Title: The doomed city

Author: John R. Carling

Illustrator: A. Forestier

Release date: December 11, 2025 [eBook #77443]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Edward J. Clode, 1910

Credits: Tom Trussel, Tim Lindell, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

[Pg iii]

The Doomed City

By

JOHN R. CARLING

Author of “The Shadow of the Czar,” “By Neva’s Waters,”

“The Viking’s Skull”

Illustrations by

A. FORESTIER

New York

Edward J. Clode

Publisher

[Pg iv]

Copyright, 1910, by

EDWARD J. CLODE

——

Entered at Stationers’ Hall

[Pg v]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | A Mysterious Wedding | 1 |

| II. | The Banquet of Florus | 18 |

| III. | The Queen of Beauty | 30 |

| IV. | The Dream of Crispus | 48 |

| V. | Simon the Zealot | 60 |

| VI. | “Delenda est Hierosolyma!” | 71 |

| VII. | The Journey to Jerusalem | 83 |

| VIII. | What Happened in the Royal Synagogue | 95 |

| IX. | “Let Us Go Hence!” | 112 |

| X. | The Vengeance of Florus | 124 |

| XI. | “To Your Tents, O Israel!” | 135 |

| XII. | “Væ Victis!” | 147 |

| XIII. | A Good Samaritan | 160 |

| XIV. | “Thou Wilt Never Take the City” | 170 |

| XV. | The Triumph of Simon | 181 |

| XVI. | The Ambition of Berenice | 198 |

| XVII. | The Making of an Emperor | 210 |

| XVIII. | The Preliminaries of a Great Siege | 228 |

| XIX. | The First Day’s Fight | 241 |

| XX. | Circumvallation | 258 |

| XXI. | The Dying City | 266 |

| XXII. | The Rescue of Vashti | 290 |

| XXIII. | Closing In | 306 |

| XXIV. | “Watchman, What of the Night?” | 325 |

| XXV. | “Judæa Capta!” | 341 |

| XXVI. | Justice the Avenger | 354 |

| Notes | ||

| Transcriber’s Note | ||

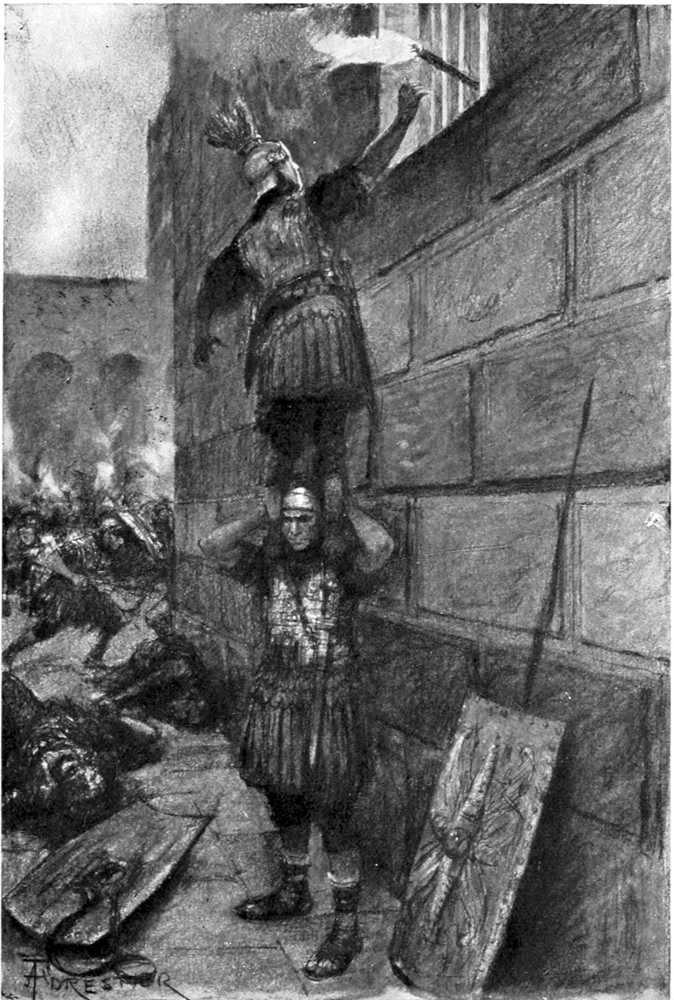

Τῶν στρατιωτῶν τις ΔΑΙΜΟΝΙΩ ΟΡΜΗ ΤΙΝΙ ΧΡΩΜΕΝΟΣ ἁρπάξει μὲν ἐκ τῆς φλεγομένης ὕλης, τό δὲ πῦρ ἐνίησι θυρίδι χρυσῇ τοῦ ἱεροῦ.

A certain soldier, MOVED BY A DIVINE IMPULSE, seized a blazing torch, and set fire to a golden window of the temple.

JOSEPHUS. Jewish War vi. 4, 5.

The purple light of evening had fallen upon the Syrian shore as Crispus, with a quick, swinging pace, trod the well-paced road that led southwards to the stately city of Cæsarea, the Roman capital of Judæa.

Evidently he loved the exercise of walking, since, had it pleased him to do so, he could have ridden, for at a respectable distance there followed, led by a couple of slaves, his two-horsed rheda, a traveling-car of sculptured bronze, provided with a leathern hood and silken awnings, and containing such necessary luggage (aptly named impedimenta by the Romans) as a man of simple tastes would require on a long journey.

Crispus, whose age was perhaps twenty-five years, had a powerful yet graceful figure, eyes of a deep gray, crisp hair of a bronzed hue, and a handsome face, as clear cut as if sculptured from marble, a face whose pure complexion spoke of pure living—a rare virtue in that age!—a face whose keen, ardent look gave promise that its owner was one born to achieve distinction, if indeed he had not already achieved it. “An antique Roman,” one would say on seeing him, since he still adhered to the wearing of the stately toga, which in the first century was fast becoming superseded by the Grecian tunic; moreover, the ring on his finger was not of gold, but of iron, in accordance with ancient usage.

[Pg 2]

In journeying along he had caught sight, by the wayside, of a stone pillar engraved with letters which told that the said pillar was distant from Rome by the space of one thousand five hundred miles. Thus far, yea, and hundreds of miles farther, did the Roman power extend in this, the twelfth year of the reign of the Emperor Nero. Crispus’ stern smile gave the keynote to his character—pride in the Empire founded by his forefathers, determination to maintain that Empire, though it cost him limb and life.

And in truth Rome counted few sons more patriotic than young Crispus Cestius Gallus, distinguished alike by feats of arms and by beauty of person; by noble birth, and by high office—for he was secretary to his father, the elder Cestius, who at that time held the dignity of imperial Legate of Syria, a dignity whose vast power and splendid emoluments made it a prize coveted of all Roman statesmen.

It was a lovely evening. A faint breeze came from the sea, whose waves, wine-dark in color, flowed with a sort of velvety ripple upon the yellow sands. To the east at the distance of a mile or more rose the Samaritan hills, mysterious and still in the evening light, their rounded summits clearly defined against the deep violet of the sky.

Now, as Crispus glanced ahead, he saw approaching a solitary figure, wearing buskins of purple, and a sleeved and embroidered tunic of the same color, cut to the latest fashion. He walked, his eyes set upon the ground, with a somewhat slow and pensive step, and would have passed by unheeding but for the cheery, rousing voice of Crispus.

“Ho, Titus! Is it thus in a strange land that you pass by your oldest friend?”

He who was thus addressed started, looked up, and, recognizing the speaker, dropped as if by magic his melancholy air, and advanced with smiling face and extended hand.

[Pg 3]

“By the gods, ’tis Crispus,” he cried in a tone of genuine delight. “Now doth Fortune favor me. To think of meeting you in this barbarian province, a thousand miles from our Sabine farms! Whither are you bound? For Cæsarea? Then will I return with you.”

Titus Flavius, destined in course of time to attain the imperial purple, was the senior of Crispus by one year: keen of eye, and with an aquiline nose, he looked every inch the soldier that he was, in spite of his perfumed and fashionable garb. A certain ruddiness of features showed him to be likewise a sort of “Antony, that revels long o’ nights.”

“What do you in this Jewish land?” asked Crispus.

“Rejoice at my presence here, for ’tis proof that I am restored to Nero’s favor.”

“I did not know that you had lost it.”

“What? Have you not heard that when Nero—what a delightful buffoon he is, to be sure!—was singing on the stage at Corinth, my sire Vespasian was so little appreciative of good music as actually to yawn, and even to fall asleep and snore, with the result that not only Pater nocens but even Filius innocens was forbidden to appear in the imperial presence.”

“I marvel that you did not both lose your heads.”

“So do I. Though banished, however, I did not lose heart, but in the spirit of a true courtier I sacrificed every day to Nero’s heavenly voice; and, on learning this (for I took good care it should reach his ears!), he recalled me to court, and marked his approval of my piety by sending me on a mission to Cæsarea.”

“A mission? Of what nature?”

