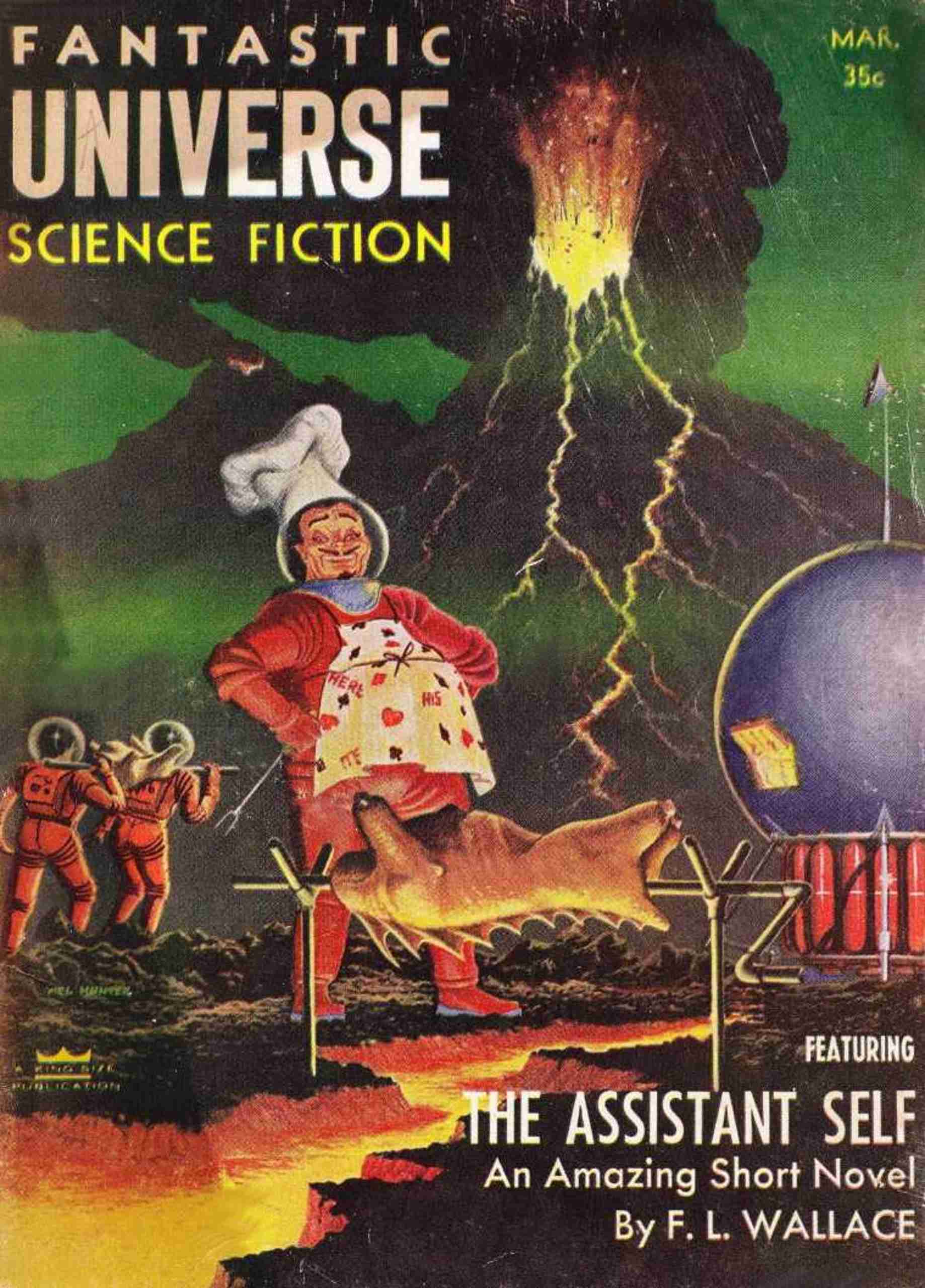

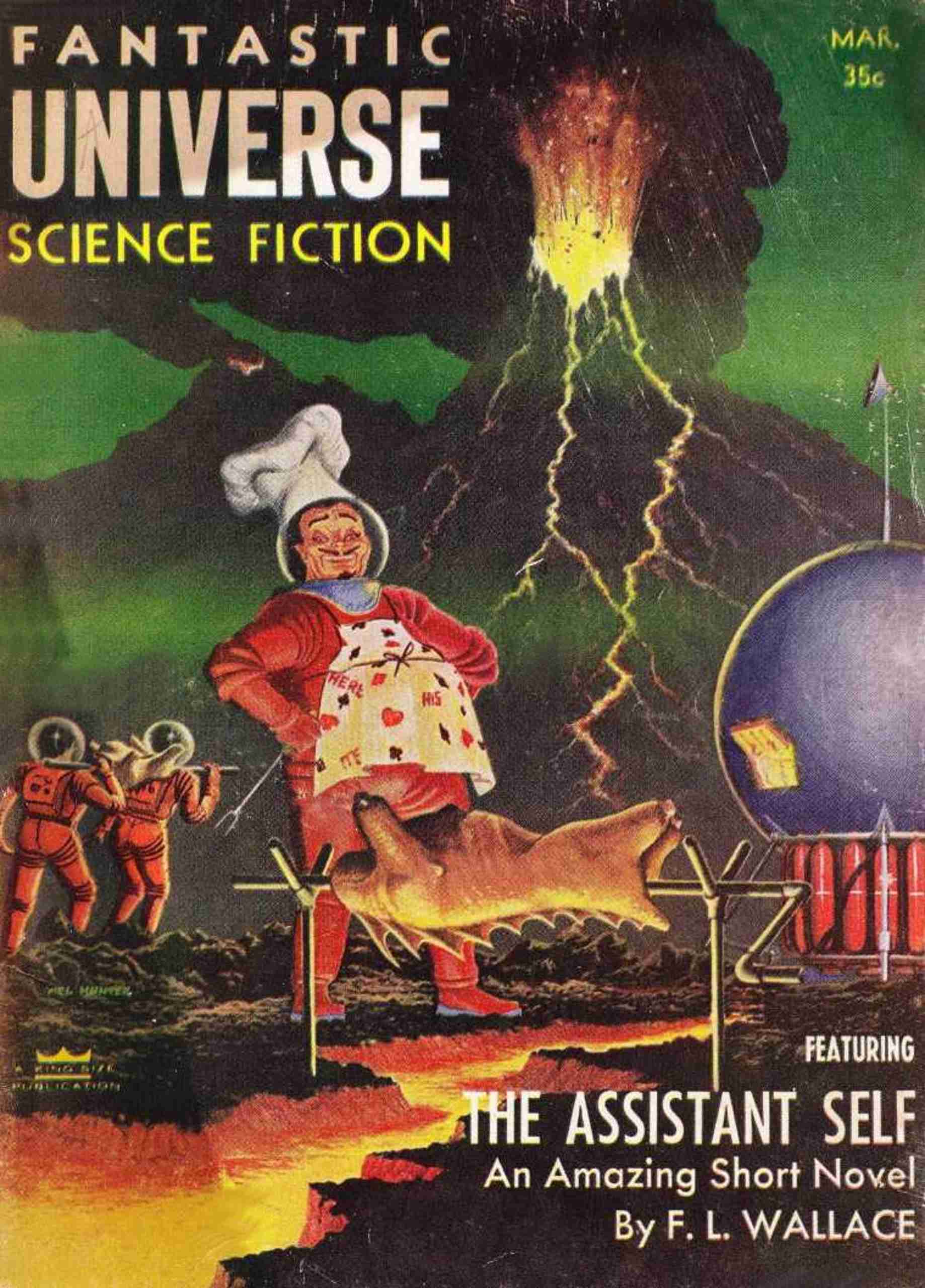

Title: The assistant self

Author: F. L. Wallace

Illustrator: Mel Hunter

Release date: December 19, 2025 [eBook #77510]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: King-Size Publications, Inc, 1956

Credits: Sean/IB and Tom Trussel

by F. L. Wallace

Sympathy for others may be one of the seven cardinal virtues. But man does not live by virtue alone, and a superabundance of any one attribute—however admirable in itself—can lead to stark tragedy. To appreciate fully the breadth of that tragedy you must follow in the footsteps of F. L. Wallace as he scatters golden nuggets of science fantasy entertainment along the frontiers of tomorrow with a prodigality undreamed of by lesser scribes. Here is a yarn that takes you straight into realms of abiding mystery and surmise.

It was a world of Utopian dreams and industrial strife—buffeted by the winds of human unreason. But Hal Talbot was a man apart.

“You always see the other person’s side,” said Laura. “Even the boss’s, especially when he fires you.”

She swept the compact into her purse and stood up. “Now see if you can understand my point of view.” With a withering contempt in her eyes she swung the purse to her shoulder and walked rapidly away.

Hal Talbot stared morosely at his drink. The worst of it was—he knew exactly how she felt. In spite of what everyone professed to believe empathy was a dreadful handicap. He had more than his share of it, and he couldn’t even hold down a simple lousy job.

He raised the glass and saw through it a man—a total stranger—standing beside the booth in amused expectation. The hell with him, Talbot thought. He drank the beer and set the glass down.

