb. Donnington Park. Lady Abney. Dr. Watts. “The Grave.” Dr. Blair. Letters. Colonel Gardiner. His Marvellous Conversion. Letters.

Lay-Preachers. Mr. Wesley’s Defence of them. Converted Clergy. Death of Lady Huntingdon’s Sons, George and Ferdinando Hastings. First Methodist Conference. Dr. Doddridge. Letters from Lady Huntingdon. Mr. Jones. The Pretender. Lord Carteret. George II. Death of Colonel Gardiner. Letters to Mr. Wesley, Dr. Doddridge, and Charles Wesley.

Death of the Earl of Huntingdon. His Lordship’s Epitaph. Letters from Sir John Thorold. Lady Huntingdon’s Piety. Letter to Dr. Doddridge. Lady Kilmorey. Duchess of Somerset. Welsh Preachers. Lady Frances Hastings. Mrs. Edwin. Lady Huntingdon’s adherence to the Church of England. Letter from Dr. Watts to Dr. Doddridge.

Mr. Whitefield arrives in England. Preaches at Lady Huntingdon’s. Letters. Lord Chesterfield. Lord Bolingbroke. Anecdotes of Mr. Whitefield’s Preaching. Appointed Chaplain to Lady Huntingdon. Christian Soldiers. Bishop of Exeter. Colonel Gumley. Mrs. Edwin. Lord St. John. Lady Suffolk. The Court Beauties. Lord Chesterfield. Marquis of Lothian. Lady Mary Hamilton. Anecdotes. Lady Townshend. English Nobility at Lady Huntingdon’s. Sir Watkin Williams Wynn. Persecution of the Welsh Methodists. Liberal Conduct of the Government. Marmaduke Gwynne, Esq.

Dr. Gibbons. Dr. Gill. Mr. Darracott. The Young Lord Huntingdon. Lord Chesterfield. The Jews. German Minister. An Impostor. David Levi. Lady Fanny Shirley. Mr. Whitefield and Mr. Wesley. Ashby-place. Mr. Baddelley. Lady Huntingdon’s Illness. Lady Anne Hastings. Mr. Hervey. Bishop of Exeter. Mr. Thompson. Duke of Somerset. Mr. Moses Bruce. Bishop Lavington.

Mr. Romaine. Earthquake in London. Mr. Romaine appointed Chaplain to Lady Huntingdon. Ashby-place. Dr. Stonhouse. Dr. Akenside. New Jersey College. Governor Belcher. President Burr. Dissenting Ministers. Dr. Doddridge. Education of Ministers. Mrs. Hester Gibbon. Mr. Law. Mr. Whitefield’s success at Rotherham. Lord Lyttleton. Mr. Hervey. Dr. Doddridge.

Mr. Whitefield at Ashby. Mr. Moses Browne. Mr. Martin Madan. Lady Frances Hastings. Dr. Stonhouse. Mr. Hartley. Death of the Prince of Wales. Anecdote. Lady Charlotte Edwin. Dr. Ayscough. Lord Lyttleton. Death of Lord Bolingbroke. Dr. Trapp. Dr. Church. Anecdotes.

Mr. Whitefield visits Scotland. Dr. Erskine and Dr. Robertson. Scotch Nobility. Mr. and Lady Jane Nimmo. Letter to Lady Huntingdon. Mr. Wardrobe. Mr. Hervey: his “Theron and Aspasio.” Letters to Lady Huntingdon. Lady Fanny Shirley. Prince and Princess of Wales. Mr. Hervey’s Method of Preaching. Letter from Lady Huntingdon. Mr. Steward. Lady Hastings.

