Title: Life histories of North American shore birds, Part 2 (of 2)

Author: Arthur Cleveland Bent

Release date: December 18, 2025 [eBook #77498]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Dover Publications, 1962

Credits: Carol Brown, Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber’s Note:

In Memory of

Chris Curnow

(1937–2023)

the Project Manager at Distributed Proofreaders

who selected this book,

and more than 2200 others,

to be preserved as free digital transcriptions

by Project Gutenberg.

The source scans used are from the Dover edition, published in 1962, an unabridged republication of the work first published by the United States Government Printing Office. Part I was originally published in 1927 as Smithsonian Institution United States National Museum Bulletin 142; Part II was originally published in 1929 as Smithsonian Institution United States National Museum Bulletin 146. In Part II, the Smithsonian publication used Plate 1 as a frontispiece. The Dover edition included Plate 1 with the rest of the plates at the end of the book.

Footnotes were renumbered sequentially. Obsolete and alternative spellings were not changed.

Misspelled words were corrected. Missing diacriticals were added. Obvious printing errors, such as partially printed letters and punctuation, were corrected. Final stops missing at the end of sentences and abbreviations were added.

[Pg i]

Shore Birds

[Pg ii]

ADVERTISEMENT

The scientific publications of the National Museum include two series, known, respectively, as Proceedings and Bulletin.

The Proceedings, begun in 1878, is intended primarily as a medium for the publication of original papers, based on the collections of the National Museum, that set forth newly acquired facts in biology, anthropology, and geology, with descriptions of new forms and revisions of limited groups. Copies of each paper, in pamphlet form, are distributed as published to libraries and scientific organizations and to specialists and others interested in the different subjects. The dates at which these separate papers are published are recorded in the table of contents of each of the volumes.

The Bulletin, the first of which was issued in 1875, consists of a series of separate publications comprising monographs of large zoological groups and other general systematic treatises (occasionally in several volumes), faunal works, reports of expeditions, catalogues of type-specimens, special collections, and other material of similar nature. The majority of the volumes are octavo in size, but a quarto size has been adopted in a few instances in which large plates were regarded as indispensable. In the Bulletin series appear volumes under the heading Contributions from the United States National Herbarium, in octavo form, published by the National Museum since 1902, which contain papers relating to the botanical collections of the Museum.

The present work forms No. 146 of the Bulletin series.

Alexander Wetmore,

Assistant Secretary, Smithsonian Institution.

Washington, D. C., December 11, 1928.

[Pg iii]

