Title: American lace & lace-makers

Author: Emily Noyes Vanderpoel

Editor: Elizabeth C. Barney Buel

Release date: December 7, 2025 [eBook #77415]

Language: English

Original publication: New Haven: Yale University Press, 1924

Credits: A Marshall and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

The new original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

PUBLISHED ON THE FOUNDATION

ESTABLISHED IN MEMORY OF

AMASA STONE MATHER

OF THE CLASS OF 1907 YALE COLLEGE

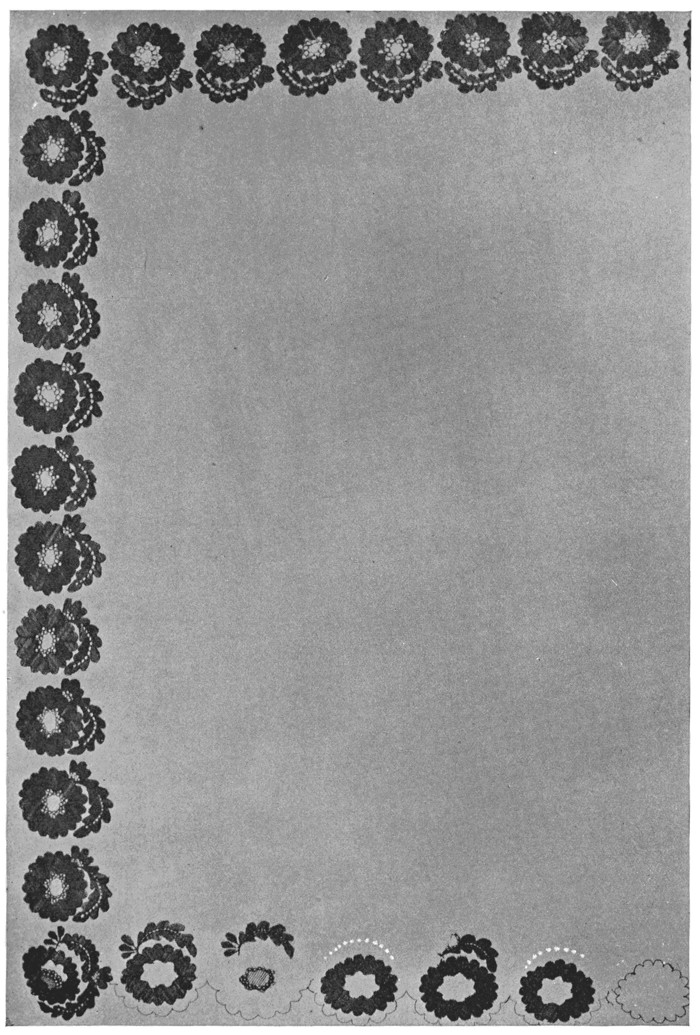

Frontispiece.

Black net, embroidered with colored carnations, by Caroline Canfield (Mrs. William Mackay). Owned by the Litchfield Historical Society of Litchfield, Connecticut.

AMERICAN LACE

&

LACE-MAKERS

BY

Emily Noyes Vanderpoel

Author of “Color Problems” and “Chronicles of a Pioneer School.”

EDITED BY

Elizabeth C. Barney Buel, A.B.

New Haven, Yale University Press.

LONDON, HUMPHREY MILFORD, OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Mcmxxiv.

Copyright 1924 by Yale University Press.

Printed in the United States of America.

THE AMASA STONE MATHER

MEMORIAL PUBLICATION FUND

The present volume is the fifth work published by the Yale University Press on the Amasa Stone Mather Memorial Publication Fund. This Foundation was established August 25, 1922, by a gift to Yale University from Samuel Mather, Esq., of Cleveland, Ohio, in pursuance of a pledge made in June, 1922, on the fifteenth anniversary of the graduation of his son, Amasa Stone Mather, who was born in Cleveland on August 20, 1884, and was graduated from Yale College in the Class of 1907. Subsequently, after traveling abroad, he returned to Cleveland, where he soon won a recognized position in the business life of the city and where he actively interested himself also in the work of many organizations devoted to the betterment of the community and to the welfare of the nation. His death from pneumonia on February 9, 1920, was undoubtedly hastened by his characteristic unwillingness ever to spare himself, even when ill, in the discharge of his duties or in his efforts to protect and further the interests committed to his care by his associates.

To

Robert Swain Gifford

A real Artist

A wise Teacher

A true Friend

AMERICAN LACE AND LACE-MAKERS

| List of Plates, Lace-makers, and Owners of Originals | xiii |

| Preface | xix |

| Introduction | 1 |

| Plates and Descriptions | 15 |

[Pg xiii]

In this List, the following abbreviations are used:

A.M.N.H. = American Museum of Natural History, New York City.

E.M. = Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts.

L.H.S. = Litchfield Historical Society, Litchfield, Connecticut.

M.F.A. = Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts.

M.M.A. = Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

S.C.I.L.A. = Sybil Carter Indian Lace Association, New York City.

| Number and Subject | Maker or Source | Ownership |

| Frontispiece. Black net, embroidered with colored carnations | Caroline Canfield (Mrs. William Mackay) | L.H.S. |

| 1. Lace-bark tree lace | Jamaica | Miss Edith Beach |

| 2. (1) Peruvian lace bag | Peruvian | A.M.N.H. |

| (2) Peruvian lace | Peruvian; prehistoric | A.M.N.H. |

| 3. Peruvian lace | Peruvian; ancient | Miss Marian Powys |

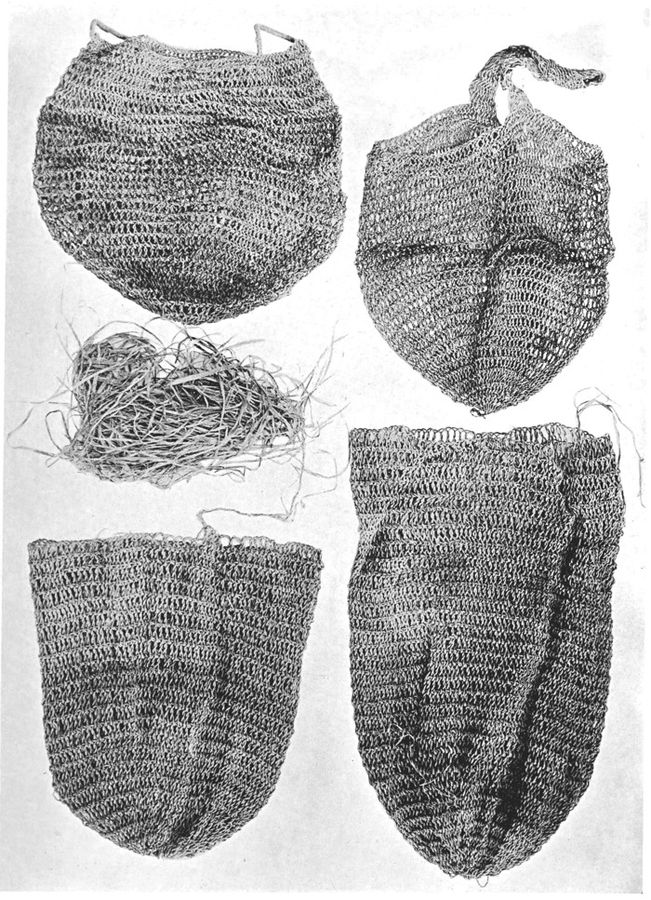

| 4. Eight lace bags | Balienti Indians | A.M.N.H. |

| 5. Lace bag | Balienti Indians | A.M.N.H. |

| 6. Details of lace bags | Balienti Indians | A.M.N.H. |

| 7. Four lace bags | Honduras Indians | A.M.N.H. |

| 8. Lace headdress | Hopi Indian | Miss Frances Morris |

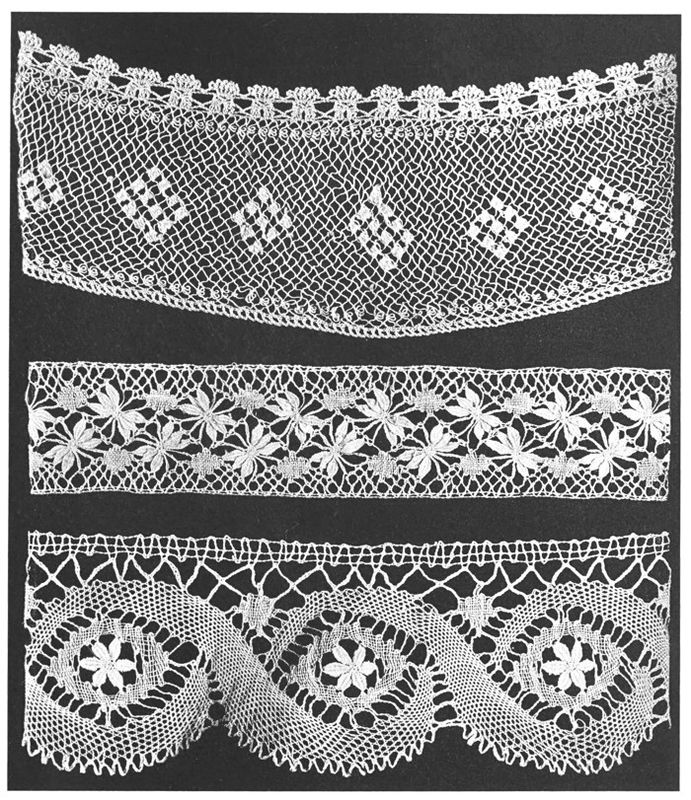

| 9. (1) Porto Rican lace | An aged Porto Rican woman | L.H.S. |

| (2) Porto Rican pillow and bobbin lace | Unknown | L.H.S. |

| (3) Porto Rican pillow and bobbin lace | Unknown | L.H.S. |

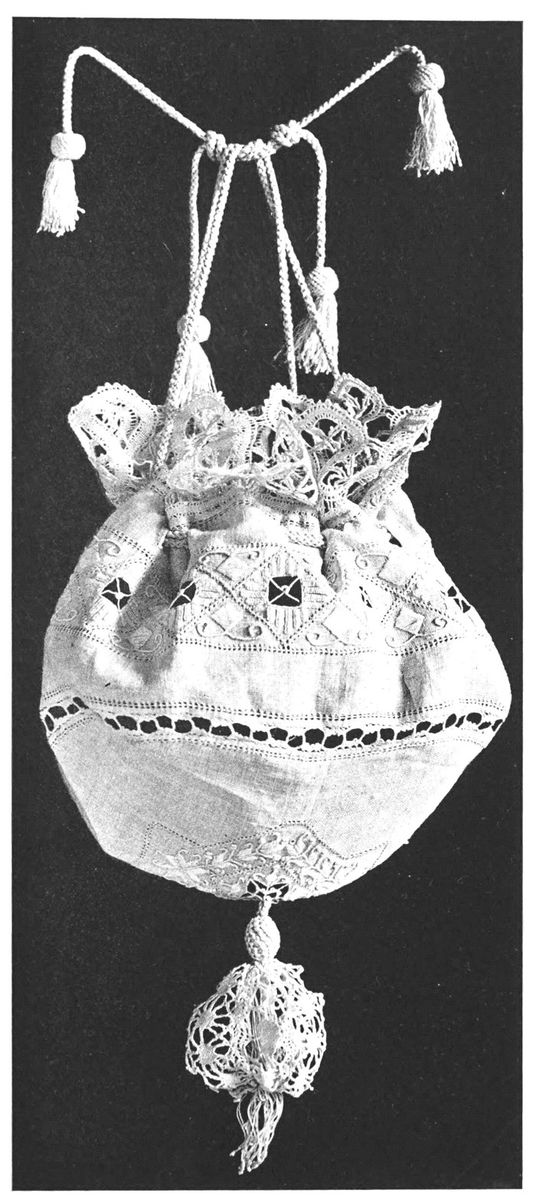

| 10. Linen cut-work hand bag | Oneida Indians | S.C.I.L.A. |

| 11. Bobbin lace pillow | Oneida Indians cover | S.C.I.L.A. |

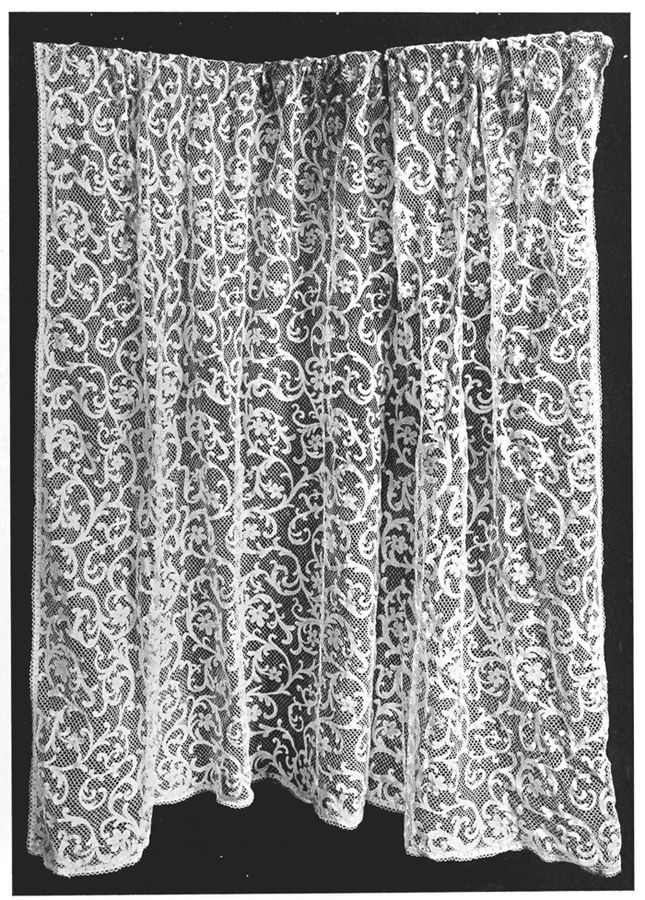

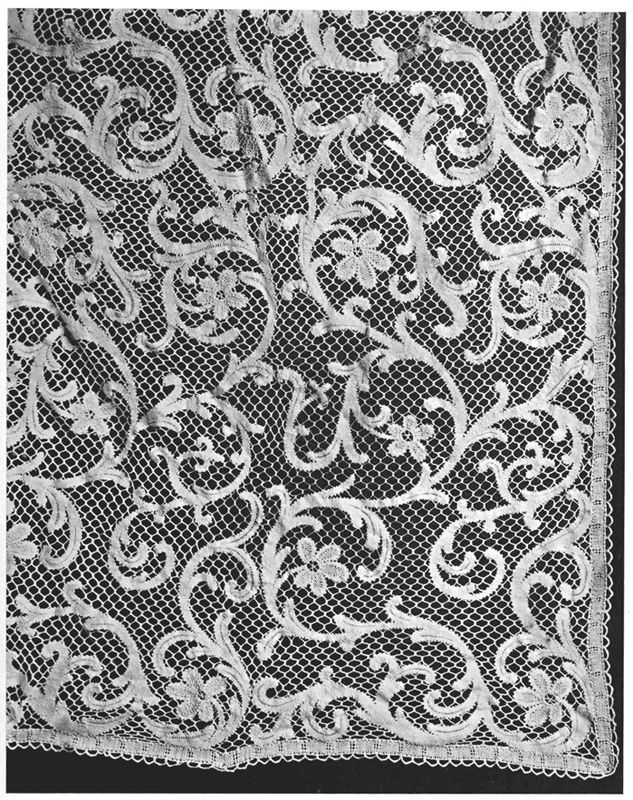

| 12. Bobbin lace bed-spread | Oneida Indians | S.C.I.L.A. |

| 13. Detail of the same | ||

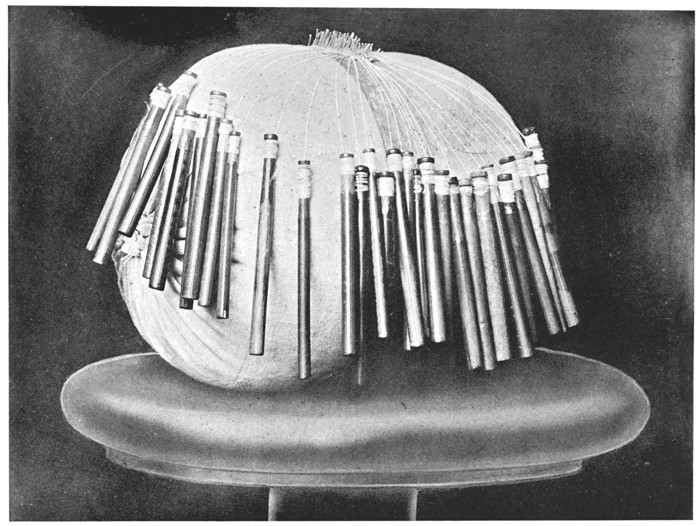

| 14. Lace pillow with bobbins | Lydia Lakeman | Miss Sarah E. Lakeman |

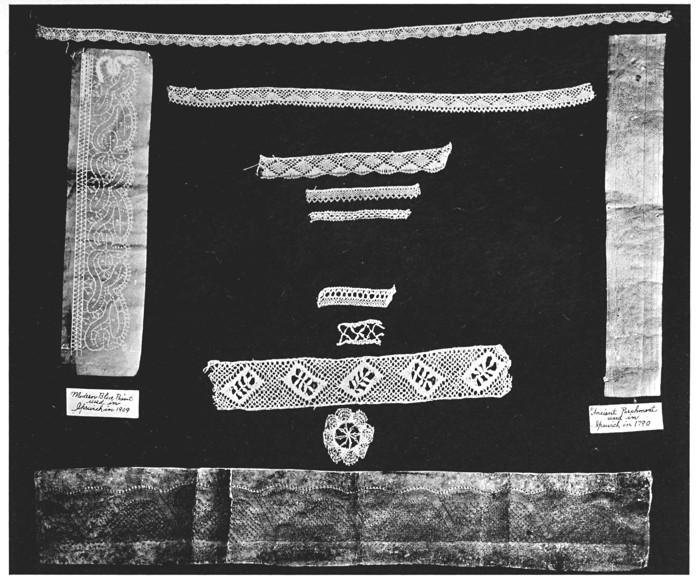

| 15. Ipswich patterns and laces | Sarah Sutton Russell and Mrs. Thomas Caldwell | Miss Sarah E. Lakeman |

| 16. Ipswich laces | Unknown | Miss Sarah E. Lakeman |

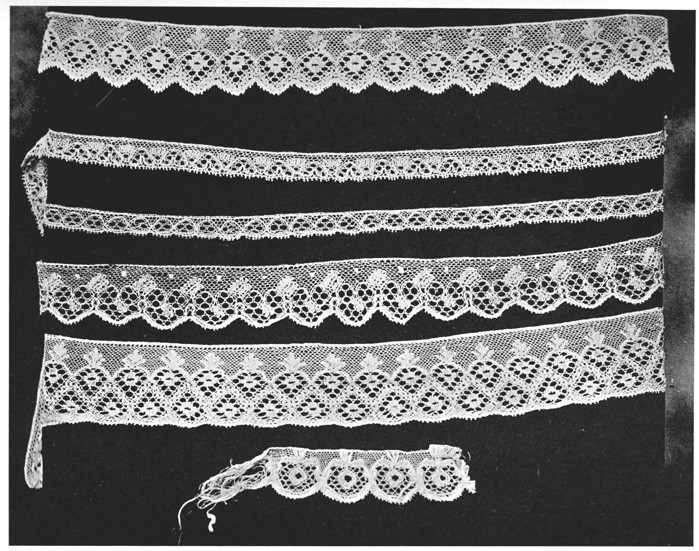

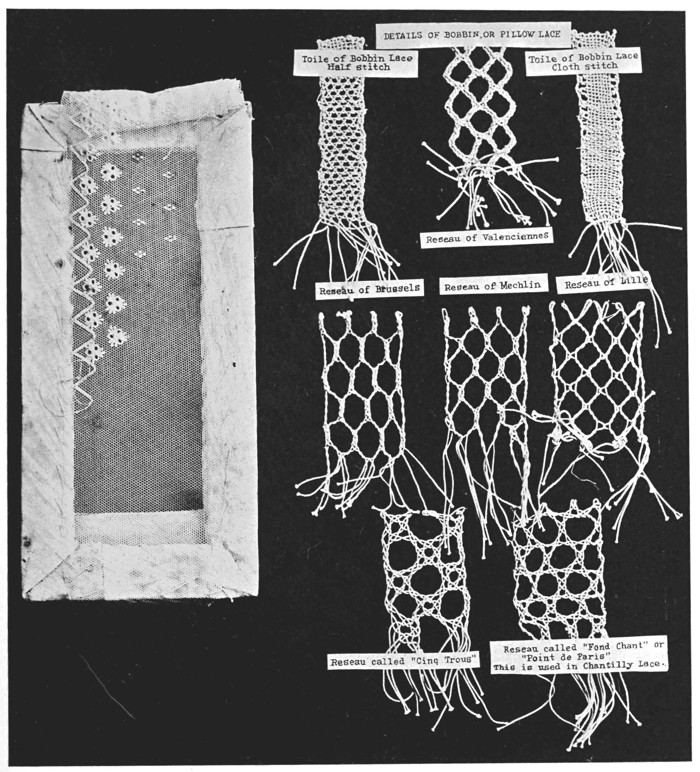

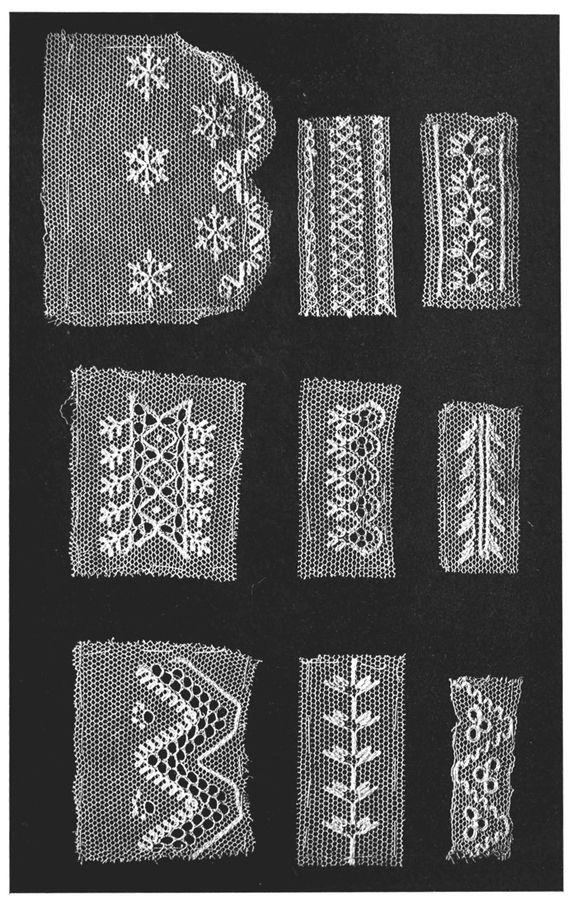

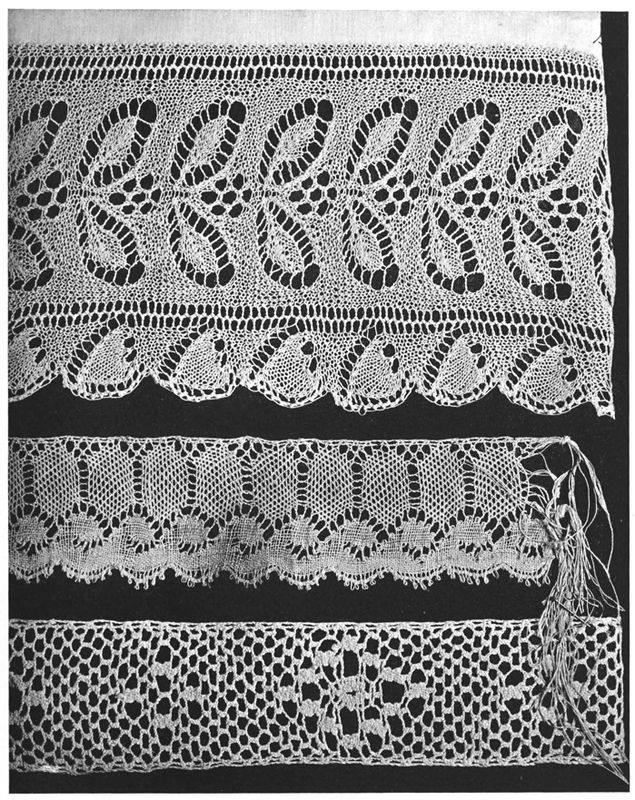

| 17. Réseaux of various laces | Unknown | E.M. |

| 18. Bobbins, thread, and samples of Limerick | Unknown | E.M. |

| 19. Samples of darned laces | Mabel Roberts (Mrs. Hezekiah Thompson) | Miss Esther H. Thompson |

| [xiv]20. Additional samples of darned laces | Mabel Roberts (Mrs. Hezekiah Thompson) | Miss Esther H. Thompson |

