Title: The Woodranger

A story of the pioneers of the Debatable Grounds

Author: George Waldo Browne

Illustrator: L. J. Bridgman

Release date: December 21, 2025 [eBook #77515]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: A. Wessels Company, 1899

Credits: Produced by Donald Cummings and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

THE WOODRANGER

A Story of the Pioneers of the Debatable Grounds

BY

AUTHOR OF

“TWO AMERICAN BOYS IN

HAWAII,” ETC.

Illustrated by

NEW YORK

A. WESSELS COMPANY

1907

Copyright, 1899

By L. C. Page and Company

(Incorporated)

All rights reserved

TO

MY MERRY LITTLE SON

HOPING IT WILL INTEREST AND INSTRUCT HIM

THIS VOLUME IS MOST AFFECTIONATELY INSCRIBED

[3]

[5]

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

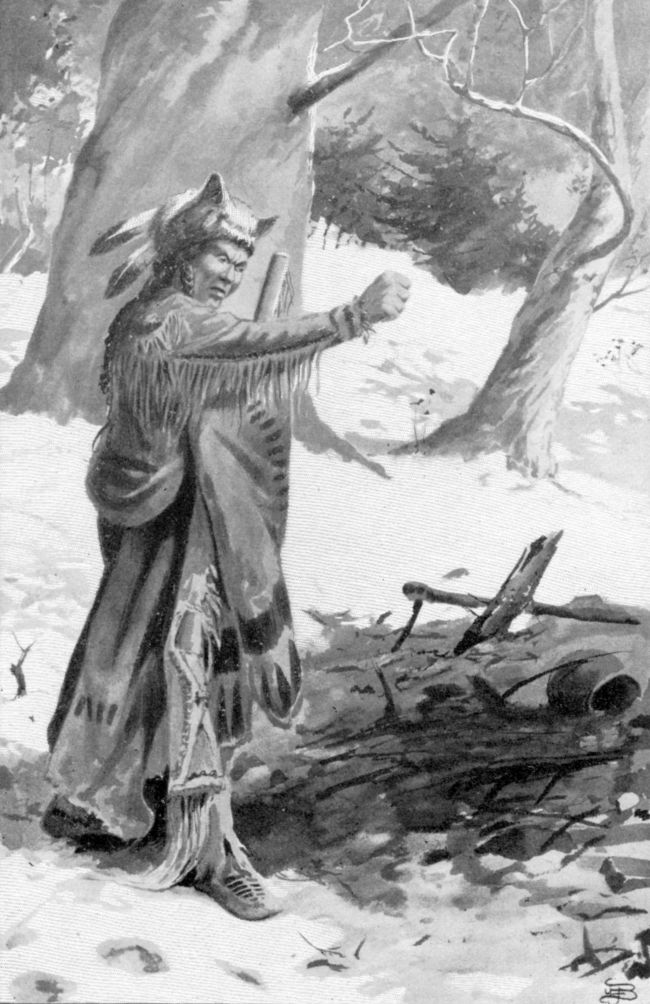

| “‘I’m Under Oath’” | Frontispiece |

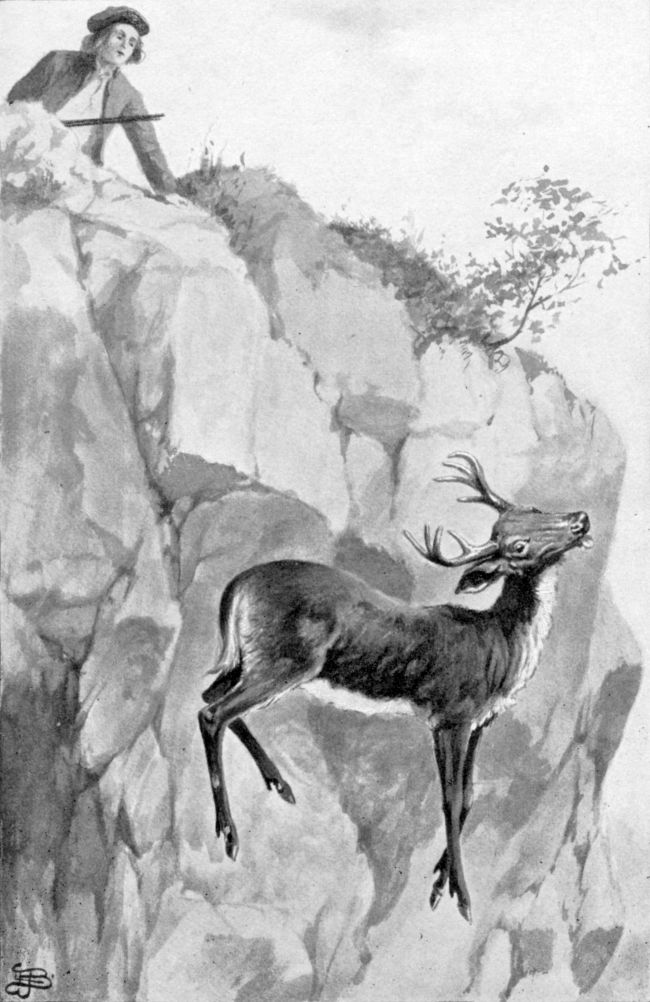

| “The Deer Sprang Out over the Dizzy Brink” | 15 |

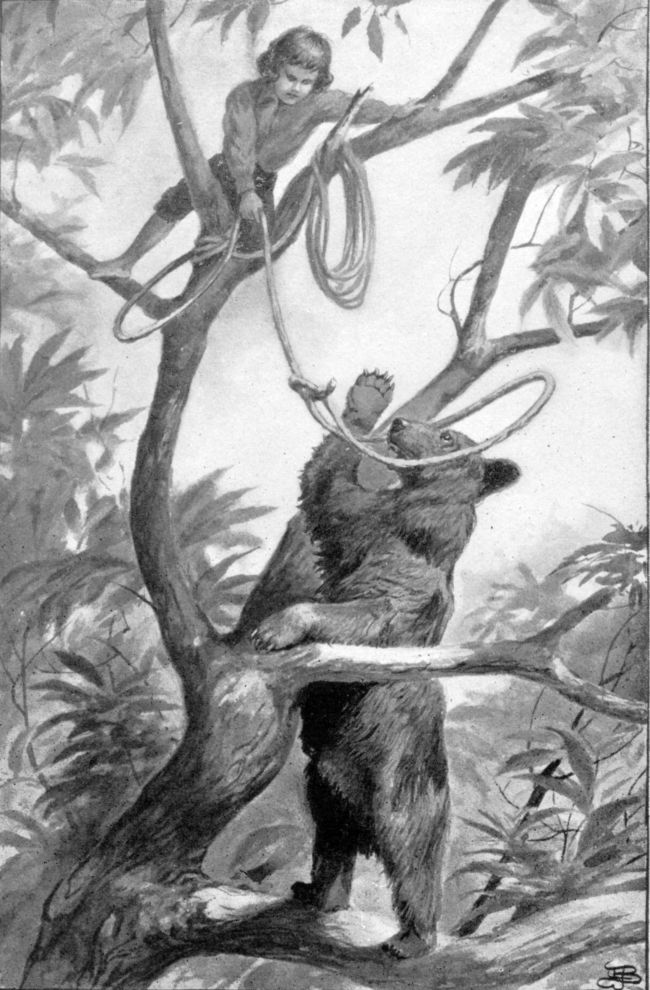

| “Archie Improved His Opportunity to Drop the Noose over Her Head” | 144 |

| “His Right Arm Moved Slowly To and Fro” | 278 |

In order to understand the scenes about to be described, it is necessary to take a hasty glance at the general situation in 1740 of the colonists in the vicinity of the Merrimack River. It should be borne in mind that New England was only a narrow strip of country along the seacoast, and was divided into four provinces,—Rhode Island, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire.

Unfortunately for the welfare of the pioneers in the last-named province, the boundary line between New Hampshire and Massachusetts was a matter of dispute for nearly a hundred years. The difference had arisen from a misconception at the outset in regard to the source of the Merrimack River, which was believed by its early discoverers and explorers to rise in the west and follow an easterly course to the ocean. Accordingly, the province of Massachusetts claimed not only all of the land to the southwest of the other province, but a strip three miles wide along the east bank of the stream to its supposed source in the great lake (Winnepesaukee), including not only the debatable [8]ground of Namaske, but a tract of country to its south and east, called the “Chestnut Country,” on account of the large number of those trees growing there.

In 1719 a part of this territory was settled by a party of colonists from the north of Ireland, known as Scotch-Irish, from their having previously emigrated to that country from Scotland. These settlers, who called their new town first Nutfield and then Londonderry, in honour of the county from whence they had come, supposed that the deeds and grants which they had received from the province of New Hampshire would allow them to hold the debatable ground. They were upright, courageous men and women, but were rigid Presbyterians, and for this reason met with little favour from their equally austere Puritan neighbours from Massachusetts.

In order to colonise the disputed territory, Massachusetts at about this time began a system of granting lands as a reward for meritorious service in fighting the Indians, and among others was a grant to the survivors of the famous “Snow Shoe Expedition” of the tract of land below Namaske Falls, which had gained the disreputable name of Old Harrytown. The leader of the expedition, Captain Tyng, was dead, but in honour of him the new town was named Tyng Township.

