Title: Ethel's trial

in becoming a missionary

Author: Lucy Ellen Guernsey

Release date: December 12, 2025 [eBook #77449]

Language: English

Original publication: Philadelphia: American Sunday-School Union, 1871

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/77449

Transcriber's notes: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

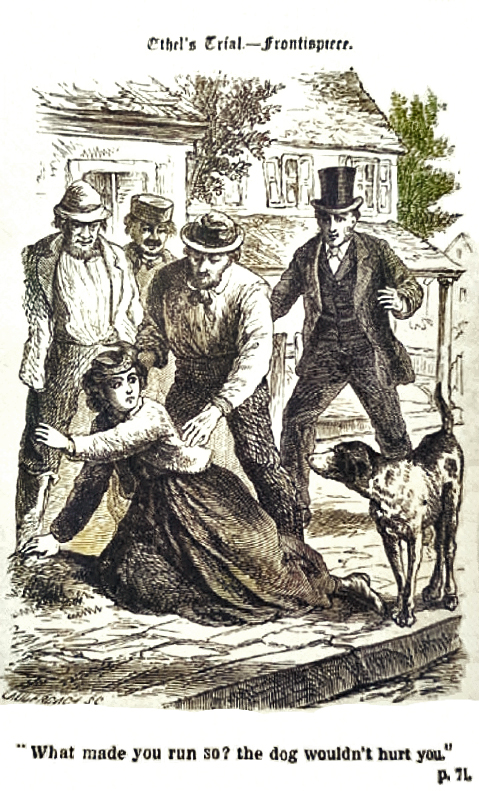

Ethel's Trial.—Frontispiece.

"What made you run so? The dog wouldn't hurt you."

IN BECOMING A MISSIONARY.

BY

LUCY ELLEN GUERNSEY

AUTHOR OF "IRISH AMY," "COMFORT ALLISON," "THE TATTLER,"

"NELLY; OR THE BEST INHERITANCE," "TWIN ROSES," ETC.

PHILADELPHIA:

AMERICAN SUNDAY-SCHOOL UNION

NO. 1122 CHESTNUT STREET.

——————————

NEW YORK: 7, 8 & 10 BIBLE HOUSE, ASTOR PLACE.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1871, by the

AMERICAN SUNDAY-SCHOOL UNION,

in the Office of the Librarian of Congress at Washington.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

PREFACE.

——————

THIS book is dedicated to the "large girls" in our Sunday-schools and

Bible-classes, and especially to those who have taken upon themselves

the name and vows of the Christian disciple. I hope they may find that

in its pages which will stimulate them to new desires after holiness,

new efforts for usefulness, and a more hearty desire to know and to do

"the whole" of God's will concerning them.

CONTENTS.

——————

CHAPTER

XVII.—AUNT DORINDA IS SURPRISED

ETHEL'S TRIAL.

——————

THE BIG BOY.

"BROTHER HENRY, I wish you would come out into the garden," said Ethel Dalton to her brother, one morning in the spring, as he sat reading his paper, after breakfast, in the pretty shady breakfast-room of Dr. Ray's house in Ironton.

"What is the matter now?" asked Mrs. Ray, Ethel's sister, smiling. "What have you found in the garden—a spider or a boa-constrictor?"

Ethel coloured, but made no reply. Mr. Dalton laid down his paper, and taking his hat went out with his sister into the garden.

"Well, what is it, my dear?" said he, kindly. "What do you wish me to do or to see?"

"There is a great rough ragged boy leaning over the railings by the hyacinth beds; and I am afraid to go there!" said Ethel.

"What are you afraid of?" asked Mr. Dalton. "What do you think the boy would do to you here on a public street, and in broad daylight?"

Ethel did not know exactly, so she did not answer.

Mr. Dalton walked on till he came in sight of the boy. He was evidently one of the hands from the iron-works at the landing below, and was rather a rough-looking subject certainly, but there was nothing alarming in his appearance. On the contrary, his eyes were bright and clear; and he had a very thoughtful and at the same time bright and good-humoured face.

"Good-morning!" said Mr. Dalton pleasantly as he came near. "Are you fond of flowers that you look at them so earnestly?"

The big boy smiled very pleasantly. "Yes, I'm very fond of them," he answered. "I've got a pretty nice little garden at our place; but I don't have much time to work at it. You see we go to work at seven and knock off at six, and I have a good many chores to do for mother besides, so I don't get much time."

"No, I should think not. You must be fond of a garden to have any time at all."

"Well, I think flowers help to make a little place look bright and cheerful," said the big boy. "Somehow, they seem to do my eyes good after I have been working in the smoke all day. I haven't got any such hyacinths as those, though."

Mr. Dalton whispered to Ethel, "Gather him a bunch of flowers, my dear."

Ethel had begun to feel a little ashamed of her fears by this time. She gathered a fine bunch of choice flowers, and handed them to the boy, who thanked her with all due politeness.

"Mother will be glad to see these," said he. "She loves flowers as well as I do; and I am going right home so she will have them before they are faded. We are all off work to-day because the blast is out of order, so I shall have a good chance to put my garden to rights."

"I suppose you like to have a holiday sometimes?" said Ethel, feeling as though she would like to say something.

The big boy smiled. "Well, yes, miss, it does come rather pleasant on some accounts; but then, you see, if I don't have the work, I don't have the pay, and three idle days makes a good deal of difference in a week, when a fellow has himself and his old mother, and nothing but his wages to live upon."

"Then you support your mother as well as yourself," said Ethel.

"Well, I don't know who has a better right," replied the lad, rather gruffly. "She supported me when I was young, and it is my business to support her now that she is old."

And nodding a good-morning, the big boy walked away.

"Well, Ethel, the great rough ragged boy does not seem to be a very dangerous character," said Mr. Dalton, smiling. "Nothing so very alarming, after all."

"I am sure he seems a very good boy," replied Ethel "but then I could not know that, you know."

"Suppose he had not been a good boy, what hurt do you think he would have done you in broad daylight, and in your brother's garden?"

Ethel hung her head.

"Ethel," said her brother, gravely, "do you know that it is a very sad thing to be such a coward? What do you think you will ever be good for in the world, if you are so afraid of everything and nothing?"

Ethel looked rather offended. "I am sure I cannot help it, brother. It is natural to me."

"It may be natural to you,—I have no doubt that it is so in some degree,—but I am not sure that you cannot help it for all that."

"People cannot help their natural dispositions," said Ethel.

"That is where you make a very serious mistake, little sister. People can help their natural dispositions, if they take the right way to do so; and it is their bounden duty to try. You have no right to indulge any disposition, however natural, which hinders your usefulness or makes you troublesome to others, and cowardice does both. It is, besides, the mother of many other faults,—of falsehood and cruelty among the rest. You can overcome this fault as you can overcome others, and only in the same way,—that is to say, by honest effort, and by prayer for the assistance of the Holy Spirit."

"I don't know what efforts to make," said Ethel, rather sullenly.

"Why, for instance, when you saw the foundry-boy leaning over the rails this morning, you might have observed him a little, instead of running away. Had you done so, you would have seen that he was a good, intelligent-looking lad in spite of his rough foundry-clothes, and that, instead of meditating any great crime, he was only admiring your hyacinths and heart's-ease. Thus you would have escaped the sin of uncharitableness, and you might have had the pleasure of doing a good and kind action of your own free will.

"So in other cases, when you see any such dreadful object as a mouse or a cricket, instead of running and screaming, you might stand still and look at the fearful monster, reasoning with yourself at the same time that the mouse or cricket cannot possibly hurt you, that it is a pretty and curious creature after all, and well worth watching. You were very much interested yesterday in my account of my travels in China and India, and of what our friend Miss Beecher has been doing in Persia. You think there is no harm in being a coward; but if every one had been as much afraid of cockroaches and spiders as you are, the gospel would never have been preached in India and China to this day. Cockroaches alone would have been an effectual barrier to the spread of Christianity!"

Ethel laughed rather uneasily. She was not pleased with the conversation, and was glad when Mr. Dalton looked at his watch, and said it was time for him to go. She gathered up her flowers, and went into the house feeling vexed and uncomfortable.

"What a fuss brother Henry makes about nothing!" said she to herself: "As if I were to blame for being delicate and nervous. I am sure I don't see how I can help it; and I don't see why I should, either. I don't want to be a regular dragoon!"