“Why, you doubtless know that yon fair city of Cæsarea is peopled both with Greeks and Jews, each claiming precedency of the other. Let procurator Florus post up an edict beginning, ‘To the Greeks and Jews of Cæsarea,’ and the Jewish mob will tear it down. Let him word it, ‘To the Jews and Greeks,’ and the [Pg 4]Greeks will not suffer it to remain up. The Greek high priest of Jupiter demands that on state occasions he shall sit upon the right hand of the procurator; the high priest of the Jews, when he comes to Cæsarea, claims the same privilege. The Greeks wish their language to be used in the law-courts to the exclusion of our own stately Latin—there’s taste for you! the Jews clamor for their own tongue. This feud is productive of continual rioting and bloodshed. Therefore Nero, appealed to by deputies from both factions, hath pronounced his decree, dispatching it from Greece by my hand.”

“And in whose favor hath Cæsar decided?”

“Nay, I know not. The decree was contained in a sealed letter addressed to Florus, who hath not yet made it public. As for me, instead of hastening back to Nero to show him how quickly I can transact his business, I, like a fool, tarry in the neighborhood of Cæsarea.”

“There being a woman in the case,” smiled Crispus; “otherwise the usually sensible Titus would not be garbed like a fashionable dandy. What would your stern republican father say to this perfuming of yourself?”

“A woman in the case? Say, rather, a goddess. No lovelier face hath ever been seen since Helen lured the Grecian ships to Troy.”

“Fickle Titus! Last autumn he was vowing eternal fidelity to Lesbia, the hetæra; it was the Greek dancing-girl Lycoris in winter; this spring it is—who?”

“Lesbia and Lycoris! Pouf!” said Titus, as if blowing these nymphs away in air. “Do not mention them, I pray you, in the same breath with this splendid eastern beauty. I am serious now, if ever I were so. I would marry her to-morrow, were she willing; nay, more, to win her I would even repudiate the religion of my ancestors, and worship her Jewish God.”

“Titus must indeed be smitten! So your fair one is a Jewess?”

[Pg 5]

“Ay, and in rank far above poor plebeian me,” said Titus, sighing like a furnace.

“You talk thus! you who are a quæstor, tribune of a legion, and a messenger of imperial Cæsar?”

“And the son of a man who was once a horse-doctor; forget not that.”

“You were brought up in the imperial household with Britannicus, enjoying the same luxuries and the same instructors as he.”

“And very nearly drinking of the same fatal cup,” commented Titus, grimly.

“The gods reserved you for a nobler destiny. But as to your fair lady—who is she?”

“A princess, beautiful, proud, scornful. Berenice her name, the daughter of that Agrippa who, some twenty years ago, was King of Palestine. He left her so much wealth that she is called ‘Golden Berenice.’ You know her?” added Titus, as he saw an odd look flit for a moment over the face of Crispus.

“I have seen her.”

“Then you know how beautiful she is.”

“Yes, she is certainly beautiful,” replied Crispus, in a tone as if grudging the admission.

“You speak coldly. ’Tis clear I shall never have you for a rival.”

“True, O Titus. When I mate it shall be with pure maid. Hath not your Berenice already had one husband?”

“She was wedded, when quite a girl, to Polemo, King of Pontus, who divorced her two years afterwards.”

“Polemo?” ejaculated Crispus, in some surprise. “Polemo?—one of my father’s friends. Why did he divorce her?”

“Nay, ask that of others. He was elderly and serious; she was youthful and gay: there, I suspect, lay the reason.”

“Their separation,” remarked Crispus, “does not appear to have left much bitterness behind, for, at a [Pg 6]banquet given by my father to all the kings of the East, Polemo and the Princess Berenice sat side by side, seeming to be on excellent terms with each other. And, what struck me as strange, their glances were so often cast in my direction that I could not help wondering whether I were the subject of their talk. Were there any children born of this marriage?”

“One—a daughter, said to have died in infancy.”

“And you would woo this Herodian princess? Do you frequent this lonely shore in order to sigh out vows to Venus?” said Crispus, pointing to love’s planet that sparkled like an eye in the blue depths above.

“I come here hoping to have the pleasure of a few words with her as she returns to Cæsarea. An hour ago, so I am told, she drove this way in her chariot.”

“You do right, then, in retracing your steps, for I can certify that no chariot has passed me.”

“Then she must have turned aside, and gone inland,” said Titus, looking to the left as if meditating a diversion among the hills in quest of the fair princess.

With a sigh he resigned the project, and strode onward beside Crispus, whose frequent questions on all that fell within the sphere of his vision showed that he was treading the shore of Palestine for the first time.

“How name you yon house?” he asked, pointing ahead to an edifice perched upon a crag that overlooked the shore road.

“I am told that it is called ‘Beth-tamar.’”

“And that, being interpreted, meaneth ‘The House of Palms,’” remarked Crispus, and smiling at Titus’ look of surprise. “O, I know something of the speech of these barbarians, having learned it in childhood from one of my father’s favorite slaves, a captive Jew; and so long as the fellow kept to his language, well and good, but when he tried to make me a proselyte to his superstition, he was promptly scourged, and put at a distance from me.”

“Hebrew!” commented Titus. “You have the better [Pg 7]of me. Would that I could speak it, for then it might dispose Berenice to look with a more favorable eye upon me. As it is, I have to say with Ovid:

What more he would have said was checked by a command delivered in an authoritative voice:

“Halt!”

Instinctively the two friends paused, and glanced aloft. Standing upon a lower spur of the crag above them, and clearly defined against the star-lit sky, was a tall figure in a flowing robe.

“Who are you that bid two Romans halt?” demanded Titus, haughtily.

“The servant of a king,” was the answer, delivered in the Latin language, though not with the true Latin accent.

“Your master’s name?” asked Titus, suspiciously.

“Polemo, King of Pontus.”

At this Crispus and Titus looked at each other, deeming it odd to be brought thus in connection with the monarch about whom they had just been talking.

“I have a message,” continued the stranger, “for one, Crispus Cestius Gallus.”

“My name,” said the bearer of it. “What would the king with me?”

“My royal master bids you tarry an hour with him ere journeying on to Cæsarea.”

“Where is the king to be found?”

“Within the walls of his mansion, Beth-tamar.”

“And should I pass on my way neglectful of the king’s bidding——?”

“Pass on, and miss a high destiny.”

“Haste thee, and tell thy lord that Crispus comes with his friend, Titus Flavius.”

The man had appeared suddenly; just as suddenly did he now disappear. Bidding his two slaves await [Pg 8]his return, Crispus turned from the maritime road, and began to climb the rough ascent. His ready acquiescence with the stranger’s wish was viewed with some uneasiness by Titus, who was, however, quickly reassured by Crispus.

“Polemo, in this matter,” said he, “acts as his own messenger, for it was he who spoke with us.”

“The king himself?” said Titus, greatly surprised.

“Even so,” replied Crispus. “We can enter Beth-tamar in perfect safety. I am not altogether unprepared for this meeting. As I was setting out from Antioch my father spoke thus to me: ‘On your way to Cæsarea you may meet with King Polemo, who hath a proposal for you. I leave you free to accept or decline, but, if you will be guided by me, you will do his bidding, however strange it may appear.’”

Language such as this moved Titus to wonder, and he became almost as eager as Crispus for the meeting with the Pontic king.

Arrived upon the platform that formed the summit of the crag, the two Romans saw before them a rectangular edifice, massive and spacious, formed like most of the buildings in that region from blocks of limestone—a bare dull-looking structure; but then the Oriental house is not to be judged by its outside, for a costly exterior suggests wealth, and in the East, wealth, then, as now, is a temptation to the powers that be.

Within the arched entrance stood a slave, who, with a profound salaam, invited the two friends to follow him. Traversing a stone passage, they quickly emerged into a spacious court, open to the sky: rooms with latticed windows looked out upon this court, and to one of these the slave conducted the visitors, and there left them. The room was Oriental in character: a cushioned divan ran round the marble walls that gleamed with gilded arabesques and lapis-lazuli. In the middle of the tesselated pavement was a fountain, [Pg 9]whose waters played with a golden sparkle in the soft radiance shed by the many lamps pendent from the fretted roof above.

As the two Romans entered, there came forward to greet them the same man that had spoken from the crag, a man of grave and stately presence, whose classic features can still be studied on the extant coins of the kingdom of Pontus. He had cast off the coarse garb he had worn without, and appeared now in a majestic robe of royal purple. On his finger glittered a gold ring, decorated with a cameo sculptured with a miniature head of Nero, a fact of some significance, since the wearing of such a ring was permitted to those only who had the high privilege of free access to the Emperor’s presence.

“Welcome to Beth-tamar!” were the monarch’s first words. “Aware that you were drawing near to Cæsarea,” he continued, addressing Crispus, “I have ventured thus to intercept your journey.”

“To what end?”

“Hath not your father told you?”

Crispus answered in the negative. Polemo seemed surprised at this; he hesitated, and glanced at Titus as if his presence were an embarrassment. Divining his thoughts, Crispus spoke:

“Titus is my fidus Achates. Let not the king take it amiss, but whatever is said must be said before him.”