In one respect the settlers of Tyng Township were [9]fortunate. They arrived during one of those transitory intervals of comparative peace, which came and went during the long and sanguinary struggle with the Indians like flashes of sunlight on a stormy day. In 1725, following several victories of the whites over their savage enemies, foremost of which was Lovewell’s fight, the chief of the Abnaki Indians, then the leading tribe in New England, signed a treaty of peace at Boston. This treaty was not broken until 1744, and the whole history of Tyng Township is included within these two dates.

As stated above, some of the Scotch-Irish, under grants from New Hampshire, had already settled in the territory granted by Massachusetts to Tyng’s men, and an intense rivalry at once sprang up between the settlements. The English were determined and aggressive, the Scotch stubborn and ready to fight to the bitter end for what they considered their rights, and before long both sides were ready to resort to arms the moment an overt act of their rivals should seem to call for such measures.

G. Waldo Browne.

As the distant baying of a hound broke like a discordant note upon the quiet of the summer afternoon, a youth sprang upright on the pinnacle of a cliff which reared its bald head above the surrounding forest, and listened for a repetition of the unexpected alarm.

The young listener presented a striking figure, the strong physique of limb and body brought into bold relief against the sky, and each feature clearly outlined, as he gazed into space. He was in his nineteenth year, above the medium height, but so symmetrical in form that he did not look out of proportion. His high cheek-bones, clear blue eyes, straight nose, well-curved chin, and firm-set mouth showed the characteristics of the Lowland sons of old Scotland. His name was Norman McNiel.

For nearly an hour he had lain there on the summit [12]of Rock Rimmon, gazing in a dreamy way over the broad panorama of wilderness, while his mind carried him back across the stormy sea to his early home in Northern Ireland, which he had left a year before to come to this country with his young foster-sister Rilma and their aged grandfather, Robert MacDonald, last of the noted MacDonalds of Glencoe.

“It was Archer’s bark!” he exclaimed. “He must have followed me, and now has started a deer from its favourite haunt in Cedar Swamp. Hark! there he sounds his warning again, and never bugle of bold clansman rang clearer over the braes o’ bonny Scotland. He is coming this way! Forsooth! A bonny hunter am I with not a grain of powder in my horn, and the last bullet sent on a fruitless errand after a wild bird. A pretty kettle of fish is this for a McNiel!”

Another cry from the hound at that moment, clearer, louder, nearer, held his entire attention, and sent the warm blood tingling through his veins. Far and wide over the valley rang the deep bass baying of the hound, the wooded hills on either side catching up the wild sound, and flinging it back and forth, until it seemed as if a dozen dogs were on the heels of some poor hunted victim.

The chase continued to draw swiftly nearer and nearer. As if the race had become too earnest for [13]it to keep up its running outcries, only an occasional short, sharp cry came from the hound. Soon this too ceased, and Norman was beginning to fear the chase was taking another course, when the sharp report of a firearm awoke the silence.

A howl from the hound quickly followed, while this was succeeded by a more pitiful cry, and the furious crashing of bodies plunging headlong through the thick undergrowth.

Immediately succeeding the renewed baying of the hound, Norman became aware of the sound of some one pushing his way rapidly through the growth off to his right, and at an acute angle to the course being taken by the deer. The next moment he was surprised to see a human figure burst into the opening at the lower end of the cliff, apparently making for the summit of Rock Rimmon. His surprise was heightened by a second discovery swiftly following the first. The newcomer was an Indian, carrying in his hand the gun with which he had shot at the deer.

Seeing Norman, instead of approaching any nearer the cliff, the red man abruptly changed his course, disappearing the next moment in the forest with the Indian’s peculiar loping gait.

“Christo, the last of the Pennacooks!” exclaimed Norman. “It was he who fired the shot. I—”

He was cut short in the midst of his speculation [14]by the sudden appearance of the hunted deer on the opposite side of the clearing.

Though Rock Rimmon has a sheer descent of nearly a hundred feet on the south, its ascent is so gradual on the north as to make it an easy feat to reach its top. A growth of stunted pitch-pines grew to within fifty yards of Norman’s standing place. The ledge was covered with moss in spots, while here and there a scrubby oak found a precarious living.

Although expecting to get a sight of the deer, as he imagined the fugitive to be, Norman was still considerably surprised to see the hunted creature bound out from the matted pines, and leap straight up the rocky pathway! Close upon its heels followed the hound, no longer keeping up its resonant baying.

The fugitive deer seemed to have a purpose in pursuing this narrow course, as it might have turned slightly to the right or left, and escaped its inevitable fate on the cliff. The large, lustrous eyes, glancing wildly around, saw nothing clearly. The blood was flowing freely from its panting sides, and it was evident its strength was nearly spent. To Norman, who had seen but a few of its kind, there was a human expression in the soft light of its great, mournful eye, and intuitively he shrank back, as he saw the doomed creature approaching.

[15]

In its fatal alarm the terrified animal had not seen him. In fact it seemed to see nothing in its pathway,—not even the precipice cutting off further retreat. As if preferring death by a mad leap over the chasm, it sped to the very brink without checking the speed of its flying feet! Norman held his breath with a feeling of horror at the inevitable fate of the poor creature. The hound, as if realising the desperate strait to which it had driven its prey, stopped. Then, with a last mournful glance backward, and a sharp cry of pain and despair, the deer sprang out over the dizzy brink, its beautiful form sinking swiftly upon the stony earth at the foot of Rock Rimmon!

[16]

So sudden and strange was the leap to death of the hunted deer, that Norman McNiel stood for a moment stupefied by a sense of horror at the strange sight. The hound, a magnificent animal, as if sharing its master’s feeling with an added shame for the part it had taken in the matter, crept to his side, and sank silently upon the rock at his feet.

“He escaped you, Archer,” said the young master, patting the dog on its head, “and me, too, for that matter. But I cannot see that either was to blame. The poor creature met his fate bravely.”

Then, to satisfy himself that the deer was really killed, he approached to the extremity of the cliff, and peered into the depths below. He discovered, at his first glance, the mutilated form of the creature. There could be no doubt of its death. The sound of footsteps at that instant arrested his attention. Looking from the shapeless body of the deer, he saw two men pushing their way through the dense [17]growth skirting the bit of clearing at the foot of the ledge.

The foremost of the newcomers was an entire stranger to him, though he guessed that he belonged to the Tyng colonists, who had settled below the falls. He wore a suit of clothes made from the coarse homespun cloth so common among the Massachusetts men, and his firearm was of the English pattern usually carried by them. He was not much, if any, over thirty years of age, with a countenance robbed of its slight share of good looks by a stubble of reddish beard.

His companion, whom Norman remembered as having seen once or twice the previous season, was several years the senior of the other, and of altogether different appearance. He was clad in a well-worn suit of buckskin, the frills on the leggins badly frayed from long contact with the briars and brushwood of the forest. His feet were encased in a pair of Indian moccasins, while he wore on his head a cap of fox skin, with the tail of the animal hanging down to the back of his neck. Though bronzed by long exposure to the summer sun and winter wind, scarred by wounds, and rendered shaggy by its untrimmed beard, his face bore that stamp of frank, honest simplicity which was sure to win for the man the respect and confidence of those he met. The silver streaks in the hair falling in profusion [18]about his neck told that he was passing the prime of life. Still there was great strength in the long, muscular limbs, and, while he moved generally with a slow, shuffling gait, he was capable of astonishing swiftness of movement whenever it was called for.

He showed his natural instinct as a woodsman by the noiseless way in which he emerged from the forest, in marked contrast to the slouching steps of his companion. Stuck in his belt could be seen the handle of a serviceable knife, while he carried a heavy, long-barrelled rifle of a pattern unknown in this vicinity at that time. The weapon showed that it had seen long and hard service.

Norman was about to speak to him, when the other exclaimed, in the tone of one announcing an important discovery:

“Look there, Woodranger! if you want to believe me. It’s the critter that got the shot we heerd, and it’s a deer as I told ye. A shot out o’ season, too, mind ye, Woodranger. Ef I could clap my eyes on the fool he’d walk to Chelmsford with me to-morrer, or I ain’t deer reeve o’ this grant o’ Tyng Township, honourably and discreetly ’p’inted by the Gineral Court o’ the Province o’ Massachusetts.”

“It seems to me, Gunwad,” said his companion, speaking in a more deliberate tone, as he advanced to the deer’s mutilated form, “that the creetur must have taken a powerful tumble over the rock hyur. [19]I reckon a jump off’n Rock Rimmon would be nigh ’bout enough to stop the breath o’ most any deer.”

“What made the deer jump off’n the rock, Woodranger? It was thet air dog at its heels! And ef there ain’t a hunk o’ lead in the critter big ernough to send the man thet fired it to Chelmsford I’ll eat the carcass, hoofs, horns, and, hide.”

With these words he bent over the still warm body of the deer, and began a diligent search for some sign of the wound supposed to have been made by the shot.

Woodranger dropped the butt of his rifle upon the ground, and stood leaning on its muzzle, while he watched with curious interest the proceeding of his companion.

Gunwad’s search was not made in vain, for a minute later he held up between the thumb and forefinger of his left hand, which was reeking with blood from its contact with the dead deer, the bullet he had hoped to find.

“What do you think of it now?” he demanded, showing by his tone and manner that he was highly pleased with his discovery. “What do ye call thet?”

“I suppose it would require no great knowledge o’ warfare to pronounce it a bullet,—leastways a pellet o’ lead fit for the weepon o’ a red. It was never the bullet o’ a white man’s gun. But that [20]does not enter into the question. That bullet was not the death o’ this deer.”

