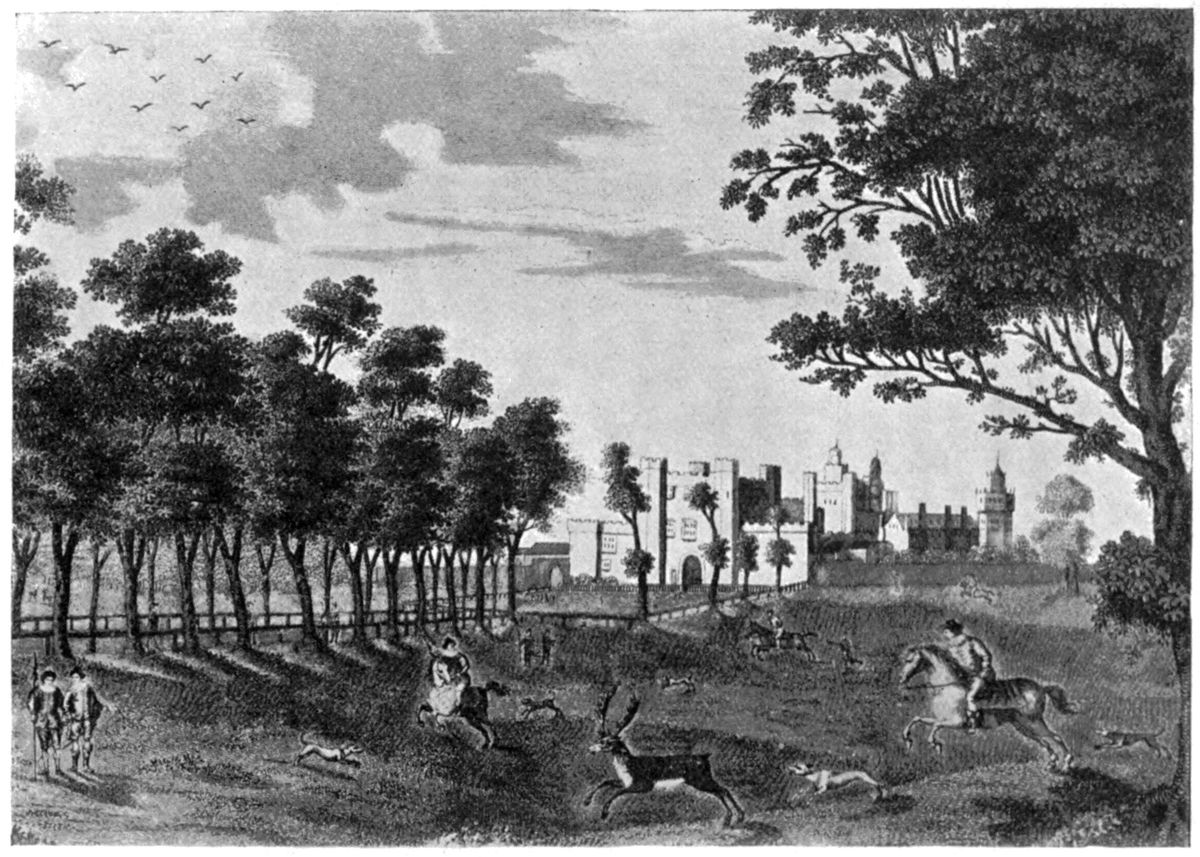

Fig. 1.—NONSUCH PALACE, GARDEN FRONT.

Drawn by

Hofnagle.

Title: Some famous buildings and their story

being the results of recent research in London and elsewhere

Author: Sir Alfred William Clapham

Walter H. Godfrey

Release date: December 6, 2025 [eBook #77412]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Technical Journals Ltd, 1913

Credits: deaurider, A Marshall and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the paragraph.

The new original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

SOME FAMOUS BUILDINGS

AND THEIR STORY

Being the results of recent research in

London and elsewhere.

BY

ALFRED W. CLAPHAM, F.S.A.,

AND

WALTER H. GODFREY

Author of

A History of Architecture in London,

The Parish of Chelsea, &c., &c.

ILLUSTRATED BY 108 PHOTOGRAPHS AND ORIGINAL PLANS

TECHNICAL JOURNALS, Ltd.

CAXTON HOUSE, WESTMINSTER, S.W.

Not the least interesting branch of modern research is that which opens for us new chapters in the history of our own country and shows us the character and ambitions in the lives of our ancestors. The public have long been familiarised with the results of scientific inquiry into the organic structure and the habits of Nature, but the labours of the historian are too often hidden in treatises of too abstruse a form to attract the general reader. And even where an attempt has been made to present these subjects of human interest in a more palatable form we too often have to lament a looseness of expression and an indifference to historical accuracy which defeat every good purpose in view.

It is in the belief that a series of short papers, each embodying some definite contribution to local or national history, may yet be made of real interest to the average reader, that this collection of studies has been compiled. The majority of the articles appeared in the pages of the Architectural Review under the title of “New Light on Old Subjects.” (February, 1911, to March, 1912.) My friend Mr. A. W. Clapham contributes those on the palaces of Nonsuch, Hertford, Havering, and Queenborough, the Tower of London, the Origin of the Domestic Hall, and the monastic buildings of Cockersand; Barking;[1] St. John’s, Clerkenwell;[2] Blackfriars[3] and Whitefriars[4] London. The reader is referred to the publications mentioned in the footnotes for Mr. Clapham’s detailed archæological examination of all the documentary evidences, and a full description of the excavations superintended by him at Barking Abbey.

[1] The Benedictine Abbey of Barking. Transactions , Essex Archæological Society. Vol. XII.

[2] St. John of Jerusalem, Clerkenwell. Transactions , St. Paul’s Ecclesiological Society. Vol. VII. Part 2.

[3] On the topography of the Dominican Priory of London. Archæologia. Vol. LXIII.

[4] Topography of the Carmelite Priory of London. Journal of the British Archæological Association. March, 1910.

Of the remaining papers, I will merely add that they represent for the most part some particular studies in the more general examination of London buildings which I have undertaken. The articles on Chelsea are an amplification of the material prepared for the Survey of that Parish.[5] That on Crosby Hall is the substance of a lecture delivered before the London and Middlesex Archæological Association, soon after the Hall’s reconstruction. The interpretation of the original Specification of Elizabethan date for the erection of the Fortune Theatre was originally undertaken for Mr. William Archer, and the full details as here presented were first published in the Architectural Review . The only paper that deals with a subject outside London is that on Abbot’s Hospital, Guildford, which provides an excuse for a short account of the chief points of interest in the history of English Almshouses and their plans. I am indebted to Mr. Clapham for details of the building dates of Eltham Palace, which are preserved in the Record Office.

[5] “Survey of London.” Vol. IV. Parish of Chelsea, Part 2. London County Council.

Both Mr. Clapham’s and my thanks are due for the kind permission granted us to reproduce old plans and drawings wherever these are in private hands and also for the use of photographs. Care has been taken to acknowledge the source of each drawing in the text, with the names of those who have extended to us their courtesy and help.

WALTER H. GODFREY.

11, Carteret Street,

Queen Anne’s Gate,

S.W.

[Pg vii]

| PAGE | |||

| I. | The Royal Palace of Nonsuch, Surrey | 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

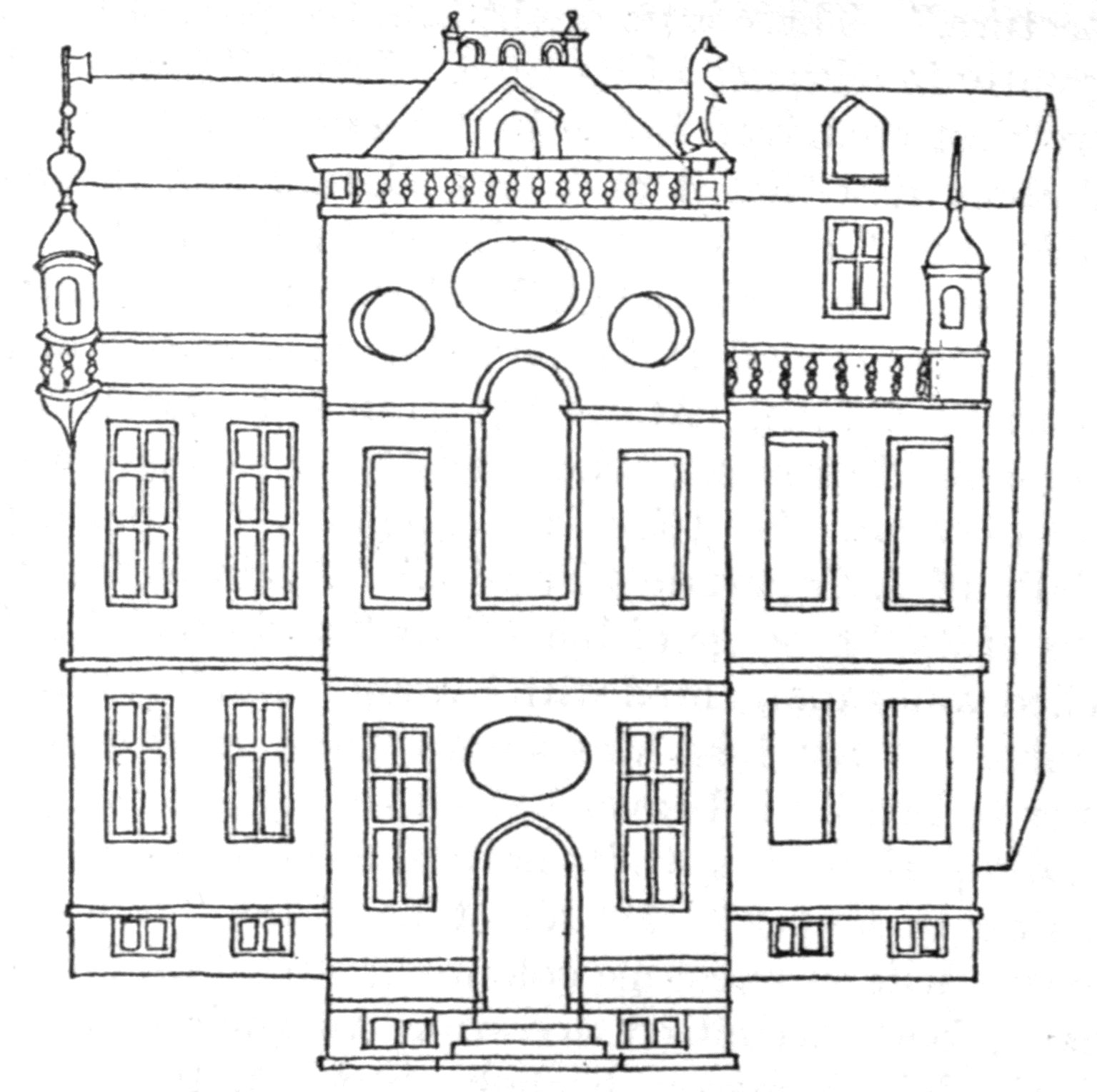

| 1. | Nonsuch Palace, Garden Front—Hofnagle | 2 | |

| 2. | Nonsuch Palace, from the South—Speed (1611) | 7 | |

| 3. | Nonsuch Palace from the N.-W.—Vetusta Monumenta, Vol. ii. (1765) | 8 | |

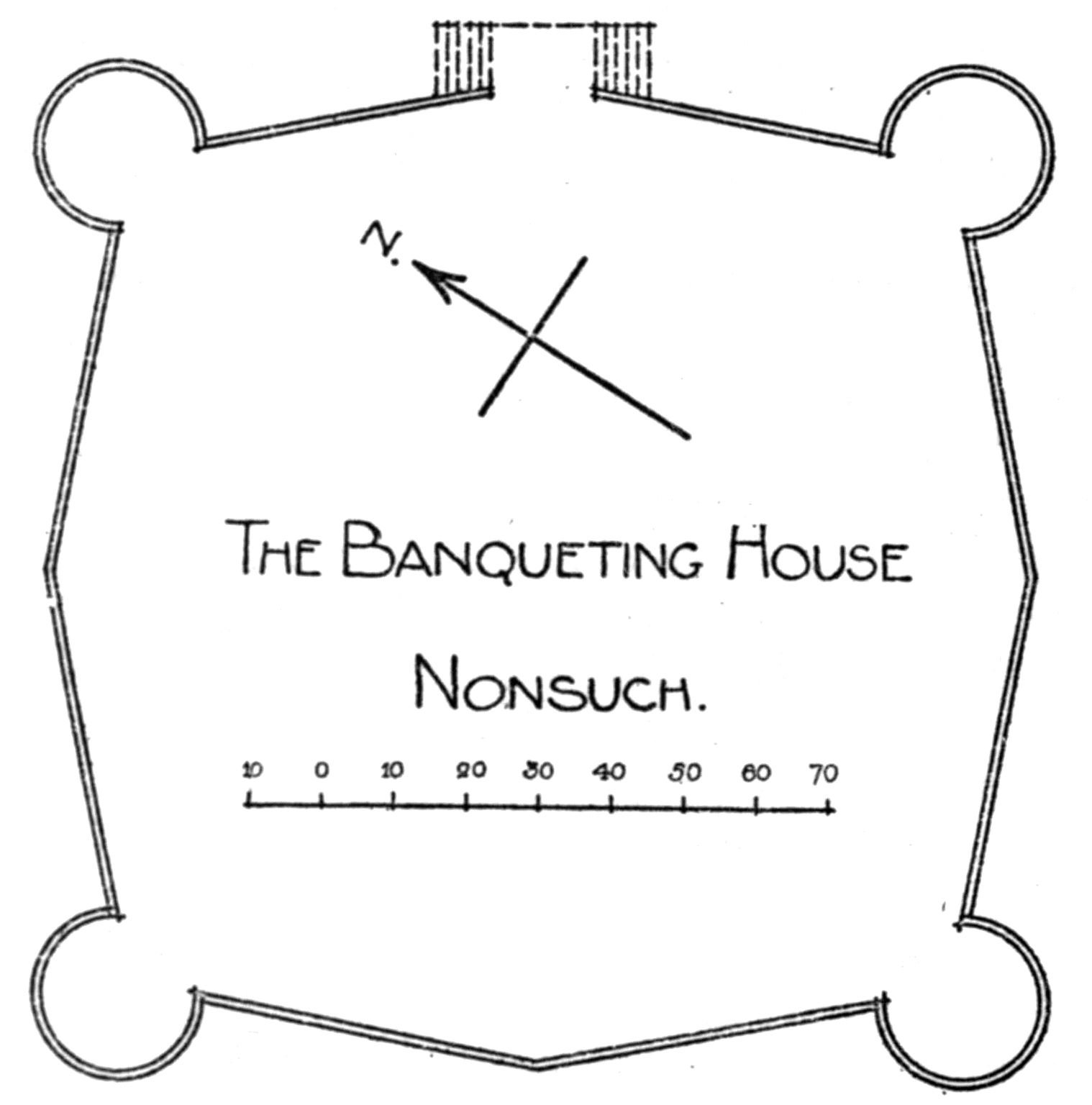

| 4. | The Banqueting House—drawn by Alfred W. Clapham | 12 | |

| II. | The Fortune Theatre, London (1600) | 13 | |

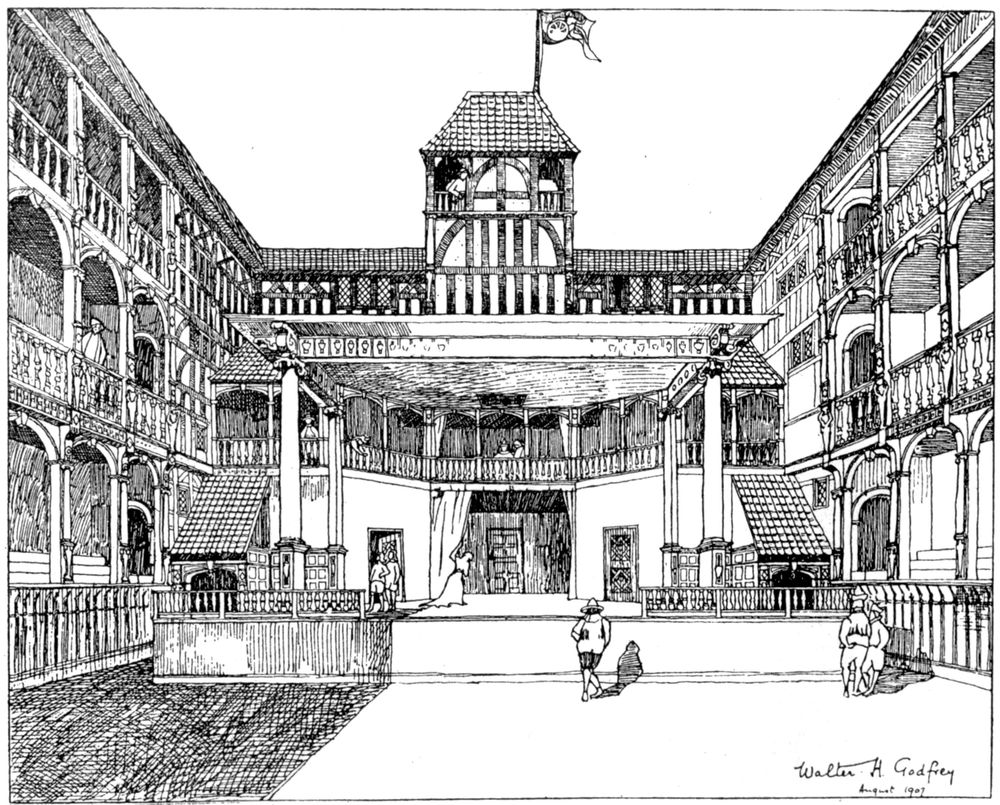

| 5. | View of Interior—drawn by Walter H. Godfrey | 14 | |

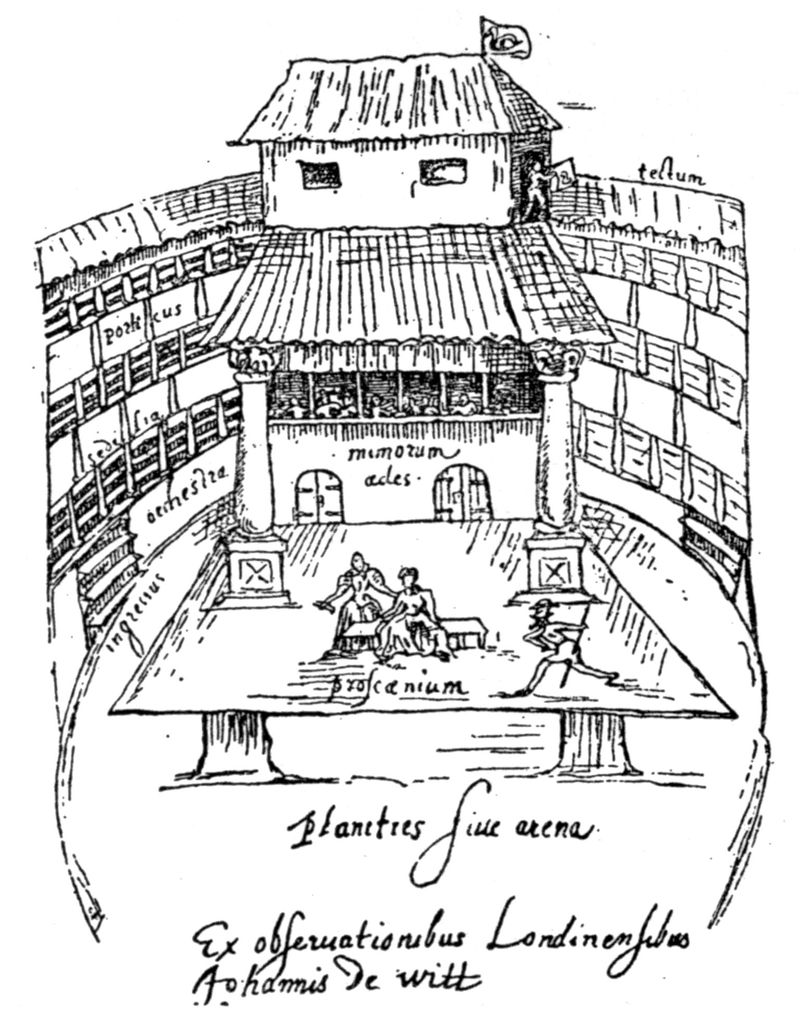

| 6. | Swan Theatre, Bankside—John de Witt | 16 | |

| 7. | The Fortune. Plan (ground floor)—by Walter H. Godfrey | 19 | |

| 8. | The Fortune. Plan (upper floor)—by Walter H. Godfrey | 20 | |

| 9. | The Fortune. Section through Stage—by Walter H. Godfrey | 25 | |

| 10. | The Fortune. Section facing Stage—by Walter H. Godfrey | 26 | |

| III. | The Tower of London and its Development | 29 | |

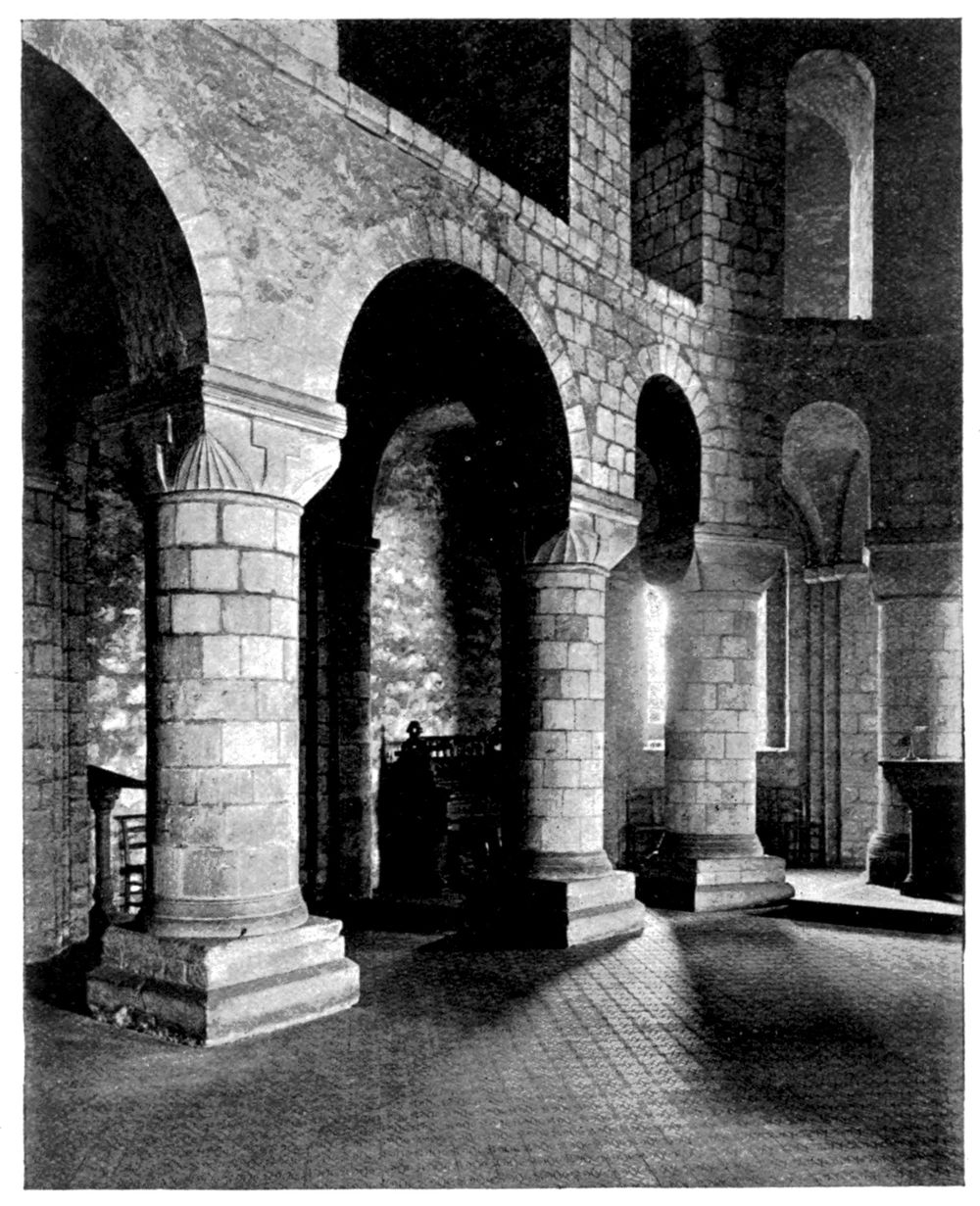

| 11. | Chapel of St. John—Photograph Architectural Review | 30 | |

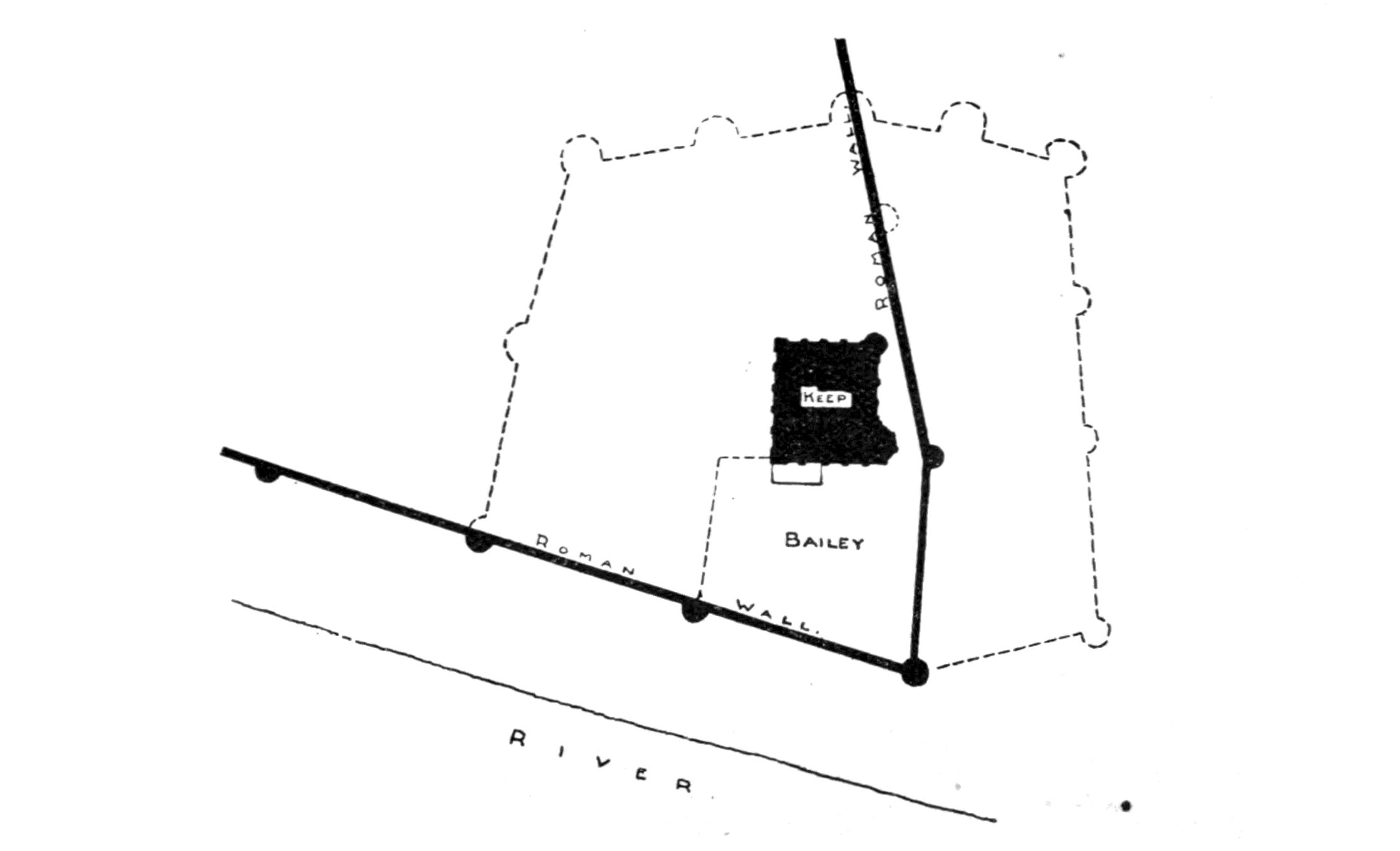

| 12. | Plan of Tower and Roman Wall—by Alfred W. Clapham | 33 | |

| 13. | Plan of Tower and its Bastions—by Alfred W. Clapham | 33 | |

| 14. | Towers on Eastern Wall—Photograph Architectural Review | 34 | |

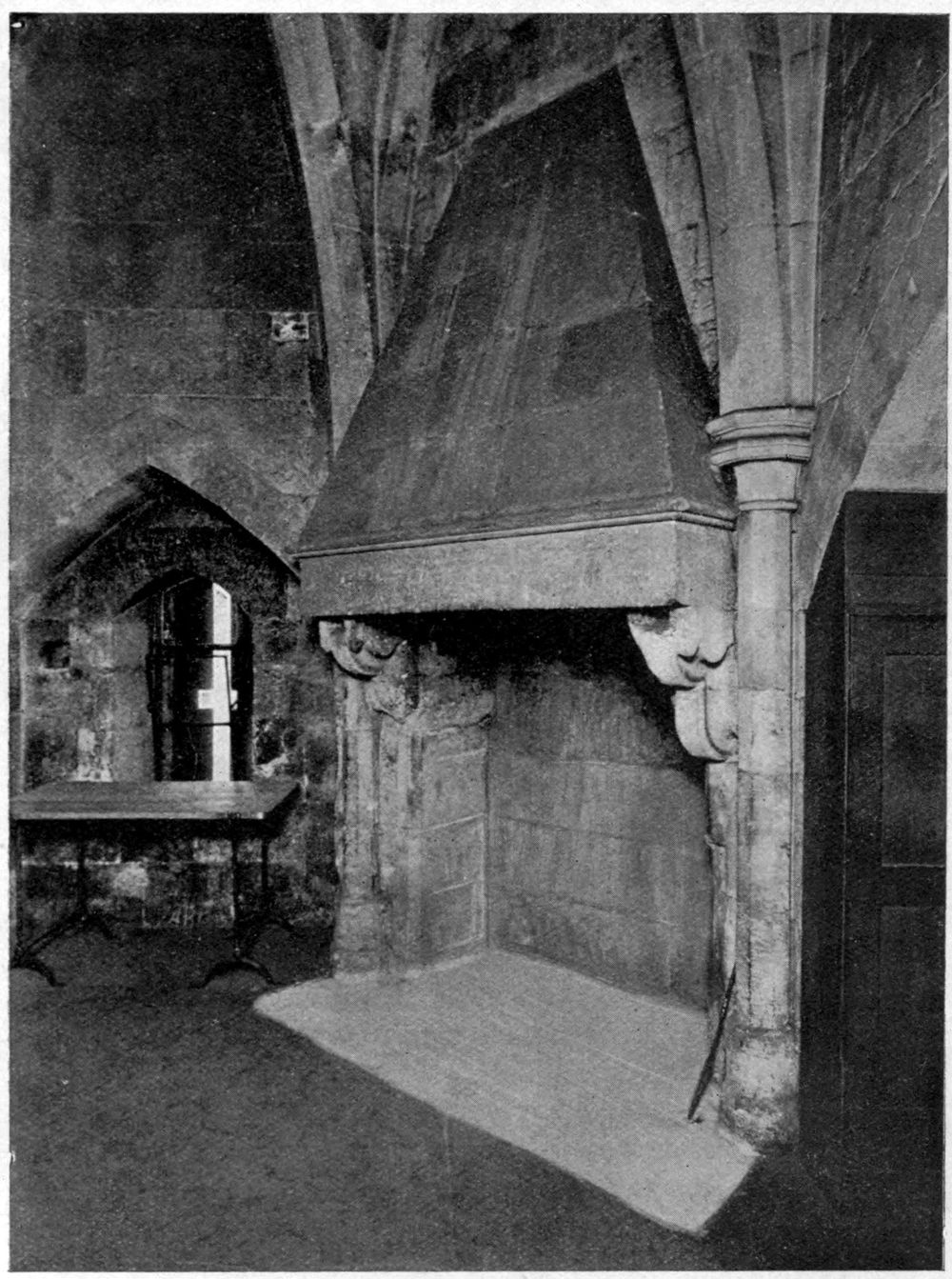

| 15. | Fireplace, Byward Tower—Photograph Architectural Review | 39 | |

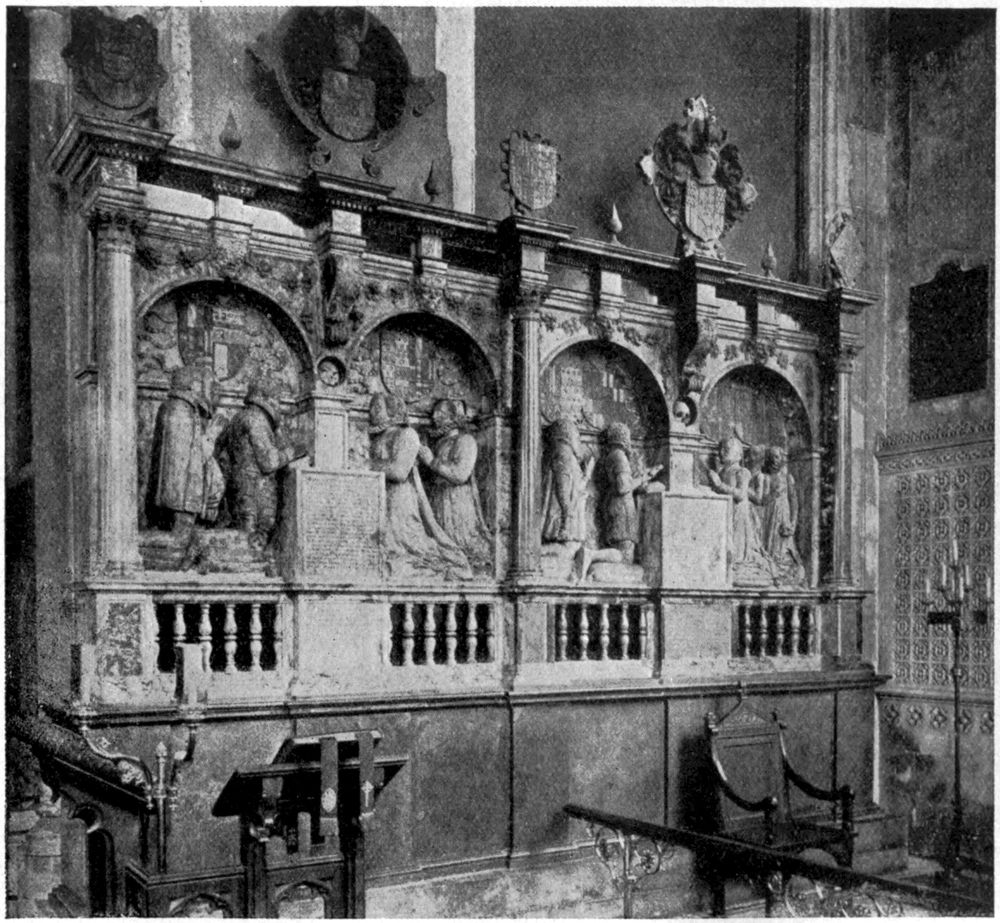

| 16. | Blount Monument, St. Peter ad Vincula—Photograph Architectural Review | 40 | |

| 17. | Pediment with Arms of William III.—Photograph Architectural Review | 43 | |