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Page | |

| Order Limicolae | 1 |

| Family Scolopacidae | 1 |

| Tringa solitaria solitaria | 1 |

| Solitary sandpiper | 1 |

| Habits | 1 |

| Distribution | 9 |

| Tringa solitaria cinnamomea | 13 |

| Western solitary sandpiper | 13 |

| Habits | 13 |

| Distribution | 15 |

| Tringa ocrophus | 16 |

| Green sandpiper | 16 |

| Habits | 16 |

| Distribution | 21 |

| Rhyacophilus glareola | 22 |

| Wood sandpiper | 22 |

| Habits | 22 |

| Distribution | 26 |

| Catoptrophorus semipalmatus semipalmatus | 27 |

| Eastern willet | 27 |

| Habits | 27 |

| Distribution | 35 |

| Catoptrophorus semipalmatus inornatus | 36 |

| Western willet | 36 |

| Habits | 36 |

| Distribution | 39 |

| Heteroscelus incanus | 41 |

| Wandering tattler | 41 |

| Habits | 41 |

| Distribution | 46 |

| Heteroscelus brevipes | 48 |

| Polynesian tattler | 48 |

| Habits | 48 |

| Distribution | 49 |

| Philomachus pugnax | 49 |

| Ruff | 49 |

| Habits | 49 |

| Distribution | 54 |

| Bartramia longicauda | 55 |

| Upland plover | 55 |

| Habits | 55 |

| Distribution | 65 |

| Tryngites subruficollis | 69 |

| Buff-breasted sandpiper | 69 [Pg iv] |

| Habits | 69 |

| Distribution | 76 |

| Actitis macularia | 78 |

| Spotted sandpiper | 78 |

| Habits | 78 |

| Distribution | 93 |

| Numenius americanus | 97 |

| Long-billed curlew | 97 |

| Habits | 97 |

| Distribution | 106 |

| Numenius arquata arquata | 109 |

| European curlew | 109 |

| Habits | 109 |

| Distribution | 112 |

| Numenius hudsonicus | 113 |

| Hudsonian curlew | 113 |

| Habits | 113 |

| Distribution | 122 |

| Numenius borealis | 125 |

| Eskimo curlew | 125 |

| Habits | 125 |

| Distribution | 134 |

| Numenius phaeopus phaeopus | 136 |

| Whimbrel | 136 |

| Habits | 136 |

| Distribution | 139 |

| Numenius tahitiensis | 140 |

| Bristle-thighed curlew | 140 |

| Habits | 140 |

| Distribution | 143 |