“You’re talking at random now. Mebbe it didn’t kill the deer, but ef the dog hadn’t driven the critter over the rock, thet lead would hev fixed it for salting.”

“I’m not so sure o’ that, friend Gunwad. If you’ll look a leetle cluser you’ll see that the bullet didn’t touch any vital. It sort o’ slewed up’ards and side—”

“Much has thet got to do erbout it!” broke in Gunwad, beginning to show anger. “I shall begin to think ye air consarned in the matter. Fust ye say it wasn’t the bullit o’ a white man, and I should like to know what cause ye hev for saying thet.”

“It was never run by any mould,” replied Woodranger, calmly, as he took the bullet in his hand; “it was hammered out.”

“Say!” exclaimed Gunwad, suddenly changing the drift of the conversation, “Ye’re a sharp one, Woodranger. They say ye’re the best guide and Injun trailer in the two provinces. Help me fasten this bizness on that Injun at the Falls, and I’ll gin ye the best pair o’ beaver skins ye ever sot eyes on for years.”

“You mean Christo,” said the other.

“I reckon he’s the only red left in these parts, and ’arly riddance to him! Jess show thet is an [21]Injun bullit, and I’ve settled his ’count, sure’s one and one make two.”

“That savours too much o’ wanton killing, Gunwad. I ain’t no special grudge ag’in this Christo, though it may be I have leetle fellowship for the race. There be honest men, for all I can say, among the dusky-skins, and Christo may be one o’ ’em. At any rate till I ketch him in red devilryment I’m not going to condemn him. Ah, Gunwad, I ’low I live by the chase, and if I do say it, who has no designment to boast o’ the simple knack o’ drawing bead on wildcat or painter, bear or stag, Old Danger never barks at the same creetur but once; but he never spits fire in the face o’ any creetur that can’t do more good by dying than living.”

“Look here, Woodranger!” exclaimed Gunwad, impatiently, “I can see through yer logic. Ye air ag’in this law o’ protecting deer.”

“I’m ag’in the law that’s ag’in man. ’Tain’t natur to fill the woods with game, and then blaze the trees with notices not to tech a creetur. Mind you, I’m ag’in wanton killing, and him don’t live as can say I ever drew bead on a deer out o’ pure malice. I have noticed that it’s the same chaps as makes these laws as are the ones to resort to wanton destruction. To kill jess for the fun o’ killing is wanton. It is the great law o’ natur for one kind to war on another, the strong on the weak, from the biggest brute to [22]the smallest worm, and man wars on ’em all. If he must do so, let there be as much fairness as is consistent with human natur. No, I’m not a liker o’ the law that professes to defend the helpless, but does it so the wanton slayer can get his glut o’ slaughter in a fall’s hunt. I—”

The Woodranger might have continued his rude philosophy much longer had not a movement of the hound on the cliff attracted their attention, and both men glanced upward to see, with surprise, Norman McNiel looking quietly down upon them.

“Hilloa!” exclaimed Gunwad, divining the situation at once, “here is the deer slayer, or I’m a fool. Stand where ye air, youngster!” raising his gun to his shoulder, as he spoke.

[23]

“Don’t make any wanton move,” warned Woodranger. “If I’m not mistaken the younker is one o’ the Scotch settlers on the river, and he’s a likely lad, or I’m no jedge o’ human natur’.”

“I jess want him to know he ain’t going to play Injun with me,” replied Gunwad. Then, speaking in a louder key to Norman, he said:

“Climb down hyur, youngster, and see thet ye air spry erbout it, for I don’t think o’ spending the night in these woods.”

“I will be with you in a moment,” said Norman, starting toward the west end of the cliff, where he could descend with comparative ease. He had overheard enough to understand that Gunwad would prove no friend to him, though he did not realise the deer reeve’s full intent.

“One o’ ’em condemned furriners!” muttered Gunwad. “I’d as soon snap him up as thet copper-skin. Hi, there, youngster! be keerful how ye handle thet shooting-iron,” as Norman inadvertently lifted the [24]weapon toward his shoulder in trying to avoid a bush.

“You have nothing to fear, as it isn’t loaded. I—”

“Isn’t loaded, eh?” demanded the deer reeve. “Let me take it.”

Norman handed him the firearm, as requested, and then turned to look at Woodranger, who was watching the scene in silence, with a look in his blue eyes that it was difficult to read.

“I reckon I’ve got all the evidence I shall need,” said Gunwad, after hastily examining the gun. “You’ll need to go with me to Chelmsford, youngster, to answer the grave charge of shooting deer out o’ season. It’ll only cost ye ten pounds, or forty days’ work for the province. Better have waited ernother day afore ye took yer leetle hunt!”

“I have shot no deer, sir,” replied Norman. “Neither have I hunted deer.”

“Don’t make yer case enny wuss by trying to lie out o’ it. The circumstances air all ag’in ye. Air ye coming erlong quiet like, or shall I hev to call on Woodranger to help me?”

“Where are you going to take me?” asked Norman, feeling his first real alarm. “Grandfather will be worried about me if I go away without telling him—”

“Old man will be worrited, eh? O’ all the oxcuses [25]to git out’n a bad fix thet’s the tarnalest. D’ye hear thet, Woodranger?”

Nettled by the words, Norman showed some of the spirit of the McNiels, exclaiming sharply:

“Sir, I have hunted no deer, shot no deer, and there is no reason why you should make me prisoner. I have transgressed no law, as far as I know.”

“Ignerance is no excuse for breaking a law, youngster. The facts air all ag’in ye. Ain’t this yer dog? and weren’t he chasing thet deer?”

“He was chasing the deer, but surely you do not blame the hound for doing what his natural instinct told him to do? To him all seasons are as one, and the laws of man unknown.”

“A good p’int, lad,” said Woodranger, speaking for the first time since Norman had reached the foot of the cliff.

“But it does not clear yer frills from the law made by honourable law-makers and sanctioned by good King George,” retorted Gunwad, angrily. “Ye ’low yer dog was chasing the deer?”

“I have not said he was my dog, sir. He came to my house about a week ago and would stay with us. I—”

“’Mounts to the same as if he wus yers. I s’pose ye deny this is yer gun and thet it’s as empty as a last year’s nutshell?”

“The gun is mine, sir, and it is empty because I [26]wasted my ammunition on a hawk an hour since. I had no more powder with me.”

“A story jess erbout in keeping with the other. Afore ye take up lying fer a bizness I should ’vise ye to do a leetle practising. But I hev got evidence ernough, so kem erlong without enny more palaver.”

Norman saw that it would be useless to remonstrate with the obstinate deer reeve, and he began to realise that he might have serious trouble with him before he could convince him and his friends of his innocence. Accordingly he hesitated before he said:

“I am innocent of this charge, sir, but if you will allow me to go home and tell sister and grandfather—”

“Go home!” again broke in Gunwad, who had no respect for another’s feelings. “If thet ain’t the coolest thing I ever heerd of. I s’pose ye think I’m innercent ernough to let ye take yer own way o’ going to Chelmsford to answer to the grave charge o’ shooting deer out o’ season. Did ye ever see the match o’ thet consarned audacity, Woodranger?”

“It seems ag’in reason for me to think the lad means to play you double, Gunwad,” said the Woodranger, deliberately. “It seems too bad to put the lad to this inconvanience. I ’low, down ’mong ’em strangers it’ll be a purty sharp amazement for him [27]to prove his innercence, but the lad’s tongue tells a purty straight story. I disbelieve he was consarned in the killing o’ the deer.”

“Oh, ho! so thet’s the way the stick floats with ye, Woodranger? Mebbe ye know crossways, but Captain Blanchard has the name o’ being square and erbove board in his dealings. Ye can go down ef ye wanter, jess to show thet the deer jumped off’n the rock o’ its own free will. Ha, ha! thet’s a kink fer ye to straighten.”

“It would be easier done ’cording to my string o’ knots, than to fairly prove the lad was to blame for its killing. I’ve heerd o’ deer jumping off’n sich places out o’ a pure wish to end their days. Up north, some years sence, I see, myself, an old sick buck march plumb down and sort o’ throw hisself over a cliff o’ rock, where the leetle life left in him was knocked flat. I was laying in ambushment for him, but seeing the creetur’s intentions I jess waited to see what he would do. As I have said afore, I do not believe in wanton killing, and deer, ’cording to my mind, is next to the human family. This air rock has peculiar ’tractions for the low-spirited, and ther’ are them as say the ghost o’ poor Rimmon haunts the place, and it ain’t so onreasonable in the light o’ some other things.”

Woodranger’s speech had reference to the legend current among the Indians that a daughter of the [28]mighty chief of the North, Chicorua, once fell in love with a Pennacook brave; but her dusky lover proved recreant to Rimmon, as the maiden was called, and she, unable to credit the stories told of her betrothed, sought this locality by stealth to learn if reports were true concerning him. Alas for her hopes! she was soon only too well satisfied of their truthfulness, and, rather than return to her home, in her grief and disappointment, she courted death by leaping from this high rock. Hence the name Rock Rimmon.

“How long has it been sence the Indian killer turned philosopher and begun to preach?” demanded Gunwad, whose coarse nature failed to appreciate the sentiments of his companion.