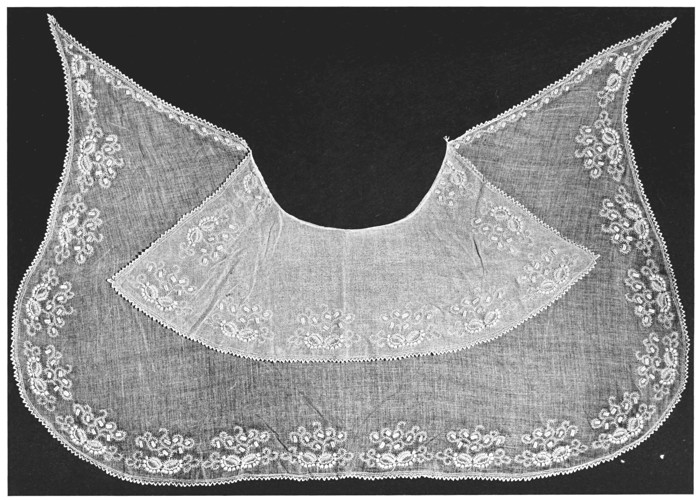

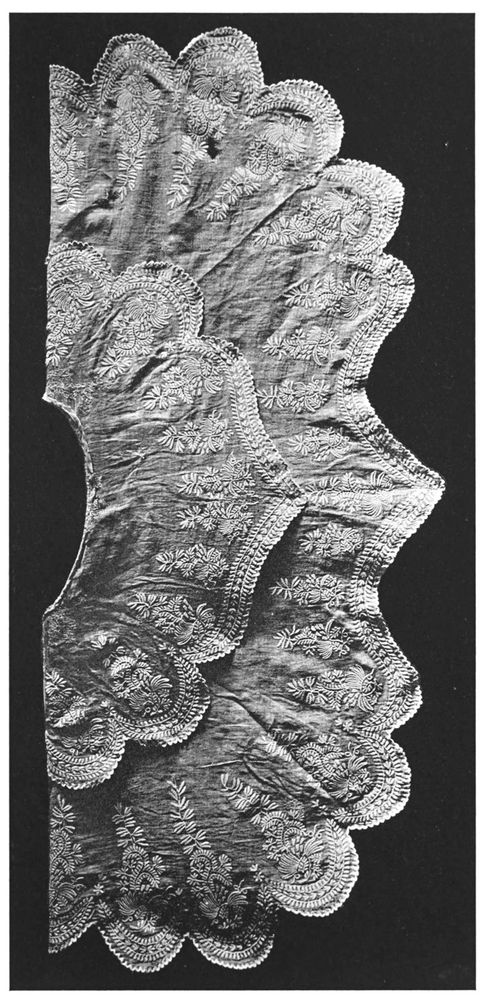

| 21. Embroidered collar | Unknown | Miss Esther H. Thompson |

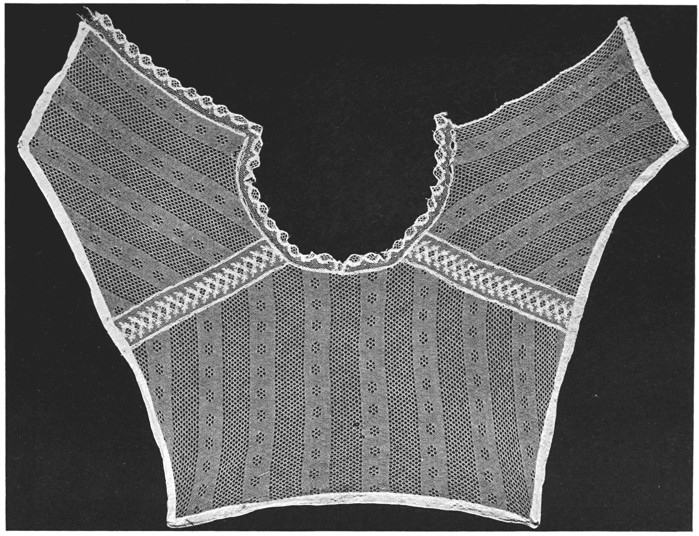

| 22. Lace guimpe | Unknown | Miss Esther H. Thompson |

| 23. English darned net | Ipswich, England laces | Mrs. Guy Antrobus (Mary Symonds) |

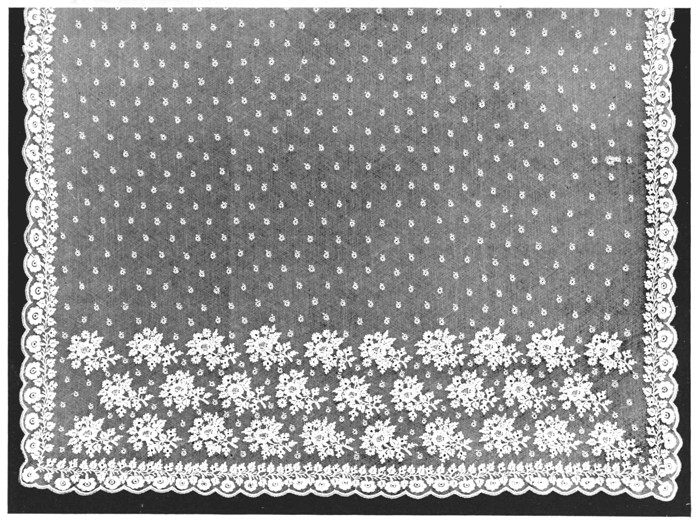

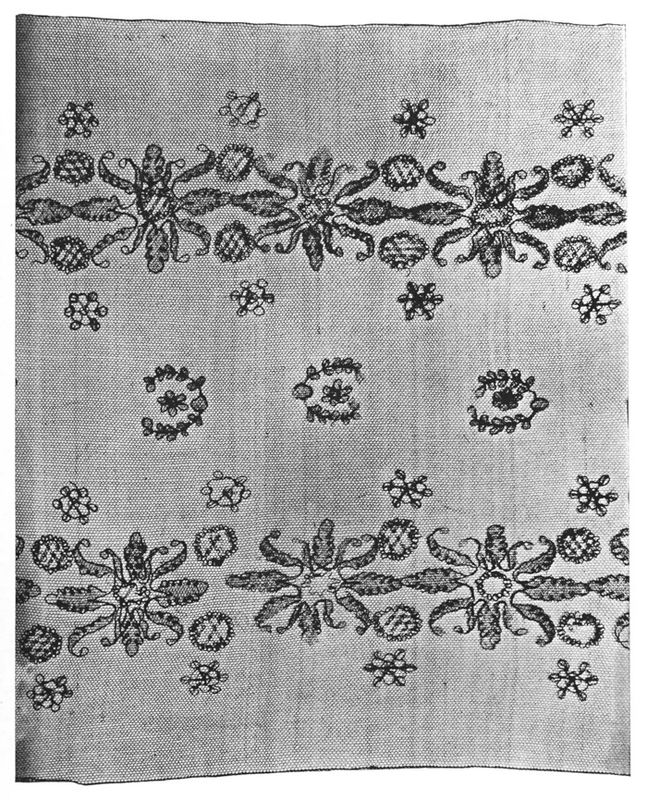

| 24. Darned net veil | Mrs. Thomas L. Rushmore | M.M.A. |

| 25. White net dress skirt | Cornelia Kingsland (Mrs. Hatherly Barstow) | M.M.A. |

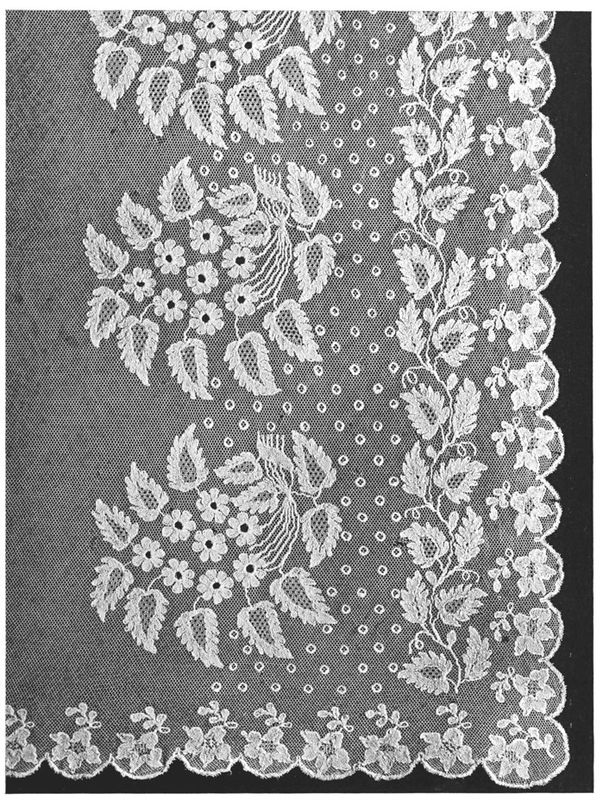

| 26. White lace veil | Catherine Roosevelt Kissam (Mrs. Francis Armstrong Livingston) | Miss Helena Knox |

| 27. Detail of the same | ||

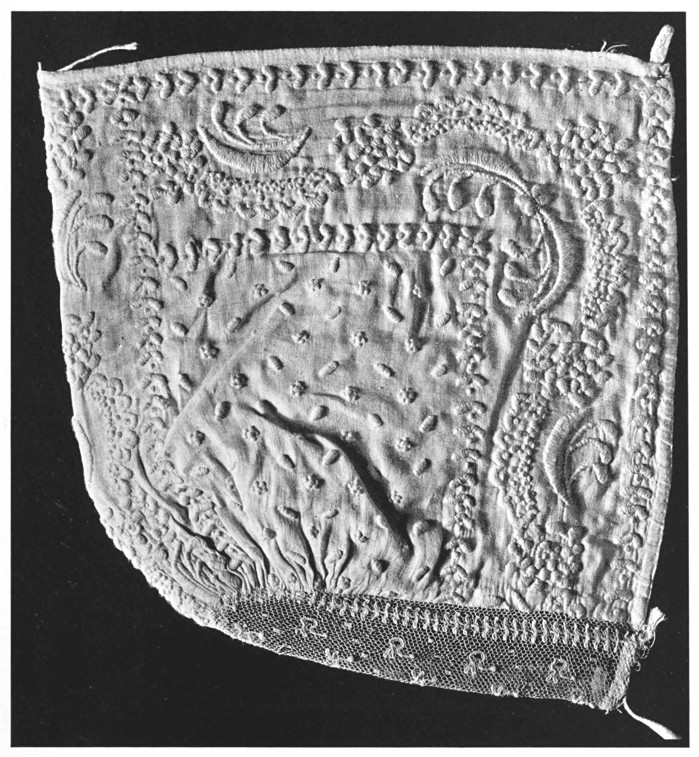

| 28. Front of white lace cap | Probably Catherine Roosevelt Kissam (Mrs. Francis Armstrong Livingston) | Miss Helena Knox |

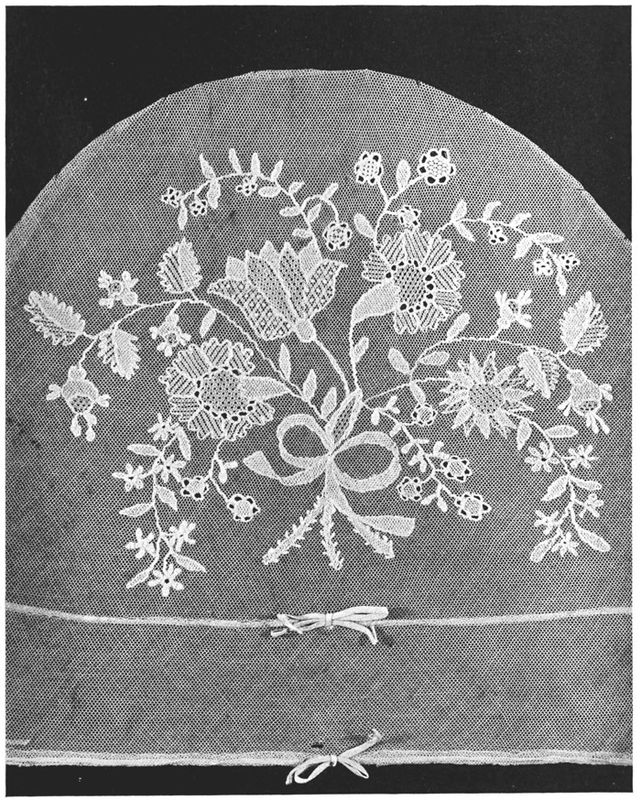

| 29. Crown of the same | ||

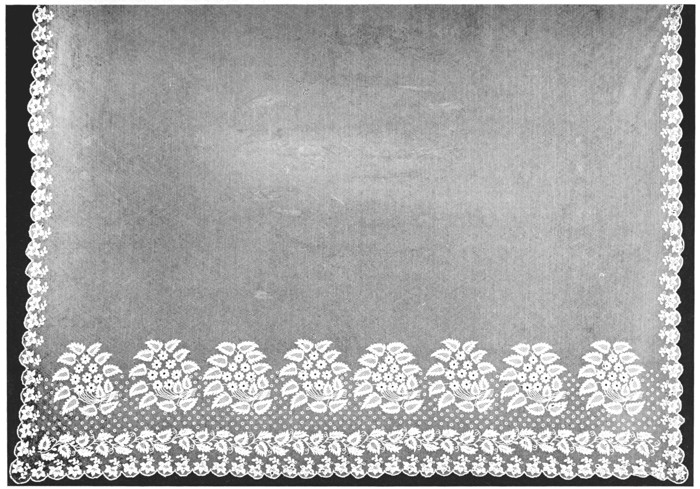

| 30. White lace veil | Mary W. Peck (Mrs. Edward D. Mansfield) | L.H.S. |

| 31. Detail of the same | ||

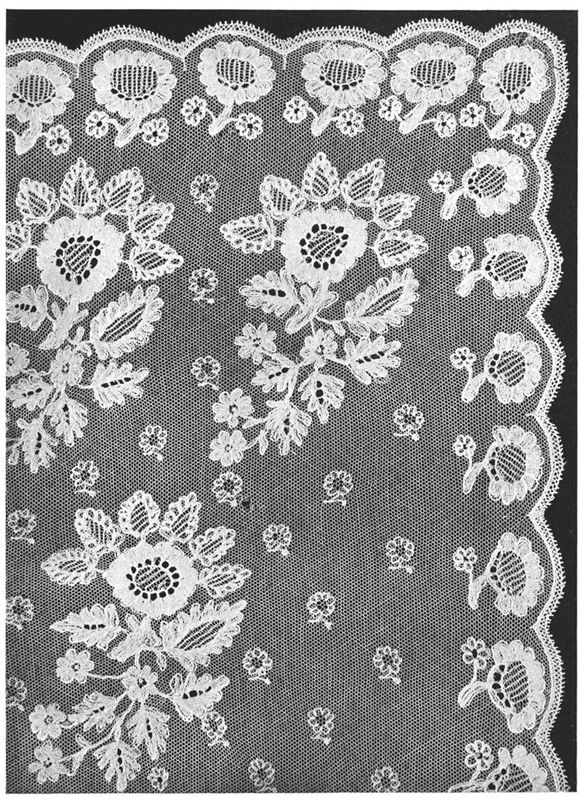

| 32. White lace veil | Elizabeth Hannah Canfield (Mrs. Frederick Augustus Tallmadge) | L.H.S. |

| 33. Detail of the same | ||

| 34. Detail of white veil | Probably Ellen McBride (Mrs. Aaron Vanderpoel) | L.H.S. |

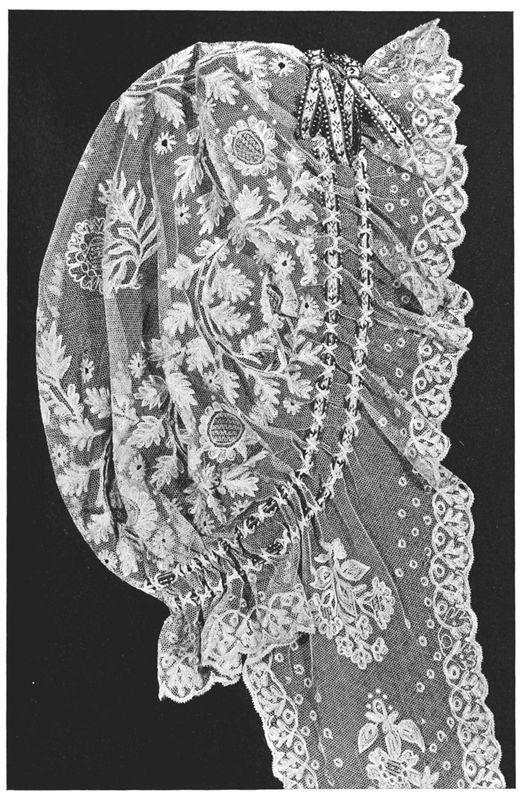

| 35. Lace cap | Elizabeth Hannah Canfield (Mrs. Frederick Augustus Tallmadge) | L.H.S. |

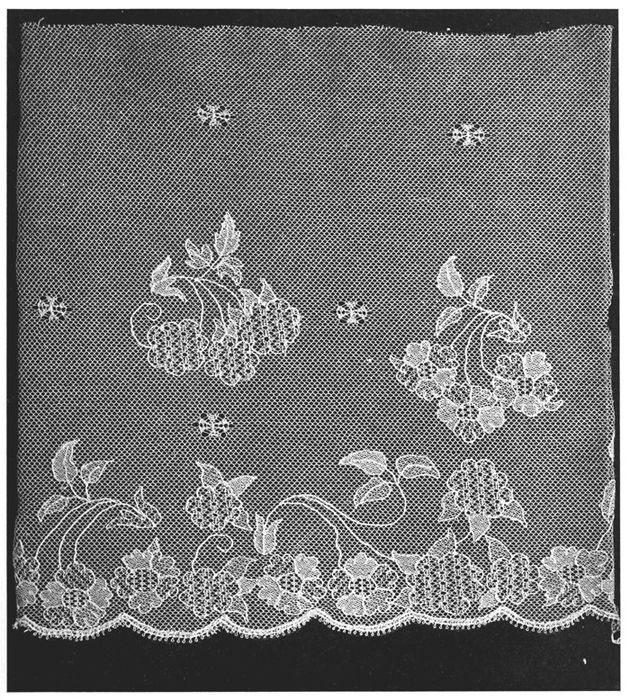

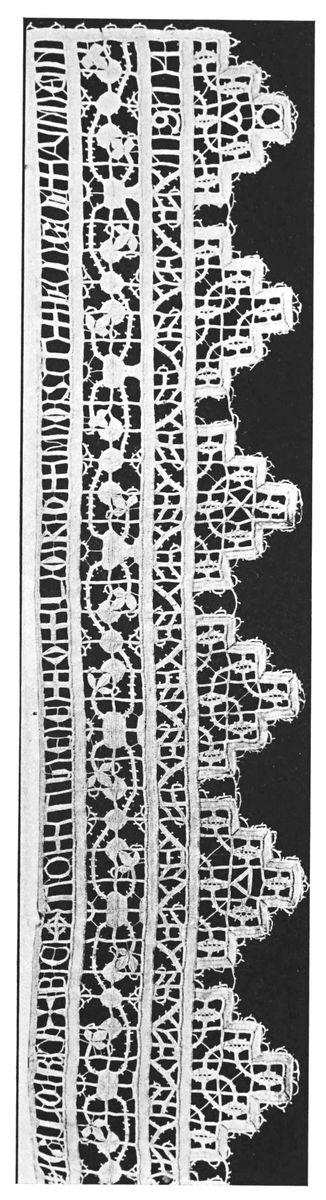

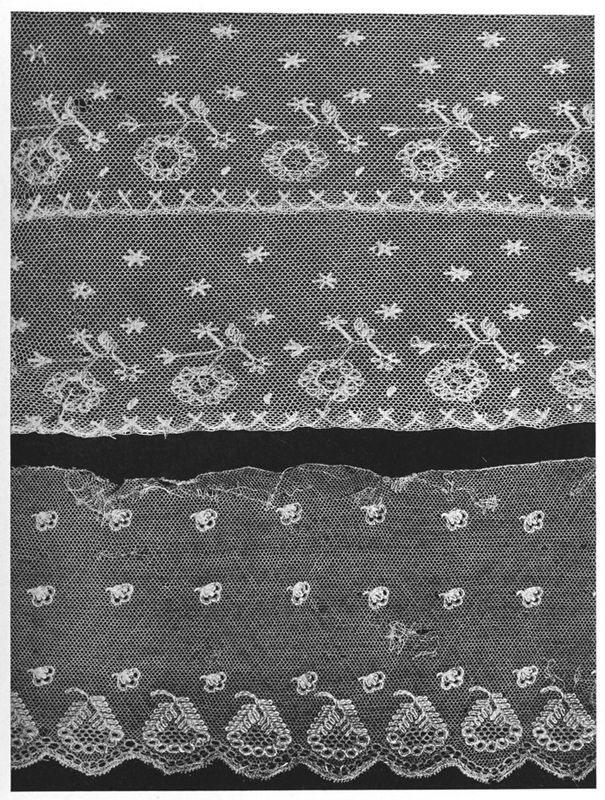

| 36. Limerick trimming lace | Limerick, Ireland | L.H.S. |

| 37. White lace veil | Sarah Elizabeth Johnson (Mrs. George Pollock Devereux) | Miss Marianna Townsend |

| 38. Detail of the same | ||

| 39. Detail of a second veil by the same hand | Sarah Elizabeth Johnson (Mrs. George Pollock Devereux) | Miss Marianna Townsend |

| 40. English wedding veil | An unknown member of the Stodart family | Miss Clara Ray |

