Title: The giant world

Author: Ray Cummings

Illustrator: Hugh Rankin

C. C. Senf

Release date: December 20, 2025 [eBook #77512]

Language: English

Original publication: Indianapolis, IN: Popular Fiction Publishing Company, 1928

Credits: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

By RAY CUMMINGS

NOTE—This: serial, while complete in itself, is a

sequel to Explorers Into Infinity, which

narrated the previous adventures of Brett and Martt

on the distant world. The story appeared in

Weird Tales for last April, May and June.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Weird Tales January, February, March 1928.]

| 1 | THE SUMMONS |

| 2 | STOLEN INTO SMALLNESS |

| 3 | THE THING IN THE FOG |

| 4 | THE WILD NIGHT RIDE |

| 5 | CLIMBING INTO LARGENESS UNFATHOMABLE |

| 6 | THE BLOOD-RED DAY |

| 7 | THE FIGHT ON THE PARAPET |

| 8 | YOUTH! |

I was startled. Yet I think that I subconsciously I was prepared for it; expecting it. The little cylinder flipped out of its tube and dropped on my desk before me. My name was on it, glowing with tiny luminous letters: Frank Elgon, Interplanetary Mails, Division 4, Great-New York. It looked just like any other Departmental message cylinder. But instinctively I knew it was not; and my heart was beating fast as I clicked it open.

Relayed through Code Headquarters. I saw that on the small rolled tape inside. And saw the signature, Dr. Gryce. It should not have been startling, but my fingers were trembling as I unrolled the tape and hooked it into the automatic decoder. And I stood gripping my chair as the line of English letters pricked themselves on the blank white sheet at which I was staring:

"Frank—I can not bear it any longer. We must go—we must find Brett at any cost. Will you stand by us? Come at once. Hurry.

Dr. Gryce."

My mind leaped back. I sat at my desk staring blankly, while in the office around me all the bustling activity of the accursed Interplanetary Mails faded before the surging visions of my memory. It was four years since that other momentous day when Dr. Gryce had sent for me. And I had gone to him; and listened amazed at his weird, fantastic theories. Our sun, planets, and stars—all the vastness of the star-filled heavens, he had told me then—were but the infinite smallness of a greater world. All this that we call our Celestial Universe was no more than an atom—of the giant world encompassing it.

Fantasy! Yet it had proved sober, tragic fact. Tragic, because Dr. Gryce's older son, Brett, had gone out there to that giant world. Gone, and never returned. Nor been heard from; four years now, while old Dr. Gryce at the end of his life waited despairingly.

I had known always that the time would come when Dr. Gryce would wait no longer. He would send for me—friend of Brett—and friend of his other two children, Martt and Francine. For a year every cylinder that had dropped on my desk had made my heart leap that it might contain this summons which now lay before me.

"I can not bear it any longer. Will you stand by us?" So simple an appeal! But I knew the turgid torrent of heartache—the final desperation of an old man's suffering—which prompted it.

Young Grante at the desk next to mine was sorting his pile of official communications newly arrived by the Venus mail. I turned to him.

"I'm going away," I told him. In spite of myself—an unfortunate mannerism when I am perturbed—my voice sounded gruff, ill-tempered. "There is no time to argue—will you please notify Official 4 that my—my post is vacant."

He raised his eyebrows. "Vacant?"

"Yes. I'm going away." I was on my feet. Outwardly calm, but within me was a seething emotion. Going away! Out there into the immensity of the Unknown, where my friend Brett had gone, not to return. Young Grante could not guess. He was thinking Great-London perhaps—or the Asiatic province. Or perchance, Venus, or Mars.

I laughed harshly. "Don't question me, Grante. Just tell them—my post is vacant."

I left the room with his amazed stare following me. In the corridor, through a window I caught a glimpse of the tenth pedestrian level; its crowd of people moving upon the diverse activities of their tiny lives. Already I felt apart from them. Frank Elgon, Division 4. Presently, to such of them as knew me, I would be no more than a memory. "That young, rather quarrelsome Elgon, who walked out of his office in a temper, and vanished." They would say that, and then forget me.

I laughed again. But the thought brought a pang of regret, and a shudder.

In ten minutes I was within a pneumatic cylinder, speeding underground to the Southern Pennsylvania area, to the home of Dr. Gryce.

II

Martt and Frannie met me at the outer gateway. Their manner held a singular gravity. I had expected them to be excited, of course. But their grave, somber smiles of greeting, their instinctively hushed voices, seemed unnatural. This was no reckless, devil-may-care spirit of high adventure which I had anticipated the twins of Dr. Gryce would display. Sober drama. Their involuntary glances at the white house nestling against the hillside carried a foreboding.

Drama, but it seemed almost to be tragedy. My heart sank. There was something very wrong here with the Gryces; something more imminent than the fact of Brett's absence over four years.

But I said nothing. Dear little Frannie gave me her two hands. They were cold.

Martt said, "Thank you for coming, Frank. Father is—waiting for you." His voice, usually flaunting, mocking at everything with the reckless spirit of youth, chilled me with its queerly broken tone.

We crossed the flowering gardens to the white house standing so peaceful in the afternoon sunlight. Martt led the way. The twins were twenty-one years old now. Alike physically, and in temperament. Both smaller than average height; slim and delicate of mold; blue-eyed, and fair of hair. They were always laughing; carefree—the spirit of irresponsible youth. But not today. I regarded Martt, trudging ahead of me—debonair, jaunty of figure in his tight black silk trousers and loose white shirt, bare-headed, his crisp, curly hair tousled by the wind. But there was a slump to his shoulders, a heaviness to his tread. And little Frannie behind him: girlishly beautiful, with her tossing golden curls, her familiar house costume of gray blouse and widely flaring knee-length trousers. But there was upon her a preternatural solemnity; a maturity of aspect indefinable.

At the doorway Martt turned and fixed me with his somber, blue-eyed gaze. And spoke with the same queer hush to his voice.

"Father is upstairs, Frank. He is—dying. He wants very much to live until you arrive."

Upon the pillows in the darkened room lay Dr. Gryce's head with its shaggy, snow-white hair, the mound of the sheet betraying his pitifully wasted body.

Martt said softly, very gently, "Frank is here, Father. You see he came in time—plenty of time."

But the head, with face to the wall, did not move; no stirring marked the fragile body lying there.

Martt gave a cry; with Frannie he rushed to the bedside. It was all too evident. In a moment Martt stood up, leaned silently against the bedpost, a hand before his eyes as though dazed. And Frannie knelt at the bed and sobbed.

We expect death all our lives, yet the instinct of life within us never ceases to feel a shock, and a revulsion. For a long time these children of Dr. Gryce did not move or speak. Then Frannie leaped to her feet. Her face was tear-stained; but her sobs were suddenly checked, and her eyes were blazing.

"Martt! His last wish—the very last thing he said—was that we go out ourselves and find Brett. He said it—he said Brett might need us—his dying wish. And I'm going, and so are you. We've got to, Martt! And we want Frank with us. Oh, Frank, you'll go with us, won't you? Out there—to join Brett?"

III

The burial was passed. We had not spoken of our enterprise, but it had never left my thoughts. This boy and girl so newly come to maturity—but I was twenty-nine. Upon me would fall the main responsibility.

We sat at last in Dr. Gryce's study—the three of us alone—to discuss our task. With the first poignancy of their shock and sorrow already dulled by time, upon the faces of Martt and Frannie was stamped grimly their simple purpose.

"But, Martt," I said, "Brett's vehicle was very intricate. It traveled in Space—but in Time as well. And grew gigantic in size. Your father's genius built it. But we have no such genius to build another——"

"You forget," he interrupted. "Think back, Frank. That day you came here. And we showed you the models of the vehicle. There were four of them——"

Then I remembered. Dr. Gryce had shown me four small models. One he had sent back into Time. A flash, like a dissipating puff of vapor it was gone into the Past; still here in Space above the taboret on which it was standing, but vanished with centuries of Time to hide it from my sight.

Another of the models, with Time unchanged, Dr. Gryce had sent into Infinite Smallness. I remembered watching it dwindling; a speck, a pinhead, then invisible even to the microscope.

Two of the models were left. Martt and Frannie, but seventeen years old then, had taken one into the garden. Had started it growing in size. I recalled our frantic efforts to check its growth, lest it demolish the house. This was the one in which Martt and Brett had gone to the giant world and in which Brett had returned alone to that distant part of our universe.

