Title: The land of the Pueblos

Author: Susan E. Wallace

Release date: December 15, 2025 [eBook #77473]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: John B. Alden, 1888

Credits: Craig Kirkwood and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

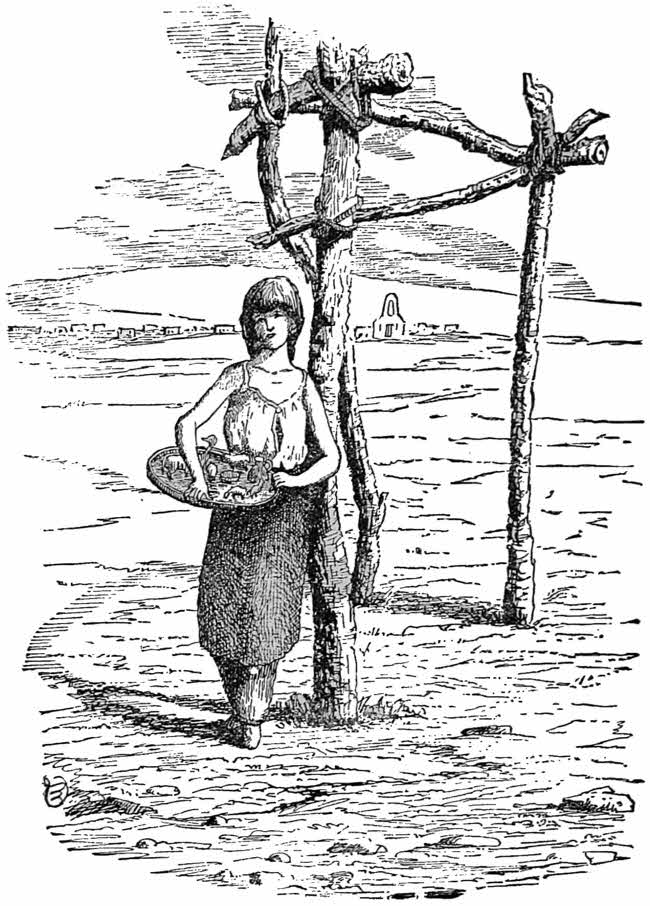

A PUEBLO GIRL SELLING CLAY IMAGES. (From a sketch by Gen. Wallace.)

BY

SUSAN E. WALLACE.

Author of “The Storied Sea,” “Ginevra,” etc.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS.

NEW YORK:

JOHN B. ALDEN, PUBLISHER.

1888.

Copyright. 1888,

BY

THE PROVIDENT BOOK COMPANY.

THE LAND OF THE PUEBLOS.