History of Mr. Whitefield’s Tabernacle and Tottenham-court Chapel. Whitefield in London. Mr. Broughton. Countess of Hertford. Fetter-lane. Mr. Cennick. Methodist Society. Tabernacle commenced. Welsh Preachers. Moorfields. Lay Preachers. Nobility at the Tabernacle. Opposition of the Dissenters. Anecdotes of Dr. Watts. Lady Huntingdon and the Moravians. Sir Thomas and Lady Abney. Tabernacle opened. Long-acre Chapel. Hon. Hume Campbell. Tottenham-court Chapel opened. Mr. Edward Shuter. Foote the Player. “The Minor.” Lord Halifax. Duke of Grafton. Mr. Fox. Mr. Pitt. Mr. Rowland Hill. Captain Joss. Mr. Matthew Wilks. Mr. Knight. Mr. Hyatt. Mr. Whitefield’s Will.

Mr. Venn begins to attract notice. Revival of Religion in the Established Church and among the Methodists. By whom first commenced. Mr. Venn’s acquaintance with Mr. Broughton, one of the Original Methodists. Dr. Haweis. Mr. Law. Illness of Mr. Venn. Accompanies Mr. Whitefield to Bristol. Remains with Lady Huntingdon at Clifton. Letter from Mr. Whitefield. Letter to Mr. Venn from Lady Huntingdon. Mr. Whitefield’s Letter to Mr. Venn. Oxford Students. Dr. Haweis. Mr. Whitefield’s Letter to Dr. Haweis. Convicts. Preaching to the Nobility at Lady Huntingdon’s. Handel. Giardini. Musical Composers.

Lady Huntingdon and Mr. Fletcher. Introduction to Lady Huntingdon by Mr. Wesley. Bishop of London. Letter to Mr. Charles Wesley. Mr. Fletcher preaches and celebrates the Communion at Lady Huntingdon’s. Letter to Mr. C. Wesley. Letter to Lady Huntingdon. Mr. Fletcher appointed Vicar of Madely. Writes to Lady Huntingdon and Mr. Charles Wesley. Visits Mr. Berridge. Letter to Lady Huntingdon. Induction to Madely. Success of his Ministry. Letter to Lady Huntingdon.

Rise of Methodism in Yorkshire. Mr. Ingham. Count Zinzendorff. Mr. Delamotte. Mr. Okeley. Mr. Rogers. Letter from Mr. Whitefield. The United Brethren. Mr. Batty. Lady Betty Hastings. Ledstone Hall. Mr. Ingham’s Marriage with Lady Margaret Hastings. Count Zinzendorff visits Yorkshire. Moravian Settlement at Fulneck. John Nelson. Mr. Whitefield’s Letter to Mr. Ingham. Mr. Grimshaw. Lord and Lady Huntingdon visit Ledstone Hall. Mr. Charles Wesley. Mr. Graves encourages John Nelson. Persecution. Provincial Magistrates. John Nelson taken to Prison. Liberated by the influence of Lady Huntingdon. Lord Sunderland. Letter from Lady Huntingdon to Mr. Ingham. The Vicar of Colne. Mr. Grimshaw’s Opinions. Moravian Nobles. John Cennick. Mr. Ingham leaves the Moravians. John Allen.

Mr. Whitefield returns to England. Writes to Mr. Ingham. Visits Yorkshire. Lady Huntingdon in Yorkshire. Extraordinary Occurrence. Mr. Graves. Mr. Milner. Mr. Grimshaw. Conference at Leeds. Mr. Ingham is chosen General Overseer. Mr. Charles Wesley. Mr. Whitefield at Haworth. Inghamite Churches. Church Discipline. Inghamite Preachers. Mr. Newton visits Yorkshire. His Letter to Mr. Wesley. Anecdote of his Preaching at Leeds. Mr. Romaine’s Opinion of the Inghamite Churches. Lady Huntingdon at Aberford. Mr. Romaine preaches in Mr. Ingham’s Chapels. Mr. George Burder. Mr. Romaine at Haworth. Mr. Grimshaw. Sandeman’s Letters. Church Government.