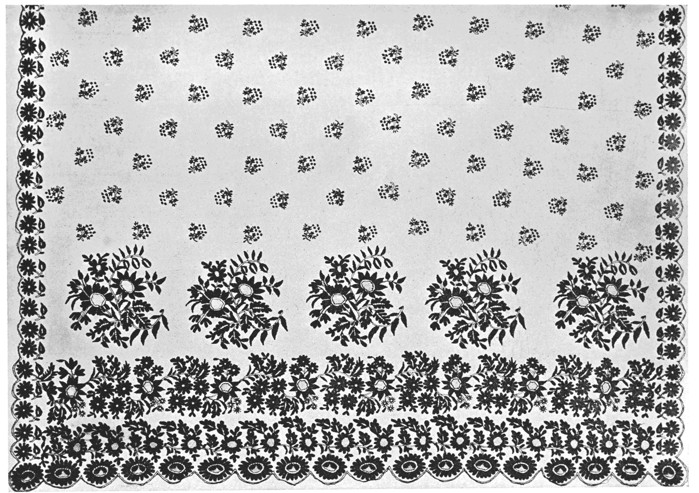

| 41. White lace veil | Marietta, or Mary, Smith | L.H.S. |

| 42. Detail of the same | ||

| 43. Second detail of the same | ||

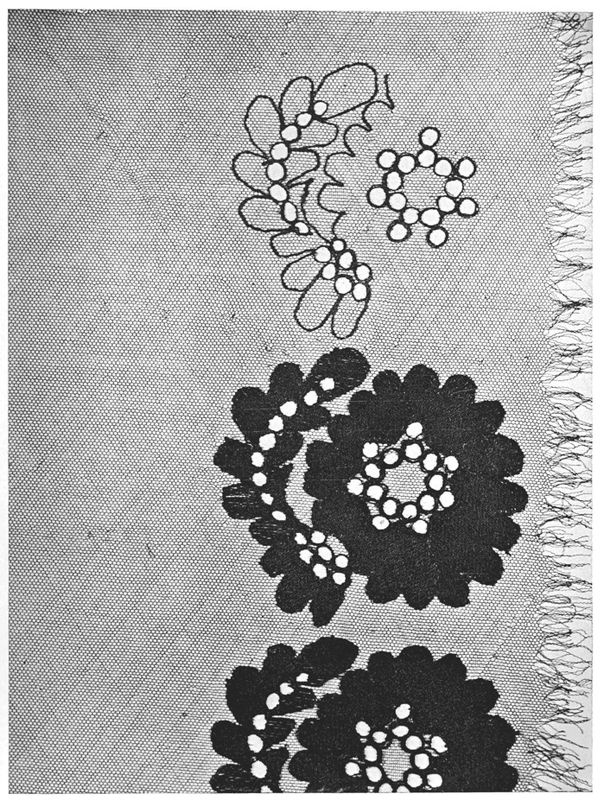

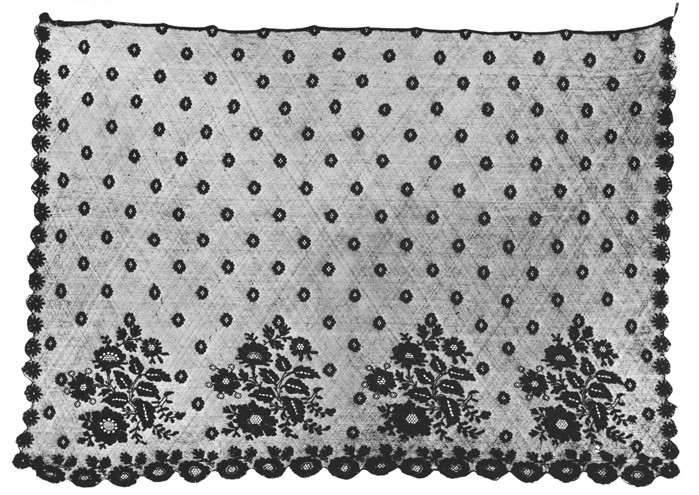

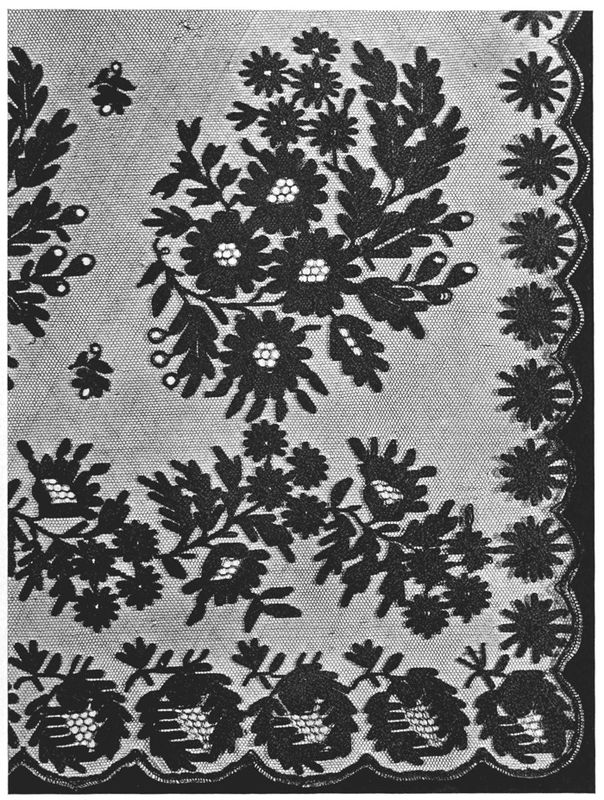

| 44. Black net shawl | Mrs. John Savage (Miss Barringer) | L.H.S. |

| 45. Detail of the same | ||

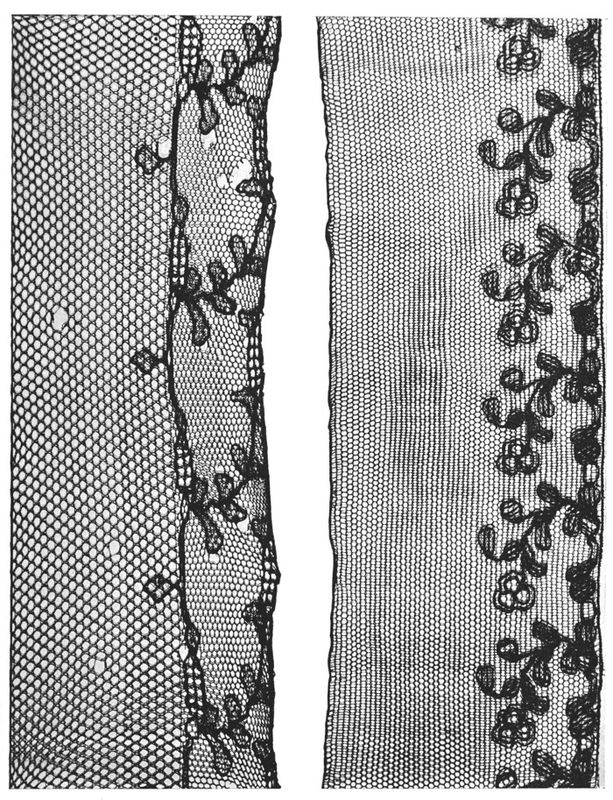

| [xv]46. (1) Black trimming lace | Elizabeth, or Betsey, Peck (Mrs. Camp Newton) | Mrs. Samuel H. Street |

| (2) Black trimming lace | Pamela Parsons | Mrs. Charles B. Curtis |

| 47. Black lace veil | An unknown member of the Buel family | L.H.S. |

| 48. Detail of the same | ||

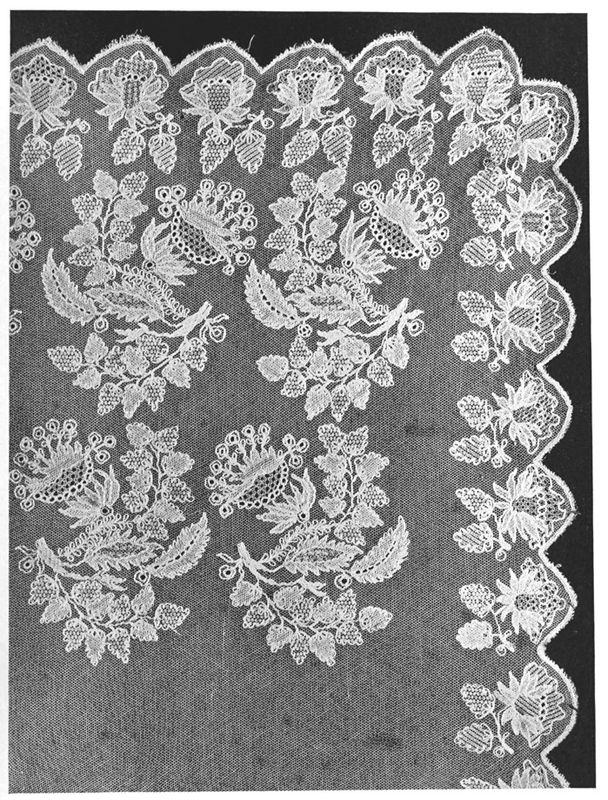

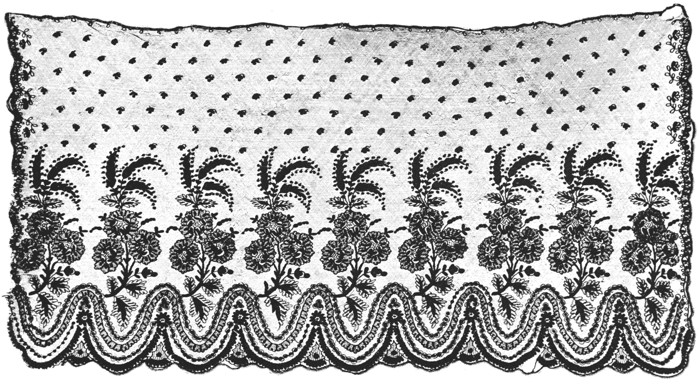

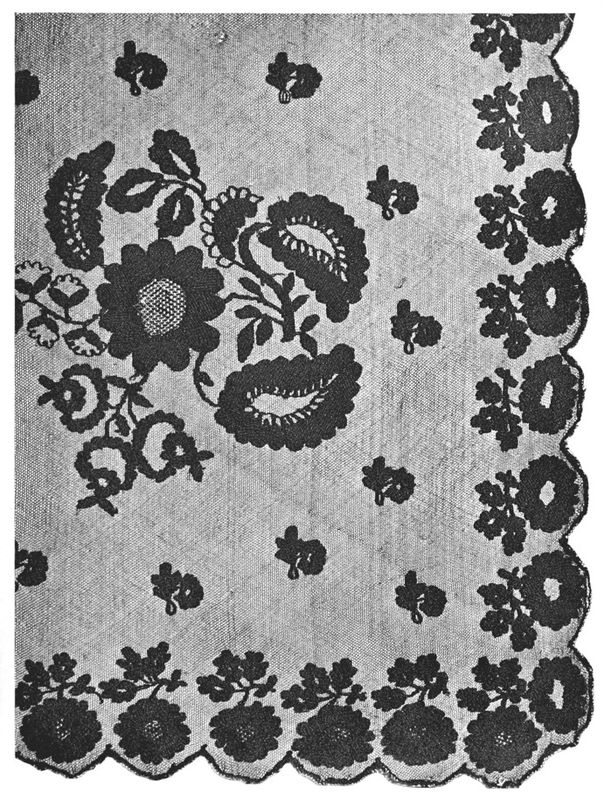

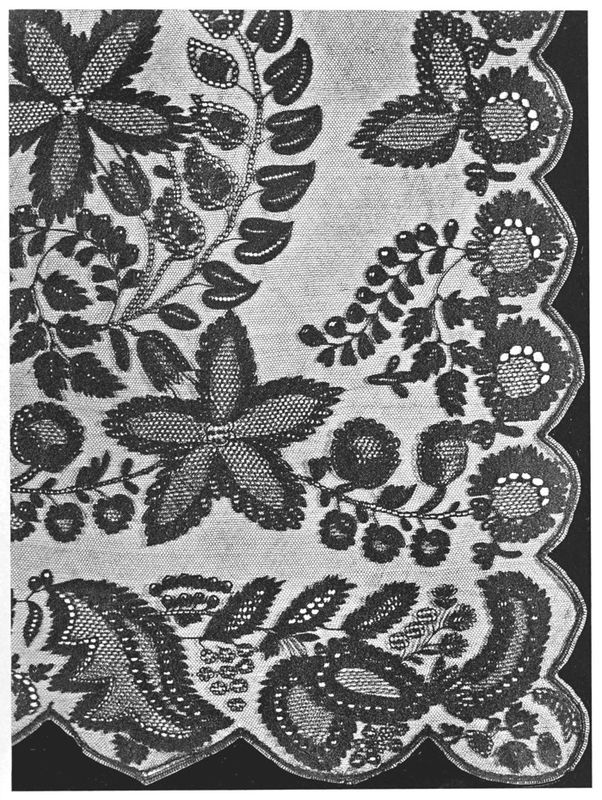

| 49. Black lace veil | Polly Marsh | Mrs. Lewis Marsh |

| 50. Detail of a second veil by the same hand | Polly Marsh | Mrs. Lewis Marsh |

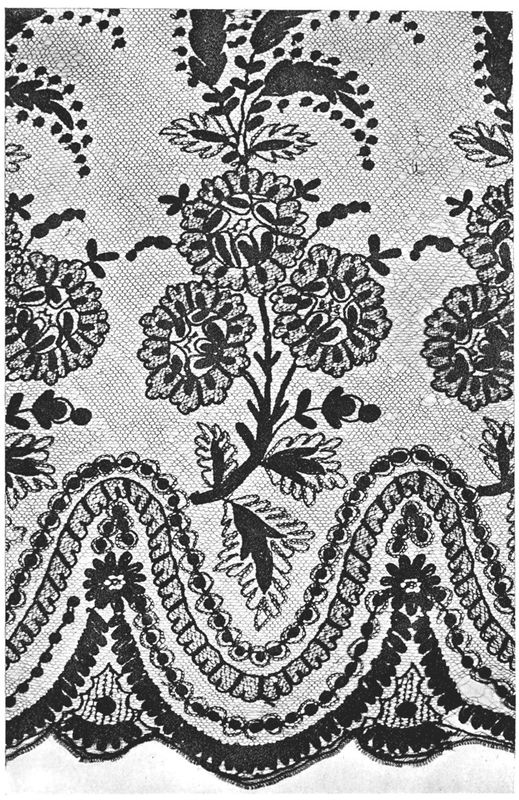

| 51. Black lace veil | Either Caroline Canfield (Mrs. William Mackay) or Elizabeth Hannah Canfield (Mrs. Frederick Augustus Tallmadge) | L.H.S. |

| 52. Detail of the same | ||

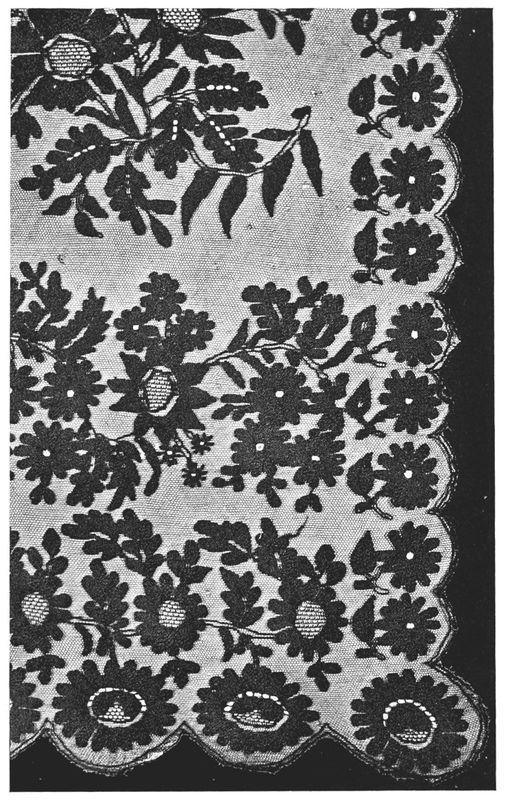

| 53. Detail of black lace veil | Louisa Lewis (Mrs. Henry Phelps) | L.H.S. |

| 54. Black lace veil | Elizabeth Hannah Canfield (Mrs. Frederick Augustus Tallmadge) | L.H.S. |

| 55. Detail of the same | ||

| 56. Lace pillow and bobbins with black trimming lace | Nina Hall Brisbane | L.H.S. |

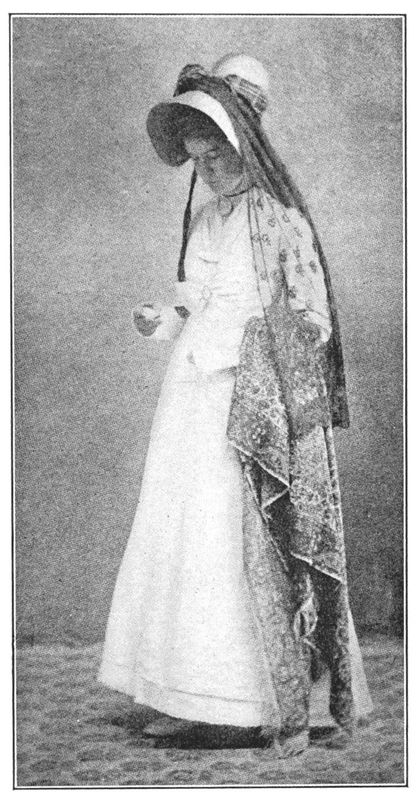

| 57. Costume of 1825 | Veil by Mary Bacon (Mrs. Chauncey Whittlesey) | Mrs. Edward W. Preston |

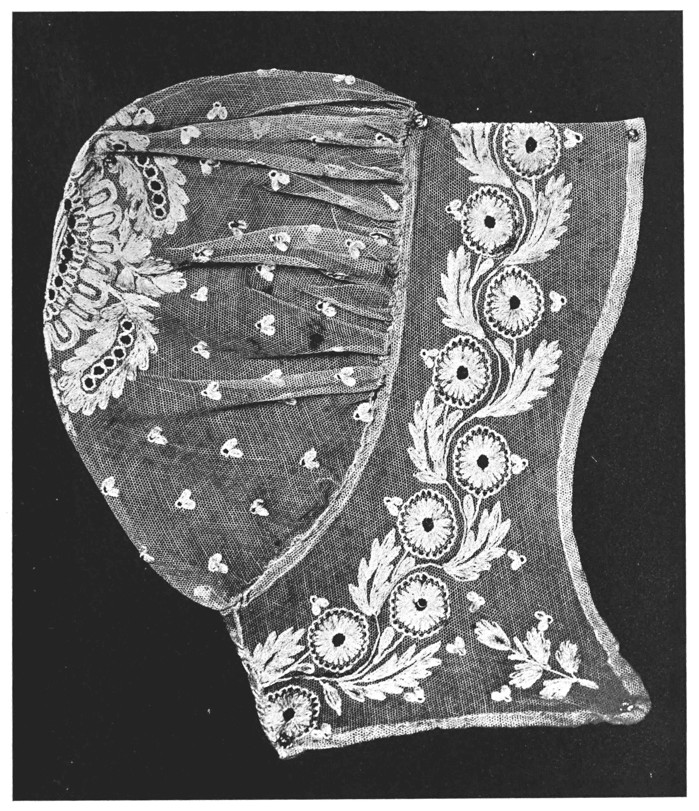

| 58. Lace cap | Elsie Philips | M.F.A. |

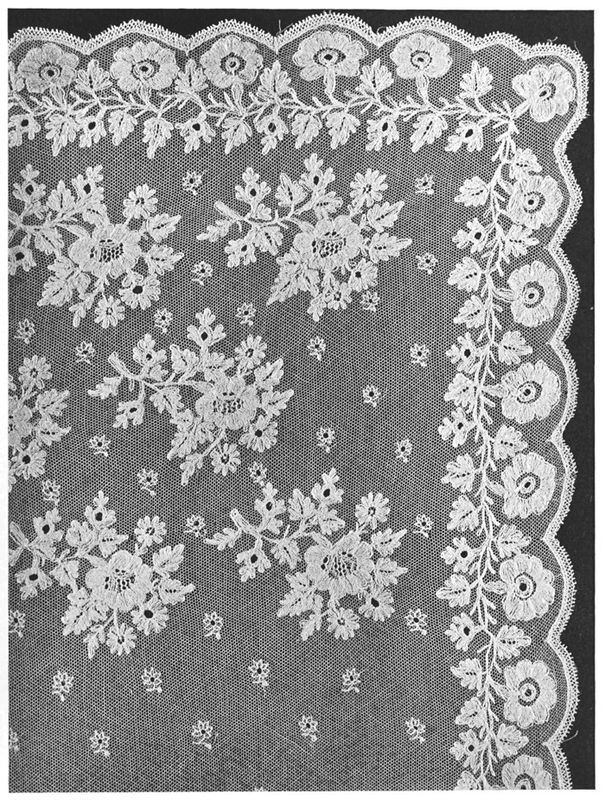

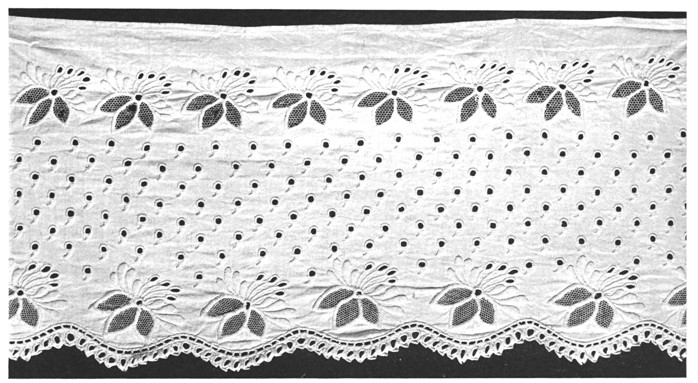

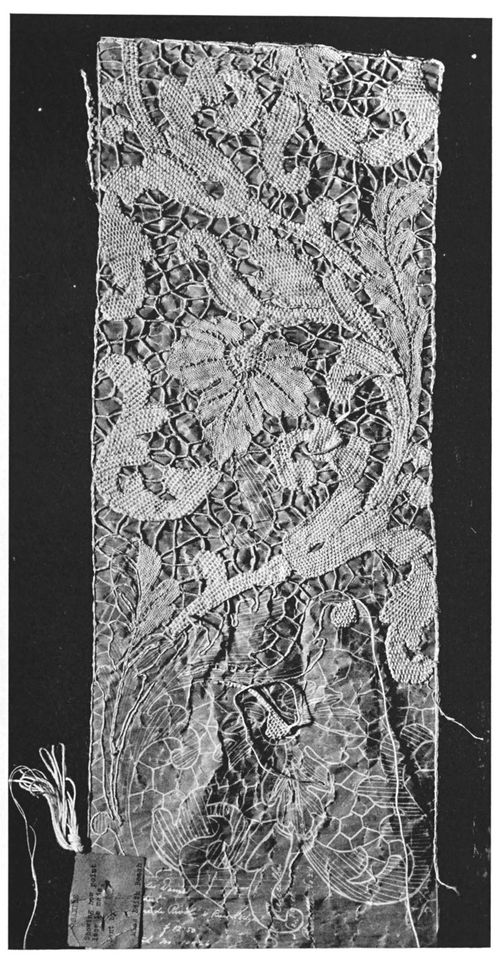

| 59. Lace flounce on dress skirt | Charlotte Webster (Mrs. Charles Sever) | M.F.A. |

| 60. Lace veil | Delia I. Beals | M.F.A. |

| 61. Detail of the same | ||

| 62. Embroidered kerchief | Rachel Leonard | M.F.A. |

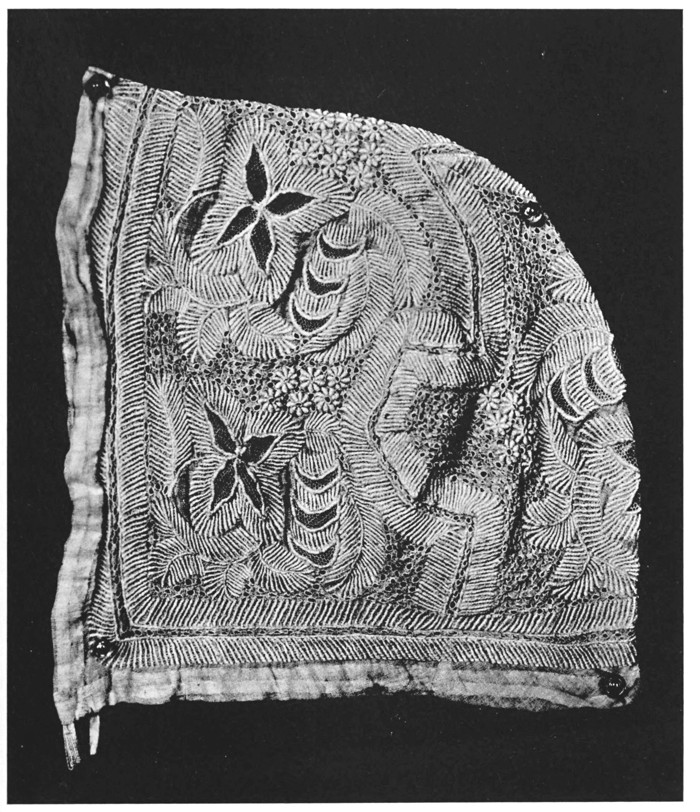

| 63. Infant’s embroidered cap | Unknown | Miss Katherine Egbert |

| 64. Embroidered waistcoat | Unknown | Mr. William S. Eaton |

| 65. Wedding-dress and marriage reception-dress | Catherine Van Houten (Mrs. Ralph Doremus) | Mrs. William Nelson |

| 66. Detail of skirt of wedding-dress in the preceding | ||

| 67. Details of waist of the same | ||

| 68. Wedding veil | Catherine Van Houten (Mrs. Ralph Doremus) | Mrs. William Nelson |