One model had remained. I had never thought of it since. Martt was saying, ". . . and we still have that last model. Father kept it very carefully." Martt's smile was wistful with the memory. "I think he—Father—had a premonition that he would not live to carry out his purpose. . . . The model is here."

He opened a locked steel box. Again I gazed silently at that small cube of milk-white metal—a cube the length of my forearm, with its tiny tower on top, its glasslike balcony, its windows and its doors.

"It's all complete," said Martt. "And I know how to operate it."

Frannie said with a touch of breathlessness, "For a month past, Father has been gathering the necessary instruments. And the supplies—you see he—he really thought he was going to live——"

"We're all ready," Martt added. "We will increase this model to normal size. Load it with our supplies. We can start tomorrow, Frank."

IV

Five million light-years from Earth! Who of finite human mind can conceive such unfathomable distance! Yet, as I crouched on the floor of the vehicle gazing down at the radiance emerging from the black void which was our first sight of the Inner Surface, the distance had seemed no more than gigantic. We were, in size, many million times our Earthly stature. The tiny Earth, from our larger viewpoint, was a little orange spinning above us in the void—a mere one-twentieth light-year away.

Martt, for all his youth, had proved competent. He had made the trip once before with Brett; he handled the vehicle carefully, and with skill. He said now, as we three crouched by the floor window, "We'll soon be down to the atmosphere, Frank. I'm checking our fall—we want no errors——"

We were reversed in Time—holding very nearly at a single instant, so that on the Inner Surface the time now was the same as it had been when we left the Earth.

We argued the point; Martt said, "I think when we land—we should choose the point in Time about four years beyond Brett's landing. So that it will be four years to us—and also to him. Don't you?"

We decided upon that, so that we would reach the Inner Surface and find Brett had been there four years. It seemed to strike a greater normality. Find Brett! Would we find him? I wondered, as I knew Martt and Frannie were wondering. But in our plans we always took it for granted.

The radiance beneath us grew brighter. And at last we entered the upper strata of atmosphere, falling gently downward. It was a fair, beautiful land, as Brett and Martt had said. A sylvan landscape, with an air of quiet peace upon it. A broad vista of land and water; patches of human habitation—houses, villages; a city.

Martt was at the telescope. "Pretty good, Frank! I've hit it—I see the city—off there, isn't it? And the crescent lake."

He changed our direction slightly. As we dropped, the broad crescent lake lay beneath us. Trees bordered its banks; and to the right was the city of low-roofed, crescent-shaped buildings banked with flowers. And beyond the city a rolling country of gently undulating hills, with a jagged mountain range up near the horizon.

From this height it was a visibly concave surface. And it was gray and colorless, for we were passing abnormally through its Time. Then Martt threw off the Time-switch; we took the normal Time-rate of the realm. And in size we were also normal.

At a height of perhaps a thousand feet Martt held us poised above the city. "They'll see us now," he said. "If—if Brett is down there he'll recognize us. I'll land in the grove where we landed before. We'll give Brett time to get there to meet us."

With the Time-switch off, color and movement had sprung into the scene. The forests were a somber growth of dull, orange-colored vegetation. The water was a shimmering purple; and above us was a purple sky, with faint clouds, and dim stars up there—stars which seemed very small and very close.

The white houses gleamed and glowed in the starlight. Yet it seemed not night; nor day either. A queerly shimmering twilight. Shadowless, as though everything were vaguely phosphorescent.

In the broad city streets there was movement. Vehicles; people. And the people now were gathered in groups, staring up at us.

We landed in the little clearing at the edge of the lake near the city. And now at the last, Frannie gave voice to the fear which was within us all. "Oh Frank, do you think Brett will be here?"

There were human figures in the near-by thickets. I saw them through the windows, but we were too busy with the landing to look closely. The vehicle came to rest. Martt and I flung open the door. The vegetation was thick near by; we stepped from the vehicle onto a soft, mossy sward, and stood in a timid group, with tumultuously beating hearts.

"Martt! Frannie! Frank!" It was his voice! Brett was here! And we saw him step from a thicket. His familiar voice; his familiar figure, but so fantastically garbed that it brought to me a wild desire to laugh, for I was half hysterical with the relief of seeing him.

Frannie cried, "Brett! My brother! You're all right, Brett, aren't you? I'm glad you're all right."

Under stress, how inarticulate are we humans! I said awkwardly, "How are you, Brett? We thought we'd come and see you."

He took Frannie in his arms. And wrung Martt's hand, and mine, while his strange companions stood in the background among the trees, watching us.

"Of course I'm all right," he declared. "And terrifically happy." A shadow crossed his face; his glance went to the vehicle's doorway. "Father didn't come with you?"

Then Martt showed a wisdom far beyond his years. This was no time to bring sorrow to Brett. Martt said smoothly, "Father is better than he has ever been, Brett. We'll tell you—later."

"Good! That's fine!" Brett's face was radiant. "You're just in time, you three. I'm to be married tonight."

But even then as I wrung his hand again, and congratulated him, I had a premonition that it was not to be.

"Life is pleasant here," said Brett. "Pleasant, and indolent. It does not make for progress, but it is happiness—and I'm beginning to wonder if that is not best, after all."

We were sitting in an arcaded passage on the roof of the home where Brett lived. Crescent archways opened to the roof, where stood banks of vivid flowers, with a vista of the city beyond. The building seemed of baked earth, rough like adobe, and of dull orange color. It was a two-storied, crescent-shaped structure, set upon a wide street-corner near the edge of the city. The home of Leela's father. I had never forgotten Leela—the girl Brett and Martt had rescued from the giant on their first visit here. Brett had fallen in love with her. It was she whom tonight he was to marry. And this was her father's home—Greedo, the old musician.

"I have lived here with them six months," Brett said.

Martt exclaimed, "Six months! Why Brett, you have been gone four years!"

We had miscalculated the Time-change of the vehicle. Our purpose had been to strike this realm of the Inner Surface at a point in Time which to Brett would be four years. But now we found it six months only.

Brett smiled. "I'm glad you didn't postpone your arrival. You've no idea how pleased I am to have you—tonight of all nights."

We had not yet seen Leela, or her father. Brett said that Leela would be up presently to greet us. The city was excited over our coming. A crowd was gathered in the street before the house; Brett had made them a brief speech; Frannie, Martt and I had stood at the parapet and waved to them.

Then Brett had spoken of a younger sister of Leela's. Her name was Zelea—they called her Zee.

Martt sat up at this. "Where was she when we were here before?"

"Away," said Brett. "She was too young to meet a man then. Only now has she come to be sixteen. You'll like her, Martt. I want you to like her."

"I will," said Martt enthusiastically, "if she's anything like Leela."

"You were telling us about the life here," I suggested. "We always called this land the Inner Surface——"

"Yes," he agreed. "It is concave, like the inner shell of some great, hollow globe. Within the space it encloses——" He gestured to where, through the arcade, a segment of purple, star-filled sky was visible. "All that which we of Earth called the Celestial Universe is enclosed by this concave shell. You would think that this must be a gigantic region——" He smiled again. "It is not. Compared to our present enormous size, I imagine the circumference of this Inner Surface is not unduly great. I don't know. These people have not explored very far. They are not wanderers—they are too indolent, too contented, to wander."

He paused to drink from a shallow receptacle which stood before us, and offered Martt and me what appeared to be arrant cylinders to smoke.

"I have learned a little of the language. Proper names are impossible to translate. But the meaning of their word for this land, I call in English. Romantica. The romantic land. It is, I fancy, about five hundred miles square. Beyond it lie forests and mountains. No one here has ever penetrated them. There are wild beasts, birds, insect life—and fish and reptiles in the water. But they are not dangerous—not aggressive. It is not because of them that these people avoid exploration. It is—just indolence."

"I don't wonder," I said. "This is very peaceful here—I have no desire to do anything in particular." From the city streets a drone of activity floated up to us; but it was almost somnolent.

"It's always like this," said Brett. "Almost no change of seasons—the light always the same. There is no disease here—or very little. Food—grains, and what we would call vegetables, grow abundantly in this rich soil. The trees give milk—even the bark and pulp of them are edible. Life is easy. There is nothing to struggle against.

"Through generations, it has made the people kindly. There is little crime. No struggle for land, or food or clothing. Crimes involving sex——" He gestured. "Wherever humans exist there will be crimes of that origin. But our women here are very sensible, and when a woman does what is right—well, you know, don't you, that most deeds of violence into which men plunge over women have a woman's wrong actions at the bottom of them? There is little of that here, for the women take care that there shall not be.