“Be it so,” said Polemo, after a brief pause. “You must, however, both give pledge, that the proposal I am about to make, whether accepted or declined, shall be kept a secret till such time as I shall choose it to be known.”

“The character of the noble Polemo,” returned Crispus, “is a sufficient guarantee that he will require of me nothing dishonorable or nothing detrimental to the interests of the Roman state.”

“Far be such thoughts from me. My aim is to add to its strength.” Assured thus, both Crispus and Titus [Pg 10]promised to hold sacred whatever the king were minded to reveal.

“Good! To come at once to the question, for I love not many words, you are doubtless aware of my misfortune in having no son to succeed me on the throne. I am,” he added mournfully, “the last of my race. In these circumstances our lord Nero has graciously conceded to me the favor of nominating a successor, with the necessary proviso that my choice must fall on a man loyal to the Empire. Such a one I have found.”

He paused and looked at Crispus, whose head began suddenly to whirl with a daring hope. Could it be that he himself was——?

“If,” continued Polemo, “if loyalty to Rome be the first qualification in my successor, who more loyal than a Roman himself? who more likely to meet with the approval of the Senate than one of the Senatorial order? For these reasons, then, and because your past deeds have shown you to be worthy of the dignity, I am minded at a date three years from now to confer upon you the scepter of Pontus. What say you to this?”

At first Crispus could say nothing for very amazement. Then, recovering somewhat, he began eagerly to question the king, and found him to all appearances sincere in making the offer.

Now, although Polemo had made a special point of Crispus’ worthiness, Crispus himself had nevertheless a secret belief that the king was actuated by some ulterior motive. He recalled a saying of his father’s: “There is fire within Polemo for all his cold exterior. To me he seems a man who, having received a great wrong, is meditating a scheme of revenge—ay, and devoting his whole life to it. The weapon may take years in the forging, but when forged it will fall, swiftly, terribly.” Recalling these words, Crispus began to wonder whether the offer just made was a part of the king’s [Pg 11]scheme of vengeance. Was he, Crispus, to be elevated to the throne merely to bring gall to some scheming and ambitious enemy? Crispus had a reasonable objection to be utilized for such a purpose; but still, what mattered? Here was an opportunity of gaining a splendid dignity, and it would be foolish to let his scruples as to the other’s motive interfere with his ambition.

A king!

“All things,” said Porus, “are comprehended in that word.”

What fancies crowded thick and fast upon Crispus’ mind as he tried to picture the future!

He would be a father to his people; would regulate their finances; foster their commerce; increase the army; promote the use of the Latin language and encourage Greek culture. In the glens of the Caucasus, bordering upon his kingdom, were wild tribes that had never yet acknowledged a conqueror. He would curb their predatory incursions, and augment his territory at their expense. Nay, he might even pass that mighty mountain-barrier, and carry his arms over Scythia, a region that had defied the attempts of the Persian, the Grecian, and the Roman. Why should he not be in the North what Alexander had been in the East, and Cæsar in the West? Then, when his kingdom had become enlarged and Latinized, he would act the patriot, and transfer his dominion to the Senate, making it a province of mighty Rome.

Dreams, perhaps, but it is in such dreams that empires have sometimes had their beginning.

“What answer do you make?”

“At present, none,” replied the cautious Crispus. “Is your gift accompanied by any stipulation?”

“One only. He who chooses the king of Pontus must also choose its queen.”

“In other words, I must take a wife, a wife to be chosen by you.”

[Pg 12]

“That is so.”

“And failing to do this—no scepter?”

“Truly said. The gift of the kingdom is dependent upon your marrying the lady of my choice. The two go together.”

“And what date do you fix for our nuptials?”

“This very night—nay, this very hour.”

“To-night? Ye gods! You hear that, Titus?”

“The lady is at hand, for in the reasonable belief that you would not refuse a throne I have had her brought here.”

“Her name?”

“Call her Athenaïs, since that is the name she will take as queen.”

“I am not to know her real name! What is her rank?”

“Superior to your own, for she is of royal blood.”

“She is of fair shape, I trust?”

“Zeuxis never delineated a face and form more lovely.”

These words served to whet Crispus’ curiosity. He expressed a wish to see his prospective bride.

“See her you will not; she will be veiled during the ceremony. Nor will you hear her voice, for she will not speak. When the rite is over you will resume your journey to Cæsarea.”

“Without seeing the face of my wife!” gasped Crispus in amazement. Was there ever so strange a marriage proposal?

“It is my will that you shall not know whom you have married. The lady is beautiful, high-born, and brings a crown as a dowry. Is not that enough?”

“And when will my bride be made known to me?”

“On the day when you assume the scepter.”

“And the date of that event?”

“As I have said, at the end of three years.”

“The word of Polemo is his bond,” said Crispus, “but seeing that—absit omen!—you may be dead ere [Pg 13]the three years be past, what warranty shall I then have of the due execution of this, your promise?”

“This,” replied the king, producing a parchment-scroll and unrolling it. “’Tis yours as soon as the nuptial ceremony be over.”

Crispus ran his eye over the scroll, and saw that it was what Roman lawyers would call an instrumentum—in other words, a legally-executed document, constituting him the heir of Polemo in the sovereignty of Pontus. It was subscribed with the signature of the king, and, what was of far more weight, with that of Nero himself.

“Do you assent?”

“I assent.”

“Consider well; remember that you are to pledge yourself to remain faithful to Athenaïs, who in turn pledges herself to remain faithful to you. Should you in this interval be found breaking your vow by offering love to any woman—yea, even though it be to your own unknown wife”—Crispus smiled at the supposition—“you lose the crown of Pontus.”

“Your terms are strange, but I abide by them.”

“You are ready to wed?”

“This very hour.”

“You promise not to lift her veil? You are content not to hear her voice? You are willing to depart as soon as the rite is over? You promise with your friend to observe secrecy as touching this night’s work?”

There was a light as of triumph in Polemo’s eyes when the two Romans gave assent to these terms. It confirmed Crispus in his belief that the king was using him as an instrument of vengeance. But, as before, he said within himself, “What matters?”

“With what rites do we wed?” asked Crispus.

“With the words customary in your own Roman nuptial ceremonies, confirming them by placing this token upon the finger of the bride,” returned Polemo.

He handed to Crispus a gold ring. It was set with [Pg 14]a ruby, upon whose surface there was graven, with beautiful and marvelous art, a device that caused a quick look of surprise to pass over the face of Crispus. As he slowly and mechanically turned the ring over in his hand the ruby darted forth sparkles that caused what was sculptured on the gem to vanish as if in a blaze of fire. At that sight Crispus gave a great start, and darted an inquiring look at the king, who replied by a smile full of a hidden meaning. Titus, who took due note of all this, was naturally not a little puzzled; he refrained from comment, however, believing that Crispus would enlighten him later.

“Follow me,” said Polemo, and, lifting a curtain, he led the way to another chamber so dimly illumined by one lamp only that the parts remote from the light were scarcely discernible, an arrangement obviously due to Polemo’s determination that Crispus should see as little as possible of his bride.

In the semi-darkness two waiting figures, both deeply veiled, were faintly visible.

Of the one that stood a little in the rear Crispus took no note, she being obviously an attendant. It was the other upon whom his eyes were set. Slender and of medium stature, she wore the usual dress of a Roman bride, the tunica recta, a long white robe with a purple fringe, and girt at the waist with a zone. The flammeum, or veil, which effectually concealed her features, was bright yellow in color, as were likewise her dainty little shoes. The bride’s hair with the point of a spear, was dispensed with on this occasion, her head being covered with a coif, so well disposed that not a single tress was visible. So completely was her person hidden that, let her dress be changed, and there was nothing by which he could identify her, if he should meet her again that same night.

Though Crispus could not see her eyes, he knew full well that she was watching him as keenly as he was watching her, a scrutiny in which the advantage [Pg 15]was all on her side. She stood, wordless and motionless, evidently awaiting the king’s pleasure.

“Athenaïs,” said he, “this is your husband.”

She made a little obeisance to Crispus, a simple act, yet performed with a grace that charmed him.

He did not know in what relation Polemo stood to the bride, but his way of speaking implied a quasi-authority over her, and since it was the fashion in those days for parents and guardians to arrange marriages with very little regard for the feelings of the two most concerned in the affair, Crispus could not help wondering whether pressure had been put upon this Athenaïs to induce her to consent to the union. He would find out.

“Lady,” he said, “I am willing to marry, but only on the understanding that you come to me without compulsion. Therefore, if you take me of your own free will, testify the same—since you are forbidden to speak—by coming forward two paces.”

Athenaïs hesitated, but only for a second. Giving him what he felt to be a grateful glance, she advanced two steps.

“A mutual agreement,” smiled Polemo. “This is as it should be.”

He whispered in the ear of the bride something that Crispus could not catch. Whatever it was it evoked from her a little ripple of laughter, so sweet and silvery, that Crispus was put into sympathy with her at once.

“If her face be as witching as her laughter!” thought he.