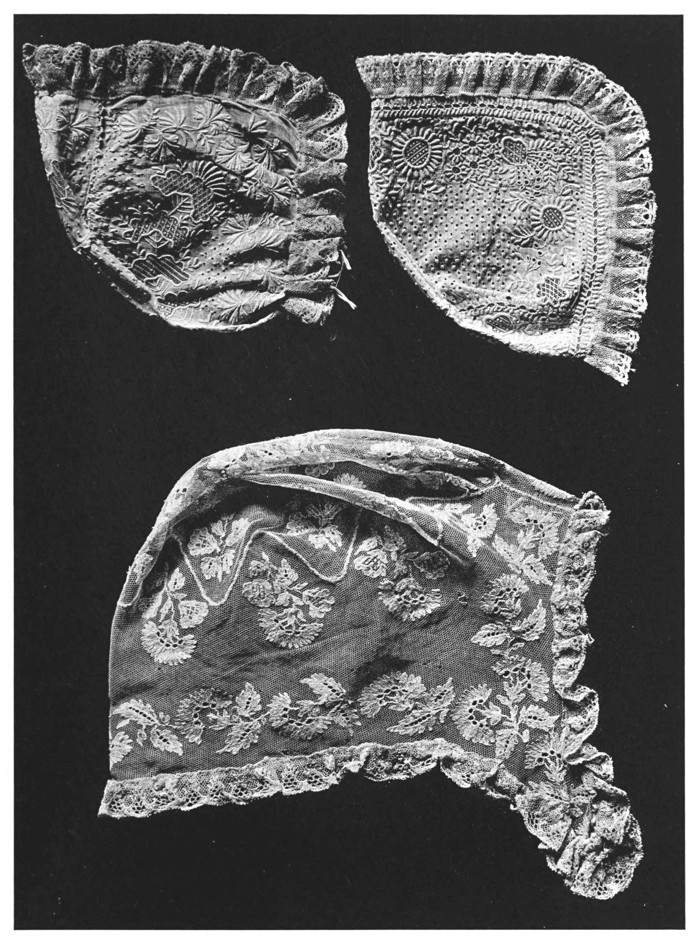

| 69. Lady’s and infant’s cap | Catherine Van Houten (Mrs. Ralph Doremus) | Mrs. William Nelson |

| 70. Collar or cape | Catherine Van Houten (Mrs. Ralph Doremus) | Mrs. William Nelson |

| 71. White lace | Mary Bacon (Mrs. Chauncey Whittlesey) | L.H.S. |

| [xvi]72. Silk net wedding veil | Martha Harness (Mrs. Isaac Darst) | Mrs. G. Glen Gould |

| 73. Embroidered collar | Elizabeth Taylor (Mrs. Andrew Perkins) | L.H.S. |

| 74. (1) Lace cap | Sybil (Bradley) Hotchkiss | Mrs. Samuel H. Street |

| (2) Embroidered collar | Elizabeth, or Betsey, Peck | Mrs. Samuel H. Street |

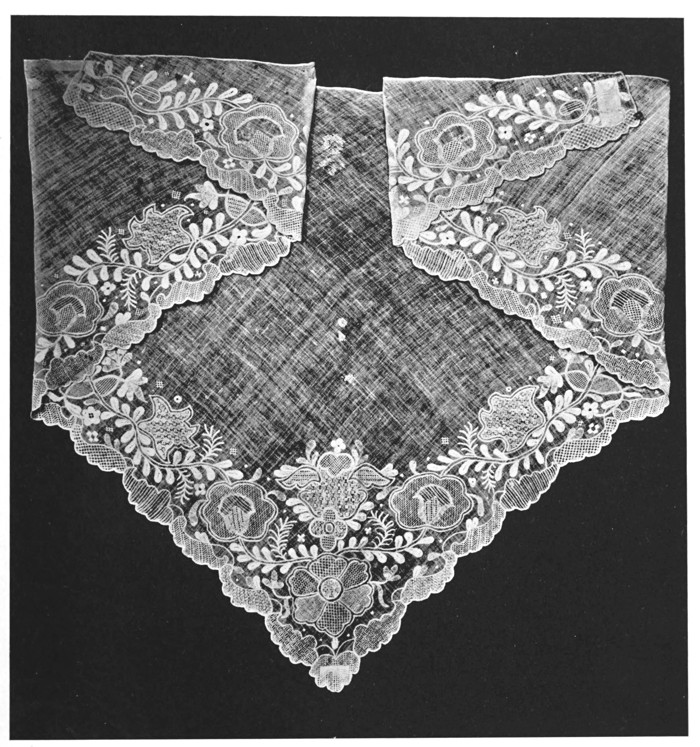

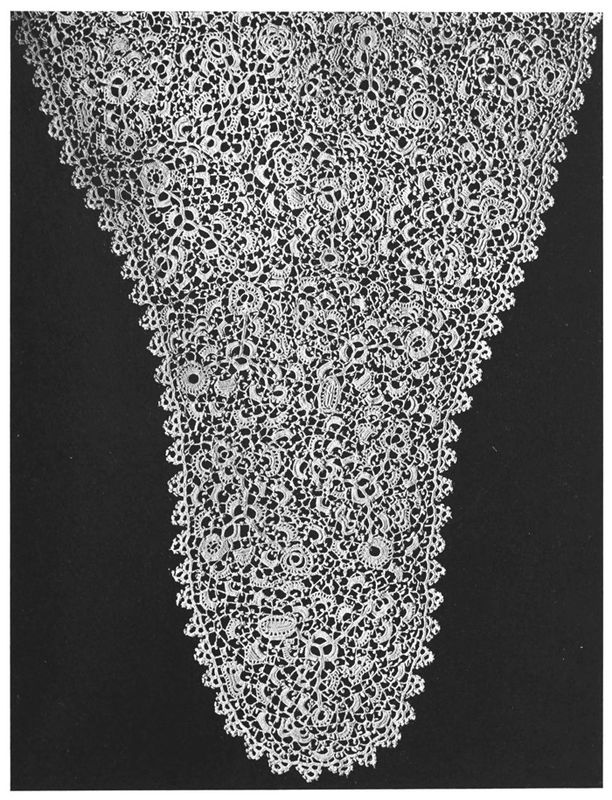

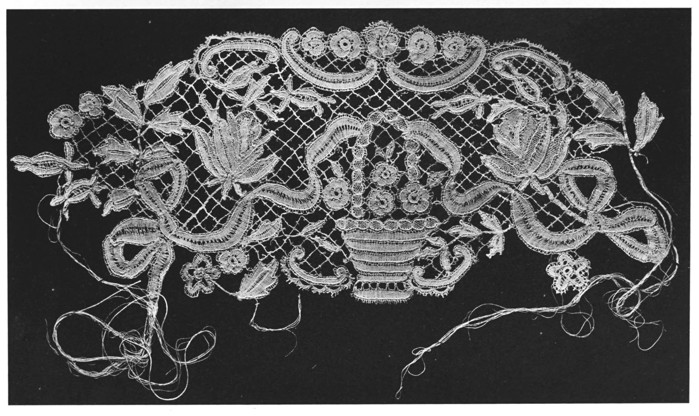

| 75. Fichu of Irish lace | Sarah McCoon Vail (Mrs. George Gould) | L.H.S. |

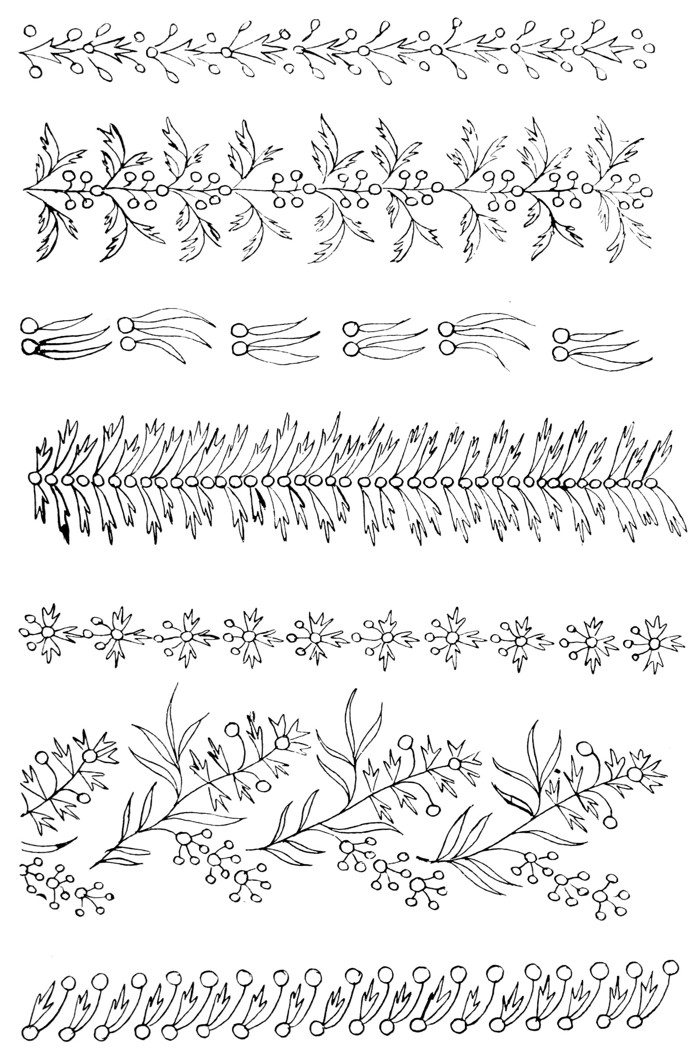

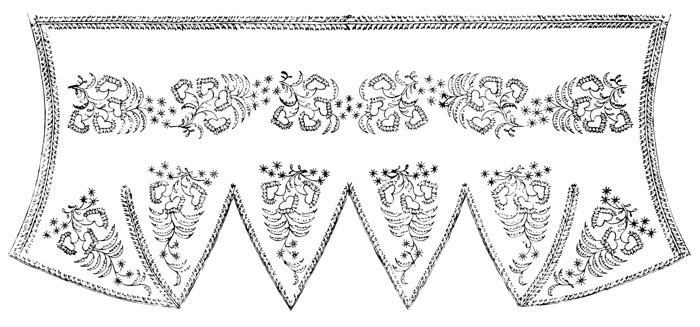

| 76. Patterns for borders | Caroline Canfield (Mrs. William Mackay) | L.H.S. |

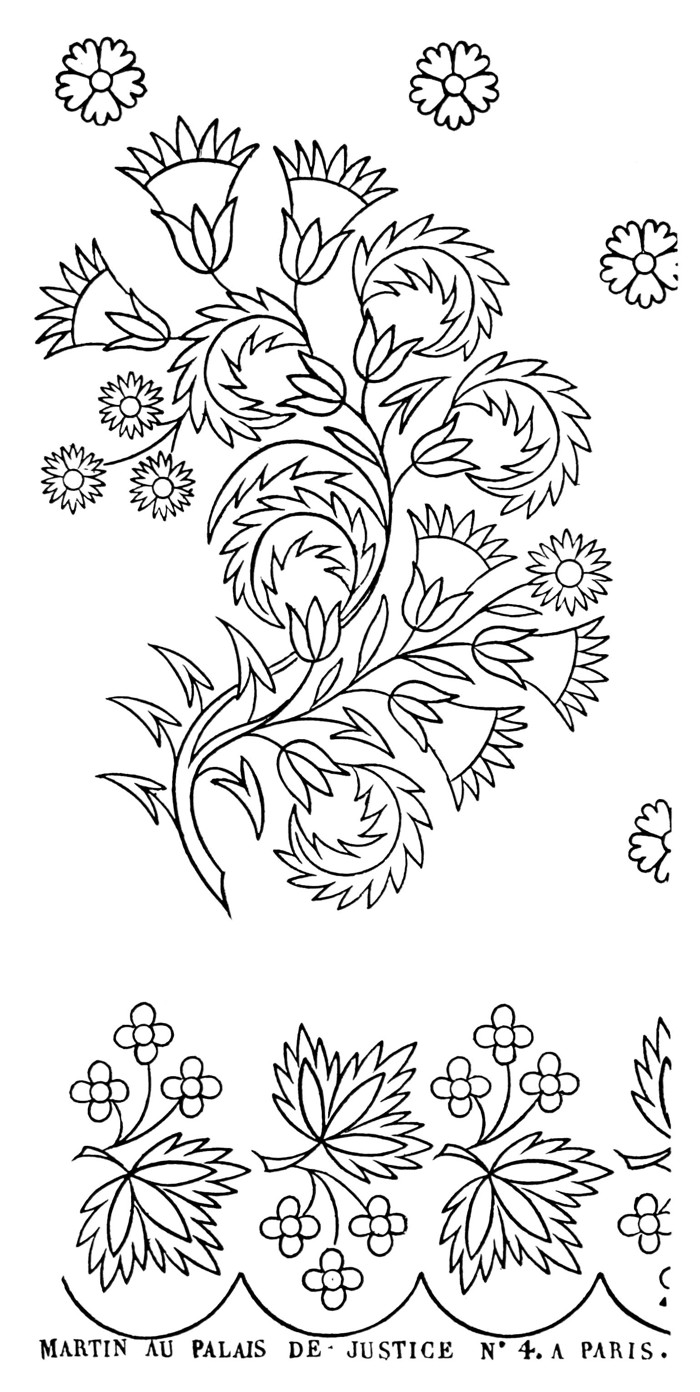

| 77. Design for cap | Caroline Canfield (Mrs. William Mackay) | L.H.S. |

| 78. Copy of design from Paris | Caroline Canfield (Mrs. William Mackay) | L.H.S. |

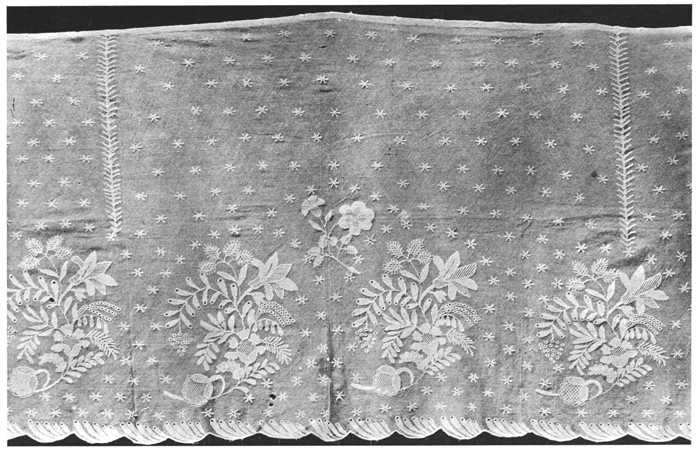

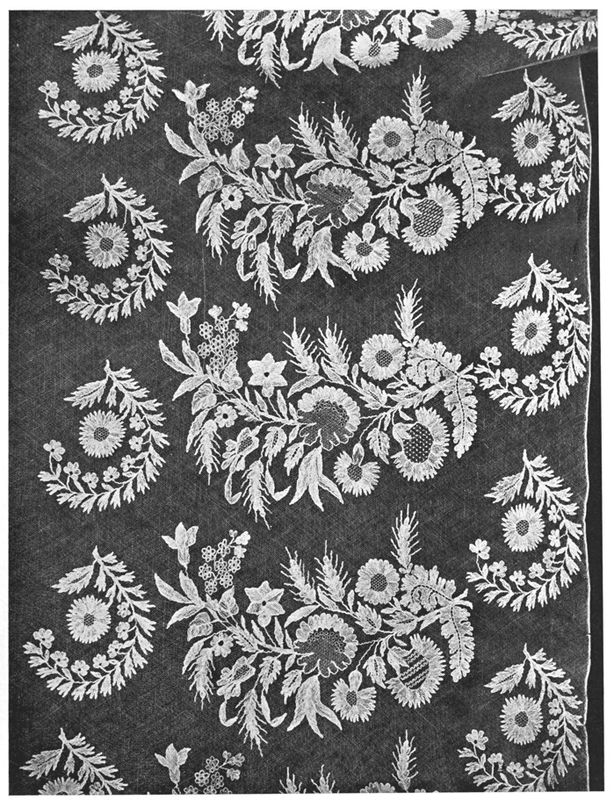

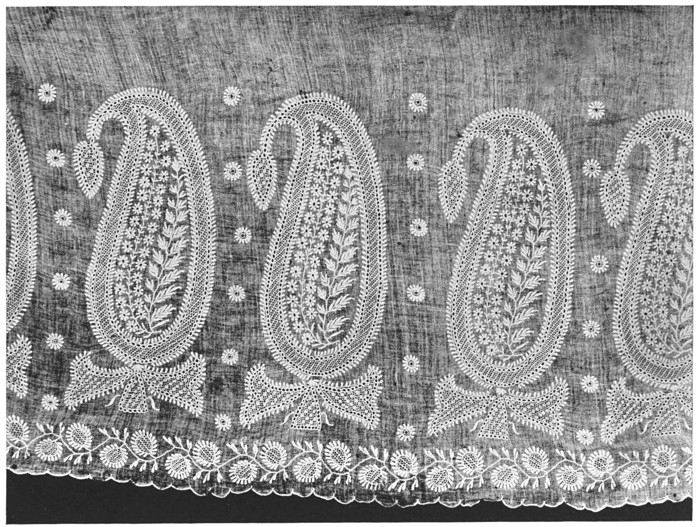

| 79. Ruffle embroidered for wedding petticoat | Caroline Canfield (Mrs. William Mackay) | L.H.S. |

| 80. Design for embroidery | Caroline Canfield (Mrs. William Mackay) | L.H.S. |

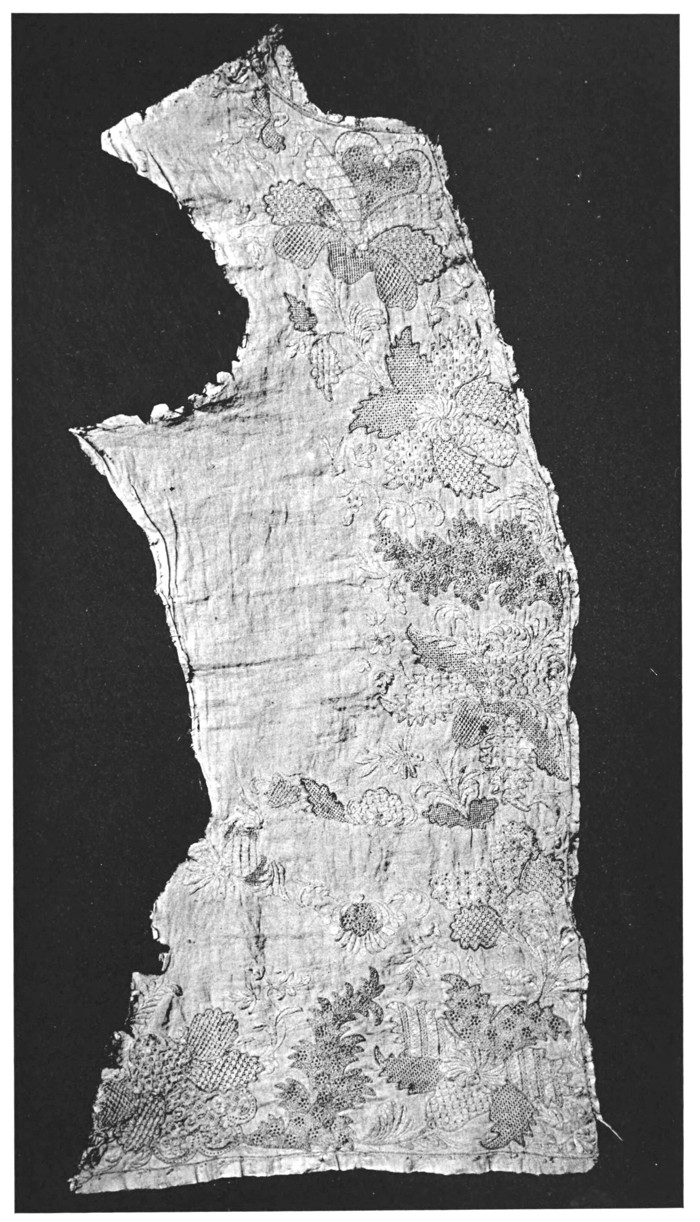

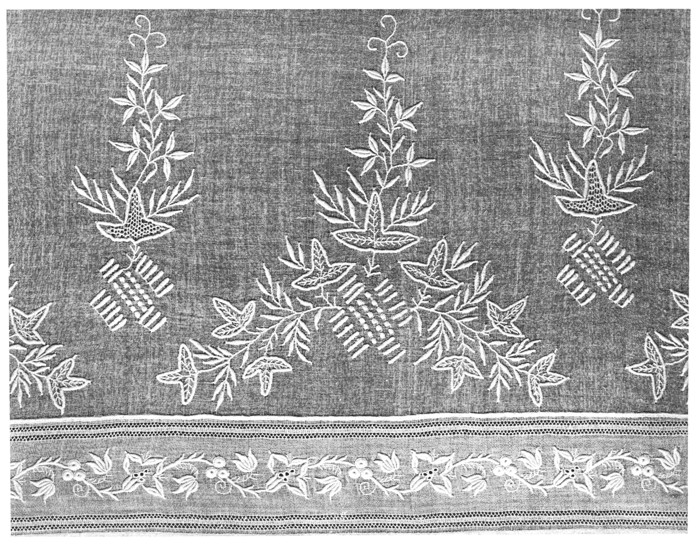

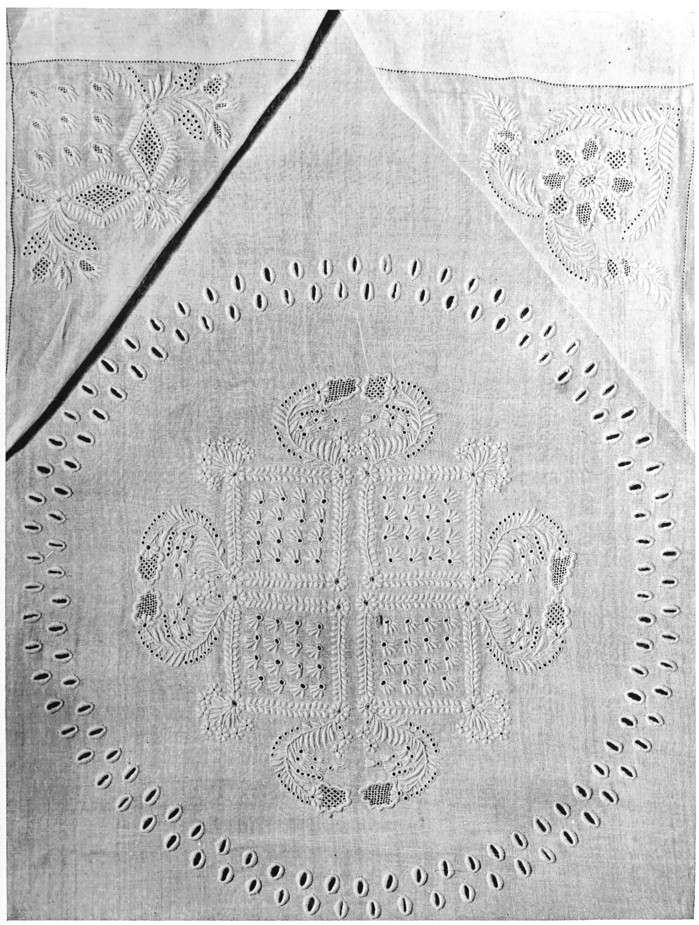

| 81. India mull dress | Design by Caroline Canfield (Mrs. William Mackay) | L.H.S. |

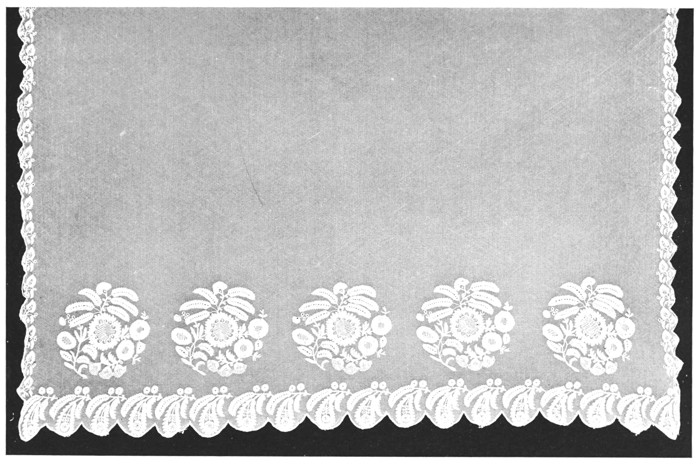

| 82. India mull dress | Ruth Freeman Packard (Mrs. George Trask) | Mrs. Ruth Quincy Powell |