“Let’s see,” said Woodranger, ignoring the other’s sneering words, “the law ag’in killing deer will be off afore you get the lad tried. If I remember right it was to last from the first day o’ January to the first day o’ August, and it being now nigh about six o’clock on the last day o’ July, there are only six hours or so left—”

“What difference does thet make?” cried Gunwad, with increasing anger. “Ef ye keep me hyur till to-morrow morning it’ll be the same. But I ain’t trying the youngster. Ef he’ll kem erlong Squire Blanchard will settle his ’count.”

“And give you half the fine, I s’pose,” continued [29]the imperturbable Woodranger, with his accustomed moderation.

“I shall ’arn it!” snapped the other. “But it’s ye making me more trubble than he, Woodranger.”

“I have a plan by which I may be able to more than even things with you, Gunwad, as bad as I have been. What time will you start for Chelmsford in the morning?”

“An hour erfore sunup.”

“Where do you think o’ taking the lad to-night?”

“Down to Shepley’s.”

“He’s away, and the women folks might object to having a deer slayer in the house.”

“I shall stay with him.”

“They might object to you, too! But that ain’t neither here nor there. I reckon the lad’s folks are going to be greatly consarned over his disappearance, so I have been thinking it would be better to let him go home now.”

Gunwad was about to utter an angry speech, when the three were startled by the ringing note of a bugle sounding sharply on the still afternoon air. The first peal had barely died away before it was followed by two others in rapid succession, louder, clearer, and more prolonged each time.

“It’s grandfather!” exclaimed Norman, excitedly. “There is something wrong at home.”

[30]

“If I should agree to answer for the lad’s being on hand to-morrow morning an hour afore sunup, would you let him go home till then?” asked Woodranger, the calmest one of the three, continuing the subject in his mind as if no interruption had occurred.

As a matter of fact, Gunwad had been puzzling himself over the best method to adopt in order to keep his prisoner safely until he could deliver him over to the proper authorities. Of a cowardly, treacherous nature, he naturally had little confidence in others. He believed the youthful captive to be a dangerous person, knowing well the valour of the McNiels, though he would not have acknowledged to any one that he feared him. Woodranger’s proposition offered a way out of his dilemma without compromising himself, in case it should fail. Accordingly he asked, with an eagerness the woodsman did not fail to observe:

“Would ye dare take the risk, Woodranger?”

[31]

“In season and out I have a knack o’ following my words like a deerhound on the track o’ a stag.”

“I know it, Woodranger, so I hope ye won’t harbour enny feeling fer my question. Ef ye say ye’ll hev the youngster on hand at Shepley’s at sunrise, I shall let him be in yer hands. But, mind ye, I shall look to ye fer my divvy in the reward if he’s not on hand.”

“I will walk along with you, lad,” said the Woodranger, without replying to Gunwad, who remained watching them as they started away, muttering under his breath:

“I s’pose it’s risky to let the youngster off in his care. Twenty-four dollars ain’t to be picked up in these sand-banks every day, and I’m sure of it if I get the leetle fool to Chelmsford. It’s a pity to let sich a good fat deer go to waste, and I’ve a mind to help myself to as much meat as I can carry off. It’s no harm, seeing the killing is done, and I had no hand in it.”

Glancing back as they were losing sight of Rock Rimmon, the Woodranger saw the deer reeve carrying out his intention, and laughed in his silent way.

Norman was not only willing but glad to have the company of the woodsman, whose fame he had heard so often mentioned by the settlers. As soon as they were beyond the hearing of Gunwad, he thanked his companion for his kindly intervention.

[32]

“I have nary desire for you to mention it, lad. But if you don’t mind, you may tell me what you can of this deer killing. It may be only a concait o’ mine, but my sarvices may be desirable afore you get out’n this affair. In that case it might be well for me to know the full particulars.”

“You are very kind, Mr.—Mr.—”

“You may call me Woodranger, as the rest do. Time may have been when I had another name, but this one suits me best now. If you have been in these parts very long, you may have heard of me, though I trust not through any malicious person. I ’low none o’ us are above having enemies. But I can see that you are anxious to get home, so tell me in a few words all you can about the deer.”

“There is really little to tell, Mr. Woodranger. I was lying on the top of Rock Rimmon when I heard Archer bark, and I felt sure he had started a deer near Cedar Swamp. Soon after, I heard some one fire a gun. A moment later I saw Christo, the friendly Indian, coming toward the cliff, but at sight of me he turned and went the other way.”

“So it was, as I thought, Christo who shot the deer. I’m sorry for that. The poor fellow has enough to answer for to pacify those who are determined to persecute him, simply because he is a red man. As if it was not enough to see the last foot o’ territory belonging to his race stripped from [33]his tribe, and the last o’ his people driven off like leaves before an autumn wind.”

This speech, coming from one whom he had heard of as an Indian fighter, seemed so strange to Norman that he exclaimed:

“So you are a friend to the Indians! I supposed you hated them.”

“We are all God’s critters, lad, and I hate not even the lowest. Though it has been my fortune to be pitted ag’inst the dusky varmints in some clus quarters, I never drew bead on an Injun with a wanton thought. Mebbe on sich ’casions as Lovewell’s fight, where the blood of white and red ran ankle deep, and that Injun fiend, bold Paugus— Hark! there’s the horn ag’in! Your kin must be anxious about you. Ha! how the old bugle awakes old-time memories. But don’t let me hinder you. I will meet you by the river to-morrer morning at sunrise, when we can start for Chelmsford. By the way, I wish you wouldn’t say anything about Christo until I think it best.”

Without further loss of time, Norman darted away from the Woodranger in a course which soon brought him in sight of the river.

On the opposite bank of the stream the young refugee discovered his grandfather, still holding to his lips the horn which was awakening the wild-wood with its clear notes, as in years long since past it [34]had rung over the hills and vales of his native land. At sight of Norman the aged bugler quickly removed his beloved instrument from his bearded lips, and while the echoes of the horn died slowly away he watched the approach of his grandson, who had pulled a canoe out from a bunch of bushes on the river bank and began his laborious trip across the rapid stream.

In the years of his vigorous manhood Robert MacDonald must have been a typical Highlander of Bonnie Scotland. As he stood there on the bank of the river, in the shifting light of the setting sun, his thin, whitened locks tossed in the gentle breeze, and his spare form half supported by a stout staff, he looked like one of the patriarchs of old appearing in the midst of that wild-wood scene. If the passage of time had left deep tracks across a brow once lofty and white as snow, if the lines about the mouth had deepened into wrinkles and the loss of teeth allowed an unpleasant compression of the lips, his clear blue eyes had lost little if any of their old-time lustre. His face kindled with a new fire, as he watched the approach of Norman.

“He’s a noble laddie, every inch o’ him!” he mused, falling deeper into his native dialect as he continued: “Weel, alack an’ a day, why should he no be a bonnie laddie wi’ the bluid o’ the MacDonalds an’ McNiels coorsin’ thro’ his veins. [35]Shame upon the ane wha wud bring dishonour tae sic a fair name. He has nane o’ his faither’s weakness. He’s MacDonald, wi’ the best o’ the McNiel only. Hoo handy he is wi’ the skim-shell o’ a craft that looks ower licht tae waft a feather ower the brawlin’ burn.”

“What can be the matter, grandfather, that you are so excited?” asked Norman, as he ran the canoe upon the sandy bank and leaped out.

“It’s the wee lassie. She left me awhile since tae look for the geese, an’ she hasna cum back. She’s been awa a lang time.”

“I would not worry, grandfather. You know the geese have an inclination to get back to their kind at old Archie’s. But I will lose no time in going to help Rilma fetch them home.”

“Dae sae, my braw laddie, for I’m awfu’ shilly the day. I canna tell thee it was a catamount’s cry, but it did hae the soond tae my auld ear. But dinna credit ower muckle an auld man’s ears, which dinna hear sae clear as on the day the redcoats mowed doon the auld clan at Glencoe.”

At the mention of the word “catamount” Norman felt a sudden fear. He knew that a pair of the dreaded creatures had been seen in the vicinity several times of late, and that the presence of the geese would be likely to call them from their skulking-places in the dense forest skirting the few log houses near by. So [36]leaving his aged relative to follow at his leisure, he bounded up the path leading to the house. Thinking of his empty gun, he was anxious to get a new supply of powder before putting himself in the pathway of any possible danger.

All of the dwellings of Tyng Township were of the most primitive character. There being no sawmill on the river at that period, the houses were built of hewn or unhewn logs, as the fancy or capacity for work of the owner dictated. The MacDonald cottage was smaller than the average, but the logs making its four walls had been hewn on the inside. The building was low-storied, and had small openings or loop-holes for windows, over which small mats of skins had been arranged to stop the apertures whenever it was desired. Originally the space of the building had been divided into only two apartments on the lower floor, but one of these had been subdivided, so there were two sleeping-rooms, one for Rilma and another for Mr. MacDonald, besides the living room, on the first floor. Norman occupied the unfinished loft for his bedchamber. Some of the houses of Tyng Township, or Old Harrytown, as it was quite as frequently called, had no floor, but in this hewn logs embedded in the sand and cemented along the seams or cracks afforded a solid foundation. A stone chimney at one end carried off the smoke from the wide-mouthed fireplace, which added [37]a cheerfulness as well as genial warmth in cold weather to the primitive dwelling.