| 18. | The Horse-Armoury—Photograph Architectural Review | 44 | |

| [viii]IV. | The Royal Palace of Eltham | 47 | |

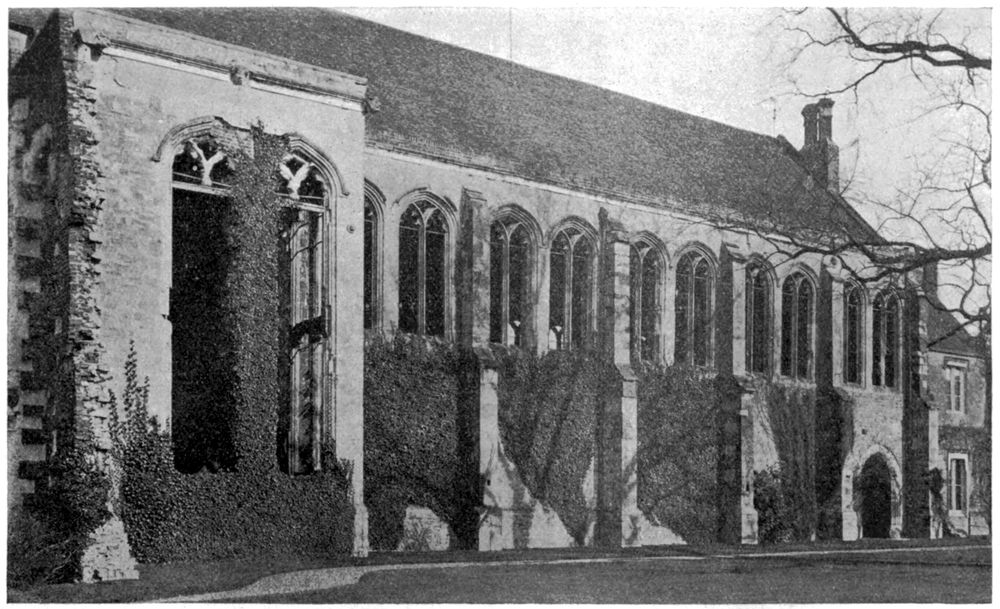

| 19. | The Hall from the South—Photograph by F. W. Nunn | 48 | |

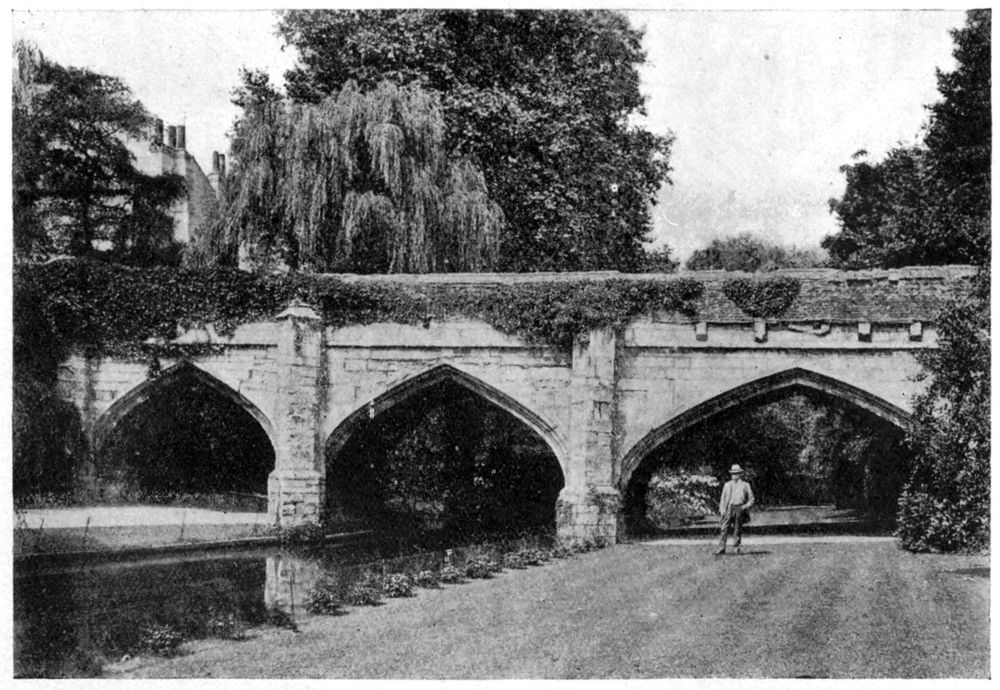

| 20. | Bridge over Moat. Photograph by F. W. Nunn | 53 | |

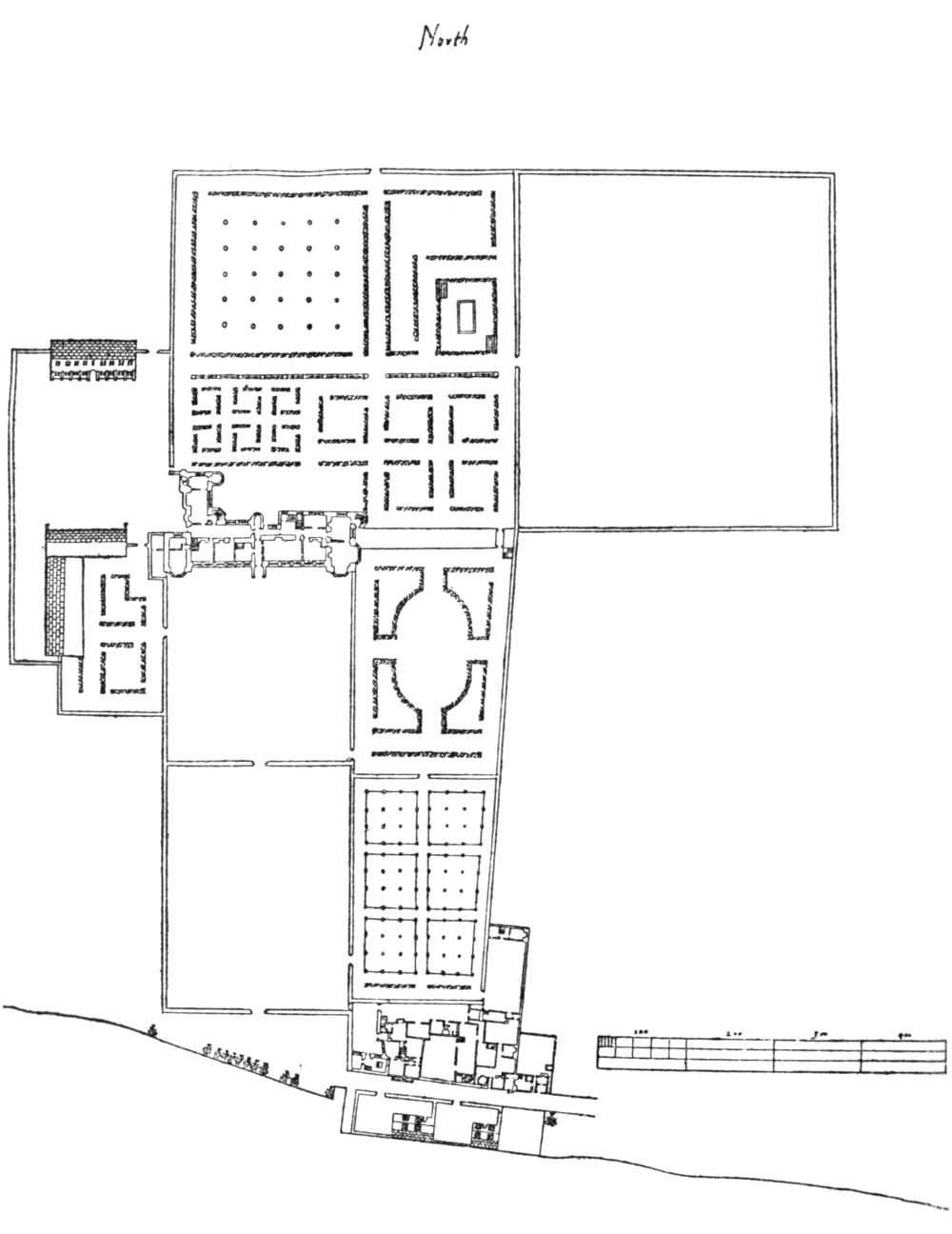

| 21. | Complete Plan of Palace—drawn by Walter H. Godfrey, from Plans in the Hatfield MSS. and the Record Office | 54 | |

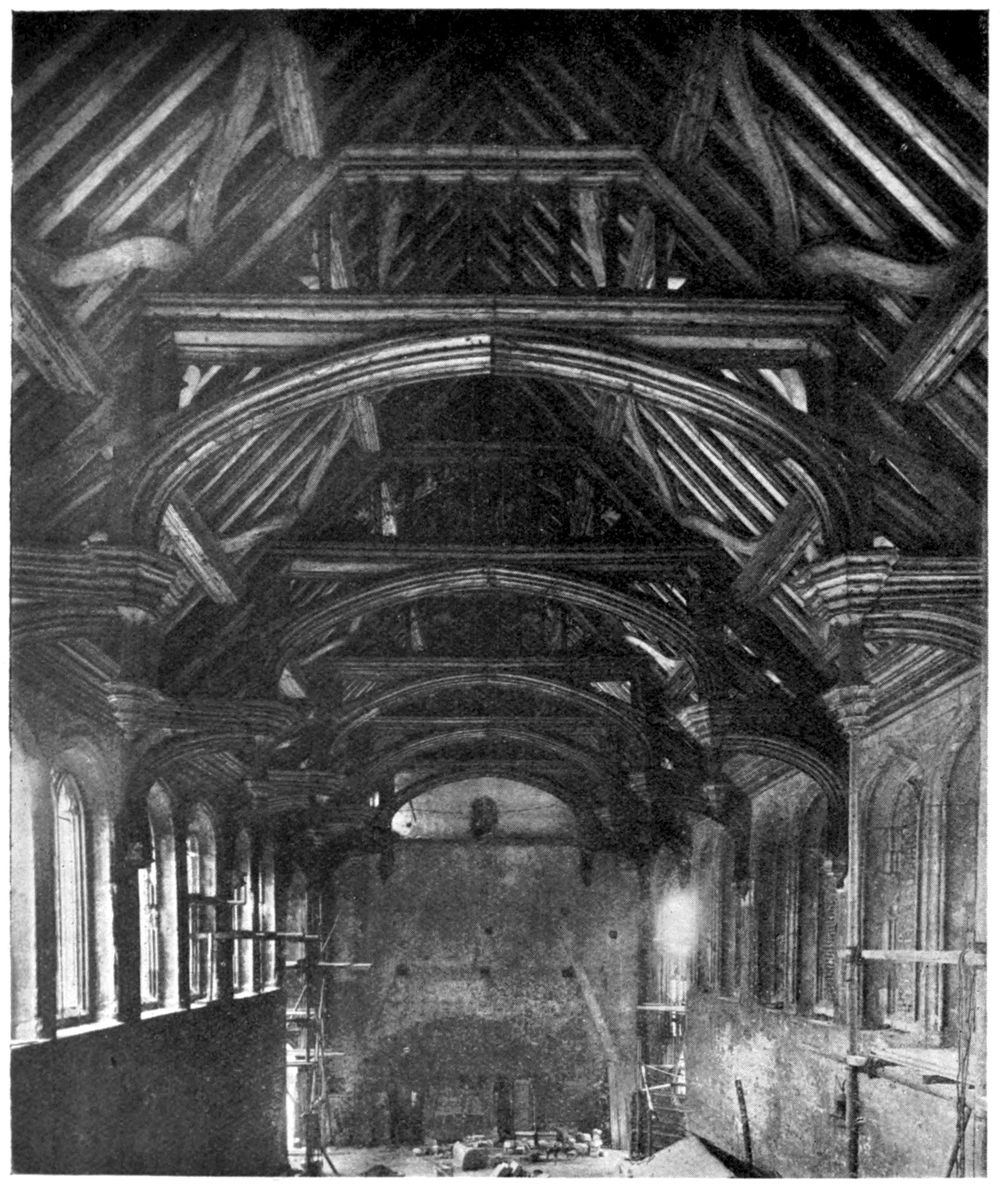

| 22. | Interior of Hall—Photograph by H.M. Office of Works | 56 | |

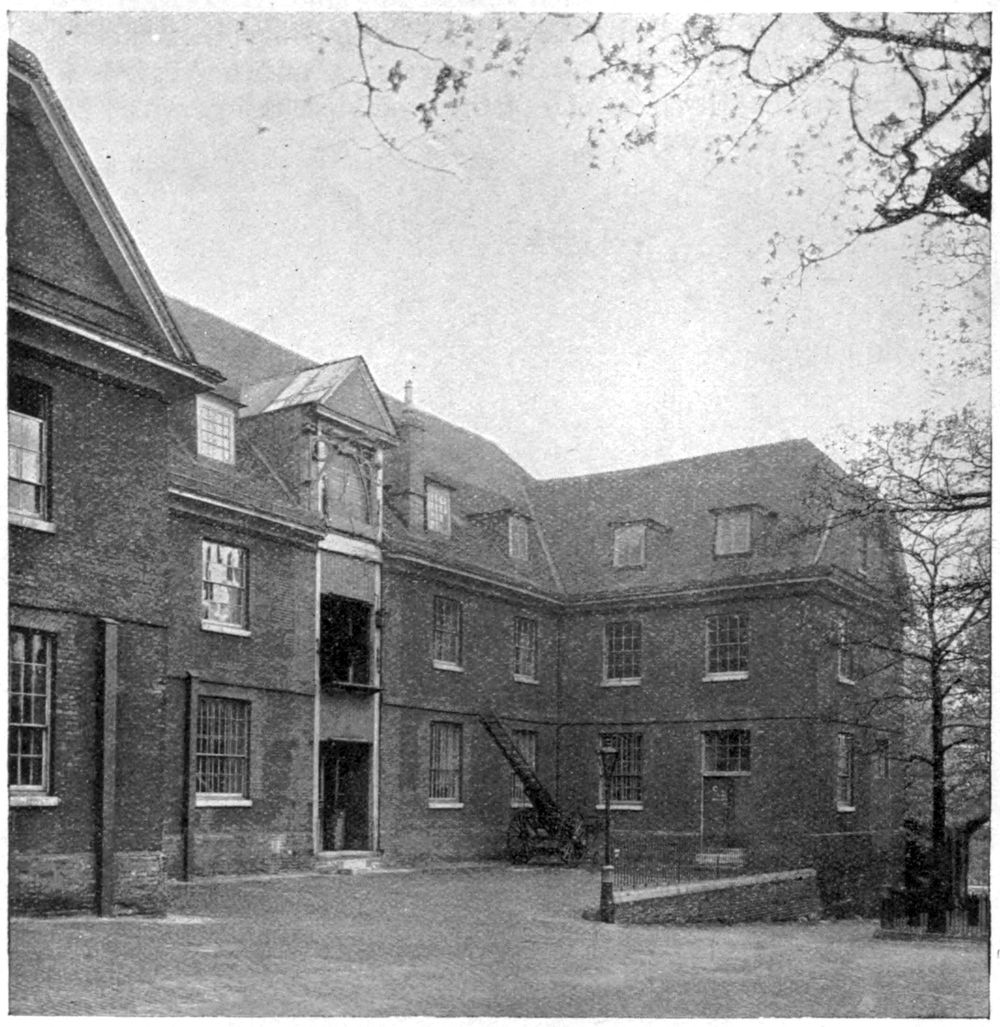

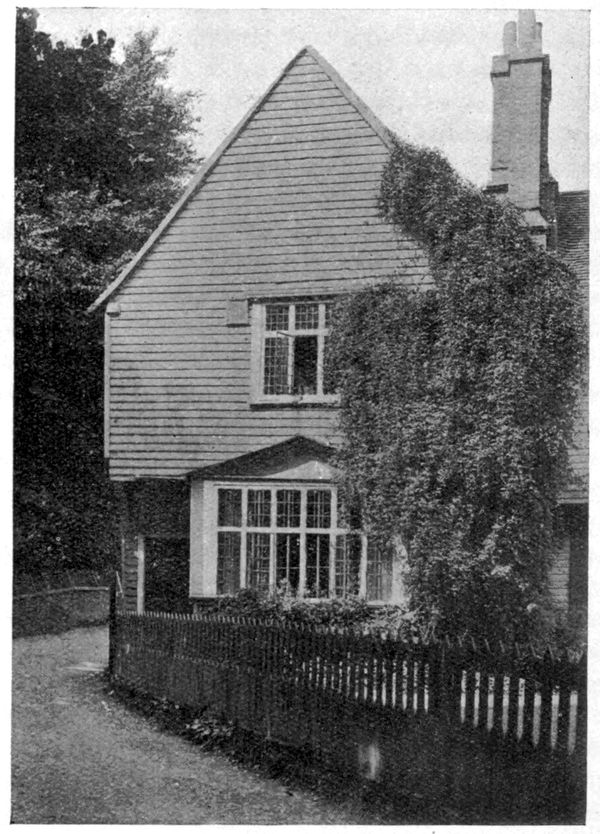

| 23. | The Chancellor’s House—Photograph by F. W. Nunn | 61 | |

| V. | The Origin of the Domestic Hall | 67 | |

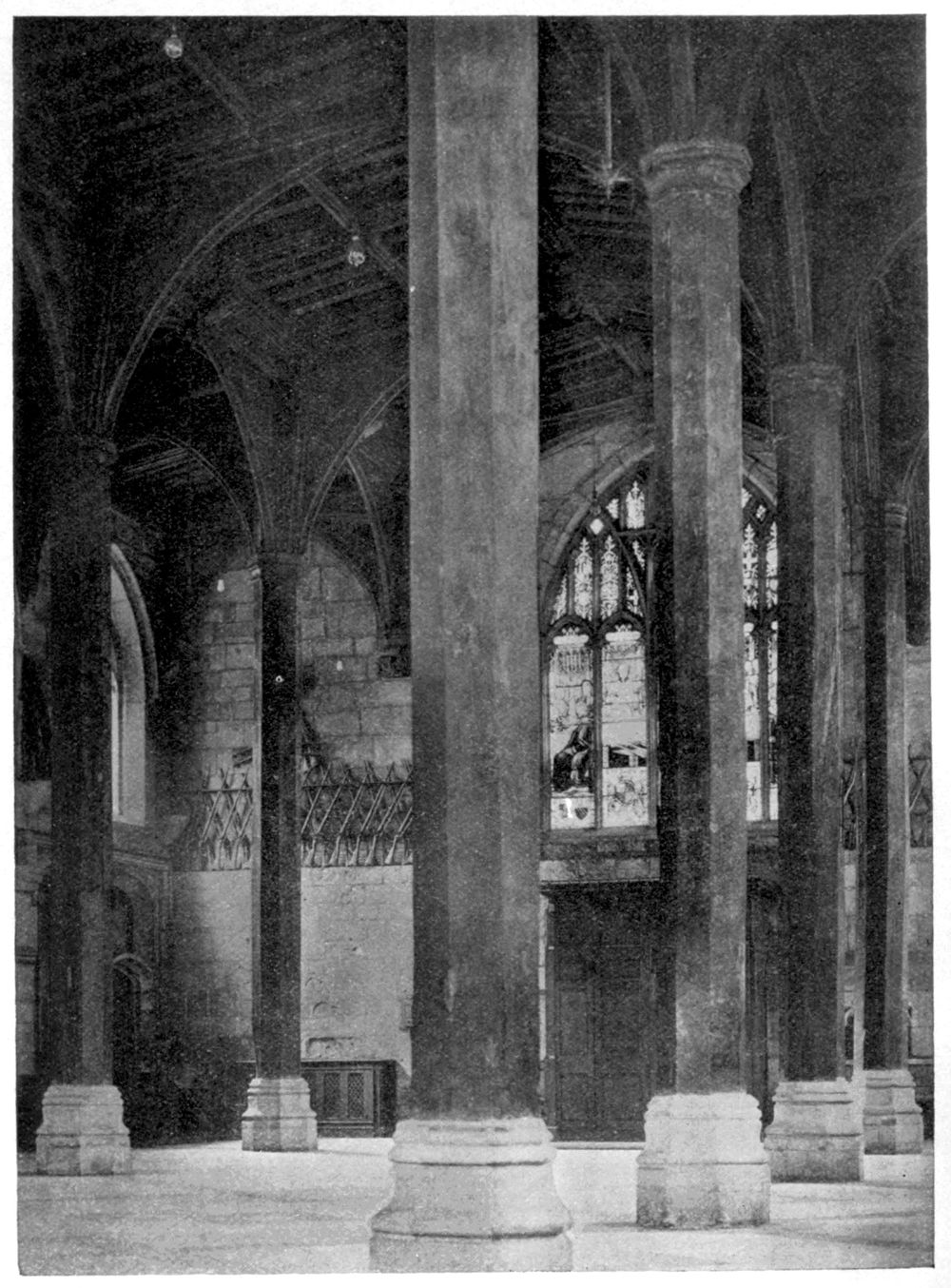

| 24. | The Guildhall, York | 68 | |

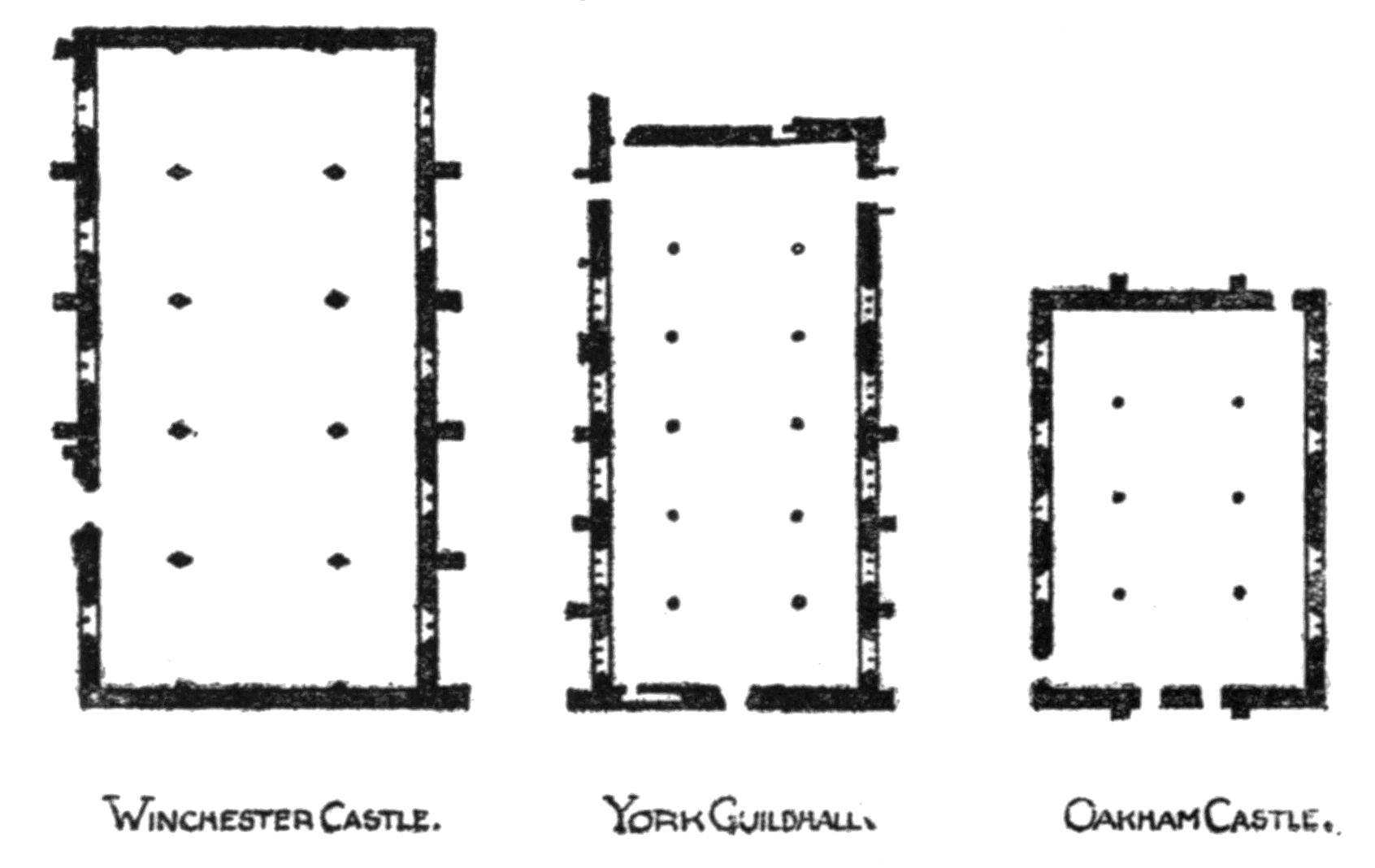

| 25. | Plans of Halls of Winchester Castle, York Guildhall, and Oakham Castle—drawn by A. W. Clapham | 72 | |

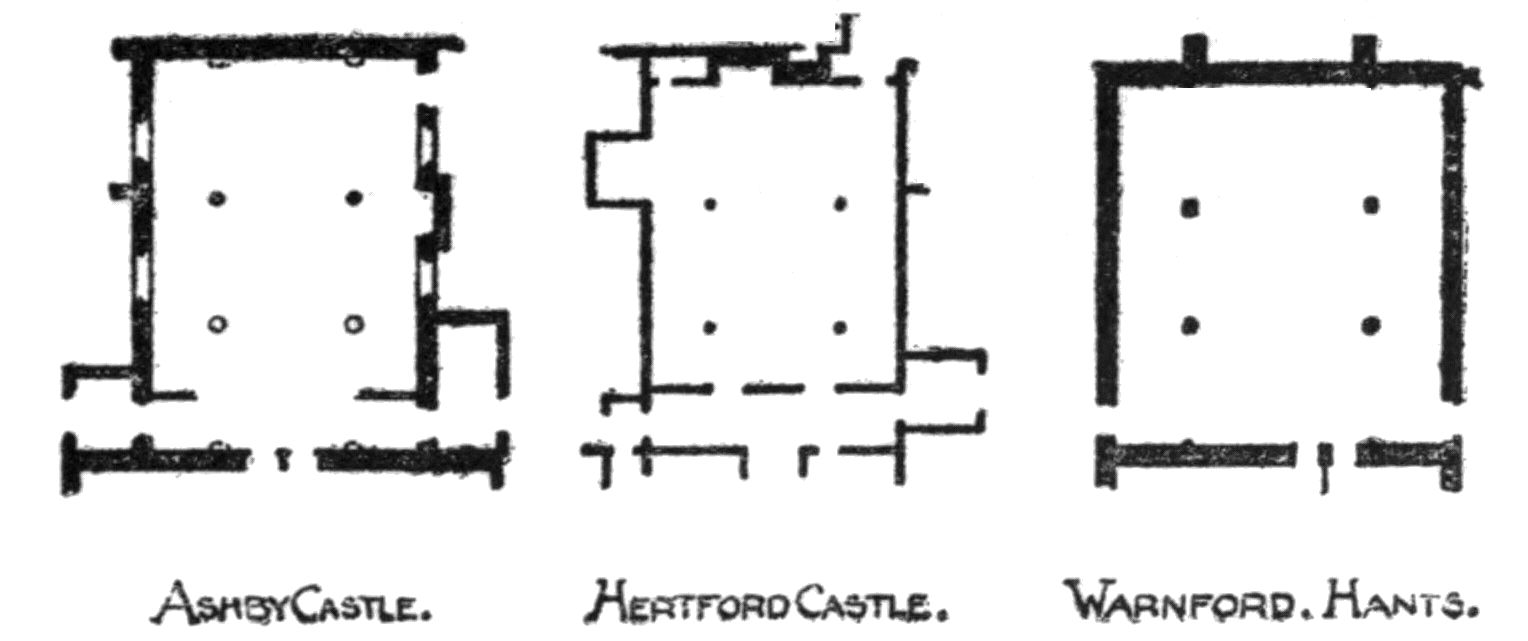

| 26. | Plans of Halls of Ashby Castle, Hertford Castle, and Warnford—drawn by A. W. Clapham | 73 | |