“Do you mind if I sit here?” the stranger asked.

Talbot looked him over carefully. He was well-dressed—too well-dressed—and he conformed in virtually every other respect to the popular conception of the executive, suave and so completely sure of himself. Therefore—he probably wasn’t.

“Suit yourself,” grunted Talbot.

The man sat down and ordered for both of them. It was all right with Talbot. He could have paid for the drinks, but he was keenly aware that his dwindling resources wouldn’t last long.

“I couldn’t help overhearing the conversation,” said the man.

“We have all our fights in public,” said Talbot, with embittered irony. “It makes things more final.”

The stranger stared at him steadily for an instant, his brows contracted. Then he asked: “Are you sure this is final?”

“You heard what she said. I can’t hold a job.”

“That’s precisely what I mean. You seem capable enough. I’m curious as to the reason.”

Talbot looked at the other more intently. He was a man of much the same general build as Talbot, but he appeared to be five or six years older.

“I mean no offense,” said the man. He fumbled in his pocket and held out a card.

Talbot took it. There was a single word in bold black letters on one side: TRANSPORTATION. The crosses on the T’s were spaceships. On the other side was a name: evan soleri, vice-president in charge of research. Talbot curled his fingers around the card.

The man smiled. “Just call me Evan.”

“All right, Evan. You’re going to offer me a job.” Talbot settled back comfortably. Things were falling into the routine pattern again.

“Perhaps. But first—do you mind telling me why you keep getting fired?”

“I don’t mind,” said Talbot. He was used to impertinent and stupid questions. He was used to getting jobs in odd places and to the ups and downs that always seemed to straighten themselves out eventually. Some day perhaps he’d find himself in a situation from which all his empathy couldn’t rescue him. But he’d worry about that when it came.

“You want to know why I get fired?” he asked, drawing the beer to him, and scowling across it. “Well, I’ll tell you. I meet someone like you. We talk, and are friendly. First thing you know he is offering me a job. I take it. In the beginning everything’s fine. I have a knack of knowing exactly what he wants. I get a raise practically overnight.

“Then one day his boss comes in and wants something in a hurry. So he talks to me very earnestly about it. Before anyone realizes what has taken place his boss is depending on me instead of on him. So what can he do? He finds some pretext and fires me.”

Evan Soleri nodded. “And you don’t object?”

“I get mad, naturally,” said Talbot. “But what else could he do? He’s worked hard for the job and I come along and threaten to take it away. The point is—I’ve got no special qualification.”

“Except empathy.”

“Except that,” agreed Talbot. He took a long drink and set the glass down. “It’s funny. I get along well with people but my adjustment index isn’t so good.”

“I’ve been thinking about that,” said Soleri. “Do you mind showing me your employment card?”

“Sure—step number one,” said Talbot. “When do I start?” He handed over the card, and waved to the waiter for refills in the same motion.

Soleri frowned at the card. “I notice you haven’t been tested in seven years. Why haven’t you gone back for re-evaluation?”

“It costs money,” Talbot replied. “Anyway, aptitudes don’t change much after twenty-four.”

“That’s usually true,” said Soleri, returning the card.

“When do I start?” said Talbot. “To save trouble shall I have them make out the termination notice at the same time? They can safely date it two months in advance. I usually last that long.”

“You may be surprised.” Soleri smiled. “I’ve a feeling you can work well at the top. You’ve been starting too low.”

Talbot studied the executive. Curiously enough, he had the same feeling—if he ever got to the top. It was hard to do on ability alone. He never lasted long enough for anyone to find out how good he was. “What sort of work am I supposed to do?” he asked.

“Interested?” said Soleri. “Have you heard of the perfect rocket motor?”

“I’ve heard of it. Everybody has.” Talbot disposed of the beer. “It’s out of my line, though. I’m strictly business administration.”

“Don’t prejudge what I have in mind,” said Soleri. “Have you also heard of Fred Frescura?”

“The heat scientist?”

“That’s right. The foremost heat and rocket scientist.” Soleri moved the glass aside. “As you know, present rockets are pretty poor. They take us around the solar system, but that’s all. And they don’t do that very well. Anyway, there’s mathematical proof that the theoretically perfect rocket motor can be built. We’ve been working on it for the past six years.”

“Why come to me?” said Talbot. “I can’t help.”

“Don’t be so sure. We want your empathy.”

“You can have it,” said Talbot. “Look. One point five on the card, maybe actually one point four by now. It levels off. You know the standard curve as well as I do.”

“The standard curve doesn’t always fit. That’s what I want to discuss.”

Talbot might have stayed to talk it over, but he caught a strong surge of panic from the executive. Panic or trouble—or both. He didn’t want either. He had quite enough of his own. It wasn’t every day he lost his job and his girl walked out on him.

“I don’t feel in the mood for hashing this over,” he affirmed. “You’re expecting a woman anyway.”

Soleri smiled quizzically. “See? I told you that you’re underestimating the strength of your empathy.”

“Nothing to it. You were looking at every pair of legs that came by.”

“I don’t think it was that easy. Why don’t you wait? Randy will be here any minute.”

Talbot shook his head. “There’s no telling what Laura will do when she wanders out like this. She won’t go home, that’s for sure.”

“I wish you’d reconsider.”

“You can’t get a test tonight,” argued Talbot. “And a test is the only thing that will give us real information. I know what you’re going to suggest—that I come in tomorrow morning. Fine. So I’ll do it—tomorrow morning.”

Again Soleri smiled. “I said that you were my man. Now I’m sure of it. Will you come in early, at seven thirty, say?”

Talbot could feel the other’s panic diminish. Maybe he was even better than he thought—if he could produce that effect just by agreeing. “Seven thirty is pretty early,” he said.

“There’s a reason for it,” Soleri assured him.

“I bet.”

Soleri took out a card and scribbled some careful directions on it. “Here,” he said. “Come in this way. Just walk right in. There won’t be anyone there at that hour of the morning except me.”

“Sure.” Talbot stuffed the card in his pocket and wandered over to the screen booth. He had trouble getting the connection, but when he did her father answered.

He had been correct in his assumption. He came out of the booth and stood for an instant at the bar, gulping down a drink. His head turned to follow the progress of a woman who had just entered the cafe. She had deep brown eyes and blonde hair, and a great deal more. That helped. She was not only pretty—she was spectacular. He liked spectacular women.

She went on by, and stopped at the booth occupied by Soleri. Quite obviously she was Randy. For a moment he regretted his decision to go in search of Laura. But only for a moment. Common sense told him he wouldn’t have a chance of taking a woman like that away from a vice-president of TRANSPORTATION. The company just happened to be the largest in existence.

Still, it felt good to have a man of Soleri’s importance seek him out. He rolled the thought around in his mind. It was unquestionably true. Soleri had come looking for him. He knew it the way he knew so many things—without thinking, by feeling alone, by the ability to put himself in another’s place.

By the time the thought had come full circle in his mind Randy and Soleri were gone. It was Laura now—or nothing.

He went in search of her. She was not in any of the bars she usually frequented. She was nowhere. There could be no doubt that she was mad at him this time, and would be for weeks—even when she learned what he had coming up. She wanted to get married and was furious with him for daring to put her off.

It took him quite a while to become absolutely convinced he wasn’t going to find her on what remained of his time, money, and drinking capacity. He started home and Laura slipped out of his mind.

It certainly wasn’t accidental—his meeting with Soleri. Soleri had been looking for him. But why? How had he known where to look? Talbot couldn’t concentrate solidly on the problem. It was all he could do to figure out where the street was going to sway to next.

One thing was certain. He’d have a lot of questions to ask Soleri in the morning.

Talbot dressed numbly. It was early, damned early, and his head throbbed. Aside from the physical discomfort involved he didn’t mind a hangover. He was more sensitive when he hung one on.

He was going to need that sensitivity when he talked to Soleri.

The man had a pretty phenomenal empathy index himself—say about 0.95. The more he thought about it the more certain he became that it must be at least 0.95. The executive had displayed uncanny acumen the night before.

Talbot swung a rack out of the closet and automatically selected a light conservative suit. Soleri would expect him to dress conservatively. He didn’t care what Soleri thought, but it was a matter of pride with him to fit neatly into any situation.

He dialed a cup of coffee, and then on second thought changed it to two cups, and gulped both of them. He studied his reflection in the mirror. It would do. He was the perfect picture of the successful executive. All he lacked was success.

He resisted the impulse to phone Laura. He was convinced she wouldn’t answer at seven in the morning. Probably she wouldn’t answer later in the day. Maybe in a week he’d call her after he got the job with TRANSPORTATION.

He went down and hailed an aircab which took him to the far side of the city. He alighted and read for the third or fourth time the instructions Soleri had written on the card. He located the entrance without difficulty and went in. Normally, he supposed, there would be a receptionist in the lobby. He didn’t see one. It was not important, for Soleri had cleared the way for him.

He ascended three flights of stairs, walked around a turn at the corridor, and there he was—in front of Soleri’s office. It would be just his luck to find that he had arrived too early. But there was definitely someone in the office. He conquered his trepidation and went in.