| Family Charadriidae | 144 |

| Vanellus-vanellus | 144 |

| Lapwing | 144 |

| Habits | 144 |

| Distribution | 148 |

| Eudromias morinellus | 150 |

| Dotterel | 150 |

| Habits | 150 |

| Distribution | 153 |

| Squatarola squatarola | 154 |

| Black-bellied plover | 154 |

| Habits | 154 |

| Distribution | 166 |

| Pluvialis apricaria altifrons | 171 |

| European golden plover | 171 |

| Habits | 171 |

| Distribution | 174 |

| Pluvialis dominica dominica | 175 |

| American golden plover | 175 |

| Habits | 175 |

| Distribution | 189 |

| Pluvialis dominica fulva | 193 [Pg v] |

| Pacific golden plover | 193 |

| Habits | 193 |

| Distribution | 201 |

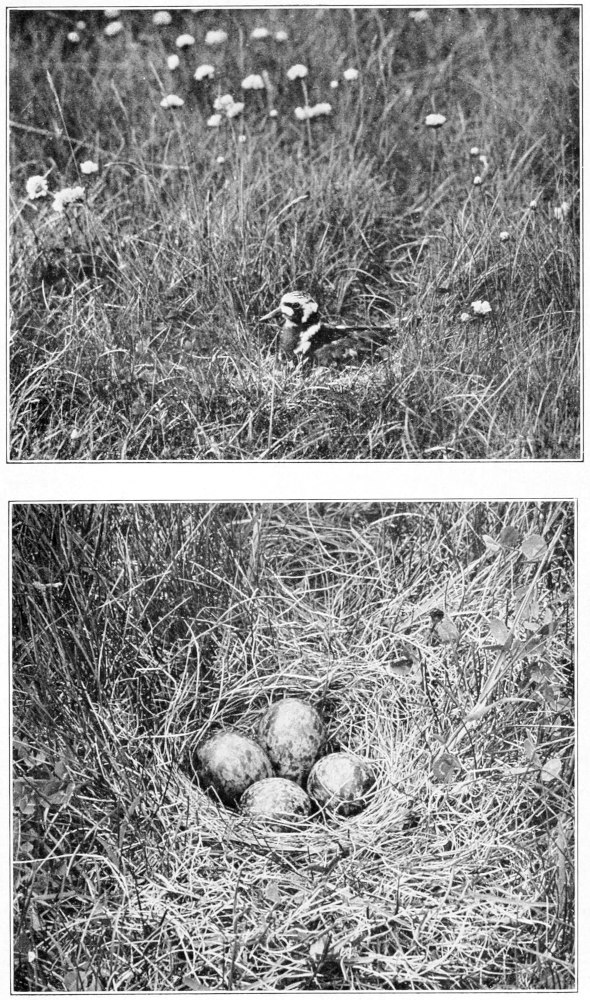

| Oxyechus vociferus | 202 |

| Killdeer | 202 |

| Habits | 202 |

| Distribution | 213 |

| Charadrius semipalmatus | 217 |

| Semipalmated plover | 217 |

| Habits | 217 |

| Distribution | 225 |

| Charadrius hiaticula | 229 |

| Ringed plover | 229 |

| Habits | 229 |

| Distribution | 232 |

| Charadrius dubius curonicus | 233 |

| Little ringed plover | 233 |

| Habits | 233 |

| Distribution | 236 |

| Charadrius melodus | 236 |

| Piping plover | 236 |

| Habits | 236 |

| Distribution | 244 |

| Charadrius nivosus nivosus | 246 |

| Snowy plover | 246 |

| Habits | 246 |

| Distribution | 251 |

| Charadrius nivosus tenuirostris | 252 |

| Cuban snowy plover | 252 |

| Habits | 252 |

| Charadrius mongolus mongolus | 253 |

| Mongolian plover | 253 |

| Habits | 253 |

| Distribution | 256 |

| Pagolla wilsonia wilsonia | 257 |

| Wilson plover | 257 |

| Habits | 257 |

| Distribution | 262 |

| Podasocys montanus | 263 |

| Mountain plover | 263 |

| Habits | 263 |

| Distribution | 267 |

| Family Aphrizidae | 269 |

| Aphriza virgata | 269 |

| Surf bird | 269 |

| Habits | 269 |

| Distribution | 277 |

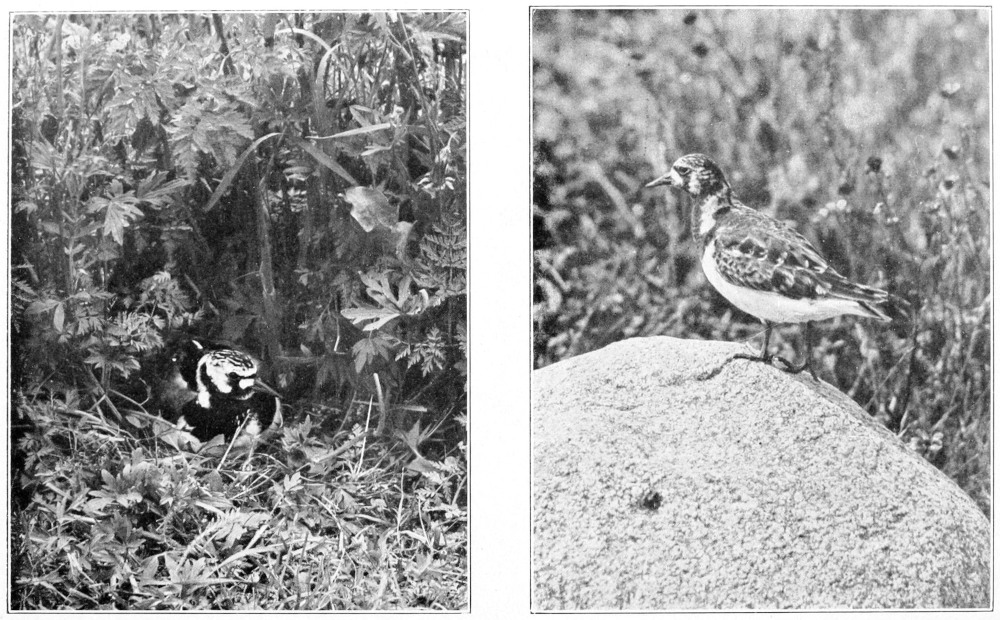

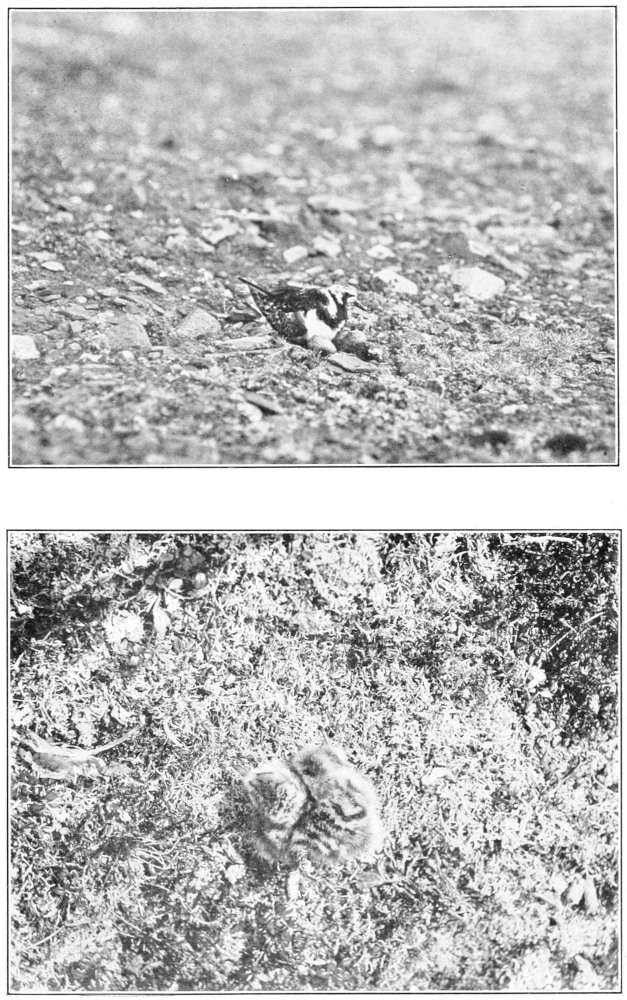

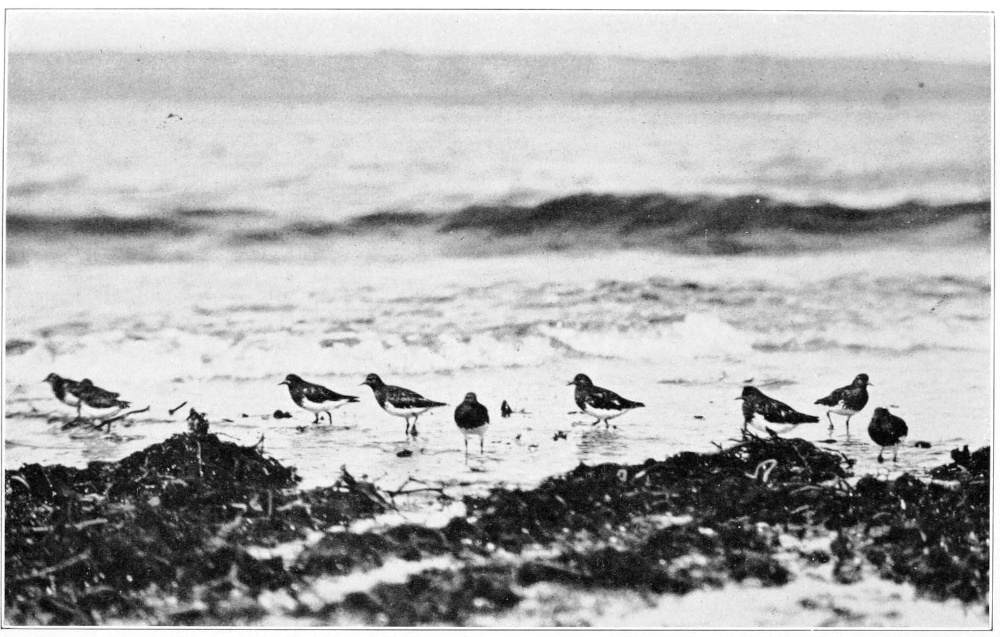

