Title: A history of English lotteries

now for the first time written

Author: John Ashton

Release date: December 16, 2025 [eBook #77478]

Language: English

Original publication: London: The Leadenhal Press Ltd, 1893

Credits: deaurider and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

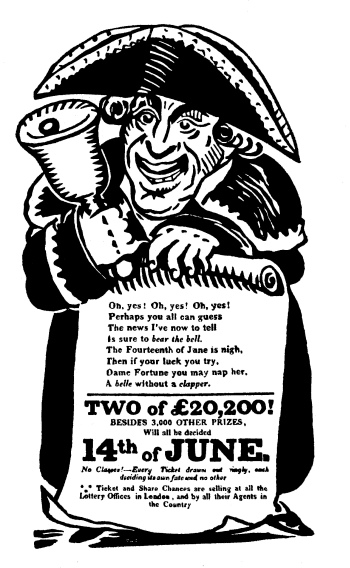

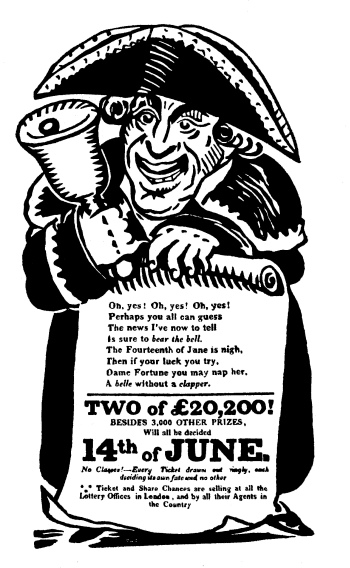

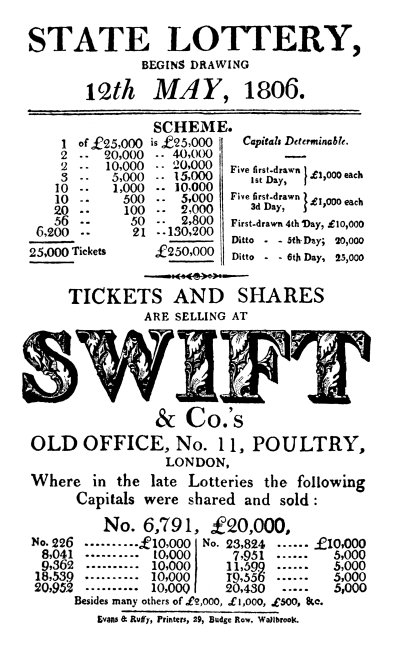

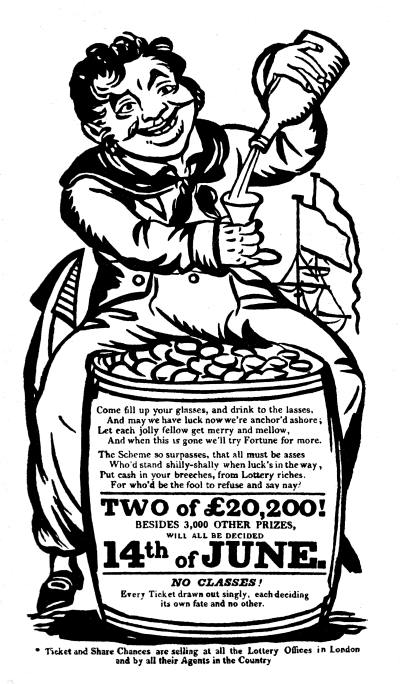

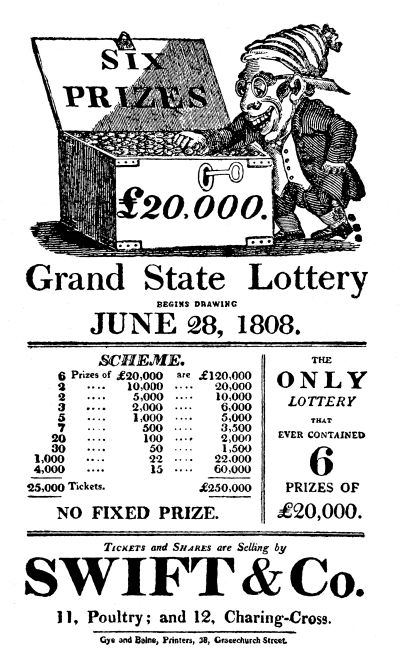

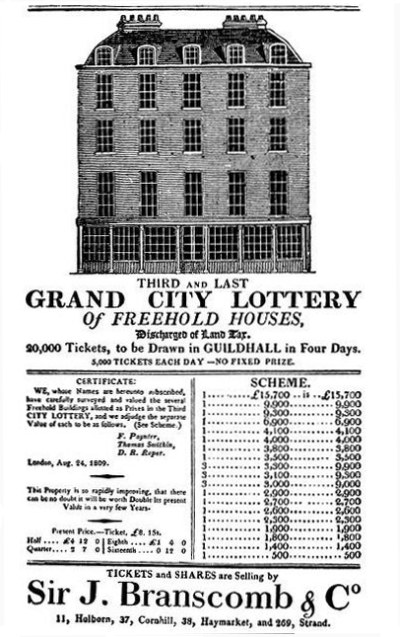

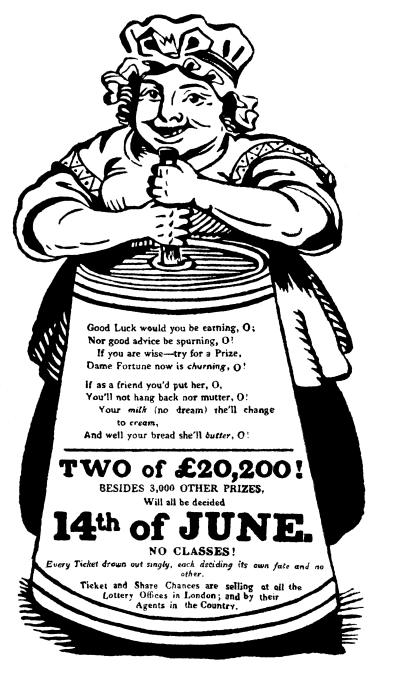

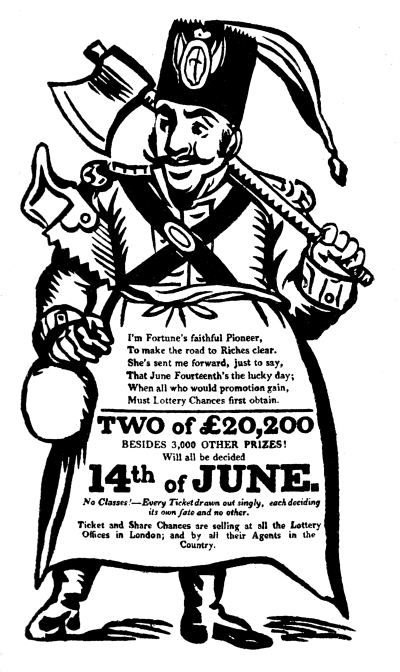

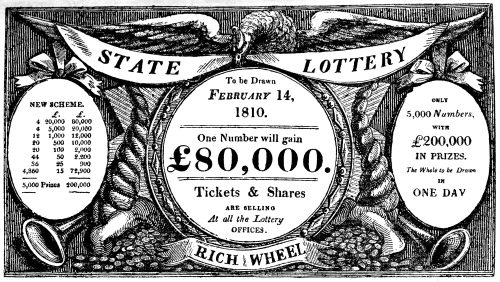

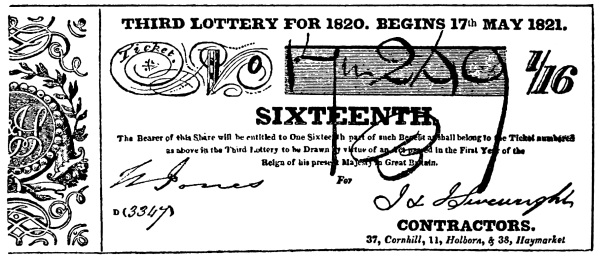

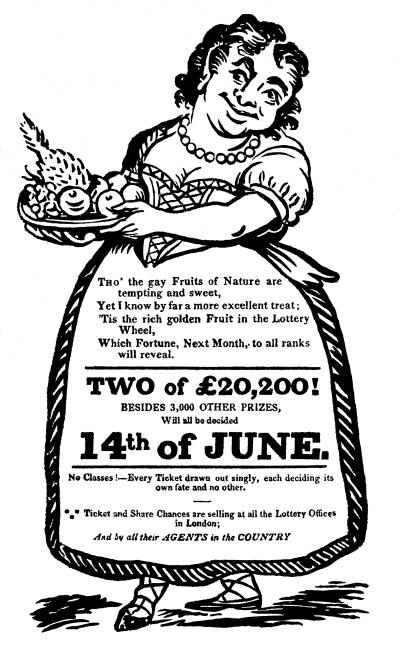

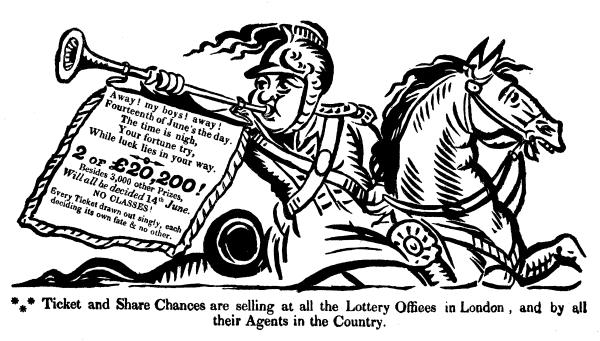

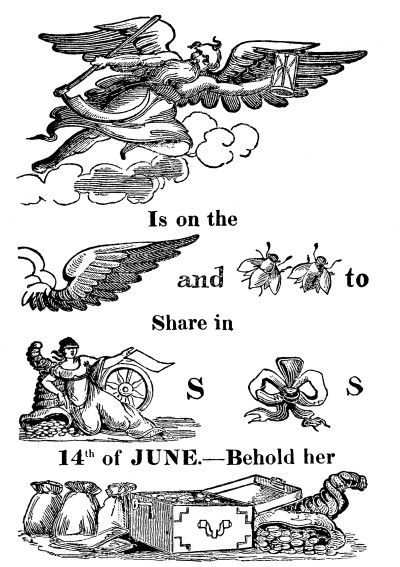

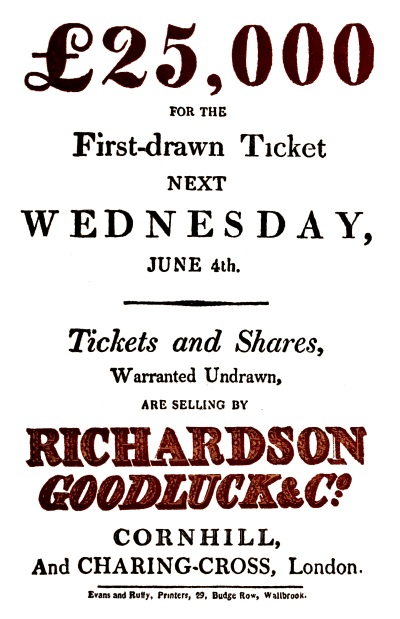

In addition to the numerous illustrations scattered throughout the text, there are twenty-eight separately inserted old Lottery Bills in facsimile on papers of various tints. It will be noted that the dirty red ink in some of them is exactly imitated.

The “skeleton” bills were issued in 1816, and those of the “14 of June” in 1821; most of the others are dated.

They are placed as follows:—

Facing title page; facing pages 1, 16,

32, 48, 70, 96, 112, 128, 138, 144 (two),

146 (two), 160, 170, 176, 192 (two),

196, 208, 220, 224 (two), 240, 280

(two), 324.

NOW FOR THE FIRST TIME WRITTEN.