| VI. | Sir Thomas More’s House at Chelsea | 77 | |

| 27. | Sir Thomas More’s Family at Chelsea—by Holbein | 78 | |

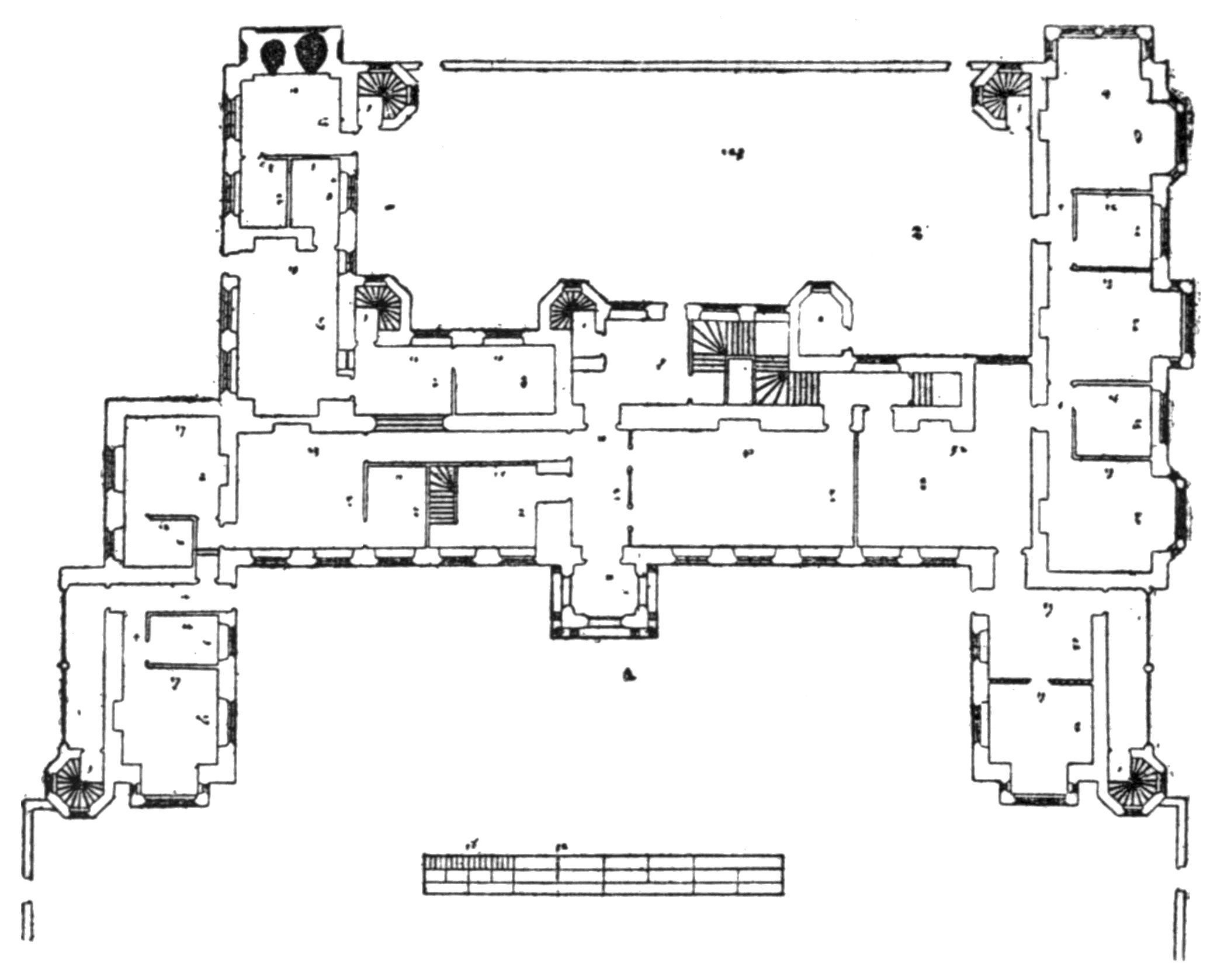

| 28. | Plan of the House (ground floor)—by J. Symonds (c. 1595) | 82 | |

| 29. | Plan of the House (first floor)—by J. Symonds (c. 1595) | 83 | |

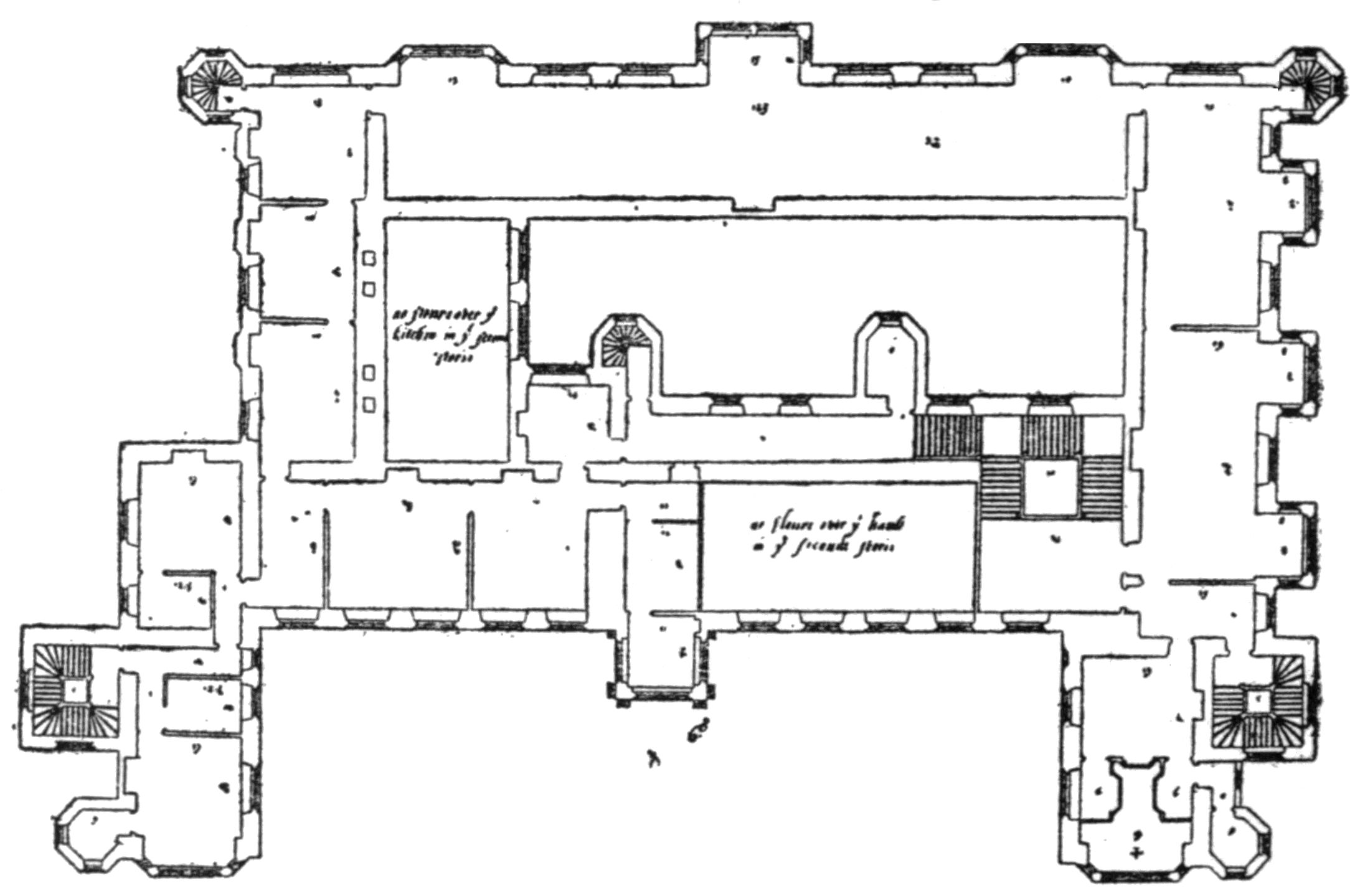

| 30. | Plan for rebuilding (ground floor)—by Spicer (c. 1595) | 86 | |

| 31. | Plan for rebuilding (first floor)—by Spicer (c. 1595) | 87 | |

| 32. | Another First Floor Plan—by Spicer (c. 1595) | 88 | |

| 33. | Estate Plan (c. 1595) | 90 | |

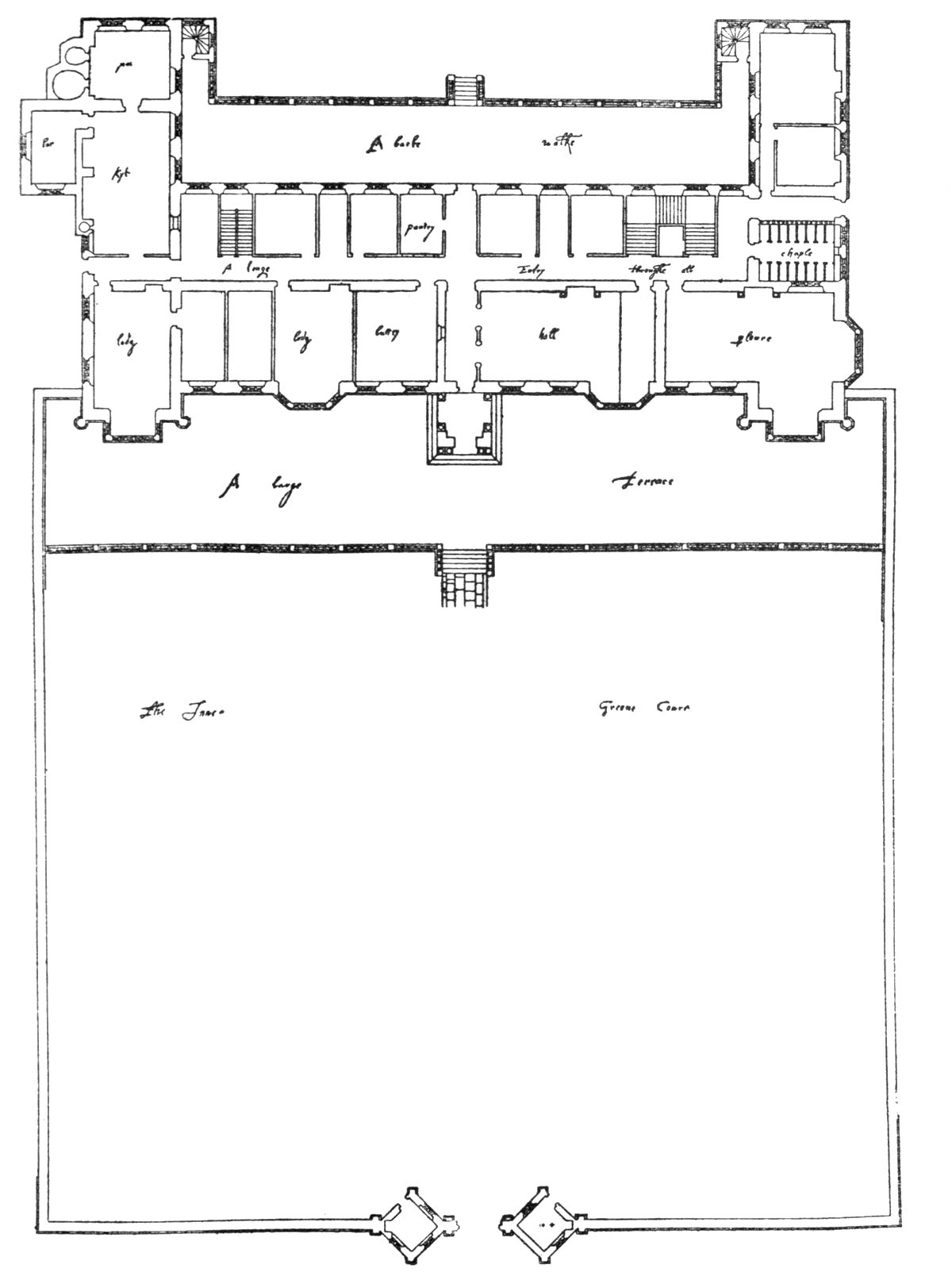

| 34. | Plan of House—by J. Thorpe (c. 1620) | 93 | |

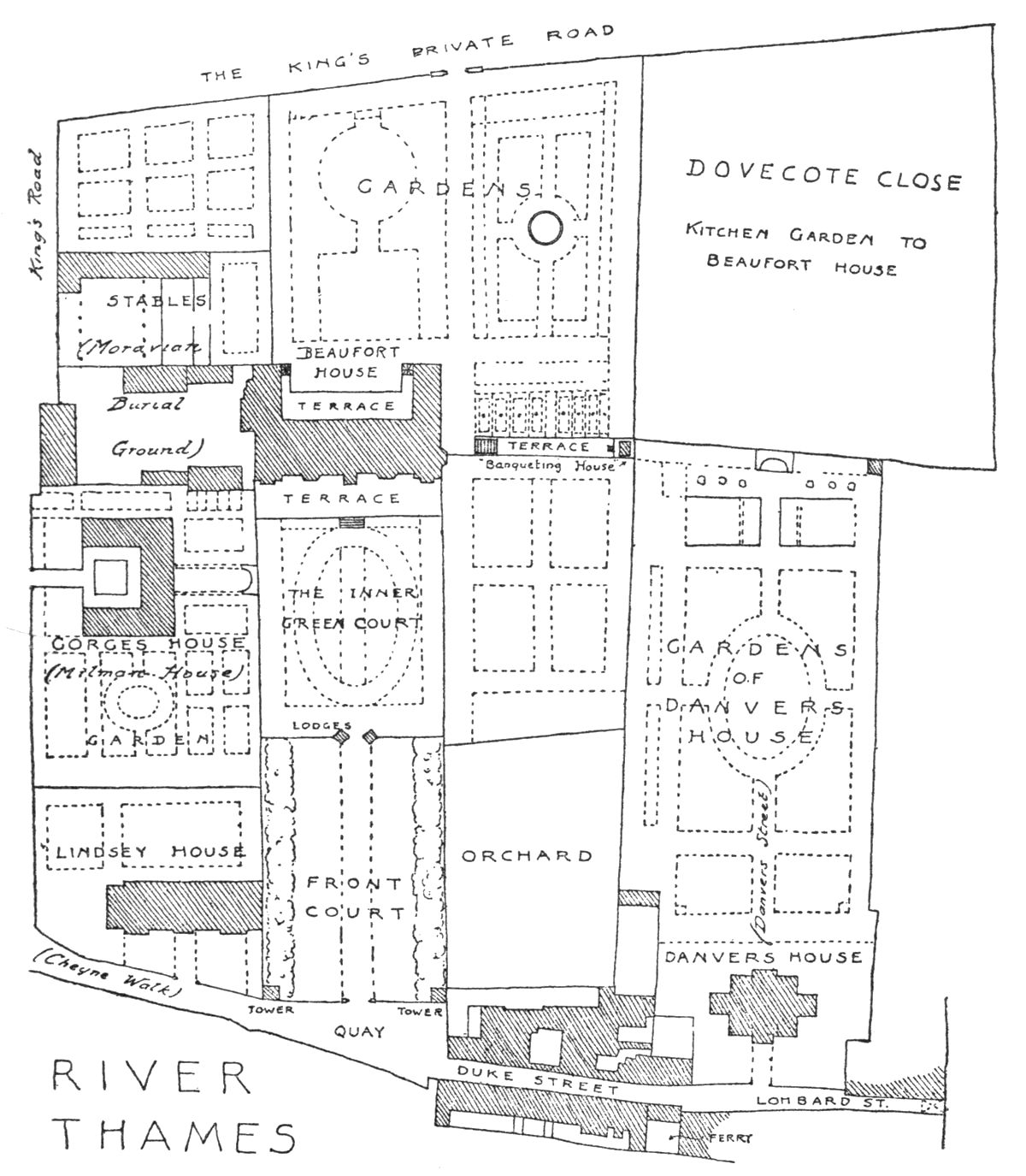

| 35. | Key-plan of Estate—by Walter H. Godfrey | 95 | |

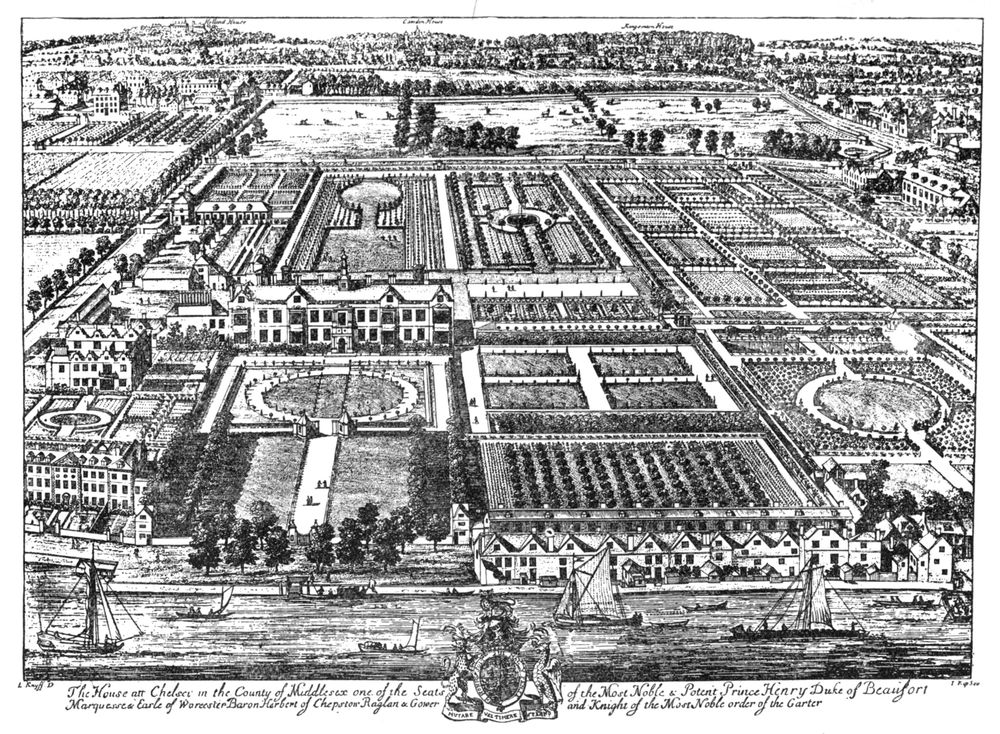

| 36. | Bird’s-eye View of Chelsea Estate—by Kip (1699) | 97 | |

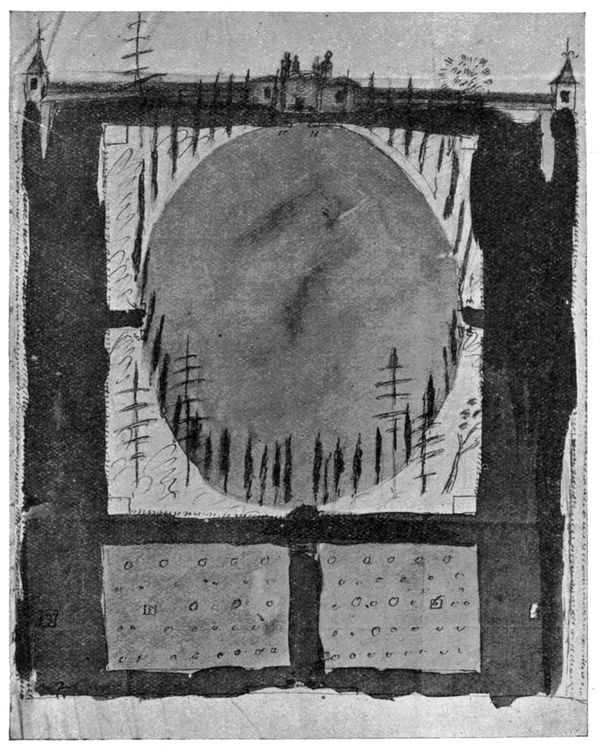

| 37. | Garden of Danvers House—by J. Aubrey | 98 | |

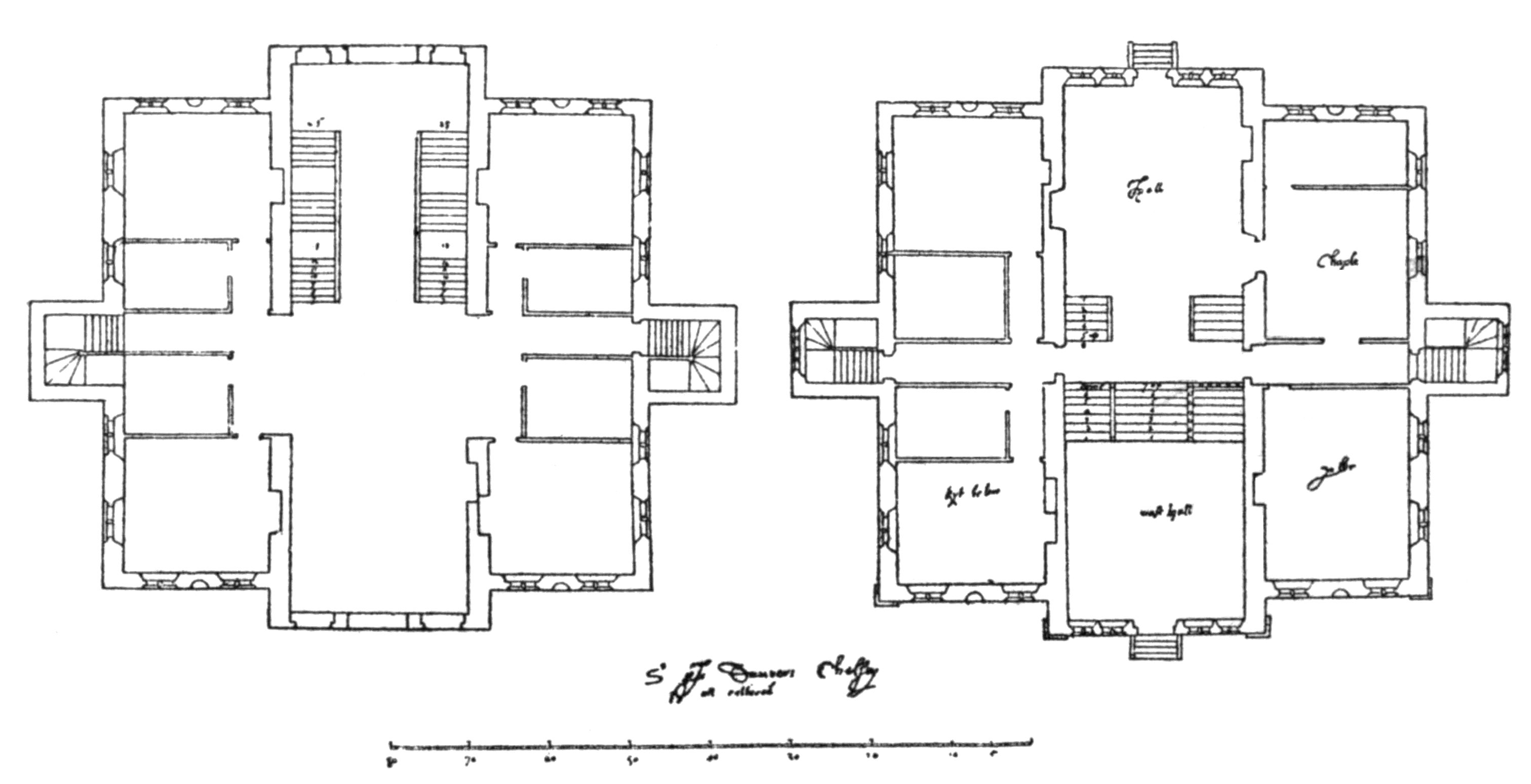

| 38. | Plans of Danvers House—by J. Thorpe (c. 1620) | 100 | |

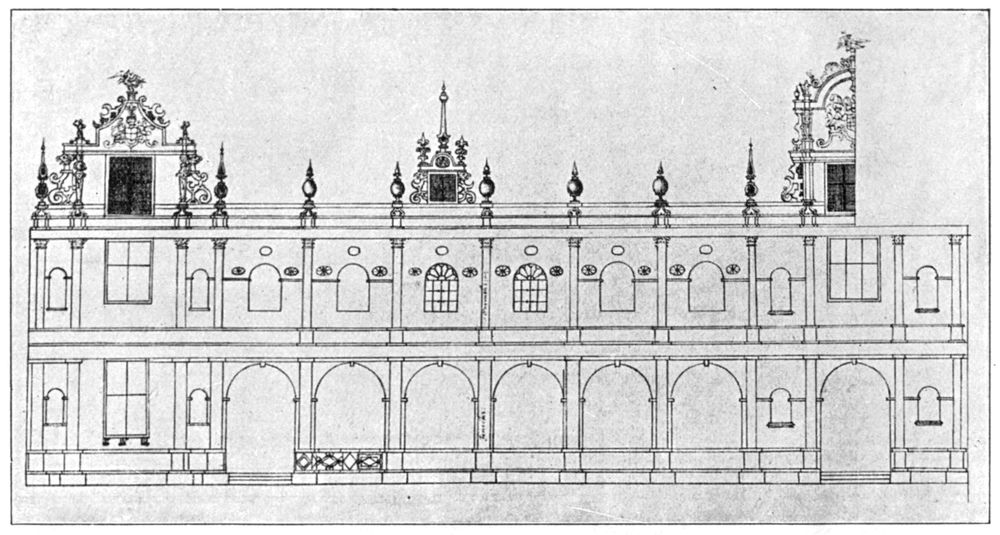

| 39. | Elevation of Danvers House—by J. Thorpe (c. 1620) | 102 | |

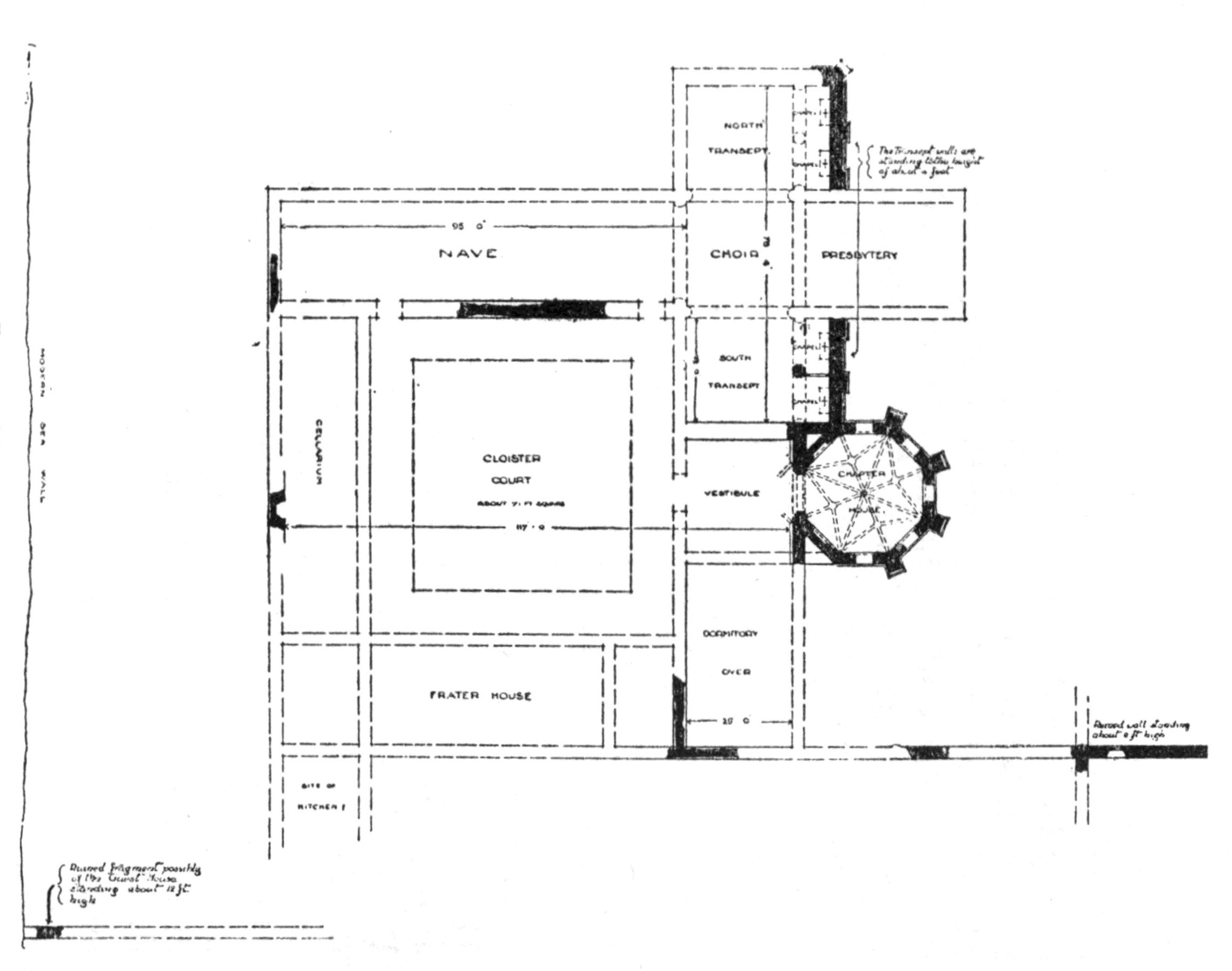

| [ix] VII. | Cockersand Abbey and its Chapter House | 105 | |

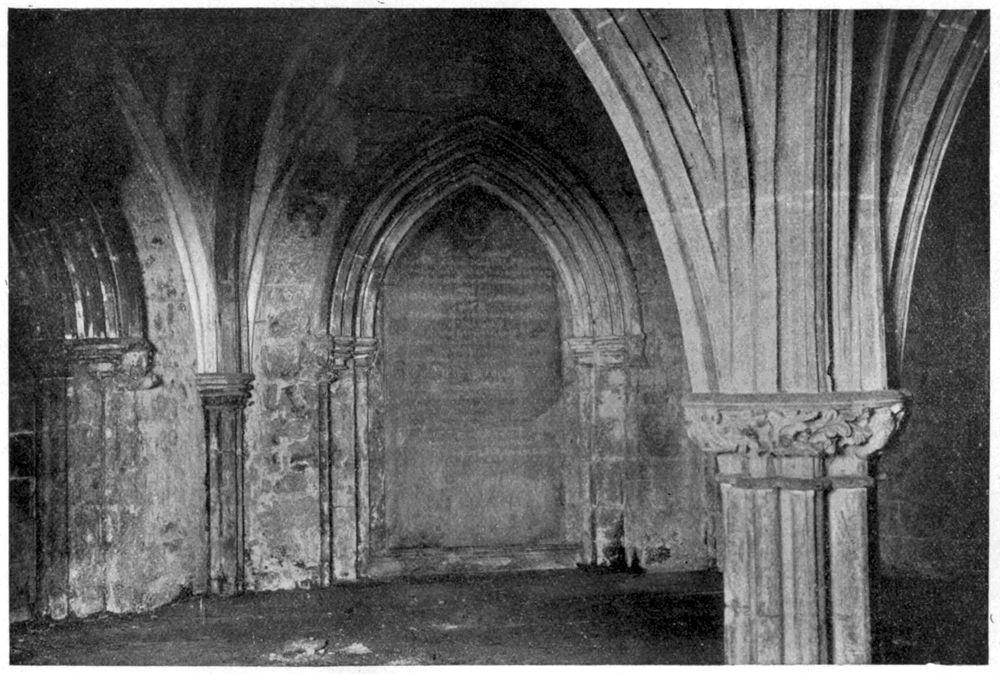

| 40. | Interior of Chapter House | 106 | |

| 41. | Plan of Abbey—by Alfred W. Clapham | 109 | |

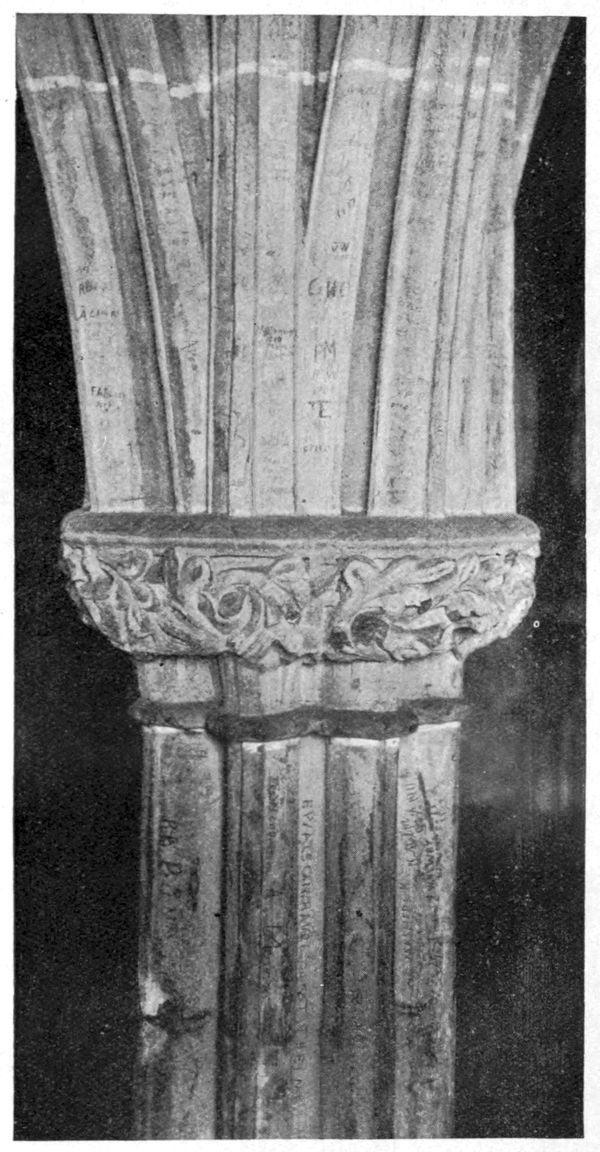

| 42. | Pier-capitals in Chapter House | 111 | |

| 43. | Exterior from West | 112 | |

| 44. | Exterior from East | 112 | |

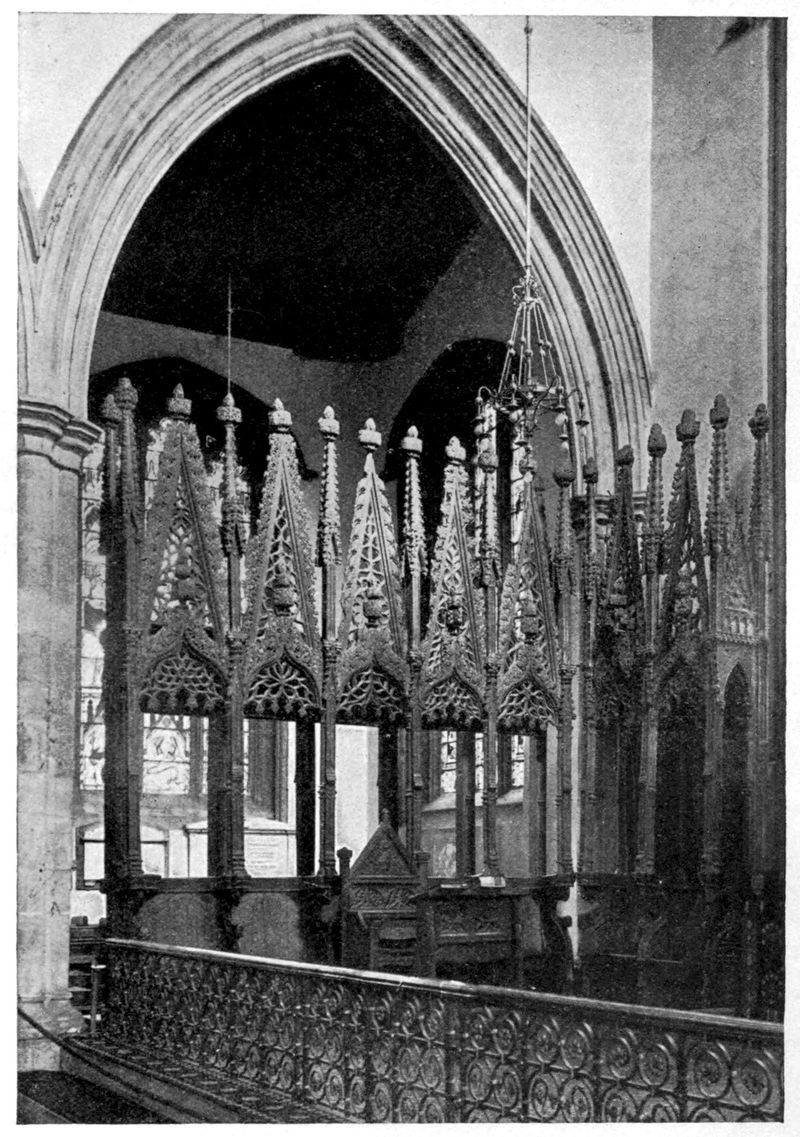

| 45. | Stalls from the Abbey (now in Lancaster) | 115 | |

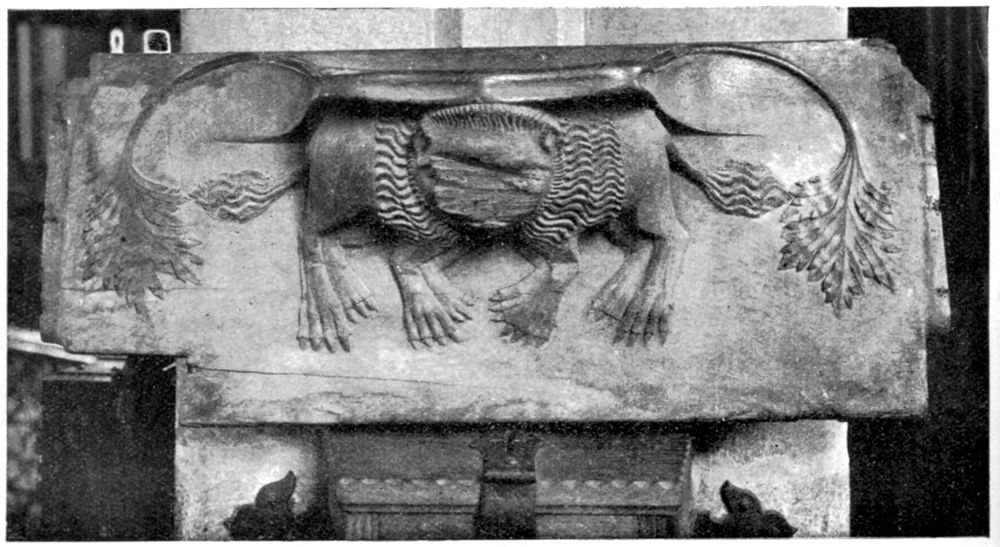

| 46. | Misericorde from Stalls | 116 | |