| Arenaria interpres | 278 |

| Turnstone | 278 |

| Habits | 278 |

| Distribution | 293 |

| Arenaria interpres interpres | 293 [Pg vi] |

| Arenaria interpres morinella | 294 |

| Arenaria melanocephala | 298 |

| Black turnstone | 298 |

| Habits | 298 |

| Distribution | 304 |

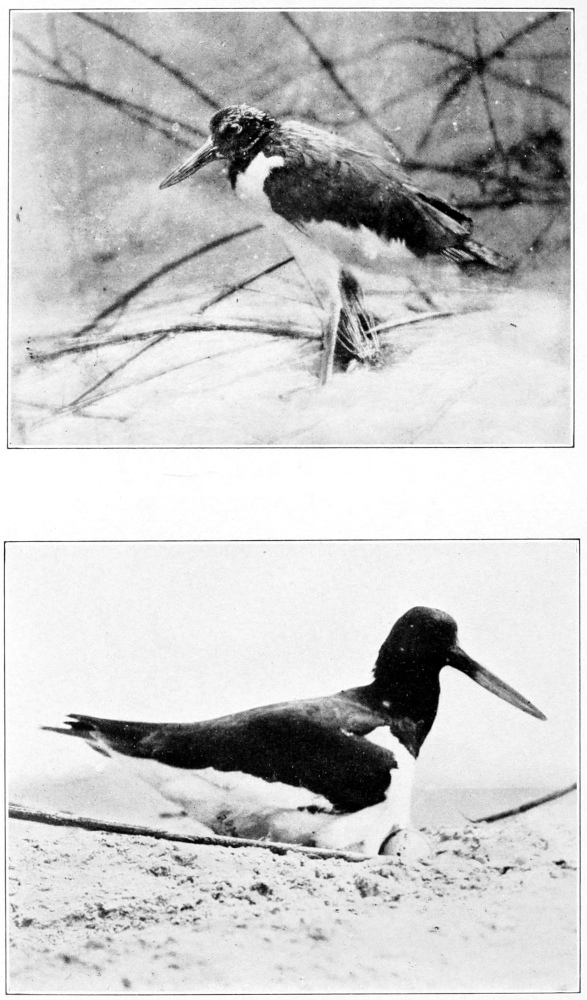

| Family Haematopodidae | 305 |

| Haematopus ostralegus | 305 |

| European oyster catcher | 305 |

| Habits | 305 |

| Distribution | 308 |

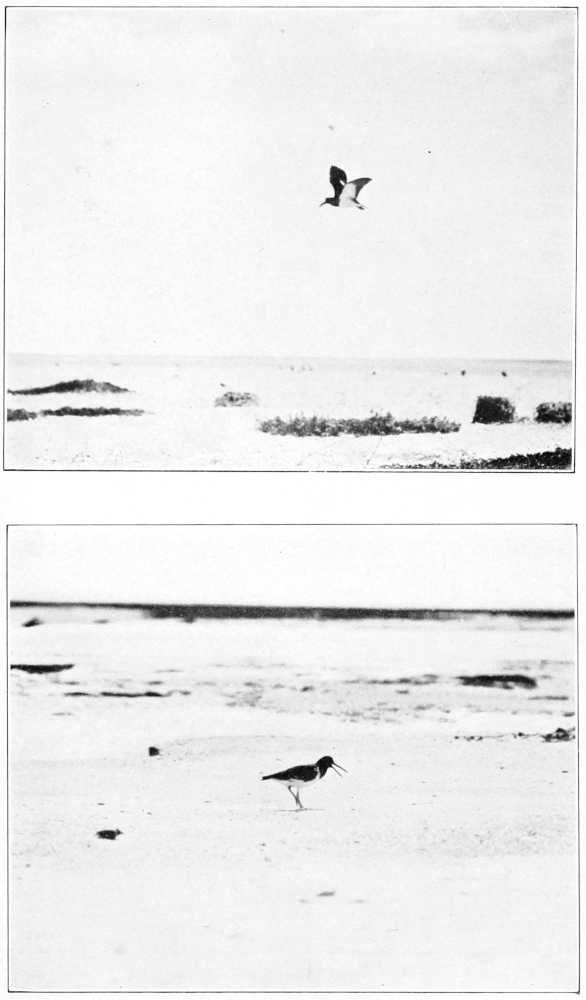

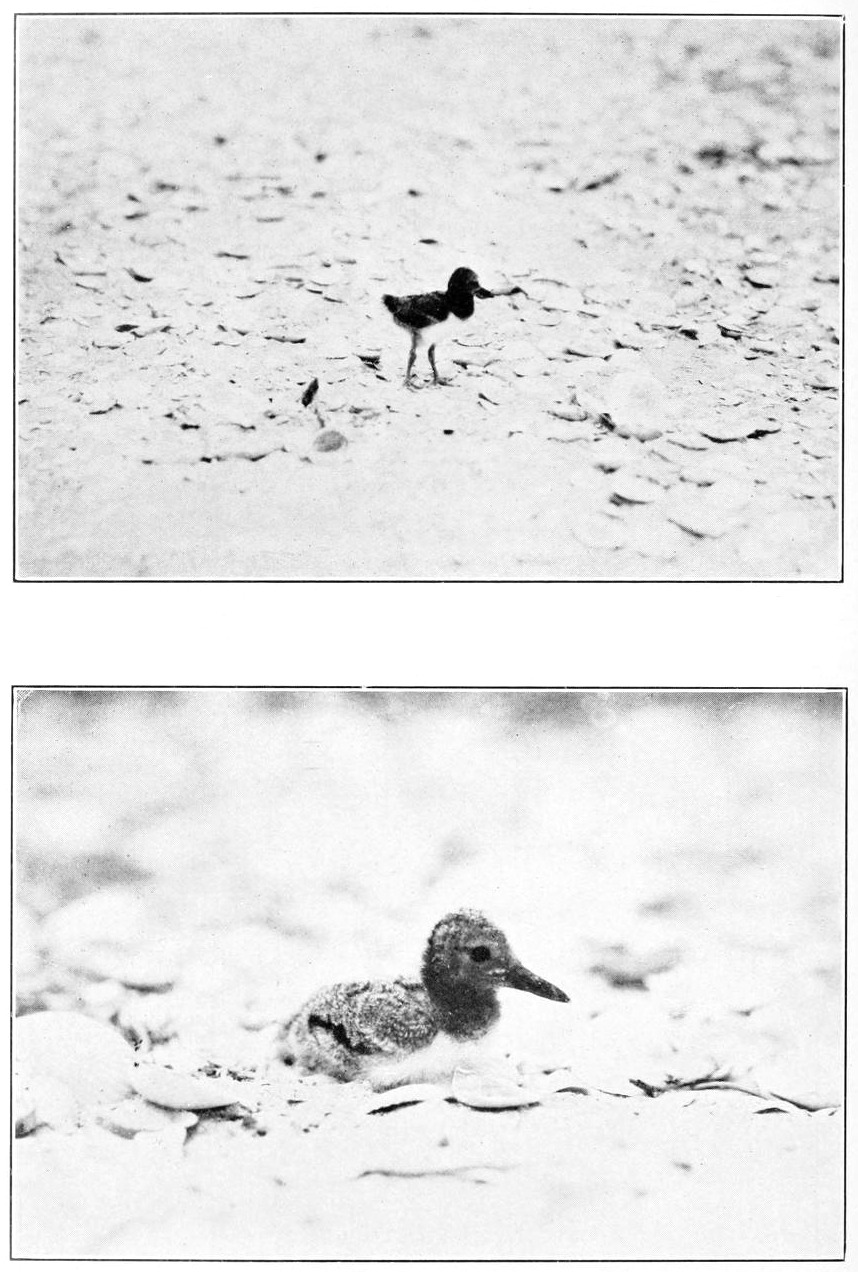

| Haematopus palliatus palliatus | 309 |

| American oyster catcher | 309 |

| Habits | 309 |

| Distribution | 315 |

| Haematopus palliatus frazari | 316 |

| Frazer oyster catcher | 316 |

| Habits | 316 |

| Distribution | 319 |

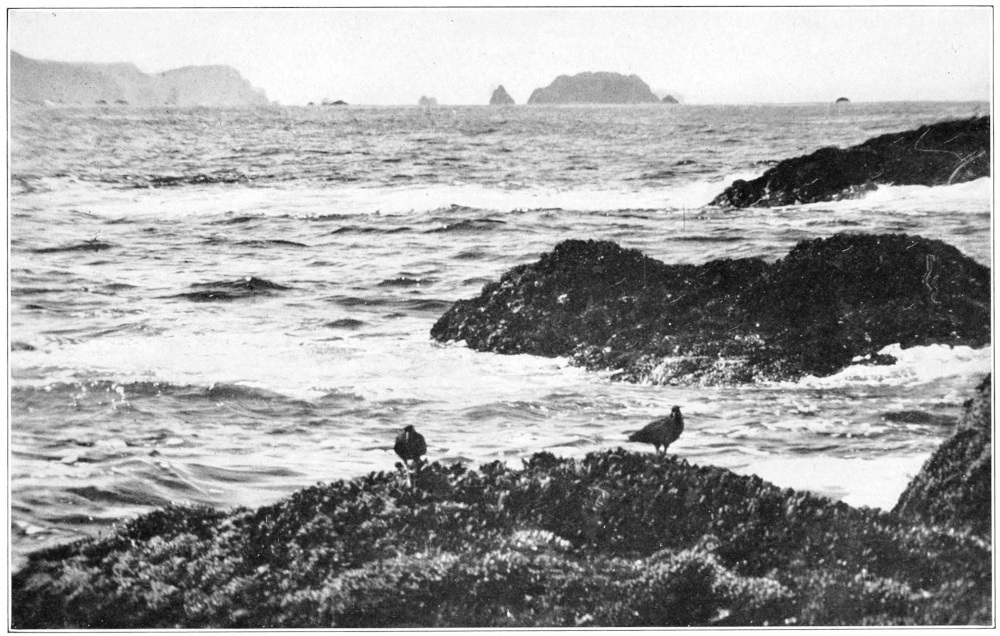

| Haematopus bachmani | 320 |

| Black oyster catcher | 320 |

| Habits | 320 |

| Distribution | 323 |

| Family Jacanidae | 324 |

| Jacana spinosa gymnostoma | 324 |

| Mexican jacana | 324 |

| Habits | 324 |

| Distribution | 327 |

| References to publications | 328 |

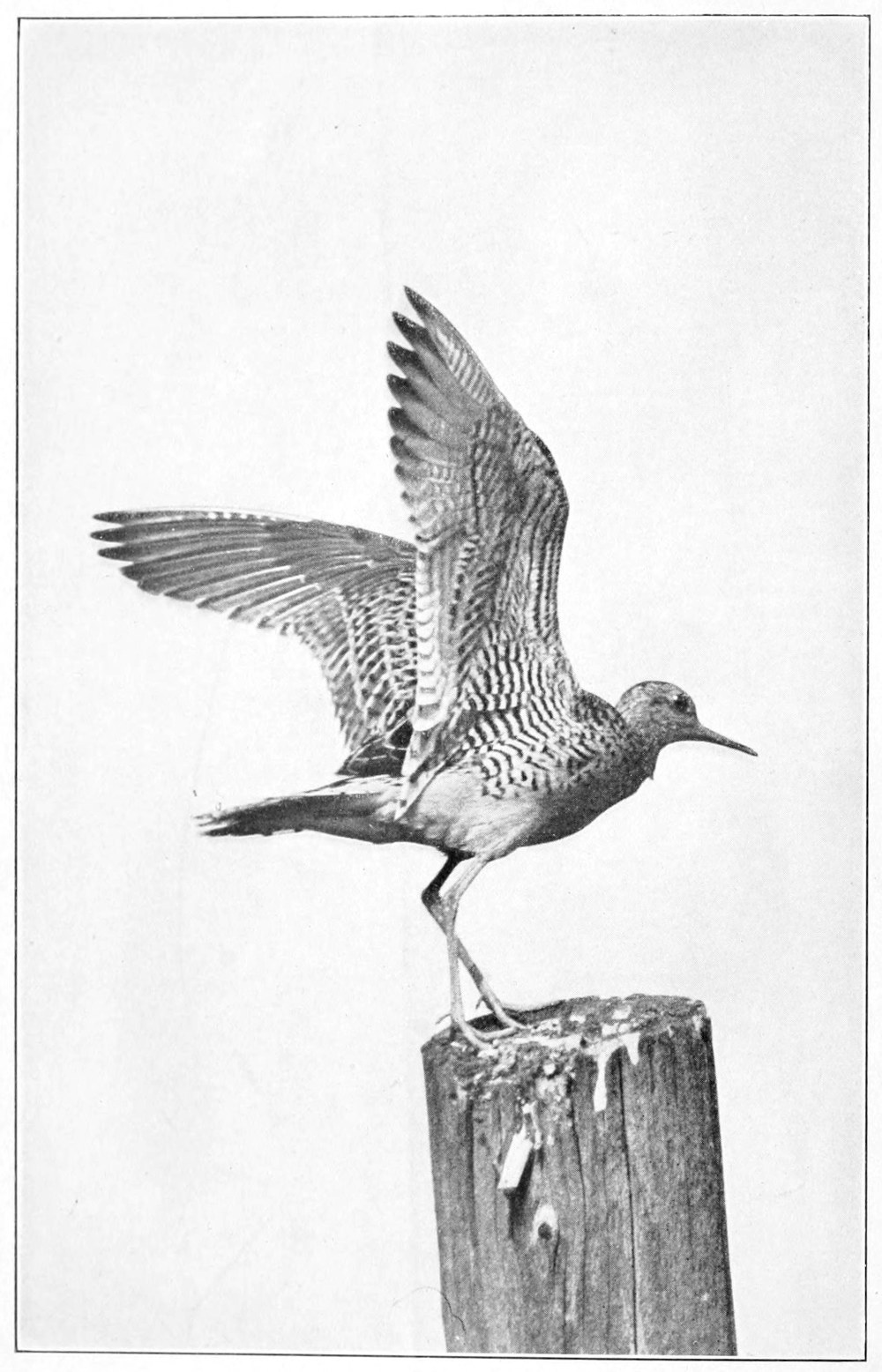

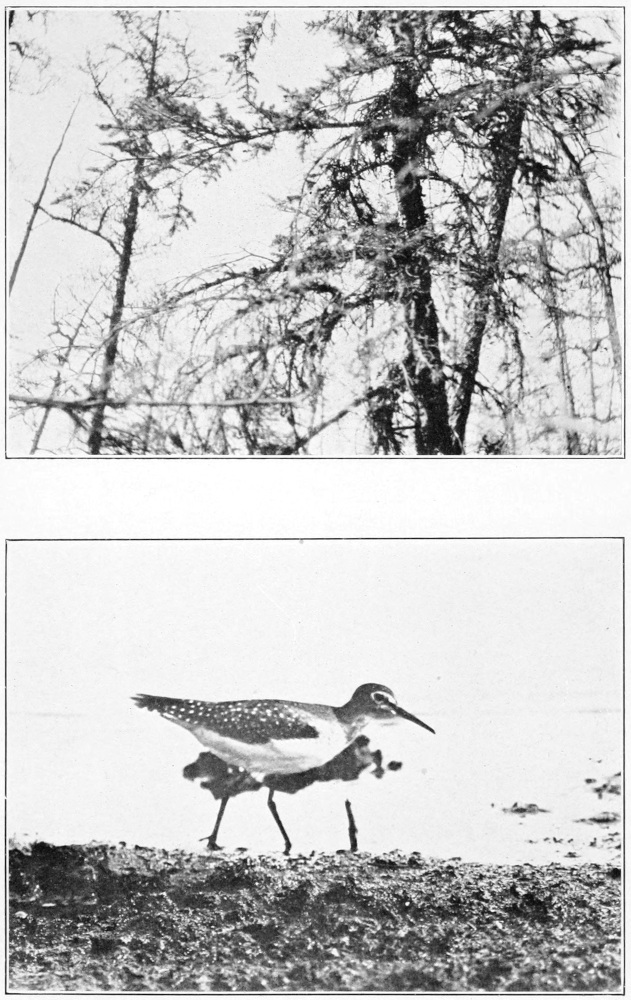

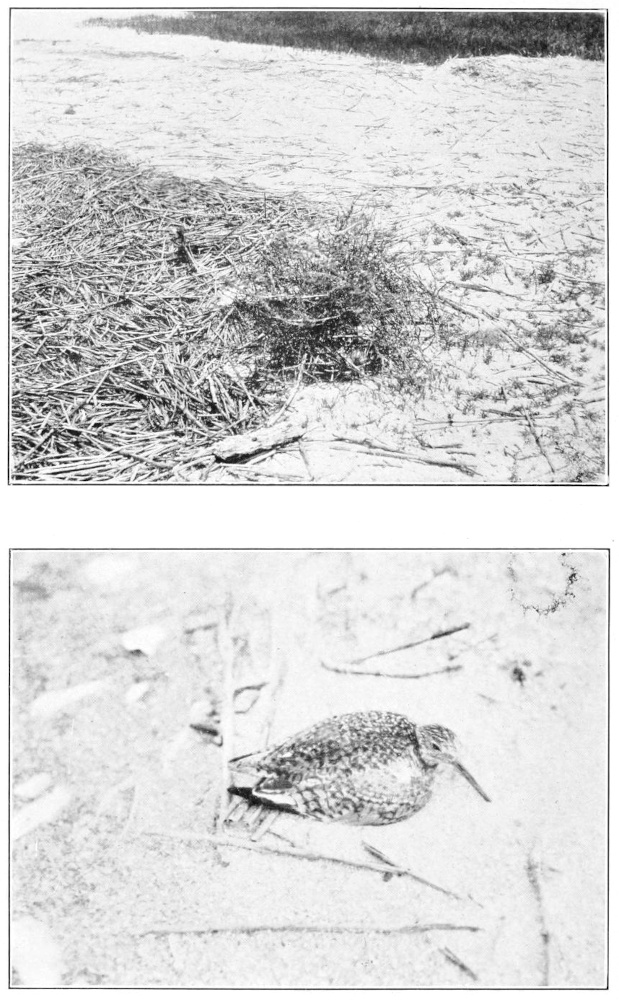

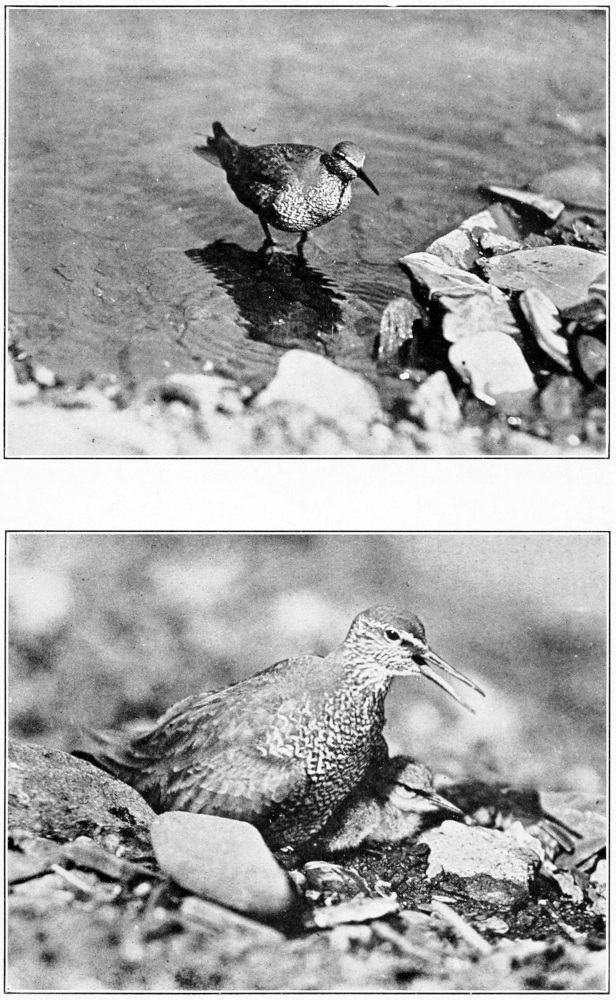

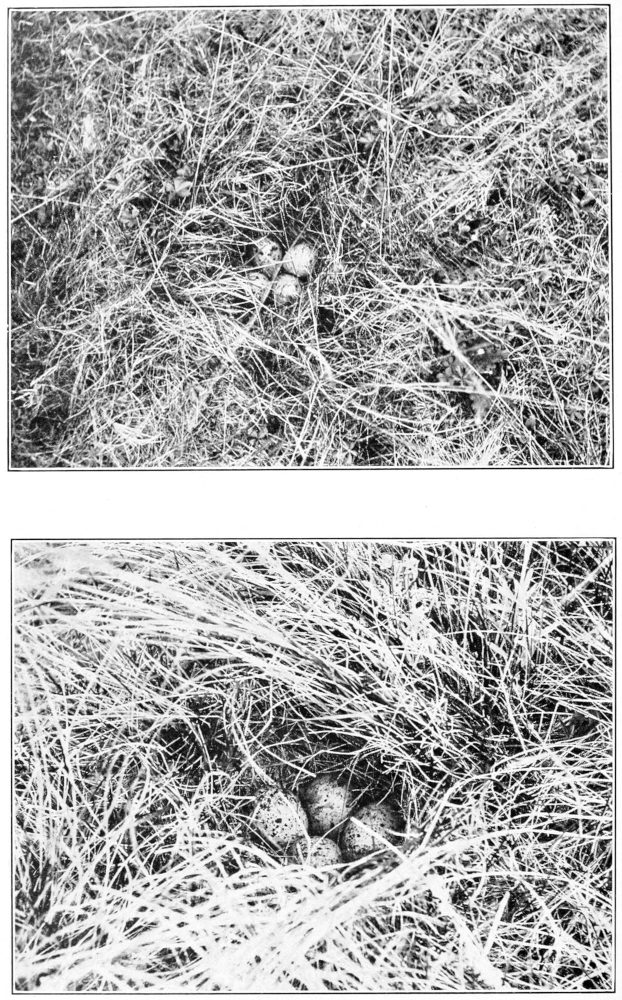

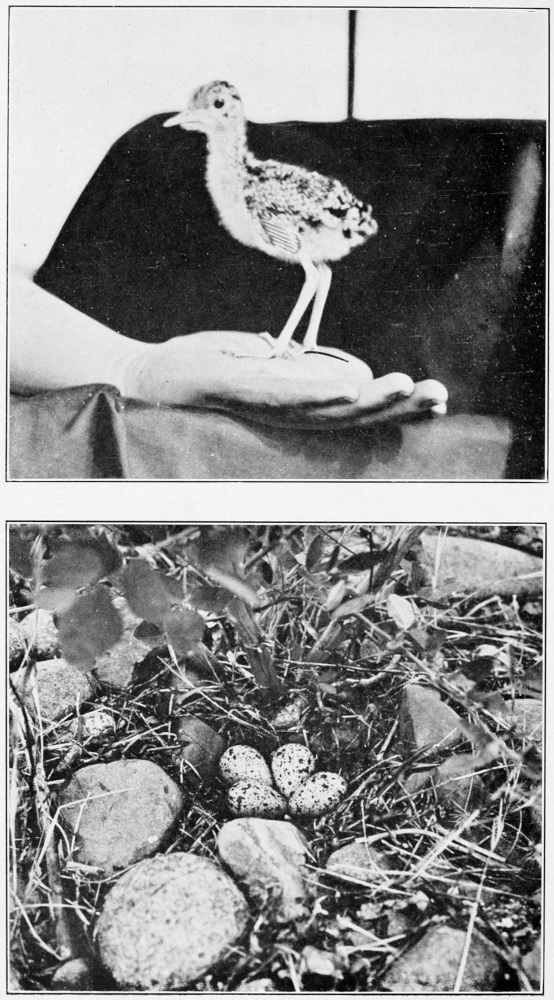

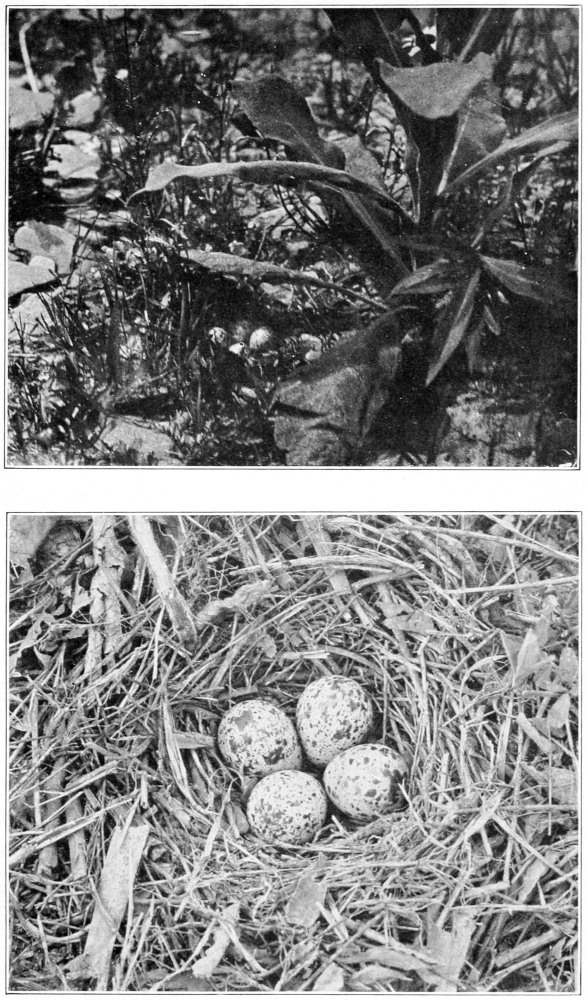

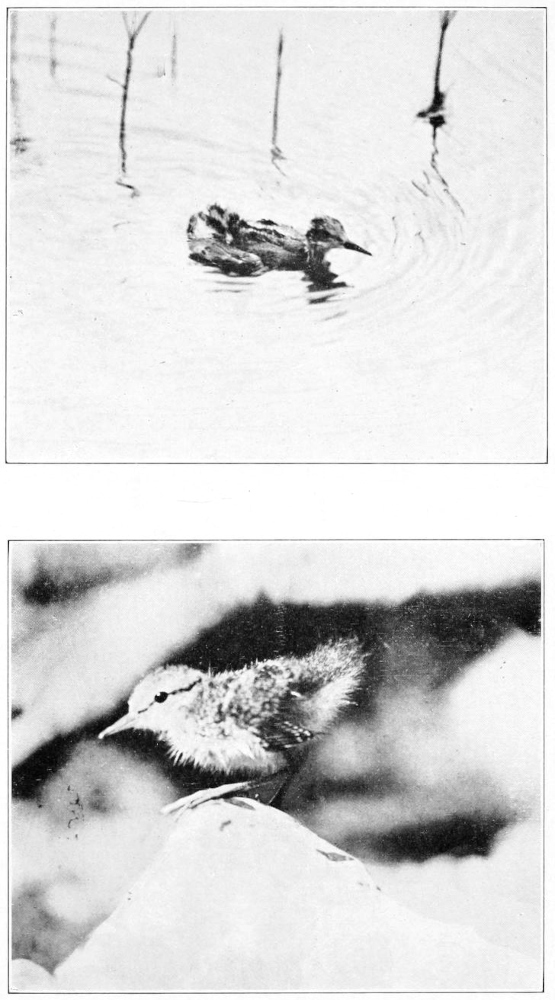

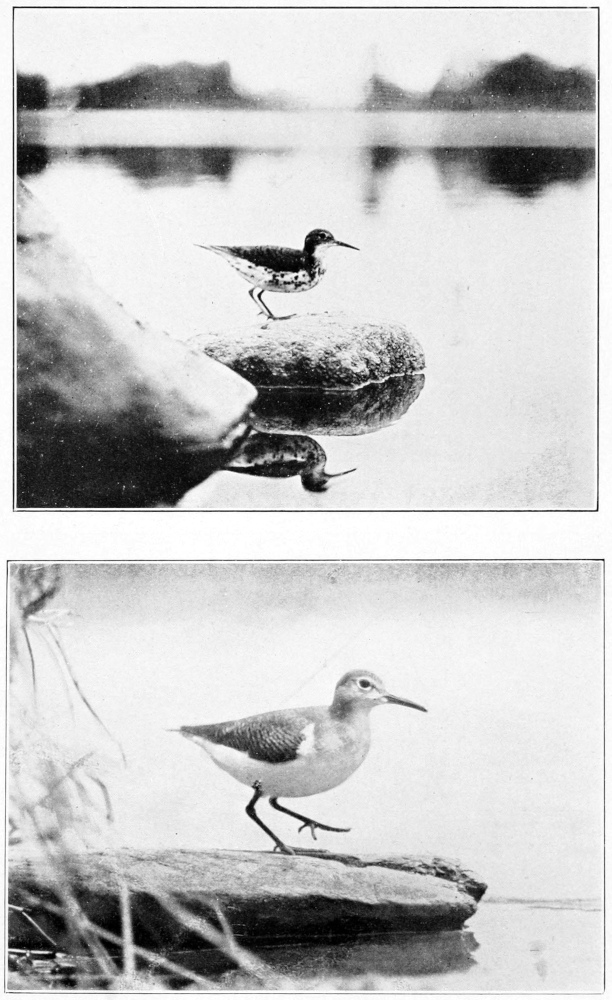

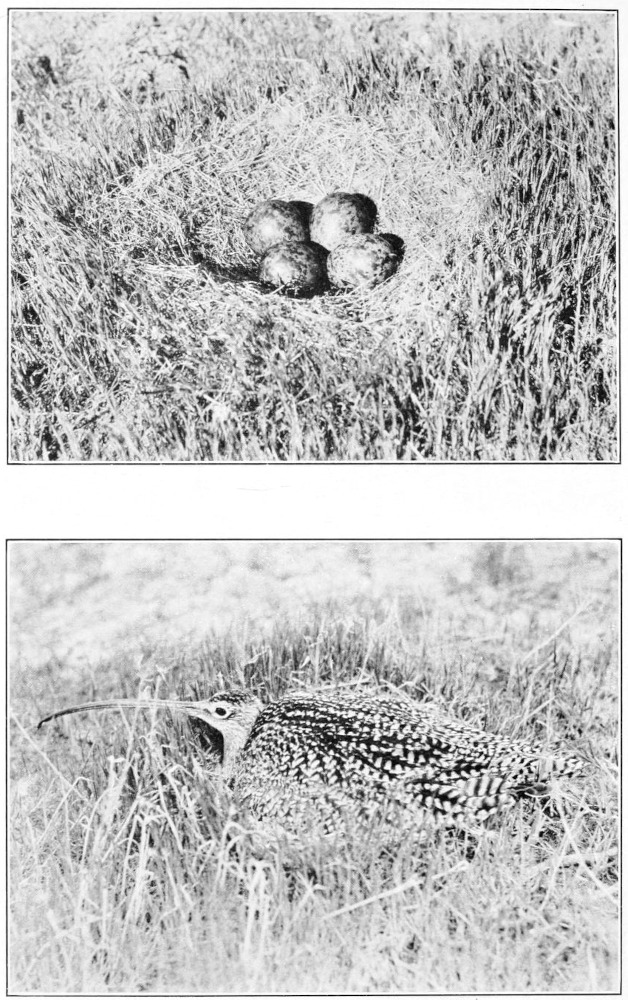

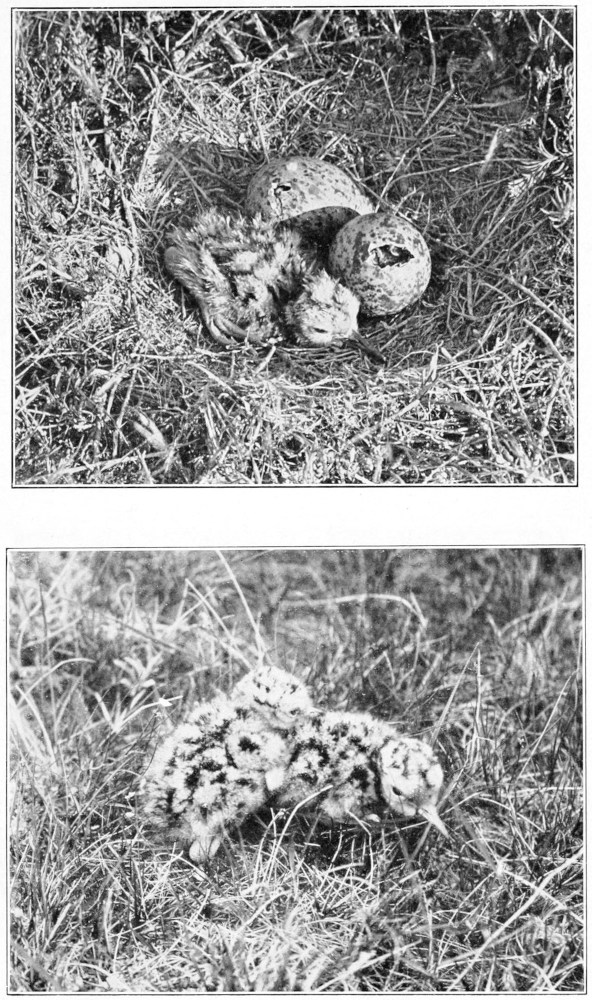

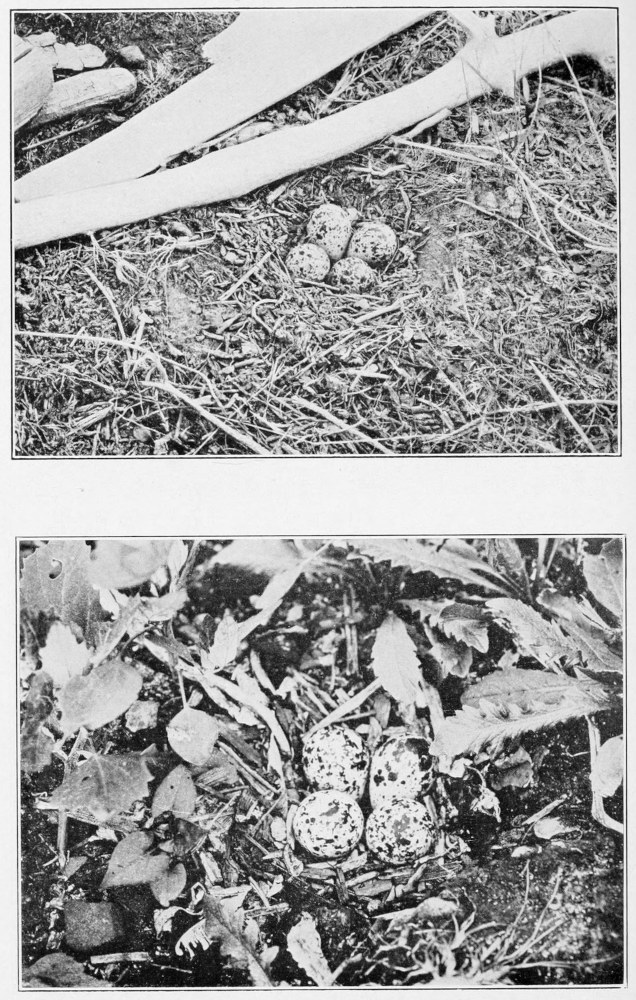

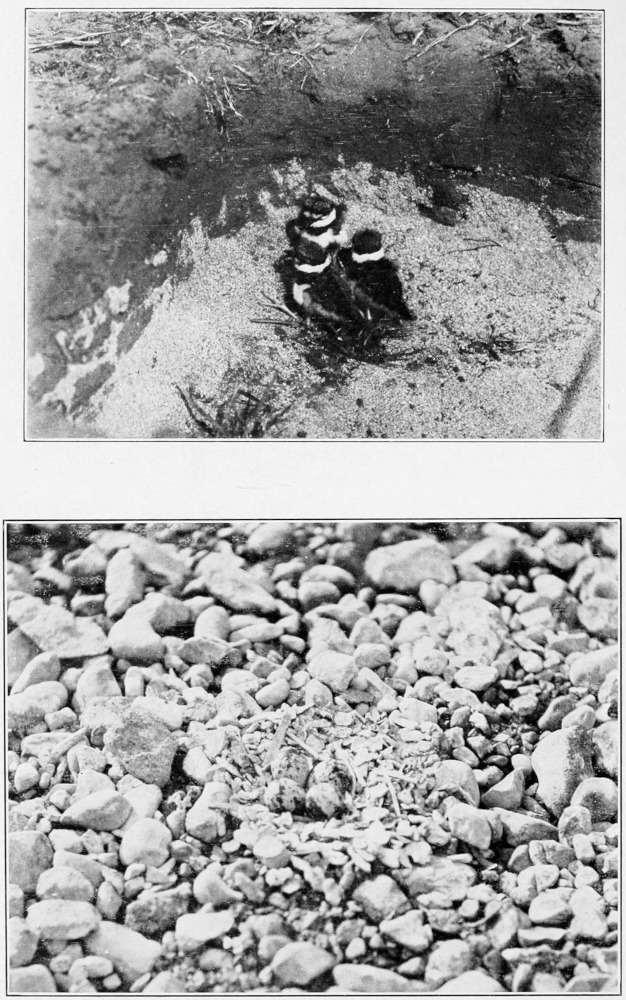

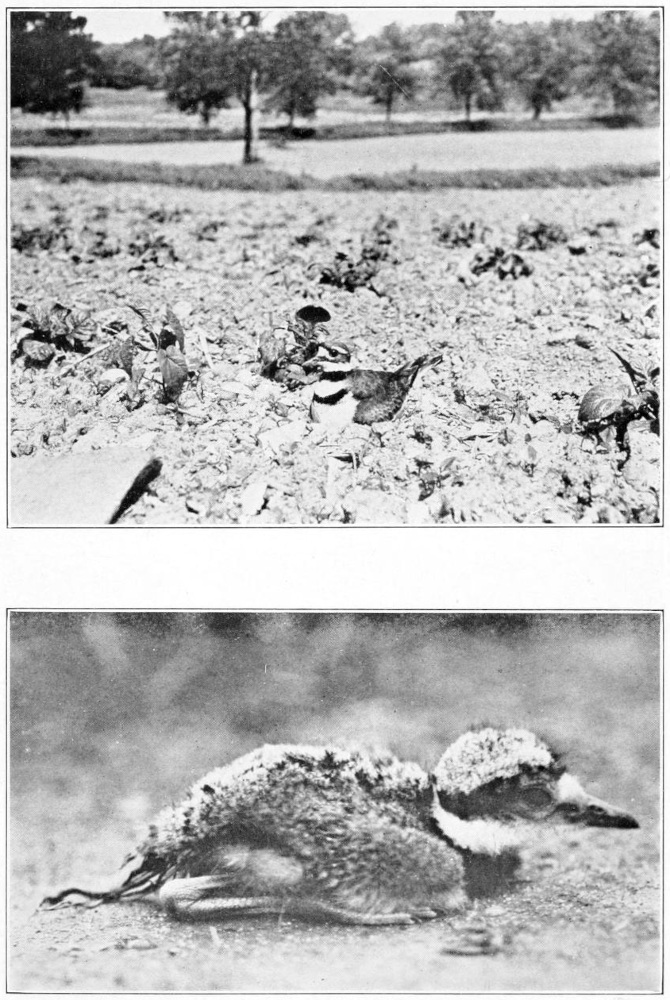

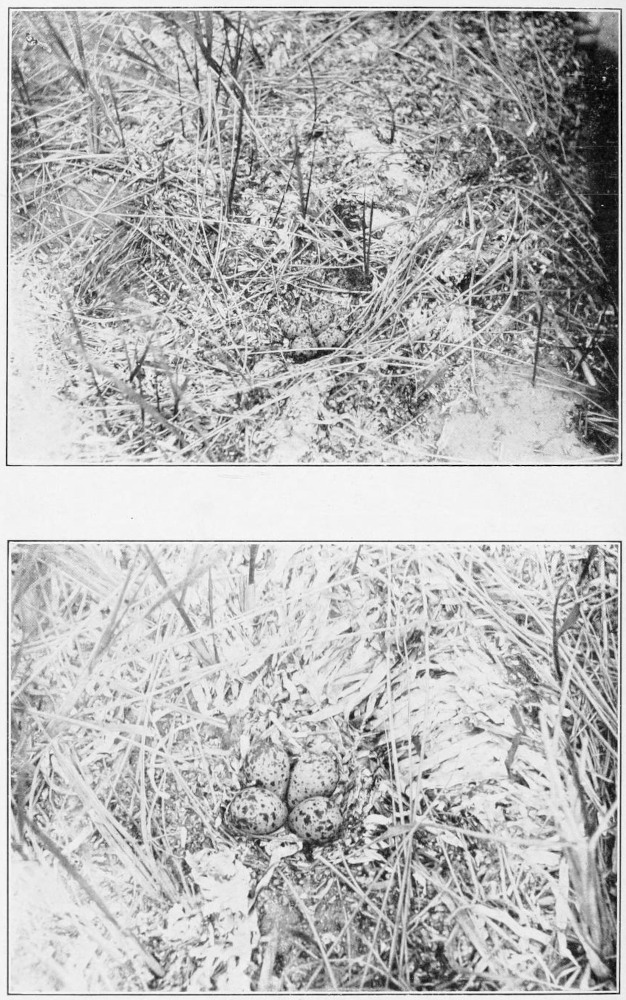

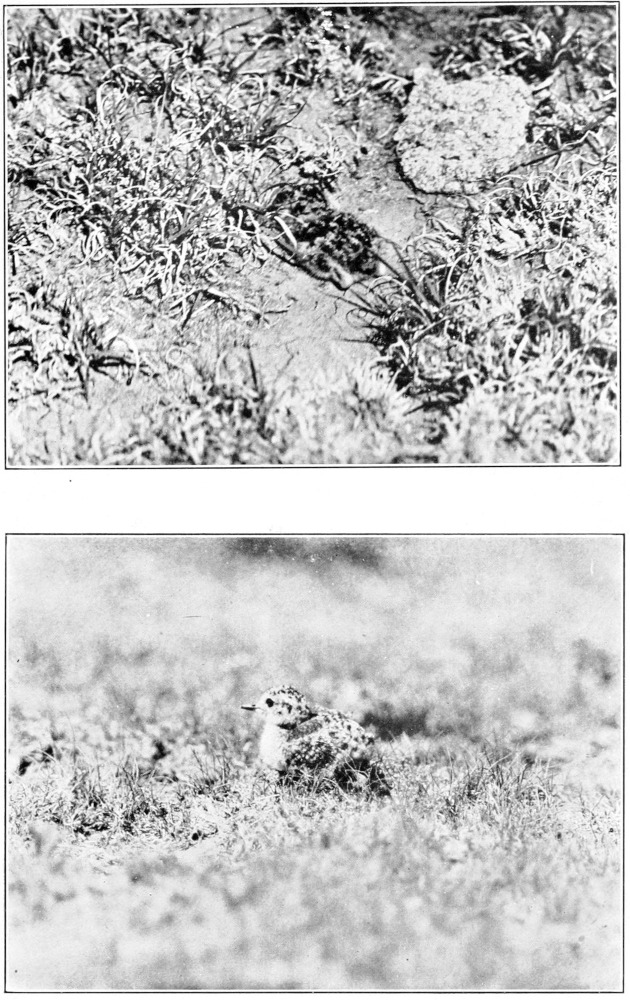

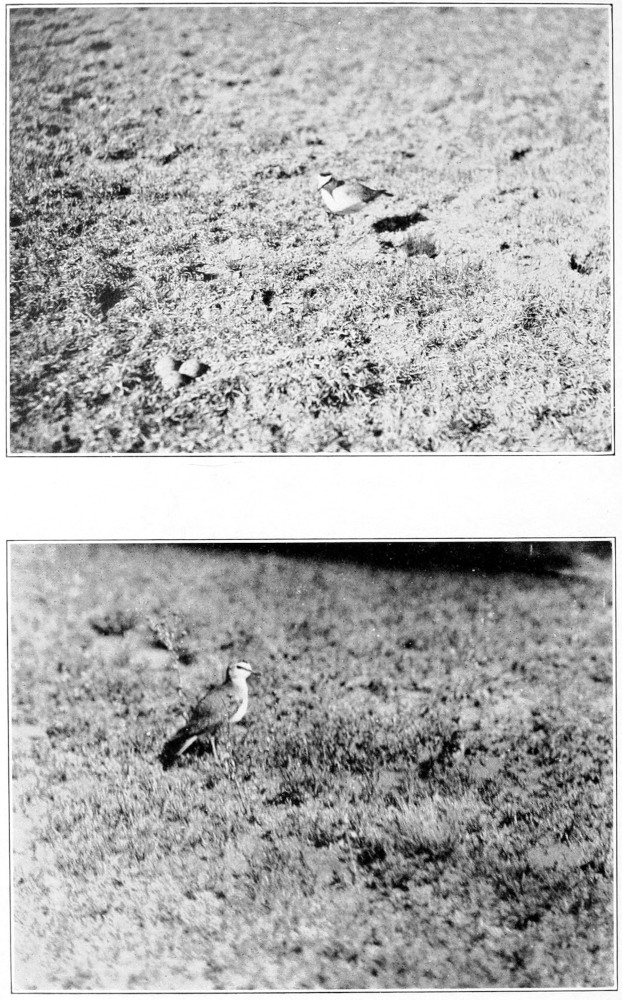

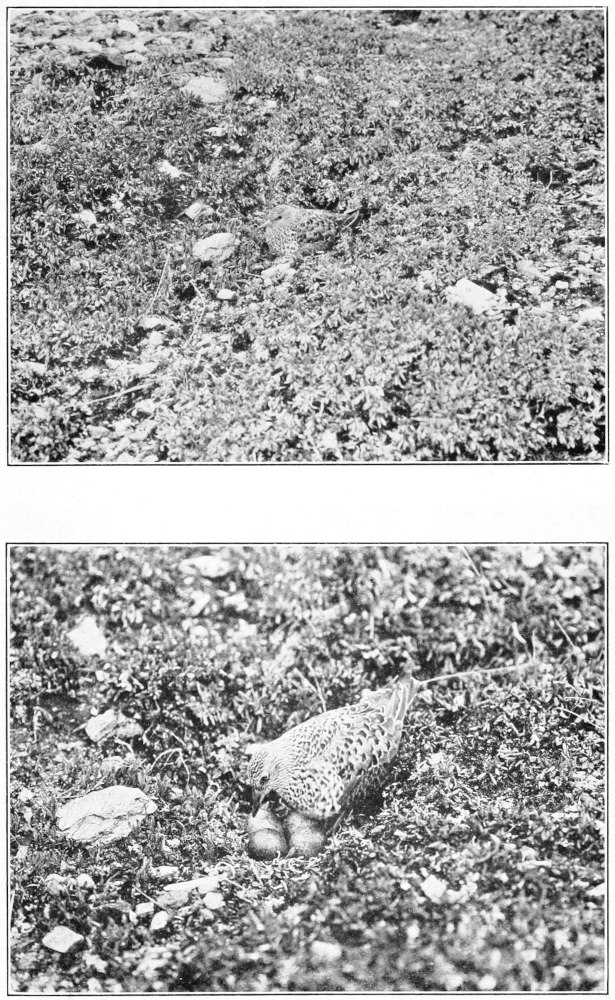

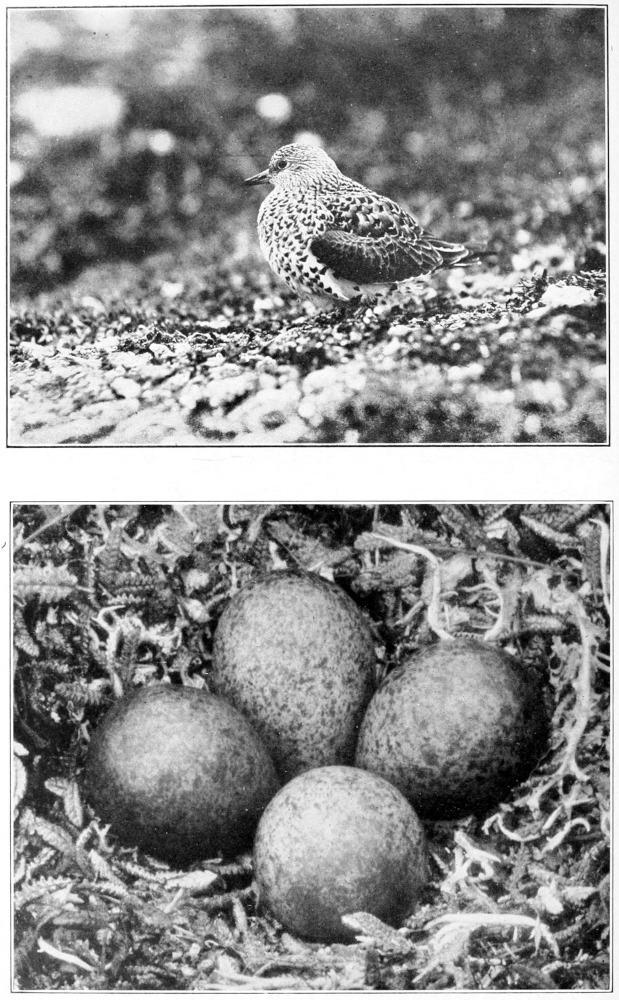

| Explanation of plates | 341 |

| Index | 407 |

[Pg vii]