Mr. Venn removed to Huddersfield. Mr. Burnett. Lord Dartmouth. Dr. Conyers. Visitation Sermon. Mr. Thornton. Lady Huntingdon visits Yorkshire. Mr. Romaine. Mr. Wesley. Mr. Madan. Letters from Dr. Conyers to Lady Huntingdon. Letter from Mr. Venn. Mr. Titus Knight. Letter from Mr. Grimshaw. Death of Mr. Grimshaw. Letter from Mr. Venn. Letter from Dr. Conyers. Letter from Mr. Fletcher. Lady Huntingdon, with Messrs. Townshend and Fletcher, visit Huddersfield. Illness of Lady Huntingdon. Mr. Whitefield in Yorkshire. William Shent. Mr. Venn’s Irregularities. Mrs. Hannah More. Defence of Mr. Venn. Letter from Mr. Fletcher. Mrs. Deane. Lady Irvine. Mr. Occum, the Indian Preacher. Captain Scott. The London Shunamite. Mr. Wilson.

Melancholy State of Mr. Ingham. Lady Huntingdon and Mr. Venn. Illness and Death of Lady Margaret Ingham. Letter from Mr. Ingham. Letter from Mr. Romaine. Mr. Ingham’s Treatise on the Faith and Hope of the Gospel. Mr. Riddell. Lady Huntingdon sends Students to Yorkshire. Letter from Mr. Riddell. Mr. Joseph Milner, of Hull, attends Lady Huntingdon’s Preachers. Begins to Preach the Gospel. Mr. Myler. Letter from Lady Huntingdon to Mr. Romaine. Mr. Tyler’s Labours at Hull. Letter from Lady Huntingdon to Mr. Milner. York. Mr. Wren. Letter from Lady Huntingdon. Letter from Mr. Wren. Mr. Glascott. Mr. Wells. Mr. Powley. Lady Huntingdon’s Chapel at York.

Death of the Hon. Henry Hastings. Lady Huntingdon’s Exertions at Brighton. Joseph Wall. Mr. Whitefield’s first Visit to Brighton. Lady Huntingdon sells her Jewels. The Chapel opened by Mr. Madan. Mr. Romaine. Oathall. Captain Scott. Anecdote. Old Abraham. Letters from Mr. Fletcher and Mr. Romaine. Christian Perfection. Mr. Maxfield and Mr. Bell. Letter from Mr. Romaine. Mr. Madan. Letters from Messrs. Berridge, Romaine, and Venn. Mr. Jones (of St. Saviour’s).

Dr. Haweis. Mr. Romaine driven from the Chapel of the Broadway. Lord Dartmouth. Letters from Messrs. Romaine and Conyers. Sinless Perfection. Letters from Messrs. Romaine and Wesley. Erasmus, Bishop of Arcadia. Mr. Toplady. Letters from Messrs. Fletcher and Berridge. Death of Lady Selina Hastings. Colonel Hastings. Account of Lady Selina’s Death. Letters from Lord Dartmouth. Mr. Venn. Mr. Fletcher. Mr. Berridge. Oathall Chapel. Letters from Mr. Berridge. Mr. Venn’s “Complete Duty of Man.” Letters from Messrs. Venn and Berridge.

Mr. Romaine. Lectureship at St. Dunstan’s. Lord Mansfield. Darkness Visible. The Bishop of Peterborough. Popular Election. St. Ann’s, Blackfriars. Probation Sermon. Contest. Canvassing. Scrutiny. Second Election. Suit in Chancery. Gratitude of Lady Huntingdon. Mr. Jesse. Mr. Shirley. Mr. Romaine’s Views of his Preferment. Lewes. Lady Huntingdon procures an opening for Mr. Romaine, for Mr. Madan, and Mr. Fletcher. The Oratorio. Musical Taste of Mr. Madan and Dr. Haweis. Lady Huntingdon’s Chapel at Lewes opened and re-opened. Mr. Mason. His Work on the Catechism. Mr. Edwards, of Ipswich. Mr. Berridge and the Bees. Southey’s “Reflections.” Their Refutation. Character of Berridge. His Wit. His Labours. Berridge and the Bishop.