| Introduction. | 5 | |

| I. | The Journey. | 7 |

| II. | Historic. | 14 |

| III. | Laws and Customs. | 37 |

| IV. | The City of the Pueblos. | 58 |

| V. | Mexican Cottages. | 62 |

| VI. | To the Turquois Mines. | 69 |

| VII. | To the Turquois Mines, continued. | 80 |

| VIII. | To the Turquois Mines, continued. | 93 |

| IX. | To the Turquois Mines, continued. | 101 |

| X. | Among the Archives.—Things New and Old. | 108 |

| XI. | Among the Archives.—A Love Letter. | 114 |

| XII. | Among the Archives, continued. | 121 |

| XIII. | Among the Archives, continued. | 127 |

| XIV. | Among the Archives, continued. | 134 |

| XV. | The Jornada Del Muerto. | 140 |

| XVI. | Something about the Apache. | 152 |

| XVII. | Old Miners. | 160 |

| XVIII. | The New Miners. | 167 |

| XIX. | The Honest Miner. | 175 |

| XX. | The Assayers. | 180 |

| XXI. | The Ruby Silver Mine.—A True Story. | 188 |

| XXII. | The Ruby Silver Mine, continued. | 196 |

| XXIII. | Mine Experience. | 203 |

| XXIV. | The Ruins of Montezuma’s Palace. | 218 |

| XXV. | To the Casas Grandes. | 234 |

| XXVI. | A Frontier Idyl. | 248 |

| XXVII. | The Pimos. | 261 |

| A Pueblo Girl Selling Clay Images, | Frontispiece |

| El Palacio, Santa Fé, | 14 |

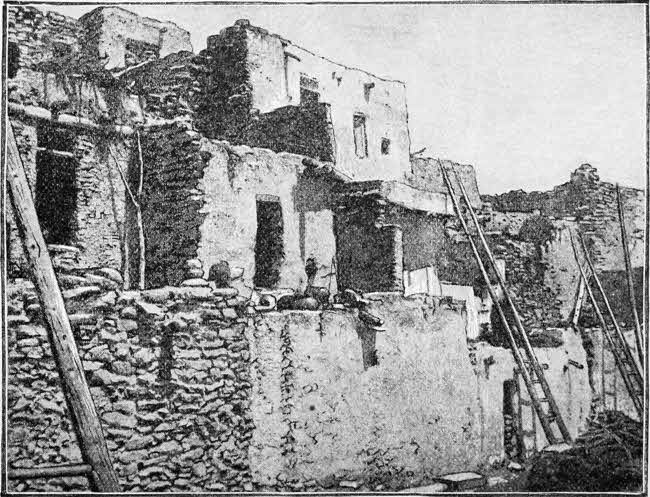

| Living Pueblo (New Mexico), | 44 |

| Zuñi War Club, Dance Ornaments, etc., | 46 |

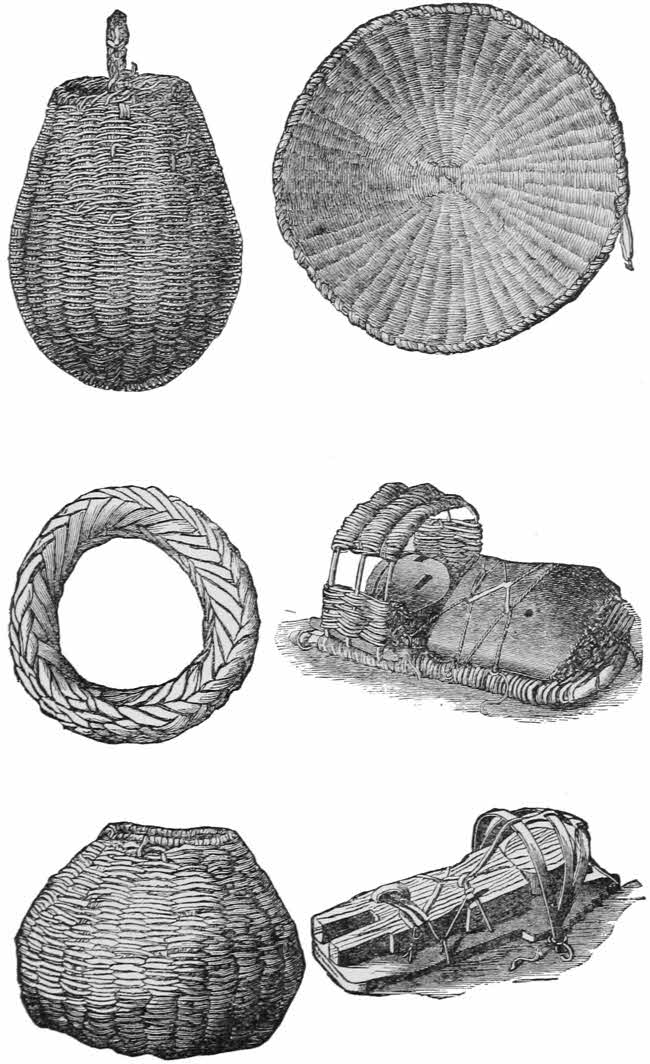

| Zuñi Basketry, and Toy Cradles, | 130 |

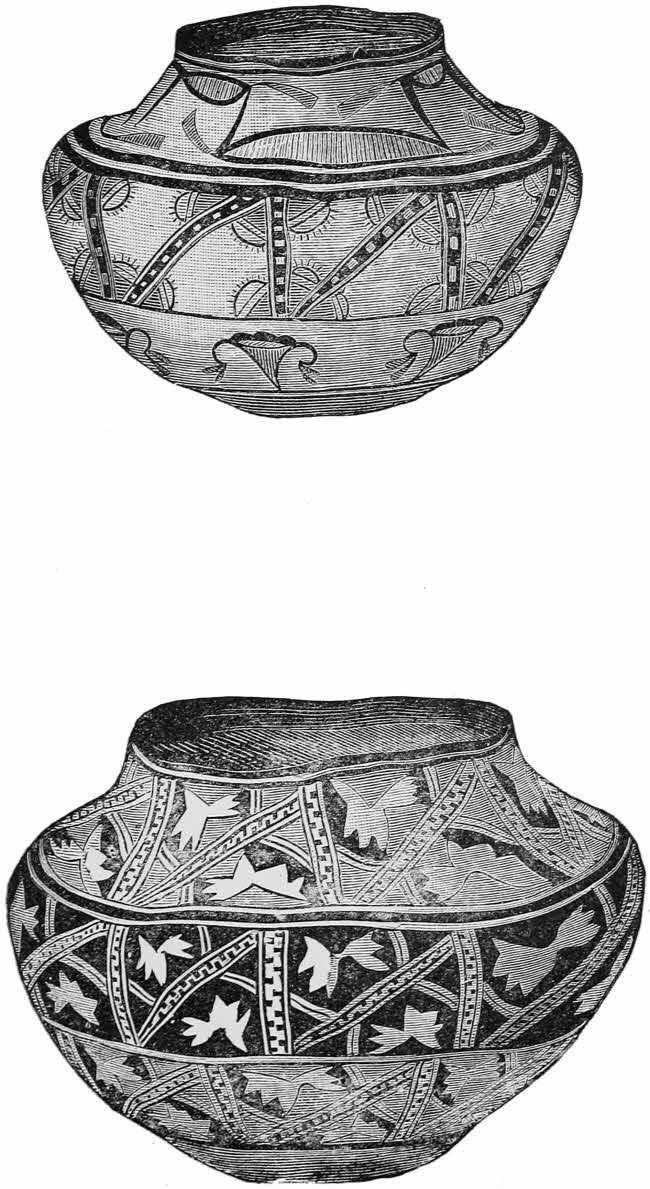

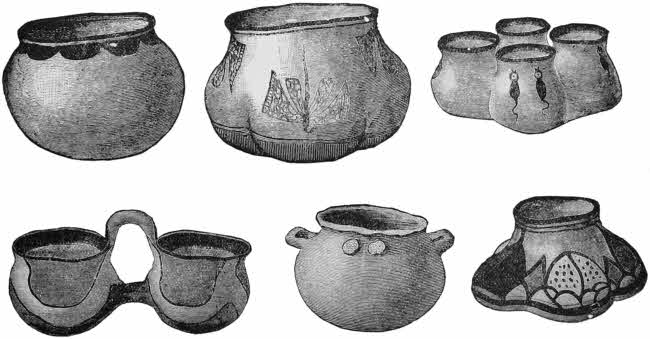

| Zuñi Water Vases, | 132 |

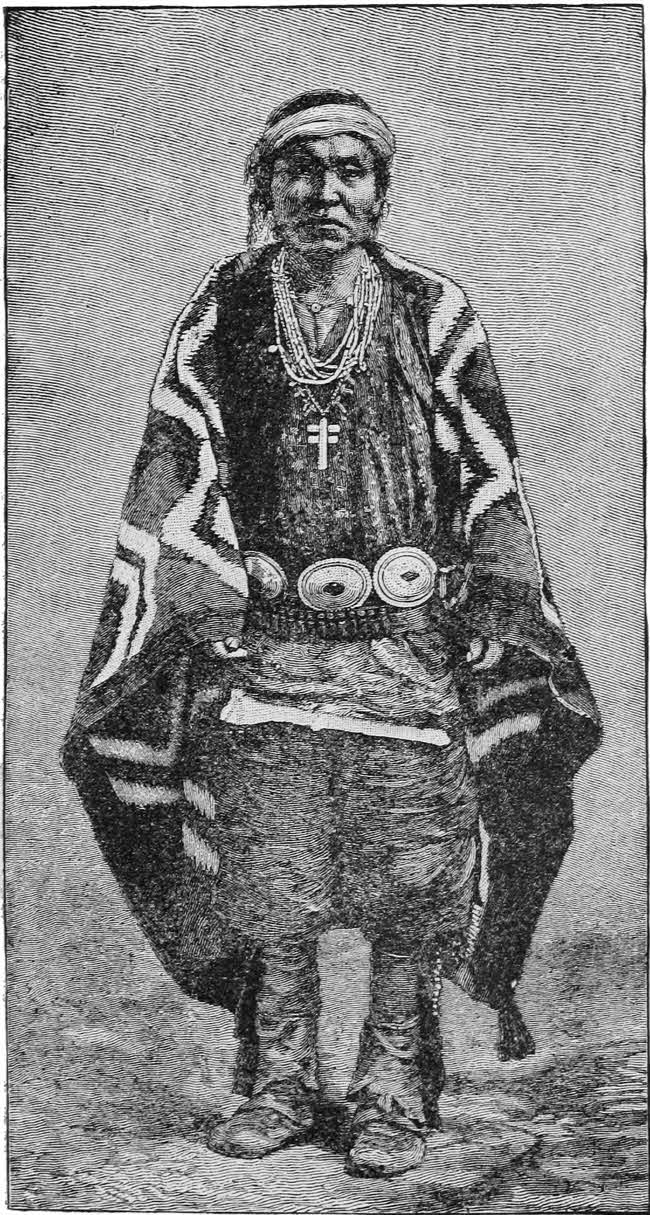

| Navajo Indian, with Silver Ornaments, | 154 |

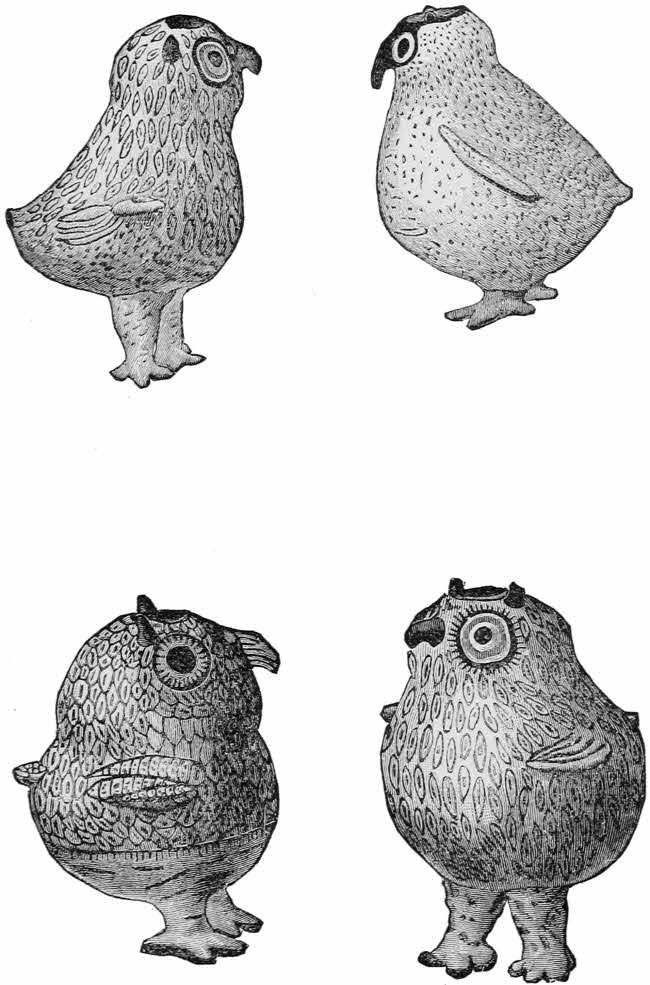

| Zuñi Effigies, | 200 |

| Tesuke Water Vases, | 234 |

| Abandoned Pueblo, | 238 |

| Zuñi Paint and Condiment Cups, | 244 |

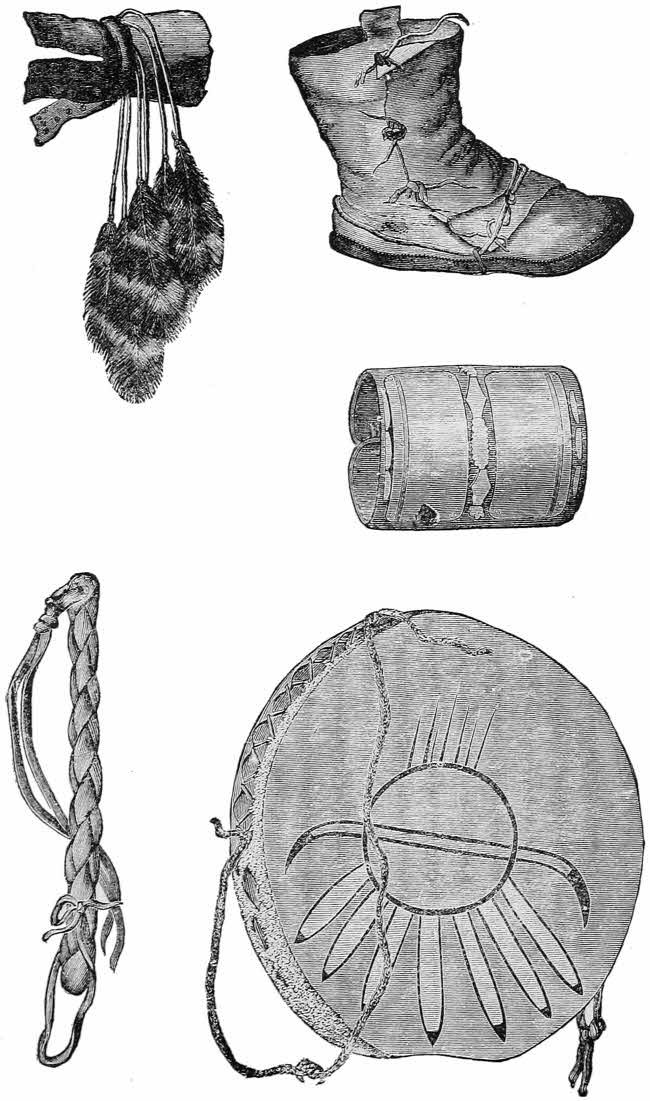

| Pueblo Wristlets, Moccasins, etc., | 246 |

[5]

Some years ago these writings appeared in the Independent, Atlantic Monthly, and The Tribune. My thanks are with the respective editors by whose courtesy they assume this altered shape. Several were published in a certain magazine which died young. I send cordial greeting to its chief, and shed a few drops of ink over the nameless one, loved of the gods. Fain would I believe no action of mine had power to hasten that early and untimely end. The hurrying march in which all must join, is so rapid, my first audience is quite out of hearing; my first inklings have faded from the memory of readers except the one, beloved of my soul, who asks why the old Pueblo papers have not been reprinted. Ah, what exquisite flattery!

And just here I kiss the fair hands unseen which send such gracious messages. Dropping flowers in my way, pansies for thoughts, rosemary for remembrance, has made them the whiter and sweeter forevermore.

The Montezuma myth is so interwoven with the past and future of the Indians that every allusion to their history and religion must of necessity contain the revered name. The repetition in the compositions now collected did not appear so glaringly when they were detached. My first impulse was to omit such passages, but second thought sends out the letters as when first offered to the public, with all their imperfections (a good many), on their head.

It would be affectation to make secret what every writer understands: (and what reader have I who is not a writer?) the pleasure with which [6]I gather my scattered children under a permanent cover. Family resemblance is strong enough to identify them anywhere, but that is no reason why they should not appear in shape which the world will little heed nor long remember. They were written when the ancient Palace I have tried to describe, was the residence of the Governor of New Mexico; and, in turning the leaves after seven years, I am touched by the same feeling which then moved me to pipe my little songs. Again I feel the deep solitude of the mountains, taste the all pervading alkali dust, and hear the sand-storm beating like sleet against the window panes. The best reward they brought were friendly voices answering in the blue distance across the Sierras, and cheering me with thought that I had won the place of welcome visitor in happy homes my feet may never enter; that through the bitter winter my room was kept by warm firesides under the evening lamp—there where the treasured books lie from day to day, looking like Elia’s old familiar faces. Dear to the heart, beautiful and forever young, are the unseen friends whose presence becomes an abiding consciousness to the writer.

Crawfordsville, Indiana, March, 1888.

[7]

THE LAND OF THE PUEBLOS.

I am 6,000 feet nearer the sky than you are. Come to the sweet and lonely valley in the West where, free from care and toil, the weary soul may rest; where there are neither railroads, manufactures, nor common schools; and, so little is expected of us in the way of public spirit, we almost venture to do as we please, and forget we should vote, and see to it that the Republic does not go to the “demnition bow-wows.”