INTRODUCTION

This is the eighth in a series of bulletins of the United States National Museum on the life histories of North American birds. Previous numbers have been issued as follows:

107. Life Histories of North American Diving Birds, August 1, 1919.

113. Life Histories of North American Gulls and Terns, August 27, 1921.

121. Life Histories of North American Petrels, Pelicans and their Allies, October 19, 1922.

126. Life Histories of North American Wild Fowl, May 25, 1923.

130. Life Histories of North American Wild Fowl, June 27, 1925.

135. Life Histories of North American Marsh Birds, March 11, 1927.

142. Life Histories of North American Shore Birds, December 31, 1927.

The same general plan has been followed, as explained in previous bulletins, and the same sources of information have been utilized. The classification and nomenclature adopted by the American Ornithologists’ Union, in its latest check list and its supplements, have been followed, mainly, with such few changes as, in the author’s opinion, will be, or should be, made to bring the work up to date and in line with recent advances in the science.

The main ranges are as accurately outlined as limited space will permit; the normal migrations are given in sufficient detail to indicate the usual movements of the species; no attempt has been made to give all the records, for economy in space, and no pretence at complete perfection is claimed. Many published records, often repeated, have been investigated and discarded; many apparently doubtful records have been verified; some published records, impossible to either verify or disprove, have been accepted if the evidence seemed to warrant it.

The egg dates are the condensed results of a mass of records taken from the data in a large number of the best egg collections in the country, as well as from contributed field notes and from a few published sources. They indicate the dates on which eggs have been actually found in various parts of the country, showing the earliest and latest dates and the limits between which half the dates fall, the height of the season.

[Pg viii]

The plumages are described in only enough detail to enable the reader to trace the sequence of molts and plumages from birth to maturity and to recognize the birds in the different stages and at the different seasons. No attempt has been made to fully describe adult plumages; this has been already well done in the many manuals. The names of colors, when in quotation marks, are taken from Ridgway’s Color Standards and Nomenclature (1912) and the terms used to describe the shapes of eggs are taken from his Nomenclature of Colors (1886 edition). The heavy-faced type in the measurements of eggs indicate the four extremes of measurements.

Many of those who contributed material for former volumes have rendered a similar service in this case. In addition to those whose contributions have been acknowledged previously, our thanks are due to the following new contributors: Photographs, notes, or data have been contributed by E. G. Alexander, C. M. Beal, W. W. Bennett, A. D. Boyle, W. J. Brown, M. H. Burroughs, J. J. Carroll, N. W. Cayley, Ralph Chislett, W. M. Congreve, S. J. Darcus, H. G. Deignare, Jonathan Dwight, F. F. Gander, T. S. Gillin, W. E. Glegg, S. P. Gordon, Frank Grasett, R. W. Harding, L. L. Haskin, E. A. Hyer, T. A. James, F. Kermode, H. M. Laing, Carl Lien, G. H. Lings, Julian Lyder, S. H. Lyman, M. J. Magee, Miss M. E. McLellan, F. C. Pellett, R. T. Peterson, H. H. Pittman, C. A. Proctor, J. C. Salyer, A. W. Schorger, Althea R. Sherman, L. W. Smith, E. L. Sumner, jr., Malcolm Taylor, jr., R. M. Thorburn, C. H. Townsend, Josselyn Van Tyne, Stanton Warburton, jr., Alexander Wetmore, F. N. Wilson, L. R. Wolfe.

Receipt of material from over 275 contributors has been acknowledged in previous volumes.

Through the courtesy of the Biological Survey, the services of Frederick C. Lincoln were again secured to compile the distribution paragraphs. With the matchless reference files of the Biological Survey at his disposal and with some advice and help from Dr. Harry C. Oberholser, his many hours of careful and thorough work have produced results far more satisfactory than could have been attained by the author, who claims no credit and assumes no responsibility for this part of the work.

Dr. Charles W. Townsend has contributed the life histories of two species; the Rev. Francis C. R. Jourdain has furnished valuable notes for two, has written nine new life histories and two of his have been transferred from the previous volume; and Dr. Winsor M. Tyler has contributed two life histories. The author is much indebted to Dr. Charles W. Richmond for many hours of careful and sympathetic work in reading the proof and correcting errors in this and all previous volumes; his expert knowledge has been of great value.

[Pg ix]

As most of the shore birds are known to us mainly, or entirely, as migrants, it has seemed desirable to describe their migrations quite fully. As it is a well-known fact that many, if not all, immature and nonbreeding shore birds remain far south of their breeding ranges all summer, it has not seemed necessary to mention this in each case. Nor did it seem necessary to say that only one brood is raised in a season, as this is a nearly universal rule with all water birds.

The manuscript for this volume was completed in April, 1928. Contributions received since then will be acknowledged later. Only information of great importance could be added. When this volume appears, contributions of photographs or notes relating to the Raptores should be sent to

The Author.

[Pg 1]

LIFE HISTORIES OF NORTH AMERICAN SHORE

BIRDS

ORDER LIMICOLAE (PART 2)

By Arthur Cleveland Bent

Of Taunton, Massachusetts

Family SCOLOPACIDAE, Snipes and Sandpipers

TRINGA SOLITARIA SOLITARIA Wilson

SOLITARY SANDPIPER

HABITS

This dainty “woodland tattler” is associated in my mind with some secluded, shady woodland pool in early autumn, where the summer drought has exposed broad muddy shores and where the brightly tinted leaves of the swamp maple float lightly on the still water. Here the solitary wader may be seen, gracefully poised on some fallen log, nodding serenely, or walking gracefully over the mud or in the shallow water. Seldom disturbed by man, it hardly seems to heed his presence; it may raise its wings, displaying their pretty linings, or it may flit lightly away to the other side of the pool, with a few sharp notes of protest and a flash of white in its tail. I have often seen it in other places where one would not expect to find shore birds, such as the muddy banks of a sluggish stream, somewhat polluted with sewage, which flows back of my garden in the center of the city, or some barnyard mud puddle, reeking with the filth of cattle; perhaps it is attracted to such unsavory places by the swarms of flies that it finds there.

Spring.—The solitary sandpiper arrives in the United States during the latter part of March, but it makes slow progress northward, for it does not reach New England until May. We generally see it singly, in pairs, or in small numbers, but according to William Brewster (1925) it sometimes occurs in favorable localities, near Umbagog Lake, Maine, in large numbers; he writes:

According to an entry in my journal I saw them there literally in “swarms” on May 20, 1880, when, as we advanced by way of the river in a boat, they were [Pg 2]ceaselessly rising and flitting on ahead, uttering their peet-weet calls, and also making a faint yet noticeable rustling sound with their wings. Thus driven they sometimes alighted, one after another, on some muddy point, until as many as seven assembled within the space of a few square feet. Nevertheless, they were for the most part paired, and the mated birds almost invariably kept together, and apart from all the rest when on wing.

The migration in the interior seems to be at least two or three weeks earlier. E. W. Hadeler tells me that in Lake County, Ohio, one is almost sure to find it, on the river where the sewer empties into it, between April 22 and May 18. Many must pass through the inland States in April, for Edward S. Thomas has recorded it in Ohio as early as March 30 and calls the average date of arrival April 15. A. G. Lawrence has recorded it in southern Manitoba as early as April 29 and it reaches its northernmost breeding grounds in Mackenzie and Alaska soon after the middle of May.

Courtship.—Dr. John B. May has sent me the following notes on a courtship display of this species which he saw in New Hampshire:

Paddling down river one day, probably between the 8th and 15th of June, I saw several pairs of solitary and spotted sandpipers where the muddy banks were exposed, near a swamp where bitterns breed. Both species were apparently courting, making considerable noise and showing their white feathers in display. Every little while one of the solitary sandpipers would fly up slowly into the air, only rising a few feet, and rising slowly with rapidly beating or quivering wings, giving a twittering whistle and spreading the tail so that the outer white feathers were very conspicuous. Then it would drop back to the mud again near where it rose. The time taken in rising a few feet would have carried it some distance with its ordinary flight.

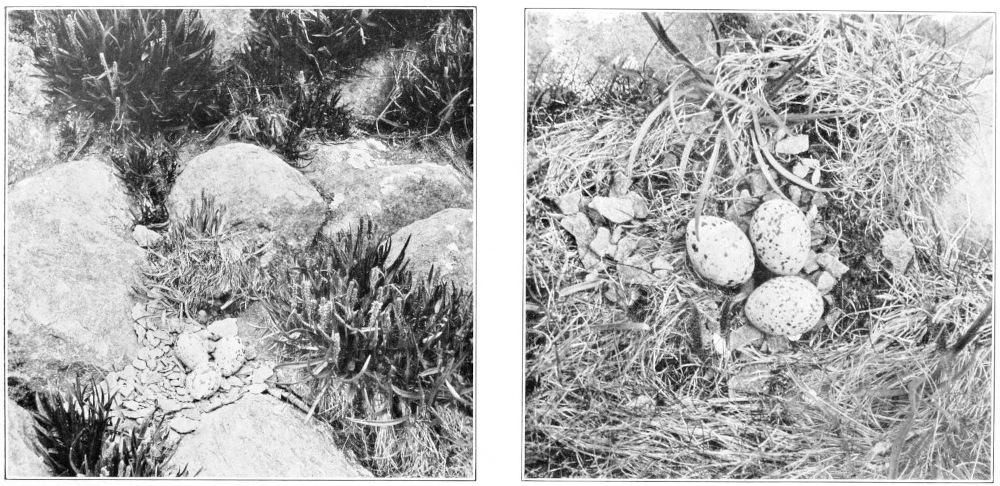

Nesting.—The nesting habits of this sandpiper long remained a mystery or were misunderstood. In looking over the literature on the subject I came across no less than seven published records of nests found on the ground and said to be positively identified as this species. These were all published prior to the discovery of the now well-known habit of nesting in the deserted nests of passerine birds. Not a single one of these records seems to be substantiated by an available specimen of the parent bird. The solitary sandpiper may occasionally nest on the ground, but it is yet to be proven.

To Evan Thomson belongs the credit for making the interesting discovery of the tree-nesting habit. This historic incident is described by J. Fletcher Street (1923) as follows:

Mr. Thomson many years ago took up a quarter section of land under the Canadian homestead act, built himself a log cabin at the edge of a muskeg, and commenced the arduous task of clearing the land. Living alone in this wilderness without neighbors and possessing a keen love for nature and a particular interest in the abundant wild life about him, he came to devote his spare moments to the study of birds, counting as his immediate associates such hermit species as the great-horned owl, long-eared owl, saw-whet owl, goshawk, and a large host of water fowl and waders. Seated one day before [Pg 3]his cabin he noticed a bird fly to a low tamarack and enter a nest. It was ostensibly one of the waders, and great was his surprise upon examining the nest to find it the structure of a robin. It contained four beautiful eggs, greenish white in ground color and heavily spotted and blotched with reddish brown. Thus, on June 16, 1903, the first authentic eggs of the solitary sandpiper were taken but it was not until a year later that the identity of the bird was definitely established. It was indeed interesting, 20 years later, to be shown the cabin and to view the original tree from which the eggs were collected. Subsequent to the finding of this nest many others have been located, the bird evidencing no particular choice of nest in which to deposit its eggs, the list including those of the bronzed grackle, Brewer’s blackbird, cedar waxwing, kingbird, robin, and Canada jay. These have been found at an elevation as low as 4 feet and as high as 40 and in locations contiguous to water and as far away as 200 yards.

Walter Raine (1904), for whom Mr. Thomson was collecting eggs at the time, was the first to publish the important news, but he waited a year until another nest was found and the parent bird shot. The following year, 1904, Mr. Thomson found two more nests and shot the parent bird from the last one. Mr. Raine (1904) then published a full account of all three nests, each of which contained four eggs. The first nest, taken June 16, 1903, was “an old nest of the American robin, built 15 feet up in a tamarack tree, that was growing in the middle of a large muskeg, dotted with tamaracks.” The second was found on June 9, 1904, an old “nest of a bronzed grackle, built in a low tree.” The third set was taken on June 24, 1904, and the parent bird was shot, as she flew from “the nest of a cedar waxwing, which was built in a small spruce tree growing in a swamp, the nest being about 5 feet from the water.” Since then numerous other nests have been found in similar situations. A. D. Henderson (1923) reported a nest found in 1914, about a “dozen feet up in a poplar tree,” and on June 7, 1922, a set of eggs was taken for him, with the parent, by a young friend:

The nest was in a white birch tree, growing at the edge of the timber, on the shore of a small lake, and about 150 yards from his home. A brood of young robins had been raised in it last season, he told me. It was about 18 feet from the ground and a typical robin’s nest, of grass and mud. The inside lining of grass was gone and the eggs lay in the bare mud cup, no material being added by the sandpiper, which I identified as the eastern form of the bird.

Mr. Henderson and Richard C. Harlow took a set of four fresh eggs on May 30, 1923, near Belvedere, Alberta, from an old robin’s nest 10 feet up in a scrubby spruce, 30 feet high, on the muskeg border of a swampy lake. A nest found by Messrs. Street (1923) and Stuart, near Red Lodge, Alberta, on May 29, 1923, was also an old robin’s nest only 4 feet from the ground in an 8-foot spruce, in a muskeg surrounded by spruces and tamaracks.

[Pg 4]

Mr. Henderson tells me that he thinks he now understands the nesting habits of this species more thoroughly, for he has found five sets of eggs this season, 1927. He says:

The principal breeding place seems to be around small lakes or ponds in muskegs; and the bird they are chiefly associated with is the rusty blackbird, which also breeds among the same surroundings, and whose nests are as suitable for the solitary sandpiper as are those of the robin. A few breed around lakes and sloughs, away from the muskegs, but the main body is in the muskeg country associated with the rusty blackbird.