"So they call their country Romantica. They are not a scientific people. They do not struggle for advancement. Art has taken the place of science. Painting. Sculpture. Music. They have developed music very far. It has a soul here. It speaks—it sings—it seems a living entity. It is—what music ought to be, but seldom is—the pure voice of love, of romance. . . . I was telling you about our country. Most of its population live in villages, and in individual dwellings strewn about the hills. There are but two large cities. This one—the largest—they call Crescent. Or at least their word for it suggests the shape of the lake. The other city is about fifty miles from here"—he gestured again—"off there where you see the line of mountains. They call it Reaf. It's a quaint city. Built largely over the water—rivers there—hot, subterranean rivers which rush underground—under the mountains. They go—who knows where? No one has ever been down them. The mountains are honeycombed with caves, tunnels, passages leading within, and up. Always up. But into them no one has ever penetrated. Legends tell fabulous tales of a great world up there. The giants, we think——"

When Brett and Martt had first come here, giants had appeared. Dwindling giants—strange, savage beings of half-human aspect. They had appeared—no one knew from where. Growing smaller until they were normal size to this realm. Not many had been seen. Some had kept on dwindling; they had grown so small, when attacked, that they had become invisible. At the thought, I moved my foot involuntarily with a shudder of uneasiness. Here on the floor beside me now, men like beasts might be lurking, so small I could not see them. Yet in a moment they might grow to a stature greater than my own. . . .

Men like beasts! . . . And I remembered that, with size gigantic, they had destroyed the third city of Romantica.

Upon Brett's face lay a cloud of apprehension. "We have never heard from them since. It is thought—I think myself—that they came from the subterranean rivers, or through the underground passages of the mountains. I conceive this concave surface upon which we're living to be the inner surface of a shell. It may not be very thick—there at Reaf. Above it—beyond it—up or down are mere comparative terms—beyond it must lie some vastly greater outside world. This whole realm is doubtless within an atom of that greater world. It would be a convex surface up there—with a sky and stars beyond. . . .

"We have never seen the giants since that time when Martt and I rescued Leela. Everyone here seems to have forgotten them——" Brett's voice was heavy with apprehension. "These people are so trustful! They forget so quickly! No one worries. Our rulers here—a venerable man and woman long past the age when death is expected—are so gentle, kindly, that they can not imagine harm coming to their people. They have forgotten the Hill City which the giants destroyed. Trampled upon it! Six or eight giants—they must have been several hundred feet tall—stamping, kicking the building! I've been there—I've seen the ruins—strewn for miles—and with buildings, colonnades and terraces mashed into the ground! There were no more than half a thousand people surviving that destruction of the Hill City—and thousands died. But everyone says now, 'The giants are gone. We are safe.'"

Brett's voice had risen to a swift vehemence. "It's been like living on a volcano to me, all these months. There are no weapons here. My own few flash-cylinders—of what use would a tiny flash of lightning be against beings so gigantic? We've got to do something. For if those giants come again——"

A step sounded in the oval doorway near at hand. Leela stood smilingly, deprecatingly before us.

II

Brett said, "Come here, Leela. This is my sister, and my friend, Frank Elgon. And here's Martt."

Leela advanced hesitantly, her face a wave of color as she met our gazes. She was smaller, and even slighter than Frannie, her figure adorned and revealed by its single, simple garment—more like a short, glistening veil than a dress. Her hair was long and dark, caught by a band at her neck, and flowing free beneath. Her arms and legs were bare. At her wrists, gray-blue bands with small tassels; on her feet, queerly high-heeled wooden sandals, with tasseled thongs crossing on her ankles. The sandals clacked as she walked; her step was mincing, with a suggestion of the Orientals of our Earth.

Brett eyed the sandals with a humorous twinkle. "For why are those, Leela?"

Her blush heightened. "In honor of our guests. I thought you would like them."

With a swift gesture, she stooped, untied the thongs and cast the sandals off. Her feet were very white, small and delicately formed, with rounded, polished nails stained pink. She stood untrammeled, lithe and graceful as a faun.

"I am glad to meet Brett's sister—and his friend. And you, Martt—I am glad to see you again." Her voice was soft as a Latin's. She shook hands with Martt and with me, and returned Frannie's affectionate embrace.

As I saw them together—these two girls of different worlds—I was struck with the dissimilarity of them. Pert, vivacious little Frannie, blue-eyed, fair of hair—brown-skinned from the outdoor life she loved. And Leela—smooth, white skin, dark hair and luminous eyes, a fragile grace to her every movement. None of my words are adequate. There was about her an aura of romance; a strange wild spirit of something for which every man in his soul has a longing; a beauty with a quality ethereal—half human, but half divine.

A twinge of conscience came to me that I—Frank Elgon—could think such thoughts and see such beauty in any girl who was not Frannie.

Leela was saying, "My father would have you come down soon. And Zee is down there—Zee is very much excited, Brett. There is so much to do before tonight——"

Brett's arm was around her. "And you—of course you're not excited, are you, Leela?"

She returned his caress, embarrassed further by his teasing. He added, "We will be down presently."

"Yes," she said; and with a pretty gesture, she left us.

The sandals lay discarded on the floor. Brett gathered them up, regarding them tenderly. "She is so easy to tease, I love to do it. But if you try that with Zee——"

"You shouldn't tease her," said Frannie. "She's a darling. I love her already."

Brett's wedding day! For all his quiet, whimsical teasing of Leela, the love he bore her enveloped him like a shining cloak. Yet his father whom he loved so dearly was dead, and Brett did not know it. I whispered to Martt about it later.

"I think we should not tell him," said Martt. "Not—until we have to."

And we did not. Looking back on it now, how much was to happen to Brett—to Martt, to us all! What fearsome things—danger, desperation, despair—were to be our allotted portion before we even thought again of old Dr. Gryce who was dead!

III

Brett was to be married that evening—a public festival and ceremony over which the whole city was in an anticipatory fever.

"The festival of lights and music," said Brett. "They hold it at periodic times. It is a wonderful sight. It generally includes a marriage—girls find it romantic. Leela selected it for us. Greedo is in charge of it—Leela and Zee always take part in its music. We must go down—they are waiting for us—there is so much for them to do between now and this evening."

"I'll help," said Frannie. "Come on, Martt—I guess you want to meet Zee, don't you?"

IV

We found Leela's father to be a grave, black-robed, kind-faced old man of an age indeterminate. Sixty, or eighty, I could not have told. In vigorous health, evidently. His figure was spare, straight, but not tall. His thick, gray-black hair he wore long to the base of the neck.

He greeted us quietly, with an admirable dignity commanding immediate respect.

"You are a musician," I said, after we had been talking for a time. "Brett has told us something about your music here. It must be very beautiful."

He smiled. "Music is a wonderful thing. It ennobles. There is in it a touch of something beyond our poor human understanding. A touch of—what you call Divinity."

"You speak our language very well," I exclaimed.

"A language is not difficult. All minds are similar—that is why music can make so universal an appeal." His voice was earnest, his eyes sparkling. It was the subject most absorbing to him.

I said, "You teach music——"

He raised a deprecating hand. "Yes. But that is nothing. I teach the fundamentals"—he struck his breast—"the rest comes from within. For myself, I am a mere retailer of sound. A peddler of something someone else has made. The composer—he is the real artist. I have hoped that some day Leela will compose. Brett has promised that he will urge her. . . . Just now, she sings." He twinkled at Leela. "I fear she thinks she sings very well. Pouf! It is nothing! She, too, is only a sound-peddler."

With a burst, Zee entered the room. A smaller replica of Leela. Yet how different! She came like a mountain torrent tumbling from the hillside. Her short, dull-red draperies whirled about her elfin figure. Her dark eyes were blazing. Black hair, flying over her shoulders with her tumultuous entrance.

"Father! That is not so!" She stamped one of her bare feet, then rose on strong, supple toes and whirled half around. The muscles stood out beneath the smooth satin skin of her calves. "Leela, why do you let him say such a thing? You sing beautifully." She whirled back. "And what am I, then?"

The old man was wholly unperturbed. "You, Zee? Why, you are a peddler of movement. Very swift, tempestuous movement, generally." He added to me, "She thinks she is an artist. She is not. She is only a dancer."

V

It was what on Earth would have been termed late evening when we started for the festival. Greedo, with his two daughters, had left half an hour before.