Mr. and Mrs. Powys. Letters. Mr. Whitefield. Mr. Fletcher. Mr. Venn. Sir C. Hotham. Howel Harris. Chapel at Brighton re-opened. Letters. Mr. Romaine. Mr. Talbot. Mr. Berridge. Anecdote of the Countess. Mr. De Courcy. Mr. Vincent Perronet. Mr. Toplady. Mr. Bliss. Mr. Pentycross. Chapel at Chichester opened. Chapels at Petworth, at Guildford, and Basingstoke. Enlargement of that at Brighton. Mr. Thomas Jones.

Public Fast. Extracts from Lady Huntingdon’s Letters. Prayer-meetings for the Nation. Mr. Venn. Mr. Berridge. Singular Effects of his Preaching. Mr. Romaine and Mr. Madan’s visit to Everton. Mr. Wesley preaches at Everton. Convulsive Motions amongst the Congregation. Letters to Lady Huntingdon. Lady Huntingdon visits Mr. Berridge. Mr. Venn and Mr. Fletcher preach at Everton. Loud Cries amongst their Hearers. Duke of York. Dr. Dodd. Murder of Mr. Johnson. Lord Ferrers. Tried by his Peers. Visited in Prison by Lady Huntingdon. Singular Conduct of Lord Ferrers. Execution.

Proposed Union among the Evangelical Clergy. Methodism in Scotland. Lady Frances Gardiner. Mr. Townshend sent to Edinburgh. Mr. De Courcy. Lady Glenorchy. Mr. Wesley. Lady Maxwell. Samson Occum, the Indian Preacher. Mohegan Indians. Dr. Haweis. Affair of Aldwincle. Lady Huntingdon purchases the Advowson; writes to Mr. Thornton. Lady Huntingdon’s Letters to Lord Dartmouth and Mr. Madan. Anecdote.

Progress of Piety at Cambridge. Rowland Hill. Oxford. St. Edmund’s Hall. The Six Students. Expulsion. Sir Richard Hill. Dr. Horne, Bishop of Norwich. Mr. Goodwyn. Charges against Lady Huntingdon. Account of the Students, and the Proceedings against them. Letter from Lady Huntingdon. Lady Buchan. Letter from Mr. Wesley. Cheltenham. Lord Dartmouth. Letter from Mr. Venn. Mr. Wells. Mr. Trinder. Mr. Whitefield to Mr. Madan. Mr. Madan to Mr. Wesley. Lady Huntingdon to Mr. Alderman Harris. Gloucestershire Association. Lady Huntingdon to Mr. Brewer. Chapels at Gloucester, Worcester, and Cheltenham. Lady Huntingdon’s Letter concerning them.

Chapel at Bath. Pope the Poet. Warburton, Bishop of Gloucester. Lady Fanny Shirley. Charles Wesley. John Wesley. Beau Nash. Anecdote. Mr. Hervey. Methodist Conference. Mr. Larwood. Potter, Archbishop of Canterbury. Dr. Doddridge. Hon. Mrs. Seawen. Mr. Cruttenden. Mr. Neal. Dr. Doddridge visits Bristol. Visits Lady Huntingdon at Bath. Anecdote. Dr. Oliver. Dr. Hartley. Prior Park. Death of Dr. Doddridge. Mr. Grinfield. The Moravians. Count Zinzendorff. Elizabeth King. Lady Gertrude Hotham. Death of Miss Hotham. Marriage of Sir Charles Hotham. Death of his Lady. His own Decease. Death of his Mother, Lady Gertrude. Mr. Theophilus Lindsay. Mrs. Brewer. Lord Huntingdon and Mr. Grimshaw. Lord Chesterfield and Mr. Stanhope. Countess of Moira. Mrs. Carteret and Mr. Cavendish. Countess Delitz. Lady Chesterfield. Earl of Bath. Lord Cork. Anecdote of George II.