| 47. | Another Misericorde | 116 | |

| VIII. | The Rebuilding of Crosby Hall at Chelsea | 119 | |

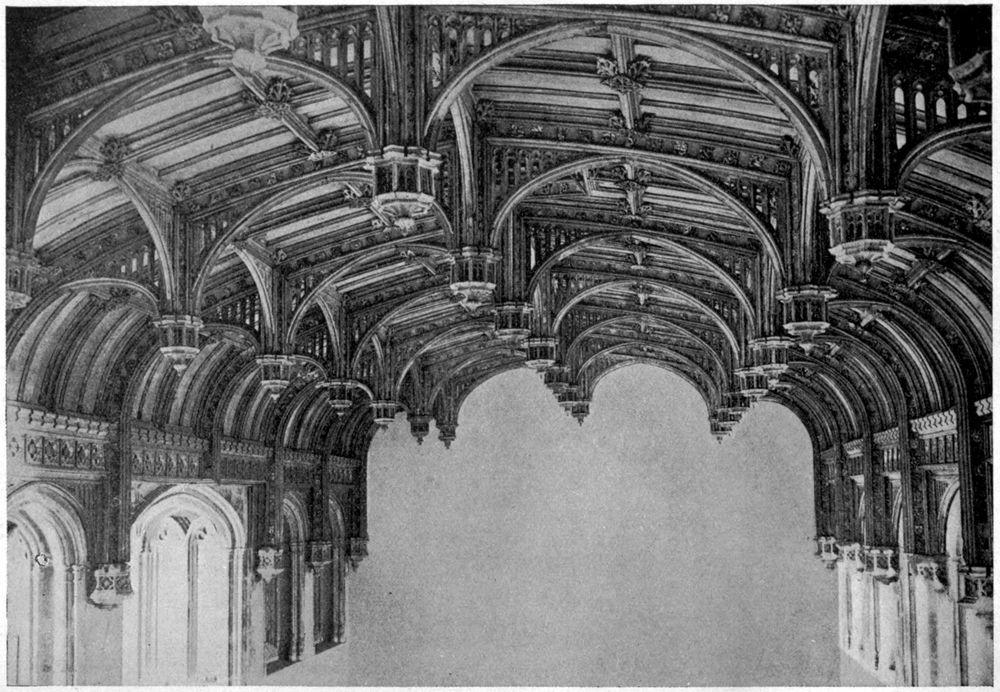

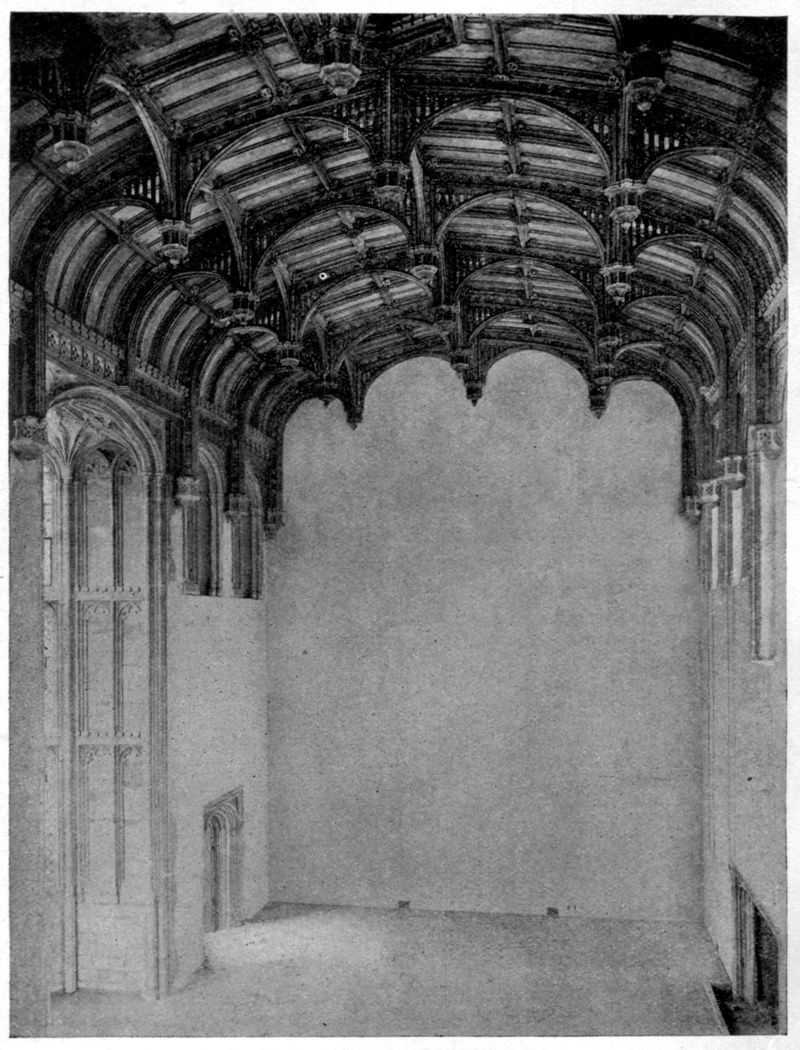

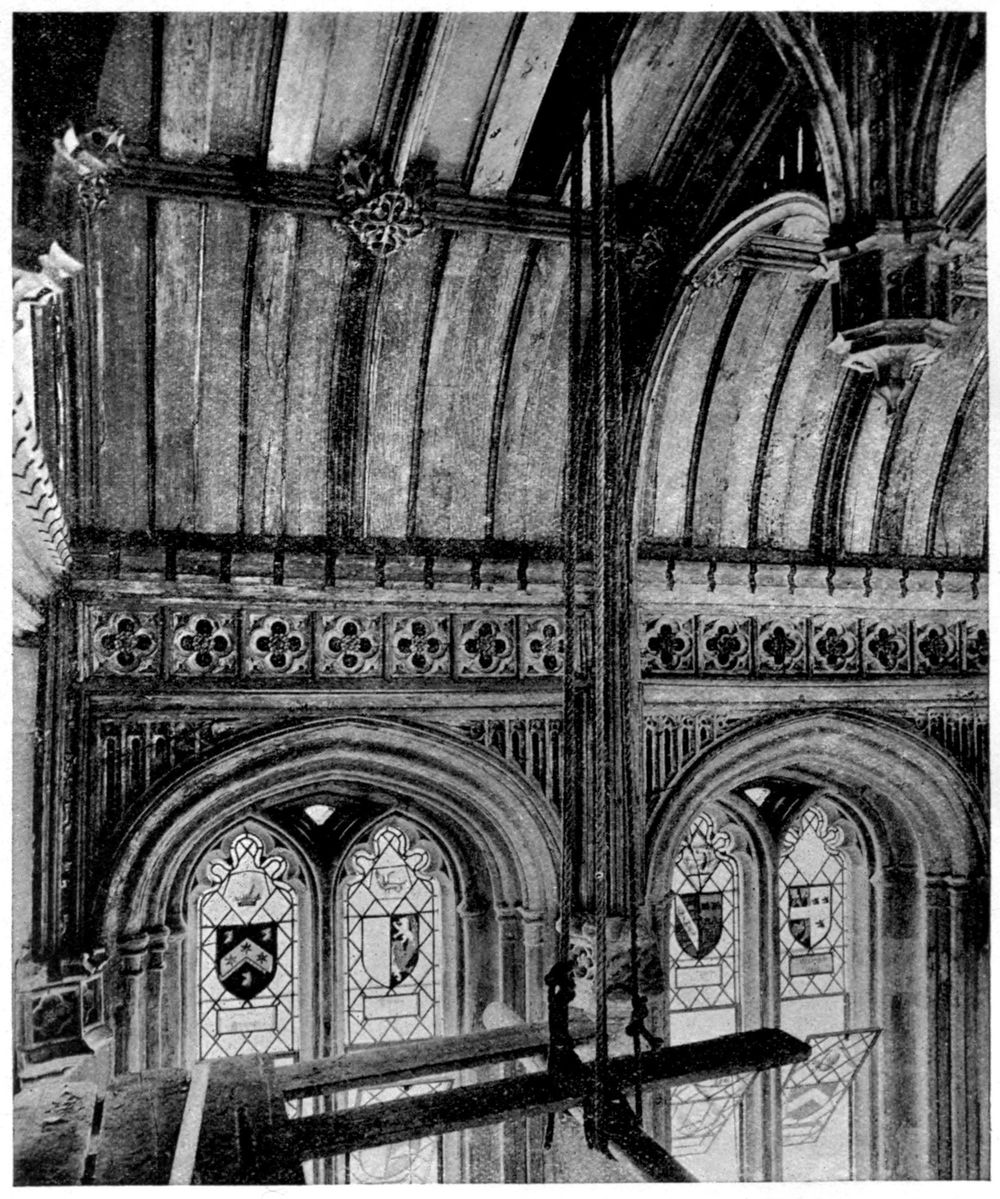

| 48. | The Roof—Photograph by London News Agency | 120 | |

| 49. | Plan of Hall in Bishopsgate—by W. H. Godfrey | 121 | |

| 50. | The Hall from the West—Photograph Architectural Review | 125 | |

| 51. | Interior of Hall—Photograph Architectural Review | 126 | |

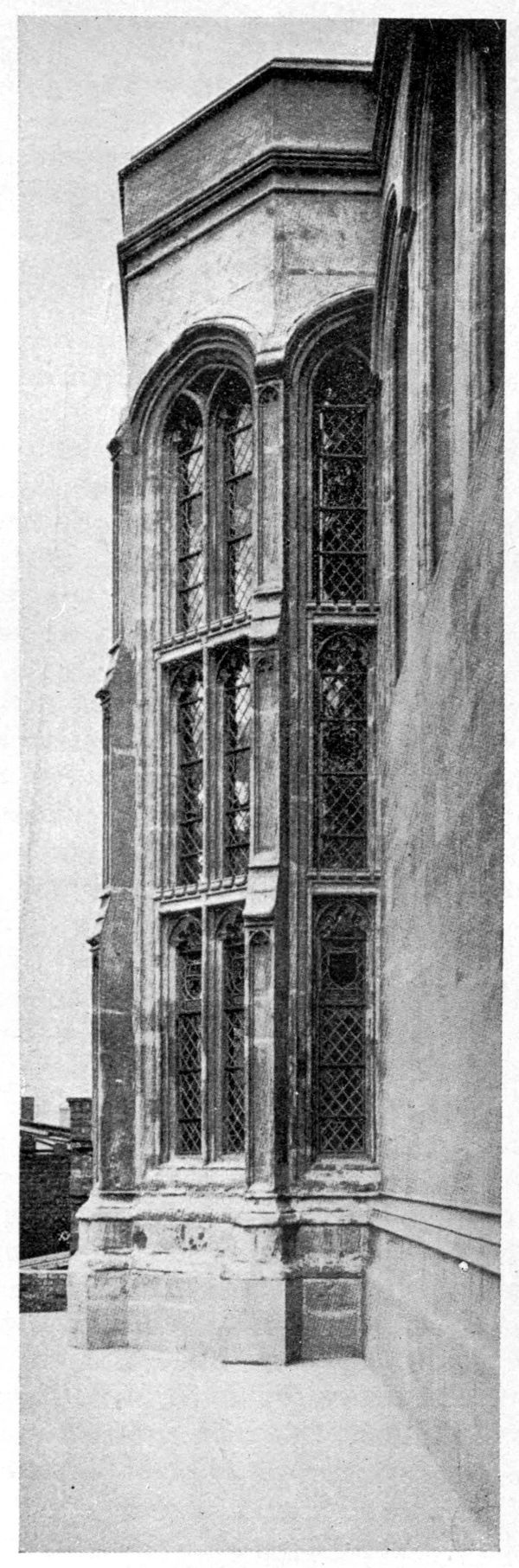

| 52. | The Oriel, Exterior—Photograph Architectural Review | 129 | |

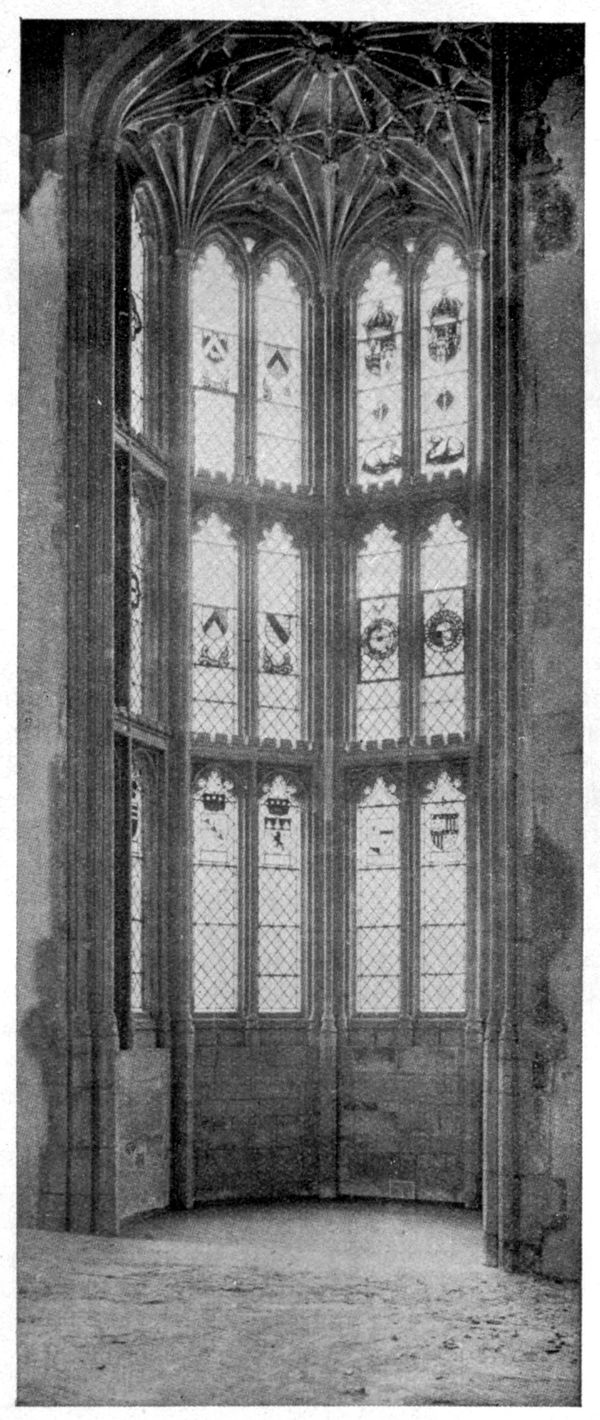

| 53. | The Oriel, Interior—Photograph Architectural Review | 130 | |

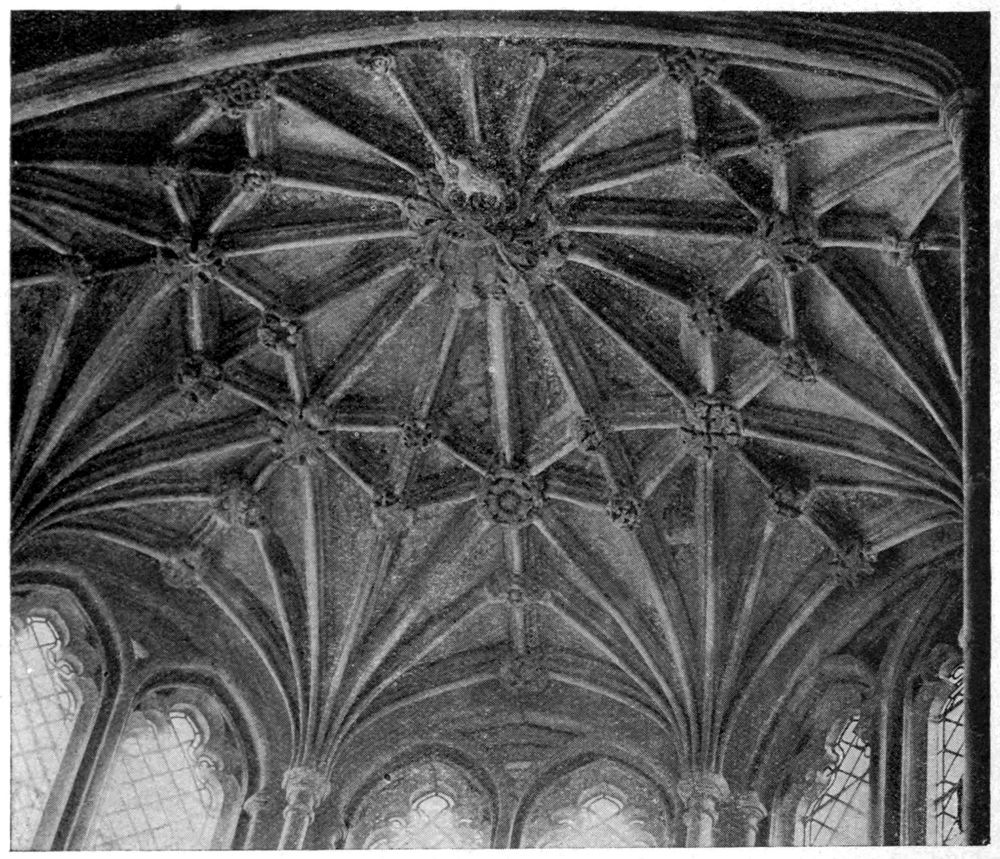

| 54. | Vault of Oriel—Photograph Architectural Review | 133 | |

| 55. | Detail of Roof and Window—Photograph Architectural Review | 134 | |

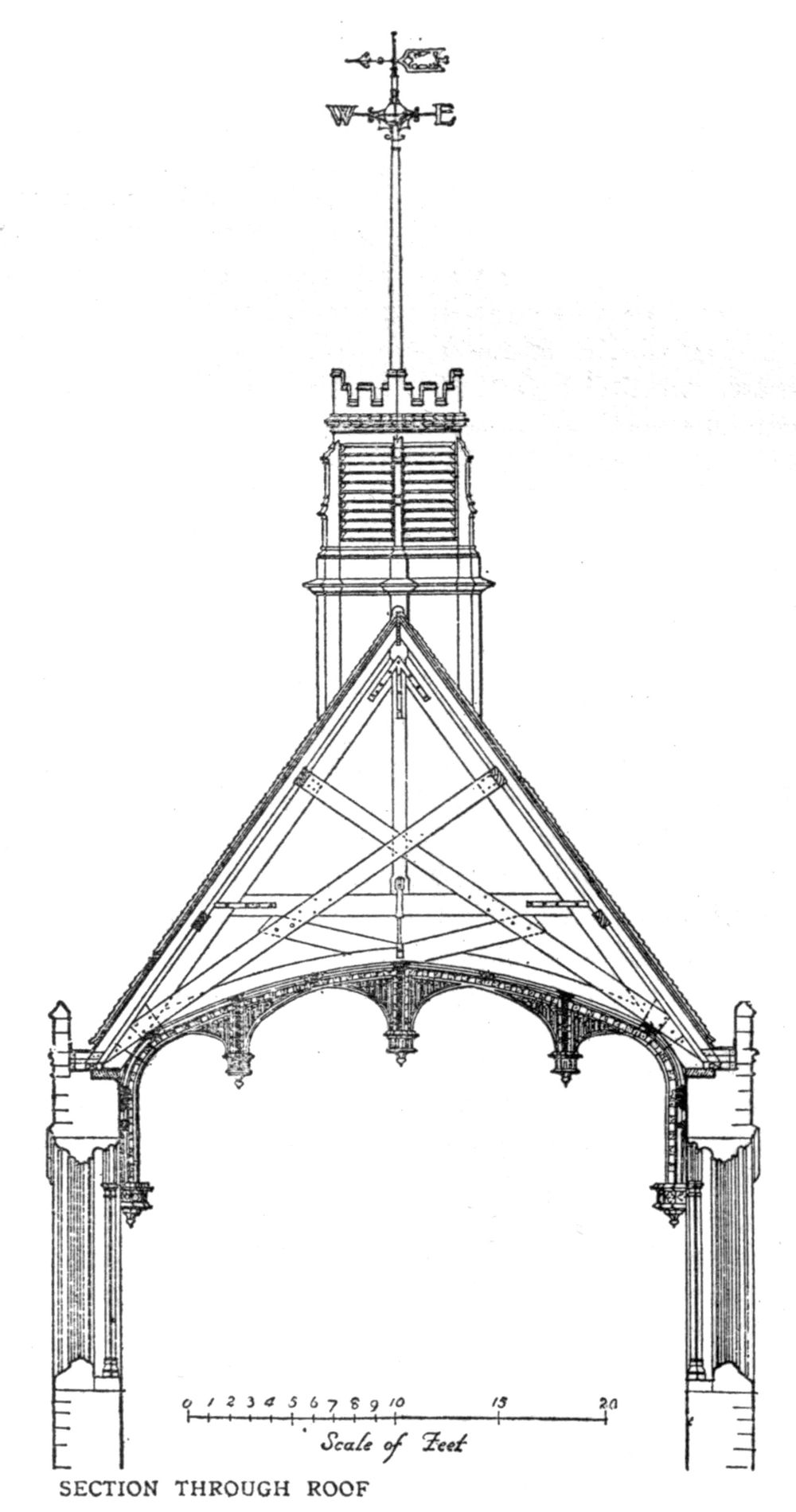

| 56. | Section through Roof | 136 | |

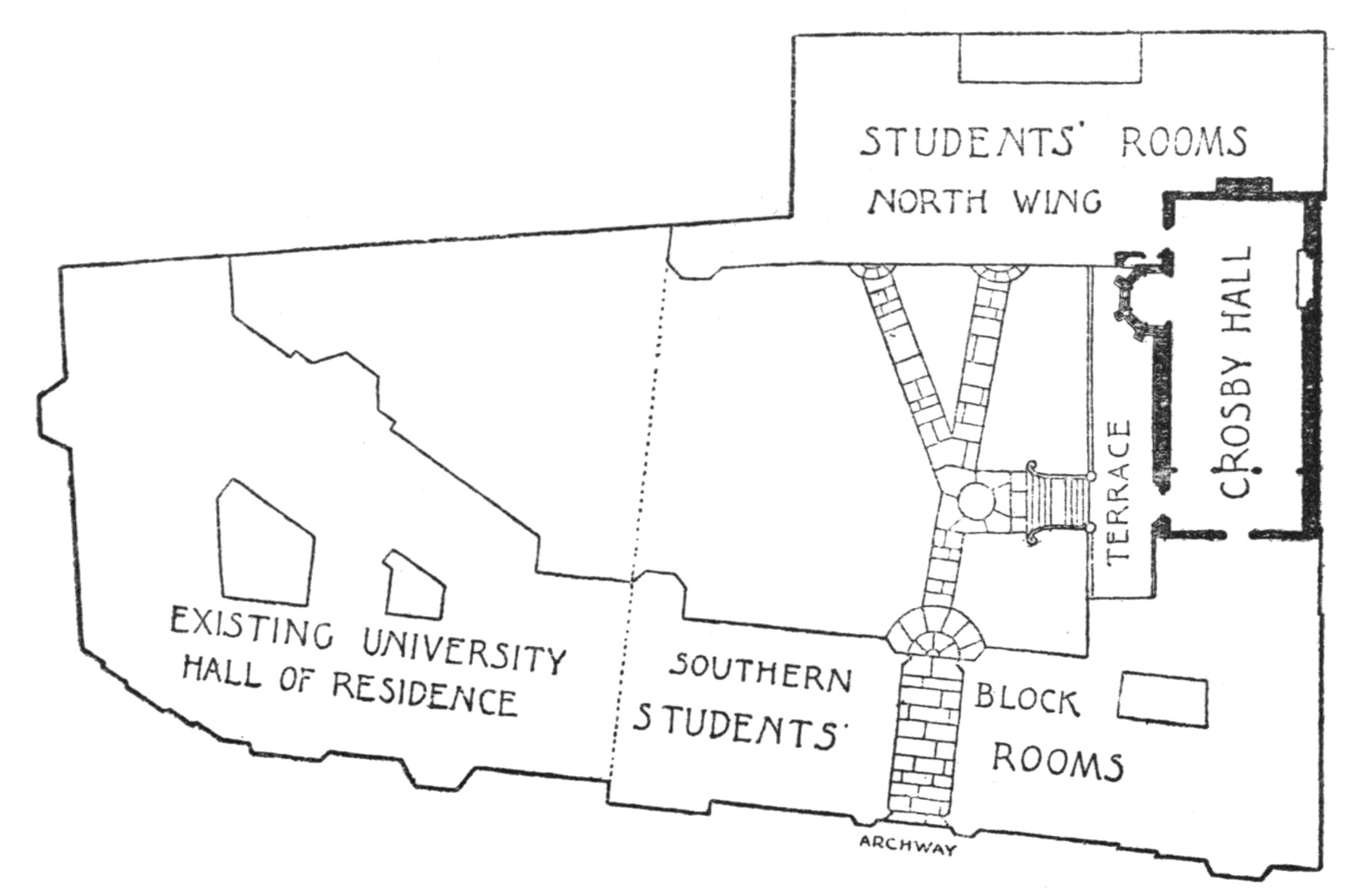

| 57. | Plan of Hall at Chelsea | 137 | |

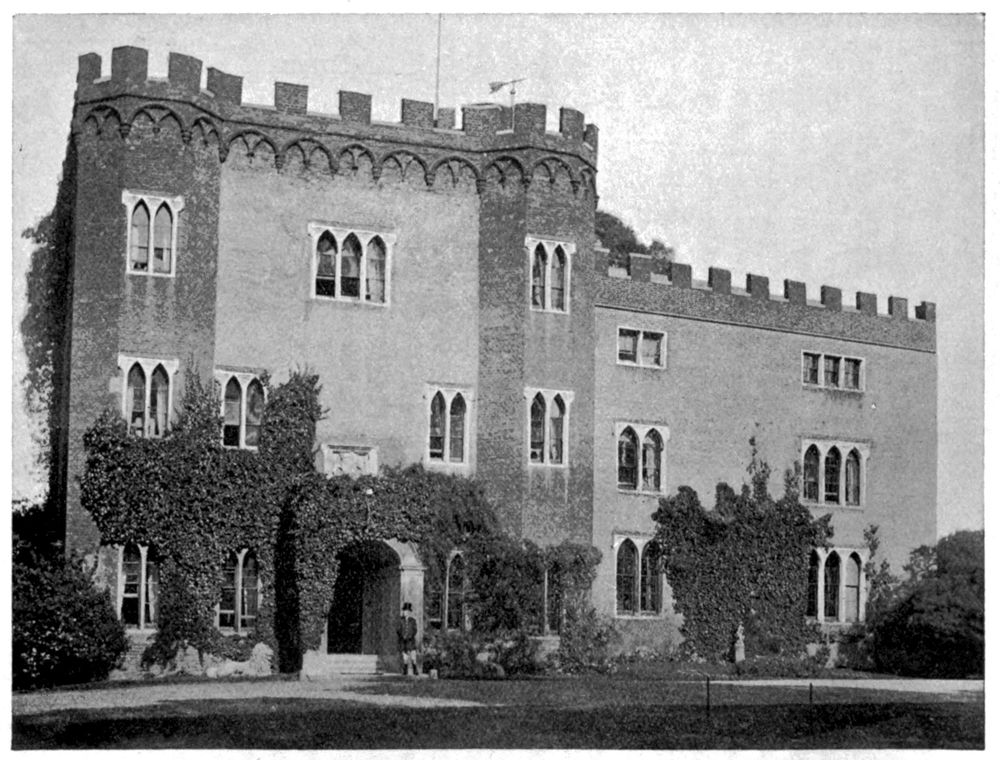

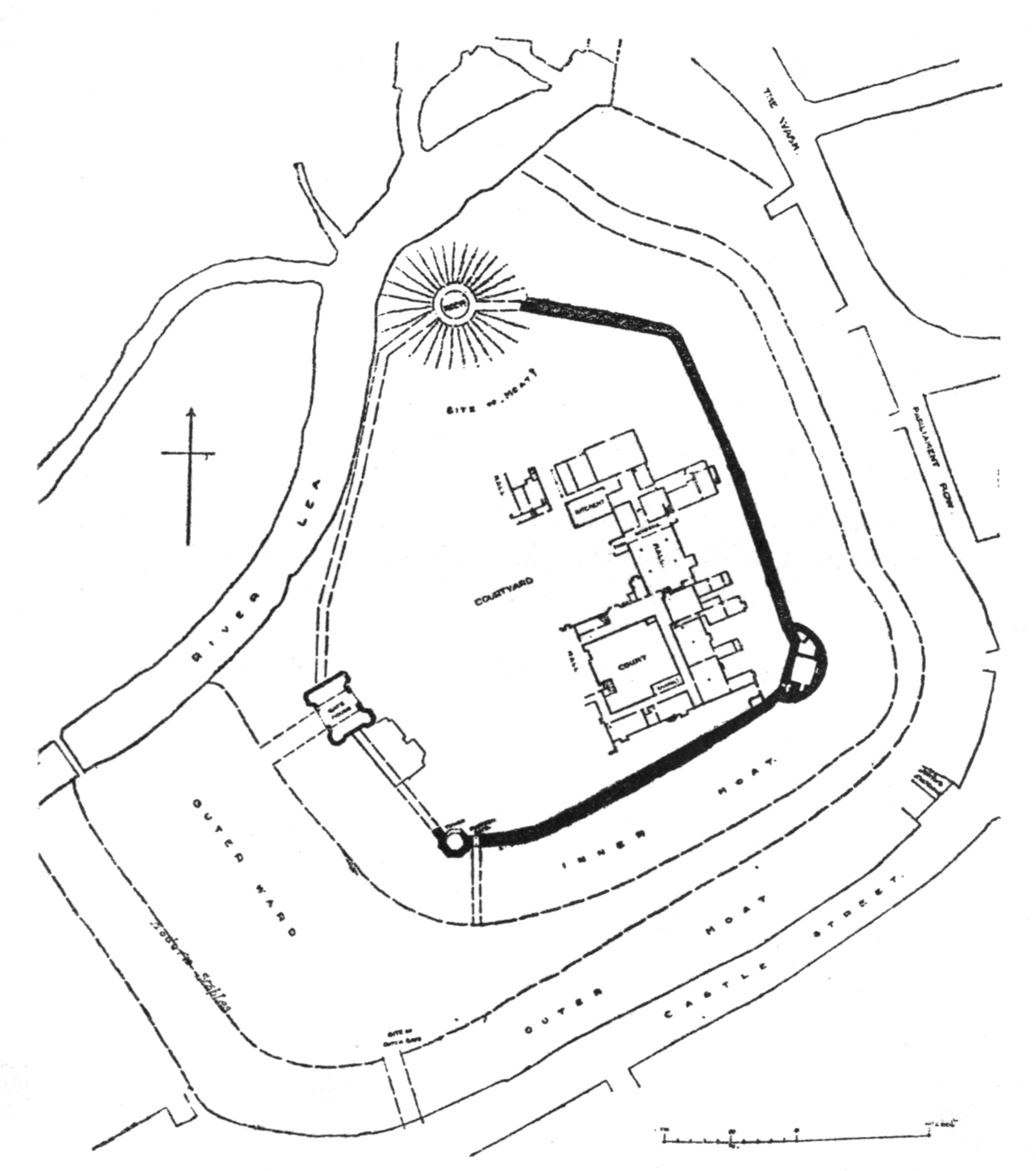

| IX. | The Palaces of Hertford and Havering | 139 | |

| 58. | Gatehouse, Hertford | 140 | |

| 59. | Ground Plan, Hertford (Public Record Office) | 142 | |

| 60. | Plan of Fortifications—by A. W. Clapham | 143 | |

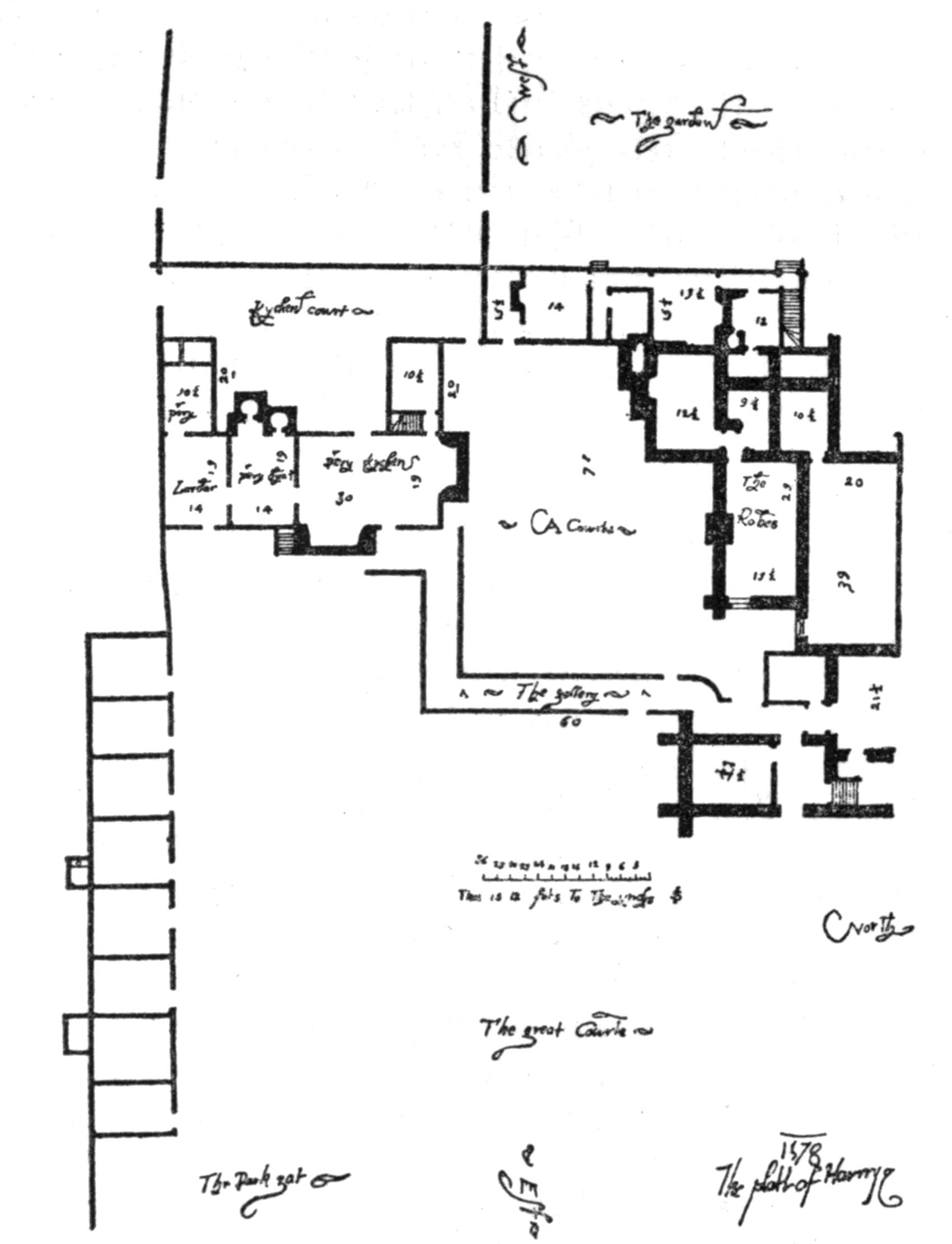

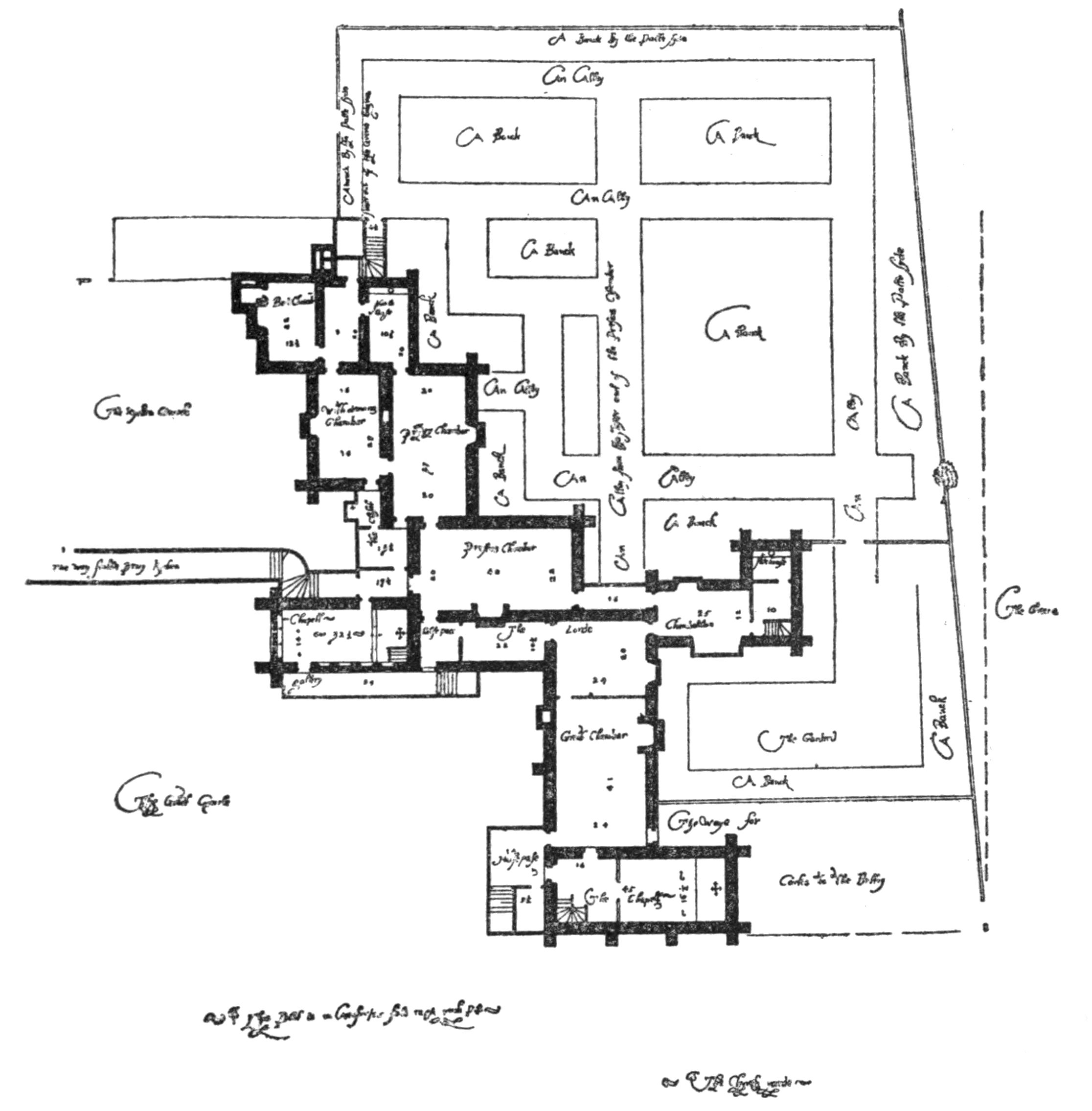

| 61. | Havering, ground plan (British Museum) | 148 | |

| 62. | Havering, first floor (Hatfield MSS.) | 149 | |

| X. | The New Exchange in the Strand | 151 | |

| 63. | Elevation of Building (c. 1610)—by Smithson | 152 | |

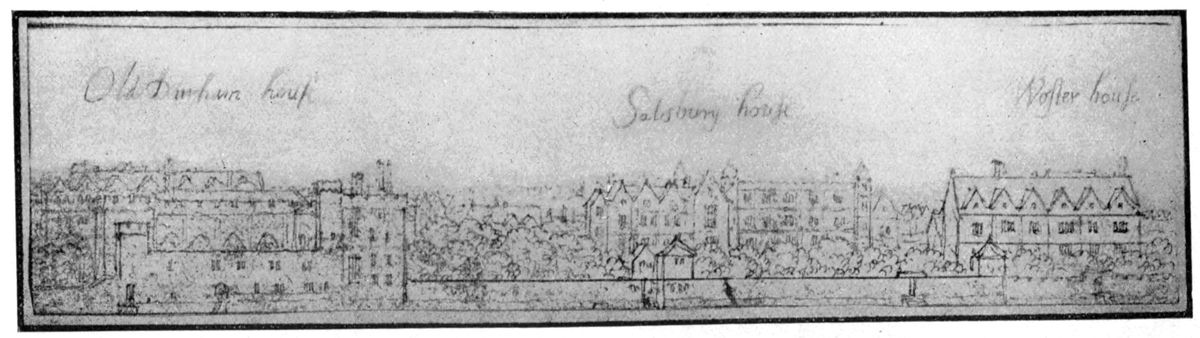

| 64. | Durham House and Salisbury House—by Hollar (Pepysian Library, Cambridge) | 155 | |