We were dressed now in the fashion of the country. Brett had suggested it; Martt had insisted upon it. I remembered with what a jaunty swagger Martt had worn his clothes upon his return to Earth that other time. He was dressed similarly now. A cloth shirt of glaring green, with a high, rolling collar in front, and low in the back; short trousers very wide and flapping at the knee. The trousers were a lighter green, with dark green stripes; his stockings were tan; and his green shoes were long and pointed. Over his shirt was a short tan jacket, wide-shouldered and with puffed sleeves, and bangles dangling from elbows and wrists. And there was a skirt to the jacket, rolling upward at the waist.

My own costume was in the same fashion; and though it was a sober gray, befitting my more mature years, I felt for a time awkward and foolish in it. But when in the crowded city streets I found that no one seemed particularly to remark me, I soon forgot it.

Brett wore a long cloak; I did not see how he was dressed. Frannie also wore a cloak. Just before leaving she tossed it aside, and stood before me, waiting for my admiration, with her characteristic twinkle, and her pert upflung face daring me to disapprove. Even by contrast with Leela and Zee, to my eyes at least Frannie was very pretty. She wore the single draped garment with silver cords crossed at her breasts to shape her figure; and with banded wrists, and tasseled bands above the knees. Her blond curls were tied with flowing tassels. The whole costume, a gray and blue, with a single deep-blue flower in her hair. And thin, flexible sandals on her little feet.

She eyed me. "Do you like me, Frank?"

"I—why, why—Frannie——" I would have told her then that I loved her, as I had very nearly told her myriad times in ten years past. But who was I to ask the love of any girl? A sorter of planetary messages, poor as a towerman in the lower traffic! "I—why yes, Frannie. Of course I like you. You're—beautiful."

She had a quaint little circular hat, stiff and round, with a dull-red plume and a tassel. We men wore hats of a solidly wooden aspect—low, round crowns and triangular brims. Martt's was sea-green, with tassels all around its brim. But mine and Brett's were sober gray, and unadorned.

We started on foot. The city streets were dim in the luminous twilight. Overhead, the sky with its thin-strewn stars was cloudless. A holiday aspect was everywhere. Crowds of people were in the streets. Young men and girls, gay with laughter. Most of them were cloaked. A vehicle, with runners like a sleigh gliding over the grassy pavement, drawn by a squat, four-legged animal, went by us. It was jammed with girls; one of them leaned out and waved at me. Her slim white arm came down; her hand twitched off my hat, sent it spinning. I caught a glimpse of her face; dark, laughing eyes, a mouth with mocking lips stained red. . . .

The sleigh passed on.

With Brett leading us we turned toward the lake. Most of the crowd seemed to be heading that way. Occasionally we were recognized. Stares of interest at us, the strangers, and cheers for Brett.

He said to me, "They're all very happy, Frank. Like children." I fancied that he sighed—he, for whom this night of all nights should have been his happiest.

In a group, with the swirling merrymakers about us, we made our way to the lake shore. The water was rippled by a gentle night breeze; the stars gleamed on the water surface with tiny silver paths. Boats were here—double canoes with outriders; and a few sailboats, small, single-masted, with triangular and crescent sails.

We found a small canoe; Brett sculled it with a broad-bladed paddle. Other boats were around us. A long canoe with a dozen sweeping paddles shot by us with the racing strokes of its men, and with shouts from its laughing girls. Another, smaller, turned over. Its men swam, and righted it. They climbed aboard, hauling up the girls. The wet draperies clung to them; they came up like dripping, gleeful water-sprites, tossing their black hair. . . . A barge went slowly along, drawn by two canoes. A lighted canopy was over its occupants—a huge, woven garland of flowers. The canopy gleamed with spots of vivid-colored lights.

"The luminous flowers," said Brett. And I saw that the large purple blossoms were gleaming with a purple light—a phosphorescence inherent in them; and red blossoms, like crimson lanterns; and others orange, and green. Music floated upward from the barge, soft and sweet over the water. The tinkle of strings—the voices of girls singing, and men humming with a deeper background of harmony. . . .

A night for love-making. The night romantic. Brett's wedding night—and yet, he had sighed. I knew why, for upon my own heart lay a weight of apprehension, heavier because it was so incongruous. Martt quite evidently did not feel it—he was shouting and laughing constantly with his pleasure. A girl from a neighboring boat tossed him a large, blood-red, glowing blossom. It fell short, went into the water and slowly sank, staining the water with its red light. Martt all but turned us over trying to rescue it.

Frannie, too, seemed gay. I tried to smile; but I felt that it was forced. The depression upon me would not be shaken off. It grew to seem almost sinister. The very atmosphere of happiness around me seemed to intensify it. These merrymakers—in the midst of life. . . . At such a moment as this, death could choose to strike. . . .

"Look!" shouted Martt. "The lights off there—is that where we're going?"

A patch of gay-colored lights gleamed from over the water ahead. "Yes," said Brett. "An island there, where they hold the festival. It's not far."

It was an irregular circular island, a mile perhaps in extent. The lake waters indented it with a hundred tiny bays, inlets, and narrow, placid waterways. We ascended one of them. The surface of the island was gently undulating, and wooded, with mossy dells—nooks arched with the luminous flowers. Nooks for love-making.

The whole island was strewn thick with the flowers; they grew upon tall, single stems—gay-colored lanterns nodding in the breeze. Beneath them were laughing couples; some hidden, sought and found by groups of marauding girls, to seize the man and laughingly whisk him away. And everywhere was music, soft as an echo. . . .

We ascended the narrow waterways, came to a lagoon with a glassy surface wherein a thousand spots of the lantern-flowers were mirrored like colored stars. Near the shore here, beyond a dock at which we landed, was a broad enclosed space with an arcade of the lantern-flowers arching over it. Brilliant with their light. Most of the crowd seemed congregated there—a milling throng on the level floor inside, with liquid strains of music mingling with the shouts and laughter.

"We'll go in there," said Brett. "I'll find seats for you—then I must leave, to join Leela and her father. There is to be a musical program. But first—just Greedo, Zee and Leela, and our marriage. Most of the music comes afterward."

Within the arcade the lights blended into a kaleidoscope of color. All the cloaks were discarded now. Costumes vividly splashed as a painter's palette. Heavy perfumes. And that soft, echoing music. I could not tell its source.

At one end of the room was a raised, canopied platform, with doors behind it. Most of the crowd were choosing low seats, like stools ranged in rows. Brett got us settled.

"I'll leave you now—and meet you over there by the right-hand end of the platform, afterward."

He left us. With Frannie between us, Martt and I sat quiet, watching and listening. We had not long to wait. The light around us began to dim; sliding curtains were obscuring the flowers over us. A hush fell upon the crowd. The soft music was stilled. A hush of expectancy.

The arcade was in gloom. The light on the platform intensified. A deep-red glow, with a single spot focused upon a small, raised dais. Into the red glow came Greedo, robed unobtrusively in black. He was carrying a crescent frame of strings. He seated himself, and in the silence swept his hands across the strings. His fingers plucked them like a harp; and then his other hand slid upon them. The staccato notes rippled clear as a mountain rill, soft, muted to seem an echo of music. And blended with them was a low, crying melody—a fragment, then silence.

Leela had appeared. She crossed through the red glow, mounted the dais, and stood in the silver light—Leela, robed to her feet in a misty silver veil through which her figure vaguely was outlined. She stood there drooping—a Naiad veiled in the fountain mist. . . . Then Greedo's music sounded. And Leela sang.

It was like nothing I had ever heard before. Music, toned strangely, with strange intervals to make it neither major nor minor. Not happiness, nor yet sadness. A wistfulness. A longing. But with the promise of fulfilment.

I listened, breathlessly; and the arcade around me faded. Greedo's figure in the shadow was forgotten. There was only the white figure of Leela; her face, the purity of girlhood, her eyes half closed, her lips parted with the song. Nothing else—save myself. I stood in a void, stretching out my arms to Romance. All that I had ever dreamed, and vaguely longed for without understanding what it meant, was upon me. All that woman could mean to man—the spirit of the ideal never to be attained in mortal flesh—seemed suddenly attained. Romance—that thing elusive—intangible as a thought in the vaguest of dreams. It was mine!

The song ended. Applause rang out. Leela was gone.

Martt breathed beside me, "Frank! Wasn't that—wonderful! It was like——Look, here comes Zee!"

Zee was on the platform—a whirlwind of veils, stained by the red light, white limbs flashing as she whirled. Greedo's music was faster now. Snapping staccato, with a thrum of melody. The lights changed to a mingled riot of color within which Zee was dancing. An elf. A sprite of the woodland, with tossing hair and fluttering arms; and a laughing face. . . . A figure in the fairy-tale of a child. . . .