BY

JOHN ASHTON.

1893.

PUBLISHED BY

The Leadenhall Prefs, Ltd:

50, Leadenhall Street, London, E.C.

Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., Ltd:

New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 743 & 745, Broadway.

THE LEADENHALL PRESS, LTD: LONDON, E. C.

(T. 4630)

[Pg v]

PREFACE.

In the following pages I have endeavoured to trace the history of the lottery in England, from the year 1569 to the present time; and it is somewhat surprising that such has not been previously attempted. It is possible that a paucity of material may have had something to do with it; but, in my case, I cannot complain of insufficient matter, but almost of an embarras des richesses; for not only could I draw on the stores of information contained in the library of the British Museum, but I also had the privilege of having the very fine collection of Mr. Andrew Tuer placed unreservedly at my disposal. Thus, I have been enabled to pick and choose my examples of lottery handbills and [Pg vi]engravings, without having to utilize all the material that came to hand. I am especially indebted to the Leadenhall Press for the very great care they have taken in rendering the engravings as near facsimiles of the originals as possible.

I have tried, as far as in my power lay, to make this book one which will be, I hope, not only agreeable and interesting to the general reader, but one which, I also hope, will find its place in very many libraries, as a book of reference, and an authority on the subject on which I have written, as I have been very scrupulous as to verifying dates, giving correct Acts of Parliament, etc.

[Pg vii]

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| Antiquity of the Lot—Old lotteries—Derivation of | |

| word —First lottery in England: its scheme | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. |