Soleri smiled and came toward him from behind the desk. His hand was extended and he was laughing. It was friendly laughter, and Talbot could sense the friendliness. But he was unemployed, and for that reason he resented it.

“My God,” said Soleri. “If we looked anything alike we’d be twins.”

Talbot stared intently, reviewing and adding to his original impressions of the other. They were within an inch and a pound of each other. Moreover they now wore identical suits and identical shoes and if there was a difference in their ties and shirts, it would have taken an expert to detect it. Talk about empathy! Soleri really had it.

But actually they didn’t resemble each other at all. Soleri’s hair was black, and Talbot’s was brown. Soleri’s eyes were dark, Talbot’s gray. Viewed from the back with a hat on they were indistinguishable. But face to face no one could have mistaken one for the other.

“It’s an impressive trick,” Soleri chuckled. “If you’re trying to convince me you’re good—relax. I believe it.”

“I’m not trying to convince you of anything,” said Talbot.

Soleri looked at him keenly. “You probably aren’t,” he said. “It ties in.”

Talbot blinked. “Are you saying it’s my empathy? One point four or five isn’t that good. Your own index must be zero point ninety-five.”

“How did you know?” said Soleri. “I never told you.”

“Why—” began Talbot, and stopped. How had, he known? It was one thing to think you knew, quite another to be always right. Something was startlingly out of place.

Empathy measurements started in adolescence. Before then the body was in a state of flux. It was still building, exploring. It did not have the experience on which to base valid opinions.

The adolescent was primarily aware of himself. He scarcely knew why he thought and felt the way he did, and had no time to encompass the emotions of others. But as he matured and some of his own problems became settled, an increasing awareness grew in him. He became better able to anticipate and participate in the feelings of others. Not merely to react to them, but to feel them as if they were his own.

After adolescence the ability to identify with others continued to increase—rapidly at first, and then more slowly. Plotted out as age against understanding, the curve resembled an hyperbola reaching for the asymptote.

Soleri smiled. “I see you’ve figured it out for yourself. We don’t think you’re usual either. A test will decide the matter.”

“The test can come later. Who’s ‘we’?”

“Myself and Randy, my secretary.”

Inwardly Talbot sighed. He could hardly blame the guy. With a secretary like that he couldn’t picture himself spending much time in an office either. Evidently Soleri and Randy didn’t. No doubt Soleri would claim that last night’s meeting had come under the heading of business as usual.

“Another thing,” he said. “How did you know I’d be at that bar?”

Soleri shook his head in humorous resignation. “You don’t let much get by you. To be wholly frank, that’s why we want you. Well, if you must know, we called your apartment several times in the last few days. You were never home. So we put plant protection on you. It’s outside their normal jurisdiction, but they learned your habits quickly enough.”

“I don’t like to be snooped at,” protested Talbot. “I don’t even know how you got my name.”

“That one’s easy,” said Soleri. “Several years ago you filed an application with us. I looked it over recently. I’m a mathematician—an amateur but fairly good. I decided that if you’d put down the various empathy measurements correctly you might be better than you thought. Over a short portion of the curve, you know, a cubic or another equation can resemble an hyperbola. After Randy gets here we’ll see.”

Talbot nodded. He could accept that. It helped to explain why he’d had so much trouble. People resented his competition. The thought gave him confidence, and he reached out easily for the next conclusion.

“But you’re not being altruistic about this,” he said. “I may have an index of zero point nine, better than yours, way at the top of the executive class. But for all you know I may have no knowledge, no subject matter in my head.” He paused to formulate the thought clearly. “You want me for something else. Specifically you’re in trouble.”

“We may not need that test. But we’ll take it anyway,” said Soleri. “Yes, it’s trouble. Do you want to see if you can tell me what it is?”

Talbot didn’t so much think as contact Soleri’s personality. He knew that atomic energy was advanced and with it almost any degree of temperature could be attained. And the hotter the exhaust, every other factor being equal, the faster the rocket. He allowed the thought to float closer.

“The technical problem is liners,” he said. “You’ve got to have something that won’t be melted or eroded by the exhaust.”

“True,” said Soleri. “Metal or ceramics won’t do—not at the temperatures we’re working with. We have made certain mathematical investigations which indicate there is a solution. Metal plus certain energy states might turn the trick.

“We can discuss techniques later. It’s sufficient for now that we’ve narrowed it down to a matter of trial and error. The rest should be easy enough: a million or so experiments and we’ll have it. We’ve hired the best brains in the field, and you can be sure we haven’t spared time or money. Only we aren’t making progress. The perfect rocket motor should drive us at—or near—the speed of light. We’re nowhere near that.”

Talbot leaned on the desk. “Competition?” he asked thoughtfully.

Soleri smiled painfully. “Perhaps. We’re big, but we’re not the only company after the motor. The difficulty arises from the fact that there’s nothing definite we can point to as wrong. If there was, plant protection would find the person or persons responsible and put an end to the obstruction in short order. What happens is simply this. Costly experiments have one insignificant detail wrong, and blow up or fail to function at all. Elaborate computations have one decimal point moved and it takes a month to locate the impediment. Who’s behind it? What official or worker is out to sabotage us? That’s what we’re trying to discover.”

“Did it ever occur to you that the perfect rocket motor may be an illusion? Perhaps it can’t be built.”

“We have Frescura to say otherwise. Rocket construction is his life’s work. Other experts in the field agree with him—though they are not always able to follow his theoretical explanations.”

“I won’t argue with them,” said Talbot. He glanced uneasily at the door of the office. A breeze was blowing it open slightly. “I see now why you wanted me to come so early. It was to make sure I wouldn’t be seen?”

“Right,” Soleri said. “I wanted to explain the situation and have you leave before the regular shift gets here. I’ll make arrangements for the test to be given outside the plant. When you come back you’ll be hired through regular channels. That way there’ll be no apparent connection with me. You’ll simply be given a position in the shop. It will be high enough to enable you to meet everyone, but it won’t be so top-level that you’ll be prevented from mingling freely.”

“I’m not sure I’m interested,” said Talbot. “If I’m as good as you think I am—why should I take a job like that?”

“It’s temporary, don’t you see? With your degree of empathy you can track down the trouble without arousing suspicion. After that we’ll put you where you belong. And your salary will be scaled to your test rating from the beginning, regardless of your workshop status. How does that sound to you?”

“Forthright,” said Talbot. “And quite generous.” He didn’t like to snoop any better than he liked being snooped at. But he’d listen.

“Randy’s due any moment,” said Soleri. “Let’s see that employment card again.”

Talbot reached for his wallet. The container the card was in didn’t detach easily. He opened it, and handed the wallet to Soleri.

Soleri examined the card with interest. He made a rough sketch of it on paper, plotting the points of the series of tests and joining them with a free-hand curve. He was so intent on the task that he failed to notice that the office door had opened the width of a man’s hand.

Talbot wouldn’t have noticed either, had he not turned at that precise instant to get a better view of the sketch and seen the hand in the crack. The hand threw a small dark object on the floor, then whipped back quickly. The door closed.

Talbot’s reactions were good but not good enough. He jogged Soleri’s elbow. “What’s that?” he said uneasily, indicating the object.

It was round and dark, hard to distinguish on the floor. It took Soleri a second to see it—a second too long. “Get down,” he shouted, shoving Talbot behind the desk.

The action threw Soleri offbalance and he fell the wrong way. He scrambled frantically for the protection of the desk but only his hand with the wallet still in it reached the merciful shadow.

A chaotic sound echoed somewhere near Talbot. He’d never heard anything like it. He didn’t have time to wonder where it came from because it was followed by another louder sound.

Instinctively he closed his eyes as an incandescent sheet of flame whipped across the room. It was accompanied by a vast thermal concussion which blotted out all sound. Take a tiny piece of the interior of the Sun—not the center, but somewhere between that and the visible outer portion—and wrap it with unimaginable insulation. Transport it to an office and strip away the covering in a microsecond. Within a limited area the explosion was even more frightful than that.

At first the desk shielded Talbot. In the intolerable light paint and pictures were burned from the wall. Chairs disappeared and the fireproof floor bubbled and vaporized. By the time the thick steel and thermoplastic desk collapsed in ashes around Talbot’s body the tiny speck of matter had dissipated most of its energy and there was only fire to fear.

Clouds of steam came from the ceiling as the sprinkler system went into action. It didn’t function well because most of it had been melted away in the first blast. Nevertheless water gushed out and turned to steam.

Talbot struggled to get out. But he was badly burned. Steam and smoke were searing his lungs, and a section of the ceiling had peeled off and fallen on his legs, pinning him to the floor. He saw a hand, all that was left of Soleri, clutching the wallet. And then he couldn’t breathe, couldn’t see or feel anything at all.

A dim, slender figure swirled dizzily in front of him. He hoped she was a nurse, but he could only see the flowing whiteness of her as she moved to the door. “You can come in, Miss Farrell,” she said.

Miss Farrell came in. She was better known to Talbot as Randy, and close up she was even more breathtaking than when he had first seen her. His vision was steadying a little now.

“Just a few minutes—not longer,” the nurse cautioned.