But only for a moment. Then the dance slowed. Maturity came suddenly. Zee mounted the dais, and the light there was abruptly green. She stood in an attitude of terror, her eyes wide, hands before her, posturing with horror.

It made my heart leap. For an instant I fancied it had been real. But the light turned silver. The horror faded into a passion of love, her white arms extended, her breasts rising and falling beneath the veils, her red lips parted with passionate longing. The abandonment of youth—so young, with newly awakened passion as yet but half understood. Then again she was whirling around the platform, leaping on her bare toes, light as a faun. . . .

Behind me, suddenly a woman screamed! The reality of a long scream of terror! Greedo's music ceased. The lights wavered. Zee was gone. A scream from the audience; then another. A chaos of mingled cries. Clattering of feet. Stools overturned. . . . Someone fell against me. I went down, recovered and climbed upright. The audience was in a panic. I heard Martt shout, "Look, Frank! Look there over the water!"

People were pushing me—surging to escape from the arcade. Shouting. Calling to one another. And the woman behind me was still screaming.

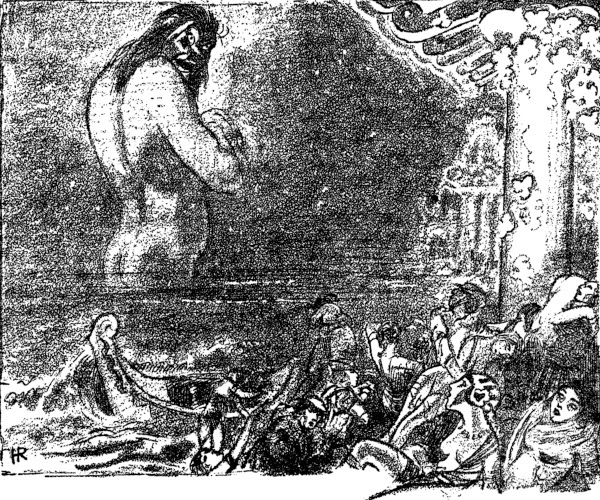

I saw it then. Through the open side of the arcade, out a mile or more over the water, the great giant figure of a man was standing, waist-deep in the lake, his naked torso towering a hundred feet above it. A giant, wading in the lake, his face grotesque, malevolently grinning in the starlight!

"The giant grinned malevolently in the starlight."

VI

The crowd within the arcade was in a wild panic of terror. I was pushed and shoved, knocked down by heedless, rushing figures. Everyone was trying to get outside. In a moment I was swept away. I could not get back to where I was sitting, or even tell where the spot had been. Martt and Frannie I could not see; the place was all a dim chaos of disheveled, panic-stricken figures. A moment before they had been so gay and jaunty! . . .

A girl rushed past me. The veiling had been torn from her shoulders. Her eyes for an instant met mine, as she searched my face hoping to recognize in me the companion from whom she had been separated. Her dark eyes were wide, red-rimmed with fear. Her face, with all the beauty of youth gone from it, was chalk-white.

She turned and rushed away from me. I thought again, "In the midst of life . . . why, this is horrible!" That giant off there—he could wade to the island in a few moments. . . .

I fought my way out of the arcade, out under the trees by the edge of the lagoon. There was more room out there. In the starlight I could see figures rushing aimlessly away, scattering under the lantern-flowers . . . others hurriedly crowding the boats. One boat was overturned. I wondered vaguely if the struggling figures in the water would be drowned.

Back near the wall of the arcade I saw a girl's figure running. It seemed familiar. Was it Frannie? I dashed after her. But people running in between us blocked me. I lost sight of her; saw her momentarily as she seemed to dart around the farther arcade corner. But when I got there, she was not in sight. Was it Frannie? Had she gone this way? Or into that door, back into the rear of the arcade?

I stood in doubt. Then I saw Brett, running past me, out under the lantern-flowers some fifty feet away. His cloak was discarded; he was bare-headed. Brett in his marriage robe! Black and white, with golden tassels gayly dangling from the rolled skirt of his jacket. He was disheveled; as he ran, I saw him tear off the jacket impatiently and toss it away.

"Brett! Oh, Brett!"

He stopped; whirled toward me. "Frank! Where's Frannie—and Martt?"

"I do not know," I said. "I lost them. That giant——"

"The giant is wading the other way now." He pulled me past a thicket, and pointed. I could see the back of the giant's naked shoulders, towering up against the stars. He was going the other way—wading toward the far-distant opposite lake shore. And now against the island's banks, the waves the giant made were beginning to pound.

Brett said: "I don't know where Leela is. I was in there with her—and with Zee. I rushed out when the alarm came—when I went back they were gone." He stood irresolute. "We must find them, Frank. And get back home." He drew a long breath. "It has come, you see, as I feared."

"I thought I saw Frannie," I said. "Running—that way. But I'm not sure. I lost sight of her——"

From behind the pavilion came a scream. The scream of a girl. Familiar. . . . The blood drained from Brett's face. "Leela!"

And then I heard Frannie screaming from there also. We ran. The two girls were standing there clinging to each other. They seemed unharmed. But they were trembling, shuddering, arms gripping one another.

"Leela! What is it?" Brett held her off, regarding her. "You're not hurt, are you? What is it?"

We four seemed alone here beside the arcade. Lantern-flowers were over us; a thicket was near by. Frannie's arms were around me.

"Frank—oh——" She choked; she seemed struggling to tell me something.

I held her close. "You're not hurt, Frannie. Just frightened. What became of Martt?"

Oh, horrible! What gruesome, horrible thing was this! Within my arms I could feel her sensibly shrinking! Her shoulders within my encircling arm, melting . . . palpably dwindling.

Horrible! And there was a great cry from Brett. "Leela! My God, Leela——"

At the horror of it, Brett and I stood dumbly staring; and again the girls clung together. They seemed dizzy; they swayed, almost fell, then steadied themselves.

Visibly smaller now, like beautifully formed little children, clinging together, no taller than my waist.

Dwindling!

Then Frannie pointed to the thicket. Two small human figures stood there—a foot high, no more. A grinning gnomelike man, with black matted hair on his naked chest; and a woman—a woman thick and shapeless. A foot in height. But they were shrinking very fast. And beside them were four small animals with horns—grotesque like a dream mingling dog and horse and moose. The animals, too, were dwindling.

Brett saw them; but neither he nor I made a move. At our feet Frannie and Leela, no higher than our ankles now, were gazing up at us, with tiny upraised arms, pleading.

"Leela! Frannie!" We knelt by them. Then Brett in an agony of terror lifted Leela in his hand. "Leela! Don't—don't get any smaller!"

Then he put her down. She ran, half fell the distance of my foot to reach Frannie. And I heard Frannie's tiny voice calling up to us in gasps, "We're going! He—that man there with the woman—caught us. Forced—down our throats—a drug. We—going——"

Smaller than my finger. Then so small we knelt to see them. They were huddled against the side of a pebble. Then they seemed struggling toward the pebble. Behind it. Under it. Under its curve. . . .

Brett cried, "Don't move, Frank! My God, we might trample on them! Don't move!"

The figures in the thicket had vanished. By the pebble which Brett guarded so carefully I thought I saw Leela and Frannie. Saw a movement, as though an ant were there, hiding under the pebble.

Then—they were not visible. We did not dare look too closely. They were gone! Still there within a foot of our straining eyes—but so immeasurably distant! Lost! Gone! Stolen into smallness!

Within the arcade, when the alarm had sounded, Martt leaped to his feet, dragging Frannie after him. He saw me knocked to the floor, but could not reach me. A press of panic-stricken people was sweeping him away, but he clung to Frannie. Then he saw me regain my feet; saw me looking around. But I did not see him; and though he shouted at me, in the noise and confusion his words were lost.

Frannie gasped, "What is it? What's the matter, Martt? What is it?"

Martt did not know. But he guessed, and his heart went cold with fear. "We must get outside, Frannie. Hold tight! This way—it's nearer! There goes Frank—we'll join him outside."

Martt was forcing a way for them through the crowd. Frannie stumbled. Her hold on him was broken. She fell; and before he could reach her he was knocked backward by a running man. When he regained his feet a swift-moving group was between him and Frannie. He saw two girls stop and help her up; then discard her. Saw her turn, confused, and run into a space where the crowd was thinner. He was being shoved away from her.

"Frannie! Wait! This way!"