|

| Posies and mottoes—Forcing the subscriptions—Towns and | |

| their mottoes—Lottery for armour in 1585—A Royal lottery | |

| at Harefield in 1602 | 17 |

| CHAPTER III. |

|

| The Virginia lottery of 1612—Private lottery—Licence for | |

| lottery to supply London with water—Two other schemes | |

| —Lottery in behalf of fishing vessels—Irish Land | |

| Lottery—One for redeeming English slaves—One for poor | |

| maimed soldiers—Gambling lottery, concession for—“Royal | |

| Oak” Lottery—Evils of lotteries—“Royal Fishing Company” | |

| Lottery—Patentees | 28 |

| CHAPTER IV. |

|

| A book lottery—One for poor military officers—Lottery for | |

| Prince Rupert’s jewels—A penny lottery—First State | [Pg viii] |

| lottery—Another in 1697—Private lotteries suppressed | |

| —Statelottery in 1710—Curious history of a private | |

| lottery—State lotteries in the reigns of Anne and | |

| George I.—Private lotteries again suppressed—Raine’s | |

| Charity—Marriage by lottery | 44 |

| CHAPTER V. |

|

| Penalties on private lotteries—State lottery not subscribed | |

| for—Lapse in State lotteries—Private lotteries | |

| —Westminster Bridge lottery—State lotteries—Discredit | |

| thrown on them—British Museum lottery—Leheup’s fraud | 59 |

| CHAPTER VI. |

|

| Crowd at a lottery—Another State lottery, eighty-seven | |

| blanks to a prize—A ticket sold twice over—Extravagant | |

| prices paid for tickets—Praying for success—A lucky | |

| innkeeper—Lottery for Cox’s Museum—Adam’s Adelphi Lottery | |

| —Blue-coat boys and the lottery—Future arrangements for | |

| drawing | 71 |

| CHAPTER VII. |

|

| Counterfeiting lottery tickets—Curious lotteries—Suicide | |

| —Method of starting a State lottery—Lottery | |

| office-keepers to be licensed—Charles (or “Patch”) Price | 86 |

| CHAPTER VIII. |

|

| Lottery for the Leverian Museum—Prosecution of unlicensed | |

| lottery office-keepers—Suicide—Robbery of employers—Sharp | |

| practice over a prize—Cheating by lottery office-keepers | |

| —Complaint of a prisoner | 103 [Pg ix] |

| CHAPTER IX. |

|

| Winners of prizes—Attempt to put down the practice of | |

| insuring—Steps taken to prevent it—Specimen handbill | |

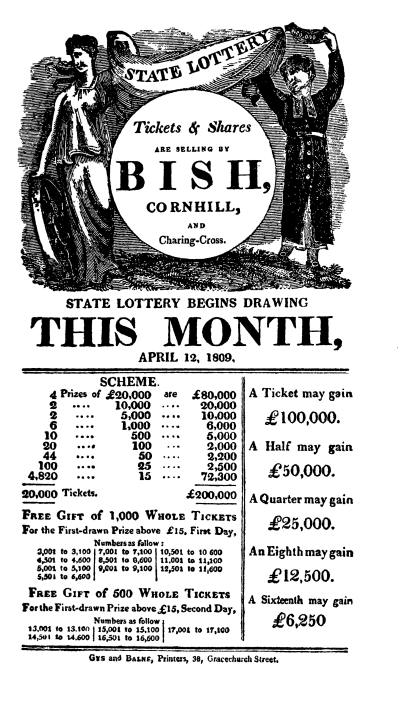

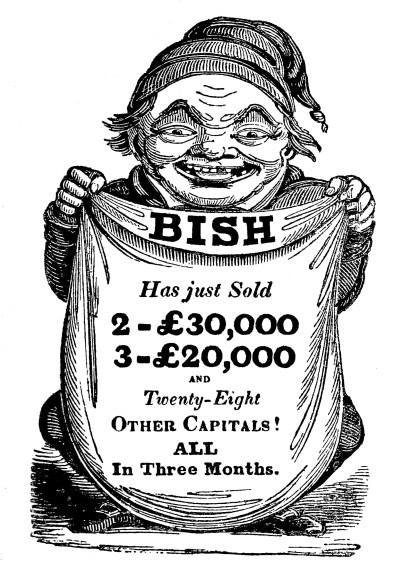

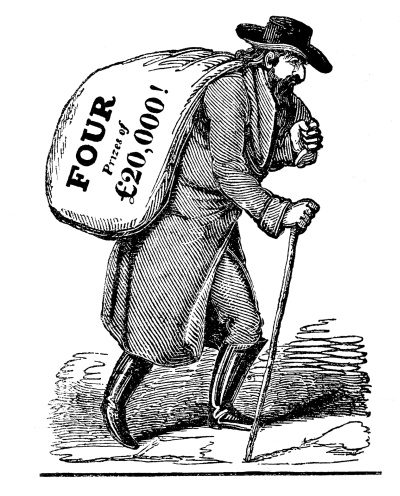

| —Bish, the lottery office-keeper—Lottery for the “Pigot” | |

| diamond—Lottery-office agencies—Shortening the time of | |

| drawing the lottery—Story of Baron d’Aguilar | 118 |

| CHAPTER X. |

|

| The Boydell Lottery—Bowyer’s “Historic” Lottery | 133 |

| CHAPTER XI. |

|

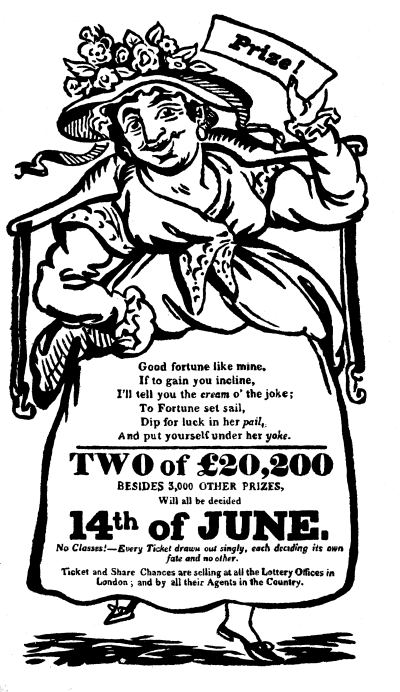

| Launching a lottery—“The City” Lottery for houses—Poetic | |

| handbills thereon—Parliamentary Committee on the lottery | |

| —Report and evidence | 147 |

| CHAPTER XII. |

|

| “The Lottery Alphabet”—“The Philosopher’s Stone”— | |

| “Fortune’s Ladder”—Enigmatical handbill—Lottery drawn | |

| on St. Valentine’s Day—“Public Prizes”—and other | |

| poetical handbills | 162 |

| CHAPTER XIII. |

|

| “Twenty Thousand; or, Tom Truelove’s Journal”—“London | |

| and the Lottery”—“The Persian Ambassador”—“An Enigma” | |

| —“Gently over the Stones” | 180 |

| CHAPTER XIV. |

|

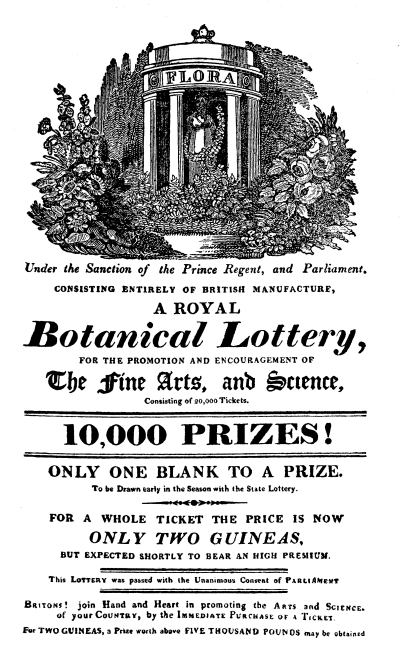

| “Master and Man”—“Altogether”—Dr. Thornton’s “Royal | |

| Botanical Lottery”—“Two Gold Finches”—“Dennis | |

| Brulgruddery”—“Shakespeare’s Seven Ages” | 189 [Pg x] |

| CHAPTER XV. |

|

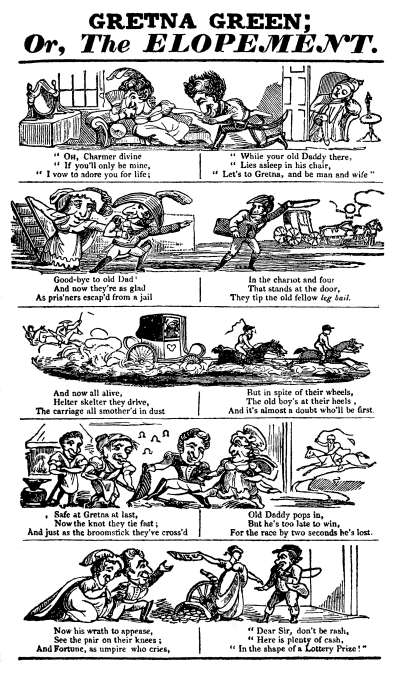

| A lucky Spaniard—Miss Mitford’s prize—The Spectator | |

| on lucky numbers—Other anecdotes on luck—“Gretna Green” | |

| —“A Prize for Poor Jack” | 204 |

| CHAPTER XVI. |

|

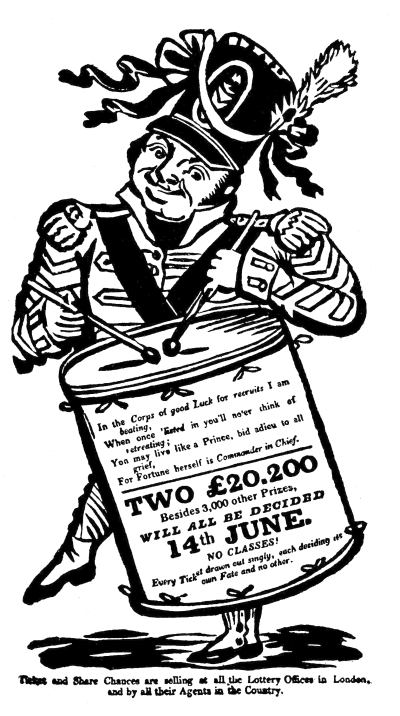

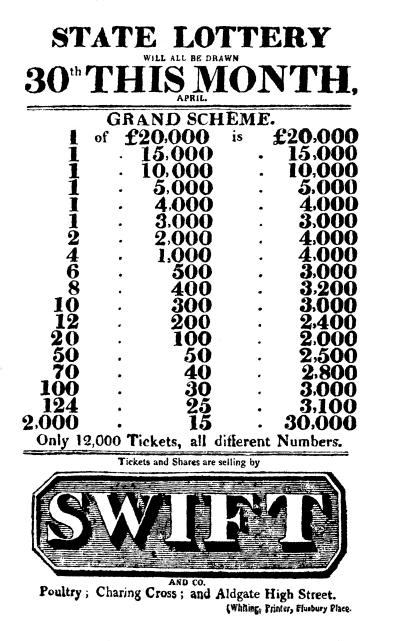

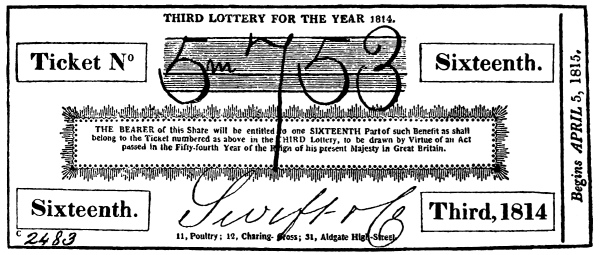

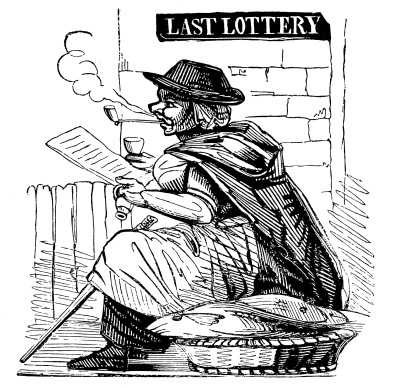

| Beginning of the end of lotteries—Curious handbills | 217 |

| CHAPTER XVII. |

|

| Protests against lotteries—Epitaph on Vansittart—“Three | |

| Royal Weddings”—More opposition to the lottery— | |

| “Twelfth Night Character” handbills—Ditto of tradesmen | 221 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. |

|

| “A Dialogue”—“The Race of Fortune”—“The Wish”—Enigmatical | |

| handbill | 245 |

| CHAPTER XIX. |

|

| Tomkins’s picture lottery—The lottery abolished—Handbills | 252 |

| CHAPTER XX. |

|

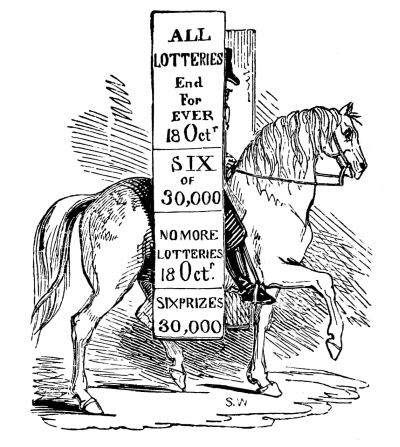

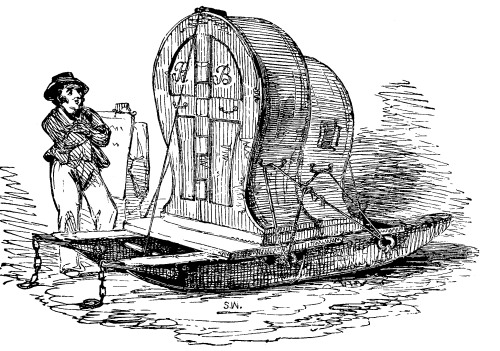

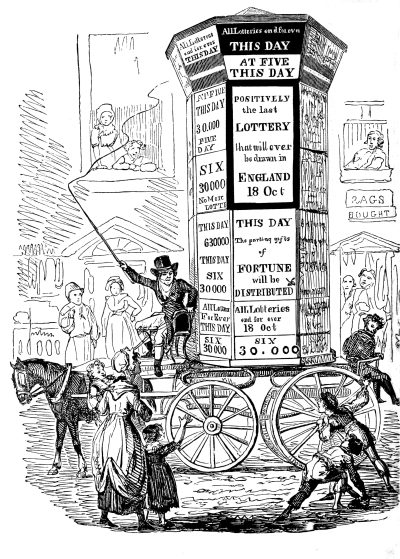

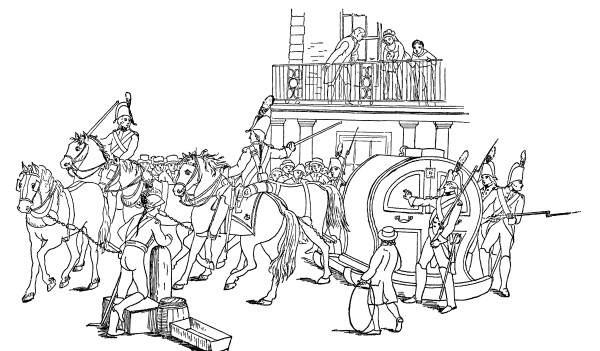

| The last lottery—Attempts to get up excitement—The | |

| procession—Alteration of date—Advertising car—“A | |

| Ballad, 1826”—Drawing of the last lottery | 265 |

| CHAPTER XXI. |

|

| Handbills—Metrical list of lottery-office keepers—Bish’s | |

| manifesto—“Epitaph in Memory of the State Lottery”— | |

| “Little Goes”—The Times thereon—Their effect on the | |

| public | 279 [Pg xi] |

| CHAPTER XXII. |

|

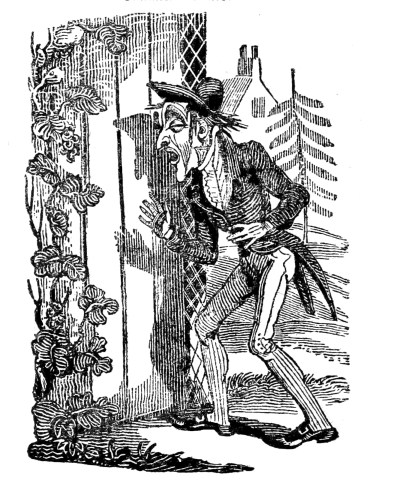

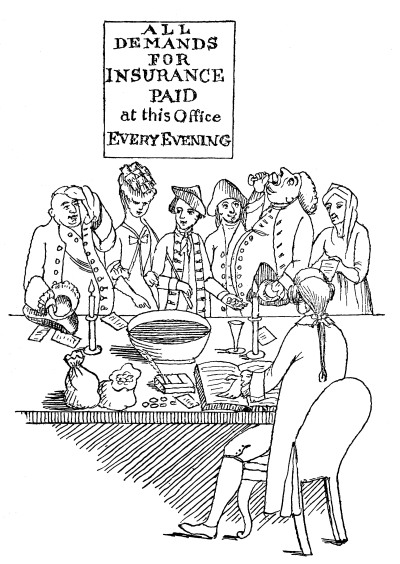

| Description of lottery office-keepers—Insuring numbers | |

| in the lottery—Servants bitten by the mania—Morocco | |

| men—Many prosecutions—Cost to the country—Several | |

| law cases—Story of Mr. Bartholomew | 293 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. |

|

| Suicides caused by the lottery—Story of a footman—Anecdote | |

| told by Theodore Hook—Description of a lottery from its | |

| commencement to its end | 310 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. |

|

| The lottery wheels—Anecdotes connected with the lottery— | |

| The Glasgow lotteries—Advertising foreign lotteries— | |

| “Art Union” Act—Dethier’s “Twelfth Cake Lottery”— | |

| Tontines—Raffling—Pious lotteries—Sweet-stuff lotteries | |

| for children—Hamburg lotteries | 325 |

| CHAPTER XXV. |

|

| “The Missing Word Competition:” its rise and fall | 339 |

| Index |

353 |

[Pg 1]

A HISTORY OF

ENGLISH LOTTERIES.

Antiquity of the Lot—Old lotteries—Derivation of word—First lottery in England: its scheme.

[Pg 2] So sang Henry Fielding in his play of “The Lottery,” which was first acted at Drury Lane Theatre, January 1, 1732; and I think those who have patience to read these pages will endorse his words.

Gambling, in some shape, is inherent in man, and dice for the casting of Lots have been found belonging to the Egyptians and Assyrians, in the tombs of prehistoric man, were used alike by the refined Greeks and Romans, and by the barbarous Northmen. The Bible teems with notices of the Lot. It was recommended by Solomon as a means of deciding disputes. “The lot causeth contentions to cease, and parteth between the mighty” (Prov. xviii. 18). It was used as a means of dividing land. “Notwithstanding the land shall be divided by lot: according to the names of the tribes of their fathers they shall inherit. According to the lot shall the possession thereof be divided between many and few” (Numb. xxvi. 55, 56). Nay, one of the Apostles, Matthias, was chosen by Lot (Acts i. 26). But if any one is curious to know how often the Lot is mentioned in Holy Scripture, let him look at Cruden’s Concordance. [Pg 3]

In this short sketch we see the antiquity of the Lot; but the Lottery, the form of gambling of which this book treats, is of comparatively modern invention. The Romans had something of the kind, but it partook more of our presents from Christmas-trees than the modern lottery. First of all were the Apophoreta, gifts which were presented to the guests at table, and which they carried home with them—a custom which obtained during the Saturnalia (something like a Silver King presenting his guests with a silver menu card, or the presents given to guests at City Companies’ dinners); and this was sometimes done in a whimsical manner, as is on record that Heliogobalus, at a banquet, presented one guest with a ticket for a gold vase, and another for six flies. Other prizes, which were drawn haphazard, were ten bears, ten pounds of gold, or ten ostriches; and, whilst one might draw a thousand pounds, another would gain a prize of a dead dog.

It is said that lotteries began in Italy in the sixteenth century, and that its name is derived from the Lotto of Florence; but I beg leave to traverse both propositions. There is no doubt but that the [Pg 4] Venetian and Genoese merchants made use of the lottery as a vehicle whereby to dispose of their stale goods, or to get rid of a valuable thing for which they could not obtain a purchaser; but the earliest I can find recorded was that of the widow of Jan van Eyck, which took place at Bruges, on February 24, 1446, where the town archives record a payment to her of two livres for her lottery.[1]

As for the name. I think that there can hardly be two opinions about it. Long before the Italian Lotto, was the Anglo-Saxon Hleot-an, sortiri, to cast lots. In the Dutch the same meaning is expressed by Lot-en, Loot-en; in Swedish, Lotta; whilst the Lot itself is in Gothic, Hlauts; Anglo-Saxon, Hlot; German, Los; Dutch, Lot; Swedish, Lott; French, Lot; and Italian, Lotto. So that there can be very little doubt of its northern derivation, the Latin synonym, Sors, being so totally different.

There is no doubt but that the lottery was imported into England from abroad; and the first of which we have any record was one in the reign [Pg 5] of Queen Elizabeth, projected in 1566, but not drawn till 1569. As far as is known, there is but one authentic record of this lottery in existence, which has been happily preserved in the muniment-room at Loseley House, in Surrey. It is in black letter, interspersed with ordinary text and italics, and the bill is five feet long by nineteen inches wide; and the text is surrounded by a border of ornamental type. At top, it has an illustration of the prizes in plate, tapestry, and money—and it is twenty inches in depth. As it is such an unique curiosity, I give the bill at length.

“A verie rich Lotterie Generall, without any blancks, contayning a number of good prices, as wel of redy money as of plate, and certaine sorts of marchaundizes, having ben valued and priced by the comaundement of the Queene’s most excellent majestie, by men expert and skilfull; and the same Lotterie is erected by her majesties order, to the intent that such commoditie as may chaunce to arise thereof, after the charges borne, may be converted towardes the reparation of the havens and strength of the Realme, and towardes such other publique good workes. The number of lots shall be foure hundreth thousand, and no more; and every lot shall be the summe of tenne shillings sterling onely, and no more. [Pg 6]

“Three Welcomes.