But her laugh, however charming to Crispus, had a very different effect upon Titus. An attentive spectator would have seen him start violently, and turn pale. He seemed on the point of breaking out into words, but checking himself, he stood mute, his whole attitude expressive of dejection, a feeling that seemed to increase as the nuptial ceremony proceeded. Crispus, [Pg 16]occupied with the matter in hand, did not notice his friend’s agitation.

At a sign from Polemo Crispus drew near to Athenaïs, Titus acting as paranymph, or, to use the modern phrase, “best man,” the veiled attendant performing a similar office for the bride.

Athenaïs, directed by the king, put forth a white and prettily-shaped hand, which Crispus took in his own.

If her feelings bore any resemblance to those of Crispus she must have felt like one in a dream, for he could scarcely believe the scene to be real. An hour ago he would have laughed had anyone prophesied for him an early marriage, and yet here he was on the point of marrying a woman of whose past history he knew nothing, a woman from whom, as soon as the ceremony was over, he must part, without seeing her face, without receiving so little as one word from her, part for a space of time to be measured, not by months, but by years! What would his friends at Rome think of a marriage contracted under auspices so strange? “Weddeth Crispus as a fool weddeth?” would surely be their comment.

Thus much, however, could be said for his act: it had his father’s sanction, and with this thought Crispus tried to suppress all misgivings.

Mechanically he found himself repeating after Polemo the final words of the rite that was to unite him for life with the unknown Athenaïs.

“Leaving all other, and keeping only to thee, I, Crispus Cestius Gallus, patrician of Rome, do take thee, Athenaïs, to be my lawful wife, to be openly acknowledged as such when it shall please thee to claim me by this token.”

So saying, he slid upon her slender finger the golden ring given him by Polemo.

No sound came from the woman who was now his wife, but her agitation was shown by her trembling [Pg 17]hand, by her accelerated breathing, by her attitude, half-reclining, in the arms of her attendant.

Her hand seemed to close voluntarily upon his own. The thrilling pressure of those fair fingers imparted to him somehow the belief that, originally reluctant to come to the ceremony, she now viewed it with pleasure, a thought that gave him pleasure in turn.

The sweet laugh that had come from her, the clasp of her pretty hand, her willingness to trust her whole future to his keeping, so moved Crispus that he began to feel a keen regret that he must immediately part from her. He became almost angry with himself for having submitted to the hard terms prescribed by Polemo.

As he released her hand she sank back half-swooning in the arms of the other woman, who, at a sign from Polemo, proceeded to draw her gently from the apartment. Till the last Crispus kept his eyes upon her, hoping that, in spite of Polemo, she might raise a corner of her veil, and give him just one glimpse at least of her face.

It was not to be, however. She melted away into the shadows around, and he saw her no more.

The two Romans walked again by the star-lit shore with Beth-tamar far behind them.

“What,” asked Titus, who, since the wedding ceremony, had been strangely silent, “what was engraved on the stone of the nuptial ring that you should start so?”

He received little enlightenment from the reply of Crispus:

“The image of a temple in flames!”

[Pg 18]

Early on the morning after his arrival at Cæsarea, Crispus was waited upon at his lodgings by Gessius Florus, procurator of Judæa, who, apprised of Crispus’ coming, lost no time in calling upon the son of the Syrian Legate, that Legate whose word was all-powerful in the East.

Previous knowledge had disposed Crispus to take an unfavorable opinion of Florus, an opinion that became strengthened on seeing the man himself. A shallow-minded Greek of Clazomenæ, and no true Roman, he had gained the procuratorship of Judæa, not through merit, but by the influence of his wife Cleopatra, who was a close friend of the reigning Empress Poppæa.

Florus, though born in Ionia, had little of the grace that is usually associated with that region, and had Crispus not known otherwise he might have taken the governor, with his round bullet head, furtive greenish-brown eyes, and heavy brutal jaw, for a member of that pugilistic fraternity whose feats with the cæstus were the delight of the lower orders among the Romans.

He was desirous that Crispus should form one at a grand banquet, to be held that night in the Prætorium, or procuratorial palace.

Crispus was about to decline the honor, when he thought of Athenaïs. For all he knew to the contrary she might be a resident of Cæsarea, and if so, her “royal blood” would certainly entitle her to an invitation. She might be among the guests. He would go, though it would be difficult, if not impossible, to recognize her.

[Pg 19]

Florus withdrew in apparent delight.

As for Titus, he departed that same day for Rome, embarking on the good ship Stella.

“There is no hope of my ever winning Berenice,” he said, though without assigning any reason for coming so suddenly to this lugubrious conclusion.

Before his departure, however, he did Crispus a good service by introducing him to a brave and worthy Roman, Terentius Rufus by name. He was the captain of the garrison stationed at Jerusalem, and had come with his cohort to Cæsarea to aid in the work of suppressing the riots that were almost certain to arise upon the coming publication of Nero’s edict relative to the precedency claimed by the Jews and the Greeks.

Terentius Rufus, like Crispus, had received an invitation to the banquet of Florus, and so, at the appointed time, the two presented themselves at the Prætorium.

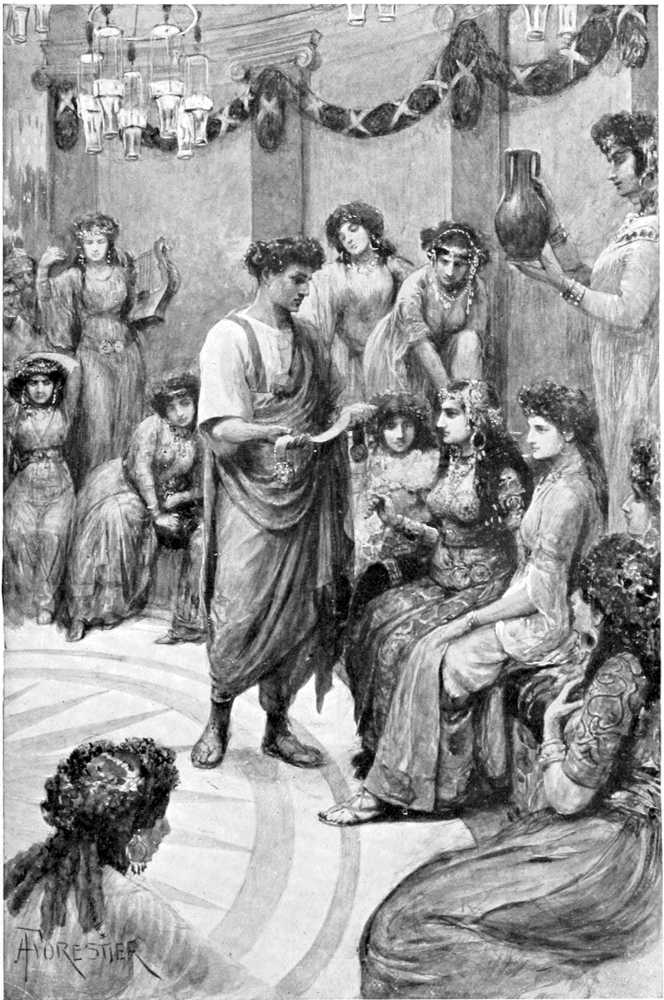

Upon making their way to the hall appropriated to the feast, a hall called Neronium after the reigning emperor, they paused a moment at the entrance to contemplate the sight. The marble saloon, supported by porphyry columns and blazing with the radiance of a thousand lamps, was a scene of glitter, movement, and color. Sweet spices burned in gilded tripods; the rarest flowers glowed from sculptured vases; the ivory triclinia with their purple cushions, the lavish display of gold and silver plate, the rich dresses and jewels of the ladies, made a picture destined to live long in the memory of Crispus.

He marveled to see such splendor in the hall of a provincial governor.

“Whence does Florus obtain the wealth that enables him to make such a display?” he asked.

“There are others who would like an answer to that question,” replied Rufus, mysteriously.

“Where is Florus?” asked Crispus, glancing around, and not seeing the procurator.

“Probably tickling his throat with a feather to [Pg 20]produce a vomit,” answered Rufus, referring to the disgusting custom practiced by many Romans of that age for the purpose of creating an appetite. “You may trust him to do full justice to the banquet.”

Crispus was not slow to recognize among the guests that type of physiognomy which, graved on Egyptian monuments long ere Rome was founded, has continued almost unchanged to the present day.

“There are many Jews here to-night,” remarked he.

“And Jewesses, too,” replied Rufus; “and here comes the fairest of them all, leaning upon the arm of Florus. For a wonder he’s sober!”

There was a sudden cessation of tongues as a curtain that draped a certain archway was lifted by two bowing slaves to give entrance to the procurator.

Glancing around, Florus immediately caught sight of Crispus, and advanced to give him welcome. He was accompanied by a lady, none other than the Princess Berenice, and as Crispus quietly surveyed her, he thought it no wonder that Titus should have fallen in love with her at first sight. She had dark hair and dark starry eyes, and a face which, when radiant with a smile as it was at that moment, was perfectly dazzling in its loveliness. Her figure, which was as beautiful as her face, was appareled in a robe of purple silk, embroidered with flowers of gold and adorned with the costliest pearls.