Santa Fé is precisely what the ancient Pueblos called it—“the dancing-ground of the sun.” The white rays quiver like light on restless waters or on mirrors, and night is only a shaded day. In our summer camp among the foothills we need no tents. It is glorious with stars of the first magnitude, that hang low in a spotless sky, free from fog, mist, or even dew; not so much as a mote between us and the shining floor of heaven.

The star-patterns of my coverlet are older than the figures which delighted our grandmothers. They come out not one by one, as in our skies; but flash suddenly through the blue. Day and night make a brief parting. The short twilight closes, and lo! in the chambers of the east Orion, belted with jewels, Arcturus and his sons, and even the dim lost Pleiad, forgetting the ruins of old Troy, brightens again. Wrapped in soft, furry robes, we lie on the quiet bosom of Mother Earth in sleep, dreamless and restful as the slumber of those who wake in Paradise. I cannot [8]say, with the enthusiastic land-speculator: “Ladies and gentlemen, in this highly-favored region the Moon is always at its full.” But her face is so fair and bright I am her avowed adorer, and many a thousand miles from

“‘a——’ the steep head of old Latmos,”

she stoops above the sleeping lover, to kiss her sweetest.

Old travelers tell you the country is like Palestine; but it is like nothing outside of the Garden eastward in Eden. New Mexico is a slice of old Mexico; that is, a western section of Spain. “Who knows but you may catch sight of some of your castles there!” Such was the invitation which came to me across the Rocky Mountains. I hearkened to the voice of the “charmer, charming never so wisely,” and, “fleeing from incessant life,” started on a journey of two thousand miles. It was in the mild September, and the Mississippi Valley flamed with banners crimson, golden, in which Autumn shrouded the faded face of the dead Summer.

We sped through Ohio, land of lovely women; past Peoria, fair Prairie City, the smoke of whose twenty-three distilleries obscures the spires of her churches beautiful as uplifted hands at prayer; through the bridge at St. Louis, where the fairies and giants once worked together, making a crossing over the great Father of Waters; on we went, journeying by night and by day.

Oh! the horror of the chamber of torture known to the hapless victims as the sleeping-car. The gay conductor, in gorgeous uniform, told us, in an easy, off-hand manner, a man had been found dead in one of the top berths some weeks before. I only wondered any who ventured there came out alive. “Each in his narrow cell forever laid” went through my mind as I lay down [9]to wakefulness and unrest in blankets filled with vermin and disease. The passengers were the same you always journey with: the young couple, tender and warm; the old couple, tough and cool; laughing girls, in fluffy curls and blue ribbons, who found a world of pleasure in pockets full of photographs; the good baby, that never cried, and the bad baby, that cried at nothing; the fussy woman everybody hated, who counted her bundles every half hour, wanted the window up, and no sooner was it raised than she wanted it down again. There, too, was the invalid in every train on the Pacific Road. A college graduate of last year, poor, ambitious, crowded four years’ study into three, broke down, and now the constant cough tells the rest of the old tale. He was attended by a young sister, warm and rosy as he was pallid and chill, who in the most appealing way took each one of us into her confidence, and told how Rob had picked up every step of the road since they left Sandusky. When we entered the wide, monotonous waste between Missouri and Colorado, how the brave girl would try to cheer the boy with riddles, stories, games, muffle him in her furs, slap his cold hands, and lay her red, ripe cheek to his, as if she were hushing a baby. In the drollest way, she resisted the blandishments of the vegetable ivory man, the stem-winder, the peanut vender, and with tragic gesture waved off the peddler of the “Adventures of Sally MacIntire, who was Captured by the Dacotahs. A Tale of Horror and of Blood!” When the dazzling conductor illuminated the passage of the car with his Kohinoor sleeve-buttons and evening-star breastpin, he would stop beside the sick boy, and in a fresh, breezy way seemed to throw out a morning atmosphere of bracing air, as well as hopeful words. “Now,” he would say, twirling his [10]thumb in a Pactolian chain which streamed across his breast and emptied into and overflowed a watch-pocket bulgy with poorly hid treasure—“now we are coming to a place fit to live in. When you get to Pike’s Peak, you will be 7,000 feet above the level of the sea. It’s like breathing champagne. You’ll come up like a cork; keep house in a snug cottage; go home in the Spring so fat you can hardly see out of your eyes.” Vain words. The poor boy knew, and we knew, he was fast nearing the awful shadow which every man born of woman must enter alone. The mighty hand was on him. He was going to Colorado Springs only to die. We parted at La Junta, crowding the windows, gayly waving good-byes. I can never forget my last sight of the sweet sister, with her outspread shawl sheltering him from the crisp wind, which blew from every direction at once, as I have seen a mother-bird flutter round her helpless nestlings. The good baby held up its sooty, chubby hand saying, “ta, ta,” as long as they were in sight, and the mothers smiled tearfully to each other when a rough miner from the Black Hills said, softly, as if talking to himself: “I reckon, if that young woman’s dress was unbuttoned, wings would fly out.”

Five hundred miles across plains level as the sea, treeless, waterless, after leaving the Arkansas River. Part of our road lay along the old California trail, the weary, weary way the first gold-seekers trod, making but twenty miles a day. Under ceaseless sunshine, against pitiless wind, it is not strange that years afterward their march was readily tracked by graves, not always inviolate from the prairie wolf. The stiff buffalo-grass rose behind the first explorers, and even horses and cattle left no trail. They took their course by the sun, shooting an arrow before [11]them; before reaching the first arrow they shot another; and in this manner marched the entire route up to the place where they found water and encamped.

Occasionally we saw a herdsman’s hut standing in the level expanse, lonely as a lighthouse; nothing else in the blank and dreary desert but the railroad track, straight as a rule, narrow as a thread, and its attendant telegraph, precious in our sight as a string of Lothair pearls. Not a stick or stone in a hundred miles. Only the sky, and the earth, clothed with low grass-like moss, the stiff sage-brush, and a vile trailing cactus, which crawls over the ground like hairy green snakes. To be left in such a spot would be like seeing the ship sail off leaving us afloat in fathomless and unknown seas.

After a day seeming long as many a month has, the fine pure air of Colorado touched with cooling balm our tired, dusty faces; and against the loveliest sunset sky, in a heavenly radiance, all amber and carmine, the Spanish peaks majestically saluted us.

Oh! the glory of that sight! Two lone summits, remote, inaccessible; the snowy, the far-off mountains of poetry and picture. Take all the songs the immortal singers have sung in praise of Alpine heights and lay them at their feet; it yet would be an offering unworthy their surpassing loveliness. Now we lost sight of them; now they came again; then vanished in the evening dusk, dropped down from Heaven like the Babylonish curtain of purple and gold which veiled the Holy of Holies from profane eyes. Fairest of earthly shows that have blest my waking vision, they stand alone in memory, not to fade from it till all fades.

At Trinidad we left the luxury of steam, and came down to the territorial conveyance. Think, [12]dear reader, of two days and a night on a buckboard—an instrument of torture deadly as was ever used in the days of Torquemada, and had anything its equal been resorted to then there would have been few heretics.

It is a low-wheeled affair floored with slats, the springs under the seats so weak that at the least jolt they smite together with a horrible blow, which is the more emphatic when over-loaded, as when we crossed the line which bounds “the most desirable of all the Territories.” Our night was without a stop, except to change horses. Jolt, jolt; bang, bang; cold to the marrow, though huddled under buffalo robes and heavy blankets. How welcome the warmth of the sun on our stiffened limbs; and the early breeze, sweet and fresh as airs across Eden when the evening and the morning were the first day! It has a sustaining quality which almost serves for food and sleep. There journeyed with us in the white moonshine spectres, shadowy, ghost-like. Now the sun comes up, we see they are kingly mountains, wrapped in robes of royal purple and wearing crowns of gold. The atmosphere is so refined and clear, they appear close beside us; but the driver says they are forty miles away. Noon comes on, hot and still, with a desert scorch. We journey over a road surprisingly free of stones; across a blank and colorless plain, bounded by mountain-walls which stand grim and stark like bastions of stone. Another night and another long day. The driver is not on his high horse now. He has no funny stories of the grizzly and cinnamon bear, which he assures us can climb trees, sticking their claws in the bark, easily as the telegraph-mender, with clamps on his feet, goes up the pole. Along the roadside stretch beautiful park-like intervales, studded with dwarf pines, that appear planted at regular distances.

[13]

Will the day never end? I have no voice nor spirit, and begin to think the wayside crosses mark graves of travelers, murdered, not by assassins, but by the buckboard; and feebly clutch my fellow-sufferer, and shake about in a limp, distracted way, pitying myself, as though I were somebody else. I can hold out no longer. But wake up! Wake up! This is the home-stretch. The horses know it and dash across a little brook which they tell me is the Rio Santa Fé.

Pleasant the sound of running water; tender the light of the evening on the mountains which encircle the ancient capital of the Pueblos. As we approach, it is invested with indescribable romance, the poetic glamor which hovers about all places to us foreign, new, and strange. We go through a straggling suburb of low, dark adobe houses. How comfortless they look! Two Mexicans are jabbering and gesticulating, evidently in a quarrel. Swarthy women, with dismal old black shawls over their heads, sit in the porches. I hear the “Maiden’s Prayer” thumped on a poor piano. How foolish in me to think that I could escape the sound of that feeble petition! Lights stream through narrow windows, sunk in deep casements, and a childish voice, strangely at variance with the words, is singing “Silver Threads among the Gold” to the twanging of a weak guitar. Softly the convent-bells are ringing a gracious welcome to the worn-out traveler. The narrow streets are scarcely wide enough for two wagons to pass. The mud walls are high and dark. We reach the open Plaza. Long one-story adobe houses front it on every side. And this is the historic city! Older than our government, older than the Spanish Conquest, it looks older than the hills surrounding it, and worn-out besides. “El Fonda!” shouts the driver, as we stop before the hotel. A voice, foreign yet familiar, gayly [14]answers: “Ah! Senora, a los pieds de usted.” At last, at last, I am not of this time nor of this continent; but away, away across the sea, in the land of dreams and visions, “renowned, romantic Spain.”

I used to think Fernandina was the sleepiest place in the world, but that was before I had seen Santa Fé. The drowsy old town, lying in a sandy valley inclosed on three sides by mountain walls, is built of adobes laid in one-story houses, and resembles an extensive brick-yard, with scattered sunburnt kilns ready for the fire. The approach in midwinter, when snow, deep on the mountains, rests in ragged patches on the red soil of New Mexico, is to the last degree disheartening to the traveler entering narrow streets which appear mere lanes. Yet, dirty and unkept, swarming with hungry dogs, it has the charm of foreign flavor, and, like San Antonio, retains some portion of the grace which long lingers about, if indeed it ever forsakes, the spot where Spain has held rule for centuries, and the soft syllables of the Spanish tongue are yet heard.