By which you may see that Ethel was rather proud of her cowardice than otherwise.

Ethel was very much the youngest of her family; so much so, that her brother and sisters were grown-up, and one of them was married at the time she was born; and that her own mother died. Mrs. Bayard, the elder sister, who had very lately lost an infant, took the little motherless baby home, and cared for it in the kindest manner; and with this sister Ethel lived till she was sixteen years old,—that is, till just before my story commences. At this time, Mr. and Mrs. Bayard had gone to California, where they expected to remain for some years; and Ethel had come to stay with her other sister, Mrs. Dr. Ray, at least till her education should be finished.

Ethel's brother, Mr. Henry Dalton, had never seen his youngest sister till within a week past. He had been a missionary in India for many years, and from thence he had sent Ethel a great many beautiful presents and interesting letters. "Brother Henry" had been a kind of hero of romance in Ethel's eyes, and she was always longing for the happy time when he should come home, and the still happier time when, her education finished so far as school and school-books went, she should return with her brother to India, and help him in his missionary work. The thought of seeing her brother the sooner was one thing which reconciled her to remaining behind when Mr. and Mrs. Bayard removed to California. There was another circumstance which had helped also, but this Ethel did not acknowledge even to herself. She was much afraid of the journey.

Mr. Dalton had arrived in Ironton a week before, and so far all Ethel's anticipations had been realized. Mr. Dalton was even handsomer than his picture; his manners were peculiarly polished and gentle; and when he preached on Sunday, Ethel was entirely satisfied. Everybody had admired the sermon; and old Miss Grimshaw, who was very critical, had offended and pleased Ethel at the same time, by saying that it was a shame for such a man as Mr. Dalton to be wasted on heathens and savages. Anybody was good enough for them, and men of such talents were wanted at home. She was a proud and happy girl as she walked home by her brother's side that day.

Mr. Dalton, on his part, was well satisfied with what he saw of his little sister. Ethel had been well and carefully brought up by Mrs. Bayard; and if she had never known a mother's care, she had never missed it. If Mrs. Bayard had erred at all, it had been on the side of kindness. She had certainly made rather a baby of Ethel, but her indulgence was not of a kind to do her nursling any great harm. Ethel had learned to obey with a word or look before she could speak plainly; she had learned to tell the truth, to be kind and polite to all, and to be specially careful of the feelings of those with whom she lived every day,—a lesson not always learned even by very good people.

"On the whole, she is an uncommonly good girl," said Mrs. Ray that evening, as she was talking with her brother about Ethel. "Juliet is a remarkably good manager with children; and she never made any difference between Ethel and her own, except that I think she indulged Ethel more than she did the boys. That was only natural, I suppose, as she was the only girl in the family after the twins died. Ethel has only one ruinous fault, and that is rather an inconvenient one, both for herself and other people."

"You mean her timidity," said Mr. Dalton.

"Timidity does not express it," replied Mrs. Ray. "She is the greatest coward I ever saw."

"But what is she afraid of?"

"Of every thing. Of mice, and rats, and spiders, and all sorts of insects; of strange cats and dogs; of cows, and horses, and pigs, and peddlers, and beggars. I dread to go out in the street with her, she is so afraid of the crossings; and she is sure to stop short in the most dangerous place of all. If she goes out in the carriage, she is certain the horses are going to run away; and she made Dr. Ray more angry than I ever saw him, by screaming the other day when one of the horses shied a little at a steam-engine. She really did put us in great danger, for the streets were crowded, and if the horses had run away, we should have been badly off. Dr. Ray scolded her well, and told her he would never take her out in the carriage again until he learned to control herself. Ethel thought herself very hardly used, but, really, I could not blame Matthew."

"Nor I," said Mr. Dalton. "These screaming people are dreadful trials in any case of danger. How came Ethel to be such a coward?"

"Why, I suppose it was partly natural, but not altogether. When she was about ten years old, Juliet was obliged to go home to see Mr. Bayard's mother, who was very ill, for several weeks, and she got Miss Carrington to stay in the house and take care of the children. Miss Carrington was afraid of her shadow; and she taught Ethel to think it 'fine' to be very timid and delicate, and to be afraid of everything. Miss Carrington always professed a great horror of strong-minded, masculine women."

"She did not suffer in that way herself, it seems," said Mr. Dalton, dryly. "I wonder Juliet should have selected such a person to take charge of the children."

"My dear brother, have you lived so long in this world without finding out that people have to take not what they want, but what they can get," said Mrs. Ray, laughing. "Juliet was obliged to leave home very suddenly. She knew that Miss Carrington was an excellent teacher and a very good, faithful, energetic housekeeper, and she thought herself fortunate in engaging her. Besides, Juliet is rather timid in the matter of burglars and spiders herself. She did not attach much consequence to Ethel's fears, thinking that she would outgrow them, and that they might be made worse by noticing them: and then, as I said, she was always very tender with Ethel. After all, it is not a very serious fault,—not like lying or mischief making."

"That is true," said Mr. Dalton; "and yet one fault indulged and petted introduces others."

GRAVE THOUGHTS.

ETHEL retreated to her room, and busied herself in learning her Italian lesson. She was very fond of learning languages; and she had lately been studying Italian with great zest; but somehow she found it hard to fix her attention on such interesting questions as "Have you the good tailor's gold?" "Will you send for some milk?" and so on.

Ethel was very sensitive to blame, especially from people that she loved; and she was apt to brood over it till she sometimes magnified a very slight censure into a serious grievance. Now, as she sat at her desk, with grammar and exercise-book before her, and with her eyes on the page, she found certain words of her brother's ringing in her ears, and giving her a very uncomfortable feeling somewhere,—she did not know whether it was in her heart or in her temper.

"If every one had been as much afraid of insects as you are, the gospel would not have been preached in India to this day. Cockroaches then would have been an effectual bar to the spread of Christianity!"

Ethel, as I have said before, had built many castles in the air on the foundation of her brother's mission in India. Ever since she could remember, ever since the first box of presents containing the curious figures of baked clay, dressed in the costumes of all the different castes, had come to her, a little girl of ten years old,—she had dreamed of going out to India with her brother as a missionary. Mrs. Bayard had an intimate friend and schoolmate who was attached to the mission in Persia, and with whom she corresponded. Ethel had helped to fill more than one box of pretty presents to be distributed among the girls of Miss Beecher's school, for she was very skilful both with needle and pencil. Miss Beecher was very much interested in Ethel, and had written her a good many letters; and Ethel felt a personal attachment to every girl in the school. It was very natural that Ethel should be interested in missionary work, and should think of becoming a missionary herself.

She knew of course that there would be many unpleasant things to be encountered; but she was apt, in her dreaming hours, to put all these things out of sight, and dwell only upon the pleasures, the delights, of travelling and seeing new and strange sights, the wonders of tropical vegetation and the luxuries of tropical fruits, and most of all the delight of helping her brother to convert and teach the heathen; for Ethel, with all her dreaminess, was honestly desirous of doing good. She had often pictured herself as meeting with some mother about to throw her baby to the crocodiles of the Ganges, and by her persuasions and arguments inducing the poor woman to turn to the true God, and save her child.

But the cockroaches! Ironton was a famous place for these humid insects—for humid they are— especially West Ironton. They had been imported by a lady who brought some boxes of sweetmeats from Havana, and they had multiplied till they were a serious nuisance: but they were seldom seen on the east side. Ethel well remembered the night she spent with Anna Burgers. The girls had been out at a concert together, and had some supper after they went up-stairs, and Ethel had dropped a bit of cake under the table. She could see it quite plainly by the moonlight as she lay in bed, and was sleepily wondering whether it would grease the carpet, and whether she ought not to pick it up, when the cake suddenly began to move rapidly toward the fireplace, as if it had become sensible that it had no business where it was. Ethel started up in bed with a little scream.

"What 'is' the matter?" asked Anna, sleepily.

"The cake!" exclaimed Ethel. "Don't you see? That piece of cake on the floor. It is running away!"

Anna looked and laughed. "I suppose a cockroach has got it," said she. "Yes, there he is! I see his back!"

"A cockroach!" repeated Ethel, more terrified than ever. "Do you have cockroaches?"

"Yes, indeed, and dreadful torments they are," replied Anna. "They come out as soon as the lights are out, and run over everything. But they don't bite that is one comfort—and they cannot get under the mosquito-bars—that is another: so you need not be afraid of them. We have tried every way to get rid of them, but without success so far."