Randy sat down beside him, touching his face lightly. He could feel the gentle pressure of her fingers through the bandages. “Don’t try to talk,” she said. “I’ll say everything that has to be said. And it won’t take long.”

He blinked in grateful understanding. It wasn’t a wholly satisfactory form of communication, but her nearness soothed him.

“We haven’t found out how that thermal capsule got there,” she said. “We know it was hot, however. It had a temperature of at least a half million degrees, despite its extreme smallness. After you get well enough to talk freely we’ll try to reconstruct what happened.”

He nodded slightly, and the effort sent a wave of pain coursing through him.

“So much for that,” she said. “You’ll get well. There won’t even be scars. You’re lucky. Did you know it?”

He knew it. But he knew also that it wasn’t only luck. Soleri had saved his life at the expense of his own.

Then she said an incredible thing. “All we found of the other poor devil was his lower arm. The card was still clutched in his hand. It was scorched but not burned. I gave it to one of our mathematicians and he has worked out two curves that might fit. The man was everything you said he was—and more. I wish he’d lived.”

Talbot closed his eyes in stunned protest. She was making a mistake, a crazy utterly incomprehensible mistake. He tried to tell her—but there was only a gurgle in his throat.

“Don’t bat your eyes at me,” she said in mock reproof. “It’s true. The lowest empathy index registered is zero point eight. Right? Well, this man was zero point five. The mathematician couldn’t be sure, but he thought it might be even lower.”

She brushed the hair away from her lovely eyes. “Perhaps I should have kept it to myself. No one could possibly have the index the curve indicated. There are limits to human credulity.”

Again he tried to tell her that it was Soleri who had died. Soleri! But the bandages were too tight and his weakness too overwhelming.

But how could she have made such a mistake? True, he’d been wearing the same clothing as Soleri and the dead man had been clutching his employment card. But a woman who had been close to Soleri, who had seen him every day, would surely know—

She leaned over, brushing her lips against his eyes. “Don’t worry,” she said. “I disposed of the remains—and put him on the payroll. Roving assignment, reporting only to you. After six months we can arrange to make it appear that he was killed in an accident.”

His eyes! She’d known Soleri well enough to remember that the dead man’s eyes were dark, not gray. Women were never in error about things like that. He blinked frantically, but she failed to draw the correct conclusion.

“Why six months?” she smiled. “Because I have the company’s interest at heart. Otherwise we’d have to pay the full death benefit. If he’s on the payroll after six months the insurance company must assume the responsibility. His salary will be much less than the death benefit. He’s dead. Nothing we can do will bring him back. We may as well save some money.”

The logic was acceptable, but she had the wrong man. He groaned in frustration and the sound escaped as a muffled protest from his tortured and burned throat.

Instantly the nurse reappeared.

“That’s all, Miss Farrell. He’ll rest better for knowing what happened. But I think you’ve told him enough.”

Randy bent over. “Everything’s all right,” she whispered. “Get well.”

And then the nurse found an unbandaged region on his right shoulder and jabbed him. He ceased to feel or hear anything.

It was that way for the next few days, a dim and shadowy routine which he was vaguely and occasionally aware of. From time to time he felt stronger but the nurse had a needle ready and always used it. They intended to make certain that he did not prematurely exert himself.

Finally a day came when the nurse wasn’t there. It had apparently been decided that he was ready to rejoin the living. He lay motionless on the bed, staring down at his folded arms. His right hand was bandaged; his left was not. He raised both hands to his face. The bandages were fewer, lighter than before.

Sooner or later, he told himself, the bandages would have to come off. Then what? Then the truth would be known to everyone. Still, he wasn’t in an enviable position. He had gone at such an early hour to Soleri’s office that no one had seen him. He had only Soleri’s word as to his honesty of purpose—and Soleri was dead. Randy had made things worse with her silly attempt to hush things up. He was in a serious mess—and had no way of knowing what was going to come out of it.

He got up shakily. He had made up his mind. He must leave the hospital. He knew it was foolish, but that didn’t stop him. He swung his legs over the side of the bed and found to his relief that he could stand. He teetered precariously for an instant and then stood upright.

There was a closet on the opposite side of the room. He wobbled toward it, wrenched the door open. It contained a robe but no clothes. As he braced himself in the doorway he caught sight of his face in the mirror on the back of the door. His brow was gleaming with perspiration and his eyes glittered darkly in the expanse of white. The bandages would have to come off.

It was painful but not as bad as he had thought it might be. He found an edge and pried at the masklike plaster. The bandages came off in one piece. His raw skin burned as air came in contact with it. It stung and burned, but he scarcely noticed the pain.

He stared at his reflection.

Now he knew what Randy had refused to tell him because she didn’t believe it herself. The empathy index of the man she supposed dead was not zero point five. It was much less than that.

It was zero.

And zero was identity.

The face looking back at him was not that of Hal Talbot. It was Evan Soleri. It was Evan Soleri even to the dark eyes and the stubble of black hair that was beginning to grow in on his burned scalp.

Talbot or Soleri, he went back to bed.

He lay very still. His mind raced back, to the scene in the office. He had thought there were two sounds, the strange one slightly before the thermal explosion. But the first had not been a sound at all. He knew that now. It was Evan Soleri’s mental reaction to the approach of death. No one else could have heard it—no one except a man whose empathy index was zero. It was the crisis that had brought out his latent ability. He had responded by recreating himself as the identity of a person a microsecond removed from extinction.

He had done this successfully—but what came next?

He had been thinking of escape. It was no longer possible. As far as his immediate future was concerned he was Evan Soleri. He might be able to prove otherwise. But it could be a dangerous undertaking. They might think he’d had his face surgically altered with the deliberate, prior intention of replacing Soleri.

Besides—well, he had liked Soleri. Without a second’s thought Soleri had given his life for a man he hardly knew. Quite possibly the person who had tossed in the thermal bomb had meant to kill Talbot. But he owed the unknown assassin something for that too.

His face hardened. In his new identity as Soleri he was in the best possible position to track down the assailant. Soleri had been powerful, wealthy, the head of the research department. The place to begin was right here, where it had started. He’d be Soleri.

Talbot-Soleri rang for the nurse. He’d been inactive long enough. He had no very definite plans, but he’d take care of things as they came up. The nurse came in. She stared at him in consternation.

“You are not supposed to sit up,” she said. “And you must have been mad to take those bandages off. Here, I’ll put them back.”

He scowled at her, and she didn’t come near. “Get Miss Farrell,” he said. “Tell her I must see her at once.”

“The doctor gave strict orders that you’re not to be disturbed,” said the nurse hesitantly. She paled as he returned her stare, for there was a dangerous light in his eyes.

“Get her,” he demanded.

When Randy entered the room there was a moment of complete silence. She seemed stunned by his aspect of well-being.

“The miracle of medicine,” he said dryly. “Randy, I want to look over the personnel records of everyone in the department. Please get them and bring them to me here.”

“Everything?” She looked at him in amazement. “You went over the technical staff last week.”

“It doesn’t matter,” he told her. “I’ve got some ideas I want to tie down.” That was true, of course, but mostly he wanted to make sure he wouldn’t slip up on anyone he was supposed to recognize. He’d get by anyway, naturally. He could always claim a slight loss of memory due to shock. But such a claim wouldn’t inspire confidence—and he didn’t want anyone to become suspicious.

“While you’re at it bring the office staff too,” he added. There was one person he’d have to know as much about as possible. Much of it wouldn’t be in any file. But he’d worry about the intangibles later.

Randy plainly thought his request was foolish, but she complied. Soon files were wheeled to his bedside. That was the nice thing about being a big wheel in a big company, and no pun intended. Everything was handy. Even the hospital was inside the plant.

But there were also disadvantages. The company was so big that there was a lot to learn. Still, he had to begin somewhere. Randy undoubtedly thought some of his requests were strange, but she brought what he asked for. Though not eidetic, his memory was good. He began industriously to absorb the information. Names, faces, facts and diagrams settled firmly in his mind.

It was a lengthy, painful process. Sometimes he became confused as to his actual identity. Was he Talbot or Soleri? The thought occurred to him that he might never be able to step out of the character he had consciously as well as unconsciously assumed.

There was no data on what might happen to him. None at all.

On the day of his discharge his skin was still tender but the burns had healed. He felt weak but that was not surprising in view of the number of days he had spent in bed. The department managed without him and when difficulties developed he relayed brief orders through Randy. She was his buffer. He didn’t want to take part in running the plant until he had more insight on Soleri.

He learned many things, but there were technicalities to be mastered which he was sure he could pick up faster on the outside. The doctor wanted to send a nurse with him but he refused, finally consenting to have Randy accompany him. Perhaps he was taking a needless risk. But he was convinced he could handle Randy.

It was dark when they left the factory hospital, and took the elevator to the roof. He leaned on Randy somewhat more than he had to. It was a pleasure and a distraction. But he remained on his guard notwithstanding.

Randy was not a secretary at all. The files had revealed that much. Soleri had been so anxious to find out what was holding up the project that he had hired a first-rate psychologist and had put her in a position where she could work without being suspected. The psychologist was Randy. She wouldn’t fool easy. And that, in a sense, was a challenge. If he could get by her he could convince anyone.