It was a primeval stronghold before the Spanish conquest, and a town of some importance to the white race when Pennsylvania was a wilderness, and the first Dutch governor was slowly drilling the Knickerbocker ancestry in the difficult evolution of marching round the town pump. Once the capital and centre of the Pueblo kingdom, [15]it is rich in historic interest, and the archives of the Territory, kept, or rather neglected, in the leaky old Palacio del Gobernador, where I write, hold treasure well worth the seeking of student and antiquary. The building itself has a history full of pathos and stirring incident as the ancient fort of St. Augustine, and is older than that venerable pile. It had been the palace of the Pueblos immemorially before the holy name Santa Fé was given in baptism of blood by the Spanish conquerors; palace of the Mexicans after they broke away from the crown; and palace ever since its occupation by El Gringo. In the stormy scenes of the seventeenth century it withstood several sieges; was repeatedly lost and won, as the white man or the red held the victory. Who shall say how many and how dark the crimes hidden within these dreary earthen walls?

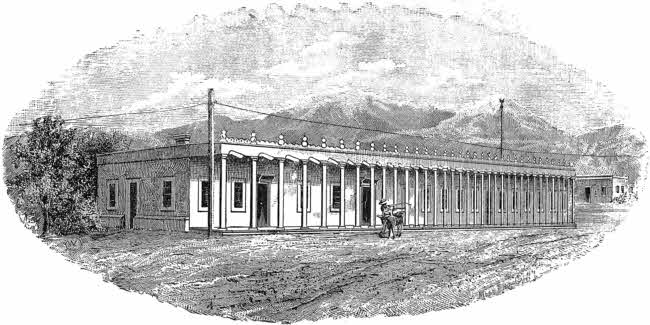

El Palacio, Santa Fé. (From Pencil Sketch by Gen. Wallace.)

Hawthorne, in a strain of tender gayety, laments the lack of the poetic element in our dear native land, where there is no shadow, no mystery, no antiquity, no picturesque and gloomy wrong, nor anything but commonplace prosperity in broad and simple daylight. Here is every requisite of romance,—the enchantment of distance, the charm of the unknown,—and, in shadowy mists of more than three hundred years, imagination may flower out in fancies rich and strange. Many a picturesque and gloomy wrong is recorded in mouldy chronicles, of the fireside tragedies enacted when a peaceful, simple people were driven from their homes by the Spaniard, made ferocious by his greed of gold and conquest; and the cross was planted, and sweet hymns to Mary and her Son were chanted on hearths slippery with the blood of men guilty only of the sin of defending them.

Four hundred years ago the Pueblo Indians [16]were freeholders of the vast unmapped domain lying between the Rio Pecos and the Gila, and their separate communities, dense and self-supporting, were dotted over the fertile valleys of Utah and Colorado, and stretched as far south as Chihuahua, Mexico. Bounded by rigid conservatism as a wall, in all these ages they have undergone slight change by contact with the white race, and are yet a peculiar people, distinct from the other aboriginal tribes of this continent as the Jews are from the other races in Christendom. The story of these least known citizens of the United States takes us back to the days of Charles V. and the “spacious times of great Elizabeth.”

About the year 1528 an exploring expedition set out, by order of the king of Spain, from San Domingo to invade Florida, a name then loosely given to the wide area between the bay of Fernandina and the Mississippi River. It was commanded by Pamfilo de Narvaez; the same it will be remembered, who had been sent by the jealous governor of Cuba to capture Cortez, and who, after having declared him an outlaw, was himself easily defeated. His troops deserted to the victorious banner, and when brought before the man he had promised to arrest, Narvaez said, “Esteem yourself fortunate, Señor Cortez, that you have taken me prisoner.” The conqueror replied, with proud humility and with truth, “It is the least of the things I have done in Mexico.”

This anecdote illustrates the haughty and defiant spirit of the general who sailed for battle gayly as to a regatta, with a fleet of five vessels and about six hundred men, of whom eighty were mounted. He carried blood-hounds to track natives, chains and branding-irons for captives; was clothed with full powers to kill, burn, plunder, enslave; and was appointed governor [17]over all the country he might reduce to possession.

The leader and his command perished by shipwreck and disasters, all but four. Among the survivors was one Alvar Nuñez Cabeça de Vaca, treasurer for the king and high sheriff, who is described in the annals of that period as having the most beautiful and noble figure of the conquerors of the New World; and in the best days of chivalry his valor on the battle-field, his resolution in danger, his constancy and resignation in hardship, won for him the proud title “Illustrious Warrior.” Ten years he, with three companions, rambled to and fro between the Atlantic and Gulf of California. The plain statement of their privations and miseries must of necessity be filled with marvels; that of Cabeça de Vaca, duly attested and sworn to, is weakened by wild exaggerations, and the Relacion of this Western Ulysses is touched with high colorings and embellished with fantastic fables equal to the moving accidents by flood and field of the heroic king of Ithaca. He tells of famishing with hunger till they devoured dogs with relish; of marching “without water and without way” among savages of giant stature, dressed in robes, “with wrought ties of lion-skin, making a brave show,—the women dressed in wool that grows on trees;”[1] of meeting cyclopean tribes, who had the sight of but one eye; of being enslaved and going naked—“as we were unaccustomed to being so, twice a year we cast our skin, like serpents;” of his escape, and, after living six years with friendly Indians, of being again made captive by barbarians, who amused themselves by pulling out his beard and beating him cruelly; of living on the strange fruits of mezquit and prickly-pear; of mosquitoes, whose bite made men appear to have “the plagues of [18]holy Lazarus;” of herds of wonderful cows, with hair an inch thick, frizzled and resembling wool, roaming over boundless plains.

Holding his course northwest, he came to a people “with fixed habitations of great size, made of earth, along a river which runs between two ridges;” and here we have the earliest record of Pueblo or Town Indians, so named as distinguished from nomads or hunting tribes, dwelling in lodges of buffalo-skin and boughs. It is difficult to trace his course along the nameless rivers of Texas; he must have ascended the Red River and then struck across to the Canadian, which runs for miles through a deep cañon, in which are yet seen extensive ruins of ancient cities. Undoubtedly he was then among the Pueblo Indians, in the northwestern part of New Mexico. He described them as an intelligent race, with fine persons, possessing great strength, and gave them the name “Cow Nation,” because of the immense number of buffaloes killed in their country and along the river for fifty leagues. The region was very populous, and throughout were signs of a better civilization. The women were better treated and better clad; “they had shawls of cotton;[2] their dress was a skirt of cotton that came to the knees, and skirts of dressed deer-skins to the ground, opened in front and fastened with leather straps. They washed their clothes with a certain soapy root which cleansed them well.[3] They also wore shoes.” This is the first account of the natives of that country wearing covering on their feet—doubtless the moccasins still worn by them.

The gentle savages hailed the white men as children of the sun, and, in adoration, brought [19]their blind to have their eyes opened, their sick that, by the laying on of hands, they might be healed. Mothers brought little children for blessings, and many humbly sought but to touch their garments, believing virtue would pass out of them. The rude hospitality was freely accepted; the sons of the morning feasted on venison, pumpkins, maize bread, the fruit of the prickly-pear; and, refreshed by the banquet, made their worshipers understand that they too were suffering with a disease of the heart, which nothing but gold and precious stones could cure. The Pueblos were then as now a race depending on agriculture rather than the chase, and were in distress because rain had not fallen in two years, and all the corn they had planted had been eaten by moles. They were afraid to plant again until it rained, lest they should lose the little seed left, and begged the fair gods “to tell the sky to rain;” which the celestial visitants obligingly did, and, in answer to the prayers of the red men, breathed on their buffalo skins, and bestowed a farewell blessing upon them at parting.

They again pushed westward in search of riches, always further on, crossed a portion of the Llano Estacado, or Staked Plain, and traveled “for a hundred leagues through a thickly settled country, with towns of earth abounding in maize and beans.” Hares were very numerous. When one was started the Indians would attack him with clubs, driving him from one to another till he was killed or captured.[4]

Everywhere they found order, thrift, friendly welcome. The Indians gave Cabeça de Vaca fine turquoises, buffalo robes, or, as he calls them, [20]“blankets of cow skins,” and fine emeralds made into arrow-heads, very precious, held sacred, and used only in dances and celebrations. They said these jewels had been received in exchange for bunches of plumes and the bright feathers of parrots; they were brought a long distance from lofty mountains in the north, where were crowded cities of very large and strong houses.[5]

It appears from his Relacion that Cabeça de Vaca passed over the entire territory of New Mexico, went down the Gila to a point near its mouth, struck across to the river San Miguel, thence to Culiacan, and so on to Mexico, where the four wanderers, worn by hardship, gaunt and spectral by famine, were received with distinction by the Viceroy, Mendoza, and Cortez, Marquis of the Valley.

The venturesome hero was summoned to Valladolid to appear before Charles V., and hastened to lay at the feet of his imperial master the gathered spoil which cost ten years of life: the hide of a bison, a few valueless stones resembling emerald, and a handful of worthless turquoises.

Before he set sail for Spain, Cabeça de Vaca told his marvelous story to sympathetic and eager listeners; and, besides, airy rumors had already floated down the valley of Anahuac of a land toward the north where seven high-walled cities, “the Seven Cities of Cibola,” were defended by impregnable outworks. They were least among the provinces, where were countless greater cities of houses built with numerous stories, “lighted by jewels,” and containing treasure stored away in secret rooms, rich as Atahualpa’s ransom. Various rovers gave accounts of natives clad in curious raiment, richer and softer [21]than Utrecht velvet, who wore priceless gems, whole ropes and chains of turquoises, in ignorance of their actual value. One of these stragglers, an Indian, reported that the houses “of many lofts” were made of lime and stone; he had seen them “with these eyes.” The gates and smaller pillars of the principal ones were of turquoise, and their princes were served by beautiful girls, whom they enslaved; and their spear-heads, drinking-cups, and ornamental vessels were of pure gold. There were wondrous tales, too, of opal mountains,[6] lifted high in an atmosphere of such amazing clearness that they could be seen at vast distances; of valleys glittering with garnets and beryls; of clear streams of water flowing over silver sands; of strange flora; of the shaggy buffalo; of the fearful serpent with castanets in its tail;[7] of a bird like the peacock;[8] and a Llano, broad as the great desert of Africa, over which hovered a mirage more dazzling than the Fata Morgana, more delusive than the spectre of the Brocken.