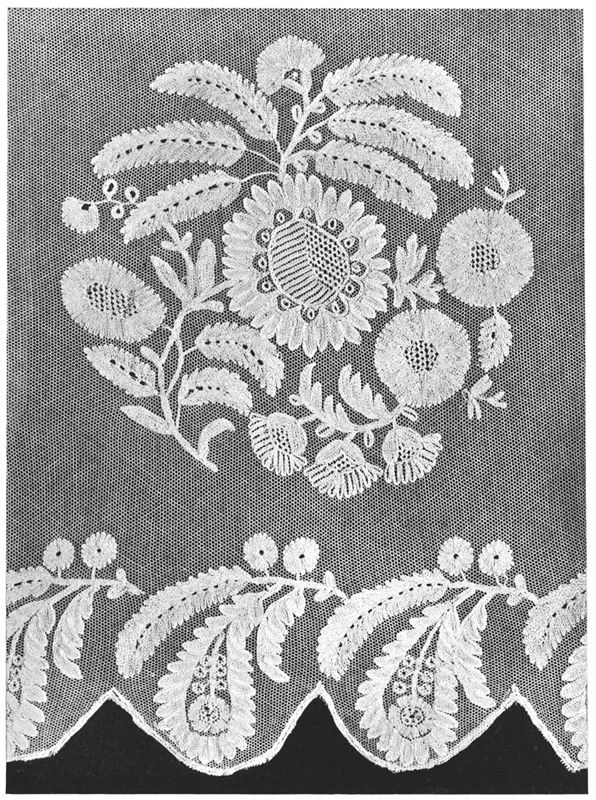

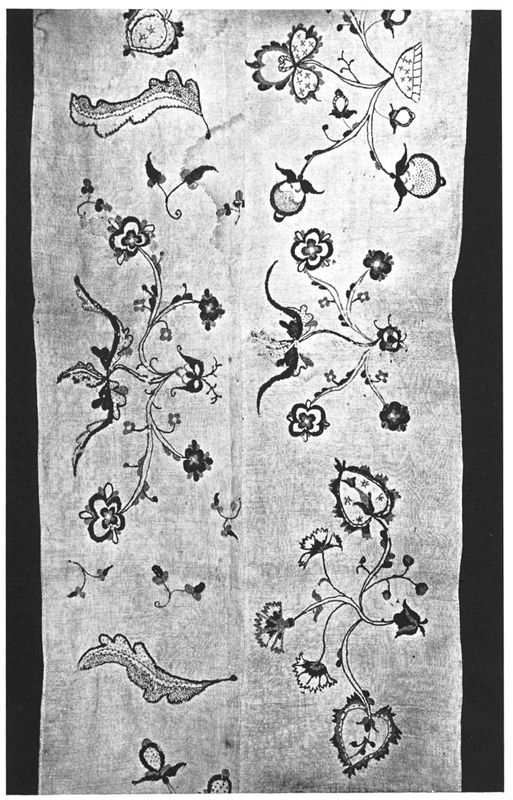

| 83. India mull dress skirt | Louisa Lewis (Mrs. Henry Phelps) | L.H.S. |

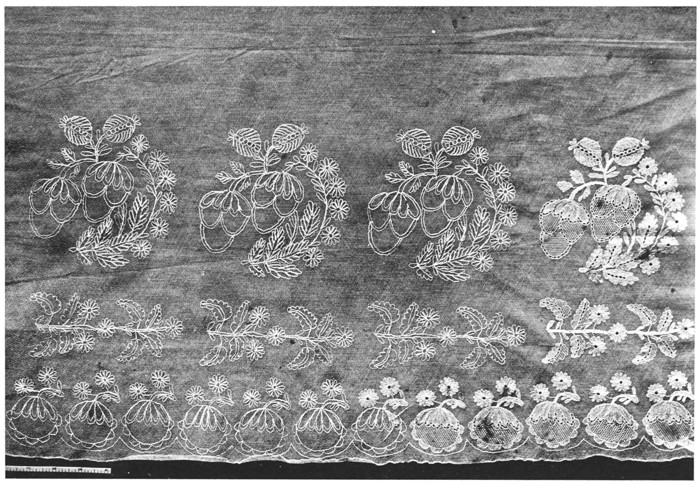

| 84. India mull dress skirt | Louisa Lewis (Mrs. Henry Phelps) | L.H.S. |

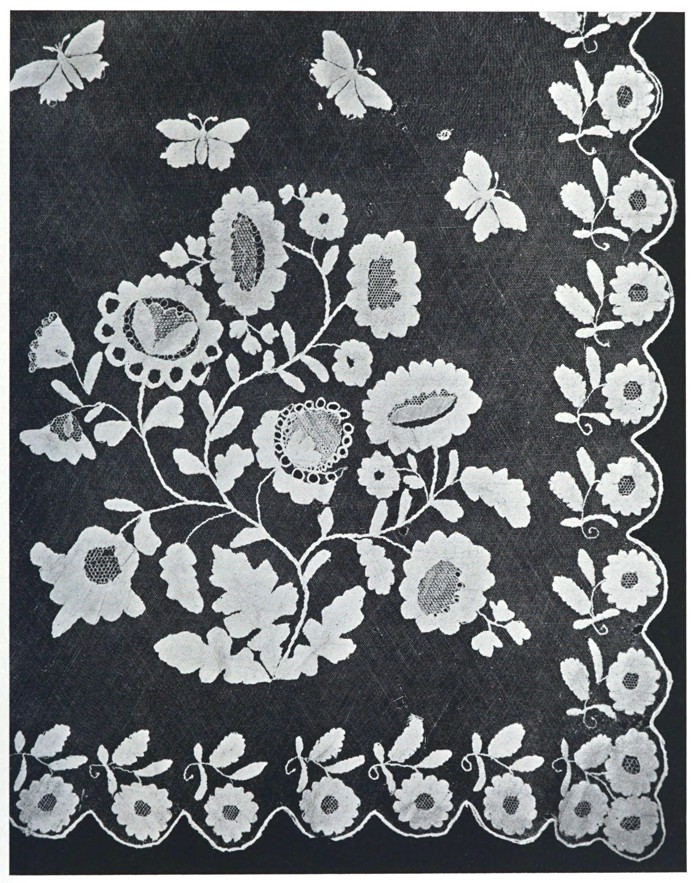

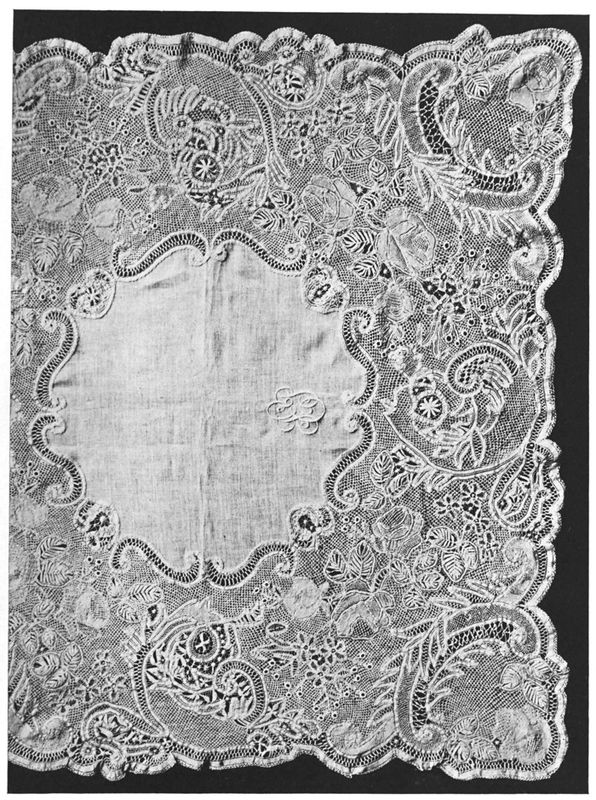

| 85. Handkerchief | Eliza (Brock) Mitchell | Miss Edith Eliot |

| 86. Bed curtains | Polly Cheney | L.H.S. |

| 87. Waist of infant’s dress | Elizabeth W. Davenport | L.H.S. |

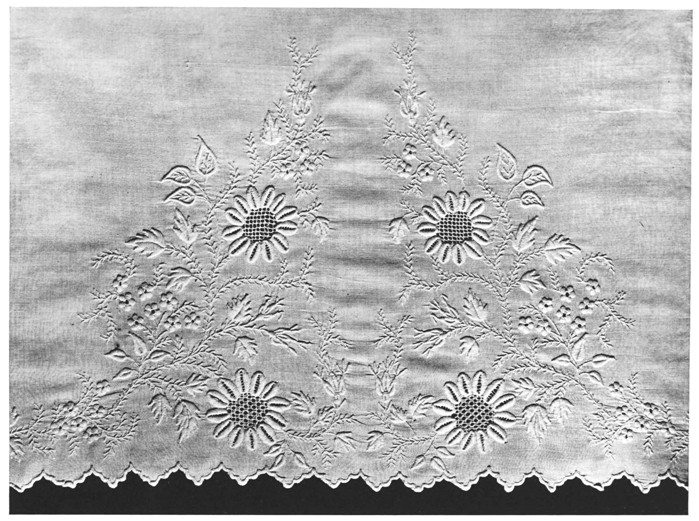

| 88. Front of skirt of the same | ||

| 89. Infant’s dress | Mary W. Peck (Mrs. Edward D. Mansfield) | L.H.S. |

| 90. Six infant’s caps | Mary Ann Laidlaw (Mrs. Henry Buel) | Mrs. Francis H. Blake and Miss Katharine L. Buel |

| 91. (1) Knitted lace | Mrs. Wilson Tingley White | Mrs. Charles William Follett |

| (2) Pillow lace | A California Indian girl | L.H.S. |

| (3) Pillow lace insertion | Probably Sarah Chedsey (Mrs. Samuel Alling) | L.H.S. |

| 92. Black lace scarf | Pamela Parsons | Mrs. Charles B. Curtis |

| 93. Infant’s cap | Isabella Woodbridge Sheldon (Mrs. George Lecky Cornell) | Mrs. Charles B. Curtis |

| 94. Altar cloth of Greek design | Isabel Douglas Curtis (Mrs. Charles B. Curtis) | Christ Church, Rye |

| 95. Detail of the same | ||

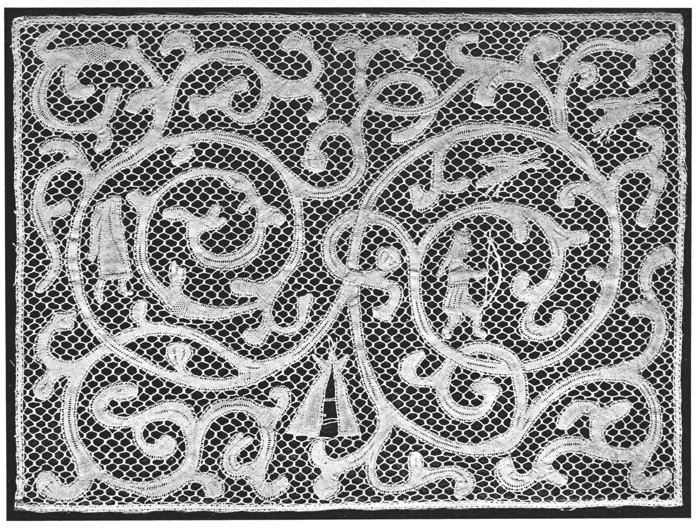

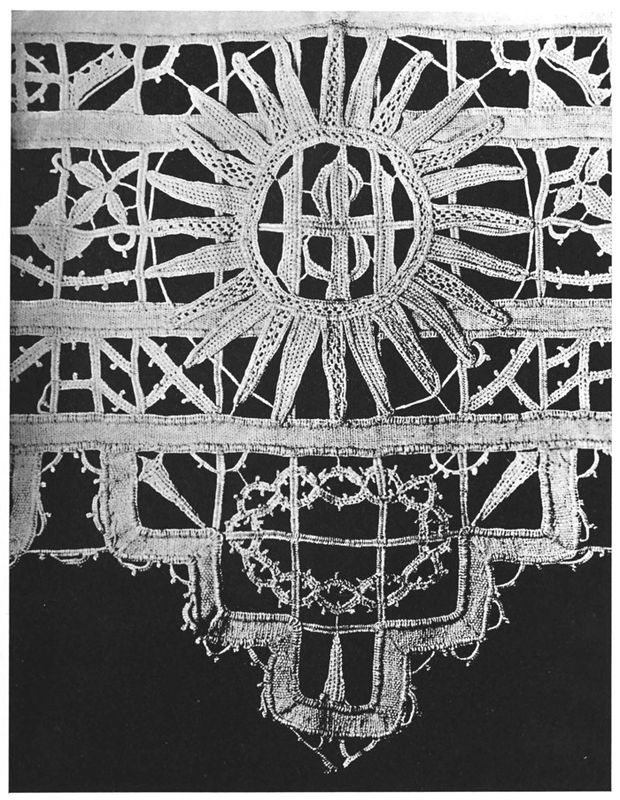

| [xvii]96. Tape lace | Isabel Douglas Curtis (Mrs. Charles B. Curtis) | L.H.S. |

| 97. Tape lace | Rachel Tracy Noyes (Mrs. Charles Edward Whitehead) | L.H.S. |

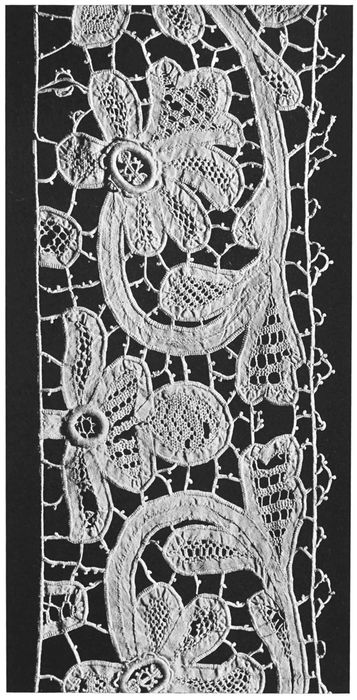

| 98. Tape lace and darned net | Esther Thompson | Miss Esther H. Thompson |

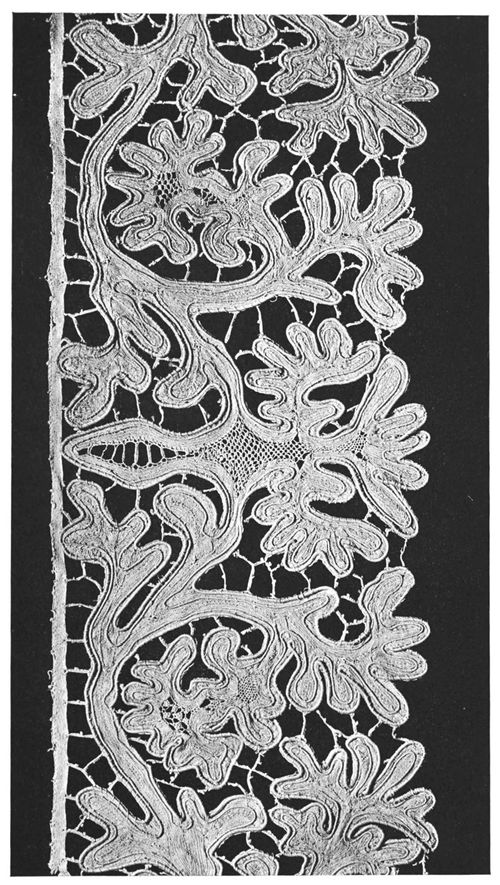

| 99. Tape laces | Mrs. Butterworth | Miss Esther H. Thompson |

| 100. Table cover | Mrs. Hannah MacLaren Shepherd-Wolff | Unknown |

| 101. Filet lace in frame | Sarah Belknap (Mrs. Edward Rowland) | Miss Edith Beach |

| 102. Filet lace | Elsie Belknap (Mrs. R. E. K. Whiting) | Miss Edith Beach |

| 103. Chalice-veil | Margaret Taylor Johnstone | Unknown |

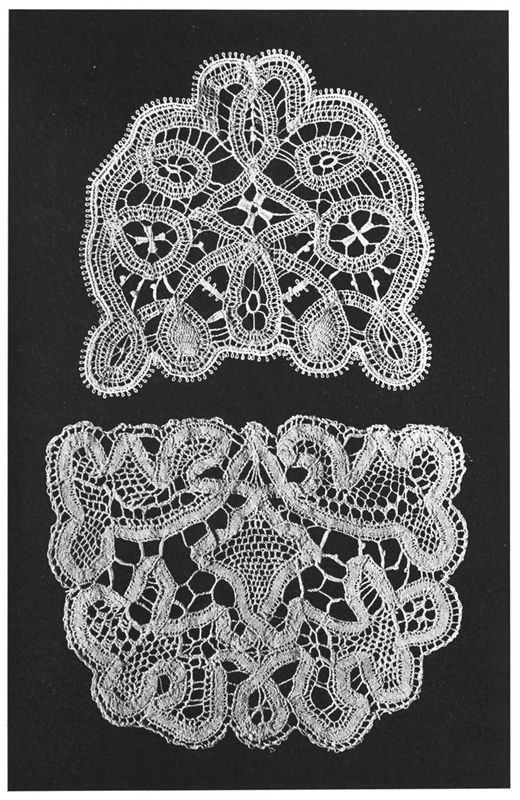

| 104. (1) Pattern and sample of pillow lace | Edith Beach | Miss Edith Beach |

| (2) Bobbin lace made on a pillow | Edith Beach | Miss Edith Beach |

| 105. Pillow lace for a fan | Edith Beach | Miss Edith Beach |

| 106. Venetian point lace and pattern | Edith Beach | Miss Edith Beach |

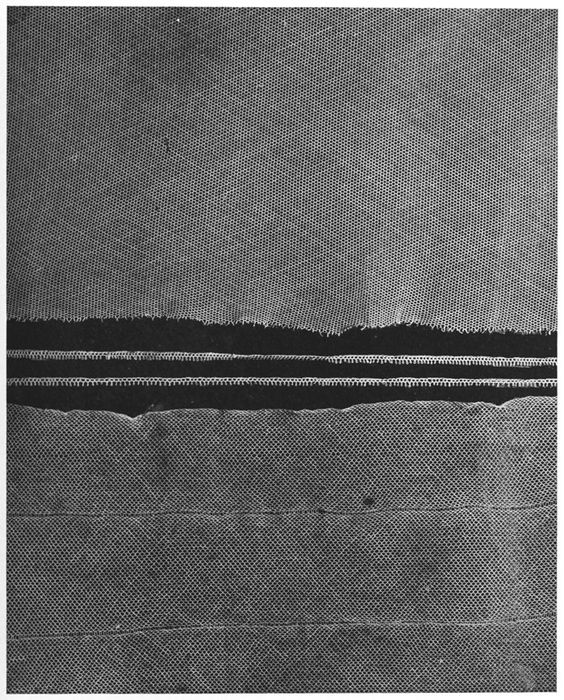

| 107. (1) Machine-made net | Dean Walker | Miss Sophia A. Walker |

| (2) Machine-made net with stitches dropped | Dean Walker | Miss Sophia A. Walker |

| 108. (1) Trimming lace on machine-made net | Clarissa Richardson | Miss Sophia A. Walker |

| (2) Trimming lace on machine-made net | Julia Adams (Mrs. Horatio Mason) | Miss Sophia A. Walker |

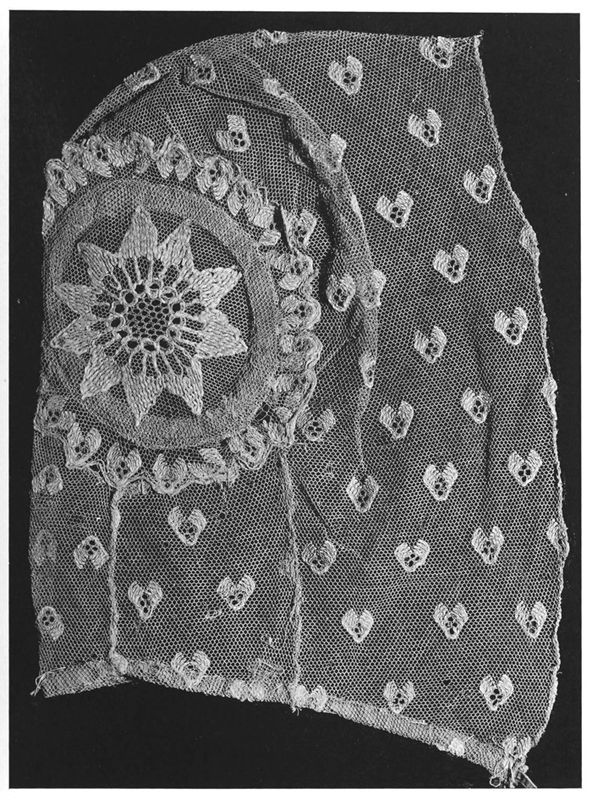

| 109. Cap embroidered on machine-made net | Julia Adams (Mrs. Horatio Mason) | Miss Sophia A. Walker |

| 110. Medal awarded to Dean Walker | William T. Walker |

[xix]

Grateful acknowledgment is due all those who have contributed the fine material from which the plates for this book have been made. They have been most generous in giving and in lending the laces and embroideries and in furnishing facts and details as to the making of them. There is a wealth of material in the country which we are not able to show for want of space. We desire to express our gratitude to the following contributors:

Miss Edith Beach,

Miss Marian Powys,

Miss Esther H. Thompson,

Miss Sarah E. Lakeman,

Miss Helena Knox,

Miss Marianna Townsend,

Miss Clara Ray,

Miss Natalie Lincoln,

Miss Edith Eliot,

Miss Emily Wheeler,

Miss Frances Morris,

The Misses Alice and Edith Kingsbury,

Mrs. Charles B. Curtis,

Mrs. Lewis Marsh,

Mrs. Guy Antrobus (Mary Symonds),

Mrs. William Nelson,

Mrs. Edward W. Preston,

Mrs. Ruth Quincy Powell,

Mrs. Samuel H. Street,

Mrs. Charles W. Follett,

Mrs. Francis H. Blake,

Miss Sophia A. Walker,

Miss Margaret Taylor Johnstone,

Sybil Carter Indian Lace Association, New York City,

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City,

American Museum of Natural History, New York City,

New York Public Library,

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,

Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts,

Litchfield Historical Society, Litchfield, Connecticut.

The few books that have contributed their share to the work deserve mention. They may be consulted by those who wish more data as to the making of lace in general and as to the dates and details of the invention of machine-made lace, the importation into the United States of the machinery with which to make it, and the consequent excitement in both England and New England.

Fine Thread, Lace and Hosiery in Ipswich, by Jesse Fewkes; and Ipswich Mills and Factories, by T. Frank Waters. (Proceedings of the Ipswich Historical Society.) The Salem Press Company.

Point and Pillow Lace, by Mary Sharp. Dutton.

[xx]

Development of Embroidery in America, by Candace Thurber Wheeler. Harper.

Practical Book of Early American Arts and Crafts, by Harold Donaldson Eberlein and Abbott McClure; with a chapter on early lace by Mabel Foster Bainbridge. Lippincott.

Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition. Article on Lace.