| 65. | Durham House—from Faithorne’s map | 156 | |

| 66. | West Central London—from Hollar’s map | 156 | |

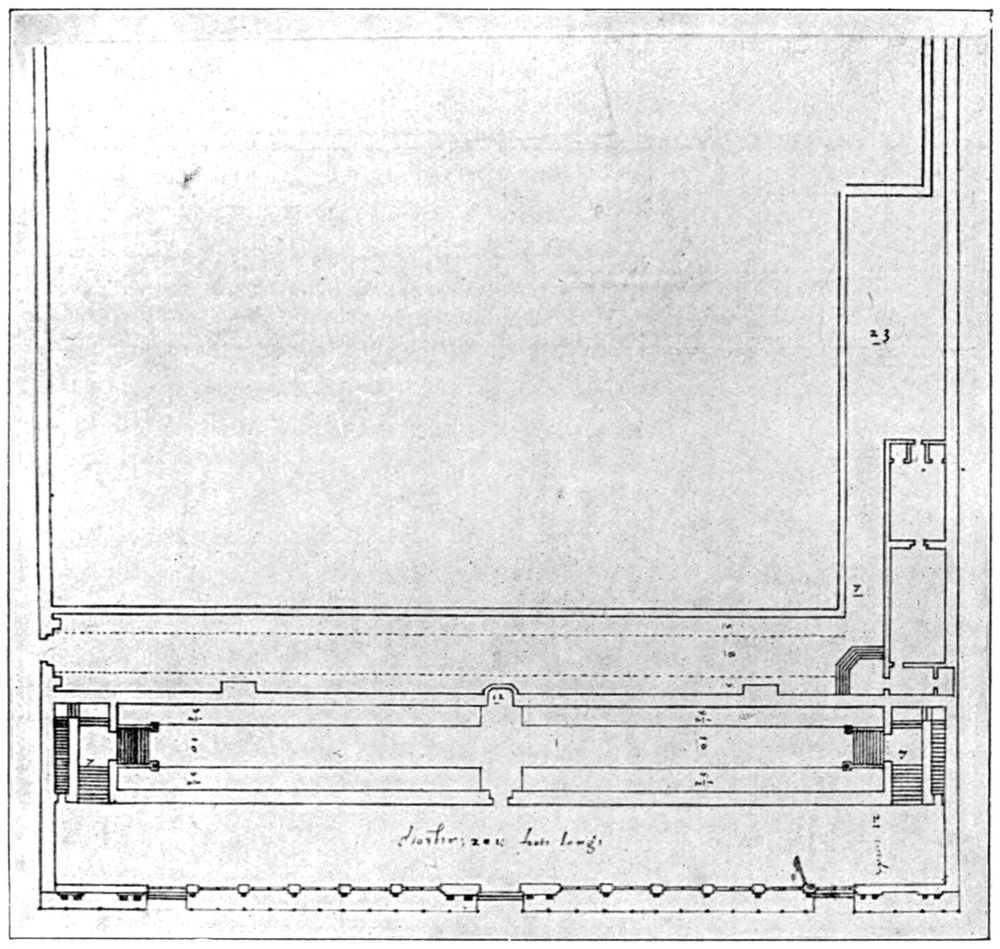

| [x] | 67. | MS. Plan of Durham House and the New Exchange (1626) | 158 |

| 68. | Plan of New Exchange (c. 1610)—by Smithson | 161 | |

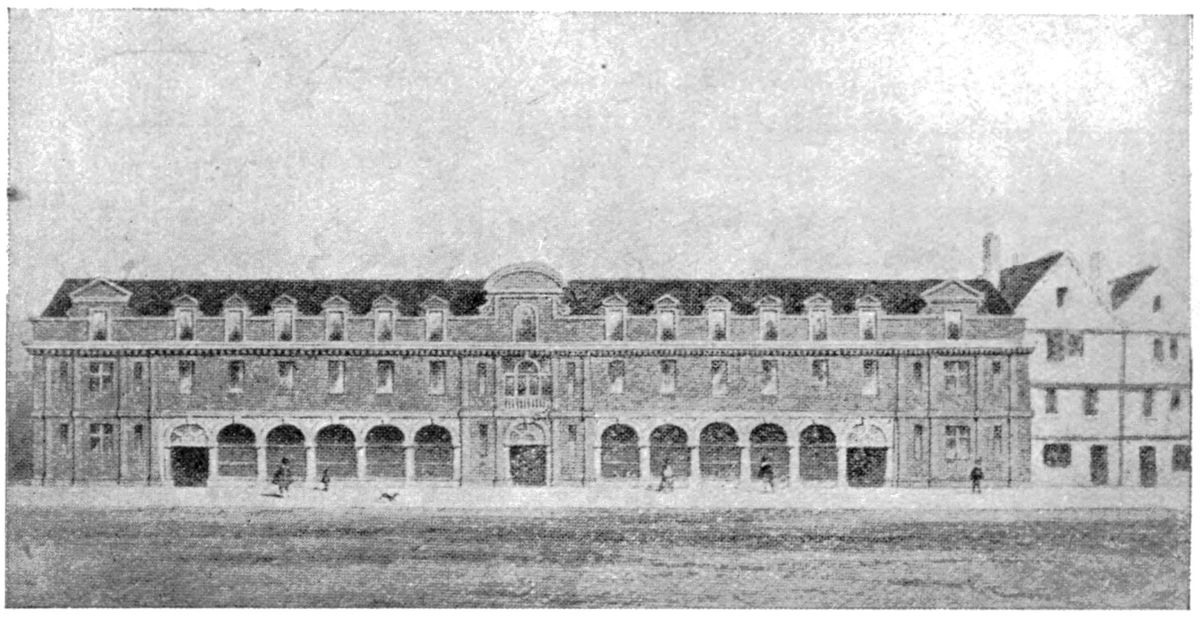

| 69. | The New Exchange—by T. Hosmer Shepherd | 162 | |

| 70. | Plan of Site of Durham House (Stow’s Survey, Ed. 1720) | 162 | |

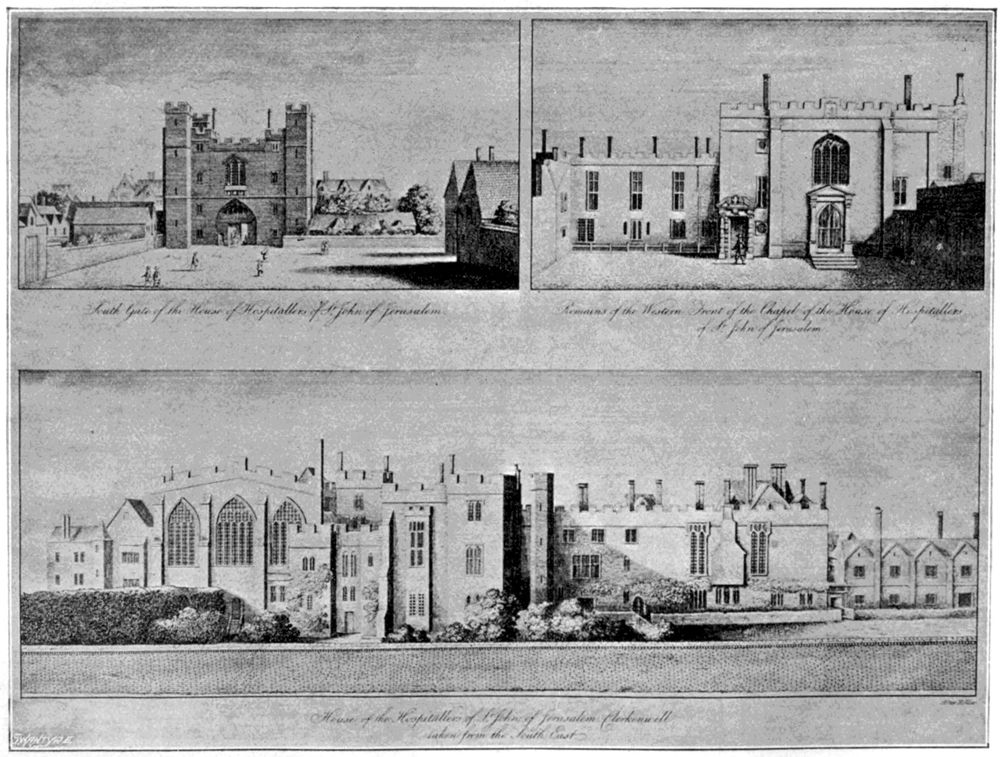

| XI. | St. John of Jerusalem, Clerkenwell | 165 | |

| 71. | The Monastic Buildings—by Hollar | 166 | |

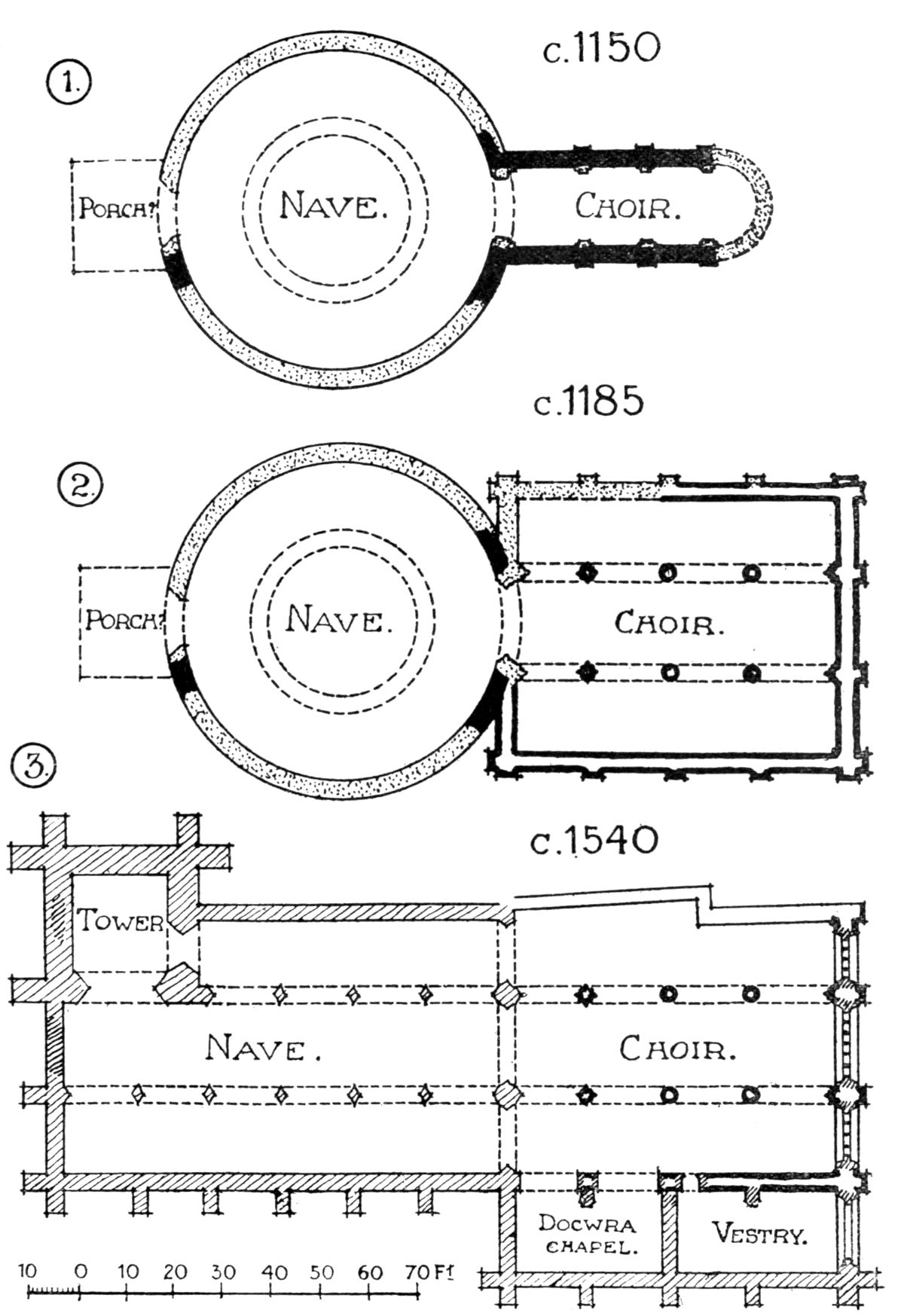

| 72. | Plans showing development of the Church—drawn by A. W. Clapham | 169 | |

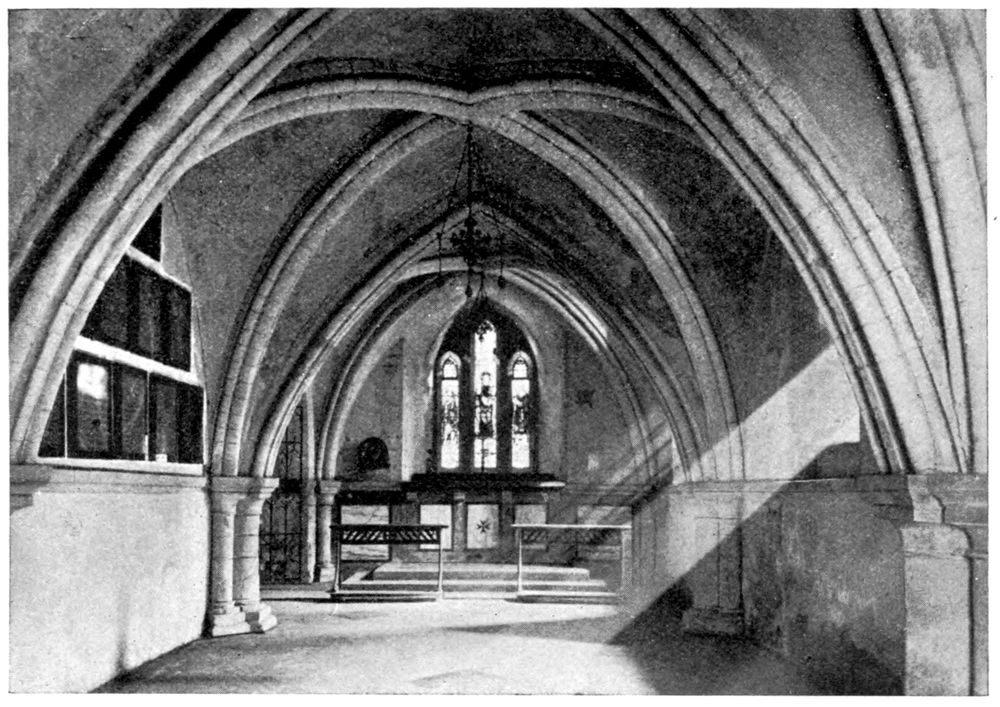

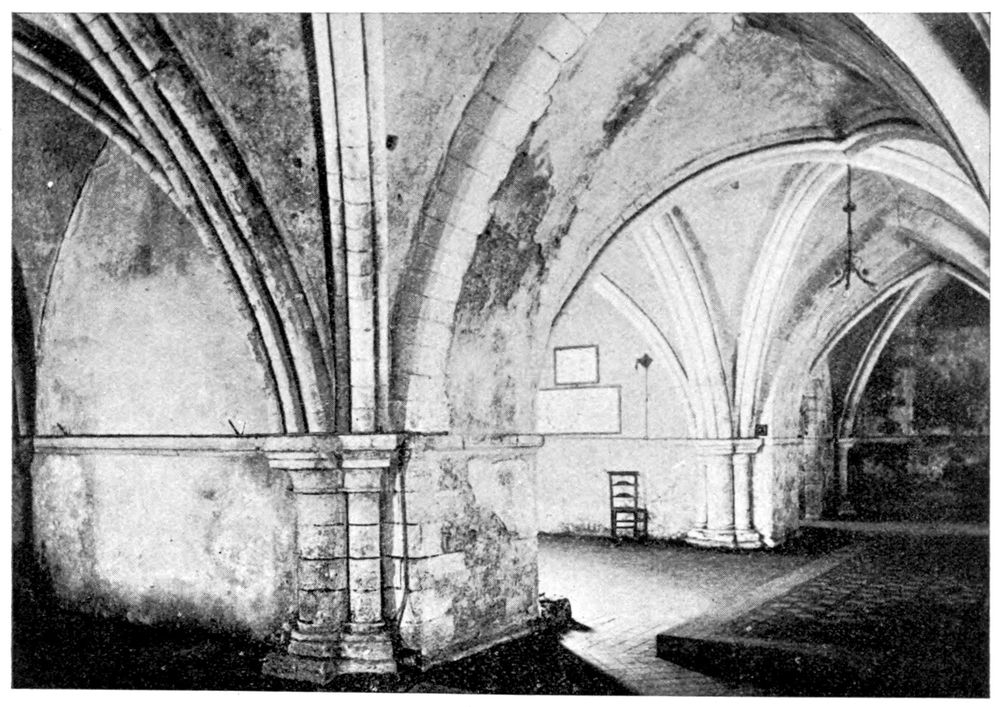

| 73. | The Crypt looking East—Photograph by H. W. Fincham | 170 | |

| 74. | East end of Crypt—Photograph by H. W. Fincham | 173 | |

| 75. | South Chapel, Crypt—Photograph by H. W. Fincham | 173 | |

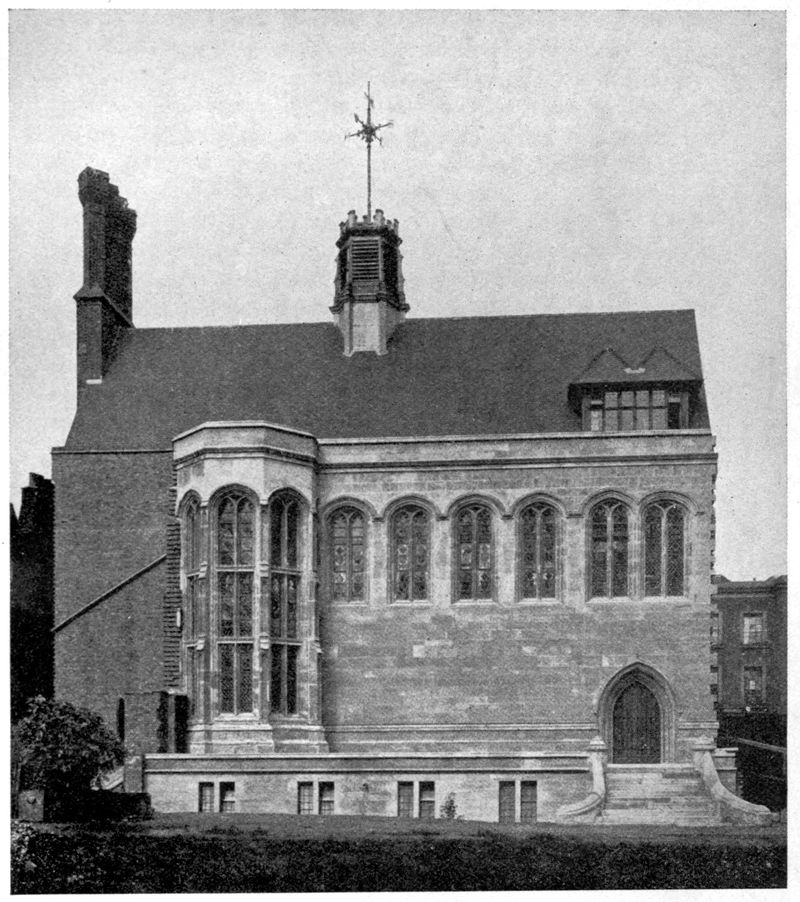

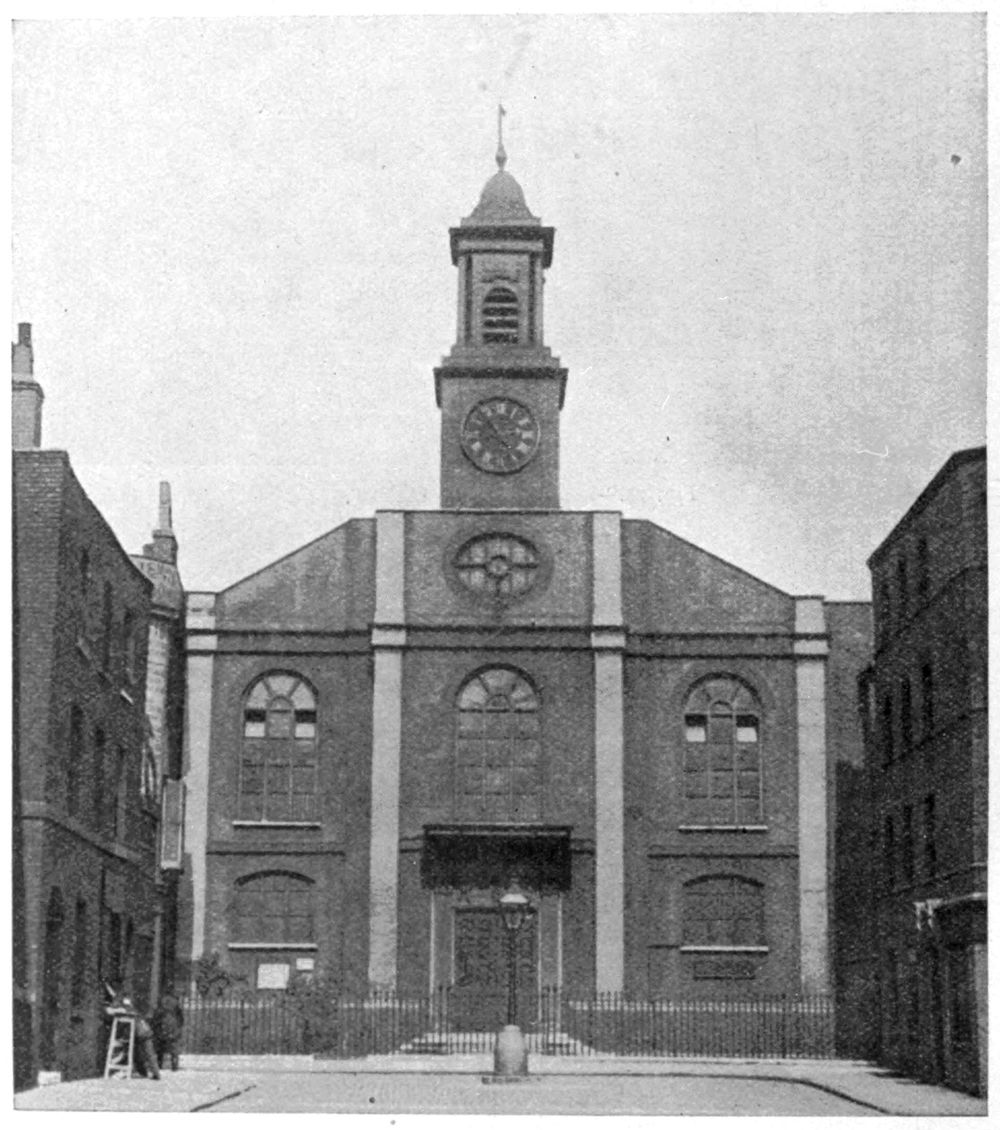

| 76. | West front of Church—Photograph by H. W. Fincham | 174 | |

| 77. | West door of Church—Photograph by H. W. Fincham | 175 | |

| 78. | Fireplace, St. John’s Gate—Photograph by H. W. Fincham | 176 | |

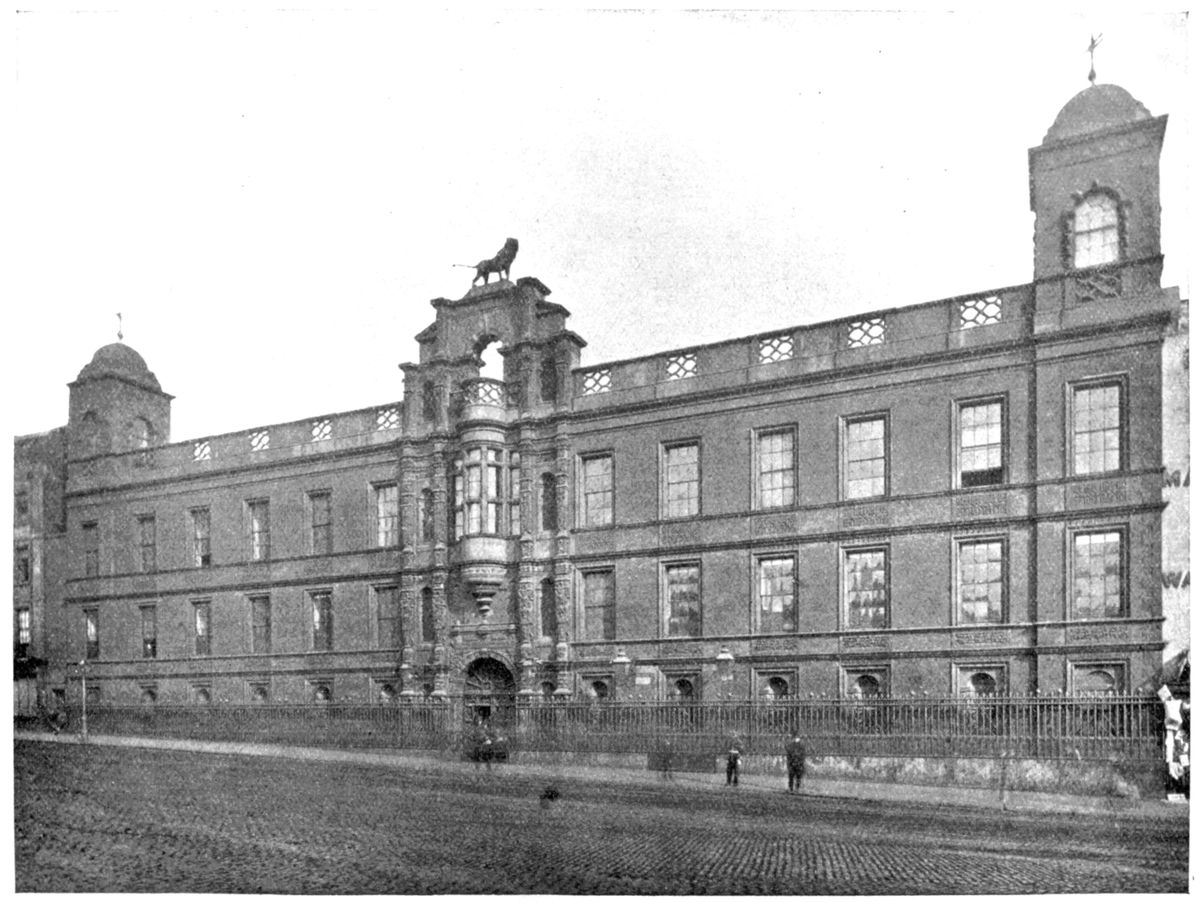

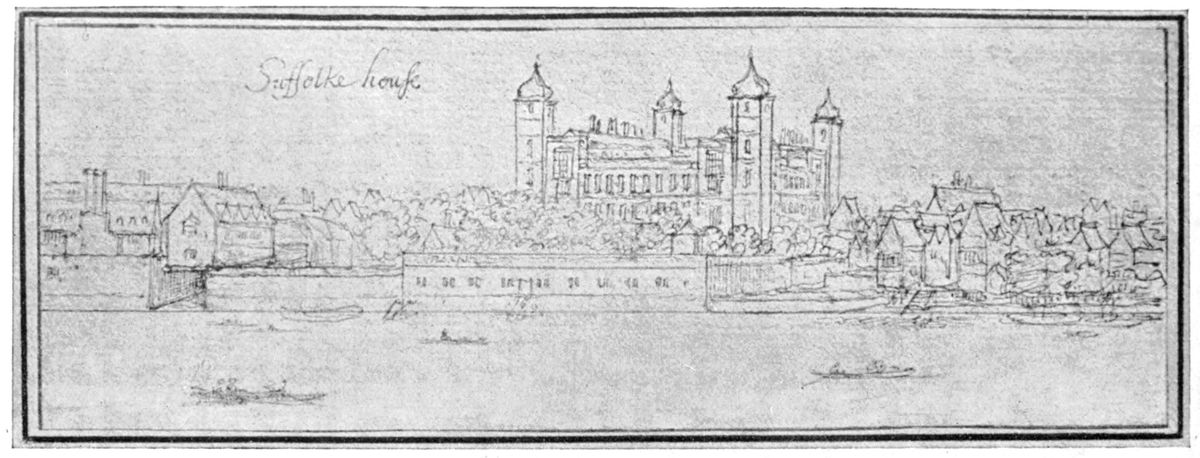