An aircab was waiting. He leaned very close to her as she helped him in. He was almost sure that his empathy should tell him something and it did. Her eyes darkened, and she became obviously disturbed by his nearness. He settled back in the cab and waited.

The driver turned about, and asked: “Where to?”

He pretended not to hear. The driver repeated the question and Randy gave him the address. The information itself didn’t tell him much but his sensitivity filled in the missing details. She had been to the apartment many times, and stayed late.

They didn’t talk much on the way. The cab flitted over the city lights with a steady droning. He became uneasy. She too was sensing a strangeness in him. He regretted his decision to have her accompany him, and resolved to send her home as soon as he could reasonably do so.

They landed on the roof of a tall apartment building. She paid the driver and told him not to wait. No chance for subtlety there.

“I’m quite all right,” he said as she helped him out. “It was just a momentary touch of dizziness.”

“I know,” she said. “But you’re not going to get away. I intend to make sure you’re all right.” And that was that.

Soleri’s apartment was on the twentieth floor. It was elaborate and large, and furnished with exquisite taste. He approved of Soleri’s taste—in more than one respect. He sat down and looked it over.

“Glad to be back?” she asked.

He nodded.

“Sit and rest. I’ll punch dinner. Anything special?”

“Nothing special. Whatever you want.” She touched his arm as she went into the kitchen. He wished she hadn’t. He had enough to contend with without that.

Presently she came back. “We’ll have something light and nourishing in a few minutes,” she said.

She went to the recording system and began examining the calls that had come in during Soleri’s absence. He had to remind himself that it was an absence. Officially Soleri hadn’t died.

He watched her intently. He wished her eyes weren’t brown and wonderful.

“Anything important?” he said with an effort.

“A message from Andrew Taft. I told him you were hurt but not badly. He wants you to visit him next week.”

Andrew Taft was president of TRANSPORTATION. Everyone knew that. But there wasn’t anything in the files to give him a lead as to the duration or extent of their friendship. Perhaps Soleri had known Taft from boyhood. He didn’t want to put his newly acquired personality to such a severe test before he could be more certain of the facts.

“Make an excuse for me,” he said.

She looked at him inquiringly. “Do you think you should? Eleanor will be there. She heard about the accident and is coming in from Mars.”

He might have known there would be some such complication. Soleri was a powerful and attractive man and there had been more than one woman in his life. It was another unexpected pitfall, a further challenge to his wariness. He grimaced. “Eleanor’s a nice girl but she means nothing to me,” he said.

“Oh?” Randy’s lips tightened. “Is that why you’re going to marry her?”

At the moment he hated Soleri, empathy or not. If it had been at all possible he would have dropped the pretense. But he couldn’t—and he had to depend solely on his abnormal sensitivity. He told Randy what she wanted to hear.

“You know how it is,” he said blandly. “I’ve got to get that motor built. It’s costing far more than we expected. Somebody’s got to play company politics.”

She seemed a trifle mollified. “You needn’t tell me. I’ve had a thorough grounding in business psychology.” She moved quickly past him. “Dinner’s ready,” she said. “You’ve got to build up your strength—for company politics.”

He would have preferred silence but Randy insisted on holding up both ends of the conversation. Nothing important was discussed, but it gave him a chance to break down her defenses, and get to know her better.

After dinner they sat over a drink, and talked. Much of his empathy was tied up in the difficult task of simply duplicating Soleri. He couldn’t get through to her with the accuracy he would have liked. But he did succeed in turning the conversation from Eleanor. She was willing. After the first flash of hatred she was completely willing to forget the girl existed.

She looked at the clock. “Time for bed,” she said.

It was awkward. He started to get up, avoiding her eyes. “I guess so,” he said, letting her assist him, thrilled by her nearness.

There was nothing else he could do. She was attractive and he wanted her for himself. But she was desperately and unhappily in love with Soleri. He couldn’t let her know.

“Randy,” he whispered softly as she clung to him. Laura seemed suddenly unreal and very far away, and he wished he’d never heard of Eleanor.

Later he awakened to find her lying beside him, tense and still. She hadn’t been sleeping. In a surge of apprehension he wondered if she had discovered the truth about him.

“Is anything the matter?” he asked.

“Nothing.”

“Nothing? Is that why you’re not sleeping?”

“Well, there is. I was thinking,” she said. “It was what I saw when I ran into the office right after the explosion. The smoke was very thick and you were lying behind what was left of the desk. For an instant I wondered which one of you had died.”

“How could you tell?” he said. “I was badly burned. My face—”

“Your eyes are brown,” she said. “Brown. Anyway I knew. You couldn’t die.”

“Try to forget about it,” he said. “That nightmare is over. I’m alive.”

“And so is Eleanor.”

He sighed, wishing again that he could tell her everything. But Soleri would never deny the romance-shattering reality that stood between them. “You’ve always known about her.”

“So I have.” She moved closer to him. “I’m content with this brief dream of happiness.”

That was better. He caressed her lightly, tenderly. “It’s all right,” he said soothingly. “Nothing has changed between us.”

“I know, darling,” she murmured. He thought he heard her laugh before she went to sleep.

At last he fell asleep.

For the next few days Talbot was feverishly busy. Just what inner drives had dominated Soleri and how would he have reacted to any given situation? What had been his precise relationships with the people Talbot would be meeting daily? Fortunately there was an accumulation of recorded calls and messages. He played and re-played them. He subscribed to a clipping service and pieced together a fairly complete account of Soleri’s social activities.

There were other rewarding sources. He scanned minutes of TRANSPORTATION meetings. He examined financial statements to give himself another sidelight on the life he had usurped. Pictures, letters—even the apartment—added to his growing knowledge.

Handwriting presented no difficulty. He found Soleri’s signature, and duplicated it on second trial. Soon he didn’t even have to try—it became second nature to him to forge Soleri’s name on letters and documents. Mannerisms came easily too. Ways of walking, the quick thoughtful smile that appeared at intervals, the clothes he wore and how he wore them—-all these distinguishing characteristics he copied with little conscious effort. He was as much Soleri as another person could be.

He rested and regained his strength, painstakingly sharpening himself until he was ready. Randy appeared frequently on the call plate, keeping him informed of what went on at the plant. But she didn’t return to the apartment. He would have rejoiced in her presence but he didn’t ask her. It would have meant taking a dangerous, unnecessary risk.

Finally he went back to work, nodding cheerfully to the receptionist in the outer office as he turned left at the stairs. There was no trace of damage in his private office. It had been rebuilt and refurnished and was now exactly as he remembered it.

Randy came in at once, cool and beautiful. “I told Frescura you’d like to see him,” she said. “He’ll be in his lab until noon.”

Frescura, the famous heat and rocket scientist! He’d have to handle that interview with care. He had no way of knowing how much technical information the man had imparted to Soleri.

“I’ll see him but I hadn’t planned on it until later,” he said. It was a false statement, but there was no need to take her completely into his confidence.

“I’m sorry,” she said with feigned meekness. “I was trying to anticipate.”

He knew that she was actively hating him for Eleanor. He’d have to find some way to ease the tension. But at the moment other problems loomed more urgently. He became expediently stern.

“Forget the secretarial pose,” he growled. “You’re a psychologist. Your job is to find out who is resorting to deliberate sabotage in the plant. What does plant protection say about the thermal bomb?”

She met his gaze candidly. “Nothing. Anyone at all might have had access to the hall.”

“Then we’ll have to work at it from the other end,” he said.

She laid a sheaf of papers on his desk. He knew they were documents of no great importance. “Shall I tell Frescura you won’t be out?” she asked.

“I’ll see him,” he said.

She looked at him oddly, and turned to go.

“Randy.”

“Yes?”

He didn’t know exactly what to say, so he tried it out for sound. “I still want to find out why we’re not getting the motor. But it’s more than simple sabotage now. A man was killed—a man I regarded as a friend, even though I didn’t know him well. We’ve got to find out who is responsible. That comes first. Do you understand?”

Her wonderful brown eyes regarded him steadily. She turned away. “I understand,” she said.

“Keep it in mind,” he said. He got up and went to see Frescura.

Fred Frescura was a big man with more hair on his face than on his head. He was nearly bald but his eyebrows and mustache were thick and black. He had an air of concentration and childlike enjoyment of his work. Neither impression, decided Talbot, was strictly accurate.

He crumpled a sheet of calculations as Talbot came in, and moved out from behind the desk. “I’m glad to see you,” he said gruffly. “For a while we weren’t sure whether you’d been cremated in the holocaust.”

“It was more like an inferno,” said Talbot. “I survived.”

“So I see,” said Frescura. “I tried to get to the hospital but Randy wouldn’t let me in. For three days she camped in the corridor.”

“She takes excellent care of me,” acknowledged Talbot. He glanced at the desk and suddenly turned pale.

Frescura laughed reassuringly. “Don’t worry. These capsules are harmless or I wouldn’t be here.” He picked up a few of the tiny black cylinders and juggled them casually. “I was just attempting a reconstruction. What size was the thermal capsule which you saw?”

Talbot touched the spheres gingerly. They were jet-black and fathomlessly unreflective. “This, I think,” he said. “Or possibly this.”