Eggs.—The solitary sandpiper lays almost invariably four eggs; I believe there is only one set of five recorded. They are ovate pyriform in shape, with a slight gloss, and the shell is very fragile. There are two distinct types of ground color, green and buff. These two types are well illustrated by the Rev. F. C. R. Jourdain (1907) in an excellent colored plate. In the green type the ground colors vary from “pale glaucous green,” or “pale turtle green,” to greenish white; and in the buff type, from “cream buff” to “cartridge buff.” They are rather thickly spotted and blotched with irregular markings, usually more thickly about the larger end, where the spots are sometimes confluent. The underlying spots and blotches in various shades of “purple drab” and “heliotrope gray” are often quite conspicuous. Over these the eggs are boldly marked with dark rich browns, “claret brown,” “liver brown,” “bay” and “chocolate,” or even darker colors where the pigment is thickest. One beautiful egg, figured by Mr. Jourdain (1907), has a “pale glaucous green” ground color, with only two blotches of very dark brown near the larger end, heavily splashed elsewhere with “pallid purple drab,” and sparingly peppered with light brown. The measurements of 68 eggs average 36 by 25.5 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 38.5 by 27, 33.7 by 23.8 and 36.1 by 23.6 millimeters.

Plumages.—I have never seen this species in natal down, but Ora W. Knight (1908) says that “the downy young are a general grayish buff above with darker suffusions on the back; a darker line through each eye from bill to nape; darkish crown line; below white with slight dusky suffusion on flanks.”

Young birds in juvenal plumage are grayish brown above, lighter and more olivaceous than in adults, and thickly spotted with white or buffy white; the sides of the head and neck are grayish, indistinctly streaked with dusky on the neck. A partial postjuvenal molt occurs in the fall producing a first winter plumage, in which young birds may be distinguished by retained juvenal wing coverts. Young birds are also more profusely spotted on the upper parts and less distinctly streaked on the neck and breast than adults. At the first prenuptial molt, the following spring, the young bird becomes practically adult.

[Pg 5]

Adults have a partial prenuptial molt, between February and May, involving the body plumage, the tail and some scapulars, wing coverts, and tertials. The complete postnuptial molt begins in July with the change of the body plumage and may last through September, but the primaries are not molted until the winter months, December to February. The winter plumage is similar to the nuptial, but the upper parts are grayer and less distinctly spotted; the neck and chest are only very indistinctly streaked with grayish.

Food.—Dr. Elliott Coues (1874) has described the feeding habits of solitary sandpipers so well that I can not do better than to quote his words, as follows:

They differ from most of their relatives in their choice of feeding grounds or of places where they usually alight to rest while migrating; a difference accompanied, I suppose, by a corresponding modification in diet. Their favorite resorts are the margins of small, stagnant pools, fringed with rank grass and weeds; the miry, tide-water ditches that intersect marshes; and the soft, oozy depressions in low meadows and water savannas. They frequent also the interior of woods not too thick and collect there about the rain puddles, the water of which is delayed in sinking by the matted layer of decaying leaves that covers the ground. After heavy rains I have seen them running about like grass plovers on open, level commons, covered only with short turf. They also have a fancy, shared by few birds except the titlarks, for the pools of liquid manure usually found in some out of the way place upon the thrifty farmer’s premises. They find abundant food in all these places, aquatic insects of all sorts, and especially their curious larvae, worms, grubs, and perhaps the smallest sorts of molluscs; with all these they also take into their gizzards a quantity of sand and gravel, to help along the grinding process. With food to be had in such plenty with little labor the birds become, particularly in the fall, extremely fat.

Edward H. Forbush (1912) says:

In the fall, on its return from the north, it has a habit of wading into the water in stagnant ditches or ponds, where it advances one foot at a time, and by rapidly moving the forward foot stirs up the vegetation at the bottom ever so slightly. This motion is so swift and delicate that the leg seems to be merely trembling, as if the bird were chilled by contact with the water, but it is done with intent to disturb insects among the algae at the bottom without roiling the water, and the eager bird, leaning forward, plunges in its bill and head, sometimes to the eyes, and catches the alarmed water insects as they dart away. I have watched this carefully with a glass while lying in the grass only 10 or 12 feet from the bird. It is easy by stirring the bottom slightly with a stick to cause a similar movement of the water insects, but I never could agitate it so delicately as to avoid clouding the water with sediment from the bottom.

Giraud (1844) says that “on the wing it is very active, and is sometimes seen darting after winged insects, which it is expert in catching.” Other observers have noted in its food various insects and their larvae, dragon-fly nymphs, water-scavenger beetles, water boatmen, grasshoppers, caterpillars, spiders, worms, small crustaceans, and small frogs.

[Pg 6]

Behavior.—The solitary sandpiper is always light, graceful, and dainty in all its movements. In spite of the unsavory places in which it often feeds, its trim figure is always neat and clean. In flight it is light and airy as it flits away for a short distance, only to alight again and lift its prettily lined wings high above its back before folding them. It flies higher than the spotted sandpiper and more swiftly, often in a zigzag manner, a trick probably learned by dodging branches in the woods, and the wings are raised well above the body on the upward stroke.

Walter H. Rich (1907) says:

There is scarcely another bird which flies with so little apparent effort. His strokes are slow and regular, a short sailing between each motion, but he moves very fast. Let him be alarmed and he will quicken his speed until he seems only a black streak in the air, and as he rises to top the surrounding trees it needs good and quick work with the gun to stop him.

It frequently indulges in a peculiar tilting and nodding habit, similar to that of the spotted sandpiper, but it is more deliberate and not so pronounced; it seems to be more of a bow than a tip-up more like the bobbing of the yellowlegs. It moves about rather sluggishly, wading in shallow water or even standing motionless, where its colors blend into its dark background and make it difficult to see. If it wades beyond its depth, it swims readily and can even dive to escape its enemies. John T. Nichols says in his notes:

In feeding it frequently lowers the head with a drilling motion, especially when immersing its bill in the water, apparently probing in the mud at such times, whereas as a rule our tattlers feed by snatching. It frequently stops to scratch its head with one foot. When bathing it ducks and splashes and sits in the water soaking, and at the conclusion of the bath, trips out onto the mud, raises the wings once or twice, and preens itself thoroughly. I have seen a solitary, alighted in a pool on the marsh, preening its feathers without dipping its bill in the water, and am not aware whether it has this bill-dipping habit common with some of its relatives.

Harrison F. Lewis has sent me the following notes on the rather peculiar behavior of a solitary sandpiper which he watched for some time:

The sandpiper, which was well aware that I was watching it, stepped slowly out onto the open surface of the mud of the bog, and, standing there with its left side toward me, repeated several times the following curious actions. It spread its wings about halfway, holding them stiffly in the plane of its back, neither raised nor lowered, so that the dark markings on its axillards were slightly visible. At the same time it drew its head as far backward and its tail as far forward over its back as possible, and slowly lowered its breast until it almost seemed to touch the mud. After remaining rigid in this position for 10 to 15 seconds, it would suddenly relax and become its normal self, only to repeat the entire procedure almost immediately. I could think of no purpose for these actions, unless they were an attempt at concealment by making the bird’s outlines and colors as unlike as possible to [Pg 7]those normally to be expected in a sandpiper. Although it did not conceal itself from me by this means, it made itself appear extremely unlike a bird.

Solitary sandpipers are usually very tame and unsuspicious, often to the verge of stupidity, as the following incident, related by Doctor Coues (1874) well illustrates:

Once coming up to a fence that went past a little pool, and peeping through the slats, I saw eight tattlers of this species wading about in the shallow water, searching for food. I pulled trigger on one; the others set up a simultaneous outcry, and I expected them, of course, to fly off, but they presently quieted down and began feeding again. Without moving from my place, I fired three times more, killing a single bird at each discharge; still no effect upon the survivors, except as before. Then I climbed over the fence, and stood in full view of the four remaining birds; they merely flapped to the further side of the pool, and stood still looking at me, nodding away, as if agreed that the whole thing was very singular. I stood and deliberately loaded and fired three times more, taking one bird each time; and it was only as I was ramming another charge, that the sole surviving bird concluded to make off, which he did, I will add in justice to his wits, in a great hurry.

Mr. Brewster (1925) says:

Not less confiding than sluggish, they will usually allow a man to approach in the open to within less than a dozen yards, and sometimes he may almost lay his hands on young and inexperienced birds, while several of these may continue to gaze at him with obviously serene unconcern immediately after he has discharged his gun directly over their heads. There are times, however, especially in calm weather, when the report of a gun, or the sound of one’s paddle striking against the side of a boat, will instantly startle all the solitary sandpipers within 20 rods, causing them to rise on wing with loud outcries, and to fly off singly, in various directions, to more or less distant places. In summer and autumn they invariably act thus independently of one another when flushed, and also when engaged in feeding, although by no means averse to assembling rather numerously where food is especially plentiful or easily obtained.

Voice.—Mr. Nichols has described this very satisfactorily, in his notes, as follows:

The ordinary notes of the solitary sandpiper are very close to those of the spotted, but probably always differentiable. They are sharper, cleaner cut, less variable. The full-flight note is a sharp piping peep weep weep, more often three than two syllabled when a bird is definitely leaving a locality, or by wandering birds which ordinarily fly high. In birds flushed on, or making longer or shorter flights to different parts of the same marsh where they were living, the same note was usually double peep weep, rarely single.

A quite dissimilar call, less frequently heard, is a fine pit pit pit, or chi tit. This may have no significance other than being a reduction of the preceding, when the bird is less definitely on the wing, but seems to depend on their being another individual fairly close by. There is likely homology between it and the short flocking call of the lesser yellowlegs, and if correctly determined, a certain analogy thereto is also established, perhaps as much as possible with this non-social species. Of similar quality was a peculiar kikikiki from one of two birds in company which came to decoys nicely, as they went on past my rig without alighting.

[Pg 8]

A third kind of note, isolated pips, suggesting the call of the water thrush, is expressive of excitement when a bird is on the ground, as when just alighted.

Field marks.—The field characters are also well described by Mr. Nichols, as follows:

In flight the under surface of the solitary sandpiper’s wings appears blackish. Birds on the ground not infrequently raise the wings over the back, displaying this mark to advantage. Its tail, spread when about to alight, appears white with a contrasting dark center. When traveling in the air its flight is either swift and darting or else resembles that of a yellowlegs, a little jerkier. When about to alight it usually drops down abruptly, much as the Wilson’s snipe does; and when flying only a few yards it has a peculiar jerky flight with wings partially spread. On the ground it looks much like a yellowlegs, but is darker, smaller, and stands relatively lower. Its legs are olive green; very rarely an individual in spring has quite yellow legs.

Fall.—The fall migration of the solitary sandpiper is a general southward movement all across the continent, performed in a leisurely manner. The earliest birds, probably adults, reach New England in July; and late birds, probably young, linger through October. Mr. Brewster (1925) says:

On August 2, 1873, I saw fully 100 along the Androscoggin River between the lake and Errol Dam, and almost as many more, a few hours later, while going up the Magalloway River some 7 or 8 miles. At that date in almost any year there is, throughout the whole Umbagog region, almost no muddy shore of pond, lake, river, lagoon, or brook, whether open to the sun or densely shaded by overhanging foliage, which is not frequented by one or more solitary sandpipers. Hence we may safely assume that in the region at large they are regularly present in far greater numbers during August than at any other time of year.

When with us in the fall they are more likely to be seen on open meadows or salt marshes than they are in the spring, often in company with lesser yellowlegs. Mr. Nichols writes to me:

In the first half of August, 1919, this species was unusually plentiful, living on the bay marsh at Mastic, Long Island, with maximum numbers August 9 to 10. The birds frequented the larger bits of flooded dead marsh that yellowlegs love and were also found in smaller, less open, pools more overshadowed by grass. On August 16 and 17 two birds were also repeatedly found feeding on patches of weed matted at the surface of an adjacent creek, exceedingly tame. The presence of these solitary sandpipers on a coastal marsh may have been due to conditions of high-water level prevailing at the time, flooding the muddy borders of inland pools where they are ordinarily to be looked for.

Capt. Savile G. Reid (1884) says that in Bermuda “they generally come with the other species in August. They soon betake themselves to the wooded swamps, where they may be found singly or in pairs throughout the autumn.”

On the Pacific coast both races of the solitary sandpiper occur regularly on the fall migration, but the western race is undoubtedly much commoner and is supposed by some to be the only race found west of the Rocky Mountains. The migration occurs mainly in August and [Pg 9]early September. J. A. Munro tells me that he gets both forms regularly at Okanagan Landing, British Columbia.

Winter.—A few birds may spend the winter in the West Indies, but the main winter home of the species is in South America. The distribution of the two forms in winter is not well understood and probably both races are more or less mixed. W. H. Hudson (1920) writes:

I was once pleased and much amused to discover in a small, sequestered pool in a wood, well sheltered from sight by trees and aquatic plants, a solitary sandpiper living in company with a blue bittern. The bittern patiently watched for small fishes and when not fishing dozed on a low branch overhanging the water, while its companion ran briskly along the margin snatching up minute insects from the water. When disturbed they rose together, the bittern with its harsh, grating scream, the sandpiper daintily piping its fine, bright notes—a wonderful contrast! Every time I visited the pool afterwards I found these two hermits, one so sedate in manner the other so lively, living peacefully together.

DISTRIBUTION

Range.—North America chiefly east of the Rocky Mountains to South America.

Breeding range.—The only unquestioned eggs of the solitary sandpiper that have been collected have come from Alberta where it is known to breed from the northern part south as far as Stony Plain and Red Lodge. A pair of adult birds with young also were collected in 1921, 30 miles below Fort Simpson, Mackenzie (Williams, 1922), while the same observer found them common in the vicinity of Fort Norman, Mackenzie, as late as August 14.

It has been reported breeding as far south as Iowa (Keokuk and Winneshiek Counties); Ohio (Columbus); and Pennsylvania (Pocono Mountain and Beaver); and east to New Hampshire (Isle of Shoals, Franconia, and Appledore); Maine (Penobscot and Aroostook Counties); and Quebec (Lake Mistassinni and Godbout). The circumstances attendant upon each of these and intermediate cases are such as to cause doubts concerning their authenticity, although it seems probable that the species did, (and possibly still does) breed somewhere in eastern North America.

Winter range.—The solitary sandpipers wintering in South America have been determined subspecifically only on a few occasions, so it should be understood that the following outline includes both solitaria and cinnamomea. Specimens collected in Colombia by Chapman and Todd all prove to be solitaria, while Chapman obtained both races in Ecuador.

The winter range of the species extends north to Vera Cruz (Playa Vicente); rarely Florida (probably Pensacola, probably [Pg 10]Waukeenah, Sevenoaks, and Safety Harbor); rarely Georgia (Chatham County); probably the Bahama Islands (Inagua); Jamaica; and Porto Rico. East to Porto Rico; eastern Venezuela (mouth of the Orinoco River); British Guiana (Bartica); Dutch Guiana (Surinam and Maroni River); French Guiana (Cayenne); Brazil (Mixiana, Para, Chapada, Urucuia, and Pitanguy); Paraguay (Colonia Risso); Uruguay (Rocha, Montevideo, and Colonia); and Argentina (Buenos Aires and Azul). South to Argentina (Azul and Cordoba). West to Argentina (Cordoba, Tucuman, Salta, and Oran); Bolivia (Caiza); Peru (Chorillos, Cajabamba, and Tumbez); Ecuador (Guayaquil and Quito); Colombia (Cali, Novita, Medellin, Puerto Berrio, and Santa Marta); Costa Rica (San Jose); Guatemala (Los Amates and Duenas); Yucatan (Tabi); and Vera Cruz (Playa Vicente).[1]

[1] The migration dates here given probably include, in many cases, observations and records for both solitaria and cinnamomea.