She greeted Crispus with a sweet smile of recognition.

“Do not neglect me to-night as you did at Antioch,” she said half-jestingly, and then giving him a witching glance she passed on, with Florus, to her place at the banquet. While the procurator reclined at full length upon the triclinium, Berenice sat erect beside him, for the posture assumed by men at the banquet was deemed unbecoming in women.

Crispus and Rufus had places assigned them at the triclinium adjoining that of Florus, and upon the same [Pg 21]couch with them reclined a shrewd-looking, keen-eyed man, who, so Rufus informed Crispus, went by the name of Tertullus, and was a distinguished forensic orator.

“Mark well his noble name,” said Rufus, laughingly. “Tertullus, thrice-Tully! What could be more suitable for an orator? Take my advice, Crispus,” continued he, “if you have a lawsuit while at Cæsarea, fail not to employ my friend Tertullus, who never undertook a case he did not win.”

“Save once,” corrected Tertullus. “Paul of Tarsus escaped the stoning we had marked out for him.”

“Ah! I am forgetting him. The dog, it seems, is a Roman citizen. He appealed to Nero, who let him off.”

“And what was the result?” commented Tertullus. “A few months later Rome was in flames, lit by the hands of his disciples. The wretches! Haters of mankind! I know of only one class of men more vile than they, and that is the sect of the Zealots, whose latest victim I am.”

“How mean you?” asked Rufus.

“Have you not heard? No? Well, a few days ago I was journeying from Jericho to the Jewish capital. Knowing the state of the country, I traveled in the company of an armed caravan that was going the same way. We took a long circuit northwards to avoid the dreaded Pass of Adummim; all to no purpose. Manahem and his Zealots, like vultures scenting their quarry afar, swooped down upon us. I was one of the few that escaped. When is Florus going to dispatch an expedition against that robber crew?”

“Did you lose aught?”

“Some gold plate, and—what I treasured above all earthly things—a myrrhine vase, so precious that I weep when I think of it.”

“Don’t think of it, then,” said Rufus. “Turn to a more pleasant theme, the Princess Berenice. She looks more charming and more youthful than ever to-night. [Pg 22]Now, how old should you take her to be?” he continued, addressing Crispus.

“Not much past twenty,” he hazarded.

Rufus laughed pleasantly.

“Why, ’tis sixteen years ago since she married Polemo. She cannot be a day younger than thirty-eight.”

Crispus was surprised to hear it.

“There is many a young girl here to-night,” said he, “who looks older than the princess.”

“Berenice takes extreme pains to preserve her beauty,” remarked Rufus. “’Tis said that, like Poppæa, she bathes daily in asses’ milk to render her skin soft and supple.”

Florus now gave the signal for the feast, and there entered a train of pretty Greek maidens with baskets containing wreaths of flowers, for to dine ungarlanded would have been a departure from fashionable usage. Berenice chose a wreath of violets; Florus made a similar selection.

“The flower honored by a princess must be my choice, too,” he whispered.

This little by-play did not pass unnoticed by Crispus.

“Florus is madly in love with her,” commented Rufus. “For the matter of that, who isn’t?”

“I thought that Florus already had a wife,” said Crispus.

“That’s no obstacle in these lax days, when a man takes a new wife with each year. It is whispered that Florus contemplates divorcing Cleopatra.”

“Where is Cleopatra at this present time?” asked Crispus.

“In Rome,” answered Tertullus, as he fixed a garland of roses upon his head, “looking after her precious husband’s interests. He takes advantage of her absence to pay court to Berenice, who cares not a whit for him, and intends no hurt to Cleopatra. Berenice is not to be too hastily condemned,” he continued, observing Crispus’ frown. “Her action in this matter, [Pg 23]as in all others, is guided by two motives—love of her people, and love of her own superstition. Now, Florus, in the exercise of his procuratorship, can, if he be so minded, inflict injuries upon the Jewish people, and can also, though to a limited extent, interfere with the administration of their public worship. ‘But,’ argues our fair Berenice, ‘he is not likely to adopt these courses while seeking to win me, who am a Jewess. Therefore, for the good of the Jews I will amuse him with hopes.’ Now after this long speech,” added Tertullus, “let me eat. I can see the lampreys coming, and they are my favorite dish.”

And the delicacy being set before him, Tertullus applied himself thereto. After a time he raised his voice and addressed the procurator.

“I have myself, O Florus, given great attention to the breeding of lampreys, but I confess that I can never get them to attain the delicate flavor of those bred by you.”

Two or three other guests made similar remarks.

Florus smiled with the air of a man who, having discovered an excellent thing, is determined to keep it to himself.

“Now, it is precisely because I happen to know how the delicate flavor is acquired,” whispered Rufus, “that I avoid partaking of that dish.”

“By the trident of Neptune,” said Tertullus, “I wish you would communicate the secret to me, for I am mightily fond of lampreys.”

“Well, keep it a secret, for Florus may not thank me for telling it. Whenever one of his slaves commits a fault worthy of death, the poor wretch, instead of being hanged, is flung into the piscina to feed the lampreys. By the gods, I do not jest,” he added, as he noted Tertullus’ look of incredulity. “Get his chief piscinarius into a corner, put a dagger to his throat, and he’ll confess that what I say is true.”

As the Roman law gave to a master the power of [Pg 24]life and death over his slaves, Florus’ peculiar practice did not evoke from Crispus the abhorrence that the man of the twentieth century would express at such a deed. As for Tertullus, he even went so far as to intimate that he might adopt the practice himself.

“If a slave must die,” argued he, “let him die in a way that will add to his master’s enjoyment.”

Crispus sought to change the subject of conversation by asking Rufus the name of the richly-clothed man who reclined on the left of Florus; he was a majestic-looking, dark-skinned personage, with hair and beard finely dressed. At the beginning of the feast he had drawn forth a little ivory casket, from which he had produced an asp that had immediately twined itself around his bare arm, and there it remained partaking occasionally of such morsels as its master chose to give.

“That,” replied Tertullus, “is Theomantes, the priest of Zeus Cæsarius, and a skilled diviner.”

“And the serpent he carries with him, if you are fool enough to believe it,” remarked Rufus, “is an incarnation of the great Zeus himself. You can see by the place assigned to Theomantes how highly he is esteemed. Every Roman governor nowadays must have a soothsayer in attendance upon him, and Florus would not be out of the fashion. It is this Theomantes who supplies our procurator with the liquid for his daily bath.”

“The liquid? What liquid?”

“Well, not water, which is good enough for common mortals like you and me, nor yet milk, which the fair Berenice finds so excellent a cosmetic. Florus’ taste runs in favor of blood.”

“Blood!” ejaculated Crispus.

“Even so. Do you not know that by some physicians blood is deemed very efficacious in strengthening the human frame when exhausted by debauchery? So our dear governor bathes daily in a sanguinary fluid drawn from the veins of oxen slain in sacrifice, his superstitious fancy disposing him to believe that there will [Pg 25]be more virtue in blood of that sort. Oh, it’s not an uncommon practice, I assure you. We’ve even drawn from the Greek a name for it, calling it taurobolium.”

“Every man to his taste,” commented Crispus, dryly; and continuing his inquiries as to the guests, he asked, “Who is that fierce graybeard reclining next to Theomantes?”

“Ananias, son of Nebedeus, at one time high priest of the Jews,” replied Rufus.

“And a cheating knave!” commented Tertullus. “In his prosecution of Paul of Tarsus before Felix he employed me as advocate, and hath never yet paid me my fee. But I’ll be even with him.”

“Do you mark,” continued Rufus, “how, from time to time, Ananias glowers at Theomantes? He considers that he himself should be sitting next the governor.”

“He is welcome to the place for me,” laughed Crispus. “And who is the fair damsel beside him? His daughter?”

“Daughter me no daughter, forsooth!” returned Rufus. “That is Asenath, a Syrian dancing-girl, and his latest favorite.”

“I must reluctantly confess he hath a pretty taste,” said Tertullus; “she is a delicious armful.”

“And she is desirous, you see, that we should observe the fact,” remarked Rufus.

The girl in question was a lovely brunette, attired in a Coan robe which, even in that decadent age, was deemed a trifle too extreme, consisting as it did of silk so transparent in texture that the shapely limbs of the wearer could be seen as through colored glass.

And, be it observed, she was not the only female at the banquet thus diaphanously clad!

“That’s the girl,” continued Rufus, “to please whom he burnt in his own house the incense that it is not lawful to burn anywhere save upon the altar of [Pg 26]the Jewish temple. And as she was once curious to view the Jewish worship, Ananias had the way from his house to the temple carpeted for her pretty feet, and canopied to shield her from the sun. And he himself was so fastidiously minded that he was accustomed to wear silk gloves at the altar to avoid soiling his dainty fingers with the blood of the sacrifices,[1] though why a Sadducee, such as he, should want to worship God at all is a mystery to me. In the opinion of Ananias man dies as a dog dies. It seems to me that a God who creates man from dust merely to turn him into dust again is scarcely deserving of worship. What say you?”