Anna was asleep again in five minutes, but Ethel could not sleep. She well remembered now how she had lain and shivered all night; how, every time she dropped asleep, she had wakened with a start from a dream of the horrid creatures running over her; and how in the morning she found that one of them had taken refuge in the toe of her boot. She had fully decided that she would never spend another night with Anna Burgers.

But there were a great many cockroaches in India. Ethel knew that very well; and there were other creatures even worse, such as centipedes, and large spiders and lizards, which ran all about the houses, and were encouraged because they caught insects. And there were snakes, too,—horrible poisonous cobras and tic polongas. And then the wolves, and jackals, and the tigers! Ethel remembered the story her brother had written to her of a tiger which had walked into a friend's bungalow, in the middle of a terrible storm, and laid itself down at the gentleman's feet, trembling and foaming like a frightened dog. True, the tiger had retired and done nobody any harm, but Ethel felt that the very sight of him would have killed her. And then the storms; and she could never sleep in a high wind, and was dreadfully afraid of lightning. Then there was crossing the ocean; that could not be helped. To be sure, Henry talked much of returning to India by the way of California, when the Pacific railroad should be finished; but then there were such dreadful railroad accidents, and the Indians on the plains did such horrible things!

Ethel had known all these things all her life, but somehow she had never before thought of them as hindrances in the way of her favorite plan. Now, as she thought them all over, she began to see that her fears were likely utterly to defeat the great wish of her life.

"I wish I was not such a coward," she thought. "I don't see what I am to do. I am sure I should die if I should find a centipede on my dress. I should never wait to have him bite me; and then the snakes! But I don't see how I can help it. I am naturally timid. Sister Juliet said she really thought I could not help it, and Miss Carrington always said she hated strong-minded women. I am sure I 'cannot' help it if I was made delicate and nervous. But then to give up going on a mission after I have looked forward to it all my life. Oh dear, what shall I do!"

And Ethel laid her head down on her desk and fairly cried. It was very hard certainly to have one's cherished life-plan overset and defeated by cockroaches, and to see an army of spiders standing in the way of teaching the gospel to the heathen; but there seemed no help for it, so Ethel thought at last, for she was quite sure that she could never overcome her fears so as to face these dreadful dangers.

There was no use in crying about it, however; and if she had red eyes at the Italian class, that hateful Delia Wilkins would be sure to notice them and ask her what was the matter before all the girls. It would not do to neglect her lessons either; so Ethel dried her eyes and applied herself with new diligence to "sending the son of the good tailor for some milk." When her fears were not concerned, she was a conscientious girl; and she knew it was her duty to make the most of her school-days.

"Henry said he found all the languages he knew useful to him at one time and another. But, oh, those horrid cockroaches!"

THE BURGLAR ALARM.

DINNER was late at Dr. Ray's. He was a physician in very large practice, and was hardly ever at home for more than a few minutes from ten in the morning till six at night. He was a kind-hearted and good-tempered man, very fond of young people, and it was a great pleasure to him to receive his sister-in-law into his family. He had been very angry at Ethel for screaming, and trying to throw herself out of the carriage, when the horses started to run, and had reproved her severely.

"I shall be careful how I take you out again," he said, in conclusion. "Apart from the danger to life and limb, I don't like to lose my temper; and if there is anything which exasperates me beyond endurance, it is to have a woman scream when there is anything serious the matter."

Ethel had not forgotten and, I fear, she had not forgiven her brother-in-law's reproof. She had been rather cool to him ever since, and had secretly wondered how sister Emily had ever married "such a rough sort of person." But Dr. Ray, who was really the injured party, had quite forgotten Ethel's offence, and was ready to be good friends with her again.

"Oh, Ethel! I was looking for you," said he, as Ethel entered the room, with her hat on and her books in her hands.

"I have just come home from Italian class," replied Ethel.

"But do you carry all that load of books over to the west side every day?" asked the doctor, looking at the books which Ethel rather wearily deposited on a side table. "That will never do. We shall have you with a backache presently."

"They are a load," admitted Ethel; "but the signorina wishes us always to bring our dictionaries."

"Then you must ride, and you must have a smaller dictionary. I have one somewhere, which I should think would answer your purpose; and I will give you a lot of car tickets."

"A 'lot' of car tickets," repeated Ethel to herself. "What a coarse expression." Then asked aloud, in a tone of some surprise, "Do you understand Italian, brother?"

"I did once, at least," replied the doctor, somewhat dryly. "I lived four years in Florence, where they are supposed to speak that language with considerable fluency. You see, Ethel, you can't always tell from a toad's personal appearance how far he can hop."

Dr. Ray's memory was a treasury of proverbs from all nations, and he took a certain mischievous delight in producing the oddest of them for the benefit of his fastidious little sister-in-law.

"But you must have some car tickets," he continued, taking up his outer coat and putting his hands first into one pocket and then into another. "I have some, I know, in a paper box. That isn't it." He laid down a pretty little chip box, which Ethel took up.

"What a nice little box! How pretty it would be, varnished with black sealing-wax and trimmed with gold paper."

"Well, you may have it, as soon as the leeches are out of it," replied the doctor, still rummaging his pockets.

"Leeches!" exclaimed Ethel, with a little scream, and dropping the box as if it burned her fingers. "Oh, brother, you 'don't' carry leeches in your 'pockets?'"

"Where would you have me carry them?—In my mouth?" asked the doctor. "No; I don't carry them about with me as pets; but I have to put some on a lady's throat after dinner; and I stopped and bought them on my way, to save them the trouble and expense of sending."

Ethel shuddered. "I am sure I should rather die than have those horrid things on my throat."

"Well, perhaps you would; but then you see Mrs. Gray has a baby three months old, and several children besides, one of which is quite helpless: so she cannot afford to die rather than have leeches on her throat. Here are your car tickets at last. Now don't go walking all the way over to Addison Square again with twenty pounds of books on your arm. That won't do at all! Where is Emily? Oh, here she comes. Let us have dinner, my love. I must be off directly afterward."

"Oh, inconsistent man!" said Mrs. Ray. "How long have you preached that people should sit still after dinner."

"Much longer than you or I have practised it, madam. But Mrs. Gray is in great distress, and need, you know, makes the old wife to trot!"

Ethel could never understand the sorts of half laughing conversation which went on between her sister and her husband. She would have liked to be elevated all the time, and, above all, she hated to be laughed at. She was rather inclined to make a martyr of Emily; but Emily was so undeniably happy and cheerful that she had been obliged to give up the idea, and conclude that Emily liked it. She thanked her brother rather coolly for the car tickets, but did not promise to use them. Much as she was afraid of crossings, and cows, and other dangers of the walk to West Ironton, she feared the street-car and the drawbridge more. She once happened to be in the car with a crazy man, and she had never ventured to enter one since, unless she had somebody with her.

"The Cunningham's had a great fright last night," said Dr. Ray at dinner-time.

"How so?" asked Mrs. Ray.

"A burglar attempted to get into the house. He tried to open old Mrs. Cunningham's bedroom window, and had actually raised it, when the old lady jumped up, and snatching her cane which she always kept at her bedside, she dealt the man a sound rap over the fingers, at the same time calling her son at the top of her voice, and making all the noise she could. The man outside beat a hasty retreat, leaving the window open. We must have our fastenings looked over, Emily. I dare say some of them are out of order."

"I will do it for you," said Mr. Dalton, "I am an experienced house tinker and carpenter, especially where bolts, are concerned."

"Why, you don't really think we are in any danger, do you?" asked Ethel, laying down her knife and fork, and turning pale.

"No more than other people," replied Dr. Ray; "but burglars are apt to go in squads, and it is well to be prepared. We are no more likely to be robbed because we look to our window-fastenings than a man is likely to die because he has made his will."

"What would be the best thing to do if the house should be broken into?" asked Emily.

"Bolt your door, and make all the noise you can," replied her husband. "Very few houses are worth the risk of a fight."

"I should not dare to make any noise," said Ethel. "I should be too much frightened to scream."

"That would be a very good effect of fright in most cases," replied the doctor. "In general, screaming is both useless and dangerous; but in the case of housebreakers, the great thing is to raise an alarm."