“The first person to whome any lot shal happen, shall have for his welcome, (bysides the advantage of his adventure,) the value of fiftie poundes sterling, in a piece of sylver plate gilte.

“The second to whome any lot shall happen, shall have in like case for his welcome, (bysydes his adventure) the summe of thirtie poundes, in a piece of plate gilte.

“The third to whome any price shall happen, shall have for his welcome, besides his adventure, the value of twentie pounds, in a piece of plate gilte.

“The Prices.

“Whoever shall winne the greatest and most excellent price, shall receive the value of five thousande poundes sterling, that is to say, three thousande pounds in ready money, seven hundred poundes in plate gilte and white, and the rest in good tapisserie meete for hangings, and other covertures, and certain sortes of good linen cloth.[2] [Pg 7]

“2nd, 'great price’ £3500, i.e. £2000 in money, £600 in plate, the rest in good tapisserie, &c., as above.

“3rd, £3000, i.e. £1500 in money, £500 in plate, the rest, &c.

“4th, £2000, i.e. £1000 in money, £400 in plate, the rest, &c.

“5th, £1500, i.e. £750 in money, £300 in plate, the rest, &c.

“6th, £1000, i.e. £500 in money, £200 in plate, the rest, &c.

“7th, £700, i.e. £400 in money, £100 in plate, the rest, &c.

“8th, £500, i.e. £250 in money, £100 in plate, the rest, &c.

“9th, £400, i.e. £250 in money, £100 in plate, the rest, &c.

“10th, £300, i.e. £200 in money, £50 in plate, the rest, &c.

“11th, £250, i.e. £150 in money, £50 in plate, the rest, &c.

“12th, £200, i.e. £150 in money, the rest in good tapisserie and linen cloth.

“13th, £140, i.e. £100 in money, £40 in plate, tapisserie, or linen cloth. [Pg 8]

“12 prices, every price of the value of £100, that is to say, 3 score and 10 pounds ready money, and £30 in plate, tapisserie, or linen cloth.

“20 and 4 prices, every price of £50, £30 in ready money, £20 in plate, tapisserie, &c.

“3 score prices of 4 and 20 pounds and ten shillings (£24 10/-), £17 in ready money, and £7 10/- in plate, &c.

“4 score and 10 prices, every price of £22 10/- i.e. £15 in money, £17 10/- in plate, &c.

“One hundreth and 14 of £18, i.e. £12 in money, £6 5/- in plate gilte and white.

“120 prices of £12 10/-, i.e. £7 10/- in money, £5 in like plate.

“150 prices of £8, i.e. £5 in money, £3 in linen cloth.

“200 prices of £6 10/-, i.e. £4 in money, 50/- in linen cloth.

“300 prices of £4 10/-, i.e. 50/- in money, 40/- in linen cloth.

“500 prices of £3 10/-, i.e. 40/- in money, 30/- in linen cloth.

“500 prices of 50/- in money.

“2000 prices of 40/- in plate.

“6000 prices of 25/- in money. [Pg 9]

“10,000 prices of 15/- in money.

“9418 prices of 14/- in money.

“And all the rest, to the accomplishing of the aforesayd number of lottes, shall be allowed for every adventure at the least 2 shillˢ and 6 pens in ready money.

“Conditions ordained for the advantage of the Adventurers in this Lotterie, bysides the Prices before mentioned in the Charte.

“The Queenes Majestie, of hir power royall, giveth libertie to all maner of persons that will adventure any money in this Lotterie, to resort to the places underwritten, and to abyde and depart from the same in manner and forme foliowing; that is to say, to the Citie of London, at any time within the space of one moneth next following the feast of S. Bartholomew this present yeare 1567, and there to remain seven days. And to these cities and towns following: York, Norwich, Exceter, Lincolne, Coventrie, Southampton, Hull, Bristol, Newcastell, Chester, Ipswich, Sarisbury, Oxforde, Cambridge, and Shrewesbury, in [Pg 10] the Realme of Englande, and Dublyn and Waterforde in the Realme of Irelande, at any time within the space of three weekes next after the publication of the Lotterie in every of the sayd severall places, and there to remaine also seven whole days, without any molestation or arrest of them for any maner of offence, saving treason, murder, pyracie, or any other felonie, or for breach of hir Majesties peace, during the time of their comming, abiding, or retourne.[3]

“And that every person adventuring their money in this Lotterie may have the like liberty in comming and departing to and from the Citie of London, during all the time of the reading of the same Lotterie, untill their last adventure be to them answered.

“Also, that whosoever under one devise, prose or poesie, shall adventure to the number of thirtie lottes and upward, within three monethes next following after the sayd feast of Saint Bartholomew, and by the hazarde of the prices contained in this Lotterie gaineth not the [Pg 11] thirde pennie, or so much as wanteth of the same, shall be allowed unto them in a yearely pencion, to begin from the day when the reading of the sayd Lotterie shall ende, and to continue yearely during their life.

“Whoever shall game the best, second, and third great prices, having not put in the posies whereunto the sayd prices shall be answerable into the Lotterie within three moneths next after the said feast of Saint Bartholomew, shall have abated and taken out of the summe of money contained in the said best price, one hundreth and fiftie pounds, and of the sayd second price, one hundreth pounds, and out of the said third price four score pounds, to be given to any towne corporate or haven, or to any other place, for any good and desirable use, as the partie shall name or appoint in writing.

“And whosoever shall gaine a hundreth poundes or upwarde in any price, saving the three severall best prices next aforementioned, having not put in his lots, whereby he shall gaine any such price, within three moneths next following the sayd feast of Saint Bartholomew, shall have abated and deducted (as above is sayd) out of every hundred pounds, five pounds, to be employed as is next before sayd. [Pg 12]

“Whosoever, having put in thirtie lottes under one devise or posie, within the sayd three moneths, shalle winne the last lot of all, if, before that lot wonne he have not gained so much as hath ben by him put in, shall for his tarying and yll fortune be comforted with the reward of two hundreth poundes, and for every lot that he shall have put in besydes the said thirty lots, he shall have twentie shillings sterlyng.

“And, whosoever having put in XXX lots under one devise or posie, within the sayd three moneths, shal win the last lot save one, and have not gayned so much as he hath put in, shal likewise be comforted for his long tarrying with the reward of C. pounds, and for every lot that he shal have put in above XXX shall receive ten shillings sterling.

“Item, whosoever shall adventure from fortie lottes upwarde, under one devise or posie, shall have libertie to lay downe the one halfe in readie money, and give in bond for the other halfe to the Commissioner that in that behalfe shal be appointed to have the charge for that citie or towne where the partie shal thinke good to pay his money, with condition to pay in the same money, for the which they shal be bound, [Pg 13] six weekes at the least before the day appointed for the reading of the lotterie, upon payn to forfaite the money payde, and the benefit of any price. Which day of reading shall begyn within the Citie of London the XXV day of June next coming.

“And in case it shall fortune the same day of the reading to be prolonged upon any urgent nedeful cause to a further day, the parties having adventured and put their money into the lotterie, shall be allowed for the same after the rate of ten in the hundred from the day of the prorogation of the sayd readyng untill the very day of the first reading of the lotterie.

“Item, every person to whome, in the time of reading, any price shall happen and be due, the same price shal be delivered unto him the next day following to dispose of the same at his pleasure, without that he shall be compelled to tary for the same until the ende of the reading. And, being a straunger borne, he shal have libertie to convert the same, being money, into wares, to be by him transported into foraine parts, paying only halfe custome for the same and other duties that otherwise he should answer therefore. [Pg 14]

“Whosoever at the time of the reading shall have three of his owne posies or devises, comming together successively and immediately one after another, the same having put in the sayd three posies within thre moneths (as before), shall have for the same posies or devises so comming together one after an other, three pounds sterling over and besides the price answerable therfore.

“And whosoever at the time of the reading shall have four posies or devises comming together successively and immediately one after another, having put in his sayde posies within three monethes (as before mentioned) shall have for the sayd foure posies and devises six poundes sterling, besides the prices.

“And whosoever at the time of the reading shall have five posies or devises comming together successively and immediately one after another, having put in his lottes within thre moneths (as before), shall have for the sayd five posies or devises ten pounds sterling, besides the prices.

“And whosoever shall have the like adventure six times together, having put in his lots, as afore, shal have for those VI posies or devises XXV pounds sterling and the prices. [Pg 15]

“And whosoever shall have the like adventure seven times together, having put in his lots as afore, shall have for those seven posies or devises a hundreth pounds sterling, and the prices.

“And whosoever shall have the like adventure eight times together, having put in his lots as afore, shall have for those eight two hundreth pounds sterling, and the prices.

“And so the posies or devises resorting together by increase of number, he to whom they shal happen in that sorte, having put in his money, as afore is said, shal have for every tyme of increase one hundreth poundes sterling, and the prices.

“The receipt and collection of this present Lotterie shall endure for the rest of the Realme besides London, until the XVᵗʰ day of April next coming, which shal be in the yere 1568.

“And the receipt and collection of the City of London shal continue unto the first day of May next following; at which dayes, or before, all the collectors shal bring in their bokes of the collection of lottes to such as shal be appointed to receive their accomptes, upon paine, if they do faile to do so, to lose the profite and wages appointed to them for their travell in that behalfe. Finally, it is to [Pg 16] be understanded that hir Majestie and the Citie of London will answere to all and singular persons havyng adventured their money in this Lotterie, to observe all articles and conditions contained in the same from point to point inviolably.

“The shewe of the prices and rewardes above mencioned shall be set up to be seene in Cheapsyde in London, at the signe of the Queene’s Majesties’ arms, in the house of M. Dericke, goldsmith, servant to the Queene’s most excellent Majestie.

“God save the Queen.

“Imprinted at London, in Paternoster Rowe, by Henrie Bynneman, anno 1567.”

[Pg 17]

Posies and mottoes—Forcing the subscriptions—Towns and their mottoes—Lottery for armour in 1585— A Royal lottery at Harefield in 1602.

We see by this bill that in order that the subscribers should be anonymous, their shares were not to be taken in their names; but, as in some competitions nowadays—notably in architecture—the competitors are only known by their mottoes, so every subscriber to this lottery was to use a devise or posie. Of the posies of this particular lottery one at least remains, and it may be found in Geffrey Whitney’s “Choice of Emblemes” (Leyden, 1586), p. 61.

“Written to the like effecte, vppon

Video, & taceo

Her Maiesties poesie, at the great Lotterie in London

begon M.D.LXVIII. and ended M.D.LXIX.

[Pg 18]

I see, and houlde my peace: a Princelie Poësie righte,

For euerie faulte, shoulde not provoke, a Prince, or man of mighte.

For if that Iove shoulde shoote, so oft as men offende,

The Poëttes saie, his thunderboltes shoulde soon bee at an ende.

Then happie wee that haue, a Princesse so inclin’de,

That when as iustice drawes hir sworde, hath mercie in her minde,

And to declare the same, how prone shee is to save:

Her Maiestie did make her choice, this Poësie for to have.

Sed piger ad pænas princeps, ad præmia velox:

Cuique doles, quoties cogitur esse ferox.”

In a little black-letter book in the Loxley collection, intituled “Prises drawn in the Lottery, from the XVI to the XXVI day of February,” which is considered to relate to this lottery, are very many of these posies, with the names of the persons, etc., whose ventures they represented, the number of the lots, and the prizes they gained, which were, naturally, in most cases under the ten shillings subscribed.

The highest prize drawn during these ten days seems to have been £16 13s. 3d., and the “devise” or motto was, “Not covetous.”