Frescura laid five of the capsules down, rolling the other two in his hand. “I’m afraid that doesn’t help much,” he said at last. “It depends, you see, on how thick the covering was, and we can only guess at that. Let’s say the temperature was over a hundred thousand degrees.”

The temperature didn’t interest Talbot. He didn’t care by how much he’d nearly been vaporized. “Why don’t we use capsule material like this?” he said. “It ought to make a good tube liner.”

Frescura’s brows seemed to thicken and grow larger. “Are you seriously suggesting that I start my experiments from the beginning? Four years ago I told you we couldn’t use it. Now you act as if it’s something new.”

Talbot got out of the dilemma hastily. He regretted that he had not spent more time on the technical aspects. He’d tried to be thorough, but failures were never recorded as thoroughly as triumphs.

“It’s a thought,” he said, hoping the remark would pass for executive stubbornness. “Maybe we overlooked something.”

“Maybe we didn’t,” growled Frescura. “The thinnest skin we can make will hold a piece of matter at a hundred thousand degrees for ten minutes. If we make it two inches thick it will last twenty-nine minutes and fourteen seconds. Constructed out of this a liner that would do us any good would be a quarter mile in diameter at its widest section. Is that practical?”

“You might look into it again. You may have some new ideas,” said Talbot. He had avoided stumbling badly—and he’d learned something, although he should have known it in advance. The thermal bomb had been made in the plant. He looked up quickly. “Just when did the technicians arrive that morning? How many were in early?”

“I went over that,” said Frescura. “So did plant protection. At least fifty men were asked in ahead of their shift. Several came in without being asked. But none of them were near your office.”

It was puzzling and significant. Soleri had been in charge for years with no attempt on his life until he, Talbot, had been brought in.

Talbot filed the fact away for future reference. Someone had known Talbot was going to come in that morning. Soleri had made it plain that Randy knew. But who else?

Whom besides Randy had Soleri talked to? He couldn’t ask, but it was of vital importance. Whoever it was he had carefully manufactured the bomb in the laboratory, calculating the time by the thickness of the skin. That somebody had stuffed the capsule in his pocket and gone to Soleri’s office. When only a few seconds remained, he had rolled it through the door, giving himself just enough time to escape. But who was he? Talbot had no idea.

He discussed the thermal bomb for a moment or two and then switched to the progress on the motor. He listened to Frescura, who was more than willing to talk. Soon, unless he could slide out of the invitation, he was going to have to answer some far more pointed questions from Taft.

Still discussing high, very high, and stellar temperature chemistry, they went into the main experimental shop. This gave Talbot the opportunity of meeting the men he was supposed to have worked with for several years. There was a great difference between a picture and a page of statistics—even psychologically loaded statistics—and the man himself. He did a creditable job of imitating Soleri as he spoke to them. He had gone a long way toward merging with the dead man’s personality. But there was always an incalculable risk involved in anything he might say or do.

Frescura stopped expectantly beside a large construction site enclosure. “This is the latest,” he said in a hushed voice.

Talbot looked at the work in progress critically. He was still at sea as to its more technical aspects. “Is this the project we were working on before the accident?” he asked.

“Not exactly,” Frescura replied. “I’ve mentioned the theory before. But the application is new.”

Talbot was relieved. He wouldn’t be expected to know much about it. “Go over it for my benefit,” he urged. “Quite a bit has happened in the interval.”

Frescura glanced at him queerly, and he regretted having made the request. “You ought to remember this,” said the scientist. “Well, it’s off the mainline of our experiments, but I thought we might get some constructive results. We make the tube of dissimilar metals, one jacketing the other. When it is heated we get a thermocouple effect. An electric charge is generated. The charge on the inside of the tube repels the exhaust molecules so that they don’t actually come in contact with the inside surface. This reduces both heating and erosion.”

Talbot rubbed his head. “I remember. Is it ready to go?”

“It is,” said Frescura grimly. “But don’t stand there unless you want another accident.”

Talbot got out of the way hastily. He was blundering in practically every statement he made. There was far more to a person than personality, or his outward appearance. In Talbot’s particular case knowledge was lacking—not textbook information, but intimate details that could be acquired only by working closely with the man he was impersonating. So far it hadn’t been serious. But he’d have to watch himself.

Frescura moved a switch, and there was a rumble within the enclosure. A tiny, barely visible flame shot out a foot from where Talbot had been standing. The rumble rose to a shriek, and quickly passed beyond the range of hearing. The flame disappeared, but Talbot could still feel the heat.

Frescura picked up a wrench and tossed it into the path of the exhaust. The instrument vanished and the huge curved backstop a hundred feet away was suddenly coated with a thin film of molten metal. Frescura grinned at him.

“You’ve got to watch these things,” he said. He peered into an eyepiece on the enclosure, making several adjustments before he seemed satisfied. “Take a look,” he said to Talbot.

Talbot looked, his eyes gradually growing accustomed to the intense light that passed through the dense filters. He could see the inside of the rocket tube, and the fierce incandescence shooting by. Actually none of the exhaust gasses touched the walls of the tube, for there was a static area an inch in thickness next to the wall where nothing seemed to penetrate.

As he tried to see more clearly exactly what was happening the enclosure began to vibrate again, shaking the foundation. But the metal held. The shriek declined to a rumble and then the sound died away completely.

Talbot blinked and straightened up. Frescura was jotting down readings from the instruments on the enclosure. He made a few quick calculations. “The test corresponds to a rocket speed of thirty thousand miles a second,” he said.

It was a long way from what they wanted, but it was about fifteen times better than anything that had been attained before. “Not bad,” Talbot said, cautiously. “Maybe we should settle for this. One sixth the speed of light. Twenty-five years to the nearest star.”

Frescura scowled at him. “Make it thirty,” he said. “They’ve got to get up speed and slow down. Thirty to the star and thirty back. Sixty years for the round trip, not counting exploration time.”

“I understand,” Talbot said. “But with a young crew—boys not over twenty-two or three—it’s possible to send a ship to the nearest star and reasonably expect it to return.”

“They’ll be eighty when they come back,” said Frescura. “Their friends will all be dead.”

“There are some lads who will volunteer—if the rewards are high enough.”

“No doubt,” said Frescura. “But there’s one detail which prevents it—building a rocket motor which will last for more than a few seconds.”

“You’ve already accomplished a great deal,” said Talbot.

“This?” Frescura laughed. “No good at all. You saw what just happened.”

“I did. You shut off the motor.”

Frescura looked at Talbot with sour amusement. “It was the automatics that cut off the flow of fuel. Didn’t you see it? The inner charge repelled matter, but it couldn’t stop radiation. Radiation heated the tube. As it grew hot beyond a certain temperature the thermocouple charge diminished, intensifying the heat transfer to the tube. When it went, it fell apart in a hurry.”

Talbot frowned. “There’s no way around it?”

“None I know of. I’ll keep trying of course. With another hundred million dollars we might make this work even though it’s far from what we’re after.”

Talbot shook his head in admiration. Frescura tossed huge sums about with utmost ease. “Keep with it,” he said. “We’ve got to lick this or it will finish us.”

“We’ll come out on top,” said Frescura optimistically.

Unfortunately Talbot didn’t have the same confidence. “Economize where you can,” he cautioned.

“There is no such thing as economy in research,” Frescura affirmed.

“There had better be. We’re running low. Accounting is beginning to ask questions. We’ll have to go to the board of directors before long.”

“I guess so. The accident cost plenty.” Frescura leaned against the enclosure, rubbing it with unconscious affection. “If you need help, let me know. I’ll add my weight to yours.”

“I’ll let you know,” said Talbot as he walked away.

The trouble with Frescura was that he was a theoretical scientist, completely indifferent to cost. As he went through the plant he saw countless examples of waste. There was endless duplication, and the place seemed overstaffed. But, though he could undoubtedly reduce costs with efficient administration, that was not the most vital problem.

He had to locate and unmask a man who did not shrink from cold-blooded murder. It couldn’t have been Soleri. A successful saboteur would not have sought out Talbot to help him. Neither would he have killed himself. And it could not have been Randy. The trouble had begun long before she had been hired. It wasn’t Frescura, for he had not only initiated the project. He had pushed it through with all the influence at his command.

Taft was still unaccounted for. But he was the president of the company and it was inconceivable that he would launch a criminal conspiracy against his own interests.

Nevertheless Talbot made up his own mind. His extreme sensitivity was his most valuable weapon. He intended to find out just how far it would take him. He completed the tour of the plant and went back to the office.

He called Randy, and immediately took up the problem of Taft. “I still haven’t answered his invitation,” he told her.

Her eyes clouded. “I know,” she said. “I’ll notify the department heads that you won’t be in the plant for a few days—beginning Wednesday.”

“I’ll be here,” he said. “I want you to dream up an excuse why I can’t go. Make it good. I trust your social sense.”

“You can’t do that,” she protested. “Have you seen the latest statement from accounting?”

“I have. We’ll need funds before long.”

“You don’t turn down an invitation from the president when you may need his help.”

“You do when there are graver issues at stake. I’ve got to begin somewhere. The top is a good place.”

“A dangerous place,” she said.

“I’m not thinking about that.”