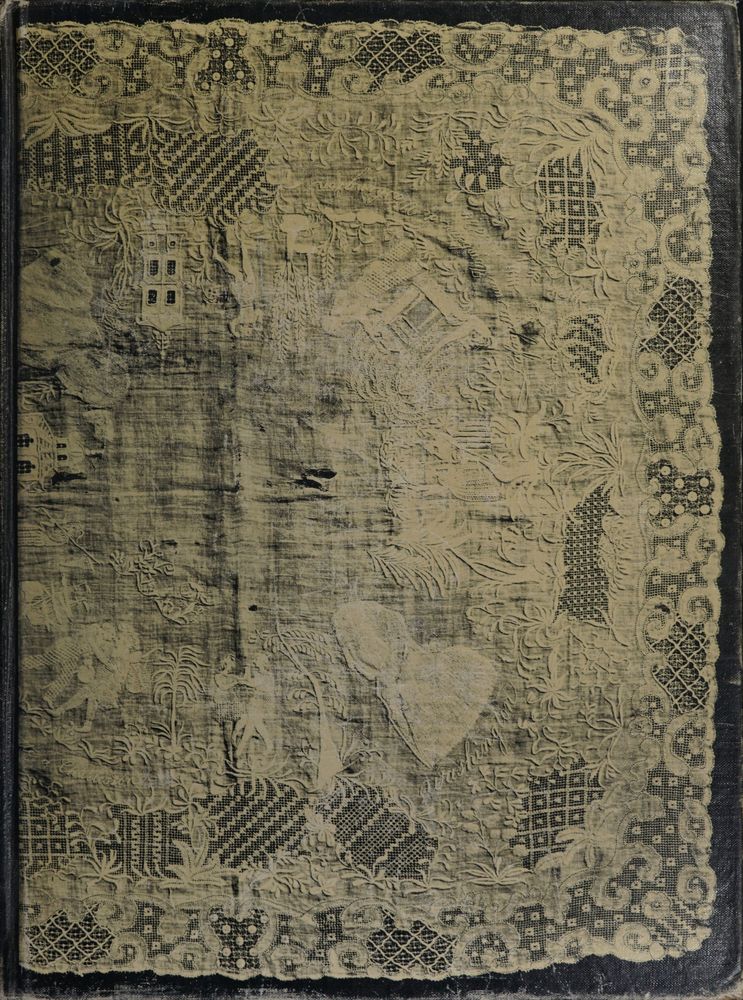

Too late for inclusion in the body of this volume, there came to the author the exquisite Washington-Lafayette handkerchief which has been photographically reproduced as a design for the binding. The original was worked in New Orleans by a French lady—possibly a Creole, for it is known that the Creoles of that city were remarkably expert with the needle. Its conjectural date is 1825–1830: most of the embroidery of its type was done between 1820 and 1840, and it is wholly probable that the direct impetus of this example was nothing other than Lafayette’s famous triumphal visit of 1824. The original is now owned by the Litchfield Historical Society, of Litchfield, Connecticut.

[1]

AMERICAN LACE AND LACE-MAKERS

As many things can be better understood and appreciated from pictures than from even a glowing description, so the lace made by the deft fingers of many an American woman cannot be portrayed in words, but must be pictured before it can be appreciated. The half-tone process can reproduce it so perfectly by copper and acid that one is almost deceived into believing that the actual fabric lies on the paper. The plates in this book will tell of the patient, persevering, artistic women with whom we are more apt to associate only the drudgery of household work done with the heavy and often clumsy tools of a hundred years ago.

From Point and Pillow Lace , an excellent work by A. M. S. (Mrs. Sharp), published in London, 1899, by John Murray, from which we shall have occasion to quote again, we take the following definition: “The English word Lace is taken from the French ‘Lacis,’ a term, however, which, when properly used, denotes only the Italian work, ‘Punto a maglia,’ or Darned netting. There are two distinct kinds of Hand-made lace: first, Lace made with the needle, that is Needle-point lace, under which heading the above-mentioned Darned netting may be included, and secondly, Lace made on a pillow with bobbins, that is Pillow lace.”

Both of these kinds of lace have been made in America, but a third kind existed there, indigenous to the soil. Few people know of it, but botanists and travellers will testify to the fact. In the island of Jamaica grows the lace-bark tree, botanically named Lagetta lintearia. It has an outer bark. Strip that off and you will find an inner bark consisting of fold after fold of lace, white in color, delicate but strong in texture, looking much like fine net but with a different mesh. It can be used with dress goods and for small mats. It is even strong enough, when tightly twisted, for the lash of a whip. This lace must have been growing in America long before the white man ever set foot on these shores.

On investigation we find that in Peru, South America, the first American hand-made lace extant was found. The more we study the civilization of Peru the higher it appears. Many wonderful things have been dug out of the old tombs. Peruvian craftsmanship is particularly shown by its textiles, of which the Museum of Natural History in New York City has a large collection. It is affirmed there that no finer thread has ever been spun in the world than that of which an especially delicate piece of Peruvian weaving is made. The designs of these textiles are primitive but beautiful, and the colors are not surpassed for their quality and harmony by those of any other country, though they are thousands of years old.

[2]

When we turn, then, to the Indians of the West, North, and South, careful observation shows that the Papagos of lower California, the Hopis, and the Balientis made laces. These Indian laces, generally made of vegetable fiber, are original and ornamental. They, too, are to be found in the Museum of Natural History in New York City.

We are fortunate in being able to give illustrations of these early laces. We do not know the technique of their making, but they must belong to the pillow and bobbin type, even if some kind of frame was used to weave them over, instead of a pillow. Some of them resemble the “punto a groppo,” or knotted lace, made early in Italy and revived not long ago in what is called macramé, much of which has been made of heavy linen or cotton thread.

In this connection it is interesting to find that Indians are apt pupils in lace-making. Trying to find some way of helping the North American Indians, Miss Sybil Carter went to Italy and learned the Italian methods of lace and cut-work making. She had a true missionary spirit, and on carrying this industry to the Indians, as she did quite successfully, she obtained results beyond her hopes. The work even led to many improvements in the Indians’ way of living, such as cleanliness, better clothing, and more comfortable homes. The agent for this work has a shop in Park Avenue, New York City, and finds a good market for it. Samples of the work have kindly been lent for illustration.

Coming now to the subject of lace among the first white settlers in America, it is quite evident from portraits and from the remains of garments worn by them that some of them brought to this country not only good but rich and dainty clothes. The sumptuary laws, passed early in colonial times against excessive ornament worn by either men or women, give proof of this and correct the assumption that the appearance of our ancestors was either severe or commonplace. It is amusing to read these laws as well as the accounts of the clothes worn on special occasions by people who actually lived in simple huts. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston contains a suit worn on training days by the first governor of Massachusetts, made of gay and superb brocade; and nothing could be richer in men’s clothing than another suit, also in the same museum, consisting of knee breeches, coat of purple velvet, and white satin waistcoat, all three largely covered with the richest embroidery. It was made to be worn by the governor when he went as ambassador to the Court of Spain, and it is still in perfect condition.

Letters of the time speak of the use of lace. We must infer, then, that women who had learned in England to make a delicate trimming for clothing would be in demand in the colonies, both to practice and to teach the art. Although very little is known of this early lace-making, it is a matter of record that a good deal of lace was made in the town of Ipswich, Massachusetts. We find the following in the old history of that town written by Felt, the earliest record we have:

[3]

Lace: This of thread and silk, was made in large quantities and for a long period by girls and women.

It was formed on a Lap Pillow, which had a piece of parchment wound round it with the particular figure, represented by pins stuck up straight, around which the work was done and the lace wrought.

Black as well as white lace was manufactured of various widths, qualities and pieces. The females of almost every family would pass their leisure hours in such employment.

1790. No less than 41,979 yards were made here annually. After the first lace factory commenced, the pillows and bobbins were soon laid aside.

What of these survive a century hence will be viewed as curious emblems of industry, and mementoes of labor performed in months, which is now done in a factory in a day.

That lace-makers came to this country from the Midland counties of England, such as Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire, we know from the town records as well as from the lace they made—lace which was originally peculiar to those counties. We are told that they were the only lace-makers in the world to use bobbins made of bamboo. The bamboo had undoubtedly come across the sea with the many oriental treasures to be found along the Massachusetts coast. Strict laws were made by the colonists obliging a certain number to spin, to take care of sheep, and to save the seed of flax and hemp.

Children were taught when very young the principles of lace-making, so that by twelve years of age they were able to earn their living by that means. We read that Bishop Alexander V. Griswold, one of the first Episcopal bishops in this country, could and did, at five years of age, make “bone lace,” a quaint term for pillow lace. The name of “bone lace” was given because bobbins were made of chicken bones. All the young people were trained thus early in habits of constant industry.

Little of this lace seems to be in existence, but enough remains to prove that in the North lace and lace-making came from England. As the Spaniards were early lace-makers, presumably the art may also have come into North America through the Spanish settlers in Mexico, and so on through New Orleans and the Southern States; but it is not so easy to trace as that by the way of Massachusetts. Happily, a pillow and bobbins used there by an early maker of lace, as well as samples of the lace itself, are still to be seen in the town of Ipswich, and have been photographed for our benefit.

The making of pillow lace in Ipswich seems to have come to an end rather suddenly, owing to the appearance of net made by machine. The origin of machine-made net is lost in an obscurity of conflicting authorities. It is known, however, that a workman in a stocking factory in Nottingham, England, about 1760, scrutinized the pillow lace on his wife’s cap and conceived a plan whereby he could copy its foundation net on a stocking frame. The resultant machine was improved upon by several inventors in turn until a good net could be produced. On this net the women [4]worked with darning and tambour stitches—tambour being a sort of chain stitch—until quite an industry sprang up in the country.

This kind of lace acquired the name of Limerick; for, to quote again from Point and Pillow Lace , “The manufacture was transferred to Ireland in the year 1829 by Mr. Charles Walker, who, while studying for Holy Orders, married the daughter of a lace manufacturer, and either moved by philanthropy, or as a speculation, took over to Ireland twenty-four girls to teach the work and settled them in Limerick. It is in reality of French origin, being the same as the ‘Broderies de Luneville’ which have been produced in France since 1800.” It is also found in Spain and Italy. The art has flourished in Limerick to this day, as is shown by Plate 36, photographed from a sample recently imported and sold by Arnold, Constable & Company, of New York City. That the same kind of lace came to this country before it went to Limerick is established by the dates of the making of some of the samples shown in our illustrations.

Grave troubles, extending even to rioting, broke out between the pillow lace-makers and the machine lace-makers, and between those who wanted to come to America and bring their machines with them and those who wished them to stay at home. Details can be found in books named in our Preface. However, the manufacture of net and that of stockings became established at Ipswich and continued simultaneously until lately, when that of the net died out.

While the proofs of this Introduction were being read, some valuable data were brought to the author’s attention by Miss Sophia A. Walker, who was for many years a teacher of art in New York City. Certain matters of her family history establish the existence of another headquarters for the manufacture of American lace, samples from which are shown in Plates 107–109. Miss Walker says:

“It surprised one reader of Mrs. Candace Wheeler’s book on embroidery to be informed that it is not known how the lace industry came into this country—possibly, it was thought, through the French settlements of Canada, perhaps through Mexico and New Orleans—for she had supposed that everybody knew what she had known from childhood: that bobbins, net, footing, and cards full of beading, or purling, were made by her grandfather, Dean Walker; also that a cap of this net, with a two-and-a-half-inch edge, was embroidered for herself by Julia Adams, wife of Horatio Mason, her maternal grandfather! So she gives here the true story of the rise—and fall—of the lace industry at Medway, Massachusetts, on the upper reaches of the Charles River, as told in the reminiscences of her father, Rev. Horace Dean Walker (1815–1885), and of her mother, Mercy Adams Mason Walker (1823–1923), supplemented by Orion Mason, the town historian, who has kindly furnished dates and facts.

“Dean Walker, a man of immense energy, made machinery on the Medway. He was also associated there with his father, Comfort Walker, in cotton and grist mills [5]founded in 1818 (the year in which the Stars and Stripes became the national flag) and in other enterprises.

“Among these was the making of ‘coach lace,’ a fine gimp from three to five inches wide, used to trim hacks and coaches. Two Englishmen, brothers named Bestrick, a machinist and a weaver, were in their employ. These two talked so much about the lace machines of the old country that Dean Walker agreed to support their families while they built such a machine, after which he and they were to manufacture in partnership. They made a machine of 1260 shuttles, which people came leagues to see. Dean Walker himself was inventor of a sewing machine; a patent for car wheels, signed by Andrew Jackson, was in the family archives; and he received from the Franklin Institute of the State of Pennsylvania the award of a silver medal [still preserved by the family; see Plate 110] for his lace. It is, then, reasonable to infer that his wit as well as his purse helped in the making of that machine.

“The net was woven and the decoration of it taught in a stone building which he erected, and which is still standing in Hillside Court. It is known as the Lace Shop, though occupied as a dwelling-house by a Polish family. The net was carried about to neighboring farms and villages to be embroidered. Only last summer my mother told me with what zest her mother and her aunt would hasten the morning’s household routine so that they might sit down to those fascinating embroidery frames. One cannot but feel that her gracious ways, refinement, and feeling for beauty, continuing through a life of more than a hundred years, were nurtured by the atmosphere of that lovely home industry.

“We know that James Bestrick came to Medway in 1823. He moved away in 1830. When the tariff was removed, the infant industry died an untimely death.”

We learn that Limerick lace had a great vogue in parts of the United States from about 1810 to 1840. It would seem that the wearing of the poke bonnet dictated by fashion about that time must have greatly encouraged the making of the large veils which every woman wanted to have hanging from her hat and down her side. They were seemingly made everywhere, in city, in country, even in remote farmhouses. It is said that Miss Porter of the famous Farmington School wore one as long as she lived, “because,” she said, “it is so convenient to use if you have any occasion to blush.”

In the early schools for girls more attention seems to have been given to instruction in needlework, lace-making, and embroidery than to anything else except manners and deportment. Before the Revolution a boarding school was kept in Philadelphia, in Second Street near Walnut, by a Mrs. Sarah Wilson, who advertised thus:

Young ladies may be educated in a genteel manner, and pains taken to teach them in regard to their behaviour, on reasonable terms. They may be taught all sorts of fine needlework, viz., working on catgut or flowering muslin, sattin stitch, quince stitch, tent stitch, crossstitch, [6]open work, tambour, embroidering curtains or chairs, writing and cyphering. Likewise waxwork in all its several branches, never as yet particularly taught here; also how to take profiles in wax, to make wax flowers and fruits and pin-baskets.

We also quote the following from Diary of a Boston School Girl , by Alice Morse Earle (page 105):

Madam Smith was evidently Anna’s teacher in sewing. The duties pertaining to a sewing school were, in those days, no light matter. From an advertisement of one I learn that there were taught at these schools:

“All kinds of Needleworks, viz: point, Brussels, Dresden, Gold, Silver and Silk Embroidery of every kind. Tambour, Feather, India and Darning, Spriggins with a Variety of Open-work to each. Tapestry plain, lined and drawn. Catgut, black and white, with a number of beautiful Stitches. Diaper and Plain Darnings. French Quiltings, Knitting, Various Sorts of markings with the Embellishments of Royal cross, Plain cross, Queen, Irish and Tent Stitches.”

In Chronicles of a Pioneer School , by E. N. Vanderpoel, Mrs. Phebe Augustus Ely Avery writes thus of her aunt:

I can tell you little that can be of use to you of my Aunt Caroline [Ely]. I know that she had a school for young ladies and taught painting, embroidery, working lace, etc. but she married before my remembrance Mr. Joel Steele and went to Bloomfield, N. J., to reside, and I saw her but seldom until the latter part of her life.

She lived to be ninety years of age and retained her love for embroidery and various kinds of fancy work, almost to the last; doing beautiful work, when nearly, or quite eighty.

She was a great reader and well posted always on past and current events.

A careful examination of the laces and embroideries done by our forebears proves them to have been not only artists—for many drew their own designs—but also most careful and conscientious craftswomen. Do we wonder at it when we consider the way in which they were brought up? To give some idea of their training, we will quote from diaries of pupils of Miss Sarah Pierce in the Litchfield Academy, Litchfield, Connecticut, from 1792 to 1833. Bear in mind that this academy was not like the boarding schools of today. There was no dormitory. The girls were boarded in the homes of Litchfield families. At the same time the town was full of young men students attending Judge Reeve’s law school, the first founded in the United States. These young men were also boarded in homes. Henry Ward Beecher writes in his Life : “Equally marked was Litchfield at that day for its social and moral as for its natural advantages. The law school of Judges Reeve and Gould, and the young ladies’ school of the Misses Pierce, made it an educational center scarcely second in the breadth of its influence to any in the land, and attracted a class of residents of high social position.”

Lucy Sheldon, born in Litchfield in 1788, daughter of Dr. Daniel Sheldon, a well-known Connecticut physician, writes thus in her diary at the age of fourteen:

Monday. This day Miss Pierce began her school I attended, resolving to renew my former studies with greater assiduity than ever, and shall endeavor to improve enough to merit the [7]approbation of my Parents and instructress, Painted on my picture of the hop gatherers, and read grammar.... Friday, Painted and read, Heard Miss Pierce tell our faults, had the pleasure to hear her say she had seen no fault in me for the week past.... Saturday, Painted and read in the explanation of the Catechism.... Sunday; In the afternoon read in Baron Haller’s letters to his daughter ... attended meeting.... Tuesday; Rose at sunrise, attended school, learnt a grammar lesson, & wrote my Journal, In the afternoon painted and spelt.

Saturday, [Miss Pierce] read a sermon from Blair particularly addressed to young people which recommended the necessity of being pious & industrious.... Have done nothing for these two or three weeks past worth notice except, having read through pilgrim’s progress, which I admire very much, and Lord Chesterfield’s Letters to his Son and think it would be well for every young Lady to read it....

Sunday. Did not attend meeting on account of the weather, In the evening read in Don Quixote and am pleased with his factious humor and Sancho’s credulous disposition. Sunday. Read ten chapters in the Bible, attended meeting all day, & heard two very good sermons, read twenty chapters in the Bible after meeting, Monday. Began to write the history of Rome.... Thursday. Attended a private school ball. Saturday. Copied history, recited geography, and heard our faults told ... have had the honor of being chosen candidate for the prize, In the afternoon copied plays for Miss Pierce, In the evening read. Monday. Had the pleasure of finding Miss —— at our house, assisted in getting tea, & spent the evening very agreeably.

Tuesday. In the evening copied my part of Ruth [a play written by Miss Pierce for her pupils to act]....

Thursday. Rehearsed my part, drew on my map & wrote. Friday, was fast, attended meeting all day, Thought Mr. Huntington preached better than I had ever heard him before. Saturday. Drew on my map and rehearsed my part, heard the young ladies say their plays.

1803. Saturday, Feb. 4th.... Heard Miss Pierce read us a piece on discretion from the Spectator which I admired very much, In the afternoon sewed.

Wednesday 8th.... I took a music lesson.

Saturday 11th. Wrote and did some plain sewing in the afternoon mended, In the evening read twelve Chapters in the Bible.

Saturday 26th. Came to school, took a music lesson, and returned home again, for the past week I have studied three geography lessons and two grammar lessons, have attended ciphering one evening, having been sick, the greater part of the week, spent the remainder of the day in doing nothing we had this week, studied Egypt, etc. I have heard the history read twice this week.

Saturday 12th.... sewed, read 35 pages in Homer’s Iliad.

Saturday, 19th, Have studied for the week past two geography lessons, painted and made a frock, been to ciphering three evenings, I have studied the Latitude of every kingdom, and island in the world.

Saturday 26th.... spent as usual in studying geography, hearing the history & painting ... have studied the boundaries of the seas & description of the New England States etc., Miss Pierce gave me 9 credit marks for my frock....

Lucy Sheldon married Theron Beach, and continued to live in her father’s house to the age of one hundred years. Her water-color of the Hop Pickers hangs there still.

Diary of Mary Bacon, of Roxbury, Connecticut, in the fifteenth year of her age:

[8]

I left Roxbury at eleven o’clock Thursday June 10 1802, accompanied by my Father after riding about ten miles we stopped at Mr. Mosely about three o’clock where we refreshed ourselves and mounted our horses about four ... saw many beautiful meadows and the little birds warbling sweet notes ... we reach’d Litchfield about Six o’clock. Papa got me into Board at Mr. Andrew Adams’s.

Monday, June 4. arose about half past five took a walk with Miss Adams to Mr. Smith’s to speak for an embroidery frame after breakfast went to school heard the young Ladies read history studied a Geography lesson and recited it. Afternoon I read and spelt, after my return home my employment was writing and studying I spent the evening with Mrs. Adams....

Sunday June 27th Mrs. Adams in the afternoon read in Moral Entertainments which were excellent. After meeting read in the book called female education....

Thursday July 1 ... took a lesson in music, returned to Mr. Adams, pricked off 2 or three tunes....

Wednesday July 7 had the pleasure of attending independence ball....

Saturday July the 10 ... in the Afternoon went to Parson Champion’s with the young Ladies to quilting....

July 14th Arose at four wrote two Letters....

Wednesday July 21st Arose at half past four O’clock took a lesson in music at five in the morning.

July 27th ... heard Mrs. Adams good advice....

Wednesday.... Miss Pierce drew my landscape....

Friday August 27th ... school was dismissed at four went to dansing school....

Friday Sept 3rd ... got me a white vail....

Thursday September 9th 1802 ... spent the Rest of The Day in writing my Gurnal Spent The Eavening in Picking wool....

Tuesday September 14 1802.... I Neglected my Gurnal Ever Since I received my Piano Fort the 9 of October [September?].

From Caroline Chester’s diary, 1815 (she was fifteen years old):

Dec. 19th It is one of Miss Pierce’s rules to have her scholars rise before sunrise and Dr. Swift observes “that he never knew any man to come to greatness and eminence who lay in bed of a morning.” Czar Peter, a famous philosopher, used to rise to see the morning break, and used to say that he wondered how a man could be so stupid as not to rise to see the most glorious sight in the universe; that they took delight in looking at a beautiful picture, the trifling work of a mortal, but neglected one painted by the hand of the Deity.

Miss Pierce formulated a set of rules for her pupils, copies of which, belonging to several of them, are still extant. These rules, made in 1825, show Miss Pierce to have felt that all actions, small and great, should be controlled by the highest principles. From a copy made by Sarah Kingsbury, of Waterbury, we take the following:

(1) You are expected to rise early and be drest neatly, to exercise before breakfast and to retire to rest when the family in which you reside desire you to and you must consider it a breach of politeness if you are requested a second time to rise in the morning or retire in the evening.

(2) You are requested not only to exercise in the morning but also in the evening sufficiently for the preservation of health.

[9]

(3) It is expected that you never detain the family by unnecessary delay either at meals or family prayers; to be absent when grace is asked at table and when the family have assembled to read the word of God and to solicit His favour discovers a want of reverence to His holy name, a cold and insensible heart which feels no gratitude for the innumerable benefits received daily from his hand.

(4) It is expected as rational and immortal beings that you read a portion of the scripture both morning and evening with meditation and prayer, that you never read the word of God lightly or make use of any scriptural phrase in a light manner.

(5) It is expected that you attend public worship every Sabbath unless some unavoidable circumstance prevent which you dare to offer as a sufficient apology in the day of Judgment.

(6) Your deportment must be grave and decent while in the house of God and you must remember that all light conduct in a place of worship is offensive to well-bred people and highly displeasing to your Maker and Preserver.

(7) The Sabbath must be kept holy, no part of it wasted in sloth, frivolous conversation or light reading. Remember dear youth that for every hour, but particularly for the hours of the Sabbath you must give an account to God.

(8) Every hour during the week must be fully occupied either in useful employment or rational amusement while out of school; two hours must be employed each day in close study and every hour during the week must be fully occupied.

(9) No person must interrupt their companions either in school or in the hours devoted to study by talking, laughing, or any unnecessary noise.

(10) Those hours devoted to any particular occupation must not be devoted to any other employment. Nothing great can be accomplished without attention to order and regularity.

(11) The truth must be spoken at all times, on all occasions though it might appear advantageous to tell a falsehood.

(12) You must suppress all emotion of anger and discontent. Remembering how many blessings God is continually bestowing upon you for which he requires not only contentment but a cheerful temper.

(13) You are expected to be polite in your manners, neat in your person and room, careful of your books and clothes, attentive to economy in all your expenses.

Under such influences and guided by such principles our American lace-makers grew up. These Litchfield schoolgirls were typical of their class. If we wonder at the quantity and beauty of the lace of a hundred years ago, we must remember how little amusement there was for young people. There were few books and newspapers, no afternoon teas, no bridge, no movies, few theaters, and no matinées; so that a quiet afternoon with time to design and carry to a finish an embroidered collar for one’s best gown, or a lace veil with which to decorate one’s Sunday bonnet, was a great pleasure.