Chapter at Bath. Bretby Hall. Mr. Townsend and Mr. Jesse. Mr. Romaine. Mr. Shrapnell. Mrs. Wordsworth. Letters from Mr. Romaine. Chapel opened at Bath. Mr. Whitefield and Mr. Townsend. Mr. Fletcher’s Labours at Bath. Lord and Lady Glenorchy. Letter from Lady Glenorchy to Lady Huntingdon. Death of Lord and Lady Sutherland. Lady Huntingdon, the Wesleys, and Mr. Whitefield. Letter from Lady Huntingdon to Mr. Wesley. Horace Walpole. Lady Betty Cobbe. Nobility attend Lady Huntingdon’s Chapel. Letter from Mr. Whitefield to Mr. Powys. Mr. Stillingfleet. Mr. Venn and Sir Charles Hotham. Anecdotes of Mr. Venn. Mr. Andrews and the Bishop of Gloucester. Mr. Venn at Trevecca. Mr. Lee. Captain Scott and Mr. Venn. Anecdotes of Captain Scott. Letter from Mr. Venn. Mr. Howel Davies. Anecdote. Dr. Haweis. Mr. Cradock Glascott’s Letter from Mr. Fletcher.

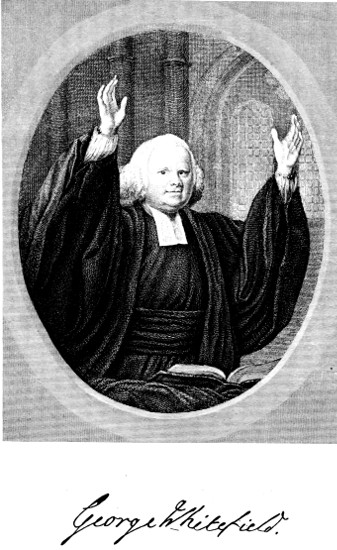

George Whitefield

[1]

LIFE AND TIMES

OF THE

COUNTESS OF HUNTINGDON

Antiquity of the Shirley Family—Saxon origin—Norman dignities—Royal alliances—Foreign crowns—British coronets—the Clanricardes—Battle of Aghrim—the Parkers—The Lord High Chancellor found guilty—the Levinges—Irish alliances—Birth of Lady Selina—her early character—First religious impressions—The grave of youth—Piety—Private prayer—Fashionable life—Marriage—The Huntingdon family—its ancestry—The Earl of Huntingdon—his character—“Tears of the Muses”—Self-righteousness—The Methodists—Lady Margaret Hastings—The light of Religious Truth—Force of Example—Conversion.

SELINA, Countess of Huntingdon, the most extraordinary woman perhaps of an age fertile in extraordinary characters, and in many respects the greatest whom England has produced, was descended from the ancient and honourable house of Shirley—a house as remarkable for a long successive union of piety with nobility, as for the rarely-equalled purity of its genealogical tree, one of whose ancient branches is coeval with the time of Edward the Confessor. All its intermarriages having taken place with the most ancient and illustrious English houses, many of its line having distinguished themselves in the military history of their country—it would be difficult to find a family more illustrious or better entitled to the claim of true nobility. The devotion and fidelity they have always borne to their Sovereign Princes are great and singular. Their high and renowned alliances joined them in a near degree of propinquity of blood to the Royal Stem of England, both Saxon and Norman; to those of France, Scotland, Denmark, Aragon, Leon, Castile, the Roman Empire, and almost all the princely houses of Christendom. Within the kingdom of Great Britain, they are connected with the most honourable and princely houses of the Barons of Berkeley, Dukes of Norfolk and Buckingham, Earls[2] of Arundel, Oxford, Northumberland, Shrewsbury, Kent, Derby, Worcester, Huntingdon, Pembroke, Nottingham, Suffolk, Berkshire, and to most of the ancient and flourishing families of the nobility and gentry of the monarchy. Thus the living descendants of this illustrious house have the honour to issue from the blood of Emperors, Kings, Princes, Dukes, and some of the most renowned Earls. The lands and seigniories which they have held from the remotest period have added to their honour; but, above all earthly things, we hold their ardent and inextinguishable zeal for the advancement of the service of the Most High God, and their singular liberality towards the Church—for they have, at all periods, evinced the sincerity of their devotion by the great number of places of worship they have founded, built, re-edified, endowed, or enriched, with their means and revenue, in various parts of the kingdom.