The public generally evidently did not take kindly to this venture, for [Pg 20] on September 13, 1567, the Lord Mayor found it necessary to supplement the foregoing Proclamation of the Queen, of August 23, by one of his own, guaranteeing the honesty of the scheme. “Nowe to avoyde certaine doubtes since the publication of the sayde Lotterie, secretely moved concernyng the answering thereof, wherein though the wiser sort may finde cause to satisfie themselves therin, yet to the satisfaction of the simpler sorte, the Lorde Maior of the sayd Citie, and his brethren the Aldermen of the sayd Citie, by assent of the Common Councell of the same, doe signifie and declare to all people by this proclamation that, according to the articles of hir Majesties order conteined in the sayd charte so published, every person shal be duly answered accordyng to the tenour of hir highnesse sayd proclamation.”

Still the public looked askance at it, and the subscriptions came in but slowly; so the Queen issued another proclamation on January 3, 1568, postponing the drawing, or “reading,” as it was called, giving her reasons therefor thus: “Forasmuch as in sundry parts of the realme, the principal persons that were appointed to be the treasurers for the [Pg 21] money that should be gathered in the severall shyres of the realme, had not received their instructions and charge in such due time as was requisite, by reason that upon the first nomination of them, there were, after sundry alterations of some by reason of sicknesse, of others by reason that they were dead aboute the time of their nomination; and of some others, that afterward were so otherwise occupied in publike offices, as the said service could not be by them executed, so as of the sayd space of three moneths, there passed over a good part, to the detriment of the adventurers.”

Yet it did not go off, and, to further stimulate the prosecution of the scheme, the Earl of Leicester and Sir William Cecil, as Lords of the Council, on July 12, 1568, sent a circular “To all and every the Quene’s Ma’t’s Justices of the Peace, Treasurers, and Collectors of the Lottery, and to all Mayors, Sheriffs, Bayliefes, Constables, and to all others her highnes officers, ministers and subjects, spirituall and temporale, as well as wtin corporations, lib’ties, and franchises, as wtout, in the Counties of Kent, Sussex, Surry, Southehampton and the Isle of Wight,” apprising them of the appointment of a Surveyor of the [Pg 22] Lottery, and enjoining them to do all in their power to get subscribers.

This surveyor certainly did put the screw on most unmercifully, visiting and writing to the country gentlemen, giving them “to understonde what waie is devised for a further collection, and for animating or moving the people, desiring you to put the same in practise as sone as possible you may.”

This certainly did stimulate the subscriptions, and we find by entries in their archives and by their posies that the towns all over England contributed municipally.

Winchester.—“July 30, 1568. Itm. That £3 be taken out of the Coffers of the cytie and be put into the lottrey, and so moche more money as shall make up evyn Lotts wᵗʰ those that are contrybutory of the cytie, so that it passᵈ not 10s.”

Wells.—“Oct. 15, 1568. At this Convoc’on the M’r and his brethrene w’the the condiscent of all the burgesses, hath fully agreed that ev’y occupacōn w’thin the Towne aforesayde shall make their lotts for the Lottery accordynge, as well to the Queene’s Ma’ty’s p’clamacōn as to her p’vy L’res assigned in that behalf.”

Yarmouth seems to have sent two subscriptions. [Pg 23]

All the City Companies subscribed, and, at last, the lottery was drawn, as Holinshed tells us (1569) that “A great lotterie being holden at London in Poules Church yard, at the west dore, was begun to be drawne the eleuenth of Januarie, and continued daie and night till the sixt of Maie, wherein the said drawing was fullie ended.” Let us hope that the ports and havens benefited therefrom.

The next lottery of which we have any knowledge is mentioned by Stowe in his “Annales,” under date of 1585. “A lotterie for marvellous rich and beautifull armor was begunne to be drawne at London in S. Paules Churchyard, at the great West gate (an house of timber and boord being there erected for that purpose) on S. Peters day in the morning, which lotterie continued in drawing day and night, for the space of two or three dayes.”

In 1602 Queen Elizabeth visited Sir Thomas Egerton, the Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, at his mansion at Harefield, Middlesex. She had a [Pg 25] particular liking for presents, and on the preceding New Year’s Day he had given her an amulet of gold garnished with sparks of rubies, pearls, and half-pearls, and his wife, dame Elizabeth, presented her Majesty with “a round kirtell of velvet satten, cut and embroidered all over like Esses of Venice gold, and a border embroidered like pyramids; and a doublet of silver chamlett, embroidered with pearls like leaves, flourished with silver.” He was well aware of her proclivities, for when she paid him this visit, he presented her with a divertissement called “a Lottery.” Enter—

“A Marriner with a boxe under his arme, contayning all the severall things following, supposed to come from the Carricke,[5] came into the Presence, singing this Song:—

“And the Song ended, he uttered this short speech: God save you, faire Ladies all; and for my part, if ever I be brought to answere my sinnes God forgive me my sharking, and lay usury to my charge. I am a Marriner, and am now come from the sea, where I had the Fortune to light upon these few trifles. I must confesse I came but lightly by them; but I no sooner had them, but I made a vow, that as they came to my hands by Fortune, so I would not part with them but by Fortune. To that end I ever since carried these Lots about me, that, if I met with fit company, I might devide my booty among them. And now (I thanke my good Fortunes) I am lighted into the best company of the world, a [Pg 27] company of the fairest Ladyes that ever I saw. Come, Ladyes, try your Fortunes; and if any light vpon an vnfortunate Blanke, let her thinke that Fortune doth but mock her in these trifles, and meanes to pleasure her in greater matters.”

There were thirty-three lots, of which five were blanks, and the “Marriner” had an appropriate couplet to say to all. The prizes were as follow:—1, Fortune’s Wheel (?); 2, a Purse; 3, a Maske;[7] 4, a Looking Glasse; 5, a Hand-kerchiefe; 6, a Plaine Ring; 7, a Ring with this posie: “As faithfull as I finde;” 8, a Paire of Gloves; 9, a Dozen of Points;[8] 10, a Lace; 11, a Paire of Knives; 12, a Girdle; 13, a Payre of Writing Tables; 14, a Payre of Garters; 15, a Coyfe[9] and Crosse Cloath;[10] 16, a Falling Band; 17, a Stomacher; 18, a Paire of Sizzers; 19, a Chaine; 20, a Praier Book; 21, a Snuftkin;[11] 22, a Fanne; 23, a Paire of Bracelets; 24, a Bodkin; 25, a Necklace; 26, a Cushinet;[12] 27, a Dyall; 28, a Nutmeg with a blanke parchment in it.[13]

[Pg 28]

The Virginia lottery of 1612—Private lottery—Licence for lottery to supply London with water—Two other schemes—Lottery in behalf of fishing vessels—Irish Land Lottery—One for redeeming English slaves—One for poor maimed soldiers— Gambling lottery, concession for—“Royal Oak” Lottery—Evils of lotteries—“Royal Fishing Company” Lottery—Patentees.

The next public lottery of which we hear was that of 1612, when “the King’s maiestie in speciall favor for the present plantation of English Colonies in Virginia, granted a liberall Lottery, in which was contained five thousand pound in prizes certayne, besides rewardes of casualitie, and began to be drawne, in a new built house at the West end of Paul’s the 29th of June, 1612. But of which Lottery, for want of filling uppe the number of lots, there were then taken out and throwne away threescore thousande blanckes, without abating of any one prize; and by the twentith of July all was drawne and finished. This Lottery was so plainely carryed, and honestly performed, that it gave full [Pg 29] satisfaction to all persons. Thomas Sharpliffe, a Taylor, of London, had the chiefe prize, viz. foure thousand Crownes in fayre plate, which was sent to his house in very stately manner: during the whole tyme of the drawing of this lottery there were alwaies present diuers worshipfull Knights and Esquiers, accompanied with sundry graue discreet Cittizens.”

In 1612, one Cornelius Drebbel wrote a letter in Latin to Prince Henry, complaining that the Lord Mayor had refused him permission to hold a lottery; that he had no other means of subsistence, and he begged the Prince to use his influence with the Lord Treasurer (Salisbury) for leave to have one beyond the jurisdiction of the city. He also wrote to the Lord Treasurer, enclosing a scheme of the proposed conditions of his lottery.

In 1620 the holding of lotteries was suspended by Order in Council; but on March 31, 1627, a licence was given to Michael Parker and Everard Mainwaring to raise money by means of a lottery, to be employed in carrying out the object indicated in the grant of same date to Sir Nicholas Saunder, Henry Saunder, and Michael Parker, which gave them [Pg 30] power to convey water by a covered aqueduct from certain springs near Hoddesdon, in co. Herts, and to disperse the same through the streets and houses, paying to the Crown a rent of £4000 per annum. And again, on February 11, 1831, Parker and Mainwaring obtained a licence to set forth lotteries for raising money for bringing springs of water to London. It is said, though I can find no warrant for it, that the first lottery with money prizes was drawn in 1630.

There was another scheme for bringing water to London, for in 1637 the Regent and Professors of the Musæum Minervæ petitioned the King for money, and proposed several schemes for raising the same, the third of them being, “By the Lottery granted to George Gage and others for bringing a river to London, much money was collected, but, the undertaking failing, the money remains in deposito, to be disposed to Sir Edward Peyto and Colonel Hambleton upon the like project. It is proposed that either this money be employed for the building of an academy, or that another lottery may be granted for that purpose.”

Yet another water scheme. “Jan. 14, 1689. Warrant to pass the Privy Seal appointing Sir Robert Pointz, K.B., and Edward Rudge, alderman of [Pg 31] London, for the just carriage and managing of the lottery authorized by the King for the use of the aqueduct undertaken by Sir Edward Stradling, Sir Walter Roberts and others.”

On February 9, 1640, the Earl of Pembroke sent a remonstrance to the King about the damage the “Dunkirkers and other subjects of the King of Spain” had done to the English busses, or fishing vessels, and suggesting that “towards the cost of setting out their busses the next summer, they pray a grant of a standing lottery, as the Virginia Company had in 1612, to be managed by the most discreet of their association;” and this his Majesty, Charles I., was graciously pleased to grant.

In 1653, according to the Perfect Account of the Daily Intelligence, November 23 of that year, a lottery was held, and this is the

“Advertisement

At the Committee for Claims for Lands in Ireland.

Ordered, That a Lottery be at Grocers Hall, London, on Thursday, 15 Decem. 1653, both for Provinces and Counties, to begin at 8 of the clock in the forenoon of the same day; and all persons concerned therein are to take notice thereof.” [Pg 32]

There was a lottery scheme August 7, 1660, which was granted. “The Petition of Capt. Thomas Gardiner to the King, to empower him to hold a lottery in England and Wales for three years, for ransom of English slaves in Tunis, Algiers, or the Turkish galleys, or for any other charitable use, paying in a third of the profits, and reserving the rest for his expenses, and repair of his fortunes, ruined by loyalty.”

In November, 1660, Captain William Pleydell petitioned “for leave to sell by lottery, during one year, some plate which he and others have procured, in order to gain relief for himself, and to obtain £10 each per annum for 12 poor maimed soldiers, named, of Lord Cottington’s life-guard, who live by begging in the street.”

[Pg 33] This was a comparatively worthy object, although the “relief for himself” might be capable of a very broad construction; but Charles II. was liberal in his concessions. There was one man, Francis, or Francisco, Corbett who was groom of the Privy Chambers to the Queen, who obtained a licence for a gambling lottery—possibly something like roulette at Monte Carlo, called L’Ocha di Catalonia. On November 23, 1661, an order was made forbidding a lottery carried on by Francisco Finochelli, as being the same with the L’Ocha di Catalonia, for which the sole licence was granted to Francisco Corbett, of whom we shall hear more; but it is best to proceed chronologically, if possible.

We next hear of him in connection with the famous “Royal Oak Lottery,” for on August 25, 1663, when a licence was granted to Captain James Roche, Adjutant of the Guards, and Francis Corbett to set up and exercise the lotteries of the Royal Oak and Queen’s Nosegay, in any place in England and Wales; none else to set up the same, or any lottery that approaches it, except Sir Anthony Des Marces, Bart., and Lawrence Dupuy, to whom a similar licence has already been granted. Meanwhile, Corbett and Finochelli had become partners, as we see by the docket on the memorial of August 28 of same year, of one Simon Marcelli, of money transactions between Captain Roche, Francis Corbett, and Jean Francisco Finochelli, relative to the lottery of the Royal Oak [Pg 34] set up at Smithfield Fair. Captain Roche furnished £95, on condition of not giving the company the patent till repaid; but, the sum being paid, he gave up the patent.