But she did not hear him. And then he could no longer see her; there were too many people in between. He struggled in that direction, then he thought he saw me, and turned momentarily the other way. . . .

Martt found himself alone, outside the arcade. The crowd was thinner. Still he was not certain of the cause of all this panic. Then he saw the giant. Stood, and stared with tumultuously beating heart.

A man bumped into him; for an instant he thought that it was Brett. Memory of Brett reminded him that Brett was probably within the arcade, back of the platform-stage. He saw an opening, there in the arcade wall; he thought it was a doorway, leading back of the stage. He started for it, ran headlong into a girl standing there, staring out over the water to where the giant now had faced about and was wading away.

"Martt!"

"You, Zee! Where's Brett? Where are Leela and your father?"

She clung to him, her draperies drooping, her hair tumbling in great dark waves over her white shoulders as she shook her head.

"I do not know. They were in there a moment ago. Frannie came in—she and Leela were at the other door. Martt—that giant——"

"He's going away, Zee. Look! You see him turned about? Don't be frightened. We must find Brett. I don't know where Frank is—I lost him. There he is—isn't that Frank? Oh—Frank!"

They ran toward a man's figure, passing along a distant line of trees. But when they caught up with it, the man was a stranger. Ahead of them, hidden by a thicket, voices were shouting. A rhythmic call. Martt and Zee listened; but Martt could not understand the shouted words.

"What is it, Zee? Can you understand them?"

"They're saying, 'The messenger from Reaf!' Some messenger from Reaf has come with news."

"Come on. Let's go see what it is."

He gripped her hand. They ran swiftly through the woods. They were already several hundred feet from the arcade. The lagoon was on its other side; ahead of them was a patch of woods, dark, for the lantern-flowers did not grow along here. And beyond the woods, the shore of the island where the shouting sounded.

They ran. Soon Zee was ahead, leaping like a young chamois, her veils and hair flying.

"Wait!" he called. "Not so fast!"

She stopped abruptly. And Martt stopped. There was a pounding on the shore; waves rolling up, as though the peaceful lake were torn by a storm.

"What's that, Zee?" But the shouting began again; and without answering, Zee started ahead.

The starlit lake came into view. Like a distant, monstrous shadow, the retreating giant was visible against the stars. On the shore, white waves were rolling up. A boat was here, with its sail flapping. A wave caught it, turned it over.

On the strand a group of people were standing with the man who had come in this boat from Reaf. Zee joined the group. In a moment she returned.

"He says—the messenger says—that giants are in Reaf! The city is emptied—the people have scattered into the country. The road to Crescent is crowded with people coming here."

"Giants! There—as well as here——"

"Yes. They did not attack. There were two giants. They stood in the lake and laughed while the people fled from the city. Hundreds were killed in the rush to get out—hundreds were swept away into the subterranean rivers and the giants stood and laughed. The city is deserted, and the two giants are there now."

Men were helping the messenger right his boat. The group on the shore scattered back over the island, calling, "Giants! Giants are in Reaf!"

The messenger climbed into his boat, headed it out over the now calmer lake.

Martt and Zee momentarily were alone. He stared at her. He was stunned, confused. Giants, everywhere. This thing that had been worrying Brett for so long had come. Death, everywhere.

"Let's get back, Zee. We must find Brett."

It seemed shorter along the shore—a turn of the island near by, into the lagoon, and thus back to the arcade. They started off, running again. It was deserted along here. Zee was leading. Suddenly she stopped in full flight, gripped Martt, drew him behind a huge, pot-bellied tree trunk which stood near the water's edge.

"Zee, what——?"

"There, over there."

"Where? I don't see anything."

She whispered insistently, "Over there—in that open space. Back from the shore."

She was crouching, and he crouched beside her; followed her gesture with his gaze—and saw what she saw.

Tiny moving figures on the ground. Four of them, small dark blobs against the white sand. They were about a hundred feet away from where Martt and Zee were crouching. They had come out of the woods evidently, and were crossing this patch of white sand, heading for the water. Martt blinked and rubbed his eyes, staring at them. They moved in tiny leaps, bounding soundlessly over the sand. Each of them a foot long perhaps. Strange in shape; animal or human, he could not say.

"What are they, Zee?"

But she did not answer. Her little body was shrinking against him; he could feel her shudder.

The figures seemed long and thin, horizontal to the ground, with something sticking upright like a tower from the middle of them. Martt gasped. He had thought them four animals, with humps like upright towers. They were not. He saw them now as running dogs with horns, each with a tiny human figure on its back. And he gasped again. They were growing larger!

They crossed the sand in bounds and momentarily stopped. Already they were fully half normal size. Four horned animals that might have been grotesque dogs, or horses. Saddled; and mounted upon them, a heavy-set, half-naked man; a strange, shapeless woman—and two girls!

Normal size now! No, already they were larger! Growing rapidly larger! Frannie and Leela!

Martt half started to his feet. He opened his mouth to shout impulsively, but Zee drew him back and silenced him. The four animals were taking to the water. Swimming with heads stretched out. Martt could see Frannie and Leela bending forward, each clutching the horn of her mount. In single file the animals swam swiftly out into the starlit lake. They did not seem to be growing any further. Twice normal size perhaps. Soon they were four dark blobs on the shining water. Visually seeming smaller by distance. V-shaped lines of silver phosphorescence streamed out in the water behind them with their swift forward progress.

And presently they were vanished.

Martt and Zee stood up. They could not explain it. They tried to, but could not. But the main facts were clear. That had been a man and woman giant, and four of their animals. They had captured Frannie and Leela. Had made the girls and the animals change size like themselves. They had all, just now, been very small in size. To escape observation coming across the island to its shore, Martt concluded.

He said, "We must get to Brett—tell him about this. And then—go after them——"

Again they started running along the shore, intending to turn at the lagoon-mouth for the arcade. Martt's thoughts flew swift as his legs. Leela and Frannie captured . . . they must be rescued . . . then all of them would get into the vehicle and go to Earth—get out of this danger. . . .

Zee was saying, "That is Reaf, off that way where they went."

The wading giant had also gone that way. The messenger had said that Reaf was deserted, that giants were there. Evidently Reaf was the place at which these giants first appeared. Evidently it was the point of entrance and departure for them into and out of this realm. Leela and Frannie were being taken to Reaf. . . .

Martt's heart leaped. An idea was forming in his mind. A plan—a mad, reckless plan. But it seemed possible of success. . . . He thought of the vehicle. It would be of no use against these giants. It was too unwieldy. Besides, shut up in it one could not attack. And when they stopped it to disembark, the giants would overwhelm it. Or, if at the moment it was too gigantic for them, then they would escape before the occupants of the vehicle could get out to stop them. . . . And besides, the vehicle was too precious—no chances like that should be taken with it.

Martt told himself that he must get Brett to hide the vehicle. Guard it somehow. . . .

A mad idea, this plan he was pondering. . . . They came to the lagoon-mouth; and here, to crystallize Martt's plan, to make it seem feasible—here lay a small sailboat, deserted by its owner. It lay, half pulled up on the sand, around the bend of the lagoon.

"Zee! Stop! Wait! I want to talk to you."

Zee had been bounding ahead of him. She stopped, waited, faced him. He was breathless.

"That sailboat," he said. "It's one of the fast kind, isn't it?"

"Yes." She regarded it. "Yes. Very fast."

It was no more than a shell. A flat, spoon-shaped affair, with a small cockpit just large enough for two; and it had a very tall, flexible mast, and an overlarge crescent sail. The sail was flapping. Out on the lake the wind had risen. It was blowing directly toward Reaf.

"Zee, listen—could you sail that boat?"

"Oh, yes."

"You could handle it in that wind out there?"

"Yes. Of course."

"And it would go—how fast, Zee?"

"You mean—to Reaf?" She was as excited as he.

"Yes. To Reaf. We could get there. Go after them. Cautiously. We could hide before we got there. I've a plan——"

"How long to Reaf?" She pondered. "Three—what you call hours. We go fast in a wind like that."

"Yes. That's it. Fast. Three hours. Zee, listen. Reaf must be where the giants go to leave for their own world. They're taking Frannie and Leela there. You see? And if we can get there—get into Reaf"—he gestured—"Zee, if they—those giants are very big, then we to them are small. Tiny. And it's quite dark. It would be dark in the caverns near Reaf—the houses there near the subterranean rivers. We would be so small the giants might not see us."