The Shirleys derive their descent from Sasuallo or Sewallus de Etingdon, whose name (says Dugdale, in his “Antiquities of Warwickshire”) argues him to have been of the old English stock; which Sewallus resided at Nether-Etingdon, in the county of Warwick, about the reign of Edward the Confessor, the seat of his ancestors for many generations before. After the Conquest, the lordship of Nether-Etingdon was given to Henry, Earl of Ferrars, in Normandy, who was one of the principal adventurers with the Norman Duke William, and was held under him by this Sewallus; to whose posterity, in the male line, it has continued to the present day.

From this Sewallus descended, in a direct line, Sir Henry Shirley, Bart., who was sheriff of Leicester in the last year of the reign of James the First. He married, in 1615, Lady Dorothy Devereux, the youngest of the two daughters of that great but unfortunate favourite of Queen Elizabeth, Robert, Earl of Essex, and sister and co-heiress to her brother, the last Earl of Essex. By this alliance, the Earls Ferrars quarter the arms of France and England with their own; the Earl of Essex having been maternally descended from Richard Plantagenet, Earl of Cambridge, grandson to King Edward III., and grandfather to King Edward IV., and also from Thomas Plantagenet, Duke of Gloucester, youngest son of Edward III. Sir Henry Shirley had, by the Lady Dorothy Devereux,[2] two sons and[3] one daughter, Lettice,[3] who married William de Burgh, Earl of Clanricarde. His eldest son, Charles, died unmarried about the year 1649; and Sir Henry Shirley was succeeded by his son, Sir Robert Shirley, who, for his loyalty to Charles I., was[4] imprisoned[4] in the Tower of London, by Oliver Cromwell, where he died during his confinement, not without suspicion of poison. It was his singular praise to have done the best in the worst times, and to have hoped even in the most calamitous circumstances. By his wife, Catherine, daughter of Humphrey Okeover, Esq., of Okeover, in the county of Stafford, he had two sons: Sir Seymour Shirley, his successor, and Sir Robert, afterwards Earl Ferrers;—also two daughters: Catherine, married to Peter Venables, Baron of Kinderton; and Dorothy, to George Vernon, Esq., of Sudbury, in Derbyshire. The only son of Sir Seymour Shirley, by the Lady Diana Bruce, daughter of the Earl of Aylesbury, surviving his father but a short time, the title of Baronet devolved on his uncle, Sir Robert Shirley, the grandfather of Lady Huntingdon; which Sir Robert Shirley, First Earl Ferrers, was born at East-Sheen, in Surrey, during his father’s confinement in the Tower; and on December 14, 1677, his Majesty King Charles II., taking into consideration that this Sir Robert Shirley was grandson and heir to Lady Dorothy Devereux, the younger of the two sisters and heirs of Robert Devereux, the last Earl of Essex of that family, and that the issue male of the elder sister and co-heiress, the Lady Frances, who married William Seymour, Marquis of Hertford, was then extinct, was pleased to confirm unto him and his heirs the ancient Baronies of Ferrars of Chartley, Bourchier, and Lovaine; which honour had been in abeyance between the Ladies Frances and Dorothy Devereux, and their descendants, from the decease of their brother, the Earl of Essex, without issue. Sir Robert Shirley being so declared Lord Ferrars of Chartley, &c., was introduced into the House of Peers, January 28, 1677–8, and took his place according to the ancient writ of summons to John de Ferrars, his lineal ancestor [February 6, 27th Edward I.] He was Master of the Horse and Steward of the Household to Queen Catherine, consort of King Charles II., and was sworn of the Privy Council to King William [May 25, 1699]. In the reign of Queen Anne, he was again sworn of the Privy Council [November 25, 1708], according to the act for the union of the two kingdoms; and on the 3rd September, 1711, was advanced to the titles of Viscount Tamworth and Earl Ferrars, by reason of his descent from the ancient and noble family of Ferrars.