A friar named Niza, with one of the companions of Cabeça de Vaca, went out “to explore the country” three hundred leagues away, to a city they called Cibola,[9] clearly identified as old Zuni, on a river of the same name, one hundred and eighty miles northwest of Santa Fé. This flighty reporter testified to Mendoza that he had been in the cities of Cibola, and had seen the turquoise columns and soft, feathery cloaks of those who dwelt in king’s palaces. Their houses were made of stone, several stories high with flat roofs, arranged in good order; they possessed many emeralds and precious stones, but valued [22]turquoises above all others. They had vessels of gold and silver more abundant than in Peru.

“Following as the Holy Ghost did lead,” he ascended a mountain, from which he surveyed the promised land with a speculator’s eyes; then, with the help of friendly Indians, he raised a heap of stones, set up a cross, the symbol of taking possession, and under the text, “The heathen are given as an inheritance,” named the province “El Nuevo Regno de San Francisco” (the New Kingdom of St. Francis); and from that day to this San Francisco has been the patron saint of New Mexico.

In our prosaic age of doubt and question it is hard to understand the faith with which sane men trusted these bold falsehoods. They were mad with the lust of gold and passion for adventure; and valiant cavaliers who had won renown in the battles of the Moor among the mountains of Andalusia, and had seen the silver cross of Ferdinand raised above the red towers of the Alhambra, now turned their brave swords against the feeble natives of the New World. Less than half a century had gone by since the discovery of America; the conquests of Pizarro and Cortez were fresh in men’s minds, and an expedition containing the enchanting quality called hazard was soon organized. Illustrious noblemen sold their vineyards and mortgaged their estates to fit the adventurers out, assured they would never need more gold than they would bring back from the true El Dorado. The young men saw visions; the old men dreamed dreams; volunteers flocked to the familiar standards; and an army was soon ready “to discover and subdue to the crown of Spain the Seven Cities of Cibola.”

Francisco Vasquez Coronado, who left a lovely young wife and great wealth to lead the romantic enterprise, was proclaimed captain-general; [23]and Castenada, historian of the campaign, writes, “I doubt whether there has ever been collected in the Indies so brilliant a troop.” The whole force numbered fifteen hundred men and one thousand horses; sheep and cows were driven along to supply the new settlements in fairyland. The army mustered in Compostella, under no shadow darker than the wavy folds of the royal banner, and one fair spring morning, the day after Easter, 1540, marched out in armor burnished high, with roll of drums, the joyful appeal of bugles, and all the pomp and circumstance the old Spaniard loved so well. The proud cavaliers, “very gallant in silk upon silk,” kindled with enthusiasm, and answered with loud shouts the cheers of the people who thronged the house-tops. The viceroy led the army two days on the march, exhorted the soldiers to obedience and discipline, and returned to await reports.

When the mind is prepared for wonders the wonderful is sure to appear, and time fails to tell what prodigies the high-born gentlemen beheld: the Indians of monstrous size, so tall the tallest Spaniard could reach no higher than their breasts; a unicorn, which escaped their chase. “His horn, found in a deep ravine, was a fathom and a half in length; the base was thick as one’s thigh; it resembled in shape a goat’s horn, and was a curious thing.” They were the first white men who looked down the gloomy cañon of the Colorado to the black rushing river, walled by sheer precipices fifteen hundred feet high. Two men tried to descend its steep sides. They climbed down perhaps a quarter of the way, when they were stopped by a rock which seemed from above no greater than a man, but which in reality was higher than the top of the cathedral tower at Seville. They passed places where “the [24]earth trembled like a drum, and ashes boiled in a manner truly infernal;” watched magnetic stones roll together of their own accord; and suffered under a storm of hail-stones, “large as porringers,” which indented their helmets, wounded the men, broke their dishes, and covered the ground to the depth of a foot and a half with ice-balls; and the wind raised the horses off their feet, and dashed them against the sides of the ravine. They fought many tribes of Indians, and were relieved to meet none who were “man-eaters and none anthropophagi.”[10]

The route of Coronado is traced with tolerable clearness up the Colorado to the Gila; up the Gila to the Casa Grande, called Chichiticale, or Red House, standing more than three centuries ago, as it does now, in a mezquit jungle on the edge of the desert; “and,” writes his secretary, “our general was above all distressed at finding this Chichiticale, of which so much had been said, dwindled down to one mud house, in ruins and roofless, but which seemed to have been fortified.” With true Spanish philosophy, he covered his disappointment, and gave the place an alluring mystery, with the idea that “this house, built of red earth, was the work of a civilized people come from a distance.” And into the distance he went, through Arizona, the lower border of Colorado, and turned southeast to where Santa Fé now stands, then the central stronghold of the Pueblo empire. They fought and marched, destroyed villages, leveled the poor temples of the heathen, planted the cross, and sang thanksgiving hymns over innumerable souls [25]to be saved,—all very well as far as it went; but the mud-built pueblos yielded neither gold nor precious metals.

Acoma, fifty miles east of Zuni, is thus accurately described by Castenada, under the name of Acuco: “It is a very strong place, built upon a rock very high and on three sides perpendicular. The inhabitants are great brigands, and much dreaded by all the province. The only means of reaching the top is by ascending a staircase cut in solid rock: the first flight of steps numbered two hundred, which could only be ascended with difficulty; when a second flight of one hundred more followed, narrower and more difficult than the first. When surmounted, there remained about twelve more at the top, which could only be ascended by putting the hands and feet in holes cut in the rock. There was space on this summit to store a great quantity of provisions, and to build large cisterns.”[11]

The chiefs told Coronado that their towns were older than the memory of seven generations. They were all built on the same plan, in blocks shaped like a parallelogram, and were from two to four stories high, with terraces receding from the outside. The lower story, without openings, was entered from above by ladders, which were pulled up, and secured them against Indian warfare. There was no interior communication between the stories; the ascent outside was made from one terrace to another. The houses were of sun-dried bricks, and for plaster they used a mixture of ashes, earth, and coal. Every village had from one to seven estufas, built partly underground, walled over the top with flat roofs, and [26]used for political and religious purposes. As in certain other mystic lodges which date back to the days of King Solomon, women were not admitted. All matters of importance were there discussed; there the consecrated fires were kept burning, and were never allowed to go out. The women wore on their shoulders a sort of mantle, which they fastened round the neck, passing it under the right arm, and skirts of cotton. “They also,” writes Castenada, “make garments of skins very well dressed, and trick off the hair behind the ears in the shape of a wheel, which resembles the handle of a cup.” They wore pearls on their heads and necklaces of shells. Everywhere were plenty of glazed pottery and vases of curious form and workmanship, reminding the Spaniards of the jars of Guadarrama in old Spain.

The gallant freebooters traversed deserts, swam rivers, scaled mountains, in a three years’ chase after visionary splendors; but the opal valley and the vanishing cities, with their sunny turquoise gates and jeweled colonnades, faded into the common light of day. Though the adventurers failed in their mocking “quest of great and exceeding riches,” they explored and added to the Spanish crown, by right of occupation, an area twelve times as large as the State of Ohio.

I dwell on these earliest records because it is the habit of travelers visiting ruins, which in the dry, dewless air of New Mexico are almost imperishable, to ascribe them to an extinct race and lost civilization, superior to any now extant here. They muse over Aztec glories faded, and temples fallen, in the spirit of the immortal antiquary, who saw in a ditch “slightly marked” a Roman wall, surrounding the stately and crowded prætorium, with its all-conquering standards bearing the great name of Cæsar.

These edifices are not mysterious except to [27]revered fancies, and their tenants were not divers nations, but clans, tribes of one blood, and civilized only as compared with the savages surrounding them—the tameless Apache, the brutish Ute, the degraded Navajo, against whose attacks they devised their system of defense, so highly extolled by rambling Bohemians, and threw up “impregnable works,” which are only low embankments wide enough for the posting of sentinels.

I have been through many abandoned and inhabited pueblos, examining them with the utmost care, and can discover no essential in which they differ from one another or from those of Castenada’s time. In each one there is the terraced wall; the vault-like lower story, used as granary, without openings, and entered from above by ladders; the small upper rooms, with tiny windows of selenite and mica; the same round oven; the glazed pottery; the circular estufa with its undying fire; acequias for irrigation, not built like Roman aqueducts, but mere ditches and canals; and from the sameness of the remains I infer that no important facts are to reward the search of dreaming pilgrim or patient student.

Each village had its peculiar dialect, and chose its own governor. The report of the Rev. John Menaul, of the Laguna Mission, March 1, 1879, gives an abstract of their laws, identical with those framed by “the council of old men,” the dusky senators described by Castenada; and then, as now, the governor’s orders were proclaimed from the top of the estufa, every morning, by the town-crier.

After the invasion of Coronado, New Granada, as it was then called, was crossed by padres, vagabonds of various grades, and later by armies of subjugation. The same tale is told: how the [28]peace-loving Pueblo was found, as his descendants are, cultivating fields along the rivers or near some unfailing spring, living in community houses wonderfully alike, and keeping alive the sacred fire under laws which like those of the Medes and Persians, change not. The fair strangers were at first graciously welcomed and feasted; but the red men soon learned that the children of the sun, before whom they knelt, whose march-worn feet they kissed in adoration, were come merely for robbery and spoil. The Indian was condemned not only to give up his scanty possessions, and leave the warm precincts of the cheerful day to work in dismal mines, but he must put out the holy flame, and worship the God of his pitiless master. Conversion was ever a main object of the zealous conquistador, and Vargas, one of the early Spanish governors, applying for troops to carry on the crusade, writes—and his record still stands—“You might as well try convert Jews without the Inquisition as Indians without soldiers.” The first revolt (1640), while Arguello was governor of the province, grew out of the whipping and hanging of forty Pueblos, who refused to give up their own religion and accept the holy Catholic faith.

The Pueblos constantly rebelled, and escaped to the lair of the mountain lion, the den of the grizzly and cinnamon bear, the hole of the fox and coyote. They sought shelter from the avarice and bigotry of their Christian persecutors in the steeps of distant cañons, and found where to lay their head in the hollows of inaccessible rocks; and this brings us to the cliff houses, latterly the subject of confused exaggeration and absurd conjecture.