Dr. Ray intended no allusion to Ethel's conduct in the carriage, indeed, he had forgotten all about it. But Ethel chose to think that he was talking at her, as she said, and she drew herself up and tried to look very dignified, while the tears came into her eyes and the colour to her cheeks. Dr. Ray took no notice of her, but continued talking to his wife and brother-in-law. Mr. Dalton related various anecdotes of thieves in India, and thus diverged to the Thugs and the Malay pirates.

"Oh, dear!" thought Ethel. "There is another thing. I am sure I shall never dare to go to India. I wish I had never thought of it. I wish they would stop talking. I shall never dare to go to bed."

"Well, I must be off," said the doctor, starting up. "Harry, I shall leave you to look over the windows and doors, especially of my office; but don't make the door so safe that I cannot get in; for I dare say I shall be out late."

"I do wish the doctor would spare himself a little," said Mrs. Ray. "He has been out in the cold all day; and now he is going clear up to Mrs. Gray's again, and on foot too."

"Why doesn't he ride?" asked Ethel.

"He has had the gray horse out, and the other is a little lame," replied Emily. "Matthew spares every one but himself."

"And me!" thought Ethel, but she did not say so. As she was holding the candle for Mr. Dalton to put a screw in the window-fastening, she said, rather timidly:

"Brother Henry, do you think it is safe to leave the office door with only a night-latch?"

"Safer, on the whole, than having Emily get up in the cold to let in the doctor," replied Mr. Dalton.

"But suppose somebody else should get a night-key to fit the latch?"

"Why, then, somebody could open the door and walk in, no doubt; but such a thing is not very likely to happen."

"Well, it does not seem safe to me," persisted Ethel. "I wish the doctor would have Thomas Jones sleep in the office, and open the door for him."

"Thomas Jones's wife might demur to that," said Mr. Dalton, smiling. "Perhaps she is afraid of burglars as well."

"And then perhaps Thomas might be in league with the robbers," said Ethel, musingly. "I have often heard of such things."

"Oh Ethel! Ethel!" exclaimed her brother. "How many burglars you do make to yourself! Do you know anything about poor Thomas Jones, which should lead you to think that he would conspire to rob his employers?"

"Nothing; only such things 'have' happened, you know!"

"And such things have happened as young ladies stealing goods out of the shops," said Mr. Dalton. "But you would not like to have any one suspect you of going to stores for such purposes, would you?"

"Of course not," said Ethel; "but that is different. Thomas Jones is a common working-man."

"And is Thomas Jones's character for honesty any less dear to him because his daily bread and that of his family depend upon it. You ought never to hint such a suspicion without the strongest reason. You might do the poor man an injury which he would never get over; and, besides, such fancies are a serious violation of that charity which 'thinketh no evil.'"

Ethel was silent, feeling somewhat ashamed of herself.

Mr. Dalton saw that she did so, and changed the subject. After he had looked over all the window-fastenings and bolts, and pronounced them as safe as they could be made, he went up to his room and brought down a good-sized box, which his sister had never seen before.

"My two big trunks have come at last," said he. "I was obliged to leave them behind in the custom house at Boston. I have brought each of you a work-box; but they are not alike. How shall we decide the choice?" As he spoke, he brought out two light wooden cases, and set them on the table. They were of about the same size, but of different shapes.

"Let us choose without seeing them; and let Ethel choose first," said Mrs. Ray.

This was agreed upon, and each took the case nearest to her. Mrs. Ray's turned out to be a very roomy, commodious work-box, beautifully lacquered and varnished, and containing various compartments and "cubby-holes." Ethel's was much more showy. It was a miniature cabinet, with one large drawer at the bottom, and various smaller ones above shut in by little doors. The whole was beautifully inlaid with different kinds of wood, and trimmed with silver. Ethel exclaimed with delight.

"The very thing I have always wished for so much," said she. "Do see all the cunning little drawers!"

"You have not found them all yet," said Mr. Dalton. "Look again."

Ethel looked, but she could find no more.

Mr. Dalton pressed down one of the ornamental studs, and opened a little shallow drawer, whose existence no one would have suspected.

"Now you will have a safe place to put your money and jewelry when you have any," said he.

"But, then, mine is prettier than Emily's," said Ethel, after she had admired each drawer separately, and shut up the doors to contemplate the general effect. "It is not fair that I should have the prettiest. Let Emily take this, and I will have hers."

"No, no; we will abide by our choice," said Mrs. Ray. "Besides, mine is more convenient for me than your beautiful cabinet. My needle-work is nearly all of a practical character, you know. Really and truly, my dear, I would much rather have this box," she added, seeing that Ethel still looked dissatisfied. "I should have chosen this, if I had seen them both. Go get your basket, and put your working things into your pretty drawers."

"She is very generous, is she not?" said Mr. Dalton, when Ethel had left the room.

"She is, indeed," returned Emily, warmly. "She has nothing selfish about her, except when her fears are concerned. Her cowardice lies at the bottom of almost all her faults."

The excitement of the new work-box and of unpacking some beautiful choice and ivory ornaments put the burglars out of Ethel's held, and kept them out till she went to bed. And no sooner did she find herself alone in her room than they came trooping back, not in single files but in battalions. She hardly dared to open her windows and shut her blinds; and as she did so, she was struck with a new terror at observing how very close the branches of the elm-tree came to her window. An active man could easily climb the tree and get in. She drew back hastily, and bolted both window and blind in a great hurry.

"How I do wish brother Henry slept in the next room, and not across the hall," she thought. "I don't see why Emily did not give him the front room, on this side. I should never make him hear. Then the doctor is out, and I dare say will not be at home till morning; and Thomas and Mary would never hear, even if—" And then Ethel stopped, remembering what her brother had said of the charity which thinketh no evil.

Then she began to think about the office door, with no fastening but the night-latch.

"I dare say plenty of people have the same shaped keys, for all brother Henry says about it; and, besides, what would be easier than to pick the lock? I declare it is too bad," said Ethel, half aloud and almost crying. "It is downright selfish for Dr. Ray to expose all our lives by leaving the door open."

Ethel thought about the open door till she could bear it no longer. "I shall hear the doctor as soon as he comes up on the steps," said she. "I am sure I shall not sleep a bit for dreaming of those horrid wretches Henry was talking about; and I will run down and open the door before Dr. Ray has time to knock."

So saying, Ethel stepped softly down the backstairs, and bolted not only the office door but the inner door leading from the office into the hall. Mrs. Ray usually slept in the bedroom on the lower floors; but her room was in course of being papered and painted, and she and the doctor occupied one room in the third story. When Ethel had finished her fortifications, she ran up-stairs, and going to bed as expeditiously as possible, she was soon asleep.

She was presently aroused by a noise under her window. She started up and listened. Some one was trying the windows of Emily's room. She heard him go from one window to another, and finally she heard the sash yield, and a man jump in. She was sure of it! There could be no mistake. She heard him treading softly about, opening first one door and then another till he passed into the office, by a door which opened through a closet, and which Ethel had quite forgotten. Just at that minute she remembered another leading from the office into the track hall. A desk stood against this door, which was seldom used, and as Ethel listened breathlessly, she heard the robber removing this desk with evident caution, to avoid making a noise. Once in the hall, there was nothing to hinder him and his confederates from coming up-stairs and murdering the whole family.

It was too much. Ethel flew from the bed and tugged frantically at the bell, uttering scream on scream, so utterly beside herself that when Henry knocked at her door and then opened it, she only screamed the louder, taking him for one of the robbers.

"For goodness' sake, what is the matter?" called out Emily, from the upper landing. "What does ail Ethel?"

"Robbers! Burglars in the study!" gasped Ethel, when she discovered at last who her brother was: "I heard a man get into the window of Emily's room. There, don't you hear?" as a movement was heard below.

"There is somebody down-stairs," said Henry, listening. He advanced to the stair-head, followed by Ethel, who dared not stay behind. Lo! There was the doctor coming up as coolly as possible, trimming his candle as he ascended.

"Halloo! What is the row?" he asked, looking up and seeing all the family assembled on the landing. "What is all this noise' about? And what in the name of common sense, Emily, made you bolt all the office doors? I knocked and rung till I was tired, and I had to make a burglar of myself; and get in at the window after all—so much for your fastenings, Henry,— and then I thought I should spend the night in the office. Didn't you hear the bell, Jones?"

"The bell is down, sir! The painters took it down this afternoon. But who bolted the office door? I didn't!"