Corbett must have found the lotteries profitable, for on December 3 of the same year, a grant was made to Francis Corbett of licence to set up lotteries of a new invention, called the Royal Oak and Triomfo Imperiale, in any city in the kingdom, permitting no others to exercise the same except Sir Anthony Des Marces, Lawrence Dupuy, and Captain James Roche, to whom a similar privilege is given, on paying five shillings weekly to the poor where the lotteries are. But as soon as he got the concession, Corbett seems to have sold out; for there is a petition of Sir Anthony Des Marces, Bart., Lawrence Dupuy, and Richard Baddeley, for a licence to exercise the lottery of the Royal Oak and all others in England, Wales, and Ireland, as they had purchased the other partners’ interests, spent large sums of money thereon, and were checked in the exercise of them. Yet, still later on in the same month, in order to obtain this licence, they had to sign an indenture by which they agreed to pay a certain sum yearly to Sir John Crosland and [Pg 35] Captain Edward Bennett, in consideration of the services of Secretary Bennet in procuring for them the licence. On that indenture being signed came at once, the warrant for them to set up the lotteries of the Royal Oak and L’Ocha di Catalonia, applying the whole profits to support the fishing trade only, the patentees receiving fit recompense for their trouble. So that we see that there were small “Panama scandals” in those days. Indeed, this lottery seems to have been a swindle; for, in a letter, January 6, 1664, from Nathaniel Cale, who had been Mayor of Bristol, to Joseph Williamson, secretary to Sir Henry Bennet, and afterwards keeper of State Papers, he says he “will forward any lottery at the Bristol fair, except the Royal Oak, which broke half the cashiers in Bristol, when last there.” Yet, on the 11th of the same month, he writes to the same that he has prevailed with the Mayor, Sir John Knight, to allow the Royal Oak Lottery during the eight days of the fair; and, perhaps, the leave may be extended. But he has a prejudice against it; for, at its last being there, many young men ruined themselves, and his own son lost £50. [Pg 36]

The sequel to this story is told later on. On February 14, 1664, Sir John Knight wrote to Williamson that he had received his letters in behalf of the Royal Oak Lottery men, who have spent three weeks there. Last year they were there five months, and the cry of the poor sort of people was great against them, because, not being allowed by the great seal, they were clear against law. Will tolerate them some longer, but thinks they will soon be warped out. Nathaniel Cale writes that the Mayor has granted fourteen days to the Royal Oak, and then will grant more.

It would be impossible to close the notice of this lottery without quoting from a very rare little 12mo book,[14] as it gives us the inner life of the scheme; and, besides, is amusing. The indictment, as the wont of such documents, is cumbrous and heavy, and was terrible. The first witness called was Captain Pasthope, who was examined by one of the managers.

“Man. Sir, do you know Squire Lottery, the prisoner at the Bar?

[Pg 37] “Pasthope. Yes, I have known him intimately for near 40 years; ever since the Restoration of King Charles.

“Man. Pray, will you give the Bench and Jury an Account of what you know of him; how he came into England, and how he has behav’d ever since?

“Pasthope. In order to make my Evidence more plain, I hope it will not be judg’d much out of form, to premise two or three things.

“Man. Take your own method to explain yourself; we must not abridge or direct you in any respect.

“Pasthope. In the year 60 and 61, among a great many poor Cavaliers, ’twas my hard fate to be driven to Court for a Subsistence, where I continued in a neglected state, painfully waiting the moving of the waters for several months; when, at last, a Rumour was spread that a certain Stranger was landed in England; that, in all probability, if we could get him the Sanction of a Patent, would be a good Friend to us.

“Man. You seem to intimate as if he was a Stranger; pray, do you know what Countryman he was? [Pg 38]

“Pasthope. The report of his Country was very different; some would have him a Walloon, some a Dutchman, some a Venetian, and others, a Frenchman; indeed, by his Policy, cunning Design, Forethought, etc., I am very well satisfied he could be no Englishman.

“Man. What kind of Credentials did he bring with him to recommend him with so much advantage?

“Pasthope. Why, he cunningly took upon him the Character of a Royal Oak Lottery, and pretended a mighty friendship to antiquated Loyalists; but, for all that, there were those at Court that knew he had been banish’d out of several Countries for disorderly Practices, till at last he pitch’d upon poor easy credulous England for his Refuge.

“Man. You say, then, he was a Foreigner, that he came in with the Restoration, usurp’d the Title of a Royal Oak, was establish’d in Friendship to the Cavaliers, and that for disorderly Practices he had been banish’d out of several Countries; till, at last, he was forc’d to fix upon England as the fittest Asylum. But, pray, Sir, how came you so intimately acquainted with him at first?

“Pasthope. I was about to tell you. In order to manage his [Pg 39] Affairs, it was thought requisite he should be provided with several Coadjutors, which were to be dignify’d with the Character of Patentees; amongst which number, by the help of a friendly Courtier, I was admitted for one.

“Man. Oh! then I find you was a Patentee. Pray, how long did you continue in your Patentee’s Post? and what were the Reasons that urg’d you to quit it at last?

“Pasthope. I kept my Patentee’s Station nine years, in which time I had clear’d £4000, and then, upon some Uneasiness and Dislike, I sold it for £700.”

Francisco Corbett seems to have regretted the sale of his portion of this lucrative lottery, for, in 1663, he petitioned for a share, at least, in the lottery granted him by his Majesty, of which he was deprived by the interposition of others during his late absence; also for restoration to his place as groom of the Privy Chambers to the Queen, into which another had intruded, and for payment of some part of a pension promised him by his Majesty. We hear of him once more in a petition to the King written in Italian, probably in 1664, in which he said he was ill, on his journey to Paris, and too ill on his arrival to [Pg 40] see Madame. His Majesty promised him favour, if, owing to the impediments that Sir Henry Bennet makes to his game, he cannot profit by his promised letter of change. Had received no profit, and failed to obtain the money he hoped for in Paris, and begged that he might return to throw himself at his Majesty’s feet; but what became of him, I do not know.

That these lotteries were an acknowledged evil is well shown by the Domestic State Papers. Take, for instance, “July 11, 1663.—The King to the Mayor, Sheriffs, etc., of Norwich. Is informed of the ill consequences resulting from the frequency of lotteries, puppet-shows, etc., whereby the meaner sort of people are diverted from their work. Empowers him and his successors, magistrates of the city, to determine the length of stay of such shows in the city, notwithstanding any licences from his Majesty, or the Master of Revels.”

In 1664 this permission was relaxed, for Secretary Bennet wrote to the Mayor of Norwich, that, although the King had given authority to the magistrates of that town to allow or disallow the keeping of shows, games, and lotteries, in order to avoid abuses happening by their [Pg 41] licentious exercise; but now he signified his pleasure that no lotteries are to be allowed, except as appointed by Sir Anthony Des Marces, to whom the management of the same is granted for the benefit of the Royal Fishing Company.

Yet we find Court favour superseding this arrangement, for the same year a warrant was made out for a licence to Thomas Killigrew to set up a lottery for three years, after the expiration of the three years’ lottery granted to the Royal Fishing Company, called the Pricking Book Lottery, on rental of £50, to be paid to the said company. But Killigrew could not wait, and wrote offering £600 at once, or £650 in two payments, for the Pricking Book Lottery, of which Sir Anthony Des Marces had the power of disposal, and suggested that it was about the best offer he could expect.

However, there were others in the field hankering after this profitable gamble, for there is a letter from some person unknown to Killigrew, asking him to prevail with Sir Henry Bennet that some friends may have liberty from Sir Anthony Des Marces and Co. to use the Pricking Lottery, paying £200 a year as long as Sir Anthony has the management [Pg 42] of it; which, excepting £100 fine, is as much as the Fishing Commissioners ever offered. The reasons why they offered no more were—that there were never more than eight lotteries in England, and they were licensed by the Master of the Revels, and let at such rent as from £25 to £30 a year. Another person offered to give Sir Anthony £1000 for the reversion of the two unexpired terms in the lottery.

I fancy all this lusting after the profits of lotteries was noticed in high places, for there is a proclamation dated from Whitehall, July 21, 1665, forbidding any persons to use or exercise lotteries in Great Britain or Ireland, except Sir Anthony Des Marces, Louis Marquis de Duras, Joseph Williamson, Lawrence Dupuy, and Richard Baddeley, to whom the sole right of managing them is granted, in order to raise a stock for the Royal Fishing Company. But Sir Anthony was not content with this concession. He petitioned in 1666, together with his partners, for a grant for seven years of all lotteries in Scotland, and the foreign plantations. It seems possible that the interests of these patentees, or monopolists, was sold; for, on February 25, 1667, the Marquis of [Pg 43] Blanquefort and George Hamilton petitioned the King for the sole licence of holding lotteries in his Majesty’s dominions, giving as a reason that the Royal Company to whom it was granted, in 1664, for three years now expired, were indifferent to the renewal of their licence. And this must evidently have been arranged, for, on the same date, a warrant was issued giving them the sole licence of all sorts of lotteries in the kingdom of England and Ireland and the plantations for seven years.

[Pg 44]

A book lottery—One for poor military officers—Lottery for Prince Rupert’s jewels—A penny lottery—First State lottery—Another in 1697—Private lotteries suppressed—State lottery in 1710—Curious history of a private lottery—State lotteries in the reigns of Anne and George I.—Private lotteries again suppressed—Raine’s Charity—Marriage by lottery.

Very numerous were the unfortunate Cavaliers who had been ruined by supporting the Royal cause, and who could get no compensation from the Government. To help them, some asked to get rid of their plate, etc., by lottery, as we have seen in 1660, and, for their assistance, in 1668 a book lottery was established. In the Gazette of May 18 of that year is the following advertisement:—“Mr. Ogilby’s lottery of books opens on Monday, the 25th instant, at the Old Theatre between Lincoln’s Inn Fields and Vere Street, where all persons concerned may repair on Monday, May 18, and see the volumes, and put in their money.” On May 25 [Pg 45] is announced, “Mr. Ogilby’s lottery of books (adventures coming in so fast that they cannot, in so short a time, be methodically registered) opens not till Tuesday, the 2nd of June; then not failing to draw, at the Old Theatre,” etc.

Letters patent, in behalf of the Loyalists, were from time to time renewed, and from the Gazette of October 11, 1675, it appears, by those dated June 19 and December 17, 1764, there were granted, for thirteen years to come, “all lotteries whatsoever, invented, or to be invented, to several truly loyal and indigent officers, in consideration of their many faithful services and sufferings, with prohibition to all others to use or set up the said lotteries,” unless deputation were obtained from those officers.

Prince Rupert died November 29, 1682, and his jewels were to be disposed of by means of a lottery, but the public had been so cheated by previous schemes, that they would not subscribe unless the King consented to see that all was fair, and that Francis Child, the goldsmith (or banker) at Temple Bar, should be trustee on their behalf.