It is well known that the first foreign invasions were by far the most merciless, and it appears reasonable that hunted natives made a hiding-place [29]in these fastnesses; that there they allied themselves with the Navajo, who, from a remote period, had dwelt in the northern plains, beat back the enemy, and, as Spanish rigor relaxed, returned from exile to their fields and adobe houses as before. Mud walls had been proof against arrow, spear, and battle-axe, but could not withstand the finer arms of the fairer race. The cave or cliff-dwellings of Utah, Colorado, and Arizona are exact copies of the community tenements of Southern and Moquis pueblos, varying with situation and quality of material used. The architecture of these human nests and eyries—in some places seven hundred and a thousand feet from the bottom of the cañon—has been magnified out of all bounds. Eager explorers, hurried away by imagination, have even compared the civilization which produced them with

I found nothing in them to warrant such flights of fancy, and, like all castles in air, they lessen wofully at a near view. Those along the Rio Mancos and Du Chelly are mere pigeon-holes in the sides of cañons, roofed by projecting ledges of rock. The walls, six or eight inches thick, are built of flat brook-stones hacked on the edge with stone hatchets, or rather hammers, to square angles; in some cases they are laid in mud mortar and finished with mud plaster, troweled, Pueblo fashion, with the bare hand. Certainly, mortal never fled to these high perches from choice, or failed to desert them as soon as the danger passed. Whether we believe that the hunters were Christian or heathen, we must admit that this was a last refuge for the hunted, made desperate by terror. The masonry is smoothed, so none but the sharpest eyes can notice the difference [30]between it and the rock itself, and in no instance is there trace of chimney or fire-place.[12] The whole idea of the work is concealment.

One might well ask, with sight-seeing Niza strolling through fabled Cibola, “if the men of that country had wings by which to reach these high lofts.” Unfortunately for the romancers, “they showed him a well-made ladder, and said they ascended by this means.” And well-made ladders the cliff dwellers had—steps cut in the living rock of the mountain, and scaling-ladders stout and light.

The solitary watch-towers along the McElmo, Colorado, and wide-spread relics of cities in the cañon of the Hovenweep Utah, near the old Spanish trail through the mountains from Santa Fé to Salt Lake, are built on the same general plan, and divided into snug cells and peep-holes, averaging six by eight feet. Perpendiculars are regarded; stones dressed to uniform size are laid in mud mortar. A distinguishing feature is in the round corners, one at least appearing in nearly every little house. “Most peculiar, however, is the dressing of the walls of the upper and lower front rooms, both being plastered with a thin layer of firm adobe cement of about the eighth of an inch in thickness, and colored a deep maroon red, with a dingy white band eight inches in breadth running around floor, sides, and ceiling”[13]—ideas of improvements probably derived from their enlightened conquerors. There is a story that a hatchet found there would cut cold steel, but I have not been able to learn its origin or trace it to any reliable authority.

In every room entered was the unfailing mark [31]of the Pueblo—pottery glazed and streaked, as manufactured by no other tribe of Indians and invariably reduced to fragments, either through superstition or to prevent its falling into the hands of the enemy. No entire vase or jar has appeared among the masses strewed from one end to the other of their ancient dominion. I have picked up quantities of this pottery near old towns, where it covers the ground like broken pavement, but have not seen one piece four inches square.

After their first experiments the Spaniards saw the policy of conciliating a confederation so numerous and powerful as the Pueblos, and as early as the time of Philip II. mountains, pastures, and waters were declared common to both races; ordinances were issued granting them lands for agriculture, but the title in no instance was of higher grade than possession. The fee-simple remained in the crown of Spain, then in the government of Mexico, by virtue of her independence, and under the treaty of Guadaloupe Hidalgo, February 2, 1848, passed to the United States.

When General Kearney took possession of the country the Pueblos were among the first to give allegiance to our government, and, as allies, were invaluable in chasing the barbarous tribes—their old enemies, whom they tracked with the keen scent and swiftness of blood-hounds. They now number not less than twenty thousand peaceful, contented citizens, entitled to confidence and respect, and by decree of the supreme court (1871) they became legal voters.

Without written language, or so much as the lowest form of picture-writing, they usually speak a little Spanish, enough for purposes of trade, and, less stolid and unbending than the nomads, in manner are extremely gentle and friendly. [32]Their quaint primitive customs, curious myths, and legends afford rich material for the poet, and their antiquities open an endless field to the delving archæologist.

Nominally Catholics, they are really only baptized heathen. A race so rigidly conservative must by very nature be true to the ancient ceremonials, and their religion is not the least attractive study offered by this interesting people. Even the dress of the women (oh, happy women!) has remained unchanged,—the same to-day as described by Coronado’s secretary in 1541.

There passes my window at this moment a young Indian girl from Tesuque, a village eight miles north of Santa Fé. Like the beloved one of the Canticles, she is dark but comely, and without saddle or bridle sits astride her little burro in cool defiance of city prejudice. Always gayly dressed, with ready nod and a quick smile, showing the whitest teeth, we call her Bright Alfarata, in memory of the sweet singer of the blue Juniata; though the interpreter says her true name is Poy-ye, the Rising Moon. Neither of us understands a word of the other’s language, so I beckon to her. She springs to the ground with the supple grace of an antelope, and comes to me, holding out a thin, slender hand, the tint of Florentine bronze, seats herself on the window-sill, and in the shade of the portal we converse in what young lovers are pleased to call eloquent silence. Her donkey will not stray, but lingers patiently about, like the lamb he resembles in face and temper, and nibbles the scant grass which fringes the acequia. I think his mistress must be a lady of high degree, perhaps the caçique’s daughter, she wears such a holiday air, unusual with Indian women, and is so richly adorned with beads of strung periwinkles. She wears loose moccasins, “shoes of silence,” which [33]cannot hide the delicate and shapely outline of her feet, leggins of deer-skin, a skirt reaching below the knee, and a cotton chemise. Her head has no covering but glossy jet-black hair, newly washed with amolé, banged in front, and “is tricked off behind the ears in the shape of a wheel which resembles the handle of a cup”—the distinguishing fashion of maidenhood now as it was more than three hundred years ago. Tied by a scarlet cord across her forehead is a pendant of opaline shell, the lining of a mussel shell, doubtless the very ornament called precious pearl and opal which dazzled the eyes and stirred the covetous hearts of the first conquistadores. Our Pueblo belle wraps about her drapery such as Castenada’s maiden never dreamed of,—a flowing mantle which has followed the march of progress. Thrown across the left shoulder and drawn under her bare and beautiful right arm is a handsome red blanket, with the letters U. S. woven in the centre.

One secret cause of the Pueblos’ ready adherence to our government is their tradition that,

Montezuma, the brother and equal of God, built the sacred city Pecos, marked the lines of its fortifications, and with his own royal hand kindled the sacred fire in the estufa. Close beside it he planted a tree upside down, with the prophecy that, if his children kept alive the flame till his tree fell, a pale nation, speaking an unknown tongue, should come from the pleasant country where the sun rises, and free them from Spanish rule. He promised the chosen ones that he would return in fullness of time, and then went to the glorious rest prepared for him in his tabernacle the sun.

I have seen the remains of that forsaken city, [34]once a mighty fortress, now desolate with the desolation of Zion. Thorns have come up in her palaces, nettles and brambles in the fortresses thereof. It is a habitation for dragons and a court for owls. The site, admirably chosen for defense, is on a promontory, somewhat in the shape of a foot, which gave a broad lookout to the sentry. In the valley below, the waters of the river Pecos flow softly, and park-like intervals fill the spaces toward foot-hills which skirt the everlasting mountain walls. The adobe houses have crumbled to the dust of which they were made, and heaped among their ruins are large blocks of stone, oblong and square, weighing a ton or more, and showing signs of being once laid in mortar.

The outline of the immense estufa, forty feet in diameter, is plainly visible, sunken in the earth and paved with stone; but all trace of the upper story of the council chamber has vanished. On the mesa there is not a tree, not even the dwarf cedar, which strikes its roots in sand, and lives almost without water or dew; but, strange to see, across the centre of the estufa lies the trunk of a large pine, several feet in circumference—an astonishing growth in that sterile soil. The Indian resting in its fragrant shade, listening to the never-ceasing west wind swaying slender leaves that answered to its touch like harp-strings to the harper’s hand, clothed the stately evergreen with loving superstition, which hovers round it even in death; for this is the Montezuma tree, planted when the world was young.

When Pecos was deserted the people went out as Israel from Egypt, leaving not a hoof behind. They destroyed everything that could be of service to an enemy, and the ground is yet covered with scraps of broken pottery marked with their peculiar tracery.

[35]

The Oriental Gheber built his temple over deep subterranean fires, and the steady light shone on after altar and shrine were abandoned and forgotten; but the fire-worshipers on the stony mesa at Pecos had a very different work. The only fuel at hand was cedar from the adjacent hills; and, shut in the dark inclosure, filled with pitchy smoke and suffocating gas, it is not strange that death sometimes relieved the watch. When the chiefs, who had seen the kingly friend of the red man, grew old, and the hour came for their departure to their home in the sun, they charged the young men to guard the treasure hidden in the silent chamber. Another generation came and went; prophecy and promise were handed down from age to age, and the Pueblo sentinel, true to his unwritten creed, guarded the consecrated place beside the miracle-tree, daily climbed the lonely watch-tower, looked toward the sun-rising, and listened for the coming of the beautiful feet of them that on the mountain-top bring glad tidings. Their days of persecution ended, they no longer ate their bread with tears, and a century of prosperous content went by. Then they were shorn of their strength, and their power was broken by inroads of warring nations. The cunning Navajo harried their fields and trampled the ripening maize; the thieving and tameless Comanche carried off their wives, and sold their children into slavery, and their numbers were so reduced that the warriors were too feeble to attempt a rescue. Hardly enough survived to minister in the holy place; hope wavered, and the mighty name of Montezuma was but a dim, proud memory.

Yet the devoted watchmen dreamed of a day when he should descend with the sunlight—crowned, plumed, and anointed—to fill the dingy estufa with a glory like that when the Divine [36]Presence shook the mercy-seat between the cherubim. The eternal fire flickered, smouldered in embers, but endured through all change and chance, like a potent will; it was the visible shadow of the Invisible One, whose name it is death to utter. Sent by his servant and lawgiver, his word was sure; they would rest on the promise till sun and earth should die.