"Nor I!" said Emily.

"And I am sure I didn't," said Mrs. Jones. "It must have been Miss Ethel. I thought I heard her go down-stairs."

Everybody looked at Ethel, whose cheeks were as scarlet as they had been pale before. Dr. Ray set down his candle, dropped into his chair, and burst into one of his great hearty laughs, in which he was joined after a minute by every one of the company.

"Oh, Ethel! Ethel! You will be the death of me," groaned the doctor, holding his hand to his side. "So you first bolted me out of my own house, and when I was forced to break into it, you were for treating me as a burglar. It is a hard case if a man can't break into his own premises."

"I don't know whether the law would make that burglary or not," said Mr. Dalton.

"If I am sent to State's prison, Ethel will have to go too as an accessory before the fact," returned the doctor. "But come, go to bed. You will all have your deaths of cold, and that will be worse than robbery. Come, Ethel, never mind. There is no great harm done, and the joke is worth the trouble." And laughing again, the doctor proceeded up-stairs to bed.

Ethel retreated to her room, feeling as though she should like to take to her bed and never leave it again. She was very sensitive to laughter, especially to Dr. Ray's, who, good-natured as he was, was a little given to teasing. How soundly she must have slept! A dozen robbers might have gone over the house without her hearing them. Heartily ashamed and vexed, she crept into and cried herself to sleep.

A LONG TALK.

ETHEL would have given a great deal for a good excuse for staying in her own room the next morning; and she lingered so long, that Emily came to see what was the matter.

"Come, Ethel, breakfast is ready and waiting. Why don't you come down?"

"I would rather not," said Ethel, colouring violently. "I don't care for any breakfast, if Anna will bring me some tea."

"Are you sick?" asked her sister.

"No; but I don't want to come down—not till the doctor is gone."

"Oh!" exclaimed Emily, suddenly enlightened. "I see now what is the matter. You are afraid Matthew will laugh at you; is that it?"

"Well, he does laugh at me, and you know he does, Emily," replied Ethel, tearfully. "I can't bear it."

"Oh, you should not mind. You know he would do anything in the world for you; and besides, Ethel," added Emily, gravely, "I think you may be very well satisfied if Matthew does nothing but laugh at what happened last night. A good many gentlemen would not have thought it a very nice joke to be fastened out in the cold and rain, after such a hard day's work as Matthew had yesterday. It was not very pleasant for him to go round trying the doors and windows of his own house; and if he does nothing but laugh at the trouble you caused him, I think you can hardly complain."

Emily's words presented the matter in a new light to Ethel, who had heretofore considered herself as altogether the aggrieved party. She remembered all at once that Dr. Ray had not spoken a single unkind word after all the trouble she had given him. As she hesitated a moment before speaking, Emily coughed violently.

"You are coughing again," said Ethel, anxiously; for Emily had suffered several months from a very painful affection of the throat, which was apt to return if she took the least cold.

"Yes, I am afraid I took cold last night. I was so startled, I never stopped to put on my stockings and shoes. Come, are you ready?"

Ethel hesitated no longer, but followed her sister down-stairs, feeling very shy and very much ashamed of herself.

Dr. Ray's eyes twinkled, and he pulled the end of his mustache, as he was apt to do when enjoying a joke; but he bade Ethel good-morning very kindly, and made no allusion to the events of the night before. His face grew suddenly grave as Emily coughed again.

"That won't do," said he. "How have you taken cold?"

"Last night, I suppose," said Emily.

"Humph! Yes, I suppose so. The next time, don't run out on the cold matting with your bare feet, even if the house be on fire. You must stay by the fire all day to-day and nurse yourself."

"Oh, brother! And lose the concert which she has been looking forward to all the week," exclaimed Ethel.

"I am very sorry, sister, but there is no help for it," said the doctor, kindly but gravely. "Emily has been too ill lately to run any risks; and it is a very chilly, damp day,—one of the worst of this very trying spring. If she should take another hard cold, there is no saying what might come of it."

This was all the doctor said; not a word of reproach was addressed to Ethel either by him or his wife, but Ethel felt this very forbearance to be a severe reproach, and began to justify and excuse herself in her usual pathetic tone.

"I suppose you think it is all my fault, brother; but I am sure I don't see why. I am not to blame for being naturally timid and nervous."

"Perhaps not. I do not know that anybody said you were," replied Dr. Ray. "Whether you are to blame for petting and nursing your fears, indulging your fancies, and making no effort to overcome them is another matter. 'I' think you are; and I tell you plainly, little sister, that unless you do make an effort to overcome these useless and 'seemless' fears, you will never be good for anything in this world unless it be to exercise the patience and forbearance of those about you. Come into the office, Emily, and let me look into your throat."

"Yes, that is always the way," said Ethel, indignantly, as Dr. Ray and his wife left the room; "I am always the one to blame. It is too bad!"

"Gently, gently," said Mr. Dalton. "Who do you think was to blame, if not yourself?"

"I don't know that any one was to blame, unless it might be you and the doctor, for telling such horrid stories and frightening me to death," said Ethel.

"Ethel, I want to have a serious talk with you about this matter," said Mr. Dalton, gravely, "a good deal depends upon it. Suppose you come up to my room, and help me to put away my things. I am going to unpack my big trunks."

Ethel followed her brother with a martyr-like air, as of one unjustly condemned going to execution. Henry did not seem very much disposed to begin the lecture. He unpacked his boxes, talked over their contents, and gave the history of each article as he took it out, till Ethel almost forgot what she had come for. At last Henry said, somewhat abruptly:

"Ethel, you believe in God, don't you?"

"Why, Henry, what a question! Of course I do!" replied Ethel.

"I am not so sure about the 'of course;' but we will let that go for the present. You believe that there is a God: what do you believe about him? Think now, before you answer."

Ethel thought a little, and then answered, "I believe that he is everywhere present, that he is all-powerful, all-wise, and perfectly good."

"Do you think you love him?"

"Yes," said Ethel, seriously. "I do believe, brother, that I love him."

"And do you think he loves you?"

"He must love me, I suppose: why, yes, of course he does, or he would not have done so much for me," said Ethel. "Yes, I am sure he loves me!"

"Then, Ethel, what are you afraid of?" asked her brother, gravely. "Cannot this almighty, all-wise, all-good, and everywhere present God, whom you love and who loves you, protect you for one single night? Which of his attribute do you distrust—his power or his wisdom or his goodness, that you live in this constant terror?"

Ethel looked as if a new idea had been presented to her.

"Ethel, when Juliet taught you to say your prayers, as a little child, did she not teach you one which begins, 'Lighten our darkness?'"

"She did," replied Ethel, surprised. "How did you know?"

"Because our own mother taught Juliet, Emily, and me, when we were little children," replied Mr. Dalton.

"That was not my mamma," said Ethel.

"No, your mamma came afterward, and a very sweet, lovely woman she was. I loved her dearly, and mourned her loss greatly, though I never saw her many times. But will you repeat that prayer for me, Ethel?"

Ethel repeated in a low, reverent voice:

"Lighten our darkness, O Lord, we beseech thee, and by thy great mercy

defend us from all terrors and dangers of this night, for the love of

thy Son, our Saviour Jesus Christ."

"That is the way I learned it," said Mr. Dalton. "I remember asking mother what terrors meant; and she said they meant fears: that we asked our Father in heaven to protect us from all dangers, and from the fear of them. Do you still use this prayer, Ethel?"

"Yes, brother, after my other prayers. It seems so natural, somehow. It makes me think of sister Juliet."

"Ethel, what is it to pray in faith?"

"It is to ask God for what we need or desire, believing that he will give us what we ask for if it is best for us to have it," answered Ethel.

"Exactly so. And what is the promise made to the prayer of faith?"

"There are so many of them," said Ethel, hesitating.

"Yes, I know there are a great many of them," said her brother, smiling; "but tell me one of them?"

"'Whatsoever ye shall ask in prayer, believing, ye shall receive.' That is one," replied Ethel, after thinking a little.

"Yes, that is one, and a very large and full one," said her brother. "Do you believe it?"

"It is God's word," replied Ethel; "so it must be true."

"Yes, but do you believe it?" asked her brother, with a keen glance. "It does not seem to me that you can believe it, or that you can have any real trust in God whatever."

"I don't see why you should say so," said Ethel.