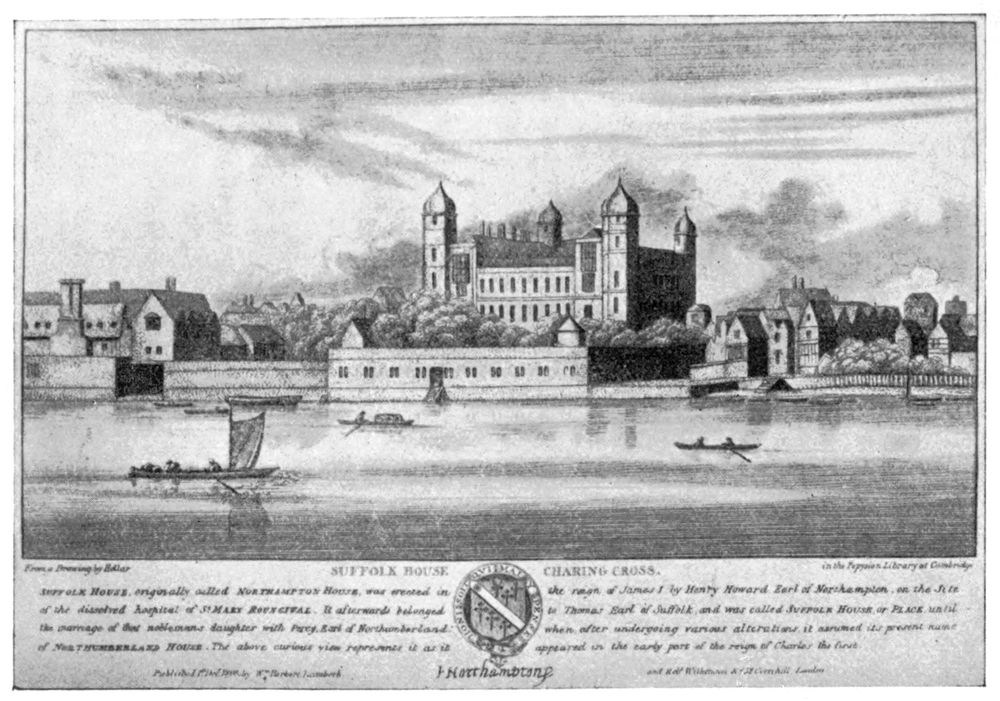

| XII. | Northumberland House, Strand | 179 | |

| 79. | North Front (before 1874)—Photograph London Stereoscopic Co. | 180 | |

| 80. | Plan in the Smithson Collection | 185 | |

| 81. | View from River (c. 1650)—by Hollar | 186 | |

| 82. | The same, engraved in Londina Illustrata | 191 | |

| 83. | North Front—after Canaletto | 192 | |

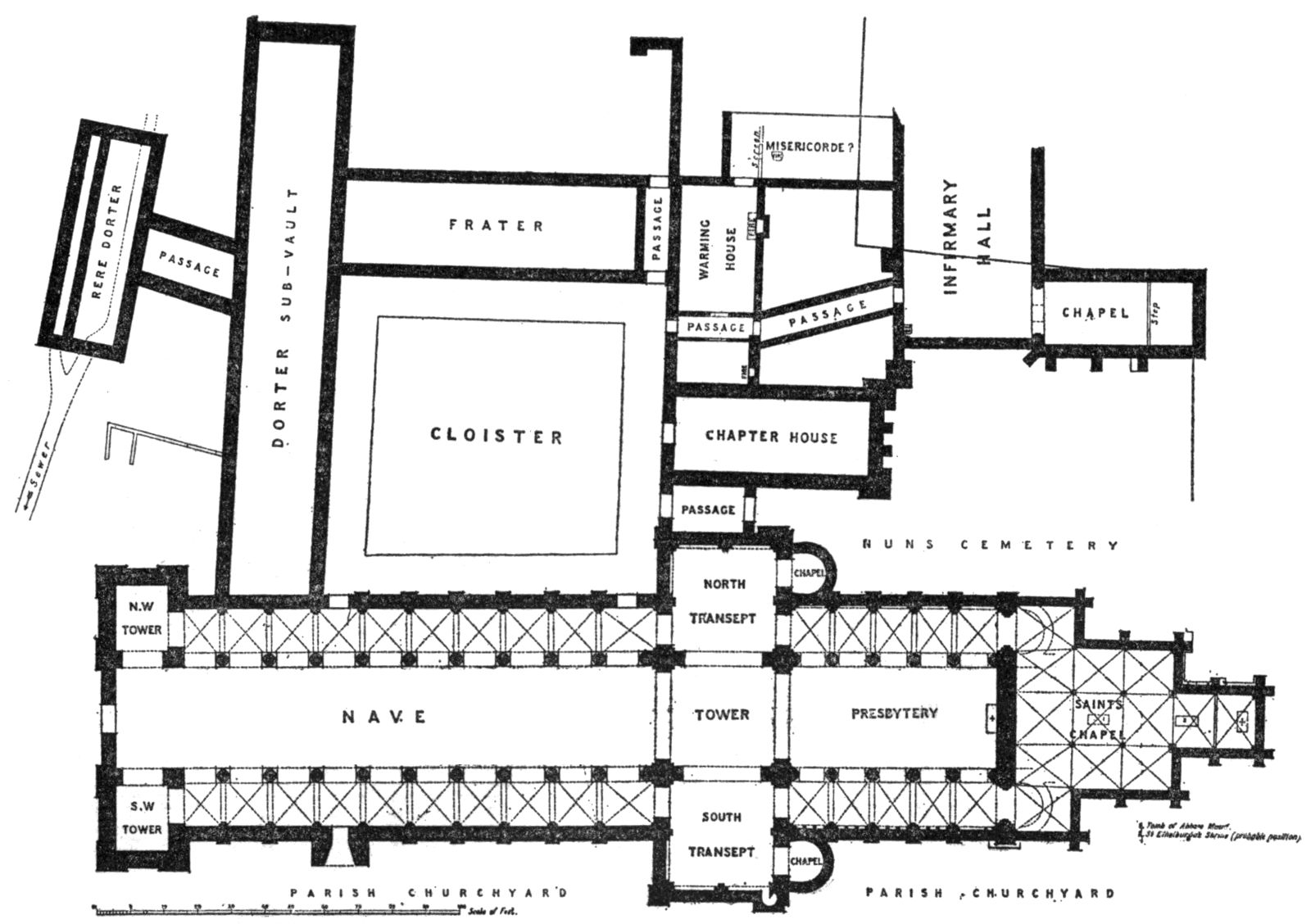

| XIII. | The Abbey of Barking, Essex | 197 | |

| 84. | Remains of South Transept—Photograph by A. P. Wire | 198 | |

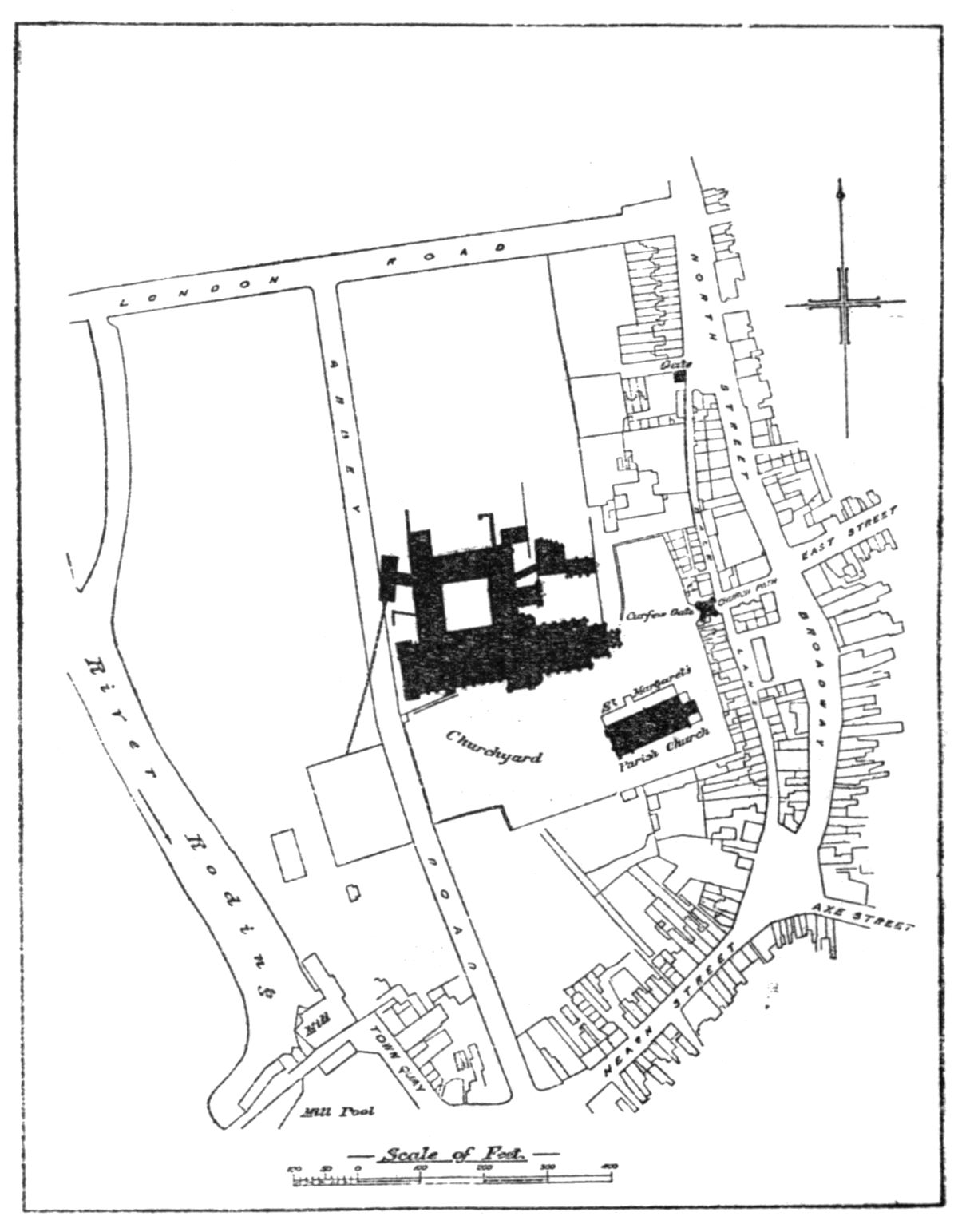

| 85. | Plan of the Precinct | 202 | |

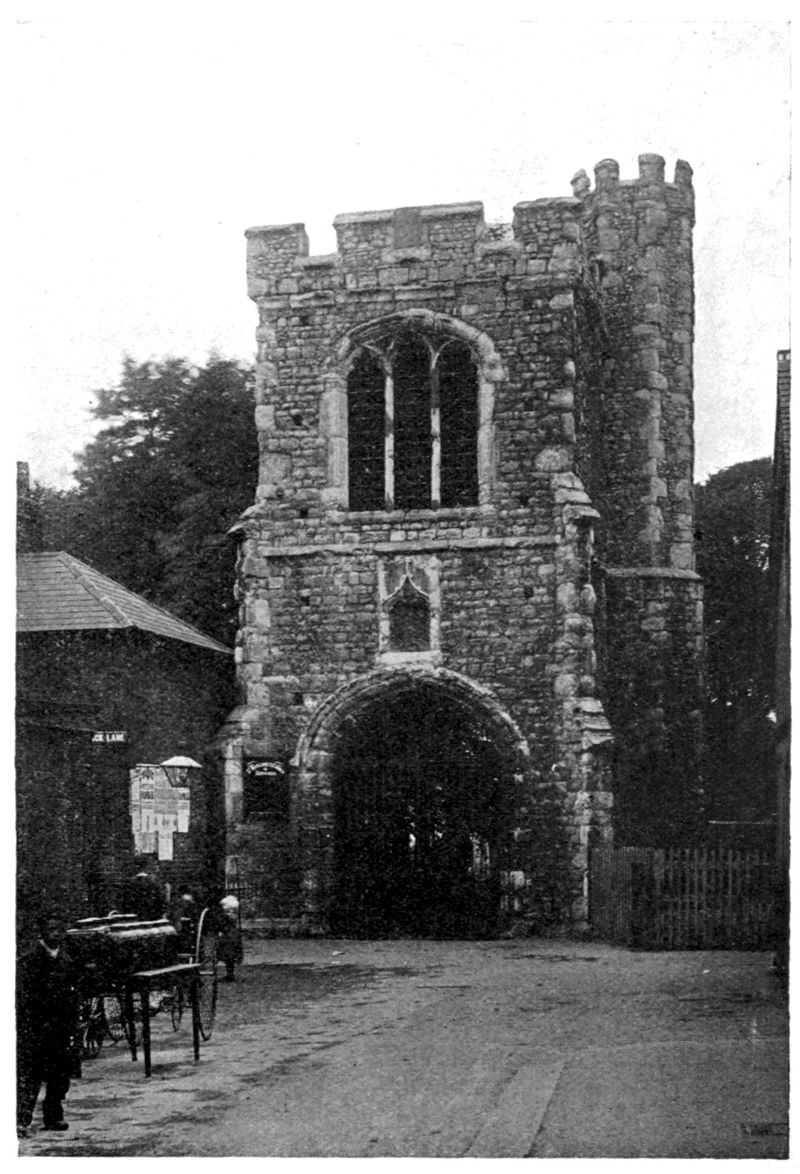

| 86. | The Curfew Gatehouse—Photograph by A. P. Wire | 203 | |

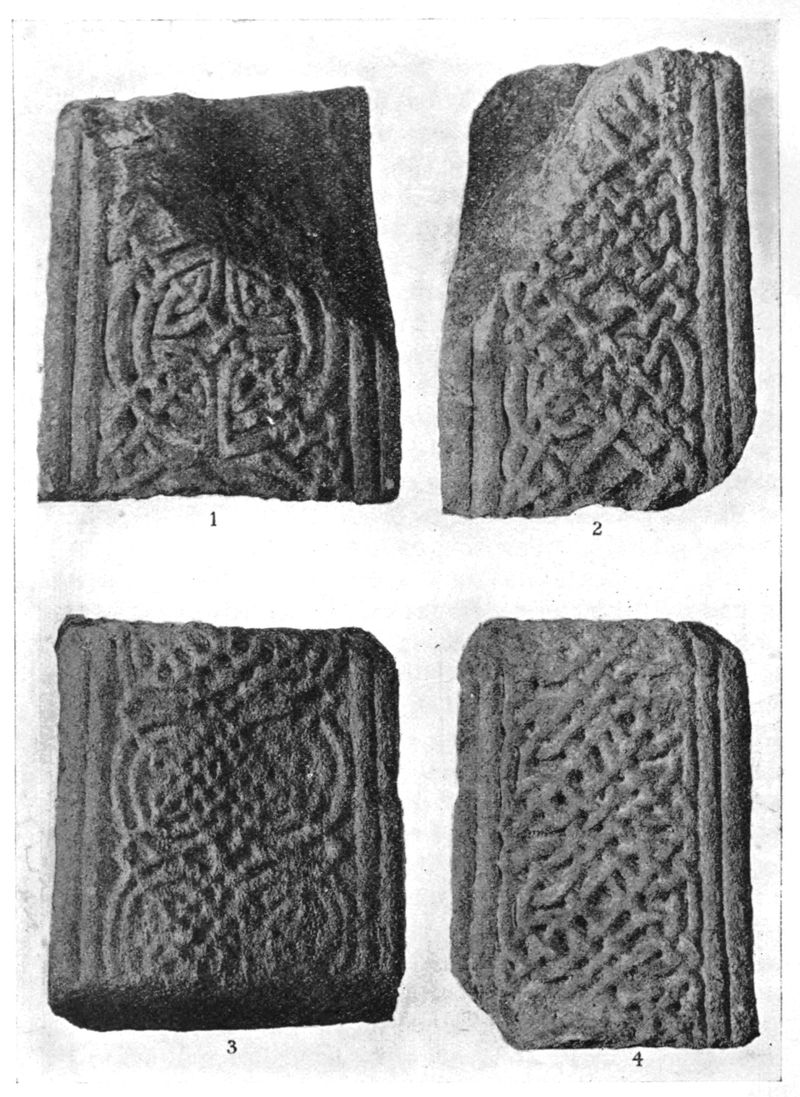

| 87. | The Saxon Cross—Photograph by A. P. Wire | 204 | |

| 88. | Plan of Abbey—by A. W. Clapham | 207 | |

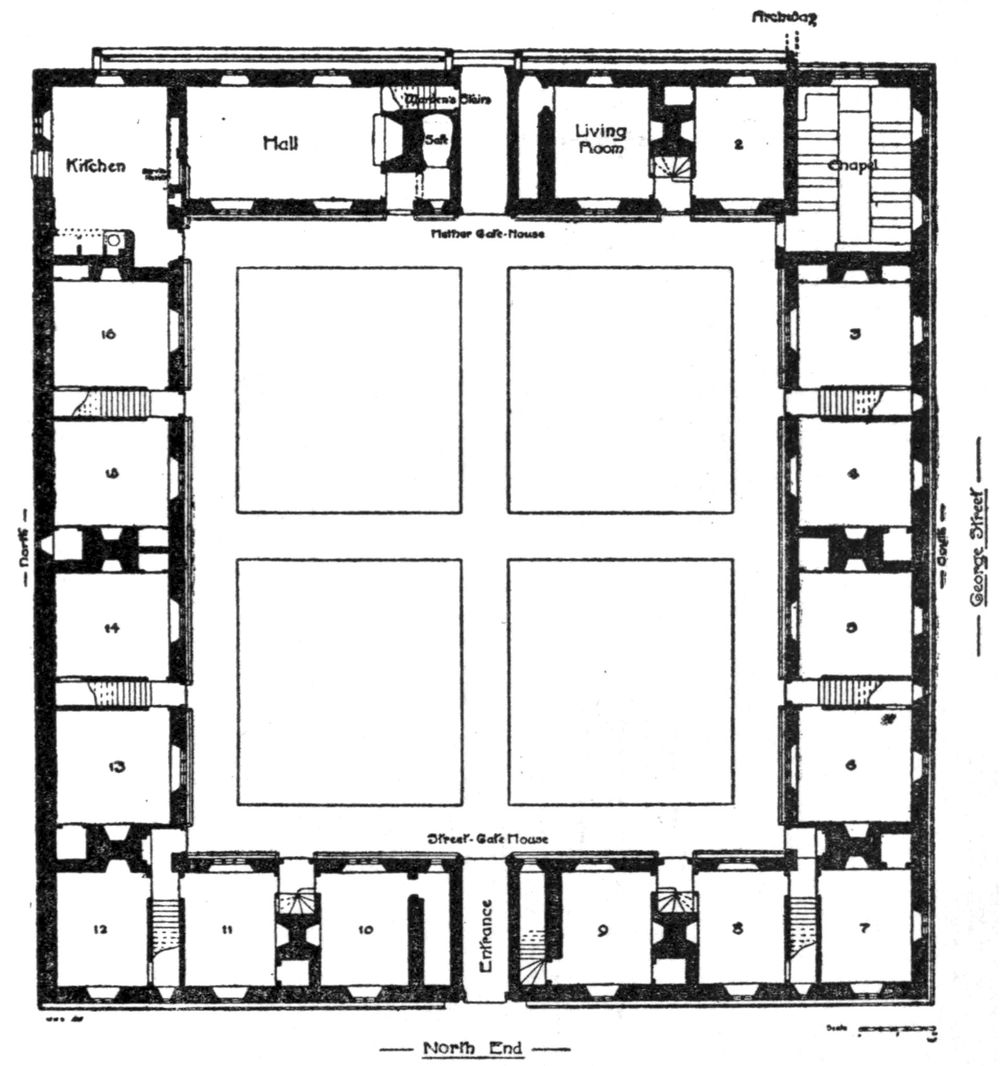

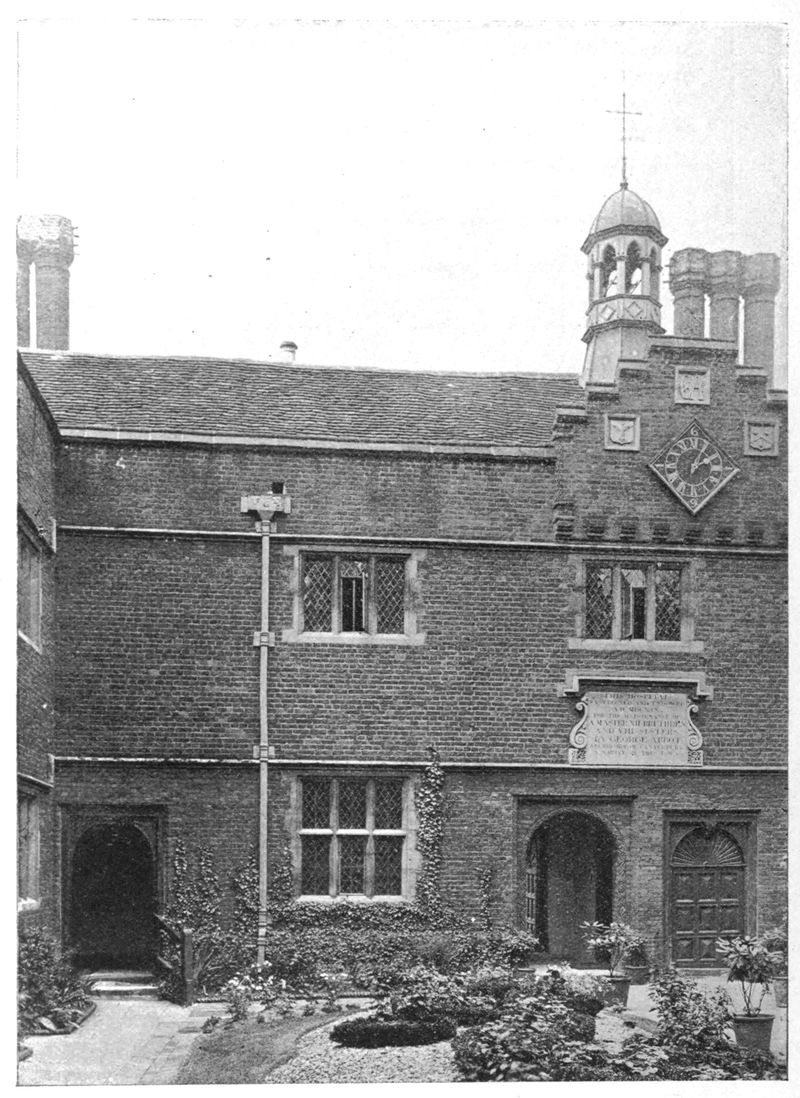

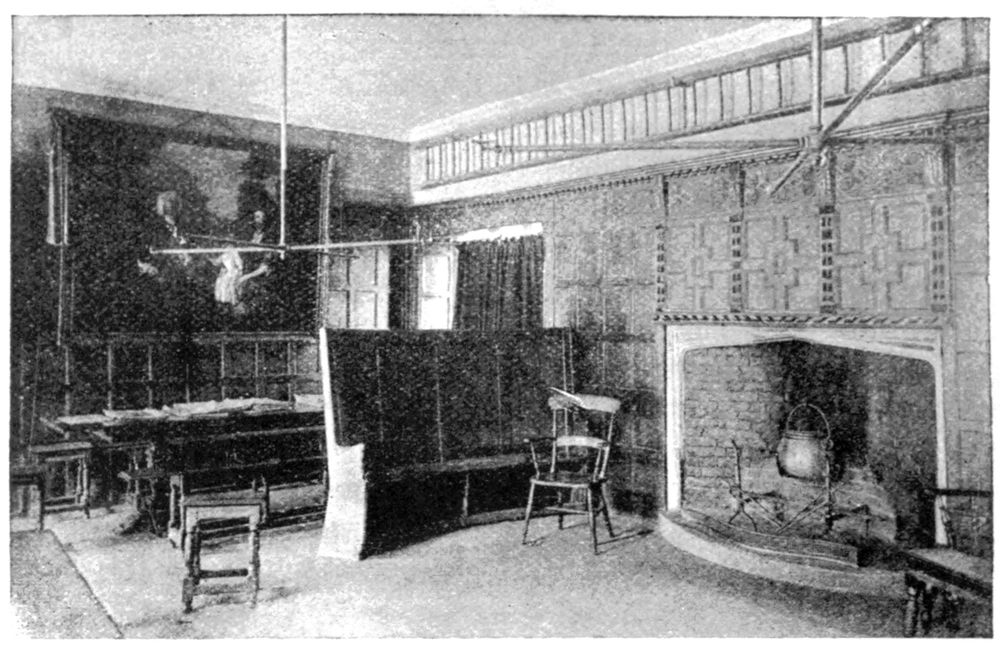

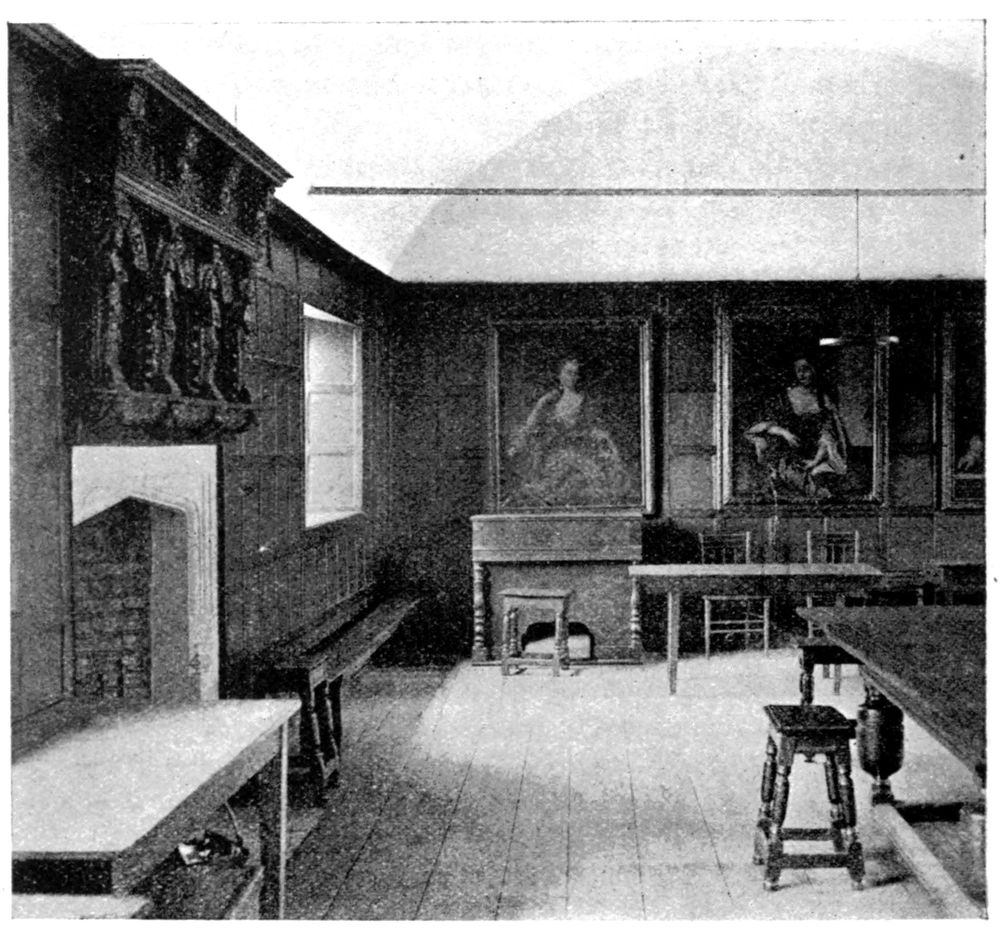

| [xi] XIV. | Abbot’s Hospital, Guildford, and its Predecessors | 215 | |

| 89. | Front of Hospital | 216 | |

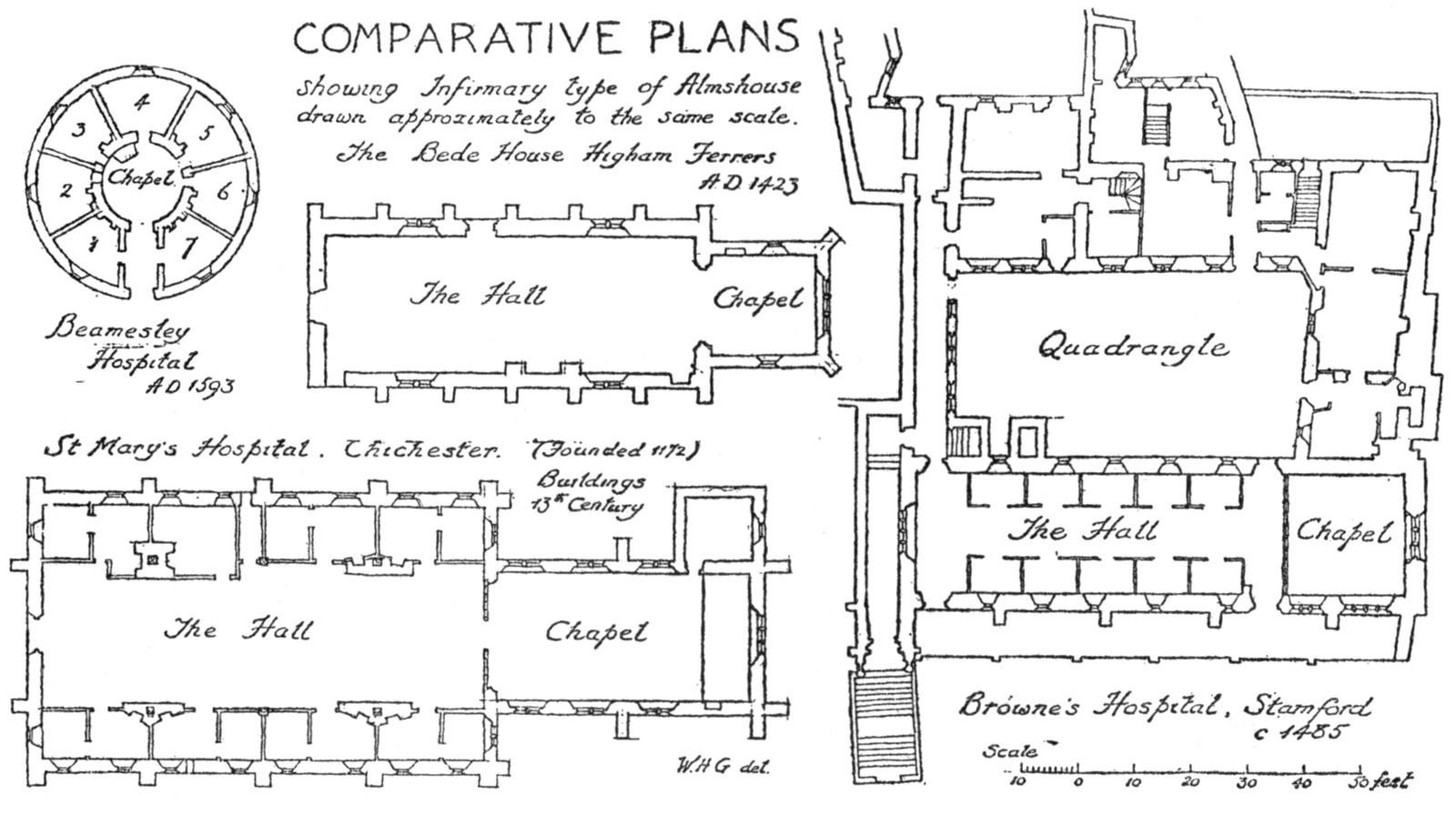

| 90. | Plans of Infirmary Types— Beamsley Hospital, Yorks; St. Mary’s Hospital, Chichester; The Bede House, Higham Ferrers; Browne’s Hospital, Stamford |