At last, at last, constant faith and patient vigil had their reward. On the wings of the wind across the snowy Sierras was heard a sound like the rushing of many waters—the loud steps of the promised deliverer. East, toward Santo Domingo, southward from the Rio Grande, there entered Santa Fé an army of men with faces whiter than the conquered Mexican. Their strange, harsh language was heard in the streets; a foreign flag bearing the colors of the morning, white and red, blue and gold, was unrolled above the crumbling palace of the Pueblos. The prophecy was fulfilled, and at noon that day the magic tree at Pecos fell to the ground.

After the American occupation, the remnant of the tribe in Pecos joined that of Jemez, which speaks the same language. It is said the caçique, or governor, carried with him the Montezuma fire, and in a new estufa, sixty miles from the one hallowed by his gracious presence, the faithful are awaiting the second advent of the beloved prophet, priest, and king, who is to come in glory and establish his throne forever and ever.

[37]

The number of Pueblo or Town Indians of New Mexico and Arizona has been variously estimated at from sixteen to twenty-five thousand. The dumb secrecy of the red race makes it difficult for the census-taker to reach correct figures among them. They have a suspicion that the Sagamore with medicine-book, ink and pen has come to question them with wicked intent; that numbering the people means plotting for mischief; and they secrete their children and give false figures, so it is impossible to arrive at an accurate estimate of their numbers. In the cultured East there is a popular superstition that the noble aboriginal soul disdains artifice, and is open as sunlight to the sweet influences of truth and straightforward testimony:—an illusion rising from the misty enchantments of distance. Come among them, and you will soon learn to make allowance for every assertion; and as for vanity and self-love I have never seen any equal that of the children of nature debased by contact with the white men. They cannot be instructed, because they know everything, nor surprised, because their fathers had all wisdom before you were born. Show them the most curious and beautiful article you possess; they survey it with stolid composure as an object long familiar. I once saw an officer, thinking to floor a Caçique, unfold the wonders of a telescope to the untutored mind, and explain how, by bending his beady eyes to a certain point the child of the sun might see the spots on his father; when the blanketed philosopher coolly observed that he had [38]often looked through such machines. We then gave it up. Like the Chinese they so closely resemble, nothing can be named which they did not have ages ago; and having so long possessed all knowledge, they steadily resist your efforts to show them their ignorance. They think themselves the envy of the civilized world. Among such a people one soon learns to repress assumption of superiority or effort to impress the calm listener with your grammatical sentences. The poverty of their language is indescribable. Where there is no writing, and of course no standard of comparison, the change in the sound of words goes on rapidly, while the great principle of utterance or general grammar remains. Mere change of accent under such circumstances produces a dialect. It is not easy to catch the lawless Indian tongues; those of the wandering tribes are peculiarly unmanageable, and it is wise to have a common meeting-place in the little Spanish which they pick up. They have no preposition, article, conjunction, or relative pronoun, and to a great degree lack the mood and tense of the verb. A dual and negative form runs throughout the languages, and sentences are often composed, not of the words which the objects mentioned separately mean, but of words meaning certain things in certain connections. The disheartened student, groping in the dark for signs and rules, and finding none, is glad to turn from his bewildering labor to the interpreter who has learned by ear.

The Pueblos have nineteen different villages in New Mexico, numbering in all nearly ten thousand souls. The towns are evidently smaller than they were formerly, as is plainly proved by ruins of houses throughout their ancient dominion, and old worn foot-paths, abandoned or almost untrodden, that lead from town to town, beaten by [39]centuries of wayfaring in some period whereof there is no history.

They are slowly decreasing in numbers, and, says a gentleman resident among them ten years, “why they should gradually disappear like the nomadic and warlike tribes, is a question not easily solved except by the hypothesis that their time has come. Their great failing is lack of self-assertion. Conquered and brought down from freedom and peace two centuries ago, to a condition of servitude and an enforced religion, the power of ‘The Fair God’ has rested heavily on them ever since.”

There are singular characteristics among these Pueblos. Each village is a separate domain or clan, self-supporting, entirely independent of the government of the other Pueblos and the great world in the country across the Sierras where the sun rises. There is no common bond of union among them, and so little intercourse have they with each other that their language, everywhere subject to great mutations, is so altered that they communicate when needful through the Spanish, of which most Indian men understand enough to make their wishes known. There are three dialects among the tribes of New Mexico, and three or four more among those of Arizona. Few Indians understand more than one. In the seven Moqui villages of Arizona, within a radius of ten miles, three distinct tongues are spoken. The inhabitants are identical in blood, manners, laws and mode of life. For centuries they have been isolated from the rest of the world, and it is almost incomprehensible to the restless, aggressive, fairer race how these Pueblos refuse any inter-communication. Tegua and the two adjacent towns are separated by a few miles from Mooshahneh and another pair. Oraybe is not a great distance from both. Each mud-walled [40]community-house has so little interest in the others that there is neither trade nor visiting between them. One might think the women, at least, would sometimes pick up their knitting and go out for a little social enjoyment and the friendly gossip so dear to the feminine heart, or that crafty hunters, tracking deer and coyote, would follow the abandoned trails of the forefathers winding among the towns, but they do not; they are too sluggish and dead, and it is the rarest thing for a man to marry outside of his own little tribe. I have heard the assertion that so far from dying out before the march of civilization the increase goes steadily on—not in all the tribes, but in the aggregate. It is not true. The prehistoric ruins plainly prove that in long forgotten days the Pueblos were numerous and powerful; a nation and a company of nations. The Rio Grande valley was then dotted with clusters of towns, and Santa Fé was the centre of four confederacies, and among the most populous of cities. Down the little Rio on both banks are remains of villages, heaps of crumbling adobes, and the unfailing sign of fleeing tribes, scraps of broken pottery, glazed and painted with their peculiar markings. Thinking of the bold theories about population, one naturally asks, Who took the census when De Soto went wandering up and down the everglades of Florida seeking the alluring, ever vanishing Fountain of Youth.

Every Pueblo, or village, has its own officers and government independent of all the others, and exactly the same and according to the ancient customs. First there is the Caçique, chief officer of church and state, priest of Montezuma, and director of all temporal affairs of the pueblo. It is not known how the Caçique was originally installed in his office, he alone having power to appoint his successor—which duty is [41]among the first he performs after succeeding to his office; nor can the most inquiring mind of the most energetic newspaper correspondent discover the origin of their judicial system.

The Caçique, aided by three Principales, selected by himself, appoints the Governor “and all the officers.” The appointments are communicated to the council of Principales, and then proclaimed to the people. No matter how weak and shrunken in numbers the tribe, it still has its full corps of officers, all sons of Montezuma, though evidently many generations removed from the conquering chiefs who reveled in the jeweled halls of their illustrious ancestor.

The Governor is appointed by the Caçique for one year, and is the executive officer of the town. He is chief in power and nothing can be done without the order of the Governor, especially in those things relating to the political government. The position is purely honorary as regards salary, and the honors do not cease with the office, for the dignified place of Principal is awaiting him at the close of his term, and there is no anti-third term rule to prohibit his holding the place many times during his life.

Immediately after the Governor succeeds to his office he repairs to Santa Fé and seeks the agent for the Pueblo Indians to receive confirmation. This is an empty ceremony, the agent being without the authority to object or remove, but it is followed in obedience to precedent and custom, and there is no harm in humoring the ambition of the gentle wards of the government. On such days of lofty state the happy fellow, in paint and solemn dignity, brings a silver-headed cane, and hands it to the agent, who returns it to the Governor, and the august inaugural ceremony is ended. Under the Mexican rule, it is said, the new incumbent knelt before the Governor of [42]the Territory, and was confirmed by a process of laying on of hands, and some simple formula of Spanish sentences.

The Principales, or ex-Governors, compose a council of wise men, and are the constitutional advisers of the Governor, deciding important questions by their vote.

The Alguacil, or Sheriff, carries out the orders of the Governor, and is overseer and director of the public works.

The Fiscal Mayor attends to the ordinary religious ceremonies.

The Capitan de la Guerre, captain of war, with his under-captains and lieutenants, has very light duty to perform in these piping times of peace. He is head of the ancient customs, dances, and whatever pertains to the moral life of the people. The several priests acting under him order the dances, and enforce special obedience of those dedicated to any particular god or ancient order. Each of the officers has a number of lieutenants under him.

This is a gallant array of officials for such a tribe as Tesuque, numbering less than a hundred, or Pojouque, in all twenty-six, or Zia fifty-eight haughty aborigines. I have not been able to find if they have badges and insignia of office, but I do know they strut along the streets of Santa Fé as though they were at the head of tribes like the sands of the sea-shore, like the leaves of the forest, the stars of heaven, according to the swelling sentences of the proud speeches which our early friend J. F. Cooper gave his heroes. The uniform worn is usually buckskin pants, fringed leggins, moccasins, and, in lordly defiance of the prejudices of civilization, with untaught grace the Caçique wears his pink calico shirt outside his pantaloons. It breezily flutters in the eternal west wind, but the sun is his father, the earth [43]is his mother; he heeds not that cold breath though it blow from heights of perpetual snow. The tenderness of romance invests the degraded descendant of the noble Aztecan, and wherever he turns, the shades of Cooper and Prescott attend him.

As a class the Pueblos are the most industrious, useful, and orderly people on the frontier; at peace with each other and the surrounding Mexicans. They raise large crops of grain, ploughing with a crooked stick, the oriental implement in the days of Moses, and frequently stirring the soil with a rude hoe, for where irrigation is necessary constant work is required. Threshing is done by herds of goats or flocks of sheep, the floor being a plastered mud ring enclosed in upright poles. The wheat is piled up in the centre, the animals are turned into the pen, and driven round and round until the grain is all trampled out. Then the mass is thrown into the air; the wind carries away the broken straw, leaving the grain mixed with quantities of gravel, sand, etc. It is washed before being ground, but the flour is always more or less gritty. They raise corn, beans, vegetables, and grapes, the latter rich and sweet, and own large herds of cattle and sheep. They possess in common much of the best land of the Territory which, for cultivation, is parceled out to the various families who raise their own crops and take their produce to market.

Paupers and drones are unknown among them, because all are obliged to work and make contribution to the possessions of the community to which they belong.

At Taos nearly four hundred persons live in two buildings over three hundred feet in length, and about a hundred and fifty feet wide at the base. They are on opposite sides of a little [44]creek, said to have been connected in ancient times by a bridge, a grim and threatening fortress of savage strength, many times attacked by the Spaniards but never captured. If there are family feuds and quarrels, the outside world has no knowledge of them; men, women, and children, mothers-in-law and all, live together in absolute harmony. On the highest story a sentinel is posted. One might think this ancient custom could be dispensed with in the generation of peace since the American occupation, but they hold the wise Napoleonic idea, if you would have peace be always ready for war.

