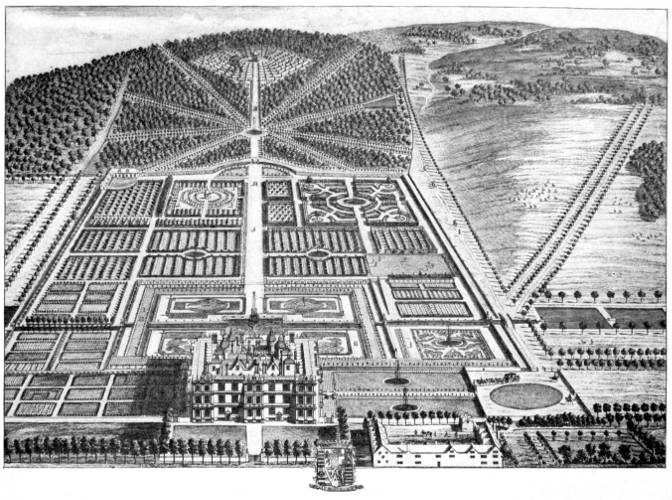

LONG LEATE

By L. Knyff and J. Kip

Title: The treatment of nature in English poetry between Pope and Wordsworth

Author: Myra Reynolds

Release date: December 17, 2025 [eBook #77487]

Language: English

Original publication: Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1909

Credits: Jamie Brydone-Jack, Karin Spence and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

BETWEEN POPE AND WORDSWORTH

By

MYRA REYNOLDS

CHICAGO

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

1909

Copyright 1909 By

The University of Chicago

Composed and Printed By

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago, Illinois, U. S. A.

[v]

The eighteenth century is a period of transition and as such its literature holds two elements, a vital impulse past its prime but still dominant, and a new conception gradually emerging into dominance. It is the interweaving of these elements, the slow fading of the old, the slow gain of the new in fulness, definiteness, and ardor of statement, that make this period peculiarly interesting for detailed study. The interest persists even when the transition to be studied is limited to so narrow a section of human experience as the attitude toward Nature.

The investigation, the results of which are embodied in this book, was primarily undertaken to determine the place of Nature in the poetry before Wordsworth. Every genius is, to be sure, more or less of a miracle, and certainly not to be accounted for by any conditions of literary heredity or even environment. But he cannot, on the other hand, be justly thought of as an isolated phenomenon. Though not the direct heir of any particular predecessors, he is, nevertheless, in a vital and inescapable way, the heir of the general tone and temper of his own and preceding times. In that fact lies the justification of a study along historical lines of any recognized tendency in thought. The pleasure of the biologist in the lower forms of life is paralleled by the delight of the student of literature in tracing out the first vague, ineffective attempts to express ideas that are afterward regnant. In the present study the final effect is one of surprise to discover not only how early the new thought of Nature finds expression, but how completely the ideas of the period of Wordsworth were represented in the germ in the eighteenth century. The whole impression is that before the work of such men as Wordsworth, Scott, Coleridge, Shelley, Keats, and Byron, there was a great stir of getting ready. It may fairly be said that before Wordsworth most[vi] of his characteristic thoughts on Nature had received explicit statement.

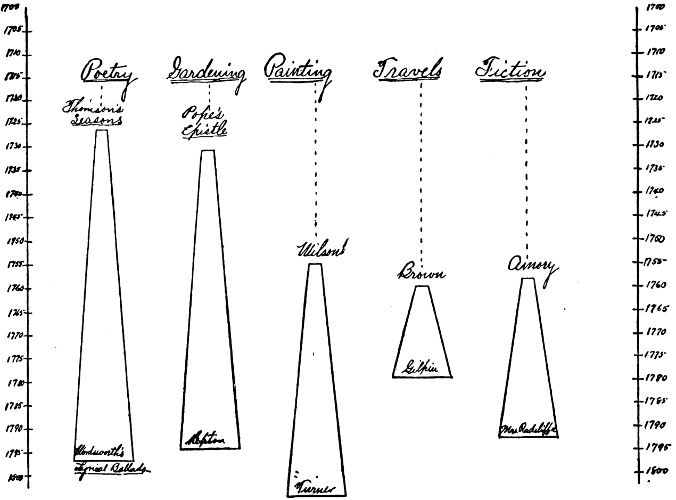

In the pursuance of this study it soon became apparent that to confine it to poetry was to limit the investigation unwarrantably. The interest of the work was many times increased, and the deductions were rendered much more certain, when the same transitions, the same periods of change, the same tastes, the same emotions, revealed themselves side by side in poetry, painting, fiction, travels, and gardens. Furthermore, the vitality of the new impulse toward Nature is shown by the number of directions in which it insistently demanded expression. Almost independently of each other the various arts seem to have been pushed forward from within to some sort of recognition of the growing interest in the external world. In each art there seemed to be an unconscious preparation for the master that was to come. Notably does this appear from the chapter on painting. Constable and Turner were foreshadowed and prepared for as evidently as was Wordsworth. When at the end of such a period of preparation the great poet or artist comes, he is great by virtue of his power to penetrate beneath literary conventions and to give final literary form to the half-articulate thoughts and feelings out of which the thoughts and feelings of his own epoch grow. He has his natural place in the development. The significance of his work rests in the fact that while it directs the future it also sums up the past.

The first edition of this book has long been out of print. The natural impulse, after an interval of ten years, is to subject a new edition to a complete revision, with the rewriting of many portions. Revision as drastic as might be desirable has not, however, proved practicable. Various studies of special authors have been brought up to date in the light of new material concerning them, as, notably, in the sketch of Lady Winchilsea. Two chapters, the one on “Painting” and the one on “Gardening,” are entirely new, and it has, fortunately, proved possible to add a number of interesting illustrations of these chapters, mainly from old prints. With these exceptions the book remains substantially as it was[vii] ten years ago. In no case has further study made it necessary to modify any of the general conclusions on the basis of the earlier work. More intensive work in the different realms has happily but reinforced these conclusions.

Myra Reynolds

August, 1909

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| List of Illustrations | xi | |

| Introduction | xv | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I | The Treatment of Nature in English Classical Poetry | 1 |

| II | Indications of a New Attitude toward Nature in the Poetry of the Eighteenth Century | 58 |

| III | Fiction | 203 |

| IV | Travels | 223 |

| V | Gardening | 246 |

| VI | Landscape Painting | 273 |

| VII | General Summary | 327 |

| Bibliographical Index | 369 | |

| General Index | 378 | |

[xi]

| FACING PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Long Leate | 249 |

| “The House and gardens of the Rt. Hon. Thomas Lord Viscount Weymouth, Baron Warminster, L. Knyff, Del. I. Kip, Sculp.” | |

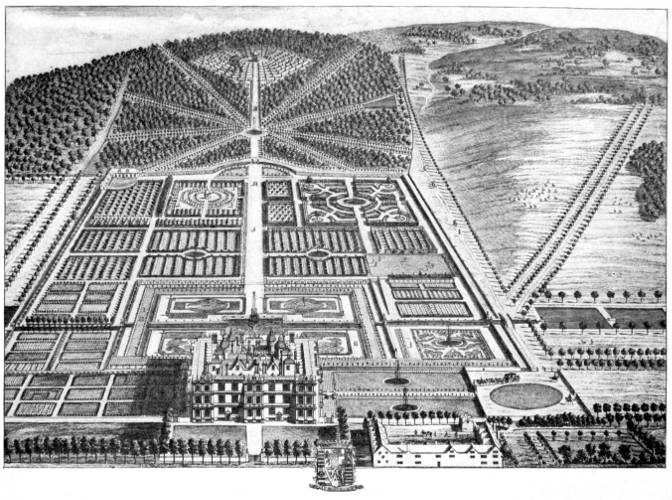

| Hagley Park | 261 |

| “A View in Hagley Park, belonging to Sir Thos. Lyttleton Bart., to whom this Plate is inscrib’d by his most obed’t. Serv’t. T. Smith. G. Vivares Sculp.” Published Oct. 1749. | |

| John Maitland, Duke of Lauderdale | 275 |

| “From the original of Sir Peter Lely in the Collection of the Right Hon. the Earl of Lauderdale. Drawn by Wm. Hilton, R.A. and Engraved with Permission by I. S. Agar.” The print here reproduced was published March 1, 1820. | |

| Mrs. Carnac | 280 |

| By Sir Joshua Reynolds. In the Wallace Collection, London. From a photograph by the Muchmore Art Company, London. | |

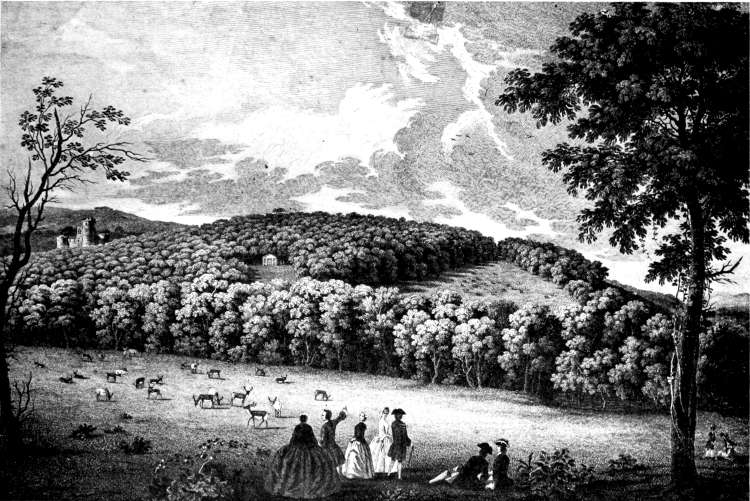

| Squire Hallet and His Wife | 283 |

| By Thomas Gainsborough. Now in the possession of Lord Rothschild. From a photograph by Braun, Clement & Cie. | |

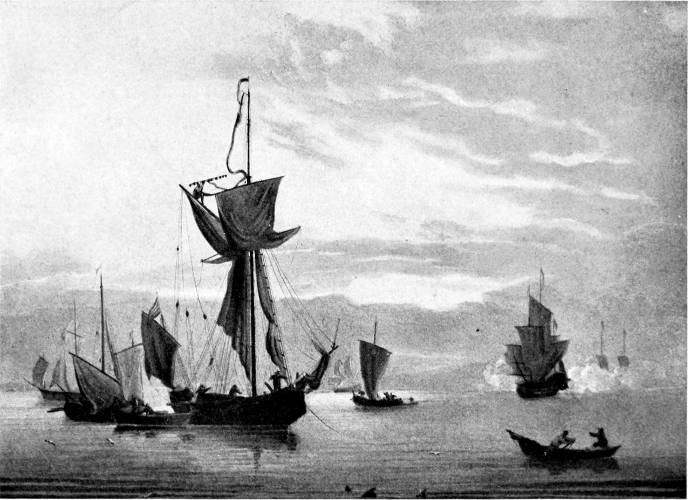

| A Calm | 286 |

| By Willem van de Velde. In the Gallery at Dulwich, London. “Drawn, engraved and published by R. Cockburn, Dulwich, 1818.” | |

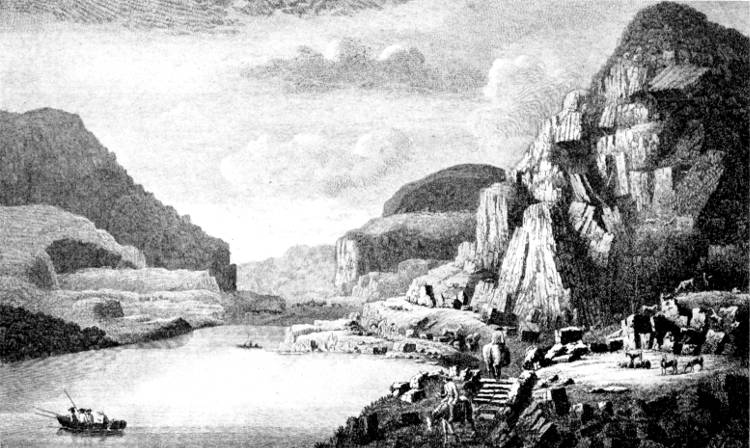

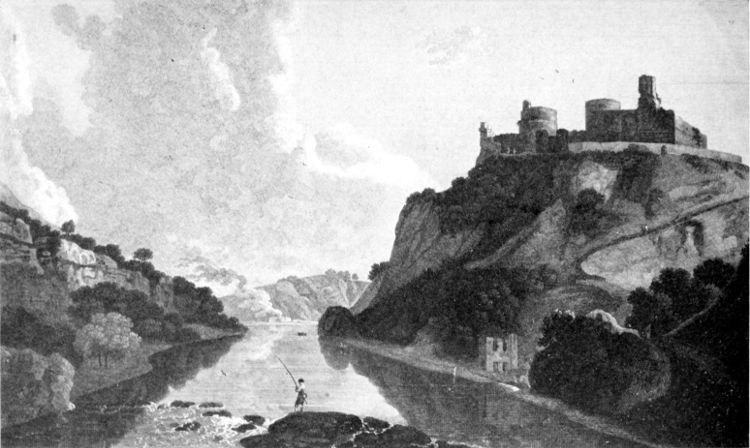

| Dunnington Cliff | 288 |

| “A View of Dunnington Cliff. On the River Trent (Five [xii]Miles South East of Derby) belonging to the Right Honourable the Earl of Huntington, to whom this Plate is inscrib’d by his Lordships most Dutiful and most humble Serv’t. T. Smith. G. Vivares Sculp. Act of Parliam’t. Augt. 25, 1745.” | |

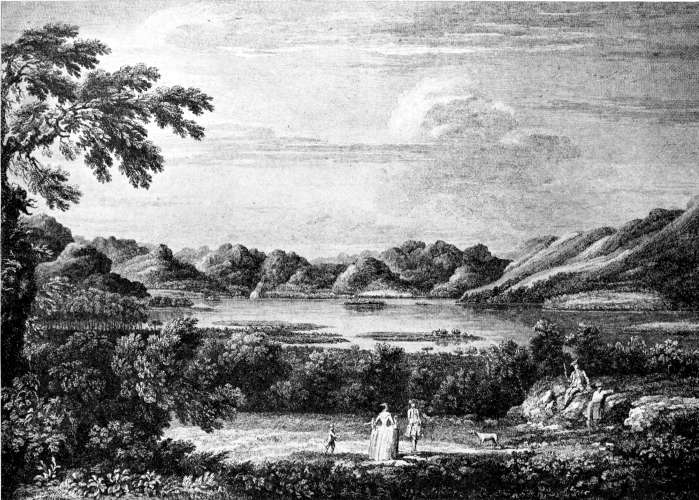

| Derwentwater | 291 |

| “A View of Derwent-Water, Towards Borrodale. A Lake near Keswick in Cumberland. To Edward Stephenson Esq’r. of Cumberland. This Plate is inscrib’d by his most Obliged humble Servant Will’m. Bellers. Painted after Nature by William Bellers. Engraved by Messrs. Chatelin & Ravenet. Published according to Act of Parliament October the 10th 1752.” | |

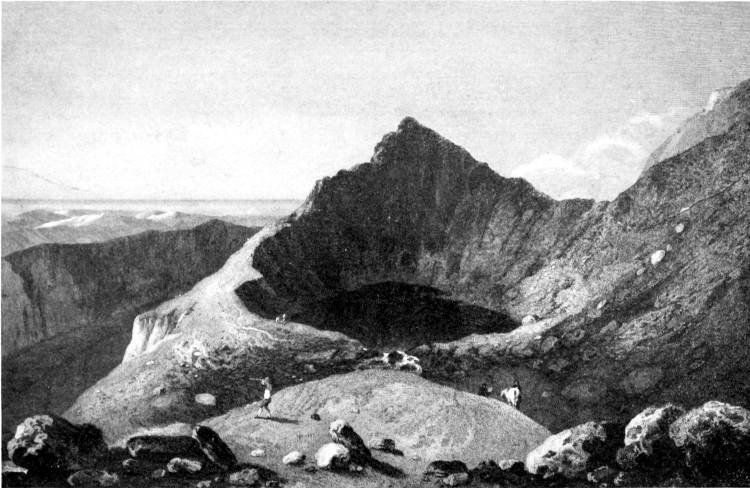

| Mount Snowdon | 293 |

| “A View of Snowden, in the Vale of Llan Beriis, in Caernarvon Shire. I. Boydell. Del. & Sculp. Published according to Act of Parliament by J. Boydell at the Globe near Durham Yard in the Strand 1750.” | |

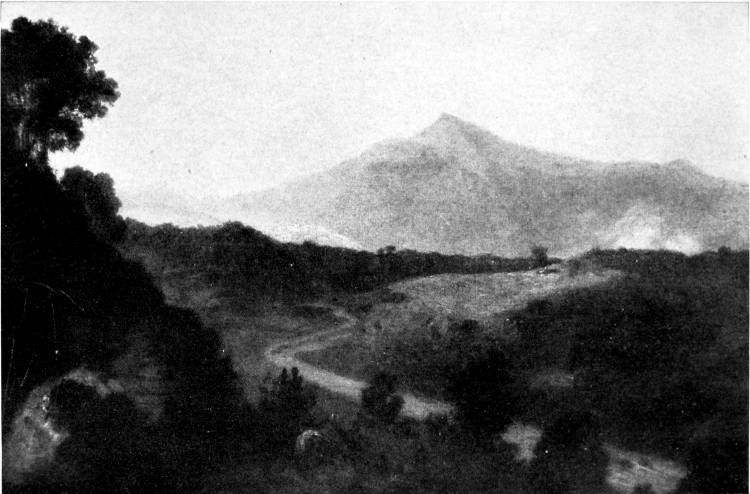

| Cader-Idris | 297 |

| “The Summit of Cader-Idris Mountain in North Wales. Richard Wilson pinx’t. E. & M. Rooker sculpser’t. Published July 17, 1775 by John Boydell, Engraver in Cheapside London.” | |

| Kilgarren Castle | 300 |

| “Kilgarren Castle in South Wales, Richard Wilson pinx’t. Will’m. Elliott sculp’t. Published July 17th 1775 by John Boydell Engraver in Cheapside London.” | |

| Snowdon | 304 |

| By Richard Wilson. In the Manchester City Art Gallery. From a photograph by Sherratt and Hughes, Manchester. | |

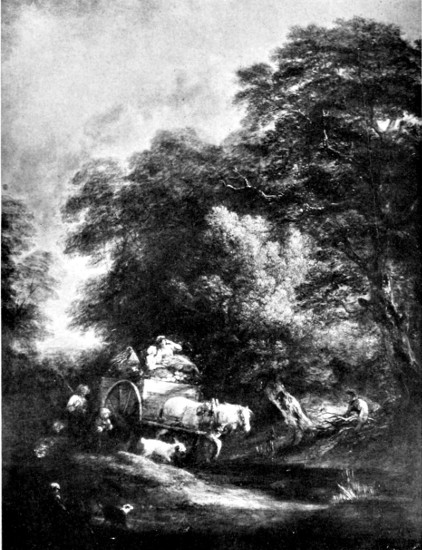

| The Market Cart | 307 |

| Painted by Thomas Gainsborough. In the National Gallery. | |

| Pembroke | 311 |

| “Engraved by I. Walker from an Original Picture by Paul Sandby Esq. R. A. Published May 1st 1797.” | [xiii] |

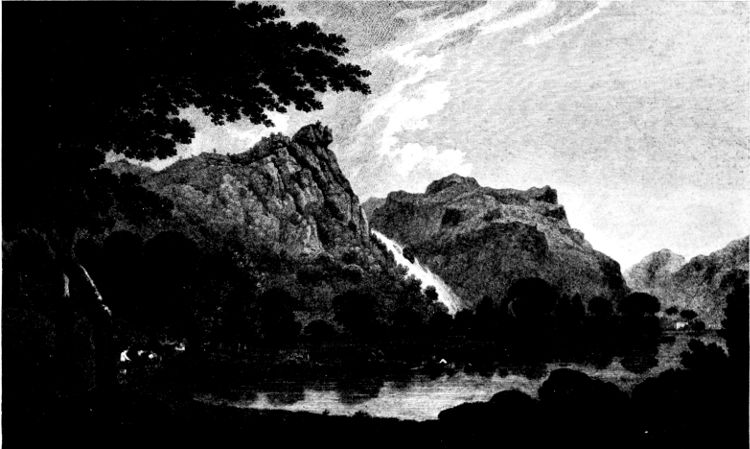

| Lodore Waterfall | 315 |

| “Drawn by Jos’h. Farington. Engraved by W. Byrne and T. Medland. London. Published as the Act directs, April, 1785.” | |

| The Wood Cutters | 318 |

| Painted by G. Morland. Engraved by W. Ward. Published by T. Simpson, St. Paul’s Church Yard, London, 1792. |

[xv]

The general theme of the treatment of Nature in literature is not a new one. Schiller’s essay entitled “Ueber die naive und sentimentale Dichtung” (1794), was the first attempt to state and explain the difference between the classical way of looking at Nature and the modern way. The externality in the classical attitude toward Nature, he attributed to the fact that the Greeks were in their thoughts and habits of life so a part of Nature that they felt no impulse to seek her with the passionate longing of the modern poet, whose ardent and heartfelt love of Nature is but the result of a mode of thought and life out of harmony with her. This essay, however inadequate as a presentation of the Greek attitude toward Nature,[1] determined the lines of much succeeding study.

Alexander von Humboldt in his “Kosmos” (1845–58), in the midst of his scientific generalization and his encyclopedic accumulation of natural facts, takes occasion to discuss the treatment of Nature in poetry and landscape painting. The chapter on landscape painting is chiefly confined to such topographical, botanical, and other pictorial representations as serve to add to our knowledge of distant lands. The boundaries of the whole question are enlarged by a representation of the profound feeling for Nature in Semitic and IndoEuropean[xvi] races. There is a brief study of the mediaeval feeling for Nature as it appears in Dante, and finally of the treatment of Nature in some prose writers of the eighteenth century. The only English poets mentioned are Shakspere, Thomson, and Byron, the subject of English poetry being disposed of in less than a page.

In Ruskin’s “Modern Painters” (1843–60) are several most interesting chapters on landscape in classical, mediaeval, and modern times. “Of the Pathetic Fallacy” and “The Moral of Landscape” are also suggestive though misleading studies.

Victor de Laprade’s “La sentiment de la nature” (1866, 1868) contains in full the theories already suggested in the preface to his “Les symphones.” In the introductory chapters he outlines his conception of the development of art. He regards architecture as essentially the expression of man’s interest in religion; sculpture of his interest in the demi-god or hero; painting of his interest in the complex and varied life of man as man; while the characteristic art of the present age is music with which the love of Nature is closely allied, since both affect the mind indirectly through indeterminate and vaguely suggestive harmonies, and both tend by their complexity and subtlety to rouse sweet reveries, luxurious emotion, nameless longings, ineffectual aspirations, but leave the conscience and the will untouched. No one can read these critical studies by Laprade or his earlier poems without feeling his enthusiastic joy in the presence of Nature. But he feared this joy and counted it a part of the concupiscence of the flesh except as it became an avenue to communion with the divine spirit. His indictment against the passion for Nature in modern music, painting, poetry, fiction, science is that the material is everywhere exalted at the expense of the spiritual. To be of value the presentation of the external[xvii] world in whatever realm of art should subordinate its appeal to the senses, and emphasize its appeal to man’s inner life. Laprade’s work is a plea for idealism as against realism. In all his brilliant presentation of the attitude toward external Nature of different races in different epochs, this point of view must be taken into account. In his rapid survey of English poetry the poets to receive closest attention are Shakspere, Spenser, and Milton. In later times the most significant of the poets who “gravitent autour de Lord Byron” are Wordsworth and Shelley, who, in their attitude toward Nature, are respectively moralist and metaphysician. Byron’s distinction is that he alone found “le juste équilibre entre l’exubérance de la nature et celle du pur esprit.” Thomson’s “Seasons” are of value because of good genre pictures and vivid descriptions of English sports, but the initial force in the return to Nature is Burns.

Unquestionably the most important of the books that treat of Nature in the realm of art is Biese’s “Die Entwickelung des Naturgefühls im Mittelalter und in der Neuzeit” (1888).[2] The book is written with enthusiasm and is stimulating and suggestive. The subject-matter is well in hand, and so thoroughly organized that the great movements in the historical development of the love of Nature are easily grasped. The plan is comprehensive, including not only poetry, but, in briefer outline, landscape painting and gardening, and, incidentally, even fiction and philosophy. The least satisfactory portion of the book is the treatment of the love of Nature in English life and thought. There is some stress on[xviii] the development of the English garden, but English landscape painting is not mentioned. In the casual mention of English fiction the emphasis is on Defoe. In poetry two epochs are recognized, that of Shakspere and that of Byron. The chapter on Shakspere is a close and valuable study. The work of Byron is estimated with justness and sympathy, as is also that of Shelley. But the study of Wordsworth as a poet of Nature is singularly inadequate. His genius is considered as essentially of the pastoral-idyllic order, with now and then glimpses of an “echte Liebe für die Natur,” and an unmistakable pantheism. He is chiefly important as having done for England what Scott did for Scotland and Moore for Ireland, and as sounding certain notes which rang again in Byron “in verstärkter Tonart.” Thomson is the only eighteenth-century poet studied. Here again is a failure to recognize the real importance of the poet’s work. Biese acknowledges the truth of Thomson’s separate pictures of Nature, and his genuine love of the country, but denies his importance as a “pathfinder,” saying that he but followed where Pope’s “Pastorals” and “Windsor Forest” had marked out the way.

In 1887 appeared John Veitch’s “The Feeling for Nature in Scottish Poetry.” The first volume begins with the early romances and national epics, and takes up the chief poets down to James VI. The second volume is devoted to the modern period from Ramsay to David Gray. Most of the authors treated belong to the nineteenth century, but there are admirable brief studies of Ramsay, Thomson, Hamilton of Bangour, Bruce, Fergusson, and Burns. There is also a short but interesting chapter on the rise of landscape painting, with especial attention to its development in Scotland. Veitch’s book is written out of a full knowledge and warm appreciation of Scottish poetry and of Scottish Nature, and[xix] his critical dicta are usually trustworthy, though he shows, perhaps, a tendency to overemphasize the influence of Scottish poetry on the love of Nature in succeeding English poetry.

In John Campbell Shairp’s “Poetic Interpretation of Nature” (1889) are to be found studies of Homer, Lucretius, and Virgil; of Chaucer, Shakspere, and Milton; and of Wordsworth. Two chapters are devoted to the eighteenth century. Ramsay is the poet to whom the reappearance of the feeling for natural beauty is traced. Thomson is praised for his minute faithfulness in description, and his genuine love of the country, but his tawdry diction and superficial conception of Nature are heavy indictments against him. The chapter on Collins, Gray, Goldsmith, Burns, Cowper, Ossian, and the Ballads is interesting, but from its brevity is necessarily inadequate. The most suggestive chapter in the book is the one in which there is a classification of the ways in which poets deal with Nature.[3] The whole subject of the treatment of Nature in poetry is an attractive one to Mr. Shairp, and he frequently recurs to it in his “Studies in Poetry and Philosophy” and “Aspects of Poetry.”

In many books, also, not devoted exclusively to the treatment of Nature in literature there are special studies and much running comment of a valuable sort. This is true of almost all essays on the early nineteenth-century poets, and especially so of the various essays on Wordsworth. There is something to be found in manuals of English literature, as in[xx] Gosse’s “Eighteenth Century” in the chapter, “The Dawn of Naturalism,” in various notes in Perry’s “English Literature of the Eighteenth Century,” Phelps’ “The English Romantic Movement,” and others; also, in some histories, as in Lecky’s “History of England in the Eighteenth Century;” in some philosophical studies, as in Leslie Stephen’s “English Thought in the Eighteenth Century” (“The Literary Reaction”), and in Stopford Brooke’s “Theology in the English Poets” (passim); in various literary studies, as in McLaughlin’s “Studies in Mediaeval Life and Literature” (“The Mediaeval Feeling for Nature”), Vernon Lee’s “Euphorion” (“The Outdoor Poetry”), Symonds’ “Essays Speculative and Suggestive” (“Landscape,” “Nature Myths and Allegories”), Burroughs’ “Fresh Fields” (“Birds and Poets”), and Fischer’s “Drei Studien zur Englischen Litteraturgeschichte” “Ueber den Einfluss der See auf die Englische Litteratur”).[4]

The books indicated show that there is much interest in the general theme of Nature as an element of art. The literary periods that have been most studied are, however, the[xxi] Greek and Roman, the mediaeval, and the modern. The treatment of Nature in so barren a time as the eighteenth century in England has naturally received little close attention. In my own work on this period I have endeavored to discover what indications there are that the attitude toward Nature of the early nineteenth century is but the legitimate outcome of influences actively at work during the eighteenth century. This study is therefore one of origins.

I have divided my work into three parts. I have endeavored to give first a general statement of the chief characteristics that marked the treatment of Nature under the dominance of the English classical poets. Then follows a detailed study of such eighteenth-century poets as show some new conception of Nature. The third division is made up of briefer studies of the fiction, the books of travel, the landscape gardening, and the painting of the eighteenth century, the purpose being to determine in how far the spirit found in the poetry reveals itself in other realms in which the love of Nature might be expected to find expression.

[1]

The poetry of the English classical period falls naturally into four subdivisions:

1. The period of inception may be reckoned as beginning with Waller’s first couplets in 1621 and including the work of his followers, Denham, Davenant, and Cowley.[5]

2. The period of establishment includes the work between the Restoration and about 1700. Dryden is the central figure.

3. The period of culmination is a brief period covering less than the first quarter of the eighteenth century. Pope is the central figure.

4. The period of decadence extends from about 1725 to the end of the century.

Any generalizations concerning the attitude of this classical period toward Nature must be based on a large number of specific instances, but in collecting and using these specific instances certain cautions must be observed. Chief among these is the necessity of keeping in mind the point of view from which the study should be made. It is not the purpose to discover all that has been said about Nature by the classical poets between 1623 and 1798. It is the purpose, rather, to eliminate exceptions, and to dwell on the general, obvious qualities, the typical features, of the classical poet’s conception of Nature. This principle determines the relative importance of the periods noted above. Illustrations drawn from a large number of poems in the second and third periods would serve as the basis for a general statement. Illustrations from[2] periods one and four would need to be scrutinized, for they might be purely classical, or they might be survivals of the Elizabethan romantic age or prophecies of the modern romantic age. Cowley, for instance, belongs to the first classical period because he wrote in couplets, but his diction, his conceits, and in some respects his attitude toward Nature are post-Elizabethan rather than classical. Illustrations from his poems are of value, therefore, for the present purpose, only when they are in accord with the spirit afterward found in the time of Dryden and Pope. So, too, Milton and Marvell, though coming chronologically within the first and second periods, stand in the main quite aloof from any tendencies that can be called classical, and their poetry is referred to only when it seems to illustrate the dominant classical conception. Abundant and valuable illustration of the classical conception may be drawn from the fourth period because tendencies are nowhere more clearly shown than in the inevitable exaggerations of a time of decadence, but the legitimacy of any illustration is determined by its likeness to the dominating traits of the preceding periods. While this study is confined in the main to the poets of the period, journals, letters, travels, essays, and plays have been quoted where they serve as proof that the poetry represents the spirit of the age in which it was written.

Pope called Wycherley an “obstinate lover of the town,”[6] and the phrase may well be taken to mark one characteristic of the orthodox classicists. Poems, letters, journals, biographies, and essays bear witness to the reluctance with which the men and women of this age bade farewell to the “dear, damned, distracting town.”[7] Charles Lamb’s lifelong devotion to Fleet Street and the Strand, and the sentiment of the cockneys who, as Hazlitt said, preferred hanging in London[3] to a natural death out of it,[8] have their true prototypes in the classical age. “When a man is tired of London he is tired of life,” is Dr. Johnson’s dictum. Gibbon said that when he visited the country it was to see his friends and not the trees. Boswell’s only justification of a hastily expressed liking for the country was that he had “appropriated the finest descriptions in the ancient Classicks to certain scenes there.”[9] But not even the classics could reconcile most people to a country life. It was dreary, monotonous, difficult. There was no society, no news. The days went yawningly by with no vivid interests, no stirring occurrences. “No person of sense,” exclaimed Mr. Mallet’s sister, “would live six miles out of London.”[10] To live in the country was to be buried. Lord Bathurst looked upon his sojourn in his country home as a “sound nap”[11] preparatory to Parliament. “If you wish to know how I live, or rather lose, a life in the country,” wrote Pope, “Martial will inform you in one line:

Pope found pure air and regular hours a physical necessity, but he often rebelled at his banishment from town delights, as did his “fond virgin” when compelled to seek wholesome country air.

[4]

Isabella in Dryden’s “The Wild Gallant” speaks the general sentiment: “He I marry must promise me to live at London. I cannot abide to be in the country, like a wild beast in the wilderness.”[14] So, too, Harriet, in “The Man of Mode,” counted all beyond Hyde Park a desert, and said that her love of the town was so intense as to make her hate the country even in pictures and hangings.[15] In “Epsom Wells” the apostle of “a pretty innocent country life” is the boor, Clodpate, but Lucia assures him that people really live nowhere but in London, for the “insipid dull being” of country folk cannot be called life.[16] It was in much the same spirit that Lady Mary Pierrepont responded to Lord Montagu’s proposition that they should live at Wharnecliffe. “Very few people,” she said, “that have settled entirely in the country but have grown at length weary of one another.”[17] Her preference for town life recurs in her poem, “The Bride in the Country.”

[5]

When Shenstone’s young squire went forth to London in search of a wife the desired lady declared that she “could breathe nowhere else but in town.”[19] Lyttleton’s fair maiden finds country life “supinely calm, and dully innocent,” and affirms that

Young’s Fulvia had a similar passion for the town.

In Aaron Hill’s poems we find a characteristic contest over the respective merits of city and country. Philemon exclaims,

Damon endeavors to defend

by calling in evidence Cowley’s retirement to the shades, but Philemon triumphantly shows that Cowley’s dislike of the town was a clear case of sour grapes. In the end Damon recognizes that it is weak and unmanly to prefer the country.[22] Browne’s Celia explains to Chloe that country life may become endurable if one does not give herself up to “dull landscape,” but learns to think of the country as “the town in miniature.”[23]

Such expressions as these are typical. They indicate the[6] general dislike for any life away from the city. And even those who loved the country, or thought they did, were far enough from caring for any but the tamest of its possible delights. Pope’s list of country pleasures, though half humorous, is nevertheless suggestive. In contrast to Mrs. M.’s devotion to “play-houses, parks, assemblies, London,” he depicts his own “rapture” in the presence of “gardens, rookeries, fishponds, arbours.”[24] When Bolingbroke “retired from the Court and glory to his country-seat and wife”[25] he bravely insisted that he liked the change. “Here,” he wrote from Dawley, “I shoot strong and tenacious roots. I have caught hold of the earth and neither my enemies nor my friends will find it an easy matter to transplant me again.”[26] But we must join Pope in the laugh against such a catching hold of the earth when we learn that Bolingbroke paid £200 to have his country halls painted with rakes, prongs, spades, and other insignia of husbandry in order to make it perfectly evident that he really did live on a farm.[27] The genuine lover of the country in the classical age expended his enthusiasm on the mild and easy pleasures of a well-kept country house easily accessible from the city. That a sane man could choose to live as Wordsworth did in the Lake District would have passed belief. In general, the country was thought of but as a good place to recruit one’s jaded energies, or as a refuge where disappointments might be hidden and disgrace forgotten.

According to Gay,

[7]

and his deserted, lovelorn Araminta felt that only the melancholy shades and croaking ravens of the country could suit her unhappy fate.[29] Watts thought that none but “useless souls” should “to woods retreat.”[30] On the whole, the words of the city mouse to his country cousin expressed the prevailing sentiment:

The poet might sing the charms of the country if he chose, but he was, after all, as Denham said of Virgil and Cowley, only “gilding dirt.”[32]

The attitude toward Nature in the literature of any age may be tested in two ways: by what is said, and by what is left unsaid, and of these the second is perhaps the more significant. Certainly in the poetry of the classical period the persistent ignoring of the grand and terrible in Nature comes home to the mind as a convincing proof of the prevailing distaste for wild scenery. And when we apply the other test and find that the conspiracy of silence is broken only by expressions indicative of positive dislike of such scenes, the case becomes a strong one. This point may be clearly illustrated by a somewhat detailed study of the poetical treatment of the mountains and the sea.

Rarely in the long period between Waller and Wordsworth do we find any trace of the modern feeling toward mountains. If they are spoken of at all it is to indicate the difficulty in surmounting them or to express the general distaste for anything so savagely and untamably wild. It[8] is interesting to note that passages expressing the most active dislike of mountains show really some close observation and a good deal of picturesque energy of phrase. They were evidently the outcome of a personal experience, the unpleasantness of which demanded forcible epithets. They show that when men were compelled by the exigencies of travel to go into a mountainous region there was not wanting a perception of certain characteristic mountain qualities, but that these qualities were only those exciting repulsion and terror. In no case does a sense of the sublimity and beauty of mountains find, or even apparently seek, expression. This is true in travels, fiction, biography, and letters, as well as in poetry. A few typical illustrations may be given. Howell, who went abroad twice before 1622, strikes the keynote of the travelers who came later. He distinctly objected to the “monstrous abruptness” of the “Pyereny Hills” and he found the Alps even more “high and hideous.” He was obliged to admit that the Welsh mountains were but mole-hills compared to the Alps, but he thought the scale more than turned by the fact that those “huge, monstrous excrescences of nature” were entirely useless, while “Eppint and Penminmaur” at least furnished grass for the cattle.[33] John Evelyn regarded the Alps chiefly as an unpleasant barrier between the “sweete and delicious” gardens of France and the corresponding topiary paradises of Italy, and his final conception of them is as the place where Nature swept up the rubbish of the earth to clear the Plains of Lombardy.[34] Addison was another of these early travelers, and he, too, found the journey over the Alps most trying. The “irregular, misshapen scenes” of a mountainous region gave him little pleasure.[35] He preferred[9] the safe monotony of plains. Both Evelyn and Addison expended all the descriptive energy they had to spare for mountains on Vesuvius, but it was, of course, its character as a striking and curious natural phenomenon that attracted them.[36] Burnet of the Charter House, the tutor of Lady Mary Pierrepont, in his “Theory of the Earth” gives a theological reason for the existence of mountains. He conceives the present world as a gigantic ruin, the result of sin. Originally the earth was perfectly smooth. “It had the beauty of youth and blooming nature, fresh and fruitful, and not a wrinkle, scar, or fracture in all its body; no rocks nor mountains, no hollow caves, nor gaping channels, but even and uniform all over. And the smoothness of the earth made the face of the heavens so too; the air was calm and serene; none of those tumultuary motions and conflicts of vapours, which the winds cause in ours. ’Twas suited to a golden age, and to the first innocency of nature.” But as a punishment for sin the interior fluid of the earth was allowed to break through the beautiful smooth crust, and in the ensuing chaos were piled up those “wild, vast, and indigested heaps of stone and earth,” those “great ruins” that we call mountains.[37] In 1715 Pennecuik said that the swelling hills of Tweeddale were, for the most part, green, grassy, and pleasant, but he objected to the bordering mountains as being “black, craigie, and of a melancholy aspect, with deep and horrid precipices, a wearisome and comfortless piece of way for travellers.”[38] In 1756 Thomas Amory commented on the “dreadful northern fells,” and called Westmoreland a “frightful country,” and spoke of “the ranges and groups of mountains horrible to behold.”[39] So late as[10] 1773 Dr. Johnson said of the Highlands of Scotland: “An eye accustomed to flowery pastures and waving harvests is astonished and repelled by this wide extent of hopeless sterility. The appearance is that of matter incapable of form or usefulness, dismissed by Nature from her care.”[40] In the same year Hutchinson deprecates the “dreary vicinage of mountains and inclement skies” in the Lake District. He describes Stainmore thus: “As we proceeded Spittle presented its solitary edifice to view; behind which Stainmore arises, whose heights feel the fury of both eastern and western storms; ... a dreary prospect extended to the eye; the hills were clothed in heath, and all around a scene of barrenness and deformity.... All was wilderness and horrid waste over which the wearied eye travelled with anxiety.... The wearied mind of the traveller endeavours to evade such objects, and please itself with the fancied images of verdant plains, purling streams, and happy groves.”[41]

The attitude toward mountains in the passages already referred to appears in the poetry of the period with the same general tone, though with less insistence. Throughout Waller’s poetry the only epithets applied to mountains are “savage”[42] and “craggy.”[43] Marvell, the most genuine[11] lover of Nature in this age, was yet of the age in his feeling toward mountains, for he characterizes them as ill-designed excrescences that deform the earth and frighten heaven, and he calls upon them to learn beauty from the soft access and easy slopes of a well-rounded hill.[44] The unpleasant phrase, “high, huge-bellied mountains”[45] in one of Milton’s youthful poems is hardly atoned for by the lines in “L’Allegro,”

and his poetry is, in general, marked by the absence of mountain scenery. Dryden’s most famous mountains are “drowsy” and “seem to nod.”[47] In Blackmore’s summary of the charges made by Lucretius concerning the “unartful contrivance of the world,” mountains are styled “the earth’s dishonor and encumbering load.” The only defense made by the poet is that these incumbrances do nevertheless restrain the tides, yield veins of ore, and bear forests of useful wood.[48] So John Philips defends his comfortable hypothesis that nothing is made in vain by the fact that even “that cloud-piercing hill Plinlimmon” is of some value since it furnishes “shrubby browze” for the goats.[49] And Yalden explains how erring Nature supplies her own defects by filling with mines the “vast excrescences of hills” that distort the surface of the earth.[50] Prior’s only mountain is Lebanon with[12] “craggy brow.”[51] Pope has some “bright mountains” that serve to prop the incumbent sky,[52] and he occasionally mentions mountains with such epithets as “hanging,”[53] “hollow,”[53] and “headlong.”[54] Tickell showed his attitude toward mountains in his address to Lord Lonsdale whom he proposed to visit at Lowther Castle near Penrith, declaring that he did not dread the harsh climate and rude country, for the Earl’s presence would be sufficient to “hush every wind and every mountain smooth.”[55] Parnell instances in his catalogue of the horrors of Ireland her hills that with naked heads meet the tempests.[56] Dr. Akenside speaks of a “horrid pile of hills.”[57] Along with this frank disapproval of mountains is a similar dislike for their concomitants such as precipices, wildernesses, and even dense thickets.[58]

[13]

One cause of this antipathetic attitude toward mountains and wild scenery is, doubtless, as has been often suggested, the hardships and perils of travel before good roads were built. Biese quotes several eighteenth-century letters from German travelers to show how much “die schlechten[14] Strassen” had to do with the failure to appreciate the romantic beauty of the Alps.[59] He finds another partial explanation of the small interest in mountain travel in the fact that scientific study of natural phenomena such as glaciers, geological formations, mountain flora and fauna, was as yet in its infancy and that thus one whole class of motives for enduring fatigue and braving difficulties was wanting.[60] But these two reasons do not sufficiently account for the lack of mountain fervor. It is not merely good roads and scientific enthusiasm that bid men seek mountain solitudes today. Preoccupation with terror and fatigue were not the only nor the chief reason for this general dislike of wild scenery. The two charges even more persistently and definitely brought against mountains are that they are useless, and that they are a deformity on the surface of the earth. Now the first of these is but another expression of the dominant utilitarian standards of value, and the second is an outcome of the prevailing desire for orderly and systematic arrangement. Pronounced irregularity[15] of outline was as irritating to the artistic consciousness as was exceptional license in verse forms. Mountains entered an inevitable protest against the spirit that found its highest pleasure in the symmetrical complexities of a typical eighteenth-century garden. That this protest was on a great scale with accompanying suggestions of mystery and of a remote irresistible power, gives an added reason why the age turned thus decisively from forms of nature to which a romantic age yields fullest homage. Thus the attitude toward mountains finds its real explanation not so much in external conditions as in the spirit of the times.

The place of the ocean in the classical poetry is likewise significant. It awakened no sense of elation as in Byron, no sense of mysterious kinship as in Shelley. It was simply a waste of waters, dangerous at times, and always wearisome. Though more often mentioned than the mountains, it received an even more narrow and conventional treatment. Except in some elaborate similes there are few descriptions of more than a line in length. We find merely casual mention by means of stock epithets, or very short and unmeaning descriptive phrases. To Waller the sea is “the world’s great waste,” “a watery field,” a “watery wilderness,” or a “main,” liquid, or troubled, or angry, as the case may be.[61] Dryden’s epithets are hardly more felicitous. He uses “watery”[62] with an insistence that finally becomes ludicrous. He has one or two little ocean pictures written apparently for their own sake, but his best use of the ocean is in similitudes.[62] In succeeding poets the treatment of the ocean is exceedingly commonplace and unimaginative. Such small interest as the sea aroused was of a prosaic, utilitarian sort. Young’s “Sea[16] Pieces” and “Ocean” may serve as examples, and they are little more than eulogies of England’s commercial and naval prowess. It is for Britain that “the servant Ocean” “both sinks and swells.” It is solely with reference to her prosperity that soft Zephyr, keen Eurus, Notus, and rough Boreas ”urge their toil.”

is the unvaried theme. The few descriptive passages are of periods when “storms deface the fluid glass,” and seem to have been composed in accordance with Pope’s famous recipe for poetical tempests.[64] The most popular sea poem of the eighteenth century was Falconer’s “Shipwreck” written in 1762. It is a sufficiently remarkable production when thought of as the work of a common sailor but it is difficult for the modern reader to understand the extravagant praise bestowed upon it in its own day.[65] Its tame and conventional love story, its descriptions of the sylvan scenes where Palemon and Anna gave pledges of undying affection, its moralizings on the beneficial effect of poetry, the evils of war, the corrupting lust of gold, its long digression on cities and heroes “renowned in antiquity,” its invocation to the Muses, its mythology, its reverence for “sacred Maro’s art,” are all[17] of the commonplace, classical order. There is in the actual shipwreck scene some vigorous writing, but it deals almost entirely with the emotions of the sailors, and the management of the ship. It would be difficult to find any really effective lines descriptive of the storm itself. The following quotations may stand as fairly representative of the best passages:

One of the most striking characteristics of the descriptive parts of the poem is the daring and novel use of technical sea terms. Such lines as,

are praised as minutely accurate but it certainly needs a specialist’s training to understand them.[68] There is nothing new in Falconer’s poem except his use of realism in describing[18] the ship’s maneuvers. The sea is, to be sure, more prominent than we have found it in preceding poems, but it is the same “desert waste,” the same “faithless deep,” the same “watery plain,” and is deformed by the typical classical storm. Strange as it may seem, it is yet true that the poets of sea-girt England were very slow in making the discovery of the ocean.[69] The main points in the eighteenth-century conception of the sea were its usefulness as a commercial highway and its destructive power in storms. This impression of irresistible force is sometimes vivid enough to result in strong phrasing, but the changing beauty, the majesty, the mysterious suggestiveness of the sea found no expression in English classical poetry. Even in the poems that mark the transition spirit the adequate word for the sea is surprisingly slow to come.

In connection with the failure to understand or love the mountains or the sea we may note the avoidance of winter[70] or the conception of it as the “deformed wrong side of the year.” Lyttleton thoroughly disliked “gloomy winter’s unauspicious reign,”[71] and Pope said that its bleak prospects set his very imagination a-shivering.[72] Lady Montagu called the glistening snows a painful sight, and said that the whole country was in winter “deform’d by rains and rough with blasting winds.” The “icy, cold, depressing hand” of winter, brought in a season of privations, discomfort, and dangers. Throughout the classical period the typical phrases are “shuddering winter,” “winter’s dreary gloom,” “the sad, inverted year.” Storm and blasts “deface the year.” Hailstorms “deform[19] the flowery spring.” Clouds “sadden the inverted year.” Winter’s “joyless reign” is a season marked by “dusky horrors.”

is a typical description.[73] Another indication of the dislike of this season is found in a curious “Pastoral” by Washbourne in which hell is represented as a place where it is “alwaies winter.”[74] It will be observed later that a sense of joy in winter scenes is one of the very early indications of a reviving interest in the out-door world.

Correspondent with the dislike and neglect of the grand and the terrible in Nature is a similar feeling toward such aspects of the external world as especially suggest mystery, remoteness, unseen forces. That this is true may be seen by a study of the sky phenomena that appear, or fail to appear, in this classical poetry. The day-time sky is but briefly and vaguely mentioned or it passes unobserved. A phrase so imaginative as Blackmore’s “blue gulph of interposing sky”[75][20] is rare. In general it is only the more striking aspects of the sky that are noticed, such aspects as would catch the attention of a child or of a mere casual observer. Fleeting, delicate effects are unheeded. Clouds receive little attention except as they portend or accompany a storm, and even then their chief use is in similitudes. Apparently the best-known appearance of the day-time sky is the rainbow. But though it is often mentioned there is singularly little variety in the phrases used to describe it. A brief summary of those phrases most frequently used is interesting: “Painted clouds;” “the clouds’ gaudy bow;” “the gaudy heavenly bow;” “the watery bow;” “the painted bow;” “painted tears;” “the gaudy drapery of heaven’s fair bow;” “the showery arch;” the bow “painted by Iris;” the bow “deck’d like a gaudy bride;” “the painted arch of summer skies,”[76] and so on through a wearisome list of kaleidoscopic combinations of the same words. The constant repetition of adjectives so unmeaning as “watery” and “showery,” or so external and artificial as “gaudy” and “painted” is as characteristic of the general attitude toward Nature as is the fact that the attention of poets should have been concentrated on the obvious beauties of the rainbow rather than on the finer, more subtle charms of the sky. In the same way sunrise, and especially sunset, are often mentioned and occasionally described. But there is practically no discriminating and appreciative study of what was actually to be seen in the heavens. It was more natural to sit at home and read the classics, and then announce that the[21] golden god of day “drives down his flaming chariot to the sea.”[77]

Twilight had, as might be expected, little charm or suggestiveness. Moonlight also plays a most subordinate part in this poetry.[78] We seldom find anything more direct or vivid than the time-honored statement that “fair” or “pale” Cynthia “mounts the vaulted sky,” and “adorns the night” with her silver beams.[79]

The night sky was counted beautiful because of its stars. The recurrent conception is that the azure heavens are adorned with these orbs of gold. The favorite words are “spangled” and “gilded.”[80] In Young’s “Night Thoughts” we might expect to find some faithful and sympathetic study of the[22] nocturnal heavens, but in the first eight books not seventy-five lines refer even remotely to external Nature, and in the ninth book the stress is laid on “the moral emanations of the skies.” In his efforts to find a sufficiently varied star vocabulary, Young was driven to the invention of some new phrases, but in no case do they show imaginative power. They are perfunctory and stiff and indicate that his mind was on the “system of divinity” he meant his stars to teach rather than on the stars themselves.[81] In Burnet’s “Theory of the Earth,” a work already quoted from, we find a striking, because an exaggerated, example of the way an undue love of order could modify one’s aesthetic perception. Burnet enjoyed the night sky but he felt that the stars might have been more artistically arranged:

They lie carelessly scattered as if they had been sown in the heaven like seed, by handfuls, and not by a skilful hand neither. What a beautiful hemisphere they would have made if they had been placed in rank and order; if they had all been disposed into regular figures, and the little ones set with due regard to the greater, and then all finished and made up into one fair piece or great composition according to the rules of art and symmetry! What a surprising beauty this would have been to the inhabitants of the earth! What a lovely roof to our little world! This indeed might have given us some temptation to have thought that they had been all made for us; but lest any such vain imagination should now enter into our thoughts Providence (besides more important reasons) seems on purpose to have left them under the negligence or disorder which they appear unto us.[82]

The final impression from the study of these passages that[23] refer to stars or moonlight is that the poets of this period were not unlike Peter Bell into whose heart “nature ne’er could find the way.”

Night itself, aside from its starry glories, was thought of but to be feared for its brown horrors and melancholy shades. The conception of daylight as useful and safe was a part of classical good sense. The earliest poem in which we find the beauty and something of the spiritual power of night represented is by Lady Winchilsea. Later we find the characteristic sentimental melancholy of the poets involved in a tissue of moonlight and mystery, while the faint colors and pearly dews of the dawn, and the gentle sadness of evening shades, or in extreme cases, even midnight glooms, seem to be the only fit setting for struggling emotions and vague aspirations. There are also, as we shall see, throughout the romantic revival, not infrequent studies of the sky, especially of sunrise and sunset, from what we may call the artist’s point of view. But all this belongs to the new spirit and is a very evident break from classical traditions. Poetry in which the classical note is dominant shows the utmost coldness and barrenness in all that has to do with the beauty and significance of the sky whether by night or by day.[84]

[24]

In contrast to the general turning away from the grand or the mysterious in Nature we find a certain friendly feeling toward the gentler forms of out-door life. Spring and summer, blue skies, gently sloping hills, flowery valleys, cool springs, and shady groves appear in the poetry with a frequency indicative of some real delight in them.[85] But real affection for Nature even in her idyllic forms, an affection the evident outgrowth of personal experience, is the exception rather than the rule. When such regard for Nature is apparent, however narrow in scope, it is rightly to be regarded as an indication of a new feeling toward the external world, for in general these so-called idyllic descriptions are to the last degree artificial and unreal. They show that what the poet really enjoyed was not so much Nature itself, as the creation of fanciful pictures of Nature, the flowing combination of attractive details into such scenes as he would like to find in the country in case he should go there. Garth’s description of the Fortunate Islands is typical. There

The details of this listless, luxurious description are such as are combined and recombined in many a picture of supposedly English scenes. The poet found his pleasure in the vague, highly generalized representation of such scenery as might exist in some imagined Elysium or Garden of Eden. The final effect on the mind of the reader is never one of reality. All is traditional and bookish. Perhaps there is no more effective way of showing the general characteristics of these poetical descriptions than by an accumulation of examples. Since there is no danger of spoiling the poetry, it may be permissible for purposes of emphasis, to print in italics such phrases as belong to the common poetical stock. The first passage is Rosamond’s description of Woodstock Park:

Here the union of phrases, all conventional in their character, is entirely fortuitous and undiscriminating. It is impossible not to feel that Addison picked up his items at random, according to the scheme of his verse. Take next this invocation by Broome:

[26]

Or Shenstone’s description of the place of his birth:

Or Lyttleton’s lines:

Or Congreve’s description of the scenery along the Thames:

Or Parnell’s

Or Prior’s

Or Pope’s

[27]

Or Marriott’s

Further quotation is useless. It is easy to see that these passages have no individuality. They might be transposed from poet to poet without injustice either to poem or poet. They are like ready-made clothing, cut out by the quantity to fit the average figure, and never having any niceness or perfection of fit for any individual form. They are not specific. They have no local color. They are, furthermore, absolutely superficial. There is no hint of anything deeper than the conventional external details mentioned.

Throughout the classical age the most genuine interest in Nature had to do with parks and gardens. The formal garden, however, which held its own in England till early in the eighteenth century, makes but a small figure in the poetry of the period. Its affinities were rather with prose. In later poetry we find many references to the classical garden, but they are of the nature of a scornful retrospect, and they belong to the new spirit. The subject of gardening will be presented in a separate section.

In the study of the evolution of the love of Nature from Waller to Wordsworth we may perhaps mark out three stages in the attitude toward the external world. The last of these stages is the one based on the cosmic sense, or the recognition of the essential unity between man and Nature. Of this Wordsworth stands as the first adequate representative. The second stage is marked by the recognition of the world about us as beautiful and worthy of close study, but[28] this study is detailed and external rather than penetrating and suggestive. Very much of the work of the transition period is of this sort. In the first stage Nature is counted of value chiefly as a storehouse of similitudes illustrative of human actions and passions. This first stage represents the use of Nature most characteristic of the classical poetry.