His Lordship was twice married, and had a family of twenty-seven children. His first Countess was daughter and heiress to[5] Lawrence Washington, Esq., of Caresden, in Wiltshire, who, dying October 2, 1693, was buried at Stanton-Harold; he married, as his second wife, in August, 1699, Selina, daughter of George Finch, Esq., of the city of London. This Lady Ferrars died March 20, 1762. Robert Shirley, the eldest son, was created Earl Ferrars, but died before his father. He had been twice married; first, to his cousin, Catherine, daughter to Peter Venables, Baron of Kinderton, who dying in her nonage, he married, secondly, Anne, daughter of Sir Humphrey Ferrars, heiress to her grandfather, John de Ferrars, Esq., of Tamworth Castle, last heir male of the Barons Ferrars of Groby. She bore him three sons, Robert, Ferrars, and Thomas, and a daughter, Elizabeth. Robert became, by his father’s death, heir-apparent to his grandfather, and was elected Knight of the Shire for the county of Leicester in the last Parliament called by Queen Anne. He survived both his brothers, and likewise died of the small-pox in the life-time of his grandfather, July 5, 1714, unmarried, leaving his sister Elizabeth, married, in 1716, to James Compton, Earl of Northumberland, his heir; she died March, 1740–1, leaving an only daughter, and heiress, Charlotte, Baroness Ferrars, first wife of George, Marquis Townshend.

Earl Ferrars departed this life on the 25th of December, 1717, and was succeeded in his title and estates by his second son, the Honourable Washington Shirley, who took his seat in the House of Peers as Second Earl Ferrars. His Lordship was father to Lady Huntingdon, and was born June 22, 1677, and named Washington, after his mother, the daughter and heiress, as we have said, to Lawrence Washington, Esq., by Eleanor, sister to Sir Christopher Guise, Bart., of Hynam Court, in the county of Gloucester. Lord Ferrars was a nobleman of great honour and probity, and a lover of justice; the affability and benevolence of his disposition, and the goodness of his understanding, made him beloved and esteemed throughout his life. The respect and veneration paid to him while he lived, and the universal lamentations at his death, are ample testimonies of a character not easily to be paralleled.

Lady Huntingdon’s mother was descended from a family of great respectability and antiquity, seated at Parwick, in the county of Derby, as early as 1561. Her great grandfather, Richard Levinge, Esq., of Parwick, married the aunt of Thomas Parker, an eminent lawyer, who rose to the dignity of Lord High Chancellor and Earl of Macclesfield. It was an extraordinary instance of the fallibility of human virtue, that this every way distinguished character, one of the great ornaments of the Peerage, who had so long presided at the administration of justice,[6] should himself be arraigned as a criminal on charges of corruption. He was tried at the bar of the House, and unanimously pronounced guilty; in consequence of which he was removed from his high office and fined thirty thousand pounds, as a punishment for his offence. He was the second Lord Chancellor of England impeached by the grand inquest of the nation for corruption of office; and, like his great predecessor, Lord St. Alban’s, found guilty of the charge. The prosecution was carried on with great virulence; and though rigid justice demanded a severe sentence, yet party zeal and personal animosity were supposed to have had their weight in that which was passed upon him. His Lordship’s son succeeded, as second Earl of Macclesfield; and his only daughter, Lady Elizabeth Parker, married Sir William Heathcote, of Hursley, in the county of Southampton, Bart. Upon the male descendants of this lady the honours of her father are entailed, in default, at any period, of the direct male line.