"Because, my dear child, if you really and truly trusted God, and believed that he is not only able but willing to take care of you, you would not be so afraid of everything and everybody. If, for instance, you believed really in your heart that God would hear your prayer at night, and preserve you from all harm and dangers of the night, you would go to bed and sleep without fear, because you would know that no real harm could happen to you. At least, you would try to overcome your fears by these considerations, and by degrees you would succeed."

"It is natural for me to be afraid," said Ethel, rather sullenly. "I can't help it."

"Are you sure you wish to help it, Ethel?" asked her brother. "Are you sure you do not think it rather lady-like and refined to be as you say—delicate and nervous?"

Ethel did not answer. In her heart she did think so.

"As to its being natural to you to be a coward, I have no doubt it is partly true," continued Mr. Dalton; "but it does not follow by any means that you cannot help it. People often correct their natural dispositions. Do you think sister Juliet was a very indolent person?"

"Sister Juliet!" exclaimed Ethel. "No, indeed. She was the most industrious person I ever saw—more so, even, than Emily."

"Well, Ethel, Juliet was by nature rather the most indolent little person I ever knew in my life. She was lazy about everything, and the most accomplished little 'shirk' I think I ever met with. She contrived to slip her neck out of everything, and made everybody wait on her."

"Well, I never should have guessed that," said Ethel. "Mr. Bayard used to say that she was unmercifully industrious."

"Yes, she went rather to the other extreme in after-life; but as a child, and until she was about fifteen, she was just what I describe."

"What was it that cured her?" asked Ethel.

"What cures all of us, my dear, when we are cured at all,—the grace of God. When Juliet was fifteen, she became a disciple of our Lord,—not only by name and profession, but in heart and life a Christian. The Holy Spirit showed her that indolence was a grievous sin, and a wasting of the time and talents which were given her for her master's service. She discovered that the indulgence of this sin was undermining and destroying everything good in her, as does any 'indulged' sin, however small it may seem in itself. She resolved to conquer herself, and she did so; but she had many hard struggles before she gained the victory."

"I don't see that cowardice is a sin," said Ethel.

"There is undoubtedly a degree of natural timidity which cannot be called a sin," replied her brother. "It is no sin for a child to be afraid in the dark. There is no sin in the disgust we naturally feel toward certain animals, or in that instinctive fear which leads all animals, man included, to shun what is likely to hurt them. But if we allow this fear to govern us, to interfere with our usefulness and the comfort and fear of those around us, it becomes a sin. A man is not a coward if he is afraid of being shot when he goes into battle; but he becomes one if he yields to that fear and runs away."

"It is all very well for you to talk, brother; but the fact is, you don't know anything about it," said Ethel. "You can't tell how I feel. Matthew is just so. He scolded me for being afraid and making a fuss, just as if I could help it; and I know I can't help it. Of course he does not understand. Doctors never do. Their hearts get perfectly hardened to suffering of all sorts by seeing so much of it."

"There I think you make a great mistake, Ethel," said her brother. "I do not think doctors are more hard-hearted and indifferent to suffering than other men, but they have to keep their feelings under control. You know the other day Matthew was called suddenly to see a man who had his arm crushed in the rolling-mill, and I went with him. It was a dreadful sight, as you may suppose, and the poor man was suffering terribly. Suppose that Matthew, instead of attending to his business, had begun to think how horrible the sight was, and how dreadful it was to see him suffer so.

"Suppose that the man who rescued his companion at the imminent risk of his own life had said to himself, 'Oh, I can't go near him; I shall be killed if I do.' What would have become of the sufferers? You say people get used to these things; but how do they so? They were not used to them when they began. Is it not by controlling themselves and overcoming their fears and feelings?"

Henry paused, and walked two or three times up and down the room. "I shall say no more, Ethel," he said, at last. "There is no use in talking to you so long as you justify yourself all the time. These fears of yours are a great sorrow and trouble to me; because, unless they can be overcome, they present an insuperable obstacle to a plan on which I have thought a great deal, and on which my heart has been set for several years."

Ethel's heart began to beat fast. "Do you mean—" she asked, and then stopped.

"I mean that I have for several years cherished the hope that I might take you to Persia with me, as an assistant to our friend Miss Beecher in her girls' schools. It would be very pleasant to me to have a home and housekeeper of my own; and we are always in want of help. I thought I might begin at once to teach you the languages, especially Syriac; and I calculated that at the end of the three years I expected to remain at home, you would be ready to return with me. But my pretty castle in the air is likely to vanish like a bubble," he continued, smiling rather sadly.

Ethel was so much agitated that she could hardly speak. So Henry had been cherishing the same plans as herself.

"But, brother Henry, I don't understand," she managed to say. "I thought you were going to India again."

"No; I am going back to Persia, where my work began in the first place, you know. I have always hoped that it might be so arranged, and my wishes are likely to be fulfilled so far as that is concerned. But it, seems that I must give up all thought of taking you with me, unless, at least, you can learn to be a brave woman. The journey is a long and somewhat dangerous one; and there are many unpleasant things constantly to be encountered in the life of a missionary. A coward would be only a hinderance and a burden to me. I am very sorry, very much disappointed; but, as you say, there is no use in talking, and we will drop the subject."

"But going to Persia is not like going to India," faltered Ethel.

"No; in some respects it is better, and in others rather worse. The journey is far more toilsome and dangerous. If you are afraid to go to bed with the office door unbolted, how would you bear sleeping in a tent where you have no fastenings at all, and hearing the wolves howling outside; or hiding from savage hordes in a haystack, as Miss Beecher was once obliged to do? It would not do to succumb or faint under such circumstances, you see."

The conversation was here interrupted, and Ethel escaped to her room, feeling more unhappy and ashamed than she had done in all her life before. She had often considered how she should open the subject of her becoming a missionary, to Henry. She had pictured his surprise, and had gone over and over again the objections he was likely to urge, and the arguments she would bring forward to meet them. And now, it appeared, that Henry had been cherishing the same idea,—that he had wished to take her to Persia, whither she had always wished to go, and as an assistant to her dear Miss Beecher. He had meant to have her teach the very girls in whom she had always felt such an interest. The only obstacle in the way, as it seemed, was one of which she had never thought—her own utter unfitness for the place and its duties. She could not but see that Henry was right. It would never do for a missionary to be a coward. And she was an egregious coward. She would not deny it, and hitherto she had felt no disposition to do so. She had, as Henry said, thought it "fine" to be nervous and timid. It was all because she had such delicate sensibilities. But what if these delicate sensibilities were to interfere with and thwart the grand plan of her life? What was to be done about that?

The first thing to be done about it, according to Ethel's view of the fitness of things, was to sit down and cry. Crying was an amusement in which she frequently indulged, and she did it very prettily, it must be confessed. Her tears came easily, in large, bright drops, without any violent sobs and disfiguring convulsions of the face. But somehow she did not find her usual comfort in tears. For almost the first time in her life, she had a real heart trouble, and she did not find it at all nice,—not at all like the sentimental distresses which she was apt to conjure up for herself. She was thoroughly disappointed and mortified. The real strength and earnestness which lay at the bottom of her character, and which had been enlisted on the side of her missionary scheme, was aroused by her brother's words, and protested against being baffled and put down. She was really and truly unhappy.

Ethel had for a year been a member of the church, and believed herself to be a true disciple of Christ; and it must be confessed that in most respects she was a consistent Christian. Her religious life, as far as it went, was a real, genuine life; and though her religious experience was not very deep, it was true. As fast as she was made aware of her faults, she strove to conquer them, and to live very near to her Divine Master. She had had the advantage of a thoroughly Christian bringing up and training, which had taught her to be truthful, kind, and polite, industrious and faithful in her work, conscientious and self-restrained in her amusements. Hitherto her way had been easy to her.

In all continued efforts, like pursuing a study, for instance, the hard place does not lie at the beginning, but a shorter or longer time afterward. The lion which guards the threshold does not show himself at the gate, but hides somewhere inside, ready to take us unawares. Every one who has learned music or a new language, knows what it is to come to the "hard place." It is when the interest of novelty has worn off and that of use has not begun; when we work day after day, seeming to make absolutely no progress; when we cannot understand something—meet with some unexpected difficulty—that we are discouraged, and wish we had not begun. But if we keep resolutely on doing our best, working doggedly and steadily at whatever hinders us, we presently find, we hardly know how, that the hard place is left behind, and we are going on finely again.