“Old Homer could have taught him better doctrine than that,” returned Crispus.

The conversation, it will be seen, was taking a theological turn; something of like sort was happening at the adjoining triclinium of Florus.

“I hate these Christians as much as you do,” remarked the procurator to Berenice. “But Nero hath taught us how to deal with them. And you say there are still some of this sect at Jerusalem? I had thought that my predecessor Albinus, in slaying James, the brother of this Christus, had put an end to these fanatics. You shall have your way, princess. Within a week of my coming to Jerusalem there shall not be a Christian left alive.”

“Now the gods confound these Christians!” said Tertullus aloud. “They grow daily wilder and madder in their blasphemies. They have now the effrontery to affirm that this Christus of theirs, who died in the eighteenth year of Tiberius Cæsar, was something more than a man, that this Galilæan peasant was in very truth a manifestation of the supreme deity, the creator of the universe, and the great To Pan spoken of by the divine Plato.”

At these words there was on the part of Crispus a start as of surprise.

[Pg 27]

“When do you say this Christus died?” he asked somewhat quickly.

“In the eighteenth year of Tiberius Cæsar,” replied Tertullus.

“In what month?”

“On the fourteenth of Nisan, according to the Jewish calendar.”

“Which in our style would be the seventh of April,” explained Rufus, after a rapid mental calculation.

Crispus’ surprise seemed to deepen.

“And you say the Christians call their founder To Pan? Strange!” he murmured.

“Why so?” asked Florus.

“I could tell a curious story of that month and year. But there! let it pass.”

“No, we must not let it pass,” cried Florus, and thinking to do honor to Crispus, he said to those within his immediate vicinity, “Silence, friends, for the noble Crispus’ story.”

All eyes were bent upon Crispus, who hesitated for a moment, and then, seeing expectancy written upon the faces of the guests, he began:

“Well, since you will have it: At the time just mentioned, namely the month of April in the eighteenth year of Tiberius, there chanced to be upon the Ionian Sea a merchant vessel bound for Italy. It was eventide; the breeze had died away, and the ship lay becalmed off the Isle of Paxos. Suddenly the stillness that lay upon land and sea was broken by a voice coming from the lonely shore—a voice clear and solemn, and one that carried awe to all who heard it, for it seemed scarcely to belong to earth. ‘Thamus!’ it cried. Now the pilot of the vessel happened to be one Thamus, an Egyptian, a man of humble and obscure origin, and not so much as known by name to those on board. Full of fear, he let himself be called twice ere he would answer. At the third cry he found courage to ask, ‘What want you?’ And thus did the [Pg 28]voice make reply: ‘When thou comest to Pelodes, cry aloud that the great Pan is dead.’ That was all; no more. The passengers, amazed and awed by the event, debated among themselves whether it would be wise to obey the mysterious voice. Thamus, himself, determined the matter: if on attaining the appointed place there should be wind enough to fill the sails, he would pass by in silence, but if not, he would proclaim the message. The breeze freshened, the ship glided on, but when they reached Pelodes it made no further progress, for the wind suddenly dropped again. Thamus, therefore, taking his stand upon the prow, turned his face to the land, and shouted in a loud tone, ‘Great Pan is dead!’ Then from the hitherto silent shore there arose a sound like the voice of a multitude, a sound as of weeping and wild lament.”[2]

Such was the story told by Crispus, and he finished with the odd feeling that the telling of it had pleased neither the Jewish nor the Gentile portion of his auditors.

“Whence do you derive this story?” asked Theomantes with a somewhat supercilious air.

“From my father, himself a passenger in this same vessel.”

“Who were they that made these sounds?”

“Beings more than mortal; of that he is convinced.”

“Gods and demons?”

“It may be so.”

“In a lamenting mood?”

“A wailing as of despair, so my father describes the sound.”

“Gods in despair at the death of someone? And this happened in Greece in the eighteenth year of Tiberius? Would you have us believe that the Christus crucified by Pilate and the ‘Great Pan’ of your story are one and the same, and that his death has caused the downfall of the gods?”

[Pg 29]

“I am hardly likely to adopt that explanation, believing as I do in the eternity of those gods by whose worship Rome has grown so great. The story is true, let the meaning be what it may,” added Crispus in a tone whose sharpness deterred Theomantes from making any further comment.

[Pg 30]

Now, while telling his story, Crispus had become suddenly alive to the presence of a very beautiful girl sitting at an adjoining triclinium. It was not so much her beauty, however, that attracted him as the attention she had paid to his words. She was by far the keenest and most attentive of his listeners, seeming to hang breathless upon his lips during the whole recital; of all the assembly, she seemed to be the only person to receive the story with pleasure.

“Rufus,” whispered he, “who is that girl with the lovely golden tresses? To the left of us—on the next triclinium?”

Rufus turned in leisurely fashion to survey the maid in question.

“I know not her name, or who she is. She came hither accompanied by him who reclines beside her. As I see no likeness betwixt the two, I take it he is not her father.”

The man referred to was evidently a Hebrew, and distinguished both by his noble features and rich attire.

“Her father? Not he!” said Tertullus. “That is Josephus, a Jew, and yon damsel, I’ll swear, is no Jewess. There is a grace and beauty about her that is quite Ionic.”

“Who is this Josephus?” asked Crispus.

“He is a priest of the first of the twenty-four courses,” replied Tertullus, “and a rabbi so wondrously wise from his cradle upwards that when he was only fourteen, aged priests and venerable sanhedrists [Pg 31]would consult him on points of the law too hard for their own understanding.”

“What’s your authority for that story?” said Rufus dryly.

“The best authority—his own.[3] He hath told me so many a time. At the mature age of seventeen he had exhausted the whole course of philosophy, and had decided that Pharisaism is the road to heaven. But though a Pharisee, he cultivates Grecian literature, has literary aspirations, and is said to be writing at the present time a treatise that shall prove us Greeks and Romans to be in the matter of antiquity mere children of yesterday when compared with the Jews.”

Josephus did not much interest Crispus, but the young girl did, and he continued to watch her. This was probably her first experience of a Gentile banquet, and she seemed ill at ease amid her new surroundings. And no wonder! If the naked statuary and voluptuous paintings to be seen around, the immodest Coan robes worn by the women, and the shameless license of their language were distasteful even to the pagan Crispus, how much more so to a young maiden trained in the pure and lofty principles of Judaism? Berenice, alas! reared in the atmosphere of a decadent court, could learn in the Prætorium of Florus little that was new in the shape of wickedness, but the case was far different with a young and innocent girl.

“If this Josephus be her guardian, he is not exercising much discretion,” thought Crispus. “The banquet-hall of Florus is not the place to bring a young girl to.”

At this point Ananias, the ex-high pontiff of the Jews, and Theomantes, the priest of Zeus Cæsarius, created a diversion.

“Ay, ay,” muttered Rufus, “I knew that they’d be quarreling ere long.”

The two representatives of antagonistic religions were holding an animated dispute; as the controversy [Pg 32]waxed hotter their voices rose proportionately, till at last they attracted general attention. Everyone else in the assembly left off talking to listen to the disputants.

“Mercury a thief?” cried Theomantes. “So be it, then! And is it not written in your foolish scriptures that while Adam slept God stole from his side a rib which He fashioned into the first woman? What else, then, is your God but a thief?”

Ananias’ reply was anticipated by the Princess Berenice, ever quick to defend her ancestral religion.

“I will answer you,” said she to Theomantes. “Last night some thieves broke into my house, and stole a silver vase.” She paused for a moment, then added, “But they left a golden one in its stead.”

The Jewish guests greeted Berenice’s little parable with loud applause.

“Jupiter!” laughed Florus, “I wish such thieves would come every night.”

Theomantes returned to the attack. Holding his serpent close to the face of Ananias, and causing the reptile to give a hiss that made the Hebrew priest start, he laughed and said:

“My God is greater than yours.”

“Prove it,” sneered Ananias.

“Is it not written that when your God appeared in the burning bush, Moses drew near, but when he saw the serpent, which is my god, he fled?”

“True,” replied Berenice, answering for the silent Ananias, “and a few steps sufficed to put him beyond reach of the serpent. But how can one flee from our God, Who fills all space, Who at one and the same time is in heaven and in earth, on sea and on land?”

Theomantes, about to continue the dispute, was checked by a gesture from Florus, so the heathen priest, with a somewhat dark look at Berenice, subsided into silence.

“You have here,” commented Rufus, “a specimen [Pg 33]of what is always happening in Cæsarea when Jew and Gentile meet. But, ah! here cometh the wine.”

Now, it was the fashion of that day to begin the drinking with an invocation to the reigning emperor, and hence Florus, looking around upon his guests, lifted his cup as a sign for them to do the like, saying at the same time:

“Friends, a libation to the god Nero!”

The god Nero!

Though to the pagan portion of the assembly the words conveyed no impiety, the case was otherwise with the Jews, but those present were of the worldly-wise class that sacrifices religion to policy, and hence most of them, including the Sadducee Ananias and the Pharisee Josephus, shamelessly prepared to join with Florus in offering to the wickedest man of that age a libation as to a god.