The furnishing of this typical frontier house was in keeping with its surroundings. The kitchen, or room first entered, which served as sitting-room, parlour, dining-room, and living apartment, was supplied with a three-legged table, a relic of ancient days that had been the gift of a neighbour, two old chairs which had been repaired from some broken ones, while a rude bench answered for a third seat. In one corner was an iron-bound chest, which had been the only piece of furniture, if it deserved that name, that had been brought from their native land. It held the plain wardrobes of the three. Hanging to the sooty crane in the fireplace was an iron pot, while in a niche in the rocky wall was a pewter pot, a frying-pan, and a skillet. In another small opening cut higher in the side of the building reposed the scanty supply of household utensils, a couple of pewter spoons, two wooden spoons, three knives, a couple of broken cups, a pewter dipper, and three wooden forks, with four rude plates made from two thicknesses of birch bark. There was also a small earthen pot.

Over the fireplace, hung on pegs driven in the chinks of the logs, was a long-barrelled musket of Scottish pattern, whose bruised stock and dinted iron bespoke hard usage. This was the weapon Robert MacDonald had carried in the desperate [38]fight at Glencoe, when his clan had been completely routed by the English. Near by hung a powder-horn, grotesquely carved like an imp’s head, and in close companionship was a bullet-pouch. Near it was another peg, the usual resting-place of an even more highly prized relic than any of these ancient pieces of property, namely, the bugle with which the old Highlander had called home the truant Norman.

The room, though rudely furnished, bore every trace of neatness and thrift, with an air of comfort in spite of its simple environments. The rough places in the walls were concealed by wreaths of leaves and ferns, and the table was bordered with a frill made of maple leaves knit together by their stems. On a shelf, made of pins driven into the wall, lay three books, one of them a volume of hymns, the second a collection of Scottish songs and ballads, while the third was a manuscript book of records of the Clan MacDonald, with some added notes of the McNiels.

The door was made by four small poles fastened together at the corners with wooden pins and strings cut from deer hide, the whole covered with a bear skin carefully tanned and the fur closely trimmed.

In his anxiety to go in search of Rilma, Norman did not stop to replenish his horn from the general supply of powder, but snatched that of his grandfather [39]from its peg, and, loading his gun as he went along, left the house.

His home was near a small tributary of the Merrimack, which joined the main stream a short distance below the falls. The house stood a short distance back from what was considered the main road of the locality, a regularly laid out highway running from Namaske to the adjoining town of Nutfield or Londonderry, and following an old Indian trail. This road also led, a short distance (half a mile) above the falls, past two or three dwellings, to a more spacious log house which was the home of another Scottish family by the name of Stark. Archibald Stark, the head of this household, was a fine representative of his race, and he and his beautiful wife, with their seven children, four boys and three girls, were a typical frontier family, cheerful, rugged, hospitable, and progressive.

As the geese which had caused Rilma to leave her home had been the gift of Bertha Stark, the oldest daughter of the family, Norman hurried toward the home of these people, never doubting but he should find Rilma loitering there to continue some girlish gossip.

Soon after crossing the brook, however, his sharp eyes discovered fresh footprints in the soft earth near the bank of the stream and along a path leading to a small pond in the brook, where the water had [40]been held back by a dam of fallen brushwood. He was sure the tracks had been made by Rilma.

“The geese have got away from her and gone to the Pool,” he concluded. “I shall find her there. Better still, by waiting here I can head off the foolish geese from going back to their old home, as they will be pretty sure to do.”

He had barely come to this conclusion, when he was startled by a loud squawk, quickly followed by a scream.

Something was wrong! He bounded along the narrow pathway toward the scene, while the outcries continued with increasing volume.

Meanwhile Rilma, having been obliged to go quite to Mr. Stark’s house to find her truants, was returning with them, as Norman had imagined, when, on reaching the path leading to the little pond, the contrary creatures darted toward the Pool with loud cries. She followed, but not swift enough to stop the runaways.

The geese had gained the bank of the little pond, and she was following a few yards behind them, when a dark form sprang from a thicket bordering the pathway, and seized the foremost goose.

Thinking at first it was a dog attacking her geese, Rilma called out sharply to the brute, as she bounded toward the spot. But a second glance showed her not a dog but a big wildcat!

[41]

Nothing daunted by this startling discovery, the brave girl flourished the stick she carried in her hand and ran to defend the poor goose. So furiously did she rain her blows about the wildcat’s head that it dropped its prey and sprang upon her! With one sweep of its paw it tore the stout dress from her shoulder and left the marks of its cruel claws in her flesh. But the squawking goose, fluttering about on the ground, seemed a more tempting bait for the wildcat, which abandoned its attack on Rilma and sprang again on the goose.

Flung to the ground by the fierce assault of the beast, Rilma quickly regained her feet, and, seeing her favourite goose in deadly danger, she again attempted its rescue, although the blood was flowing in a stream from the wound in her shoulder. It was at this moment that Norman appeared on the scene.

Rilma and the catamount were engaged in too close a combat for him to shoot the creature without endangering her life, so he shouted for her to retreat, as he rushed to her assistance. But it was now impossible for her to do that. Having torn her dress nearly from her, and aroused at the sight of the blood flowing so freely, the enraged beast was in the act of fixing its terrible teeth in Rilma’s body, when Norman pushed the muzzle of the gun into the wildcat’s mouth, and pulled the trigger.

A dull report followed, and the catamount fell [42]over dead. Norman was about to bear Rilma, who was now unconscious from pain and fright, away from the place, when a terrific snarl rang in his ears from over his head! Looking up, he saw to his horror a second wildcat, mate to the other, lying on the branch of an overhanging tree, and in the act of springing upon him!

[43]

Norman McNiel did not possess an excitable nature, and his thoughts did not flow with that acute swiftness so common to some persons, but he more than made up for this by a clearer comprehension of matters. The sight of the wildcat, preparing to give its fatal spring, did not rob him of his presence of mind, though he realised that in a hand-to-hand encounter with the brute he was likely to become its victim. Still, the possibility of deserting Rilma was something he did not for a moment consider. He would defend her until the last. Accordingly, as the second growl of the aroused animal grated harshly on his ears, he caught his gun by its barrel and stood ready to use it as a club.

Then the long tail of the creature lashed its sides, and its lissom form shot toward him like a cannon ball. But, as the wildcat left its perch, there was a flash so near Norman’s head that he was almost blinded, and the report of a firearm rang out. Another [44]and louder growl came from the catamount, as it fell at his feet in the throes of death.

“Look out she don’t get her claws on you!” cried a voice at his elbow, a warning Norman quickly obeyed, pulling Rilma away with him.

“She dies hard,” affirmed the newcomer, advancing to the side of Norman, “but I reckon that lead was run for her. If I had been a minute later you would have had a tussle old Woodranger himself might not have cared for.”

The speaker, who made this remark with the unconcern and cool criticism of a man with years of experience as a hunter, was in reality but a boy of eleven years of age, though as large as the majority are at thirteen or fourteen. He was not prepossessing in his looks. His countenance was marred by a beaked nose and chin inclined to meet it, while his skin was abundantly tattooed with freckles, and his coarse hair verged on an unhappy reddish hue. But the dark blue eyes redeemed somewhat the plainness of the other features, and his independent, perfect self-control of spirit more than made up for the slight Dame Nature had given him in other respects. He was familiarly called Johnny or Jack Stark by his playmates and companions, and he afterward became the celebrated General Stark, the hero of Bennington.

“You are right, Johnny,” exclaimed Norman, [45]“and if your hand had not been steady and eye true neither Rilma nor I would ever have lived to thank you for your coming. Poor lassie! I fear she has been—no! She opens her eyes,—she lives! You have no more to fear, dear sister; they are both dead. Don’t move if it hurts you. Jack and I will carry you home.”

Though not inclined to show deep emotion, Norman exhibited great joy at the returning consciousness of Rilma, whom he loved with all the tender regard of one who feels that another is all the world to him. Gently he placed the tattered dress about the bleeding form and with his hand wiped away the blood from the wounds made by the wildcat.

“Old Mother Hester!” cried Rilma, quickly gaining her feet, “did the horrid creature kill her?”

Norman understood that “Mother Hester” was the name she had given to the poor goose, whose mangled body, torn and lacerated beyond recognition, lay a short distance away.

“She is dead, Rilma, but let us be thankful that you, too, were not killed. If I had been a minute later you would have been overpowered by the fearful cat, and then Jack saved us both from the other. But they are dead, and we have no more to fear from them.”

Although grieved over the loss of her favourite goose, Rilma felt thankful that she had escaped with [46]even the dreadful scratches of the wildcat, none of which had been very deep.

“I can walk, dear brother; and I want to get away from this place as soon as possible. Jack will look after the other goose for us.”

Taking the hint, Norman led her gently along the path, saying as he did so:

“Won’t you come with us, Jack?”

“I think I will, Norman, as I have something I want to say to you as soon as you feel like hearing it. I was on my way to your house when I heard your shot, and hurried to your assistance. I will make myself useful, too, by carrying home the body of the dead goose and driving the other along. Some one can come up and look after the wildcats later.”

“You are very thoughtful, Jack, as well as brave. I do not believe there is another boy of your age who could have shot that wildcat as you did.”

“You say that because you do not know Rob Rogers. He shot a big black bear, that was nosing around his father’s house, when he was only seven, and you know I am almost eleven. Robby, since he has begun to go with Woodranger, has become a mighty hunter, and he’s only fourteen now.”

The conversation was checked at this point by the appearance of Mr. MacDonald, who had heard the firing and was greatly excited over the affair.