An interesting fact about American lace is that it has been so little commercialized. At Ipswich “Aunt Mollie” Caldwell called once a week at the houses where the pillow lace was made, took it to Boston by stagecoach, and brought back the tea, coffee, sugar, French calico, etc., needed by the makers; but the lace-bark tree grew at its own sweet will in Jamaica, the Indians made their lace for use or adornment when the [10]spirit moved them, and in the intervals of hard household work our young women relieved the pressure by making for their own or a friend’s costume, or for decoration, some dainty bit of lace or embroidery not to be bought in shops. (It has been impossible to refrain from adding samples of embroidery to the lace selected for illustration, as the two have been so much combined.) The same spirit has presided over American lace-making to this day.

An excellent further illustration of the principles in which the American lace-makers of many years ago were trained is to be found in a set of six little manuals for all kinds of needlework, published in New York in 1843:

J. S. Redfield, Clinton Hall, Corner of Nassau and Beekman streets. Publishes, and has for sale, wholesale and retail, the following popular books:

LADIES’ HAND-BOOKS.

A series of hand-books for Ladies, edited by an American Lady—elegantly bound with fancy covers and gilt edges. Imperial 32mo.

No. 1. Baby Linen—Containing Plain and Ample Instructions for the preparation of an Infant’s Wardrobe; with engraved patterns.

“Indispensable to the young wife.”—World of Fashion.

No. 2. Plain Needlework—Containing Clear and Ample Instructions whereby to attain proficiency in every department of this most Useful Employment; with engravings.

“It should be read by every housekeeper, and is highly useful to the single lady.”—Ladies’ Court Circular.

No. 3. Fancy Needlework and Embroidery—Containing Plain and Ample Directions whereby to become a perfect Mistress of those delightful Arts; with engravings.

“The directions are plain and concise, and we can honestly recommend the volume to every reader.”—New La Belle Assemblee.

No. 4. Knitting, Netting, & Crochet—Containing Plain Directions by which to become proficient in those branches of Useful and Ornamental Employment; with engravings.

“A more useful work can hardly be desired.”—Court Gazette.

No. 5. Embroidery on Muslin and Lacework, and Tatting—Containing Plain Directions for the Working of Leaves, Flowers, and other Ornamental Devices; fully illustrated by Engravings.

“It should find its way into every female school.”—Gazette of Education.

No. 6. Millinery and Dressmaking—Containing Plain Instructions for making the most useful Articles of Dress and Attire; with engraved patterns.

“In this age of economy, we are glad to welcome this practical book.”—La Belle Assemblee.

The first volume opens with a rhapsody on the birth of an infant, followed by minute directions for the cutting and making of its little garments. In the next volume, on “The Art of Plain Needlework,” we find an

INTRODUCTION:

To become an expert needle-woman should be an object of ambition to every lady. Never is beauty and feminine grace so attractive as when engaged in the honorable discharge of household duties and domestic cares. The subject treated of in this little manual is one of vast [11]importance, and to which we are indebted for a large amount of the comforts we enjoy; as without its aid we should be reduced to a state of misery and destitution, of which it is hardly possible to form an adequate conception. To learn, then, how to fabricate articles of dress and utility for family use, or, in the case of ladies blessed with the means of affluence, for the aid and comfort of the deserving poor, should form one of the most prominent branches of female education. And yet experience must have convinced those who are at all conversant with the general state of society, that it is a branch of study to which nothing like due attention is paid in the usual routine of school instruction. The effects of this are often painfully apparent in after life, when, from a variety of circumstances, such knowledge would be of the highest advantage, and subservient to the noblest ends, either of domestic comfort or of active benevolence.

The records of history inform us of the high antiquity of the art of needlework, and its beautiful mysteries were among the earliest developments of female taste and ingenuity. As civilization increased, new wants called forth new exertions: the loom poured forth its multifarious materials, and the needle, with its accompanying implements, gave form and utility to the fabrics submitted to its operations. No one can look upon the NEEDLE without emotion: it is a constant companion throughout the pilgrimage of life. We find it the first instrument of use placed in the hand of budding childhood, and it is found to retain its usefulness and charm even when trembling in the grasp of fast declining age....

In the first chapter of the same volume we read:

To secure economy of time, labor, and expense ... the lady who intends to engage in the domestic employment of preparing the linen necessary for personal and family use, should be careful to have all her materials ready ... before commencing work. The materials are ... well known.... We shall therefore proceed at once to give plain directions by which any lady may soon become expert in this necessary department of household uses, merely observing, that a neat work-box well supplied ... should be provided, and ... furnished with a lock and key....

The lady being thus provided, and having her materials, implements, &c., placed in order upon her work-table, to the edge of which, it is an advantage to have a pincushion affixed by means of a screw, may commence her work, and proceed with it with pleasure to herself, and without annoyance to any visiter [sic] who may favor her with a call. We would recommend, wherever practicable, that the work-table should be made of cedar, and that the windows of the working parlor should open into a garden, well supplied with odoriferous flowers and plants, the perfume of which, will materially cheer the spirits of those especially whose circumstances compel them to devote the greatest portion of their time to sedentary occupations. If these advantages can not be obtained, at least the room should be well ventilated, and furnished with a few cheerful plants, and a well-filled scent-jar.

These suggestions are followed by directions for making underclothes and bed linen and by pictures of various stitches, so carefully described as to be quite clear to anyone. There follows the

CONCLUSION:

The space already occupied leaves us but little opportunity for concluding remarks: but we can not dismiss the little manual we have thus prepared, without a word or two to our fair countrywomen, on the importance of a general and somewhat extensive acquaintance with [12]these arts, in which so much of the comfort of individual and domestic life depends. Economy of time, labor, and expense, is an essential requisite in every family, and will ever claim a due share of attention from her who is desirous of fulfilling, with credit to herself and advantage to others, the allotted duties of her appointed station. To those who are at the head of the majority of families, an extensive knowledge of the various departments of plain needlework is indispensable. The means placed at their disposal are limited—in many instances extremely so; and to make the most of these means, generally provided by the continual care and unremitting attention of the father and the husband, is a sacred duty, which can not be violated without the entailment of consequences which every well-regulated mind must be anxious to avoid....

Volume 3, on “Fancy Needlework,” contains in the fourth chapter the following injunction, an evidence of the honesty of feeling of the time:

In working a landscape, some recommend the placing behind the canvass [sic] a painted sky, to avoid the trouble of working one. As a compliance with such advice would tend to foster habits of idleness and deception, and thus weaken that sense of moral propriety which should, in all we do, be ever present with us, as well as destroy that nice sense of honor and sincerity which flies from every species of deceit, we hope the fair votaries of this delightful art will reject the suggestion with the contempt it merits.

In Volume 5, “Embroidery on Muslin,” we are given directions for all kinds of embroidery, including that on net. The directions last named read in part:

This is the most difficult and delicate, but at the same time, the most beautiful of all white embroidery.

... The designs can be varied, and we strongly advise all who have a taste for drawing, to improve it by designing new and elegant combinations; they will thus be perfecting themselves in the art of design, while they are adding additional attractions to the elegant ornaments of attire.

[Another method of executing designs on net is] by sewing round the edges of each leaf, &c., in glazed cotton, and on the inside of each, darning with fine cotton, doubled, leaving the centre of the flower vacant, which is afterward to be worked in herring-bone stitch, extending from one side to the other. Sometimes, instead of darning, the leaves are worked in chain stitch, which is done in rows to the extremity of the leaf, &c., and the cotton is turned back, and the process is repeated, until the whole space is occupied.... One beautiful variety is formed by filling up the centres of flowers with insertion stitch.

Then follow directions for making bobbin lace. And finally, in the Conclusion, we read:

In the foregoing pages we have endeavored to impart a knowledge of one other branch of those interesting and delightful occupations, in which female activity and skill appear so preeminently beautiful; and we trust we have succeeded in rendering our description so clear and lucid, as to preclude any serious danger of their being mistaken. We hear much in the stories of the olden time, of the potency of the magician’s wand, but it would be indeed presumption to affirm, that any magic ever exercised a more potent sway over trembling nations, than the apparently insignificant needle has exercised, and does exercise, over the most cherished interests [13]of civilized man. As the compass has conducted, by its mysterious influence, the bewildered mariner to the port of safety; so the needle, under the guidance of female skill and affection, has ever been the pole-star of human hopes; and its important fabrications have, in all ages, led the way to increased civilization, assurance, and happiness. With such a fact before us, who would not breathe the wish, that the influence of female skill and taste might be still more widely extended, and that fairy fingers might still guide the mighty helm, which is to direct the storm-tossed vessel of society into a haven of plenty, security, and peace.

In the sixth and last volume are given directions for millinery and dressmaking, from which we quote as follows:

CONCLUSION.

In the foregoing pages, we have imbodied, in a concise but intelligible form, a mass of information, which experience and observation have convinced us was much needed by thousands and tens of thousands of those who are the glory of the land that gave them birth, and who, amid their scanty and limited means, are most laudably ambitious to appear, in the truest sense of the word, respectable. To those, and to the affectionate mothers and devoted wives, who are anxious to make the most of the means placed at their disposal, we trust that our labor, and it has been truly a “labor of love,” will prove an acceptable offering....

In whatever light we view it, the needle is an object of the most fascinating character. It is a home friend; and while it confers upon us all unnumbered blessings, it is a source both of utility and pleasure, that is within the reach of all. In joy and in sorrow, in health and in sickness, in life and in death, it is our companion, our solace, and our helper. Thus, ever ready to obey our guiding will, let us be sure to profit by its silent but eloquent instructions. As the needle turns not to the right hand or the left from the occupation assigned, so let us pursue, with undeviating footsteps, the appointed path of duty; and as it ever points with strict fidelity to the attracting magnet, so let us in all our works, whether useful or ornamental, turn to Him “in whom we live, and move, and have our being.”

There is something calculated to afford high delight to the heart which expands at the prospect of any increase in the sum of human happiness, in the fact that, since the commencement of the present century, much more attention has been paid to the subject of dress, by the mass of society, than had been previously bestowed upon it. This is one of the most favorable signs of the times, since it is closely, and in some respects inseparably, connected with the elevation of the mental standard, and the development of those higher powers by which human nature is so prominently distinguished above the animal creation. No one who has paid the least attention to the subject can doubt, for a moment, the close alliance which subsists between the honest pride of appearance and the desire to secure the highest attainable amount of intellectual culture and improvement; and no one really possessing a heart can refuse to rejoice in this undeniable mark of general progression. We are sensible, that if not under proper guidance, this desire to attain a more respectable and elevated position in society may degenerate into a mere love of show and finery. But we are disposed to look on the bright side of things, and to come to the conclusion that elements are now at work which will produce not only a refined and elevated taste, but a correct and well-regulated judgment. We consider it the peculiar glory of our age, that woman is acknowledged to be fully capable of, and worthy to share in, the most exalted intellectual pursuits. To her, as well as to the boasted lords of the creation, the treasures of art are freely opened; and she is invited in the society of those [14]most loved, to walk through the glorious paths of knowledge, and to drink with them full draughts from the opened fountains of enlarged information.

To render herself worthy of this her improved and still improving condition, is the duty, and should be the pride, of every female. And when it is considered how much a neat and becoming mode of attire adds to the attractive force of woman’s charms, it will be at once seen, that to attain that object with the least unnecessary sacrifice of time, labor, and expense, is a matter of no mean consideration; and that any effort tending to this end, however humble, is deserving of the countenance and encouragement of all who are desirous of co-operating in the designs of the benevolent Creator, and who, recollecting that He himself has declared that “it is not good for man to be alone,” are desirous of investing the fair forms of those intended for our comfort and delight with every personal and mental excellence, calculated to render them worthy of the highest esteem and most devoted affection of the wise, good, and accomplished among mankind.

These quotations taken from writings of the time give something of the characteristics and surroundings of the young women who made the laces of the colonies and of the early 19th century. The surroundings were unusual, and the results in lace compare favorably with those in the silver and furniture of the same period.

That lace-making in America attained an artistic excellence realized by few is conclusively proved by the illustrations which follow.

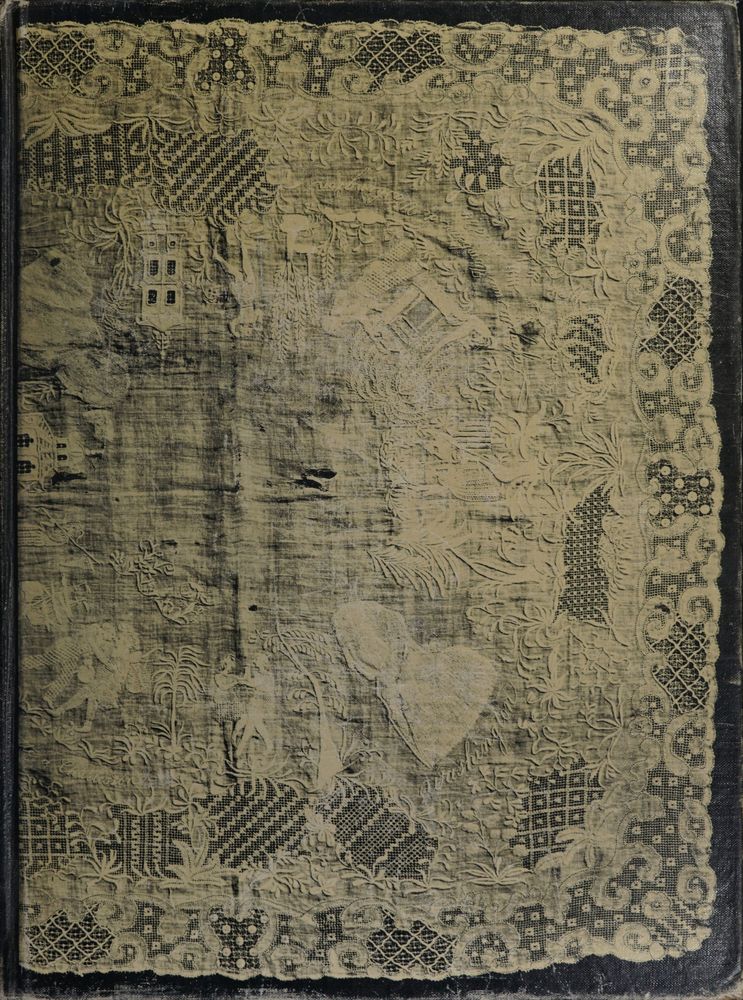

Plate 1.

Samples of lace from the lace-bark tree, or Lagetta lintearia, illustrating its manner of growth. These were brought from the island of Jamaica, West Indies, by Miss Edith Beach, of West Hartford, Connecticut. She has also a piece, resembling them, which was sent to her from Australia. It is reported that a similar variety grows in South Africa. Owned by Miss Beach.

Plate 2.

Figure 1. Peruvian lace bag found in a tomb. Probably four thousand years old.

Figure 2. Peruvian lace. Prehistoric.

These are owned by the American Museum of Natural History, New York City.

Plate 3.

Peruvian lace, two to four thousand years old. Lent by Miss Marian Powys, of the Devonshire Lace Shop, New York City. The American Museum of Natural History, New York City, which gave it to Miss Powys, states that “it was made with an oblong piece of wood like a net measure.”

Plate 4.

Eight lace bags made by the Balienti Indians of Central America. Owned by the American Museum of Natural History, New York City.

Plate 5.

Lace bag made by the Balienti Indians. Owned by the American Museum of Natural History, New York City.

Plate 6.

Four details of the lace bags made by the Balienti Indians. (See Plates 4 and 5.)

Plate 7.

Four lace bags made by the Honduras Indians of Central America. Owned by the American Museum of Natural History, New York City.

Plate 8.

Lace headdress trimmed with eagle and partridge feathers, made by a Hopi Indian. Less than one-half size. Owned by Miss Frances Morris, of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

Plate 9.

Figure 1 (at the top). Very old style of lace, knotted, not netted, made only by one aged woman who lives in the interior of the island of Porto Rico and produces but little.

Figures 2 and 3. Pillow and bobbin lace made in Porto Rico. Makers unknown.

Originals of Figures 1, 2, and 3 owned by the Litchfield Historical Society.

Plate 10.

Hand bag of linen cut-work.

(Plates 10–13 show work done by the Oneida Indians of North America, whose reservation is in Wisconsin. The lace was awarded gold medals at the Paris Exposition, 1900; at the Pan-American at Buffalo, 1901; at Liège, 1905; at Milan, 1906; and at the Australian Exposition, 1908; and at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904 it was awarded the Grand Prize, which is the highest recognition possible. Miss Carter’s association has eight centers, in which six tribes are represented: Onondagas, Oneidas, Chippewas, Sioux, Pueblos, and Mission Indians of Southern California. Loaned by the Sybil Carter Indian Lace Association, New York City, which owns the originals shown in Plates 10–13.)

Plate 11.

Bobbin lace pillow cover with Indian hunting ducks, squaw with papoose on her back, and an Indian tepee introduced into the design. About one-third size. (See description of Plate 10.)

Plate 12.

Bobbin lace bed-spread. (See description of Plate 10; also Plate 13.)

Plate 13.

Detail of bed-spread shown in Plate 12.

Plate 14.

Lace pillow with bobbins. Made by Lydia Lakeman, born at Ipswich, Massachusetts, in 1781. Originals of Plates 14–16 lent by Miss Sarah E. Lakeman.

Plate 15.

Parchment patterns used in Ipswich, Massachusetts, in 1790; blue-print pattern used in Ipswich, Massachusetts, in 1909, at the time of an effort to revive lace-making in the town; and samples of pillow and bobbin laces made there. The narrow lace, of the pattern which was called “the cat’s eye,” was made by Sarah Sutton Russell, born in Ipswich in 1775. The wider laces were made by Mrs. Thomas Caldwell, who was born in the same place in 1780. Her great-grandmother was a lace-maker, born there as well, in 1736. The patterns all had local names, one of the wider ones being called “two and thrippenny.” The pillow, patterns, and laces have come down to a granddaughter of Mrs. Caldwell, Miss Sarah E. Lakeman, of Ipswich, Massachusetts. She makes lace now and lectures on the old industry.

Plate 16.

Ipswich laces. Owned by Miss Sarah E. Lakeman. (See description of Plate 15.) Makers unknown.

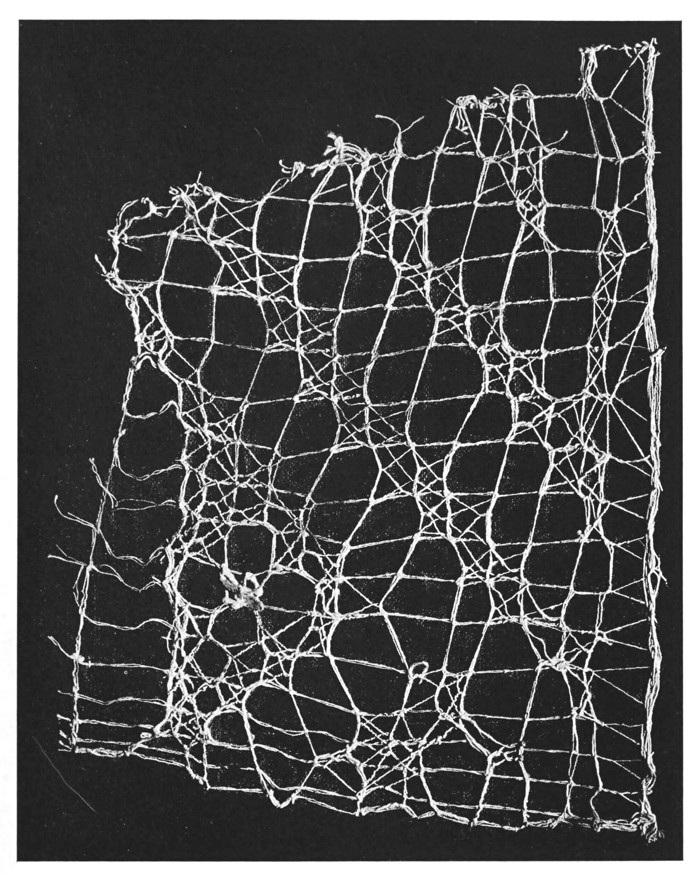

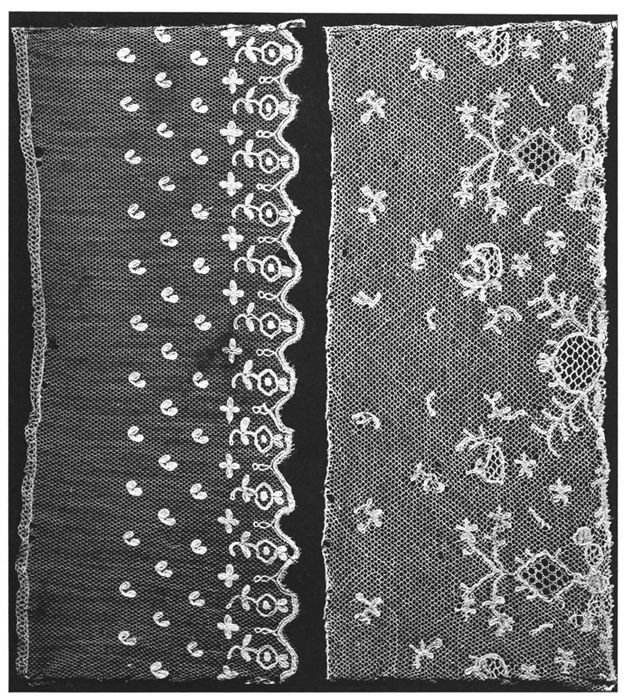

Plate 17.

Samples of the réseaux, or grounds, enlarged, which fill up the patterns of pillow and bobbin laces; also of the darned net called Limerick, still on its pasteboard frame. Makers unknown. Owned by the Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts.

Text from image:

DETAILS OF BOBBIN, OR PILLOW LACE

Toile of Bobbin Lace Half stitch

Toile of Bobbin Lace Cloth stitch

Reseau of Valenciennes

Reseau of Brussels

Reseau of Mechlin

Reseau of Lille

Reseau called “Cinq Trous”

Reseau called “Fond Chant” or “Point de Paris”

This is used in Chantilly Lace.

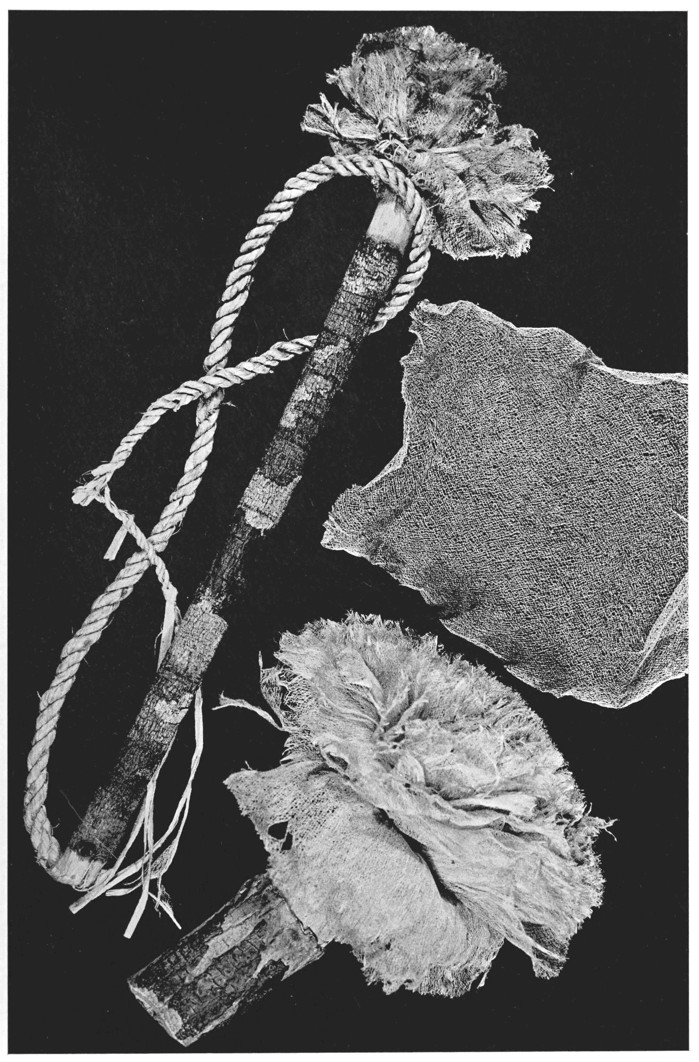

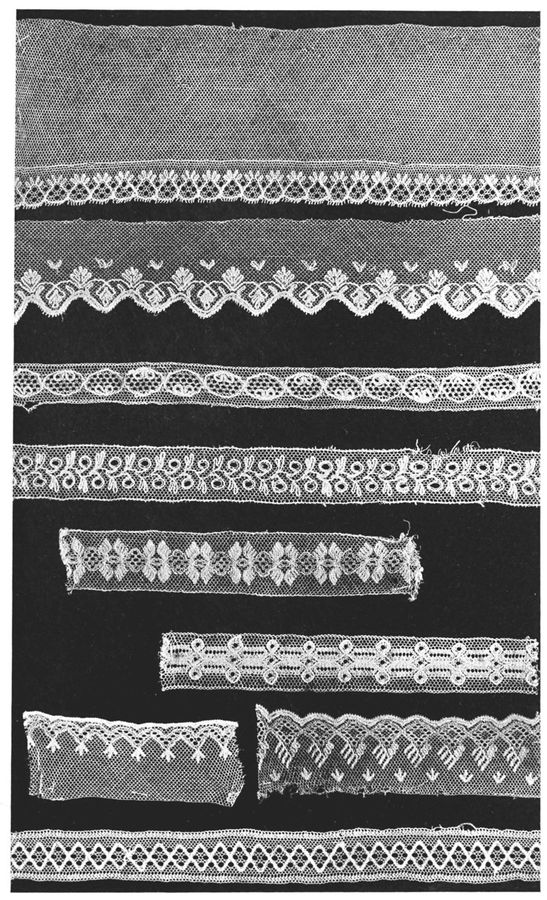

Plate 18.