It is very much so in the matter of the Christian life and experience. Nobody sees the whole of his sins and imperfections at once. If we did, we should perhaps be utterly discouraged. We go on honestly correcting one fault after another, and perhaps congratulating ourselves that we are so ready to sacrifice all for Christ, till, by-and-by, we are plainly shown that something must be given up which we are by no means ready to relinquish. We are shown that some habit or quality on which we have perhaps prided ourselves must be overcome or laid aside; our pride which we call self-respect; our resentment of injuries, just resentment, as we think it; our dainty self-indulgence which we call refined taste; or a love of the beautiful, or some darling desire of self-culture and improvement, perfectly legitimate in itself, but conflicting with the duty we owe to others. Then, indeed, comes the real hand-to-hand struggle, the real conflict with Apollyon, which shows us what we are made of. If we have the love of God in our hearts, and strive with humility, and a due dependence on the aid which is promised us, we are sure to conquer at last, though we may be sorely wounded and bruised in the battle, and even defeated over and over again; but if we decline the combat, and try to avoid it by shutting our eyes and refusing to see the enemy, woe to us. Not one more step of real progress is possible; and though we may fancy we are going forward, we shall find to our sorrow that we have turned our backs, and are travelling again to the city of Destruction.

Ethel had now come to this place. It had been easy walking hitherto. She had not been called upon for any great sacrifice or humiliation. But here was a barrier stretching right across her way. After she had made up her mind to enlist openly on the side of her Saviour, the idea of devoting her life to the cause of missions, which had at first been only a childish fancy, became a fixed and settled purpose. She had talked the matter over with Juliet, and Juliet had made no objection, provided Henry's consent could be gained. Ethel felt that she had promised herself to this work; and, yet, how was she ever to perform it? Never, it was plain, unless she could conquer her cowardice, which she had always declared she could not conquer, and which she had never really wished to conquer. She must own that cowardice to be a fault—a sin—and this in itself involved a great sacrifice of pride; and she must make many painful efforts, and probably be defeated many times. Ethel felt instinctively that if she were to give up the purpose of being a missionary for any such reason, she should never be good for anything else. If she were providentially prevented from going by her own illness or that of friends, or by some plain call of duty at home, that would be another thing; but to give up because she was afraid to go, it would be a final defeat. No: she was not willing to give it up; but, on the other hand, neither was she willing to own herself a sinner in that which kept her back, and to strive humbly after amendment. It was a very hard plan, and she saw no escape.

PROSPECTING.

NEVER had Ethel been so unhappy in her life, as she was during the next two or three weeks; never had she been so irritable, and so utterly unreasonable and troublesome in her terrors and fancies. She seemed lent upon proving to herself and others that she could not help being afraid of her own shadow and that of every one else.

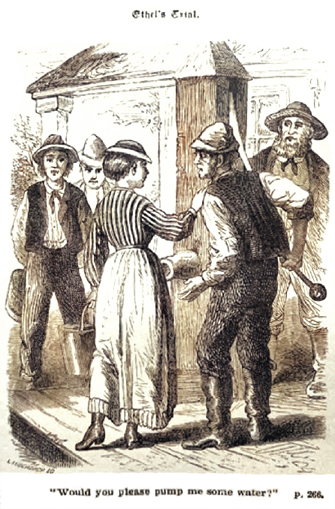

"Ethel," said her brother, one pleasant morning, "I have found out where our foundry-boy lives. I was driving with the doctor last evening, and saw him at work in his garden. Suppose you walk up with me to see the old lady, and carry her some of those flower-seeds which Emily says she has no room for in the garden. I dare say they will be very acceptable."

"I am sure she is welcome to them," said Emily. "Mr. B— gave the doctor three times more seeds than we can possibly use. I have supplied all the children's gardens on both sides of us, and there are quantities left. It is a pity somebody should not have them."

"I have another design in going, for which the seeds will furnish a good excuse," continued Mr. Dalton. "I want to 'prospect' for a Sunday-school and mission service in that neighbourhood; and I dare say this old lady can give me some idea of how the land lies."

"What! Among the foundry-men!" exclaimed Ethel.

"Exactly. Why not? They seem to be a fine set of fellows, and the place is swarming with children. If I succeed, I shall depend on your Bible-class girls for teachers. But come, will you go with me?"

"Do, Ethel; the walk will be good for you," said Emily. "I only wish I could go. I am so tired of being shut up in the house."

Emily had not been out since the night of the burglar alarm. The cold she had caught brought back all her throat trouble, and Dr. Ray was seriously concerned about her.

"I don't know what to make of Ethel," said Emily, when her sister had left the room. "I begin to think that I have never understood her at all, and that I did not know what I was about in undertaking the charge of her. Her fears have always been vexatious enough, but they are becoming perfectly intolerable. I don't so much mind myself, but she annoys the doctor so."

"Matthew is wonderfully good-natured and patient with her," observed Mr. Dalton.

"He is good-natured and patient with everybody," replied Emily; "and for that very reason I don't like to have him imposed upon; but I don't know what to do. If I say a word to Ethel, she begins to cry; and that is what I cannot bear very well just now."

"You had better not trouble yourself about her at present," said Mr. Dalton; "you are too unwell to be worried. I think, myself, that Ethel is passing through a kind of crisis."

"Yes; that is just what Matthew says when his patients are worse than usual," said Emily, laughing. "'You are passing through a "crisis,"' he says. 'You will be a great deal better after it.'"

"Exactly so," replied Mr. Dalton, laughing, in his turn. "I am inclined to believe that Ethel is passing through just such a crisis, and that she will be better after it. I think she is trying hard to justify herself in her own eyes, and I do not think she will succeed. I can see that there is a struggle in her mind, and that she is very unhappy under it. We must all try to have patience with her, and help her if possible."

The conversation was here interrupted by the entrance of Ethel, prepared for her walk.

"I wish you would stop at Mrs. Fowler's, and ask her to send up some sponge-cake and a mould of ice-cream, Ethel," said Emily. "By the way, Henry, you should make acquaintance with Mrs. Fowler. She is the daughter of old Mr. Bond, of whom we used to buy sweeties when we went to Mrs. Clark's school, and a very good religious woman. I dare say she can tell you about your foundry-men and their families, for she has lived over there on the hill."

Ethel was evidently nervous in the expectation of a lecture; but her brother did not seem disposed to lecture, and chatted on about various matters till they reached the very neat and pleasant shop, where Mrs. Fowler reigned supreme over bonbons, cakes, fruits, and flowers.

"I must ask you to write your order yourself, Miss Ethel," said Mrs. Fowler.

And as she spoke, Ethel noticed that her hand was bandaged.

"How have you hurt your hand?" she asked.

"We had an accident last night," replied Mrs. Fowler. "My girl set her dress on fire, and mine running down-stairs with it all in a blaze. Luckily, I had a large shawl at hand, which threw round her, and by getting her down on the floor, I stifled the flame before she was seriously burned. I thought we were gone for a minute, for she was perfectly beside herself with fright, and I could hardly hold her; and, aside from the danger to herself, we have light muslin curtains to the windows and over an archway. As it was, I scorched my hands and sprained my wrists; but that is nothing to what it might have been."

"No doubt you saved her life," said Mr. Dalton. "How did her dress take fire?"

"She dropped a match on her dress. She said there was only a little blaze at first; and I dare say, if she had had her wits about her, she might have put it out in a minute; but she is always scared out of her wits if the least accident happens."

Ethel blushed, as if she thought the remark a personal one, and glanced at her brother.

"Well, it was a happy circumstance to her that all people are not scared out of their wits," stud Mr. Dalton.

"So I told her," replied Mrs. Fowler. "She was very sorry when she saw how I had hurt my hand.

"'Jane,' says I, 'I don't grudge the pain in my hand at all, if you will only learn something by this business. If I had been as crazy as you, you would have been burned up, and the house too."

"'Well, Mrs. Fowler,' says she, 'I do mean to try and learn, and not to be such a coward.'

"I believe she will do it too, for she is a good girl in the main."

"My sister tells me that you have lived up on the hill, and know people there," said Mr. Dalton. "What do you think would be the prospect of success, if any one were to establish an afternoon Sunday-school and a mission service in that neighbourhood?"