Spring migration.—Early dates of arrival in the spring migration are: South Carolina, Charleston, March 27, and Aiken, March 30; North Carolina, Raleigh, April 4, and Weaverville, April 9; District of Columbia, Washington, March 30; Pennsylvania, State College, April 14, Sewickley, April 15, and Doylestown, April 16; New Jersey, Dead River, April 18; New York, York, April 18, Ithaca, April 20, and New York City, April 21; Connecticut, Litchfield, April 27, and New Haven, April 29; Massachusetts, Northampton, April 25, Melrose, April 26, and Fitchburg, April 28; Vermont, Randolph, April 26, Bennington, May 4, and Wells River, May 6; New Hampshire, Manchester, April 26, and Monadnock, May 11; Maine, Orono, May 3, Pittsfield, May 6, and Waterville, May 7; Quebec, Quebec, May 1, and Godbout, May 4; Mississippi, Bay St. Louis, March 17, and Biloxi, March 25; Louisiana, Hester, March 16; Arkansas, Monticello, March 24, and Tillar, March 31; Tennessee, Nashville, April 7; Kentucky, Bowling Green, April 8, and Russellville, April 9; Missouri, Jonesburg, March 19, and Monteer, April 6; Illinois, Rantoul, March 24, Danville, April 2, and Chicago, April 7; Indiana, Frankfort, March 15, Indianapolis, March 17, and Delhi, March 28; Ohio, Oberlin, March 28, Sandusky, March 31, and Scio, April 7; Michigan, Ann Arbor, April 23, Hillsdale, April 24, and Portage Lake, April 30; Ontario, Toronto, March 16, London, April 28, and Ottawa, May 2; Iowa, Hillsboro, April 10, National, April 14, and Sigourney, April 20; Wisconsin, Beloit, April 24, Milwaukee, April 25, and Madison, April 26; Minnesota, Minneapolis, April 17, Hallock, April 21, and Lanesboro, April 24; Texas, Santa Maria, March 3, Brownsville, March 17, Texas City, March 22, and Boerne, March 25; Kansas, Wichita, March 29, Emporia, April 10, and Independence, April 16; Nebraska, Neligh, April 20, Red Cloud, [Pg 11]April 25, and Valentine, April 27; South Dakota, Forestburg, April 16, and Huron, May 3; North Dakota, Charlson, April 27, and Bismarck, April 30; Manitoba, Aweme, April 29; Saskatchewan, Wiseton, May 13, and Osler, May 19; and Alberta, Alliance, May 2, Flagstaff, May 4, and Oonoway, May 5.

Late dates of spring departure are Colombia, La Manuelita, April 11, and eastern Santa Marta region, April 18; Costa Rica, San Jose, April 27; Yucatan, Rio Lagartoo, April 13; West Indies, San Domingo, April 27; Cuba, Isle of Pines, May 18; Bahama Islands, Nassau, May 10; Florida, St. Marks, May 10, and Pensacola, May 30; Alabama, Bayou Labatre, May 20, and Autaugaville, May 23; Georgia, Macon, May 10, and Savannah, May 17; South Carolina, Aiken, May 10, Frogmore, May 19, and Mount Pleasant, May 27; North Carolina, Weaverville, May 20, and Raleigh, May 28; District of Columbia, Washington, May 21; Maryland, Sandy Springs, May 22, and Cumberland, May 23; New Jersey, Camden, May 25, Morristown, June 7, and Bernardsville, June 11; New York, Rhinebeck, May 26, Cincinnatus, May 31, and Orient Point, June 6; Connecticut, Norwalk, May 27, and Litchfield, May 31; Rhode Island, Providence, June 3; Massachusetts, Worcester, May 30, Melrose, June 1, and New Boston, June 10; Louisiana, New Orleans, May 6, and Bains, May 12; Mississippi, Ellisville, May 17; Tennessee, Nashville, May 27, and Knoxville, June 12; Kentucky, Bowling Green, May 22; Missouri, St. Louis, May 16, and Monteer, May 20; Illinois, Chicago, May 26, Joliet, May 28, and Rantoul, May 29; Indiana, Goshen, May 24, and Holland, May 30; Ohio, Columbus, June 1, Oberlin, May 28, and Huron, May 29; Michigan, Laurium, May 26, and Detroit, May 30; Ontario, Port Perry, May 27, Toronto, June 3, and Madoc, June 7; Iowa, Sioux City, May 26, Emmetsburg, May 29, and Sioux City, May 30; Wisconsin, Madison, May 27, and La Crosse, May 29; Minnesota, Waseca, May 22, Hallock, May 25, and Minneapolis, May 31; Texas, Gainesville, May 15, Kerrville, May 20, and Hidalgo, May 23; Kansas, Lawrence, May 21, and Topeka, May 22; Nebraska, Valentine, May 20, and Lincoln, May 22; South Dakota, Huron, May 21, Vermilion, May 27, and Forestburg, May 30; North Dakota, Charlson, May 25; Manitoba, Aweme, May 26, Shell River, May 29, and Shoal Lake, June 1; and Saskatchewan, Prince Albert, June 5, and Kutanajan Lake, June 15.

Fall migration.—Early dates of arrival in the full migration are: Saskatchewan, Maple Creek, July 6; Manitoba, Margaret, July 8, and Oak Lake, July 19; South Dakota, Sioux Falls, July 1, and Forestburg, July 2; Nebraska, Valentine, July 3; Kansas, Little Blue River, July 22; Texas, Gurley, July 15, Kerrville, July 20, Brownsville, August 2; Minnesota, St. Vincent, July 2, Lanesboro, [Pg 12]July 4, and Minneapolis, July 15; Wisconsin, Shiocton, June 30, North Freedom, July 14, and Ladysmith, July 16; Iowa, Marshalltown, July 8, Sioux City, July 12, and Hillsboro, July 18; Ontario, Toronto, July 10, and Port Dover, July 13; Michigan, Detroit, July 7, and Charity Island, July 10; Ohio, Columbus, July 3, Wooster, July 8, and Painesville, July 20; Indiana, Sedan, July 15; Illinois, Chicago, July 3, Glen Ellyn, July 16, and Port Byron, July 21; Missouri, Monteer, July 29; Kentucky, Bowling Green, July 22; Mississippi, Biloxi, July 12, and Bay St. Louis, July 16; Louisiana, New Orleans, July 9; Massachusetts, Becket, July 8, Harvard, July 12, and Lynn, July 17; Rhode Island, Newport, July 4, and Providence, July 11; Connecticut, East Hartford, July 14, and Milford, July 28; New York, Camp Upton, July 8, Rochester, July 12, and Poland, July 15; Maryland, Calverton, July 14, and Cambridge, July 19; District of Columbia, Washington, July 15; North Carolina, Raleigh, July 14; South Carolina, Frogmore, July 24, and Charleston, July 26; Alabama, Stevenson, July 15, and Leighton, July 17; Florida, Pensacola, July 12, Bradenton, July 12, St. Marks, July 28, and Key West, July 28; Bahama Islands, Fortune Island, August 5; Cuba, Isle of Pines, August 20; Porto Rico, Comerio, July 29; and lesser Antilles, St. Croix, August 5.

Late dates of fall departure are: Keewatin, Echimamish River, September 15; Manitoba, Shoal Lake, September 17, and Aweme, October 5; North Dakota, Charlson, September 18; South Dakota, Forestburg, September 30; Nebraska, Valentine, October 9, Nebraska City, October 10, and Lincoln, October 20; Minnesota, St. Vincent, September 22, Parkers Prairies, September 30, and Lanesboro, October 4; Wisconsin, Elkhorn, October 10, Delavan, October 20, and Racine, October 30; Iowa, Marshalltown, October 5, and Hillsboro, October 20; Ontario, Toronto, October 2, St. Thomas, October 4, and Ottawa, October 31; Michigan, Detroit, October 1; Ohio, Weymouth, October 14, Austinburg, October 28, and Medina, November 1; Indiana, Indianapolis, October 15, Richmond, October 28, and Roanoke, November 15; Illinois, Chicago, October 6, La Grange, October 7, and De Kalb, October 10; Missouri, Jaspar City, October 9, and Independence, October 13; Kentucky, Bowling Green, October 11, Versailles, October 21, and Lexington, October 23; Tennessee, Knoxville, October 11, and Nashville, November 4; Quebec, Montreal, September 27; Maine, Portland, October 6, Pittsfield, October 8, and Hebron, October 20; New Hampshire, Tilton, September 29, Lancaster, October 5, and Errol, October 31; Vermont, Rutland, October 10, and West Barnet, October 17; Massachusetts, Lynn, October 28, and Boston, October 30; Rhode Island, Providence, October 13; New York, Rochester, October 10, Ithaca, October 19, [Pg 13]and New York City, October 31; New Jersey, Montclair, October 13, Elizabeth, October 16, and Morristown, November 1; District of Columbia, Washington, October 28; Maryland, Chesapeake Beach, November 2; and South Carolina, Long Island, November 8.

Casual records.—The typical form of the solitary sandpiper has been many times taken in Western States. Among these occurrences are: New Mexico (Guadalupito, August 7, 1903); Wyoming (Arvada, August 19, 1913); Montana (Milk River, July 25, 1874, Miles City, August 14, 1900, Gold Creek, August 20, 1910, and Three Buttes, August 6, 1874). Many specimens also have been taken in British Columbia (Atlin and Okanagan Landing), where it appears to be of regular occurrence, a specimen was taken at Griffin Point, Alaska, June 1, 1914, and one at Fort Chimo, Ungava.

Two were collected on October 12, 1897, on Chatham Island, Galapagos Archipelago; one was taken on the Clyde River, Lanarkshire, Scotland; and another was obtained at Kangek, Greenland, on August 1, 1878.

Egg dates.—Alberta: 29 records, May 24 to June 24; 15 records, May 30 to June 8.

TRINGA SOLITARIA CINNAMOMEA (Brewster)

WESTERN SOLITARY SANDPIPER

HABITS

The western race of this species is larger than the eastern. In adult nuptial plumage the upper parts are much less distinctly spotted with whitish, the white bars on the tail are decidedly narrower and the outer primary is usually finely mottled, with ashy white along the border of its inner web; this last is none too constant a character and is sometimes seen in the eastern bird. The name was derived from the fact that in young birds the light spots on the back, scapulars and wing coverts are brownish cinnamon instead of white or buffy whitish.

Courtship.—The following description of the song flight of this species was originally recorded by Dr. Joseph Grinnell (1900) under the name of the undivided species, but he now evidently thinks that it should belong here:

The song flight of this species is mostly indulged in during the early morning hours. This consists of a slow circuitous flight on rapidly beating wings high over the tree tops, accompanied by the frequent repetition of a weak song somewhat resembling the call of a sparrow hawk. At the close of this song flight the bird alights, as if exhausted, and perches silently for some time at the top of the tallest spruce in the vicinity. During the performance of the male, the female [Pg 14]may be seen feeding around some grassy pool beneath, from all appearances entirely unmindful of the ecstatic efforts of her mate.

Nesting.—Nothing definite is known of the breeding range or nesting habits of the western solitary sandpiper. It is supposed to breed in the interior of British Columbia and Alaska. The following observations, made near Circle, Alaska, by Dr. Wilfred H. Osgood (1909) throw some light on the subject:

Within a radius of several miles from Circle one or more adults were found about almost every woodland swamp. In most cases they acted like parent birds anxious for the safety of their young. Whenever we entered certain precincts, they hovered nervously about, calling loudly, or alighted on nearby trees scolding. The first pair seen near Charlie Creek exhibited such actions on the evening of June 22, and we made a hasty search in the twilight for young birds, but found nothing. The excitement of the old birds seemed to be greatest while we were in a small grassy swamp, so the next day we made a more careful search. The old birds were even more excited than before, and it was some time before we detected that, besides the loud cries ringing all about us, a faint peeping was issuing from several points in the grass. Guided by this scarcely audible peeping, we soon found three downy young birds widely separated and squatting aimlessly in the grass. They are quite small, exactly of a size, and none shows the least indication of growing feathers; evidently they belonged to one clutch, and could not have been out of the eggs more than one or two days. The eggs of this species, like those of the European green sandpiper, have been found in the nests of other birds in trees. The small opening where the birds were found was bounded on one side by an extensive area grown with willows of relatively small size, but on the other side was only a thin line of willows and then alders, birch, poplars, and heavy spruce, in which probably such birds as olive-backed thrushes, robins, and varied thrushes nested in abundance. Therefore there was ample opportunity for the sandpipers to lay their eggs in the nests of these birds.

Plumages.—The downy young referred to above are thus described by Robert Ridgway, (1919):

General color of upper parts cinnamon drab, longitudinally varied with brownish black; forehead and crown with a broad median streak of black; a sharply defined black loral streak, extending from bill to eye; a narrow black stripe across auricular region (longitudinally), or a black postauricular spot; occiput brown centrally, black exteriorly, the black border sending from each side a forward branch; an oval patch of brownish black on median portion of rump, this bordered along each side by a stripe of pale dull vinaceous-buff, the two buffy stripes converging or almost uniting both anteriorly and posteriorly; wings cinnamon drab, margined posteriorly with dull white, the brown portion with several irregular spots or blotches of black; under parts dull white.

Subsequent plumages and molts are doubtless similar to those of the eastern race.

Winter.—As mentioned under the preceding subspecies, we know very little about the winter distribution of the two races. Dr. Frank M. Chapman (1926) says that most of his specimens from Ecuador are of this form, which he calls “a common winter resident from the [Pg 15]coast to the tableland, arriving from the north at least as early as August 10.” Dr. Alexander Wetmore (1926) says:

The specimens taken at Formosa and General Roca belong certainly to the western form, on the basis of size (male, wing, 134.3; female, wing 136.7 mm.), dorsal coloration, and the presence of mottling on the inner web of the outer primary. A female from Lazcano, Uruguay, has molted the outer primaries, but on the basis of other measurements and on the presence of some dark, buff mottling on the back seems within the limit of variation of cinnamomea and is identified as the same as the other two. Though the typical subspecies solitaria is recorded definitely from Colombia by Chapman, these findings seem to cast a doubt on its presence as far south as Argentina.

DISTRIBUTION

Range.—Western North America and South America.

Breeding range.—No unquestioned set of eggs of the western solitary sandpiper has thus far been recorded. Downy young with their parents have, however, been taken in western Alberta (Henry House) and in Alaska (Circle, Kowak River, Eagle, and Charlie Creek). There also is a strong probability of their breeding in British Columbia (Cariboo District, and Ducks).

Winter range.—As mentioned under T. s. solitaria, the two races of this species on their wintering grounds in South America have been distinguished only on a few occasions. It is probable that they either occupy the same winter grounds or that their ranges overlap. All specimens collected by Wetmore (1926) from Uruguay, Paraguay, and Argentina, prove to be this form, indicating that it may winter south of true solitaria. It also has been taken by Chapman in Ecuador (Guayaquil, Loja, and Cebollal).

Spring migration.—Early dates of spring arrival are: Texas, Samuels, April 15, and Henrietta, April 19; New Mexico, State College, May 4, and Las Vegas, May 8; Colorado, Colorado Springs, May 1, Denver, May 4, and Boulder, May 5; Montana, Terry, May 7, and Billings, May 10; Alberta, Athabaska Landing, May 5, Edmonton, May 10, and Sandy Creek, May 14; Mackenzie, Fort Simpson, May 10, and Fort Providence, May 14; Arizona, Verde Valley, April 20, and Paradise, May 9; California, Los Angeles, April 10, Gridley, April 23, and Fort Crook, May 4; Oregon, Anthony, April 16, and Malheur Lake, April 17; Washington, Tacoma, May 6; British Columbia, Okanagan Landing, May 5, and Chilliwack, May 7; Yukon, Forty-mile, May 8; and Alaska, Tocatna Forks, May 12, Nulato, May 15, and Kowak River, May 18.

Late dates of spring departure are: Colorado, Boulder, May 25, Denver, May 28, and Grand Junction, June 3; and Wyoming, Fort Saders, May 25.

[Pg 16]

Fall migration.—Early dates of fall arrival are: California, Santa Barbara, July 22; Arizona, Apache, July 29, Cave Spring, August 1, and White Mountains, August 10; Montana, Terry, June 28; Wyoming, New Castle, July 7; Colorado, Lytle, July 6, Middle Park, July 13, and El Paso County, July 23; New Mexico, Zuni Mountains, July 24; and Texas, Brownsville, July 31.