[47]

“Oh, my bairns!” he cried, “hoo gled I am tae find that ye hae na been— Why, my wee lassie! What hae they been doing to ye?”

Norman gave a brief account of the encounter with the wildcats, his grandfather catching up Rilma in his arms and bearing her toward the house as he finished, forgetful of his infirmities. The old Highlander sobbed like a child at intervals, while alternately he would burst forth into expressions of endearment and thankfulness in his picturesque speech.

Seeing that Rilma was being cared for, Norman started back to help Johnny Stark find the surviving goose, which was found skulking in the bushes nearly frightened to death. Catching it after some trouble, Norman carried it homeward in his arms, while Johnny bore the body of its dead mate.

“I will get father to send Goodman Roberts to look after the carcasses of the wildcats, as soon as I get home,” said the latter, as he walked at the heels of Norman, the path being too narrow at places for a couple to walk abreast. “What I wanted to speak to you about,” he continued, “was the canoe match which is talked of to take place on the river next month. You know three Scotch boys are to race against three English boys. Brother Bill and Robby Rogers have been chosen to represent our side, and we want another. We have spoken [48]to father about it, and he agrees with us that you are the one. Now will you do it?”

“Of course I am willing to do anything I can, but I am afraid I have not had as much practice as I need. You know I have not been here as long as the rest of you, though nothing suits me better than a paddle on the water.”

“You’ll have over a month in which to practise. I’ll risk you, and so will the others. I understand John Goffe is to be one of their crew, though no one seems to know who the others will be. Johnny is a good one with the paddles, but he is nowhere with Rob. Bill will beat anybody else they can get, and with you to help our side will be safe.”

“You mustn’t be overconfident, Johnny, but if I take hold I will do the best I can.”

By the time they had reached the house Norman had decided to accept the invitation to take part in the canoe match, and Johnny Stark, having performed his errand successfully, lost no further time in running home to tell the good news.

Mr. MacDonald dressed Rilma’s wounds as best he could, with the simple means at his command, though she bravely declared that she did not suffer any pain.

It was then getting to be quite dark, and, lighting his corn-cob pipe, Mr. MacDonald took his favourite position in the doorway to smoke and meditate over [49]the events of his checkered life. These had ever been hallowed occasions to Norman and Rilma, who had sat at his feet for many an hour listening to the pathetic tales of which he seemed to have no end. In these twilight talks they had heard him tell over and over again, until every word was familiar to them, the stories of the fate of the brave MacDonalds in the Pass of Glencoe, and the downfall of the last of the McNiels.

On this evening Rilma had lain down on her simple couch for rest and release from the pain of her wounds, so that Norman was alone with his grandfather.

“Ha, ma laddie!” broke in Mr. MacDonald. “Ye’re that glum ye dinna seem like yersel’ the nicht. Trouble na ower the few scratches o’ a cat, the bonnie lassie wull sune be hersel’,” he continued, attributing Norman’s silence to thoughts of Rilma.

“I must confess, grandfather, I was not thinking of poor Rilma, though I ought to be ashamed to own it. I was thinking of a little affair which happened this afternoon, and how best I could break it to you. I would have spoken of it before, but I did not wish to arouse Rilma’s fears.”

With the characteristic reserve of his nature, the old Highlander removed his pipe from his lips without speaking, signifying as plainly by his silence as [50]he might have done by words his desire for an explanation. At a loss how to begin, Norman hesitated for a time, the only sound heard above the steady roar of Namaske being the mournful cries of a whippoorwill in the direction of Rock Rimmon, until finally he gave a detailed account of his arrest by Gunwad for hunting deer out of season.

“Ha, ma laddie!” exclaimed his grandfather, when he had finished. “Ye dinna want tae be low-speerited wi’ anxiety ower that, though it does look a bit squally for ye. I’m gled ye telt the auld man, for noo he’ll ken just hoo tae trim his licht. Then, tae, an auld man’s coonsel may na cum amiss wi’ a young heid.”

“Grandfather, I had no more to do with hunting or killing that deer than you did.”

“In intent, my braw laddie. But ye maun remember I never crossed the brawlin’ stream. But avaunt wi’ sic nonsense! It behooves us tae see what can be dune for ye, noo ye hae fa’en in the net.”

“Can they do anything with me, grandfather? Woodranger bade me be hopeful.”

“Wha is this Woodranger, laddie, that ye speak sae freely o’? I dinna ken but I may hae heard the name afore.”

“He is a man who lives by hunting and scouting, grandfather. During the Indian troubles he did great service to the families who were molested by [51]the red men, and everybody seems to like him. He has been all over the country, and he is very friendly to me.”

“Is he Scotch, laddie? That maks a’ the difference in the warld in this affair.”

“I am not sure, though I should say he is. He seems very honest.”

“Hoot! awa wi’ yer nonsense if ye canna tell an Englishman frae a Scotchman. Let me but get my auld een on him an’ I’ll tell ye if he’s a true laddie. What’s his name?”

“Just what I told you, grandfather,—Woodranger. At least that is all he would give me.”

“A bit against him, laddie. But allooin’ he is yer freend, I am a bit feart ye’re nae pleasant fixed. This Gunwad ye say is an Englishman?”

“I have no doubt of that. I can see that this foolish feeling between the colonists is going to be against me.”

“Ah, ma laddie, that’s whaur the shoe grips! Every Englishman, wumman, and bairn looks on us as intruders, as they dae every Presbyterian, wha they hate waur than wildcats. I see noo I did mak’ a bit o’ a mistak’ in droppin’ here, but auld Archie Stark thocht it was best for us. I dinna ken whaur this misunderstandin’ is gaen tae end. Seems tae me it will be the destruction o’ baith pairties. But dinna ye lat this little maitter cum intae yer dreams, my [52]laddie. Sleep gie’s ane a clear heid, an’ it’s a clear heid ye’ll need the morn amang the Britishers at Chelmsford.”

Taking this hint, Norman, after having seen that Rilma was as comfortable as could be expected, sought his humble couch under the rough rafters of his pioneer home.

[53]

After a restless sleep Norman was astir an hour before sunrise. His grandfather was already up and preparing a breakfast for him.

“You maun eat, ma laddie. It seems unco’ that ye maun gang tae meet thae Britishers alane. I fain wad gang wi’ ye.”

“That cannot be, grandfather. It would not do to leave Rilma here alone. Never fear but I shall come back safely.”

As soon as he had eaten hastily of the plain meal, Norman kissed Rilma and taking his gun started to leave the house.

“If the lassie disna mind, I’ll walk wi’ ye tae the river’s bank,” said his grandfather. “I’ll nae be gane lang, lassie, so hae nae fear.”

Norman felt that his grandfather’s real object in accompanying him was to get a look, if possible, at the Woodranger, who was expected to meet him on the river bank. But nothing of the kind was said until they came in sight of the stream, when they [54]discovered the forester already on hand. He had crossed over to the east bank, and at sight of Norman said:

“I am glad you are so promptly here, lad; it shows a good mark to be prompt. It always pays to be prompt. As we shall have to go down on this side, I thought I would come over and save—”

Woodranger, with a sudden change in his demeanour unusual to him, stopped in the midst of his speech, to fix his gaze closely on the old Highlander. The latter was eyeing him no less intently. Anxious to break the embarrassing silence, Norman said, quickly:

“My grandfather, Woodranger. He felt so anxious about me that he has come down to see me fairly started.”

“So yo’ air Woodranger?” asked Mr. MacDonald, as if such a thing was not possible, while shifting looks of doubt, curiosity, fear, and confidence crossed his features. The forester soon recovered his wonted composure, replying to the other’s interrogation:

“Men call me that, MacDonald. I have heerd o’ you, and I’m glad to meet you. I hope you have no undue consarn over the lad.”

“Th’ laddie is puir, Woodranger,” cried the old man, putting aside further reserve and grasping the forester’s hand. “Yo’ll hel’ him out o’ this trouble?”

“He shall not lack for a friend. I trust the lad [55]will have no great difficulty. Where is the dog, lad?”

“Gone, Woodranger, but I do not know where. I thought perhaps Gunwad took him with him. I did not see him after I met you.”

“I see him sneaking through the woods as if he had committed some grievous misdeed, but thought he might be pulling home.”

“Ye’re no in sympathy wi’ thae Britishers?” asked Mr. MacDonald at this juncture.

“Nay, old man; I’m neutral. It is a foolish quarrel and no good can come o’ it.”

“Neutral!” exclaimed the old Highlander, to whom, with his stubborn, aggressive nature, such a thing seemed impossible, and then a new shade of misapprehension came over his countenance, as he scrutinised the ranger’s rifle.

“A French weapon!” he exclaimed. “Nae guid can come o’ a man’s bein’ neutral an’ a-carryin’ a French gun.”

“We are in luck, lad,” said Woodranger, ignoring the last speech of Mr. MacDonald. “I l’arned last evening that Captain Blanchard had come to Tyng Township yesterday, so I see him and he says you can be tried without going to Chelmsford. That will save you twenty-five miles o’ walking.”

“I am glad of that!” exclaimed Norman, “and I hail it as a good omen. Do you hear that, grandfather? [56]I have not got to go to Chelmsford to have my trial.”

Mr. MacDonald only shook his head, seeming too much engrossed over the appearance of the Woodranger to reply by words.

“I don’t like to cut short any speech you wish to make to the old man, lad, but it’s time we were on our way. A mile or more o’ the river has run by sence we stopped here. It’s an ’arly start that makes an ’arly end to the jarney. Good morning, Mr. MacDonald; have no undue consarn over the lad.”