Bobbins made of bamboo, wood, and ivory; linen thread for making lace; and samples of Limerick lace, or darned net. Makers unknown. Owned by the Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts.

Text from image:

Darned Lace on machine net about 1830

Gift of miss Lucy Baker

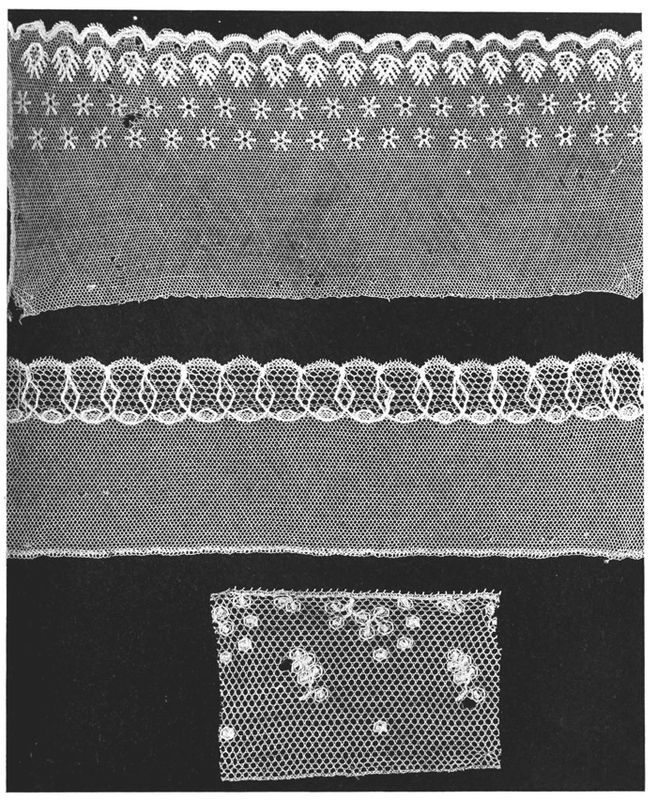

Plate 19.

Samples of American darned laces. Collected by Miss Anna P. Thompson, daughter of Hezekiah Thompson and his wife, Mabel Roberts, of New Haven, Connecticut. Owned by Miss Esther H. Thompson, of Litchfield, Connecticut. Mabel Roberts was born in 1814. At nine years of age, in the winter while at school, she made the lace shown in Figure 2 of Plate 19 and in Figure 1 of Plate 20, worked a sampler, and made a ruffled shirt for her brother, who was eight years old. (See also Figure 5 of Plate 23 and description.)

Plate 20.

Additional samples of American darned laces. Collected by Miss Anna P. Thompson. (See description of Plate 19.) The original of Figure 1 (top) was made by Mabel Roberts (Mrs. Hezekiah Thompson) when she was nine years old. Figure 2 (middle) shows the cap border of Mrs. (General) John Hubbard. (See description of Plate 91, Figure 3.) Owned by Miss Esther H. Thompson, of Litchfield, Connecticut.

Plate 21.

A collar in the same collection (see descriptions of Plates 19 and 20). Brought from Savannah by Mrs. Erastus Merwin, of Cornwall Hollow, Connecticut. Maker unknown. Worked about 1830. About one-half size. Owned by Miss Esther H. Thompson, of Litchfield, Connecticut.

Plate 22.

A guimpe in the same collection (see Plates 19–21 and descriptions); about one-half size. Maker unknown. Owned by Miss Esther H. Thompson, of Litchfield, Connecticut.

Plate 23.

One page from a sampler of darned net laces owned in Ipswich, England, brought from there by Mrs. Guy Antrobus (Mary Symonds), and lent by her for reproduction here. Figure 5 of this plate (middle of second row) proved to be of the same design as that of the American lace in Figure 1 of Plate 19. There are one hundred and forty-three different designs for darned net, insertion, and trimming lace in this little sampler book, made simply of sheets of blue paper on which the lace is sewed.

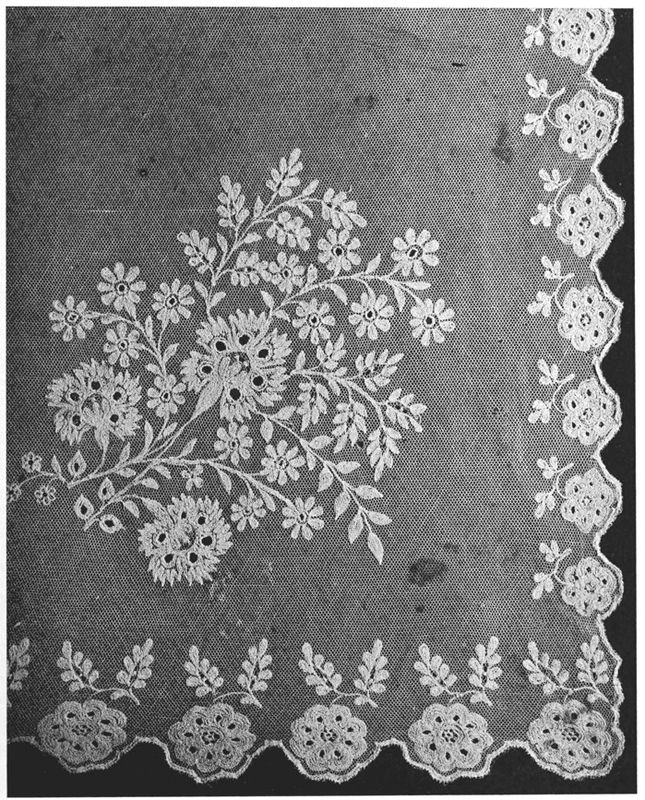

Plate 24.

Unfinished hand-run, or darned net, veil. Made by Mrs. Thomas L. Rushmore about 1825. Owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

Plate 25.

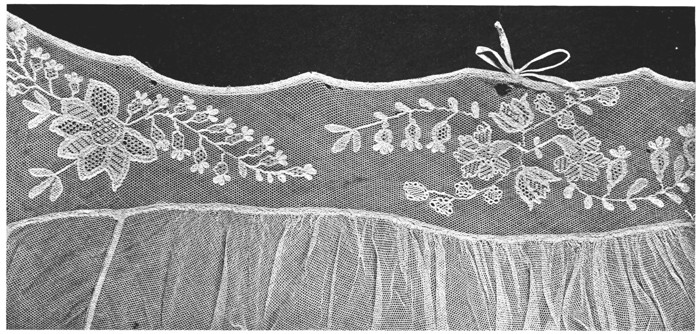

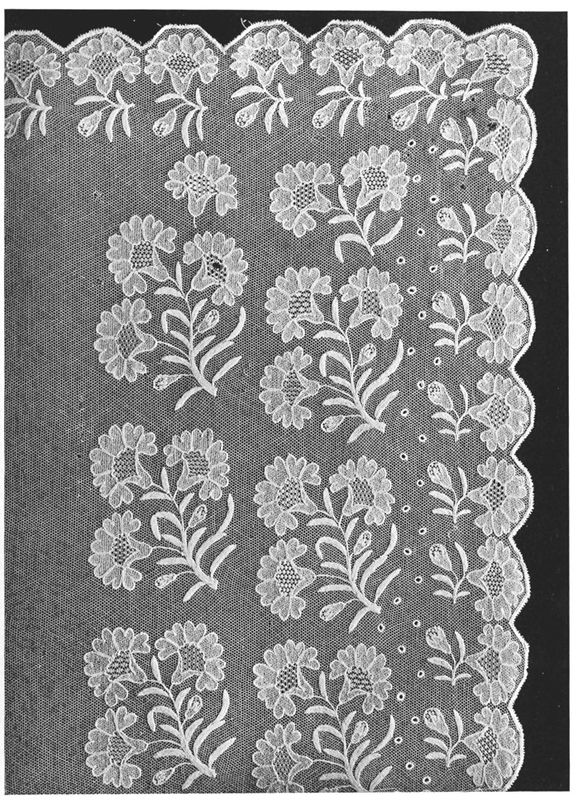

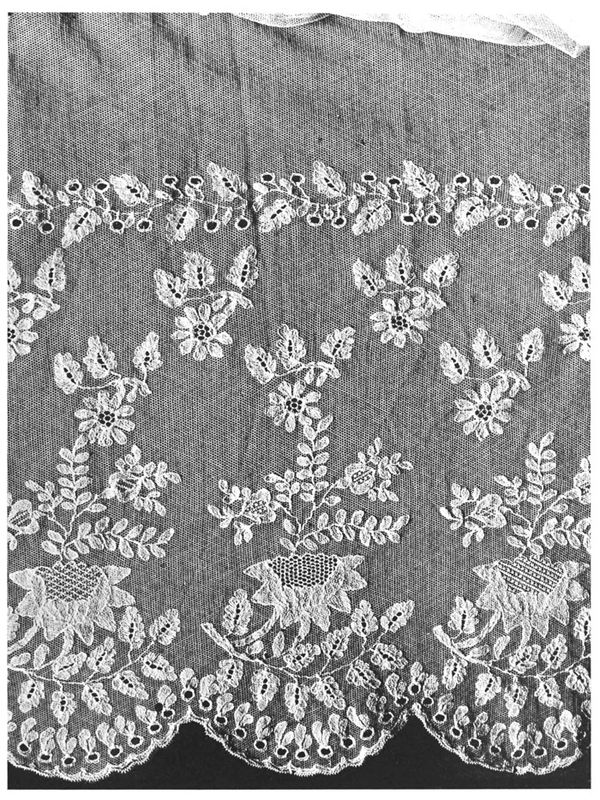

Part of a dress skirt of white net. Worked by Cornelia Kingsland, born in 1806, died in 1890, daughter of Stephen and Mary Kipp Kingsland, cousin to Mayor Kingsland, of New York City. She married Captain Hatherly Barstow, who was lost at sea two years after her marriage. She was taught lace-making in her girlhood by a French lady, was an expert needlewoman, and made two whole lace dresses—this skirt in 1822. This lace was given by her niece, Mrs. Eleanor T. Smith, to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

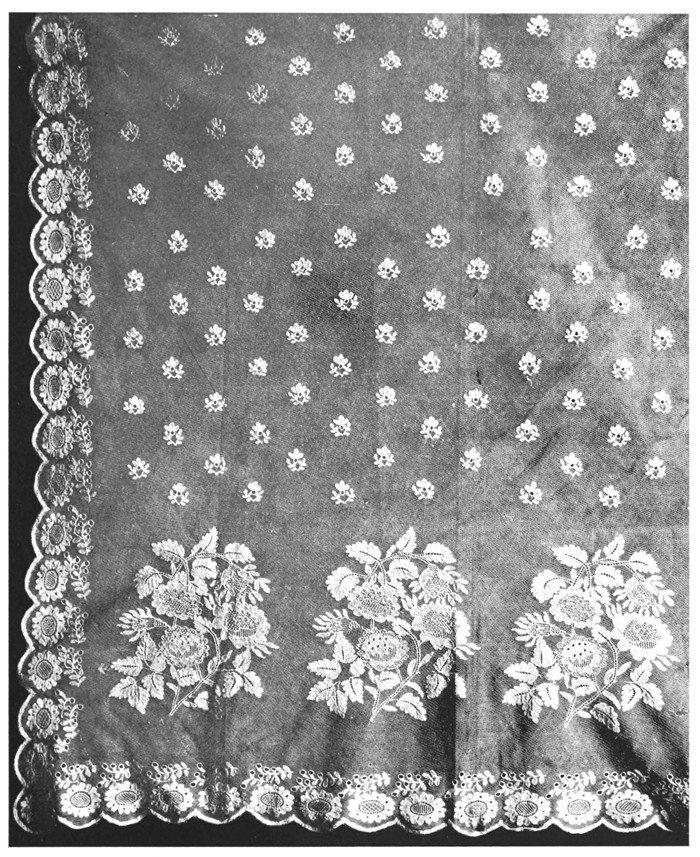

Plate 26.

White veil, 46 inches long and 42 inches deep. Worked in chain stitch, or tambour, by Catherine Roosevelt Kissam, of New York, daughter of Benjamin Kissam and his wife, Cornelia Roosevelt. She married Francis Armstrong Livingston in 1822. She attended the Moravian school at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where she was probably taught lace-making. Mr. Livingston died in 1830. This veil is owned by Miss Helena Knox. (See also Plates 27–29.)

Plate 27.

Detail of veil shown in Plate 26.

Plate 28.

Front of cap. Worked with a variety of lace stitches, probably by the same hand as the original of Plates 26 and 27. Both originals are owned by Miss Helena Knox, granddaughter of Catherine Roosevelt Kissam. (See also Plate 29.)

The school at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, was the outgrowth of a religious community founded in 1722 at Herrnhut, Germany, by Count Zinzendorf. A number of its members came to Pennsylvania and there started a colony, which later developed into two schools, one for boys and one for girls. The one for girls became very popular. Fine needlework was taught, but as an extra; as the school records say, “Tambour and fine needlework” at the rate of “seventeen shillings and sixpence, Pennsylvania currency.” Here and there are remains of the fine work done by pupils of that school—all kinds of embroidery as well as pictures. Needlework was also taught at Miss Pierce’s Female Academy in Litchfield, Connecticut, from which a number of examples remain, besides pictures painted in water-colors.

Plate 29.

Crown of cap shown in Plate 28.

Plate 30.

White veil, 48 inches long, 38 inches wide. (See also Plate 31.) The linen thread used to work this veil, like much of that used in the other white lace, is of peculiar texture, much resembling silk.

This veil was made about 1827 and worn at her wedding by Mary W. Peck, stepdaughter of Dr. Abel Catlin, who lived in Litchfield, Connecticut, in the house on the west side of North Street now occupied by Mr. Frederick Deming. Her name is on the list of pupils of Miss Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy for 1811. (She also appears on the list for 1825, but as teacher of drawing.) She married Edward D. Mansfield, a student of the Litchfield Law School. Her son, Charles, paymaster in the United States Navy, gave the veil, a baby’s dress (see Plate 89), and his mother’s album (which is ornamented with water-color paintings and contains written verses and sentiments, with autographs, of all the people prominent in Litchfield at that time) to the Litchfield Historical Society about 1890.

Plate 31.

Detail of veil shown in Plate 30.

Plate 32.

Veil. Worked by Elizabeth Hannah Canfield about 1830. The maker was a daughter of Judge Judson and Mabel Ruggles Canfield, of Sharon, Connecticut, and a sister of Caroline Canfield. (See Frontispiece and Plates 51, 52, and 76–81.) She attended the well-known school kept by Miss Sarah Pierce in Litchfield, Connecticut. This school was contemporary with the first law school founded in the United States, also in Litchfield. Miss Canfield, being very handsome, was called by the law students “the Rose of Sharon.” She married Frederick Augustus Tallmadge, son of Colonel Benjamin Tallmadge and Mary Floyd, of Litchfield. She lived subsequently in New York City. The veil was given to the Litchfield Historical Society by her daughter, Mrs. Edward W. Seymour. (See Plates 33, 35, 51, 52, 54, and 55; also the description of Plate 81.)

Plate 33.

Detail of veil shown in Plate 32.

Plate 34.

Detail of similar white veil, 38 inches long by 38 inches wide. From the collection of Ellen McBride, wife of Judge Aaron Vanderpoel, of Kinderhook and New York. Made probably by her or a sister about 1835. Owned by the Litchfield Historical Society.

Plate 35.

Lace cap. Worked by Elizabeth Hannah Canfield (Mrs. Frederick Augustus Tallmadge) about 1830. Owned by the Litchfield Historical Society. (See Plates 32, 33, 51, 54, and 55; also description of Plate 81.)

Plate 36.

A piece of Limerick trimming lace made in Limerick, Ireland. Bought in 1922 of Arnold, Constable & Company, New York City. This shows that the kind of lace taught by the girls taken to Limerick by Mr. Charles Walker in 1829 is still being made there and is of the same technique as that made in New England a hundred years ago. Owned by the Litchfield Historical Society.

Plate 37.

White veil. “Made by Sarah Elizabeth Johnson, descended on one side from the first president of King’s College, New York, and on the other from Jonathan Edwards. She married in 1827 her second cousin, George Pollock Devereux, of Raleigh, North Carolina. The ten years of her married life were spent with him on a lonely plantation in Bertie County, North Carolina, and it was during this time that the lace was made. (Probably from 1830 to 1840.) She then returned to her old home in Stratford and New Haven and died in 1867.” (Extract from a letter written by her granddaughter, Miss Marianna Townsend, who owns the veil.)

The example given in this plate measures as a whole 42 inches wide by 33 inches long. (See also Plates 38 and 39.)

Plate 38.

Detail of veil shown in Plate 37.

Plate 39.

Detail of a second veil made by Sarah Elizabeth Johnson (Mrs. George Pollock Devereux). (See Plate 37.) Owned by Miss Marianna Townsend.

Plate 40.

White net veil, 34 inches wide by 36 inches long. This plate gives one corner of the veil, with one of the four sprays. It was worked in tambour stitch, in the family, for Ann Stodart’s wedding veil when she married Horace Gooch in 1830. She was the daughter of Robert and Sarah Stodart. The bride walked in a procession from her father’s house to the church in what was then a little village, though it is now a part of London. Highly cultivated, particularly in music, she was a pupil of Mendelssohn when he lived in England, and one of the ten pupils chosen by him to play with him before Queen Victoria. In 1830 she came to America with her husband, bringing in a sailing vessel all their household goods, including two pianos and a harp. They stopped on their way West for the birth of her first child. Mr. Gooch bought a large tract of land near Cincinnati and built on it a fine house. It is a show house to this day. She had eight children when her husband died, leaving house, land, and children, but no money. She then opened in her own house a large and successful school which lasted for many years. The veil shown here is owned by her granddaughter, Miss Clara Ray.

Plate 41.

White veil. Made by Marietta, or Mary, Smith, born July 18, 1806, died November 28, 1889, daughter of James Smith and his wife, Gloriana Shelton, of Derby, Connecticut. The whole veil is 48 inches wide by 46 inches long. It was made about 1830. It contains seventeen lace stitches. (See also Plates 42 and 43.)

Quaint details of the home and habits of her forebears and of the romance which saddened without spoiling her life, are interestingly portrayed in The Salt Box House , published some years ago. At thirteen years of age she was taken to Miss Pierce’s Female Academy at Litchfield, Connecticut, where her father left her with the admonition, “Never forget your accountability,” and where she made satisfactory progress in her studies. The tone of mind of the day can be understood from a letter written to her father. Returning from school by stage coach, she recorded her arrival at a friend’s house in New Haven, where she was to await him. She wrote that there had been ten passengers in the coach, all but two of them ladies, and that the tedium of the journey had been relieved by the ladies’ taking turns in reading aloud an essay on “Good Behavior”!

Without doubt she learned at Miss Pierce’s school to make the veil shown in these plates; for Miss Mary W. Peck, who made her own wedding veil (see Plates 30, 31, and 89), was a teacher there.

The family was a social one. We read of the white crêpe frock which Marietta Smith had for a ball-dress in her fifteenth year. The romance of her life took place at seventeen, when she met a young Southerner. A mutual affection brought them together, but the two natures did not quite understand each other. They parted; but when he died, three years later, she realized her mistake with uncontrollable grief and was faithful to his memory during all her life. She had many other lovers; she read and studied, became interested in music and other things, visited and travelled; but “through all her long life the love of her youth remained a potent factor,” though she was never a grim old maid.

Miss Mary began keeping a journal—in a desultory way at first; later, as years passed, as one of the important interests of her life. She chronicles her father’s and mother’s deaths in a loving fashion. Living alone became more and more satisfactory. She wrote: “I take a world of comfort all alone in my house; nobody makes me afraid, even if they molest me in a gossiping way.... Staying in my own house in solitary state is very pleasant to me, but worries my neighbors.” The love of travel became a ruling power. The elegancies of life appealed strongly to Miss Mary. She was a welcome guest in many a great house. “The spell of intellect and culture is always irresistible to me,” she wrote; and “there are a great many ‘field-days’ in society. I love these musters at home and abroad, and in my day and generation have Vibrated through a great number. I occasionally join the gay circles, taking into consideration the expediency of airing my manners, to make sure I am modern and extant!” “Trimmed my borders and cut my grass this morning, trimmed my self in my royal robes this afternoon and made calls.”

The veil was given to the Litchfield Historical Society by the Misses Alice and Edith Kingsbury, of Waterbury, Connecticut.

Plate 42.

Detail of veil shown in Plate 41.

Plate 43.

Plate 44.

Black net shawl, unfinished, 45 inches square. Begun about 1830 by Mrs. John Savage (Miss Barringer). She lived in New York City, at the corner of Varick and Franklin streets. Mr. John Savage was born at Portland, Connecticut. He was a vestryman of Christ Church, New York City. He died in 1845. The black lace seems to be entirely of silk net worked with silk of excellent quality, for it has kept well in both color and texture. (See also Plate 45.) Owned by the Litchfield Historical Society.

Plate 45.

Detail of shawl shown in Plate 44.

Plate 46.

Figure 1 (at left). Black trimming lace. Worked by Elizabeth, or Betsey, Peck, of Woodbridge, Connecticut, and worn on a velvet cloak. She married Camp Newton in 1798. (See also Plate 74, Figure 2.) Owned by her granddaughter, Mrs. Samuel H. Street, of Woodbridge, Connecticut.

Figure 2. Black trimming lace worked by Pamela Parsons. (See Plate 92.) Owned by Mrs. Charles B. Curtis. (See descriptions of Plates 93–96.)

Plate 47.

Black veil, 40 inches wide by 21 inches long. From the Buel family of Litchfield, Connecticut. Date probably 1830. Owned by the Litchfield Historical Society.

Plate 48.

Detail of veil shown in Plate 47.

Plate 49.

Black lace veil, 27 inches long by 86 inches wide. Made by Polly Marsh, daughter of Elisha and Rhoda Kilbourn Marsh, about 1830. She was born December 9, 1804, and died January 8, 1892. She lived about three miles north of Litchfield, Connecticut, on the Goshen road, in a farmhouse where she took great pride in her parlor with its sanded floor and curtains of thin blue and white linen, which she had spun, woven, and dyed herself. She was a direct descendant of John Marsh, who went in May, 1715, alone on horseback, westward through the wilderness from Hartford, Connecticut, to find a suitable site for a new settlement. He chose what is now the town of Litchfield, Connecticut, situated on a long, high ridge running north and south. It took him five days to make the trip.