Late dates of fall departure are: Alaska, Taku River, September 15; British Columbia, Okanagan Landing, September 26; Washington, Seattle, September 11; California, Santa Barbara, September 7; Arizona, San Pedro River, October 10; Lower California, Agua Escondido, November 18; Montana, Missoula, September 4, Terry, September 5, and Bitterroot Valley, September 7; Wyoming, Yellowstone Park, September 4, and Green River, September 5; Colorado, Boulder, September 18, Florissant, October 5, and Greeley, October 25; and New Mexico, Acoma, September 27, and Glenrio, October 2.

TRINGA OCROPHUS Linnaeus

GREEN SANDPIPER

Contributed, by Francis Charles Robert Jourdain

HABITS

The green sandpiper is only an accidental visitor to North America. Swainson and Richardson (1831) record it from Hudson Bay, but this is now generally acknowledged to be probably due to error. However, Dr. T. M. Brewer (1878) mentions a specimen obtained at Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1872 or 1873 and forming part of a collection made there which was purchased by J. E. Harting from a dealer at Woolwich. The evidence is far from satisfactory and Seebohm’s remarks (1884) should be consulted, but the skins in question are still in existence in the collection of the British Museum.

Courtship.—It is a most remarkable fact that though the green sandpiper is widely distributed during the breeding season over temperate Europe and is by no means a shy or retiring bird, even though it haunts the recesses of wooded marshes and wet forests, yet there is hardly anything on record about its courtship activities. Seebohm writes that the notes “are no doubt modulated into a musical trill as the male performs his amatory excursions in the air during the pairing season,” but adds that he has never had the good fortune either to hear the love song or to find it described. Fortunately Prof. C. J. Patten (1906) met with a pair which frequented a moorland stream in the neighborhood of Sheffield from May 3 to June 4, 1903. He says:

[Pg 17]

They were always to be found in the same spot, and after feeding they frequently flitted on to a stone wall, where for a little while they would remain motionless. At intervals they suddenly shot up into the air for a short distance, darting down again to the same stone with astonishing speed. On the wing they displayed great activity and adroitness, the female twisting and turning to escape the addresses of the male.

Newton (1896) writes:

Yet in the breeding season, even in England, the cock bird has been seen to rise high in air and perform a variety of evolutions on the wing, all the while piping what without any violence of language may be called a song.

Doctor Hartert (1920), speaking of its habits on its breeding grounds, remarks that it may be seen shooting through the air with the speed of an arrow, and opines that this must be the love flight. With the exception of these notes and some references to the song (which are referred to under the heading of Voice), I can find nothing in the literature with regard to the actual courtship, except Hartert’s statement that on the ground the male trips about, with tail outspread like a fan, calling loudly. When, however, a pair has definitely settled down in its breeding territory, both birds are exceedingly noisy and demonstrative. Wheelwright (1864) speaks of the “boisterous, noisy behavior” of this bird, and in his later work on Sweden (1865) remarks:

Now, of all our waders, this is the noisiest, and there is little trouble in finding the locality where it breeds, for the old male is always about some brook in the neighborhood, and I have before noticed that the loud, wild cry of the green sandpiper and greenshank are much alike.

Nesting.—The nesting habits of the green sandpiper have been fully described, but were practically unknown to naturalists till about 1852–1860, when quite independently Forester, Weise, and Hintz (sen.), in Germany, and H. W. Wheelwright in Sweden, published the results of their discoveries. The story is told in detail by Forest-Inspector Weise, in the Journal für Ornithologie for 1855 (p. 514). He had first heard of the habit of adopting old nests of other species in trees from an old ranger, but naturally discredited it. However, in 1845, the same man brought him four sandpipers’ eggs from a nest in an old beech. Next spring Weise found a green sandpiper breeding in a pine about 25 or 30 feet from the ground. He climbed to the nest and found the four eggs so highly incubated that the young could be heard squeaking inside the shells. Two other nests in similar sites came to his notice subsequently, the last on May 25, 1855, when the four eggs were already chipped.

Forester, W. Hintz 1, writing in the same periodical for 1862 (p. 460) says that he had found sandpipers’ nests in trees as far back as 1818, but at that time he had no correspondents who took any [Pg 18]interest in birds’ eggs and only took a clutch or two for his own collection. On April 26, 1834, he found a clutch of this species in a nest of the song thrush (Turdus philomelus) and from 1852 onward, as the circumstances began to be known to German naturalists, he found a long series of nests with eggs of which he gives full details. Most of these eggs were laid in old nests of song thrush (Turdus philomelus), but some were placed in old nests of pigeon (probably Columba palumbus) or squirrel’s dreys, and in one case the young were found in an old nest of red-backed shrike (Lanius collurio). Another curious case recorded is that in which an old aspen (Populus tremula) was broken off and a hole which had been occupied in the previous year by a pied flycatcher, contained a brood of young green sandpipers, which had apparently only been hatched half an hour before. On the forester’s approach the young birds jumped from the hole and concealed themselves among the grass. Some further details are also given in a letter from Hintz sent to the Rev. H. S. Hawkins and published in Dresser’s Birds of Europe; also in the Journal für Ornithologie for 1864 (p. 186).

Summarizing these we find that the birds arrive on their nesting grounds in Germany from the beginning to the middle of April, choosing wooded localities in marshy districts with pools or slow-flowing streams in the neighborhood. Old nests of song thrush, blackbird, mistle thrush, red-backed shrike, and half-ruined nests of jay, woodpigeon, or squirrel are all adopted from time to time. Occasionally the eggs are laid in a hollow where dead leaves and pine needles have accumulated, and holes formerly used by starlings and flycatchers have been taken possession of. The height from the ground varies considerably, some nests may be as much as 35 or 40 feet above the ground while others are only a few feet up. The distance from the nearest water is also variable, as though most nests are within 500 yards, yet occasionally the birds have been known to nest half a mile away.

Meantime H. W. Wheelwright in Sweden had met with an exactly similar state of things, and in the Field newspaper of August 18, 1860, described the tree-nesting habits of this species. The editor, who was ignorant of the evidence of Weise and Hintz, openly expressed his doubts as to the accuracy of the observations, but Wheelwright stuck manfully to his facts and subsequently the editor admitted his mistake. The republication of Wheelwright’s notes in Sweden in 1866 elicited further evidence from Jagmaster Lundborg, who had on one occasion taken the eggs from what appeared to be an old squirrel’s drey or nest. The only important difference in the habits of the bird in the two countries appears to be that nests of the hooded crow (Corvus c. cornix) are freely used in Sweden and also those of the fieldfare (Turdus pilaris).

[Pg 19]

Like the greenshank, the green sandpiper has a great attachment to certain localities and in some cases the identical nest has been used for two consecutive seasons. In a district where the birds are not scarce, this naturally renders the discovery of the nest much more simple to the resident, and explains the success of Forester Hintz and others in discovering the eggs. Very little in the way of addition appears to be made by the sandpipers to their adopted home and the pine needles which are noted in the interior of old thrushes’ nests may well have dropped from the adjacent trees in the ordinary way.

Eggs.—These are normally four in number, pyriform in shape, rather thin shelled and, as compared with those of the wood sandpiper, generally large and pale in coloring, showing more of the ground colors and fewer markings. The ground color varies from some shade of pale greenish or greenish grey to warm creamy, buffish stone color and light yellowish red. The markings are generally rather fine and in the reddish eggs are rich purplish brown, shading into very dark brown, while in the greenish eggs they are generally less reddish and more purplish in tone. Numerous fine speckles are characteristic and there are generally also some underlying shell marks of violet or ashy. The measurements of 100 eggs average 39.11 by 28.04 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 42 by 28, 41.1 by 30.3, 34.6 by 26, and 34.8 by 25.7 millimeters.

Young.—As to the shares of the sexes in incubation, there are references to females shot from the nest and males on guard in the neighborhood, but how far this has been confirmed by dissection and how much is surmise it is not easy to say. The incubation period is also unknown. When the young are hatched their stay in the nest is very short. Besides Hintz’s observation, quoted above, of recently hatched young jumping from the nest into the grass on his approach. Wheelwright also found on one occasion four very small young, apparently not a day old, at the foot of a fir, while in the nest overhead were the empty shells, still wet inside. In this case the early abandonment of the nest was not due to human interference. On another occasion Hintz found three young and a chipped egg in a squirrel’s drey about 30 feet up in a birch. The young birds sprang from the nest and alighted on the ground without injuring themselves, concealing themselves at once among the grass.

Plumages.—The molts and plumages are fully described in A Practical Handbook of British Birds, edited by H. F. Witherby (1920), to which the reader is referred.

Food.—The main food of this species consists of insects, especially small coleoptera and their larvae, but larval forms of other [Pg 20]water insects such as the Phryganeidae are also taken and also larvae of Diptera. Other substances recorded include wood lice, spiders, and not infrequently the very small red worms, which are to be met with on the edges of stagnant pools, but apparently not common earthworms. Traces of vegetable matter are also recorded. H. Stevenson also includes small fresh-water mollusca, and W. Farren, algae, tender shoots of plants and on the seashore thin shelled Crustacea.

Behavior.—The green sandpiper may be met with in the British Islands in almost every month of the year except perhaps June, when it is decidedly rare, though only a few individuals stay with us through the winter. As some birds have undoubtedly stayed through the summer, breeding has been suspected on several occasions, but the evidence has always been unsatisfactory. It occurs most frequently in spring and autumn, sometimes singly and sometimes (especially in autumn), in family parties, haunting the margins of brooks and ponds.

They are much more deliberate in their movements than the common sandpiper and search the mud very thoroughly, boring into it with the bill, probably in search of the small red worms on which they feed. Without being especially shy, they have their wits about them and frequently the piping note which they utter when well on the wing (not just prior to rising) is the first indication of their presence to the shooter. The striking contrast of color between the dark greenish mantle and the snow white rump and tail coverts render its recognition a fairly simple matter. From the wood sandpiper it can be readily distinguished if a glimpse can be caught of the undersurface of the wing, for in the green sandpiper the axillars are very dark, looking almost black, whereas in the wood sandpiper they appear almost white with faint barrings.

Voice.—With regard to the notes, during the breeding season the alarm is given by a loud sharp call which is variously written as gik, giff, yick, yeck, etc., somewhat recalling the nuthatches’ call. Christoleit also describes a pairing song, which bears some resemblance to that of the other sandpipers, but does not make it clear whether it is uttered on the wing or on the ground. In forested country it is naturally not so easy to settle a point of this kind as in open country. The full song is written by him as: Tittittitluidich-luidich titluidie titluidie titluidie-titt-titt. Probably this is the love song and forms part of the courtship, but we still await a connected history of the courtship of this species.

Fall.—Hintz noticed the last birds on their German breeding grounds up to July 25, and it is about the middle of July when the first immigrants appear in the British Isles. The great majority of [Pg 21]our visitors have left by November. During the period of its stay it is rarely to be met with on the seashore, but nearly always makes its way inland by means of the water courses, preferring a sheltered brookside or an inland pool to the open marshes.

Winter.—The evidence of wintering in South Africa rests entirely on some old records by Layard, unsupported by skins, but the winter quarters undoubtedly extend to Angola, British Central Africa, and Portuguese East Africa. Unlike so many waders it does not associate in large flocks, but generally is found singly or in small parties on inland waters in preference to the coast. Large numbers winter in Egypt and a good many at suitable spots in the Mediterranean Region. In Luzon (Philippine Islands) Whitehead found it common in December in Benguet, at a height of 4,000 feet, and on Rumenzon it has been met with at 6,000 feet, while in Abyssinia, Jesse describes it as common on the highlands, but did not meet with it on the coast.

DISTRIBUTION

Breeding range.—Northern Europe; but very sparingly in Norway up to Nordland; in Sweden more generally north to the Arctic Circle; Finland to 63° 10´; North Russia south of the White Sea and on the Kamin Peninsula (66° 50´). Southward it breeds in the Baltic Republics, in North Germany (Holstein?, Oldenburg?, Hanover, Mark Brandenburg, Pommern, West and East Prussia, Silesia); sparingly in Bavaria; Czechoslovakia (Bohemia), Galizia and the Carpathians; possibly occasionally in Jutland, but records from South France and North Italy can not be relied on. In Asia it breeds across the continent in the valleys of the Ob, Yenisei, Lena, etc., south to Turkestan and Transcaspia.

Winter Range.—The main winter quarters lie in southern Europe and Africa where it ranges south to Portuguese East Africa, British Central Africa, and Angola, perhaps even to the Cape (Layard) and in Asia to Iraq, India, Ceylon, the Andamans, Burma, Cochin China, China, Hainan, Formosa, and the Malay Archipelago (Philippines).

Spring Migration.—In February and March it passes north through Morocco from its African winter quarters, and in Tunisia is most abundant on spring passage in March and April, while its stay in equatorial Africa does not extend beyond March. In the marshes of Iraq it stays till mid May, the spring in North Asia being later than in West Europe. This is also the case in India, where they do not leave till about mid May. In southeast China they pass in the first half of April, usually singly. It has been noted on passage in Corsica in April (late date May 28); some winter on the Balearic Isles where it has been noted up to the end of May, [Pg 22]while in Cyprus it is found on passage in March, April, and May (birds seen in Greece on 25th July and in South China on 11th and 24th July were either nonbreeders or extraordinarily early migrants southward). The first arrivals reach their breeding grounds in Germany about the end of March, and in the Baltic states they arrive about the end of March or early April.

Fall migration.—Leaving their breeding grounds in Central Europe about the end of July, they pass the Straits of Gibraltar about August–September and in Greece arrive in some numbers in September. In the Iraq marshes the arrival takes place during August, while in India it sometimes comes during the latter half of July, but more frequently in August. In southeastern China the first arrivals come in about the end of July or early in August, but the main body passes in September or October. In Burma it is generally distributed during the winter months, but apparently does not range down the Malay Peninsula.

Casual records.—It is a winter visitor to Japan and occurs occasionally on the Canaries, but the record from Mauritius must be regarded as doubtful, and that from Australia by R. Hall is due to confusion with T. glareola. Gould’s record from Borneo is also doubtful and the American records can only be received with some suspicion.

Egg dates.—In Germany out of some 25 records only five fall between April 15 and 24. From May 2 to 15 there are nine records, from May 18 to 29 five records, and from June 1 to 23, six records. Probably most of these late dates are due to birds laying again which have been previously robbed. In Sweden all dates fall between May 6 and June 20 (13 records) and of these eight fall between May 6 and May 21. The second half of May is the usual time in the southern Provinces, but in the north and Finland few eggs are laid before June. In Siberia eggs may be found till the first half of July.

RHYACOPHILUS GLAREOLA (Linnaeus)

WOOD SANDPIPER

Contributed by Francis Charles Robert Jourdain

HABITS

The only record of this species within North American limits is due to Chase Littlejohn (1904), who obtained a single specimen on May 27, 1894, on Sanak Island, Alaska.

Courtship.—Our information on this point is somewhat scanty. The song flight has of course been frequently described and observed, but the actual courtship of the female can only be observed under somewhat difficult conditions and there must be a considerable element [Pg 23]of luck in any case where it can be closely studied. All the evidence hitherto obtained goes to show that it is carried on in much the same way as that of the common sandpiper (Tringa hypoleucos), but the song flight forms a much more conspicuous part of the proceedings. When the male alights he has a habit of elevating his wings for a moment, until, as Seebohm says, they almost meet overhead, much as Temminck’s stint also does. Apparently this forms part of the display before the hen, but the male may also be seen running by the side of the female with drooping wings. One can as a rule only get a momentary glimpse and generally at a considerable distance. The love song is, however, quite another matter. On the heaths of West Jutland one can see the males in rapid flight even from the windows of the trains, while in North Finland the loud musical leero,leero, leero, is one of the most familiar sounds in the wood-fringed marshes. John Hancock (1874), who by persevering search found the only nest which has ever been discovered in the British Isles, in June 1853, gives a very graphic account of it. He was on a visit to Prestwick Car, in Northumberland, at that time undrained, and as he says: