Title: Nelly's dark days

Author: Hesba Stretton

Release date: December 17, 2025 [eBook #77483]

Language: English

Original publication: Glasgow: Scottish Temperance League, 1891

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

WAITING FOR FATHER.

BY THE AUTHOR OF

"JESSICA'S FIRST PRAYER," "LITTLE MEG'S CHILDREN,"

"ALONE IN LONDON," &c.

[Hesba Stretton]

One hundred and fifth thousand.

GLASGOW:

SCOTTISH TEMPERANCE LEAGUE.

LONDON: HOULSTON & SONS;

AND NATIONAL TEMPERANCE LEAGUE.

EDINBURGH: JOHN MENZIES & CO.

1891.

CONTENTS.

————

A STREET CORNER

LOCKED OUT

MORNING FEARS

ONLY A DOLL

VIOLETS

THE PRICE OF A DRAM

HALF MEASURES

A SORROWFUL FACT

FOUND DROWNED

DEEPER STILL

THE ONLY REFUGE

TRUE TO A PROMISE

DEAD AND ALIVE AGAIN

NELLY'S DARK DAYS.

————————

A STREET CORNER.

IT was nearly twelve o'clock at night on the first Sunday of the New Year. The churches and chapels had all been closed for some hours; and none of the better class of shops had been opened during the day. Business had been set on one side, even by those workmen and labourers who lived from hand to mouth, and scarcely knew beforehand where the day's meals were to come from. There had been, as usual, a prevailing feeling that the day was not a day for work or traffic of any kind; and what had been done had been, more or less, away from the public scrutiny. But though midnight was close at hand, the streets in the lower parts of Liverpool were neither quiet nor dark. Up higher, farther away from the long line of docks and the troubled stream of the mighty river, there was silence in the deserted streets where the wealthier classes had their comfortable homes; but where the poor dwelt, and wherever there was a corner of a street which afforded a good situation for traffic, or wherever it was supposed there was an "immense drinking neighbourhood capable of improvement," * there stood a gin-palace still open, with its bright gas-lights sparkling down each dark row of dingy houses with a show of cheery welcome not easy to resist.

* "Capital Spirit Vaults to Let, in an Immense Drinking Neighbourhood,

capable of great improvement by an industrious man and his wife."

(Newspaper Advt.)

At one spot where four roads met, each corner house was thus brilliantly lit up; and the doors, which swung to and fro readily and noiselessly, were constantly moving, and giving a passing glimpse, but no more, of what was going on within. The streets were so light here that a pin lying on the flagged pavement was plainly seen. So were the rags of a child who stood in the full glare of the most popular of the gin-palaces, leaning against a lamp-post, with her face turned towards the often-opening door. It was a small, meagre face, yet pretty, with a mingled and wistful expression of anxiety and happiness. The anxiety was visible whenever the door stood ajar; when it was closed, the happiness came uppermost. The secret of her brief, new-born happiness was very simple, but very deep to the child. She clasped tenderly, but carefully, in her thin bare arms a gaily dressed doll, whose finery contrasted strongly with her own rags. When the door remained closed for a few minutes, she passed the time in timid, half-fearful caresses of her shining doll; as soon as it opened she peered, with heedful and searching eyes, to the farthest corner of the interior.

"Nelly!" said a clear, shrill voice, which startled the child from an anxious gaze. "You here at this time! How's poor mother to-night?"

"Very bad," said the child sadly.

"And father's in there, I reckon?"

"Yes," said Nelly, "and oh! I want him to come home so, because mother says she'd go to sleep maybe if father was home."

The girl who had spoken to her—a bright, brisk-looking girl—pushed open the door a little way, and glancing in turned back with a decisive shake of her head.

"No use, Nelly," she said; "he won't come as long as he can stay. Well, I'll nurse you a bit to keep you warm; it's very bitter to-night. I don't much wonder at father drinking to-night, I don't."

All day long the wind had been blowing keenly from the north-east, bringing a fine, piercing sleet with it, and at nightfall the bitter cold had increased. The girl sat down on a door-step, and drew the shivering child into her lap, covering her as well as she could with her own scanty clothing.

"Father didn't use to get drunk once, did he, Bessie?" asked the child, plaintively.

"Oh dear, no!" answered Bessie, in a cheery voice.

"Tell me all about that time," said Nelly, nestling closer to Bessie.

It was an old story, often told, but neither the girl nor the child ever grew weary of it.

"It's ever so many years ago, before you was born," said Bessie; "and he lived in a beautiful house, with a parlour in front, and a kitchen behind, and two rooms upstairs, all full of beautiful furniture. Everybody that I knew called him Mister Rodney then; but I was nothing but a poor ragged little girl, raggeder than you, Nelly, selling matches in the streets. And this was how I come to know him. I was hanging about the basket-women, down by the stages, running errands for 'em, and one day, almost as cold as this, my foot slipped, and down I fell into the water. Oh! It was so cold; and I seemed to be sinking down, down, down."

"And father jumped in after you and fetched you out," interrupted Nelly, eagerly.

"Ay! He did, though he knew nothing of me, and I was nothing to him, only a little, dirty match-girl. And then he carried me all the way to his own house in his arms."

"He never, never carried me in his arms," cried the child, "they aren't strong enough now."

"No; but he was as strong as strong then," continued Bessie, "and he clipped me so fast I wasn't a bit afraid. That's how I'm never afraid of him now, Nelly. He's a good man, and kind, and clever, when he's himself; and I love him, and you love him; don't we?"

"Yes," said Nelly, drawing a long breath, "mother says she's going to heaven soon, where the other children are, and there 'll be nobody left but me to take care of father. I don't much mind, though I'd rather go with mother. Will he go on getting drunk always and always?"

"If he could only see the gentleman I saw!" exclaimed Bessie. "It's six years ago, and I was a big, grown girl, ready to push in anywhere, and I see a lot of boys and girls crowding into a great hall, and I pushed in with them, nobody stopping me. And then they sang a lot of songs, oh! beautiful songs, and some gentlemen spoke to 'em about drink, and how they'd grow up good, decent men and women if they'd keep from it. And I was one of the very last to come away, the place was so nice, and a gentleman come up to me, and he said,—

"'My girl, what is your name?'

"And I said, 'Bessie Dingle, sir.'

"And he said, 'Can you read?'

"And I said, 'No, sir.'

"And he said, 'That's a pity. Do you ever drink what will make you drunk?'

"And I was ashamed to say yes, so I answered him nothing.

"And he said, looking me full in the face with eyes as kind as kind could be, 'I wish you'd promise me never to taste it till you see me again.'

"And I said, 'Yes, I will promise, sir.'"

"And when did you see him again?" asked Nelly.

"Never!" she answered. "He wrote down on a bit of paper where he lived, and said any of the p'leece would show me where it was; and that very night I fell sick with fever and they took me to the workhouse, and the slip of paper got lost. Anyhow, I never could find it or the place, and I've never seen him again. He's sure to think I broke my promise, and did not care for him; he's almost sure to think that, but I never did."

She raised her head and looked down the long street, where the gloom seemed to press darkly against the glare of the gas-lights; it was very cheerless beyond the light, and the girl's face grew darker for a minute or two.

"It's no wonder they drink as long as the place is open," she said; "I'd like to be inside there, where it's light and warm. I wonder why the shops are all shut, and those places open. That gentleman, he said to me,—

"'My girl, you've got sharp eyes of your own; you just look round and see what makes the most mischief among the people about you, and tell me when I see you again.'

"I know what I'd say if he stood here this minute."

"Did you ever tell father about him?" asked Nelly.

"Scores and scores of times," she answered, emphatically; "and sometimes he cries and wishes he knew him, and could make him a promise like me; and sometimes he curses and calls me an idiot. If he could only see him, Nelly!"

They sat silent for a minute or two, Bessie nursing the child as tenderly as she nursed her doll. At last, the girl touched the doll with the tip of her finger, and said cheerfully,—

"Why, wherever did you get this grand plaything from?"

"It's a lady doll, and it's my very own," answered Nelly, opening her rags to display it fully; "there was a Christmas-tree at our school, and this was the very best thing there, and teacher gave it me because she said I was the best child. Isn't it a beauty, Bessie?"

"It's wonderful!" said Bessie, in a voice of admiration.

"I take such care of it," continued Nelly, eagerly, "only I'm afraid of nursing it when there are children about, for fear they should snatch it from me, you know."

As the child spoke, the clocks in the town struck twelve, and a trail of lingerers crept reluctantly out of each brilliant gin-palace. Bessie kept Nelly back from springing forward to meet her father, and then seeing him take his way homewards, she followed at a little distance, clasping the child's hand warmly in her own.

LOCKED OUT.

THE figure which staggered on before them had once been that of a tall, well-built man, strong and upright, with a firm tread and a steady hand. Bessie had known him in his better days; but such as he was now—feeble and bent, with reddened eyes and shaking hands—Nelly had never known him otherwise. Rodney loved Nelly with all that was left to him of a heart. It was perhaps the last link which bound him in nature to God and his fellow-men. She was his latest-born, and the only child remaining to him; and though he had lost the sense of all other affections, this one still glimmered and lived within him. Such as he was now, he was sure of her love for him, for she could not compare him with any better self in happier times. The state to which he had reduced himself was the only one she knew; and the drunkard felt that there was no reproach mingled with the little child's kisses upon his parched lips.

Rodney floundered on through the narrow streets leading homewards, unconscious that he was followed by the silent and noiseless girls, whose ill-shod feet made no sound upon the slushy pavement. His progress was slow and uncertain; but at length he turned down a short passage, and paused, with labouring breath, at the foot of a flight of stone steps leading to the upper flat of the building in which he lived. It was to see him safe up this perilous staircase that Bessie had come so far out of her own way. A false step here, or a giddy lurch, might be death to him. They ventured nearer to him between the dark and narrow walls as he climbed up before them; and as soon as he reached the landing, upon which several doors opened, their hearts were at rest, now all danger was over. He groped his way on from door to door until he gained his own, and then with an unexpected quickness and steadiness of hand he lifted the latch and passed in, slamming the door behind him, and turning the key noisily in the lock. Nelly sprang forward with a sudden cry.

"Oh! Bessie," she cried, wringing her small hands in distress, "whatever are I to do? When father's like that, I durstn't let him see me nor hear me, for mother says maybe he'd kill me. And mother durstn't stir to open the door or he'd nearly kill her. And it's so cold out here, and all the neighbours gone to bed, and it 'ud kill me to stay out of doors all night, wouldn't it, Bessie? Whatever are I to do?"

It was too dark for Bessie to see the terror upon the child's wan face, but she could hear it in her voice, and she could feel the little creature trembling and shivering beside her.

"Never mind," she said, soothingly, "I'm not afraid of him. He's a kind man, and he'll open the door for me, I know; or else you shall come home with me, Nelly, and I'll carry you all the way. Hegh! Mr. Rodney, sir, please to open the door again."

She knocked sharply and decisively at the door, and called out in a shrill voice, which made itself heard through all the din he was making inside. He was silent for a moment, listening, and Bessie went on in the same clear tones,—

"You've locked Nelly out, Mr. Rodney, as has been waiting and watching ever so long for you; and it's bitter cold to-night, and she's tired to death. Please unfasten the door and I'll bring her in."

There was no sound for a minute or so except the hollow and suppressed cough of the mother, who was struggling to hush the noise she made, lest it should arouse the drunken fury of her husband. Then Rodney shouted with an oath that he would not open the door again that night for any one.

"It's me, father!" sobbed the child. "Little Nelly, and its snowing out here. You didn't use to be so bad to me. Please to let me in."

She was beating now with both hands at the door, and crying aloud with cold and terror, while her mother's low cough sounded faintly within; but she dare not rise from her bed and open the door for her little girl.

"It'll teach you to come waiting and watching for me," cried Rodney, savagely; "get off from there, and be quiet, or I'll break every bone in your body. Now, I've said it!"

Nelly's hands dropped down, and she crouched upon the door-sill in silent agony; but Bessie knocked again bravely.

"Never you mind, Mrs. Rodney," she said, "I'll take Nelly home with me, and carry her every inch of the road. And, Mr. Rodney, sir, you'll be as sorry as sorry can be as soon as you come to yourself. Good-night, now; and don't you fret. Nelly's here, up in my arms, safe and sound; and I'll take care of her."

Bessie had lifted the child into her arms, but still lingered in the hope that the door would open. But it did not; and turning away with a sorrowful and heavy heart, and with Nelly sobbing herself to sleep on her bosom, she made her way toilsomely along, under her burden, and through the thickening snow, to her own poor lodging.

MORNING FEARS.

WHEN Rodney awoke in the morning, he had a vague remembrance of the night before, which made him raise his aching head, and look with a sharp prick of anxiety to see if his little child was in bed beside her mother. His wife, who had been lying awake all night, had now fallen into a profound slumber, and her hollow face, with the skin drawn tightly across it, and with a hectic flush upon her cheeks, was turned towards him; but Nelly was not there. What was it he had done the night before? In his dull and clouded mind there was a dawning recollection of having heard little hands beat against the door, and a piteous voice call to him to open it. It was quite impossible that the child could be concealed in the room, for it was very bare of furniture, and there was no corner in its narrow space where she could hide.

Through the broken panes of the uncurtained window he could see the snow lying thickly upon the roofs; and he was himself benumbed by the biting breath of the frost, which found its way, in rime and fog, through the crazy casement. Could it by any possibility have happened that he had driven out his little daughter, Nelly, who did not shrink from kissing and fondling him yet, drunkard as he was, into the deadly cold of such a winter's night? He crept quietly across the room, and unlocked the door, letting in a keener draft of the bitter wind as he opened it.

His wife moved restlessly in her sleep, and began to cough a little. He drew the door behind him, and stood looking down over the railings which protected the gallery upon which the houses opened, into the street below. The snow that had fallen during the darkness was already trodden and sullied by many footsteps; but wherever the northern wind had blown, it had drifted it into every cranny and crevice, in pure white streaks. A few boys were snow-balling one another along the street; but all the house doors, which usually stood open, were closed, and the neighbours were keeping within. If any of them had been open, he could have asked carelessly if they knew where his Nelly could be; but he did not like to knock formally at any one of them. In which of the houses at hand could he inquire for her, without exposing himself to the anger and contempt of the inhabitants?

He could not make up his mind to inquire anywhere. He was afraid of almost any answer he could get. More than once he had beaten his little girl; but they had made it up again, he and Nelly, with many tears and kisses, and he knew she had borne no malice in her heart against him. But he had never driven her out of her home before—a little creature, not eight years old, in the wild, wintry night; at midnight too, when every other shelter would be closed. Where could she be at this moment? What if she had been frozen to death in some corner, where she had tried to shield herself from the snow-storm? He wandered along the street, casting fearful glances down each flight of cellar-steps, where a child might creep for refuge, until he reached the wider thoroughfares, and the numerous gin-palaces in them.

But just now Rodney's heart was too full of his missing child to feel the temptation strongly. He fumbled mechanically in his pockets for any odd pence that might be there; but he was thinking too much of Nelly to have more than a faint, instinctive desire for the stimulus. He was cold, miserable, and downcast; but he had not as yet sunk so low that anything except the assurance that his little daughter was alive and well, could revive him. With bowed head he went on in a blind search for her, along the snowy streets, looking under archways, and up covered passages, wherever she might have found a shelter for the little face and form, which were dearer than all the world to him, cruel as he had been to them.

He turned home again at length, worn out and despondent, wishing himself dead and forgotten by all those whom he had made miserable, and more than half tempted to make an end of it altogether in the great, strong river, whose tide would sweep him out to sea. Swept away from the face of the earth—that would be the best thing for them and for him! If he only had courage to do it; but his courage was all gone, had oozed away from him, and left him only the husk of a man, fearful of his own shadow, except when he was drunk. He scarcely knew whether he trembled from cold or dread as he loitered homewards; and he could hardly climb the worn steps which he must ascend to reach his house, for the throbbing of his heart and the tremor in his limbs. He was afraid of facing his dying wife, and telling her that he could not find their last little child, the only one that she would have had to leave behind her.

But as he came within sight of the door, he saw that it stood open an inch or two, and his eye caught the gleam of a handful of fire kindled in the grate. Before his hand could touch it, the door was quickly but quietly opened, and Nelly herself stood within, her hand raised to warn him not to make any noise.

"Hush!" she whispered. "Mother's asleep still, and you're yourself again. Bessie said you'd be yourself again, and I needn't be afraid. Come in and let me warm you, daddy."

She drew him gently to the broken chair on the hearth, and began to rub his numbed fingers between her own little hands; while Rodney sunk helplessly into the seat, and leaned his head upon her small shoulder.

"Never mind, father," said Nelly, "you didn't mean to do it. Bessie says you'd never have done it of your own self. It's only the drink that does it; and I wasn't hurt, daddy; not hurt a bit. Bessie carried me all the way to her home, like you carried her once, she says. Did you ever carry Bessie, when you were a strong man, in your own arms, a long, long way?"

"Ay! I did," said Rodney, with a heavy sigh, "and now I can scarcely lift you upon my knee. Do you love poor, old father, Nelly?"

SHE DREW HIM GENTLY TO THE BROKEN CHAIR.

"To be sure I do," said the child, earnestly, "why, when mother's dead, there 'll be nobody left but me to take care of you, you know. You mustn't ever turn me out of doors then, or you might hurt yourself, and there 'd be nobody to see when you're drunk."

"I'll never get drunk again," cried Rodney, "and I'll never be cruel to you again, Nelly. Give me a kiss, and let it be a bargain."

Nelly covered his fevered face with kisses, in all a child's hopefulness and gladness; and told her mother the good news the moment she awoke. But neither the wife, nor Rodney himself, dared to believe he would have strength to keep the promise he had made.

ONLY A DOLL.

AS the night drew on, and the time at which he was accustomed to seek the excitement of the spirit-vaults or beer-shops, a sore conflict began within Rodney's soul. With the darkness came a cold, thick fog from the river, which penetrated into the ill-built houses, and wrapped freezingly about their poorly-clad inmates. What few pence he had saved from the scanty wages of the previous week, he had spent earlier in the day in buying a little food for Nelly, and some medicine to lull his wife's racking cough. There was no light in his house, and the fire was sparingly fed with tiny lumps of coal or cinder, which gave little warmth, and no brightness to his hearth. The sick woman had stayed in bed all day, and had only strength enough to speak to him from time to time; while Nelly, who was also suffering from cold, and hunger but half-satisfied, grew dull as the darkness deepened, and rocked her doll silently to and fro, as she sat on the floor in front of the fire, where the gleams of red light from the embers fell upon her. Not far away was the brilliant gin-palace, where the light fell in rainbow colours on the glittering prisms of the gas pendants, to which his dim and drunken eyes were so often lifted in stupid admiration.

A chilly depression hung about Rodney, which by and by gave place to an intense, unutterable craving for the excitement of drink, which fastened upon him, and which he felt no power to shake off. As time dreary minutes dragged by, he pictured to himself the warmth and comfort that were within a stone's-throw of him. But there was no money now in his pocket, and nothing that was worth pawning in the house. He almost repented of having spent the poor sum that had been his in food and medicine; for Nelly was still hungry, and her mother's cough had not ceased. That cough irritated him almost to frenzy; and he felt that he should die, perish that night of cold and misery, if he could not buy one dram to warm and comfort him.

He peered anxiously around, in the gloom, upon the few beggarly possessions remaining to him, and groaned aloud as he confessed to himself that they were worthless. His wandering glance fell upon Nelly, curled up sleepily on the hearth, with her doll lying on her arm. That looked gay and attractive in the red light, its blue dress and scarlet sash showing up brightly against Nelly's dingy rags.

Rodney's conscience smote him for a moment as he thought that the toy, fresh and unsoiled still, might fetch enough, if sold, to satisfy his more immediate craving this evening—but the idea once in his mind, he could not banish it. To-morrow he would work, and earn money enough to buy Nelly another quite as good as this one. If he had not spent his money for her and her mother, he would not now be driven to taking her plaything from her; and it was only a toy, nothing necessary to her, as it was necessary to get warmth, and what was more to him than food. She would not be any colder or hungrier without her doll; and she would not mind it much, as it was for him. He did not mean to take it from her against her will; but she would give it up, he knew. Leaning forward, he laid his shaking hand upon her cheek.

"Nelly," he said, in his kindest tones, "Nelly, you've got a pretty plaything there."

"Oh, yes!" she answered, opening her eyes wide, and hugging the doll closer to her. "But it isn't a plaything, father. It's a lady that has come to live with me."

"A lady, is it?" said Rodney, laughing. "Why, it's a queer place for a lady to live in. Would you mind lending her to me for a little while, Nelly?"

"What for?" asked Nelly, her eyes growing large with terror, and her hands fastening more closely around her treasure.

"No harm," he answered softly, "no harm at all, my little woman. I only want to show it to a friend of mine that's got a little girl like you that's fond of dolls. I'll bring it back very soon, all right."

"Oh! I cannot let her go!" cried Nelly, bursting into tears, and creeping away from him towards the bed where her mother lay.

"John," murmured the mother, in feeble and tremulous tones, "let the child keep her doll. It's the only comfort she's got."

Rodney sat still for another half-hour, the numbness and depression gaining upon him every minute. Nelly had sought refuge by her mother's side, and the dreary room was awfully silent. At last, he could endure it no longer; and with a hard resolution in his heart, he stirred the fire till a flickering light played about the bare walls, and then he strode across to the bedside.

"Look here, Nelly," he said, in a harsh voice, "I promised that friend of mine to show his little girl your doll; so you'd better give it up quietly, or I must take it off you. What are you afraid of? I'm not going to do you any harm, but have the doll I must. I'll bring it back again with me, if you'll only lend it me without, any more words."

"Nelly," said the mother, tenderly, "you must let him take it, my darling."

Nelly sat up in bed, rocking herself to and fro in a passion of grief and dread. Yet her father had promised to bring it back, and she had still some childish faith in him. The doll lay upon the ragged pillow, but she could not muster courage enough to give it herself into her father's hands, and with a bitter sob she pushed it, towards her mother.

"You give it him," she said.

For a minute or two, Rodney's wife looked up steadily into his face, for some sign of relenting, but though his eyes fell, and his head sank, he still held out his hand for the toy, which she gave to him, murmuring, "God have mercy upon you!"

For a second Rodney stood irresolute, but the flickering flame died out, and darkness hid him from his wife and Nelly. Without speaking again, he groped his way to the door and passed out into the street.

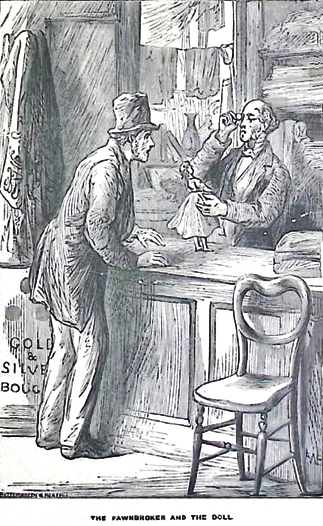

THE PAWNBROKER AND THE DOLL.

It proved a very paltry, insufficient satisfaction after all. The toy, handsome as it seemed to him, did not sell for as much as he expected at the pawn-shop, where they refused altogether to take it in pledge. He could only drink enough to stupify him for a little while, but not sufficient to give him the savage courage to go back and meet Nelly without her doll. What he had taken only served to quicken the stings of his conscience, which made it a difficult thing to return home at all.

The night was even keener than the last when Nelly watched for him at the door of the gin-palace, yet he dare not go back till she was fast asleep, and in the morning he could readily pacify her by promising to buy another doll. He hung about the entrances of the spirit-vaults with a listless hope that some liberal comrade might offer him a glass; and as long as there was any chance of it, he loitered in the streets. But they were closed at last, the brilliant lights extinguished, and the shutters put up; and Rodney was forced to return home tenfold more miserable than when he left it.

His hope that Nelly would be asleep was ill-founded. He could not see her; but the instant his foot struck against the door-sill, he heard her eager voice calling to him to bring the doll back to her. His own voice, when he answered her, was broken by a whimper, and a sob which he could not control,—

"Father couldn't bring it home," he answered; "my friend's little girl wouldn't part with it to-night. But it will come home to-morrow, Nelly."

"Oh! I know it never will," wailed the child. "I shall never see my lady any more; never any more. They've stolen her off me; and I shall never, never have her again."

He could hear her sobbing far into the night; and after she had cried herself to sleep, her breath came in long and troubled sighs. He cursed himself bitterly, vowing a hundred times that Nelly should have a doll again to-morrow. But when the day came, the daily temptation came with it; and though he found work, and borrowed a shilling from a fellow-workman, the money went where his money had gone for many a past month and year.

For some days his child was dull and quiet—bearing malice, Rodney called it, when she gave no response to his fits of fondness. But neither she nor his wife spoke to him of the lost plaything, and before long, it had passed away altogether from his weakened memory.

VIOLETS.

ALL the neighbours said it was a mystery how the Rodneys lived for the next three months, for Rodney was away for days together, only coming home now and then during his sober intervals; but it was no mystery at all. The wondrous kindness which the poor show to the poor was at work for them. Mrs. Rodney needed little food, and Nelly was always welcome to share the stinted meals in any house near at hand. Every day at dusk Bessie came in, and if she had been lucky in selling her flowers or fruit in the streets, she did not fail to bring some small, cheap dainty with her to tempt the sick woman's appetite. So the depth of the winter passed by; and the spring drew near, with its Easter week of holiday and gladness.

It was the day before Good Friday, when Rodney was returning, with lagging steps and a heavy heart, to his wretched home, after an absence of several days. Every nerve in his body was jarring, and every limb ached. He could scarcely climb the narrow and steep staircase; and when he reached his door, he was obliged to lean against it, breathing hardly after the exertion. It seemed very silent within, awfully still and silent. He listened for Nelly's chatter, or her mother's cough, which had sounded incessantly in his ears before he had left home; but there was no breath or whisper to be heard. Yet the door yielded readily to his touch, and with faint and weary feet he crossed the threshold, to find the room empty.

It was his first impression that it was empty; but when he looked round again with his dim, red eyes, whose sight was failing, they fell upon one awful occupant of the desolate room. Even that one he could not discern all at once, not till he had crossed the floor and laid his hand upon the strange object resting upon the old bed—the poor, rough shell of a coffin which the parish had provided for his wife's burial. She was not in it yet, but lay beyond it, in its shadow; her white, fixed face, very hollow and rigid, at rest upon the pillow, and her wasted hands crossed upon her breast. The neighbours had furnished their best to dress her for the grave, and a white cap covered her gray hair; while between her hands, on the heart that would beat no more, Bessie had laid a bunch of fresh spring violets.

Rodney sank down on his knees, with his arms stretched over the coffin towards his dead wife. Some of the deep, hard lines had vanished from her face, and an expression of rest and peace had settled upon it, which made her look more like the girl he had loved and married twenty years ago. How happy they had been then! And how truly he had loved her! If any man had told him to what a wretched end he would bring her, he would have asked indignantly, "Am I a dog, that I should do this thing?"

The memory of their first years together swept over him like a flood: their pleasant home, of which she had been so proud; their first-born child, and their plans and schemes for his future; the respect in which he had been held by all who knew him; and he had thrown them all away to indulge a shameful sin! And now she was dead; and even if he had the power to break through the hateful chain which fettered him body and soul, he could never make amends to her. He had killed her as surely, but more slowly and cruelly, than if he had stained his hands with her blood. God, if not man, would charge him with her murder.

The twilight came on as he knelt there, and for a few minutes the white features looked whiter and more ghastly before the darkness hid them from him. Then the night fell. It seemed more terrible than ever now—this stillness in the room which was not empty. His mind wandered in bewilderment; he could not fix his thoughts upon one subject for a minute together, not even on his wife, who was lying dead within reach of his hand. His head ached, and his brain was clouded. One dram would set him right again, and give him the courage to seek his neighbours, and inquire after Nelly; but he dared not meet them as he was. He could not bear to meet their accusing eyes, and listen to their rough reproaches, and hear how his wife had died in want, and neglect, and desertion. He must get something to drink, or he should go mad.

There was nothing in the room of any value—he knew that; yet there was one thing might give him the means of gratifying his quenchless drouth. He knew a man, serving at the counter of one of the nearest spirit-vaults, who had a love for flowers; and there was the bunch of sweet violets withering in the dead hands of his wife. For a minute or two the miserable drunkard's brain grew steady and clear, and he shuddered at the thought of thus robbing the dead; but the better moments passed quickly away. The scent of the flowers brought back to his troubled memory the lanes and hedgerows where he had rambled with her, under the showery and sunny skies of April, to gather violets—so long ago that surely it must have been in some other and happier life, and he must have been another and far better man. How happy the days had been! No poverty then; no aching limbs and wandering thoughts. He had believed in God, and loved his fellow-men. Now there was not a cur in the streets that was not a happier and nobler creature than himself.

Still, underneath the surface of these thoughts, his purpose strengthened steadily to exchange the fresh, sweet flowers for one draught of the poison which was destroying him—he knew it—body and soul. But the darkness had grown so dense that he could not, with all the straining of his be-dimmed eyes, trace the white outline of the dead face and hands; and his skin crept at the thought of touching, with his hot hand, the deathly chill of the corpse. The flowers were there; but how was he to snatch them away from the frigid grasp which held them without feeling her fingers touch his? But the pangs of his thirst gathered force from minute to minute, until overpowered by them, he stretched out his feverish and trembling hands across the coffin in the darkness, and laid them upon the dead hands of his wife.

The cold struck through him with an icy chill that he would never forget, but he would not now fail in his purpose. He loosed the violets from her fingers, and rushed away from the place, not daring to pause for an instant till he had reached the gin-palace where he could sell them.

THE PRICE OF A DRAM.

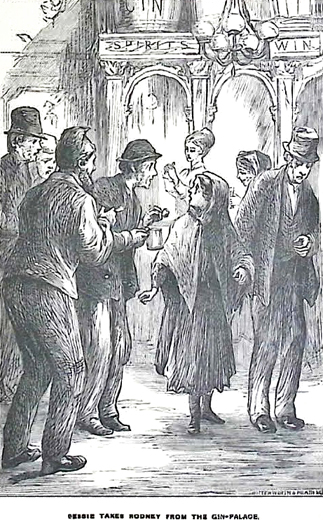

RODNEY had not left the house many minutes when Bessie Dingle entered it, shading with her hand a candle which she had borrowed from a neighbour. She stepped softly across the room, and looked down with tearful eyes upon her friend's corpse. The hands had been disturbed, and the flowers were gone. Bessie started back for an instant with terror, but guessing instinctively what had happened, and whither the miserable man had gone, without hesitation she drew her shawl over her head, and ran down the street in the direction he had taken.

She had to peep into three or four gin-palaces before she found him, lolling against the counter, and slowly draining the last few drops of the dram he had bought. There were not many customers yet in the place, for it was still early in the night; and the man behind the counter was fastening into his button-hole the bunch of violets, with their delicate white blossoms, and the broad green leaf behind them. Bessie did not pause in her hurried steps, and she threw herself half across the counter, speaking in clear and eager tones.

"You don't know where those vi'lets come from," she cried; "he's taken 'em out of the hands of his poor dead wife, where I put 'em only this afternoon, because she loved 'em so, and I thought they'd be buried with her. I think she knows what he's done, I do. Her face is gone sadder—ever so—since I saw it this afternoon; for he's stolen the posy from her, I tell you, and she lying dead!"

Bessie's voice faltered with her eagerness and grief; and the people present gathered about her and Rodney, listening with curious and awed faces; while the purchaser of the flowers laid them down quickly upon the counter.

"Dead!" he exclaimed. "Come straight from a dead woman to me!"

"Ay!" said Bessie. "Straight! And she loving him so to the very last, and telling me when she could hardly speak, 'Take care of him, take care of him!' And he goes and robs her of the only thing I could give her. That's what you make of a man," she continued, more and more eagerly; "you give him drink till there isn't a brute beast as bad; and he was a kind man to begin with, I can tell you."

"It's his own fault, my girl," said the man, in a pacifying tone; "he comes here of his own accord. We don't force him to come."

"But you do all you can to 'tice him in," answered Bessie; "if it wasn't standing here so handy, and bright, and pleasant, he wouldn't come in. There's something wrong somewhere, or Mr. Rodney 'ud never be like that, or do such a thing as that, I know. Look at him! And when I was a little girl, he jumped into the river after me, and saved my life."

She pointed towards him as he was trying to slink away through the ring that encircled them, bowing his head with a terrified and hang-dog look. The little crowd was beginning to sneer and hiss at him, but Bessie drew his hand through her own strong, young arm, and faced them with flashing eyes and a glance of indignation, before which they were silent.

"You're just as bad, every one of you," she cried; "you take the bread out of your children's mouths, and that's as bad as stealin' vi'lets from your poor, dead wife. It doesn't do her any real harm, but you starve and pinch, and cheat little children, and it harms them ev'ry day they live. None of you have any call to throw stones at him."

She thrust her way through them, and was leading Rodney to the door, when the man behind the counter called to her to take away the flowers.

"Do you think I'd take 'em from such a place as this?" she asked, more vehemently than before. "Could I go and put 'em back into her poor, dead hands, after he'd bought a glass o' gin with 'em? No, no; keep 'em, and carry 'em home with you, and tell everybody you see what your customers will do for drink. I'd sooner cut my fingers off than touch them again."

The courage her agitation had given her was well-nigh spent now, and she was glad to get Rodney out of the place. She trembled almost as much as he did, and the tears rained down her face. She did not try to speak to him until Rodney began to talk to her in a whimpering and querulous voice.

"Hush!" she said. "Hush! Don't go to say you couldn't help it, and she loving you so to the very last minute of her life. 'If he'd only pray to God to help him!' she said. And then, just before she was going away, she said, 'Bessie, you take care of him and Nelly.' And I'm going to do it, Mr. Rodney. You saved me once, and I'm going to try to save you now, if God 'll only help me. It shan't be for want of praying to Him, I promise you. Oh! If you'd only give it up now at once before you get worse and worse."

BESSIE TAKES RODNEY FROM THE GIN-PALACE.

"I can't be any worse," moaned the drunkard.

"Not much, may be," said Bessie, frankly; "you went and stole Nelly's doll for drink, and now you've stole the vi'lets. But you might be dead, and that's worse. And every day you're only getting nearer it, and if you go on drinking, you're sure to die pretty soon. Perhaps, if you go on as you are, you'll be dead in a very little while."

"I wish I was dead," he groaned.

"Why!" exclaimed Bessie, in a tone of astonishment. "And then you could never undo the harm you've done to poor little Nelly, that you love so, I know, spite of all. If you'd only think of Nelly, and think of God—I don't know much about God, you used to know more than me; but I've a feeling as if He really does care for us all, every one of us, and you, when you're drunk even. If you'd only think of Him and little Nelly, you wouldn't get drunk again, I'm sure."

"I never will again, Bessie; I never will again," he repeated fervently. And he continued saying it over and over again, till they reached the gallery at the top of the staircase.

Bessie drew him aside as he was about to turn into his own room.

"No," she said, "you couldn't bear to stay in there alone all night; it 'ud be too much for you. Mrs. Simpson, as is taking care of Nelly 'll let you sit up by her fire; and I'll go and stay in your house. I'm not afeard at all. She loved us all so—you, and Nelly, and me. We're going to bury her in the morning, and I'd like to sit up with her the last night of all."

Before long Rodney was seated by his neighbour's fire, in a silent and very sorrowful mood, with Nelly leaning against him, her arm round his neck, and her cheek pressed against his. He was quite sober now; and his spirit was filled with bitter grief, and a sense of intolerable degradation. He loathed and abhorred himself, cursed his own sin, and the greed of the people who lived upon it. If the owners of these places of temptation—members of Christian churches, some of them—could hear the deep, unutterable curses breathed against them, their souls would be ready to die within them for their own sin, and the terrible shame of it.

HALF MEASURES.

AS soon as Mrs. Rodney was buried, Bessie entered upon her charge of Rodney and Nelly. She was little more than a child herself in years, but her life in the streets had given her a keen, shrewd knowledge of human nature. She set about at once to make Rodney's home more attractive than it had been during his wife's illness. And every evening, as soon as her own necessary livelihood was earned, she hastened to spend all the time she could with him and Nelly. She could sing and talk well; and Rodney, whose good resolutions were deeper than usual, was often induced to stay at home, or pay only a brief visit to some public-house, for the sake of society, accompanied by both Bessie and Nelly, who waited for him outside the door, now and then sending in a message, till he was ashamed of keeping them longer.

There was a little change for the better. Nelly's rags were covered by a gay pink cotton frock, trimmed with a number of small flounces, which Bessie picked up cheap at a clothes-shop, and which she washed until the colour was faded. Rodney often promised to buy his little daughter the other clothes she so greatly needed; but work was slack, very slack for unsteady hands like him; and he could earn but little, more than half of which still went for drink. But he had no violent outbreak, and often when he was tempted to greater excesses, there rose before his mind the image of his dead wife, with the violets in her folded hands. This memory, with Bessie's influence and Nelly's love, had a salutary effect upon him in part; and in his heart, he had determined to be altogether a changed and reformed man some day.

By degrees Rodney recovered confidence in himself and his own power of moderation. Three months had passed since his wife's death, and he had never been so drunk as to be incapable. Bessie, with the sanguine delight of a girl, believed in his reformation, and rejoiced in it openly; while Nelly praised and fondled him every day. The slavery of the habit seemed over; he was master of it, or at least he was no more than a hired servant, who could cast off the yoke at any moment, and be altogether free. He drank still, drank deeply; but he could come out of the gin-palace with money in his pocket; a feat impossible a few months ago. The abject drunkards, who could not tear themselves away from the neighbourhood of the spirit-vaults, became objects of contempt and disgust to him. He was pursuing the rational and manly course of breaking off the habit by slow but sure degrees.

Yet there was not after all much to be proud of. The poor place at home was still bare and comfortless, in spite of Bessie's efforts; Nelly was pining for better food, and he himself was shabby and out-at-elbow. No person passing him in the street would have distinguished him from the drunken objects he despised. He was feeble and tremulous still; his eyes were red and dim, and his head was hot. The only point gained was that the vice, which still had possession of him, held him with a somewhat slighter grasp.

But when the next autumn came, and heavy fogs from the river filled the town, Bessie caught cold after cold till her spirits failed her, and she could do little more than call in at Rodney's house upon her way home to her lodgings, where she longed to lie down to rest. There was nobody to wile away the listless time at home, and if he stayed longer than usual at the beer-shop or gin-palace, there was no one waiting for him outside, for he took care to lock Nelly up safely before he left her. By little and little the old slavery established itself again in all its tyranny. He had built his house upon the sand, and the storm came and beat upon it, and it fell; and great was the fall thereof.

Night after night Rodney came home late, raving more furiously than ever, while Nelly crouched in the darkest corner of the little room in an agony of terror, not daring to stir lest she should draw his attention to her. Sometimes, as she grew better, Bessie would make her way through the chilly evenings to the house to exert her old influence, but she found that it was all gone before this new outbreak. Once he struck her brutally, and thrust her out into the rain, bidding her begone, and come back no more; but the faithful girl would not forsake him and little Nelly. She was hoping against hope.

A SORROWFUL FACT.

IT was not long before the time came when Rodney was never really sober. When he could not stagger along the narrow streets to the spirit-vaults, he sent Nelly, as scores and hundreds of little children are sent in our Christian country; and he drank himself dead drunk in the room where his wife had died. At last there was neither shame, nor sorrow, nor a consciousness of sin in his soul; only the one absorbing, insatiable craving for drink. A seven-fold possession had taken fast hold of him, and Bessie lost all hope.

It was quite dark one evening, and Rodney was lying prostrate, unable to stir, upon the low bed, with a bottle near him which he had lately drained, but without power to fumble with his nerveless fingers for any more pence which might possibly remain in his possession. His eyes were open, and in a state of drunken lethargy he was watching Nelly going softly to and fro about the room, casting terrified glances at him from time to time. He saw her bent almost double under the weight of the old iron-kettle, which she was lifting with both her little arms on to the fire; and lying there, powerless and speechless, he saw the thin, ragged frock, with its torn and faded flounces, catch the flame between the bars, and kindle rapidly into a blazing light about her.

An extreme agony came upon him. With all the might of his will, he struggled to raise himself up to save her; but he could not move. He had no more power over his own limbs than the mother's corpse would have had, if it had been lying there. For a moment, his little girl stretched out her arms to him with a scream for help; and then she sprang past him to the door, and he heard the street ring and echo with her cries, and the shrieks of frightened women and children. But still he could not stir. He lay there like a log, while great drops of terror and anguish gathered on his face.

How long it was he did not know—it might have been years of torment—before the door was flung open, and a woman's face looked in upon him, white and haggard with fear.

"She's burned to death!" she cried, "and you'll have to answer for it. I'm not sorry; I'm glad. She'll be better off now; and I hope they 'll hang you for it. You'll have to answer for the child's death."

She drew the door to again sharply, and left him in his miserable and helpless loneliness. Nelly was dead then; burned to death through his sin! The intolerable agony of his spirit gave him a little strength, and he crawled upon his hands and knees to the door, and succeeded in opening it. Down in the street below the people were talking of it, the women calling to one another to tell the horrible news; he could hear many of the words they said, with his name sometimes, and sometimes Nelly's. Dead! Was it possible that his little Nelly could be dead? Why did they not bring her home? But then a great shuddering of horror fell upon him. He could not bear to see her again, his dead child; burned to death with him lying by, too drunk to save her.

By and by his limbs gathered more power, and with pain and toil he raised himself to his feet. The tumult in the streets was subsiding, and the people were retiring to their houses. Some of them, who lived on the same flat, kicked at his door with loud and angry curses; but he had locked it as soon as his fingers could turn the key, and he kept a silence like the grave. All was quiet after a while, and the clocks of the town struck eleven. If he could only steal away now, there would be no one to stop him and ask him what he was about to do, or whither he was going. The streets were almost deserted, except about the gin-palaces. He cursed them bitterly as he went by. There was now only one purpose, one idea in his tormented brain: if his miserable feet would but carry him to the river, all should soon be ended for him. Nothing in the world to come could be worse than the hell of his own sin. The only plea Bessie herself could urge—that he should live to make amends to Nelly—had no longer an existence.

It was slow and weary work, creeping, creeping down to the river side. He saw it long before he reached it, with the lights glimmering across it from the opposite shore. He was obliged to lean often against the walls and the lamp-posts to gain breath and power to take a few more footsteps towards his grave. He was drunk no longer. His mind was terribly clear. He knew distinctly what had happened, and what was about to happen to him if his strength would only take him down to the edge of yonder black water. His conscience raised no voice against his purpose. There was a certain feeling, almost of satisfaction, that in a little while the tide would be carrying him out to sea.

He had almost gained a spot where a single effort would plunge him into the cooling waters; there were but few persons about, and they at some distance away, far enough not to hear the splash as he fell into the basin, when his unsteady foot caught upon the curb-stone, and he fell forward, dashing his head violently upon the pavement. Before many minutes had passed, a policeman was conveying him in a cab to the infirmary; and he was laid, unconscious and delirious, upon a bed in one of the wards there.

FOUND DROWNED.

THREE days after Rodney's disappearance, Bessie was sitting at an apple-stall in her old place by the landing-stages, when the news ran along the line of basket-women that the body of a drowned man had just been brought ashore at one of the wharves near at hand. Bessie's heart sank within her. There had been no tidings of Rodney since the evening she had first missed him, though she had sought everywhere for him; and she recollected too well the threat he had often made of putting an end to his life. She felt sick and giddy at the mere thought of recognizing him in this drowned man, yet she left her basket and stall in charge of a neighbour, and ran in search of the crowd which would be sure to gather about the ghastly object.

Bessie pushed through the circle of bystanders, and looked down on the dripping form lying upon the stones. The face was livid and disfigured, and the scanty hair was smooth and dark; yet it was like him, so like him that Bessie fell upon her knees beside him, sobbing passionately.

"Oh! I know him!" she cried. "He saved me from being drowned once, and now he's gone and drowned himself. Oh! I wish he could be brought to life again! Is he quite dead? Are you sure he's quite dead?"

"He's been in the water two or three days," said one of the lookers-on, speaking to another who stood near.

"Oh! Then, it must be him!" sobbed Bessie. "It must be him. It's three days since little Nelly set herself on fire while he was drunk; and he went and drowned himself. He used to say he'd do it, and I hindered him. Why wasn't I there to hinder him again?"

"Are you his daughter?" asked a policeman.

"No, I was nothing to him," answered Bessie, "only he saved me from being drowned when I was a little girl. He ought never to have come to this; he oughtn't. He was a good man, and as kind as kind could be when he was himself. Oh! Why wasn't I here, Mr. Rodney, when you came to drown yourself?"

"Do you know where his family lives?" asked the policeman again.

"He hasn't got any family now," said Bessie, with fresh tears; "his wife died at Easter, and little Nelly is dying in the hospital. They say they think she'll die to-day, but I'm to go again this evening. He's got nobody but a mother down in the country thirty miles away; and as soon as I can walk it, I was going to tell her about Nelly; and now there 'll be this to tell her as well. And he was such a good man once."

"You must tell me where you live," said the policeman; "we shall want you on the inquest, you know."

"Oh, yes," she answered, "but I haven't got any more to tell. Only I was very fond of him and Nelly, I was."

She rose from her knees and wiped her eyes, watching them earnestly as they carried the corpse into a small public-house near at hand, where it was not unwelcome, as it brought custom to the bar. The next morning she gave her evidence at the inquest, and the corpse was buried as that of John Rodney. Bessie gave up the key of the house, which she had kept in her possession; and the few poor articles of furniture in it were sold by the landlord to pay the rent that was due to him.

In the meantime, and for several weeks after, Rodney lay on the verge of death, crazy and delirious with brain-fever. His wretched life hung upon a thread, and only the marvellous skill and patience of those about him could have saved it. Nothing was known of him, and when the delirium was over, his mind and memory were at first too weak for him to give any account of himself.

As recollection returned and conscience awoke, he kept silence, brooding over the terrible history of the past. There were time and opportunity now, during the long hours, day and night, while he lay enfeebled, but sober, calling up one by one all the memories of his sad life. He knew that he should be compelled to live now, and compelled to enter upon the desolate future, with its sore burden of remorse and shame. He vowed to himself that if ever he went out into the streets again, where temptations beset him on every hand, nothing should induce him to fall again into sin.

When the time came for him to leave, he was asked where his home was, and what he intended to do. Rodney's white and sunken face flushed a little as he answered, "I've no home now," he said. "I had one once as good as a man could wish for. I earned good wages, and I'd a dear wife and little children to meet me when I came in from my day's work. But I threw it all away for drink. All my children are dead—the last that died was little Nelly. And my poor wife is dead, thank God! I've nobody in the world belonging to me, save my old mother, and I've broken her heart. I think I'll go home to her; I know she'll take me in."

With half-a-crown to pay his fare down to his mother's house in the country, Rodney left the infirmary, and found himself once more in the familiar streets, with their common, everyday sounds and sights, and their gin-palaces thrusting themselves upon his notice at every other minute of his progress through them.

DEEPER STILL.

WITH bowed head and despair tugging at his heart, Rodney passed through the noise and business of the streets. He was bent upon seeing over again the poor place where his wife had died and Nelly been killed. It was the middle of the morning as he approached it, and as he shrank from being the object of notice to his former neighbours, he slunk down the side-alleys and passages, which brought him almost opposite the building where his home had been. Again he climbed the worn steps and gave a low knock at his own door, which was quickly answered by a voice calling, "Come in."

Yes, his home was gone, quite gone. Here was another family on the same road to ruin as himself, dwelling within the old walls. Upon the hearth was a woman sitting on a low stool and nursing a wailing baby, with a bottle in reach of her hand, while the scent of gin, which made every nerve in him creep and tingle, filled the place.

She looked up with blood-shot eyes: and asked him what his business might be.

"I'd a friend who lived here once," he said, leaning against the door-post, for he felt faint and giddy, "John Rodney by name. I suppose he's gone?"

"Oh! He's dead," answered the woman, "drowned himself: and a good thing too. Everybody was glad to hear the news. His little girl set herself afire, and him lying there, the brute, too drunk to stir; couldn't lift hand or foot to help her. Mrs. Simpson, as lived next door, said how she see him crawl away after, down them steps and up the street, and three days after his body was found in the river."

"What did you say about the little girl?" he asked, sick at heart.

"Why! She set herself afire at this very grate, and him lying as it might be there, and she ran out, all in a flame, down them steps, and was burned to death. Bless you! I'd lots of folks to see the place, specially ladies; but they're forgetting it now. I couldn't bear it at first myself, but I bore up. This 'll help you bear up against anything."

She laid her hand on the bottle, smiling drearily, and Rodney shivered and shuddered throughout all his frame. He knew well what it would do for him: what a warmth, what a genial glow would run through all his veins, till some, at least, of this deadly sickness of heart would pass away. In the hospital he had had wine given to him at stated intervals, and his burden had always seemed lighter after he drank it. Here, within the narrow compass of these bare walls was the scene of his most terrible remembrance; but here also the temptation beset him with awful and renewed strength. He gazed with greedy eyes at the bottle in the woman's hand.

THE VISIT TO THE OLD HOME.

"It's all gone," she said, "or I'd have given you a drop."

Rodney turned away without a word, his brain on fire with the old hellish craving for drink. Some words were running through his mind with monotonous repetition,—

"Cool my tongue, for I am tormented in this flame."

Half-way down the narrow street lay a man in the gutter, the butt for any passer-by to kick at. The children had strewn ashes upon his head and face, from the dust-heaps which lay before each door, without disturbing the profound slumber of the drunkard. Rodney stood still and gazed at him, with a mingled feeling of wonder and envy to think of what, deep draughts he must have taken, and what utter forgetfulness had come over him. At length, he passed onwards to the more public thoroughfares. There was the old frequented gin-palace, with its easily swinging doors, and its attractive appliances to help the temptation to conquer him. He could resist no longer; and he did not turn away from the counter till the whole of the money, given to him to carry him to his mother's home, was gone.

It was some hours before Rodney came to himself; being hastened to it by a shove from the foot of the proprietor, who had allowed him to lie asleep in a corner of the place during the slack hours of the daytime. It was time for him now to make room for others who had money to spend. He gathered himself up and stood on his feet, looking drearily into the man's face.

"Where am I to go to?" he asked. "I've spent my last penny with you. I haven't got a hole to put my head in, nor a farthing in my pocket. Where am I to go to?"

"Where you were last night," said the man angrily.

"I came out of the infirmary this morning," he answered, in a bewildered tone; "where am I to go to to-night?"

"To the workhouse then," said the man; "only out of this anyhow."

He opened the door, and pushed him out.

Rodney tottered to a doorway, and sat down, gazing at the stream of people constantly passing by, with a rigid and stony face of despair. It was still twilight, and a crimson flush was tinging the sky westward, while a fresh invigorating breeze played about his burning forehead.

"Oh God! Oh God!" he cried within himself. "I meant to have kept that vow. Where can I hide myself from these places that entrap me? Would to God they'd take me into some madhouse, and put a strait-waistcoat on me! I am mad, or the devil is in me. If I could but crawl to some place where they'd lock me up and keep me from it, if I died for thirst! Oh! If there were only such a place for a madman like me!"

But there was no place for him, even to shelter him for the night. He was homeless, without a penny or a friend in the great and busy town. Or rather, there was one refuge for him—the workhouse. The thought of going there came dimly to him at first; but by and by he began to see that it was not merely the only place for him, but it was a place where he could not be assailed by the sight and smell of the poison which took away his senses. As long as he could keep to the resolution of remaining within its walls, he would be preserved from the temptation of the numberless gin-palaces which met him at every turn. It might be that after a time, the spell would be broken; the devil's witchcraft which had cost him so much.

It was a painful pilgrimage, with his heavy feet and despairing spirit, to make his way to the workhouse. He could only be admitted to the casual ward for the night; but the next morning he entered, as an inmate, this last and only refuge.

"God help me," he said to himself, "God help me to keep inside these walls. I daren't trust myself in the streets. If there's any chance for me, it's here."

THE ONLY REFUGE.

FOR a season Rodney's mind was clouded and bewildered. It is probable that if he had been in ordinary health and strength, he could not have held to his resolution to keep within the walls, which were his only defence from overpowering temptation. But though his craving often amounted to intense agony, the weakness which was the result of his long and dangerous illness made him incapable of much exertion, and the little labour he was put to completely exhausted his powers. Day after day passed by, the hours dragging along heavily. In the midst of the miserable poor who peopled the place, he lived alone, in a kind of dreary lethargy of body and soul, which rendered him almost unconscious of what was going on around him.

Gradually, however, the cloud which drunkenness had brought across his mind melted away, and his thoughts and memories grew clear. All his past life lay behind him, mapped out plainly and distinctly; his early manhood, his strength of muscle and nerve, his marriage, his children, and last of all his little Nelly,—all sacrificed, all destroyed, all lost, by his fatal obedience to the sin which had possessed him. It had come to this, that he who should have been a happy and useful man, respected and beloved, was a pauper, eating the begrudged bread of a workhouse table. He had been acting out the story told centuries ago by the Lord of truth and wisdom. He had left the Father's house and wandered into a far country, where a sore famine had arisen; and behold! he was eating the husks which the swine did eat, and no man gave unto him. That was his condition.

It was a long time before Rodney went any farther than that. Broken-hearted and cast down in spirit, he thought he must resign himself to abide in his miserable condition. An importunate remorse was gnawing in his conscience, and he said to himself, it was only just that he should be left without hope, and without God, in a world where he had brought all his misery upon himself. At this time, little Nelly was always in his thoughts, the puny, pale little child, puny and pale through his vice, hungry often, crying often, seldom merry and light-hearted as other children are, yet always patient and fond of him, always ready to be glad if he only smiled upon her. Oh! What a wretch he had been!

How often, too—his memory was vivid in recalling it—how often, when he had received any money, had he resolved to hasten home with it that Nelly's wants might be supplied, and those accursed gin-palaces had been strewn so thickly in his path that when he had reached home, it had been penniless, but raging mad with drink, striking the quiet, patient little creature if she only came in his way!

But one morning, so early that it was still an hour or two before the paupers left their pauper beds, a whisper seemed to come to his troubled conscience, partly, as it were, in a dream, which said to his awakening ears,—

"I will arise, and go to my Father."

He repeated the words over and over again. Had that poor prodigal son, living amongst swine, and eating of their husks, still a right to call any good and great being his Father? Still, it was he who had said it, without hesitation, as it seemed, in saying the word, Father: Christ, the Son of God, who knew all things, and could make no mistake, was He who had told the story. The miserable prodigal, who had spent every penny in riotous living, just as he had done, when he came to himself, had said, "I will arise, and go to my Father." Was it possible he could do the same?

Day after day Rodney pondered this question over in his heart. Long ago he had known that Jesus Christ had come to seek and to save those who were lost; and now, if he would only suffer himself to be found by Him, if he would only receive Christ and His love, He would give, even to him, the power to become one of the sons of God. Oh! If Christ would but find him! down there in his deep degradation and despair! Had He never known a drunkard like him! If He had not when He was a man on earth, He knew them now, by hundreds and thousands, in the streets of Christian cities; His pure eyes beheld them in all their vileness, in their desecrated homes, and in the gin-palaces thickly studding the streets.

The day dawn that was breaking upon his soul grew stronger and stronger, until the shadows fled away. There was neither drink nor the temptation to drink to make it dim, or to quench it. He could think now. He could repent, pray, and believe. Reason and faith could work within him, and there was no subtle foe to steal away his senses. The hour came at last, when from his inmost soul, drunkard though he had been, though his wife and little Nelly had perished through his sin, he could look up to God, and cry, "Father!"

TRUE TO A PROMISE.

IT was not many days after this that Rodney came to the conclusion that he ought not to stay any longer within the sheltering walls of the workhouse, to be a burden upon the poor-rates. He was strong enough now to earn his own living, though he could never regain the vigour he had thrown away. Weakness of body, and a sorrowful spirit within him, must be his portion in this life, though his sin was forgiven, and his heart could call God his Father. He knew also that outside the gates, within sight of them, a vehement temptation would assail him. Even there, within the refuge, if the thought of drink came across him, he could only find help against it in earnest prayer. Would the demon take him captive again if he ventured out to confront the peril?

With a trembling heart, and in an agony of prayer, Rodney left his shelter and found himself once more free and unrestrained in the streets. He was compelled to pass the places of his temptation, not once or twice only, but scores of times, with the fumes of the liquors poisoning the atmosphere about them. He could not help but breathe it, could not choose but see the gaudy and bright interiors, as his feet carried him from one fierce assault to another. Sometimes he felt as if he should be lost if he did not flee back to the shelter he had left, and end his days there shamefully. But he continued his course down to the docks, where he hoped he might happen on work to supply his wants for that day and night, for if he failed, he must return to the casual ward for a lodging.

He had earned a few pence, and was about to seek lodgings for the night, when he saw a number of decent working-men crowding into a schoolroom, which was well lit up. He stopped one of them to ask what was going on inside.

"It's a lecture," he answered, "on temperance, by Mr. Radford. He's always plenty to say, and says it out like a man. Come in, and hear him."

"Ay, I'll come in," said Rodney eagerly, forgetting both his hunger and fatigue.

The lecture had just begun, and the speaker, whose face was earnest and hearty, and who had a pleasant voice, had gained the fixed attention of his hearers.

"I'll tell you what a promise once did," he said, towards the close of his lecture: "We had a meeting of our Band of Hope some years ago, and I saw amongst the children a rough, barefoot little girl staring about her with large, eager eyes, as if she could not make out what we were about. I asked her her name, and told her to come to my house; and I wrote down my address for her. But I said to her, 'Will you promise me not to taste anything that will make you drunk till you see me again?' And she promised me."

"That's Bessie Dingle!" cried Rodney, half aloud.

And the lecturer paused for an instant, looking down kindly but gravely upon his listeners.

"I expected her to come to me within a day or two, and I should have persuaded her to join our Band of Hope; but she never came. Nearly six years were gone, and one day last autumn, when I was on the landing-stage, I heard some one cry out, 'That's him again!' And a girl of seventeen or so, a bright, busy girl, came rushing towards me from an apple-stall.

"'I've kept my promise, sir!' she cried. 'I've never took a drop to make me drunk. I said I never would till I see you again.'

"The girl had been faithful to her promise. Yes, in her place, and according to her strength, she had kept her promise, as God keeps His."

Rodney scarcely heard the end of the lecture, so full was his mind of Bessie, whom he had scarcely thought of, but who was the only friend he had left in Liverpool. He could not go away without making some inquiry after her; and when the audience was dispersing, he made his way up to the lecturer's desk:—

"Sir," he said, "that girl was Bessie Dingle. Could you tell me where I could find her this very night?"

"She left Liverpool last autumn," he answered; "she is gone to live in the country with an old woman of the name of Rodney."

"Why! That must be my mother!" exclaimed Rodney, involuntarily.

"Who are you?" inquired Mr. Radford.

"My name's John Rodney," he answered; "Bessie knows all about me. Oh, sir! I was a dreadful drunkard; and one night I saw my little girl—she was the last of them, and my poor wife was dead as well, thank God!—and the child set herself on fire, and me lying by so drunk I could not move; I could not stir a limb no more than if I'd been dead. Oh God! Oh God! It was a horrible thing."

Rodney grasped the desk with both hands to keep himself from falling, and neither he nor the stranger could speak again for some moments.

"I understood you were drowned," said Mr. Radford at length; "Bessie believes so; she told me all about it."

"No," murmured Rodney, "I went off with the intention of putting an end to myself; but I slipped on the pavement, and they carried me to the infirmary. I was there a long time, and then I went home, and other folks had taken to my house, and I'd no place to sit down in, and the liquor-vaults were the only place open to such as me, and I went in and got dead drunk again."

"Again!" repeated Mr. Radford.

"Ay, again," he said, with a deep groan; "but it was the last time. I pray God it may be the last time. Then I knew there was no hope for me as long as I could see or smell drink, and I went into the workhouse to be out of the way partly, and partly because I'd no other place to go to. I only came out this morning."

"And where are you going to now?" asked his new friend.

"Anywhere," he answered; "but I'm afraid of going where they 'll be drinking. There seems to be drink everywhere. You don't know what it is down in the low parts of the town, sir."

"Yes, I do," said Mr. Radford; "but I'll speak to a friend of mine here, who will take you to his place for to-night. He was one of the first to join us here, and he was as great a slave to drink as you ever were before."

"Sir," said Rodney, earnestly, "I believe God has forgiven me, and I believe He will help me. He has helped me this day, or I should never have been here. If you will let me join myself to you, with a promise, I'll try to keep it as Bessie kept hers, God helping me."

"I believe from my heart it would be of great use to you," answered Mr. Radford, after a moment's thought. "Mark! I do not say it will save you, but it will help you. You can give it as a reason for not drinking to your old comrades; but the chief thing will be that it will bring you into acquaintance with new comrades of your own way of thinking, who will not tempt you to drink. Remember, too, if you should break it, that's no reason why you should not promise again; yes, and again and again, if you fall again and again. Most of us promise God very often to give up our favourite sin, and when we forget our promise, He does not forbid us to renew it."

With trembling fingers, and with deep, unspoken prayer in his heart, Rodney signed his name to a form by which he pledged himself to abstain from all intoxicating drinks; and then Mr. Radford committed him to the care of his friend, who was to take him home for the night.

"What are you going to do to-morrow?" asked Mr. Radford.

"I'll make my way down to my mother's," he answered. "I shall be safer out of the town, though I ought to be ashamed to go to her in these rags. But it's no more than I deserve, and she'll be overjoyed to see me."

"Go down by train," said Mr. Radford. "I will lend you the fare, and you can repay me when you are in work again. They all think you are dead down there."

"Yes," he answered, smiling sadly, "my mother will say, 'This my son was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found.'"

With these words he went his way; and after a night's rest, more refreshing than any he had had for years, he started by the earliest train down into the country.

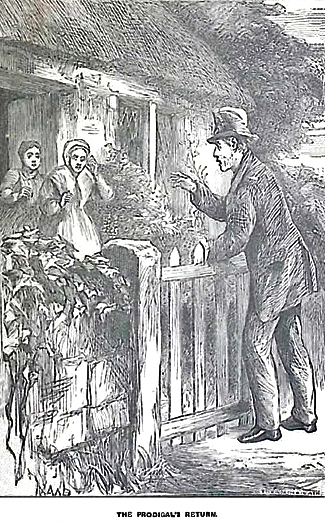

DEAD AND ALIVE AGAIN.

IT was spring-time again—twelve months since his wife had died. The hedgerows were sweet with primroses and violets, whose fresh fragrance was full of sorrowful memories to Rodney. The years, which had changed him so much, had hardly touched the face of the country. Every step of the road was familiar and dear to him. Here were the nut-bushes, where he and his brothers had come nutting in the autumn, when he was a boy; they were fringed and tasselled with yellow catkins now. On the other side of the hedge lay the corn-fields, where they had all gone gleaning together in the harvest, as happy a time as any in the whole year.

Yonder was the bank where the violets grew thickest, and where he had been used to seek the first-scented blossom for Ellen, before they were married. The wooden bridge over the shallow brook, whose water rippled round pebbles as bright as gems, where he had paddled barefoot when he was young—barefoot like little Nelly, only it had been sport to him; the willow-trees dipping down into the stream; the cottage-roofs; but above all, the thatched roof of his own cottage home; all seemed to him like another world, compared with the noisy, bustling, tempting streets of Liverpool, where, in those parts to which he had sunk, there were none but sordid sights and sounds of misery. Oh! If Nelly had only lived a young life like his own!

He reached the garden-gate, and leaned against it, looking down the long, straight, narrow walk which led to the door. It stood open, and the sun was shining brightly into the house, lighting up for him the old, polished oak dresser, with the shelves above it, well filled with plates and dishes. A lavender and rosemary bush grew close up to the door-sill, and the bees were humming busily about them. He could hear also the murmur of voices; the prattle of a child's voice talking gaily within, out of his sight.

Once he saw Bessie cross the kitchen to the little pantry, but she did not glance his way, through the open door. And he still lingered outside, scarcely knowing how he should make himself known to his mother, who believed he was dead.