A study of the abundant similitudes of this period indicates that they were drawn from a very narrow range of natural facts. The lily, the rose, the lark, the nightingale, the wren, bees, stars, drops of dew, the sea in a storm, the oak and the ivy, leaves, the Milky Way—these are the most important sources of similitudes. The poet chose his similes from facts already canonized by long literary service, or from the obvious facts of the park or the town garden. There is, in the second place, little apparent effort to secure accuracy or picturesque effect in the statement of the illustrative side of the simile. The entire emphasis is on the human fact to be illustrated. There is, therefore, in the third place, a failure to perceive subtle or delicately true analogies. In most comparisons the likeness is superficial or it is far fetched. The similes from Nature were not the literary expression of inner congruities. They were consciously sought for as a part of the necessary adornment of poetry. Sheridan says:

[29]

It is this elaborate desire for similitudes, together with the small knowledge of nature that led not only to wearisome iteration of the same similes but also to the still more wearisome iteration of the same points of comparison. A rose, for instance, is a perennially beautiful source of comparisons,[97] but in the eighteenth-century poetry it is used almost exclusively either with the lily in matters of the complexion, or by itself as representative of a young maiden. If she is overtaken by misfortune the rose is easily blasted by northern winds. If she is neglected the rose withers on its stalk. If she weeps the rose bends its head surcharged with dew. If she dies young, the rosebud is blasted before it is blown. The words of the “Angry Rose” to the poet gently satirize this prevalence of rose similes.

The nightingale also has a conventional use. He generally represents the poet and is either singing with a thorn against his breast, or is engaged in a musical contest with other birds, in which contest he quickly silences all competitors, or is himself driven away by the clamorous noise of a crowd of common birds. The lark has his own established set of applications. Dryden, Waller, and Savage represent the poet as a lark singing when the sun shines, and Waller suits the figure to the times by making the Queen the Sun.[99] Tickell called himself an artless lark.[100] Cowley professed[30] himself emulous of the lark.[101] Somerville is a morning lark.[102] Wycherley compares both Virgil and Pope to larks.[103] Any Fair One has a voice like a lark, and to Dyer’s delighted ear the maidens who spun English yarn sang like a whole choir of larks.[104] Not infrequently comparisons are drawn from the old custom of daring larks by mirrors or objects that would excite terror.[105] The wren carried aloft on the eagle’s back serves a variety of poetical purposes, but is especially apt when representing a needy poet and some powerful patron.[106] Bees are by far the most prolific source of similitude. Their number, their activity, their stings, their honey-making are all recognized means of illustration.[107]

To express great numbers the most useful similes are drawn from stars, pearly drops of dew, and, most frequently, leaves in autumn.[108] An exceedingly popular simile is that[31] of the oak and ivy, or the elm and the vine.[109] Its use is obvious. The rising and the setting sun represent various forms of prosperity and adversity.[110] From Waller on, the Milky Way typifies virtues so numerous that they shine in one undistinguished blaze.[111] A large class of similitudes is drawn from water in some form. In this respect Dryden is typical. It is surprising to observe how many of his metaphors and similes are based on seas, streams, and storms,[112] and his most excellent use of Nature is in these similitudes, though after going over many of them one comes to feel that they are all made upon much the same pattern. After Dryden conventional comparisons based on floods and angry seas are frequent.

[32]

The customary form of the river simile of this period is the comparison of some man’s character, or actions, or literary style to some historic rivers with marked features. Prior uses the rapid Volga to represent the impetuous “young Muscovite,” while he compares his own king to the gentle Thames;[113] and he compares the Romans to the Tyber.[114] Pope scornfully likens Curll to the Uridanus.[115] Cowley compares Jonathan to the fair Jordan.[116] Halifax compares the reign of Charles II to the Thames.[117] Armstrong wishes his own style to combine the qualities of the Tweed and the Severn.[118] Hughes likened his Muse to the wanton Thames.[119] Roscommon thought a dull style was like the passive Soane.[120] Somerville compared Allan Ramsay’s poetry to Avona’s silver tide.[121] Thomson said that De La Cour’s numbers went gliding along in “trickling cadence” and were like the flow of the Euphrates.[122] Chief among similes of this sort is Denham’s well-known apostrophe to the Thames.[123] There[33] is also frequent use of rivers in a more general way, as when Parnell compares the strains of the Psalmist to a rolling river,[124] and Stanhope compares Pope’s style to a gliding river,[125] and Addison compares Milton’s poems to a clean current showing an odious bottom,[126] and Dryden compares Sir Robert Howard’s style to a mighty river.[127] The use of a river as a simile for life is not infrequent. For various purposes the Nile was often used. Its annual overflow and its unknown fountain-head are the chief characteristics drawn upon. The river similes seem as a whole to be more effectively worked out and more gracefully managed than most of the other similes of the period, although they have in no case the beauty and profound symbolism characteristic of the river similes of Wordsworth, Matthew Arnold, and Lowell.

[34]

Another common form of comparison is that in which the seasons or the various aspects of the day are used to describe some person. One of the happiest examples is from Marvell.

Later similes are less graceful, but they usually have the antithetical form of expression.[129]

Fairly numerous similes are drawn from trees. Dryden gives typical examples, as,

This equal spread of roots and branches, the heavy fall of a great tree, and the superior height of some tall pine or cedar, are the chief sources of similitudes.

The abundant commonplaces, the fluent ineptitudes, of these eighteenth-century similes did not escape satire in their own day. Now and then a critic looked with scorn upon the ingenious and exhausting attempts of the poet lovers to devise comparisons adequately expressive of the beauty, the fascination, the cruelty, the coldness, the inconstancy, of their Cynthias of the minute. Butler thus notes the tendency of poor and unmeaning metaphors to advance in a mob when female charms were to be depicted:

[35]

This easy method of praising a mistress is also humorously described by Ambrose Philips:

And Swift in his “Apollo’s Edict,” 1720, specifically prohibits the use of some of the more wearisomely frequent similitudes. Some of the laws he imposes on the poets of his realm are:

In general we may say of the similitudes of this period that in no other literary form was Nature so widely used, and in no other form with so little beauty and spirit; that they were based on an insufficient and inexact knowledge of Nature; and that they were used without any sympathetic sense of inner fitness.

A further characteristic of the use of Nature in the classical[36] period is a personification of natural objects with the ulterior purpose of making them conscious of the charms or emotions of some person. When such personification arises out of an intimate identification of man with Nature, a subjective recognition of the unity of all existence, or when it is the outgrowth of a supreme passion compelling the phenomena of Nature into apparent sympathy with its own joy or grief, the expression is sure to bear the mark of inner conviction or strong emotion. But when the personification is manifestly a laborious artistic device, when it is based on neither belief nor passion, it must be considered the mark of an age slightly touched by real feeling for nature. And such, in general, were the personifications so freely used in the English classical poetry. There is an artificiality, even a grotesqueness, about some of them that forbids even temporary poetic credence on the part of the reader. A good example is in Waller’s “At Pens-hurst,” where the susceptible deer and beeches and clouds mourn with Waller over the cruelty of his stony-hearted Sacharissa.[133] At the death of any illustrious man or fair lady all Nature was convulsed with grief. When Caelestia died the rivulets were flooded by the tears of the water-gods, the brows of the hills were furrowed by new streams, the heavens wept, sudden damps overspread the plains, the lily hung its head, and birds drooped their wings. When Amaryllis had informed Nature of the death of Amyntas all creation “began to roar and howl with horrid yell.”[134] When Thomas Gunston died just before he had finished his seat at Newington, Watts declared that the curling vines would in grief untwine their amorous arms, the stately elms would drop leaves for tears, and that even the unfinished gates[37] and buildings would weep.[135] In love poetry Nature is frequently represented as abashed and discomfited before the superior charms of some fair nymph. Aurora blushes when she sees cheeks more beauteous than her own. Lilies wax pale with envy at a maiden’s fairness.[136] When bright Ophelia comes lilies droop and roses die before their lofty rival.[137] So the sun, when he sees the beautiful ladies in Hyde Park,

And when that modest luminary is aware of the presence of the fair Maria he

Nature is thus constantly compelled into admiring submission to some Delia or Phyllis or Chloris. Even further than this do the poets go; they make all the beauty of Nature a direct outcome of the lady’s charms. In the gardens at Penshurst the peace and glory of the alleys was given by Dorothea’s more than human grace.[140] No spot could resist the civilizing effect of her beauty. The most charming example of this sort of fanciful exaggeration is in Marvell’s verses on Maria and the Nunappleton gardens.

[38]

If later examples of the subordination of Nature to man were so graceful and quaintly tender as this poem of Marvell’s we might simply regard them as permissible instances of pathetic fallacy. But even taken at its best we cannot fail to see that this conception of Nature in its relation to man is quite unlike the dominant conception in the romantic school. In the one case we have the subordination of Nature; in the other the ministry of Nature. A significant comparison might be made between Marvell’s Maria, and Wordsworth’s Lucy.[142] The one is the typical fair maiden ruling over her flower world and inspiring to beautiful life all the gentle Nature forms about her. The other is “Nature’s lady.” Her whole being is molded by her susceptibility to the deeper influences of Nature untouched by art. Maria gives to the external world the charm that it has. Lucy is graced by the spirit of nature with all lovely qualities. But Marvell’s poem is really no fair criterion of the use of Nature in the classical love and elegiac poetry, for in most of that poetry the emotion, the passion, that would justify extravagant or even impossible conceptions is conspicuously absent. The extravagance of speech stood as the sign of an intensity of feeling that did not exist. The poet was not swept away by overwhelming passion. He worked out his verses with conscious deliberation. A lady-love was one of the necessary[39] poetical stage properties, so the poet cast about him for a Phyllis or an Amoret, and then cast about him for something to say to her. Such lines as Waller’s on Dorothea, who is so much admired by the plants that

are at once felt to be merely cold, tasteless hyperbole. The lines do not win a second’s suspension of disbelief. Modes of speech, a conception of Nature, such that high-wrought emotion might justify it, or that might be natural and inevitable when the poet’s thought was ruled by a living mythology, became mere frigid conventionalities when there was no passion, and when the spirits of stream and wood no longer won even poetic faith.