Fully understanding the Woodranger’s anxiety to meet Gunwad promptly, Norman hastily caught the hand of his grandfather, as he murmured his good-bye, while the forester moved silently away.

“I jest want to say a word to ye, ma laddie,” said Mr. MacDonald, in an undertone. “I dinna ken whut to mak o’ this man ca’d Woodranger, but ye canna be owre careful. He carries a French weapon, an’ is neutral in a quarrel whin every true Scot shud stan’ by his colours. I dinna ken what tae mak o’ the man.”

With this dubious warning, which no words of Norman could shake, he stood there watching the twain until their forms had disappeared in the distance. Even then he hesitated about starting homeward. His head continued to move back and forth, [57]and his lips became tightly compressed, as if fearful they might allow something to escape that he was anxious to conceal.

Tyng Township comprised a strip of territory three miles wide, and extending six miles along the east bank of the river, so it was not necessary for them to cross over. In fact, that would have necessitated a return to that side before reaching their destination. After leaving his home Norman saw but a few houses for some distance, the land being little more than sand patches, and too poor to support a crop of any kind.

“I do not wonder it is called Old Harrytown,” Norman said, as he noticed this, “and they say only the Old Harry could live here.”

“Tyng’s men got a bad bargain when they got it,” said the Woodranger. “Though it may be that they think more of the fish than the soil. They be fat and plenty. The deer, too, are sleek; but they are fading away with the red hunter. Sich be the great unwritten law that a man’s associates must go with him.”

They had not gone more than a mile before they were met by Gunwad, who showed his satisfaction at seeing them.

“Was afeerd th’ feller mought gin ye th’ slip, Woodranger.”

The forester making no reply to this statement, [58]the three walked on in silence, the appearance of the deer reeve putting an end to all conversation.

Another mile down the stream they began to come in sight of the log houses of the pioneers, who were trying under adverse circumstances to found themselves homes in the new town. As they came in sight of one of these typical homes, they saw a tall, cadaverous man mounted on the top of a blackened log fence surrounding a cleared patch bordering the house. He was bareheaded, and had no covering for his feet, save a generous coating of dirt, and his lank body was clad in a coarse shirt, made, by long contact with the earth, the colour of the soil, and a pair of gray homespun trousers stopping short in their downward career a little below the knees. As he sat there on his elevated perch, his long arms were doubled akimbo over his knees, which stuck up sharp and pointed.

At first it looked as if his occupation was the watching of the gyrations of one of his big toes, as it scraped back and forth on the charred surface of the log, but a closer inspection showed that he was gazing at a patch of broad-leaved plants looking suspiciously like that much despised weed of lane and pasture, the mullein. But if so, it had been cultivated with assiduous care, and had flourished like “the green bay-tree” of the story-writer.

At sight of our party he suddenly checked the [59]movements of his toe, his jaws stopped their rapid grinding, and he cried out in a shrill, piping voice:

“Hello, Ranger! Wot in creation is yer sweeping by fer like a falling hemlock? Ain’t fergot an ol’ man in his weakness, hev ye?”

“Not a forgit, Zack Bitlock, but as we have a lettle amazement with ’Squire Blanchard we wanted to be sure and get to him afore he should leave for down the river. A fine morning.”

“Mornin’s well ’nough; ’bout as ye air mind to look at yit. But it’s pesky gloomy to me. Say, Ranger, I kalkilate ye mus’ be a tol’rable good jedge o’ ’backer?”

“Mebbe I know the leaf from dock root, though I can’t say as I’m much o’ a jedge o’ the quality, Zack, seeing I never—”

“Look a-here, Ranger! I want yer honest opine consarnin’ thet air stuff,” pointing, as he spoke, to the rows of green, broad-leaved plants adorning his primitive garden, and comprising most of its contents.

Approaching the fence, the Woodranger looked over, saying, after a brief survey of the scene:

“I see leetle but mullein, though I must say, while not claiming to be an apt jedge in sich matters, it has made a good growth. How is it, Zack, you give so much ’tention to raising sich useless truck, though it be said it is excellent for cattle?”

[60]

“It’s my gol-danged foolishness, Ranger, which made me spend my valer’ble time raising sich truck. I ain’t got no cattle to feed it. My ol’ woman ’lowed it was mullein a goodish spell ago, but I larfed at her. An’ then, when I see thet she wuz right an’ I wuz wrong, like the hog I wuz, I had to hol’ my mouth and keep on growing mullein! Gol dang! To think, I, Zack Bitlock, in my sound mind an’ common sense, sh’u’d be a-weedin’ out an’ prunin’ up an’ ’tendin’ mullein, thinkin’ all th’ while ’twas ’backer!”

“How did it happen, Zack?” asked Woodranger, who could not help smiling at the look of utter disgust and shame on the other’s wrinkled countenance.

“It all kem o’ my blamed smartness! Ye see I figger yit out like this. Joe Butterfield, he don’t pertend to know more’n other folks, an’ so las’ year he kem to me an’ wanted to know what was th’ bes’ thing to make taters grow. He had seed mine climbin’ like all creation, and seein’ he wuz too blamed green to raise ennything but fun fer his betters, I tole him th’ very bes’ thing was rotten hemlock, an’ to put a chockin’ handful in each hill. Well, what did th’ dried-in-the-oven fool do but follow my ’vice, only he put a double portion in each hill, so as to beat me at my own game, I s’pose. I larfed to myself all th’ while ’em taters didn’t stick up a top. Ye see th’ hemlock wuz so durned dryin’ it jess baked the taters afore they c’u’d sprout. Joe [61]laid it to th’ seed, an’ I s’posed thet wuz the las’ o’ it, ’ceptin’ a good stock o’ jokes I had laid in fer spare talk with Joe.

“But I can see now th’ critter was sharper’n I ’lowed, an’ he mus’ hev smelled a mice. So when I kem to ’quire fer backer plants he gin me more’n I wanted. Leastways he give me what I s’posed wuz backer plants, an’ now, drat my pictur’! ef I ain’t been ’tendin’ an’ nussin’ ’em blamed ol’ mulleins, an’ a-workin’ my jaws all th’ while, thinkin’ what a Thanksgivin’ I’d hev chowin’ th’ backer. Oh! th’ fool ingineuity o’ some men!”

Smiling at the evident disappointment and chagrin of Zack Bitlock, Woodranger started on, when the other called out to him:

“Say! seems to me ye hev got a smart start fer th’ shootin’-match.”

“I can’t say that I’ve given the matter a thought, Zack. Been away perambulating the forests for a good space o’ time.”

“A shootin’-match, an’ ye not know yit, Ranger? I do vum! thet’s amazin’. But there is to be a tall shoot at th’ Pines this mornin’. Cap’en Goffe is to be there, an’ Dan Stevens; an’ I overheerd las’ evenin’ Rob Rogers wuz to kem. Everybuddy’ll be on hand. Coorse ye’ll go now, Ranger?”

“Onsartain, Zack, onsartain. If we have time the lad and I may be there. Good morning.”

[62]

“Ye may be thar, Woodranger, an’ I see no reason w’y ye shouldn’t; but with th’ youngster it’ll be different. I reckon he’ll be fur from hyur then, ’less my plans miscarry,” said Gunwad, who had been silent.

Without noticing this speech, the forester moved ahead at a rate of speed which showed he was anxious to make up for the few minutes lost in conversation with Goodman Bitlock. Norman kept close beside him, while Gunwad, the deer reeve, followed at his heels.

Zack Bitlock did not shift his position on the fence until he had watched them out of sight, when he left his perch, exclaiming:

“Blamed queer ef th’ ol’ Ranger is goin’ to er shoot an’ won’t own yit! Thar’s sumthin’ afoot. But I’ll l’arn their dodge or I ain’t up to shucks,” and without further delay he shuffled down the road after the others.

[63]

The destination of Norman and his companions was a small settlement at the lower end of Tyng Township called Goffe’s Village, out of respect to one of its foremost inhabitants, John Goffe, afterward known as Colonel Goffe the Ranger.

This little hamlet stood at the mouth of a small stream known as Cohas Brook, which flowed into the Merrimack five miles below the Falls of Namaske.

Before reaching Goffe’s Village, Norman and his companions passed a cross-road leading over the hill and toward the Scotch-Irish settlement on the east. About a mile up this road, at a point called “The Three Pines,” or “Chestnut Corners,” the shooting-match was expected to take place during the forenoon.

As Tyng Township was settled during an interval of peace, there was no fort or garrison within its limits. Neither was there a public house of [64]any kind, so Norman must be tried at the house of one of the most active inhabitants of the town, this having been arranged for by the Woodranger.

Somewhat to our hero’s surprise, several persons were gathered about the house, as early as it was, and he knew by their looks and low-spoken speeches that they had been watching for his coming. In fact, though he did not know it, Gunwad had taken great pains to circulate the story of his arrest, and had boasted loudly that his trial would be worth attending. News of that kind travels fast, and, as short as the time had been, quite a crowd had collected, some coming several miles from the adjoining town, Londonderry, the former home of the Scotch-Irish now in Harrytown.