Now, pagan though Crispus was, there was one thing in the Roman religion that he, in common with many others, could not approve, and that was the deification of the living emperor, especially when the deification extended to such a one as Nero. And yet to refrain from joining in the libation was dangerous, being tantamount to the guilt of læsa majestas; and of all crimes, the greatest, in the eyes of the buffoon then at the head of the empire, was the refusal to acknowledge his divinity.

Come what might, Crispus determined to have no part in the libation, and while there was on all sides a preparatory lifting of cups, his own remained untouched. He found a companion in Rufus, and some others, including the unknown maiden, whose eyes were eloquently expressive of abhorrence.

He and those of like thought were rescued from an embarrassing situation by the action of the Princess Berenice. With a pale face and agitated air she had risen to her feet, and in a voice trembling with suppressed emotion she addressed the wondering assembly.

[Pg 34]

“There once reigned,” she began, “and in this very city, a king who, on a set day, made an oration to his people; and they cried, ‘It is the voice of a god, and not of a man!’ And because he rebuked not their words the hand of heaven smote him there that he died. And that king,” she added, with a catch in her voice, “that king was my father!”

The fate of Agrippa the Elder was well known to all the guests, some of whom, indeed, had been present at that divine judgment—pronounced by the smitten king himself to be divine—and the memory of the event, added to the impressive words and solemn manner of his fair daughter, caused a thrill to pervade the assembly.

“And now, O Florus, do you desire the like fate for Nero? To call him god is to draw upon him the wrath of that eternal One, Who will not permit His glory to be given to another.”

As she sat down amid a murmur of approval from the better-minded, it became suddenly apparent to Florus that he had made a big blunder. All-desirous as he was of winning the favor of Berenice, he had strangely overlooked the fact that the libation in the form proposed by him might be distasteful to the religious ideas of the Jewish princess. He gladly seized the opportunity of extricating himself from an awkward situation by endorsing the words of Crispus, who said:

“The princess hath spoken well. Let us, O Florus, not give to a mortal, however highly placed, the honor that belongs only to the immortals.”

“Be it as the princess wishes,” said the procurator. “We will change the phrasing to one in which all may join.” With that he added, “To the health of the Emperor Nero!” and plashed upon the tesselated pavement a few drops of the ruddy wine, an example in which he was followed by the rest of the guests, Jew and Gentile alike.

[Pg 35]

“A beautiful cup, O Florus,” remarked Tertullus, attentively eyeing the goblet from which the procurator had made his libation. “I am quite charmed by it. May one ask for a closer look?”

The cup in question was one of those myrrhine vases imported from the far East, vases whose delicate semi-transparent material was as much a mystery to the ancient Romans as it is to the modern antiquary.

“Mark my word,” whispered Tertullus to Rufus, “if we shall not find on one side of that cup a natural vein of purple curving into something like the shape of a Grecian lyre.”

Florus, always glad to have the excellency of his treasures acknowledged, addressed a slave.

“Girl, pass this cup to the noble Tertullus. A judge of art, he will know how to appreciate such a work. By the gods, have a care how you carry it!”

The girl, thus bidden, conveyed the vessel to Tertullus. Its chief beauty consisted in the great variety of its colors, and the wreathing veins which here and there presented shades of purple and white, with a blending of the two. As Tertullus had said, one of these veins bore considerable resemblance to a lyre.

“I never thought to see thee again,” muttered Tertullus to himself, apostrophizing the cup. “How come you here in the hands of Florus? A rare work of art,” he added aloud, as he returned the cup to the procurator. “You have had it long?”

“These seven years.”

“Seven days, you mean,” murmured Tertullus; then aloud, “It must have cost an immense sum.”

“Thirty talents,” replied Florus with a careless air, as though the amount were a mere trifle. “There are but two vases of this kind in all the empire; they were brought to Rome by a Parthian merchant. Petronius purchased the one, I the other.”

“What a liar you are!” thought Tertullus; and [Pg 36]then, as if dismissing the matter altogether from his mind, he said in a low tone to Rufus:

“Doth Simon the Black still linger in his dungeon?”

Rufus replied in the affirmative.

“May one ask,” smiled Crispus, “who is this Simon the Black?”

“You are a stranger in Judæa, or you would not have to ask that question,” returned Rufus. “Simon the Black was till lately the chief of a robber-band of Zealots, whose haunt was among the almost inaccessible crags that overhang the Red Way, the famous pass that leads from Jerusalem to Jericho. The Jew was allowed to traverse the pass in safety; the ordinary Gentile was taken captive and held to ransom; but as to the Roman, woe to him if caught!—it being the way of Simon to hang all such without the alternative of a ransom. Hence he is called by those of the Jews who hate our rule, ‘The Scourge of the Romans,’ and is regarded by them as a patriot.

“The curious part of it all is that Florus, though often appealed to both by the Romans and Greeks of Cæsarea, refrained for a long time from sending a military expedition against this nest of robbers, and when at last he yielded to public pressure, and dispatched my Italian Cohort on the errand, his parting words to me were, ‘I do not want to be troubled with prisoners.’ I declined to take the hint, however, and brought back Simon alive, much, it would seem, to the mortification of the procurator. And here at Cæsarea the fellow lies in a dungeon, Florus strangely refusing to put him on trial.

“It’s galling to think,” added Rufus, “that my work will have to be done all over again. The pass hath been seized by another bandit—Manahem, a son of that notorious Judas of Galilee, who drew away much people after him in the days of the taxing. More catholic in his views, he plunders and slays Jews and Gentiles alike. And now again Florus—odd, is it not?—is [Pg 37]thwarting me in my wish to proceed against this new malefactor.”

“Not at all odd,” remarked Tertullus, “if my suspicion be correct; and, by Castor! I’ll try to verify it before twenty-four hours be past.” And then, speaking aloud, he turned and addressed the procurator.

“O Florus, do you take your place on the bema to-morrow? ’Tis a court day.”

The governor frowned at this introduction of business into the midst of pleasure.

“What cases are there to try?”

“There is the case of Simon the Black. The Romans and Greeks of Cæsarea are clamoring for his trial.”

“Let them clamor.”

“The long delay over this matter hath so enraged them that they swear if Simon be not brought to justice by the next court day, which is to-morrow, they will storm the prison, and will themselves bring him forth to execution.”

“And should they make the attempt,” remarked Rufus gravely, “I doubt very much, O Florus, whether we can depend upon the fidelity of our cohorts to prevent it. This Simon hath slain so many Romans that military and civilians alike are desirous of seeing him brought to justice.”

Florus, looking very ill at ease, was silent for a moment.

“You are convinced that our captive is really the Simon the Black, and that he hath committed the crimes attributed to him?”

“Quite,” replied Tertullus. “I have documents and witnesses enough to prove his guilt twenty times over.”

“Why, then, need we go to the trouble of a public trial? Since you are certain of his guilt, I will do as did Antipas with him that was called ‘The Baptist’—send an executioner to his cell. How say you? Speak the word, and within an hour you shall have his head here upon a charger.”

[Pg 38]

“Antipas’ act is a bad precedent,” returned Tertullus. “Your predecessor Festus, as Ananias there can testify, was more equitably minded. ‘It is not the manner of the Romans,’ said he, ‘to deliver any man to die, before that he which is accused have the accusers face to face, and have license to answer for himself concerning the crime laid against him.’”[4]

“Words deserving to be written in letters of gold,” commented Crispus, to the manifest displeasure of Florus.

“Moreover,” observed Rufus, “the people will never believe Simon dead if he be secretly executed.”

“They will, when they see his head over the Prætorium gate.”

“His crimes have been open and public,” said Tertullus, “let his trial be so.”

“To-morrow?” said Florus. “Why not the next day?”

“The day after to-morrow is a sabbath,” replied Tertullus. “The Jewish witnesses will refuse to attend court on that day.”

“The sabbath! the sabbath!” repeated Florus pettishly. “Why is the sabbath greater than any other day?”

“Why are you greater than other men?” asked Berenice gently.

“Because, princess, it hath pleased Cæsar to make me so.”

“Well, then, it hath pleased the Lord to make the Sabbath a greater day than any other,” smiled Berenice, never at a loss for an answer where her religion was concerned.

“Will not the noble Florus,” said Crispus, “state the reasons for his delay in bringing this prisoner to trial?”

The noble Florus did not reply to this pointed question. He frowned, and hesitated; but, with a son of the all-powerful Legate of Syria present as a witness [Pg 39]of his irregularities, he felt he could not do otherwise than grant the just request of Tertullus.

“Have, then, your way,” said he. “In the morning Simon shall be put upon his trial.”

And with that he resumed his conversation with Berenice.

“He’ll be sorry for that concession,” laughed Tertullus quietly; and then, turning to Rufus, he added, “See that Simon’s guards sleep not to-night. Florus is quite capable of taking him off secretly.”

“You mean——”

“I mean,” whispered Tertullus, “that the deferring of the trial is due to the fact that this Zealot, if brought into open court, could say something to the detriment of Florus; what, I would fain find out. Therefore, I say again, look well to the prisoner to-night.”