The London Gazette, September 27-October 1, 1683, has the following notice of this lottery: “These are to give Notice, that the Jewels of his late Highness Prince Rupert, have been particularly [Pg 46] valued and appraised by Mr. Isaac Legouch, Mr. Christopher Rosse, and Mr. Richard Beauvoir, Jewellers, the whole amounting to Twenty Thousand Pounds, and will be sold by way of Lottery, each Lot to be Five Pounds. The biggest Prize will be a great Pearl Necklace valued at £8000, and none less than £100. A printed Particular of the said Appraisement, with their Division into Lots, will be delivered gratis by Mr. Francis Child, Goldsmith, at Temple Bar, London, into whose hands, such as are willing to be Adventurers, are desired to pay their Money, on or about the first day of November next. As soon as the whole sum is paid in, a short day will be appointed (which ’tis hoped will be before Christmas) and notified in the Gazette, for the Drawing thereof, which will be done in His Majesties Presence, who is pleased to declare, that he himself will see all the Prizes put in amongst the Blanks, and that the whole shall be managed with all Equity and Fairness; nothing being intended but the Sale of the said Jewels at a moderate Value. And it is further notified for the satisfaction of all such as shall be Adventurers, that the said Mr. Child shall and will stand obliged to each of them for their several Adventures, till [Pg 47] the said Lottery be drawn. And that each Adventurer shall receive their Money back, if the said Lottery be not drawn and finished before the first day of February next.”

There are three other notices of this lottery, one of which (London Gazette, November 22-26, 1683) tells us the modus operandi of its drawing. “As soon as the Money is all come in, a day will be prefixed, and published for the drawing thereof, as has been formerly notified. In the morning of which day His Majesty will be pleased, publickly, in the Banquetting-House to see the Blanks told over, that they may not exceed their Number, and to read the Papers (which shall be exactly the same size with the Blanks) on which the Prizes are to be written; which, being rolled up in his presence, His Majesty will mix amongst the Blanks, as may also any of the Adventurers there present, that shall desire it. This being done, a Child appointed by His Majesty, or the Adventurers, shall, out of the Mass of Lots so mixed, take out the number that each Person adventures for, and put them into boxes, (which shall be provided on purpose) on the covers whereof, each Adventurer’s Name shall be written with the number of Lots He or She [Pg 48] adventures for; the Boxes to be filled in succession as the Moneys was paid in. As soon as all the Lots are thus distributed, they shall be opened as fast as may be, and the Prizes then and there delivered to those that win them; all which, ’tis hoped, will be done and finished in one day.”

I cannot find whether this lottery was ever drawn.

Perhaps the smallest sum ever adventured in a regular lottery was a penny, which was drawn at the Dorset Garden Theatre, near Salisbury Square, Fleet Street, on October 19, 1698, with a capital prize of a thousand pounds. There was a metrical pamphlet (price threepence) published thereon in the same year, entitled “The Wheel of Fortune; or, Nothing for a Penny,” etc., “written by a Person who was cursed Mad he had not the Thousand Pound Lot.” He thus describes the drawing—

[Pg 49] But not long after this, the State began to see what a profitable business lottery-keeping was, and applied it to its own purpose. In 1694, by Act of Parliament (5 Will. and Mary, c. 7), a loan of £1,000,000 was authorized to be raised by lottery in shares of £10 each, the contributors being entitled to annuities for sixteen years from September 29, 1694, charged on a yearly fund of £140,000, appropriated out of certain salt and beer duties named in the Act. Holders of the blanks received 10 per cent. on every share, and 2500 fortunate ticket-holders a larger payment; of which the principal prize was £1000 a year. The contributors were allowed 14 per cent. for prompt payment from the day of payment to September 29, 1694.

In 1697 (8 Will. III. c. 22) a loan of £1,400,000 was authorized to be raised by a lottery of 140,000 tickets of £10 each. Of these, 3500 were [Pg 50] to be prizes of from £10 to £1000; the holders of 136,500 blanks, and of 2800, £10 prizes, were to receive back £10 with interest from June 24, 1697, at the rate of ¼ d. per day (i.e. 2½ per cent. per day, or £3 16s. 0½d. per cent. per annum) until the whole was paid.

Then came a virtuous wave, and by 10 and 11 Will. III. c. 17 lotteries were suppressed after December 29, 1699, the preamble to which Act sets forth that, “Whereas several evil-disposed persons, for divers years past, have set up many mischievous and unlawful games, called lotteries, not only in the Cities of London and Westminster, and in the suburbs thereof, and places adjoining, but in most of the eminent towns and places in England, and in the Dominion of Wales, and have thereby most unjustly and fraudulently got to themselves great sums of money from the children and servants of several gentlemen, traders and merchants, and from other unwary persons, to the utter ruin and impoverishment of many families, and to the reproach of the English laws and government, by cover of several patents or grants under the great seal of England for the said lotteries, or some of them; which said grants or patents are against the common good, trade, welfare and peace [Pg 51] of His Majesty’s kingdoms: for remedy whereof be it enacted, adjudged and declared, and it is hereby enacted, adjudged and declared by the King’s most excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the lords spiritual and temporal, and commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, That all such lotteries, and all other lotteries, are common and publick nuisances, and that all grants, patents and licences for such lotteries, or any other lotteries, are void and against law.”

But this show of virtue only lasted a very short time, for in 1710 (8 Anne, c. 4) a loan of £1,500,000 was negotiated by means of a lottery—of £150,000 tickets at £10 each, every ticket-holder becoming entitled to an annuity for thirty-two years, the blanks to 14s. per annum, and the prizes to greater annuities, from £5 to £1000 per annum.

Previous to this there was a private lottery, the story of which Hutchins tells in his “History of the County of Dorset.”[15] The Sydenham here spoken of was the nephew of the celebrated Thomas Sydenham, M.D., who adopted the cool treatment in small-pox, and used [Pg 52] quinine (or bark, as it was then called) and laudanum in agues. “This manor and farm continued in the Sydenhams, till William Sydenham, the last of the family, esquire of the body to King William III., and the last that held that office, put up his estate at a private lottery. It was generally supposed that there was some trick designed; for it was contrived, or at least hoped, that the fortunate ticket would fall to the share of a confidant in the family, who they imagined would have been prevailed upon to return the estate upon a small consideration. That ticket happened to be hers; but, to their great disappointment, she immediately married Doyly Michel, Esq. But, it being necessary that Mr. Sydenham and his two daughters should make a formal surrender of the estate to the vendee, on their refusal they were committed to Dorchester prison about 1709, where they ended their days.”

In 1711 there were two State Lotteries. The first (9 Anne, c. 6) was for a loan of £1,500,000 by the sale of 150,000 lottery tickets at £10 each; the whole money to be repaid, both on blanks and prizes, in thirty-two years, with interest at 6 per cent. per annum, payable half-yearly; and the additional sum of £428,570 to be divided amongst [Pg 53] the prizes, and paid with the same interest in thirty-two years. The second (9 Anne, c. 23) was a loan of £2,000,000, by the sale of 20,000 lottery tickets at £100 each, divided into five classes with the chance of receiving from £10 to £135, according to the class drawn, with interest at 6 per cent. until paid off. This lottery consisted of all prizes, these being formed by dividing an additional sum of £602,200 among the subscribers, those in the lowest class obtaining a profit of £10.

There were also two in 1712. One (10 Anne, c. 19) was a loan of £1,800,000 by the sale of 180,000 tickets at £10 each; the whole sum advanced, with an additional capital of £541,740, to be repaid in thirty-two years, with interest at 6 per cent., payable half-yearly. The other (10 Anne, c. 26) was for the same amount, only they were to be £100 tickets divided into five classes, with an additional capital of £541,990, to be repaid with interest at 6 per cent. in thirty-two years.

Next year, 1713 (12 Anne, stat. I. c. 11), there was a comparatively small lottery of half a million, granted to discharge the debt and arrears of the civil list, raised by the sale of 50,000 lottery tickets [Pg 54] at £10 each; the whole sum, with an additional capital of £133,010, to be repaid with interest at 4 per cent. in thirty-two years. In the last year of the reign of Queen Anne, 1714 (12 Anne, stat. II. c. 9), a loan was negotiated of £1,400,000, by means of 140,000 lottery tickets at £10 each, the blanks to have their whole money repaid, with interest at 5 per cent. in thirty-two years, and the prizes to be formed by an additional capital of £476,400: the whole capital of the prizes to bear 4 per cent. interest.

Whether Jacobite trouble was the cause or not, there was no State lottery until 1719. But private lotteries seem to have been to the fore, so much so that in 1718 they were again made illegal by Act of Parliament (5 Geo. I. c. 9, s. 43), whereby a fine of £100 could be inflicted on the transgressors, but the Act was a dead letter. In 1719 two State lotteries were launched (5 Geo. I. c. 3), both for the same amount, and under similar conditions, except that the first was to bear interest at 4 per cent. until redeemed by Parliament, and the second was to be paid at the expiration of thirty-two years. They were each for half a million, to cover which, 168,665 tickets of £3 each were [Pg 55] issued, making a total of £505,995, the excess over the half-million being taken for the expenses of the lottery.

In 1719 was instituted a very curious lottery, which exists to this day, and is thoroughly legal. It is no less than a marriage portion given by lottery every year to a girl who has been brought up in Raine’s School, in the parish of St. George-in-the-East, London. I take the following newspaper cutting, which, though not dated, the occurrence it narrates must have taken place between 1842 and 1862, during the time the Rev. Bryan King was rector.

“Wednesday, being the first of May, a most interesting ceremony took place connected with the asylum and schools founded in 1719 by Mr. Henry Raine, formerly a brewer, near Parson’s Island, Wapping. This gentleman, having amassed a princely fortune, endowed, by deed of gift, the above charity. There are vested in trustees, formed into a corporation, a perpetual annuity of £240 a year, and the sum of £4000, which is laid out in a purchase. The charity combines two objects. It provides for the scriptural education of fifty boys and fifty girls; and in the asylum provision is made for forty other girls, who are [Pg 56] taught needle and house work, in order to qualify them for service, to which they are put when they have been put upon the foundation three or four years. During the whole of this time they are entirely maintained; and, after the age of twenty-two years, six of them, producing certificates of their good behaviour during their servitude, and continuing unmarried, and members of the Episcopal Church of England, draw twice a year for a marriage portion of £100, to settle them in the world, with such honest and industrious persons as the majority of the trustees shall approve of. The bridegrooms must belong to the parish of St. George-in-the-East, St. John, Wapping, or St. Paul, Shadwell, and be members of the Church of England.

“On Wednesday morning, at nine o’clock, Sarah Salmon and Mary Ann Pitman were married in consonance with the terms of the will; after which the whole of the trustees and children of both establishments attended Divine Service. The procession to and from the church was most orderly, and thousands assembled to witness the interesting scene. Immediately after the return of the governors and children to the asylum, the process of 'drawing’ took place. There were four candidates, [Pg 57] and four pieces of paper being rolled up by the governors, three of which were blanks, were dropped into a wide-necked tea-canister, and shaken well together. After a hymn had been sung, each candidate was taken by the arm by a governor, and led to the drawing. Having taken out one roll each, they were led to the opposite end of the room. The rector, the Rev. B. King, then desired each of them to open their tickets, and the prize of £100 was discovered to be in the possession of Jane McCormack. The successful candidate was then addressed in a most touching manner by the rector, and exhorted to seek a partner for life who would strive to make her happy by his affection, and keep her comfortable by his industry. Those who were unsuccessful, he also addressed with much earnestness and feeling, bidding them not despair, as they would have the opportunity of trying again. To witness this part of the ceremony, not fewer than a thousand persons were present, including the principal families in the neighbourhood, and a great number of ladies.”

Since the above was written, this charity has been revised, and, by the scheme of January 26, 1886, the governors are empowered to set apart the [Pg 58] yearly sum of £105 out of the income of the foundation, to provide marriage portions, according to the will of the founder; but they may, in any year, intermit the payment of any marriage portion, and they may, at any time, by resolution, altogether abolish the payment of marriage portions, and devote the money to educational purposes under the scheme.

[Pg 59]

Penalties on private lotteries—State lottery not subscribed for—Lapse in State lotteries—Private lotteries—Westminster Bridge lottery—State lotteries—Discredit thrown on them—British Museum lottery—Leheup’s fraud.