Among the others was a boy of fourteen, who attracted more than his share of attention. His name was Robert Rogers, and he was destined to be known within a few years, not only throughout New England but the entire country, as chief of that famous band of Indian fighters, “Rogers’s Rangers.” Already he was considered a crack shot with the rifle, and the fleetest runner in that vicinity. A strong bond of friendship bound him to the Woodranger, who had become his tutor in the secrets and hidden ways of woodcraft. No doubt he owed much of his future success to this early training. He was strongly and favourably impressed by the appearance [65]of Norman, and he said aside to a companion:

“He’s a likely youth; and mind you, Mac, if they are overhard with him there’s going to be trouble,” an expression finding an echo in older hearts there, though the others were more cautious in their utterances.

“Hush, Robby!” admonished the boy’s friend; “say nothing rash. Captain Blanchard has the credit of being an extremely fair man, and, withal, one with a handy knack of getting out of a bad scrape easily. Here he comes, as prompt as usual.”

Norman was being led into the house by Gunwad, who had now assumed charge of his prisoner. They were met at the door by a tall, rather austere appearing man, whom our hero knew by the little he had overheard was ’Squire Blanchard.

“You are promptly on hand, Goodman Gunwad,” said the latter; “come right in this way,” escorting the little party into the house, which was more commodious than most of the dwellings.

The deer reeve frowned at the salutation of Captain Blanchard, for it did not please him. Notwithstanding the simplicity of those times, a stronger class feeling existed than is known to-day. As a distinguishing term, the expression “Mister,” which we apply without reserve or distinction, was given [66]only to those who were looked upon as in the upper class, “Goodman” being used in its place when a person of supposed inferior position was addressed. The cause for Gunwad’s vexation is apparent, as he aspired to rank higher than a “Goodman.” But he thought it policy to conceal his chagrin, though no doubt it made him more irritable in the scenes which followed.

At the same time that the prisoner was led into the house by his captor, a small group of men, in the unmistakable dress of the Scotch-Irish, and headed by a tall, bony young man named John Hall, gathered about the door.

Woodranger nodded familiarly to these stern-looking men, but before entering the house he turned to speak to a medium-sized man, with the air of a woodsman and the breeding of a gentleman about him. He was none other than Captain Goffe, who, while he did not belong to the Tyng colony, was living in the midst of these men. It is safe to say that he was on friendly terms with every person present, or who might be there that day. The spectators, noticing this brief consultation between the forester and the soldier-scout, nodded their heads knowingly.

’Squire Blanchard then put an end to all conversation by saying:

“I understand this is your prisoner whom you [67]charge with killing deer out of season, Goodman Gunwad?”

“He is, cap’en.”

“Are your witnesses all here?”

“All I shall need, I reckon.”

“Are your witnesses here, prisoner?”

“I have none, sir.”

“Then, unless objection is raised by the prisoner or the complainant, the case will be opened without further delay. I think there is a little matter several are anxious to attend to,” alluding to the forthcoming shooting-match.

“Th’ sooner th’ better, cap’en,” said Gunwad, showing by his appearance that he was well pleased. “I reckon it won’t take long to salt his gravy.”

“I understand you charge this young man, whose name I believe is McNiel—”

“A son, cap’en, of thet hated McNiel—”

“Silence, sir, while I am speaking!” commanded ’Squire Blanchard. “You charge this Norman McNiel with shooting deer out of season?”

“I do, sir.”

“You will take oath and then describe what reason you have for considering the prisoner guilty.”

As soon as he had been properly sworn Gunwad went on to describe in his blunt, rough way how he had been attracted to Rock Rimmon by a gun-shot. Upon reaching the spot he had found a dead deer [68]there, while the prisoner and his dog were the only living creatures that he saw in the vicinity. The youth’s gun was empty, and he acknowledged his hound had started and followed the deer.

“I knowed the youngster o’ a furriner,” he concluded, “as the boy livin’ with thet ol’ refugee o’ a MacDonald at the Falls, so I lost no time in clappin’ my hands on him.”

These allusions to Norman’s father and grandfather it could be seen were given to antagonise, as much as possible, the Scotch-Irish spectators. But ’Squire Blanchard ended, or cut short, his speech by asking if he had witnesses to prove his statements.

“Woodranger here was with me, an’ I reckon his word is erbout as good as enny the youngster can fetch erlong. Woodranger, step this way, an’ tell th’ ’squire whut ye know erbout this young poacher.”

In answer to ’Squire Blanchard’s request, but not to Gunwad’s, the forester took the witness-stand, and, after being duly sworn, answered the questions asked him without hesitation or wavering.

“You were with Gunwad yesterday, Woodranger, when he met the prisoner at Rock Rimmon?”

“I was, cap’en.”

“And you saw the deer he had shot?”

“I see the carcass o’ a dead deer laying at the foot o’ Rock Rimmon, cap’en.”

“It was the deer the prisoner is supposed to have [69]shot?” asked ’Squire Blanchard, noticing the Woodranger’s cautious way of replying.

“It was the only deer I see.”

“You saw Gunwad take a bullet from its body?”

“I did. I see, too, that the lead had not found a vital spot.”

“Do you mean to say the deer was not killed by the shot?”

“That’s what I mean.”

Gunwad was seen to scowl at this acknowledgment, while the spectators listened for the next question and reply in breathless eagerness.

“What was the cause of the creature’s death, then?”

“It was killed by its fall from Rock Rimmon. To be more correct, I should say its leap from the top of Rimmon, which you mus’ know is a smart jump.”

“But it was driven over the cliff by a hound at its heels?”

“It could have gone round if it had wished. I ’low it was hard pressed, but it looked to me the critter took that way to get out o’ a bad race.”

A murmur of surprise ran around the crowded room, while Gunwad was heard to mutter an oath between his teeth.

“You say that for the benefit of the prisoner?” demanded Blanchard, sharply.

[70]

“I do not need to, cap’en. Besides, I’m under oath.”

“Do you mean to say that a deer would jump off Rock Rimmon intent on its own destruction, Woodranger? Now, as a man who lives in the forest, knows its most hidden secrets and worships its solitudes, answer me if you can.”

Even Gunwad was silent now, and the knot of talkers outside the door, realising that the conversation between the justice and the witness had reached a point of more than ordinary interest, abruptly ended their discussion, to listen with the others.

“Cap’en Blanchard,” said the Woodranger, in his simple, straightforward way, “I ’low I’ve spent a goodish portion o’ my life in the woods, ranging ’em fur and wide it may be, sometime on the trail o’ a red man, sometime stalking the deer, the bear, or the painter. Being a man not advarse to l’arning, though the little book wit I got inter my head onc’t has slipped out, I have picked up some o’ Natur’s secrets. I can foller the Indian’s trail where some might not read a sign. The trees tell me the way to go in the darkness o’ night; and the leaf forewarns me the weather for the morrer. If I do say it, and I think I may be pardoned for the boasting, few white men can show greater knack at trailing the Indian or stalking the four-footed critters o’ the woods. My eye is trained to its mark, my hand to its work, and [71]Ol’ Danger here,” tapping the barrel of his long rifle, “never has to bark the second time at the same critter. I hope you’ll pardon me for saying all this, seeing no man has enny right to boast o’ the knacks o’ Natur’. If I have been a better scholard in her school than in that o’ man, it is because her teachings have been more to my heart. Her ways are ways of peace and read like an open book, but the ways o’ man are ways o’ consait and past finding out. Though I live by my rifle, I do not believe in wanton killing, and I never drew bead on critter with a malicious thought.

“But pardon me for so kivering the trail o’ your question as not to find it. One is apt to study the manners o’ ’em into whose company he is constantly thrown. So I have studied the ways o’ the critters o’ the woods very keerfully, to find ’em with many human traits. They have their joys and their sorrers, their loves and hates, their hopes and despairs, just like the human animal. In the wilds o’ the North I once saw a sick buck walk deliberately up to the top o’ a high bluff, and, after stopping a minute, while he seemed to be saying his prayers, jump to death on the rocks below. At another time, I sat and watched a leetle mole, old and sick, dig him a leetle hole in the earth, crawl in, and kiver himself over to die. I remember once I had a dog, and if I do say it, as knows best, he was the [72]keenest hound on the scent and the truest fri’nd a man ever had. But at last his limbs come to be cramped with rheumatiz, his eyesight was no longer to be trusted, and his poor body wasted away for the food he had no appetite to eat. In his distress he lay down in my pathway, and asked me, in that language the more pathetic for lacking words, to put an end to his misery by a shot from my gun.

“I say, Cap’en Blanchard, I’ve witnessed sich as these, and, mind ye, while I do not pretend that deer leaped to its death o’ its own free will on Rock Rimmon, in the light o’ sich doings as I’ve known it might have done it rather than to find heels for the hound any longer.”

Though the Woodranger had spoken at this great length, and in his roundabout manner, not a sound fell on the scene to break the clear flow of his voice. It was evident his wild, rude philosophy had taken effect in the rugged breasts of those hardy pioneers. Even ’Squire Blanchard paused for a considerable space before asking his next question.

“Granting all that, Woodranger, it has but slight bearing on the fact of the prisoner’s guilt or innocence. I understand you to say it was his hound which had started the deer, and which was driving the creature that way—to its death, according to your own words.”

“If I ’lowed as much as that, cap’en, I said more’n [73]the truth will bear me out in. I will answer you by asking you a question.”

“Go ahead in your way, Woodranger,” consented the other. “I suppose I should accept from you what I would from no other person.”

“Thank you, cap’en. This is the leetle p’int I’ve to unravel from my string o’ knots: If a nigger should come to your house and stop overnight, would that make him your slave for the rest o’ his life?”

“No.”