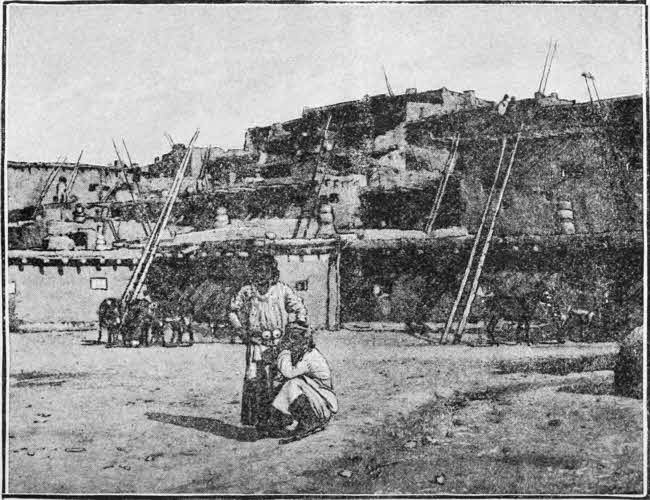

LIVING PUEBLO. (New Mexico).

Each Pueblo contains from one to seven estufas, used as a council-house and a place of worship, where they carry on their heathen rites and ceremonies, and deliberate on the public weal; a consecrated spot to which women are not admitted; a senate-chamber where long debates on public affairs are maintained, and the business of the tribe transacted by the council of wise men, cunning prophets, and able warriors, whose duty it is to manage the internal affairs of the town. The Governor assembles his constitutional advisers in the lodge, where matters are discussed and decided by the majority. One of their wise regulations is a secret police whose duty is to prevent vice and disorder, and report in the under-ground estufa the conduct of suspected persons. The dingy little “temples of sin,” as the old Catholics call them, are hung round with dim and fading legends and shadowy superstitions. Their worshipers have not the slightest approach to music in the horrible noises they make there—a kind of sledge-hammer beating on rude drums and blowing of ear-splitting whistles—nor have they any idea of rhythm or poetry. No correct tradition is kept without one of these arts, and in the absence of all recorded law a perfect devotion [45]to custom carries their poor civilization forward as it was in the beginning. It keeps the Pueblos a separate and distinct people, bounded by a dead wall of conservatism to this day. Says the Rev. Dr. Menaul of the Laguna mission, “Religion enters into everything they do, i. e. everything is done according to ancient custom. The new-born babe comes upon the stage of life under its auspices, is fed and clothed, or not clothed, according to custom. It is hushed to sleep with a custom-song, gets custom-medicine, and grows up in the very bosom of religious custom. The father plants and reaps his fields, makes his moccasins, knits his stockings, carries the baby on his back, in fact does all that he does in strict conformity to custom. The mother grinds the meal, makes the bread, wears her clothing, and keeps her house, makes her water-pots, and paints them with religious symbols, according to custom. The whole inner and outer life of the Indian is one of perfect devotion to religious custom, or obedience to his faith.” And this adoration of the past makes them the most difficult of all people to be reached by outside influence, a rigid unbending adherence to old time observances sets their faces as a flint against everything new and foreign, and our mission-work seems dashing against a dead wall. Nothing is subject to change among them except language; they have the most shifting forms of human speech, so the students tell us, and desiring no improvement or alteration, how can we influence them by religious teaching? How plant new ideas where there is no room to receive them?

Of all the millions of native Americans who have perished under the withering influence of European civilization, there is not a single instance on record of a tribe or nation having been reclaimed, ecclesiastically or otherwise, by artifice [46]and argument. Individual savages have been educated with a fair degree of success, but there is no tribe that is not savage. The Koran says, “Every child is born into the religion of nature; its parents make it a Jew, a Christian, or a Magian.” These North American Indians are more alike than the children of Japhet. Our culture is a failure offered to them, unless one can be detached from his tribe; return him to his people, and he goes back to the dances and incantations, the mystic lodges and time-hallowed ceremonials of the fathers. It seems as difficult to train him as to teach the birds of the air a new note, or the beaver another mode of making his dam; we cannot re-create the head or the heart of the red man. He wants his freedom, his tribe, his ancient customs; he desires no change, and his sense of spiritual things is instinctive like a child’s.

This rigidity of organism makes sad waste of religious teaching. Catholic and Protestant have been alike unsuccessful. Jonathan Edwards failed as signally as the missionaries of the Territories who have lived among them for generations. There is a scarce perceptible progress. The young men have no wish to be better or different from their fathers, and they are slightly changed (can we say for the better?) since Columbus gave to Spain the gift of the New World.

Hardest of all is it to teach the Indian how divine a woman may be made, and it is argued that women are best fitted to reach the burden-bearing sisters of the red race. The Quakers succeeded no better than the Puritans, and St. Mary of the Conception was not more discouraged than the self-sacrificing bride from New England, who comes to the land of sand and thorn to teach the dusky mothers how to sing and sew, and broken in health and spirit, returns to her native hills again.

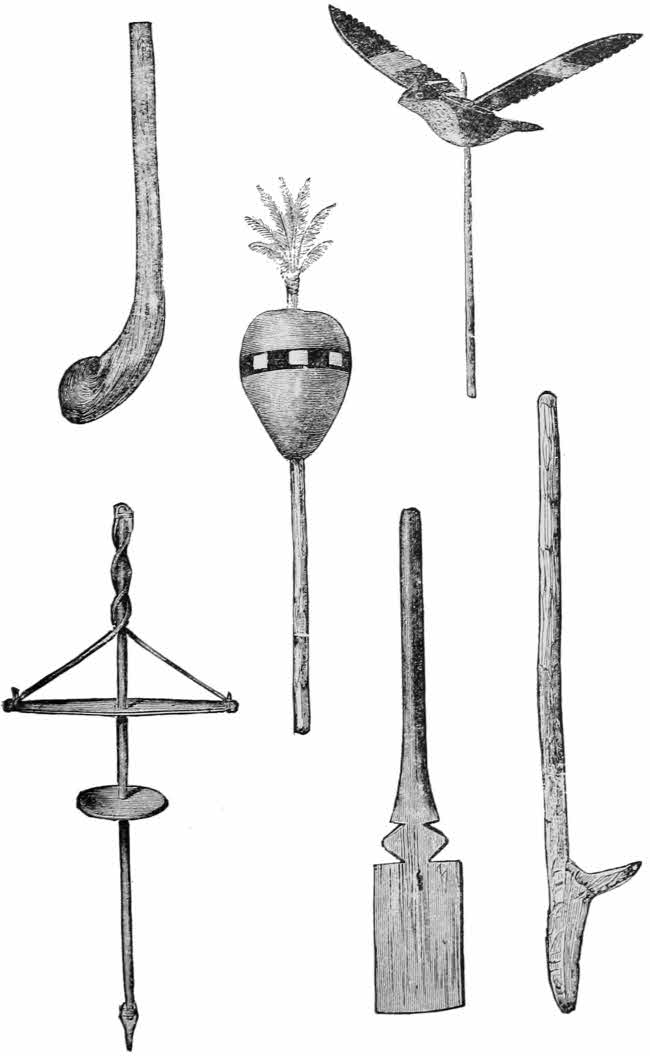

Zuñi War Club, Dance Ornaments, etc.

[47]

In winter the main industry of the Pueblos is practicing for the public dances, a training pursued with anxious care by the priesthood dedicated to the duty, as by the ambitious danseuse who fain would copy the famous winged sylphide leap attained by the lithe limbs and flying feet of Taglioni.

Their Te Deum after victories, and most sacred and beloved rite, is the cachina dance, which they celebrate at certain seasons of the year with great rejoicings. I have never seen it but am told it is full of contortions and fantastic leaps, ending in a jerky trot, unlike polka or mazurka, and still less resembling the gliding, sinuous action of the world-old Teutonic waltz, most delicate modulation of graceful movement vouchsafed the children of men.

When the Spaniards first conquered this country and imposed their religion on the natives, the idolatrous cachina was prohibited on pain of death. History records the natives held it so cruel a deprivation, that the interdict was one of the main causes of the great rebellion of 1680, when Don Antonio de Oterim was Governor and Captain General of Nueva Espagna. Many of the night dances are held in the deepest secrecy; of these the uninitiated may not speak; but other holy days commemorative of abundant harvests are high festivals to which citizens of Santa Fé are cordially invited. You-pel-lay, or the green corn dance, is a national thanksgiving involving the deepest interest and mighty preparation, besides fasting and purification. Some weeks before the carnival we accepted an invitation from the Caçique of Santo Domingo, where unusual pomp and circumstance attend the celebration of this harvest home.

It was in the mild September. Our ambulance was roomy and comfortable, the mules [48]were fresh, the party just such as the dear reader loves, the breeze sweet as the unbreathed air of Eden. I will not tire your patience with raptures about Rocky Mountain sunlight and scenery; the glorious peaks are always in sight, the aerial tints from the hand of the great Master are shifting and changeable as eastern skies at sunset—floating veils of exquisite hue hinting of a viewless glory beyond. The wagon road is always good, and with song and story we beguiled the way and listened with eager interest to a delightful legend, prettily told by a reporter from St. Louis, which he said he had from one of the medicine men of the Pueblos. All about “a spirit yet a woman, too,” who with bright green garments and silky yellow tresses flits above the maize fields, and in the night, robed with darkness as a garment, draws a magic circle round them to keep off blight and vermin.

It had rather a familiar air and flavor, and when the story was ended, one of the audience dryly inquired if the narrator had ever heard of Longfellow. St. Louis then came down reluctantly and confessed to having stolen the tradition from Hiawatha.

We missed our way, and in consequence had to jolt over one bad hill, so steep and cut with steps it reminded me of the gigantic precipitous stairs in the flight of Israel Putnam, a blood-curdling picture of affrighted rider and steed, the delight and terror of my childhood. But this was a mighty hill of adamant, on which the flood, earthquakes and the centuries counted only in heaven have beaten and spent their strength in vain. We did not care for delays. Time is no object on the frontier. We lag along with exasperating slowness if you want to get through; are not expected at any place, sleep where the night overtakes us, and loiter at will in no fear of [49]being behind time or caught in a shower, a hap-hazard, good-for-nothing way of travel which gives a mild, game flavor to the journey. If you have a drop of gypsy blood in you it will come to the surface, strawberry-mark and all, in New Mexico.