Once more came a wave of virtue against private lotteries, and in 1721, by the 36th sec. of 8 Geo. I. c. 2, was prescribed a penalty of £500 for carrying on such lotteries, in addition to any penalties inflicted by any former Acts; the offender being committed to prison for one year, and thenceforward until such times as the £500 should be fully paid and satisfied. Yet the Government themselves, the very same year, brought out a lottery to raise £700,000 by 70,000 tickets at £10 each; 6998 prizes from £10,000 to £20; 63,002 blanks at £8 each, about nine blanks to a prize, paid soon after being drawn. And there were lotteries for the same amount and on the same terms in 1722, 1723, and 1724. [Pg 60]

After that a curious thing in the history of lotteries happened, the reason whereof may be that the offer was not sufficiently tempting. In 1726 a lottery was launched for raising a million, by 100,000 tickets at £10 each, the prizes to be made stock at 3 per cent. But 11,093 of these tickets were returned into the Exchequer unsold, and drawn in prizes and blanks only £103,272 10s., whereby £7657 10s. was lost to the Exchequer.

This may probably account for there being no other State lottery till 1731 (4 Geo. II. c. 9), when £800,000 was raised by 80,000 tickets of £10 each, the blanks being entitled to £7 10s. each, and the whole bearing interest at 3 per cent. This capital was merged (25 Geo. II. c. 27) into the Consolidated Three per Cents., and this course of converting into stock, instead of paying the money, was adopted in many subsequent lotteries.

Once more they were prohibited by legislation, for “An Act for the more effectual preventing of excessive and deceitful gaming” was passed in 1739 (12 Geo. II. c. 28), the first section of which dealt with private lotteries. Yet the Government acted on Shakespeare’s dictum—

[Pg 61] and, as we shall see, kept lotteries to themselves, whilst condemning them as sinful in the hands of private speculators—which was perhaps necessary, as in the Gentleman’s Magazine, 1739, p. 329, I find a private lottery for £325,000, in which there were two prizes of £10,000 each (and in number 16,310), down to £10, whilst there were 48,690 blanks.

This was a lottery drawn between December 10, 1739, and January 25, 1740, for building the first bridge over the Thames, in lieu of the old Horse-*ferry—12,500 tickets at £5 each, not more than three blanks to a prize. It really was drawn at Stationers’ Hall, but there is no doubt but that the illustration is meant for the Guildhall. Below the design are the following verses, which show the valuation put upon the lottery even then:—

This has connection with the same lottery, but a description would be too long for these pages, so I only quote the three concluding lines of the verses under the engraving, to show how, in the height of its folly, they could moralize on the lottery—

“The Lottery; or, The Characters of several in genious, designing Gentlewomen, that have put into it. A Noted lottery Pachter.”[17]

[Pg 63] This was probably intended as a satire upon Cox, who kept a lottery office near the Royal Exchange, and was a bookseller, which is shown in his portrait (a very fat man, with his coat buttoned all down, and a sash round his body), where in his sash is stuck a book, marked “Book Sold.”

Up to the early eighteenth century, the only communication between Westminster and the Surrey side of the river was by a ferry (still commemorated in Horse-ferry Road), which was the property of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and for the privilege of which he paid an annual rent of twenty pence. The landing-place on the Surrey side was close to the Episcopal palace. This ferry, however, was inconvenient, and, in 1736, an Act of Parliament was procured (9 Geo. II. c. 29), after much opposition on the part of the city of London, “For building a bridge cross the river Thames, from the New Palace Yard, in the city of Westminster, to the opposite shore in the County of Surrey.” Commissioners for building the bridge were to be chosen, to meet in the Jerusalem Chamber, June 22, 1736, and adjourn to appoint in what manner and with what materials the bridge shall be built. No houses to be erected thereon.

[Pg 64]

The result of their deliberations was another Act (10 Geo. II. c. 16) for explaining and amending the above. By this £700,000 was to be raised by way of lottery, the residue of the money after payment of the prizes to be applied towards the building of the bridge, and tolls might be levied at the following rates:—“Every coach, etc., drawn by six horses, 2s.; by four horses, 1s. 6d.; by less than four horses, 1s. For every waggon, etc., drawn by four horses, 1s. 6d., and by less than four horses, 1s. For every horse, etc., not drawing, 2d. For every foot passenger on Sundays, 1d., and on every other day, ½d. For every drove of oxen, 1s. per score. For every drove of calves, hogs, sheep, or lambs, 6d. per score.”

I have before me the originals of two schemes for the erection of this bridge. One is “For raising £60,000 without any Tax upon the Inhabitants of the City of Westminster, for the building a Bridge cross the River of Thames, the Legs of Stone, and the Arches turn’d with Bricks (made on purpose, like those us’d in the Dome of St. Paul’s which is 110 Foot wide) after the manner of the Brick-Bridge of Thoulouse, the greatest Arch of which is 100 [Pg 65] Foot span; and to become a free Bridge, in twenty-one years, except a small Duty to keep it in repair.” It was proposed to raise a loan of £60,000 at 5 per cent. interest on the security of the tolls to be levied, which, it was calculated, would be repaid within the period specified, the tolls being estimated to produce £6000 per annum. The other is “A Plan of a Lottery to raise upwards of £100,000, free of all Expences and Deductions, for Building a Bridge at Westminster,” and it was proposed to have a lottery of £625,000, in 125,000 tickets at £5 each, only three blanks to a prize, and to deduct 16 per cent. from all prizes, which would amount to £100,000.

There was another Act passed in 1738 (11 Geo. II. c. 25) respecting this bridge, which provided that the bridge should be built from the wool staple at Westminster, of what materials the Commissioners should think fit, and they were to account yearly. On January 29, 1739, the first stone was laid by Henry, Earl of Pembroke, and the same year another Act was passed (12 Geo. II. c. 33), which not only empowered the Commissioners to make compulsory purchases of houses and land, but allowed them to issue a lottery of £325,000, and to take 15 per cent. of [Pg 66] that sum, amounting to £48,750, for the purpose of building the bridge. An Act confirming this was passed (13 Geo. II. c. 16), and on December 8, 1740, the drawing of the Bridge Lottery began at Stationers’ Hall. The total cost of the bridge, which took eleven years and nine months to build, was £389,500, and it was opened on November 17, 1750.

There were State lotteries in 1743-4-5-6-7-8, for sums varying from £1,000,000 to £6,300,000, all of which were converted into stock by Acts of Parliament in the reign of George III. In 1751 the next State lottery was authorized by Parliament (24 Geo. II. c. 2), £700,000 in tickets of £10 each; but, somehow, this did not go down with the public. The Gentleman’s Magazine for July, 1751 (p. 328), says, “Those inclined to become adventurers in the present lottery were cautioned in the papers to wait some time before they purchased tickets, whereby the jobbers would be disappointed of their market and obliged to sell at a lower price. At the present rate of tickets the adventurer plays at 35 per cent. loss.”

This was further illustrated by some figures which appeared in the [Pg 67] London Magazine for August, same year, giving the following odds against winning, the chances being—

| 34,999 | to 1 | against | a £10,000 | prize. | |

| 11,665 | ” | ” | 5,000 | ” | or upwards. |

| 6,363 | ” | ” | 3,000 | ” | |

| 3,683 | ” | ” | 2,000 | ” | |

| 1,794 | ” | ” | 1,000 | ” | |

| 874 | ” | ” | 500 | ” | |

| 249 | ” | ” | 100 | ” | |

| 99 | ” | ” | 50 | ” | |

| 6 | ” | ” | 20 | ” | or any prize. |

In fact, such discredit was thrown upon this lottery, that a Mr. Holland publicly offered to lay four hundred guineas, that four hundred tickets, when drawn, would not, on an average, amount to more than £9 15s. each, prizes and blanks; and his offer was never accepted. As Adam Smith observed, it was an incontrovertible fact that the world never had seen, and never would see, a fair lottery.

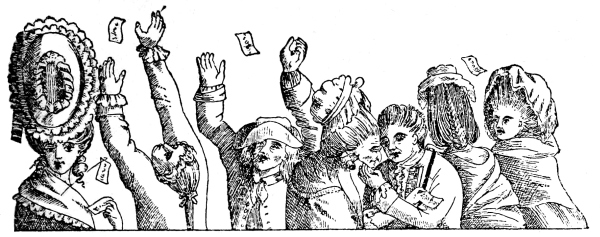

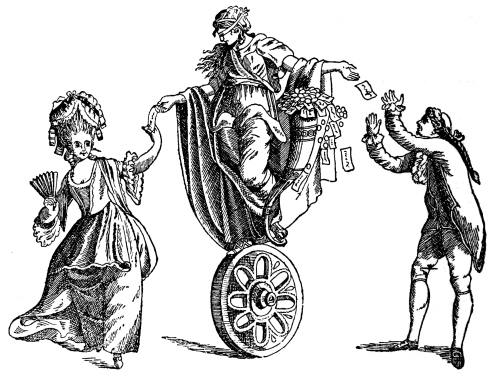

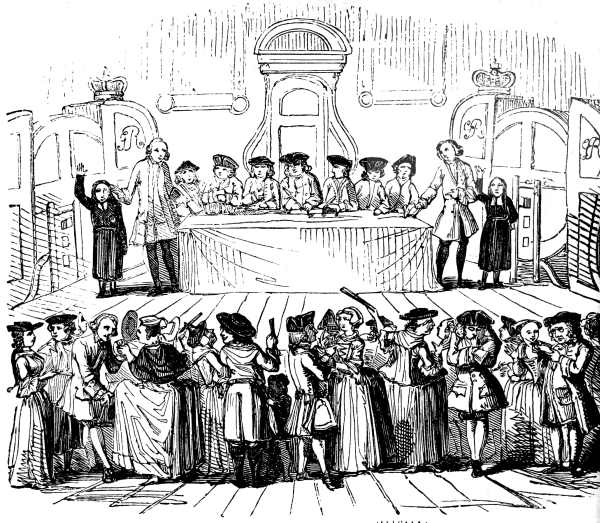

Hone, in his “Every-Day Book,” gives the two following illustrations of the drawing of this lottery. Unfortunately, I have been unable to verify them, but it strikes me that the first one is of earlier date, judging by the costumes, and that the halls in which the lottery is drawn are totally different. [Pg 68]

Drawing of the Lottery in Guildhall, 1751.

[Pg 69] By an Act of Parliament (26 Geo. II. c. 22), passed in 1753, the nation purchased for £20,000 the library and collection of Sir Hans Sloane, and incorporated with it the library of Sir Robert Cotton, and that known as the Harleian library, thus forming the nucleus of the British Museum. The next thing was to find a house wherein to keep this collection, and to raise money for the same, at the least cost. This was done, in the same Act, by means of a lottery, the managers and trustees of which were, singularly enough, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Lord Chancellor, and the Speaker, each of whom was to have £100 for his trouble. The subscription to the lottery was £300,000, in tickets of £3 each. £200,000 was to be distributed in prizes varying from £10,000 to £10, and the remainder was to go towards the purchasing of the Sloane collection and library, and the Harleian library, finding suitable cases for the property acquired, house-room and attendants. The lottery was to be drawn on November 26, 1753, and all prizes were to be paid by December 31, 1754, when those not presented would be forfeited.

And this Act is the only trace I can find of this lottery, although I [Pg 70] have had the willing and zealous aid of the officials of the British Museum in searching after it.

In connection with this lottery was a gross fraud, into which the House of Commons caused an inquiry to be made, and the committee eventually reported that Peter Leheup, Esq., had privately disposed of a great number of tickets before the office was opened, to which the public were directed, by an advertisement, to apply; that he, also, delivered great numbers to particular persons, upon lists of names which he knew to be fictitious; and that, in particular, Sampson Gideon became proprietor of more than six thousand, which he sold at a premium. The House resolved that Leheup had been guilty of a violation of the Act and a breach of trust, and the Attorney-General was instructed to prosecute him. On June 9, 1855, he was found guilty, and sentenced to pay a fine of £1000, which he could well afford, as it is said he had made £40,000 by his rascality.

[Pg 71]