“You’d better,” she said. “Unless—have you got a cushion?”

“In a way,” he said. “Somebody wants this project to fail, badly enough kill anyone who stands in his way. Good, we’ll let it come close to failure. We’ll see if there is any attempt made to interfere—”

“You’re the boss,” she shrugged.

“I hope it works.”

“It will.”

He flung himself into his work for the remainder of the afternoon. Facts and figures went into his head and what came out was a reasonable duplication of what Soleri had known.

He finished late. Most of the office force had gone home. A few technicians were working in the shop. Tired and numb he took an aircab. Twenty moments later he was letting himself into his apartment. He wasn’t imagining it. There was someone in the apartment. Still, Soleri would inevitably have visitors now and then. It was nothing to be afraid of. He went in.

Randy smiled at him. “Hello, darling,” she said.

Frescura got up hastily as he heard Taft’s familiar voice in Randy’s office. “I’ll leave,” he said, folding the sheet Talbot had just signed.

“Stick around,” Talbot urged. “I’m sure he wants to see you.” He hadn’t thought Taft would come so soon, but he was not at all displeased. He was equally grateful for Frescura’s presence, feeling confident that it would provoke some interesting reactions. But he was destined to be disappointed.

Frescura wriggled his thick mustache. “I came up to ask Randy something. I’ll go talk to her. If Taft wants to see me he’ll come out to the lab.”

“Suit yourself,” said Talbot.

Frescura left. He could hear him conversing briefly with Taft in Randy’s office before Taft came in.

Andrew Taft was not the lean graying figure so familiar to the newscast public. He was tall, but he was also considerably heavier than he appeared to be on the screen. Distinguished citizens had certain prerogatives, and the networks saw to it that the lighting dealt kindly with them.

“Sorry about the party,” Taft said on entering. “I flew up to try to persuade you to change your mind.”

Talbot shook hands, using his most cautious Soleri approach. “You know how it is,” he said in half-apology. “I’ve fallen behind since the tragedy. I’ve got to dig my way out.”

“I’ve worried about you,” said Taft. “So has Eleanor.” He glanced up quickly. “Your insistence on shunning social engagements doesn’t have anything to do with her, does it?”

“It doesn’t,” Talbot assured him.

“South Africa may be a nice place to live. But it’s quite a distance. And I really am in a mess here.”

“Nonsense. You can fly there in a few hours,” said Taft.

“Eight,” Talbot reminded him. “Service isn’t good to that part of the globe.”

“You can cut the time in half if you charter a direct flight,” said Taft. “I suppose it would tire you out. But over-work can kill. You ought to call Eleanor. You know she won’t take the initiative.”

Talbot decided to risk a decisive move. “I’ll call her now,” he said.

“No, wait until I leave,” said Taft hastily. “I don’t want her to know I came to see you.”

“Tonight then,” suggested Talbot.

“Tonight’s fine,” said Taft. He chatted on inconsequentially for a time. Talbot could see that Soleri’s relationship with Eleanor’s family—though nominally cordial—was actually quite superficial, except possibly with Eleanor herself. He would have to be careful not to trip there.

“What’s behind all this?” said Taft finally. “I know you. You work hard, but you can also relax. You’re not the kind to turn down an invitation just because you’re busy.”

He’d judged the man correctly. Taft was shrewd, and quick to protect his own interests, daughter or company. “I may as well be frank,” said Talbot heavily. “I’m afraid we’re not going to develop the perfect rocket motor—or anything close to it.”

“That’s not what you said in your last report.”

“Official optimism.”

“It’s not Frescura’s attitude. I talked to him in Randy’s office and he’s brimming over with enthusiasm.”

“Frescura will back his own work if it takes the last cent of the stockholders’ money.”

“Don’t forget that some of that money belongs to him. He has stock in the company too. In fact, his holdings exceed yours.”

“I know. But we’ve spent six times the amount we originally estimated. And the end’s not even in sight. I haven’t made up my mind, but I’ve been wondering lately. Perhaps we should abandon this line of research entirely. It may be the wisest course.”

Taft stared at him, aghast. “You must be out of your mind. What would we do with this plant? Close it down?”

“We don’t have to. We can lease research facilities to other companies. We can tackle short-range projects that will pay off.”

Taft got up and paced the floor. “You’re in favor of abandoning the perfect rocket motor?”

“I didn’t say that. I merely said that I was thinking about it. Of course an alternative would be to reduce the scale of our efforts. Cut it back to a few men—something that we can afford.”

“I don’t know,” said Taft in agitation. “Frescura isn’t going to like this.”

“That’s another matter I wanted to discuss with you,” said Talbot. “Frescura is a valuable man—too brilliant to be wasted on a project that has no chance of success. We should assign him to something more worthy of his talent.”

Taft sat down. “You are actually saying that we should forget about going to the stars.”

“Not exactly. I think the idea should be placed in the proper perspective. Later developments may enable us to resurrect it.” Talbot was somewhat bewildered. Taft’s reaction had surprised him—although he couldn’t have said quite what it was that he had expected.

“Don’t you see what it means?” said Taft, his face lighting up. “If we develop the motor in our own shops it will be ours. We won’t have to license it to others. Every bit of interstellar trade will be carried in our ships. Ours alone. Monopoly.”

“Monopoly is nice,” said Talbot. “Bankruptcy isn’t. That’s what we face unless we cut down.”

“TRANSPORTATION is years away from bankruptcy,” said Taft sharply.

It was a shock to hear even that admission. Talbot’s own knowledge of the company’s financial position was fair. But Taft was in a better position to know the facts and if he said, even privately, that ruin was years away it could be assumed that he had grave doubts about the stability of the corporation.

The startling fact stood revealed in all its naked ugliness. The largest company in the solar system was none too secure. And it was the reckless expenditures that Soleri was directing that had led them to the brink of disaster. At least he had uncovered one motive. Someone with a knowledge of the truth was out to wreck TRANSPORTATION.

Before he could collect his thoughts there was an unexpected interruption. The door opened and Frescura came in, his face dark with anger. “As long as this is a stockholders’ meeting I thought I’d make it a quorum,” he said.

This much Talbot knew. Taft was the largest individual holder, owning something less than fifty percent of the total corporate shares. Frescura held a lesser percentage, though fractionally more than Soleri did. Together the three of them constituted an actual working majority. It had been their combined votes which had backed the project from the beginning.

“I didn’t mean to eavesdrop,” said Frescura. “Randy touched the wrong button while we were talking and I overheard part of the conversation. It concerned me—so I came in.”

“We were discussing policy,” said Taft soothingly. “Nothing was decided. You understand that.”

“I understand,” said Frescura in a hard set tone. “I also understand that this man is dangerous. He is not Soleri.”

The assurance that Talbot had gradually been acquiring suddenly collapsed. He sat motionless, while a cold constriction tightened about his heart.

Taft looked from Talbot to Frescura. “You can’t be serious? I ought to be able to recognize my chief executive and my own daughter’s fiance.”

“Ordinally you would. But this man is a clever impostor,” said Frescura. “He wants to abandon the project. Soleri would have recoiled from the thought.”

“I see no significance in that. Anyone can change his mind.”

“Proof is on the way,” said Frescura. He seemed very sure of himself. “I began to suspect him when he put questions to me Soleri would not have needed to ask.”

“It still isn’t proof.” But Taft was wavering. He turned and stared uncertainly at Talbot.

“You can’t expect me to defend myself from a charge like this,” said Talbot. He realized at once that it was a weak answer, and tried to strengthen it. “The fire in my office wasn’t trivial. It’s true, I may have suffered a slight memory loss. The bursting of a few tiny blood vessels in my brain would account for it. But that doesn’t mean I’m less capable than before.”

There was no possibility of escape. At Frescura’s command plant protection would close every exit in the building. And then he’d be charged with sabotage and murder.

He had to sit it out. If he was exposed his only chance would be to claim that for a time he had actually thought himself to be Soleri. They’d investigate him psychologically, but mind tests weren’t exact and he had a good chance of making them believe he was telling the truth.

“Nobody’s doubting your mental competence,” said Taft. “But there is some question as to who you are. Are you Evan Soleri?”

“What can I say to that?” said Talbot. “Are you Andrew Taft?”

“That’s not a defense,” said Frescura with smooth confidence. “It won’t be difficult to establish your identity.” He turned abruptly. “Come in Randy.”

The door opened and Randy entered the room. Talbot was sure she had been listening to the entire conversation. He had never doubted her loyalty, but if Frescura had convinced her that he was not worthy of loyalty—

Frescura took the folder from her. Talbot knew what was coming but curiously it relieved him. At least Randy wasn’t responsible.

“You can leave now,” Frescura said sharply to her. Talbot knew she would continue to listen outside the door, and was glad he would not have to see her face.

“His right hand was badly burned,” Frescura was saying. “New skin was grafted on. We can’t prove anything from that.”

“Fingerprints?” said Taft. “It’s an old method of identification, but I’ve often wondered why it has fallen into disrepute.”

“Because of the prevalence of skin grafts,” said Frescura. “But for certain purposes it’s still the most accurate method.” He smiled. “It’s in the hospital record that his left hand wasn’t burned. No skin was grafted on. The prints on that hand will show us who he really is.”