He drew a long breath. "My plan, Zee, is to get in there, hide, and find a giant from whom we can steal the drugs. With the drugs——"

She was trembling with excitement. No fear now. Reckless as only youth can be. "Oh Martt, if we could get the drugs! Brett said the giants must be using drugs. And make ourselves larger than the giants——"

"Yes. Then I can fight them. Rescue Leela and Frannie. We've got to do it. Bring Leela and Frannie safely back. We'll say, 'Here they are, Brett.' But if we wait, if we stop now it will be too late."

Before Martt's eyes was the vision of himself and Zee returning victoriously with the rescued girls. And with the drugs in his possession. There would be no danger then. The giants, knowing the drugs were stolen, would not dare remain. . . . They would all escape up into their own world. . . .

"Will you do it, Zee? Shall we go?"

"Yes."

Martt thought of his flash-cylinder. "I wish I had it, Zee."

"Where is it?"

"In the vehicle. But we have no time to get it."

"I think it would not be of much use."

"No. I don't think so either. But all I've got is this." He displayed a knife whose blade, as long as his hand, slid back into its handle for a sheath.

"Good," she said. He replaced the knife. They climbed into the boat. Martt shoved it off.

In a moment they were beyond the quiet lagoon, heading out into the starlit lake, with the lights of the island fading behind them.

II

The wind was strong when they were beyond the island. The sail bellied out in front of them like a great crescent dish; the spoon-shaped boat, barely skimming the surface of the water, rode high on a white wave beneath it. Zee lay on her side, upraised upon an elbow with her hand on the knife-blade rudder that trailed the water behind them. Beside her, hunched with arms wrapping his upraised knees, Martt sat and peered ahead under the sail.

The lake was dim in the starlight; its concavity rose to the horizon. It seemed empty ahead. No boats. The wading giant had vanished; the swimming figures were gone.

As they sailed with the wind, the night seemed windless and calm, save that the lake boiled under them, swiftly passing. Martt was in no mood to talk. Zee, too, was silent, engrossed with her task of guiding the boat.

Occasionally, with a surreptitious, sidelong glance, Martt regarded her intent little face, earnest and solemn. Long, dark lashes, tendrils of dark hair around the slim white column of her throat; her outstretched limbs revealed by the stirring draperies. . . . A lock of her hair flew across his cheek. He touched it, cast it away.

"Zee?"

"Yes, Martt?"

"I was thinking—you dance very beautifully."

She turned to him, and smiled; a whimsical smile, and her eyes were dark woodland dells of fairyland. "Father does not think so. A peddler of movement—violent, tempestuous movement! Do you think that, Martt?"

"No," he assured her. "Of course I don't." As she turned back to her steering, his fingers furtively caught a hem of her robe and held it.

There was a long silence. Then he said, as though there had been no silence, "Of course I don't. I think you dance beautifully." And he added, "It made me——" His tongue was about to say, "It made me love you," but his beating heart smothered the words. He amended, "It made me think that your father was very wrong to say that. And about Leela, too."

At the mention of Leela he saw a shadow cross Zee's face. He tensed himself; set his jaw grimly. This was no time for thoughts of love. Leela, and his sister Frannie, were captured by giants. There was work, danger for him and for Zee, up ahead in this starlit night. He would need all his wits, all his resourcefulness. . . .

He remembered the one visit he had formerly made to Reaf; tried to recall how the city lay. Tried to plan what he and Zee would do, now when they got there.

He said, "Zee, the rivers at Reaf that plunge into the mountains—no one has been in them very far?"

"No," she said.

"Can you walk along their banks, inside, under the mountains?"

She nodded. "In some places there are narrow ledges beside the water. But how far—no one knows."

"And in other places—near Reaf, I mean—there are tunnels? Passageways?"

"Yes. Back into the caves and beyond."

"I think," he said, "that back through there is the way to the giants' huge outer world. They've come down, and through the ground behind the mountains. Do you suppose they'll take Leela and Frannie up to their own realm? Or keep them in Reaf?"

"I think—we do not know anything about it," she said.

He smiled grimly. "You're right, we don't. Why the giants should come here at all I don't know. But we're going to know more about it before we get through with them, Zee. What I'm hoping is that we might find one of them alone. We've got to get the drugs away from them somehow. We've got to."

Martt remembered once arguing with Brett about the giants. Brett had thought that they used some drug—two drugs—one to shrink proportionately each of their body cells, and the other similarly to increase the size of the cells. Drugs of the kind had already been sought for on Earth. Nitrogen was the basis for growth. And the new element, Parogen, had been found to cause a shrinkage. In Mars they had developed such drugs further—but they were still impractical for human use.

These giants evidently had something of the kind. And it must be radio-active—it must cause a radiation affecting vegetable or animal matter in near proximity to the changing body. The garments of the giants expanded and contracted with their bodies. But Brett had said that a weapon in your hand—particularly one of mineral—would not change size. . . . The thought was to some slight degree, at least, comforting to Martt; the giants would be unarmed.

Zee's voice broke in on his thoughts. "Look, there are the mountains behind Reaf."

Over the lake, ahead of them the distant horizon was a haze of phosphorescence. But to the left a line of shore had become visible; and now Martt saw up ahead the vague, dark outlines of the mountains. Sharp, jagged peaks, tinged with a green-white.

Another hour. The shore to the left was nearer. Undulating land along the lake. A ribbon of road along the water . . . Martt thought he could see blobs moving along it. Away from Reaf, moving toward Crescent.

"The refugees from Reaf," said Zee. "The messenger said all the roads were crowded."

Another half-hour. Ahead the mountains frowned, rising sheer from the water. The lake was more shallow here; they began passing flat, muddy islands, with river channels flowing between them as in a delta. A blur there, at the foot of the mountains, was Reaf. The silver phosphorescence of the lake was darkening; the water looked muddy, turgid. In a narrow channel between two islands, Martt noticed a quite visible current flowing toward Reaf. It rippled the water as it passed over a bar which Zee skilfully avoided.

There were other islands, with water bubbling up from them, and clouds of steam rising. Zee trailed her hand overboard.

"We are in the warm water now. Feel it, Martt."

The lake water, fed by boiling springs from all this region, was noticeably warmer. And every moment the current toward Reaf was becoming stronger. Martt knew that all this part of the lake converged to the mouths of the subterranean rivers at Reaf; converged and plunged under the ground.

The city of Reaf was now in sight. It spread sidewise over an area of a mile or two. The houses were perched on stilts, like flat, awkward, long-legged birds squatting in the water.

During all this time Martt and Zee had been watching closely for any sign of giants. There were none in sight—nothing that seemed alive over this turgid water, the disconsolate group of houses, the sheer cliffs with the sullen mountains above them. Two yawning black openings showed where the rivers entered. . . .

A deserted city, its inhabitants fled. Some had been drowned, the messenger said. There would be no floating bodies; the current would have sucked them all into those yawning black mouths. . . . A deserted city. But somewhere in there among the houses, giants might be lurking. . . .

Martt said abruptly, "We'd better get the sail down. They can see it too easily." They were still some two miles from the outskirts of the city. But no more than half a mile from the nearer shore. It swung past them to the left; perpendicular black cliffs rising from the water with a narrow rocky strip along the bottom against which the water sucked.

Zee helped Martt lower the sail. There were poles aboard; the lake here was no more than five feet deep. They could pole the boat ashore. Walk unobserved toward the nearer river-mouth. Into the city, to hide among its buildings.

With a thrill of apprehension Martt realized that they might already have been seen. But he thought it unlikely. From the hot water, vapor was rising in a fog. It hung like a white shroud over Reaf. Once in it, surrounded by the fog, they would be comparatively safe.

"Zee, can you swim?"

"Oh, yes," she said. "But Martt, if you get in the water, be very careful of the rivers."

Silently they poled the boat to shore. Drew it up from the current, left it on a shelving rock ledge. The strip here was some ten feet wide; the hot, black lake in front, sluggishly surging toward Reaf; and above them the smooth cliff-face.

The wind had turned—a swirling current turned by the mountains. The fog from Reaf came rolling down upon them. It grew dark; the stars were obscured. In the humid steam they could see no more than twenty feet.

"Good," said Martt. "This is what we want." He spoke in a half-whisper; stoutly, but his heart was beating fast. He drew his knife and opened its blade. "Come on, Zee. And listen, you keep close to me. Whatever happens, we must keep together. And if you see anything—or hear anything—don't speak. Just touch my arm."