Her Ladyship’s grandfather, the Right Hon. Sir Richard Levinge, Knight, of Parwick, Recorder of, and member for, Chester, having attained great eminence at the English Bar, was appointed, in 1690, Solicitor-General in Ireland and Speaker of the House of Commons. He was created a Baronet of that kingdom by Queen Anne, October 26, 1704; he was a man of good judgment and great integrity; and set himself with great application to the functions of his important post. In 1711, Sir Richard was nominated Attorney-General, and in 1720, Lord Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas. A few years after his removal to Ireland he purchased the estate of High Park, now Knockdrin Castle, in the county of Westmeath, the present residence of the Levinge family. Sir Richard married, first, in 1680, Mary, daughter and co-heiress of Sir Gawen Corbyn, of London, Knt., by whom he had three sons and three daughters; the eldest of the latter, Mary, married Washington, Earl Ferrars; the second, Dorothea, married first Sir John Rawdon, of Moira, and afterwards, Dr. Charles Cobb, Archbishop of Dublin; the third, Grace, married Edward Kennedy, Esq., of Mullow, in the county of Longford.

Sir Richard Levinge married, second, Mary, daughter of the Hon. Robert Johnson, one of the Barons of the Exchequer in Ireland, by whom he had one son, who died July 13, 1724, and was interred in St. Mary’s, in Dublin. His eldest son, Sir Richard, succeeded to him as the second Baronet. He was for many years member of Parliament for Blessington, and died November 2, 1731, without issue. Lady Levinge survived him till the 25th of February, 1747. She was a daughter of Sir[7] Arthur Rawdon (brother of Mary, Countess of Granard, and nephew of Edward, Earl Conway), by Helena, daughter and heiress to Sir James Graham, third and youngest son of William, Earl of Monteith and Airth, in Scotland. The title devolved upon Sir Richard’s brother, Sir Charles Levinge, whose grandson, Sir Richard Levinge, the present representative of the family, married the eldest daughter of Lord Rancliffe, and has a very numerous family. Miss Selina Levinge, sister to Sir Richard, married the Rev. Henry Lambert Bayley, of Ballyarthur, in the county of Wicklow; and Miss Anne Levinge espoused the Rev. William Gregory, second son of W. Gregory, Esq., Secretary of the Civil Department in Ireland, and grandson, maternally, of William, first Earl of Clancarthy, and nephew of the present Archbishop of Tuam.

Dorothy Levinge, one of the three sisters of the Right. Hon. Sir Richard Levinge, Bart., married Henry Buckston, Esq., whose ancestors had been seated at Bradborne, in Derbyshire, for several centuries. His descendant, the Rev. German Buckston of Bradborne, is the present representative of that family.

Lady Selina Shirley was the second of the three daughters and co-heiresses of Washington, second Earl Ferrars, and was born August 24, 1707. Her eldest sister, the Lady Elizabeth, was married to Joseph Gascoigne Nightingale, Esq., of Enfield, in the county of Middlesex, and Mamhead, in the county of Devon; and the youngest, Lady Mary, to Thomas Needham, Viscount Kilmorey, of the kingdom of Ireland, nephew to the Earl of Huntingdon. His Lordship dying Feb. 3, 1768, without issue by Lady Kilmorey, who died August 12, 1784, was succeeded by his next surviving brother, John, tenth Viscount, grandfather of Francis, present Earl of Kilmorey. Lady Elizabeth Nightingale had a son, named Washington Nightingale, who died, unmarried, in 1754; and a daughter, Elizabeth, sole heiress to her father and mother, who was married to Wilmot, Earl of Lisburne, an Irish Peer, and died May 19, 1755, in giving birth to Wilmot Vaughan, second Earl of Lisburne. On the death of Sir Robert Nightingale, Bart., one of the directors of the East India Company, who died, unmarried, in 1722, the family estates devolved upon his cousin, Robert Gascoigne, Esq., second son of the Rev. Joseph Gascoigne, of Enfield; and the baronetcy lay dormant for three quarters of a century, until it was claimed, in 1797, by Lieut.-Colonel Edward Nightingale, father of the present Baronet. But the eldest son of Mr. Gascoigne had assumed the name of Nightingale previous to his marriage with the Lady Elizabeth Shirley, in 1725, who was interred with him in Westminster[8] Abbey, where a well-known and unrivalled monument by Roubilliac is erected to their memory.