He shook the folder at Talbot. “This man signed an authorization shortly before you came. When I heard what he said to you my suspicions were confirmed. I sent Randy down to plant protection for a comparison of prints. Here are the results.”

He opened the folder, and looked at the three typed pages within. He stood there motionless, staring in consternation until the papers slid out and fluttered to the floor. His face was ashen. He reached out for support and lowered himself into a chair.

“What does it say?” said Taft impatiently. “My God, what’s happening around this place anyway?” He scooped up the papers and read them silently. He passed them over to Talbot. “I’m sorry,” he said. “Truly sorry. I should never have had even the slightest doubt about you.”

Talbot’s sight blurred as he read the comment from plant protection: “Comparison of prints with those in our file reveals that Evan Soleri signed this authorization. The left hand prints match perfectly. The right hand indicates a skin graft from which no identification can be made.”

Empathy had saved him. It had collapsed the difference between one person and another to nothing—zero. It had changed more than his face to match the subject identity. To the tips of his fingers he was now Soleri. The change hadn’t been made all at once; perhaps it had taken a week to reach completion. But here he was, safely Soleri—or trapped in the other identity. For the moment he preferred to think of it as safety.

“There are other tests,” he said to Frescura. “I’ll take them all, including the empathy index.”

Frescura stirred dully. “It will be zero point ninety-five,” he said.

“Don’t bait him,” said Taft sharply. “He made a mistake, granted. He accused you unjustly. But you must remember that you attacked a project he has devoted his life to. He’s emotionally upset. What he did was understandable.”

Frescura’s eyes roamed across the ceiling. “I couldn’t let you stop me,” he whispered.

Taft grasped his shoulder encouragingly. “Nothing will stop us. We’re going to the stars—no matter what it costs. However, you’ve been working too hard. I’ll send my doctor to you. He’s strict about some things but he’s the best. He’ll get you back in shape.”

Taft turned to Talbot. “As for you, I don’t like memory lapses, even in minor matters. I want you to promise me you’ll see my doctor after he gets through with Frescura.”

“I’ll be glad to,” Talbot said, without animosity. “I’ve been wondering what to do.”

Taft swung back to Frescura. By some personal miracle the man had pulled himself together again. He was alert and forceful. Taft regarded him with approval.

“That’s better. Go home and rest. Don’t work today.”

“You’re right,” Frescura said. “I should do that. I’ll have to drop by the lab and tell the boys I won’t be in for a few days.”

“Evan will tell them. We’ll call a cab and get you on your way. Don’t worry about anything. The project will be continued.”

They waited until Frescura left in an aircab. Taft got up, shaking his head bewilderedly. “Well, I’ll go too. Don’t forget that call tonight.”

“I won’t. I’ll be sure and call her.”

“Good.” Taft wiped his forehead. “This has been a hassle. We have them occasionally but I’ve never seen one to equal this.” Still shaking his head he went away.

Talbot leaned back and closed his eyes. He had achieved a victory that was far from superficial and it gave him a feeling of personal solidity. He was Soleri and he was going to be Soleri and nobody would ever know the difference.

But the rest didn’t make sense.

Both Taft and Frescura were now beyond suspicion. He had nothing to go on—nothing at all. He’d have to re-examine the whole problem from the beginning. Somewhere within the plant was a criminal conspirator who didn’t want TRANSPORTATION to develop the perfect rocket motor. He was still there. He had killed once, and he wouldn’t hesitate to kill again.

Why? If he could put his finger on the man’s motivating impulse he could track him down with little trouble. Somehow it seemed to go far beyond ordinary commercial rivalry.

Talbot heard a sound at his elbow and opened his eyes. Randy was standing beside the desk.

“Sleeping?” she asked, smiling at him.

“No, just thinking,” he said.

She leaned toward him. “Think about this then. I want to leave early.”

He stared at her, puzzled. “No. There’s work to do.”

“But there isn’t,” she assured him. “I ought to know.”

He realized then that she wanted him to know that she had listened to most of the conversation. Probably she’d read the note from plant protection. Talbot thought of the call he’d have to make later. He had no desire to make her listen to that too.

“All right,” he said. “I guess you know by now that I can’t play the stern employer when you look at me like that.”

She smiled at him, turned and went out.

He remained in his office thinking throughout the afternoon. He went home late—and alone.

In a dim corner of the apartment Talbot fingered a picture of Eleanor. Soleri’s taste in women closely paralleled his own. From a distance Eleanor could be mistaken for Laura. She was a trifle prettier perhaps, more lighthearted and whimsical, and more used to having her own way.

He didn’t want to put through a long-distance call to her. He was entangled enough as it was with Randy, the three-cornered struggle between himself, Taft and Frescura and the unknown obstructionist in the plant, not to mention the perfectly efficient rocket motor that was never going to be built.

He laid the picture face downwards on his desk, and went to the screen. But he didn’t call Eleanor Taft in her South African home. He called Randy.

She answered in a charming state of dishabille. “Is this the way you always come to the screen?” he asked.

“I knew it was you,” she replied. “I’m only surprised that you didn’t call sooner.”

“Put some clothes on,” he said.

“Don’t you like it? Or are you asking me to come over?”

“I like it,” he said. “But don’t come over. Not yet. I want some information. Precisely what did you do this afternoon?”

She made a face. “It was awful. Candidly I thought I’d stumbled into an old fashioned mental institution. I never would have believed I was eavesdropping on a high-level conference between the three top minds in the biggest corporation in the system.”

“We’re human too,” he said gloomily. “At least I think we are. What I meant was: What did you do when Frescura came out of my office and Taft went in?”

“Do you want a detailed report?”

“Yes—all of it. Exactly as it happened.”

“Well, Frescura came out and talked to Taft for a moment. Taft went in to see you, and Frescura wanted some information from another office. He sent me to get it. When I came back he handed me the folder and told me to take it to plant protection. He said to wait there for results and bring it back as soon as I could.”

“Is that all?”

“That’s all.”

“Good,” Talbot said. “Put on your clothes and come over.”

“I’m glad you changed your mind.”

“So am I. But I won’t be home when you get here. I may not be back until quite late. Whatever you do, don’t leave the apartment until I return. Promise?”

“What choice do you give me? I’ll wait.”

He cut off the screen and reached for a jacket. With methodical persistence he went through Soleri’s possessions until he found a gun. He had expected to find one. He checked it swiftly to make sure that it was loaded and in working condition. It was. He pocketed it with satisfaction and called a cab. He had to hurry.

He saw from the air that the entire plant was dark except for a light in one of the offices. Even from a distance he thought he could tell which office it was. The cab landed, and he got out. There was a guard at the office entrance. He questioned the man quickly, and thoroughly.

The plant was closed down tight. All of the other gates were securely locked and would remain closed until morning. The guard hadn’t seen anyone leave or enter the building. He didn’t know whether or not the office was occupied but it was reasonable to suppose that someone might be working late. Talbot stood back and looked. The light wasn’t visible from the corridor entrance.

Talbot told the guard to stop anyone who came out. He went in and made a tour of the offices. They were all dark. The man in the lighted office had apparently heard Talbot enter the building and had left ahead of him.

Talbot moved warily into the main shop. It was huge, cavernous and dim. He would not have been able to see at all except for the luminous strip which edged the aisles. Shadows loomed on the walls and ceiling and it would have been a simple matter for an intruder to conceal himself behind one of the machines.

He went on. None of the laboratories were lighted. Back and forth across the plant he went, always sure there was a man just ahead of him he could never quite overtake. He turned and had begun to retrace his route when a light snapped on in the middle section of the building. He felt the gun in his pocket and walked to the edge of the circle of light.

Frescura was standing completely motionless behind a machine, his head inclined. He looked up abruptly as Talbot approached. “I knew you would come back,” said Talbot.

“I did,” acknowledged Frescura.

“You lied this afternoon,” Talbot said. “Randy didn’t ‘accidentally’ touch the button which enabled you to hear what I was saying. She wasn’t there. You sent her away so that you could listen.”

Frescura smiled and said nothing.

“You figured out what I was going to recommend to Taft. But you wanted to be sure. Another thing, I didn’t slip. You knew from the beginning or you would never have thought of the fingerprint subterfuge. You had to be the one who rolled in the bomb.”

“Of course,” said Frescura. “Soleri confided to only two people that he was going to bring you in—myself and Randy. If Soleri had survived he would have remembered that. Therefore I guessed the truth instantly. I knew what you were capable of. That’s why I tried to get rid of both you, and Soleri.”

“You must have sweated while I was in the hospital,” said Talbot. “It’s a good thing Randy was watching over me.”

“It was a good thing for you that I was nervous,” said Frescura. “Later, when you got well and didn’t say anything I knew exactly what had happened. I thought I could handle you.”

“That was your biggest mistake. I caused all sorts of trouble. But why did you have to get rid of anyone? Was it because you were close to success? Or because you wanted the discovery for yourself when the company failed?”

“You’re still thinking in terms of money,” said Frescura. “There are things of far greater importance. The discovery was mine. It was mine from the very beginning. I did all the fundamental work. After the first year I could have built a motor that would drive a ship near the speed of light.”