221 | |

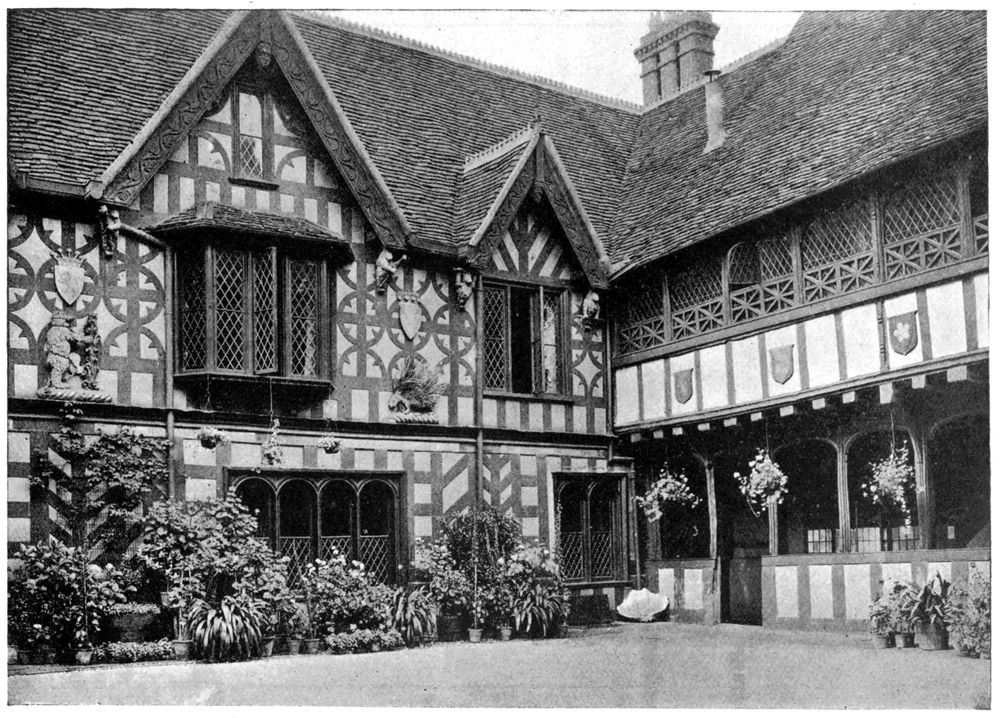

| 91. | Quadrangle, Leicester’s Hospital, Warwick | 223 | |

| 92. | Great Chamber, Whitgift Hospital—drawn by W. H. Godfrey | 224 | |

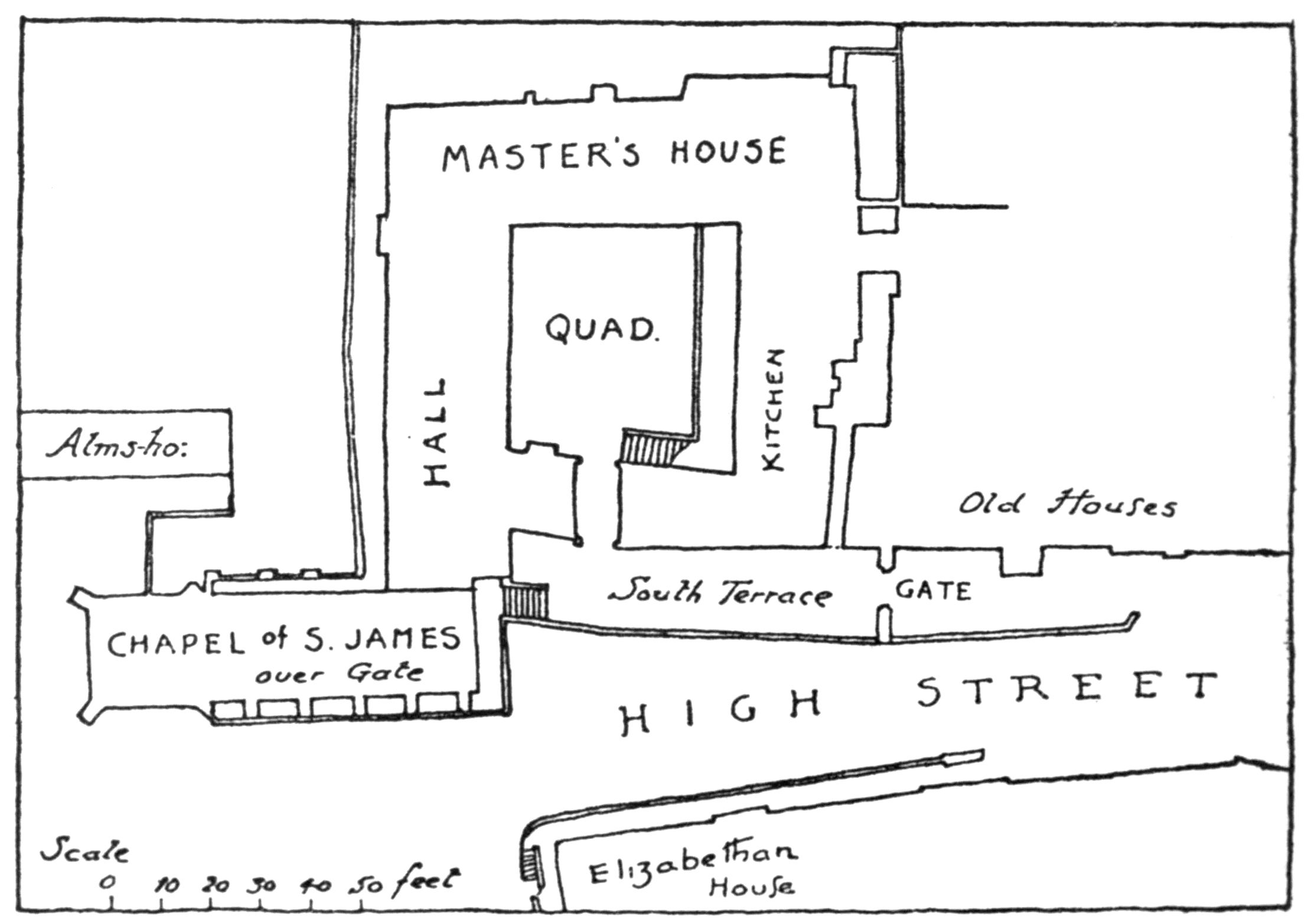

| 93. | Leicester’s Hospital, Warwick, Plan | 226 | |

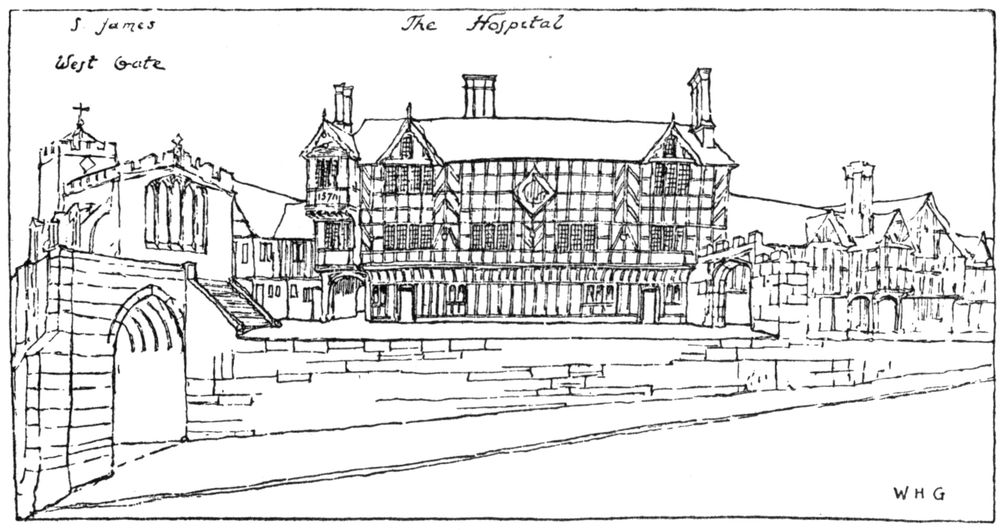

| 94. | Leicester’s Hospital—drawn by W. H. Godfrey | 227 | |

| 95. | Whitgift Hospital—Plan by W. H. Godfrey | 229 | |

| 96. | Abbot’s Hospital, Plan | 230 | |

| 97. | Abbot’s Hospital, Courtyard | 231 | |

| 98. | Abbot’s Hospital, Lower Hall | 232 | |

| 99. | Abbot’s Hospital, Upper Hall | 232 | |

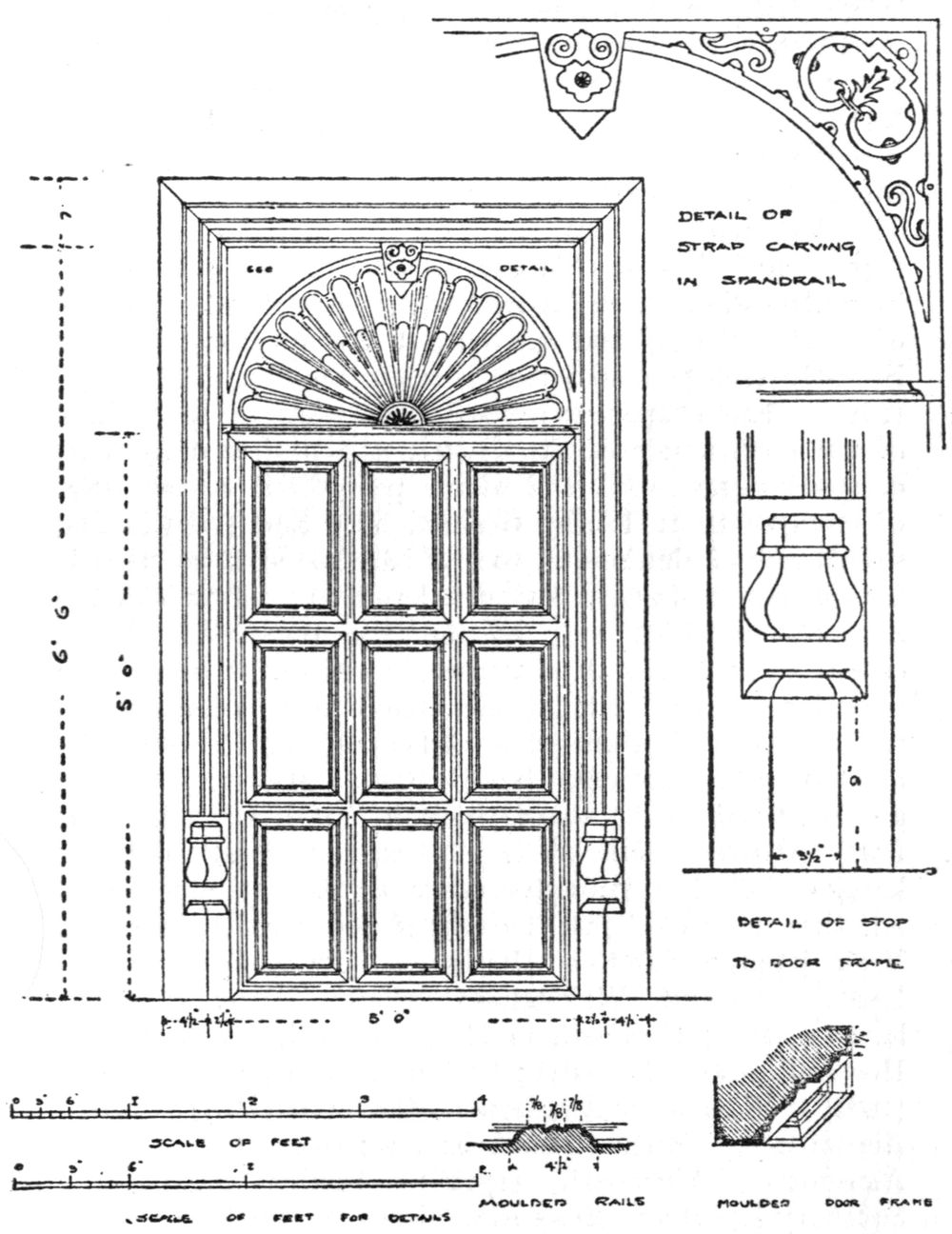

| 100. | Abbot’s Hospital, Detail of door—drawn by Sydney A. Newcombe | 235 | |

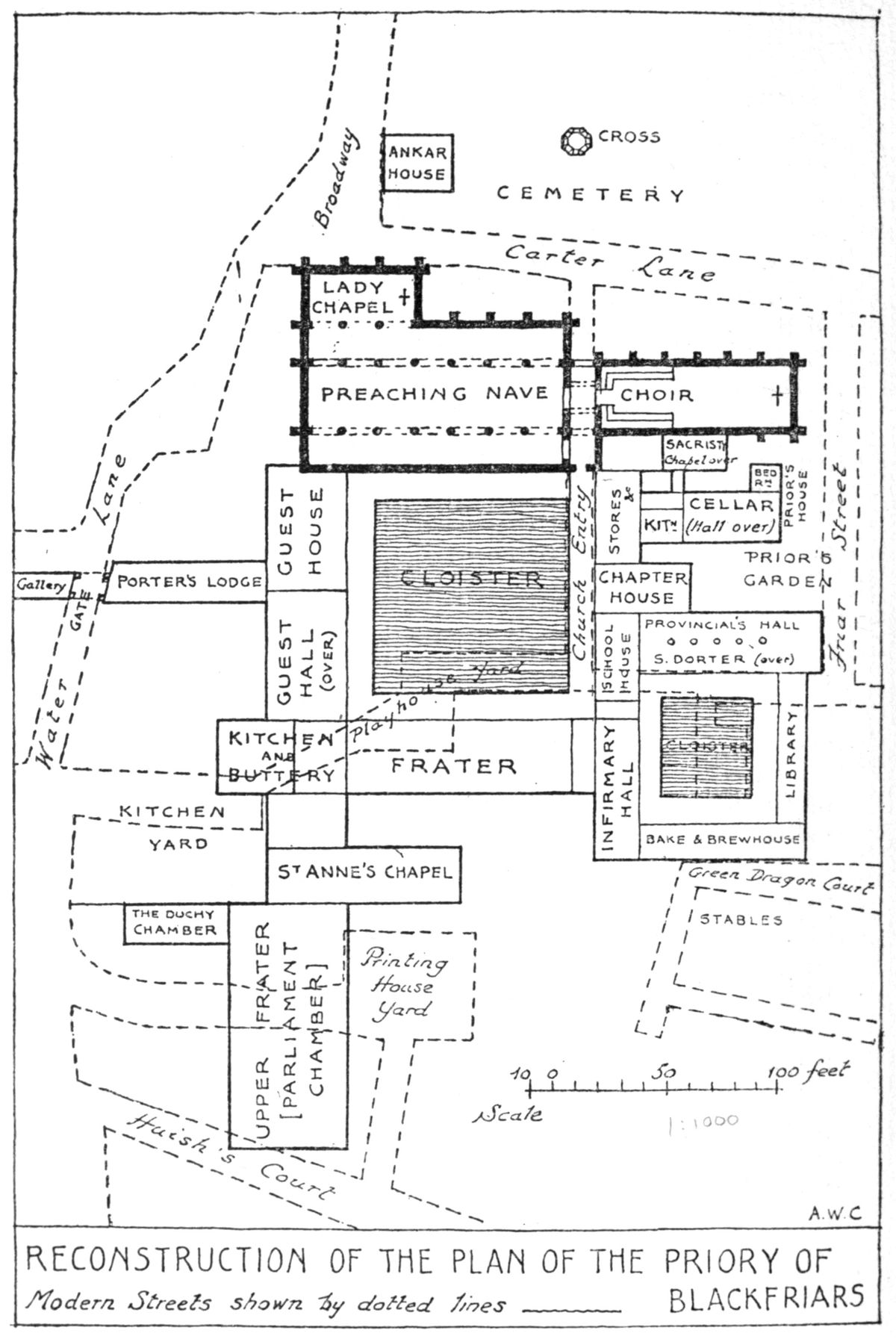

| XV. | The Friars as Builders—Blackfriars and Whitefriars, London | 239 | |

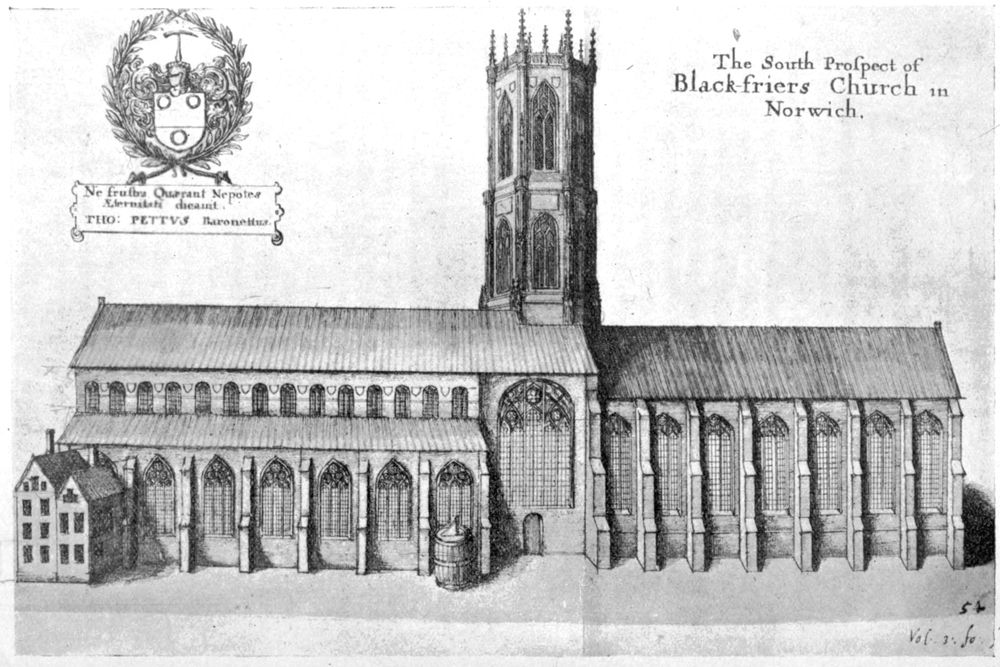

| 101. | Blackfriars, Norwich | 240 | |

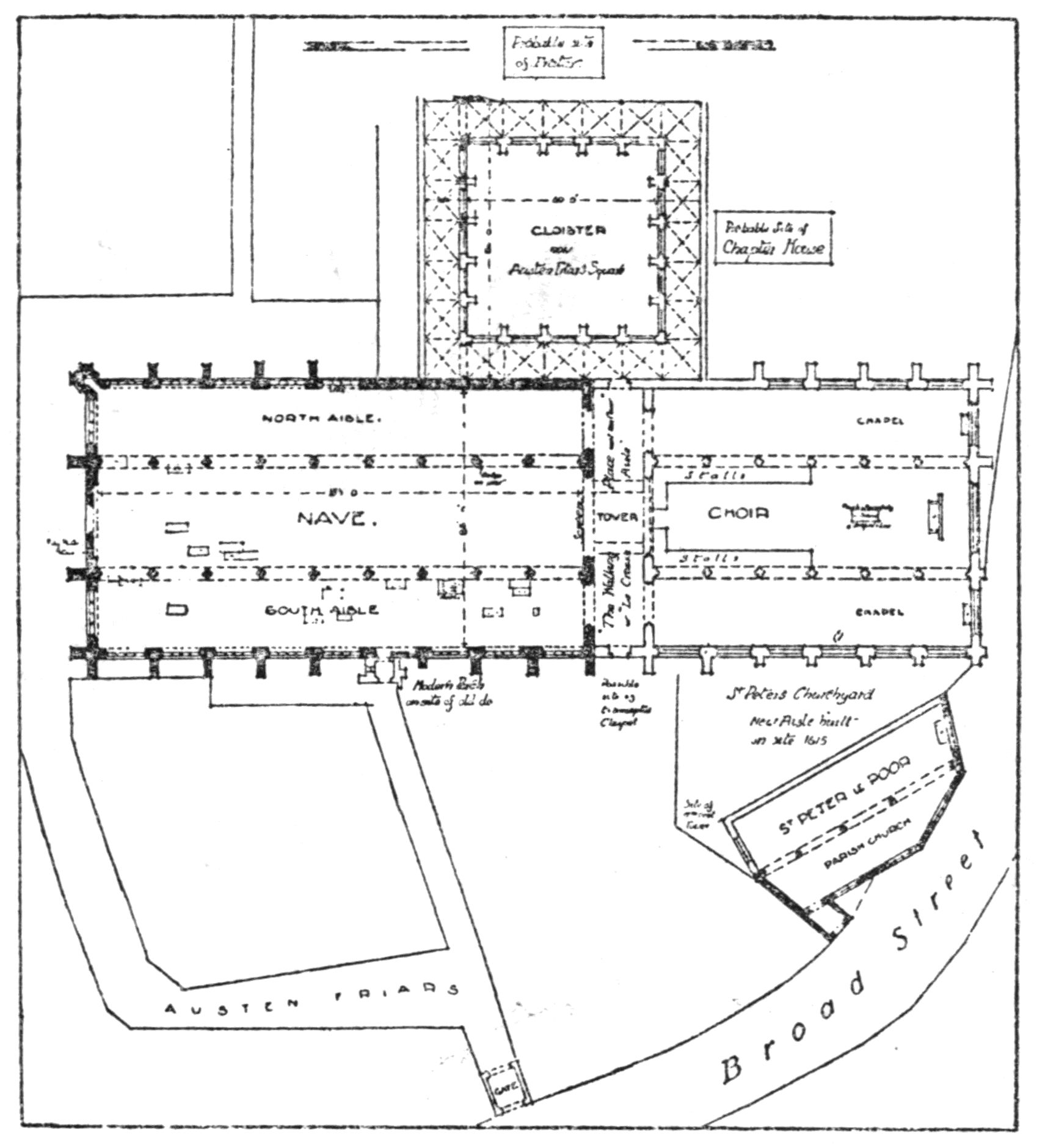

| 102. | Plan of Austin Friars, London—drawn by A. W. Clapham | 249 | |

| 103. | Plan of Greyfriars, London | 251 | |

| 104. | Preaching Cross, Blackfriars, Hereford—from Britton | 252 | |

| 105. | Blackfriars, London—Plan by A. W. Clapham | 254 | |

| 106. | Whitefriars, London—Plan by A. W. Clapham | 264 | |

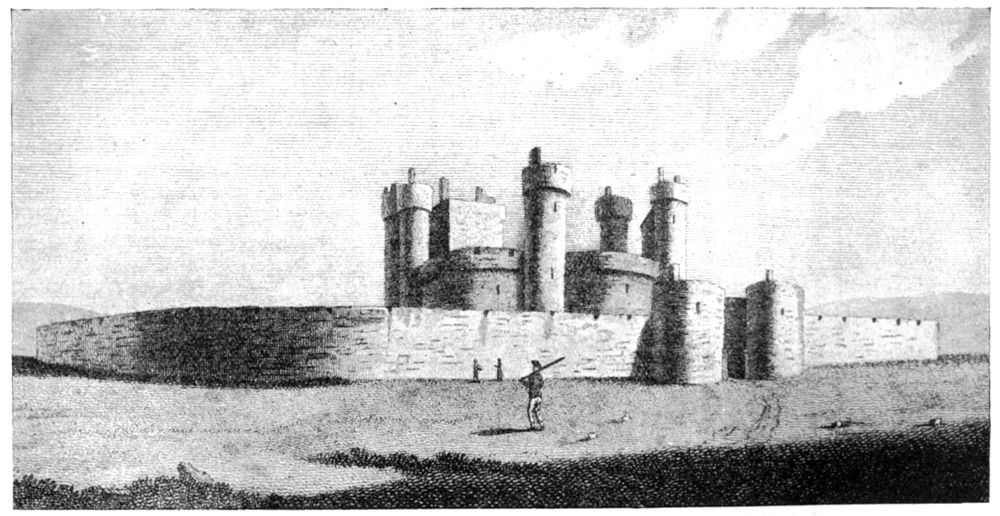

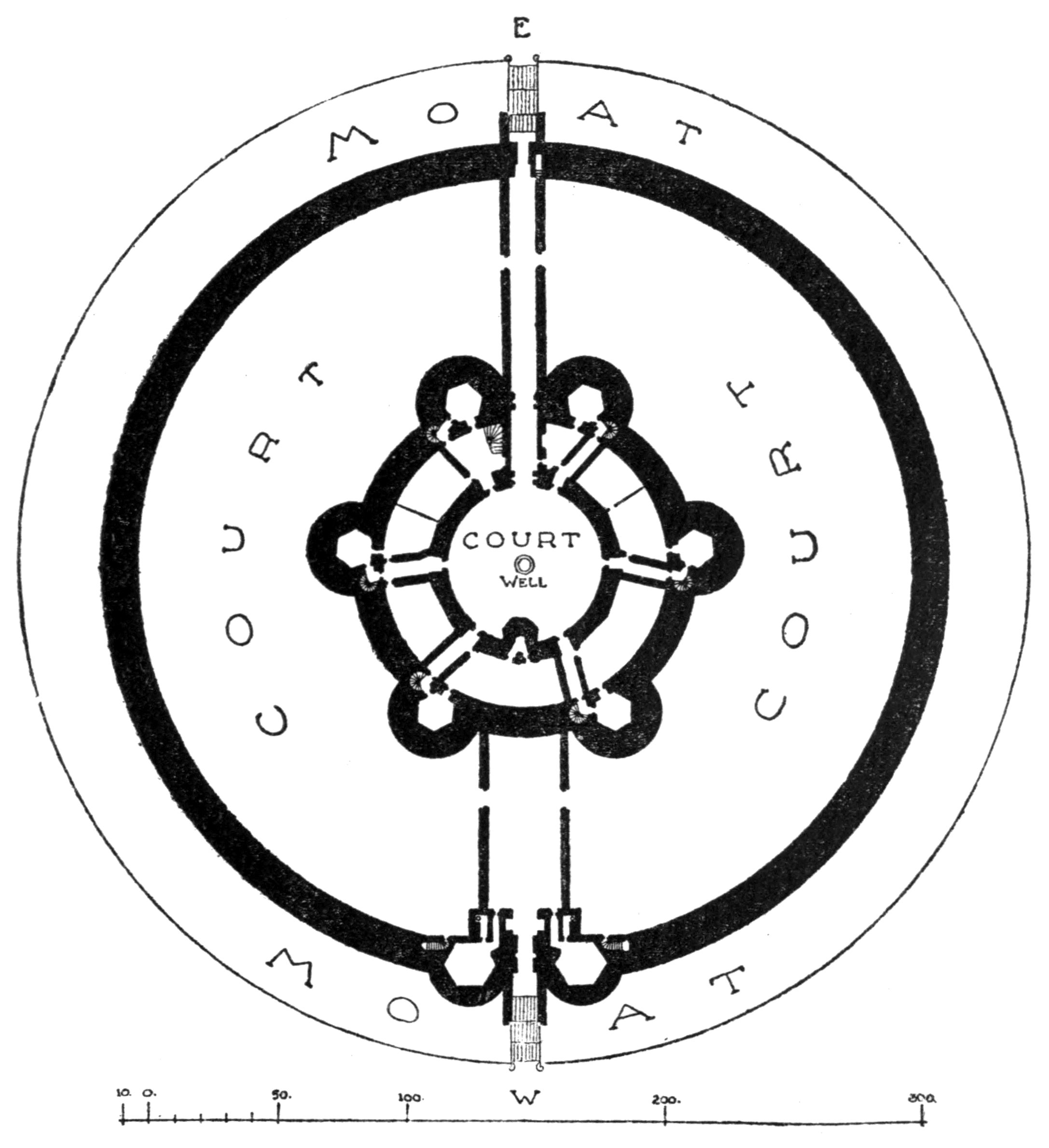

| XVI. | Queenborough Castle and its Builder, William of Wykeham | 269 | |

| 107. | Queenborough Castle—from a Drawing by Hollar | 270 | |

| 108. | Queenborough Castle—Plan from the Hatfield MSS. | 273 | |

THE ROYAL PALACE OF NONSUCH,

SURREY

Fig. 1.—NONSUCH PALACE, GARDEN FRONT.

Drawn by

Hofnagle.

[3]

The wanton destruction of the celebrated palace of Nonsuch, sacrificed to the extravagance and consequent embarrassments of the first Duchess of Cleveland, was probably the heaviest loss which English architecture has suffered since the Dissolution of the Monasteries. As an example of domestic architecture, just at the period of its transition, it was unique in combining in one building the familiar and almost unaltered features of the old English home with the most daring and fantastic ideas of the Italian Renaissance. Any additional information, therefore, which bears upon its character is of special value, not from an archæological so much as from an architectural point of view. Hence the discovery of an entirely new view of Nonsuch Palace is ample excuse for marshalling once again the facts of its architectural history.

The building activity of the first two Tudor kings is a somewhat neglected subject, since nearly all their greatest works have perished and the modern mind refuses to visualise the gorgeous descriptions of the chroniclers, even when illustrated by the somewhat bizarre creations of contemporary artists.

And yet the more the subject is studied the more the conclusion is forced upon one that the old-time historians were guilty of little exaggeration, and that the Tudor palaces were amongst the remarkable buildings of Europe. The Spanish gentlemen who accompanied Phillip II. to England were amazed at the magnificence of the palaces of the English kings, in comparison with which they admitted the Alcazar at Madrid, the residence of Castilian royalty, was a thing of no account.

Henry VII.’s chapel fortunately remains intact as an example of the structure which a Tudor king (otherwise [4]noted for his excessive parsimony) thought suitable for his tomb-house. His palace at Richmond and his great hospital at the Savoy were on a corresponding scale of profusion. With his son Henry VIII. the ideas of the Renaissance were given a freer hand. The father had employed an Italian to design his tomb, and the son, towards the close of his reign, invited Italian architects to design his buildings.

The architectural works of Henry VIII. consist chiefly of a series of palaces, no fewer than five, which he erected in the course of his thirty-eight years’ reign, apart from a number of manorial residences, such as his riverside mansion at Chelsea. Of these palaces, Bridewell, Guisnes, and Nonsuch have entirely vanished, but the gatehouse and other remains at St. James’s exist, and the mutilated remains at Beaulieu, in Essex, are still remarkable.

It is with the latest (in point of date) and in every way the most remarkable of these that we are at present concerned. The palace of Nonsuch achieved a reputation throughout Europe which has never been accorded to any other English building before or since.

Situated on the richly-wooded slopes of the Surrey hills, amongst the fairest prospects in the Home Counties, the ancient manor-house of Cuddington (between Cheam and Ewell) appears to have early attracted the attention of Henry VIII. In 1538 he acquired the manor from Richard de Cuddington, and with a delightfully Tudor directness proceeded at once quietly to remove the church and village and divert the roads, that nothing might interrupt the view from his windows or destroy the symmetry of his house and grounds. The site being thus cleared of its ancient buildings, the new palace was begun.

Many tons of stone quarried at Merstham, in the Reigate hills, were used on the works, and the great priory church at Merton was destroyed piecemeal to provide materials. The accounts still existing for the year 1539 preserve the names of every man employed, from the clerk of works to the labourers and apprentices, some 230 in all.

[5]

Although it had been in progress for nine years, Nonsuch was still incomplete at Henry’s death in 1547, but was nevertheless far enough advanced to be habitable.

The celebrated Sir Thomas Cawarden, Master of the Revels, was warden of the palace and parks of Nonsuch during the final years of Henry VIII. and in the time of Edward VI., but in 1557 Queen Mary granted the building and parks to Henry, Earl of Arundel, and his son-in-law, Lord Lumley, who eventually completed it by adding the outer courtyard.

Under Queen Elizabeth Nonsuch reached its zenith. For many years it was her favourite residence, and after her death it rapidly declined. Sold by the Commonwealth, it reverted to the Crown at the Restoration, and finally came to an ignominious end at the rapacious hands of the Duchess of Cleveland, who destroyed the house and cut up the park into farms.

What is known of the building itself is derived chiefly from the Parliamentary Survey taken in 1650 (which gives a detailed account of the palace and grounds) and from two views—one by Hofnagel (published in Braun and Hohenberg’s “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”) and the other an inset in Speed’s Map of Surrey. Both of these represent the garden or south front of the house, and the appearance of the north front and sides has up to the present time been quite conjectural. I am able, however, to reproduce a third view, taken from the north-west, showing this front and the flank of the building. The original engraving (from a picture then in the possession of Lord Fitzwilliam) was published by the Society of Antiquaries in 1765, with the title “Richmond Palace from the Green.” That this picture is not Richmond, but Nonsuch, is capable of easy proof. The angle-turret on the extreme right at once suggests this, and a careful perusal of the Parliamentary Survey leaves not the slightest doubt on the point. The avenue, the bowling-green, and the two gatehouses, the inner one with its clock-turret, are all fully described, and one can only be [6]surprised that this interesting fact has never before been discovered.

The palace consisted of two main courtyards surrounded by buildings and almost equal in size (the outer 115 ft.[6] by 132 ft., the inner 137 ft. by 116 ft.). The style employed in the first of these presents nothing extraordinary. Built, according to Evelyn, by Lord Lumley, but more probably by his father-in-law, the Earl of Arundel, early in Elizabeth’s reign, it was constructed of stone throughout, with a handsome gatehouse three stories high, with octagonal angle-turrets in the centre of the north front. This gate stood on the axis of the great avenue that led up to the house from the London Road.

[6] The transcript of the Survey in Archæologia , Vol. V., gives this dimension incorrectly as 150 ft., an error copied by all succeeding writers.

Nonsuch had the unusual arrangement amongst English Tudor plans of two gatehouses, the one behind the other. This was probably due to the outer courtyard not having been contemplated in the original design. The inner gate stood between the two courts, and was, with the whole of the buildings behind it, the work of Henry VIII.

The architect appears to have been a Florentine artist named Antonio Toto dell’ Nunziata, upon whom Henry VIII. conferred a patent of denization in 1538. He is referred to by Vasari (Lives of the Painters ), who asserts that he entered the service of the King of England, for whom he executed numerous works, and more especially the principal palace of that monarch, by whom he was very largely remunerated.[7] His name occurs with some frequency in the records of the later years of Henry VIII. He resided in the parish of St. Bride, Fleet Street.

[7] Professor Blomfield throws doubts upon Toto as the author of the design.

Fig. 2.—NONSUCH PALACE, FROM THE SOUTH.

Drawn by

Speed (1611).

Fig. 3.—NONSUCH PALACE, FROM THE NORTH-WEST.

Vetusta Monumenta, Vol. ii. (1765).

In 1544 that much-discussed Italian, John of Padua, makes his appearance as Devizer of the King’s Buildings, and as Nonsuch was the most important then in progress, [9]it is quite possible that he also was employed upon the works.

This first building, the joint product of Italian design and English craftsmanship, was entered from the north by an ascent of eight steps under the inner gatehouse, which is described in the Survey of 1650 as “of free stone three stories high, leaded and turreted in the four corners, in the middle of which gatehouse stands a clock case turreted and leaded all over wherein is placed a clock and bell.” The remarkable appearance of this gate is best shown in Speed’s view, which also shows the charming oriel window (somewhat similar to that at Hengrave Hall, Suffolk) over the inner arch, and the sundial above.

The remainder of the building was two stories high, of which the walls of the ground floor, according to the Survey, were of stone and the upper portions of timber. Externally, however, the garden or south front was of timber construction from the ground up. Facing the privy garden, with its marble fountains, obelisks, and pyramids, this front was flanked by two polygonal turrets five stories high, carried up well above the main building and finished with lead parapets and lanterns with heraldic lions bearing standards, “the king’s beastes” of Tudor documents, on every angle. “These turrets,” says the Survey, “command the prospect and view of both the Parks of Nonsuch and of most of the country round about and are the chief ornament of the whole house of Nonsuch.”

In the centre of the front was a large oriel window, probably to the Presence Chamber, which was on the first floor.

The building was a timber frame, the spaces between the studding being occupied by pargetted panels bearing the celebrated series of “statues, pictures, and other antique forms,” which aroused such universal admiration during the century and a half of their existence.

Nonsuch appears to have been one of the earliest instances of this type of work in England. Le Neve, [10]who saw the house when half destroyed, describes them as done in plaster-work made of rye-dough [sic], very costly. “There are,” says Evelyn, “some mezzorelievos as big as life—the story of ye heathen Gods, emblems, compartments, &c.” On the garden front were represented the labours of Hercules. There is evidence that these reliefs were painted, and to enhance further the richness of the whole design the faces of the half-timber work were covered with gilded scales of lead or slate nailed on, after the fashion still to be seen in many Continental towns.

Apart from the abstract question of taste, it can easily be imagined that a building so adorned must have presented an appearance of extreme sumptuousness, and while it is impossible to regard it quite as a serious essay in architecture, yet as an example of a rare exotic grafted on an alien stem it is of extraordinary interest.

It can only be compared in the history of English art with that lordly pleasure-house which King Henry VIII. erected near Guisnes in the Calais pale on the occasion of the Field of the Cloth of Gold. That a marked similarity existed between the two buildings is evident from the minute description of the Guisnes palace to be found in Hall’s Chronicle.

The existing remains of the palace consist solely of the base of a chalk wall, faced with red brick in Old English bond, some 275 ft. in length and lying at right angles to the great avenue leading from the London Road. In all probability this formed a part of the wall surrounding the privy garden, and the main building lay rather to the north of it, on the axis of the avenue.

Some little distance to the west of the house was a building known as the Banqueting House. It is described in the Parliamentary Survey as “one structure of timber building of quadrangular form pleasantly situated upon the highest part of the said Nonsuch Park commonly called ‘the Banquetting House’ being compassed round [11]with a brick wall the four corners whereof represent four half moons or fortified angles.” The house itself was three stories high, with a lantern above and a balcony placed “for prospect” at each of the four corners.

Considering the material, it is not surprising that it has quite disappeared; but the artificial platform upheld by brick retaining walls is in existence. The “fortified angles” which caught the eye of the Parliamentary Commissioner are still preserved, and, with them, remains of the double flight of stone steps leading up to the entrance.

“The Banquet House” figures largely in Elizabethan literature, though its origin and date of introduction are somewhat obscure. There can be little doubt that it was due to one of those vagaries of fashion, combined with the sixteenth-century passion for the new and strange, which attempted to transplant a custom from its native southern soil to the uncongenial air of England. The fashion once started, however, held its place with remarkable tenacity, and received its final form under the hand of Sir Christopher Wren and his school in the Orangeries at Kensington and Richmond.

The example at Nonsuch is one of the earliest in this country to which a definite date can be assigned. It is mentioned as a completed building in the first year of Edward VI., and consequently must have formed part of the original work of Henry VIII. and his Italian advisers.

A document preserved at Loseley Place contains an inventory of goods received for furnishing the Banqueting House in 1547. They include nine Turkey carpets and one carpet of green satin embroidered upon with sundry of the king’s beasts, antique heads, grapes and birds, &c. Evidently the interior decoration of Nonsuch fell little short of the exterior in magnificence.

One other building deserves a passing mention. “The Standing” in the park was used by Elizabeth as a convenient vantage ground from which to view the hunting. No trace of it remains, but, fortunately, a complete [12]structure of this class is still standing in the Hunting Lodge in Epping Forest, and it too is associated with the name of this queen. The upper stories of the timber framing were left open between the studding or uprights, forming a convenient gallery from which to view the sport.

Fragments of the destroyed palace found their way to Gaynsford Hall, Carshalton, to Durdans by Epsom, and to the vicarage at Ewell; but these houses have since been rebuilt and all the authentic remains of the most remarkable of Tudor buildings lie buried beneath the turf of Nonsuch Park. The archæologist is apt to think that monastic houses and feudal castles are alone worthy of his attention; but the recovery of the ground plan of Nonsuch would be an achievement of even greater architectural value, while its wealth of historic associations places it far above them all in sentimental interest.

—A. W. C.

Fig. 4.—THE BANQUETING HOUSE.

Drawn by

Alfred W. Clapham.

THE FORTUNE THEATRE,

LONDON (1600)

Fig. 5.—VIEW OF INTERIOR.

Drawn by

Walter H. Godfrey.

[15]

The original contract, dated 1599–1600, for the building of the “Fortune” Theatre was brought under my notice by Mr. William Archer, the well-known author and dramatic critic, to whose friendly criticism and help this article chiefly owes its inspiration. The document is preserved at Dulwich College, and was transcribed by J. O. Halliwell Phillipps in his Outlines of the Life of Shakespeare , and it is from his transcript that the quotations below are taken. Apart from its interest to architects of the present day, as illustrative of building methods of over 300 years ago, the contract has considerable value in the light it throws upon that most controversial of all topics—the form of the Elizabethan stage. It is not my intention here to consider in detail any of the theories heretofore advanced, but I wish in as brief a space as possible to place before the reader just sufficient of the available data to enable him to understand the reconstruction of the Fortune Theatre which has been attempted in the accompanying plans.

The sources from which these data have been drawn fall naturally into two classes. The first, which has as yet by no means been exhausted, although used almost exclusively by the literary critics, is to be found in the internal evidence which the plays of the period afford, partly in their text, but chiefly in their stage directions. The second is to be found in the contemporary evidence of descriptions or drawings made while the theatres still existed, of which the most important are the “Fortune” and “Hope” contracts, the early maps, and the remarkable drawing reproduced here of the interior of the Swan Theatre preserved in the commonplace book of a certain Van Buchell, at the Utrecht University Library, and purporting [16]to be drawn from a sketch by a traveller named Johannes de Witt, who visited London about the year 1600. The interpretation of this latter evidence falls as naturally into the province of the architect as that of the former belongs to the sphere of the literary and dramatic critic.

Fig. 6.—SWAN THEATRE, BANKSIDE.

Drawn by

John de Witt.

Everyone familiar with Visscher’s beautiful drawing of London in the year 1616 will remember seeing in the foreground, on the south side of the Thames, three buildings resembling amphitheatres in form, marked respectively (reading from east to west), the “Globe,” the “Bear [17]Garden,”[8] and the “Swan.” The correctness of the two former inscriptions may very reasonably be questioned, but I do not think there is any ground for doubting the veracity of the drawing, since two theatres existed on Bankside in 1616—the Rose (1592) and the Hope (1614), besides the more celebrated Globe, which lay probably beyond the limit of the map. The Swan is correctly placed, as we know by its position in Paris Garden. But whether depicted or not, the Globe Theatre of 1616 could not be Shakespeare’s Globe, which was erected in 1598–9 and burnt down in 1613, and it is important to bear this in mind in considering the “Fortune” contract, which definitely states that the new theatre is to follow the pattern of the “late erected plaie-howse on the Banck ... called the Globe.” There are many other early maps both anterior and subsequent to Visscher which show the Bankside theatres, but their examination and collation are not as yet sufficiently advanced to give us any trustworthy information, although a valuable step towards this end has already been taken by Dr. William Martin. (Vide Home Counties Magazine , Vol. IX.)

[8] The “Bear Garden” was pulled down in 1613, and the Hope Theatre erected “neere or uppon the saide place where the same game place [the Bear Garden] did heretofore stande.”

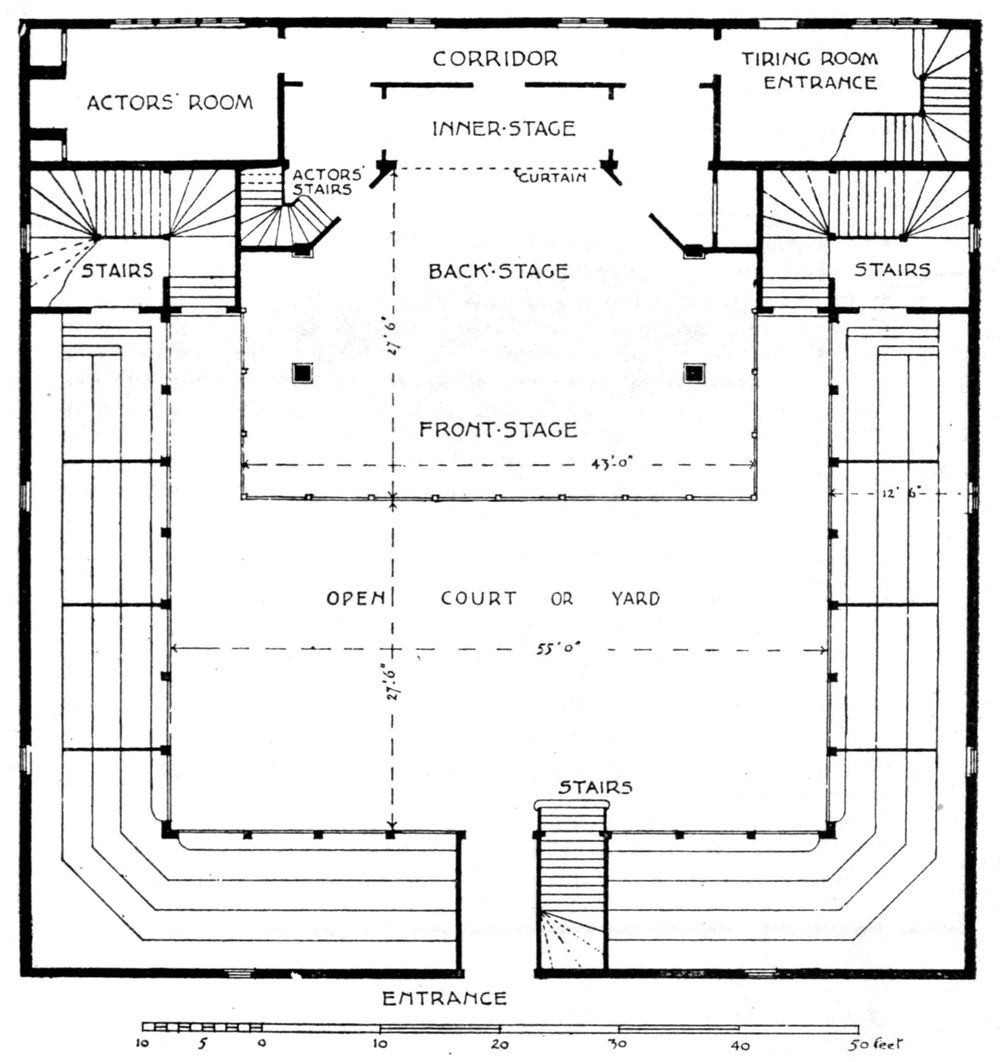

Fig. 7.—THE FORTUNE. PLAN (GROUND FLOOR).

Drawn by

Walter H. Godfrey.

The “Fortune” document itself consists of rather more than a mere contract, and possesses somewhat the character of a specification, being not unlike the hasty compromise between the two which has been known to be indulged in even in these days of careful architectural practice. The portion which bears on the actual form of the building reads as follows:—

This Indenture made the eighte daie of Januarye 1599, and in the twoe and fortyth yeare of the reigne of our sovereigne ladie Elizabeth, by the grace of God Queene of England, Fraunce and Irelande, defender of the faythe, &c., betwene Phillipp Henslowe and Edwarde Allen of the parishe of Sainte Saviours in Southwark, in the countie of Surrey, gentlemen, on th’ one parte, and Peeter Streete cittizein and carpenter of London on th’ other parte.——Witnesseth that, whereas the saide Phillipe [18]Henslowe and Edward Allen the daie of the date hereof have bargayned, compounded and agreed with the saide Peter Streete for the erectinge, buildinge, and settinge upp of a newe howse and stadge for a plaie-howse, in and uppon a certeine plott or parcell of grounde appoynted oute for that purpose, Scytuate and beinge nere Goldinge Lane in the parishe of Sainte Giles withoute Cripplegate of London; to be by him the said Peeter Streete, or somme other sufficyent woorkmen of his provideinge and appoyntemente, and att his propper costes and chardges, for the consideracion hereafter in theis presentes expressed, made, erected, builded, and sett upp in manner and forme followeinge; that is to saie, the frame of the saide howse to be sett square, and to conteine fowerscore foote of lawfull assize everye waie square withoute, and fiftie five foote of like assize square everye waie within, with a good suer and stronge foundacion of pyles, bricke, lyme, and sand, bothe withoute and within, to be wroughte one foote of assize att the leiste above the grounde; and the said frame to conteine three stories in heighth, the first or lower storie to conteine twelve foote of lawfull assize in heighth, the seconde storie eleaven foote of lawfull assize in heigth, and the third or upper storie to conteine nyne foote of lawfull assize in height. All which stories shall conteine twelve foote and a half of lawfull assize in breadth throughoute, besides a juttey forwardes in eyther of the saide twoe upper stories of tenne ynches of lawfull assize; with fower convenient divisions for gentlemens roomes, and other sufficient and convenient divisions for twoepennie roomes; with necessarie seates to be placed and sett as well in those roomes as througheoute all the rest of the galleries of the saide howse; and with suche like steares, conveyances and divisions, withoute and within, as are made and contryved in and to the late erected plaie-howse on the Banck, in the saide parishe of Sainte Saviours, called the Globe; with a stadge and tyreinge-howse to be made, erected and sett upp within the saide frame; with a shadowe or cover over the saide stadge; which stadge shal be placed and sett, as alsoe the stearecases of the saide frame, in suche sorte as is prefigured in a plott thereof drawen; and which stadge shall conteine in length fortie and three foote of lawfull assize, and in breadth to extende to the middle of the yarde of the saide howse; the same stadge to be paled in belowe with good stronge and sufficyent newe oken bourdes, and likewise the lower storie of the saide frame withinside, and the same lower storie to be alsoe laide over and fenced with stronge yron pykes; and the saide stadge to be in all other proporcions contryved and fashioned like unto the stadge of the saide plaiehowse called the Globe; with convenient windowes and lightes glazed to the said tyreinge-howse. And the saide frame, stadge, and stearecases to be covered with tyle, and to have sufficient gutter of lead, to carrie and convey the water frome the coveringe of the saide stadge, to fall backwardes. And alsoe all the saide frame and the stairecases thereof to be sufficyently enclosed withoute with lathe, lyme and haire. And the gentlemens roomes and twoepennie roomes to be seeled with lathe, lyme, and haire; and all the flowers of the saide galleries, stories and stadge to be bourded with good and sufficyent newe deale bourdes [21]of the whole thicknes, wheare neede shal be. And the saide howse and other thinges before mencioned to be made and doen, to be in all other contrivitions, conveyances, fashions, thinge and thinges, effected, finished and doen, accordinge to the manner and fashion of the saide howse called the Globe; saveinge only that all the principall and maine postes of the said frame, and stadge forwarde, shal be square and wroughte palasterwise, with carved proporcions called satiers to be placed and sett on the topp of every of the same postes; and saveinge alsoe that the saide Peter Streete shall not be chardged with anie manner of paynteinge in or aboute the saide frame, howse or stadge, or anie parte thereof, nor rendringe the walls within, nor seelinge anie more or other roomes than the gentlemens roomes, twoepennie roomes and stadge, before remembred. Nowe theereuppon the saide Peeter Streete dothe covenaunte, promise and graunte for himself, his executors and administrators, to and with the said Phillipp Henslowe and Edward Allen and either of them, and the ’xecutors and administrators of them, and either of them by theis presentes, in manner and forme followeinge, that is to saie; that he the said Peeter Streete, his executors or assignes, shall and will, at his or their owne propper costes and chardges, well, woorkmanlike and substancyallie make, erect, sett upp and fully finishe in and by all thinges, accordinge to the true meaninge of theis presentes, with good, strong and substancyall newe tymber and other necessarie stuff, all the saide frame and other woorkes whatsoever in and uppon the saide plott or parcell of grounde, beinge not by anie aucthoretie restrayned, and haveinge ingres, egres and regres to doe the same, before the fyve and twentith daie of Julie next commeinge after the date hereof; and shall alsoe, att his or theire like costes and chardges, provide and finde all manner of woorkemen, tymber, joystes, rafters, boordes, dores, boltes, hinges, brick, tyle, lathe, lyme, haire, sand, nailes, leede, iron, glasse, woorkmanshipp and other thinges whatsoever, which shal be needeful, convenyent and necessarie for the saide frame and woorkes and everie parte thereof; and shall alsoe make all the saide frame in every poynte for scantlinges lardger and bigger in assize than the scantlinges of the timber of the saide newe erected howse called the Globe....

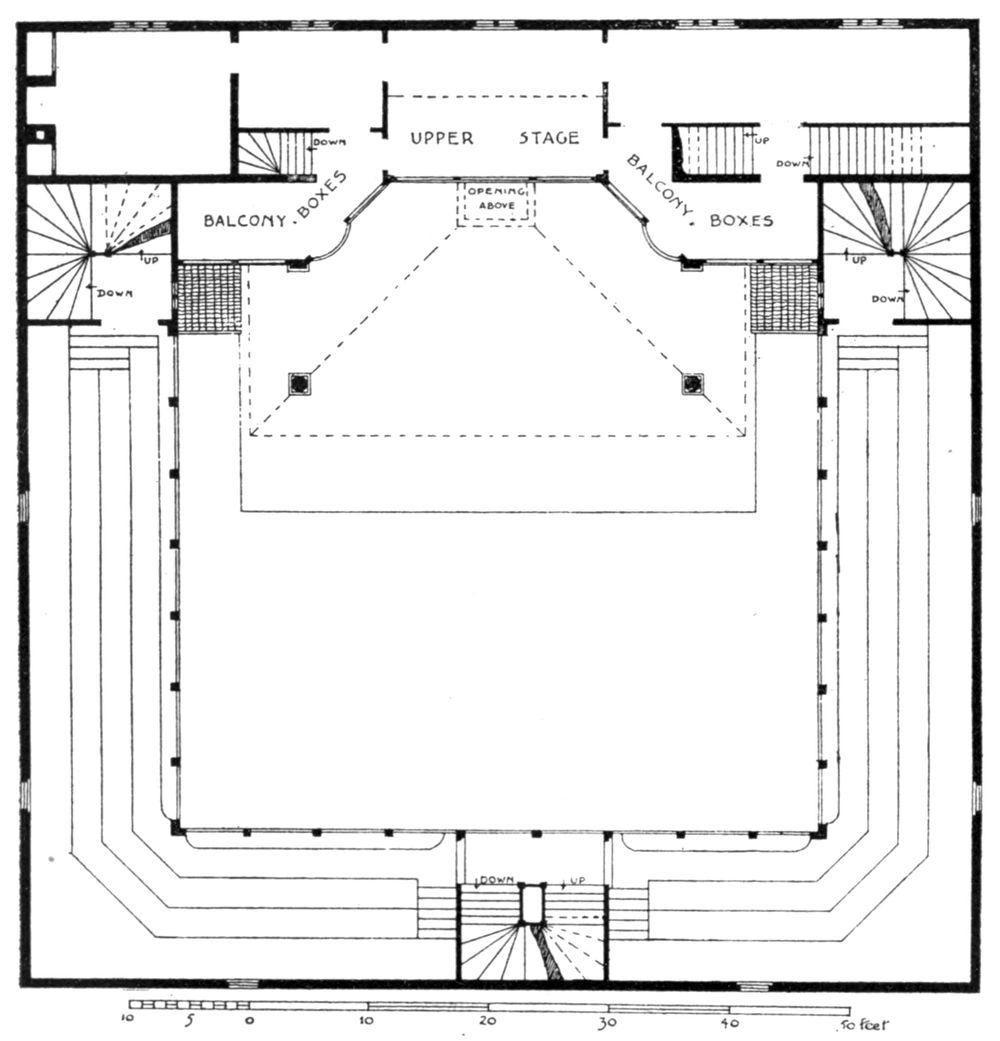

Fig. 8.—THE FORTUNE. PLAN (UPPER FLOOR).

Drawn by

Walter H. Godfrey.

The remainder of this interesting document sets forth the conditions under which the contractor is to be paid the sum of £440 “of lawfull money of Englande,” the total cost of the works. In the absence of the “plott” or plan mentioned in the document, we are fortunate in having the main dimensions of the theatre so precisely laid down for us,[9] and it is an easy matter to put them on paper. But [22]beyond these main dimensions of height and area we have really little indication of the arrangement of the stage, or the disposition of the main features of the theatre. We have, therefore, to draw our inferences from other sources, and see that their application does not clash with the terms of the specification.

[9] The “Hope” contract referred to above is a document second only in interest to the one under consideration. Its deficiency, however, in omitting all dimensions, prevents any satisfactory attempt at reconstruction. The theatre was to be built on the model of the Swan, and to be of similar “large compasse, forme, wideness and height.”

It must be first remembered that the prototype of the Elizabethan public theatres was the old galleried innyard, of which London itself possessed some of the finest examples in the land. In these inns the companies of players first gave their performances, and several names of the early theatres are reminiscent of these first associations. The Fortune was, as far as we know, the only theatre that was square on plan like the inns themselves. With the help of their analogy and of our main dimensions we are therefore able to construct the “frame” itself fairly safely, with its three tiers of open galleries supported, towards the “yard,” with posts, “wrought pilaster-wise,” adorned with carved satyrs—if thus we may interpret the description. But how is the yard entered? Various documents bearing on the disputes between proprietors and players regarding the profits of the theatres, make it almost certain that the main body of the public entered at one door into the yard, each person making the same payment, and that those who wished could then proceed to the galleries, where an extra sum was exacted from them by the “gatherers,” who made a circuit of these parts of the house, probably hence described as the “twopennie-rooms.” There was one other door, the “tyring-house door,” or stage door, through which privileged members of the public were also admitted, but whether these went thence to the gentlemen’s rooms in the galleries or whether they were accommodated with seats on the stage itself, is still a matter of much controversy.[10]

[10] These and many other points regarding the Shakespearian Stage have been ably discussed by Mr. W. J. Lawrence in his two volumes entitled The Elizabethan Playhouse and other Studies .