Rufus promised that he would see to the matter.

At this point the ears of the guests were attracted by a sound like that of cords passing over pulleys, and looking whence it came, they saw a curtain that draped a wide archway ascend, revealing behind it a stage.

And now, while the palate of the guests was being regaled with the choicest of wines, their eyes were gratified by a series of beautiful tableaux drawn from the domain of classic mythology. The last of these represented the Judgment of Paris; by a trifling departure from the original story, the prize of the fairest goddess was to be a golden zone.

Paris, apparently unable to come to a decision as to which of the three diaphanously-attired goddesses was the fairest, made the award dependent upon their dancing. At this there followed pas seuls of such a character that the modest maiden who sat by Josephus was compelled to avert her gaze.

Venus, having received the award from the hand of the Dardan shepherd, advanced to the edge of the stage, and surveyed the audience.

“Alas!” she cried with a sudden sigh, “Paris has [Pg 40]made a mistake, for I see one here more lovely than myself. Let the gift be hers, and let her be hailed as Queen of Beauty.”

With that she unclasped the golden cestus and flung it into the middle of the hall just as the curtain was falling upon the tableau.

A slave, picking up the fallen zone, carried it to Florus.

“‘ΚΑΛΛΙΣΤΗ’—‘for the fairest,’” said he, reading the sapphire letters set in the golden cestus. “The question is,” continued Florus, looking round upon a bevy of ladies who had drawn near to view the zone, and it was well worth viewing for its beautiful workmanship, “the question is, who is the fairest?”

But, however fair each lady might secretly deem herself, as there was not found any bold enough to come forward and claim this title, it became clear that, if the zone must be bestowed at all, it would be necessary to appoint an umpire to decide this ticklish matter.

The ladies, entering with a zest into the scheme, were quite willing, so they averred, to submit their charms to adjudication.

“A pretty little tableau, this,” whispered Rufus to Crispus, “prearranged by Florus for the purpose of flattering the vanity of Berenice. His liking for her is so well known that whoever is appointed umpire—unless he be a very independent character—will lack the courage to decide for any but the princess.”

A proposal on the part of Tertullus to appoint the umpire by lot was received with acclamation. Crispus, somewhat against his will, was forced by Rufus to take his place among the candidates for the office, and, what is more, when his turn came for putting his hand into the balloting urn he drew forth the tessera inscribed with the decisive word, “Judex.”

He compressed his lips, much preferring that the honor should have fallen upon some other.

Rufus now made a proposition.

[Pg 41]

“Methinks it is but fair,” said he, “that the lady round whose waist the zone is clasped should bestow a kiss upon the adjudicator.”

This was laughingly made one of the conditions of the contest.

And now, amid much mirth, about twenty of the ladies began to prepare for the event. The rest, either from modesty or distrustful of their charms, drew aside, content to look on.

Among those who would fain have withdrawn, not only from the contest, but also from the palace itself, was the young girl who had so much attracted the notice of Crispus.

“Let us go,” she whispered in a distressed voice to Josephus. “This is no place for me.”

But he sought gently to persuade her, by dwelling upon the value and beauty of the jeweled zone, the ease with which it was obtainable, the pride and pleasure she would feel in being hailed as the Queen of Beauty.

“The zone will not fall to me,” said she. “Look, and see how many beautiful women there are around.”

“None so beautiful as you, Vashti.”

She shook her golden tresses at what she deemed his partiality. In the end, however, she consented to let her will be overborne by his.

The fair contestants were now moving to the place of judgment, a spacious hemicycle at one end of the banqueting hall. Among them were the Princess Berenice, and the Syrian Asenath, the favorite of Ananias.

As Vashti moved forward, her air of innocence and purity seemed to give secret offense to the wanton dancing-girl; her lip curled with contempt, and resolving to strip the other of her veil of modesty, she came out with a proposal of a malicious and daring character.

“How can it be told,” cried she, “who is the loveliest, so long as we remain clothed? The robe may [Pg 42]hide deformities. Let it be a condition, O Florus, that in this contest we appear naked.”

Speaking thus, she laid both hands upon her swelling hips ready to fling off her robes at the least encouragement.

Now, seeing that in the Floralia at Rome women were accustomed to dance quite naked, and that at Etruscan banquets the ladies often showed their fair forms without any clothing whatever, the proposal of Asenath was not quite so startling as it would be at the present day.

There were, of course, screams of dissent from the fair contestants themselves, but to the gilded and decadent youth of that assembly, Gentile and Jew alike, living only for sensuality, Asenath’s suggestion met with a ready approval. Not even the high priest, Ananias, lifted his voice against it. The Princess Berenice stood like a statue, stately and still, neither assenting nor dissenting. As for Vashti, her cheeks had become of a deathly white, her whole air and attitude were eloquent of a vivid horror at finding herself amid a circle of gilded youth who stood by waiting only the word of Florus, to assist her, volentem, nolentem, in the task of disrobing.

“What says the excellent Florus?” cried Asenath.

“The proposal seems to me to be fair, for the robe, as you say, may hide deformities. But,” he continued, becoming secretly conscious that Crispus did not favor the idea, “the question is out of my hands; it rests with the adjudicator.”

“And he,” replied Crispus, “decides that the ladies shall remain clothed. This is a contest for beauty, and there is no beauty where there is no modesty.”

“O good and pious youth, ascend to heaven!” said Asenath with a mocking laugh; and realizing that her chance of winning the zone was gone, she stepped from the contending circle to the side of Ananias, who looked by no means pleased with the decision of Crispus. He, [Pg 43]the priest of a religion that claimed to be purer far than any of the pagan systems, had received a tacit rebuke from a pagan—a mortifying experience, the more so as he secretly felt it to be deserved.

Compliant with the directions of Florus, the contestants took their station upon a low marble seat that lined the hemicycle; and, when so placed, presented a variety of faces so dazzling in beauty as to make the adjudicator’s task a hard one.

As if to enhance his difficulty, Crispus received at that moment a piece of news somewhat startling in character.

Touched upon the shoulder by a hand, he turned, and, to his surprise, found Polemo by his side. If the Pontic king had been present at the banquet Crispus had certainly missed seeing him, nor could he now tell from what corner he had sprung.

“Athenaïs is among the contestants!” whispered the king; and ere Crispus could put a question to him, Polemo had slipped among the crowd that was standing around to watch the sight, and had vanished as mysteriously as he had appeared, leaving Crispus in a whirl of amazement.

His wife among the contestants!

Stern justice required that the prize should be given to the fairest, but still, for all that, it would be a graceful compliment to let his wife have the honor; it would certainly please her, who was now the one woman whom it behoved him to please. But how to identify her?

There was additional embarrassment in the fact that the chosen lady, on receiving the girdle, was to bestow a kiss upon the judge that had so honored her. To be kissed, in the presence of his unknown wife, by a lady adjudged by him to be the fairest of all present! If by some good fortune the lady chosen should happen to be Athenaïs, well!—but if not, what would her feelings be? No wonder Crispus shrank from the task [Pg 44]of selection, and thought for a moment of retiring in favor of some other umpire.

The contestants were now ready awaiting the judgment.

Permitted to adopt whatever attitude they pleased, the majority posed as if for a sculptor. A few stood or sat, but the greater part assumed a reclining posture, as being the better adapted to display the grace of their figure. Extraneous ornaments were allowed; and hence one lady, lyre in hand, posed as the muse Polyhymnia; a second, toying with a golden vase, assumed the character of a Danaïd; a third, for the purpose of showing the curve of a graceful arm, held aloft a silver lamp; while a fourth displayed a snowy limb in the feigned operation of tying her sandal; and so on of the rest, each forming in herself a living picture that would have charmed the eye of an artist.

Midway in the hemicycle sat Berenice, who, neglecting all adventitious aids, merely sat erect, as if relying solely upon her beauty, and next her came the timid Vashti, taking that place as being the only one left vacant.

Holding the girdle in his hand, Crispus went very slowly along the semicircle, passing from one fair form to another, and studying each with a critical eye.

The behavior of the ladies during this severe scrutiny offered a variety of contrasts. Some blushed, as did Vashti; others, like Berenice, sat with serene dignity, as if unconscious of the matter in hand; some sought to win favor by a caressing glance; others used the witchery of a sweet smile; and one or two there were that could not refrain from laughter.

The completion of his survey left Crispus undecided, and disappointed: Athenaïs, if she were really among these ladies, was evidently determined to keep her secret, since she had given no sign by which he might recognize her. Among the many sparkling rings worn by that fair bevy, there was none that he could identify as [Pg 45]the pledge placed by him upon the finger of his bride twenty-four hours ago, the ring set with a ruby sculptured with the likeness of a temple in flames.

Since his bride chose to hide her identity there remained nothing for him but to act in the spirit of strict impartiality by awarding the zone to her whose beauty in his judgment was most deserving of it, a difficult matter where all were so beautiful. Even that arbiter elegantiarum, Petronius (of whose friendship Florus had boasted), had he been present would have found the question a perplexing one.