They started, creeping silently along the rocks in the fog. It seemed miles. The water was hot beside them. The fog, like a gray curtain, opened reluctantly before their advance. Presently the ghostly outlines of houses were visible, a group of them clinging forlornly together near the shore. Wooden platforms like balconies connected them. A bridge came over and down to the rocks.

Then other buildings. A large one of two stories, backed against the cliff-face. Martt and Zee went under it, groping in the blackness among its piling. The close, heavy air smelt of fish.

They came out to find that the rocky shore had ended. A narrow incline walk led out and up over the water to another group of ghostly buildings. They were some thirty feet away, standing on stilts some ten feet high. In the gray darkness of the fog their shadowy outlines were barely visible.

Martt stopped. "Zee," he whispered, "how far are we from the nearest river-mouth?"

"Not far," she said. "Listen."

In the silence he heard the rush of water. As he stood there, suddenly this whole adventure seemed impractical. There were no giants here. They had all gone on, up into largeness unfathomable, taking Leela and Frannie with them. How could he follow? Even if he dared plunge under the mountains, he could never reach that outer realm. It was gigantic—compared to his present size it might be a million miles away.

Or, if there were giants still lurking here in Reaf, of what use to seek them out and be killed by them?

For an instant Martt hopelessly considered turning back. But he never reached the decision; Zee's fingers gripped his arm—cold, shuddering fingers. He stared, as he saw her staring, and within him his blood seemed to stop its flow.

Something was coming down the narrow incline bridge at the foot of which Martt and Zee were standing frozen, transfixed with horror. Something . . . in all the dark murk of fog Martt could not make it out. An animal? It seemed oblong, the size of a large dog. He could see its moving legs—eight or ten legs, moving as it walked. He felt Zee stir beside him; he withstood his impulse to run. That would make too much noise; the thing would bound after them—catch them. . . .

There was a rotting post beside Zee. She and Martt crouched there and watched with a horrified fascination the thing as it came padding down the incline. It was vaguely green-white; it seemed luminous. As it approached, Martt saw it was a sleek body, moving lithe like a panther. A green-white thing. And then he saw that it was headless. A blunt end, with a gaping, dripping mouth and a shining green eye on a protruding stalk. It stopped, turned the eye to look upward and back.

Martt's breath was stopped. In the silence he seemed to hear his own tumultuously beating heart, and Zee's. The thing was coming on again. Now Martt could hear sounds from it. A whining; a babbling. And from the houses, up there at the end of the incline, came another sound. A great, heavy breathing. A giant was up there asleep! This thing—like nothing of Zee's world—belonged to the giants! Martt's heart, for all his horror, leaped with exultation. A giant, asleep! A giant smaller in size now, if he were up in those houses. He would have the drugs; they could steal the drugs from him while he slept.

The thing on the incline was quite close. It glowed with its own light, greenly phosphorescent, like the ghost of something in a dream, leprous with its missing head.

Another moment. It was passing close beside Martt. A luminous liquid dripping from the gaping slit of its mouth. Its eye on the stalk peered ahead. Its voice was clearly audible. A whine; and babbling sounds like words.

Revulsion, even more than fear, swept Martt. This thing was muttering words! Animal, or human—it was talking, babbling to itself. Strange words of an unknown tongue—but human words. Babbling them as though with reason unhinged. Gruesome! This leprous thing—leprous of body; and leprous of mind!

It passed within an arm's length of Martt as he crouched. And suddenly, without conscious thought, he struck at it with his naked knife. Horrible! The knife sank, but the thing was scarce ponderable! Martt's hand with the knife went down and through the luminous green body, with a feeling of warmth and a wet stickiness, but no more.

The force of the blow, unresisted, threw Martt off his balance. He fell forward, but still clutched the knife. The thing, with a sharp, horrible cry of pain, lurched backward. Then stood with its eye quivering, poised for its attack.

Frannie forced her way out of the crowded arcade, with its struggling, panic-stricken occupants. She was confused, terrified. Separated from me, and then from Martt, her only idea was to find us again; or find Brett. Outside the arcade she turned aimlessly to where the crowd momentarily was least dense. Panic-stricken people—all strangers. Then she saw Leela in the shadow of a doorway of the arcade, and ran to her.

"Leela! What is it? What has happened?"

People around them were shouting. Leela said, "Giants. There is a giant off there in the lake. I was looking for Brett. He came out here. Oh, Frannie——"

The two girls clung to each other. It was dark where they stood. At the moment the crowd had surged the other way. Suddenly Frannie became aware of a dark form looming beside her. A man twice the size of herself. She tried to scream, but a great palm went over her face. She felt herself being jerked from her feet. . . .

She half fainted; recovered to find herself in a thicket within a few feet of the arcade. Leela was beside her. Leela panted, "Don't scream, Frannie! They'll—kill us if we scream!"

The man was with them, and a thick-set lump of a woman. Not so large now. Almost normal in size, for they were dwindling. The man was naked to the waist, a gray-white, barrel-like chest matted with hair. A face, fearsome with menacing eyes, and a head of matted black locks.

And in the thicket were four horned animals; saddled, like large horses with spreading antlers. The animals were dwindling. . . .

The man rasped a command at Leela. From his belt he drew small pellets, white like tiny pills of medicine. He thrust one at Leela, forced it down her throat. Leela gasped, "You must take it, Frannie. He says—it is harmless—but if we resist—he will kill."

Then the man thrust his fingers into Frannie's mouth, his arm holding her roughly. She gulped, swallowed. It was an acrid taste. . . .

The man pushed her roughly from the thicket. And pushed Leela. His triumphant laugh was the rasp of a file on metal. Leela and Frannie stumbled to the wall of the arcade, stood clinging together. And suddenly, with the realization of what was upon her, Leela screamed. And Frannie screamed, though she did not yet understand.

A wave of nausea possessed Frannie. Her head was reeling. Voices sounded near by—familiar men's voices. My voice, and Brett's! We came running at the sound of the screams.

Frannie held tight to the swaying Leela as Brett and I rushed up. And I took Frannie in my arms. Brett was demanding, "Leela, what is it? You're not hurt, are you? What is it?"

Frannie wanted to try and tell me. "Frank—oh——" She choked; her throat was constricted.

And then Frannie really knew! Within my arms she felt herself shrinking! Growing smaller; but it was not so much that; rather was it that my encircling arm was expanding, holding her more loosely.

With the horror of it, Brett and I stood apart. Frannie's nausea was passing; her head was steadier, but dizzy with the strange movement of the scene around her. She clung to Leela, and, of everything within her vision, only Leela was unchanging. The wall of the arcade was slowly passing upward; its nearer corner was moving slowly away; Brett and I were growing. Our waists reaching to Frannie's head; and then our knees. She gazed upward to where, fifteen or twenty feet above her, our horrified faces stared down.

The mind always takes its personal viewpoint. Frannie and Leela were dwindling into smallness. But now that the nausea and dizziness were past, to them, they alone were normal. Everything else seemed changing . . . the whole scene, growing gigantic. . . .

It was a slow, crawling growth—a steady, visible movement. The ground beneath their feet was a fine white sand. To Frannie's sight this patch of sand had originally been some ten feet, with the arcade wall on one side, and a thicket on the other. But the ground was shifting outward with herself as a center. Under her bare feet she could feel its steady movement—drawing outward, shifting so that her feet were drawn apart. She had to move them constantly.

Beside her now she saw my foot and ankle as large as herself; the towering shafts of my legs—my face a hundred feet or more above her. The arcade wall stretched up almost out of sight—lantern-flowers loomed up there like great colored suns. . . . The thicket was a hundred feet away—a tangle of jungle.

Then Frannie saw the giant Brett reach down and pick Leela up on his hand—saw Leela whirled gasping into the air. A moment, then Brett set her gently back on the ground. She was some twenty feet from Frannie. She ran, half stumbled across the rough white ground until again the girls were together.

The arch of my sandaled foot was now as tall as Frannie. The arcade wall was very distant; the thicket was a blur in the distance. That small patch of white sand had unrolled to a great stony plain. Rough; yellow-white stones strewn everywhere. Frannie saw my feet and Brett's—as large as the arcade once had been—moving away with great surging bounds up into the air and back. A boulder was near by—a rock as tall as Frannie. It was visibly growing. She gripped Leela—together they crept to the boulder's side, huddled there.

But they could not remain still. The boulder was expanding. It towered over them; but it was drawing away as well, for the ground was expanding. Constantly they shifted their position to remain close to it, to huddle under its protecting curve. It had been a rock taller than their heads; it was now a mountain. It loomed above them—a bulging cliff-face of naked, ragged rock.