"It would be a grand thing, and no mistake," replied Mrs. Fowler, warmly. "There are quantities of children, and another class who need teaching still more,—I mean the half grown-up boys and girls, who now do nothing but hang about and gossip all Sunday afternoon."

"But are they not a very rough set?" said Ethel. "I should not think it would answer at all for young ladies to try teaching among them."

Mrs. Fowler laughed. "I don't believe there is one of them who would ever give a young lady a saucy word or look. They are almost all American-born; and all the middle-aged and elderly men are married, and have families of their own. Besides, I never knew a lady to be affronted when she was about any work of kindness."

"Nor I; either,—at least, not in this country," said Mr. Dalton. "Can you tell me of any good people to whom I can apply?"

"I don't think you will go amiss with any of them, unless it may be some of the families up by the Brewery. There are some Roman Catholics in that neighbourhood, and one family of professed infidels. The people are no great church goers; but I think that is more than anything because there is no place to go."

"There is the church on the avenue; that is not very far-off," remarked Ethel.

"Yes; but the seats are all rented and the rents are very high, especially since they fixed over the church, and put in all that paint and stained glass," said Mrs. Fowler. "Seats which used to rent for fifteen dollars have been raised to seventy and eighty dollars, and no poor man can afford to pay such prices."

"Ah, that opens the way to a very wide subject, which you and I will talk over some day," said Mr. Dalton. "But can you give me the names of some of the good people up there?"

Ethel fidgeted a great deal while her brother, with pocket-book in hand, stood talking over the counter with Mrs. Fowler. Presently, Mr. Dalton turned around to her.

"I think this Mrs. Trim must be the mother of our acquaintance, Ethel. Mrs. Fowler says she is a widow with one son, who works in the foundry."

"Our acquaintance!" repeated Ethel, to herself. "Henry talks as though we knew him intimately. I do wish he would not stand talking here so long. What if somebody should come in?"

At last somebody did come in, and Mr. Dalton, bidding Mrs. Fowler good-afternoon, left the shop and walked on toward the suburb, where most of the foundry hands lived.

"Mrs. Fowler seems to talk as though the prospect was encouraging," remarked Mr. Dalton. "She is a very intelligent woman. I should like to secure her help in our Sunday-school, if we succeed in starting it."

"I think she is very forward," said Ethel. "She stood and talked with you as though she had—as though she was—" Ethel's sentence seemed to grow rather entangled.

"Well, as though she had or was what?" asked her brother. "I thought she stood and talked as though she were a sensible, brave Christian woman. That is the impression which I received of her character."

Ethel did not answer; and they walked on a little way in silence, till they came to a house in front of which lay a fine large dog stretched out across the sidewalk. Ethel shrank back with her usual little scream.

"What now?" asked Mr. Dalton.

"Oh, brother, that great horrid dog: I can't go past him. I am sure he is not safe. Suppose he should be mad, and bite me?"

"And suppose you should be mad, and bite him?" said Mr. Dalton. "I know who I think looks the more sensible of the two at this moment. Come, Ethel, you really must not be so silly. The dog is perfectly gentle, as you may see by looking at him; and if he were not, you are going exactly the right way to work to make him attack you. There is nothing which provokes dogs, and animal's in general, so much as to see people afraid of them. There! See how politely he makes way for us."

The big dog, at this moment, sat up on his haunches, and beating his tail lazily against the ground, he seemed to invite their notice. Unluckily, at that moment, he caught sight of a cow in the street, and evidently conceiving that he was bound to preserve the street free from all trespassers, he rushed open mouthed at the intruder, who, of course, put down her head and ran straight-forward, after the manner of cows when attacked.

Ethel screamed at the top of her voice, and started to run also, but, catching her foot in her dress, she tripped and down she fell, sprawling in any thing but a desirable or graceful attitude, just at the feet of a group of foundry-men who were coming home from their work.

Before Mr. Dalton could reach her, one of the men had raised Ethel,—his black hands leaving a very visible impression on her delicate gray plush jacket.

"Well, you did get a tumble, sure enough," said the foundry-man, kindly. "What was the matter? What made you run so? The dog wouldn't hurt you."

Ethel burst into tears of shame and vexation, and seemed likely to go into hysterics on the spot.

"My sister is, unfortunately, very timid," said Mr. Dalton, coming up. "Have you hurt yourself, Ethel?"

But Ethel was, by this time, far beyond speaking.

"The young lady had better come right into our house," said a young man of the group, opening, as he spoke, the gate of the very house where the dog had been lying. "Mother will just about have supper ready; and a cup of tea will do her good. But, my goodness, miss, you needn't be afraid of my old Lion. He plays with all the young ones in the street."

"Thank you; we will come in, since you are so kind," said Mr. Dalton. "I believe you are the very man I was looking for."

"And you are the gentleman I saw down in the doctor's garden," returned Richard Trim. "I see you going by with the doctor last night. Come right in, miss."

"Come, Ethel," said her brother, so decidedly that Ethel made no difficulty about the matter.

As the other man passed along, Ethel heard the one who had picked her up say to his companion, "Well, if 'my' girl was to make such a fool of herself as that, I'd box her ears."

The big boy led the way around the corner of the house into a clean sunny kitchen. The table was set for supper, and a wonderfully neat, cheerful-looking little old woman was just taking some very tempting-looking biscuits out of the stove-oven.

"I've brought you some company, ma," said the big boy. "This is the young lady who sent you the flowers the other day. She got a fall just now, and I brought her in to rest and have some tea."

"Why, yes, to be sure," exclaimed Mrs. Trim, in a cheery, high-pitched voice, which seemed exactly in keeping with her appearance. "And so you had a fall, dear? Did you hurt you? There, there, don't cry," she continued, soothing Ethel as though she had been a baby. "Tell granny where you hurt you?"

"I didn't hurt myself much," sobbed Ethel; "but—but—I was so frightened."

"Lion ran after that cow of Green's, and scared her," explained the big boy. "You see, that cow is always trying to get into our yard," he added, turning to Mr. Dalton. "She is as cunning as an imp, and can open any gate; and she has got in two or three times and raised the mischief: so Lion drives her off whenever he sees her."

"He is a clever dog," observed Mr. Dalton. "But why do you not have the cow taken up?"

"Well, I hate to do that," replied Richard Trim. "You see, she belongs to a widow woman, who has not much else to depend on. The children pretend to watch her, but they get playing, and then she slips away. But I hope, now you have come, you will stop and take tea with us, Mr. —"

"My name is Dalton," said Mr. Dalton. "This is my sister, Miss Ethel Dalton."

The big boy nodded to Ethel in acknowledgment of the introduction.

"Yes, do stay and take tea with us," chimed in the old woman. "I am sure your little sister will feel better when she has had a cup of tea. Young girls are apt be 'narvous,' so I wouldn't mind, dear," she added, kindly, turning to Ethel. "We should be so pleased to have you stay. I kept the flowers you sent me ever so long. I never saw anything so sweet. Now do stay. You won't put me out the least bit."

Mr. Dalton saw that the invitation was sincere, and that Ethel would be the better for the rest. Indeed, with her red eyes, she was hardly presentable in the street.

"You are very kind, I am sure; and we shall be glad of a cup of tea," said he. "Indeed, we were coming to see you, at any rate. My sister, Mrs. Ray, has sent your son some flower-seeds. She had a present of a large quantity, more than she has any room for, and, knowing that you are fond of flowers, she hopes you will accept these."

"I'm sure she is very kind," said the big boy, colouring through all his black, as he looked at the parcel of seeds,—varieties of balsams, Drummond's phlox, Salpiglossis, and other desirable sorts, all of Vick's best. "I don't feel as though I ought to take such a present."

"Nonsense," said Mr. Dalton, smiling. "You would do as much for me in a minute; and I dare say I shall want your help about carrying out a plan I have in my head. I have brought you Vick's catalogue with the seeds. There is a deal of valuable information in it."

"Well, I am sure," said the big boy, and then he stopped and turned over the seeds again; "just see, ma, six kinds of balsams."

"You must take the lady some of our tomato and pepper plants," said his mother. "You know you always have such good luck with them. But now go and wash yourself, for tea is all ready. You couldn't have done anything for Dicky which would have pleased him so much," she added, as her son left the room. "He generally does buy a few flower-seeds every spring, besides what we save from our own garden; but it has been rather a hard winter for us, what with sickness and Dicky's being out of work a part of the time. Not that I ought to complain, either."