To speak of the poetic diction of the classical poetry has become a commonplace of criticism. By universal consent certain words and phrases seem to have been stamped as reputable, national, and present, and to have formed the authorized storehouse of poetical supplies. If one writer hit out a good word or phrase, it became common property like air or sunshine, and other writers did not waste their time beating the bush for a different form of words. Frequently words in the accepted diction may be traced to some Latin author, but the point to be noted here is that, whatever the origin of the word, its use is incessant. The fatal grip with which certain words clung to the poetical mind in the classical period receives interesting exemplification from a comparison of Chapman’s and Pope’s translations of Homer. It will be observed that in frequent passages Pope uses the words “purple,” “deck,” “adorn,” and “paint,” chief words in the[40] classical poetic diction. But in the corresponding passages in Chapman some other form of words is used. And in most cases Pope’s use of these terms has no warrant in the original. Likewise, in Dryden’s translation of Virgil the stock diction is used when there is no idea or picture in the Latin to call for it and when the use of the stock phraseology results in distinct loss of force or beauty. Compare, for instance, Virgil’s vivid “flavescet” and Dryden’s tame “the fields adorned”[144] used with reference to harvests of ripened grain. Or compare “novis rubeant quam prata coloribus” and “painted meads;”[145] “noctem ducentibus astris,” and “stars adorn the skies.”[146] We find the same spirit illustrated in Dryden’s modernization of Chaucer. The fresh, spontaneous simplicity of a poet like Chaucer serves exceptionally well to show the comparatively insipid and feeble treatment of Nature on the part of those poets who were content to take their expressions, as well as their facts, at second hand. “The briddes” becomes “the painted birds;” “a goldfinch” is amplified into a “goldfinch with gaudy pride of painted plumes.” “At the sun upriste” becomes

The same point is well exemplified in some of the changes made by Percy in the Ballads. For instance,

was modernized to,

[41]

Full illustration would require much more space than is here at command, but the point to be made is clear, namely, that even when the poet had his natural facts furnished for him, he instinctively put them into the molds of an accepted poetic diction.

By all odds the most frequent and significant words in this stock poetic diction, so far as it has to do with the presentation of nature, are indicative of dress or adornment in some form. The word “paint” is everywhere. Snakes and lizards and birds; morning and evening; gardens, meadows, and fields; prospects, scenes, and landscapes; hills and valleys; clouds and skies; sunbeams and rainbows; rivers and waves; and flowers from tulips to white lilies—nothing escapes. It is little wonder that Somerville called God “the Almighty Painter.”[149] The word “paint” is really an Elizabethan survival, and as such came into the possession of Cowley, whose use of it is absolutely vicious. A rainbow is “painted tears.” The wings of birds are “painted oars.” David after the fight with the giant is “painted gay with blood,” and the blood of the Egyptians lost in the Red Sea “new paints the waters’ name.”[150] “Gaudy” is another word of frequent occurrence. In general the meaning was as now, “ostentatiously fine” as we see in Shakspere’s phrase, “rich but not gaudy,” and in Dryden’s “gaudy pride of painted plumes.” In that sense it was fitly applied to peacocks,[42] and perhaps even to rainbows, but such phrases as “a gaudy fly,”[151] the “gaudy plumage”[152] of falcons; the “gaudy axles of the fixed stars,”[153] the “gaudy month” of May,[154] the “gaudy opening dawn,”[155] the “gaudy milky soil”[156] and the “gaudy Tagus”[157] seem to have no exact meaning. “Bright” might often serve as a synonym, but not in the application of the word to flies and falcons. The word “adorn” is likewise eminently serviceable. Fruit adorns the trees, fleecy flocks adorn the hills, flowers adorn the green, rainbows adorn clouds, blades of grass adorn fields, vegetables adorn gardens, Phoebus adorns the west and is himself adorned with all his light, and Emma’s eyes adorn the fields she looks on. “Deck” is another favorite. Flora’s rich gifts deck the field, herbs deck the spring, and corals deck the deep. Vales, meadows, fields, mountains, rivers, shores, plains, paths, turf, gardens—all are profusely “damasked” or “enamell’d” or “embroidered.” The wings of butterflies and linnets are “gilded.” The rising sun gilds the morn; the gaudy bow gilds the sky; gaudy light gilds the heavens; lightning gilds the storm; meteors and stars gild the night; and a duchess gilds the rural sphere when she condescends to visit the country.

These milliner-like words were not, however, the only ones that the poet could claim as lawful heritage. He knew, for instance, that he could always call honey “a dewy harvest,” or “balmy dew,” or “ambrosial spoils,” and have[43] his hearers know what he meant. His birds, though almost necessarily a “choir,” could be “feathered” or “tuneful” or “plumy” or “warbling” according to his taste. His fish were easily labeled as “finny,” “scaly,” or “watery.”

Breezes were “whispering,” “balmy,” “ambrosial;” zephyrs were “gentle,” “soft,” and “bland;” gales were “odoriferous,” “wanton,” “Elysian;” and no other kinds of winds blew except in storm similes. “Vernal” and “verdant” come in at every turn. From Waller on, the epithet “watery” seems eminently satisfactory to the poetic mind. Dryden may be taken as illustrative. To him the ocean is a “watery desert,” a “watery deep,” a “watery plain,” a “watery way,” a “watery reign.” The shore is a “watery brink,” or a “watery strand.” Fish are a “watery line” or a “watery race.” Sea-birds are “watery fowl.” The launching of ships is a “watery war.” Streams are “watery floods.” Waves are “watery ranks.”[158] The word occurs with wearisome iteration in succeeding poets. It is applied not only to the sea but to rivers, clouds, and rain, to glades, meads, and flowers, to landscapes, to mists, to the sky, to the sun, and to the rainbow. The set phrases for the sky are such as “azure sky,” “heaven’s azure,” “concave azure,” “azure vault,” “azure waste,” “blue sky,” “blue arch,” “blue expanse,” “blue vault,” “blue vacant,” “blue serene,” “aërial concave,” “aetherial vault,” “aërial vault,” “vaulted sky,” “vaulted azure,” with such other changes as may be rung on these words. The chief words applied to stars, “spangle” and “twinkle,” have been already noted. The usual adjectives for streams and[44] brooks are pleasant, easy words like “liquid,” “lucid,” “limpid,” “purling,” “murmuring,” and “bubbling.” “Rural,” “rustic,” and “sylvan” are epithets applied to anything belonging to the country, whether to the hours spent there, the songs of the birds, or the charming country-maidens and their loves, their bowers, their bliss, their toil. “Flowery” is so constantly used as descriptive of brooks, borders, banks, vales, hills, paths, plains, and meads, that it really has not much more meaning than the definite article prefixed to a noun. “Vocal” is applied to vales, shades, hills, shores, mountains, grots, and woodlands. “Pendent” and “hanging” belong to cliffs, precipices, mountains, shades, and woods. “Headlong” and “umbrageous” are favorite adjectives for groves or shades of any sort. “Mossy” applies to grottos, fountains, streams, caves, turf, banks, and so on. “Gray” is the usual descriptive word for twilight, and “brown” for night. “Lawns” are usually “dewy.”

Some words in this poetic diction are no longer much used. “Breathing,” is an example. It usually referred to the air in gentle motion, as “breathing gales,” but we also find “breathing earth,” referring to mists, and “breathing sweets,” and “breathing flowers” or “breathing roses,” where the reference is to perfume. “Maze” and “mazy” are also much used. The Thames and other streams lead along “mazy trains.” The track of the hare is an “airy maze.” Paths meet in narrow mazes and stars unite in a mazy, complicated dance. Milton’s stream flows with “mazy error.” This word “error” is frequently used in its exact derived meaning. In another place Milton speaks of streams that wander with “serpent error.”[159] Blair has a stream that slides along in “grateful errors.”[160] In Falconer the light strays through the forest with[45] “gay romantic error.”[161] In Gay the fly floats about with “wanton errors.”[162] Dyer winds along a mazy path with “error sweet.”[163] Armstrong’s “error” leads him through endless labyrinths.[164] Addison’s waves roll in “restless errors,”[165] and Thomson treads the “maze of autumn with cheerful error.”[166] “Amusive” is a word applied by Pitt to the ocean, and by Mallet to clouds; Shenstone says that country joys “amuse securely.”[167] It seems to be half apologetic in tone in some cases; in others it merely means pleasing. Thomson used the word as verb or adjective several times.[168] We also find it in Parnell.[169] “Lawn” is used in the sense of an open glade in the woods. Even so late as Wordsworth this meaning persists.[170] One unpleasant but not uncommon word is “sweat.” It may be a survival from the metaphysical conceits, for we find in Dr. Donne a reference to the “sweet sweat of roses,” and Cowley has flowery Hermon “sweat” beneath the dews of night. Dryden has flowers sweat at night.[171] Fenton’s flowers

[46]

Even Gray talks about the “sickly dews”[173] of night, and Thomson has caverns “sweat.”[174] Garth, as a physician, may possibly be excused for having the “sickening flowers” drink up the silver dew, and the grass tainted with “sickly sweats of dew,” but when he has the fair oak adorned with “luscious sweats,”[175] he has gone into the realm of aesthetics, and no excuse can prevail.

The power of fashion in words in a conventional age is further shown by the prevalence of adjectives ending in “y.” They are favorites with Dryden, and hold their own steadily through the century that followed. Beamy, bloomy, forky, branchy, flamy, purply, steepy, spumy, surgy, foamy, blady, dampy, chinky, sweepy, sheltry, moony, paly, tusky, heapy, miny, saggy, and many more, occur where at present there would be no ending or the ending “-ing.”