[23]

The staircases themselves are our next difficulty. It is quite clear from the Fortune contract that some of these were within the yard, since their roofs are distinctly specified, but their position must remain the subject of conjecture. I am inclined to think that they would be circular stairs placed in the angles of the yard nearest the entrance, but in the accompanying plan they are shown on each side of the stage, thus making use of a space for which any other purpose is not easily conceived, and obviating the obstruction of view which the first-named positions would entail. For information on this point we naturally turn to the Swan drawing, but meet with some disappointment, for the indication of “ingressus” there appears to suggest an impracticable staircase, unless it were a temporary access from the arena to the first tier of seats. This may be so, as it is known that the Swan was used for wild beast shows as well as theatrical performances, and indeed the whole appearance of the stage and mimorum ædes suggests a temporary or movable character.

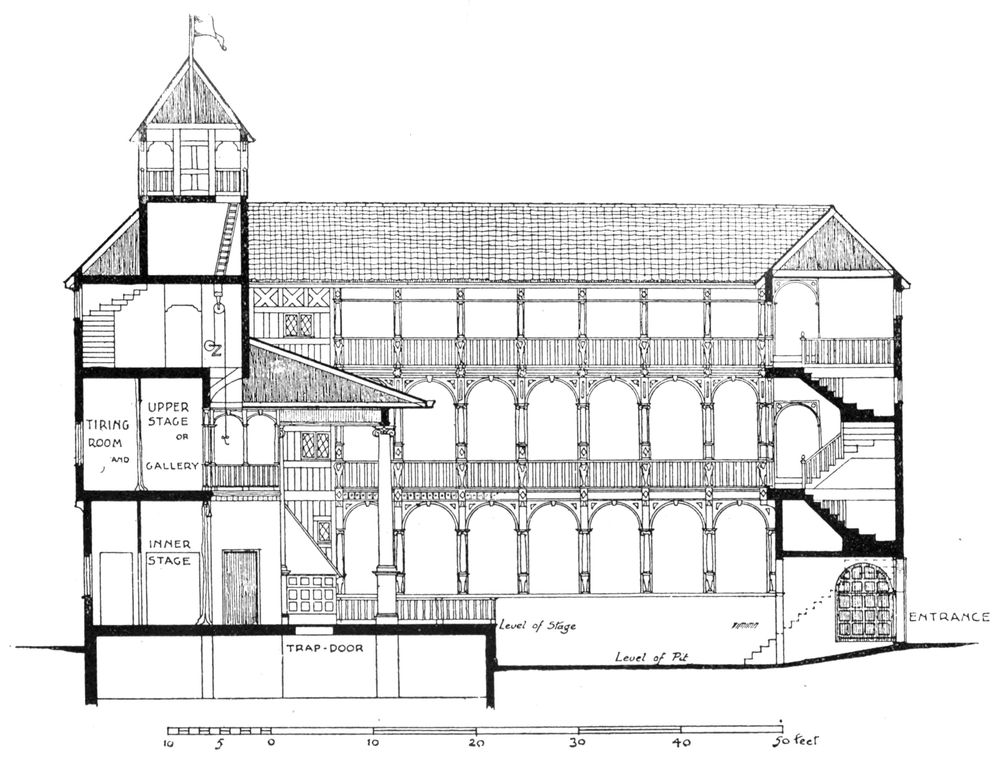

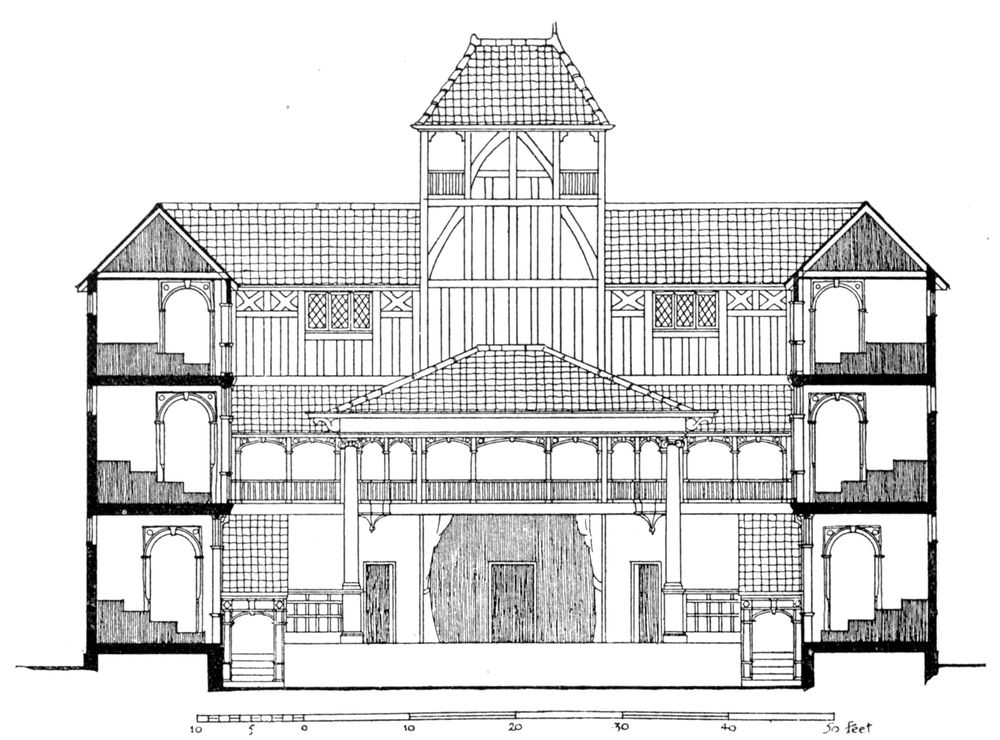

So far our task has been comparatively simple, but the stage itself, its “shadow” or roof, and the buildings behind, afford a problem which is far from having been as yet finally solved. I have, however, followed Mr. Archer’s views in these drawings, and must refer the reader to his and Mr. Lawrence’s writings on the subject for more detailed information. The following will indicate the idea in outline.

The contract specifies that the stage is to be 43 ft. wide and to extend to the centre of the yard; it also definitely mentions the “shadowe or cover” which is to be tiled, and provided with a lead gutter brought back to the rear of the stage. This latter direction certainly points to a roof similar to that shown in the “Swan” drawing, and it is reasonable to suppose that in like manner it was supported by independent columns. The lords’ boxes or minstrels’ [24]gallery,[11] in the centre of which is the upper stage, again merely follows Van Buchell’s sketch, which is corroborated by such stage directions as that in Marston’s Antonio’s Revenge (v. 2): “while the measure is dancing, Andrugio’s ghost is placed betwixt the music-houses.” This upper stage fulfilled such separate functions as Juliet’s balcony, Christopher Sly’s point of vantage in The Taming of the Shrew , or the battlements of Angiers in King John . But in the Swan Theatre there is no sign of an “inner” or rear stage beneath this gallery, and it is here that we are bound to fall back upon the literary evidence. I will quote Mr. Archer’s own words. Writing of a book by Dr. Wegener on the subject he says: “Especially as it seems to me, does he establish beyond dispute the fact that Elizabethan dramatists habitually counted on and employed that rear stage which does not appear in the Swan drawing. It served by turns as a bedroom, a cave, a shop, a study, a counting-house, a tomb. It could be curtained off, and Wegener believes that it could also be shut off by folding or sliding doors; but on this point his evidence is scarcely conclusive. That the upper stage was immediately over the rear stage is proved by the situation in Marlowe’s Jew of Malta , in which Barabas is caught in the trap he had planned for Calymath. He says to Ferneze:—

[11] John Melton, in his Astrologaster: or the Figre Caster (1620), speaking of a visit to “the Fortune in Golding-lane,” says: “There indeed a man may behold shagge-hayr’d deuills runne roaring ouer the stage with squibs in their mouthes, while drummers make thunder in the tyring-house, and the twelve-penny hirelings make artificial lightning in their heauens.”

Ferneze, however, is so shocked by the atrocious plan that he cuts the cable while Barabas, instead of his intended victim, is on the trap door. At the same moment the [27]curtains of the rear stage are opened and a boiling cauldron is revealed, into which Barabas is precipitated. It is manifest that this cauldron must have been on the inner stage. Indeed the evidence for a rear stage is even stronger than Wegener represents it to be. He says that we have no explicit mention of this stage region; forgetting, it would seem, the direction in Greene’s Alphonsus, King of Arragon , ‘Let there be a brazen head set in the middle of the place behind the stage out of which cast flames of fire.’”[12]

[12] Tribune , Aug. 10, 1907.

Fig. 9.—THE FORTUNE. SECTION THROUGH STAGE.

Drawn by

Walter H. Godfrey.

Fig. 10.—THE FORTUNE. SECTION FACING STAGE.

Drawn by

Walter H. Godfrey.

“It is no exaggeration to say that the great majority of plays contain evidence of the use of the rear stage, either as a curtained recess or as an open corridor, supplementing the two doors by providing two additional entrances. In many plays it is alternately a curtained recess and a corridor. The plays are very few in which no use at all seems to have been made of it.”[13]

[13] Tribune , Jan. 11, 1908.

From the body of evidence on this point we must conclude that the Swan drawing does not correctly show the back of the stage; or, as I would suggest, the rear wall as there represented is possibly merely a temporary stage property with its imitation of heavy barred doors, required for the one play, concealing in this exceptional case the more usual inner stage.

This point considered, the remaining arrangements are more or less a matter of detail. It would be quite unnecessary to go into the reasons for the canted side walls, the railing to stage, the planning of tiring-rooms, all of which must be to a great extent a matter of opinion. The existence of one other feature alone is incontestable—it is the turret from which the trumpeter gave the signal to the people without that the play was about to commence. It appears clearly in the “Swan” sketch, and also on nearly every external indication of the theatres in the early maps, where it rises from the encircling roof, being made the [28]more conspicuous by the flag which bore the symbol of the theatre’s name. In some drawings there appear to be three turrets, but two of these are probably the terminal finish to the staircases. As it rose above the stage of Shakespeare and the galleried courtyard with its Elizabethan audience, this timber turret crowned with picturesqueness a scene only second in dramatic interest to the ancient hillside theatre of Athens, which nursed the Hellenic drama—a drama unfolded in like manner beneath the open sky and the inspiring light of the sun.

—W. H. G.

THE TOWER OF LONDON AND ITS

DEVELOPMENT

[30]

Fig. 11.—CHAPEL OF ST. JOHN.

Photograph by

Architectural Review.

[31]

Most of the great capitals of modern Europe are cities of comparatively recent growth and importance. Berlin, Madrid, The Hague, and St. Petersburg fill little or no space in the mediæval history of their respective states, while Vienna and Brussels have been promoted from a humbler position. Rome, London, Paris, and Lisbon may, however, claim that exalted status which accrues only to the city that has been for centuries the centre of the national life. Such a position inevitably leaves its mark on the civic architecture, which, however, has been too often expunged and obliterated by the varying fashions and fortunes of more modern times. Thus it happens that London devastated by the great fire, Lisbon by the earthquake, and Paris, to a less extent, by the revolutionary changes of recent times, retain comparatively few of the concrete monuments of their great past, and even Rome herself is a memorial rather of the Renaissance than of the Middle Age. It is not surprising, then, that in the great palatine fortress of the Tower, London possesses a building, standing as it does largely intact, which is almost without a parallel amongst the European capitals. The mediæval military architecture of England generally can hardly be said to approach, far less to rival, that of the Continent, for the more settled condition and greater cohesion of the English state rendered these huge defensive works unnecessary. Scores of English castles have no recorded siege, and comparatively few of the English towns, save those on the Scotch and Welsh borders and on the coast towards France, were defended by walls. Nevertheless the fortress projected by the Conqueror and built by his successor is perhaps the most important example of military architecture which the country affords, and an attempt to explain its origin and growth will not be without interest.

[32]

The Norman Conquest found London defended on the landward side by its Roman walls, repaired in Saxon times, and by the remains of the wall, also of Roman date, along the river front. These walls were protected at intervals by semi-circular bastions more or less regularly spaced, the positions of many of which are shown on Ogilby and Morgan’s survey of the city taken in 1677. The south-eastern angle of the area thus enclosed was the site chosen by the early Norman kings for their new fortress, which was to overawe and keep in check the London citizens. It has long been a matter for some surprise that, with the exception of the White Tower or Keep and the basement of the Wakefield Tower, no trace of Norman work exists in any other part of the fortress, all the remaining towers and walls being of more recent date. The explanation of the circumstance which I here offer appears to me, from its very simplicity, to contain all the elements of probability.

Fig. 12.—PLAN OF TOWER AND ROMAN WALL.

Drawn by

Alfred W. Clapham.

Fig. 13.—PLAN OF TOWER AND ITS BASTIONS.

Drawn by

Alfred W. Clapham.

Fig. 14.—TOWERS ON EASTERN WALL.

Photograph by

Architectural Review.

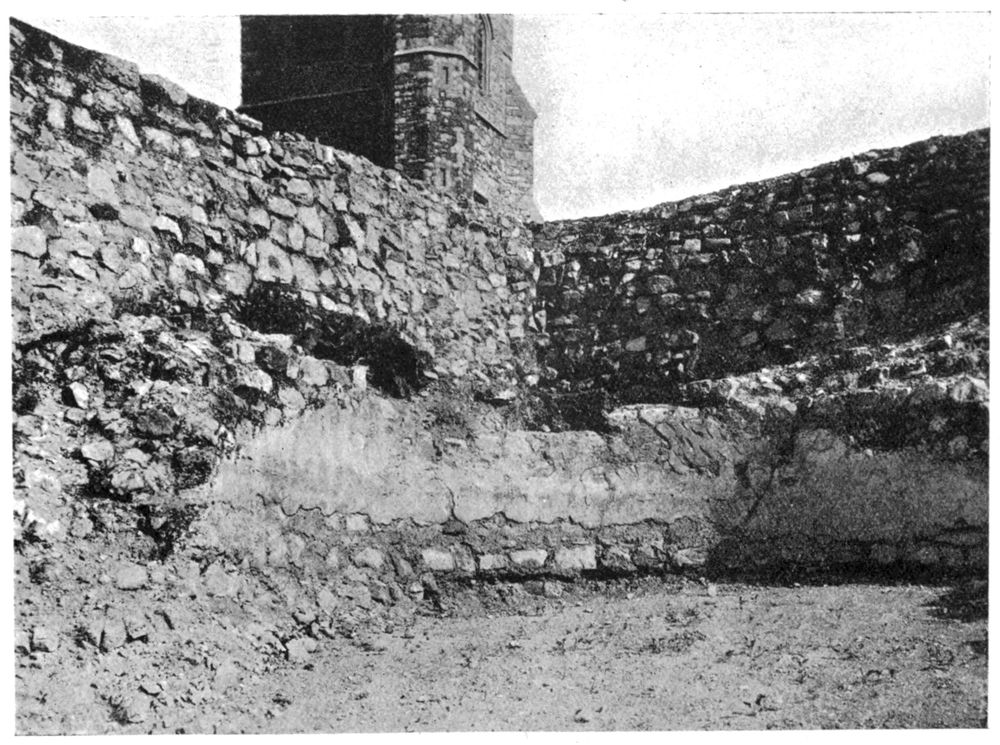

At the date of the building of the White Tower the Roman wall at this angle was probably standing intact, and the Norman builders determined to incorporate a portion of it in the defences of the castle. The course of the Roman wall on the east side of the city is well known, but the position of the southern or river front has been the subject of much conjecture. The existing evidence is, however, in my opinion, sufficient to establish this, at any rate with regard to the south-east angle. The mediæval building known as the Wardrobe Tower, of which a portion still remains standing, has been proved to stand on the base of a Roman bastion. The line of the still existing city wall between Aldgate and the Tower Ditch when produced southwards exactly strikes this point, and a portion of its base adjoining the tower has been uncovered. The lines of this fragment, however, prove that from here the wall turned slightly and headed in a direct line for the centre of the modern Lanthorn Tower, which stands partly on the foundations of its predecessor destroyed in the eighteenth century. From this there seems little doubt that the Lanthorn, like the [35]Wardrobe Tower, was built on the base of a Roman bastion. Now, the bastions to the north and south of Aldgate shown on Ogilby’s map of London are spaced about 200 ft. apart, which is approximately the distance between the Wardrobe and Lanthorn Towers. The wall must of necessity have turned at this point, and the same dimension set off on a line running parallel to the river gives the positions in succession of the Wakefield, the Bell, and the northern bastion of the Middle Tower. It seems, then, almost more than probable that we have here the river line of the Roman wall and the position of the first four bastions on its southern face. It may be further noted that all four towers are in perfect alignment, and that each of them is or was of circular form. The Norman builders probably found some of these towers still standing with the wall between them, and constructed their Keep as near as possible to the eastern line, without disturbing it, and leaving a considerable space on the south side between it and the southern wall. By this proceeding they obtained a bailey ready made enclosed on the north by the Keep and on the east and south by the Roman wall and the bastions which later became the Wardrobe, Lanthorn, and Wakefield Towers. All that was needed to complete the defences was a protection on the western side, and this was temporarily provided by a wooden stockade, the remains of which were brought to light some years ago. Subsequently a great gatehouse, called “Coldharbour,” and a strong curtain were erected on its site. These buildings formed the whole extent of the early castle, which was probably isolated by the destruction of a portion of the city wall immediately outside its limits. There is no evidence that its defences included either a fosse or mound, and thus two of the most characteristic features of Norman castle-building were absent.

It may seem improbable that buildings still standing in the twentieth century should have retained the exact positions, through successive rebuildings, of their Roman predecessors; but the more one studies the features of [36]London topography the more one is struck by the extraordinary persistence of ancient building lines. To mention two instances only: the modern warehouse on the site of the old Barbers’ Hall in Monkwell Street reproduces exactly the lines of the Roman bastion which formed its western termination, and the Apothecaries’ Hall in Blackfriars represents exactly, in position and dimensions, the hall of the guest-house where the Emperor Charles V. lodged during his visit to London in 1522.

The great Keep of the Tower of London, in spite of the unfortunate repairs and alterations of Sir Christopher Wren, must always remain amongst the finest examples of its class in the country. If it does not cover so much ground as Colchester, and is less lofty than Rochester, it possesses, in the Chapel of St. John, a feature which is unapproached by any other Norman keep in the country; and here, fortunately, the structure has been left largely in its original state. The chapel at Colchester, which occupies the same relative position, is also apsidal, but at the Tower alone is found the encircling ambulatory and the aisled nave. In the stages beneath the chapel are two crypts, the lower a gloomy vault, with massive walls and barrel roof, which carries the mind back irresistibly to the early days of Norman rule. The many writers on the Tower have found themselves unable to identify the original entrance to the Keep, but once the early arrangement of the castle is understood its position becomes quite obvious. In the western bay on the south side, at the first-floor level, is a large arched opening with a small niche cut in the thickness of the wall on either side; this, now fitted with a modern window, is the original door. It was approached by an external and probably roofed staircase from the bailey, all trace of which is now lost. A similar arrangement is found in most of the existing keep-towers of this period, the examples at Newcastle and Rising (Norfolk) being perhaps the best preserved.

The first great enlargement of the Tower probably took place in the latter half of the twelfth century, when the great [37]ditch was begun, and the western half of the inner circle of fortifications projected, which eventually transformed the castle from the early keep-and-bailey type to the concentric form which it afterwards assumed. Here again the position of the Roman city wall appears to have played a part, for this enlargement consisted of that part only of the later fortress which was within its limits, bounded outwardly by the Bell, Devereux, and Bowyer Towers. The great ditch was begun by Longchamp, Bishop of Ely and regent of the kingdom during the absence of Richard I.; but the buildings—the curtain with its towers—appear to be of slightly later date. It is evident from the remarks of Fitzstephen (temp. Henry II.) that at this date the southern wall of the city was in great part undermined and castdown by the action of the tides, and consequently the Bell Tower, though on its line, presents no more ancient features above ground than the time of John. It is, however, an exceedingly massive work, being built solid for a considerable height, and may well incorporate in its base the remains of a Roman bastion.

The line of the inner circle of defence was completed under Henry III., when the eastern half, without the ancient city wall, was added, bounded by the Martin, Salt, and the intermediate towers. Most of the existing towers were rebuilt under this king, with the exception of those already noted, but many have been marred by nineteenth-century restoration, and the Flint, Brick, and Constable’s Towers have been almost entirely rebuilt. It may be noted (if our theory be correct) that where the position of these towers was not determined by the pre-existence of the Roman works they are spaced much closer together. The first of the later towers on the east, the Salt, is comparatively close to the Lanthorn, and the straight line of the southern Roman wall is at once abandoned when nothing in the shape of old foundations could assist the thirteenth-century builder.

King Henry III. was also responsible for the second and outer line of fortifications, and for the construction of the [38]Tower Wharf. The former is on the east, north, and west sides, little more than a revetment to the great ditch. It is pierced, however, with loops, and two sally-ports are observable on the north front. On the river front this line also was defended by towers, which include the great water-gate called St. Thomas’s Tower.

There is little doubt that a great hall of timber existed in the inner bailey in Norman times, but it was not until the thirteenth century that the hall of stone was erected against its southern curtain. This building has now entirely disappeared, and even in Elizabethan times it was in a ruinous state. It abutted on the west against the Wakefield Tower, and an idea of its appearance is given in the well-known fifteenth-century view of the Tower. The upper stage of the Wakefield Tower was rebuilt with it, and communicated by a short passage with the dais end, forming a feature corresponding in some respects to the oriel of purely domestic work. The deep embrasure of the eastern window forms a small oratory—one of the many that the Tower formerly contained.

One of the most remarkable features of the fortress is the elaborate system of defences guarding the entrance from the outside world. To reach the Keep from Tower Hill it was necessary to pass through no fewer than six gatehouses—the Bulwark and Lion Gates, the Middle and Byward Towers, the Bloody Tower, and Coldharbour. The other entrances included two water-gates, and a small postern and bridge on the eastern side, protected by the Irongate and Develin Towers.

To Henry VIII. must be assigned the final important changes to the building—the construction of the two great bastions on the north face, now called Legge’s and Brass Mount. They appear in a view of Edward VI.’s coronation procession, and can hardly be earlier than his father’s time. The Lions’ Tower, now vanished, was a work of similar character, so called from the small zoological collection kept there by the later kings.

[39]

Fig. 15.—FIREPLACE, BYWARD TOWER.

Photograph by

Architectural Review.

[40]

Fig. 16.—BLOUNT MONUMENT, ST. PETER AD VINCULA.

Photograph by

Architectural Review.

[41]

Turning now, more particularly, to the architectural part of our subject, it will be found that the towers on the inner and outer circuit, which have not been rebuilt, present an infinite variety of form and construction, and each of them retains some feature of interest. The Bell Tower, besides its early vaulting, possesses a charming early eighteenth-century bell-cote; the fifth gatehouse, called the Bloody Tower, has remains of a richly-ribbed vault of the fifteenth century and a massive portcullis of timber still in working order. The great water-gate, called St. Thomas’s Tower or the Traitor’s Gate, has its little hexagonal vaulted oratory, while the water-gate of the Palace, called, for some reason unknown, the Cradle Tower, is, where unrestored, an excellent example of fourteenth-century work with a graceful vault springing from embattled corbels. The Salt Tower contains an original thirteenth-century fireplace with a massive stone hood and a curious joggled arch; the Well Tower, though small, contains an early vault; and the Martin Tower, with its eighteenth-century patchwork, has an appearance equally picturesque and venerable. The Devereux Tower adjoins a large Tudor casemate of brick, and the Beauchamp is well known for the tragic list of noble names cut upon its walls of those whom ambition or misfortune led to their final resting place in the little chapel near by.

The two outer gatehouses, called respectively the Middle and Byward Towers, are worthy of careful study. Both are of similar form—an entrance flanked by two circular bastions, the ground floors of which have groined and ribbed vaults of the fourteenth century. In addition to this the Byward Tower contains a fine early fireplace with a stone hood not unlike that in the Salt Tower, but rather more ornate. The inner face of this tower was transformed in Tudor times into a dwelling-house, and its half-timber walls and mullioned windows are still intact. Another example of Tudor domestic work is to be found in “The King’s House,” the lodging of the Lieutenant of the Tower. A succession of [42]picturesque gables with enriched bargeboards looks on to the green, made pleasant in summer by a number of trees—a scene of peace and retirement which needs the ominous presence of the two Tower ravens to recall the fact that this was the place of private execution.

Not the least interesting building in the Tower is the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula. Quite apart from the overwhelming associations of the place that enshrines the bones of queens and would-be kings, the victims of Tudor despotism or Stuart spite, there is sufficient in the building to demand attention on its architectural merit alone. One monument, that of the Blounts, father and son, is of quite unusual excellence. The mouldings and enrichments, and especially the carved masks which ornament the frieze, are of almost Italian delicacy and charm, while the pomp of heraldry in the many quartered shields adds considerably to the richness of the design. The armed alabaster effigy of Sir Richard Cholmeley, Lieutenant of the Tower under Henry VIII., stands near by, and is an excellent example of the period.

Two buildings of considerable merit were erected within the precincts during the second half of the seventeenth century. The earliest in date is the horse-armoury built by Sir Christopher Wren, and reputed to be his first work in London. It still stands against the inner eastern wall between the Salt and Broad-Arrow Towers, and while marked by a suitable simplicity of design its proportions with the roof brought out over a broad projecting cornice are admirable.

The Great Armoury, begun under James II., and completed in the time of his successor, occupied the site of the modern barracks. It was a large building with projecting wings, and an enriched façade with a sculptured pediment in the centre. It was unfortunately destroyed by fire in 1841, and nothing was saved with the exception of the carved pediment adorned with the arms of William III., now built into a wall on the eastern side of the Tower.

[43]

Fig. 17.—PEDIMENT WITH ARMS OF WILLIAM III.

Photograph by

Architectural Review.

[44]

Fig. 18.—THE HORSE-ARMOURY.

Photograph by

Architectural Review.

[45]

The modern history of the Tower is a long record of destruction and misguided restoration, and its position has sunk to the level of a show. To the average Londoner it ranks with the Zoo and the waxworks, and he regards a visit to the Tower as one of those childish things which he has long put away.

—A. W. C.

THE ROYAL PALACE

OF ELTHAM

Fig. 19.—THE HALL FROM THE SOUTH.

Photograph by

F. W. Nunn.

[49]

If Eltham Palace were not overshadowed by the close proximity of London it would undoubtedly receive a greater share of public attention, and the lordly buildings that were for long the favourite resort of our kings would, if situated in a more distant county, attract as many visitors as numerous less interesting buildings receive as a matter of course year by year. Eltham, once a fair village of Kent, is now becoming rapidly swallowed up in the ever-widening geographical expression “the suburbs of London,” and in that unsympathetic atmosphere it is almost as completely buried as is Pompeii beneath the dust and lava of a volcano, or Dunwich beneath the waters of the North Sea. Yet the remains of the royal buildings are not only exceedingly beautiful, but are of extraordinary interest as representing a palace which must have been one of the largest and most elaborate of the mediæval period. Its moat enclosed a building averaging 340 ft. by 300 ft. in area, and the total length of the courts of the palace probably approached 1,000 ft., with a width of from four to five hundred. This rivals Hampton Court, which is 720 ft. by 400 ft., and is not insignificant even when compared with the great scheme of Inigo Jones for Whitehall, which was to have measured 1,200 ft. by 900 ft.

A most remarkable plan of the whole of the apartments within the circumference of the moat has just come under my notice, preserved among the many treasures in the Hatfield papers, and with Lord Salisbury’s kind permission I have used it in preparing the plan on pages 54–55. The original drawing is in outline, and is endorsed “Eltham House,” the second word being in Lord Burghley’s handwriting. In the Public Record Office (State Papers Domestic, Elizabeth, Vol. 234, No. 78) is a plan of [50]the outer courtyard of offices, beyond the moat, of which Hasted publishes a reproduction and Mr. Gregory[14] includes a copy, apparently from an engraving, in his book. This plan, which has puzzled many earlier writers, including Pugin (who in spite of the explicit wording seems to have supposed it to be of the main court and was surprised at the absence of the hall), is signed by John Thorpe, and has the date 1590, in pencil, on the back. The plan at Hatfield is unsigned, but is to the same scale (20 ft. to the inch), and may well have been also the work of Thorpe, although it is executed with much greater care than the plan of the offices in the State Papers. Together the two plans give us the whole extent of the palace and the buildings within its precincts. (See pp. 54 and 55.)

[14] The Story of Royal Eltham , by R. R. C. Gregory.

The site at Eltham has never been properly investigated, and the field is open for a very considerable amount of work in verifying or correcting these plans and identifying the positions of the buildings shown thereon. In presenting, therefore, the general arrangement as outlined on the existing manuscripts I intend to do no more than introduce the subject and place one or two considerations at the disposal of those who may complete the work. By the courtesy of Mr. R. R. C. Gregory and Mr. F. W. Nunn I am permitted to reproduce some interesting photographs which were specially taken for the former’s book on Eltham, showing a few of the remains as they stand at the present day.

Although the two plans are full of detail, and evidently drawn with great care, they share with practically all ancient plans a certain inaccuracy which is often very puzzling. There can be no doubt at all about the competence of the surveyors of the Elizabethan period to make perfectly accurate drawings, and their draughtsmanship is surprisingly similar to that of the present day, showing moreover a care which is often above the modern [51]average. Yet they fail us repeatedly, wherever enough of the old work remains to test their accuracy, and their errors are apparently so needless that we are quite at a loss to account for them. Not a little controversy has been waged over the collection of Thorpe’s drawings in the Soane Museum on this very point, and while the draughtsman has incurred serious blame, and much scepticism has been aroused as to the genuineness of the plans, the problem has been left unsolved, and one continues to find at least as much evidence to corroborate as to confute their author. Perhaps if the architect of the present day would reflect upon his own experience he would find less to surprise him in the work of his sixteenth-century predecessor. It is not a rare but a frequent occurrence, even in these days of accurate instruments and multiplied facilities for drawing, to meet with plans that are hastily drawn and inaccurately set down. The surveyor has often to make a rapid survey; he occasionally misreads his own notes and figures; a few important dimensions are sometimes omitted, and when the drawing is made at some distance from the site a little guesswork intrudes; and so much is this so that even official surveys—though absolutely trustworthy for their own purposes—are found to have their percentage of mistakes. But if these lapses occur in finished plans, how numerous are the errors in unfinished drafts or sketch-plans which are made for general purposes only! And who is to say, when we come upon an old drawing, often accidentally preserved in a parcel of MSS., that this is merely a first sketch—a rough draft of which the corrected version has long ago perished? These considerations, I submit, should make us less ready to blame the draughtsman, but at the same time will prepare us for a greater vigilance in checking his work and taking his evidence with the greatest caution.

The plan of the palace proper at Eltham, comprising the buildings within the moat, is, as far as one can judge, very fairly accurate. The foundations of the outside line [52]of fortifications still exist, and correspond in the main to those shown. This outer wall is apparently of sixteenth-century date, and is not unlikely to have been partly the work of Queen Elizabeth. It formed on three sides a broad terrace between the moat and Bishop Bec’s original walls. That the palace was first fortified by Bec[15] is made extremely likely by the general resemblance of the plan to his castle at Somerton, where the area enclosed by the moat has a square plan similar to that of Eltham, with one side lengthened in the same manner, making one of the angles less and one more than a right angle.

[15] Pugin gives the following note: “Somerton Castle in Lincolnshire built also by Anthony Beke, was of a quadrangle plan with four polygonal towers at the corners, and was encompassed by very strong banks and deep moats beyond the walls.” Robert de Graystanes, an ancient historian of the Church of Durham, in his account of Bishop Bec’s works, says: “Castrum de Somerton juxta Lincoln, et manerium de Eltham juxta London, curiosissime ædificavit; sed primum regi et secundum reginae postea contulit” (Anglia Sacra i. 755).

The three principal towers at the angles and the one in the centre of the south front are probably his work. The last-named tower evidently guarded the south entrance, and it may have been the remains of this that have been spoken of as “castle-like” in earlier descriptions of the ruins. Some later hand probably inserted the fireplaces in these towers.

A reference to the large-scale Ordnance map will show how accurately the fortifications follow the line of the Elizabethan plan. The view of the palace and moat published by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck in 1735, of which there is a copy in the King’s Library (British Museum), shows the north-east part of this wall fairly intact, and the eastern bastion raised like a tower and covered with a shaped lead roof resembling a cupola. It is probable that most of the building shown by Buck upon the outer walls was erected after the palace was despoiled, and the roofed bastion is not unlikely to have been but an eighteenth-century summer-house, the work perhaps of one of the line of Sir John Shaw.

[53]

Fig. 20.—BRIDGE OVER MOAT.

Photograph by

F. W. Nunn.

[55]

Fig. 21.—COMPLETE PLAN OF PALACE.

Drawn by

Walter H. Godfrey.

[56]

Fig. 22.—INTERIOR OF HALL.

Photograph by

H.M. Office of Works.

[57]

The western line of the outer wall is overhung by buildings evidently of the Tudor period, and the fine range of bay windows shown on the Elizabethan plan is borne out in all but a few minor particulars by existing foundations. Further than this, a large portion of the main block of buildings that crosses the fortified area from west to east is here to corroborate the survey, and the great hall with its apartments to the east is found upon the precise line indicated on the drawing. The hall itself is correctly shown, except for the position of one buttress and an adjoining piece of brickwork, and the beautiful fifteenth-century bridge adds valuable evidence supporting the plan.

Of the things revealed by this plan, none will prove of greater interest than the beautiful chapel which, to gain its right orientation, was placed so picturesquely across the great courtyard.

In the Parliamentary Survey of Eltham in 1649 the “fair chapel” is mentioned first in the list of royal apartments, before the hall itself, and in this document we come upon a little bit of unexpected news regarding London. Sir Theodore Mayerne, formerly physician to James I.—he was seventy-six years of age at the time of the survey—is found to be ranger of the park at a salary of £6 1s. 8d., paid from the customs of the Port of London. The survey tells us, however, that he no longer resided at Eltham, but at his house at “Chelsey,” thus confirming the tradition that it was he who originally built the only one of Chelsea’s old palaces that remains—the house which, rebuilt by the Earls of Lindsey, still stands, although divided into several dwellings, overlooking the Thames, just west of Battersea Bridge.

This survey goes on to relate that, beside the fair chapel and great hall, there were forty-six rooms and offices on the ground floor, with two large cellars; and on the upper floor, seventeen lodging rooms on the king’s side, twelve on the queen’s side, and nine on the prince’s side,—in all thirty-eight. Further research would no doubt identify [58]the position of these three suites of apartments, which are not, of course, evident on a plan of the ground floor. The survey mentions the outer “green court” with its thirty-five “bayes of building” on three sides, which contained the offices to which we refer below.

It appears from the building accounts of the reign of Henry VI. that the chapel was being completed in his reign, as mention is made of the construction of a screen and of the two staircases to the gallery above. But the “fair chapel” of the Parliamentary Survey, shown on the Hatfield plan, was the work of Henry VIII. The accounts still exist of the taking down of the old chapel, and of its rebuilding by Henry some twelve feet nearer to the hall. The very massive wall standing west of the chapel on the plan probably marks the position of the western end of the former building. Henry VIII. has left detailed directions as to the erection and furnishing of this chapel, which must have been one of the most beautiful buildings of its time.

The accounts also fix the date of the great hall, which has so far been only conjectural. One of the fortnightly returns of expenditure when the roof was being framed together is headed “Coste and expence don upon the bildying of the newe Halle wytn the manor of Elthm in the charge of James Hatefeld from Sonday the xixth day of Septembr the xixth yer of the reigne of our Sovreign lord King Edward the iiijth unto Sonday the iiid of Octobr the yer aforeseid.” The wages of the freemasons, hardhewers, carpenters (including chief warden and underwarden) plumbers, smythes, labourers, and clerke are all given. We also learn that thirty great iron “spykynggs” for the roof were bought, such, no doubt, as were found in the framework of the roof of Crosby Hall, and ten great “clampes of yron for the bynddyng of the princyples.” Moreover there is a note of six loads of “Raygatestone” at four shillings a load, the same stone employed at Crosby Hall, commonly known as Reigate firestone. In all £140 13s. 6d. was spent in the fortnight.

[59]

From this it appears that Crosby Hall, built in 1466, was started some ten years or more before the hall of Eltham Palace; and yet the former is of much later character in almost all its details, and particularly in its panelled roof. The royal palace evidently clung to the traditional methods of design, and they were certainly capable of a more magnificent effect. It will be seen that the octagonal hearth, about which there has been much conjecture, is shown clearly in the plan in front of the throne.